The Role of Family in the Process of Socialization Essay

Socialization is a fundamental process through which a family acquires cultural and personal identity. Each person undergoes natural, planned, negative, or positive socialization in his or her life, regardless of gender or age. A family is one of the agencies that introduce a child to aspects like culture, physical, and psychological identities or behaviours and environment, which are some of the major elements of socialization.

Commonly, there are three types of families, single parent, nuclear, and extended; each of the family may differently expose a child to the aspects of socialization. The main role of a family is to nurture, mould, and guide children in the society; therefore, a child who does not belong to any family may undergo a negative socialization process.

Since the adoption of the word society, different sociologists like Max Weber have come up with a number of social theories namely feminist theory, conflict theory, consensus theory, theory of ‘self’, concept of the human mind, looking glass-self theory, and symbolic theory among others. Therefore, according to sociologists, the dynamic environment and familial identity in correlation with the elements of socialization determine the social behaviour of an individual in both childhood and adulthood.

A family is a fundamental institution that assists an individual or child to develop into an acceptable member of the society. Although each parent in a family has a role in the upbringing of a child, in many cases, the mother initiates the socialization process in a child.

Besides giving the sense of belonging or identity, a family imparts culture, traditions, norms, social roles, and values into the child (Merton, 1957, p.10). The processes of listening, language learning, and respect to authority start at the family level. Furthermore, it is the role of the family to provide a decent living environment for the children.

All children are a product of their environment; thus, to impart positive social values in a child, parents should choose an environment free from any negative influence. Drug abuse, criminal activities, and immoral behaviours are some of the negative aspects an environment might impart in a growing child. Most children learn from their friends, peers, parents, neighbours, and schoolmates.

Therefore, parents should familiarize with the friends of their children to ensure that the children do not deviate from the conventional social behaviours through external forces. In the light of this revelation, it suffices to conclude that, a family is a social institution that ensures that a child conforms to the acceptable standards of the society. The societal attributes that a family instils in a child include personality, skills/knowledge, social stability/order, cultural transmission, life aspirations, and social discipline among others.

The elements of socialization that a family imparts into a child are three. The first aspect is the inheritance of physical features and the psychological well being of a child. Parents pass their physical features to their children while psychological satisfaction of a child occurs when he or she grows up (Herman & Reynolds, 1994, p.17).

If a child experiences traumatic events like violence, or rape, he or she undergoes psychological instability even in adulthood. Secondly, environment is a crucial element of socialization especially to young stars.

The home, school, or institution in which a child lives in, determine the moral conducts of the child. A child who undergoes physically torture at home may become a drug addict, abuse alcohol, and/or venture into criminal activities like robbery or even commit suicide (Homans, 1962, p.34). The final concept is the element of culture whereby, a family initiates a child into specific cultural attributes. Depending on the sexual identity, parents bestow different gender roles to their children.

Mothers guide girls/daughters on their roles as wives and future mothers while fathers teach boys/sons on their roles as future fathers. In addition, each family or community has different cultural practices like initiation, dress code, and other formalities, which a family passes to its children to ensure they fit in the immediate society. Thus, physical and psychological inheritance, environment, and culture are the key elements a family fosters into a child.

Although most families have similar ways of socialization, some aspects instilled in a child differ from one family to another. A child from a nuclear or single parent family may have limited interaction with other relatives or members of the society.

Each family ensures that its children learn and practice the prevalent culture; however, a child from a single parent family may only learn culture from one parent. Moreover, each parent/family has diverse ways of imparting social skills to children. While some parents are harsh and strict, others rely on dialogue to instil moral values in their children.

Some parents enrol their children into boarding schools, others restrict their children from interacting with relatives or other members of the extended families, others employee house helps to monitor their children, and others quit their jobs to raise their children. Therefore, the methodology adapted by families may differ, but eventually the norms, values, and morals instilled have a similar relationship in one way or another.

The different theories of sociology attempt to correlate social science with other disciplines. For instance, the functionalism theory relates sociology to other scientific phenomena like research and biological organisms among others to explore the society/sociology as a subject.

Fundamentally, each of the adapted sociological theories exclusively focuses on one subject or phenomenon. Therefore, if an individual reads the social theories concurrently, he or she will understand the concept of sociology. Thus, the socialization theory plays a role in effecting the adaptation of exemplary personality or social attributes like obedience and compelling individuals to conform to their societal practices.

Sociologists have adapted different sociological theories to try to explain the subject of sociology. Also referred to as the consensus theory, functionalist theory describes the integration of human beings in the society through the sharing of the common cultural practices (Layton, 1997, P.20). The functionalist theory defines socialization as a functional requisite that leads to a stable society through the establishment of permanent social norms.

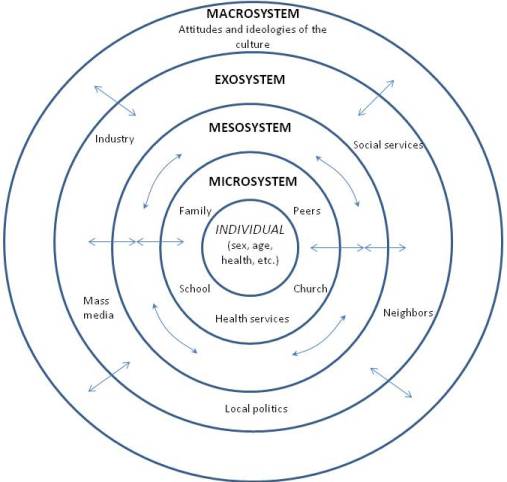

According to Durkheim, many systems, both physical and scientific, interact to determine the social behaviour of an individual (Michener, 1999, p.50). The systems are usually independent of the social laws surrounding the individual. The balance or equilibrium between humans and the society maintains a stable society. Religion, culture, and tradition are some of the elements, which shape up the society.

The society establishes specific social control tactics, which conform to the desired values and practices. For instance, if an individual adapts unbecoming behaviour like sneering through condemnation from the people around him or her, s/he will learn to discard the behaviour. Therefore, in relation to family as a channel of socialization, the functionalist theory describes a family as a societal institution established to ensure that there is continuity of a stable society.

Adopted from the ideologies of Karl Max, conflict theory describes socialization as competition, in which human beings not only interact, but also disagree and fight to maintain power (Clause, 1968, p.5). Therefore, the tenacity to compete for wealth and power defines the society as an unequal environment where a person or group decides to dominate over the others. Hence, capitalism, oppression, class systems, and materialism are some of the permanent characteristics of the society.

According to Max, the political, social, and economic stability of the society is in line with the conflict theory (Westen, 2002, p.40). Through family as a socializing institution, an individual must fall in some of the aforementioned groups. A child from a ruling class family will fight to maintain the status quo in the society. The conflict theory gives a sense of belonging to the society especially during socialization.

The family, as a social environment, may change due to external and internal forces like conflicts, divorce, emigration, death, and other natural calamities like floods. Due to the above issues, a child may abruptly change his or her living environment, which may also change the course of his/her socialization process. Similarly, a child may lose a parent in early age leaving him or her in the care of stepparents, foster parents, and grandparents.

The unfortunate ones end up as street children. The new environment may neglect or expose the child to new social practices or impart negative social practices in them. Political instability is among the elements that may scatter a family, and consequently affect the transmission of social norms in children. Furthermore, some of the traumatic events may also divert or impart negative social values like hatred in children.

Gardener Murphy has developed the theory of ‘self’ as a fundamental aspect in socialization. According to Murphy, an individual or self is a reflection of the environment especially the people one interacts with in life (Mead, 1967, p.80). The theory of ‘looking-glass self’ describes an individual’s characters as the mirror of the society. Appearance, judgment, and self-feeling of an individual develop through social interaction with the society (Mead, 1967, p.75).

Similarly, George Herbert Meads’ theory of ‘self’ describes the relationship of parentage or family to social development of the child (Mead, 1967, p.60). Before a child adapts to the external environment, he or she will initially practice the behaviour of the parents (Westen, 2002, p.50). Through the family, a child learns that to develop her awareness he or she will have to interact with others in the society, thus, socialization. In connection with the family, the theory of self describes a family as a fundamental unit in socialization.

Although the family is the commonly known social environment, other social institutions like the state, school, and church play a vital role in building an individual’s personality. The diversity of a social environment determines the conduct of an individual in adulthood. A child who visits religious gatherings like churches, temples, and mosques will attentively listen and shape his or her moral conduct according to the sermons.

On the other hand, a parent who does not worship in any church will pass the similar attributes to their children or generations. Secondly, the state drafts and enacts laws that each citizen has to uphold. Different states/countries or societies have different laws, which the members have to live by, and a breach in any of the laws leads to a punishment.

Apart from family/home, the school imparts social attributes in children. Knowledge, skills, and aspirations are some of the virtues a child/individual picks from school. Sometimes, children may adapt the behavioural conducts of their teachers or instructors. Finally, while at school or home, children acquire playmates who sometimes determine their behaviour. A child or an individual will adapt the behavioural conduct of his/her peers; therefore, negative or positives social values may originate from playmates.

Depending on the surrounding environment, a child conforms to its social norms; similarly, a child will pick up a new behaviour if he or she changes the environment. Thus, it is the role of the society to ensure the social conduct of its environment is not only acceptable, but also safe for the future of an individual. A dynamic environment may confuse a child, which leads to psychological trauma. Therefore, parents should ensure their children stay in a stable environment.

In the contemporary world, the social norms or values are not only dynamic, but also acquired through other channels other than the family, school, or church. Globally, the technological development of computers and the Internet services has led to the adaptation of diverse ways of socialization.

Globalization promotes multiculturalism, interracial marriages, and other diverse social interactions (Goffman, 1961, p.10). Contemporarily, children learn both negative and positive social aspects through social sites like facebook, tweeter, and LinkedIn among others. Sadly, the current upward trend in globalization rarely instils positive values in the young stars.

Besides practicing unacceptable social behaviours like pornography, young people also disregard physical social interactions. Whether at school, home or in the public, children concentrate on their mobile phones, surfing the Internet or interacting with friends or strangers through the social sites. In addition, the young stars have the unfortunate chance to choose what is right or awry without the seasoned guidance of the adults.

In the same light, entertainment channels like television, cinemas, and music playing systems promote different social values into teenagers or individuals. The aforementioned systems are among the common environments that a child in the current society faces as he or she grows into adulthood. Unfortunately, with the fast changes in globalization, there is poor assimilation of children into the society.

Modern parents concentrate on careers and, as a result, they neglect their roles in parentage; therefore, they leave their children to learn vital social values from peers or immediate environment. Consequently, children end up adopting criminal behaviours while some may not even fit into the society. Therefore, the family, as the primary social institution, should integrate into the dynamic environment in the present worldwide; otherwise, the next generations may lack vital social norms.

In conclusion, a family is the principal unit in socialization. The family imparts cultural practices, determines the living environment, and the physical and psychological identity of the children. Socialization, as a subject, has led to the adoption of different sociological theories that have enabled the effective study of the subject.

Marxist, conflict, and consensus theories are among the common theories studied in sociology. Social institutions like family, schools, churches, and mosques also instil positive social practices in individuals. Finally, the dynamic environment and globalization have led to the adaptation of new social practices; unfortunately, some of these new socialization trends promote antisocial behaviours among the youths.

Clausen, J. A. (1968). Socialization and Society . Boston: Little Brown and Company.

Goffman, E. (1961). Encounters: Two Studies in the Sociology of Interaction . London: Macmillan Publishing Co.

Herman, N. J., & Reynolds, L.T. (1994). Symbolic Interaction: An Introduction to Social Psychology . New York: Altamira Press.

Homans, G. C. (1962). Sentiments and Activities . New York: The Free Press Of Glencoe.

Layton, R. (1997). An Introduction to Theory in Anthropology . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mead, G. H. (1967 ). Mind, Self, & Society: From the Standpoint of a Social Behaviourist . Chicago: University of Chicago press.

Merton, R. (1957). Social Theory and Social Structure revised and enlarged . London: The Free Press of Glencoe.

Michener, H. A., & John D. (1999). Social Psychology . Harcourt: Brace College Publishers.

Westen, D. (2002) Psychology: Brain, Behaviour & Culture . New York: Wiley & Sons.

- Sociology of sports

- Socialization as a Lifelong Process

- Socialization Process and Conflict Resolution

- Effects of Ethnocentrism Essay

- Michel Foucault

- Effect of Ethnocentrism on an Individual and Society

- Heroes and Celebrities

- Analysis and Interpretation of Short Fiction

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, October 11). The Role of Family in the Process of Socialization. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-importance-of-the-family-in-the-socialization-process/

"The Role of Family in the Process of Socialization." IvyPanda , 11 Oct. 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/the-importance-of-the-family-in-the-socialization-process/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'The Role of Family in the Process of Socialization'. 11 October.

IvyPanda . 2018. "The Role of Family in the Process of Socialization." October 11, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-importance-of-the-family-in-the-socialization-process/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Role of Family in the Process of Socialization." October 11, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-importance-of-the-family-in-the-socialization-process/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The Role of Family in the Process of Socialization." October 11, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-importance-of-the-family-in-the-socialization-process/.

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Communication and Culture

- Communication and Social Change

- Communication and Technology

- Communication Theory

- Critical/Cultural Studies

- Gender (Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Studies)

- Health and Risk Communication

- Intergroup Communication

- International/Global Communication

- Interpersonal Communication

- Journalism Studies

- Language and Social Interaction

- Mass Communication

- Media and Communication Policy

- Organizational Communication

- Political Communication

- Rhetorical Theory

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Family, culture, and communication.

- V. Santiago Arias V. Santiago Arias College of Media and Communication, Texas Tech University

- and Narissra Maria Punyanunt-Carter Narissra Maria Punyanunt-Carter College of Media and Communication, Texas Tech University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.504

- Published online: 22 August 2017

Through the years, the concept of family has been studied by family therapists, psychology scholars, and sociologists with a diverse theoretical framework, such as family communication patterns (FCP) theory, dyadic power theory, conflict, and family systems theory. Among these theories, there are two main commonalities throughout its findings: the interparental relationship is the core interaction in the familial system because the quality of their communication or coparenting significantly affects the enactment of the caregiver role while managing conflicts, which are not the exception in the familial setting. Coparenting is understood in its broader sense to avoid an extensive discussion of all type of families in our society. Second, while including the main goal of parenting, which is the socialization of values, this process intrinsically suggests cultural assimilation as the main cultural approach rather than intergroup theory, because intercultural marriages need to decide which values are considered the best to be socialized. In order to do so, examples from the Thai culture and Hispanic and Latino cultures served to show cultural assimilation as an important mediator of coparenting communication patterns, which subsequently affect other subsystems that influence individuals’ identity and self-esteem development in the long run. Finally, future directions suggest that the need for incorporating a nonhegemonic one-way definition of cultural assimilation allows immigration status to be brought into the discussion of family communication issues in the context of one of the most diverse countries in the world.

- parental communication

- dyadic power

- family communication systems

- cultural assimilation

Introduction

Family is the fundamental structure of every society because, among other functions, this social institution provides individuals, from birth until adulthood, membership and sense of belonging, economic support, nurturance, education, and socialization (Canary & Canary, 2013 ). As a consequence, the strut of its social role consists of operating as a system in a manner that would benefit all members of a family while achieving what is considered best, where decisions tend to be coherent, at least according to the norms and roles assumed by family members within the system (Galvin, Bylund, & Brommel, 2004 ). Notwithstanding, the concept of family can be interpreted differently by individual perceptions to an array of cultural backgrounds, and cultures vary in their values, behaviors, and ideas.

The difficulty of conceptualizing this social institution suggests that family is a culture-bound phenomenon (Bales & Parsons, 2014 ). In essence, culture represents how people view themselves as part of a unique social collective and the ensuing communication interactions (Olaniran & Roach, 1994 ); subsequently, culture provides norms for behavior having a tremendous impact on those family members’ roles and power dynamics mirrored in its communication interactions (Johnson, Radesky, & Zuckerman, 2013 ). Thus, culture serves as one of the main macroframeworks for individuals to interpret and enact those prescriptions, such as inheritance; descent rules (e.g., bilateral, as in the United States, or patrilineal); marriage customs, such as ideal monogamy and divorce; and beliefs about sexuality, gender, and patterns of household formation, such as structure of authority and power (Weisner, 2014 ). For these reasons, “every family is both a unique microcosm and a product of a larger cultural context” (Johnson et al., 2013 , p. 632), and the analysis of family communication must include culture in order to elucidate effective communication strategies to solve familial conflicts.

In addition, to analyze familial communication patterns, it is important to address the most influential interaction with regard to power dynamics that determine the overall quality of family functioning. In this sense, within the range of family theories, parenting function is the core relationship in terms of power dynamics. Parenting refers to all efforts and decisions made by parents individually to guide their children’s behavior. This is a pivotal function, but the quality of communication among people who perform parenting is fundamental because their internal communication patterns will either support or undermine each caregiver’s parenting attempts, individually having a substantial influence on all members’ psychological and physical well-being (Schrodt & Shimkowski, 2013 ). Subsequently, parenting goes along with communication because to execute all parenting efforts, there must be a mutual agreement among at least two individuals to conjointly take care of the child’s fostering (Van Egeren & Hawkins, 2004 ). Consequently, coparenting serves as a crucial predictor of the overall family atmosphere and interactions, and it deserves special attention while analyzing family communication issues.

Through the years, family has been studied by family therapists, psychology scholars, and sociologists, but interaction behaviors define the interpersonal relationship, roles, and power within the family as a system (Rogers, 2006 ). Consequently, family scholarship relies on a wide range of theories developed within the communication field and in areas of the social sciences (Galvin, Braithwaite, & Bylund, 2015 ) because analysis of communication patterns in the familial context offers more ecological validity that individuals’ self-report measures. As many types of interactions may happen within a family, there are many relevant venues (i.e., theories) for scholarly analysis on this subject, which will be discussed later in this article in the “ Family: Theoretical Perspectives ” section. To avoid the risk of cultural relativeness while defining family, this article characterizes family as “a long-term group of two or more people related through biological, legal, or equivalent ties and who enact those ties through ongoing interactions providing instrumental and/or emotional support” (Canary & Canary, 2013 , p. 5).

Therefore, the purpose of this article is to provide an overview of the most relevant theories in family communication to identify frustrations and limitations with internal communication. Second, as a case in point, the United States welcomes more than 50 million noncitizens as temporary visitors and admits approximately 1 million immigrants to live as lawful residents yearly (Fullerton, 2014 ), this demographic pattern means that nearly one-third of the population (102 million) comes from different cultural backgrounds, and therefore, the present review will incorporate culture as an important mediator for coparenting, so that future research can be performed to find specific techniques and training practices that are more suitable for cross-cultural contexts.

Family: Theoretical Perspectives

Even though the concept of family can be interpreted individually and differently in different cultures, there are also some commonalities, along with communication processes, specific roles within families, and acceptable habits of interactions with specific family members disregarding cultural differences. This section will provide a brief overview of the conceptualization of family through the family communication patterns (FCP) theory, dyadic power theory, conflict, and family systems theory, with a special focus on the interparental relationship.

Family Communication Patterns Theory

One of the most relevant approaches to address the myriad of communication issues within families is the family communication patterns (FCP) theory. Originally developed by McLeod and Chaffee ( 1973 ), this theory aims to understand families’ tendencies to create stable and predictable communication patterns in terms of both relational cognition and interpersonal behavior (Braithwaite & Baxter, 2005 ). Specifically, this theory focuses on the unique and amalgamated associations derived from interparental communication and its impact on parenting quality to determine FCPs and the remaining interactions (Young & Schrodt, 2016 ).

To illustrate FCP’s focus on parental communication, Schrodt, Witt, and Shimkowski ( 2014 ) conducted a meta-analysis of 74 studies (N = 14,255) to examine the associations between the demand/withdraw family communication patterns of interaction, and the subsequent individual, relational, and communicative outcomes. The cumulative evidence suggests that wife demand/husband withdraw and husband demand/wife withdraw show similar moderate correlations with communicative and psychological well-being outcomes, and even higher when both patterns are taken together (at the relational level). This is important because one of the main tenets of FCP is that familial relationships are drawn on the pursuit of coorientation among members. Coorientation refers to the cognitive process of two or more individuals focusing on and assessing the same object in the same material and social context, which leads to a number of cognitions as the number of people involved, which results in different levels of agreement, accuracy, and congruence (for a review, see Fitzpatrick & Koerner, 2005 ); for example, in dyads that are aware of their shared focus, two different cognitions of the same issue will result.

Hereafter, the way in which these cognitions are socialized through power dynamics determined socially and culturally by roles constitutes specific interdependent communication patterns among family members. For example, Koerner and Fitzpatrick ( 2006 ) provide a taxonomy of family types on the basis of coorientation and its impact on communication pattern in terms of the degree of conformity in those conversational tendencies. To wit, consensual families mostly agree for the sake of the hierarchy within a given family and to explore new points of view; pluralistic families allow members to participate equally in conversations and there is no pressure to control or make children’s decisions; protective families maintain the hierarchy by making decisions for the sake of achieving common family goals; and laissez-faire families, which are low in conversation and conformity orientation, allow family members to not get deeply involved in the family.

The analysis of family communication patterns is quintessential for family communication scholarly work because it influences forming an individual’s self concept in the long run. As a case in point, Young and Schrodt ( 2016 ) surveyed 181 young adults from intact families, where conditional and interaction effects between communication patterns and conformity orientation were observed as the main predictors of future romantic partners. Moreover, this study concluded that FCPs and interparental confirmation are substantial indicators of self-to-partner confirmation, after controlling for reciprocity of confirmation within the romantic relationship. As a consequence, FCP influences children’s and young adults’ perceptions of romantic behavior (e.g., Fowler, Pearson, & Beck, 2010 ); the quality of communication behavior, such as the degree of acceptation of verbal aggression in romantic dyads (e.g., Aloia & Solomon, 2013 ); gender roles; and conflict styles (e.g., Taylor & Segrin, 2010 ), and parental modeling (e.g., Young & Schrodt, 2016 ).

This suggests three important observations. First, family is a very complex interpersonal context, in which communication processes, specific roles within families, and acceptable habits of interactions with specific family members interact as subsystems (see Galvin et al., 2004 ; Schrodt & Shimkowski, 2013 ). Second, among those subsystems, the core interaction is the individuals who hold parenting roles (i.e., intact and post divorced families); the couple (disregarding particular sexual orientations), and, parenting roles have a reciprocal relationship over time (Le, McDaniel, Leavitt, & Feinberg, 2016 ). Communication between parenting partners is crucial for the development of their entire family; for example, Schrodt and Shimkowski ( 2013 ) conducted a survey with 493 young adult children from intact (N = 364) and divorced families (N = 129) about perceptions of interparental conflict that involves triangulation (the impression of being in the “middle” and feeling forced to display loyalty to one of the parents). Results suggest that supportive coparental communication positively predicts relational satisfaction with mothers and fathers, as well as mental health; on the other hand, antagonist and hostile coparental communication predicted negative marital satisfaction.

Consequently, “partners’ communication with one another will have a positive effect on their overall view of their marriage, . . . and directly result[ing in] their views of marital satisfaction” (Knapp & Daly, 2002 , p. 643). Le et al. ( 2016 ) conducted a longitudinal study to evaluate the reciprocal relationship between marital interaction and coparenting from the perspective of both parents in terms of support or undermining across the transition to parenthood from a dyadic perspective; 164 cohabiting heterosexual couples expecting their first child were analyzed from pregnancy until 36 months after birth. Both parents’ interdependence was examined in terms of three variables: gender difference analysis, stability over time in marriage and coparenting, and reciprocal associations between relationship quality and coparenting support or undermining. The findings suggest a long-term reciprocal association between relationship quality and coparenting support or undermining in heterosexual families; the quality of marriage relationship during prenatal stage is highly influential in coparenting after birth for both men and women; but, coparenting is connected to romantic relationship quality only for women.

Moreover, the positive association between coparenting and the parents’ relationship relates to the spillover hypothesis, which posits that the positive or negative factors in the parental subsystem are significantly associated with higher or lower marital satisfaction in the spousal subsystem, respectively. Ergo, overall parenting performance is substantially affected by the quality of marital communication patterns.

Dyadic Power

In addition, after analyzing the impact of marital interaction quality in families on marital satisfaction and future parental modeling, it is worth noting that marital satisfaction and coparenting are importantly mediated by power dynamics within the couple (Halstead, De Santis, & Williams, 2016 ), and even mediates marital commitment (e.g., Lennon, Stewart, & Ledermann, 2013 ). If the quality of interpersonal relationship between those individuals who hold parenting roles determines coparenting quality as well, then the reason for this association lies on the fact that virtually all intimate relationships are substantially characterized by power dynamics; when partners perceive more rewards than costs in the relationship, they will be more satisfied and significantly more committed to the relationship (Lennon et al., 2013 ). As a result, the inclusion of power dynamics in the analysis of family issues becomes quintessential.

For the theory of dyadic power, power in its basic sense includes dominance, control, and influence over others, as well as a means to meet survival needs. When power is integrated into dyadic intimate relationships, it generates asymmetries in terms of interdependence between partners due to the quality of alternatives provided by individual characteristics such as socioeconomic status and cultural characteristics such as gender roles. This virtually gives more power to men than women. Power refers to “the feeling derived from the ability to dominate, or control, the behavior, affect, and cognitions of another person[;] in consequence, this concept within the interparental relationship is enacted when one partner who controls resources and limiting the behavioral options of the other partner” (Lennon et al., 2013 , p. 97). Ergo, this theory examines power in terms of interdependence between members of the relationship: the partner who is more dependent on the other has less power in the relationship, which, of course, directly impact parenting decisions.

As a case in point, Worley and Samp ( 2016 ) examined the balance of decision-making power in the relationship, complaint avoidance, and complaint-related appraisals in 175 heterosexual couples. Findings suggest that decision-making power has a curvilinear association, in which individuals engaged in the least complaint avoidance when they were relatively equal to their partners in terms of power. In other words, perceptions of one another’s power potentially encourage communication efficacy in the interparental couple.

The analysis of power in intimate relationships, and, to be specific, between parents is crucial because it not only relates to marital satisfaction and commitment, but it also it affects parents’ dyadic coping for children. In fact, Zemp, Bodenmann, Backes, Sutter-Stickel, and Revenson ( 2016 ) investigated parents’ dyadic coping as a predictor of children’s internalizing symptoms, externalizing symptoms, and prosocial behavior in three independent studies. When there is a positive relationship among all three factors, the results indicated that the strongest correlation was the first one. Again, the quality of the marital and parental relationships has the strongest influence on children’s coping skills and future well-being.

From the overview of the two previous theories on family, it is worth addressing two important aspects. First, parenting requires an intensive great deal of hands-on physical care, attention to safety (Mooney-Doyle, Deatrick, & Horowitz, 2014 ), and interpretation of cues, and this is why parenting, from conception to when children enter adulthood, is a tremendous social, cultural, and legally prescribed role directed toward caregiving and endlessly attending to individuals’ social, physical, psychological, emotional, and cognitive development (Johnson et al., 2013 ). And while parents are making decisions about what they consider is best for all family members, power dynamics play a crucial role in marital satisfaction, commitment, parental modeling, and overall interparental communication efficacy in the case of postdivorce families. Therefore, the likelihood of conflict is latent within familial interactions while making decisions; indeed, situations in which family members agree on norms as a consensus is rare (Ritchie & Fitzpatrick, 1990 ).

In addition to the interparental and marital power dynamics that delineates family communication patterns, the familial interaction is distinctive from other types of social relationships in the unequaled role of emotions and communication of affection while family members interact and make decisions for the sake of all members. For example, Ritchie and Fitzpatrick ( 1990 ) provided evidence that fathers tended to perceive that all other family members agree with his decisions or ideas. Even when mothers confronted and disagreed with the fathers about the fathers’ decisions or ideas, the men were more likely to believe that their children agreed with him. When the children were interviewed without their parents, however, the majority of children agreed with the mothers rather than the fathers (Ritchie & Fitzpatrick, 1990 ). Subsequently, conflict is highly present in families; however, in general, the presence of conflict is not problematic per se. Rather, it is the ability to manage and recover from it and that could be problematic (Floyd, 2014 ).

One of the reasons for the role of emotions in interpersonal conflicts is explained by the Emotion-in-Relationships Model (ERM). This model states that feelings of bliss, satisfaction, and relaxation often go unnoticed due to the nature of the emotions, whereas “hot” emotions, such as anger and contempt, come to the forefront when directed at a member of an interpersonal relationship (Fletcher & Clark, 2002 ). This type of psychophysical response usually happens perhaps due to the different biophysical reactive response of the body compared to its reaction to positive ones (Floyd, 2014 ). There are two dimensions that define conflict. Conflict leads to the elicitation of emotions, but sometimes the opposite occurs: emotions lead to conflict. The misunderstanding or misinterpretation of emotions among members of a family can be a source of conflict, as well as a number of other issues, including personality differences, past history, substance abuse, mental or physical health problems, monetary issues, children, intimate partner violence, domestic rape, or maybe just general frustration due to recent events (Sabourin, Infante, & Rudd, 1990 ). In order to have a common understanding of this concept for the familial context in particular, conflict refers to as “any incompatibility that can be expressed by people related through biological, legal, or equivalent ties” (Canary & Canary, 2013 , p. 6). Thus, the concept of conflict goes hand in hand with coparenting.

There is a myriad of everyday family activities in which parents need to decide the best way to do them: sometimes they are minor, such as eating, watching TV, or sleeping schedules; others are more complicated, such as schooling. Certainly, while socializing and making these decisions, parents may agree or not, and these everyday situations may lead to conflict. Whether or not parents live together, it has been shown that “the extent to which children experience their parents as partners or opponents in parenting is related to children’s adjustment and well-being” (Gable & Sharp, 2016 , p. 1), because the ontology of parenting is materialized through socialization of values about every aspect and duty among all family members, especially children, to perpetuate a given society.

As the findings provided in this article show, the study of family communication issues is pivotal because the way in which those issues are solved within families will be copied by children as their values. Values are abstract ideas that delineate behavior toward the evaluation of people and events and vary in terms of importance across individuals, but also among cultures. In other words, their future parenting (i.e., parenting modeling) of children will replicate those same strategies for conflict solving for good or bad, depending on whether parents were supportive between each other. Thus, socialization defines the size and scope of coparenting.

The familial socialization of values encompasses the distinction between parents’ personal execution of those social appraisals and the values that parents want their children to adopt, and both are different things; nonetheless, familial socialization does not take place in only one direction, from parents to children. Benish-Weisman, Levy, and Knafo ( 2013 ) investigated the differentiation process—or, in other words, the distinction between parents’ own personal values and their socialization values and the contribution of children’s values to their parents’ socialization values. In this study, in which 603 Israeli adolescents and their parents participated, the findings suggest that parents differentiate between their personal values and their socialization values, and adolescents’ values have a specific contribution to their parents’ socialization values. As a result, socialization is not a unidirectional process affected by parents alone, it is an outcome of the reciprocal interaction between parents and their adolescent children, and the given importance of a given value is mediated by parents and their culture individually (Johnson et al., 2013 ). However, taking power dynamics into account does not mean that adolescents share the same level of decision-making power in the family; thus, socialization take place in both directions, but mostly from parents to children. Finally, it is worth noticing that the socialization of values in coparenting falls under the cultural umbrella. The next section pays a special attention to the role of culture in family communication.

The Role of Culture in Parenting Socialization of Values

There are many individual perceived realities and behaviors in the familial setting that may lead to conflict among members, but all of them achieve a common interpretation through culture; indeed, “all family conflict processes by broad cultural factors” (Canary & Canary, 2013 , p. 46). Subsequently, the goal of this section is to provide an overview of the perceived realities and behaviors that exist in family relationships with different cultural backgrounds. How should one approach the array of cultural values influencing parental communication patterns?

An interesting way of immersing on the role of culture in family communication patterns and its further socialization of values is explored by Schwartz ( 1992 ). The author developed a value system composed of 10 values operationalized as motivational goals for modern society: (a) self-direction (independence of thought and action); (b) stimulation (excitement, challenge, and novelty); (c) hedonism (pleasure or sensuous gratification); (d) achievement (personal success according to social standards); (e) power (social status, dominance over people and resources); (f) conformity (restraint of actions that may harm others or violate social expectations); (g) tradition (respect and commitment to cultural or religious customs and ideas); (h) benevolence (preserving and enhancing the welfare of people to whom one is close); (i) universalism (understanding, tolerance, and concern for the welfare of all people and nature); and (j) security (safety and stability of society, relationships, and self).

Later, Schwartz and Rubel ( 2005 ) applied this value structure, finding it to be commonly shared among over 65 countries. Nevertheless, these values are enacted in different ways by societies and genders about the extent to which men attribute more relevance to values of power, stimulation, hedonism, achievement, and self-direction, and the opposite was found for benevolence and universalism and less consistently for security. Also, it was found that all sex differences were culturally moderated, suggesting that cultural background needs to be considered in the analysis of coparental communication when socializing those values.

Even though Schwartz’s work was more focused on individuals and societies, it is a powerful model for the analysis of the role of culture on family communication and parenting scholarships. Indeed, Schwartz et al. ( 2013 ) conducted a longitudinal study with a sample of 266 Hispanic adolescents (14 years old) and their parents that looked at measures of acculturation, family functioning, and adolescent conduct problems, substance use, and sexual behavior at five time points. Results suggest that higher levels of acculturation in adolescents were linked to poorer family functioning; however, overall assimilation negatively predicted adolescent cigarette smoking, sexual activity, and unprotected sex. The authors emphasize the role of culture, and acculturation patterns in particular, in understanding the mediating role of family functioning and culture.

Ergo, it is crucial to address the ways in which culture affects family functioning. On top of this idea, Johnson et al. ( 2013 ) observed that Western cultures such as in the United States and European countries are oriented toward autonomy, favoring individual achievement, self-reliance, and self-assertiveness. Thus, coparenting in more autonomous countries will socialize to children the idea that achievement in life is an outcome of independence, resulting in coparenting communication behaviors that favor verbal praise and feedback over physical contact. As opposed to autonomy-oriented cultures, other societies, such as Asian, African, and Latin American countries, emphasize interdependence over autonomy; thus, parenting in these cultures promotes collective achievement, sharing, and collaboration as the core values.

These cultural orientations can be observed in parents’ definitions of school readiness and educational success; for Western parents, examples include skills such as counting, recognizing letters, or independently completing tasks such as coloring pictures, whereas for more interdependent cultures, the development of obedience, respect for authority, and appropriate social skills are the skills that parents are expecting their children to develop to evaluate school readiness. As a matter of fact, Callaghan et al. ( 2011 ) conducted a series of eight studies to evaluate the impact of culture on the social-cognitive skills of one- to three-year-old children in three diverse cultural settings such as Canada, Peru, and India. The results showed that children’s acquisition of specific cognitive skills is moderated by specific learning experiences in a specific context: while Canadian children were understanding the performance of both pretense and pictorial symbols skillfully between 2.5 and 3.0 years of age, on average, Peruvian and Indian children mastered those skills more than a year later. Notwithstanding, this finding does not suggest any kind of cultural superiority; language barriers and limitations derived from translation itself may influence meanings, affecting the results (Sotomayor-Peterson, De Baca, Figueredo, & Smith-Castro, 2013 ). Therefore, in line with the findings of Schutz ( 1970 ), Geertz ( 1973 ), Grusec ( 2002 ), Sotomayor-Peterson et al. ( 2013 ), and Johnson et al. ( 2013 ), cultural values provide important leverage for understanding family functioning in terms of parental decision-making and conflict, which also has a substantial impact on children’s cognitive development.

Subsequently, cultural sensitivity to the analysis of the familial system in this country needs to be specially included because cultural differences are part of the array of familial conflicts that may arise, and children experience real consequences from the quality of these interactions. Therefore, parenting, which is already arduous in itself, and overall family functioning significantly become troublesome when parents with different cultural backgrounds aim to socialize values and perform parenting tasks. The following section provides an account of these cross-cultural families.

Intercultural Families: Adding Cultural Differences to Interparental Communication

For a country such as the United States, with 102 million people from many different cultural backgrounds, the presence of cross-cultural families is on the rise, as is the likelihood of intermarriage between immigrants and natives. With this cultural diversity, the two most prominent groups are Hispanics and Asians, particular cases of which will be discussed next. Besides the fact that parenting itself is a very complex and difficult task, certainly the biggest conflict consists of making decisions about the best way to raise children in terms of their values with regard to which ethnic identity better enacts the values that parents believe their children should embrace. As a result, interracial couples might confront many conflicts and challenges due to cultural differences affecting marital satisfaction and coparenting.

Assimilation , the degree to which a person from a different cultural background has adapted to the culture of the hostage society, is an important phenomenon in intermarriage. Assimilationists observe that children from families in which one of the parents is from the majority group and the other one from the minority do not automatically follow the parent from the majority group (Cohen, 1988 ). Indeed, they follow their mothers more, whichever group she belongs to, because of mothers are more prevalent among people with higher socioeconomic status (Gordon, 1964 ; Portes, 1984 ; Schwartz et al., 2013 ).

In an interracial marriage, the structural and interpersonal barriers inhibiting the interaction between two parents will be reduced significantly if parents develop a noncompeting way to communicate and solve conflicts, which means that both of them might give up part of their culture or ethnic identity to reach consensus. Otherwise, the ethnic identity of children who come from interracial marriages will become more and more obscure (Saenz, Hwang, Aguirre, & Anderson, 1995 ). Surely, parents’ noncompeting cultural communication patterns are fundamental for children’s development of ethnic identity. Biracial children develop feelings of being outsiders, and then parenting becomes crucial to developing their strong self-esteem (Ward, 2006 ). Indeed, Gordon ( 1964 ) found that children from cross-racial or cross-ethnic marriages are at risk of developing psychological problems. In another example, Jognson and Nagoshi ( 1986 ) studied children who come from mixed marriages in Hawaii and found that the problems of cultural identification, conflicting demands in the family, and of being marginal in either culture still exist (Mann & Waldron, 1977 ). It is hard for those mixed-racial children to completely develop the ethnic identity of either the majority group or the minority group.

The question of how children could maintain their minority ethnic identity is essential to the development of ethnic identity as a whole. For children from interracial marriage, the challenge to maintain their minority ethnic identity will be greater than for the majority ethnic identity (Waters, 1990 ; Schwartz et al., 2013 ) because the minority-group spouse is more likely to have greater ethnic consciousness than the majority-group spouse (Ellman, 1987 ). Usually, the majority group is more influential than the minority group on a child’s ethnic identity, but if the minority parent’s ethnicity does not significantly decline, the child’s ethnic identity could still reflect some characteristics of the minority parent. If parents want their children to maintain the minority group’s identity, letting the children learn the language of the minority group might be a good way to achieve this. By learning the language, children form a better understanding of that culture and perhaps are more likely to accept the ethnic identity that the language represents (Xin & Sandel, 2015 ).

In addition to language socialization as a way to contribute to children’s identity in biracial families, Jane and Bochner ( 2009 ) indicated that family rituals and stories could be important in performing and transforming identity. Families create and re-create their identities through various kinds of narrative, in which family stories and rituals are significant. Festivals and rituals are different from culture to culture, and each culture has its own. Therefore, exposing children to the language, rituals, and festivals of another culture also could be helpful to form their ethnic identity, in order to counter problems of self-esteem derived from the feeling of being an outsider.

To conclude this section, the parenting dilemma in intercultural marriages consists of deciding which culture they want their children to be exposed to and what kind of heritage they want to pass to children. The following section will provide two examples of intercultural marriages in the context of American society without implying that there are no other insightful cultures that deserve analysis, but the focus on Asian-American and Hispanics families reflects the available literature (Canary & Canary, 2013 ) and its demographic representativeness in this particular context. In addition, in order to acknowledge that minorities within this larger cultural background deserve more attention due to overemphasis on larger cultures in scholarship, such as Chinese or Japanese cultures, the Thai family will provide insights into understanding the role of culture in parenting and its impact on the remaining familial interaction, putting all theories already discussed in context. Moreover, the Hispanic family will also be taken in account because of its internal pan-ethnicity variety.

An Example of Intercultural Parenting: The Thai Family

The Thai family, also known as Krob Krua, may consist of parents, children, paternal and maternal grandparents, aunts, uncles, grandchildren, in-laws, and any others who share the same home. Thai marriages usually are traditional, in which the male is the authority figure and breadwinner and the wife is in charge of domestic items and the homemaker. It has been noted that Thai mothers tend to be the major caregivers and caretakers in the family rather than fathers (Tulananda, Young, & Roopnarine, 1994 ). On the other hand, it has been shown that Thai mothers also tend to spoil their children with such things as food and comfort; Tulananda et al. ( 1994 ) studied the differences between American and Thai fathers’ involvement with their preschool children and found that American fathers reported being significantly more involved with their children than Thai fathers. Specifically, the fathers differed in the amount of socialization and childcare; Thai fathers reported that they obtained more external support from other family members than American fathers; also, Thai fathers were more likely to obtain support for assisting with daughters than sons.

Furthermore, with regard to the family context, Tulananda and Roopnarine ( 2001 ) noted that over the years, some attention has been focused on the cultural differences among parent-child behaviors and interactions; hereafter, the authors believed that it is important to look at cultural parent-child interactions because that can help others understand children’s capacity to socialize and deal with life’s challenges. As a matter of fact, the authors also noted that Thai families tend to raise their children in accordance with Buddhist beliefs. It is customary for young Thai married couples to live with either the wife’s parents (uxorilocal) or the husband’s parents (virilocal) before living on their own (Tulananda & Roopnarine, 2001 ). The process of developing ethnicity could be complicated. Many factors might influence the process, such as which parent is from the minority culture and the cultural community, as explained in the previous section of this article.

This suggests that there is a difference in the way that Thai and American fathers communicate with their daughters. As a case in point, Punyanunt-Carter ( 2016 ) examined the relationship maintenance behaviors within father-daughter relationships in Thailand and the United States. Participants included 134 American father-daughter dyads and 154 Thai father-daughter dyads. The findings suggest that when quality of communication was included in this relationship, both types of families benefit from this family communication pattern, resulting in better conflict management and advice relationship maintenance behaviors. However, differences were found: American fathers are more likely than American daughters to employ relationship maintenance behaviors; in addition, American fathers are more likely than Thai fathers to use relationship maintenance strategies.

As a consequence, knowing the process of ethnic identity development could provide parents with different ways to form children’s ethnic identity. More specifically, McCann, Ota, Giles, and Caraker ( 2003 ), and Canary and Canary ( 2013 ) noted that Southeast Asian cultures have been overlooked in communication studies research; these countries differ in their religious, political, and philosophical thoughts, with a variety of collectivistic views and religious ideals (e.g., Buddhism, Taoism, Islam), whereas the United States is mainly Christian and consists of individualistic values.

The Case of Hispanic/Latino Families in the United States

There is a need for including Hispanic/Latino families in the United States because of the demographic representativeness and trends of the ethnicity: in 2016 , Hispanics represent nearly 17% of the total U.S. population, becoming the largest minority group. There are more than 53 million Hispanics and Latinos in the United States; in addition, over 93% of young Hispanics and Latinos under the age of 18 hold U.S. citizenship, and more than 73,000 of these people turn 18 every month (Barreto & Segura, 2014 ). Furthermore, the current Hispanic and Latino population is spread evenly between foreign-born and U.S.-born individuals, but the foreign-born population is now growing faster than the number of Hispanic children born in the country (Arias & Hellmueller, 2016 ). This demographic trend is projected to reach one-third of the U.S. total population by 2060 ; therefore, with the growth of other minority populations in the country, the phenomenon of multiracial marriage and biracial children is increasing as well.

Therefore, family communication scholarship has an increasing necessity to include cultural particularities in the analysis of the familial system; in addition to the cultural aspects already explained in this article, this section addresses the influence of familism in Hispanic and Latino familial interactions, as well as how immigration status moderates the internal interactions, reflected in levels of acculturation, that affect these families negatively.

With the higher marriage and birth rates among Hispanics and Latinos living in the United States compared to non-Latino Whites and African American populations, the Hispanic familial system is perhaps the most stereotyped as being familistic (Glick & Van Hook, 2008 ). This family trait consists of the fact that Hispanics place a very high value on marriage and childbearing, on the basis of a profound commitment to give support to members of the extended family as well. This can be evinced in the prevalence of extended-kind shared households in Hispanic and Latino families, and Hispanic children are more likely to live in extended-family households than non-Latino Whites or blacks (Glick & Van Hook, 2008 ). Living in extended-family households, most likely with grandparents, may have positive influences on Hispanic and Latino children, such as greater attention and interaction with loving through consistent caregiving; grandparents may help by engaging with children in academic-oriented activities, which then affects positively cognitive educational outcomes.

However, familism is not the panacea for all familial issues for several reasons. First, living in an extended-family household requires living arrangements that consider adults’ needs more than children’s. Second, the configuration of Hispanic and Latino households is moderated by any immigration issues with all members of the extended family, and this may cause problems for children (Menjívar, 2000 ). The immigration status of each individual member may produce a constant state of flux, whereas circumstances change to adjust to economic opportunities, which in turn are limited by immigration laws, and it gets even worse when one of the parents isn’t even present in the children’s home, but rather live in their home country (Van Hook & Glick, 2006 ). Although Hispanic and Latino children are more likely to live with married parents and extended relatives, familism is highly affected by the immigration status of each member.

On the other hand, there has been research to address the paramount role of communication disregarding the mediating factor of cultural diversity. For example, Sotomayor-Peterson et al. ( 2013 ) performed a cross-cultural comparison of the association between coparenting or shared parental effort and family climate among families from Mexico, the United States, and Costa Rica. The overall findings suggest what was explained earlier in this article: more shared parenting predicts better marital interaction and family climate overall.

In addition, parenting quality has been found to have a positive relationship with children’s developmental outcomes. In fact, Sotomayor-Peterson, Figueredo, Christensen, and Taylor ( 2012 ) conducted a study with 61 low-income Mexican American couples, with at least one child between three and four years of age, recruited from a home-based Head Start program. The main goal of this study was to observe the extent that shared parenting incorporates cultural values and income predicts family climate. The findings suggest that the role of cultural values such as familism, in which family solidarity and avoidance of confrontation are paramount, delineate shared parenting by Mexican American couples.

Cultural adaptation also has a substantial impact on marital satisfaction and children’s cognitive stimulation. Indeed, Sotomayor-Peterson, Wilhelm, and Card ( 2011 ) investigated the relationship between marital relationship quality and subsequent cognitive stimulation practices toward their infants in terms of the actor and partner effects of White and Hispanic parents. The results indicate an interesting relationship between the level of acculturation and marital relationship quality and a positive cognitive stimulation of infants; specifically, marital happiness is associated with increased cognitive stimulation by White and high-acculturated Hispanic fathers. Nevertheless, a major limitation of Hispanic acculturation literature has been seen, reflecting a reliance on cross-sectional studies where acculturation was scholarly operationalized more as an individual difference variable than as a longitudinal adaptation over time (Schwartz et al., 2013 ).

Culture and Family Communication: the “so what?” Question

This article has presented an entangled overview of family communication patterns, dyadic power, family systems, and conflict theories to establish that coparenting quality plays a paramount role. The main commonality among those theories pays special attention to interparental interaction quality, regardless of the type of family (i.e., intact, postdivorce, same-sex, etc.) and cultural background. After reviewing these theories, it was observed that the interparental relationship is the core interaction in the familial context because it affects children from their earlier cognitive development to subsequent parental modeling in terms of gender roles. Thus, in keeping with Canary and Canary ( 2013 ), no matter what approach may be taken to the analysis of family communication issues, the hypothesis that a positive emotional climate within the family is fostered only when couples practice a sufficient level of shared parenting and quality of communication is supported.

Nevertheless, this argument does not suggest that the role of culture in the familial interactions should be undersold. While including the main goal of parenting, which is the socialization of values, in the second section of this article, the text also provides specific values of different countries that are enacted and socialized differently across cultural contexts to address the role of acculturation in the familial atmosphere, the quality of interactions, and individual outcomes. As a case in point, Johnson et al. ( 2013 ) provided an interesting way of seeing how cultures differ in their ways of enacting parenting, clarifying that the role of culture in parenting is not a superficial or relativistic element.

In addition, by acknowledging the perhaps excessive attention to larger Asian cultural backgrounds (such as Chinese or Japanese cultures) by other scholars (i.e., Canary & Canary, 2013 ), an insightful analysis of the Thai American family within the father-daughter relationship was provided to exemplify, through the work of Punyanunt-Carter ( 2016 ), how specific family communication patterns, such as maintenance relationship communication behaviors, affect the quality of familial relationships. Moreover, a second, special focus was put on Hispanic families because of the demographic trends of the United States, and it was found that familism constitutes a distinctive aspect of these families.

In other words, the third section of this article provided these two examples of intercultural families to observe specific ways that culture mediates the familial system. Because one of the main goals of the present article was to demonstrate the mediating role of culture as an important consideration for family communication issues in the United States, the assimilationist approach was taken into account; thus, the two intercultural family examples discussed here correspond to an assimilationist nature rather than using an intergroup approach.

This decision was made without intending to diminish the value of other cultures or ethnic groups in the country, but an extensive revision of all types of intercultural families is beyond the scope of this article. Second, the assimilationist approach forces one to consider cultures that are in the process of adapting to a new hosting culture, and the Thai and Hispanic families in the United States comply with this theoretical requisite. For example, Whites recognize African Americans as being as American as Whites (i.e., Dovidio, Gluszek, John, Ditlmann, & Lagunes, 2010 ), whereas they associate Hispanics and Latinos with illegal immigration in the United States (Stewart et al., 2011 ), which has been enhanced by the U.S. media repeatedly since 1994 (Valentino et al., 2013 ), and it is still happening (Dixon, 2015 ). In this scenario, “ask yourself what would happen to your own personality if you heard it said over and over again that you were lazy, a simple child of nature, expected to steal, and had inferior blood? . . . One’s reputation, whether false or true, cannot be hammered, hammered, hammered, into one’s head without doing something to one’s character” (Allport, 1979 , p. 142, cited in Arias & Hellmueller, 2016 ).

As a consequence, on this cultural canvas, it should not be surprising that Lichter, Carmalt, and Qian ( 2011 ) found that second-generation Hispanics are increasingly likely to marry foreign-born Hispanics and less likely to marry third-generation or later coethnics or Whites. In addition, this study suggests that third-generation Hispanics and later were more likely than in the past to marry non-Hispanic Whites; thus, the authors concluded that there has been a new retreat from intermarriage among the largest immigrant groups in the United States—Hispanics and Asians—in the last 20 years.

If we subscribe to the idea that cultural assimilation goes in only one direction—from the hegemonic culture to the minority culture—then the results of Lichter, Carmalt, and Qian ( 2011 ) should not be of scholarly concern; however, if we believe that cultural assimilation happens in both directions and intercultural families can benefit both the host and immigrant cultures (for a review, see Schwartz et al., 2013 ), then this is important to address in a country that just elected a president, Donald Trump, who featured statements racially lambasting and segregating minorities, denigrating women, and criticizing immigration as some of the main tenets of his campaign. Therefore, we hope that it is clear why special attention was given to the Thai and Hispanic families in this article, considering the impact of culture on the familial system, marital satisfaction, parental communication, and children’s well-being. Even though individuals with Hispanic ancentry were in the United States even before it became a nation, Hispanic and Latino families are still trying to convince Americans of their right to be accepted in American culture and society.

With regard to the “So what?” question, assimilation is important to consider while analyzing the role of culture in family communication patterns, power dynamics, conflict, or the functioning of the overall family system in the context of the United States. This is because this country is among the most popular in the world in terms of immigration requests, and its demographics show that one out of three citizens comes from an ethnic background other than the hegemonic White culture. In sum, cultural awareness has become pivotal in the analysis of family communication issues in the United States. Furthermore, the present overview of family, communication, and culture ends up supporting the idea of positive associations being derived from the pivotal role of marriage relationship quality, such that coparenting and communication practices vary substantially within intercultural marriages moderated by gender roles.

Culture is a pivotal moderator of these associations, but this analysis needs to be tethered to societal structural level, in which cultural differences, family members’ immigration status, media content, and level of acculturation must be included in family research. This is because in intercultural marriages, in addition to the tremendous parenting role, they have to deal with cultural assimilation and discrimination, and this becomes important if we care about children’s cognitive development and the overall well-being of those who are not considered White. As this article shows, the quality of familial interactions has direct consequences on children’s developmental outcomes (for a review, see Callaghan et al., 2011 ).

Therefore, the structure and functioning of family has an important impact on public health at both physiological and psychological levels (Gage, Everett, & Bullock, 2006 ). At the physiological level, the familial interaction instigates expression and reception of strong feelings affecting tremendously on individuals’ physical health because it activates neuroendocrine responses that aid stress regulation, acting as a stress buffer and accelerating physiological recovery from elevated stress (Floyd & Afifi, 2012 ; Floyd, 2014 ). Robles, Shaffer, Malarkey, and Kiecolt-Glaser ( 2006 ) found that a combination of supportive communication, humor, and problem-solving behavior in husbands predicts their wives’ cortisol and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)—both physiological factors are considered as stress markers (see 2006 ). On the other hand, the psychology of individuals, the quality of family relationships has major repercussions on cognitive development, as reflected in educational attainment (Sohr-Preston et al., 2013 ), and highly mediated by cultural assimilation (Schwartz et al., 2013 ), which affects individuals through parenting modeling and socialization of values (Mooney-Doyle, Deatrick, & Horowitz, 2014 ).

Further Reading

- Allport, G. W. (1979). The nature of prejudice . Basic books.

- Arias, S. , & Hellmueller, L. (2016). Hispanics-and-Latinos and the US Media: New Issues for Future Research. Communication Research Trends , 35 (2), 4.

- Barreto, M. , & Segura, G. (2014). Latino America: How AmericaÕs Most Dynamic Population is Poised to Transform the Politics of the Nation . Public Affairs.

- Benish‐Weisman, M. , Levy, S. , & Knafo, A. (2013). Parents differentiate between their personal values and their socialization values: the role of adolescents’ values. Journal of Research on Adolescence , 23 (4), 614–620.

- Child, J. T. , & Westermann, D. A. (2013). Let’s be Facebook friends: Exploring parental Facebook friend requests from a communication privacy management (CPM) perspective. Journal of Family Communication , 13 (1), 46–59.

- Canary, H. , & Canary, D. J. (2013). Family conflict (Key themes in family communication). Polity.

- Dixon, C. (2015). Rural development in the third world . Routledge.

- Dovidio, J. F. , Gluszek, A. , John, M. S. , Ditlmann, R. , & Lagunes, P. (2010). Understanding bias toward Latinos: Discrimination, dimensions of difference, and experience of exclusion. Journal of Social Issues , 66 (1), 59–78.

- Fitzpatrick, M. A. , & Koerner, A. F. (2005). Family communication schemata: Effects on children’s resiliency. The evolution of key mass communication concepts: Honoring Jack M. McLeod , 115–139.

- Fullerton, A. S. (2014). Work, Family Policies and Transitions to Adulthood in Europe. Contemporary Sociology: A Journal of Reviews , 43 (4), 543–545.

- Galvin, K. M. , Bylund, C. L. , & Brommel, B. J. (2004). Family communication: Cohesion and change . Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

- Lichter, D. T. , Carmalt, J. H. , & Qian, Z. (2011, June). Immigration and intermarriage among Hispanics: Crossing racial and generational boundaries. In Sociological Forum (Vol. 26, No. 2, pp. 241–264). Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

- Koerner, A. F. , & Fitzpatrick, M. A. (2006). Family conflict communication. The Sage handbook of conflict communication: Integrating theory, research, and practice , 159–183.

- McLeod, J. M. , & Chaffee, S. H. (1973). Interpersonal approaches to communication research. American behavioral scientist , 16 (4), 469–499.

- Sabourin, T. C. , Infante, D. A. , & Rudd, J. (1993). Verbal Aggression in Marriages A Comparison of Violent, Distressed but Nonviolent, and Nondistressed Couples. Human Communication Research , 20 (2), 245–267.

- Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Advances in experimental social psychology , 25 , 1–65.

- Schrodt, P. , Witt, P. L. , & Shimkowski, J. R. (2014). A meta-analytical review of the demand/withdraw pattern of interaction and its associations with individual, relational, and communicative outcomes. Communication Monographs , 81 (1), 28–58.

- Stewart, C. O. , Pitts, M. J. , & Osborne, H. (2011). Mediated intergroup conflict: The discursive construction of “illegal immigrants” in a regional US newspaper. Journal of language and social psychology , 30 (1), 8–27.

- Taylor, M. , & Segrin, C. (2010). Perceptions of Parental Gender Roles and Conflict Styles and Their Association With Young Adults' Relational and Psychological Well-Being. Communication Research Reports , 27 (3), 230–242.

- Tracy, K. , Ilie, C. , & Sandel, T. (Eds.). (2015). International encyclopedia of language and social interaction . Vol. 1. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Tulananda, O. , Young, D. M. , & Roopnarine, J. L. (1994). Thai and American fathers’ involvement with preschool‐age children. Early Child Development and Care , 97 (1), 123–133.

- Turkle, S. (2012). Alone together: Why we expect more from technology and less from each other . New York: Basic Books.

- Twenge, J. M. (2014). Generation Me—revised and updated: Why today’s young Americans are more confident, assertive, entitled—and more miserable than ever before . New York: Simon and Schuster.

- U.S. Department of Homeland Security (2014). Yearbook of immigration statistics: 2013 . Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics.

- Valentino, N. A. , Brader, T. , & Jardina, A. E. (2013). Immigration opposition among US Whites: General ethnocentrism or media priming of attitudes about Latinos? Political Psychology , 34 (2), 149–166.

- Worley, T. R. , & Samp, J. (2016). Complaint avoidance and complaint-related appraisals in close relationships: A dyadic power theory perspective. Communication Research , 43 (3), 391–413.

- Xie, Y. , & Goyette, K. (1997). The racial identification of biracial children with one Asian parent: Evidence from the 1990 census. Social Forces , 76 (2), 547–570.

- Weigel, D. J. , & Ballard-Reisch, D. S. (1999). All marriages are not maintained equally: Marital type, marital quality, and the use of the maintenance behaviors. Personal Relationships , 6 , 291–303.

- Weigel, D. J. , & Ballard-Reisch, D. S. (1999). How couples maintain marriages: A closer look at self and spouse influences upon the use of maintenance behaviors in marriages. Family Relations , 48 , 263–269.

- Aloia, L. S. , & Solomon, D. H. (2013). Perceptions of verbal aggression in romantic relationships: The role of family history and motivational systems. Western Journal of Communication , 77 (4), 411–423.

- Arias, V. S. , & Hellmueller, L. C. (2016). Hispanics-and-Latinos and the U.S. media: New issues for future research. Communication Research Trends , 35 (2), 2–21.

- Bales, R. F. , & Parsons, T. (2014). Family: Socialization and interaction process . Oxford: Routledge.

- Beach, S. R. , Barton, A. W. , Lei, M. K. , Brody, G. H. , Kogan, S. M. , Hurt, T. R. , . . ., Stanley, S. M. (2014). The effect of communication change on long‐term reductions in child exposure to conflict: Impact of the Promoting Strong African American Families (ProSAAF) program. Family Process , 53 (4), 580–595.

- Benish-Weisman, M. , Levy, S. , & Knafo, A. (2013). Parents differentiate between their personal values and their socialization values: The role of adolescents’ values. Journal of Research on Adolescence , 23 (4), 614–620.