Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

- Race in America 2019

1. How Americans see the state of race relations

Table of contents.

- Majorities of whites, blacks and Hispanics say race relations are bad

- Majority of Americans say Trump has made race relations worse

- For the most part, Americans see positive intergroup relations

- No consensus on best approach to improving race relations

- Opinions about the amount of attention paid to race vary across racial and ethnic groups

- Majority of Americans say racial discrimination is overlooked

- One-in-five black adults say all or most whites in the U.S. are prejudiced against black people

- Across racial and ethnic groups, similar shares say they hear racist or racially insensitive comments from friends or family

- Seven-in-ten say a white person using the N-word is never acceptable; about four-in-ten say it’s never acceptable for blacks

- Majorities see advantages for whites, disadvantages for blacks

- Many see racial discrimination and less access to good schools or jobs as major reasons blacks may have a harder time getting ahead

- Most agree blacks are treated less fairly than whites by police and justice system

- Plurality says country hasn’t gone far enough in giving black people equal rights with whites

- Most say legacy of slavery affects black people’s position in society a great deal or fair amount

- Blacks more likely than other groups to say their race has hurt their ability to succeed; whites most likely to say their race has helped

- Majorities of blacks, Asians and Hispanics say they have faced discrimination

- Most blacks say their family talked to them about challenges they might face because of their race

- Most blacks see their race as central to their overall identity

- Acknowledgments

- Methodology

A majority of Americans say race relations in the United States are bad, and of those, about seven-in-ten say things are getting even worse. Roughly two-thirds say it has become more common for people to express racist or racially insensitive views since Donald Trump was elected, even if not necessarily more acceptable.

Opinions about the state of race relations, Trump’s handling of the issue and the amount of attention paid to race vary considerably across racial and ethnic groups. Blacks, Hispanics and Asians are more likely than whites to say Trump has made race relations worse and that there’s too little attention paid to race in the U.S. these days. In addition, large majorities of blacks, Hispanics and Asians say people not seeing discrimination where it exists is a bigger problem in the U.S. than people seeing it where it doesn’t exist, but whites are about evenly divided on this.

This chapter also explores Americans’ views of intergroup relations; whether they think the better approach to improving race relations is to focus on what different groups have in common or on the unique experiences of each racial and ethnic group; whether they have ever heard friends or family members make potentially racist or racially insensitive comments or jokes and, if so, did they confront them; and views about white people and black people using the N-word.

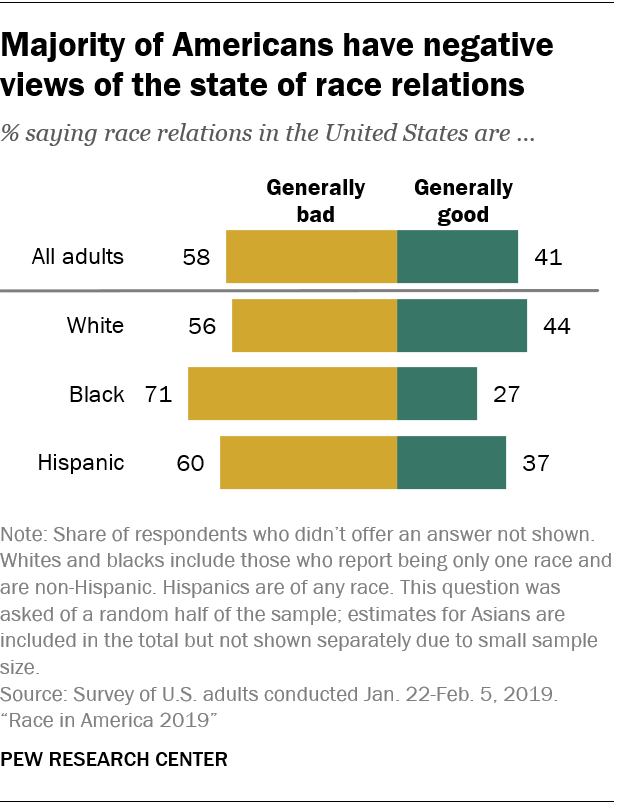

About six-in-ten Americans (58%) say race relations in the U.S. are generally bad, a view that is held by majorities across racial and ethnic groups. Still, blacks (71%) are considerably more likely than whites (56%) and Hispanics (60%) to express negative views about the state of race relations.

Democrats have more negative views of the current state of race relations than Republicans. About two-thirds of Democrats (67%) say race relations are bad, while Republicans are more evenly divided (46% say race relations are bad and 52% say they are good). These partisan differences are virtually unchanged when looking only at white Democrats and Republicans.

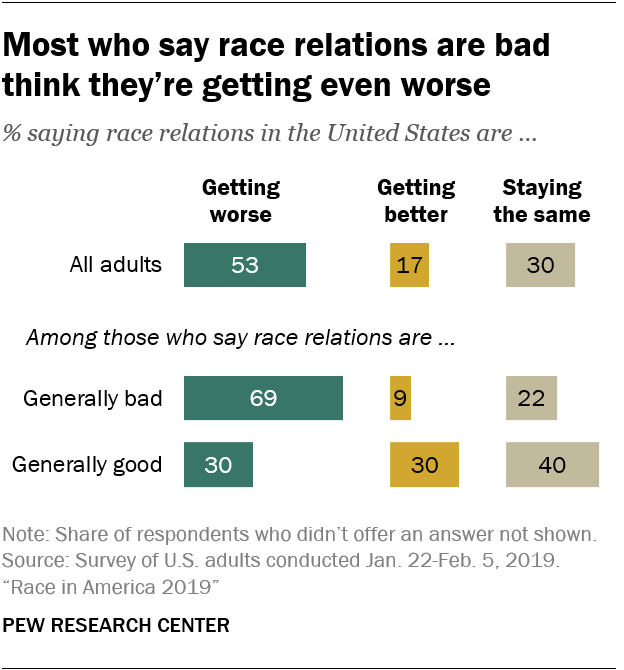

Overall, 53% of the public says race relations are getting worse. Views are particularly pessimistic among those who say race relations are currently bad: 69% of this group says race relations are getting even worse, and 22% say they’re staying the same. Just 9% think they’re getting better. Among those who say race relations are good, 30% see things getting even better, while 30% say they’re getting worse and 40% don’t see much change.

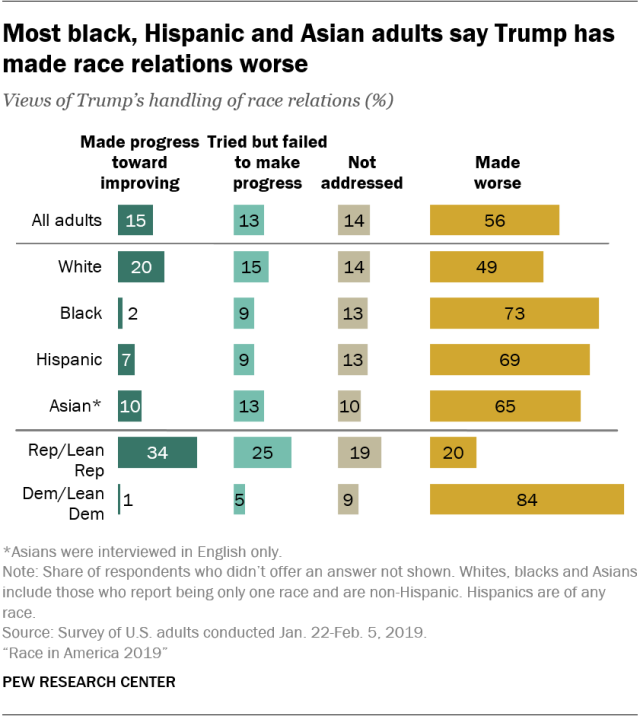

Two years into Donald Trump’s presidency, 56% of Americans say Trump has made race relations worse. A relatively small share (15%) say the president has made progress toward improving race relations, and 13% say he has tried but failed to make progress; 14% say Trump has not addressed race relations.

Assessments of the president’s performance on race relations vary considerably along racial and ethnic lines. Most blacks (73%), Hispanics (69%) and Asians (65%) say Trump has made race relations worse, compared with about half of whites (49%).

Democrats and Republicans have widely different opinions of the president’s handling of race relations. Fully 84% of Democrats say Trump has made race relations worse, compared with 20% of Republicans. And while 34% of Republicans say Trump has made progress toward improving race relations, virtually no Democrats (1%) say the same. Among Democrats, views on this don’t vary much along racial or ethnic lines, but white Democrats (86%) are somewhat more likely than black Democrats (79%) to say Trump has made race relations worse.

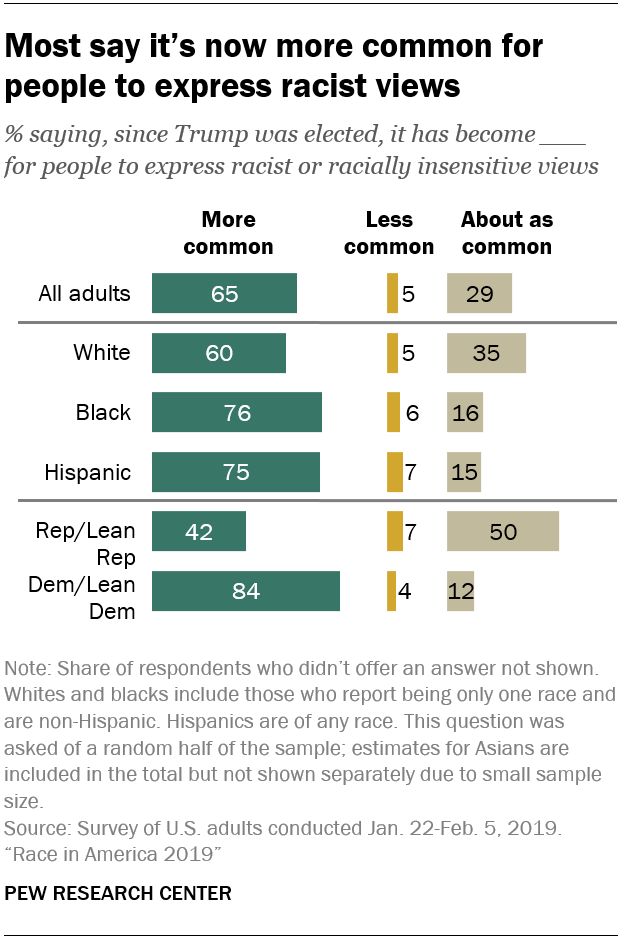

Most Americans say it’s become more common for people to express racist or racially insensitive views since Trump’s election

Majorities across racial and ethnic groups say it has become more common for people to express racist or racially insensitive views since Trump was elected, but blacks (76%) and Hispanics (75%) are more likely than whites (60%) to say this is the case. Whites are more likely than blacks and Hispanics to say expressing these views is about as common as it was before Trump’s election.

Democrats are twice as likely as Republicans to say it has become more common for people to express racist or racially insensitive views since Trump was elected (84% vs. 42%). Half of Republicans – vs. 12% of Democrats – say people expressing these views is about as common as it was before, while small shares in each group say it is now less common than before Trump’s election. These partisan differences remain when looking only at white Democrats and Republicans.

Among whites and blacks, the view that expressing racist or racially insensitive views is now more common is particularly prevalent among those with more education. Some 84% of blacks with a bachelor’s degree or more education and 86% with some college experience offer this opinion, compared with 66% of blacks with a high school diploma or less education. Among whites, the difference is between those with at least a bachelor’s degree (71% say expressing these views has become more common) and those with some college (55%) or no college experience (53%).

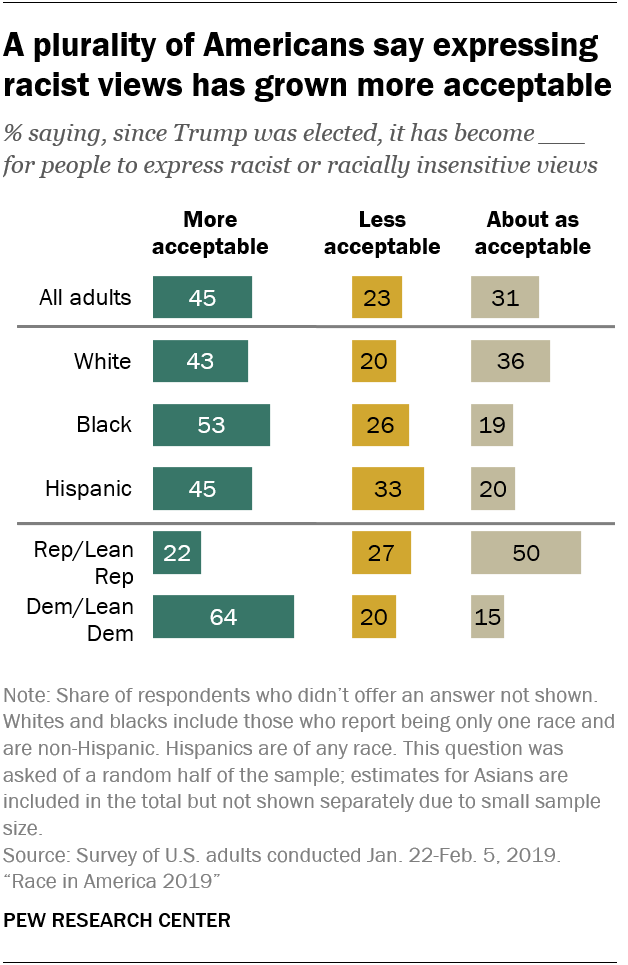

More than four-in-ten say it’s now more acceptable for people to express racist or racially insensitive views

While most Americans say it’s become more common for people to express racist or racially insensitive views since Trump’s election, fewer (45%) say this has become more acceptable. About a quarter (23%) say it’s now less acceptable for people to express these views, and 31% say it’s about as acceptable as it was before Trump was elected.

Overall, blacks (53%) are more likely than whites (43%) or Hispanics (45%) to say it’s become more acceptable for people to express racist or racially insensitive views. Among Democrats, however, whites are the most likely to say this (70% of white Democrats vs. 55% of black and 57% of Hispanic Democrats).

Again, educational attainment is linked to these views. Among whites, blacks and Hispanics, the view that it has become increasingly acceptable for people to express racist or racially insensitive views is more prevalent among those with more education. Overall, 58% of adults with at least a bachelor’s degree say this has become more acceptable since Trump’s election, compared with 44% of those with some college and 36% of those with a high school diploma or less education.

Views on whether it’s become more acceptable for people to express racist views since Trump was elected are also strongly linked with partisanship. More than six-in-ten Democrats (64%) say this is now more acceptable; 22% of Republicans say the same. Republicans are far more likely than Democrats to say this is about as acceptable as it was before Trump’s election (50% vs. 15%).

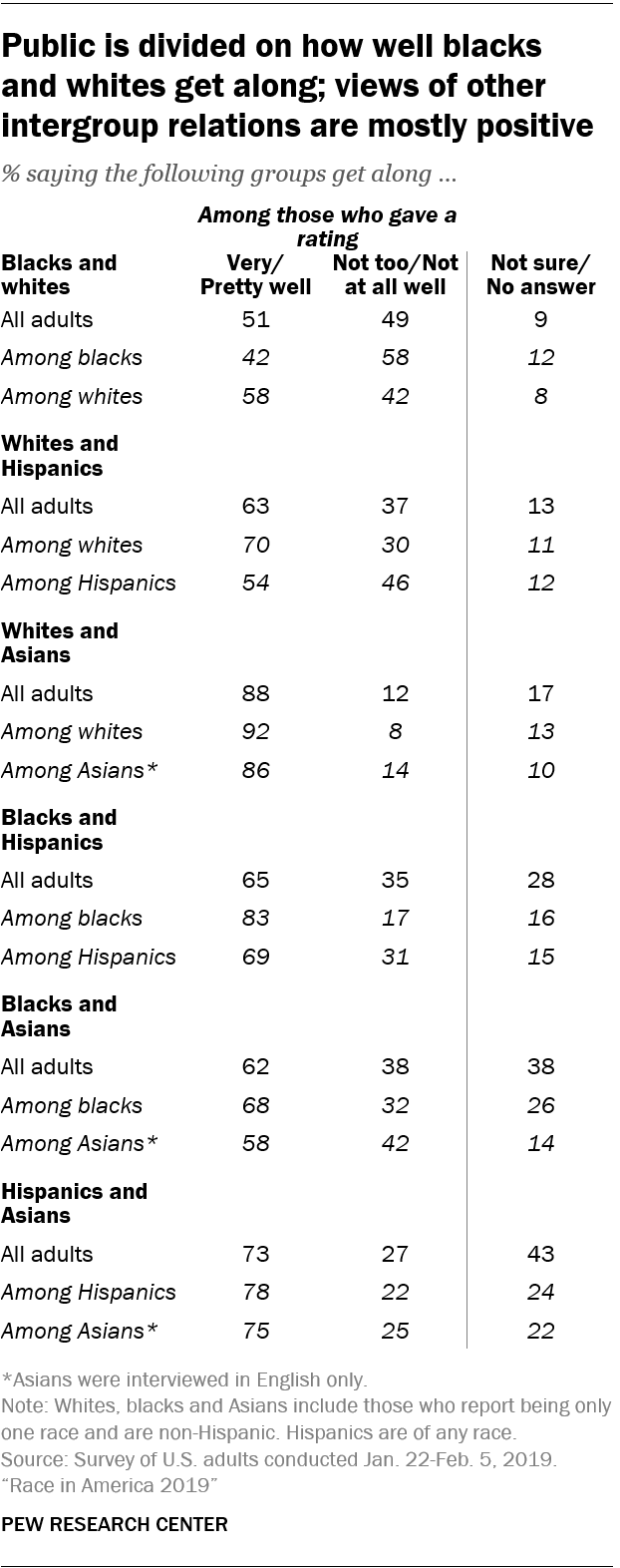

Despite their generally negative assessments of the current state of race relations, Americans tend to say that most racial and ethnic groups get along well with one another. Among those who gave an answer, about six-in-ten or more say this is the case for whites and Asians (88% say these groups get along very or pretty well), Hispanics and Asians (73%), blacks and Hispanics (65%), whites and Hispanics (63%) and blacks and Asians (62%). Relatively large shares do not know enough about how some of these groups get along to give an answer.

Assessments of how well blacks and whites get along are more divided. Among those who gave a rating, 51% say these groups generally get along well, while 49% say they don’t get along too well or at all. Whites are far more positive than blacks in their views of how the two groups get along. About six-in-ten whites (58%) say blacks and whites get along well; the same share of blacks say these groups do not get along well.

There’s a significant age gap among blacks on this issue: Blacks ages 50 and older express more positive views of black-white relations than do their younger counterparts. Among those in the older group, 53% say blacks and whites get along very well or pretty well, compared with 33% of black adults younger than 50.

Whites and Hispanics also offer considerably different views of how their groups get along, though majorities of each say they get along very well or pretty well (70% of whites vs. 54% of Hispanics). And while large shares of blacks and Hispanics say their groups generally get along, blacks (83%) are more likely than Hispanics (69%) to say this.

While those who say race relations are good are consistently more positive about how these groups get along, more than half of those who say race relations are bad also say intergroup relations – with the exception of black-white relations – are also generally positive. When it comes to how blacks and whites get along, just 36% of those who say race relations are bad say these groups get along well, compared with 76% of those who say race relations are good.

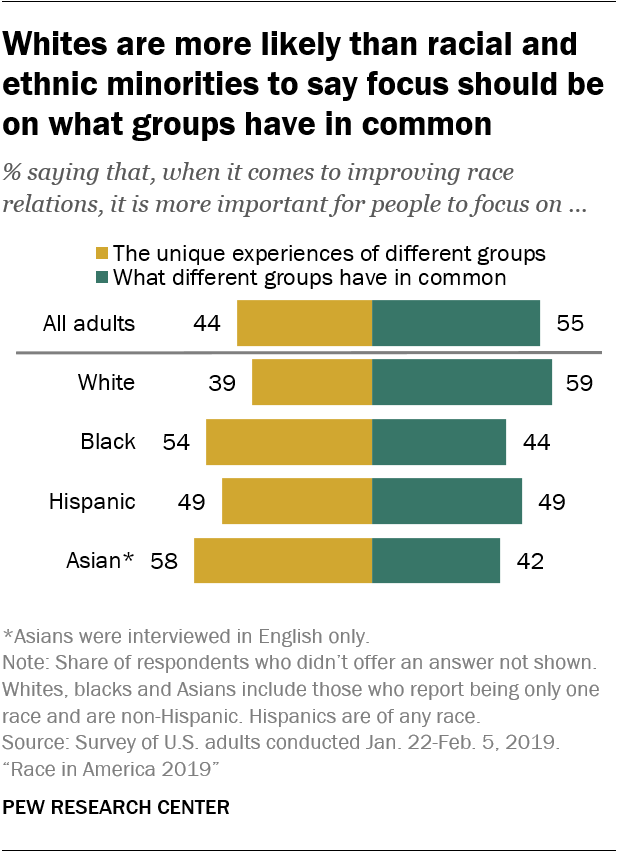

More than half of Americans (55%) say that, when it comes to improving race relations, it is more important to focus on what different racial and ethnic groups have in common; 44% say it’s more important to focus on each group’s unique experiences.

Asians (58%), blacks (54%) and Hispanics (49%) are more likely than whites (39%) to say it’s more important to focus on the unique experiences of different racial and ethnic groups. Still, about four-in-ten or more of these racial and ethnic minorities say the better approach to improving race relations is to focus on what different groups have in common.

Among whites, opinions vary considerably across age groups. Younger whites are the most likely to say that, when it comes to improving race relations, it’s more important to focus on what makes different groups unique: 54% of those younger than 30 say this. In contrast, majorities of whites ages 30 to 49 (57%), 50 to 64 (63%) and 65 and older (67%) say it’s more important to focus on what different racial and ethnic groups have in common. Age is not significantly linked to views about this among blacks or Hispanics.

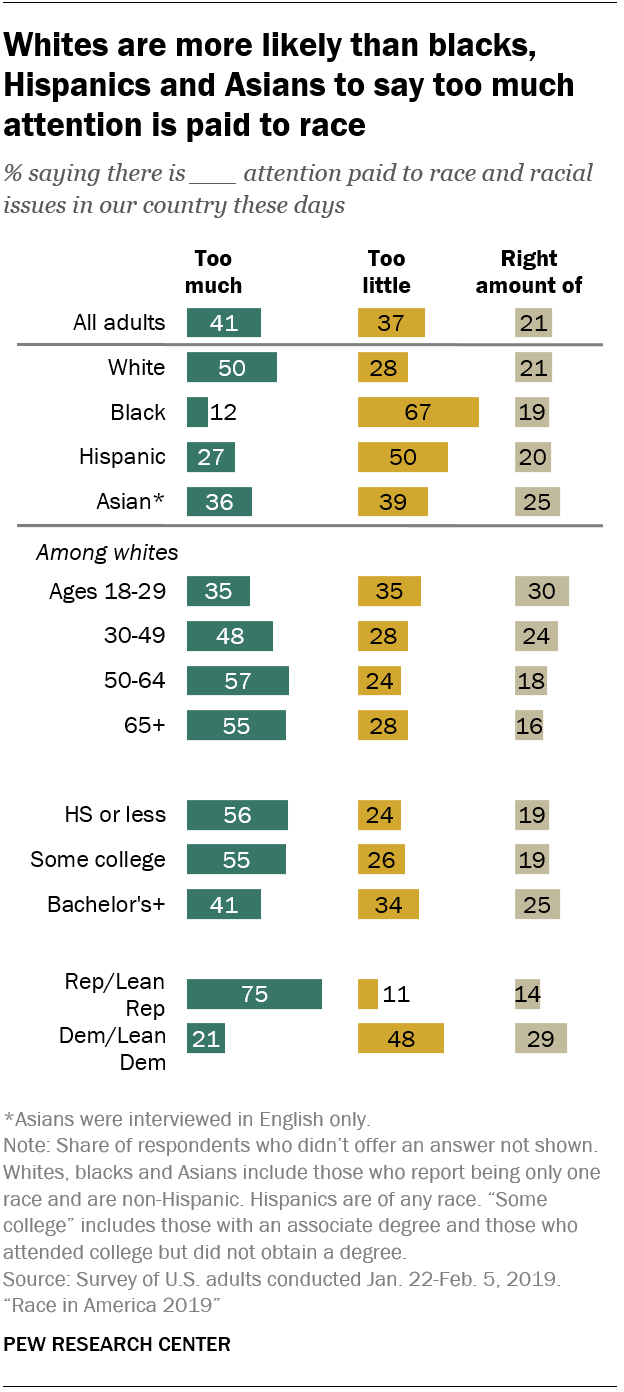

About four-in-ten Americans (41%) say there’s too much attention paid to race and racial issues in the country these days; 37% say there’s too little attention, and 21% say it’s about right. Whites are far more likely than other racial and ethnic groups to say there’s too much attention paid to race, while blacks are more likely than other groups to say too little attention is paid to these issues.

Half of whites say too much attention is paid to race and racial issues these days, while smaller shares say there is too little (28%) or about the right amount of attention (21%). In contrast, about two-thirds of blacks (67%) and half of Hispanics say there’s too little focus on race. Asians are more divided, with similar shares saying there’s too little (39%) and too much (36%) attention paid to race and racial issues. A quarter of Asians say the amount of attention paid is about right.

Among whites, the view that the country is too focused on race is more common among those who are older and without a bachelor’s degree. Opinions also differ considerably across party lines: Three-quarters of white Republicans think there’s too much attention paid to race and racial issues, compared with 21% of white Democrats. About half of white Democrats (48%) say there’s too little attention paid to these issues and 29% say it’s about right. Black Democrats are far more likely than their white counterparts to say there’s too little attention paid to race: 71% say that’s the case.

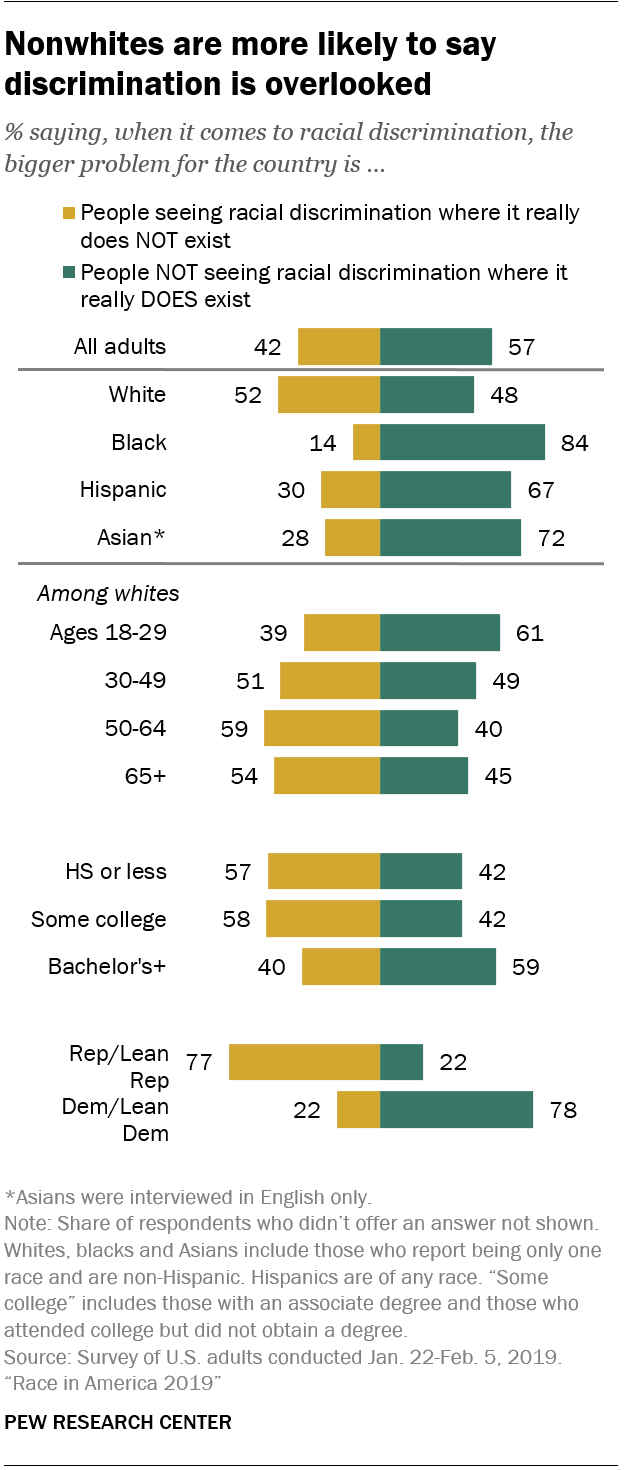

When it comes to racial discrimination, a majority of Americans (57%) say the bigger problem for the country is people not seeing discrimination where it really exists, rather than people seeing racial discrimination where it really does not exist (42% say this is the bigger problem).

More than eight-in-ten black adults (84%) and somewhat smaller majorities of Hispanics (67%) and Asians (72%) say the bigger problem is people not seeing racial discrimination where it really exists. Among whites, about as many say the bigger problem is people overlooking discrimination (48%) rather than seeing it where it doesn’t exist (52%).

Younger whites, as well as whites with a bachelor’s degree or more education, are more likely than older and less-educated whites to say the bigger problem for the country is people not seeing racial discrimination where it really exists. Views also differ sharply by party, with white Democrats and white Republicans offering views that are the mirror image of each other: 78% of white Democrats say the bigger problem is people not seeing discrimination where it really exists, while 77% of Republicans say the bigger problem is people seeing discrimination where it doesn’t exist.

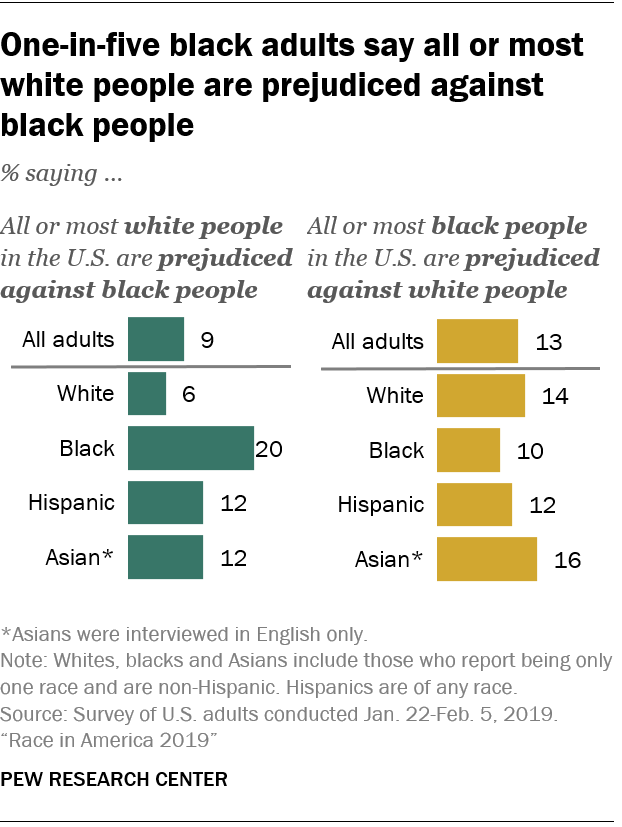

Relatively small shares of Americans overall think all or most white people in the country are prejudiced against black people (9%) or that all or most black people are prejudiced against whites (13%). But majorities say at least some whites and blacks are prejudiced against the other group (70% say this about each group).

Among blacks, one-in-five say all or most white people in the U.S. are prejudiced against black people; 6% of whites say the same. The difference, while significant, is less pronounced when it comes to the shares of blacks (10%) and whites (14%) who say all or most black people are prejudiced against white people; 12% of Hispanics and 16% of Asians say this.

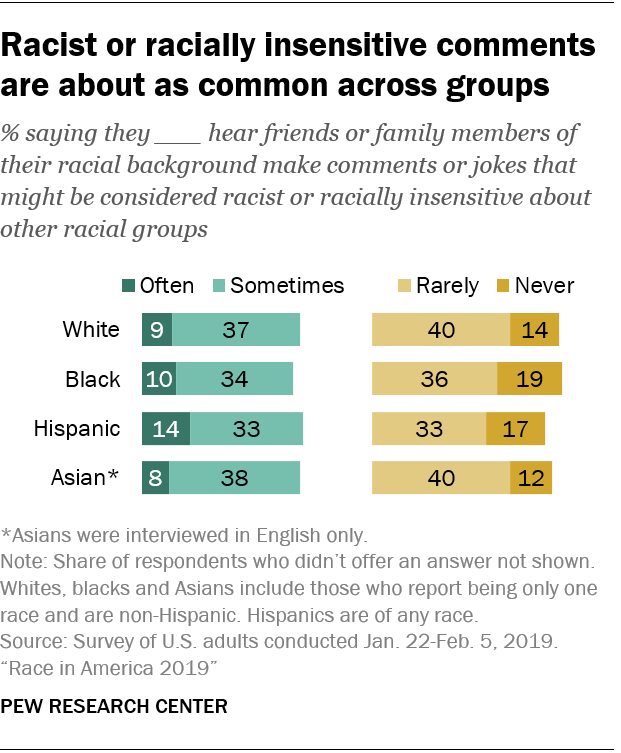

Whites (46%), blacks (44%), Hispanics (47%) and Asians (47%) are about equally likely to say they often or sometimes hear comments or jokes that can be considered racist or racially insensitive from friends or family members who share their racial background. About half in each group say this rarely or never happens.

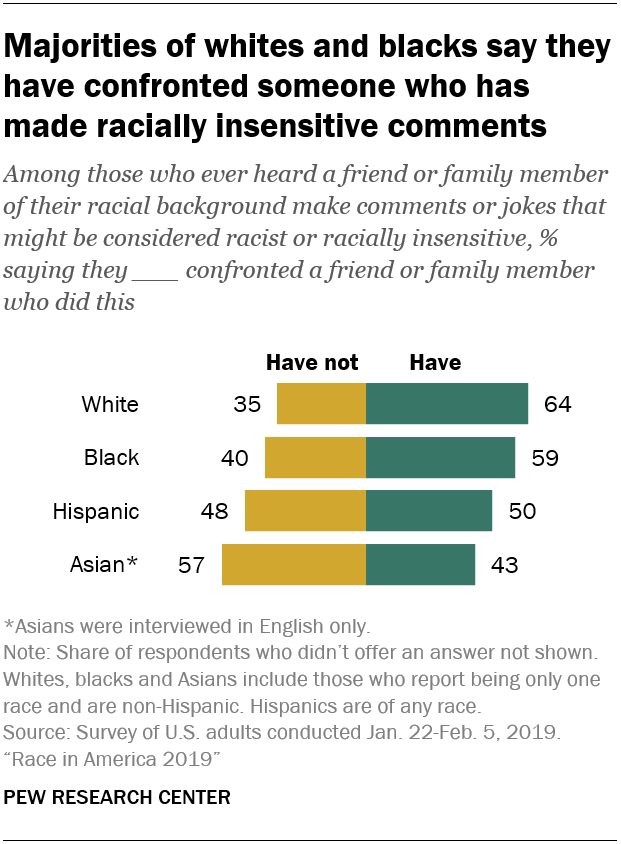

Among those who say they hear these types of comments, even if rarely, majorities of whites (64%) and blacks (59%) say they have confronted a friend or family member who shares their racial background about this; 50% of Hispanics and 43% of Asians say they have done this.

While many say they have confronted a friend or family member who has made a racist comment, the public is skeptical that others would do the same. Only 6% of all adults think all or most white people would confront a white friend or family member who made such a comment about people who are black, and 3% say that all or most black people would do the same if a black friend or family member made a racist comment about people who are white.

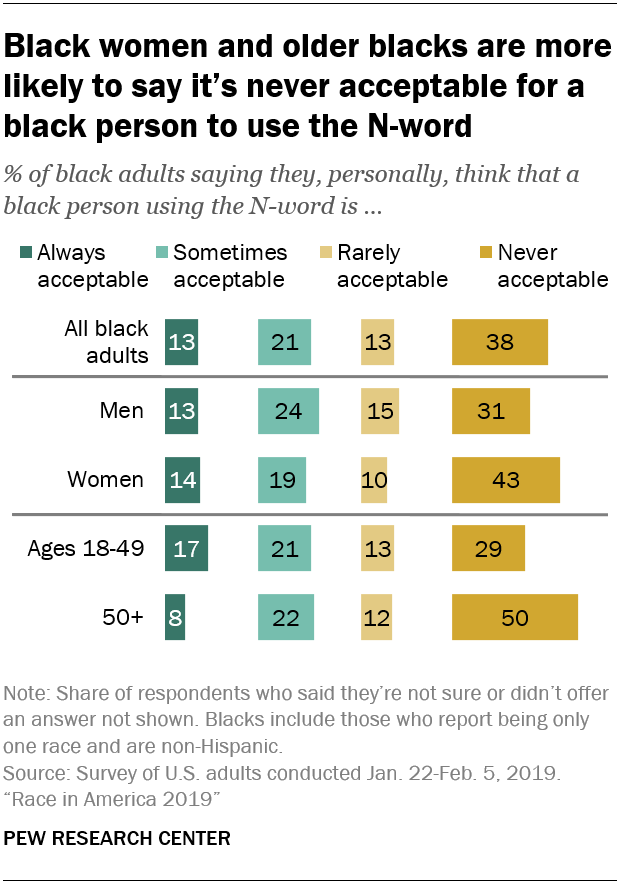

Most Americans (70%) – including similar shares of blacks and whites – say they, personally, think it’s never acceptable for a white person to use the N-word; about one-in-ten say this is always (3%) or sometimes (6%) acceptable. Opinions are more divided when it comes to black people using the N-word: About half say this is rarely (15%) or never (38%) acceptable, while a third say it is sometimes (20%) or always (13%) acceptable. Again, black and white adults offer similar views.

Among blacks, opinions about the use of the N-word by black people vary across genders and age groups. Black women are more likely than black men to say this is never acceptable (43% vs. 31%). And while half of blacks ages 50 and older say it’s never acceptable for black people to use the N-word, 29% of blacks younger than 50 say the same.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Race & Ethnicity

- Race Relations

- Racial Bias & Discrimination

What the data says about crime in the U.S.

#blacklivesmatter turns 10, how black americans view the use of face recognition technology by police, ai and human enhancement: americans’ openness is tempered by a range of concerns, americans’ trust in scientists, other groups declines, most popular, report materials.

- Interactive Who shares your views on race?

- American Trends Panel Wave 43

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Black Progress: How far we’ve come, and how far we have to go

Subscribe to governance weekly, abigail thernstrom and at abigail thernstrom senior fellow, manhattan institute stephan thernstrom st stephan thernstrom.

March 1, 1998

- 16 min read

Let’s start with a few contrasting numbers.

60 and 2.2. In 1940, 60 percent of employed black women worked as domestic servants; today the number is down to 2.2 percent, while 60 percent hold white- collar jobs.

44 and 1. In 1958, 44 percent of whites said they would move if a black family became their next door neighbor; today the figure is 1 percent.

18 and 86. In 1964, the year the great Civil Rights Act was passed, only 18 percent of whites claimed to have a friend who was black; today 86 percent say they do, while 87 percent of blacks assert they have white friends.

Progress is the largely suppressed story of race and race relations over the past half-century. And thus it’s news that more than 40 percent of African Americans now consider themselves members of the middle class. Forty-two percent own their own homes, a figure that rises to 75 percent if we look just at black married couples. Black two-parent families earn only 13 percent less than those who are white. Almost a third of the black population lives in suburbia.

Because these are facts the media seldom report, the black underclass continues to define black America in the view of much of the public. Many assume blacks live in ghettos, often in high-rise public housing projects. Crime and the welfare check are seen as their main source of income. The stereotype crosses racial lines. Blacks are even more prone than whites to exaggerate the extent to which African Americans are trapped in inner-city poverty. In a 1991 Gallup poll, about one-fifth of all whites, but almost half of black respondents, said that at least three out of four African Americans were impoverished urban residents. And yet, in reality, blacks who consider themselves to be middle class outnumber those with incomes below the poverty line by a wide margin.

A Fifty-Year March out of Poverty

Fifty years ago most blacks were indeed trapped in poverty, although they did not reside in inner cities. When Gunnar Myrdal published An American Dilemma in 1944, most blacks lived in the South and on the land as laborers and sharecroppers. (Only one in eight owned the land on which he worked.) A trivial 5 percent of black men nationally were engaged in nonmanual, white-collar work of any kind; the vast majority held ill-paid, insecure, manual jobs—jobs that few whites would take. As already noted, six out of ten African-American women were household servants who, driven by economic desperation, often worked 12-hour days for pathetically low wages. Segregation in the South and discrimination in the North did create a sheltered market for some black businesses (funeral homes, beauty parlors, and the like) that served a black community barred from patronizing “white” establishments. But the number was minuscule.

Related Books

Gary Orfield, Holly J. Lebowitz

January 1, 2000

William H. Frey

July 24, 2018

Bruce Katz, Robert E. Lang

January 31, 2003

Beginning in the 1940s, however, deep demographic and economic change, accompanied by a marked shift in white racial attitudes, started blacks down the road to much greater equality. New Deal legislation, which set minimum wages and hours and eliminated the incentive of southern employers to hire low-wage black workers, put a damper on further industrial development in the region. In addition, the trend toward mechanized agriculture and a diminished demand for American cotton in the face of international competition combined to displace blacks from the land.

As a consequence, with the shortage of workers in northern manufacturing plants following the outbreak of World War II, southern blacks in search of jobs boarded trains and buses in a Great Migration that lasted through the mid-1960s. They found what they were looking for: wages so strikingly high that in 1953 the average income for a black family in the North was almost twice that of those who remained in the South. And through much of the 1950s wages rose steadily and unemployment was low.

Thus by 1960 only one out of seven black men still labored on the land, and almost a quarter were in white-collar or skilled manual occupations. Another 24 percent had semiskilled factory jobs that meant membership in the stable working class, while the proportion of black women working as servants had been cut in half. Even those who did not move up into higher-ranking jobs were doing much better.

A decade later, the gains were even more striking. From 1940 to 1970, black men cut the income gap by about a third, and by 1970 they were earning (on average) roughly 60 percent of what white men took in. The advancement of black women was even more impressive. Black life expectancy went up dramatically, as did black homeownership rates. Black college enrollment also rose—by 1970 to about 10 percent of the total, three times the prewar figure.

In subsequent years these trends continued, although at a more leisurely pace. For instance, today more than 30 percent of black men and nearly 60 percent of black women hold white-collar jobs. Whereas in 1970 only 2.2 percent of American physicians were black, the figure is now 4.5 percent. But while the fraction of black families with middle-class incomes rose almost 40 percentage points between 1940 and 1970, it has inched up only another 10 points since then.

Affirmative Action Doesn’t Work

Rapid change in the status of blacks for several decades followed by a definite slowdown that begins just when affirmative action policies get their start: that story certainly seems to suggest that racial preferences have enjoyed an inflated reputation. “There’s one simple reason to support affirmative action,” an op-ed writer in the New York Times argued in 1995. “It works.” That is the voice of conventional wisdom.

In fact, not only did significant advances pre-date the affirmative action era, but the benefits of race-conscious politics are not clear. Important differences (a slower overall rate of economic growth, most notably) separate the pre-1970 and post-1970 periods, making comparison difficult.

We know only this: some gains are probably attributable to race-conscious educational and employment policies. The number of black college and university professors more than doubled between 1970 and 1990; the number of physicians tripled; the number of engineers almost quadrupled; and the number of attorneys increased more than sixfold. Those numbers undoubtedly do reflect the fact that the nation’s professional schools changed their admissions criteria for black applicants, accepting and often providing financial aid to African-American students whose academic records were much weaker than those of many white and Asian-American applicants whom these schools were turning down. Preferences “worked” for these beneficiaries, in that they were given seats in the classroom that they would not have won in the absence of racial double standards.

On the other hand, these professionals make up a small fraction of the total black middle class. And their numbers would have grown without preferences, the historical record strongly suggests. In addition, the greatest economic gains for African Americans since the early 1960s were in the years 1965 to 1975 and occurred mainly in the South, as economists John J. Donahue III and James Heckman have found. In fact, Donahue and Heckman discovered “virtually no improvement” in the wages of black men relative to those of white men outside of the South over the entire period from 1963 to 1987, and southern gains, they concluded, were mainly due to the powerful antidiscrimination provisions in the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

With respect to federal, state, and municipal set-asides, as well, the jury is still out. In 1994 the state of Maryland decided that at least 10 percent of the contracts it awarded would go to minority- and female-owned firms. It more than met its goal. The program therefore “worked” if the goal was merely the narrow one of dispensing cash to a particular, designated group. But how well do these sheltered businesses survive long-term without extraordinary protection from free-market competition? And with almost 30 percent of black families still living in poverty, what is their trickle-down effect? On neither score is the picture reassuring. Programs are often fraudulent, with white contractors offering minority firms 15 percent of the profit with no obligation to do any of the work. Alternatively, set-asides enrich those with the right connections. In Richmond, Virginia, for instance, the main effect of the ordinance was a marriage of political convenience—a working alliance between the economically privileged of both races. The white business elite signed on to a piece-of-the-pie for blacks in order to polish its image as socially conscious and secure support for the downtown revitalization it wanted. Black politicians used the bargain to suggest their own importance to low-income constituents for whom the set-asides actually did little. Neither cared whether the policy in fact provided real economic benefits—which it didn’t.

Why Has the Engine of Progress Stalled?

In the decades since affirmative action policies were first instituted, the poverty rate has remained basically unchanged. Despite black gains by numerous other measures, close to 30 percent of black families still live below the poverty line. “There are those who say, my fellow Americans, that even good affirmative action programs are no longer needed,” President Clinton said in July 1995. But “let us consider,” he went on, that “the unemployment rate for African Americans remains about twice that of whites.” Racial preferences are the president’s answer to persistent inequality, although a quarter-century of affirmative action has done nothing whatever to close the unemployment gap.

Persistent inequality is obviously serious, and if discrimination were the primary problem, then race-conscious remedies might be appropriate. But while white racism was central to the story in 1964, today the picture is much more complicated. Thus while blacks and whites now graduate at the same rate from high school today and are almost equally likely to attend college, on average they are not equally educated. That is, looking at years of schooling in assessing the racial gap in family income tells us little about the cognitive skills whites and blacks bring to the job market. And cognitive skills obviously affect earnings.

The National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) is the nation’s report card on what American students attending elementary and secondary schools know. Those tests show that African-American students, on average, are alarmingly far behind whites in math, science, reading, and writing. For instance, black students at the end of their high school career are almost four years behind white students in reading; the gap is comparable in other subjects. A study of 26- to 33-year-old men who held full-time jobs in 1991 thus found that when education was measured by years of school completed, blacks earned 19 percent less than comparably educated whites. But when word knowledge, paragraph comprehension, arithmetical reasoning, and mathematical knowledge became the yardstick, the results were reversed. Black men earned 9 percent more than white men with the same education—that is, the same performance on basic tests.

Other research suggests much the same point. For instance, the work of economists Richard J. Murnane and Frank Levy has demonstrated the increasing importance of cognitive skills in our changing economy. Employers in firms like Honda now require employees who can read and do math problems at the ninth-grade level at a minimum. And yet the 1992 NAEP math tests, for example, revealed that only 22 percent of African-American high school seniors but 58 percent of their white classmates were numerate enough for such firms to consider hiring them. And in reading, 47 percent of whites in 1992 but just 18 percent of African Americans could handle the printed word well enough to be employable in a modern automobile plant. Murnane and Levy found a clear impact on income. Not years spent in school but strong skills made for high long-term earnings.

The Widening Skills Gap

Why is there such a glaring racial gap in levels of educational attainment? It is not easy to say. The gap, in itself, is very bad news, but even more alarming is the fact that it has been widening in recent years. In 1971, the average African-American 17-year-old could read no better than the typical white child who was six years younger. The racial gap in math in 1973 was 4.3 years; in science it was 4.7 years in 1970. By the late 1980s, however, the picture was notably brighter. Black students in their final year of high school were only 2.5 years behind whites in both reading and math and 2.1 years behind on tests of writing skills.

Had the trends of those years continued, by today black pupils would be performing about as well as their white classmates. Instead, black progress came to a halt, and serious backsliding began. Between 1988 and 1994, the racial gap in reading grew from 2.5 to 3.9 years; between 1990 and 1994, the racial gap in math increased from 2.5 to 3.4 years. In both science and writing, the racial gap has widened by a full year.

There is no obvious explanation for this alarming turnaround. The early gains doubtless had much to do with the growth of the black middle class, but the black middle class did not suddenly begin to shrink in the late 1980s. The poverty rate was not dropping significantly when educational progress was occurring, nor was it on the increase when the racial gap began once again to widen. The huge rise in out-of-wedlock births and the steep and steady decline in the proportion of black children growing up with two parents do not explain the fluctuating educational performance of African-American children. It is well established that children raised in single-parent families do less well in school than others, even when all other variables, including income, are controlled. But the disintegration of the black nuclear family—presciently noted by Daniel Patrick Moynihan as early as 1965—was occurring rapidly in the period in which black scores were rising, so it cannot be invoked as the main explanation as to why scores began to fall many years later.

Some would argue that the initial educational gains were the result of increased racial integration and the growth of such federal compensatory education programs as Head Start. But neither desegregation nor compensatory education seems to have increased the cognitive skills of the black children exposed to them. In any case, the racial mix in the typical school has not changed in recent years, and the number of students in compensatory programs and the dollars spent on them have kept going up.

Related Content

John R. Allen

June 11, 2020

Camille Busette

Online-only

2:00 pm - 3:00 pm EDT

What about changes in the curriculum and patterns of course selection by students? The educational reform movement that began in the late 1970s did succeed in pushing students into a “New Basics” core curriculum that included more English, science, math, and social studies courses. And there is good reason to believe that taking tougher courses contributed to the temporary rise in black test scores. But this explanation, too, nicely fits the facts for the period before the late 1980s but not the very different picture thereafter. The number of black students going through “New Basics” courses did not decline after 1988, pulling down their NAEP scores.

We are left with three tentative suggestions. First, the increased violence and disorder of inner-city lives that came with the introduction of crack cocaine and the drug-related gang wars in the mid-1980s most likely had something to do with the reversal of black educational progress. Chaos in the streets and within schools affects learning inside and outside the classroom.

In addition, an educational culture that has increasingly turned teachers into guides who help children explore whatever interests them may have affected black academic performance as well. As educational critic E. D. Hirsch, Jr., has pointed out, the “deep aversion to and contempt for factual knowledge that pervade the thinking of American educators” means that students fail to build the “intellectual capital” that is the foundation of all further learning. That will be particularly true of those students who come to school most academically disadvantaged—those whose homes are not, in effect, an additional school. The deficiencies of American education hit hardest those most in need of education.

And yet in the name of racial sensitivity, advocates for minority students too often dismiss both common academic standards and standardized tests as culturally biased and judgmental. Such advocates have plenty of company. Christopher Edley, Jr., professor of law at Harvard and President Clinton’s point man on affirmative action, for instance, has allied himself with testing critics, labeling preferences the tool colleges are forced to use “to correct the problems we’ve inflicted on ourselves with our testing standards.” Such tests can be abolished—or standards lowered—but once the disparity in cognitive skills becomes less evident, it is harder to correct.

Closing that skills gap is obviously the first task if black advancement is to continue at its once-fast pace. On the map of racial progress, education is the name of almost every road. Raise the level of black educational performance, and the gap in college graduation rates, in attendance at selective professional schools, and in earnings is likely to close as well. Moreover, with educational parity, the whole issue of racial preferences disappears.

The Road to True Equality

Black progress over the past half-century has been impressive, conventional wisdom to the contrary notwithstanding. And yet the nation has many miles to go on the road to true racial equality. “I wish I could say that racism and prejudice were only distant memories, but as I look around I see that even educated whites and African American…have lost hope in equality,” Thurgood Marshall said in 1992. A year earlier The Economist magazine had reported the problem of race as one of “shattered dreams.” In fact, all hope has not been “lost,” and “shattered” was much too strong a word, but certainly in the 1960s the civil rights community failed to anticipate just how tough the voyage would be. (Thurgood Marshall had envisioned an end to all school segregation within five years of the Supreme Court s decision in Brown v. Board of Education.) Many blacks, particularly, are now discouraged. A 1997 Gallup poll found a sharp decline in optimism since 1980; only 33 percent of blacks (versus 58 percent of whites) thought both the quality of life for blacks and race relations had gotten better.

Thus, progress—by many measures seemingly so clear—is viewed as an illusion, the sort of fantasy to which intellectuals are particularly prone. But the ahistorical sense of nothing gained is in itself bad news. Pessimism is a self-fulfilling prophecy. If all our efforts as a nation to resolve the “American dilemma” have been in vain—if we’ve been spinning our wheels in the rut of ubiquitous and permanent racism, as Derrick Bell, Andrew Hacker, and others argue—then racial equality is a hopeless task, an unattainable ideal. If both blacks and whites understand and celebrate the gains of the past, however, we will move forward with the optimism, insight, and energy that further progress surely demands.

Governance Studies

William H. Frey, Chiraag Bains, Andre M. Perry, Robert Maxim, Manann Donoghoe, Carol Graham

May 7, 2024

Nicol Turner Lee

August 6, 2024

Robert Maxim

May 3, 2024

Along with Stanford news and stories, show me:

- Student information

- Faculty/Staff information

We want to provide announcements, events, leadership messages and resources that are relevant to you. Your selection is stored in a browser cookie which you can remove at any time using “Clear all personalization” below.

A pandemic that disproportionately affected communities of color, roadblocks that obstructed efforts to expand the franchise and protect voting discrimination, a growing movement to push anti-racist curricula out of schools – events over the past year have only underscored how prevalent systemic racism and bias is in America today.

What can be done to dismantle centuries of discrimination in the U.S.? How can a more equitable society be achieved? What makes racism such a complicated problem to solve? Black History Month is a time marked for honoring and reflecting on the experience of Black Americans, and it is also an opportunity to reexamine our nation’s deeply embedded racial problems and the possible solutions that could help build a more equitable society.

Stanford scholars are tackling these issues head-on in their research from the perspectives of history, education, law and other disciplines. For example, historian Clayborne Carson is working to preserve and promote the legacy of Martin Luther King Jr. and religious studies scholar Lerone A. Martin has joined Stanford to continue expanding access and opportunities to learn from King’s teachings; sociologist Matthew Clair is examining how the criminal justice system can end a vicious cycle involving the disparate treatment of Black men; and education scholar Subini Ancy Annamma is studying ways to make education more equitable for historically marginalized students.

Learn more about these efforts and other projects examining racism and discrimination in areas like health and medicine, technology and the workplace below.

Update: Jan. 27, 2023: This story was originally published on Feb. 16, 2021, and has been updated on a number of occasions to include new content.

Understanding the impact of racism; advancing justice

One of the hardest elements of advancing racial justice is helping everyone understand the ways in which they are involved in a system or structure that perpetuates racism, according to Stanford legal scholar Ralph Richard Banks.

“The starting point for the center is the recognition that racial inequality and division have long been the fault line of American society. Thus, addressing racial inequity is essential to sustaining our nation, and furthering its democratic aspirations,” said Banks , the Jackson Eli Reynolds Professor of Law at Stanford Law School and co-founder of the Stanford Center for Racial Justice .

This sentiment was echoed by Stanford researcher Rebecca Hetey . One of the obstacles in solving inequality is people’s attitudes towards it, Hetey said. “One of the barriers of reducing inequality is how some people justify and rationalize it.”

How people talk about race and stereotypes matters. Here is some of that scholarship.

For Black Americans, COVID-19 is quickly reversing crucial economic gains

Research co-authored by SIEPR’s Peter Klenow and Chad Jones measures the welfare gap between Black and white Americans and provides a way to analyze policies to narrow the divide.

How an ‘impact mindset’ unites activists of different races

A new study finds that people’s involvement with Black Lives Matter stems from an impulse that goes beyond identity.

For democracy to work, racial inequalities must be addressed

The Stanford Center for Racial Justice is taking a hard look at the policies perpetuating systemic racism in America today and asking how we can imagine a more equitable society.

The psychological toll of George Floyd’s murder

As the nation mourned the death of George Floyd, more Black Americans than white Americans felt angry or sad – a finding that reveals the racial disparities of grief.

Seven factors contributing to American racism

Of the seven factors the researchers identified, perhaps the most insidious is passivism or passive racism, which includes an apathy toward systems of racial advantage or denial that those systems even exist.

Scholars reflect on Black history

Humanities and social sciences scholars reflect on “Black history as American history” and its impact on their personal and professional lives.

The history of Black History Month

It's February, so many teachers and schools are taking time to celebrate Black History Month. According to Stanford historian Michael Hines, there are still misunderstandings and misconceptions about the past, present, and future of the celebration.

Numbers about inequality don’t speak for themselves

In a new research paper, Stanford scholars Rebecca Hetey and Jennifer Eberhardt propose new ways to talk about racial disparities that exist across society, from education to health care and criminal justice systems.

Changing how people perceive problems

Drawing on an extensive body of research, Stanford psychologist Gregory Walton lays out a roadmap to positively influence the way people think about themselves and the world around them. These changes could improve society, too.

Welfare opposition linked to threats of racial standing

Research co-authored by sociologist Robb Willer finds that when white Americans perceive threats to their status as the dominant demographic group, their resentment of minorities increases. This resentment leads to opposing welfare programs they believe will mainly benefit minority groups.

Conversations about race between Black and white friends can feel risky, but are valuable

New research about how friends approach talking about their race-related experiences with each other reveals concerns but also the potential that these conversations have to strengthen relationships and further intergroup learning.

Defusing racial bias

Research shows why understanding the source of discrimination matters.

Many white parents aren’t having ‘the talk’ about race with their kids

After George Floyd’s murder, Black parents talked about race and racism with their kids more. White parents did not and were more likely to give their kids colorblind messages.

Stereotyping makes people more likely to act badly

Even slight cues, like reading a negative stereotype about your race or gender, can have an impact.

Why white people downplay their individual racial privileges

Research shows that white Americans, when faced with evidence of racial privilege, deny that they have benefited personally.

Clayborne Carson: Looking back at a legacy

Stanford historian Clayborne Carson reflects on a career dedicated to studying and preserving the legacy of civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr.

How race influences, amplifies backlash against outspoken women

When women break gender norms, the most negative reactions may come from people of the same race.

Examining disparities in education

Scholar Subini Ancy Annamma is studying ways to make education more equitable for historically marginalized students. Annamma’s research examines how schools contribute to the criminalization of Black youths by creating a culture of punishment that penalizes Black children more harshly than their white peers for the same behavior. Her work shows that youth of color are more likely to be closely watched, over-represented in special education, and reported to and arrested by police.

“These are all ways in which schools criminalize Black youth,” she said. “Day after day, these things start to sediment.”

That’s why Annamma has identified opportunities for teachers and administrators to intervene in these unfair practices. Below is some of that research, from Annamma and others.

New ‘Segregation Index’ shows American schools remain highly segregated by race, ethnicity, and economic status

Researchers at Stanford and USC developed a new tool to track neighborhood and school segregation in the U.S.

New evidence shows that school poverty shapes racial achievement gaps

Racial segregation leads to growing achievement gaps – but it does so entirely through differences in school poverty, according to new research from education Professor Sean Reardon, who is launching a new tool to help educators, parents and policymakers examine education trends by race and poverty level nationwide.

School closures intensify gentrification in Black neighborhoods nationwide

An analysis of census and school closure data finds that shuttering schools increases gentrification – but only in predominantly Black communities.

Ninth-grade ethnic studies helped students for years, Stanford researchers find

A new study shows that students assigned to an ethnic studies course had longer-term improvements in attendance and graduation rates.

Teaching about racism

Stanford sociologist Matthew Snipp discusses ways to educate students about race and ethnic relations in America.

Stanford scholar uncovers an early activist’s fight to get Black history into schools

In a new book, Assistant Professor Michael Hines chronicles the efforts of a Chicago schoolteacher in the 1930s who wanted to remedy the portrayal of Black history in textbooks of the time.

How disability intersects with race

Professor Alfredo J. Artiles discusses the complexities in creating inclusive policies for students with disabilities.

Access to program for black male students lowered dropout rates

New research led by Stanford education professor Thomas S. Dee provides the first evidence of effectiveness for a district-wide initiative targeted at black male high school students.

How school systems make criminals of Black youth

Stanford education professor Subini Ancy Annamma talks about the role schools play in creating a culture of punishment against Black students.

Reducing racial disparities in school discipline

Stanford psychologists find that brief exercises early in middle school can improve students’ relationships with their teachers, increase their sense of belonging and reduce teachers’ reports of discipline issues among black and Latino boys.

Science lessons through a different lens

In his new book, Science in the City, Stanford education professor Bryan A. Brown helps bridge the gap between students’ culture and the science classroom.

Teachers more likely to label black students as troublemakers, Stanford research shows

Stanford psychologists Jennifer Eberhardt and Jason Okonofua experimentally examined the psychological processes involved when teachers discipline black students more harshly than white students.

Why we need Black teachers

Travis Bristol, MA '04, talks about what it takes for schools to hire and retain teachers of color.

Understanding racism in the criminal justice system

Research has shown that time and time again, inequality is embedded into all facets of the criminal justice system. From being arrested to being charged, convicted and sentenced, people of color – particularly Black men – are disproportionately targeted by the police.

“So many reforms are needed: police accountability, judicial intervention, reducing prosecutorial power and increasing resources for public defenders are places we can start,” said sociologist Matthew Clair . “But beyond piecemeal reforms, we need to continue having critical conversations about transformation and the role of the courts in bringing about the abolition of police and prisons.”

Clair is one of several Stanford scholars who have examined the intersection of race and the criminal process and offered solutions to end the vicious cycle of racism. Here is some of that work.

Police Facebook posts disproportionately highlight crimes involving Black suspects, study finds

Researchers examined crime-related posts from 14,000 Facebook pages maintained by U.S. law enforcement agencies and found that Facebook users are exposed to posts that overrepresent Black suspects by 25% relative to local arrest rates.

Supporting students involved in the justice system

New data show that a one-page letter asking a teacher to support a youth as they navigate the difficult transition from juvenile detention back to school can reduce the likelihood that the student re-offends.

Race and mass criminalization in the U.S.

Stanford sociologist discusses how race and class inequalities are embedded in the American criminal legal system.

New Stanford research lab explores incarcerated students’ educational paths

Associate Professor Subini Annamma examines the policies and practices that push marginalized students out of school and into prisons.

Derek Chauvin verdict important, but much remains to be done

Stanford scholars Hakeem Jefferson, Robert Weisberg and Matthew Clair weigh in on the Derek Chauvin verdict, emphasizing that while the outcome is important, much work remains to be done to bring about long-lasting justice.

A ‘veil of darkness’ reduces racial bias in traffic stops

After analyzing 95 million traffic stop records, filed by officers with 21 state patrol agencies and 35 municipal police forces from 2011 to 2018, researchers concluded that “police stops and search decisions suffer from persistent racial bias.”

Stanford big data study finds racial disparities in Oakland, Calif., police behavior, offers solutions

Analyzing thousands of data points, the researchers found racial disparities in how Oakland officers treated African Americans on routine traffic and pedestrian stops. They suggest 50 measures to improve police-community relations.

Race and the death penalty

As questions about racial bias in the criminal justice system dominate the headlines, research by Stanford law Professor John J. Donohue III offers insight into one of the most fraught areas: the death penalty.

Diagnosing disparities in health, medicine

The COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately impacted communities of color and has highlighted the health disparities between Black Americans, whites and other demographic groups.

As Iris Gibbs , professor of radiation oncology and associate dean of MD program admissions, pointed out at an event sponsored by Stanford Medicine: “We need more sustained attention and real action towards eliminating health inequities, educating our entire community and going beyond ‘allyship,’ because that one fizzles out. We really do need people who are truly there all the way.”

Below is some of that research as well as solutions that can address some of the disparities in the American healthcare system.

Stanford researchers testing ways to improve clinical trial diversity

The American Heart Association has provided funding to two Stanford Medicine professors to develop ways to diversify enrollment in heart disease clinical trials.

Striking inequalities in maternal and infant health

Research by SIEPR’s Petra Persson and Maya Rossin-Slater finds wealthy Black mothers and infants in the U.S. fare worse than the poorest white mothers and infants.

More racial diversity among physicians would lead to better health among black men

A clinical trial in Oakland by Stanford researchers found that black men are more likely to seek out preventive care after being seen by black doctors compared to non-black doctors.

A better measuring stick: Algorithmic approach to pain diagnosis could eliminate racial bias

Traditional approaches to pain management don’t treat all patients the same. AI could level the playing field.

5 questions: Alice Popejoy on race, ethnicity and ancestry in science

Alice Popejoy, a postdoctoral scholar who studies biomedical data sciences, speaks to the role – and pitfalls – of race, ethnicity and ancestry in research.

Stanford Medicine community calls for action against racial injustice, inequities

The event at Stanford provided a venue for health care workers and students to express their feelings about violence against African Americans and to voice their demands for change.

Racial disparity remains in heart-transplant mortality rates, Stanford study finds

African-American heart transplant patients have had persistently higher mortality rates than white patients, but exactly why still remains a mystery.

Finding the COVID-19 Victims that Big Data Misses

Widely used virus tracking data undercounts older people and people of color. Scholars propose a solution to this demographic bias.

Studying how racial stressors affect mental health

Farzana Saleem, an assistant professor at Stanford Graduate School of Education, is interested in the way Black youth and other young people of color navigate adolescence—and the racial stressors that can make the journey harder.

Infants’ race influences quality of hospital care in California

Disparities exist in how babies of different racial and ethnic origins are treated in California’s neonatal intensive care units, but this could be changed, say Stanford researchers.

Immigrants don’t move state-to-state in search of health benefits

When states expand public health insurance to include low-income, legal immigrants, it does not lead to out-of-state immigrants moving in search of benefits.

Excess mortality rates early in pandemic highest among Blacks

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has been starkly uneven across race, ethnicity and geography, according to a new study led by SHP's Maria Polyakova.

Decoding bias in media, technology

Driving Artificial Intelligence are machine learning algorithms, sets of rules that tell a computer how to solve a problem, perform a task and in some cases, predict an outcome. These predictive models are based on massive datasets to recognize certain patterns, which according to communication scholar Angele Christin , sometimes come flawed with human bias .

“Technology changes things, but perhaps not always as much as we think,” Christin said. “Social context matters a lot in shaping the actual effects of the technological tools. […] So, it’s important to understand that connection between humans and machines.”

Below is some of that research, as well as other ways discrimination unfolds across technology, in the media, and ways to counteract it.

IRS disproportionately audits Black taxpayers

A Stanford collaboration with the Department of the Treasury yields the first direct evidence of differences in audit rates by race.

Automated speech recognition less accurate for blacks

The disparity likely occurs because such technologies are based on machine learning systems that rely heavily on databases of English as spoken by white Americans.

New algorithm trains AI to avoid bad behaviors

Robots, self-driving cars and other intelligent machines could become better-behaved thanks to a new way to help machine learning designers build AI applications with safeguards against specific, undesirable outcomes such as racial and gender bias.

Stanford scholar analyzes responses to algorithms in journalism, criminal justice

In a recent study, assistant professor of communication Angèle Christin finds a gap between intended and actual uses of algorithmic tools in journalism and criminal justice fields.

Move responsibly and think about things

In the course CS 181: Computers, Ethics and Public Policy , Stanford students become computer programmers, policymakers and philosophers to examine the ethical and social impacts of technological innovation.

Homicide victims from Black and Hispanic neighborhoods devalued

Social scientists found that homicide victims killed in Chicago’s predominantly Black and Hispanic neighborhoods received less news coverage than those killed in mostly white neighborhoods.

Algorithms reveal changes in stereotypes

New Stanford research shows that, over the past century, linguistic changes in gender and ethnic stereotypes correlated with major social movements and demographic changes in the U.S. Census data.

AI Index Diversity Report: An Unmoving Needle

Stanford HAI’s 2021 AI Index reveals stalled progress in diversifying AI and a scarcity of the data needed to fix it.

Identifying discrimination in the workplace and economy

From who moves forward in the hiring process to who receives funding from venture capitalists, research has revealed how Blacks and other minority groups are discriminated against in the workplace and economy-at-large.

“There is not one silver bullet here that you can walk away with. Hiring and retention with respect to employee diversity are complex problems,” said Adina Sterling , associate professor of organizational behavior at the Graduate School of Business (GSB).

Sterling has offered a few places where employers can expand employee diversity at their companies. For example, she suggests hiring managers track data about their recruitment methods and the pools that result from those efforts, as well as examining who they ultimately hire.

Here is some of that insight.

How To: Use a Scorecard to Evaluate People More Fairly

A written framework is an easy way to hold everyone to the same standard.

Archiving Black histories of Silicon Valley

A new collection at Stanford Libraries will highlight Black Americans who helped transform California’s Silicon Valley region into a hub for innovation, ideas.

Race influences professional investors’ judgments

In their evaluations of high-performing venture capital funds, professional investors rate white-led teams more favorably than they do black-led teams with identical credentials, a new Stanford study led by Jennifer L. Eberhardt finds.

Who moves forward in the hiring process?

People whose employment histories include part-time, temporary help agency or mismatched work can face challenges during the hiring process, according to new research by Stanford sociologist David Pedulla.

How emotions may result in hiring, workplace bias

Stanford study suggests that the emotions American employers are looking for in job candidates may not match up with emotions valued by jobseekers from some cultural backgrounds – potentially leading to hiring bias.

Do VCs really favor white male founders?

A field experiment used fake emails to measure gender and racial bias among startup investors.

Can you spot diversity? (Probably not)

New research shows a “spillover effect” that might be clouding your judgment.

Can job referrals improve employee diversity?

New research looks at how referrals impact promotions of minorities and women.

Doing Race: 21 Essays for the 21st Century

Doing Race focuses on race and ethnicity in everyday life: what they are, how they work, and why they matter. Going to school and work, renting an apartment or buying a house, watching television, voting, listening to music, reading books and newspapers, attending religious services, and going to the doctor are all everyday activities that are influenced by assumptions about who counts, whom to trust, whom to care about, whom to include, and why. Race and ethnicity are powerful precisely because they organize modern society and play a large role in fueling violence around the globe. Doing Race is targeted to undergraduates; it begins with an introductory essay and includes original essays by well-known scholars. Drawing on the latest science and scholarship, the collected essays emphasize that race and ethnicity are not things that people or groups have or are, but rather sets of actions that people do. Doing Race provides compelling evidence that we are not yet in a “post-race” world and that race and ethnicity matter for everyone. Since race and ethnicity are the products of human actions, we can do them differently. Like studying the human genome or the laws of economics, understanding race and ethnicity is a necessary part of a twenty first century education.

About the Author

PAULA M. L. MOYA, is the Danily C. and Laura Louise Bell Professor of the Humanities and Professor of English at Stanford University. She is the Burton J. and Deedee McMurtry University Fellow in Undergraduate Education and a 2019-20 Fellow at the Center for the Study of Behavioral Sciences.

Moya’s teaching and research focus on twentieth-century and early twenty-first century literary studies, feminist theory, critical theory, narrative theory, American cultural studies, interdisciplinary approaches to race and ethnicity, and Chicanx and U.S. Latinx studies.

She is the author of The Social Imperative: Race, Close Reading, and Contemporary Literary Criticism (Stanford UP 2016) and Learning From Experience: Minority Identities, Multicultural Struggles (UC Press 2002) and has co-edited three collections of original essays, Doing Race: 21 Essays for the 21st Century (W.W. Norton, Inc. 2010), Identity Politics Reconsidered (Palgrave 2006) and Reclaiming Identity: Realist Theory and the Predicament of Postmodernism (UC Press 2000).

Previously Moya served as the Director of the Program of Modern Thought and Literature, Vice Chair of the Department of English, Director of the Research Institute of Comparative Studies in Race and Ethnicity, and also the Director of the Undergraduate Program of the Center for Comparative Studies in Race and Ethnicity.

She is a recipient of the Dean’s Award for Distinguished Teaching, a Ford Foundation postdoctoral fellowship, the Outstanding Chicana/o Faculty Member award. She has been a Brown Faculty Fellow, a Clayman Institute Fellow, a CCSRE Faculty Research Fellow, and a Clayman Beyond Bias Fellow.

Mulberry Street, Little Italy, New York, c 1900. Photo courtesy Library of Congress

How to see race

Race is a shapeshifting adversary: what seems self-evident takes training to see, and twists under political pressure.

by Gregory Smithsimon + BIO

We think we know what race is. When the United States Census Bureau says that the country will be majority non-white by 2044, that seems like a simple enough statement. But race has always been a weaselly thing.

Today my students, including Black and Latino students, regularly ask me why Asians (supposedly) ‘assimilate’ with whites more quickly than Blacks and Latinos. Strangely, in the 1920s, the US Supreme Court denied Asians citizenship on the basis that they could never assimilate; fast-forward to today, and Asian immigrants are held up as exemplars of assimilation. The fact that race is unyielding enough to shut out someone from the national community, yet malleable enough for my students to believe that it explains a group’s apparent assimilation, hints at what a shapeshifting adversary race is. Race is incredibly tenacious and unforgiving, a source of grave inequality and injustice. Yet over time, racial categories evolve and shift.

To really grasp race, we must accept a double paradox. The first one is a truism of antiracist educators: we can see race, but it’s not real. The second is stranger: race has real consequences, but we can’t see it with the naked eye. Race is a power relationship; racial categories are not about interesting cultural or physical differences, but about putting other people into groups in order to dominate, exploit and attack them. Fundamentally, race makes power visible by assigning it to physical bodies. The evidence of race right before our eyes is not a visual trace of a physical reality, but a by-product of social perceptions, in which we are trained to see certain features as salient or significant. Race does not exist as a matter of biological fact, but only as a consequence of a process of racialisation .

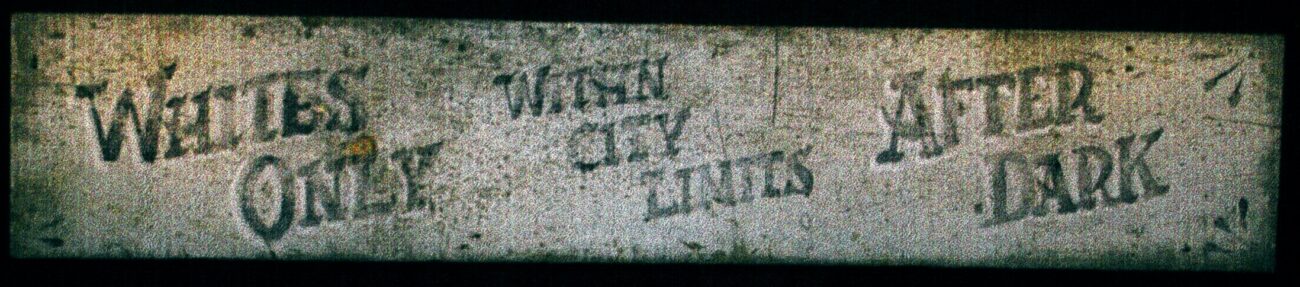

O ccasionally there are historical moments when the creation of race and its political meaning get spelled out explicitly. The US Constitution divided people into white, Black or Indian, which were meant to stand in for power categories: those eligible for citizenship, those subjected to brutal enslavement, and those targeted for genocide. In the first census, each resident counted as one person, each slave as three-fifths a person, and each Indian was not counted at all.

But racialisation is often more insidious. It means that we see things that don’t exist, and fail to recognise things that do. The most powerful racial category is often invisible: whiteness. The benefit of being in power is that whites can imagine that they are the norm and that only other people have race. An early US census instructed people to leave the race section blank if they were white, and indicate only if someone were something else (‘B’ for Black, ‘M’ for Mulatto). Whiteness was literally unmarked.

A brief aside on the politics of typography, in case you’re wondering: throughout this article I leave ‘white’ as is, but I capitalise ‘Black’, as well as ‘Indian’ and ‘Irish’. Why? Well, as the writer and activist W E B DuBois said in the early 20th century, during the decades-long campaign to capitalise ‘Negro’: ‘I believe that 8 million Americans are entitled to a capital letter.’ I could argue that I don’t capitalise white because ‘white’ rarely rises to the level of a cultural identification – but the real reason I don’t is because race is never fair, so it’s fitting for inequality be written into the words we use for races.

Putting whiteness under inspection shows how powerful race is, despite the instability of racial categories. For decades, ‘whiteness’ was an explicit standard for citizenship. (Blacks could technically be citizens, but enjoyed none of the legal benefits. Asians born outside the US were prohibited from becoming citizens until the mid-20th century.) Eligibility for citizenship – painted as whiteness – has remained a category since its inscription in the Constitution, but those eligible for membership in that group have changed. Groups such as Germans, Irish, Italians and Jews were popularly defined as non-citizens and non-white when they first arrived, and then became white. What we see as white today is not the same as it was 100 years ago.

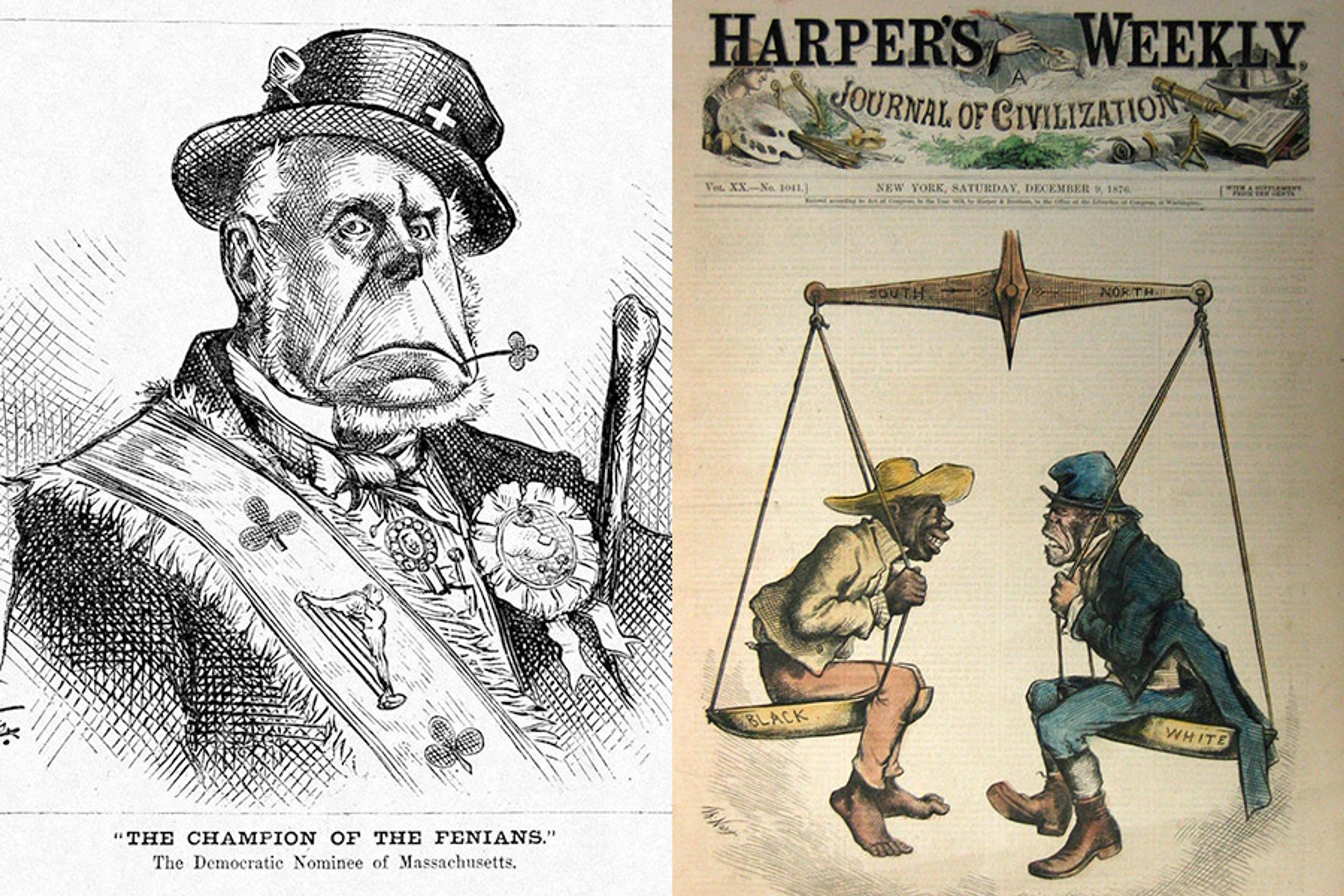

Thomas Nast’s cartoons are notorious in this regard. His caricatures of Irishmen and Blacks are particularly shocking because they are a type we no longer see today. Working-class Irishmen are represented as chimpanzees in crumpled top hats and curled-up shoes. Their faces have a large dome-shaped upper lip surrounded by bushy sideburns:

At times, Nast partnered the Irishman with an equally offensive image of a Black American, with big ‘Sambo’-style lips, perhaps a large rump and clunky bare feet. Today, few Americans have an image in their minds of what an Irish American should look like. Unless, perhaps, they meet a man named O’Connor with red hair, Americans today rarely think to themselves: ‘Of course! He looks Irish.’

Americans can’t see German, Irish or French, but they could . Not all white people look the same

But Nast was not only sketching nasty caricatures of Irishmen; he was doing so in a way that would appear believable to his audience. In a similar example of invisible ethnicity, 15 per cent of Americans in 2014 reported German heritage. This ethnic group is widespread and numerous. So let me pose a simple question: what do German Americans look like? One in seven Americans are German American; how many of the German Americans you meet have you identified that way? Even more so than later immigrant groups such as Italian, Irish or Jewish, German is invisible.

Americans can’t see German, Irish or French, but they could . It’s not the case that all white people look the same. My parents are both of predominantly Irish heritage. One summer, my family was travelling and had a layover in Ireland long enough for us to see the city of Dublin for the first time. We had not left the airport before my seven-year-old son said what I was already thinking: ‘Everybody here looks like grandma and grandpa!’ My family, according to my seven-year-old, looked like people from Ireland.

A few years later, I was to meet a French colleague at a busy Paris train station at rush hour, but neither of us knew what the other one looked like, and there were hundreds of people. I tried to guess which of the women entering, exiting, waiting, smoking, texting and milling about was the person I was to meet, but to no avail. Then I turned, and from a block away, through a crowd of hundreds, a woman waved directly at me. She had picked me out. I had been vaguely aware, before then, that no matter how familiar I got with Paris, I stood out on the subway: I might feel perfectly French riding the train, reading the advertisements in French and understanding the conductor, but when I got home and looked in the mirror, I knew my face was different from the diverse visages I saw in public.

Later I asked my colleague, and she said she knew I wasn’t French. How so? I asked. She scrutinised me. ‘ La mâchoire .’ It was your jaw, she said, with a satisfied smile. Until that day, I never knew there was such a thing as an Irish chin, but I had one. And no doubt, if Nast ever met my earliest American ancestors on the street, he’d know they looked Irish too. We don’t see Irish anymore, we don’t recognise it, we no longer caricature it. But we could.

T he racial category of Asian is just as unstable and entangled with political power as whiteness is. The US census started counting ‘Chinese’ back in 1870 (with no other category for people from the continent of Asia). Around the same time, the census started counting a similarly excluded group, American Indians, which the Constitution had designated as ripe for expropriation. Tellingly, Indian racial categories were unstable from the start: after not being counted at all, Indians were then included but tallied in the ‘white’ column – except in areas where there were large numbers of Indians, where they became their own category.

For Asians, as Paul Schor points out in his fascinating history Counting Americans (2017), the US government counted Chinese and Japanese but still left the rest of Asia blank, adding ‘Filipino, Hindu, and Korean’ in the 20th century. For something so clearly created by people, lists of racial groups are never comprehensive and typically ill-defined. Looking across the Eurasian continent, the US government today is still vague about where white ends and Asian begins. People in the US who were born east of Greece and west of Thailand are often unsure which boxes to check in the US census every 10 years. Like storm-borne waves or wind-blown sand dunes, race is a daunting obstacle that shifts and changes.

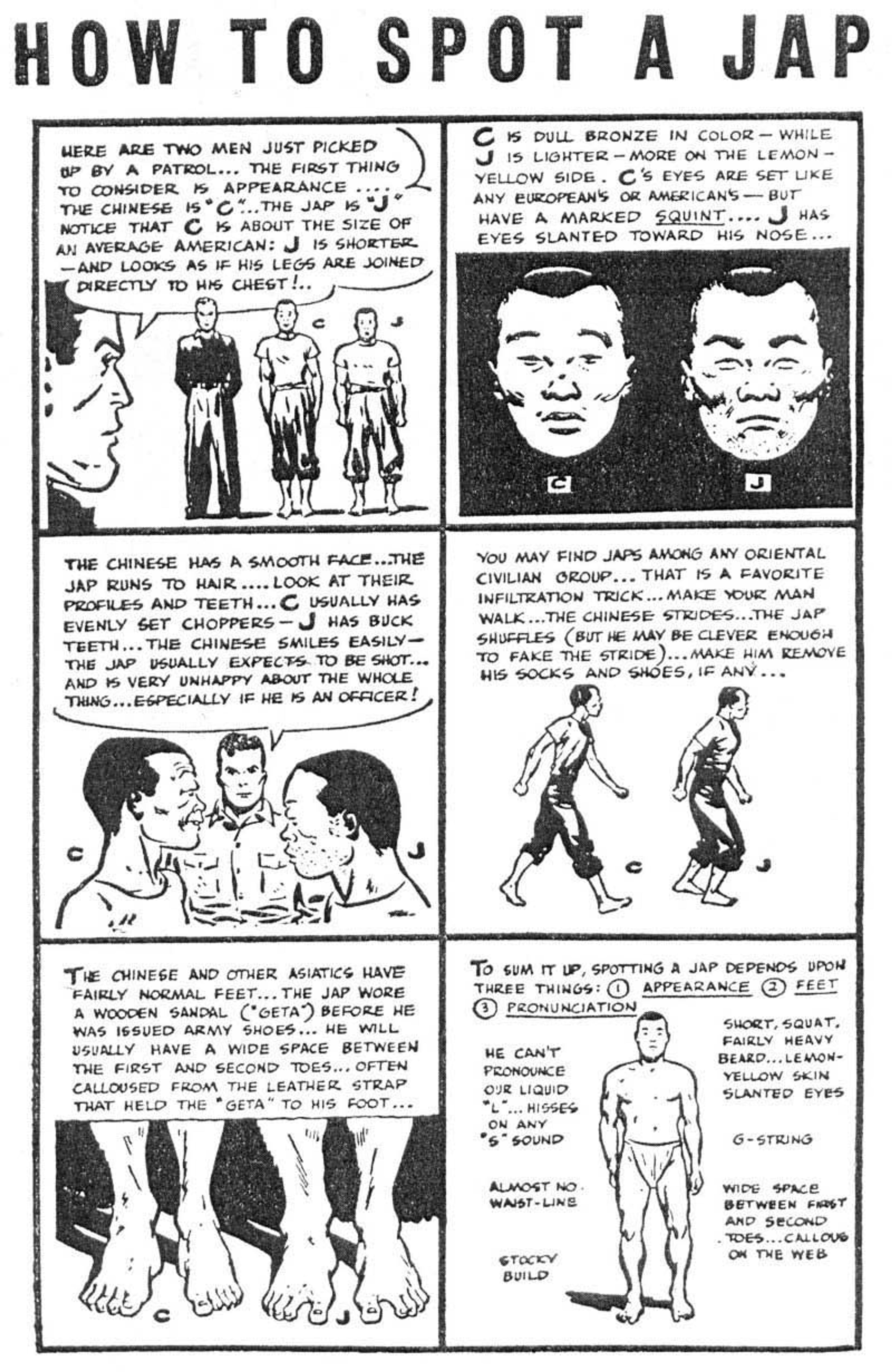

During the Second World War, China was a US ally, while Japan was an enemy. The US military decided it necessary to identify racial differences between the Chinese and the Japanese. In a series of cartoon illustrations, they tried to educate American soldiers about what to look for – what to see – in order to distinguish a Japanese solider who might be trying to blend in among a Chinese population.

Today, the ‘How to Spot a Jap’ leaflets are an offensive novelty – used either to illustrate the history of racist stereotyping or sold on postcards as ironic curiosities. But they can also be examined in another way. In The Civilizing Process (1978), the sociological theorist Norbert Elias studied books on manners from the European Renaissance to understand the process of the creation of what he called habitus . Manners that we see as utterly natural and inevitable today, like not blowing one’s nose at the table, or eating off the serving spoon, or belching or farting in public, are, in fact, socially constructed and learned behaviours.

At the historical moment at which they were introduced, books of manners were required to teach what is today utterly obvious to adults. They make for incredible reading. In his chapter ‘On Blowing One’s Nose’, for instance, Elias quotes a ‘precept for gentlemen’ that matter-of-factly explains: ‘When you blow your nose or cough, turn round so that nothing falls on the table.’ ‘Do not blow your nose with the same hand that you use to hold the meat.’ ‘It is unseemly to blow your nose into the tablecloth.’ Some of the recommendations are as poetic as they are graphic: ‘Nor is it seemly, after wiping your nose, to spread out your handkerchief and peer into it as if pearls and rubies might have fallen out of your head.’ It appears that actions that seem completely natural had to be taught explicitly.

Genetic inheritance isn’t what matters. What we literally see is shaped by politics

The ‘How to Spot a Jap’ flyers were printed to serve much the same function as the manners books that Elias studied. They tried to create and implant a racial habitus that distinguished the Japanese from the Chinese. That Second World War poster looks offensive today – crude, reductionist, insulting – and it is. We think that recognising such ridiculousness makes us less racist than the people who made it. It doesn’t. It merely means that we have different racial categories than in 1942.

Chinese and Japanese people look no more ‘similar’ or ‘different’ from one another than Irish Americans do from French Americans. That doesn’t mean that there aren’t differences as a matter of statistical distribution, but only that what we think we know about race has to be learned, and that what people ‘know’ and ‘see’ as salient and obvious changes over time. Most Americans cannot distinguish a white American of Irish origin versus one of French origin walking down the street, yet they hardly need pamphlets explaining what to look for to tell if someone is white or Black. If the distinction between Japanese and Chinese had remained as significant in the US today as it was to US soldiers during the Second World War, many people would see it as similarly self-evident.

On-the-street racial distinctions don’t have to be ‘perfect’. People often don’t recognise the author Malcolm Gladwell as Black, although he is; other times whites are mistaken for Blacks. For the purposes of making or unmaking a racial difference, genetic inheritance isn’t what matters. What we literally see is shaped by politics. The same two groups can be visibly different racially or indistinguishable racially, depending on the political context and power relations by which they’re categorised.

F rancis Galton was a pioneer in modern statistics. But he was also a eugenicist. Among other things, Galton became notorious for photos in the late 19th century that purported to reveal the ‘Jewish type’. At the time, people believed that Irish, Jewish, Japanese, Chinese or German denoted races. When Jews were a race, people thought that they could tell who was Jewish by looking at them. Today, many Jewish people recoil at the idea that there is a Jewish ‘race’, and find the suggestion that there is a Jewish ‘look’ inherently racist. At various times, then, the US Army, Thomas Nast and the father of the statistical method of regression analysis all believed that there were visually distinct and observable races that many Americans today would be generally unable to identify – certainly not with the level of certainty they’d feel with respect to racial categories such as Caucasian, African American, Latino or Asian.

I suspect that a visitor from a planet without race would have a very difficult time slotting anyone on Earth into the racial categories we use today. If they were asked to group people visually, there is no statistical possibility that they’d use the same set of arbitrary boxes, and even if these categories were described for them in detail, they would probably not sort actual people in the same way as the modern US does.