- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- College University and Postgraduate

- Academic Writing

- Research Papers

How to Write and Publish Your Research in a Journal

Last Updated: May 26, 2024 Fact Checked

Choosing a Journal

Writing the research paper, editing & revising your paper, submitting your paper, navigating the peer review process, research paper help.

This article was co-authored by Matthew Snipp, PhD and by wikiHow staff writer, Cheyenne Main . C. Matthew Snipp is the Burnet C. and Mildred Finley Wohlford Professor of Humanities and Sciences in the Department of Sociology at Stanford University. He is also the Director for the Institute for Research in the Social Science’s Secure Data Center. He has been a Research Fellow at the U.S. Bureau of the Census and a Fellow at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences. He has published 3 books and over 70 articles and book chapters on demography, economic development, poverty and unemployment. He is also currently serving on the National Institute of Child Health and Development’s Population Science Subcommittee. He holds a Ph.D. in Sociology from the University of Wisconsin—Madison. There are 13 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 700,623 times.

Publishing a research paper in a peer-reviewed journal allows you to network with other scholars, get your name and work into circulation, and further refine your ideas and research. Before submitting your paper, make sure it reflects all the work you’ve done and have several people read over it and make comments. Keep reading to learn how you can choose a journal, prepare your work for publication, submit it, and revise it after you get a response back.

Things You Should Know

- Create a list of journals you’d like to publish your work in and choose one that best aligns with your topic and your desired audience.

- Prepare your manuscript using the journal’s requirements and ask at least 2 professors or supervisors to review your paper.

- Write a cover letter that “sells” your manuscript, says how your research adds to your field and explains why you chose the specific journal you’re submitting to.

- Ask your professors or supervisors for well-respected journals that they’ve had good experiences publishing with and that they read regularly.

- Many journals also only accept specific formats, so by choosing a journal before you start, you can write your article to their specifications and increase your chances of being accepted.

- If you’ve already written a paper you’d like to publish, consider whether your research directly relates to a hot topic or area of research in the journals you’re looking into.

- Review the journal’s peer review policies and submission process to see if you’re comfortable creating or adjusting your work according to their standards.

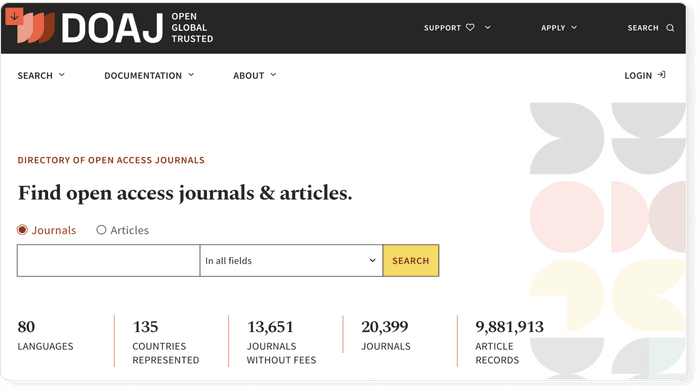

- Open-access journals can increase your readership because anyone can access them.

- Scientific research papers: Instead of a “thesis,” you might write a “research objective” instead. This is where you state the purpose of your research.

- “This paper explores how George Washington’s experiences as a young officer may have shaped his views during difficult circumstances as a commanding officer.”

- “This paper contends that George Washington’s experiences as a young officer on the 1750s Pennsylvania frontier directly impacted his relationship with his Continental Army troops during the harsh winter at Valley Forge.”

- Scientific research papers: Include a “materials and methods” section with the step-by-step process you followed and the materials you used. [5] X Research source

- Read other research papers in your field to see how they’re written. Their format, writing style, subject matter, and vocabulary can help guide your own paper. [6] X Research source

- If you’re writing about George Washington’s experiences as a young officer, you might emphasize how this research changes our perspective of the first president of the U.S.

- Link this section to your thesis or research objective.

- If you’re writing a paper about ADHD, you might discuss other applications for your research.

- Scientific research papers: You might include your research and/or analytical methods, your main findings or results, and the significance or implications of your research.

- Try to get as many people as you can to read over your abstract and provide feedback before you submit your paper to a journal.

- They might also provide templates to help you structure your manuscript according to their specific guidelines. [11] X Research source

- Not all journal reviewers will be experts on your specific topic, so a non-expert “outsider’s perspective” can be valuable.

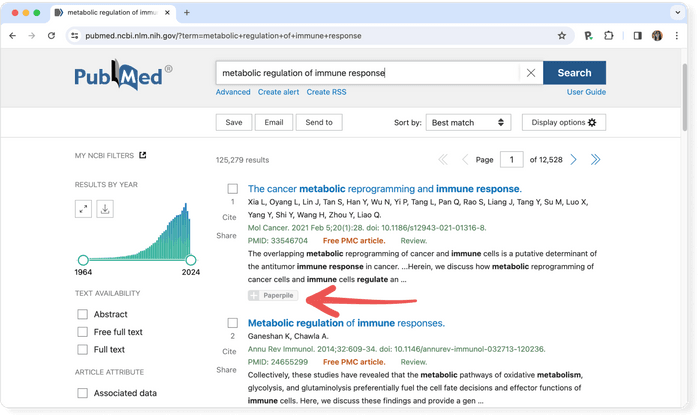

- If you have a paper on the purification of wastewater with fungi, you might use both the words “fungi” and “mushrooms.”

- Use software like iThenticate, Turnitin, or PlagScan to check for similarities between the submitted article and published material available online. [15] X Research source

- Header: Address the editor who will be reviewing your manuscript by their name, include the date of submission, and the journal you are submitting to.

- First paragraph: Include the title of your manuscript, the type of paper it is (like review, research, or case study), and the research question you wanted to answer and why.

- Second paragraph: Explain what was done in your research, your main findings, and why they are significant to your field.

- Third paragraph: Explain why the journal’s readers would be interested in your work and why your results are important to your field.

- Conclusion: State the author(s) and any journal requirements that your work complies with (like ethical standards”).

- “We confirm that this manuscript has not been published elsewhere and is not under consideration by another journal.”

- “All authors have approved the manuscript and agree with its submission to [insert the name of the target journal].”

- Submit your article to only one journal at a time.

- When submitting online, use your university email account. This connects you with a scholarly institution, which can add credibility to your work.

- Accept: Only minor adjustments are needed, based on the provided feedback by the reviewers. A first submission will rarely be accepted without any changes needed.

- Revise and Resubmit: Changes are needed before publication can be considered, but the journal is still very interested in your work.

- Reject and Resubmit: Extensive revisions are needed. Your work may not be acceptable for this journal, but they might also accept it if significant changes are made.

- Reject: The paper isn’t and won’t be suitable for this publication, but that doesn’t mean it might not work for another journal.

- Try organizing the reviewer comments by how easy it is to address them. That way, you can break your revisions down into more manageable parts.

- If you disagree with a comment made by a reviewer, try to provide an evidence-based explanation when you resubmit your paper.

- If you’re resubmitting your paper to the same journal, include a point-by-point response paper that talks about how you addressed all of the reviewers’ comments in your revision. [22] X Research source

- If you’re not sure which journal to submit to next, you might be able to ask the journal editor which publications they recommend.

Expert Q&A

You might also like.

- If reviewers suspect that your submitted manuscript plagiarizes another work, they may refer to a Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) flowchart to see how to move forward. [23] X Research source Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- ↑ https://www.wiley.com/en-us/network/publishing/research-publishing/choosing-a-journal/6-steps-to-choosing-the-right-journal-for-your-research-infographic

- ↑ https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13187-020-01751-z

- ↑ https://libguides.unomaha.edu/c.php?g=100510&p=651627

- ↑ https://www.canberra.edu.au/library/start-your-research/research_help/publishing-research

- ↑ https://writingcenter.fas.harvard.edu/conclusions

- ↑ https://writing.wisc.edu/handbook/assignments/writing-an-abstract-for-your-research-paper/

- ↑ https://www.springer.com/gp/authors-editors/book-authors-editors/your-publication-journey/manuscript-preparation

- ↑ https://apus.libanswers.com/writing/faq/2391

- ↑ https://academicguides.waldenu.edu/library/keyword/search-strategy

- ↑ https://ifis.libguides.com/journal-publishing-guide/submitting-your-paper

- ↑ https://www.springer.com/kr/authors-editors/authorandreviewertutorials/submitting-to-a-journal-and-peer-review/cover-letters/10285574

- ↑ https://www.apa.org/monitor/sep02/publish.aspx

- ↑ Matthew Snipp, PhD. Research Fellow, U.S. Bureau of the Census. Expert Interview. 26 March 2020.

About This Article

To publish a research paper, ask a colleague or professor to review your paper and give you feedback. Once you've revised your work, familiarize yourself with different academic journals so that you can choose the publication that best suits your paper. Make sure to look at the "Author's Guide" so you can format your paper according to the guidelines for that publication. Then, submit your paper and don't get discouraged if it is not accepted right away. You may need to revise your paper and try again. To learn about the different responses you might get from journals, see our reviewer's explanation below. Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

RAMDEV GOHIL

Oct 16, 2017

Did this article help you?

David Okandeji

Oct 23, 2019

Revati Joshi

Feb 13, 2017

Shahzad Khan

Jul 1, 2017

Apr 7, 2017

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Don’t miss out! Sign up for

wikiHow’s newsletter

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

Understanding the Publishing Process

What’s happening with my paper? The publication process explained

The path to publication can be unsettling when you’re unsure what’s happening with your paper. Learn about staple journal workflows to see the detailed steps required for ensuring a rigorous and ethical publication.

Your team has prepared the paper, written a cover letter and completed the submission form. From here, it can sometimes feel like a waiting game while the journal has your paper. It can be unclear exactly who is currently handling your paper as most individuals are only involved in a few steps of the overall process. Journals are responsible for overseeing the peer review, publication and archival process: editors, reviewers, technical editors, production staff and other internal staff all have their roles in ensuring submissions meet rigorous scientific and ethical reporting standards.

Read on for an inside look at how a conventional peer-reviewed journal helps authors transform their initial submission to a certified publication.

Note that the description below is based on the process at PLOS journals. It is likely that at other journals, various roles (e.g. technical editor) may in fact also be played by the editor, and some journals may not have journal staff at all, with all roles played by volunteer academics. As such, please consider the processes and waypoints, rather than who performs them, as the key information.

Internal Checks on New Submissions

Estimated time: 10 days.

When a journal first receives your submission, there are typically two separate checks to confirm that the paper is appropriate and ready for peer review:

- Technical check. Performed by a technical editor to ensure that the submission has been properly completed and is ready for further assessment. Blurry figures, missing ethical statements, and incomplete author affiliations are common issues that are addressed at this initial stage. Typically, there are three technical checks: upon initial submission, alongside the first decision letter, and upon acceptance.

- Editorial screening . Once a paper passes the first check, an editor with subject expertise assesses the paper and determines whether it is within the journal’s scope and if it could potentially meet the required publication criteria. While there may be requests for further information and minor edits from the author as needed, the paper will either be desk rejected by the editor or allowed to proceed to peer review.

Both editors at this point will additionally make notes for items to be followed-up on at later stages. The publication process involves finding a careful balance for when each check occurs. Early checks need to be thorough so that editors with relevant expertise can focus on the scientific content and more advanced reporting standards, but no one wants to be asked to reformat references only to have their paper desk rejected a few days later.

Peer Review

Estimated time: 1 month.

Depending on the journal’s editorial structure, the editor who performed the initial assessment may also oversee peer review or another editor with more specific expertise may be assigned. Regardless of the journal’s specific process, the various roles and responsibilities during peer review include:

When you have questions or are unsure who your manuscripts is currently with, reach out to the journal staff for help (eg. [email protected]). They will be your lifeline, connecting you to all the other contributors working to assess the manuscript.

Whether an editor needs a reminder that all reviews are complete or a reviewer has asked for an extension, the journal acts as a central hub of communication for those involved with the publication process. As editors and reviewers are used to hearing from journal staff about their duties, any messages you send to the journal can be forwarded to them with proper context and instructions on how to proceed appropriately. Additionally, journal staff will be able to inform you of any delays, such as reviewer availability during summer and holiday periods.

Revision Decision

Estimated time: 1 day.

Editors evaluate peer reviewer feedback and their own expert assessment of the manuscript to reach a decision. After your editor submits a decision on your manuscript, the journal may review it before formally processing the decision and sending it on to you.

A technical editor may scan the manuscript and the review comments to ensure that journal standards have been followed. At this stage, the technical editor will also add requests to ensure the paper, if published, will adhere to journal requirements for data sharing, copyright, ethical reporting and the like.

Performing the second technical check at this stage and adding the journal requirements to the decision letter ultimately saves time by allowing authors to resolve the journal’s queries while making revisions based on comments from the reviewers.

Revised Submission Received

Estimated time: 3 days.

Upon receiving your revised submission, a technical editor will assess the revisions to confirm that the requests from the journal have been properly addressed. Before the paper is returned to the editor for their consideration, the journal needs to be confident that the paper won’t have any issues related to the metadata and reporting standards that could prevent publication. The editor may contact you to resolve any serious issues, though minor items can wait until the paper is accepted.

Subsequent Peer Review

Estimated time: 2 weeks, highly variable.

When your resubmitted paper has passed the required checks, it’ll be assigned back to the same editor who handled it during the first round of peer review. At this point, your paper has gone through two sets of journal checks and one round of peer review. If all has gone well so far, the paper should feel quite solid both in terms of scientific content and proper reporting standards.

When the editor receives your revised paper, they are asked to check if all reviewer comments have been adequately addressed and if the paper now adheres to the journal’s publication criteria. Depending on the situation, some editors may feel confident making this decision based on their own expertise while others may re-invite the previous reviewers for their opinions.

Individual responsibilities are the same as the initial round of peer review, but it is generally expected that later stages of peer review proceed quicker unless new concerns have been introduced as part of the revision.

Preliminary Acceptance

Estimated time: 1 week.

Your editor is satisfied with the scientific quality of your work and has chosen to accept it in principle. Before it can proceed to production and typesetting, the journal office will perform it’s third and final technical check, requesting any formatting changes or additional details that may be required.

When fulfilling these final journal requests, double check the final files to confirm all information is correct. If you need to make changes beyond those specifically required in the decision letter, inform the journal and explain why you made the unrequested changes. Any change that could affect the scientific meaning of the work will need to be approved by the handling editor. While including your rationale for the changes will help avoid delays, if there are extensive changes made at this point the paper may need to go through another round of formal review.

Formal Acceptance and Publication

Estimated time: 2 weeks.

After a technical editor has confirmed that all requests from the provisional acceptance letter have been addressed, you will receive your formal acceptance letter. This letter indicates that your paper is being passed from the Editorial department to the production department—that all information has been editorially approved. The scientific content has been approved through peer review, and the journal’s publication requirements have been met.

Congratulations to you and your co-authors! Your article will be available as soon as the journal transforms the submission into a typeset, consistently structured scientific manuscript, ready to be read and cited by your peers.

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

Home → Get Published → How to Publish a Research Paper: A Step-by-Step Guide

How to Publish a Research Paper: A Step-by-Step Guide

Jordan Kruszynski

- January 4, 2024

You’re in academia.

You’re going steady.

Your research is going well and you begin to wonder: ‘ How exactly do I get a research paper published?’

If this is the question on your lips, then this step-by-step guide is the one for you. We’ll be walking you through the whole process of how to publish a research paper.

Publishing a research paper is a significant milestone for researchers and academics, as it allows you to share your findings, contribute to your field of study, and start to gain serious recognition within the wider academic community. So, want to know how to publish a research paper? By following our guide, you’ll get a firm grasp of the steps involved in this process, giving you the best chance of successfully navigating the publishing process and getting your work out there.

Understanding the Publishing Process

To begin, it’s crucial to understand that getting a research paper published is a multi-step process. From beginning to end, it could take as little as 2 months before you see your paper nestled in the pages of your chosen journal. On the other hand, it could take as long as a year .

Below, we set out the steps before going into more detail on each one. Getting a feel for these steps will help you to visualise what lies ahead, and prepare yourself for each of them in turn. It’s important to remember that you won’t actually have control over every step – in fact, some of them will be decided by people you’ll probably never meet. However, knowing which parts of the process are yours to decide will allow you to adjust your approach and attitude accordingly.

Each of the following stages will play a vital role in the eventual publication of your paper:

- Preparing Your Research Paper

- Finding the Right Journal

- Crafting a Strong Manuscript

- Navigating the Peer-Review Process

- Submitting Your Paper

- Dealing with Rejections and Revising Your Paper

Step 1: Preparing Your Research Paper

It all starts here. The quality and content of your research paper is of fundamental importance if you want to get it published. This step will be different for every researcher depending on the nature of your research, but if you haven’t yet settled on a topic, then consider the following advice:

- Choose an interesting and relevant topic that aligns with current trends in your field. If your research touches on the passions and concerns of your academic peers or wider society, it may be more likely to capture attention and get published successfully.

- Conduct a comprehensive literature review (link to lit. review article once it’s published) to identify the state of existing research and any knowledge gaps within it. Aiming to fill a clear gap in the knowledge of your field is a great way to increase the practicality of your research and improve its chances of getting published.

- Structure your paper in a clear and organised manner, including all the necessary sections such as title, abstract, introduction (link to the ‘how to write a research paper intro’ article once it’s published) , methodology, results, discussion, and conclusion.

- Adhere to the formatting guidelines provided by your target journal to ensure that your paper is accepted as viable for publishing. More on this in the next section…

Step 2: Finding the Right Journal

Understanding how to publish a research paper involves selecting the appropriate journal for your work. This step is critical for successful publication, and you should take several factors into account when deciding which journal to apply for:

- Conduct thorough research to identify journals that specialise in your field of study and have published similar research. Naturally, if you submit a piece of research in molecular genetics to a journal that specialises in geology, you won’t be likely to get very far.

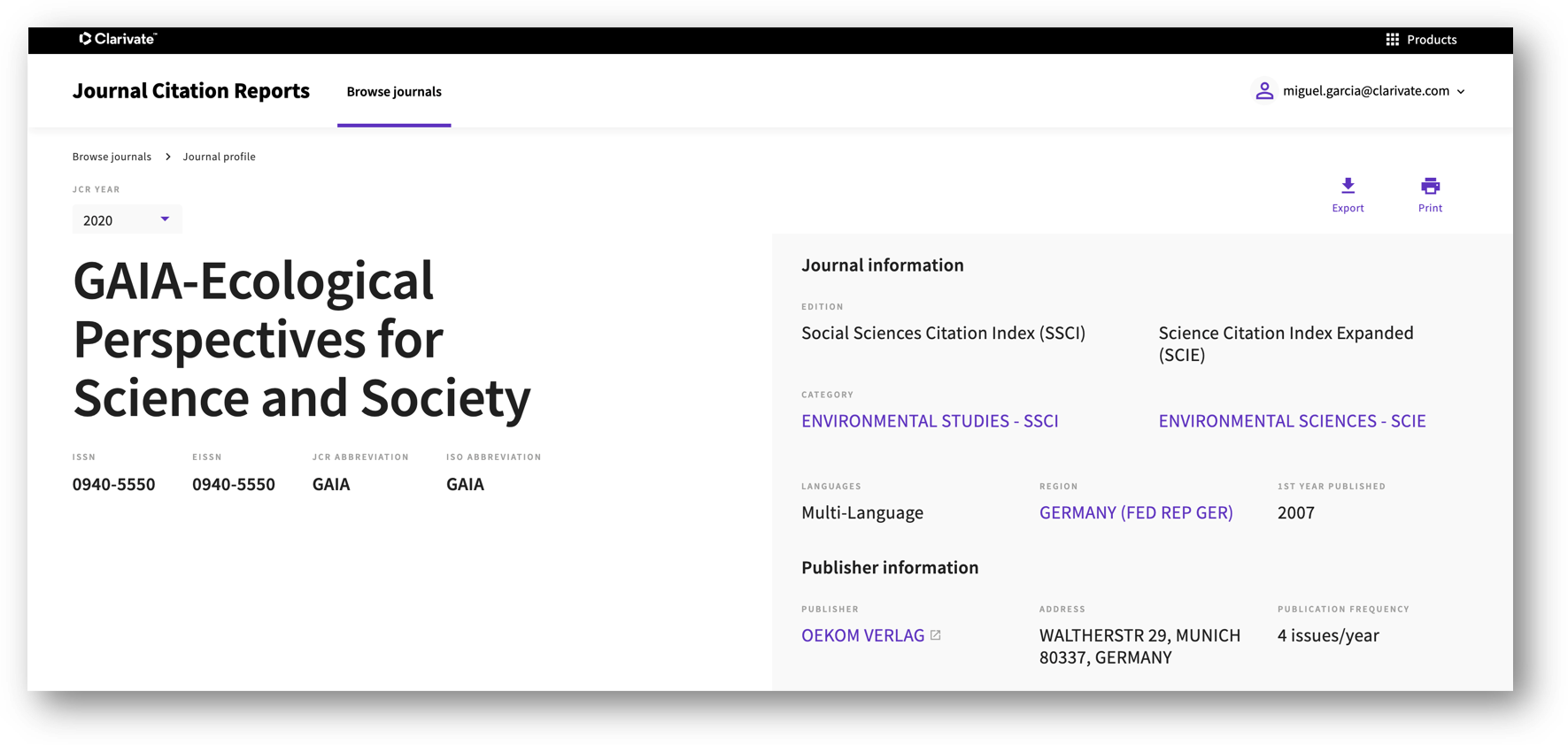

- Consider factors such as the journal’s scope, impact factor, and target audience. Today there is a wide array of journals to choose from, including traditional and respected print journals, as well as numerous online, open-access endeavours. Some, like Nature , even straddle both worlds.

- Review the submission guidelines provided by the journal and ensure your paper meets all the formatting requirements and word limits. This step is key. Nature, for example, offers a highly informative series of pages that tells you everything you need to know in order to satisfy their formatting guidelines (plus more on the whole submission process).

- Note that these guidelines can differ dramatically from journal to journal, and details really do matter. You might submit an outstanding piece of research, but if it includes, for example, images in the wrong size or format, this could mean a lengthy delay to getting it published. If you get everything right first time, you’ll save yourself a lot of time and trouble, as well as strengthen your publishing chances in the first place.

Step 3: Crafting a Strong Manuscript

Crafting a strong manuscript is crucial to impress journal editors and reviewers. Look at your paper as a complete package, and ensure that all the sections tie together to deliver your findings with clarity and precision.

- Begin by creating a clear and concise title that accurately reflects the content of your paper.

- Compose an informative abstract that summarises the purpose, methodology, results, and significance of your study.

- Craft an engaging introduction (link to the research paper introduction article) that draws your reader in.

- Develop a well-structured methodology section, presenting your results effectively using tables and figures.

- Write a compelling discussion and conclusion that emphasise the significance of your findings.

Step 4: Navigating the Peer-Review Process

Once you submit your research paper to a journal, it undergoes a rigorous peer-review process to ensure its quality and validity. In peer-review, experts in your field assess your research and provide feedback and suggestions for improvement, ultimately determining whether your paper is eligible for publishing or not. You are likely to encounter several models of peer-review, based on which party – author, reviewer, or both – remains anonymous throughout the process.

When your paper undergoes the peer-review process, be prepared for constructive criticism and address the comments you receive from your reviewer thoughtfully, providing clear and concise responses to their concerns or suggestions. These could make all the difference when it comes to making your next submission.

The peer-review process can seem like a closed book at times. Check out our discussion of the issue with philosopher and academic Amna Whiston in The Research Beat podcast!

Step 5: Submitting Your Paper

As we’ve already pointed out, one of the key elements in how to publish a research paper is ensuring that you meticulously follow the journal’s submission guidelines. Strive to comply with all formatting requirements, including citation styles, font, margins, and reference structure.

Before the final submission, thoroughly proofread your paper for errors, including grammar, spelling, and any inconsistencies in your data or analysis. At this stage, consider seeking feedback from colleagues or mentors to further improve the quality of your paper.

Step 6: Dealing with Rejections and Revising Your Paper

Rejection is a common part of the publishing process, but it shouldn’t discourage you. Analyse reviewer comments objectively and focus on the constructive feedback provided. Make necessary revisions and improvements to your paper to address the concerns raised by reviewers. If needed, consider submitting your paper to a different journal that is a better fit for your research.

For more tips on how to publish your paper out there, check out this thread by Dr. Asad Naveed ( @dr_asadnaveed ) – and if you need a refresher on the basics of how to publish under the Open Access model, watch this 5-minute video from Audemic Academy !

Final Thoughts

Successfully understanding how to publish a research paper requires dedication, attention to detail, and a systematic approach. By following the advice in our guide, you can increase your chances of navigating the publishing process effectively and achieving your goal of publication.

Remember, the journey may involve revisions, peer feedback, and potential rejections, but each step is an opportunity for growth and improvement. Stay persistent, maintain a positive mindset, and continue to refine your research paper until it reaches the standards of your target journal. Your contribution to your wider discipline through published research will not only advance your career, but also add to the growing body of collective knowledge in your field. Embrace the challenges and rewards that come with the publication process, and may your research paper make a significant impact in your area of study!

Looking for inspiration for your next big paper? Head to Audemic , where you can organise and listen to all the best and latest research in your field!

Keep striving, researchers! ✨

Table of Contents

Related articles.

You’re in academia. You’re going steady. Your research is going well and you begin to wonder: ‘How exactly do I get a

Behind the Scenes: What Does a Research Assistant Do?

Have you ever wondered what goes on behind the scenes in a research lab? Does it involve acting out the whims of

How to Write a Research Paper Introduction: Hook, Line, and Sinker

Want to know how to write a research paper introduction that dazzles? Struggling to hook your reader in with your opening sentences?

Blog Podcast

Privacy policy Terms of service

Subscribe to our newsletter!

Discover more from Audemic: Access any academic research via audio

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

How to Write and Publish a Research Paper for a Peer-Reviewed Journal

- Open access

- Published: 30 April 2020

- Volume 36 , pages 909–913, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Clara Busse ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0178-1000 1 &

- Ella August ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5151-1036 1 , 2

273k Accesses

15 Citations

721 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Communicating research findings is an essential step in the research process. Often, peer-reviewed journals are the forum for such communication, yet many researchers are never taught how to write a publishable scientific paper. In this article, we explain the basic structure of a scientific paper and describe the information that should be included in each section. We also identify common pitfalls for each section and recommend strategies to avoid them. Further, we give advice about target journal selection and authorship. In the online resource 1 , we provide an example of a high-quality scientific paper, with annotations identifying the elements we describe in this article.

Similar content being viewed by others

Literature reviews as independent studies: guidelines for academic practice

What is Qualitative in Research

Scientific Truth in a Post-Truth Era: A Review*

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Writing a scientific paper is an important component of the research process, yet researchers often receive little formal training in scientific writing. This is especially true in low-resource settings. In this article, we explain why choosing a target journal is important, give advice about authorship, provide a basic structure for writing each section of a scientific paper, and describe common pitfalls and recommendations for each section. In the online resource 1 , we also include an annotated journal article that identifies the key elements and writing approaches that we detail here. Before you begin your research, make sure you have ethical clearance from all relevant ethical review boards.

Select a Target Journal Early in the Writing Process

We recommend that you select a “target journal” early in the writing process; a “target journal” is the journal to which you plan to submit your paper. Each journal has a set of core readers and you should tailor your writing to this readership. For example, if you plan to submit a manuscript about vaping during pregnancy to a pregnancy-focused journal, you will need to explain what vaping is because readers of this journal may not have a background in this topic. However, if you were to submit that same article to a tobacco journal, you would not need to provide as much background information about vaping.

Information about a journal’s core readership can be found on its website, usually in a section called “About this journal” or something similar. For example, the Journal of Cancer Education presents such information on the “Aims and Scope” page of its website, which can be found here: https://www.springer.com/journal/13187/aims-and-scope .

Peer reviewer guidelines from your target journal are an additional resource that can help you tailor your writing to the journal and provide additional advice about crafting an effective article [ 1 ]. These are not always available, but it is worth a quick web search to find out.

Identify Author Roles Early in the Process

Early in the writing process, identify authors, determine the order of authors, and discuss the responsibilities of each author. Standard author responsibilities have been identified by The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) [ 2 ]. To set clear expectations about each team member’s responsibilities and prevent errors in communication, we also suggest outlining more detailed roles, such as who will draft each section of the manuscript, write the abstract, submit the paper electronically, serve as corresponding author, and write the cover letter. It is best to formalize this agreement in writing after discussing it, circulating the document to the author team for approval. We suggest creating a title page on which all authors are listed in the agreed-upon order. It may be necessary to adjust authorship roles and order during the development of the paper. If a new author order is agreed upon, be sure to update the title page in the manuscript draft.

In the case where multiple papers will result from a single study, authors should discuss who will author each paper. Additionally, authors should agree on a deadline for each paper and the lead author should take responsibility for producing an initial draft by this deadline.

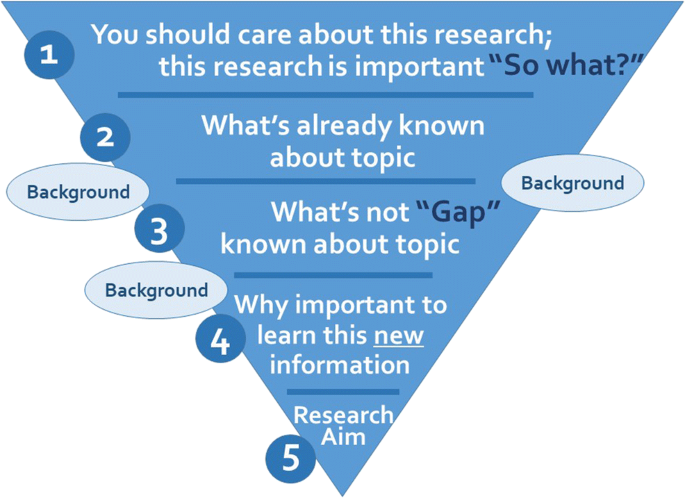

Structure of the Introduction Section

The introduction section should be approximately three to five paragraphs in length. Look at examples from your target journal to decide the appropriate length. This section should include the elements shown in Fig. 1 . Begin with a general context, narrowing to the specific focus of the paper. Include five main elements: why your research is important, what is already known about the topic, the “gap” or what is not yet known about the topic, why it is important to learn the new information that your research adds, and the specific research aim(s) that your paper addresses. Your research aim should address the gap you identified. Be sure to add enough background information to enable readers to understand your study. Table 1 provides common introduction section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

The main elements of the introduction section of an original research article. Often, the elements overlap

Methods Section

The purpose of the methods section is twofold: to explain how the study was done in enough detail to enable its replication and to provide enough contextual detail to enable readers to understand and interpret the results. In general, the essential elements of a methods section are the following: a description of the setting and participants, the study design and timing, the recruitment and sampling, the data collection process, the dataset, the dependent and independent variables, the covariates, the analytic approach for each research objective, and the ethical approval. The hallmark of an exemplary methods section is the justification of why each method was used. Table 2 provides common methods section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

Results Section

The focus of the results section should be associations, or lack thereof, rather than statistical tests. Two considerations should guide your writing here. First, the results should present answers to each part of the research aim. Second, return to the methods section to ensure that the analysis and variables for each result have been explained.

Begin the results section by describing the number of participants in the final sample and details such as the number who were approached to participate, the proportion who were eligible and who enrolled, and the number of participants who dropped out. The next part of the results should describe the participant characteristics. After that, you may organize your results by the aim or by putting the most exciting results first. Do not forget to report your non-significant associations. These are still findings.

Tables and figures capture the reader’s attention and efficiently communicate your main findings [ 3 ]. Each table and figure should have a clear message and should complement, rather than repeat, the text. Tables and figures should communicate all salient details necessary for a reader to understand the findings without consulting the text. Include information on comparisons and tests, as well as information about the sample and timing of the study in the title, legend, or in a footnote. Note that figures are often more visually interesting than tables, so if it is feasible to make a figure, make a figure. To avoid confusing the reader, either avoid abbreviations in tables and figures, or define them in a footnote. Note that there should not be citations in the results section and you should not interpret results here. Table 3 provides common results section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

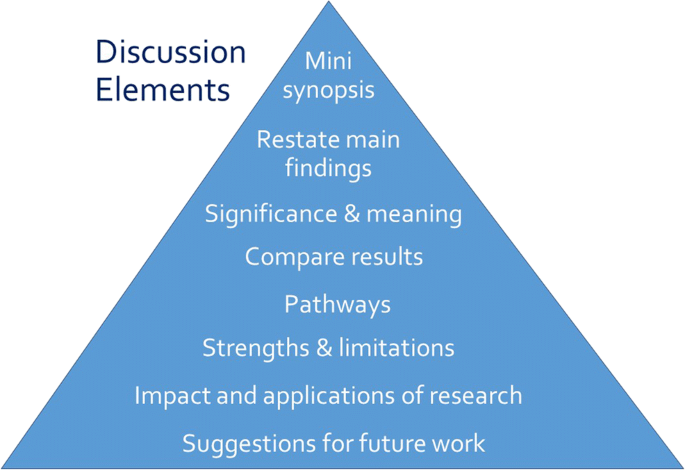

Discussion Section

Opposite the introduction section, the discussion should take the form of a right-side-up triangle beginning with interpretation of your results and moving to general implications (Fig. 2 ). This section typically begins with a restatement of the main findings, which can usually be accomplished with a few carefully-crafted sentences.

Major elements of the discussion section of an original research article. Often, the elements overlap

Next, interpret the meaning or explain the significance of your results, lifting the reader’s gaze from the study’s specific findings to more general applications. Then, compare these study findings with other research. Are these findings in agreement or disagreement with those from other studies? Does this study impart additional nuance to well-accepted theories? Situate your findings within the broader context of scientific literature, then explain the pathways or mechanisms that might give rise to, or explain, the results.

Journals vary in their approach to strengths and limitations sections: some are embedded paragraphs within the discussion section, while some mandate separate section headings. Keep in mind that every study has strengths and limitations. Candidly reporting yours helps readers to correctly interpret your research findings.

The next element of the discussion is a summary of the potential impacts and applications of the research. Should these results be used to optimally design an intervention? Does the work have implications for clinical protocols or public policy? These considerations will help the reader to further grasp the possible impacts of the presented work.

Finally, the discussion should conclude with specific suggestions for future work. Here, you have an opportunity to illuminate specific gaps in the literature that compel further study. Avoid the phrase “future research is necessary” because the recommendation is too general to be helpful to readers. Instead, provide substantive and specific recommendations for future studies. Table 4 provides common discussion section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

Follow the Journal’s Author Guidelines

After you select a target journal, identify the journal’s author guidelines to guide the formatting of your manuscript and references. Author guidelines will often (but not always) include instructions for titles, cover letters, and other components of a manuscript submission. Read the guidelines carefully. If you do not follow the guidelines, your article will be sent back to you.

Finally, do not submit your paper to more than one journal at a time. Even if this is not explicitly stated in the author guidelines of your target journal, it is considered inappropriate and unprofessional.

Your title should invite readers to continue reading beyond the first page [ 4 , 5 ]. It should be informative and interesting. Consider describing the independent and dependent variables, the population and setting, the study design, the timing, and even the main result in your title. Because the focus of the paper can change as you write and revise, we recommend you wait until you have finished writing your paper before composing the title.

Be sure that the title is useful for potential readers searching for your topic. The keywords you select should complement those in your title to maximize the likelihood that a researcher will find your paper through a database search. Avoid using abbreviations in your title unless they are very well known, such as SNP, because it is more likely that someone will use a complete word rather than an abbreviation as a search term to help readers find your paper.

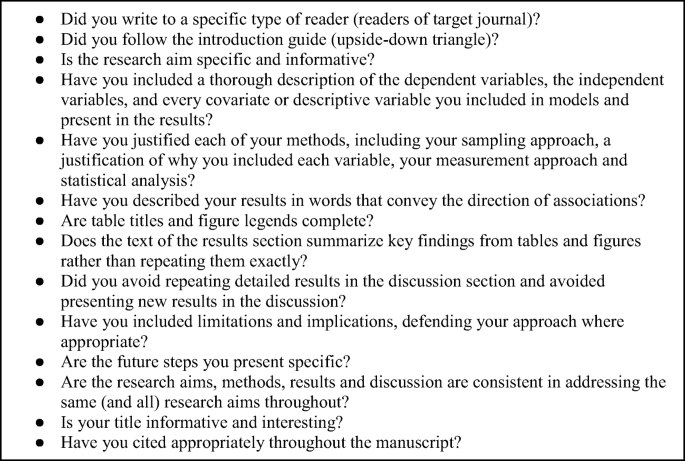

After you have written a complete draft, use the checklist (Fig. 3 ) below to guide your revisions and editing. Additional resources are available on writing the abstract and citing references [ 5 ]. When you feel that your work is ready, ask a trusted colleague or two to read the work and provide informal feedback. The box below provides a checklist that summarizes the key points offered in this article.

Checklist for manuscript quality

Data Availability

Michalek AM (2014) Down the rabbit hole…advice to reviewers. J Cancer Educ 29:4–5

Article Google Scholar

International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Defining the role of authors and contributors: who is an author? http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/browse/roles-and-responsibilities/defining-the-role-of-authosrs-and-contributors.html . Accessed 15 January, 2020

Vetto JT (2014) Short and sweet: a short course on concise medical writing. J Cancer Educ 29(1):194–195

Brett M, Kording K (2017) Ten simple rules for structuring papers. PLoS ComputBiol. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005619

Lang TA (2017) Writing a better research article. J Public Health Emerg. https://doi.org/10.21037/jphe.2017.11.06

Download references

Acknowledgments

Ella August is grateful to the Sustainable Sciences Institute for mentoring her in training researchers on writing and publishing their research.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Maternal and Child Health, University of North Carolina Gillings School of Global Public Health, 135 Dauer Dr, 27599, Chapel Hill, NC, USA

Clara Busse & Ella August

Department of Epidemiology, University of Michigan School of Public Health, 1415 Washington Heights, Ann Arbor, MI, 48109-2029, USA

Ella August

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ella August .

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interests.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

(PDF 362 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Busse, C., August, E. How to Write and Publish a Research Paper for a Peer-Reviewed Journal. J Canc Educ 36 , 909–913 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-020-01751-z

Download citation

Published : 30 April 2020

Issue Date : October 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-020-01751-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Manuscripts

- Scientific writing

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

You are using an outdated browser . Please upgrade your browser today !

How to Write and Publish a Research Paper in 7 Steps

What comes next after you're done with your research? Publishing the results in a journal of course! We tell you how to present your work in the best way possible.

This post is part of a series, which serves to provide hands-on information and resources for authors and editors.

Things have gotten busy in scholarly publishing: These days, a new article gets published in the 50,000 most important peer-reviewed journals every few seconds, while each one takes on average 40 minutes to read. Hundreds of thousands of papers reach the desks of editors and reviewers worldwide each year and 50% of all submissions end up rejected at some stage.

In a nutshell: there is a lot of competition, and the people who decide upon the fate of your manuscript are short on time and overworked. But there are ways to make their lives a little easier and improve your own chances of getting your work published!

Well, it may seem obvious, but before submitting an academic paper, always make sure that it is an excellent reflection of the research you have done and that you present it in the most professional way possible. Incomplete or poorly presented manuscripts can create a great deal of frustration and annoyance for editors who probably won’t even bother wasting the time of the reviewers!

This post will discuss 7 steps to the successful publication of your research paper:

- Check whether your research is publication-ready

- Choose an article type

- Choose a journal

- Construct your paper

- Decide the order of authors

- Check and double-check

- Submit your paper

1. Check Whether Your Research Is Publication-Ready

Should you publish your research at all?

If your work holds academic value – of course – a well-written scholarly article could open doors to your research community. However, if you are not yet sure, whether your research is ready for publication, here are some key questions to ask yourself depending on your field of expertise:

- Have you done or found something new and interesting? Something unique?

- Is the work directly related to a current hot topic?

- Have you checked the latest results or research in the field?

- Have you provided solutions to any difficult problems?

- Have the findings been verified?

- Have the appropriate controls been performed if required?

- Are your findings comprehensive?

If the answers to all relevant questions are “yes”, you need to prepare a good, strong manuscript. Remember, a research paper is only useful if it is clearly understood, reproducible and if it is read and used .

2. Choose An Article Type

The first step is to determine which type of paper is most appropriate for your work and what you want to achieve. The following list contains the most important, usually peer-reviewed article types in the natural sciences:

Full original research papers disseminate completed research findings. On average this type of paper is 8-10 pages long, contains five figures, and 25-30 references. Full original research papers are an important part of the process when developing your career.

Review papers present a critical synthesis of a specific research topic. These papers are usually much longer than original papers and will contain numerous references. More often than not, they will be commissioned by journal editors. Reviews present an excellent way to solidify your research career.

Letters, Rapid or Short Communications are often published for the quick and early communication of significant and original advances. They are much shorter than full articles and usually limited in length by the journal. Journals specifically dedicated to short communications or letters are also published in some fields. In these the authors can present short preliminary findings before developing a full-length paper.

3. Choose a Journal

Are you looking for the right place to publish your paper? Find out here whether a De Gruyter journal might be the right fit.

Submit to journals that you already read, that you have a good feel for. If you do so, you will have a better appreciation of both its culture and the requirements of the editors and reviewers.

Other factors to consider are:

- The specific subject area

- The aims and scope of the journal

- The type of manuscript you have written

- The significance of your work

- The reputation of the journal

- The reputation of the editors within the community

- The editorial/review and production speeds of the journal

- The community served by the journal

- The coverage and distribution

- The accessibility ( open access vs. closed access)

4. Construct Your Paper

Each element of a paper has its purpose, so you should make these sections easy to index and search.

Don’t forget that requirements can differ highly per publication, so always make sure to apply a journal’s specific instructions – or guide – for authors to your manuscript, even to the first draft (text layout, paper citation, nomenclature, figures and table, etc.) It will save you time, and the editor’s.

Also, even in these days of Internet-based publishing, space is still at a premium, so be as concise as possible. As a good journalist would say: “Never use three words when one will do!”

Let’s look at the typical structure of a full research paper, but bear in mind certain subject disciplines may have their own specific requirements so check the instructions for authors on the journal’s home page.

4.1 The Title

It’s important to use the title to tell the reader what your paper is all about! You want to attract their attention, a bit like a newspaper headline does. Be specific and to the point. Keep it informative and concise, and avoid jargon and abbreviations (unless they are universally recognized like DNA, for example).

4.2 The Abstract

This could be termed as the “advertisement” for your article. Make it interesting and easily understood without the reader having to read the whole article. Be accurate and specific, and keep it as brief and concise as possible. Some journals (particularly in the medical fields) will ask you to structure the abstract in distinct, labeled sections, which makes it even more accessible.

A clear abstract will influence whether or not your work is considered and whether an editor should invest more time on it or send it for review.

4.3 Keywords

Keywords are used by abstracting and indexing services, such as PubMed and Web of Science. They are the labels of your manuscript, which make it “searchable” online by other researchers.

Include words or phrases (usually 4-8) that are closely related to your topic but not “too niche” for anyone to find them. Make sure to only use established abbreviations. Think about what scientific terms and its variations your potential readers are likely to use and search for. You can also do a test run of your selected keywords in one of the common academic search engines. Do similar articles to your own appear? Yes? Then that’s a good sign.

4.4 Introduction

This first part of the main text should introduce the problem, as well as any existing solutions you are aware of and the main limitations. Also, state what you hope to achieve with your research.

Do not confuse the introduction with the results, discussion or conclusion.

4.5 Methods

Every research article should include a detailed Methods section (also referred to as “Materials and Methods”) to provide the reader with enough information to be able to judge whether the study is valid and reproducible.

Include detailed information so that a knowledgeable reader can reproduce the experiment. However, use references and supplementary materials to indicate previously published procedures.

4.6 Results

In this section, you will present the essential or primary results of your study. To display them in a comprehensible way, you should use subheadings as well as illustrations such as figures, graphs, tables and photos, as appropriate.

4.7 Discussion

Here you should tell your readers what the results mean .

Do state how the results relate to the study’s aims and hypotheses and how the findings relate to those of other studies. Explain all possible interpretations of your findings and the study’s limitations.

Do not make “grand statements” that are not supported by the data. Also, do not introduce any new results or terms. Moreover, do not ignore work that conflicts or disagrees with your findings. Instead …

Be brave! Address conflicting study results and convince the reader you are the one who is correct.

4.8 Conclusion

Your conclusion isn’t just a summary of what you’ve already written. It should take your paper one step further and answer any unresolved questions.

Sum up what you have shown in your study and indicate possible applications and extensions. The main question your conclusion should answer is: What do my results mean for the research field and my community?

4.9 Acknowledgments and Ethical Statements

It is extremely important to acknowledge anyone who has helped you with your paper, including researchers who supplied materials or reagents (e.g. vectors or antibodies); and anyone who helped with the writing or English, or offered critical comments about the content.

Learn more about academic integrity in our blog post “Scholarly Publication Ethics: 4 Common Mistakes You Want To Avoid” .

Remember to state why people have been acknowledged and ask their permission . Ensure that you acknowledge sources of funding, including any grant or reference numbers.

Furthermore, if you have worked with animals or humans, you need to include information about the ethical approval of your study and, if applicable, whether informed consent was given. Also, state whether you have any competing interests regarding the study (e.g. because of financial or personal relationships.)

4.10 References

The end is in sight, but don’t relax just yet!

De facto, there are often more mistakes in the references than in any other part of the manuscript. It is also one of the most annoying and time-consuming problems for editors.

Remember to cite the main scientific publications on which your work is based. But do not inflate the manuscript with too many references. Avoid excessive – and especially unnecessary – self-citations. Also, avoid excessive citations of publications from the same institute or region.

5. Decide the Order of Authors

In the sciences, the most common way to order the names of the authors is by relative contribution.

Generally, the first author conducts and/or supervises the data analysis and the proper presentation and interpretation of the results. They put the paper together and usually submit the paper to the journal.

Co-authors make intellectual contributions to the data analysis and contribute to data interpretation. They review each paper draft. All of them must be able to present the paper and its results, as well as to defend the implications and discuss study limitations.

Do not leave out authors who should be included or add “gift authors”, i.e. authors who did not contribute significantly.

6. Check and Double-Check

As a final step before submission, ask colleagues to read your work and be constructively critical .

Make sure that the paper is appropriate for the journal – take a last look at their aims and scope. Check if all of the requirements in the instructions for authors are met.

Ensure that the cited literature is balanced. Are the aims, purpose and significance of the results clear?

Conduct a final check for language, either by a native English speaker or an editing service.

7. Submit Your Paper

When you and your co-authors have double-, triple-, quadruple-checked the manuscript: submit it via e-mail or online submission system. Along with your manuscript, submit a cover letter, which highlights the reasons why your paper would appeal to the journal and which ensures that you have received approval of all authors for submission.

It is up to the editors and the peer-reviewers now to provide you with their (ideally constructive and helpful) comments and feedback. Time to take a breather!

If the paper gets rejected, do not despair – it happens to literally everybody. If the journal suggests major or minor revisions, take the chance to provide a thorough response and make improvements as you see fit. If the paper gets accepted, congrats!

It’s now time to get writing and share your hard work – good luck!

If you are interested, check out this related blog post

[Title Image by Nick Morrison via Unsplash]

David Sleeman

David Sleeman worked as Senior Journals Manager in the field of Physical Sciences at De Gruyter.

You might also be interested in

Academia & Publishing

Library Community Gives Back: 2023 Webinar Speakers’ Charity Picks

From error to excellence: embracing mistakes in library practice, the impact of transformative agreements on scholarly publishing, visit our shop.

De Gruyter publishes over 1,300 new book titles each year and more than 750 journals in the humanities, social sciences, medicine, mathematics, engineering, computer sciences, natural sciences, and law.

Pin It on Pinterest

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

How to Write and Publish a Research Paper for a Peer-Reviewed Journal

Clara busse.

1 Department of Maternal and Child Health, University of North Carolina Gillings School of Global Public Health, 135 Dauer Dr, 27599 Chapel Hill, NC USA

Ella August

2 Department of Epidemiology, University of Michigan School of Public Health, 1415 Washington Heights, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-2029 USA

Associated Data

Communicating research findings is an essential step in the research process. Often, peer-reviewed journals are the forum for such communication, yet many researchers are never taught how to write a publishable scientific paper. In this article, we explain the basic structure of a scientific paper and describe the information that should be included in each section. We also identify common pitfalls for each section and recommend strategies to avoid them. Further, we give advice about target journal selection and authorship. In the online resource 1 , we provide an example of a high-quality scientific paper, with annotations identifying the elements we describe in this article.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13187-020-01751-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Introduction

Writing a scientific paper is an important component of the research process, yet researchers often receive little formal training in scientific writing. This is especially true in low-resource settings. In this article, we explain why choosing a target journal is important, give advice about authorship, provide a basic structure for writing each section of a scientific paper, and describe common pitfalls and recommendations for each section. In the online resource 1 , we also include an annotated journal article that identifies the key elements and writing approaches that we detail here. Before you begin your research, make sure you have ethical clearance from all relevant ethical review boards.

Select a Target Journal Early in the Writing Process

We recommend that you select a “target journal” early in the writing process; a “target journal” is the journal to which you plan to submit your paper. Each journal has a set of core readers and you should tailor your writing to this readership. For example, if you plan to submit a manuscript about vaping during pregnancy to a pregnancy-focused journal, you will need to explain what vaping is because readers of this journal may not have a background in this topic. However, if you were to submit that same article to a tobacco journal, you would not need to provide as much background information about vaping.

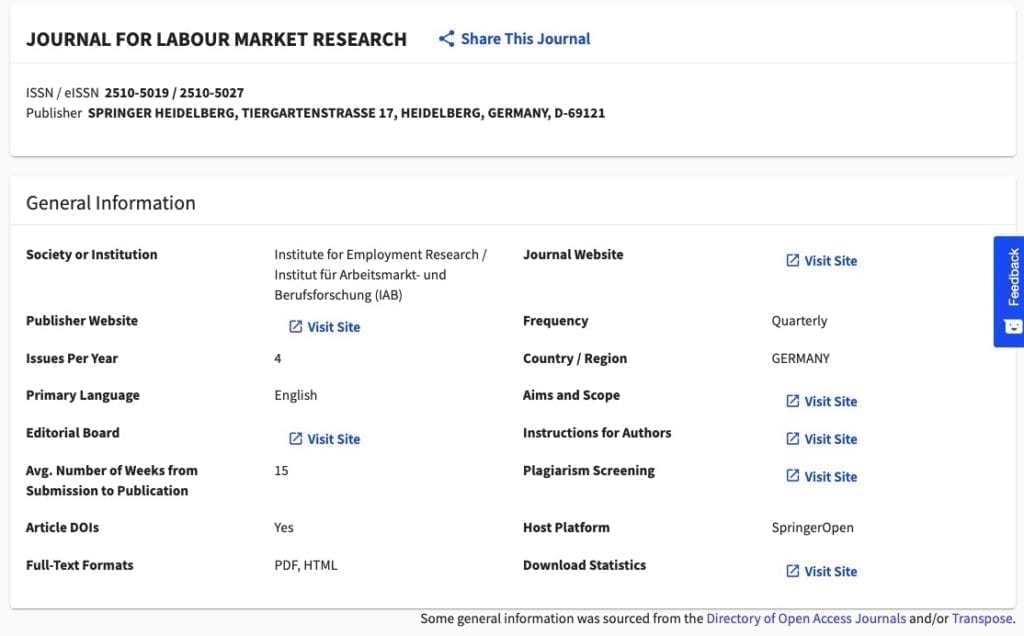

Information about a journal’s core readership can be found on its website, usually in a section called “About this journal” or something similar. For example, the Journal of Cancer Education presents such information on the “Aims and Scope” page of its website, which can be found here: https://www.springer.com/journal/13187/aims-and-scope .

Peer reviewer guidelines from your target journal are an additional resource that can help you tailor your writing to the journal and provide additional advice about crafting an effective article [ 1 ]. These are not always available, but it is worth a quick web search to find out.

Identify Author Roles Early in the Process

Early in the writing process, identify authors, determine the order of authors, and discuss the responsibilities of each author. Standard author responsibilities have been identified by The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) [ 2 ]. To set clear expectations about each team member’s responsibilities and prevent errors in communication, we also suggest outlining more detailed roles, such as who will draft each section of the manuscript, write the abstract, submit the paper electronically, serve as corresponding author, and write the cover letter. It is best to formalize this agreement in writing after discussing it, circulating the document to the author team for approval. We suggest creating a title page on which all authors are listed in the agreed-upon order. It may be necessary to adjust authorship roles and order during the development of the paper. If a new author order is agreed upon, be sure to update the title page in the manuscript draft.

In the case where multiple papers will result from a single study, authors should discuss who will author each paper. Additionally, authors should agree on a deadline for each paper and the lead author should take responsibility for producing an initial draft by this deadline.

Structure of the Introduction Section

The introduction section should be approximately three to five paragraphs in length. Look at examples from your target journal to decide the appropriate length. This section should include the elements shown in Fig. 1 . Begin with a general context, narrowing to the specific focus of the paper. Include five main elements: why your research is important, what is already known about the topic, the “gap” or what is not yet known about the topic, why it is important to learn the new information that your research adds, and the specific research aim(s) that your paper addresses. Your research aim should address the gap you identified. Be sure to add enough background information to enable readers to understand your study. Table Table1 1 provides common introduction section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

The main elements of the introduction section of an original research article. Often, the elements overlap

Common introduction section pitfalls and recommendations

Methods Section

The purpose of the methods section is twofold: to explain how the study was done in enough detail to enable its replication and to provide enough contextual detail to enable readers to understand and interpret the results. In general, the essential elements of a methods section are the following: a description of the setting and participants, the study design and timing, the recruitment and sampling, the data collection process, the dataset, the dependent and independent variables, the covariates, the analytic approach for each research objective, and the ethical approval. The hallmark of an exemplary methods section is the justification of why each method was used. Table Table2 2 provides common methods section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

Common methods section pitfalls and recommendations

Results Section

The focus of the results section should be associations, or lack thereof, rather than statistical tests. Two considerations should guide your writing here. First, the results should present answers to each part of the research aim. Second, return to the methods section to ensure that the analysis and variables for each result have been explained.

Begin the results section by describing the number of participants in the final sample and details such as the number who were approached to participate, the proportion who were eligible and who enrolled, and the number of participants who dropped out. The next part of the results should describe the participant characteristics. After that, you may organize your results by the aim or by putting the most exciting results first. Do not forget to report your non-significant associations. These are still findings.

Tables and figures capture the reader’s attention and efficiently communicate your main findings [ 3 ]. Each table and figure should have a clear message and should complement, rather than repeat, the text. Tables and figures should communicate all salient details necessary for a reader to understand the findings without consulting the text. Include information on comparisons and tests, as well as information about the sample and timing of the study in the title, legend, or in a footnote. Note that figures are often more visually interesting than tables, so if it is feasible to make a figure, make a figure. To avoid confusing the reader, either avoid abbreviations in tables and figures, or define them in a footnote. Note that there should not be citations in the results section and you should not interpret results here. Table Table3 3 provides common results section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

Common results section pitfalls and recommendations

Discussion Section

Opposite the introduction section, the discussion should take the form of a right-side-up triangle beginning with interpretation of your results and moving to general implications (Fig. 2 ). This section typically begins with a restatement of the main findings, which can usually be accomplished with a few carefully-crafted sentences.

Major elements of the discussion section of an original research article. Often, the elements overlap

Next, interpret the meaning or explain the significance of your results, lifting the reader’s gaze from the study’s specific findings to more general applications. Then, compare these study findings with other research. Are these findings in agreement or disagreement with those from other studies? Does this study impart additional nuance to well-accepted theories? Situate your findings within the broader context of scientific literature, then explain the pathways or mechanisms that might give rise to, or explain, the results.

Journals vary in their approach to strengths and limitations sections: some are embedded paragraphs within the discussion section, while some mandate separate section headings. Keep in mind that every study has strengths and limitations. Candidly reporting yours helps readers to correctly interpret your research findings.

The next element of the discussion is a summary of the potential impacts and applications of the research. Should these results be used to optimally design an intervention? Does the work have implications for clinical protocols or public policy? These considerations will help the reader to further grasp the possible impacts of the presented work.

Finally, the discussion should conclude with specific suggestions for future work. Here, you have an opportunity to illuminate specific gaps in the literature that compel further study. Avoid the phrase “future research is necessary” because the recommendation is too general to be helpful to readers. Instead, provide substantive and specific recommendations for future studies. Table Table4 4 provides common discussion section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

Common discussion section pitfalls and recommendations

Follow the Journal’s Author Guidelines

After you select a target journal, identify the journal’s author guidelines to guide the formatting of your manuscript and references. Author guidelines will often (but not always) include instructions for titles, cover letters, and other components of a manuscript submission. Read the guidelines carefully. If you do not follow the guidelines, your article will be sent back to you.

Finally, do not submit your paper to more than one journal at a time. Even if this is not explicitly stated in the author guidelines of your target journal, it is considered inappropriate and unprofessional.

Your title should invite readers to continue reading beyond the first page [ 4 , 5 ]. It should be informative and interesting. Consider describing the independent and dependent variables, the population and setting, the study design, the timing, and even the main result in your title. Because the focus of the paper can change as you write and revise, we recommend you wait until you have finished writing your paper before composing the title.

Be sure that the title is useful for potential readers searching for your topic. The keywords you select should complement those in your title to maximize the likelihood that a researcher will find your paper through a database search. Avoid using abbreviations in your title unless they are very well known, such as SNP, because it is more likely that someone will use a complete word rather than an abbreviation as a search term to help readers find your paper.

After you have written a complete draft, use the checklist (Fig. (Fig.3) 3 ) below to guide your revisions and editing. Additional resources are available on writing the abstract and citing references [ 5 ]. When you feel that your work is ready, ask a trusted colleague or two to read the work and provide informal feedback. The box below provides a checklist that summarizes the key points offered in this article.

Checklist for manuscript quality

(PDF 362 kb)

Acknowledgments

Ella August is grateful to the Sustainable Sciences Institute for mentoring her in training researchers on writing and publishing their research.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Data Availability

Compliance with ethical standards.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

How to Write and Publish a Research Paper for a Peer-Reviewed Journal

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Maternal and Child Health, University of North Carolina Gillings School of Global Public Health, 135 Dauer Dr, 27599, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

- 2 Department of Maternal and Child Health, University of North Carolina Gillings School of Global Public Health, 135 Dauer Dr, 27599, Chapel Hill, NC, USA. [email protected].

- 3 Department of Epidemiology, University of Michigan School of Public Health, 1415 Washington Heights, Ann Arbor, MI, 48109-2029, USA. [email protected].

- PMID: 32356250

- PMCID: PMC8520870

- DOI: 10.1007/s13187-020-01751-z

Communicating research findings is an essential step in the research process. Often, peer-reviewed journals are the forum for such communication, yet many researchers are never taught how to write a publishable scientific paper. In this article, we explain the basic structure of a scientific paper and describe the information that should be included in each section. We also identify common pitfalls for each section and recommend strategies to avoid them. Further, we give advice about target journal selection and authorship. In the online resource 1, we provide an example of a high-quality scientific paper, with annotations identifying the elements we describe in this article.

Keywords: Manuscripts; Publishing; Scientific writing.

© 2020. The Author(s).

- Communication

- Publishing*

- Search Search

- CN (Chinese)

- DE (German)

- ES (Spanish)

- FR (Français)

- JP (Japanese)

- Open Research

- Booksellers

- Peer Reviewers

- Springer Nature Group ↗

Publish an article

- Roles and responsibilities

- Signing your contract

- Writing your manuscript

- Submitting your manuscript

- Producing your book

- Promoting your book

- Submit your book idea

- Manuscript guidelines

- Book author services

- Publish a book

- Publish conference proceedings

Join thousands of researchers worldwide that have published their work in one of our 3,000+ Springer Nature journals.

Step-by-step guide to article publishing

1. Prepare your article

- Make sure you follow the submission guidelines for that journal. Search for a journal .

- Get permission to use any images.

- Check that your data is easy to reproduce.

- State clearly if you're reusing any data that has been used elsewhere.

- Follow our policies on plagiarism and ethics .

- Use our services to get help with English translation, scientific assessment and formatting. Find out what support you can get .

2. Write a cover letter

- Introduce your work in a 1-page letter, explaining the research you did, and why it's relevant.

3. Submit your manuscript

- Go to the journal homepage to start the process

- You can only submit 1 article at a time to each journal. Duplicate submissions will be rejected.

4. Technical check

- We'll make sure that your article follows the journal guidelines for formatting, ethics, plagiarism, contributors, and permissions.

5. Editor and peer review

- The journal editor will read your article and decide if it's ready for peer review.

- Most articles will be reviewed by 2 or more experts in the field.

- They may contact you with questions at this point.

6. Final decision

- If your article is accepted, you'll need to sign a publishing agreement.

- If your article is rejected, you can get help finding another journal from our transfer desk team .

- If your article is open access, you'll need to pay a fee.

- Fees for OA publishing differ across journals. See relevant journal page for more information.

- You may be able to get help covering that cost. See information on funding .

- We'll send you proofs to approve, then we'll publish your article.

- Track your impact by logging in to your account

Get tips on preparing your manuscript using our submission checklist .

Each publication follows a slightly different process, so check the journal's guidelines for more details

Open access vs subscription publishing

Each of our journals has its own policies, options, and fees for publishing.