Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 11 December 2014

Large-Scale Quantitative Analysis of Painting Arts

- Daniel Kim 1 ,

- Seung-Woo Son 2 &

- Hawoong Jeong 3 , 4

Scientific Reports volume 4 , Article number: 7370 ( 2014 ) Cite this article

22k Accesses

47 Citations

64 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Scientific data

Scientists have made efforts to understand the beauty of painting art in their own languages. As digital image acquisition of painting arts has made rapid progress, researchers have come to a point where it is possible to perform statistical analysis of a large-scale database of artistic paints to make a bridge between art and science. Using digital image processing techniques, we investigate three quantitative measures of images – the usage of individual colors, the variety of colors and the roughness of the brightness. We found a difference in color usage between classical paintings and photographs and a significantly low color variety of the medieval period. Interestingly, moreover, the increment of roughness exponent as painting techniques such as chiaroscuro and sfumato have advanced is consistent with historical circumstances.

Similar content being viewed by others

A vision chip with complementary pathways for open-world sensing

The environmental price of fast fashion

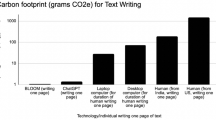

The carbon emissions of writing and illustrating are lower for AI than for humans

Introduction.

Humans have expressed physical experiences and abstract ideas in artistic paintings such as cave paintings, frescos in cathedrals and even graffiti on city walls. Such paintings, to convey intended messages, consist of three fundamental building blocks: points, lines and planes. Recent studies have shed light on interesting mathematical patterns between these building blocks in paintings.

Artistic styles were analyzed through various statistical techniques such as fractal analysis 1 , the wavelet-based technique 2 , the multi-resolution hidden Markov method 3 , the Fisher kernel based approach 4 and the sparse coding model 5 , 6 . Recently, these methods have also been applied to other cultural heritages such as literature 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 and music 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 . Such quantitative analysis is called “stylometry,” which originates from literature analysis to identify characteristic literary style 9 .

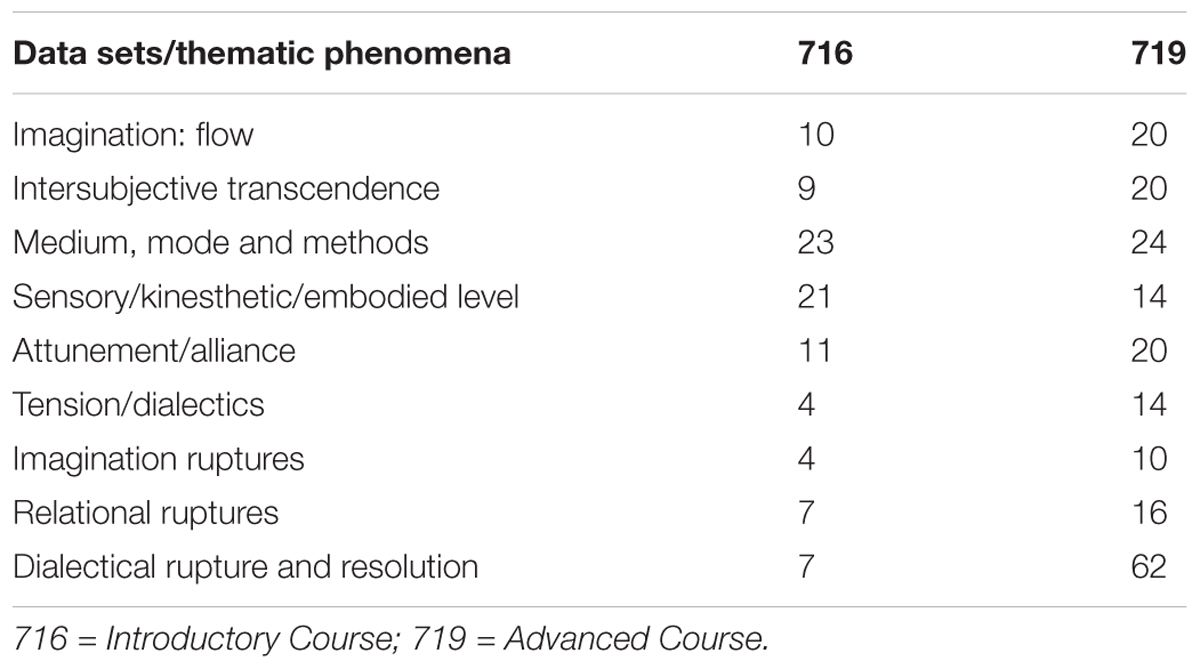

In this study, we add a new dimension to the body of stylometry studies by analyzing a large-scale database of artistic paintings. With digital image processing techniques we quantify the change in variety of painted colors and their spatial structures over ten historical periods of western paintings – medieval, early renaissance, northern renaissance, high renaissance, mannerism, baroque, rococo, neoclassicism, romanticism and realism – starting from the 11th century to the mid-19th century. Digital images of the paintings were obtained from the Web Gallery of Art 15 , which is a searchable database for European paintings and sculptures consisting of over 29,000 pieces ranging from the years 1000 to 1850. Most of the identifiable images contain information of schools, periods and artists and are good quality in resolution to apply statistical analysis.

Here we focus on the following three quantities – the usage of each color, variety of painted colors and the roughness of the brightness of images. First, we count how often a certain color appears in a painting for each period. From the frequency histogram, we find a clear difference between classical paintings and photographs. Next, we measure a fractal dimension of painted colors for each period in a color space, which is analogically considered to reflect the color ‘palette’ of that period. Interestingly, the fractal dimension of the medieval period is lower than that of other periods. The detailed results and our inference are discussed in this section. Last, we consider how rough or smooth an image is in the sense of its brightness. In order to quantify roughness of brightness, a well-known roughness exponent measurement in statistical physics is applied. We find that the roughness exponent increases gradually over the 10 periods, which is consistent with the historical circumstances like the birth of the new painting techniques such as chiaroscuro and sfumato 16 , 17 ( Chiaroscuro and sfumato are major painting techniques developed and widely used during the Renaissance period. Literally, the compound word chiaroscuro is formed from the Italian words chiaro (light) and oscuro (dark), which refers to an artistic technique to delineate tonal contrasts and voluminous objects with a dramatic use of light. Precursors of chiaroscuro are Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) and Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571–1610) and Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669) is a representative artist well-known for his use of chiaroscuro . The Italian word sfumato is derived from the Italian term fumo which literally means “smoke”. Leonardo da Vinci mentioned sfumato as a blending of colors without lines or borders, in the manner of smoke or beyond the focus plane. In other words, sfumato is a painting technique to express gradual fade-out between object and background avoiding harsh outlines.). Analyzing these three properties, we propose new approaches to quantitatively analyze a large scale database of paintings. Applying our method to the controversial Jackson Pollock's drip paintings, it is possible to infer that his drip paintings are quite different from works of other painters.

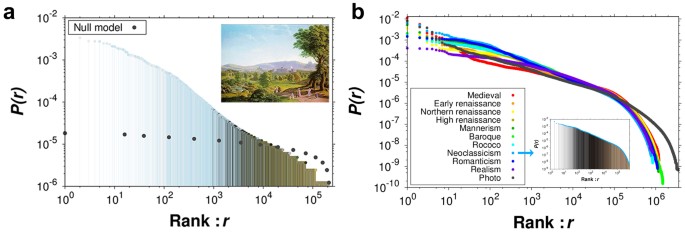

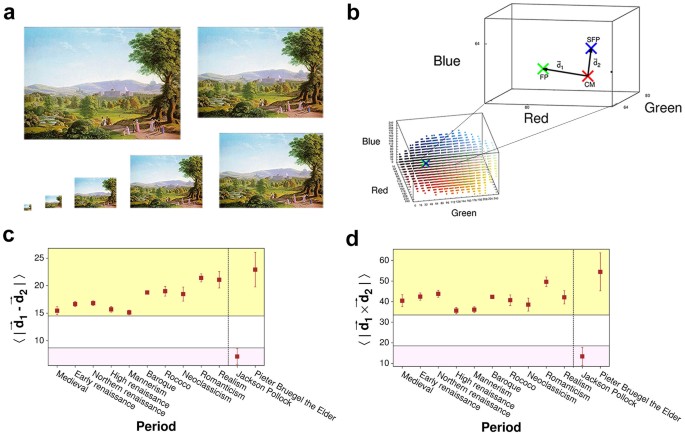

Chromo-spectroscopy

First we investigate how many different kinds of color appear in a painting and how often a certain color is painted, which is similar to Zipf's plot for word frequencies in literature 18 . It is named as “chromo-spectroscopy.” A color is considered to be like a word for a painter. As an example of chromo-spectroscopy, Fig. 1a displays the fraction of each color used in a painting in descending rank order. If each color is chosen from a palette uniformly at random, the frequency of each color would follow a binomial distribution for a random process (see more detail in the supplement ) and its rank plot would show an inverse of its cumulative, i.e., the regularized incomplete beta function 19 . This is because the rank plot is the inverse of its cumulative density function (see black dots in Fig. 1a ). However, interestingly, the rank-ordered color-usage distribution (RCD) shows a long tail distribution, which is different from the inverse function of the regularized incomplete beta function (see Fig. 1a ).

Rank-ordered color-usage distributions for an image and periods.

(a) Fraction distribution of each color in a descending rank order for the art work of German painter Johann Erdmann Hummel (1769-1852), “Schloss Wilhelmshöhe with the Habichtswald” (This image is out of copyright.). The horizontal axis indicates the rank of a color in frequency and the vertical axis denotes the proportion of a color in an image. The most (least) used color is located at the leftmost (rightmost) position on the horizontal axis. The black dots represent color choices from the same palette uniformly at random. (b) Rank-ordered color-usage distributions (RCDs) of the 10 periods and photographs. Note that the distribution of photographs clearly shows a different tail. Inset: RCD for the neoclassicism period. The displayed color corresponds to its rank. Note that the fraction is normalized by the image size and the number of paintings in each period.

Figure 1b shows RCDs for 10 periods of European art history and photographs. The RCD of a period represents how many colors are used and how often a specific color appears during the period. All periods of painting show a universal distribution curve, but the rank of each color for each period is rather different. The RCD of photographs is similar to that of paintings at the beginning of a power-law part but the exponential tail deviates significantly from paintings, as shown in Fig. 1b . In order to clarify the difference of the tail section of RCDs between paintings and photographs, we analyze RCDs of images of photographs after applying several painting filters from popular software. There are clear changes in the tail of the distribution when only the oil painting filter is applied. An oil painting filter usually consists of two parameters – range and level – which are related to the size of an art paint brush and smearing intensity. It seems these two parameters influence the shape of the exponential tail of the RCD. Another interesting fact is that there is no clear difference between RCDs of photographs and hyper-realism paintings, which are extremely finely drawn with microscope and are hard to distinguish from photographs with unaided eyes (see Figure S4b in the supplement ). This suggests that paintings are only quantitatively distinguished from photographs by the tail section of the RCD. The tail of RCD represents frequency of noisy colors or a level of details in the image.

Fractal pattern and color palette

RCDs for all periods of paintings show quite universal distribution curves. However, the most commonly painted color is different for each period. To characterize the variety of colors more quantitatively, while ignoring its individual frequency, we investigate the fractal pattern of the painted color in the RGB color space for each period.

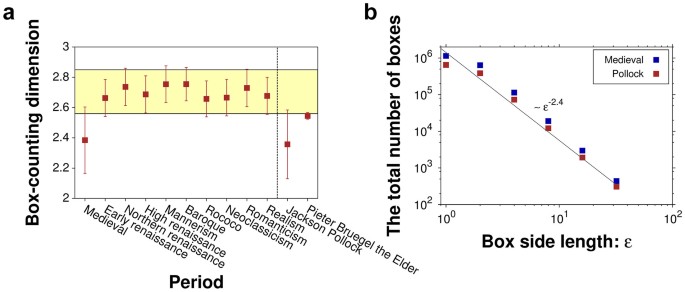

To examine the fractal characteristics of painted colors for each period, we measure the box-counting dimension 20 of the paintings in the RGB color space and compare them with two iconoclastic artists: Pieter Bruegel the Elder and Jackson Pollock. Each color used in the painting is plotted on a point in the RGB color space. Based on the definition of the box-counting dimension, we iteratively change the length of box ε from ε = 1 to ε = 32 and count the number of non-empty boxes. A non-empty box indicates that corresponding colors within the box are used in the painting at least once. If the distribution of colors in the color space is homogeneous, the box counting dimension is 3. In other words, if the box counting dimension is less than 3, the distributions in the color space is heterogeneous and fractal, which means some axes are preferred or the distribution is composed of a preferred color scheme in the color space. In this sense, measuring the box-counting dimension quantifies the spatial uniformity or fractality of painted colors for each artistic period.

Figure 2a shows that the box-counting dimensions of paintings from the 10 historic periods are in the range between 2.6 and 2.8 except for the medieval period. As Fig. 2b shows, only the box-counting dimension of the medieval period is close to that of Jackson Pollock's drip paintings (below 2.4), where he used limited colors intentionally. In addition, the box counting dimension for the paintings of Pieter Bruegel the Elder is approximately 2.55. A low box-counting dimension represents that there is a strong preference in a small number of selected colors in the medieval age. That is, the color palette in the medieval age is significantly different from the other periods.

Box-counting dimension and its tendency.

(a) The results of box-counting dimension over the 10 artistic periods display a significant difference of the medieval period from the other periods. Error bars indicate the standard deviation. (b) The number of boxes to cover the color space versus box size. The fractal dimension in the color space of Jackson Pollock's drip paintings is measured around 2.35, similar to that of medieval paintings (see also Figure S5 in the supplement ), but dissimilar to that of another iconoclastic artist Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

One can find the reason why the box counting dimensions for the medieval age and Jackson Pollock are different from others in the historical facts. First, specific rare pigments were preferred for political purposes and religious reasons in the medieval age despite their expensive cost. Second, no technique of physical mixing between different pure colors was used in that period due to the tendency to emphasize the purity of colors and materials themselves. Artists recoated on a colored canvas to represent various colors in the middle age. The drip paintings of Jackson Pollock are also formed from recoating each single color dripping pattern on other layers and the number of used colors is smaller than other western paintings before 20 th century. Furthermore, oil colors and color mixing techniques were not fully developed until the Renaissance age. The introduction of new expression tools, like pastels and fingers and painting techniques, such as chiaroscuro and sfumato , made much more colorful and natural expressions possible after the Renaissance period 21 . The difference of fractal dimensions between the medieval and other periods quantitatively may quantitatively reflect the historical facts and the painting technical difference in art history.

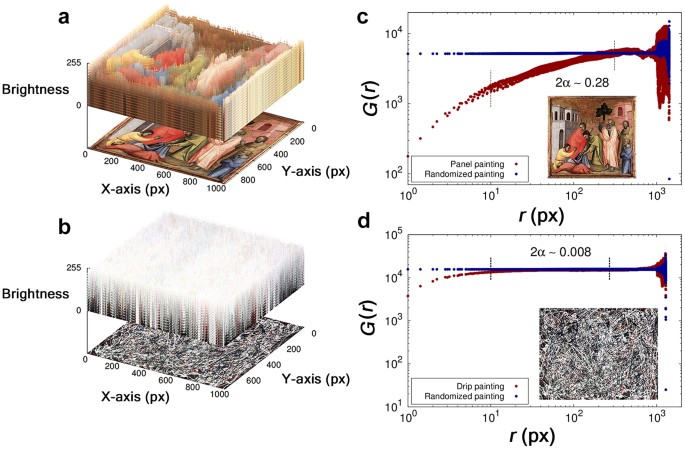

Spatial renormalization and fixed point analysis

In the RGB color space, each painting has its own set of scattered color pixels. In order to analyze the characteristics of color usages, considering the variety of color in the paintings, we define three representative points in the RGB color space. First, center of usage frequency in the color space may be compared to center of mass in physics. One can calculate center of usage frequency (CM) in the color space with the usage information and spatial position of colors such as the center of mass of physical objects. Second, iteratively resizing a painting is necessary to get the fixed point of the painting borrowed from real space renormalization concept in physics. Repeatedly resizing a painting, a painting eventually becomes one pixel. That is the fixed point of the painting (FP). The third fixed point of the randomized painting (SFP) is the same as mentioned in the second one except for shuffling the pixels of the painting. If the spatial information of the scattered color is irrelevant, FP and SFP would not be significantly different. Note that center of mass point of a shuffled image (SCM) is the same as the original CM. Then, two vectors d 1 ( d 2 ) pointing from CM to FP (SFP) can be compared to quantify the randomness of the spatial arrangement of the colors in paintings. If d 1 and d 2 are similar, the used colors in a painting are not diverse or the spatial arrangement of the colors in a painting is close to random. Figure 3c suggests that the color arrangement of Jackson Pollock's drip paintings is quite different from other paintings, showing that Pollock's art work is quite random, especially in the spatial arrangement of colors. On the other hand, the two fixed points of Pieter Bruegel the Elder's paintings are far away each other.

Spatial renormalization of original and shuffled images.

(a) An example of transforming an image into a fixed point. ( Figure 1a also contains the image which is out of copyright.) (b) An illustrative example of the center of mass (CM), the fixed point (FP) and the shuffled fixed point (SFP) in RGB color space. (c) Norm of difference of d 1 and d 2 over 10 periods and comparison with Pollock's drip paintings and Pieter Bruegel the Elder's paintings. (d) Norm of cross product of d 1 and d 2 over 10 periods and comparison with Pollock's drip paintings and Pieter Bruegel the Elder's paintings.

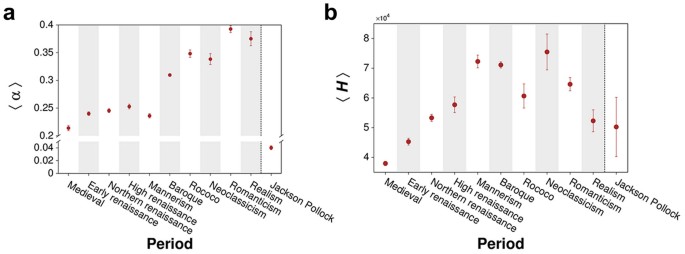

Surface roughness and brightness contrast

Though we mainly focus on the usage of colors, ignoring its spatial arrangement over the first two subsections, spatial correlation of colors is also important to understand the artistic style of the paintings, as shown in previous RG analysis, because a painting is a composition of colors in the proper place. The spatial arrangement of colors makes various artistic effects possible. For example, contrast, as one of the artistic effects, is an important element to express shape and space in two dimensional fine arts. Among various types of contrast, brightness contrast is the most important in art history due to the cultural background of Europe which usually adopts the contrast of light and darkness as a metaphorical expression. In this subsection, taking both the color information of pixels and their spatial arrangement into account, we examine the prevalence of brightness contrast in European paintings over 10 artistic periods.

To quantify brightness contrast, we utilize the two-point height difference correlation (HDC) and its roughness exponent α, the slope of HDC curve in a double logarithmic plot of the surface growth model in statistical physics 22 . First we get the brightness in grey-scale from the RGB color information through a weighted transformation (see Methods) and define a “brightness surface” of an image by adopting the brightness of a pixel as a height at that position of the image as shown in Fig. 4a and b . A three-dimensional surface, like a deep-pile carpet, is obtained from the 2-dimensional painting, where the HDC is calculated as a function of distance r . This method is widely used in condensed matter and statistical physics to analyze the roughness of a growing surface, for example a semiconductor surface grown by chemical deposition 22 . For comparison, a shuffled image, by changing a pixel's position randomly, is analyzed together.

Constructing brightness surfaces and measuring roughness exponents.

(a) and (b) Illustrative examples of brightness surfaces. The brightness of each point is considered as its height. (c) An example of a two-point HDC function G ( r ) on the brightness surface of an image in the inset, a panel painting of Italian painter Taddeo Gaddi (1348–1353) titled “St John the Evangelist Drinking from the Poisoned Cup” (This image is out of copyright.). The horizontal axis indicates the distance r , where a unit is a pixel, between two distinct points on the surface. Red points show the HDC of an original image and blue ones represent that of a randomized image. The slope is approximately 2α~0.28. (d) The HDC function for an image shown in the inset, painting of American painter Jackson Pollock (1912–1956) titled “Number 20, 1948, 1948” (This image is reproduced by permission of the Artists Rights Society and Society of Artist's Copyright of Korea, © 2014 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation/ARS, NY - SACK, Seoul), showing no difference from a randomly shuffled image only except for short distance less than 10 pixels, which is less than 1% of the image width.

As shown in Fig. 4a and b , since the brightness of a point is defined as its height, the height difference between two points represents the brightness difference. The two-point HDC of a randomly shuffled painting is displayed in blue dots in Fig. 4c and d for comparison. The slope α for randomized images is 0 since there is no spatial correlation any more. Figure 4d shows an example of Jackson Pollock's drip painting, which is hard to distinguish from randomly shuffled painting when only the spatial correlation is considered. The roughness exponent of Jackson Pollock's drip painting is very small comparing to that of other European paintings.

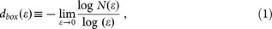

Since HDC describes the spatial correlation between color pixels on a surface as a function of distance, the slope of the HDC function, i.e., the roughness exponent α, denotes the average brightness difference according to the contrast effect. Figure 5a shows that the roughness exponent α gradually increases over the 10 artistic periods, which is consistent with historical circumstances. First, the increasing tendency of α is related to changes in painting techniques and genres, such as from portraits to landscape. In the history of western art, many new painting techniques were developed and spread during the Renaissance period. For example, chiaroscuro , which is one of the canonical painting modes in the Renaissance period 16 , characterizes strong contrasts between light and shade. The roughness exponent and the HDC capture the level of brightness and relative spatial position. Hence, a roughness exponent α of a painting could be a quantitative indicator of a chiaroscuro technique and its increasing tendency over artistic periods reflects the spread of the chiaroscuro technique over the continent 21 . In addition, the Renaissance art movement led that painting genres became more diverse. Therefore, more portraits and landscape paintings were encouraged. Large objects in paintings such as a torso, i.e., the upper body of portraits, or mountains and sky in landscapes decrease the brightness difference in a short distance, but makes the increment of the HDC bigger as distance increases 21 . Therefore, the historical renovation of painting techniques and the diversification of painting genres are clearly captured in an increasing tendency of the roughness exponent α.

The trend of roughness exponents and image entropies.

(a) The trend of roughness exponents over 10 art historical periods shows increasing behavior. (b) Statistical tendency of image entropy values of brightness surfaces over the periods; error bars indicate the standard error of the mean.

Another example, sfumato is another major painting mode developed in the Renaissance period to express a vanishing or shading around objects in a painting 17 . Smoothing the edges of objects in a painting makes the variance of brightness decrease because it doesn't allow abrupt changes at the boundary. In this case, image entropy 23 would be a good measurement for the sfumato technique, which indicates the variance of brightness in a specific locale. Since the variance is inversely proportional to homogeneity, the image entropy describes the level of local homogeneity of brightness in a painting.

Figure 5b shows that the image entropy H increases up to Neoclassicism and then decreases, which is somewhat different from the roughness exponent since the image entropy only considers the complexity of the color gradient around a pixel locally comparing to the fact that the roughness exponent also consider the color brightness difference of remote distance. We think that the different behaviors of these two measures may reflect the tendency that the chiaroscuro technique is still developing but the sfumato declines. It may be rejecting mysterious expression and respecting the realistic one.

From the analysis of a large-scale European painting image archive, we display that chromo-spectroscopy of 10 art historical periods shows a universal distribution curve which distinguishes art paintings from photographs. Additionally, fractal analysis allows us to rediscover the expansion of the color palette after the medieval period, which is consistent with the fact that the color palette of the medieval age was relatively narrow comparing to other periods because of historical circumstances. Furthermore, we measure the roughness exponent and image entropy of brightness surfaces over the 10 art historical periods. We find that these mathematical measurements quantitatively describe the birth of new painting techniques and their increasing use. Our approaches successfully provide quantitative indicators reflecting historical developments of artistic styles. Applying them, it is possible to deduce that the Jackson Pollock's drip paintings are not typical art work, of course, these are still controversial in the art world.

There are several limitations of our approaches and we provide suggestions for future works. First, although the database is quite large, our dataset does not cover all paintings of the 10 art historical periods. In this reason, it is possible that there exist sampling bias in our results which we have not yet figured out. For better statistics, analyzing much bigger (higher resolution) images such as the Google Art Project 24 will give us more concrete insight for artistic style. Another possible error is unintended color distortion while converting original paintings into digital images, which may cause color information loss or bias. Even though we have checked that our results are not significantly changed from artificial color quality reductions, we could not follow all possible distortion effects. It is also true that present colors in the paintings are different from the original ones when they were completed. Old paintings are hard to preserve and usually suffer from degradation of physical materials of paintings such as oxidation and corrosion. These are big remaining issues not only for this study but also for all stylometric analyses in arts. Nonetheless, we expect that our quantitative study would be helpful to bridge the gap between art and science.

Source of dataset and statistics of paintings

In this study, we analyzed the digital images of European paintings in the Web Gallery of Art which exhibits artworks ranging from 11th century to mid-19th century 15 . The European paintings are classified into 10 art historical periods: medieval, early renaissance, northern renaissance, high renaissance, mannerism, baroque, rococo, neoclassicism, romanticism and realism. We filtered non-painting images, such as sculptures, miniatures, illustrations, architecture, pottery, glass paintings and wares. The number of refined images for each period is summarized in SI Table S1 . In total we have analyzed 8,798 painting artworks. As shown in Fig. S1 , over 94% of images are larger than 700 × 700 pixels and the largest one is 1350 × 1533. Therefore, the quality of the images is good enough to perform a statistical analysis. Furthermore, in order to discuss the difference between paintings and photographs, two more datasets are collected for hyper-realism and photographs. We collected 105 hyper-realism images from hyper-realism artists' web sites 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , the largest one is 2974 × 1954 and the two sets of photographs from the official Instagram site of National Geographic 32 and the online photo gallery of a Korean portal site 33 .

Box-counting dimensions

In order to investigate the fractal patterns of painted colors in the RGB color space, we measured box-counting dimensions 20 . The box-counting dimension is defined as the following:

where N (ε) is the number of non-empty boxes and the side length of each box is ε. A ε value represents the color quality in a digitized unit, for example, ε = 1 corresponds to 256 3 possible colors in 24-bit RGB color system and ε = 32 is associated with 8 3 possible colors in 8-bit RGB color system. Each ε value corresponds to log 2 (256/ε) 3 -bit RGB color system. Changing ε = 32, 16, 8, 4, 2 and 1 (see Figure S6 in the supplement ) and examining N (ε) for each ε, we measured d box (ε).

Gray-scale transformation

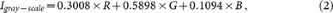

To consider brightness surfaces of images, we converted digital color images into grayscale images using the following weighted filter:

where R, G and B are the red, green and blue intensities of a pixel and I gray-scale is the brightness of a certain color, which is interpreted as a height on the image. The reason for the difference in weighting values is due to the color sensitivity of a human eye 34 and there exist several other weighting filters for R, G and B intensities for specific purposes. However, there was no significant difference in the results with different filters.

Two-point height difference correlation function

To measure the roughness exponents of brightness (height) surfaces, a two-point height difference correlation (HDC) function is calculated 22 . The definition is

which follows the simple scaling form, G ( r ) ~ r 2α , for small r and where r is a distance between two pixel points, the over-bar represents the spatial average at a fixed distance r for all possible points, N r is the number of possible pairs at a distance r , h ( x ) is the height at a point x (0 ≤ h ( x ) ≤ 255) and α is the roughness exponent. The roughness exponent was measured in a double-logarithmic plot of G versus r , where the fitting range was used from r a = 10 to r b , where the HDC saturates to the same value both for the original and randomized paintings. It approximately corresponds to 30% of the image width and a square root of 9% of the image area.

Image entropy

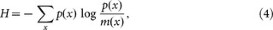

Entropy of a gray-scale image 23 , is given by the following equation:

Taylor, R., Micolich, A. & Jonas, D. Fractal analysis of Pollock's drip paintings. Nature 399, 422 (1999).

Article CAS ADS Google Scholar

Lyu, S., Rockmore, D. N. & Farid, H. A digital technique for art authentification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 17006–17010 (2004).

Johnson, C. R., Jr et al. Image processing for artist identification–computerized analysis of Vincent van Gogh's painting brushstrokes. IEEE Signal Proc. Mag. Special Issue on Visual Cultural Heritage. 25, 37–48 (2008).

Article ADS Google Scholar

Bressan, M., Cifarelli, C. & Perronnin, F. An Analysis of the relationship between painters based on their work. 15th IEEE Int. Conf. Image Proc. 113–116 (2008).

Olshausen, B. A. & DeWeese, M. R. Applied mathematics: The statistics of style. Nature 463, 1027–1028 (2010).

Hughes, J. M., Graham, D. J. & Rockmore, D. N. Quantification of artistic style through sparse coding analysis in the drawings of Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 1279–1283 (2010).

De Morgan, S. E. Memoir of Augustus de Morgan, by his wife Sophia Elisabeth de Morgan, with Selection of his Letters (Longmans, London, 1882).

Lutostowski, W. The Origin and Growth of Platos Logic (Longmans, Green, London., 1897).

Holmes, D. I. & Kardos, J. Who was the author? An introduction to stylometry. Chance 16, 5–8 (2003).

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Hughes, J. M., Foti, N. J., Krakauer, D. C. & Rockmore, D. N. Quantitative patterns of stylistic influence in the evolution of literature. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 7862–7686 (2012).

Google Scholar

Manaris, B. et al. Zipf's law, music classification and aesthetics. Comput. Music J. 29, 55–69 (2005).

Article Google Scholar

Huron, D. The ramp archetype: A study of musical dynamics in 14 piano composers. Psychol. Music 19, 33–45 (1991).

Casey, M., Rhodes, C. & Slaney, M. Analysis of minimum distances in high-dimensional music spaces. IEEE Trans. Speech Audio Proc. 16, 1015–1028 (2008).

Sapp, C. Hybrid numeric/rank similarity metrics for musical performances. Proc. ISMIR 99, 501–506 (2008).

Krén, E. & Marx, D. Web Gallery of Art, image collection, virtual museum, searchable database of European fine arts (1000-1900) http://www.wga.hu/ (1996) Date of access 09/05/2009

The National Gallery, London: Western European painting 1250–1900 http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/glossary/chiaroscuro Date of access 03/04/2013.

Earls, I. Renaissance Art: A Topical Dictionary (Greenwood Press, 1987).

Zipf, G. K. Human Behaviour and the Principle of Least Effort: An Introduction to Human Ecology (Addison-Wesley Press, Cambridge, 1949).

Abramowitz, M. & Stegun, I. A. Handbook of Mathematical Functions: with Formulas, Graphs and Mathematical Tables (Dover Publications, New York., 1965).

Gouyet, J. F. & Mandelbrot, B. Physics and Fractal Structures. (Springer-Verlag, New York., 1996).

Gage, J. Color and Meaning: Art, Science and Symbolism (University of California Press, Berkeley., 2000).

Barabási, A. L. & Stanley, H. E. Fractal Concepts in Surface Growth (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1995).

Brink, A. D. Using spatial information as an aid to maximum entropy image threshold selection. Pattern Recogn. Lett. 17, 29–36 (1996).

Google Inc. Google Cultural Institute http://www.google.com/culturalinstitute/project/art-project (2011) Date of Access 14/02/2011

Jacques Bodin gallery http://www.jacquesbodin.com/ Date of Access 07/04/2010.

Roberto Bernardi http://www.robertobernardi.com/ Date of Access 07/04/2010.

Raphaella Spence http://www.raphaellaspence.com/ Date of Access 07/04/2010.

Hubert de Lartigue Accueil http://www.hubertdelartigue.com/ Date of Access 07/04/2010.

Gus Heinze on artnet http://www.artnet.com/artist/26318/gus-heinze.html Date of Access 07/04/2010.

Bernardo Torrens http://www.bernardotorrens.com/ Date of Access 07/04/2010.

The Hyperrealism Paintings by Denis Peterson http://www.denispeterson.com/ Date of Access 07/04/2010.

National Geographic official Instagram. http://instagram.com/natgeo (1999) Date of access 20/08/2014

Naver, officially launched in 1999, was the first Korean portal site to develop its own search engine. http://www.naver.com/ (1999) Date of access 20/07/2009

Pratt, W. K. Digital Image Processing (John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1991).

Download references

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) Grant funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (No. 2011-0028908).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Physics, Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, Daejeon, 305-701, Korea

Department of Applied Physics, Hanyang University, Ansan, 426-791, Korea

Seung-Woo Son

Department of Physics and Institute for the BioCentury, Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, Daejeon, 305-701, Korea

Hawoong Jeong

Asia Pacific Center for Theoretical Physics, Pohang, 790-784, Korea

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

D.K. designed and performed research, analyzed data and wrote the paper; S.-W.S. designed and performed research and wrote the paper; H.J. designed research and wrote paper. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Kim, D., Son, SW. & Jeong, H. Large-Scale Quantitative Analysis of Painting Arts. Sci Rep 4 , 7370 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep07370

Download citation

Received : 13 January 2014

Accepted : 24 September 2014

Published : 11 December 2014

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/srep07370

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Impressions of guangzhou city in qing dynasty export paintings in the context of trade economy: a color analysis of paintings based on k-means clustering algorithm.

- Shanshan Ji

Heritage Science (2024)

Kolmogorov compression complexity may differentiate different schools of Orthodox iconography

- Daniel Peptenatu

- Ion Andronache

- Herbert Franz Jelinek

Scientific Reports (2022)

Dating ancient paintings of Mogao Grottoes using deeply learnt visual codes

- Qingquan Li

Science China Information Sciences (2018)

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing: AI and Robotics newsletter — what matters in AI and robotics research, free to your inbox weekly.

Arts-Based Research

- First Online: 29 September 2022

Cite this chapter

- Robert E. White ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8045-164X 3 &

- Karyn Cooper 4

1281 Accesses

In its purest form, art may be simultaneously immediate and eternal: immediate in its ability to grasp one’s attention, to provoke or inspire; eternal in its ability to create deep and permanent impressions. Responses to art may be visceral, emotional or psychological by turns or even together. As such, a work of art may possess almost unlimited potential to educate (Leavy, 2017). Although a pursuit of matters artistic may be a worthy pursuit for its own sake, the arts also represent invaluable opportunities across all research disciplines. As such, arts-based research exists at intersections between art and science. According to McNiff ( 2008 ), both arts-based research and science involve the use of systematic experimentation with the goal of gaining knowledge about life.

Aristotle once said or, at least, was said to have said, man by nature seeks to know. Research, in the broadest sense, is an effort to know and I believe that the forms of knowing vary enormously…. – Elliot Eisner, Stanford Graduate School of Education

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Barone, T. (2001). Touching eternity: The enduring outcomes of teaching . Teachers College Press.

Google Scholar

Barone, T., & Eisner, E. W. (1997). Arts-based educational research. In R. M. Jaeger (Ed.), Complementary methods for research in education (pp. 95–109). American Educational Research Association.

Barone, T., & Eisner, E. W. (2012). Arts-based research . Sage.

Book Google Scholar

Behar, R. (2007). Ethnography in a time of blurred genres. Anthropology & Humanism, 32 (2), 145–155.

Article Google Scholar

Cahnmann-Taylor, M. (2008). Arts-based research: Histories and new directions. In M. Cahnmann-Taylor & R. Siegesmund (Eds.), Arts-based research in education: Foundations for practice (pp. 3–15). Routledge.

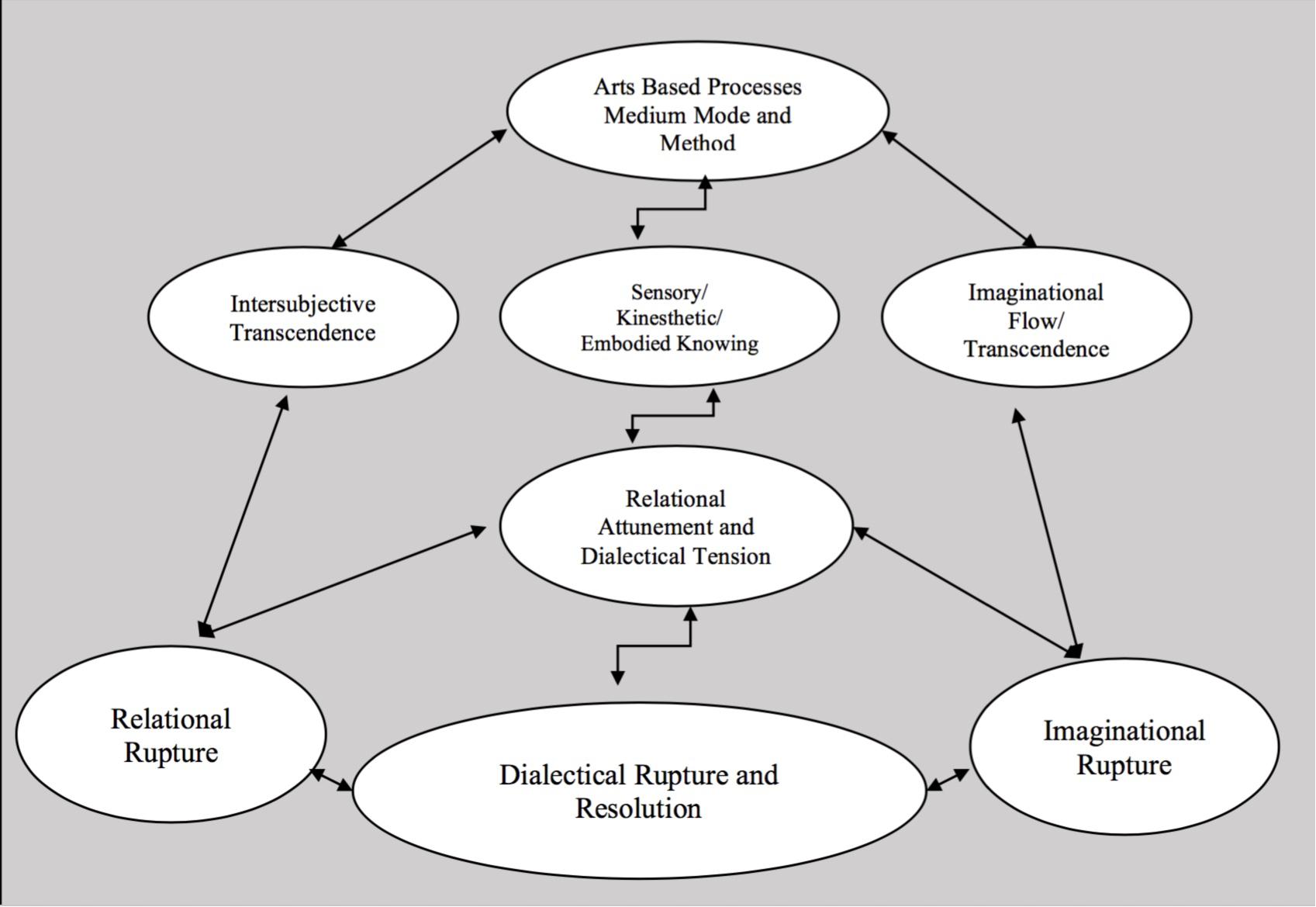

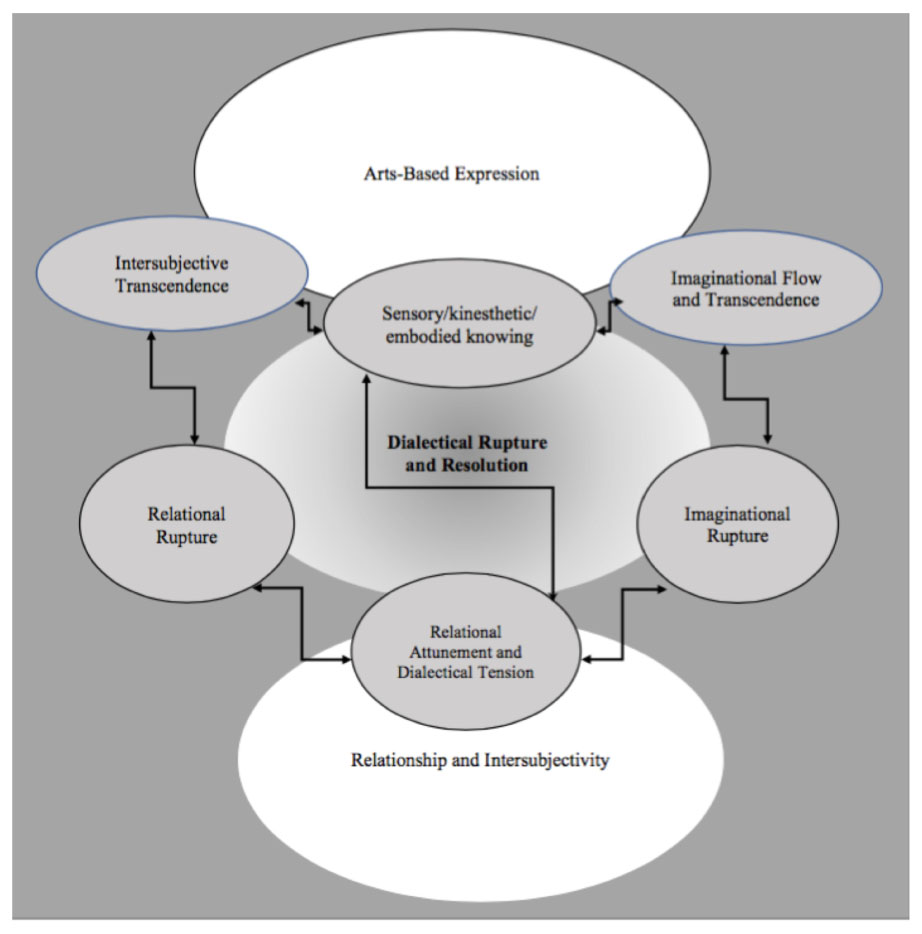

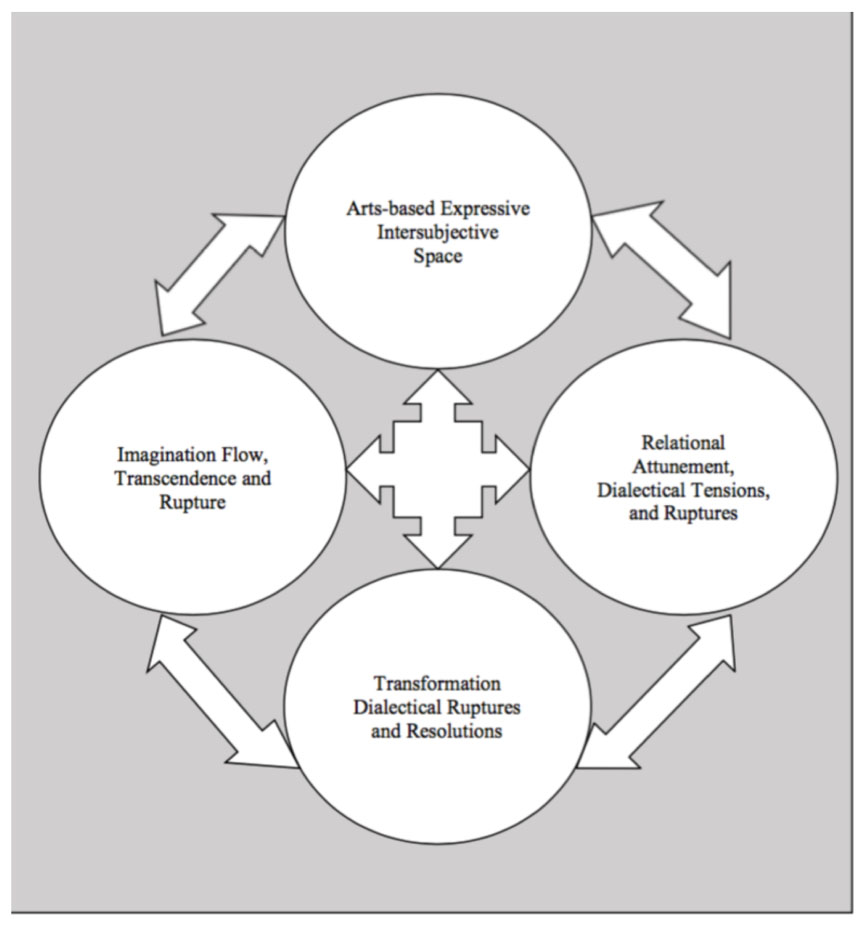

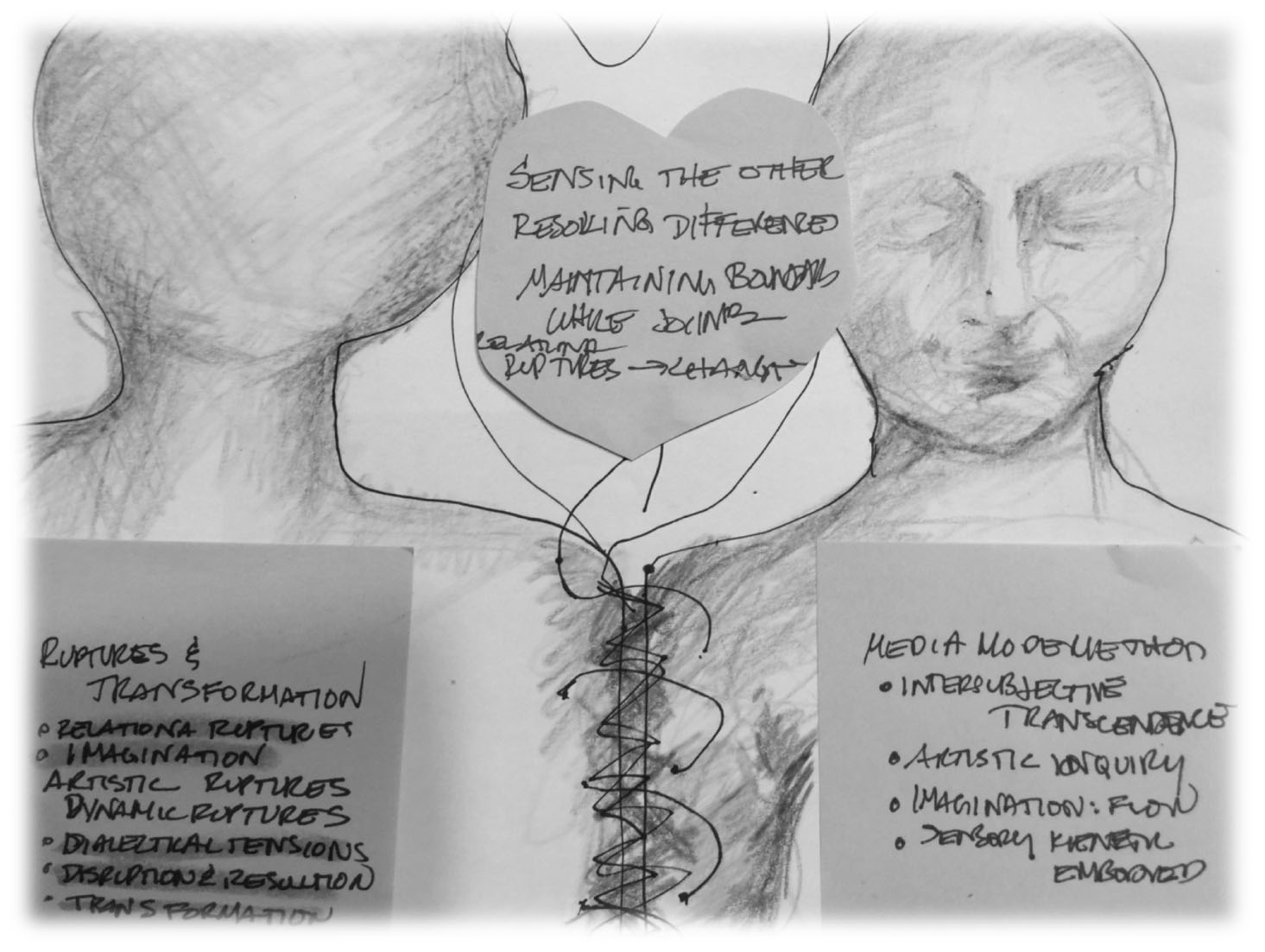

Chilton, G., Gerber, N. & Scotti, V. (2015). Towards an aesthetic intersubjective paradigm for arts based research: An art therapy perspective. Critical Approaches to Arts-based Research, 5 (1), 1–27. Retrieved December 24, 2018, from; https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308971008_Towards_an_aesthetic_intersubjective_paradigm_for_arts_based_research_An_art_therapy_perspective

Chilton, G., & Leavy, P. (2014). Arts-based research practice: Merging social research and the creative arts. In P. Leavy (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of qualitative research (pp. 403–422). Oxford University Press.

Cole, A., & Knowles, J. G. (2008). Arts-informed research. In J. G. Knowles & A. Cole (Eds.), Handbook of the arts in qualitative research: Perspectives, methodologies, examples, and issues (pp. 55–70). Sage.

Chapter Google Scholar

Cooper, K., & White, R. E. (2012). Qualitative research in the postmodern era: Contexts of qualitative research. Springer.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2008). The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Collecting and interpreting qualitative materials, Volume 4 (pp. 1–42). Sage.

Eisner, E. W. (1991). The enlightened eye: Qualitative inquiry and the enhancement of educational practice . Merrill.

Eisner, E. W. (1993). Forms of understanding and the future of educational research. Educational Researcher, 22 (7), 5–11.

Eisner, E. W. (2002). The arts and the creation of mind . Yale University Press.

Eisner, E. W. (2008). Art and knowledge. In J. G. Knowles & A. Cole (Eds.), Handbook of the arts in qualitative research (pp. 3–12). Sage.

Eliot, T. S. (1961). The love song of J. Alfred Prufrock. In M. Mack, L. Dean, & W. Frost (Eds.), Modern poetry (Vol. VII, 2nd ed., pp. 130–134). Prentice-Hall.

Finley, S. (2005). Arts-based inquiry: Performing revolutionary pedagogy. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed., pp. 681–694). Sage.

Finley, S. (2008). Arts-based research. In J. G. Knowles & A. Cole (Eds.), Handbook of the arts in qualitative research: Perspectives, methodologies, examples, and issues (pp. 71–82). Sage.

Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of culture: Selected essays . Basic Books.

Geertz, C. (1988). Works and lives: The anthropologist as author . Polity Press.

Gerber, A. S. (2012). Field experiments: Design, analysis and interpretation . W. W. Norton.

Gray, C. (1996). Inquiry through practice: Developing appropriate research strategies . Retrieved, December 27, 2018, from: http://carolegray.net/Papers%20PDFs/ngnm.pdf

Greene, M. (1993). Diversity and inclusion: Toward a curriculum for human beings. Teachers College Record, 95 (2), 211–221.

Hesse, H. (2002). The glass bead game/Das Glasperlenspiel . Picador Books.

Irwin, R. L. (2014). Turning to a/r/tography. KOSEA Journal, 15 (1), 1–40.

Irwin, R. L., Beer, R., Springgay, S., Grauer, K., & Xiong, G. (2006). The rhizomatic relations of A/R/Tography. Studies in Art Education, 48 (1), 70–88.

Irwin, R. L., & de Cosson, A. (2004). A/R/Tography: Rendering oneself through arts-based living inquiry . Pacific Educational Press.

Irwin, R. L., & Springgay, S. (2008). A/r/tography as practice-based research. In S. Springgay, R. L. Irwin, C. Leggo, & P. Gouzouasis (Eds.), Being with A/r/tography (pp. xix–xxxiii). Sense Publishers.

Knowles, J. G., & Promislow, S. (2008). Using an arts methodology to create a thesis or dissertation. In J. G. Knowles & A. Cole (Eds.), Handbook of the arts in qualitative research: Perspectives, methodologies, examples, and issues (pp. 511–526). Sage.

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (2003). Metaphors we live by . Chicago University Press.

Leavy, P. (2015). Method meets art: Arts-based research practice (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Leavy, P. (2017). Introduction to arts-based research. In P. Leavy (Ed.), Handbook of arts-based research (pp. 3–22). The Guilford Press.

Malchiodi, C. A. (2017). Creative arts therapies and arts-based research. In P. Leavy (Ed.), Handbook of arts-based research (pp. 68–87). The Guilford Press.

McNiff, S. (2005). Foreword. In D. Kalmanowitz, B. Lloyd, & S. McNiff (Eds.), Art therapy and political violence: With art, without illusion (pp. xii–xvi). Routledge.

McNiff, S. (2008). Art-based research. In J. G. Knowles & A. Cole (Eds.), Handbook of the arts in qualitative research: Perspectives, methodologies, examples, and issues (pp. 29–40). Sage.

McNiff, S. (2009). Cross-cultural psychotherapy and art. Art Therapy, 26 (3), 100–106.

McNiff, S. (2015). Imagination in action: Secrets for unleashing creative expression . Shambala Publications.

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1962). Phenomenology of perception . Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Nyasulu, E. (2019) Eisner’s connoisseurship model . Retrieved November 6, 2018 from: https://www.academia.edu/23230956/Eisners_Connoisseurship_Model

O’Toole, J., & Beckett, D. (2010). Educational research: Creative thinking & doing . Oxford University Press.

Polkinghorne, D. (1988). Narrative Knowing and the Human Sciences . State University of New York.

Saldaña, J. (2011). Fundamentals of qualitative research . Oxford University Press.

Saldaña, J. (2015). The coding manual for qualitative researchers . Sage.

Savin-Baden, M., & Major, C. H. (2012). Qualitative research: The essential guide to theory and practice . Routledge.

Savin-Baden, M., & Wimpenny, K. (2014). A practical guide to arts-related research . Sense.

Schratz, M., & Walker, R. (1995). Research as social change: New opportunities for qualitative research . Routledge.

Simons, H., & McCormack, B. (2007). Integrating arts-based Inquiry in evaluation methodology: Opportunities and challenges. Qualitative Inquiry, 13 (2), 292–311.

Sinner, A., Leggo, C., Irwin, R., Gouzouasis, P., & Grauer, K. (2006). Art-based educational research dissertations: Reviewing the practices of new scholars. Canadian Journal of Education, 29 (4), 1223–1270.

Springgay, S., Irwin, R. L., & Kind, S. (2005). A/r/tography as living inquiry through art and text. Qualitative Inquiry, 11 (6), 897–912.

Sullivan, G. (2006). Research acts in art practice. Studies in Art Education, 48 (1), 19–35.

Suppes, P., Han, B., & Lu, Z.-L. (1998). Brain-wave recognition of sentences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 95 (26), 15861–15866.

Tierney, W. G. (1999). Guest editor’s introduction: Writing life’s history. Qualitative Inquiry, 5 (3), 307–312.

Turner, M. (1996). The literary mind: Origins of thought and language . Oxford University Press.

Wang, Q., Coemans, S., Siegesmund, R., & Hannes, K. (2017). Arts-based methods in socially engaged research practice: A classification framework. Art Research International, 2 (2), 5–39.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Education, St. Francis Xavier University, Antigonish, NS, Canada

Robert E. White

OISE, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Karyn Cooper

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Robert E. White .

Researching Creations: Applying Arts-Based Research to Bedouin Women’s Drawings

Ephrat Huss

Julie Cwikel

Ben Gurion University of the Negev, Beer-Sheva, Israel

Huss, E. & Cwikel, J. (2005). Researching creations: Applying arts-based research to Bedouin women’s drawings. The International Journal of Qualitative Methods 4 (4), 44-62.

All problem solving has to cope with an overcoming of the fossilized shape … the discovery that squares are only one kind of shape among infinitely many. —Rudolf Arnheim, 1996, p. 35

In this article, the author examines the combination of arts-based research and art therapy within Bedouin women ’ s empowerment groups. The art fulfills a double role within the group of both helping to illuminate the women ’ s self-defined concerns and goals, and simultaneously enriching and moving these goals forward. This creates a research tool that adheres to the feminist principles of finding new ways to learn from lower income women from a different culture, together with creating a research context that is of direct potential benefit and enrichment for the women. The author, through examples of the use of art within lower income Bedouin women ’ s groups, examines the theoretical connection between arts-based research and art therapy, two areas that often overlap but whose connection has not been addressed theoretically.

Keywords: art-based research, art therapy, researching women from a nondominant culture

Introduction: Why use the arts in research?

While I am talking with Bedouin women about their drawings, the tin hut in the desert that is the community center in which we work sometimes reverberates with lively stories and emotional closeness, and sometimes I, as a Jewish Israeli art therapist and researcher, and they, as a Bedouin Israeli women’s empowerment group, are lost to each other: When I suggest that we summarize the meaning of the art therapy sessions for the women, they nod their heads politely and thank me, and ignore my questions.

My aim in this article is to see how art-based research literature and art therapy literature can jointly contribute to both working with and understanding women from a different culture.

Art as communication (rather than as therapy) can be defined as the association between words, behavior, and drawing created in a group setting. McNiff (1995), a prominent art therapist and one of the pioneers of art-based research, suggested that art therapy research should move from justification (of art therapy) to creative inquiry into the roles of the art itself.

I will first review arts-based research in an effort to understand the use of art as research. I will then survey art therapy’s practice-based knowledge concerning working with art with women from a different culture, and third, I will apply both of these knowledge bases to Bedouin women’s drawings and words from within my case study.

Art as a form of inquiry

The aim in arts-based research is to use the arts as a method, a form of analysis, a subject, or all of the above, within qualitative research; as such, it falls under the heading of alternative forms of research gathering. It is used in education, social science, the humanities, and art therapy research. Within the qualitative literature, there is an “explosion” in arts-based forms of research (Mullen, 2003).

How does arts-based research help us to understand women from a different culture? It seems that classic verbal methods of interviewing or questionnaire answering are not effective forms of inquiry with these women. Bowler (1997) described the difficulties she found in using questionnaires and interviewing, both of which stress Western-style verbal articulation, as research methods with lower income Asian women. She found that the women try to give the “right” answer or to be polite. In-depth interviewing was also conceived of as a strange and foreign way of constructing and exploring the world for these women (Bowler, 1997; Lawler, 2002; Ried, 1993). The women are often mistakenly conceived of as “mute” because they do not verbalize information along Western lines of inquiry (Goldberger & Veroff, 1995).

The search for a method that “gives voice” to silenced women is a central concern for feminist methodologies. De-Vault (1999) analyzed Western discourse as constructed along male content areas and suggested that we “need to interview in ways that allow the exploration of un-articulated aspects of women’s experiences … and explore new methodologies” (p. 65). Using art as a way of initiating self-expression can be seen as such a methodological innovation.

The arts-based paradigm states that by handing over creativity (the contents of the research) and its interpretation (an explanation of the contents) to the research participant, the participant is empowered, the relationship between researcher and research participant is intensified and made more equal, and the contents are more culturally exact and explicit, using emotional as well as cognitive ways of knowing. Mason (2002) and Sclater (2003) have suggested that drawing or storytelling, or the use of vignettes or pictures as a trigger within an interview, already common in work with children, could also help adults connect ideological abstractions to specific situations, using both personal and collective elements of cultural experience.

Thus, culture and gender unite in making Western research methods insufficient for understanding women from a different culture. Using visual data-gathering methods, then, can be seen as a movement offering alternate avenues of self-expression for women from traditional cultures.

The arts are considered “soft,” female ways of knowing; they tend to be used as a counterpoint to the seriousness of words (Mason, 2002). Alternatively (and mistakenly), as in photography, arts are considered a depiction of absolute reality (Pink, 2001).

Silverman (2000) argued that research must access what people do, and not only what people say.

Art brings “doing” into the research situation. However, the inclusion of arts in research poses many methodological difficulties, described by Eisner (1997) in the title of his article as “The Promises and Perils of Alternative Research Gathering methods.” Denzin and Lincoln (1998) described personal experience methods as going “inwards and outwards, backwards and forwards” (p. 152). The art product by definition creates more “gaps” and entrances than closed statements or conclusions (this is what enables so many different people to connect to one picture!). The art process also includes moves between silences, times of doing, listening, talking, watching, thinking, and different gaps and connections between the above. For example, Mason (2002), a qualitative researcher, described how research participants agonize about where to put whom when drawing a genogram or family diagram. She claimed that this process of “agonizing,” or creating the genogram, is an important component of the finished genogram and should not be left out.

Issues in arts-based research

Sclater (2003) explored the above-described complications of defining the “contours” of art-based research, as difficulties in defining issues related to the quality of art, to the relationship with the research participant, and to the relationship between art and words in arts based research.

Defining issues related to the quality of art

Mullen (2003) concluded that art-based research is focused on process as expressing the context of lived situations rather than the final products disconnected from the context of its creation. Mahon (2000) argued, through the concept of embedded aesthetics, that the aesthetic product is not inherent from within but is always part of broader social contexts, which both transform and are transformed by the art product and around which there is always a power struggle over different cultural meanings (see also Barone, 2003). At the same time, Mahon claimed that art includes elements and aesthetic languages that are specific to itself and that cannot be translated into action research or communication, or understood as direct translations of social interactions. The boundaries of quality are seen as marginalizing whoever does not conform to them, as in folk, vernacular, and outsider forms of art. In art-based research, elitism is replaced by art as communication, whereby reactions to the art work are more important than the quality of the art in terms of external aesthetic criteria. Within this paradigm, the criteria of communication and social responsibility predominate over craftsmanship (Finley, 2003; Mullen, 2003; Sclater, 2003).

Defining issue related to the relationship with the research participant

Another consideration for arts-based research is the setting of standards or limits around the roles of artist, researcher, and facilitator of creative activities. Mullen (2003) suggested,

We need to find ways not just to represent others creatively, but to enable them to represent themselves. The challenge is to go beyond insightful texts, to move ourselves and others into action, with the effect of improving lives. (p. 117)

Therefore, multiple or blurred roles are advantageous, as they reflect the complexity of reality within any research situation. By handing over creativity and its interpretation to the research participant, and including these elements within the research, the relationship between researcher and research participant is intensified, eliciting emotion and facilitating transformation. Thus, the blurring of the contours or roles of the researcher and research participant is seen as advantageous.

For example, cameras were given to lower income rural Chinese women, who, through photography, were able to communicate their concerns to policy makers with whom they would not engage in a direct verbal confrontation (Wang & Burris, 1994).

Defining issues related to the relationship between art and words in arts-based research

Art-based research literature addresses the problematic issue of how to work with the relationship between the verbal and nonverbal elements of the data, the art form, and its interpretation within a research context. Within research, the theoretical framework of understanding a work of art is harnessed to the reason art was used within the research puzzle (Mason, 2002). The use of verbal and nonverbal elements can be seen as a triangulation of data. It is important to understand why we are including art and to think about how the use of visual contents will help solve the “puzzle” of the research (Davis & Srinivasan, 1994; Finley, 2003; Mason, 2002). Save and Nuutinen (2003) defined the relationship between drawing\ and words (after researching a dialogue between the alternate use of pictures and words) as “creating a field of many understandings, creating a ‘third thing’ that is sensory, multi-interpretive, intuitive, and ever-changing, avoiding the final seal of truth” (p. 532).

Connections between art therapy and arts-based research

Art therapy, or any therapy, aims to connect, integrate, and transform experience and behavior. Art-based research also aims to transform, in that it can “use the imagination not only to examine how things are, but also how they could be” (Mullen, 2003, p. 117). It aims to connect and empower by creating something together with the research participants rather than the classic research orientation that takes information away from them (Finley, 2003; Sclater, 2003).

Sarasema (2003), a qualitative researcher, discussed the therapeutic advantages of storytelling for widowed research participants, claiming that art-based research is a way of creating knowledge that “connects head to heart” (p. 603).

Both art therapy and arts-based research involve the use of dialogue, observation, participant observation, and heuristic, hermeneutic, phenomenological, and grounded techniques of interpretation. Both relate to the ethical issues of art and interpretation ownership and a relational definition of art, including the skills of working simultaneously with both visual and verbal components (Burt, 1996; Mason, 2000; B. Moon, 2000; H. Moon, 2002; Talbot Green, 1989).

The difference between the two fields could be defined as art therapy implementing a theoretical psychological metaframework that organizes the therapeutic relationship while using the inherent qualities of different art materials and processes (Kramer, 1997). However, within art therapy, there are researchers who wish to discard these psychological metaframeworks and to focus more on “art-based” art therapy. For instance, in feminist, and studio or community art therapy, art is used both as an expression and a critique of society (Allen, 1995; B. Moon, 2000). Savneet (2000) claimed that art with women from the Developing World, such as the Bedouin women, can serve as a decolonizing tool by giving voice to women holding a polytheistic view of the world, as long as the interpreters of the art are the women and not an external interpreter. The nonverbal image should speak for itself, reducing the possibility of the artist-client’s being spoken over (Hogan, 1997). In addition, the image can be subversive, creating a narrative or counternarrative additional to the dominant one of words. The distancing or intermediating element of art can be helpful in interactions of inequality or of conflict (Dokter, 1998; Liebmann, 1996).

Art-based research, art therapy, and culture

Arts-based research literature focuses on art as a way to connect different people and to express different cultures, giving voice to nondominant narratives.

The culture of the viewer of the art will influence or interact with how the art is understood (Denzin & Lincoln, 1998). Another possibility is to accept that art does not define cultures from the outside but enables multiple and complex views of that culture (Eisner, 1997; Pink, 2001).

Art therapy literature also stresses the ability of art to help make cultural issues manifest within pictures by the fact that each picture shows differing understandings and conceptions of the content drawn, rendering new perspectives (Gerity, 2000). Quiet people can create “loud” art work. Art connects to individual-subjective rather than generalized and stereotyped levels of experience. Thus, we see that factors inherent in the art language help integrate the individual with the culture (Campanelli, 1991; Campbell, 1999; Hiscox & Calisch, 1998).

Art therapy literature also addresses the complexity of art as a culturally embedded vessel in itself. Hocoy (2002) has argued that art as self-expression is a deeply Western construct, not necessarily suited to people from different cultures. Acton (2001) warned against being a “color blind” art therapist, ignoring the cultural differences and approaches to healing of different people and their manifestations within art. Hogan (2003) stressed that art therapists can claim to be culturally sensitive but actually dominate the participants by offering an art process or interpretation that is alien and strange to them (Acton, 2001). Conversely, Hocoy (2002) pointed out that assuming that everything is a cultural difference can also create misunderstandings of pictures. Cultural possibilities for misunderstanding are, on the one hand, bridged by the third object—the artwork—but, on the other, intensified by it. Thus, art is not a “magic” way of overcoming cultural differences but has the potential to enable the multifaceted nature of different cultural identities. The analyses of the art, and the relationship, are harnessed to the therapeutic aims, taking culture into account. In general, art therapy literature supplies much practice-based knowledge of how to take culture into account while focusing on harnessing the artwork and relationship to the therapeutic goals of the interaction.

Having briefly summarized and created a connection between the central issues within arts-based research, and within art therapy with a different culture, I will now apply them to some drawings by the Bedouin women from my research, as a set of relevant data on which to continue examining the above concepts.

The context of the Bedouin women

My aim is to outline briefly the levels of change and stress that some women in this culture are currently experiencing.

Meir (1997) has suggested that under the influence of the dominant Israeli culture (and despite ongoing political friction between the Israeli government and the Bedouins’ claim to the right to continue a traditional nomadic lifestyle), Bedouin society is undergoing change from a collective to an individualistic culture, and from a nomadic lifestyle to fixed settlements. This has resulted in the devaluation of women and children, who no longer work in the fields and tend animals as part of the economic support system, as well as changes in the traditional role of elders. In addition, the loss of the traditional Bedouin tribal supportive roles with an externalization of these responsibilities to state authorities, who invest limited resources and cultural relevance, has resulted in the decline of collective family support and funds. These changes are creating high levels of stress (Abu-Rabia-Abu-Kuider, 1994; Meir, 1997).

The status of Arab women in Israel can thus be defined as doubly oppressed, both by their patriarchal society and by the Israeli political regime. Paradoxically, Bedouin women’s dependence on the males in their family has sometimes increased due to perceptions of women’s exposure to work, education, and individualism as a threat to tradition. Indeed, Bedouin women in the Negev were found to be intensely affected by poverty and the interconnected social and health problems that this entails (Cwikel, 2002; Cwikel, Wiesel, & Al-Krenawi, 2003).

Conversely, Arab feminists Hijab (1988) and Sabbagh (1997) have differentiated between issues of concern for Western women in Western society and those for Arab women. In the West, concerns focus on issues such as reproductive rights, legal equity, expression of self through work and art, and sexual freedom; for Arab women, concerns center on education, health, and employment opportunities as well as legal reform and political participation. Power is measured in relation to other women and not in relation to men (Hijab, 1988; Sabbagh, 1997).

We have found that there are many difficulties for Western female researchers who are not from within the Bedouin communities to understand the diverse concerns of Bedouin women. Bedouin middle- class women will also be from a different “culture” from that of Bedouin working-class women. We see that there is a paramount need to find alternative research methods that can enable outsiders to “hear” the concerns of the Bedouin women and that can enable the Bedouin women to communicate those concerns first to themselves and then to the dominant culture.

Using art as a research method: The Bedouin women’s drawings

The following examples of drawings are from three ongoing groups, in which the art activity was introduced for a few sessions, aiming to enrich, reflect on, or enhance the existing self-defined concerns of the group rather than to present an external study objective or research agenda. The three groups were all of poor Bedouin women living in a township in the Negev, including a group of single mothers meeting as a support group, a group of women undergoing vocational training to open early childhood centers within their homes for extra income, and a group of women without writing skills, wishing to learn arts and crafts as enrichment and eventually to make products to sell.

The art activity in all the groups and meetings divided into set stages, although the contents were in accordance to the group’s wishes. The meetings were undertaken by means of a Bedouin social worker learning art therapy, so as to enhance cultural suitability and to enable the women to talk in Arabic.

As stated, the aim of the art was two pronged.

The first direction is art as empowerment, enrichment, or self-expression. This is in accordance with feminist research that aims to be of direct benefit to the participants (especially as the aims of the group and the contents were defined by them).

The second direction is art as a research method, or a way to understand the concerns of the women (which is a preliminary step to any type of empowering or enriching intervention).

Following is a detailed explanation of the art stages and examples of each of the stages from the different case studies. The intent is not to present a full case study but to examine the interaction between arts-based research and art as empowerment, and lower income Bedouin women.

From a bird’s eye overview, the method of using art described within this article undergoes the following stages, which can be repeated, refining, redefining, deepening, or enriching the contents through doing, observing, and talking.

Participant interacts with art making (within the context of the group leader and group).

Participant interacts with art and group and group leader simultaneously.

Participant observes the pictures as a group exhibition.

Participant re-interacts with the above stages of art making, discussing, and observing, over an issue that arose in the former “wave.”

Step 1: The art-making stage

Each participant draws a picture in oil pastels, or makes a clay statue of a subject agreed on in the initial discussion and connected to the overall aim of the group:

Oil pastels with different sizes of paper, and clay are offered. Oil pastels enable both lines and areas to be created quickly with minimal mess. Clay might be a more familiar medium for Bedouin women.

Drawing can be used in a combination of directive and nondirective forms, similar to different levels of structuring an interview.

The type of art making is process rather than product oriented, termed diagrammic art within art therapy (Liebmann, 1996), which helps access and raise an issue rather than working on a product that exists independent of the creator, as in an art class. This means not that the art does not “lead” the artist but that the products are relational, used to communicate rather than to display talent (Hogan, 2003).

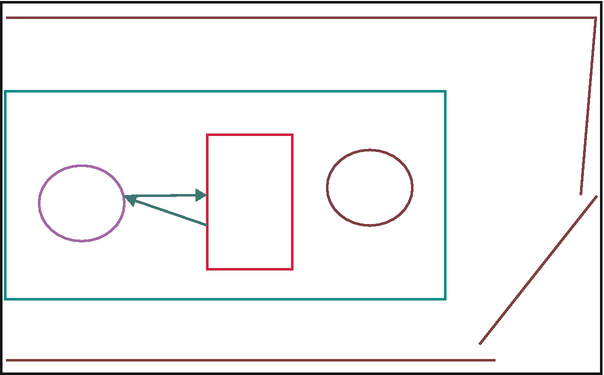

In the sketch shown in Figure 1 , the black circle (left) symbolizes the drawer, the red (vertical) oblong, her picture, and the arrows, the mutual influence of her on the picture and the picture, on her. The brown circle (right) is the context within which this reflective activity takes place, created by and observed by the group leader or researcher, symbolizing the dominant culture.

The question of whether to suggest a topic to draw can be seen as analogous to decisions concerning the level of structure of an interview. I chose to suggest a few topics, so as to make the drawing less threatening for people not used to drawing. Oil pastels include the elements of color and line, encouraging a “story” to be told. On the other hand, clay might be a more familiar medium for some women, and three-dimensionality evokes different types of storytelling. Time is then given to work individually or in pairs (according to what is preferred by the women) on the subject.

The assumption is that the engagement in the art process creates a novel interaction with the subject matter, showing differing perspectives and enhancing a connection between the emotive and the cognitive which in turn promotes a process of reflection and prioritizing elements to be included in the art. This creates a silent prestage of creative organization of personal data from inside onto the empty page, before or together with translating it to the group and to the researcher-observer.

Each type of art assignment embodies a different “culture” within the room in terms of collectivist or individualist interactions. Dosamantes-Beaudry (1999) showed how cultural self construal is depicted by working individually or in pairs in dance therapy. The use of time, space, materials, and so on are all expressions of power and will influence the type of discussion that emerges, enacted both physically and symbolically within the organization of the arts behavior.

An additional question arises if the group leader or researcher, beyond becoming an observer and student of the participant’s pictures, also draws so as to make transparent and clarify her position. According to arts-based research, the aim is to “blur the boundaries” of the (unequal) relationship between researcher and research participant. According to art therapy, this point is much disputed, with some advocating the above and others considering the danger of taking the client-drawer’s space, or intimidating or influencing the client.

All of these considerations become the research context. They need to be examined reflexively as they express the researcher’s cultural bias.

For example, I was certain that oil pastels were the most flexible medium, perhaps being the closest to a writing tool, which is the dominant medium within my culture, but the older Bedouin women responded immediately to clay. One single mother, an abandoned first wife and an older Bedouin woman did not draw but, when I included clay, immediately made a clay ashtray before bursting into tears. She explained that the ashtray was like an older woman, an empty and discarded container. A mundane clay ashtray thus becomes an object of intense meaning and communication illustrating the communicative rather than aesthetic quality of art. As Finley (2003) stated, within this paradigm, the reactions to the poem are more important than the poem itself. The above example also illustrates how the visual stimuli initiated associations that were not decided on in advance, and that were influenced by the material and by the context of the group.

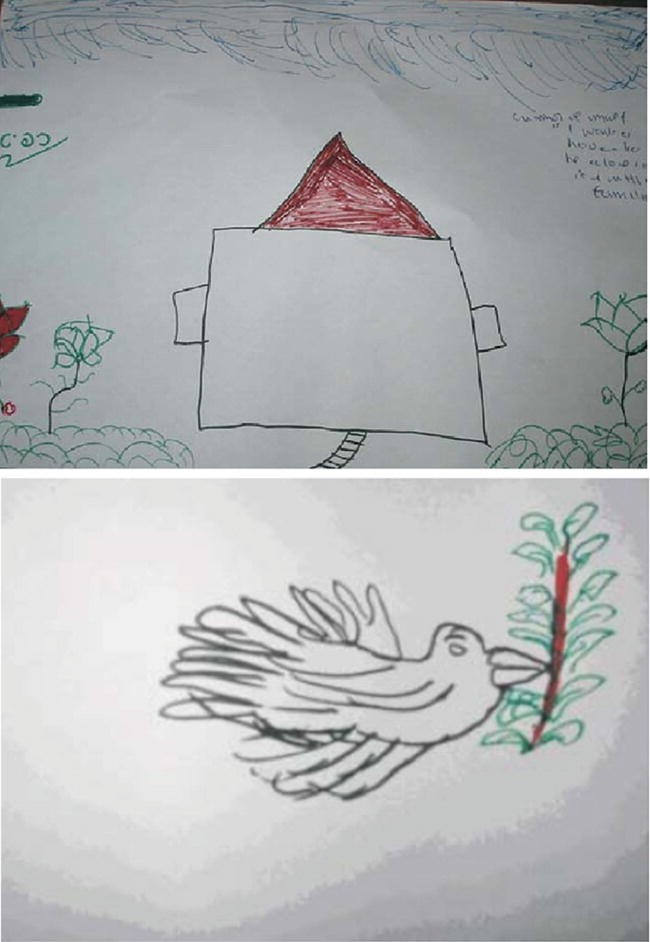

An example of a woman’s interaction with her art was an older woman from the single mothers’ group, who did not speak at Figure 2 all at the beginning but repeated a schema of squares within each meeting. In one meeting, she stated that it was a house. It is not clear if the squares were an illustration of the house, the idea of a house emerged from the graphic shape of the squares, or the idea of a house emerged from within the context of the things other women said, or all of the different elements combined together. Arnheim (1996) stressed the inherent dynamics of an art gestalt that influences the observer (rather than just being a neutral vessel for projection (Figure 2 ).

The example in Figure 3 illustrates how the dialogue between art and the individual can be transforming in itself. One young third wife, whose husband is in jail for violence, said of her picture of a house with flowers, that her father did not allow her to plant flowers by the house and did not allow her to play with other children, and he chose her husband for her. About the picture, she said, “I want a house; I want to build a house of my own. Most important, I want to plant a garden by the house.” The picture contained past and future in a causal narrative, based on a specific instant that gained symbolic meaning. The narrative is poetically organized, with three elements from the past and three from the future, corresponding to the three pictures. The dialogue was transformative, in that it allowed the drawer “to use imagination to examine how things are, but also how they could be otherwise” (Finley, 2003, p. 292). This exemplifies the arts-based paradigm that has as an aim to “go beyond insightful texts, to move ourselves and others into action, with the effect of improving lives” (Mullen, 2003. p. 117).

Another example was when an older woman, who was silent in all the meetings, made a cow, saying that a women is like a cow: When she has no milk left, she is discarded. A younger woman made a horse, saying that a woman is like a horse, strong and able to carry many burdens. Here, the art “answered” the art.

Another woman made an ashtray, and while describing how tired she was of managing as a single mother with no money, she broke the ashtray into many tiny bits in nervous movements creating, a physical embodiment of her emotional state. When the women talked to her and suggested solutions, she started sticking all the pieces together again. She looked at her hands and laughed, noticing this.

One woman ignored the two directives and decided to draw, first in pencil Figure 2 , Figure 3 and then in paint, a stylized sunset picture she had once seen in a magazine. She worked quickly and carefully, begging for a few more minutes at the end. I framed the picture for her. She stated that she wanted to execute a picture like that to decorate her house, as she could not afford to buy one. She had worked hard and was proud of the result (Figure 4 ).

Although for me, as a Western-oriented art therapist, the discussion or individualized creativity of the product is most important (rather than copying a preexisting picture), for this woman, activating the will power and concentration to execute or copy a picture that she could not afford to buy, so as to have the product, was an empowering experience that connected her intensely to the art experience. It seems that the autonomy and intimacy inherent in the exclusive interaction between the drawer and her drawing enabled the woman to pursue her aims rather than to comply with our directives (Hogan, 1997). The woman’s self-directedness is a good example of a negotiation of power as against the dominant culture represented by our suggestions.

Another example of the complex interplay of power between the researcher and women follows. For example, although each of the women in the early childhood training group had 5 to 10 children and were very knowledgeable about early childhood, when I asked them what they would like to focus on in the drawings, they answered with questions conveying helplessness, such as what should be done with a crying child, what games to play, how to connect to the children, and what to feed them. Conversely, they were very clear and confident about the contents of their drawings in relation to early childhood. The art seemed to be express power and knowledge, whereas their words expressed helplessness. Perhaps the drawing enabled a simultaneous double transference: Words were used to express helplessness toward representatives of the dominant culture, but confidence and knowledge were expressed through their drawings. The multifaceted component of the drawing and then talking about it, simultaneously expressed and overcame the disempowerment of learning within the context of the dominant culture.

The discussion stage

After completing the artwork, we laid them out in a circle on the floor at the drawers’ feet, facing toward the group, both clearly connected to their creator, and also creating a group exhibition. The participants ask one another questions about their art work, and the women explain or connect to other’s art work in a free discussion.

The following sketch illustrates the complexity and multiple interactions that occur simultaneously in this situation.

Thus, the art work, group interaction, and so on cannot be analyzed separately, out of context with the other elements.

For example, one young woman was too shy to talk about her drawing of a black circle (Figure 5 ).

“I think you are drawing that you feel closed in a circle you can’t get out of because there are so many people in your small house.” (Friend)

Her friend sitting next to her said that she thought the girl was sad there were so many people in her small house that is like a closed circle that one cannot get out of. The woman nodded in agreement.