Why Every Educator Needs to Teach Problem-Solving Skills

Strong problem-solving skills will help students be more resilient and will increase their academic and career success .

Want to learn more about how to measure and teach students’ higher-order skills, including problem solving, critical thinking, and written communication?

Problem-solving skills are essential in school, careers, and life.

Problem-solving skills are important for every student to master. They help individuals navigate everyday life and find solutions to complex issues and challenges. These skills are especially valuable in the workplace, where employees are often required to solve problems and make decisions quickly and effectively.

Problem-solving skills are also needed for students’ personal growth and development because they help individuals overcome obstacles and achieve their goals. By developing strong problem-solving skills, students can improve their overall quality of life and become more successful in their personal and professional endeavors.

Problem-Solving Skills Help Students…

develop resilience.

Problem-solving skills are an integral part of resilience and the ability to persevere through challenges and adversity. To effectively work through and solve a problem, students must be able to think critically and creatively. Critical and creative thinking help students approach a problem objectively, analyze its components, and determine different ways to go about finding a solution.

This process in turn helps students build self-efficacy . When students are able to analyze and solve a problem, this increases their confidence, and they begin to realize the power they have to advocate for themselves and make meaningful change.

When students gain confidence in their ability to work through problems and attain their goals, they also begin to build a growth mindset . According to leading resilience researcher, Carol Dweck, “in a growth mindset, people believe that their most basic abilities can be developed through dedication and hard work—brains and talent are just the starting point. This view creates a love of learning and a resilience that is essential for great accomplishment.”

Set and Achieve Goals

Students who possess strong problem-solving skills are better equipped to set and achieve their goals. By learning how to identify problems, think critically, and develop solutions, students can become more self-sufficient and confident in their ability to achieve their goals. Additionally, problem-solving skills are used in virtually all fields, disciplines, and career paths, which makes them important for everyone. Building strong problem-solving skills will help students enhance their academic and career performance and become more competitive as they begin to seek full-time employment after graduation or pursue additional education and training.

Resolve Conflicts

In addition to increased social and emotional skills like self-efficacy and goal-setting, problem-solving skills teach students how to cooperate with others and work through disagreements and conflicts. Problem-solving promotes “thinking outside the box” and approaching a conflict by searching for different solutions. This is a very different (and more effective!) method than a more stagnant approach that focuses on placing blame or getting stuck on elements of a situation that can’t be changed.

While it’s natural to get frustrated or feel stuck when working through a conflict, students with strong problem-solving skills will be able to work through these obstacles, think more rationally, and address the situation with a more solution-oriented approach. These skills will be valuable for students in school, their careers, and throughout their lives.

Achieve Success

We are all faced with problems every day. Problems arise in our personal lives, in school and in our jobs, and in our interactions with others. Employers especially are looking for candidates with strong problem-solving skills. In today’s job market, most jobs require the ability to analyze and effectively resolve complex issues. Students with strong problem-solving skills will stand out from other applicants and will have a more desirable skill set.

In a recent opinion piece published by The Hechinger Report , Virgel Hammonds, Chief Learning Officer at KnowledgeWorks, stated “Our world presents increasingly complex challenges. Education must adapt so that it nurtures problem solvers and critical thinkers.” Yet, the “traditional K–12 education system leaves little room for students to engage in real-world problem-solving scenarios.” This is the reason that a growing number of K–12 school districts and higher education institutions are transforming their instructional approach to personalized and competency-based learning, which encourage students to make decisions, problem solve and think critically as they take ownership of and direct their educational journey.

Problem-Solving Skills Can Be Measured and Taught

Research shows that problem-solving skills can be measured and taught. One effective method is through performance-based assessments which require students to demonstrate or apply their knowledge and higher-order skills to create a response or product or do a task.

What Are Performance-Based Assessments?

With the No Child Left Behind Act (2002), the use of standardized testing became the primary way to measure student learning in the U.S. The legislative requirements of this act shifted the emphasis to standardized testing, and this led to a decline in nontraditional testing methods .

But many educators, policy makers, and parents have concerns with standardized tests. Some of the top issues include that they don’t provide feedback on how students can perform better, they don’t value creativity, they are not representative of diverse populations, and they can be disadvantageous to lower-income students.

While standardized tests are still the norm, U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona is encouraging states and districts to move away from traditional multiple choice and short response tests and instead use performance-based assessment, competency-based assessments, and other more authentic methods of measuring students abilities and skills rather than rote learning.

Performance-based assessments measure whether students can apply the skills and knowledge learned from a unit of study. Typically, a performance task challenges students to use their higher-order skills to complete a project or process. Tasks can range from an essay to a complex proposal or design.

Preview a Performance-Based Assessment

Want a closer look at how performance-based assessments work? Preview CAE’s K–12 and Higher Education assessments and see how CAE’s tools help students develop critical thinking, problem-solving, and written communication skills.

Performance-Based Assessments Help Students Build and Practice Problem-Solving Skills

In addition to effectively measuring students’ higher-order skills, including their problem-solving skills, performance-based assessments can help students practice and build these skills. Through the assessment process, students are given opportunities to practically apply their knowledge in real-world situations. By demonstrating their understanding of a topic, students are required to put what they’ve learned into practice through activities such as presentations, experiments, and simulations.

This type of problem-solving assessment tool requires students to analyze information and choose how to approach the presented problems. This process enhances their critical thinking skills and creativity, as well as their problem-solving skills. Unlike traditional assessments based on memorization or reciting facts, performance-based assessments focus on the students’ decisions and solutions, and through these tasks students learn to bridge the gap between theory and practice.

Performance-based assessments like CAE’s College and Career Readiness Assessment (CRA+) and Collegiate Learning Assessment (CLA+) provide students with in-depth reports that show them which higher-order skills they are strongest in and which they should continue to develop. This feedback helps students and their teachers plan instruction and supports to deepen their learning and improve their mastery of critical skills.

Explore CAE’s Problem-Solving Assessments

CAE offers performance-based assessments that measure student proficiency in higher-order skills including problem solving, critical thinking, and written communication.

- College and Career Readiness Assessment (CCRA+) for secondary education and

- Collegiate Learning Assessment (CLA+) for higher education.

Our solution also includes instructional materials, practice models, and professional development.

We can help you create a program to build students’ problem-solving skills that includes:

- Measuring students’ problem-solving skills through a performance-based assessment

- Using the problem-solving assessment data to inform instruction and tailor interventions

- Teaching students problem-solving skills and providing practice opportunities in real-life scenarios

- Supporting educators with quality professional development

Get started with our problem-solving assessment tools to measure and build students’ problem-solving skills today! These skills will be invaluable to students now and in the future.

Ready to Get Started?

Learn more about cae’s suite of products and let’s get started measuring and teaching students important higher-order skills like problem solving..

Center for Teaching

Teaching problem solving.

Print Version

Tips and Techniques

Expert vs. novice problem solvers, communicate.

- Have students identify specific problems, difficulties, or confusions . Don’t waste time working through problems that students already understand.

- If students are unable to articulate their concerns, determine where they are having trouble by asking them to identify the specific concepts or principles associated with the problem.

- In a one-on-one tutoring session, ask the student to work his/her problem out loud . This slows down the thinking process, making it more accurate and allowing you to access understanding.

- When working with larger groups you can ask students to provide a written “two-column solution.” Have students write up their solution to a problem by putting all their calculations in one column and all of their reasoning (in complete sentences) in the other column. This helps them to think critically about their own problem solving and helps you to more easily identify where they may be having problems. Two-Column Solution (Math) Two-Column Solution (Physics)

Encourage Independence

- Model the problem solving process rather than just giving students the answer. As you work through the problem, consider how a novice might struggle with the concepts and make your thinking clear

- Have students work through problems on their own. Ask directing questions or give helpful suggestions, but provide only minimal assistance and only when needed to overcome obstacles.

- Don’t fear group work ! Students can frequently help each other, and talking about a problem helps them think more critically about the steps needed to solve the problem. Additionally, group work helps students realize that problems often have multiple solution strategies, some that might be more effective than others

Be sensitive

- Frequently, when working problems, students are unsure of themselves. This lack of confidence may hamper their learning. It is important to recognize this when students come to us for help, and to give each student some feeling of mastery. Do this by providing positive reinforcement to let students know when they have mastered a new concept or skill.

Encourage Thoroughness and Patience

- Try to communicate that the process is more important than the answer so that the student learns that it is OK to not have an instant solution. This is learned through your acceptance of his/her pace of doing things, through your refusal to let anxiety pressure you into giving the right answer, and through your example of problem solving through a step-by step process.

Experts (teachers) in a particular field are often so fluent in solving problems from that field that they can find it difficult to articulate the problem solving principles and strategies they use to novices (students) in their field because these principles and strategies are second nature to the expert. To teach students problem solving skills, a teacher should be aware of principles and strategies of good problem solving in his or her discipline .

The mathematician George Polya captured the problem solving principles and strategies he used in his discipline in the book How to Solve It: A New Aspect of Mathematical Method (Princeton University Press, 1957). The book includes a summary of Polya’s problem solving heuristic as well as advice on the teaching of problem solving.

Teaching Guides

- Online Course Development Resources

- Principles & Frameworks

- Pedagogies & Strategies

- Reflecting & Assessing

- Challenges & Opportunities

- Populations & Contexts

Quick Links

- Services for Departments and Schools

- Examples of Online Instructional Modules

Don’t Just Tell Students to Solve Problems. Teach Them How.

The positive impact of an innovative uc san diego problem-solving educational curriculum continues to grow.

- Daniel Kane - [email protected]

Published Date

Share this:, article content.

Problem solving is a critical skill for technical education and technical careers of all types. But what are best practices for teaching problem solving to high school and college students?

The University of California San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering is on the forefront of efforts to improve how problem solving is taught. This UC San Diego approach puts hands-on problem-identification and problem-solving techniques front and center. Over 1,500 students across the San Diego region have already benefited over the last three years from this program. In the 2023-2024 academic year, approximately 1,000 upper-level high school students will be taking the problem solving course in four different school districts in the San Diego region. Based on the positive results with college students, as well as high school juniors and seniors in the San Diego region, the project is getting attention from educators across the state of California, and around the nation and the world.

{/exp:typographee}

In Summer 2023, th e 27 community college students who took the unique problem-solving course developed at the UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering thrived, according to Alex Phan PhD, the Executive Director of Student Success at the UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering. Phan oversees the project.

Over the course of three weeks, these students from Southwestern College and San Diego City College poured their enthusiasm into problem solving through hands-on team engineering challenges. The students brimmed with positive energy as they worked together.

What was noticeably absent from this laboratory classroom: frustration.

“In school, we often tell students to brainstorm, but they don’t often know where to start. This curriculum gives students direct strategies for brainstorming, for identifying problems, for solving problems,” sai d Jennifer Ogo, a teacher from Kearny High School who taught the problem-solving course in summer 2023 at UC San Diego. Ogo was part of group of educators who took the course themselves last summer.

The curriculum has been created, refined and administered over the last three years through a collaboration between the UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering and the UC San Diego Division of Extended Studies. The project kicked off in 2020 with a generous gift from a local philanthropist.

Not getting stuck

One of the overarching goals of this project is to teach both problem-identification and problem-solving skills that help students avoid getting stuck during the learning process. Stuck feelings lead to frustration – and when it’s a Science, Technology, Engineering and Math (STEM) project, that frustration can lead students to feel they don’t belong in a STEM major or a STEM career. Instead, the UC San Diego curriculum is designed to give students the tools that lead to reactions like “this class is hard, but I know I can do this!” – as Ogo, a celebrated high school biomedical sciences and technology teacher, put it.

Three years into the curriculum development effort, the light-hearted energy of the students combined with their intense focus points to success. On the last day of the class, Mourad Mjahed PhD, Director of the MESA Program at Southwestern College’s School of Mathematics, Science and Engineering came to UC San Diego to see the final project presentations made by his 22 MESA students.

“Industry is looking for students who have learned from their failures and who have worked outside of their comfort zones,” said Mjahed. The UC San Diego problem-solving curriculum, Mjahed noted, is an opportunity for students to build the skills and the confidence to learn from their failures and to work outside their comfort zone. “And from there, they see pathways to real careers,” he said.

What does it mean to explicitly teach problem solving?

This approach to teaching problem solving includes a significant focus on learning to identify the problem that actually needs to be solved, in order to avoid solving the wrong problem. The curriculum is organized so that each day is a complete experience. It begins with the teacher introducing the problem-identification or problem-solving strategy of the day. The teacher then presents case studies of that particular strategy in action. Next, the students get introduced to the day’s challenge project. Working in teams, the students compete to win the challenge while integrating the day’s technique. Finally, the class reconvenes to reflect. They discuss what worked and didn't work with their designs as well as how they could have used the day’s problem-identification or problem-solving technique more effectively.

The challenges are designed to be engaging – and over three years, they have been refined to be even more engaging. But the student engagement is about much more than being entertained. Many of the students recognize early on that the problem-identification and problem-solving skills they are learning can be applied not just in the classroom, but in other classes and in life in general.

Gabriel from Southwestern College is one of the students who saw benefits outside the classroom almost immediately. In addition to taking the UC San Diego problem-solving course, Gabriel was concurrently enrolled in an online computer science programming class. He said he immediately started applying the UC San Diego problem-identification and troubleshooting strategies to his coding assignments.

Gabriel noted that he was given a coding-specific troubleshooting strategy in the computer science course, but the more general problem-identification strategies from the UC San Diego class had been extremely helpful. It’s critical to “find the right problem so you can get the right solution. The strategies here,” he said, “they work everywhere.”

Phan echoed this sentiment. “We believe this curriculum can prepare students for the technical workforce. It can prepare students to be impactful for any career path.”

The goal is to be able to offer the course in community colleges for course credit that transfers to the UC, and to possibly offer a version of the course to incoming students at UC San Diego.

As the team continues to work towards integrating the curriculum in both standardized high school courses such as physics, and incorporating the content as a part of the general education curriculum at UC San Diego, the project is expected to impact thousands more students across San Diego annually.

Portrait of the Problem-Solving Curriculum

On a sunny Wednesday in July 2023, an experiential-learning classroom was full of San Diego community college students. They were about half-way through the three-week problem-solving course at UC San Diego, held in the campus’ EnVision Arts and Engineering Maker Studio. On this day, the students were challenged to build a contraption that would propel at least six ping pong balls along a kite string spanning the laboratory. The only propulsive force they could rely on was the air shooting out of a party balloon.

A team of three students from Southwestern College – Valeria, Melissa and Alondra – took an early lead in the classroom competition. They were the first to use a plastic bag instead of disposable cups to hold the ping pong balls. Using a bag, their design got more than half-way to the finish line – better than any other team at the time – but there was more work to do.

As the trio considered what design changes to make next, they returned to the problem-solving theme of the day: unintended consequences. Earlier in the day, all the students had been challenged to consider unintended consequences and ask questions like: When you design to reduce friction, what happens? Do new problems emerge? Did other things improve that you hadn’t anticipated?

Other groups soon followed Valeria, Melissa and Alondra’s lead and began iterating on their own plastic-bag solutions to the day’s challenge. New unintended consequences popped up everywhere. Switching from cups to a bag, for example, reduced friction but sometimes increased wind drag.

Over the course of several iterations, Valeria, Melissa and Alondra made their bag smaller, blew their balloon up bigger, and switched to a different kind of tape to get a better connection with the plastic straw that slid along the kite string, carrying the ping pong balls.

One of the groups on the other side of the room watched the emergence of the plastic-bag solution with great interest.

“We tried everything, then we saw a team using a bag,” said Alexander, a student from City College. His team adopted the plastic-bag strategy as well, and iterated on it like everyone else. They also chose to blow up their balloon with a hand pump after the balloon was already attached to the bag filled with ping pong balls – which was unique.

“I don’t want to be trying to put the balloon in place when it's about to explode,” Alexander explained.

Asked about whether the structured problem solving approaches were useful, Alexander’s teammate Brianna, who is a Southwestern College student, talked about how the problem-solving tools have helped her get over mental blocks. “Sometimes we make the most ridiculous things work,” she said. “It’s a pretty fun class for sure.”

Yoshadara, a City College student who is the third member of this team, described some of the problem solving techniques this way: “It’s about letting yourself be a little absurd.”

Alexander jumped back into the conversation. “The value is in the abstraction. As students, we learn to look at the problem solving that worked and then abstract out the problem solving strategy that can then be applied to other challenges. That’s what mathematicians do all the time,” he said, adding that he is already thinking about how he can apply the process of looking at unintended consequences to improve both how he plays chess and how he goes about solving math problems.

Looking ahead, the goal is to empower as many students as possible in the San Diego area and beyond to learn to problem solve more enjoyably. It’s a concrete way to give students tools that could encourage them to thrive in the growing number of technical careers that require sharp problem-solving skills, whether or not they require a four-year degree.

You May Also Like

Uc san diego team wins entrepreneurship challenge for third year in a row, a change of direction, study: surgical intervention improves quality of life for patients with acoustic neuroma, wearable ultrasound patch enables continuous, non-invasive monitoring of cerebral blood flow, stay in the know.

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.

You have been successfully subscribed to the UC San Diego Today Newsletter.

Campus & Community

Arts & culture, visual storytelling.

- Media Resources & Contacts

Signup to get the latest UC San Diego newsletters delivered to your inbox.

Award-winning publication highlighting the distinction, prestige and global impact of UC San Diego.

Popular Searches: Covid-19 Ukraine Campus & Community Arts & Culture Voices

Teaching problem solving: Let students get ‘stuck’ and ‘unstuck’

Subscribe to the center for universal education bulletin, kate mills and km kate mills literacy interventionist - red bank primary school helyn kim helyn kim former brookings expert @helyn_kim.

October 31, 2017

This is the second in a six-part blog series on teaching 21st century skills , including problem solving , metacognition , critical thinking , and collaboration , in classrooms.

In the real world, students encounter problems that are complex, not well defined, and lack a clear solution and approach. They need to be able to identify and apply different strategies to solve these problems. However, problem solving skills do not necessarily develop naturally; they need to be explicitly taught in a way that can be transferred across multiple settings and contexts.

Here’s what Kate Mills, who taught 4 th grade for 10 years at Knollwood School in New Jersey and is now a Literacy Interventionist at Red Bank Primary School, has to say about creating a classroom culture of problem solvers:

Helping my students grow to be people who will be successful outside of the classroom is equally as important as teaching the curriculum. From the first day of school, I intentionally choose language and activities that help to create a classroom culture of problem solvers. I want to produce students who are able to think about achieving a particular goal and manage their mental processes . This is known as metacognition , and research shows that metacognitive skills help students become better problem solvers.

I begin by “normalizing trouble” in the classroom. Peter H. Johnston teaches the importance of normalizing struggle , of naming it, acknowledging it, and calling it what it is: a sign that we’re growing. The goal is for the students to accept challenge and failure as a chance to grow and do better.

I look for every chance to share problems and highlight how the students— not the teachers— worked through those problems. There is, of course, coaching along the way. For example, a science class that is arguing over whose turn it is to build a vehicle will most likely need a teacher to help them find a way to the balance the work in an equitable way. Afterwards, I make it a point to turn it back to the class and say, “Do you see how you …” By naming what it is they did to solve the problem , students can be more independent and productive as they apply and adapt their thinking when engaging in future complex tasks.

After a few weeks, most of the class understands that the teachers aren’t there to solve problems for the students, but to support them in solving the problems themselves. With that important part of our classroom culture established, we can move to focusing on the strategies that students might need.

Here’s one way I do this in the classroom:

I show the broken escalator video to the class. Since my students are fourth graders, they think it’s hilarious and immediately start exclaiming, “Just get off! Walk!”

When the video is over, I say, “Many of us, probably all of us, are like the man in the video yelling for help when we get stuck. When we get stuck, we stop and immediately say ‘Help!’ instead of embracing the challenge and trying new ways to work through it.” I often introduce this lesson during math class, but it can apply to any area of our lives, and I can refer to the experience and conversation we had during any part of our day.

Research shows that just because students know the strategies does not mean they will engage in the appropriate strategies. Therefore, I try to provide opportunities where students can explicitly practice learning how, when, and why to use which strategies effectively so that they can become self-directed learners.

For example, I give students a math problem that will make many of them feel “stuck”. I will say, “Your job is to get yourselves stuck—or to allow yourselves to get stuck on this problem—and then work through it, being mindful of how you’re getting yourselves unstuck.” As students work, I check-in to help them name their process: “How did you get yourself unstuck?” or “What was your first step? What are you doing now? What might you try next?” As students talk about their process, I’ll add to a list of strategies that students are using and, if they are struggling, help students name a specific process. For instance, if a student says he wrote the information from the math problem down and points to a chart, I will say: “Oh that’s interesting. You pulled the important information from the problem out and organized it into a chart.” In this way, I am giving him the language to match what he did, so that he now has a strategy he could use in other times of struggle.

The charts grow with us over time and are something that we refer to when students are stuck or struggling. They become a resource for students and a way for them to talk about their process when they are reflecting on and monitoring what did or did not work.

For me, as a teacher, it is important that I create a classroom environment in which students are problem solvers. This helps tie struggles to strategies so that the students will not only see value in working harder but in working smarter by trying new and different strategies and revising their process. In doing so, they will more successful the next time around.

Related Content

Esther Care, Helyn Kim, Alvin Vista

October 17, 2017

David Owen, Alvin Vista

November 15, 2017

Loren Clarke, Esther Care

December 5, 2017

Global Education K-12 Education

Global Economy and Development

Center for Universal Education

Annelies Goger, Katherine Caves, Hollis Salway

May 16, 2024

Sofoklis Goulas, Isabelle Pula

Melissa Kay Diliberti, Elizabeth D. Steiner, Ashley Woo

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 11 January 2023

The effectiveness of collaborative problem solving in promoting students’ critical thinking: A meta-analysis based on empirical literature

- Enwei Xu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6424-8169 1 ,

- Wei Wang 1 &

- Qingxia Wang 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 10 , Article number: 16 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

16 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Science, technology and society

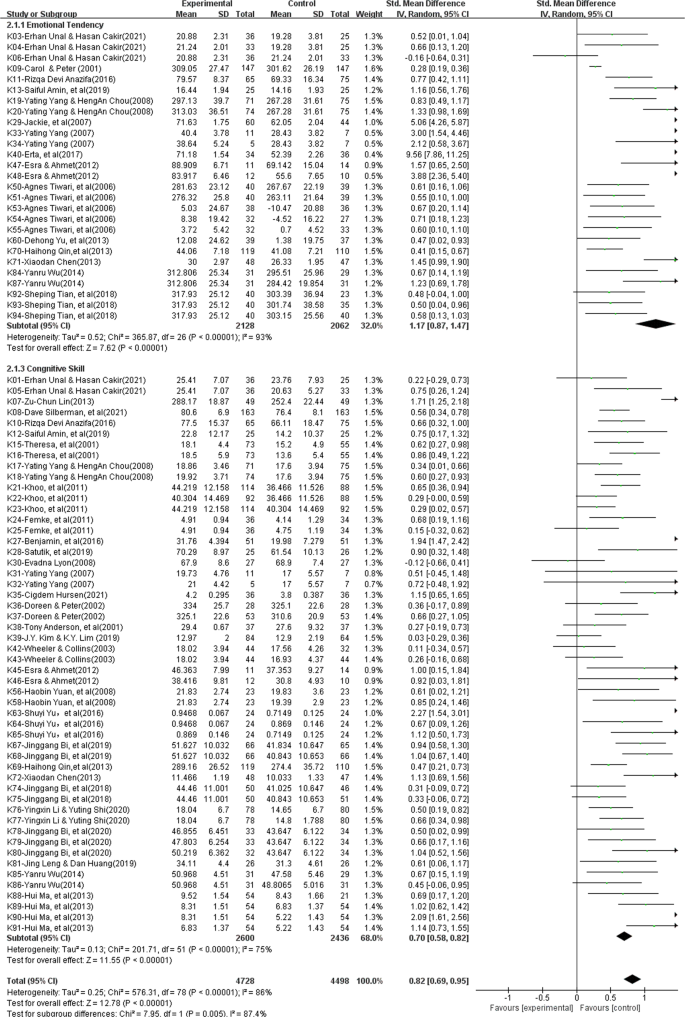

Collaborative problem-solving has been widely embraced in the classroom instruction of critical thinking, which is regarded as the core of curriculum reform based on key competencies in the field of education as well as a key competence for learners in the 21st century. However, the effectiveness of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking remains uncertain. This current research presents the major findings of a meta-analysis of 36 pieces of the literature revealed in worldwide educational periodicals during the 21st century to identify the effectiveness of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking and to determine, based on evidence, whether and to what extent collaborative problem solving can result in a rise or decrease in critical thinking. The findings show that (1) collaborative problem solving is an effective teaching approach to foster students’ critical thinking, with a significant overall effect size (ES = 0.82, z = 12.78, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.69, 0.95]); (2) in respect to the dimensions of critical thinking, collaborative problem solving can significantly and successfully enhance students’ attitudinal tendencies (ES = 1.17, z = 7.62, P < 0.01, 95% CI[0.87, 1.47]); nevertheless, it falls short in terms of improving students’ cognitive skills, having only an upper-middle impact (ES = 0.70, z = 11.55, P < 0.01, 95% CI[0.58, 0.82]); and (3) the teaching type (chi 2 = 7.20, P < 0.05), intervention duration (chi 2 = 12.18, P < 0.01), subject area (chi 2 = 13.36, P < 0.05), group size (chi 2 = 8.77, P < 0.05), and learning scaffold (chi 2 = 9.03, P < 0.01) all have an impact on critical thinking, and they can be viewed as important moderating factors that affect how critical thinking develops. On the basis of these results, recommendations are made for further study and instruction to better support students’ critical thinking in the context of collaborative problem-solving.

Similar content being viewed by others

Testing theory of mind in large language models and humans

Determinants of behaviour and their efficacy as targets of behavioural change interventions

Impact of artificial intelligence on human loss in decision making, laziness and safety in education

Introduction.

Although critical thinking has a long history in research, the concept of critical thinking, which is regarded as an essential competence for learners in the 21st century, has recently attracted more attention from researchers and teaching practitioners (National Research Council, 2012 ). Critical thinking should be the core of curriculum reform based on key competencies in the field of education (Peng and Deng, 2017 ) because students with critical thinking can not only understand the meaning of knowledge but also effectively solve practical problems in real life even after knowledge is forgotten (Kek and Huijser, 2011 ). The definition of critical thinking is not universal (Ennis, 1989 ; Castle, 2009 ; Niu et al., 2013 ). In general, the definition of critical thinking is a self-aware and self-regulated thought process (Facione, 1990 ; Niu et al., 2013 ). It refers to the cognitive skills needed to interpret, analyze, synthesize, reason, and evaluate information as well as the attitudinal tendency to apply these abilities (Halpern, 2001 ). The view that critical thinking can be taught and learned through curriculum teaching has been widely supported by many researchers (e.g., Kuncel, 2011 ; Leng and Lu, 2020 ), leading to educators’ efforts to foster it among students. In the field of teaching practice, there are three types of courses for teaching critical thinking (Ennis, 1989 ). The first is an independent curriculum in which critical thinking is taught and cultivated without involving the knowledge of specific disciplines; the second is an integrated curriculum in which critical thinking is integrated into the teaching of other disciplines as a clear teaching goal; and the third is a mixed curriculum in which critical thinking is taught in parallel to the teaching of other disciplines for mixed teaching training. Furthermore, numerous measuring tools have been developed by researchers and educators to measure critical thinking in the context of teaching practice. These include standardized measurement tools, such as WGCTA, CCTST, CCTT, and CCTDI, which have been verified by repeated experiments and are considered effective and reliable by international scholars (Facione and Facione, 1992 ). In short, descriptions of critical thinking, including its two dimensions of attitudinal tendency and cognitive skills, different types of teaching courses, and standardized measurement tools provide a complex normative framework for understanding, teaching, and evaluating critical thinking.

Cultivating critical thinking in curriculum teaching can start with a problem, and one of the most popular critical thinking instructional approaches is problem-based learning (Liu et al., 2020 ). Duch et al. ( 2001 ) noted that problem-based learning in group collaboration is progressive active learning, which can improve students’ critical thinking and problem-solving skills. Collaborative problem-solving is the organic integration of collaborative learning and problem-based learning, which takes learners as the center of the learning process and uses problems with poor structure in real-world situations as the starting point for the learning process (Liang et al., 2017 ). Students learn the knowledge needed to solve problems in a collaborative group, reach a consensus on problems in the field, and form solutions through social cooperation methods, such as dialogue, interpretation, questioning, debate, negotiation, and reflection, thus promoting the development of learners’ domain knowledge and critical thinking (Cindy, 2004 ; Liang et al., 2017 ).

Collaborative problem-solving has been widely used in the teaching practice of critical thinking, and several studies have attempted to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of the empirical literature on critical thinking from various perspectives. However, little attention has been paid to the impact of collaborative problem-solving on critical thinking. Therefore, the best approach for developing and enhancing critical thinking throughout collaborative problem-solving is to examine how to implement critical thinking instruction; however, this issue is still unexplored, which means that many teachers are incapable of better instructing critical thinking (Leng and Lu, 2020 ; Niu et al., 2013 ). For example, Huber ( 2016 ) provided the meta-analysis findings of 71 publications on gaining critical thinking over various time frames in college with the aim of determining whether critical thinking was truly teachable. These authors found that learners significantly improve their critical thinking while in college and that critical thinking differs with factors such as teaching strategies, intervention duration, subject area, and teaching type. The usefulness of collaborative problem-solving in fostering students’ critical thinking, however, was not determined by this study, nor did it reveal whether there existed significant variations among the different elements. A meta-analysis of 31 pieces of educational literature was conducted by Liu et al. ( 2020 ) to assess the impact of problem-solving on college students’ critical thinking. These authors found that problem-solving could promote the development of critical thinking among college students and proposed establishing a reasonable group structure for problem-solving in a follow-up study to improve students’ critical thinking. Additionally, previous empirical studies have reached inconclusive and even contradictory conclusions about whether and to what extent collaborative problem-solving increases or decreases critical thinking levels. As an illustration, Yang et al. ( 2008 ) carried out an experiment on the integrated curriculum teaching of college students based on a web bulletin board with the goal of fostering participants’ critical thinking in the context of collaborative problem-solving. These authors’ research revealed that through sharing, debating, examining, and reflecting on various experiences and ideas, collaborative problem-solving can considerably enhance students’ critical thinking in real-life problem situations. In contrast, collaborative problem-solving had a positive impact on learners’ interaction and could improve learning interest and motivation but could not significantly improve students’ critical thinking when compared to traditional classroom teaching, according to research by Naber and Wyatt ( 2014 ) and Sendag and Odabasi ( 2009 ) on undergraduate and high school students, respectively.

The above studies show that there is inconsistency regarding the effectiveness of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking. Therefore, it is essential to conduct a thorough and trustworthy review to detect and decide whether and to what degree collaborative problem-solving can result in a rise or decrease in critical thinking. Meta-analysis is a quantitative analysis approach that is utilized to examine quantitative data from various separate studies that are all focused on the same research topic. This approach characterizes the effectiveness of its impact by averaging the effect sizes of numerous qualitative studies in an effort to reduce the uncertainty brought on by independent research and produce more conclusive findings (Lipsey and Wilson, 2001 ).

This paper used a meta-analytic approach and carried out a meta-analysis to examine the effectiveness of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking in order to make a contribution to both research and practice. The following research questions were addressed by this meta-analysis:

What is the overall effect size of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking and its impact on the two dimensions of critical thinking (i.e., attitudinal tendency and cognitive skills)?

How are the disparities between the study conclusions impacted by various moderating variables if the impacts of various experimental designs in the included studies are heterogeneous?

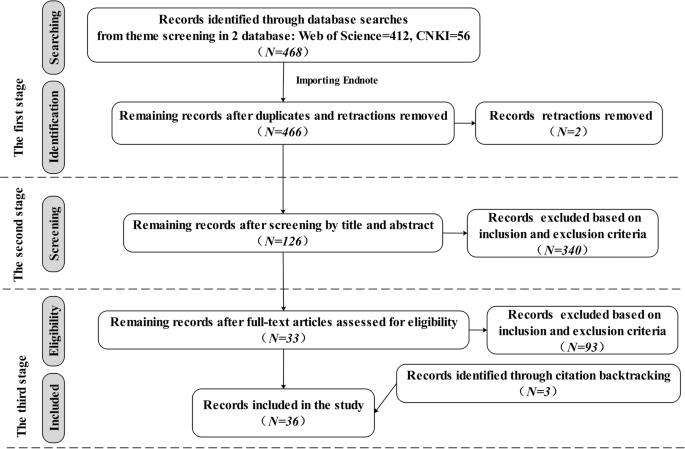

This research followed the strict procedures (e.g., database searching, identification, screening, eligibility, merging, duplicate removal, and analysis of included studies) of Cooper’s ( 2010 ) proposed meta-analysis approach for examining quantitative data from various separate studies that are all focused on the same research topic. The relevant empirical research that appeared in worldwide educational periodicals within the 21st century was subjected to this meta-analysis using Rev-Man 5.4. The consistency of the data extracted separately by two researchers was tested using Cohen’s kappa coefficient, and a publication bias test and a heterogeneity test were run on the sample data to ascertain the quality of this meta-analysis.

Data sources and search strategies

There were three stages to the data collection process for this meta-analysis, as shown in Fig. 1 , which shows the number of articles included and eliminated during the selection process based on the statement and study eligibility criteria.

This flowchart shows the number of records identified, included and excluded in the article.

First, the databases used to systematically search for relevant articles were the journal papers of the Web of Science Core Collection and the Chinese Core source journal, as well as the Chinese Social Science Citation Index (CSSCI) source journal papers included in CNKI. These databases were selected because they are credible platforms that are sources of scholarly and peer-reviewed information with advanced search tools and contain literature relevant to the subject of our topic from reliable researchers and experts. The search string with the Boolean operator used in the Web of Science was “TS = (((“critical thinking” or “ct” and “pretest” or “posttest”) or (“critical thinking” or “ct” and “control group” or “quasi experiment” or “experiment”)) and (“collaboration” or “collaborative learning” or “CSCL”) and (“problem solving” or “problem-based learning” or “PBL”))”. The research area was “Education Educational Research”, and the search period was “January 1, 2000, to December 30, 2021”. A total of 412 papers were obtained. The search string with the Boolean operator used in the CNKI was “SU = (‘critical thinking’*‘collaboration’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘collaborative learning’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘CSCL’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘problem solving’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘problem-based learning’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘PBL’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘problem oriented’) AND FT = (‘experiment’ + ‘quasi experiment’ + ‘pretest’ + ‘posttest’ + ‘empirical study’)” (translated into Chinese when searching). A total of 56 studies were found throughout the search period of “January 2000 to December 2021”. From the databases, all duplicates and retractions were eliminated before exporting the references into Endnote, a program for managing bibliographic references. In all, 466 studies were found.

Second, the studies that matched the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the meta-analysis were chosen by two researchers after they had reviewed the abstracts and titles of the gathered articles, yielding a total of 126 studies.

Third, two researchers thoroughly reviewed each included article’s whole text in accordance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Meanwhile, a snowball search was performed using the references and citations of the included articles to ensure complete coverage of the articles. Ultimately, 36 articles were kept.

Two researchers worked together to carry out this entire process, and a consensus rate of almost 94.7% was reached after discussion and negotiation to clarify any emerging differences.

Eligibility criteria

Since not all the retrieved studies matched the criteria for this meta-analysis, eligibility criteria for both inclusion and exclusion were developed as follows:

The publication language of the included studies was limited to English and Chinese, and the full text could be obtained. Articles that did not meet the publication language and articles not published between 2000 and 2021 were excluded.

The research design of the included studies must be empirical and quantitative studies that can assess the effect of collaborative problem-solving on the development of critical thinking. Articles that could not identify the causal mechanisms by which collaborative problem-solving affects critical thinking, such as review articles and theoretical articles, were excluded.

The research method of the included studies must feature a randomized control experiment or a quasi-experiment, or a natural experiment, which have a higher degree of internal validity with strong experimental designs and can all plausibly provide evidence that critical thinking and collaborative problem-solving are causally related. Articles with non-experimental research methods, such as purely correlational or observational studies, were excluded.

The participants of the included studies were only students in school, including K-12 students and college students. Articles in which the participants were non-school students, such as social workers or adult learners, were excluded.

The research results of the included studies must mention definite signs that may be utilized to gauge critical thinking’s impact (e.g., sample size, mean value, or standard deviation). Articles that lacked specific measurement indicators for critical thinking and could not calculate the effect size were excluded.

Data coding design

In order to perform a meta-analysis, it is necessary to collect the most important information from the articles, codify that information’s properties, and convert descriptive data into quantitative data. Therefore, this study designed a data coding template (see Table 1 ). Ultimately, 16 coding fields were retained.

The designed data-coding template consisted of three pieces of information. Basic information about the papers was included in the descriptive information: the publishing year, author, serial number, and title of the paper.

The variable information for the experimental design had three variables: the independent variable (instruction method), the dependent variable (critical thinking), and the moderating variable (learning stage, teaching type, intervention duration, learning scaffold, group size, measuring tool, and subject area). Depending on the topic of this study, the intervention strategy, as the independent variable, was coded into collaborative and non-collaborative problem-solving. The dependent variable, critical thinking, was coded as a cognitive skill and an attitudinal tendency. And seven moderating variables were created by grouping and combining the experimental design variables discovered within the 36 studies (see Table 1 ), where learning stages were encoded as higher education, high school, middle school, and primary school or lower; teaching types were encoded as mixed courses, integrated courses, and independent courses; intervention durations were encoded as 0–1 weeks, 1–4 weeks, 4–12 weeks, and more than 12 weeks; group sizes were encoded as 2–3 persons, 4–6 persons, 7–10 persons, and more than 10 persons; learning scaffolds were encoded as teacher-supported learning scaffold, technique-supported learning scaffold, and resource-supported learning scaffold; measuring tools were encoded as standardized measurement tools (e.g., WGCTA, CCTT, CCTST, and CCTDI) and self-adapting measurement tools (e.g., modified or made by researchers); and subject areas were encoded according to the specific subjects used in the 36 included studies.

The data information contained three metrics for measuring critical thinking: sample size, average value, and standard deviation. It is vital to remember that studies with various experimental designs frequently adopt various formulas to determine the effect size. And this paper used Morris’ proposed standardized mean difference (SMD) calculation formula ( 2008 , p. 369; see Supplementary Table S3 ).

Procedure for extracting and coding data

According to the data coding template (see Table 1 ), the 36 papers’ information was retrieved by two researchers, who then entered them into Excel (see Supplementary Table S1 ). The results of each study were extracted separately in the data extraction procedure if an article contained numerous studies on critical thinking, or if a study assessed different critical thinking dimensions. For instance, Tiwari et al. ( 2010 ) used four time points, which were viewed as numerous different studies, to examine the outcomes of critical thinking, and Chen ( 2013 ) included the two outcome variables of attitudinal tendency and cognitive skills, which were regarded as two studies. After discussion and negotiation during data extraction, the two researchers’ consistency test coefficients were roughly 93.27%. Supplementary Table S2 details the key characteristics of the 36 included articles with 79 effect quantities, including descriptive information (e.g., the publishing year, author, serial number, and title of the paper), variable information (e.g., independent variables, dependent variables, and moderating variables), and data information (e.g., mean values, standard deviations, and sample size). Following that, testing for publication bias and heterogeneity was done on the sample data using the Rev-Man 5.4 software, and then the test results were used to conduct a meta-analysis.

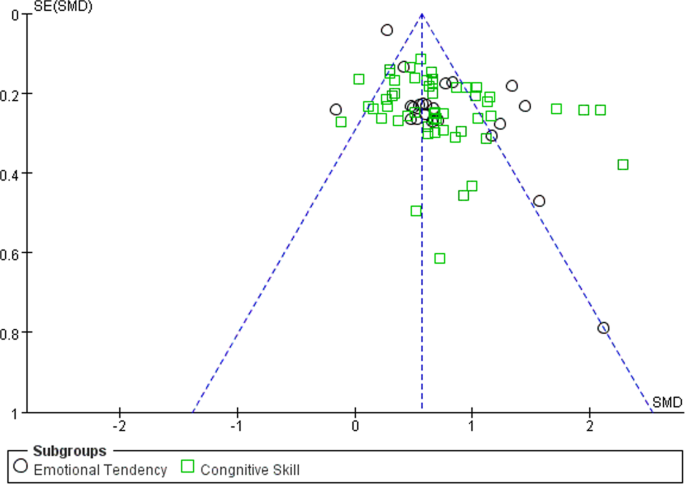

Publication bias test

When the sample of studies included in a meta-analysis does not accurately reflect the general status of research on the relevant subject, publication bias is said to be exhibited in this research. The reliability and accuracy of the meta-analysis may be impacted by publication bias. Due to this, the meta-analysis needs to check the sample data for publication bias (Stewart et al., 2006 ). A popular method to check for publication bias is the funnel plot; and it is unlikely that there will be publishing bias when the data are equally dispersed on either side of the average effect size and targeted within the higher region. The data are equally dispersed within the higher portion of the efficient zone, consistent with the funnel plot connected with this analysis (see Fig. 2 ), indicating that publication bias is unlikely in this situation.

This funnel plot shows the result of publication bias of 79 effect quantities across 36 studies.

Heterogeneity test

To select the appropriate effect models for the meta-analysis, one might use the results of a heterogeneity test on the data effect sizes. In a meta-analysis, it is common practice to gauge the degree of data heterogeneity using the I 2 value, and I 2 ≥ 50% is typically understood to denote medium-high heterogeneity, which calls for the adoption of a random effect model; if not, a fixed effect model ought to be applied (Lipsey and Wilson, 2001 ). The findings of the heterogeneity test in this paper (see Table 2 ) revealed that I 2 was 86% and displayed significant heterogeneity ( P < 0.01). To ensure accuracy and reliability, the overall effect size ought to be calculated utilizing the random effect model.

The analysis of the overall effect size

This meta-analysis utilized a random effect model to examine 79 effect quantities from 36 studies after eliminating heterogeneity. In accordance with Cohen’s criterion (Cohen, 1992 ), it is abundantly clear from the analysis results, which are shown in the forest plot of the overall effect (see Fig. 3 ), that the cumulative impact size of cooperative problem-solving is 0.82, which is statistically significant ( z = 12.78, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.69, 0.95]), and can encourage learners to practice critical thinking.

This forest plot shows the analysis result of the overall effect size across 36 studies.

In addition, this study examined two distinct dimensions of critical thinking to better understand the precise contributions that collaborative problem-solving makes to the growth of critical thinking. The findings (see Table 3 ) indicate that collaborative problem-solving improves cognitive skills (ES = 0.70) and attitudinal tendency (ES = 1.17), with significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 7.95, P < 0.01). Although collaborative problem-solving improves both dimensions of critical thinking, it is essential to point out that the improvements in students’ attitudinal tendency are much more pronounced and have a significant comprehensive effect (ES = 1.17, z = 7.62, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.87, 1.47]), whereas gains in learners’ cognitive skill are slightly improved and are just above average. (ES = 0.70, z = 11.55, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.58, 0.82]).

The analysis of moderator effect size

The whole forest plot’s 79 effect quantities underwent a two-tailed test, which revealed significant heterogeneity ( I 2 = 86%, z = 12.78, P < 0.01), indicating differences between various effect sizes that may have been influenced by moderating factors other than sampling error. Therefore, exploring possible moderating factors that might produce considerable heterogeneity was done using subgroup analysis, such as the learning stage, learning scaffold, teaching type, group size, duration of the intervention, measuring tool, and the subject area included in the 36 experimental designs, in order to further explore the key factors that influence critical thinking. The findings (see Table 4 ) indicate that various moderating factors have advantageous effects on critical thinking. In this situation, the subject area (chi 2 = 13.36, P < 0.05), group size (chi 2 = 8.77, P < 0.05), intervention duration (chi 2 = 12.18, P < 0.01), learning scaffold (chi 2 = 9.03, P < 0.01), and teaching type (chi 2 = 7.20, P < 0.05) are all significant moderators that can be applied to support the cultivation of critical thinking. However, since the learning stage and the measuring tools did not significantly differ among intergroup (chi 2 = 3.15, P = 0.21 > 0.05, and chi 2 = 0.08, P = 0.78 > 0.05), we are unable to explain why these two factors are crucial in supporting the cultivation of critical thinking in the context of collaborative problem-solving. These are the precise outcomes, as follows:

Various learning stages influenced critical thinking positively, without significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 3.15, P = 0.21 > 0.05). High school was first on the list of effect sizes (ES = 1.36, P < 0.01), then higher education (ES = 0.78, P < 0.01), and middle school (ES = 0.73, P < 0.01). These results show that, despite the learning stage’s beneficial influence on cultivating learners’ critical thinking, we are unable to explain why it is essential for cultivating critical thinking in the context of collaborative problem-solving.

Different teaching types had varying degrees of positive impact on critical thinking, with significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 7.20, P < 0.05). The effect size was ranked as follows: mixed courses (ES = 1.34, P < 0.01), integrated courses (ES = 0.81, P < 0.01), and independent courses (ES = 0.27, P < 0.01). These results indicate that the most effective approach to cultivate critical thinking utilizing collaborative problem solving is through the teaching type of mixed courses.

Various intervention durations significantly improved critical thinking, and there were significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 12.18, P < 0.01). The effect sizes related to this variable showed a tendency to increase with longer intervention durations. The improvement in critical thinking reached a significant level (ES = 0.85, P < 0.01) after more than 12 weeks of training. These findings indicate that the intervention duration and critical thinking’s impact are positively correlated, with a longer intervention duration having a greater effect.

Different learning scaffolds influenced critical thinking positively, with significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 9.03, P < 0.01). The resource-supported learning scaffold (ES = 0.69, P < 0.01) acquired a medium-to-higher level of impact, the technique-supported learning scaffold (ES = 0.63, P < 0.01) also attained a medium-to-higher level of impact, and the teacher-supported learning scaffold (ES = 0.92, P < 0.01) displayed a high level of significant impact. These results show that the learning scaffold with teacher support has the greatest impact on cultivating critical thinking.

Various group sizes influenced critical thinking positively, and the intergroup differences were statistically significant (chi 2 = 8.77, P < 0.05). Critical thinking showed a general declining trend with increasing group size. The overall effect size of 2–3 people in this situation was the biggest (ES = 0.99, P < 0.01), and when the group size was greater than 7 people, the improvement in critical thinking was at the lower-middle level (ES < 0.5, P < 0.01). These results show that the impact on critical thinking is positively connected with group size, and as group size grows, so does the overall impact.

Various measuring tools influenced critical thinking positively, with significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 0.08, P = 0.78 > 0.05). In this situation, the self-adapting measurement tools obtained an upper-medium level of effect (ES = 0.78), whereas the complete effect size of the standardized measurement tools was the largest, achieving a significant level of effect (ES = 0.84, P < 0.01). These results show that, despite the beneficial influence of the measuring tool on cultivating critical thinking, we are unable to explain why it is crucial in fostering the growth of critical thinking by utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving.

Different subject areas had a greater impact on critical thinking, and the intergroup differences were statistically significant (chi 2 = 13.36, P < 0.05). Mathematics had the greatest overall impact, achieving a significant level of effect (ES = 1.68, P < 0.01), followed by science (ES = 1.25, P < 0.01) and medical science (ES = 0.87, P < 0.01), both of which also achieved a significant level of effect. Programming technology was the least effective (ES = 0.39, P < 0.01), only having a medium-low degree of effect compared to education (ES = 0.72, P < 0.01) and other fields (such as language, art, and social sciences) (ES = 0.58, P < 0.01). These results suggest that scientific fields (e.g., mathematics, science) may be the most effective subject areas for cultivating critical thinking utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving.

The effectiveness of collaborative problem solving with regard to teaching critical thinking

According to this meta-analysis, using collaborative problem-solving as an intervention strategy in critical thinking teaching has a considerable amount of impact on cultivating learners’ critical thinking as a whole and has a favorable promotional effect on the two dimensions of critical thinking. According to certain studies, collaborative problem solving, the most frequently used critical thinking teaching strategy in curriculum instruction can considerably enhance students’ critical thinking (e.g., Liang et al., 2017 ; Liu et al., 2020 ; Cindy, 2004 ). This meta-analysis provides convergent data support for the above research views. Thus, the findings of this meta-analysis not only effectively address the first research query regarding the overall effect of cultivating critical thinking and its impact on the two dimensions of critical thinking (i.e., attitudinal tendency and cognitive skills) utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving, but also enhance our confidence in cultivating critical thinking by using collaborative problem-solving intervention approach in the context of classroom teaching.

Furthermore, the associated improvements in attitudinal tendency are much stronger, but the corresponding improvements in cognitive skill are only marginally better. According to certain studies, cognitive skill differs from the attitudinal tendency in classroom instruction; the cultivation and development of the former as a key ability is a process of gradual accumulation, while the latter as an attitude is affected by the context of the teaching situation (e.g., a novel and exciting teaching approach, challenging and rewarding tasks) (Halpern, 2001 ; Wei and Hong, 2022 ). Collaborative problem-solving as a teaching approach is exciting and interesting, as well as rewarding and challenging; because it takes the learners as the focus and examines problems with poor structure in real situations, and it can inspire students to fully realize their potential for problem-solving, which will significantly improve their attitudinal tendency toward solving problems (Liu et al., 2020 ). Similar to how collaborative problem-solving influences attitudinal tendency, attitudinal tendency impacts cognitive skill when attempting to solve a problem (Liu et al., 2020 ; Zhang et al., 2022 ), and stronger attitudinal tendencies are associated with improved learning achievement and cognitive ability in students (Sison, 2008 ; Zhang et al., 2022 ). It can be seen that the two specific dimensions of critical thinking as well as critical thinking as a whole are affected by collaborative problem-solving, and this study illuminates the nuanced links between cognitive skills and attitudinal tendencies with regard to these two dimensions of critical thinking. To fully develop students’ capacity for critical thinking, future empirical research should pay closer attention to cognitive skills.

The moderating effects of collaborative problem solving with regard to teaching critical thinking

In order to further explore the key factors that influence critical thinking, exploring possible moderating effects that might produce considerable heterogeneity was done using subgroup analysis. The findings show that the moderating factors, such as the teaching type, learning stage, group size, learning scaffold, duration of the intervention, measuring tool, and the subject area included in the 36 experimental designs, could all support the cultivation of collaborative problem-solving in critical thinking. Among them, the effect size differences between the learning stage and measuring tool are not significant, which does not explain why these two factors are crucial in supporting the cultivation of critical thinking utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving.

In terms of the learning stage, various learning stages influenced critical thinking positively without significant intergroup differences, indicating that we are unable to explain why it is crucial in fostering the growth of critical thinking.

Although high education accounts for 70.89% of all empirical studies performed by researchers, high school may be the appropriate learning stage to foster students’ critical thinking by utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving since it has the largest overall effect size. This phenomenon may be related to student’s cognitive development, which needs to be further studied in follow-up research.

With regard to teaching type, mixed course teaching may be the best teaching method to cultivate students’ critical thinking. Relevant studies have shown that in the actual teaching process if students are trained in thinking methods alone, the methods they learn are isolated and divorced from subject knowledge, which is not conducive to their transfer of thinking methods; therefore, if students’ thinking is trained only in subject teaching without systematic method training, it is challenging to apply to real-world circumstances (Ruggiero, 2012 ; Hu and Liu, 2015 ). Teaching critical thinking as mixed course teaching in parallel to other subject teachings can achieve the best effect on learners’ critical thinking, and explicit critical thinking instruction is more effective than less explicit critical thinking instruction (Bensley and Spero, 2014 ).

In terms of the intervention duration, with longer intervention times, the overall effect size shows an upward tendency. Thus, the intervention duration and critical thinking’s impact are positively correlated. Critical thinking, as a key competency for students in the 21st century, is difficult to get a meaningful improvement in a brief intervention duration. Instead, it could be developed over a lengthy period of time through consistent teaching and the progressive accumulation of knowledge (Halpern, 2001 ; Hu and Liu, 2015 ). Therefore, future empirical studies ought to take these restrictions into account throughout a longer period of critical thinking instruction.

With regard to group size, a group size of 2–3 persons has the highest effect size, and the comprehensive effect size decreases with increasing group size in general. This outcome is in line with some research findings; as an example, a group composed of two to four members is most appropriate for collaborative learning (Schellens and Valcke, 2006 ). However, the meta-analysis results also indicate that once the group size exceeds 7 people, small groups cannot produce better interaction and performance than large groups. This may be because the learning scaffolds of technique support, resource support, and teacher support improve the frequency and effectiveness of interaction among group members, and a collaborative group with more members may increase the diversity of views, which is helpful to cultivate critical thinking utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving.

With regard to the learning scaffold, the three different kinds of learning scaffolds can all enhance critical thinking. Among them, the teacher-supported learning scaffold has the largest overall effect size, demonstrating the interdependence of effective learning scaffolds and collaborative problem-solving. This outcome is in line with some research findings; as an example, a successful strategy is to encourage learners to collaborate, come up with solutions, and develop critical thinking skills by using learning scaffolds (Reiser, 2004 ; Xu et al., 2022 ); learning scaffolds can lower task complexity and unpleasant feelings while also enticing students to engage in learning activities (Wood et al., 2006 ); learning scaffolds are designed to assist students in using learning approaches more successfully to adapt the collaborative problem-solving process, and the teacher-supported learning scaffolds have the greatest influence on critical thinking in this process because they are more targeted, informative, and timely (Xu et al., 2022 ).

With respect to the measuring tool, despite the fact that standardized measurement tools (such as the WGCTA, CCTT, and CCTST) have been acknowledged as trustworthy and effective by worldwide experts, only 54.43% of the research included in this meta-analysis adopted them for assessment, and the results indicated no intergroup differences. These results suggest that not all teaching circumstances are appropriate for measuring critical thinking using standardized measurement tools. “The measuring tools for measuring thinking ability have limits in assessing learners in educational situations and should be adapted appropriately to accurately assess the changes in learners’ critical thinking.”, according to Simpson and Courtney ( 2002 , p. 91). As a result, in order to more fully and precisely gauge how learners’ critical thinking has evolved, we must properly modify standardized measuring tools based on collaborative problem-solving learning contexts.

With regard to the subject area, the comprehensive effect size of science departments (e.g., mathematics, science, medical science) is larger than that of language arts and social sciences. Some recent international education reforms have noted that critical thinking is a basic part of scientific literacy. Students with scientific literacy can prove the rationality of their judgment according to accurate evidence and reasonable standards when they face challenges or poorly structured problems (Kyndt et al., 2013 ), which makes critical thinking crucial for developing scientific understanding and applying this understanding to practical problem solving for problems related to science, technology, and society (Yore et al., 2007 ).

Suggestions for critical thinking teaching

Other than those stated in the discussion above, the following suggestions are offered for critical thinking instruction utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving.

First, teachers should put a special emphasis on the two core elements, which are collaboration and problem-solving, to design real problems based on collaborative situations. This meta-analysis provides evidence to support the view that collaborative problem-solving has a strong synergistic effect on promoting students’ critical thinking. Asking questions about real situations and allowing learners to take part in critical discussions on real problems during class instruction are key ways to teach critical thinking rather than simply reading speculative articles without practice (Mulnix, 2012 ). Furthermore, the improvement of students’ critical thinking is realized through cognitive conflict with other learners in the problem situation (Yang et al., 2008 ). Consequently, it is essential for teachers to put a special emphasis on the two core elements, which are collaboration and problem-solving, and design real problems and encourage students to discuss, negotiate, and argue based on collaborative problem-solving situations.

Second, teachers should design and implement mixed courses to cultivate learners’ critical thinking, utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving. Critical thinking can be taught through curriculum instruction (Kuncel, 2011 ; Leng and Lu, 2020 ), with the goal of cultivating learners’ critical thinking for flexible transfer and application in real problem-solving situations. This meta-analysis shows that mixed course teaching has a highly substantial impact on the cultivation and promotion of learners’ critical thinking. Therefore, teachers should design and implement mixed course teaching with real collaborative problem-solving situations in combination with the knowledge content of specific disciplines in conventional teaching, teach methods and strategies of critical thinking based on poorly structured problems to help students master critical thinking, and provide practical activities in which students can interact with each other to develop knowledge construction and critical thinking utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving.

Third, teachers should be more trained in critical thinking, particularly preservice teachers, and they also should be conscious of the ways in which teachers’ support for learning scaffolds can promote critical thinking. The learning scaffold supported by teachers had the greatest impact on learners’ critical thinking, in addition to being more directive, targeted, and timely (Wood et al., 2006 ). Critical thinking can only be effectively taught when teachers recognize the significance of critical thinking for students’ growth and use the proper approaches while designing instructional activities (Forawi, 2016 ). Therefore, with the intention of enabling teachers to create learning scaffolds to cultivate learners’ critical thinking utilizing the approach of collaborative problem solving, it is essential to concentrate on the teacher-supported learning scaffolds and enhance the instruction for teaching critical thinking to teachers, especially preservice teachers.

Implications and limitations

There are certain limitations in this meta-analysis, but future research can correct them. First, the search languages were restricted to English and Chinese, so it is possible that pertinent studies that were written in other languages were overlooked, resulting in an inadequate number of articles for review. Second, these data provided by the included studies are partially missing, such as whether teachers were trained in the theory and practice of critical thinking, the average age and gender of learners, and the differences in critical thinking among learners of various ages and genders. Third, as is typical for review articles, more studies were released while this meta-analysis was being done; therefore, it had a time limit. With the development of relevant research, future studies focusing on these issues are highly relevant and needed.

Conclusions

The subject of the magnitude of collaborative problem-solving’s impact on fostering students’ critical thinking, which received scant attention from other studies, was successfully addressed by this study. The question of the effectiveness of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking was addressed in this study, which addressed a topic that had gotten little attention in earlier research. The following conclusions can be made:

Regarding the results obtained, collaborative problem solving is an effective teaching approach to foster learners’ critical thinking, with a significant overall effect size (ES = 0.82, z = 12.78, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.69, 0.95]). With respect to the dimensions of critical thinking, collaborative problem-solving can significantly and effectively improve students’ attitudinal tendency, and the comprehensive effect is significant (ES = 1.17, z = 7.62, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.87, 1.47]); nevertheless, it falls short in terms of improving students’ cognitive skills, having only an upper-middle impact (ES = 0.70, z = 11.55, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.58, 0.82]).

As demonstrated by both the results and the discussion, there are varying degrees of beneficial effects on students’ critical thinking from all seven moderating factors, which were found across 36 studies. In this context, the teaching type (chi 2 = 7.20, P < 0.05), intervention duration (chi 2 = 12.18, P < 0.01), subject area (chi 2 = 13.36, P < 0.05), group size (chi 2 = 8.77, P < 0.05), and learning scaffold (chi 2 = 9.03, P < 0.01) all have a positive impact on critical thinking, and they can be viewed as important moderating factors that affect how critical thinking develops. Since the learning stage (chi 2 = 3.15, P = 0.21 > 0.05) and measuring tools (chi 2 = 0.08, P = 0.78 > 0.05) did not demonstrate any significant intergroup differences, we are unable to explain why these two factors are crucial in supporting the cultivation of critical thinking in the context of collaborative problem-solving.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included within the article and its supplementary information files, and the supplementary information files are available in the Dataverse repository: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/IPFJO6 .

Bensley DA, Spero RA (2014) Improving critical thinking skills and meta-cognitive monitoring through direct infusion. Think Skills Creat 12:55–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2014.02.001

Article Google Scholar

Castle A (2009) Defining and assessing critical thinking skills for student radiographers. Radiography 15(1):70–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radi.2007.10.007

Chen XD (2013) An empirical study on the influence of PBL teaching model on critical thinking ability of non-English majors. J PLA Foreign Lang College 36 (04):68–72

Google Scholar

Cohen A (1992) Antecedents of organizational commitment across occupational groups: a meta-analysis. J Organ Behav. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030130602

Cooper H (2010) Research synthesis and meta-analysis: a step-by-step approach, 4th edn. Sage, London, England

Cindy HS (2004) Problem-based learning: what and how do students learn? Educ Psychol Rev 51(1):31–39

Duch BJ, Gron SD, Allen DE (2001) The power of problem-based learning: a practical “how to” for teaching undergraduate courses in any discipline. Stylus Educ Sci 2:190–198

Ennis RH (1989) Critical thinking and subject specificity: clarification and needed research. Educ Res 18(3):4–10. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189x018003004

Facione PA (1990) Critical thinking: a statement of expert consensus for purposes of educational assessment and instruction. Research findings and recommendations. Eric document reproduction service. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ed315423

Facione PA, Facione NC (1992) The California Critical Thinking Dispositions Inventory (CCTDI) and the CCTDI test manual. California Academic Press, Millbrae, CA

Forawi SA (2016) Standard-based science education and critical thinking. Think Skills Creat 20:52–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2016.02.005

Halpern DF (2001) Assessing the effectiveness of critical thinking instruction. J Gen Educ 50(4):270–286. https://doi.org/10.2307/27797889

Hu WP, Liu J (2015) Cultivation of pupils’ thinking ability: a five-year follow-up study. Psychol Behav Res 13(05):648–654. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1672-0628.2015.05.010