- Search by keyword

- Search by citation

Page 1 of 5

Selected cannabis cultivars modulate glial activation: in vitro and in vivo studies

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic autoimmune disease of the central nervous system characterized by neuroinflammation, demyelination and axonal loss. Cannabis, an immunomodulating agent, is known for its ab...

- View Full Text

Cannabis and cancer: unveiling the potential of a green ally in breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer

Cancer comes in second place on the list of causes of death worldwide. In 2018, the 5-year prevalence of breast cancer (BC), prostate cancer (PC), and colorectal cancer (CRC) were 30%, 12.3%, and 10.9%, respec...

Envisaging challenges for the emerging medicinal Cannabis sector in Lesotho

Cultivation of Cannabis and its use for medical purposes has existed for millennia on the African continent. The plant has also been widely consumed in the African continent since time immemorial. In particula...

Cannabidiol’s cytotoxicity in pancreatic cancer is induced via an upregulation of ceramide synthase 1 and ER stress

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) remains one of the most aggressive malignancies with a median 5 year-survival rate of 12%. Cannabidiol (CBD) has been found to exhibit antineoplastic potential and may p...

An emerging trend in Novel Psychoactive Substances (NPSs): designer THC

Since its discovery as one of the main components of cannabis and its affinity towards the cannabinoid receptor CB1, serving as a means to exert its psychoactivity, Δ 9 -tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ 9 -THC) has inspired m...

Investigating sex differences and age of onset in emotion regulation, executive functioning, and cannabis use in adolescents and young adults

Young adults have historically high levels of cannabis use at a time which coincides with emotional and cognitive development. Age of regular onset of cannabis use and sex at birth are hypothesized to influenc...

Factors associated with the use of cannabis for self-medication by adults: data from the French TEMPO cohort study

Medical cannabis, legalized in many countries, remains illegal in France. Despite an experiment in the medical use of cannabis that began in March 2021 in France, little is known about the factors associated w...

Cannabis use associated with lower mortality among hospitalized Covid-19 patients using the national inpatient sample: an epidemiological study

Prior reports indicate that modulation of the endocannabinoid system (ECS) may have a protective benefit for Covid-19 patients. However, associations between cannabis use (CU) or CU not in remission (active ca...

State licenses for medical marijuana dispensaries: neighborhood-level determinants of applicant quality in Missouri

When state governments impose quotas on commercial marijuana licenses, regulatory commissions use an application process to assess the feasibility of prospective businesses. Decisions on license applications a...

Effect of organic biostimulants on cannabis productivity and soil microbial activity under outdoor conditions

In 2019 and 2020, we investigated the individual and combined effects of two biofertilizers (manure tea and bioinoculant) and one humic acid (HA) product on cannabis biochemical and physiological parameters an...

Neuroimaging studies of cannabidiol and potential neurobiological mechanisms relevant for alcohol use disorders: a systematic review

The underlying neurobiological mechanisms of cannabidiol’s (CBD) management of alcohol use disorder (AUD) remains elusive.

A narrative review of the therapeutic and remedial prospects of cannabidiol with emphasis on neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders

The treatment of diverse diseases using plant-derived products is actively encouraged. In the past few years, cannabidiol (CBD) has emerged as a potent cannabis-derived drug capable of managing various debilit...

Comment on “Hall et al., Topical cannabidiol is well tolerated in individuals with a history of elite physical performance and chronic lower extremity pain”

A national study of clinical discussions about cannabis use among veteran patients prescribed opioids.

The Veterans Health Administration tracks urine drug tests (UDTs) among patients on long-term opioid therapy (LTOT) and recommends discussing the health effects of cannabis use.

Evaluation of dispensaries’ cannabis flowers for accuracy of labeling of cannabinoids content

Cannabis policies have changed drastically over the last few years with many states enacting medical cannabis laws, and some authorizing recreational use; all against federal laws. As a result, cannabis produc...

Oral Cannabis consumption and intraperitoneal THC:CBD dosing results in changes in brain and plasma neurochemicals and endocannabinoids in mice

While the use of orally consumed Cannabis, cannabidiol (CBD) and tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) containing products, i.e. “edibles”, has expanded, the health consequences are still largely unknown. This study examine...

Recent advances in the development of portable technologies and commercial products to detect Δ 9 -tetrahydrocannabinol in biofluids: a systematic review

The primary components driving the current commercial fascination with cannabis products are phytocannabinoids, a diverse group of over 100 lipophilic secondary metabolites derived from the cannabis plant. Alt...

Associations between simultaneous use of alcohol and cannabis and cannabis-related problems in 2014–2016: evidence from the Washington panel survey

To address the research question of how simultaneous users of alcohol and cannabis differ from concurrent users in risk of cannabis use problems after the recreational marijuana legalization in Washington State.

Characteristics of patients with non-cancer pain and long-term prescription opioid use who have used medical versus recreational marijuana

Marijuana use is increasingly common among patients with chronic non-cancer pain (CNCP) and long-term opioid therapy (LTOT). We determined if lifetime recreational and medical marijuana use were associated wit...

Cannabis use, decision making, and perceptions of risk among breastfeeding individuals: the Lactation and Cannabis (LAC) Study

Our primary objective was to understand breastfeeding individuals’ decisions to use cannabis. Specifically, we investigated reasons for cannabis use, experiences with healthcare providers regarding use, and po...

Distribution of legal retail cannabis stores in Canada by neighbourhood deprivation

In legal cannabis markets, the distribution of retail stores has the potential to influence transitions from illegal to legal sources as well as consumer patterns of use. The current study examined the distrib...

Examining attributes of retailers that influence where cannabis is purchased: a discrete choice experiment

With the legalization of cannabis in Canada, consumers are presented with numerous purchase options. Licensed retailers are limited by the Cannabis Act and provincial regulations with respect to offering sales...

Effects of acute cannabis inhalation on reaction time, decision-making, and memory using a tablet-based application

Acute cannabis use has been demonstrated to slow reaction time and affect decision-making and short-term memory. These effects may have utility in identifying impairment associated with recent use. However, th...

Analysis of social media compliance with cannabis advertising regulations: evidence from recreational dispensaries in Illinois 1-year post-legalization

In the USA, an increasing number of states have legalized commercial recreational cannabis markets, allowing a private industry to sell cannabis to those 21 and older at retail locations known as dispensaries....

Comparison of perceptions in Canada and USA regarding cannabis and edibles

Canada took a national approach to recreational cannabis that resulted in official legalization on October 17, 2018. In the United States (US), the approach has been more piecemeal, with individual states pass...

Attitudes of Swiss psychiatrists towards cannabis regulation and medical use in psychiatry: a cross-sectional study

Changes in regulation for cannabis for nonmedical use (CNMU) are underway worldwide. Switzerland amended the law in 2021 allowing pilot trials evaluating regulative models for cannabis production and distribut...

Cannabis and pathologies in dogs and cats: first survey of phytocannabinoid use in veterinary medicine in Argentina

In animals, the endocannabinoid system regulates multiple physiological functions. Like humans, animals respond to preparations containing phytocannabinoids for treating several conditions. In Argentina, laws ...

The holistic effects of medical cannabis compared to opioids on pain experience in Finnish patients with chronic pain

Medical cannabis (MC) is increasingly used for chronic pain, but it is unclear how it aids in pain management. Previous literature suggests that MC could holistically alter the pain experience instead of only ...

The potential for Ghana to become a leader in the African hemp industry

Global interest in hemp cultivation and utilization is on the rise, presenting both challenges and opportunities for African countries. This article focuses on Ghana’s potential to establish a thriving hemp se...

Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome presenting with ventricular bigeminy

The is a case of a 28-year-old male presenting to an emergency department (ED) via emergency medical services (EMS) with a chief complaint of “gastritis.” He was noted to have bigeminy on the pre-arrival EMS e...

Driving-related behaviors, attitudes, and perceptions among Australian medical cannabis users: results from the CAMS 20 survey

Road safety is an important concern amidst expanding worldwide access to legal cannabis. The present study reports on the driving-related subsection of the Cannabis as Medicine Survey 2020 (CAMS-20) which surv...

High levels of pesticides found in illicit cannabis inflorescence compared to licensed samples in Canadian study using expanded 327 pesticides multiresidue method

As Cannabis was legalised in Canada for recreational use in 2018 with the implementation of the Cannabis Act , Regulations were put in place to ensure safety and consistency across the cannabis industry. This incl...

Correction: Potency and safety analysis of hemp delta-9 products: the hemp vs. cannabis demarcation problem

The original article was published in Journal of Cannabis Research 2023 5 :29

Cannabis use for exercise recovery in trained individuals: a survey study

Cannabis use, be it either cannabidiol (CBD) use and/or delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) use, shows promise to enhance exercise recovery. The present study aimed to determine if individuals are using CBD and...

The COVID-19 pandemic and cannabis use in Canada―a scoping review

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada, the cannabis industry has adapted to public health emergency orders which had direct and indirect consequences on cannabis consumption. The objective of this...

DMSO potentiates the suppressive effect of dronabinol on sleep apnea and REM sleep in rats

Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) is an amphipathic molecule with innate biological activity that also is used to dissolve both polar and nonpolar compounds in preclinical and clinical studies. Recent investigations o...

Potency and safety analysis of hemp delta-9 products: the hemp vs. cannabis demarcation problem

Hemp-derived delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol (∆ 9 THC) products are freely available for sale across much of the USA, but the federal legislation allowing their sale places only minimal requirements on companies. Pro...

The Correction to this article has been published in Journal of Cannabis Research 2023 5 :33

A comparison of advertised versus actual cannabidiol (CBD) content of oils, aqueous tinctures, e-liquids and drinks purchased in the UK

Cannabidiol (CBD)-containing products are sold widely in consumer stores, but concerns have been raised regarding their quality, with notable discrepancies between advertised and actual CBD content. Informatio...

Cannabis sativa demonstrates anti-hepatocellular carcinoma potentials in animal model: in silico and in vivo studies of the involvement of Akt

Targeting protein kinase B (Akt) and its downstream signaling proteins are promising options in designing novel and potent drug candidates against hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The present study explores the...

Conflicting forces in the implementation of medicinal cannabis regulation in Uruguay

Uruguay is widely known as a pioneer country regarding cannabis regulation policies, as it was the first state to regulate the cannabis market for both recreational and medicinal purposes in 2013. However, not...

Why a distinct medical stream is necessary to support patients using cannabis for medical purposes

Since 2001, Canadians have been able to obtain cannabis for medical purposes, initially through the Access to Cannabis for Medical Purposes Regulations (ACMPR). The Cannabis Act (Bill C-45) came into force on ...

Propylene glycol and Kolliphor as solvents for systemic delivery of cannabinoids via intraperitoneal and subcutaneous routes in preclinical studies: a comparative technical note

Substance administration to laboratory animals necessitates careful consideration and planning in order to enhance agent distribution while reducing any harmful effects from the technique. There are numerous m...

No difference in COVID-19 treatment outcomes among current methamphetamine, cannabis and alcohol users

Poor outcomes of COVID-19 have been reported in older males with medical comorbidities including substance use disorder. However, it is unknown whether there is a difference in COVID-19 treatment outcomes betw...

Cannabis for morning sickness: areas for intervention to decrease cannabis consumption during pregnancy

Cannabis use during pregnancy is increasing, with 19–22% of patients testing positive at delivery in Colorado and California. Patients report using cannabis to alleviate their nausea and vomiting, anxiety, and...

The therapeutic potential of purified cannabidiol

The use of cannabidiol (CBD) for therapeutic purposes is receiving considerable attention, with speculation that CBD can be useful in a wide range of conditions. Only one product, a purified form of plant-deri...

Naturalistic examination of the anxiolytic effects of medical cannabis and associated gender and age differences in a Canadian cohort

The aim of the current study was to examine patterns of medical cannabis use in those using it to treat anxiety and to investigate if the anxiolytic effects of cannabis were impacted by gender and/or age.

The Desert Whale: the boom and bust of hemp in Arizona

This paper examines the factors that led to the collapse of hemp grown for cannabidiol (CBD) in Arizona, the United States of America (USA), and particularly in Yuma County, which is a well-established agricul...

Reasonable access: important characteristics and perceived quality of legal and illegal sources of cannabis for medical purposes in Canada

Throughout the past two decades of legal medical cannabis in Canada, individuals have experienced challenges related to accessing legal sources of cannabis for medical purposes. The objective of our study was ...

The reintroduction of hemp in the USA: a content analysis of state and tribal hemp production plans

The reintroduction of Cannabis sativa L . in the form of hemp (< 0.3% THC by dry weight) into the US agricultural sector has been complex and remains confounded by its association with cannabis (> 0.3% THC by dry ...

The Cannabis sativa genetics and therapeutics relationship network: automatically associating cannabis-related genes to therapeutic properties through chemicals from cannabis literature

Understanding the genome of Cannabis sativa holds significant scientific value due to the multi-faceted therapeutic nature of the plant. Links from cannabis gene to therapeutic property are important to establish...

Affiliated with

An official publication of the Institute of Cannabis Research

- Editorial Board

- Instructions for Authors

- Instructions for Editors

- Sign up for article alerts and news from this journal

Annual Journal Metrics

2022 Citation Impact 3.7 - 2-year Impact Factor 3.4 - 5-year Impact Factor 0.741 - SNIP (Source Normalized Impact per Paper)

2023 Speed 21 days submission to first editorial decision for all manuscripts (Median) 211 days submission to accept (Median)

2023 Usage 596,678 downloads 1,834 Altmetric mentions

- More about our metrics

Journal of Cannabis Research

ISSN: 2522-5782

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 04 February 2020

Marijuana legalization and historical trends in marijuana use among US residents aged 12–25: results from the 1979–2016 National Survey on drug use and health

- Xinguang Chen 1 ,

- Xiangfan Chen 2 &

- Hong Yan 2

BMC Public Health volume 20 , Article number: 156 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

108k Accesses

71 Citations

84 Altmetric

Metrics details

Marijuana is the most commonly used illicit drug in the United States. More and more states legalized medical and recreational marijuana use. Adolescents and emerging adults are at high risk for marijuana use. This ecological study aims to examine historical trends in marijuana use among youth along with marijuana legalization.

Data ( n = 749,152) were from the 31-wave National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), 1979–2016. Current marijuana use, if use marijuana in the past 30 days, was used as outcome variable. Age was measured as the chronological age self-reported by the participants, period was the year when the survey was conducted, and cohort was estimated as period subtracted age. Rate of current marijuana use was decomposed into independent age, period and cohort effects using the hierarchical age-period-cohort (HAPC) model.

After controlling for age, cohort and other covariates, the estimated period effect indicated declines in marijuana use in 1979–1992 and 2001–2006, and increases in 1992–2001 and 2006–2016. The period effect was positively and significantly associated with the proportion of people covered by Medical Marijuana Laws (MML) (correlation coefficients: 0.89 for total sample, 0.81 for males and 0.93 for females, all three p values < 0.01), but was not significantly associated with the Recreational Marijuana Laws (RML). The estimated cohort effect showed a historical decline in marijuana use in those who were born in 1954–1972, a sudden increase in 1972–1984, followed by a decline in 1984–2003.

The model derived trends in marijuana use were coincident with the laws and regulations on marijuana and other drugs in the United States since the 1950s. With more states legalizing marijuana use in the United States, emphasizing responsible use would be essential to protect youth from using marijuana.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Marijuana use and laws in the united states.

Marijuana is one of the most commonly used drugs in the United States (US) [ 1 ]. In 2015, 8.3% of the US population aged 12 years and older used marijuana in the past month; 16.4% of adolescents aged 12–17 years used in lifetime and 7.0% used in the past month [ 2 ]. The effects of marijuana on a person’s health are mixed. Despite potential benefits (e.g., relieve pain) [ 3 ], using marijuana is associated with a number of adverse effects, particularly among adolescents. Typical adverse effects include impaired short-term memory, cognitive impairment, diminished life satisfaction, and increased risk of using other substances [ 4 ].

Since 1937 when the Marijuana Tax Act was issued, a series of federal laws have been subsequently enacted to regulate marijuana use, including the Boggs Act (1952), Narcotics Control Act (1956), Controlled Substance Act (1970), and Anti-Drug Abuse Act (1986) [ 5 , 6 ]. These laws regulated the sale, possession, use, and cultivation of marijuana [ 6 ]. For example, the Boggs Act increased the punishment of marijuana possession, and the Controlled Substance Act categorized the marijuana into the Schedule I Drugs which have a high potential for abuse, no medical use, and not safe to use without medical supervision [ 5 , 6 ]. These federal laws may have contributed to changes in the historical trend of marijuana use among youth.

Movements to decriminalize and legalize marijuana use

Starting in the late 1960s, marijuana decriminalization became a movement, advocating reformation of federal laws regulating marijuana [ 7 ]. As a result, 11 US states had taken measures to decriminalize marijuana use by reducing the penalty of possession of small amount of marijuana [ 7 ].

The legalization of marijuana started in 1993 when Surgeon General Elder proposed to study marijuana legalization [ 8 ]. California was the first state that passed Medical Marijuana Laws (MML) in 1996 [ 9 ]. After California, more and more states established laws permitting marijuana use for medical and/or recreational purposes. To date, 33 states and the District of Columbia have established MML, including 11 states with recreational marijuana laws (RML) [ 9 ]. Compared with the legalization of marijuana use in the European countries which were more divided that many of them have medical marijuana registered as a treatment option with few having legalized recreational use [ 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ], the legalization of marijuana in the US were more mixed with 11 states legalized medical and recreational use consecutively, such as California, Nevada, Washington, etc. These state laws may alter people’s attitudes and behaviors, finally may lead to the increased risk of marijuana use, particularly among young people [ 13 ]. Reported studies indicate that state marijuana laws were associated with increases in acceptance of and accessibility to marijuana, declines in perceived harm, and formation of new norms supporting marijuana use [ 14 ].

Marijuana harm to adolescents and young adults

Adolescents and young adults constitute a large proportion of the US population. Data from the US Census Bureau indicate that approximately 60 million of the US population are in the 12–25 years age range [ 15 ]. These people are vulnerable to drugs, including marijuana [ 16 ]. Marijuana is more prevalent among people in this age range than in other ages [ 17 ]. One well-known factor for explaining the marijuana use among people in this age range is the theory of imbalanced cognitive and physical development [ 4 ]. The delayed brain development of youth reduces their capability to cognitively process social, emotional and incentive events against risk behaviors, such as marijuana use [ 18 ]. Understanding the impact of marijuana laws on marijuana use among this population with a historical perspective is of great legal, social and public health significance.

Inconsistent results regarding the impact of marijuana laws on marijuana use

A number of studies have examined the impact of marijuana laws on marijuana use across the world, but reported inconsistent results [ 13 ]. Some studies reported no association between marijuana laws and marijuana use [ 14 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 ], some reported a protective effect of the laws against marijuana use [ 24 , 26 ], some reported mixed effects [ 27 , 28 ], while some others reported a risk effect that marijuana laws increased marijuana use [ 29 , 30 ]. Despite much information, our review of these reported studies revealed several limitations. First of all, these studies often targeted a short time span, ignoring the long period trend before marijuana legalization. Despite the fact that marijuana laws enact in a specific year, the process of legalization often lasts for several years. Individuals may have already changed their attitudes and behaviors before the year when the law is enacted. Therefore, it may not be valid when comparing marijuana use before and after the year at a single time point when the law is enacted and ignoring the secular historical trend [ 19 , 30 , 31 ]. Second, many studies adapted the difference-in-difference analytical approach designated for analyzing randomized controlled trials. No US state is randomized to legalize the marijuana laws, and no state can be established as controls. Thus, the impact of laws cannot be efficiently detected using this approach. Third, since marijuana legalization is a public process, and the information of marijuana legalization in one state can be easily spread to states without the marijuana laws. The information diffusion cannot be ruled out, reducing the validity of the non-marijuana law states as the controls to compare the between-state differences [ 31 ].

Alternatively, evidence derived based on a historical perspective may provide new information regarding the impact of laws and regulations on marijuana use, including state marijuana laws in the past two decades. Marijuana users may stop using to comply with the laws/regulations, while non-marijuana users may start to use if marijuana is legal. Data from several studies with national data since 1996 demonstrate that attitudes, beliefs, perceptions, and use of marijuana among people in the US were associated with state marijuana laws [ 29 , 32 ].

Age-period-cohort modeling: looking into the past with recent data

To investigate historical trends over a long period, including the time period with no data, we can use the classic age-period-cohort modeling (APC) approach. The APC model can successfully discompose the rate or prevalence of marijuana use into independent age, period and cohort effects [ 33 , 34 ]. Age effect refers to the risk associated with the aging process, including the biological and social accumulation process. Period effect is risk associated with the external environmental events in specific years that exert effect on all age groups, representing the unbiased historical trend of marijuana use which controlling for the influences from age and birth cohort. Cohort effect refers to the risk associated with the specific year of birth. A typical example is that people born in 2011 in Fukushima, Japan may have greater risk of cancer due to the nuclear disaster [ 35 ], so a person aged 80 in 2091 contains the information of cancer risk in 2011 when he/she was born. Similarly, a participant aged 25 in 1979 contains information on the risk of marijuana use 25 years ago in 1954 when that person was born. With this method, we can describe historical trends of marijuana use using information stored by participants in older ages [ 33 ]. The estimated period and cohort effects can be used to present the unbiased historical trend of specific topics, including marijuana use [ 34 , 36 , 37 , 38 ]. Furthermore, the newly established hierarchical APC (HAPC) modeling is capable of analyzing individual-level data to provide more precise measures of historical trends [ 33 ]. The HAPC model has been used in various fields, including social and behavioral science, and public health [ 39 , 40 ].

Several studies have investigated marijuana use with APC modeling method [ 17 , 41 , 42 ]. However, these studies covered only a small portion of the decades with state marijuana legalization [ 17 , 42 ]. For example, the study conducted by Miech and colleagues only covered periods from 1985 to 2009 [ 17 ]. Among these studies, one focused on a longer state marijuana legalization period, but did not provide detailed information regarding the impact of marijuana laws because the survey was every 5 years and researchers used a large 5-year age group which leads to a wide 10-year birth cohort. The averaging of the cohort effects in 10 years could reduce the capability of detecting sensitive changes of marijuana use corresponding to the historical events [ 41 ].

Purpose of the study

In this study, we examined the historical trends in marijuana use among youth using HAPC modeling to obtain the period and cohort effects. These two effects provide unbiased and independent information to characterize historical trends in marijuana use after controlling for age and other covariates. We conceptually linked the model-derived time trends to both federal and state laws/regulations regarding marijuana and other drug use in 1954–2016. The ultimate goal is to provide evidence informing federal and state legislation and public health decision-making to promote responsible marijuana use and to protect young people from marijuana use-related adverse consequences.

Materials and methods

Data sources and study population.

Data were derived from 31 waves of National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), 1979–2016. NSDUH is a multi-year cross-sectional survey program sponsored by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The survey was conducted every 3 years before 1990, and annually thereafter. The aim is to provide data on the use of tobacco, alcohol, illicit drug and mental health among the US population.

Survey participants were noninstitutionalized US civilians 12 years of age and older. Participants were recruited by NSDUH using a multi-stage clustered random sampling method. Several changes were made to the NSDUH after its establishment [ 43 ]. First, the name of the survey was changed from the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse (NHSDA) to NSDUH in 2002. Second, starting in 2002, adolescent participants receive $30 as incentives to improve the response rate. Third, survey mode was changed from personal interviews with self-enumerated answer sheets (before 1999) to the computer-assisted person interviews (CAPI) and audio computer-assisted self-interviews (ACASI) (since 1999). These changes may confound the historical trends [ 43 ], thus we used two dummy variables as covariates, one for the survey mode change in 1999 and another for the survey method change in 2002 to control for potential confounding effect.

Data acquisition

Data were downloaded from the designated website ( https://nsduhweb.rti.org/respweb/homepage.cfm ). A database was used to store and merge the data by year for analysis. Among all participants, data for those aged 12–25 years ( n = 749,152) were included. We excluded participants aged 26 and older because the public data did not provide information on single or two-year age that was needed for HAPC modeling (details see statistical analysis section). We obtained approval from the Institutional Review Board at the University of Florida to conduct this study.

Variables and measurements

Current marijuana use: the dependent variable. Participants were defined as current marijuana users if they reported marijuana use within the past 30 days. We used the variable harmonization method to create a comparable measure across 31-wave NSDUH data [ 44 ]. Slightly different questions were used in NSDUH. In 1979–1993, participants were asked: “When was the most recent time that you used marijuana or hash?” Starting in 1994, the question was changed to “How long has it been since you last used marijuana or hashish?” To harmonize the marijuana use variable, participants were coded as current marijuana users if their response to the question indicated the last time to use marijuana was within past 30 days.

Chronological age, time period and birth cohort were the predictors. (1) Chronological age in years was measured with participants’ age at the survey. APC modeling requires the same age measure for all participants [ 33 ]. Since no data by single-year age were available for participants older than 21, we grouped all participants into two-year age groups. A total of 7 age groups, 12–13, ..., 24–25 were used. (2) Time period was measured with the year when the survey was conducted, including 1979, 1982, 1985, 1988, 1990, 1991... 2016. (3). Birth cohort was the year of birth, and it was measured by subtracting age from the survey year.

The proportion of people covered by MML: This variable was created by dividing the population in all states with MML over the total US population. The proportion was computed by year from 1996 when California first passed the MML to 2016 when a total of 29 states legalized medical marijuana use. The estimated proportion ranged from 12% in 1996 to 61% in 2016. The proportion of people covered by RML: This variable was derived by dividing the population in all states with RML with the total US population. The estimated proportion ranged from 4% in 2012 to 21% in 2016. These two variables were used to quantitatively assess the relationships between marijuana laws and changes in the risk of marijuana use.

Covariates: Demographic variables gender (male/female) and race/ethnicity (White, Black, Hispanic and others) were used to describe the study sample.

Statistical analysis

We estimated the prevalence of current marijuana use by year using the survey estimation method, considering the complex multi-stage cluster random sampling design and unequal probability. A prevalence rate is not a simple indicator, but consisting of the impact of chronological age, time period and birth cohort, named as age, period and cohort effects, respectively. Thus, it is biased if a prevalence rate is directly used to depict the historical trend. HAPC modeling is an epidemiological method capable of decomposing prevalence rate into mutually independent age, period and cohort effects with individual-level data, while the estimated period and cohort effects provide an unbiased measure of historical trend controlling for the effects of age and other covariates. In this study, we analyzed the data using the two-level HAPC cross-classified random-effects model (CCREM) [ 36 ]:

Where M ijk represents the rate of marijuana use for participants in age group i (12–13, 14,15...), period j (1979, 1982,...) and birth cohort k (1954–55, 1956–57...); parameter α i (age effect) was modeled as the fixed effect; and parameters β j (period effect) and γ k (cohort effect) were modeled as random effects; and β m was used to control m covariates, including the two dummy variables assessing changes made to the NSDUH in 1999 and 2002, respectively.

The HAPC modeling analysis was executed using the PROC GLIMMIX. Sample weights were included to obtain results representing the total US population aged 12–25. A ridge-stabilized Newton-Raphson algorithm was used for parameter estimation. Modeling analysis was conducted for the overall sample, stratified by gender. The estimated age effect α i , period β j and cohort γ k (i.e., the log-linear regression coefficients) were directly plotted to visualize the pattern of change.

To gain insight into the relationship between legal events and regulations at the national level, we listed these events/regulations along with the estimated time trends in the risk of marijuana from HAPC modeling. To provide a quantitative measure, we associated the estimated period effect with the proportions of US population living with MML and RML using Pearson correlation. All statistical analyses for this study were conducted using the software SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Sample characteristics

Data for a total of 749,152 participants (12–25 years old) from all 31-wave NSDUH covering a 38-year period were analyzed. Among the total sample (Table 1 ), 48.96% were male and 58.78% were White, 14.84% Black, and 18.40% Hispanic.

Prevalence rate of current marijuana use

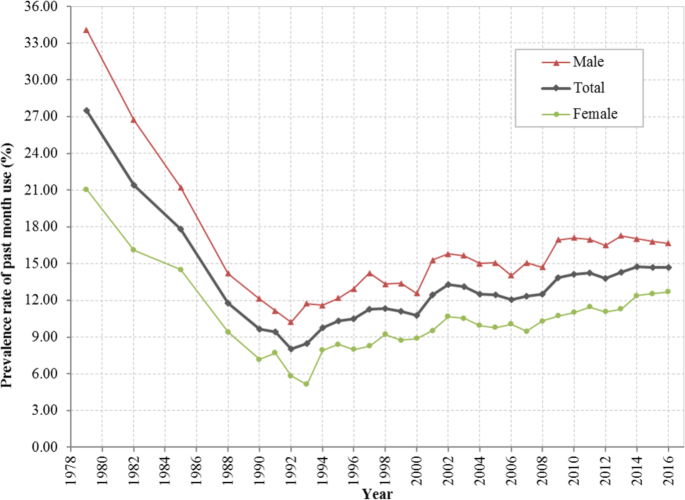

As shown in Fig. 1 , the estimated prevalence rates of current marijuana use from 1979 to 2016 show a “V” shaped pattern. The rate was 27.57% in 1979, it declined to 8.02% in 1992, followed by a gradual increase to 14.70% by 2016. The pattern was the same for both male and female with males more likely to use than females during the whole period.

Prevalence rate (%) of current marijuana use among US residents 12 to 25 years of age during 1979–2016, overall and stratified by gender. Derived from data from the 1979–2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH)

HAPC modeling and results

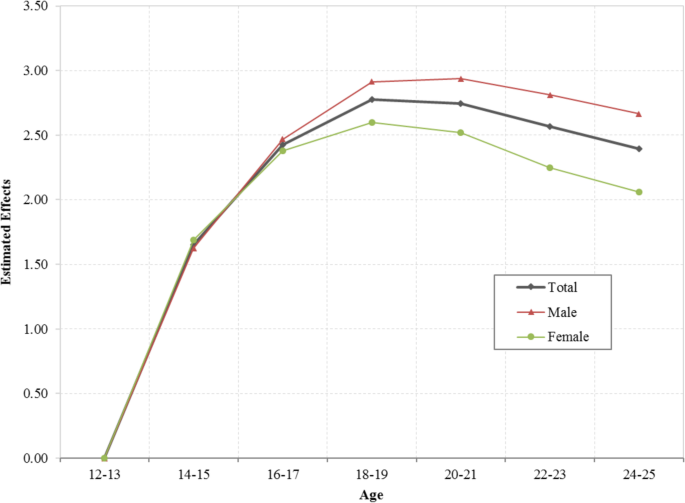

Estimated age effects α i from the CCREM [ 1 ] for current marijuana use are presented in Fig. 2 . The risk by age shows a 2-phase pattern –a rapid increase phase from ages 12 to 19, followed by a gradually declining phase. The pattern was persistent for the overall sample and for both male and female subsamples.

Age effect for the risk of current marijuana use, overall and stratified by male and female, estimated with hierarchical age-period-cohort modeling method with 31 waves of NSDUH data during 1979–2016. Age effect α i were log-linear regression coefficients estimated using CCREM (1), see text for more details

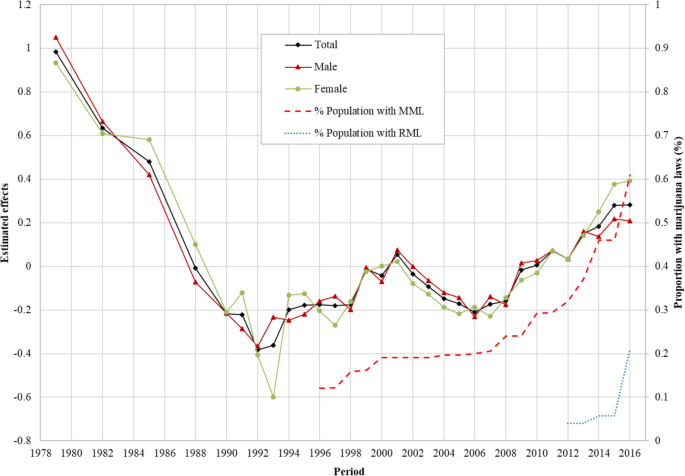

The estimated period effects β j from the CCREM [ 1 ] are presented in Fig. 3 . The period effect reflects the risk of current marijuana use due to significant events occurring over the period, particularly federal and state laws and regulations. After controlling for the impacts of age, cohort and other covariates, the estimated period effect indicates that the risk of current marijuana use had two declining trends (1979–1992 and 2001–2006), and two increasing trends (1992–2001 and 2006–2016). Epidemiologically, the time trends characterized by the estimated period effects in Fig. 3 are more valid than the prevalence rates presented in Fig. 1 because the former was adjusted for confounders while the later was not.

Period effect for the risk of marijuana use for US adolescents and young adults, overall and by male/female estimated with hierarchical age-period-cohort modeling method and its correlation with the proportion of US population covered by Medical Marijuana Laws and Recreational Marijuana Laws. Period effect β j were log-linear regression coefficients estimated using CCREM (1), see text for more details

Correlation of the period effect with proportions of the population covered by marijuana laws: The Pearson correlation coefficient of the period effect with the proportions of US population covered by MML during 1996–2016 was 0.89 for the total sample, 0.81 for male and 0.93 for female, respectively ( p < 0.01 for all). The correlation between period effect and proportion of US population covered by RML was 0.64 for the total sample, 0.59 for male and 0.49 for female ( p > 0.05 for all).

Likewise, the estimated cohort effects γ k from the CCREM [ 1 ] are presented in Fig. 4 . The cohort effect reflects changes in the risk of current marijuana use over the period indicated by the year of birth of the survey participants after the impacts of age, period and other covariates are adjusted. Results in the figure show three distinctive cohorts with different risk patterns of current marijuana use during 1954–2003: (1) the Historical Declining Cohort (HDC): those born in 1954–1972, and characterized by a gradual and linear declining trend with some fluctuations; (2) the Sudden Increase Cohort (SIC): those born from 1972 to 1984, characterized with a rapid almost linear increasing trend; and (3) the Contemporary Declining Cohort (CDC): those born during 1984 and 2003, and characterized with a progressive declining over time. The detailed results of HAPC modeling analysis were also shown in Additional file 1 : Table S1.

Cohort effect for the risk of marijuana use among US adolescents and young adults born during 1954–2003, overall and by male/female, estimated with hierarchical age-period-cohort modeling method. Cohort effect γ k were log-linear regression coefficients estimated using CCREM (1), see text for more details

This study provides new data regarding the risk of marijuana use in youth in the US during 1954–2016. This is a period in the US history with substantial increases and declines in drug use, including marijuana; accompanied with many ups and downs in legal actions against drug use since the 1970s and progressive marijuana legalization at the state level from the later 1990s till today (see Additional file 1 : Table S2). Findings of the study indicate four-phase period effect and three-phase cohort effect, corresponding to various historical events of marijuana laws, regulations and social movements.

Coincident relationship between the period effect and legal drug control

The period effect derived from the HAPC model provides a net effect of the impact of time on marijuana use after the impact of age and birth cohort were adjusted. Findings in this study indicate that there was a progressive decline in the period effect during 1979 and 1992. This trend was corresponding to a period with the strongest legal actions at the national level, the War on Drugs by President Nixon (1969–1974) President Reagan (1981–1989) [ 45 ], and President Bush (1989) [ 45 ],and the Anti-Drug Abuse Act (1986) [ 5 ].

The estimated period effect shows an increasing trend in 1992–2001. During this period, President Clinton advocated for the use of treatment to replace incarceration (1992) [ 45 ], Surgeon General Elders proposed to study marijuana legalization (1993–1994) [ 8 ], President Clinton’s position of the need to re-examine the entire policy against people who use drugs, and decriminalization of marijuana (2000) [ 45 ] and the passage of MML in eight US states.

The estimated period effect shows a declining trend in 2001–2006. Important laws/regulations include the Student Drug Testing Program promoted by President Bush, and the broadened the public schools’ authority to test illegal drugs among students given by the US Supreme Court (2002) [ 46 ].

The estimated period effect increases in 2006–2016. This is the period when the proportion of the population covered by MML progressively increased. This relation was further proved by a positive correlation between the estimated period effect and the proportion of the population covered by MML. In addition, several other events occurred. For example, over 500 economists wrote an open letter to President Bush, Congress and Governors of the US and called for marijuana legalization (2005) [ 47 ], and President Obama ended the federal interference with the state MML, treated marijuana as public health issues, and avoided using the term of “War on Drugs” [ 45 ]. The study also indicates that the proportion of population covered by RML was positively associated with the period effect although not significant which may be due to the limited number of data points of RML. Future studies may follow up to investigate the relationship between RML and rate of marijuana use.

Coincident relationship between the cohort effect and legal drug control

Cohort effect is the risk of marijuana use associated with the specific year of birth. People born in different years are exposed to different laws, regulations in the past, therefore, the risk of marijuana use for people may differ when they enter adolescence and adulthood. Findings in this study indicate three distinctive cohorts: HDC (1954–1972), SIC (1972–1984) and CDC (1984–2003). During HDC, the overall level of marijuana use was declining. Various laws/regulations of drug use in general and marijuana in particular may explain the declining trend. First, multiple laws passed to regulate the marijuana and other substance use before and during this period remained in effect, for example, the Marijuana Tax Act (1937), the Boggs Act (1952), the Narcotics Control Act (1956) and the Controlled Substance Act (1970). Secondly, the formation of government departments focusing on drug use prevention and control may contribute to the cohort effect, such as the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs (1968) [ 48 ]. People born during this period may be exposed to the macro environment with laws and regulations against marijuana, thus, they may be less likely to use marijuana.

Compared to people born before 1972, the cohort effect for participants born during 1972 and 1984 was in coincidence with the increased risk of using marijuana shown as SIC. This trend was accompanied by the state and federal movements for marijuana use, which may alter the social environment and public attitudes and beliefs from prohibitive to acceptive. For example, seven states passed laws to decriminalize the marijuana use and reduced the penalty for personal possession of small amount of marijuana in 1976 [ 7 ]. Four more states joined the movement in two subsequent years [ 7 ]. People born during this period may have experienced tolerated environment of marijuana, and they may become more acceptable of marijuana use, increasing their likelihood of using marijuana.

A declining cohort CDC appeared immediately after 1984 and extended to 2003. This declining cohort effect was corresponding to a number of laws, regulations and movements prohibiting drug use. Typical examples included the War on Drugs initiated by President Nixon (1980s), the expansion of the drug war by President Reagan (1980s), the highly-publicized anti-drug campaign “Just Say No” by First Lady Nancy Reagan (early 1980s) [ 45 ], and the Zero Tolerance Policies in mid-to-late 1980s [ 45 ], the Anti-Drug Abuse Act (1986) [ 5 ], the nationally televised speech of War on Drugs declared by President Bush in 1989 and the escalated War on Drugs by President Clinton (1993–2001) [ 45 ]. Meanwhile many activities of the federal government and social groups may also influence the social environment of using marijuana. For example, the Federal government opposed to legalize the cultivation of industrial hemp, and Federal agents shut down marijuana sales club in San Francisco in 1998 [ 48 ]. Individuals born in these years grew up in an environment against marijuana use which may decrease their likelihood of using marijuana when they enter adolescence and young adulthood.

This study applied the age-period-cohort model to investigate the independent age, period and cohort effects, and indicated that the model derived trends in marijuana use among adolescents and young adults were coincident with the laws and regulations on marijuana use in the United States since the 1950s. With more states legalizing marijuana use in the United States, emphasizing responsible use would be essential to protect youth from using marijuana.

Limitations

This study has limitations. First, study data were collected through a household survey, which is subject to underreporting. Second, no causal relationship can be warranted using cross-sectional data, and further studies are needed to verify the association between the specific laws/regulation and the risk of marijuana use. Third, data were available to measure single-year age up to age 21 and two-year age group up to 25, preventing researchers from examining the risk of marijuana use for participants in other ages. Lastly, data derived from NSDUH were nation-wide, and future studies are needed to analyze state-level data and investigate the between-state differences. Although a systematic review of all laws and regulations related to marijuana and other drugs is beyond the scope of this study, findings from our study provide new data from a historical perspective much needed for the current trend in marijuana legalization across the nation to get the benefit from marijuana while to protect vulnerable children and youth in the US. It provides an opportunity for stack-holders to make public decisions by reviewing the findings of this analysis together with the laws and regulations at the federal and state levels over a long period since the 1950s.

Availability of data and materials

The data of the study are available from the designated repository ( https://nsduhweb.rti.org/respweb/homepage.cfm ).

Abbreviations

Audio computer-assisted self-interviews

Age-period-cohort modeling

Computer-assisted person interviews

Cross-classified random-effects model

Contemporary Declining Cohort

Hierarchical age-period-cohort

Historical Declining Cohort

Medical Marijuana Laws

National Household Survey on Drug Abuse

National Survey on Drug Use and Health

Recreational Marijuana Laws

Sudden Increase Cohort

The United States

CDC. Marijuana and Public Health. 2017. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/marijuana/index.htm . Accessed 13 June 2018.

SAMHSA. Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. 2016 [cited 2018 Jan 31]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015.htm

Committee on the Health Effects of Marijuana: An Evidence Review and Research Agenda, Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice, Health and Medicine Division, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The health effects of cannabis and cannabinoids: the current state of evidence and recommendations for research. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2017.

Collins C. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(9):879.

PubMed Google Scholar

Belenko SR. Drugs and drug policy in America: a documentary history. Westport: Greenwood Press; 2000.

Google Scholar

Gerber RJ. Legalizing marijuana: Drug policy reform and prohibition politics. Westport: Praeger; 2004.

Single EW. The impact of marijuana decriminalization: an update. J Public Health Policy. 1989:456–66.

Article CAS Google Scholar

SFChronicle. Ex-surgeon general backed legalizing marijuana before it was cool [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2018 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.sfchronicle.com/business/article/Ex-surgeon-general-backed-legalizing-marijuana-6799348.php

PROCON. 31 Legal Medical Marijuana States and DC. 2018 [cited 2018 Oct 4]. Available from: https://medicalmarijuana.procon.org/view.resource.php?resourceID=000881

Bifulco M, Pisanti S. Medicinal use of cannabis in Europe: the fact that more countries legalize the medicinal use of cannabis should not become an argument for unfettered and uncontrolled use. EMBO Rep. 2015;16(2):130–2.

European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. Models for the legal supply of cannabis: recent developments (Perspectives on drugs). 2016. Available from: http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/pods/legal-supply-of-cannabis . Accessed 10 Jan 2020.

European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. Cannabis policy: status and recent developments. 2017. Available from: http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/topics/cannabis-policy_en#section2 . Accessed 10 Jan 2020.

Hughes B, Matias J, Griffiths P. Inconsistencies in the assumptions linking punitive sanctions and use of cannabis and new psychoactive substances in Europe. Addiction. 2018;113(12):2155–7.

Article Google Scholar

Anderson DM, Hansen B, Rees DI. Medical marijuana laws and teen marijuana use. Am Law Econ Rev. 2015;17(2):495-28.

United States Census Bureau. Annual Estimates of the Resident Population by Single Year of Age and Sex for the United States, States, and Puerto Rico Commonwealth: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2016 2016 Population Estimates. 2017 [cited 2018 Mar 14]. Available from: https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk

Chen X, Yu B, Lasopa S, Cottler LB. Current patterns of marijuana use initiation by age among US adolescents and emerging adults: implications for intervention. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2017;43(3):261–70.

Miech R, Koester S. Trends in U.S., past-year marijuana use from 1985 to 2009: an age-period-cohort analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;124(3):259–67.

Steinberg L. The influence of neuroscience on US supreme court decisions about adolescents’ criminal culpability. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14(7):513–8.

Sarvet AL, Wall MM, Fink DS, Greene E, Le A, Boustead AE, et al. Medical marijuana laws and adolescent marijuana use in the United States: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction. 2018;113(6):1003–16.

Hasin DS, Wall M, Keyes KM, Cerdá M, Schulenberg J, O’Malley PM, et al. Medical marijuana laws and adolescent marijuana use in the USA from 1991 to 2014: results from annual, repeated cross-sectional surveys. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(7):601–8.

Pacula RL, Chriqui JF, King J. Marijuana decriminalization: what does it mean in the United States? National Bureau of Economic Research; 2003.

Donnelly N, Hall W, Christie P. The effects of the Cannabis expiation notice system on the prevalence of cannabis use in South Australia: evidence from the National Drug Strategy Household Surveys 1985-95. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2000;19(3):265–9.

Gorman DM, Huber JC. Do medical cannabis laws encourage cannabis use? Int J Drug Policy. 2007;18(3):160–7.

Lynne-Landsman SD, Livingston MD, Wagenaar AC. Effects of state medical marijuana laws on adolescent marijuana use. Am J Public Health. 2013 Aug;103(8):1500–6.

Pacula RL, Powell D, Heaton P, Sevigny EL. Assessing the effects of medical marijuana laws on marijuana and alcohol use: the devil is in the details. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2013.

Harper S, Strumpf EC, Kaufman JS. Do medical marijuana laws increase marijuana use? Replication study and extension. Ann Epidemiol. 2012;22(3):207–12.

Stolzenberg L, D’Alessio SJ, Dariano D. The effect of medical cannabis laws on juvenile cannabis use. Int J Drug Policy. 2016;27:82–8.

Wang GS, Roosevelt G, Heard K. Pediatric marijuana exposures in a medical marijuana state. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(7):630–3.

Wall MM, Poh E, Cerdá M, Keyes KM, Galea S, Hasin DS. Adolescent marijuana use from 2002 to 2008: higher in states with medical marijuana laws, cause still unclear. Ann Epidemiol. 2011;21(9):714–6.

Chen X, Yu B, Stanton B, Cook RL, Chen D-GD, Okafor C. Medical marijuana laws and marijuana use among U.S. adolescents: evidence from michigan youth risk behavior surveillance data. J Drug Educ. 2018;47237918803361.

Chen X. Information diffusion in the evaluation of medical marijuana laws’ impact on risk perception and use. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(12):e8.

Chen X, Yu B, Stanton B, Cook RL, Chen DG, Okafor C. Medical marijuana laws and marijuana use among US adolescents: Evidence from Michigan youth risk behavior surveillance data. J Drug Educ. 2018;48(1-2):18-35.

Yang Y, Land K. Age-Period-Cohort Analysis: New Models, Methods, and Empirical Applications. Boca Raton: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2013.

Yu B, Chen X. Age and birth cohort-adjusted rates of suicide mortality among US male and female youths aged 10 to 19 years from 1999 to 2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(9):e1911383.

Akiba S. Epidemiological studies of Fukushima residents exposed to ionising radiation from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant prefecture--a preliminary review of current plans. J Radiol Prot. 2012;32(1):1–10.

Yang Y, Land KC. Age-period-cohort analysis of repeated cross-section surveys: fixed or random effects? Sociol Methods Res. 2008;36(3):297–326.

O’Brien R. Age-period-cohort models: approaches and analyses with aggregate data. Boca Raton: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2014.

Book Google Scholar

Chen X, Sun Y, Li Z, Yu B, Gao G, Wang P. Historical trends in suicide risk for the residents of mainland China: APC modeling of the archived national suicide mortality rates during 1987-2012. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2018;54(1):99–110.

Yang Y. Social inequalities in happiness in the United States, 1972 to 2004: an age-period-cohort analysis. Am Sociol Rev. 2008;73(2):204–26.

Reither EN, Hauser RM, Yang Y. Do birth cohorts matter? Age-period-cohort analyses of the obesity epidemic in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(10):1439–48.

Kerr WC, Lui C, Ye Y. Trends and age, period and cohort effects for marijuana use prevalence in the 1984-2015 US National Alcohol Surveys. Addiction. 2018;113(3):473–81.

Johnson RA, Gerstein DR. Age, period, and cohort effects in marijuana and alcohol incidence: United States females and males, 1961-1990. Substance Use Misuse. 2000;35(6–8):925–48.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 NSDUH: Summary of National Findings, SAMHSA, CBHSQ. 2014 [cited 2018 Sep 23]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHresultsPDFWHTML2013/Web/NSDUHresults2013.htm

Bauer DJ, Hussong AM. Psychometric approaches for developing commensurate measures across independent studies: traditional and new models. Psychol Methods. 2009;14(2):101–25.

Drug Policy Alliance. A Brief History of the Drug War. 2018 [cited 2018 Sep 27]. Available from: http://www.drugpolicy.org/issues/brief-history-drug-war

NIDA. Drug testing in schools. 2017 [cited 2018 Sep 27]. Available from: https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/drug-testing/faq-drug-testing-in-schools

Wikipedia contributors. Legal history of cannabis in the United States. 2015. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Legal_history_of_cannabis_in_the_United_States&oldid=674767854 . Accessed 24 Oct 2017.

NORML. Marijuana law reform timeline. 2015. Available from: http://norml.org/shop/item/marijuana-law-reform-timeline . Accessed 24 Oct 2017.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Epidemiology, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, 32608, USA

Bin Yu & Xinguang Chen

Department of Epidemiology and Health Statistics School of Health Sciences, Wuhan University, Wuhan, 430071, China

Xiangfan Chen & Hong Yan

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

BY designed the study, collected the data, conducted the data analysis, drafted and reviewed the manuscript; XGC designed the study and reviewed the manuscript. XFC and HY reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Hong Yan .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Florida. Data in the study were public available.

Consent for publication

All authors consented for the publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: table s1..

Estimated Age, Period, Cohort Effects for the Trend of Marijuana Use in Past Month among Adolescents and Emerging Adults Aged 12 to 25 Years, NSDUH, 1979-2016. Table S2. Laws at the federal and state levels related to marijuana use.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Yu, B., Chen, X., Chen, X. et al. Marijuana legalization and historical trends in marijuana use among US residents aged 12–25: results from the 1979–2016 National Survey on drug use and health. BMC Public Health 20 , 156 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8253-4

Download citation

Received : 15 June 2019

Accepted : 21 January 2020

Published : 04 February 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8253-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Adolescents and young adults

- United States

BMC Public Health

ISSN: 1471-2458

- General enquiries: [email protected]

New study highlights significant increases in cannabis use in United States

Long-term trends parallel changes in policy over 43 years.

A new study by a researcher at Carnegie Mellon University assessed cannabis use in the United States between 1979 and 2022, finding that a growing share of cannabis consumers report daily or near-daily use and that their numbers now exceed those of daily and near-daily alcohol drinkers. The study concludes that long-term trends in cannabis use parallel corresponding changes in policy over the same period. The study appears in Addiction .

"The data come from survey self-reports, but the enormous changes in rates of self-reported cannabis use, particularly of daily or near-daily use, suggest that changes in actual use have been considerable," says Jonathan P. Caulkins, professor of operations research and public policy at Carnegie Mellon's Heinz College, who conducted the study. "It is striking that high-frequency cannabis use is now more commonly reported than is high-frequency drinking."

Although prior research has compared cannabis-related and alcohol-related outcomes before and after state-level policy changes to changes over the same period in states without policy change, this study examined long-term trends for the United States as a whole. Caulkins looked at days of use, not just prevalence, and drew comparisons with alcohol, but did not attempt to identify causal effects.

The study used data from the U.S. National Survey on Drug Use and Health (and its predecessor, the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse), examining more than 1.6 million respondents across 27 surveys from 1979 to 2022. Caulkins contrasted rates of use in four milestone years that reflected significant policy change points: 1979 (when the first data became available and the relatively liberal policies of the 1970s ended), 1992 (the end of 12 years of conservative Reagan-Bush-era policies), 2008 (the year before the U.S. Department of Justice signaled explicit federal non-interference with state-level legalizations), and 2022 (the year for the most recent data available). Among the study's findings:

- Reported cannabis use declined to a low in 1992, with partial increases through 2008 and substantial growth since then, particularly for measures of more intensive use.

- Between 2008 and 2022, the per capita rate of reporting past-year use increased 120%, and days of use reported per capita increased 218% (in absolute terms, the rise was from 2.3 billion to 8.1 billion days per year).

- From 1992 to 2022, the per capita rate of reporting daily or near-daily use rose 15-fold. While the 1992 survey recorded 10 times as many daily or near-daily alcohol users as cannabis users (8.9 million versus 0.9 million), the 2022 survey, for the first time, recorded more daily and near-daily users of cannabis than of alcohol (17.7 million versus 14.7 million).

- While far more people drink than use cannabis, high-frequency drinking is less common. In 2022, the median drinker reported drinking on 4-5 days in the previous month versus using cannabis on 15-16 days in the previous month. In 2022, prior-month cannabis consumers were almost four times as likely to report daily or near-daily use (42% versus 11%) and 7.4 times more likely to report daily use (28% versus 3.8%).

"These trends mirror changes in policy, with declines during periods of greater restriction and growth during periods of policy liberalization," explains Caulkins. He notes that this does not mean that policy drove changes in use; both could have been manifestations of changes in underlying culture and attitudes. "But whichever way causal arrows point, cannabis use now appears to be on a fundamentally different scale than it was before legalization."

Among the study's limitations, Caulkins says that because the study relied on general population surveys, the data are self-reported, lack validation from biological samples, and exclude certain subpopulations that may use at different rates than the rest of the population.

- Controlled Substances

- Health Policy

- Illegal Drugs

- STEM Education

- Educational Policy

- Political Science

- General anxiety disorder

- Psychoactive drug

- Clinical depression

- Circadian rhythm

- Functional training

Story Source:

Materials provided by Carnegie Mellon University . Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

Journal Reference :

- Jonathan P. Caulkins. Changes in self‐reported cannabis use in the United States from 1979 to 2022 . Addiction , 2024; DOI: 10.1111/add.16519

Cite This Page :

Explore More

- Caterpillars Detect Predators by Electricity

- 'Electronic Spider Silk' Printed On Human Skin

- Engineered Surfaces Made to Shed Heat

- Innovative Material for Sustainable Building

- Human Brain: New Gene Transcripts

- Epstein-Barr Virus and Resulting Diseases

- Origins of the Proton's Spin

- Symbiotic Bacteria Communicate With Plants

- Birdsong and Human Voice: Same Genetic Blueprint

- Molecular Dysregulations in PTSD and Depression

Trending Topics

Strange & offbeat.

Science Friday

Federal law makes weed research complicated. can a van help.

Scientists want to understand how commercially available cannabis products affect users. They have to get creative to research it legally.

Illustration by Sahra Denner for Science Friday

To understand the effects of cannabis use on exercise, scientists drove stoned people to a tiny gym and watched them sprint.

The experiment was a part of a recent study from the University of Colorado Boulder, which upended expectations that the drug would cause sluggishness and low energy . While cannabis didn’t enhance users’ performance, it did improve their mood during the run, which mimicked the sensation of a “runner’s high.” Getting those precise results took a lot of planning, including outfitting a special van so researchers could shuttle high study volunteers from their homes to the research space. These extra steps (and vehicles) were necessary to make the study legal. Because even though it’s legal to use cannabis in Colorado, there are federal restrictions on researching it—including which cannabis can be studied at all.

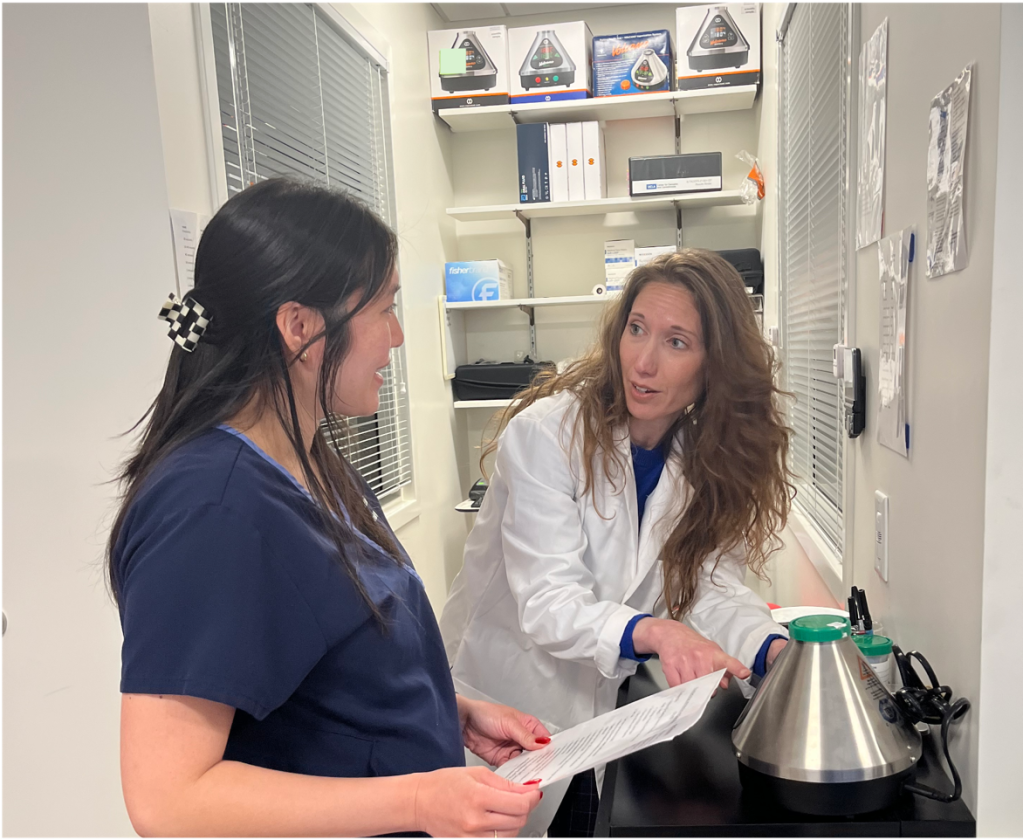

Cannabis use in the U.S. has risen dramatically among both young people and older adults as more states have legalized it over the past decade. And researchers across the country want to understand how the products millions of people now have access to can affect our health. “There’s all of these questions that users and patients want to know the answers to that we just don’t have yet,” says Dr. Angela Bryan, a co-author of the exercise study and principal investigator at CU Boulder’s health and risk behavior lab, CUChange .

In order to study the weed that’s legally available at dispensaries, she designs her studies so cannabis never enters her lab.

Driving Around Roadblocks

Cannabis is classified as a Schedule I drug by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), meaning that it’s deemed to have a high potential for abuse, and there is no federally accepted medical use for it—regardless of whether it’s legal to use in a given state. Researchers at universities that receive federal funding can’t give study participants cannabis on campus unless they register with the DEA. And even then, they can only use limited cannabis products provided by a short list of approved growers.

Using A Lab On Wheels To Study Weed From Dispensaries

For scientists who do obtain cannabis through the DEA for on-campus research, lengthy registration and transaction processes along with the limited choice of products can be a substantial challenge. Before 2022, there was only one lab that grew and produced DEA-approved cannabis products, and researchers complained that those were of lower quality and had a much lower THC content than what’s on the legal market. Also, research-grade manufacturers historically haven’t been able to replicate the diversity of commercial products like vapes, high-potency THC concentrate, and edibles that are popular in legal states. To research products that are comparable to what users have access to on the legal market, some scientists have elected to forgo a DEA registration entirely.

Bryan’s research questions were specifically about how commercial cannabis products affect users. So, CUChange worked with the CU Boulder legal team and their human subjects committee to develop the “CannaVan,” also referred to as the mobile research laboratory.

“We landed on the solution of, ‘Well, if we can’t bring the people to the lab, we’ll bring the lab to the people,’” Bryan says. In 2017, CU Boulder’s fleet of CannaVans hit the road , helping researchers study the effects of cannabis on consumers in Boulder.

Conducting research with the mobile lab sometimes involves parking outside a participant’s home, where the person will independently use their product and immediately go out to the van to complete an experimental procedure, like a cognitive test or a blood draw. Other times, the van will simply transport participants from where they use their cannabis to campus, where the researchers can perform tests in a lab. The researchers don’t buy the cannabis themselves, but instruct study participants to purchase the product from a given list of vendors.

Some of the researchers have noticed that study participants share their curiosity about cannabis. Madeline Stanger, a professional research assistant on a project focused on older adults, says that the participants she’s worked with are curious about trying a new treatment option that might improve their quality of life.

“It’s so encouraging when people are like, ‘This is a miracle.’ And then we get people that are like, ‘This isn’t having any effect at all.’ It’s really satisfying when people are benefiting from it, but it’s also good to know what isn’t working,” Stanger says.

So far, CUChange studies have investigated questions about a number of different aspects of cannabis use. Along with the effects of cannabis on physical activity , researchers have learned more about how high-potency THC concentrates affect the body, and how cannabis affects sleep . One of the lab’s studies from 2020 found that smokers who used 70%-90% THC concentrate reported similar levels of intoxication as smokers who took a product at about a quarter the potency. Those results could point to a “tolerance” effect for regular cannabis users, or a saturation point in cannabinoid receptors, but more research is needed.

Even though the team has learned a lot , Bryan acknowledges there are limitations to driving around the DEA. For example, some of their experiments require participants to buy their own cannabis products and document how much they consume. Drug trials where participants don’t know which product they’re consuming are generally considered better at measuring the drug’s isolated effect, because they eliminate the factor of the participant’s awareness. “It’s hard for us to have that experimental control,” Bryan says. “We always have to be cautious when we talk about our findings, understanding that people knew exactly what they were taking.”

Studying Cannabis Nationwide

Bryan and her colleagues’ research goals and generous funding have led them to unique methods, but the laws that make that necessary affect scientists across the US. Teams studying cannabis at different institutions take different approaches based on the questions they want to answer and the resources they have available.

Dr. Carrie Cuttler, an associate professor at Washington State University and the director of its Health and Cognition Lab, has watched research participants use cannabis over Zoom for some of her studies. Her lab has investigated links between cannabis and creativity , as well as the drug’s effects on cognition, mental health, and stress. She developed her research methods with Washington State authorities, and created a procedure where she watches participants use cannabis remotely. “I just observe a legal act,” she says.

Cuttler says the Zoom method lets her avoid illegal entanglement with a Schedule I drug, but a drawback is she’s unable to take the physiological measurements, like blood draws or heart rate, that the mobile laboratory enables. However, because the participant is on camera, Cuttler’s team is able to see one thing the CannaVan team doesn’t: how the user is actually consuming the product. “We time the duration of inhalations. We time the duration of holds. We count puffs,” she says. “We make sure they’re using the product that they were randomly assigned to use.”

Other approaches to researching without a DEA registration include analyzing international cannabis use data from countries like the Netherlands or Canada, and requesting self-reported data from users in the US. However, despite the hurdles, many scientists’ cannabis research interests lead them to opt for DEA registration.

For example, Dr. Ziva Cooper, director of the UCLA Center for Cannabis and Cannabinoids is DEA registered, and for her experiments she can securely store cannabis on campus, check its THC and CBD content, and administer it in an exact quantity.

“Here, it’s like an uber controlled environment,” Cooper says. Her research questions are about the isolated, controlled effect of cannabinoids on the human body, not the effects of typical legal drug use. “Why do I use that [DEA] farm?” she says, “It essentially goes back to, why do I do the type of science I do?”

Will Research Keep Up With Evolving Cannabis Use?

Bryan says scientists trying to understand the health effects of cannabis are barely able to keep up with the booming cannabis market, which is producing easily accessible, chemically diverse products that are more potent than ever . At the same time, cannabis is being used in a medical context in over 35 states.

In 2018 and 2022, respectively, the Farm Bill and Medical Marijuana and Cannabidiol Research Expansion Act were signed into federal law, expanding access to cannabinoids for researchers. But Bryan says it looks like the sale and use of cannabis in Colorado will continue to evolve faster than the DEA and FDA’s product offerings for researchers. Cannabis’s Schedule I status has made research harder, but Cooper says there are other issues “above and beyond that” that make the work difficult, like producing a research-grade cannabis supply and finding funding to begin with.

Earlier this month, the U.S. Department of Justice proposed that cannabis be rescheduled to Schedule III , the same class as codeine. In a 2023 interview before the reschedule was proposed, Dr. Igor Grant, director of University of California Center for Medicinal Cannabis Research said such a change would make research a lot more practical. For one, the tightest security requirements on storage of the drug would be relaxed, making research less costly, Cooper says. But even if cannabis is reclassified, the impracticalities of research wouldn’t disappear overnight, Grant said. “You’re still dealing with something that’s federally seen as an addictive substance, and regulated.”

One thing that could change is how cannabis products are made. Right now, the FDA does not apply any safety standards to them because the drug is federally illegal. But if it moves to Schedule III, the FDA could publish standards for cannabis products under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. That could make cannabis products safer, Cooper says, but urgent questions about how legal products affect users continue to surface.

“Until cannabis is taken off the schedule completely (like nicotine or alcohol) we can’t bring legal market products into the lab,” Bryan said in an email. Those who want to research state-legal products will have to continue using workarounds.

“We really want to do work that ultimately improves public health,” Bryan says. “We want to do it in a way that’s rigorous in terms of the science, but has direct application to improving people’s lives.”

Meet the Writer

About emma lee gometz.

Emma Lee Gometz is Science Friday’s Digital Producer of Engagement. She’s a writer and illustrator who loves drawing primates and tending to her coping mechanisms like G-d to the garden of Eden.

Explore More

Understanding the cannabis-body connection with exercise.

The first human study on how cannabis affects exercise sheds light on the body’s endocannabinoid system.

A van outfitted as a mobile laboratory helps scientists study how legal cannabis products affect users—without breaking the law.

Privacy Overview

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Hawaii J Med Public Health

- v.73(4); 2014 Apr

Therapeutic Benefits of Cannabis: A Patient Survey

Clinical research regarding the therapeutic benefits of cannabis (“marijuana”) has been almost non-existent in the United States since cannabis was given Schedule I status in the Controlled Substances Act of 1970. In order to discover the benefits and adverse effects perceived by medical cannabis patients, especially with regards to chronic pain, we hand-delivered surveys to one hundred consecutive patients who were returning for yearly re-certification for medical cannabis use in Hawai‘i.