50 Best Sports Psychology Research Topics

When it comes to selecting sports psychology research topics, it might seem like a challenging task in the eyes of many students. But once you choose a topic from our list and master the tricks of writing a professional research paper, you present yourself as an expert researcher in no time.

What makes a sports psychologist proficient? Sports psychology requires a proficient application of psychological knowledge and skills to address athletes’ most favorable performance and well-being. When studying psychology, your lecturers require you to be skilled and creative in writing and presenting research findings.

At HelpForHomework, we help you deliver your findings like a pro by guiding you through your research process. After choosing the best topics, we connect you to a team of professional writers who explain the step-by-step processes of writing top-notch research papers. Our support staff is available 24/7 to assist you. Alternatively, you can order research paper writing services by clicking the contact us button.

Need help doing your assignment?

How We Select The Best Sports Psychology Research Topics

We select unique topics

Originality is essential in research writing. That is why we formulate unique ideas and identify shallowly researched topics for you to expound on them.

Feasibility

Before publishing this article, we carried out feasibility tests on the sports psychology research topics. When carrying out the tests, we ask:

- Is the project sustainable?

- Is the project relevant?

- Is the research question possible to answer

- Is the scope of the research question manageable?

At HelpForHomework, we generate sports psychology topics that are interesting to write and appealing to your audience. If you are looking for fascinating ideas, check out the list below.

Expert Tip: After finding relevant sports psychology research topics, ensure you confirm and ask for guidance from your professor at an early stage. Also, it would be helpful if you contact our support department after selecting a topic.

Best Sports Psychology Topics

Are you looking for the best sports psychology research topics? We have some recommendations for you.

- Historical and modern perspective of sports psychology

- How to utilize and improve sports psychology for better customer experience in a sports merchandise store

- Importance of employing sports psychologists in elite sports

- Role of sports psychology and nutrition in musculoskeletal injuries in professional rugby

- Scientific application in sports psychology in sports

- Sports psychology and health: Strategies for creating a healthy and high-performance workplace

- Sports psychology in your local football or soccer league

- Sports psychology perspective on the importance of motivation in increases success

- Sports psychology: An essential aspect for athletes success

- Sports psychology: how to deal with fatigue

Excellent Sports Psychology Research Topics

Finding excellent sports psychology research topics can be a hassle. That is why we have generated top ideas to help you in your next project.

- Application of Artificial Intelligence in sports psychology

- Application of psychophysiology in sports psychology

- Personality dimensions in sports psychology

- Psychological factors affecting physical performance and sports

- Role of sports psychology in individual development in sports

- Sports psychology in police training: Building understanding across all police disciplines

- Sports psychology in your country: Review of sports psychology journals

- Sports psychology perspective of anxiety

- Sports psychology perspective of electronic sports

- The role of sports psychology in controlling obesity

Interesting Sports Psychology Research Topics

If you are looking for exciting sports psychology research topics, you are on the right platform. Check them out and contact the support for more guidance.

- Analysis and visualization of anxiety in final football matches

- Case study: Relationship between competitive anxiety and mental toughness

- Effects of temperament and anxiety on sports performance

- How do anxiety and ego depletion affect sports performance?

- Impact of spectator behavior on individual player’s psychology

- Impact of spectator behavior on team performance

- Managing anxiety levels in sports performance

- Sports psychology perspective: Measuring anxiety in sports

- Understanding fear and anxiety management in extreme sports

- Use of music in mental training

Expert Sports Psychology Research Topics

When you select expert-generated sports psychology research topics, you will for sure impress your audience. We hope you find the best topic from the list below:

- Challenges of gender studies in sport psychology

- Compare and contrast anxiety and self-confidence between a team and individual sports at your college

- Controlling fans aggression

- Dealing with negative stereotypes in sports: Women soccer

- Mental toughness and sports competition anxiety for male and female MMA fighters

- Psychological and physiological impacts of doping in sports

- Relationship between arousal-anxiety and sports behavior

- Sports psychology: Children anxiety in sports

- Sports psychology: Effects of racial abuse on athletes

- Volitional regulation and motivation of young boxers

Exciting Sports Psychology Research Topics

Although looking for sports psychology topics can be mind-boggling, we have cut the hassle and generated fascinating topics for you.

- Application of sports psychology in goal setting

- Effectiveness of psychological intervention during a long-term sports injury rehabilitation

- Literature review: Impacts of physical activity in the treatment of depression

- Neuropsychology of sports rehabilitation

- Organizations support mechanisms for soccer players in major leagues. How does league organization affect performance?

- Social factors affecting sports performance in your country

- Sports psychology: Anxiety and emotions of women in sports

- Systematic review: How do skiers manage stress and anxiety before a competition?

- The role of imagery in sports performance

- Theoretical aspects of motivation in sports rehabilitation

Final Verdict

Have you found top-quality sports psychology research topics? If not, contact our support team and let us share other ideas. You can be sure we will offer you reliable psychology research writing services. So bring all the questions and let us help you in the best way as we always do. Press the contact button and consult us. also check out Neuropsychology Research topics.

Recent Posts

- Do You Say Masters or Master’s?

- Writing A Case Conceptualization

- Degree Accelerator Guide: Fast-Track Your College Education

- Care Plan Approaches

- 3/4 Page Essay Writing Guide: Structure, Tips & Topics

You cannot copy content of this page

What We’ve Learned Through Sports Psychology Research

Scientists are probing the head games that influence athletic performance, from coaching to coping with pressure

Tom Siegfried, Knowable Magazine

:focal(800x602:801x603)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/3c/1c/3c1cf8e9-0694-438d-89ef-6ea678a8239e/sports-psychology-1600x1200_web.jpg)

Since the early years of this century, it has been commonplace for computerized analyses of athletic statistics to guide a baseball manager’s choice of pinch hitter, a football coach’s decision to punt or pass, or a basketball team’s debate over whether to trade a star player for a draft pick.

But many sports experts who actually watch the games know that the secret to success is not solely in computer databases, but also inside the players’ heads. So perhaps psychologists can offer as much insight into athletic achievement as statistics gurus do.

Sports psychology has, after all, been around a lot longer than computer analytics. Psychological studies of sports appeared as early as the late 19th century. During the 1970s and ’80s, sports psychology became a fertile research field. And within the last decade or so, sports psychology research has exploded as scientists have explored the nuances of everything from the pursuit of perfection to the harms of abusive coaching.

“Sport pervades cultures, continents and indeed many facets of daily life,” write Mark Beauchamp, Alan Kingstone and Nikos Ntoumanis, authors of an overview of sports psychology research in the 2023 Annual Review of Psychology .

Their review surveys findings from nearly 150 papers investigating various psychological influences on athletic performance and success. “This body of work sheds light on the diverse ways in which psychological processes contribute to athletic strivings,” the authors write. Such research has the potential not only to enhance athletic performance, they say, but also to provide insights into psychological influences on success in other realms, from education to the military. Psychological knowledge can aid competitive performance under pressure, help evaluate the benefit of pursuing perfection and assess the pluses and minuses of high self-confidence.

Confidence and choking

In sports, high self-confidence (technical term: elevated self-efficacy belief) is generally considered to be a plus. As baseball pitcher Nolan Ryan once said, “You have to have a lot of confidence to be successful in this game.” Many a baseball manager would agree that a batter who lacks confidence against a given pitcher is unlikely to get to first base.

And a lot of psychological research actually supports that view, suggesting that encouraging self-confidence is a beneficial strategy. Yet while confident athletes do seem to perform better than those afflicted with self-doubt, some studies hint that for a given player, excessive confidence can be detrimental. Artificially inflated confidence, unchecked by honest feedback, may cause players to “fail to allocate sufficient resources based on their overestimated sense of their capabilities,” Beauchamp and colleagues write. In other words, overconfidence may result in underachievement.

Other work shows that high confidence is usually most useful in the most challenging situations (such as attempting a 60-yard field goal), while not helping as much for simpler tasks (like kicking an extra point).

Of course, the ease of kicking either a long field goal or an extra point depends a lot on the stress of the situation. With time running out and the game on the line, a routine play can become an anxiety-inducing trial by fire. Psychological research, Beauchamp and co-authors report, has clearly established that athletes often exhibit “impaired performance under pressure-invoking situations” (technical term: “choking”).

In general, stress impairs not only the guidance of movements but also perceptual ability and decision-making. On the other hand, it’s also true that certain elite athletes perform best under high stress. “There is also insightful evidence that some of the most successful performers actually seek out, and thrive on, anxiety-invoking contexts offered by high-pressure sport,” the authors note. Just ask Michael Jordan or LeBron James.

Many studies have investigated the psychological coping strategies that athletes use to maintain focus and ignore distractions in high-pressure situations. One popular method is a technique known as the “quiet eye.” A basketball player attempting a free throw is typically more likely to make it by maintaining “a longer and steadier gaze” at the basket before shooting, studies have demonstrated.

“In a recent systematic review of interventions designed to alleviate so-called choking, quiet-eye training was identified as being among the most effective approaches,” Beauchamp and co-authors write.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/db/00/db007d50-eb78-4314-aff0-6be80d65ec0b/gettyimages-1946568854_web.jpg)

Another common stress-coping method is “self-talk,” in which players utter instructional or motivational phrases to themselves in order to boost performance. Saying “I can do it” or “I feel good” can self-motivate a marathon runner, for example. Saying “eye on the ball” might help a baseball batter get a hit.

Researchers have found moderate benefits of self-talk strategies for both novices and experienced athletes, Beauchamp and colleagues report. Various studies suggest that self-talk can increase confidence, enhance focus, control emotions and initiate effective actions.

Moderate performance benefits have also been reported for other techniques for countering stress, such as biofeedback, and possibly meditation and relaxation training.

“It appears that stress regulation interventions represent a promising means of supporting athletes when confronted with performance-related stressors,” Beauchamp and co-authors conclude.

Pursuing athletic perfection

Of course, sports psychology encompasses many other issues besides influencing confidence and coping with pressure. Many athletes set a goal of attaining perfection, for example, but such striving can induce detrimental psychological pressures. One analysis found that athletes pursuing purely personal high standards generally achieved superior performance. But when perfectionism was motivated by fear of criticism from others, performance suffered.

Similarly, while some coaching strategies can aid a player’s performance, several studies have shown that abusive coaching can detract from performance, even for the rest of an athlete’s career.

Beauchamp and his collaborators conclude that a large suite of psychological factors and strategies can aid athletic success. And these factors may well be applicable to other areas of human endeavor where choking can impair performance (say, while performing brain surgery or flying a fighter jet).

But the authors also point out that researchers shouldn’t neglect the need to consider that in sports, performance is also affected by the adversarial nature of competition. A pitcher’s psychological strategies that are effective against most hitters might not fare so well against Shohei Ohtani, for instance.

Besides that, sports psychology studies (much like computer-based analytics ) rely on statistics. As Adolphe Quetelet, a pioneer of social statistics, emphasized in the 19th century, statistics do not define any individual—average life expectancy cannot tell you when any given person will die. On the other hand, he noted, no single exceptional case invalidates the general conclusions from sound statistical analysis.

Sports are, in fact, all about the quest of the individual (or a team) to defeat the opposition. Success often requires defying the odds—which is why gambling on athletic events is such a big business. Sports consist of contests between the averages and the exceptions, and neither computer analytics nor psychological science can tell you in advance who is going to win. That’s why they play the games.

Get the latest Science stories in your inbox.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 05 February 2024

The role of the six factors model of athletic mental energy in mediating athletes’ well-being in competitive sports

- Amisha Singh ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4456-3510 1 ,

- Mandeep Kaur Arora 2 &

- Bahniman Boruah 1

Scientific Reports volume 14 , Article number: 2974 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

1546 Accesses

Metrics details

- Human behaviour

In the realm of high-performance sports, athletes often prioritize success at the expense of their well-being. Consequently, sports psychology researchers are now focusing on creating psychological profiles for athletes that can forecast their performance while safeguarding their overall well-being. A recent development in this field is the concept of athletic mental energy (AME), which has been associated with both sporting success and positive emotions. Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore if AME in athletes can mediate this directly observed relationship between performance and psychological well-being. For stronger predictive validity these relationships were examined across two studies with each involving distinct sets of participants engaged in various sports disciplines, including football, cricket, basketball, archery, and more. The self-report measures of sports performance, athletic mental energy (AME), and psychological well-being (PWB) were administered post-competition on the local, regional, state, national, international, and professional level athletes of age 18 and above. Our study found that both, the affective and cognitive components of AME mediated the athletes’ performance and psychological well–being relationship. Interestingly, the study found no significant gender differences in AME and PWB scores. While family structures didn’t yield significant variations in AME scores, there were some descriptive distinctions in PWB scores across different family structures. Our research offers preliminary evidence suggesting that AME can play a pivotal role in preserving athletes’ psychological well-being following competitive events.

Similar content being viewed by others

Validation and personality conditionings of the 3 × 2 achievement goal model in sport

Narcissistic coaches and athletes’ individual rowing performance

Validation of Sport Anxiety Scale-2 (SAS-2) among Polish athletes and the relationship between anxiety and goal orientation in sport

Introduction.

Engagement in sports has a profound impact on the physical, psychological, and social well-being of athletes, as demonstrated by various studies indicating that sports training leads to improvements in athletes’ cardiovascular health, neuromuscular function, and respiratory capacity, along with other physiological benefits such as enhanced metabolism, better sleep, and a strengthened immune system 1 , 2 , 3 . Beyond the physical advantages, sports participation also nurtures essential psychological skills like self-esteem, competence, resilience, and motivation, all of which can positively influence various aspects of an athlete’s life 1 . Furthermore, organized sports activities offer a platform for athletes to communicate, build relationships, collaborate, and cultivate a sense of belonging 4 . However, it’s important to acknowledge that an individual’s engagement in competitive sports is not without its challenges and stressors 1 , 5 . Athletes confront a range of stressors stemming from their training and competitions, including sport-specific challenges (e.g., the pressure to win, injuries, and team selection), general life issues (e.g., family relationships and economic conditions), and organizational aspects (e.g., team selection, accommodations, and travel support) 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 . These challenges can lead to both physical and psychological problems for athletes. Physically, stress can increase the risk of cardiovascular disease, hyperglycemia, stomach and intestinal ulcers, and asthma 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 . Psychologically, athletes may experience decreased well-being, deteriorating sports performance, mood disorders, eating disorders, depression, anxiety, overtraining, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, burnout, and increased episodes of depression 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 . Additionally, the stress resulting from past unsatisfactory performance can manifest as pain, discomfort, and performance anxiety, all of which can significantly affect an athlete’s well-being and performance efficiency 20 , 21 , 22 .

Athletes need psychological skills to tackle these challenges by managing emotions, handling stressors, and achieving their goals 23 , 24 . Training in these skills not only fosters effective coping strategies but also yields psychological benefits that boost their performance and overall well-being in competitive sports, making them crucial for success 25 , 26 .

Over time, the field of sports psychology has shifted its focus from solely improving athletic performance to considering athlete well-being as an integral part of performance 27 . Well-being is a multidimensional phenomenon that encompasses cognitive and affective dimensions resulting from an individual’s assessment of various aspects of life 28 . The close connection between performance and psychological well-being in sports has prompted researchers to investigate the underlying factors influencing the performance-well-being relationship, enabling practitioners to develop programs and interventions aimed at preventing ill-being resulting from underperformance or high-performance expectations.

One emerging concept of particular interest in sports is "athletic mental energy (AME)," which may play a vital role in athletes’ performance and psychological well-being. Generally, mental energy refers to an individual’s capacity to concentrate on a task and block out distractions 29 . Notably, historical figures like Newton, Galileo, Archimedes, and Einstein possessed strong mental energy, which enabled them to accomplish remarkable feats 30 . The International Life Science Institute (ILSI) suggests that mental energy relates to an individual’s belief in their ability to accomplish a given task. Lu et al. 79 expanded on the ILSI concept of mental energy and defined AME as a multifaceted construct specific to sports, characterized by an athlete’s perceived state of energy, comprising cognitive components such as confidence, concentration, motivation, and mood. These components have been frequently observed in flow research, where Olympic athletes with high AME report an optimal level of activation necessary for peak performance, success, and experiences of flow 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 . For instance, athletes with higher confidence and concentration tend to fear failure less, perform better, report better performance, and have more frequent experiences of flow during optimal performance 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 . Motivation is also recognized as a vital component of AME, with numerous studies in sports psychology emphasizing its relevance for peak performance. The emotional components of AME, including vigor, calmness, and tirelessness, are positively correlated with athletic performance, well-being, and a positive mental state 38 , 45 , 46 , 47 . High AME has been associated with lower athletic burnout and stress, moderating the negative effects of stress and burnout in athletes 48 . For example, research suggests that Olympic medalists in rowing with high vigor experience lower levels of depression and fatigue compared to their counterparts 49 , 50 . In alignment with the principles of positive psychology, AME encompasses positive elements that can help athletes manage stress resulting from perceived performance and safeguard their well-being. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that athletes with high AME are more likely to deliver exceptional sports performance, exhibit greater engagement and consistency in training and competitions, and experience higher levels of well-being compared to athletes with lower AME levels. However, further research is necessary to validate these assumptions.

Researchers are increasingly interested in developing athletes’ mental and emotional profiles to predict both their performance and well-being. The predictive validity of such profiles holds theoretical and practical implications for future research and intervention development. To our knowledge, this study represents the first attempt to examine the influence of AME on the relationship between athletes’ performance and psychological well-being post-competition. Additionally, our study draws support from various established models and concepts in psychology, including Morgan’s iceberg profile, Hanin’s Individual Zone of Optimal Functioning (IZOF), the Profile of Mood States (POMS) by McNair, Lorr, and Droppleman, psychological skills by Mahoney et al. 53 , performance strategies by Thomas et al. 54 , mental skills by Durand-Bush et al. 55 , mental toughness by Jones et al. 56 , and resilience by Fletcher and Sarkar 35 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 . These models have consistently demonstrated the relationship between performance and psychological state in athletes, further reinforcing the significance of our research in exploring the mediating role of AME in athletes’ performance and psychological well-being.

The present study

Athletes experience significant pressure to excel in competitive sports, impacting their psychological well-being. Poor performance can exacerbate stress and anxiety, harming mental health. Nonetheless, recent research suggests that harnessing athletic mental energy (AME) can help preserve athletes’ well-being. Therefore, through our research we aimed to investigate the connection between sports performance and psychological well-being, using athletic mental energy (AME) as a mediator. The hypothesis was that AME would play a mediating role in the relationship between performance and psychological well-being. Two cross-sectional studies with quantitative research designs were conducted with different groups of participants. Study 1 aimed to explore the mediating effects of AME on the relationship between an athlete’s performance and psychological well-being, while Study 2 sought to replicate the findings of Study 1 and further confirm the role of AME as a mediator in the relationship between athletes’ performance and psychological well-being.

To examine the mediating effects of athletic mental energy on the relationship between athletes’ performance and psychological well-being.

Participants

For study 1 participants were 50 athletes (males = 50%) with an average age of 20.34 years (SD = ± 1.86) from 10 states of India. At the time of the data collection, 70% of participants were regularly engaged in competitive sports from 15 different individual and team sports, including archery (6), athletics (7), bodybuilding (1), baseball (1), boxing (1), kho-kho (1), rock-climbing (1), table tennis (1), sprinting (1), taekwondo (1), cricket (3), hockey (3), football (12), kabaddi (4), and volleyball (7). The sample was representative of diverse competitive levels, with 58% of participants being national and international athletes.

The average hours of engagement in sports training per week were 23.04 h (SD = 10.68), furthermore, on average the athletes were active in sports for 3.86 (SD = 1.94) years. Lastly, some exclusion criteria were pre-defined across both studies including the exclusion of winter and traditional sports, players competing in parasport, and participants who had not participated in any competitive encounters for the last month (one week for participants in study 2) due to injury, illness, or non-selection.

Measurements and procedures

The study adhered to the American Psychological Association’s (APA) Code of Ethics throughout its entirety. The Departmental Research Council (DRC) approved the study before initiation. Coaches, physical education instructors, and sports clubs were informed of the research’s purpose via email and phone calls by the lead author. Subsequent agreements included details on contacting players, assessment duration, location, and other requirements. During appointments with participants, the study’s purpose, nature, design, and ethical rights were explained, including informed consent, debriefing, anonymity, data safety, confidentiality, and the right to withdraw. Participants received a hard copy of a multi-section questionnaire which was built through the approval of the experts including 2 academicians, 2 counselors, and 1 psychometrician for the sequence and presentation of the Questionnaire. Section A collected demographic and sports profiles (e.g., gender, location, age, family structure, sport category, types of sports, highest competition participated in, and years of athletic experience). Section B included psychological scales: Performance Satisfaction (PS), Psychological Well-being (PWB), and Athletic Mental Energy Scale (AMES). To mitigate social desirability bias, participants were informed that the study aimed to understand their life experiences as sports performers, with no right or wrong answers. Mental energy, as a state construct, is best measured close to competition to reflect the exact mental and emotional state 38 , 57 , 58 , 59 . However, participants completed the scales within one month after the competition due to tight schedules and depleted energy, mood, and motivation during competitions. They were asked to reflect on their sporting experiences from the past month when responding to items.

Demographic questionnaire

In section A, the demographic profile questionnaire contains participants’ information including gender, location, age, and family structure while the sport profile questionnaire contains participants’ information related to sports including sport category, types of sports, highest competition participated in, and years of athletic experiences, etc.

Psychological well-being (PWB)

Psychological Well-being (PWB) is an 18-item scale by Ryff and Keyes (1995), assessing six components: autonomy, environmental mastery, purpose in life, personal growth, positive relations with others, and self-acceptance. Participants rated their agreement with each statement on a 7-point scale (1 = strongly agree; 7 = strongly disagree). Cronbach’s α for the total PWB score was 0.78 60 , 61 , 62 . For the final analysis, we used the total score of PWB.

Athletic mental energy scale (AMES).

The athletic mental energy scale (AMES), by Lu et al. 79 , comprises 18 items measuring athletes’ perception of their energy state, including vigor, confidence, motivation, tirelessness, concentration, and calm. Participants rated their feelings on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, 6 = completely so). Cronbach’s α for the total AMES score was 0.92 48 , 63 . We used the total score of AMES for the main analysis in Study 1 and scores on each subscale in Study 2.

Subjective performance (SP)

Subjective Performance scale (SP) by Brown (2017) was used to assess participants’ satisfaction with past competitive performances over a month (or a week in Study 2) using an 11-point rating scale (0 = totally dissatisfied, 10 = totally satisfied; cf. Pensgaard and Duda, 2003). This approach allows for comparisons among athletes across different sports, offers sensitivity in performance assessment, and minimizes environmental influences (for example, opponent’s skill level) 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 .

Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis has been performed with SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) Version 23. None of the participants were identified as univariate outliers through the inspection by a boxplot. All the participants were kept for analysis. Furthermore, the scores of AMES, PWB, and SP were normally distributed through the assessment of Q-Q plots and the Shapiro–Wilk test (W 50) = 0.84, p = 0.07). Furthermore, we used mediation analysis using Hayes Process v4.1 macro in examining the mediating effects of the AMES on the performance and psychological well-being relationship. The significance level across both studies was set at p < 0.05.

The reliability of a measure in any research study is the measure of internal consistency and is accepted if the Alpha (α) value of the latent construct is greater than 0.70 69 . Internal consistency reliability for the current study was assessed using Cronbach’s Alpha. The results revealed that the AMES with 18 items (α = 0.92) and the PWB Scale with 18 items (α = 0.78) were found reliable for Indian athletes (n = 50).

The sample of athletes (N = 50) consisted of 25 (50%) females with the highest percentage of athletes from Delhi i.e., 25 (50%), followed by Haryana and Uttar Pradesh i.e., 7 (14%). The remaining athletes were from Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Manipur, and Mumbai 1 (2% each), 4% from Himachal Pradesh and Jharkhand (2 each), and 3 (6%) from Rajasthan. Furthermore, 17 (34%) athletes were living in joint families, 19 (38%) in nuclear families, and 14 (28%) in single-parent families. For sport profile, 19 (38%) sample of athletes belonged to the individual and 31 (62%) belonged to the team sport category, 13 (26%) Junior category and 37 (74%) belonged to the senior category. The sport category of the participants was 01 each for baseball, bodybuilding, boxing, kho-kho, rock climbing, sprinting, table tennis, taekwondo (2% each), 03 each in Cricket and hockey (6% each), 04 in kabaddi (8%), 06 in Archery (12%), 07 in athletics (14%), and 12 in Football (24%). A maximum number of athletes were engaged in a regular training session 35 (70%). Lastly, in the current sample of athletes, 4(8%) were professionals, 5(10%) were international-level athletes, 24 (48%) were national-level athletes, 14 (28%) were state-level athletes, and 3 (6%) were regional and local-level athletes.

We found an overall mean score of 4.23 (SD = 0.97) for AME, indicating an overall moderate AME experience amongst athletes. Motivation ( \( \overline{{\text{X}}} \) = 4.62; SD = 1.04) and Concentration ( \( \overline{{\text{X}}} \) = 4.41; SD = 1.05) had the highest mean values, demonstrating that players feel motivated and persist in high concentration levels during training or competition. Furthermore, an overall mean score of PWB ( \( \overline{{\text{X}}} \) = 4.81; SD = 0.74) shows an overall moderate PWB experience amongst athletes. Personal growth ( \( \overline{{\text{X}}} \) = 5.28; SD = 1.17) and Self-acceptance ( \( \overline{{\text{X}}} \) = 5.12; SD = 0.95) in PWB had the highest mean values, demonstrating that the players generally have a sense of growth, are open to new experiences, and have a positive attitude towards themselves through the acknowledgment and acceptance of all the aspects in life. Lastly, the descriptive statistics for SP reveal overall moderate (M = 6.3; SD = 1.66) SP experiences amongst athletes.

Also, the data was collected from athletes from three different family structures i.e., joint (n = 15), nuclear (n = 16), and the single-parent family (n = 19), and the results from descriptive statistics reveal an overall mean score of 83.66 (SD = 21.97) for the psychological well-being of athletes living in a joint family, 83.50 (SD = 20.01) for the nuclear family, and 83.62 (SD = 18.93) for a single-parent family.

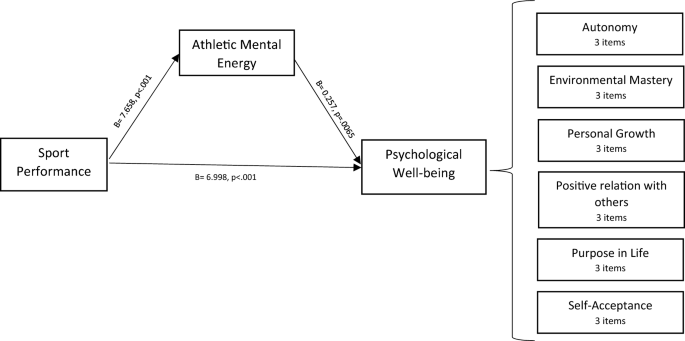

Lastly, the study assessed the mediating role of AME on the post-competitive relationship between subjective performance and psychological well-being. The results demonstrated a non-significant indirect effect of the impact of subjective performance on psychological well-being (b = 1.24, t = 7.0). However, the direct effect of subjective performance on PWB in the presence of a mediator was found significant (b = 9.58, p < 0.001). Hence, athletic mental energy did not mediate the relationship between subjective performance and PWB. To save space, we show only the figure of the mediating effect of AME on the athletes’ performance-psychological well-being relationship (refer to Fig. 1 ). The mediation analysis summary is presented in Table 1 .

Mediation analysis representing the relationship between Sport performance and psychological well-being with athletic mental energy as a mediator.

Discussion for study 1

Our study extended Lu et al. 79 work on AME by examining its mediating effects on the relationship between athletes’ performance and psychological well-being post-competition. The results of the descriptive statistics on the mean score of the psychological well-being of athletes from a joint family, nuclear family, and single-parent family indicate some group differences. However, the significance of this group difference is yet to be tested. Furthermore, the results from the mediation analysis revealed that athletic mental energy did not mediate the relationship between sport performance and PWB. Nonetheless, the first study provides preliminary evidence of the direct effect of athletes’ performance on PWB. Furthermore, the results of our study could be explained either due to the small sample size or due to the long gap time interval between the participants’ involvement in sports competition and the conduction of the test which ultimately fails to record the actual state of athletes’ mental energy in relation to their competitive performance. Therefore, for the second study, a greater number of participants and a lesser time frame for test administration shall be kept for the participants to reflect their exact psychological state relating to their competitive encounter.

The aim of our second was to recreate Study 1 and further confirm the mediating effects of AME on the athletes’ performance and psychological well-being relationship.

For study 2 participants were 100 athletes (males = 50%) with an average age of 23.11 years (SD = ± 2.32) from 14 states in India. At the time of the data collection, 78% of athletes were regularly participating in training seasons. Also, the participants were from 15 different types of individual and team sports including aerobics (3), athletics (15), archery (1), badminton (4), basketball (11), baseball (1), cricket (3), football (20), handball (2), hockey (4), kho-kho (8), roller skating (1), sprinting (2), table tennis (2), and volleyball (23). 40% of participants were national level players followed by 5% professional and international level players. The average hours of engagement of athletes in sports training per week were 15.77 h (SD = 9.54) and the number of years athletes were active in sports on average was 4.35 years (SD = 1.14). The exclusion criteria were kept the same as in Study 1.

Study 2 followed a procedure consistent with Study 1, maintaining data collection methods, assessment measures, and statistical analyses. The Cronbach’s α for Psychological Well-being (PWB) and athletic mental energy scale (AMES) in Study 2 were 0.74 and 0.93, indicating satisfactory internal consistency. Upon securing informed consent, participants received a multi-section questionnaire. To align with the need to capture participants’ accurate psychological states, AME assessments were conducted within one week of the competitive encounters 25 , 45 , 58 , 59 . Participants who agreed to this timeline were included in the study, while others were excluded. Participants were instructed to reflect on their experiences from competitive sports encounters in the past week when responding to the questionnaire items.

In Study 2, data analysis paralleled the procedures in Study 1. All data were initially screened to ensure they met the prerequisites for t-tests and ANOVA. Univariate outliers were absent based on boxplot examination, resulting in the retention of all participants for analysis. Normality checks for psychological well-being, athletic mental energy, and subjective performance were performed using skewness and kurtosis values within acceptable limits (skewness between ± 2 (George and Mallery, 2020), and kurtosis from a range of − 10 to + 10 (Collier, 2020), alongside the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test confirming a normal distribution (W (100) = 0.053, p = 0.20). This mediation analysis was executed in two phases, initially examining the total AME score in Phase 1 and subsequently assessing the scores for the six AME factors.

As assessed through Cronbach’s Alpha, the scales, AMES with 18 items (α = 0.93) and the PWB Scale with 18 items (α = 0.74) were found reliable for Indian athletes (n = 100).

The participants (N = 100) consisted of 50 (50%) females and 50 (50%) male athletes with the highest percentag e of athletes from Delhi i.e., 53%, followed by Haryana (18%) and Uttar Pradesh (17%). The remaining athletes were from Rajasthan (2%), followed by Arunachal Pradesh, Bhopal, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Jammu & Kashmir, Jharkhand, Manipur, Mumbai, Punjab, and Uttarakhand (10%). Furthermore, 34% of athletes belonged to joint families with an equal percentage of athletes from nuclear families, and 32% of athletes were from single-parent families. For the sport profile, 22% of athletes belonged to the individual sport category and 78% belonged to the team sport category in which 22% Junior category, and 78% belonged to the senior category. The highest percentage of athletes were from Volleyball (23%) followed by football (20%), athletics (15%), basketball (11%), kho-kho (8%), and remaining other sport categories (23%). A maximum percentage of athletes were engaged in a regular training session (78%). Lastly, in the current sample of athletes, 3% were professionals, 2% were international-level athletes, 40% were national-level athletes, 18% were state-level athletes, and 37% were regional and local-level athletes.

The results from descriptive statistics for AME reveal overall moderate AME experiences amongst athletes with a mean score of 4.12 (SD = 0.95). Vigor ( \( \overline{{\text{X}}} \) = 4.17; SD = 1.13) and Motivation ( \( \overline{{\text{X}}} \) = 4.61; SD = 1.10) had the highest mean value, demonstrating that the athletes felt energetic and enthusiastic about sports and generally felt motivated towards training and competition Similarly, descriptive statistics for PWB reveal overall moderate PWB experiences amongst athletes (M = 4.79; SD = 0.65). Similar to the study1, Personal growth ( \( \overline{{\text{X}}} \) = 5.32; SD = 1.08) and self-acceptance ( \( \overline{{\text{X}}} \) = 5.06; SD = 0.82) had the highest mean value. Also, the descriptive statistics for SP show overall moderate SP experiences amongst athletes (M = 6.22; SD = 1.64).

Similar to study 1, the data was collected from athletes belonging to three different family structures including the joint family (n = 34), the nuclear family (n = 34), the single-parent family (n = 32), and, the overall descriptive statistics show the difference in the mean scores on the psychological well-being of athletes belonging to the joint family ( \( \overline{{\text{X}}} \) = 83.85, SD = 17.84), the nuclear family ( \( \overline{{\text{X}}} \) = 77.85, SD = 14.27), and the single-parent family ( \( \overline{{\text{X}}} \) = 86.71, SD = 21.52).

Furthermore, an independent sample t-test was conducted to compare the Athletic Mental Energy and Psychological well-being of Male and Female athletes. The mean difference for PWB (− 0.18) and AME (− 0.11) was calculated using Cohen’s d and a small effect size was found for male and female participants indicating negligible difference between both the groups. No significant differences (t (98) = − 0.56, p = 0.57) were found in the scores of Males ( \( \overline{{\text{X}}} \) = 71.26, SD = 15.40) and Females ( \( \overline{{\text{X}}} \) = 73.16, SD = 18.41) for Athletic Mental Energy. The magnitude of the differences in the means (mean difference = − 0.11, 95% CI: − 0.51 to 0.28) was very small. Similarly, for psychological well-being, there were no significant differences (t (98) = -0.92, p = 0.35) in scores for Males ( \( \overline{{\text{X}}} \) = 81.04, SD = 17.17) and Females ( \( \overline{{\text{X}}} \) = 84.42, SD = 19.28) and the differences in the magnitude of the means (mean difference = − 0.18, 95% CI: − 0.58 to 0.21) was very less.

Additionally, we used one-way ANOVA to test if the AME of athletes differs across different family structures. Participants were divided into 3 groups (Group 1: Joint family; Group 2: Nuclear family; Group 3: Single-parent family). The ANOVA results suggest that the Athletic Mental Energy does not differ significantly (F2, 97 = 1.44, p > 0.005).

Lastly, the study assessed the mediating role of AME on the relationship between SP and PWB in phase 1. The results revealed a significant indirect effect of the influence of SP on PWB (b = 1.97, t = 2.33), supporting our study hypothesis. In addition, the direct effect of SP on PWB in the presence of a mediator was also found significant (b = 6.99, p < 0.001). Hence, a total score of AME mediated the relationship between SP and PWB (refer to Fig. 2 .). The summary of the mediation analysis is presented in Table 2 .

Mediation analysis represents the relation between performance and psychological well-being with athletic mental energy as a mediator.

Study 2 part B

It was further hypothesized that each of the six factors of AME i.e., vigor, confidence, motivation, concentration, tirelessness, and calm mediate the relationship between performance and PWB.

For this, the study assessed the mediating role of each of the subdimensions of AME including vigor, confidence, motivation, concentration, tireless, and calm on the relationship between players’ performance and PWB. The results unveiled a significant indirect impact of subjective performance on psychological well-being through vigor (b = − 0.41, t = 3.41). The minus sign indicates competitive partial mediation asserting that a portion of the effect of players’ performance on players’ PWB is mediated through vigor, whereas subjective performance still explains a portion of psychological well-being that is independent of vigor. Additionally, the results revealed a significant indirect impact of subjective performance on psychological well-being through confidence (b = 0.51, t = 2.33), motivation (b = 0.64, t = 2.77), concentration (b = 0.002, t = 2.22), tireless (b = 0.68, t = 1.96), and calm (b = 0.32, t = 2.16) indicating complementary partial mediation supporting our hypothesis. Moreover, the direct effect of player’s performance on psychological well-being in the presence of the mediators was also found significant (b = 7.20, p < 0.001). Hence, all six factors of AMES partially mediated the relationship between SP and PWB (refer to Fig. 3 ). The summary of the mediation analysis is presented in Table 3 .

Mediation analysis representing the relationship between performance and psychological well-being with affective (vigor, tirelessness, and calm) and cognitive components (confidence, motivation, concentration) of Athletic Mental Energy as mediators.

Discussion for study 2

The aim of our second study was to replicate Study 1 and uncover further evidence on the mediating effects of AME on the athletes’ performance-wellbeing relationship. With a different set of participants, a larger sample size, and minimizing the timings of test conduction from the competition, we found that the total score of AME along with the six factors of AME mediated the sport performance and psychological well-being relationship. Thus, Study 2 provided initial evidence of the original aim of the study. The theoretical and practical implications, future directions, and research limitations are thoroughly interpreted and discussed in the section below.

Ethics statement

To fairly meet the ethical criteria, APA ethical guidelines were followed while conducting the study which included taking informed consent, ensuring participants’ right to withdraw throughout the study, ensuring anonymity, and data safety. The research has been approved by the Departmental Research Committee of the Department of Psychology, University of Delhi, India.

Consent to participate

All the participants signed the consent form before taking part in the research.

General discussion

Considering mental energy as an important factor in athletes’ well-being, we extended Lu et al. 79 work on AME and investigated its mediating effects on the relationship between sport players’ performance and well-being. The results revealed a significant indirect effect of performance on psychological well-being through AME. Hence, AME mediated the relationship between performance and PWB. Moreover, all three affective (i.e., vigor, tireless, and calm) and cognitive components (i.e., confidence, concentration, and motivation) of the AME played significant roles in mediation.

The first emotional component i.e., Vigor is considered an individual’s feeling with elevated arousal 49 , 50 . Hence, athletes with heightened vigor would maximize their efforts in strengthening their performance with enthusiasm irrespective of their performance-related setbacks. Similarly, we found that athletes with high levels of vigor were better able to deal with performance-related setbacks and scored higher on well-being dimensions. Research also indicates that while dealing with challenges and obstacles, individuals can get back to equilibrium psychologically, physically, and socially by exerting more effort in addressing the problem and overcoming the obstacles 70 . Thus, it is highly likely that athletes high in vigor put more effort into coping with the existing performance-related pressures and stressors in competitive sports, and thus, are better able to preserve their well-being as compared to their counterparts. In support, Morgan 51 , (1980) found that Olympic athletes who scored high on vigor were more successful and had lower depression, fatigue, anxiety, anger, and confusion as compared to athletes who scored low on vigor 51 . Furthermore, similar to Lu et al. 79 conception of vigor and tirelessness, we found that the players’ levels of well-being were impacted by their performance through tirelessness. Chuang, Lu, Gill, and Fang 38 also contended that athletes who performed extremely well during sport competitions reported experiencing a heightened sense of control, energy, and emotional equilibrium 38 , 46 . Conversely, athletes who feel dissatisfied with their performance in sports are at higher risk of experiencing a lower sense of energy and disequilibrium, thus compromising their sense of well-being. Therefore, preserving athletes’ energy levels post-competition through techniques involving physiological and psychological recovery becomes an important aspect of maintaining their improved sense of well-being as well as preparing them for the next competition 46 . Furthermore, our findings on the mediating effects of calm in a performance-well-being relationship are very insightful in sport psychology research as Loehr 46 contended that elite athletes should experience a state of calm by being mentally and physically relaxed and should not have fear of failure even if they encounter highly demanding situations during a competitive encounter 53 . Since athletes’ past experiences of unsatisfactory performance can create some level of future performance anxiety in athletes leading to heightened arousal and distraction, it is likely that athletes who have the skill to remain calm can ease their performance anxiety, and are better able to cope with their fear of failure, and maintain their sense of physical and mental well-being 13 , 23 , 31 , 71 , 72 , 73 . Furthermore, athletes with such emotional stability have reported high levels of resilience in them 35 , 74 . Thus, there is a higher possibility that athletes who tend to remain calm are better able to recover quickly from performance-related setbacks. In support, the calm factor of AME is frequently found in flow research wherein athletes who report sensations of calmness, relaxation, and effortlessness while engaging in any activity frequently experience flow that helps them to fully immerse themselves in preparing for the next competition without getting distracted from the thoughts related to fear of failure or experiencing performance-related anxiety 32 , 47 .

Just like the affective components of AME, the cognitive components including confidence, concentration, and motivation played an equally important role in mediating the athletes’ performance-wellbeing relationship post-competition. The confidence factor of AME indicates an athlete’s belief in one’s ability to accomplish a task 35 , 75 . The sport–confidence model also suggests that a high level of confidence in athletes can trigger adaptive emotions and larger efforts to deal with adversities, challenges, and sport-specific stressors including in-match failure and performance demands. These adaptive emotions help athletes to manage future performance anxiety and maintain a sense of well-being 35 , 36 , 68 , 75 . In addition to this, concentration played an important role in mediating the relationship between performance and well-being. Concentration refers to an individual’s mental ability to block unwanted distractions while focusing one’s attention on achieving a given task 33 , 44 , 75 . Athletes with strong concentration excel in competitions by enhancing focus, blocking past performance-related thoughts, reducing stress, and maintaining well-being 37 , 77 , 78 . Conversely, low concentration in athletes leads to impaired focus during stress, hindering working memory efficiency 63 , 79 . Such athletes struggle to concentrate, easily getting distracted by thoughts of past failures, ultimately causing increased anxiety, stress, and decreased well-being. Thus, our finding of the positive impact of the concentration on performance and psychological well-being relationship is consistent with previous research. Lastly, the mediating effect of motivation on the post-competitive performance- psychological well-being relationship has also been evident in our study. Motivation is the intensity of goal-directed behavior 42 , 80 , 81 . Generally, highly motivated individuals possess higher persistence to achieve their goals. Therefore, an athlete with higher motivation to perform well would persist longer in training to perform his best even when facing adversity 70 , 82 . Thus, sport players with high levels of motivation will exert more effort to handle the competing demands during sports competitions regardless of their past record of unsatisfactory performance. Thus, preserving their mental well-being. Hence, all six factors of AMES played important roles in mediating the relationship between athletes’ performance and psychological well-being.

The difference in the results of mediation analysis across both the studies (Study 1 and Study 2) could be explained either due to the difference in the sample size or due to the difference in the timings (one month in Study 1 and 1 week in Study 2) of psychometric assessment conduction. However, the reasons for the differences in the results are complicated to understand because the participants in both studies were from different sports including team and individual sports, playing at different competitive levels, and belonging to different demographic backgrounds. Nonetheless, our study provides preliminary evidence that AME is a protective factor in preserving athletes’ PWB even after an unsatisfactory competitive encounter. It is to be noted that Athletic mental energy can also be useful in a sport player’s day-to-day life through the transfer effects. Gould and Carson 83 suggested that athletes learn intrapersonal, interpersonal, cognitive, and behavioral skills from sports and adapt them to their daily lives 83 . Thus, athletes with high AME will not just benefit in sports but will also benefit in handling stressors from daily life. However, this is only one possibility we can make through our study. Future studies are advised to examine how AME helps athletes deal with adversities in daily life. In addition to this, our study provides several other implications for the researchers.

Our study highlights the vital role of a protective factor in sports excellence, athletic success, and well-being 33 , 34 , 35 , 44 , 65 , 70 . Despite proposals in the 1990s about mental energy’s impact on player performance, empirical reports remain limited. Our research addresses this gap by exploring the affective and cognitive components of mental energy and their connections to athlete performance and psychological well-being, complementing Lu et al. 79 . We build on Chuang, Lu, Gill, and Fang’s work 38 by examining the interplay between athletes’ performance, mental energy, and psychological states, suggesting the need for post-competition mental state management 5 , 19 , 21 , 34 .

Lastly, athletes from joint families, nuclear families, and single-parent families showed distinct differences in psychological well-being (PWB) mean scores, highlighting variations across family structures. This aligns with Ryan and Willits 84 , emphasizing the impact of family relationships on well-being 84 , 85 . However, no significant differences emerged in Athletic Mental Energy (AME) among athletes based on sex or family structure. Similarly, PWB showed no significant variation between male and female athletes, indicating that neither sex nor family structure influences AME or PWB. In conclusion, our findings suggest that sex and family structure do not affect players’ psychological well-being or athletic mental energy. Therefore, enhancing AME through interventions may assist athletes in managing emotions and stress associated with suboptimal performance while promoting well-being and preparing them for future competitions. However, it is essential to note that additional research is necessary to corroborate our primary findings.

Practical applications

Athletic Mental Energy (AME) holds a central role in sports psychology, predicting success, reducing athlete stress and burnout, and enhancing positive mental states 13 , 31 , 48 . Our study emphasizes AME’s significance, showing it as a mediator between athlete performance and psychological well-being. Sports professionals can use this insight in athlete training, especially post-competition, to help manage performance-related stress and improve well-being 86 . Lu et al. 79 suggest cultivating AME through mental and physical training, influenced by factors like nutrition, sleep, relationships, and time management. Sport psychologists can integrate psychological skills training into daily routines, while tailored plans for healthy habits, routines, and sleep cycles can optimize mental energy levels 31 , 48 .

Strengths and limitations

Our research employed an empirical approach to delve into the mediating role of Athletic Mental Energy (AME) in the post-competitive performance-psychological well-being dynamic, encompassing two distinct studies with separate participant groups. Employing diverse assessment methods is a research strategy aimed at gaining a comprehensive understanding, and in this pursuit, we used two different assessment approaches 20 , 87 . However, it’s important to acknowledge the limitations of our study. Firstly, the cross-sectional nature of our research limits its ability to establish variable patterns over time. Future studies would benefit from adopting a longitudinal design to explore the intricate relationship between athletes’ performance, AME, and psychological well-being over extended periods, providing a more accurate depiction of temporal changes. We excluded parasport participants, warranting investigation in this context. Cultural variations may affect generalizability, necessitating exploration in different settings. While we employed subjective performance measures to accommodate the diversity of sports, employing objective performance metrics and expanding the sample size would enhance generalizability. Additionally, measuring AME closer to competition would yield more precise results 25 , 45 , 58 , 59 , 88 . Lastly, the evolving concept of AME requires further examination, identifying potential latent factors beyond the six psychological components explored and their relevance in athletes’ post-competition well-being.( Supplementary information )

Conclusions

Our research examined the mediating role of AME in the link between post-competition performance and psychological well-being. We found that athletes’ performance significantly impacts their psychological well-being through factors within athletic mental energy, including confidence, motivation, concentration, vigor, tirelessness, and calmness. We recommend sports psychologists and professionals prioritize interventions that enhance athletes’ AME, especially after competitions. This equips athletes to effectively handle performance-related stress and improves their overall well-being. Additionally, we advocate for further research to explore the positive aspects and constituent elements of AME in sports, aiming to advance athlete welfare and performance. \( \overline{{\text{X}}} \)

Data availability

The data analysed for this research paper are available from the first and corresponding author upon fair request meeting institutional guidelines.

Abbreviations

Sample size

Athletic mental energy

Athletic mental energy scale

Psychological wellbeing

Subjective performance

Concentration

International life science institute

Statistical package for social sciences

American psychological association

Level of statistical significance alpha

Individual zone of optimal functioning

Items of AME

Items of PWB

Amisha Singh

Mandeep Kaur Arora

Bahniman Boruah

Giles, S., Fletcher, D., Arnold, R., Ashfield, A. & Harrison, J. Measuring well-being in sport performers: Where are we now and how do we progress?. Sports Med. 50 (7), 1255–1270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-020-01274-z (2020).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Page, S. J., O’Connor, E. & Peterson, K. Leaving the disability ghetto: A qualitative study of factors underlying achievement motivation among athletes with disabilities. J. Sport Soc. Issues 25 (1), 40–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723501251004 (2001).

Article Google Scholar

Kenney, W. L., Wilmore, J. H. & Costill, D. L. Physiology of Sport and Exercise (Human Kinetics, 2015).

Google Scholar

Beauchamp, M. R. & Eys, M. A. Group Dynamics in Exercise and Sport Psychology (Routledge, 2014).

Book Google Scholar

MacIntyre, T. E. et al. Editorial: Mental health challenges in elite sport: Balancing risk with reward. Front. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01892 (2017).

Lu, F., Hsu, Y. W., Chan, Y. S., Cheen, J. & Kao, K. T. Assessing college student-athletes’ life stress: Initial measurement development and validation. Meas. Phys. Educ. Exerc. Sci. 16 , 254–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/1091367X.2012.693371b (2012).

MacAuley, D. Oxford Handbook of Sport and Exercise Medicine (Oxford University, 2012).

Rice, S. M. et al. The mental health of elite athletes: A narrative systematic review. Sport Med. 46 , 1333–1353. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-016-0492-2 (2016).

Crow, R. B. & Macintosh, E. W. Conceptualizing a meaningful definition of hazing in sport. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 9 , 433–451. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184740903331937 (2009).

Mountjoy, M. et al. International Olympic Committee consensus statement: Harassment and abuse (non-accidental violence) in sport. Br. J. Sports Med. 50 , 1019–1029. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2016-096121 (2016).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Wachsmuth, S., Jowett, S. & Harwood, C. G. Confict among athletes and their coaches: What is the theory and research so far?. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984x.2016.1184698 (2017).

Steptoe, A. & Kivimäki, M. Stress and cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 9 (6), 360–370. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrcardio.2012.45 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Bosarge, P. L. & Kerby, J. D. Stress-induced hyperglycemia: Is it harmful following trauma?. Adv. surg. 47 , 287–297 (2013).

Marik, P. E., Vasu, T., Hirani, A. & Pachinburavan, M. Stress ulcer prophylaxis in the new millennium: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Care Med. 38 , 2222–2228. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181f17adf (2010).

Theoharides, T. C. et al. Contribution of stress to asthma worsening through mast cell activation. Ann. Allerg. Asthma Immunol. 109 , 14–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2012.03.003 (2012).

DiBartolo, P. M. & Shaffer, C. A comparison of female college athletes and nonathletes: Eating disorder symptomatology and psychological well-being. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 24 , 33–42 (2002).

Humphrey, J. H., Yow, D. A. & Bowden, W. W. Stress in College Athletics: Causes, Consequences, Coping (The Haworth Half-Court Press, 2000).

Lundqvist, C. & Andersson, G. Let’s talk about mental health and mental disorders in elite sports: A narrative review of theoretical perspectives. Front. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021 (2021).

Chang, C., Putukian, M. & Aerni, G. Mental health issues and psychological factors in athletes: Detection, management, effect on performance and prevention: American medical society for sports medicine position statement—executive summary. Br. J. Sports Med. 54 , 216–220 (2020).

Smith, R. Toward a cognitive-affective model of athletic burnout. J. Sport Psychol. 8 , 36–50. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsp.8.1.36 (1986).

Gustafsson, H. & Skoog, T. The mediational role of perceived stress in the relation between optimism and burnout in competitive athletes. Anxiety Stress Coping. 25 , 183–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2011.594045 (2012).

Fletcher, D., Hanton, S. & Mellalieu, S. D. An organizational stress review: Conceptual and theoretical issues in competitive sport. In Literature Reviews in Sport Psychology (eds Hanton, S. & Mellalieu, S. D.) 321–373 (Nova Science, 2006).

Lazarus, R. S. & Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping (Springer, 1984).

Arnold, R., Fletcher, D. & Daniels, K. Development and validation of the organizational stressor indicator for athletes (OSI-SP). J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 35 (2), 180–196 (2013).

Leguizamo, F. et al. Personality, coping strategies, and mental health in high-performance athletes during confinement derived from the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Public Health https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.561198 (2021).

Durand-Bush, N. & Salmela, J. H. The development and maintenance of expert athletic performance: Perceptions of world and olympic champions. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 14 , 154–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200290103473 (2002).

Sebbens, J., Hassmén, P., Crisp, D. & Wensley, K. Mental health in sport (MHS): Improving the early intervention knowledge and confidence of elite sport staff. Front. Psychol. 7 , 911. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00911 (2016).

Disabato, D. J., Goodman, F. R., Kashdan, T. B., Short, J. L. & Jarden, A. Different types of well-being? A cross-cultural examination of hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Psychol. Assess. 28 (5), 471–482. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000209 (2016).

O’Connor, P. J. & Burrowes, J. Mental energy: Defining the science. Nutr. Rev. 64 , S1–S11. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887/2006.tb00251.x (2006).

Lykken, D. T. Mental energy [Editorial]. Intelligence 33 (4), 331–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2005.03.005 (2005).

Jackson, S. A. & Roberts, G. C. Positive performance states of athletes: Toward a conceptual understanding of peak performance. Sport Psychol. 6 , 156–171 (1992).

Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. J. Leisure Res. 24 (1), 93–94 (1990).

Orlick, T. & Partington, J. Mental links to excellence. Sport Psychol. 2 (2), 105–130. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.2.2.105 (1988).

Gould, D., Dieffenbach, K. & Moffett, A. Psychological characteristics and their development in olympic champions. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 14 (3), 172–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200290103482 (2002).

Fletcher, D. & Sarkar, M. A grounded theory of psychological resilience in olympic champions. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 13 (5), 669–678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2012.04.007 (2012).

Weinberg, R. S. & Gould, D. Foundations of Sport and Exercise Psychology 6th edn. (Human Kinetics, 2015).

Abdullah, M., Maliki, A. B., Musa, R., Kosni, N. & Juahir, H. Intelligent prediction of soccer technical skill on youth soccer player’s relative performance using multivariate analysis and artificial neural network techniques. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Eng. Inform. Technol. 6 , 668. https://doi.org/10.1851/ijaseit.6.5.975 (2016).

Chuang, W. C., Lu, F. J. H., Gill, D. L. & Fang, B. B. Pre-competition mental energy and performance relationships among physically disabled table tennis players. PeerJ https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.13294 (2022).

Lochbaum, M., Zanatta, T., Kirschling, D. & May, E. The profile of moods states and athletic performance: A meta-analysis of published studies. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 11 (1), 50–70. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe11010005 (2021).

Garfield, C. A. & Bennett, H. Z. Perk Performance: Mental Training Techniques of the World’s Greatest Athletes (Tarcher, 1984).

Ravizz, K. Peak experience in sport. J. Humanist. Psychol. 17 , 35–40 (1977).

Feltz, D. L., Short, S. E. & Sullivan, P. J. Self-efficacy in Sport (Human Kinetics, 2008).

Feltz, D., Moritz, S. & Sullivan, P. Self efficacy in sport: Research and strategies for working with athletes, teams and coaches. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 3 , 293–295. https://doi.org/10.1260/174795408785100699 (2008).

Anderson, R., Hanrahan, S. L. & Mallett, C. J. Investigating the optimal psychological state for peak performance in Australian elite athletes. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 26 , 318–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2014.885915 (2014).

Horowitz, M., Alder, N. & Kegeles, S. A scale for measuring the occurrence of positive state of mind: A preliminary report. Psychosom. Med. 50 , 477–483. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-198809000-00004 (1988).

Loehr, J. E. How to Overcome Stress and Play at Your Peak All the Time 66–76 (Tennis, 1984).

Loehr, J. E. Leadership: full engagement for success. In The Sport Psychology Handbook (ed. Murphy, S.) 157–158 (Human Kinetics, 2005).

Chiou, S. S. et al. Seeking positive strengths in buffering athletes’ life stress-burnout relationship: The moderating roles of athletic mental energy. Front. Psychol. 10 , 3007. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.03007 (2020).

Lane, A. M. & Terry, P. C. The nature of mood: Development of a conceptual model with a focus on depression. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 12 , 16–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200008404211 (2000).

Lane, A. M. & Chappell, R. H. Mood and performance relationships at the world student games basketball competition. J. Sport Behav. 24 , 182–196 (2001).

Morgan, W. P. Prediction of performance in athletics. In Coach, Athlete, and the Sport Psychologist (eds Klavora, P. & Daniel, J. V.) 173–186 (Human Kinetics, 1979).

Prapavessis, H. The POMS and sports performance: A review. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 12 (1), 34–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/1041320000840421 (2000).

Mahoney, M. J., Gabriel, T. J. & Perkins, T. S. Psychological skills and exceptional athletic performance. Sport Psychol. 1 , 181–199. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.1.3.181 (1987).

Thomas, P. R., Murphy, S. M. & Hardy, L. Test of performances strategies: development and preliminary validation of a comprehensive measure of athletes’ psychological skills. J. sports sci. 17 (9), 697–711. https://doi.org/10.1080/026404199365560 (1999).

Durand-Bush, N., Salmela, J. H. & Green-Demers, I. The Ottawa mental skills assessment tool (OMSAT-3). Sport Psychol. 15 , 1–19 (2001).

Jones, G., Hanton, S. & Connaughton, D. Aframework of mental toughness in the world’sbest performers. Sport Psychol. 21 (2), 243–264. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.21.2.243 (2007).

Campbell, E. & Jones, G. Psychological well-being in wheelchair sport participants and nonparticipants. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 11 (4), 404–415. https://doi.org/10.1123/apaq.11.4.404 (1994).

Campbell, E. & Jones, G. Pre-competition anxiety and self-confidence in elite and non-elite wheelchair sport participants. J. Sports Sci. 13 , 416–417. https://doi.org/10.1123/APAQ.14.2.95 (1997).

Hanton, S., Thomas, O. & Maynard, I. Competitive anxiety responses in the week leading up to competition: The role of intensity, direction and frequency dimensions. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 5 , 169–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.08.022 (2004).

Ryff, C. D. In the eye of the beholder: Views of psychological well-being among middle-aged and older adults. Psychol. Aging 4 , 195–210. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.4.2.195 (1989).

Ryff, C. D. Happiness is everything, or is it? explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 57 , 1069–1081. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069 (1989).

Ryff, C. D., Lee, Y. H., Essex, M. J. & Schmutte, P. S. My children and me: mid-life evaluations of grown children and of self. Psychol. Aging 9 , 195–205. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.9.2.195 (1994).

Lu, F. J. H. et al. Measuring athletic mental energy (AME): Instrument development and validation. Front. Psychol. 9 , 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02363 (2018).

Levy, A. R., Nicholls, A. R. & Polman, R. C. J. Pre-competitive confidence, coping, and subjective performance in sport. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 21 , 721–729. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.01075.x (2011).

Arnold, R., Fletcher, D. & Daniels, K. Organisational stressors, coping, and outcomes in competitive sport. J. Sports Sci. 35 , 694–703. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2016.1184299 (2017).

Kiely, M., Warrington, G., McGoldrick, A. & Cullen, S. Physiological and performance monitoring in competitive sporting environments: A review for elite individual sports. Strength Cond. J. 41 (6), 62–74. https://doi.org/10.1519/SSC.0000000000000493 (2019).

D’Isanto, T., D’Elia, F., Raiola, G. & Altavilla, G. Assessment of Sport Performance: Theoretical aspects and practical indications. Sport Mont. 17 , 79–82. https://doi.org/10.26773/smj.190214 (2019).

Arnold, R. & Fletcher, D. Stress, Well-Being, and Performance in Sport (Routledge, 2021).

Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. & Hair, J. Partial least squares structural equation modeling: Rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance. Long Range Plan. 46 , 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2013.08.016 (2013).

Folkman, S. Personal control and stress and coping processes: A theoretical analysis. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 46 (4), 839–852. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.46.4.839 (1984).

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Ishak, W. W., Kahloon, M. & Fakhry, H. Oxytocin role in enhancing well-being: A literature review. J. Affect. Disord. 130 (1–2), 1–9 (2011).

Cheng, W. N. K., Hardy, L. & Markland, D. Toward a three-dimensional conceptualization of performance anxiety: Rationale and initial measurement development. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 10 (2), 271–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2008.08.001 (2009).

Baumeister, R. F. & Showers, C. J. A review of paradoxical performance effects: Choking under pressure in sports and mental tests. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 16 (4), 361–383. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420160405 (1986).

Ennis, G., Happell, B. & Reid-Searl, K. Clinical leadership in mental health nursing: The importance of a calm and confident approach. Perspect Psychiatr. Care 51 (1), 57–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12070 (2015).

Vealey, R. S. & Chase, M. A. Self-confidence in sport. In Advances in Sport Psychology (ed. Horn, T. S.) 430–435 (Human Kinetics, 2008).

Paul, M., Garg, K. & Singh Sandhu, J. Role of biofeedback in optimizing psychomotor performance in sports. Asian J. Sports Med. 3 (1), 29–40. https://doi.org/10.5812/asjsm.34722 (2012).

Gillen, G. Chapter 2 - general considerations: evaluations and interventions for those living with functional limitations secondary to cognitive and perceptual impairments. In Cognitive and Perceptual Rehabilitation (ed. Gillen, G.) 32–44 (Mosby, 2009).

Chapter Google Scholar

Williams, J. M., Nideffer, R. M., Wilson, V. E., Sagal, M. S. & Peper, E. Concentration and strategies for controlling it. In Applied Sport Psychology: Personal Growth to Peak Performance 7th edn (eds Williams, J. M. & Krane, V.) 304–325 (McGraw-Hill, 2015).

Gaillard, A. W. K. Concentration, stress, and performance. In Performance Under Stress 8–12 (Taylor & Francis Group, 2018).

Gill, D. L., Williams, L. & Reifstech, E. Psychological Dynamics of Sport And Exercise (Human Kinetics, 2017).

Gill, D. L. & Williams, L. Psychological dynamics of sport and exercise 3rd edn. (Human Kinetics, 2008).

Sarkar, M., Fletcher, D. & Brown, D. J. What doesn’t kill me: Adversity-related experiences are vital in the development of superior Olympic performance. J. Sci. Med. Sport 18 , 475–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2014.06.010 (2015).

Gould, D. & Carson, S. Life skills development through sport: Current status and future directions. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 1 , 58–78 (2008).

Ryan, A. K. & Willits, F. K. Family ties, physical health, and psychological well-being. J. aging health 19 (6), 907–920. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264307308340 (2007).

Tewari, P. Sport visuals and theprint media in India: A comparativeanalysis of photographic coverage in leading newspapers . https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.26297.83045 (2015).

Jeong, T. S., Reilly, T., Morton, J., Bae, S. W. & Drust, B. Quantification of the physiological loading of one week of “pre-season” and one week of “in-season” training in professional soccer players. Journal of sports sciences 29 (11), 1161–1166. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2011.583671 (2011).

Brustad, R. A critical Analysis of Knowledge Construction in Sport Psychology 2nd edn. (Human Kinetics, 2002).

Hanton, S., Thomas, O. M., Maynard, I. & W.,. Time-to-event changes in the intensity, directional and frequency of intrusions of Competitive State Anxiety. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 5 , 169–181 (2004).

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to extend their appreciation toward all the participants and gatekeepers for their utmost cooperation in this research. Without them, this research was not possible.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, University of Delhi, New Delhi, India

Amisha Singh & Bahniman Boruah

Department of Psychology, Kamala Nehru College, University of Delhi, New Delhi, 110007, India

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions