We use some essential cookies to make this website work. We’d like to set some additional cookies to understand how you use the website and to improve it. We also use cookies set by other sites to help us deliver content from their services. You can read more about our cookies before you choose.

- Accept additional cookies

- Reject additional cookies

This is a new website – your feedback will help us to improve it.

Making the case

Making the case for evidence-based patient information: the importance of evidence to support shared decision-making and how NHS libraries can play a key role

On behalf of Health Education England and as part of a Senior Leadership Programme, a group of health library and knowledge specialists across England worked together on a shared project exploring how evidence is used in the creation and review of information for patients.

The project titled, ‘Making the case: evidence-based patient information’ explores the real need for patients and the public to have access to high quality, reliable health information.

As individuals are being encouraged to self-manage and be partners in their care they need access to a range of resources tailored to their literacy level.

The aims of the project were:

- influence and advocate the importance of evidence for health information for patients, carers and the public in healthcare settings

- identify key learning to support others in influencing the evidence base of patient leaflets in their local NHS settings.

As health librarians, we play a key role in providing evidence for patient care as part of our service to healthcare staff.

We have skills in finding the evidence, appraising it and making it readily available in formats needed by our healthcare colleagues.

The need for patient information to be evidence based is driven by a number of strategic priorities including:

- patient experience

- self-management

- shared decision-making

- health system sustainability

The project focused on the production of patient leaflets within NHS Trusts. These are usually written by local clinical staff for specific conditions or procedures.

We were looking at the current level of involvement by NHS KLS in the production and review of leaflets and the key stakeholders who play a role in this process.

Information was gathered from case studies of three NHS Trusts, through telephone interviews with NHS librarians delivering and supporting the production of patient information and a literature search on good quality patient information.

The findings of the work are outlined in the report, along with other useful resources highlighting:

- importance of KLS role in supporting evidence-based information

- key policy drivers

- influencing key stakeholders

- challenges of clinical language.

The report makes a number of recommendations including making patient information a part of our ‘offer’ as a service forming part of KLS existing role as champions of evidence-based practice within their organisations.

Key themes from the case studies and learning from networks were the significance of influencing skills and the importance of demonstrating the impact of this work and sharing best practice.

- Making the case; evidence-based patient information.’ A report of the findings

- Learning log

- Stakeholder map

Contact the Knowledge for Healthcare team on [email protected] for any of the resources in an accessible format.

There are other examples of best practice, highlighted to demonstrate the positive impact NHS libraries have experienced. It is another aspect of the work many NHS libraries are already engaged in as part of patient care.

If you have any queries about the project please contact a member of the project team:

Emily Hopkins, Health Education England Deena Maggs, The King’s Fund Victoria Treadway, NHS RightCare Vicki Veness, Royal Surrey County Hospital NHS Foundation Trust Jacqui Watkeys, Walsall Healthcare NHS Trust Suzanne Wilson, Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust

Page last reviewed: 15 June 2021

Quality outcomes in NHS library and knowledge services

Performance Measurement and Metrics

ISSN : 1467-8047

Article publication date: 15 January 2021

Issue publication date: 16 August 2021

This paper aims to demonstrate the approach taken in delivering the quality and impact elements of Knowledge for Healthcare, the strategic development framework for National Health Service (NHS) library and knowledge services in England. It examines the work undertaken to enhance quality and demonstrate the value and impact of health library and knowledge services. It describes the interventions developed and implemented over a five-year period 2015–2020 and the move towards an outcome rather than process approach to impact and quality.

Design/methodology/approach

The case study illustrates a range of interventions that have been developed, including the outcomes of implementation to date. The methodology behind each intervention is informed by the evidence base and includes professional engagement.

The outcomes approach to the development and implementation of quality and impact interventions and assets provides evidence to demonstrate the value of library and knowledge staff to the NHS in England to both high-level decision-makers and service users.

Originality/value

The interventions are original concepts developed within the NHS to demonstrate system-wide impacts and change. The Evaluation Framework has been developed based on the impact planning and assessment (IPA) methodology. The interventions can be applied to other healthcare systems, and the generic learning is transferable to other library and knowledge sectors, such as higher education.

- Service improvement

Edwards, C. and Gilroy, D. (2021), "Quality outcomes in NHS library and knowledge services", Performance Measurement and Metrics , Vol. 22 No. 2, pp. 106-116. https://doi.org/10.1108/PMM-07-2020-0040

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2020, Clare Edwards and Dominic Gilroy

Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

Introduction

Health Education England (HEE) is the steward of development and investment in library and knowledge services on behalf of the National Health Service (NHS). HEE's Knowledge for Healthcare ( HEE, 2014 ) is the strategic development framework for NHS-funded library and knowledge services in England, which has set out an ambitious vision to ensure the use of the right knowledge and evidence at the right time. It calls for service transformation, redesign and collaboration ( Lacey Bryant et al. , 2018 ). One of the strategic work streams underpinning Knowledge for Healthcare is quality and impact.

Value and Impact Toolkit

Metrics for Success

Evaluation Framework

Quality Assurance Framework

Grieves and Pritchard (2018) note the importance of an outcomes and impact-centred model in developing an agile evidence base. This enables the library and knowledge staff to demonstrate to stakeholders that they “fully understand the value our customers place upon services, the contribution we make to strategic objectives, our value for money and the longer-term impact”. An outcomes focus has been adopted in the implementation of these interventions.

Methodology

The HEE Library and Knowledge Services team uses driver diagrams as a strategic planning tool. A driver diagram ( Figure 1 ) informed the development of interventions to be implemented by quality and impact group (QIG) to achieve the vision of Knowledge for Healthcare. In most instances, each intervention resulted in a project to oversee the development and implementation of a tool to improve service quality and demonstrate value and impact. In some instances, such as with the research and innovation aim, the intervention consisted of a range of projects and initiatives. Intervention and project were overseen by task and finish groups which included representatives from HEE, NHS-employed library and knowledge staff, higher education healthcare librarians and subject matter experts. An evidence-based approach was followed, including a literature review, piloting and evaluation processes.

Our next steps are to refresh the “impact” tool, promote widespread adoption and publish case studies in order to attract more decision makers to make the best use of the service ( HEE, 2014 ).

An initial intervention was to enhance the existing NHS library and knowledge services impact toolkit. This toolkit was based on sound evidence ( Weightman et al. , 2009 ); however, it was acute hospital focussed, and the evidence showed that many library and knowledge staff were not routinely measuring the impacts made by their service. Library and knowledge staff also often confused impact and user feedback ( Ayre et al. , 2018 ). A refresh of the original tool was required, grounded in current evidence of the type of positive impacts being demonstrated by health librarians ( Brettle et al. , 2016 ) and applicable to all healthcare settings.

A Value and Impact task and finish group was set up to review and update the Impact toolkit. The methodology used included a literature search, a baseline survey on the use of the existing toolkit and development and piloting of a questionnaire ( Ayre et al. , 2018 ).

The task and finish group used the standard methods and procedures for assessing the impact of libraries BS IS0 16439:2014 to define impact for NHS libraries as a difference or change in an individual or group resulting from the contact with library services. The group adopted Saracevic and Kantor’s (1997) definition of value as the perceived value approach which relies on an individual's own perception of the value of an impact.

The refreshed Impact Toolkit ( HEE, 2016b ) includes a generic questionnaire, an impact case study template and a resource that brings together a range of material useful in measuring value and impact. The main change to the questionnaire is the recommendation that impact is gathered in relation to one specific incident (or use) rather than overall use of the library ( Ayre et al. , 2018 ). The questionnaire focusses on impact as both immediate and probable future outcomes. Knock et al. (2017) provided an overview of the collaborative approach used in the development of the toolkit, its contents and intention to collate the outcomes of both the questionnaire and case studies nationally to provide a clear picture of the impact of health libraries in the NHS in England.

Since the launch of the toolkit, in 2016, there has been a considerable increase in the generation and sharing of impact evidence across England to demonstrate the value of the library and knowledge services to the NHS. Examples of this include Warrington and Halton Teaching Hospitals, where an impact mural was added in a prominent location within the teaching space, and University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire's Clinical Evidence-Based Information Service (CEBIS) which regularly use social media to tweet about their impact work.

A survey was carried out in spring 2019 to determine how many services had implemented the Impact toolkit. With a response rate of 100%, this survey showed that 75% of library and knowledge services were using the toolkit and of these, 80% were using the generic questionnaire, demonstrating progress towards the initial target in Knowledge for Healthcare of 95% of services using the toolkit.

The development of impact case studies has become the most powerful means of demonstrating the impact and value of services across England. Library and knowledge staff are encouraged to submit case studies to a national repository managed by the HEE team, with over 350 accepted to date. Many of these narratives have been developed into impact vignettes ( Plate 1 ).

Impact data only deliver their full potential value where they are used to evidence the critical functions that library and knowledge staff fulfil in the NHS and healthcare environment. Gilroy and Turner (2018) demonstrated how library and knowledge staff were championing their organisational impact at the local level, using impact evidence in a variety of ways including in annual reports and promotional materials to highlight their value to stakeholders.

The use of quotes from individual stakeholders and opinion leaders who have benefited from the use of services is an important part of the case study development. This recommendation is used in promotional material at the national and local level, ensuring the role of health library and knowledge services is visible to high-level decision-makers influencing thinking and policy.

Quality and Improvement Outcomes Framework (Outcomes Framework)

We will refresh the Library Quality Assurance Framework to ensure it continues to drive service improvement and is aligned with wider education and service monitoring (Knowledge for Healthcare, 2014).

An initial objective was to refresh the existing Library Quality Assurance Framework (LQAF), first introduced in 2010 ( De la Mano and Harrison, 2012 ). However, to align with the needs of Knowledge for Healthcare, it was decided to completely review the existing quality process. Many of the reasons for review were the same as those highlighted by Reid (2019) ; standards of service delivery had improved ( Lacey Bryant et al. , 2018 ); context had changed and the perception that it was becoming “too easy” to attain the highest ranking of excellence.

A key emphasis of the review was the focus on outcomes rather than process. Grey et al. (2012) highlighted that any future strategic development of health library services should promote the importance of quality improvement outcomes (rather than processes) as the key to improving services.

The development has been grounded in an evidence-based approach using the quality improvement methodology of plan, do, study, act (PDSA). The piloting stage and use of a range of methods, both evaluative and knowledge gathering, have been important to ensure the development of a robust framework for implementation ( Edwards and Gilroy, 2019 ).

All NHS organisations enable their workforce to freely access proactive library and knowledge services that meet organisational priorities within the framework of Knowledge for Healthcare.

All NHS decision-making is underpinned by high-quality evidence and knowledge mobilised by skilled library and knowledge specialists.

Library and knowledge specialists identify the knowledge and evidence needs of the workforce in order to deliver effective and proactive services.

All NHS organisations receive library and knowledge services provided by teams with the right skill mix to deliver on organisational and Knowledge for Healthcare priorities.

Library and knowledge specialists improve the quality of library and knowledge services using evidence from research, innovation and good practice.

Library and knowledge specialist demonstrate that their services make a positive impact on healthcare.

The maturity model has five levels from 0, which represents no development against the outcome, through to 4, a service that is highly developed and continually improving against the outcome.

Defining quality is difficult as there are multiple definitions which capture its myriad elements. Booth's (2003) analogy encourages consideration of as many different aspects, perspectives and types of evidence as possible to provide a realistic overview of quality. The evaluation of library and knowledge services against the levels for each of the outcomes therefore relies on a range of evidence to demonstrate progress. Based on the structure of the Public Library Improvement Model for Scotland ( 2017 ), the Outcomes Framework provides the scope, NHS strategic context, key questions to consider and examples of outcome-focussed evidence.

HEE's policy on NHS library and knowledge services in England ( HEE, 2016a ) emphasises the need for all NHS staff to be able to freely access library and knowledge services in order to use the right evidence and knowledge to deliver excellent healthcare and health improvement. To ensure that the NHS is engaged and delivering on this policy, the Outcomes Framework has taken an organisational approach. Outcomes 1 to 3 are focussed on the organisation to ensure that library and knowledge services are embedded and seen as business critical ( Lacey Bryant et al. , 2018 ). This ensures integration of the Outcomes Framework with the HEE Quality Framework ( HEE, 2019b ) covering the wider education and learning environment.

A baseline self-evaluation of the framework is being planned for submission by all NHS trusts across England in 2021. This differs from the LQAF for which only 70% of services carried out the initial baseline ( De la Mano and Harrison, 2012 ). To ensure consistency, a single national process is being established to validate the self-evaluation submissions. The result of this will be the first truly national and comparable review of quality within NHS-funded library and knowledge services in England.

The Outcomes Framework provides a structure to ensure services evolve to meet the changing needs of organisations and individuals. The framework should lead to increasing satisfaction and improved outcomes for users of the services. Grey et al. (2012) noted that quality improvement systems produce valuable outcomes including a positive impact on strategic planning, promotion, new and improved services and staff development.

Metrics and the impact evaluation framework

Metrics will be reviewed, and additional meaningful measures introduced, as part of action planning to implement the strategic framework (Knowledge for Healthcare, 2014).

A task and finish group carried out an extensive review of what makes a good metric and how these have been applied to library and knowledge services in the NHS. The methodology included a survey with library and knowledge staff about current approaches; a review of the history of metrics in NHS-funded libraries and a scoping literature search.

The resulting Principles for Metrics Report and Recommendations ( HEE, 2016c ) identifies a set of principles for good metrics for health library and knowledge services, as meaningful, actionable, reproducible and comparable. It defines metrics as “criteria against which something is measured” ( Showers, 2015 ). It also provides a template [1] to support the development and sharing of metrics that are adaptable across all service situations.

Fricker (EAHIL, 2017) emphasised how good metrics contribute to better engagement and understanding with stakeholders and highlighted the principles which will equip librarians to develop meaningful metrics in support of their service development and improvement.

This work has improved our understanding of metrics and has provided a major learning point since the production of Knowledge for Healthcare in 2014. This learning is now being used at the national level to inform the refresh of the strategy.

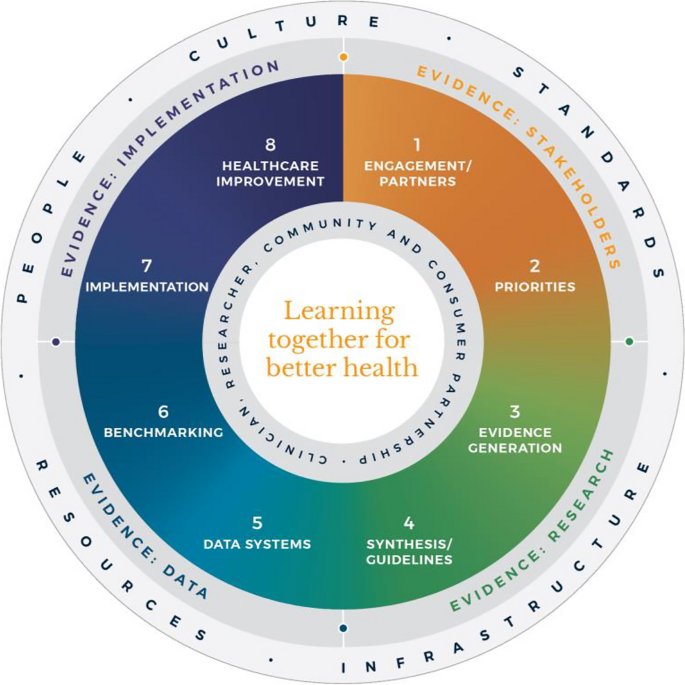

Working with Sharon Markless [2] , an impact Evaluation Framework ( HEE, 2017 ) was created to measure the progress and impact of delivery of the Knowledge for Healthcare vision. This used the impact planning and assessment (IPA) methodology and defined impact as “any effect of the service [or of an event or initiative] on an individual or group” ( Streatfield and Markless, 2009 ). This aligns well with the definition in the Value and Impact Toolkit.

The Evaluation Framework is based on the premise that it is very difficult to provide clear evidence of impact in complex systems such as healthcare. Therefore, the approach taken is to identify a series of indicators which, when taken together, suggest that progress is being made ( Streatfield and Markless, 2009 ). The overall emphasis in any evaluation framework is on achieving outcomes which show “changes in behaviour, relationships, activities or actions of people, groups and organisations with whom a programme works directly” ( Earl et al. , 2001 ).

Organisations are more effective in mobilising evidence and internally generated knowledge.

Patients, carers and the public are empowered to use information to make health and well-being choices.

Improved consistency and increased productivity and efficiency of healthcare library and knowledge services.

Enhanced quality of healthcare library and knowledge services.

Partnership working is the norm in delivering knowledge to healthcare.

Increased capability, confidence and capacity of library and knowledge services workforce.

It was important to ensure that appropriate evidence and data were available to demonstrate progress against the objectives. Most of the data and evidence required are generated by the activity carried out by the library and knowledge services delivering to the NHS at the local level, with additional evidence from national activity. A review resulted in the revision of existing NHS library service data sets and the development of some new processes.

A learning point has been to consider what data and evidence should be collected routinely compared to ad hoc requests for specific evidence requirements. A monitoring dashboard is being developed for review and reporting of the data sets against agreed metrics and to demonstrate trends and differences made against each of the objectives. The further goal is to have the significant longitudinal data and evidence to truly tell the story of the impact of the library and knowledge services in the NHS.

Overview of building the evidence base

As part of our commitment to quality, knowledge teams will continue to undertake and publish research in the field, thereby building the evidence base for service improvement and sharing best practice (Knowledge for Healthcare, 2014).

A range of initiatives have been taken forward by QIG towards achieving this aim with an emphasis on encouraging library and knowledge services to share good practice and innovation.

An important step had already been taken in promoting service improvement by recognising and rewarding innovation through the Sally Hernando Awards for Innovation [3] ( De la Mano and Harrison, 2012 ). These awards have been refined with more focus on the evaluation and impact of service innovation.

A key aim of Knowledge for Healthcare is to increase the numbers of clinical librarians within the NHS. Brettle et al. (2016) urged future researchers to build a significant and comprehensive international evidence base about the effectiveness and impact of clinical librarian services. QIG supported a national project to contribute to this evidence base. A task and finish group continued this research, demonstrating the impact of clinical librarians in assisting in decision-making surrounding patient safety, quality of care and efficiency ( Divall and James, 2019 ).

The Outcomes Framework also encourages library and knowledge staff to ensure developments are evidence based and to develop a research culture within the library service. This aligns to the work presented by Thorpe and Howlett (2019) on the development of an Australian maturity model for evidence-based practice.

The work of the QIG has produced a range of streamlined interventions that are applied and implemented nationally in a single consistent way. This approach to development and implementation is enabling the creation of an outcomes-focussed national evidence base to demonstrate the value and impact of library and knowledge services across the NHS system. Aligned to this is the use of the evidence and the interventions to support service improvement.

The impact vignettes have been used successfully with stakeholders to raise the profile of library and knowledge staff, a primary example being the A Million Decisions campaign [4] , delivered in partnership with the Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals (CILIP). Local services are using this effectively for both advocacy and promotion.

As Gann and Pratt (2013) conclude, there is a need for library and knowledge staff to identify ways to evaluate themselves and ensure current measures have meaning for those outside the library world and in the context of organisations' mission and objectives. Quality and impact tools facilitate this at a system level and allow for the development of policy. For example, the implementation of a library and knowledge staff ratio policy ( HEE, 2020 ) has been underpinned by the evidence from the use of the impact tools and collection of metrics and impact. In 2014, an unrealistic target was set of an increase in clinical librarians, from 58 to 80%, at this time, we have only reached 63%. However, the library and knowledge workforce metrics, impact on clinical librarians’ research and the impact vignettes have formed the evidence, that speaks clearly to stakeholders and employers, to enable a recommendation on an improved staffing ratio to increase the number of embedded librarians and knowledge specialist. The policy states that organisations should “strive to achieve a ratio of at least 1 qualified librarian or knowledge specialist per 1,250 WTE NHS staff”.

Although the different interventions can be used separately, the collective outputs provide a powerful narrative of the value of library and knowledge staff to the NHS from an impact and patient outcomes perspective.

The QIG driver diagram illustrates the primary aim of enhancing the quality and demonstrating the value of healthcare library and knowledge staff. The interventions described in this paper are enabling this change and have been used to demonstrate the system-wide value and impact of library and knowledge staff to the NHS in England.

In 2020, Knowledge for Healthcare will be reviewed and refreshed. Originally drafted to cover a 15-year time span and published as a five-year strategy, this is a useful juncture to take stock. The next steps for QIG will be for further evaluation of all the interventions. Effective knowledge services are business critical for the NHS. It follows that there are two crucial next steps: embedding the use of these evidence-based interventions in a consistent way in local NHS-funded library and knowledge services; generating the evidence base that allows NHS executives, clinicians and managers, as well as librarians and knowledge specialists, to tell the impact story to a range of different audiences and for different purposes, be that advocacy, promotion or sharing good practice and innovation.

Driver diagram

Examples of impact case study vignettes

https://kfh.libraryservices.nhs.uk/value-and-impact-toolkit/tools/metrics/

Sharon Markless, https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/sharon.markless.html

The Sally Hernando Awards are for innovation in NHS library services are named in memory of Sally Hernando (1957–2010), formerly head of knowledge management and e-learning at NHS south-west. Sally led on many innovative national developments and was a great supporter of developing library services to their fullest potential.

A Million Decisions is a joint campaign led by HEE's Library and Knowledge Services team and the CILIP Health Libraries Group and with CILIP https://www.cilip.org.uk/general/custom.asp?page=AMillionDecisions

Ayre , S. , Brettle , A. , Gilroy , D. , Knock , D. , Mitchelmore , R. , Pattison , S. , Smith , S. and Turner , J. ( 2018 ), “ Developing a generic tool to routinely measure the impact of health libraries ”, Health Information and Libraries Journal , Vol. 35 No. 3 , pp. 227 - 245 , doi: 10.1111/hir.12223 .

Booth , A. ( 2003 ), “ What is quality and how can we measure it? ”, Scottish Health Information Network, SHINE , Vol. 43 , pp. 2 - 6 , available at: https://www.academia.edu/2723791/What_is_quality_and_how_can_we_measure_it .

Brettle , A. , Maden , M. and Payne , C. ( 2016 ), “ The impact of clinical librarian services on patients and health care organisations ”, Health Information and Libraries Journal , Vol. 33 No. 2 , pp. 100 - 120 , available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/hir.12136 .

De la Mano , M. and Harrison , J. ( 2012 ), “ Quality evaluation of health libraries in England: a new framework ”, Performance Measurement and Metrics , Vol. 13 No. 3 , pp. 139 - 153 .

Divall , P. and James , C. ( 2019 ), “ The impact of the clinical librarians in the NHS: findings of a national study ”, paper presented at 10th International Evidence Based Library and Information Practice (EBLIP 10) Conference , Glasgow, Scotland , 17-19 June , abstract available at: https://eblip10.org/Home/tabid/7677/Default.aspx .

Earl , S. , Carden , F. and Smutylo , T. ( 2001 ), “ Outcome mapping: building learning and reflection into development programs ”, International Development Research Centre , available at: https://www.idrc.ca/sites/default/files/openebooks/959-3/index.html .

Edwards , C. and Ferguson , L. ( 2015 ), “ Knowledge for healthcare – quality and impact ”, CILIP Update , Vol. 2015 November , pp. 35 - 37 .

Edwards , C. and Gilroy , D. ( 2019 ), “ The development and implementation of quality improvement standards for NHS library and knowledge services ”, Paper Presented at 10th International Evidence Based Library and Information Practice (EBLIP 10) Conference , Glasgow, Scotland , 17-19 June , abstract available at: https://eblip10.org/Home/tabid/7677/Default.aspx .

Fricker , A. ( 2017 ), “ Building better metrics – drive better conversations ”, Paper Presented at International Congress of Medical Librarianship (ICML) and European Association for Health Information and Libraries (EAHIL) Conference , Dublin, Ireland , 12-16 June , abstract available at: https://eahil2017.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Abstracts-ICML-EAHIL-2017.pdf .

Gann , L.B. and Pratt , G.F. ( 2013 ), “ Using library search service metrics to demonstrate library value and manage workload ”, Journal of the Medical Library Association , Vol. 101 No. 3 , pp. 227 - 229 .

Gilroy , D. and Turner , J. ( 2018 ), “ Showcasing the impact of health libraries in England ”, Paper Presented at European Association for Health Information and Libraries (EAHIL) Conference , Cardiff, Wales , 9 - 13 July , abstract available at: https://eahilcardiff2018.wordpress.com/programme-2/ .

Grey , H. , Sutton , G. and Treadway , V. ( 2012 ), “ Do quality improvement systems improve health library services? A systematic review ”, Health Information and Libraries Journal , Vol. 29 No. 3 , pp. 180 - 196 , doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2012.00996.x .

Grieves , K. and Pritchard , O. ( 2018 ), “ Articulating value and impact through outcome-centered service delivery: the student and learning support experience at the University of Sunderland ”, Performance Measurement and Metrics , Vol. 19 No. 1 , pp. 2 - 11 .

Health Education England ( 2014 ), “ Knowledge for healthcare: a development framework ”, available at: https://www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/Knowledge_for_healthcare_a_development_framework_2014.pdf .

Health Education England ( 2016a ), “ NHS library and knowledge services in England policy ”, available at: https://www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/NHS%20Library%20and%20Knowledge%20Services%20in%20England%20Policy.pdf .

Health Education England ( 2016b ), “ Value and impact toolkit ”, available at: https://kfh.libraryservices.nhs.uk/value-and-impact-toolkit/ .

Health Education England ( 2016c ), “ Principles for metrics report and recommendations ”, available at: http://kfh.libraryservices.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Metrics-Principles-Report-Final-2016.pdf .

Health Education England ( 2017 ), “ The evaluation framework ”, available at: https://kfh.libraryservices.nhs.uk/ef-intro/ef-view/ .

Health Education England ( 2019a ), “ Quality and improvement outcomes framework for NHS funded library and knowledge services in England ”, available at: https://www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/HEE%20Quality%20and%20Improvement%20Outcomes%20Framework.pdf .

Health Education England , ( 2019b ), “ Quality framework ”, available at: https://healtheducationengland.sharepoint.com/Comms/Digital/Shared%20Documents/Forms/AllItems.aspx?id=%2FComms%2FDigital%2FShared%20Documents%2Fhee%2Enhs%2Euk%20documents%2FWebsite%20files%2FQuality%2FHEE%20Quality%20Framework%2Epdf&parent=%2FComms%2FDigital%2FShared%20Documents%2Fhee%2Enhs%2Euk%20documents%2FWebsite%20files%2FQuality&p=true&originalPath=aHR0cHM6Ly9oZWFsdGhlZHVjYXRpb25lbmd sYW5kLnNoYXJlcG9pbnQuY29tLzpiOi9nL0NvbW1zL0RpZ2l0YWwvRVhtRW85eU1fdUpOc lY0NzE1c3VqS3dCelRVbV9OM1hvWnZ0SE15a19yTnBEZz9ydGltZT0wM2tadUJXdTEwZw .

Health Education England ( 2020 ), “ HEE LKS staff ratio policy ”, available at: https://www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/HEE%20LKS%20Staff%20Ratio%20Policy%20January%202020.pdf .

Knock , D. , Smith , S. , Gilroy , D. , Turner , J. , Ayre , S. and Brettle , A. ( 2017 ), “ Health Education Englands' library and knowledge services value and impact toolkit: a collaborative approach to demonstrating the impact of libraries within Europe's largest health provider ”, Paper Presented at International Congress of Medical Librarianship (ICML) and European Association for Health Information and Libraries (EAHIL) Conference , Dublin, Ireland , 12-16 June , abstract available at: https://eahil2017.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Abstracts-ICML-EAHIL-2017.pdf .

Lacey Bryant , S. , Bingham , H. , Carlyle , R. , Day , A. , Ferguson , L. and Stewart , D. ( 2018 ), “ International perspectives and initiatives ”, Health Information and Libraries Journal , Vol. 35 No. 1 , pp. 70 - 77 , available at: https://search.proquest.com/docview/2007356955?accountid=26452 .

Reid , P.H. ( 2019 ), “ How good is our public library service? The evolution of a new quality standards framework for Scottish public libraries 2012-2017 ”, Journal of Librarianship and Information Science , (online) 3rd July , doi: 10.1177/0961000619855430 .

Saracevic , T. and Kantor , P.B. ( 1997 ), “ Studying the value of library and information services. Part I. establishing a theoretical framework ”, Journal of the American Society for Information Science , Vol. 48 No. 6 , pp. 527 - 542 , doi: 10.1002/(ISSN)1097-4571 .

Scottish Library and Information Council ( 2017 ), “ How good is our public library? A public library improvement model for Scotland ”, available at: https://scottishlibraries.org/advice-guidance/frameworks/how-good-is-our-public-library-service/ .

Showers , B. ( 2015 ), “ Metrics: counting what really matters ”, CILIP Update , February , pp. 42 - 44 .

Streatfield , D. and Markless , S. ( 2009 ), “ What is impact assessment and why is it important? ”, Performance Measurement and Metrics , Vol. 10 No. 2 , pp. 134 - 141 , doi: 10.1108/14678040911005473 .

Thorpe , C. and Howlett , A. ( 2019 ), “ Developing certainty via a maturity model for evidence-based library and information practice in university libraries ”, 10th International Evidence Based Library and Information Practice (EBLIP 10) Conference , Glasgow, Scotland , 17-19 June , abstract available at: https://eblip10.org/Home/tabid/7677/Default.aspx .

Weightman , A. , Urquhart , C. , Spink , S. and Thomas , R. ( 2009 ), “ The value and impact of information provided through library services for patient care: developing guidance for best practice ”, Health Information and Library Journal , Vol. 26 No. 1 , pp. 63 - 71 , available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2008.00782.x .

Further reading

Brettle , A. and Maden , M. ( 2016 ), What Evidence is There to Support the Employment of Professionally Trained Library, Information and Knowledge Workers? A Systematic Scoping Review of the Evidence , London , CILIP , (online) available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301626933_What_evidence_is_there_to_support_the_employment_of_trained_and_professionally_registered_library_information_and_knowledge_workers_A_systematic_scoping_review_of_the_evidence .

Acknowledgements

Members of QIG: Linda Ferguson, Alan Fricker, Jenny Turner, Mic Heaton, Prof Alison Brettle and all those who contributed to the QIG task and finish groups. Sharon Markless, for facilitating the development of the Evaluation Framework, https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/sharon.markless.html , HEE colleagues that have supported the QIG developments: Dr Ruth Carlyle, Sue Robertson, Holly Case-Wyatt.

Corresponding author

Related articles, we’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

elearning for healthcare

About the antimicrobial resistance and infections programme, amr toolkit, case studies, uti learning resources, further materials, further information, health education england project team, elearning team, antimicrobial stewardship for community pharmacy staff project team, antibiotic review kit – (ark), antimicrobial prescribing for common infections elearning session, how to access.

The Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) and Infections programme has been designed to support health and care staff – both clinical and non-clinical – in a variety of settings to understand the threats posed by antimicrobial resistance, and the ways they can help to tackle this major health issue. This programme has been developed by Health Education England (HEE) in collaboration with Public Health England (PHE), NHS England and NHS Improvement, Care Quality Commission and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

Antibiotic (antimicrobial) resistance poses a major threat to everyday life and modern day medicine where lives could be lost as a result of antibiotics not working as they should. All health and care staff, as well as the public, have a very important role in preserving the power of antibiotics and in controlling and preventing the spread of infections. Amongst the approaches to reduce this threat includes adequate infection prevention and control practices, good antimicrobial stewardship and the use of diagnostics.

Visit HEE website for more information on our AMR work .

HEE has produced an AMR toolkit , making available credible and helpful resources relating to antimicrobial resistance, as well as learning about the management of infective states, infection prevention and control and antimicrobial stewardship.

Antimicrobial Prescribing for Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs)

The Antimicrobial Prescribing for Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs) elearning provides a quick overview on the key points to consider when prescribing antibiotics for UTIs, as outlined in the NICE guidance on managing common infections.

The session covers why the management of UTIs matter, what you need to know as a clinician, what you can do in your clinical practice and where can you find more information.

This bite-sized session is accompanied by an assessment and learners have the flexibility of assessing their knowledge before and/or after engaging with the session.

The AMR toolkit can support you in addressing any further learning needs you identify through completing this elearning.

Introduction to Antimicrobial Resistance

The Introduction to Antimicrobial Resistance session supports health and care staff, including non-clinical staff working for independent contractors within the NHS, as well as volunteers across health and care settings and service provision:

- discuss why there is such a concern about misuse of antibiotics and antimicrobial resistance.

- list the key risks for development of antimicrobial resistance.

- identify their role in tackling antimicrobial resistance.

It provides an overview for clinical and non-clinical staff. It will also be of benefit to all health and care staff, including those non-clinical staff working for independent contractors within the NHS, as well as volunteers across health and care settings and service provision.

ARK is an antimicrobial stewardship initiative that aims to safely reduce antibiotic use in hospitals by helping staff stop unnecessary antibiotic treatments. This protects patients from drug side-effects like Clostridium difficile and antibiotic resistant infections.

This elearning was developed in partnership with British Society of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy (BSAC) and covers the rationale for the Antibiotic Review Kit, presents the ARK Decision Aid and also includes some brief scenarios, with reflection questions to consolidate learning.

Antimicrobial Stewardship for Community Pharmacy staff

How Community Pharmacies Can Keep Antibiotics Working

This free elearning session addresses the impact of antimicrobial resistance and the hugely important role community pharmacy staff can play in it.

This elearning will help community pharmacy staff:

- understand the connection between antibiotic use and antibiotic resistance

- identify their role in optimising antibiotic use in the general population who visit their pharmacy

- use the Antibiotic Checklist to personalise patient advice when dispensing antibiotics

- improve their self-care/safety-netting advice using the Treat Antibiotics Responsibly, Guidance, Education, Tools (TARGET) Treating Your Infection leaflets

- be aware of the global impact of antibiotic resistance

This has been developed by Public Health England in partnership with British Society of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy (BSAC), Royal Pharmaceutical Society, University of Leeds, University of Nottingham. Graphic design provided by The Letter G.

Antimicrobial Stewardship for Pharmacy Staff – c ase study

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society supported key pharmacists within NHS Trusts and Sustainability and Transformation Partnerships (STPs) to develop the skills and behaviours to become effective antimicrobial clinicians, leaders and mentors via a pilot training programme in London and the south east of England.

You can view the individual case studies from the training here .

Action on AMR – case study

Action on AMR focussed on equipping teams with QI skills to deliver their improvement work and share successful initiatives, rather than demonstrating a significant reduction in Gram-negative bloodstream infections (GNBSI) rates in the region. It is hoped that infection rates will be reduced in future as the teams progress their improvement work using the skills and knowledge gained.

Antimicrobial Stewardship (AMS) change – case study

The University of Manchester – AMS change project developed a cohort of “AMS CHANGErs”: experts in behaviour change related to AMS, with the capability, opportunity and motivation to drive change in health professional practices related to AMS.

The following report – AMS Change: Practical training to apply behavioural science to antimicrobial stewardship , outlines the development and training that has been created. It can support the development of AMS Change projects in local areas.

AMR Public Awareness

This short animation is aimed at the public and has been produced in partnership with PHE, intended to be used by health and social care staff in a variety of settings with the aim of helping prescribers respond appropriately to patients requesting antibiotics without medical need. The creation of the animation was influenced by the work of the Wellcome Trust in understanding how the public responds to information about antimicrobial resistance.

AMR GP and Primary Care Awareness

Also developed is an introductory film entitled a guide for GPs on antimicrobial resistance aimed at GPs and primary care staff to provide an introduction into the risks associated with the over-use of antibiotics, and to encourage appropriate dispersion of the animation above. It supports a range of educational materials for GPs and other primary care prescribers called the TARGET toolkit .

Urinary Tract Infection Management in the Elderly

Surveillance shows that previous urinary tract (bladder) infections, urinary catheterisation, hospitalisation, being prescribed antibiotics in the previous month and old age are key risk factors for these infections in the out of hospital setting. This short film aims to support health and care workers looking after older adults with suspected urinary tract infections (UTIs) and introduces resources that can be used to diagnose, manage and prevent UTIs in the out of hospital setting. In particular Public Health England’s (PHE) diagnostic flowchart and a patient leaflet to facilitate the management of suspected UTIs in the older frail population. ‘To Dip Or Not To Dip’ has a network of health and social care professionals who are improving the management of UTI in older people in care settings throughout the UK. To join this community email [email protected]

Blood Culture Pathway Awareness

We collaborated with NHS England and NHS Improvement to produce 2 animated videos to improve antimicrobial stewardship by raising awareness and promoting an optimal blood culture pathway as set out by Public Health England.

The first animation is a general overview , designed to raise awareness of the issues and will explain the background of AMR, the importance of an optimal blood culture pathway in AMS, and some of the factors to consider in the pre-analytical, analytical and post-analytical phases.

The second animation is a step-by-step guide of good practice in taking a blood culture sample in the pre-analytical phase.

Improving the blood culture pathway

Blood culture pathway: Taking a blood culture

Primary Care Antibiotic Prescribing

This film is aimed at health and care staff who recommend, prescribe, dispense and supply antibiotics in primary care. It highlights processes, considerations and actions that should occur to support safe and effective antibiotic prescribing and signposts to further available resources. The film is based on the TARGET Toolkit and NICE Guidance on ‘Managing common infections and antimicrobial stewardship’.

This will help health and care staff to:

- understand the connection between antibiotic use and antibiotic resistance.

- identify their role in optimising antibiotic use and stewardship.

- ensure compliance with national guidance when recommending, prescribing, dispensing and administering antibiotics.

- improve their self-care/safety-netting advice to patients on the appropriate use of antibiotics.

Secondary Care Antibiotic Prescribing

This film is aimed at health and care staff who recommend, prescribe, dispense and supply antibiotics in secondary care. It highlights processes, considerations and actions that should occur to support safe and effective antibiotic prescribing and signposts to further available resources. The film is based on Public Health England’s ‘ Start Smart – Then Focus: Antimicrobial Stewardship Toolkit ’ and NICE Guidance on antimicrobial stewardship.

Educational resources for health and care workers

For care workers

- Urinary tract infections (UTIs)’ A leaflet for older adults and carers [ Word ; PDF and User Guide ] and leaflet for those under 65 years ‘Treating your infection – URINARY TRACT INFECTION’ [ Word ; PDF and Fully Referenced ].

- To Dip or Not to Dip? Training handbook ; elearning ; animation ; poster and leaflet .

- Oxford AHSN: Good hydration and urine infections (Part 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 & 6 ).

- Infection Control In Care Homes films.

- eLearning for Healthcare (elfh) Continence and Catheter Care ; Promoting Best Practice in Catheter Care and Management of Incontinence and Urinary Catheters .

For health workers

- Managing UTI eModule explains the importance and appropriateness of diagnostics and offers advice on how to assess and treat patients with a range of urinary symptoms.

- Webinar on UTIs highlights simple key actions to help improve your antibiotic prescribing while improving the patient experience and their self-care, therefore freeing up your time.

- Antibiotic presentation core slides lasts 60 minutes and includes a clinical scenario on UTIs, slide notes and references.

- PHE quick reference tools for diagnosis of UTIs including knowing when to use the microbiology laboratory and how to understand results.

- To Dip or Not to Dip? Presentation for GPs.

- NHSI Preventing Healthcare Associated Gram-Negative Bacterial Bloodstream Infections toolkit

- NICE: Urinary tract infection products

- HEE: Antimicrobial resistance – A training resources guide

Practical resources for health and care workers to share with patients and carers

- ‘Urinary tract infections (UTIs)’ A leaflet for older adults and carers [ Word ; PDF and User Guide ]

- Preventing Urinary Tract Infections Poster

- To Dip or Not to Dip? Leaflet [1] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/government-response-the-review-on-antimicrobial-resistance [2] http://www.pulsetoday.co.uk/clinical/clinical-specialties/infectious-diseases/what-the-new-uti-guidance-means-for-gps/20036770.article

- TARGET leaflet ‘Treating your infection – URINARY TRACT INFECTION’ for those under 65 years [ Word ; PDF and Fully Referenced ].

TARGET (Treat Antibiotics Responsibly, Guidance, Education, Tools) helps influence prescribers’ and patients’ personal attitudes, social norms and perceived barriers to optimal antibiotic prescribing. It includes a range of resources that can each be used to support prescribers’ and patients’ responsible antibiotic use, helping to fulfil CPD and revalidation requirements. Free resources include:

- leaflets to share with patients (translated into more than 20 languages)

- resources for clinical and waiting areas

- audit toolkits, self-assessment and action planning

- training resources

Keep Antibiotics Working

Public Health England (PHE) first launched ‘ Keep Antibiotics Working ‘ national campaign in October 2017 across England. This was to support the government’s efforts to reduce inappropriate prescriptions for antibiotics by raising awareness of the issue of antimicrobial resistance and reducing demand from the public. The campaign’s key aims are:

- alert and inform the public to the issue of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in a way that they understand, in a manner which they understand, and increase recognition of personal risk of inappropriate usage

- reduce public expectation for antibiotics by increasing understanding amongst patients about why they might not be given antibiotics, so reducing demand

- support healthcare professional (HCP) change by boosting support for alternatives to prescription

The messaging for the national campaign aims to move patients to a better understanding that taking antibiotics when you don’t need them means they are less likely to work for you in the future and to trust their doctors’ advice regarding the best appropriate treatment for them.

A free health education resource, e-Bug , is also available for health and care staff to reduce antibiotic resistance by helping children and young people understand infections and antibiotic use. It is a valuable resource, not only because it is free to access, but it’s also available in 27 languages, being used in 221 countries worldwide.

Antibiotic Guardian

Antibiotic Guardian , a campaign led by PHE, urges members of the public and healthcare professionals to take action in helping to slow antibiotic resistance and ensure our antibiotics work now and in the future. To become an Antibiotic Guardian, people choose 1 pledge about how they can personally prevent infections and make better use of antibiotics and help protect these vital medicines.

FutureLearn

Clinical staff who have an active interest and prior experience in the prevention, diagnosis and management of infectious disease should consider accessing the free, interactive 6 week online course on Antimicrobial Stewardship by the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, University of Dundee and FutureLearn. For more information, please visit FutureLearn .

For more information on HEE’s work on antimicrobial resistance, please visit our website .

Antonio De Gregorio

Mohamed Sadak

Janet Flint

Dr Sanjiv Ahluwalia

Vanessa Petroni-Caesar

Diane Ashiru Oredope

Jon Collins

Tracy Watkins

Rashmi Chavda

Alex Drinkall

Louise Garrahan

Cliodna McNulty

Rosie Allison

Diane ashiru-oredope.

Philip Howard

Tracey Thornley

Sara Chapman

Dr Martin Llewelyn

Annie Joseph

Professor Jo Hart

Dr Lucie Byrne-Davis

Dr Tessa Lewis

Dr Donna Lecky

Available to all.

The Antimicrobial Resistance and Infections programme is freely available to access here . Please note your progress and completion of sessions will not be recorded and you will not be able to generate a record of completion. If you require evidence of learning, please register and then log in to access this programme on the elfh Hub.

If you already have an account with elfh, then you can enrol on to the Antimicrobial Resistance and Infections programme by logging in to the elfh Hub, selecting My Account > Enrolment and selecting the programme. You can then access the programme immediately in the My elearning section.

In order to access the Antimicrobial Resistance and Infections programme, you will need an elfh account. If you do not have one, then you can register by selecting the Register button below.

Register >

To view the Antimicrobial Resistance and Infections programme, select the View button below. If you already have an account with elfh, you will also be able to login and enrol on the programme from the View button.

NHS healthcare staff in England

The Antimicrobial Resistance and Infections programme is also available to NHS healthcare staff via the Electronic Staff Record (ESR). Accessing this elearning via ESR means that your completions will transfer with you throughout your NHS career.

Further details are available here .

Not an NHS organisation?

If you are not an NHS health or care organisation and therefore do not qualify for free access elfh Hub, you may be able to access the service by creating an OpenAthens account.

To check whether or not you qualify for free access via OpenAthens, you can view the eligibility criteria and register on the ‘ OpenAthens ’ portal.

Registering large numbers of users

If you are a HR, IT or Practice Manager and would like to register and enrol large numbers of staff within your organisation for access onto the Antimicrobial Resistance and Infections programme, please contact elfh directly.

Organisations wishing to use their own LMS

For HR departments wanting to know more about gaining access to courses using an existing Learning Management System please contact elfh directly to express interest.

Access for care home or hospice staff

To register for the Antimicrobial Resistance and Infections programme, select the ‘Register’ button above. Select the option ‘I am a care home or hospice worker’ then enter your care home / hospice name or postcode and select it from the options available in the drop down list. Finally enter your care home / hospice registration code and select ‘Register’. You may need to see your employer to get this code.

If your employer does not have a code, then they need to contact the elfh Support Team . The Support Team can either give the employer the Registration Code or arrange a bulk upload of all staff.

Access for social care professionals

Access to elfh content is available to all social care professionals in England whose employers are registered with the Skills for Care National Minimum Data Set for Social Care (NMDS-SC). Every employer providing NMDS-SC workforce information to Skills for Care has been given a user registration code for their staff. This code enables you to self-register for access to the Antimicrobial Resistance and Infections programme. Please contact your employer for more details about the registration code. For information about registering your organisation with the NMDS-SC your employer should access www.nmds-sc-online.org.uk or contact the Skills for Care Support Service on 0845 8730129. If you have a registration code select the ‘register’ button above.

More information

Please select the following link for more information on how to use the elfh Hub .

Advertisement

- Facebook Messenger

- Our Services

- Case Studies

- Get in Touch

User research about national library services for Health Education England

- User research

We were asked by Health Education England (HEE) to conduct a programme of research with users of NHS library and knowledge services.

Health Education England were considering options to provide new national services to support or replace the multitude of local tools, platforms and methods used by NHS staff to find and use evidence and information.

HEE had already led work to develop some ideas about possible improvements to national library services. But they had done this work from the perspective of NHS librarians, so they rightly wanted to better understand user behaviours and needs before proceeding.

We ran a programme of user research to understand how NHS staff access and use information, and to identify needs for a prospective national information service.

We conducted 26 one-to-one interviews with NHS staff from a diverse set of roles, ran a workshop with 5 end user role representatives to generate proto-personas and user journey scenarios, analysed 454 responses to our user needs survey, and conducted 2 field visits to observe users in their own context.

A particular challenge during this research was the breadth of end user roles amongst the 1.3 million NHS workforce. To address this, we worked with the HEE team to prioritise key user roles and to ensure that each role was represented in our research. These user roles included tutors, preceptors and mentors, practicing clinicians, staff in training, non-clinical staff and clinical researchers.

We presented our work (which included 38 validated and prioritised user needs) to Health Education England stakeholders, and our findings were used to inform their case to invest in national library and knowledge platforms.

Related Case Studies

Gathering evidence to inform wellcome connecting science's training programme strategy.

Wellcome Connecting Science (WCS) funds, develops anddelivers courses, conferences and other events across theworld. By engaging with WCS learning…

A critique of the leaver survey approach for HIT Training

HIT Training Ltd (HIT) is the leading specialist training and apprenticeship provider for the UK’s hospitality, catering and retail…

Cookies on the NHS England website

We’ve put some small files called cookies on your device to make our site work.

We’d also like to use analytics cookies. These send information about how our site is used to a service called Google Analytics. We use this information to improve our site.

Let us know if this is OK. We’ll use a cookie to save your choice. You can read more about our cookies before you choose.

Change my preferences I'm OK with analytics cookies

Case studies: Perinatal Pelvic Health Services

Annex 1: Collected Case Studies from Early Implementer and Fast Follower Systems

The following case studies support the Implementation guidance: Perinatal Pelvic Health Services .

Case study 1: South East London – Engagement with diverse groups

South East London PPHS engaged with diverse groups in the local community to increase awareness of pelvic health conditions and offer women knowledge, skills and confidence to manage their pelvic health in the perinatal period.

Joint Strategic Needs Assessments (JSNAs) were reviewed for each borough in the LMNS to identify the make-up of the overall population and the female population by ethnicity and languages spoken. 22 key local groups were identified.

The Lead Pelvic Health Physio and Project Manager ran virtual coffee mornings via Zoom. Open questions were used to understand the groups’ experiences of pelvic floor care. Women that attended were also taught how and when to refer, and how to self-manage their condition. Sessions with the local Latin-American community were run in Spanish and information leaflets were also shared in Spanish. Findings from these outreach sessions included:

- Some women did not know there were services that offer help

- Some women thought it was normal to be incontinent after childbirth or were embarrassed about their symptoms.

- Many of the women did not know the differences between the roles of healthcare professionals in the UK for example, Midwives versus Health Visitors

- Women did not know that pelvic health physiotherapists can provide care and treatment for pelvic floor issues.

- Women also expressed a desire to have more sessions to discuss other health care topics and like the idea of having consultations in their own communities.

From these community outreach sessions, the team found that building networks in local communities takes time and healthcare professionals need to be prepared to travel to places where communities meet. Collaborating with other groups, even if not within the same geographical footprint, can be useful. It also helps to have health professionals from the same background as the community running the session and, if not, the use of interpreters is vital.

Case study 3: Norfolk and Waveney – Antenatal and postnatal information

Norfolk and Waveney identified inconsistencies in the antenatal and postnatal information provided to women across their three Trusts. The PPHS now ensures that all women using maternity services are signposted to standardised information.

An initial scoping meeting and service user survey was carried out with the local MNVP to guide content. Service users asked for video content and interactive online sessions, as well as a mobile app. Feedback also indicated that patient choice was important, as well as separating antenatal and postnatal information so that women can easily access suitable information at different time points.

A website was developed for pelvic health education and information , as well as the single point of access. The webpages include videos, resources, functionality to book onto monthly pelvic health webinars, and advice on how to self-refer to pelvic health physiotherapy.

A suite of communications resources were also developed, including: postcards signposting how to book appointments; paper leaflets containing pelvic health information; posters and banners for spaces pregnant women visit, such as continuity of carer hubs; and social media templates. Clinical stakeholder meetings and service user focus groups were held prior to launch to gather feedback on the materials.

A free mobile application is also offered to all pregnant women following the dating scan to support them with pelvic floor exercises. The clinical team run antenatal and postnatal pelvic health sessions to help women adhere to pelvic floor exercises, as well as to provide general pelvic health advice. These sessions are held at various community locations including continuity of carer hubs, libraries, and family hubs.

Case study 4: Herefordshire and Worcestershire – Public health campaign

Herefordshire and Worcestershire co-produced a public health campaign and online platform to raise awareness of pelvic floor dysfunction and provide information on how to do pelvic floor exercises.

The campaign was co-produced with the MNVP and focus groups were held to understand what content needed to be included. A website ( www.squeezelifthold.co.uk ) was developed, which includes information on the pelvic floor, a workout programme, and a monthly blog. Content is added regularly to ensure that it is up to date with evidence-based information. It also includes a tool to translate the content into different languages. Newsletters, social media, and paid advertising have been successfully used to increase traffic to the website.

Case study 5: Norfolk and Waveney – Self-assessment facilitating self-referral

Perinatal pelvic health self-referral varied across the Norfolk and Waveney LMNS, with only one of the three providers offering self-referral prior to the PPHS.

To plan for the implementation of self-referral and a single point of access across the System, meetings were held with the MNVP, clinical stakeholders, allied health professionals, contracts and commissioning, and the local Just One Norfolk platform led by Children and Young people services.

The LMNS procured the ePAQ-Pelvic Floor Patient Reported Outcome Measure. Women are invited to complete the self-assessment questionnaire antenatally following the dating scan and again four to six months after giving birth. Women receive instant access to their own pelvic floor questionnaire report, and the results are also stored in their maternity records and postnatally on acute Trust health records, and copied to the GP if problems are identified. The results are triaged by a pelvic health physiotherapist who then places women on the following pathways:

- No concerns: Signpost to self-management information on the website and invite to monthly advice sessions

- Mild symptoms: One-to-one advice session with a therapy assistant practitioner and guided use of a mobile application

- Symptoms of pelvic floor dysfunction: Referral to a specialist physiotherapist or, where required, consultant care.

An LMNS-wide standard operating pathway for ePAQ-Pelvic Floor was put in place and is regularly reviewed and updated. ePAQ-Pelvic Floor is also being written into Trust Guidelines (e.g. for bladder care). Clinical review meetings of ePAQ-pelvic floor are held regularly at each Trust.

Since implementing ePAQ, Norfolk and Waveney are seeing an improved rate of identification of sensitive issues such as anal incontinence and referrals are being made earlier in pregnancy, which is enabling more time to treat antenatally. Physiotherapists are asked to complete an evaluation to identify whether referrals via the triage system are appropriate, and so far none have been inappropriate.

Case study 6: South East London – PFE education classes

Standardised face-to-face and virtual antenatal pelvic floor education classes have been implemented across South East London, to offer women support to build the knowledge, skills, and confidence required to manage their own pelvic health in the perinatal period.

An online survey was conducted to understand what content would be useful to service users, and morning coffee sessions were held with community groups. Before launch, maternity staff were invited to attend a drop-in session and information about the classes and other interventions are also shared with midwives on their mandatory pelvic health training.

Women with risk factors for pelvic floor dysfunction (in line with NICE clinical guidelines) are advised to attend the classes and women who do not have symptoms are welcome to attend if they would like to. GPs and Health Visitors are also aware of this service and can advise patients to attend.

The classes last one and a half hours and are delivered online by a pelvic health midwife and/or pelvic health physiotherapist. A minimum of 12 classes a month are available, with one class a week per maternity provider. Some classes are held in the evening. Women book onto classes online and those who attend are sent post-class resources, including links to pelvic health videos and an evaluation survey.

Posters for the classes are available on information boards across providers and there are virtual links to the posters on local perinatal apps. Classes are further publicised via social media and relevant local organisations. Evaluation results have been positive overall, with 85.7% of attendees feeling confident about their knowledge of pelvic floor symptoms and how to find advice and support in their maternity unit and 100% feeling confident on what to do to prevent pelvic floor issues. Further, 89% of participants felt more confident about how to do PFE and 96.4 % reporting that the class has motivated them to practice PFE regularly during pregnancy.

Case study 7: Frimley – Risk assessment tool

Prior to the development of a PPHS in Frimley, few women were referred to pelvic health physiotherapy services perinatally. The PPHS therefore wanted to improve identification of both those with symptoms, but also those that are at risk of developing issues.

The team therefore created a pelvic floor risk assessment tool that enables the pathway to be individualised according to a woman’s risk. The tool also helps to prompt discussion, sharing of information and signposting for all women.

The tool was developed based on a review of evidence for pregnancy and birth related risk factors for pelvic floor dysfunction. Items for inclusion in the tool were discussed and agreed with the steering group, community matrons and midwifery team leads, with sign off via local governance groups.

The tool was initially trialled with one midwifery team and then implementation was phased across providers, with support provided by PPHS leads, including training sessions, resources, and guidance.

The tool is conducted at booking and at 10 days postnatally. A short version is also completed at 28 weeks if a woman begins to experience symptoms. Results are recorded in the new maternity electronic patient record and women receive support accordingly:

- Low risk of pelvic floor dysfunction: directed to resources on the pelvic health website.

- Medium/high risk of pelvic floor dysfunction: offered a group pelvic health workshop led by a Pelvic Health Physiotherapy Associate Practitioner (band 4). Virtual workshops are offered for those who cannot attend in person. Women who do not speak English have the option to view a recording with a family member or to attend an online meeting with a translation function, with advice to direct questions to their midwife at their next appointment where a translator is present.

- Symptoms of pelvic floor dysfunction: one-to-one physiotherapy according to the agreed pathway.

As the assessment takes place at booking, and some women will subsequently experience a miscarriage, a ‘non-pregnancy’ virtual pelvic floor class is also offered for women who have had a miscarriage. Use of the tool has raised awareness of pelvic health among midwives and encouraged better collaboration between physiotherapy and maternity departments. Referral numbers to pelvic health physiotherapy services for pelvic floor dysfunction antenatally and within a year of birth have increased significantly since its introduction.

Case study 8: Birmingham and Solihull – Implementation of the OASI Care Bundle

Birmingham and Solihull have two maternity providers, but the OASI Care Bundle had only been implemented in one prior to the PPHS. To ensure equity across the System footprint, the PPHS worked with the other maternity provider to implement the Care Bundle.

Initially, staff were surveyed on their knowledge and understanding of perineal protection techniques. The perineal specialist midwife also had conversations with staff on perineal protection, which helped them understand staff views and enthusiasm for perineal protection.

The following activities were carried out to support implementation of the OASI Care Bundle:

- An interactive e-learning package on ‘Perineal Protection and Repair’ was created, with videos demonstrating perineal repair and protection techniques.

- Perineal protection displays were put up on the labour ward.

- Electronic notes were updated to include OASI Care Bundle documentation, including an antenatal discussions leaflet.

- OASI Care Bundle education was incorporated into community midwifery pelvic health training sessions.

- The PPHS perineal specialist midwife spent a day on the labour ward each week for staff to drop-in and practice techniques or discuss perineal protection.

- A ‘Spotlight on’ video training series was developed, with each video providing information on a different aspect of perineal protection.

- Facebook posts with information and evidence for perineal protection techniques are regularly shared.

Since implementation of the OASI Care bundle there has been an increase in the use of warm compress in vaginal births from 9% to 50%.

Case study 9: Lancashire and South Cumbria – Implementation of the OASI Care Bundle

Lancashire and South Cumbria wanted to ensure the OASI Care Bundle was implemented across the System to reduce the risk of third- and fourth-degree tears and improve outcomes for pelvic health.

Implementation teams were formed and collaboration was established with the maternity education team. The education team also worked closely with university training providers to support student midwives with OASI training. Throughout implementation, focus groups were held with local MNVPs about plans and the resources.

All relevant staff were emailed the OASI care bundle manual and there was an OASI Care Bundle ‘learning bus’ to raise awareness pre-launch. Throughout the launch month regular ‘on-the-job’ training sessions were held and OASI badges were given to staff after they had attended training to increase visibility. A train the trainer model was applied, so initially all band 7 midwife coordinators and consultant/mid-grade doctors were trained. In response to feedback that some staff, particularly those working in the community, lacked confidence performing episiotomy and suturing, a multi-disciplinary ‘OASI Care bundle and suturing workshop’ was also developed. The workshops were successful and have therefore been opened to all midwifery staff. A refresher training package facilitated by the maternity education team has been built into maternity mandatory training days and at each departmental induction.

Case study 10: South East London – Education and training for health care professionals

South East London PPHS undertook a gap analysis across all providers in the LMNS to assess what education was currently available for health professionals on pelvic health care. The analysis found wide variation in the type of training available, the frequency and regularity of training opportunities, who attended and whether training was mandatory. It was subsequently agreed across all providers that a standard package of mandatory Pelvic Health Training needed to be developed for the whole LMNS.

An Education and Learning programme was developed by the PPHS delivery group, which included an obstetrician, urogynaecologist, MNVP chairs, pelvic health physiotherapist, consultant midwife, project manager, and a consultant nurse in urogynaecology.

The group oversaw the development of a mandatory training session for maternity staff and a separate session for Doctors, GPs and Health Visitors. The sessions include the key themes identified from a service user survey, as well as information from services users with lived experience. The content of the training session was peer reviewed by a psychologist who is leading the local Maternal Mental Health Service pilot to ensure that emotional and psychological elements are included.

Mandatory training has now been rolled out across all three maternity providers. The objectives of this mandatory training are for staff to:

- Understand the anatomy and function of the pelvic floor musculature,

- Identify pelvic floor dysfunction and know when to refer to the PPHS,

- Understand the NICE recommendations for the prevention and management of pelvic floor problems,

- Understand the impact of pelvic floor dysfunction in women,

- Teach a basic pelvic floor exercise programme, and

- Provide pelvic health care.

The sessions are 45 minutes to an hour and delivered by a Pelvic Health Midwife or Pelvic Health Physiotherapist twice a month at each of the providers. Where possible, the training is multi-professional. Ad-hoc sessions with Obstetrics and Gynaecology trainees and maternity support workers are also delivered, with a recommendation for them to also complete the pelvic health e-learning module developed by Health Education England (HEE) . GP sessions have been organised via GP training Hubs and Health Visitor sessions have been organised with specialist Health Visitor practice educators across all boroughs. These sessions are delivered by the PPHS project manager and the pelvic health physiotherapy lead.

Case study 11: Frimley – Pelvic health champions

Frimley LMNS implemented a new initiative to identify perinatal patients with pelvic floor dysfunction within the wider community workforce. They provided education awareness sessions for GP’s, Midwives, Mental Health Teams and Health Visitors to increase pelvic health education within the area and awareness of how the PPHS was changing access to perinatal physiotherapy care.

Engagement with GPs was focused on sharing the care pathway and referral system for perinatal mothers to ensure they are referred into the service. Mental Health teams and Health Visitors were offered training on pelvic floor dysfunction, including on identification of symptoms and how to access and refer to the PPHS.