Race in America

A Smithsonian magazine special report

History | June 4, 2020

158 Resources to Understand Racism in America

These articles, videos, podcasts and websites from the Smithsonian chronicle the history of anti-black violence and inequality in the United States

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/51/45/5145a77b-1b5b-45eb-a293-8dc149061a8c/talking_about_race_mobile.png)

Meilan Solly

Associate Editor, History

In a short essay published earlier this week, Smithsonian Secretary Lonnie G. Bunch wrote that the recent killing in Minnesota of George Floyd has forced the country to “confront the reality that, despite gains made in the past 50 years, we are still a nation riven by inequality and racial division.”

Amid escalating clashes between protesters and police, discussing race—from the inequity embedded in American institutions to the United States’ long, painful history of anti-black violence—is an essential step in sparking meaningful societal change. To support those struggling to begin these difficult conversations, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture recently launched a “ Talking About Race ” portal featuring “tools and guidance” for educators, parents, caregivers and other people committed to equity.

“Talking About Race” joins a vast trove of resources from the Smithsonian Institution dedicated to understanding what Bunch describes as America’s “tortured racial past.” From Smithsonian magazine articles on slavery’s Trail of Tears and the disturbing resilience of scientific racism to the National Museum of American History’s collection of Black History Month resources for educators and a Sidedoor podcast on the Tulsa Race Massacre, these 158 resources are designed to foster an equal society, encourage commitment to unbiased choices and promote antiracism in all aspects of life. Listings are bolded and organized by category.

Table of Contents

1. Historical Context

2. Systemic Inequality

3. Anti-Black Violence

5. Intersectionality

6. Allyship and Education

Historical Context

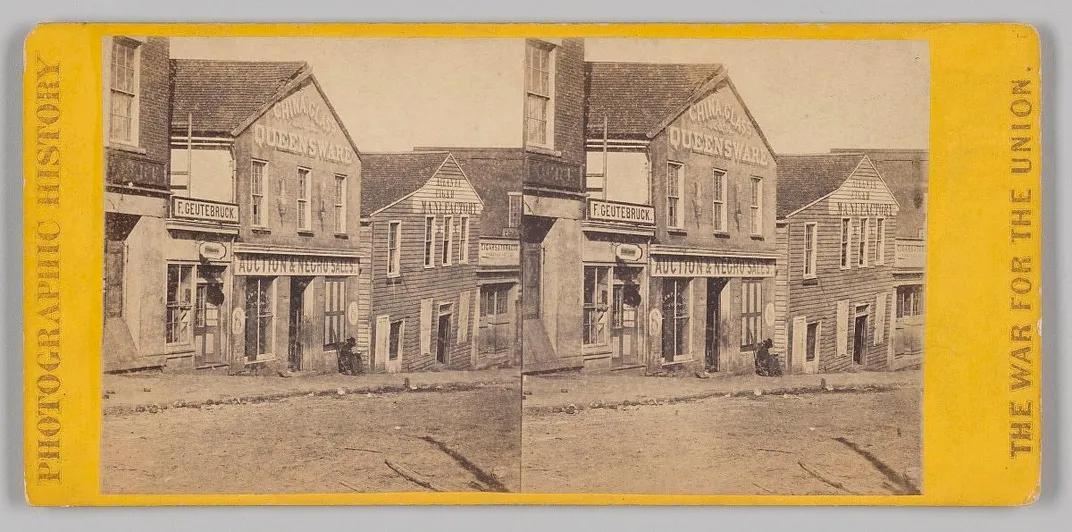

Between 1525 and 1866, 12.5 million people were kidnapped from Africa and sent to the Americas through the transatlantic slave trade . Only 10.7 million survived the harrowing two month journey. Comprehending the sheer scale of this forced migration—and slavery’s subsequent spread across the country via interregional trade —can be a daunting task, but as historian Leslie Harris told Smithsonian ’s Amy Crawford earlier this year, framing “these big concepts in terms of individual lives … can [help you] better understand what these things mean.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/93/17/9317bc68-84d5-4342-8809-e5c2e8c8c6d7/nmaahc-jn2012-1181-000001.jpg)

Take, for instance, the story of John Casor . Originally an indentured servant of African descent, Casor lost a 1654 or 1655 court case convened to determine whether his contract had lapsed. He became the first individual declared a slave for life in the United States. Manuel Vidau , a Yoruba man who was captured and sold to traders some 200 years after Casor’s enslavement, later shared an account of his life with the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, which documented his remarkable story—after a decade of enslavement in Cuba, he purchased a share in a lottery ticket and won enough money to buy his freedom—in records now available on the digital database “ Freedom Narratives .” (A separate, similarly document-based online resource emphasizes individuals described in fugitive slave ads , which historian Joshua Rothman describes as “sort of a little biography” providing insights on their subjects’ appearance and attire.)

Finally, consider the life of Matilda McCrear , the last known survivor of the transatlantic slave trade. Kidnapped from West Africa and brought to the U.S. on the Clotilda , she arrived in Mobile, Alabama, in July 1860—more than 50 years after Congress had outlawed the import of enslaved labor. McCrear, who died in 1940 at the age of 81 or 82, “ displayed a determined, even defiant streak ” in her later life, wrote Brigit Katz earlier this year. She refused to use her former owner’s last name, wore her hair in traditional Yoruba style and had a decades-long relationship with a white German man.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/19/4a/194a3435-712d-424f-ad2d-09ee04ccc14b/clotilda.jpg)

How American society remembers and teaches the horrors of slavery is crucial. But as recent studies have shown, many textbooks offer a sanitized view of this history , focusing solely on “positive” stories about black leaders like Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass . Prior to 2018, Texas schools even taught that states’ rights and sectionalism—not slavery—were the main causes of the Civil War . And, in Confederate memorials across the country, writes historian Kevin M. Levin , enslaved individuals are often falsely portrayed as loyal slaves .

Accurately representing slavery might require an updated vocabulary , argued historian Michael Landis in 2015: Outdated “[t]erms like ‘compromise’ or ‘plantation’ served either to reassure worried Americans in a Cold War world, or uphold a white supremacist, sexist interpretation of the past.” Rather than referring to the Compromise of 1850 , call it the Appeasement of 1850—a term that better describes “the uneven nature of the agreement,” according to Landis. Smithsonian scholar Christopher Wilson wrote, too, that widespread framing of the Civil War as a battle between equal entities lends legitimacy to the Confederacy , which was not a nation in its own right, but an “illegitimate rebellion and unrecognized political entity.” A 2018 Smithsonian magazine investigation found that the literal costs of the Confederacy are immense: In the decade prior, American taxpayers contributed $40 million to the maintenance of Confederate monuments and heritage organizations.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6d/5b/6d5b0523-79e6-4b9e-bbcf-5ffb70bb18ff/nmaahc-2008_9_26_001.jpg)

To better understand the immense brutality ingrained in enslaved individuals’ everyday lives, read up on Louisiana’s Whitney Plantation Museum , which acts as “part reminder of the scars of institutional bondage, part mausoleum for dozens of enslaved people who worked (and died) in [its] sugar fields, … [and] monument to the terror of slavery,” as Jared Keller observed in 2016. Visitors begin their tour in a historic church populated by clay sculptures of children who died on the plantation’s grounds, then move on to a series of granite slabs engraved with hundreds of enslaved African Americans’ names. Scattered throughout the experience are stories of the violence inflicted by overseers.

The Whitney Plantation Museum is at the forefront of a vanguard of historical sites working to confront their racist pasts. In recent years, exhibitions, oral history projects and other initiatives have highlighted the enslaved people whose labor powered such landmarks as Mount Vernon , the White House and Monticello . At the same time, historians are increasingly calling attention to major historical figures’ own slave-holding legacies : From Thomas Jefferson to George Washington , William Clark of Lewis and Clark , Francis Scott Key , and other Founding Fathers , many American icons were complicit in upholding the institution of slavery. Washington , Jefferson , James Madison and Aaron Burr , among others, sexually abused enslaved females working in their households and had oft-overlooked biracial families.

Though Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, the decree took two-and-a-half years to fully enact. June 19, 1865—the day Union Gen. Gordon Granger informed the enslaved individuals of Galveston, Texas, that they were officially free—is now known as Juneteenth : America’s “second independence day,” according to NMAAHC. Initially celebrated mainly in Texas, Juneteenth spread across the country as African Americans fled the South in what is now called the Great Migration .

At the onset of that mass movement in 1916, 90 percent of African Americans still lived in the South, where they were “held captive by the virtual slavery of sharecropping and debt peonage and isolated from the rest of the country,” as Isabel Wilkerson wrote in 2016. ( Sharecropping , a system in which formerly enslaved people became tenant farmers and lived in “converted” slave cabins , was the impetus for the 1919 Elaine Massacre , which found white soldiers collaborating with local vigilantes to kill at least 200 sharecroppers who dared to criticize their low wages.) By the time the Great Migration—famously chronicled by artist Jacob Lawrence —ended in the 1970s, 47 percent of African Americans called the northern and western United States home.

Listen to Sidedoor: A Smithsonian Podcast

The third season of Sidedoor explored a South Carolina residence’s unique journey from slave cabin to family home and its latest incarnation as a centerpiece at the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Conditions outside the Deep South were more favorable than those within the region, but the “hostility and hierarchies that fed the Southern caste system” remained major obstacles for black migrants in all areas of the country, according to Wilkerson. Low-paying jobs, redlining , restrictive housing covenants and rampant discrimination limited opportunities, creating inequality that would eventually give rise to the civil rights movement.

“The Great Migration was the first big step that the nation’s servant class ever took without asking,” Wilkerson explained. “ … It was about agency for a people who had been denied it, who had geography as the only tool at their disposal. It was an expression of faith, despite the terrors they had survived, that the country whose wealth had been created by their ancestors’ unpaid labor might do right by them.”

Systemic Inequality

Racial, economic and educational disparities are deeply entrenched in U.S. institutions. Though the Declaration of Independence states that “all men are created equal,” American democracy has historically—and often violently —excluded certain groups. “Democracy means everybody can participate, it means you are sharing power with people you don’t know, don’t understand, might not even like,” said National Museum of American History curator Harry Rubenstein in 2017. “That’s the bargain. And some people over time have felt very threatened by that notion.”

Instances of inequality range from the obvious to less overtly discriminatory policies and belief systems. Historical examples of the former include poll taxes that effectively disenfranchised African American voters; the marginalization of African American soldiers who fought in World War I and World War II but were treated like second-class citizens at home; black innovators who were barred from filing patents for their inventions; white medical professionals’ exploitation of black women’s bodies (see Henrietta Lacks and J. Marion Sims ); Richard and Mildred Loving ’s decade-long fight to legalize interracial marriage; the segregated nature of travel in the Jim Crow era; the government-mandated segregation of American cities ; and segregation in schools .

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d6/bb/d6bbf57c-5330-4b4f-b5fd-79b09196e885/nmaahc-2011_155_211_001.jpg)

Among the most heartbreaking examples of structural racism’s subtle effects are accounts shared by black children. In the late 1970s, when Lebert F. Lester II was 8 or 9 years old, he started building a sand castle during a trip to the Connecticut shore . A young white girl joined him but was quickly taken away by her father. Lester recalled the girl returning, only to ask him, “Why don’t [you] just go in the water and wash it off?” Lester says., “I was so confused—I only figured out later she meant my complexion .” Two decades earlier, in 1957, 15-year-old Minnijean Brown had arrived at Little Rock Central High School with high hopes of “making friends, going to dances and singing in the chorus.” Instead, she and the rest of the Little Rock Nine —a group of black students selected to attend the formerly all-white academy after Brown v. Board of Education desegregated public schools—were subjected to daily verbal and physical assaults. Around the same time, photographer John G. Zimmerman captured snapshots of racial politics in the South that included comparisons of black families waiting in long lines for polio inoculations as white children received speedy treatment.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/76/38/763805c9-ffca-41a3-8c52-8e5f7cd066c2/nmaahc-2011_17_201.jpg)

In 1968, the Kerner Commission , a group convened by President Lyndon Johnson, found that white racism, not black anger, was the impetus for the widespread civil unrest sweeping the nation. As Alice George wrote in 2018, the commission’s report suggested that “[b]ad policing practices, a flawed justice system, unscrupulous consumer credit practices, poor or inadequate housing, high unemployment, voter suppression and other culturally embedded forms of racial discrimination all converged to propel violent upheaval.” Few listened to the findings, let alone its suggestion of aggressive government spending aimed at leveling the playing field. Instead, the country embraced a different cause: space travel . The day after the 1969 moon landing, the leading black paper the New York Amsterdam News ran a story stating, “Yesterday, the moon. Tomorrow, maybe us.”

Fifty years after the Kerner Report’s release, a separate study assessed how much had changed ; it concluded that conditions had actually worsened. In 2017, black unemployment was higher than in 1968, as was the rate of incarcerated individuals who were black. The wealth gap had also increased substantially, with the median white family having ten times more wealth than the median black family. “We are resegregating our cities and our schools, condemning millions of kids to inferior education and taking away their real possibility of getting out of poverty,” said Fred Harris, the last surviving member of the Kerner Commission, following the 2018 study’s release.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fe/74/fe7488a2-1c4f-4bcb-b736-57d64089f4ec/nmaahc-2011_57_11_8.jpg)

Today, scientific racism —grounded in such faulty practices as eugenics and the treatment of race “as a crude proxy for myriad social and environmental factors,” writes Ramin Skibba—persists despite overwhelming evidence that race has only social, not biological, meaning. Black scholars including Mamie Phipps Clark , a psychologist whose research on racial identity in children helped end segregation in schools, and Rebecca J. Cole , a 19th-century physician and advocate who challenged the idea that black communities were destined for death and disease, have helped overturn some of these biases. But a 2015 survey found that 48 percent of black and Latina women scientists, respectively, still report being mistaken for custodial or administrative staff . Even artificial intelligence exhibits racial biases , many of which are introduced by lab staff and crowdsourced workers who program their own conscious and unconscious opinions into algorithms.

Anti-Black Violence

In addition to enduring centuries of enslavement, exploitation and inequality, African Americans have long been the targets of racially charged physical violence. Per the Alabama-based Equal Justice Initiative , more than 4,400 lynchings —mob killings undertaken without legal authority—took place in the U.S. between the end of Reconstruction and World War II.

Incredibly, the Senate only passed legislation declaring lynching a federal crime in 2018 . Between 1918 and the Justice for Victims of Lynching Act’s eventual passage, more than 200 anti-lynching bills failed to make it through Congress. (Earlier this week, Sen. Rand Paul said he would hold up a separate, similarly intentioned bill over fears that its definition of lynching was too broad. The House passed the bill in a 410-to-4 vote this February.) Also in 2018, the Equal Justice Initiative opened the nation’s first monument to African American lynching victims . The six-acre memorial site stands alongside a museum dedicated to tracing the nation’s history of racial bias and persecution from slavery to the present.

One of the earliest instances of Reconstruction-era racial violence took place in Opelousas, Louisiana, in September 1868. Two months ahead of the presidential election, Southern white Democrats started terrorizing Republican opponents who appeared poised to secure victory at the polls. On September 28, a group of men attacked 18-year-old schoolteacher Emerson Bentley, who had already attracted ire for teaching African American students, after he published an account of local Democrats’ intimidation of Republicans. Bentley escaped with his life, but 27 of the 29 African Americans who arrived on the scene to help him were summarily executed. Over the next two weeks, vigilante terror led to the deaths of some 250 people, the majority of whom were black.

In April 1873, another spate of violence rocked Louisiana. The Colfax Massacre , described by historian Eric Foner as the “bloodiest single instance of racial carnage in the Reconstruction era,” unfolded under similar circumstances as Opelousas, with tensions between Democrats and Republicans culminating in the deaths of between 60 and 150 African Americans, as well as three white men.

Between the turn of the 20th century and the 1920s, multiple massacres broke out in response to false allegations that young black men had raped or otherwise assaulted white women. In August 1908, a mob terrorized African American neighborhoods across Springfield, Illinois, vandalizing black-owned businesses, setting fire to the homes of black residents, beating those unable to flee and lynching at least two people. Local authorities, argues historian Roberta Senechal , were “ineffectual at best, complicit at worst.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5e/84/5e8491dd-6096-4821-a323-e5afd5c07083/1024px-tulsaraceriot-1921.png)

False accusations also sparked a July 1919 race riot in Washington, D.C. and the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921 , which was most recently dramatized in the HBO series “ Watchmen .” As African American History Museum curator Paul Gardullo tells Smithsonian , tensions related to Tulsa’s economy underpinned the violence : Forced to settle on what was thought to be worthless land, African Americans and Native Americans struck oil and proceeded to transform the Greenwood neighborhood of Tulsa into a prosperous community known as “Black Wall Street.” According to Gardullo, “It was the frustration of poor whites not knowing what to do with a successful black community, and in coalition with the city government [they] were given permission to do what they did.”

Over the course of two days in spring 1921, the Tulsa Race Massacre claimed the lives of an estimated 300 black Tulsans and displaced another 10,000. Mobs burned down at least 1,256 residences, churches, schools and businesses and destroyed almost 40 blocks of Greenwood. As the Sidedoor episode “ Confronting the Past ” notes, “No one knows how many people died, no one was ever convicted, and no one really talked about it nearly a century later.”

The second season of Sidedoor told the story of the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921.

Economic injustice also led to the East St. Louis Race War of 1917. This labor dispute-turned-deadly found “people’s houses being set ablaze, … people being shot when they tried to flee, some trying to swim to the other side of the Mississippi while being shot at by white mobs with rifles, others being dragged out of street cars and beaten and hanged from street lamps,” recalled Dhati Kennedy, the son of a survivor who witnessed the devastation firsthand. Official counts place the death toll at 39 black and 9 white individuals, but locals argue that the real toll was closer to 100.

A watershed moment for the burgeoning civil rights movement was the 1955 murder of 14-year-old Emmett Till . Accused of whistling at a white woman while visiting family members in Mississippi, he was kidnapped, tortured and killed. Emmett’s mother, Mamie Till Mobley, decided to give her son an open-casket funeral, forcing the world to confront the image of his disfigured, decomposing body . ( Visuals , including photographs, movies, television clips and artwork, played a key role in advancing the movement.) The two white men responsible for Till’s murder were acquitted by an all-white jury. A marker at the site where the teenager’s body was recovered has been vandalized at least three times since its placement in 2007.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b9/63/b96308dd-3056-4d87-909c-c7aabc05c8f7/nmaahc-2013_92_003.jpg)

The form of anti-black violence with the most striking parallels to contemporary conversations is police brutality . As Katie Nodjimbadem reported in 2017, a regional crime survey of late 1920s Chicago and Cook County, Illinois, found that while African Americans constituted just 5 percent of the area’s population, they made up 30 percent of the victims of police killings. Civil rights protests exacerbated tensions between African Americans and police, with events like the Orangeburg Massacre of 1968, in which law enforcement officers shot and killed three student activists at South Carolina State College, and the Glenville shootout , which left three police officers, three black nationalists and one civilian dead, fostering mistrust between the two groups.

Today, this legacy is exemplified by broken windows policing , a controversial approach that encourages racial profiling and targets African American and Latino communities. “What we see is a continuation of an unequal relationship that has been exacerbated, made worse if you will, by the militarization and the increase in fire power of police forces around the country,” William Pretzer , senior curator at NMAAHC, told Smithsonian in 2017.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1b/55/1b558d42-ae6d-453b-936b-e42aa61d6654/2012_169_6.jpg)

The history of protest and revolt in the United States is inextricably linked with the racial violence detailed above.

Prior to the Civil War, enslaved individuals rarely revolted outright. Nat Turner , whose 1831 insurrection ended in his execution, was one of the rare exceptions. A fervent Christian , he drew inspiration from the Bible. His personal copy , now housed in the collections of the African American History Museum, represented the “possibility of something else for himself and for those around him,” curator Mary Ellis told Smithsonian ’s Victoria Dawson in 2016.

Other enslaved African Americans practiced less risky forms of resistance, including working slowly, breaking tools and setting objects on fire. “Slave rebellions, though few and small in size in America, were invariably bloody,” wrote Dawson. “Indeed, death was all but certain.”

One of the few successful uprisings of the period was the Creole Rebellion . In the fall of 1841, 128 enslaved African Americans traveling aboard The Creole mutinied against its crew, forcing their former captors to sail the brig to the British West Indies, where slavery was abolished and they could gain immediate freedom.

An April 1712 revolt found enslaved New Yorkers setting fire to white-owned buildings and firing on slaveholders. Quickly outnumbered, the group fled but was tracked to a nearby swamp; though several members were spared, the majority were publicly executed, and in the years following the uprising, the city enacted laws limiting enslaved individuals’ already scant freedom. In 1811, meanwhile, more than 500 African Americans marched on New Orleans while chanting “Freedom or Death.” Though the German Coast uprising was brutally suppressed, historian Daniel Rasmussen argues that it “had been much larger—and come much closer to succeeding—than the planters and American officials let on.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/16/06/16063c51-b65d-4769-819e-b24ad1e18175/woolworth-four-19601.jpg)

Some 150 years after what Rasmussen deems America’s “ largest slave revolt ,” the civil rights movement ushered in a different kind of protest. In 1955, police arrested Rosa Parks for refusing to yield her bus seat to a white passenger (“I had been pushed around all my life and felt at this moment that I couldn’t take it any more,” she later wrote). The ensuing Montgomery bus boycott , in which black passengers refused to ride public transit until officials met their demands, led the Supreme Court to rule segregated buses unconstitutional. Five years later, the Greensboro Four similarly took a stand, ironically by staging a sit-in at a Woolworth’s lunch counter . As Christopher Wilson wrote ahead of the 60th anniversary of the event, “What made Greensboro different [from other sit-ins ] was how it grew from a courageous moment to a revolutionary movement.”

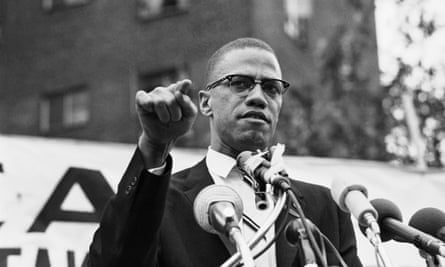

During the 1950s and ’60s, civil rights leaders adopted varying approaches to protest: Malcolm X , a staunch proponent of black nationalism who called for equality by “any means necessary,” “made tangible the anger and frustration of African Americans who were simply catching hell,” according to journalist Allison Keyes. He repeated the same argument “over and over again,” wrote academic and activist Cornel West in 2015: “What do you think you would do after 400 years of slavery and Jim Crow and lynching? Do you think you would respond nonviolently? What’s your history like? Let’s look at how you have responded when you were oppressed. George Washington—revolutionary guerrilla fighter!’”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6a/9c/6a9c3344-4b98-4f3e-988b-d388c1f5853c/gettyimages-113491383.jpg)

Martin Luther King Jr . famously advocated for nonviolent protest, albeit not in the form that many think. As biographer Taylor Branch told Smithsonian in 2015, King’s understanding of nonviolence was more complex than is commonly argued. Unlike Mahatma Gandhi’s “passive resistance,” King believed resistance “depended on being active, using demonstrations, direct actions, to ‘amplify the message’ of the protest they were making,” according to Ron Rosenbaum. In the activist’s own words , “[A] riot is the language of the unheard. And what is it America has failed to hear?… It has failed to hear that the promises of freedom and justice have not been met. ”

Another key player in the civil rights movement, the militant Black Panther Party , celebrated black power and operated under a philosophy of “ demands and aspirations .” The group’s Ten-Point Program called for an “immediate end to POLICE BRUTALITY and MURDER of Black people,” as well as more controversial measures like freeing all black prisoners and exempting black men from military service. Per NMAAHC , black power “emphasized black self-reliance and self-determination more than integration,” calling for the creation of separate African American political and cultural organizations. In doing so, the movement ensured that its proponents would attract the unwelcome attention of the FBI and other government agencies.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bd/64/bd645528-cc59-42fd-8d11-85d8f41482e4/boys_marching.jpg)

Many of the protests now viewed as emblematic of the fight for racial justice took place in the 1960s. On August 28, 1963, more than 250,000 people gathered in D.C. for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom . Ahead of the 50th anniversary of the march, activists who attended the event detailed the experience for a Smithsonian oral history : Entertainer Harry Belafonte observed, “We had to seize the opportunity and make our voices heard. Make those who are comfortable with our oppression—make them uncomfortable—Dr. King said that was the purpose of this mission,” while Representative John Lewis recalled, “Looking toward Union Station, we saw a sea of humanity; hundreds, thousands of people. … People literally pushed us, carried us all the way, until we reached the Washington Monument and then we walked on to the Lincoln Memorial..”

Two years after the March on Washington, King and other activists organized a march from Selma, Alabama, to the state capital of Montgomery. Later called the Selma March , the protest was dramatized in a 2014 film starring David Oyelowo as MLK. ( Reflecting on Selma , Smithsonian Secretary Lonnie Bunch, then-director of NMAAHC, deemed it a “remarkable film” that “does not privilege the white perspective … [or] use the movement as a convenient backdrop for a conventional story.”)

Organized in response to the manifest obstacles black individuals faced when attempting to vote, the Selma March actually consisted of three separate protests. The first of these, held on March 7, 1965, ended in a tragedy now known as Bloody Sunday . As peaceful protesters gathered on the Edmund Pettus Bridge —named for a Confederate general and local Ku Klux Klan leader—law enforcement officers attacked them with tear gas and clubs. One week later, President Lyndon B. Johnson offered the Selma protesters his support and introduced legislation aimed at expanding voting rights. During the third and final march, organized in the aftermath of Johnson’s announcement, tens of thousands of protesters (protected by the National Guard and personally led by King) converged on Montgomery. Along the way, interior designer Carl Benkert used a hidden reel-to-reel tape recorder to document the sounds—and specifically songs—of the event .

The protests of the early and mid-1960s culminated in the widespread unrest of 1967 and 1968. For five days in July 1967, riots on a scale unseen since 1863 rocked the city of Detroit : As Lorraine Boissoneault writes, “Looters prowled the streets, arsonists set buildings on fire, civilian snipers took position from rooftops and police shot and arrested citizens indiscriminately.” Systemic injustice in such areas as housing, jobs and education contributed to the uprising, but police brutality was the driving factor behind the violence. By the end of the riots, 43 people were dead. Hundreds sustained injuries, and more than 7,000 were arrested.

The Detroit riots of 1967 prefaced the seismic changes of 1968 . As Matthew Twombly wrote in 2018, movements including the Vietnam War, the Cold War, civil rights, human rights and youth culture “exploded with force in 1968,” triggering aftershocks that would resonate both in America and abroad for decades to come.

On February 1, black sanitation workers Echol Cole and Robert Walker died in a gruesome accident involving a malfunctioning garbage truck. Their deaths, compounded by Mayor Henry Loeb’s refusal to negotiate with labor representatives, led to the outbreak of the Memphis sanitation workers’ strike —an event remembered both “as an example of powerless African Americans standing up for themselves” and as the backdrop to King’s April 4 assassination .

Though King is lionized today, he was highly unpopular at the time of his death. According to a Harris Poll conducted in early 1968, nearly 75 percent of Americans disapproved of the civil rights leader , who had become increasingly vocal in his criticism of the Vietnam War and economic inequity. Despite the public’s seeming ambivalence toward King—and his family’s calls for nonviolence— his murder sparked violent protests across the country . In all, the Holy Week Uprisings spread to nearly 200 cities, leaving 3,500 people injured and 43 dead. Roughly 27,000 protesters were arrested, and 54 of the cities involved sustained more than $100,000 in property damage.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/af/55/af5563b7-5342-40c9-9860-945f0a294b88/2017_76_3_001_credit-gift_of_abigail_wiebenson__sons.jpg)

In May, thousands flocked to Washington, D.C. for a protest King had planned prior to his death. Called the Poor People’s Campaign , the event united racial groups from all quarters of America in a call for economic justice. Attendees constructed “ Resurrection City ,” a temporary settlement made up of 3,000 wooden tents, and camped out on the National Mall for 42 days.

“While we were all in a kind of depressed state about the assassinations of King and RFK, we were trying to keep our spirits up, and keep focused on King’s ideals of humanitarian issues, the elimination of poverty and freedom,” protester Lenneal Henderson told Smithsonian in 2018. “It was exciting to be part of something that potentially, at least, could make a difference in the lives of so many people who were in poverty around the country.”

Racial unrest persisted throughout the year, with uprisings on the Fourth of July , a protest at the Summer Olympic Games , and massacres at Orangeburg and Glenville testifying to the tumultuous state of the nation.

The Black Lives Matter marches organized in response to the killings of George Floyd, Philando Castile, Freddie Gray, Eric Garner, Sandra Bland, Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown and other victims of anti-black violence share many parallels with protests of the past .

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/48/ec/48ecd873-a4e6-4919-9dbf-9693a11ce133/gettyimages-1217135506.jpg)

Football player Colin Kaepernick ’s decision to kneel during the national anthem—and the unmitigated outrage it sparked —bears similarities to the story of boxer Muhammad Ali , historian Jonathan Eig told Smithsonian in 2017: “It’s been eerie to watch it, that we’re still having these debates that black athletes should be expected to shut their mouths and perform for us,” he said. “That’s what people told Ali 50 years ago.”

Other aspects of modern protest draw directly on uprisings of earlier eras. In 2016, for instance, artist Dread Scott updated an anti-lynching poster used by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in the 1920s and ’30s to read “ A Black Man Was Lynched by Police Yesterday .” (Scott added the words “by police.”)

Though the civil rights movement is often viewed as the result of a cohesive “grand plan” or “manifestation of the vision of the few leaders whose names we know,” the American History Museum’s Christopher Wilson argues that “the truth is there wasn’t one, there were many and they were often competitive .”

Meaningful change required a whirlwind of revolution, adds Wilson, “but also the slow legal march. It took boycotts, petitions, news coverage, civil disobedience, marches, lawsuits, shrewd political maneuvering, fundraising, and even the violent terror campaign of the movement’s opponents—all going on [at] the same time.”

Intersectionality

In layman’s terms, intersectionality refers to the multifaceted discrimination experienced by individuals who belong to multiple minority groups. As theorist Kimberlé Crenshaw explains in a video published by NMAAHC , these classifications run the gamut from race to gender, gender identity, class, sexuality and disability. A black woman who identifies as a lesbian, for instance, may face prejudice based on her race, gender or sexuality.

Crenshaw, who coined the term intersectionality in 1989, explains the concept best: “Consider an intersection made up of many roads,” she says in the video. “The roads are the structures of race, gender, gender identity, class, sexuality, disability. And the traffic running through those roads are the practices and policies that discriminate against people. Now if an accident happens, it can be caused by cars traveling in any number of directions, and sometimes, from all of them. So if a black woman is harmed because she is in an intersection, her injury could result from discrimination from any or all directions.”

Understanding intersectionality is essential for teasing out the relationships between movements including civil rights, LGBTQ rights , suffrage and feminism. Consider the contributions of black transgender activists Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera , who played pivotal roles in the Stonewall Uprising ; gay civil rights leader Bayard Rustin , who was only posthumously pardoned this year for having consensual sex with men; the “rank and file” women of the Black Panther Party ; and African American suffragists such as Mary Church Terrell and Nannie Helen Burroughs .

All of these individuals fought discrimination on multiple levels: As noted in “ Votes for Women: A Portrait of Persistence ,” a 2019 exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery, leading suffrage organizations initially excluded black suffragists from their ranks , driving the emergence of separate suffrage movements and, eventually, black feminists grounded in the inseparable experiences of racism, sexism and classism.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/65/0e/650ef0c5-c647-49b1-91fa-f15cae6978cc/2012_83_6_001.jpg)

Allyship and Education

Individuals striving to become better allies by educating themselves and taking decisive action have an array of options for getting started. Begin with NMAAHC’s “ Talking About Race ” portal, which features sections on being antiracist , whiteness , bias , social identities and systems of oppression , self-care , race and racial identity , the historical foundations of race , and community building . An additional 139 items —from a lecture on the history of racism in America to a handout on white supremacy culture and an article on the school-to-prison pipeline —are available to explore via the portal’s resources page .

In collaboration with the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience, the National Museum of the American Indian has created a toolkit that aims to “help people facilitate new conversations with and among students about the power of images and words, the challenges of memory, and the relationship between personal and national value,” says museum director Kevin Gover in a statement . The Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center offers a similarly focused resource called “ Standing Together Against Xenophobia .” As the site’s description notes, “This includes addressing not only the hatred and violence that has recently targeted people of Asian descent, but also the xenophobia that plagues our society during times of national crisis.”

Ahead of NMAAHC’s official opening in 2016, the museum hosted a series of public programs titled “ History, Rebellion, and Reconciliation .” Panels included “Ferguson: What Does This Moment Mean for America?” and “#Words Matter: Making Revolution Irresistible.” As Smithsonian reported at the time, “It was somewhat of a refrain at the symposium that museums can provide ‘safe,’ or even ‘sacred’ spaces , within which visitors [can] wrestle with difficult and complex topics.” Then-director Lonnie Bunch expanded on this mindset in an interview, telling Smithsonian , “Our job is to be an educational institution that uses history and culture not only to look back, not only to help us understand today, but to point us towards what we can become.” For more context on the museum’s collections, mission and place in American history, visit Smithsonian ’s “ Breaking Ground ” hub and NMAAHC’s digital resources guide .

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/94/80/9480f374-0b40-43e2-b111-e51bda889fba/credit-alankarchmer_220.jpg)

Historical examples of allyship offer both inspiration and cautionary tales for the present. Take, for example, Albert Einstein , who famously criticized segregation as a “disease of white people” and continually used his platform to denounce racism. (The scientist’s advocacy is admittedly complicated by travel diaries that reveal his deeply troubling views on race .)

Einstein’s near-contemporary, a white novelist named John Howard Griffin, took his supposed allyship one step further, darkening his skin and embarking on a “human odyssey through the South,” as Bruce Watson wrote in 2011. Griffin’s chronicle of his experience, a volume titled Black Like Me , became a surprise bestseller, refuting “the idea that minorities were acting out of paranoia,” according to scholar Gerald Early, and testifying to the veracity of black people’s accounts of racism.

“The only way I could see to bridge the gap between us,” wrote Griffin in Black Like Me , “was to become a Negro.”

Griffin, however, had the privilege of being able to shed his blackness at will—which he did after just one month of donning his makeup. By that point, Watson observed, Griffin could simply “stand no more.”

Sixty years later, what is perhaps most striking is just how little has changed. As Bunch reflected earlier this week, “The state of our democracy feels fragile and precarious.”

Addressing the racism and social inequity embedded in American society will be a “monumental task,” the secretary added. But “the past is replete with examples of ordinary people working together to overcome seemingly insurmountable challenges. History is a guide to a better future and demonstrates that we can become a better society—but only if we collectively demand it from each other and from the institutions responsible for administering justice.”

Editor ’s Note, July 24, 2020: This article previously stated that some 3.9 million of the 10.7 million people who survived the harrowing two-month journey across the Middle Passage between 1525 and 1866 were ultimately enslaved in the United States. In fact, the 3.9 million figure refers to the number of enslaved individuals in the U.S. just before the Civil War. We regret the error.

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

Meilan Solly | | READ MORE

Meilan Solly is Smithsonian magazine's associate digital editor, history.

- My Reading List

- Account Settings

- Newsletters & alerts

- Gift subscriptions

- Accessibility for screenreader

Resources to understand America’s long history of injustice and inequality

Protest and activism

Income inequality

Policing and criminal justice

Arrests of minors aged 10 to 17

Per 100,000 people

Adult incarceration rate

Source: U.S. Department of Justice

Arrests of minors

aged 10 to 17

Incarceration rate

of adult population

We noticed you’re blocking ads!

A global story

This piece is part of 19A: The Brookings Gender Equality Series . In this essay series, Brookings scholars, public officials, and other subject-area experts examine the current state of gender equality 100 years after the 19th Amendment was adopted to the U.S. Constitution and propose recommendations to cull the prevalence of gender-based discrimination in the United States and around the world.

The year 2020 will stand out in the history books. It will always be remembered as the year the COVID-19 pandemic gripped the globe and brought death, illness, isolation, and economic hardship. It will also be noted as the year when the death of George Floyd and the words “I can’t breathe” ignited in the United States and many other parts of the world a period of reckoning with racism, inequality, and the unresolved burdens of history.

The history books will also record that 2020 marked 100 years since the ratification of the 19th Amendment in America, intended to guarantee a vote for all women, not denied or abridged on the basis of sex.

This is an important milestone and the continuing movement for gender equality owes much to the history of suffrage and the brave women (and men) who fought for a fairer world. Yet just celebrating what was achieved is not enough when we have so much more to do. Instead, this anniversary should be a galvanizing moment when we better inform ourselves about the past and emerge more determined to achieve a future of gender equality.

Australia’s role in the suffrage movement

In looking back, one thing that should strike us is how international the movement for suffrage was though the era was so much less globalized than our own.

For example, how many Americans know that 25 years before the passing of the 19th Amendment in America, my home of South Australia was one of the first polities in the world to give men and women the same rights to participate in their democracies? South Australia led Australia and became a global leader in legislating universal suffrage and candidate eligibility over 125 years ago.

This extraordinary achievement was not an easy one. There were three unsuccessful attempts to gain equal voting rights for women in South Australia, in the face of relentless opposition. But South Australia’s suffragists—including the Women’s Suffrage League and the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, as well as remarkable women like Catherine Helen Spence, Mary Lee, and Elizabeth Webb Nicholls—did not get dispirited but instead continued to campaign, persuade, and cajole. They gathered a petition of 11,600 signatures, stuck it together page by page so that it measured around 400 feet in length, and presented it to Parliament.

The Constitutional Amendment (Adult Suffrage) Bill was finally introduced on July 4, 1894, leading to heated debate both within the houses of Parliament, and outside in society and the media. Demonstrating that some things in Parliament never change, campaigner Mary Lee observed as the bill proceeded to committee stage “that those who had the least to say took the longest time to say it.” 1

The Bill finally passed on December 18, 1894, by 31 votes to 14 in front of a large crowd of women.

In 1897, Catherine Helen Spence became the first woman to stand as a political candidate in South Australia.

South Australia’s victory led the way for the rest of the colonies, in the process of coming together to create a federated Australia, to fight for voting rights for women across the entire nation. Women’s suffrage was in effect made a precondition to federation in 1901, with South Australia insisting on retaining the progress that had already been made. 2 South Australian Muriel Matters, and Vida Goldstein—a woman from the Australian state of Victoria—are just two of the many who fought to ensure that when Australia became a nation, the right of women to vote and stand for Parliament was included.

Australia’s remarkable progressiveness was either envied, or feared, by the rest of the world. Sociologists and journalists traveled to Australia to see if the worst fears of the critics of suffrage would be realised.

In 1902, Vida Goldstein was invited to meet President Theodore Roosevelt—the first Australian to ever meet a U.S. president in the White House. With more political rights than any American woman, Goldstein was a fascinating visitor. In fact, President Roosevelt told Goldstein: “I’ve got my eye on you down in Australia.” 3

Goldstein embarked on many other journeys around the world in the name of suffrage, and ran five times for Parliament, emphasising “the necessity of women putting women into Parliament to secure the reforms they required.” 4

Muriel Matters went on to join the suffrage movement in the United Kingdom. In 1908 she became the first woman to speak in the British House of Commons in London—not by invitation, but by chaining herself to the grille that obscured women’s views of proceedings in the Houses of Parliament. After effectively cutting her off the grille, she was dragged out of the gallery by force, still shouting and advocating for votes for women. The U.K. finally adopted women’s suffrage in 1928.

These Australian women, and the many more who tirelessly fought for women’s rights, are still extraordinary by today’s standards, but were all the more remarkable for leading the rest of the world.

A shared history of exclusion

Of course, no history of women’s suffrage is complete without acknowledging those who were excluded. These early movements for gender equality were overwhelmingly the remit of privileged white women. Racially discriminatory exclusivity during the early days of suffrage is a legacy Australia shares with the United States.

South Australian Aboriginal women were given the right to vote under the colonial laws of 1894, but they were often not informed of this right or supported to enroll—and sometimes were actively discouraged from participating.

They were later further discriminated against by direct legal bar by the 1902 Commonwealth Franchise Act, whereby Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were excluded from voting in federal elections—a right not given until 1962.

Any celebration of women’s suffrage must acknowledge such past injustices front and center. Australia is not alone in the world in grappling with a history of discrimination and exclusion.

The best historical celebrations do not present a triumphalist version of the past or convey a sense that the fight for equality is finished. By reflecting on our full history, these celebrations allow us to come together, find new energy, and be inspired to take the cause forward in a more inclusive way.

The way forward

In the century or more since winning women’s franchise around the world, we have made great strides toward gender equality for women in parliamentary politics. Targets and quotas are working. In Australia, we already have evidence that affirmative action targets change the diversity of governments. Since the Australian Labor Party (ALP) passed its first affirmative action resolution in 1994, the party has seen the number of women in its national parliamentary team skyrocket from around 14% to 50% in recent years.

Instead of trying to “fix” women—whether by training or otherwise—the ALP worked on fixing the structures that prevent women getting preselected, elected, and having fair opportunities to be leaders.

There is also clear evidence of the benefits of having more women in leadership roles. A recent report from Westminster Foundation for Democracy and the Global Institute for Women’s Leadership (GIWL) at King’s College London, shows that where women are able to exercise political leadership, it benefits not just women and girls, but the whole of society.

But even though we know how to get more women into parliament and the positive difference they make, progress toward equality is far too slow. The World Economic Forum tells us that if we keep progressing as we are, the global political empowerment gender gap—measuring the presence of women across Parliament, ministries, and heads of states across the world— will only close in another 95 years . This is simply too long to wait and, unfortunately, not all barriers are diminishing. The level of abuse and threatening language leveled at high-profile women in the public domain and on social media is a more recent but now ubiquitous problem, which is both alarming and unacceptable.

Across the world, we must dismantle the continuing legal and social barriers that prevent women fully participating in economic, political, and community life.

Education continues to be one such barrier in many nations. Nearly two-thirds of the world’s illiterate adults are women. With COVID-19-related school closures happening in developing countries, there is a real risk that progress on girls’ education is lost. When Ebola hit, the evidence shows that the most marginalized girls never made it back to school and rates of child marriage, teen pregnancy. and child labor soared. The Global Partnership for Education, which I chair, is currently hard at work trying to ensure that this history does not repeat.

Ensuring educational equality is a necessary but not sufficient condition for gender equality. In order to change the landscape to remove the barriers that prevent women coming through for leadership—and having their leadership fairly evaluated rather than through the prism of gender—we need a radical shift in structures and away from stereotypes. Good intentions will not be enough to achieve the profound wave of change required. We need hard-headed empirical research about what works. In my life and writings post-politics and through my work at the GIWL, sharing and generating this evidence is front and center of the work I do now.

GIWL work, undertaken in partnership with IPSOS Mori, demonstrates that the public knows more needs to be done. For example, this global polling shows the community thinks it is harder for women to get ahead. Specifically, they say men are less likely than women to need intelligence and hard work to get ahead in their careers.

Other research demonstrates that the myth of the “ideal worker,” one who works excessive hours, is damaging for women’s careers. We also know from research that even in families where each adult works full time, domestic and caring labor is disproportionately done by women. 5

In order to change the landscape to remove the barriers that prevent women coming through for leadership—and having their leadership fairly evaluated rather than through the prism of gender—we need a radical shift in structures and away from stereotypes.

Other more subtle barriers, like unconscious bias and cultural stereotypes, continue to hold women back. We need to start implementing policies that prevent people from being marginalized and stop interpreting overconfidence or charisma as indicative of leadership potential. The evidence shows that it is possible for organizations to adjust their definitions and methods of identifying merit so they can spot, measure, understand, and support different leadership styles.

Taking the lessons learned from our shared history and the lives of the extraordinary women across the world, we know evidence needs to be combined with activism to truly move forward toward a fairer world. We are in a battle for both hearts and minds.

Why this year matters

We are also at an inflection point. Will 2020 will be remembered as the year that a global recession disproportionately destroyed women’s jobs, while women who form the majority of the workforce in health care and social services were at risk of contracting the coronavirus? Will it be remembered as a time of escalating domestic violence and corporations cutting back on their investments in diversity programs?

Or is there a more positive vision of the future that we can seize through concerted advocacy and action? A future where societies re-evaluate which work truly matters and determine to better reward carers. A time when men and women forced into lockdowns re-negotiated how they approach the division of domestic labor. Will the pandemic be viewed as the crisis that, through forcing new ways of virtual working, ultimately led to more balance between employment and family life, and career advancement based on merit and outcomes, not presentism and the old boys’ network?

This history is not yet written. We still have an opportunity to make it happen. Surely the women who led the way 100 years ago can inspire us to seize this moment and create that better, more gender equal future.

- December 7,1894: Welcome home meeting for Catherine Helen Spence at the Café de Paris. [ Register , Dec, 19, 1894 ]

- Clare Wright, You Daughters of Freedom: The Australians Who Won the Vote and Inspired the World , (Text Publishing, 2018).

- Janette M. Bomford, That Dangerous and Persuasive Woman, (Melbourne University Press, 1993)

- Cordelia Fine, Delusions of Gender: The Real Science Behind Sex Differences, (Icon Books, 2010)

This piece is part of 19A: The Brookings Gender Equality Series. Learn more about the series and read published work »

About the Author

Julia gillard, distinguished fellow – global economy and development, center for universal education.

Gillard is a distinguished fellow with the Center for Universal Education at the Brookings Institution. She is the Inaugural Chair of the Global Institute for Women’s Leadership at King’s College London. Gillard also serves as Chair of the Global Partnership for Education, which is dedicated to expanding access to quality education worldwide and is patron of CAMFED, the Campaign for Female Education.

Read full bio

MORE FROM JULIA GILLARD

Advancing women’s leadership around the world

More from the 19a series.

The gender revolution is stalling—What would reinvigorate it?

What’s necessary to reinvigorate the gender revolution and create progress in the areas where the movement toward equality has slowed or stalled—employment, desegregation of fields of study and jobs, and the gender pay gap?

The fate of women’s rights in Afghanistan

John R. Allen and Vanda Felbab-Brown write that as peace negotiations between the Afghan government and the Taliban commence, uncertainty hangs over the fate of Afghan women and their rights.

- Media Relations

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Civil Rights Act of 1964

By: History.com Editors

Updated: January 10, 2023 | Original: January 4, 2010

The Civil Rights Act of 1964, which ended segregation in public places and banned employment discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex or national origin, is considered one of the crowning legislative achievements of the civil rights movement. First proposed by President John F. Kennedy , it survived strong opposition from southern members of Congress and was then signed into law by Kennedy’s successor, Lyndon B. Johnson . In subsequent years, Congress expanded the act and passed additional civil rights legislation such as the Voting Rights Act of 1965 .

Lead-up to the Civil Rights Act

Following the Civil War , a trio of constitutional amendments abolished slavery (the 13 Amendment ), made the formerly enslaved people citizens ( 14 Amendment ) and gave all men the right to vote regardless of race ( 15 Amendment ).

Nonetheless, many states—particularly in the South—used poll taxes, literacy tests and other measures to keep their African American citizens essentially disenfranchised. They also enforced strict segregation through “ Jim Crow ” laws and condoned violence from white supremacist groups like the Ku Klux Klan .

For decades after Reconstruction , the U.S. Congress did not pass a single civil rights act. Finally, in 1957, it established a civil rights section of the Justice Department, along with a Commission on Civil Rights to investigate discriminatory conditions.

Three years later, Congress provided for court-appointed referees to help Black people register to vote. Both of these bills were strongly watered down to overcome southern resistance.

When John F. Kennedy entered the White House in 1961, he initially delayed supporting new anti-discrimination measures. But with protests springing up throughout the South—including one in Birmingham, Alabama , where police brutally suppressed nonviolent demonstrators with dogs, clubs and high-pressure fire hoses—Kennedy decided to act.

In June 1963 he proposed by far the most comprehensive civil rights legislation to date, saying the United States “will not be fully free until all of its citizens are free.”

Civil Rights Act Moves Through Congress

Kennedy was assassinated that November in Dallas, after which new President Lyndon B. Johnson immediately took up the cause.

“Let this session of Congress be known as the session which did more for civil rights than the last hundred sessions combined,” Johnson said in his first State of the Union address. During debate on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives , southerners argued, among other things, that the bill unconstitutionally usurped individual liberties and states’ rights.

In a mischievous attempt to sabotage the bill, a Virginia segregationist introduced an amendment to ban employment discrimination against women. That one passed, whereas over 100 other hostile amendments were defeated. In the end, the House approved the bill with bipartisan support by a vote of 290-130.

The bill then moved to the U.S. Senate , where southern and border state Democrats staged a 75-day filibuster—among the longest in U.S. history. On one occasion, Senator Robert Byrd of West Virginia, a former Ku Klux Klan member, spoke for over 14 consecutive hours.

But with the help of behind-the-scenes horse-trading, the bill’s supporters eventually obtained the two-thirds votes necessary to end debate. One of those votes came from California Senator Clair Engle, who, though too sick to speak, signaled “aye” by pointing to his own eye.

Lyndon Johnson Signs The Civil Rights Act of 1964

Having broken the filibuster, the Senate voted 73-27 in favor of the bill, and Johnson signed it into law on July 2, 1964. “It is an important gain, but I think we just delivered the South to the Republican Party for a long time to come,” Johnson, a Democrat , purportedly told an aide later that day in a prediction that would largely come true.

Did you know? President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 with at least 75 pens, which he handed out to congressional supporters of the bill such as Hubert Humphrey and Everett Dirksen and to civil rights leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr. and Roy Wilkins.

What Is the Civil Rights Act?

Under the Civil Rights Act of 1964, segregation on the grounds of race, religion or national origin was banned at all places of public accommodation, including courthouses, parks, restaurants, theaters, sports arenas and hotels. No longer could Black people and other minorities be denied service simply based on the color of their skin.

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act barred race, religious, national origin and gender discrimination by employers and labor unions, and created an Equal Employment Opportunity Commission with the power to file lawsuits on behalf of aggrieved workers.

Additionally, the act forbade the use of federal funds for any discriminatory program, authorized the Office of Education (now the Department of Education) to assist with school desegregation, gave extra clout to the Commission on Civil Rights and prohibited the unequal application of voting requirements.

Legacy of the Civil Rights Act

Civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. said that the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was nothing less than a “second emancipation.”

The Civil Rights Act was later expanded to bring disabled Americans, the elderly and women in collegiate athletics under its umbrella.

It also paved the way for two major follow-up laws: the Voting Rights Act of 1965 , which prohibited literacy tests and other discriminatory voting practices, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968, which banned discrimination in the sale, rental and financing of property. Though the struggle against racism would continue, legal segregation had been brought to its knees in the United States.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Fighting Racism and Discrimination: History, Memory and Contemporary Challenges

Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny – Martin Luther King Jr.

The commemoration of the International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination was opened by Irina Bokova, Director-General of UNESCO, and keynote speaker William Bell Sr., Mayor of Birmingham, Alabama (United States of America) , one of the world’s most emblematic cities in the fight against racism.

In her opening address, the Director-General underlined the importance of learning from historical injustices to build lasting peace:

“We will fight against racism and discrimination by teaching respect and tolerance, by sharing the common history of all humanity – including its most tragic chapters.”

Recalling the importance of understanding the dynamics of exclusion and exploitation in our societies, the Director-General called for unity in today’s combat against discrimination around the world, highlighting initiatives such as the International Coalition of Cities against Racism (ICCAR), which promotes cooperation and collaboration in the fight against discrimination at the local and municipal level.

As Mayor of Birmingham, the lead city in the US Coalition of Cities against Racism, William Bell retraced the history and global impact of the Civil Rights movement, underlining our common responsibility in promoting respect for human rights and dignity around the world today:

“Human rights extends to everyone, and we must work constantly to let everybody know that they have an obligation to work towards eliminating racism”.

With speakers including city officials, policy-makers, international experts and civil society actors involved in combating racism and discrimination around the world, and with more than 200 participants including many school and university students, the day’s events featured panel discussions, workshop sessions and a multimedia exhibition.

Other recent news

Introductory Essay: The Struggle Continues: Stony the Road (1898–1941)

To what extent did Founding principles of liberty, equality, and justice become a reality for African Americans in the first half of the twentieth century?

- I can explain the challenges and opportunities African Americans faced as a result of the Great Migration.

- I can compare the views of Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois on how best to achieve equality for African Americans.

- I can explain how lynching and other forms of racial violence continued to threaten African Americans.

- I can identify and explain the ways in which African Americans took action to confront restraints upon their rights and dignity.

- I can explain why African Americans’ service during two world wars created conditions to challenge segregation and racism within the United States after the end of World War II.

Essential Vocabulary

The struggle continues: stony the road (1898-1941).

The first half of the twentieth century witnessed significant change for all Americans as the United States entered an increasingly industrialized and urban age. Blacks specifically seized opportunities for social mobility, industrial jobs, higher education, military service, artistic achievement, and activism in the new society. The signs of hope and progress they saw were mitigated by the ever-present cloud of segregation and discrimination.

Still, many Black Americans participated in the new opportunities afforded by a changing nation. Millions left southern farms and sought jobs and social mobility by moving to southern cities, northern cities, and the West during the Great Migration . Those who left the perpetual indebtedness of sharecropping , in which they had rented land from white landowners in exchange for a portion of the crop, sometimes moved West to farm. But more often they migrated to cities, where they found limited employment opportunities in low-paying service sector work, such as jobs for janitors or maids. They also faced housing discrimination and were forced to reside in segregated Black neighborhoods. However, Black churches and civic organizations were often a foundation of mutual support and strength, and many Black Americans improved their lives.

The number of Black schools and colleges grew quickly after the Civil War. Black education achieved an impressive record of increasing Black literacy from around 20 percent in 1870 to almost 80 percent in 1920. These gains were realized despite southern state governments cuts to the already meager funding and white supremacists watching Black schools to ensure they did not promote Black equality.

Black Americans organized into groups to fight for equality and justice, laying the foundation of the Civil Rights. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was the most prominent organization that led the struggle for Black civil rights after its founding in 1909. Its mission included contesting racial prejudice and segregation with striving for civil rights and educational opportunities. W. E. B. Du Bois, Ida B. Wells, and Mary Church Terrell helped establish the NAACP. Du Bois served as the editor of its publication, The Crisis, and brought the struggles of Black Americans to light.

A new generation of Black intellectuals conducted a continuing and vibrant debate over the place of a Black person in the United States and the best path to racial equality. The most prominent debaters were Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois.

Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois differed in their thoughts on how best to achieve equality for Blacks. Washington’s life was shaped by slavery, poverty, and the work ethic fostered at Hampton Institute. Du Bois was 12 years younger than Washington and was born and raised in the small community of Great Barrington, Massachusetts. Du Bois praised Washington’s famous 1895 speech at the Cotton States Exposition, but later grew critical of Washington and his leadership.

Booker T. Washington graduated from Hampton Institute (today known as Hampton University) and was the first head of the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, one of many Black colleges formed in the period. In his famous “Atlanta Exposition Address” (1895), Washington advocated vocational education, hard work, and moral virtues for Blacks as a means of proving themselves to whites and advancing socially and economically.

W. E. B. Du Bois was a critic of Washington’s stance, which he thought too accommodationist, or too willing to compromise with whites. Du Bois was Harvard educated, and in his most famous work, The Souls of Black Folk (1903), he maintained that Blacks should pursue a liberal arts education and fight for full political and civic equality. He argued that a “Talented Tenth” would provide the leadership and vision in achieving progress in racial equality. Although these Black intellectuals held radically different visions, they concurred on the goal of achieving greater Black equality.

Another figure of the time, Marcus Garvey, presented an alternate view supporting racial separation rather than integration. Garvey was an immigrant from Jamaica who founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). He supported Black separatism and a pan-African movement advocating migration back to Africa. He employed more militant rhetoric and advocated armed self-defense.

Black artists, writers, and musicians expressed themselves creatively in different media to convey their Black pride and celebrate African and African American history. The most famous movement of Black culture in the first half of the twentieth century was the Harlem Renaissance . This was a flourishing of Black art among a remarkable concentration of artists in the Harlem neighborhood of New York City in the 1920s and that also included Black artists and culture around the nation and world. In 1925, Alain Locke helped launch the movement with the anthology “The New Negro,” which advanced Black self-expression and art. The rich array of artists included writer Zora Neale Hurston, poet Langston Hughes, and musicians Josephine Baker, Louis Armstong, and Duke Ellington. These artists and many others left an indelible mark not only upon Black culture but on American culture more generally.

A number of violent racial incidents marred race relations throughout this period. Black Americans were the victims of lynchings , and Congress did not pass an antilynching bill despite repeated calls for one. The Great Migration to urban cities fueled racial tensions and led to a number of race riots during and immediately after World War I in several cities across the country. In the infamous Tulsa Massacre of 1921, armed white mobs burned down several square blocks of Black neighborhoods, including a wealthier part of town called “Black Wall Street,” where successful, enterprising Blacks lived and worked. The white mobs fired their weapons at Blacks, killing dozens.

The racial violence after World War I was replicated during World War II, most notably in Detroit in 1943 as tensions over segregated neighborhoods stirred crowds of whites and Blacks to violence. Hundreds were injured, and President Roosevelt sent the army to quell the violence.

The wider political reform movements of the first half of the twentieth century did not offer Black Americans significant relief. Southern progressivism supported segregation as a means of achieving greater social order. Many labor unions excluded Black workers and thus forced them to rely upon mutual-aid societies. Moreover, the popularity of Social Darwinism , even among scientists and intellectuals, meant that belief in a racial hierarchy became widespread, relegating those of darker skin to the bottom. The federal government generally followed discriminatory hiring practices, most notably during the Wilson administration. Blacks also often received less government assistance. For example, during the New Deal, President Franklin Roosevelt’s response to the Great Depression, the administration deferred to racist local and state governments on the distribution of aid. Still, Blacks welcomed the federal relief they received during those difficult times, and many switched from the Republican Party, often called the party of Lincoln, to the Democratic Party.

Local and state governments also continued to suppress Black voter registration, especially in the South. The court deferred to the states to set voting qualifications in Giles v. Harris (1903), though in Nixon v. Herndon (1927) it did ban discrimination when it was egregiously and overtly aimed at restricting the Black vote in primaries. The court affirmed the Nixon ruling in Smith v. Allwright (1944), by banning the attempt in Texas to exclude Blacks by allowing primaries to be regulated by private associations like political parties that could discriminate.

Black men and women played a vital role in the war effort during both world wars. Pictured are a group of the Tuskegee Airmen at a U.S. base in February 1944 and women working at a welding plant on the home front in 1943.

Even though they did not enjoy the full rights of citizenship at home, Blacks served in the fight against autocracy during two world wars—350,000 soldiers in World War I and 1.2 million in World War II. Black soldiers in the armed forces mostly served in segregated units that were typically assigned menial support labor. However, many fought courageously, such as the Harlem Hellfighters in the 369th Regiment of the 93rd Division at the Meuse-Argonne offensive in 1918, and the bomber and fighter squadrons flown by the highly decorated Tuskegee Airmen. Other significant contributions to the war included the Redball Express, which brought desperately needed supplies and troops to Europe during the Battle of the Bulge. Black members of the armed services resisted racist acts in the armed forces during World War II. After fighting fascism abroad, they were more likely to make a stand against segregation and racism at home after the war.

By World War II, Black leaders such as A. Philip Randolph were directly confronting the Roosevelt administration and the larger society to protest discrimination in the armed services and defense industries. When Randolph threatened a 100,000-person march on Washington, Roosevelt signed Executive Order 8802, banning discrimination in hiring for federal agencies and contractors, and established the Fair Employment Practice Committee (FEPC) to enforce the order. This success was a landmark in Black direct action in the struggle for freedom and equality.

The first half of the twentieth century was a period of segregation and second-class status for Black Americans. However, they took action to defy the restraints upon their rights and personal dignity. They formulated and debated paths to equality, expressed their creativity in dynamic and powerful ways, fought for a country that denied them equal opportunity, cooperated for mutual support, and took direct action to confront oppression and injustice. These generations of Black intellectuals, artists, soldiers, and activists demonstrated the moral courage that laid the foundation of the civil rights movement.

Reading Comprehension Questions

- What factors led to the Great Migration? How did the Great Migration change life for the many Black Americans who moved? How did it alter the Black experience in the United States?

- Compare and contrast the ideas of Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois. How would they critique each other’s ideas? On what did they agree?

- Why do you think Blacks served their country in the armed forces when they suffered discrimination and segregation within both the military and the larger society?

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Growing up black in America: here's my story of everyday racism

As a middle-class, light-skinned black man I am ‘better’ by American standards but there is no amount of assimilation that can shield you from racism in the US

I am a black man who has grown up in the United States. I know what it is like to feel the sting of discrimination. As a middle-class, light-skinned black man I also know that many others suffered (and continue to suffer) a lot worse than me. I grew up around a lot of white people. In elementary school, I remember being told that I was one of the “good ones” – not like the “bad ones” I was meant to understand; I was different.