Bullying by supervisors is alive and well – now is the time to tackle it

The arrangements that trap PhD students in toxic relationships with abusive supervisors must be reformed – here’s how, says Timothy Ijoyemi

Timothy Ijoyemi

You may also like

Popular resources

.css-1txxx8u{overflow:hidden;max-height:81px;text-indent:0px;} Rather than restrict the use of AI, embrace the challenge

Emotions and learning: what role do emotions play in how and why students learn, leveraging llms to assess soft skills in lifelong learning, how hard can it be testing ai detection tools, a diy guide to starting your own journal.

In recent years, a chorus of former PhD students have broken their silence over abusive behaviour suffered at the hands of their supervisors. Their horrifying accounts variously relate being belittled and humiliated in front of colleagues, having supervisors explode with anger upon hearing of scientific setbacks, even supervisors sullying their students’ reputations in the eyes of prospective employers. The toll of this sustained torment on students’ mental health can be devastating, with reports of anxiety and depression, post-traumatic stress disorder and even suicide having emerged.

Supervisor bullying deters talented students from pursuing academic careers. It can also compromise academic integrity by pressuring students to falsify data to avoid provoking backlash. This is a lose-lose situation for all of academia.

To make matters worse, the unprecedented demands of the Covid-19 pandemic risk diverting attention from nascent efforts to address supervisor bullying precisely when many of the conditions that feed into it, such as work frustration and economic inequality, have worsened. More optimistically, the state of flux created by the pandemic also presents an opportunity to finally get to grips with this issue requiring bold and urgent action.

But why focus on supervisor bullying of PhD students when bullying affects academics at all levels? While all forms of bullying must be eradicated, the power imbalance of the student-supervisor relationship makes students uniquely vulnerable to bullying from superiors who can destroy careers before they’ve even begun.

- So you want a novel way to support untapped research talent?

- Advice for early career researchers on handling workplace inequality, prejudice and exclusion

- Early career researchers can say no, too

Indeed, once a student has progressed to a certain point in their PhD, their supervisor is usually so intertwined with the project that they are virtually indispensable to its completion. Students jumping ship partway through their PhD are likely to lose access to essential resources bound to their existing supervisor, including research funding and access to crucial lab equipment, not to mention their supervisor’s expertise. Any student raising the ire of a malicious supervisor also risks forgoing the glowing reference and authorship credit on papers that could be pivotal to landing their first postdoc. It’s little wonder that so few PhD students report their experiences of bullying.

The arrangements that trap students in toxic relationships with abusive supervisors are something that universities and other stakeholders can and must work together to reform. A key focus must be making it easier for students to change supervisor partway through their projects. Here, funders could make provision for finance allocated to PhD students to be transferred to a new supervisor if bullying has occurred. Where this isn’t possible, universities should have a fund available to plug or mitigate funding shortfalls that accrue to students decoupling from abusive supervisors.

Furthermore, investigative committees should have the power to force offending supervisors to continue providing access to equipment or other resources needed by a targeted student to complete their project, with conditions around this carefully set to eliminate opportunities for reprisal – for example, mandating that the former supervisor be absent during specified access times.

Any effort to ease supervisor transition must be paired with a robust anti-bullying policy that sets out disciplinary action to be taken against supervisors found to have bullied. Consequences for repeat or particularly egregious offenders should be severe, ranging up to dismissal.

Research has found that reporting of academic bullying is low largely because targets doubt that it will lead to meaningful action. To inspire greater confidence, anti-bullying policies must be communicated to incoming PhD students as a prominent part of their induction, with clear definitions given of what constitutes bullying, how complaints will be investigated, what disciplinary actions may result and what measures can be taken to minimise negative impacts on reporting students. To increase confidence further, at least one example should be given of a previous case where a complaint was upheld with a resolution favourable to the targeted student.

Ensuring that investigations are conducted fairly is essential to earning supervisor and student support. As such, investigative committees should be made up of individuals external to an accused supervisor’s department. This would help avert conflicts of interest that could otherwise impel investigators to protect or sabotage an accused colleague.

Beyond the university itself, there’s much that can be done to tackle supervisor bullying. Funding bodies should follow the lead of the Wellcome Trust by attaching conditions to their grants that allow funding to be withdrawn from supervisors found to have bullied. Where this occurs, funding should be transferred to another principal investigator from the same department to reduce impacts on others funded by the same grant. Funders could also collaborate with universities to obtain records of academic bullying by grant applicants and factor these into funding decisions.

Gatekeepers for academic metrics, including those that publish institutional rankings, could also collaborate with universities to incorporate bullying records into their assessment criteria. This would benefit gatekeepers by driving up standards in the institutions on which their existence depends, while those institutions would benefit from outperforming competitors on a metric bound to influence student enrolment. Most important would be the benefit to students now belonging to institutions better incentivised to root out supervisor bullying.

The stories of supervisor bullying that have emerged in recent times are a terrible stain on higher education. It’s past time for the multi-pronged effort needed to reform a system in which bullying has been able to thrive. In the ruins of the pandemic, opportunity for drastic change abounds. It would be grossly unjust to the next generation of PhD students if inaction prevails.

Timothy Ijoyemi has more than 10 years’ experience in higher education. He has a passion for equity, diversity and inclusion, and at UCL School of Management he researches and supports on various projects to improve student and staff experience.

If you found this interesting and want advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the THE Campus newsletter .

Rather than restrict the use of AI, embrace the challenge

Let’s think about assessments and ai in a different way, how students’ genai skills affect assignment instructions, how not to land a job in academia, contextual learning: linking learning to the real world, three steps to unearth the hidden curriculum of networking.

Register for free

and unlock a host of features on the THE site

Why is Bullying so Frequent in Academia? Diagnostics and Solutions for Bully-Proof Organizations

When I was in graduate school, my fellow students and I often joked about a paradox: How come that our Management departments (employing dozens of faculty experts in human resources, social psychology, and group dynamics) are a breeding ground for bullies?

Indeed, one thing that struck me throughout graduate school was how common bullying was. Over the five years of my PhD, I have been the target and witness of intimidation attempts, threats, and destructive criticism. In contrast, the “supportive environment”, the “emotional safety”, and the “constructive feedback” that management scholars praise as necessary conditions for thriving work environments were rare, if not absent.

In general, horror stories about bullies were widespread in all the departments I visited, and most people around me knew at least one “bully”: A professor regularly engaged in aggressive, hostile, or even destructive behaviors towards PhDs students or colleagues.

What do we mean by bullying?

Bullying can be tricky to define. First, it encompasses a large range of behaviors (e.g., incivility, intimidation, social isolation, humiliation, emotional abuse or physical aggression) in various contexts (school, family, workplace, social media). Second, it is hard to measure: Bullies rarely talk about their bullying behaviors, and victims do not necessarily report them [1-5]. However, there is a consensus that bullying is an aggressive behavior characterized by hostile intent, power imbalance and repetition [6].

A case study in bullying: Academia

Academia provides an interesting setting to understand bullying. Such behaviors appear unfortunately more common in higher education than in other industries: 33% of academics report being victim of bullying (vs. 2% to 20% of people employed in other industries depending on the country considered [2,7]). In particular, bullying behaviors seem particularly frequent in advisor-advisee relationships: The Nature 2019 PhD survey on more than 6300 early career-researchers revealed that 21% of respondents had been bullied during their PhD, and that for 48% of them the perpetrator was their supervisor. In most cases, the victims of bullying felt unable to report these behaviors, for fear of personal repercussions [8]. The qualitative data from the survey also give insights on the specific type of bullying actions advisors engage in, such as acting aggressively or being overly critical.

When do people bully?

Bullying has been connected to some specific personality traits such as aggressiveness, Machiavellianism, or lack of empathy. However, it would be incorrect to reduce bullying to something that “evil people” do: The environment plays a major role, and organizational structures and processes can deter or on the contrary encourage bullying [5]. Academia, for example, has multiple features that can be conducive to bullying:

- A strong power imbalance between advisors and advisees.

- A loose organizational structure, with little oversight.

- An organizational culture in which the end justifies the means.

- An unidimensional hiring and promotion process.

Power imbalance

The strongest power asymmetry in academia is between graduate students and their supervisor. Very early on, PhDs are required to closely work with a supervisor who is supposed to guide them through their PhD journey. Graduate students are highly dependent on their supervisor for access to data, research budget, networking opportunities, recommendation letters… In addition, this relationship is characterized by a certain degree of opacity and informality: Interactions between supervisors and PhDs are rarely monitored or attended by third parties. This dependence and isolation can pave the way for bullying behaviors.

Loose Management

A “laissez-faire” or inadequate leadership can lead to bullying behaviors [9–11]: If figures of authority in the organization are perceived as weak, it is assumed that they will not intervene in bullying situations, which gives free reign to potential bullies to abuse others [5].

Academic departments are organized as “entrepreneurial spaces” in which professors are expected to self-manage most aspects of their work: time management, teaching, research pipeline, collaboration with co-authors, or supervision of graduate students. In addition, most academics dislike interference in what they are doing and how they are doing it: Many acknowledge that they pursued a career in academia precisely because they did not want to have a boss. However, this absence of leadership makes it easier for bullies to engage in abusive behaviors without facing repercussions.

High-Performance Organizational Culture

The academic culture is full of mythologies that justify bullying. It praises values of dominance, competitiveness, and high achievement in which bullying behavior may be perceived as only slightly transgressive, or even as an efficient way to “toughen up” aspiring academics.

The very revealing adage of academia, “publish or perish”, sets the tone of this culture. Publications in top journals define the pecking order among academics, and by the same token, make most behaviors justifiable as long as they can help achieve this goal. This ethos, that makes publishing a matter of survival, legitimizes abusive behaviors.

In addition, many academics rationalize and romanticize their past suffering, and frame it as a necessary condition to success: “Yes, the Ph.D. was tough, but it was a transformative experience, and the thick skin that I developed is now helping me thrive.” Once people hold this view, they are less likely to view bullying as an issue that needs to be solved, and less likely to take the suffering of graduate students seriously. After all, if they complain about bullying, maybe they are not “cut for the job".

This organizational culture makes particularly difficult both for PhD programs to intervene into abusive situations and for PhDs to report the behaviors they are victim of: Once everybody has internalized the idea that suffering is necessary to succeed, there is no more reason to fight against it.

“Brilliant Jerks”

Finally, academics are selected and promoted on their publication records, and much less so on their social skills and emotional intelligence. This may be surprising given that academics manage many different relationships (e.g., supervisor-supervisee, co-authors, authors-reviewers, professor-students…), have a job in which collaborations are frequent and essential, and are expected to mentor the new generations of scholars.

This narrow selection process can have multiple negative effects. It weeds out people who have good social skills but have a weaker publication record, it signals that social skills are not worth developing, and most importantly it legitimizes the stereotype of the “brilliant jerks”: prolific researchers who lack basic social skills (i.e., emotional regulation, self-reflection, and perspective-taking). Indeed, it is not rare to find that departments are willing to recruit, promote or even protect bullies, as long as they have the right number of publications, sending the message that toxic behaviors can be bargained [12].

Building a Bully-Proof Organization

While the economic cost of workplace bullying is difficult to assess, the negative consequences are well-documented. Victims are more likely to suffer from emotional issues, health disorders, extreme stress, feelings of worthlessness and shame [13]. Organizations suffer from an erosion of creativity, a reduced organizational commitment, job dissatisfaction, a decreasing productivity, an increased absenteeism, and a higher turnover rate [14–16]. How can we then avoid these behaviors, and build “bully-proof” organizations, in academia and elsewhere?

1. Not hiring bullies: “the people make the place”

The most obvious solution is not to hire people who are more likely to engage in this type of behavior. This strategy requires that organizations try to screen bullies during the recruitment and promotion process. Research suggests [17–19] that bullies are more likely to exhibit specific personality traits:

- They are aggressive, hostile, competitive, assertive, confrontational, impulsive, and moody.

- They have difficulty to self-analyze, to regulate their emotions and lack empathy.

- On the OCEAN personality inventory, they are typically low in Agreeableness and Conscientiousness and high in Neuroticism and Extraversion.

- They can also be high in narcissism and psychopathy.

However, the diagnostic value of these personality traits is low: Screening on personality alone would exclude many people who are not bullies and let in many others who are bullies.

In addition, organizations should base their recruitment and promotion decisions not only on productivity and achievement, but also on social skills and emotional intelligence. Research suggests that hiring toxic workers can be incredibly costly for companies, even when those toxic workers are high performers [20]: Between hiring a superstar (very high performer) and avoiding a toxic worker, companies are often better off avoiding the toxic worker.

2. Evaluating structural factors that allow bullies to thrive

Another important step is to determine organizational features that might enable bullying. Many aspects of organizational culture may accidentally foster bullying and should therefore be considered carefully:

- The quest for excellence (e.g., top chefs in the kitchen industry) [21]; an organizational culture that celebrates toughness (e.g., army, prisons, firefighters) [22–25].

- A socialization process that features initiation rituals (e.g., hazing) [5,26].

- A large number of informal and casual behaviors that make more difficult for some employees to distinguish “proper and professional” behaviors from “borderline and inappropriate” behaviors [27].

Those features can serve useful purposes. However, when many of them are present, it is important to be mindful that they can facilitate bullying.

3. The “no asshole rule”

On the 20th of January 2021, Joe Biden swore in nearly 1,000 federal employees. During this virtual ceremony, he felt the need to emphasize that under his watch, disrespect and condescendence among his collaborators would not be tolerated. As a leader, publicly and strongly reaffirming that bullying and other destructive behaviors do not have room in the organization can be a very powerful move.

To be effective however, this zero-tolerance policy must be accompanied with effective policies that discourage and punish bullying, and on the contrary reward constructive interactions [28]. If leaders do not walk the talk, they risk promoting a culture of impunity and hypocrisy within the organization.

To go further…

- Woolston, C. PhDs: the tortuous truth. Nature 575, 403–406 (2019).

- Minor, D. & Housman, M. G. Toxic Workers. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2015, 13189 (2015).

- Moss, S. Research is set up for bullies to thrive. Nature 560, 529–529 (2018).

- Breevaart, K., Wisse, B. & Schyns, B. Trapped at Work: The Barriers Model of Abusive Supervision. Acad. Manag. Perspect. (2021)

- Chirila, T. & Constantin, T. Understanding Workplace Bullying Phenomenon through its Concepts: A Literature Review. Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 1175–1179 (2013).

- Keashly, L. & Jagatic, K. North American Perspectives on Hostile Behaviors and Bullying at Work. in Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace: Developments in Theory, Research, and Practice (CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, 2011).

- Keashly, L. & Neuman, J. H. Bullying in higher education: what current research, theorizing, and practice tell us. in Workplace Bullying In Higher Education (Routledge, 2013).

- Randall, P. An overview of adult bullying. in Bullying in Adulthood: Assessing the Bullies and their Victims (Routledge, 2002).

- Salin, D. Ways of explaining workplace bullying: A review of enabling, motivating and precipitating structures and processes in the work environment. Hum. Relat. 56, 1213–1232 (2003).

- Bullying. Wikipedia (2021).

- Rayner, C. & Cooper, C. L. Workplace Bullying. in Handbook of workplace violence 121–145 (Sage Publications, Inc, 2006).

- Einarsen, S., Raknes, B. rn I. & Matthiesen, S. B. Bullying and harassment at work and their relationships to work environment quality: An exploratory study. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 4, 381–401 (1994).

- Hoel, H. & Cooper, C. L. Destructive conflict and bullying at work. (Manchester School of Management, UMIST Manchester, 2000).

- Leymann, H. The content and development of mobbing at work. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 5, 165–184 (1996).

- Nelson, E. D. & Lambert, R. D. Sticks, stones and semantics: The ivory tower bully’s vocabulary of motives. Qual. Sociol. 24, 83–106 (2001).

- Workplace Bullying Institute. Results of the 2010 and 2007 WBI US Workplace Bullying Survey. (2010).

- Bryant, M., Buttigieg, D. & Hanley, G. Poor bullying prevention and employee health: some implications. Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 2, 48–62 (2009).

- Pate, J. & Beaumont, P. Bullying and harassment: a case of success? Empl. Relat. 32, 171–183 (2010).

- Zapf, D. Organisational, work group related and personal causes of mobbing/bullying at work. Int. J. Manpow. 20, 70–85 (1999).

- Jolliffe, D. & Farrington, D. P. Examining the relationship between low empathy and bullying. Aggress. Behav. Off. J. Int. Soc. Res. Aggress. 32, 540–550 (2006).

- Mitsopoulou, E. & Giovazolias, T. Personality traits, empathy and bullying behavior: A meta-analytic approach. Aggress. Violent Behav. 21, 61–72 (2015).

- Seigne, E., Coyne, I., Randall, P. & Parker, J. Personality traits of bullies as a contributory factor in workplace bullying: An exploratory study. Int. J. Organ. Theory Behav. (2007).

- Johns, N. & Menzel, P. J. ‘ If you can’t stand the heat!’… Kitchen violence and culinary art. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. (1999).

- Archer, D. Exploring “bullying” culture in the para‐military organisation. Int. J. Manpow. (1999).

- Ashforth, B. Petty Tyranny in Organizations. Hum. Relat. 47, 755–778 (1994).

- Ireland, J. L. “Bullying” among prisoners: A review of research. Aggress. Violent Behav. 5, 201–215 (2000).

- Neuman, J. H. & Baron, R. A. Workplace Violence and Workplace Aggression: Evidence Concerning Specific Forms, Potential Causes, and Preferred Targets. J. Manag. 24, 391–419 (1998).

- Hoel, H. & Salin, D. 10 Organisational antecedents of workplace bullying. Bullying Emot. Abuse Workplace Int. Perspect. Res. Pract. 203–218 (2003).

- Pearson, C. M., Andersson, L. M. & Porath, C. L. Assessing and attacking workplace incivility. Organ. Dyn. 29, 123–137 (2000).

- Hanson, B. C. Diagnose and Eliminate Workplace Bullying. Harvard Business Review (2011).

Found this post insightful? Get email alerts for new posts by subscribing:

PhD in Organizational Behavior

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- 28 August 2018

Research is set up for bullies to thrive

- Sherry Moss 0

Sherry Moss is a professor of organizational studies at Wake Forest University’s School of Business in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, USA.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

A young woman contacted me earlier this year to discuss her PhD adviser. He would follow her around the lab, shaming her in others’ presence, yelling that she was incompetent and that her experiments were done incorrectly. She wanted nothing more than to minimize contact with him, but she felt trapped. Starting in another lab would mean losing nearly three years of work.

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Nature 560 , 529 (2018)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-06040-w

Reprints and permissions

Related Articles

- Research management

I’m worried I’ve been contacted by a predatory publisher — how do I find out?

Career Feature 15 MAY 24

How I fled bombed Aleppo to continue my career in science

Career Feature 08 MAY 24

Hunger on campus: why US PhD students are fighting over food

Career Feature 03 MAY 24

Japan can embrace open science — but flexible approaches are key

Correspondence 07 MAY 24

US funders to tighten oversight of controversial ‘gain of function’ research

News 07 MAY 24

France’s research mega-campus faces leadership crisis

News 03 MAY 24

Illuminating ‘the ugly side of science’: fresh incentives for reporting negative results

Senior Research Assistant in Human Immunology (wet lab)

Senior Research Scientist in Human Immunology, high-dimensional (40+) cytometry, ICS and automated robotic platforms.

Boston, Massachusetts (US)

Boston University Atomic Lab

Postdoctoral Fellow in Systems Immunology (dry lab)

Postdoc in systems immunology with expertise in AI and data-driven approaches for deciphering human immune responses to vaccines and diseases.

Global Talent Recruitment of Xinjiang University in 2024

Recruitment involves disciplines that can contact the person in charge by phone.

Wulumuqi city, Ürümqi, Xinjiang Province, China

Xinjiang University

Tenure-Track Assistant Professor, Associate Professor, and Professor

Westlake Center for Genome Editing seeks exceptional scholars in the many areas.

Westlake Center for Genome Editing, Westlake University

Faculty Positions at SUSTech School of Medicine

SUSTech School of Medicine offers equal opportunities and welcome applicants from the world with all ethnic backgrounds.

Shenzhen, Guangdong, China

Southern University of Science and Technology, School of Medicine

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Advertisement

Abuse and Exploitation of Doctoral Students: A Conceptual Model for Traversing a Long and Winding Road to Academia

- Original Paper

- Published: 31 July 2021

- Volume 180 , pages 505–522, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Aaron Cohen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8143-2769 1 &

- Yehuda Baruch ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0678-6273 2

4121 Accesses

14 Citations

17 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

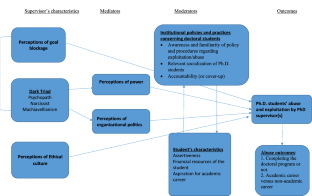

This paper develops a conceptual model of PhD supervisors’ abuse and exploitation of their students and the outcomes of that abuse. Based on the literature about destructive leadership and the “dark side” of supervision, we theorize about why and how PhD student abuse and exploitation may occur. We offer a novel contribution to the literature by identifying the process through which PhD students experience supervisory abuse and exploitation, the various factors influencing this process, and its outcomes. The proposed model presents the Dark Triad, perceptions of goal blockage, and perceptions of ethical culture as potential characteristics of the PhD supervisor and implies the mediation of the perceptions of power and politics in the relationship between the Dark Triad and student abuse and exploitation. Institutional policies and practices concerning doctoral students and their characteristics are proposed as moderators in such a relationship. Finally, the model suggests that student abuse and exploitation may hinder or even end students’ academic careers. The manuscript discusses the theoretical and practical contributions and managerial implications of the proposed model and recommends further exploration of the dark sides of academia.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Counteroffers for faculty at research universities: who gets them, who doesn’t, and what factors produce them?

Ethical Issues in Research: Perceptions of Researchers, Research Ethics Board Members and Research Ethics Experts

Bullying in higher education: an endemic problem.

We refer to PhDs, but this applies to any doctorate, such as the Doctor of Business Administration (DBA) or Doctor of Science (DSc).

Acharya, S. (2005). The ethical climate in academic dentistry in India: Faculty and student perceptions. Journal of Dental Education, 69 (6), 671–680. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.0022-0337.2005.69.6.tb03950.x .

Article Google Scholar

Ali, J., Ullah, H., & Sanauddin, N. (2019). Postgraduate research supervision: Exploring the lived experience of Pakistani postgraduate students. FWU Journal of Social Sciences, 13 (1), 14–25.

Google Scholar

Anderson, M. S., & Seashore-Louis, K. (1994). The graduate student experience and subscription to the norms of science. Research in Higher Education , 35 (3), 273–299. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02496825 .

Anthun, K. S., & Innstrand, S. T. (2016). The predictive value of job demands and resources on the meaning of work and organisational commitment across different age groups in the higher education sector. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 38 (1), 53–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2015.1126890 .

Appelbaum, S. H., Deguire, K. J., & Lay, M. (2005). The relationship of ethical climate to deviant workplace behavior. Corporate Governance, 5 (4), 43–56. https://doi.org/10.1108/14720700510616587 .

Ashforth, B. (1994). Petty tyranny in organizations. Human Relations, 47 (7), 755–778. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679404700701 .

Austin, J. T., & Vancouver, J. B. (1996). Goal constructs in psychology: Structure, process, and content. Psychological Bulletin, 120 (3), 338–375. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.120.3.338 .

Babiak, P., & Hare, R. D. (2006). Snakes in suits: When psychopaths go to work . New York, NY: HarperCollins.

Baka, Ł. (2018). When do the ‘dark personalities’ become less counterproductive? The moderating role of job control and social support. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics, 24 (4), 557–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/10803548.2018.1463670 .

Baloch, M. A., Meng, F., Xu, Z., Cepeda-Carrion, I., & Bari, M. W. (2017). Dark triad, perceptions of organizational politics and counterproductive work behaviors, The moderating effect of political skills. Frontiers in Psychology, 8 , 1972. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01972 .

Baruch, Y. (2013). Careers in academe: The academic labour market as an eco-system. Career Development International, 18 (2), 196–210. https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-09-2012-0092 .

Baruch, Y., & Hall, D. T. (2004). The academic career: A model for future careers in other sectors? Journal of Vocational Behavior, 64 (2), 241–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2002.11.002 .

Baskin, M. E. B., Vardaman, J. M., & Hancock, J. I. (2015). The role of ethical climate and moral disengagement in well-intended employee rule breaking. Journal of Behavioral and Applied Management, 16 (2), 71–90.

Baruch, Y., & Vardi, Y. (2016). A fresh look at the dark side of contemporary careers: Toward a realistic discourse. British Journal of Management, 27 (2), 355–372. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12107 .

Becker, K. D. (2019). Graduate students’ experiences of plagiarism by their professors. Higher Education Quarterly, 73 (2), 251–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/hequ.12179 .

Bégin, C., & Géarard, L. (2013). The role of supervisors in light of the experience of doctoral students. Policy Futures in Education, 11 (3), 267–276. https://doi.org/10.2304/pfie.2013.11.3.267 .

Berti, M., & Simpson, A. (2019). The dark side of organizational paradoxes: The dynamics of disempowerment. Academy of Management Review . https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2017.0208 .

Boddy, C. R. (2006). The dark side of management decisions: Organizational psychopaths. Management Decision, 44 (10), 1461–1475. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2017.0208 .

Boddy, C. R. (2014). Corporate psychopaths, conflict, employee affective well-being and counterproductive work behaviour. Journal of Business Ethics, 121 (1), 107–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1688-0 .

Bruhn, J. G. (2008). Value dissonance and ethics failure in academia: A causal connection? Journal of Academic Ethics, 6 (1), 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-008-9054-z .

Campbell, W. K., Hoffman, B. J., Campbell, S. M., & Marchisio, G. (2011). Narcissism in organizational contexts. Human Resource Management Review, 21 (4), 268–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2010.10.007 .

Caplow, T., & McGee, R. J. (2001). The academic marketplace . New Brunswick/London: Transaction Publications.

Chen, C. C., Chen, M. Y. C., & Liu, Y. C. (2013). Negative affectivity and workplace deviance: The moderating role of ethical climate. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24 (15), 2894–2910. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2012.753550 .

Chernyak-Hai, L., & Tziner, A. (2021). Attributions of managerial decisions, emotions, and OCB. The moderating role of ethical climate and self-enhancement. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 37 (1), 36–48. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2021a4 .

Cohen, A. (2016). Are they among us? A conceptual framework of the relationship between the dark triad personality and counterproductive work behaviors (CWBs). Human Resource Management Review, 26 (1), 69–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2015.07.003 .

Cohen, A. (2018). Counterproductive work behaviors: Understanding the dark side of personalities in organizational life, Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315454818 .

Crane, A. (2013). Modern slavery as a management practice, exploring the conditions and capabilities for human exploitation. Academy of Management Review, 38 (1), 49–69. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2011.0145 .

Cyranoski, D., Gilbert, N., Ledford, H., Nayar, A., & Yahia, M. (2011). Education: The PhD factory. Nature, 472 , 276–279. https://doi.org/10.1038/472276a .

Davenport, N., Schwartz, R.D., & Elliott, G.P. (1999). Mobbing: Emotional abuse in the American workplace . Civil Society Publ., Iowa, IA.

Devlin, H. (2018). In the science lab, some bullies can thrive unchecked for decades. The Guardian , August 29, 1–3.

Devos, C., Boudrenghien, G., Van der Linden, N., Azzi, A., Frenay, M., Galand, B., & Klein, O. (2017). Doctoral students’ experiences leading to completion or attrition: A matter of sense, progress and distress. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 32 (1), 61–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-016-0290-0 .

Dineen, B. R., Lewicki, R. J., & Tomlinson, E. C. (2006). Supervisory guidance and behavioral integrity: Relationships with employee citizenship and deviant behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91 (3), 622–635. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.3.622 .

Dupré, K. E., & Barling, J. (2006). Predicting and preventing supervisory workplace aggression. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 11 (1), 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.11.1.13 .

Dziech, B., & Weiner, L. (1984). The lecherous professor . Boston: Beacon Press.

Editorial. (2018). No place for bullies in science. Nature, 559 , 151.

Eigenstetter, M., Dobiasch, S., & Trimpop, R. (2007). Commitment and counterproductive work behavior as correlates of ethical climate in organizations. Monatsschrift für Kriminologie und Strafrechtsreform, 90 (2–3), 224–244.

Einarsen, S. (1999). The nature and causes of bullying at work. International Journal of Manpower, 20 (1/2), 16–27. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437729910268588 .

Erkutlu, H., & Chafra, J. (2019). Leader psychopathy and organizational deviance. International Journal of Workplace Health Management, 12 (4), 197–213. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJWHM-12-2018-0154 .

Ferris, G. R., Adams, G., Kolodinsky, R. W., Hochwarter, W. A., & Ammeter, A. P. (2002). Perceptions of organizational politics: Theory and research directions. In F. J. Yammarino & F. Dansereau (Eds.), Research in multi-level issues. The many faces of multi-level issues (Vol. 1, pp. 179–254). Elsevier Science/JAI Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1475-9144(02)01034-2 .

Ferris, G., Ellen, B., McAllister, C., & Maher, L. (2019). Reorganizing organizational politics research: A review of the literature and identification of future research directions. Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 6 (1), 299–323. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012218-015221 .

Ferris, G. R., Gail, R. S., & Patricia, F. M. (1989). Politics in organizations. In R. A. Giacalone & P. Rosenfeld (Eds.), Impression management in the organization (pp. 143–170). Lawrence Erlbaum.

Gardner, S. K. (2007). “I heard it through the grapevine”: Doctoral student socialization in chemistry and history. Higher Education, 54 (5), 723–740. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-006-9020-x .

Golde, C. M., & Dore, T. M. (2001). At cross purposes: What the experiences of today’s doctoral students reveal about doctoral education. Wisconsin University: Educational Resources Information Center (ERIC) 63. http://www.phd-survey.org .

Goodyear, R. K., Crego, C. A., & Johnston, M. W. (1992). Ethical issues in the supervision of student research: A study of critical incidents. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 23 (3), 203–210. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.23.3.203 .

Gruzdev, I., Terentev, E., & Dzhafarova, Z. (2020). Superhero or hands-off supervisor? An empirical categorization of PhD supervision styles and student satisfaction in Russian universities. Higher Education, 79 , 773–789. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00437-w .

Hall, D. T., & Chandler, D. E. (2005). Psychological success: When the career is a calling. Journal of Organizational Behavior , 26 , 155–176. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4093976 .

Harrison, E. D., Fox, C. L., & Hulme, J. A. (2020). Student anti-bullying and harassment policies at UK universities. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management . https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2020.1767353 .

Harvey, P., Stoner, J., Hochwarter, W., & Kacmar, C. (2007). Coping with abusive supervision: The neutralizing effects of ingratiation and positive affect on negative employee outcomes. The Leadership Quarterly, 18 (3), 264–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2007.03.008 .

Hauge, L. J., Skogstad, A., & Einarsen, S. (2007). Relationships between stressful work environments and bullying: Results of a large representative study. Work and Stress, 21 , 220–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370701705810 .

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44 (3), 513–524. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513 .

Hofstede, G. H. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations (2nd edn.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Horner, J., & Minifie, F. D. (2011). Research ethics III: Publication practices and authorship, conflicts of interest, and research misconduct. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 54 , S346–S362. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2010/09-0263) .

Hu, H. H. (2012). The influence of employee emotional intelligence on coping with supervisor abuse in a banking context. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 40 (5), 863–874. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2012.40.5.863 .

Hsieh, H. H., & Wang, Y. D. (2016). Linking perceived ethical climate to organizational deviance: The cognitive, affective, and attitudinal mechanisms. Journal of Business Research, 69 (9), 3600–3608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.01.001 .

Ishak, N. K., Haron, H., & Ismail, I. (2019). Ethical leadership, ethical climate and unethical behaviour in institutions of higher learning. In FGIC 2nd conference on governance and integrity (Vol. 2019, pp. 408–422). KnE Social Sciences. https://doi.org/10.18502/kss.v3i22.5064 .

Jacob, R., Kuzmanovska, I., & Ripin, N. (2018). AVETH survey on supervision of doctoral students . ETH Zurich

Jacobson, K. J., Hood, J. N., & Van Buren III, H. J. (2014). Workplace bullying across cultures: A research agenda. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 14 (1), 47–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470595813494192 .

Jam, F. A., Khan, T. I., Anwar, F., Sheikh, R. A., Kaur, S., & Malaysia, L. (2012). Neuroticism and job outcomes: Mediating effects of perceived organizational politics. African Journal of Business Management , 6(7), 2508–2515. http://www.academicjournals.org/AJBM .

Janke, S., Daumiller, M., & Rudert, S. C. (2019). Dark pathways to achievement in science: Researchers’ achievement goals predict engagement in questionable research practices. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 10 (6), 783–791. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550618790227 .

Johnson, C. M., Ward, K. A., & Gardner, S. K. (2017). Doctoral student socialization. In J. Shin & P. Teixeira (Eds.), Encyclopedia of international higher education systems and institutions . Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer.

Jones, M. (2013). Issues in doctoral studies—Forty years of journal discussion: Where have we been and where are we going? International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 8 , 83–104. https://doi.org/10.28945/1871 .

Keashly, L., & Nueman, J.H. (2010). Faculty experiences with bullying in higher education: Causes, consequences, and management. Administrative Theory and Praxis , 32 (1), 48–70. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25611038 .

Khosa, A., Burch, S., Ozdil, E., & Wilkin, C. (2019). Current issues in Ph.D. supervision of accounting and finance students: Evidence from Australia and New Zealand. The British Accounting Review . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2019.100874 .

Kiley, M. (2019). Doctoral supervisory quality from the perspective of senior academic managers. Australian Universities Review , 61 (1), 12–21. http://hdl.handle.net/1885/186707 .

Kitchener, K. S. (1988). Dual role relationships: What makes them so problematic? Journal of Counseling and Development, 67 , 217–221. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.1988.tb02586.x .

Kossek, E. E., Su, R., & Wu, L. (2017). “Opting out” or “pushed out”? Integrating perspectives on women’s career equality for gender inclusion and interventions. Journal of Management, 43 (1), 228–254. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316671582 .

Krasikova, D. V., Green, S. G., & LeBreton, J. M. (2013). Destructive leadership: A theoretical review, integration, and future research agenda. Journal of Management, 39 (5), 1308–1338. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206312471388 .

Lee, A., & McKenzie, J. (2011). Evaluating doctoral supervision: Tensions in eliciting students’ perspectives. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 48 (1), 69–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2010.543773 .

Lian, H., Brown, D. J., Ferris, D. L., Liang, L. H., Keeping, L. M., & Morrison, R. (2014). Abusive supervision and retaliation: A self-control framework. Academy of Management Journal, 57 (1), 116–139. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0977 .

Litalien, D., & Guay, F. (2015). Dropout intentions in Ph.D. studies: A comprehensive model based on interpersonal relationships and motivational resources. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 41 , 218–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2015.03.004 .

Löfström, E., & Pyhältö, K. (2014). Ethical issues in doctoral supervision: The perspectives of Ph.D. students in the natural and behavioral sciences. Ethics and Behavior, 24 (3), 195–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2013.830574 .

Löfström, E., & Pyhältö, K. (2017). Ethics in the supervisory relationship: Supervisors’ and doctoral students’ dilemmas in the natural and behavioural sciences. Studies in Higher Education, 42 (2), 232–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1045475 .

Löfström, E., & Pyhältö, K. (2020). What are ethics in doctoral supervision, and how do they matter? Doctoral students’ perspective. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 64 (4), 535–550. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2019.1595711 .

Lyons, M. (2019). The dark triad of personality: Narcissism, machiavellianism, and psychopathy in everyday life . Cambridge, MA: Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/C2017-0-01262-4 .

Mahmoudi, M. (2019). Academic bullies leave no trace. BioImpacts, 9 (3), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.15171/bi.2019.17 .

Mahmoudi, M., Ameli, S., & Moss, S. (2019). The urgent need for modification of scientific ranking indexes to facilitate scientific progress and diminish academic bullying. BioImpacts, 9 (5), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.15171/bi.2019.30 .

Mahmud, S., & Bretag, T. (2013). Postgraduate research students and academic integrity: ‘It’s about good research training.’ Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 35 (4), 432–443. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2013.812178 .

Mainhard, T., Van Der Rijst, R., Van Tartwijk, J., & Wubbels, T. (2009). A model for the supervisor–doctoral student relationship. Higher Education, 58 (3), 359–373. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-009-9199-8 .

Malički, M., Katavić, V., Marković, D., Marušić, M., & Marušic, A. (2019). Perceptions of ethical climate and research pressures in different faculties of a university: Cross-sectional study at the University of Split, Croatia. Science and Engineering Ethics, 25 , 231–245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-017-9987-y .

Martin, B. (1998). Tied Knowledge: Power in Higher Education. Available (consulted 28 July 2006) at: http://www.uow.edu.au/~bmartin/pubs/98tk/index.html

Martin, B. (2013). Countering supervisor exploitation. Journal of Scholarly Publishing, 45 (1), 74–86. https://doi.org/10.3138/jsp.45-1-004 .

Mason, A., & Hickman, J. (2019). Students supporting students on the PhD journey: An evaluation of a mentoring scheme for international doctoral students. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 56 (1), 88–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2017.1392889 .

Meng, Y., Tan, J., & Li, J. (2017). Abusive supervision by academic supervisors and postgraduate research students’ creativity: The mediating role of leader–member exchange and intrinsic motivation. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 20 (5), 605–617. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2017.1304576 .

Meng, Q., & Wang, G. (2018). A research on sources of university faculty occupational stress: A Chinese case study. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 11 , 597–605.

Mendoza, P. (2007). Academic capitalism and doctoral student socialization: A case study. Journal of Higher Education , 78 , 71–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2007.11778964 .

Moore, C., Detert, J. R., Klebe Treviño, L., Baker, V. L., & Mayer, D. M. (2012). Why employees do bad things: Moral disengagement and unethical organizational behavior. Personnel Psychology, 65 (1), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2011.01237.x .

Morris, S. E. (2011). Doctoral students’ experiences of supervisory bullying. Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 19 (2), 547–555.

Moss, S. (2018). Research is set up for bullies to thrive. Nature, 560 , 529–529. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-06040-w .

Mulki, J. P., Jaramillo, J. F., & Locander, W. B. (2008). Effect of ethical climate on turnover intention: Linking attitudinal- and stress theory. Journal of Business Ethics, 78 (4), 559–574. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-007-9368-6 .

Nilsson, W. (2015). Positive institutional work: Exploring institutional work through the lens of positive organizational scholarship. Academy of Management Review, 40 (3), 370–398. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2013.0188 .

Nilstun, T., Löfmark, R., & Lundqvist, A. (2010). Scientific dishonesty—Questionnaire to doctoral students in Sweden. Journal of Medical Ethics, 36 (5), 315–318. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.2009.033654 .

Oberlander, S. E., & Spencer, R. J. (2006). Graduate students and the culture of authorship. Ethics and Behavior, 16 (3), 217–232. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327019eb1603_3 .

O’Boyle, E. H., Forsyth, D. R., & O’Boyle, A. S. (2011). Bad apples or bad barrels: An examination of group- and organizational-level effects in the study of counterproductive work behavior. Group and Organization Management, 36 (1), 39–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601110390998 .

Pagliaro, S., Lo Presti, A., Barattucci, M., Giannella, V. A., & Barreto, M. (2018). On the effects of ethical climate(s) on employees’ behavior: A social identity approach. Frontiers in Psychology, 9 , 960. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00960 .

Paulhus, D. L., & Williams, K. M. (2002). The dark triad of personality: Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. Journal of Research in Personality, 36 (6), 556–563. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(02)00505-6 .

Pena Saint Martin, F., Martin, B., Lopez, H. E. A., Moheno, L.Von Der W., (2014). Graduate students as proxy mobbing targets: insights from three Mexican universities. Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers. 1331. https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers/1331 .

Perry, C. (2015). The “Dark Traits” of sociopathic leaders: Could they be a threat to universities? Australian Universities’ Review, 57 (1), 17–25.

Peterson, D. K. (2002). Deviant workplace behavior and the organization’s ethical climate. Journal of Business and Psychology, 17 , 47–61. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016296116093 .

Phillips, E. M., & Pugh, D. S. (2010). How to get a PhD: A handbook for students and their supervisors , 5th edn. London, UK, Open University Press.

Pyhältö, K., Toom, A., Stubb, J., & Lonka, K. (2012a). Challenges of becoming a scholar: A study of doctoral students’ problems and well-being. International Scholarly Research Notices . https://doi.org/10.5402/2012/934941 .

Pyhältö, K., Vekkaila, J., & Keskinen, J. (2012b). Exploring the fit between doctoral students’ and supervisors’ perceptions of resources and challenges vis-à-vis the doctoral journey. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 7 , 395–414.

Rigler Jr., K. L., Bowlin, L. K., Sweat, K., Watts, S., & Throne, R. (2017). Agency, socialization, and support: A critical review of doctoral student attrition. In The 3rd international conference on doctoral education . University of Central Florida.

Robertson, M. (2019). Power and doctoral supervision teams: developing team building skills in collaborative doctoral research . Abingdon, Oxford: Routledge.

Roksa, J., Feldon, D. F., & Maher, M. (2018). First-generation students in pursuit of the PhD: Comparing socialization experiences and outcomes to continuing-generation peers. The Journal of Higher Education, 89 (5), 728–752. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2018.1435134 .

Roksa, J., Jeong, S., Feldon, D., & Maher, M. (2017, November). Socialization experiences and research productivity of Asians and Pacific Islanders: “Model Minority” stereotype and domestic vs. international comparison. In Paper presented at the ASHE conference .

Rosen, C., Chang, C., & Levy, P. (2006). Personality and politics perceptions: A new conceptualization and illustration using OCBs. In E. Vigoda-Gadot & A. Drory (Eds.), Handbook of organizational politics (pp. 29–52). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Rosenberg, A., & Heimberg, R. G. (2009). Ethical issues in mentoring doctoral students in clinical psychology. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 16 (2), 181–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2008.09.008 .

Scarborough, J. L., Bernard, J. M., & Morse, R. E. (2006). Boundary considerations between doctoral students and master’s students. Counseling and Values, 51 (1), 53–65.

Schyns, B. (2015). Dark personality in the work place: Introduction to the special issue. Applied Psychology, 64 (1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12041 .

Slaughter, S., Archerd, C. J., & Campbell, T. I. D. (2004). Boundaries and quandaries: How professors negotiate market relations. The Review of Higher Education, 28 (1), 129–165. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2004.0032 .

Smallwood, S. (2004). Doctor dropout: High attrition from Ph.D. programs is sucking away time, talent, and money, and breaking some heart, too. Chronicle of Higher Education, p. A10.

Smith, S. F., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2013). Psychopathy in the workplace: The knowns and unknowns. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 18 (2), 204–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2012.11.007 .

Spain, S. M., Harms, P., & LeBreton, J. M. (2014). The dark side of personality at work. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35 (S1), S41–S60. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1894 .

Spector, P. E. (2011). The relationship of personality to counterproductive work behavior (CWB): An integration of perspectives. Human Resource Management Review, 21 (4), 342–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2010.10.002 .

Stead, R., Fekken, G. C., Kay, A., & McDermott, K. (2012). Conceptualizing the dark triad of personality: Links to social symptomatology. Personality and Individual Differences, 53 (8), 1023–1028.

Strathern, M. (2003). Audit cultures: Anthropological studies in accountability, ethics and the academy . London, Routledge.

Sullivan, L. E., & Ogloff, J. R. (1998). Appropriate supervisor–graduate student relationships. Ethics and Behavior, 8 (3), 229–248. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327019eb0803_4 .

Swazey, J. P., Anderson, M. S., & Louis, K. S. (1993). Ethical problems in academic research. American Scientist , 81 , 542–553. https://www.jstor.org/stable/29775057 .

Taylor, S. G., Griffith, M. D., Vadera, A. K., Folger, R., & Letwin, C. R. (2019). Breaking the cycle of abusive supervision: How disidentification and moral identity help the trickle-down change course. Journal of Applied Psychology, 104 (1), 164–182. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000360 .

Tepper, B. J. (2000). Consequences of abusive supervision. Academy of Management Journal, 43 (2), 178–190. https://doi.org/10.5465/1556375 .

Tepper, B. J. (2007). Abusive supervision in work organizations: Review, synthesis, and research agenda. Journal of Management, 33 (3), 261–289. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206307300812 .

Tepper, B. J., Henle, C. A., Lambert, L. S., Giacalone, R. A., & Duffy, M. K. (2008). Abusive supervision and subordinates’ organization deviance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93 (4), 721–732. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.4.721 .

Thompson, B., & Ravlin, E. (2017). Protective factors and risk factors: Shaping the emergence of dyadic resilience at work. Organizational Psychology Review, 7 (2), 143–170. https://doi.org/10.1177/2041386616652673 .

Tijdink, J. K., Bouter, L. M., Veldkamp, C. L., van de Ven, P. M., Wicherts, J. M., & Smulders, Y. M. (2016). Personality traits are associated with research misbehavior in Dutch scientists: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE, 11 (9), e0163251. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0163251 .

Twale, D.J., & De Luca, B.M. (2008). Faculty incivility: The rise of the academic bully culture and what to do about it . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, W. K. (2009). The narcissism epidemic . New York, NY: Free Press.

Vähämäki, M., Saru, E., & Palmunen, L. M. (2021). Doctoral supervision as an academic practice and leader–member relationship: A critical approach to relationship dynamics. The International Journal of Management Education, 19 (3), 100510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2021.100510 .

Vardi, Y., & Weitz, E. (2016). Misbehavior in organizations: A dynamic approach . New York, London: Routledge.

Victor, B., & Cullen, J. B. (1988). The organizational bases of ethical work climates. Administrative Science Quarterly, 33 (1), 101–125. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392857 .

Vigoda-Gadot, E., Talmud, I., & Peled, A. (2011). Internal politics in academia: Its nature and mediating effect on the relationship between social capital and work outcomes. International Journal of Organization Theory and Behavior, 14 (1), 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOTB-14-01-2011-B001 .

Weidman, J. C., & Stein, E. L. (2003). Socialization of doctoral students to academic norms. Research in Higher Education , 44 , 641–656. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40197334

Weidman, J. C., Twale, D. J., and Stein, E. L. (2001). Socialization of graduate and professional students in higher education: A perilous passage? ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report , 28. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco.

Wisker, G., & Robinson, G. (2013). Doctoral ‘orphans’: Nurturing and supporting the success of postgraduates who have lost their supervisors. Higher Education Research and Development, 32 (2), 300–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2012.657160 .

Wrzesniewski, A., McCauley, C., Rozin, P., & Schwartz, B. (1997). Jobs, careers, and callings: People’s relations to their work. Journal of Research in Personality, 31 (1), 21–33. https://doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.1997.2162 .

Wu, R. (2017). Academic socialization of Chinese doctoral students in Germany: Identification, interaction and motivation. European Journal of Higher Education, 7 (3), 276–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2017.1290880 .

Wu, J., & LeBreton, J. M. (2011). Reconsidering the dispositional basis of counterproductive work behavior: The role of aberrant personality. Personnel Psychology, 64 (3), 593–626. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2011.01220.x .

Yamada, S., Cappadocia, M. C., & Pepler, D. (2014). Workplace bullying in Canadian graduate psychology programs: Student perspectives of student–supervisor relationships. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 8 (1), 58–67. https://doi.org/10.1037/tep0000015 .

Ying, L., & Cohen, A. (2018). Dark triad personalities and counterproductive work behaviors among physicians in China. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 33 (4), e985–e998. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.2577 .

Zadek, S., Pruzan, P., & Evans, R. (1997). Building corporate accountability . London: Earthscan.

Zhao, C. M., Golde, C. M., & McCormick, A. C. (2007). More than a signature: How advisor choice and advisor behaviour affect doctoral student satisfaction. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 31 (3), 263–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098770701424983 .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Division of Public Administration, School of Political Science, University of Haifa, 3498838, Haifa, Israel

Aaron Cohen

Southampton Business School, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK

Yehuda Baruch

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Aaron Cohen .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

We have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cohen, A., Baruch, Y. Abuse and Exploitation of Doctoral Students: A Conceptual Model for Traversing a Long and Winding Road to Academia. J Bus Ethics 180 , 505–522 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04905-1

Download citation

Received : 07 April 2021

Accepted : 25 July 2021

Published : 31 July 2021

Issue Date : October 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04905-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Destructive leadership

- Student abuse and exploitation

- Ethical culture

- Academic career

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

"My PhD broke me"—bullying in academia and a call to action

Workplace bullying —repetitive abusive, threatening, humiliating and intimidating behaviour—is on the rise globally. And matters are worse in academia. In the UK, for example, up to 42% of academics report being bullied in the workplace while the national average across all professions ranges from just 10-20%.

Why do bullies bully? According to researchers from Brock University in Canada the goals of bullying come from internal motivations and desires, which can be conscious or not. Bullying takes many forms: the malicious mistreatment of someone including persistent criticism, inaccurate accusations, exclusion and ostracism, public humiliation, the spreading of rumors, setting people up to fail, or overloading someone with work. Bullying is different from accidental or reactive aggression, since it is goal-directed meaning that the purpose is to harm someone when there is a power imbalance.

While anyone is at risk of being bullied in academia, research has found that some of us are more vulnerable compared to others. For example, early career researchers (ECRs), including trainees (e.g. graduate students, postdocs), minority groups, adjunct professors, research associates, and untenured professors are at a higher risk to experience bullying. Employees with more years in a job report feeling less bullied than others subordinate to them, meaning that junior members of a research group or Faculty may be at greater risk of bullying.

The existence of sharp power differentials is a major factor in workplace bullying in academia

These specific groups are more vulnerable to bullying in academia than others because of the existence of sharp power differentials , a major contributing factor to bullying in the workplace. For example, men and supervisors of large successful research groups are observed to perpetrate bullying behavior more often than women and other minorities, though exceptions do exist. Other research has shown that the pressure associated with publishing, getting research funding, and lack of leadership and people management training in science may also contribute to bullying.

In some cases , principal investigators (PI) can also experience bullying from students, peers, or administrators. Take the example of one PI who was bullied by an administrator for being too ambitious, making her overly conscious of her success. When she moved to another institution, she did not make collaborations with other researchers in different departments, as she had previously, because she did not want to appear to be too ambitious. This is also an example of the long-term impact bullying can have on future work.

To highlight that bullying can take different forms and occur at all career stages, we include here four anonymous testimonials from victims of academic bullying in the life sciences:

I got pregnant during my PhD and I was told it was not an issue. However, during the course of my pregnancy, I was removed from my projects and left out of discussions about the work that needed to be done. When I asked for an explanation, I was told that science could not wait for me while I was pregnant, even though I was eager to work, and the law permitted me to do so. After my child was born, I was made to return to work after just three weeks, while legally I was permitted up to a year off work. In the lab, I was given bits and pieces of others’ projects and not permitted to work on my own project. I worked without complaining but this took a toll on my emotional health with time. It was after my then-toddler son broke his arm that everything got worse. I needed to take a week off for his hospital stay, but my supervisor called me to his office and told me that I was a useless researcher and that I didn’t belong in science, and then he fired me. I knew it was illegal for him to do so, but I didn’t want to fight him because I was dependent on him to finish my PhD. I met with him after a week and he told me that I could work, but without pay, to make up for the duration of my pregnancy when I was paid. I did as I was told for the next six months, and somehow with the support of my husband and my best friend, was able to graduate and leave. I now have a permanent faculty position at a university in my home country, but my PhD broke me. International Female PhD Student

After I joined the lab, my supervisors told me that they needed to re-apply for funding, and that they were relying on my results for the application. Unfortunately, they wanted to employ a method that they were unfamiliar with, and as a beginner, I had very limited resources. I managed to get help from someone at another department and it took me three months to set up the method in the lab, but it turned out to be unsuitable for our project. My supervisors were unhappy about this and started blaming me for not smart enough to get the results they expected. I was constantly told that things didn’t work in my hands, and that they would need to decide whether to prolong my contract. This threat was dangled in front of me every few months, and it scared me. I contemplated leaving the lab and moving on, but my supervisors told me that it would look bad for them and offered me another project instead. Things didn’t improve after this either: my project worked fine, but my supervisors continued threatening to terminate my contract. I decided to graduate after three and a half years of enduring this, but my supervisors then threatened to block me from finishing. I was gas lighted throughout my Master’s and never understood what they really wanted. Why did they offer me a position if I wasn’t good enough? I decided to switch fields after my PhD and am much happier now. Male Graduate Student Completing His Graduate Studies in His Home Country

Within 3-weeks of starting a new research associate position, I was asked to lead the writing of a grant. The research focus of the group was beyond my experience, and I had little exposure to the research environment of the group. The PI had not established the big picture of the grant; it was left up to me. Furthermore, he provided little to no guidance with writing the grant (e.g. his expectations, what had previously been done, etc.). It was a very overwhelming experience. When I sent out a draft of the grant, I was pulled into a private meeting with the PI and the co-PI, who both told me that my work was crap and that since I was the highest paid member of the group I should have been producing amazing work. They said that all my responsibilities would be given to someone else in the group. I was given menial tasks like uploading files on the One Drive for several months. Most days, I would not have enough work to do or struggle with the work I was required to do because there was not enough guidance. I have been doing research for 16 years but had never been so bored as I was in this position. A few months later, I was asked to do a few more projects, but again was told my work was not good. The culture in the research group was unforgiving and exclusive. Outside of the job, through my hard work and determination, I obtained another position and was able to leave. When I sent in my resignation, I was even intimidated to leave earlier than I planned because it would cost them less. I stood my ground and left when I planned to. This job increased my imposter syndrome by a hundred-fold. I was convinced that I was the problem and the dumb one. When I told my husband about the interactions with the PI, he would comment on how ridiculous the situation was. When I was in this situation, it was too hard to see how crappy it was. It’s been about a month since I left, and I feel so much better. I have worked hard to combat my imposter syndrome, and this summer I will begin a tenure track position in a STEM field. In 2019, this is so rare, so I celebrate that! Female Research Associate in Home Country

I work as a postdoctoral researcher and my supervisor routinely tells us whom we can talk to, eat our lunch or take coffee breaks with. I recently started collaborating on a project with another postdoctoral researcher in the department but only after discussing it with my supervisor and gaining his approval. We worked on the project part-time for a few months. I approached my supervisor after we had some interesting results, and he suddenly decided that I needed to stop working on it despite the fact that it looked promising. He informed me that he was shocked that I was working on it in the first place and that he didn’t like me to do things behind his back. He also accused me of leaving him out of my activities in the lab. I was also tasked with informing my collaborator, who was livid that we needed to end the project abruptly. However, he understood and let it go, even though it was unfair for him too. My supervisor then blamed my collaborator for inciting me into doing the project in the first place and threatened him too. I do whatever my supervisor asks of me, but I am not sure if that’s the right thing to do. Unfortunately, I feel as though I have no choice since he pays me. International Male Postdoc

The impacts of bullying are manifold. Studies have reported a long-term health effects in bullying victims, such as anxiety, sleep disorders, chronic fatigue, anger, depression, destabilization of identity, aggression, low self-esteem, loss of confidence, and other health problems. Bullying also has an impact on the institutions where the victims work, including negative work environments, absenteeism, lower engagement, higher turnover, and reduced performance.

Recognizing what bullying looks like is just the first step towards tackling it. Many institutions have opted to use a top-down approach to tackle the problem through policies to report bullying via the human resource office or sometimes an ombudsman. Other institutions may not have specific policies to deal with bullying and often victims are not made aware of existing avenues of recourse. Funding agencies may also choose to get involved, for example after being accused of bullying by her colleagues in 2018 Professor Nazneem Rahman lost 3.5 million GBP in funding from the Wellcome Trust in the UK. In addition to what is currently being done at research institutions and funding agencies, legislation should be put into place by the government to ensure that victims are heard and that there are consequences for the perpetrators.

Apart from institutional actions, bottom-up approaches are also available, such as overcoming the bystander effect. The bystander effect is when individuals are less likely to offer help to a victim when other people are present. Research since the 60s has shown that the presence of other people will inhibit one’s own intention to help and overcoming this effect could be an effective way to mitigate bullying in academia.

A study of whistleblowers found that 71% of employees tend not to directly report wrongdoing as the perceived personal cost is higher than the perceived reward. People tend to feel that personal costs may be higher if reporting happens through face-to-face meetings with authorities. Hence, anonymous reporting channels are needed.

Bullying is an entrenched problem in academia, supported by workplaces with power differentials. Combating bullying is a challenging task at multiple levels and over the next year a group of us eLife Community Ambassadors will embark on an initiative to shine a light on the problem, investigate its root causes and eventually formulate a set of universal measures to tackle bullying in the workplace and give relief to its victims. Stay tuned for more on our progress!

by Nafisa M. Jadavji, Emily Furlong, Pawel Grzechnik, Małgorzata Anna Gazda, Sarah Hainer, Juniper Kiss, Renuka Kudva, Samantha Seah, Huanan Shi

Related Articles

Overcoming hardships for internationals in academia

Let’s get rid of confidential ‘reference letters’ in academia — a tool misused by abusive supervisors

Towards an increased awareness on the importance of Computational Reproducibility in Biological Sciences in Latin America

My Successful Mentoring Experiment

From Lone Wolf to Pack Power: Empowering Early-Career Researchers through Scientific Communities

Academic unions - Rectifying myths based on frontline experiences

Office of the Graduate Ombudsman / Disrupting Academic Bullying

Strategies For People Experiencing Academic Bullying

Resources for Support

If you wish to tell someone about your experience, or talk with someone about resources and steps you can take, you can click on this link , which will take you the Disrupting Academic Bullying Referral Form . It is your decision to include as little or as much identifying information about yourself and/or the parties involved as you wish. The information is confidential and will be sent to the Graduate Student Ombudsperson . If you include contact information, he will email you to see if you would like to set up a confidential and informal meeting to discuss your experience further. If you do not wish to meet with him, he will not take any further action, and your report will be used anonymously to track general trends.

Below are suggestions for things you can potentially do to help lessen the negative impacts of bullying on your quality of life regardless of whether or not you choose to go through other channels to resolve your issues. The video is an excerpt from a presentation done by Ombudsperson Bryan Hanson that provides a quick overview of strategies, while more detail is available in the drop downs below.

Your browser does not support iframes. Link to iframe content: https://www.youtube.com/embed/vn4kWuvT2h4

Know Resources for Support

If you are being bullied, you are not alone. There are people in the Virginia Tech community here to help you. The Support Resources page has information about places you can go for help outside your department.

However, help may be closer at hand.

Talk to your advisor If your advisor is not your bully, they could be a good person to talk to about what you are going through. Below are some actions they could potentially take. Whether they do or not is up to them, but these are some of the options available to them to help you deal with the problem.

- Listen to your experience and concerns.

- Provide some context to your experiences and give you their perspective on whether what you are experiencing is normal for graduate school or not.

- Depending on who is bullying you and the power relationships involved, your advisor may be able to talk to the bully and ask what their perception is of the situation, and potentially mediate some sort of resolution.

- Your advisor might be able to bring the issue up the ladder to the department head, program director or the dean of your college and potentially advocate for you if that is something you are comfortable with.

These are also actions that a faculty member who is not your advisor may be able to take if you have a close relationship with them.

Talk to your committee

If your advisor is bullying you, you could potentially talk to another member of your committee, your program director, or department head.

Other members of your committee might be able to listen to you, provide some context to your experiences, and potentially talk to your advisor. However, many faculty are reluctant to get involved in the relationships between their colleague and a student.

Yet one advantage of talking to members of your committee is to have them hear your perspective. It may be that they are only hearing your advisor’s side of the story and that may be affecting how they consider and/or treat you and your work. Sharing your perspective with them may give them a better understanding of the situation that changes how they interact with you.

Talk to your Program Director or Department Head

If switching advisors is a step that is necessary, your program director and/or department head can help with the logistics.

One issue to keep in mind about approaching people in your department is that they are not confidential . You don’t have much control over what they do with the information you give them or what next steps they take. Ideally, they would defer to you as to what you were comfortable with them sharing or doing next, but this may not always be the case.

Talk to the Ombudsperson

Another option is to go to the Ombudsperson . He is a confidential resource and will not discuss your situation with anyone else unless you give him permission. Therefore, he can provide a good sounding board to talk about your experiences and get some feedback on what your options are going forward. He can talk you through the next steps that are available and discuss the potential outcomes for different actions. He can point you to different resources to help you meet your needs or resolve your issues. He can coach you in communication strategies to help you approach situations or meetings with more clarity and confidence. He can also facilitate meetings between you and someone with whom you are having difficulties if that is a step you want to take.

Seek Out Allies

Being bullied can make you feel isolated, alone, and create the impression that no one supports you. Reaching out to friends and colleagues you trust can help lessen those feelings. Being bullied doesn’t make you weak or undeserving of support and help.

Bullying doesn’t always happen in isolation, it is possible that others have been or are currently being bullied by the same person. If other students are experiencing or witnessing similar behavior, you may be able to work together to bring your concerns to relevant people in the department or university administration. It is harder to dismiss the concerns of multiple students, especially if they can show it is a pattern of behavior.

Try to identify people in your circles who can offer different types of support.

- Someone who can listen.