documentary

What is Design Thinking in Education?

In a world where artificial intelligence, exemplified by tools like ChatGPT, is reshaping our world, the human touch of design thinking becomes even more crucial. You might already be familiar with design thinking and curious about how to harness it alongside AI, or perhaps you’re new to this method. Regardless of your experience level, I’m going to share why design thinking is your human advantage in an AI-world. We’ll explore its impact on students and educators, particularly when integrated into the curriculum to design learning experiences that are both innovative and empathetic.

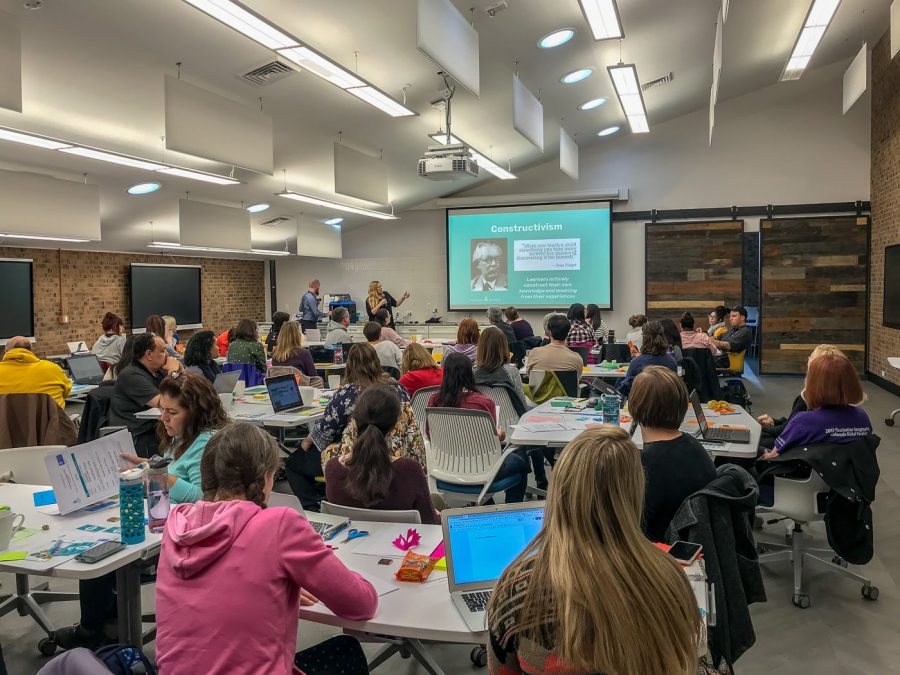

Back in 2017, I spearheaded a two-year research study at Design39 Campus in San Diego, CA, focusing on how educators used design thinking to transcend traditional educational practices. This study was pivotal in understanding how to scale from pockets of innovation to a culture of innovation. It’s rare to see a public school integrate these practices, and I always wondered, “Why is this the exception and not the norm?” How might design thinking when combined with AI tools, complement standards-based curricula by prompting students to tackle real-world challenges. We investigated the methods educators used to learn about design thinking and how they crafted learning experiences at the nexus of knowledge, skills, and mindsets, aiming to foster creative problem-solving in an increasingly AI-integrated world. The results revealed it had nothing to do with the technology. It had to do with people.

Design thinking is both a method and a mindset.

What makes design thinking unique in comparison to other frameworks such as project based learning, is that in addition to skills there is an emphasis on developing mindsets such as empathy, creative confidence, learning from failure and optimism.

Seeing their students and themselves enhance and develop their skills and mindset of a design thinker demonstrated the value in using design thinking and fueled their motivation to continue. In addition, it strengthened their self-efficacy and helped them embrace, not fear change.

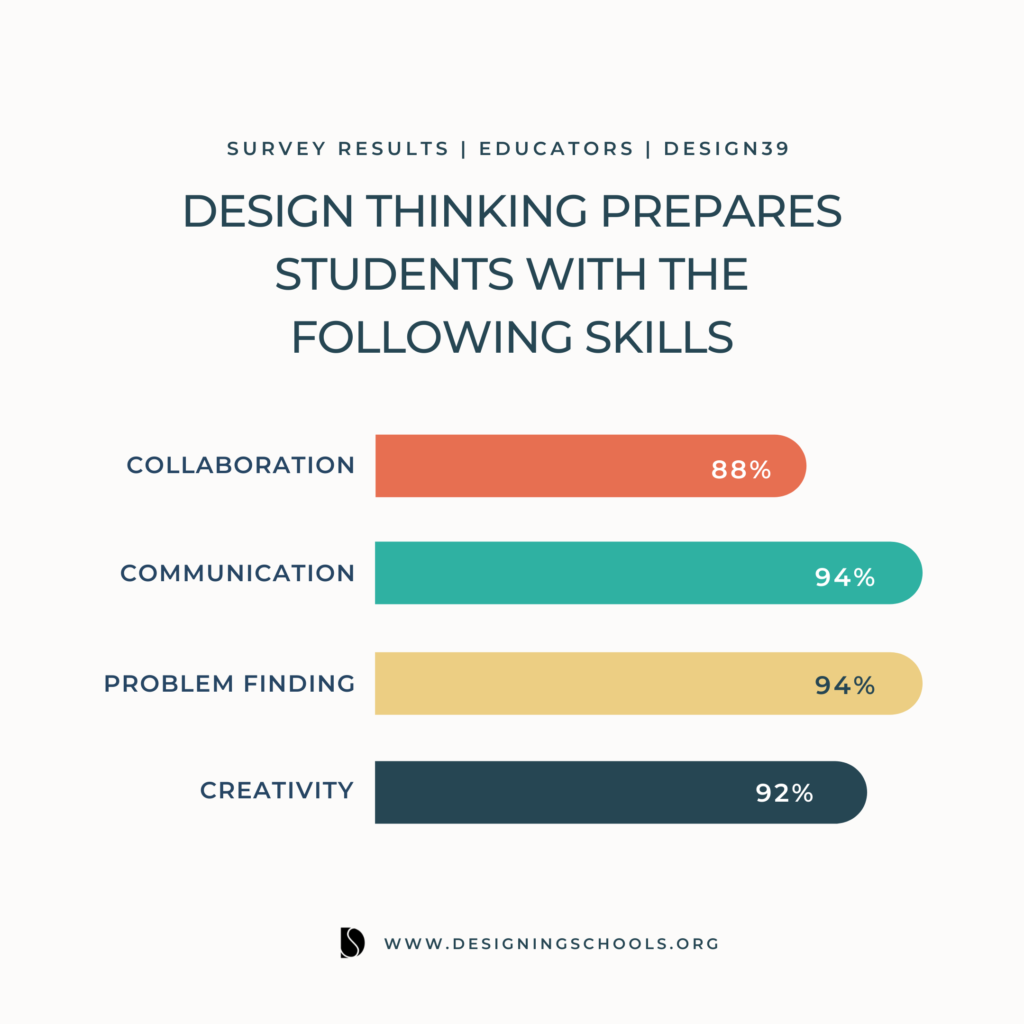

The results indicate strong agreement amongst the educators between developing in demand skills such as creativity, problem finding, collaboration and communication and practicing design thinking.

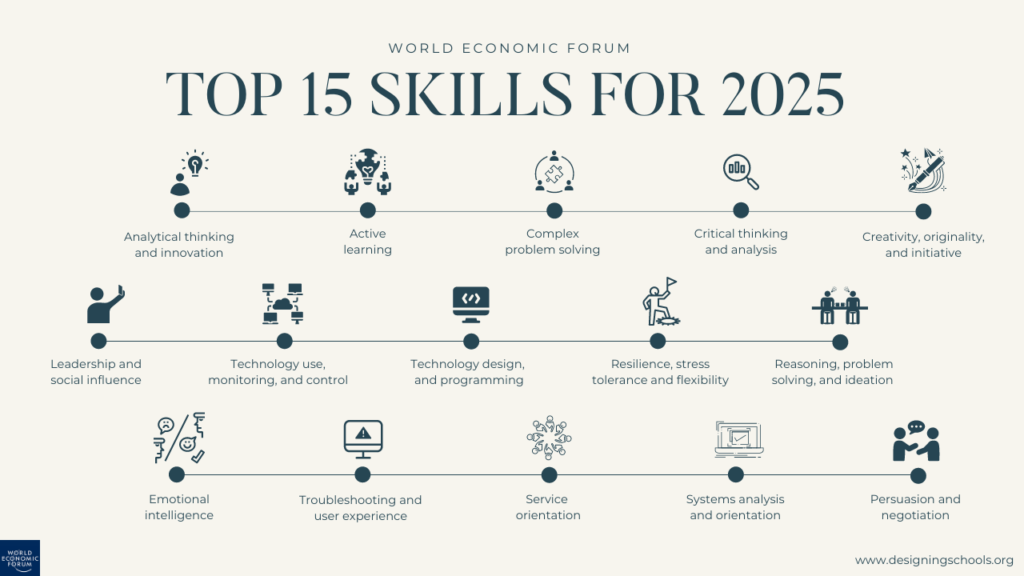

As workplaces determine how to leverage new and emerging technologies in ways that serve humanity, the two critical skills expected will be the ability to solve unstructured problems and to engage in complex communication, two areas that allow workers to augment what machines can do (Levy & Murnane, 2013.)

Brynjolfsson and McAfee (2014) call this era, “The Second Machine Age,” characterized by advances in technology, such as the rise of big data, mobility, artificial intelligence, robotics and the internet of things. The World Economic Forum calls this era, “The Fourth Industrial Revolution.”

Regardless of the name we give this era, Schwab warned, as did Brynjolfsson and McAfee, that failure by organizations to prepare and adapt could cause inequality and fragment societies.

That era that we once talked about, is not here.

The rise of generative Ai.

As Erik Brynjolfsson shares, “There is no economic law that says as technology advances, so does equal opportunity.” The World Economic Forum reinforces this by sharing, that while the dynamics of today’s world have the potential to create enormous prosperity, the challenge to societies, particularly businesses, governments and education systems, will be to create access to opportunities that will allow everyone to share in the prosperity.

Schwab, Brynjolfsson and McAfee advocate for schools being able to play a powerful role in shaping a future that is technology-driven and human-centered. Design thinking, a human-centered framework is one method that can provide educators with the skills and mindset to navigate away from the traditional model established during the industrial area. To a learner-centered vision where we design learning experiences at the intersection of knowledge, skills, and mindsets.

The Future of Work

Designing schools for today’s learner is not just about solving a workforce or technology challenge. It’s also about solving a human challenge, where every individual has the access and opportunity to reach their potential.

Despite the changing expectations of the workplace brought forth by this era, today’s education systems largely remain unchanged. Leaving graduates without the knowledge, skills and mindsets to thrive in future workplaces and as citizens. Furthermore, the lack of equity has led to what Paul Attewell calls a growing digital use divide deepening the fragmentation of society.

A decade ago, some of the most in-demand occupations or specialties today did not exist across many industries and countries. Furthermore, 60% of children in kindergarten will live in a world where the possible opportunities do not yet exist (World Economic Forum, 2017).

In Technology, Jobs and the Future of Work, McKinsey states that 60% of all occupations have at least 30% of activities that can be automated. 40% of employers say lack of skills is the main reason for entry level job vacancies. And 60% of new graduates said they were not prepared for the world of work in a knowledge economy, noting gaps in technical and soft skills. Before our experience with ChatGPT I’m reminded of Imaginable by Jane McGonigal where she shares, “Almost everything important that’s ever happened, was unimaginable shortly before it happened.”

With an influx of technology over the past decade, with iPads and Chromebooks, and now the acceleration of AI technology, particularly over the past year, we have to wonder what gaps exist that prevent us from accelerating and scaling the change we want to see in schools.

One reason is that this challenge is complex and overwhelming. This is where design thinking practices are helpful in moving from idea to impact. Design thinking practices provide the structure and scaffolds needed to take a complex idea and simplify it.

The Design Thinking Process

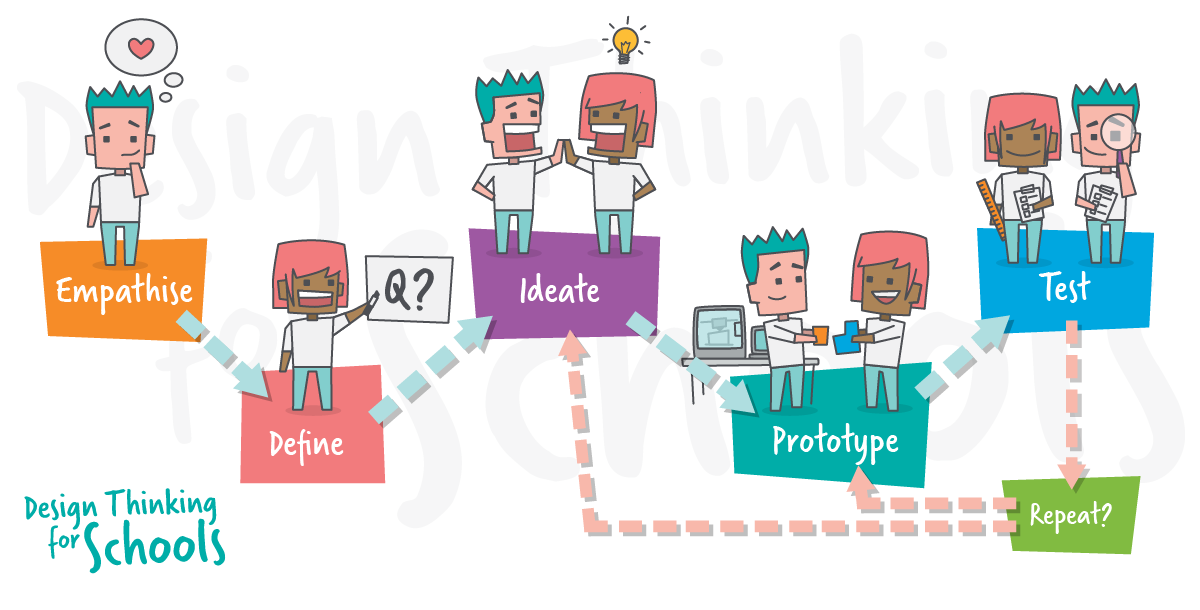

Too often design thinking is seen as a series of hexagons to jump through. Check off one and move onto the next. Design thinking is a non-linear framework that nurtures your mindset toward navigating change.

It can be used in three areas:

- Problem finding

- Problem solving

- Opportunity exploration

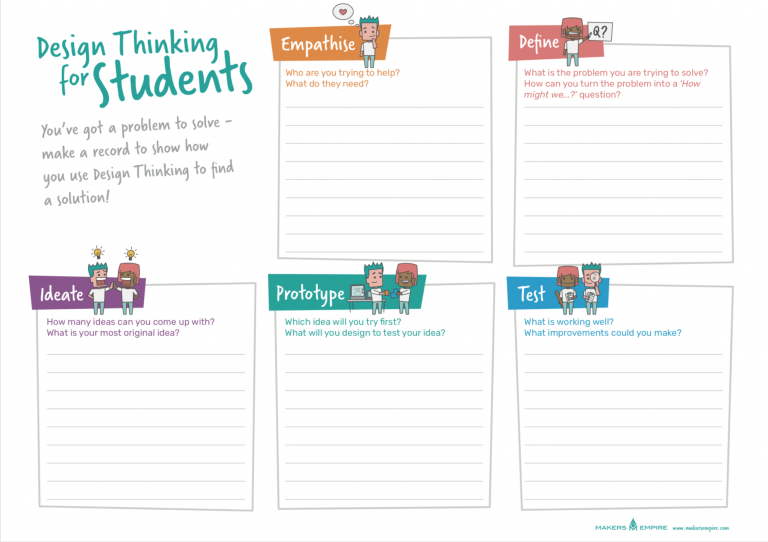

The design thinking model is nonlinear. Resulting in a back and forth between the stages of inspiration, ideation and implementation, in an effort to continuously improve upon their potential solution (Shively et al., 2018). These stages were expanded by the d.School into empathy, define, ideate, prototype and iterate. In fact, there are many exercises that can be used to apply each area of the process.

Let’s walk through each phase. Then I’ll share examples of how it is being used. I also want to preface this by saying that simply going through these stages is where most people misunderstand design thinking and don’t see the results they hoped for. These phases are here to help you develop an action-oriented mindset. Moving from identifying a problem to designing and then testing a solution to quickly get feedback. Each of these phases have numerous exercises to also help facilitate experiences based on your scenario.

Phase 1: Empathy

When you begin with empathy, what you think is challenged by what you learn. This alone is what makes design thinking so unique and is the first phase. During the empathy stage, you observe, engage and immerse yourself in the experience of those you are designing for. Continuously asking, “why” to understand why things are the way they are.

This phase is where we see the most challenges, yet this phase is the most critical. An empathy map is probably the most common exercise. Yet there are others such as, “Heard, Seen, Respected.” Another challenge in this area is not speaking directly to the user. For example, I’ve sat in many “design thinking” experiences where the group will speculate on behalf of the users. For example, educators speculating about parents, administrators speculating about teachers.

The purpose behind an empathy exercise is that when we begin with empathy, what we think is challenged by what we learn. While you can practice with each other, ultimately you must speak directly to who you are designing for.

Phase 2: Define

During the define stage you unpack the empathy findings and create an actionable problem statement often starting with, “how might we…” This statement not only emphasizes an optimistic outlook, it invites the designer to think about how this can be a collaborative approach.

Phase 3: Ideate

During the ideate phase you generate a series of possibilities for design. The focus here is quantity not quality. As you want to generate as many possibilities to see how they may merge together. As Guy Kawasaki shares, “Don’t worry be crappy.” Feasibility is not important at this step. Rather the key is to not think about what is possible but what can be possible. At the end, one of the ideas, or the merging of many ideas, is chosen to expand upon in the next phase.

This is another phase where we see challenges. It is not enough to simply tell someone to get a piece of paper and then come up with lots of ideas. As adults, this is incredibly challenging and is also a muscle that needs to be developed. In fact, one of my favorite exercises is 1-2-4-all. Another is walking questions, where the prompt begins with “What if…” and then after each person writes something it is handed to the person on their right.

Phase 4: Prototype

During the prototype phase, ideas that were narrowed down from ideation are created in a tangible form so that they can be tested. During this phase, the designer has an opportunity to test their prototype and gain feedback.

Phase 5: Iteration

By quickly testing the prototype, the user can refine the idea. And have a deeper understanding to go back and ask questions to the group they are designing for. The feedback received from the user allows the designer to engage in a deeper level of empathy to refine the questions asked and the problem being defined. This brings us back to phase 1.

You can find more of these exercises to lead your group through each phase at sessionlab.com .

As schools strive to create student learning experiences that prepare them for their future, design thinking can play a critical role in complementing students’ knowledge with the skills and mindsets to be creative problem solvers.

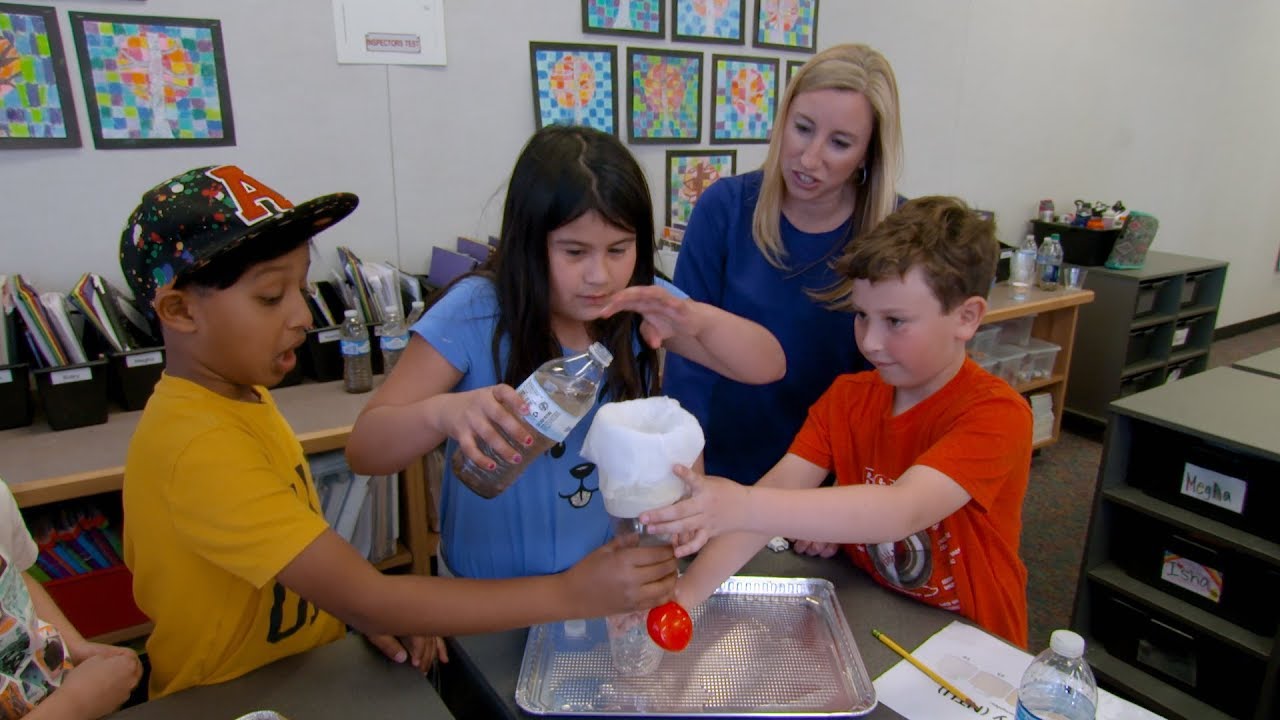

Examples of Design Thinking in K12

While new approaches tend to be viewed with skepticism, an increasing number of studies are coming forward reflecting the promise of transferability of skills and mindsets from the classroom to real-world problems when utilizing design thinking. As expectations are raised about what student skills and mindsets are needed, the level of support for educators must increase as well to experience success in new strategies and the outcomes they promise.

When student learning experiences include design thinking, their skills continue to be enhanced and developed. This in turn allows them to apply these strategies to be problem finders and problem solvers. Helping them be more comfortable with change and empowering them to solve unstructured problems. And work with new information, gaining knowledge, skills and mindsets that cannot be found in the confines of a textbook.

In “The Second Machine Age,” the authors share:

Technological progress is going to leave behind some people, perhaps even a lot of people, as it races ahead. As we’ll demonstrate, there’s never been a better time to be a worker with special skills or the right education. Because these people can use technology to create and capture value. However, there’s never been a worse time to be a worker with only “ordinary” skills and abilities to offer, because computers, robots, and other digital technologies are acquiring these skills and abilities at an extraordinary rate. The Second Machine Age | Erik Brynjolfsson | Andrew McAffee

Design thinking strengthens the mindsets and skills that today’s world demands with the ability to become creative problem solvers. Through nurturing the skills and mindsets developed through engaging in design thinking, schools can create more equitable use environments for all learners that leverage technology to accelerate creative tasks that can bridge the digital use divide.

Case Study 1: Design Thinking in Grade 6

A recent study by the Stanford Graduate School of Education highlights that through instruction, students transfer design thinking strategies beyond the classroom. And that the biggest benefits were to low-achieving students (Chin et al., 2019).

The study included 200 students from grade 6. The researchers worked with the educators during class time to coach half the group of students on two specific design thinking strategies. And then assigned them a project where they could apply these skills.

The two strategies included seeking out constructive feedback and identifying multiple possible outcomes to a challenge. Each of these strategies were designed to prevent what the researchers called, “early closure”. Identifying the potential solution before examining the problem.

After class the students were presented with different challenges to see how they would approach them. The students who were taught about constructive criticism asked for feedback when presented with the new challenge and were more likely to go back and revise their work.

This area was significant, as a pre-test revealed that low-achieving students were behind their high achieving peers when seeking out feedback, a gap that the researchers say disappeared after classroom instruction, highlighting the need for this to be taught to all students, not just advanced students in electives.

As Attewell shares, “Placing computers in the hands of every student is not a solution because the challenge lies in addressing the “ digital use divide – changing the tasks that students do when provided with computers.”

He further highlights the students who gain the types of skills highlighted by the Future of Jobs Report are white and affluent students. These students are more likely to use technology to develop trending skills with greater levels of adult support. Whereas minority students are more likely to use it for rote learning tasks, with lower levels of adult support.

While design thinking is often found in pockets, presented to students already interested in this area, or the students who are in certain electives, the study led by the Stanford Graduate School of Education demonstrates the advances that can be made when this is offered to all students.

Case Study 2: Design Thinking in Geography

Another study (Caroll et al., 2010) focused on the implementation of a design curriculum during a middle school geography class. And explored how students expressed their understanding of design thinking in classroom activities, how affective elements impacted design thinking in the classroom environment and how design thinking is connected to academic standards and content in the classroom. The students were a diverse group with 60% Latino, 30% African-American, 9% Pacific Islander and 1% White.

The task was for students to use the design process to learn about systems in geography. The study found that students increased their levels of creative confidence. And that design thinking fostered the ability to imagine without boundaries and constraints. A key element to success was that educators needed to see the value of design thinking. And it must be integrated into academic content.

A challenge often associated with design thinking in education is not integrating it into mainstream education as an equitable experience for all learners despite showing that lower achieving students benefit more (Chin et al, 2019).

If students are to experience dynamic learning experiences, then organizations must raise the level of support for educators and give them the time and space to learn and integrate design thinking.

How Educators Use Design Thinking

Educators are facing a number of challenges in their professional practice. Many of the requirements today are tools and methods they did not grow up with. Furthermore, the profession is tasked with designing new methods often within traditional systems that have constraints that may serve as roadblocks to change (Robinson & Aronica, 2016).

A 2018 study by PwC with the Business Higher Education Forum shared that an average of 10% of K-12 teachers feel confident incorporating higher-level technology that affords students the opportunity to use technology to design learning that is active, not passive.

As a result, students do not spend much time in school actively practicing the higher-level trending skills expected by employers. Moreover, the report shows that more than 60% of classroom technology use is passive, while only 32% is active use. While the study suggests that many teachers do not have the skills to engage students in the active use of technology, 79% said they would like to have more professional development for how to leverage technology to design learning that is active.

Case Study 3: Design39 Campus

As I shared earlier I led a two-year research study at Design39 Campus. The study examines how it helped teachers evolve their practice. At Design39 teachers are called “Learning Experience Designers” (LEDs). Borko and Putnam (1995) share that how educators think is related to their knowledge. To understand how LEDs are using design thinking to complement the standards-based curriculum, it was important to understand how they acquired and applied this knowledge.

Despite design thinking having its roots outside of education, when asked, “What does design thinking mean to you?” The LEDs identified many commonalities amongst their own work as educators and design thinking. Moreover, they appreciated the alignment of their work with the vocabulary and structure of the design thinking framework.

Over 50% of the LEDs interviewed identified design thinking as providing them with a common vocabulary and structure for what they already do. The LEDs identified educators as inherent design thinkers due to the shared human-centered focus of working with users. In this experience educators design challenges with cyclical learning tasks involving testing, feedback and iteration, and a design mindset to address the wide variety of complex problems within their individual classrooms and across education organizations.

One LED shared:

I just look at it as a process, a process in my mind that we kind of naturally go through as educators, and so with the design thinking process I feel that it is codifying what we do and so we start off always in empathy and empathy is the heart of design thinking and so we are problem solving, who are we problem solving for – people, our learners and so this entire process that we go through of brain dumping it, trying it, getting feedback and coming back to it again so that we can make sure we were really insightful about what the problem really was for the users and we continue around this process to fine tune a potential solution is the design thinking process. Learning Experience Designer | Design39 Campus

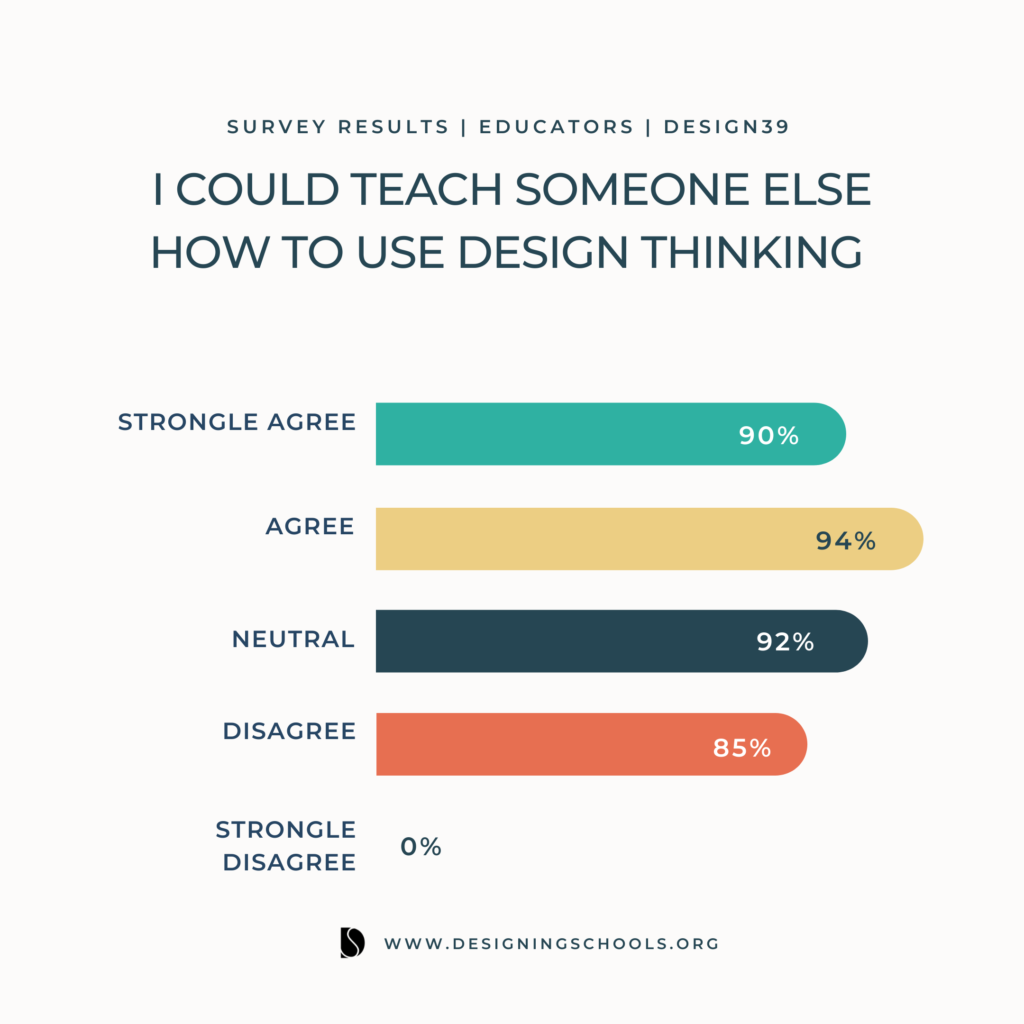

One of the ways mastery of knowledge is demonstrated is by teaching others. To assess their mastery of design thinking in education, learning experience designers were asked to describe their confidence in teaching someone else how to integrate design thinking into their curriculum.

Many LEDs acknowledged that although this is what it often looked like in the first year of the school opening, they have since had the time, space and collaborative opportunities to explore and create deeper integration. This was a point of reference mentioned by 78% of LEDs.

I think a lot of people see design thinking as one science activity, we design think everything from rules to problems that come up in the playground, it’s all through the day, they (the learners) are always looking for problems to solve. Learning Experience Designer | Design39 Campus

In another example, four LEDs made a note using the exact same language that “design thinking is not always cardboard and duct tape.” What allows them to design learning that is more meaningful one LED highlighted:

Not every day is about using duct tape and cardboard, sometimes to do the design to solve the problems you have to hunker down and read and research and so some days, design thinking is highlighting and taking notes. Learning Experience Designer | Design39 Campus

Another LED elaborated on this idea by sharing that

Design thinking is a way of thinking, not always a product that is created at the end. Learning Experience Designer | Design39 Campus

LEDs in all focus groups shared how ultimately design thinking was an opportunity to design lessons that are “ bigger than we are .”

This allowed for the LEDs to design learning experiences. With this, the end result was not to just design a potential solution to a challenge that was identified. Or to simply go from one standard to another, checking off boxes along the way, but that the solution, the work the learners were doing lived beyond the classroom for an authentic audience, where learners are working on real world problems and presenting their solutions to a real world audience.

Almost all of the LEDs shared that to them design thinking was a mindset. It is a process of inquiry that allowed for a more human centered environment where the learner was the focus.

This highlighted a critical shift in the culture at Design39, an element Sarason (2004) discussed in saying no one ever asks:

“Why is school not a place where educators learn as well?”

Bring a Design Thinking Workshop to Your School

We’ve invested in technology. Now it’s time to invest in people. Let’s discuss how design thinking practices can enhance the work you are doing in your school, giving everyone the mindset and skills to navigate change with enthusiasm and optimism. Use this calendar to schedule a time with Sabba to discuss bringing a workshop to your school. Workshops can be delivered both virtually and in-person.

Attewell, P. (2001). The first and second digital divides. Sociology of Education, 74(3), 252-259

Borko, H., & Putnam, R.T. (1995). Expanding a teacher’s knowledge base: A cognitive psychological perspective on professional development. In T. Gusky & M. Huberman (Eds), Professional development in education: New paradigms and practices (pp.35-65). Teachers College Press.

Brown, T & Wyatt, J. (2010). Design thinking for social innovation. Stanford Social Science Review, 8 (1), 30-35.

Brynjolfsson, E. (2014). The second machine age: Work, progress, and prosperity in a time of brilliant technologies (1st t ed.). W. W. Norton & Company.

Carroll, M., Goldman, S., Britos, L., Koh, J., Royalty, A., & Hornstein, M. (2010). Destination, imagination and the fires within: Design thinking in a middle school classroom. International Journal of Art and Design Education, (29)1, 37-53.

Chin, D. B., Doris, Blair, K.P., Wolf, R., & Conlin, L., Cutumisu, M., Pfaffman, J., Schwartz, D.L. (2019). Educating and measuring choice: A test of the transfer of design thinking in problem solving and learning. Journal of the Learning Sciences. 1-44.

Levy, F., & Murnane, R. (2013). Dancing with Robots. NEXT Report.

McKinsey Global Institute (2017). Technology, Jobs and the Future of Work. McKinsey.

PwC (2017). Technology in U.S. Schools: Are we preparing our students for the jobs of tomorrow . Pricewater House Coopers. https://www.pwc.com/us/en/about-us/corporate-responsibility/library/preparing-students-for-technology-jobs.html .

Robinson, K., & Aronica, L. (2016). Creative schools: the grassroots revolution that’s transforming education. Penguin Books.

Shively, K., Stith, K.M., & Rubenstein, L.D. (2018). Measuring what matters: Assessing creativity, critical thinking, and the design process. Gifted Child Today, 41(3) 149-158.

World Economic Forum. (2018). The future of jobs: Employment, Skills and Workforce Strategy for the Fourth Industrial Revolution . World Economic Forum.

I believe that the future should be designed. Not left to chance. Over the past decade, using design thinking practices I've helped schools and businesses create a culture of innovation where everyone is empowered to move from idea to impact, to address complex challenges and discover opportunities.

stay connected

designing schools

[…] importance of learning experiences at the intersection of developing learning skills and mindsets. Design thinking is one approach that can help you master both. In my experience it’s rare that design thinking […]

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

« How Education Leaders Use Social Media to Build Trust, Encourage Creativity, and Inspire a Collective Vision

Creative Career Map: How Students Can Navigate the Future of Work with Design Thinking »

Browse By Category

Social Influence

Design Thinking

Join the Community

All of my best and life changing relationships began online. Whether it's a simple tweet, a DM or an email. It always begins and ends with the relationships we create. Each week I'll send the skills and strategies you need to build your human advantage in an AI world straight to your inbox.

As Simon Sinek Says: "Alone is hard. Together is better."

©DesigningSchools. All rights reserved. 2023

Instagram is my creative outlet. It's where you can see stories that take you behind the scenes and where I love having audio chats in my DM.

@designing_schools

Browse Course Material

Course info, instructors.

- Prof. Justin Reich

- Elizabeth Huttner-Loan

- Alyssa Napier

Departments

- Supplemental Resources

As Taught In

- Education Policy

- Educational Technology

Design Thinking for Leading and Learning

Course description.

How do we prepare K-12 students and learning communities to be as successful as possible? If future jobs require creativity, problem-solving, and communication, how do we teach these skills in meaningful ways? How do we bring together passionate school leaders to create systemic solutions to educational challenges? …

How do we prepare K-12 students and learning communities to be as successful as possible? If future jobs require creativity, problem-solving, and communication, how do we teach these skills in meaningful ways? How do we bring together passionate school leaders to create systemic solutions to educational challenges? Come explore these questions and more in Design Thinking for Leading and Learning.

The course is organized into three sections that combine design thinking content with real-world education examples, as well as opportunities for learners to apply concepts in their own setting.

This course is part of the Open Learning Library , which is free to use. You have the option to sign up and enroll in the course if you want to track your progress, or you can view and use all the materials without enrolling.

You are leaving MIT OpenCourseWare

Design in Educational Technology: Design Thinking, Design Process, and the Design Studio

- Graphic Design

Research output : Book/Report › Book

This book is the result of a research symposium sponsored by the Association for Educational Communications and Technology [AECT]. The fifteen chapters were developed by leaders in the field and represent the most updated and cutting edge methodology in the areas of instructional design and instructional technology. The broad concepts of design, design thinking, the design process, and the design studio, are identified and they form the framework of the book. This book advocates the conscious adoption of a mindset of design thinking, such as that evident in a range of divergent professions including business, government, and medicine. At its core is a focus on "planning, inventing, making, and doing." (Cross, 1982), all of which are of value to the field of educational technology. Additionally, the book endeavors to develop a deep understanding of the design process in the reader. It is a critical skill, often drawing from other traditional design fields. An examination of the design process as practiced, of new models for design, and of ways to connect theory to the development of educational products are all fully explored with the goal of providing guidance for emerging instructional designers and deepening the practice of more advanced practitioners. Finally, as a large number of leading schools of instructional design have adopted the studio form of education for their professional programs, we include this emerging topic in the book as a practical and focused guide for readers at all levels.

Bibliographical note

Publisher link.

- 10.1007/978-3-319-00927-8

Other files and links

- Link to publication in Scopus

- Link to the citations in Scopus

Fingerprint

- Design Process Keyphrases 100%

- Design Thinking Keyphrases 100%

- Design Studio Keyphrases 100%

- Educational Technology Design Keyphrases 100%

- Educational Technology Arts and Humanities 100%

- Instructional Designs Arts and Humanities 100%

- Instructional Design Social Sciences 66%

- Designer Arts and Humanities 50%

T1 - Design in Educational Technology

T2 - Design Thinking, Design Process, and the Design Studio

AU - Hokanson, Brad

AU - Gibbons, Andrew

N1 - Publisher Copyright: © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2014. All rights are reserved.

PY - 2014/1/1

Y1 - 2014/1/1

N2 - This book is the result of a research symposium sponsored by the Association for Educational Communications and Technology [AECT]. The fifteen chapters were developed by leaders in the field and represent the most updated and cutting edge methodology in the areas of instructional design and instructional technology. The broad concepts of design, design thinking, the design process, and the design studio, are identified and they form the framework of the book. This book advocates the conscious adoption of a mindset of design thinking, such as that evident in a range of divergent professions including business, government, and medicine. At its core is a focus on "planning, inventing, making, and doing." (Cross, 1982), all of which are of value to the field of educational technology. Additionally, the book endeavors to develop a deep understanding of the design process in the reader. It is a critical skill, often drawing from other traditional design fields. An examination of the design process as practiced, of new models for design, and of ways to connect theory to the development of educational products are all fully explored with the goal of providing guidance for emerging instructional designers and deepening the practice of more advanced practitioners. Finally, as a large number of leading schools of instructional design have adopted the studio form of education for their professional programs, we include this emerging topic in the book as a practical and focused guide for readers at all levels.

AB - This book is the result of a research symposium sponsored by the Association for Educational Communications and Technology [AECT]. The fifteen chapters were developed by leaders in the field and represent the most updated and cutting edge methodology in the areas of instructional design and instructional technology. The broad concepts of design, design thinking, the design process, and the design studio, are identified and they form the framework of the book. This book advocates the conscious adoption of a mindset of design thinking, such as that evident in a range of divergent professions including business, government, and medicine. At its core is a focus on "planning, inventing, making, and doing." (Cross, 1982), all of which are of value to the field of educational technology. Additionally, the book endeavors to develop a deep understanding of the design process in the reader. It is a critical skill, often drawing from other traditional design fields. An examination of the design process as practiced, of new models for design, and of ways to connect theory to the development of educational products are all fully explored with the goal of providing guidance for emerging instructional designers and deepening the practice of more advanced practitioners. Finally, as a large number of leading schools of instructional design have adopted the studio form of education for their professional programs, we include this emerging topic in the book as a practical and focused guide for readers at all levels.

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?scp=85029564974&partnerID=8YFLogxK

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/citedby.url?scp=85029564974&partnerID=8YFLogxK

U2 - 10.1007/978-3-319-00927-8

DO - 10.1007/978-3-319-00927-8

AN - SCOPUS:85029564974

SN - 9783319009261

BT - Design in Educational Technology

PB - Springer International Publishing

Design Thinking in Education: Perspectives, Opportunities and Challenges

This very informative article discusses design thinking as a process and mindset for collaboratively finding solutions for wicked problems in a variety of educational settings. Through a systematic literature review the article organizes case studies, reports, theoretical reflections, and other scholarly work to enhance our understanding of the purposes, contexts, benefits, limitations, affordances, constraints, effects and outcomes of design thinking in education.

Specifically, the review pursues four questions:

- What are the characteristics of design thinking that make it particularly fruitful for education?

- How is design thinking applied in different educational settings?

- What tools, techniques and methods are characteristic for design thinking?

- What are the limitations or negative effects of design thinking?

The goal of the article is to describe the current knowledge base to gain an improved understanding of the role of design thinking in education.

Read more...

- Our Mission

Design Thinking

Find and share resources to help students engage in innovative processes for tackling complex real-world problems in human-centered ways.

.css-13ygqr6:hover{background-color:#d1ecfa;}.css-13ygqr6:visited{color:#979797;}.css-13ygqr6.node--video:before{content:'';display:inline-block;height:20px;width:20px;margin:0 4px 0 0;background:url(data:image/svg+xml,%3Csvg%20width%3D%2242px%22%20height%3D%2242px%22%20viewBox%3D%220%200%2042%2042%22%20alt%3D%22Video%20icon%22%20data-testid%3D%22play-circle%22%20version%3D%221.1%22%20xmlns%3D%22http%3A%2F%2Fwww.w3.org%2F2000%2Fsvg%22%3E%3Ctitle%3EVideo%3C%2Ftitle%3E%3Cdefs%3E%3C%2Fdefs%3E%3Cg%20id%3D%22play-circle%22%20fill%3D%22%23000000%22%3E%3Cpath%20d%3D%22M21%2C0%20C9.38%2C0%200%2C9.38%200%2C21%20C0%2C32.62%209.38%2C42%2021%2C42%20C32.62%2C42%2042%2C32.62%2042%2C21%20C42%2C9.38%2032.62%2C0%2021%2C0%20L21%2C0%20Z%20M21%2C36.7733333%20C12.32%2C36.7733333%205.22666667%2C29.7266667%205.22666667%2C21%20C5.22666667%2C12.2733333%2012.32%2C5.22666667%2021%2C5.22666667%20C29.68%2C5.22666667%2036.7733333%2C12.32%2036.7733333%2C21%20C36.7733333%2C29.68%2029.68%2C36.7733333%2021%2C36.7733333%20L21%2C36.7733333%20Z%22%20id%3D%22circle%22%3E%3C%2Fpath%3E%3Cpath%20d%3D%22M29.54%2C19.88%20L17.7333333%2C12.9733333%20C16.8466667%2C12.46%2015.7733333%2C13.1133333%2015.7733333%2C14.0933333%20L15.7733333%2C27.9066667%20C15.7733333%2C28.9333333%2016.8933333%2C29.54%2017.7333333%2C29.0266667%20L29.5866667%2C22.12%20C30.4266667%2C21.6066667%2030.4266667%2C20.3933333%2029.54%2C19.88%20L29.54%2C19.88%20Z%22%20id%3D%22triangle%22%3E%3C%2Fpath%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3C%2Fsvg%3E) no-repeat left bottom/18px 18px;} Filmmaking Is a Powerful Way for Students to Demonstrate Learning

Flexible Seating and Student-Centered Classroom Redesign

Designing a Public School From Scratch

Crafting Fair Assessments for Flexible Assignments

Birmingham Covington: Building a Student-Centered School

Design Thinking: A Problem Solving Framework

Teaching empathy through design thinking.

Designed for Engagement

Science Takes Flight With Paper Airplanes

Arts Integration: Resource Roundup

Using Design Thinking to Explore Inclusivity

Why Learning Space Matters

Incorporating Design Thinking in the Study of Literature

Design Thinking in Education: Empathy, Challenge, Discovery, and Sharing

As a model for reframing methods and outcomes, design thinking reconnects educators to their creativity and aspirations for helping students develop as deep thinkers and doers.

Building Products for Real-World Clients

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Design in educational technology : design thinking, design process, and the design studio

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

37 Previews

Better World Books

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

PDF access not available for this item.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station12.cebu on November 11, 2022

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

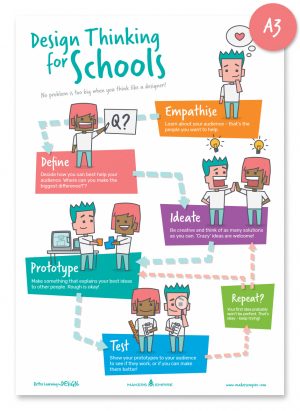

What is Design Thinking? A Handy Guide for Teachers

In this post, Mandi Dimitriadis, Director of Learning at Makers Empire, will help you understand more about Design Thinking. You’ll get to know what Design Thinking is, why Design Thinking is important, the phases of the Design Thinking process and how you might teach your students how to use Design Thinking to reframe problems and needs as actionable statements.

Designers use particular ways of thinking to create innovative new products and design solutions to challenging problems. As educators, we can learn a lot from the way designers think.

What is Design Thinking?

- A solutions-based approach to solving problems.

- An iterative, non-linear process.

- A way of thinking and working.

- Supported by a collection of strategies and methods.

- Develop empathy and understand the needs of the people we are designing solutions for.

- Define problems and opportunities for designing solutions.

- Generate and visualise creative ideas.

- Develop prototypes.

- Test solutions and seek feedback.

Why is Design Thinking important?

Consider the rapidly changing world we live in. To thrive in the future students will need to be adaptable and flexible. They will need to be prepared to face situations that they have never seen before. Design Thinking is one of the best tools we can give our students to ensure they:

- Have creative confidence in their abilities to adapt and respond to new challenges.

- Are able to identify and develop innovative, creative solutions to problems they and others encounter.

- Develop as optimistic, empathetic and active members of society who can contribute to solving the complex challenges the world faces.

How can students use Design Thinking?

So what does Design Thinking look like in action?

Watch these inspiring videos made by schools in Australia showing how students used Design Thinking and Makers Empire to solve common real-world problems in their classroom, school and communities.

Please note that the Makers Empire app depicted in this video is a much earlier version of the app.

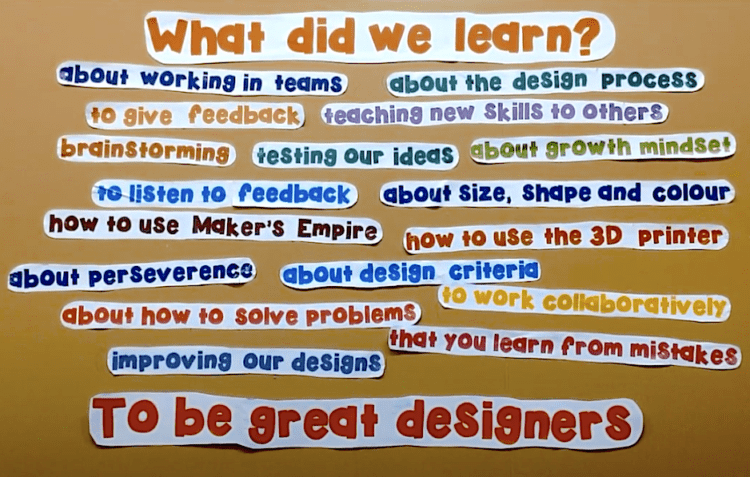

How did the students in the videos use design thinking.

In the Forbes primary school bag tag video, for example, we saw our first graders:

- Developing and agreeing on criteria for their designs.

- Selecting tools and materials – in this case, Makers Empire and 3D printing.

- Supporting each other to learn how to use the new tools.

- Producing a working prototype.

The testing process for our first graders involved:

- Giving each other feedback

- Assessing their designs against the previous agreed criteria

- Making modifications and improvements to their designs

- Testing their designs in the context they would be used.

- Reflecting on their problem-solving processes and learning outcomes.

How can we teach Design Thinking with little time to plan?

Makers Empire teachers never cease to impress us with their innovative and creative ideas for using Makers Empire to help students achieve curriculum learning outcomes. However, we also know how busy teachers are and how difficult it can be to find time to plan engaging, curriculum-aligned units of work. So we created ready-made Challenge Courses .

Each themed course is a complete design program comprising videos, quizzes, tutorials & design challenges. Challenge Courses are aligned to curriculum outcomes and teach real world-problem solving using Design Thinking. Challenge courses take 4-10 weeks to complete so teachers might plan to have students do a course during one lesson/week over a term. During that term, students will address all aspects of the Design and Technologies curriculum without teachers needing to do any extra planning.

How can we learn more about Design Thinking?

Makers Empire offers customisable Design Thinking and 3D design learning programs to school districts, education departments , and groups of schools .

Through our professional learning programs, teachers learn how to use Design Thinking and 3D design to transform the way they teach STEM subjects and help equip students with the skills and attitudes they’ll need to thrive in the future.

We’ve delivered Design Thinking and 3D technology programs to groups of 200+ schools in Australia, America and the Middle East so we have the right experience, skills and team to help you.

How will you teach Design Thinking?

Now it’s your turn. Think about projects you can do with your students that will help enhance and deepen learning. How might you support your students to:

- Develop empathy , insights and understandings.

- Define a problem as an actionable question.

- Generate and visualise ideas.

- Develop prototypes; and

- Evaluate and test their designed solutions.

Makers Empire is an excellent way to teach Design Thinking to students. You can sign up for a free school trial at the top of this website. Don’t forget to download our free Design Thinking posters and worksheets , too.

Mandi Dimitriadis

Mandi Dimitriadis, DipT. is a highly respected educator and speaker who works internationally with elementary, primary and middle schools to help teachers develop Design Thinking, embrace maker pedagogy and cover Design & Technology Curriculum. She is an experienced classroom teacher who recognises the power of technology to enhance teaching and improve educational outcomes. Mandi has extensive experience with curriculum development, having previously developed programs for the Australian Government’s Department of Education.

How to Enhance Design Thinking with ChatGPT

New technologies are always posing challenges in the educational sector. It’s not the technology that’s the issue, but the people and processes. Educators’ approaches to these digital advancements must not be to deny their existence but to understand how they can be used to transform assessment. AI tools, such as ChatGPT, offer students access to a wealth of information and can be most useful as research and practice guides in active and applied problem-solving tasks such as those used in design thinking.

So how can teachers embrace ChatGPT and use it to enhance design thinking approaches?

ChatGPT is capable of facilitating the generation of novel ideas, enhancing creativity and improving product development (Haleem, 2022). It can reinforce the principles of design thinking through its ability to generate student centred solutions with its iterative problem solving approach (Enhold, 2022). For each of the phases in design thinking, ChatGPT can be a useful tool.

Share this:

2024 Makers Empire Projects for Australian Schools

Makers Empire has hit the ground running again in 2024 with our pop…

Review of the 2024 Flashforge Adventurer 5M Pro 3D Printer: A True Leap Forward

Flashforge has released a new Pro version of their popular Adventur…

Register Your Interest for the 2024 STEM Advanced Manufacturing Moreton Bay Future Skills School Program

Following successful programs in Queensland in 2023, junior and sen…

Learning at Home | Coronavirus | COVID-19 | Resources for Teachers and Parents

To the worldwide Makers Empire community, At Makers Empire, we̵…

Failing to Succeed: 6 Habits of Successful ‘Failers’ That Teachers Should Know

I spend a lot of time talking with teachers about the important rol…

Competitions, Challenges & Experiences Your Students Will Love | Design Thinking | STEM

At Makers Empire, we want to help children become creators, innovat…

[Videos] American Teachers Share Their Fave Makers Empire Projects, Aha! Moments & Tips

We recently asked some of our American elementary and middle school…

10 Coronavirus 3D Design Challenges For Students | Help People Affected By COVID-19

We’ve seen a recent surge of activity around the world as health au…

10 Design Challenges for Children To Help Create Positive Feelings During COVID-19

We are all navigating unchartered territory as we learn to cope wit…

Try Makers Empire for free!

Start learning 3D design in minutes. Make teaching design and technology fun and effective!

- USA (415) 652 0206

- AUS 61 (0)8 8120 3150

- Contact Makers Empire

- Get Tech Support

- Knowledgebase / FAQs

- 3D Design Software

- Class & School Subscriptions

- Learning by Design Course

- Custom Solutions

- Shop Makers Empire

- Knowledgebase

- Technical Support

- Free Printables

- Education Research

- Grants for Schools

- Makers Empire Blog

- Gallery of Designs

- Our Teachers

- Teacher Interviews

- Monthly Competitions

- Our Partners & Awards

- In the News

- Testimonials

- Major Milestones

- Terms of Service | Privacy

We acknowledge and pay our respects to the Kaurna people, the traditional custodians whose ancestral lands we gather on. We acknowledge the deep feelings of attachment and relationship of the Kaurna people to country and we respect and value their past, present and ongoing connection to the land and cultural beliefs.

Please wait while you are redirected to the right page...

Design Thinking for Education

Conceptions and Applications in Teaching and Learning

- © 2015

- Joyce Hwee Ling Koh 0 ,

- Ching Sing Chai 1 ,

- Benjamin Wong 2 ,

- Huang-Yao Hong 3

National Institute of Education, Singapore, Singapore

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

National Chengchi University, Taipei, Taiwan

Examines Design Thinking from an education context

Provides better understanding of applications of design thinking in educational settings

Stimulates conversation among educational researches to further consider the theoretical development of Design Thinking

40k Accesses

75 Citations

13 Altmetric

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this book

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Other ways to access

Licence this eBook for your library

Institutional subscriptions

Table of contents (8 chapters)

Front matter, design thinking and education.

- Joyce Hwee Ling Koh, Ching Sing Chai, Benjamin Wong, Huang-Yao Hong

Critical Perspectives on Design and Design Thinking

Design thinking and 21st century skills, design thinking and children, design thinking and preservice teachers, design thinking and in-service teachers, developing and evaluating design thinking, back matter.

- 21st century skill

- design thinking and children

- design thinking and students

- design thinking and teachers

- design thinking in education

- design thinking in teaching and learning

- lesson planning

- reflection in action

- learning and instruction

About this book

“The authors clearly define the aims of the text as being to further the debate amongst teachers, teacher educators and educational researchers on the theoretical development of design thinking within the context of educational settings. … a book that would hold appeal for all of those with an interest in design thinking in an educational context, irrespective of their position; educational researcher. pre-service teacher, in-service teacher or teacher educator. … I recommend this text as essential reading … .” (David Wooff, Design and Technology Education, Vol. 21 (3), 2016)

Authors and Affiliations

Joyce Hwee Ling Koh, Ching Sing Chai, Benjamin Wong

Huang-Yao Hong

Bibliographic Information

Book Title : Design Thinking for Education

Book Subtitle : Conceptions and Applications in Teaching and Learning

Authors : Joyce Hwee Ling Koh, Ching Sing Chai, Benjamin Wong, Huang-Yao Hong

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-444-3

Publisher : Springer Singapore

eBook Packages : Humanities, Social Sciences and Law , Education (R0)

Copyright Information : Springer Science+Business Media Singapore 2015

Hardcover ISBN : 978-981-287-443-6 Published: 11 May 2015

Softcover ISBN : 978-981-10-1333-1 Published: 23 October 2016

eBook ISBN : 978-981-287-444-3 Published: 25 April 2015

Edition Number : 1

Number of Pages : XII, 131

Number of Illustrations : 1 b/w illustrations, 5 illustrations in colour

Topics : Teaching and Teacher Education , Learning & Instruction

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

YOUR RESOURCE FOR EMPOWERING LEARNERS

Educational Technology

(edtech) resource, stem education & educational technology (edtech).

.jpg)

Click here for other podcast platforms.

David Lee

Tech & Innovation Specialist at Singapore American School

Author of Design Thinking in the Classroom , Google Innovator,

Apple Distinguished Educator, ISTE Certified Educator, Keynote Speaker, Consultant, Certified Wix Trainer, M.Ed. Educational Technology,

Former STEM Coordinator, Design Specialist, and ICT Teacher

Official partner of DesignGoes2School

"Design education is revolutionizing minds and transforming perspectives even beyond privileged communities to the slums. Moulding the dreamers' dream into life and birthing a design-savvy generation with zero limits."

Thanks for submitting!

Exploring the Training Path of Design Thinking of Students in Educational Technology

Ieee account.

- Change Username/Password

- Update Address

Purchase Details

- Payment Options

- Order History

- View Purchased Documents

Profile Information

- Communications Preferences

- Profession and Education

- Technical Interests

- US & Canada: +1 800 678 4333

- Worldwide: +1 732 981 0060

- Contact & Support

- About IEEE Xplore

- Accessibility

- Terms of Use

- Nondiscrimination Policy

- Privacy & Opting Out of Cookies

A not-for-profit organization, IEEE is the world's largest technical professional organization dedicated to advancing technology for the benefit of humanity. © Copyright 2024 IEEE - All rights reserved. Use of this web site signifies your agreement to the terms and conditions.

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 26 April 2024

(No) Hope for the future? A design agenda for rewidening and rewilding higher education with utopian imagination

- Rikke Toft Nørgård ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0481-6683 1 &

- Kim Holflod 1

International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education volume 21 , Article number: 30 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

347 Accesses

6 Altmetric

Metrics details

This article argues for exploring, connecting, and applying utopian imagination, speculative design, and planetary thinking as a way forward for higher education to reimagine and move towards more hopeful planetary futures. It examines hopepunk and solarpunk perspectives on possible futures to propose a design agenda for rewidening and rewilding higher education and educational technology with utopian imagination. Firstly, the article outlines and develops a framework for wider and wilder futures in higher education, emerging from utopian thinking and desire. Secondly, it connects hopepunk with speculative design and solarpunk with planetary design to highlight and put forward rebellious strategies of hope in envisioning more preferable futures. Thirdly, it approaches the field of educational technology within the context of wide and wild education to establish four planetary orientations concerning educational technology: Higher Education for, in, with, and by the world. Taken together, the article proposes a design agenda for educational technology that integrates utopian imagination and solarpunk practices with planetary educational technology to catalyse the development of more preferable futures in a more-than-human world.

Grimdark and narrow futures in higher education

What does a world that works for everyone look like? How can it translate to higher education institutions? And what role or potential lies within utopian imagination to think, talk, and act critically, holistically, and reflexively in both anticipating and shaping higher education futures?

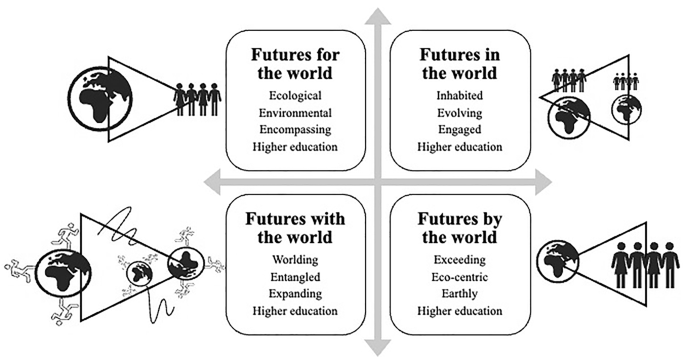

This article argues for exploring, connecting, and applying utopian imagination, speculative design, and planetary thinking as a way forward for higher education – that also resonates with and has implications for the domain of educational technology – to reimagine and desire more just and hopeful futures. The term utopia generally refers to an imagined, ideal, and often perfect society, while the term dystopia is utopias dark twin pointing towards the undesirable society marked by negative qualities or frightening characteristics. This article applies the concepts to examine and discuss potential futures. In this context, hopepunk and solarpunk attitudes – are specific value-driven rebellious utopian strategies originating from popular and aesthetic culture and often point towards collective and imaginative bettering of worlds through radical hope and planetary justice and consciousness. Here, such approaches are coupled with orientations of higher education as being for , in , with , and by the world, that might help guide us towards futures that transcend present dull and domesticated educational utopias (Webb, 2016 ). It is, however, important to acknowledge that any discussions centered on more hopeful or just futures inherently involve making normative judgments, where some futures are deemed more preferable than others.

The normative dimensions of designing for possible futures relate to, for instance, Voros’ concept of preferable futures within futures studies (Voros, 2001 ), Nelson & Stolterman’s foregrounding of desiderata , the pursuit of that-which-ought-to-be and materialising the ideal in the real within design studies (Nelson & Stolterman, 2014 ), along with Levitas’ utopia as method and utopian imagination (Levitas, 2013 ) and other applications of utopian thinking within higher education studies (see, e.g., Amsler & Facer, 2017 ; Barnett et al., 2022 ; Bayne, 2023 ; Nørgård, 2022 ; Ross, 2022 ), that all underscore this normative dimension. Such notions of higher education oriented towards educating for utopian desire (Abensour, 1999 ) not solely grounded in ‘pragmatic feasibility’ or ‘realistic futures’ necessitates a transformation of both higher education institutions themselves and our own perspectives and relationships with the world around us.

Neglecting our interconnected existence with each other, the planet, and the entangled web of more-than-human entities and futures leaves us trapped in bleak and challenging present circumstances inside and outside our higher education institutions. As such, there are calls to envision alternative futures – both in and beyond higher education – that extend thinking toward a deeper notion of relationality (e.g., Akama et al., 2020 ; Escobar, 2017 ) and necessary radical change in social systems because of an ecological imperative and planetary challenges (Levitas, 2017 ), and, consequently, new approaches towards considering the futures of educational technology (Macgilchrist, 2021 ). To progress forward, we require, on the one hand, more utopian imaginative models and hope-driven attitudes to envision futures that are genuinely worth pursuing. On the other hand, we also need a less ego-centric and more eco-centric mindset of planetary sensibilities to believe that these envisioned futures are planet-wide and hopeful for ‘all of us’.

The climate crisis and the looming specter of a planetary catastrophe have given rise to the emergence of various educational approaches, including eco-pedagogies (Kahn, 2010 ; Molina-Motos, 2019 ; Misiaszek, 2020 ), post-anthropocentric and post-human thinking (Banerji & Paranjape, 2016 ; Bodén et al., 2021 ; Braidotti, 2013 ; Bridle, 2022 ; Snaza et al., 2014 ) and a planetary turn in design (Akama et al., 2020 ; Samson & Haldrup, 2023 ; Wahl, 2016 ). These responses are potential strategies to address the increasing tangibility of societal and planetary dystopian scenarios and grimdark futures, both in everyday life and educational settings. Moreover, discussions within and surrounding higher education about the Anthropocene and Capitalocene bring attention to an era shaped by human activities and a concept linked to environmental degradation influenced by the dynamics of capitalism and its related economic and social structures. These discussions, especially concerning the neoliberal and performative aspects of universities and higher education, underscore how domesticated, dull, and pessimistic prospects have come to exert influence on higher education institutions. This influence has constrained and altered the perspectives and actions of academic individuals, including students and teachers alike (Ball, 2003 ).

While there is a consensus among higher education scholars regarding the necessity for change, the scope and vision of this change vary widely. Some advocate for more pragmatic and incremental shifts, while others adopt a more holistic and imaginative stance (Levitas, 2004 , 2013 ; Webb, 2016 ). The latter group emphasises the need to envision alternative futures and propose methods and modes of thinking that can actively contribute to the discovery and process towards more hopepunk futures that connect to a contemporary movement and aesthetic about speculating, changing, and bettering the world and its future(s) through its emphasis on optimism, cooperation, community-building, the rejection of apathy, and the embodiment of radical hope.

In the context of higher education and educational technologies, there is a need for improved frameworks and methodologies to evaluate our current practices, considering the state and prospects of desired and preferable futures for us all, both human and more-than-human entities, in a planetary and pluriversal perspective. This foundational approach to shaping the future closely aligns with design practices found in speculative design (Dunne & Raby, 2013 ), design fiction prototyping (Bleecker at al., 2022 ), and approaches to designing for improved educational futures (Abegglen et al., 2023 ; Hall et al., 2022 ). These transformative design approaches depart from our existing anticipatory regimes in education (Amsler & Facer, 2017 ), where we consistently find ourselves shaping the future of higher education and educational technologies based on projected and predictable dull futures that are essentially already present in our current reality. To envision wider and wilder futures, drawing conceptual inspiration from Arturo Escobar ( 2017 ), accentuating the pluriversal design imperative of wider , i.e., people-wide, and wilder , i.e., planet-wide, it is important to design beyond pragmatic real utopias , as criticised by Webb ( 2016 ), and for futures that are more than practically achievable and realistically feasible, given the current situation and the foreseeable future on the horizon.

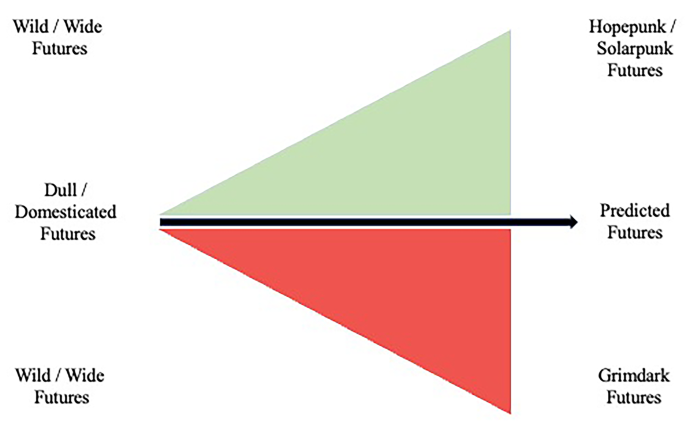

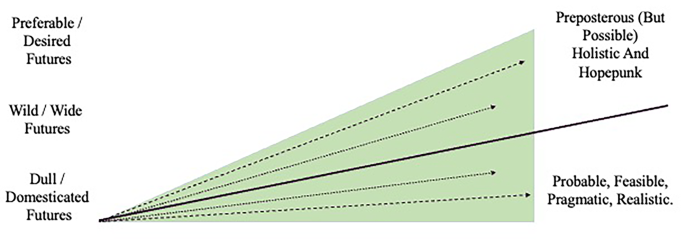

Here, the article examines and proposes an alternative perspective to counteract the practice of domesticating and narrowing future scenarios. Consequently, the approach diverges from more conventional notions of fostering human optimism or striving for planetary justice when discussing educational technologies in higher education. Here, we advocate for a more-than-human approach (Akama et al., 2020 ), emphasising the entangled relationality of humans and non-humans and recognising the complex agency of the non-human in the, e.g., biological, social, and cultural worlds, which challenges the prevailing discourse in educational technology theory and practice. Such more-than-human approaches, combined with planetary and solarpunk attitudes, prioritise people-wide (hopepunk) and planet-wide (solarpunk) utopian imaginations for preferable futures. They do so at the expense of capitalism’s perpetual growth and totalitarian technologies’ dominance, as Levitas ( 2017 ) argues. This offers a path forward for educational design and technology, which often grapple with the looming specter of exclusively human-centered or ‘Global North’ anticipatory futures in higher education. The array of potential futures confronting us in higher education is vast and dynamic. Importantly, these futures are not binary utopian or dystopian outcomes that can be definitively reached. Instead, they represent an ongoing (r)evolutionary process, where certain actions may lead us toward grimdark educational landscapes while others may guide us toward more radical and hopeful ones (Nørgård, 2022 ). In other words, this article explores the full array of futures – from the present grimdark to the imaginative hopepunk and solarpunk, and from the dull, domesticated, and predictable futures to wider and wilder preposterous futures (see Fig. 1 ).

The domain of all possible futures we are confronted with in higher education. The ones close to the predicted future (in the singular) are dull and domesticated, while the ones spanning the outer cone are wilder and wider. The first half of the cone leads us into more grimdark futures; the other half leads us into more hopepunk futures

Through cultivating hopepunk and solarpunk attitudes within the field of higher education and educational technology, as well as rewidening and rewilding higher education using utopian imagination, the article points towards more hopeful, preferable futures for the people and the planet.

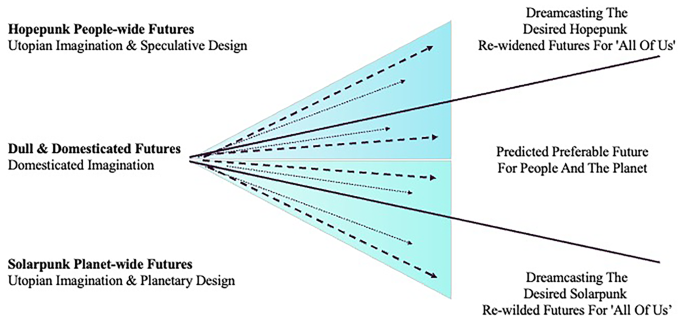

First, the article outlines and develops an imaginative model for wider and wilder futures in higher education, growing from utopian thinking and desire. This section emphasises the interplay between utopian imagination and design approaches such as speculative design and future scenarios. Second, extending utopian examination and reflection, we connect speculative design with the popular cultural phenomenon of hopepunk that accentuates rebellious strategies of hope in envisioning better, more hopeful futures. From here, as the third part of the article, we extend the mentioned perspectives through planetary design and solarpunk concepts, moving beyond the human-centric perspective towards eco-centric future-making for the planet. Finally, the article approaches the field of educational technology within the context of wide and wild higher education, establishing four planetary orientations through educational technology: Higher education for the world, Higher Education in the world, Higher Education with the world, and Higher Education by the world.

Imagining with hope toward utopian higher education futures

In the introduction, we outlined alternative approaches to thinking about higher education futures and educational technologies, namely hopepunk, solarpunk, wider and wilder futures, utopian and dystopian futures, and both human and more-than-human approaches – and a need to emphasise more just, desirable, and preferable planet- and people-wide futures for ‘all of us’ that encompass the agencies of not only humans but also more-than-humans. Perhaps we should, then, dare to dream of wider and wilder futures - and herein not approach utopia as a feasible destination but as an ever-moving, ever-evolving future world to continuously strive for. For this, we must escape present-day utopian studies and approaches in higher education that have become domesticated (Webb, 2016 ). As such, there is a pressing need to advance and imagine wilder and wider higher education utopias that do not merely ‘predict’ the future or point towards ‘probable’ futures but, rather, make us engage the multiple ‘possible’ futures – even ones that might initially be deemed ‘preposterous’ (see Voros, 2017 for a description of the different kinds of possible futures).

Utopia is etymologically conceptualised as a no place or nowhere , often connected to and framed by acts of social dreaming. However, utopian studies – particularly in higher education - are vast, diverse, contested, and plural, accentuating, e.g., both real utopias, possible/feasible utopias, and imaginative utopias. Here, we draw inspiration from Levitas ( 1990 , 2013 , 2017 ) to advance and explore the concept of utopia in higher education. We approach this idea from various perspectives, such as holistic, critical, imaginary, reflexive, prescriptive, normative, contingent, and future-oriented angles (Levitas, 2004 , 2013 : 84). Our goal is not just to envision what might be but to imagine otherwise . Levitas, moreover, frames the interdependencies among economic, social, existential, and ecological processes within an integrated framework. Challenges arise when our attention is predominantly directed towards analysing and explaining existing phenomena, referred to as that which-is , thereby neglecting the realm of ethical and moral considerations denoted as that-which-ought-to-be . Additionally, this oversight transpires without regard for the preferences and longings resonating from that-which-is-desired (desiderata), as Nelson and Stolterman ( 2012 ) explained. As such, “the point is not for utopia to assign ‘true’ or ‘just’ goals to desire but rather to educate desire, to stimulate it, to awaken it…. Desire must be taught to desire better, to desire more, and above all to desire otherwise.” (Abensour, 1999 : 146). Levitas draws attention to the perspective that pragmatic and feasible utopias are not enough and that we will only end up with more of the same if we do not demand the impossible (or preposterous) (Levitas, 2004 ). We might thus say that higher education systems need holistic, hopeful utopias – utopias of social dreaming (Dunne & Raby, 2013 ), collective visioning (Wahl, 2016 ), extended relationality (Holflod, 2023b ), and hopepunk imagination (Nørgård, 2022 ). However, education of desire and imaginative utopias are not consistently eutopias , i.e., always positive, but more critical and reflexive towards desiderata . Addressing utopian studies in line with this perspective, Fitting ( 2009 , p. 12) accentuates the following:

It is a mistake to approach Utopias with positive expectations, as though they offered visions of happy worlds, spaces of fulfillment and cooperation, representations which correspond generically to the idyll or the pastoral rather than the utopia. Indeed, the attempt to establish positive criteria of the desirable society characterizes liberal political theory from Locke to Rawls, rather than the diagnostic interventions of the Utopians, which, like those of the great revolutionaries, always aim at the alleviation and elimination of the sources of exploitation and suffering, rather than at the composition of blueprints for bourgeois comfort. (Fitting, 2009 , p. 12)

Levitas’ utopian approach might allow us to imagine what an alternative society could look like and even what it might feel like to inhabit it (Levitas, 2017 , p. 3) when “utopia is the expression of the desire for a better way of being or of living, and as such is braided through human culture” (Levitas, 2013 , p. xii). Moreover, she emphasises that we must perceive and engage with utopia primarily as a method rather than a destination. This method involves provisional, reflexive, and dialogic processes (Holflod et al., 2023 ) and enactments of collective visioning and processual future-making (Barnett et al., 2022 ). As educational design researchers, this understanding corresponds with speculative design as a way of stimulating idealism (Holflod, 2023a ; Nørgård, 2022 ), reminding us of alternative and imaginable worlds and not something to make real – but as somewhere to aim for rather than build. (Dunne & Raby, 2013 , 73). Acknowledging the domestication of educational utopias (Webb, 2016 ), we thus might need to envision imaginative and preposterous but possible futures – for utopian visions towards a plurality of both voices, ways of knowing, and societal re-constitution (Levitas, 2013 ).

With imaginative and hopepunk utopian higher education futures possibly sounding abstract and preposterous, speculative design and design futures might be tangible ways of grounding such a utopian approach. In our discussions – with educators, students, and practitioners - about possible and imaginable futures, we have found inspiration in the futures cone that frames and directs our utopian thinking in classifications of utopia (see Fig. 2 ) as projected, probable, plausible, possible, and preposterous in relation to an imagined future (Voros, 2017 ). These different classes represent different ways of thinking towards the future – best thought of as nested classes of futures moving from the narrowest projected future (in the singular) to the broadest seemingly preposterous futures. Notably, the cone of possible futures is ever-expanding (except for the projected singular future) as we move further and further into the future, indicating trajectories rather than destinations. As a tangible tool for envisioning alternative futures, the futures cone might help guide and widen our imagination. Though it might not be tailored specifically to the utopian approach expressed by Levitas, it provides a tangible framework for exploring, analysing, and pursuing different classes of possible futures – even wildly imaginable, reflexive, and critical – higher education futures.

The domain of all preferable and desired futures we might imagine within higher education. The pathways close to the dull and domesticated futures (bottom of triangle) are probable and ‘realistic’, while the pathways unfolding in the upper half of wilder/wider futures are ‘preposterous’ and holistic. The bottom half leads us into domesticated utopias as preferable and probable futures to settle for, while the other half leads us into utopian imagination towards desired and hopepunk futures for people and planets

Speculative design and hopepunk higher education: re-widening futures

In the previous section, we argued that transcending pragmatic utopian perspectives towards, e.g., holistic, hopepunk and processual future imagination is needed. As such, a shift from a predictive/projected to a visionary/hopepunk attitude towards higher education institutions – and herein educational technologies – is critical:

There are several ways of looking at the future, but two methods predominate. The first is by prediction and the second is ‘visioning’. Prediction is, perforce, based on extrapolation of past trends. Through this process the future can only be viewed as though along a corridor of constraining possibilities. The corridor might widen along its length but the process of prediction is essentially a restrictive one. Visioning, on the other hand, is a process that begins with the desired future state and then looks backwards to the present (building a new corridor between the states). Visioning is a tool that, under various guises, has been developed by the business community to help corporate planning. The present state can be a difficult barrier to what could be – the future state (Stewart, 1993). Therefore, visioning is radically different from conventional futurology which is predictive, prophetic and tends to offer pictures of exaggerated optimism or pessimism. (McRae, 1994) (in Wahl, 2006 , p. 714).

Within a speculative design approach, this needs to happen from the bottom up (Dunne & Raby, 2013 ) to escape totalitarian utopian ‘blueprint’ frameworks or fixed destinations and have in their place ever-evolving micro-utopias of collective visions. Building on the utopian method enables us to imagine more hopeful futures and evoke both personal and collective desire as ‘that things might be otherwise, and might be better, is the defining characteristic of utopian thought’ (Levitas, 2017 , p. 6). However, to rewiden our futures under the present realities of higher education, we need a certain kind of hope. To not ‘just be hopeful’ (Dunne & Raby, 2013 ), we must invoke hopepunk attitudes as more rebellious stances towards both the present and future.

Hopepunk is more than conjuring an idealistic, bright vision of the future. By engaging in discussions about futures worth having and problems in working towards them, the community of higher education thinkers and technologists can engage in processes of collective visioning about (more) preferable futures and approach design processes to materialise them (Wahl, 2006 , 2016 ). Here, hopepunk thinkers and practitioners can come together to engage utopian imagination through design agendas to materialise pathways towards more just and hopeful futures. According to Aja Romano, hopepunk is not a naïve optimist or purely hopeful state – but an active political choice ‘made with full self-awareness that things might be bleak or even frankly hopeless, but you’re going to keep hoping, loving, being kind nonetheless’ (Romano, 2018 ). It is, on the one hand, a utopian insistence on believing in the possibility of wilder and wider futures and then fighting for those preferable futures to happen, and, on the other hand, rebellion against dull and domesticated futures that diminish our utopian imagination and belief in that things could be otherwise.