An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Wiley - PMC COVID-19 Collection

The coronavirus ( COVID ‐19) pandemic's impact on mental health

Bilal javed.

1 Faculty of Sciences, PMAS Arid Agriculture University, Rawalpindi Pakistan

2 Roy & Diana Vagelos Laboratories, Department of Chemistry, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia Pennsylvania, USA

Abdullah Sarwer

3 Nawaz Sharif Medical College, University of Gujrat, Gujrat Pakistan

4 Department of General Medicine, Allama Iqbal Memorial Teaching Hospital, Sialkot Pakistan

Erik B. Soto

5 Graduate School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh Pennsylvania, USA

Zia‐ur‐Rehman Mashwani

Throughout the world, the public is being informed about the physical effects of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and steps to take to prevent exposure to the coronavirus and manage symptoms of COVID‐19 if they appear. However, the effects of this pandemic on one's mental health have not been studied at length and are still not known. As all efforts are focused on understanding the epidemiology, clinical features, transmission patterns, and management of the COVID‐19 outbreak, there has been very little concern expressed over the effects on one's mental health and on strategies to prevent stigmatization. People's behavior may greatly affect the pandemic's dynamic by altering the severity, transmission, disease flow, and repercussions. The present situation requires raising awareness in public, which can be helpful to deal with this calamity. This perspective article provides a detailed overview of the effects of the COVID‐19 outbreak on the mental health of people.

1. INTRODUCTION

A pandemic is not just a medical phenomenon; it affects individuals and society and causes disruption, anxiety, stress, stigma, and xenophobia. The behavior of an individual as a unit of society or a community has marked effects on the dynamics of a pandemic that involves the level of severity, degree of flow, and aftereffects. 1 Rapid human‐to‐human transmission of the SARS‐CoV‐2 resulted in the enforcement of regional lockdowns to stem the further spread of the disease. Isolation, social distancing, and closure of educational institutes, workplaces, and entertainment venues consigned people to stay in their homes to help break the chain of transmission. 2 However, the restrictive measures undoubtedly have affected the social and mental health of individuals from across the board. 3

As more and more people are forced to stay at home in self‐isolation to prevent the further flow of the pathogen at the societal level, governments must take the necessary measures to provide mental health support as prescribed by the experts. Professor Tiago Correia highlighted in his editorial as the health systems worldwide are assembling exclusively to fight the COVID‐19 outbreak, which can drastically affect the management of other diseases including mental health, which usually exacerbates during the pandemic. 4 The psychological state of an individual that contributes toward the community health varies from person‐to‐person and depends on his background and professional and social standings. 5

Quarantine and self‐isolation can most likely cause a negative impact on one's mental health. A review published in The Lancet said that the separation from loved ones, loss of freedom, boredom, and uncertainty can cause a deterioration in an individual's mental health status. 6 To overcome this, measures at the individual and societal levels are required. Under the current global situation, both children and adults are experiencing a mix of emotions. They can be placed in a situation or an environment that may be new and can be potentially damaging to their health. 7

2. CHILDREN AND TEENS AT RISK

Children, away from their school, friends, and colleagues, staying at home can have many questions about the outbreak and they look toward their parents or caregivers to get the answer. Not all children and parents respond to stress in the same way. Kids can experience anxiety, distress, social isolation, and an abusive environment that can have short‐ or long‐term effects on their mental health. Some common changes in children's behavior can be 8 :

- Excessive crying and annoying behavior

- Increased sadness, depression, or worry

- Difficulties with concentration and attention

- Changes in, or avoiding, activities that they enjoyed in the past

- Unexpected headaches and pain throughout their bodies

- Changes in eating habits

To help offset negative behaviors, requires parents to remain calm, deal with the situation wisely, and answer all of the child's questions to the best of their abilities. Parents can take some time to talk to their children about the COVID‐19 outbreak and share some positive facts, figures, and information. Parents can help to reassure them that they are safe at home and encourage them to engage in some healthy activities including indoor sports and some physical and mental exercises. Parents can also develop a home schedule that can help their children to keep up with their studies. Parents should show less stress or anxiety at their home as children perceive and feel negative energy from their parents. The involvement of parents in healthy activities with their children can help to reduce stress and anxiety and bring relief to the overall situation. 9

3. ELDERS AND PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES AT RISK

Elderly people are more prone to the COVID‐19 outbreak due to both clinical and social reasons such as having a weaker immune system or other underlying health conditions and distancing from their families and friends due to their busy schedules. According to medical experts, people aged 60 or above are more likely to get the SARS‐CoV‐2 and can develop a serious and life‐threatening condition even if they are in good health. 10

Physical distancing due to the COVID‐19 outbreak can have drastic negative effects on the mental health of the elderly and disabled individuals. Physical isolation at home among family members can put the elderly and disabled person at serious mental health risk. It can cause anxiety, distress, and induce a traumatic situation for them. Elderly people depend on young ones for their daily needs, and self‐isolation can critically damage a family system. The elderly and disabled people living in nursing homes can face extreme mental health issues. However, something as simple as a phone call during the pandemic outbreak can help to console elderly people. COVID‐19 can also result in increased stress, anxiety, and depression among elderly people already dealing with mental health issues.

Family members may witness any of the following changes to the behavior of older relatives 11 ;

- Irritating and shouting behavior

- Change in their sleeping and eating habits

- Emotional outbursts

The World Health Organization suggests that family members should regularly check on older people living within their homes and at nursing facilities. Younger family members should take some time to talk to older members of the family and become involved in some of their daily routines if possible. 12

4. HEALTH WORKERS AT RISK

Doctors, nurses, and paramedics working as a front‐line force to fight the COVID‐19 outbreak may be more susceptible to develop mental health symptoms. Fear of catching a disease, long working hours, unavailability of protective gear and supplies, patient load, unavailability of effective COVID‐19 medication, death of their colleagues after exposure to COVID‐19, social distancing and isolation from their family and friends, and the dire situation of their patients may take a negative toll of the mental health of health workers. The working efficiency of health professionals may decrease gradually as the pandemic prevails. Health workers should take short breaks between their working hours and deal with the situation calmly and in a relaxed manner. 5

5. STIGMATIZATION

Generally, people recently released from quarantine can experience stigmatization and develop a mix of emotions. Everyone may feel differently and have a different welcome by society when they come out of quarantine. People who recently recovered may have to exercise social distancing from their family members, friends, and relatives to ensure their family's safety because of unprecedented viral nature. Different age groups respond to this social behavior differently, which can have both short‐ and long‐term effects. 1

Health workers trying to save lives and protect society may also experience social distancing, changes in the behavior of family members, and stigmatization for being suspected of carrying COVID‐19. 6 Previously infected individuals and health professionals (dealing pandemic) may develop sadness, anger, or frustration because friends or loved ones may have unfounded fears of contracting the disease from contact with them, even though they have been determined not to be contagious. 5

However, the current situation requires a clear understanding of the effects of the recent outbreak on the mental health of people of different age groups to prevent and avoid the COVID‐19 pandemic.

6. TAKE HOME MESSAGE

- Understanding the effects of the COVID‐19 outbreak on the mental health of various populations are as important as understanding its clinical features, transmission patterns, and management.

- Spending time with family members including children and elderly people, involvement in different healthy exercises and sports activities, following a schedule/routine, and taking a break from traditional and social media can all help to overcome mental health issues.

- Public awareness campaigns focusing on the maintenance of mental health in the prevailing situation are urgently needed.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

B.J. and A.S. devised the study. B.J. collected and analyzed the data and wrote the first draft. E.B.S. edited and revised the manuscript. A.S. and Z.M. provided useful information. All the authors contributed to the subsequent drafts. The authors reviewed and endorsed the final submission.

Javed B, Sarwer A, Soto EB, Mashwani Z‐R. The coronavirus (COVID‐19) pandemic's impact on mental health . Int J Health Plann Mgmt . 2020; 35 :993–996. 10.1002/hpm.3008 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Open access

- Published: 11 April 2023

Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health, anxiety, and depression

- Ida Kupcova 1 ,

- Lubos Danisovic 1 ,

- Martin Klein 2 &

- Stefan Harsanyi 1

BMC Psychology volume 11 , Article number: 108 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

9084 Accesses

12 Citations

38 Altmetric

Metrics details

The COVID-19 pandemic affected everyone around the globe. Depending on the country, there have been different restrictive epidemiologic measures and also different long-term repercussions. Morbidity and mortality of COVID-19 affected the mental state of every human being. However, social separation and isolation due to the restrictive measures considerably increased this impact. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), anxiety and depression prevalence increased by 25% globally. In this study, we aimed to examine the lasting effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the general population.

A cross-sectional study using an anonymous online-based 45-question online survey was conducted at Comenius University in Bratislava. The questionnaire comprised five general questions and two assessment tools the Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) and the Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS). The results of the Self-Rating Scales were statistically examined in association with sex, age, and level of education.

A total of 205 anonymous subjects participated in this study, and no responses were excluded. In the study group, 78 (38.05%) participants were male, and 127 (61.69%) were female. A higher tendency to anxiety was exhibited by female participants (p = 0.012) and the age group under 30 years of age (p = 0.042). The level of education has been identified as a significant factor for changes in mental state, as participants with higher levels of education tended to be in a worse mental state (p = 0.006).

Conclusions

Summarizing two years of the COVID-19 pandemic, the mental state of people with higher levels of education tended to feel worse, while females and younger adults felt more anxiety.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

The first mention of the novel coronavirus came in 2019, when this variant was discovered in the city of Wuhan, China, and became the first ever documented coronavirus pandemic [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. At this time there was only a sliver of fear rising all over the globe. However, in March 2020, after the declaration of a global pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO), the situation changed dramatically [ 4 ]. Answering this, yet an unknown threat thrust many countries into a psycho-socio-economic whirlwind [ 5 , 6 ]. Various measures taken by governments to control the spread of the virus presented the worldwide population with a series of new challenges to which it had to adjust [ 7 , 8 ]. Lockdowns, closed schools, losing employment or businesses, and rising deaths not only in nursing homes came to be a new reality [ 9 , 10 , 11 ]. Lack of scientific information on the novel coronavirus and its effects on the human body, its fast spread, the absence of effective causal treatment, and the restrictions which harmed people´s social life, financial situation and other areas of everyday life lead to long-term living conditions with increased stress levels and low predictability over which people had little control [ 12 ].

Risks of changes in the mental state of the population came mainly from external risk factors, including prolonged lockdowns, social isolation, inadequate or misinterpreted information, loss of income, and acute relationship with the rising death toll. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, anxiety and depression prevalence increased by 25% globally [ 13 ]. Unemployment specifically has been proven to be also a predictor of suicidal behavior [ 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 ]. These risk factors then interact with individual psychological factors leading to psychopathologies such as threat appraisal, attentional bias to threat stimuli over neutral stimuli, avoidance, fear learning, impaired safety learning, impaired fear extinction due to habituation, intolerance of uncertainty, and psychological inflexibility. The threat responses are mediated by the limbic system and insula and mitigated by the pre-frontal cortex, which has also been reported in neuroimaging studies, with reduced insula thickness corresponding to more severe anxiety and amygdala volume correlated to anhedonia as a symptom of depression [ 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 ]. Speaking in psychological terms, the pandemic disturbed our core belief, that we are safe in our communities, cities, countries, or even the world. The lost sense of agency and confidence regarding our future diminished the sense of worth, identity, and meaningfulness of our lives and eroded security-enhancing relationships [ 24 ].

Slovakia introduced harsh public health measures in the first wave of the pandemic, but relaxed these measures during the summer, accompanied by a failure to develop effective find, test, trace, isolate and support systems. Due to this, the country experienced a steep growth in new COVID-19 cases in September 2020, which lead to the erosion of public´s trust in the government´s management of the situation [ 25 ]. As a means to control the second wave of the pandemic, the Slovak government decided to perform nationwide antigen testing over two weekends in November 2020, which was internationally perceived as a very controversial step, moreover, it failed to prevent further lockdowns [ 26 ]. In addition, there was a sharp rise in the unemployment rate since 2020, which continued until July 2020, when it gradually eased [ 27 ]. Pre-pandemic, every 9th citizen of Slovakia suffered from a mental health disorder, according to National Statistics Office in 2017, the majority being affective and anxiety disorders. A group of authors created a web questionnaire aimed at psychiatrists, psychologists, and their patients after the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Slovakia. The results showed that 86.6% of respondents perceived the pathological effect of the pandemic on their mental status, 54.1% of whom were already treated for affective or anxiety disorders [ 28 ].

In this study, we aimed to examine the lasting effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the general population. This study aimed to assess the symptoms of anxiety and depression in the general public of Slovakia. After the end of epidemiologic restrictive measures (from March to May 2022), we introduced an anonymous online questionnaire using adapted versions of Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) and Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) [ 29 , 30 ]. We focused on the general public because only a portion of people who experience psychological distress seek professional help. We sought to establish, whether during the pandemic the population showed a tendency to adapt to the situation or whether the anxiety and depression symptoms tended to be present even after months of better epidemiologic situation, vaccine availability, and studies putting its effects under review [ 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 ].

Materials and Methods

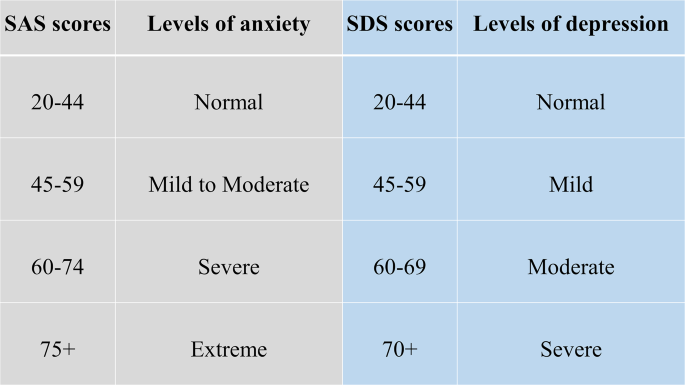

This study utilized a voluntary and anonymous online self-administered questionnaire, where the collected data cannot be linked to a specific respondent. This study did not process any personal data. The questionnaire consisted of 45 questions. The first three were open-ended questions about participants’ sex, age (date of birth was not recorded), and education. Followed by 2 questions aimed at mental health and changes in the will to live. Further 20 and 20 questions consisted of the Zung SAS and Zung SDS, respectively. Every question in SAS and SDS is scored from 1 to 4 points on a Likert-style scale. The scoring system is introduced in Fig. 1 . Questions were presented in the Slovak language, with emphasis on maintaining test integrity, so, if possible, literal translations were made from English to Slovak. The questionnaire was created and designed in Google Forms®. Data collection was carried out from March 2022 to May 2022. The study was aimed at the general population of Slovakia in times of difficult epidemiologic and social situations due to the high prevalence and incidence of COVID-19 cases during lockdowns and social distancing measures. Because of the character of this web-based study, the optimal distribution of respondents could not be achieved.

Categories of Zung SAS and SDS scores with clinical interpretation

During the course of this study, 205 respondents answered the anonymous questionnaire in full and were included in the study. All respondents were over 18 years of age. The data was later exported from Google Forms® as an Excel spreadsheet. Coding and analysis were carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0, Armonk, NY, USA). Subject groups were created based on sex, age, and education level. First, sex due to differences in emotional expression. Second, age was a risk factor due to perceived stress and fear of the disease. Last, education due to different approaches to information. In these groups four factors were studied: (1) changes in mental state; (2) affected will to live, or frequent thoughts about death; (3) result of SAS; (4) result of SDS. For SAS, no subject in the study group scored anxiety levels of “severe” or “extreme”. Similarly for SDS, no subject depression levels reached “moderate” or “severe”. Pearson’s chi-squared test(χ2) was used to analyze the association between the subject groups and studied factors. The results were considered significant if the p-value was less than 0.05.

Ethical permission was obtained from the local ethics committee (Reference number: ULBGaKG-02/2022). This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All methods were carried out following the institutional guidelines. Due to the anonymous design of the study and by the institutional requirements, written informed consent for participation was not required for this study.

In the study, out of 205 subjects in the study group, 127 (62%) were female and 78 (38%) were male. The average age in the study group was 35.78 years of age (range 19–71 years), with a median of 34 years. In the age group under 30 years of age were 34 (16.6%) subjects, while 162 (79%) were in the range from 31 to 49 and 9 (0.4%) were over 50 years old. 48 (23.4%) participants achieved an education level of lower or higher secondary and 157 (76.6%) finished university or higher. All answers of study participants were included in the study, nothing was excluded.

In Tables 1 and 2 , we can see the distribution of changes in mental state and will to live as stated in the questionnaire. In Table 1 we can see a disproportion in education level and mental state, where participants with higher education tended to feel worse much more than those with lower levels of education. Changes based on sex and age did not show any statistically significant results.

In Table 2 . we can see, that decreased will to live and frequent thoughts about death were only marginally present in the study group, which suggests that coping mechanisms play a huge role in adaptation to such events (e.g. the global pandemic). There is also a possibility that living in times of better epidemiologic situations makes people more likely to forget about the bad past.

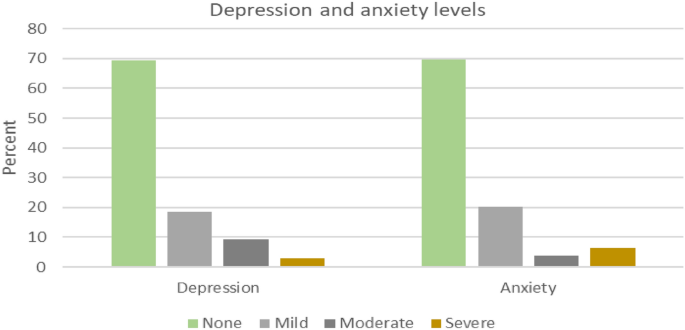

Anxiety and depression levels as seen in Tables 3 and 4 were different, where female participants and the age group under 30 years of age tended to feel more anxiety than other groups. No significant changes in depression levels based on sex, age, and education were found.

Compared to the estimated global prevalence of depression in 2017 (3.44%), in 2021 it was approximately 7 times higher (25%) [ 14 ]. Our study did not prove an increase in depression, while anxiety levels and changes in the mental state did prove elevated. No significant changes in depression levels go in hand with the unaffected will to live and infrequent thoughts about death, which were important findings, that did not supplement our primary hypothesis that the fear of death caused by COVID-19 or accompanying infections would enhance personal distress and depression, leading to decreases in studied factors. These results are drawn from our limited sample size and uneven demographic distribution. Suicide ideations rose from 5% pre-pandemic to 10.81% during the pandemic [ 35 ]. In our study, 9.3% of participants experienced thoughts about death and since we did not specifically ask if they thought about suicide, our results only partially correlate with suicidal ideations. However, as these subjects exhibited only moderate levels of anxiety and mild levels of depression, the rise of suicide ideations seems unlikely. The rise in suicidal ideations seemed to be especially true for the general population with no pre-existing psychiatric conditions in the first months of the pandemic [ 36 ]. The policies implemented by countries to contain the pandemic also took a toll on the population´s mental health, as it was reported, that more stringent policies, mainly the social distancing and perceived government´s handling of the pandemic, were related to worse psychological outcomes [ 37 ]. The effects of lockdowns are far-fetched and the increases in mental health challenges, well-being, and quality of life will require a long time to be understood, as Onyeaka et al. conclude [ 10 ]. These effects are not unforeseen, as the global population suffered from life-altering changes in the structure and accessibility of education or healthcare, fluctuations in prices and food insecurity, as well as the inevitable depression of the global economy [ 38 ].

The loneliness associated with enforced social distancing leads to an increase in depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress in children in adolescents, with possible long-term sequelae [ 39 ]. The increase in adolescent self-injury was 27.6% during the pandemic [ 40 ]. Similar findings were described in the middle-aged and elderly population, in which both depression and anxiety prevalence rose at the beginning of the pandemic, during the pandemic, with depression persisting later in the pandemic, while the anxiety-related disorders tended to subside [ 41 ]. Medical professionals represented another specific at-risk group, with reported anxiety and depression rates of 24.94% and 24.83% respectively [ 42 ]. The dynamic of psychopathology related to the COVID-19 pandemic is not clear, with studies reporting a return to normal later in 2020, while others describe increased distress later in the pandemic [ 20 , 43 ].

Concerning the general population, authors from Spain reported that lockdowns and COVID-19 were associated with depression and anxiety [ 44 ]. In January 2022 Zhao et al., reported an elevation in hoarding behavior due to fear of COVID-19, while this process was moderated by education and income levels, however, less in the general population if compared to students [ 45 ]. Higher education levels and better access to information could improve persons’ fear of the unknown, however, this fact was not consistent with our expectations in this study, as participants with university education tended to feel worse than participants with lower education. A study on adolescents and their perceived stress in the Czech Republic concluded that girls are more affected by lockdowns. The strongest predictor was loneliness, while having someone to talk to, scored the lowest [ 46 ]. Garbóczy et al. reported elevated perceived stress levels and health anxiety in 1289 Hungarian and international students, also affected by disengagement from home and inadequate coping strategies [ 47 ]. Wathelet et al. conducted a study on French University students confined during the pandemic with alarming results of a high prevalence of mental health issues in the study group [ 48 ]. Our study indicated similar results, as participants in the age group under 30 years of age tended to feel more anxious than others.

In conclusion, we can say that this pandemic changed the lives of many. Many of us, our family members, friends, and colleagues, experienced life-altering events and complicated situations unseen for decades. Our decisions and actions fueled the progress in medicine, while they also continue to impact society on all levels. The long-term effects on adolescents are yet to be seen, while effects of pain, fear, and isolation on the general population are already presenting themselves.

The limitations of this study were numerous and as this was a web-based study, the optimal distribution of respondents could not be achieved, due to the snowball sampling strategy. The main limitation was the small sample size and uneven demographic distribution of respondents, which could impact the representativeness of the studied population and increase the margin of error. Similarly, the limited number of older participants could significantly impact the reported results, as age was an important risk factor and thus an important stressor. The questionnaire omitted the presence of COVID-19-unrelated life-changing events or stressors, and also did not account for any preexisting condition or risk factor that may have affected the outcome of the used assessment scales.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to compliance with institutional guidelines but they are available from the corresponding author (SH) on a reasonable request.

Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727–33.

Liu Y-C, Kuo R-L, Shih S-R. COVID-19: the first documented coronavirus pandemic in history. Biomed J. 2020;43:328–33.

Advice for the public on COVID-19 – World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public . Accessed 13 Nov 2022.

Osterrieder A, Cuman G, Pan-Ngum W, Cheah PK, Cheah P-K, Peerawaranun P, et al. Economic and social impacts of COVID-19 and public health measures: results from an anonymous online survey in Thailand, Malaysia, the UK, Italy and Slovenia. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e046863.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Mofijur M, Fattah IMR, Alam MA, Islam ABMS, Ong HC, Rahman SMA, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on the social, economic, environmental and energy domains: Lessons learnt from a global pandemic. Sustainable Prod Consum. 2021;26:343–59.

Article Google Scholar

Vlachos J, Hertegård E, Svaleryd B. The effects of school closures on SARS-CoV-2 among parents and teachers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118:e2020834118.

Ludvigsson JF, Engerström L, Nordenhäll C, Larsson E, Open Schools. Covid-19, and child and teacher morbidity in Sweden. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:669–71.

Miralles O, Sanchez-Rodriguez D, Marco E, Annweiler C, Baztan A, Betancor É, et al. Unmet needs, health policies, and actions during the COVID-19 pandemic: a report from six european countries. Eur Geriatr Med. 2021;12:193–204.

Onyeaka H, Anumudu CK, Al-Sharify ZT, Egele-Godswill E, Mbaegbu P. COVID-19 pandemic: a review of the global lockdown and its far-reaching effects. Sci Prog. 2021;104:368504211019854.

The Lancet null. India under COVID-19 lockdown. Lancet. 2020;395:1315.

Lo Coco G, Gentile A, Bosnar K, Milovanović I, Bianco A, Drid P, et al. A cross-country examination on the fear of COVID-19 and the sense of loneliness during the First Wave of COVID-19 outbreak. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:2586.

COVID-19 pandemic. triggers 25% increase in prevalence of anxiety and depression worldwide. https://www.who.int/news/item/02-03-2022-covid-19-pandemic-triggers-25-increase-in-prevalence-of-anxiety-and-depression-worldwide . Accessed 14 Nov 2022.

Bueno-Notivol J, Gracia-García P, Olaya B, Lasheras I, López-Antón R, Santabárbara J. Prevalence of depression during the COVID-19 outbreak: a meta-analysis of community-based studies. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2021;21:100196.

Hajek A, Sabat I, Neumann-Böhme S, Schreyögg J, Barros PP, Stargardt T, et al. Prevalence and determinants of probable depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic in seven countries: longitudinal evidence from the european COvid Survey (ECOS). J Affect Disord. 2022;299:517–24.

Piumatti G, Levati S, Amati R, Crivelli L, Albanese E. Trajectories of depression, anxiety and stress among adults during the COVID-19 pandemic in Southern Switzerland: the Corona Immunitas Ticino cohort study. Public Health. 2022;206:63–9.

Korkmaz H, Güloğlu B. The role of uncertainty tolerance and meaning in life on depression and anxiety throughout Covid-19 pandemic. Pers Indiv Differ. 2021;179:110952.

McIntyre RS, Lee Y. Projected increases in suicide in Canada as a consequence of COVID-19. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290:113104.

Funkhouser CJ, Klemballa DM, Shankman SA. Using what we know about threat reactivity models to understand mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Behav Res Ther. 2022;153:104082.

Landi G, Pakenham KI, Crocetti E, Tossani E, Grandi S. The trajectories of anxiety and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic and the protective role of psychological flexibility: a four-wave longitudinal study. J Affect Disord. 2022;307:69–78.

Holt-Gosselin B, Tozzi L, Ramirez CA, Gotlib IH, Williams LM. Coping strategies, neural structure, and depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal study in a naturalistic sample spanning clinical diagnoses and subclinical symptoms. Biol Psychiatry Global Open Sci. 2021;1:261–71.

McCracken LM, Badinlou F, Buhrman M, Brocki KC. The role of psychological flexibility in the context of COVID-19: Associations with depression, anxiety, and insomnia. J Context Behav Sci. 2021;19:28–35.

Talkovsky AM, Norton PJ. Negative affect and intolerance of uncertainty as potential mediators of change in comorbid depression in transdiagnostic CBT for anxiety. J Affect Disord. 2018;236:259–65.

Milman E, Lee SA, Neimeyer RA, Mathis AA, Jobe MC. Modeling pandemic depression and anxiety: the mediational role of core beliefs and meaning making. J Affect Disorders Rep. 2020;2:100023.

Sagan A, Bryndova L, Kowalska-Bobko I, Smatana M, Spranger A, Szerencses V, et al. A reversal of fortune: comparison of health system responses to COVID-19 in the Visegrad group during the early phases of the pandemic. Health Policy. 2022;126:446–55.

Holt E. COVID-19 testing in Slovakia. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21:32.

Stalmachova K, Strenitzerova M. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on employment in transport and telecommunications sectors. Transp Res Procedia. 2021;55:87–94.

Izakova L, Breznoscakova D, Jandova K, Valkucakova V, Bezakova G, Suvada J. What mental health experts in Slovakia are learning from COVID-19 pandemic? Indian J Psychiatry. 2020;62(Suppl 3):459–66.

Rabinčák M, Tkáčová Ľ, VYUŽÍVANIE PSYCHOMETRICKÝCH KONŠTRUKTOV PRE, HODNOTENIE PORÚCH NÁLADY V OŠETROVATEĽSKEJ PRAXI. Zdravotnícke Listy. 2019;7:7.

Google Scholar

Sekot M, Gürlich R, Maruna P, Páv M, Uhlíková P. Hodnocení úzkosti a deprese u pacientů se zhoubnými nádory trávicího traktu. Čes a slov Psychiat. 2005;101:252–7.

Lipsitch M, Krammer F, Regev-Yochay G, Lustig Y, Balicer RD. SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infections in vaccinated individuals: measurement, causes and impact. Nat Rev Immunol. 2022;22:57–65.

Accorsi EK, Britton A, Fleming-Dutra KE, Smith ZR, Shang N, Derado G, et al. Association between 3 doses of mRNA COVID-19 vaccine and symptomatic infection caused by the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron and Delta Variants. JAMA. 2022;327:639–51.

Barda N, Dagan N, Cohen C, Hernán MA, Lipsitch M, Kohane IS, et al. Effectiveness of a third dose of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine for preventing severe outcomes in Israel: an observational study. Lancet. 2021;398:2093–100.

Magen O, Waxman JG, Makov-Assif M, Vered R, Dicker D, Hernán MA, et al. Fourth dose of BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine in a nationwide setting. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:1603–14.

Dubé JP, Smith MM, Sherry SB, Hewitt PL, Stewart SH. Suicide behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic: a meta-analysis of 54 studies. Psychiatry Res. 2021;301:113998.

Kok AAL, Pan K-Y, Rius-Ottenheim N, Jörg F, Eikelenboom M, Horsfall M, et al. Mental health and perceived impact during the first Covid-19 pandemic year: a longitudinal study in dutch case-control cohorts of persons with and without depressive, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorders. J Affect Disord. 2022;305:85–93.

Aknin LB, Andretti B, Goldszmidt R, Helliwell JF, Petherick A, De Neve J-E, et al. Policy stringency and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal analysis of data from 15 countries. The Lancet Public Health. 2022;7:e417–26.

Prochazka J, Scheel T, Pirozek P, Kratochvil T, Civilotti C, Bollo M, et al. Data on work-related consequences of COVID-19 pandemic for employees across Europe. Data Brief. 2020;32:106174.

Loades ME, Chatburn E, Higson-Sweeney N, Reynolds S, Shafran R, Brigden A, et al. Rapid systematic review: the impact of social isolation and loneliness on the Mental Health of Children and Adolescents in the Context of COVID-19. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;59:1218–1239e3.

Zetterqvist M, Jonsson LS, Landberg Ã, Svedin CG. A potential increase in adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury during covid-19: a comparison of data from three different time points during 2011–2021. Psychiatry Res. 2021;305:114208.

Mooldijk SS, Dommershuijsen LJ, de Feijter M, Luik AI. Trajectories of depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic in a population-based sample of middle-aged and older adults. J Psychiatr Res. 2022;149:274–80.

Sahebi A, Nejati-Zarnaqi B, Moayedi S, Yousefi K, Torres M, Golitaleb M. The prevalence of anxiety and depression among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: an umbrella review of meta-analyses. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2021;107:110247.

Stephenson E, O’Neill B, Kalia S, Ji C, Crampton N, Butt DA, et al. Effects of COVID-19 pandemic on anxiety and depression in primary care: a retrospective cohort study. J Affect Disord. 2022;303:216–22.

Goldberg X, Castaño-Vinyals G, Espinosa A, Carreras A, Liutsko L, Sicuri E et al. Mental health and COVID-19 in a general population cohort in Spain (COVICAT study).Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2022;:1–12.

Zhao Y, Yu Y, Zhao R, Cai Y, Gao S, Liu Y, et al. Association between fear of COVID-19 and hoarding behavior during the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic: the mediating role of mental health status. Front Psychol. 2022;13:996486.

Furstova J, Kascakova N, Sigmundova D, Zidkova R, Tavel P, Badura P. Perceived stress of adolescents during the COVID-19 lockdown: bayesian multilevel modeling of the Czech HBSC lockdown survey. Front Psychol. 2022;13:964313.

Garbóczy S, Szemán-Nagy A, Ahmad MS, Harsányi S, Ocsenás D, Rekenyi V, et al. Health anxiety, perceived stress, and coping styles in the shadow of the COVID-19. BMC Psychol. 2021;9:53.

Wathelet M, Duhem S, Vaiva G, Baubet T, Habran E, Veerapa E, et al. Factors Associated with Mental Health Disorders among University students in France Confined during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2025591.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to provide our appreciation and thanks to all the respondents in this study.

This research project received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute of Medical Biology, Genetics and Clinical Genetics, Faculty of Medicine, Comenius University in Bratislava, Sasinkova 4, Bratislava, 811 08, Slovakia

Ida Kupcova, Lubos Danisovic & Stefan Harsanyi

Institute of Histology and Embryology, Faculty of Medicine, Comenius University in Bratislava, Sasinkova 4, Bratislava, 811 08, Slovakia

Martin Klein

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

IK and SH have produced the study design. All authors contributed to the manuscript writing, revising, and editing. LD and MK have done data management and extraction, SH did the data analysis. Drafting and interpretation of the manuscript were made by all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Stefan Harsanyi .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethical permission was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Medical Biology, Genetics and Clinical Genetics, Faculty of Medicine, Comenius University in Bratislava (Reference number: ULBGaKG-02/2022). The need for informed consent was waived by the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Medical Biology, Genetics and Clinical Genetics, Faculty of Medicine, Comenius University in Bratislava due to the anonymous design of the study. This study did not process any personal data and the dataset does not contain any direct or indirect identifiers of participants. This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All methods were carried out following the institutional guidelines.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Kupcova, I., Danisovic, L., Klein, M. et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health, anxiety, and depression. BMC Psychol 11 , 108 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01130-5

Download citation

Received : 14 November 2022

Accepted : 20 March 2023

Published : 11 April 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01130-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Mental health

BMC Psychology

ISSN: 2050-7283

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Program Finder

- Admissions Services

- Course Directory

- Academic Calendar

- Hybrid Campus

- Lecture Series

- Convocation

- Strategy and Development

- Implementation and Impact

- Integrity and Oversight

- In the School

- In the Field

- In Baltimore

- Resources for Practitioners

- Articles & News Releases

- In The News

- Statements & Announcements

- At a Glance

- Student Life

- Strategic Priorities

- Inclusion, Diversity, Anti-Racism, and Equity (IDARE)

- What is Public Health?

Mental Health and COVID-19

- Mental Health Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

- Origins of Mental Health

- Job Openings

- Faculty Profiles

- PET Alumni Profiles - Postdocs

- PET Alumni Profiles - Predocs

- Trainee Profiles

- NIMH T32 Mental Health Services and Systems Training Grant

- Funded Training Program in Data Integration for Causal Inference in Behavioral Health

- Aging and Dementia Funded Training Program

- COVID-19 and Mental Health Research

- Mental Health Resources During COVID-19

- News and Media

- Social Determinants of Mental and Behavioral Health

Our Work in Action

- Global Mental Health

- Related Faculty

- Courses of Interest

- Training and Funding Opportunities

- Mental Health in the Workplace: A Public Health Summit

- Autism and Developmental Disabilities

- Alumni Newsletters

- Alumni Updates

- Postdoctoral Fellows

- Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) Students in Mental Health

- Master of Health Science (MHS) Students in Mental Health

- In the News

- Past Seminars 2020-21 AY: Wednesday Seminar Series

- Make a Gift

- Available Datasets

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a huge impact on public health around the globe in terms of both physical and mental health, and the mental health implications of the pandemic may continue long after the physical health consequences have resolved. This research area aims to contribute to our understanding of the COVID-19 pandemics implications for mental health, building on a robust literature on how environmental crises, such as SARS or natural disasters, can lead to mental health challenges, including loneliness, acute stress, anxiety, and depression. The social distancing aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic may have particularly significant effects on mental health. Understanding how mental health evolves as a result of this serious global pandemic will inform prevention and treatment strategies moving forward, including allocation of resources to those most in need. Critically, these data can also serve as evidence-based information for public health organizations and the public as a whole.

Understanding the Mental Health Implications of a Pandemic

Introduction

The world is entering into a new phase with COVID-19 spreading rapidly. People will be studying various consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic and mental and behavioral health should be a core part of that effort. There is a robust literature on how environmental crises, such as SARS or natural disasters, can lead to mental health challenges, including loneliness, acute stress, anxiety, and depression. The social distancing aspects of the current pandemic may have particularly significant effects on mental health. Understanding how mental health evolves as a result of this serious global outbreak will inform prevention and treatment strategies moving forward, including allocation of resources to those most in need. Critically, these data can also serve as evidence-based information for public health organizations and the public as a whole.

The data will be leveraged to address many questions, such as:

- Which individuals are at greatest risk for high levels of mental health distress during a pandemic?

- As individuals spend more time inside and isolated, how does their mental health distress evolve?

- How do different behaviors (such as media consumption) relate to mental health?

Read more about how our experts are measuring mental distress amid a pandemic.

We have been working to ensure that measurement of mental health measures is a key part of large-scale national and international data collections relative to COVID-19.

Read more about conducting research studies on mental health during the pandemic.

Mental Health Resources

See our resources guide here.

Members of the COVID-19 Mental Health Measurement Working Group

- M. Daniele Fallin, JHSPH

- Calliope Holingue, Kennedy Krieger Institute, JHSPH

- Renee M. Johnson, JHSPH

- Luke Kalb, Kennedy Krieger Institute, JHSPH

- Frauke Kreuter, University of Maryland, University of Mannheim

- Courtney Nordeck, JHSPH

- Kira Riehm, JHSPH

- Emily J. Smail, JHSPH

- Elizabeth Stuart, JHSPH

- Johannes Thrul, JHSPH

- Cindy Veldhuis, Columbia University School of Nursing

The Johns Hopkins COVID-19 Mental Health Measurement Working Group developed key questions to add to existing large domestic and international surveys to measure the mental health impact of the pandemic.

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

The effect of covid-19 on mental health and wellbeing in a representative sample of australian adults.

A correction has been applied to this article in:

Corrigendum: The Effect of COVID-19 on Mental Health and Wellbeing in a Representative Sample of Australian Adults

- Read correction

- 1 Research School of Psychology, The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT, Australia

- 2 Centre for Research on Ageing, Health and Wellbeing, Research School of Population Health, The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT, Australia

- 3 Centre for Mental Health Research, Research School of Population Health, The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT, Australia

- 4 Department of Global Health, Research School of Population Health, The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT, Australia

- 5 National Centre for Epidemiology and Population Health, Research School of Population Health, The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT, Australia

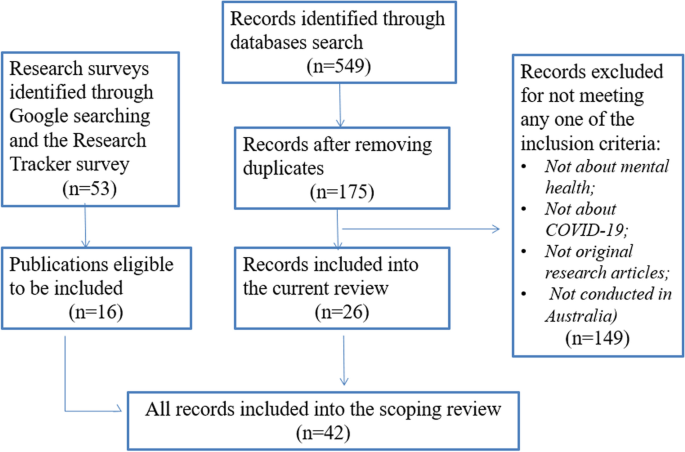

There is minimal knowledge about the impact of large-scale epidemics on community mental health, particularly during the acute phase. This gap in knowledge means we are critically ill-equipped to support communities as they face the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic. This study aimed to provide data urgently needed to inform government policy and resource allocation now and in other future crises. The study was the first to survey a representative sample from the Australian population at the early acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Depression, anxiety, and psychological wellbeing were measured with well-validated scales (PHQ-9, GAD-7, WHO-5). Using linear regression, we tested for associations between mental health and exposure to COVID-19, impacts of COVID-19 on work and social functioning, and socio-demographic factors. Depression and anxiety symptoms were substantively elevated relative to usual population data, including for individuals with no existing mental health diagnosis. Exposure to COVID-19 had minimal association with mental health outcomes. Recent exposure to the Australian bushfires was also unrelated to depression and anxiety, although bushfire smoke exposure correlated with reduced psychological wellbeing. In contrast, pandemic-induced impairments in work and social functioning were strongly associated with elevated depression and anxiety symptoms, as well as decreased psychological wellbeing. Financial distress due to the pandemic, rather than job loss per se , was also a key correlate of poorer mental health. These findings suggest that minimizing disruption to work and social functioning, and increasing access to mental health services in the community, are important policy goals to minimize pandemic-related impacts on mental health and wellbeing. Innovative and creative strategies are needed to meet these community needs while continuing to enact vital public health strategies to control the spread of COVID-19.

Introduction

The new coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic is unprecedented in recent history, with global impacts including high rates of mortality and morbidity, and loss of income and sustained social isolation for billions of people. The effect this crisis will have on population mental health, both in the short- and long-term, is unknown. There is minimal evidence about the acute phase mental health impacts of large-scale epidemics across communities. Existing work has focused on those individuals most directly affected by disease (e.g., infected individuals and their families, healthcare workers ( 1 – 5 ) and examined mental health impacts across broader communities only after the acute phase has passed ( 1 ). In the acute phase however, fear about potential exposure to infection, loss of employment, and financial strain are also likely to increase psychological distress in the broader population ( 1 – 4 ). This distress may be further exacerbated in individuals who have experienced prior traumatic events ( 2 ). In the longer term, grief and trauma are likely to emerge ( 3 ) and, as financial and social impacts become entrenched, risk of depression and suicidality may increase ( 2 , 6 – 8 ).

Reports of the mental health impacts of previous severe health epidemics have focused primarily on disease survivors [e.g., of Ebola virus disease ( 2 ) and SARS ( 1 )]. Almost invariably, these studies show survivors experience greater psychological distress post-epidemic than others from affected communities ( 1 , 3 ). Risk for psychological distress may also be greater for people employed in occupations that potentially expose them to infection ( 4 , 5 ), and in those who have friends or family members who have been infected ( 3 ). However, in the acute phase of COVID-19, there are clear reasons to also expect that Government policies and physical distancing measures aimed at limiting disease spread will impact mental health in the broader community. For instance, loss of employment ( 6 ), financial strain ( 9 ), and social isolation ( 8 , 10 ) are all well-documented correlates of mental health problems. In many countries, physical distancing measures have already resulted in an enormous increase in unemployment ( 11 ), likely causing significant financial strain for many.

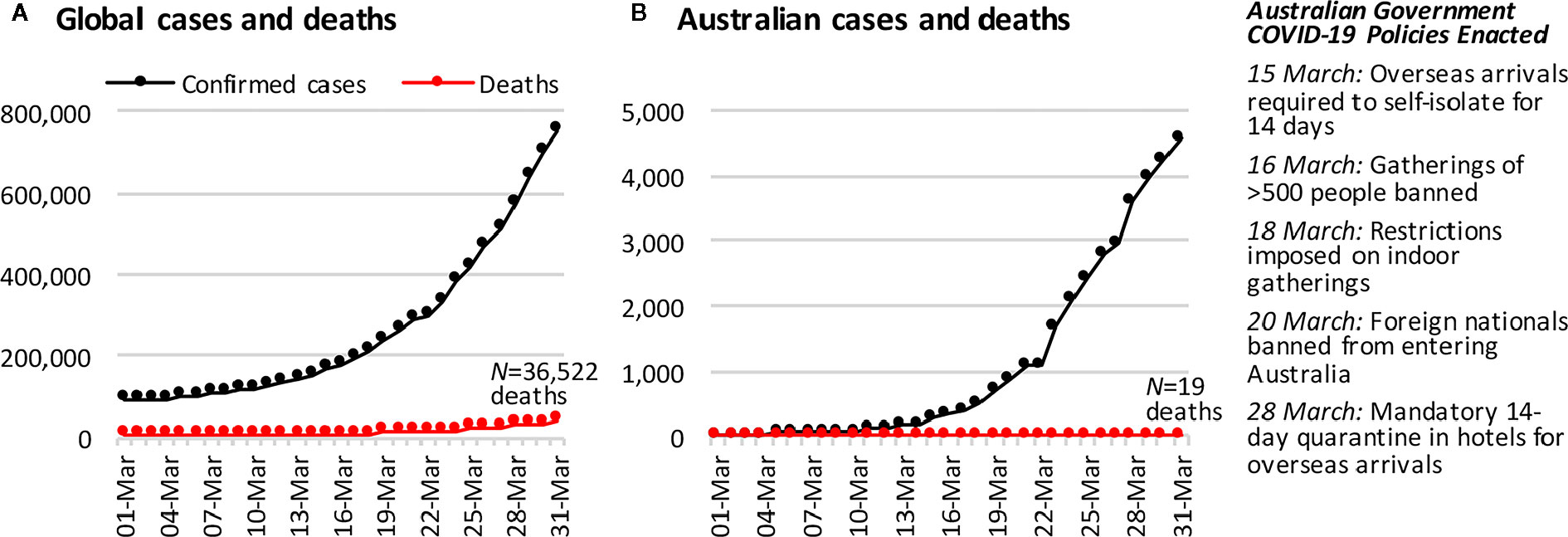

Gathering early evidence of the impacts of COVID-19 is vital for informing mental health service delivery as the pandemic and its extended effects continue. The present study surveyed a representative sample of Australians from 28 to 31 March 2020, during the acute phase of the pandemic in Australia. Figure 1 shows the number of confirmed cases in Australia had just started to escalate at this time, relative to global cases. A total of 19 deaths had been reported in Australia by the survey close, relative to over 36,500 across the globe. In the fortnight leading up to the survey, the Australian government had closed restaurants, bars, and churches, severely restricted the size of public and private gatherings, banned foreign nationals from entering Australia, and was enforcing strict quarantine measures for Australians returning from overseas.

Figure 1 The cumulative number of COVID-19 confirmed cases and deaths (A) across the globe and (B) in Australia, in the month leading up to the first survey wave of this study. Case and death data are from https://covid19.who.int/ .

The present study aimed to document the initial mental health scenario across the Australian community and examine its association with exposure to the broad COVID-19 environment at this critical acute phase by: (1) measuring the current prevalence of clinically significant symptoms of generalized anxiety and depression, including associations with other recent adversities; and (2) investigating the degree to which symptom severity is associated with exposure to COVID-19, and pandemic-related impacts on employment, finances, and social functioning. We also accounted for exposure to the catastrophic bushfires that occurred across Australia in November 2019–January 2020. We hypothesized that greater exposure to COVID-19, and impairment in employment, finances, and social functioning, would be associated with higher psychological distress and decreased psychological wellbeing

Study Design and Sample

We established a new longitudinal study—The Australian National COVID-19 Mental Health, Behavior and Risk Communication (COVID-MHBRC) Survey—to investigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on a representative sample of the Australian adult population (≥18 years). Participants were required to be able to respond to an online English language survey. The study comprises seven survey waves initiated online fortnightly, via Qualtrics Research Services. Recruitment was conducted using quota sampling to obtain a representative sample on the basis of age group, gender, and geographical location (State/Territory). Participants gave written informed consent after receiving a complete description of the study. The study was approved by The Australian National University Human Research Ethics Committee (number 2020/152). The full study protocol is available here: https://psychology.anu.edu.au/files/COVID_MHBRCS_protocol.pdf .

We report data (N = 1,296) from the first assessment (Wave 1, 28–31 March 2020). The sample size requirement estimate was based on planned power analyses for finding an effect of f 2 = 0.1 in linear and logistic regression models, setting 1 - β = .95 and α = .05, and taking into account variations in the prevalence of binary outcomes and attrition over the stages of the longitudinal survey, and an allowance for 10% unusable data. Our sample of N = 1,296 was only 2% less than our target sample of N = 1,320 (see Supplement S1 for additional details). Only 2–3% of the data were unusable for the present analyses.

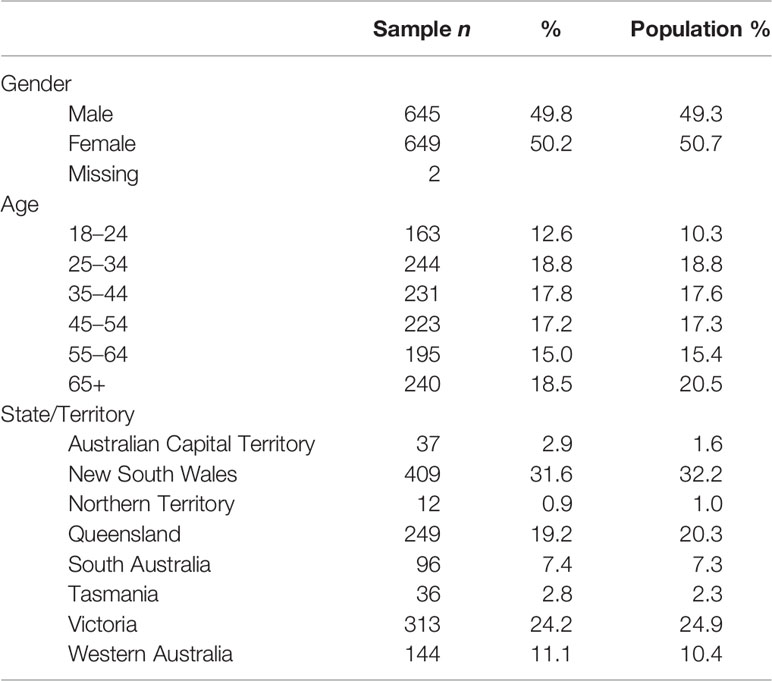

Table 1 reports Wave 1 sample distributions by gender, age, and location. These distributions aligned well with population data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics ( 12 ), demonstrating that a representative sample of the Australian community was achieved.

Table 1 Sample demographics and comparison with population data from the 2016 Australian Census ( 12 ).

Survey Measures

Symptoms of depression and anxiety over the last 2 weeks were assessed by the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) ( 13 ) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) ( 13 ) respectively. These measures align closely with diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder respectively ( 14 ). General psychological wellbeing over the last 2 weeks was measured using the World Health Organization Wellbeing Index (WHO-5) ( 15 ).

COVID-19 exposure was computed as the sum of self-reports of possible or actual exposures to the virus, of the related population health response, or of close social impact including: having been diagnosed with the virus, awaiting results from a test, having tested negative to the test, being in direct contact with a carrier of the virus, having had to isolate in the past, having chosen to isolate in the past, being currently forced to isolate, currently choosing to isolate, having a family member diagnosed with the virus, having a family member in isolation, knowing someone who was diagnosed, knowing someone in isolation, or being asked to work from home because of the virus.

Our measures of the work and social impacts of COVID-19 were whether someone had lost their job due to COVID-19 (yes/no); was working from home due to COVID-19 (yes/no); was experiencing financial distress due to COVID-19 (six-point Likert-type rating, from Not at all to Extremely); and the overall extent to which their work and social activities were impaired by COVID-19, measured using the Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS) ( 16 ). For the WSAS, participants rated the level of impairment COVID-19 had caused (eight-point Likert-type rating, from Not at all impaired to Very severely impaired) for five work and social domains (ability to work, home management, social leisure activities, private leisure activities, and ability to form and maintain close relationships).

We also measured other background factors that could be associated with mental health: age (in years); gender (male/female/other); years of education; partner status (yes/no); living alone (yes/no); living with dependent children (yes/no); existing health, neurological, or psychological conditions, diagnosed by an appropriate clinician (yes/no); recent exposure to bushfire smoke (yes/no) or fire (yes/no); and impact of other recent adverse life events (five-point Likert-type rating, from Not at all to Extremely). Regarding the bushfire exposure variables, our reason for separating out smoke from fire is that many Australians who were exposed to smoke lived far away from the actual fires and their home/region was never under direct threat. The major impact for smoke-but-not-fire affected individuals was poor air quality, which prohibited people from spending time outside for several weeks over the Summer.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted in R version 3.6.3 under RStudio version 1.1.456 ( 17 ). Multiple linear regression was the primary technique employed to assess correlates of poor mental health. Models were checked and showed an absence of multicollinearity, outliers, and non-normality in the residuals. However, as is typical in non-clinical samples, the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 variables had high frequencies at their lowest possible values, resulting in incorrigible skew. Therefore, compound Poisson-gamma (Tweedie distribution) generalized linear models ( 18 ) were estimated as a check on the linear models ( Supplement S2 ). Their results were consistent with the linear models. Likewise, the models included categorical predictors with small subsample sizes, so cross-validation was conducted to ensure that the models were stable ( Supplement S3 ). Overall, <1% of data were missing. Models reported in the main text dealt with these cases using listwise deletion. We also multiply imputed the missing values and reran the models, which produced the same pattern of findings ( Supplement S5 ).

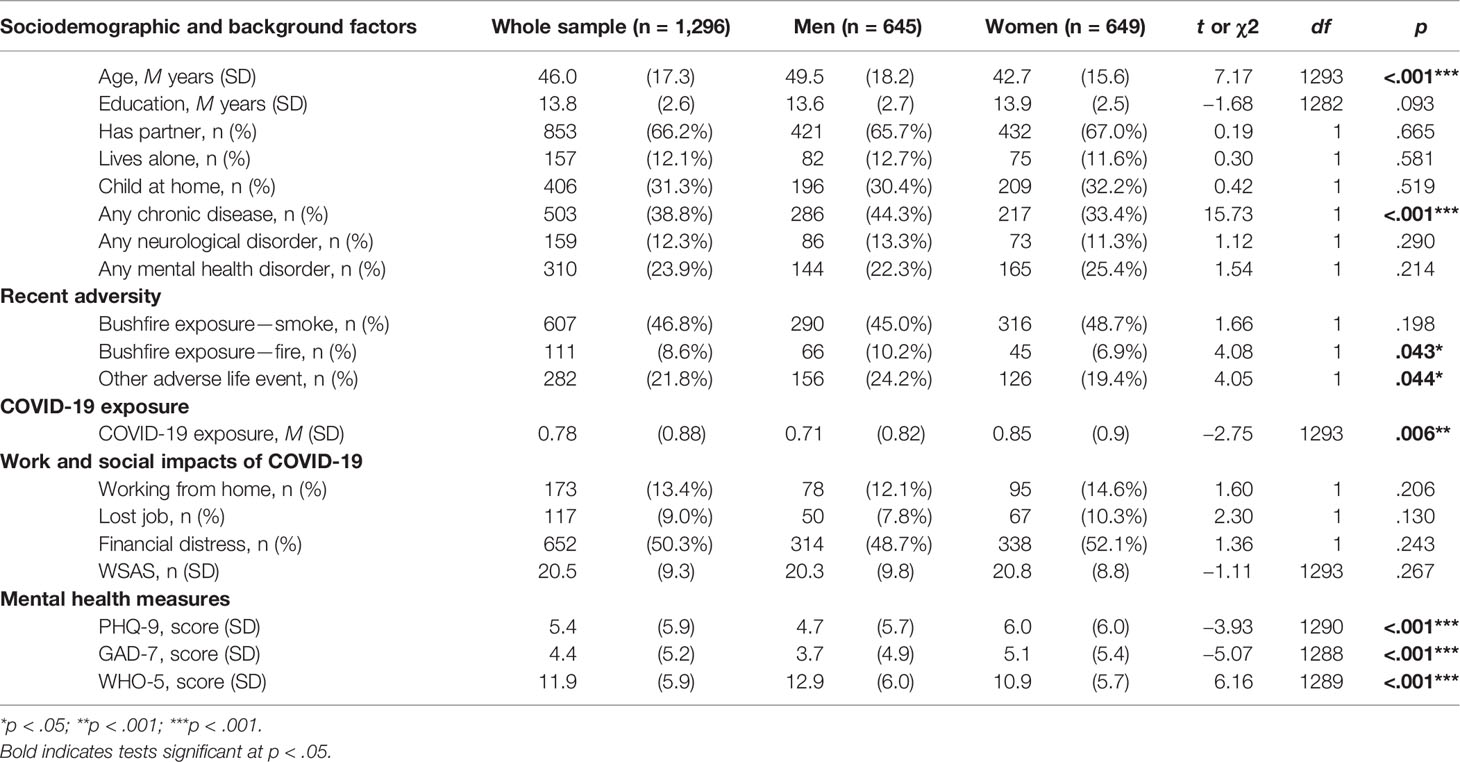

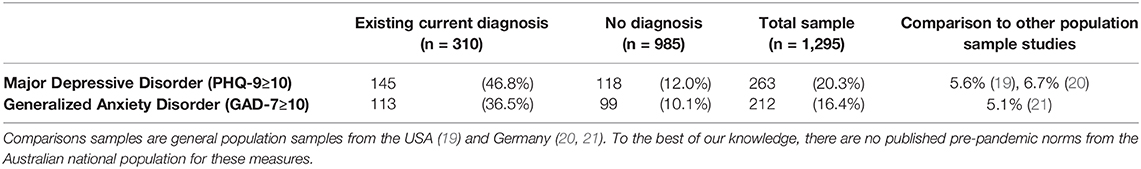

Table 2 presents our sample characteristics. Overall, 20.3 and 16.4 of our sample scored above the clinical cut-offs on our depression (PHQ-9) and anxiety (GAD-7) measures respectively. Table 3 shows these rates are notably elevated compared to other community-based samples. Even among individuals without a current diagnosis, the rates remained elevated well above levels seen in other representative community-based samples.

Table 2 Description of sample characteristics, including comparison of men and women.

Table 3 Prevalence of depression and generalized anxiety based on self-reported current mental health diagnosis.

Investigation of the relationships between our predictor measures and three mental health outcome measures used a Bonferroni adjusted significance threshold of 0.17 to control for the three sets of comparisons, i.e., α = .05/3 = .017. Note, all three measures showed good reliability (see Supplement S6 ).

Our initial univariate tests revealed that higher levels of depression and anxiety symptoms, and lower psychological wellbeing (WHO-5), were all associated with job loss and financial distress, and overall work and social impairment due to COVID-19, as measured by the WSAS. Being required to work from home was not associated with any mental health effects at this acute stage of the pandemic, all ps > 0.27 (see Supplement S6 for all univariate results).

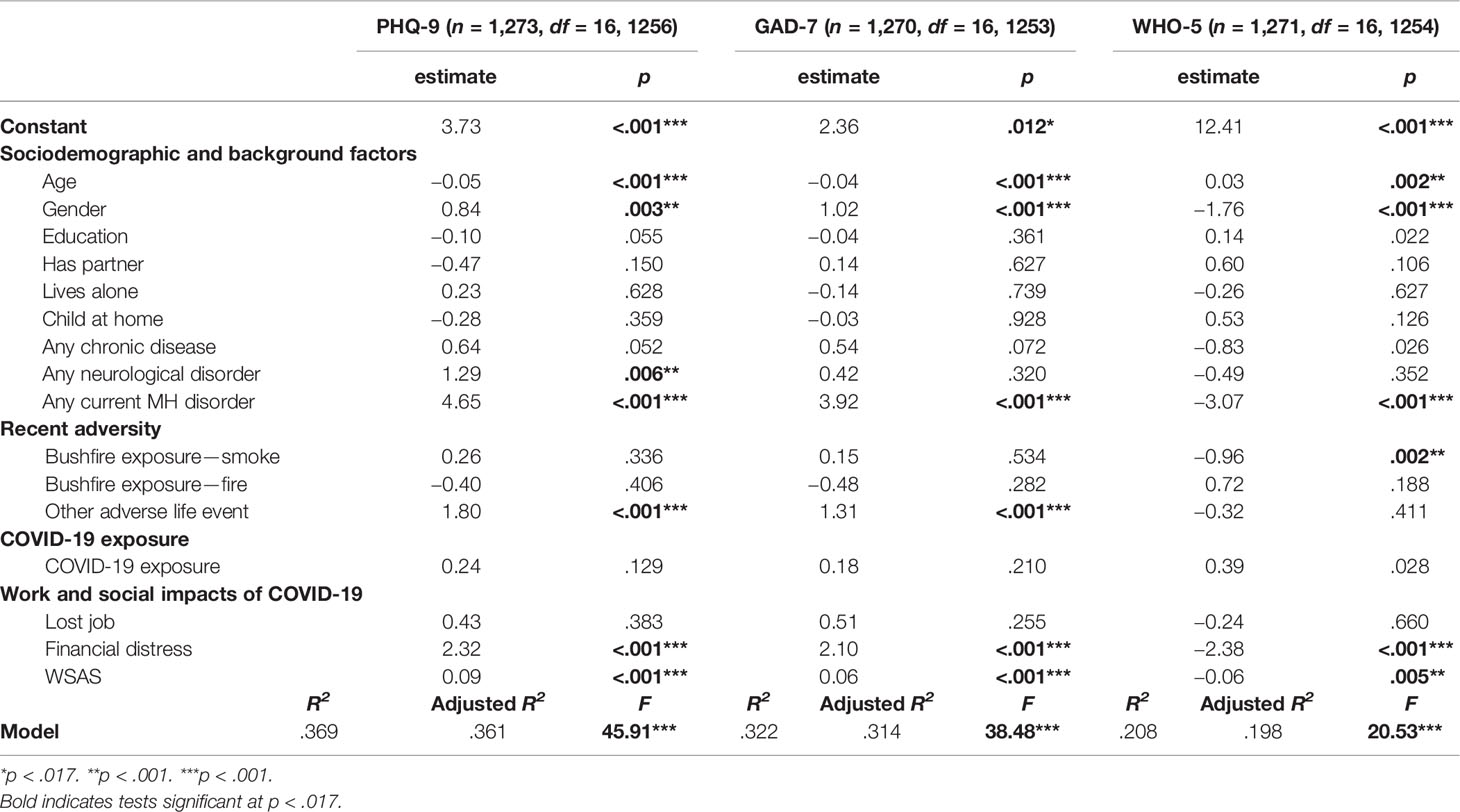

The linear regression models, presented in Table 4 , established that the effects of financial distress and overall work and social impairment were independent, and not better accounted for by demographic or other background factors. Job loss however did not have a significant independent association with mental health after accounting for financial distress and other covariates, all ps > 0.25.

Table 4 Linear regression models for each mental health outcome.

In contrast, the regression analyses found no significant unique association between exposure to COVID-19 and depression or anxiety symptoms, or wellbeing.

Depression and anxiety symptoms were also elevated in people who had experienced other recent adversities, although this did not include direct exposure to the recent catastrophic Australian bushfires. Exposure to bushfire smoke was however associated with decreased wellbeing.

Finally, within these regression models, we also found that younger age, identifying as female, and having at least one current mental health disorder were each independently associated with higher levels of depression and anxiety, and decreased wellbeing.

We found the social, work, and financial disruptions induced by the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic were associated with considerable impairments in community mental health in Australian adults. In contrast, exposure to COVID-19 was not found to predict mental health in this cohort. A key strength of this study was the testing of a representative community sample early in the pandemic, providing rapid evidence of population mental health status. The results highlight that epidemics may cause serious problems for community mental health in the acute phase of disease.

Indeed, our results suggest that, at a population level, changes to social and work functioning due to COVID-19 were more strongly associated with decrements in mental health than amount of disease contact. This finding is consistent with a recent UK-based finding that their citizens were more concerned about how societal changes will impact their psychological and financial wellbeing, than becoming unwell with the virus ( 7 ). This finding is also consistent with emergent work indicating that loneliness is playing a central role in the observed mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic ( 22 – 24 ). Altogether then, it is evident that the necessary public health arrangements surrounding the pandemic are having serious implications for community mental health, via their disruption to social and work functioning.

However, this does not mean the mental health costs of pandemic-related social changes will inevitably be greater than those caused by exposure to disease. In Australia, mortality rates were very low at the time of this study, and the health system had capacity to meet demand. The relatively low case rates were also reflected in our sample; although the majority of the sample had some exposure, such as needing to self-isolate, only 36 participants reported direct exposure to the virus (self or close contact diagnosed). The short-term mental health impacts of disease contact may be considerably greater in communities that have high mortality rates, and health systems over-burdened by disease. In the longer-term, disease contact may also lead to elevated levels of trauma and grief for affected individuals ( 3 ).

The elevated levels of psychological distress observed in this study indicate mental health services are likely to experience increased demand during pandemics. Following recommended physical distancing guidelines, these will need to be delivered flexibly, leveraging resources for telehealth and internet-based Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT) programs, which have been shown to be effective in preventing and treating common mental disorders ( 7 , 25 , 26 ). There may also be an increased role for community cohesion strategies ( 27 ) and peer support ( 28 ), for instance, drawing on the experience and knowledge of people already living with mental health issues to support those experiencing these issues for the first time.

The findings also provide clear evidence that minimizing social and financial disruption during the COVID-19 pandemic should be a central goal of public health policy. A key challenge is how to best achieve this goal without compromising public safety by, for instance, relaxing physical distancing restrictions too early. Our results suggest policy approaches that target financial support to those experiencing financial strain may be useful, rather than on the basis of lost employment alone. We also found that well-established risk factors for poorer mental health—younger age, identifying as female, and having a pre-existing mental health condition—continue to be associated with increased risk within the pandemic context. Governments should consider additional measures to monitor and support these at-risk groups. Psychosocial interventions to support multiple aspects of wellbeing, including minimizing financial debt, may have positive impacts on depression and anxiety in the community ( 29 ). Clinicians should also remain vigilant for potential added social and financial impacts that existing clients in primary care and psychological settings may be experiencing.

A possible limitation of the present study is the use of self-report scales that may not characterize mental health status with the accuracy of structured clinical interviews, although both the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 have previously demonstrated strong alignment with clinical diagnosis in population samples ( 14 ), and the WHO-5 is also well-validated ( 15 ). Another potential issue is the influence of selection bias on the prevalence of mental health problems seen in this sample, however, the likelihood of this is low. We were careful to ensure the recruitment advertisement did not mention the topic or nature of our survey (e.g., no mention of mental health or COVID-19 at all), and the service we used also recruits participants for non-psychological research (i.e., market research panel). Most importantly, we did obtain a sample that was representative of the Australian population by age, gender, and location. It is however important to note that online survey methods may bias samples towards people who have good internet literacy and access ( 30 ). This type of bias may have a disproportionate impact on subsections of the population, such as older adults.

Finally, this initial report of our work is cross-sectional. The observed associations may not reflect causal effects, and the nature of any causal relationships may be more complicated than our interpretation suggests (e.g., possible bi-directional effects between psychological distress and social/occupational functioning). We intend to balance the necessity of providing our first wave findings in a timely fashion, to rapidly inform ongoing global responses to the pandemic, by reporting longitudinal outcomes as they become available in the coming months. Examination of population subgroups within our sample may also be possible in longitudinal analyses, although additional targeted studies may be required to provide greater insight into how specific vulnerable groups are affected. These findings should also be considered in combination with other studies that survey the mental health impacts of COVID-19 in communities that have adopted different approaches to managing the pandemic and/or have differing social structures (e.g., low GDP) to Australia.

In conclusion, the current study provides a snapshot of the acute phase impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of the Australian adult community. The findings are concerning, suggesting markedly elevated rates of depression and anxiety, even among individuals with no current diagnosis. This worsening of mental health may also have been exacerbated by the recent severe bushfire season Australians had experienced in the months leading up to the pandemic, although bushfire exposure was controlled for in our analyses. Overall, the findings suggest that interventions to counteract the social, financial and role disruptions induced by COVID-19, particularly among people with existing health conditions, are likely to have the greatest impact on community mental health and wellbeing.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Australian National University Human Research Ethics Committee. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the design and conceptualization of the study, which was coordinated by AD. AD, PJB, and LMF contributed to the literature review. AD, PJB, YS, MS, and NC contributed to the data analyses and formulation of the manuscript, with input from all other authors. AD, PJB, NC, and MS drafted the manuscript and all authors critically revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This study was funded by the ANU College of Health and Medicine, ANU Research School of Psychology, and ANU Research School of Population Health. PJB is supported by National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Fellowship 1158707. ALC is supported by NHMRC Fellowships 1122544 and 1173146. LMF is supported by Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (ARC DECRA) DE190101382. YS is supported by ARC DECRA DE180100015. AG and ARM are supported by funding provided by the ACT Health Directorate for ACACIA: The ACT Consumer and Carer Mental Health Research Unit.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Patrice Ford for assistance with preparing this manuscript and Georgia Baines for media monitoring.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.579985/full#supplementary-material

1. Gardner PJ, Moallef P. Psychological impact on SARS survivors: Critical review of the English language literature. Can Psychology/Psychologie Can (2015) 56:123–35. doi: 10.1037/a0037973

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

2. James PB, Wardle J, Steel A, Adams J. Post-Ebola psychosocial experiences and coping mechanisms among Ebola survivors: a systematic review. Trop Med Int Health (2019) 24:671–91. doi: 10.1111/tmi.13226

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

3. Van Bortel T, Basnayake A, Wurie F, Jambai M, Koroma AS, Muana AT, et al. Psychosocial effects of an Ebola outbreak at individual, community and international levels. Bull World Health Organ (2016) 94:210–4. doi: 10.2471/BLT.15.158543

4. Ricci-Cabello I, Meneses-Echavez JF, Serrano-Ripoll MJ, Fraile-Navarro D, Fiol de Roque MA, Moreno GP, et al. Impact of viral epidemic outbreaks on mental health of healthcare workers: a rapid systematic review. medRxiv (2020). doi: 10.1101/2020.04.02.20048892

5. Wu P, Fang Y, Guan Z, Fan B, Kong J, Yao Z, et al. The Psychological Impact of the SARS Epidemic on Hospital Employees in China: Exposure, Risk Perception, and Altruistic Acceptance of Risk. Can J Psychiatry (2009) 54:302–31. doi: 10.1177/070674370905400504

6. Kim TJ, von dem Knesebeck O. Perceived job insecurity, unemployment and depressive symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Int Arch Occup Environ Health (2016) 89:561–73. doi: 10.1007/s00420-015-1107-1

7. Holmes EA, O’Connor RC, Perry VH, Tracey I, Wessely S, Arseneault L, et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry (2020) 7:547–60. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1

8. Ma J, Batterham PJ, Calear AL, Han J. A systematic review of the predictions of the Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicidal Behavior. Clin Psychol Rev (2016) 46:34–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.04.008

9. Fitch C, Hamilton S, Bassett P, Davey R. The relationship between personal debt and mental health: a systematic review. Ment Health Rev J (2011) 16:153–66. doi: 10.1108/13619321111202313

10. Leigh-Hunt N, Bagguley D, Bash K, Turner V, Turnbull S, Valtorta N, et al. An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Public Health (2017) 152:157–71. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2017.07.035

11. U.N. News. COVID-19: impact could cause equivalent of 195 million job losses, says ILO chief . U.N. News (2020). Available at: https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/04/1061322 .

Google Scholar

12. Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2016 Census QuickStats. Australian Bureau of Statistics (2016). Available at: https://quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/036

13. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med (2006) 166:1092–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

14. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Lowe B. The Patient Health Questionnaire Somatic, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptom Scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry (2010) 32:345–59. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.03.006

15. Topp CW, Ostergaard SD, Sondergaard S, Bech P. The WHO-5 Well-Being Index: a systematic review of the literature. Psychother Psychosom (2015) 84:167–76. doi: 10.1159/000376585

16. Mundt JC, Marks IM, Shear MK, Greist JH. The Work and Social Adjustment Scale:a simple measure of impairment in functioning. Br J Psychiatry (2002) 180:461–4. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.5.461

17. R.C. Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing . Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria (2013).

18. Smithson M, Shou Y. Generalized linear models for bounded and limited quantitative variables . Belmont, CA: SAGE Publications (2019).

19. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: Validity of a Brief Depression Severity Measure. J Gen Internal Med (2001) 16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

20. Kocalevent RD, Hinz A, Brahler E. Standardization of the depression screener patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry (2013) 35:551–5. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.04.006

21. Löwe B, Decker O, Müller S, Brähler E, Schellberg D, Herzog W, et al. Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care (2008) 46:266–74. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318160d093

22. González-Sanguino C, Ausín B, ÁngelCastellanos M, Saiz J, López-Gómez A, Ugidos C, et al. Mental health consequences during the initial stage of the 2020 Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) in Spain. Brain Behav Immun (2020) 87:172–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.040

23. Li LZ, Wang S. Prevalence and predictors of general psychiatric disorders and loneliness during COVID-19 in the United Kingdom. Psychiatry Res (2020) 291:113267. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113267

24. Palgi Y, Shrira A, Ring L, Bodner E, Avidor S, Bergman Y, et al. The loneliness pandemic: Loneliness and other concomitants of depression, T anxiety and their comorbidity during the COVID-19 outbreak. J Affect Disord (2020) 275:109–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.036

25. Batterham PJ, Mackinnon AJ, Christensen H. The panic disorder screener (PADIS): Development of an accurate and brief population screening tool. Psychiatry Res (2015) 228:72–6. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.04.016

26. Spek V, Cuijpers P, Nyklicek I, Riper H, Keyzer J, Pop V. Internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy for symptoms of depression and anxiety: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med (2007) 37:319–28. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008944

27. Townshend I, Awosoga O, Kulig J, Fan H. Social cohesion and resilience across communities that have experienced a disaster. Natural Hazards (2014) 76:913–38. doi: 10.1007/s11069-014-1526-4