Loading metrics

Open Access

Ten simple rules for effective presentation slides

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Biomedical Engineering and the Center for Public Health Genomics, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia, United States of America

- Kristen M. Naegle

Published: December 2, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009554

- Reader Comments

Citation: Naegle KM (2021) Ten simple rules for effective presentation slides. PLoS Comput Biol 17(12): e1009554. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009554

Copyright: © 2021 Kristen M. Naegle. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: The author received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The author has declared no competing interests exist.

Introduction

The “presentation slide” is the building block of all academic presentations, whether they are journal clubs, thesis committee meetings, short conference talks, or hour-long seminars. A slide is a single page projected on a screen, usually built on the premise of a title, body, and figures or tables and includes both what is shown and what is spoken about that slide. Multiple slides are strung together to tell the larger story of the presentation. While there have been excellent 10 simple rules on giving entire presentations [ 1 , 2 ], there was an absence in the fine details of how to design a slide for optimal effect—such as the design elements that allow slides to convey meaningful information, to keep the audience engaged and informed, and to deliver the information intended and in the time frame allowed. As all research presentations seek to teach, effective slide design borrows from the same principles as effective teaching, including the consideration of cognitive processing your audience is relying on to organize, process, and retain information. This is written for anyone who needs to prepare slides from any length scale and for most purposes of conveying research to broad audiences. The rules are broken into 3 primary areas. Rules 1 to 5 are about optimizing the scope of each slide. Rules 6 to 8 are about principles around designing elements of the slide. Rules 9 to 10 are about preparing for your presentation, with the slides as the central focus of that preparation.

Rule 1: Include only one idea per slide

Each slide should have one central objective to deliver—the main idea or question [ 3 – 5 ]. Often, this means breaking complex ideas down into manageable pieces (see Fig 1 , where “background” information has been split into 2 key concepts). In another example, if you are presenting a complex computational approach in a large flow diagram, introduce it in smaller units, building it up until you finish with the entire diagram. The progressive buildup of complex information means that audiences are prepared to understand the whole picture, once you have dedicated time to each of the parts. You can accomplish the buildup of components in several ways—for example, using presentation software to cover/uncover information. Personally, I choose to create separate slides for each piece of information content I introduce—where the final slide has the entire diagram, and I use cropping or a cover on duplicated slides that come before to hide what I’m not yet ready to include. I use this method in order to ensure that each slide in my deck truly presents one specific idea (the new content) and the amount of the new information on that slide can be described in 1 minute (Rule 2), but it comes with the trade-off—a change to the format of one of the slides in the series often means changes to all slides.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

Top left: A background slide that describes the background material on a project from my lab. The slide was created using a PowerPoint Design Template, which had to be modified to increase default text sizes for this figure (i.e., the default text sizes are even worse than shown here). Bottom row: The 2 new slides that break up the content into 2 explicit ideas about the background, using a central graphic. In the first slide, the graphic is an explicit example of the SH2 domain of PI3-kinase interacting with a phosphorylation site (Y754) on the PDGFR to describe the important details of what an SH2 domain and phosphotyrosine ligand are and how they interact. I use that same graphic in the second slide to generalize all binding events and include redundant text to drive home the central message (a lot of possible interactions might occur in the human proteome, more than we can currently measure). Top right highlights which rules were used to move from the original slide to the new slide. Specific changes as highlighted by Rule 7 include increasing contrast by changing the background color, increasing font size, changing to sans serif fonts, and removing all capital text and underlining (using bold to draw attention). PDGFR, platelet-derived growth factor receptor.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009554.g001

Rule 2: Spend only 1 minute per slide

When you present your slide in the talk, it should take 1 minute or less to discuss. This rule is really helpful for planning purposes—a 20-minute presentation should have somewhere around 20 slides. Also, frequently giving your audience new information to feast on helps keep them engaged. During practice, if you find yourself spending more than a minute on a slide, there’s too much for that one slide—it’s time to break up the content into multiple slides or even remove information that is not wholly central to the story you are trying to tell. Reduce, reduce, reduce, until you get to a single message, clearly described, which takes less than 1 minute to present.

Rule 3: Make use of your heading

When each slide conveys only one message, use the heading of that slide to write exactly the message you are trying to deliver. Instead of titling the slide “Results,” try “CTNND1 is central to metastasis” or “False-positive rates are highly sample specific.” Use this landmark signpost to ensure that all the content on that slide is related exactly to the heading and only the heading. Think of the slide heading as the introductory or concluding sentence of a paragraph and the slide content the rest of the paragraph that supports the main point of the paragraph. An audience member should be able to follow along with you in the “paragraph” and come to the same conclusion sentence as your header at the end of the slide.

Rule 4: Include only essential points

While you are speaking, audience members’ eyes and minds will be wandering over your slide. If you have a comment, detail, or figure on a slide, have a plan to explicitly identify and talk about it. If you don’t think it’s important enough to spend time on, then don’t have it on your slide. This is especially important when faculty are present. I often tell students that thesis committee members are like cats: If you put a shiny bauble in front of them, they’ll go after it. Be sure to only put the shiny baubles on slides that you want them to focus on. Putting together a thesis meeting for only faculty is really an exercise in herding cats (if you have cats, you know this is no easy feat). Clear and concise slide design will go a long way in helping you corral those easily distracted faculty members.

Rule 5: Give credit, where credit is due

An exception to Rule 4 is to include proper citations or references to work on your slide. When adding citations, names of other researchers, or other types of credit, use a consistent style and method for adding this information to your slides. Your audience will then be able to easily partition this information from the other content. A common mistake people make is to think “I’ll add that reference later,” but I highly recommend you put the proper reference on the slide at the time you make it, before you forget where it came from. Finally, in certain kinds of presentations, credits can make it clear who did the work. For the faculty members heading labs, it is an effective way to connect your audience with the personnel in the lab who did the work, which is a great career booster for that person. For graduate students, it is an effective way to delineate your contribution to the work, especially in meetings where the goal is to establish your credentials for meeting the rigors of a PhD checkpoint.

Rule 6: Use graphics effectively

As a rule, you should almost never have slides that only contain text. Build your slides around good visualizations. It is a visual presentation after all, and as they say, a picture is worth a thousand words. However, on the flip side, don’t muddy the point of the slide by putting too many complex graphics on a single slide. A multipanel figure that you might include in a manuscript should often be broken into 1 panel per slide (see Rule 1 ). One way to ensure that you use the graphics effectively is to make a point to introduce the figure and its elements to the audience verbally, especially for data figures. For example, you might say the following: “This graph here shows the measured false-positive rate for an experiment and each point is a replicate of the experiment, the graph demonstrates …” If you have put too much on one slide to present in 1 minute (see Rule 2 ), then the complexity or number of the visualizations is too much for just one slide.

Rule 7: Design to avoid cognitive overload

The type of slide elements, the number of them, and how you present them all impact the ability for the audience to intake, organize, and remember the content. For example, a frequent mistake in slide design is to include full sentences, but reading and verbal processing use the same cognitive channels—therefore, an audience member can either read the slide, listen to you, or do some part of both (each poorly), as a result of cognitive overload [ 4 ]. The visual channel is separate, allowing images/videos to be processed with auditory information without cognitive overload [ 6 ] (Rule 6). As presentations are an exercise in listening, and not reading, do what you can to optimize the ability of the audience to listen. Use words sparingly as “guide posts” to you and the audience about major points of the slide. In fact, you can add short text fragments, redundant with the verbal component of the presentation, which has been shown to improve retention [ 7 ] (see Fig 1 for an example of redundant text that avoids cognitive overload). Be careful in the selection of a slide template to minimize accidentally adding elements that the audience must process, but are unimportant. David JP Phillips argues (and effectively demonstrates in his TEDx talk [ 5 ]) that the human brain can easily interpret 6 elements and more than that requires a 500% increase in human cognition load—so keep the total number of elements on the slide to 6 or less. Finally, in addition to the use of short text, white space, and the effective use of graphics/images, you can improve ease of cognitive processing further by considering color choices and font type and size. Here are a few suggestions for improving the experience for your audience, highlighting the importance of these elements for some specific groups:

- Use high contrast colors and simple backgrounds with low to no color—for persons with dyslexia or visual impairment.

- Use sans serif fonts and large font sizes (including figure legends), avoid italics, underlining (use bold font instead for emphasis), and all capital letters—for persons with dyslexia or visual impairment [ 8 ].

- Use color combinations and palettes that can be understood by those with different forms of color blindness [ 9 ]. There are excellent tools available to identify colors to use and ways to simulate your presentation or figures as they might be seen by a person with color blindness (easily found by a web search).

- In this increasing world of virtual presentation tools, consider practicing your talk with a closed captioning system capture your words. Use this to identify how to improve your speaking pace, volume, and annunciation to improve understanding by all members of your audience, but especially those with a hearing impairment.

Rule 8: Design the slide so that a distracted person gets the main takeaway

It is very difficult to stay focused on a presentation, especially if it is long or if it is part of a longer series of talks at a conference. Audience members may get distracted by an important email, or they may start dreaming of lunch. So, it’s important to look at your slide and ask “If they heard nothing I said, will they understand the key concept of this slide?” The other rules are set up to help with this, including clarity of the single point of the slide (Rule 1), titling it with a major conclusion (Rule 3), and the use of figures (Rule 6) and short text redundant to your verbal description (Rule 7). However, with each slide, step back and ask whether its main conclusion is conveyed, even if someone didn’t hear your accompanying dialog. Importantly, ask if the information on the slide is at the right level of abstraction. For example, do you have too many details about the experiment, which hides the conclusion of the experiment (i.e., breaking Rule 1)? If you are worried about not having enough details, keep a slide at the end of your slide deck (after your conclusions and acknowledgments) with the more detailed information that you can refer to during a question and answer period.

Rule 9: Iteratively improve slide design through practice

Well-designed slides that follow the first 8 rules are intended to help you deliver the message you intend and in the amount of time you intend to deliver it in. The best way to ensure that you nailed slide design for your presentation is to practice, typically a lot. The most important aspects of practicing a new presentation, with an eye toward slide design, are the following 2 key points: (1) practice to ensure that you hit, each time through, the most important points (for example, the text guide posts you left yourself and the title of the slide); and (2) practice to ensure that as you conclude the end of one slide, it leads directly to the next slide. Slide transitions, what you say as you end one slide and begin the next, are important to keeping the flow of the “story.” Practice is when I discover that the order of my presentation is poor or that I left myself too few guideposts to remember what was coming next. Additionally, during practice, the most frequent things I have to improve relate to Rule 2 (the slide takes too long to present, usually because I broke Rule 1, and I’m delivering too much information for one slide), Rule 4 (I have a nonessential detail on the slide), and Rule 5 (I forgot to give a key reference). The very best type of practice is in front of an audience (for example, your lab or peers), where, with fresh perspectives, they can help you identify places for improving slide content, design, and connections across the entirety of your talk.

Rule 10: Design to mitigate the impact of technical disasters

The real presentation almost never goes as we planned in our heads or during our practice. Maybe the speaker before you went over time and now you need to adjust. Maybe the computer the organizer is having you use won’t show your video. Maybe your internet is poor on the day you are giving a virtual presentation at a conference. Technical problems are routinely part of the practice of sharing your work through presentations. Hence, you can design your slides to limit the impact certain kinds of technical disasters create and also prepare alternate approaches. Here are just a few examples of the preparation you can do that will take you a long way toward avoiding a complete fiasco:

- Save your presentation as a PDF—if the version of Keynote or PowerPoint on a host computer cause issues, you still have a functional copy that has a higher guarantee of compatibility.

- In using videos, create a backup slide with screen shots of key results. For example, if I have a video of cell migration, I’ll be sure to have a copy of the start and end of the video, in case the video doesn’t play. Even if the video worked, you can pause on this backup slide and take the time to highlight the key results in words if someone could not see or understand the video.

- Avoid animations, such as figures or text that flash/fly-in/etc. Surveys suggest that no one likes movement in presentations [ 3 , 4 ]. There is likely a cognitive underpinning to the almost universal distaste of pointless animations that relates to the idea proposed by Kosslyn and colleagues that animations are salient perceptual units that captures direct attention [ 4 ]. Although perceptual salience can be used to draw attention to and improve retention of specific points, if you use this approach for unnecessary/unimportant things (like animation of your bullet point text, fly-ins of figures, etc.), then you will distract your audience from the important content. Finally, animations cause additional processing burdens for people with visual impairments [ 10 ] and create opportunities for technical disasters if the software on the host system is not compatible with your planned animation.

Conclusions

These rules are just a start in creating more engaging presentations that increase audience retention of your material. However, there are wonderful resources on continuing on the journey of becoming an amazing public speaker, which includes understanding the psychology and neuroscience behind human perception and learning. For example, as highlighted in Rule 7, David JP Phillips has a wonderful TEDx talk on the subject [ 5 ], and “PowerPoint presentation flaws and failures: A psychological analysis,” by Kosslyn and colleagues is deeply detailed about a number of aspects of human cognition and presentation style [ 4 ]. There are many books on the topic, including the popular “Presentation Zen” by Garr Reynolds [ 11 ]. Finally, although briefly touched on here, the visualization of data is an entire topic of its own that is worth perfecting for both written and oral presentations of work, with fantastic resources like Edward Tufte’s “The Visual Display of Quantitative Information” [ 12 ] or the article “Visualization of Biomedical Data” by O’Donoghue and colleagues [ 13 ].

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the countless presenters, colleagues, students, and mentors from which I have learned a great deal from on effective presentations. Also, a thank you to the wonderful resources published by organizations on how to increase inclusivity. A special thanks to Dr. Jason Papin and Dr. Michael Guertin on early feedback of this editorial.

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 3. Teaching VUC for Making Better PowerPoint Presentations. n.d. Available from: https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/making-better-powerpoint-presentations/#baddeley .

- 8. Creating a dyslexia friendly workplace. Dyslexia friendly style guide. nd. Available from: https://www.bdadyslexia.org.uk/advice/employers/creating-a-dyslexia-friendly-workplace/dyslexia-friendly-style-guide .

- 9. Cravit R. How to Use Color Blind Friendly Palettes to Make Your Charts Accessible. 2019. Available from: https://venngage.com/blog/color-blind-friendly-palette/ .

- 10. Making your conference presentation more accessible to blind and partially sighted people. n.d. Available from: https://vocaleyes.co.uk/services/resources/guidelines-for-making-your-conference-presentation-more-accessible-to-blind-and-partially-sighted-people/ .

- 11. Reynolds G. Presentation Zen: Simple Ideas on Presentation Design and Delivery. 2nd ed. New Riders Pub; 2011.

- 12. Tufte ER. The Visual Display of Quantitative Information. 2nd ed. Graphics Press; 2001.

Journal Club: How to Prepare Effectively and Smash Your Presentation

Journal club. It’s so much more than orally dictating a paper to your peers.

It’s an opportunity to get a bunch of intelligent people in one place to share ideas. It’s a means to expand the scientific vocabulary of you and the audience. It’s a way to stimulate inventive research design.

But there are so many ways it can go wrong.

Poorly explained papers dictated blandly to an unengaged audience. Confusing heaps of data shoehorned into long presentations. Everybody stood awkwardly outside a meeting room you thought would be free.

Whether you are unsure what journal club is, are thinking of starting one, or simply want to up your presentation game—you’ve landed on the ultimate journal club guide.

The whats, the whys, and the hows, all in one place.

What Is a Journal Club in Science?

A journal club is a series of meetings in which somebody is elected to present a research paper, its methods, and findings to a group of colleagues.

The broad goal is to stimulate discussion and ideas that the attendees may apply to their own work. Alternatively, someone may choose a paper because it’s particularly impactful or ingenious.

Usually, the presenter alternates per a rota, and attendance may be optional or compulsory.

The presenter is expected to choose, analyze, and present the paper to the attendees with accompanying slides.

The presentation is then followed by a discussion of the paper by the attendees. This is usually in the form of a series of questions and answers directed toward the presenter. Ergo , the presenter is expected to know and understand the paper and subject area to a moderate extent.

Why Have a Journal Club?

I get it. You’re a busy person. There’s a difficult research problem standing between you and your next tenure.

Why bother spending the time and energy participating in a series of meetings that don’t get you closer to achieving your scientific goals?

The answer: journal club does get you closer to achieving your scientific goals!

But it does this in indirect ways that subtly make you a better scientist. For example:

- It probably takes you out of your comfort zone.

- It makes you a better communicator.

- It makes you better at analyzing data.

- It improves your ability to critique research.

- It makes you survey relevant literature.

- It exposes you and your audience to new concepts.

- It exposes your audience to relevant literature.

- It improves the reading habits of you and your audience.

- It gets clever people talking to each other.

- It gives people a break from practical science.

It also provides a platform for people to share ideas based on their collective scientific experience. And every participant has a unique set of skills. So every participant has the potential to provide valuable insight.

This is what a good journal club should illicit.

Think of journal club as reading a book. It’s going to enrich you and add beneficially to the sum of your mental furniture, but you won’t know how until you’ve read it.

Need empirical evidence to convince you? Okay!

In 1988 a group of medical interns was split into two groups. One received journal club teaching and the other received a series of seminars. Approximately 86% of the journal club group reported improved reading habits. This compares to 0% in the group who received seminar-based teaching. [1]

Journal Club Template Structure

So now you know what journal club is, you might wonder, “how is it organized and structured?”

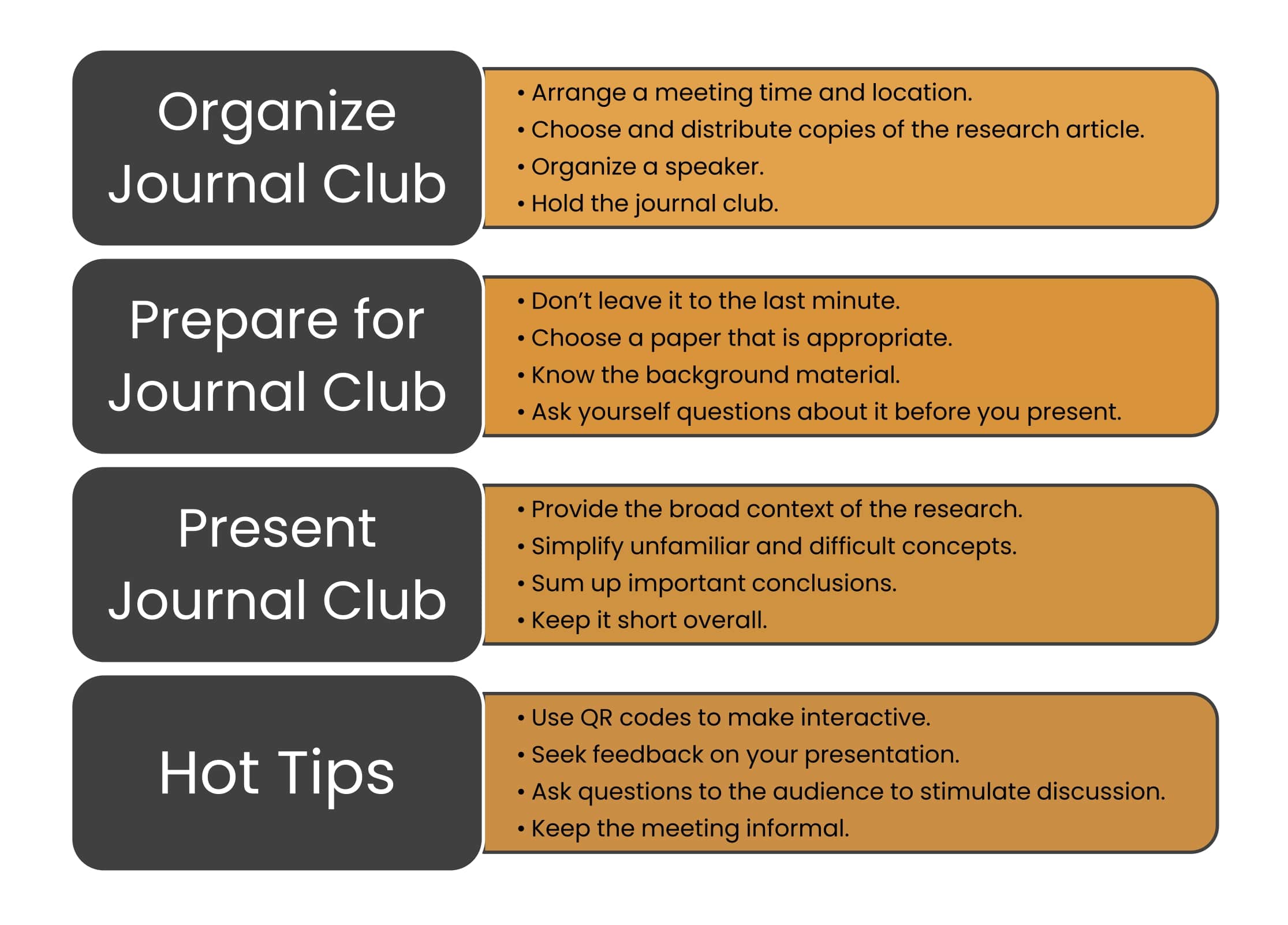

That’s what the rest of this article delves into. If you’re in a rush and need to head back to the lab, here’s a graphical summary (Figure 1).

Nobody likes meetings that flounder around and run over time. And while I have no data to prove it, I reckon people take less away from such meetings. Here’s a basic journal club template that assumes you are the presenter.

Introduce the Paper, Topic, Journal, and Authors

Let your audience know what you will be talking about before diving right in. Remember that repetition (of the important bits) can be a good thing.

Introducing the journal in which the paper is published will give your audience a rough idea of the prestige of the work.

And introducing the authors and their respective institutes gives your audience the option of stowing this information away and following it up with further reading in their own time.

Provide a Reason Why You Chose the Paper

Have the authors managed to circumvent sacrificing animals to achieve a goal that traditionally necessitated animal harm? Have the authors repurposed a method and applied it to a problem it’s not traditionally associated with? Is it simply a monumental feat of work and success?

People are probably more likely to listen and engage with you if they know why, in all politeness, you have chosen to use their time to talk about a given paper.

It also helps them focus on the relevant bits of your presentation and form cogent questions.

Orally Present Key Findings and Methods of the Paper

Simple. Read the paper. Understand it. Make some slides. Present.

Okay, there are a lot of ways you can get this wrong and make a hash of it. We’ll tell you how to avoid these pitfalls later on.

But for now, acknowledge that a journal club meeting starts with a presentation that sets up the main bit of it—the discussion.

Invite Your Audience to Participate in a Discussion

The discussion is the primary and arguably most beneficial component of journal club since it gives the audience a platform to share ideas. Ideas formulated by their previous experience.

And I’ve said already that these contributions are unique and have the potential to be valuable to your work.

That’s why the discussion element is important.

Their questions might concur and elaborate on the contents of the paper and your presentation of it.

Alternatively, they might disagree with the methods and/or conclusions. They might even disagree with your presentation of technical topics.

Try not to be daunted, however, as all of this ultimately adds to your knowledge, and it should all be conducted in a constructive spirit.

Summarize the Meeting and Thank Your Audience for Attending

There’s no particularly enlightening reason as to why to do these things. Summarizing helps people come away from the meeting feeling like it was a positive and rewarding thing to attend.

And thanking people for their time is a simple courtesy.

How Do You Organize It?

Basic steps if you are the organizer.

Okay, we’ve just learned what goes into speaking at the journal club. But presenter or not, the responsibility of organizing it might fall to you.

So, logistically , how do you prepare a journal club? Simply follow these 5 steps:

- Distribute copies of the research article to potential participants.

- Arrange a meeting time and location.

- Organize a speaker.

- Hold the journal club.

- Seek feedback on the quality of the meeting.

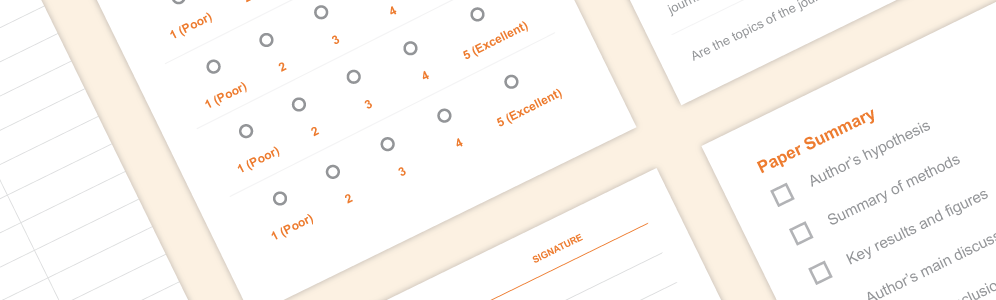

Apart from point 5, these are fairly self-explanatory. Regarding point 5, feedback is essential to growing as a scientist and presenter. The easiest way to seek feedback is simply to ask.

Alternatively, you could create a form for all the meetings in the series and ask the audience to complete and return it to you.

Basic Steps If You Are the Speaker

If somebody has done all the logistics for you, great! Don’t get complacent, however.

Why not use the time to elevate your presentation to make your journal club contribution memorable and beneficial?

Don’t worry about the “hows” because we’re going to elaborate on these points, but here are 5 things you can do to ace your presentation:

- Don’t leave it to the last minute.

- Know your audience.

- Keep your presentation slides simple.

- Keep your audience engaged.

- Be open to questions and critiques.

Regarding point 1, giving yourself sufficient time to thoroughly read the article you have chosen to present ensures you are familiar with the material in it. This is essential because you will be asked questions about it. A confident reply is the foundation of an enlightening discussion.

Regarding point 3, we’re going to tell you exactly how to prepare effective slides in its own section later. But if you are in a rush, minimize the use of excessive text. And if you provide background information, stick to diagrams that give an overview of results from previous work. Remember: a picture speaks louder than a thousand words.

Regarding point 4, engagement is critical. So carry out a practice run to make sure you are happy with the flow of your presentation and to give you an idea of your timing. It is important to stick to the time that is allotted for you.

This provides good practice for more formal conference settings where you will be stopped if you run over time. It’s also good manners and shows consideration for the attendees.

And regarding point 5, as the presenter, questions are likely to be directed toward you. So anticipate questions from the outset and prepare for the obvious ones to the best of your ability.

There’s a limit to everyone’s knowledge, but being unable to provide any sort of response will be embarrassing and make you seem unprepared.

Anticipate that people might also disagree with any definitions you make and even with your presentation of other people’s data. Whether or not you agree is a different matter, but present your reasons in a calm and professional manner.

If someone is rude, don’t rise to it and respond calmly and courteously. This shouldn’t happen too often, but we all have “those people” around us.

How Do You Choose a Journal Club Paper?

Consider the quality of the journal.

Just to be clear, I don’t mean the paper itself but the journal it’s published in.

An obscure journal is more likely to contain science that’s either boring, sloppy, wrong, or all three.

And people are giving up their time and hope to be stimulated. So oblige them!

Journal impact factor and rejection rate (the ratio of accepted to rejected articles) can help you decide whether a paper is worth discussing.

Consider the Impact and Scope of the Paper

Similar to the above, but remember, dross gets published in high-impact journals too. Hopefully, you’ve read the paper you want to present. But ask yourself what makes this particular paper stand out from the millions of others to be worth presenting.

Keep It Relevant and Keep It Interesting

When choosing a paper to present, keep your audience in mind. Choose something that is relevant to the particular group you are presenting to. If only you and a few other people understand the topic, it can come off as elitist.

How Do You Break Down and Present the Paper?

Know and provide the background material.

Before you dive into the data, spend a few minutes talking about the context of the paper. What did the authors know before they started this work? How did they formulate their hypothesis? Why did they choose to address it in this way?

You may want to reference an earlier paper from the same group if the paper represents a continuation of it, but keep it brief.

Try to explain how this paper tackles an unanswered question in the field.

Understand the Hypothesis and Methods of the Paper

Make a point of stating the hypothesis or main question of the paper, so everyone understands the goal of the study and has a foundation for the presentation and discussion.

Everyone needs to start on the same foot and remain on the same page as the meeting progresses.

Turn the Paper into a Progression of Scientific Questions

Present the data as a logical series of questions and answers. A well-written paper will already have done the hard work for you. It will be organized carefully so that each figure answers a specific question, and each new question builds on the answer from the previous figure.

If you’re having trouble grasping the flow of the paper, try writing up a brief outline of the main points. Try putting the experiments and conclusions in your own words, too.

Feel free to leave out parts of the figures that you think are unnecessary, or pull extra data from the supplemental figures if it will help you explain the paper better.

Ask Yourself Questions about the Paper Before You Present

We’ve touched on this already. This is to prepare you for any questions that are likely to be asked of you. When you read the paper, what bits didn’t you understand?

Simplify Unfamiliar and Difficult Concepts

Not everyone will be familiar with the same concepts. For example, most biologists will not have a rigorous definition of entropy committed to memory or know its units. The concept of entropy might crop up in a biophysics paper, however.

Put yourself in the audience’s shoes and anticipate what they might not fully understand given their respective backgrounds.

If you are unsure, ask them if they need a definition or include a short definition in your slides.

Sum Up Important Conclusions

After you’ve finished explaining the nitty-gritty details of the paper, conclude your presentation of the data with a list of significant findings.

Every conclusion will tie in directly to proving the major conclusion of the paper. It should be clear at this point how the data answers the main question.

How Do You Present a Journal Club Powerpoint?

Okay, so we’ve just gone through the steps required to break down a paper to present it effectively at journal club. But this needs to be paired with a PowerPoint presentation, and the two bridged orally by your talk. How do you ace this?

Provide Broad Context to the Research

We are all bogged down by minutia and reagents out of necessity.

Being bogged down is research. But it helps to come up for air. Ultimately, how will the research you are about to discuss benefit the Earth and its inhabitants when said research is translated into actual products?

Science can be for its own sake, but funded science rarely is. Reminding the journal club audience of the widest aims of the nominated field provides a clear starting point for the discussion and shows that you understand the efficacy of the research at its most basic level.

The Golden Rule: A Slide per Minute

Remember during lectures when the lecturer would open PowerPoint, and you would see, with dismay, that their slides went up to 90 or something daft? Then the last 20 get rushed through, but that’s what the exam question ends up being based on.

Don’t be that person!

A 10-15 minute talk should be accompanied by? 10-15 slides! Less is more.

Be Judicious about the Information You Choose to Present

If you are present everything in the paper, people might as well just read it in their own time, and we can call journal club off.

Try to abstract only the key findings. Sometimes technical data is necessary for what you are speaking about because their value affects the efficacy of the data and validity of the conclusions.

Most of the time, however, the exact experimental conditions can be left out and given on request. It’s good practice to put all the technical data that you anticipate being asked for in a few slides at the end of your talk.

Use your judgment.

Keep the Amount of Information per Slide Low for Clarity

Your audience is already listening to you and looking at the slides, so they have a limited capacity for what they can absorb. Overwhelming them with visual queues and talking to them will disengage them.

Have only a few clearly related images that apply directly to what you speaking about at the time. Annotate them with the only key facts from your talk and develop the bigger picture verbally.

This will be hard at first because you must be on the ball and confident with your subject area and speaking to an audience.

And definitely use circles, boxes, and arrows to highlight important parts of figures, and add a flowchart or diagram to explain an unfamiliar method.

Keep It Short Overall

The exact length of your meeting is up to you or the organizer. A 15-minute talk followed by a 30-minute discussion is about the right length, Add in tea and coffee and hellos, and you get to an hour.

We tend to speak at 125-150 words per minute. All these words should not be on your slides, however. So, commit a rough script to memory and rehearse it.

You’ll find that the main points you need to mention start to stand out and fall into place naturally. Plus, your slides will serve as visual queue cards.

How Do You Ask a Question in Journal Club?

A well-organized journal club will have clear expectations of whether or not questions should be asked only during the discussion, or whether interruptions during the presentation are allowed.

And I don’t mean literally how do you soliloquize, but rather how do you get an effective discussion going.

Presenters: Ask Questions to the Audience

We all know how it goes. “Any questions?” Silence.

Scientists, by their very nature, are usually introverted. Any ideas they might want to contribute to a discussion are typically outweighed by the fear of looking silly in front of their peers. Or they think everyone already knows the item they wish to contribute. Or don’t want to be publicly disproven. And so on.

Prepare some questions to ask the audience in advance. As soon as a few people speak, everyone tends to loosen up. Take advantage of this.

Audience: Think About Topics to Praise or Critique

Aside from seeking clarification on any unclear topics, you could ask questions on:

- Does the data support the conclusions?

- Are the conclusions relevant?

- Are the methods valid?

- What are the drawbacks and limitations of the conclusions?

- Are there better methods to test the hypothesis?

- How will the research be translated into real-world benefits?

- Are there obvious follow-up experiments?

- How well is the burden of proof met?

- Is the data physiologically relevant?

- Do you agree with the conclusions?

How to Keep It Fun

Make it interactive.

Quizzes and polls are a great way to do this! And QR codes make it really easy to do on-the-fly. Remember, scientists, are shy. So why not seek their participation in an anonymized form?

You could poll your audience on the quality of the work. You could make a fun quiz based on the material you’ve covered. You could do a live “what happened next?” You could even get your feedback this way. Here’s what to do:

- Create your quiz or poll using Google forms .

- Make a shareable link.

- Paste the link into a free QR code generator .

- Put the QR code in the appropriate bit of your talk.

Use Multimedia

Talking to your audience without anything to break it up is a guaranteed way of sending them all to sleep.

Consider embedding demonstration videos and animations in your talk. Or even just pausing to interject with your own anecdotes will keep everyone concentrated on you.

Keep It Informal

At the end of the day, we’re all scientists. Perhaps at different stages of our careers, but we’ve all had similar-ish trajectories. So there’s no need for haughtiness.

And research institutes are usually aggressively casual in terms of dress code, coffee breaks, and impromptu chats. Asking everyone to don a suit won’t add any value to a journal club.

Your Journal Club Toolkit in Summary

Anyone can read a paper, but the value lies in understanding it and applying it to your own research and thought process.

Remember, journal club is about extracting wisdom from your colleagues in the form of a discussion while disseminating wisdom to them in a digestible format.

Need some inspiration for your journal club? Check out the online repositories hosted by PNAS and NASPAG to get your juices flowing.

We’ve covered a lot of information, from parsing papers to organizational logistics, and effective presentation. So why not bookmark this page so you can come back to it all when it’s your turn to present?

While you’re here, why not ensure you’re always prepared for your next journal club and download bitesize bio’s free journal club checklist ?

And if you present at journal club and realize we’ve left something obvious out. Get in touch and let us know. We’ll add it to the article!

- Linzer M et al . (1988) Impact of a medical journal club on house-staff reading habits, knowledge, and critical appraisal skills . JAMA 260 :2537–41

Forgot your password?

Lost your password? Please enter your email address. You will receive mail with link to set new password.

Back to login

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- How to prepare and...

How to prepare and deliver an effective oral presentation

- Related content

- Peer review

- Lucia Hartigan , registrar 1 ,

- Fionnuala Mone , fellow in maternal fetal medicine 1 ,

- Mary Higgins , consultant obstetrician 2

- 1 National Maternity Hospital, Dublin, Ireland

- 2 National Maternity Hospital, Dublin; Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Medicine and Medical Sciences, University College Dublin

- luciahartigan{at}hotmail.com

The success of an oral presentation lies in the speaker’s ability to transmit information to the audience. Lucia Hartigan and colleagues describe what they have learnt about delivering an effective scientific oral presentation from their own experiences, and their mistakes

The objective of an oral presentation is to portray large amounts of often complex information in a clear, bite sized fashion. Although some of the success lies in the content, the rest lies in the speaker’s skills in transmitting the information to the audience. 1

Preparation

It is important to be as well prepared as possible. Look at the venue in person, and find out the time allowed for your presentation and for questions, and the size of the audience and their backgrounds, which will allow the presentation to be pitched at the appropriate level.

See what the ambience and temperature are like and check that the format of your presentation is compatible with the available computer. This is particularly important when embedding videos. Before you begin, look at the video on stand-by and make sure the lights are dimmed and the speakers are functioning.

For visual aids, Microsoft PowerPoint or Apple Mac Keynote programmes are usual, although Prezi is increasing in popularity. Save the presentation on a USB stick, with email or cloud storage backup to avoid last minute disasters.

When preparing the presentation, start with an opening slide containing the title of the study, your name, and the date. Begin by addressing and thanking the audience and the organisation that has invited you to speak. Typically, the format includes background, study aims, methodology, results, strengths and weaknesses of the study, and conclusions.

If the study takes a lecturing format, consider including “any questions?” on a slide before you conclude, which will allow the audience to remember the take home messages. Ideally, the audience should remember three of the main points from the presentation. 2

Have a maximum of four short points per slide. If you can display something as a diagram, video, or a graph, use this instead of text and talk around it.

Animation is available in both Microsoft PowerPoint and the Apple Mac Keynote programme, and its use in presentations has been demonstrated to assist in the retention and recall of facts. 3 Do not overuse it, though, as it could make you appear unprofessional. If you show a video or diagram don’t just sit back—use a laser pointer to explain what is happening.

Rehearse your presentation in front of at least one person. Request feedback and amend accordingly. If possible, practise in the venue itself so things will not be unfamiliar on the day. If you appear comfortable, the audience will feel comfortable. Ask colleagues and seniors what questions they would ask and prepare responses to these questions.

It is important to dress appropriately, stand up straight, and project your voice towards the back of the room. Practise using a microphone, or any other presentation aids, in advance. If you don’t have your own presenting style, think of the style of inspirational scientific speakers you have seen and imitate it.

Try to present slides at the rate of around one slide a minute. If you talk too much, you will lose your audience’s attention. The slides or videos should be an adjunct to your presentation, so do not hide behind them, and be proud of the work you are presenting. You should avoid reading the wording on the slides, but instead talk around the content on them.

Maintain eye contact with the audience and remember to smile and pause after each comment, giving your nerves time to settle. Speak slowly and concisely, highlighting key points.

Do not assume that the audience is completely familiar with the topic you are passionate about, but don’t patronise them either. Use every presentation as an opportunity to teach, even your seniors. The information you are presenting may be new to them, but it is always important to know your audience’s background. You can then ensure you do not patronise world experts.

To maintain the audience’s attention, vary the tone and inflection of your voice. If appropriate, use humour, though you should run any comments or jokes past others beforehand and make sure they are culturally appropriate. Check every now and again that the audience is following and offer them the opportunity to ask questions.

Finishing up is the most important part, as this is when you send your take home message with the audience. Slow down, even though time is important at this stage. Conclude with the three key points from the study and leave the slide up for a further few seconds. Do not ramble on. Give the audience a chance to digest the presentation. Conclude by acknowledging those who assisted you in the study, and thank the audience and organisation. If you are presenting in North America, it is usual practice to conclude with an image of the team. If you wish to show references, insert a text box on the appropriate slide with the primary author, year, and paper, although this is not always required.

Answering questions can often feel like the most daunting part, but don’t look upon this as negative. Assume that the audience has listened and is interested in your research. Listen carefully, and if you are unsure about what someone is saying, ask for the question to be rephrased. Thank the audience member for asking the question and keep responses brief and concise. If you are unsure of the answer you can say that the questioner has raised an interesting point that you will have to investigate further. Have someone in the audience who will write down the questions for you, and remember that this is effectively free peer review.

Be proud of your achievements and try to do justice to the work that you and the rest of your group have done. You deserve to be up on that stage, so show off what you have achieved.

Competing interests: We have read and understood the BMJ Group policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: None.

- ↵ Rovira A, Auger C, Naidich TP. How to prepare an oral presentation and a conference. Radiologica 2013 ; 55 (suppl 1): 2 -7S. OpenUrl

- ↵ Bourne PE. Ten simple rules for making good oral presentations. PLos Comput Biol 2007 ; 3 : e77 . OpenUrl PubMed

- ↵ Naqvi SH, Mobasher F, Afzal MA, Umair M, Kohli AN, Bukhari MH. Effectiveness of teaching methods in a medical institute: perceptions of medical students to teaching aids. J Pak Med Assoc 2013 ; 63 : 859 -64. OpenUrl

Expert Consult

Journal Club: How to Build One and Why

By Michelle Sharp, MD; Hunter Young, MD, MHS

Published April 6, 2022

Journal clubs are a longstanding tradition in residency training, dating back to William Osler in 1875. The original goal of the journal club in Osler’s day was to share expensive texts and to review literature as a group. Over time, the goals of journal clubs have evolved to include discussion and review of current literature and development of skills for evaluating medical literature. The ultimate goal of a journal club is to improve patient care by incorporating evidence into practice.

Why are journal clubs important?

In 2004, Alper et al . reported that it would take more than 600 hours per month to stay current with the medical literature. That leaves residents with less than 5 hours a day to eat, sleep, and care for patients if they want to stay current, and it’s simply impossible. Journal clubs offer the opportunity for residents to review the literature and stay current. Furthermore, Lee et al . showed that journal clubs improve residents’ critical appraisal of the literature.

How do you get started?

The first step to starting a journal club is to decide on the initial goal. A good initial goal is to lay the foundation for critical thinking skills using literature that is interesting to residents. An introductory lecture series or primer on study design is a valuable way to start the journal club experience. The goal of the primer is not for each resident to become a statistician, but rather to lay the foundation for understanding basic study designs and the strengths and weaknesses of each design.

The next step is to decide on the time, frequency, and duration of the journal club. This depends on the size of your residency program and leadership support. Our journal club at Johns Hopkins is scheduled monthly during the lunch hour instead of a noon conference lecture. It is essential to pick a time when most residents in your program will be available to attend and a frequency that is sustainable.

How do you get residents to come?

Generally, if you feed them, they will come. In a cross-sectional analysis of journal clubs in U.S. internal medicine residencies, Sidorov found that providing food was associated with long-lasting journal clubs. Factors associated with higher resident attendance were fewer house staff, mandatory attendance, formal teaching, and an independent journal club (separate from faculty journal clubs).

The design or format of your journal club is also a key factor for attendance. Not all residents will have time during each rotation to read the assigned article, but you want to encourage these residents to attend nonetheless. One way to engage all residents is to assign one or two residents to lead each journal club, with the goal of assigning every resident at least one journal club during the year. If possible, pick residents who are on lighter rotations, so they have more time outside of clinical duties to dissect the article. To enhance engagement, allow the assigned residents to pick an article on a topic that they find interesting.

Faculty leadership should collaborate with residents on article selection and dissection and preparation of the presentation. Start each journal club with a 10- to 20-minute presentation by the assigned residents to describe the article (as detailed below) to help residents who did not have time to read the article to participate.

What are the nuts and bolts of a journal club?

To prepare a successful journal club presentation, it helps for the structure of the presentation to mirror the structure of the article as follows:

Background: Start by briefly describing the background of the study, prior literature, and the question the paper was intended to address.

Methods: Review the paper’s methods, emphasizing the study design, analysis, and other key points that address the validity and generalizability of the results (e.g., participant selection, treatment of potential confounders, and other issues that are specific to each study design).

Results: Discuss the results, focusing on the paper’s tables and figures.

Discussion: Restate the research question, summarize the key findings, and focus on factors that can affect the validity of the findings. What are potential biases, confounders, and other issues that affect the validity or generalizability of the findings to clinical practice? The study results should also be discussed in the context of prior literature and current clinical practice. Addressing the questions that remain unanswered and potential next steps can also be useful.

Faculty participation: At our institution, the faculty sponsor meets with the assigned residents to address their questions about the paper and guide the development of the presentation, ensuring that the key points are addressed. Faculty sponsors also attend the journal club to answer questions, emphasize key elements of the paper, and facilitate the open discussion after the resident’s presentation.

How do you measure impact?

One way to evaluate your journal club is to assess the evidence-based practice skills of the residents before and after the implementation of the journal club with a tool such as the Berlin questionnaire — a validated 15-question survey that assesses evidence-based practice skills. You can also conduct a resident satisfaction survey to evaluate the residents’ perception of the implementation of the journal club and areas for improvement. Finally, you can develop a rubric for evaluation of the resident presenters in each journal club session, and allow faculty to provide feedback on critical assessment of the literature and presentation skills.

Journal clubs are a great tradition in medical training and continue to be a valued educational resource. Set your goal. Consider starting with a primer on study design. Engage and empower residents to be part of the journal club. Enlist faculty involvement for guidance and mentorship. Measure the impact.

Advertisement

How to Prepare an Outstanding Journal Club Presentation

- Request Permissions

Rishi Sawhney; How to Prepare an Outstanding Journal Club Presentation. The Hematologist 2006; 3 (1): No Pagination Specified. doi: https://doi.org/10.1182/hem.V3.1.1308

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Dr. Sawhney is a member of the ASH Trainee Council and a Fellow at the Medical University of South Carolina.

Journal club presentations provide a forum through which hematology trainees keep abreast of new developments in hematology and engage in informal discussion and interaction. Furthermore, honing presentation skills and mastering the ability to critically appraise the evidence add to our armamentarium as clinicians. Outlined here is a systematic approach to preparing a journal club presentation, with emphasis on key elements of the talk and references for electronic resources. Use of these tools and techniques will contribute to the success of your presentation.

I. ARTICLE SELECTION:

The foundation of an outstanding journal club presentation rests on the choice of an interesting and well-written paper for discussion. Several resources are available to help you select important and timely research, including the American College of Physicians (ACP) Journal Club and the Diffusion section of The Hematologist . McMaster University has created the McMaster Online Rating of Evidence (MORE) system to identify the highest-quality published research. In fact, the ACP Journal Club uses the MORE system to select their articles 1 . Specific inclusion criteria have been delineated in order to distinguish papers with the highest scientific merit 2 . Articles that have passed this screening are then rated by clinicians on their clinical relevance and newsworthiness, using a graded scale 3 . With the help of your mentors and colleagues, you can use these criteria and the rating scale as informal guidelines to ensure that your chosen article merits presentation.

II. ARTICLE PRESENTATION:

Study Background: This section provides your audience with the necessary information and context for a thoughtful and critical evaluation of the article's significance. The goals are 1) to describe the rationale for and clinical relevance of the study question, and 2) to highlight the preclinical and clinical research that led to the current trial. Review the papers referenced in the study's "Background" section as well as previous work by the study's authors. It also may be helpful to discuss data supporting the current standard of care against which the study intervention is being measured.

Study Methodology and Results: Clearly describe the study population, including inclusion/exclusion criteria. A diagrammatic schema is easy to construct using PowerPoint software and will help to clearly illustrate treatment arms in complex trials. Explain the statistical methods, obtaining assistance from a statistician if needed. Take this opportunity to verbally and graphically highlight key results from the study, with plans to expand on their significance later in your presentation.

Author's Discussion: Present the authors' conclusions and their perspective on the study results, including explanations of inconsistent or unexpected results. Consider whether the conclusions drawn are supported by the data presented.

III. ARTICLE CRITIQUE:

This component of your presentation will define the success of your journal club. A useful and widely accepted approach to this analysis has been published in JAMA's series "User's guide to the medical literature." The Centre for Health Evidence in Canada has made the complete full-text set of these user's guides available online 4 . This site offers review guidelines for a menu of article types, and it is an excellent, comprehensive resource to focus your study critique. A practical, user-friendly approach to literature evaluation that includes a worksheet is also available on the ASH Web site for your use 5 .

While a comprehensive discussion of scientific literature appraisal is beyond the scope of this discussion, several helpful tips warrant mention here. In assessing the validity of the study, it is important to assess for potential sources of bias, including the funding sources and authors' affiliations. It is also helpful to look for accompanying editorial commentary, which can provide a unique perspective on the article and highlight controversial issues. You should plan to discuss the trade-offs between potential benefits of the study intervention versus potential risks and the cost. By utilizing the concept of number needed to treat (NNT), one can assess the true impact of the study intervention on clinical practice. Furthermore, by incorporating the incidence rates of clinically significant toxicities with the financial costs into the NNT, you can generate a rather sophisticated analysis of the study's impact on practice.

IV. CONCLUSIONS, IMPLICATIONS, AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS:

Restate the authors' take-home message followed by your own interpretation of the study. Provide a personal perspective, detailing why you find this paper interesting or important. Then, look forward and use this opportunity to "think outside the box." Do you envision these study results changing the landscape of clinical practice or redirecting research in this field? If so, how? In articles about therapy, future directions may include moving the therapy up to first-line setting, assessing the drug in combination regimens or other disease states, or developing same-class novel compounds in the pipeline. Searching for related clinical trials on the NIH Web site 6 can prove helpful, as can consultation with an expert in this field.

Good journal club discussions are integral to the educational experience of hematology trainees. Following the above approach, while utilizing the resources available, will lay the groundwork for an outstanding presentation.

WEB BASED REFERENCES

www.acpjc.org

hiru.mcmaster.ca/more/InclusionCriteria.htm

hiru.mcmaster.ca/more/RatingFormSample.htm

www.cche.net/main.asp

www.hematology.org/Trainees

www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials

- Previous Article

- Next Article

Email alerts

Affiliations.

- Current Issue

- About The Hematologist

- Advertising in The Hematologist

- Editorial Board

- Permissions

- Submissions

- Email Alerts

- ASH Publications App

American Society of Hematology

- 2021 L Street NW, Suite 900

- Washington, DC 20036

- TEL +1 202-776-0544

- FAX +1 202-776-0545

ASH Publications

- Blood Advances

- Blood Neoplasia

- Blood Vessels, Thrombosis & Hemostasis

- Hematology, ASH Education Program

- ASH Clinical News

- The Hematologist

- Publications

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Terms of Use

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

- Publication Recognition

How to Make a PowerPoint Presentation of Your Research Paper

- 4 minute read

- 123.6K views

Table of Contents

A research paper presentation is often used at conferences and in other settings where you have an opportunity to share your research, and get feedback from your colleagues. Although it may seem as simple as summarizing your research and sharing your knowledge, successful research paper PowerPoint presentation examples show us that there’s a little bit more than that involved.

In this article, we’ll highlight how to make a PowerPoint presentation from a research paper, and what to include (as well as what NOT to include). We’ll also touch on how to present a research paper at a conference.

Purpose of a Research Paper Presentation

The purpose of presenting your paper at a conference or forum is different from the purpose of conducting your research and writing up your paper. In this setting, you want to highlight your work instead of including every detail of your research. Likewise, a presentation is an excellent opportunity to get direct feedback from your colleagues in the field. But, perhaps the main reason for presenting your research is to spark interest in your work, and entice the audience to read your research paper.

So, yes, your presentation should summarize your work, but it needs to do so in a way that encourages your audience to seek out your work, and share their interest in your work with others. It’s not enough just to present your research dryly, to get information out there. More important is to encourage engagement with you, your research, and your work.

Tips for Creating Your Research Paper Presentation

In addition to basic PowerPoint presentation recommendations, which we’ll cover later in this article, think about the following when you’re putting together your research paper presentation:

- Know your audience : First and foremost, who are you presenting to? Students? Experts in your field? Potential funders? Non-experts? The truth is that your audience will probably have a bit of a mix of all of the above. So, make sure you keep that in mind as you prepare your presentation.

Know more about: Discover the Target Audience .

- Your audience is human : In other words, they may be tired, they might be wondering why they’re there, and they will, at some point, be tuning out. So, take steps to help them stay interested in your presentation. You can do that by utilizing effective visuals, summarize your conclusions early, and keep your research easy to understand.

- Running outline : It’s not IF your audience will drift off, or get lost…it’s WHEN. Keep a running outline, either within the presentation or via a handout. Use visual and verbal clues to highlight where you are in the presentation.

- Where does your research fit in? You should know of work related to your research, but you don’t have to cite every example. In addition, keep references in your presentation to the end, or in the handout. Your audience is there to hear about your work.

- Plan B : Anticipate possible questions for your presentation, and prepare slides that answer those specific questions in more detail, but have them at the END of your presentation. You can then jump to them, IF needed.

What Makes a PowerPoint Presentation Effective?

You’ve probably attended a presentation where the presenter reads off of their PowerPoint outline, word for word. Or where the presentation is busy, disorganized, or includes too much information. Here are some simple tips for creating an effective PowerPoint Presentation.

- Less is more: You want to give enough information to make your audience want to read your paper. So include details, but not too many, and avoid too many formulas and technical jargon.

- Clean and professional : Avoid excessive colors, distracting backgrounds, font changes, animations, and too many words. Instead of whole paragraphs, bullet points with just a few words to summarize and highlight are best.

- Know your real-estate : Each slide has a limited amount of space. Use it wisely. Typically one, no more than two points per slide. Balance each slide visually. Utilize illustrations when needed; not extraneously.

- Keep things visual : Remember, a PowerPoint presentation is a powerful tool to present things visually. Use visual graphs over tables and scientific illustrations over long text. Keep your visuals clean and professional, just like any text you include in your presentation.

Know more about our Scientific Illustrations Services .

Another key to an effective presentation is to practice, practice, and then practice some more. When you’re done with your PowerPoint, go through it with friends and colleagues to see if you need to add (or delete excessive) information. Double and triple check for typos and errors. Know the presentation inside and out, so when you’re in front of your audience, you’ll feel confident and comfortable.

How to Present a Research Paper

If your PowerPoint presentation is solid, and you’ve practiced your presentation, that’s half the battle. Follow the basic advice to keep your audience engaged and interested by making eye contact, encouraging questions, and presenting your information with enthusiasm.

We encourage you to read our articles on how to present a scientific journal article and tips on giving good scientific presentations .

Language Editing Plus

Improve the flow and writing of your research paper with Language Editing Plus. This service includes unlimited editing, manuscript formatting for the journal of your choice, reference check and even a customized cover letter. Learn more here , and get started today!

- Manuscript Preparation

Know How to Structure Your PhD Thesis

- Research Process

Systematic Literature Review or Literature Review?

You may also like.

What is a Good H-index?

What is a Corresponding Author?

How to Submit a Paper for Publication in a Journal

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

5 Tips for Journal Club First-Timers

By Lucy Bauer

Monday, March 30, 2015

Research communities often uphold the ideal of scientific collaboration. But what does “collaboration” really mean? The picture that comes to mind can be people sitting, talking, and exchanging ideas that push toward the goal of creating better health. How can this exchange practically happen? One way is through a journal club. Recently, I had the privilege of presenting a journal article to my lab group’s journal club in the PAIN (Pain And Integrative Neuroscience) lab for Dr. Catherine Bushnell . One goal of our lab is to look at the relationship and differences between itch and pain.

Me explaining part of the spinal neuron pathway in itch

So, what is the purpose of a journal club?

A journal club is a regular gathering of scientists to discuss a scientific paper found in a research journal. One or two members of the club present a summary of the chosen paper that the whole group has read. Then, the discussion begins. Attendees ask clarifying questions, inquire about different aspects of the experimental design, critique the methods, and bring a healthy amount of skepticism (or praise) to the results.

For my first journal club at the NIH, we considered a paper that looks at how itch is mediated in the spinal cord from the skin up to the brain. The authors show that mice lacking a gene for a specific type of spinal neuron constantly scratch specific areas of their bodies corresponding to the missing spinal interneuron. When these mice receive a stem cell implant, a normal reaction to itch is restored. This paper generated much discussion about neuronal development, ethical considerations, and how the results relate to our research within the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH).

The ideas found and discussed at the journal club can help expand and balance each scientist’s scope of what is happening in the world of research while informing experimental plans and research directions. Here are five things I learned from my experience leading a journal club that can help you prepare to get the most out of your discussions:

1. Know the background material.

Prepare beforehand for your journal club presentation by knowing the research that has preceded and is related to the paper you will be presenting. This will make your discussion more informed and effective. Of course, it is likely impossible to know everything that would relate to your journal club presentation, but even a little bit of background information is helpful.

2. Make your presentation concise.

Every paper has many details about methods, results, discussion, future directions, etc. It is very helpful to give your audience the general flow of the entire paper and research before adding in all the details.

3. Simplify unfamiliar concepts.

Journal clubs often have members of varying backgrounds. Hence, not all concepts will be familiar to everyone in the group. It can be helpful to give a short summary of techniques and results. Detailed explanations can be provided later on, because the primary focus of presenting the paper should be giving an overview of the research.

4. Ask yourself questions about the paper before you present.

As the presenter, you may be the semi-“expert” on the paper, but as you get to know the research, you may discover some questions you have about the methods. Share with the group the questions you came across yourself and any answers you may have found to address them.

5. Ask specific questions to the members of the journal club.

When entering into discussion time, ask the group for their thoughts on specific topics found in the paper to create a starting point for conversation about the paper. Questions can be about methods, results, general ideas, and much more!

Journal clubs are great forums for the exchange of thoughts and ideas. Clubs held at the NIH are just one way through which necessary scientific discussion and collaboration can take place. Be sure to look into journal clubs happening near you!

If you’re at the NIH, the Office of Intramural Training and Education (OITE) hosts Summer Journal Clubs that are ideal for trainees just getting their feet wet. And for our colleagues around the world, the NIH National Library of Medicine (NLM) provides an online platform to discuss journal articles in our connected world via the PubMed Commons Journal Clubs .

Related Blog Posts

- Isaac Fights to Inspire Others

- Need for Speed

- What’s in a Name, Postbac IRTA?

- IRP Graduate Students Show Off Their Work at Annual Symposium

- Brain Pathway Amplifies Pain After Injury

This page was last updated on Wednesday, July 5, 2023

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Business Jargons

A Business Encyclopedia

Presentation

Definition : A presentation is a form of communication in which the speaker conveys information to the audience. In an organization presentations are used in various scenarios like talking to a group, addressing a meeting, demonstrating or introducing a new product, or briefing a team. It involves presenting a particular subject or issue or new ideas/thoughts to a group of people.

It is considered as the most effective form of communication because of two main reasons:

- Use of non-verbal cues.

- Facilitates instant feedback.

Business Presentations are a tool to influence people toward an intended thought or action.

Parts of Presentation

- Introduction : It is meant to make the listeners ready to receive the message and draw their interest. For that, the speaker can narrate some story or a humorous piece of joke, an interesting fact, a question, stating a problem, and so forth. They can also use some surprising statistics.

- Body : It is the essence of the presentation. It requires the sequencing of facts in a logical order. This is the part where the speaker explains the topic and relevant information. It has to be critically arranged, as the audience must be able to grasp what the speaker presents.

- Conclusion : It needs to be short and precise. It should sum up or outline the key points that you have presented. It could also contain what the audience should have gained out of the presentation.

Purpose of Presentation

- To inform : Organizations can use presentations to inform the audience about new schemes, products or proposals. The aim is to inform the new entrant about the policies and procedures of the organization.

- To persuade : Presentations are also given to persuade the audience to take the intended action.

- To build goodwill : They can also help in building a good reputation

Factors Affecting Presentation

Audience Analysis

Communication environment, personal appearance, use of visuals, opening and closing presentation, organization of presentation, language and words, voice quality, body language, answering questions, a word from business jargons.

Presentation is a mode of conveying information to a selected group of people live. An ideal presentation is one that identifies and matches the needs, interests and understanding level of the audience. It also represents the facts, and figures in the form of tables, charts, and graphs and uses multiple colours.

Related terms:

- Verbal Communication

- Visual Communication

- Non-Verbal Communication

- Communication

- 7 C’s of Communication

Reader Interactions

Abbas khan says

October 2, 2022 at 11:33 pm

Thank you so much for providing us with brief info related to the presentation.

Farhan says

February 23, 2023 at 9:45 am

yusra shah says

July 3, 2023 at 2:04 am

it was helpful👍

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

JavaScript seems to be disabled in your browser. For the best experience on our site, be sure to turn on Javascript in your browser.

- Compare Products

Have a question? +1 604 877 0713 or Email Us at [email protected]

Your cart has an existing quote

Your shopping cart contains an active quote order and cannot be modified. To modify your shopping cart, please remove the current quote order before making changes to your cart. If you require changes to the quote, please contact your local sales representative.

- Sign In Email Address Password Sign In Forgot your password?

Register for an account to quickly and easily purchase products online and for one-click access to all educational content.

- 10 Journal Club Tips: How to Run, Lead, and Present Like a Pro

Ten Tips for Scientific Journal Clubs: How to Organize, Lead, and Participate Well

What is a journal club? A scientific journal club is a dedicated meeting where researchers gather to discuss publications from peer-reviewed journals. These meetings help researchers keep up with current findings, exercise their critical thinking skills, and improve their presentation and debate abilities.

Journal club formats vary depending on the preferences of organizers and participants. Online journal clubs organized using virtual meeting platforms (e.g. Zoom, Google Meets, Webex) are increasing in popularity with research labs and institutions.

In a well-run journal club, participants engage in lively discussions, while critically and honestly evaluating a study's strengths and weaknesses. They take away insights on what to do—and what not to do—in their own work. They feel inspired by new findings and walk away with ideas for their own research. On the contrary, ineffective journal clubs lack active participation. There may be a fear of openly voicing thoughts and opinions, or attendees may just be there for the free refreshments. In the end, the attendees take away nothing useful and think it's a waste of time. Whether you’re an organizer or a participant, follow these tips to run and lead a successful journal club, and to create engaging journal club presentations.

1. Make It a Routine

Schedule the journal club at a recurring time and location, so that it becomes a regular part of everyone's schedule. Choose a time that will be the least disruptive to everyone's experiments. Perhaps host it during lunchtime and invite people to eat while the presenter is speaking. Or perhaps host it in late afternoon with coffee and snacks provided.

We try and make the meeting times agreeable to most people and at times that are conducive to the work day of a grad student. We hold our journal clubs after seminars or presentations so it doesn’t interrupt experiments.

Shan Kasal, Graduate Student, The University of Chicago

2. Designate a Leader