- Register or Log In

- 0) { document.location='/search/'+document.getElementById('quicksearch').value.trim().toLowerCase(); }">

The Ontological Argument Essay Questions

1. Summarize the two versions of the ontological argument given by Anselm and explain the similarities and differences between them.

2. Do you agree with Gaunilo’s criticism of Anselm’s argument? Explain.

3. What is Anselm’s response to Gaunilo, and does it succeed? Explain.

Select your Country

Essay – Ontological Argument

September 15, 2020.

“It is impossible to argue for the existence of God from his attributes”. Discuss

This essay was submitted by one of my students. At first glance, the ontological argument seems a bit odd: is it really possible to argue God exists by just using defintiions and philosophical ideas? But perhaps Anselm is not trying to prove God exists, more giving grounds for havingthe id ea of a supreme being as something great, profound and on the edge of human understanding. I give my comments as the essay progresses. PB

Arguably, we cannot derive the existence of God from His definition due to the inherently ambiguities of the predicate, existence, and indeed the nature of the subject Himself, God. Beyond this, the definition that would be used – a supremely perfect being – deeply undermines the theological idea of an epistemological space (extolled by John Hick), which allows us to develop a more meaningful relationship with God based on faith.

Excellent opening paragraph which brings in the idea of epistemic distance, introduced by John Hick, and hits at an attack on Anselm’s first premise, that God is that which nothing greater can be conceived.

This type of argument, an ‘ontological argument’ is a priori, and deductive. Medieval Platonic Monk Anselm produced one, which tries to show that God is ‘de dicto necessary’ (i.e. necessary through language). It begins with Anselm, who argues (in his ‘Prosologion’) that God is ‘that – thus – which – nothing – greater – can – be – conceived’. He makes the case that if we were to compare a log to a horse they might say that the horse is greater (i.e. having movement). Likewise, if they were to compare a horse to a human, they might conclude that the human is greater (i.e. having faculties of reason). Therefore, there must be some ‘supreme good’ which allows these comparisons to be drawn, and from which other matter confers value. This, he knows to be God (akin to Plato’s ‘Form of the Good’).

Again, a good paragraph, which is really discussing the issue of placing a comparison (greater than) at the heart of the first discussion in Prosologion.

From this definition in Anselm’s ‘Proslogion’, he argues that things can either exist in the mind (in re)/continually or in the mind AND reality (in re & in intellect)/necessarily. And, as God is that – thus – which – nothing – greater – can – be – conceived, He must therefore exist both in the mind AND in reality, for this must be better than to exist in the mind alone (and God is a supremely perfect being. In other words, by virtue of the way we define God, Anselm believes His existence to be necessary; alluding to Psalm 14 (the fool says in his heart, “there is no God”).

Yes, and of course, the idea of the necessary being is something Anselm discusses further in the second version of his ontological argument. Sometimes this is expressed in terms of an a analogy with a triangle. A triangle necessarily has three sides, whereas many attributes (predicates as Kant calls them) of a thing are just contingent (ie grass is only contingently green because if there’s a draught it is actually brown). Anselm’s argument is that only God has certain qualities by necessity (and so in the end the Gaunilo analogy of the island, see next paragraph, is a false analogy, says Anselm).

A contemporary of Anselm, Gaunilo, responds by writing (his ‘On behalf of the fool’) that this allows anything to be ‘thought into existence’. He imagines a perfect ‘lost island’, with warm seas, white sandy beaches and so on. This island could either exist in the mind, or in the mind AND reality. Since it’s better to exist in the mind AND reality, this island must therefore exist in reality (i.e. being perfect). Clearly, as this island doesn’t exist, the argument falls short for God too (a ‘reductio ad absurdum’). However, this is one of the weaker criticisms of the Ontological argument, as it doesn’t make sense to think of islands necessarily. They are, by definition, dynamic landforms which shift and come into or go out of existence over millions of years. That is, they are wholly contingent.

Exactly Anselm’s point and beautifully expressed here.

As aforementioned, the greatest drawback of this type of argument is its assumption that existence is a predicate at all. As an existent God appears not to add anything to our understanding of Him. A well-educated Theologian and a well-educated atheist have exactly the same conceptions of God, even if there’s disagreement over His existence.

Again this is an excellent point as an atheist would simply reply to Anselm that God necessarily does not exist.

This was the argument set out most notably by German Philosopher Kant, in response to a reformulation of the Ontological argument by Descartes (in brief, that a supremely perfect being must have the ‘perfection’ of existence’). Beyond existence appearing not to be a predicate, there’s arguably no reason why we cannot believe that if such a supremely perfect being existed, He would have existence. (But, since He doesn’t, He does not). For example, one can describe the perfect mermaid as being half-human, half-fish and as having existence, whilst still rejecting the concept of a perfect mermaid in its entirety. Therefore, the problems with understanding both the nature of existence and the essence of God mean that we cannot derive the existence of God from His definition, Anselm argues, that things can either be self-evidently true in themselves, or self-evidently true in themselves and to us. Although, for them to be self-evidently true in themselves and to us, we must have complete understanding of existence and God (i.e. the predicate and the subject), which we do not. As such, one can make the case that God’s definition makes His existence self-evidently true in itself but this form or argument (from definition) does not convincingly show that God’s existence is self-evidently true to us.

Very good paragraph, clearly argued and correctly linking Kant to Descartes, whose version of the ontological argument is not quite as subtle as Anselm’s. It is a good point to stress that something defined as self-evidently true is not the same as something established as self-evidently true. And the whole basis of the argument is rejected by thinkers like Aquinas who felt that God is beyond understanding and so applying such logical and linguistic categories was misplaced.

Finally, many theologians write about a ‘self-limitation’ of God’s divine attributes, in order for Him to allow us a more genuine relationship to develop. In other words if God’s existence was completely known to us by definition, we would have no choice as to whether to believe in Him or not. What makes a relationship with God valuable is the fact that we freely choose to believe in it through faith. 1 Corinthians (i.e. St Paul) refers to this ambiguity when it is written that we ‘see God through a glass, darkly’. There is scant Biblical evidence to the contrary, that God’s definition is completely known to us. Theologian John Hick refers to this as our epistemological space’ (or ‘knowledge gap’) in which to operate.

Yes, sometimes referred to as ‘epistemic distance”.

To conclude, we certainly cannot derive God’s existence from His definition due to the problematic logic, with which He is referred and because taking this to be true would critically undermine our freedom to engage in a relationship with Him. Or, as DZ Phillips suggests, perhaps it doesn’t make sense to question God’s existence at all. Instead, we shall take this as the starting point for theology, in the same way that other academic subjects of integrity have axioms on which further investigation rests (e.g. Maths, Physics, Chemistry).

Excellent essay, very clearly and throughly argued. The student might have referred to some modern thinkers such as Alvin Plantinga who has sought to rehabilitate the ontological argument by defining God as ‘maximally excellent’, or Norman Malcolm, who argues that that Kant’s criticism of the argument is quite misleading, since the question is not whether existence is a predicate but whether necessary existence is a predicate (1960). Reference might have been made to Anselm’s second version because this embraces the idea of necessary existence being an attribute of God’s perfection.

Total 37/40 A*

Study with us

Practise Questions 2020

Religious Studies Guides – 2020

Check out our great books in the Shop

Leave a Reply Cancel

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Presentations made painless

- Get Premium

106 Ontological Argument Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

Inside This Article

The ontological argument is a philosophical argument that seeks to prove the existence of God through the concept of existence itself. It has been a topic of debate among philosophers for centuries, with many different variations and interpretations. If you are studying this argument and need some inspiration for essay topics, look no further! Here are 106 ontological argument essay topic ideas and examples to help get you started:

- An analysis of Anselm's original ontological argument

- The role of faith in the ontological argument

- Descartes' ontological argument for the existence of God

- The ontological argument in the context of modern philosophy

- Kant's critique of the ontological argument

- The ontological argument and the problem of evil

- The ontological argument and the concept of perfection

- The ontological argument and the nature of existence

- The ontological argument and the concept of necessary existence

- The ontological argument and the concept of contingent existence

- The ontological argument and the nature of reality

- The ontological argument and the concept of infinity

- The ontological argument and the concept of causality

- The ontological argument and the concept of time

- The ontological argument and the concept of space

- The ontological argument and the concept of consciousness

- The ontological argument and the concept of free will

- The ontological argument and the concept of morality

- The ontological argument and the concept of truth

- The ontological argument and the concept of beauty

- The ontological argument and the concept of justice

- The ontological argument and the concept of love

- The ontological argument and the concept of freedom

- The ontological argument and the concept of knowledge

- The ontological argument and the concept of power

- The ontological argument and the concept of authority

- The ontological argument and the concept of wisdom

- The ontological argument and the concept of virtue

- The ontological argument and the concept of happiness

- The ontological argument and the concept of suffering

- The ontological argument and the concept of death

- The ontological argument and the concept of life

- The ontological argument and the concept of change

- The ontological argument and the concept of permanence

- The ontological argument and the concept of impermanence

- The ontological argument and the concept of reality

- The ontological argument and the concept of illusion

- The ontological argument and the concept of appearance

- The ontological argument and the concept of essence

- The ontological argument and the concept of existence

- The ontological argument and the concept of non-existence

- The ontological argument and the concept of being

- The ontological argument and the concept of non-being

- The ontological argument and the concept of identity

- The ontological argument and the concept of difference

- The ontological argument and the concept of similarity

- The ontological argument and the concept of dissimilarity

- The ontological argument and the concept of unity

- The ontological argument and the concept of diversity

- The ontological argument and the concept of harmony

- The ontological argument and the concept of conflict

- The ontological argument and the concept of order

- The ontological argument and the concept of chaos

- The ontological argument and the concept of structure

- The ontological argument and the concept of randomness

- The ontological argument and the concept of determinism

- The ontological argument and the concept of indeterminism

- The ontological argument and the concept of necessity

- The ontological argument and the concept of contingency

- The ontological argument and the concept of possibility

- The ontological argument and the concept of impossibility

- The ontological argument and the concept of certainty

- The ontological argument and the concept of uncertainty

- The ontological argument and the concept of doubt

- The ontological argument and the concept of belief

- The ontological argument and the concept of disbelief

- The ontological argument and the concept of faith

- The ontological argument and the concept of reason

- The ontological argument and the concept of emotion

- The ontological argument and the concept of intuition

- The ontological argument and the concept of logic

- The ontological argument and the concept of paradox

- The ontological argument and the concept of contradiction

- The ontological argument and the concept of consistency

- The ontological argument and the concept of inconsistency

- The ontological argument and the concept of coherence

- The ontological argument and the concept of incoherence

- The ontological argument and the concept of simplicity

- The ontological argument and the concept of complexity

- The ontological argument and the concept of clarity

- The ontological argument and the concept of obscurity

- The ontological argument and the concept of falsehood

- The ontological argument and the concept of ignorance

- The ontological argument and the concept of understanding

- The ontological argument and the concept of misunderstanding

- The ontological argument and the concept of insight

- The ontological argument and the concept of oversight

- The ontological argument and the concept of revelation

- The ontological argument and the concept of concealment

- The ontological argument and the concept of mystery

- The ontological argument and the concept of confusion

- The ontological argument and the concept of enlightenment

- The ontological argument and the concept of foolishness

- The ontological argument and the concept of intelligence

- The ontological argument and the concept of stupidity

- The ontological argument and the concept of genius

These are just a few ideas to get you started on your ontological argument essay. Remember to choose a topic that interests you and that you can delve into deeply to provide a strong argument. Good luck!

Want to create a presentation now?

Instantly Create A Deck

Let PitchGrade do this for me

Hassle Free

We will create your text and designs for you. Sit back and relax while we do the work.

Explore More Content

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

© 2023 Pitchgrade

A Level Philosophy & Religious Studies

The Ontological argument summary notes

OCR Philosophy

This page contains summary revision notes for the Ontological argument topic. There are two versions of these notes. Click on the A*-A grade tab, or the B-C grade tab, depending on the grade you are trying to get.

Find the full revision page here.

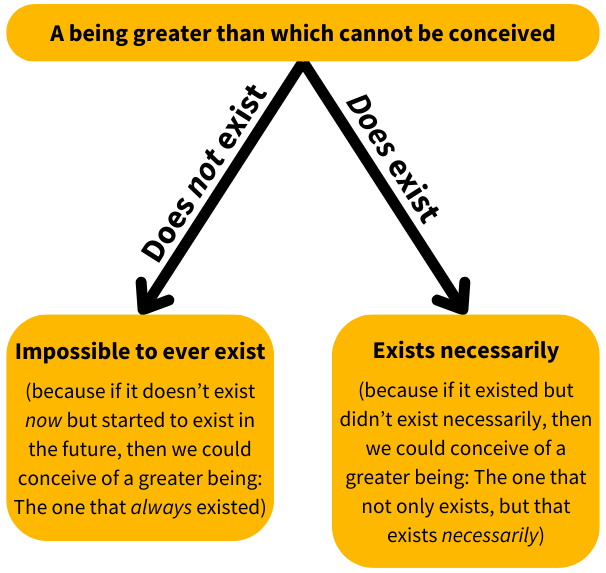

Anselm’s ontological argument

- P1. God is the greatest conceivable being

- P2. It is greater to exist in the mind and reality than in the mind alone

- P3. God exists in the mind

- C1. God exists in reality

- Malcolm interprets the idea of the greatest being as God being unlimited, not dependent on anything else for existence. God has no limitation which could possibly cause God’s non-existence. So, God contains the impossibility of non-existence.

- Gaunilo attempts to show Anselm’s logic is absurd by applying it to another case which yields an absurd result.

- Imagine the greatest possible island. If it’s greater to exist then this island must exist.

- This would work for the greatest possible version of anything.

- Anselm’s argument suggests reality would be overloaded with greatest possible things, which seems absurd.

- Gaunilo is attempting to deny that the ontological argument’s conclusion follows from the premises. So he is denying that it really is a valid deductive argument.

- However, Gaunilo’s critique is not particularly strong.

- There is no self-contradiction arising from Anselm’s logic also proving the existence of a perfect island. At most this seems counter-intuitive, but Gaunilo has not demonstrated actual absurdity, i.e., inconsistency.

Evaluation:

- However, there is a difference between God and an island (and anything else) which explains why the logic works for God but not anything else.

- An island is contingent by definition. It is land enclosed by water, so it depends on a sea/sun/planet for its existence. Everything else in the world is also contingent.

- You cannot use a priori reasoning to prove the existence of a contingent thing, because the existence of a contingent thing is not a matter of its definition. Its existence is a matter of whether what it depends on happens to exist.

- E.g. whether the island exists is a matter of whether the sea/planet/sun it depends on exists. That cannot be determined merely by thinking about the definition of the greatest island.

- So, the greatest island would still be the greatest island even if it didn’t exist.

- There is nothing in the definition of the greatest being which implies dependence, however, making it necessary.

- Nothing prevents determining the existence of a necessary being by a priori reasoning, unlike contingent beings.

- So, that is why the argument works for God but not anything else.

Gaunilo’s critique that God is beyond our understanding

- Gaunilo objects to P3, the claim that God is in our mind/understanding.

- He makes the traditional point that God is meant to be beyond our understanding.

- In that case, Anselm can’t go on to conclude that God being the greatest being requires that he is not just in our understanding, but also in reality.

- So, the ontological argument fails.

- Anselm deals with this kind of criticism, however.

- He points out that we don’t need to have a full understanding of God in our mind for the argument to work.

- We need only know/understand that God – whatever God is – is the greatest imaginable being.

- We don’t have to actually know what God is , or what is involved in being the greatest being – we simply have to understand that God is the greatest being.

- When we combine that with the premises that it is greater to exist, we can understand that God must exist.

- Anselm’s argument is successful because we can understand the concept of a being greater than any other possible being.

- Anselm’s analogy proves this further – we cannot look directly at the sun, but we can still see sunlight.

- Similarly, we cannot know God’s actual nature, but we can know that whatever God is, God is the greatest possible being.

- Gaunilo is committing a straw man fallacy, he’s attacking a claim Anselm didn’t make. Anselm didn’t mean God is in the mind in the sense of us having full knowledge of God’s nature – he just means we understand that God is greater than any other conceivable being.

Kant’s critique that existence is not a predicate

- When Anselm says that if God didn’t exist, God wouldn’t be the greatest being (God), he’s saying that existence is part of what defines God.

- Anselm goes on to conclude that God must exist.

- However, this treats the concept of ‘existence’ like a predicate, like a description of what a thing is, which defines a thing.

- Kant objects that existence is not a predicate.

- Imagine I was to say ‘the cat exists’. In that sentence, the term ‘exists’ doesn’t seem to actually describe the cat itself. It doesn’t describe a quality that the cat possesses. It simply describes that the cat exists – not the cat itself.

- So, existence is not a predicate. When Anselm says God would not be God if God didn’t exist, Anselm is wrong. God would be just as great/perfect even if non-existent. Anselm can’t go on to conclude that God must exist, therefore.

- Kant’s criticism is stronger than Gaunilo’s because he actually points out the assumption the ontological argument makes rather than pointing to a supposed absurdity.

- However, Kant’s criticism fails for two reasons.

- Firstly, Kant’s criticism fails to attack Descartes’ ontological argument, which therefore seems to be in a stronger position than Anselm’s

- Descartes bases his argument on his rationalist epistemology. He claims that God’s existence can be known through rational intuition.

- It is not possible to rationally conceive of the most supremely perfect being without existence.

- Descartes’ rejected the aristotelian logic of subject-predicate analysis. So, his argument does not infer God’s existence by assuming that existence is a predicate of God.

- He illustrates with a triangle. You intuitively know that a triangle cannot be without three sides. Similarly, we can intuitively know that God cannot be without existence.

- Secondly, Malcolm defends Anselm and the subject-predicate form of the argument.

- Kant is correct, but only about contingent existence.

- A contingent thing depends on something else for its existence.

- However a necessary being contains the reason for its existence within itself.

- So, necessary existence is a defining quality of a thing, in a way contingent existence is not.

- So necessary existence is a predicate.

- So, both Anselm and Descartes’ versions of the ontological argument succeed against Kant’s criticism.

- Against Anselm, Kant makes the same mistake Gaunilo did – comparing God to contingent beings and thinking the ontological argument fails because it doesn’t work in the case of contingent beings (like cats and coins).

Kant’s critique that existence being a predicate doesn’t establish actual existence

- Kant’s 1st critique is stronger because it doesn’t make the mistake of his other objection of denying that necessary existence is a predicate.

- Here, Kant argues that even if necessary existence were a predicate of God, that doesn’t establish God’s existence in reality.

- Kant improves on the style of argument Gaunilo was making with his lost island critique.

- Kant is again going to give us a much clearer reason than Gaunilo did for doubting the deductive validity of the ontological argument.

- Gaunilo was trying to argue that we may judge something necessary in our mind, but this doesn’t make it necessary in reality.

- Kant develops this using Descartes’ illustration of a triangle.

- It is necessary that a triangle has three sides.

- This shows that if a triangle exists, then it necessarily has three sides.

- Similarly, Anselm may have shown that the concept of God necessarily has the predicate of existence.

- However, again similarly, this only shows that if God exists, then God exists necessarily.

- The ontological argument does not show that God does actually exist necessarily.

- Malcolm responds to Kant – he says it makes no sense to say that a necessary being could possibly not exist. Necessary seems to mean ‘must exist’.

- If God is a necessary being then God must exist – it makes no sense to say if a necessary being existed – since a necessary being must exist – there is no if.

- So, Kant fails according to Malcolm.

- The issue is, Malcolm has only shown that God is a non-dependent being.

- In his ontological argument, Malcolm argued that if God exists, God exists necessarily because nothing could cause God to cease existing, as God is unlimited and non-dependent.

- This is what Malcolm established as God’s necessity. But this only establishes that God is necessary in the sense of being non-dependent, not in the sense of must exist.

- A being could be non-dependent and yet not exist. If it existed, then it would be necessary.

- So, the necessity of God’s existence established by the ontological argument only relates to the manner of God’s existence if God exists.

- Ontological arguments cannot show that God actually exists, then.

Graham Oppy, editor: Ontological arguments

Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2018, x and 284 pp, $34.99 (paper)

- Book Review

- Published: 27 June 2019

- Volume 86 , pages 91–96, ( 2019 )

Cite this article

- Kevin J. Harrelson 1

243 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

The Many - Faced Argument (ed. Hick and McGill, Macmillan 1967). A very large volume, edited by Miroslaw Szatkowski, appeared in 2013 ( Ontological Proofs Today, Ontos Verlag). That includes much advanced work, but is expensive and much less accessible than the volume under review.

See especially p. 57.

“The Ontological Argument as Cartesian Therapy,” Canadian Journal of Philosophy 35(4), pp. 521–562.

“Ontological Arguments” in Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy ; https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ontological-arguments/ , accessed May 22, 2019.

Lewis, David, "Anselm and Actuality," Nous volume 4, number 2 (1970), pp. 175–188.

The Nature of Necessity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1974), p. 221.

See his “Three Versions of the Ontological Argument” in Ontological Proofs Today, Miroslaw Szatkowski (editor), Ontos Verlag 2012, pp. 143–162.

NB: Descartes gives such a restriction, but this involves “clear and distinct perception” by the meditator.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Ball State University, Muncie, USA

Kevin J. Harrelson

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Kevin J. Harrelson .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Harrelson, K.J. Graham Oppy, editor: Ontological arguments. Int J Philos Relig 86 , 91–96 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11153-019-09720-3

Download citation

Published : 27 June 2019

Issue Date : 15 August 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11153-019-09720-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Overview – Does God Exist?

A level philosophy looks at 4 arguments relating to the existence of God . These are:

- The ontological argument

- The teleological argument

- The cosmological argument

The problem of evil

There are various versions of each argument as well as numerous responses to each. The key points of each argument are summarised below:

Ontological arguments

The ontological arguments are unique in that they are the only arguments for God’s existence that use a priori reasoning. All ontological arguments are deductive arguments .

Versions of the ontological argument aim to deduce God’s existence from the definition of God. Thus, proponents of ontological arguments claim ‘God exists’ is an analytic truth .

Anselm’s ontological argument

“Hence, even the fool is convinced that something exists in the understanding, at least, than which nothing greater can be conceived. For, when he hears of this, he understands it. And whatever is understood, exists in the understanding. And assuredly that, than which nothing greater can be conceived, cannot exist in the understanding alone. For, suppose it exists in the understanding alone: then it can be conceived to exist in reality; which is greater. […] Hence, there is no doubt that there exists a being, than which nothing greater can be conceived, and it exists both in the understanding and in reality.” – St. Anselm, Proslogium , Chapter 2

Anselm of Canterbury (1033-1109) was the first to propose an ontological argument in his book Proslogium .

His argument can be summarised as:

- By definition, God is a being greater than which cannot be conceived

- We can coherently conceive of such a being i.e. the concept is coherent

- It is greater to exist in reality than to exist only in the mind

- Therefore, God must exist

In other words, imagine two beings:

- One is said to be maximally great in every way, but does not exist.

- The other is maximally great in every way and does exist.

Which being is greater? Presumably, the second one – because it is greater to exist in reality than in the mind.

Since God is a being that we cannot imagine to be greater, this description better fits the second option (the one that exists) than the first.

Descartes’ ontological argument

Descartes offers his own version of the ontological argument:

- I have the idea of God

- The idea of God is the idea of a supremely perfect being

- A supremely perfect being does not lack any perfection

- Existence is a perfection

- Therefore, God exists

This argument is very similar to Anselm’s , except it uses the concept of a perfect being rather than a being greater than which cannot be conceived .

Descartes argues this shows that ‘God does not exist’ is a self-contradiction . Hume uses this claim as the basis for his objection to the ontological argument.

Gaunilo’s island

Gaunilo of Marmoutiers (994-1083) argues that if Anselm’s argument is valid, then anything can be defined into existence. For example:

- The perfect island is, by definition, an island greater than which cannot be conceived

- We can coherently conceive of such an island i.e. the concept is coherent

- Therefore, this island must exist

The conclusion of this argument is obviously false.

Gaunilo argues that if Anselm’s argument were valid, then we could define anything into existence – the perfect shoe, the perfect tree, the perfect book, etc.

Hume: ‘God does not exist’ is not a contradiction

The ontological argument reasons from the definition of God that God must exist. This would make ‘God exists’ an analytic truth (or what Hume would call a relation of ideas , as the analytic/synthetic distinction wasn’t made until years later).

The denial of an analytic truth/relation of ideas leads to a contradiction. For example, “there is a triangle with 4 sides” is a contradiction.

Contradictions cannot be coherently conceived . If you try to imagine a 4-sided triangle, you’ll either imagine a square or a triangle. The idea of a 4-sided triangle doesn’t make sense.

So, is “God does not exist” a contradiction? Descartes (and Anselm) certainly thought so.

But Hume argues against this claim. Anything we can conceive of as existent , he says, we can also conceive of as non-existent . This shows that “God exists” cannot be an analytic truth/relation of ideas, and so ontological arguments must fail somewhere.

A summary of Hume’s argument can be stated as:

- If ontological arguments succeed, ‘God does not exist’ is a contradiction

- A contradiction cannot be coherently conceived

- But ‘God does not exist’ can be coherently conceived

- Therefore, ‘God does not exist’ is not a contradiction

- Therefore, ontological arguments do not succeed

Kant: existence is not a predicate

Kant argues that existence is not a property (predicate) of things in the same way, say, green is a property of grass .

To say something exists doesn’t add anything to the concept of it.

Imagine a unicorn. Then imagine a unicorn that exists . What’s the difference between the two ideas? Nothing! Adding existence to the idea of a unicorn doesn’t make unicorns suddenly exist.

When someone says “God exists”, they don’t mean “there is a God and he has the property of existence”. If they did, then when someone says “God does not exist”, they’d mean, “there is a God and he has the property of non existence” – which doesn’t make sense!

Instead, what people mean when they say “God exists” is that “God exists in the world” . This cannot be argued from the definition of God and could only be proved via ( a posteriori ) experience. Thus the ontological argument fails to prove God’s (actual) existence.

Norman Malcolm’s ontological argument

Kant’s objection to the ontological argument is generally considered to be the most powerful argument against it.

So, in response, some philosophers have developed alternate versions that avoid this criticism.

Malcolm accepts that Descartes and Anselm (at least as presented above) are wrong.

Instead, Malcolm argues that it’s not existence that is a perfection, but the logical impossibility of non-existence ( necessary existence , in other words).

This (necessary existence) is a predicate, so avoids Kant’s argument above. Malcolm’s ontological argument is as follows:

- Either God exists or does not exist

- God cannot come into existence or go out of existence

- If God exists, God cannot cease to exist

- Therefore, if God exists, God’s existence is necessary

- Therefore, if God does not exist, God’s existence is impossible

- Therefore, God’s existence is either necessary or impossible

- God’s existence is impossible only if the concept of God is self-contradictory

- The concept of God is not self-contradictory

- Therefore, God’s existence is not impossible

- Therefore, God exists necessarily

Malcolm’s argument essentially boils down to:

- God’s existence is either necessary or impossible (see above)

- God’s existence is not impossible

- Therefore God’s existence is necessary

Possible response:

We may respond to point 8, as discussed in the concept of God section , that the concept of God is self-contradictory.

Alternatively, we may argue that the meaning of “necessary” changes between premise 4 and the conclusion (10) and thus Malcolm’s argument is invalid. In premise 4, Malcolm is talking about necessary existence in the sense of a property that something does or does not have. By the conclusion, Malcolm is talking about necessary existence in the sense that it is a necessary truth that God exists. But this is not the same thing. We can accept that if God exists , then God has the property of necessary existence, but deny the conclusion that God exists necessarily.

Teleological arguments

The teleological arguments are also known as arguments from design.

These arguments aim to show that certain features of nature or the laws of nature are so perfect that they must have been designed by a designer – God.

Hume’s teleological argument

In Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion , Hume considers a version of the teleological argument (through the character Cleanthes ), which he goes on to reject (through the character of Philo ).

“The intricate fitting of means to ends throughout all nature is just like (though more wonderful than) the fitting of means to ends in things that have been produced by us – products of human designs, thought, wisdom, and intelligence. Since the effects resemble each other, we are led to infer by all the rules of analogy that the causes are also alike, and that the author of nature is somewhat similar to the mind of man, though he has much larger faculties to go with the grandeur of the work he has carried out. By this argument… we prove both that there is a God and that he resembles human mind and intelligence.” – Hume, Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion, Part 5

Hume’s argument here draws an analogy between things designed by humans and nature:

- The ‘fitting of means to ends’ in human design (e.g. the fitting of the many parts of a watch to achieve the end of telling the time) resemble the ‘fitting of means to ends’ in nature (e.g. the many parts of a human’s eye to achieve the end of seeing things)

- Similar effects have similar causes

- The causes of human designs (e.g. watches) are minds

- So, by analogy , the cause of design in nature is also a mind

- And, given the ‘grandeur of the work’ of nature, this other mind is God .

William Paley: Natural Theology

William Paley (1743-1805) wasn’t the first to propose a teleological argument for the existence of God, but his version is perhaps the most famous.

The reason for this is that a watch, unlike the stone, has many parts organised for a purpose. Paley says this is the hallmark of design:

“When we come to inspect the watch, we perceive (what we could not discover in the stone) that its several parts are framed and put together for a purpose , e.g. that they are so formed and adjusted as to produce motion, and that motion so regulated as to point out the hour of the day.” – William Paley, Natural Theology, Chapter 1

Nature and aspects of nature, such as the human eye, are composed of many parts. These parts are organised for a purpose – in the case of the eye, to see .

So, like the watch, nature has the hallmarks of design – but “ with the difference, on the side of nature, of being greater and more” . And for something to be designed, it must have an equally impressive designer .

Paley says this designer is God.

Hume: problems with the analogy

Hume (as the character Philo) points out various problems with the analogy between the design of human-made objects and nature, such as:

- We can observe human-made items being designed by minds , but we have no such experience of this in the case of nature. Instead, designs in nature could be the result of natural processes (what Philo calls ‘generation and vegetation’).

- The analogy focuses on specific aspects of nature that appear to be designed (e.g. the human eye) and generalises this to the conclusion that the whole universe must be designed.

- Human machines (e.g. watches and cars) obviously have a designer and a purpose. But biological things (e.g. an animal or a plant, such as a cabbage) do not have an obvious purpose or designer – they appear to be the result of an unconscious process of ‘generation and vegetation’. The universe is more like the latter (i.e. a biological thing) than the former (i.e. a machine) and so, by analogy, the cause of the universe is better explained by this unconscious processes of ‘generation and vegetation’ rather than the conscious design of a mind.

An argument from analogy is only as strong as the similarities between the two things being compared (nature and human designs). These differences weaken the jump from human-made items being designed to the whole universe being designed.

Hume: Spatial dis order

Hume (as the character Philo) argues that although there are examples of order within nature (which suggests design), there is also much “vice and misery and disorder” in the world (which is evidence against design).

If God really did design the world, Hume argues, there wouldn’t be such disorder. For example:

- There are huge areas of the universe that are empty, or just filled with random rocks or are otherwise uninhabitable. This suggests that the universe isn’t designed but instead we just happen, by coincidence, to be in a part that has spatial order.

- Some parts of the world (e.g. droughts, hurricanes, etc.) go wrong and cause chaos. Hume argues that if the world is designed , these chaotic features suggest that the designer isn’t very good.

- Animals have bodies that feel pain and that could have been made in such ways that they could have happier lives. If God designed animals and humans, you would expect He would make animals and humans in this way so that their lives would be easier and happier.

These features are examples of spatial dis order – features that wouldn’t make sense to include if you designed the universe.

Hume argues that such examples of disorder show that the universe isn’t designed. Or, if the universe is designed, then the designer is neither omnipotent nor omnibenevolent (as God is claimed to be).

Hume: causation

Hume famously argues that we never experience causation – only the ‘constant conjunction’ of one event following another. If this happens enough times, we infer that A causes B.

For example, experience (ever since you were a baby) tells you that if one snooker ball hits another (A), the second snooker ball will move (B). You don’t actually experience A causing B, but it’s reasonable to expect this relationship to hold in the future because you’ve seen it and similar examples hundreds of times.

But imagine that you take a sip of tea and at the same time your friend coughs. Would it be reasonable to infer that drinking the tea caused your friend to cough based on this one instance? Obviously not. The point is: You cannot infer causation from a single instance.

Applying this to teleological arguments, Hume (as the character Philo) argues that the creation of the universe was a unique event – we only have experience of this one universe. And so, like the tea example, we can’t infer a causal relationship between designer and creation based on just one instance.

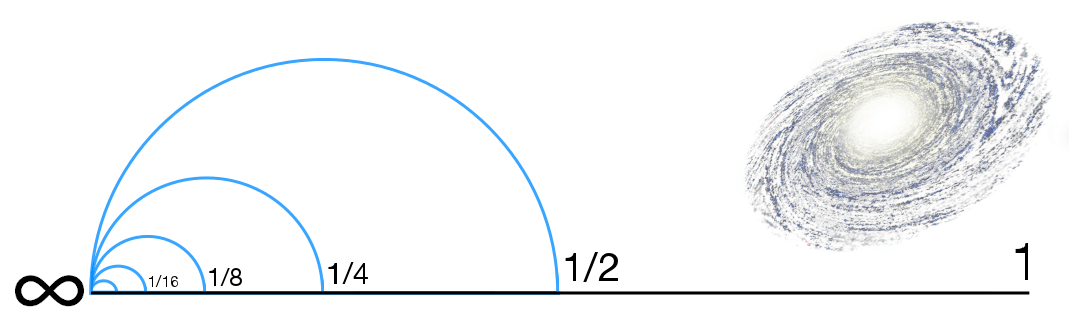

Hume: finite matter, infinite time

“Instead of supposing matter to be infinite, as Epicurus did, let us suppose it to be finite and also suppose space to be finite, while still supposing time to be infinite. A finite number of particles in a finite space can have only a finite number of transpositions; and in an infinitely long period of time every possible order or position of particles must occur an infinite number of times.” – Hume, Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion, Part 8

Hume’s objection here assumes the following:

- Time is infinite

- Matter is finite

Given these assumptions, it is inevitable that matter will organise itself into combinations that appear to be designed.

It’s a bit like the monkeys and typewriters thought experiment:

Given an infinite amount of time, a monkey will eventually type the complete works of Shakespeare.

This is the nature of infinity. It’s inevitable that the monkey will write something that appears to be intelligent, even though it’s just hitting letters at random.

The same principle applies to the teleological argument, argues Hume: Given enough time, it is inevitable that matter will arrange itself into combinations that appear to be designed , even though they’re not.

Darwin: evolution by natural selection

Charles Darwin’s (1809-1882) theory of evolution by natural selection explains how complex organisms – complete with parts organised for a purpose – can emerge from nature without a designer.

For example, it may seem that God designed giraffes to have long necks so they could reach leaves in high trees. But the long necks of giraffes can be explained without a designer , for example:

- Competition for food is tough

- An animal that cannot acquire enough food will die before it can breed and produce offspring

- An animal with a (random genetic mutation for a) neck that’s 1cm longer than everyone else’s will be able to access 1cm more food

- This competitive advantage makes it more likely to survive and produce offspring

- The offspring are likely to inherit the gene for a longer neck, making them more likely to survive and reproduce as well

- Longer necked-animals become more common as a result

- The environment becomes more competitive as more and more animals can reach the 1cm higher leaves

- An animal with a neck 2cm longer has the advantage in this newly competitive environment

- Repeat process over hundreds of millions of years until you have modern day giraffes

The key idea is that – given enough time and genetic mutations – it is inevitable that animals and plants will adapt to their environment, thus creating the appearance of design.

This directly undermines Paley’s claim that anything that has parts organised to serve a purpose must be designed.

Swinburne: The Argument from Design

Swinburne’s version of the teleological argument distinguishes between:

- Examples of order in nature ( spatial order )

- And the order of the laws of nature ( temporal order )

Swinburne accepts that science, for example evolution , can explain the apparent design of things like the human eye (i.e. spatial order) and so Paley’s teleological argument does not succeed in proving God’s existence. However, Swinburne argues, we can’t explain the laws of nature (i.e. temporal order) in the same way.

For example, the law of gravity is such that it allows galaxies to form, and planets to form within these galaxies, and life to form on these planets. But if gravity had the opposite effect – it repelled matter, say – then life would never be able to form. If gravity was even slightly stronger, planets wouldn’t be able to form. So how do we explain why these laws are the way they are?

Unlike spatial order, we can’t give a scientific explanation of why the laws of nature are as they are. Science can explain and predict things using these laws – but it has to first assume these laws. Science can’t explain why these laws are the way they are. In the absence of a scientific explanation of the laws of nature, Swinburne argues, the best explanation of temporal order is a personal explanation.

We give personal explanations of things all the time – for example, ‘this sentence exists because I chose to write it’ or ‘that building exists because someone designed and built it’. Swinburne argues that, by analogy, we can explain the laws of nature (i.e. temporal order) in a similarly personal way: The laws of nature are the way they are because someone designed them.

In the absence of a scientific explanation of temporal order, Swinburne argues, the best explanation is the personal one: The laws of nature were designed by God .

Multiple universes

Hume’s earlier argument (finite matter, infinite time) can be adapted to respond to Swinburne’s teleological argument.

But instead of arguing that time is infinite, as Hume does, we could argue that the number of universes is infinite.

This idea of multiple universes is popular among some physicists, as it explains various phenomena in quantum mechanics.

But anyway, if there are an infinite number of universes (or even just a large enough number), it is likely that some of these universes will have laws of nature (temporal order) that support the formation of life. Of course, when such universes do exist, it is just sheer luck. If each universe has randomly different scientific laws, there will also be many universes where the temporal order does not support life.

Is the designer God?

Both Hume and Kant have argued that even if the teleological argument succeeded in proving the existence of a designer , this designer would not necessarily be God (as defined in the Concept of God section).

For example:

- God’s power is supposedly infinite ( omnipotence ), yet the universe is not infinite

- Designers are not always creators. Designer and creator might be two separate people (e.g. the guy who designs a car doesn’t physically build it)

- The design of the universe may be the result of many small improvements by many people

- Designers can die even if their creations live on. How do we know the designer is eternal , as God is supposed to be?

Cosmological arguments

The Kalam Argument

The Kalam argument is perhaps the simplest version of the cosmological argument in the A level philosophy syllabus. It says:

- Whatever begins to exist has a cause

- The universe began to exist

- Therefore, the universe has a cause

Aquinas: Five Ways

St. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) gave five different versions of the cosmological argument. A level philosophy requires you to know these three:

Argument from motion

Argument from causation.

- Contingency argument

Aquinas’ first way is the argument from motion .

“It is certain, and evident to our senses, that in the world some things are in motion… It is [impossible that something] should be both mover and moved, i.e. that it should move itself. Therefore, whatever is in motion must be put in motion by another. If that by which it is put in motion be itself put in motion, then this also must needs be put in motion by another, and that by another again. But this cannot go on to infinity, because then there would be no first mover, and, consequently, no other mover; seeing that subsequent movers move only inasmuch as they are put in motion by the first mover… Therefore it is necessary to arrive at a first mover, put in motion by no other; and this everyone understands to be God.” – Aquinas, Summa Theologica , Part 1 Question 3

A summary of this argument:

- E.g. a football rolling along the ground

- E.g. someone kicked the ball

- If A is put in motion by B , then something else ( C ) must have put B in motion, and so on

- If this chain goes on infinitely, then there is no first mover

- If there is no first mover, then there is no other mover, and so nothing would be in motion

- But things are in motion

- Therefore, there must be a first mover

- The first mover is God

Aquinas’ second way – the argument from causation – is basically the same as the argument from motion, except it talks about a first cause rather than a first mover:

- E.g. throwing a rock caused the window to smash

- C is caused by B , and B is caused by A , and so on

- If this chain of causation was infinite, there would be no first cause

- If there were no first cause, there would be no subsequent causes or effects

- But there are causes and effects in the world

- Therefore, there must have been a first cause

- The first cause is God

Argument from contingency

Aquinas’ third way relies on a distinction between necessary and contingent existence. It’s a similar distinction to necessary and contingent truth from the epistemology module.

Things that exist contingently are things that might not have existed.

For example, the tree in the field wouldn’t exist if someone hadn’t planted the seed years ago. So, the tree exists contingently. Its existence is contingent on someone planting the seed.

So, using this idea of contingent existence, Aquinas argues that:

- Everything that exists contingently did not exist at some point

- If everything exists contingently, then at some point nothing existed

- If nothing existed, then nothing could begin to exist

- But since things did begin to exist, there was never nothing in existence

- Therefore, there must be something that does not exist contingently, but that exists necessarily

- This necessary being is God

Descartes’ Cosmological Argument

Descartes’ version of the cosmological argument is a lot more long-winded than the Kalam argument or any of Aquinas’ .

The key points are along these lines:

- I can’t be the cause of my own existence because if I was I would have given myself all perfections (e.g. omnipotence, omniscience, etc.)

- I depend on something else to exist

- I am a thinking thing and have the idea of God

- Whatever caused me to exist must also be a thinking thing that has the idea of God

- Whatever caused me to exist must either be the cause of its own existence or caused by something else

- If it was caused by something else then this something else must also either be the cause of its own existence or caused by something else

- There cannot be an infinite chain of causes

- So there must be something that caused its own existence

- Whatever causes its own existence is God

There’s a bit more to Descartes’ version than this. For example, he talks about a cause needed to keep him in existence and how there must be ‘as much reality’ in the cause as in the effect. But the points above constitute the main argument.

Leibniz: Sufficient reason

Note: This is another cosmological argument from contingency , like Aquinas’ third way above

Leibniz’s argument is premised on his principle of sufficient reason. The principle of sufficient reason says that every truth has an explanation of why it is the case (even if we can’t know this explanation).

Leibniz then defines two different types of truth:

- Truths of reasoning: this is basically another word for necessary or analytic truths

- Truths of fact: this is basically another word for contingent or synthetic truths

The sufficient reason for truths of reasoning (i.e. analytic truths) is revealed by analysis. When you analyse and understand “3+3=6”, for example, you don’t need a further explanation why it is true.

But it is more difficult to provide sufficient reason for truths of fact (i.e. contingent truths) because you can always provide more detail via more contingent truths. For example, you can explain the existence of a tree by saying someone planted a seed. But you could then ask why the person planted the seed, or why seeds exist in the first place, or why the laws of physics are the way they are, and so on. This process of providing contingent reasons for contingent facts goes on forever.

“Therefore, the sufficient or ultimate reason must needs be outside of the sequence or series of these details of contingencies, however infinite they may be.” – Leibniz, Monadology , Section 37

So, to escape this endless cycle of contingent facts and provide sufficient reason for truths of fact (i.e. contingent truths), we need to step outside the sequence of contingent facts and appeal to a necessary substance. This necessary substance is God , Leibniz says.

Is a first cause necessary?

Most of the cosmological arguments assume something along the lines of ‘there can’t be an infinite chain of causes’ (except the cosmological arguments from contingency ). For example, they say stuff like there must have been a first cause or a prime mover .

But we can respond by rejecting this claim. Why must there be a first cause? Perhaps there is just be an infinite chain of causes stretching back forever.

- An infinite chain of causes would mean an infinite amount of time has passed prior to the present moment

- If an infinite amount of time has passed, then the universe can’t get any older (because infinity + 1 = infinity)

- But the universe is getting older (e.g. the universe is a year older in 2020 than it was in 2019)

- Therefore an infinite amount of time has not passed

- Therefore there is not an infinite chain of causes

Hume’s objections to causation

Another assumption (or premise) of many of the cosmological arguments above (not so much the contingency ones) is something like ‘everything has a cause’.

But Hume’s fork can be used to question this claim that ‘everything has a cause’:

- Relation of ideas: ‘Everything has a cause’ is not a relation of ideas because we can conceive of something without a cause. For example, we can imagine a chair that just springs into existence for no reason – it’s a weird idea, but it’s not a logical contradiction like a 4-sided triangle or a married bachelor.

- Matter of fact: ‘Everything has a cause’ cannot be known as a matter of fact either, says Hume. We never actually experience causation – we just see event A happen and then event B happen after. Even if we see B follow A a million times, we never experience A causing B, just the ‘constant conjunction’ of A and B.

Further, in the specific case of the creation of the universe, we only ever experience event B (i.e. the continued existence of the universe) and never what came before (i.e. the thing that caused the universe to exist).

This all casts doubt on the premise of cosmological arguments that ‘everything has a cause’.

Russell: Fallacy of composition

Bertrand Russell argues that cosmological arguments fall foul of the fallacy of composition . The fallacy of composition is an invalid inference that because parts of something have a certain property, the entire thing must also have this property. Examples:

- Just because all the players on a football team are good, this doesn’t guarantee the team is good. For example, the players might not work well together.

- Just because a sheet of paper is thin, it doesn’t mean things made from sheets of paper are thin. For example, a book with enough sheets of paper can be thick.

Applying this to the cosmological argument, we can raise a similar objection to Hume’s above : just because everything within the universe has a cause, doesn’t guarantee that the universe itself has a cause.

Or, to apply it to Leibniz’s cosmological argument : just because everything within the universe requires sufficient reason to explain its existence, doesn’t mean the universe itself requires sufficient reason to explain its existence. Russell says: “the universe is just there, and that’s all.”

- Ok, but everything within the universe exists contingently

- And if everything within the universe didn’t exist, then the universe itself wouldn’t exist either (because that’s all the universe is: the collection of things that make it up)

- So the universe itself exists contingently, not just the stuff within it

- And so the universe itself requires sufficient reason to explain its existence

Is the first cause God?

Aquinas’ first and second ways and the Kalam argument only show that there is a first cause . But they don’t show that this first cause is God .

So, even if we accept that there was a first cause, it doesn’t necessarily follow that God exists – much less the specific being described in the concept of God .

So, even if the cosmological argument is sound, it doesn’t necessarily follow that God exists.

This objection doesn’t work so well against Descartes’ version because he specifically reasons that there is a first cause and that this first cause is an omnipotent and omniscient God .

Similarly, you could argue that any being that exists necessarily (such as follows from Aquinas’ third way and Leibniz’s cosmological argument ) would be God.

The problem of evil uses the existence of evil in the world to argue that God (as defined in the concept of God ) does not exist.

These arguments can be divided into two forms:

- The logical problem of evil is a deductive argument that says the existence of God is logically impossible given the existence of evil in the world

- The evidential problem of evil is an inductive argument which says that, while it is logically possible that God exists, the amount of evil and unfair ways it is distributed in our world is pretty strong evidence that God doesn’t exist

And evil can be divided into two types of evil:

One final definition: a theodicy is an explanation of why an omnipotent and omniscient God would permit evil.

The logical problem of evil

“Epicurus’s old questions have still not been answered. Is he willing to prevent evil, but not able? Then he is impotent. Is he able, but not willing? Then he is malevolent. Is he both able and willing? Then where does evil come from?” – Hume, Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion, Part 10

J.L. Mackie: Evil and Omnipotence

Inconsistent triad.

The simple version of Mackie’s argument is that the following statements are logically inconsistent – i.e. one or more of them contradict each other:

- God is omnipotent

- God is omnibenevolent

- Evil exists

Mackie’s argument is that, logically, a maximum of 2 of these 3 statements can be true but not all 3. This is sometimes referred to as the inconsistent triad .

He argues that if God is omnibenevolent then he wants to stop evil. And if God is omnipotent, then he’s powerful enough to prevent evil.

But evil does exist in the world. People steal, get murdered, and so on. So either God isn’t powerful enough to stop evil, doesn’t want to stop evil, or both.

In the concept of God , God is defined as an omnipotent and omnibenevolent being. If such a being existed, argues Mackie, then evil would not exist. But evil does exist. Therefore, there is no omnipotent and omnibenevolent being. Therefore, God does not exist.

Reply 1: good couldn’t exist without evil

People often make claims like “you can’t appreciate the good times without experiencing some bad times”.

This is basically what this reply says: without evil, good couldn’t exist.

Mackie’s response

Mackie questions whether this statement is true at all. Why can’t we have good without evil?

Imagine if we lived in a world where everything was red. Presumably, we wouldn’t have created a word for ‘red’, nor would we know what it meant if someone tried to explain it to us. But it would still be the case that everything is red, we just wouldn’t know.

It’s a similar story with good and evil.

God could have created a world in which there was no evil. Like the red example, we wouldn’t have the concept of evil. But it would still be the case that everything is good – we just wouldn’t be aware of it.

Reply 2: the world is better with some evil than none at all

You could develop reply 1 above to argue that some evil is necessary for certain types of good. For example, you couldn’t be courageous (good) without having to overcome fear of pain, death, etc. (evil).

We can define first and second order goods:

- First order good: e.g. pleasure

- Second order good: e.g. courage

The argument is that second order goods seek to maximise first order goods. And second order goods are more valuable than first order goods. But without first order evils, second order goods couldn’t exist.

Let’s say we accept that first order evil is necessary for second order good to exist. How do you explain second order evil ?

Second order evils seek to maximise first order evils such as pain. So, for example, malevolence or cruelty are examples of second order evils.

But we could still have a world in which people were courageous (second order good) in overcoming pain (first order evil) without these second order evils. So why would an omnipotent and omnibenevolent God allow the existence of second order evils if there is no greater good in doing so?

Reply 3: we need evil for free will

We can develop the second order evil argument above further and argue that second order evil is necessary for free will. And free will is inherently such a good and valuable thing that it outweighs the bad that results from people abusing free will to do evil things.

So, while allowing free will brings some suffering, the net good of having free will is greater than if we didn’t. Therefore, it’s logically possible that an omnipotent and omnibenevolent God would allow evil (both first order and second order) for the greater good of free will.

- An omnipotent God can create any logically possible world

- If it’s logically possible to freely choose to act in a way that’s good on one occasion, then it’s logically possible to freely choose to act in a way that’s good on every occasion

- So, an omnipotent God could create a world in which everyone freely chooses to act in a way that’s good

In other words, there is a logically possible world with both free will and without second order evils.

This, surely, would be the best of both worlds and maximise good most effectively: you would have second order goods, plus the good of free will, but without second order evils. This is a logically possible world – the logically possible world with the most good.

So, why wouldn’t an omnipotent and omniscient God create this specific world? Second order evils do not seem logically necessary, and yet they exist.

Alvin Plantinga: God, Freedom and Evil

Plantinga argues that we don’t need a plausible theodicy to defeat the logical problem of evil. All we need to show is that the existence of evil is not logically inconsistent with an omnipotent and omnibelevolent God.

So, even if the explanation of why God would allow evil doesn’t seem particularly plausible, as long as it’s a logical possibility then we have defeated the logical problem of evil .

Free will defence

Even Mackie himself admits that God’s existence is not logically incompatible with some evil (first order evil). But his argument is that second order evil isn’t necessary .

Plantinga argues, however, that it’s logically possible (which is all we need to show to defeat the logical problem of evil) that God would allow second order evil for a greater good. His argument is as follows:

- A morally significant action is one that is either morally good or morally bad

- A being that is significantly free is one that is able to do or not do morally significant actions

- A being created by God to only do morally good actions would not be significantly free

- So, the only way God could eliminate evil (including second order evil) would be to eliminate significantly free beings

- But a world that contains significantly free beings is more good than a world that does not contain significantly free beings

In short, this argument shows that it’s at least logically possible that God would allow second order evil for the greater good of significant freedom.

Perhaps God could have created the world where everyone chose to only do morally good actions ( as Mackie describes above ) – but such a world wouldn’t be significantly free. Free will is inherently good and so significant free will could outweigh the negative of people using that significant free will to commit second order evils.

Natural evil as a form of moral evil

The free will defence above explains why an omnipotent and omnibenevolent God would allow moral evil. But it doesn’t explain natural evil.

When innocent people are killed in natural disasters, it doesn’t seem this is the result of free will. So, even if an omnipotent and omnibenevolent God would allow moral evil, why does this kind of evil exist as well?

Plantinga argues that it’s possible natural evil is the result of non-human actors such as Satan, fallen angels, demons, etc. This would make natural evil another form of moral evil, the existence of which would be explained by free will.

Even if this doesn’t sound very plausible , it’s at least possible . And remember, Plantinga’s argument is that we only need to show evil is not logically inconsistent with God’s existence to defeat the logical problem of evil.

The evidential problem of evil

Unlike the logical problem of evil , the evidential problem of evil can allow that God’s existence is possible .

However, it argues the amount and distribution of evil in the world provides good evidence that God probably doesn’t exist.

- Innocent babies born with painful congenital diseases

- The sheer number of people currently living in slavery, extreme poverty or fear

- The millions of innocent and anonymous people throughout history killed for no good reason

We can reject the logical problem of evil and accept that God would allow some evil. But would an omnipotent and omnibenevolent God allow so much evil? And to people so undeserving of it?

The evidential problem of evil argues that if God did exist, there would be less evil and it would be less concentrated among those undeserving of it.

Free will (again)

Sure, God could have made a world with less evil. But this would mean less free will. And on balance, having free will creates more good than the evil it also creates.

OK, maybe God would allow some evil for the greater good of free will. But it seems possible – simple, even – that God could have created a world with less evil than our world without sacrificing the greater good of free will.

For example, our world exactly as it is, with the same amount of free will, but with 1% less cancer. God could have created this world, so why didn’t He?

The evidential problem of evil could insist that the amount of evil – or unfair ways it is distributed – could easily be reduced without sacrificing some greater good, and so it seems unlikely that God exists, in this world, given this particular distribution of evil.

John Hick: Evil and the God of Love

Soul making.

Hick argues that humans are unfinished beings. Part of our purpose in life is to develop personally, ethically and spiritually – he calls this ‘soul making’.

As discussed above , it would be impossible for people to display (second order) virtues such as courage without fear of (first order) evils such as pain or death. Similarly, we couldn’t learn virtues such as forgiveness if people never treated us wrongly.

Of course, God could just have given us these virtues right off the bat. But, Hick says, virtues acquired through hard work and discipline are “good in a richer and more valuable sense”. Plus, there are some virtues, such as a genuine and authentic love of God, that cannot simply be given (otherwise they wouldn’t be genuine).

This explanation goes some way towards explaining why God would allow the amount and distribution of evil we see. He then addresses some specific examples of evils that may not seem to fit with an omnipotent and omnibenevolent God:

Why God allows animals to suffer

The evidential problem of evil can ask Hick why God would allow animals to suffer when there is no benefit. After all, they can’t develop spiritually like we can.

Hick’s response is that God wanted to create epistemic distance between himself and humanity – i.e. a world in which his existence could be doubted. If God just proved he existed, we wouldn’t be free to develop a relationship with him.

Why God allows such terrible evils

Hick argues that it’s not possible for God to just get rid of terrible evil – e.g. baby torture – and leave only ordinary evil. The reason for this is that terrible evils are only terrible in contrast to ordinary evils. So, if God did get rid of terrible evils, then the worst ordinary evils would become the new terrible evils. If God kept getting rid of terrible evils then he would have to keep reducing free will and thus the development of personal and spiritual virtues ( soul making ).

Why God allows such pointless evils

Hick argues that pointless evils – e.g. anonymously dying in vain trying to save someone – are somewhat of a mystery. However, if every time we saw someone suffering we knew it was for some higher purpose (i.e. it wasn’t pointless), then we would never be able to develop deep sympathy.

Again, this goes back to the soul making theodicy: without seemingly unfair and pointless evil, we would never be able to develop virtues such as hope and faith – both of which require a degree of uncertainty.

<<<The Concept of God

Religious language>>>.

I Think Therefore I Teach

Tips for A level students. Lesson ramblings for teachers (helpful ideas too!)

Ontological: Argument based on reason

Share this:

Leave a reply cancel reply.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Discover more from I Think Therefore I Teach

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

81 Ontology Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

🏆 best ontology topic ideas & essay examples, 👍 good research topics about ontology, 📌 most interesting ontology topics to write about, ❓ ontology questions examples.

- The Ontological Argument for the Existence of God Kant’s objection to the ontological argument stems from his view of the concept that a being that is conceived in the human mind, and which exists in the real world, is superior to an idea […]

- Rene Descartes’ Ontological Reasoning One of the branches of his ontological thought was the discussion of the existence of God. The purpose of this paper is review and analyze the arguments Rene Descartes provided to evidence the existence of […]

- Epistemology, Ontology, and Researcher Positionality However, the awareness of such characteristic features of the qualitative research process and the influential role of the researcher’s positionality allows for predicting the bias and addressing it effectively for more reliability and credibility of […]

- Control Breast Cancer: Nursing Phenomenon, Ontology and Epistemology of Health Management Then, the evidence received is presented in an expert way leading to implementation of the decision on the management of the disease.

- Ontology in Deleuze’s The Fold This power can be presented as the compressive force of the university contributing to the return of all pleats of the matter to the surrounded area.

- Ontology and Events in Architecture. Bernard Tschumi He stresses the change of paradigm and the presence of violence that governs the dynamic, at times incompatible relationships within architectural objects determined by the human intrusion in them and reconsideration of function and form, […]

- Comparison Ontology Modeling With Other Data-Based Model This is the organized representation of the information that the database requires including the information objects, the linkages in between the information objects and the guidelines that are used in the running of the relevant […]

- Philosophy of Science: Paradigm, Ontology, Epistemology On several occasions, it determines the magnitude of truth in a particular set of scientific results, thereby the merits or demerits of the same. This makes it the category of philosophy that studies the nature […]

- Anselm: Ontological Argument for the God’s Existence He considers the understanding of God’s existence as some of the things that exist in the stated place. He states that the love for God is the main aspect of the just among the human […]

- Ontological Views of the Quality of Life Thus, the development of instruments used in the assessment of QoL commenced in the 1970s and aided healthcare providers in making medical decisions. QoL varies according to the nursing environment and perceptions of patients and […]

- Hobbes’ Ontology within “Leviathan” Nevertheless, Hobbes seems to distinguish his writings on the Law of Nature from realistic conditions, with the philosophy based on maxims of the knowledge of human nature and behavior that apply moral precepts on science […]

- Philosophy: St. Anselm’s Ontological Argument One of the earliest ontological arguments, in defense of the de facto existence of God, is that of Anselm of Canterbury.

- Ontological Proof of God’s Existence It is because other marvelous things that cannot be conceived can either be an object or not specifically God, as the argument claims.

- Ontology and Epistemology in Leadership Research In the frames of this research on leadership as a practice, it is impossible to clarify what has been already known, what could be expected, and what lessons could be offered. It is a practice […]

- Ontology and Epistemology in the Contemporary Society Holistic, a term used by the writer, is appropriate as the nature of the writing tends to elaborate the idea of describing the concepts of knowledge as a whole and the differentiation of parts that […]

- Ontology, Free Will, Fate and Determinism On the other hand, fate is simply the predetermined course of the events or the predetermined future. It is pragmatic that people should not believe in the cause and effect.

- Ontological and Wager Argument While Anselm and Wager are major proponents of the ontological argument, Hume and Kant are some of the opponents of the ontological argument. Ontological argument is a controversial argument that supports the existence of God.

- Educational Research: Epistemological and Ontological Perspectives This applies to the statement that the researcher you are is the person you are since the knowledge and truth possessed from the surrounding will influence the researcher’s way of doing things.

- The Ontological Argument to Prove God’s Existence According to Anselm “if the existence of a being is necessary, then, ‘that being is greater than one which existence is not necessary’”.

- Ontological Vision vs. Teleological Argument For instance, one is to keep in mind that the so-called ontological vision is recognized to be one of the most reliable arguments, which proves the existence of the Sole Supreme Being.

- Ontological Difficulties in Literary Works A difficulty in literary criticism in negative terms refers to an element of writing that points to or indicative of a rift between a poet or an author and the reader.