Depression Detectives

A blog for the radical citizen science project Depression Detectives

Top 10 research questions

Our Depression Detectives have come up with 59 possible research questions and voted on their top ten. We are now discussing, narrowing and finetuning them, and finding ways how they could be researched. Every day, we are looking at one of the top ten questions. Then we will then have another vote to decide on the final favourite question, which will be the basis of our study.

THE TOP TEN

- Do people with depression feel that they predominantly receive help to treat their “symptoms“ vs “origins”? How could this be changed?

- What is the effectiveness of treatments on offer from GPs on the NHS (mainly anti-depressants and short-term counselling) and what proportion of patients recover with just this, what proportion go on to have a major crisis which enables them to access more in-depth treatment, and what proportion end up self-funding something which actually works in the long-term?

- How do people who say that they have recovered from depression describe their recovery: Do they think they are “cured” or just “coping better”, “able to spot triggers better”, etc.?

- How does chronic depression/dysphoria differ from, say a single episode, or discrete episodes of reactive depression? Are there markers (biological, psychological, behavioural, and current or in a person’s history e.g. trauma) that distinguish them?

- What would need to happen to make a wider range of support available, including more time-intensive interventions? How could access to psychological therapies be improved?

- What is the link between autism and depression? Misdiagnosis – are ‘symptoms’ of depression are actually ’traits’ of autism (being quiet, withdrawn and needing to shut yourself away from the stimulus of people and the outside world) which would explain why trying to get someone out and mixing with people as a way out of depression would not work and in fact make things 100x worse?

- How can others best support family members or friends with depression? What do people with depression find most helpful?

- What are the specific problems that emerge from having a parent with depression, and what can be done to help counter these effects?

- Can parents learn and teach healthy emotional behaviours and positive strategies (e.g. through therapy), even if they can’t always do them themselves?

- Can we ask GPs what training they received in mental health, whether they think it was adequate to prepare them for GP consultations, what more they would like to learn and what services do they wish they could refer patients to? Doing 6 months in inpatient psychiatry as an optional part of a rotation doesn’t really prepare you for dealing with the majority of mental health issues in the community.

One thought on “Top 10 research questions”

- Pingback: Working together to improve depression research – UKRI

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

HTML Text Top 10 research questions / Depression Detectives by blogadmin is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0

Plain text Top 10 research questions by blogadmin @ is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0

Report this page

To report inappropriate content on this page, please use the form below. Upon receiving your report, we will be in touch as per the Take Down Policy of the service.

Please note that personal data collected through this form is used and stored for the purposes of processing this report and communication with you.

If you are unable to report a concern about content via this form please contact the Service Owner .

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

7 Depression Research Paper Topic Ideas

Nancy Schimelpfening, MS is the administrator for the non-profit depression support group Depression Sanctuary. Nancy has a lifetime of experience with depression, experiencing firsthand how devastating this illness can be.

Cara Lustik is a fact-checker and copywriter.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Cara-Lustik-1000-77abe13cf6c14a34a58c2a0ffb7297da.jpg)

In psychology classes, it's common for students to write a depression research paper. Researching depression may be beneficial if you have a personal interest in this topic and want to learn more, or if you're simply passionate about this mental health issue. However, since depression is a very complex subject, it offers many possible topics to focus on, which may leave you wondering where to begin.

If this is how you feel, here are a few research titles about depression to help inspire your topic choice. You can use these suggestions as actual research titles about depression, or you can use them to lead you to other more in-depth topics that you can look into further for your depression research paper.

What Is Depression?

Everyone experiences times when they feel a little bit blue or sad. This is a normal part of being human. Depression, however, is a medical condition that is quite different from everyday moodiness.

Your depression research paper may explore the basics, or it might delve deeper into the definition of clinical depression or the difference between clinical depression and sadness .

What Research Says About the Psychology of Depression

Studies suggest that there are biological, psychological, and social aspects to depression, giving you many different areas to consider for your research title about depression.

Types of Depression

There are several different types of depression that are dependent on how an individual's depression symptoms manifest themselves. Depression symptoms may vary in severity or in what is causing them. For instance, major depressive disorder (MDD) may have no identifiable cause, while postpartum depression is typically linked to pregnancy and childbirth.

Depressive symptoms may also be part of an illness called bipolar disorder. This includes fluctuations between depressive episodes and a state of extreme elation called mania. Bipolar disorder is a topic that offers many research opportunities, from its definition and its causes to associated risks, symptoms, and treatment.

Causes of Depression

The possible causes of depression are many and not yet well understood. However, it most likely results from an interplay of genetic vulnerability and environmental factors. Your depression research paper could explore one or more of these causes and reference the latest research on the topic.

For instance, how does an imbalance in brain chemistry or poor nutrition relate to depression? Is there a relationship between the stressful, busier lives of today's society and the rise of depression? How can grief or a major medical condition lead to overwhelming sadness and depression?

Who Is at Risk for Depression?

This is a good research question about depression as certain risk factors may make a person more prone to developing this mental health condition, such as a family history of depression, adverse childhood experiences, stress , illness, and gender . This is not a complete list of all risk factors, however, it's a good place to start.

The growing rate of depression in children, teenagers, and young adults is an interesting subtopic you can focus on as well. Whether you dive into the reasons behind the increase in rates of depression or discuss the treatment options that are safe for young people, there is a lot of research available in this area and many unanswered questions to consider.

Depression Signs and Symptoms

The signs of depression are those outward manifestations of the illness that a doctor can observe when they examine a patient. For example, a lack of emotional responsiveness is a visible sign. On the other hand, symptoms are subjective things about the illness that only the patient can observe, such as feelings of guilt or sadness.

An illness such as depression is often invisible to the outside observer. That is why it is very important for patients to make an accurate accounting of all of their symptoms so their doctor can diagnose them properly. In your depression research paper, you may explore these "invisible" symptoms of depression in adults or explore how depression symptoms can be different in children .

How Is Depression Diagnosed?

This is another good depression research topic because, in some ways, the diagnosis of depression is more of an art than a science. Doctors must generally rely upon the patient's set of symptoms and what they can observe about them during their examination to make a diagnosis.

While there are certain laboratory tests that can be performed to rule out other medical illnesses as a cause of depression, there is not yet a definitive test for depression itself.

If you'd like to pursue this topic, you may want to start with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). The fifth edition, known as DSM-5, offers a very detailed explanation that guides doctors to a diagnosis. You can also compare the current model of diagnosing depression to historical methods of diagnosis—how have these updates improved the way depression is treated?

Treatment Options for Depression

The first choice for depression treatment is generally an antidepressant medication. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the most popular choice because they can be quite effective and tend to have fewer side effects than other types of antidepressants.

Psychotherapy, or talk therapy, is another effective and common choice. It is especially efficacious when combined with antidepressant therapy. Certain other treatments, such as electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) or vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), are most commonly used for patients who do not respond to more common forms of treatment.

Focusing on one of these treatments is an option for your depression research paper. Comparing and contrasting several different types of treatment can also make a good research title about depression.

A Word From Verywell

The topic of depression really can take you down many different roads. When making your final decision on which to pursue in your depression research paper, it's often helpful to start by listing a few areas that pique your interest.

From there, consider doing a little preliminary research. You may come across something that grabs your attention like a new study, a controversial topic you didn't know about, or something that hits a personal note. This will help you narrow your focus, giving you your final research title about depression.

Remes O, Mendes JF, Templeton P. Biological, psychological, and social determinants of depression: A review of recent literature . Brain Sci . 2021;11(12):1633. doi:10.3390/brainsci11121633

National Institute of Mental Health. Depression .

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition . American Psychiatric Association.

National Institute of Mental Health. Mental health medications .

Ferri, F. F. (2019). Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2020 E-Book: 5 Books in 1 . Netherlands: Elsevier Health Sciences.

By Nancy Schimelpfening Nancy Schimelpfening, MS is the administrator for the non-profit depression support group Depression Sanctuary. Nancy has a lifetime of experience with depression, experiencing firsthand how devastating this illness can be.

- Media Center

- Events & Webinars

- Healthy Minds TV

- Email Signup

- Get Involved

- Anxiety Disorders

- Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

- Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

- Bipolar Disorder

- Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD)

- Eating Disorders

- Mental Illness (General)

- Inaccessible

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

- Schizophrenia

- Suicide Prevention

- Other Brain-Related Illnesses

- Basic Research

- New Technologies

- Early Intervention/ Diagnostic Tools

- Next Generation Therapies

- Donate Today

- Make a Memorial/Tribute Gift

- Create an Event/Memorial Page

- Find an Event/Memorial Page

- Make a Stock/Securities Gift/IRA Charitable Rollover Gift

- Donate Cryptocurrency

- Other Giving Opportunities

- Monthly Giving

- Planned Giving

- Research Partners

- Donor Advised Funds

- Workplace Giving

- Team Up for Research!

- Sponsorship Opportunities

Frequently Asked Questions about Depression

Depression (major depressive disorder or clinical depression) is a common but serious mood disorder. It causes severe symptoms that affect how you feel, think, and handle daily activities, such as sleeping, eating, or working. To be diagnosed with depression, the symptoms must be present for at least two weeks.

Impactful Depression Research Discoveries by Foundation Grantees:

- Rapid-Acting Antidepressant Heralded as Biggest Breakthrough in Depression Research in 50 years

- Development of TMS for Treatment-Resistant Depression

- Interactive Parent-Child Therapy Reduced Depression Symptoms in Very Young Children

- Foundation Grantee Shows Treating Inflammation May Improve Resistant Depression

Recent Depression Research Discoveries by Foundation Grantees:

- Impact of Mother’s Depressive Symptoms Just Before and After Childbirth Upon Child’s Brain Development

- Study Links Brain Connectivity Patterns with Response to Specific Antidepressant and Placebo

- Over Two Decades, 90 BBRF Grants Helped Build a Scientific Foundation for the First Rapid-Acting Antidepressants

- After 60 Years, Study Finds Children of Mothers with Bacterial Infections During Pregnancy Have Elevated Psychosis Risk

For more lay-friendly, summarized Depression Research Discoveries, click here .

Clinical depression is a serious condition that negatively affects how a person thinks, feels, and behaves. In contrast to normal sadness, clinical depression is persistent, often interferes with a person’s ability to experience or anticipate pleasure, and significantly interferes with functioning in daily life. Untreated, symptoms can last for weeks, months, or years; and if inadequately treated, depression can lead to significant impairment, other health-related issues, and in rare cases, suicide.

A person is diagnosed with a major depression when he or she experiences at least five of the symptoms listed below for two consecutive weeks. At least one of the five symptoms must be either (1) depressed mood or (2) loss of interest or pleasure. Symptoms include:

- Depressed mood most of the day, nearly every day

- Markedly diminished interest or pleasure in activities most of the day, nearly every day

- Changes in appetite that result in weight losses or gains unrelated to dieting

- Changes in sleeping patterns

- Loss of energy or increased fatigue

- Restlessness or irritability

- Feelings of anxiety

- Feelings of worthlessness, helplessness, or hopelessness

- Inappropriate guilt

- Difficulty thinking, concentrating, or making decisions

- Thoughts of death or attempts at suicide

The first step to being diagnosed is to visit a doctor for a medical evaluation. Certain medications, and some medical conditions such as thyroid disorder, can cause similar symptoms as depression. A doctor can rule out these possibilities by conducting a physical examination, interview and lab tests. If the doctor eliminates a medical condition as a cause, he or she can implement treatment or refer the patient to a mental health professional. Once diagnosed, a person with depression can be treated by various methods. The mainstays of treatment for depression are any of a number of antidepressant medications and psychotherapy, which can also be used in combination.

For severe, treatment-resistant depression, studies have been done showing Deep Brain Stimulation may be an option. Learn more in this webinar featuring Dr. Helen Mayberg :

Depression is twice as common among women as among men. About 20 percent of women will experience at least one episode of depression across their lifetime. Scientists are examining many potential causes for and contributing factors to women’s increased risk for depression. Biological, life cycle, hormonal and psychosocial factors unique to women may be linked to women’s higher depression rates. Researchers have shown, for example, that hormones affect brain chemistry, impacting emotions and mood. Before adolescence, girls and boys experience depression at about the same frequency. By adolescence, however, girls become more likely to experience depression than boys. Research points to several possible reasons for this imbalance. The biological and hormonal changes that occur during puberty likely contribute to the sharp increase in rates of depression among adolescent girls. In addition, research has suggested that girls are more likely than boys to continue feeling bad after experiencing difficult situations or events, suggesting they are more prone to depression.

Women are particularly vulnerable to depression after giving birth, when hormonal and physical changes and the new responsibility of caring for a newborn can be overwhelming. Many new mothers experience a brief episode of mild mood changes known as the “baby blues.” These symptoms usually dissipate by the 10th day. PPD lasts much longer than 10 days, and can go on for months following child birth. Acute PPD is a much more serious condition that requires active treatment and emotional support for the new mother. Some studies suggest that women who experience PPD often have had prior depressive episodes.

Menopause is defined as the state of an absence of menstrual periods for 12 months. Menopause is the point at which estrogen and progesterone production decreases permanently to very low levels. The ovaries stop producing eggs and a woman is no longer able to get pregnant naturally. During the transition into menopause, some women experience an increased risk for depression. Scientists are exploring how the cyclical rise and fall of estrogen and other hormones may affect the brain chemistry that is associated with depressive illness.

For older adults who experience depression for the first time later in life, other factors, such as changes in the brain or body, may be at play. For example, older adults may suffer from restricted blood flow, a condition called ischemia. Over time, blood vessels become less flexible. They may harden and prevent blood from flowing normally to the body’s organs, including the brain. If this occurs, an older adult with no family or personal history of depression may develop what some doctors call “vascular depression.” Those with vascular depression also may be at risk for a coexisting cardiovascular illness, such as heart disease or a stroke.

Researchers are looking for ways to better understand, diagnose and treat depression among all groups of people. Studying strategies to personalize care for depression, such as identifying characteristics of the person that predict which treatments are more likely to work, is an important goal.

The ability of ketamine to produce a rapid and efficacious antidepressant response by a completely novel mechanism is considered by many experts the most important finding in the depression field in 50 years. Originally developed as an anesthetic, ketamine is an antagonist of the NMDA receptor on a subset of brain cells. It often produces rapid (within hours) antidepressant actions in patients who have failed to respond to conventional antidepressants (i.e., are considered treatment-resistant). Ketamine is psychoactive and has potentially dangerous side effects; it has a past history of being abused as a street drug. Studies aimed at characterizing the mechanisms by which ketamine works rapidly and effectively in severely depressed individuals is likely to lead to novel targets and agents that are safer and more long-lasting, and could revolutionize the treatment of depression. Numerous BBRF Grants support this work , including a number that are attempting to develop ketamine analogs – compounds that act like ketamine but lack its side-effects.

Treatment-resistant depression (TRD) is a term used in clinical psychiatry to describe cases of major depressive disorder that do not respond to standard treatments (at least two courses of antidepressant treatments). For many people, antidepressant treatment and/or ‘talk’ therapy (such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy) ease symptoms of depression, but with treatment-resistant depression, little to no relief is realized. Treatment-resistant depression symptoms can range from mild to severe and may require trying a number of approaches to identify what helps. (Source: Biological Psychiatry)

Treatment of resistant depression has most commonly been treated with electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). ECT has been modified to avoid the pain previously associated with it and is the most effective and quick-acting treatment for resistant depression. The downside is that it works by inducing brain seizures and can impair memory. Its therapeutic benefits can also fade over time. New methods of brain stimulation also offer the possibility of relief. These technologies exploit the fact that the brain is an electrical organ: it responds to electrical and magnetic stimulation to modulate brain circuits and change brain activity. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), pioneered by Dr. Mark George with the support of NARSAD grants, was approved by the FDA in 2008 as a treatment for some otherwise untreatable depressions. rTMS is a noninvasive method that works through a coil held over the target area of the brain. A magnetic field passes through the skull to activate the appropriate brain circuit and no seizures are induced. Deep brain stimulation (DBS), a technique adapted for treating depression by Dr. Helen Mayberg with the support of NARSAD grants, works through electrodes planted deep in the brain. Another method, vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), stimulates the vagus nerve in the neck to therapeutically activate brain function. Magnetic seizure therapy (MST) combines rTMS and ECT to achieve a safer form of seizure therapy. MST has been supported through NARSAD Grants to Dr. Sarah Lisanby. Recently, Foundation grantees at the University of Pittsburgh have successfully experimented on a small number of patients with treatment-resistant depression, discovering underlying metabolic deficiencies and successfully treating these. In one subset of patients, a deficiency in cerebral folate was addressed by administering folinic acid. Patients’ depression symptoms declined significantly when these metabolic problems were treated. For some individuals, depression reached remission.

Learn more about TMS for depression in this webinar featuring Dr. Sarah Lisanby :

The first attempts at defining depression as a biologically-based illness hinged on a theory of a ‘chemical imbalance’ in the brain. It was thought that too much or too little of essential signal-transmitting chemicals—neurotransmitters—were present in the brain. This idea has been useful—that the brain is a kind of chemical soup in which there may be too much dopamine or too little serotonin, but it is now begin replaced by much more sophisticated knowledge about how the brain works, made possible by basic research. All the current antidepressants were developed during the period when the chemical-soup theory was in vogue. But now, many researchers are looking to understand in greater detail the brain biology that underlies depression’s symptoms so that novel therapies can be found.

Throughout this website you will find ideas for new depression treatments in greater detail. Efforts to create new classes of antidepressants, based on novel targets have borne fruit. A docking port on brain cells called the mu opioid receptor is the focus of one such effort. Other efforts focus not on the serotonin pathway, as do current “SSRI” drugs such as Prozac, but another pathway, that of another key neurotransmitter, called glutamate. A previously obscure brain area called the lateral habenula may be involved in depression pathology in some instances, due to glutamate hyperactivity. A drug able to specifically lower the activity in that region is a plausible drug discovery objective. Other researchers have been working on the idea that drugs that can mimic the biochemical and biological factors rendering certain people resilient to factors such as severe or chronic stress may have a future in depression treatment. A drug is now being tested that in preliminary trials has helped to reduce postpartum depression. Other researchers have been studying the ability to help women resist depression in the perinatal period through hormone treatments, or, in other work, via treatments that target the maternal immune system, which may be implicated in a subset of postpartum depression. Research has begun to see if administering certain strains of bacteria in depressed individuals might give a boost to their immune system and help reduce depression symptoms. Trying to alleviate depression via changes in diet – e.g., a Mediterranean diet, in one recent study – or omega-3 (“fish oil”) supplements is the subject of other Foundation-supported research. Yet another path that may lead to better outcomes in the future is bright-light therapy, which was first used to help people with seasonal affective disorder. It may have wider applications. It is also important to note research by grantees that has suggested the ability of even a short course of talk therapy to help alleviate depression in mothers with major depression, while at the same time helping their children. Such therapy worked best when it focused on the mother’s relationship with her child, the research revealed.

Dr. J. John Mann presented a webinar titled: Brain Plasticity: The Effects of Antidepressants on Major Depression in which he discusses why we need to better understand how antidepressants including SSRIs, lithium, and ketamine exert their therapeutic effects, so we can find newer more effective and rapidly acting treatments for depression:

Brain imaging has confirmed the biological nature of many psychiatric illnesses over the past twenty years. Yvette Sheline, M.D., in the mid-1990s, used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to identify structural brain changes in depressed patients and established depression as a brain disease.

Using positron emission tomography (PET) scan images, Dr. Helen Mayberg of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, identified, in 2013, specific brain activity that can potentially predict whether people with major depressive disorder will best respond to an antidepressant medication or psychotherapy. This important new work offers a first potential imaging biomarker for treatment selection. A team of researchers including NARSAD Grantee Stefan G. Hoffman, Ph.D., of Boston University and Frida E. Polli, Ph.D., of Massachusetts Institute of Technology have used brain imaging to predict the success of cognitive behavioral therapy, a specific type of talk therapy often used to help treat a wide range of mental illnesses including anxiety disorders, depression, and schizophrenia. Research by Dr. Conor Liston of Weill Cornell Medical School, and colleagues, has used brain scans to identify four distinct “biotypes” of depression. Strikingly, patients in one of these four categories were about three times more likely to respond to a noninvasive treatment known as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) than patients in two of the other categories. This is a good example of the power that biomarkers can have in the years just ahead to help direct people with depression to treatments most likely to help them.

Variations in genes – different kinds of DNA mutations, both common and rare – have been solidly linked to a number of serious psychiatric disorders including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and autism. It is reasonable to wonder why similar progress has not been made yet in the study of the genetic factors contributing to depression. Researchers have made many attempts to search for such factors, but have not come up with results that statisticians consider “statistically meaningful.” One way of explaining the issue in studying depression concerns that very large number of people whom it affects. The power of massive genomic studies of patients (who are compared with unaffected individuals) evaporates if the people being compared have similar illnesses that have very different underlying genetic profiles. People with major depression might be grouped according to sex; whether or not they have recurrent depression; age at onset; symptom patterns; whether or not they were abused or under chronic stress early in life, for example. There is very good reason for progress on the genetic front, however. Foundation grantee Patrick Sullivan, M.D. and others have had success in finding the first reliable signals of commonly seen genetic variations in people with schizophrenia. To do so, they need to assemble a patient sample, across continents, numbering in the tens of thousands. They founded the Psychiatric Genomic Consortium to accomplish this. PGC scientists estimate that the inflection point in depression studies may be 75,000 to 100,000 study participants, a goal the PGC is working toward. It’s not that there is no genetic signal in depression, in other words. It’s a question of assembling a well-documented sample of patients of sufficient size to “tease out” the embedded genetic “signals,” which will point toward risk genes for the illness.

News and Events

Developing Biological Markers to Improve Clinical Care in Autism

ADVICE ON MENTAL HEALTH: Warning Signs & What to Look For: Anxiety and Depression in Childhood

‘Brains Within Brains’: Organoid Experiments Show How Pathologies Emerge in the Developing Brain

A RESEARCHER’S PERSPECTIVE: What Can We Do When Medicine is Not Enough in the Treatment of Schizophrenia?

2022 International Mental Health Research Symposium

OCD: Using Genome Data to Predict Risk, Symptoms and Treatment Response

Developing New Treatments for Mania Using Brain-Based Risk Markers

Self-Control Gone Awry: The Cognitive Neuroscience Behind Bulimia Nervosa

Cognitive Impairment in Psychosis: What it is and How it's Treated

Advice on Diagnosing and Treating Bipolar Disorder

2020 International Mental Health Research Symposium Presentations

Using Rapid-Acting Brain Stimulation for Treatment-Resistant Depression

Donations are welcome

100% of every dollar donated for research is invested in our research grants. Our operating expenses are covered by separate foundation grants.

The Brain & Behavior Research Foundation is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization, our Tax ID # is 31-1020010.

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

- Virtual Tour

- Staff Directory

- En Español

You are here

Nih research matters.

April 23, 2024

Research in Context: Treating depression

Finding better approaches.

While effective treatments for major depression are available, there is still room for improvement. This special Research in Context feature explores the development of more effective ways to treat depression, including personalized treatment approaches and both old and new drugs.

Everyone has a bad day sometimes. People experience various types of stress in the course of everyday life. These stressors can cause sadness, anxiety, hopelessness, frustration, or guilt. You may not enjoy the activities you usually do. These feelings tend to be only temporary. Once circumstances change, and the source of stress goes away, your mood usually improves. But sometimes, these feelings don’t go away. When these feelings stick around for at least two weeks and interfere with your daily activities, it’s called major depression, or clinical depression.

In 2021, 8.3% of U.S. adults experienced major depression. That’s about 21 million people. Among adolescents, the prevalence was much greater—more than 20%. Major depression can bring decreased energy, difficulty thinking straight, sleep problems, loss of appetite, and even physical pain. People with major depression may become unable to meet their responsibilities at work or home. Depression can also lead people to use alcohol or drugs or engage in high-risk activities. In the most extreme cases, depression can drive people to self-harm or even suicide.

The good news is that effective treatments are available. But current treatments have limitations. That’s why NIH-funded researchers have been working to develop more effective ways to treat depression. These include finding ways to predict whether certain treatments will help a given patient. They're also trying to develop more effective drugs or, in some cases, find new uses for existing drugs.

Finding the right treatments

The most common treatments for depression include psychotherapy, medications, or a combination. Mild depression may be treated with psychotherapy. Moderate to severe depression often requires the addition of medication.

Several types of psychotherapy have been shown to help relieve depression symptoms. For example, cognitive behavioral therapy helps people to recognize harmful ways of thinking and teaches them how to change these. Some researchers are working to develop new therapies to enhance people’s positive emotions. But good psychotherapy can be hard to access due to the cost, scheduling difficulties, or lack of available providers. The recent growth of telehealth services for mental health has improved access in some cases.

There are many antidepressant drugs on the market. Different drugs will work best on different patients. But it can be challenging to predict which drugs will work for a given patient. And it can take anywhere from 6 to 12 weeks to know whether a drug is working. Finding an effective drug can involve a long period of trial and error, with no guarantee of results.

If depression doesn’t improve with psychotherapy or medications, brain stimulation therapies could be used. Electroconvulsive therapy, or ECT, uses electrodes to send electric current into the brain. A newer technique, transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), stimulates the brain using magnetic fields. These treatments must be administered by specially trained health professionals.

“A lot of patients, they kind of muddle along, treatment after treatment, with little idea whether something’s going to work,” says psychiatric researcher Dr. Amit Etkin.

One reason it’s difficult to know which antidepressant medications will work is that there are likely different biological mechanisms that can cause depression. Two people with similar symptoms may both be diagnosed with depression, but the causes of their symptoms could be different. As NIH depression researcher Dr. Carlos Zarate explains, “we believe that there’s not one depression, but hundreds of depressions.”

Depression may be due to many factors. Genetics can put certain people at risk for depression. Stressful situations, physical health conditions, and medications may contribute. And depression can also be part of a more complicated mental disorder, such as bipolar disorder. All of these can affect which treatment would be best to use.

Etkin has been developing methods to distinguish patients with different types of depression based on measurable biological features, or biomarkers. The idea is that different types of patients would respond differently to various treatments. Etkin calls this approach “precision psychiatry.”

One such type of biomarker is electrical activity in the brain. A technique called electroencephalography, or EEG, measures electrical activity using electrodes placed on the scalp. When Etkin was at Stanford University, he led a research team that developed a machine-learning algorithm to predict treatment response based on EEG signals. The team applied the algorithm to data from a clinical trial of the antidepressant sertraline (Zoloft) involving more than 300 people.

EEG data for the participants were collected at the outset. Participants were then randomly assigned to take either sertraline or an inactive placebo for eight weeks. The team found a specific set of signals that predicted the participants’ responses to sertraline. The same neural “signature” also predicted which patients with depression responded to medication in a separate group.

Etkin’s team also examined this neural signature in a set of patients who were treated with TMS and psychotherapy. People who were predicted to respond less to sertraline had a greater response to the TMS/psychotherapy combination.

Etkin continues to develop methods for personalized depression treatment through his company, Alto Neuroscience. He notes that EEG has the advantage of being low-cost and accessible; data can even be collected in a patient’s home. That’s important for being able to get personalized treatments to the large number of people they could help. He’s also working on developing antidepressant drugs targeted to specific EEG profiles. Candidate drugs are in clinical trials now.

“It’s not like a pie-in-the-sky future thing, 20–30 years from now,” Etkin explains. “This is something that could be in people’s hands within the next five years.”

New tricks for old drugs

While some researchers focus on matching patients with their optimal treatments, others aim to find treatments that can work for many different patients. It turns out that some drugs we’ve known about for decades might be very effective antidepressants, but we didn’t recognize their antidepressant properties until recently.

One such drug is ketamine. Ketamine has been used as an anesthetic for more than 50 years. Around the turn of this century, researchers started to discover its potential as an antidepressant. Zarate and others have found that, unlike traditional antidepressants that can take weeks to take effect, ketamine can improve depression in as little as one day. And a single dose can have an effect for a week or more. In 2019, the FDA approved a form of ketamine for treating depression that is resistant to other treatments.

But ketamine has drawbacks of its own. It’s a dissociative drug, meaning that it can make people feel disconnected from their body and environment. It also has the potential for addiction and misuse. For these reasons, it’s a controlled substance and can only be administered in a doctor’s office or clinic.

Another class of drugs being studied as possible antidepressants are psychedelics. These include lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) and psilocybin, the active ingredient in magic mushrooms. These drugs can temporarily alter a person’s mood, thoughts, and perceptions of reality. Some have historically been used for religious rituals, but they are also used recreationally.

In clinical studies, psychedelics are typically administered in combination with psychotherapy. This includes several preparatory sessions with a therapist in the weeks before getting the drug, and several sessions in the weeks following to help people process their experiences. The drugs are administered in a controlled setting.

Dr. Stephen Ross, co-director of the New York University Langone Health Center for Psychedelic Medicine, describes a typical session: “It takes place in a living room-like setting. The person is prepared, and they state their intention. They take the drug, they lie supine, they put on eye shades and preselected music, and two therapists monitor them.” Sessions last for as long as the acute effects of the drug last, which is typically several hours. This is a healthcare-intensive intervention given the time and personnel needed.

In 2016, Ross led a clinical trial examining whether psilocybin-assisted therapy could reduce depression and anxiety in people with cancer. According to Ross, as many as 40% of people with cancer have clinically significant anxiety and depression. The study showed that a single psilocybin session led to substantial reductions in anxiety and depression compared with a placebo. These reductions were evident as soon as one day after psilocybin administration. Six months later, 60-80% of participants still had reduced depression and anxiety.

Psychedelic drugs frequently trigger mystical experiences in the people who take them. “People can feel a sense…that their consciousness is part of a greater consciousness or that all energy is one,” Ross explains. “People can have an experience that for them feels more ‘real’ than regular reality. They can feel transported to a different dimension of reality.”

About three out of four participants in Ross’s study said it was among the most meaningful experiences of their lives. And the degree of mystical experience correlated with the drug’s therapeutic effect. A long-term follow-up study found that the effects of the treatment continued more than four years later.

If these results seem too good to be true, Ross is quick to point out that it was a small study, with only 29 participants, although similar studies from other groups have yielded similar results. Psychedelics haven’t yet been shown to be effective in a large, controlled clinical trial. Ross is now conducting a trial with 200 people to see if the results of his earlier study pan out in this larger group. For now, though, psychedelics remain experimental drugs—approved for testing, but not for routine medical use.

Unlike ketamine, psychedelics aren’t considered addictive. But they, too, carry risks, which certain conditions may increase. Psychedelics can cause cardiovascular complications. They can cause psychosis in people who are predisposed to it. In uncontrolled settings, they have the risk of causing anxiety, confusion, and paranoia—a so-called “bad trip”—that can lead the person taking the drug to harm themself or others. This is why psychedelic-assisted therapy takes place in such tightly controlled settings. That increases the cost and complexity of the therapy, which may prevent many people from having access to it.

Better, safer drugs

Despite the promise of ketamine or psychedelics, their drawbacks have led some researchers to look for drugs that work like them but with fewer side effects.

Depression is thought to be caused by the loss of connections between nerve cells, or neurons, in certain regions of the brain. Ketamine and psychedelics both promote the brain’s ability to repair these connections, a quality called plasticity. If we could understand how these drugs encourage plasticity, we might be able to design drugs that can do so without the side effects.

Dr. David Olson at the University of California, Davis studies how psychedelics work at the cellular and molecular levels. The drugs appear to promote plasticity by binding to a receptor in cells called the 5-hydroxytryptamine 2A receptor (5-HT2AR). But many other compounds also bind 5-HT2AR without promoting plasticity. In a recent NIH-funded study, Olson showed that 5-HT2AR can be found both inside and on the surface of the cell. Only compounds that bound to the receptor inside the cells promoted plasticity. This suggests that a drug has to be able to get into the cell to promote plasticity.

Moreover, not all drugs that bind 5-HT2AR have psychedelic effects. Olson’s team has developed a molecular sensor, called psychLight, that can identify which compounds that bind 5-HT2AR have psychedelic effects. Using psychLight, they identified compounds that are not psychedelic but still have rapid and long-lasting antidepressant effects in animal models. He’s founded a company, Delix Therapeutics, to further develop drugs that promote plasticity.

Meanwhile, Zarate and his colleagues have been investigating a compound related to ketamine called hydroxynorketamine (HNK). Ketamine is converted to HNK in the body, and this process appears to be required for ketamine’s antidepressant effects. Administering HNK directly produced antidepressant-like effects in mice. At the same time, it did not cause the dissociative side effects and addiction caused by ketamine. Zarate’s team has already completed phase I trials of HNK in people showing that it’s safe. Phase II trials to find out whether it’s effective are scheduled to begin soon.

“What [ketamine and psychedelics] are doing for the field is they’re helping us realize that it is possible to move toward a repair model versus a symptom mitigation model,” Olson says. Unlike existing antidepressants, which just relieve the symptoms of depression, these drugs appear to fix the underlying causes. That’s likely why they work faster and produce longer-lasting effects. This research is bringing us closer to having safer antidepressants that only need to be taken once in a while, instead of every day.

—by Brian Doctrow, Ph.D.

Related Links

- How Psychedelic Drugs May Help with Depression

- Biosensor Advances Drug Discovery

- Neural Signature Predicts Antidepressant Response

- How Ketamine Relieves Symptoms of Depression

- Protein Structure Reveals How LSD Affects the Brain

- Predicting The Usefulness of Antidepressants

- Depression Screening and Treatment in Adults

- Serotonin Transporter Structure Revealed

- Placebo Effect in Depression Treatment

- When Sadness Lingers: Understanding and Treating Depression

- Psychedelic and Dissociative Drugs

References: An electroencephalographic signature predicts antidepressant response in major depression. Wu W, Zhang Y, Jiang J, Lucas MV, Fonzo GA, Rolle CE, Cooper C, Chin-Fatt C, Krepel N, Cornelssen CA, Wright R, Toll RT, Trivedi HM, Monuszko K, Caudle TL, Sarhadi K, Jha MK, Trombello JM, Deckersbach T, Adams P, McGrath PJ, Weissman MM, Fava M, Pizzagalli DA, Arns M, Trivedi MH, Etkin A. Nat Biotechnol. 2020 Feb 10. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0397-3. Epub 2020 Feb 10. PMID: 32042166. Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Ross S, Bossis A, Guss J, Agin-Liebes G, Malone T, Cohen B, Mennenga SE, Belser A, Kalliontzi K, Babb J, Su Z, Corby P, Schmidt BL. J Psychopharmacol . 2016 Dec;30(12):1165-1180. doi: 10.1177/0269881116675512. PMID: 27909164. Long-term follow-up of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for psychiatric and existential distress in patients with life-threatening cancer. Agin-Liebes GI, Malone T, Yalch MM, Mennenga SE, Ponté KL, Guss J, Bossis AP, Grigsby J, Fischer S, Ross S. J Psychopharmacol . 2020 Feb;34(2):155-166. doi: 10.1177/0269881119897615. Epub 2020 Jan 9. PMID: 31916890. Psychedelics promote neuroplasticity through the activation of intracellular 5-HT2A receptors. Vargas MV, Dunlap LE, Dong C, Carter SJ, Tombari RJ, Jami SA, Cameron LP, Patel SD, Hennessey JJ, Saeger HN, McCorvy JD, Gray JA, Tian L, Olson DE. Science . 2023 Feb 17;379(6633):700-706. doi: 10.1126/science.adf0435. Epub 2023 Feb 16. PMID: 36795823. Psychedelic-inspired drug discovery using an engineered biosensor. Dong C, Ly C, Dunlap LE, Vargas MV, Sun J, Hwang IW, Azinfar A, Oh WC, Wetsel WC, Olson DE, Tian L. Cell . 2021 Apr 8: S0092-8674(21)00374-3. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.03.043. Epub 2021 Apr 28. PMID: 33915107. NMDAR inhibition-independent antidepressant actions of ketamine metabolites. Zanos P, Moaddel R, Morris PJ, Georgiou P, Fischell J, Elmer GI, Alkondon M, Yuan P, Pribut HJ, Singh NS, Dossou KS, Fang Y, Huang XP, Mayo CL, Wainer IW, Albuquerque EX, Thompson SM, Thomas CJ, Zarate CA Jr, Gould TD. Nature . 2016 May 26;533(7604):481-6. doi: 10.1038/nature17998. Epub 2016 May 4. PMID: 27144355.

Connect with Us

- More Social Media from NIH

Transforming the understanding and treatment of mental illnesses.

Información en español

Celebrating 75 Years! Learn More >>

- Health Topics

- Brochures and Fact Sheets

- Help for Mental Illnesses

- Clinical Trials

- Download PDF

- Order a free hardcopy

What is depression?

Everyone feels sad or low sometimes, but these feelings usually pass. Depression (also called major depression, major depressive disorder, or clinical depression) is different. It can cause severe symptoms that affect how a person feels, thinks, and handles daily activities, such as sleeping, eating, or working.

Depression can affect anyone regardless of age, gender, race or ethnicity, income, culture, or education. Research suggests that genetic, biological, environmental, and psychological factors play a role in the disorder.

Women are diagnosed with depression more often than men, but men can also be depressed. Because men may be less likely to recognize, talk about, and seek help for their negative feelings, they are at greater risk of their depression symptoms being undiagnosed and undertreated. Studies also show higher rates of depression and an increased risk for the disorder among members of the LGBTQI+ community.

In addition, depression can co-occur with other mental disorders or chronic illnesses, such as diabetes, cancer, heart disease, and chronic pain. Depression can make these conditions worse and vice versa. Sometimes, medications taken for an illness cause side effects that contribute to depression symptoms as well.

What are the different types of depression?

There are two common types of depression.

- Major depression includes symptoms of depressed mood or loss of interest, most of the time for at least 2 weeks, that interfere with daily activities.

- Persistent depressive disorder (also called dysthymia or dysthymic disorder) consists of less severe depression symptoms that last much longer, usually for at least 2 years.

Other types of depression include the following.

- Seasonal affective disorder comes and goes with the seasons, with symptoms typically starting in the late fall and early winter and going away during the spring and summer.

- Depression with symptoms of psychosis is a severe form of depression in which a person experiences psychosis symptoms, such as delusions or hallucinations.

- Bipolar disorder involves depressive episodes, as well as manic episodes (or less severe hypomanic episodes) with unusually elevated mood, greater irritability, or increased activity level.

Additional types of depression can occur at specific points in a woman’s life. Pregnancy, the postpartum period, the menstrual cycle, and menopause are associated with physical and hormonal changes that can bring on a depressive episode in some people.

- Premenstrual dysphoric disorder is a more severe form of premenstrual syndrome, or PMS, that occurs in the weeks before menstruation.

- Perinatal depression occurs during pregnancy or after childbirth. It is more than the “baby blues” many new moms experience after giving birth.

- Perimenopausal depression affects some women during the transition to menopause. Women may experience feelings of intense irritability, anxiety, sadness, or loss of enjoyment.

What are the signs and symptoms of depression?

Common signs and symptoms of depression include:

- Persistent sad, anxious, or “empty” mood

- Feelings of hopelessness or pessimism

- Feelings of irritability, frustration‚ or restlessness

- Feelings of guilt, worthlessness, or helplessness

- Loss of interest or pleasure in hobbies and activities

- Fatigue, lack of energy, or feeling slowed down

- Difficulty concentrating, remembering, or making decisions

- Difficulty sleeping, waking too early in the morning, or oversleeping

- Changes in appetite or unplanned weight changes

- Physical aches or pains, headaches, cramps, or digestive problems without a clear physical cause that do not go away with treatment

- Thoughts of death or suicide or suicide attempts

Depression can also involve other changes in mood or behavior that include:

- Increased anger or irritability

- Feeling restless or on edge

- Becoming withdrawn, negative, or detached

- Increased engagement in high-risk activities

- Greater impulsivity

- Increased use of alcohol or drugs

- Isolating from family and friends

- Inability to meet responsibilities or ignoring other important roles

- Problems with sexual desire and performance

Not everyone who is depressed shows all these symptoms. Some people experience only a few symptoms, while others experience many. Depression symptoms interfere with day-to-day functioning and cause significant distress for the person experiencing them.

If you show signs or symptoms of depression and they persist or do not go away, talk to a health care provider. If you see signs of depression in someone you know, encourage them to seek help from a mental health professional.

If you or someone you know is struggling or having thoughts of suicide, call or text the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline at 988 or chat at 988lifeline.org . In life-threatening situations, call 911 .

How is depression diagnosed?

To be diagnosed with depression, a person must have symptoms most of the day, nearly every day, for at least 2 weeks. One of the symptoms must be a depressed mood or a loss of interest or pleasure in most activities. Children and adolescents may be irritable rather than sad.

Although several persistent symptoms, in addition to low mood, are required for a depression diagnosis, people with only a few symptoms may benefit from treatment. The severity and frequency of symptoms and how long they last vary depending on the person.

If you think you may have depression, talk to a health care provider, such as a primary care doctor, psychologist, or psychiatrist. During the visit, the provider may ask when your symptoms began, how long they have lasted, how often they occur, and if they keep you from going out or doing your usual activities. It may help to take some notes about your symptoms before the visit.

Certain medications and medical conditions, such as viruses or thyroid disorders, can cause the same symptoms as depression. A provider can rule out these possibilities by doing a physical exam, interview, and lab tests.

Does depression look the same in everyone?

Depression can affect people differently depending on their age.

- Children may be anxious or cranky, pretend to be sick, refuse to go to school, cling to a parent, or worry that a parent may die.

- Older children and teens may get into trouble at school, sulk, be easily frustrated‚ feel restless, or have low self-esteem. They may have other disorders, such as anxiety, an eating disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, or substance use disorder. Older children and teens are also more likely to experience excessive sleepiness (called hypersomnia) and increased appetite (called hyperphagia).

- Young adults are more likely to be irritable, complain of weight gain and hypersomnia, and have a negative view of life and the future. They often have other disorders, such as generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, panic disorder, or substance use disorder.

- Middle-aged adults may have more depressive episodes, decreased libido, middle-of-the-night insomnia, or early morning waking. They often report stomach problems, such as diarrhea or constipation.

- Older adults often feel sadness, grief, or other less obvious symptoms. They may report a lack of emotions rather than a depressed mood. Older adults are also more likely to have other medical conditions or pain that can cause or contribute to depression. Memory and thinking problems (called pseudodementia) may be prominent in severe cases.

Depression can also look different in men versus women, such as the symptoms they show and the behaviors they use to cope with them. For instance, men (as well as women) may show symptoms other than sadness, instead seeming angry or irritable.

For some people, symptoms manifest as physical problems (for example, a racing heart, tightened chest, chronic headaches, or digestive issues). Many men are more likely to see a health care provider about these physical symptoms than their emotional ones. While increased use of alcohol or drugs can be a sign of depression in any person, men are also more likely to use these substances as a coping strategy.

How is depression treated?

Depression treatment typically involves psychotherapy (in person or virtual), medication, or both. If these treatments do not reduce symptoms sufficiently, brain stimulation therapy may be another option.

Choosing the right treatment plan is based on a person’s needs, preferences, and medical situation and in consultation with a mental health professional or a health care provider. Finding the best treatment may take trial and error.

For milder forms of depression, psychotherapy is often tried first, with medication added later if the therapy alone does not produce a good response. People with moderate or severe depression usually are prescribed medication as part of the initial treatment plan.

Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy (also called talk therapy or counseling) can help people with depression by teaching them new ways of thinking and behaving and helping them change habits that contribute to depression. Psychotherapy occurs under the care of a licensed, trained mental health professional in one-on-one sessions or with others in a group setting.

Psychotherapy can be effective when delivered in person or virtually via telehealth. A provider may support or supplement therapy using digital or mobile technology, like apps or other tools.

Evidence-based therapies to treat depression include cognitive behavioral therapy and interpersonal therapy. Using other forms of psychotherapy, such as psychodynamic therapy, for a limited time also may help some people with depression.

- Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) : With CBT, people learn to challenge and change unhelpful thoughts and behaviors to improve their depressive and anxious feelings. Recent advances in CBT include adding mindfulness principles and specializing the therapy to target specific symptoms like insomnia.

- Interpersonal therapy (IPT) : IPT focuses on interpersonal and life events that impact mood and vice versa. IPT aims to help people improve their communication skills within relationships, form social support networks, and develop realistic expectations to better deal with crises or other issues that may be contributing to or worsening their depression.

Learn more about psychotherapy .

Antidepressants are medications commonly used to treat depression. They work by changing how the brain produces or uses certain chemicals involved in mood or stress.

Antidepressants take time—usually 4−8 weeks—to work, and problems with sleep, appetite, and concentration often improve before mood lifts. Giving a medication a chance to work is important before deciding whether it is right for you.

Treatment-resistant depression occurs when a person doesn’t get better after trying at least two antidepressants. Esketamine is a medication approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment-resistant depression. Delivered as a nasal spray in a doctor’s office, clinic, or hospital, the medication acts rapidly, typically within a couple of hours, to relieve depression symptoms. People will usually continue to take an antidepressant pill to maintain the improvement in their symptoms.

Another option for treatment-resistant depression is to combine an antidepressant with a different type of medication that may make it more effective, such as an antipsychotic or anticonvulsant medication.

All medications can have side effects. Talk to a health care provider before starting or stopping any medication. Learn more about antidepressants .

Note : In some cases, children, teenagers, and young adults under 25 years may experience an increase in suicidal thoughts or behavior when taking antidepressants, especially in the first few weeks after starting or when the dose is changed. The FDA advises that patients of all ages taking antidepressants be watched closely, especially during the first few weeks of treatment.

Information about medication changes frequently. Learn more about specific medications like esketamine, including the latest approvals, side effects, warnings, and patient information, on the FDA website .

Brain stimulation therapy

Brain stimulation therapy is an option when other depression treatments have not worked. The therapy involves activating or inhibiting the brain with electricity or magnetic waves.

Although brain stimulation therapy is less frequently used than psychotherapy and medication, it can play an important role in treating depression in people who have not responded to other treatments. The therapy generally is used only after a person has tried psychotherapy and medication, and those treatments usually continue. Brain stimulation therapy is sometimes used as an earlier treatment option when severe depression has become life-threatening, such as when a person has stopped eating or drinking or is at a high risk of suicide.

The FDA has approved several types of brain stimulation therapy. The most used are electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS). Other brain stimulation therapies are newer and, in some cases, still considered experimental. Learn more about brain stimulation therapies .

Natural products

The FDA has not approved any natural products for treating depression. Although research is ongoing and findings are inconsistent, some people report that natural products, including vitamin D and the herbal dietary supplement St. John’s wort, helped their depression symptoms. However, these products can come with risks, including, in some cases, interactions with prescription medications.

Do not use vitamin D, St. John’s wort, or other dietary supplements or natural products without first talking to a health care provider. Rigorous studies must test whether these and other natural products are safe and effective.

How can I take care of myself?

Most people with depression benefit from mental health treatment. Once you begin treatment, you should gradually start to feel better. Go easy on yourself during this time. Try to do things you used to enjoy. Even if you don’t feel like doing them, they can improve your mood.

Other things that may help:

- Try to get physical activity. Just 30 minutes a day of walking can boost your mood.

- Try to maintain a regular bedtime and wake-up time.

- Eat regular, healthy meals.

- Do what you can as you can. Decide what must get done and what can wait.

- Connect with people. Talk to people you trust about how you are feeling.

- Delay making important life decisions until you feel better. Discuss decisions with people who know you well.

- Avoid using alcohol, nicotine, or drugs, including medications not prescribed for you.

How can I find help for depression?

You can learn about ways to get help and find tips for talking with a health care provider on the NIMH website.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) also has an online tool to help you find mental health services in your area.

How can I help a loved one who is depressed?

If someone you know is depressed, help them see a health care provider or mental health professional. You also can:

- Offer support, understanding, patience, and encouragement.

- Invite them out for walks, outings, and other activities.

- Help them stick to their treatment plan, such as setting reminders to take prescribed medications.

- Make sure they have transportation or access to therapy appointments.

- Remind them that, with time and treatment, their depression can lift.

What are clinical trials and why are they important?

Clinical trials are research studies that look at ways to prevent, detect, or treat diseases and conditions. These studies help show whether a treatment is safe and effective in people. Some people join clinical trials to help doctors and researchers learn more about a disease and improve health care. Other people, such as those with health conditions, join to try treatments that aren’t widely available.

NIMH supports clinical trials across the United States. Talk to a health care provider about clinical trials and whether one is right for you. Learn more about participating in clinical trials .

For more information

Learn more about mental health disorders and topics . For information about various health topics, visit the National Library of Medicine’s MedlinePlus .

The information in this publication is in the public domain and may be reused or copied without permission. However, you may not reuse or copy images. Please cite the National Institute of Mental Health as the source. Read our copyright policy to learn more about our guidelines for reusing NIMH content.

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES National Institutes of Health NIH Publication No. 24-MH-8079 Revised 2024

Yearly paid plans are up to 65% off for the spring sale. Limited time only! 🌸

- Form Builder

- Survey Maker

- AI Form Generator

- AI Survey Tool

- AI Quiz Maker

- Store Builder

- WordPress Plugin

HubSpot CRM

Google Sheets

Google Analytics

Microsoft Excel

- Popular Forms

- Job Application Form Template

- Rental Application Form Template

- Hotel Accommodation Form Template

- Online Registration Form Template

- Employment Application Form Template

- Application Forms

- Booking Forms

- Consent Forms

- Contact Forms

- Donation Forms

- Customer Satisfaction Surveys

- Employee Satisfaction Surveys

- Evaluation Surveys

- Feedback Surveys

- Market Research Surveys

- Personality Quiz Template

- Geography Quiz Template

- Math Quiz Template

- Science Quiz Template

- Vocabulary Quiz Template

Try without registration Quick Start

Read engaging stories, how-to guides, learn about forms.app features.

Inspirational ready-to-use templates for getting started fast and powerful.

Spot-on guides on how to use forms.app and make the most out of it.

See the technical measures we take and learn how we keep your data safe and secure.

- Integrations

- Help Center

- Sign In Sign Up Free

- 45 Survey questions for a depression questionnaire (+templates)

.jpg)

Eren Eltemur

Maintaining mental health is important, and depression is a big problem in the modern world. With the highly developed technological world, humankind keeps getting lonelier day by day. For this reason, diagnosing depression has become important, and a depression questionnaire can help professionals as a powerful tool. It makes it easier to gather data from patients using depression survey questions.

Since it is so important to gather data from clients with depression test questions, in this article, we cover what a depression questionnaire is , how to create an online depression questionnaire , and 45 great survey questions examples to use in your depression questionnaire. So if you are a mental health professional or want to create a questionnaire about depression, you can use this article as a go-to guide.

- What is a depression questionnaire?

A depression questionary is a way of assessing the severity of depressive symptoms associated with depression . Even though it can help professionals, individuals also self-measure their depression with surveys. Although it cannot give definite answers to measuring depression , it can be a helpful tool.

It can consist of a series of questions related to their feelings, appetite, sleep patterns , and other topics, such as their interest in activities . The quality of life is improved by having good mental health and well-being. For this reason, readers should take a step and take action to measure their depression with these helpful questions.

The definition of depression questionnaire

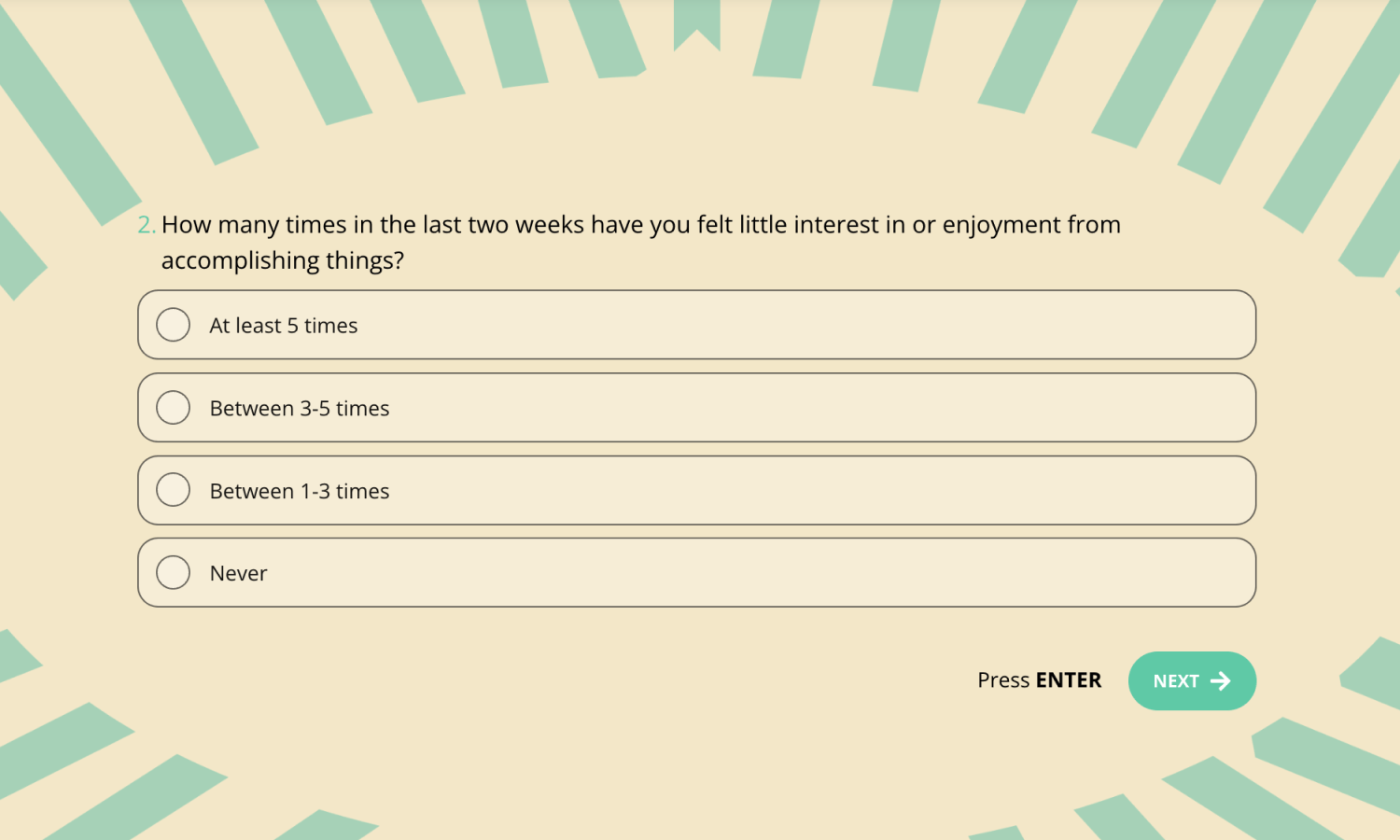

- 45 survey question examples to use in your depression questionnaire

Since we are well aware of the necessity of adequate questions as forms.app, we gathered 45 great questions for the survey questionnaire about depression. You can use these questions in your depression research questionnaire to create well-developed and professional surveys. Since there are different types of depression questionnaire examples, these questions are separated into groups with their intended use. Including these questions will give you information about your potential clients and see:

- if they are having trouble staying asleep or sleeping too much

- if they are feeling down, depressed, or hopeless all the time

- if they had a diagnosis of depression or received treatments for depression earlier

- If they read too much newspaper or watch television

- if they lost their interest and pleasure in life

- or in extreme cases, if they are having trouble moving or speaking so slowly.

Self-report questionnaires

This type is specifically focused on individual experience. Individuals can measure themselves with questions related to their feelings, symptoms, sadness, loss of interest , and suicidal thoughts.

SELF-CARE/MOBILITY

1 - Have you experienced physical symptoms such as aches and pains, digestive issues, or changes in appetite?

2 - Have you noticed any changes in your sleep patterns, such as waking up too early or feeling unrested after a full night's sleep?

3 - Do you feel self-conscious or embarrassed about your movement or speech patterns?

4 - Do you feel like your movements or speech are slower than usual or that you have trouble getting your words out?

5 - How frequently did you feel drained of energy over the last two weeks?

USUAL ACTIVITIES

6 - How frequently did you struggle to fall asleep, stay asleep, or oversleep over the previous two weeks?

7 - Have you been crying more or more easily than usual?

8 - How frequently did you find it difficult to focus over the past two weeks on activities like reading the news or watching TV?

9 - Do you have difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep most nights?

10 - Are there any changes in your sexual desire compared to usual?

ANXIETY/ DEPRESSION

11 - How many times in the last two weeks have you felt dejected, miserable, or hopeless?

12 - How many times in the last two weeks have you felt little interest in or enjoyment from accomplishing things?

13 - How frequently have you felt inferior to yourself, like a failure, or like you have let yourself or your family down over the last two weeks?

14 - Do you consider yourself more impatient than usual?

15 - Have you been feeling self-conscious, like a failure, or having disappointed yourself or your family?

16 - Do you feel guilty about something you have done?

17 - Do you have any recent trust issues in your relationships?

18 - Have you been feeling bad or sad most days, or have you lost interest in activities that you once enjoyed?

19 - Have you had thoughts of self-harm or suicide?

Self-report depression question example

Observer-Rated Questionnaires

20 - This type of questionnaire can be used by professionals or anyone other than the patient. Typically, they evaluate a variety of symptoms, such as alterations in mood, behavior, and physical health .

21 - Have you felt like your mental health issues are negatively affecting your ability to function at work, school, or in your personal life?

22 - Have you discussed your sleep problems with your primary care physician or another healthcare provider?

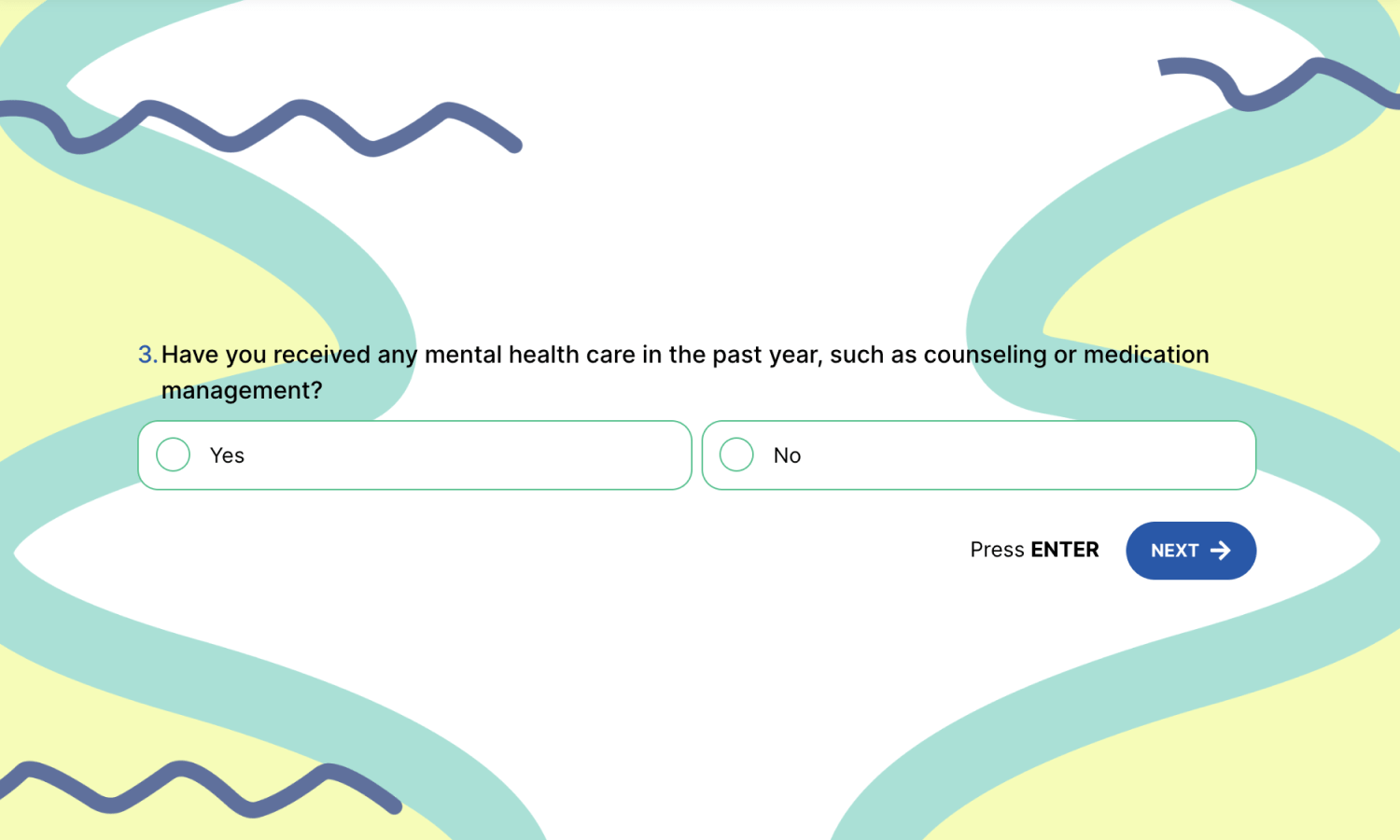

23 - Have you received any mental health care in the past year, such as counseling or medication management?

24 - Have you observed any changes in the individual's social functioning or engagement with others over the past week?

25 - Have you observed any changes in the individual's movement or speech patterns, such as slowing down or appearing agitated?

26 - How frequently has the individual reported feeling fatigued or lacking in energy over the past week?

27 - Over the past week, how frequently has the individual exhibited symptoms of sadness, hopelessness, or low mood?

28 - Over the past week, how frequently has the individual exhibited symptoms of irritability or restlessness?

29 - Have you observed any changes in the individual's ability to engage in social or recreational activities over the past week?

30 - Have you observed any changes in the individual's communication patterns or ability to express themselves effectively over the past week?

Observer-rated depression question example

Suicide risk questionnaires

This type of questionnaire focuses on suicidal intentions or attempts . It should be considered that these questions must be used by professionals but can also help to create awareness. It should be noted that patients may not be aware of their suicidal behavior. For this reason, creating awareness can help to save a life.

31 - Have you ever considered harming yourself or taking your own life?

32 - Have you thought about dying or getting killed?

33 - Have you ever considered suicide or attempted it before?

34 - Have you cut yourself or burned yourself? Or have you engaged in other self-harming behaviors?

35 - Have you been feeling more agitated, irritable, or anxious lately? Does this make you think about committing suicide?

36 - Have you had a substantial behavioral shift that would point to a possible suicide attempt, such as giving away possessions or saying goodbye to loved ones?

37 - Have your concentration or focus decreased as a result of having suicidal thoughts?

38 - Have you recently gone through a big loss or trauma that could have triggered feelings of hopelessness or thoughts of suicide?

39 - Have you ever felt guilty or unworthy, which could be motivating your suicidal thoughts?

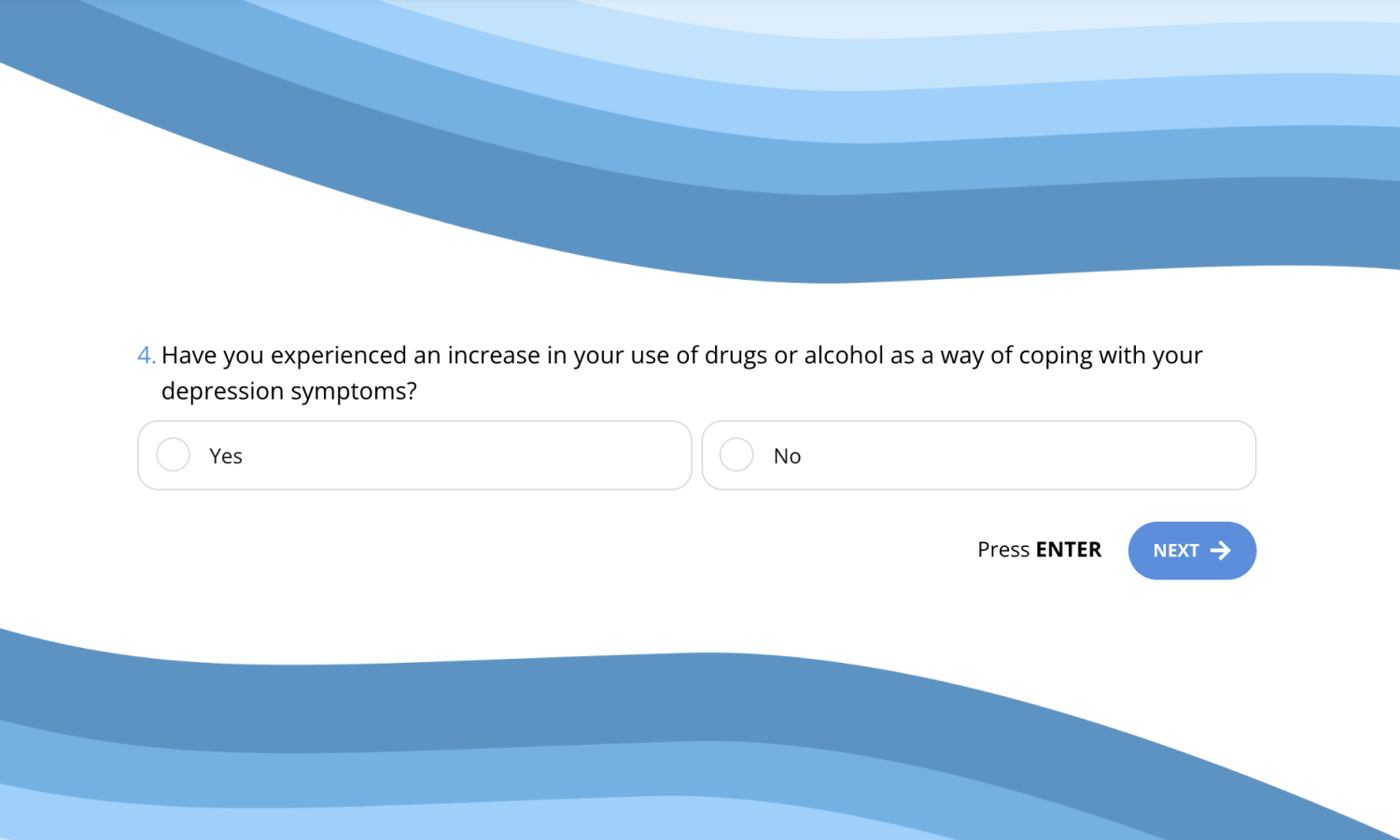

40 - Have you experienced an increase in your use of drugs or alcohol as a way of coping with your depression symptoms?

Suicide risk depression question example

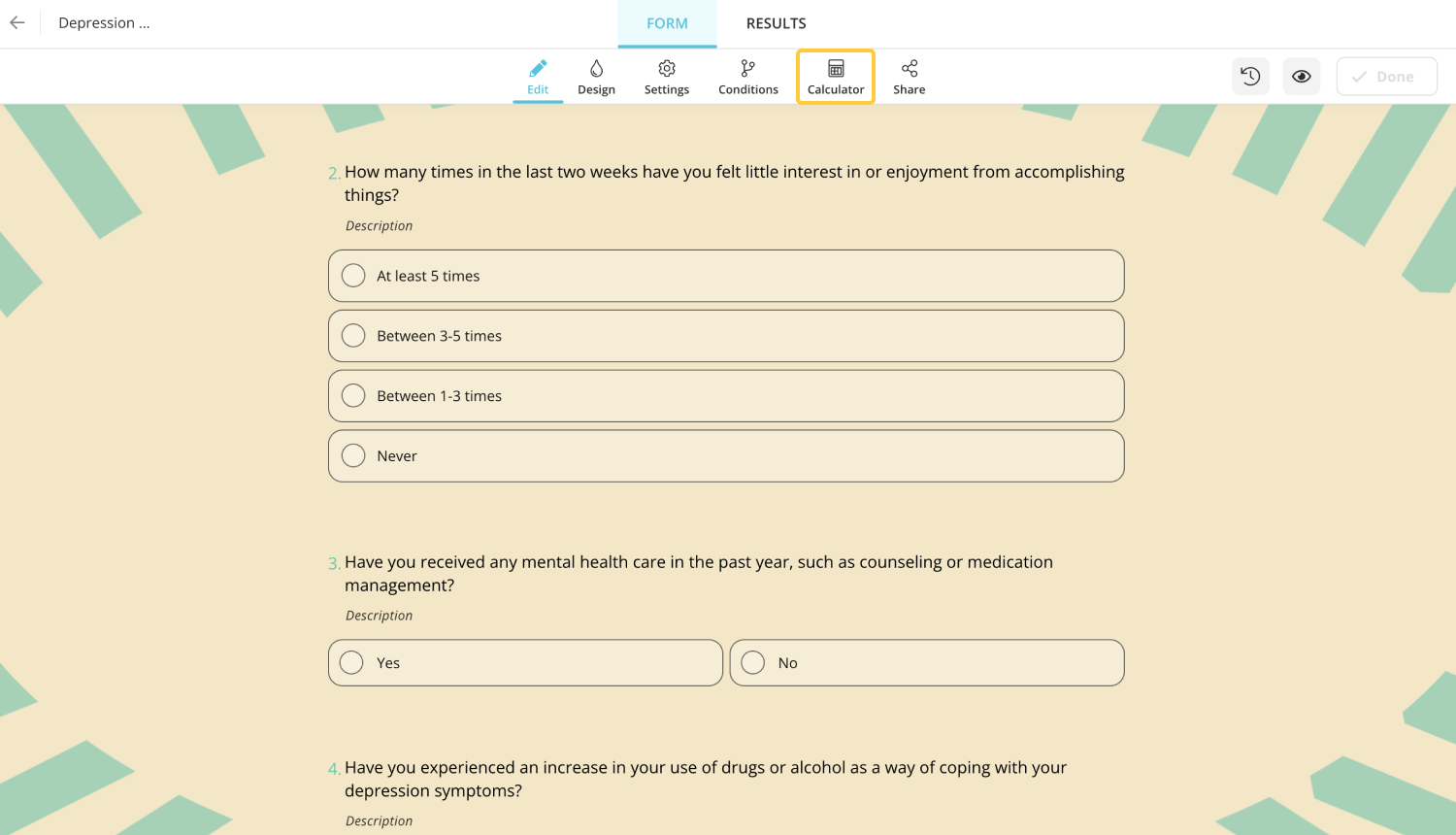

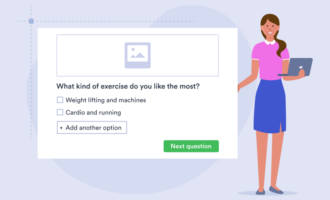

- How to create an online depression questionnaire

Creating a depression questionnaire is an easy task with forms.app. You can customize pre-made depression questionnaires or create yours from scratch . You can create well-developed questionnaires using features like conditional logic and a calculator, and in addition to these, you can add multiple layers to your survey with different form fields. Here are some form fields you can use in your questionnaire to enrich your question variety:

- Single selection: Allows responders to pick up just one option.

- Multiple selections: Allow responders to select from a variety of alternatives.

- Picture selections: Enables responders with visual options to choose from.

- Selection matrix: Offers a graphic alternative for multiple or single choices.

- Short text: Short answer field for manual typing.

- Long text: Long answer field for manual typing.

- Yes/No: With only to possible outcomes, you can get conclusive responses.

How to automatically show results on your depression test

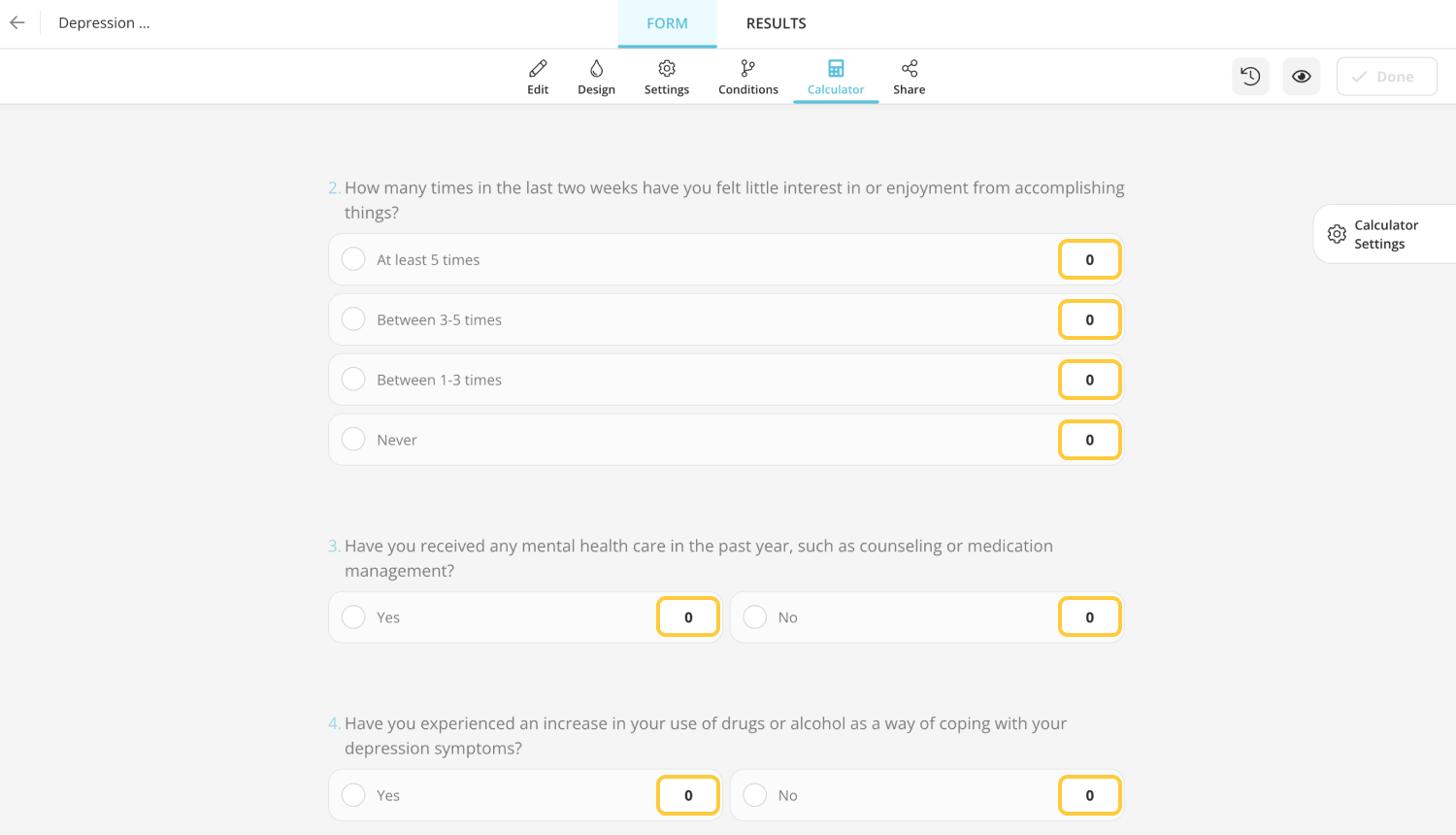

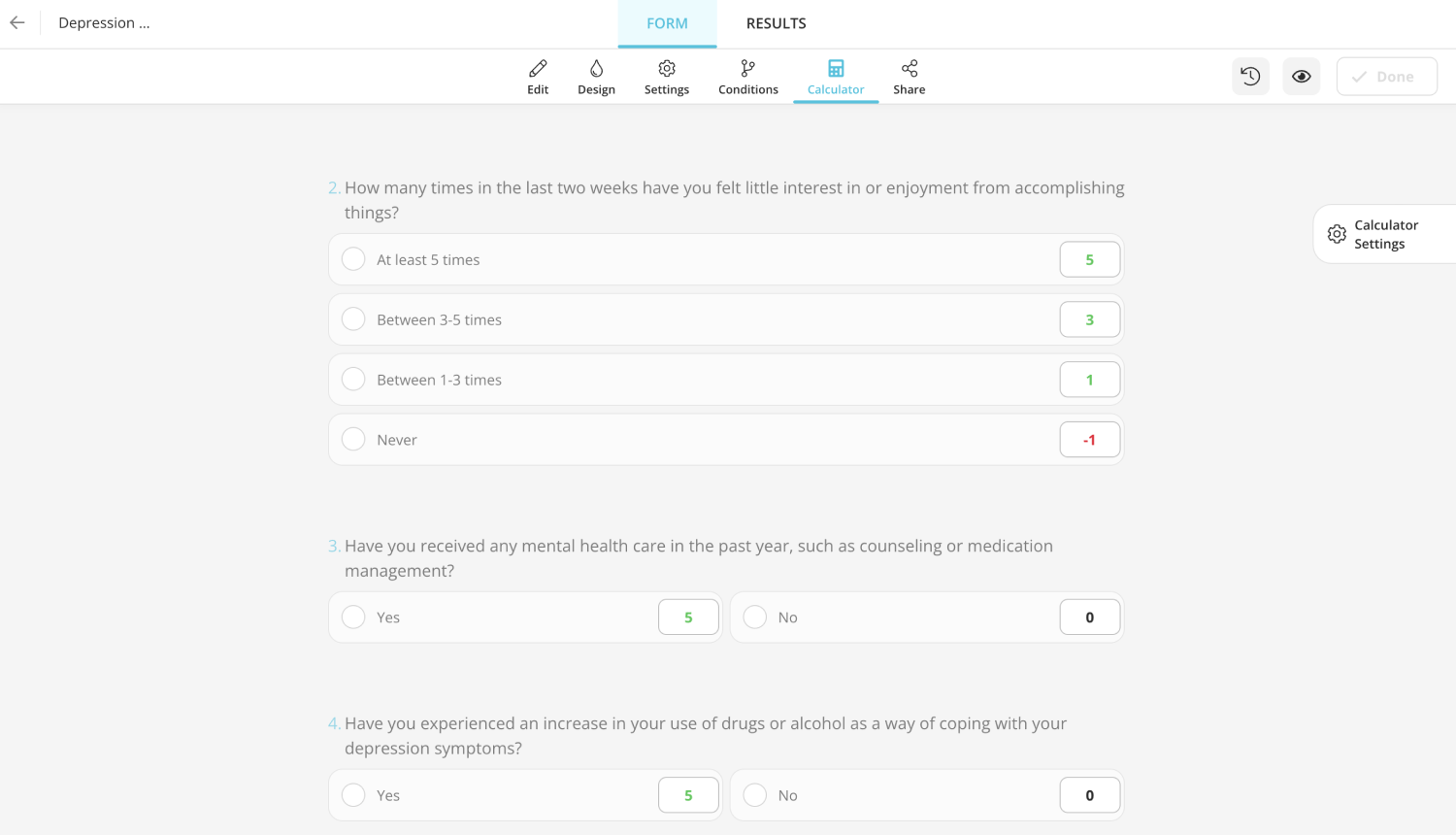

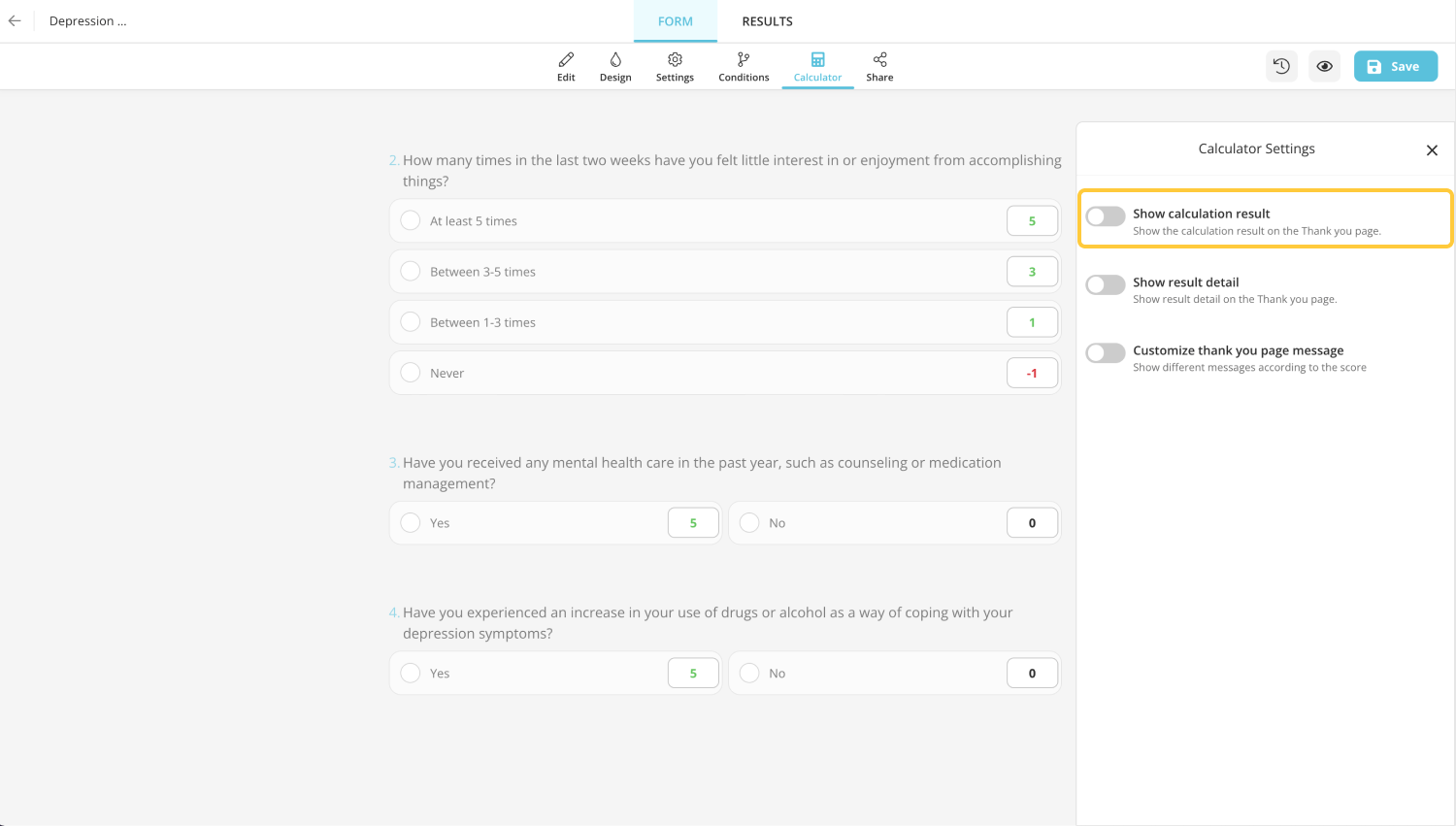

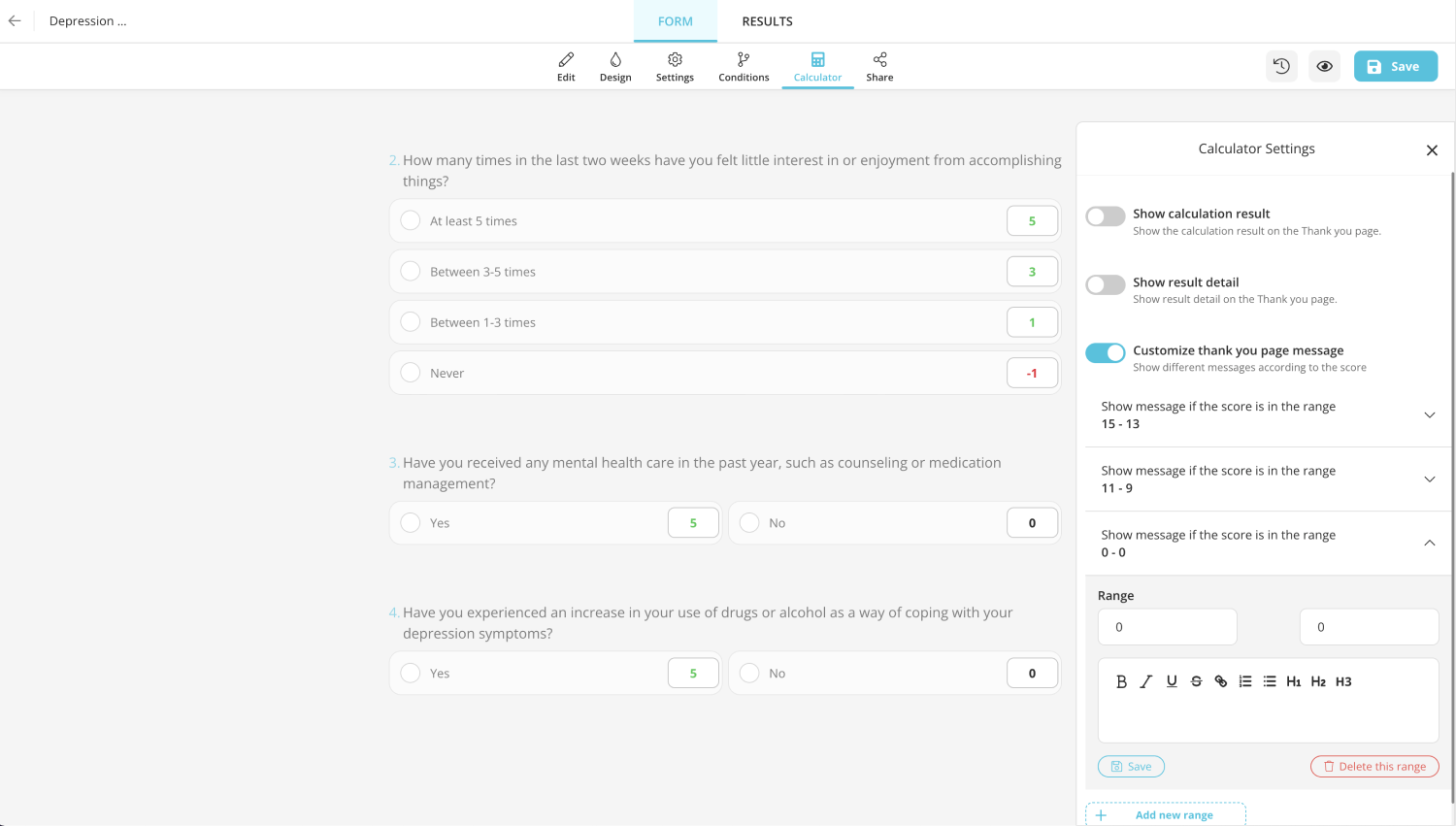

forms.app offers a calculator feature that can be used for measurement and showing results. You can give scores to each answer by setting up calculations. By assigning scores to necessary fields, you can get automated results for your depression surveys. Follow these 5 easy steps to use the calculator feature actively:

1 - Switch to the “Calculator” tab.

2 - Click on a score field of an option on the right side of each option.

3 - Enter a positive value directly or a negative value

4 - On the calculation settings, click on “show calculation result” to show people their score

5 - Lastly, enable “Customize thank you page message” to add ranges and custom messages for people in a certain score range.

In conclusion, it is a fact that professionals must use these types of questions. But creating awareness and creating a short and easy way as the first step before professional support can also be helpful. forms.app offers a fast and easy way to create and customize depression questionnaires that focus on different aspects and topics.

- Form Features

- Data Collection

Table of Contents

Related posts.

Web surveys: Definition, types, examples & tips ( +free templates)

Işılay Kırbaş

Volunteer recruitment: A complete guide

Sevgi Soylu

Top 100 prize ideas for your online giveaways & contests

Şeyma Beyazçiçek

227 Depression Research Topics & Essay Titles + Examples

If you’re looking for a good depression research title, you’re at the right place! StudyCorgi has prepared a list of titles for depression essays and research questions that you can use for your presentation, persuasive paper, and other writing assignments. Read on to find your perfect research title about depression!

🙁 TOP 7 Depression Title Ideas

🏆 best research topics on depression, ❓ depression research questions, 👍 depression research topics & essay examples, 📝 argumentative essay topics about depression, 🌶️ hot depression titles for a paper, 🔎 creative research topics about depression, 🎓 most interesting depression essay topics, 💡 good titles for depression essays.

- Teenage Depression: Causes and Symptoms