The tragedy of Egypt’s Mohamed Morsi

Subscribe to the center for middle east policy newsletter, shadi hamid shadi hamid senior fellow - foreign policy , center for middle east policy @shadihamid.

June 19, 2019

Though deeply flawed, Mohamed Morsi was a product of Egypt’s brief experiment with democracy, writes Shadi Hamid. His memory highlights what the country has lost. This piece was originally published in the Atlantic .

Mohamed Morsi’s life, especially his later life, was the product of a series of accidents. When I first met him, he was a senior but relatively obscure and not particularly important official in the Muslim Brotherhood—and one could easily imagine him staying that way. He was a loyalist, a functionary, and an enforcer. Then he became something else: Egypt’s first democratically elected president—and also the last, at least for the foreseeable future. Visionary leaders sometimes emerge during moments of crisis and transition. But just as often, ordinary men and women find themselves in the midst of historical events, both shaping them and being shaped by them.

Morsi, who died in a Cairo courtroom Monday, was elected in 2012 and deposed in a military coup a year later. He was many, but not all, of the things his critics derided him for. He wasn’t what you would call charismatic. He was not a strategic thinker. He seemed a man particularly unsuited for the responsibility bestowed upon him. In retrospect, knowing what they know now, many in the Brotherhood—in prison, in exile, in hiding—would wish that the organization’s leadership had never opted to field a presidential candidate. But this had little to do with Morsi. Morsi wasn’t meant to be president.

The Brotherhood’s original candidate for president was the businessman Khairat al-Shater, towering in his physical presence, preternaturally confident, and perhaps overwhelmed by ambition. Some called him Egypt’s most powerful man. He was disqualified from running based on a legal technicality. Like so many other things, this, for the group, seemed to confirm that the military sought to block the Brotherhood’s rise by any means necessary. And so Morsi, derided in the Egyptian media as Shater’s “spare tire,” became the accidental candidate and then the accidental president.

When I sat down with Morsi back in May 2010, the longtime dictator Hosni Mubarak was still in office, and the kind of uprising that could force him out seemed implausible. At that point, Morsi insisted the Brotherhood had no interest in power and even objected to the use of the word opposition to describe the group. Repression was intensifying, and political space was closing years after the brief promise of the (first) Arab Spring in 2004 and 2005. The November 2010 parliamentary elections were arguably the most fraudulent in the country’s history, reducing the Brotherhood from 88 seats to 0. Members of the Muslim Brotherhood seemed deflated but not necessarily in despair. They were playing the long game, which is what the Brotherhood always preferred to play. To be tempted by power, on the other hand, led them, and ultimately Morsi himself, into a series of missteps and miscalculations.

The campaign for president in the spring of 2012 took place in a chaotic, uncertain Egypt. Though burdened by a weak candidate, and with only two months to campaign, Brotherhood activists fanned across the country, promoting Morsi’s so-called renaissance project (which had been Shater’s “renaissance project”). In one coordinated show of strength, they held 24 simultaneous mass rallies across the country in a single day. At one rally, I asked a young Brotherhood activist if he was enthusiastic about Morsi. He smiled and then laughed.

Related Books

Kenneth M. Pollack, Daniel L. Byman, Akram Al-Turk, Pavel K. Baev, Michael S. Doran, Khaled Elgindy, Stephen R. Grand, Shadi Hamid, Bruce D. Jones, Suzanne Maloney, Jonathan D. Pollack, Bruce Riedel, Ruth Hanau Santini, Salman Shaikh, Ibrahim Sharqieh, Ömer Taşpınar, Shibley Telham, Sarah E. Yerkes

November 4, 2011

Noha Aboueldahab

February 1, 2018

Shadi Hamid

October 1, 2014

It was easy to dismiss Morsi then, and it will be easy to dismiss him now, as a footnote in history. Buried without fanfare and under the glare of a near-totalitarian state—the most repressive in Egypt’s history—he will be easy to forget. But the brief 12 months in which he found himself in power was an unusual time for Egypt. Morsi was incompetent and polarizing, and managed to alienate nearly everyone outside the Brotherhood. Ultimately, he and the Muslim Brotherhood failed. But he was not a fascist or a new pharaoh, as his opponents liked to claim. In a previous piece for The Atlantic , a colleague and I scored Morsi’s one year in power using the Polity IV index, one of the most widely used empirical measures of autocracy and democracy, and then compared it to other cases. We concluded that “decades of transitions show that Morsi, while inept and majoritarian, was no more autocratic than a typical transitional leader and was more democratic than other leaders during societal transitions.”

But to keep the focus narrowly on Morsi, as a person or as a president, is to miss something important, and that something has become clearer to me in the five years since we wrote that piece. That year may have witnessed unprecedented polarization, fear, and uncertainty, but for that time Egypt was the freest, in relative terms, that it had been since its independence in 1952. Egyptians were shouting, protesting, striking, and hoping, both for and against Morsi. This, of course, is also what made the year frightening: the freewheeling intellectual combat, the seemingly endless sparring of ideas and individuals, but also the sheer sense of openness (and the insecurity that came with it). No other period, or even year, comes close. This was not because of Morsi, but because Egypt—with the help of millions of Egyptians—was trying to become a democracy, albeit a flawed one. And Morsi himself, also deeply flawed, was a product of that brief experiment. To remember Morsi, then, is to remember what was lost.

Related Content

H.A. Hellyer

November 27, 2012

October 16, 2013

July 12, 2013

Foreign Policy

Egypt Middle East & North Africa

Center for Middle East Policy

Sharan Grewal, Shady ElGhazaly Harb

May 22, 2024

Sharan Grewal

May 21, 2024

Suzanne Maloney

May 20, 2024

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Mohamed Morsi, Egypt’s First Democratically Elected President, Dies

By Declan Walsh and David D. Kirkpatrick

- June 17, 2019

KHARTOUM, Sudan — Mohamed Morsi, Egypt’s first democratically elected president, collapsed and died while on trial in a Cairo courtroom on Monday, six years after the military ousted him in tumultuous circumstances that pushed Egypt back to autocratic rule.

The Egyptian authorities gave no official cause of death, but critics blamed the poor conditions in the prison where Mr. Morsi had spent the past six years. They said the authorities had deprived him of vital medicine for diabetes, high blood pressure and liver disease; held him in solitary confinement for long periods; and ignored repeated public warnings that the lack of proper medical care could be fatal.

“I think there is a very strong case to be made that this was criminal negligence, deliberate malfeasance in providing Morsi basic prisoner rights,” Sarah Leah Whitson, the executive director for the Middle East and North Africa at Human Rights Watch, said Monday. “He was very obviously singled out for mistreatment.”

His death was a somber milestone in Egypt’s ill-fated democratic transition after the Arab Spring in 2011.

Mr. Morsi, 67, won Egypt’s first free presidential election in 2012 as a senior leader of the Muslim Brotherhood, but was removed from power a year later in a military takeover. Since then he faced a raft of charges including terrorism, spying and breaking out of prison in trials that human rights groups say are deeply flawed.

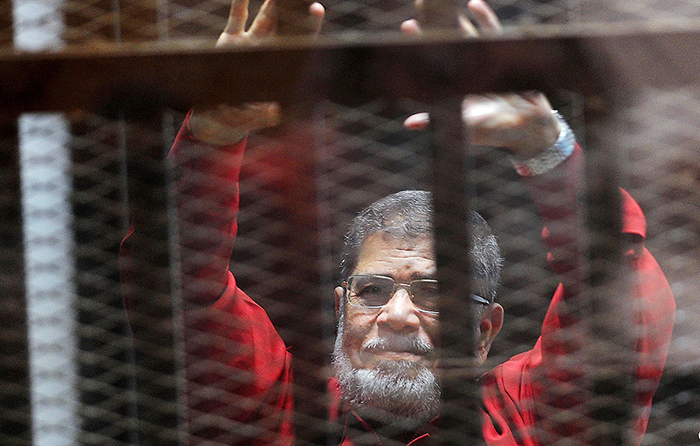

He was in court to face espionage charges on Monday afternoon when he fell unconscious and died, Nabil Sadek, Egypt’s prosecutor general, said in a statement.

Mr. Morsi had spoken for five minutes from the glass cage where prisoners are kept before the hearing was adjourned, Mr. Sadek said. Moments later Mr. Morsi collapsed and was rushed to a hospital, where he was pronounced dead on arrival.

In his final comments, Mr. Morsi continued to insist that he was Egypt’s legitimate president, one of his lawyers told The Associated Press.

The first freely elected president in Arab history, and the first Islamist to occupy that role, Mr. Morsi was elected on June 17, 2012, seven years to the day before he died. His election was the apex of the Arab Spring uprising, and a high point for the Muslim Brotherhood, a 91-year-old Islamist movement founded in Egypt and whose influence extends across the Arab world.

For many Egyptians, Mr. Morsi’s election was their greatest hope for a definitive break with the country’s long history of autocracy after decades of harsh and corrupt rule under President Hosni Mubarak, who was ousted in the 2011 uprising.

Some Egyptians worried that he might impose strict Islamic moral codes, while critics in Washington and around the region raised alarms that he might even seek to establish a form of theocratic rule.

Mr. Morsi surprised many by seeking cordial relations with the United States and maintaining diplomatic ties with Israel. He developed a warm working relationship with President Barack Obama, and the two men worked together to help stop a bout of fighting between Israel and the Palestinian militant group Hamas in the fall of 2012.

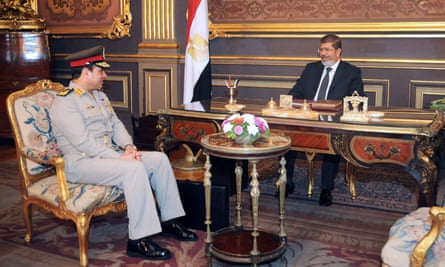

But at home, Mr. Morsi’s rule was troubled from the start. He governed clumsily, at one point issuing a decree that critics said put him above the rule of law. Supporters said the decree was part of his efforts to grapple with a hostile security establishment that was actively maneuvering to undermine his authority.

In the early summer of 2013, giant protests against Mr. Morsi filled Tahrir Square, the crucible of the 2011 uprising, providing the military with an excuse to oust him.

His defense minister, Gen. Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, seized power on July 3, 2013 . Six weeks later, Egyptian security forces shot dead at least 817 protesters , mostly from the Muslim Brotherhood, in what human rights groups called the largest mass shooting of demonstrators in recent history.

Mr. el-Sisi was elected president in 2014 and still rules the country with an iron grip, with Egypt’s democratic hopes largely extinguished.

A referendum in April to allow Mr. el-Sisi to remain in power until 2030 was passed overwhelmingly in a flawed vote that allowed no opposition voices.

Egyptian television channels, which are tightly controlled by the security services, offered equivocal coverage of Mr. Morsi’s death. Some did not interrupt their usual programming to report the demise of a former president.

Other channels aired footage portraying the Muslim Brotherhood as a terrorist organization. “Lies are an integral part of the Muslim Brotherhood,” said a voice on CBC Extra, a private station, after a segment that showed Islamic State fighters threatening to attack Egyptian soldiers.

There was no immediate comment from President el-Sisi’s office.

The handful of people in Egypt willing to speak sympathetically about Mr. Morsi avoided his politics and focused on the conditions of his detention. “He was a victim of brutal prison conditions,” Gamal Eid, a lawyer and human rights advocate, said by phone from Cairo.

Mr. Morsi had been charged with various crimes in politicized trials that have dragged through Egypt’s slow-moving courts. In 2016 his son, Abdullah, told The New York Times that the family feared that the former president might fall into a diabetic coma.

Unlike most prisoners in Egyptian prisons, Mr. Morsi was barred from receiving deliveries of food and medicine from his family, said Ms. Whitson of Human Rights Watch. In addition to being held in solitary confinement, he was denied access to the news media, letters or other communication with the outside world. His wife and other family members were allowed visit just three times in the six years he was imprisoned.

In March of last year, a panel of British politicians and lawyers reviewing his treatment concluded that Mr. Morsi had received “inadequate medical care, particularly inadequate management of his diabetes and inadequate management of his liver disease.”

Failure to address his care, the group warned, could put Mr. Morsi’s life in danger. In a statement on Monday, Crispin Blunt, a member of Parliament who led the panel, said: “Sadly, we have been proved right.”

Mr. Sadek, the Egyptian prosecutor, ordered an immediate investigation into the cause of death. In a statement, he said he would seek Mr. Morsi’s medical file and order a committee to prepare a report on the cause of death.

Investigators will use surveillance footage from the courtroom and question witnesses who were with Mr. Morsi when he died, the statement said.

After overthrowing Mr. Morsi, Mr. el-Sisi sought to banish the Muslim Brotherhood , calling it a terrorist group and sparing little effort to discredit it among the Egyptian public. Most Brotherhood leaders are in jail or exile, and thousands of its members languish in Egypt’s crowded prisons.

In April, President Trump pushed to designate the Brotherhood a terrorist organization under pressure from Mr. el-Sisi, a close ally. The Pentagon and State Department objected, saying the group did not meet the definition of a terrorist entity .

Mr. Morsi was born into a family of modest means in Sharqiya, in the Nile Delta. He earned a Ph.D. in material science from the University of Southern California and later taught at Zagazig University, near Sharqiya. He was almost unknown to the Egyptian public, and most Islamists, before he ran for president in 2012.

The Brotherhood initially chose a more dynamic and well-known figure as its candidate. Mr. Morsi, the understudy, got the nomination only when the first choice was disqualified.

Speaking privately, many Brotherhood members now fault Mr. Morsi for his failures during the year he spent in office, in particular his inability to build broader public support and outmaneuver the hostile security services and Mr. el-Sisi.

Mr. Morsi never led the Brotherhood, a position held by its Supreme Guide, Mohammed Badie, since 2010. Mr. Badie was also imprisoned in 2013 and has been sentenced to seven terms of life imprisonment and a death sentence in various trials since then.

Mr. Morsi’s death is unlikely to have much effect on the current direction of the group, already driven deep underground by the crackdown that followed his ouster.

Peter Mandaville, a professor at George Mason University and a former adviser to the State Department on political Islam, argued that Mr. Morsi’s death was resonating beyond the Brotherhood with other Egyptians who voted for him or “have concerns about the current government’s human rights record.”

“You already see it on Egyptian social media,” Professor Mandaville said. “Everybody is qualifying it with ‘this guy was a flawed politician and president’ but saying that what happened here today tells us something about the current state of the rule of law and respect for rights in Egypt.”

Mr. Morsi’s son Ahmed mourned his father on Facebook, writing : “Father, we will meet again, with God.”

Declan Walsh reported from Khartoum, and David D. Kirkpatrick from London. Nada Rashwan and Farah Saafan contributed reporting from Cairo.

The Tragedy of Egypt's Mohamed Morsi

Mohamed Morsi was a deeply flawed but democratically elected president. His death shows how much his country has lost.

Mohamed Morsi’s life, especially his later life, was the product of a series of accidents. When I first met him, he was a senior but relatively obscure and not particularly important official in the Muslim Brotherhood—and one could easily imagine him staying that way. He was a loyalist, a functionary, and an enforcer. Then he became something else: Egypt’s first democratically elected president—and also the last, at least for the foreseeable future. Visionary leaders sometimes emerge during moments of crisis and transition. But just as often, ordinary men and women find themselves in the midst of historical events, both shaping them and being shaped by them.

Morsi, who died in a Cairo courtroom Monday, was elected in 2012 and deposed in a military coup a year later. He was many, but not all, of the things his critics derided him for. He wasn’t what you would call charismatic. He was not a strategic thinker. He seemed a man particularly unsuited for the responsibility bestowed upon him. In retrospect, knowing what they know now, many in the Brotherhood—in prison, in exile, in hiding—would wish that the organization’s leadership had never opted to field a presidential candidate. But this had little to do with Morsi. Morsi wasn’t meant to be president.

The Brotherhood’s original candidate for president was the businessman Khairat al-Shater, towering in his physical presence, preternaturally confident, and perhaps overwhelmed by ambition. Some called him Egypt’s most powerful man. He was disqualified from running based on a legal technicality. Like so many other things, this, for the group, seemed to confirm that the military sought to block the Brotherhood’s rise by any means necessary. And so Morsi, derided in the Egyptian media as Shater’s “spare tire,” became the accidental candidate and then the accidental president.

Read: Egypt’s only democratic leader helped kill its democracy

When I sat down with Morsi back in May 2010, the longtime dictator Hosni Mubarak was still in office, and the kind of uprising that could force him out seemed implausible. At that point, Morsi insisted the Brotherhood had no interest in power and even objected to the use of the word opposition to describe the group. Repression was intensifying, and political space was closing years after the brief promise of the (first) Arab Spring in 2004 and 2005. The November 2010 parliamentary elections were arguably the most fraudulent in the country’s history, reducing the Brotherhood from 88 seats to 0. Members of the Muslim Brotherhood seemed deflated but not necessarily in despair. They were playing the long game, which is what the Brotherhood always preferred to play. To be tempted by power, on the other hand, led them, and ultimately Morsi himself, into a series of missteps and miscalculations.

The campaign for president in the spring of 2012 took place in a chaotic, uncertain Egypt. Though burdened by a weak candidate, and with only two months to campaign, Brotherhood activists fanned across the country, promoting Morsi’s so-called renaissance project (which had been Shater’s “renaissance project”). In one coordinated show of strength, they held 24 simultaneous mass rallies across the country in a single day. At one rally, I asked a young Brotherhood activist if he was enthusiastic about Morsi. He smiled and then laughed.

It was easy to dismiss Morsi then, and it will be easy to dismiss him now, as a footnote in history. Buried without fanfare and under the glare of a near-totalitarian state—the most repressive in Egypt’s history—he will be easy to forget. But the brief 12 months in which he found himself in power was an unusual time for Egypt. Morsi was incompetent and polarizing, and managed to alienate nearly everyone outside the Brotherhood. Ultimately, he and the Muslim Brotherhood failed. But he was not a fascist or a new pharaoh, as his opponents liked to claim. In a previous piece for The Atlantic , a colleague and I scored Morsi’s one year in power using the Polity IV index, one of the most widely used empirical measures of autocracy and democracy, and then compared it to other cases. We concluded that “decades of transitions show that Morsi, while inept and majoritarian, was no more autocratic than a typical transitional leader and was more democratic than other leaders during societal transitions.”

But to keep the focus narrowly on Morsi, as a person or as a president, is to miss something important, and that something has become clearer to me in the five years since we wrote that piece. That year may have witnessed unprecedented polarization, fear, and uncertainty, but for that time Egypt was the freest, in relative terms, that it had been since its independence in 1952. Egyptians were shouting, protesting, striking, and hoping, both for and against Morsi. This, of course, is also what made the year frightening: the freewheeling intellectual combat, the seemingly endless sparring of ideas and individuals, but also the sheer sense of openness (and the insecurity that came with it). No other period, or even year, comes close. This was not because of Morsi, but because Egypt—with the help of millions of Egyptians—was trying to become a democracy, albeit a flawed one. And Morsi himself, also deeply flawed, was a product of that brief experiment. To remember Morsi, then, is to remember what was lost.

A Monthly Newsmagazine from Institute of Contemporary Islamic Thought (ICIT)

To Gain access to thousands of articles, khutbas, conferences, books (including tafsirs) & to participate in life enhancing events

Visit our digital library.

News & Analysis

Mursi’s Legacy: Unlikely Democratic, Reluctant Martyr

Muslim brotherhood’s baggage set up one of their own to fail, eric walberg, shawwal 27, 1440 2019-07-01.

Muhammad Mursi (1951–2019) was the fifth President of Egypt (June 30, 2012–July 3, 2013), deposed by General ‘Abd al-Fattah al-Sisi in a coup d’état barely a year after he was elected to office. In his last words, Mursi accused the regime of “assassinating” him through years of poor prison conditions and deliberate withholding of medication or even checkups by a doctor despite his failing health (he suffered from high blood pressure and was diabetic, a deadly combination that can result in premature death if not treated in a timely manner).

Mursi is survived by his wife Najlah ‘Ali Mahmud (not “First Lady” but rather “First Servant of the Egyptian people”). Mursi had five children, two are US citizens born in California. His body was quickly buried, without an inquest and with only close family members present, but not his wife. His wish that he be buried in his hometown Adwa was denied.

Human Rights Watch Director for the Middle East Sarah Leah Whitson said Mursi’s treatment in prison was “horrific, and those responsible should be investigated and appropriately prosecuted.” The United Na-tions High Commissioner for Human Rights, called for a “prompt, impartial, thorough, and transparent investigation” into Mursi’s death.

Among major world leaders only Turkey, Jordan, Iran, Malaysia, and Qatar expressed regret at his death. Turkish President Recep Tayip Erdogan said, “Mursi did not die a natural death. He was killed. Turkey will do whatever it takes to prosecute Egypt in international courts.”

Mursi’s legacy is mixed. An engineer who studied at the University of Southern California, he was an unlikely figure to be thrust onto Egypt’s central stage, not a major thinker in the Muslim Brotherhood (MB), without any political experience. He was an unconvincing second choice for the MB as presidential candidate, a poor speaker, but brave and principled.

The charismatic, millionaire businessman Khayratal-Shatir, a major financier and chief strategist of the Brotherhood, was disqualified at the last minute based on previous trumped-up convictions, and Mursi was only allowed to register a few hours before the deadline. He was vilified by hysterical secular westernizers, and undermined by a campaign of lawlessness and planned shortages, but was popular to the end among devout Muslims. The media and the elite were against him and drowned out the Muslim wisdom not to overthrow a ruler as long as you are “not commanded to disobey Allah. If he is commanded to disobey, then there is no listening or obedience” (narrated by ‘Abdullah ibn ‘Umar and recorded by al-Bukhari, #2796).

The MB, like Iran’s Islamic order, doesn’t fit into Western secular thinking. The MB supported the mujahidin in Afghanistan, but they are not the Taliban. They never supported al-Qaeda. They are more in line with Turkey’s Islamically inclined AKP or perhaps even Iran’s Islamic government somewhat.

Here are a few key moments in Mursi’s presidency:

- On Oct. 19, 2012, Mursi traveled to Egypt’s northwestern Matrouh in his first official visit to deliver a speech on Egyptian unity at el-Tenaim Masjid. Immediately prior to his speech he participated in prayers where he openly said “Amin” as Shaykh Futuh ‘Abd al-Nabi Mansur, the local head of religious endowment, declared, “Deal with the Jews and their supporters. Oh Allah, disperse them, rent them asunder. Oh Allah, demonstrate Your might and greatness upon them. Show us Your omnipotence, oh Lord.” The prayers were broadcast on Egyptian state television and translated and posted by MEMRI, a Zionist media watchdog.

- On Nov. 22, 2012, Mursi issued a declaration that intended to protect the work of the Constituent Assembly drafting the new constitution from judicial interference, until a new constitution is ratified in a referendum. This was overblown as an “Islamist coup,” but Mursi was just trying to get around the Supreme Court, stacked with anti-MB judges, who would declare the MB’s programs and new constitution as… unconstitutional. In the referendum to ratify the new constitution, it was approved by approximately two-thirds of voters.

- The declaration also required a retrial of those accused in the Mubarak-era killings of protesters, who had been acquitted. Additionally, the declaration authorized Mursi to take any measures necessary to protect the revolution.

- Mursi took ginger steps to try and strengthen ties with Iran following years of animosity since the Islamic Revolution in 1979. However, his actions were met with Sunni Muslim opposition both inside and outside of Egypt.

- He spoke up for the rights of Christians and emphasized that Islam requires there to be an ethical component in economic affairs to ensure that the poor share in society’s wealth.

Like Erdogan in Turkey, in the heady days after the 2011 uprisings in the Arab world, Mursi got swept up in Islamic revolutionary fever, calling for overthrow of the (‘Alawi) “infidels,” a kind of belated revenge for the slaughter of the Syrian MB by Hafiz al-Asad in 1981. But then, just about everyone was (and still is) supporting the Syrian opposition, from Obama to most Sunnis, soon-to-be-ISIS, and leftists.

The last straw for the military was when Mursi attended an Islamist rally on June 15, 2013, where Salafi clerics called for jihad in Syria and denounced supporters of Bashar al-Asad as infidels. Mursi announced that his government had expelled Syria’s ambassador and closed the Syrian embassy in Cairo, calling for international intervention on behalf of the opposition forces and establishment of a no-fly zone.

Mursi’s attendance at the rally was later revealed to be a major factor in the army’s decision to side with anti-Mursi protesters during the June 30 anti-government protests. In November 2012, the National Salvation Front (NSF) had suddenly appeared, and overnight 22 million Egyptians signed a nationwide petition calling for Mursi’s immediate resignation.

Is it possible that Mursi might have survived if he hadn’t broken relations with Syria and called for jihad? The Egyptian military looked at Syria and saw their own future. The Syrian army was battling to hold the country together in the face of a dubious coalition of Islamists with lots of support from Saudi Arabia and the US. They decided they had to overthrow their own Brotherhood-led government before it took them on and ended their privileged hegemony. The Egyptian military is trained and equipped by the US. Egypt runs on Saudi dollars. Best to keep the US and Saudis on your side and the message by then was “Dump the Brotherhood.”

We will never know, but the plan from the start clearly was for the all-powerful military to give the Brotherhood some rope, and then take charge and hang them (metaphorically and literally) if they actually tried to govern, counting on the vengefulness of the old guard and the screaming liberals if the MB pushed too hard. The liberals were weak, and could be conned into supporting a coup, and then easily brought to heel with a few arrests and massacres.

This power politics is not confined to the Arab world. Iran and Venezuela are both targets of Western-backed campaigns to destroy any attempt, Islamic or socialist, to escape the clutches of the US empire. Donald Trump welcomed al-Sisi to the White House in April 2019, after the Egyptian pharaoh declared himself president for life (in a referendum that he won with 88.3% approval). Trump said, “We’ve never had a better relationship, Egypt and the United States, than we do right now. I think he’s doing a great job.” After the meeting, Trump pushed for the US to designate the Brotherhood as a terrorist organization.

Just as Erdogan came to regret his betrayal of al-Asad (and barely survived a coup in July 2016), so Mursi and the entire MB can only regret flirting with militant jihad abroad, from the 1980s on. Even if al-Asad is an ‘Alawi and you don’t approve of that sect of Islam, you don’t overthrow him as long as he doesn’t command you “to disobey Allah.”

But then, 30 years ago it was official Egyptian and US policy to encourage Islamists from Egypt to go and fight in Afghanistan. And the campaign against al-Asad was/is almost unanimous in the West. So again, I sympathize with bad judgment by the MB.

MB spokesman Dr. ‘Abd al-Mawjud al-Dardiri said, “The nation elected Mursi to a four-year term and should stand by that. To do otherwise would disrupt the country’s nascent democracy. It is not fair to a democracy.” Lesson from Iran and Syria: if you’re going to have an Islamic revolution, make sure the people and army are on your side.

Al-Sisi clearly models himself on Egypt’s 19th-century dictator-pasha Muhammad ‘Ali. The parallel is stark between al-Sisi’s and Muhammad ‘Ali’s clever invitation to all his Mamluk rivals to his citadel in 1811. He invited them to the centre of power and proceeded to slaughter a thousand of them to consolidate his rule. Invite your foes into the open and then murder them.

A legend of the pasha was that he had 300,000 street children rounded up and shipped to Aswan where they were taught skills and became assets to his construction of a new Egypt. Al-Sisi launched just such a program “Homeless Children” in May 2017, planning to gather up street waifs and whisk them to an army camp for training.

Then there’s the new Aswan Dam, criticized as a white elephant, even as Egypt hovers on the brink of bankruptcy (along with it is a scaled-down version of the MB’s proposed industrial corridor along the Nile). This nostalgia for the past is perhaps an attempt at taking the wind out of the sails of ISIS, the actual terrorists masquerading as Muslims, yearning for the caliphate, but is just as misguided.

By attempting to destroy the MB, the legitimate Islamic movement, al-Sisi gives fuel to the ISIS fires. That was what the MB could have tackled, not a secular dictator persecuting devout Muslims. On the contrary, terrorism has increased dramatically since 2013, with at least 500 deaths.

The Ministry of Education has decreed that the revolution of January 25, 2011, and the uprising on June 30, 2013 will no longer be mentioned in high school history textbooks. The “Arab Spring” didn’t happen. President Mursi is dead, assassinated. Al-Shatir and other MB leaders are on death row. Al-Sisi is dictator for life.

The end of history? Hardly. As for Mursi, he enters the realm of legend, a kind of foil for Usamah bin Ladin, as a true martyr to Islam.

Know More »

Article from

Crescent international vol. 48, no. 5, related articles.

El-Sisi: Pharoah Forever!

Ayman ahmed, dhu al-hijjah 11, 1441 2020-08-01.

General Abdel Fattah El-Sisi has been in power for seven years but he has made a real mess of everything in Egypt. Far from solving any of t...

The sultan and the Shaytan

Shawwal 27, 1437 2016-08-01.

Using the garb of Sufism, the self-styled religious preacher, Fethullah Gulen has turned out to be a US-Zionist puppet who is prepared to ad...

Sisi regime heading for Syrian-style crisis

Crescent international, rajab 07, 1444 2023-01-29.

BRICS: Will Egypt’s Coup Leader el-Sisi Escape Scrutiny in South Africa?

Iqbal jassat, muharram 15, 1445 2023-08-02.

To Gain access to thousands of articles, khutbas, conferences, books (including tafsirs) & to participate in life enhancing events, Visit our Digital Library

Important links: home | archives | news | authors | subscribe | donate | about us | contact us | google search, magazine sections: main stories | editorials | opinion | news & analysis | special reports | islamic movement | book review | editor's desk | background | letters to the editor, digital library: articles | books | events | multimedia | people | themes, crescent international © 1438 ah. all rights reserved., designed & maintained by dynamisigns ., forgot password , not a member sign up.

Watch CBS News

Mohammed Morsi, deposed president of Egypt, has collapsed and died in court, according to state TV

Updated on: June 17, 2019 / 8:35 PM EDT / CBS/AP

Cairo — Egypt's former president, Mohammed Morsi, the Muslim Brotherhood leader who rose to office in the country's first free elections in 2012 and was ousted a year later by the military, collapsed in court during a trial and died, state TV and his family said. State TV, citing a medical source, said Morsi died from a sudden heart attack, the Reuters news agency reports.

Morsi had been Egypt's elected president following the abdication of Hosni Mubarak in 2011, but was deposed after a military coup in 2013 that installed General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi into power.

Egyptian state TV says the 67-year-old Morsi was attending a court session Monday in his trial on espionage charges when he blacked out and then died before he could be taken to a hospital. Morsi had just addressed the court, speaking from the glass cage he was kept in during sessions and warning that he had "many secrets" he could reveal, a judicial official said.

A few minutes afterward, he collapsed, the official said, speaking on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to talk to the press. Morsi's son, Ahmed, confirmed the death of his father in a Facebook post.

Morsi, a leader of Egypt's largest Islamist group, the now outlawed Muslim Brotherhood, was elected president in 2012 in the country's first free elections following the ouster the year before of longtime leader Hosni Mubarak. The military ousted Morsi in 2013 after massive protests and crushed the Brotherhood in a major crackdown, arresting Morsi and many others of the group's leaders. Morsi had been imprisoned since his arrest and was previously sentenced to death for his alleged role in a mass prison break that took place during the 2011 uprising that toppled Mubarak.

Mohammed Sudan, leading member of the Muslim Brotherhood in London, described Morsi's death as "premediated murder" saying that the former president was banned from receiving medicine or visits and there was little information about his health condition. Monday's session was part of a retrial, being held inside Cairo's Tura Prison, on charges of espionage with the Palestinian Hamas militant group.

"He has been placed behind glass cage (during trials). No one can hear him or know what is happening to him. He hasn't received any visits for a months or nearly a year. He complained before that he doesn't get his medicine. This is premediated murder. This is slow death."

The judicial official said Morsi had asked to speak to the court during the session. The judge permitted it, and Morsi gave a speech saying he had "many secrets" that, if he told them, he would be released, but he added that he wasn't telling them because it would harm Egypt's national security. A spokesman for the Interior Ministry did not answer calls seeking comment.

Morsi was a longtime senior figure in Egypt's most powerful Islamist group, the Muslim Brotherhood. He was elected in 2012 in the country's first free presidential election, held a year after an Arab Spring uprising ousted Egypt's longtime authoritarian leader Hosni Mubarak. His Muslim Brotherhood also held a majority in parliament.

The military, led by then-Defense Minister Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi, ousted Morsi after massive protests against the Brotherhood's domination of power. El-Sissi was subsequently elected president and has waged a massive crackdown on Islamists and other opponents since.

Since Morsi's ouster, Egypt's government has declared the Brotherhood a terrorist organization and largely crushed it with a heavy crackdown. Tens of thousands of Egyptians have been arrested since 2013, mainly Islamists but secular activists who were behind the 2011 uprising.

He has been sentenced to 20 years after being convicted of ordering Brotherhood members to break up a protest against him, resulting in deaths. An earlier death sentence was overturned. Multiple cases are still pending.

Morsi was held in a special wing in the sprawling Tora detention complex nicknamed Scorpion Prison. Rights groups say its poor conditions fall far below Egyptian and international standards.

Correction: An earlier version of this article stated Hosni Mubarak died in 2012. He abdicated the presidency in 2011 and was sentenced to life in prison in 2012. He was released in 2017 and is alive at age 91.

More from CBS News

Teen dies after being pulled from Discovery Cove pool in Orlando, police say

Supreme Court sides with NRA in free speech dispute with New York regulator

Court orders business mogul to pay whopping $1 billion divorce settlement

North Korea flies hundreds of balloons full of trash over South Korea

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Mohamed Morsi, ousted president of Egypt, dies in court

Imprisoned former leader, 67, collapses and dies while on trial on espionage charges

Egypt’s first democratically elected civilian president, Mohamed Morsi , has collapsed during a court session and died, almost six years after he was forced from power in a bloody coup.

Morsi, a senior figure in the now-banned Muslim Brotherhood , was attending a session in his trial on espionage charges on Monday when he blacked out and died, according to state media.

“After the case was adjourned, he fainted and died. His body was then transferred to the hospital,” reported the Egyptian state newspaper al-Ahram, referring to Morsi’s retrial for allegedly spying for the Palestinian Islamist organisation Hamas.

Egypt’s public prosecutor said Morsi, 67, was pronounced dead on arrival at a Cairo hospital, after he fainted inside the defendants “cage” in the courtroom. Nabil Sadiq’s statement said the cause of death was being investigated but that “there were no visible, recent external injuries on the body of the deceased”.

The Brotherhood accused the government of “assassinating” Morsi through years of poor prison conditions, and called on Egyptians to gather for a mass funeral.

“We heard the banging on the glass cage from the rest of the other inmates and them screaming loudly that Morsi had died,” Morsi’s lawyer, Osama El Helw, told AFP.

Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, reacted angrily to news of Morsi’s death. “History will never forget those tyrants who led to his death by putting him in jail and threatening him with execution,” he said in a televised speech.

Morsi became president in 2012, following Egypt’s first and only free elections after the dictator Hosni Mubarak was forced from power. He won 51.7% of the vote and his rule marked the peak of power for Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood, which had functioned for decades as an underground political organisation.

But his time in power was cut short a year later as demonstrators once again took to the streets – this time to protest against Morsi’s rule and demand fresh elections. Egypt’s military seized power in a coup on 3 July 2013, bringing the then defence minister, Abdel-Fatah al-Sisi, to power.

As president, Sisi has overseen an extensive crackdown on the Muslim Brotherhood and anyone suspected of supporting the group, which Egypt now considers a terrorist organisation.

Morsi was arrested after the 2013 coup and has faced trial on three separate counts of leaking state secrets to Qatar, killing protesters during a sit-in outside the presidential palace, and spying for Hamas.

He received multiple long sentences, including a life sentence for spying for Qatar and a 20-year sentence for killing protesters. A death sentence for charges relating to a mass jailbreak during the revolution was overturned in a retrial in November 2016.

Morsi was subject to retrials in several cases, and was sentenced to a further two years in prison and fined 2 million Egyptian pounds (£83,000) in 2017 for insulting the judiciary.

Many of his supporters met an even worse fate. On 14 August 2013, Egyptian security forces raided two protest encampments that had been set up in Cairo to demand that Morsi be reinstated. At least 1,150 were killed in five separate incidents when Egyptian forces opened fire on protesters, according to Human Rights Watch.

The former president, who had a history of ill health including diabetes and liver and kidney disease, was held in solitary confinement in Tora prison in Cairo.

In 2018, a panel of three British parliamentarians reported that Morsi was being kept in solitary confinement for 23 hours a day , with just one hour allowed for exercise. Crispin Blunt, who led the UK group, called on Monday for an investigation into Morsi’s death. “The Egyptian government has a duty to explain his unfortunate death and there must be proper accountability for his treatment in custody,” he said.

Morsi’s supporters said his death was not a surprise. “We had been expecting the worst for some time,” said Wael Haddara, a former adviser, speaking from Canada.

“In many ways, this was the expected result of the military’s actions,” he said. “But he was a friend, and a symbol for many Egyptians, so it’s painful.”

- Mohamed Morsi

- Middle East and north Africa

- Muslim Brotherhood

British MPs ask Egypt for access to jailed ex-president over health concerns

Nine executed in Egypt over Hisham Barakat assassination

Egypt sentences 75 Muslim Brotherhood supporters to death

Into the Hands of the Soldiers review: how democracy failed in Egypt

Sisi wins second term as Egyptian president after purge of challengers

The Guardian view on Egyptian democracy: it would be a good idea

Former Egypt president Mohamed Morsi found guilty of insulting judiciary

Generation revolution: how Egypt’s military state betrayed its youth

Most viewed.

Mohamed Morsi: death of Egypt’s former president shows deep state was always going to triumph

Lecturer in Middle Eastern History, University of Reading

Disclosure statement

Dina Rezk receives funding from the Arts and Humanities Research Council for her research.

University of Reading provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

Mohamed Morsi, Egypt’s first democratically elected president, died on June 17 in court in Cairo where he was on trial facing charges of espionage. He will be remembered for a short and divisive presidency and his failure to deliver the hopeful visions of Egypt’s “Arab Spring”. His legacy: the unprecedented consolidation of authoritarian rule by Egypt’s current military regime.

In the summer of 2012, Morsi’s narrow victory was hailed by the West in the wake of the uprising that saw the ouster of his predecessor Hosni Mubarak. But within a year, even Egyptians who had cast their votes for Morsi were clamouring for his removal, in what some described as the largest public protests in world history.

Morsi was not a popular president. His electoral triumph against Mubarak lackey Ahmad Shafik was so close that it aroused suspicions of a deal with the army. Neither of the two candidates represented Egypt’s liberal voice, whose votes were split between a plethora of candidates and who failed to consolidate as an effective “third way” during the first round of voting.

An engineer by training, Morsi in fact had little experience in politics before his rapid rise to power in 2012. Within months of his inauguration it seemed clear that he was unable to command the support of the Egyptian people. On the international stage, a series of embarrassing blunders intensified the wave of domestic criticism that culminated in his downfall in 2013.

Read more: Morsi's authority ebbed away, but Egypt is dangerously divided

The balance sheet

Initially, Morsi showed promise. His first speech to the Egyptian people deployed the language of national unity and reform of the security state, clearly appealing to the sentiments expressed in the 2011 revolution of “bread, freedom and social justice.” In November 2012, he brokered a ceasefire between Israel and Hamas in Gaza, reassuring the international community that Egypt would continue to play the role of mediator in the Arab-Israeli conflict.

Just one day after this success, however, Morsi announced a presidential decree that marked the beginning of the end of his rule. On November 22, 2012 he issued a constitutional declaration , appointed a new public prosecutor, and gave himself what many saw as dictatorial powers – making presidential decrees immune to judicial oversight. While Morsi claimed that these measures were necessary to protect the revolution and transition to a constitutional democracy, he was accused of appointing himself as “Egypt’s new pharaoh”.

In response to widespread protests, Morsi annulled the declaration but insisted on proceeding with a snap referendum on the new constitution which passed with a 63% majority but a low voter turnout of only 33%.

The constitutional crisis was a critical turning point and provided the army with a window of opportunity to present itself as “the saviour” of the Egyptian people. In late April 2013, the Tamarod (meaning “rebel”) campaign was officially launched with the goal of collecting 15m signatures by June 30 – the anniversary of Morsi’s presidential victory – to call for early elections. Evidence has since emerged suggesting that the movement operated with the approval and support of the military and security agencies as well as supporters of the former Mubarak regime. Leaked recordings of conversations between Egyptian military figures revealed that the group drew funds from a bank account administered by the Ministry of Defence and replenished by the United Arab Emirates.

Millions of Egyptians heeded Tamarod’s call and on July 3, the defence minister Abdel Fattah al-Sisi declared that the army had suspended the constitution and deposed the president in order to “end the state of conflict and division” that had marked Morsi’s presidency.

Sisi clampdown

In retrospect, Morsi’s brief time in power looks relatively benign when compared to the authoritarianism that followed Sisi’s military coup. The Muslim Brotherhood has long been demonised by the political elite since the founding of Egypt’s republic in 1952. In fact, Morsi’s brief presidency clearly demonstrated that the interests of the “deep state” would ultimately triumph. The Muslim Brotherhood could never have dominated Egypt in the way that many feared because they simply had too many enemies.

Read more: Egypt: hopes for democratic future die as al-Sisi marches country towards dictatorship – with parliament's blessing

Today, the Muslim Brotherhood is regarded as a terrorist group and an existential threat to the Egyptian people. Not only is it a crime to be associated with the organisation, but the Egyptian regime has made it clear that any dissent whatsoever will be crushed.

The Muslim Brotherhood no doubt sees Morsi as the latest martyr in an ongoing battle with the Sisi government. He was sentenced to death in 2015 in a ruling that was subsequently overturned in 2016.

The inhumanity of Morsi’s treatment in prison, where he was kept predominantly in solitary confinement, will evoke previous acts of brutality against the group, not least the public massacre of over 1,000 supporters of the Brotherhood in August 2013, described by Human Rights Watch as the worst mass killing in Egypt’s history. The UN has called for an investigation into Morsi’s death.

Unfortunately, while high profile, Morsi’s fate is by no means exceptional. He is simply the latest and most visible victim of a regime committed to imposing its will on the nation without concern for the human cost. Nonetheless, the vast majority of Egyptians will not be mourning the death of their first democratically elected president.

- Mohammed Morsi

- North Africa

- Abdel Fattah el-Sisi

Data Manager

Research Support Officer

Director, Social Policy

Head, School of Psychology

Senior Research Fellow - Women's Health Services

Mohamed Morsi’s death: World reaction

Malaysia, Qatar pay tribute to former Egyptian president, but reaction from other governments has been largely muted.

The United Nations has called for an “independent inquiry” into the death of former Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi , who died aged 67 after collapsing in a Cairo court on Monday, according to state media.

Morsi, who was buried on Tuesday, was a top figure in the Muslim Brotherhood and the first democratically elected president in Egypt’s modern history.

Keep reading

Hrw: academic held by egyptian authorities at risk of death hrw: academic held by egyptian ..., what challenges do turkey, egypt face in restoring ties what challenges do turkey, egypt face in ..., egypt upholds life sentences for 10 muslim brotherhood figures egypt upholds life sentences for 10 ..., egypt and turkey hold ‘frank’ official talks, first since 2013 egypt and turkey hold ‘frank’ official ....

He had been in jail since he was toppled by the military in 2013 after mass protests against his rule.

His death has been mourned by many people around the world, including in Turkey where mosques held special prayers on Tuesday, while leaders in Malaysia and Qatar offered tributes.

However, the reaction has been largely muted in many capitals.

Here are some of the statements on the sudden death of Morsi :

UN rights office calls for ‘transparent investigation’

The United Nations human rights office has called for a “ prompt, impartial, thorough and transparent investigation” into Morsi’s death.

“Concerns have been raised regarding the conditions of Mr. Morsi’s detention, including access to adequate medical care, as well as sufficient access to his lawyers and family, during his nearly six years in custody,” Rupert Colville, spokesman for the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, said on Monday.

Tunisia’s Ennahda party

The Tunisian Ennahda political party said it received the news with great sadness and shock and extended condolences to Morsi’s family and the Egyptian people.

The movement expressed hope that “the painful incident would be a reason to put an end to the suffering of thousands of political prisoners in Egypt” and for starting dialogue for a new democratic political life in Egypt.

Jordan’s Muslim Brotherood

Jordan’s Muslim Brotherhood held “the coup authorities in Egypt responsible for Morsi’s death after his detention for seven years in solitary imprisonment”.

The group also held the international community responsible for “the crimes of the coup” in Egypt.

Qatar’s Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani

Qatari Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani offered his condolences to Morsi’s family and Egyptian people.

“We received with great sorrow the news of the sudden death of former president Dr Mohamed Morsi. I offer my deepest condolences to his family and Egyptian people. We belong to God and to him we shall return,” Sheikh Tamim said in a Twitter post.

تلقينا ببالغ الأسى نبأ الوفاة المفاجئة للرئيس السابق الدكتور محمد مرسي .. أتقدم إلى عائلته وإلى الشعب المصري الشقيق بخالص العزاء.. إنا لله وإنا إليه راجعون — تميم بن حمد (@TamimBinHamad) June 17, 2019

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan

Recep Tayyip Erdogan , the president of Turkey, on Monday blamed Egypt’s “tyrants” for the death of Morsi.

“History will never forget those tyrants who led to his death by putting him in jail and threatening him with execution,” Erdogan, a close ally of Morsi, said in a televised speech in Istanbul.

The Turkish leader called the former Egyptian president a “martyr,” Turkey had been among Morsi’s biggest supporters.

“May Allah rest our Morsi brother, our martyr’s soul in peace,” said Erdogan, who had forged close ties with the former president.

Thousands in Istanbul joined in prayer on Tuesday for Morsi on Tuesday. The prayer was called by Turkey’s religious authority Diyanet and took place in the city’s Fatih mosque.

Erdogan is expected to attend an absentee funeral for Morsi in Istanbul on Tuesday.

United Nations

United Nations spokesman Stephane Dujarric offered condolences to Morsi’s relatives and supporters.

Human Rights Watch

Sarah Leah Whitson, executive director of Human Rights Watch ‘s Middle East and North Africa division, called Morsi’s death “terrible but entirely predictable”, given the government’s failure to allow him adequate medical care.

“What we have been documenting for the past several years is the fact that he has been in the worst conditions. Every time he appeared before the judge, he requested private medical care and medical treatment,” Whitson told Al Jazeera.

“He was been deprived of adequate food and medicine. The Egyptian government had known very clearly about his declining medical state. He had lost a great deal of weight and had also fainted in court a number of times.

“He was kept in the solitary confinement with no access to television, email or any communication with friends and family,” Whitson said, arguing that there would not be a credible independent investigation on Morsi’s death “because their [Egyptian government] job and role is to absolve themselves of wrongdoing ever”.

BREAKING – #Egypt news says only democratically elected Pres #Morsy has died in prison after stroke. This is terrible but ENTIRELY predictable, given govt failure to allow him adequate medical care, much less family visits. @hrw was just finalizing a report on his health. — Sarah Leah Whitson (@sarahleah1) June 17, 2019

Mohamed Morsi’s son

In a Facebook post, Morsi’s son, Ahmed, confirmed the death of his father.

“In front of Allah, my father and we shall unite,” he wrote.

Muslim Brotherhood

Mohammed Sudan, a leading member of the Muslim Brotherhood in London, described Morsi’s death as “premeditated murder”, saying that the former president was banned from receiving medicine or visits and there was little information about his health condition.

“He has been placed behind [a] glass cage [during trials]. No one can hear him or know what is happening to him. He hasn’t received any visits for months or nearly a year. He complained before that he doesn’t get his medicine. This is premeditated murder. This is slow death.”

The Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice political party said in a statement that Egyptian authorities is responsible for Morsi’s “deliberate slow death”.

“[The Egyptian authorities] put him in solitary confinement… they withheld medication and gave him disgusting food… they did not give him the most basic human rights,” the political party said in a statement published on its website.

The Brotherhood also called for crowds to gather outside Egyptian embassies around the world.

Egyptian politicians close to Morsi

In a joint statement, Amr Darrag, a senior member of the Muslim Brotherhood and a minister of planning and international cooperation under Morsi, and Yehia Hamed, a former Egyptian investment minister under Morsi, said an international independent investigation into the death of Morsi should be made public.

“The Egyptian regime knew that the continued denial of access to medical treatment would lead to his premature death. To that effect, the death of President Morsi is tantamount to state sponsored murder,” they said in the statement.

“The first democratically elected President has died through a concerted and active campaign by the Egyptian regime. This is a gross violation of international law. It must not be allowed to stand.”

Independent Detention Review Panel

In a statement released after Morsi’s death, Crispin Blunt, chairman of the UK’s Independent Detention Review Panel, said his death in custody was representative of Egypt’s inability to treat prisoners in accordance with both Egyptian and international law.

“The Egyptian government has a duty to explain his unfortunate death and there must be proper accountability for his treatment in custody. We found culpability for torture rests not only with direct perpetrators but those who are responsible for or acquiesce in it,” he said in a statement.

“The only step now is a reputable independent international investigation.”

Last year, a report by three UK MPs, under the panel, warned that the lack of medical treatment could result in Morsi’s “premature death”.

Amnesty International

Amnesty International urged Egyptian authorities to investigate the death of Morsi.

“We call on Egyptian authorities to conduct an impartial, thorough and transparent investigation into the circumstances of Mursi’s death, including his solitary confinement and isolation from the outside world,” t he London-based rights group said in a twitter post.

It also called for an investigation into the medical care Morsi was receiving, and for anyone found responsible for mistreatment to be held accountable.

Egypt must carry out a thorough and impartial investigation into the death of former President Mohamed Morsi who collapsed in a courtroom today. He was held in solitary confinement for six years and was only allowed three family visits during that time. https://t.co/nadwJOIjxO — Amnesty International (@amnesty) June 17, 2019

Hamas issued a statement paying tribute to Morsi, who had been a close ally of the Palestinian movement administering the besieged Gaza Strip.

It praised Morsi’s “long struggle spent in the service of Egypt and its people, and primarily the Palestinian cause”.

At the Al-Aqsa Mosque in occupied East Jerusalem, funeral prayers were performed by Palestinians on Monday night.

Pakistan Jamaat-e-Islami

Pakistan’s religious-political group, Jamaat-e-Islami , said the “Muslim world has lost a true hero”.

“Morsi stood tall in the face of all pressures aimed at forcing him to withdraw his struggle for fundamental rights of the people of Egypt and his support to Palestine,” the group’s chief Senator Siraj-ul- Haq said in a statement on Twitter.

He announced that the party on Tuesday would hold funeral prayers in absentia for Morsi across Pakistan.

Malaysia expresses condolences

Malaysia’s foreign ministry said it was “shocked and saddened by the sudden death” of Morsi.

“During his tenure as president, Mr Morsi showed courage and moral fortitude in his attempt to lead Egypt away from decades of authoritarian rule and establish true democracy there,” Foreign Minister Saifuddin Abdullah said in a statement.

“I would like to extend my deepest condolences to the bereaved family of Mr Morsi and the people of Egypt.”

- Mohamed Morsi

- Gallery pages of politicians

- Gallery pages of engineers

- Gallery pages about people of Egypt

- Uses of Wikidata Infobox

Navigation menu

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Mohamed Mohamed Morsi Eissa al-Ayyat (/ ˈ m ɔːr s i /; Arabic: محمد محمد مرسي عيسى العياط IPA: [mæˈħæmmæd ˈmoɾsi ˈʕiːsæ (ʔe)l.ʕɑjˈjɑːtˤ]; 8 August 1951 - 17 June 2019) was an Egyptian politician, engineer, and professor who served as the fifth president of Egypt, from 2012 to 2013, when General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi removed him from office in a coup ...

Freedom and Justice Party. Muslim Brotherhood. Mohamed Morsi (born August 20, 1951, Al-Sharqiyyah governorate, Egypt—died June 17, 2019, Cairo, Egypt) was an Egyptian engineer and politician who was president of Egypt (2012-13). He was removed from the presidency by a military action in July 2013, following massive demonstrations against ...

He insisted that he was still the country's legitimate president. Morsi and his wife had four sons, Ahmed, Omar, Osama and Abdullah, and a daughter, Shaimaa. Mohamed Morsi Issa al-Ayyat ...

Mohamed Morsi was born on August 8, 1951, in the Sharqia Governorate, in the village of El-Adwah, Egypt, to a farmer father, and a housewife mother. He was the eldest of five brothers. In 1975, he obtained a bachelor's degree in engineering from Cairo University and then completed his post-graduation in 1978.

Mohamed Morsi's life, especially his later life, was the product of a series of accidents. When I first met him, he was a senior but relatively obscure and not particularly important official in ...

Mohamed Morsi, Egypt's first democratically elected president, has died at the age of 67 after a court appearance in Cairo, according to state media. A member of the Muslim Brotherhood ...

Mr. Morsi, 67, won Egypt's first free presidential election in 2012 as a senior leader of the Muslim Brotherhood, but was removed from power a year later in a military takeover.

Mohamed Morsi ( Arabic: محمد محمد مرسى عيسى العياط, ALA-LC: Muḥammad Muḥammad Mursī 'Īsá al-'Ayyāṭ ; 8 August 1951 - 17 June 2019) was an Egyptian politician. [1] With the support of the Muslim Brotherhood he became the fifth President of Egypt on 30 June 2012. On 3 July 2012, the Egyptian defense minister ...

Mohamed Morsi's life, especially his later life, was the product of a series of accidents. When I first met him, he was a senior but relatively obscure and not particularly important official in ...

Mohamed Morsi Issa el Ayat is a former chairman of the Muslim Brotherhood's Freedom and Justice Party (FJP) and a long-time leader in the Muslim Brotherhood. He is a trained engineer educated at the University of Southern California. After winning the presidency on June 24, 2012, Morsi resigned as head of the FJP and from the Muslim ...

Muhammad Mursi (1951-2019) was the fifth President of Egypt (June 30, 2012-July 3, 2013), deposed by General 'Abd al-Fattah al-Sisi in a coup d'état barely a year after he was elected to office. ... after the Egyptian pharaoh declared himself president for life (in a referendum that he won with 88.3% approval). Trump said, "We've ...

Egypt's former president Mohamed Morsi dies at age 67 02:08. Cairo — Egypt's former president, Mohammed Morsi, the Muslim Brotherhood leader who rose to office in the country's first free ...

Egypt's first democratically elected civilian president, Mohamed Morsi, has collapsed during a court session and died, almost six years after he was forced from power in a bloody coup. Morsi, a ...

Mohamed Hossam/EPA. Mohamed Morsi, Egypt's first democratically elected president, died on June 17 in court in Cairo where he was on trial facing charges of espionage. He will be remembered for ...

Muhammad Mursi Biography Born on the eastern edge of the Nile Delta during the reign of Al-Sharqiyyah. Muhammad Mursi pursued his undergraduate education at Cairo University majoring in ...

Post-Morsi's election 2012 July. On 8 July, Mohamed Morsi issued a decree calling back into session the dissolved parliament for 10 July 2012. Morsi's decree also called for new parliamentary elections to be held within 60 days of the adoption of a new constitution for the country, which is tentatively expected for late 2012. A constitutional assembly selected by the erstwhile parliament has ...

18 Jun 2019. The United Nations has called for an "independent inquiry" into the death of former Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi, who died aged 67 after collapsing in a Cairo court on Monday ...

Complete Biography of Muhammad Mursi Story Of Mursi in Urdu/HindhIn this video we explain the biography and real story Of X president of Egypt Muhammad Mursi...

Mohamed Morsi. English: Dr. Mohamed Morsi (August 8, 1951 - June 17, 2019) was the fifth president of Egypt, from 30 June 2012 to 3 July 2013, when he was removed by Field Marshal Abdel Fattah el-Sisi after June 2013 Egyptian protests and 2013 Egyptian coup d'état. He was the first democratically elected head of state in Egyptian history.

Muhammad Mursi Isa al-Ayyat (arabiska: محمد مرسى عيسى العياط IPA: [mæˈħæmmæd ˈmoɾsi ˈʕiːsæ (ʔe)l.ʕɑjˈjɑːtˤ]), född 20 augusti 1951 i Ash-Sharqiyya, död 17 juni 2019 i Kairo, [7] var en egyptisk politiker som var Egyptens president från den 30 juni 2012 till den 3 juli 2013. Därefter avsattes han i en ...

Muhammad Muhammad Mursí Issa Al-Aját (arabsky محمد محمد مرسي عيسى العياط ; 20. srpna 1951 Adva - 17. června 2019 Káhira) byl egyptský politik a materiálový inženýr.Byl pátým, ale prvním a dosud jediným demokraticky zvoleným prezidentem Egypta, úřad zastával od 30. června 2012 do 3. července 2013, kdy byl svržen vojenským převratem.