- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Christian Schools Boom in a Revolt Against Curriculum and Pandemic Rules

With public schools on the defensive, is this a blip or a ‘once-in-100-year moment for the growth of Christian education’?

By Ruth Graham

MONETA, Va. — On a sunny Thursday morning in September, a few dozen high school students gathered for a weekly chapel service at what used to be the Bottom’s Up Bar & Grill and is now the chapel and cafeteria of Smith Mountain Lake Christian Academy.

Five years ago, the school in southwestern Virginia had just 88 students between kindergarten and 12th grade. Its finances were struggling, quality was inconsistent by its own admission, and classes met at a local Baptist church.

Now, it has 420, with others turned away for lack of space. It has grown to occupy a 21,000-square-foot former mini-mall, which it moved into in 2020, plus two other buildings down the road.

Smith Mountain Lake is benefiting from a boom in conservative Christian schooling, driven nationwide by a combination of pandemic frustrations and rising parental anxieties around how schools handle education on issues including race and the rights of transgender students.

“This is a once-in-100-year moment for the growth of Christian education,” said E. Ray Moore, founder of the conservative Christian Education Initiative.

In the 2019-20 school year, 3.5 million of the 54 million American schoolchildren attended religious schools, including almost 600,000 in “conservative Christian” schools, according to the latest count by the Education Department.

Those numbers are now growing.

The median member school in the Association of Christian Schools International, one of the country’s largest networks of evangelical schools, grew its K-12 enrollment by 12 percent between 2019-20 and 2020-21. The Association of Classical Christian Schools, another conservative network, expanded to educating about 59,200 students this year from an estimated 50,500 in the 2018-19 school year. (Catholic schools, by contrast, are continuing a long trend of decline .)

When the pandemic swept across the country in the spring of 2020, many parents turned to home-schooling.

Others wanted or needed to have their children in physical classrooms. In many parts of the country, private schools stayed open even as public schools moved largely online. Because many parents were working from home, they got a historically intimate look at their children’s online classes — leading to what some advocates for evangelical schools call “the Zoom factor.”

“It’s not necessarily one thing,” said Melanie Cassady, director of academy relations at Christian Heritage Academy in Rocky Mount, Va., about 25 miles southwest of Smith Mountain Lake Christian Academy. “It’s that overall awareness that the pandemic has really brought to light to families of what’s going on inside the schools, inside the classroom, and what teachers are teaching. They’ve come to that point where they have to make a decision: Am I OK with this?”

Christian Heritage Academy had 185 students at the end of the last school year, and 323 this fall. Blueprints for a $10 million expansion project now hang in the school’s entryway.

“It has been absolutely shocking,” said Jeff Keaton, the founder and president of RenewaNation, a Virginia-based conservative evangelical organization whose work includes starting and consulting with evangelical schools. One of his brothers, Troy Keaton, is a pastor and the chair of the Smith Mountain Lake board.

In Virginia, much of the recent controversy has focused on new standards for teaching history, including beefing up Black history offerings. Starting next summer, public-school teachers in the state will also be evaluated on their “cultural competency,” which includes factors like using teaching materials that “represent and validate diversity.” School districts have also grappled with new state guidelines this fall on transgender students’ access to bathrooms and locker rooms of their choice, and rights to use their preferred names and pronouns.

“Of course we do not teach C.R.T.,” said Jon Atchue, a member of the school board in Franklin County, Va., adding that teaching about historical injustices is not the same thing as Marxism or critical race theory, which is an academic framework for analyzing historical patterns of racism and how they persist. “It’s a windmill that folks are fighting with.” Mr. Atchue emphasized that he was speaking only for himself, not the board.

Jeff Keaton called this period “the second Great Awakening in Christian education in the United States since the 1960s and ’70s.”

That previous “Great Awakening” was spurred by a number of factors, starting when white Southern parents founded “segregation academies” as a backlash to racial integration created by the Supreme Court’s 1954 ruling in Brown v. Board of Education. Other Supreme Court rulings on school prayer and evolution in the 1960s, debates about sex education, desegregation busing, and fears of “secular humanism” in the 1970s contributed to the alienation of many white conservatives.

Before the pandemic, private school enrollment overall had declined gradually since the turn of the millennium, while the subset of non-Catholic religious schools held steady, suggesting that the recent growth in conservative evangelical schools is a distinct phenomenon rather than part of a general retreat from public schools.

Today, some schools — generally newer and smaller — advertise themselves directly as standing athwart history. “Critical Race Theory will not be included in our curriculum or teaching,” promises a new school opened by a large church in Lawrence, Kan. “The idea of gender fluidity has no place in our churches, schools or homes,” the headmaster of another new school in Maricopa, Ariz., writes on his school’s website.

But most schools do not make such overt references. “They use words like alternative or Christian or traditional , ” said Adam Laats, a historian at Binghamton University.

Academic quality and costs vary widely, with some schools led by people without educational credentials and others touting more rigorous standards than public schools. Smith Mountain Lake uses curriculum from Bob Jones University Press, which says it offers “Christian educational materials with academic excellence from a biblical worldview.”

More significant, said Mr. Laats, are the words that conservative schools do not use, like “inclusion” and “diversity,” in contrast with a growing number of public and private schools. About 68 percent of students at conservative Christian private schools are white, according to the Education Department, a figure that is comparable to other categories of private schools but significantly higher than public schools.

Conservatives reject comparisons between their opposition to critical race theory and the desegregation backlash of the last century. “I don’t know a single school that even comes close to promoting that kind of concept,” Jeff Keaton said. “What they don’t like is critical theory, where they pit kids against each other in oppressed and oppressor groups .”

If many conservative Protestant schools in the 1960s and 1970s were founded to keep white children away from certain people, then the goal today is keeping children away from certain ideas, said J. Russell Hawkins, a professor of humanities and history at Indiana Wesleyan University. “But the ideas being avoided are still having to do with race,” he said.

Skepticism of public education is a long-running theme in American conservatism. But the specter of critical race theory is now a constant topic on conservative talk radio and television news. In a speech in May, former Attorney General William P. Barr referred to public schools as “the government’s secular-progressive madrassas.”

Like many Christian schools across the country, Smith Mountain Lake has benefited not just from national controversies but intense local battles. A school board meeting in July in Franklin County, Va., from which the school draws many of its students, attracted about 180 community members for a heated discussion of critical race theory and masking in schools. Smith Mountain Lake does not require masks.

In Franklin County, public school enrollment has dropped to 6,125 this year from 7,270 in 2017-18. Over the same period, the number of home-schooled students in the district almost doubled to 1,010, including 32 students who withdrew after a new mask mandate was put into place in mid-September.

Although the district does not count the number of students in other schools, Kara Bernard, the district’s home-school coordinator, said, “We are losing students to private Christian schools.”

Deana Wright enrolled her children in Smith Mountain Lake in July, soon after speaking at a school board meeting in Franklin County. She and her husband did not want their children to keep wearing masks in school, and she had also started reading about what her district was teaching about race. She was “shocked” to come across terms like “cultural competency” and “educational equity” — euphemisms, as she saw it, for critical race theory.

“We’re just so grateful that the Christian academy is here,” she said.

Some teachers are grateful, too.

Shelley Kist, who is in her first year teaching Spanish at Smith Mountain Lake, took a pay cut to come to the school after 17 years in public schools.

In her classes at the Christian school, she leads students in prayers in Spanish, assigns Bible verses they must memorize in Spanish, and discusses career opportunities in overseas missionary work. And she is comfortable weaving cultural commentary into her lessons. She recently made a connection in class between the fact that each Spanish noun is assigned a gender and the concept of “God’s assigned genders” for men and women.

The question for private schools is whether growth in reaction to a pandemic and a culture war is sustainable after concerns about both have receded. “This will be a blip in some places,” Troy Keaton, the chairman of Smith Mountain Lake’s board, conceded while seated at a conference table at his church. “But this is a long-term opportunity for people that know how to love, care, teach and do high-quality things.”

At the school, just over the hill from his church, a student band had led a contemporary worship song at the chapel service that morning: “I won’t bow to idols,” the students sang. “I’ll stand strong and worship you.”

Ruth Graham is a Dallas-based national correspondent covering religion, faith and values. She previously reported on religion for Slate. More about Ruth Graham

- Subscriber Login

Since 1900, the Christian Century has published reporting, commentary, poetry, and essays on the role of faith in a pluralistic society.

© 2023 The Christian Century.

Contact Us Privacy Policy

Imagining the future of theological education

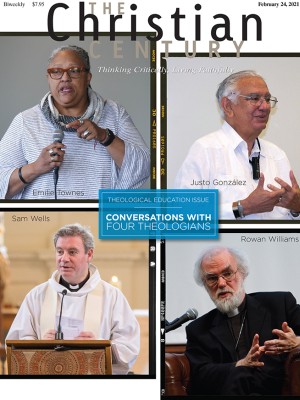

Conversations with rowan williams, justo gonzález, emilie townes, and sam wells.

If theological education was ever in peril, it is now. The general state of higher education is gloomy, with the pandemic only adding to the gloom, but as everyone involved in Christian higher education knows, seminaries and Christian colleges were imperiled before the crisis. Since 2016 there have been 60 nonprofit college closings or mergers, 25 of which were church affiliated. The Association of Theological Schools reports nine seminary closures in the last decade, most of them in the last five years.

So when I sat down with four leading theologians to consider the future of theological education, I was surprised to find they were all passionately optimistic about the enterprise. They had reservations about a university-centric or cloistered monastic approach, but none held the view that the fate of theological education need be determined by its place in higher education. This conviction followed from their view that theological education is an essential work of the church and so shares the church’s destiny.

Shifting the center from the university to the church produces a vision of Christian education that is more daring, provocative, and hopeful than other outlooks. Theologians Rowan Williams, Justo González, Emilie Townes, and Sam Wells each offer distinctive images and fresh possibilities for improving theological education today. They envision an education shaped by the strangeness of the gospel rather than the structures of the university.

Seminary comes from a word that literally means “seedbed” or “nursery,” and this image has long provided the norm for theological education. Seminaries protect seedlings—that is, seminarians—from outside threats so they grow up to be strong. But what if the image of the wild were to replace that of the seedbed as the key site for theological education? What if wilderness better forms disciples?

Williams, the former archbishop of Canterbury, likened theological education to learning about “the world that faith trains you to inhabit.” He went on:

It’s not about a set of issues or problems; it’s about a landscape you move into—the new creation, if you like. You inhabit this new set of relationships, this new set of perspectives. You see differently; you sense differently; you relate differently. Theology exists because people were aware of how different [their new understanding] felt. So instead of just saying, “Well, we’ve had some nice religious experiences, let’s carry on,” people said, “You know, we’ve been catapulted into a new environment that we don’t begin to understand. This is what it feels like, but how is it all drawn up?”

Williams proposes that we see theology as an attempt to map out the new creation, which itself requires a new kind of education.

How might this look in practice? Williams identified St. Mellitus College in London as an educational innovator that is trying to map out the new territory. Students there “pitch [their] own tent” in the wilderness, said Williams, through full-time pastoral assignments they take on while attending seminars and lectures at academic centers. While field education is not new to theological education, this school captures a different dynamic by requiring that schooling take place while students are in full-time ministry. This puts schooling in service to ministry rather than the other way around: the classroom exists for the sake of the church.

Jesus trained disciples by sending them out in pairs to subdue demons, heal the sick, announce the kingdom, and send Satan crashing like a lightning bolt. Theological education, conceived of differently, might not protect seminarians from the dangers of the world so much as send them out right into the thick of it. In this model, ministers and ministers-in-training meet people in their own spaces rather than shelter themselves from situations that might disrupt their ideas. Such experiences teach us to live in the new creation, where all people are loved unconditionally and the map matches the terrain.

If theological education teaches Christians to camp in the new creation, the church must be a “learning church,” said Williams, aware of its history of learning and its capacity to learn more. Theological education is never about receiving prepackaged conclusions and “putting them in your pocket.” It requires a church that’s not “nervous of people’s learning processes.” He continued, “The church should say, OK, the faith we share is strong enough to stand up. Do some probing, some real exploration, some hard questioning. Don’t try to make it easy for yourself or anybody. We actually can cope with that because the truth we’re given is robust.” Christians then bring their adventurous spirit to the classroom of faith because the landscape of faith demands it.

Justo González is no stranger to adventure in theological education. The youngest person to earn a doctorate in historical theology at Yale, González quit full-time teaching in 1977 to become a pastor of pastors through writing and innovation in theological education for Hispanics. My conversation with González built upon his 2015 book The History of Theological Education , in which he argues that theological education is part of the essence of the church and so is the calling of all Christians, lay and clergy.

When I asked González about effective methods for theological education, he stopped me. “Before we talk about methods, let me talk about metaphors. When we were working on developing the [Hispanic Theological Initiative] we always talked about developing a ‘pipeline.’ At some point, I really had the notion . . . that rather than a pipeline, I’d like to talk about drip hoses. You know, the thing you use in the garden with holes in it.”

In a pipeline, success is measured by how much water gets to the end: how many students go to graduate school or seminary, complete their degree, and go into ministry. But with a drip hose, “the dripping of water is purposeful.” The water at the first hole is just as important as the water at the last hole. This is because “the purpose of theological education is mission. The purpose of theological education is to irrigate the land around it—it’s not to push people forward.” (See “Irrigating the land” in the December 30, 2020, issue .)

Like Williams, González challenges the premise of a seminary that extracts the student from the world for a set period, creates a new product, and shoots the graduate back into the world. He underlines that theological education’s task is not to create specialists but to educate every person. The drip hose metaphor invites institutions to educate all Christians, for every vocation. This metaphor impacts every arena of theological education, from student and faculty recruitment to curriculum and programs, and so also provides opportunities to address inequities in current processes. The individual course is every bit as important as degree completion; the lay student is as much a priority as the ordained clergyperson.

González elaborated: “If somebody starts going to seminary and learns some things and then decides not to continue but goes on into some form of Christian ministry with what they have learned, this is a success. It’s not a failure. Same thing all the way through. The most successful process of theological education is not how many people go on to some other school to study, it’s how they apply that in their daily life in the world. Changing that metaphor to me is crucial because it changes your whole perspective of how you’re doing things.”

Like Williams, González sees education and experience as going hand in hand. “The best education for pastors is that which takes place in the context of the church at its mission. . . . Which means that in many ways, the context cannot just be the classroom. The context has to be the church and the world around it—and that, I think, for every course of study.”

González accordingly imagines scenarios in which seminaries recover mentoring as the basic form of theological education. Seminaries could “train mentors who could continue the education of pastors” as they preach on Wednesday evenings, plan worship, or teach church history for Sunday school. Such partnerships might offer a cost-effective, collaborative approach to theological education that trains for the adventure of ministry.

Today’s seminaries and churches have built new pipelines through courses of study, certificate programs, online degrees, and other outcome-based forms of education. But the drip hose metaphor can repurpose theological education to build up the whole church by equipping each disciple for the work to which God has called them. Theological education irrigates the land of the community of faith; it is for all citizens of the kingdom. From the local church to the graduate school, the steady stream of theological education permeates the landscape, equipping each person according to their unique vocation.

Williams’s and González’s images help us see more clearly both the land of the faith and the training suited for it. But as I tried to picture them in practice, I wondered how they might confront the individualism and racism endemic to American culture. Today’s seminaries, with varying degrees of success, have sought to address these twin tendencies by bringing seminarians into diverse communities with diverse faculties. If theological education happens instead within communities that are already segregated, as so many in the United States are, then how can theological education push us beyond our familiar experiences and toward a conversion of our imaginations?

Emilie Townes helped me see seminary as a way of challenging such dangerous insularity. Flourishing in the new creation requires a deep interrogation of the sin we too easily tolerate. Townes, the dean of Vanderbilt Divinity School, sees transcending individualism while building community and enlarging our perspectives of the gospel as essential to the experience of conversion that marks good theological education. Such conversion is a matter of developing what Townes, following Toni Morrison, calls a “dancing mind.”

Dancing minds move through the new creation gracefully. They are rigorous and open as they engage the head, heart, and legs. Theological education, done with this kind of mind, pulls us out of the “what” and places us beside the “who.” Townes helps us see that theological education is relentlessly relational. By engaging theological education with our neighbor, with friend and stranger alike, we “think larger, bigger, wider— and recognize we’re going to find God there. There will be lots of questions we have to face.” Facing them is crucial for our conversion.

If we were to build new models of theological education through our church communities as they are, we might end up with models that are more racist and individualistic rather than less, and so avoid the questions and friendships we need for conversion. Townes calls this “a very myopic view of the world, religion, God, worship.” And if a minister-to-be sees herself as a solo hiker in the wilderness of faith, she limits her vision of the terrain and refuses crucial support for navigating it. The interdependence and interculturality of the community of faith make possible a flourishing that rugged individualism can never know. Community, Townes insists, is “where we find the holy.” True community, beloved community, provides occasions for conversion as we become friends with people of different experiences, ideas, and cultures—as we enlarge our vision of God and the world through openness to new perspectives and people. That God meets us in community gives us the strength to ask the hard questions we need to ask in order to dance.

Townes is constantly searching for ways “to build community and make it larger and larger, to open up the doors and the windows and have a whole lot more people around the welcome table than what we have so often.” Extending González’s proposal of education for all, Townes underlines that theological education is with all. “We’re not doing it in a vacuum; we’re doing it with a community of folks trying to figure it out, too.” Townes also shows us that the “new understanding” advocated by Williams is impossible without the broadest possible community of faith.

Many White seminarians trace their first real awareness of their own racism and the racism of their communities to experiences in seminary, where they were trained under diverse faculties and became friends with people from diverse cultures. Such experiences can transform the way we see God and the world, as our hearts and minds expand. By doing this hard work of facing hard questions, we develop legs to dance.

“The bottom line of womanist thought,” Townes explained, is learning to “join in community with others.” And when you do this, “people can see welcome and respect, hope . . . love, justice, grace . . . that whole, holy chorus.” The holy chorus provides the music for our dancing minds. In community, we learn to eat, serve, confess, forgive, lament, laugh, and dance with God and the whole people of God. Theological education is about forging new and unlikely friendships as we find God has more friends than we could have imagined.

Townes sees this as a joyful endeavor. This is why she insists, “we must always live in hope.” Despite the challenges facing theological education today, Townes chooses hope. She explains: “Hope is sometimes a misappropriated, undervalued, romanticized gift from God. The kind of hope I’m talking about has legs on it, is ornery when it needs to be; it proclaims the gospel, and even if we may not know why we’re saying what we’re saying, we say it anyway because somewhere in there we know God sits and rests with us. That kind of hope will get us through.” Theological education gives us the language of hope. And when we learn to speak rightly, we see how to live faithfully and, with God’s help, become Christian. Rigorous and open dancing minds see that inviting everyone to the welcome table is not about political correctness or a progressive agenda. It’s about the party God throws for all of us.

Sam Wells echoes Townes’s idea of theological education as a dance by proposing that theological education has an asset that the academy at large doesn’t have: the leading of the Holy Spirit. If theological education is an adventure for all disciples, then the Holy Spirit is the guide. Too often, Christian-based learning environments have been defensively oriented. But Wells, vicar of St. Martin-in-the-Fields church in London, sees good theological education as teaching for surprise by following the Holy Spirit’s lead. It embraces the world as a “theater, playground, and garden to be enjoyed.”

When I met Wells at his home in Guildford, England, much of our discussion centered on the Holy Spirit. Wells’s vision prioritizes an improvisational approach that is sensitive to the Spirit. If theological education is part of the essence of the church, it should teach us to follow the Spirit in discipleship, ministry, and mission. Wells defines ministry as “creating the environments where the Holy Spirit can be reliably expected to show up.” If theological education is about following the Spirit, we have to be sure its structures provide room for whatever the Spirit is up to.

Wells points to a few examples at St. Martin’s of creating spaces where the Spirit shows up as surprising friendships are forged. St. Martin’s has a Sunday international group, and Wells described the sometimes surprising juxtapositions. “For the first time in his life,” he said, a conservative from the financial district might come “face to face with someone who has clung on to a truck, who has come to Britain, who turns out to be a fabulously articulate, funny, engaging person, who has been treated abominably by our government and society. And yet is gracious, and forgiving, and not bitter. And then you think, ‘I want to be like him .’” There is also a theology group in which a refugee from Botswana is “no longer perceived as somebody you give sandwiches and keep off the streets; he’s perceived as a person who chairs a meeting for 35 mostly White people.”

Such spaces “turn the tables” as you begin to see “an upside-down kingdom.” Wells explained that when we make room for the Holy Spirit to show up, we respond like the disciples at Emmaus who “ran all the way back to Jerusalem to tell [their friends], ‘We’ve seen the Lord!’” The structures of good theological education are nimble and improvisational.

How might theological education build flexibility into its models to allow for holy encounter? Seminaries could be reconceived as outposts of the church, communal training grounds for laity and clergy with curricula shaped by vocation rather than one-size-fits-all approaches, replete with encounter-oriented experiences that open us to God and others and with multiple entrances and exits to make room for the movement of the Spirit who seeks to transform us. According to Wells, such education exposes students to the joy of experiencing God in the world and “recognizing that profoundly disruptive nature of the gospel that is not here to make our lives better or easier, but it’s here to turn our lives upside down.” The work of the church is invigorating because it’s energized by the Spirit’s relentless desire to teach us how to play with God in the world. The breath-giving play of the Spirit increases our capacity for surprise as we learn to trust God and one another.

Wells reminds us that good theological education gets us involved with God. Following the Spirit requires discernment. While it may be difficult to assess the clarity of such discernment, we can be confident that education that does not require courage, make us uncomfortable, or disrupt our lives is not good theological education. The absence of bravery, discomfort, or disruption is a sign that we are not following the Spirit. If Townes’s vision keeps us from teaching a false gospel, Wells’s vision keeps us tethered to the Spirit of surprise rather than the status quo of university structures.

These conversations have led me to envision a theological education that centers on four priorities. First, theological education should be church-centric: what is happening in our churches sets the agenda for the academy.

Second, from the church to the graduate school, theological education should offer a wide variety of instruction, course structures, degree programs, certificates, and more that attend to the vocation of each person, making more entrances and exits for laity and clergy. While many seminaries are already doing some of this, the difference lies in prioritizing vocational learning over degree completion.

Third, the entire culture of theological education—from hiring, admissions, fieldwork, syllabi, and assessments to community events and outreach—should challenge the isms that have long poisoned theological education, from racism and individualism to sexism and ethnocentrism. While this is happening in some seminary classrooms, it’s not a thoroughgoing reality in the structures, administrations, and policies of our universities, seminaries, and churches. We need diverse boards, administrators, supervisors, staff, faculty, and pastors to educate a broad community; culturally flexible models that fit a range of life experiences; and diverse curricula to combat the false gospel that these are tangential matters to faithful discipleship, ministry, and mission.

Finally, we should make room for the Spirit by becoming seasoned risk takers. We should be teaching, learning, and doing things that stretch us, scare us, or even cause us pain. Theological education is about exploration and discovery, which require constant attention, courage, and improvisation in instruction and learning. Perhaps theological education needs more classes in casting out demons and fewer in church marketing.

Following the Spirit in theological education brings danger and wonder, disruption and surprise, pain and beauty as we encounter new spaces, embrace new people, and become more fully human. While this may be attractive in theory, in practice we have a lot to let go of to get there, like our desires to be right, safe, comfortable, certain, responsible, respectable, organized, and in control. These desires are every bit as strong as our selfish fears that lead us to grasp privilege, position, power, and pride.

Good theological education helps us develop legs to dance to the holy chorus with the broad community of unlikely friends we call church. The university is as good a place as any for theological education, so long as we are not afraid to disentangle it from the presumptions of the academy that get in the way of hearing the holy music. Maybe at this moment, at this time, we can construct a new normal for theological education as education for this grand adventure of calling, conversion, and surprise, and so learn to live in God’s country.

Benjamin D. Wayman

Benjamin D. Wayman teaches theology at Greenville University and is a pastor at St. Paul’s Free Methodist Church in Greenville, Illinois.

We would love to hear from you. Let us know what you think about this article by writing a letter to the editors .

Most Recent

Coffee justice in mexico, california hate crime hotline gives hindus more evidence of shortfall in fbi reporting, pope francis apologizes for using homophobic slurs while saying 'no' to gay priests, karl barth in a nutshell, most popular.

Missed opportunities at the UMC general conference

Making room in the UMC for the Spirit’s work

The wilderness of a rural ministry circuit

The making of God

The challenge of Christian Education

Building institutions in an age of uncertainty.

Christian higher education, like higher education in general, is in a significant period of transition and change. The challenges of population shifts from rural to urban, rapid escalation of operational costs, proliferation of mobile technologies, changing public attitudes toward higher education, the rapid decline in cultural, moral consensus, the dominance of naturalism and/or secularism in nearly all academic disciplines, coupled with the increasing loss of community and belonging that people desire, has left the higher education enterprise scrambling to find viable answers and solutions for these new realities.

Christian higher education institutions have an even greater challenge in that they are no longer necessarily viewed benignly by the general culture. The pressures facing Christian colleges and universities are many and are relentless. It takes courage, strength, and vision to see past these challenges in order to build institutions that will not only survive this period of upheaval and change, but will contribute significantly to strengthening the faith and witness of their graduates in the uncertain years ahead.

Dockery and Morgan have compiled a strong lineup of contributors for this volume. Most of them are connected in some way to Trinity International University, but there are significant contributors coming from other institutions as well. Dockery himself is likely the foremost scholar/practitioner/author in the realm of Christian higher education today. His long experience of leading Christian, higher educational institutions and his prolific scholarship clearly qualify him to address not only the challenges, but also to cast the vision for a robust, strategic future for those institutions that are seeking to either reclaim or strengthen their commitment to providing a truly Christian, higher education for their students.

What Makes an Education Truly Christian?

The first section of the book lays the foundation for a robust understanding of and compelling case for Christian higher education. The authors present their ideas on what makes an education truly Christian. Nathan Finn and John Woodbridge’s chapters are particularly insightful and helpful in clarifying the need for emphasizing the centrality and authority of Scripture, and the supreme value of knowing Christ ahead all other pursuits.

The second section builds on the foundations laid in the opening chapters and begins the process of applying them to the acts of teaching and learning and proposing the most appropriate way(s) to use them in approaching various academic disciplines. The helpfulness of these chapters is mixed, but I found two chapters especially thought-provoking and useful in more clearly framing the critical issues. Gene Fant Jr.’s chapter on the humanities is worthy of continued discussion and consideration as he makes a strong case for the place of humanities in a genuinely Christian liberal arts education. He also clearly delineates how the humanities must be viewed from a distinctly Christian perspective. The other chapter in this section that I found especially good are from Eric Johnson and Russell Kosits on the social sciences. Among several important observations in the chapter, they make the point that finding faculty (especially in the social sciences) who are properly qualified in their fields and are also theologically sound and able to think “Christianly” about their disciplines is very difficult. This is one of the challenges that this volume doesn’t address in any detail.

The final section of the book aims to apply this emerging vision for Christian higher education to the broader contexts of worship, right living, intercultural concerns, missions, the church, leadership, etc. These chapters offer some helpful insights into applying what is called the “integrative” approach to a truly Christian liberal arts education. oMost of these chapters combine philosophical discussion with ideas for practical application.

Undefined Phrases

Taken as a whole, the book is at various points inspiring, informational, educational, and insightful. At other points, it’s over-reliant on jargon and catch-phrases that go undefined and are therefore less than helpful. Throughout the volume, the phrases which are repeated often are: “Christ-centered”; “engaging the culture”; “integration of faith and learning”; and “all truth is God’s truth.” One of the authors does attempt to define the phrase, “integration of faith and learning.” I wish she had gone further in her attempt. When undefined, these commonly used phrases leave far too much room for wide ranging interpretations which inevitably lead to a failure to achieve the kind of truly Christian higher education the authors are championing. The pressures facing Christian colleges and universities are many and are relentless. Click To Tweet

Each one of those phrases deserves at least a chapter-length treatment in order to clearly define them and assess the range of interpretations which have been applied to them over the years. The damage done to the mission of Christian higher education by the misinterpretation and misapplication of these terms would also be important to recognize.

For example; the phrase “all truth is God’s truth” is an absolutely true statement. However, the very real difficulty in appropriating that phrase is knowing when one has actually discovered truth that can then be considered God’s truth. When we apply that phrase too quickly to the apparent “truths” of any discipline, we run the risk of declaring a “truth” to be God’s truth which may well not ultimately be true. In the social sciences as well as the hard sciences, what is considered to be true at any given point in time very often changes as new discoveries emerge that contradict the previous “truth.”

Perhaps defining and analyzing these oft-repeated phrases is beyond the bounds of what this book is intended to do. However, such a discussion would go a long way toward helping schools actually achieve the vision for a truly Christian higher education that the authors are encouraging.

I do recommend the book for anyone who is involved in Christian higher education. It is thought-provoking, occasionally inspiring, helpful in identifying key issues, and strikes a balance between philosophizing and offering practical guidance regarding forming and implementing a distinctive, Christian approach to higher education.

Tim Tomlinson

Tim Tomlinson (PhD, University of Minnesota) is President of Bethlehem College & Seminary, where he has served since 2009. Prior to his role at BCS, Dr. Tomlinson served as a long-time faculty member and administrator at the University of Northwestern-St. Paul.

Credo Magazine

Share this Article

Advertisment.

The Christian Post

To enjoy our website, you'll need to enable JavaScript in your web browser. Please click here to learn how.

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Recommended

Support for Israel, dispensationalism declines among younger Evangelicals

Pope Francis apologizes for using 'homophobic terms' in meeting with bishops

Carl and Laura Lentz tease ‘new chapter’ in video trailer

Disney-owned Hulu to roll out gay-themed reality dating shows on streaming platform

Nearly 40% of Christians prefer not to tell people about their faith: survey

The woke right: The Constitution is a 'dead letter'? (part 1)

Are the walls closing in on the trans-industrial complex?

A Jew sentenced to death under Iranian Sharia Law

The cost of freedom: How campus protests push limits of expression

American Evangelicals have a persecution fetish

5 top challenges facing christian higher education today.

Everyday, it seems society plummets further into moral decay as truth becomes relative and biblical values are pushed by the wayside. In such times, the importance of Christian higher education and the development of Christian thinkers cannot be overestimated.

Yet, more than ever before, Christian colleges and universities are faced with innumerable challenges as they strive to prepare students to pursue biblical truth and to embody a Gospel witness in a fallen world.

In a society consumed with political correctness, the authority of Scripture becomes meaningless at best. As culture becomes increasingly hostile to biblical values, Christian institutions' commitments on issues of gender and sexuality, human origins, and the sanctity of life — from conception to death — are constantly challenged.

Get Our Latest News for FREE

Scripture warns that such challenges are to be expected; Jesus promises his disciples that in this world we "will have tribulation" ( John 16:33 ), and the Apostle Paul assures readers that "all who desire to live a godly live in Christ Jesus will be persecuted" ( 2 Timothy 3:12 ).

However, such challenging times also present an opportunity for Christian colleges to proclaim the fullness of Christ by being a voice of truth, compassion and reconciliation in a divided world.

Rather than conforming to pressures of the world ( Romans 12:2 ), Christian colleges and universities are tasked with developing Christian thinkers through the integration of faith and learning.

Here are five challenges facing Christian higher education today — and what administrators and scholars within Christian academies should do about them.

Pressure to Waver on Biblical Commitments

In recent years, issues of gender and human sexuality have become increasingly mainstream — and they're only becoming more prevalent. A new study released by Barna Group found that 12 percent of Gen Z teens — those born between 1999 and 2015 — described their sexual orientation as something other than heterosexual, with 7 percent identifying as bisexual.

Overall, 37 percent of future college students said their gender and sexuality is "very important" to their sense of self, compared to 28 percent of their Gen X parents. In total, about a third of teens know someone who is transgender, and the majority (69%) say it's acceptable to be born one gender and to feel like another.

In light of these statistics, it's clear that more than ever before, Christian campus leaders, faculty, and professors must know how to tackle the complex issues of transgenderism, homosexuality, pornography, and how to care for LGBTQ students while holding fast to a biblical perspective on these matters.

In addition to issues of gender and human sexuality, Christian institutions are forced to defend their biblical views on human origins, the inerrancy of Scripture, religious freedom, and the sanctity of life. As more and more federal and state policies that impact the work of Christian colleges and universities are implemented, refusing to compromise on faith-based principles can seem like an impossible feat for many schools.

Yet, Scripture warns against "evolving" on such issues and commands Christians to fight for the authority of Scripture ( John 8:32 ; NKJV). Christian institutions today are tasked with equipping students to deal with the cultural challenges unseen less than several decades ago.

When students are taught how to think critically about relevant issues through a biblical framework, they are able to thoughtfully engage with an antagonistic world ( John 17:14–16 ); stand firm in their faith ( 1 Timothy 6:12 ); and combat the idols of our time ( 1 Thessalonians 1:9-10 ).

Threats to Freedom

Many secular colleges today silence the voices of Christian students in the name of political correctness and tolerance — even though the U.S. Constitution protects students' right to express personal religious and political beliefs in writing, speech, and visual or performing arts while at a public university. Last year, a Christian organization called Students for Life (SFL) made headlines after filing a federal lawsuit against Colorado State University because the college denied the pro-life group funding to pay for a campus speaker with anti-abortion views.

Unfortunately, Christian universities are today finding themselves under similar scrutiny. Those who are opposed to same-sex marriage, abortion, and other moral issues are branded bigots by the secular media and liberal activists. For example, the 2017 "Shame List" from Campus Pride — which identifies the "absolute worst campuses for LGBTQ youth" in the United States — listed dozens of Christian colleges as promoting "religious bigotry that is unsafe, harmful and perpetuates harassment toward LGBTQ youth." Some of the entrants in the "absolute worst" category included Wheaton College, Covenant College, Dallas Theological Seminary, Dordt College, Bob Jones University, and dozens more.

As Christian colleges face increasing threats to freedom and are mocked by their secular counterparts, biblically minded-professors must intelligently address such issues with students while instilling in them the confidence to live out the Gospel and hold to the inerrancy of Scripture in a pluralistic world.

Financial Difficulties

Due to the increasing cost of higher education, many Christian colleges are faced with low enrollment rates and other financial issues. Unexpected costs, the high price of textbooks, room, and board, and facing the reality of student loans can all be major deterrents for many students who would otherwise prefer to attend a Christian institution.

According to Allie Bidwell of U.S. News & World Report , the average cost of attending a four-year public university is $8,893, while the cost of attending a private university is $30,090. While many Christian colleges offer scholarships and other forms of aid, the cost of attending a private college increased by nearly four-percent from 2012 to 2013, and that number is only rising.

For these reasons, Christianity Today notes that "financial counselors at Christian institutions find themselves caught between theological justifications for hefty loans and the financial reality they know will hit down the line." The outlet notes that last year, the National Association of Evangelicals (NAE) asked the leaders of major denominations and ministries: Would you encourage young people to attend a Christian college over a state school even if it meant graduating with more debt? In response, only about a third answered "yes,' and over half said "maybe."

It's crucial that Christian colleges and universities understand the financial realities facing higher education today and explore innovative ways for schools to meet these challenges.

Competing with Public Counterparts

In an increasingly postmodern society, the new generation of college students are less interested in Christianity and more concerned with diversity, according to Barna Group.

Among Gen Z members between 13 and 18 years old, 13 percent consider themselves atheists, compared to just 6 percent of adults overall. While 59 percent of Gen Z identifies as Christian, only 1 in 11 teens is considered by Barna to be an "engaged Christian," (i.e., not "Christian in name only").

One out of five teens in the Barna study view Christianity as negative and judgmental, and some of the biggest barriers to belief are the problem of evil (29%), perceived hypocrisy among Christians (23%), and the conflict between science and Scripture (20%).

To combat this trend, many Christian college administrators are making conscious efforts to diversify their schools and explore how campuses can better reflect God's vision of a church drawn from all demographics. Many Christian schools today hold lectures, seminars, and classes addressing the cultural concerns held by college students while making no apologies for the centrality of Christ.

What we learn, study, and absorb impacts our worldview; Colossians 2:8 warns about secular philosophies that can captivate your mind: "See to it that no one takes you captive through hollow and deceptive philosophy, which depends on human tradition and the elemental spiritual forces of this world rather than on Christ."

While today's teens are bombarded with philosophies that contradict biblical principles, Christian professors have the opportunity to thoughtfully challenge such notions while presenting Christianity as a relationship with Christ -- not merely an adherence to a list of rules.

Hiring Biblically Sound Faculty and Staff

Christ-centered colleges and universities offer an education that incorporates faith into academics — but that's only possible if the faculty and staff are committed, Bible-believing Christians who tie their primary allegiance to Scripture.

In an op-ed for the Gospel Coalition, Justin Taylor, senior vice president and publisher for books at Crossway, highlighted the importance of careful vetting when hiring faculty and staff.

"[The] number one issue in maintaining an intentional Christian commitment is faculty hiring...Christian schools must go to the next level with prospective faculty candidates and ask probing questions about their involvement with and service in their church. If we expect them to represent the Christian life of the mind before our students, they must be articulate about the Christian life of the mind in their job interview. Are any faculty candidates being turned down because of a lack of mission fit, in spite of their other appealing qualifications? If that's never happening, I would suggest it is time to revisit how you are handing your hiring practices, in order to maintain that intentional Christian mission."

Integrating faith in the classroom allows students to view every discipline, from biology and chemistry to art and history, as intertwined with God's perfect plan for His creation. College is a common time to wrestle with the challenges, doubts, and questions that come with living a gospel-centered life, and Christian schools provide a place for students to confidently explore doubts and questions of the faith in thoughtful and safe environment.

For these reasons and more, those who represent Christian higher education must be willing to confront secular culture with a Christian worldview and nurture and equip the next generation of Christian leaders.

Was this article helpful?

Help keep The Christian Post free for everyone.

By making a recurring donation or a one-time donation of any amount, you're helping to keep CP's articles free and accessible for everyone.

We’re sorry to hear that.

Hope you’ll give us another try and check out some other articles. Return to homepage.

Most Popular

Pastor Jamal Bryant announces engagement to Karri Turner

Pope says gay men should be barred from seminary, accused of using derogatory word

Alabama pastor charged with rape, sodomy may have used church to contact victims

5-year-old boy released from hospital after parents, brothers killed in crash leaving church

Russell Brand reflects on 'beautiful' first month as a Christian: 'I'm so excited to learn more'

More articles.

Interest in Harrison Butker's social media, apparel spikes after Benedictine College speech: report

Washington state ends investigation of pro-life pregnancy centers; no charges filed

Christian convert in Somalia attacked by knife-wielding Muslim relatives, loses family

Group of brands.

Christian Perspectives in Education

Send out your light and your truth let them guide me. psalm 43:3.

Home > School of Education > Christian Perspectives in Education

Christian Perspectives in Education (CPE) is an online, peer-reviewed journal that focuses upon Christian perspectives in theory, research, and practices of education. ISSN: 2159-807X

Call for Papers:

All past issues can be found at : http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cpe/all_issues.html

Christian Perspectives in Education is published by Liberty University's School of Education. All views and opinions expressed within the published articles are those of the author(s) and do not represent the views and/or opinions of Liberty University, the School of Education, the CPE journal, or the editors. Published articles and all information within the publications are solely the responsibility of the author of the article.

Current Issue: Volume 10, Issue 1 (2017) Winter 2017

Flipped Classrooms in the Humanities: Findings from a Quasi-Experimental Study Bryce F. Hantla

- Journal Home

- About This Journal

- Aims & Scope

- Related Links

- SOE Scholars Crossing

- Scholars Crossing

- Most Popular Papers

- Receive Email Notices or RSS

Advanced Search

Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

- Modeling the Future of Religion in America

1. How U.S. religious composition has changed in recent decades

Table of contents.

- Generational ‘snowball’

- Disaffiliation among older adults

- Education, politics and geography tied to differences in religious switching

- Other drivers of change

- Scenario 1: Steady switching

- Scenario 2: Rising disaffiliation with limits

- Scenario 3: Rising disaffiliation without limits

- Scenario 4: No switching

- Additional scenarios: What if migration stops or people stop switching after the age of 30?

- Acknowledgments

- Modeling of switching

- The projection approach

- Appendix A: Sources of religion data

- Appendix B: Supplemental analyses

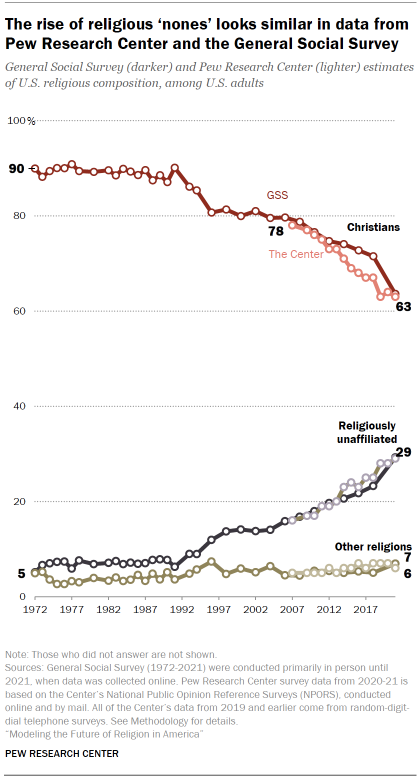

Only a few decades ago, a Christian identity was so common among Americans that it could almost be taken for granted. As recently as the early 1990s, about 90% of U.S. adults identified as Christians. But today, about two-thirds of adults are Christians. 6 The change in America’s religious composition is largely the result of large numbers of adults switching out of the religion in which they were raised to become religiously unaffiliated.

In other words, a steadily shrinking share of young adults who were raised Christian (in childhood) have retained their religious identity in adulthood over the past 30 years. At the same time, having no religious affiliation has become “stickier”: A declining percentage of people raised without a religion have converted or taken on a religion later in life.

While religious switching is the focus of this report, other demographic forces that can cause religious change – transmission, migration, fertility and mortality – will be briefly discussed in the second half of this chapter.

Switching gained significant momentum in the 1990s, according to the General Social Survey (GSS) – a large, nationally representative survey that has consistent data on religious affiliation going back several decades. In 1972, when the GSS first began asking Americans, “What is your religious preference?” 90% identified as Christian and 5% were religiously unaffiliated. In the next two decades, the share of “nones” crept up slowly, reaching 9% in 1993. But then disaffiliation started speeding up – in 1996, the share of unaffiliated Americans jumped to 12%, and two years later it was 14%. This growth has continued, and 29% of Americans now tell the GSS they have “no religion.” 7

Pew Research Center has been measuring religious identity since 2007 using a slightly different question wording – “What is your present religion, if any?” – as well as a different set of response options. Since 2007, the percentage of adults who say they are atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular” in the Center’s surveys has grown from 16% to 29%. During this time, the share of U.S. adults who identify as Christian has fallen from 78% to 63%.

There are many theories on why disaffiliation sped up so much in the 1990s and how long this trend might continue. For example, some scholars contend that secularization is the result of increasing “existential security” – as societal conditions improve and scientific advances allow people to live longer lives with fewer worries about meeting basic needs, they have less need for religion to cope with insecurity (or so the theory goes). 8 Others say that in the U.S., an association of Christianity with conservative politics has driven many liberals away from the faith. Still other theories involve declining trust in religious institutions , clergy scandals , rising rates of religious intermarriage , smaller families, and so on. When asked, Americans give a wide range of reasons for leaving religion behind , Pew Research Center has found.

Whatever the deeper causes, religious disaffiliation in the U.S. is being fueled by switching patterns that started “snowballing” from generation to generation in the 1990s. The core population of “nones” has an increasingly “sticky” identity as it rolls forward, and it is gaining a lot more people than it is shedding, in a dynamic that has a kind of demographic momentum.

Christians have experienced the opposite pattern. With each generation, progressively fewer adults retain the Christian identity they were raised with, which in turn means fewer parents are raising their children in Christian households.

One way of gauging the momentum behind the U.S. switching trend is to look at the other side of the coin – the rate at which Americans retain the religion in which they were raised, as opposed to switching out. By studying retention patterns, researchers can determine whether a religious identity is becoming more or less sticky.

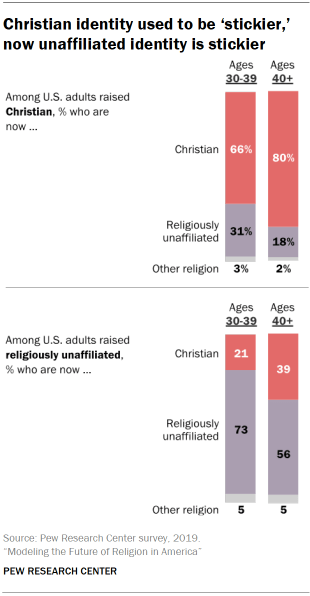

Until recently, Christian identity was stickier than unaffiliated identity, which means that the share of people who remained Christian after being raised as Christians was greater than the share of people who remained unaffiliated after being raised with no religion.

Today, Christianity still is the stickier affiliation for older Americans. But among younger adults, the unaffiliated identity has become the stickier one. Among people who are 40 and older, 80% of those raised as Christians are still Christian today, compared with just 56% of those who were raised unaffiliated (in childhood) and still do not identify with a religion today (in adulthood). However, among people in their 30s, only 66% of those raised Christian are still Christian today, compared with 73% of those raised unaffiliated who still are today.

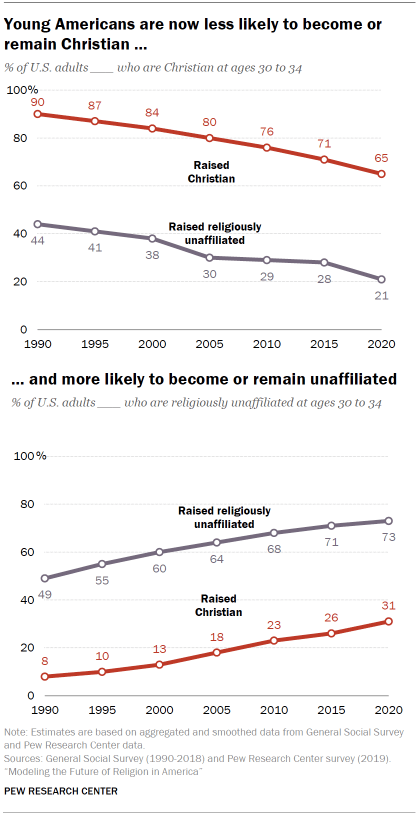

An analysis of GSS data by birth decade shows a similar pattern: Roughly 90% of people who were born in the 1960s and raised Christian were still Christian when they turned 30. Among those born in the 1970s, fewer than 85% remained Christian at 30. Among those born in the 1980s, it is about 80%. Too few of those born in the 1990s have turned 30 to estimate their switching patterns, but Christians in this youngest cohort appear to be disaffiliating even more than older cohorts.

The “snowballing” dynamic is being driven by an acceleration in switching among young Christians – those ages 15 to 29. People under 30 tend to grapple with identities of all kinds, and young adulthood is often a time of major change, when many people leave their parents’ household, start careers and form lasting romantic partnerships. But there is a second dynamic that began in the 1990s that added a new layer of change: Starting in the mid-1990s, it became more common for adults in middle age and beyond to discard Christian identity. Before that, changing religions after 30 was rare. About 95% or more of people who were born prior to the 1940s and were raised Christian were still Christian from ages 30 to 65. But among those born in the ’40s, ’50s and ’60s, there has been more substantial movement away from Christianity after age 30. For example, 91% of Americans born in the 1960s were still Christian at age 30, but 83% identify as Christian today. Recent switching among older U.S. adults may be the result of a period effect (when something about the environment affects people of all ages for a period of time, such as the COVID-19 pandemic’s consequences for the mental and physical health of people of all ages). It might also be the result of a tipping point: Once Christians began to lose their overwhelming majority, people of all ages who had ties to Christianity – but did not attend church, pray often or see religion as an important part of their lives – may have begun to identify as unaffiliated in larger numbers. As “nones” grew in size and visibility, being unaffiliated may have become more socially acceptable in some circles, opening the floodgates to further disaffiliation. While this pattern is new – and it is unclear how long it might last – it indicates that disaffiliation is extending into segments of the population that may have been unaffected in the past. (For more information about late-adult switching, see Appendix B .)

A closer look at the characteristics of adults who have left Christianity and are now religiously unaffiliated indicates that other traits – such as age, gender, education, political identity and region of residence – also are tied to disaffiliation.

U.S. adults who have moved away from Christianity are younger, on average, than those who have remained Christian after a Christian upbringing. More than a quarter of former Christians (27%) are under 30, compared with 14% of all adults who were raised Christian and remain Christian. This age pattern aligns with a decades-long trend in which each cohort of young adults is less religiously affiliated than the preceding one.

Americans who have moved away from Christianity are more likely to be men, while women are more likely to retain their Christian identity. A slight majority of U.S. adults who were raised Christian and are now unaffiliated (54%) are male. Among people who have remained Christian, 57% are women.

People who have become unaffiliated after a Christian upbringing are a little more likely to have graduated college than those who remain Christian, with 35% and 31%, respectively, holding college degrees. This reflects a broader pattern: In the U.S., people with higher levels of educational attainment tend to be less religious by some traditional measures, such as how often they pray or attend religious services .

Seven-in-ten adults who were raised Christian but are now unaffiliated are Democrats or Democratic-leaning independents, compared with 43% of those who remained Christian and 51% of U.S. adults overall. Some scholars argue that disaffiliation from Christianity is driven by an association between Christianity and political conservatism that has intensified in recent decades. 9

People who have left Christianity are underrepresented in the South, where 33% of former Christians live, compared with 42% of people who have remained Christian and 38% of U.S. adults overall. 10

Those who have disaffiliated after being raised Christian are more likely than others to live in the West (28% live there, compared with 20% of those who remain Christian and 23% of all U.S. adults). Surveys often find that U.S. adults tend to be more religious, on a number of measures, in the South , and less so in the West and Northeast. This may indicate that people adapt to the religious contexts in which they live and/or sort themselves into like-minded communities.

Switching is the primary, but by no means the only, process causing religious change in the U.S. Populations can grow or shrink through a few other mechanisms. Patterns of religious transmission, migration and fertility explain some of the shift in the religious landscape in recent decades.

Transmission

The share of Christians is in decline partly because religion is not always transmitted by Christian parents to their children.

For the purposes of the projections in this report, religious identities are considered to be “transmitted” when children are raised in their parents’ religion and identify with it as early adolescents. There are a variety of reasons why children of religiously affiliated parents may be raised without a religion and, therefore, that religion is not transmitted. For example, a child may have parents without strong religious commitment, or parents with different religions, or parents who have decided to let children explore and make decisions about religion on their own.

Consider the hypothetical case of an adult survey respondent who says her mother was Christian, her father was Jewish, she was not raised in any religion, and she currently does not identify with any religion. A person like this has not switched religions, since switching is defined as leaving the religion in which one was raised. However, in this example, neither parent transmitted their religion.

By the same token, not all unaffiliated parents transmit their identity. For example, a 14-year-old child of unaffiliated parents could acquire a Christian identity outside the parental home in various ways, such as from other family members, a teacher or a friend.

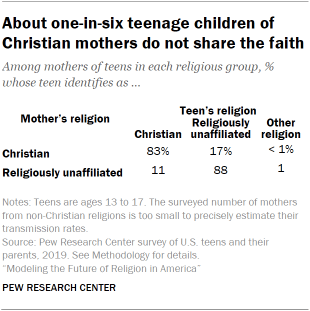

In this study, transmission rates are calculated based on the mother’s religion because mothers tend to successfully transmit their religion more often than fathers do, and roughly a quarter of teens live in single-parent households, which are almost exclusively headed by mothers.

Today, transmission of the mother’s religious identity happens in the vast majority of families. In a 2019 Pew Research Center survey of teens and their parents , an overwhelming majority of both Christian and unaffiliated mothers had transmitted their religious identities to their teenagers. More than eight-in-ten Christian mothers had Christian teens, while 17% of their teens identified as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular,” and less than 1% said they were members of another religious group.

The teens of unaffiliated mothers show a similar pattern: 88% are unaffiliated themselves, 11% are Christians, and 1% identify with a non-Christian religion. The survey sample did not contain enough mothers who belong to non-Christian religions to report on their precise transmission rates, but their patterns seem broadly similar to those with Christian and unaffiliated mothers – the vast majority of teens raised by mothers of “other religions” also identify with a religion in this category.

Even though the shares of Christian and religiously unaffiliated mothers who transmit their affiliation (or lack thereof) are fairly similar, the impact of failed transmission in Christian families is far greater, numerically, because there are more than twice as many Christian mothers as unaffiliated ones. At these rates, and as long as Christians are the substantially larger group, many more people will adopt a religiously unaffiliated identity rather than a Christian one during childhood, which in turn increases the population share of the unaffiliated.

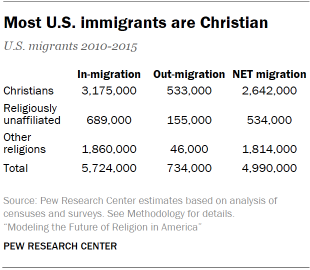

Migration contributes to U.S. religious change because the composition of immigrants and emigrants is not identical to that of the overall U.S. population. About a million immigrants come to the U.S. each year, and one-in-seven people in the U.S. were born elsewhere . In the 1990s and early 2000s , the largest number of recent arrivals to the U.S. were from Mexico and other Christian-majority countries in Central and South America. Today, new arrivals are more likely to come from Asia. In 2018, the top country of origin for new immigrants was China (which is majority unaffiliated), followed by India (which is majority Hindu). Most of the world’s people who identify as religiously unaffiliated, Hindu, Buddhist, Sikh and Jain live in either China or India, and this is reflected in the changing profile of immigrants. Christians still make up a majority of immigrants to the U.S., including a majority of immigrants from Mexico, the third-largest source of new immigrants in recent years. But the estimated share of new immigrants who are Christian (55%) is lower than the Christian share of the existing U.S population (64%), meaning that immigration is not boosting the Christian population share. The same is true of religiously unaffiliated people: 12% of new immigrants are estimated to be religiously unaffiliated, compared with 30% of the existing U.S. population.

But immigration is leading to growth in the share of other religions like Hindus and Muslims – 32% of new immigrants are estimated to be adherents of other religions (versus 6% of the U.S. population), according to recent data on the origin and size of migrant flows to the U.S. and an earlier Pew Research Center analysis of the typical religious composition of migrants from each country. 11

In countries with wide differences in fertility rates between religious groups, those differences can cause significant changes in religious composition over time.

Recently, religiously unaffiliated women in the U.S. have tended to have fewer children than Christians and women of other religions. In this report’s models, the average unaffiliated woman is expected to have 1.6 children in her lifetime, while the average Christian woman will have 1.9 children, and the average woman of other religions (an umbrella category that includes Jews, Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists and many smaller groups) will have 2.0 children (see Methodology for more details). Since the U.S. has a very large population and mothers tend to transmit their religions to children, these small differences can add up to noticeable changes over time. However, higher fertility among Christians compared with the religiously unaffiliated has not been nearly enough to maintain the Christian share of the population, although it has slightly offset some of the impact of disaffiliation.

Age structures and mortality

The youthfulness of religious groups has an impact on the future that is intertwined with fertility because young populations have higher shares of people who are in, or soon will enter, their reproductive years. In other words, they have more growth potential than older populations. If two groups have identical total fertility rates, the group with the younger age structure can grow more rapidly because of the population momentum produced by having a larger share of women of reproductive age. Young populations also tend to have a smaller share of people who die each year.

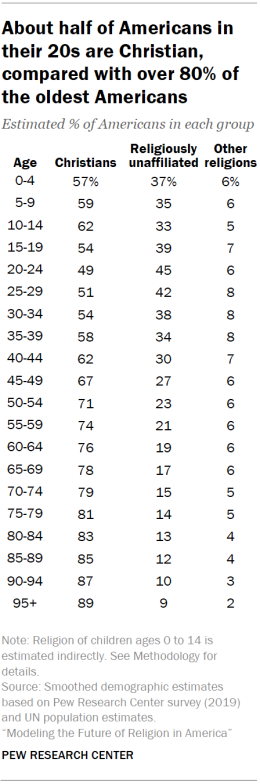

Christians are older, on average, than the unaffiliated or people of non-Christian religions. The average U.S. Christian is 43, compared with an average age of 33 among the unaffiliated and 38 among people of other religions. More than 80% of Americans older than 75 are Christian, compared with roughly half of people in their prime childbearing years (ages 20 to 34), many of whom will transmit their religion to the next generation, if past patterns hold. More than 40% of Americans between 20 and 34 are religiously unaffiliated, compared with under 15% of the oldest Americans. These are among the reasons why religious “nones” are projected to grow as a share of the U.S. population even in the scenario with no further religious switching.

Due to a lack of sufficient data on mortality differences between people in the three religious identity categories studied in this report, each group is assumed to have the same mortality patterns. In other words, for purposes of these projections, life expectancy is assumed to be similar among members of each group at a given age. It is also assumed to be rising over time, despite a dip caused by the coronavirus pandemic. 12

- This chapter focuses on results of public opinion surveys of U.S. adults. Most other population shares presented in this report are estimates for Americans of all ages. See Methodology for details on estimating the religious affiliations of children. ↩

- Prior to 2020, the General Social Survey (GSS) was conducted primarily through face-to-face interviews. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, in 2020 and 2021, the GSS gathered panel and cross-sectional survey data primarily online. Since most data for the cross-sectional survey was collected in 2021, NORC now describes the cross-sectional survey data as the 2021 GSS (see page 4 of the codebook for the latest GSS data). The change in the “mode” of survey administration was concomitant with the GSS finding a rise in religious “nones” from 23% in 2018 to 29% in 2021 and a corresponding drop in the share of U.S. adults who identified as Christian from 72% to 64%. Some of the change in the GSS between 2018 and 2021 may be due to this “mode effect.” For a basic explanation of mode effects, see Pew Research Center’s video “ Methods 101: Mode Effects. ” For more details on the GSS data used in this report, see the Methodology . ↩

- Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart. 2011. “ Sacred and Secular: Religion and Politics Worldwide .” ↩

- Some research indicates that Americans tend to develop firm, enduring political identities earlier than religious ones, and their political views may influence their religious beliefs more than the other way around. See Margolis, Michele. 2018. “From Politics to the Pews: How Partisanship and the Political Environment Shape Religious Identity.” In addition, some scholars assert that the rise of the “nones” since the 1990s is due in part to a reaction or “backlash” following an increase in the visibility of the “religious right” and its conservative positions on polarizing issues. See Hout, Michael, and Claude S. Fischer. 2014. “ Explaining Why More Americans Have No Religious Preference: Political Backlash and Generational Succession, 1987-2012 .” Sociological Science. ↩

- Regions are based on the U.S. Census Bureau’s definitions of South, Northeast, Midwest and West. ↩

- Recent and future migration flows are estimated based on the most recent five-year period with complete global migration data at the time of analysis (mid-2010 to mid-2015). ↩

- Due primarily to the COVID-19 pandemic, life expectancy decreased by 1.5 years between 2019 and 2020, according to the CDC . This reduction is expected to be temporary, so unadjusted UN estimates were used in projections. ↩

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Christianity

- Non-Religion & Secularism

- Religious Characteristics of Demographic Groups

- Religious Demographics

- Religious Identity & Affiliation

- Religiously Unaffiliated

Majority of U.S. Catholics Express Favorable View of Pope Francis

9 facts about u.s. catholics, how common is religious fasting in the united states, 5 facts about muslims and christians in indonesia, 8 in 10 americans say religion is losing influence in public life, most popular, report materials.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

© 2024 Pew Research Center

Peter DeWitt's

Finding common ground.

A former K-5 public school principal turned author, presenter, and leadership coach, DeWitt provides insights and advice for education leaders. He can be found at www.petermdewitt.com . Read more from this blog .

11 Critical Issues Facing Educators in 2023

- Share article

For several years, I wrote a list of 10, 11, or even 15 critical issues facing education at the end of a year to give a glimpse into issues to consider for the following year. Then COVID happened and blew my last list of issues up. Why? Because it never occurred to me to put a pandemic on the list of critical issues in 2019.

We have educational issues to consider every year that also highlight what teachers, leaders, and students face. Education has often been a dumping ground for criticism of educators who are tasked with teaching children content, feeding them when they come in hungry because they live in poverty or are homeless, and, at the same time, practicing school safety drills because students and teachers have to prepare for fending off the next school shooter.

Television shows and movies poke fun at educators and school, politicians have “plans” about how they can do it better, although the large majority of them ever step foot in a school since they graduated. During all of that “entertainment,” educators are supposed to just go in and do their jobs for the love of education and children.

And that’s exactly what they do.

11 Issues for 2023

These issues were chosen based on the number of times they came up in stories on Education Week or in workshops and coaching sessions that I do in my role as a leadership coach and workshop facilitator.

For full disclosure, some of the issues will be difficult to read, but they are the reality for teachers, leaders, staff, and students around the country. With that being said, the issues on the list are not exhaustive, and as always, if you have an issue to add to the list, find me on social media and let me know which ones are a top priority for you.