The Aruna Shanbaug case which changed euthanasia laws in India

A landmark verdict

The Supreme Court on March 9 ruled that individuals had a right to die with dignity, allowing passive euthanasia with guidelines. The need to change euthanasia laws was triggered by the famous Aruna Shanbaug case. The top court in 2011 had recognised passive euthanasia in Aruna Shanbaug case by which it had permitted withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment from patients not in a position to make an informed decision.

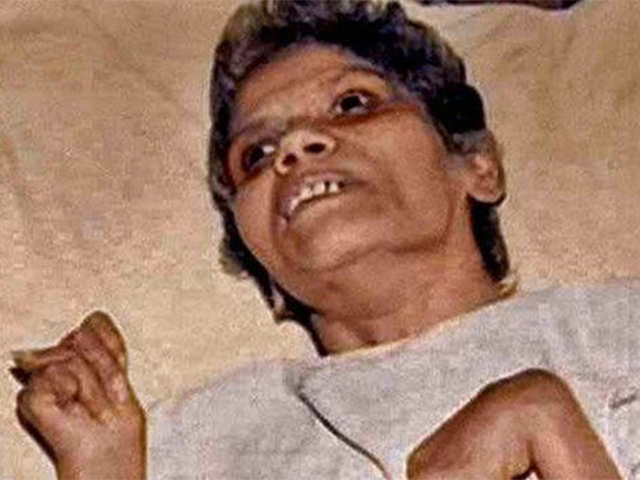

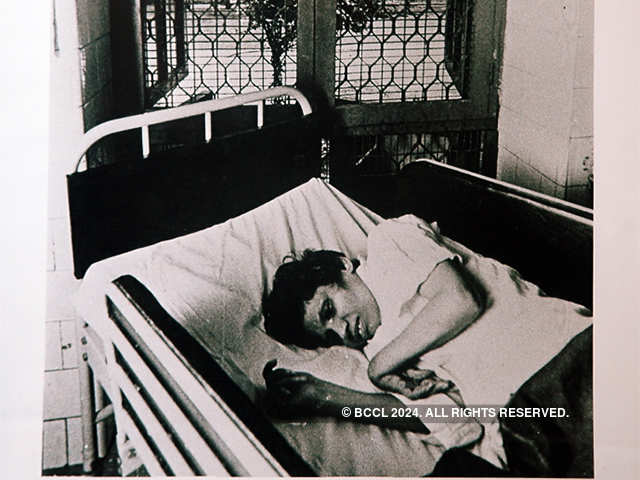

Aruna Ramchandra Shanbaug was a nurse in the King Edwards Memorial Hospital in Mumbai. In November 1973, she was assaulted by ward boy, Sohanlal Bhartha Valmiki, of the same hospital while changing her clothes in the hospital basement. Valmiki strangulated Shanbaug with a dog chain around her neck.

Living in a coma

The attack cut off oxygen supply from her brain leaving her blind, deaf, paralysed and in a vegetative state for the next 42 years. From the day of the assault till the day she died on May 18, 2015, Aruna could only survive on mashed food. She could not move her hands or legs, could not talk or perform the basic functions of a human being.

What happened to Valmiki

In 1974, Valmiki was charged with attempted murder and for robbing Aruna's earrings, but not for rape. The police did not take into account that she was sodomized. A trial court sentenced Valmiki seven years imprisonment. This was reduced to six years because he had already served a year in lock up. Valmiki walked out of jail in 1980 and still claims he did not rape Shanbaug.

Facing opposition

The Supreme Court accepted the petition and constituted a medical board to report back on Aruna's health and medical condition. The medical board, comprising three eminent doctors, reported that the patient was not brain dead and responded to some situations in her own way. They felt that there was no need for euthanasia in the case. The staff at KEM Hospital and the Bombay Municipal Corporation filed their counter-petitions in the case, opposing euthanasia for Aruna. The nurses at KEM Hospital were quite happy to look after the patient and they had been doing that for years before petitioner Pinky Virani emerged on the scene.

Finally at peace

On May 18, 2015, Shanbaug then 66, died of severe pneumonia. She was on ventilator support in KEM's acute care unit.

To post this comment you must

Log In/Connect with:

Fill in your details:

Will be displayed

Will not be displayed

Share this Comment:

Aruna Ramchandra Shanbaug Vs Union of India – Case Analysis

Introduction.

The concept of “Euthanasia” has not only been a brand new concept for the Indian medical industry; its public acceptance has been a debatable topic too. In the course of discussing the legality of Euthanasia, it has always been a general query whether the provision of the right to life under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution also encompasses the concept of the right to die . Therefore, the dire need for improvement in medical law and the potential of the patient’s family members to abuse this privilege have made the right to die a crucial issue. There is still an ongoing discussion over whether the “Right to Life” may be construed to include the “Right to Die.” On the other hand, the idea of euthanasia in India has met with various mixed reactions as the medical sector increasingly focuses on patients’ informed permission. This case of Aruna Ramchandra Shanbaug continues by separating passive and active euthanasia.

Facts of Aruna Shanbaug Vs Union of India

Aruna Shanbaug Vs Union of India case has paved the way for the legalization of passive euthanasia in India. Aruna Ramchandra, the victim, was a nurse at King Edward Memorial Hospital of Mumbai. One of the sweepers of the hospital had attacked her on 27 th November 1973. He had choked and strangulated her via a dog chain with the intent to rape her and restrain her movements. Subsequent to realizing that Ms Aruna was menstruating, he sodomized her. On 28 th November 1973, she was found lying on the floor, wounded, with blood everywhere and all over her. She was found in an unconscious condition by one of the cleaners. Consequent to such heinous strangulation via the dog chain, the supply of oxygen to her brain had ceased entirely, causing severe damage to the cortex of her brain. She had sustained a brain stem contusion besides having a cervical cord injury.

After 36 years of the incident, a petition for the case was filed under Article 32 of the Indian Constitution by a friend of Ms Aruna in 2009. For these many years, Ms Aruna has been in a permanent vegetative state and has become highly feeble and infirm.

Legal Issues Involved in Aruna Shanbaug Vs Union of India Case

Following Legal Issues Involved in Aruna Shanbaug Case

- Does Article 21 of the Constitution include the right to die embedded within the right to life?

- What is the difference between passive euthanasia and active euthanasia?

- Can individuals be allowed to give a “Living Will”, i.e. directives on medical treatment, if they become incompetent or unable to communicate in the future?

- Should the right to die and the right to die with dignity be studied comparatively?

Petitioner’s Arguments in Aruna Shanbaug Case

The petitioner in Aruna Shanbaug Vs Union of India case, contended that the right to life enumerated under Article 21 of the Constitution defines the right to live a fulfilled life with utmost dignity. It must, therefore, also include the right to die with dignity.

Individuals suffering from any terminal illness or permanent vegetative state must be included under the right to die with dignity to end the prolonged suffering and agony.

Ms Aruna lacks any awareness of her surroundings and is even unable to chew her food; she cannot express anything on her own and is just bedridden for the past 36 years with no scope for improvement. The patient is virtually dead, and the respondents, by not feeding Ms Shanbaug, will not be killing her.

Respondent’s Arguments in Aruna Shanbaug Case

The Respondent’s arguments in Aruna Ramchandra Shanbung Case are, the hospital dean contended that Ms Shanbaug was being fed and cared for by the nurse and hospital staff for as many as 36 years.

Now that the patient has crossed as many as 60 years of age, she might naturally succumb to death. The staff had exceptional and utmost responsibility and willingness to take care of her. Therefore, they opposed and resented the idea of Ms Shanbaug being euthanized.

They begged the court not to permit the act of killing since the staff had been diligently and with respect taking care of all her fundamental necessities and prerequisites. Therefore, if euthanasia has been legitimized, such a step can be profoundly inclined to abuse.

One medical attendant has even been willing to care for her without being remunerated. Therefore, it is evident that the petitioner, unlike the hospital staff, neglects to have a close-to-home connection with the patient and lacks the necessary emotional attachment. Moreover, since the hospital staff diligently and with utmost dignity took care of Ms Shanbaug for many years, they looked after her basic needs with care.

Legalization of passive euthanasia can be prone to misuse by family members and relatives. They pleaded with the court to reject the allowance of euthanasia.

Terminating Ms Shanbaug’s life would be immoral and inhuman since she has a right to live. Moreover, the hospital staff’s exceptional and selfless service must also be considered.

Furthermore, since the patient is not in a condition to consent to withdrawal from the life support system, the big issue is who would consent for Ms Shanbaug.

Decision of Aruna Shanbaug Vs Union of India Case

The court in the Aruna Shanbaug Vs Union of India case, distinguished between active and passive euthanasia. Active euthanasia can be seen as the positive and deliberate termination of one’s life by injecting and administering lethal substances. It is considered to be a crime worldwide except permitted by legislation. In India, active euthanasia is a straight infringement of Section 302 and Section 304 of the IPC. [1]

The High Court, under article 226 , was entitled to make decisions regarding the withdrawal of the life support system. The apex court enlisted a proper procedure and guidelines for granting passive euthanasia in the “rarest of rare circumstances” while rejecting the plea made by the petitioner. A bench was constituted by the Chief Justice of the High Court when an application was received, before which a committee of three reputed doctors nominated was referred. A thorough examination of the patient, state, and family members was conducted along with a notice issued by the bench.

Therefore, in support of the “Parens Patriae” concept, the Supreme Court entrusted the authority to decide the end of a person’s life in the High Court in order to avoid any abuse. As a result, in certain circumstances and with the High Court’s consent after following the proper procedure, the Supreme Court permitted passive euthanasia.

However, Supreme Court opined that passive euthanasia could be allowed in exceptional and rare cases with due approval from the patient’s family members and doctors.

Supreme Court held that it should be sparingly used and not become a tool for eroding Article 21 of the Indian Consitution. Therefore, the court’s assessment of the medical report and the definition of brain death provided in the Transplantation of Human Organs Act, 1994 , clearly explains that Ms Aruna’s brain was not dead.

Despite being in a Permanent Vegetative State, she had a stable state. She had sensations and could breathe without assistance. Therefore, ending her life was not warranted.

Ratio Decidendi of Aruna Shanbaug Case

The Supreme Court stated the following reasoning for its judgment in the Aruna Shanbaug Vs Union of India Case:

- It is pretty implied that all over the world, active euthanasia has been stated as illegal in the absence of any legislation permitting it. In contrast, even in the absence of legislation, passive euthanasia has been stated as legal.

- The report presented by the committee of doctors stated that Ms Shanbaug’s brain was then responsive to likes and dislikes, which she can express through small gestures and sounds like smiling and blinking eyes. Therefore, she was responding to the outside environment.

- The potential threat of misuse of passive euthanasia cannot be ruled out, which holds every chance of breaching Article 21 of the Constitution of India in the event of low ethical standards prevailing in our society and with increasing corruption. Therefore, there is a dire need for a balanced approach in such a sensitive issue, which includes a person’s death and life.

Critical Analysis of Aruna Shanbaug Case Judgment

Concept of euthanasia in brief.

Euthanasia could be termed as a mercy killing, which defines any act or practice that contributes to painlessly putting to death of persons suffering from painful and irremediable disease or paralysed physical condition or permitting them to die by withdrawing treatment or any artificial life support system.

In the concerned case, High Court has provided specific guidelines concerning passive euthanasia. These guidelines enumerate the lawful procedure for withdrawing any medical treatment or artificial life support system to any patient that could lead to a person’s death. Such a judgment has legalized passive euthanasia in India under certain conditions that the High Court shall fix.

In 2018, in the case of Common Cause v. Union of India , Supreme Court stated that while considering the legality of passive euthanasia, it has to be noted that the right to die with dignity is included under Article 21 of the Constitution along with the right to life. Therefore, it is very much relevant to withdraw the life support system of patients suffering from a terminal illness who are in a coma for a lifetime; so that they can die with dignity. [2] The notion of “living will” was also provided in the concerned case. The concept of “living will” is a document that facilitates in taking the consent of a patient in advance in the event if and when, during the term of the treatment, the patient gets seriously ill or paralysed in future or becomes the victim of a situation or medical condition wherein he is unable to give consent or take any decisions. The document then serves as the concerned patient’s living will or living consent.

Right to Die v. Right to Die with Dignity

The right to life has been expressly provided in the Constitution under Article 21. On the contrary, the right to die has always been debatable and has not been expressly provided anywhere in the Constitution. However, the right to die has been diversely interpreted by various courts in their judgments based on their individual opinion and knowledge.

In the landmark case of State of Maharashtra v. Maruti Sripati Dubal , the Bombay High Court stated that the right to die had been included in the right to life as per enumerate under Article 21 of the Constitution. It was further stated that Section 309 of IPC is unconstitutional to the extent that it violates the provisions of Article 21 of the Constitution since the right to die directs towards the right to commit unnatural death. [3]

Later on, Supreme Court, in the case of P. Rathinam v. Union of India , passed the judgment, thereby recognizing the right not to live, which has been included in the right to live as enumerated under Article 21 of the Constitution. [4]

However, the Supreme Court, in the case of Gian Kaur v. State of Punjab , overruled the decision given in the P.Ratinam case and stated that the right to life should not include the right to die. Albeit, the right to life shall include a life that is lived with human dignity and further extends to the inclusion of the right to die with dignity. [5]

The Court held that there is a fundamental difference between the right to die and the right to die with dignity. The right to die shall include taking away a person’s natural life span, thereby causing unnatural death. However, the right to die with dignity shall include undertaking a process or causing a situation to accelerate the process of death in case of patients who are in a Permanent Vegetative State or under the influence of a coma for a lifetime. Therefore, the recognition of the right to die with dignity through passive euthanasia could be applied to terminate the lifelong suffering and mental agony of patients having paralysed physical conditions or incurable diseases.

It is evident that both of these rights are opposite and poles apart and should not be misinterpreted on purpose. Lately, the right to die with dignity has been recognized by upholding and legalizing the execution of Passive Euthanasia (both voluntary and involuntary).

Aruna Shanbaug’s case has, for the first time, laid down the guidelines relating to the procedure for execution of Passive Euthanasia in India. Prior to this, rarely was the concept brought into concern. The judgment in the concerned case has opened up a new horizon in regard to the right to die with dignity, thereby expanding the ambit of Article 21 of the Constitution.

[1] K D Gaur, Textbook on Indian Penal Code, 749.

[2] Vikram Deo Singh Tomar v. State of Bihar,1988 (Supp) SCC 734.

[3] 1987 (1) Bom CR.

[4] 1994 SCC (3) 3944. (1996) 2 SCC 648.

[5] (1996) 2 SCC 648.

Share This Post

Related posts.

Amrapali Mukherjee

I have completed my Masters in Commercial and Corporate Law from the Queen Mary University of London with upper merit and a distinction in the dissertation, currently, I am working as a Legal Advisor for a partnership firm at Kolkata.

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Submit?

- About Medical Law Review

- Publishers' Books for Review

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

- < Previous

INDIA AND EUTHANASIA: THE POIGNANT CASE OF ARUNA SHANBAUG

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Sushila Rao, INDIA AND EUTHANASIA: THE POIGNANT CASE OF ARUNA SHANBAUG, Medical Law Review , Volume 19, Issue 4, Autumn 2011, Pages 646–656, https://doi.org/10.1093/medlaw/fwr028

- Permissions Icon Permissions

‘It is my belief that death is a friend to whom we should be grateful, for it frees us from the manifold ills which are our lot.’ Mahatma Gandhi 1

The debate surrounding the legalisation of euthanasia in India has proven both protracted and intractable. In many ways, the deliberations have meandered along predictable lines: opponents cry themselves hoarse about the ‘sanctity of life’ being violated by self-styled angels of death, and cite eclectic religious authorities to shore up their claim. 2 Proponents of a more liberal view, on the other hand, insist that a ‘right to life’ 3 must include a concomitant right to choose when that life becomes unbearable or not worth living. 4 They point to permissive laws in foreign jurisdictions such as the Netherlands and Oregon as being more in tune with a rights-oriented culture. 5

On 7 March 2011, the Indian Supreme Court delivered a ‘path-breaking’ judgment in the case of Aruna Ramchandra Shanbaug v Union of India 6 (hereinafter Aruna ) , permitting ‘passive euthanasia’ in certain circumstances. This judgment has thrust the issue firmly back in the media's spotlight, 7 and galvanised votaries and adversaries alike. It is hoped that the public reaction, as well the Court's pleas for legislation on the subject, will soon bear fruit in the form of a nuanced and deliberated law.

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1464-3790

- Print ISSN 0967-0742

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Home > Cases > Euthanasia and the Right to Die with Dignity

Euthanasia and the Right to Die with Dignity

Common Cause v Union of India

In 2018 the Supreme Court recognised the right to die with dignity as a fundamental right and prescribed guidelines for terminally ill patients to enforce the right. In 2023 the Supreme Court modified the guidelines to make the right to die with dignity more accessible.

K.M. Joseph J

Ajay Rastogi J

Aniruddha Bose J

Hrishikesh Roy J

C.T. Ravikumar J

Petitioner: Common Cause

Lawyers: Prashant Bhushan

Respondent: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (Union of India)

Lawyers: P. S. Narasimha; K.V. Jagdishvaran; S.S. Shamshery

Intervenor: Jai Kishan Agarwal; Delhi Medical Council; Society for the Right to Die with Dignity; Dr. Surendra Dhelia; Indian Society of Critical Care Medicine; Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy

Lawyers: Arvind Datar; Sanjay Hegde; Praveen Khattar; R.R. Kishore.

Case Details

Case Number: WP (C) 215/2005

Next Hearing:

Last Updated: December 26, 2023

TAGS: Dignity , euthanasia , Guidelines , Right to Die , Right to Life

Whether the constitutional guarantee of the Right to Life includes the Right to Die.

Whether euthanasia can be made lawful only by legislation.

Whether there is a difference between passive and active euthanasia.

Whether individuals can give ‘advance directives’ on medical treatment for if they lose the ability to communicate in the future.

Case Description

In 2002, Common Cause, a registered society had written to the Ministries of Law & Justice, Health & Family Welfare, and Company Affairs as well as State Governments, on the issue of the right to die with dignity.

In 2005, Common Cause approached the Supreme Court under Article 32, praying for the declaration that the right to die with dignity is a fundamental right under Article 21. It also prayed the Court to issue directions to the Union Government to allow terminally ill patients to execute ‘living wills’ for appropriate action in the event that they are admitted to hospitals. As an alternative, Common Cause sought guidelines from the Court on this issue, and the appointment of an expert committee comprising lawyers, doctors, and social scientists to determine the aspect of executing living wills.

Common Cause argued that terminally ill persons or those suffering from chronic diseases must not be subjected to cruel treatments. Denying them the right to die in a dignified manner extends their suffering. It prayed the Court to secure the right to die with dignity by allowing such persons to make an informed choice through a living will.

On February 25th 2014, a three-Judge Bench of the Supreme Court comprising the then P. Sathasivan CJI, Ranjan Gogoi and Shiva Kirti Singh JJ had referred the matter to a larger bench, to settle the issue in light of inconsistent opinions in Aruna Ramchandra Shanbaug v Union Of India (2011) and Gian Kaur v State of Punjab (1996).

On March 9th 2018, a five-Judge Bench comprising Dipak Misra CJI, A K Sikri, A. M. Khanvilkar, D Y Chandrachud and Ashok Bhushan JJ held that the right to die with dignity is a fundamental right. An individual’s right to execute advance medical directives is an assertion of the right to bodily integrity and self-determination and does not depend on any recognition or legislation by a State.

On March 8th 2018 the Supreme Court delivered two concurring opinions:

- Majority opinion authored by Dipak Misra CJI on behalf of himself and AM Khanwilkar J

- Concurring opinion authored by DY Chandrachud J

On July 19th, 2019, the Indian Society for Critical Care filed a miscellaneous application requesting a 5-Judge Constitution Bench to modify some of the guidelines prescribed in the 2018 Judgment. They claim that the procedure for terminally ill patients to exercise their right to die is extremely cumbersome and requires streamlining. The case is being heard by a 5-Judge Constitution Bench led by Justice K.M. Joseph.

Documents (7)

Order Directing the Modification of the SC's 2018 Guidelines

January 24, 2023

Joint Proposal Comparing 2018 SC Guidelines and Suggested Changes, submitted by ISCC and the Union of India

Chart Comparing 2018 SC Guidelines and Suggested Changes, Submitted by ISCC

January 18, 2023

Judgment: Dipak Misra CJI's Majority Opinion

March 9, 2018

Judgment: D.Y. Chandrachud J's Concurring Opinion

Judgement: Supreme Court recognises the right to die with dignity

Writ Petition: by Common Cause

April 26, 2005

Reports (8)

Streamlining the Process for Passive Euthanasia: Judgement Summary

July 18, 2023

Right to Die Guidelines Day #4: Bench Accepts Joint Proposal and Delivers Final Order

Right to Die Guidelines Day #3: Bench Directs Union and Sr. Adv. Datar to Submit Joint Proposal

January 19, 2023

Right to Die Guidelines Day #2: Sr. Adv. Datar Suggests Changes to Advance Directive Requirements

Right to Die Guidelines Day #1: Sr. Adv. Arvind Datar Argues Current Process is Cumbersome

January 17, 2023

Writ Petition Summary

June 26, 2021

Dipak Misra CJI’s Opinion in Plain English

D.Y. Chandrachud J’s Opinion in Plain English

Case Analysis on Aruna Shanbaug v/s Union of India

Aruna shanbaug v/s. union of india[3].

- Justice Markandey Katju

- Justice Gyan Sudha Mishra

- Whether Article 21[6] of the Indian Constitution include the Right to die embedded within the Right to Life?

- What is the difference between passive and active euthanasia?

- Whether a person incapable to provide consent, be bestowed non-voluntary passive euthanasia?

- Whether suicide should be considered as a crime under Section 309[7] of IPC?

- It is a well-settled principle all around the globe that passive euthanasia is illegal until and unless there is legislation that is permitting the same and on the other hand passive euthanasia is legal even without the legislation.

- The Report presented by the expert panel of the doctor (under Section 45 of the Indian Evidence Act) certifies that the patient is not brain dead and it was submitted in the report that the patient expresses her likes and dislikes via small gestures and sounds, she smiles and blinks and even responds to the outside environment and even to her surrounding as well.

- The court was also of the opinion that due to a decrease in the ethical standard and increasing corruption in society, there is a threat that can lead to the misuse of passive euthanasia and which will result in the infringement of the Article 21 of the Constitution which Right to life with utmost dignity. So the court was of the opinion that the balanced approach should be adopted in the sensitive issue where there is a matter of one's life and death.

- The bench was also of the opinion that Section 309 of IPC should be scraped out as they believe a person undergoing depression committing suicide needs help and not punishment.

- The High Court under Article 226[8] would be entitled to make decisions regarding the withdrawal of the life support system. A bench must be constituted by the Chief Justice of the High Court when an application is received, before which a committee of three reputed doctors nominated must be referred. There should be a thorough examination of the patient and state and family members are provided with a notice issued by the bench. The High Court must give a speedy decision. Such a judgment has legalized passive euthanasia in India under certain conditions that the High Court shall fix.

- Active Euthanasia - where a person is killed by a deadly means such as a fatal injection given to a cancer patient who is in agony.

- Passive Euthanasia - when life-sustaining medical care is withheld or withdrawn such as withholding the antibiotics when a patient would die without them or withdrawing the patient's heart and lungs machine from coma.

Right To Die

Right to euthanasia.

- Active Euthanasia

- Passive Euthanasia

- Voluntary: When the patient himself gives consent to administering passive euthanasia.

- Involuntary: When the patient is incompetent to give consent the consent is given by the patient relative or someone on behalf of the patient.

- (2011) 4 SCC 454.

- The Constitution of India, art 32.

- The Constitution of India, art 21.

- The Indian Penal Code 1860, s.309

- The Constitution of India, art 226.

- The Indian Penal Code 1860, S.306

- (1996) 2 SCC 648.

- (1994) 3 SCC 394.

- (1987) 1 Bom CR.

- Law Commission of India, 196th report on Medical treatment to terminally ill patients (protection of patients and medical practitioners) March, 2006, http://lawcommissionofindia.nic.in/reports/rep196.pdf.

- Sandip Roy The rapist who never was: Let's not forget the man who destroyed Aruna Shanbaug's life, first post.

- Garvita Garg - Law Student at Delhi Metropolitan Education, 4th Year

- Sanskar Pradhan - Law Student at Delhi Metropolitan Education, 4th Year

Law Article in India

Please drop your comments, you may like.

Qualities Of A Good Charge ...

Disposal of Arrest Warrant ...

Issuance of Arrest Warrant ...

Witness Eligibility Criteri...

Revision: Ex-Parte Order Fo...

Anticipatory Bail in CrPc: ...

Legal question & answers, lawyers in india - search by city.

Law Articles

How to file for mutual divorce in delhi.

How To File For Mutual Divorce In Delhi Mutual Consent Divorce is the Simplest Way to Obtain a D...

Increased Age For Girls Marriage

It is hoped that the Prohibition of Child Marriage (Amendment) Bill, 2021, which intends to inc...

Facade of Social Media

One may very easily get absorbed in the lives of others as one scrolls through a Facebook news ...

Section 482 CrPc - Quashing Of FIR: Guid...

The Inherent power under Section 482 in The Code Of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (37th Chapter of t...

The Uniform Civil Code (UCC) in India: A...

The Uniform Civil Code (UCC) is a concept that proposes the unification of personal laws across...

Role Of Artificial Intelligence In Legal...

Artificial intelligence (AI) is revolutionizing various sectors of the economy, and the legal i...

File caveat In Supreme Court Instantly

Euthanasia: Global Scenario and Its Status in India

- Review Paper

- Published: 19 July 2017

- Volume 24 , pages 349–360, ( 2018 )

Cite this article

- Raghvendra Singh Shekhawat 1 ,

- Tanuj Kanchan 1 ,

- Puneet Setia 1 ,

- Alok Atreya 2 &

- Kewal Krishan 3

1299 Accesses

5 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The legal and moral validity of euthanasia has been questioned in different situations. In India, the status of euthanasia is no different. It was the Aruna Ramachandra Shanbaug case that got significant public attention and led the Supreme Court of India to initiate detailed deliberations on the long ignored issue of euthanasia. Realising the importance of this issue and considering the ongoing and pending litigation before the different courts in this regard, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India issued a public notice on May 2016 that invited opinions from the citizens and the concerned stakeholders on the proposed draft bill entitled The Medical Treatment of Terminally Ill Patients (Protection of Patients and Medical Practitioners) Bill. Globally, only a few countries have legislation with discreet and unambiguous guidelines on euthanasia. The ongoing developments have raised a hope of India getting a discreet law on euthanasia in the future.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

A Patient’s Right to Refuse Medical Treatment Through the Implementation of Advance Directives

Legislative Debates on Death with Dignity and Euthanasia. An Approach to the Spanish Situation

The Practice of Euthanasia and Assisted Suicide Meets the Concept of Legalization

Bbc.co.uk. (2009). BBC — Religions — Hinduism: Euthanasia, assisted dying and suicide . Retrieved June 29, 2017, from http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/hinduism/hinduethics/euthanasia.shtml .

Bbc.co.uk. (2012). BBC — Religions — Islam: Euthanasia, assisted dying, medical ethics and suicide . Retrieved June 29, 2017, from http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/islam/islamethics/euthanasia.shtml .

Bma.org.uk. (2017). BMA — End - of - life care and physician - assisted dying . Retrieved June 29, 2017, from https://www.bma.org.uk/collective-voice/policy-and-research/ethics/end-of-life-care .

Buiting, H., van Delden, J., Onwuteaka-Philpsen, B., Rietjens, J., Rurup, M., van Tol, D., Gevers, J., Maas, P., & Heide, A. (2009). Reporting of euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide in the Netherlands: Descriptive study. BMC Medical Ethics . doi: 10.1186/1472-6939-10-18 .

Google Scholar

Castro, M., Antunes, G., Marcon, L., Andrade, L., Rückl, S., & Andrade, V. (2017). Euthanasia and assisted suicide in western countries: A systematic review. Revista Bioética, 24, 355–367.

Article Google Scholar

Ceaser, M. (2008). Euthanasia in legal limbo in Colombia. The Lancet, 371 (9609), 290–291.

Chambaere, K., & Bernheim, J. (2015). Does legal physician-assisted dying impede development of palliative care? The Belgian and Benelux experience. Journal of Medical Ethics, 41 (8), 657–660. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2014-102116 .

Chavan, P. (2017). Should euthanasia be allowed in India? Ministry of Health & Family Welfare wants your opinion . Retrieved June 28, 2017, from http://www.thehealthsite.com/news/should-euthanasia-be-allowed-in-india-ministry-of-health-family-welfare-wants-your-opinion-po0516/ .

Cohen-Almagor, R. (2015). First do no harm: Euthanasia of patients with dementia in Belgium: Table 1. Journal of Medicine and Philosophy . doi: 10.1093/jmp/jhv031 .

Daily News & Analysis. (2011). The hits and misses of the Aruna Shanbaug verdict. Retrieved June 29, 2017, from http://www.dnaindia.com/india/analysis-the-hits-and-misses-of-the-aruna-shanbaug-verdict-1517522 .

Dyer, C. (2003). Swiss parliament may try to ban “suicide tourism”. BMJ, 326 (7383), 242. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7383.242 .

Findlaw. (2017). FindLaw’s court of appeals of New Mexico case and opinions . Retrieved June 29, 2017, from http://caselaw.findlaw.com/nm-court-of-appeals/1710738.html .

Frati, P., Gulino, M., Mancarella, P., Cecchi, R., & Ferracuti, S. (2014). Assisted suicide in the care of mentally ill patients: The Lucio Magri’s case. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, 21, 26–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2013.10.017 .

Gauthier, S., Mausbach, J., Reisch, T., & Bartsch, C. (2014). Suicide tourism: A pilot study on the Swiss phenomenon. Journal of Medical Ethics, 41 (8), 611–617. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2014-102091 .

Grim Reaper, M. D. (2017). National review . Retrieved June 28, 2017, from https://www.nationalreview.com/magazine/2016-04-25-0100/euthanasia-policy-holland-the-netherlands-slippery-slope .

House Bill 814, 49th Legislature—State of New Mexico—First Session, 2009. (2009). Retrieved from https://www.nmlegis.gov/sessions/09%20Regular/bills/house/HB0814.pdf .

Indiankanoon.org. (2017). Aruna Ramchandra Shanbaug vs Union of India & Ors on 7 March, 2011 . Retrieved June 29, 2017, from https://indiankanoon.org/doc/235821/ .

Jotkowitz, A. (2006). The Groningen protocol: Another perspective. Journal of Medical Ethics, 32 (3), 157–158. doi: 10.1136/jme.2005.012476 .

Kanchan, T., Atreya, A., & Krishan, K. (2015). Aruna Shanbaug: Is her demise the end of the road for legislation on euthanasia in India? Science and Engineering Ethics, 22 (4), 1251–1253. doi: 10.1007/s11948-015-9687-4 .

Langley, A. (2017). ‘Suicide tourists’ go to the Swiss for help in dying . Nytimes.com. Retrieved June 28, 2017, from http://www.nytimes.com/2003/02/04/world/suicide-tourists-go-to-the-swiss-for-help-in-dying.html?mcubz=2 .

Liddane, N. (2013). Abandoned to principle: an overview of the law on euthanasia & assisted suicide in the UK and Ireland & the case for reform. Cork Online Law Review, 12, 79–103.

Mani, R., Amin, P., Chawla, R., Divatia, J., Kapadia, F., Khilnani, P., Myatra, S., Prayag, S., Rajagopalan, R., Todi, S., Uttam, R., Balakrishnan, S., Dalmia, A., & Kuthiala, A. (2005). Limiting life-prolonging interventions and providing palliative care towards the end-of-life in Indian intensive care units. Indian Journal of Critical Care Medicine, 9 (2), 96. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.17097 .

Mani, R., Amin, P., Chawla, R., Divatia, J., Kapadia, F., Khilnani, P., Myatra, S., Prayag, S., Rajagopalan, R., Todi, S., & Uttam, R. (2012). Guidelines for end-of-life and palliative care in Indian intensive care units’ ISCCM consensus ethical position statement. Indian Journal of Critical Care Medicine, 16 (3), 166. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.102112 .

Medical treatment to terminally ill patients (protection of patients and medical practitioners). (2006). http://lawcommissionofindia.nic.in/reports.htm . Retrieved June 29, 2017, from http://lawcommissionofindia.nic.in/reports/rep196.pdf .

Menon, S. (2013). Euthanasia: A matter of life or death? Singapore Medical Journal, 54 (3), 116–128. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2013043 .

Ministry of Health & Family Welfare (MoHFW). (2016). Medical treatment of terminally - ill patients (protection of patients and medical. Practitioners) Act . Retrieved June 29, 2017, from http://www.prsindia.org/uploads/media/draft/Draft%20Passive%20Euthanansia%20Bill.pdf .

Myatra, S., Salins, N., Iyer, S., Macaden, S., Divatia, J., Muckaden, M., Kulkarni, P., Simha, S., & Mani, R. (2014). End-of-life care policy: An integrated care plan for the dying. Indian Journal of Critical Care Medicine, 18 (9), 615. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.140155 .

Nationalrighttolifenews.org. (2017). British Medical Association rejects attempt to push it neutral on assisted suicide by 2 to 1 majority | NRL News Today . Retrieved June 29, 2017, from http://www.nationalrighttolifenews.org/news/2016/06/british-medical-association-rejects-attempt-to-push-it-neutral-on-assisted-suicide-by-2-to-1-majority/#.WVSSV-uGPIU .

Openparliament.ca. (2017). Bill C-14 | openparliament.ca (online). https://openparliament.ca/bills/42-1/C-14/ . Accessed June 29, 2017.

Passive Euthanasia—A Relook. Report No. 241. (2012). http://lawcommissionofindia.nic.in/ . Retrieved June 29, 2017, from http://lawcommissionofindia.nic.in/reports/report241.pdf .

Payton, S. (1992). The concept of the person in the parens patriae jurisdiction over previously competent persons. Journal of Medicine and Philosophy, 17 (6), 605–645. doi: 10.1093/jmp/17.6.605 .

Rajagopal, K. (2016). Open to framing law on euthanasia, says Centre. The Hindu . Retrieved June 29, 2017, from http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/Open-to-framing-law-on-euthanasia-says-Centre/article14028780.ece .

Raus, K. (2016). The extension of Belgium’s Euthanasia Law to include competent minors. Journal of Bioethical Inquiry, 13 (2), 305–315. doi: 10.1007/s11673-016-9705-5 .

Reuters. (2017). Euthanasia tourists snap up pet shop drug in Mexico (online). http://www.reuters.com/article/us-mexico-euthanasia-idUSN0329945820080603 . Accessed June 29, 2017.

Services.parliament.uk. (2007). Assisted dying (No. 2) bill 2015 - 16 — UK Parliament . Retrieved June 29, 2017, from http://services.parliament.uk/bills/2015-16/assisteddyingno2.html .

The Times of India. (2016). Doctor group seeks law to spare patients needless med spend — Times of India . Retrieved June 29, 2017, from http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/Doctor-group-seeks-law-to-spare-patients-needless-med-spend/articleshow/53145801.cms .

Trachsel, M., Irwin, S., Biller-Andorno, N., Hoff, P., & Riese, F. (2016). Palliative psychiatry for severe persistent mental illness as a new approach to psychiatry? Definition, scope, benefits, and risks. BMC Psychiatry . doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0970-y .

Vizcarrondo, F. (2014). Neonatal euthanasia: The Groningen protocol. The Linacre Quarterly, 81 (4), 388–392. doi: 10.1179/0024363914z.00000000086 .

Wma.net. (2017). WMA — The World Medical Association - WMA Resolution on Euthanasia . Retrieved June 29, 2017, from https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-resolution-on-euthanasia/ .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Forensic Medicine and Toxicology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Jodhpur, India

Raghvendra Singh Shekhawat, Tanuj Kanchan & Puneet Setia

Department of Forensic Medicine, Nepal Medical College Teaching Hospital, Kathmandu, Nepal, India

Alok Atreya

Department of Anthropology, Panjab University, Chandigarh, India

Kewal Krishan

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Raghvendra Singh Shekhawat .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Shekhawat, R.S., Kanchan, T., Setia, P. et al. Euthanasia: Global Scenario and Its Status in India. Sci Eng Ethics 24 , 349–360 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-017-9946-7

Download citation

Received : 18 June 2017

Accepted : 03 July 2017

Published : 19 July 2017

Issue Date : April 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-017-9946-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Aruna Shanbaug

- Physician-assisted suicide (PAS)

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Subscribe Now! Get features like

- Latest News

- Entertainment

- Real Estate

- Lok Sabha election 2024 voting live

- Lok Sabha Election 2024

- Election Schedule 2024

- IPL 2024 Schedule

- IPL Points Table

- IPL Purple Cap

- IPL Orange Cap

- The Interview

- Web Stories

- Virat Kohli

- Mumbai News

- Bengaluru News

- Daily Digest

Explained | Supreme Court’s landmark judgment on passive euthanasia, living will

Sc was hearing a plea by ngo common cause to declare ‘right to die with dignity’ as a fundamental right within the fold of right to live with dignity..

The Supreme Court ruled on Friday that individuals have a right to die with dignity, in a verdict that permits the removal of life-support systems for the terminally ill or those in incurable comas.

The court also permitted individuals to decide against artificial life support, should the need arise, by creating a “living will”.

SC was hearing a plea by NGO Common Cause to declare ‘right to die with dignity’ as a fundamental right within the fold of right to live with dignity, which is guaranteed under Article 21 of the Constitution.

Here’s all you need to know about euthanasia and ‘living will’:

• Living will

A ‘living will’ is a concept where a patient can give consent that allows withdrawal of life support systems if the individual is reduced to a permanent vegetative state with no real chance of survival.

It is a type of advance directive that may be used by a person before incapacitation to outline a full range of treatment preferences or, most often, to reject treatment. A living can detail a person’s preferences for tube-feeding, artificial hydration, and pain medication when an individual cannot communicate his/her choices.

In its verdict on Friday, SC has attached strict conditions for executing “a living will that was made by a person in his normal state of health and mind”.

The US, UK, Germany and Netherlands have advance medical directive laws that allow people to create a ‘living will’.

• Active and passive euthanasia

Active euthanasia, the intentional act of causing the death of a patient in great suffering, is illegal in India. It entails deliberately causing the patient’s death through injections or overdose.

But passive euthanasia, the withdrawal of medical treatment with the deliberate intention to hasten a terminally ill patient’s death was allowed by the Supreme Court in Friday’s landmark verdict.

The court also laid down guidelines on who would execute the will and how a nod for passive euthanasia would be granted by a medical board set up to determine and carry out any “advance directive”.

In cases where there is no “advance directive”, the patient, family, friends and legal guardians can’t take the decision on their own, but can approach a high court for stopping treatment .

• Aruna Shanbaug case

In 2011, the Supreme Court, while hearing the case of Aruna Shanbaug, who was in a vegetative state for more than 40 years, had legalised passive euthanasia partially.

A nurse at KEM Hospital in Mumbai, Shanbaug was in a vegetative state since 1973 after a brutal sodomisation and strangling with a dog-chain during a sexual assault. She died in 2015 while on a ventilator for several days after suffering from pneumonia.

SC gave patients living in a vegetative state the right to have treatment or food withdrawn, and laid down guidelines to process passive euthanasia in the case of incompetent patients. The guidelines included seeking a declaration from a high court, after getting clearance from a medical board and state government.

• Terminally Ill Patients (Protection of Patients and Medical Practitioners) Bill

I n 2012, the union health ministry posted a draft of the Terminally Ill Patients (Protection of Patients and Medical Practitioners) Bill on its website and invited public reactions.

The Bill is popularly referred to as the Passive Euthanasia Bill although its draft did not use the emotive word “euthanasia” to skirt complications around the term, a health ministry official told HT in 2016. It says every advance medical directive (also called ‘living will’) or medical power of attorney executed by a person shall be taken into consideration in matter of withholding or withdrawing medical treatment but it shall not be binding on any medical practitioner.

The draft bill has a controversial clause that allows a minor aged above 16 to take an informed decision and express a desire to withhold or withdraw medical treatment and allow nature to take its own course

• Medical experts on euthanasia

Doctors have a mixed reaction to legalising euthanasia. They say the government needs to take a careful approach before legalising passive euthanasia when the measures to prolong the life of the patient are withdrawn.

Most doctors, however, agree that euthanasia should be made legal in cases where there is no scope of a patient recovering. But many feel that India is not yet ready for a decision like this which requires a mix of sensitivity and maturity.

• Misuse of law

A major concern is the misuse of the law. If it is legal to passively allow or hasten death, what’s to say an aged parent won’t be hastened in favour of an inheritance, or a spouse have treatment withdrawn for the sake of a hefty insurance payout?

• Euthanasia in other countries

Euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide have been legal in The Netherlands and Belgium since 2001 and 2002. In the US, Switzerland and Germany, euthanasia is illegal but physician-assisted suicide is legal. Euthanasia remains illegal in the UK, France, Canada and Australia

- Supreme Court

- Life Support System

Join Hindustan Times

Create free account and unlock exciting features like.

- Terms of use

- Privacy policy

- Weather Today

- HT Newsletters

- Subscription

- Print Ad Rates

- Code of Ethics

- MI vs SRH Live

- IPL Live Score

- T20 World Cup Schedule

- IPL 2024 Auctions

- T20 World Cup 2024

- Cricket Teams

- Cricket Players

- ICC Rankings

- Cricket Schedule

- T20 World Cup Points Table

- Other Cities

- Income Tax Calculator

- Budget 2024

- Petrol Prices

- Diesel Prices

- Silver Rate

- Relationships

- Art and Culture

- Taylor Swift: A Primer

- Telugu Cinema

- Tamil Cinema

- Board Exams

- Exam Results

- Competitive Exams

- BBA Colleges

- Engineering Colleges

- Medical Colleges

- BCA Colleges

- Medical Exams

- Engineering Exams

- Horoscope 2024

- Festive Calendar 2024

- Compatibility Calculator

- The Economist Articles

- Lok Sabha States

- Lok Sabha Parties

- Lok Sabha Candidates

- Explainer Video

- On The Record

- Vikram Chandra Daily Wrap

- EPL 2023-24

- ISL 2023-24

- Asian Games 2023

- Public Health

- Economic Policy

- International Affairs

- Climate Change

- Gender Equality

- future tech

- Daily Sudoku

- Daily Crossword

- Daily Word Jumble

- HT Friday Finance

- Explore Hindustan Times

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Subscription - Terms of Use

- THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO

- Prospective Students

- Search Search

- bioethics euthanasia india past and present

The Bioethics of Euthanasia in India: Past and Present

Hinduism’s response to the question of euthanasia

By Purushottama Bilimoria | December 18, 2014

The Los Angeles Times carried an article (January 2013) on the elderly citizens of the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu, who, perhaps ailing and suffering from debilitating pain, are being quietly sent off to their deaths, often with the use of a potion known as thalaikoothal. But what is Hinduism’s response to the question of euthanasia? How have the majority of Hindus been dealing with this issue? This becomes a critical question especially when confronted with, on the one hand, the availability of technologically advanced medical treatment regimes and, on the other hand, a significant lack of resources for the palliative care of a the subcontinent’s rapidly aging population of 1.1 billion. Surveys of ancient scriptural sources on the issue yield several ambiguities and contradictions. Hindu legalistic prohibitions against taking one's own life appear in Manusmriti , II. 90-91, V. 89; Yajnavalkyasmrti III.253, among other corpus known as Dharma Shastras Manusmriti also mentions fasting in order to draw attention to an injustice in a situation, human or cosmic, which might lead to one's death. These sources constitute the classical pronouncements on temporal law for Hindus, and are considered to be authoritative even today. Ancient Brahmanic-Hindu lawmakers (attributed with authorship of the aforementioned shastric texts) made self-killing an exception for a lower-caste man guilty of the murder of a Brahmin, who may thus throw himself into a fire ( Manu XI.73: Yajna . III.248) as well as for those who committed other heinous crimes against themselves (like taking liquor) or against others (e.g. adulterous relationships with higher caste members, incest, theft, perjury, etc.). Might there be limits and other sanctions, however, for a conditional intervention in circumstances which call for the swift release of the soul of the dreadfully injured individual, marking a turning point in the individual’s karmic cycle? Or, is the reverence for life balanced by the principle of dignified death, an implication derived from the inevitable decay of all creatures? For answers scholars often turn to historical instances and recorded practices, such as ascetic atmaghata or jauhar (mass suicide in the face of impending calamity, natural or human-made), the controversial sati ("suttee," though more needs to be said about the element of involuntary homicide involved here), fasting to death (that Mahatma Gandhi adopted as a political strategy and that Vinoba Bhave used to find release from his incapacitating illness). Instructively, there are parallel practices in India’s Jaina religious tradition such as sallekhana, prayovesana, santhara (voluntary fasting to death). Secular Hindus—Hindus and Jains who are less committed to their religion than to the culture and to the political ideal of India as Hindu, hence, like Gandhi, “secular” in Charles Taylor's sense of secularity—often cite the Jaina practice as evidence of a humanist approach toward empathic care for the severely ill, or toward those who are deprived of their "fundamental rights" to work, to a living wage, to equality and to the decent standard of life decreed in the Indian Constitution (articles 14-21). Secular Hindus argue that from the latter juridical rule a negative entailment can be derived (as indeed Indian courts have argued). To whit: when one of these basic rights is not forthcoming or abrogated by the state, the aggrieved citizen may exercise the right to die or resort to non-culpable auto-homicide. In recent times cases involving attempted suicide have come before the secular courts. A landmark case was of a vendor whose licence to sell vegetables on a street-side stall was revoked by the city administration; he there-upon took the drastic step of setting himself on fire in public, only to be arrested and charged by the police with criminal offence under section 309 of the Indian Penal Code. It is interesting that the state’s High Courts and, in at least two instances, the nation's Apex Court have compared such acts of attempted suicide to euthanasia (in the medical context) and adjudged the former to be constitutionally defensible–even though euthanasia is not yet protected under the law, and the analogical reasoning might therefore be a trifle over-determined. All of these considerations suggest a preparedness on the part of Hindus and of a large number of secular Indians to adopt an open (though cautious) attitude toward euthanasia based on the particularity of the case. Hindu and non-Hindu Indians alike ask whether euthanasia is, in a given situation, a humane means of minimizing the sufferer's immense pain and continuing harm to her potential good hereafter—rather than bend to an the ideology of deterrence inscribed in the outmoded colonial penal system still prevalent in India. Sources : Magnier, Mark. “In southern India, relatives sometimes quietly kill their elders.” Los Angeles Times , January 13, 2013, News. http://articles.latimes.com/2013/jan/15/world/la-fg-india-mercy-killings-20130116 . Bilimoria, P. “Jaina ethic of voluntary death, A Report from India.” Bioethics 331-355 (October 1992), Vol 6 No 4, pp. 331-355. Bilimoria, P. “Legal Rulings on Suicide in India and Implications for the Rights to Die.” Asian Philosophy (Nottingham) Autumn 1995, Vol 5, No 2. pp. 159-180.83. Bilimoria, P. “The Debate on Euthanasia in India.” Indian Ethics . Volume II. Edited by P. Bilimoria, Renuka Sharma, J. Prabhu, Amy Rayner. Indian Ethics vol II Gender, Justice and Ecology. Dordrecht: Springer; New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2015. Image Credit: Zuhair A. Al-Traifi / flickr creative commons. Managing Editor, Myriam Renaud To subscribe to Sightings and receive it by email every Monday and Thursday, please click here .

Author, Purushottama Bilimoria, is Honorary Professor of Philosophy and Comparative Studies at Deakin University in Australia and Senior Fellow, University of Melbourne, Visiting Scholar and Lecturer at University of California, Berkeley and Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley, and Shivadasani Fellow of Oxford University. His research focuses on classical Indian philosophy and comparative ethics, Continental thought, cross-cultural philosophy of religion, diaspora studies, bioethics, and personal law in India. Recent publications are Indian Ethics I (Ashgate 2007, OUP 2008), Sabdapramana: Word and Knowledge (Testimony) in Indian Philosophy (revised reprint, Delhi: DK PrintWorld, 2008); Emotions In Indian-Thought Systems (with A. Wenta) (Routledge 2015), and Indian Ethics Vol II ( Springer 2015).

Purushottama Bilimoria

See All Articles by Purushottama Bilimoria

Euthanasia: Global Scenario and Its Status in India

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Forensic Medicine and Toxicology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Jodhpur, India. [email protected].

- 2 Department of Forensic Medicine and Toxicology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Jodhpur, India.

- 3 Department of Forensic Medicine, Nepal Medical College Teaching Hospital, Kathmandu, Nepal, India.

- 4 Department of Anthropology, Panjab University, Chandigarh, India.

- PMID: 28726026

- DOI: 10.1007/s11948-017-9946-7

The legal and moral validity of euthanasia has been questioned in different situations. In India, the status of euthanasia is no different. It was the Aruna Ramachandra Shanbaug case that got significant public attention and led the Supreme Court of India to initiate detailed deliberations on the long ignored issue of euthanasia. Realising the importance of this issue and considering the ongoing and pending litigation before the different courts in this regard, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India issued a public notice on May 2016 that invited opinions from the citizens and the concerned stakeholders on the proposed draft bill entitled The Medical Treatment of Terminally Ill Patients (Protection of Patients and Medical Practitioners) Bill. Globally, only a few countries have legislation with discreet and unambiguous guidelines on euthanasia. The ongoing developments have raised a hope of India getting a discreet law on euthanasia in the future.

Keywords: Aruna Shanbaug; Euthanasia; Indian law; Physician-assisted suicide (PAS).

Publication types

- Euthanasia / ethics

- Euthanasia / legislation & jurisprudence*

- Legislation, Medical*

- Patient Rights / legislation & jurisprudence*

- Suicide, Assisted / ethics

- Suicide, Assisted / legislation & jurisprudence*

Aruna Ramchandra Shanbaug v. Union Of India: Case Analysis

By Mounica Kasturi, Symbiosis Law School, Pune

“ Editor’s Note: Fundamental Rights are necessary for leading a dignified and fulfilling life. Probably the most important Fundamental Right in the Indian Constitution is the Right to Life under Article 21. It is a right that encompasses within its broad domain the right to legal aid, right to a clean environment, and a plethora of other rights. The question that came to be considered in the present case was whether inherent in this sacred right is the right to die-whether a person can be allowed to control his death and decide to end his life. Right to die has become important considering the advancement in medical jurisprudence and also the possibility of misuse of this right by family members. This case dealt with euthanasia in detail by distinguishing between active and passive euthanasia. Laws relating to euthanasia in different jurisdictions were considered. The court deleted into a scenario where the patient was incapable of giving consent and specified who could approach the Court on his behalf. It also laid down guidelines prescribing the situation and procedure of administering passive euthanasia.”

INTRODUCTION

The Constitution of India guarantees ‘Right to Life’ to all its citizens. The constant, ever-lasting debate on whether ‘Right to Die’ can also be read into this provision still lingers in the air. On the other hand, with more and more emphasis being laid on the informed consent of the patients in the medical field, the concept of Euthanasia in India has received a mixed response.

The Hon’ble Supreme Court of India, in the present matter, was approached under Article 32 of the Indian Constitution to allow for the termination of the life of Aruna Ramchandra Shanbaug, who was in a permanent vegetative state. The petition was filed by Ms. Pinki Virani, claiming to be the next friend of the petitioner. The Court in earlier cases has clearly denied the right to die and thus legally, there was no fundamental right violation that would enable the petitioner to approach the court under Article 32. Nonetheless, the Supreme Court taking cognizance of the gravity of the matter involved and the allied public interest in deciding about the legality of euthanasia accepted the petition.

It was stated that the petitioner Aruna Ramachandra Shanbaug was a staff Nurse working in King Edward Memorial Hospital, Parel, Mumbai. On the evening of 27th November, 1973 she was attacked by a sweeper in the hospital who wrapped a dog chain around her neck and yanked her back with it. He tried to rape her but finding that she was menstruating, he sodomized her. To immobilize her during this act he twisted the chain around her neck. The next day, a cleaner found her in an unconscious condition lying on the floor with blood all over. It was alleged that due to strangulation by the dog chain the supply of oxygen to the brain stopped and the brain got damaged.

Thirty six years had lapsed since the said incident. She had been surviving on mashed food and could not move her hands or legs. It wass alleged that there is no possibility of any improvement in the condition and that she was entirely dependent on KEM Hospital, Mumbai. It was prayed to direct the Respondents to stop feeding Aruna and let her die in peace.

FINDINGS OF THE COURT APPOINTED DOCTORS

The respondents, KEM Hospital and Bombay Municipal Corporation filed a counter petition. Since, there were disparities in the petitions filed by the petitioner and respondents, the court decided to appoint a team of three eminent doctors to investigate and report on the exact physical and mental conditions of Aruna Shanbaug.

They studied Aruna Shanbaug’s medical history in detail and opined that she is not brain dead. She reacts to certain situations in her own way. For example, she likes light, devotional music and prefers fish soups. She is uncomfortable if a lot of people are in the room and she gets distraught. She is calm when there are fewer people around her. The staff of KEM Hospital was taking sufficient care of her. She was kept clean all the time . Also, they did not find any suggestion from the body language of Aruna as to the willingness to terminate her life. Further, the nursing staff at KEM Hospital was more than willing to take care of her. Thus, the doctors opined that that euthanasia in the instant matter is not necessary.

ISSUES RAISED

- When a person is in a permanent vegetative state (PVS), should withholding or withdrawal of life sustaining therapies be permissible or `not unlawful’?

- If the patient has previously expressed a wish not to have life-sustaining treatments in case of futile care or a PVS, should his/ her wishes be respected when the situation arises?

- In case a person has not previously expressed such a wish, if his family or next of kin makes a request to withhold or withdraw futile life-sustaining treatments, should their wishes be respected?

To be able to adjudicate upon the aforementioned issues, the court explained as to what is euthanasia. Euthanasia or mercy killing is of two types: active and passive. Active euthanasia entails the use of lethal substances or forces to kill a person e.g. a lethal injection given to a person with terminal cancer who is in terrible agony. Passive euthanasia entails withholding of medical treatment for continuance of life, e.g. withholding of antibiotics where without giving it a patient is likely to die, or removing the heart lung machine, from a patient in coma.

A further categorization of euthanasia is between voluntary euthanasia and non-voluntary euthanasia. Voluntary euthanasia is where the consent is taken from the patient, whereas non-voluntary euthanasia is where the consent is unavailable e.g. when the patient is in coma, or is otherwise unable to give consent. While there is no legal difficulty in case of the former, the latter poses several problems. The present case dealt with passive non-voluntray euthanasia.

RIGHT TO DIE

In the case of State of Maharashtra v. Maruty Shripati Dubal , [i] the contention was that Section 309 of the Indian Penal Code was unconstitutional as it is violative of Article 19 and 21. It was held in this case by the Bombay high court that ‘right to life’ also includes ‘right to die’ and section 309 was struck down. The court clearly said in this case that right to die is not unnatural; it is just uncommon and abnormal. In the case of P.Rathinam v. Union of India , [ii] it was held that the scope of Article 21 includes the ‘right to die’. P. Rathinam held that Article 21 has also a positive content and is not merely negative in its reach. In the case of Gian Kaur v. State of Punjab , [iii] the validity of Section 306 of the IPC was in question, which penalised the abetment of suicide. This case overruled P.Rathinam but the court opined that in the context of a terminally ill patient or one in the PVS, the right to die is not termination of life prematurely but rather accelerating the process of death which has already commenced. [iv] Further, it was also submitted that the right to live with human dignity [v] must also include a death with dignity and not one of subsisting mental and physical agony.

Reliance was placed on the landmark judgement of Airedale NHS Trust v. Bland , [vi] where for the first time in the English history, the right to die was allowed through the withdrawal of life support systems including food and water. This case placed the authority to decide whether a case is fit or not for euthanasia in the hands of the Court. Also, in the case of Mckay v. Bergsted , [vii] the Supreme Court of Navada, after due evaluation of the state interest and the patient’s interest, upheld the permission for the removal of respirator. However, in the instant case, Aruna could breathe by herself and did not need any external assistance to breath and thus, distinguished from the Mckay case.

MEDICAL ETHICS

The Supreme Court dealt with the aspect of informed consent and right to the bodily integrity of the patient as followed by the US after the Nancy Cruzan case [viii] . Informed Consent is the kind of consent wherein the patient is fully aware of all the future courses of his treatment, his chances of recovery, and all the side effects of all of these alternative courses of treatment. If a person is in a position to give a completely informed consent and he is still not asked, the physician can be booked for assault, battery, or even culpable homicide. The concept of informed consent comes into question only when the patient is able to understand the consequences of her treatment or has earlier when in sound conditions made a declaration.

In this case, the consent of Aruna could not be obtained and thus, the question as to who should decide on her behalf became more prominent. This was decided by beneficence. Beneficence is acting in the patient’s best interest. Acting in the patient’s best interest means following a course of action that is best for the patient, and is not influenced by personal convictions, motives or other considerations. Public interest and the interests of the state were also considered. The mere legalisation of euthanasia could lead to a wide spread misuse of the provision and thus, the court looked at various jurisprudences to evolve with the safeguards.

GLOBAL APPROACH

The general legal position all over the world was that while active euthanasia is illegal unless there is legislation permitting it; passive euthanasia is legal even without legislation provided certain conditions and safeguards are maintained. Certain countries had passed legislations to allow for active euthanasia or doctor assisted suicide. In the former, the physician or someone else administers it, while in the latter the patient himself does so, though on the advice of the doctor.

Netherlands:

- Euthanasia in the Netherlands is regulated by the Termination of Life on Request and Assisted Suicide (Review Procedures) Act ,2002.

- It states that euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide are not punishable if the attending physician acts in accordance with the criteria of due care. These criteria concern the patient’s request, the patient’s suffering (unbearable and hopeless), the information provided to the patient, the presence of reasonable alternatives, consultation of another physician and the applied method of ending life.

Switzerland:

- Article 115 of the Swiss Penal Code considers assisting suicide a crime if, and only if, the motive is selfish. The code does not give physicians a special status in assisting suicide; although, they are most likely to have access to suitable drugs. Ethical guidelines have cautioned physicians against prescribing deadly drugs.

- The Swiss law is unique because (1) the recipient need not be a Swiss national, and (2) a physician need not be involved. Many persons from other countries, especially Germany, go to Switzerland to undergo euthanasia.

Active Euthanasia is illegal in all states in U.S.A., but physician assisted dying is legal in the states of Oregon, Washington and Montana. Further, Washington and Montana also have similar legislations in place. Countries like Belgium, Canada have also joined the move. On the other hand, countries such as Spain, UK, do not express their solidarity towards euthanasia.

The Hon’ble Division Bench of the Supreme Court of India, comprising Justice Markandey Katju and Justice Gyan Sudha Mishra, delivered this historic judgment on March 7, 2011. The Court opined that based on the doctors’ report and the definition of brain death under the Transplantation of Human Organs Act, 1994, Aruna was not brain dead. She could breathe without a support machine, had feelings and produced necessary stimulus. Though she is in a PVS, her condition was been stable. So, terminating her life was unjustified.

Further, the right to take decision on her behalf vested with the management and staff of KEM Hospital and not Pinki Virani. The life saving technique was the mashed food, because of which she was surviving. The removal of life saving technique in this case would have meant not feeding her. The Indian law in no way advocated not giving food to a person. Removal of ventilators and discontinuation of food could not be equated. Allowing of euthanasia to Aruna would mean reversing the efforts taken by the nurses of KEM Hospital over the years.

Moreover, in furtherance of the parens patriae principle, the Court to prevent any misuse in the vested the power to determine the termination of life of person in the High Court. Thus, the Supreme Court allowed passive euthanasia in certain conditions, subject to the approval by the High Court following the due procedure. When an application for passive euthanasia is filed the Chief Justice of the High Court should forthwith constitute a Bench of at least two Judges who should decide to grant approval or not. Before doing so the Bench should seek the opinion of a committee of three reputed doctors to be nominated by the Bench after consulting such medical authorities/medical practitioners as it may deem fit. Simultaneously with appointing the committee of doctors, the High Court Bench shall also issue notice to the State and close relatives e.g. parents, spouse, brothers/sisters etc. of the patient, and in their absence his/her next friend, and supply a copy of the report of the doctor’s committee to them as soon as it is available. After hearing them, the High Court bench should give its verdict. The above procedure should be followed all over India until Parliament makes legislation on this subject.

However, Aruna Shanbaug was denied euthanasia as the court opined that the matter was not fit for the same. If at any time in the future, the staff of KEM hospital or the management felt a need for the same, they could approach the High Court under the procedure prescribed.

This case clarified the issues revolving around euthanasia and also laid down guidelines with regard to massive euthanasia. Alongside, the court also made a recommendation to repeal Section 309 of the Indian Penal Code. This case is a landmark case as it prescribed the procedure to be followed in an area that has not been legislated upon.

Edited by Kudrat Agrawal

[i] 1987 (1) Bom CR.

[ii] 1994 SCC (3) 394.

[iii] (1996) 2 SCC 648.

[iv] Supra Note 3,¶ 25.

[v] Vikram Deo Singh Tomar v. State of Bihar ,1988 (Supp) SCC 734.

[vi] MHD (1993) 2 WLR 316.

[vii] 801 P.2d 617 (Nev. 1990).

[viii] Cruzan v. Director, Missouri Department of Health, 110 S. Ct. 2841.

[ix] Supra note 2.

[x] Supra note 3.

Related Posts:

4 thoughts on “Aruna Ramchandra Shanbaug v. Union Of India: Case Analysis”

very well written

beatifully explained .. thnx alot

a’ight but which is the ratio decidendi and which is the obiter dicta T-T

put some effort into it. -your legal studies teacher

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Give it a try, you can unsubscribe anytime :)

Thanks, I’m not interested

Aruna Ramchandra Shanbaug v. Union of India Case Analysis (Passive Euthanasia)

Table of Contents

Background of the case

The petitioner in this case, Aruna Ramchandra Shanbaug used to work as a Nurse in King Edward Memorial Hospital, Parel, Mumbai. On the evening of the 27th November 1973 a sweeper of the same hospital attacked her and he wrapped her neck with a dog chain and yanked her back with it. The sweeper also tried to rape her but when he found out that she was menstruating he sodomized her. To prevent her from moving or creating any chaos, he twisted that chain really hard around her neck. Next day, a cleaner found her body lying on the floor unconscious with blood all over. It was believed that the supply of oxygen to the brain stopped because of strangulation by the chain and hence the brain got damaged. This incident caused permanent damage to her brain and led her into a permanent vegetative state (PVS). Later an activist-journalist Pinki Virani filed a petition in the Supreme Court under Article 32 of the constitution alleging that there is no possibility for her to revive again and get better. So she should be allowed to go with the passive euthanasia and should be absolved from her pain and agony.

To this petition the respondent parties i.e, KEM Hospital and Bombay Municipal Corporation filed a counter petition. This led to a rise in the disparities among both the groups. Since there were disparities, the Supreme Court in order to get a better picture of the situation appointed a team of 3 eminent doctors to investigate and provide a report of the exact mental and physical condition of Aruna Shanbaug. During this study doctors investigated her entire medical history and opined that her brain is not dead. She has her own way of understanding and reacting to situations. Also, Aruna’s body language did not show any sign of her willingness to terminate her life. Neither the nursing staff of the hospital showed any carelessness towards taking care of her. Thus, it was believed by the doctor that the euthanasia in the current matter is not essential. She stayed in this position for 42 years and died in 2015.

- Does withdrawal of life sustaining systems and means for a person who is in a permanent vegetative state (PVS), should be permissible ?

- If a patient declares previously that he/she does not want to have life sustaining measures in case of futile care or a PVS, should his/her wishes be respected in such a situation?

- Does the family or next of kin of a person get to make a request to withhold or withdraw life sustaining systems, in case a person himself has not placed such a request previously?

The Hon’ble Division Bench of the Supreme Court of India, comprising Justice Markandey Katju and Justice Gyan Sudha Mishra, delivered this judgement on 7th of March, 2011. The court declared that Aruna is not brain dead and for its judgement relied on the doctor’s report and definition of brain death given under the Transportation of Human Organs Act, 1994. She was able to breathe on her own without a machine’s support, she had feelings and used to show some symptoms. Though she was in a PVS but still her condition was stable. So the grounds presented here are not sufficient for terminating her life. It would be unjustifiable. Further, the court while addressing the issue opined that in the present case next to the kin of the patient would be the staff of the KEM Hospital not Pinki Virani. Thus, the right to take any such decision on behalf of her is vested in KEM Hospital. In the present case it was the food on which she was surviving. Thus removal of life saving techniques would here mean depriving her of food which is not justified in Indian Law in any way.

The Supreme Court allowed passive euthanasia in certain conditions. But the court decided that in order to prevent misuse of this provision in the future, the power to determine the termination of a person’s life would be subjected to High Court’s approval following a due procedure.

Whenever any application will be filed in High Court for passive euthanasia, the Chief Justice of the High Court should constitute a Bensh of atleast two judges decinding the matter that whether such termination should be granted or not. The Bench before laying out any judgement should consider the opinion of a committee of 3 reputed doctors. These doctors are also nominated by the Bench after discussing with the appropriate medical practitioners. Along with appointing this committee, it is also the duty of the court to issue a notice to the state, relatives, kins and friends and also provide them with a copy of the report made by a committee of doctors, as soon as it is possible. And after hearing all the sides, the court should deliver the judgement. This procedure is to be followed in India everywhere until any legislation is passed on the subject.

In the Ultimate decision of this case, by keeping all the important facts of the case in consideration, Aruna Shaunbaug was denied euthanasia. Court also opined that if at any time in the future, the hospital staff feels a need for the same, they can approach the High Court under these prescribed rules. The verdict of this case has helped in clarifying the issues relating to passive euthanasia in India by providing a broad structure of guidelines which are to be followed. The court also recommended the repealing of section 309 of the IPC. We have discussed all about the case. Now let’s discuss the emergence of two important features which came out in this case and have been discussed a lot in subsequent events.

Judgement Analysis

Euthanasia .