- Ethics & Leadership

- Fact-Checking

- Media Literacy

- The Craig Newmark Center

- Reporting & Editing

- Ethics & Trust

- Tech & Tools

- Business & Work

- Educators & Students

- Training Catalog

- Custom Teaching

- For ACES Members

- All Categories

- Broadcast & Visual Journalism

- Fact-Checking & Media Literacy

- In-newsroom

- Memphis, Tenn.

- Minneapolis, Minn.

- St. Petersburg, Fla.

- Washington, D.C.

- Poynter ACES Introductory Certificate in Editing

- Poynter ACES Intermediate Certificate in Editing

- Ethics & Trust Articles

- Get Ethics Advice

- Fact-Checking Articles

- International Fact-Checking Day

- Teen Fact-Checking Network

- International

- Media Literacy Training

- MediaWise Resources

- Ambassadors

- MediaWise in the News

Support responsible news and fact-based information today!

Nikole Hannah-Jones’ essay from ‘The 1619 Project’ wins commentary Pulitzer

Of all the thousands upon thousands of stories and projects produced by American media last year, perhaps the one most-talked about was The New York Times Magazine’s ambitious “The 1619 Project,” which recognized the 400th anniversary of the moment enslaved Africans were first brought to what would become the United States and how it forever changed the country.

It was a phenomenal piece of journalism.

And while the project in its entirety did not make the list of Pulitzer Prize finalists, the introductory essay by Nikole Hannah-Jones , the creator of the landmark project, was honored with a prestigious Pulitzer Prize for commentary.

After the announcement that she has been awarded the Pulitzer Prize, Hannah-Jones told the Times’ staff it was “the most important work of my life.”

While nearly impossible, and almost insulting, to try and describe in a handful of words or even sentences, Hannah-Jones’ essay was introduced with this headline: “Our Democracy’s Founding Ideals Were False When They Were Written. Black Americans Have Fought to Make Them True.”

In her essay, Hannah-Jones wrote, “But it would be historically inaccurate to reduce the contributions of black people to the vast material wealth created by our bondage. Black Americans have also been, and continue to be, foundational to the idea of American freedom. More than any other group in this country’s history, we have served, generation after generation, in an overlooked but vital role: It is we who have been the perfecters of this democracy.”

RELATED TRAINING: Make Diversity a Priority During the Pandemic

Hannah-Jones’ and “The 1619 Project,” however, were not without controversy. There was criticism of the project, particularly from conservatives. Former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich called it “propaganda.” A commentator for The Federalist tweeted the goal of the project was to “delegitimize America, and further divide and demoralize its citizenry.”

But the most noteworthy criticism came from a group of five historians. ln a letter to the Times , they wrote that they were “dismayed at some of the factual errors in the project and the closed process behind it.” They added, “These errors, which concern major events, cannot be described as interpretation or ‘framing.’ They are matters of verifiable fact, which are the foundation of both honest scholarship and honest journalism. They suggest a displacement of historical understanding by ideology.”

Wall Street Journal assistant editorial features editor Elliot Kaufman wrote a column with the subhead: “The New York Times tries to rewrite U.S. history, but its falsehoods are exposed by surprising sources.”

In a rare move, the Times responded to the criticism with its own response . New York Times Magazine editor-in-chief Jake Silverstein wrote, “Though we respect the work of the signatories, appreciate that they are motivated by scholarly concern and applaud the efforts they have made in their own writings to illuminate the nation’s past, we disagree with their claim that our project contains significant factual errors and is driven by ideology rather than historical understanding. While we welcome criticism, we don’t believe that the request for corrections to The 1619 Project is warranted.”

That was just a portion of the rather lengthy and stern, but respectful response defending the project.

RELATED TRAINING: Covering Hate and Extremism, From the Fringes to the Mainstream

In the end, the 1619 Project — and Hannah-Jones’ essay, in particular — will be remembered for one of the most impactful and thought-provoking pieces on race, slavery and its impact on America that we’ve ever seen.

And maybe there was another reason for the pushback besides those questioning its historical accuracy.

As The Atlantic’s Adam Serwer wrote in December , “U.S. history is often taught and popularly understood through the eyes of its great men, who are seen as either heroic or tragic figures in a global struggle for human freedom. The 1619 Project, named for the date of the first arrival of Africans on American soil, sought to place ‘the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of our national narrative.’ Viewed from the perspective of those historically denied the rights enumerated in America’s founding documents, the story of the country’s great men necessarily looks very different.”

There’s no question that Hannah-Jones’ essay, which requires the kind of smart thinking and discussion that this country needs to continue having, deserved to be recognized with a Pulitzer as the top commentary of 2019. After all, and this is not hyperbole, it’s one of the most important essays ever.

In addition, we should acknowledge the other two finalists in this category: Washington Post sports columnist Sally Jenkins and Los Angeles Times columnist Steve Lopez.

RELATED TRAINING: Writing with Voice and Structure, with Lane DeGregory

Jenkins continues to be among the best sports columnists in the country. Meanwhile, has any writer done more to shine a light on homelessness than Lopez? This is the third time in the past four years (and fourth time overall) that Lopez has been a finalist in the commentary category.

In any other year, both would be deserving of Pulitzer Prizes. But 2019 will be remembered for Nikole Hannah-Jones’ powerful essay and project.

More Pulitzer coverage from Poynter

- With most newsrooms closed, Pulitzer Prize celebrations were a little different this year

- Here are the winners of the 2020 Pulitzer Prizes

- Here are the 2020 Pulitzer Prize-winning editorial cartoons

- Pulitzers honor Ida B. Wells, an early pioneer of investigative journalism and civil rights icon

- Reporting about climate change was a winner in this year’s Pulitzers

- ‘Lawless,’ an expose of villages without police protection, wins Anchorage Daily News its third Public Service Pulitzer

- The iconic ‘This American Life’ won the first-ever ‘Audio Reporting’ Pulitzer

- The Washington Post won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting for a novel climate change story

Opinion | Gannett fires editor for talking to Poynter, and other media news

Firing a single mother of three who was speaking up for more newsroom resources is a horrible look that deserves scrutiny and criticism.

Donald Trump repeated inaccurate claims on the economy in a local news interview in Pennsylvania

Trump repeated a bevy of inaccurate claims about the economy during an interview with WGAL-TV, a Lancaster, Pennsylvania, station

Opinion | Gannett fired an editor for talking to me

Sarah Leach spoke to Poynter in an attempt to staff up her team. She may have been successful, even if she won't be at Gannett to see it through.

Opinion | Kristi Noem’s media headaches now extend to conservative outlets

The South Dakota governor’s past few days have been so bad that she’s canceling on conservative media. Conservative media might soon cancel on her.

Q&A: HBO Max’s new ‘Girls on the Bus’ set out to show a cool, fun side of journalism

Former New York Times reporter and show co-creator Amy Chozick on how fact inspired fiction, pitfalls she avoided and today’s media environment

Start your day informed and inspired.

Get the Poynter newsletter that's right for you.

The 1619 Project

75 pages • 2 hours read

The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more. For select classroom titles, we also provide Teaching Guides with discussion and quiz questions to prompt student engagement.

Chapter Summaries & Analyses

Preface-Chapter 2

Chapters 3-4

Chapters 5-7

Chapters 8-10

Chapters 11-14

Chapters 15-16

Chapters 17-18

Key Figures

Index of Terms

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Summary and Study Guide

The 1619 Project is a series of essays, poems, and short fiction about the lasting legacy and implications of slavery in the United States. Named after the year the White Lion anchored and sold the first enslaved African people to the English colonies, these essays rethink the United States origin story to explain how a country founded on ideals of freedom preserved the institution of slavery and the lasting legacy of it. Nikole Hannah-Jones , Caitlin Roper, Ilena Silverman, and Jake Silverstein edited the collection.

Nikole Hannah-Jones, the author of the book’s preface and its first and last essays, is a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and celebrated academic who has won multiple awards for her work, including two George Polk Awards, a Peabody, and three National Magazine Awards. Hannah-Jones is a staff writer at The New York Times Magazine and a professor at Howard University; she reports on and studies racial injustice and the persistence of racial segregation in the United States. In The 1619 Project , Hannah-Jones explains that when she learned about the landing of the White Lion in 1619, she began to understand a history that the popular American narrative erased and ignored. As the 400th anniversary of 1619 loomed nearer, she knew it would go uncelebrated, unacknowledged, and unpacked. Hannah-Jones then pitched her idea to The New York Times Magazine —“a special issue that would mark the four-hundredth anniversary [of 1619] by exploring the unparalleled impact of African slavery on the development of our country and its continuing impact on our society” (xxii).

Get access to this full Study Guide and much more!

- 7,600+ In-Depth Study Guides

- 4,850+ Quick-Read Plot Summaries

- Downloadable PDFs

Published in 2021, this book is a hybrid collection of nonfiction, including essays from writers, academics, journalists, and historians exploring 18 different American institutions and phenomena: Democracy, Race, Sugar, Fear, Dispossession, Capitalism, Politics, Citizenship, Self-Defense, Punishment, Inheritance, Medicine, Church, Music, Healthcare, Traffic, Progress, and Justice. The collection also includes poems and short fiction.

Once published, The 1619 Project garnered praise and criticism alike. This book appeared after a year of political upheaval, nationwide protests, and calls for racial justice after the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery—all amid the Covid-19 global pandemic. Some historians challenged and attempted to discredit the arguments presented—especially “the framing, which treated slavery and anti-Blackness as foundational to America” or the “assertion that Black Americans have served as this nation’s most ardent freedom fighters […] or the idea that modern American life has been shaped not by the majestic ideals of our founding, but by its grave hypocrisy” (Hannah-Jones et al. xxv). Congress soon presented legislation to prevent The 1619 Project from being taught in schools and universities. President Trump spoke out against the project, establishing the “1776 Commission” as one of his last acts as President. This sought to discredit the project by “reinforc[ing] the exceptional nature of our country and to put forth a ‘patriotic’ narrative” (Hannah-Jones et al. xxvii).

The SuperSummary difference

- 8x more resources than SparkNotes and CliffsNotes combined

- Study Guides you won ' t find anywhere else

- 100+ new titles every month

This collection includes racial slurs targeting Black people and other mixed-race populations. The editors, however, have purposefully chosen to use the term “enslaved person” rather than “slave,” as the former “accurately conveys the condition without stripping the individual of his or her humanity” (xiii).

Plot Summary

In August 1619, a year before the Mayflower made land , the White Lion anchored in the harbor at Jamestown. This ship carried enslaved Africans stolen from their country and sold to Englishmen in the American Colonies. This sale was the first of enslaved peoples in Anglo-America and marked the beginning of the institution of American chattel slavery. This text reexamines the founding mythology of America and posits that over and over again, Black Americans have been the actual fighters of freedom. To suggest that our country’s founding happened in 1619 rather than with the Mayflower or the 1776 signing of the Declaration of Independence challenges the ingrained mythology of the United States, which says we are a country built on ideals of freedom and liberty. By contrast, the writers, authors, and scholars in this collection argue that many American establishments derived from the legal institution of slavery with the goal of cementing the status of enslaved people as property.

Perhaps the most radical claim is Hannah-Jones’s contention in “Democracy” that the American Revolution was fought to protect the colonists’ “property”—that is, their claim to an enslaved population—from the British Empire. Not only did slavery provide free labor and serve as property that could be traded, sold, and reproduced, building the wealth of many colonists, but it also provided a way to create a government without an apparent ruling class. Poor white colonists (whose numbers were already limited precisely because the “working class” mostly comprised enslaved people) saw that Black people had no legal rights, and they identified with the wealthier white colonists in power. The colonists built a country off the backs of the enslaved, protecting the institution of slavery through the Constitution, which protected the property rights of enslavers.

Throughout the collection, the authors make it clear that the institution of chattel slavery in the United States was not simply in the background of history but rather at the center. Chapter 2 (“Race”) examines how colonial law “invented” whiteness and Blackness in their current form to safeguard slavery. Chapter 3 (“Sugar”) discusses the pivotal role sugar cultivation played in the development of American chattel slavery. Chapter 4 (“Fear”) documents the fear of Black rebellion that continues to spark white violence. Chapter 5 (“Dispossession”) discusses Indigenous Americans’ relationships to whiteness, Blackness, and slavery. Chapter 6 (“Capitalism”) considers the mutually reinforcing relationship between capitalism and white supremacy. Chapter 7 (“Politics”) explores the racism baked into the US political system.

From here, the book moves on to more specific topics. Chapter 8 (“Citizenship”) recounts Black Americans’ struggles for citizenship. Chapter 9 (“Self-Defense”) questions which US citizens can claim self-defense, especially with regards to gun rights. Chapter 10 (“Punishment”) examines the mass incarceration of Black Americans. Chapter 11 (“Inheritance”) explores the factors that have prevented Black Americans from building intergenerational wealth in the way that white Americans have. Chapter 12 (“Medicine”) discusses systemic racism within the US medical system and its implications for Black Americans’ health. Chapter 13 (“Church”) considers the role religion has played in Black freedom struggles. Chapter 14 (“Music”) traces traditionally Black musical genres back to their origins and discusses their complex relationship to race and racism. Chapter 15 (“Healthcare”) situates the contemporary debate about healthcare in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War and the plight of newly “free” Black Americans. Chapter 16 (“Traffic”) explores how seemingly benign infrastructure reflects the legacy of slavery and segregation. Chapter 17 (“Progress”) argues that the idea of progress can act as an impediment to real-world progress. Finally, in Chapter 18 (“Justice”), Hannah-Jones returns to summarize the project’s implications with an eye towards building a more equitable future.

Don't Miss Out!

Access Study Guide Now

Featured Collections

Black History Month Reads

View Collection

Books on U.S. History

Contemporary Books on Social Justice

Nation & Nationalism

New York Times Best Sellers

Politics & Government

Safety & Danger

The Best of "Best Book" Lists

Find anything you save across the site in your account

The 1619 Project and the Demands of Public History

By Lauren Michele Jackson

In August of 2019, a special issue of the Times Magazine appeared, wearing a portentous cover—a photograph, shot by the visual artist Dannielle Bowman, of a calm sea under gray skies, the line between earth and land cleanly bisecting the frame like the stroke of a minimalist painting. On the lower half of the page was a mighty paragraph, printed in bronze letters. It began:

In August of 1619, a ship appeared on this horizon, near Point Comfort, a coastal port in the British colony of Virginia. It carried more than 20 enslaved Africans, who were sold to the colonists. America was not yet America, but this was the moment it began.

The name of this endeavor was introduced at the very bottom of the page, in print small enough to overlook: “The 1619 Project.” The titular year encapsulated a dramatic claim: that it was the arrival of what would become slavery in the colonies, and not the independence declared in 1776, that marked “the country’s true birth date,” as the issue’s editors wrote.

Seldom these days does a paper edition have such blockbuster draw. New Yorkers not in the habit of seeking out their Sunday Times ventured to bodegas to nab a hard copy. (Today you can find a copy on eBay for around a hundred dollars.) Commentators, such as the Vox correspondent Jamil Smith, lauded the Project—which consisted of eleven essays, nine poems, eight works of short fiction, and dozens of photographs, all documenting the long-fingered reach of American slavery—as an unprecedented journalistic feat. Impassioned critics emerged at both ends of the political spectrum. On the right, a boorish resistance developed that would eventually include everything from the Trump Administration’s error-riddled 1776 Commission report to states’ panicked attempts to purge their school curricula of so-called critical race theory . On the other side, unsentimental leftists, such as the political scientist Adolph Reed, Jr., accused the series of disregarding the struggles of a multiracial working class. But accompanying the salient historical questions was an underlying problem of genre. Journalism is, by its nature, a provisional and fragmentary undertaking—a “first draft of history,” as the saying goes—proceeding in installments that journalists often describe humbly as “pieces.” What are the difficulties that greet a journalistic endeavor when it aspires to function as a more concerted kind of history, and not just any history but a remodelling of our fundamental national narrative?

In the preface to a new book version of the 1619 Project, Nikole Hannah-Jones , a Times Magazine reporter and the leading force behind the endeavor, recalls that it began, as many journalistic projects do, in the form of a “simple pitch.” She proposed a large-scale public history, harnessing all of the paper’s institutional might and gloss, that would “bring slavery and the contributions of Black Americans from the margins of the American story to the center, where they belong.” The word “project” was chosen to “emphasize that its work would be ongoing and would not culminate with any single publication,” the editors wrote. Indeed, the undertaking from the beginning was a cross-platform affair for the Times , with special sections of the newspaper, a series on its podcast “The Daily,” and educational materials developed in partnership with the Pulitzer Center. By academic standards, the proposed argument was not all that provocative. The year 1619 itself has long been depicted as a tragic watershed. Langston Hughes wrote of it, in a poem that serves as the new book’s epigraph, as “The great mistake / That Jamestown made / Long ago.” In 2012, the College of William & Mary launched the “ Middle Passage Project 1619 Initiative ,” which sponsored academic and public events in anticipation of the approaching quadricentennial. “So much of what later becomes definitively ‘American’ is established at Jamestown,” the organizers wrote. But the legacy-media muscle behind the 1619 Project would accomplish what its predecessors in poetry and academia did not, thrusting the date in question into the national lexicon. There was something coyly American about the effort—public knowledge inculcated by way of impeccable branding.

The historical debates that followed are familiar by now. Four months after the special issue was released, the Times Magazine published a letter , jointly signed by five historians, taking issue with certain “errors and distortions” in the Project. The authors objected, especially, to a line in the introductory essay by Hannah-Jones stating that “one of the primary reasons the colonists decided to declare their independence from Britain was because they wanted to protect the institution of slavery.” Several months later, Politico published a piece by Leslie M. Harris, a historian and professor at Northwestern who’d been asked to help fact-check the 1619 Project. She’d “vigorously disputed” the same line, to no avail. “I was concerned that critics would use the overstated claim to discredit the entire undertaking,” she wrote. “So far, that’s exactly what has happened.”

The pushback from scholars was not just a matter of factuality. History is, in some senses, no less provisional than journalism. Its facts are subject to interpretation and disagreement—and also to change. But one detected in the historians’ complaints a discomfort with the 1619 Project’s fourth-estate bravado, its temperamental challenge to the slow and heavily qualified work of scholarly revelation. This concern was arguably borne out further in the Times’ corrections process. Hannah-Jones amended the line in question; in both the magazine and the book, it now states that “some of the colonists” were motivated by Britain’s growing abolitionist sentiment, a phrasing that neither retreats from the original claim nor shores it up convincingly. In the book, Hannah-Jones also clarifies another passage that had been under dispute, which had claimed that “for the most part” Black Americans fought for freedom “alone.” The original wording remains, but a qualifying clause has been added: “For the most part, Black Americans fought back alone, never getting a majority of white Americans to join and support their freedom struggles.” As Carlos Lozada pointed out in the Washington Post , the addition seems to redefine the meaning of the word “alone” rather than revise or replace it. In my view, the original wording was acceptable as a rhetorical flourish, whereas the amended version sounds fuzzy.

In the book’s preface, Hannah-Jones doesn’t dwell, as she well could have, on the truly deranged ire the Project has triggered on the right over the past few years. ( Donald Trump ’s ignorant bluster is mercifully confined to a single paragraph.) But neither is she entirely honest about the scope of fair criticism that the work has received. She files both academic disagreement (from “a few scholars”) and fury from the likes of Tom Cotton under the convenient label “backlash,” and suggests that any readers with qualms resent the Project for focussing “too much on the brutality of slavery and our nation’s legacy of anti-Blackness.” (Meanwhile, even the five historians behind the letter wrote that they “applaud all efforts to address the enduring centrality of slavery and racism to our history.”) The editors of the book, who include Hannah-Jones and the Times Magazine’s editor, Jake Silverstein, want to “address the criticisms historians offered in good faith”; accordingly, they’ve updated other passages, including ones on Lincoln and on constitutional property rights. But even the use of the term “good faith” suggests a hawkish mentality regarding the revisions process: you’re either against the Project or you’re with it, all in. There is little room in a venue as public as the 1619 Project’s for the learning opportunities that arise when research sets its ego aside and evolves in plain sight.

As Hannah-Jones notes, the disagreements needn’t undermine the 1619 Project as a whole. (After all, one of the letter’s signatories, James M. McPherson, an emeritus professor at Princeton, admitted in an interview that he’d “skimmed” most of the essays.) But the high-profile disputes over Hannah-Jones’s claims have eclipsed some of the quieter scrutiny that the Project has received, and which in the book goes unmentioned. In an essay published in the peer-reviewed journal American Literary History last winter, Michelle M. Wright, a scholar of Black diaspora at Emory, enumerated other objections, including the series’ near-erasure of Indigenous peoples. Wright sees the 1619 Project as replacing one insufficient creation story with another. “Be wary of asserting origins: they tend to shift as new archival evidence turns up,” she wrote.

The Project’s original hundred pages of magazine material have, in the new volume, swelled to more than five hundred, and certain formatting changes seem designed to serve its “big book” aspirations. Lyrical titles from the magazine issue, such as “Undemocratic Democracy” and “How Slavery Made Its Way West,” have been traded for broadly thematic ones (“Democracy,” “Dispossession”) and now join sixteen other single-word chapter titles, such as “Politics” (by the Times columnist Jamelle Bouie), “Self-Defense” (by the Emory professor Carol Anderson), and “Progress” (by the historian and best-selling anti-racism author Ibram X. Kendi). Along with the preface and an updated version of the original ruckus-raising essay, Hannah-Jones has written a closing piece, cementing her role as the 1619 custodian. In the manner of an academic text, the Project is showier about its scholarship this time around, sometimes cumbersomely so, with in-text citations of monographs with interminable titles. New essays, by scholars including Martha S. Jones and Dorothy Roberts, pointedly bolster the contributions from within the academy. Perhaps also pointedly, endnotes at the back of the book list the source material, which the series in magazine form had been accused of withholding.

At the same time, many of the essays in the book remain shaped according to the conventions of the magazine feature. First, a contemporary scene is set: the day after the 2020 election; the day Derek Chauvin killed George Floyd on a Minneapolis street; Obama’s first campaign for President; Obama’s farewell address. Then there is a section break, followed by a leap way back in time, the sort of move that David Roth, of Defector, has called, not without admiration, “The New Yorker Eurostep,” after a similarly swerving basketball maneuver. For the 1619 Project, though, the “Eurostep” isn’t merely a literary device, used in the service of storytelling; it is also a tool of historical argument, bolstering the Project’s assertion that one long-ago date explicates so much of what has come since. Modern-day policing evolved from white fears of Black freedom. Slave torture pioneered contemporary medical racism. For each of those points a historical narrative is unfolded, dilating here and leapfrogging there until the writer has traversed the promised four hundred years and established a neat causal connection.

For instance, an essay by the lawyer and professor Bryan Stevenson traces the modern plague of mass incarceration back to the Thirteenth Amendment, which ended slavery but made an exception for those convicted of crimes. In his eight pages outlining the “unbroken links” between then and now, Stevenson breezes past the constellation of policies that gave rise to mass incarceration in the span of a single sentence—“Richard Nixon’s war on drugs, mandatory minimum sentences, three-strikes laws, children tried as adults, ‘broken windows’ ”—and explains that those policies have “many of the same features” as the Black Codes that controlled freed Black people a century and a half ago. (The language here has been softened: in his original magazine piece, Stevenson deemed the Black Codes and the latter-day policies “essentially the same.”) It is not an untruthful accounting but it is an unstudious one, devoid of the sort of close reading that enlivens well-told histories. Alighting only so briefly on events of great consequence, many of “The 1619 Project” contributions end up reading like the CliffsNotes to more compelling bodies of work.

At its best, the book’s repetitive structure allows the stand-alone essays to converse fruitfully with one another. Matthew Desmond, explaining the origins of the American economy, describes the lengths the Framers went to secure the country’s chattel, including by adding a provision to the Constitution granting Congress the power to “suppress insurrections.” The implications of that provision and others like it are explored in the essay “Self-Defense,” by Anderson, whose note that “the enslaved were not considered citizens” acquires richer significance if you’ve read Martha S. Jones’s preceding chapter on citizenship. But the formula wears over time. With few exceptions—among them, a piece by Wesley Morris, a masterly stylist—the voices of the individual writers are unrecognizable, hewn to flatness by the primacy of the Project’s thesis. Regretfully, this is true even of the book’s poems and short fiction, which, in a rather utilitarian gesture, are presented between chapters along with a time line that aids the volume’s march toward the present.

For instance, the book’s very first listed event—the arrival of the White Lion in August, 1619—is followed by a poem by Claudia Rankine, which sits on the opposite page and borrows its name from that ship: “The first / vessel to land at Point Comfort / on the James River enters history, / and thus history enters Virginia.” A short piece by Nafissa Thompson-Spires depicts the interior monologue of a campaigner for Shirley Chisholm, the first Black woman to run for President, after Chisholm decided to visit George (“segregation forever”) Wallace in the hospital following an assassination attempt in 1972—a visit noted in a time line on the preceding page. As in much of the other fiction in the volume, Thompson-Spires’s prose is left winded by the responsibilities of exposition: “It seemed best not to try to convert the whites but to instead focus on registering voters, especially older ones on our side of town, many of whom, including Gran and PawPaw, couldn’t have passed even a basic literacy test.”

The didacticism does let up on occasion. An ennobling found poem by Tracy K. Smith derives its text from an 1870 speech by the Mississippi Senator Hiram Rhodes Revels, the first Black member of congress, who, a month after his swearing in, had to argue to keep Georgia’s duly elected Black legislators, who’d been denied their seats by the Democrats. (“My term is short, fraught, / and I bear about me daily / the keenest sense of the power / of blacks to shed hallowed light, / to welcome the Good News.”) A poem by Rita Dove channels the antsiness of Addie, Cynthia, Carol, and Carole, the four children who perished in a church bombing in Birmingham on September 15, 1963: “This morning’s already good—summer’s / cooling, Addie chattering like a magpie— / but today we are leading the congregation. / Ain’t that a fine thing!” But, on the whole, the literary creativity fits awkwardly with the task of record-keeping. It is a shame to assemble some of the finest and most daring authors of our time only to hem them in with time stamps.

So what are the facts? There are plenty in the volume that aren’t likely to be disputed. In the late seventeenth century, South Carolina made its whites legally responsible for policing any slave found off of the plantation without permission, with penalties for those who neglected to do so. In 1857, the Supreme Court decided against Dred Scott, ruling that Black people “are not included, and were not intended to be included, under the word ‘citizens’ in the Constitution, and can therefore claim none of the rights and privileges which that instrument provides.” In 1919, the U.S. Army strode into Elaine, Arkansas, and gunned down hundreds of Black residents. In 1960, Senator Barry Goldwater mourned the decline of states’ rights heralded by Brown v. Board of Education, contending that protecting racial equality was not federal business. In 1985, six adults and five children in Philadelphia received “the commissioner’s recipe for eviction,” as Gregory Pardlo writes in a poem, including “M16s, Uzi submachine guns, sniper rifles, tear gas . . . and one / state police / helicopter to drop two pounds of mining explosives combined with two / pounds of C-4.” In 2020, Black Americans were reportedly 2.8 times more likely to die after contracting COVID -19 . What the 1619 Project accounts for is the brutal racial logic governing the “afterlife of slavery,” as Saidiya V. Hartman has put it in her transformative scholarship (which is referenced only once in this book, in an endnote, but without which a project such as 1619 might very well not exist).

The book’s final essay, by Hannah-Jones, argues in favor of reparations so that America may “finally live up to the magnificent ideals upon which we were founded.” By “we” here she is referring to the nation as a whole, but embedded in Hannah-Jones’s vision is a more provincial collective identity. The convoluted apparatuses of anti-Black racism don’t spare individuals based on the specifics of their family trees. Black Americans encompass those whose roots in this country date back for many generations, or for one. Yet Hannah-Jones’s unstated but unsubtle suggestion is that a particular subset of Black people, namely those of us who can trace our ancestry to slavery within the nation’s borders, are the truest inheritors of America, both its ills and its ideals. We represent the country’s best “defenders and perfecters,” are “the most American of all,” and are not “the problem, but the solution.” These dubious honors are pinned, like badges of pride, at the volume’s beginning and end, and, for me, the imposition of patriotism is more bothersome than any debated factual claim. In spite of all of the ugly evidence it has assembled, the 1619 Project ultimately seeks to inspire faith in the American project, just as any conventional social-studies curriculum would.

This faith finds its most sentimental expression in another new book about 1619, “ Born on the Water ,” which was co-authored by Hannah-Jones and Renée Watson for school-aged readers. Beautifully illustrated by Nikkolas Smith, it centers on a young Black girl’s familiar dilemma during a classroom genealogy assignment—what knowledge does she have to share about an ancestry that was torn asunder by the Middle Passage? One answer comes on the story’s final page, in which the girl is seated at her desk, smiling, her hands poised midway through crayoning stars and stripes for “the flag of the country my ancestors built, / that my grandma and grandpa built, / that I will help build, too.” Here the 1619 Project has left the genres of journalism and history for the realm of fable. But a similar thinking resides at the center of the 1619 Project in all of its evolving forms—past, present, and future, arranged in a single line.

New Yorker Favorites

- Some people have more energy than we do, and plenty have less. What accounts for the difference ?

- How coronavirus pills could change the pandemic.

- The cult of Jerry Seinfeld and his flip side, Howard Stern.

- Thirty films that expand the art of the movie musical .

- The secretive prisons that keep migrants out of Europe .

- Mikhail Baryshnikov reflects on how ballet saved him.

- Sign up for our daily newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker .

Books & Fiction

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Mary Grimm

By Naomi Fry

By Alexandra Schwartz

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Nikole Hannah-Jones on turning 'The 1619 Project' into a docuseries

Gurjit Kaur

Michel Martin

NPR's Michel Martin speaks with journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones about her new docuseries, The 1619 Project , which is based on the journalism project of the same name.

Copyright © 2023 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by an NPR contractor. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

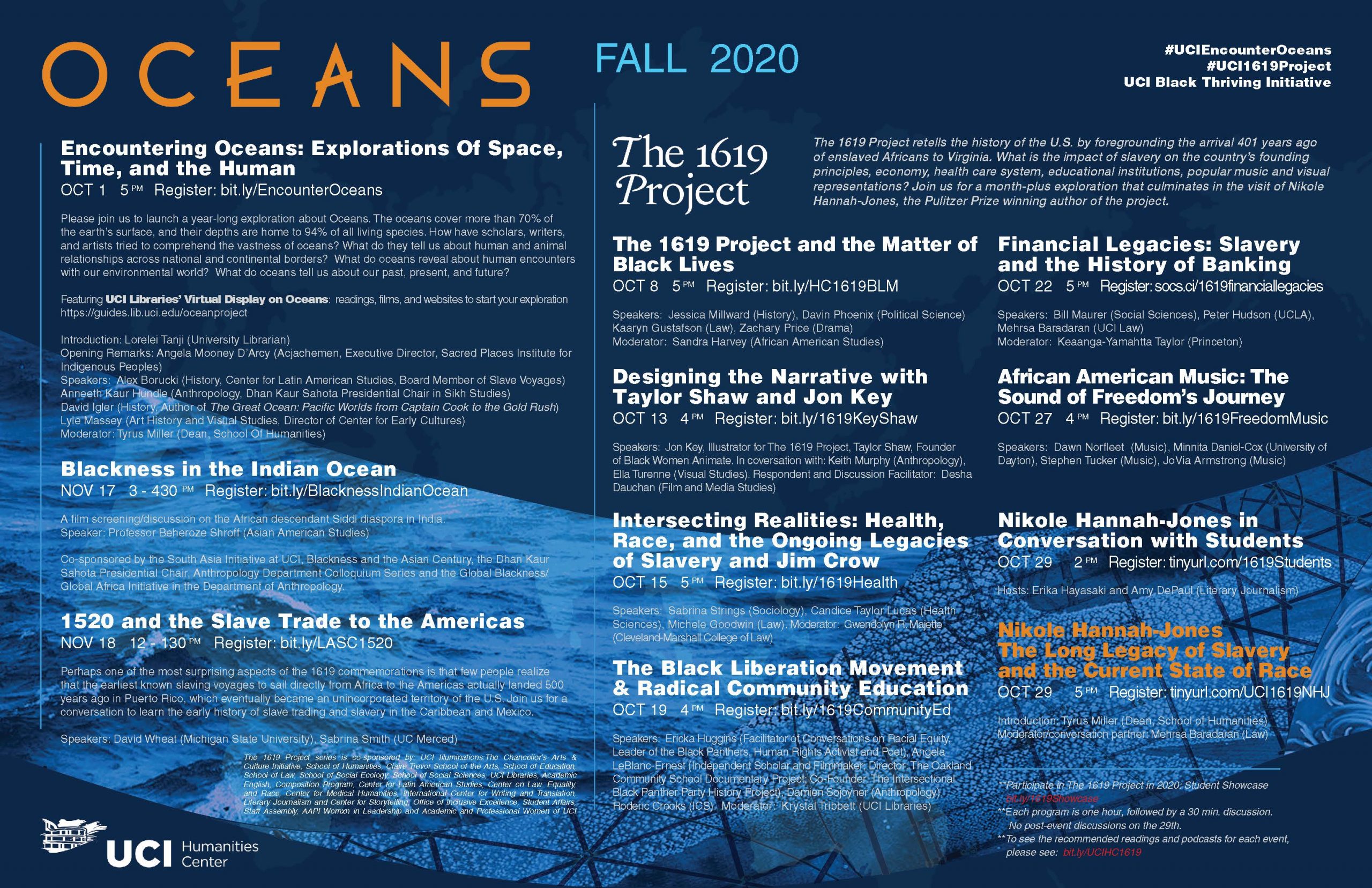

- Humanities Center

- Message from the Director

- About the Center

- Faculty Advisory Committee

- Spotlight Archive

- Annual Theme

- Digital Humanities Exchange (DHX)

- Research Clusters

- Routes of Enslavement in the Americas

- Faculty Grants

- Faculty Research Support

- Graduate Students at the Humanities Center

- Research Development & Grants

- School and Campus Centers

The 1619 Project

Contact Humanities Center

Humanities Gateway 1st Floor Irvine, CA 92697-3375

See the humanities in action

Copyright © 2023 UC Regents. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy

The 1619 Project

Curriculum, reading support and discussion prompts, podcasts and streaming media, doing your own research on the 1619 project and related subjects, multidisciplinary resources, reference librarian/business liaison.

- 1619 project : New York Times magazine [special issue], August 18, 2019 The goal of The 1619 Project is to reframe American history by making explicit how slavery is the foundation on which the United States of America is built, and by considering what it would mean to regard 1619 as the nation's birth year.

- Why we published The 1619 Project Includes a table of contents for The 1619 Project. An introduction by the editor of The New York Times Magazine, Jake Silverstein.

- The 1619 Project Broadside A companion piece to The 1619 Project, featuring objects from the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture.

The 1619 Project: Index of Literary Works

Page 28 ....... Clint Smith on the Middle Passage Page 29 ....... Yusef Komunyakaa on Crispus Attucks Page 42 ....... Eve L. Ewing on Phillis Wheatley Page 43 ....... Reginald Dwayne Betts on the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 Page 46 ....... Barry Jenkins on Gabriel's Rebellion Page 47 ....... Jesmyn Ward on the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves Page 58 ....... Tyehimba Jess on Black Seminoles Page 59 ....... Darryl Pinckney on the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 Page 59 ....... ZZ Packer on the New Orleans massacre of 1866 Page 68 ....... Yaa Gyasi on the Tuskegee syphilis experiment Page 69 ....... Jacqueline Woodson on Sgt. Isaac Woodard Page 78 ....... Rita Dove and Camille T. Dungy on the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing Page 79 ....... Joshua Bennett on the Black Panther Party Page 84 ....... Lynn Nottage on the birth of hip-hop Page 84 ....... Kiese Laymon on the Rev. Jesse Jackson’s “rainbow coalition” speech Page 85 ....... Clint Smith on the Superdome after Hurricane Katrina

- Reading guide for the 1619 Project essays Includes previews, main topic lists, and discussion questions for each of the 18 essays included in the 1619 Project.

- Reading guide for The 1619 Project creative works Lists discussion or response questions that can be used with the reading of the 17 creative texts (poems and fiction pieces) that explore major events in U.S. history and are included in The 1619 Project.

- The 1619 Project Curriculum Includes lesson plans, reading guides, and other materials for teaching The 1619 Project. Materials range from K-12 education and beyond, and can be adapted for classroom use.

- The 1619 Project Podcast Listening Guide A guide to each episode of the podcast, including questions and discussion prompts.

- Anti-Racism Resources by Nicola Andrews Last Updated Mar 15, 2024 150 views this year

- White Privilege Resource Guide by Amy Gilgan Last Updated Aug 30, 2023 604 views this year

- Last Updated: Mar 12, 2024 1:53 PM

- URL: https://library.usfca.edu/the-1619-project

2130 Fulton Street San Francisco, CA 94117-1080 415-422-5555

- Facebook (link is external)

- Instagram (link is external)

- Twitter (link is external)

- YouTube (link is external)

- Consumer Information

- Privacy Statement

- Web Accessibility

Copyright © 2022 University of San Francisco

A Matter of Facts

The New York Times ’ 1619 Project launched with the best of intentions, but has been undermined by some of its claims.

W ith much fanfare , The New York Times Magazine devoted an entire issue in August to what it called the 1619 Project. The project’s aim, the magazine announced, was to reinterpret the entirety of American history. “Our democracy’s founding ideals,” its lead essay proclaimed, “were false when they were written.” Our history as a nation rests on slavery and white supremacy, whose existence made a mockery of the Declaration of Independence’s “self-evident” truth that all men are created equal. Accordingly, the nation’s birth came not in 1776 but in 1619, the year, the project stated, when slavery arrived in Britain’s North American colonies. From then on, America’s politics, economics, and culture have stemmed from efforts to subjugate African Americans—first under slavery, then under Jim Crow, and then under the abiding racial injustices that mark our own time—as well as from the struggles, undertaken for the most part by black people alone, to end that subjugation and redeem American democracy.

The opportunity seized by the 1619 Project is as urgent as it is enormous. For more than two generations, historians have deepened and transformed the study of the centrality of slavery and race to American history and generated a wealth of facts and interpretations. Yet the subject, which connects the past to our current troubled times, remains too little understood by the general public. The 1619 Project proposed to fill that gap with its own interpretation.

To sustain its particular take on an immense subject while also informing a wide readership is a remarkably ambitious goal, imposing, among other responsibilities, a scrupulous regard for factual accuracy. Readers expect nothing less from The New York Times , the project’s sponsor, and they deserve nothing less from an effort as profound in its intentions as the 1619 Project. During the weeks and months after the 1619 Project first appeared, however, historians, publicly and privately, began expressing alarm over serious inaccuracies.

Adam Serwer: The fight over the 1619 Project is not about the facts

On December 20, the Times Magazine published a letter that I signed with four other historians—Victoria Bynum, James McPherson, James Oakes, and Gordon Wood. Our letter applauded the project’s stated aim to raise public awareness and understanding of slavery’s central importance in our history. Although the project is not a conventional work of history and cannot be judged as such, the letter intended to help ensure that its efforts did not come at the expense of basic accuracy. Offering practical support to that end, it pointed out specific statements that, if allowed to stand, would misinform the public and give ammunition to those who might be opposed to the mission of grappling with the legacy of slavery. The letter requested that the Times print corrections of the errors that had already appeared, and that it keep those errors from appearing in any future materials published with the Times ’ imprimatur, including the school curricula the newspaper announced it was developing in conjunction with the project.

The letter has provoked considerable reaction, some of it from historians affirming our concerns about the 1619 Project’s inaccuracies, some from historians questioning our motives in pointing out those inaccuracies, and some from the Times itself. In the newspaper’s lengthy formal response, the New York Times Magazine editor in chief, Jake Silverstein, flatly denied that the project “contains significant factual errors” and said that our request for corrections was not “warranted.” Silverstein then offered new evidence to support claims that our letter had described as groundless. In the interest of historical accuracy, it is worth examining his denials and new claims in detail.

No effort to educate the public in order to advance social justice can afford to dispense with a respect for basic facts. In the long and continuing battle against oppression of every kind, an insistence on plain and accurate facts has been a powerful tool against propaganda that is widely accepted as truth. That tool is far too important to cede now.

M y colleagues and I focused on the project’s discussion of three crucial subjects: the American Revolution, the Civil War, and the long history of resistance to racism from Jim Crow to the present. No effort to reframe American history can succeed if it fails to provide accurate accounts of these subjects.

The project’s lead essay, written by the Times staff writer Nikole Hannah-Jones, includes early on a discussion of the Revolution. Although that discussion is brief, its conclusions are central to the essay’s overarching contention that slavery and racism are the foundations of American history. The essay argues that “one of the primary reasons the colonists decided to declare their independence from Britain was because they wanted to protect the institution of slavery.” That is a striking claim built on three false assertions.

“By 1776, Britain had grown deeply conflicted over its role in the barbaric institution that had reshaped the Western Hemisphere,” Hannah-Jones wrote. But apart from the activity of the pioneering abolitionist Granville Sharp, Britain was hardly conflicted at all in 1776 over its involvement in the slave system. Sharp played a key role in securing the 1772 Somerset v. Stewart ruling, which declared that chattel slavery was not recognized in English common law. That ruling did little, however, to reverse Britain’s devotion to human bondage, which lay almost entirely in its colonial slavery and its heavy involvement in the Atlantic slave trade. Nor did it generate a movement inside Britain in opposition to either slavery or the slave trade. As the historian Christopher Leslie Brown writes in his authoritative study of British abolitionism, Moral Capital , Sharp “worked tirelessly against the institution of slavery everywhere within the British Empire after 1772, but for many years in England he would stand nearly alone.” What Hannah-Jones described as a perceptible British threat to American slavery in 1776 in fact did not exist.

“In London, there were growing calls to abolish the slave trade,” Hannah-Jones continued. But the movement in London to abolish the slave trade formed only in 1787, largely inspired, as Brown demonstrates in great detail, by American antislavery opinion that had arisen in the 1760s and ’70s. There were no “growing calls” in London to abolish the trade as early as 1776.

“This would have upended the economy of the colonies, in both the North and the South,” Hannah-Jones wrote. But the colonists had themselves taken decisive steps to end the Atlantic slave trade from 1769 to 1774. During that time, Maryland, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Connecticut, and Rhode Island either outlawed the trade or imposed prohibitive duties on it. Measures to abolish the trade also won approval in Massachusetts, Delaware, New York, and Virginia, but were denied by royal officials. The colonials’ motives were not always humanitarian: Virginia, for example, had more enslaved black people than it needed to sustain its economy and saw the further importation of Africans as a threat to social order. But the Americans who attempted to end the trade did not believe that they were committing economic suicide.

Assertions that a primary reason the Revolution was fought was to protect slavery are as inaccurate as the assertions, still current, that southern secession and the Civil War had nothing to do with slavery. In his reply to our letter, though, Silverstein ignored the errors we had specified and then imputed to the essay a very different claim. In place of Hannah-Jones’s statement that “the colonists decided to declare their independence from Britain … because they wanted to protect the institution of slavery,” Silverstein substituted “that uneasiness among slaveholders in the colonies about growing antislavery sentiment in Britain and increasing imperial regulation helped motivate the Revolution.” Silverstein makes a large concession here about the errors in Hannah-Jones’s essay without acknowledging that he has done so. There is a notable gap between the claim that the defense of slavery was a chief reason behind the colonists’ drive for independence and the claim that concerns about slavery among a particular group, the slaveholders, “helped motivate the Revolution.”

But even the evidence proffered in support of this more restricted claim—which implicitly cedes the problem with the original assertion—fails to hold up to scrutiny. Silverstein pointed to the Somerset case, in which, as I’ve noted, a British high court ruled that English common law did not support chattel slavery. Even though the decision did not legally threaten slavery in the colonies, Silverstein wrote, it caused a “sensation” when reported in colonial newspapers and “slavery joined other issues in helping to gradually drive apart the patriots and their colonial governments.”

In fact, the Somerset ruling caused no such sensation. In the entire slaveholding South, a total of six newspapers—one in Maryland, two in Virginia, and three in South Carolina—published only 15 reports about Somerset , virtually all of them very brief. Coverage was spotty: The two South Carolina newspapers that devoted the most space to the case didn’t even report its outcome. American newspaper readers learned far more about the doings of the queen of Denmark, George III’s sister Caroline, whom Danish rebels had charged with having an affair with the court physician and plotting the death of her husband. A pair of Boston newspapers gave the Somerset decision prominent play; otherwise, most of the coverage appeared in the tiny-font foreign dispatches placed on the second or third page of a four- or six-page issue.

Above all, the reportage was almost entirely matter-of-fact, betraying no fear of incipient tyranny. A London correspondent for one New York newspaper did predict, months in advance of the actual ruling, that the case “will occasion a greater ferment in America (particularly in the islands) than the Stamp Act,” but that forecast fell flat. Some recent studies have conjectured that the Somerset ruling must have intensely riled southern slaveholders, and word of the decision may well have encouraged enslaved Virginians about the prospects of their gaining freedom, which could have added to slaveholders’ constant fears of insurrection. Actual evidence, however, that the Somerset decision jolted the slaveholders into fearing an abolitionist Britain—let alone to the extent that it can be considered a leading impetus to declaring independence—is less than scant.

Slaveholders and their defenders in the West Indies, to be sure, were more exercised, producing a few proslavery pamphlets that strongly denounced the decision. Even so, as Trevor Burnard’s comprehensive study of Jamaica in the age of the American Revolution observes, “ Somerset had less impact in the West Indies than might have been expected.” Which is not to say that the Somerset ruling had no effect at all in the British colonies, including those that would become the United States. In the South, it may have contributed, over time, to amplifying the slaveholders’ mistrust of overweening imperial power, although the mistrust dated back to the Stamp Act crisis in 1765. In the North, meanwhile, where newspaper coverage of Somerset was far more plentiful than in the South, the ruling’s principles became a reference point for antislavery lawyers and lawmakers, an important development in the history of early antislavery politics.

In addition to the Somerset ruling, Silverstein referred to a proclamation from 1775 by John Murray, the fourth earl of Dunmore and royal governor of Virginia, as further evidence that fears about British antislavery sentiment pushed the slaveholders to support independence. Unfortunately, his reference was inaccurate: Dunmore’s proclamation pointedly did not offer freedom “to any enslaved person who fled his plantation,” as Silverstein claimed. In declaring martial law in Virginia, the proclamation offered freedom only to those held by rebel slaveholders. Tory slaveholders could keep their enslaved people. This was a cold and calculated political move. The proclamation, far from fomenting an American rebellion, presumed a rebellion had already begun . Dunmore, himself an unapologetic slaveholder—he would end his career as the royal governor of the Bahamas, overseeing an attempt to establish a cotton slavery regime on the islands—aimed to alarm and disrupt the patriots, free their human property to bolster his army, and incite fears of a wider uprising by enslaved people. His proclamation was intended as an act of war, not a blow against the institution of slavery, and everyone understood it as such.

Sanford Levinson: The Constitution is the crisis

Dunmore’s proclamation (unlike the Somerset decision three years earlier) certainly touched off an intense panic among Virginia slaveholders, Tory and patriot alike, who were horror-struck that it might spark a general insurrection, as the groundbreaking historian Benjamin Quarles showed many years ago. To the hundreds of enslaved men, women, and children who escaped to Dunmore’s lines, the governor was unquestionably, as Richard Henry Lee disparagingly remarked , the “African hero.” To the 300 formerly enslaved black men who joined what the governor called Lord Dunmore’s Ethiopian Regiment, outfitted with uniforms emblazoned with the slogan “Liberty to slaves,” he was a redeemer.

The spectacle likely stiffened the resolve for independence among the rebel patriots whom Dunmore singled out, but they were already rebels. The proclamation may conceivably have persuaded some Tory slaveholders to switch sides, or some who remained on the fence. It would have done so, however, because Dunmore, exploiting the Achilles’ heel of any slaveholding society, posed a direct and immediate threat to lives and property (which included, under Virginia law, enslaved persons), not because he affirmed slaveholders’ fears of “growing antislavery sentiment in Britain.” The offer of freedom in a single colony to persons enslaved by men who had already joined the patriots’ ranks—after a decade of mounting sentiment for independence, and after the American rebellion had commenced—cannot be held up as evidence that the slaveholder colonists wanted to separate from Britain to protect the institution of slavery.

To back up his argument that Dunmore’s proclamation, against the backdrop of a supposed British antislavery outpouring, was a catalyst for the Revolution, Silverstein seized upon a quotation not from a Virginian, but from a South Carolinian, Edward Rutledge, who was observing the events at a distance, from Philadelphia. “A member of South Carolina’s delegation to the Continental Congress wrote that this act did more to sever the ties between Britain and its colonies ‘than any other expedient which could possibly have been thought of,’” Silverstein wrote.

Although he would become the youngest signer of the Declaration of Independence, Rutledge, a hyper-cautious patriot, was torn, late in 1775, about whether the time was yet ripe to move forward with a formal separation from Britain. By early December, while serving his state in the Continental Congress, he had moved toward finally declaring independence, in response to various events that had expanded the Americans’ rebellion, including the American invasion of Canada; news of George III’s refusal to consider the Continental Congress’s petition for reconciliation; the British burning of the town of Falmouth, Maine; and, most recently, Dunmore’s proclamation, full news of which was only just reaching Philadelphia.

In a private letter explaining his evolving thoughts, Rutledge described the proclamation as “tending in my judgment, more effectively to work an eternal separation” between Britain and America “than any other expedient which could possibly have been thought of.” By quoting only the second half of that statement, Silverstein altered its meaning, turning Rutledge’s personal and speculative observation into conclusive proof of a sweeping claim.

This is not the only flaw in Silverstein’s discussion. He seems unaware that, in the end, Rutledge himself was not sufficiently moved by Dunmore’s proclamation to support independence, and he rather notoriously led the opposition inside the Congress before switching at the last minute on July 1, 1776. Moreover, a man whom John Adams had earlier described as “a Swallow—a Sparrow—a Peacock; excessively vain, excessively weak, and excessively variable and unsteady—jejune, inane, & puerile” may not be the most reliable source.

To buttress his case, Silverstein also quoted the historian Jill Lepore: “Not the taxes and the tea, not the shots at Lexington and Concord, not the siege of Boston: rather, it was this act, Dunmore’s offer of freedom to slaves, that tipped the scales in favor of American independence.” But Silverstein’s claim about Dunmore’s proclamation and the coming of independence is no more convincing when it turns up, almost identically, in a book by a distinguished authority; Lepore also relies on a foreshortened version of the Rutledge quote, presenting it as evidence of what the proclamation actually did, rather than as one man’s expectation as to what it would do. As for Silverstein’s main contention, meanwhile, neither Lepore nor Rutledge said anything about the colonists’ fear of growing antislavery sentiment in Britain.

O nly the Civil War surpasses the Revolution in its importance to American history with respect to slavery and racism. Yet here again, particularly with regard to the ideas and actions of Abraham Lincoln, Hannah-Jones’s argument is built on partial truths and misstatements of the facts, which combine to impart a fundamentally misleading impression.

The essay chooses to examine Lincoln within the context of a meeting he called at the White House with five prominent black men from Washington, D.C., in August 1862, during which Lincoln told the visitors of his long-held support for the colonization of free black people, encouraging them voluntarily to participate in a tentative experimental colony. Hannah-Jones wrote that this meeting was “one of the few times that black people had ever been invited to the White House as guests”; in fact, it was the first such occasion. The essay says that Lincoln “was weighing a proclamation that threatened to emancipate all enslaved people in the states that had seceded from the Union,” but that he “worried about what the consequences of this radical step would be,” because he “believed that free black people were a ‘troublesome presence’ incompatible with a democracy intended only for white people.”

In fact, Lincoln had already decided a month earlier to issue a preliminary version of the Emancipation Proclamation with no contingency of colonization, and was only awaiting a military victory, which came in September at Antietam. And Lincoln had supported and signed the act that emancipated the slaves in D.C. in June, again with no imperative of colonization—the consummation of his emancipation proposal from 1849, when he was a member of the House of Representatives.

Not only was Lincoln’s support for emancipation not contingent on colonization, but his pessimism was echoed by some black abolitionists who enthusiastically endorsed black colonization, including the early pan-Africanist Martin Delany (favorably quoted elsewhere by Hannah-Jones) and the well-known minister Henry Highland Garnet, as well as, for a time, Frederick Douglass’s sons Lewis and Charles Douglass. And Lincoln’s views on colonization were evolving. Soon enough, as his secretary, John Hay, put it, Lincoln “sloughed off” the idea of colonization, which Hay called a “hideous & barbarous humbug.”

But this Lincoln is not visible in Hannah-Jones’s essay. “Like many white Americans,” she wrote, Lincoln “opposed slavery as a cruel system at odds with American ideals, but he also opposed black equality.” This elides the crucial difference between Lincoln and the white supremacists who opposed him. Lincoln asserted on many occasions, most notably during his famous debates with the racist Stephen A. Douglas in 1858, that the Declaration of Independence’s famous precept that “all men are created equal” was a human universal that applied to black people as well as white people. Like the majority of white Americans of his time, including many radical abolitionists, Lincoln harbored the belief that white people were socially superior to black people. He insisted, however, that “in the right to eat the bread without the leave of anybody else, which his own hand earns, [the Negro] is my equal, and the equal of Judge Douglas, and the equal of every other man.” To state flatly, as Hannah-Jones’s essay does, that Lincoln “opposed black equality” is to deny the very basis of his opposition to slavery.

Nor was Lincoln, who had close relations with the free black people of Springfield, Illinois, and represented a number of them as clients, known to treat black people as inferior. After meeting with Lincoln at the White House, Sojourner Truth, the black abolitionist, said that he “showed as much respect and kindness to the coloured persons present as to the white,” and that she “never was treated by any one with more kindness and cordiality” than “by that great and good man.” In his first meeting with Lincoln, Frederick Douglass wrote, the president greeted him “just as you have seen one gentleman receive another, with a hand and voice well-balanced between a kind cordiality and a respectful reserve.” Lincoln addressed him as “Mr. Douglass” as he encouraged his visitor to spread word in the South of the Emancipation Proclamation and to help recruit and organize black troops. Perhaps this is why in his response, instead of repeating the claim that Lincoln “opposed black equality,” Silverstein asserted that Lincoln “was ambivalent about full black citizenship.”

Michael Gerhardt and Jeffrey Rosen: How to revive Madison’s constitution

Did Lincoln believe that free black people were a “troublesome presence”? That phrase comes from an 1852 eulogy he delivered in honor of Henry Clay, describing Clay’s views of colonization and free black people. Lincoln did not use those words in his 1862 meeting or on any occasion other than the eulogy. And Lincoln did not believe that the United States was “a democracy intended only for white people.” On the contrary, in his stern opposition to the Supreme Court’s racist Dred Scott v. Sandford decision in 1857, he made a point of noting that, at the time the Constitution was ratified, five of the 13 states gave free black men the right to vote, a fact that helped explode Chief Justice Roger B. Taney’s contention that black people had “no rights which the white man was bound to respect.”

To be sure, on this subject as on many others, one could easily cherry-pick isolated episodes from Lincoln’s long career to portray him very differently. As a first-term Illinois state legislator, in a display of party loyalty, Lincoln voted in favor of a sham, highly partisan Whig resolution against black suffrage in the state, introduced as a campaign gambit before the 1836 election against the Democrats who had enacted a restrictive black code. More than 20 years later, in 1859, fending off racist demagogy about his antislavery politics, he carefully denied a charge that he was proposing to give voting rights to black men, while still upholding black people’s human rights. But Lincoln fully recognized the political inclusion of free black people in several states at the nation’s founding, and he lamented how most of those states had either abridged or rescinded black voting rights in the intervening decades. Far from agreeing with Taney and others that American democracy was intended to be for white people only, Lincoln rejected the claim, citing simple and unimpeachable facts.

As president, moreover, Lincoln acted on his beliefs, taking enormous political and, as it turned out, personal risks. In March 1864, as he approached a difficult reelection campaign, Lincoln asked the Union war governor of Louisiana to establish the beginning of black suffrage in a new state constitution, “to keep the jewel of liberty within the family of freedom.” A year later, in his final speech, Lincoln publicly broached the subject of enlarging black enfranchisement, which was the final incitement to a member of the crowd, John Wilkes Booth, to assassinate him.

Silverstein acknowledged that Hannah-Jones’s essay presented a partial account of Lincoln’s ideas about abolition and racial equality, but excused the imbalance because the essay covered so much ground. “Admittedly, in an essay that covered several centuries and ranged from the personal to the historical, she did not set out to explore in full his continually shifting ideas about abolition and the rights of black Americans,” he wrote. In fact, throughout the essay’s lengthy discussion of Lincoln and colonization, what Silverstein called Lincoln’s “attitudes” are frozen in time, remote from political difficulties. Still, Silverstein contended, Hannah-Jones’s essay “provides an important historical lesson by simply reminding the public, which tends to view Lincoln as a saint, that for much of his career, he believed that a necessary prerequisite for freedom would be a plan to encourage the four million formerly enslaved people to leave the country.” Whether or not the public still regards Lincoln as a saint, a myth cannot be corrected by a distorted view. As Silverstein himself acknowledged, “At the end of his life, Lincoln’s racial outlook had evolved considerably in the direction of real equality.”

M oving beyond the Civil War , the essay briefly examined the history of Reconstruction, the long and bleak period of Jim Crow, and the resistance that led to the rise of the modern civil-rights movement. “For the most part,” Hannah-Jones wrote, “black Americans fought back alone.”

This is the third claim that my colleagues and I criticized, and although it covers the longest period of the three, it can be dealt with most directly. Before, during, and after the Civil War, some white people were always an integral part of the fight for racial equality. From lethal assaults on white southern “scalawags” for opposing white supremacy during Reconstruction through resistance to segregation led by the biracial NAACP through the murders of civil-rights workers, white and black, during the Freedom Summer, in 1964, and in Selma, Alabama, a year later, liberal and radical white people have stood up for racial equality. A. Philip Randolph, the founder of the modern civil-rights movement, stated in his speech at the March on Washington, in 1963, “This civil-rights revolution is not confined to the Negro, nor is it confined to civil rights, for our white allies know that they cannot be free while we are not.”

Silverstein, in his reply, observed that civil-rights advances “have almost always come as a result of political and social struggles in which African-Americans have generally taken the lead.” But when it comes to African Americans’ struggles for their own freedom and civil rights, this is not what Hannah-Jones’s essay asserted.

T he specific criticisms of the 1619 Project that my colleagues and I raised in our letter, and the dispute that has ensued, are not about historical trajectories or the intractability of racism or anything other than the facts—the errors contained in the 1619 Project as well as, now, the errors in Silverstein’s response to our letter. We wholeheartedly support the stated goal to educate widely on slavery and its long-term consequences. Our letter attempted to advance that goal, one that, no matter how the history is interpreted and related, cannot be forwarded through falsehoods, distortions, and significant omissions. Allowing these shortcomings to stand uncorrected would only make it easier for critics hostile to the overarching mission to malign it for their own ideological and partisan purposes, as some had already begun to do well before we wrote our letter.

Taking care of the facts is, I believe, all the more important in light of current political realities. The New York Times has taken a lead in combatting the degradation of truth and assault on a free press propagated by Donald Trump’s White House, aided and abetted by Vladimir Putin’s Russia, and spun by the far right on social media. American democracy is in a perilous condition, and the Times can report on that danger only by upholding its standards “without fear or favor.” That is why it is so important that lapses such as those pointed out in our letter receive attention and timely correction. When describing history, more is at stake than the past.

No historian better expressed this point, as part of the broader imperative for factual historical accuracy, than W. E. B. Du Bois. In Black Reconstruction in America , published in 1935, Du Bois challenged a reigning school of American historians working under the tutelage and guidance of William Archibald Dunning of Columbia University. The Dunning School, coupled with a broader current of Lost Cause defenders, produced works that characterized Reconstruction as vicious and vindictive, imposing the rule of corrupt and ignorant black people on a stricken postwar South. Those works, Du Bois understood, helped perpetuate racial oppression. Part of the genius of Black Reconstruction in America lay in Du Bois’s ability to mount a commanding counterinterpretation built on basic facts that the Dunning School had ignored or suppressed about the experiment in democratic government during Reconstruction and how it was overthrown and eventually replaced with Jim Crow.

In exposing the falsehoods of his racist adversaries, Du Bois became the upholder of plain, provable fact against what he saw as the Dunning School’s propagandistic story line. Du Bois repeatedly pointed out the “deliberate contradiction of plain facts.” Time and again in Black Reconstruction , he appealed to the facts against one or another false interpretation: “the plain, authentic facts of our history … perfectly clear and authenticated facts … the very cogency of my facts … the whole body of facts … certain quite well-known facts that are irreconcilable with this theory of history.” Only by carefully marshaling the facts was Du Bois able to establish the truth about Reconstruction. Indifference to the facts or their sloppy deployment, he argued, could lead and had led even intelligent scholars into “wide error.” Du Bois’s lesson should not be lost.

This Phoenix district isn't teaching controversial history. It's teaching kids to think

Opinion: balsz school district doesn't teach kids what to think about history, but rather how to think and share their ideas respectfully..

A tiny elementary school district covering a blue-collar, minority neighborhood behind Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport has found itself at the center of a national debate over race in education .

You wouldn’t know that by walking into the 500-student David Crockett Elementary School.

The Black, Hispanic and Native American students in kindergarten through fifth grade are busy trying to get up to standard in basic subjects, a task made difficult by the reality that more than 90% of them come from economically disadvantaged households.

Still, “the home of the Bears” has become a target of Tom Horne’s rampage against critical race theory .

“Students should be taught … that race, an accident of birth, is irrelevant to anything,” the state education superintendent has said. “I am open minded about almost all political issues, but this belief is in the marrow of my bones and not subject to the slightest compromise.”

Balsz never adapted '1619 Project' for its classes

Horne has claimed that the Balsz Elementary School District has adopted CRT into its curriculum by adapting the controversial “1619 Project,” a sweeping work of journalism that traces U.S. history to the start of slavery, showing how racism in the past has affected policy, practice and people in the present.

Educators, however, say that never happened.

“As I see it, it comes down to some of how history is taught,” said Todd Schwarz, president of the Balsz district school board, sitting on a bench near the Crockett playground.

“We did consider, at one point, having someone come in and talk to teachers about ‘The 1619 Project,’ which was a very interesting historical study. It’s not a perfect history. No history is. … The idea was ‘How do we incorporate some of what we’re reading here into our lessons?’

“It turned out, after one professional development session, that it didn’t seem like it was going to work for an elementary school district.

“We stopped it; we dropped it. But there’s a ghost on the internet that keeps popping up when you Google the Balsz Elementary School District. ‘Oh, the 1619 Project.’ ”

Horne uses critical race theory to drive a wedge

The controversy starts with the very definition of CRT.

Horne has called the 5-year-old 1619 Project “the primary source” for teaching CRT, which “has distorted the meaning of the previously attractive word ‘equity.’ To proponents of critical race theory, it means distributing benefits by racial percentages, rather than by individual merit.”

That’s not what educators at Balsz say.

“From my perspective, critical race theory is something that was initiated decades ago as a theory that leans into the philosophies and understanding of giving a voice to those who don’t usually have a voice in research,” said George Barnes, superintendent of the Balsz district.

“I think over the last 10 years, there’s been some pretty hot conversation on what CRT is, and the misnomer that giving kids a space to learn more about themselves and more about our country is going to cause some sort of negative feelings in the community, overall.”

Horne uses critical race theory: To drag us backward

Schwarz, a politician, says it more plainly.

“What I see is conservatives using the term ‘critical race theory’ to just drive a wedge,” he said. “It’s a phrase that they use to drive a wedge between teachers and families, between schools and families, between white people and Black people, quite frankly.”

How the district teaches history on race

Educators in districts like Balsz say they can’t function without bond and override elections to pay competitive salaries and improve schools. But such measures won’t win support if administrators don’t have trust.

It feels like that’s the point for conservatives like Horne, so desperate to cling to power that they’ll distort history and ruin futures to pull it off.

To be sure, “The 1619 Project” is a massive collection of historical essays that are far over the head of most any fifth-grader.

Horne: Schools teach critical race theory under different names

But it didn’t come up in Skyler Atterbom’s class, where fifth-grade students were learning about Reconstruction, a period of advancements following the Civil War before the vicious snapback of Jim Crow.

Atterbom showed a short NBC News Learn video on YouTube about the Freedman’s Bureau, which legalized marriages, reunited families and brought Black literacy rates up from nothing (it was illegal to teach slaves to read or write) to about 30%, in part by establishing schools such as Howard University in Washington, D.C.

By 1872, historically Black colleges and universities had granted about 1,000 degrees, but the programs that provided a vital bridge between slavery and citizenship were unpopular among white people. The bureau’s funding was cut drastically following Lincoln’s assassination, leading to its disbandment.

“I think the goal with that is to let the kids think for themselves and teach them how to tackle challenging topics in a respectful and thoughtful way. And that’s all I try to do,” Atterbom said.

Students are taught to share ideas with respect

For Atterbom, it’s not about teaching kids what to think, it’s about teaching them how to think and to share their ideas in a respectful and thoughtful way, starting with listening.

“If I’ve done my job right, they’ve learned to communicate and write more effectively,” he said. “And then also, more importantly to me, to communicate to each other more effectively.