Community Blog

Keep up-to-date on postgraduate related issues with our quick reads written by students, postdocs, professors and industry leaders.

Types of Research – Explained with Examples

- By DiscoverPhDs

- October 2, 2020

Types of Research

Research is about using established methods to investigate a problem or question in detail with the aim of generating new knowledge about it.

It is a vital tool for scientific advancement because it allows researchers to prove or refute hypotheses based on clearly defined parameters, environments and assumptions. Due to this, it enables us to confidently contribute to knowledge as it allows research to be verified and replicated.

Knowing the types of research and what each of them focuses on will allow you to better plan your project, utilises the most appropriate methodologies and techniques and better communicate your findings to other researchers and supervisors.

Classification of Types of Research

There are various types of research that are classified according to their objective, depth of study, analysed data, time required to study the phenomenon and other factors. It’s important to note that a research project will not be limited to one type of research, but will likely use several.

According to its Purpose

Theoretical research.

Theoretical research, also referred to as pure or basic research, focuses on generating knowledge , regardless of its practical application. Here, data collection is used to generate new general concepts for a better understanding of a particular field or to answer a theoretical research question.

Results of this kind are usually oriented towards the formulation of theories and are usually based on documentary analysis, the development of mathematical formulas and the reflection of high-level researchers.

Applied Research

Here, the goal is to find strategies that can be used to address a specific research problem. Applied research draws on theory to generate practical scientific knowledge, and its use is very common in STEM fields such as engineering, computer science and medicine.

This type of research is subdivided into two types:

- Technological applied research : looks towards improving efficiency in a particular productive sector through the improvement of processes or machinery related to said productive processes.

- Scientific applied research : has predictive purposes. Through this type of research design, we can measure certain variables to predict behaviours useful to the goods and services sector, such as consumption patterns and viability of commercial projects.

According to your Depth of Scope

Exploratory research.

Exploratory research is used for the preliminary investigation of a subject that is not yet well understood or sufficiently researched. It serves to establish a frame of reference and a hypothesis from which an in-depth study can be developed that will enable conclusive results to be generated.

Because exploratory research is based on the study of little-studied phenomena, it relies less on theory and more on the collection of data to identify patterns that explain these phenomena.

Descriptive Research

The primary objective of descriptive research is to define the characteristics of a particular phenomenon without necessarily investigating the causes that produce it.

In this type of research, the researcher must take particular care not to intervene in the observed object or phenomenon, as its behaviour may change if an external factor is involved.

Explanatory Research

Explanatory research is the most common type of research method and is responsible for establishing cause-and-effect relationships that allow generalisations to be extended to similar realities. It is closely related to descriptive research, although it provides additional information about the observed object and its interactions with the environment.

Correlational Research

The purpose of this type of scientific research is to identify the relationship between two or more variables. A correlational study aims to determine whether a variable changes, how much the other elements of the observed system change.

According to the Type of Data Used

Qualitative research.

Qualitative methods are often used in the social sciences to collect, compare and interpret information, has a linguistic-semiotic basis and is used in techniques such as discourse analysis, interviews, surveys, records and participant observations.

In order to use statistical methods to validate their results, the observations collected must be evaluated numerically. Qualitative research, however, tends to be subjective, since not all data can be fully controlled. Therefore, this type of research design is better suited to extracting meaning from an event or phenomenon (the ‘why’) than its cause (the ‘how’).

Quantitative Research

Quantitative research study delves into a phenomena through quantitative data collection and using mathematical, statistical and computer-aided tools to measure them . This allows generalised conclusions to be projected over time.

According to the Degree of Manipulation of Variables

Experimental research.

It is about designing or replicating a phenomenon whose variables are manipulated under strictly controlled conditions in order to identify or discover its effect on another independent variable or object. The phenomenon to be studied is measured through study and control groups, and according to the guidelines of the scientific method.

Non-Experimental Research

Also known as an observational study, it focuses on the analysis of a phenomenon in its natural context. As such, the researcher does not intervene directly, but limits their involvement to measuring the variables required for the study. Due to its observational nature, it is often used in descriptive research.

Quasi-Experimental Research

It controls only some variables of the phenomenon under investigation and is therefore not entirely experimental. In this case, the study and the focus group cannot be randomly selected, but are chosen from existing groups or populations . This is to ensure the collected data is relevant and that the knowledge, perspectives and opinions of the population can be incorporated into the study.

According to the Type of Inference

Deductive investigation.

In this type of research, reality is explained by general laws that point to certain conclusions; conclusions are expected to be part of the premise of the research problem and considered correct if the premise is valid and the inductive method is applied correctly.

Inductive Research

In this type of research, knowledge is generated from an observation to achieve a generalisation. It is based on the collection of specific data to develop new theories.

Hypothetical-Deductive Investigation

It is based on observing reality to make a hypothesis, then use deduction to obtain a conclusion and finally verify or reject it through experience.

According to the Time in Which it is Carried Out

Longitudinal study (also referred to as diachronic research).

It is the monitoring of the same event, individual or group over a defined period of time. It aims to track changes in a number of variables and see how they evolve over time. It is often used in medical, psychological and social areas .

Cross-Sectional Study (also referred to as Synchronous Research)

Cross-sectional research design is used to observe phenomena, an individual or a group of research subjects at a given time.

According to The Sources of Information

Primary research.

This fundamental research type is defined by the fact that the data is collected directly from the source, that is, it consists of primary, first-hand information.

Secondary research

Unlike primary research, secondary research is developed with information from secondary sources, which are generally based on scientific literature and other documents compiled by another researcher.

According to How the Data is Obtained

Documentary (cabinet).

Documentary research, or secondary sources, is based on a systematic review of existing sources of information on a particular subject. This type of scientific research is commonly used when undertaking literature reviews or producing a case study.

Field research study involves the direct collection of information at the location where the observed phenomenon occurs.

From Laboratory

Laboratory research is carried out in a controlled environment in order to isolate a dependent variable and establish its relationship with other variables through scientific methods.

Mixed-Method: Documentary, Field and/or Laboratory

Mixed research methodologies combine results from both secondary (documentary) sources and primary sources through field or laboratory research.

Academic conferences are expensive and it can be tough finding the funds to go; this naturally leads to the question of are academic conferences worth it?

The term research instrument refers to any tool that you may use to collect, measure and analyse research data.

PhD stress is real. Learn how to combat it with these 5 tips.

Join thousands of other students and stay up to date with the latest PhD programmes, funding opportunities and advice.

Browse PhDs Now

An In Press article is a paper that has been accepted for publication and is being prepared for print.

A well written figure legend will explain exactly what a figure means without having to refer to the main text. Our guide explains how to write one.

Nina’s in the first year of her PhD in the Department of Psychology at the University of Bath. Her project is focused on furthering our understanding of fatigue within adolescent depression.

Ellen is in the third year of her PhD at the University of Oxford. Her project looks at eighteenth-century reading manuals, using them to find out how eighteenth-century people theorised reading aloud.

Join Thousands of Students

Research Design 101

Everything You Need To Get Started (With Examples)

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewers: Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) & Kerryn Warren (PhD) | April 2023

Navigating the world of research can be daunting, especially if you’re a first-time researcher. One concept you’re bound to run into fairly early in your research journey is that of “ research design ”. Here, we’ll guide you through the basics using practical examples , so that you can approach your research with confidence.

Overview: Research Design 101

What is research design.

- Research design types for quantitative studies

- Video explainer : quantitative research design

- Research design types for qualitative studies

- Video explainer : qualitative research design

- How to choose a research design

- Key takeaways

Research design refers to the overall plan, structure or strategy that guides a research project , from its conception to the final data analysis. A good research design serves as the blueprint for how you, as the researcher, will collect and analyse data while ensuring consistency, reliability and validity throughout your study.

Understanding different types of research designs is essential as helps ensure that your approach is suitable given your research aims, objectives and questions , as well as the resources you have available to you. Without a clear big-picture view of how you’ll design your research, you run the risk of potentially making misaligned choices in terms of your methodology – especially your sampling , data collection and data analysis decisions.

The problem with defining research design…

One of the reasons students struggle with a clear definition of research design is because the term is used very loosely across the internet, and even within academia.

Some sources claim that the three research design types are qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods , which isn’t quite accurate (these just refer to the type of data that you’ll collect and analyse). Other sources state that research design refers to the sum of all your design choices, suggesting it’s more like a research methodology . Others run off on other less common tangents. No wonder there’s confusion!

In this article, we’ll clear up the confusion. We’ll explain the most common research design types for both qualitative and quantitative research projects, whether that is for a full dissertation or thesis, or a smaller research paper or article.

Research Design: Quantitative Studies

Quantitative research involves collecting and analysing data in a numerical form. Broadly speaking, there are four types of quantitative research designs: descriptive , correlational , experimental , and quasi-experimental .

Descriptive Research Design

As the name suggests, descriptive research design focuses on describing existing conditions, behaviours, or characteristics by systematically gathering information without manipulating any variables. In other words, there is no intervention on the researcher’s part – only data collection.

For example, if you’re studying smartphone addiction among adolescents in your community, you could deploy a survey to a sample of teens asking them to rate their agreement with certain statements that relate to smartphone addiction. The collected data would then provide insight regarding how widespread the issue may be – in other words, it would describe the situation.

The key defining attribute of this type of research design is that it purely describes the situation . In other words, descriptive research design does not explore potential relationships between different variables or the causes that may underlie those relationships. Therefore, descriptive research is useful for generating insight into a research problem by describing its characteristics . By doing so, it can provide valuable insights and is often used as a precursor to other research design types.

Correlational Research Design

Correlational design is a popular choice for researchers aiming to identify and measure the relationship between two or more variables without manipulating them . In other words, this type of research design is useful when you want to know whether a change in one thing tends to be accompanied by a change in another thing.

For example, if you wanted to explore the relationship between exercise frequency and overall health, you could use a correlational design to help you achieve this. In this case, you might gather data on participants’ exercise habits, as well as records of their health indicators like blood pressure, heart rate, or body mass index. Thereafter, you’d use a statistical test to assess whether there’s a relationship between the two variables (exercise frequency and health).

As you can see, correlational research design is useful when you want to explore potential relationships between variables that cannot be manipulated or controlled for ethical, practical, or logistical reasons. It is particularly helpful in terms of developing predictions , and given that it doesn’t involve the manipulation of variables, it can be implemented at a large scale more easily than experimental designs (which will look at next).

That said, it’s important to keep in mind that correlational research design has limitations – most notably that it cannot be used to establish causality . In other words, correlation does not equal causation . To establish causality, you’ll need to move into the realm of experimental design, coming up next…

Need a helping hand?

Experimental Research Design

Experimental research design is used to determine if there is a causal relationship between two or more variables . With this type of research design, you, as the researcher, manipulate one variable (the independent variable) while controlling others (dependent variables). Doing so allows you to observe the effect of the former on the latter and draw conclusions about potential causality.

For example, if you wanted to measure if/how different types of fertiliser affect plant growth, you could set up several groups of plants, with each group receiving a different type of fertiliser, as well as one with no fertiliser at all. You could then measure how much each plant group grew (on average) over time and compare the results from the different groups to see which fertiliser was most effective.

Overall, experimental research design provides researchers with a powerful way to identify and measure causal relationships (and the direction of causality) between variables. However, developing a rigorous experimental design can be challenging as it’s not always easy to control all the variables in a study. This often results in smaller sample sizes , which can reduce the statistical power and generalisability of the results.

Moreover, experimental research design requires random assignment . This means that the researcher needs to assign participants to different groups or conditions in a way that each participant has an equal chance of being assigned to any group (note that this is not the same as random sampling ). Doing so helps reduce the potential for bias and confounding variables . This need for random assignment can lead to ethics-related issues . For example, withholding a potentially beneficial medical treatment from a control group may be considered unethical in certain situations.

Quasi-Experimental Research Design

Quasi-experimental research design is used when the research aims involve identifying causal relations , but one cannot (or doesn’t want to) randomly assign participants to different groups (for practical or ethical reasons). Instead, with a quasi-experimental research design, the researcher relies on existing groups or pre-existing conditions to form groups for comparison.

For example, if you were studying the effects of a new teaching method on student achievement in a particular school district, you may be unable to randomly assign students to either group and instead have to choose classes or schools that already use different teaching methods. This way, you still achieve separate groups, without having to assign participants to specific groups yourself.

Naturally, quasi-experimental research designs have limitations when compared to experimental designs. Given that participant assignment is not random, it’s more difficult to confidently establish causality between variables, and, as a researcher, you have less control over other variables that may impact findings.

All that said, quasi-experimental designs can still be valuable in research contexts where random assignment is not possible and can often be undertaken on a much larger scale than experimental research, thus increasing the statistical power of the results. What’s important is that you, as the researcher, understand the limitations of the design and conduct your quasi-experiment as rigorously as possible, paying careful attention to any potential confounding variables .

Research Design: Qualitative Studies

There are many different research design types when it comes to qualitative studies, but here we’ll narrow our focus to explore the “Big 4”. Specifically, we’ll look at phenomenological design, grounded theory design, ethnographic design, and case study design.

Phenomenological Research Design

Phenomenological design involves exploring the meaning of lived experiences and how they are perceived by individuals. This type of research design seeks to understand people’s perspectives , emotions, and behaviours in specific situations. Here, the aim for researchers is to uncover the essence of human experience without making any assumptions or imposing preconceived ideas on their subjects.

For example, you could adopt a phenomenological design to study why cancer survivors have such varied perceptions of their lives after overcoming their disease. This could be achieved by interviewing survivors and then analysing the data using a qualitative analysis method such as thematic analysis to identify commonalities and differences.

Phenomenological research design typically involves in-depth interviews or open-ended questionnaires to collect rich, detailed data about participants’ subjective experiences. This richness is one of the key strengths of phenomenological research design but, naturally, it also has limitations. These include potential biases in data collection and interpretation and the lack of generalisability of findings to broader populations.

Grounded Theory Research Design

Grounded theory (also referred to as “GT”) aims to develop theories by continuously and iteratively analysing and comparing data collected from a relatively large number of participants in a study. It takes an inductive (bottom-up) approach, with a focus on letting the data “speak for itself”, without being influenced by preexisting theories or the researcher’s preconceptions.

As an example, let’s assume your research aims involved understanding how people cope with chronic pain from a specific medical condition, with a view to developing a theory around this. In this case, grounded theory design would allow you to explore this concept thoroughly without preconceptions about what coping mechanisms might exist. You may find that some patients prefer cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) while others prefer to rely on herbal remedies. Based on multiple, iterative rounds of analysis, you could then develop a theory in this regard, derived directly from the data (as opposed to other preexisting theories and models).

Grounded theory typically involves collecting data through interviews or observations and then analysing it to identify patterns and themes that emerge from the data. These emerging ideas are then validated by collecting more data until a saturation point is reached (i.e., no new information can be squeezed from the data). From that base, a theory can then be developed .

As you can see, grounded theory is ideally suited to studies where the research aims involve theory generation , especially in under-researched areas. Keep in mind though that this type of research design can be quite time-intensive , given the need for multiple rounds of data collection and analysis.

Ethnographic Research Design

Ethnographic design involves observing and studying a culture-sharing group of people in their natural setting to gain insight into their behaviours, beliefs, and values. The focus here is on observing participants in their natural environment (as opposed to a controlled environment). This typically involves the researcher spending an extended period of time with the participants in their environment, carefully observing and taking field notes .

All of this is not to say that ethnographic research design relies purely on observation. On the contrary, this design typically also involves in-depth interviews to explore participants’ views, beliefs, etc. However, unobtrusive observation is a core component of the ethnographic approach.

As an example, an ethnographer may study how different communities celebrate traditional festivals or how individuals from different generations interact with technology differently. This may involve a lengthy period of observation, combined with in-depth interviews to further explore specific areas of interest that emerge as a result of the observations that the researcher has made.

As you can probably imagine, ethnographic research design has the ability to provide rich, contextually embedded insights into the socio-cultural dynamics of human behaviour within a natural, uncontrived setting. Naturally, however, it does come with its own set of challenges, including researcher bias (since the researcher can become quite immersed in the group), participant confidentiality and, predictably, ethical complexities . All of these need to be carefully managed if you choose to adopt this type of research design.

Case Study Design

With case study research design, you, as the researcher, investigate a single individual (or a single group of individuals) to gain an in-depth understanding of their experiences, behaviours or outcomes. Unlike other research designs that are aimed at larger sample sizes, case studies offer a deep dive into the specific circumstances surrounding a person, group of people, event or phenomenon, generally within a bounded setting or context .

As an example, a case study design could be used to explore the factors influencing the success of a specific small business. This would involve diving deeply into the organisation to explore and understand what makes it tick – from marketing to HR to finance. In terms of data collection, this could include interviews with staff and management, review of policy documents and financial statements, surveying customers, etc.

While the above example is focused squarely on one organisation, it’s worth noting that case study research designs can have different variation s, including single-case, multiple-case and longitudinal designs. As you can see in the example, a single-case design involves intensely examining a single entity to understand its unique characteristics and complexities. Conversely, in a multiple-case design , multiple cases are compared and contrasted to identify patterns and commonalities. Lastly, in a longitudinal case design , a single case or multiple cases are studied over an extended period of time to understand how factors develop over time.

As you can see, a case study research design is particularly useful where a deep and contextualised understanding of a specific phenomenon or issue is desired. However, this strength is also its weakness. In other words, you can’t generalise the findings from a case study to the broader population. So, keep this in mind if you’re considering going the case study route.

How To Choose A Research Design

Having worked through all of these potential research designs, you’d be forgiven for feeling a little overwhelmed and wondering, “ But how do I decide which research design to use? ”. While we could write an entire post covering that alone, here are a few factors to consider that will help you choose a suitable research design for your study.

Data type: The first determining factor is naturally the type of data you plan to be collecting – i.e., qualitative or quantitative. This may sound obvious, but we have to be clear about this – don’t try to use a quantitative research design on qualitative data (or vice versa)!

Research aim(s) and question(s): As with all methodological decisions, your research aim and research questions will heavily influence your research design. For example, if your research aims involve developing a theory from qualitative data, grounded theory would be a strong option. Similarly, if your research aims involve identifying and measuring relationships between variables, one of the experimental designs would likely be a better option.

Time: It’s essential that you consider any time constraints you have, as this will impact the type of research design you can choose. For example, if you’ve only got a month to complete your project, a lengthy design such as ethnography wouldn’t be a good fit.

Resources: Take into account the resources realistically available to you, as these need to factor into your research design choice. For example, if you require highly specialised lab equipment to execute an experimental design, you need to be sure that you’ll have access to that before you make a decision.

Keep in mind that when it comes to research, it’s important to manage your risks and play as conservatively as possible. If your entire project relies on you achieving a huge sample, having access to niche equipment or holding interviews with very difficult-to-reach participants, you’re creating risks that could kill your project. So, be sure to think through your choices carefully and make sure that you have backup plans for any existential risks. Remember that a relatively simple methodology executed well generally will typically earn better marks than a highly-complex methodology executed poorly.

Recap: Key Takeaways

We’ve covered a lot of ground here. Let’s recap by looking at the key takeaways:

- Research design refers to the overall plan, structure or strategy that guides a research project, from its conception to the final analysis of data.

- Research designs for quantitative studies include descriptive , correlational , experimental and quasi-experimenta l designs.

- Research designs for qualitative studies include phenomenological , grounded theory , ethnographic and case study designs.

- When choosing a research design, you need to consider a variety of factors, including the type of data you’ll be working with, your research aims and questions, your time and the resources available to you.

If you need a helping hand with your research design (or any other aspect of your research), check out our private coaching services .

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

10 Comments

Is there any blog article explaining more on Case study research design? Is there a Case study write-up template? Thank you.

Thanks this was quite valuable to clarify such an important concept.

Thanks for this simplified explanations. it is quite very helpful.

This was really helpful. thanks

Thank you for your explanation. I think case study research design and the use of secondary data in researches needs to be talked about more in your videos and articles because there a lot of case studies research design tailored projects out there.

Please is there any template for a case study research design whose data type is a secondary data on your repository?

This post is very clear, comprehensive and has been very helpful to me. It has cleared the confusion I had in regard to research design and methodology.

This post is helpful, easy to understand, and deconstructs what a research design is. Thanks

how to cite this page

Thank you very much for the post. It is wonderful and has cleared many worries in my mind regarding research designs. I really appreciate .

how can I put this blog as my reference(APA style) in bibliography part?

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

News alert: UC Berkeley has announced its next university librarian

Secondary menu

- Log in to your Library account

- Hours and Maps

- Connect from Off Campus

- UC Berkeley Home

Search form

Research methods--quantitative, qualitative, and more: overview.

- Quantitative Research

- Qualitative Research

- Data Science Methods (Machine Learning, AI, Big Data)

- Text Mining and Computational Text Analysis

- Evidence Synthesis/Systematic Reviews

- Get Data, Get Help!

About Research Methods

This guide provides an overview of research methods, how to choose and use them, and supports and resources at UC Berkeley.

As Patten and Newhart note in the book Understanding Research Methods , "Research methods are the building blocks of the scientific enterprise. They are the "how" for building systematic knowledge. The accumulation of knowledge through research is by its nature a collective endeavor. Each well-designed study provides evidence that may support, amend, refute, or deepen the understanding of existing knowledge...Decisions are important throughout the practice of research and are designed to help researchers collect evidence that includes the full spectrum of the phenomenon under study, to maintain logical rules, and to mitigate or account for possible sources of bias. In many ways, learning research methods is learning how to see and make these decisions."

The choice of methods varies by discipline, by the kind of phenomenon being studied and the data being used to study it, by the technology available, and more. This guide is an introduction, but if you don't see what you need here, always contact your subject librarian, and/or take a look to see if there's a library research guide that will answer your question.

Suggestions for changes and additions to this guide are welcome!

START HERE: SAGE Research Methods

Without question, the most comprehensive resource available from the library is SAGE Research Methods. HERE IS THE ONLINE GUIDE to this one-stop shopping collection, and some helpful links are below:

- SAGE Research Methods

- Little Green Books (Quantitative Methods)

- Little Blue Books (Qualitative Methods)

- Dictionaries and Encyclopedias

- Case studies of real research projects

- Sample datasets for hands-on practice

- Streaming video--see methods come to life

- Methodspace- -a community for researchers

- SAGE Research Methods Course Mapping

Library Data Services at UC Berkeley

Library Data Services Program and Digital Scholarship Services

The LDSP offers a variety of services and tools ! From this link, check out pages for each of the following topics: discovering data, managing data, collecting data, GIS data, text data mining, publishing data, digital scholarship, open science, and the Research Data Management Program.

Be sure also to check out the visual guide to where to seek assistance on campus with any research question you may have!

Library GIS Services

Other Data Services at Berkeley

D-Lab Supports Berkeley faculty, staff, and graduate students with research in data intensive social science, including a wide range of training and workshop offerings Dryad Dryad is a simple self-service tool for researchers to use in publishing their datasets. It provides tools for the effective publication of and access to research data. Geospatial Innovation Facility (GIF) Provides leadership and training across a broad array of integrated mapping technologies on campu Research Data Management A UC Berkeley guide and consulting service for research data management issues

General Research Methods Resources

Here are some general resources for assistance:

- Assistance from ICPSR (must create an account to access): Getting Help with Data , and Resources for Students

- Wiley Stats Ref for background information on statistics topics

- Survey Documentation and Analysis (SDA) . Program for easy web-based analysis of survey data.

Consultants

- D-Lab/Data Science Discovery Consultants Request help with your research project from peer consultants.

- Research data (RDM) consulting Meet with RDM consultants before designing the data security, storage, and sharing aspects of your qualitative project.

- Statistics Department Consulting Services A service in which advanced graduate students, under faculty supervision, are available to consult during specified hours in the Fall and Spring semesters.

Related Resourcex

- IRB / CPHS Qualitative research projects with human subjects often require that you go through an ethics review.

- OURS (Office of Undergraduate Research and Scholarships) OURS supports undergraduates who want to embark on research projects and assistantships. In particular, check out their "Getting Started in Research" workshops

- Sponsored Projects Sponsored projects works with researchers applying for major external grants.

- Next: Quantitative Research >>

- Last Updated: Apr 25, 2024 11:09 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/researchmethods

Cookies on this website

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. If you click 'Accept all cookies' we'll assume that you are happy to receive all cookies and you won't see this message again. If you click 'Reject all non-essential cookies' only necessary cookies providing core functionality such as security, network management, and accessibility will be enabled. Click 'Find out more' for information on how to change your cookie settings.

Study designs

This short article gives a brief guide to the different study types and a comparison of the advantages and disadvantages.

See also Levels of Evidence

These study designs all have similar components (as we’d expect from the PICO):

- A defined population (P) from which groups of subjects are studied

- Outcomes (O) that are measured

And for experimental and analytic observational studies:

- Interventions (I) or exposures (E) that are applied to different groups of subjects

Overview of the design tree

Figure 1 shows the tree of possible designs, branching into subgroups of study designs by whether the studies are descriptive or analytic and by whether the analytic studies are experimental or observational. The list is not completely exhaustive but covers most basics designs.

Figure: Tree of different types of studies (Q1, 2, and 3 refer to the three questions below)

> Download a PDF by Jeremy Howick about study designs

Our first distinction is whether the study is analytic or non-analytic. A non-analytic or descriptive study does not try to quantify the relationship but tries to give us a picture of what is happening in a population, e.g., the prevalence, incidence, or experience of a group. Descriptive studies include case reports, case-series, qualitative studies and surveys (cross-sectional) studies, which measure the frequency of several factors, and hence the size of the problem. They may sometimes also include analytic work (comparing factors “” see below).

An analytic study attempts to quantify the relationship between two factors, that is, the effect of an intervention (I) or exposure (E) on an outcome (O). To quantify the effect we will need to know the rate of outcomes in a comparison (C) group as well as the intervention or exposed group. Whether the researcher actively changes a factor or imposes uses an intervention determines whether the study is considered to be observational (passive involvement of researcher), or experimental (active involvement of researcher).

In experimental studies, the researcher manipulates the exposure, that is he or she allocates subjects to the intervention or exposure group. Experimental studies, or randomised controlled trials (RCTs), are similar to experiments in other areas of science. That is, subjects are allocated to two or more groups to receive an intervention or exposure and then followed up under carefully controlled conditions. Such studies controlled trials, particularly if randomised and blinded, have the potential to control for most of the biases that can occur in scientific studies but whether this actually occurs depends on the quality of the study design and implementation.

In analytic observational studies, the researcher simply measures the exposure or treatments of the groups. Analytical observational studies include case””control studies, cohort studies and some population (cross-sectional) studies. These studies all include matched groups of subjects and assess of associations between exposures and outcomes.

Observational studies investigate and record exposures (such as interventions or risk factors) and observe outcomes (such as disease) as they occur. Such studies may be purely descriptive or more analytical.

We should finally note that studies can incorporate several design elements. For example, a the control arm of a randomised trial may also be used as a cohort study; and the baseline measures of a cohort study may be used as a cross-sectional study.

Spotting the study design

The type of study can generally be worked at by looking at three issues (as per the Tree of design in Figure 1):

Q1. What was the aim of the study?

- To simply describe a population (PO questions) descriptive

- To quantify the relationship between factors (PICO questions) analytic.

Q2. If analytic, was the intervention randomly allocated?

- No? Observational study

For observational study the main types will then depend on the timing of the measurement of outcome, so our third question is:

Q3. When were the outcomes determined?

- Some time after the exposure or intervention? cohort study (‘prospective study’)

- At the same time as the exposure or intervention? cross sectional study or survey

- Before the exposure was determined? case-control study (‘retrospective study’ based on recall of the exposure)

Advantages and Disadvantages of the Designs

Randomised Controlled Trial

An experimental comparison study in which participants are allocated to treatment/intervention or control/placebo groups using a random mechanism (see randomisation). Best for study the effect of an intervention.

Advantages:

- unbiased distribution of confounders;

- blinding more likely;

- randomisation facilitates statistical analysis.

Disadvantages:

- expensive: time and money;

- volunteer bias;

- ethically problematic at times.

Crossover Design

A controlled trial where each study participant has both therapies, e.g, is randomised to treatment A first, at the crossover point they then start treatment B. Only relevant if the outcome is reversible with time, e.g, symptoms.

- all subjects serve as own controls and error variance is reduced thus reducing sample size needed;

- all subjects receive treatment (at least some of the time);

- statistical tests assuming randomisation can be used;

- blinding can be maintained.

- all subjects receive placebo or alternative treatment at some point;

- washout period lengthy or unknown;

- cannot be used for treatments with permanent effects

Cohort Study

Data are obtained from groups who have been exposed, or not exposed, to the new technology or factor of interest (eg from databases). No allocation of exposure is made by the researcher. Best for study the effect of predictive risk factors on an outcome.

- ethically safe;

- subjects can be matched;

- can establish timing and directionality of events;

- eligibility criteria and outcome assessments can be standardised;

- administratively easier and cheaper than RCT.

- controls may be difficult to identify;

- exposure may be linked to a hidden confounder;

- blinding is difficult;

- randomisation not present;

- for rare disease, large sample sizes or long follow-up necessary.

Case-Control Studies

Patients with a certain outcome or disease and an appropriate group of controls without the outcome or disease are selected (usually with careful consideration of appropriate choice of controls, matching, etc) and then information is obtained on whether the subjects have been exposed to the factor under investigation.

- quick and cheap;

- only feasible method for very rare disorders or those with long lag between exposure and outcome;

- fewer subjects needed than cross-sectional studies.

- reliance on recall or records to determine exposure status;

- confounders;

- selection of control groups is difficult;

- potential bias: recall, selection.

Cross-Sectional Survey

A study that examines the relationship between diseases (or other health-related characteristics) and other variables of interest as they exist in a defined population at one particular time (ie exposure and outcomes are both measured at the same time). Best for quantifying the prevalence of a disease or risk factor, and for quantifying the accuracy of a diagnostic test.

- cheap and simple;

- ethically safe.

- establishes association at most, not causality;

- recall bias susceptibility;

- confounders may be unequally distributed;

- Neyman bias;

- group sizes may be unequal.

Public Health Doctoral Studies (PhD and DrPH): Types of Studies

- Searching the Literature

- Find Articles

- Methodology

- Grey Literature

- Test/Survey/Measurement Tools

- Types of Studies

- Workshops & Special Events

- Writing Support

- Literature Review Videos/Tutorials

- Citation Support

- Formatting Your Paper

- Ordering from your Home Library

Study Definitions

Meta-Analysis

A quantitative method of combining the results of independent studies, which are drawn from the published literature, and synthesizing summaries and conclusions.

Systematic Review

A review which endeavors to consider all published and unpublished material on a specific question. Studies that are judged methodologically sound are then combined quantitatively or qualitatively depending on their similarity.

Randomized Control Trial (RCT)

A clinical trial involving one or more new treatments and at least one control treatment with specified outcome measures for evaluating the intervention. The treatment may be a drug, device, or procedure. Controls are either placebo or an active treatment that is currently considered the "gold standard". If patients are randomized via mathmatical techniques then the trial is designated as a randomized controlled trial.

Cohort Study

In cohort studies, groups of individuals, who are initially free of disease, are classified according to exposure or non-exposure to a risk factor and followed over time to determine the incidence of an outcome of interest. In a prospective cohort study, the exposure information for the study subjects is collected at the start of the study and the new cases of disease are identified from that point on. In a retrospective cohort study, the exposure status was measured in the past and disease identification has already begun.

Case-Control Study

Studies that start by identifying persons with and without a disease of interest (cases and controls, respectively) and then look back in time to find differences in exposure to risk factors.

Cross-Sectional Study

Studies in which the presence or absence of disease or other health-related variables are determined in each member of a population at one particular time.

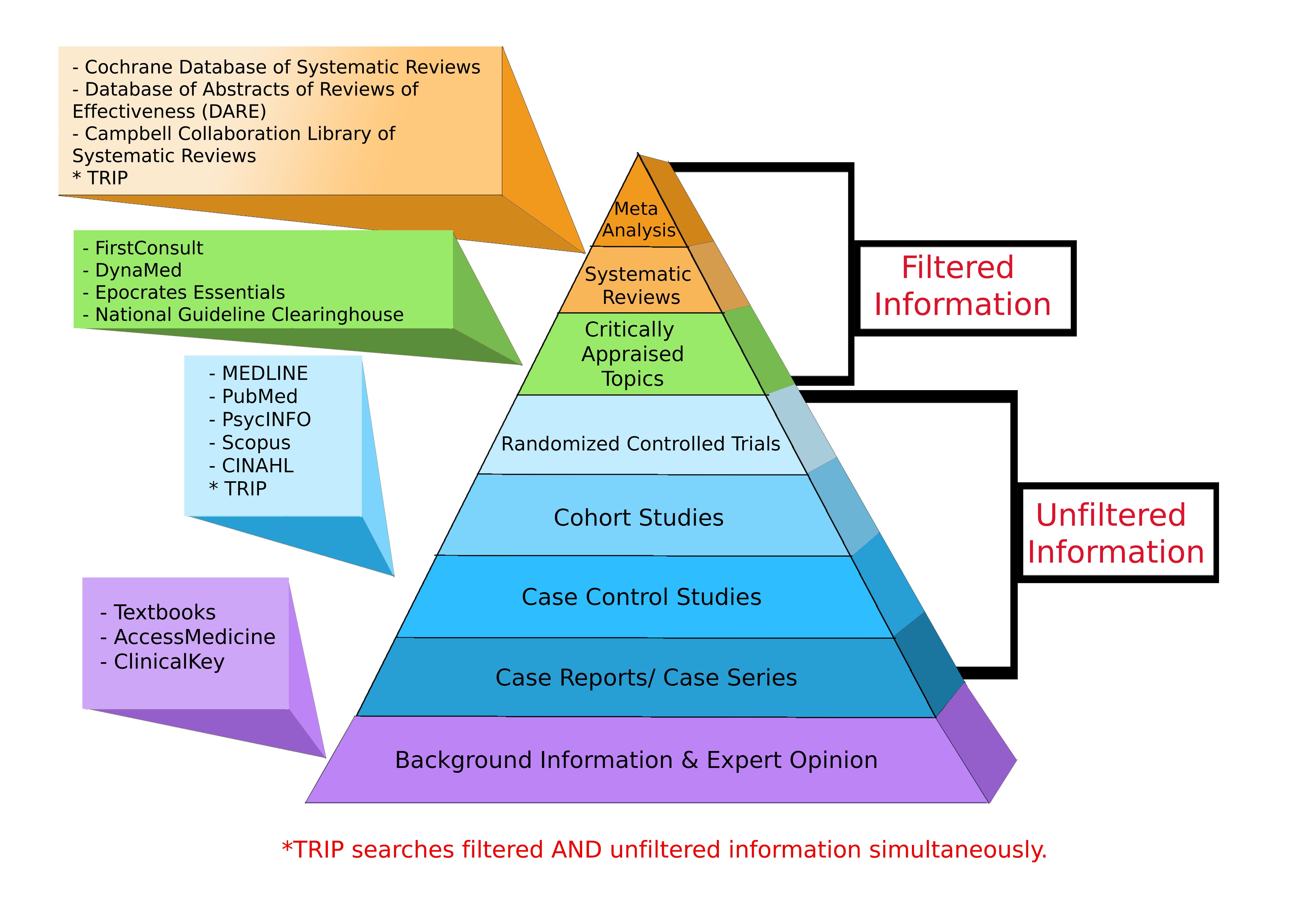

Levels of Evidence Pyramid

Levels of Evidence Pyramid created by Andy Puro, September 2014

Experimental vs. Observational Studies

An observational study is a study in which the investigator cannot control the assignment of treatment to subjects because the participants or conditions are not being directly assigned by the researcher.

- Examines predetermined treatments, interventions, policies, and their effects

- Four main types: case-series , case-control , cross-sectional , and cohort studies

In an experimental study , the investigators directly manipulate or assign participants to different interventions or environments.

- Controlled trials - studies in which the experimental drug or procedure is compared with another drug or procedure

- Uncontrolled trials - studies in which the investigators' experience with the experimental drug or procedure is described, but the treatment is not compared with another treatment

Formal Trials versus Observational Studies (Ravi Thadhani, Harvard Medical School)

Study Designs (Centre for Evidence Based Medicine, University of Oxford)

Learn about Clinical Studies (ClinicalTrials.gov, National Institutes of Health)

Definitions taken from: Dawson B, Trapp R.G. (2004). Chapter 2. Study Designs in Medical Research. In Dawson B, Trapp R.G. (Eds), Basic & Clinical Biostatistics, 4e Retrieved September 15, 2014 from http://accessmedicine.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=356&Sectionid=40086281.

- << Previous: Test/Survey/Measurement Tools

- Next: Statistics >>

- Last Updated: Apr 8, 2024 10:53 AM

- URL: https://guides.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/PhD

- Himmelfarb Intranet

- Privacy Notice

- Terms of Use

- GW is committed to digital accessibility. If you experience a barrier that affects your ability to access content on this page, let us know via the Accessibility Feedback Form .

- Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library

- 2300 Eye St., NW, Washington, DC 20037

- Phone: (202) 994-2850

- [email protected]

- https://himmelfarb.gwu.edu

- En español – ExME

- Em português – EME

An introduction to different types of study design

Posted on 6th April 2021 by Hadi Abbas

Study designs are the set of methods and procedures used to collect and analyze data in a study.

Broadly speaking, there are 2 types of study designs: descriptive studies and analytical studies.

Descriptive studies

- Describes specific characteristics in a population of interest

- The most common forms are case reports and case series

- In a case report, we discuss our experience with the patient’s symptoms, signs, diagnosis, and treatment

- In a case series, several patients with similar experiences are grouped.

Analytical Studies

Analytical studies are of 2 types: observational and experimental.

Observational studies are studies that we conduct without any intervention or experiment. In those studies, we purely observe the outcomes. On the other hand, in experimental studies, we conduct experiments and interventions.

Observational studies

Observational studies include many subtypes. Below, I will discuss the most common designs.

Cross-sectional study:

- This design is transverse where we take a specific sample at a specific time without any follow-up

- It allows us to calculate the frequency of disease ( p revalence ) or the frequency of a risk factor

- This design is easy to conduct

- For example – if we want to know the prevalence of migraine in a population, we can conduct a cross-sectional study whereby we take a sample from the population and calculate the number of patients with migraine headaches.

Cohort study:

- We conduct this study by comparing two samples from the population: one sample with a risk factor while the other lacks this risk factor

- It shows us the risk of developing the disease in individuals with the risk factor compared to those without the risk factor ( RR = relative risk )

- Prospective : we follow the individuals in the future to know who will develop the disease

- Retrospective : we look to the past to know who developed the disease (e.g. using medical records)

- This design is the strongest among the observational studies

- For example – to find out the relative risk of developing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) among smokers, we take a sample including smokers and non-smokers. Then, we calculate the number of individuals with COPD among both.

Case-Control Study:

- We conduct this study by comparing 2 groups: one group with the disease (cases) and another group without the disease (controls)

- This design is always retrospective

- We aim to find out the odds of having a risk factor or an exposure if an individual has a specific disease (Odds ratio)

- Relatively easy to conduct

- For example – we want to study the odds of being a smoker among hypertensive patients compared to normotensive ones. To do so, we choose a group of patients diagnosed with hypertension and another group that serves as the control (normal blood pressure). Then we study their smoking history to find out if there is a correlation.

Experimental Studies

- Also known as interventional studies

- Can involve animals and humans

- Pre-clinical trials involve animals

- Clinical trials are experimental studies involving humans

- In clinical trials, we study the effect of an intervention compared to another intervention or placebo. As an example, I have listed the four phases of a drug trial:

I: We aim to assess the safety of the drug ( is it safe ? )

II: We aim to assess the efficacy of the drug ( does it work ? )

III: We want to know if this drug is better than the old treatment ( is it better ? )

IV: We follow-up to detect long-term side effects ( can it stay in the market ? )

- In randomized controlled trials, one group of participants receives the control, while the other receives the tested drug/intervention. Those studies are the best way to evaluate the efficacy of a treatment.

Finally, the figure below will help you with your understanding of different types of study designs.

References (pdf)

You may also be interested in the following blogs for further reading:

An introduction to randomized controlled trials

Case-control and cohort studies: a brief overview

Cohort studies: prospective and retrospective designs

Prevalence vs Incidence: what is the difference?

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

No Comments on An introduction to different types of study design

you are amazing one!! if I get you I’m working with you! I’m student from Ethiopian higher education. health sciences student

Very informative and easy understandable

You are my kind of doctor. Do not lose sight of your objective.

Wow very erll explained and easy to understand

I’m Khamisu Habibu community health officer student from Abubakar Tafawa Balewa university teaching hospital Bauchi, Nigeria, I really appreciate your write up and you have make it clear for the learner. thank you

well understood,thank you so much

Well understood…thanks

Simply explained. Thank You.

Thanks a lot for this nice informative article which help me to understand different study designs that I felt difficult before

That’s lovely to hear, Mona, thank you for letting the author know how useful this was. If there are any other particular topics you think would be useful to you, and are not already on the website, please do let us know.

it is very informative and useful.

thank you statistician

Fabulous to hear, thank you John.

Thanks for this information

Thanks so much for this information….I have clearly known the types of study design Thanks

That’s so good to hear, Mirembe, thank you for letting the author know.

Very helpful article!! U have simplified everything for easy understanding

I’m a health science major currently taking statistics for health care workers…this is a challenging class…thanks for the simified feedback.

That’s good to hear this has helped you. Hopefully you will find some of the other blogs useful too. If you see any topics that are missing from the website, please do let us know!

Hello. I liked your presentation, the fact that you ranked them clearly is very helpful to understand for people like me who is a novelist researcher. However, I was expecting to read much more about the Experimental studies. So please direct me if you already have or will one day. Thank you

Dear Ay. My sincere apologies for not responding to your comment sooner. You may find it useful to filter the blogs by the topic of ‘Study design and research methods’ – here is a link to that filter: https://s4be.cochrane.org/blog/topic/study-design/ This will cover more detail about experimental studies. Or have a look on our library page for further resources there – you’ll find that on the ‘Resources’ drop down from the home page.

However, if there are specific things you feel you would like to learn about experimental studies, that are missing from the website, it would be great if you could let me know too. Thank you, and best of luck. Emma

Great job Mr Hadi. I advise you to prepare and study for the Australian Medical Board Exams as soon as you finish your undergrad study in Lebanon. Good luck and hope we can meet sometime in the future. Regards ;)

You have give a good explaination of what am looking for. However, references am not sure of where to get them from.

Subscribe to our newsletter

You will receive our monthly newsletter and free access to Trip Premium.

Related Articles

Cluster Randomized Trials: Concepts

This blog summarizes the concepts of cluster randomization, and the logistical and statistical considerations while designing a cluster randomized controlled trial.

Expertise-based Randomized Controlled Trials

This blog summarizes the concepts of Expertise-based randomized controlled trials with a focus on the advantages and challenges associated with this type of study.

A well-designed cohort study can provide powerful results. This blog introduces prospective and retrospective cohort studies, discussing the advantages, disadvantages and use of these type of study designs.

Types of Research Studies and How To Interpret Them

The field of nutrition is dynamic, and our understanding and practices are always evolving. Nutrition scientists are continuously conducting new research and publishing their findings in peer-reviewed journals. This adds to scientific knowledge, but it’s also of great interest to the public, so nutrition research often shows up in the news and other media sources. You might be interested in nutrition research to inform your own eating habits, or if you work in a health profession, so that you can give evidence-based advice to others. Making sense of science requires that you understand the types of research studies used and their limitations.

The Hierarchy of Nutrition Evidence

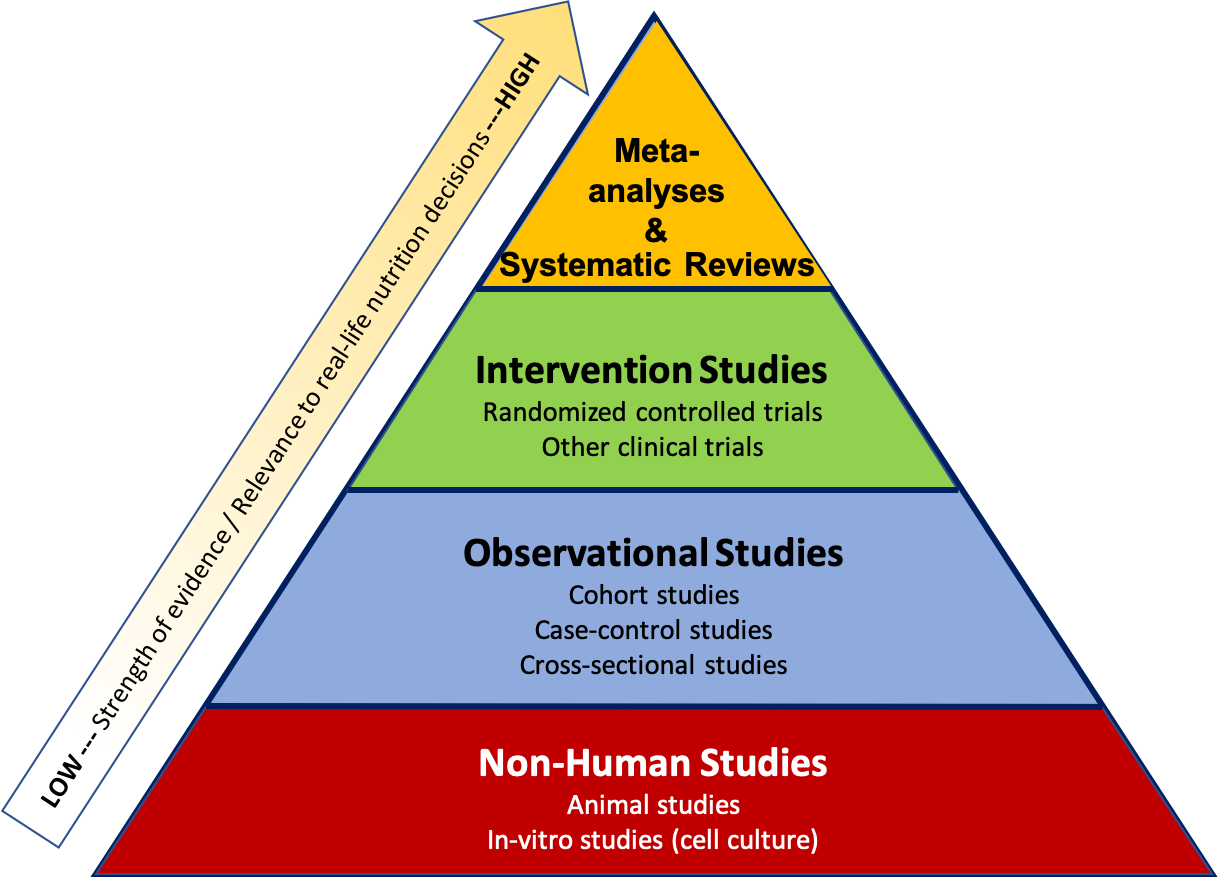

Researchers use many different types of study designs depending on the question they are trying to answer, as well as factors such as time, funding, and ethical considerations. The study design affects how we interpret the results and the strength of the evidence as it relates to real-life nutrition decisions. It can be helpful to think about the types of studies within a pyramid representing a hierarchy of evidence, where the studies at the bottom of the pyramid usually give us the weakest evidence with the least relevance to real-life nutrition decisions, and the studies at the top offer the strongest evidence, with the most relevance to real-life nutrition decisions .

Figure 2.3. The hierarchy of evidence shows types of research studies relative to their strength of evidence and relevance to real-life nutrition decisions, with the strongest studies at the top and the weakest at the bottom.

The pyramid also represents a few other general ideas. There tend to be more studies published using the methods at the bottom of the pyramid, because they require less time, money, and other resources. When researchers want to test a new hypothesis , they often start with the study designs at the bottom of the pyramid , such as in vitro, animal, or observational studies. Intervention studies are more expensive and resource-intensive, so there are fewer of these types of studies conducted. But they also give us higher quality evidence, so they’re an important next step if observational and non-human studies have shown promising results. Meta-analyses and systematic reviews combine the results of many studies already conducted, so they help researchers summarize scientific knowledge on a topic.

Non-Human Studies: In Vitro & Animal Studies

The simplest form of nutrition research is an in vitro study . In vitro means “within glass,” (although plastic is used more commonly today) and these experiments are conducted within flasks, dishes, plates, and test tubes. These studies are performed on isolated cells or tissue samples, so they’re less expensive and time-intensive than animal or human studies. In vitro studies are vital for zooming in on biological mechanisms, to see how things work at the cellular or molecular level. However, these studies shouldn’t be used to draw conclusions about how things work in humans (or even animals), because we can’t assume that the results will apply to a whole, living organism.

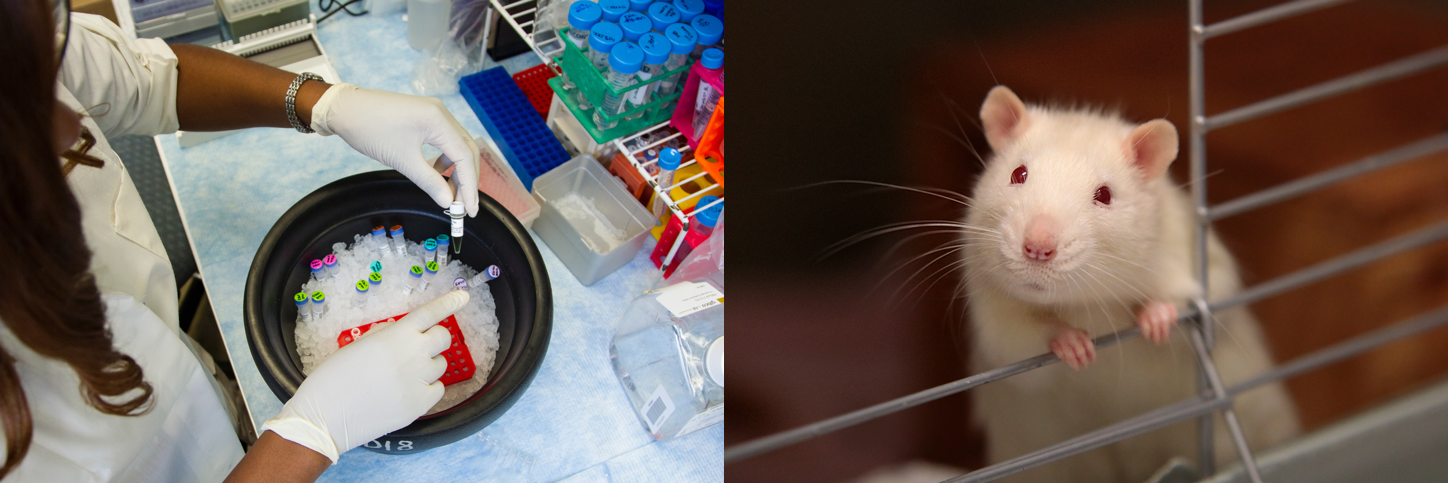

Animal studies are one form of in vivo research, which translates to “within the living.” Rats and mice are the most common animals used in nutrition research. Animals are often used in research that would be unethical to conduct in humans. Another advantage of animal dietary studies is that researchers can control exactly what the animals eat. In human studies, researchers can tell subjects what to eat and even provide them with the food, but they may not stick to the planned diet. People are also not very good at estimating, recording, or reporting what they eat and in what quantities. In addition, animal studies typically do not cost as much as human studies.

There are some important limitations of animal research. First, an animal’s metabolism and physiology are different from humans. Plus, animal models of disease (cancer, cardiovascular disease, etc.), although similar, are different from human diseases. Animal research is considered preliminary, and while it can be very important to the process of building scientific understanding and informing the types of studies that should be conducted in humans, animal studies shouldn’t be considered relevant to real-life decisions about how people eat.

Observational Studies

Observational studies in human nutrition collect information on people’s dietary patterns or nutrient intake and look for associations with health outcomes. Observational studies do not give participants a treatment or intervention; instead, they look at what they’re already doing and see how it relates to their health. These types of study designs can only identify correlations (relationships) between nutrition and health; they can’t show that one factor causes another. (For that, we need intervention studies, which we’ll discuss in a moment.) Observational studies that describe factors correlated with human health are also called epidemiological studies . 1

One example of a nutrition hypothesis that has been investigated using observational studies is that eating a Mediterranean diet reduces the risk of developing cardiovascular disease. (A Mediterranean diet focuses on whole grains, fruits and vegetables, beans and other legumes, nuts, olive oil, herbs, and spices. It includes small amounts of animal protein (mostly fish), dairy, and red wine. 2 ) There are three main types of observational studies, all of which could be used to test hypotheses about the Mediterranean diet:

- Cohort studies follow a group of people (a cohort) over time, measuring factors such as diet and health outcomes. A cohort study of the Mediterranean diet would ask a group of people to describe their diet, and then researchers would track them over time to see if those eating a Mediterranean diet had a lower incidence of cardiovascular disease.

- Case-control studies compare a group of cases and controls, looking for differences between the two groups that might explain their different health outcomes. For example, researchers might compare a group of people with cardiovascular disease with a group of healthy controls to see whether there were more controls or cases that followed a Mediterranean diet.

- Cross-sectional studies collect information about a population of people at one point in time. For example, a cross-sectional study might compare the dietary patterns of people from different countries to see if diet correlates with the prevalence of cardiovascular disease in the different countries.

Prospective cohort studies, which enroll a cohort and follow them into the future, are usually considered the strongest type of observational study design. Retrospective studies look at what happened in the past, and they’re considered weaker because they rely on people’s memory of what they ate or how they felt in the past. There are several well-known examples of prospective cohort studies that have described important correlations between diet and disease:

- Framingham Heart Study : Beginning in 1948, this study has followed the residents of Framingham, Massachusetts to identify risk factors for heart disease.

- Health Professionals Follow-Up Study : This study started in 1986 and enrolled 51,529 male health professionals (dentists, pharmacists, optometrists, osteopathic physicians, podiatrists, and veterinarians), who complete diet questionnaires every 2 years.

- Nurses Health Studies : Beginning in 1976, these studies have enrolled three large cohorts of nurses with a total of 280,000 participants. Participants have completed detailed questionnaires about diet, other lifestyle factors (smoking and exercise, for example), and health outcomes.

Observational studies have the advantage of allowing researchers to study large groups of people in the real world, looking at the frequency and pattern of health outcomes and identifying factors that correlate with them. But even very large observational studies may not apply to the population as a whole. For example, the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study and the Nurses Health Studies include people with above-average knowledge of health. In many ways, this makes them ideal study subjects, because they may be more motivated to be part of the study and to fill out detailed questionnaires for years. However, the findings of these studies may not apply to people with less baseline knowledge of health.

We’ve already mentioned another important limitation of observational studies—that they can only determine correlation, not causation. A prospective cohort study that finds that people eating a Mediterranean diet have a lower incidence of heart disease can only show that the Mediterranean diet is correlated with lowered risk of heart disease. It can’t show that the Mediterranean diet directly prevents heart disease. Why? There are a huge number of factors that determine health outcomes such as heart disease, and other factors might explain a correlation found in an observational study. For example, people who eat a Mediterranean diet might also be the same kind of people who exercise more, sleep more, have higher income (fish and nuts can be expensive!), or be less stressed. These are called confounding factors ; they’re factors that can affect the outcome in question (i.e., heart disease) and also vary with the factor being studied (i.e., Mediterranean diet).

Intervention Studies

Intervention studies , also sometimes called experimental studies or clinical trials, include some type of treatment or change imposed by the researcher. Examples of interventions in nutrition research include asking participants to change their diet, take a supplement, or change the time of day that they eat. Unlike observational studies, intervention studies can provide evidence of cause and effect , so they are higher in the hierarchy of evidence pyramid.

The gold standard for intervention studies is the randomized controlled trial (RCT) . In an RCT, study subjects are recruited to participate in the study. They are then randomly assigned into one of at least two groups, one of which is a control group (this is what makes the study controlled ). In an RCT to study the effects of the Mediterranean diet on cardiovascular disease development, researchers might ask the control group to follow a low-fat diet (typically recommended for heart disease prevention) and the intervention group to eat a Mediterrean diet. The study would continue for a defined period of time (usually years to study an outcome like heart disease), at which point the researchers would analyze their data to see if more people in the control or Mediterranean diet had heart attacks or strokes. Because the treatment and control groups were randomly assigned, they should be alike in every other way except for diet, so differences in heart disease could be attributed to the diet. This eliminates the problem of confounding factors found in observational research, and it’s why RCTs can provide evidence of causation, not just correlation.

Imagine for a moment what would happen if the two groups weren’t randomly assigned. What if the researchers let study participants choose which diet they’d like to adopt for the study? They might, for whatever reason, end up with more overweight people who smoke and have high blood pressure in the low-fat diet group, and more people who exercised regularly and had already been eating lots of olive oil and nuts for years in the Mediterranean diet group. If they found that the Mediterranean diet group had fewer heart attacks by the end of the study, they would have no way of knowing if this was because of the diet or because of the underlying differences in the groups. In other words, without randomization, their results would be compromised by confounding factors, with many of the same limitations as observational studies.

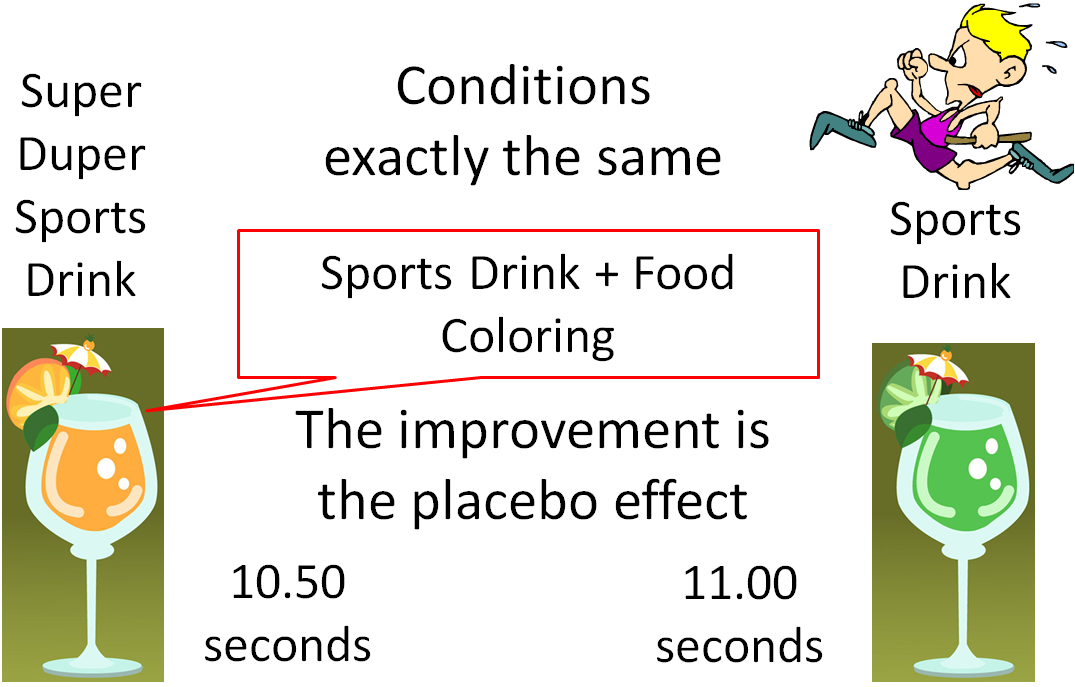

In an RCT of a supplement, the control group would receive a placebo —a “fake” treatment that contains no active ingredients, such as a sugar pill. The use of a placebo is necessary in medical research because of a phenomenon known as the placebo effect. The placebo effect results in a beneficial effect because of a subject’s belief in the treatment, even though there is no treatment actually being administered.

For example, imagine an athlete who consumes a sports drink and then runs 100 meters in 11.0 seconds. On a different day, under the exact same conditions, the athlete is given a Super Duper Sports Drink and again runs 100 meters, this time in 10.5 seconds. But what the athlete didn’t know was that the Super Duper Sports Drink was the same as the regular sports drink—it just had a bit of food coloring added. There was nothing different between the drinks, but the athlete believed that the Super Duper Sports Drink was going to help him run faster, so he did. This improvement is due to the placebo effect. Ironically, a study similar to this example was published in 2015, demonstrating the power of the placebo effect on athletic performance. 3

Figure 2.4. An example of the placebo effect

Blinding is a technique to prevent bias in intervention studies. In a study without blinding, the subject and the researchers both know what treatment the subject is receiving. This can lead to bias if the subject or researcher have expectations about the treatment working, so these types of trials are used less frequently. It’s best if a study is double-blind , meaning that neither the researcher nor the subject know what treatment the subject is receiving. It’s relatively simple to double-blind a study where subjects are receiving a placebo or treatment pill, because they could be formulated to look and taste the same. In a single-blind study , either the researcher or the subject knows what treatment they’re receiving, but not both. Studies of diets—such as the Mediterranean diet example—often can’t be double-blinded because the study subjects know whether or not they’re eating a lot of olive oil and nuts. However, the researchers who are checking participants’ blood pressure or evaluating their medical records could be blinded to their treatment group, reducing the chance of bias.

Like all studies, RCTs and other intervention studies do have some limitations. They can be difficult to carry on for long periods of time and require that participants remain compliant with the intervention. They’re also costly and often have smaller sample sizes. Furthermore, it is unethical to study certain interventions. (An example of an unethical intervention would be to advise one group of pregnant mothers to drink alcohol to determine its effects on pregnancy outcomes, because we know that alcohol consumption during pregnancy damages the developing fetus.)

VIDEO: “ Not all scientific studies are created equal ” by David H. Schwartz, YouTube (April 28, 2014), 4:26.

Meta-Analyses and Systematic Reviews

At the top of the hierarchy of evidence pyramid are systematic reviews and meta-analyses . You can think of these as “studies of studies.” They attempt to combine all of the relevant studies that have been conducted on a research question and summarize their overall conclusions. Researchers conducting a systematic review formulate a research question and then systematically and independently identify, select, evaluate, and synthesize all high-quality evidence that relates to the research question. Since systematic reviews combine the results of many studies, they help researchers produce more reliable findings. A meta-analysis is a type of systematic review that goes one step further, combining the data from multiple studies and using statistics to summarize it, as if creating a mega-study from many smaller studies . 4

However, even systematic reviews and meta-analyses aren’t the final word on scientific questions. For one thing, they’re only as good as the studies that they include. The Cochrane Collaboration is an international consortium of researchers who conduct systematic reviews in order to inform evidence-based healthcare, including nutrition, and their reviews are among the most well-regarded and rigorous in science. For the most recent Cochrane review of the Mediterranean diet and cardiovascular disease, two authors independently reviewed studies published on this question. Based on their inclusion criteria, 30 RCTs with a total of 12,461 participants were included in the final analysis. However, after evaluating and combining the data, the authors concluded that “despite the large number of included trials, there is still uncertainty regarding the effects of a Mediterranean‐style diet on cardiovascular disease occurrence and risk factors in people both with and without cardiovascular disease already.” Part of the reason for this uncertainty is that different trials found different results, and the quality of the studies was low to moderate. Some had problems with their randomization procedures, for example, and others were judged to have unreliable data. That doesn’t make them useless, but it adds to the uncertainty about this question, and uncertainty pushes the field forward towards more and better studies. The Cochrane review authors noted that they found seven ongoing trials of the Mediterranean diet, so we can hope that they’ll add more clarity to this question in the future. 5

Science is an ongoing process. It’s often a slow process, and it contains a lot of uncertainty, but it’s our best method of building knowledge of how the world and human life works. Many different types of studies can contribute to scientific knowledge. None are perfect—all have limitations—and a single study is never the final word on a scientific question. Part of what advances science is that researchers are constantly checking each other’s work, asking how it can be improved and what new questions it raises.

Self-Check:

Attributions:

- “Chapter 1: The Basics” from Lindshield, B. L. Kansas State University Human Nutrition (FNDH 400) Flexbook. goo.gl/vOAnR , CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

- “ The Broad Role of Nutritional Science ,” section 1.3 from the book An Introduction to Nutrition (v. 1.0), CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

References:

- 1 Thiese, M. S. (2014). Observational and interventional study design types; an overview. Biochemia Medica , 24 (2), 199–210. https://doi.org/10.11613/BM.2014.022

- 2 Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. (2018, January 16). Diet Review: Mediterranean Diet . The Nutrition Source. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/healthy-weight/diet-reviews/mediterranean-diet/

- 3 Ross, R., Gray, C. M., & Gill, J. M. R. (2015). Effects of an Injected Placebo on Endurance Running Performance. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise , 47 (8), 1672–1681. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000000584

- 4 Hooper, A. (n.d.). LibGuides: Systematic Review Resources: Systematic Reviews vs Other Types of Reviews . Retrieved February 7, 2020, from //libguides.sph.uth.tmc.edu/c.php?g=543382&p=5370369

- 5 Rees, K., Takeda, A., Martin, N., Ellis, L., Wijesekara, D., Vepa, A., Das, A., Hartley, L., & Stranges, S. (2019). Mediterranean‐style diet for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews , 3 . https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009825.pub3

- Figure 2.3. The hierarchy of evidence by Alice Callahan, is licensed under CC BY 4.0

- Research lab photo by National Cancer Institute on Unsplas h ; mouse photo by vaun0815 on Unsplash

- Figure 2.4. “Placebo effect example” by Lindshield, B. L. Kansas State University Human Nutrition (FNDH 400) Flexbook. goo.gl/vOAnR

Experiments that are conducted outside of living organisms, within flasks, dishes, plates, or test tubes.

Research that is conducted in living organisms, such as rats and mice.

In nutrition, research that is conducted by collecting information on people’s dietary patterns or nutrient intake to look for associations with health outcomes. Observational studies do not give participants a treatment or intervention; instead, they look at what they’re already doing and see how it relates to their health.

Relationships between two factors (e.g., nutrition and health).

Research that follows a group of people (a cohort) over time, measuring factors such as diet and health outcomes.

Research that compares a group of cases and controls, looking for differences between the two groups that might explain their different health outcomes.

Research that collects information about a population of people at one point in time.

Looking into the future.

Looking at what happened in the past.

Factors that can affect the outcome in question.

Research that includes some type of treatment or change imposed by the researchers; sometimes called experimental studies or clinical trials.

The gold standard for intervention studies, because the research involves a control group and participants are randomized.

A “fake” treatment that contains no active ingredients, such as a sugar pill.

The beneficial effect that results from a subject's belief in a treatment, not from the treatment itself.

technique to prevent bias in intervention studies, where either the research team, the subject, or both don’t know what treatment the subject is receiving.

Neither the research team nor the subject know what treatment the subject is receiving.