the future

For more than 40 years, IDEO has helped the world's leading organizations make the future. Find out how design can set you apart, help you grow, and solve your toughest challenges.

Breakthrough Products

We design magical products, brands, services, and experiences that people truly value.

Strategic Futures

We make your strategy tangible by building visions your teams can see, feel, and believe in.

Creative Capabilities

We build critical skills that help you lead organizational transformation, build resilience, and create change.

From Barbie Playhouses to Sonic Jets

From New Venture to Population-Level Impact

An IDEO project grows into a healthcare provider fighting chronic disease.

Reinventing Supersonic Flight With Boom

Ultrafast air travel is coming back, with an all-new passenger experience.

Changing the Conversation on Menopause

How QVC is reframing midlife as a time for women to thrive.

From electrified fleets to plastic-free packaging

Activating Strategy

Human-centered approaches for bringing strategy to life

Realizing a Waste Free Future Together

A coalition of retail leaders join forces to address single-use plastic-bag waste.

Planetary Protection at a Human Scale

A conservation leader rewrites the role humans play in the narrative of climate change.

From catalytic mindsets to innovation labs

Leading for Creativity

Learn to scale creative problem solving from Tim Brown, Chair of IDEO.

Helping Students Navigate Campus Life at NYU

How an organizational culture change is helping newbies at NYU navigate campus life.

Building an Accelerator for Climate Leaders

An innovation accelerator bolsters the impact of climate startups.

.jpg)

Get updates from IDEO

Shape the Future with IDEO

Inspire, inform, and co-create with IDEO , the world’s leading design firm. We tackle challenges across the globe, spanning diverse topics and communities. From designing waste out of the food system to simplifying prescription home delivery , your voice, ideas, feedback, and partnership is central to having a lasting positive impact.

Share more information about you so we can tailor our design research opportunity recommendations. You'll receive customized invitations to apply to design research opportunities.

View Opportunities

Browse public opportunities you can apply to directly. You can also see examples of past opportunities to understand what our opportunities and application process really looks like.

OPPORTUNITIES

Read through our frequently asked questions to understand the basics and particulars of participating in design research with IDEO and get easy access to our team for support or help.

“Working with IDEO gave me the opportunity to think creatively about some of the everyday challenges I face as a clinician. Doing it collaboratively with their team of smart creative professionals was not only satisfying but really fun! It was exciting to be part of developing a solution for the problems my patients face.”

Frank Brodie, MD, MBA

Participate in an interview or small group conversation

Share your experience, opinions, or expertise about various topics to inspire design or provide feedback in a remote zoom video call, on the phone, or in-person.

Be an advisor or part of a co-creation or co-design council

Either individually or as part of a small group, provide feedback, expertise, or perspectives throughout the life of an IDEO project.

Complete independent design research activities

Contribute your ideas, expertise, or feedback via paid research surveys, usability tests, or written and multimedia diary studies.

Experience a live prototype of a product, service, or experience

Walkthrough and provide feedback on life-size mockups of designs like voting booths , airplane cabins , or school cafeterias .

Contribute to connecting with and recruiting from your community

Connect IDEO to your network, lead local initiatives, or help shape IDEO projects and partnerships.

Deeply collaborate or embed alongside IDEO designers

Work with an IDEO project team as a part or full-time designer or expert-in-resident to experience design thinking and push our way of working.

Want to browse projects you can apply for directly? Check out our public Opportunities to see our calls for participation.

DESIGN RESEARCH QUESTIONS

Do you have feedback about our process? Questions about a project or initiative? Review our Frequently Asked Questions or send us an email .

OTHER INQUIRIES

Looking to partner with us, apply for a job, book a speaker, or find out more about our company or work? Learn about other ways to connect with IDEO.

Root out friction in every digital experience, super-charge conversion rates, and optimize digital self-service

Uncover insights from any interaction, deliver AI-powered agent coaching, and reduce cost to serve

Increase revenue and loyalty with real-time insights and recommendations delivered to teams on the ground

Know how your people feel and empower managers to improve employee engagement, productivity, and retention

Take action in the moments that matter most along the employee journey and drive bottom line growth

Whatever they’re are saying, wherever they’re saying it, know exactly what’s going on with your people

Get faster, richer insights with qual and quant tools that make powerful market research available to everyone

Run concept tests, pricing studies, prototyping + more with fast, powerful studies designed by UX research experts

Track your brand performance 24/7 and act quickly to respond to opportunities and challenges in your market

Explore the platform powering Experience Management

- Free Account

- For Digital

- For Customer Care

- For Human Resources

- For Researchers

- Financial Services

- All Industries

Popular Use Cases

- Customer Experience

- Employee Experience

- Net Promoter Score

- Voice of Customer

- Customer Success Hub

- Product Documentation

- Training & Certification

- XM Institute

- Popular Resources

- Customer Stories

- Artificial Intelligence

Market Research

- Partnerships

- Marketplace

The annual gathering of the experience leaders at the world’s iconic brands building breakthrough business results, live in Salt Lake City.

- English/AU & NZ

- Español/Europa

- Español/América Latina

- Português Brasileiro

- REQUEST DEMO

- Experience Management

- Research Design

Try Qualtrics for free

Research design for business.

17 min read To get the information you need to drive key business decisions and answer burning questions, you need a research methodology that works — and it all starts with research design. But what is it? In our ultimate guide to research design for businesses, we breakdown the process, including research methods, examples, and best practice tips to help you get started.

If you have a business problem that you’re trying to solve — from product usage to customer engagement — doing research is a great way to understand what is going wrong.

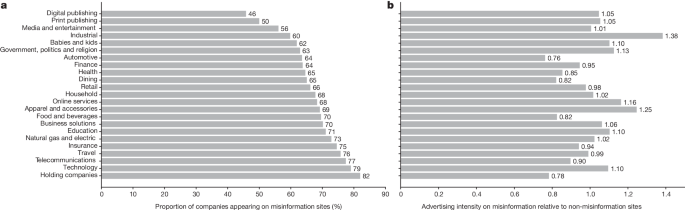

Yet despite this, less than 40% of marketers use consumer research to drive decisions [1] .

So why are businesses missing out on vital business insights that could help their bottom line?

One reason is that many simply don’t know which research method to use to correctly investigate their problem and uncover insights.

This is where our ultimate guide to research design can help. But first…

What is research design?

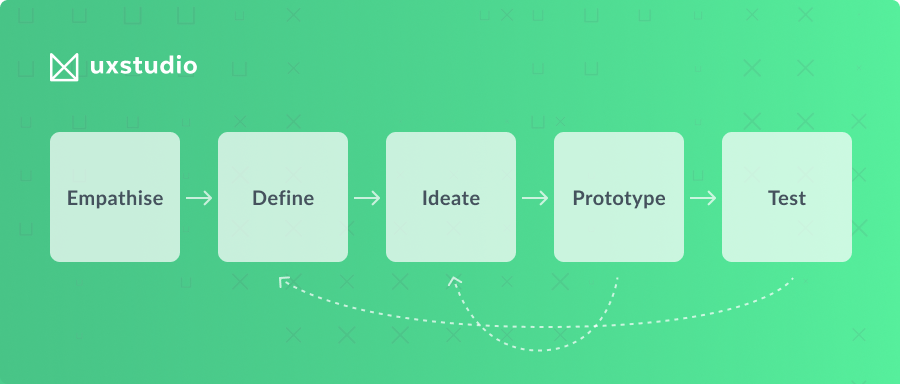

Research design is the overall strategy (or research methodology) used to carry out a study. It defines the framework and plan to tackle established problems and/or questions through the collection, interpretation, analysis, and discussion of data.

While there are several types of research design (more on that later), the research problem defines which should be used — not the other way around. In working this way, researchers can be certain that their methods match their aims — and that they’re capturing useful and actionable data.

For example, you might want to know why sales are falling for a specific product. You already have your context and other research questions to help uncover further insights. So, you start with your research problem (or problem statement) and choose an approach to get the information you need.

Free eBook: Quantitative and qualitative research design

Key considerations before a research project

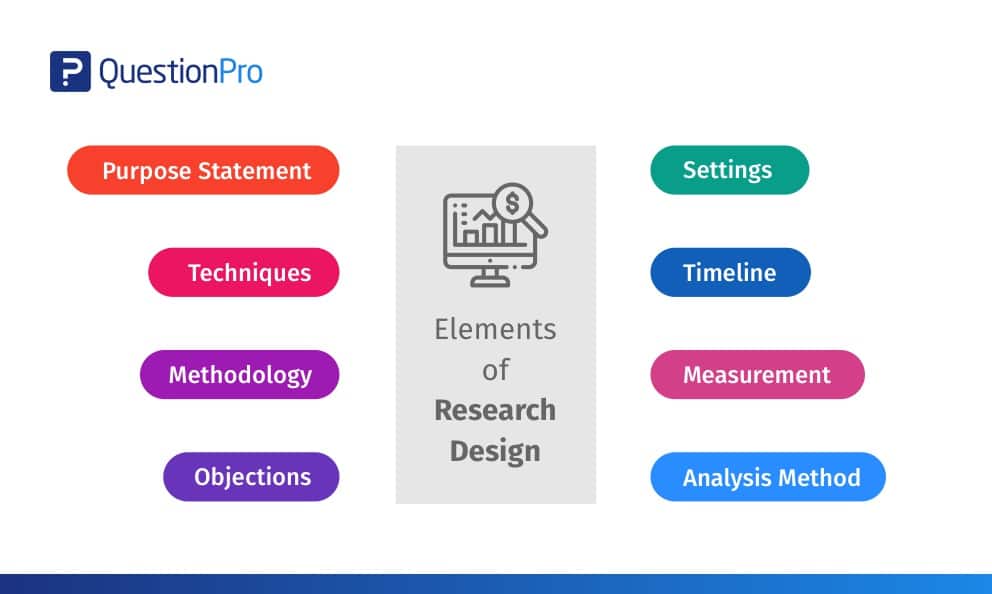

After you have your research problem and research questions to find out more information, you should always consider the following elements:

- Do you want to use a qualitative or quantitative approach?

- What type of research would you like to do (e.g. — create a survey or conduct telephone interviews)?

- How will you choose your population and sample size fairly?

- How will you choose a method to collect the data for ease of operation? The research tool you use will determine the validity of your study

- How will you analyze data after collection to help the business concern?

- How will you ensure your research is free from bias and neutral?

- What’s your timeline?

- In what setting will you conduct your research study?

- Are there any challenges or objections to conducting your research — and if so, how can you address them?

Ultimately, the data received should be unambiguous, so that the analysts can find accurate and trustworthy insights to act upon. Neutrality is key!

Types of approaches in research design

There are two main approaches to research design that we’ll explore in more detail — quantitative and qualitative.

Qualitative research design

Qualitative research designs tend to be more flexible and inductive (broad generalizations rather than specific observations), allowing you to adjust your approach based on the information you find throughout the research process. It looks at customer or prospect data (X data).

For example, if you want to generate new ideas for content campaigns, a qualitative approach would make the most sense. You can use this approach to find out more about what your audience would like to see, the particular challenges they are facing (from a business perspective), their overall experiences, and if any topics are under-researched.

To put it simply, qualitative research design looks at the whys and hows — as well as participants’ thoughts, feelings, and beliefs. It seeks to find reasons to explain decisions using the data captured.

However, as the data collected from qualitative research is typically written rather than numerical, it can be difficult to quantify information using statistical techniques.

When should you use qualitative research design?

It is best used when you want to conduct a detailed investigation of a topic to understand a holistic view. For example, to understand cultural differences in society, qualitative research design would create a research plan that allowed as many people from different cultures to participate and provided space for elaboration and anecdotal evidence.

If you want to incorporate a qualitative research design, you may choose to use methods like semi-structured focus groups, surveys with open-ended questions, or in-depth interviews in person or on the phone.

Quantitative research design

Quantitative research design looks at data that helps answer the key questions beginning with ‘Who’, ‘How’, ‘How many’ and ‘What’. This can include business data that explores operation statistics and sales records and quantifiable data on preferences.

Unlike qualitative research design, quantitative research design can be more controlled and fixed. It establishes variables, hypotheses, and correlations and tests participants against this knowledge. The aim is to explore the numerical data and understand its value against other sets of data, providing us with a data-driven way to measure the level of something.

When should you use quantitative research design?

If you want to quantify attitudes, opinions, behaviors, or any other defined variable (and general results from a large sample population), a quantitative approach is a way to go.

You could use quantitative research to validate findings from qualitative research. One provides depth and insight into the whys and hows, while the other delivers data to support them.

If you want to incorporate a quantitative research design, you may choose to use methods like secondary research collection or surveys with closed-ended questions.

Now that you know the differences between the two research approaches , we can go further and address their sub-categories.

Research methods: the subsets of qualitative and quantitative research

Depending on the aim/objective of your research, there are several research methods (for both qualitative and quantitative research) for you to choose from:

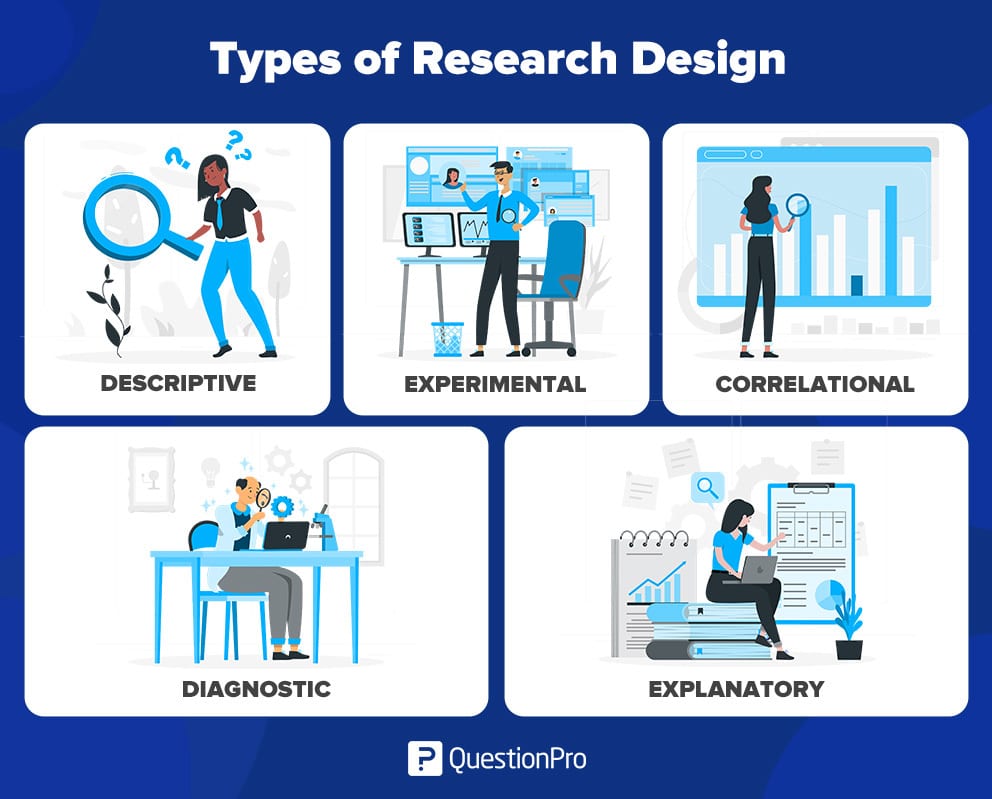

Types of quantitative research design

- Descriptive – provides information on the current state of affairs, by observing participants in a natural situation

- Experimental – provides causal relationship information between variables within a controlled situation

- Quasi-experimental – attempts to build a cause and effect relationship between an independent variable and a dependent variable

- Correlational – as the name suggests, correlational design allows the researcher to establish some kind of relation between two closely related topics or variables

Types of qualitative research design

- Case studies – a detailed study of a specific subject (place, event, organization)

- Ethnographic research – in-depth observational studies of people in their natural environment (this research aims to understand the cultures, challenges, motivations and settings of those involved)

- Grounded theory – collecting rich data on a topic of interest and developing theories inductively

- Phenomenology – investigating a phenomenon or event by describing and interpreting the shared experiences of participants

- Narrative research – examining how stories are told to understand how participants perceive and make sense of their experiences

Other subsets of qualitative and quantitative research design

- Exploratory – explores a new subject area by taking a holistic viewpoint and gathering foundational insights

- Cross-sectional – provides a snapshot of a moment in time to reflect the state

- Longitudinal – provides several snapshots of the same sample over a period to understand causal relationships

- Mixed methods – provide a bespoke application of design subsets to create more precise and nuanced results

- Observational – involves observing participants’ ongoing behavior in a natural situation

Let’s talk about these research methods in more detail.

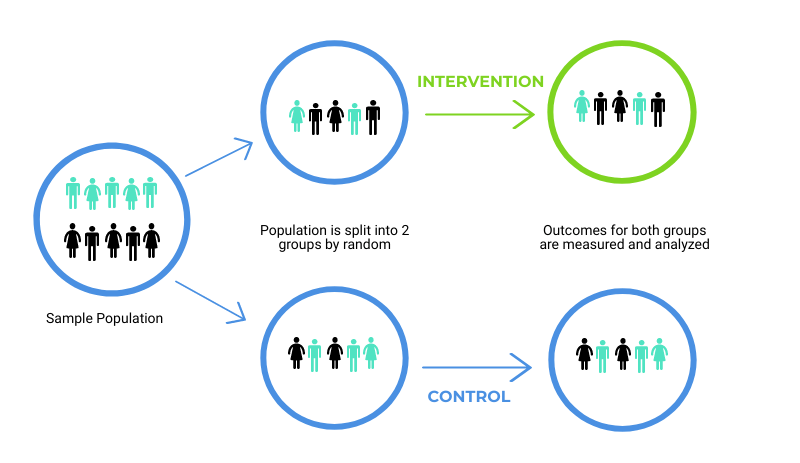

Experimental

As a subset of quantitative research design types, experimental research design aims to control variables in an experiment to test a hypothesis. Researchers will alter one of the variables to see how it affects the others.

Experimental research design provides an understanding of the causal relationships between two variables – which variable impacts the other, to what extent they are affected, and how consistent is the effect if the experiment is repeated.

To incorporate experimental research design, researchers create an artificial environment to more easily control the variables affecting participants. This can include creating two groups of participants – one acting as a control group to provide normal data readings, and another that has a variable altered. Therefore, having representative and random groups of participants can give better results to compare.

Image source: World Bank Blogs

Descriptive

Descriptive research design is a subset of qualitative design research and, unlike experimental design research, it provides descriptive insights on participants by observing participants in an uncontrolled, geographically-bound natural environment.

This type gives information on the current state of participants when faced with variables or changing circumstances. It helps answer who, what, when, where, and how questions on behavior, but it can’t provide a clear understanding of the why.

To incorporate a descriptive research design, researchers create situations where observation of participants can happen without notice. In capturing the information, researchers can analyze data to understand the different variables at play or find additional research areas to investigate.

Exploratory

Exploratory research design aims to investigate an area where little is known about the subject and there are no prior examples to draw insight from. Researchers want to gain insights into the foundational data (who, what, when, where, and how) and the deeper level data (the why).

Therefore, an exploratory research design is flexible and a subset of both quantitative and qualitative research design.

Like descriptive research design, this type of research method is used at the beginning stages of research to get a broader view, before proceeding with further research.

To incorporate exploratory research design, researchers will use several methods to gain the right data. These can include focus groups, surveys, interviews in person or on the phone, secondary desk research, controlled experiments, and observation in a natural setting.

Cross-sectional

Just like slicing through a tomato gives us a slice of the whole fruit, cross-sectional research design gives us a slice representing a specific point in time. Researchers can observe different groups at the same time to discover what makes the participant behavior different from one another and how behavior correlates. This is then used to form assumptions that can be further tested.

There are two types to consider. In descriptive cross-sectional research design, researchers do not get involved or influence the participants through any controls, so this research design type is a subset of quantitative research design. Researchers will use methods that provide a descriptive (who, what, when, where, and how) understanding of the cross-section. This can be done by survey or observation, though researcher bias can be an undesirable outcome if the method is not conscious of this.

Analytical cross-sectional research design looks at the why behind the outcome found in the cross-section, aligning this as a subset of qualitative research design. This understanding can be gained through emailed surveys. To gain stronger insights, group sample selection can be altered from a random selection of participants to researchers selecting participants into groups based on their differences.

Since only one cross-section is taken, this can be a cheaper and quicker way to carry out research when resources are limited. Yet, no causal relationships can be gained by comparing data across time, unlike longitudinal research design.

Longitudinal

Longitudinal research design takes multiple measures from the same participants or groups over an extended period. These repeated observations enable researchers to track variables, identify correlations and see if there are causal relationships that can confirm hypothesis predictions.

As the research design is focused on understanding the why behind the data, this is a subset of qualitative research design. However, the real-time data collection at each point in time will also require analysis based on the quantitative markers found through quantitative research design.

Researchers can incorporate longitudinal research design by using methods like panel studies for collecting primary data first-hand. The study can be retrospective (based on event data that has already occurred) or prospective (based on event data that is yet to happen).

While being the most useful method to get the data you need to address your business concern, this can be time-consuming and there can be issues with maintaining the integrity of the sample over time. Alternatively, you can use existing data sets to provide historical trends (which could be verified through a cross-sectional research design).

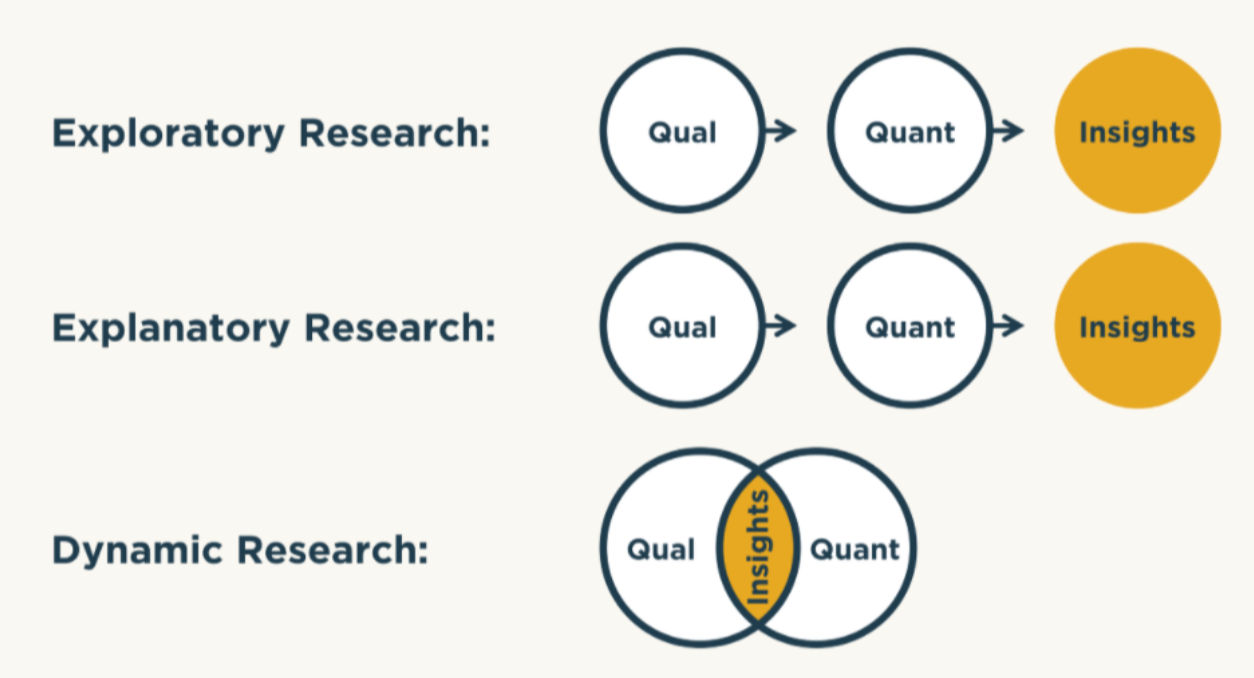

Mixed methods

Mixed methods aim to provide an advanced and bespoke response to solving your business problem. It combines the methods and subsets above to create a tailored method that gives researchers flexibility and options for carrying out research.

The mixed-method research design gives a thorough holistic view of the layers of data through quantitative and qualitative subset design methods. The resulting data is strengthened by the application of context and scale (quantitative) in alignment with the meaning behind behavior (qualitative), giving a richer picture of participants.

Mixed method research design is useful for getting greater ‘texture’ to your data, resulting in precise and meaningful information for analysis. The disadvantages and boundaries of a single subset can be offset by the benefits of using another to complement the investigation.

This subset does place more responsibility on the researcher to apply the subset designs appropriately to gain the right information. The data is interpreted and assessed by the researcher for its validity to the end results, so there is potential for researcher bias if they miss out on vital information that skews results.

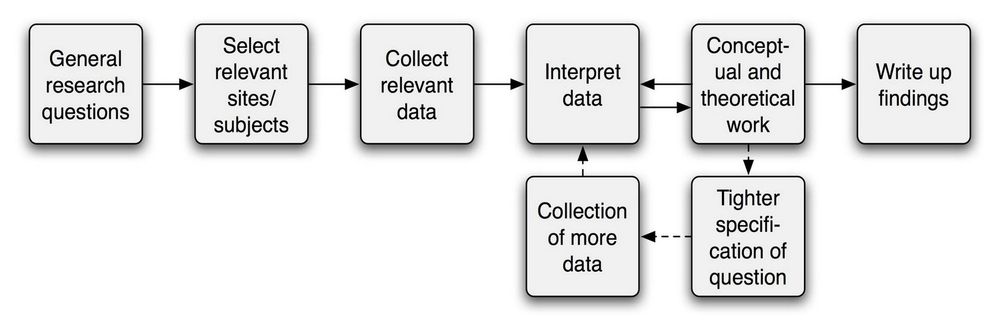

Image Source: Full Stack Researcher

Find the research design method(s) that work for you

No matter what information you want to find out — there’s a research design method that’s right for you.

However, it’s up to you to determine which of the methods above are the most viable and can deliver the insight you need. Remember, each research method has its advantages and disadvantages.

It’s also important to bear in mind (at all times), the key considerations before your research project:

- Are there any challenges or objections to conducting your research — and if so, how can you address them?.

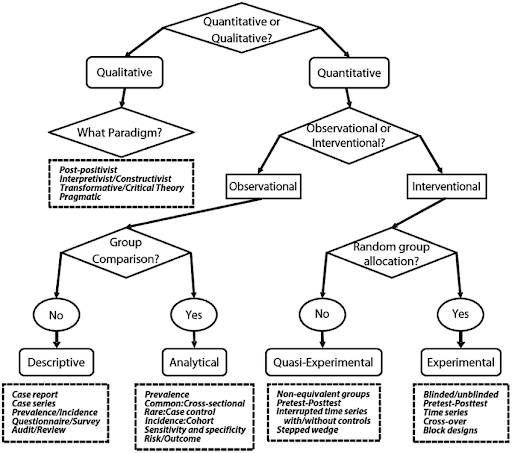

But if you’re unsure about where to begin, start by answering these questions with our decision tree:

Image Source: Research Gate

If you need more help, why not try speaking to one of our Qualtrics team members?

Our team of experts can help you with all your market research needs — from designing your study and finding respondents, to fielding it and reporting on the results.

[1] https://www.google.com/url?q=https://www.thinkwithgoogle.com/consumer-insights/consumer-trends/marketing-consumer-research-statistics/&sa=D&source=editors&ust=1629103799724264&usg=AOvVaw3H6LaHl4EJ4KQURNplqL31

Related resources

Market intelligence 10 min read, marketing insights 11 min read, ethnographic research 11 min read, qualitative vs quantitative research 13 min read, qualitative research questions 11 min read, qualitative research design 12 min read, primary vs secondary research 14 min read, request demo.

Ready to learn more about Qualtrics?

Research Design 101

Everything You Need To Get Started (With Examples)

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewers: Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) & Kerryn Warren (PhD) | April 2023

Navigating the world of research can be daunting, especially if you’re a first-time researcher. One concept you’re bound to run into fairly early in your research journey is that of “ research design ”. Here, we’ll guide you through the basics using practical examples , so that you can approach your research with confidence.

Overview: Research Design 101

What is research design.

- Research design types for quantitative studies

- Video explainer : quantitative research design

- Research design types for qualitative studies

- Video explainer : qualitative research design

- How to choose a research design

- Key takeaways

Research design refers to the overall plan, structure or strategy that guides a research project , from its conception to the final data analysis. A good research design serves as the blueprint for how you, as the researcher, will collect and analyse data while ensuring consistency, reliability and validity throughout your study.

Understanding different types of research designs is essential as helps ensure that your approach is suitable given your research aims, objectives and questions , as well as the resources you have available to you. Without a clear big-picture view of how you’ll design your research, you run the risk of potentially making misaligned choices in terms of your methodology – especially your sampling , data collection and data analysis decisions.

The problem with defining research design…

One of the reasons students struggle with a clear definition of research design is because the term is used very loosely across the internet, and even within academia.

Some sources claim that the three research design types are qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods , which isn’t quite accurate (these just refer to the type of data that you’ll collect and analyse). Other sources state that research design refers to the sum of all your design choices, suggesting it’s more like a research methodology . Others run off on other less common tangents. No wonder there’s confusion!

In this article, we’ll clear up the confusion. We’ll explain the most common research design types for both qualitative and quantitative research projects, whether that is for a full dissertation or thesis, or a smaller research paper or article.

Research Design: Quantitative Studies

Quantitative research involves collecting and analysing data in a numerical form. Broadly speaking, there are four types of quantitative research designs: descriptive , correlational , experimental , and quasi-experimental .

Descriptive Research Design

As the name suggests, descriptive research design focuses on describing existing conditions, behaviours, or characteristics by systematically gathering information without manipulating any variables. In other words, there is no intervention on the researcher’s part – only data collection.

For example, if you’re studying smartphone addiction among adolescents in your community, you could deploy a survey to a sample of teens asking them to rate their agreement with certain statements that relate to smartphone addiction. The collected data would then provide insight regarding how widespread the issue may be – in other words, it would describe the situation.

The key defining attribute of this type of research design is that it purely describes the situation . In other words, descriptive research design does not explore potential relationships between different variables or the causes that may underlie those relationships. Therefore, descriptive research is useful for generating insight into a research problem by describing its characteristics . By doing so, it can provide valuable insights and is often used as a precursor to other research design types.

Correlational Research Design

Correlational design is a popular choice for researchers aiming to identify and measure the relationship between two or more variables without manipulating them . In other words, this type of research design is useful when you want to know whether a change in one thing tends to be accompanied by a change in another thing.

For example, if you wanted to explore the relationship between exercise frequency and overall health, you could use a correlational design to help you achieve this. In this case, you might gather data on participants’ exercise habits, as well as records of their health indicators like blood pressure, heart rate, or body mass index. Thereafter, you’d use a statistical test to assess whether there’s a relationship between the two variables (exercise frequency and health).

As you can see, correlational research design is useful when you want to explore potential relationships between variables that cannot be manipulated or controlled for ethical, practical, or logistical reasons. It is particularly helpful in terms of developing predictions , and given that it doesn’t involve the manipulation of variables, it can be implemented at a large scale more easily than experimental designs (which will look at next).

That said, it’s important to keep in mind that correlational research design has limitations – most notably that it cannot be used to establish causality . In other words, correlation does not equal causation . To establish causality, you’ll need to move into the realm of experimental design, coming up next…

Need a helping hand?

Experimental Research Design

Experimental research design is used to determine if there is a causal relationship between two or more variables . With this type of research design, you, as the researcher, manipulate one variable (the independent variable) while controlling others (dependent variables). Doing so allows you to observe the effect of the former on the latter and draw conclusions about potential causality.

For example, if you wanted to measure if/how different types of fertiliser affect plant growth, you could set up several groups of plants, with each group receiving a different type of fertiliser, as well as one with no fertiliser at all. You could then measure how much each plant group grew (on average) over time and compare the results from the different groups to see which fertiliser was most effective.

Overall, experimental research design provides researchers with a powerful way to identify and measure causal relationships (and the direction of causality) between variables. However, developing a rigorous experimental design can be challenging as it’s not always easy to control all the variables in a study. This often results in smaller sample sizes , which can reduce the statistical power and generalisability of the results.

Moreover, experimental research design requires random assignment . This means that the researcher needs to assign participants to different groups or conditions in a way that each participant has an equal chance of being assigned to any group (note that this is not the same as random sampling ). Doing so helps reduce the potential for bias and confounding variables . This need for random assignment can lead to ethics-related issues . For example, withholding a potentially beneficial medical treatment from a control group may be considered unethical in certain situations.

Quasi-Experimental Research Design

Quasi-experimental research design is used when the research aims involve identifying causal relations , but one cannot (or doesn’t want to) randomly assign participants to different groups (for practical or ethical reasons). Instead, with a quasi-experimental research design, the researcher relies on existing groups or pre-existing conditions to form groups for comparison.

For example, if you were studying the effects of a new teaching method on student achievement in a particular school district, you may be unable to randomly assign students to either group and instead have to choose classes or schools that already use different teaching methods. This way, you still achieve separate groups, without having to assign participants to specific groups yourself.

Naturally, quasi-experimental research designs have limitations when compared to experimental designs. Given that participant assignment is not random, it’s more difficult to confidently establish causality between variables, and, as a researcher, you have less control over other variables that may impact findings.

All that said, quasi-experimental designs can still be valuable in research contexts where random assignment is not possible and can often be undertaken on a much larger scale than experimental research, thus increasing the statistical power of the results. What’s important is that you, as the researcher, understand the limitations of the design and conduct your quasi-experiment as rigorously as possible, paying careful attention to any potential confounding variables .

Research Design: Qualitative Studies

There are many different research design types when it comes to qualitative studies, but here we’ll narrow our focus to explore the “Big 4”. Specifically, we’ll look at phenomenological design, grounded theory design, ethnographic design, and case study design.

Phenomenological Research Design

Phenomenological design involves exploring the meaning of lived experiences and how they are perceived by individuals. This type of research design seeks to understand people’s perspectives , emotions, and behaviours in specific situations. Here, the aim for researchers is to uncover the essence of human experience without making any assumptions or imposing preconceived ideas on their subjects.

For example, you could adopt a phenomenological design to study why cancer survivors have such varied perceptions of their lives after overcoming their disease. This could be achieved by interviewing survivors and then analysing the data using a qualitative analysis method such as thematic analysis to identify commonalities and differences.

Phenomenological research design typically involves in-depth interviews or open-ended questionnaires to collect rich, detailed data about participants’ subjective experiences. This richness is one of the key strengths of phenomenological research design but, naturally, it also has limitations. These include potential biases in data collection and interpretation and the lack of generalisability of findings to broader populations.

Grounded Theory Research Design

Grounded theory (also referred to as “GT”) aims to develop theories by continuously and iteratively analysing and comparing data collected from a relatively large number of participants in a study. It takes an inductive (bottom-up) approach, with a focus on letting the data “speak for itself”, without being influenced by preexisting theories or the researcher’s preconceptions.

As an example, let’s assume your research aims involved understanding how people cope with chronic pain from a specific medical condition, with a view to developing a theory around this. In this case, grounded theory design would allow you to explore this concept thoroughly without preconceptions about what coping mechanisms might exist. You may find that some patients prefer cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) while others prefer to rely on herbal remedies. Based on multiple, iterative rounds of analysis, you could then develop a theory in this regard, derived directly from the data (as opposed to other preexisting theories and models).

Grounded theory typically involves collecting data through interviews or observations and then analysing it to identify patterns and themes that emerge from the data. These emerging ideas are then validated by collecting more data until a saturation point is reached (i.e., no new information can be squeezed from the data). From that base, a theory can then be developed .

As you can see, grounded theory is ideally suited to studies where the research aims involve theory generation , especially in under-researched areas. Keep in mind though that this type of research design can be quite time-intensive , given the need for multiple rounds of data collection and analysis.

Ethnographic Research Design

Ethnographic design involves observing and studying a culture-sharing group of people in their natural setting to gain insight into their behaviours, beliefs, and values. The focus here is on observing participants in their natural environment (as opposed to a controlled environment). This typically involves the researcher spending an extended period of time with the participants in their environment, carefully observing and taking field notes .

All of this is not to say that ethnographic research design relies purely on observation. On the contrary, this design typically also involves in-depth interviews to explore participants’ views, beliefs, etc. However, unobtrusive observation is a core component of the ethnographic approach.

As an example, an ethnographer may study how different communities celebrate traditional festivals or how individuals from different generations interact with technology differently. This may involve a lengthy period of observation, combined with in-depth interviews to further explore specific areas of interest that emerge as a result of the observations that the researcher has made.

As you can probably imagine, ethnographic research design has the ability to provide rich, contextually embedded insights into the socio-cultural dynamics of human behaviour within a natural, uncontrived setting. Naturally, however, it does come with its own set of challenges, including researcher bias (since the researcher can become quite immersed in the group), participant confidentiality and, predictably, ethical complexities . All of these need to be carefully managed if you choose to adopt this type of research design.

Case Study Design

With case study research design, you, as the researcher, investigate a single individual (or a single group of individuals) to gain an in-depth understanding of their experiences, behaviours or outcomes. Unlike other research designs that are aimed at larger sample sizes, case studies offer a deep dive into the specific circumstances surrounding a person, group of people, event or phenomenon, generally within a bounded setting or context .

As an example, a case study design could be used to explore the factors influencing the success of a specific small business. This would involve diving deeply into the organisation to explore and understand what makes it tick – from marketing to HR to finance. In terms of data collection, this could include interviews with staff and management, review of policy documents and financial statements, surveying customers, etc.

While the above example is focused squarely on one organisation, it’s worth noting that case study research designs can have different variation s, including single-case, multiple-case and longitudinal designs. As you can see in the example, a single-case design involves intensely examining a single entity to understand its unique characteristics and complexities. Conversely, in a multiple-case design , multiple cases are compared and contrasted to identify patterns and commonalities. Lastly, in a longitudinal case design , a single case or multiple cases are studied over an extended period of time to understand how factors develop over time.

As you can see, a case study research design is particularly useful where a deep and contextualised understanding of a specific phenomenon or issue is desired. However, this strength is also its weakness. In other words, you can’t generalise the findings from a case study to the broader population. So, keep this in mind if you’re considering going the case study route.

How To Choose A Research Design

Having worked through all of these potential research designs, you’d be forgiven for feeling a little overwhelmed and wondering, “ But how do I decide which research design to use? ”. While we could write an entire post covering that alone, here are a few factors to consider that will help you choose a suitable research design for your study.

Data type: The first determining factor is naturally the type of data you plan to be collecting – i.e., qualitative or quantitative. This may sound obvious, but we have to be clear about this – don’t try to use a quantitative research design on qualitative data (or vice versa)!

Research aim(s) and question(s): As with all methodological decisions, your research aim and research questions will heavily influence your research design. For example, if your research aims involve developing a theory from qualitative data, grounded theory would be a strong option. Similarly, if your research aims involve identifying and measuring relationships between variables, one of the experimental designs would likely be a better option.

Time: It’s essential that you consider any time constraints you have, as this will impact the type of research design you can choose. For example, if you’ve only got a month to complete your project, a lengthy design such as ethnography wouldn’t be a good fit.

Resources: Take into account the resources realistically available to you, as these need to factor into your research design choice. For example, if you require highly specialised lab equipment to execute an experimental design, you need to be sure that you’ll have access to that before you make a decision.

Keep in mind that when it comes to research, it’s important to manage your risks and play as conservatively as possible. If your entire project relies on you achieving a huge sample, having access to niche equipment or holding interviews with very difficult-to-reach participants, you’re creating risks that could kill your project. So, be sure to think through your choices carefully and make sure that you have backup plans for any existential risks. Remember that a relatively simple methodology executed well generally will typically earn better marks than a highly-complex methodology executed poorly.

Recap: Key Takeaways

We’ve covered a lot of ground here. Let’s recap by looking at the key takeaways:

- Research design refers to the overall plan, structure or strategy that guides a research project, from its conception to the final analysis of data.

- Research designs for quantitative studies include descriptive , correlational , experimental and quasi-experimenta l designs.

- Research designs for qualitative studies include phenomenological , grounded theory , ethnographic and case study designs.

- When choosing a research design, you need to consider a variety of factors, including the type of data you’ll be working with, your research aims and questions, your time and the resources available to you.

If you need a helping hand with your research design (or any other aspect of your research), check out our private coaching services .

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

10 Comments

Is there any blog article explaining more on Case study research design? Is there a Case study write-up template? Thank you.

Thanks this was quite valuable to clarify such an important concept.

Thanks for this simplified explanations. it is quite very helpful.

This was really helpful. thanks

Thank you for your explanation. I think case study research design and the use of secondary data in researches needs to be talked about more in your videos and articles because there a lot of case studies research design tailored projects out there.

Please is there any template for a case study research design whose data type is a secondary data on your repository?

This post is very clear, comprehensive and has been very helpful to me. It has cleared the confusion I had in regard to research design and methodology.

This post is helpful, easy to understand, and deconstructs what a research design is. Thanks

how to cite this page

Thank you very much for the post. It is wonderful and has cleared many worries in my mind regarding research designs. I really appreciate .

how can I put this blog as my reference(APA style) in bibliography part?

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

The Four Types of Research Design — Everything You Need to Know

Updated: December 11, 2023

Published: January 18, 2023

When you conduct research, you need to have a clear idea of what you want to achieve and how to accomplish it. A good research design enables you to collect accurate and reliable data to draw valid conclusions.

In this blog post, we'll outline the key features of the four common types of research design with real-life examples from UnderArmor, Carmex, and more. Then, you can easily choose the right approach for your project.

Table of Contents

What is research design?

The four types of research design, research design examples.

Research design is the process of planning and executing a study to answer specific questions. This process allows you to test hypotheses in the business or scientific fields.

Research design involves choosing the right methodology, selecting the most appropriate data collection methods, and devising a plan (or framework) for analyzing the data. In short, a good research design helps us to structure our research.

Marketers use different types of research design when conducting research .

There are four common types of research design — descriptive, correlational, experimental, and diagnostic designs. Let’s take a look at each in more detail.

Researchers use different designs to accomplish different research objectives. Here, we'll discuss how to choose the right type, the benefits of each, and use cases.

Research can also be classified as quantitative or qualitative at a higher level. Some experiments exhibit both qualitative and quantitative characteristics.

.png)

Free Market Research Kit

5 Research and Planning Templates + a Free Guide on How to Use Them in Your Market Research

- SWOT Analysis Template

- Survey Template

- Focus Group Template

You're all set!

Click this link to access this resource at any time.

Experimental

An experimental design is used when the researcher wants to examine how variables interact with each other. The researcher manipulates one variable (the independent variable) and observes the effect on another variable (the dependent variable).

In other words, the researcher wants to test a causal relationship between two or more variables.

In marketing, an example of experimental research would be comparing the effects of a television commercial versus an online advertisement conducted in a controlled environment (e.g. a lab). The objective of the research is to test which advertisement gets more attention among people of different age groups, gender, etc.

Another example is a study of the effect of music on productivity. A researcher assigns participants to one of two groups — those who listen to music while working and those who don't — and measure their productivity.

The main benefit of an experimental design is that it allows the researcher to draw causal relationships between variables.

One limitation: This research requires a great deal of control over the environment and participants, making it difficult to replicate in the real world. In addition, it’s quite costly.

Best for: Testing a cause-and-effect relationship (i.e., the effect of an independent variable on a dependent variable).

Correlational

A correlational design examines the relationship between two or more variables without intervening in the process.

Correlational design allows the analyst to observe natural relationships between variables. This results in data being more reflective of real-world situations.

For example, marketers can use correlational design to examine the relationship between brand loyalty and customer satisfaction. In particular, the researcher would look for patterns or trends in the data to see if there is a relationship between these two entities.

Similarly, you can study the relationship between physical activity and mental health. The analyst here would ask participants to complete surveys about their physical activity levels and mental health status. Data would show how the two variables are related.

Best for: Understanding the extent to which two or more variables are associated with each other in the real world.

Descriptive

Descriptive research refers to a systematic process of observing and describing what a subject does without influencing them.

Methods include surveys, interviews, case studies, and observations. Descriptive research aims to gather an in-depth understanding of a phenomenon and answers when/what/where.

SaaS companies use descriptive design to understand how customers interact with specific features. Findings can be used to spot patterns and roadblocks.

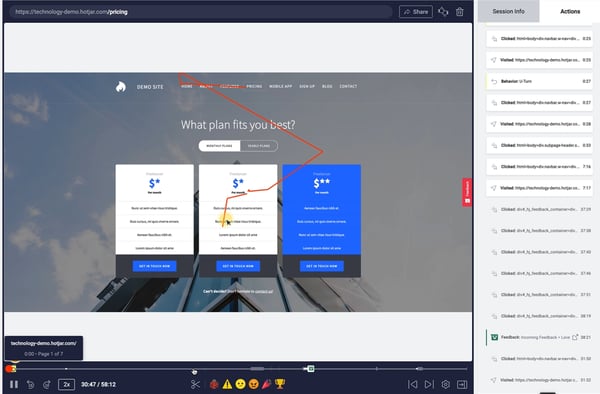

For instance, product managers can use screen recordings by Hotjar to observe in-app user behavior. This way, the team can precisely understand what is happening at a certain stage of the user journey and act accordingly.

Brand24, a social listening tool, tripled its sign-up conversion rate from 2.56% to 7.42%, thanks to locating friction points in the sign-up form through screen recordings.

Carma Laboratories worked with research company MMR to measure customers’ reactions to the lip-care company’s packaging and product . The goal was to find the cause of low sales for a recently launched line extension in Europe.

The team moderated a live, online focus group. Participants were shown w product samples, while AI and NLP natural language processing identified key themes in customer feedback.

This helped uncover key reasons for poor performance and guided changes in packaging.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

How to Leverage Ethnography to Do Proper Design Research

Whatever your method or combination of methods (e.g., semi-structured interviews and video ethnography), the “golden rules” are:

Build rapport – Your “test users” will only open up in trusting, relaxed, informal, natural settings. Simple courtesies such as thanking them and not pressuring them to answer will go a long way. Remember, human users want a human touch, and as customers they will have the final say on a design’s success.

Hide/Forget your own bias – This is a skill that will show in how you ask questions, which can subtly tell users what you might want to hear. Instead of asking (e.g.) “The last time you used a pay app on your phone, what was your worst security concern?”, try “Can you tell me about the last time you used an app on your phone to pay for something?”. Questions that betray how you might view things can make people distort their answers.

Embrace the not-knowing mindset and a blank-slate approach – to help you find users’ deep motivations and why they’ve created workarounds. Trying to forget—temporarily—everything you’ve learned about one or more things can be challenging. However, it can pay big dividends if you can ignore the assumptions that naturally creep into our understanding of our world.

Accept ambiguity – Try to avoid imposing a rigid binary (black-and-white/“yes”-or-“no”) scientific framework over your users’ human world.

Don’t jump to conclusions – Try to stay objective. The patterns we tend to establish to help us make sense of our world more easily can work against you as an observer if you let them. It’s perfectly human to rely on these patterns so we can think on our feet. But your users/customers already will be doing this with what they encounter. If you add your own subjectivity, you’ll distort things.

Keep an open mind to absorb the users’ world as present it – hence why it’s vital to get some proper grounding in user research. It takes a skilled eye, ear and mouth to zero in on everything there is to observe, without losing sight of anything by catering to your own agendas, etc.

Gentle encouragement helps; Silence is golden – a big part of keeping a naturalistic setting means letting your users stay comfortable at their own pace (within reason). Your “Mm-mmhs” of encouragement and appropriate silent stretches can keep your research safe from users’ suddenly putting politeness ahead of honesty if they feel (or feel that you’re) uncomfortable.

Overall, remember that two people can see the same thing very differently, and it takes an open-minded, inquisitive, informal approach to find truly valuable insights to understand users’ real problems.

Learn More about Design Research

Take our Service Design course, featuring many helpful templates: Service Design: How to Design Integrated Service Experiences

This Smashing Magazine piece nicely explores the human dimensions of design research: How To Get To Know Your Users

Let Invision expand your understanding of design research’s value, here: 4 types of research methods all designers should know .

Literature on Design Research

Here’s the entire UX literature on Design Research by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Learn more about Design Research

Take a deep dive into Design Research with our course Service Design: How to Design Integrated Service Experiences .

Services are everywhere! When you get a new passport, order a pizza or make a reservation on AirBnB, you're engaging with services. How those services are designed is crucial to whether they provide a pleasant experience or an exasperating one. The experience of a service is essential to its success or failure no matter if your goal is to gain and retain customers for your app or to design an efficient waiting system for a doctor’s office.

In a service design process, you use an in-depth understanding of the business and its customers to ensure that all the touchpoints of your service are perfect and, just as importantly, that your organization can deliver a great service experience every time . It’s not just about designing the customer interactions; you also need to design the entire ecosystem surrounding those interactions.

In this course, you’ll learn how to go through a robust service design process and which methods to use at each step along the way. You’ll also learn how to create a service design culture in your organization and set up a service design team . We’ll provide you with lots of case studies to learn from as well as interviews with top designers in the field. For each practical method, you’ll get downloadable templates that guide you on how to use the methods in your own work.

This course contains a series of practical exercises that build on one another to create a complete service design project . The exercises are optional, but you’ll get invaluable hands-on experience with the methods you encounter in this course if you complete them, because they will teach you to take your first steps as a service designer. What’s equally important is that you can use your work as a case study for your portfolio to showcase your abilities to future employers! A portfolio is essential if you want to step into or move ahead in a career in service design.

Your primary instructor in the course is Frank Spillers . Frank is CXO of award-winning design agency Experience Dynamics and a service design expert who has consulted with companies all over the world. Much of the written learning material also comes from John Zimmerman and Jodi Forlizzi , both Professors in Human-Computer Interaction at Carnegie Mellon University and highly influential in establishing design research as we know it today.

You’ll earn a verifiable and industry-trusted Course Certificate once you complete the course. You can highlight it on your resume, CV, LinkedIn profile or on your website.

All open-source articles on Design Research

Adding quality to your design research with an ssqs checklist.

- 8 years ago

Open Access—Link to us!

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge . Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change , cite this page , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge !

Privacy Settings

Our digital services use necessary tracking technologies, including third-party cookies, for security, functionality, and to uphold user rights. Optional cookies offer enhanced features, and analytics.

Experience the full potential of our site that remembers your preferences and supports secure sign-in.

Governs the storage of data necessary for maintaining website security, user authentication, and fraud prevention mechanisms.

Enhanced Functionality

Saves your settings and preferences, like your location, for a more personalized experience.

Referral Program

We use cookies to enable our referral program, giving you and your friends discounts.

Error Reporting

We share user ID with Bugsnag and NewRelic to help us track errors and fix issues.

Optimize your experience by allowing us to monitor site usage. You’ll enjoy a smoother, more personalized journey without compromising your privacy.

Analytics Storage

Collects anonymous data on how you navigate and interact, helping us make informed improvements.

Differentiates real visitors from automated bots, ensuring accurate usage data and improving your website experience.

Lets us tailor your digital ads to match your interests, making them more relevant and useful to you.

Advertising Storage

Stores information for better-targeted advertising, enhancing your online ad experience.

Personalization Storage

Permits storing data to personalize content and ads across Google services based on user behavior, enhancing overall user experience.

Advertising Personalization

Allows for content and ad personalization across Google services based on user behavior. This consent enhances user experiences.

Enables personalizing ads based on user data and interactions, allowing for more relevant advertising experiences across Google services.

Receive more relevant advertisements by sharing your interests and behavior with our trusted advertising partners.

Enables better ad targeting and measurement on Meta platforms, making ads you see more relevant.

Allows for improved ad effectiveness and measurement through Meta’s Conversions API, ensuring privacy-compliant data sharing.

LinkedIn Insights

Tracks conversions, retargeting, and web analytics for LinkedIn ad campaigns, enhancing ad relevance and performance.

LinkedIn CAPI

Enhances LinkedIn advertising through server-side event tracking, offering more accurate measurement and personalization.

Google Ads Tag

Tracks ad performance and user engagement, helping deliver ads that are most useful to you.

Share Knowledge, Get Respect!

or copy link

Cite according to academic standards

Simply copy and paste the text below into your bibliographic reference list, onto your blog, or anywhere else. You can also just hyperlink to this page.

New to UX Design? We’re Giving You a Free ebook!

Download our free ebook The Basics of User Experience Design to learn about core concepts of UX design.

In 9 chapters, we’ll cover: conducting user interviews, design thinking, interaction design, mobile UX design, usability, UX research, and many more!

We’re a strategic design company that helps people live better and work smarter.

Smart design is a strategic design company that helps people live better and work smarter., innovation 2.0: healthcare.

Seeking the perfect pour

Empower her health: FemTech interview series

Gx ecosystem, fueling the future of athletic performance, meet the smarties, six steps to co-design: what it is and why your company needs it m..., let’s design a smarter world together, design for digital well-being, elevating the voices of young people through co-design, design thinking isn’t design. time to shift gears..

Bringing tech to the next level

Stay up to date on our latest insights

A new customer experience for hearing health.

2023 Good Design Awards

A great case study for cgos: the 10-yr innovation journey of gatorade’s gx ecosystem, 2023 fast company innovation by design awards, the 2023 gq home awards, 2023 core77 design awards, the problem with refillable beauty.

Guiding principles

Research in practice.

Our practice

We are not our users. Design research guides teams to uncover insights and inform the experiences we create. It begins with the rigorous study of the people we serve and their context. This is the heart of Enterprise Design Thinking . While in the Loop , design research leads teams to continuously build understanding and empathy through observation, prototyping possible solutions, and reflecting on the feedback from our users themselves.

Ethics and Responsibility

Sponsor User Program

Latest Articles

More than just medicine: how design thinking uncovered modern patient needs

Enterprise Design Thinking

1 minute read

The Total Economic Impact™ Of IBM’s Design Thinking Practice

60 minute read

Project Monocle: a case for design research

5 minute read

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 20 March 2023.

A research design is a strategy for answering your research question using empirical data. Creating a research design means making decisions about:

- Your overall aims and approach

- The type of research design you’ll use

- Your sampling methods or criteria for selecting subjects

- Your data collection methods

- The procedures you’ll follow to collect data

- Your data analysis methods

A well-planned research design helps ensure that your methods match your research aims and that you use the right kind of analysis for your data.

Table of contents

Step 1: consider your aims and approach, step 2: choose a type of research design, step 3: identify your population and sampling method, step 4: choose your data collection methods, step 5: plan your data collection procedures, step 6: decide on your data analysis strategies, frequently asked questions.

- Introduction

Before you can start designing your research, you should already have a clear idea of the research question you want to investigate.

There are many different ways you could go about answering this question. Your research design choices should be driven by your aims and priorities – start by thinking carefully about what you want to achieve.

The first choice you need to make is whether you’ll take a qualitative or quantitative approach.

Qualitative research designs tend to be more flexible and inductive , allowing you to adjust your approach based on what you find throughout the research process.

Quantitative research designs tend to be more fixed and deductive , with variables and hypotheses clearly defined in advance of data collection.

It’s also possible to use a mixed methods design that integrates aspects of both approaches. By combining qualitative and quantitative insights, you can gain a more complete picture of the problem you’re studying and strengthen the credibility of your conclusions.

Practical and ethical considerations when designing research

As well as scientific considerations, you need to think practically when designing your research. If your research involves people or animals, you also need to consider research ethics .

- How much time do you have to collect data and write up the research?

- Will you be able to gain access to the data you need (e.g., by travelling to a specific location or contacting specific people)?

- Do you have the necessary research skills (e.g., statistical analysis or interview techniques)?

- Will you need ethical approval ?

At each stage of the research design process, make sure that your choices are practically feasible.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Within both qualitative and quantitative approaches, there are several types of research design to choose from. Each type provides a framework for the overall shape of your research.

Types of quantitative research designs

Quantitative designs can be split into four main types. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs allow you to test cause-and-effect relationships, while descriptive and correlational designs allow you to measure variables and describe relationships between them.

With descriptive and correlational designs, you can get a clear picture of characteristics, trends, and relationships as they exist in the real world. However, you can’t draw conclusions about cause and effect (because correlation doesn’t imply causation ).

Experiments are the strongest way to test cause-and-effect relationships without the risk of other variables influencing the results. However, their controlled conditions may not always reflect how things work in the real world. They’re often also more difficult and expensive to implement.

Types of qualitative research designs

Qualitative designs are less strictly defined. This approach is about gaining a rich, detailed understanding of a specific context or phenomenon, and you can often be more creative and flexible in designing your research.

The table below shows some common types of qualitative design. They often have similar approaches in terms of data collection, but focus on different aspects when analysing the data.

Your research design should clearly define who or what your research will focus on, and how you’ll go about choosing your participants or subjects.

In research, a population is the entire group that you want to draw conclusions about, while a sample is the smaller group of individuals you’ll actually collect data from.

Defining the population

A population can be made up of anything you want to study – plants, animals, organisations, texts, countries, etc. In the social sciences, it most often refers to a group of people.

For example, will you focus on people from a specific demographic, region, or background? Are you interested in people with a certain job or medical condition, or users of a particular product?

The more precisely you define your population, the easier it will be to gather a representative sample.

Sampling methods

Even with a narrowly defined population, it’s rarely possible to collect data from every individual. Instead, you’ll collect data from a sample.

To select a sample, there are two main approaches: probability sampling and non-probability sampling . The sampling method you use affects how confidently you can generalise your results to the population as a whole.

Probability sampling is the most statistically valid option, but it’s often difficult to achieve unless you’re dealing with a very small and accessible population.

For practical reasons, many studies use non-probability sampling, but it’s important to be aware of the limitations and carefully consider potential biases. You should always make an effort to gather a sample that’s as representative as possible of the population.

Case selection in qualitative research

In some types of qualitative designs, sampling may not be relevant.

For example, in an ethnography or a case study, your aim is to deeply understand a specific context, not to generalise to a population. Instead of sampling, you may simply aim to collect as much data as possible about the context you are studying.

In these types of design, you still have to carefully consider your choice of case or community. You should have a clear rationale for why this particular case is suitable for answering your research question.

For example, you might choose a case study that reveals an unusual or neglected aspect of your research problem, or you might choose several very similar or very different cases in order to compare them.

Data collection methods are ways of directly measuring variables and gathering information. They allow you to gain first-hand knowledge and original insights into your research problem.

You can choose just one data collection method, or use several methods in the same study.

Survey methods

Surveys allow you to collect data about opinions, behaviours, experiences, and characteristics by asking people directly. There are two main survey methods to choose from: questionnaires and interviews.

Observation methods

Observations allow you to collect data unobtrusively, observing characteristics, behaviours, or social interactions without relying on self-reporting.

Observations may be conducted in real time, taking notes as you observe, or you might make audiovisual recordings for later analysis. They can be qualitative or quantitative.

Other methods of data collection

There are many other ways you might collect data depending on your field and topic.

If you’re not sure which methods will work best for your research design, try reading some papers in your field to see what data collection methods they used.

Secondary data

If you don’t have the time or resources to collect data from the population you’re interested in, you can also choose to use secondary data that other researchers already collected – for example, datasets from government surveys or previous studies on your topic.

With this raw data, you can do your own analysis to answer new research questions that weren’t addressed by the original study.

Using secondary data can expand the scope of your research, as you may be able to access much larger and more varied samples than you could collect yourself.

However, it also means you don’t have any control over which variables to measure or how to measure them, so the conclusions you can draw may be limited.

As well as deciding on your methods, you need to plan exactly how you’ll use these methods to collect data that’s consistent, accurate, and unbiased.

Planning systematic procedures is especially important in quantitative research, where you need to precisely define your variables and ensure your measurements are reliable and valid.

Operationalisation

Some variables, like height or age, are easily measured. But often you’ll be dealing with more abstract concepts, like satisfaction, anxiety, or competence. Operationalisation means turning these fuzzy ideas into measurable indicators.

If you’re using observations , which events or actions will you count?

If you’re using surveys , which questions will you ask and what range of responses will be offered?

You may also choose to use or adapt existing materials designed to measure the concept you’re interested in – for example, questionnaires or inventories whose reliability and validity has already been established.

Reliability and validity

Reliability means your results can be consistently reproduced , while validity means that you’re actually measuring the concept you’re interested in.

For valid and reliable results, your measurement materials should be thoroughly researched and carefully designed. Plan your procedures to make sure you carry out the same steps in the same way for each participant.

If you’re developing a new questionnaire or other instrument to measure a specific concept, running a pilot study allows you to check its validity and reliability in advance.

Sampling procedures

As well as choosing an appropriate sampling method, you need a concrete plan for how you’ll actually contact and recruit your selected sample.

That means making decisions about things like:

- How many participants do you need for an adequate sample size?

- What inclusion and exclusion criteria will you use to identify eligible participants?

- How will you contact your sample – by mail, online, by phone, or in person?

If you’re using a probability sampling method, it’s important that everyone who is randomly selected actually participates in the study. How will you ensure a high response rate?

If you’re using a non-probability method, how will you avoid bias and ensure a representative sample?

Data management

It’s also important to create a data management plan for organising and storing your data.

Will you need to transcribe interviews or perform data entry for observations? You should anonymise and safeguard any sensitive data, and make sure it’s backed up regularly.

Keeping your data well organised will save time when it comes to analysing them. It can also help other researchers validate and add to your findings.

On their own, raw data can’t answer your research question. The last step of designing your research is planning how you’ll analyse the data.

Quantitative data analysis

In quantitative research, you’ll most likely use some form of statistical analysis . With statistics, you can summarise your sample data, make estimates, and test hypotheses.

Using descriptive statistics , you can summarise your sample data in terms of:

- The distribution of the data (e.g., the frequency of each score on a test)

- The central tendency of the data (e.g., the mean to describe the average score)

- The variability of the data (e.g., the standard deviation to describe how spread out the scores are)

The specific calculations you can do depend on the level of measurement of your variables.

Using inferential statistics , you can:

- Make estimates about the population based on your sample data.

- Test hypotheses about a relationship between variables.

Regression and correlation tests look for associations between two or more variables, while comparison tests (such as t tests and ANOVAs ) look for differences in the outcomes of different groups.

Your choice of statistical test depends on various aspects of your research design, including the types of variables you’re dealing with and the distribution of your data.

Qualitative data analysis

In qualitative research, your data will usually be very dense with information and ideas. Instead of summing it up in numbers, you’ll need to comb through the data in detail, interpret its meanings, identify patterns, and extract the parts that are most relevant to your research question.

Two of the most common approaches to doing this are thematic analysis and discourse analysis .

There are many other ways of analysing qualitative data depending on the aims of your research. To get a sense of potential approaches, try reading some qualitative research papers in your field.

A sample is a subset of individuals from a larger population. Sampling means selecting the group that you will actually collect data from in your research.

For example, if you are researching the opinions of students in your university, you could survey a sample of 100 students.

Statistical sampling allows you to test a hypothesis about the characteristics of a population. There are various sampling methods you can use to ensure that your sample is representative of the population as a whole.

Operationalisation means turning abstract conceptual ideas into measurable observations.

For example, the concept of social anxiety isn’t directly observable, but it can be operationally defined in terms of self-rating scores, behavioural avoidance of crowded places, or physical anxiety symptoms in social situations.

Before collecting data , it’s important to consider how you will operationalise the variables that you want to measure.

The research methods you use depend on the type of data you need to answer your research question .

- If you want to measure something or test a hypothesis , use quantitative methods . If you want to explore ideas, thoughts, and meanings, use qualitative methods .

- If you want to analyse a large amount of readily available data, use secondary data. If you want data specific to your purposes with control over how they are generated, collect primary data.

- If you want to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables , use experimental methods. If you want to understand the characteristics of a research subject, use descriptive methods.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, March 20). Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 3 June 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/research-design/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research Research Tools and Apps

Research Design: What it is, Elements & Types

Can you imagine doing research without a plan? Probably not. When we discuss a strategy to collect, study, and evaluate data, we talk about research design. This design addresses problems and creates a consistent and logical model for data analysis. Let’s learn more about it.

What is Research Design?

Research design is the framework of research methods and techniques chosen by a researcher to conduct a study. The design allows researchers to sharpen the research methods suitable for the subject matter and set up their studies for success.

Creating a research topic explains the type of research (experimental, survey research , correlational , semi-experimental, review) and its sub-type (experimental design, research problem , descriptive case-study).

There are three main types of designs for research:

- Data collection

- Measurement

- Data Analysis

The research problem an organization faces will determine the design, not vice-versa. The design phase of a study determines which tools to use and how they are used.

The Process of Research Design