- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Should Higher Education Be Free?

- Vijay Govindarajan

- Jatin Desai

Disruptive new models offer an alternative to expensive tuition.

In the United States, our higher education system is broken. Since 1980, we’ve seen a 400% increase in the cost of higher education, after adjustment for inflation — a higher cost escalation than any other industry, even health care. We have recently passed the trillion dollar mark in student loan debt in the United States.

- Vijay Govindarajan is the Coxe Distinguished Professor at Dartmouth College’s Tuck School of Business, an executive fellow at Harvard Business School, and faculty partner at the Silicon Valley incubator Mach 49. He is a New York Times and Wall Street Journal bestselling author. His latest book is Fusion Strategy: How Real-Time Data and AI Will Power the Industrial Future . His Harvard Business Review articles “ Engineering Reverse Innovations ” and “ Stop the Innovation Wars ” won McKinsey Awards for best article published in HBR. His HBR articles “ How GE Is Disrupting Itself ” and “ The CEO’s Role in Business Model Reinvention ” are HBR all-time top-50 bestsellers. Follow him on LinkedIn . vgovindarajan

- JD Jatin Desai is co-founder and chief executive officer of The Desai Group and the author of Innovation Engine: Driving Execution for Breakthrough Results .

Partner Center

EdSource is committed to bringing you the latest in education news.

But we can’t do this without readers like you.

Will you join our spring campaign as one of 50 new monthly supporters before May 22?

Student journalists on the frontlines of protest coverage

How can California teach more adults to read in English?

Hundreds of teachers in limbo after spike in pink slips

How earning a college degree put four California men on a path from prison to new lives | Documentary

Patrick Acuña’s journey from prison to UC Irvine | Video

Family reunited after four years separated by Trump-era immigration policy

Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: California and beyond

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

May 14, 2024

Getting California kids to read: What will it take?

April 24, 2024

Is dual admission a solution to California’s broken transfer system?

College & Careers

Tuition-free college is critical to our economy

Morley Winograd and Max Lubin

November 2, 2020, 13 comments.

EdSource’s journalism is always free for everyone — because we believe an informed public is necessary for a more equitable future for every student. Join our spring campaign as one of 50 new monthly supporters before May 22.

To rebuild America’s economy in a way that offers everyone an equal chance to get ahead, federal support for free college tuition should be a priority in any economic recovery plan in 2021.

Research shows that the private and public economic benefit of free community college tuition would outweigh the cost. That’s why half of the states in the country already have some form of free college tuition.

The Democratic Party 2020 platform calls for making two years of community college tuition free for all students with a federal/state partnership similar to the Obama administration’s 2015 plan .

It envisions a program as universal and free as K-12 education is today, with all the sustainable benefits such programs (including Social Security and Medicare) enjoy. It also calls for making four years of public college tuition free, again in partnership with states, for students from families making less than $125,000 per year.

The Republican Party didn’t adopt a platform for the 2020 election, deferring to President Trump’s policies, which among other things, stand in opposition to free college. Congressional Republicans, unlike many of their state counterparts, also have not supported free college tuition in the past.

However, it should be noted that the very first state free college tuition program was initiated in 2015 by former Tennessee Gov. Bill Haslam, a Republican. Subsequently, such deep red states with Republican majorities in their state legislature such as West Virginia, Kentucky and Arkansas have adopted similar programs.

Establishing free college tuition benefits for more Americans would be the 21st-century equivalent of the Depression-era Works Progress Administration initiative.

That program not only created immediate work for the unemployed, but also offered skills training for nearly 8 million unskilled workers in the 1930s. Just as we did in the 20th century, by laying the foundation for our current system of universal free high school education and rewarding our World War II veterans with free college tuition to help ease their way back into the workforce, the 21st century system of higher education we build must include the opportunity to attend college tuition-free.

California already has taken big steps to make its community college system, the largest in the nation, tuition free by fully funding its California Promise grant program. But community college is not yet free to all students. Tuition costs — just more than $1,500 for a full course load — are waived for low-income students. Colleges don’t have to spend the Promise funds to cover tuition costs for other students so, at many colleges, students still have to pay tuition.

At the state’s four-year universities, about 60% of students at the California State University and the same share of in-state undergraduates at the 10-campus University of California, attend tuition-free as well, as a result of Cal grants , federal Pell grants and other forms of financial aid.

But making the CSU and UC systems tuition-free for even more students will require funding on a scale that only the federal government is capable of supporting, even if the benefit is only available to students from families that makes less than $125,000 a year.

It is estimated that even without this family income limitation, eliminating tuition for four years at all public colleges and universities for all students would cost taxpayers $79 billion a year, according to U.S. Department of Education data . Consider, however, that the federal government spent $91 billion in 2016 on policies that subsidized college attendance. At least some of that could be used to help make public higher education institutions tuition-free in partnership with the states.

Free college tuition programs have proved effective in helping mitigate the system’s current inequities by increasing college enrollment, lowering dependence on student loan debt and improving completion rates , especially among students of color and lower-income students who are often the first in their family to attend college.

In the first year of the TN Promise , community college enrollment in Tennessee increased by 24.7%, causing 4,000 more students to enroll. The percentage of Black students in that state’s community college population increased from 14% to 19% and the proportion of Hispanic students increased from 4% to 5%.

Students who attend community college tuition-free also graduate at higher rates. Tennessee’s first Promise student cohort had a 52.6% success rate compared to only a 38.9% success rate for their non-Promise peers. After two years of free college tuition, Rhode Island’s college-promise program saw its community college graduation rate triple and the graduation rate among students of color increase ninefold.

The impact on student debt is more obvious. Tennessee, for instance, saw its applications for student loans decrease by 17% in the first year of its program, with loan amounts decreasing by 12%. At the same time, Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) applications soared, with 40% of the entire nation’s increase in applications originating in that state in the first year of their Promise program.

Wage inequality by education, already dreadful before the pandemic, is getting worse. In May, the unemployment rate among workers without a high school diploma was nearly triple the rate of workers with a bachelor’s degree. No matter what Congress does to provide support to those affected by the pandemic and the ensuing recession, employment prospects for far too many people in our workforce will remain bleak after the pandemic recedes. Today, the fastest growing sectors of the economy are in health care, computers and information technology. To have a real shot at a job in those sectors, workers need a college credential of some form such as an industry-recognized skills certificate or an associate’s or bachelor’s degree.

The surest way to make the proven benefits of higher education available to everyone is to make college tuition-free for low and middle-income students at public colleges, and the federal government should help make that happen.

Morley Winograd is president of the Campaign for Free College Tuition . Max Lubin is CEO of Rise , a student-led nonprofit organization advocating for free college.

The opinions in this commentary are those of the author. Commentaries published on EdSource represent diverse viewpoints about California’s public education systems. If you would like to submit a commentary, please review our guidelines and contact us .

Share Article

Comments (13)

Leave a comment, your email address will not be published. required fields are marked * *.

Click here to cancel reply.

XHTML: You can use these tags: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy .

Genia Curtsinger 2 years ago 2 years ago

Making community college free to those who meet the admission requirements would help many people. First of all, it would make it easy for students and families, for instance; you go to college and have to pay thousands of dollars to get a college education, but if community college is free it would help so you could be saving money and get a college education for free, with no cost at all. It would make … Read More

Making community college free to those who meet the admission requirements would help many people. First of all, it would make it easy for students and families, for instance; you go to college and have to pay thousands of dollars to get a college education, but if community college is free it would help so you could be saving money and get a college education for free, with no cost at all. It would make it more affordable to the student and their families.

Therefore I think people should have free education for those who meet the admission requirements.

nothing 2 years ago 2 years ago

I feel like colleges shouldn’t be completely free, but a lot more affordable for people so everyone can have a chance to have a good college education.

Jaden Wendover 2 years ago 2 years ago

I think all colleges should be free, because why would you pay to learn?

Samantha Cole 2 years ago 2 years ago

I think college should be free because there are a lot of people that want to go to college but they can’t pay for it so they don’t go and end up in jail or working as a waitress or in a convenience store. I know I want to go to college but I can’t because my family doesn’t make enough money to send me to college but my family makes too much for financial aid.

Nick Gurrs 2 years ago 2 years ago

I feel like this subject has a lot of answers, For me personally, I believe tuition and college, in general, should be free because it will help students get out of debt and not have debt, and because it will help people who are struggling in life to get a job and make a living off a job.

NO 3 years ago 3 years ago

I think college tuition should be free. A lot of adults want to go to college and finish their education but can’t partly because they can’t afford to. Some teens need to work at a young age just so they can save money for college which I feel they shouldn’t have to. If people don’t want to go to college then they just can work and go on with their lives.

Not saying my name 3 years ago 3 years ago

I think college tuition should be free because people drop out because they can’t pay the tuition to get into college and then they can’t graduate and live a good life and they won’t get a job because it says they dropped out of school. So it would be harder to get a job and if the tuition wasn’t a thing, people would live an awesome life because of this.

Brisa 3 years ago 3 years ago

I’m not understanding. Are we not agreeing that college should be free, or are we?

m 2 years ago 2 years ago

it shouldnt

Trevor Everhart 3 years ago 3 years ago

What do you mean by there is no such thing as free tuition?

Olga Snichernacs 3 years ago 3 years ago

Nice! I enjoyed reading.

Anonymous Cat 3 years ago 3 years ago

Tuition-Free: Free tuition, or sometimes tuition free is a phrase you have heard probably a good number of times. … Therefore, free tuition to put it simply is the opportunity provide to students by select universities around the world to received a degree from their institution without paying any sum of money for the teaching.

Mister B 3 years ago 3 years ago

There is no such thing as tuition free.

EdSource Special Reports

Fewer than half of California students are reading by third grade, experts say. Worse still, far fewer Black and Latino students meet that standard. What needs to change?

For the four men whose stories are told in this documentary, just the chance to earn the degree made it possible for them to see themselves living a different life outside of prison.

Amid Israel-Hamas war, colleges draw lines on faculty free speech

The conflict in Gaza has rekindled efforts to control controversy and conversation on campuses. The UC system could be the latest to weigh in.

Dissent, no funding yet for statewide teacher training in math and reading

A bill sponsored by State Superintendent Tony Thurmond would provide math and reading training for all teachers. But money is scarce, and some English language advocates have problems with phonics.

EdSource in your inbox!

Stay ahead of the latest developments on education in California and nationally from early childhood to college and beyond. Sign up for EdSource’s no-cost daily email.

Stay informed with our daily newsletter

Winter 2024

Why Free College Is Necessary

Higher education can’t solve inequality, but the debate about free college tuition does something extremely valuable. It reintroduces the concept of public good to education discourse.

[contentblock id=subscribe-ad]

Free college is not a new idea, but, with higher education costs (and student loan debt) dominating public perception, it’s one that appeals to more and more people—including me. The national debate about free, public higher education is long overdue. But let’s get a few things out of the way.

College is the domain of the relatively privileged, and will likely stay that way for the foreseeable future, even if tuition is eliminated. As of 2012, over half of the U.S. population has “some college” or postsecondary education. That category includes everything from an auto-mechanics class at a for-profit college to a business degree from Harvard. Even with such a broadly conceived category, we are still talking about just half of all Americans.

Why aren’t more people going to college? One obvious answer would be cost, especially the cost of tuition. But the problem isn’t just that college is expensive. It is also that going to college is complicated. It takes cultural and social, not just economic, capital. It means navigating advanced courses, standardized tests, forms. It means figuring out implicit rules—rules that can change.

Eliminating tuition would probably do very little to untangle the sailor’s knot of inequalities that make it hard for most Americans to go to college. It would not address the cultural and social barriers imposed by unequal K–12 schooling, which puts a select few students on the college pathway at the expense of millions of others. Neither would it address the changing social milieu of higher education, in which the majority are now non-traditional students. (“Non-traditional” students are classified in different ways depending on who is doing the defining, but the best way to understand the category is in contrast to our assumptions of a traditional college student—young, unfettered, and continuing to college straight from high school.) How and why they go to college can depend as much on things like whether a college is within driving distance or provides one-on-one admissions counseling as it does on the price.

Given all of these factors, free college would likely benefit only an outlying group of students who are currently shut out of higher education because of cost—students with the ability and/or some cultural capital but without wealth. In other words, any conversation about college is a pretty elite one even if the word “free” is right there in the descriptor.

The discussion about free college, outside of the Democratic primary race, has also largely been limited to community colleges, with some exceptions by state. Because I am primarily interested in education as an affirmative justice mechanism, I would like all minority-serving and historically black colleges (HBCUs)—almost all of which qualify as four-year degree institutions—to be included. HBCUs disproportionately serve students facing the intersecting effects of wealth inequality, systematic K–12 disparities, and discrimination. For those reasons, any effort to use higher education as a vehicle for greater equality must include support for HBCUs, allowing them to offer accessible degrees with less (or no) debt.

The Obama administration’s free community college plan, expanded in July to include grants that would reduce tuition at HBCUs, is a step in the right direction. Yet this is only the beginning of an educational justice agenda. An educational justice policy must include institutions of higher education but cannot only include institutions of higher education. Educational justice says that schools can and do reproduce inequalities as much as they ameliorate them. Educational justice says one hundred new Universities of Phoenix is not the same as access to high-quality instruction for the maximum number of willing students. And educational justice says that jobs programs that hire for ability over “fit” must be linked to millions of new credentials, no matter what form they take or how much they cost to obtain. Without that, some free college plans could reinforce prestige divisions between different types of schools, leaving the most vulnerable students no better off in the economy than they were before.

Free college plans are also limited by the reality that not everyone wants to go to college. Some people want to work and do not want to go to college forever and ever—for good reason. While the “opportunity costs” of spending four to six years earning a degree instead of working used to be balanced out by the promise of a “good job” after college, that rationale no longer holds, especially for poor students. Free-ninety-nine will not change that.

I am clear about all of that . . . and yet I don’t care. I do not care if free college won’t solve inequality. As an isolated policy, I know that it won’t. I don’t care that it will likely only benefit the high achievers among the statistically unprivileged—those with above-average test scores, know-how, or financial means compared to their cohort. Despite these problems, today’s debate about free college tuition does something extremely valuable. It reintroduces the concept of public good to higher education discourse—a concept that fifty years of individuation, efficiency fetishes, and a rightward drift in politics have nearly pummeled out of higher education altogether. We no longer have a way to talk about public education as a collective good because even we defenders have adopted the language of competition. President Obama justified his free community college plan on the grounds that “Every American . . . should be able to earn the skills and education necessary to compete and win in the twenty-first century economy.” Meanwhile, for-profit boosters claim that their institutions allow “greater access” to college for the public. But access to what kind of education? Those of us who believe in viable, affordable higher ed need a different kind of language. You cannot organize for what you cannot name.

Already, the debate about if college should be free has forced us all to consider what higher education is for. We’re dusting off old words like class and race and labor. We are even casting about for new words like “precariat” and “generation debt.” The Debt Collective is a prime example of this. The group of hundreds of students and graduates of (mostly) for-profit colleges are doing the hard work of forming a class-based identity around debt as opposed to work or income. The broader cultural conversation about student debt, to which free college plans are a response, sets the stage for that kind of work. The good of those conversations outweighs for me the limited democratization potential of free college.

Tressie McMillan Cottom is an assistant professor of sociology at Virginia Commonwealth University and a contributing editor at Dissent . Her book Lower Ed: How For-Profit Colleges Deepen Inequality is forthcoming from the New Press.

This article is part of Dissent’s special issue of “Arguments on the Left.” Click to read contending arguments from Matt Bruenig and Mike Konczal .

Sign up for the Dissent newsletter:

Socialist thought provides us with an imaginative and moral horizon.

For insights and analysis from the longest-running democratic socialist magazine in the United States, sign up for our newsletter:

- University News

- Faculty & Research

- Health & Medicine

- Science & Technology

- Social Sciences

- Humanities & Arts

- Students & Alumni

- Arts & Culture

- Sports & Athletics

- The Professions

- International

- New England Guide

The Magazine

- Current Issue

- Past Issues

Class Notes & Obituaries

- Browse Class Notes

- Browse Obituaries

Collections

- Commencement

- The Context

Harvard Squared

- Harvard in the Headlines

Support Harvard Magazine

- Why We Need Your Support

- How We Are Funded

- Ways to Support the Magazine

- Special Gifts

- Behind the Scenes

Classifieds

- Vacation Rentals & Travel

- Real Estate

- Products & Services

- Harvard Authors’ Bookshelf

- Education & Enrichment Resource

- Ad Prices & Information

- Place An Ad

Follow Harvard Magazine:

Right Now | Subsidy Shuffle

Could College Be Free?

January-February 2020

Illustration by Adam Niklewicz

Email David Deming

Visit David Deming's website.

Hear David Deming discuss free college on HKS PolicyCast

etting ahead— or getting by—is increasingly difficult in the United States without a college degree. The demand for college education is at an all-time high, but so is the price tag. David Deming—professor of public policy at the Kennedy School and professor of education and economics at the Graduate School of Education—wants to ease that tension by reallocating government spending on higher education to make public colleges tuition-free.

Deming’s argument is elegant. Public spending on higher education is unique among social services: it is an investment that pays for itself many times over in higher tax revenue generated by future college graduates, a rare example of an economic “free lunch.” In 2016 (the most recent year for which data are available), the United States spent $91 billion subsidizing access to higher education. According to Deming, that spending isn’t as progressive or effective as it could be. The National Center for Education Statistics indicates that it would cost roughly $79 billion a year to make public colleges and universities tuition-free. So, Deming asks, why not redistribute current funds to make public colleges tuition-free, instead of subsidizing higher education in other, roundabout ways?

Of the estimated $91 billion the nation spends annually on higher education, $37 billion go to tax credits and tax benefits. These tax programs ease the burden of paying for both public and private colleges, but disproportionately benefit middle-class children who are probably going to college anyway. Instead of lowering costs for those students, Deming points out, a progressive public-education assistance program should probably redirect funds to incentivize students to go to college who wouldn’t otherwise consider it.

Another $13 billion in federal spending subsidize interest payments on student loans for currently enrolled undergraduates. And the remaining $41 billion go to programs that benefit low-income students and military veterans, including $28.4 billion for Pell Grants and similar programs. Pell Grants are demand-side subsidies: they provide cash directly to those who pay for a service, i.e., students; supply-side subsidies (see below) channel funds to suppliers, such as colleges. Deming asserts that Pell Grant money, which travels with students, voucher-style, is increasingly gobbled up by low-quality, for-profit colleges. These colleges are often better at marketing their services than at graduating students or improving their graduates’ prospects, despite being highly subsidized by taxpayers . “The rise of for-profit colleges has, in some ways, been caused by disinvestment in public higher education. Our public university systems were built for a time when 20 percent of young people attended college,” says Deming. “Now it’s more like 60 percent, and we haven’t responded by devoting more resources to ensuring that young people can afford college and succeed when they get there.” As a result, an expensive, for-profit market has filled the educational shortage that government divestment has caused.

The vast majority of states have continuously divested in public education in recent decades, pushing a higher percentage of the cost burden of schools onto students. Deming believes this state-level divestment is the main reason for the precipitous rise in college tuition, which has outpaced the rest of the Consumer Price Index for 30 consecutive years. (Compounding reasons include rising salaries despite a lack of gains in productivity—a feature of many human-service-focused industries such as education and healthcare.) Against this backdrop, Deming writes, “at least some—and perhaps all—of the cost of universal tuition-free public higher education could be defrayed by redeploying money that the government is already spending.” (The need for some funding programs would remain, however, given the cost of room, board, books, and other college supplies.)

Redirecting current funding to provide tuition-free public-school degrees is only one part of Deming’s proposal. He knows that making public higher education free could hurt the quality of instruction by inciting a race to the bottom, stretching teacher-student ratios and pinching other academic resources. He therefore argues that any tuition-free plan would need to be paired with increased state and federal investment, and programs focused on getting more students to graduate. Because rates of degree completion strongly correlate with per-student spending, Deming proposes introducing a federal matching grant for the first $5,000 of net per-student spending in states that implement free college. “Luckily,” he says, “spending more money is a policy lever we know how to pull.”

Deming argues that shifting public funding to supply-side subsidies, channeled directly to public institutions, could nudge states to reinvest in public higher education. Such reinvestment would dampen the demand for low-quality, for-profit schools; increase college attendance in low-income communities; and improve the quality of services that public colleges and universities could offer. Early evidence of these positive effects has surfaced in some of the areas that are piloting free college-tuition programs, including the state of Tennessee and the city of Kalamazoo, Michigan.

Higher education is an odd market because buyers (students) often don’t have good information about school quality and it’s a once-in-a-lifetime decision. Creating a supply-side subsidy system would take some freedom of choice away from prospective undergraduates who want government funding for private, four-year degrees. But, for Deming, that’s a trade-off worth making, if the state is better able to measure the effectiveness of certain colleges and allocate subsidies accordingly. Education is more than the mere acquisition of facts—which anyone can access freely online—because minds, like markets, learn best through feedback. Quality feedback is difficult to scale well without hiring more teachers and ramping up student-support resources. That’s why Deming thinks it’s high time for the public higher-education market to get a serious injection of cash.

You might also like

Lord Mayor for a Day

Harvard's Michael Mainelli, the 695th Lord Mayor of London.

Law Professor Rebecca Tushnet on Who Gets to Keep the Ring

Harvard law professor gets into the details of romantic legal reform.

Faculty Senate Debate Continued

Harvard professors highlight governance concerns.

Most popular

Update: Harvard Encampment Ends

As protest numbers dwindled, organizers and administrators reached an agreement

Advertisement

More to explore

Dominica’s “Bouyon” Star

Musician “Shelly” Alfred’s indigenous Caribbean sound

What is the Best Breakfast and Lunch in Harvard Square?

The cafés and restaurants of Harvard Square sure to impress for breakfast and lunch.

University People

Harvard Portraitist Nina Skov Jensen Paints Celebrities and Princesses

Nina Skov Jensen ’25, portraitist for collectors and the princess of Denmark.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Should College Be Free?

The Democratic Party is split over whether you should have to pay to get a degree.

By Spencer Bokat-Lindell

Mr. Bokat-Lindell is a writer in The New York Times Opinion section.

This article is part of the Debatable newsletter. You can sign up here to receive it on Tuesdays and Thursdays.

“I believe we should move to make college affordable for everybody,” begins a new, subtweet-y campaign ad from Pete Buttigieg that started airing in Iowa on Thanksgiving.

The mayor of South Bend, Ind., was not only promoting his plan to make public college tuition-free for families earning up to $100,000 a year. He was also drawing a stark, if implicit, contrast with his competitors Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders, who have made eliminating tuition for all students at public colleges (and for Mr. Sanders, at trade schools and apprenticeship programs as well) a core issue of their candidacies.

“There are some voices saying, ‘Well, that doesn’t count unless you go even further — unless it’s even free for the kids of millionaires,’” Mr. Buttigieg continues in the ad. “But I only want to make promises that we can keep.”

The debate: Every American is entitled to a free K-12 education. But in many countries around the world , that right effectively extends to college as well. Should the United States follow suit?

WHAT PEOPLE ARE SAYING

Rich kids should have to pay for college.

Critics of free public college, including Mr. Buttigieg and Senator Amy Klobuchar, argue that it’s a wasteful, even regressive, idea, since students from families wealthy enough to afford tuition would disproportionately reap the benefits. That’s because kids from higher-income families are more likely to attend college and lower-income students on average pay less in net tuition.

By the numbers: Sandy Baum and Alexandra Tilsley at the Urban Institute estimate that more than a third of the total subsidies required for universal free public college would flow to students from families earning $120,000 or more, who already tend to enjoy better K-12 educations.

Ms. Baum and Ms. Tilsley write in The Washington Post:

A national free-tuition plan would provide disproportionate benefits to the relatively affluent while leaving many low- and moderate-income students struggling to complete the college degrees that many jobs now demand . Ironically, free-tuition programs would exacerbate inequality even as they promise to level the playing field. … A progressive educational policy should offer much more narrowly targeted help for students.

“Pete Buttigieg’s college affordability plan is actually the most progressive”

“Universal Free College Would Be a Regressive Scandal”

Higher education is a public good, and public goods should be universal

Supporters of free tuition say that talking points about free-riding “millionaires and billionaires” are misleading — not least because millionaires and billionaires are far less likely to send their children to public universities.

A different crunch of the numbers: Mike Konczal, a fellow at the Roosevelt Institute, estimates that families within the top 1 percent of the income distribution would capture 1.4 percent of total spending on free college — slightly regressive in relative terms, but arguably not an exorbitant price to pay for the 98.6 percent of spending that would benefit everyone else. And crucially, supporters say, under the Sanders and Warren plans, that spending would be financed by raising taxes on the rich.

But Jordan Weissman contends in Slate that to quibble about the relative progressivity of different college tuition funding proposals is largely to miss the point. For many proponents, universal free public college is part of a broader political vision to establish higher education as a public good that everyone buys into, like the fire department or library.

The entire policy agenda of the social-Democratic left is based on the idea that simple, universal government programs are generally better than means-tested benefits, because letting everybody enjoy nice things like higher education for free or cheap creates buy-in for a robust welfare state, whereas programs for the poor are easily targeted for cuts.

Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York pursued this line of thought in a Twitter thread :

Another angle: The notion that the children of millionaires and billionaires shouldn’t have access to free college, some critics say, rests too comfortably on the assumption that wealth is and will continue to be transferred seamlessly from generation to generation — itself a regressive feature of the American class system. That assumption also doesn’t account for the reality that some wealthy parents may wield their financial power to coerce and even abuse their college-age children .

Free public college may not work

Eliminating tuition at state schools would bleed them dry, writes Noah Smith in Bloomberg. The rub, he argues, is that most public universities receive much of their funding from state governments, and many state governments don’t want to increase their education budgets — in fact, they want to cut them. Mr. Smith writes :

If even Vermont’s government won’t pony up the cash, who will? Those on the socialist left seem to believe that the federal government will step in, but this seems overly optimistic given decades of cuts to every major spending item except health care. As soon as a Republican administration or Congress gets into power, federal education spending would be under threat .

The result, Mr. Smith says, would be an era of painful austerity for both students and staff.

The emphasis on college is misplaced

College, free or otherwise, should be lower on the national political priority list, writes Matt Bruenig, the founder of People’s Policy Project.

Defending the value of education for education’s sake is one thing. But Mr. Bruenig sees the issue as a largely economic problem, to which free public college is an inadequate solution: Both its supporters and its opponents seem to accept the premise that a traditional higher education is the only avenue to a limited number of middle-class jobs. But most Americans don’t go to college, he says, and “pushing more and more people through college will not automatically transform all the jobs into good ones.”

Rather, Mr. Bruenig writes :

We should as a society designate ages 18-24 as the attachment zone during which all paths into a career are fully supported by public benefits and services. Students get their free school. But, under the exact same umbrella, nonstudents get their free vocational training, subsidized apprenticeships, in-work subsidies, public jobs, and whatever else it takes to ensure a lasting labor force attachment. That would be a program that is actually in fitting with the ideals of universalism.

Do you have a point of view we missed? Email us at [email protected] . Please note your name, age and location in your response, which may be included in the next newsletter.

MORE PERSPECTIVES ON FREE COLLEGE

“Tuition-Free College Could Cost Less Than You Think,” writes David Deming. [The New York Times]

“For poorer families, even ‘free public college’ isn’t free if only tuition costs are covered,” writes Tiffany Jones. [The New York Times]

David Leonhardt explains his idea of “the best version” of free college . [The New York Times]

Students 13 and older sound off on whether they think college should be free. [The New York Times]

WHAT YOU’RE SAYING

Here’s what readers had to say about the last debate: Sweet Potatoes Are Overrated. Turducken Is Performative.

In response to last week’s headline, I received a note from Judith Butler, the queer theorist and scholar whose work developed the concept of gender performativity :

To Spencer Bokat-Lindell, I very much appreciated your piece on Turducken as performative Turkey, but wanted to caution against the association of ‘performative’ with fake. The term gained meaning through J.L. Austin’s theory of speech acts. There he gives the example of legal performatives such as “I sentence you” or “I pronounce you man and wife.” In those cases the speech act makes something real happen in the world. Someone goes to jail or two people get married. Similarly, in Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly, a title that appears to echo in your interesting piece, assemblies form and act, sometimes exemplifying the very principles for which they call. They bring about a reality, or seek to, but they are not producing a falsehood by virtue of their performativity. Although some take performative to mean ersatz , that is not the main meaning of the term in speech act theory or its queer theory appropriation. Such a construal suggests that performative effects are not real or are the opposite of real. But they can be, under certain circumstances, one way of bringing about a reality. In any case, I enjoyed your piece.

Spencer Bokat-Lindell is a writer for the Opinion section. @bokatlindell

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

- Student Loans

- Paying for College

Should College Be Free? The Pros and Cons

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/KellyDilworthheadshot-c65b9cbc3b284f138ca937b8969079e6.jpg)

Types of Publicly Funded College Tuition Programs

Pros: why college should be free, cons: why college should not be free, what the free college debate means for students, how to cut your college costs now, frequently asked questions (faqs).

damircudic / Getty Images

Americans have been debating the wisdom of free college for decades, and more than 30 states now offer some type of free college program. But it wasn't until 2021 that a nationwide free college program came close to becoming reality, re-energizing a longstanding debate over whether or not free college is a good idea.

And despite a setback for the free-college advocates, the idea is still in play. The Biden administration's free community college proposal was scrapped from the American Families Plan . But close observers say that similar proposals promoting free community college have drawn solid bipartisan support in the past. "Community colleges are one of the relatively few areas where there's support from both Republicans and Democrats," said Tulane economics professor Douglas N. Harris, who has previously consulted with the Biden administration on free college, in an interview with The Balance.

To get a sense of the various arguments for and against free college, as well as the potential impacts on U.S. students and taxpayers, The Balance combed through studies investigating the design and implementation of publicly funded free tuition programs and spoke with several higher education policy experts. Here's what we learned about the current debate over free college in the U.S.—and more about how you can cut your college costs or even get free tuition through existing programs.

Key Takeaways

- Research shows free tuition programs encourage more students to attend college and increase graduation rates, which creates a better-educated workforce and higher-earning consumers who can help boost the economy.

- Some programs are criticized for not paying students’ non-tuition expenses, not benefiting students who need assistance most, or steering students toward community college instead of four-year programs.

- If you want to find out about free programs in your area, the University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education has a searchable database. You’ll find the link further down in this article.

Before diving into the weeds of the free college debate, it's important to note that not all free college programs are alike. Most publicly funded tuition assistance programs are restricted to the first two years of study, typically at community colleges. Free college programs also vary widely in the ways they’re designed, funded, and structured:

- Last-dollar tuition-free programs : These programs cover any remaining tuition after a student has used up other financial aid , such as Pell Grants. Most state-run free college programs fall into this category. However, these programs don’t typically help with room and board or other expenses.

- First-dollar tuition-free programs : These programs pay for students' tuition upfront, although they’re much rarer than last-dollar programs. Any remaining financial aid that a student receives can then be applied to other expenses, such as books and fees. The California College Promise Grant is a first-dollar program because it waives enrollment fees for eligible students.

- Debt-free programs : These programs pay for all of a student's college expenses , including room and board, guaranteeing that they can graduate debt-free. But they’re also much less common, likely due to their expense.

Proponents often argue that publicly funded college tuition programs eventually pay for themselves, in part by giving students the tools they need to find better jobs and earn higher incomes than they would with a high school education. The anticipated economic impact, they suggest, should help ease concerns about the costs of public financing education. Here’s a closer look at the arguments for free college programs.

A More Educated Workforce Benefits the Economy

Morley Winograd, President of the Campaign for Free College Tuition, points to the economic and tax benefits that result from the higher wages of college grads. "For government, it means more revenue," said Winograd in an interview with The Balance—the more a person earns, the more they will likely pay in taxes . In addition, "the country's economy gets better because the more skilled the workforce this country has, the better [it’s] able to compete globally." Similarly, local economies benefit from a more highly educated, better-paid workforce because higher earners have more to spend. "That's how the economy grows," Winograd explained, “by increasing disposable income."

According to Harris, the return on a government’s investment in free college can be substantial. "The additional finding of our analysis was that these things seem to consistently pass a cost-benefit analysis," he said. "The benefits seem to be at least double the cost in the long run when we look at the increased college attainment and the earnings that go along with that, relative to the cost and the additional funding and resources that go into them."

Free College Programs Encourage More Students to Attend

Convincing students from underprivileged backgrounds to take a chance on college can be a challenge, particularly when students are worried about overextending themselves financially. But free college programs tend to have more success in persuading students to consider going, said Winograd, in part because they address students' fears that they can't afford higher education . "People who wouldn't otherwise think that they could go to college, or who think the reason they can't is [that] it's too expensive, [will] stop, pay attention, listen, decide it's an opportunity they want to take advantage of, and enroll," he said.

According to Harris, students also appear to like the certainty and simplicity of the free college message. "They didn't want to have to worry that next year they were not going to have enough money to pay their tuition bill," he said. "They don't know what their finances are going to look like a few months down the road, let alone next year, and it takes a while to get a degree. So that matters."

Free college programs can also help send "a clear and tangible message" to students and their families that a college education is attainable for them, said Michelle Dimino, an Education Director with Third Way. This kind of messaging is especially important to first-generation and low-income students, she said.

Free College Increases Graduation Rates and Financial Security

Free tuition programs appear to improve students’ chances of completing college. For example, Harris noted that his research found a meaningful link between free college tuition and higher graduation rates. "What we found is that it did increase college graduation at the two-year college level, so more students graduated than otherwise would have."

Free college tuition programs also give people a better shot at living a richer, more comfortable life, say advocates. "It's almost an economic necessity to have some college education," noted Winograd. Similar to the way a high school diploma was viewed as crucial in the 20th century, employees are now learning that they need at least two years of college to compete in a global, information-driven economy. "Free community college is a way of making that happen quickly, effectively, and essentially," he explained.

Free community college isn’t a universally popular idea. While many critics point to the potential costs of funding such programs, others identify issues with the effectiveness and fairness of current attempts to cover students’ college tuition. Here’s a closer look at the concerns about free college programs.

It Would Be Too Expensive

The idea of free community college has come under particular fire from critics who worry about the cost of social spending. Since community colleges aren't nearly as expensive as four-year colleges—often costing thousands of dollars a year—critics argue that individuals can often cover their costs using other forms of financial aid . But, they point out, community college costs would quickly add up when paid for in bulk through a free college program: Biden’s proposed free college plan would have cost $49.6 billion in its first year, according to an analysis from Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. Some opponents argue that the funds could be put to better use in other ways, particularly by helping students complete their degrees.

Free College Isn't Really Free

One of the most consistent concerns that people have voiced about free college programs is that they don’t go far enough. Even if a program offers free tuition, students will need to find a way to pay for other college-related expenses , such as books, room and board, transportation, high-speed internet, and, potentially, child care. "Messaging is such a key part of this," said Dimino. Students "may apply or enroll in college, understanding it's going to be free, but then face other unexpected charges along the way."

It's important for policymakers to consider these factors when designing future free college programs. Otherwise, Dimino and other observers fear that students could potentially wind up worse off if they enroll and invest in attending college and then are forced to drop out due to financial pressures.

Free College Programs Don’t Help the Students Who Need Them Most

Critics point out that many free college programs are limited by a variety of quirks and restrictions, which can unintentionally shut out deserving students or reward wealthier ones. Most state-funded free college programs are last-dollar programs, which don’t kick in until students have applied financial aid to their tuition. That means these programs offer less support to low-income students who qualify for need-based aid—and more support for higher-income students who don’t.

Community College May Not Be the Best Path for All Students

Some critics also worry that all students will be encouraged to attend community college when some would have been better off at a four-year institution. Four-year colleges tend to have more resources than community colleges and can therefore offer more support to high-need students.

In addition, some research has shown that students at community colleges are less likely to be academically successful than students at four-year colleges, said Dimino. "Statistically, the data show that there are poorer outcomes for students at community colleges […] such as lower graduation rates and sometimes low transfer rates from two- to four-year schools."

With Congress focused on other priorities, a nationwide free college program is unlikely to happen anytime soon. However, some states and municipalities offer free tuition programs, so students may be able to access some form of free college, depending on where they live. A good resource is the University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education’s searchable database of Promise Programs , which lists more than 100 free community college programs, though the majority are limited to California residents.

In the meantime, school leaders and policymakers may shift their focus to other access and equity interventions for low-income students. For example, higher education experts Eileen Strempel and Stephen Handel published a book in 2021 titled "Beyond Free College: Making Higher Education Work for 21st Century Students." The book argues that policymakers should focus more strongly on college completion, not just college access. "There hasn't been enough laser-focus on how we actually get people to complete their degrees," noted Strempel in an interview with The Balance.

Rather than just improving access for low-income college students, Strempel and Handel argue that decision-makers should instead look more closely at the social and economic issues that affect students , such as food and housing insecurity, child care, transportation, and personal technology. For example, "If you don't have a computer, you don't have access to your education anymore," said Strempel. "It's like today's pencil."

Saving money on college costs can be challenging, but you can take steps to reduce your cost of living. For example, if you're interested in a college but haven't yet enrolled, pay close attention to where it's located and how much residents typically pay for major expenses, such as housing, utilities, and food. If the college is located in a high-cost area, it could be tough to justify the living expenses you'll incur. Similarly, if you plan to commute, take the time to check gas or public transportation prices and calculate how much you'll likely have to spend per month to go to and from campus several times a week.

Now that more colleges offer classes online, it may also be worth looking at lower-cost programs in areas that are farther from where you live, particularly if they allow you to graduate without setting foot on campus. Also, check out state and federal financial aid programs that can help you slim down your expenses, or, in some cases, pay for them completely. Finally, look into need-based and merit-based grants and scholarships that can help you cover even more of your expenses. Also, consider applying to no-loan colleges , which promise to help students graduate without going into debt.

Should community college be free?

It’s a big question with varying viewpoints. Supporters of free community college cite the economic contributions of a more educated workforce and the individual benefit of financial security, while critics caution against the potential expense and the inefficiency of last-dollar free college programs.

What states offer free college?

More than 30 states offer some type of tuition-free college program, including Arkansas, California, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Missouri, Montana, Michigan, Nevada, New York, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Virginia, and Washington State. The University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education lists over 100 last-dollar community college programs and 16 first-dollar community college programs, though the majority are limited to California residents.

Is there a free college?

There is no such thing as a truly free college education. But some colleges offer free tuition programs for students, and more than 30 states offer some type of tuition-free college program. In addition, students may also want to check out employer-based programs. A number of big employers now offer to pay for their employees' college tuition . Finally, some students may qualify for enough financial aid or scholarships to cover most of their college costs.

Scholarships360. " Which States Offer Tuition-Free Community College? "

The White House. “ Build Back Better Framework ,” see “Bringing Down Costs, Reducing Inflationary Pressures, and Strengthening the Middle Class.”

The White House. “ Fact Sheet: How the Build Back Better Plan Will Create a Better Future for Young Americans ,” see “Education and Workforce Opportunities.”

Coast Community College District. “ California College Promise Grant .”

Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. “ The Dollars and Cents of Free College ,” see “Biden’s Free College Plan Would Pay for Itself Within 10 Years.”

Third Way. “ Why Free College Could Increase Inequality .”

Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. “ The Dollars and Cents of Free College ,” see “Free-College Programs Have Different Effects on Race and Class Equity.”

University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education. “ College Promise Programs: A Comprehensive Catalog of College Promise Programs in the United States .”

Why Education Should Be Free: Exploring the Benefits for a Progressive Society

Written by Dan

Last updated February 13, 2024

The question of whether education, particularly higher education, should be free is a continuing debate marked by a multitude of opinions and perspectives.

Education stands as one of the most powerful tools for personal and societal advancement, and making it accessible to all could have profound impacts on a nation’s economic growth and social fabric.

Proponents of tuition-free education argue that it could create a better-educated workforce, improve the livelihoods of individuals, and contribute to overall economic prosperity.

However, the implementation of such a system carries complexity and considerations that spark considerable discourse among policymakers, educators, and the public.

Related : For more, check out our article on The #1 Problem In Education here.

Within the debate on free education lies a range of considerations, including the significant economic benefits it might confer.

A well-educated populace can be the driving force behind innovation, entrepreneurship, and a competitive global stance, according to research.

Moreover, social and cultural benefits are also cited by advocates, who see free higher education as a stepping stone towards greater societal well-being and equality.

Nevertheless, the challenges in implementing free higher education often center around fiscal sustainability, the potential for increased taxes, and the restructuring of existing educational frameworks.

Table of Contents

Key Takeaways

- Free higher education could serve as a critical driver of economic growth and innovation.

- It may contribute to social equality and cultural enrichment across communities.

- Implementation of tuition-free higher education requires careful consideration of economic and structural challenges.

Related : For more, check out our article on AI In Education here.

The Economic Benefits of Free Education

Free education carries the potential for significant economic impact, notably by fostering a more qualified workforce and alleviating financial strains associated with higher education.

Boosting the Workforce with Skilled Workers

Free education initiatives can lead to a rise in college enrollment and graduation rates, as seen in various studies and practical implementations.

This translates into a larger pool of skilled workers entering the workforce, which is critical for the sustained growth of the economy. With more educated individuals, industries can innovate faster and remain competitive on a global scale.

The subsequent increase in productivity and creative problem-solving bolsters the country’s economic profile.

Reducing Student Loan Debt and Financial Insecurity

One of the most immediate effects of tuition-free education is the reduction of student loan debt . Students who graduate without the burden of debt have more financial freedom and security, enabling them to contribute economically through higher consumer spending and investments.

This financial relief also means that graduates can potentially enter the housing market earlier and save for retirement, both of which are beneficial for long-term economic stability.

Reducing this financial insecurity not only benefits individual lives but also creates a positive ripple effect throughout the economy.

Related : For more, check out our article on Teaching For Understanding here.

Social and Cultural Impacts

Free education stands as a cornerstone for a more equitable society, providing a foundation for individuals to reach their full potential without the barrier of cost.

It fosters an inclusive culture where access to knowledge and the ability to contribute meaningfully to society are viewed as inalienable rights.

Creating Equality and Expanding Choices

Free education mitigates the socioeconomic disparities that often dictate the quality and level of education one can attain.

When tuition fees are eliminated, individuals from lower-income families are afforded the same educational opportunities as their wealthier counterparts, leading to a more level playing field .

Expanding educational access enables all members of society to pursue a wider array of careers and life paths, broadening personal choices and promoting a diverse workforce.

Free Education as a Human Right

Recognizing education as a human right underpins the movement for free education. Human Rights Watch emphasizes that all children should have access to a quality, inclusive, and free education.

This aligns with international agreements and the belief that education is not a privilege but a right that should be safeguarded for all, regardless of one’s socioeconomic status.

Redistributions within society can function to finance the institutions necessary to uphold this right, leading to long-term cultural and social benefits.

Challenges and Considerations for Implementation

Implementing free education systems presents a complex interplay of economic and academic factors. Policymakers must confront these critical issues to develop sustainable and effective programs.

Balancing Funding and Taxpayer Impact

Funding for free education programs primarily depends on the allocation of government resources, which often requires tax adjustments .

Legislators need to strike a balance between providing sufficient funding for education and maintaining a level of taxation that does not overburden the taxpayers .

Studies like those from The Balance provide insight into the economic implications, indicating a need for careful analysis to avoid unintended financial consequences.

Ensuring Quality in Free Higher Education Programs

Merit and quality assurance become paramount in free college programs to ensure that the value of education does not diminish. Programs need structured oversight and performance metrics to maintain high academic standards.

Free college systems, by extending access, may risk over-enrollment, which can strain resources and reduce educational quality if not managed correctly.

Global Perspectives and Trends in Free Education

In the realm of education, several countries have adopted policies to make learning accessible at no cost to the student. These efforts often aim to enhance social mobility and create a more educated workforce.

Case Studies: Argentina and Sweden

Argentina has long upheld the principle of free university education for its citizens. Public universities in Argentina do not charge tuition fees for undergraduate courses, emphasizing the country’s commitment to accessible education.

This policy supports a key tenet of social justice, allowing a wide range of individuals to pursue higher education regardless of their financial situation.

In comparison, Sweden represents a prime example of advanced free education within Europe. Swedish universities offer free education not only to Swedish students but also to those from other countries within the European Union (EU).

For Swedes, this extends to include secondary education, which is also offered at no cost. Sweden’s approach exemplifies a commitment to educational equality and a well-informed citizenry.

International Approaches to Tuition-Free College

Examining the broader international landscape , there are diverse approaches to implementing tuition-free higher education.

For instance, some European countries like Spain have not entirely eliminated tuition fees but have kept them relatively low compared to the global average. These measures still align with the overarching goal of making education more accessible.

In contrast, there have been discussions and proposals in the United States about adopting tuition-free college programs, reflecting a growing global trend.

While the United States has not federally mandated free college education, there are initiatives, such as the Promise Programs, that offer tuition-free community college to eligible students in certain states, showcasing a step towards more inclusive educational opportunities.

Policy and Politics of Tuition-Free Education

The debate surrounding tuition-free education encompasses a complex interplay of bipartisan support and legislative efforts, with community colleges frequently at the policy’s epicenter.

Both ideological and financial considerations shape the trajectory of higher education policy in this context.

Bipartisan Support and Political Challenges

Bipartisan support for tuition-free education emerges from a recognition of community colleges as vital access points for higher education, particularly for lower-income families.

Initiatives such as the College Promise campaign reflect this shared commitment to removing economic barriers to education. However, political challenges persist, with Republicans often skeptical about the long-term feasibility and impact on the federal budget.

Such divisions underscore the politicized nature of the education discourse, situating it as a central issue in policy-making endeavors.

Legislative Framework and Higher Education Policy

The legislative framework for tuition-free education gained momentum under President Biden with the introduction of the American Families Plan .

This plan proposed substantial investments in higher education, particularly aimed at bolstering the role of community colleges. Central to this policy is the pledge to cover up to two years of tuition for eligible students.

The proposal reflects a significant step in reimagining higher education policy, though it requires navigating the intricacies of legislative procedures and fiscally conservative opposition to translate into actionable policy.

Frequently Asked Questions

This section addresses common queries regarding the prospect of free college education, its impact, and practical considerations for implementation.

What are the most compelling arguments for making college education free?

The most compelling arguments for tuition-free college highlight the removal of financial barriers, potential to increase social mobility, and a long-term investment in a more educated workforce , which can lead to economic growth.

How could the government implement free education policies without sacrificing quality?

To implement free education without compromising quality, governments need to ensure sustainable funding, invest in faculty, and enable effective administration. Such measures aim to maintain high standards while extending access.

In countries with free college education, what has been the impact on their economies and societies?

Countries with free college education have observed various impacts, including a more educated populace , increased rates of innovation, and in some instances, stronger economic growth due to a skilled workforce.

How does free education affect the accessibility and inclusivity of higher education?

Free education enhances accessibility and inclusivity by leveling the educational playing field, allowing students from all socioeconomic backgrounds to pursue higher education regardless of their financial capability.

What potential downsides exist to providing free college education to all students?

Potential downsides include the strain on governmental budgets, the risk of oversaturating certain job markets, and the possibility that the value of a degree may diminish if too many people obtain one without a corresponding increase in jobs requiring higher education.

How might free education be funded, and what are the financial implications for taxpayers?

Free education would likely be funded through taxation, and its financial implications for taxpayers could range from increased taxes to reprioritization of existing budget funds. The scale of any potential tax increase would depend on the cost of the education programs and the economic benefits they’re anticipated to produce.

Related Posts

About The Author

I'm Dan Higgins, one of the faces behind The Teaching Couple. With 15 years in the education sector and a decade as a teacher, I've witnessed the highs and lows of school life. Over the years, my passion for supporting fellow teachers and making school more bearable has grown. The Teaching Couple is my platform to share strategies, tips, and insights from my journey. Together, we can shape a better school experience for all.

Join our email list to receive the latest updates.

Add your form here

Free college for all Americans? Yes, but not too much

Subscribe to the brown center on education policy newsletter, dick startz dick startz professor of economics - university of california, santa barbara @profitofed.

July 22, 2019

Promising free college has obvious political attraction for presidential candidates. From my perspective, free college is the right idea, but some of the promises go too far; in fact, exactly twice too far. There is a very strong argument for promising two years “free” at public colleges; the argument for a four-year free ride—not so much.

In a nutshell, my argument is that America has long supported free K-12 education and that two years of college is pretty much what K-12 used to be, with most Americans now obtaining at least some college education. For most people, getting some college is the key to the middle-class—creating a case for public support during the first two years after high school.

Douglas Harris has a great Chalkboard post that will bring you up to date on what candidates have said, and will give you many of the pros and cons for various higher education proposals. Harris also talks about popular support for different proposals in another Chalkboard post . Here, I’m going to stick to the narrower question of why paying for two years of public college is the right goal.

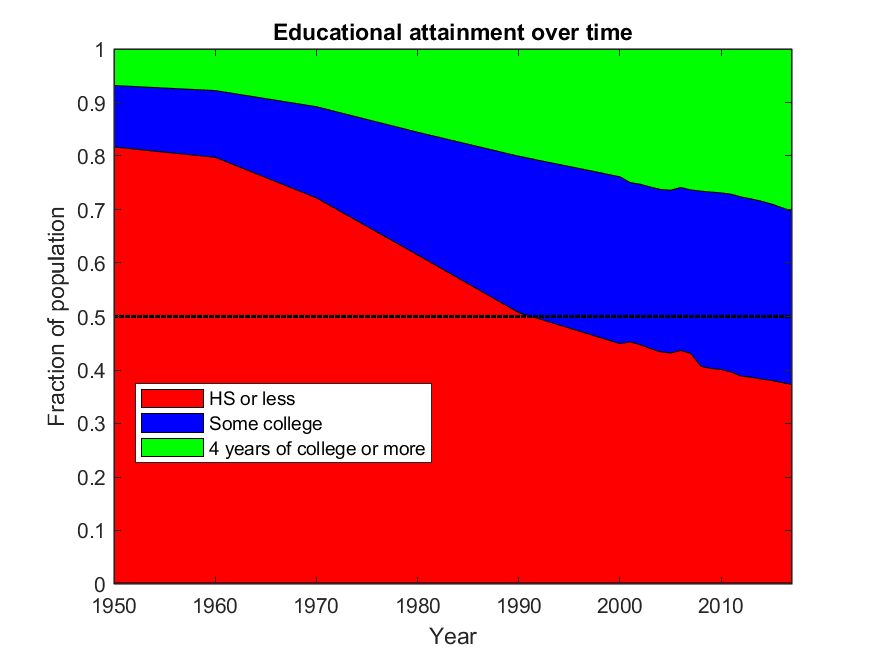

In the picture that follows I present educational attainment numbers for the American population from 1950 through the most current data. I’ve divided the population into those with a high school education or less, colored in red, those with some college but less than four years, blue, and those with four or more years of college, colored in green. (The category “some college” includes vocational training such as certificate programs at community colleges as well as more purely academic courses.

The vertical axis shows the fraction of the population with a given educational attainment—categories are stacked at each point in time to sum to 100%.

You can see that in the early post-war years, most Americans had no more than a high school education. Today the majority has picked up at least some college. I’ve also drawn in a line at the 50% point on the theory that the middle is “middle class.” Up until about 1990, the median American had a high school education or less. That’s fallen to about a third, and the median American now has some college. So “some college” has replaced high school or less as the standard educational attainment. If it made sense in the past to provide free public education through high school, then doing the equivalent today means paying for some level of college. Note that the green (4+ years of college) area is still way, way above the 50% line. Only about 30% of the population currently attains that much education. So such an appeal to the past does not provide an argument for four years of free college.

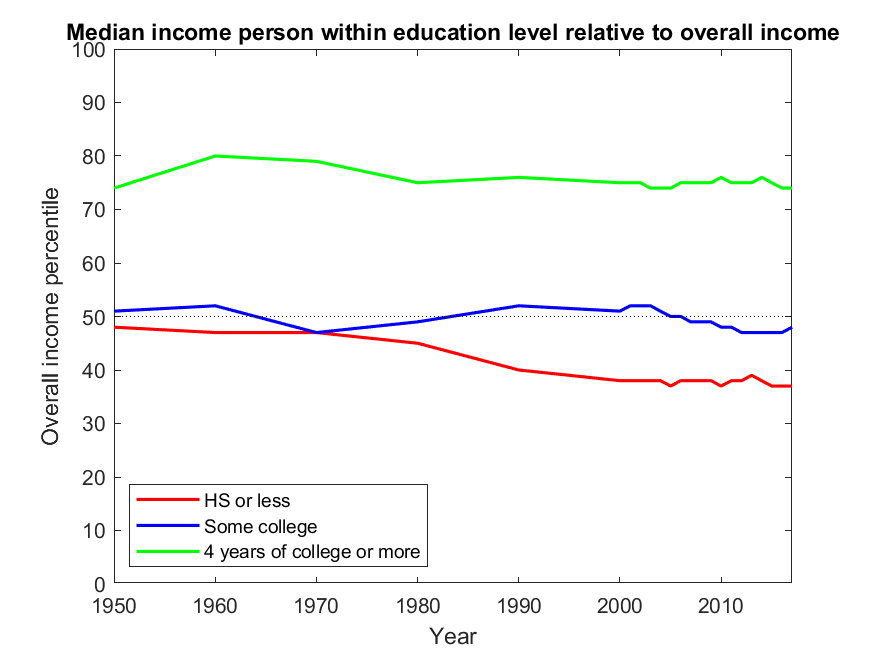

There are many motivations for increasing education, but probably the strongest is that it leads to better jobs and higher incomes. The next figure links educational attainment to income, plotting median income in each educational group against the overall national income distribution. In “the old days,” the median person in both the high school or less and the some college categories earned near the middle of the national income distribution. That’s still true for “some college.” The middle person with some college education gets to be right in the middle of the national income distribution. But getting to the middle is now much more difficult for those in the “high school or less” category. The middle person in the bottom group reaches just above the bottom third of the national income distribution. So in terms of income, “some college” has replaced “high school or less” as the middle-class norm.

Some presidential candidates propose free community college, others advocate that all public college should be free. One reaction to the latter position is that we shouldn’t be subsidizing college graduates as they typically end up with higher incomes than the rest of the population. Look at the green line in the figure above. Not only does the average person with four or more years of college have a higher income than most people—they have a much higher income. You can argue that the 70th percentile of income is still middle class. (In the United States, it seems that everyone below the top 0.1% thinks of themselves as being in the middle class.) But the fact is that the income in the top educational attainment group is a lot higher.

The argument that “some college” is the new “high school” and should be similarly free makes sense to me, but this logic doesn’t extend to a free ride for four years.

Data from census and American Community Survey from IPUMS USA, University of Minnesota, www.ipums.org.

Higher Education

Governance Studies

Brown Center on Education Policy

Annelies Goger, Katherine Caves, Hollis Salway

May 16, 2024

Sofoklis Goulas, Isabelle Pula

Melissa Kay Diliberti, Elizabeth D. Steiner, Ashley Woo

- Follow us on Facebook

- Follow us on Twitter

- Criminal Justice

- Environment

- Politics & Government

- Race & Gender

Expert Commentary

The pros and cons of ‘free college’ and ‘college promise’ programs: What the research says

We've gathered and summarized a sampling of research to help journalists understand the implications and impacts of “free college,” “tuition-free” and “college promise” programs.

Republish this article

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License .

by Denise-Marie Ordway, The Journalist's Resource October 8, 2019

This <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org/economics/free-college-promise-tuition-research/">article</a> first appeared on <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org">The Journalist's Resource</a> and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.<img src="https://journalistsresource.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cropped-jr-favicon-150x150.png" style="width:1em;height:1em;margin-left:10px;">

More than 19.9 million students are taking classes at colleges and universities across the United States this semester, up from 14.9 million two decades ago, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

As enrollment has swelled, so has the price of college. The average combined cost of undergraduate tuition, fees, room and board at four-year schools has doubled since 2000 . The average cost of attendance for full-time students living on campus at an in-state, public college or university during the 2017-18 academic year totaled $24,320 . It totaled $50,338 at private institutions.

Heavy student debt loads created America’s student loan crisis. A recent report from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis shows that outstanding student loan debt topped $1.6 trillion in the U.S. during the second quarter of 2019.

State and federal lawmakers and 2020 presidential candidates have put forward a range of plans aimed at reducing college costs to curb student debt and encourage more Americans to pursue degrees. Most programs and proposals focus on eliminating tuition at community colleges and state universities. But some also aim to cover educational costs such as mandatory student fees, which schools charge to help pay for student events, health services and other campus offerings.

These initiatives often are referred to as “free college” — even when they only cover tuition — and as “tuition-free” programs. A number of cities, counties and states have introduced “college promise” programs, which also pay students’ tuition and, sometimes, other expenses at two- and four-year institutions.

Recent research indicates there are hundreds of college promise programs in the U.S. Some are small, serving students in a city or public school district. Others are open to students across a state. In 2015, Tennessee became the first state in the country to offer free tuition at all of its community colleges and technical schools with its Tennessee Promise Scholarship . Earlier this month, officials in San Antonio announced AlamoPROMISE , which will allow students who graduate from one of 25 local high schools to receive 60 credits worth of free tuition at five area community colleges starting in fall 2020.

New York’s Excelsior Scholarship , launched in 2017, is the nation’s first statewide program to provide free tuition at state-funded two- and four-year colleges. The program is open to New York residents who have a household income of $125,000 or less and agree to live and work in New York for the same amount of time they receive the scholarship.

To help journalists understand the implications and impacts of these efforts, we’ve gathered and summarized a sampling of research on “free college,” “tuition-free” and “college promise” programs. Because most programs are relatively new, scholars are continuing to study them. We will add new research to this collection as it is published or released.

Also check out these five tips for reporting on free college and college promise programs from Laura Perna, an education professor at the University of Pennsylvania who’s also executive director of its Alliance for Higher Education and Democracy.

Merit Aid, College Quality, and College Completion: Massachusetts’ Adams Scholarship as an In-Kind Subsidy Cohodes, Sarah R; Goodman, Joshua S. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics , 2014.