Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- 15 June 2021

Community–academic partnerships helped Flint through its water crisis

- E. Yvonne Lewis 0 &

- Richard C. Sadler 1

E. Yvonne Lewis is founder and chief executive of the National Center for African American Health Consciousness, Flint; co-community principal investigator at the Flint Center for Health Equity Solutions; co-director of the Healthy Flint Research Coordinating Center Community Core; and director of outreach, Genesee Health Plan, Flint, Michigan, USA.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Richard C. Sadler is associate professor of public health at Michigan State University, Flint, Michigan, USA.

Flint in Michigan is infamous for its water crisis. From 2014, the state government decided to divert the city’s water supply through ageing pipes that contained lead, a neurotoxin, making many people unwell and leading to some deaths. Residents were left searching out water that was safe for drinking, washing and bathing. Nine public officials face criminal negligence charges around wilful neglect of duty and for allegedly concealing and misrepresenting data. A US$640-million class-action lawsuit is moving its way through the courts.

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Nature 594 , 326-329 (2021)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-01586-8

Reprints and permissions

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Related Articles

- Water resources

- Environmental sciences

Neglecting sex and gender in research is a public-health risk

Comment 15 MAY 24

Interpersonal therapy can be an effective tool against the devastating effects of loneliness

Correspondence 14 MAY 24

Inequality is bad — but that doesn’t mean the rich are

How to achieve safe water access for all: work with local communities

Comment 22 MAR 24

The Solar System has a new ocean — it’s buried in a small Saturn moon

News 07 FEB 24

Groundwater decline is global but not universal

News & Views 24 JAN 24

Forestry social science is failing the needs of the people who need it most

Editorial 15 MAY 24

One-third of Southern Ocean productivity is supported by dust deposition

Article 15 MAY 24

Diana Wall obituary: ecologist who foresaw the importance of soil biodiversity

Obituary 10 MAY 24

Postdoc in CRISPR Meta-Analytics and AI for Therapeutic Target Discovery and Priotisation (OT Grant)

APPLICATION CLOSING DATE: 14/06/2024 Human Technopole (HT) is a new interdisciplinary life science research institute created and supported by the...

Human Technopole

Research Associate - Metabolism

Houston, Texas (US)

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)

Postdoc Fellowships

Train with world-renowned cancer researchers at NIH? Consider joining the Center for Cancer Research (CCR) at the National Cancer Institute

Bethesda, Maryland

NIH National Cancer Institute (NCI)

Faculty Recruitment, Westlake University School of Medicine

Faculty positions are open at four distinct ranks: Assistant Professor, Associate Professor, Full Professor, and Chair Professor.

Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

Westlake University

PhD/master's Candidate

PhD/master's Candidate Graduate School of Frontier Science Initiative, Kanazawa University is seeking candidates for PhD and master's students i...

Kanazawa University

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Advertisement

A city and a water crisis: Flint, Michigan and the 1950/1960s water crisis

- Environmental Education

- Published: 03 September 2022

- Volume 13 , pages 14–22, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Nicholas A. Timmerman ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2229-4068 1

Explore all metrics

The city of Flint and the Flint River has a long history of pollution, industrial waste, mismanagement of ecosystems, and issues of access to clean water that were significant factors in water management decisions for the city’s residents. In the 1950s and 1960s, the industrial and residential pollution control demands placed on the Flint River exceeded the river’s capacity. Particularly, the city needed to provide clean water to residents and an adequate flow rate to remove pollution from the very same water source. Many reasons emerged for the water crisis of the 1950s and 1960s, namely a rapid increase in population and demand for industrial growth, which taxed the city’s water and sewage infrastructure beyond its limits. During this era, city government took steps to increase pollution mitigation plans, increase river water flow rates, and develop reservoirs to store water reserves for use during high-demand seasons. One of the massive infrastructure plans included constructing a direct water pipeline to Lake Huron to provide Flint residents with an abundant clean water supply from one of the Great Lakes. Nonetheless, many plans enacted proved inadequate to address the immediate water emergency, and infrastructure plans such as constructing the water pipeline to Lake Huron failed to materialize, which could have prevented the Flint Water Crisis of the 2010s.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Data availability

Code availability.

Adams M, Tuel J (2016) Fighting for Flint: a Virginia tech team exposes lead poisoning. Virginia Tech Mag. https://www.archive.vtmag.vt.edu/spring16/fighting-for-flint.html . Accessed 25 Sept 2021

Adams M, Streeter H (1937) Third Biennial Report, 1935–1936, Michigan Stream Control Commission. Sewer Works J 9(5):857

Google Scholar

Bastien H (1956) In the open. The Flint Journal, pp 72. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.libproxy.umflint.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A1244BFFBAB8B8CE7%40WHNPX-17070FE113C62025%402435802-1704FF18B458B580%4071-1704FF18B458B580%40 . Accessed 18 May 2020

Batten T (1955) Flint and Michigan: a study in interdependence. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

Baughey R (1927) Flint’s great growth is industrial classic. The Detroit Free Press, pp 68. https://proxy.lib.wayne.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.proxy.lib.wayne.edu/historical-newspapers/march-6-1927-page-68-124/docview/1814240263/se-2 . Accessed 5 July 2019

Buick Given O.K. (1952) The Flint Journal, pp 38. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.libproxy.umflint.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A1244BFFBAB8B8CE7%40WHNPX-1714470F99EA637A%402434099-1714316025F08E9F%4037-1714316025F08E9F%40 . Accessed 18 May 2020

Cioc M (2002) The Rhine: an eco-biography, 1815–2000. University of Washington Press, Seattle

Cities sewage facilities as inadequate: city officials, aware of problem, welcome discussion (1959) The Flint Journal , pp 1. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.libproxy.umflint.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A1244BFFBAB8B8CE7%40WHNPX-170BE3072BF089AE%402436746-1707007CAB0AE73D%400-1707007CAB0AE73D%40 . Accessed 17 May 2020

Clark A (2018) The poisoned city: Flint’s water and the American urban tragedy. Metropolitan Books, Henry Holt and Company, New York

Coates W (1950) Areas Closed to Swimmers. The Flint Journal, pp 15. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.libproxy.umflint.edu/apps/news/document-viewp=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A1244BFFBAB8B8CE7%40WHNPX-1714EF584AE24B39%402433457-1712DCF7F26FCEA8%4014-1712DCF7F26FCEA8%40 . Accessed 18 May 2020

Coates H (1955) WRC defers Gilkey Creek action as AC tells anti-pollution Plans. The Flint Journal, pp 27. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.libproxy.umflint.edu/apps/news/document-viewp=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A1244BFFBAB8B8CE7%40WHNPX-1705F7C7962B3AC4%402435290-1705F2EF01AC5D4D%4026-1705F2EF01AC5D4D%40 . Accessed 18 May 2020

Coates W (1956) Buick waste-control termed ‘amazing’: commended for efforts against river pollution. The Flint Journal, pp 33. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.libproxy.umflint.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A1244BFFBAB8B8CE7%40WHNPX-17075067B610F878%402435591-1706B3FC08D086ED%4032-1706B3FC08D086ED%40 . Accessed 18 May 2020

Coevering J (1948) Many Michigan Rivers polluted, swimmers told. The Detroit Free Press, pp 17. https://proxy.lib.wayne.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/june-23-1948-page-17-30/docview/1817120705/se-2 . Accessed 25 September 2021

Committee Reports of FAS Due Tonight (1957). The Flint Journal, pp 5. https://proxy.lib.wayne.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/june-23-1948-page-17-30/docview/1817120705/se-2 . Accessed 18 Oct 2020

Cook L (1958) Flint, GM shows success, also problem of more jobless. The Detroit Free Press, pp 3. https://proxy.lib.wayne.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/august-15-1958-page-3-36/docview/1818170753/se-2 . Accessed 18 Oct 2020

Crow C (1945) The City of flint grows up: the success story of an American Community. Harper & Brothers, New York

Darby Trial Set at Niles; Opens Dec. 17 (1963). The Flint Journal, pp 13. https://proxy.lib.wayne.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/august-15-1958-page-3-36/docview/1818170753/se-2 . Accessed 13 Nov 2020

Davis K (2021) Tainted tap: Flint’s journey from crisis to recovery. The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill

Division of Finance (1951) Prospectus Relating to Public Offering of $1,500,000.00 Water Supply System Revenue Bonds, Series 3. The City of Flint, Flint, Mich.

Dowdell J, Laclergue D, Marshall E, Van Wieren R (2007) Flint futures: alternative futures for brownfield redevelopment in Flint. Theses, University of Michigan, Michigan

Dowdy H (1955a) Here’s story of one of fringe residents who must live with pollution. The Flint Journal, pp 72. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.libproxy.umflint.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A1244BFFBAB8B8CE7%40WHNPX-1706EF1D91A27E8D%402435215-1706EB4EE60AC761%4071-1706EB4EE60AC761%40 . Accessed 18 May 2020

Dowdy H (1955b) Sewage often floating in suburban ditches. The Flint Journal, pp 12. https://infoweb-newsbankcom.libproxy.umflint.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A1244BFFBAB8B8CE7%40WHNPX-1706EF2D5768F2CD%402435219-1704B2205784EA50%4011-1704B2205784EA50%40 . Accessed 18 May 2020

Dowdy H (1956) Buick’s Waste Plant ‘Amazing. The Flint Journal, pp 65. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.libproxy.umflint.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A1244BFFBAB8B8CE7%40WHNPX-1706EF2D5768F2CD%402435219-1704B2205784EA50%4011-1704B2205784EA50%40 . Accessed 17 May 2020

Dowdy H (1957) Reasoning behind ‘New Flint’ plan given. The Flint Journal, pp 61. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.libproxy.umflint.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A1244BFFBAB8B8CE7%40WHNPX-1706EF2D5768F2CD%402435219-1704B2205784EA50%4011-1704B2205784EA50%40 . Accessed 18 Oct 2020

Dowdy H (1958) New Flint still alive despite court decision. The Flint Journal, pp 1. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.libproxy.umflint.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A1244BFFBAB8B8CE7%40WHNPX-17090E903877CA3B%402436486-170658A6389BF51D%400-170658A6389BF51D%40 . Accessed 18 Oct 2020

Dowdy H (1959) Research project here apparently will end: Dr. Zimmer Gets Post in East. The Flint Journal, pp 7. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.libproxy.umflint.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A1244BFFBAB8B8CE7%40WHNPX-17090E903877CA3B%402436486-170658A6389BF51D%400-170658A6389BF51D%40 . Accessed 18 Oct 2020

Dowdy H (1961) Hepatitis One Disease Traced to Pollution. The Flint Journal, pp 49. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.libproxy.umflint.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A1244BFFBAB8B8CE7%40WHNPX-1713FACDB634D54B%402437448-1713F9571C7740A6%4048-1713F9571C7740A6%40 . Accessed 6 June 2020

Doyle M (2018) The source: how rivers made America and America remade its rivers. W. W. Norton & Company, New York

Dunaway F (2018) Seeing green: the use and abuse of American environmental images. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Ellis, Arndt, and Truesdell, Inc. (1972) Master plan for the Holloway Reservoir Regional Park. Ellis, Arndt, and Truesdell, Inc., Flint, Michigan

Elmore B (2014) Citizen Coke: The making of Coca-Cola capitalism. W.W. Norton & Company, New York

Evenden M (2018) Beyond the organic machine? New Approaches in River Historiography. Environ Hist 23:698–720

Article Google Scholar

FAS Backs ‘New Flint’ Plan (1957) The Flint Journal, pp 1. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.libproxy.umflint.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A1244BFFBAB8B8CE7%40WHNPX-1706A2DF49778B03%402436170-1704A636BA97D505%400-1704A636BA97D505%40 . Accessed 18 Oct 2020

FAS Committee Gives 5 reasons for its decision (1958). The Flint Journal, pp 1. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.libproxy.umflint.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A1244BFFBAB8B8CE7%40WHNPX-1706A2DF49778B03%402436170-1704A636BA97D505%400-1704A636BA97D505%40 . Accessed 18 May 2020

Flint J (1960) MSU professor says flint has real worry on subject of water. The Flint Journal, p 6. https://infowebnewsbank-com.libproxy.umflint.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A1244BFFBAB8B8CE7%40WHNPX-1706C5E7CAC25728%402436989-1704EFF44DAD5130%405-1704EFF44DAD5130%40 . Accessed 5 June 2020

Flint buying up land for reservoir project (1950). The Detroit Free Press, pp A6. https://proxy.lib.wayne.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/september-17-1950-page-6-121/docview/1817461123/se-2 . Accessed 25 Sept 2021

Genesee County Metropolitan Planning Commission (1968). People: Today and Tomorrow, Genesee County, Michigan. Battelle memorial Institute, Columbus

Glampetroni L (1964) Darby gets sole blame: judge absolves ex-city official, Businessman in Conspiracy Trial. Flint J 1

GM Spending $2,250,000 to eliminate stream pollution (1950) The Flint Journal, 17

Golden H (1956) See the cities, the wonders of Michigan. The Detroit Free Press, pp 31. https://proxy.lib.wayne.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/august-18-1956-page-31-36/docview/1818094791/se-2 . Accessed 25 Sept 2021

Grace S (2013) Dam nation: how water shaped the west and will determine its future. Globe Pequot Press, Guilford

Gustin L (1965) River pollution by industry continues, says water chief. The Flint Journal, pp 5. https://infoweb-newsbankcom.libproxy.umflint.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A1244BFFBAB8B8CE7%40WHNPX-16F914249A00F708%402439096-16F8C6CC231416EC%404-16F8C6CC231416EC%40 . Accessed 7 June 2020

Gustin L (1966) Continued efforts to end water, air pollution are promised by GM officials. The Flint Journal, pp 15. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.libproxy.umflint.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A1244BFFBAB8B8CE7%40WHNPX-1718D99C4F67E874%402439181-1718D7F90411CCF3%4014-1718D7F90411CCF3%40 . Accessed 7 June 2020

Hammer P (2019) The Flint water crisis, the Karegnondi water authority and strategic-structural racism. Crit Sociol 45(1):103–119

Hanna-Attisha M (2018) What the eyes don’t see: a story of crisis, resistance, and hope in an American City. One World, New York

Harding, H (2021) Look up how your Michigan community grew (or Shrank) in the 2020 Census. The Detroit News. https://www.detroitnews.com/story/news/local/michigan/2021/08/13/search-our-census-database-michigan-population-change/8118790002/ . Accessed 25 Sept 2021

Hart W (1951) $600,000 included to finish expansion of disposal plant. The Flint Journal, pp 52. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.libproxy.umflint.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A1244BFFBAB8B8CE7%40WHNPX-17143461CC7E0877%402433707-17142DA1CC773C04%4051-17142DA1CC773C04%40 . Accessed 18 May 2020

Hawley A, Zimmer B (1961) Resistance to unification in a metropolitan community. In: Janowitz M (ed) Community Political Systems. The Free Press, Glencoe, pp 146–177

Heffernan P (1958) Southern Michigan has thirst for water from Lake Huron. The New York Times, pp F. https://proxy.lib.wayne.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/southern-michigan-has-thirst-water-lake-huron/docview/114360442/se-21 . Accessed 25 Sept 2021

Here is Summary of Conclusions Reached in Sewage-Disposal Study (1956). The Flint Journal, pp 23. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.libproxy.umflint.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A1244BFFBAB8B8CE7%40WHNPX-17074F3A8C7F1D2A%402435812-17070D1A8EC8845E%4022-17070D1A8EC8845E%40 . Accessed 17 May 2020

Highsmith A (2015) Demolition means progress: Flint, Michigan, and the fate of the American Metropolis. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Book Google Scholar

Hurley A (1992) Challenging corporate polluters: race, class, and environmental politics in Gary, Indiana, since 1945. Indiana Mag Hist 88(4):273–302

Hurley A (1995) Environmental Inequalities: class, race, and industrial pollution in Gary Indiana, 1945–1980. The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill

Hyde T (2015) Transmittal of final report – high lead at three residences in Flint, Michigan. United State Environmental Protection Agency

Jakobsson E (2008) Narratives About the River and the Dam: Some Reflections on How Historians Perceive the Harnessed River, in Technological Society. In: Dahlin Hauken A (ed) Multidisciplinary and Long-Timer Perspectives. Stavenger, Haugaland Akademi

Kelly W, Kay T, Bactel W (1971) Flint’s industrial water supply— joint discussion. Am Water Works Assoc J 63(3):149

Kimmer, R. (2015) Braiding sweetgrass: indigenous wisdom, scientific knowledge, and the teachings of plants. Milkweed Editions, Minneapolis

Long Study Preceded City Action (1959) The Flint Journal , pp 9. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.libproxy.umflint.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A1244BFFBAB8B8CE7%40WHNPX-1706D1E9F1475DAE%402436872-1704F1A2762C92D7%4011-1704F1A2762C92D7%40 . Accessed 23 April 2020

Magner M (1995) GM propels Genesee to No. 8 on EPA Pollution List. The Flint Journal, pp 3. https://proxy.lib.wayne.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/southern-michigan-has-thirst-water-lake-huron/docview/114360442/se-2 . Accessed 7 June 2020

Maines G (1953) Men… A City… and Buick… (1903–1953): An account of how Buick and later General Motors are up in Flint. Advertisers Press Inc, Flint

Mallea A (2018) A river in the city of fountains: an environmental history of Kansas City and the Missouri River. University Press of Kansas, Lawrence

Mauch C, Thomas Z (2008) Rivers in history: perspectives on waterways in Europe and North America. University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh

Maysilles D (2011) Ducktown smoke: the fight over one of the South’s greatest environmental disasters. The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill

McClenahan W, Becker W (2011) Eisenhower and the Cold War Economy. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore

Metcalf & Eddy Engineers (1955) Report to city manager, city of Flint, Michigan upon adequacy of existing water supply, December 13, 1955. Metcalf & Eddy, Boston

Metcalf & Eddy Engineers (1957) Report to city manger, city of Flint, Michigan: comprehensive investigation of improvements and additions to the water supply of Flint and Environs. Metcalf & Eddy, Boston

Metcalf & Eddy Engineers (1960) Report to city manager, city of Flint, Michigan: a financial program for a water supply from Lake Huron and Improvements to the Water Service Facilities for the City of Flint and Environs. Metcalf & Eddy, Boston

Moore K (1967a) Detroit water line delayed into 1968. The Flint Journal, pp 49. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.libproxy.umflint.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A1244BFFBAB8B8CE7%40WHNPX-1717BCA7532AE10D%402439751-1717B9EE53F43FA8%4048-1717B9EE53F43FA8%40 . Accessed 7 June 2020

Moore K (1967b) Flint water line ahead of schedule. The Flint Journal, pp 17. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.libproxy.umflint.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A1244BFFBAB8B8CE7%40WHNPX-1717BCA7532AE10D%402439751-1717B9EE53F43FA8%4048-1717B9EE53F43FA8%40 . Accessed 7 June 2020

Owens D (2017) Where the water goes: life and death along the Colorado River. Riverhead Books, New York

Pallotta R (1962) Identity of city land agent bared: Port Huron Broker Reports Dealing with Claude Darby Sr. Flint J 1

Parking-Lot Owner Hails City Action (1955). The Flint Journal , pp 20. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.libproxy.umflint.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A1244BFFBAB8B8CE7%40WHNPX-1706D1E9F1475DAE%402436872-1704F1A2762C92D7%4011-1704F1A2762C92D7%40 . Accessed 18 May 2020

Perrow C (2002) Organizing America: wealth, power, and the origins of corporate capitalism. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Pieper K, Tang M, Edwards M (2017) Flint water crisis caused by interrupted corrosion control: investigating “Ground Zero” Home. Environ Sci Technol 52(4):2007–2014

Pollution Cut at Buick Plant (1950). The Flint Journal, pp 12. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.libproxy.umflint.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A1244BFFBAB8B8CE7%40WHNPX-1714ADB72CDEA8A6%402433598-1712CCE7972EBC71%4011-1712CCE7972EBC71%40 . Accessed 18 May 2020

Proposed would boost water supply: also termed aid against river pollution (1950). The Flint Journal, pp 31. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.libproxy.umflint.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A1244BFFBAB8B8CE7%40WHNPX-171443CD32038D6F%402433397-1714378448C0DA03%4030-1714378448C0DA03%40 . Accessed 18 May 2020

Reisner M (1993) Cadillac desert: the American West and Its Disappearing Water. Penguin Books, New York

Report on Fish Mortality in Flint River at Flushing, Michigan, Report 234 (1933). Institute for Fisheries Research, pp 2–3. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/AAG2862.0234.001 . Accessed 18 May 2020

Rogers H (2013) Gone Tomorrow: The Hidden Life of Garbage. New Press, New York

Rome A (2001) The Bulldozer in the Countryside: Suburban Sprawl and the Rise of American Environmentalism. Cambridge University Press, New York

Sanitation Delay Scored: state hearings set for townships (1952). The Flint Journal, pp 35. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.libproxy.umflint.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A1244BFFBAB8B8CE7%40WHNPX-17140580B30B0C9F%402434190-171236D1155EA62D%4034-171236D1155EA62D%40 . Accessed 17 May 2020

Schmid M (2014) The Environmental History of Rivers in the Early Modern Period, in An Environmental History of the Early Modern Period. In: Knoll M, Reith R (ed) Experiments and Perspectives. Lit Verlag, Berlin

Sellers C (2015) Crabgrass crucible: suburban nature and the rise of environmentalism in twentieth century America. The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill

Sick Fish: Reported to be Dying by the Hundreds in the Flint River (1895). The Detroit Free Press, pp 7. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.libproxy.umflint.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A1244BFFBAB8B8CE7%40WHNPX-1714ADB72CDEA8A6%402433598-1712CCE7972EBC71%4011-1712CCE7972EBC71%40 . Accessed 19 May 2020

Slump Forces Second Management Shakeup (1958). The Flint Journal , pp 39. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.libproxy.umflint.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A1244BFFBAB8B8CE7%40WHNPX-17095DFF88BFEF5C%402436430-1709032D2DA50F65%4038-1709032D2DA50F65%40 . Accessed 18 May 2020

Source of River Pollution Which Kills Fish Sought (1950). The Flint Journal, pp 20. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.libproxy.umflint.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A1244BFFBAB8B8CE7%40WHNPX-171443CD32038D6F%402433397-1714378448C0DA03%4030-1714378448C0DA03%40 . Accessed 18 May 2020

Spears E (2016) Baptized in PCBs: race, pollution, and justice in an all-American town. The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill

State and City Officials Attend: Water Made Pure Enough for Fish (1956). The Flint Journal, pp 17. https://infowebnewsbank-com.libproxy.umflint.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A1244BFFBAB8B8CE7%40WHNPX-17070F96C4C5A990%402435738-17070C5776FEE0DC%4016-17070C5776FEE0DC%40 . Accessed 17 May 2020

Stradling D (2017) The New Cuyahoga: straightening Cleveland’s Crooked River. In: Knoll M, Lubken U, Schott D (eds) Rivers Lost, Rivers Regained: Rethinking City River Relations. University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, pp 107–122

Chapter Google Scholar

Stream Pollution Problems Studied (1950). The Flint Journal, pp 26. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.libproxy.umflint.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A1244BFFBAB8B8CE7%40WHNPX-1714484E69C46129%402433316-1714374792F3BB9B%4025-1714374792F3BB9B%40 . Accessed 18 May 2020

Three Tons of Fish Die in Flint River Due to Pollution (1950). The Flint Journal, pp 11. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.libproxy.umflint.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A1244BFFBAB8B8CE7%40WHNPX-1714EF6F09C7D84C%402433424-1712DCC9CB7218FE%4010-1712DCC9CB7218FE%40 . Accessed 18 May 2020

Toor P, Cox J, Wyckoff M (2014) Environmental and development challenges and opportunities for Kearsley Reservoir and the adjoining neighborhoods in the city of Flint. In Planning & Zoning Center at Michigan State University, Michigan

Voss R (1959) Conservationists Honor Buick For Halting Its Pollution of River. The Flint Journal, pp 11. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.libproxy.umflint.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A1244BFFBAB8B8CE7%40WHNPX-170BE2E88C212887%402436741-170B3EF5DC8B7F6F%4010-170B3EF5DC8B7F6F%40 . Accessed 18 May 2020

Warn Against Fish From Unnamed Creek (1954). The Flint Journal, pp 11. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.libproxy.umflint.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A1244BFFBAB8B8CE7%40WHNPX-1706C5D956B23615%402434856-1704B2909BBB8FBD%4010-1704B2909BBB8FBD%40 . Accessed 17 May 2020

Water Critics’ Stand Is Weak (1959). The Flint Journal, pp 8. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.libproxy.umflint.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A1244BFFBAB8B8CE7%40WHNPX-1706CECA4393E78E%402436795-1704F16DB2B133E8%407-1704F16DB2B133E8%40 . Accessed 18 May 2020

Water Resources, Prevention and Abatement of Water Pollution Act 222 of 1949 (2020) Legislative Council, State of Michigan. https://legislature.mi.gov/documents/mcl/archive/2017/February/mcl-Act-222-of-1949.pdf . Accessed 25 Sept 2021

Welch P (1938) Digestion experiments at Flint, Michigan, on Sewage Sludge, Garbage and Lime Sludge Mixtures. Sewage Works J 10(2):247–260

CAS Google Scholar

White R (1996) The organic machine: the remaking of the Columbia River. Hill and Wang, New York

Wiitala S, Vanlier K, Krieger R (1963) Water resources of the Flint area, Flint: Water Supply Paper 1499-E . U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington D.C.

Worster D (1992) Rivers of empire: water, aridity, and the growth of the American West. Oxford University Press, New York

Zimmer B (n.d.) Flint Area Study Report. University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor

Zimmer B (1957) Flint Area Study Report, vol 1. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Social Sciences and Humanities, Langston University, Langston, OK, USA

Nicholas A. Timmerman

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Nicholas A. Timmerman .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests, additional information, publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Timmerman, N.A. A city and a water crisis: Flint, Michigan and the 1950/1960s water crisis. J Environ Stud Sci 13 , 14–22 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-022-00796-4

Download citation

Accepted : 23 August 2022

Published : 03 September 2022

Issue Date : March 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-022-00796-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Flint River

- Water crisis

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

The Psychosocial Effects of the Flint Water Crisis on School-Age Children

Lead poisoning has well-known impacts for the developing brain of young children, with a large literature documenting the negative effects of elevated blood lead levels on academic and behavioral outcomes. In April of 2014, the municipal water source in Flint, Michigan was changed, causing lead from aging pipes to leach into the city’s drinking water. In this study, we use Michigan’s universe of longitudinal, student-level education records, combined with home water service line inspection data containing the location of lead pipes, to empirically examine the effect of the Flint Water Crisis on educational outcomes of Flint public school children. We leverage parallel causal identification strategies, a between-district synthetic control analysis and a within-Flint difference-in-differences analysis, to separate out the direct health effects of lead exposure from the broad effects of living in a community experiencing a crisis. Our results highlight a less well-appreciated consequence of the Flint Water Crisis – namely, the psychosocial effects of the crisis on the educational outcomes of school-age children. These findings suggest that cost estimates which rely only on the negative impact of direct lead exposure substantially underestimate the overall societal cost of the crisis.

This work has been supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program under Grant No. DGE-1656518 and by the Institute of Education Sciences under Grant No. R305B140009 and R305B170015. We are grateful to Sean Reardon, Carolyn Hoxby, Eric Bettinger, Ben Domingue, Jeremy Freese, Tom Dee, David Rehkopf, Eli Ben-Michael, Avi Feller, Jesse Rothstein, Emily Morton, Marissa Thompson, and Paula Lantz for helpful comments. We also wish to thank Jasmina Camo-Biogradlija, Kyle Kwaiser, Jonathan Hartman, Nicole Wagner, and the Education Policy Initiative staff for assisting with access to Michigan’s restricted-use educational data. This research used data structured and maintained by the MERI-Michigan Education Data Center (MEDC). MEDC data is modified for analysis purposes using rules governed by MEDC and are not identical to those data collected and maintained by the Michigan Department of Education (MDE) and/or Michigan’s Center for Educational Performance and Information (CEPI). Results, information, and opinions solely represent the analysis, information and opinions of the authors and are not endorsed by, or reflect the views or positions of, grantors, MDE and CEPI or any employee thereof. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research.

MARC RIS BibTeΧ

Download Citation Data

More from NBER

In addition to working papers , the NBER disseminates affiliates’ latest findings through a range of free periodicals — the NBER Reporter , the NBER Digest , the Bulletin on Retirement and Disability , the Bulletin on Health , and the Bulletin on Entrepreneurship — as well as online conference reports , video lectures , and interviews .

Brought to you by:

The Flint Water Crisis

By: Marie McKendall, Nancy M. Levenburg

The city of Flint, Michigan, a previous hub for General Motors auto manufacturing, began to experience budget shortfalls in 2007. By 2011, the city was running a deficit of nearly $26 million, and…

- Length: 32 page(s)

- Publication Date: Apr 1, 2018

- Discipline: Organizational Behavior

- Product #: NA0530-PDF-ENG

What's included:

- Teaching Note

- Educator Copy

$4.95 per student

degree granting course

$8.95 per student

non-degree granting course

Get access to this material, plus much more with a free Educator Account:

- Access to world-famous HBS cases

- Up to 60% off materials for your students

- Resources for teaching online

- Tips and reviews from other Educators

Already registered? Sign in

- Student Registration

- Non-Academic Registration

- Included Materials

The city of Flint, Michigan, a previous hub for General Motors auto manufacturing, began to experience budget shortfalls in 2007. By 2011, the city was running a deficit of nearly $26 million, and the state assumed control of Flint through the appointment of an emergency manager. In 2014, immediately after state officials decided to begin sourcing Flint's tap water from the Flint River in order to save money, residents began complaining about the cost, color, and quality of their water. Over the next 18 months, residents reported suffering from various illnesses and an outbreak of Legionnaire's Disease occurred in the area. During this time, state officials continued to assure residents that their water was safe despite three water-boil advisories, the water rusting parts at General Motors' Flint engine plant, and the straightforward warnings from an EPA employee that an unsafe situation existed. Public pressure built as an ACLU reporter broke the story, an outside researcher's tests uncovered unsafe levels of lead in the water, and a Michigan State University pediatrician found elevated lead levels in children coinciding with the switch to Flint River water. In October of 2015, Flint switched back to sourcing water from Detroit; finally, in January of 2016, Michigan's Governor (Rick Snyder) declared a state of emergency and activated the Michigan National Guard to patrol the city and assist the American Red Cross with the distribution of bottled water and water filters. The citizens of Flint had been exposed to poisoned water for 18 months.

What went wrong? What dysfunctions and conditions in federal and state organizations led to flawed decision making and catastrophic outcomes? The case provides a general overview of the city of Flint, events leading up to the Flint water crisis, information about the involved government agencies, and a chronology of the tap water sourcing decision. The case prompts readers to analyze and understand that a variety of factors, including multiple actors, ambiguities, corporate structures, and organizational complexities can combine to result in unethical decisions and outcomes.

Learning Objectives

Learning objectives include: (1) Describe the roles of various participants in a complex situation and recognize how those roles interacted in Flint; (2) Identify the kinds of rational and cognitive mistakes that can be made during a decision process; (3) Analyze how organizational culture and structure can influence the actions of employees in organizations; (4) Examine how flawed organizational systems and goals combined with human error can create a catastrophic outcome and offer suggestions for how a situation like Flint's water crisis could be avoided; (5) Hypothesize about the role of moral courage in their future business lives; and (6) Understand the concept, components, and consequences of environmental racism.

Apr 1, 2018

Discipline:

Organizational Behavior

Geographies:

Industries:

Utilities sector

North American Case Research Association (NACRA)

NA0530-PDF-ENG

We use cookies to understand how you use our site and to improve your experience, including personalizing content. Learn More . By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies and revised Privacy Policy .

Exploring what works, what doesn’t, and why.

The children of Flint, ten years later

- Share on LinkedIn

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Facebook

- Share on WhatsApp

- Share through Email

Dionna Brown calls herself a survivor of the Flint water crisis. Ten years ago, in April of 2014, the city switched its water supply to the Flint River. The move happened under an emergency manager, appointed by the state of Michigan to help the beleaguered city find its financial footing. But the river water was corrosive, awash with chloride from road salt runoff, and the city failed to add corrosion inhibitors to the water. Aging pipes began to leach iron and lead. The result was more than 100,000 residents being exposed to unsafe levels of lead in their drinking water.

Brown, then a junior in high school, remembers she needed to make a lot more effort to focus after the switch. “I was combining words and numbers a lot,” she says. “I had to work harder to just learn.” In 2018, a blood test revealed elevated levels of lead. Then came diagnoses of ADHD and dyslexia.

Brown didn’t let her learning challenges stop her: She graduated from Howard University and is on track to get a master’s degree next month. But like many Flint residents, she feels marked by the crisis. The most vulnerable people were and are children, thousands of whom live with the consequences of poor decisions made by politicians and health officials. Yet, some positive developments have emerged. Community members have fought court battles to force the replacement of lead pipes. A coalition of public agencies, grassroots groups, and nonprofits—backed by federal, state, and foundation funding—has spent years building a creative care network to buffer some of the worst outcomes of the water crisis.

Still, the people of Flint continue to deal with ongoing physical, mental, and emotional challenges. Rates of depression exceed national averages for both children and adults. And almost half of the parents enrolled in the Flint Registry , which tracks the health of over 21,000 people affected by the water crisis, said that their children were living with behavioral problems as of 2022. These included attention issues, aggression, depression, hyperactivity, and trouble adapting. Many of these issues are worsened by ongoing stress from the years of crisis.

Dionna Brown, 24, outside her father’s car wash in Flint, Michigan in March. Brown grew up in Flint but did not get tested for lead poisoning until 2018. She found out that she had elevated lead levels; she is also coping with ADHD and dyslexia.

Brown hugs her father, Dion Brown, Sr., after getting her car washed. Despite the struggles she experienced after Flint's water switch, she graduated from Howard University. Next month she expects to receive a master's degree in sociology from Wayne State University.

Brandon Gilleylen still remembers mud-colored water spouting from his faucet a few weeks after the ill-fated water switch. “It was just shocking to see,” says the Flint native.

Almost immediately, residents complained of the water’s foul taste and smell. Many began to lose hair and break out in skin rashes. Not long after Gilleylen’s tap water turned brown, the city announced a boil-water notice because Flint’s water was found to contain fecal coliform, a sign of disease-causing pathogens. Boil-water notices for additional issues came soon after. Gilleylen and his wife, parents of a one-year-old child, duly followed directions and boiled the water they used to cook, bathe, and make baby formula.

What they wouldn’t know until more than a year later was that lead had leached from corroded water pipes. Boiling the water essentially concentrated the lead, and about 100,000 Flint residents had already been exposed—including the Gilleylens’ baby. Brandon’s wife, Ashaley Hart-Gilleylen, says she was racked with worry about their little girl. “It was really, really tough mentally, wondering what happened to her and how she’s going to be affected,” she says.

Brandon Gilleylen remembers standing in line for bottled water and feeling an “apocalyptic” sense of dread. “When is the water going to run out? Are we going to have any water left?” he would think. “We’re stuck with brown water coming out our faucets, and nobody’s listening to what we all have to say.”

Officials ignored residents who said the water was making them sick and flat-out rejected scientific evidence. In September 2015, researchers from Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University released results from a study of 252 Flint homes showing that 40 percent had water with elevated levels of lead, including one with levels twice what the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) considers to be hazardous waste. Still, state officials denied there was a serious risk.

Later that month, doctors at the city’s Hurley Medical Center announced that the percentage of children with elevated blood lead levels had doubled since 2013. The state again dismissed the science; a spokesperson described the research as “unfortunate” and mounting concerns as “near-hysteria.” But one day later, the city of Flint issued a lead warning; a week later, Genesee County, which contains Flint, declared a public health emergency.

During a protest in April 2016, a Flint resident holds a jug of her fouled tap water, a bag containing hair she has lost, and a sign calling for Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder's resignation.

Photo: Jake May / The Flint Journal via AP, File

U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy inspects a bottle of tap water from a Flint home during a visit in February 2016.

Photo: Jake May / The Flint Journal-MLive.com via AP

For families like the Gilleylens, a waiting game ensued: Would they start to see signs of lead poisoning in their children? As the Gilleylens’ daughter neared kindergarten, she began throwing violent temper tantrums, which her father says were well beyond the norm for a child her age, and which they attributed to the effects of the lead poisoning.

Ashaley Hart-Gilleylen was pregnant by the time the city switched back to Detroit water in October 2015. A few months later, she would miscarry. “I know it was something to do with the lead,” she says.

By January of this year, roughly 15 percent of kids in the Flint Registry had been diagnosed with anxiety and 10 percent with depression. (The national rates for kids of similar ages are 9.4 percent for anxiety and 4.4 percent for depression.) “We’re alarmed” but not surprised, says Nicole Jones, an epidemiologist at Michigan State University and the registry’s codirector. “The things that we’re seeing are things that we expected to be associated not only with exposure to lead, but exposure to the trauma of an environmental crisis.”

A recent study points to the wider impact of the water crisis. Test scores in math dropped for 3rd through 8th graders across Flint following the crisis, while the number of K–12 students with special education needs rose by eight percent. The results showed little variation between kids living in homes with lead service lines and those without. Sam Trejo, a Princeton University sociologist and lead author of the study, says the findings point to the Flint water crisis “not just as the tragic events that led some kids to be exposed to more lead in their water … but instead as a broader kind of emergent crisis that affected an entire city.”

Trejo’s study is consistent with other research documenting how Flint remains caught up in the water crisis, with one in four residents suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder and struggling with ongoing physical health issues. Many still feel betrayed by local and state leadership.

Adults in the registry have fared even worse than kids when it comes to mental health, with more than a third diagnosed with depression. In addition, the data show many adults have chronic conditions like high blood pressure, which can be caused by lead exposure.

“The community response was to wrap our children and families with goodness. What we’ve learned is that despite all the good stuff that we’ve been able to put in place, people continue to struggle.” Mona Hanna-Attisha, pediatrician

It’s an overcast Sunday in January on the Northside of Flint, but it’s warm inside the spacious sanctuary at Christ Fellowship Missionary Baptist Church. Rev. Allen C. Overton steps into the pulpit and begins his sermon. The pastor’s rolling baritone turns somber as he touches on the water crisis. “It’s a catastrophic tragedy that, 10 years later, I’m still on conference calls with my attorneys because every lead line has not been removed in this city.” Shouts of “Yes!” and “That’s right” ring out from the pews.

Back in the fall of 2014, Overton was watching television when General Motors announced it would stop using Flint water; the company was concerned that high levels of chloride could corrode its machinery. It would eventually come out that the failure to add corrosion inhibitors to the river water resulted not only in lead contamination but also in a reduction in chlorine levels, allowing other contaminants to flourish, including E. coli and Legionella bacteria. When more chlorine was added to fight bacteria, a buildup of trihalomethanes—disinfection byproducts linked to cancer—became yet another problem. At the time, though, state officials assured residents that even so, the water was acceptable for human consumption. Overton was shocked, and thought, “We got a problem.”

Rev. Allen C. Overton sits inside Flint's Christ Fellowship Missionary Baptist Church in March.

Overton was a spokesperson for Concerned Pastors for Social Action, a Flint-area coalition of ministers. He began calling city and state offices to ask what was going on; he was repeatedly told the water was safe to drink. In 2016, Concerned Pastors became part of a group that brought a lawsuit against the city of Flint and the state of Michigan, which led to a settlement that included a commitment to replace all of the city’s lead and galvanized steel pipes.

Such pipes represent much of Flint’s infrastructure, given that Flint’s housing stock was largely in place by the late 1950s, says Richard Sadler, a medical geographer at Michigan State’s College of Human Medicine. Sadler led a 2017 study which mapped clusters of homes whose residents had high blood lead levels; one such cluster was located just a few blocks away from Overton’s church. Concerned Pastors has been back to court several times to force action, as Flint missed multiple court-ordered deadlines to replace its aging pipes. The city claims that 95 percent of the work is done, and now that the Biden Administration has set aside money to address the issue nationally, Overton feels optimistic. “I’m trusting and believing that the city administration is going to get it done this year,” he says.

Concerned Pastors is just one of the local groups that has rallied for Flint since the crisis began 10 years ago. Many local churches and nonprofits sprang into action, and groups like the Red Cross organized small armies of volunteers to staff water drives handing out bottled water to residents and to deliver clean water and fresh food to people who were homebound.

After-school programs, healthy-foods initiatives, and community health centers worked in tandem to stitch together a safety net for distressed families. The Genesee Health System, a public entity providing mental health services, used funds from a settlement to create what is now the Children’s Integrated Services Assessment Clinic , which tests local children for lead exposure and carries out neuropsychological assessments of children. Meanwhile, the Pediatric Public Health Initiative (PPHI), created by Michigan State and Hurley Children’s Hospital, targets care to focus on lessening the impacts of the water crisis through community programs, advocacy, training, and evaluation.

“The community response was to wrap our children and families with goodness,” says Mona Hanna-Attisha, the pediatrician whose announcement about the sharp jump in kids’ lead levels back in 2015 finally got officials to acknowledge the crisis. And yet, she says, the people of Flint continue to face enormous socioeconomic challenges. Hanna-Attisha is associate dean for public health at Michigan State’s College of Human Medicine and director of the PPHI. “What we’ve learned,” she says, “is that despite all the good stuff that we’ve been able to put in place, people continue to struggle.”

Flint pediatrician and whistleblower Mona Hanna-Attisha speaks to a crowd of over 100 people during a launch event for the Flint Registry, set up to track lead exposure, in 2018.

Photo: Bronte Wittpenn / The Flint Journal-MLive.com via AP

Hanna-Attisha is leading a new program called Rx Kids , which gives $1,500 prenatal cash payments to pregnant women in Flint and $500 per month for babies during their first year of life. The program launched in January with funding from a host of public and private sources. “We’re doing something that hasn’t been done before—we’re prescribing away poverty,” Hanna-Attisha says.

The task is daunting: The University of Michigan reports that nearly 70 percent of Flint kids still grow up in poverty. And almost half of registry adults say they have difficulty covering the cost of housing and food. Good nutrition is especially crucial, as calcium, iron, and vitamin C reduce the body’s absorption of lead.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

- Email address By clicking “Subscribe,” you agree to receive email communications from Harvard Public Health.

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

A decade after the crisis, some lessons are clear, Hanna-Attisha says, citing, among others, a need “to invest in prevention, to invest in public health, to address inequities, and to respect science … and not have to rely on children to be resilient to overcome insurmountable challenges.”

Shaketta Brooks worries about those challenges. She and her nine-year-old son, sunny-natured and with a bright smile, are at the Flint Public Library, where they've been taking turns reading aloud from a book on Martin Luther King, Jr.

Her son was born premature just four months after Flint’s water switch. When women are exposed to lead before or during pregnancy, their risk of giving birth prematurely increases, as does the risk of miscarriage and having a low-birth-weight baby.

Brooks's son spent months in the neonatal intensive care unit at a local hospital. “They said he was underdeveloped,” she says, and he needed a blood transfusion. Children exposed to lead in the womb can suffer damage to the brain and nervous system, which can cause learning and behavior problems later on. He is among the more than 20 percent of kids with special-education or early-intervention plans in the Flint Registry .

Shaketta Brooks embraces her nine-year-old son on the Genesee Valley Trail in March. Brooks says she often walked here in 2014, the year the water crisis began.

Brooks and her son walk in their neighborhood in Flint.

Lead can be particularly harmful to young children, due to rapid growth of their bodies and brains. Because lead can damage the central nervous system, “it affects their cognition, it affects their learning, it affects their attention,” notes Jones, the Michigan State epidemiologist.

Brooks says her son can be hyperactive, so she signs him up for sports like basketball and boxing for exercise. But she’s “on eggshells” watching him run because of his asthma, another condition that can be linked to lead exposure.

Jones understands the fear: Lead exposure, she says, “is a lifelong concern."

On a quiet morning in a wooded corner of the city, the Flint River flowed serenely past Buick City, an old General Motors site, on its bendy route north toward Saginaw Bay. Marcell Simmons, 23, kayaks the river every summer. As a paddle guide for the Flint River Watershed Coalition, he educates people about the wildlife and plants that surround the river: bald eagles, great blue herons, and vegetation like water lilies and cattails, which Simmons eats from time to time just to prove to other paddlers these plants are edible.

He tries to foster respect for the river. “It was straight-up love for the city,” Simmons says about why he wanted the job. Barely a teen in 2014, he didn’t escape the fallout of the crisis. After the switch to Flint River water, his school performance took a hit. “I was a whole lot sharper prior to the water crisis,” says Simmons, who struggles with attention issues. “I don't know if it’s ADHD or if it’s lead,” he says, “so I just work with it.” A decade later, he’s still furious about what happened. “You can’t help but to be enraged,” he says.

In January, Simmons testified virtually at an EPA hearing to gather comments for a plan to strengthen the Lead and Copper Rule , the 1991 law regulating lead levels in drinking water. The EPA had proposed lowering the remedial action level from 15 to 10 parts per billion (a part per billion is roughly the equivalent of one drop in 500 barrels of water). Simmons spoke in favor of the change. “We are the United States of America,” he said, in a tone of disbelief. “Children, right now, are having developmental issues that started from the day they were born.”

"I was a whole lot sharper prior to the water crisis,” says Marcell Simmons, a clean water activist in Flint, Michigan. A decade later, he’s still furious about what happened. “You can’t help but to be enraged.”

Dionna Brown also spoke at the hearing. “No amount of lead in drinking water is deemed safe,” she said. Brown came from a middle-class family and didn’t use the services being offered in Flint. “I have to work harder to get what I want,” she says. “It's not okay that I have to work harder, but there’s nothing I can’t do if I put my mind to it.”

While in college, Brown became involved with the nonprofit Young, Gifted & Green, where she now works to eliminate lead in communities like Flint. She says the water crisis helped open her eyes to historic environmental injustice. “This is the history of America,” she says. “ We see where the power plants are located, where the trash incinerators are, where all these environmental hazards are placed—they’re placed in Black, brown, and low-income areas.”

Besides wide-scale lead exposure, the crisis also sparked a deadly outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease, which sickened dozens and took the lives of at least 12 people. Nine public officials, including emergency managers appointed by the state, were criminally charged for their roles in the disaster. None were convicted and, last year, all remaining charges were dismissed.

The crisis was an injustice on many fronts, says Debra Furr-Holden, dean of the New York University School of Global Public Health. Furr-Holden lived in Flint as a child and worked as a public health researcher at Michigan State during the crisis. Indeed, if Flint were not a poor, majority-Black city, she says, the water crisis might never have happened. “This tolerance for water that the government knew was not potable being allowed to flow out of people’s taps—we just don’t believe this would have ever happened in an East Lansing or Lansing or Grand Rapids,” she says, calling the crisis an outright “act of environmental racism.”

The full health effects of the water crisis on the children of Flint won’t be known for another 10 to 15 years, Furr-Holden notes. “We already know what lead does in the body … what lead does to the brain,” she says. “Can we overcome that with intervention? Yes, but we won’t know how well we did until these kids reach adolescence and young adulthood.”

Furr-Holden credits the assessment clinic, the Pediatric Public Health Initiative, and the replacement of lead service lines as critical to the recovery. Another key is the state’s expansion of Medicaid for children in Flint who will need years of support, she says, to address the ongoing health effects and psychological trauma from the disaster.

The people of Flint carry on. Shaketta Brooks volunteers with the National Parents Union, devoted to the rights of minority and low-income parents. “It’s part of the healing for me,” she says.

Marcell Simmons attends community college and plans to pursue a career in communications. He says he’s eager to kayak the river once the weather warms. Dionna Brown says she plans to go to law school in 2026. “I’m a child of the Flint water crisis,” she says. “I’m the example that Flint kids are successful and can be successful, even though so many people doubted us.”

The Gilleylen family welcomed another child in 2017. They say their daughter’s behavior has improved some, and she thrives as a young athlete. They’re now planning to buy their first home, outside the city limits.

This story was supported by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2023 Impact Fund for Reporting on Health Equity and Health Systems .

Top image: Marcell Simmons, a watershed guide and clean water activist, at the Flint River near downtown Flint in March.

More in Environmental Health

“A healthy environment supports healthy people.”

Where environmental injustice meets workers’ health

Microplastics, strokes, and heart attacks

TODAY'S HOURS:

The Flint Water Crisis: A Guide to Information Resources

- Background Reading

- Information from UM-Flint and UM Ann Arbor

Healthy Flint Research Coordinating Center

Research articles, lead toxicity: relevant databases, water: relevant databases, topics related to the flint water crisis.

- Commentary & Primary Sources

- Community Resources

Have a Question? Need Some Help?

Email: [email protected] Phone: (810) 762-3400 Text message: (810) 407-5434 (text messages only)

- Healthy Flint Research Coordinating Center The Healthy Flint Research Coordinating Center (HFRCC) is a collaboration with the Flint Community, UM-Flint, UM-Ann Arbor, and MSU. more info... less info... Working to aid Flint recovery and rebuild from the water crisis by: • Assisting in coordination, dissemination, and building synergy in research efforts in Flint. • Facilitating community and academic partnerships through workshops. • Utilizing a community managed ethics board review (CERB) of proposals. • Creating a data repository to share data that can aid the creation of a healthy Flint and lessen redundant research. Opendataflint.org • Offering Community-Driven Research Day. • Increasing community voice with structured community dialogues. • Including a broad coordinated cross-section of Flint stakeholders.

- Open Data for Flint | HFRCC Open Data Flint (ODF), as part of the Healthy Flint Research Coordinating Center (HFRCC) is an open access repository for all kinds of data and data-related resources about the Flint community within the state of Michigan. It is a place to both find data to use and share data for others to use. more info... less info... Open Data Flint is an open-to-the-community data repository whose aim is to assist the community of Flint, Michigan to: • Bring together data to help build the evidence base to achieve a healthier Flint community. • Gain a deeper understanding of the far-reaching impact of the water crisis on the Flint population.

- Flint Water Study Website of the Virginia Tech independent research team and their collaborators, who are helping to understand and research the Flint water crisis.

- "Flint Water Crisis: Data-Driven Risk Assessment via Residential Water Testing" Article presented at Data for Good Exchange 2016, reports on researcher's data model that predicts locations in Flint to have lead contaminated water. [September 2016] more info... less info... Abernethy, J., Anderson, C., Dai, C., Farahi, A., Nguyen, L., Rauh, A., . . . Yang, S. (2016, September 30). Flint water crisis: Data-driven risk assessment via residential water testing. In Data For Good Exchange 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016, from https://arxiv.org/abs/1610.00580 doi:arXiv:1610.00580

Primary journal index for nursing and allied health professions.

1937-present. Covers nursing, biomedicine, health sciences librarianship, alternative/complementary medicine, consumer health, and 17 allied health disciplines. Includes journal articles, evidence-based care sheets, health care books, nursing dissertations, selected conference proceedings, standards of practice, educational software, audiovisuals, and book chapters. Short video tutorials on using CINAHL

Journal articles & citations, government publications, conference papers, reports, theses, and other education-related documents. The ERIC Thesaurus can help identify useful subject terms.

Also available via EBSCOhost and the U.S. Department of Education (open access version). This database is sponsored by the U.S. Department of Education to provide extensive access to education-related literature. ERIC provides coverage of journal articles, conferences, meetings, government documents, theses, dissertations, reports, audiovisual media, bibliographies, directories, books and monographs. Covers:

- Adult, career and vocational education

- Elementary & early childhood education

- Education management

- Higher education, including junior colleges

- Second-language learning

- Special education

- Teacher education

- Tests, measurement, & evaluation

Many ERIC Documents are online in ERIC, and older ones are available on microfiche on the 1st floor of the Thompson Library.

Covers clinical medicine, nutrition, pathology, education, psychiatry, experimental medicine, toxicology, health services administration, nursing.

MEDLINE and its content is also available in other versions:

- MEDLINE via Ovid

- MEDLINE via Web of Science

- PubMed : Comprises more than 21 million citations for biomedical literature from MEDLINE, life science journals, and online books.

Covers all aspects of medicine and health care administration. Includes some nursing and allied health. Some users have recently had to reset their passwords to use all the features of Ovid-based MEDLINE. Contact a librarian if you have any questions.

1946-present. MEDLINE is widely recognized as the premier source for bibliographic and abstract coverage of biomedical literature. MEDLINE encompasses information from Index Medicus, Index to Dental Literature, and International Nursing, as well as other sources of coverage in the areas of allied health, biological and physical sciences, humanities and information science as they relate to medicine and health care, communication disorders, population biology, and reproductive biology. MEDLINE and its content is also available in other versions:

- MEDLINE via FirstSearch

Comprises more than 21 million citations for biomedical literature from MEDLINE, life science journals, and online books.

PubMed indexes over 4,000 biomedical, nursing, dentistry and related journals, with over 21 million citations in MEDLINE, PreMEDLINE and related databases. PubMed is produced by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) and provides links between article citations and relevant data in other NCBI ENTREZ databases, including Nucleotide and Protein Sequences, Protein Structures, Complete Genomes, Taxonomy, and others. Proximity searching is available, which allows you to find terms within specified distances from each other. Includes journal literature, 1950-present; selected online books. This version uses Outside Tool to link to resources at U-M Flint.

Free digital archive of biomedical and life sciences journal literature at the U.S. National Library of Medicine. An open access version is available for users not affiliated with UM-Flint.

PubMed Central (PMC) is a free archive of biomedical and life sciences journal literature at the U.S. National Institutes of Health's National Library of Medicine (NIH/NLM). In keeping with NLMs legislative mandate to collect and preserve the biomedical literature, PMC serves as a digital counterpart to NLMs extensive print journal collection. Launched in February 2000, PMC was developed and is managed by NLMs National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). PMC has material dating back to mid- to late-1800s or early 1900s for some journals.

Covers journal articles, monographs, technical reports, theses, and other literature in all areas of toxicology, including chemicals and pharmaceuticals, pesticides, environmental pollutants, and mutagens and teratogens.

Extensive coverage of environmental science and related disciplines, and including scholarly journals, trade and industry journals, magazines, technical reports, conference proceedings, and government publications.

Includes AGRICOLA, TOXLINE, ESPM (Environmental Sciences and Pollution Management), and Environmental Impact Statements (EIS) databases and provides full-text titles from around the world, including scholarly journals, trade and industry journals, magazines, technical reports, conference proceedings, and government publications. This database includes specialized resources covering such topics as the effects of pollution on people and animals and environmental action and policy responses. Includes content from these databases:

- Bacteriology Abstracts (Microbiology B)

- Biotechnology Research Abstracts

- Ecology Abstracts

- Environmental Engineering Abstracts

- Environmental Impact Statements

- Health & Safety Science Abstracts

- Industrial and Applied Microbiology Abstracts (Microbiology A)

- Pollution Abstracts

- Risk Abstracts

- Sustainability Science Abstracts

- Toxicology Abstracts

- Water Resources Abstracts

Extensive coverage of Earth's air, land, and water environments, and including scholarly journals, trade and industry journals, magazines, technical reports, conference proceedings, and government publications.

Includes Aquatic Sciences and Fisheries Abstracts (ASFA), Oceanic Abstracts, and Meteorological & Geoastrophysical Abstracts (MGA). It provides full-text titles from around the world, including scholarly journals, trade and industry journals, magazines, technical reports, conference proceedings, and government publications. The database includes specialized resources studying the critical issues affecting Earths air, land, and water environments.

- Art as commentary

- Early childhood development

- Citizen scientists

- Emergency manager law

- Environmental health

- Government regulations

- Health care access

- Infrastructure

- Investigative journalism

- Lead and Copper Rule

- Lead toxicity

- Volunteerism

- Water filtration

- Water Resource Development Act (S.2848)

- Water rights

- Water supply policy

- Water supply regulation

Related subject guide

- The Flint Water Crisis: A Guide to Information Resources by Paul Streby Last Updated Mar 1, 2024 398 views this year

- << Previous: Information from UM-Flint and UM Ann Arbor

- Next: Commentary & Primary Sources >>

- Last Updated: Mar 1, 2024 5:00 PM

- URL: https://libguides.umflint.edu/watercrisis

Flint Water Crisis Exposed Children to Elevated Lead Levels

T he water crisis in Flint, Michigan, has led to a significant rise in the exposure of children to harmful lead levels, according to new research from Cornell University. This crisis began in 2014 when the city’s water supply was switched from Lake Huron to the Flint River as a cost-saving measure. The corrosive water from the Flint River was not adequately treated to prevent lead leaching from old pipes, leading to contaminated drinking water.

In the study, titled “Child Lead Screening Behaviors and Health Outcomes Following the Flint Water Crisis,” researchers revealed that one in four children who were screened had elevated blood lead levels — a rate much higher than the national average. The team found that despite lead screenings being free of charge, Flint’s children were under-screened, with only 77% of nearly 250 children surveyed having been tested since the crisis began. This figure is below the desired rate of at least 90% following such a public health emergency.

Jerel Ezell, the lead author of the study and a Flint native, underscored the gravity of the situation. “Our methods allow us to say that there was a substantial uptick in negative health outcomes among Flint children following the water crisis,” he stated. The symptoms associated with elevated lead exposure included learning delays, hyperactivity, emotional agitation, and skin rashes. Furthermore, the study highlighted that Black and low-income children faced higher rates of such conditions.

The research also indicated that long-term community distrust and health concerns persist years after the crisis began. More than 90% of children reportedly drank bottled water, which could lead to additional health issues due to the lack of nutrients and fluoride, increasing their risk for dental problems.

Ezell’s research emphasizes the need for ongoing monitoring of health risks potentially linked to the water crisis and addresses systemic factors that limited screening. He pointed out that the underwhelming screening rates could be attributed to parental distrust, logistical barriers, or a failure of officials to effectively communicate the need for these tests. “When government and health care institutions don’t have real skin in the game and aren’t made to be accountable, you have to build confidence and strengthen resources to help communities protect themselves,” he said.

Relevant articles:

– Water crisis increased Flint children’s lead exposure , cornell.edu

– Conducting evaluations of evidence that are transparent, timely and can lead to health-protective actions , National Institutes of Health (NIH) (.gov)

– What ACEs/PCEs do you have? , acestoohigh.com

– Physical interventions to interrupt or reduce the spread of respiratory viruses , National Institutes of Health (NIH) (.gov)

![The water crisis in Flint, Michigan, has led to a signi […] The water crisis in Flint, Michigan, has led to a signi […]](https://img-s-msn-com.akamaized.net/tenant/amp/entityid/BB1m1RYw.img?w=768&h=512&m=6)

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Community–academic partnerships helped Flint through its water crisis

E. yvonne lewis.

founder and chief executive of the National Center for African American Health Consciousness, Flint; co-community principal investigator at the Flint Center for Health Equity Solutions; co-director of the Healthy Flint Research Coordinating Center Community Core; and director of outreach, Genesee Health Plan, Flint, Michigan, USA

Richard C. Sadler

Associate professor of public health at Michigan State University, Flint, Michigan, USA

A city that faced a public-health emergency shows how collaborations with neighbourhood advocates can advance health equity.

Graphical Abstract

Residents of Flint, Michigan, attended community blood-testing events in 2016 after lead contamination was found in the city’s water supply.

BRETT CARLSEN/GETTY

Flint in Michigan is infamous for its water crisis. From 2014, the state government decided to divert the city’s water supply through ageing pipes that contained lead, a neurotoxin, making many people unwell and leading to some deaths. Residents were left searching out water that was safe for drinking, washing and bathing. Nine public officials face criminal negligence charges around wilful neglect of duty and for allegedly concealing and misrepresenting data. A US$640-million class-action lawsuit is moving its way through the courts.

But Flint should be known for more than its public-health tragedy. Accounts of the crisis often cast pioneering scientists and physicians as lone heroes, assuming that those who documented the lead in the water and blood of Flint’s residents were the ones who brought officials to account. That assumption erases the work of community activists who got academics to look for lead and its damaging health effects in the first place. Flint is a working example of how community members and academics can collaborate on problems – such as how to collect data or develop robust models of health risks and injustices – and on finding solutions.

Flint’s water crisis came to light because of strong research partnerships between activists, academics and other specialists. These partnerships continue to advance work that matters to the community. Efforts include identifying neighbourhood conditions (including crime levels, asthma rates and access to healthy food) and assessing projects to improve them. It requires a commitment that research does not just end up in a thesis or paper, but becomes information that is useful to community members.

Here’s one example. The Genesee Health Plan is a non-profit benefit programme that provides basic health-care coverage to uninsured residents of Genesee County, which includes Flint. It was established in 2001 and is supported by property taxes. One of us (E.Y.L.) helped to provide the other (R.C.S.) with data from a sample of Genesee Health Plan enrollees to produce maps of chronic conditions. One map showed the health plan’s wide adoption in our community, and officials used it to advocate for voter support when the tax measure was renewed in 2018. This partnership was possible only because of the connections already formed between E.Y.L., who is a community organizer, and R.C.S., a geographer and public-health specialist at Michigan State University (MSU) in Flint.

Long-standing efforts to ensure Flint community members have a voice in research have gained momentum. One tangible result was the creation of the Healthy Flint Research Coordinating Center in 2016. To form the centre, E.Y.L. and another Flint resident representing community organizations joined up with six researchers – two each at MSU, the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor and the University of Michigan–Flint. It works to minimize redundant research, maximize creation of new community–academic partnerships and ensure that research receives a community ethics review.

Also established in 2016 to support equitable community–academic partnerships was the Flint Center for Health Equity Solutions, funded by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH). E.Y.L. is the centre’s overall community principal investigator. Each of its four divisions and two research projects is co-directed by a community member and an academic. The divisions are: methodology (which R.C.S. directs); dissemination and implementation sciences; administrative; and consortium partners. A programme within the centre – in which people with substance-use disorders are coached by their peers – has expanded and is now supported by additional external funding.

Here, we distil how we’ve made community-based research work, and provide lessons others might use.

Distinct challenges

Each of us experienced different challenges before we formed our community partnership, which might offer some pointers for others considering such collaborations. To that end, here, we relate our stories individually.

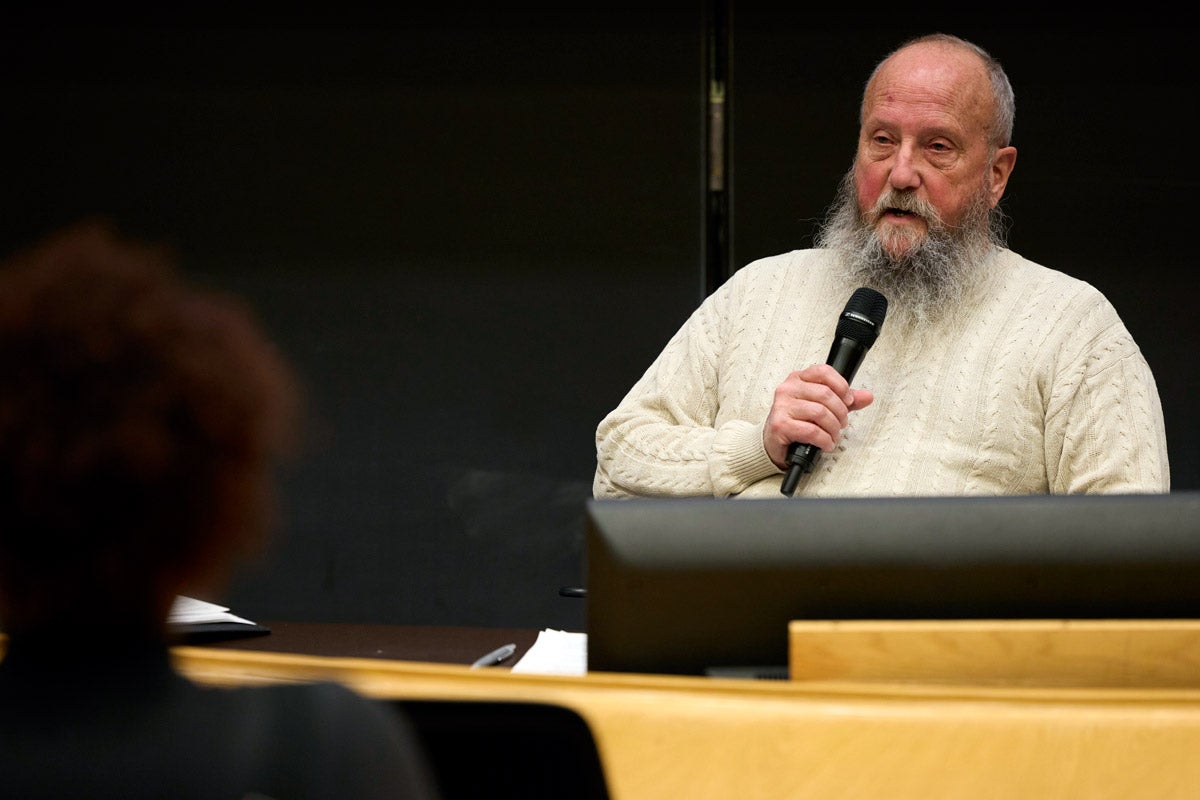

R.C.S. writes:

I grew up in Flint, and joined MSU as a faculty member in 2015. I knew that the kind of community-focused work I was most passionate about makes it harder to rack up the publications and citations required to progress in most academic institutions, which often treat these as a proxy for high-quality research.

I still worked to hit those markers, publishing more than 50 papers in 6 years. I secured several grants from agencies that fund research that has community value – including agencies in the NIH, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services. My focus was on work that mattered to the community, and I didn’t worry whether journals had high impact factors or huge name recognition.

The community-engaged philosophy of the College of Human Medicine at MSU – where I gained tenure this year – made it more open to alternative metrics, such as volunteering on local non-profit committees, conducting community-based mapping and talking about research at local meetings. The key was to frame my academic output on a longer time scale than that of publications – long enough to see meaningful change.

E.Y.L. writes: