Biological Psychology: Development and Theories Essay

Introduction.

Biology and psychology help researchers, medical professionals and psychologists to understand the behavior of human beings and animals. Therefore, biological psychology is used to examine the behavior of the humans and animals in order to facilitate in the treatment of the brain. Biological psychology is also referred to as behavioral neural science, biopsychology, clinical neuropsychology, and physiological psychology. Biological psychologists use the knowledge that they acquire from psychology to help them treat mental illness cases efficiently.

They also focus on issues related to mental processes and the manner in which they are initiated in the brain (Chavez, 2009). The goal of this paper therefore is to define biological psychology, discuss the historical development of biological psychology, stipulate important theorists who are associated with biological psychology, show the relationship between biological psychology and other fields of psychology and neuroscience, and discuss the major assumptions of that are associated with bio-psychology.

Biological Psychology

Bio-psychology studies human emotional and affective processes thereby helping biological psychologists to devise ways of assisting people to cope with different mental problems. It focuses on the brain and the manner in which it influences the performance of the entire nervous system. In this case, it focuses on people’s ability to think, feel, learn, perceive and sense. Studies reveal that these characteristics are similar in humans and animals (Hubpages Inc, 2012). It also focuses on the biological processes that influence normal and abnormal behavior in humans and animals.

Historical Development of Biological Psychology

The environment influences the evolution process of human beings and animals. As the state of the environment changes, the behavior of human beings and animals also changes in order to help them adapt to their new surroundings. As a result, it is true that biology and psychology work together to help people understand the relationship between human and animal behavior. Therefore, the idea of bio-psychology was first put into practice during the Greek era. It was adopted between the 18h and 19 th centuries. In this case, Plato proposed that the brain is the vital organ that facilitates reasoning. On the other hand, Descartes stipulated that the mind and body work in a different manner. He argued that the mind is non-physical and that it influences behavior among human beings and animals (Pinel, 2009).

Researchers and theorists who supported biological psychology made it possible for people to understand mental illnesses deeply and how they influence people’s behaviors. However, when the concept of biological phycology was proposed, many people argued that it would not be possible to understand how the brain works without touching and testing it. As a result, animals were dissected and tested in order to help people understand the complexities that are found in the brain. Without testing the brain, it would not be possible for people to understand how the brain works. Today, many psychologists, researchers and doctors are working hard in order to help them treat those people who have mental problems (Lee, 2011). However, they cannot manage to treat people who have mental problems if they do not understand the functions of the brain thoroughly.

Theorists Associated With Biological Psychology

The major theorists associated with biological psychology are Rene Descartes, Thomas Willis and Luigi Galvani. Descartes believed that the flow of animal spirits influences their behavior. He also believed that human beings follow the same trend. On the other hand, Thomas Willis stipulated that the structure of the brain influences the behavior of human beings and animals. He is associated with the discovery of the white and gray matter that is present in the brain. Moreover, Luigi Galvani stipulated that the nervous tissues are powered by electricity (Lee, 2011).

Relationship Between Biopsychology and Other Fields of Psychology and Neuroscience

Biopsychology is a vital area of study because it supplies information to all fields of psychology. This is because all fields of psychology focus on the study of behaviors and the functions of the brain. Moreover, studies show that biological psychologists study cognitive neuroscience, evolutionary psychology, and neuropsychology. For example, biopsychology analyzes behavioral problems and the manner in which they influence the performance of the brain and the nervous system (Hubpages Inc, 2012). Other fields of psychology and neuroscience follow the same trend. Therefore, it is true that biopsychology is related to psychology and neuroscience.

Assumptions Associated With Biopsychology

Studies reveal that social, psychological and biological factors influence the mental and physical wellbeing of a person. As a result, there are various assumptions that support the validity of biopsychology. There are two assumptions which govern biopsychology. The first assumption stipulates that mental processes influence biological processes (Chavez, 2009). On the other hand, biological processes influence mental processes. Therefore, it is true that both mental and biological processes are related to each other.

From the analysis therefore, it is true that biopsychology is a branch of psychology. Biopsychology adopts biological concepts in order to explain animal and human behavior. However, if medical professionals, researchers and psychologists fail to develop a better understanding of the human mind, the term biopsychology will seize to exist. Therefore, it is true that human beings should learn more about the brain so that they can be able to address the complexities of the brain efficiently.

Chavez, C. H. (2009). What is biological psychology? Web.

Hubpages Inc. (2012). Biological Psychology Definition . Web.

Lee, J. (2011). Biopsychology. Web.

Pinel, J. P. (2009). Biopsychology. Boston MA: Allyn and Bacon.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2020, May 30). Biological Psychology: Development and Theories. https://ivypanda.com/essays/biological-psychology-development-and-theories/

"Biological Psychology: Development and Theories." IvyPanda , 30 May 2020, ivypanda.com/essays/biological-psychology-development-and-theories/.

IvyPanda . (2020) 'Biological Psychology: Development and Theories'. 30 May.

IvyPanda . 2020. "Biological Psychology: Development and Theories." May 30, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/biological-psychology-development-and-theories/.

1. IvyPanda . "Biological Psychology: Development and Theories." May 30, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/biological-psychology-development-and-theories/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Biological Psychology: Development and Theories." May 30, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/biological-psychology-development-and-theories/.

- Abnormal Psychology's Historical Perspectives

- Contemporary Neuroimaging and Methods in Adult Neuropsychology

- Biopsychology: Learning and Memory Relationship

- Working Memory Concept: Psychological Views

- People with Disabilities: The Systemic Ableism

- Health Psychology: Eating and Stress' Relations

- Psychological Distress in Racial and Ethnic Minority Students

- Relationship Between Depression and Sleep Disturbance

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

The Role of the Biological Perspective in Psychology

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Daniel B. Block, MD, is an award-winning, board-certified psychiatrist who operates a private practice in Pennsylvania.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/block-8924ca72ff94426d940e8f7e639e3942.jpg)

Main Topic Areas

Example of the biological perspective, strengths of the biological perspective, weaknesses of the biological perspective.

There are many different ways of thinking about topics in psychology. The biological perspective is a way of looking at psychological issues by studying the physical basis for animal and human behavior. It is one of the major perspectives in psychology and involves such things as studying the brain, immune system , nervous system, and genetics.

One of the major debates in psychology has long centered on the relative contributions of nature versus nurture . Those who take up the nurture side of the debate suggest that it is the environment that plays the greatest role in shaping behavior. The biological perspective tends to stress the importance of nature.

The Biological Perspective

This field of psychology is often referred to as biopsychology or physiological psychology. This branch of psychology has grown tremendously in recent years and is linked to other areas of science including biology, neurology, and genetics.The biological perspective is essentially a way of looking at human problems and actions.

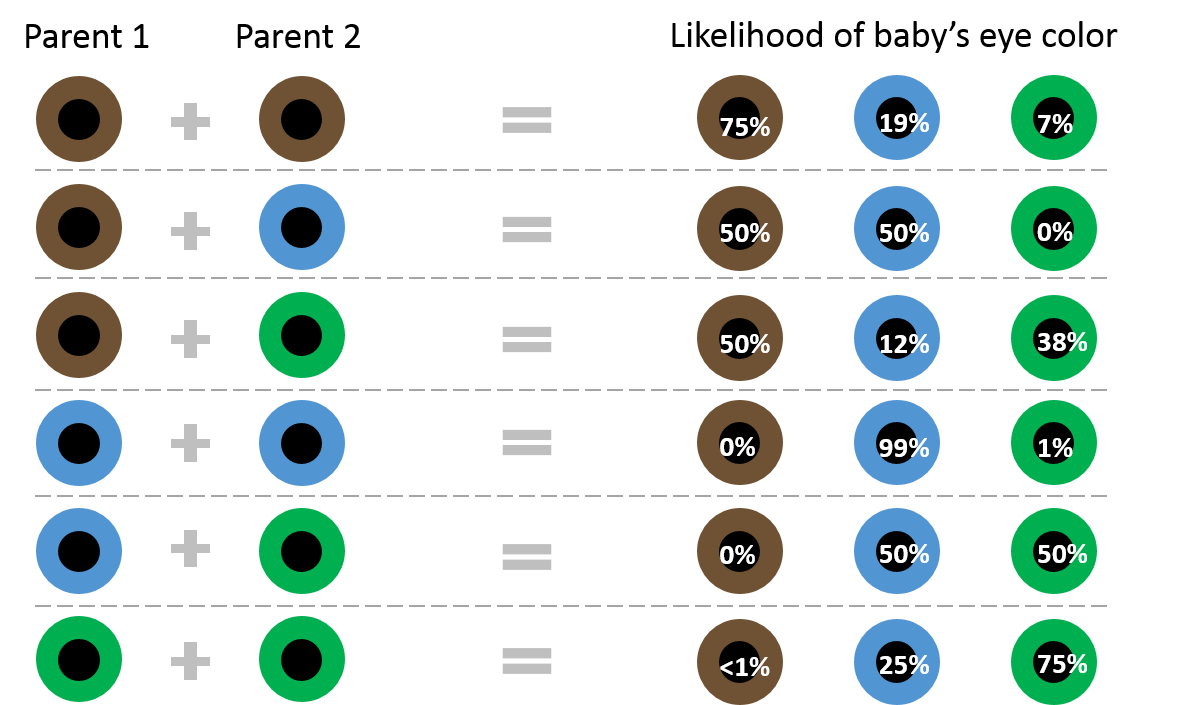

The study of physiology and biological processes has played a significant role in psychology since its earliest beginnings . Charles Darwin first introduced the idea that evolution and genetics play a role in human behavior.

Natural selection, first described by Charles Darwin, influences whether certain behavior patterns are passed down to future generations. Behaviors that aid in survival are more likely to be passed down while those that prove dangerous are less likely to be inherited.

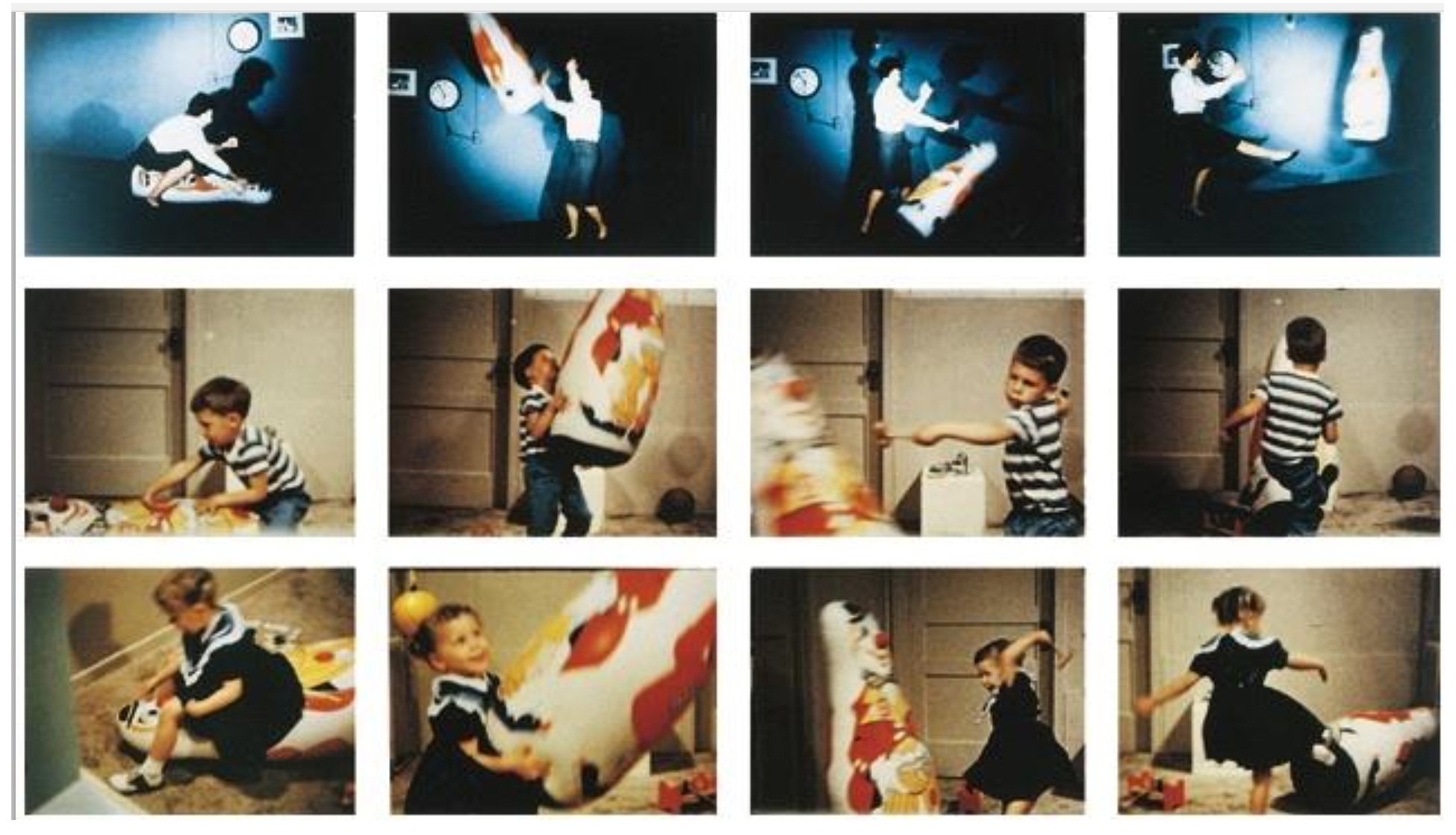

Consider an issue like aggression. The psychoanalytic perspective might view aggression as the result of childhood experiences and unconscious urges. The behavioral perspective considers how the behavior was shaped by association, reinforcement , and punishment . A psychologist with a social perspective might look at the group dynamics and pressures that contribute to such behavior.

The biological viewpoint, on the other hand, would involve looking at the biological roots that lie behind aggressive behaviors. Someone who takes the biological perspective might consider how certain types of brain injury might lead to aggressive actions. Or they might consider genetic factors that can contribute to such displays of behavior.

Biopsychologists study many of the same things that other psychologists do, but they are interested in looking at how biological forces shape human behaviors. Some topics that a psychologist might explore using this perspective include:

- Analyzing how trauma to the brain influences behaviors

- Assessing the differences and similarities in twins to determine which characteristics are tied to genetics and which are linked to environmental influences

- Exploring how genetic factors influence such things as aggression

- Investigating how degenerative brain diseases impact how people act

- Studying how genetics and brain damage are linked to mental disorders

This perspective has grown considerably in recent years as the technology used to study the brain and nervous system has grown increasingly advanced.

Today, scientists use tools such as PET and MRI scans to look at how brain development, drugs, disease, and brain damage impact behavior and cognitive functioning.

An example of the biological perspective in psychology is the study of how brain chemistry may influence depression. Antidepressants affect these neurotransmitter levels, which may help alleviate depression symptoms.

However, research on biological psychology has also disputed the idea that serotonin levels are responsible for depression, so more research is needed in this area to better understand the impact of brain chemicals on depression symptoms.

The use of brain imaging to understand how the brain and nervous system influence human behavior is another example of the biological perspective in psychology.

The Biological Perspective of Personality

The biological perspective of personality is another example of how looking at biological and genetic factors can be used to understand different aspects of psychology. The biological perspective of personality focuses on the biological factors that contribute to personality differences.

This perspective suggests that personality is influenced by genetic and biological factors. Temperament, which is the biologically-influenced pattern that emerges early in life, is one example of how the biological perspective can be used to understand human personality.

One of the strengths of using the biological perspective to analyze psychological problems is that the approach is usually very scientific. Researchers utilize rigorous empirical methods, and their results are often reliable and practical. Biological research has helped yield useful treatments for a variety of psychological disorders .

The weakness of this approach is that it often fails to account for other influences on behavior. Things such as emotions , social pressures, environmental factors, childhood experiences, and cultural variables can also play a role in the formation of psychological problems.

For that reason, it is important to remember that the biological approach is just one of the many different perspectives in psychology. By utilizing a variety of ways of looking a problem, researchers can come up with different solutions that can have helpful real-world applications.

A Word From Verywell

There are many different perspectives from which to view the human mind and behavior and the biological perspective represents just one of these approaches.

By looking at the biological bases of human behavior, psychologists are better able to understand how the brain and physiological processes might influence the way people think, act, and feel. This perspective also allows researchers to come up with new treatments that target the biological influences on psychological well-being.

Beauchaine TP, Neuhaus E, Brenner SL, Gatzke-Kopp L. Ten good reasons to consider biological processes in prevention and intervention research . Dev Psychopathol . 2008;20(3):745-774. doi:10.1017/S0954579408000369

Moncrieff J, Cooper RE, Stockmann T, Amendola S, Hengartner MP, Horowitz MA. The serotonin theory of depression: A systematic umbrella review of the evidence . Mol Psychiatry . 2022. doi:10.1038/s41380-022-01661-0

Hockenbury, DH & Hockenbury SE. Discovering Psychology . New York: Worth Publishers; 2011.

Pastorino, EE, Doyle-Portillo, SM. What Is Psychology? Foundations, Applications, and Integration . Boston, MA: Cengage Learning; 2015.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 2. Introduction to Major Perspectives

2.1 Biological Psychology

Jennifer Walinga

Learning Objectives

- Understand the core premises of biological psychology and the early thinkers.

- Critically evaluate empirical support for various biological psychology theories.

- Explore applications and implications of key concepts from this perspective.

Biological psychologists are interested in measuring biological, physiological, or genetic variables in an attempt to relate them to psychological or behavioural variables . Because all behaviour is controlled by the central nervous system, biological psychologists seek to understand how the brain functions in order to understand behaviour. Key areas of focus include sensation and perception; motivated behaviour (such as hunger, thirst, and sex); control of movement; learning and memory; sleep and biological rhythms; and emotion. As technical sophistication leads to advancements in research methods, more advanced topics such as language, reasoning, decision making, and consciousness are now being studied.

Biological psychology has its roots in early structuralist and functionalist psychological studies, and as with all of the major perspectives, it has relevance today. In section 1.2, we discuss the history and development of functionalism and structuralism. In this chapter, we extend this discussion to include the theoretical and methodological aspects of these two approaches within the biological perspective and provide examples of relevant studies.

The early structural and functional psychologists believed that the study of conscious thoughts would be the key to understanding the mind. Their approaches to the study of the mind were based on systematic and rigorous observation, laying the foundation for modern psychological experimentation. In terms of research focus, Wundt and Titchener explored topics such as attention span, reaction time, vision, emotion, and time perception, all of which are still studied today.

Wundt’s primary method of research was introspection , which involves training people to concentrate and report on their conscious experiences as they react to stimuli. This approach is still used today in modern neuroscience research; however, many scientists criticize the use of introspection for its lack of empirical approach and objectivity. Structuralism was also criticized because its subject of interest – the conscious experience – was not easily studied with controlled experimentation. Structuralism’s reliance on introspection, despite Titchener’s rigid guidelines, was criticized for its lack of reliability. Critics argued that self-analysis is not feasible, and that introspection can yield different results depending on the subject. Critics were also concerned about the possibility of retrospection, or the memory of sensation rather than the sensation itself.

Today, researchers argue for introspective methods as crucial for understanding certain experiences and contexts.Two Minnesota researchers (Jones & Schmid, 2000) used autoethnography, a narrative approach to introspective analysis (Ellis, 1999), to study the phenomenological experience of the prison world and the consequent adaptations and transformations that it evokes. Jones, serving a year-and-a-day sentence in a maximum security prison, relied on his personal documentation of his experience to later study the psychological impacts of his experience.

From Structuralism to Functionalism

As structuralism struggled to survive the scrutiny of the scientific method, new approaches to studying the mind were sought. One important alternative was functionalism, founded by William James in the late 19th century, described and discussed in his two-volume publication The Principles of Psychology (1890) (see Chapter 1.2 for details). Built on structuralism’s concern for the anatomy of the mind, functionalism led to greater concern about the functions of the mind, and later on to behaviourism.

One of James’s students, James Angell, captured the functionalist perspective in relation to a discussion of free will in his 1906 text Psychology: An Introductory Study of the Structure and Function of Human Consciousness :

Inasmuch as consciousness is a systematising, unifying activity, we find that with increasing maturity our impulses are commonly coordinated with one another more and more perfectly. We thus come to acquire definite and reliable habits of action. Our wills become formed. Such fixation of modes of willing constitutes character. The really good man is not obliged to hesitate about stealing. His moral habits all impel him immediately and irrepressibly away from such actions. If he does hesitate, it is in order to be sure that the suggested act is stealing, not because his character is unstable. From one point of view the development of character is never complete, because experience is constantly presenting new aspects of life to us, and in consequence of this fact we are always engaged in slight reconstructions of our modes of conduct and our attitude toward life. But in a practical common-sense way most of our important habits of reaction become fixed at a fairly early and definite time in life.

Functionalism considers mental life and behaviour in terms of active adaptation to the person’s environment. As such, it provides the general basis for developing psychological theories not readily testable by controlled experiments such as applied psychology. William James’s functionalist approach to psychology was less concerned with the composition of the mind than with examining the ways in which the mind adapts to changing situations and environments. In functionalism, the brain is believed to have evolved for the purpose of bettering the survival of its carrier by acting as an information processor . [1] In processing information the brain is considered to execute functions similar to those executed by a computer and much like what is shown in Figure 2.3 below of a complex adaptive system.

The functionalists retained an emphasis on conscious experience. John Dewey, George Herbert Mead, Harvey A. Carr, and especially James Angell were the additional proponents of functionalism at the University of Chicago. Another group at Columbia University, including James McKeen Cattell, Edward L. Thorndike, and Robert S. Woodworth, shared a functionalist perspective.

Biological psychology is also considered reductionist . For the reductionist , the simple is the source of the complex . In other words, to explain a complex phenomenon (like human behaviour) a person needs to reduce it to its elements. In contrast, for the holist , the whole is more than the sum of the parts . Explanations of a behaviour at its simplest level can be deemed reductionist. The experimental and laboratory approach in various areas of psychology (e.g., behaviourist, biological, cognitive) reflects a reductionist position. This approach inevitably must reduce a complex behaviour to a simple set of variables that offer the possibility of identifying a cause and an effect (i.e., the biological approach suggests that psychological problems can be treated like a disease and are therefore often treatable with drugs).

The brain and its functions (Figure 2.4) garnered great interest from the biological psychologists and continue to be a focus for psychologists today. Cognitive psychologists rely on the functionalist insights in discussing how affect, or emotion , and environment or events interact and result in specific perceptions . Biological psychologists study the human brain in terms of specialized parts, or systems, and their exquisitely complex relationships. Studies have shown neurogenesis [2] in the hippocampus (Gage, 2003). In this respect, the human brain is not a static mass of nervous tissue. As well, it has been found that influential environmental factors operate throughout the life span. Among the most negative factors, traumatic injury and drugs can lead to serious destruction. In contrast, a healthy diet, regular programs of exercise, and challenging mental activities can offer long-term, positive impacts on the brain and psychological development (Kolb, Gibb, & Robinson, 2003).

The brain comprises four lobes:

- Frontal lobe: also known as the motor cortex, this portion of the brain is involved in motor skills, higher level cognition, and expressive language .

- Occipital lobe: also known as the visual cortex, this portion of the brain is involved in interpreting visual stimuli and information .

- Parietal lobe: also known as the somatosensory cortex, this portion of the brain is involved in the processing of other tactile sensory information such as pressure, touch, and pain.

- Temporal lobe: also known as the auditory cortex, this portion of the brain is involved in the interpretation of the sounds and language we hear .

Another important part of the nervous system is the peripheral nervous system , which is divided into two parts:

- The somatic nervous system, which controls the actions of skeletal muscles .

- The sympathetic nervous system , which controls the fight-or-flight response , a reflex that prepares the body to respond to danger in the environment .

- The parasympathetic nervous system , which works to bring the body back to its normal state after a fight-or-flight response.

Research Focus: Internal versus External Focus and Performance

Within the realm of sport psychology, Gabrielle Wulf and colleagues from the University of Las Vegas Nevada have studied the role of internal and external focus on physical performance outcomes such as balance, accuracy, speed, and endurance. In one experiment they used a ski-simulator and directed participants’ attention to either the pressure they exerted on the wheels of the platform on which they were standing (external focus), or to their feet that were exerting the force (internal focus). On a retention test, the external focus group demonstrated superior learning (i.e., larger movement amplitudes) compared with both the internal focus group and a control group without focus instructions. The researchers went on to replicate findings in a subsequent experiment that involved balancing on a stabilometer. Again, directing participants’ attention externally, by keeping markers on the balance platform horizontal, led to more effective balance learning than inducing an internal focus, by asking them to try to keep their feet horizontal. The researchers showed that balance performance or learning, as measured by deviations from a balanced position, is enhanced when the performers’ attention is directed to minimizing movements of the platform or disk as compared to those of their feet. Since the initial studies, numerous researchers have replicated the benefits of an external focus for other balance tasks (Wulf, Höß, & Prinz, 1998).

Another balance task, riding a paddle boat, was used by Totsika and Wulf (2003). With instructions to focus on pushing the pedals forward, participants showed more effective learning compared to participants with instructions to focus on pushing their feet forward. This subtle difference in instructions is important for researchers of attentional focus. The first instruction to push the pedal is external, with the participant focusing on the pedal and allowing the body to figure out how to push the pedal. The second instruction to push the feet forward is internal, with the participant concentrating on making his or her feet move.

In further biologically oriented psychological research at the University of Toronto, Schmitz, Cheng, and De Rosa (2010) showed that visual attention — the brain’s ability to selectively filter unattended or unwanted information from reaching awareness — diminishes with age, leaving older adults less capable of filtering out distracting or irrelevant information. This age-related “leaky” attentional filter fundamentally impacts the way visual information is encoded into memory. Older adults with impaired visual attention have better memory for “irrelevant” information. In the study, the research team examined brain images using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) on a group of young (mean age = 22 years) and older adults (mean age = 77 years) while they looked at pictures of overlapping faces and places (houses and buildings). Participants were asked to pay attention only to the faces and to identify the gender of the person. Even though they could see the place in the image, it was not relevant to the task at hand ( Read about the study’s findings at http://www.artsci.utoronto.ca/main/newsitems/brains-ability ).

The authors noted:

In young adults, the brain region for processing faces was active while the brain region for processing places was not. However, both the face and place regions were active in older people. This means that even at early stages of perception, older adults were less capable of filtering out the distracting information. Moreover, on a surprise memory test 10 minutes after the scan, older adults were more likely to recognize what face was originally paired with what house.

The findings suggest that under attentionally demanding conditions, such as a person looking for keys on a cluttered table, age-related problems with “tuning in” to the desired object may be linked to the way in which information is selected and processed in the sensory areas of the brain. Both the relevant sensory information — the keys — and the irrelevant information — the clutter — are perceived and encoded more or less equally. In older adults, these changes in visual attention may broadly influence many of the cognitive deficits typically observed in normal aging, particularly memory.

Key Takeaways

- Biological psychology – also known as biopsychology or psychobiology – is the application of the principles of biology to the study of mental processes and behaviour.

- Biological psychology as a scientific discipline emerged from a variety of scientific and philosophical traditions in the 18th and 19th centuries.

- In The Principles of Psychology (1890), William James argued that the scientific study of psychology should be grounded in an understanding of biology.

- The fields of behavioural neuroscience, cognitive neuroscience, and neuropsychology are all subfields of biological psychology.

- Biological psychologists are interested in measuring biological, physiological, or genetic variables in an attempt to relate them to psychological or behavioural variables.

Exercises and Critical Thinking

- Try this exercise with your group: Take a short walk together without talking to or looking at one another. When you return to the classroom, have each group member write down what they saw, felt, heard, tasted, and smelled. Compare and discuss reflecting on some of the assumptions and beliefs of the structuralists. Consider what might be the reasons for the differences and similarities.

- Where can you see evidence of insights from biological psychology in some of the applications of psychology that you commonly experience today (e.g., sport, leadership, marketing, education)?

- Study the functions of the brain and reflect on whether you tend toward left- or right-brain tendencies.

Image Attributions

Figure 2.3: Complex Adaptive System by Acadac (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Complex-adaptive-system.jpg) is in the public domain.

Figure 2.4: Left and Right Brain by Webber (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Left_and_Right_Brain.jpg) is in the public domain.

Angell, James Rowland. (1906).”Character and the Will”, Chapter 22 in Psychology: An Introductory Study of the Structure and Function of Human Consciousness , Third edition, revised. New York: Henry Holt and Company, p. 376-381.

Ellis, Carolyn. (1999). Heartful Autoethnography. Qualitative Health Research , 9 (53), 669-683.

Gage, F. H. (2003, September). Brain, repair yourself. Scientific American, 46–53.

James, W. (1890). The Principles of Psychology . New York, NY: Henry Holt and Co.

Jones, R.S. & Schmid, T. J. (2000). Doing Time: Prison experience and identity . Stamford, CT: JAI Press.

Kolb, B., Gibb, K., & Robinson, T. E. (2003). Brain plasticity and behavior. Current Directions in Psychological Science , 12 , 1–5.

Schmitz, T.W., Cheng, F.H. & De Rosa, E. (2010). Failing to ignore: paradoxical neural effects of perceptual load on early attentional selection in normal aging. Journal of Neuroscience , 30 (44), 14750 –14758.

Totsika, V., & Wulf, G. (2003). The influence of external and internal foci of attention on transfer to novel situations and skills. Research Quarterly Exercise and Sport , 74 , 220–225.

Wulf, G., Höß, M., & Prinz, W. (1998). Instructions for motor learning: Differential effects of internal versus external focus of attention. Journal of Motor Behavior, 30 , 169–179.

- A system for taking information in one form and transforming it into another. ↵

- The generation or growth of new brain cells, specifically when neurons are created from neural stem cells. ↵

Introduction to Psychology - 1st Canadian Edition Copyright © 2014 by Jennifer Walinga is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

Biological Psychology

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 179954

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Biological psychology applies the principles of biology to investigate the physiological, genetic, and developmental mechanisms underlying behavior in humans and other animals.

- Front Matter

- 1: Biopsychology as a Course of Study

- 2: Research Methods and Ethical Considerations of Biological Psychology and Neuroscience

- 3: Evolution, Genes, and Behavior

- 4: Nervous System Anatomy

- 5: Communication within the Nervous System

- 6: The Effects of Psychoactive Drugs

- 8: Sensation and Perception

- 9: Movement

- 10: Learning and Memory

- 11: Wakefulness and Sleep

- 12: Ingestive Behaviors - Eating and Drinking

- 13: Sexuality and Sexual Development

- 14: Intelligence and Cognition

- 15: Language and the Brain

- 16: Emotion and Stress

- 17: Biological Bases of Psychological Disorders

- 18: Supplemental Content

- Back Matter

- 1: Background to Biological Psychology

- 2: Organisation of the nervous system

- 3: Neuronal communication

- 4: Sensing the environment and perceiving the world

- 5: Interacting with the world

- 6: Dysfunction of the nervous system

- 1: First Steps

- 2: Processing the Data from One Participant in the ERP CORE N400 Experiment

- 3: Processing Multiple Participants in the ERP CORE N400 Experiment

- 4: Filtering the EEG and ERPs

- 5: Referencing and Other Channel Operations

- 6: Assigning Events to Bins, Averaging, Baseline Correction, and Assessing Data Quality

- 7: Inspecting the EEG and Interpolating Bad Channels

- 8: Artifact Detection and Rejection

- 9: Artifact Correction with Independent Component Analysis

- 10: Scoring and Statistical Analysis of ERP Amplitudes and Latencies

- 11: EEGLAB and ERPLAB Scripting

- 12: Appendix 1: A Very Brief Introduction to EEG and ERPs

- 13: Appendix 2: Troubleshooting Guide

- 14: Appendix 3: Example Processing Pipeline

- Yawning and an Introduction to Sleep

- 1: Sleep Wellness

- 2: The Sleeping Brain - Neuroanatomy, Polysomnography, and Actigraphy

- 3: Circadian Rhythm

- 6: Sleep Disorders

- 7: Politics, Sleep, and You

Psychology as a Biological Science

(11 reviews)

Robert Biswas-Diener, Portland State University

Ed Diener, Universities of Utah

Copyright Year: 2020

Publisher: Noba

Language: English

Formats Available

Conditions of use.

Learn more about reviews.

Reviewed by Angela Mar, Lecturer, University of Texas Rio Grande Valley on 12/14/21

The text does not provide an index nor references list. Moreover, the text is missing an integral part of biological psychology: the neuron. Students must first understand how the neuron works and the structure of the neuron to better understand... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 3 see less

The text does not provide an index nor references list. Moreover, the text is missing an integral part of biological psychology: the neuron. Students must first understand how the neuron works and the structure of the neuron to better understand complicated functions.

Content Accuracy rating: 4

I found the text unbiased and straightforward. Evolutionary psychology can be a topic in which an author's opinion can come out and stray away from the information that students need. I did not see any errors and accuracy does not seem to be a concern.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 5

With biological psychology there is always the potential for new groundbreaking information, but the text does a good job at mentioning new research in order to stay relevant.

Clarity rating: 3

There are some modules that are too in depth and thus don't quite fit into a textbook that should be an overview of biological psychology. It is understandable that these topics are interesting, but way outside the scope of a 2nd or 3rd year course.

Consistency rating: 4

I like how the modules fit into a framework that flows well and organized to enhance students success.

Modularity rating: 4

The text is divided into major topics consisting of several modules. I found that there were too many modules for some of the topics in order to cover in a 15 week semester. My understanding is that some of the modules could be removed or added as desired, which is something that traditional textbooks lack.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 5

The textbook is well organized, albeit lengthy. I am not sure if the order of the modules can be changed as per the professor's preferences, but that would be a great functionality.

Interface rating: 4

I did not come across any interface issues, but I only interacted with the onlin version of the textbook.

Grammatical Errors rating: 5

I did not notice any grammatical errors within the textbook.

Cultural Relevance rating: 3

I would like to see more culturally significant examples throughout the modules. Inclusivity is very important for students.

Reviewed by Hilary Stebbins, Associate Professor Psychological Sciences, University of Mary Washington on 7/1/20

This text covered a number of sub-fields of biological psychology that I would want to expose students to. However, despite the fact that there was in an-depth module on hormones and behavior, the text neglected to include a module about neural... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 2 see less

This text covered a number of sub-fields of biological psychology that I would want to expose students to. However, despite the fact that there was in an-depth module on hormones and behavior, the text neglected to include a module about neural communication or the role of glial cells. Some modules (psychophysiological methods in neuroscience, hormones and behavior, psychopharmacology) assume knowledge of neural communication, which is not actually covered in the text. In addition, despite the inclusion of modules on drives and well-being, I was disappointed to note that there was nothing specific in the text regarding sleep-wake regulation or circadian rhythms. I also found some of the specific modules to contain less information than I would expect. For example, there is a module on psychophysiological methods including fMRI, EEG, etc., but not much on more invasive methods involving manipulation of the nervous system. In addition, some modules on cognitive, developmental, and social aspects of psychology fail to take a biological perspective.

The material that is present seems accurate and I appreciate that each module is written by somebody with expertise in that field, helping to ensure a more accurate representation of the material. Many of the authors represent a “who’s who” within their fields. Some modules felt oversimplified, and the missing information might lead to misunderstandings by both the students and professor using the text. It’s possible that any user would need to rely on supplementary material to get a more nuanced understanding of the material.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 4

Due to the slightly superficial nature of most modules, the information is less likely to become obsolete than many biological psychology texts. In addition, the modular structure makes it easy to update specific sections when needed. There are some recent developments in the field that I feel are not represented, such as the increasing importance of glial cells in cellular communication, some advanced methodology such as diffusion tensor imaging or optogenetics, and the role of drugs such as ketamine for treatment of psychological disorders. I hope that the included video links are routinely monitored so as not to result in dead links for students.

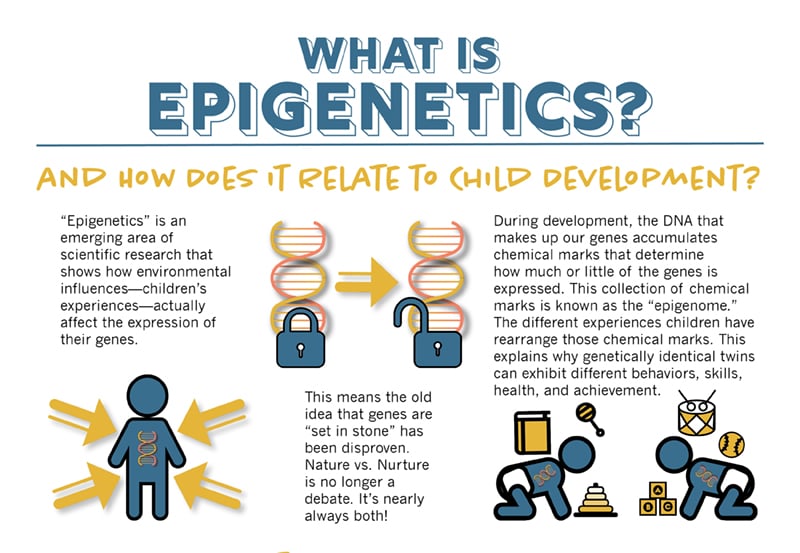

The clarity of the information is dependent on the module that you are using. Some modules do a very good job at defining terminology and writing at a level appropriate for an introductory level student while others assume knowledge about biological mechanisms not detailed earlier in the text. For example, there is a module on epigenetic changes without a lot of background information on basic concepts in genetics. In addition, while there are a number of pictures included in the text to break up the content, there are few diagrams or figures that can help to supplement and clarify the material.

Consistency rating: 3

Despite each module being written by a different author, the overall structure is similar and it is easy to find things like learning objectives and discussion questions for each. For a text that focuses on psychology as a biological science, I would hope that each module would emphasize the topic covered from a biological perspective, and this is not the case. While there is more of an emphasis on biological psychology compared to what you would expect in a typical introductory psychology text, many modules (e.g. memory, attention, cognitive development) fail to take much of a biological perspective at all. Thus, the quality of the module is hit or miss depending on the topic.

Modularity rating: 5

The modular organization of the text is one of its most appealing aspects, as each can easily be assigned as a stand alone component. For the most part, each module feels fairly easy to digest as a reading assignment and I appreciate that some include videos to help to supplement the material and engage the reader.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 4

The organization and flow is much like what you would expect from most texts on biological psychology. What makes this text strong in terms of modularity hurts it a bit in terms of flow since some topics are repeated in a number of modules while others are left out altogether. This results in the awkward placement of some information (like what a synapse is in the psychopharmacology module) in comparison with a more traditional biological psychology text.

Interface rating: 5

I found the interface to be easily navigable and was able to find relevant information quickly. Since some material appeared in unexpected modules, I liked the search feature, which allowed me to quickly identify references to specific topics. I also liked the opportunity to see the definition of vocabulary words when they appeared in the text.

I did not notice any grammatical errors. Overall the writing was strong with good editing.

This text takes a fairly western perspective, although it does attempt to include pictures of a number of cultures and backgrounds to convey its inclusivity. Unfortunately, almost every picture where a “scientist” is portrayed is that of someone who is white. Based on the author descriptions, the authorship is about 60% male and about 85% white. It would be nice if future updates included a bit more diversity in terms of authorship as well as discussion of relevant topics to biological psychology such as gender identity.

I like the format of this text, but it’s not clear who the target audience is. It feels too specific and biology focused for an introductory psychology course, but does not include enough relevant information about biological mechanisms for a course in biological psychology - even an introductory one. I could see myself using specific modules to supplement other material in my courses, but I can’t see adopting this as the primary text.

Reviewed by Melanie Peffer, Research Associate, University of Colorado Boulder on 6/11/20

This text covers a wide range of interesting topics and could be useful in a wide variety of educational contexts. However, I feel that many of the topics are too advanced for an introductory psychology course. read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 4 see less

This text covers a wide range of interesting topics and could be useful in a wide variety of educational contexts. However, I feel that many of the topics are too advanced for an introductory psychology course.

Content Accuracy rating: 5

Content was accurate and error-free.

Some topics like epigenetics change rapidly, however necessary updates will be easy to implement.

Clarity varies depending on the section. Some modules are quite technical, whereas others are accessible to an introductory psychology student.

Each module uses a similar framework and identifies key terms which are included in a vocabulary section. I did not that the use of learning objectives varied widely in style and effectiveness across modules.

The course has clearly delineated modules by topic area, and each module is clearly broken up into submodules.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 3

I found myself questioning the organization of the modules and how topics flowed from one to another. It also seems odd that some modules are the only ones in a particular topic area. If one is using selections from this text it would not be an issue. However, it may be challenging to implement this textbook if it is to be used as a standalone text.

Interface rating: 3

Images and text displayed clearly, but there were navigation problems present on several of the pages. The links were broken and/or did not redirect as they were suppose too.

I did not note any grammatical errors.

Cultural Relevance rating: 5

The images used included a variety of races, ethnicities, and backgrounds. I did not observe any culturally insensitive materials.

Reviewed by Beth Mechlin, Associate Professor of Psychology & Neuroscience, Earlham College on 12/19/19

This textbook has some really interesting modules. There is a decent amount about biological psychology, and it may work well for an Introduction to Psychology course. However, I do not think it has enough detail for a Brain and Behavior (or... read more

This textbook has some really interesting modules. There is a decent amount about biological psychology, and it may work well for an Introduction to Psychology course. However, I do not think it has enough detail for a Brain and Behavior (or similar lower level biological psychology or behavioral neuroscience) course. There are some great modules that go in-depth on specific topics ("Hormones and Behavior" and "Biochemistry of Love" modules are very interesting). Unfortunately, some topics I consider foundational appear to be missing from this text. There is not a section that provides an overview of neurons, action potentials, and neurotransmitters; and I consider these topics to be crucial for an Introduction to Psychology (or Brain and Behavior) course. Thus, supplemental reading would be needed in order to adequately cover these topics.

Content appears to be accurate.

The content in this textbook generally appears to include recent scientific research (although I think the “Healthy Life” module could be updated). It seems that updates based on recent studies will be easy to implement.

Clarity rating: 4

Most of this textbook is clear and easy to understand. However, some modules contain higher level information that may require some background knowledge to fully comprehend. The actual text of the modules is generally strong, but including more images (diagrams, figures, tables, etc.) would strengthen the majority of the modules included in this book.

Consistency rating: 5

Most terms and general organization appear consistent throughout the book. However, each module is written by a different author, so there are some stylistic differences from one module to the next.

This textbook is very modular. Each reading can stand on its own. However, that means that some topics are covered multiple times, while others are left out.

Generally well organized. A professor can easily present the modules in any order s/he chooses. Some specific modules might be better with a few more subheadings in sections.

Easy to navigate to different topics. I like that you can hover over some words to get definitions. Links to videos and additional resources at the end of each module are also helpful.

I did not notice any grammatical errors.

I did not find this textbook to be offensive or insensitive. However, I think that health disparities (based on race and socioeconomic status) are an important topic in the field of Healthy Psychology, and they were barely mentioned in “The Healthy Life” module.

Reviewed by Katherine Hebert, Assistant Professor, Colorado State University on 12/6/19

This book would provide appropriate depth for a 300-level course, but not a 400-level. There is no description of neurons, synaptic communication, long-term potentiation, etc. So essentially the book gives a good overview of the important topics,... read more

This book would provide appropriate depth for a 300-level course, but not a 400-level. There is no description of neurons, synaptic communication, long-term potentiation, etc. So essentially the book gives a good overview of the important topics, but does not actually delve very deeply into the biology behind them.

The content seems accurate and sources are cited well.

Since the book doesn't delve too deeply into the physiology of behavior, and tends towards overviews of the behavior, it won't need too much updating.

Clarity rating: 5

The book is generally consistently clear throughout; I think an undergraduate would be able to follow along successfully, and the embedded videos and links would be a helpful resource.

There are certainly some inconsistencies from chapter to chapter, and this could potentially be jarring for students. Overall, the inconsistencies are more in terms of style and organization.

This varies from chapter to chapter. Many of the chapters could benefit from additional headings / more explicit organization, but overall there are no major issues.

The topics feel as though any chapter relating to cognitive science or neuroscience was grabbed and put into the book. There are many chapters that would not typically be covered in a biological psychology course, and they do not feel as if they've been written explicitly with a biological perspective, so it feels a bit muddy and jumps around quite a bit.

Interface was pretty clean.

Hardly any typos.

Cultural Relevance rating: 4

I did not come across anything that could be construed as offensive. That being said, the book does not necessarily target inclusivity explicitly within its contents.

These chapters would be a great addition to a 200-level course, and maybe a 300-level course, but would not be sufficient for a 400-level course. There was hardly any content at all on cellular/molecular biological psychology.

Reviewed by Casey Henley, Assistant Professor, Michigan State University on 11/18/19

This text covers a broad range of psychology topics and provides a biological aspect to each. The detail and depth provided for each topic, though, ranges considerably throughout the book. Additionally, the addition of some topics, specifically... read more

This text covers a broad range of psychology topics and provides a biological aspect to each. The detail and depth provided for each topic, though, ranges considerably throughout the book. Additionally, the addition of some topics, specifically function of the neuron, would strengthen the text. The structure of the glossary may be frustrating to some. Since a glossary exists for each chapter, when these individual glossaries are combined into the Vocabulary section at the end of the text, it can lead to repeated information.

The material in this text was accurate, but the level of detail of each chapter varies quite a bit.

The text will need to be updated as new research becomes available. The structure of the book will allow for additional material to be added easily.

The text is well written, but the variation in level of detail throughout the chapters may lead to confusion at times. Some chapters assume a prior knowledge that may not have been explicitly covered previously in the text.

There is variation in the level of consistency among chapters. Some give a very cursory overview of their topic whereas others dive in with more depth and detail. Some chapters can stand on their own; some need background information to be fully understood.

The text lends itself well to modular use. However, this benefit can disrupt the ability to read straight through. Topics are repeated, sometimes without much additional information, so the reader is seeing the same information.

The topics are organized in a logical way, but content is sometimes repeated, and sometimes not enough background information is given. There is some consistency issues among chapters.

I had no issues related to the interface.

I found no grammatical errors.

The text did not appear to be culturally insensitive or offensive. Examples were inclusive of different races, ethnicities, and backgrounds.

Reviewed by Chris Linn, Associate Professor, SUNO on 4/4/19

For a special topics course, this book is appropriately comprehensive. It covers everything I would expect from a course on the biological underpinnings of human behavior and is not limited to a physiological perspective. As an introductory... read more

For a special topics course, this book is appropriately comprehensive. It covers everything I would expect from a course on the biological underpinnings of human behavior and is not limited to a physiological perspective. As an introductory psychology course, some of the modules are too specialized (e.g. module on autism). I would like to see more diagrams in some modules, but the embedded videos are a terrific addition.

I thought this book was highly accurate, although this varied according to the module author. Some of the modules seemed oversimplified, but it was fine as an introduction, overall.

I think this book is highly relevant for any psychology student interested in behavior from a biological perspective. I would have enjoyed this book myself as an undergraduate. Biology students with an interest in behavior would also find the book useful. As biological issues are some of the fasted advancing in psychology, the longevity of some modules might be limited. I would hope to see new additions in the future to keep pace.

Most, but not all, authors were extremely clear. This is as would be expected because modules were written by some of the top authors in their field.

Within modules, I do not see any issues with consistency. The flow of the book has its limits, as each module was written by a different author. I think this is a minor issue, and it did not distract from my overall enjoyment of the book.

Each module can largely stand alone. For the most part, modules could be assigned in any order and can even be assigned as readings for different classes. For example, it would be appropriate to assign the chapter on the history of mental illness to an abnormal psychology class or a class on the history of psychology.

Within modules, the topics are generally organized well.

The interface is fine and easy to use on a computer screen. I do not know if this would carry over to other devices, such as tablets or cellular phones. Some students might prefer a hard copy of the book. While I love the embedded video clips, they would not be available to students that with to print the pdf.

I did not notice any grammatical issues.

The text did not contain a section on cultural psychology, as I recall. Give the subject matter, I would not necessarily expect it to. However, David Buss does make mention of culture in his module on evolutionary psychology.

This text is a wonderful read, but I don't think this book is a good fit for a general, introductory psychology course. There are a few subject areas that are missing. For example, it does not attempt to address some of the more applied fields in psychology such as clinical or industrial/organizational. However I would highly recommend it for a "special topics" course in biological topics in psychology. I would personally consider using this book myself for such a course, but I might omit some of the modules that are less biological in nature. I might also select certain modules as readings for other courses.

Reviewed by Scott Bowen, Professor, Wayne State University on 12/7/18

This somewhat comprehensive textbook would be appropriate for an introduction to psychology as a biological science. While it covers a number of major areas of basic biological psychology with some in-depth discussion, there are some are some... read more

This somewhat comprehensive textbook would be appropriate for an introduction to psychology as a biological science. While it covers a number of major areas of basic biological psychology with some in-depth discussion, there are some are some missing topics that are very necessary. For example, there is no real discussion, nor are there pictures or diagrams about the basic unit of the nervous system, the neuron. It seems that another chapter is needed to discuss the neuron, how it functions, and how it communicates with other neurons. This omission could lead the reader to struggle with later chapters that discussion sensation and perception as well as psychopharmacology. The inclusion of a vocabulary section, discussion questions, and citations at the end of each chapter is a nice feature that would be beneficial to the student.

From what I reviewed, the material within this textbook was generally accurate. Some of the text was oversimplified at times, but I don’t think that detracts from the text.

The content appears to be up-to-date, so it should not become obsolete. I checked several of the modules and found that they had 2018 dates so the content is current. I think that the chapters are organized in such a way that new sections can be added as needed.

I found the text to be written clearly and at a level that most undergraduates could follow for a basic introduction to Biological Psychology. The lack of coverage of the neuron in the early chapters could create confusion in later chapters where neurotransmitters and signaling is discussed.

The text appears to be consistent across chapters although some chapters don’t seem to go into the depth that other chapters do.

I found the book to be clearly organized and readily divisible into smaller independent modules.

I found the book to be clearly and logically organized.

I had no problems with navigating through the chapters. The images/charts were all clear and there was no distortion.

I didn’t find any grammatical errors.

I didn’t find any of the text to be culturally insensitive or offensive in any way. There are several examples of inclusivity of race diversity, ethnicities, and backgrounds.

I completed a training webinar on open source textbooks and was asked to review a textbook as part of that experience. Generally, I think this text is a good source for an undergraduate beginning to learn the basics of biological psychology. However, I couldn’t find discussion or diagrams on neurons and how they function, so the text will have to be supplemented for this information (or a module needs to be written to cover this gap). This open textbook will have to be supplemented with recent published articles but is definitely a viable option when compared to high cost textbooks.

Reviewed by Chelsea McCoy Asadorian, Instructor, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University on 2/1/18

This textbook is very comprehensive in my opinion. It covers all the major areas of basic psychology and includes some in-depth discussion of examples within these. For example, within biological basis on behavior, there are discussions on both... read more

This textbook is very comprehensive in my opinion. It covers all the major areas of basic psychology and includes some in-depth discussion of examples within these. For example, within biological basis on behavior, there are discussions on both the macro level (brain and hormonal regulation) as well as molecular (epigenetics in psychology). There is a vocabulary section at the end of each chapter as well as discussion questions and citations. From Noba, there are many instructor's resources available as well. Still, there are gaps, which is expected when covering such a large field. This text does give students the basics so with light supplement it would seem appropriate for a introductory course or with supplement could aid in upper level courses.

From what I was able to review, this text is accurate and thorough. While details can be a little oversimplified at times, I think these are necessary in the scope of an overview of an entire field.

The author attempts to keep the content as current as possible by including details on areas that are "hot" in research right now. I don't believe that this will make this text obsolete quickly. It does at least bring in newer concepts rather than sticking to the traditional. I think that it allows is organized in such a manner that new sections could be easily added to existing as needed. Even for an individual instructor it would be easy to select the overview chapters within an unit and then simply use review articles if they should want to drive deeper into a different topic that what the author choose to use.

I think this text is written at a level that is easy to follow for an undergraduate student. In additional, the vocabulary section are the end of the chapter are useful aides as well.

I think this text is consistent across chapters.

Yes, this text is broken into sections that are mostly able to stand alone.

Overall, I think it's well done.

I didn't find any issues with the interface.

I found no issues worth mentioning.

I didn't find any material that seemed to be offensive. It might benefit from a little more discussion on cultural impacts on psychology.

Overall, I found this text to be a good source for basics within each area. I think this text as one of the few open access in this area could be used in addition to recently published reviews to give the students both the basics and detailed information without the high cost of commercial textbooks. This may not be the best option if you want one source to support a course.

Reviewed by Patti Harrison, Lecturer, Virginia Tech on 6/20/17

I found this textbook to be quite comprehensive, including the "traditional" topics usually covered in a biopsychology text , but also adding fascinating chapters on topics such as epigenetics and aging. The coverage of the material seemed... read more

I found this textbook to be quite comprehensive, including the "traditional" topics usually covered in a biopsychology text , but also adding fascinating chapters on topics such as epigenetics and aging. The coverage of the material seemed ideally appropriate for a 3000 or 4000 level course for psychology and biology majors, including higher level concepts that required understanding from other areas of science, not just biology and chemistry. Although the throughness of the content did vary by chapter/topic, overall I was impressed with the material that was presented and would certainly have no problem augmenting any area in which I considered the text to be deficient. I did notice one glaring absence - a chapter covering the neuron and how it fires, as well as the function of glial cells - also something I could easily provdie myself, but unusual to be missing from a biopsychology text. While many higher-order concepts were covered, it is highly unusual to find any physiological psychology text that does not discuss the neuron because it is the basic unit of the nervous system and understadning its physiology is essential to such areas as sensroy function and psychopharmacology.

The index at the end of the book was quite thorough. However the glossaries were placed at the end of each chapter, and, as with the content of the chapters, varied in thoroughness - also a very easily corrected problem for any adaptations of the text.

Given the rate at which information changes in the field of neuroscience, I was impressed with its accuracy and inclusiveness. In this field accuracy often is not the issue, but new structures/concepts are being found every day, so they are more frequently the material that is easy to leave out. I found this book to contain coverage of topics that are currently on the front line of investigation, such as entrainment and the psychophysiology of emotion, with a high degree of accuracy.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 3

As I previously mentioned, the very basic concepts of cell firing and maintaining the resting potential of the neuron were completely absent from discussion anywhere int his text. Therefore by the time the student hits the chapter on psychopharmacology, he/she will be unprepared to understand the basic mechanisms of how different drugs work. I found the chapter on psychopharmacology to be particularly short, offering only the most simplistic introduction to the topic, whereas it is central to the field of psychology, particularly clinical psychology. Almost all clients are on psychoactive medications and the therapist should have a slightly better than average understanding of how these drugs work. This text will provide only an introductory psychology level perspective on that area.

The writing was very engaging, something to be treasured in the STEM fields, where emphasis is usually more on the information being presented than on the style in which it is being presented. Since each chapter had a different author(s), this varied, but only slightly across chapters.

The consistency across chapters is poor. Some writers are clearly masters of their fields and provide extremely well-written and detailed accounts of their field, while others write short, concise introductions to their area, but leave the reader with little "meat to chew on." The internal consistency within the chapters was high and I did not always feel as if I were being introduced to another voice as I moved from chapter to chapter.

The book's modularity is what contributes to the ease of which one could address its omissions. Modules were complete and did not rely on other modules in order to fit well into the scheme of things. I would find this book easy to adapt to my own purposes, supplementing when I thought necessary and omitting topics that I did not consider particularly relevant to the course, without taking away from the "book" quality of the text.

The overall flow of the book was good. Chapters were organized in such a way that the topics seemed to flow logically from one to the next. There was some duplication in coverage, but this makes omitting certain chapters easier if the instructor wants to include other material without losing all of the material from any particular chapter.

I accessed the book as a pdf requiring Adobe Acrobat and printed selected topics for closer inspection. Both methods permitted me to find exactly what I wanted when I wanted it. It ws very easy to move throughout the book by just sliding my mouse. Between the table of contents and the index, I had no trouble locating particular terms or concepts.

The grammar was excellent - and I am a grammar gestapo, according to my students. These folks do not only write well, but they write in grammatically correct English - a rare finding in my opinion.

Given the biological nature of the book, I did not find it to be biased toward any particular culture. There were some discussions of social functioning and interpersonal relationships that were geared more toward Western European values than toward Easter/Mideastern values, but not offensively so.

I very much enjoyed reading this text and will probably adopt it for my physiological psychology text the next time I teach the course.

Reviewed by Richard Deyo, Professor, Winona State University on 8/21/16

If a comprehensive introduction to psychology as a biological science is expected from this 40-module open textbook, the reader will be disappointed. This is because each topic has been given unexpectedly cursory coverage. For example, recalling... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 1 see less

If a comprehensive introduction to psychology as a biological science is expected from this 40-module open textbook, the reader will be disappointed. This is because each topic has been given unexpectedly cursory coverage. For example, recalling that the title of the book promises to inform students about psychology as a biological science, the glossary contains no definitions for the terms neuron, nerve cell, or glial cell. Unfortunately, there really is very little about this book that would appeal to a professor wishing to take the neuroscience approach to the teaching of an Introductory Psychology course. The lack of depth extends to most topics. For example, the discussion of research methods fails to include a discussion of the different types of research designs or their interpretation, nor is there even a discussion of independent or dependent variables despite the reference to those undefined terms in a later chapter. The figures and graphics in this text are largely ineffective as tools for clarifying concepts. For example, there is no detailed diagram of how a neuron works, or even an image of how one looks, but there are two different photographs of a finger with a string tied around it (page 321 and page 342). The student is not provided with adequate information to understand difficult concepts such as neurotransmission, but is treated to numerous appealing images of babies, families, and puppies.

The material that was included was generally accurate. However there were a few minor inaccuracies in the discussion of the brain that were mainly due to oversimplification.

This book is no more vulnerable to longevity issues than any other. It will need to be updated annually. I did use the search feature on the PDF reader to check out the age of the sources and it appears that the chapters are largely updated thru the end of 2014 with three sources from 2015. So a revision will be needed at the end of 2016 to keep current.

Clarity rating: 1

The lack of depth in many of the early chapters creates serious issues with clarity in later chapters. For example, the failure to define and discuss research designs creates a problem in later chapters that refer to experimental designs (e.g. page 172) or correctly refer to the problems of interpreting correlational research (e.g., page 189). The authors of later chapters appear to assume that the students have a working knowledge that is probably not there unless it has been covered in supplemental materials outside of this book. An old idiom came to mind by the time I reached the fifth chapter: “Too many cooks spoil the broth.” This work has by my count 61 authors. To be fair, it is hard to write a book with more than two or three authors (Kandel’s Principles of Neural Science being one of the few successful examples). This work needed a strong editor.

Consistency rating: 1

Some chapters were very shallow and other chapters were assuming a depth of knowledge that was at a much higher level. The book reads as if it were aimed at two different groups of students.

Modularity rating: 1

The book is clearly organized into independent modules. The problem, however, is that the content in any one module is inadequate to cover that topic without extensive use of outside materials. Said another way the modules themselves fail to give the students adequate content to come prepared to discuss in lecture. In short, this book has many modules but not enough content within each module to support a lecture that would enrich a student’s knowledge.

There is a clear organization that is easy to follow (just not enough content).

Interface rating: 2

The free PDF version was cumbersome to navigate. The images and figures that are included (with one or two exceptions) are clear and can be enlarged without too much distortion.

No problems here.

The text is not culturally insensitive or offensive in any way. It is inclusive of diverse races, ethnicities, and backgrounds.

I read this text after completing a training webinar that had me fired up to try an open textbook. I was further encouraged by the fact that one of the contributors has written a textbook I had previously used and valued. Maybe my expectations were too high. I came in with over 25 years of experience teaching with high quality commercially edited and reviewed textbooks. This open textbook is not in any way comparable in quality to any text I have used previously. I now have a renewed appreciation for the editorial process and I guess it is true that you get what you pay for. Respectfully, I just cannot recommend adopting this book, especially if you are a professor at a MNSCU institution and need to be in compliance with the “Common Course Outcomes.”

Table of Contents

- Psychology as Science

- Biological Basis of Behavior

- Sensation and Perception

- Learning and Memory

- Cognition and Language

- Development

- Personality

- Emotions and Motivation

- Psychological Disorders

Ancillary Material

About the book.

This textbook provides standard introduction to psychology course content with a specific emphasis on biological aspects of psychology. This includes more content related to neuroscience methods, the brain and the nervous system. This book can be modified: feel free to add or remove modules to better suit your specific needs. Please note that the publisher requires you to login to access and download the PDF.

About the Contributors

Robert Biswas-Diener has written a number of books including Happiness: Unlocking the mysteries of psychological wealth and The Courage Quotient . He is senior editor for the free-textbook platform, Noba.

Ed Diener is a psychologist, professor, and author. Diener is a professor of psychology at the Universities of Utah and Virginia, and Joseph R. Smiley Distinguished Professor Emeritus from the University of Illinois as well as a senior scientist for the Gallup Organization.

Contribute to this Page

Where Biology Meets Psychology : Philosophical Essays

Valerie Gray Hardcastle is Assistant Professor of Philosophy at Virginia Polytechnic Institute.

A great deal of interest and excitement surround the interface between the philosophy of biology and the philosophy of psychology, yet the area is neither well defined nor well represented in mainstream philosophical publications. This book is perhaps the first to open a dialogue between the two disciplines. Its aim is to broaden the traditional subject matter of the philosophy of biology while informing the philosophy of psychology of relevant biological constraints and insights.The book is organized around six themes: functions and teleology, evolutionary psychology, innateness, philosophy of mind, philosophy of science, and parallels between philosophy of biology and philosophy of mind. Throughout, one finds overlapping areas of study, larger philosophical implications, and even larger conceptual ties. Woven through these connections are shared concerns about the status of semantics, scientific law, evolution and adaptation, and cognition in general.

Contributors