- Annotated Bibliography

- Argumentative

- Book Reviews

- Case Studies

- Communication and Media

- Computer Technologies

- Consideration

- Environment

- Explanation

- Informative

- Personal Experience

- Research Proposals

Elements of Dance

Dance can be defined as the art form that involves human movement which acts as the medium for understanding, sensing, communicating ideas, experiences, and feelings. Dancing is an important activity since it provides a means of acquiring knowledge. This is true since dancing develops problem solving techniques, creative and critical thinking skills, kinesthetic abilities, and communication abilities. The objective of dance education is to occupy students in artistic feels by the processes of response, creation and performance (Ann, 2008).

The elements of dance are the concepts and expressions for building up movement skills and also to enable dance understood as an art form. Elements of dance include body, space, time, action, and energy. These elements work together and must be present in a dance simultaneously. Changing or doing away with one of the elements of dance then there will be no meaningful dance.

Let’s find out together!

The body in a dance is the movable shape which can be seen by audience and felt by the individual dancer. At times the body may be quite still or sometimes shifting during when the dancer is moving or travelling through the area of dancing. Some times dancers emphasize particular body parts in a dance expression or their entire body. Looking at the entire body of the dancer one may consider the general shape design as either symmetrical, twisted or some other design employed by the dancer at that time. Considering the body systems is also another way of describing the body in dance for instance, breath, muscles, balance, organs, bones and reflexes (Schrader, 2005).

During dancing the dancers may stay in particular position and move their body parts only or move the whole body, or they can as well move from one place to another in the space provided. The dancers may change the level, pathways, size, and direction of the movements they make. They may also focus their attention and movement outwards into space or inwards towards themselves. The travelling line may be somewhat direct headed for one point in space, or indistinct and winding. Spatial relations involving dancers themselves or dancers and the surrounding objects are the center for design constructs such as in front of, beside, through, over, near, around or far (Cone, 2005).

You can use our chat service now for more immediate answers. Contact us anytime to discuss the details of the order

According to Hawkins (1988), the movements in dance may also depict different relationships of timing for instance, sequential or simultaneous timing; or rapid to slow speed; or short to long duration; emphasizes in expected or random intervals. As well time may be coordinated in other way for instance, sensed time, event-sequence, and clock time. Dancers may use a collective sense of sensed time to bring dance to a halt.

According to Schrader (2005), action is defined as human movement of whichever kind, included in dancing. This can include facial movements, dance steps, lifts, catches, and carries, and even daily movements for example walking. Dancers may decide and make movements which have already been done, or may decide to add original movements to the dance movement archive already existing. It is possible that dancers may amend the movement that they have copied from other dancers. Dance consists of streams of pauses and movement, therefore apart from sequences and steps; action also refers to movements and pauses of relative immobility.

Hawkins (1988) defines energy in dancing as the strength of an action, and can as well be the psychic and physical energy that characterizes and causes movement. Options regarding energy consist of differences in flow of movement and use of tension, weight, and force. Energy may vary instantaneously, and a number of energy types may be along with in play. Energy options may also bring out arousing states. For instance, a powerful thrust might be violent or teasingly energetic depending upon the purpose and condition. A subtle touch might prove uncertain or affectionate, or possibly suggest concern.

Calculate the Price of Your Paper

Related essays

- Epworth Sleepiness Exam

- Older Adults Patient Education Issues

- Comparison of Education in Europe, Asia, and US

- Teaching Students with Heath Impairments

Along with the first order offer - 15% discount (with the code "MY15") , you save extra 10% since we provide 300 words/page instead of 275 words/page.

Critical Stages/Scènes critiques

The IATC journal/Revue de l'AICT – December/Décembre 2019: Issue No 20

Movement through Language: A Reflection on the Use of Spoken Text in Dance Performances

Rosa Lambert *

Today, the Belgian dance scene features many international choreographers whose works explore how spoken text can contribute to the creation of dance. As a consequence, their works reveal the interconnections and affiliations between language and movement. In this essay, Rosa Lambert examines two solo performances by Mette Edvardsen, Black (2011) and No Title (2014), to demonstrate how a redefinition of dance beyond physical movement is both the subject of contemporary experiments and of recent theoretical reflections. Keywords: Black, No Title, Mette Edvardsen, post-dance, language choreography

Introduction

Today, the Belgian dance scene is populated by a number of international choreographers whose works push dance beyond its traditional boundaries of physical movement. In the works of Daniel Linehan, Mette Edvardsen, Bryana Fritz, Mette Ingvartsen, Eleanor Bauer and Louis Vanhaverbeke (amongst others), we can observe an eagerness to explore how other materials, such as spoken text, contribute to the creation of dance. In contrast with prevailing assumptions of dance being antithetical to language, [1] these works reveal the capacity of language to provoke movement.

In this essay, I will focus on two solo performances by Mette Edvardsen, Black (2011) and No Title (2014) , to demonstrate how a redefinition of dance beyond physical movement is both the subject of contemporary experiments and of recent theoretical reflections.

February 2011, Brussels. Mette Edvardsen enters an empty stage. She puts her hands in front of her, as if she was placing them on a desk. She looks at her hands, cautiously. Pronounces: “table, table, table, table, table, table, table, table.” She moves one hand to her back: “chair, chair, chair, chair, chair, chair, chair, chair.” [2] Placing her two hands above her, looking upwards: “lamp, lamp, lamp, lamp, lamp, lamp, lamp, lamp.” For the rest of the performance, Edvardsen walks throughout the space, points at invisible objects in the room and makes them appear by naming these objects eight times each. This elegantly simple, rhythmic construction sparks the audience’s imagination. Because the words refer to objects that are not present in the room, they trigger us to construct a mental image of them. This results in an oscillation between reality and imagination: while the objects remain nonexistent, the repetitions help us evoke them in our mind. Paradoxically, the objects appear remarkably present through their absence.

February 2014, Brussels. Mette Edvardsen enters an empty stage, eyes closed. She stands still, waits for several seconds. Utters: “the beginning.” She waits for several seconds more: “is gone. The space is empty.” Pause. “And gone. The prompter has turned off his reading lamp, and gone.” With her eyes closed during the entire performance, she evokes a variety of things, such as “the distinction between writing and drawing,” “Krushchev’s cat,” “waiting in lines,” that are all “gone.” However, pointing at an object’s disappearance does not result in its withdrawal, but rather in its presence. As Edvardsen suggests, “it is not enough to say that something is gone in order to make it disappear” (“Double-interview” 73). Even though the objects are “gone,” listeners are still triggered to imagine this object. As a result, there is not only an oscillation between reality and imagination (as we see within Black) , but there is also a constant oscillation between presence and absence on the level of the text itself.

Since 2002, Edvardsen has been creating a fascinating and diverse oeuvre of works, comprised of solo as well as collective performances. She has worked with objects and technologies ( Private Collection, 2002; Time Will Show (Detail), 2004; We to Be, 2015), collaborated with musician Matteo Fargion ( oslo, 2017; Penelope Sleeps, 2019) and initiated a library of living books ( Time Has Fallen Asleep in the Afternoon Sunshine , 2010-ongoing). In recent years, language has become a recurring element within her canon of work. She has radically moved words into the realm of dance: “In Black I discovered the efficiency of language to name and make appear, and in No Title I was negating and looking into what is not. And I found a certain elasticity in language, in the possibilities and limits of language, of naming and knowing”(“Double-interview” 75). For Edvardsen, using language in dance is a way to “widen the notion of what dance could be” (“The Picture of a Stone” 219).

Movement—gone?

While contemporary choreographers have been experimenting with different ways to connect language and dance, dance scholars have been making attempts to define dance beyond the confines of physical movement. At the outset of these attempts stands the notion of “exhausting dance,” coined by dance scholar André Lepecki in his eponymous book, Exhausting Dance (2006). Lepecki defines this concept in relation to Bruce Nauman’s, Juan Dominguez’s, Xavier Le Roy’s, Jérôme Bel’s, Trisha Brown’s, La Ribot’s, William Pope’s and Vera Mantero’s desires to withdraw from virtuous, flowing movement (5). Building on the work of dance historian Mark Franko, Lepecki emphasizes that “aligning dance’s being with movement . . . is a fairly recent historical development” (2). While modernist dancers foregrounded this alignment, Lepecki contends that recent contemporary choreographers “exhaust” the bond between dance and physical movement (4), creating “dances that refuse to be confined to a constant ‘flow or continuum of movement’” (5). He uses the concept “exhausting dance” to analyze these works, and contributes to an understanding of dance that retires from producing virtuous bodily movement.

If we agree upon a definition of dance that is no longer restricted to the enactment of moving bodies, then what, truly, is the material that dance is made of? In the case of Black and No Title , it seems that dance, in its departure from the (human) body, moves towards other elements of performance, such as language. In her analysis of Edvardsen’s Black , dance scholar Efrosini Protopapa convincingly revisits Lepecki’s notion of exhaustion. She highlights that exhaustion should not be understood as an endpoint, “but rather as an opening out of new possibilities in/for dance” (168).

According to Protopapa, contemporary choreographers are “questioning what dance can do for them” and “in so doing, they find themselves working with a variety of tools and fields of knowledge” (180). Thus, Protopapa indicates that the contemporary exhaustion of movement does not imply a standstill within dance. Rather, in recent works, dance has not been restricted to the portrayal of physical movements. It has instead been expressed through other media, such as the organization of objects, words, mathematics and philosophy (Protopapa 180). Therefore, she does not describe Edvardsen’s Black as a dance without movement, but as “a dance that remains largely immaterial” (184).

In his reflection on the nature of dance vis-à-vis body movement, dancer and theorist Mårten Spångberg develops a similar argument. In the final chapter of the book Post-Dance (2017), which he co-edited with Mette Edvardsen and Danjel Andersson, he explains how contemporary experiments in dance and choreography can be assembled under the notion of “post-dance.” This term covers a variety of practices that all reflect on the medium of dance by transforming it from within: it “is always-already an exhausted dance but doesn’t care about it any longer and explores what else it can be” (Vujanović 46).

Spångberg’s chapter advocates for the artistic value of contemporary experiments within dance, even though performers no longer use physical movement to create “dance” (350). To allow for a broader understanding of what dance exactly entails, Spångberg sets off with enlarging the definitions of both “dance” and “choreography.” Dance is defined as pure movement, while choreography is understood to be the structure or pattern that works to tame movement. By removing the human dancer from both definitions, he makes room for the idea of “a choreographer whose expression happens to be literature” (363). As such, Spångberg considers “literary structures” as solid principles which evoke movement, and he includes them in the realm of dance and choreography (372).

In comparison with Lepecki and Protopapa, Spångberg’s argument allows a more radical understanding of texts as “choreographic structures” (364). The convoluted relationship between text and choreography is illustrated by the following fragment in Edvardsen’s No Title . While Edvardsen utters: “B–gone, A–gone, going from B to A is gone, C . . . gone,” she seemingly announces the disappearance of choreography, since, following Lepecki, “Going from A to B to C” can be understood as a choreographic pattern ( Singularities 68).

However, Lepecki seems to overlook a crucial dynamic that structures No Title ; namely, the impossibility to make something entirely disappear simply by claiming it is “gone.” Subsequently, choreography has not entirely disappeared, because language is dancing. Interestingly, Edvardsen does in fact go from one point to another in space while uttering this sentence, which further expresses the incomplete withdrawal from choreography. Finally, the phrase “going from B to A to C” can refer to the use of letters, words and language as a choreographic structure—which adds yet another layer to the interpretation of this fragment.

As such, this fragment points to the complexity of the relationship between language and choreography. This fragment embodies a prime concern within dance scholarship; namely, the question of how to define the ontology of choreography. Based on the etymology of choreography ( choreo/graphein ), questions have been raised as to whether or not choreography can be seen as a particular from of (bodily) writing (Gardner 2008; Foster 2010; Franko 2011). Interestingly, because she uses spoken language instead of physical movement, Edvardsen’s works reassesses this relation between language and choreography. She gives a twist to their presumed relation: choreography is not only a form of bodily writing, and it can in fact reside within language itself, in the form of words that are pronounced on stage.

Moving Words

What form does language take when it is created as dance? In Black, dance is articulated through the composition of words. This is done, for example, by manner in which the last “table” in “table table table table table table table table” raises slightly upwards and how Edvardsen’s pronunciation of “full full full full full full full full,” during the watering of her invisible plant, sounds exactly like sloshing water pouring out of a full water bottle. Furthermore, in No Title , dance is expressed in the repetition of the “me—not gone”-phrase that is altered slightly each time it occurs. For example, first, we hear “me—not god, not all, not gone,” and, later on, “I was not here, I was not gone.” The repetitions of and variations on this phrase are the linguistic equivalent of repetitions of and variations on a particular moving sequence that reappears throughout a dance with human bodies. As such, the phrases’ rhythmic structures provoke a sense of movement in language.

Moreover, the physical endeavor of pronouncing words also connects language to movement. The seemingly evident observation that speech is language filtered through a voice, supported by a body and projected in to space (Fischer-Lichte 125) helps to consider language as something that can produce movement and dance. A review of No Title beautifully describes how the text is fully entangled with Edvardsen’s body: “Edvardsen’s voice does not simply pronounce words but expresses its own muscular quality” (Minns and Albano 2018). In other words, Edvardsen thinks—and talks—as a choreographer. This is, for instance, discernible in how she embodies, pronounces and articulates the various repetitions that occur in Black. The eight-fold repetition of certain words is clearly a difficult task, since we witness Edvardsen’s mouth and jaw muscles struggle with the pronunciation of “particle particle particle particle particle particle particle particle.”

Towards the end of No Title , Edvardsen speeds up the rhythm of her text, and, after a while, it is no longer possible to hear each and every single word or phrase. This is similar to how a dancer’s virtuous and rapid (physical) movements hinder us from being able to observe each individual gesture. As Edvardsen explains, the act of embodying words allows her to foreground the rhythmic qualities of a text: “a poem is not only about understanding the meaning of a poem: it is the texture of it, the rhythm, the musicality” (Simpson 2016). Edvardsen’s works foreground how the pronunciation of a word is in fact a physical activity. This stems from her roots as a choreographer; she makes precise choices in the way in which her body interacts with the text. In other words, the rhythm of the text intensifies the physical act of pronunciation and, in foregrounding both these rhythmic and physical aspects of language, Edvardsen creates a dance through words.

Moving Imagination

The rhythm of the text and the way in which the body engages with the words work together to create a sense of dance within language. Moreover, the text is structured on a semantic level through the constant interplay between presence and absence ( Black ), and between appearance and disappearance ( No Title ). The continuous friction that results from this has a peculiar effect on the audience’s imagination. The empty space in which the words are pronounced contrasts with the way in which the rhythm of the text explicitly triggers the listeners to envisage the word’s references. In other words, the audience is constantly swaying between what is present in their minds and what is absent on stage. In this sense, the text produces a sense of motion, now located within the imagination of the audience.

The previously mentioned sequence of No Title , in which Edvardsen announces the disappearance of choreography, exemplifies this dynamic. It almost seems as if the echoes of the words compose a choreographic pattern on the empty space. Immediately after she announces the (impossible) disappearance of choreography (“Going from B to A to C—gone”), she draws a line and writes next to it “line.” Then, she attempts to remove this actual line and the word “line” with her hands (see Figure 2). Because her eyes are closed, she is not able to remove the chalk and after a few seconds, she is wiping the floor next to the line. This simple action is preceded by an enumeration of various things that appear vividly present, precisely by virtue of the fact that they were claimed to be “gone.” In combination with the different words that still linger around in the space, her failed attempt of wiping the floor shows how it is impossible to successfully delete something when it has already entered the performance space.

A similar strategy is at work in Black. Throughout this performance, the repetition of the words “table” and “chair” occur several times. The first time she pronounces these words, Edvardsen clearly situates the table and the chair within the space: her gestures mark the contours of the furniture. However, after several repetitions, the words are no longer precisely marked in space, because Edvardsen ceases to make gestures that depict the position of these words. Nevertheless, we still remember exactly where the furniture was placed originally, because the previous utterances and their accompanying gestures still echo through the space. The patterns that arise here, from words emerged out of bodies, with accompanying gestures through space, can be considered choreographic structures.

Therefore, the audience’s imagination and memory are central within both pieces. As Edvardsen points out: “for me art needs to be about imagination and the capacity to evoke, to create poetry, to make things up and propose visions” (“Double-interview” 73). Unfolding through empty spaces, with Edvardsen as the only presence in the room, Black and No Title invite us to actively participate, situate, color, and imagine the objects to which Edvardsen’s words refer. In other words, the repetition of each word in Black “creates a peculiar focus in which appearance and disappearance, beginning and ending are intertwined” (Peeters 19). In No Title , the negated thing appears precisely by virtue of negation. As Edvardsen explains: “through language another access to imagination opened, I found” (73). Therefore, “it is not so much an interest in language as such but more what it makes possible” (75). In Edvardsen’s hands, words become fluid, start to dance, through an empty space, evoking images in the minds of the audience.

Concluding Remarks

In Black and No Title, the organization of words in time and space turns language into dance. Because words will never fully turn into mere sounds, a remnant of their meaning continues to shine through them. The relationship between language and movement operates on several levels: through the internal rhythm of language, through the entanglement between text and body, and through the ability of language to set the imagination of the audience in motion . The words of Black and No Title , intertwined with Edvardsen’s body, vibrate through space, guide the spectators’ imagination and, therefore, dance.

The use of spoken language in dance performances is an important feature of the contemporary Belgian dance scene. By building on recent theoretical studies that investigate the nature of dance, I tried to illustrate how Edvardsen’s Black and No Title mirror these claims; namely, that dance can express itself beyond physical movement. These performances experiment with the capacity of words to flicker, fumble and slip through (imaginary) spaces.

[1] See, for instance Muto (2016); Cvejic (2015); Franko (2011) and Gardner (2008). These authors elaborate on the relation between dance and language through the notion of “choreography” as dance-writing. Their writings offer nuanced readings of dance in relation to language.

[2] Unspecified quotes refer to sections in the performances in which Mette Edvardsen pronounces these sentences. The sentences or paragraphs in which these quotes are embedded clarify whether they are from either Black or No Title.

Bibliography

Alano, Caterina, and Nicholas Minns. “Mette Edvardsen, No Title, Fest en Fest, Laurie Grove Studios.” Review. Writing About Dance. 20 July 2018.

Cvejic, Bojana. Choreographing Problems: Expressive Concepts in Contemporary Dance and Performance. Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

Edvardsen, Mette. Black . Performance, 24 Feb. 2011, Kaaistudio’s, Brussels.

—. “No Title.” Performance, 4 Feb. 2014, Kaaistudio’s, Brussels.

—. “The Picture of a Stone.” Post-Dance , edited by Danjel Andersson et al., MDT, 2017, pp. 216–21.

—. Not Not Nothing. Varamo Press, 2019.

Edvardsen, Mette, and Mette Ingvartsen. “Double-interview between Mette Edvardsen and Mette Ingvartsen.” Choreography , vol. 1, no. 1, 2016, pp. 70–76.

Fischer-Lichte, Erika. The Transformative Power of Performance . Routledge, 2004.

Foster, Susan Leigh. Choreographing Empathy . Routledge, 2010.

Franko, Mark. “Writing for the Body.” Common Knowledge , vol. 17, no. 2, 2011, pp. 321–34.

Gardner, Sally. “Notes on Choreography.” Performance Research , vol. 13, no. 1, 2008, pp. 55–60.

Lepecki, André. Exhausting Dance: Performance and the Politics of Movement . Routledge, 2006.

—. Singularities: Dance in the Age of Performance . Routledge, 2016.

Muto, Daisuke. “Choreography as Meshwork: The Production of Motion and the Vernacular.” Choreography and Corporeality: Relay in Motion , edited byThomas DeFrantz and Philipa Rothfield, Palgrave Macmillan, 2016, pp. 31–50.

Peeters, Jeroen. Something, Some Things, Something Else. Varamo Press, 2019.

Protopapa, Efrosini. “Contemporary Choreographic Practice: From Exhaustion to Possibilising.” Contemporary Theatre Review , vol. 26, no. 2, 2016, pp. 168–182.

Simpson, Veronica. Interview by Mette Edvardsen. Studio International , 27 Dec. 2016.

Spångberg, Mårten. “Post-dance, an Advocacy.” Post-Dance , edited by Danjel Andersson et al., MDT, 2017, pp. 349–93.

Vujanović, Ana. “A Late Night Theory of Post-Dance, a self-interview.” Post-Dance , edited by Danjel Andersson et al., MDT, 2017, pp. 44–66.

* Rosa Lambert has obtained a Master in Theatre and Film studies in 2017 and is currently working on an FWO-funded PhD project in performance studies at the University of Antwerp ( Research Centre for Visual Poetics ). In her project “Moving With(in) Language: Kinetic Textuality in Contemporary Performing Arts,” she looks into the affiliation between language and movement, as exposed within the work of contemporary theatre, performance and dance artists.

Copyright © 2019 Rosa Lambert Critical Stages/Scènes critiques e-ISSN: 2409-7411

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

- ← To Become Merged in the Sea . . . or On Old Women on Stage

- Insupportable vieillesse ? →

You May Also Like

City Narratives in European Performances of Crisis: The Examples of Athens and Nicosia

A Case Study of the Intercultural Production of Väike Jumalanna (The Little Goddess)

Seeking the Other: Staging the Paroxysms of Orientalism

Language and Other Literacies in and Through Dance

- First Online: 15 March 2023

Cite this chapter

- Jaye Knutson 6

Part of the book series: Springer Texts in Education ((SPTE))

227 Accesses

This chapter examines how the body is the basis for language development and literacy. That language is metonymic, representation of sensory experience, feeling, and emotion and grounded in the body with gesture serving as a kinesthetic repository that primes or draws out the words or expressions needed or desired. Teachers of all disciplines rely on language literacy to convey and support knowledge in content areas. Teachers recognize that a bodily experience of an idea, concept, experience or emotion provides a strong foundation for language development. If we recognize the value of educating citizenry for the twenty-first century, then we must recognize the role the body plays in language literacy. Physical literacy, full bodied and holistic, must be valued and fostered by teachers of dance, physical education and sports so that individuals are empowered to achieve their fullest potential in both action, thought and word.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Barton, G. (2014). Literacy in the arts: Retheorising learning and teaching. In G. Barton (Ed.), Literacy and the arts: Interpretation and expression of symbolic form (pp. 3–19) . Springer International Publishing. ISBN 978-3-319-04845-1

Google Scholar

Batson, G., & Wilson, M. A. (2014). Body and mind in motion: Dance and neuroscience in conversation . With Margaret Wilson, Intellect Ltd.

Beilin, H., & Fireman, G. (1999). The foundation of Piaget’s theories: Mental and physical action. Advances in Child Development and Behavior, 27 , 221–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0065-2407(08)60140-8

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Brodie, J. A., & Lobel, E. E. (2012). Dance and somatics: Mind-body principles of teaching and performance. McFarland & Co. Inc.

Burkhardt, J., & Brennan, C. (2012). The effects of recreational dance interventions on the health and well-being of children and young people: A systematic review. Arts & Health, 4 (2), 1–14.

Article Google Scholar

“Dancing: The Individual and Tradition.” (1993). Directed by Anonymous, produced by Rhoda Grauer, Muffie Meyer, and Ellen Hovde., ArtHaus Musik. Alexander Street. https://video-alexanderstreet-com.proxy-tu.researchport.umd.edu/watch/dancing-the-individual-and-tradition

Dils, A. (2009). Why dance literacy ? In C. Stock (Ed.), Dance dialogues: Conversations across cultures, artforms and practices. Proceedings of the 2008 World Dance Alliance Global Summit , Brisbane, 13–18 July. On-line publication, QUT Creative Industries and Ausdance.

Eddy, M. (2016). Mindful movement: The evolution of the somatic arts and conscious action . Intellect.

Eisner, E. (1998). What do the arts teach? Improving Schools, 1 (3), 32–36.

Foster, S. L. (2011, September 11). Kinesthetic empathies & the politics of compassion. Susan Foster! Susan Foster! Three Performed Lectures. The Pew Center for Arts and Heritage. http://danceworkbook.pcah.us/susan-foster/kinesthetic-empathies.html

Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. Basic Books.

Gilbert, A. G. (2018). Brain compatible dance education (2nd ed.). Human Kinetics.

Grosz, E. (1995). Space, time and perversion: Essays on the politics of bodies . Routledge.

Hackney, P. (2003). Making connections: Total body integration through Bartenieff fundamentals . Gordon and Breach Publishers. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203214299

Book Google Scholar

Hughes-Decatur, H. (2011). Embodied literacies: Learning to first embody and then read the body in education. English Teaching: Practice and Critique, 10 (3), 72–89

Laban/Bartenieff Institute of Movement Studies (LIMS). (2021). What is a CMA? https://labaninstitute.org/what-we-do/certified-movement-analysts/

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1981). Metaphors we live by . The University of Chicago Press.

Linden, P. (1994). Somatic literacy: Bringing somatic education into physical education. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance, 65 (7), 15–21.

Lobel, E. E., & Brodie, J. A. (2006). Somatics in dance-dance in somatics. Journal of Dance Education, 6 (3), 69–71.

Matthews, E. (2006). Merleau-Ponty: A guide for the perplexed . Continuum.

McArdle, F., & Wright, S. K. (2014).First literacies: Art, creativity, play, constructive meaning making . In G. Barton (Ed.), Literacy and the arts: Interpretation and expression of symbolic form (pp. 3–19). Springer International Publishing. ISBN 978-3-319-04845-1

McDonald, D., Emmanuel, S. M., & Stewart, J. (Eds.). (2014). Kierkegaard’s concepts: Classicism to enthusiasm, 15(II) . Ashgate.

Movescape Center. (2021). The dynamosphere: Mapping human effort. https://movescapecenter.com/dynamosphere-mapping-human-effort/

Payne, H. L., & Costas, B. (2020). Creative dance as experiential learning in state primary education: The potential benefits. Journal of Experiential Education, 3 (3), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053825920968587

Roth, W. M., & Lawless, D. V. (2002). How does the body get into the mind? Human Studies, 25 (3), 333–358.

Sadoski, M. (2018). Reading comprehension is embodied: Theoretical and practical considerations. Educational Psychology Review, 30 (2), 331–349.

Sheilah Kast Show. (2018, September 26). On the record. WYPR [Radio Broadcast]. https://www.wypr.org/post/mobile-concerts-and-re-imagined-jewelry

Todd, M. E. (1937). The thinking body . Dance Horizons.

Watson, L. (1991). Gifts of unknown things: A true story of nature, healing, and Initiation from Indonesia’s dancing island. Destiny Books.

Whitehead, M. (2001). The concept of physical literacy. European Journal of Physical Education, 6 , 127–138.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Dance, Towson University, Towson, MD, USA

Jaye Knutson

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jaye Knutson .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Graduate Reading Education, Towson University, TOWSON, MD, USA

Stephen G. Mogge

Graduate Reading Education, Towson University, Towson, MD, USA

Shelly Huggins

Dance Education, Towson University, Towson, MD, USA

Department of Kinesiology, Towson University, Towson, MD, USA

Elin E. Lobel

Department of Secondary and Middle School Education, Towson University, Towson, MD, USA

Pamela Segal

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Knutson, J. (2023). Language and Other Literacies in and Through Dance. In: Mogge, S.G., Huggins, S., Knutson, J., Lobel, E.E., Segal, P. (eds) Multiple Literacies for Dance, Physical Education and Sports. Springer Texts in Education. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-20117-2_6

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-20117-2_6

Published : 15 March 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-20116-5

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-20117-2

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.17: Introduction to Dance

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 199415

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Learning Objectives

With this chapter, you will begin working toward:

- Demonstrating a culturally informed dance aesthetic.

- Identifying the purposes of dance.

“Dance evaporates—everything goes…we just have this little hint. The deterioration actually adds to the meaning of it.”—dancer and film director Connie Hochman on trying to capture the ephemera

Introduction

There are many definitions of dance, with people defining dance in their own way. In this chapter, you will consider your personal definition of dance. You will learn the purposes of dance. You will reflect on your experiences and upbringing to determine their influence on your dance aesthetic.

- Poetry, prose, and music are arts that exist in time. It is through the manipulation of rhythm and tempo that these arts are created.

- Painting, sculpture, and architecture are arts that exist in space. It is through the design of space that these arts are created.

- Dance is the only art that is a creation in both time and space.

How do you define dance?

Elements of Dance

Dance can be studied in terms of its raw materials. We can describe movement thoroughly by breaking dance down into its basic components. A complete understanding of the building blocks of dance allows us to analyze, interpret and speak about dance in a thorough and understandable way. To increase dance literacy and appreciate dance as an art form, we must look at the elements of dance. Through the manipulation of these elements by the human body, dance happens. The elements of dance will be discussed in more detail later in Chapter 2. To describe dance, it is useful to analyze it in terms of these Elements of Dance:

Purposes of Dance

Dance can be studied in terms of its purpose and function within a culture. Cultures impact how people engage with the world, as environmental influences, societal behaviors, and attitudes are intertwined within the development and shaping of dance forms. In this respect, dance is a carrier of culture. The purposes of dance include:

- Religious Dance / Dance to Please the Gods

- Social Dance / Dance to Please Ourselves

- Performance Dance / Dance to Please Others

- Protest Dance/Dance to Affect Social Change

Religious Dance

The earliest dances were likely religious in nature. Some religions embrace dance and use it as a part of their rituals. Other religions have eschewed dance or banned it for a number of different reasons.

The Ancient Greeks and Africans used to dance to solidify their community. Ancient Greek dance, as well as ancient African dance, was divinely inspired. Everyone participated in religious ceremonies as cultivated amateurs and up-standing citizens. A big part of the program was processions and circle dances. The realities of the cosmos ruled the symbolism of the dances, and references to the sun, moon, and constellations figured into the movements.

Types of Religious Dance

Dances of imitation, medicine dances, commemorative dances, dances for spiritual connection.

Particularly in primitive and indigenous cultures, dances of imitation are performed. Dancers imitate animals and natural phenomena to embody specific qualities, like channeling the prowess of an animal. The dances serve various purposes, often promoting favorable outcomes, such as good weather and hunting.

Shamans, as spiritual leaders, serve as intermediaries between the human and spirit worlds. Both men and women may be Shamans. The religion is animistic (attributes a spirit to all things), and rituals address medicine, religion, a reverence for nature, and ancestor worship. On the summer solstice, Shamans perform a fire ritual at night. The Shaman drums carry the ancestral spirits of the Shaman.

Dances are created to remember a special day, event, and meaningful moment. Some commemorative dances are very old. Maypole dances have early pagan roots. It is a celebration of the rebirth of spring. The Second Line is a West African form of dance that is a ritual to celebrate the life of the recently departed. After the slaves were brought to the new world, this dance became more of a celebration for parties and Mardi Gras festivals.

In some cultures, the dancers seek to suppress their ego to find oneness with God. In others, dance may be used to connect with dead ancestors spiritually. Some religions use dance to tell their origin stories and preserve their heritage.

Social Dance

In social dance, we establish a connection with others. Social dance can be sorted into four general categories based on the purpose of the dance.

Types of Social Dance

Courtship dances, work dances, communal dances.

In cultures where marriages are arranged, men and women do not engage in courtship dances. In other cultures, dance may serve as simple flirtation or involve more complex rituals.

Some dances are centered around the work that groups perform. Dances that mimic work routines were used in past times to help build unity and continuity among the crew.

Dance has always been used in conjunction with training for war. Several cultures throughout history used dance as grounds for war preparation. The Greeks participated in pyrrhic dances and used weapons to mimic war tactics in preparation for battle. Capoeira was created by enslaved Africans in Brazil, using dance as a guise for practicing fighting. The Māori of Aotearea/New Zealand dance the Haka as an intimidation tactic that instills warriors with ferocious energy. In South Africa, the Indlamu dance was inspired by Zulu warriors during the Anglo-Zulu wars, was derived from the war dances of amabutho (warriors), and was mainly used to motivate the men before they embarked on their long marches into battles barefoot. Today, cultures continue to pass down these traditions to new generations as tradition.

Communal dances are often a part of festivals and parties. Dances like springtime’s Maypole dance and the Jewish hora bring a whole community together to share happy times. Communal dances also can be a way for a community to share grief and memories, like the Table of Silence performed at Lincoln Center every year to commemorate 9/11.

Performance Dance

Performance dances are presentational and often are entertainment for an audience. Some amateur dancers put on shows, but there are also professional dancers who attain highly polished technique.

Types of Performance Dance

- Musical Theater

Protest Dance

Protest dance is a response to social situations and the human condition. For slaves of the American South, the cakewalk was a way to mock their white oppressors. Kurt Joos created the modern dance The Green Table after World War 1. It reflected hard truths about society and the price of war. Bill T. Jones creates ensemble dances that reveal realities of social injustice. Jo’Artis “Big Mijo” Ratti uses krumping to express his rage and frustration in response to the killing of George Floyd.

Dance Aesthetic

Your aesthetic is that which you find pleasing or beautiful. It is your tastes and preferences, your “likes” and “dislikes.” Your perception of dance will be informed by your aesthetic, which might result in subjective judgments about the dances you see. Therefore, it is essential to acknowledge when these biased opinions emerge to be receptive to the dances you are witnessing and objectively respond to them. By keeping an open mind, we can better our understanding of the uniqueness of each dance as an art form.

Cultural Traditions

Culture is shared values, beliefs, and customs shared amongst a group of people that contribute to a person’s dance aesthetic. The rhythms of West Africa or Argentina that you grew up listening to can also play a part in shaping rhythmic tastes. Dance is an important way that the lore and traditions of a culture are preserved over time as it is passed down from generation to generation.

Different religions incorporate dance into their worship. Some religions include it as an intrinsic part of their ritual, and even link dance to the spiritual experience. Other religions eschew dance altogether. Your religious upbringing and experiences may influence your dance aesthetic.

The program on Safeguarding intangible cultural heritage in formal and non-formal education is a UNESCO initiative, which recognizes that:

- Education plays a key role in safeguarding intangible cultural heritage.

- Intangible cultural heritage can provide context-specific content and pedagogy for education programs and thus act as a leverage to increase the relevance and quality of education and improve learning outcomes.

UNESCO considers dance an intangible cultural resource. UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage division recognizes the following in its Summary Report on education : “The creative process of inter generational transmission is at the center of intangible cultural heritage safeguarding.”

Family Influence

Different generations may prefer different dances. The dances your parents and their friends do is probably different from what you and your friends like. Maybe you have a grandparent who can teach you some older dances.

Do you watch dance on television, in movies, online, in live concerts and shows, at half-time? The many factors of your experiences influence your dance aesthetic.

Personal Response

You will also have a personal response to dance. Do you prefer to move fast or slow, bouncy or gliding, all over the room or just a little bit? Do you want your dance to demonstrate emotion, or do you prefer a show of virtuosity?

Kinesthetic

Consider your physical response to dance as you think about your dance aesthetic. Dance is capable of eliciting joy, sorrow, and a wide spectrum of emotions. What aspect of the dance spoke to your personal experiences?

Dance is a beautiful and meaningful stand-alone art. It can be performed without any ancillary arts. But it is also an art that partners successfully with other arts. Costume, scenery, poetry, drama, and music are often a part of the spectacle. As you watch dances this semester be aware of the music, costumes, and staging that help to lend color and meaning to the dance.

In preserving a culture’s dances one is able to preserve its stories and other art forms as well.

People have different ideas about how to define dance. One way to understand dance is to analyze its movement elements: body, energy, space, and time.

We can also study dance in terms of its purpose. Religious dances serve to imitate animals or natural elements, to achieve healing, to commemorate an occasion, or to reach spiritual connection. Social dances can serve in courtship, to find unity in work, unity in war, or camaraderie in the community. Performance dance is created and practiced for presentation to an audience. Western performance dance forms that have developed include ballet, modern, tap, jazz, musical theater, and hip hop. Protest dance can be created to effect social change.

One’s dance aesthetic is shaped and influenced by numerous factors. Family, media, personal response, and kinesthetic response are all contributors to a personal aesthetic.

Safeguarding intangible cultural heritage in education; UNESCO; https://ich.unesco.org/en/education-01017

2 Elements of Dance

Learning Objectives

- Recall the Elements of Dance

- Distinguish between the Elements of Dance

- Analyze, identify, and describe the Elements of Dance

What Are the Elements of Dance?

The Elements of Dance are the basic building blocks of dance that help us identify and describe movement, assisting in the ability to analyze, interpret, and speak/write about dance as an artistic practice. When viewing dance, we want to put into words what we are witnessing by analyzing its most important qualities. The elements of the dance provide us with the tools to do so.

In dance, the body can be in constant motion and even arrive at points of stillness. However, even in stillness, the dancers are inherently aware of themselves. No matter the case, all forms of dance can be broken down into their primary elements: BODY , ENERGY , SPACE , and TIME . To easily remember the dance elements, we use the acronym: B. E. S. T., which stands for BODY , ENERGY , SPACE , and TIME . Dance can be seen as the use of the BODY with different kinds of ENERGY moving through SPACE and unfolding in TIME .

Let’s take a quick look at the elements of dance before we dig in further.

Randy Barron, Teaching Artist on the Kennedy Center’s National Roster, made this video to explain the Elements of Dance:

The body is the dancer’s instrument of expression. When an audience looks at dance, they see the dancer’s body and what is moving. The dance could be made up of a variety of actions and still poses. It could use the whole body or emphasize one part of the body . Exploring body shapes and movement actions increases our awareness of movement possibilities.

Body Shapes

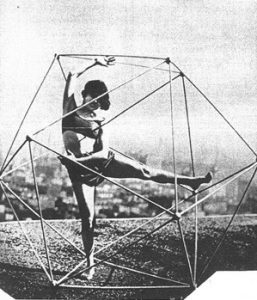

The choreographer who is designing a dance may look at their dancers as sculpture. They choose shapes for the dancers to make with their bodies. These can be curved, straight, angular, twisted, wide, narrow, symmetrical , or asymmetrical . These shapes can be geometric designs, such as circles or diagonals. They could make literal shapes such as tree branches or bird wings. They can also make conceptual shapes (abstract) such as friendship, courage, or sadness. Sometimes a choreographer emphasizes the negative space or the empty area around the dancers’ bodies instead of just the positive space the dancer occupies. Look at the positive and negative spaces in Fig. 2

Body Moves/Actions

Dance movements or actions fall into two main categories:

Locomotor : (traveling moves) walk, run, jump, hop, skip, leap, gallop, crawl, roll, etc.

Nonlocomotor : (moves that stay in place) melt, stretch, bend, twist, swing, turn, shake, stomp, etc.

Below is an example of body movements and shapes by modern dance choreographer Paul Taylor.

Excerpt from modern dance choreographer Paul Taylor’s Esplanade. Observe how the dancers use locomotor movement as they run and form circular formations and create lines in space .

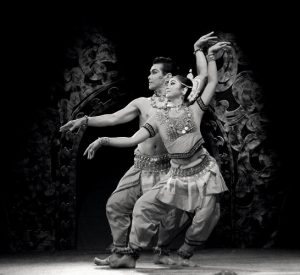

Each part of the body (head, shoulders, elbows, hips, knees, feet, eyes, etc.) can move alone (isolated) or in combination. In the classical Indian dance form Bharatanatyam, dancers stomp their feet in a percussive rhythm. At the same time, the dancer performs mudras, codified hand gestures that are important in the storytelling aspect of Bharatanatyam, to communicate words, concepts, or feelings.

Observe in the video below how the dancer alternately emphasizes her feet and legs with her hand and arm gestures. In classical Indian dance forms, facial expressions and hand gestures play an important role in storytelling.

Excerpt from Pushpanjali, where choreographer Savitha Sastry performs a classical Indian dance solo called Bharatanatyam. Observe how the dancer alternately emphasizes the feet and legs with hand and arm gestures.

In the next video, dancers are participating in the GAGA technique developed by Israeli choreographer Ohad Naharin. In this movement language, dancers are directed to listen to their inner sensations to elicit physical responses and movement. Notice how the dancers are integrating the entire body to create fluid and successive movement.

Check Your Understanding

An exploration of “how” a movement is done rather than “what” it is gives us a richer sense of dance as an expressive art. A dancer can walk, reach for an imaginary object and turn, making these movements look completely different by changing the use of energy . For example, anger could be shown with a loud quick walk, a sharp reach, and a strong twisting turn. Happiness could be depicted by using a delicate gliding walk, a gentle reach out, and a smooth, light turn. energy is what brings the dancer’s intent or emotion to the audience. The element of energy is sometimes called efforts or movement qualities .

Dancer and movement analyst Rudolf Laban broke it down into four efforts , each of which is a pair of opposites:

- Space (direct or indirect use of space ) When the dancer is paying attention to the use of space , they can be direct, single-focused, and targeted in their use of it. Conversely, they can be indirect, multi-focused, and aware of many things in the space around them.

Weight or force (strong or light use of weight) The dancer can emphasize the effort or use of force by fighting against it, throwing their weight and strength into movements. The opposite is using a yielding, light sense of weightlessness in their movements.

- Time (sudden or sustained use of time) Not to be confused with tempo, the dancer’s use of time can be reflected in their movement. It can appear hurried, as though fighting against time. Conversely, the dancer can have a relaxed attitude toward time as though they have all the time in the world.

- Flow (bound or free use of the flow of movement) When the dancer’s flow is bound up, they can appear to be careful and cautious, only allowing small amounts of flow. The opposite is when the dancer appears to throw the movement around without inhibition, letting the movement feel carefree.

Another way we can define energy is by looking at the movement qualities . Movement qualities are energy released during various time-spans to portray distinct qualities. There are six dynamic movement qualities .

- Sustained (slow, smooth, continuous)

- Percussive (sharp, choppy, jagged)

- Swinging (swaying, to and fro, pendulum-like)

- Suspended (a moment of stillness, the high point, a balance)

- Collapsed (fall, release, relax)

- Vibratory (shake, wiggle, tremble)

Notice the kinds of energy the dancers are displaying in the examples below.

In the first video, the dancers are using efforts of direct, strong, sudden and bound movements. In terms of movement qualities , the dancers are using percussive, vibratory , and moments of collapse.

Hip-hop dance crew Kaba Modern use the efforts of direct, strong, sudden, and bound movements. In terms of movement qualities , the dancers use percussive , vibratory , and moments of collapse.

In the National Opera of Ukraine’s preclude from Chopiniana, the dancers are using efforts of light and free movements. The movement qualities are sustained and suspended.

Let’s look at where the dance takes place. Is the dance expansive, using lots of space , or is it more intimate, using primarily personal space? An exploration of space increases our awareness of the visual design aspects of movement.

- Personal Space: The space around the dancer’s body can also be called near space. A dance primarily in personal space can give a feeling of introspection or intimacy.

- Negative Space / Positive Space : Sometimes, a choreographer emphasizes the negative space or the empty area around the dancers’ bodies instead of just the positive space the dancer occupies. Look at the positive and negative space in the photograph below.

- General Space : The defined space where the dancer can move can be a small room, a large stage, or even an outdoor setting.

- Directions : While dances made for the camera often have the performers facing forward as they dance, they can also change directions by turning, going to the back, right, left, up, or down.

- Pathways or Floor Patterns: Where the dancer goes through space is often an important design element. They can travel in a circle, figure eight, spiral, zig-zag, straight lines, and combinations of lines.

Excerpt from George Balanchine’s ballet Apollo. Notice the interlocking of circles of the dancers’ arms and the straight lines made by the dancers’ legs.

In this next video, notice various floor patterns such as circular pathways and straight lines that are made by the group of dancers. Observe the dancers’ use of gestures that go from near to far reach, from personal space to filling the general space. The choreography also uses levels from low to high.

Dance is an art of time ; movement develops and reveals itself in time . Adding a rhythmic sense to movement helps transform ordinary movement into dance and informs when the dancer moves.

- Pulse : The basic pulse or underlying beat

- Speed (tempo): Fast, moderate, slow

- Rhythm Pattern : A grouping of long or short beats, accents, or silences

- Natural Rhythm : Timing which comes from the rhythms of the breath, the heartbeat, or natural sources like the wind or the ocean

- Syncopation : Accents the off-beat in a musical phrase

Compare the different uses of time in the two videos below. In the first video, the dancers have no musical accompaniment and use their breath to initiate movement and cue each other for the timing. Their movement is also slow to moderate in tempo and imitates the natural rhythm of the ocean.

Excerpt from modern dance choreographer Doris Humphrey’s Water Study. In this video, the dancers have no musical accompaniment and use their breath to initiate movement and cue each other for the timing. Their movement is also slow to moderate in tempo and imitates the natural rhythm of the ocean.

Promo clip of Step Afrika!, where the dancers are creating rhythm patterns with body percussion. There is an emphasis on syncopation and varying tempos with accents.

All dance forms share foundational concepts known as the Elements of Dance. The Elements of Dance are overarching concepts and terminology that are useful when observing, creating, analyzing, and discussing dance. Dance can be broken down into its primary elements : Body , Energy , Space , and Time . These can be easily recalled through the acronym B.E.S.T.

The body is the mobile instrument of the dancer and informs what is moving. The body category includes shapes, actions, whole- body , and body -part movements. Energy is how the body moves. When speaking about energy , we can refer to effort or movement qualities. Space is where movement occurs and includes personal and general space , levels , directions , pathways and floor patterns , various sizes of movements, range of movement, and relationships . Time is when the dancers move. The time category includes pulse , speed , rhythmic patterns , natural rhythm , and syncopation.

As an observer of dance, it can be easy to allow our biases to influence how we perceive dance. By using dance vocabulary and stating what we observe, we can be more objective in our discussions of dance. Using the Elements of Dance, we can view dance through an unbiased lens to consider its structural elements and deepen our understanding and appreciation of dance as an art form.

1. Try making shapes that depict literal and abstract concepts. Some examples of literal shapes might be a flower, a seashell, or a rainbow. Some abstract shapes might be circles, diamonds, or even concepts such as friendship, heroism, or depression.

2. Make a short (10 second) dance phrase and perform it twice with two different types of energy.

3. On paper, draw a map with a continuous pathway without lines overlapping. After mapping your pathway, try adding locomotor movements on various levels that complement your pathway design.

4. Make a sentence introducing yourself and your favorite food. For example: “Cissy Whipp likes chips and guacamole.” or “Vanessa Kanamoto likes grilled shrimp.” Now try clapping the rhythm your sentence makes. (Notice how the two examples have very different rhythms.) Create a movement pattern that matches the rhythm pattern of your sentence. Practice until you can repeat it four times in a row.

The Elements of Dance website from Perpich Center for Arts Education in partnership with University of MN Dance Program https://www.elementsofdance.org/

The body is the dancer’s instrument of expression and is the first element of dance. The body is the mobile instrument of the dancer and helps inform us what is moving.

The element of Energy is an exploration of how a movement is done rather than what it is, and gives us a richer sense of dance as an expressive art. When speaking about energy, we can refer to effort or movement qualities.

The element of Space refers to where movement occurs and includes personal and general space, levels, directions, pathways and floor patterns, various sizes of movements, range of movement, and relationships.

The element of Time refers to when the dancers move and how the movement uses time. The Time category includes pulse, speed, rhythmic patterns, natural rhythm, and syncopation.

refers to body designs that use the same shape on both sides of the body, creating balance.

body designs use different shapes from one side of the body to the other, creating an unbalanced look.

is the empty area around the dancers’ bodies.

is the area of space the dancers’ bodies occupy.

movements are movements that travel in space.

movements are those performed in place.

refers to attack-like quality to produce sharp, sudden, and abrupt movements

are a term coined by dancer and movement analyst Rudolf Laban to describe the Movement Qualities or Energy of movement.

are energy released during various time spans to portray distinct qualities.

The element of flow refers to how much effort is exerted by a dancer to control movement. Bound flow has a “fighting-like” quality that is performed in a restrictive manner that is easy to stop. Free flow has a “relaxed-like” quality that is difficult to stop.

movements performed in a slow and smooth continuous rate

movements have a pendular or circular-like quality.

movements occur at the peak of a movement defying gravity before succumbing to it.

is a release of energy from the body.

movements use rapid and repeated bursts of energy.

is the defined space in which the dancer can move.

describe the various heights movement can occur in space.

describe the facing of a performer as they dance or pose. It can be forward, backward, right, left, up, down, or they can also change directions by turning.

are sometimes called Floor Patterns and describe where the dancer goes through space, i.e., curved, straight, circular, diagonal, etc.

of motion refers to how much or how little personal space is used when dancing or posing.

is the immediate area surrounding the body and is described as a three-dimensional volume of space.

refers to the proximity of the dancer to others or to objects in the dance space (in front, behind, over, under, connected, apart).

describe where the dancer goes through space, i.e., curved, straight, circular, diagonal, etc.

the basic pulse or underlying beat of movement and/or music.

also known as tempo, describes the pace of the music or movement.

A grouping of long or short beats, accents or silences.

Timing which comes from the rhythms of the breath, the heartbeat, or natural sources like the wind or the ocean.

accents the off-beat in a musical phrase.

So You Think You Know Dance? Copyright © 2022 by LOUIS: The Louisiana Library Network is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Essay on Dance

500 words essay on dance.

Dancer refers to a series of set of movement to music which we can either do alone or with a partner. Dancing helps us express our feelings and get active as well. If we look back at history, dance has been a part of our human history since the earliest records. Thus, an essay on dance will take us through it in detail.

My Hobby My Passion

Dance is my favourite hobby and I enjoy dancing a lot. I started dancing when I was five years old and when I got older; my parents enrolled me in dance classes to pursue this passion.

I cannot go a day without dance, that’s how much I love dancing. I tried many dance forms but discovered that I am most comfortable in Indian classical dance. Thus, I am learning Kathak from my dance teacher.

I aspire to become a renowned Kathak dancer so that I can represent this classical dance internationally. Dancing makes me feel happy and relaxed, thus I love to dance. I always participate in dance competitions at my school and have even won a few.

Dance became my passion from an early age. Listening to the beats of a dance number, I started to tap my feet and my parents recognized my talent for dance. Even when I am sad, I put on music to dance to vent out my feelings.

Thus, dance has been very therapeutic for me as well. In other words, it is not only an escape from the world but also a therapy for me.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Hidden Language of the Soul

Dance is also called the hidden language of the soul as we use it to express ourselves when words fall short. The joy which comes with dancing helps us get over our sorrow and adversity sometimes.

Moreover, it is simply a translator for our hearts. What is most important to remember is that dance is not supposed to be perfect. There is no right way of dancing, as long as your heart is happy, you can dance.

When we talk about dance, usually a professional dancer comes to our mind. But, this is where we go wrong. Dance is for anybody and everybody from a ballet dancer to the uncle dancing at a wedding .

It is what unites us and helps us come together to celebrate joy and express our feelings. Therefore, we must all dance without worrying if we are doing it right or not. It is essential to understand that when you let go of yourself in dance, you truly enjoy it only then.

Conclusion of the Essay on Dance

All in all, dance is something which anyone can do. There is no right way or wrong way to dance, there is just a dance. The only hard part is taking the first step, after that, everything becomes easier. So, we must always dance our heart out and let our body move to the rhythm of music freely.

FAQ of Essay on Dance

Question 1: Why is Dance important?

Answer 1: Dance teaches us the significance of movement and fitness in a variety of ways through a selection of disciplines. It helps us learn to coordinate muscles to move through proper positions. Moreover, it is a great activity to pursue at almost any age.

Question 2: What is dancing for you?

Answer 2: Dancing can enhance our muscle tone, strength, endurance and fitness. In addition, it is also a great way to meet new friends. Most importantly, it brings happiness to us and helps us relax and take a break from the monotony of life.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

The language of dance

The Language Of Dance

Alexandra L.

Checked : Yusel A. , Greg B.

Latest Update 19 Jan, 2024

Table of content

What constitutes the language of dance?

What influences the language of dance, how to improve one’s learning of this language, try to discover the story, purchase teaching aides, try a fixed schedule for learning, interchange roles.

The language of dance is a unique amalgamation of symbols and expressions manifested through body gestures. It usually takes years of dedicated passion and fusion of mind and body to absorb this language. Dancers take immense pride in sharing this unique language with the viewers and establish secure communication in the process. A deep sense of rhythm is required to master the art seamlessly and do away with all kinds of superficialities that there can be. So, why this language is important?

Many artists use this language as a tool for communication- to express agony, inner lives, political standpoints, feelings, the collective consciousness of a society, and popular stories. With years of constant practice, one can easily add to this vocabulary crucial in learning the language. Dance maintains a holistic approach in helping learners overcome anxiety and low self-esteem through its blend of body movements and expressions. In many instances, such an art form as dance remains pertinent in mastering a second language, effortlessly. Furthermore, the room to explore, know, and reinvent is endless in this sphere of art.

Instructors pass on coded messages through their learners performing on stage. How far the learners are efficient in delivering the message or communicate the meaning to countless viewers decide the fate of a performance. Dance language is not an abstract term but needs an enormous amount of knowledge, practice, and patience to obtain. When dancing in a group, the motto remains to emanate the message collaboratively without letting any hindrances stop the flow of ideas. Each inhibition or stereotype should be chased away in the process of learning and which is further aided by dance instructors.

Components of language are influenced or shaped by cultural influences, society, and dance forms. Avant-garde dance genre uses varied ways of communication confronting the challenges that there might be in exploring the different realms of languages. Each dance form has an inventive and individualised approach of replicating the language on stage, and there are no cons of learning any of the forms. The creative ambition of each dance form is limitless and is garnered by respective instructors who leave no stone unturned to make sure justice is done. Needless to say that each new style has its sense of creativity and language and therefore one is needed to study the form at length. Initially, the process is severe further accentuated by the rich history of each genre that a learner is expected to learn and perform with grace. However, an aspiring instructor could always make the process steady overcoming any weakness or shortcomings whatsoever that a learner can face. While physical fitness is absolutely necessary to hone this language, nothing could substitute hard work and passion required despite hostile circumstances.

In any kind of dance form, the subject of the story to be communicated is significant since it decides the language. For beginners, a lucid and meticulous guide is the stepping stone towards nailing this complicated language and conveying it smoothly to the viewers. No matter what the occasion or obstacles are, these few pro tips would always guide a beginner in capturing the essence of this language and spread it evenly to everyone watching.

Behind every choreography or set of body movements lies a story that needs to be fully comprehended. At first, it might appear a bit strenuous to learn the language, but slowly the meaning could be unearthed. The use of symbols and motifs are prevented since ancient times, and these are to be preserved within oneself while learning. Why because these elements constitute the entirety of dance’s language and help one achieve greater perfection in due course of time. Be it ballet, hip hop, or contemporary, hours should be divested in learning the idea behind the choreography juxtaposed against the music or theme and how they are related to the language.

Many supervisors who focus on this unique concept of language publish materials and schedule workshops for learners. The motto is to render the language understandable to various groups irrespective of their demographic variances. There are multiple levels of learning and are generally decided by the instructor. The guides are essential not just for learning but enhancing one’s creative faculties that would inevitably help one in churning personal creations. It is imperative to start learning the concepts from the very beginning to get rid of future obstacles in the learning process. Symbols and cultural elements in dance forms hold constellation of ideas and give birth to a beautiful language.

We Will Write an Essay for You Quickly

The process of acquiring or imbibing the language of dance was never an easy feat. It requires dedicated repetition where one needs to breakdown the theories and discovers more about the history of these. To do the activities unflinching, instructors always advice in favour of sticking to a schedule that would separate the learning hours from the rest of the events. Each moment spent in learning, one learns, nurtures grows, and rejuvenates. There is no alternative to learning it meticulously in order to pass it on to generations.

In order to learn from different perspectives, interchanging parts among dance partners could be an astounding idea. It is almost impossible and simultaneously flawed to learn the language from a fixed standpoint. It could essentially disfigure the meaning or distort the message that is being conveyed. Learners also tend to lose the creativity or flexibility required for understanding. Therefore, professional dance instructors vote in favour of role interplay to maintain the circulation of ideas and knowledge within one.

Many pedagogical instruments are used for the purpose of teaching, and this might even include stage paraphernalia. The primary goal is to introduce a high level of spontaneity with which performers can deliver the langue and communicate them to the society at large.

Looking for a Skilled Essay Writer?

- University of California, San Diego Doctor of Philosophy

No reviews yet, be the first to write your comment

Write your review

Thanks for review.

It will be published after moderation

Latest News

What happens in the brain when learning?

10 min read

20 Jan, 2024

How Relativism Promotes Pluralism and Tolerance

Everything you need to know about short-term memory

Scholars' Bank

Dance as communication: how humans communicate through dance and perceive dance as communication, description:.

Show full item record

Files in this item

This item appears in the following Collection(s)

- Clark Honors College Theses [1307]

Related items

Showing items related by title, author, creator and subject.

- Consuming Justice: Exploring Tensions Between Environmental Justice and Technology Consumption Through Media Coverage of Electronic Waste, 2002-2013 Wolf-Monteiro, Brenna ( University of Oregon , 2017-09-06 ) The social and environmental impacts of consumer electronics and information communications technologies (CE/ICTs) reflect dynamics of a globalized and interdependent world. During the early 21st century the global consumption ...

- Moving from cantaleta to encanto or challenging the modernization posture in communication for development and social change: A Colombian case study of the everyday work of development communicators Porras, Estella ( University of Oregon , 2008-09 ) The field of international development communication has given scant attention to the role of communication practitioners who are critical players in facilitating participation and community engagement in development. ...

- Saving Polar Bears in the Heartland? Using Framing Theory to Create Regional Environmental Communications Lewman, Hannah Hope ( University of Oregon , 2018-06 ) Despite the overwhelming evidence for anthropogenic (human-caused) climate change, a significant portion of the American public remains unconvinced. This disconnect between scientific certainty and public skepticism calls ...

Search Scholars' Bank

All of scholars' bank.

- By Issue Date

This Collection

- Most Popular Items

- Statistics by Country

- Most Popular Authors

Dance and the Visual Arts

Focusing on works by Trisha Brown, Lin Hwai-Min, Jonah Bokaer, and others, the onstage worlds of eight different dances are examined from a visual perspective.

Introduction: Convergent Histories—Dance and the Visual Arts

The experimental climate of the 1960s and 1970s in the United States is often cited as the midcentury apex for socially transgressive and politically progressive art. Allan Kaprow’s Happenings and the experimental performances of Judson Dance Theater were among the counterculture movements that energized and engendered social, aesthetic, and political challenges to the status quo, questioning formal properties of artmaking. Radical arts practices imploded the boundaries of movement and form, drastically reconfiguring aesthetic conventions in dance and the visual arts. During this period, artists expressed anti-authoritarian commitments by creating works that exposed exclusionary politics at institutional levels. Institutional critiques offered across places of production questioned the right of the establishment to define the limits and location of artmaking, and to determine who qualifies as being an artist. As visual artists began questioning the institutional stronghold of galleries and museums, choreographers challenged the so-called decontextualization of the proscenium stage. Social situations produced by artists in alternative spaces sought to blur art and the everyday, calling upon the energy of civic participation to collectively create and/or sustain the work, while simultaneously reconsidering how bodies within artistic contexts interact with their environments.