What is an MTA?

A Material Transfer Agreement (MTA) is a contract governing the transfer of materials between two parties. It defines the rights of the provider and the recipient with respect to the materials and any derivatives. MTAs can help to ensure a common understanding as to what is being shared, for what purpose, and how it can be used. MTAs regularly govern the transfer of biological materials, such as samples but can also cover associated data, such as meta data or the clinical state of the donor. For more information see: Material Transfer Agreements: A Multipurpose Tool for International Cooperation.

Why use an MTA?

A prompt response to a public health emergency can depend upon the ability to move relevant samples and associated data from one place to another. The movement of such samples and associated data must be as simple and transparent as possible, whilst protecting the interests of the owners of the samples and associated data. Increasing awareness of the potential value of certain samples and associated data has increased the demand for these protections. Read more

When to use an MTA

There are a number of scenarios where an MTA might help clarify conditions associated with the movement or use of samples and associated data. These might include... Read more

MTAs and public health emergencies

During a public health emergency, it will be important to ensure that samples and associated data can be moved, accessed and used for a variety of important purposes, including the identification and characterization of the responsible pathogen, diagnostic purposes, clinical decision making, epidemiology as well as the development or validation of diagnostic tools. Read More

A prompt response to a public health emergency can depend upon the ability to move relevant samples and associated data from one place to another. The movement of such samples and associated data must be as simple and transparent as possible, whilst protecting the interests of the owners of the samples and associated data. Increasing awareness of the potential value of certain samples and associated data has increased the demand for these protections. MTAs play an important role in enabling transfers and subsequent use by the recipient, whilst protecting the interests of the transferee. For a summary of why these agreements are important and a discussion of some of the challenges in using them see: Science Commons: Material Transfer Agreement Project MTAs are frequently entered into to provide clarity in terms of the parties’ expectations. Equally important, they provide a written record of the provenance of the materials. Further, in the case of infectious diseases and hazardous materials, they will assist in setting out parties’ expectations about liability and who is responsible for particular risks that may arise during the course of using the material. Ultimately a decision must be made about whether the objective for the MTA process is to make it smooth, fast and efficient; or to ensure that it is maximally beneficial to those who most need it. While objectives for an MTA will differ widely, the best outcome will take both goals into account and create a balance that responds to different needs and communities. Recent public health emergencies of international concern (PHEICs) with Ebola virus disease in West Africa and zika virus in Latin America have demonstrated the many difficulties of negotiating MTAs in an emergency context, and showed a clear need for agreed fundamental principles and scalable, sustainable approaches for MTA negotiation (for more information see: Overarching Principles ) .

There are a number of scenarios where an MTA might help clarify conditions associated with the movement or use of samples and associated data. These might include: 1. Export or international movement of samples and associated data; 2. Domestic movement of samples and associated data to a separate legal entity (or in some cases perhaps even for different parts of the same legal entity); 3. Determining the eventual use or further distribution of samples and associated data shared for one purpose but with the potential for additional uses; 4. Uses or purposes where there are specific rules or regulations, or when a third party, such as a government agency such as a Ministry of Health, is (or needs to be) involved; 5. Where the material being moved has a potentially important intrinsic value (either the material itself or the possibility of using it in other processes or for product development); and 6. As part of larger overarching agreements, such as research protocols or bilateral agreements. MTAs can be very simple documents, or more complex legal agreements. The level of detail may be determined by the potential commercial value of the material being transferred and the intended uses to which it will be put. A discussion of how these agreements might match the details of the transfer see: Use and Misuse of Material Transfer Agreements: Lessons in Proportionality from Research, Repositories, and Litigation

During a public health emergency, it will be important to ensure that samples and associated data can be moved, accessed and used for a variety of important purposes, including the identification and characterization of the responsible pathogen, diagnostic purposes, clinical decision making, epidemiology as well as the development or validation of diagnostic tools. Given the emergency context, it will be desirable to have in place simple and transparent measures that protect the interests of all parties. This might include provisions to protect the supplier that transferred the samples in good faith during an outbreak. During the public consultation on this tool, several respondents noted the absence of a public health-specific overarching international framework governing access to and sharing of samples and associated data from diseases other than influenza. Very different views were expressed as to the desirability or feasibility of developing such a framework. In its absence and given that a prompt response to a public health emergency can depend upon the ability to move relevant samples and associated data from one place to another. The movement of such samples and associated data must be as simple and transparent as possible, whilst protecting the interests of the owners of the samples and associated data. The tool embraces views expressed by many of those involved in its development of the importance of continuing to work towards the “broader public good”. In a public health context, this will involve both the shorter-term goals of preventing the spread of disease and reducing mortality and morbidity, and longer-term goals of preventing future outbreaks and building capacity to mitigate their impact. Some comments received during the public consultation highlighted possible differences in understanding of the meaning of a broader public good and the challenges of accomplishing this in the presence of commercial and self-interests. In the early days of an emergency, it will likely be government representatives who are signing agreements to transfer materials. Governments will likely be unable – and unwilling – to negotiate commercial terms that apply to future, potentially unknown, commercial actors. Furthermore, there aren’t necessarily existing researchers/manufacturers working with the pathogen of concern with which to negotiate, or any established marketplace for countermeasures that can be used to inform the value of any potential benefits. As a result, even if potential manufacturers are identified and engaged in the negotiations, they’re unlikely to have a good understanding of their chances of success in developing a countermeasure, their capacity to produce such a product, what the value of that product might be, etc. The tool is intended for use prior to a public health emergency to build relevant human capacity – not to develop an MTA during such an outbreak. MTA negotiations are more likely to become protracted where parties perceive a need to protect their own interests and manage risks. Where this is not possible, either because a standard MTA is implemented without change, or because a funding agency or other party (such as a biorepository) uses a standard MTA, the process of transfer is often expedited. There have been attempts to develop model MTAs for use during public health emergencies.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.13(2); 2015 Feb

Use and Misuse of Material Transfer Agreements: Lessons in Proportionality from Research, Repositories, and Litigation

Tania bubela.

School of Public Health, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

Jenilee Guebert

Amrita mishra, associated data.

Material transfer agreements exist to facilitate the exchange of materials and associated data between researchers as well as to protect the interests of the researchers and their institutions. But this dual mandate can be a source of frustration for researchers, creating administrative burdens and slowing down collaborations. We argue here that in most cases in pre-competitive research, a simple agreement would suffice; the more complex agreements and mechanisms for their negotiation should be reserved for cases where the risks posed to the institution and the potential commercial value of the research reagents is high.

The material transfer agreements designed to facilitate the exchange of materials between researchers are unnecessarily burdensome and obstructive and in most cases could be replaced by simpler tools.

Introduction

A material transfer agreement (MTA) is a type of legally enforceable contract employed by research institutions and companies to set the terms under which their materials and associated data may be obtained and used by others ( Box 1 ) [ 1 , 2 ]. These agreements provide a mechanism to protect the interests of the owners of discoveries and inventions, while promoting data and material sharing in the research community. The latter is an admirable goal in an age where research is increasingly collaborative, multinational, and multidisciplinary. Yet MTAs have a bad reputation among researchers for being overly complex and, in practice, hindering the exchange of research reagents. This article examines what is wrong with current practices in negotiating and drafting MTAs; it suggest s a way forward in which the complexity of the agreement should reflect the likely risks and benefits of sharing hard-earned reagents with other researchers.

Box 1. Anatomy of an MTA

MTAs may apply to anything from materials that are simply under the control of the originator but have no formal intellectual property rights attached to them to proprietary materials protected by patents and trade secrets [ 3 , 4 ]. They range in complexity from simple conditions of use to complex legal agreements [ 5 ] with many terms [ 3 – 5 ]. They may comprise standard form agreements or they may be specifically negotiated. Broadly speaking, MTAs delimit the rights and responsibilities of the providers and recipients of materials, and they describe the materials to be transferred and the payment or other benefit to be exchanged in return. As such, they conform to standard common law requirements for legally enforceable contracts: an intention to create a legal relationship, a “meeting of the minds” (offer and acceptance of terms), and an exchange of consideration (e.g., money, goods, and/or services). MTAs commonly place limits on the use of materials, their physical handling, and distribution to third parties. For example, the use of materials may be limited to noncommercial or preclinical research, or to specific fields of use, such as research on a specific disease. Distribution to third parties may be prohibited, or subject to permission from the provider. Other standard terms limit the liability of providing institutions with respect to the quality of the materials and any third party intellectual property rights that may have been infringed in their creation. They also outline dispute resolution mechanisms, legal jurisdiction, the duration of the relationship, and conditions for its termination, including the return or destruction of the materials. MTAs sometimes also contain problematic “reach-through” terms, however, that lay proprietary claims on subject matter developed using the material or that incorporates the material.

The Problem with MTAs As Used by Research Institutions

Research staff and students usually lack both the knowledge and legal authority to enter into contracts, like MTAs, on behalf of their institutions. To address this lack of capacity, most institutions have offices with a dedicated staff to negotiate, draft, and execute MTAs [ 2 , 5 ]. This centralization of contract services in a technology transfer or research services office is problematic because it can lead not only to delays but also to conflicts between the interests of researchers and the interests of their institutions. Researchers commonly express frustration with institutional processes [ 6 ]. Surveys and interview-based studies of researchers have come to the conclusion that access to research reagents is hampered by negotiations over MTAs, whose complexity rarely reflects the value to the institution of the materials to be shared [ 7 – 9 ]. There is a cultural divide between research communities, which may simply want to share their data and materials, and institutional contracts or technology transfer staff. The latter are in the difficult position of trying to fulfill two mandates: first, to commercialize the research at their institution to achieve a financial return on investment and, second, to promote the desired community-level sharing of materials and data [ 10 – 12 ].

A further criticism of MTAs is that their terms may expand the rights of the institution well beyond those granted under formal intellectual property laws [ 13 , 14 ] in the following ways. First, MTAs may control the use of materials that would usually not be eligible for intellectual property protection or where such intellectual property has expired. Second, MTAs may set limits on use in countries where the inventors or owners have not sought or been granted patent protection. Third, and most problematic, MTAs may grant rights over patented inventions far beyond those contemplated by patent policy. A patent is a bargain between the inventor(s) and society: inventors gain the right to exclude others from exploiting an invention for a limited period (usually 20 years); in exchange, society gains knowledge by way of a detailed description of that invention. The terms of an MTA may, however, extend rights beyond the patented invention if they “reach through” the patent to lay claim (e.g., for royalties) on anything developed using the invention or that incorporates the invention. Examples include inventions that incorporate a patented nucleotide or amino acid sequence, or an invention developed using a common method or reagent. Such reach-through rights are discouraged by most policies and guidelines for best practice in licensing university-generated innovation [ 15 , 16 ]. These best practice policies and guidelines should equally apply to MTAs, because MTAs are a type of license (a permission to use) where the subject matter of the license is material and associated data [ 17 ].

Lessons from Mouse Research

Public funding agencies invest considerable resources in the generation of research reagents, and the return on this investment is maximized when those reagents are shared. Sharing avoids duplication of effort in the development of reagents and enables replication and further innovation based on published methods. The United States’ National Institutes of Health (NIH) has been particularly proactive in developing and instituting policies for the sharing of materials [ 18 – 20 ]. These policies were, in part, a response to restrictions over access to two transgenic mouse technologies: OncoMouse, a mouse strain with a genetic predisposition to cancer, developed by researchers at Harvard and exclusively licensed by DuPont; and Cre-lox, a technology for generating conditional mouse mutants, developed by DuPont researchers [ 21 , 22 ]. In both cases, the NIH stepped in to negotiate access and distribution on less restrictive terms than the original MTAs proposed by DuPont [ 23 – 25 ].

NIH policy from 1999 directs that research reagents generated through the use of public funds be transferred amongst researchers either with “no formal agreement, a cover letter, the Simple Letter Agreement of the Uniform Biological Materials Transfer Agreement (UBMTA), or the UBMTA itself” ( Box 2 ) [ 19 , 26 ]. Nevertheless, estimates suggest that only approximately 35% of mouse strains are made available to the research community [ 27 ]. This deficit is due in part to scientific competition: researchers want to retain priority in their field, and they fear being scooped by other researchers using their materials or data. Also, distribution of materials to research groups on request can be expensive in terms of the resources and time involved, especially for popular research reagents. Although research archives like biorepositories, biobanks, and databases can relieve the burden of distribution from research groups, there are still many direct and indirect costs associated with preparing the materials for deposit.

Box 2. Simplified Models for Sharing Materials

In March 1995, the NIH put in place a simplified system for sharing nonproprietary materials amongst research institutions [ 26 ]. To date, 532 institutions, mainly in the US, are signatories to this UBMTA Master Agreement, meaning that materials can be transferred amongst researchers at those institutions upon execution of a simple implementing letter that provides a record of the transfer. The UBMTA applies to the material, progeny, and unmodified derivatives. Materials may be used for teaching and academic research that is not in human subjects and is compliant with all laws and policies governing research. There are no restrictions on publication. The materials may be used by the recipient and those working under his or her direction; transfer to third parties is prohibited. Standard warranties and liabilities apply, including that the materials may be the subject of patent rights or applications. The materials are provided on a cost recovery basis only. While the UBMTA is not perfect—the legal language could be more accessible, and some terms apply not only to the original material but also to modifications that contain or incorporate it—the UBMTA supports a simplified system for transfer. Other institutions, such as the University of California, transfer materials based on a modified UBMTA, which defeats the purpose of a unified distribution system by requiring review and signoff by recipient institutions.

Nonacademic organisations that distribute research reagents also use mechanisms based on the UBMTA. For example, Addgene, a nonprofit plasmid repository, uses an implementing letter accompanied by an MTA for nonprofit or academic institutions [ 28 ]. While the MTA can be emailed or mailed, Addgene has implemented a novel, proprietary, and award-winning electronic MTA (eMTA) system, which handles the majority of agreements [ 29 ]. The system is designed to accept online signatures and to be simple to use for technology transfer officers at depositing and requesting institutions. In addition, unlike the University of California, Addgene does not allow "red lining" or editing of its MTA. The depositors all use the same MTA, and the recipients must E-sign as is or the material cannot be accessed. This saves time on legal wrangling over terms for materials with little value outside of the research context.

Other simplified MTA distribution systems also exist, such as those of The Jackson Laboratory (JAX) [ 30 ] and the Structural Genomics Consortium (SGC), a not-for-profit public—private partnership that provides 3-D structures of biologically significant human proteins and probes for drug development [ 31 ]. It distributes probes under an MTA with four clauses stating use for laboratory research (not in humans or non-laboratory animals) only in compliance with national laws, for teaching, and not-for-profit research purposes. The SGC retains rights to the materials, encourages publication in the scientific literature, and prohibits transfer to third parties.

JAX embodies the NIH material sharing policy [ 27 , 30 ]. As one of the world’s oldest biomedical archives for mouse-related reagents, JAX both generates its own resources and accepts mice from research groups after an assessment of their novelty and quality. Many lessons may be learned from the JAX model. Because of JAX’s reputation as a public archive, it can set terms and conditions on deposit that foster a culture of sharing in the community. These terms enable JAX to distribute mouse strains to academic and not-for-profit researchers under a simple notification that the mice are for research purposes and are not for sale or transfer to third parties without permission [ 32 , 33 ]. In addition, JAX enables depositors to decide the conditions under which to distribute mouse strains to industry, if at all [ 30 ]. By distributing mice to industry only when it has received notification of an executed MTA between the industry recipient and the depositor’s institution, JAX acts as a broker, thus maintaining the trust of the research community [ 6 , 33 ].

Another example from the mouse research community is the International Knockout Mouse Consortium (IKMC) and the associated International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium (IMPC), which were created and supported by several international funding agencies. The IKMC is generating mutants in all protein-coding mouse genes in a standard mouse strain, and the IMPC is phenotyping a substantial proportion of these using standardized protocols [ 34 , 35 ]. Both consortia rely on new and established archives to distribute this high throughput resource [ 35 ]. One of the IKMC repositories at the University of California at Davis distributes portions of the resource to both academia and industry using an MTA closely modeled on the UBMTA ( Box 2 ) [ 36 ]. This is made possible by a special provision in its resource development contract from the NIH, known as Authorization and Consent [ 37 ]. This provision insulates the resource generators located in the US, as government contractors, from potential patent infringement litigation over background intellectual property over the myriad technologies used to create the resource [ 37 ]. However, this protection is not available in other countries. The European repositories that are part of the consortium, in particular, have found it difficult to distribute to industry because of fears of patent infringement claims over background intellectual property. In addition, differences in legal cultures and drafting styles make European MTAs more cumbersome than their US counterparts [ 6 ]. These factors impede distribution to the research community at large and hinder sharing of mouse lines amongst consortia members. Sharing among the consortia’s repositories is needed not only to accelerate phenotyping efforts, but also to alleviate issues with cross-border distribution, biosecurity for the resources, and sustainability of the repositories.

The lesson for the IKMC and the IMPC is that simple and uniform conditions for depositing mutant mice in archives, such as those employed by JAX, have a knock-on effect enabling equally simple conditions for their distribution ( Fig. 1 ), thereby reducing the transactional costs and complexities associated with the sharing of research reagents. Indeed, leading research universities in North America reduce the administrative burden even further by not using MTAs when exchanging nonhazardous or nonhuman biological materials. In other circumstances, research institutions may use standard agreements, such as the UBMTA, or Simple Letter Agreement, to enhance administrative efficiency ( Box 2 ). There are some benefits to the latter approach in accurate record keeping of the use of research reagents (a metric for research impact akin to the citation of a publication) and identification of potential collaborators for the developers of the research reagents.

The terms of deposit may set the terms for subsequent withdrawal. Variation in deposit terms requires considerable informatics infrastructure to manage and apply terms for later withdrawal. The system is therefore streamlined when deposit terms are constant for the bulk of resources in repositories. Note that repositories may also act as brokers between depositors and users, only distributing upon provision of evidence of an executed MTA.

Additional complexities arise, however, when the transfer of materials involves human samples [ 38 , 39 ]. Informed consent given by research participants determines the use of their samples; for example, limiting research to a specific disease. Thus, if each sample in a biobank is collected using a different consent form, the samples may be deposited on different terms. Those terms must then attach to the sample and, in turn, dictate the distribution terms. This adds a layer of complexity to the transactions managed by biobanks, requires significant informatics resources, and may impede the ability of biobanks to accept legacy materials and data from the research community. Additional constraints arise for associated data that may link to patient records or other identifiable information. In this case, MTAs must comply with national or regional privacy laws in setting conditions for storage and use of samples and associated data. In other words, managing legal interoperability may be as problematic as managing data or metadata interoperability. Simplified practices and standardised legal terms, including consent, for input and distribution reduce these problems considerably.

Lessons from Litigation

Legal action is costly in financial terms as well as in human energy and emotion [ 40 ], so much so that instances of litigation can serve as a metric for assessing the value of the issue to the parties. For example, litigation is a metric for the value of a patented invention [ 41 ] or the value of a contract, with real estate, employment, and construction contracts commonly litigated. This begs the question, do MTAs have any value as measured by the number of cases of litigation? When we searched for variations of the phrase “material transfer agreement” in the Westlaw US Premier Service (all Federal, Supreme Court, District Court, and State cases); Westlaw’s United Kingdom (UK) Law database; and the EUR-Lex database for European cases, we found only 23 cases, and one additional case in the Lex-Machina database, which covers intellectual property litigation that has been filed in a state or federal non-appellate level court (see S1 Text for a summary of the 24 sets of litigation) [ 42 ]. Even if our search missed some cases, clearly the proportion of material or data transfers that ever results in litigation is extremely small. Two contrary conclusions may be drawn from this: either MTAs are so well drafted and monitored that litigation is avoided—in other words, MTAs effectively discourage litigation—or institutional contracts staff or offices lack the resources to monitor and enforce the terms of their MTAs and, in general, the value of their subject matter is low. In our opinion, this latter explanation is most likely.

The 23 cases of litigation we identified fell into two categories: first, direct litigation, which claims a breach of the terms of the MTA, including confidentiality provisions (four cases) or a related action, such as unjust enrichment, where one party unjustly benefits at the expense of the other, giving rise to an obligation to make restitution even in the absence of wrongdoing (one case); and, second, indirect litigation, in which the MTA is used as evidence in a larger lawsuit (18 cases). Some of these cases are related to technical points of law; for example, the very existence of an MTA between two parties may be used as evidence to prove that a party has a legal presence in a particular jurisdiction (e.g., a US State) so that a particular court can hear the dispute. In a related use, a specific term in an MTA about how disputes are to be resolved may dictate the appropriate jurisdiction (e.g., a specific district court) in a broader dispute. The presence or absence of an MTA may be evidence of standard, university, company, or industry practice; for example, the MTA may be evidence of whether research was done as part of a collaboration or as part of sponsored research, which distinction has implications for identifying inventor(s) on a patent, and the owner of those patent rights. In that vein, the terms of an MTA may provide evidence of ownership of materials, inventorship of a patent, or contain an obligation to assign (transfer) patent rights. Ownership of patents and/or the existence of a license to use a patented invention are both important considerations in patent infringement litigation and may serve as a defence.

Only six cases concerned corporate parties with no involvement of a research institution or affiliated researcher. In all the other cases, litigation occurred between research institutions, institutions and their employees, and institutions and corporations. The cases were dominated by biomedical applications, with only six cases in other fields, including biofuels and agriculture. Some cases were particularly vitriolic and generated negative comments against some parties. Without doubt, these legal disputes had the potential to damage research relationships and the reputations of all actors involved.

Two cases stood out that may cause concern for the research community. One researcher at the University of Pittsburgh was criminally prosecuted for mail fraud for ordering microbial materials from the American Type Culture Collection using his institutional approved account on behalf of a fellow researcher at an unapproved institution, in violation of an MTA that prohibited transfer of materials to third parties [ 43 ]. The action was dismissed because of lack of evidence of misrepresentation, and the observation that the indictment did not allege that either of the researchers “even knew about the transfer restriction.” In the second case, the State University of New York attempted to dismiss an employee because he founded a company to sell and ship mice owned by Upstate Medical University, charged the shipping costs to a State University grant contract, and failed to comply with university MTAs [ 44 ]. The judge found that since he did not intend to profit personally, believed his company would benefit the University and provide financial support for his research, and the university administrators were aware of his actions, he should be suspended rather than dismissed [ 44 ]. Again, given the vast quantity of transactions over research tools in the US, these two cases do not imply significant risks for researchers.

Box 3 summarizes broad lessons from litigation on when complex and carefully negotiated MTAs are warranted. These circumstances indicate where the focus and capacity development for institutional contracts staff and offices should lie. These may otherwise be overwhelmed by MTAs in contexts where simpler mechanisms for exchange exist and are more appropriate.

Box 3. When Might Complex MTAs Be Warranted?

Lessons may be drawn from litigation on when more complex MTAs might be warranted. In keeping other uses of MTAs as simple and standardized as possible, the human and financial capacity of institutional contracts offices may be directed where they are most needed. MTAs should be used in transfers of materials to industry, especially when an industry partner is evaluating material during negotiations of broader licensing agreements [ 45 – 49 ]. MTAs should also be used for materials that will be used in clinical or commercial development [ 45 – 47 ]. In the latter context, given that development trajectories are often uncertain, MTAs should include clear definitions and terms that trigger an obligation to renegotiate the MTA if the nature of the research collaboration changes; for example, from preclinical to clinical or from noncommercial to commercial research [ 50 – 53 ]. In ongoing litigation over chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) between the University of Pennsylvania (Penn) and St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, problems arose when the definition of a modified derivative in an MTA did not change when the use of a CAR by researchers at Penn changed from preclinical to clinical research [ 50 – 53 ]. In a case such as this, especially when pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies become involved in the research, reusable, standard, “boilerplate” terms are not acceptable. However, avoidance of problems and navigation of complex research relationships requires expertise in institutional contracts offices for negotiating, drafting, and monitoring the terms of agreements. Such expertise is often lacking.

In keeping with general observations on reach-through rights, research institutions should beware of industry agreements that contain expansive proprietary and licensing rights in favour of the industry partner [ 54 ].

Since MTAs may play an important role in determining ownership on patent applications and the assignment of proprietary rights, MTAs should fairly and clearly recognize the respective contributions of the parties [ 55 , 56 ]. Research institutions need to assist employees in navigating their relationships with industry, or they may lose valuable intellectual property rights [ 57 – 59 ]. When materials have been widely distributed to the research community in the absence of an MTA, it is usually too late for an institution or researcher to claim proprietary rights and benefits from the user community [ 60 ]. In these circumstances, launching litigation is costly for all parties.

The Shape of MTAs to Come

The lessons learned from materials and data sharing in the mouse research community and from the rare instances where research relationships failed and litigation ensued suggest some core principles upon which to build the MTAs of the future.

- Keep it simple: The core message from the mouse community is that both the deposit and distribution of MTAs should be kept as simple as possible, so that institutions can realistically monitor and enforce the terms. MTAs should also be commensurate with a realistic assessment of the risks and benefits to the institutions, both in terms of legal liabilities and potential revenue generation. In the case of research tools, the benefits are rarely monetary; the main benefits arise from the use of research reagents to advance the scientific field, giving due acknowledgement of their source.

- Management of risks should be proportionate to the type and likelihood of benefits: Institutional contracts staff should evaluate the presence or likelihood of the following categories of risks relative to the likely benefits to accrue to the institution and/or its researchers and use MTAs or simpler agreements accordingly. First, risks relate to safety in the use of the materials; for example, ensuring that the research-grade materials are not used in research on human subjects, or that materials are used in compliance with ethical standards. A second class of risk is legal: inappropriate use of reagents may result in legal action by victims against institutions; third parties may claim that the material infringes their intellectual property rights, or that the materials supplied are not of the quality claimed by the distributor. A third class of risk is to reputation: MTAs may require appropriate acknowledgment of the originator or the distributing archive in any ensuing publications or other research outputs, so promoting the reputation of the source and providing a metric for the value of the material. The final category of risk is that third parties misappropriate the credit or financial reward that should accrue to the originator of the material: MTAs may limit distribution of reagents or materials to third parties, ensuring that users return to the originator to access materials under its terms, or may limit commercial use of the materials. These standard concerns are covered under the UBMTA and similarly simple agreements.

- Avoid reach-through claims: Problems arise when institutions attempt to overreach their interests in an invention using reach-through claims [ 6 ]. These terms are problematic not only in terms of intellectual property policy but also from a negotiation perspective, and they will likely delay the execution of a final agreement. These terms are almost impossible to enforce, and therefore are of limited benefit. A policy against reach-through should apply for all MTAs—research institutions should be very wary of such terms that commonly attach to research materials shared by industry. Equally, institutions should not be tempted to insert reach-through provisions into MTAs, even if only attempting to promote access to research tools. While it may be good practice, especially in all forms of licensing agreements with industry, to retain rights in materials for further research, it is problematic to insist on an expanded set of rights to research using derivative materials. Indeed, such a provision in the original MTA for the distribution of European resources within IKMC was perceived to be highly problematic for international partners [ 6 ]. Here, systemic problems arise when deposit MTAs, or MTAs that share a resource with members of a consortium, contain reach-through provisions that need to be enforced by the receiving institution on behalf of the originating institution. In this scenario, the receiving institution derives no direct benefits, but is contractually obliged to enforce rights on behalf of another institution.

In conclusion, since MTAs are central mediators in the exchange of data and materials generated using public funds, they should embody policies and guidelines that encourage sharing and foster related community norms. Currently, complex MTAs and protracted negotiations create transactional bottlenecks that frustrate sharing, and they are unlikely ever to be monitored and enforced. Standard and simple agreements, by contrast, decrease the administrative burden for researchers, their institutions, and repositories. Institutions should adopt these simple agreements in cases where the risk is low and the benefits are noncommercial. They can then focus their energies on those cases where more complex agreements are warranted, especially in relations with industry and in contexts closer to commercial development and/or clinical application.

Supporting Information

Acknowledgments.

We thank Dr. Lauryl Nutter and Dr. Ann Flenniken for expert input and research support, as well as expert input from Dr. Michael Hagn, Dr. Kent Lloyd, Dr. Paul Schofield and Mr. David Einhorn, former legal counsel for JAX. We especially thank the mouse model research community, which has actively participated in research interviews and exchanges for the past decade. We would also like to thank Zackariah Breckenridge and Stephanie Kowal for research and editorial assistance.

Abbreviations

Funding statement.

Funding to TB is provided by the Canadian Stem Cell Network ( http://www.stemcellnetwork.ca/ ), NorComm II funded by Genome Canada ( www.genomecanada.ca ) and Ontario Genomics Institute (Co-Lead Investigators: Colin McKerlie and Steve Brown; http://www.ontariogenomics.ca/about/genome-canada ), and the PACEOMICS project funded by Genome Canada ( paceomics.org ), Genome Alberta ( http://genomealberta.ca/ ), the Canadian Institutes for Health Research ( http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/193.html ), and Alberta Innovates-Health Solutions (Co-Lead Investigators: Christopher McCabe and Tania Bubela; http://www.aihealthsolutions.ca/ ). AM was supported by postdoctoral fellowship funding from NorComm2 ( www.norcomm2.org ).

- Research and Innovation Services

Material Transfer Agreements

- Material Transfer Agreements (MTA) Policy

Material Transfer Agreements (MTA) guidance

MTAs are required for the transfer of materials and data between UCL and another party, such as a university or private company. This page sets out the policy, procedure, and guidance for MTAs at UCL.

On this page

What is a Material Transfer Agreement (MTA)?

Importance of an mta, benefits of an mta, what do we mean by materials.

- When do you need an MTA?

Who can sign an MTA?

How long does ucl take to complete an mta .

- How to request an MTA

MTAs are legal contracts that set out the terms and conditions of the transfer and use of materials and/or data between the owner or provider and a recipient. Material transfer agreements (MTAs) protect UCL and the UCL researcher by recording the transfer of materials and/or data.

MTAs also set out any relevant legislative and regulatory requirements which the recipient and provider must comply with.

Commercial organisations, non-profit organisations and other academic institutions, will only release materials if there is an MTA in place between the provider and the recipient.

An MTA offers important benefits to the provider and recipient. It can:

- give them control over the distribution and use of the material

- help them gain access to the results of the research, both for information purposes and for commercial exploitation.

The MTA policy covers agreements relating to the transfer of materials, data or both.

MTAs are used for materials, including but not limited to:

- Nucleotides

- Transgenic animals

- Pharmaceuticals

- Other chemicals

- Other materials with scientific or commercial value

An MTA can also cover data, where data is being received alongside the materials. This can include anonymised, pseudo anonymised or personal data.

Data Transfer Agreements (DTA)

A Data Transfer Agreement (DTA) is a type of MTA.

A DTA is used where only data/data sets are being transferred. A DTA will be used for the transfer of anonymised data, pseudonymised or personal data.

When do you need an MTA?

An MTA is required by UCL for all incoming and outgoing material transfers except when purchased on the open market.

Incoming transfers

Where UCL is requesting a provider to supply it with materials, either with or without paying a fee.

Purchasing materials on the open market

All material transfers are subject to UCL’s MTA Policy. However, a separate contract is not required for purchases on the open market. These purchases will come with their own terms and conditions. It is important that these terms and conditions are carefully reviewed, as they will commit UCL to certain legal obligations.

Please make sure you refer to the usual UCL Procurement policies and procedures (login required).

Outgoing transfers

An MTA is required by UCL for any outgoing transfer of:

- UCL developed materials including those listed above

- UCL developed materials that contain or incorporate components received from a third party

- Materials developed for or on behalf of UCL

- Human blood, tissue, and/or plasma harvested at UCL or by UCL researchers at third party facilities

MTAs can only be signed by an authorised UCL signatory in line with UCL’s Delegated Authorities.

The Research and Innovation Services (RIS) team makes sure the terms and conditions of the MTA are suitable for the transfer of the materials.

Any unauthorised employee who executes an MTA may face disciplinary action.

Most MTAs can be completed within 90 days. However, the length of time depends on the responsiveness and negotiating stance of the recipient organisation.

Additional negotiation

If your MTA has any of the following considerations, this may require negotiation and increase the amount of time it takes to sign the agreement.

- Commercial licenses which will need UCL Business' input into the terms

- MTAs for "state-of-the-art" materials

- For-profit entities

- Where UCL is charging a fee or paying a fee for the materials

- Publication rights

- Intellectual property (IP) rights

- Inventorship

- Governing law

- Warranties

- Indemnities

- IP clauses which include ownership of non-severable modifications and improvements to the materials

- Revenue sharing of non-severable modifications and improvements to the materials

Conflicts and disagreement

Should there be a conflict between the terms of the MTA and funding terms and conditions, Research and Innovation Services (RIS) will advise the UCL researcher to request written approval from the funding body to deviate from the funding terms and conditions.

The UCL researcher will need to create a new Worktribe contract request and include the above-written approval.

RIS will then agree to a formal amendment to the funding terms and conditions to reflect the change.

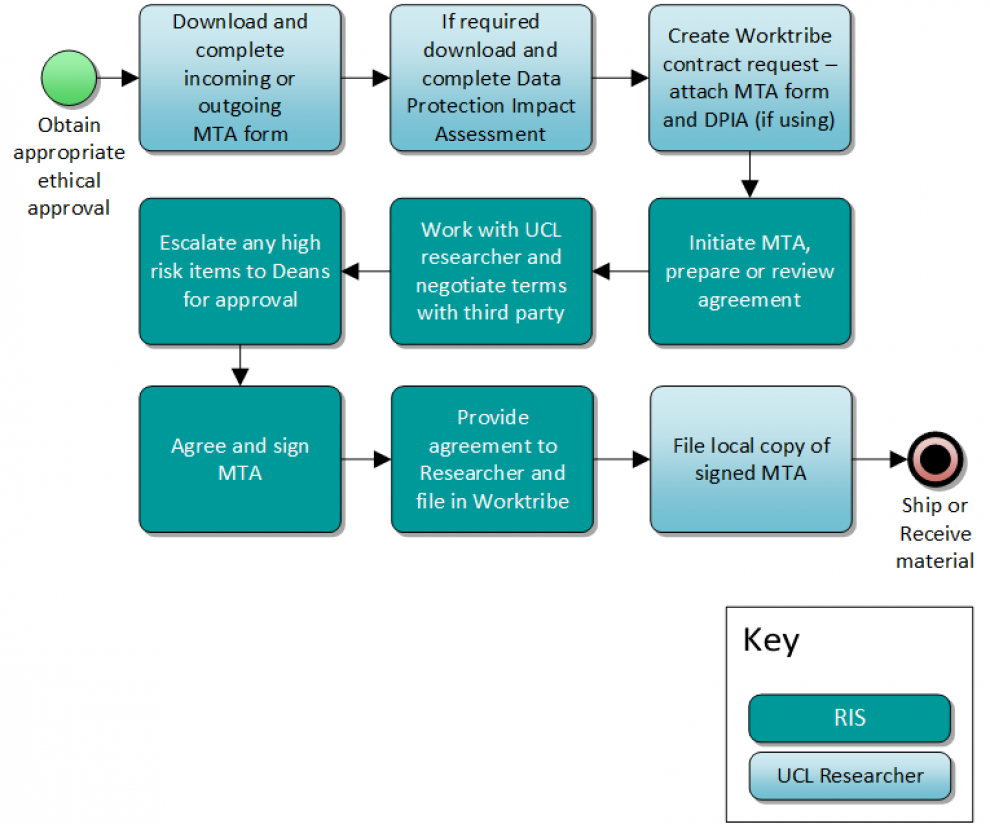

How to request an MTA

If you require an MTA, the process begins with the completion of either the MTA or DTA Incoming/Outgoing form, to be included with the submission of a Worktribe contract request.

For clinical trials/studies MTAs , contact the UCLH/UCL Joint Research Office who are responsible for negotiating, approving and signing agreements relating to clinical trials/studies.

For material transfers where UCL is charging another party for a service , contact UCL Consultants .

To use the Addgene service , you should request or deposit your materials in the usual way.

The process for incoming and outgoing MTAs is the same:

- Once you have identified you require an MTA, inform your Research Group Leader

- Read UCL’s MTA policy (UCL login required)

- If you are requesting an Incoming MTA or DTA, please complete the Incoming MTA form. If you are requesting an Outgoing MTA/DTA, please complete the Outgoing MTA form.

- Complete a Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) , where the material includes or is for pseudonymised or personal data

- Ensure you have appropriate ethical approval . Material transfer (including data transfers) commonly requires specific ethical approval and assessment, including transfer of Human tissue ethics and Human tissue integrity , Animal research at UCL , and Biological Services

- Create a contract request in Worktribe and upload all relevant documentation and information related to the MTA. Where it is linked to a current project, ensure that the Worktribe contract request is linked to the project in Worktribe (see exceptions above)

- You will receive a notification from the contracts team once your MTA has been approved. Once the MTA is signed by the recipient and provider, you may arrange the transfer of the materials.

MTA process diagram

Please note

- Remember where applicable to submit your DPIA early to reduce any delays.

- If there are any high-risk terms (see Section 3.3 of the MTA policy ) your request will be escalated to your Dean for approval.

- Transfers must be consistent with regulatory requirements eg ethical, import and export controls and legislation.

- It is your responsibility to ensure all approvals, ethics and other UCL approvals (such as those related to animals) are in place prior to submitting a Worktribe contract request for an MTA.

- It is your responsibility to ensure that all costs, including transport/delivery costs, are covered by the project budget or that budget is available to cover these costs.

Related links

- Material Transfer Agreement Policy

- UCLH/UCL Joint Research Office

- UCL Business (UCLB)

- UCL Consultants

- UCL Commerical and Procurement Services

- European Research & Innovation Office (ERIO)

- Contact Award Services

- Contact Contract Services

- Contact Compliance and Assurance

- Contact Planning, Insight and Improvement

- Find departmental contacts

- Researchers Toolkit

- Online submission systems

- Funder Golden Rules

- Institutional Information

- Sponsored Research Criteria

System access

Transforming the understanding and treatment of mental illnesses.

Información en español

Celebrating 75 Years! Learn More >>

- Research Funded by NIMH

- Research Conducted at NIMH (Intramural Research Program)

- Priority Research Areas

- Research Resources

Material Transfer Agreements

Note: The information presented on this page has been adapted from materials provided by the NIH Office of Technology Transfer (OTT) .

What Is An MTA?

An MTA (or Material Transfer Agreement) is a mechanism to facilitate the free transfer of proprietary materials and/or information between NIMH scientists and other institutions, whether they are for-profit or non-profit institutions. MTAs are used when the following circumstances obtain:

- The receiving party wishes to obtain proprietary material and/or information to use for his/her own research purposes.

- No research collaboration between the parties is planned.

- Neither rights in intellectual property nor rights for commercial purposes may be granted under this type of agreement.

- The agreement clearly sets forth the terms and conditions under which the recipient of the material and/or information, provided by either the NIMH scientist or other party, may use it.

- Education Home

- Medical Education Technology Support

- Graduate Medical Education

- Medical Scientist Training Program

- Public Health Sciences Program

- Continuing Medical Education

- Clinical Performance Education Center

- Center for Excellence in Education

- Research Home

- Biochemistry & Molecular Genetics

- Biomedical Engineering

- Cell Biology

- Microbiology, Immunology, & Cancer Biology (MIC)

- Molecular Physiology & Biological Physics

- Neuroscience

- Pharmacology

- Public Health Sciences

- Office for Research

- Clinical Research

- Clinical Trials Office

- Funding Opportunities

- Grants & Contracts

- Research Faculty Directory

- Cancer Center

- Cardiovascular Research Center

- Carter Immunology Center

- Center for Behavioral Health & Technology

- Center for Brain Immunology & Glia

- Center for Diabetes Technology

- Center for Immunity, Inflammation & Regenerative Medicine

- Center for Public Health Genomics

- Center for Membrane & Cell Physiology

- Center for Research in Reproduction

- Myles H. Thaler Center for AIDS & Human Retrovirus Research

- Child Health Research Center (Pediatrics)

- Division of Perceptual Studies

- Research News: The Making of Medicine

- Core Facilities

- Virginia Research Resources Consortium

- Center for Advanced Vision Science

- Charles O. Strickler Transplant Center

- Keck Center for Cellular Imaging

- Institute of Law, Psychiatry & Public Policy

- Translational Health Research Institute of Virginia

- Clinical Home

- Anesthesiology

- Dermatology

- Emergency Medicine

- Family Medicine

- Neurosurgery

- Obstetrics & Gynecology

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopaedic Surgery

- Otolaryngology

- Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation

- Plastic Surgery, Maxillofacial, & Oral Health

- Psychiatry & Neurobehavioral Sciences

- Radiation Oncology

- Radiology & Medical Imaging

- UVA Health: Patient Care

- Diversity Home

- Diversity Overview

- Student Resources

- GME Trainee Resources

- Faculty Resources

- Community Resources

- Material Transfer Agreements

How to obtain a Material Transfer Agreement or a Data Use Agreement

Step One : Complete the appropriate form from the Grants and Contracts site

Step Two : Submit form (and draft MTA/DUA if you received one) to [email protected]

Step Three : Obtain and submit additional documentation. If your MTA requires additional documentation, such as IRB approval submit the contract request form early and obtain the additional approvals in parallel with contract negotiations. If you are uncertain about what additional approvals may be required, contact your assigned contract negotiator. The following are examples of approvals that may be required depending on the circumstances:

- IRB approval http://www.virginia.edu/vpr/irb/hsr/

- Export control approval http://export.virginia.edu/

- Certification of de-identification of data

Frequently Asked Questions

MTA and DUAs are legally binding agreements and can only be signed by authorized University officials.

A Material Transfer Agreement (MTA) is a contract that documents the transfer of materials from one researcher to another. A Data Use Agreement (DUA) is a contract that documents the transfer of certain types of data from one researcher to another.

If you are sending or receiving materials or data (that is not already covered by another agreement), you are required to use an MTA or DUA that meets the legal and policy requirements of the University of Virginia.

These simple contracts establish important legal rights that could significantly impact your research such as your ability to publish or preservation of your intellectual property rights. MTAs and DUAs also address regulatory compliance and liability issues.

Additional approvals required will depend on the circumstances. If materials are leaving the US, then export control review is required. If the transfer relates to human subjects, IRB approval may be required. In the case of data, you may be asked to obtain a determination that any Personal Health Information (PHI) has been de-identified in compliance with HIPAA. Ask your contract negotiator for guidance.

- Post-award Administration

- Contracts and Clinical Trials Agreements

- Intellectual Property (IP) and Entrepreneurial Activities

- Getting Started in Clinical Research

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Medical Student Research Programs at UVA

- Medical Student Research Symposium

- MSSRP On-Line Preceptor Form

- MSSRP On-Line Student Match Form

- On-line Systems

- Other Medical Student Research Opportunities

- Research: Financial Interest of Faculty

- Review of Proposed Consulting Agreements

- Transfers of NIH/Public Health Service awards

- Unmatched MSSRP projects – 2024

- Research Centers and Programs

- Roles and responsibilities in research administration

- Other Offices Supporting Research

- SBIR and STTR Awards

- Information for students and postdoctoral trainees

- For Research Administrators

- For New Research Faculty

- Funding Programs for Junior Faculty

- NIH for new faculty

- School of Medicine surplus equipment site

- Forms and Documents

- FAQs – SOM offices supporting research

- 2024 Faculty Research Retreat

- Anderson Lecture and Symposia

- Skip to navigation

- Skip to content

- UMB Shuttle

University of Maryland, Baltimore

About UMB History, highlights, administration, news, fast facts

- Accountability and Compliance

- Administration and Finance

- Center for Information Technology Services

- Communications and Public Affairs

- Community Engagement

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- External Relations

- Government Affairs

- Philanthropy

- Office of the President

- Office of the Provost

Research and Development

- University Counsel

- Administrative Officers

- Boards of Visitors

- Faculty Senate

- Staff Senate

- Center for Health and Homeland Security

- Council for the Arts & Culture

- Interprofessional Education

- Leaders in Education: Academy of Presidential Scholars

- Middle States Self-Study

- President's Council for Women

- President's Symposium and White Paper Project

- For the Media

- Steering Committee Roster

- Logistics Committee Roster

- UMB Police and Public Safety

- Graduation Celebration 2024

- Founders Week

- UMB Holiday Craft Fair

Academics Schools, policies, registration, educational technology

- School of Dentistry

- Graduate School

- School of Medicine

- School of Nursing

- School of Pharmacy

- School of Social Work

- Carey School of Law

- Health Sciences and Human Services Library

- Thurgood Marshall Law Library

Admissions Admissions at UMB are managed by individual schools.

- Carey School of Law Admissions

- Graduate School Admissions

- School of Dentistry Admissions

- School of Medicine Admissions

- School of Nursing Admissions

- School of Pharmacy Admissions

- School of Social Work Admissions

- Tuition and Fees

- Student Insurance

- Academic Calendar

- Financial Assistance for Prospective Students

- Financial Assistance for Current Students

- Financial Assistance for Graduating Students

Research Offices, contracts, investigators, UMB research profile

- Organized Research Centers and Institutes

- UMB Institute for Clinical & Translational Research

- Sponsored Programs Administration

- Sponsored Projects Accounting and Compliance (SPAC)

- Kuali Research

- Clinical Trials and Corporate Contracts

- CICERO Log-in

- Conflict of Interest

- Human Research Protections

- Environmental Health and Safety

- Export Compliance

- Effort Reporting

- Research Policies and Procedures

- Center for Innovative Biomedical Resources

- Baltimore Life Science Discovery Accelerator (UM-BILD)

- Find Funding

- File an Invention Disclosure

- Global Learning for Health Equity Network

- Manage Your Grant

- Research Computing

- UM Research HARBOR

- Center for Violence Prevention

- Office of Research and Development

- Center for Clinical Trials and Corporate Contracts

- Technology Transfer/UM Ventures

- Contact Research and Development

Services For students, faculty, and staff, international and on-campus

- Student Health Resources

- Educational Support and Disability Services

- Writing Center

- URecFit and Wellness

- Intercultural Leadership and Engagement

- Educational Technology

- Student Counseling Center

- UMB Scholars for Recovery

- UMB Student Affairs

- Human Resource Services

- Travel Services

- Strategic Sourcing and Acquisition Services

- Office of the Controller

- Office of the Ombuds

- Employee Assistance Program (EAP)

- Workplace Mediation Service

- Faculty Center for Teaching and Learning

- UMB Travel: Start Here

- International Students, Scholars, and Employees

- Center for Global Engagement

- International Travel SOS

- International Operations

- Parking and Transportation Services

- UMB shuttle

- SMC Campus Center Event Services

- Donaldson Brown Riverfront Event Center

- All-Gender Bathrooms

- Environmental Services

- Interprofessional Program for Academic Community Engagement

University Life Alerts, housing, dining, calendar, libraries, and recreation

- Emergency Reference Guide

- Campus Life Weekly with USGA

- Starting a New Universitywide Organization

- University Student Government Association

- Planned Closures

- Intramural Sports

- Safety Education

- About URecFit and Wellness

- How to Get Your One Card

- One Card Uses

- Lost One Card

- One Card Policies

- Photo Services

- One Card Forms

- One Card FAQs

- Office Hours and Directions

Give to UMB Sustain excellence and meet UMB's educational needs for today and tomorrow.

Thank You for Your Gift to UMB

The University of Maryland, Baltimore (UMB) is excited to share its new online giving page.

With enhanced searchability, a streamlined checkout process, and new ways to give such as Venmo, PayPal, Apple Pay, and Google Pay in addition to credit card, donors can support UMB quickly and securely.

- Ways to Give

- Where to Give

- Staying Connected: You and UMB

- The UMB Foundation

- Office of Philanthropy

- Maryland Charity Campaign

- Corporate Contracts

Material Transfer Agreements

620 W. Lexington St. Fourth Floor Baltimore, MD 21201

P 410-706-6723

A Material Transfer Agreement (MTA) is a contract that governs the transfer of tangible research materials between two organizations — from the owner or authorized licensee to another organization — for research or evaluative purposes.

The MTA defines the rights of the provider and the recipient with respect to the materials and any derivatives. Biological materials — such as reagents, cell lines, plasmids, and vectors — are the most frequently transferred materials, but MTAs also may be used for other types of materials, such as knockout mice, chemical compounds, and even some types of software.

For more information or if you have questions or concerns, please contact Stephanie Deasey at 410-706-2463.

'Outgoing' materials - sending materials to an external organization ▾

MTA Questionnaire and UMB Non-Profit Outgoing MTA

To access the questionnaire, click the link above, or go to the myUMB Portal and select UMBiz from the Administrative Systems menu.

The Center for Clinical Trials and Corporate Contracts (CCT) wants to expedite the routine requests you receive for your tangible materials. If you are sending your nonproprietary material out to another nonprofit institution, you may use the UMB Nonprofit Outgoing MTA. The recipient may print out this convenient MTA, have it signed by their institution, and return it to CCT. CCT will forward it to you, and you will be able to rapidly respond to requests for your material.

For materials that are considered proprietary, the CCT wants to maximize UMB's ability to protect your material and any resulting technology. Please provide the information requested in the MTA questionnaire. Your answers to the questionnaire will give CCT much of the information we will need to begin the MTA process. CCT may contact you to gain further information.

'Incoming' materials - receiving materials from an external organization ▾

MTA Questionnaire

The Center for Clinical Trials and Corporate Contracts (CCT) recognizes that you may require tangible materials for your research from sources outside our campus, and we want to expedite your request. While facilitating the transfer, CCT also wants to protect, where possible and practicable, any technology that may result from your research and ensure that any agreement conforms to fundamental University policies.

Please start by providing the information requested in the MTA questionnaire. Your answers to the questionnaire will give CCT much of the information we will need to begin the MTA process. CCT may contact you to gain further information.

UMB is a signatory for a standardized form of MTA known as the Uniform Biological Material Transfer Agreement (UBMTA). When the material is provided by one of a group of signatory institutions , which includes many other universities, the UBMTA may be employed to expedite the contracting process.

The University of Maryland, Baltimore is the founding campus of the University System of Maryland. 620 W. Lexington St., Baltimore, MD 21201 | 410-706-3100 © 2023-2024 University of Maryland, Baltimore. All rights reserved.

Material Transfer Agreements

Export Control

Guidance on Imports

- Guidance on importing plant materials / organisms that affect plants

Sharing Confidential Information: Confidential Disclosure Agreements

- Incoming CDAs: receiving confidential information from another institution or company

- Outgoing CDAs: sharing confidential information with another institution or company

Transferring Research Materials: Material Transfer Agreements

- Incoming MTAs: receiving material from another institution or company

- Outgoing MTAs: transferring material to another institution or company

Export Controls

Export control laws are federal regulations that control the conditions under which certain information, technologies, and commodities can be transmitted overseas to anyone, including U.S. citizens, or to a foreign national on U.S. soil.

You must contact Research Affairs - Research Integrity immediately if your research involves the transmission of research information or technology to someone overseas, or sharing information or technology with someone other than a U.S. citizen or permanent resident within the United States. This includes discussing your research with research colleagues or students in your laboratory who are foreign nationals.

Most LLU research activities will most likely be excluded from export control laws. But you must consult with Research Integrity to be sure.

Other Helpful Links:

- Travel Tips from the National Counterintelligence Executive regarding traveling overseas with mobile phones, laptops, PDAs, and other electronic devices.

- Best Practices for Academics Traveling Overseas -- tips from the FBI

Guidance on Etiologic Agents

Etiologic agents are those microorganisms and microbial toxins that cause disease in humans and include bacteria, bacterial toxins, viruses, fungi, rickettsiae, protozoans, and parasites.

See CDC's Etiologic Agent Import Permit Program

Guidance on Importing Plant Materials / Organisms That Affect Plants

Permits are required for the importation, transit, domestic movement and environmental release of Organisms that impact plants, and the importation and transit of Plants and Plant Products under authority of the Plant Protection and Honeybee Acts.

The protection of agricultural products is taken very seriously , so it is important to make sure that all requirements are followed.

Where to Start:

See the U.S. Department of Agriculture site (under the division Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, also known as APHIS) that describes the regulation of the importation of plant materials. This is a good place to start looking for the various types of permits and regulations that may be required. Note: The U.S. Fish and Wildlife and other agencies may also have additional requirements.

If you have a specific project in mind, please contact Research Affairs - Research Integrity for assistance.

See the following for specific types of permits:

Organism and Soil Permits Organism Permits include Plant Pests such as insects and snails; Plant Pathogens such as fungi, bacteria, and viruses; Biological Control Agents, Bees, Plant Pest Diagnostic Laboratories, Soil Microbe Isolation Laboratories, Federal Noxious Weeds and Parasitic Plants.

Plant and Plant Product Permits Plant and Plant Product Permits include Plants for Planting such as nursery stock, small lots of seed; Plant Products such as fruits and vegetable, timber, cotton and cut flowers; Protected Plants and Plant Products such as orchids, and Threatened and Endangered plant species; Transit Permits to ship regulated articles into, through, and out of the U.S.; and Departmental Permits to import prohibited plant materials for research.

- See the USDA website on importing plants, the inspection stations, how to import plants, etc.

Confidential Disclosure Agreements

Confidential Disclosure Agreements (CDAs), also referred to as Non-Disclosure Agreements (NDAs), allow Loma Linda University faculty to exchange confidential information with outside parties under obligations that protect and preserve the confidentiality of that information. Generally CDAs are entered into for the purpose of exploring a potential research collaboration or license agreement.

A CDA serves three purposes :

- It alerts the receiving party to the confidentiality of the information to be received;

- It specifies the responsibilities required of the receiving party; and

- It helps preserve LLU patent rights. Under United States patent law, there is a grace period of one year in which to file a patent application after the invention has been made known to the public. However, in most other countries a patent application must be filed before the invention is ever disclosed to the public. Executing a CDA before discussing an invention with an outside party prevents public disclosure and preserves the possibility of foreign patent protection. CDAs can be used as evidence in subsequent patent processing, e.g., to defeat an allegation that the invention is not novel because the inventor treated it as public information. This kind of allegation arises frequently from those contesting a potentially lucrative patent, so a CDA is more than a "mere formality."

CDAs may cover a mutual exchange of information, also referred to as two-way, or may be one-way to cover information disclosed by only one party.

At Loma Linda University, the need for a confidential disclosure agreement usually arises in one of three ways:

- A LLU researcher wishes to share information about an invention with an outside company . An outgoing CDA will protect the intellectual property (i.e. patent) involved.

- A LLU researcher is receiving confidential information from an outside company that relates to LLU intellectual property or the researcher's ongoing research related to that intellectual property. An incoming CDA ensures that LLU's intellectual property and research activities remain uncontaminated by the outside entity's confidential information.

- A LLU researcher conducting an industry-sponsored clinical trial is required to sign a CDA to maintain the confidentiality of a clinical study protocol and any other study-related information provided by the sponsor. These types of CDAs are administered by the Clinical Trial Center .

Research Affairs - Financial Management is here to help faculty share information to advance their research. The agreements covering these exchanges are legally binding contracts . Once signed, LLU and faculty must comply with the provisions they contain.

See also: Frequently Asked Questions for Confidential Disclosure Agreements .

Incoming CDAs: Receiving Confidential Information from another Institution or Company

To receive confidential or proprietary information from another institution or company, please forward the following information to the Financial Management Contract Analyst ( Note: If the information is from a clinical trial sponsor, then follow the procedure outlined by the Clinical Trial Center .)

- A completed CDA Request Form

- An electronic version of the provider's CDA (preferably in MS Word format). Note: A CDA is normally supplied by the provider. You should obtain that CDA prior to initiating the request.

- Name of company or outside party with contact name , phone number or email address

- Subject matter to be discussed — brief description

- Purpose of the disclosure or exchange of information

Financial Management will review this information to determine if the terms are acceptable under LLU policy. If acceptable, Financial Management will obtain the necessary signatures to execute the CDA. If the terms are not acceptable, Financial Management will negotiate with the provider to revise the unacceptable terms.

Outgoing CDAs: Sharing Confidential Information with Another Institution or Company

To share confidential or proprietary information with another institution or company, please forward the following information to Director of Research Affairs - Financial Management .

- Type of agreement needed — mutual or one-way

At this point:

- Financial Management will negotiate terms of the agreement with the recipient.

- Financial Management will obtain necessary signatures to execute the CDA.

- Upon execution you will receive a copy of the fully executed agreement via email.

- At that time the provider may share the information with the recipient you.

When transferring or receiving tangible research material or raw datasets with another researcher or company, whether non-profit or commercial, an advance agreement is necessary.

A Material Transfer Agreement (MTA) is a contract that governs the transfer of tangible research materials between two organizations when the recipient intends to use it for his or her own research purposes.

A Data Transfer Agreement (DTA) is an agreement requesting a disclosure of protected health information (PHI) contained in a limited data set.

MTAs/DTAs set out the protections, rights, and obligations of both parties. The Research Affairs - Financial Management (RAFM) Contracts Analyst reviews and approves these agreements for both the transfer of outgoing material and data requests as well as the transfer of all incoming material and data requests. Our goal is to ensure that MTAs/DTAs do not restrict your academic freedom or hinder future research, protect potential LLU inventions and intellectual property, and that they include HIPAA ( Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act ) regulations.

Types of material requests may include biological materials such as reagents, cell lines, plasmids, and vectors (including DNA, live animals, and clinical specimens), chemical compounds, databases and software codes. Types of data requests may include data derived from human subject research or HIPAA-protected information.

Why is an agreement required for material transfer?

Most providers of material and data require an agreement so that there is a common understanding of how the materials or data will be used and set limitations on its use. However, both parties involved in the exchange will benefit from the arrangement.

Transfers done without a MTA/DTA offer no protection for either the providing institution or the receiving institution. An agreement establishes ownership to any potential inventions which may be developed by the use of the materials or data. Such issues as confidentiality, publication rights, ownership and licensing rights of any intellectual property, limitations on use of the requested material/data, liability and indemnification are addressed in a MTA/DTA. Companies may ask to own all rights to inventions arising from use of the material/data or prohibit your ability to publish the results of your research. In addition, if the transfer includes material/data that is owned by a third party, further transfer of that material/data is commonly restricted by the MTA/DTA. Violation of that requirement may provoke litigation. However, it is often possible to transfer the material/data, if the new recipient agrees, in an agreement, to honor the obligations imposed by the original provider.

Every MTA/DTA is different because materials being transferred in or out of the institution all have specific properties, specific risks and specific applications. Therefore, these agreements must be reviewed individually to reach a mutual understanding on the terms and conditions, the investigator's obligations to the provider, and the use the investigator plans for the material/data.

For these reasons, Financial Management reviews, negotiates, and approves all MTAs/DTAs. The agreements covering these exchanges are legally binding contracts. Once signed, LLU and faculty must comply with the provisions they contain.

See also: Frequently Asked Questions for Material Transfer Agreements .

Research Affairs - Financial Management is here to help faculty acquire materials and data to advance their research.

INCOMING MTAs: Receiving Material/Data from another Institution or Company

LLU faculty must have a MTA/DTA in place before receiving materials or data from another academic institution, nonprofit entity or industry.

Materials from Academic / Non-Profit / Government Institutions

To obtain materials from another academic, non-profit, or government institution, please forward the following documents to the Contract Analyst at [email protected] :

- A completed Contract Request Form .

- An electronic version of the provider's MTA (preferably in MS Word format). Note: An MTA is normally supplied by the provider of the material. You should obtain a copy prior to initiating the request.

Incoming Material Process

- The Contract Analyst will review these documents to determine if the terms are acceptable under LLU policy

- The Contract Analyst will obtain safety approval from the Institutional Biosafety Committee (IBC).

- If acceptable, the Contract Analyst will prepare the MTA for execution.

- If the terms are not acceptable, the Contract Analyst will negotiate the terms with the provider.

- The Contract Analyst will obtain necessary signatures.

- Upon execution you will receive a copy of the fully executed MTA via email.

- At this time you are permitted to accept the material.

For Materials from Industry

Industrial sponsors may freely distribute its materials to academic institutions with the expectation of acquiring patent rights and new intellectual property. This may create a conflict when the company providing the materials has not provided funds for the research that will be performed by the faculty member.

To obtain materials from Industry, please forward the following documents to the Contract Analyst at [email protected] :