Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Information Literacy

11 A Beginner’s Guide to Information Literacy

By emily metcalf.

Introduction

Welcome to “A Beginner’s Guide to Information Literacy,” a step-by-step guide to understanding information literacy concepts and practices.

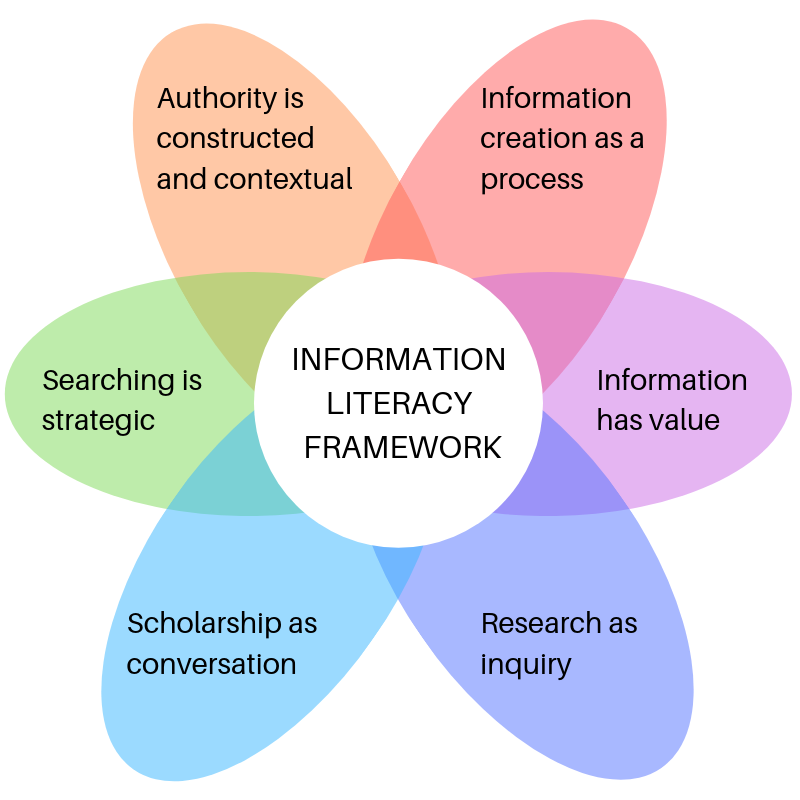

This guide will cover each frame of the “ Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education ,” a document created by the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL) to help educators and librarians think about, teach, and practice information literacy (see Figure 11.1). The goal of this guide is to break down the basic concepts in the Framework and put them in accessible, digestible language so that we can think critically about the information we’re exposed to in our daily lives.

To start, let’s look at the ACRL definition of “information literacy,” so we have some context going forward:

Information Literacy is the set of integrated abilities encompassing the reflective discovery of information, the understanding of how information is produced and valued, and the use of information in creating new knowledge and participating ethically in communities of learning.

Boil that down and what you have are the essentials of information literacy: asking questions, finding information, evaluating information, creating information, and doing all of that responsibly and ethically.

We’ll be looking at each of the frames alphabetically, since that’s how they are presented in the framework. None of these frames is more important than another, and all need to be used in conjunction with the others, but we have to start somewhere, so alphabetical it is!

In order, the frames are

- Authority is constructed and contextual

- Information creation as a process

- Information has value

- Research as inquiry

- Scholarship as conversation

- Searching as strategic exploration

Just because we’re laying this out alphabetically does not mean you have to go through it in order. Some of the sections reference frames previously mentioned, but for the most part you can jump to wherever you like and use this guide however you see fit. You can also open up the framework using the link above or in the attached resources to read the framework in its original form and follow along with each section.

The following sections originally appeared as blog posts for the Texas A&M Corpus Christi’s library blog. Edits have been made to remove institutional context, but you can see the original posts in the Mary and Jeff Bell Library blog archives .

Authority is Constructed and Contextual

The first frame is “ Authority is Constructed and Contextual .” There’s a lot to unpack in that language, so let’s get started.

Start with the word “authority.”

At the root of “authority” is the word “author.” So start there: who wrote the piece of information you’re reading? Why are they writing? What stake do they have in the information they’re presenting? What are their credentials (You can straight up google their name to learn more about them)? Who are they affiliated with? A public organization? A university? A company trying to make a profit? Check it out.

Now let’s talk about how authority is “constructed.”

Have you ever heard the phrase “social construct”? Some people say gender is a social construct or language, written and spoken, is a construct. “Constructed” basically means humans made it up at some point to instill order in their communities. It’s not an observable, scientifically inevitable fact. When we say “authority” is constructed, we’re basically saying that we as individuals and as a society choose who we give authority to, and sometimes we might not be choosing based on facts.

A common way of assessing authority is by looking at an author’s education. We’re inclined to trust someone with a PhD over someone with a high school diploma because we think the person with a PhD is smarter. That’s a construct. We’re conditioned to think that someone with more education is smarter than people with less education, but we don’t know it for a fact.

There are a lot of reasons someone might not seek out higher education. They might have to work full time or take care of a family or maybe they just never wanted to go to college. None of these factors impact someone’s intelligence or ability to think critically.

If aliens land on South Padre Island, TX, there will be many voices contributing to the information collected about the event. Someone with a PhD in astrophysics might write an article about the mechanical workings of the aliens’ spaceship. Cool; they are an authority on that kind of stuff, so I trust them.

But the teenager who was on the island and watched the aliens land has first-hand experience of the event, so I trust them too. They have authority on the event even though they don’t have a PhD in astrophysics.

So, we cannot think someone with more education is inherently more trustworthy or smarter or has more authority than anyone else. Some people who are authorities on a subject are highly educated, some are not.

Likewise, let’s say I film the aliens landing and stream it live on Facebook. At the same time, a police officer gives an interview on the news that says something contradicting my video evidence. All of a sudden, I have more authority than the police officer. Many of us are raised to trust certain people automatically based on their jobs, but that’s also a construct. The great thing about critical thinking is that we can identify what is fact and fiction, and we can decide for ourselves who to trust.

The final word is “contextual.”

This one is a little simpler. If I go to the hospital and a medical doctor takes out my appendix, I’ll probably be pretty happy with the outcome. If I go to the hospital and Dr. Jill Biden, a professor of English, takes out my appendix, I’m probably going to be less happy with the results.

Medical doctors have authority in the context of medicine. Dr. Jill Biden has authority in the context of education. And Doctor Who has authority in the context of inter-galactic heroics and nice scarves.

This applies when we talk about experiential authority, too. If an eighth-grade teacher tells me what it’s like to be a fourth-grade teacher, I will not trust their authority. I will, however, trust a fourth-grade teacher to tell me about teaching fourth grade.

The Takeaway

Basically, when we think about authority, we need to ask ourselves, “Do I trust them? Why?” If they do not have experience with the subject (like witnessing an event or holding a job in the field) or subject expertise (like education or research), then maybe they aren’t an authority after all.

P.S. I’m sorry for the uncalled-for dig, Dr. Biden. I’m sure you’d do your best with an appendectomy.

Ask Yourself

- In what context are you an authority?

- If you needed to figure out how to do a kickflip on a skateboard, who would you ask? Who’s an authority in that situation?

Information Creation as a Process

The second frame is “ Information Creation as a Process .”

Information Creation

So first of all, let’s get this out of the way: everyone is a creator of information. When you write an essay, you’re creating information. When you log the temperature of the lizard tank, you’re creating information. Every Word Doc, Google Doc, survey, spreadsheet, Tweet, and PowerPoint that you’ve ever had a hand in? All information products. That YOU created. In some way or another, you created that information and put it out into the world.

One process you’re probably familiar with if you’re a student is the typical research paper. You know your professor wants about five to eight pages consisting of an introduction that ends in a thesis statement, a few paragraphs that each touch on a piece of evidence that supports your thesis, and then you end in a conclusion paragraph which starts with a rephrasing of your thesis statement. You save it to your hard drive or Google Drive and then you submit it to your professor.

This is one process for creating information. It’s a boring one, but it’s a process.

Outside of the classroom, the information-creation process looks different, and we have lots of choices to make.

One of the choices you’ll need to make is the mode or format in which you present information. The information I’m creating right now comes to you in the mode of an Open Educational Resource . Originally, I created these sections as blog posts. Those five-page essays I mentioned earlier are in the mode of essays.

When you create information (outside of a course assignment), it’s up to you how to package that information. It might feel like a simple or obvious choice, but some information is better suited to some forms of communication. And some forms of communication are received in a certain way, regardless of the information in them.

For example, if I tweet “Jon Snow knows nothing,” it won’t carry with it the authority of my peer-reviewed scholarly article that meticulously outlines every instance in which Jon Snow displays a lack of knowledge. Both pieces of information are accurate, but the processes I went through to create and disseminate the information have an effect on how the information is received by my audience.

And that is perhaps the biggest thing to consider when creating information: your audience.

The Audience Matters

If I just want my twitter followers to know Jon Snow knows nothing, then a tweet is the right way to reach them. If I want my tenured colleagues and other various scholars to know Jon Snow knows nothing, then I’m going to create a piece of information that will reach them, like a peer-reviewed journal article.

Often, we aren’t the ones creating information; we’re the audience members ourselves. When we’re scrolling on Twitter, reading a book, falling asleep during a PowerPoint presentation—we’re the audience observing the information being shared. When this is the case, we have to think carefully about the ways information was created.

Advertisements are a good example. Some are designed to reach a 20-year old woman in Corpus Christi through Facebook, while others are designed to reach a 60-year old man in Hoboken, NJ over the radio. They might both be selling the same car, and they’re going to put the same information (size, terrain, miles per gallon, etc.) in those ads, but their audiences are different, so their information-creation process is different, and we end up with two different ads for different audiences.

Be a Critical Audience Member

When we are the audience member, we might automatically trust something because it’s presented a certain way. I know that, personally, I’m more likely to trust something that is formatted as a scholarly article than I am something that is formatted as a blog. And I know that that’s biased thinking and it’s a mistake to make that assumption.

It’s risky to think like that for a couple of reasons:

- Looks can be deceiving. Just because someone is wearing a suit and tie doesn’t mean they’re not an axe murderer and just because something looks like a well-researched article, doesn’t mean it is one.

- Automatic trust unnecessarily limits the information we expose ourselves to. If I only ever allow myself to read peer-reviewed scholarly articles, think of all the encyclopedias and blogs and news articles I’m missing out on!

If I have a certain topic I’m really excited about, I’m going to try to expose myself to information regardless of the format and I’ll decide for myself (#criticalthinking) which pieces of information are authoritative and which pieces of information suit my needs.

Likewise, as I am conducting research and considering how best to share my new knowledge, I’m going to consider my options for distributing this newfound information and decide how best to reach my audience. Maybe it’s a tweet, maybe it’s a Buzzfeed quiz, or maybe it’s a presentation at a conference. But whatever mode I choose will also convey implications about me, my information creation process, and my audience.

You create information all of the time. The way you package and share it will have an effect on how others perceive it.

- Is there a form of information you’re likely to trust at first glance? Either a publication like a newspaper or a format like a scholarly article?

- Can you think of some voices that aren’t present in that source of information?

- Where might you look to find some other perspectives?

- If you read an article written by medical researchers that says chocolate is good for your health, would you trust the article?

- Would you still trust their authority if you found out that their research was funded by a company that sells chocolate bars? Funding and stakeholders have an impact on the creation process, and it’s worth thinking about how this can compromise someone’s authority.

Information Has Value

Onwards and upwards! We’re onto frame 3: “ Information Has Value .”

What Counts as Value?

There are a lot of different ways we value things. Some things, like money, are valuable to us because we can exchange them for goods and services. On the other hand, some things, like a skill, are valuable to us because we can exchange them for money (which we exchange for more goods and services). Some things are valuable to us for sentimental reasons, like a photograph or a letter. Some things, like our time, are valuable because they are finite.

The Value of Information

Information has all kinds of value.

One kind is monetary. If I write a book and it gets published, I’m probably going to make some money off of that (though not as much money as the publishing company will make). So that’s valuable to me.

But I’m also getting my name out into the world, and that’s valuable to me too. It means that when I apply for a job or apply for a grant, someone can google me and think, “Oh look! She wrote a book! That means she has follow-through and will probably work hard for us!” That kind of recognition is a sort of social value. That social value, by the way, can also become monetary value. If I’ve produced information, a university might give me a job, or an organization might fund my research. If I’ve invented a machine that will floss my teeth for me, the patent for my invention could be worth a lot of money (plus it’d be awesome. Cool factor can count as value.).

In a more altruistic slant, information is also valuable on a societal level. When we have more information about political candidates, for example, it influences how we vote, who we elect, and how our country is governed. That’s some really valuable information right there. That information has an effect on the whole world (plus outer space, if we elect someone who’s super into space exploration). If someone is trying to keep information hidden or secret, or if they’re spreading misinformation to confuse people, it’s probably a sign that the information they’re hiding is important, which is to say, valuable.

On a much smaller scale, think about the information on food packages. If you’re presented with calorie counts, you might make a different decision about the food you buy. If you’re presented with an item’s allergens, you might avoid that product and not end up in an Emergency Room with anaphylactic shock. You know what’s super valuable to me? NOT being in an Emergency Room!

But if you do end up in the Emergency Room, the information that doctors and nurses will use to treat your allergic reaction is extremely valuable. That value of that information is equal to the lives it’s saved.

Acting Like Information is Valuable

When we create our own information by writing papers and blog posts and giving presentations, it’s really important that we give credit to the information we’ve used to create our new information product for a couple of reasons.

First, someone worked really hard to create something, let’s say an article. And that article’s information is valuable enough to you to use in your own paper or presentation. By citing the author properly, you’re giving the author credit for their work, which is valuable to them. The more their article is cited, the more valuable it becomes because they’re more likely to get scholarly recognition and jobs and promotions.

Second, by showing where you’re getting your information, you’re boosting the value of your new information product. On the most basic level, you’ll get a higher grade on your paper, which is valuable to you. But you’re also telling your audience, whether it’s your professor or your boss or your YouTube subscribers, that you aren’t just making stuff up—you did the work of researching and citing, and that makes your audience trust you more. It makes the audience value your information more.

Remember early on when I said the frames all connect? “Information Has Value” ties into the other information literacy frames we’ve talked about, “Information Creation as a Process” and “Authority as Constructed and Contextual.” When I see you’ve cited your sources of information, then I, as the audience, think you’re more authoritative than someone who doesn’t cite their sources. I also can look at your information product and evaluate the effort you’ve put into it. If you wrote a tweet, which takes little time and effort, I’ll generally value it less than if you wrote a book, which took a lot of time and effort to create. I know that time is valuable, so seeing that you were willing to dedicate your time to create this information product makes me feel like it’s more valuable.

Information is valuable because of what goes into its creation (time and effort) and what comes from it (an informed society). If we didn’t value information, we wouldn’t be moving forward as a society, we’d probably have died out thousands of years ago as creatures who never figured out how to use tools or start a fire.

So continue to value information because it improves your life, your audiences’ lives, and the lives of other information creators. More importantly, if we stop valuing information a smarter species will eventually take over and it’ll be a whole Planet of the Apes thing and I just don’t have the energy for that right now.

- Can you think of some ways in which a YouTube video on dog training has value? Who values it? Who profits from it?

- Think of some information that would be valuable to someone applying to college. What does that person need to know?

Research as Inquiry

Easing on down the road, we’ve come to frame number 4: “ Research as Inquiry .”

“Inquiry” is another word for “curiosity” or “questioning.” I like to think of this frame as “Research as Curiosity,” because I think it more accurately captures the way our adorable human brains work.

Inquiring Minds Want to Know

When you think to yourself, “How old is Madonna?” and you google it to find out she’s 62 (as of the creation of this resource), that’s research! You had a question (“how old is Madonna?”), you applied a search strategy (googling “Madonna age”) and you found an answer (62). That’s it! That’s all research has to be!

But it’s not all research can be. This example, like most research, is comprised of the same components we use in more complex situations. Those components are a question and an answer, inquiry and research, “how old is Madonna?” and “62.” But when we’re curious, we go back to the inquiry step again and ask more questions and seek more answers. We’re never really done, even when we’ve answered the initial question and written the paper and given the presentation and received accolades and awards for all our hard work. If it’s something we’re really curious about, we’ll keep asking and answering and asking again.

If you’re really curious about Madonna, you don’t just think, “How old is Madonna?” You think “How old is Madonna? Wait, really ? Her skin looks amazing! What’s her skincare routine? Seriously, what year was she born? Oh my god, she wrote children’s books! Does my library have any?” Your questions lead you to answers which, when you’re really interested in a topic, lead you to more and more questions. Humans are naturally curious ; we have this sort of instinct to be like, “huh, I wonder why that is?” and it’s propelled us to learn things and try things and fail and try again! It’s all research as inquiry.

And to satisfy your curiosity, yes, the library I currently work at does own one of Madonna’s children’s books. It’s called The Adventures of Abdi , and you can find it in our Juvenile Collection on the second floor at PZ8 M26 Adv 2004. And you can find a description of her skincare routine in this article from W Magazine: https://www.wmagazine.com/story/madonna-skin-care-routine-tips-mdna . You’re welcome.

Identifying an Information Need

One of the tricky parts of research as inquiry is determining a situation’s information need. It sounds simple to ask yourself, “What information do I need?” and sometimes we do it unconsciously. But it’s not always easy. Here are a few examples of information needs:

- You need to know what your niece’s favorite Paw Patrol character is so you can buy her a birthday present. Your research is texting your sister. She says, “Everest.” And now you’re done. You buy the present, you’re a rock star at the birthday party. Your information need was a short answer based on a three-year old’s opinion.

- You’re trying to convince someone on Twitter that Nazis are bad. You compile a list of opinion pieces from credible news publications like the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times , gather first-hand narratives of Holocaust survivors and victims of hate crimes, find articles that debunk eugenics, etc. Your information need isn’t scholarly publications, it’s accessible news and testimonials. It’s articles a person might actually read in their free time, articles that aren’t too long and don’t require access to scholarly materials that are sometimes behind paywalls.

- You need to write a literature review for an assignment, but you don’t know what a literature review is. So first you google “literature review example.” You find out what it is, how one is created, and maybe skim a few examples. Next, you move to your library’s website and search tool and try “oceanography literature review,” and find some closer examples. Finally, you start conducting research for your own literature review. Your information need here is both broader and deeper. You need to learn what a literature review is, how one is compiled, and how one searches for relevant scholarly articles in the resources available to you.

Sometimes it helps to break down big information needs into smaller ones. Take the last example, for instance: you need to write a literature review. What are the smaller parts?

- Information Need 1: Find out what a literature review is

- Information Need 2: Find out how people go about writing literature reviews

- Information Need 3: Find relevant articles on your topic for your own literature review

It feels better to break it into smaller bits and accomplish those one at a time. And it highlights an important part of this frame that’s surprisingly difficult to learn: ask questions. You can’t write a literature review if you don’t know what it is, so ask. You can’t write a literature review if you don’t know how to find articles, so ask. The quickest way to learn is to ask questions. Once you stop caring if you look stupid, and once you realized no one thinks poorly of people who ask questions, life gets a lot easier.

So, let’s add this to our components of research: ask a question, determine what you need in order to thoroughly answer the question, and seek out your answers. Not too painful, and when you’re in love with whatever you’re researching, it might even be fun.

- When you have a question, ask it.

- When you’re genuinely interested in something, keep asking questions and finding answers.

- When you have a task at hand, take a second to think realistically about the information you’ll need to accomplish that task. You don’t need a peer-reviewed article to find out if praying mantises eat their mates, but you might if you want to find out why.

- What’s the last thing you looked up on Wikipedia? Did you stop when you found an answer, or did you click on another link and another link until you learned about something completely different?

- If you can’t remember, try it now! Search for something (like a favorite book or tv show) and click on linked words and phrases within Wikipedia until you learn something new!

- What was the last thing you researched that you were really excited about? Do you struggle when teachers and professors tell you to “research something that interests you”? Instead, try asking yourself, “What makes me really angry?” You might find you have more interests than you realized!

Scholarship as Conversation

We’ve made it friends! My favorite frame: “ Scholarship as Conversation .” Is it weird to have a favorite frame of information literacy? Probably. Am I going to talk about it anyway? You betcha!

What does “Scholarship as Conversation” mean?

Scholarship as conversation refers to the way scholars reference each other and build off of one another’s work, just like in a conversation. Have you ever had a conversation that started when you asked someone what they did last weekend and ended with you telling a story about how someone (definitely not you) ruined the cake at your mom’s dog’s birthday party? And then someone says, “but like I was saying earlier…” and they take the conversation back to a point in the conversation where they were reminded of a different point or story? Conversations aren’t linear, they aren’t a clear line to a clear destination, and neither is research. When we respond to the ideas and thoughts of scholars, we’re responding to the scholars themselves and engaging them in conversation.

Why do I Love this Frame so Much?

Let me count the ways.

I really enjoy the imagery of scholarship as a conversation among peers. Just a bunch of well-informed curious people coming together to talk about something they all love and find interesting. I imagine people literally sitting around a big round table talking about things they’re all excited about and want to share with each other. It’s a really lovely image in my head. Eventually the image kind of reshapes and devolves into that painting of dogs playing poker, but I love that image too!

It harkens back to pre-internet scholarship, which sounds excruciating and exhausting, but it was all done for the love of a subject. Scholars used to literally mail each other manuscripts seeking feedback. Then, when they got an article published in a journal, scholars interested in the subject would seek out and read the article in the physical journal it was published in. Then they’d write reviews of the article, praising or criticizing the author’s research or theories or style. As the field grew, more and more people would write and contribute more articles to criticize and praise and build off of one another.

So, for example, if I wrote an article that was about Big Foot and then Joe wrote an article saying, “Emily’s article on Big Foot is garbage; here’s what I think about Big Foot,” Sam and I are now having a conversation. It’s not always a fun one, but we’re writing in response to one another about something we’re both passionate about. Later, Jaiden comes along and disagrees with Joe and agrees with me (because I’m right) and they cite both me and Joe. Now we’re all three in a conversation. And it just grows and grows and more people show up at the table to talk and contribute, or maybe just to listen.

Reason Three

You can roll up to the table and just listen if you want to. Sometimes we’re just listening to the conversation. We’re at the table, but we’re not there to talk. We’re just hoping to get some questions answered and learn from some people. When we’re reading books and articles or listening to podcasts or watching movies, we’re listening to the conversation. You don’t have to do groundbreaking research to be part of a conversation. You can just be there and appreciate what everyone’s talking about. You’re still there in the conversation.

Reason Four

You can contribute to the conversation at any time. The imagery of a conversation is nice because it’s approachable: just pull up a chair and start talking. With any new subject, you should probably listen a little at first, ask some questions, and then start giving your own opinion or theories, but you can contribute at any time. Since we do live in the age of internet research, we can contribute in ways people 50 years ago never dreamed of. Besides writing essays in class (which totally counts because you’re examining the conversation and pulling in the bits you like and citing them to give credit to other scholars), you can talk to your professors and friends about a topic, you can blog about it, you can write articles about it, you can even tweet about it (have you ever seen Humanities folk on Twitter? They go nuts on there having actual, literal scholarly conversations). Your ways for engaging are kind of endless!

Reason Five

Yep, I’m listing reasons.

Conversations are cyclical. Like I said above, they’re not always a straight path and that’s true of research too. You don’t have to engage with who spoke most recently; you can engage with someone who spoke ten years ago, someone who spoke 100 years ago, you can even respond to the person who started the conversation! Jump in wherever you want. And wherever you do jump in, you might just change the course of the conversation. Because sometimes we think we have an answer, but then something new is discovered or a person who hadn’t been at the table or who had been overlooked says something that drastically impacts what we knew, so now we have to reexamine it all over again and continue the conversation in a trajectory we hadn’t realized was available before.

Lastly, this frame is about sharing and responding and valuing one another’s work. If Joe, my Big Foot nemesis, responds to my article, they’re going to cite me. If Jaiden then publishes a rebuttal, they’re going to cite both Joe and me, because fair is fair. This is for a few reasons: 1) even if Jaiden disagrees with Joe’s work, they respect that Joe put effort into it and it’s valuable to them. 2) When Jaiden cites Joe, it means anyone who jumps into the conversation at the point of Jaiden’s article will be able to backtrack and catch up using Jaiden’s citations. A newcomer can trace it back to Joe’s article and trace that back to mine. They can basically see a transcript of the whole conversation so they can read Jaiden’s article with all of the context, and they can write their own well-informed piece on Big Foot.

There’s a lot to take away from this frame, but here’s what I think is most important:

- Be respectful of other scholars’ work and their part in the conversation by citing them.

- Start talking whenever you feel ready, in whatever platform you feel comfortable.

- Make sure everyone who wants to be at the table is at the table. This means making sure information is available to those who want to listen and making sure we lift up the voices that are at risk of being drowned out.

- What scholarly conversations have you participated in recently? Is there a Reddit forum you look in on periodically to learn what’s new in the world of cats wearing hats? Or a Facebook group on roller skating? Do you contribute or just listen?

- Think of a scholarly conversation surrounding a topic—sharks, ballet, Game of Thrones. Who’s not at the table? Whose voice is missing from the conversation? Why do you think that is?

Searching as Strategic Exploration

You’ve made it! We’ve reached the last frame: Searching as Strategic Exploration .

“Searching as Strategic Exploration” addresses the part of information literacy that we think of as “Research.” It deals with the actual task of searching for information, and the word “Exploration” is a really good word choice, because it’s evocative of the kind of struggle we sometimes feel when we approach research. I imagine people exploring a jungle, facing obstacles and navigating an uncertain path towards an ultimate goal (Note: the goal is love and it was inside of us all along). I also kind of imagine all the different Northwest Passage explorations, which were cool in theory, but didn’t super-duper work out as expected.

But research is like that! Sometimes we don’t get where we thought we were headed. But the good news is this: You probably won’t die from exposure or resort to cannibalism in your research. Fun, right?

Step 1: Identify a Goal

The first part of any good exploration is identifying a goal. Maybe it’s a direct passage to Asia or the diamond the old lady threw into the ocean at the end of Titanic. More likely, the goal is to satisfy an information need. Remember when we talked about “Research as Inquiry?” All that stuff about paw patrol and Madonna’s skin care regimen? Those were examples of information needs. We’re just trying to find an answer or learn something new.

So great! Our goal is to learn something new. Now we make a strategy.

Step 2: Make a Strategy

For many of your information needs you might just need to Google a question. There’s your strategy: throw your question into Google and comb through the results. You might limit your search to just websites ending in .org, .gov, or .edu. You might also take it a step further and, rather than type in an entire question fully formed, you just type in keywords. So “Who is the guy who invented mayonnaise?” becomes “mayonnaise inventor.” Identifying keywords is part of your strategy and so is using a search engine and limiting the results you’re interested in.

Step 3: Start Exploring

Googling “mayonnaise inventor” probably brings you to Wikipedia where we often learn that our goals don’t have a single, clearly defined answer. For example, we learn that mayonnaise might have gotten its name after the French won a battle in Port Mahon, but that doesn’t tell us who actually made the mayonnaise, just when it was named. Prior to being named, the sauce was called “aioli bo” and was apparently in a Menorcan recipe book from 1745 by Juan de Altimiras. That’s great for Altimiras, but the most likely answer is that mayonnaise was invented way before him and he just had the foresight to write down the recipe. Not having a single definite answer is an unforeseen obstacle tossed into our path that now affects our strategy. We know we have a trickier question than when we first set sail.

But we have a lot to work with! We now have more keywords like “Port Mahon,” “the French,” and Wikipedia taught us that the earliest known mention of “mayonnaise” was in 1804, so we have “1804” as a keyword too.

Let’s see if we can find that original mention. Let’s take our keywords out of Wikipedia where we found them and voyage to a library’s website! At my library we have a tool that searches through all of our resources. We call it the “Quick Search.” You might have a library available to you, either at school, on a university’s campus, or a local public library. You can do research in any of these places!

So into the Quick Search tool (or whatever you have available to you) go our keywords: “1804,” “mayonnaise,” and “France.” The first result I see is an e-book by a guy who traveled to Paris in 1804, so that might be what we’re looking for. I search through the text and I do, in fact, find a reference to mayonnaise on page 99! The author (August von Kotzebue) is talking about how it’s hard to understand menus at French restaurants, for “What foreigner, for instance, would at first know what is meant by a mayonnaise de poulet, a galatine de volaille, a cotelette a la minute, or even an epigramme d’agneau?” He then goes on to recommend just ordering the fish, since you’ll know what you’ll get (Kotzebue 99).

So that doesn’t tell us who invented mayonnaise, but I think it’s pretty funny! So I’d call that detour a win.

Step 4: Reevaluate

When we hit ends that we don’t think are successful, we can always retrace our steps and reevaluate our question. Dead ends are a part of exploration! We’ve learned a lot, but we’ve also learned that maybe “who invented mayonnaise?” isn’t the right question. Maybe we should ask questions about the evolution of French cuisine or about ownership of culinary experimentation.

I’m going to stick with the history of mayonnaise, for just a little while longer, but my “1804 mayonnaise France” search wasn’t as helpful as I’d hoped, so I’ll try something new. Let’s try looking at encyclopedias.

I searched in a database called Credo Reference (which is a database filled with encyclopedia entries) and just searching “mayonnaise.” I can see that the first entry, “Minorca or Menorca” from The Companion to British History , doesn’t initially look helpful, but we’re exploring, so let’s click on it. It tells us that mayonnaise was invented in 1756 by a French commander’s cook and its name comes from Port Mahon where the French fended off the British during a siege ( Arnold-Baker, 2001 ). That’s awesome! It’s what Wikipedia told us! But let’s corroborate that fact. I click on The Hutchinson Chronology of World History entry for 1756, which says mayonnaise was invented in France in 1756 by the duc de Richelieu ( Helicon, 2018 ). I’m not sure I buy it. I could see a duke’s cook inventing mayonnaise, but I have a hard time imagining a duke and military commander taking the time to create a condiment.

But now I can go on to research the duc de Richelieu and his military campaigns and his culinary successes. Just typing “Duke de Richelieu” into the library’s Quick Search shows me a TON of books (16,742 as of writing this) on his life and he influence on France. So maybe now we’re actually exploring Richelieu or the intertwined history of French cuisine and the lives of nobility.

What Did We Just Do?

Our strategy for exploring this topic has had a lot of steps, but they weren’t random. It was a wild ride, but it was a strategic one. Let’s break the steps down real quick:

- We asked a question or identified a goal

- We identified keywords and googled them

- We learned some background information and got new keywords from Wikipedia and had to reevaluate our question

- We followed a lead to a book but hit a dead end when it wasn’t as useful as we’d hoped

- We identified an encyclopedia database and found several entries that support the theory we learned in Wikipedia, which forced us to reevaluate our question again

- We identified a key player in our topic and searched for him in the library’s Quick Search tool and the resources we found made us reevaluate our question yet again

Other strategies could include looking through an article’s reference list, working through a mind map , outlining your questions, or recording your steps in a research log so you don’t get lost—whatever works for you!

Exploration is tricky. Sometimes you circle back and ask different questions as new obstacles arise. Sometimes you have a clear path and you reach your goal instantly. But you can always retrace your steps, try new routes, discover new information, and maybe you’ll get to your destination in the end. Even if you don’t, you’ve learned something.

For instance, today we learned that if you can’t understand a menu in French, you should just order the fish.

- Where do you start a search for information? Do you start in different places when you have different information needs?

- If your research question was “What is the impact of fast fashion on carbon emissions?” What keywords would you use to start searching?

The Framework for Information Literacy in Higher Education is one heck of a document. It’s complicated, its frames intertwine, it’s written in a way that can be tricky to understand. But essentially, it’s just trying to get us to understand that the ways we interact with information are complicated and we need to think about our interactions to make sure we’re behaving in an ethical and responsible way.

Why do your professors make you cite things? Because those citations are valuable to the original author, and they prove your engagement with the scholarly conversation. Why do we need to hold space in the conversation for voices that we haven’t heard from before? Because maybe no one recognized the authority in those voices before. The old process for creating information shut out lots of voices while prioritizing others. It’s important for us to recognize these nuances when we see what information is available to us and important for us to ask, “Whose voice isn’t here? Why? Am I looking hard enough for those voices? Can I help amplify them?” And it’s important for us to ask, “Why is the loudest voice being so loud? What motivates them? Why should I trust them over others?”

When we think critically about the information we access and the information we create and share, we’re engaging as citizens in one big global conversation. Making sure voices are heard, including your own voice, is what moves us all towards a more intelligent and understanding society.

Of course, part of thinking critically about information means thinking critically about both this guide and the framework. Lots of people have criticized the framework for including too much library jargon. Other folks think the framework needs to be rewritten to explicitly address how information seeking systems and publishing platforms have arisen from racist, sexist institutions. We won’t get into the criticisms here, but they’re important to think about. You can learn more about the criticism of the framework in a blog post by Ian Beilin , or you can do your own search for criticism on the framework to see what else is out there and form your own opinions.

The Final Takeaway

Ask questions, find information, and ask questions about that information.

Attributions

“A Beginner’s Guide to Introduction to Information Literacy” by Emily Metcalf is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA

Writing Arguments in STEM Copyright © by Jason Peters; Jennifer Bates; Erin Martin-Elston; Sadie Johann; Rebekah Maples; Anne Regan; and Morgan White is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Feedback/errata.

Comments are closed.

Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

Information Literacy: Concepts and Teaching Strategies

Are your students drowning in information? Can they spot misinformation and "fake news?" With a plethora of information available at their fingertips, information literacy skills have never been more critical.

You have likely heard of information literacy but may be unsure how to define it. You may have questions such as: Is information literacy important for my students? What learning bottlenecks might students experience related to information literacy? How can I effectively help my students to develop their information literacy?

This guide defines information literacy, outlines core information literacy concepts, identifies common information literacy-related challenges that students may face, and provides teaching strategies and activities aimed at helping you to incorporate information literacy into your courses.

Defining Information Literacy

The term information literacy has been used for over 40 years, with various definitions proposed during this period. In 2016, the Association of College & Research Libraries (ACRL) published the Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education and included the following definition:

Information literacy is the set of integrated abilities encompassing the reflective discovery of information, the understanding of how information is produced and valued, and the use of information in creating new knowledge and participating ethically in communities of learning.

In other words, information literacy involves an understanding of how information is created, accessed, shared, and valued and the abilities and mindset necessary to be able to locate, evaluate, use, and create information sources ethically and effectively .

Information literacy includes:

Conceptual understandings , such as a recognition of how and why information has value or what makes a source authoritative

Habits of mind , or dispositions such as persistence and flexibility when searching

Skills or practices , such as the ability to effectively use a database

As you review the teaching strategies, remember that a single assignment or instruction session cannot fully teach students to become information literate. You are not expected to teach every information literacy concept or skill in one course. However, you can take steps in almost any course to support students' developing information literacy, even if the course does not include a traditional research paper.

Core Information Literacy Concepts

The Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education (Association of College & Research Libraries, 2016) highlights six core information literacy concepts:

- Authority is Constructed and Contextual

- Information Creation as a Process

- Information Has Value

- Research as Inquiry

- Scholarship as Conversation

- Searching as Strategic Exploration

These core concepts describe understandings about the purpose and process of research and scholarship broadly shared among scholars, but that novice learners may not yet fully grasp. However, without understanding these concepts, many common academic or professional research practices may not make sense. Each core concept is briefly described below.

Expert researchers understand that information sources have different levels of authority or credibility, and authority is related to the expertise or credibility of the information creator . Many factors contribute to expertise, including education, experience, and social position. However, having expertise in one area does not imply expertise in others.

Experts also recognize the context in which information is needed, and will be used, can impact the level of authority needed or what would be considered authoritative. An information source that may be appropriate to use in one situation may not be considered authoritative in another situation.

Students who grasp this concept can examine information sources and ask relevant questions about origins, context, and suitability for the information need to identify credible and relevant information sources in multiple contexts. (ACRL, 2016)

For additional information view the Authority is Constructed and Contextual video.

Experts know that information products are created by different processes and come in many formats , which reflect the differences in the creation process . Some information formats may be better suited for conveying certain types of information or meeting specific information needs. Understanding how and why an information product was created can help to determine how that information can be used. Experts recognize that the creation process for an information source and the format can influence that source's actual or perceived value.

Understanding different formats of information and the related creation processes can help students determine when and how to use a specific information source and help them make informed decisions regarding the appropriate format(s) for their own information creations. (ACRL, 2016)

For additional information view the Information Creation as a Process video.

Experts know that information has many types of value (financial, personal, social). Because information is valuable, several factors (political, economic, legal) influence the creation, access, distribution, and use of information. Novice learners may struggle to understand the value of information, especially as nearly all information appears to be available for free online.

Experts, however, understand their responsibilities as information consumers and creators, including making deliberate choices about how they access and share information and when to comply with—or when to contest—current legal and socioeconomic restrictions on information. Additionally, experts recognize that not everyone has equal access to information or the equal ability to make their voice heard.

Understanding this concept will help students make sense of the legal and ethical guidelines surrounding information (and the reasons they exist) and make informed decisions both as information consumers and as information creators. (ACRL, 2016)

For additional information view the Information Has Value video.

Experts usually consider research a process focused on problems or questions, within or between disciplines, which are unanswered or unresolved and recognize research as part of an ongoing and collaborative effort to extend knowledge . They understand research is rarely a simple, straightforward search for one "perfect" answer or source; instead, it is an iterative, open-ended, and messy process in which finding answers often lead to new questions. Expert researchers accept ambiguity as part of the research process and recognize the need for adaptability and flexibility when they search.

Understanding this concept will help students recognize that research requires patience, persistence, and flexibility and will prepare them to make sense of the ambiguous nature of their search results rather than seeking a single "right" answer . (ACRL, 2016)

For additional information view the Research as Inquiry video.

Scholars, researchers, and professionals within a field engage in ongoing discussions where new ideas and research findings are continually debated . In most cases, there are often multiple competing perspectives on a topic. Experts can locate, navigate, and contribute to the conversations within their discipline or field. They recognize that providing appropriate attribution to relevant previous research is considered an obligation of participating in this conversation. As they develop their information literacy, students should learn to see themselves as contributors to these conversations. However, they may first need to learn the "language" of the discipline, such as accepted research methods, standards for evidence, and forms of attribution, before they can fully participate.

Understanding this concept will help students better evaluate the relevance of specific information sources, to make sense of many of the requirements of scholarly practice, and better understand the expectations around their own role in the conversation . (ACRL, 2016)

For additional information view the Scholarship as Conversation video.

Searching for information is often nonlinear and iterative , requiring evaluating a range of information sources and the mental flexibility to pursue alternate directions. The information searching process is a complex process influenced by cognitive, affective, and social factors. While novice learners may only use a limited number of search tools and strategies, experts understand the properties of various information search systems and make informed choices when determining search strategy and search language. Expert searchers shape their search to fit the information need, rather than relying on the same strategies, search systems, and search language without regard for the context of the search.

Students who understand this concept will be able to make appropriate decisions about where and how they search for information in different contexts . (ACRL, 2016)

For additional information view the Searching as Strategic Exploration video.

Information Literacy Learning Bottlenecks

Bottlenecks are where some students in a course may struggle, get stuck, be unable to complete required tasks, or move forward in their learning ( Decoding the Disciplines ; Middendorf & Baer, 2019 ). Information literacy-related bottlenecks can come in many forms. Some of the most common are outlined below and emphasize core concepts.

Research or inquiry-based assignments are those in which students are required to find, analyze, and use various information sources to explore an issue, answer a question, or solve a problem. Although they are common assignments, they can be sources of frustration for both you and your students.

You are likely expecting students to:

- Approach research as an open-ended and inquiry-driven process (Research as Inquiry)

- Be an active participant (provide an argument, make an interpretation) in the ongoing conversations related to their topic (Scholarship as Conversation)

However, these expectations may be unfamiliar to students who are more accustomed to the idea of research as a process of compiling and summarizing information on a topic. Additionally, effectively completing research assignments requires a wide range of knowledge and skills that novice learners may not yet have developed.

Students who can effectively complete these assignments :

- Are familiar with academic jargon (e.g., scholarly journal, literature review) and understand the meaning of the various actions often required as part of these assignments (e.g., analyze, illustrate, interpret)

- Can distinguish between expectations for different types of research or inquiry-based assignments (i.e., can recognize the different goals of an empirical research paper, a literature review, or an annotated bibliography)

- Can formulate research questions by considering missing or conflicting information from the existing conversation

- Possess the necessary background knowledge or disciplinary knowledge that allows them to navigate ongoing scholarly or professional conversations related to their topic

- Think of themselves as capable of contributing to academic or professional conversations

Related core concepts

- Research as Inquiry

- Scholarship as Conversation

Related teaching strategies

- Clarifying Expectations for Research Assignments

With so many different search tools and resources available, determining where to search for information and executing an effective search can be difficult. Identifying an appropriate search tool, crafting an effective search statement, and using initial results to guide search revisions takes significant knowledge of the properties and functions of various search tools.

Effective searching also requires students to understand the complex nature of the search process. Novice learners may, for example, approach searching as a linear process intended to find a specific number of sources as quickly as possible, rather than a strategic and complicated process for finding relevant information ( Middendorf & Baer, 2019 ).

Students who can search effectively:

- Understand how various information system, such as search engines and databases, are organized and function

- Determine when to use a search engine or a more specialized or academic database or search resource

- Are familiar with the databases or search tools that are most relevant for their specific discipline or information need

- Use different types of search language and search options as needed

- Revise their search strategy as needed, based on initial results, and seek assistance from information professionals

- Demonstrate flexibility and persistence, and understand that initial attempts do not always produce adequate results

Related core concepts

- Searching as Strategic Exploration

Related teaching strategies

- Teaching Information Searching

Evaluating information to identify credible sources that are relevant to their topic or research question and are appropriate for their information need is one of the most difficult challenges students face. It requires significant knowledge of various types of information sources and their characteristics, the processes by which information sources are produced and disseminated, the factors that provide or temper authority or credibility, and an understanding of how context can impact these other factors.

Students who can evaluate information effectively:

- Are motivated to find credible and relevant information sources ; m aintain an open mind when considering information from multiple perspectives

- Can identify/distinguish different types (e.g., journal articles, news articles, book chapters, blog posts) and categories (e.g., scholarly, popular, professional) of information sources

- Can define different types of authority, such as subject expertise (e.g., scholarship), societal position (e.g., public office or title), or special experience (e.g., participating in a historic event)

- Understand how the creation processes for various information sources can impact the way the source may be valued

- Assess information with a critical stance

- Use indicators of authority to help determine the credibility of sources while recognizing the factors that can temper authority

- Have an awareness of how their own worldview may impact how they perceive information

- Recognize that information sources may be perceived or valued differently depending on the context

- Authority is Constructed and Contextual

- Information Creation as a Process

- Teaching Source Evaluation

Using information sources ethically is one of the most crucial habits that students need to develop, but it can also be one of the most challenging that students face. More than being able to master the basics of citations, students need to understand why information is valuable and learn to navigate the complex rules, regulations, and expectations around information use.

Students who use information ethically:

- Recognize the various ways in which information can be valuable (e.g. financial, political, personal)

- Demonstrate respect for the time, effort, and skill needed to create knowledge; give credit to the ideas of others through appropriate attribution

- Demonstrate understanding of and the ability to use of the methods of attribution that are appropriate to their discipline or field

- Are familiar with concepts such as intellectual property, copyright, fair use, plagiarism, the public domain, and open access

- Critically consider what personal information they share online and make careful decisions about how they publish or share their own information products

- Understand that everyone does not have equal access to information or the equal ability to share information

- Recognize how citations are used as part of ongoing scholarly or professional conversations

- Information Has Value

- Teaching Ethical Information Use

Leverage Library Resources

Instructor Resources at University Libraries provides guidance on incorporating library resources to support student learning in your course. Explore topics such as information literacy, academic research skills, and affordable course content, and access “ready-to-share” instructional materials including videos, Carmen content, and handouts.

Teaching Strategies and Activities

Information literacy cannot be taught in a single instruction session or even a single course. Instead, it develops throughout a student's academic career. No instructor is expected to incorporate all the core information literacy concepts or address every potential learning bottleneck in a single course. However, there are many small steps that you can take to support students' developing information literacy.

The following approaches provide an overview of some helpful strategies that you can use to help your students overcome information literacy-related learning bottlenecks.

You can take several steps as you (re)design your research or inquiry-based assignments to support increased student learning and reduce the misunderstandings that are common between students and instructors.

- List all of the steps that students will need to take to complete the assignment. You may be surprised at how many there actually are! This can help you to identify steps that may be challenging for students but you may have initially overlooked because of your own familiarity with the research process.

- Identify the core concepts, such as Scholarship as Conversation or Research as Inquiry , that may be behind your expectations for the assignment.

- Question your purpose for including certain requirements, such as requiring a specific citation style or that students use specific types of sources. What are your requirements contributing to student learning in the course?

- Discuss the purpose of academic research and the goals of your specific research assignment with students.

- Define any academic jargon (such as "scholarly" or "peer-reviewed") and your action words (analyze, trace, illustrate).

- Clarify the distinctions between different types of research or inquiry-based assignments, such as the difference between a literature review and an annotated bibliography.

- Describe the types of sources that you consider to be appropriate or inappropriate for the assignment and explain why.

- Be sure that any requirements you have for sources align with the purpose and context of the assignment. For example, be careful not to expect students to use scholarly sources for topics where scholarly research may not exist.

- Provide step-by-step instructions and model the steps of the research process.

- Scaffold large research assignments by breaking them down into more manageable chunks and providing feedback after each part.

- Have a colleague or student review your assignment instructions, note anything that seems unclear, and highlight any jargon that may need to be explained. This can be even more helpful if it is a colleague outside of your discipline.

Sample Activity

Have students complete a quick activity in which they a nalyze the assignment instructions. Have them:

- Summarize what they must do

- Identify any unclear terms

- Highlight key requirements

- Discuss their responses together to identify any initial misconceptions about the purpose or process for the assignment

There are many things you can do to help students become more adept at information searching:

- Identify the core concepts, such as Searching as Strategic Exploration , Research as Inquiry , and Information Creation as a Process , that may be contributing to students challenges with information searching

- The difference between a search engine and a database, and when it is appropriate to use one or the other

- The databases or search tools that are most commonly used in the discipline

- How to create an effective search statement or use databases options and limiters (advanced search, Boolean operators); how to revise a search when needed

- Recommend specific search tools. With so many tools available, including hundreds of research databases available through University Libraries, students may need guidance for where to go to start their search.

- Recommend that students use the Subject Guides available through University Libraries to identify relevant search tools and resources.

- Provide analogies or examples to help students enhance their understanding of the search process ( Middendorf & Baer, 2019).

- Model the search process by showing how you would go about searching for information on a topic or question relevant to the course.

- Build reflection on or discussion of the search process into the assignment.

As part of a research assignment, have students complete an outline or screencast video in which they describe or demonstrate how they would go about searching for information on their topic and use the results to guide a discussion of effective search strategies.

For an example of how you can address bottlenecks related to information searching, see:

- Middendorf, J., & Baer, A., (2019). Bottlenecks of Information Literacy . In C. Gibson & S. Mader (Eds.), Building Teaching and Learning Communities: Creating Shared Meaning and Purpose , pp. 51-68

To help students with source evaluation, steps you can take include:

- Identify the core concepts, such as Authority is Constructed and Contextual or Information Creation as a Process , that may be contributing to challenges students experience when evaluating information

- The various factors that contribute to, or temper, source authority or credibility (many students have erroneously been taught to use surface factors, such as domain name or the look of the site, to make decisions about source credibility)

- How to differentiate between types (e.g. news articles, websites, scholarly journal articles, social media sources) and categories of information sources (scholarly, professional, popular)

- The role context plays in determining the authority needed

- The types of information sources that are considered authoritative or credible in your field

- Consider why you might require specific types of sources. If students can or cannot use specific sources types, is there a clear reason why?

- Clearly outline your expectations for appropriate sources for your assignments and explain your reasons for these requirements

- Clarify the distinction between terms such as credible, relevant, and scholarly

- Model the process that you take to determine whether or not you find a source to be credible and appropriate

- Provide evaluation criteria and outline steps that students can take or questions they need to consider as part of the source evaluation process

- The domain name (.com, .edu)

- The professionalism of the site

- The information provided in the About Us page

- Encourage students to consider factors such as the authority of the author or publisher, motivation for publishing the source, relevance of the source to the research question or topic, and the appropriateness of the source for the context

- Encourage your students to practice lateral reading, where they read across multiple sites as part of the source evaluation process—for example, searching for the author or publisher or site sponsor via a search engine to learn more about them rather than remaining on the same site. For more information, see What Reading Laterally Means (Caulfield, 2017).

- After receiving instructions for a research assignment, have students work together to develop class guidelines for evaluating sources, with recommendations for the types of sources that would or would not be considered appropriate to use

Other resources to support lateral reading include:

- Teaching Lateral Reading (Civic Online Reasoning)

- Evaluating Online Sources: A Toolkit (Baer & Kipnis, Rowan University)

- Lateral Reading (University of Louisville Libraries)

- Identify the core concepts, such as Information Has Value or Scholarship as Conversation , that may be contributing to challenges students experience when using information ethically

- The expectations for when and why attribution is required in academic research

- The expectations for attribution in your discipline or field

- Locating the information needed to include in a citation

- Reading a citation to identify relevant information

- The distinctions between plagiarism and copyright infringement

- Consider your purpose for requiring a specific citation style. While there can be good reasons for insisting on specific styles, doing so can also create an unnecessary burden, especially for students outside of your discipline.

- Identify the key aspect(s) of the citation process that you want to emphasize when it comes to grading (i.e. is it more important that students have the citation format perfect, or that they are using their sources effectively?)

- Provide resources, such as the University Libraries' Citation Help Guide , to help students develop their citation skills, especially if requiring a discipline-specific citation style

- Practice "reading" citations with your students—many students may struggle to identify the different parts of a citation

- Teach students to use sources/citations to locate additional citations (forward and backward citation tracing)

- Talk with your students about the ways that scholars and researchers use sources and citations to document and engage with the conversation(s) on their topic and establish their own credibility. Emphasize citation as part of the process of engaging in scholarly and professional conversations.

Provide students with a relevant sample article from which all citations have been removed or redacted. Discuss how the lack of citations contributes to their ability to evaluate the article's credibility and use the article effectively to answer a question or learn more about the topic.

Comparing Search Tools Activity

Evaluating sources using lateral reading, interpreting a research or inquiry-based activity.

- Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education (website)

- Choosing & Using Sources: A Guide to Academic Research (e-book)

- Choosing & Using Sources: Instructor Resources (e-book)

- Transforming information literacy instruction: Threshold concepts in theory and…

- University Libraries Information Literacy Virtual Workshop Series (videos)

- University Libraries Subject Guides (website)

- University Libraries Subject Librarians (website)

Learning Opportunities

Association of College & Research Libraries. (2016). Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework .

Baer, A., & Kipnis, D. (2020). Evaluating Online Sources: A Toolkit. https://libguides.rowan.edu/EvaluatingOnlineSources .

Caulfield, M. (2017). Web Literacy for Student Fact-Checkers . Pressbooks.

Stanford University. (n.d.) Civic Online Reasoning. https://cor.stanford.edu/curriculum/collections/teaching-lateral-reading/ .

Decoding the Discipline. (n.d.) http://decodingthedisciplines.org/ .

Middendorf, J., & Baer, A., (2019). Bottlenecks of Information Literacy . In C. Gibson & S. Mader (Eds.), Building Teaching and Learning Communities: Creating Shared Meaning and Purpose , pp. 51-68.

Ohio State University Libraries.(n.d.) Citation Help. Retrieved from https://guides.osu.edu/citation .

TILT Higher Ed. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://tilthighered.com/ .

Related Teaching Topics

Supporting student learning and metacognition, designing research or inquiry-based assignments, search for resources.

Classroom Q&A

With larry ferlazzo.

In this EdWeek blog, an experiment in knowledge-gathering, Ferlazzo will address readers’ questions on classroom management, ELL instruction, lesson planning, and other issues facing teachers. Send your questions to [email protected]. Read more from this blog.

Ways to Strengthen Students’ Information-Literacy Skills

- Share article

(This is the final post in a two-part series. You can see Part One here .)

The new question-of-the-week is:

What are the best ways teachers can help students combat “fake news” and develop information-literacy skills?

In Part One, we heard responses from Carla Truttman, Josh Perlman, Jennifer Casa-Todd, Bryan Goodwin, and Frank W. Baker.

Today, this series will finish up with suggestions from Elliott Rebhun, Michael Fisher, Dr. Barbara R. Blackburn, Dr. Laura Greenstein, and Douglas Reeves. I also include comments from readers.

Response From Elliott Rebhun

Elliott Rebhun is the editor-in-chief of Scholastic’s Classroom Magazine Group. He started at Scholastic in 2003 as the editor of The New York Times UPFRONT®, the company’s high school social studies news magazine. Prior to Scholastic, he worked at The Times, both in print and digital, and at Newsweek . He has a B.A. from the College of Arts and Sciences and a B.S. from the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania:

Media literacy has become a focus of instruction nationwide, and while teaching our students that staying informed is important, we also have a responsibility to make sure that kids know how and where to obtain accurate, unbiased information and think critically about that information. P-12 teachers find themselves addressing this daily as they share with their students the skills needed to problem solve and empathize when thinking about issues within our global society, as well as to discern whether the information they obtain is factual or fictional.

Teachers may ask themselves what they can do to weave media literacy into their daily classroom instruction so that students learn how to seek credible information. Students should know the value of reading the news, and facilitating regular classroom discussions about current events is a wonderful way to enhance the culture of literacy within a classroom. News articles written specifically for students across different grade levels and free online resources with civics and media-literacy content such as We the People provide a context for talking about current events and media literacy as an important part of citizenry.

We should also encourage students to seek information on topics of interest, providing kids with opportunities to learn about the world around them and engage in their communities. As part of this, it’s important for educators to explain to their students what fake news is and demonstrate how they should responsibly analyze facts and interpret news to discern what is true and what is false. We cover this topic extensively in Scholastic Classroom Magazines across genres, including news, science, and health. To start, there are four simple strategies that educators of all grade levels can utilize to help their students become conscious and thoughtful consumers of news.

- Be critical. You can’t trust all of the content that you find online, even when someone you know sends it to you. It’s important to think critically about what you read on the internet.

- Search for indicators. Analyze the sources that a news piece cites and be observant of advertisements that can reveal a lot about any hidden goals of an outlet.

- Corroborate. Spend time doing research of your own. Make sure that the source is credible and see if you can verify other sources of the same news.

- Check to be sure. Nonpartisan fact-checking sites such as Factcheck.org and Politifact.com are tools that can help you verify what is true and uncover what is false.

Media-literacy lessons are valuable for students across grade levels, and age-appropriate news content is a wonderful resource to begin these conversations in classrooms. It’s never too late to make media literacy a priority so that our students become good citizens who are knowledgeable, who participate in society, and who work to make it better, because the future belongs to them, and they deserve a great one.

Response From Michael Fisher

Michael Fisher is a former teacher who is now a full-time author and instructional coach. He works with schools around the country, helping to sustain curriculum upgrades, design curriculum, and modernize instruction in immersive technology. His latest book is The Quest for Learning: How to Maximize Student Engagement , published by Solution Tree. For more information, visit The Digigogy Collaborative ( digigogy.com ) or find Michael on Twitter ( @fisher1000 ):

In our book, The Quest for Learning , Marie Alcock, Allison Zmuda, and I discuss concerns with working so openly on the web with networks, resources, and multimedia. We use the acronym VIA to think about information literacy and source validity. The V in VIA stands for “Verifiable Details.” The I stands for “Intuition,” and the A stands for “Authoritative Connection.”

Verifiable Details: Students should get into the habit of comparing resources and corroborating information. For instance, it’s interesting to look at how different news sources handle breaking news. Students can look for similarities in the different sources to determine what information is the most believable. Students can use tools like NewsPaperMap.com to see news sources from all over the world. This gives them the opportunity to look at other countries’ perspectives on the news that our domestic sources are reporting on. They should also be noticing whether or not the sources have links to additional information, references for their claims, citations, and quotes from verifiable sources.

Intuition : If a source sounds salacious or outlandish or too good to be true—then it probably isn’t true. Beyond verifiable details, students should also learn to go with their gut—if a resource seems to be off or misleading, then it probably is. If the resource is demonstratively different from other sources on the same topic, then it is likely questionable. If the source was paid for by a special-interest group, then that might also be a red flag.

Authoritative Connection: What is the affiliation of the creator of the source? What is the parent source of the material? Students should be able to recognize known credible sources. They should also know something about the author that is creating material that is shared online and in print. Does the author have knowledge of the subject matter or topic? What else has the author written or experienced around the topic? Does the author or the parent source have any dubious actions in their background? What is the domain of the source? If it ends in an unfamiliar domain like .biz, .coop, .info, or .club, then the authoritative connection may be thin or nonexistent.

Trustworthy work comes from critical thinking VIA students’ thinking about validity and truth. Students need these cues to prevent them from “researching” and reporting on whatever the first five results in a Google search are.

Also, students could benefit from learning how to use Snopes.com or websites like Politifact to verify the claims that an entity or author might make.

Response From Dr. Barbara R. Blackburn