The leading authority in photography and camera gear.

Become a better photographer.

12.9 Million

Annual Readers

Newsletter Subscribers

Featured Photographers

Photography Guides & Gear Reviews

How to Create an Engaging Photo Essay (with Examples)

Photo essays tell a story in pictures. They're a great way to improve at photography and story-telling skills at once. Learn how to do create a great one.

Learn | Photography Guides | By Ana Mireles

Shotkit may earn a commission on affiliate links. Learn more.

Photography is a medium used to tell stories – sometimes they are told in one picture, sometimes you need a whole series. Those series can be photo essays.

If you’ve never done a photo essay before, or you’re simply struggling to find your next project, this article will be of help. I’ll be showing you what a photo essay is and how to go about doing one.

You’ll also find plenty of photo essay ideas and some famous photo essay examples from recent times that will serve you as inspiration.

If you’re ready to get started, let’s jump right in!

Table of Contents

What is a Photo Essay?

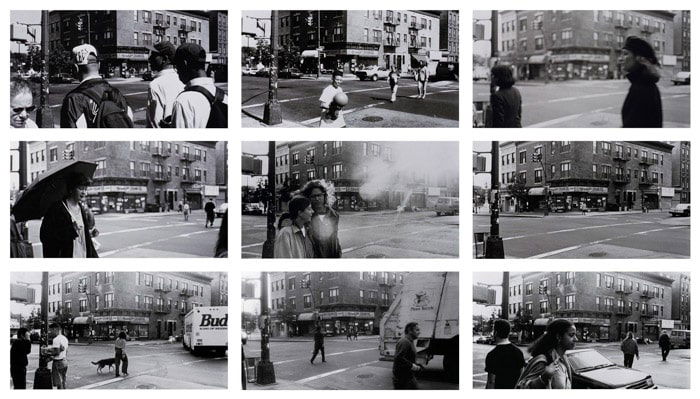

A photo essay is a series of images that share an overarching theme as well as a visual and technical coherence to tell a story. Some people refer to a photo essay as a photo series or a photo story – this often happens in photography competitions.

Photographic history is full of famous photo essays. Think about The Great Depression by Dorothea Lange, Like Brother Like Sister by Wolfgang Tillmans, Gandhi’s funeral by Henri Cartier Bresson, amongst others.

What are the types of photo essay?

Despite popular belief, the type of photo essay doesn’t depend on the type of photography that you do – in other words, journalism, documentary, fine art, or any other photographic genre is not a type of photo essay.

Instead, there are two main types of photo essays: narrative and thematic .

As you have probably already guessed, the thematic one presents images pulled together by a topic – for example, global warming. The images can be about animals and nature as well as natural disasters devastating cities. They can happen all over the world or in the same location, and they can be captured in different moments in time – there’s a lot of flexibility.

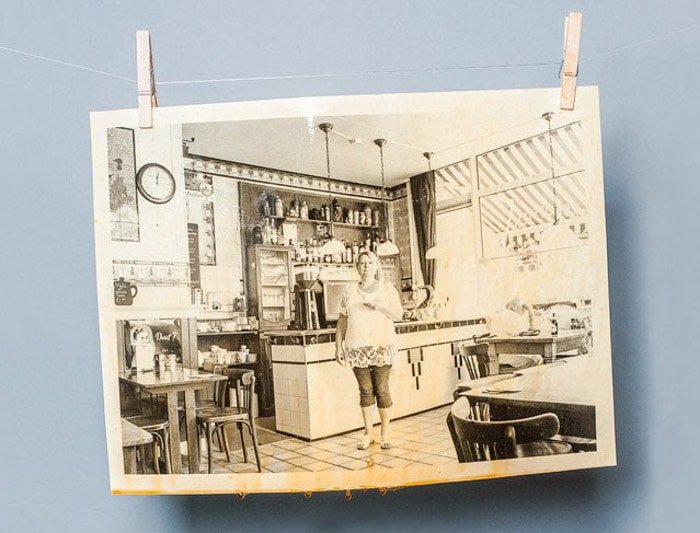

A narrative photo essa y, on the other hand, tells the story of a character (human or not), portraying a place or an event. For example, a narrative photo essay on coffee would document the process from the planting and harvesting – to the roasting and grinding until it reaches your morning cup.

What are some of the key elements of a photo essay?

- Tell a unique story – A unique story doesn’t mean that you have to photograph something that nobody has done before – that would be almost impossible! It means that you should consider what you’re bringing to the table on a particular topic.

- Put yourself into the work – One of the best ways to make a compelling photo essay is by adding your point of view, which can only be done with your life experiences and the way you see the world.

- Add depth to the concept – The best photo essays are the ones that go past the obvious and dig deeper in the story, going behind the scenes, or examining a day in the life of the subject matter – that’s what pulls in the spectator.

- Nail the technique – Even if the concept and the story are the most important part of a photo essay, it won’t have the same success if it’s poorly executed.

- Build a structure – A photo essay is about telling a thought-provoking story – so, think about it in a narrative way. Which images are going to introduce the topic? Which ones represent a climax? How is it going to end – how do you want the viewer to feel after seeing your photo series?

- Make strong choices – If you really want to convey an emotion and a unique point of view, you’re going to need to make some hard decisions. Which light are you using? Which lens? How many images will there be in the series? etc., and most importantly for a great photo essay is the why behind those choices.

9 Tips for Creating a Photo Essay

Credit: Laura James

1. Choose something you know

To make a good photo essay, you don’t need to travel to an exotic location or document a civil war – I mean, it’s great if you can, but you can start close to home.

Depending on the type of photography you do and the topic you’re looking for in your photographic essay, you can photograph a local event or visit an abandoned building outside your town.

It will be much easier for you to find a unique perspective and tell a better story if you’re already familiar with the subject. Also, consider that you might have to return a few times to the same location to get all the photos you need.

2. Follow your passion

Most photo essays take dedication and passion. If you choose a subject that might be easy, but you’re not really into it – the results won’t be as exciting. Taking photos will always be easier and more fun if you’re covering something you’re passionate about.

3. Take your time

A great photo essay is not done in a few hours. You need to put in the time to research it, conceptualizing it, editing, etc. That’s why I previously recommended following your passion because it takes a lot of dedication, and if you’re not passionate about it – it’s difficult to push through.

4. Write a summary or statement

Photo essays are always accompanied by some text. You can do this in the form of an introduction, write captions for each photo or write it as a conclusion. That’s up to you and how you want to present the work.

5. Learn from the masters

How Much Do You REALLY Know About Photography?! 🤔

Test your photography knowledge with this quick quiz!

See how much you really know about photography...

Your answer:

Correct answer:

SHARE YOUR RESULTS

Your Answers

Making a photographic essay takes a lot of practice and knowledge. A great way to become a better photographer and improve your storytelling skills is by studying the work of others. You can go to art shows, review books and magazines and look at the winners in photo contests – most of the time, there’s a category for photo series.

6. Get a wide variety of photos

Think about a story – a literary one. It usually tells you where the story is happening, who is the main character, and it gives you a few details to make you engage with it, right?

The same thing happens with a visual story in a photo essay – you can do some wide-angle shots to establish the scenes and some close-ups to show the details. Make a shot list to ensure you cover all the different angles.

Some of your pictures should guide the viewer in, while others are more climatic and regard the experience they are taking out of your photos.

7. Follow a consistent look

Both in style and aesthetics, all the images in your series need to be coherent. You can achieve this in different ways, from the choice of lighting, the mood, the post-processing, etc.

8. Be self-critical

Once you have all the photos, make sure you edit them with a good dose of self-criticism. Not all the pictures that you took belong in the photo essay. Choose only the best ones and make sure they tell the full story.

9. Ask for constructive feedback

Often, when we’re working on a photo essay project for a long time, everything makes perfect sense in our heads. However, someone outside the project might not be getting the idea. It’s important that you get honest and constructive criticism to improve your photography.

How to Create a Photo Essay in 5 Steps

Credit: Quang Nguyen Vinh

1. Choose your topic

This is the first step that you need to take to decide if your photo essay is going to be narrative or thematic. Then, choose what is it going to be about?

Ideally, it should be something that you’re interested in, that you have something to say about it, and it can connect with other people.

2. Research your topic

To tell a good story about something, you need to be familiar with that something. This is especially true when you want to go deeper and make a compelling photo essay. Day in the life photo essays are a popular choice, since often, these can be performed with friends and family, whom you already should know well.

3. Plan your photoshoot

Depending on what you’re photographing, this step can be very different from one project to the next. For a fine art project, you might need to find a location, props, models, a shot list, etc., while a documentary photo essay is about planning the best time to do the photos, what gear to bring with you, finding a local guide, etc.

Every photo essay will need different planning, so before taking pictures, put in the required time to get things right.

4. Experiment

It’s one thing to plan your photo shoot and having a shot list that you have to get, or else the photo essay won’t be complete. It’s another thing to miss out on some amazing photo opportunities that you couldn’t foresee.

So, be prepared but also stay open-minded and experiment with different settings, different perspectives, etc.

5. Make a final selection

Editing your work can be one of the hardest parts of doing a photo essay. Sometimes we can be overly critical, and others, we get attached to bad photos because we put a lot of effort into them or we had a great time doing them.

Try to be as objective as possible, don’t be afraid to ask for opinions and make various revisions before settling down on a final cut.

7 Photo Essay Topics, Ideas & Examples

Credit: Michelle Leman

- Architectural photo essay

Using architecture as your main subject, there are tons of photo essay ideas that you can do. For some inspiration, you can check out the work of Francisco Marin – who was trained as an architect and then turned to photography to “explore a different way to perceive things”.

You can also lookup Luisa Lambri. Amongst her series, you’ll find many photo essay examples in which architecture is the subject she uses to explore the relationship between photography and space.

- Process and transformation photo essay

This is one of the best photo essay topics for beginners because the story tells itself. Pick something that has a beginning and an end, for example, pregnancy, the metamorphosis of a butterfly, the life-cycle of a plant, etc.

Keep in mind that these topics are linear and give you an easy way into the narrative flow – however, it might be difficult to find an interesting perspective and a unique point of view.

- A day in the life of ‘X’ photo essay

There are tons of interesting photo essay ideas in this category – you can follow around a celebrity, a worker, your child, etc. You don’t even have to do it about a human subject – think about doing a photo essay about a day in the life of a racing horse, for example – find something that’s interesting for you.

- Time passing by photo essay

It can be a natural site or a landmark photo essay – whatever is close to you will work best as you’ll need to come back multiple times to capture time passing by. For example, how this place changes throughout the seasons or maybe even over the years.

A fun option if you live with family is to document a birthday party each year, seeing how the subject changes over time. This can be combined with a transformation essay or sorts, documenting the changes in interpersonal relationships over time.

- Travel photo essay

Do you want to make the jump from tourist snapshots into a travel photo essay? Research the place you’re going to be travelling to. Then, choose a topic.

If you’re having trouble with how to do this, check out any travel magazine – National Geographic, for example. They won’t do a generic article about Texas – they do an article about the beach life on the Texas Gulf Coast and another one about the diverse flavors of Texas.

The more specific you get, the deeper you can go with the story.

- Socio-political issues photo essay

This is one of the most popular photo essay examples – it falls under the category of photojournalism or documental photography. They are usually thematic, although it’s also possible to do a narrative one.

Depending on your topic of interest, you can choose topics that involve nature – for example, document the effects of global warming. Another idea is to photograph protests or make an education photo essay.

It doesn’t have to be a big global issue; you can choose something specific to your community – are there too many stray dogs? Make a photo essay about a local animal shelter. The topics are endless.

- Behind the scenes photo essay

A behind-the-scenes always make for a good photo story – people are curious to know what happens and how everything comes together before a show.

Depending on your own interests, this can be a photo essay about a fashion show, a theatre play, a concert, and so on. You’ll probably need to get some permissions, though, not only to shoot but also to showcase or publish those images.

4 Best Photo Essays in Recent times

Now that you know all the techniques about it, it might be helpful to look at some photo essay examples to see how you can put the concept into practice. Here are some famous photo essays from recent times to give you some inspiration.

Habibi by Antonio Faccilongo

This photo essay wan the World Press Photo Story of the Year in 2021. Faccilongo explores a very big conflict from a very specific and intimate point of view – how the Israeli-Palestinian war affects the families.

He chose to use a square format because it allows him to give order to things and eliminate unnecessary elements in his pictures.

With this long-term photo essay, he wanted to highlight the sense of absence and melancholy women and families feel towards their husbands away at war.

The project then became a book edited by Sarah Leen and the graphics of Ramon Pez.

Picture This: New Orleans by Mary Ellen Mark

The last assignment before her passing, Mary Ellen Mark travelled to New Orleans to register the city after a decade after Hurricane Katrina.

The images of the project “bring to life the rebirth and resilience of the people at the heart of this tale”, – says CNNMoney, commissioner of the work.

Each survivor of the hurricane has a story, and Mary Ellen Mark was there to record it. Some of them have heartbreaking stories about everything they had to leave behind.

Others have a story of hope – like Sam and Ben, two eight-year-olds born from frozen embryos kept in a hospital that lost power supply during the hurricane, yet they managed to survive.

Selfie by Cindy Sherman

Cindy Sherman is an American photographer whose work is mainly done through self-portraits. With them, she explores the concept of identity, gender stereotypes, as well as visual and cultural codes.

One of her latest photo essays was a collaboration with W Magazine entitled Selfie. In it, the author explores the concept of planned candid photos (‘plandid’).

The work was made for Instagram, as the platform is well known for the conflict between the ‘real self’ and the one people present online. Sherman started using Facetune, Perfect365 and YouCam to alter her appearance on selfies – in Photoshop, you can modify everything, but these apps were designed specifically to “make things prettier”- she says, and that’s what she wants to explore in this photo essay.

Tokyo Compression by Michael Wolf

Michael Wolf has an interest in the broad-gauge topic Life in Cities. From there, many photo essays have been derived – amongst them – Tokyo Compression .

He was horrified by the way people in Tokyo are forced to move to the suburbs because of the high prices of the city. Therefore, they are required to make long commutes facing 1,5 hours of train to start their 8+ hour workday followed by another 1,5 hours to get back home.

To portray this way of life, he photographed the people inside the train pressed against the windows looking exhausted, angry or simply absent due to this way of life.

You can visit his website to see other photo essays that revolve around the topic of life in megacities.

Final Words

It’s not easy to make photo essays, so don’t expect to be great at it right from your first project.

Start off small by choosing a specific subject that’s interesting to you – that will come from an honest place, and it will be a great practice for some bigger projects along the line.

Whether you like to shoot still life or you’re a travel photographer, I hope these photo essay tips and photo essay examples can help you get started and grow in your photography.

Let us know which topics you are working on right now – we’ll love to hear from you!

Check out these 8 essential tools to help you succeed as a professional photographer.

Includes limited-time discounts.

You'll Also Like These:

Ana Mireles is a Mexican researcher that specializes in photography and communications for the arts and culture sector.

Penelope G. To Ana Mireles Such a well written and helpful article for an writer who wants to inclue photo essay in her memoir. Thank you. I will get to work on this new skill. Penelope G.

Herman Krieger Photo essays in black and white

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

👋 WELCOME TO SHOTKIT!

🔥 Popular NOW:

Unlock the EXACT blueprint to capture breathtaking iPhone photos!

23 Photo Essay Ideas and Examples (to Get Your Creative Juices Flowing!)

A Post By: Kevin Landwer-Johan

Looking for inspiration? Our 23 photo essay ideas will take your photography skills to new heights!

A single, strong photograph can convey a lot of information about its subject – but sometimes we have topics that require more than one image to do the job. That’s when it’s time to make a photo essay: a collection of pictures that together tell the bigger story around a chosen theme.

In the following sections, we’ll explore various photo essay ideas and examples that cover a wide range of subjects and purposes. From capturing the growth of your children to documenting local festivals, each idea offers an exciting opportunity to tell a story through your lens, whether you’re a hobbyist or a veteran professional.

So grab your camera, unleash your creativity, and let’s delve into the wonderful world of photo essay examples!

What is a photo essay?

Simply put, a photo essay is a series of carefully selected images woven together to tell a story or convey a message. Think of it as a visual narrative that designed to capture attention and spark emotions.

Now, these images can revolve around a broad theme or focus on a specific storyline. For instance, you might create a photo essay celebrating the joy of companionship by capturing 10 heartwarming pictures of people sharing genuine laughter. On the other hand, you could have a photo essay delving into the everyday lives of fishermen in Wales by following a single fisherman’s journey for a day or even a week.

It’s important to note that photo essays don’t necessarily have to stick to absolute truth. While some documentary photographers prefer to keep it authentic, others may employ techniques like manipulation or staging to create a more artistic impact. So there is room for creativity and interpretation.

Why you should create a photo essay

Photo essays have a way of expressing ideas and stories that words sometimes struggle to capture. They offer a visual narrative that can be incredibly powerful and impactful.

Firstly, photo essays are perfect when you have an idea or a point you want to convey, but you find yourself at a loss for words. Sometimes, emotions and concepts are better conveyed through images rather than paragraphs. So if you’re struggling to articulate a message, you can let your photos do the talking for you.

Second, if you’re interested in subjects that are highly visual, like the mesmerizing forms of architecture within a single city, photo essays are the way to go. Trying to describe the intricate details of a building or the play of light and shadows with words alone can be challenging. But through a series of captivating images, you can immerse your audience in the architecture.

And finally, if you’re aiming to evoke emotions or make a powerful statement, photo essays are outstanding. Images have an incredible ability to shock, inspire, and move people in ways that words often struggle to achieve. So if you want to raise awareness about an environmental issue or ignite a sense of empathy, a compelling series of photographs can have a profound impact.

Photo essay examples and ideas

Looking to create a photo essay but don’t know where to start? Here are some handy essay ideas and examples for inspiration!

1. A day in the life

Your first photo essay idea is simple: Track a life over the course of one day. You might make an essay about someone else’s life. Or the life of a location, such as the sidewalk outside your house.

The subject matter you choose is up to you. But start in the morning and create a series of images showing your subject over the course of a typical day.

(Alternatively, you can document your subject on a special day, like a birthday, a wedding, or some other celebration.)

2. Capture hands

Portraits focus on a subject’s face – but why not mix it up and make a photo essay that focuses on your subject’s hands?

(You can also focus on a collection of different people’s hands.)

Hands can tell you a lot about a person. And showing them in context is a great way to narrate a story.

3. Follow a sports team for a full season

Sports are all about emotions – both from the passionate players and the dedicated fans. While capturing the intensity of a single game can be exhilarating, imagine the power of telling the complete story of a team throughout an entire season.

For the best results, you’ll need to invest substantial time in sports photography. Choose a team that resonates with you and ensure their games are within a drivable distance. By photographing their highs and lows, celebrations and challenges, you’ll create a compelling photo essay that traces their journey from the first game to the last.

4. A child and their parent

Photographs that catch the interaction between parents and children are special. A parent-child connection is strong and unique, so making powerful images isn’t challenging. You just need to be ready to capture the special moments as they happen.

You might concentrate on a parent teaching their child. Or the pair playing sports. Or working on a special project.

Use your imagination, and you’ll have a great time with this theme.

5. Tell a local artist’s story

I’ve always enjoyed photographing artists as they work; studios have a creative vibe, so the energy is already there. Bring your camera into this environment and try to tell the artist’s story!

An artist’s studio offers plenty of opportunities for wonderful photo essays. Think about the most fascinating aspects of the artist’s process. What do they do that makes their art special? Aim to show this in your photos.

Many people appreciate fine art, but they’re often not aware of what happens behind the scenes. So documenting an artist can produce fascinating visual stories.

6. Show a tradesperson’s process

Do you have a plumber coming over to fix your kitchen sink? Is a builder making you a new deck?

Take photos while they work! Tell them what you want to do before you start, and don’t forget to share your photos with them.

They’ll probably appreciate seeing what they do from another perspective. They may even want to use your photos on their company website.

7. Photograph your kids as they grow

There’s something incredibly special about documenting the growth of our little ones. Kids grow up so quickly – before you know it, they’re moving out. Why not capture the beautiful moments along the way by creating a heartwarming photo essay that showcases their growth?

There are various approaches you can take, but one idea is to capture regular photos of your kids standing in front of a distinct point of reference, such as the refrigerator. Over a year or several years, you can gather these images and place them side by side to witness your childrens’ incredible transformations.

8. Cover a local community event

A school fundraiser, a tree-planting day at a park, or a parade; these are are all community events that make for good photo essay ideas.

Think like a photojournalist . What type of images would your editor want? Make sure to capture some wide-angle compositions , some medium shots, and some close-ups.

(Getting in close to show the details can often tell as much of a story as the wider pictures.)

9. Show fresh market life

Markets are great for photography because there’s always plenty of activity and lots of characters. Think of how you can best illustrate the flow of life at the market. What are the vendors doing that’s most interesting? What are the habits of the shoppers?

Look to capture the essence of the place. Try to portray the people who work and shop there.

10. Shoot the same location over time

What location do you visit regularly? Is there a way you can make an interesting photo essay about it?

Consider what you find most attractive and ugly about the place. Look for aspects that change over time.

Any outdoor location will look different throughout the day. Also think about the changes that occur from season to season. Create an essay that tells the story of the place.

11. Document a local festival

Festivals infuse cities and towns with vibrant energy and unique cultural experiences. Even if your own town doesn’t have notable festivals, chances are a neighboring town does. Explore the magic of these celebrations by documenting a local festival through your lens.

Immerse yourself in the festivities, arriving early and staying late. Capture the colorful displays and the people who make the festival come alive. If the festival spans multiple days, consider focusing on different areas each time you visit to create a diverse and comprehensive photo essay that truly reflects the essence of the event.

12. Photograph a garden through the seasons

It might be your own garden . It could be the neighbor’s. It could even be the garden at your local park.

Think about how the plants change during the course of a year. Capture photos of the most significant visual differences, then present them as a photo essay.

13. Show your local town or city

After spending several years in a particular area, you likely possess an intimate knowledge of your local town or city. Why not utilize that familiarity to create a captivating photo essay that showcases the essence of your community?

Delve into what makes your town special, whether it’s the charming streets, unique landmarks, or the people who shape its character. Dedicate time to capturing the diverse aspects that define your locale. If you’re up for a more extensive project, consider photographing the town over the course of an entire year, capturing the changing seasons and the dynamic spirit of your community.

14. Pick a local cause to highlight

Photo essays can go beyond passive documentation; they can become a part of your activism, too!

So find a cause that matters to you. Tell the story of some aspect of community life that needs improvement. Is there an ongoing issue with litter in your area? How about traffic; is there a problematic intersection?

Document these issues, then make sure to show the photos to people responsible for taking action.

15. Making a meal

Photo essay ideas can be about simple, everyday things – like making a meal or a coffee.

How can you creatively illustrate something that seems so mundane? My guess is that, when you put your mind to it, you can come up with many unique perspectives, all of which will make great stories.

16. Capture the life of a flower

In our fast-paced lives, it’s easy to overlook the beauty that surrounds us. Flowers, with their mesmerizing colors and rapid life cycles, offer a captivating subject for a photo essay. Try to slow down and appreciate the intricate details of a flower’s existence.

With a macro lens in hand, document a single flower or a patch of flowers from their initial shoots to their inevitable wilting and decomposition. Experiment with different angles and perspectives to bring viewers into the enchanting world of the flower. By freezing these fleeting moments, you’ll create a visual narrative that celebrates the cycle of life and the exquisite beauty found in nature’s delicate creations.

17. Religious traditions

Religion is often rich with visual expression in one form or another. So capture it!

Of course, you may need to narrow down your ideas and choose a specific aspect of worship to photograph. Aim to show what people do when they visit a holy place, or how they pray on their own. Illustrate what makes their faith real and what’s special about it.

18. Historic sites

Historic sites are often iconic, and plenty of photographers take a snapshot or two.

But with a photo essay, you can illustrate the site’s history in greater depth.

Look for details of the location that many visitors miss. And use these to build an interesting story.

19. Show the construction of a building

Ever been away from a familiar place for a while only to return and find that things have changed? It happens all the time, especially in areas undergoing constant development. So why not grab your camera and document this transformation?

Here’s the idea: Find a building that’s currently under construction in your area. It could be a towering skyscraper, a modern office complex, or even a small-scale residential project. Whatever catches your eye! Then let the magic of photography unfold.

Make it a habit to take a photo every day or two. Watch as the building gradually takes shape and evolves. Capture the construction workers in action, the cranes reaching for the sky, and the scaffolding supporting the structure.

Once the building is complete, you’ll have a treasure trove of images that chronicle its construction from start to finish!

20. Document the changing skyline of the city

This photo essay example is like the previous one, except it works on a much larger scale. Instead of photographing a single building as it’s built, find a nice vantage point outside your nearest city, then photograph the changing skyline.

To create a remarkable photo essay showcasing the changing skyline, you’ll need to scout out the perfect vantage point. Seek high ground that offers a commanding view of the city, allowing you to frame the skyline against the horizon. Look for spots that give you an unobstructed perspective, whether a rooftop terrace, a hillside park, or even a nearby bridge.

As you set out on your photography expedition, be patient and observant. Cities don’t transform overnight; they change gradually over time. Embrace the passage of days, weeks, and months as you witness the slow evolution unfold.

Pro tip: To capture the essence of this transformation, experiment with various photographic techniques. Play with different angles, framing, and compositions to convey the grandeur and dynamism of the changing skyline. Plus, try shooting during the golden hours of sunrise and sunset , when the soft light bathes the city in a warm glow and accentuates the architectural details.

21. Photograph your pet

If you’re a pet owner, you already have the perfect subject for a photo essay!

All pets , with the possible exception of pet rocks, will provide you with a collection of interesting moments to photograph.

So collect these moments with your camera – then display them as a photo essay showing the nature and character of your pet.

22. Tell the story of a local nature preserve

Ah, the wonders of a local nature preserve! While it may not boast the grandeur of Yosemite National Park, these hidden gems hold their own beauty, just waiting to be discovered and captured through the lens of your camera.

To embark on this type of photo essay adventure, start by exploring all the nooks and crannies of your chosen nature preserve. Wander along its winding trails, keeping an eye out for unique and captivating subjects that convey the essence of the preserve.

As you go along, try to photograph the intricate details of delicate wildflowers, the interplay of light filtering through a dense forest canopy, and the lively activities of birds and other wildlife.

23. Show the same subject from multiple perspectives

It’s possible to create an entire photo essay in a single afternoon – or even in a handful of minutes. If you don’t love the idea of dedicating yourself to days of photographing for a single essay, this is a great option.

Simply find a subject you like, then endeavor to capture 10 unique images that include it. I’d recommend photographing from different angles: up above, down low, from the right and left. You can also try getting experimental with creative techniques, such as intentional camera movement and freelensing. If all goes well, you’ll have a very cool set of images featuring one of your favorite subjects!

By showcasing the same subject from multiple perspectives, you invite viewers on a visual journey. They get to see different facets, textures, and details that they might have overlooked in a single photograph. It adds depth and richness to your photo essay, making it both immersive and dynamic.

Photo essay ideas: final words

Remember: Photo essays are all about communicating a concept or a story through images rather than words. So embrace the process and use images to express yourself!

Whether you choose to follow a sports team through a thrilling season, document the growth of your little ones, or explore the hidden treasures of your local town, each photo essay has its own magic waiting to be unlocked. It’s a chance to explore your creativity and create images in your own style.

So look at the world around you. Grab your gear and venture out into the wild. Embrace the beauty of nature, the energy of a bustling city, or the quiet moments that make life special. Consider what you see every day. What aspects interest you the most? Photograph those things.

You’re bound to end up with some amazing photo essays!

Now over to you:

Do you have any photo essay examples you’re proud of? Do you have any more photo essay ideas? Share your thoughts and images in the comments below!

Read more from our Tips & Tutorials category

Kevin Landwer-Johan is a photographer, photography teacher, and author with over 30 years of experience that he loves to share with others.

Check out his website and his Buy Me a Coffee page .

- Guaranteed for 2 full months

- Pay by PayPal or Credit Card

- Instant Digital Download

- All our best articles for the week

- Fun photographic challenges

- Special offers and discounts

- Share your Views

- Submit a Contest

- Recommend Contest

- Terms of Service

- Testimonials

Photo Contests – Photography competitions

- Filter Photo Contests

- All Photo Contests

- Get FREE Contests Updates

- Photo Contest Tips

- Photography Deals

What is a Photo Essay? 9 Photo Essay Examples You Can Recreate

A photo essay is a series of photographs that tell a story. Unlike a written essay, a photo essay focuses on visuals instead of words. With a photo essay, you can stretch your creative limits and explore new ways to connect with your audience. Whatever your photography skill level, you can recreate your own fun and creative photo essay.

9 Photo Essay Examples You Can Recreate

- Photowalk Photo Essay

- Transformation Photo Essay

- Day in the Life Photo Essay

- Event Photo Essay

- Building Photo Essay

- Historic Site or Landmark Photo Essay

- Behind the Scenes Photo Essay

- Family Photo Essay

- Education Photo Essay

Stories are important to all of us. While some people gravitate to written stories, others are much more attuned to visual imagery. With a photo essay, you can tell a story without writing a word. Your use of composition, contrast, color, and perspective in photography will convey ideas and evoke emotions.

To explore narrative photography, you can use basic photographic equipment. You can buy a camera or even use your smartphone to get started. While lighting, lenses, and post-processing software can enhance your photos, they aren’t necessary to achieve good results.

Whether you need to complete a photo essay assignment or want to pursue one for fun or professional purposes, you can use these photo essay ideas for your photography inspiration . Once you know the answer to “what is a photo essay?” and find out how fun it is to create one, you’ll likely be motivated to continue your forays into photographic storytelling.

1 . Photowalk Photo Essay

One popular photo essay example is a photowalk. Simply put, a photowalk is time you set aside to walk around a city, town, or a natural site and take photos. Some cities even have photowalk tours led by professional photographers. On these tours, you can learn the basics about how to operate your camera, practice photography composition techniques, and understand how to look for unique shots that help tell your story.

Set aside at least two to three hours for your photowalk. Even if you’re photographing a familiar place—like your own home town—try to look at it through new eyes. Imagine yourself as a first-time visitor or pretend you’re trying to educate a tourist about the area.

Walk around slowly and look for different ways to capture the mood and energy of your location. If you’re in a city, capture wide shots of streets, close-ups of interesting features on buildings, street signs, and candid shots of people. Look for small details that give the city character and life. And try some new concepts—like reflection picture ideas—by looking for opportunities to photographs reflections in mirrored buildings, puddles, fountains, or bodies of water.

2 . Transformation Photo Essay

With a transformation photography essay, you can tell the story about change over time. One of the most popular photostory examples, a transformation essay can document a mom-to-be’s pregnancy or a child’s growth from infancy into the toddler years. But people don’t need to be the focus of a transformation essay. You can take photos of a house that is being built or an urban area undergoing revitalization.

You can also create a photo narrative to document a short-term change. Maybe you want to capture images of your growing garden or your move from one home to another. These examples of photo essays are powerful ways of telling the story of life’s changes—both large and small.

3 . Day in the Life Photo Essay

Want a unique way to tell a person’s story? Or, perhaps you want to introduce people to a career or activity. You may want to consider a day in the life essay.

With this photostory example, your narrative focuses on a specific subject for an entire day. For example, if you are photographing a farmer, you’ll want to arrive early in the morning and shadow the farmer as he or she performs daily tasks. Capture a mix of candid shots of the farmer at work and add landscapes and still life of equipment for added context. And if you are at a farm, don’t forget to get a few shots of the animals for added character, charm, or even a dose of humor. These types of photography essay examples are great practice if you are considering pursuing photojournalism. They also help you learn and improve your candid portrait skills.

4 . Event Photo Essay

Events are happening in your local area all the time, and they can make great photo essays. With a little research, you can quickly find many events that you could photograph. There may be bake sales, fundraisers, concerts, art shows, farm markets, block parties, and other non profit event ideas . You could also focus on a personal event, such as a birthday or graduation.

At most events, your primary emphasis will be on capturing candid photos of people in action. You can also capture backgrounds or objects to set the scene. For example, at a birthday party, you’ll want to take photos of the cake and presents.

For a local or community event, you can share your photos with the event organizer. Or, you may be able to post them on social media and tag the event sponsor. This is a great way to gain recognition and build your reputation as a talented photographer.

5. Building Photo Essay

Many buildings can be a compelling subject for a photographic essay. Always make sure that you have permission to enter and photograph the building. Once you do, look for interesting shots and angles that convey the personality, purpose, and history of the building. You may also be able to photograph the comings and goings of people that visit or work in the building during the day.

Some photographers love to explore and photograph abandoned buildings. With these types of photos, you can provide a window into the past. Definitely make sure you gain permission before entering an abandoned building and take caution since some can have unsafe elements and structures.

6. Historic Site or Landmark Photo Essay

Taking a series of photos of a historic site or landmark can be a great experience. You can learn to capture the same site from different angles to help portray its character and tell its story. And you can also photograph how people visit and engage with the site or landmark. Take photos at different times of day and in varied lighting to capture all its nuances and moods.

You can also use your photographic essay to help your audience understand the history of your chosen location. For example, if you want to provide perspective on the Civil War, a visit to a battleground can be meaningful. You can also visit a site when reenactors are present to share insight on how life used to be in days gone by.

7 . Behind the Scenes Photo Essay

Another fun essay idea is taking photos “behind the scenes” at an event. Maybe you can chronicle all the work that goes into a holiday festival from the early morning set-up to the late-night teardown. Think of the lead event planner as the main character of your story and build the story about him or her.

Or, you can go backstage at a drama production. Capture photos of actors and actresses as they transform their looks with costuming and makeup. Show the lead nervously pacing in the wings before taking center stage. Focus the work of stagehands, lighting designers, and makeup artists who never see the spotlight but bring a vital role in bringing the play to life.

8. Family Photo Essay

If you enjoy photographing people, why not explore photo story ideas about families and relationships? You can focus on interactions between two family members—such as a father and a daughter—or convey a message about a family as a whole.

Sometimes these type of photo essays can be all about the fun and joy of living in a close-knit family. But sometimes they can be powerful portraits of challenging social topics. Images of a family from another country can be a meaningful photo essay on immigration. You could also create a photo essay on depression by capturing families who are coping with one member’s illness.

For these projects on difficult topics, you may want to compose a photo essay with captions. These captions can feature quotes from family members or document your own observations. Although approaching hard topics isn’t easy, these types of photos can have lasting impact and value.

9. Education Photo Essay

Opportunities for education photo essays are everywhere—from small preschools to community colleges and universities. You can seek permission to take photos at public or private schools or even focus on alternative educational paths, like homeschooling.

Your education photo essay can take many forms. For example, you can design a photo essay of an experienced teacher at a high school. Take photos of him or her in action in the classroom, show quiet moments grading papers, and capture a shared laugh between colleagues in the teacher’s lounge.

Alternatively, you can focus on a specific subject—such as science and technology. Or aim to portray a specific grade level, document activities club or sport, or portray the social environment. A photo essay on food choices in the cafeteria can be thought-provoking or even funny. There are many potential directions to pursue and many great essay examples.

While education is an excellent topic for a photo essay for students, education can be a great source of inspiration for any photographer.

Why Should You Create a Photo Essay?

Ultimately, photographers are storytellers. Think of what a photographer does during a typical photo shoot. He or she will take a series of photos that helps convey the essence of the subject—whether that is a person, location, or inanimate object. For example, a family portrait session tells the story of a family—who they are, their personalities, and the closeness of their relationship.

Learning how to make a photo essay can help you become a better storyteller—and a better photographer. You’ll cultivate key photography skills that you can carry with you no matter where your photography journey leads.

If you simply want to document life’s moments on social media, you may find that a single picture doesn’t always tell the full story. Reviewing photo essay examples and experimenting with your own essay ideas can help you choose meaningful collections of photos to share with friends and family online.

Learning how to create photo essays can also help you work towards professional photography ambitions. You’ll often find that bloggers tell photographic stories. For example, think of cooking blogs that show you each step in making a recipe. Photo essays are also a mainstay of journalism. You’ll often find photo essays examples in many media outlets—everywhere from national magazines to local community newspapers. And the best travel photographers on Instagram tell great stories with their photos, too.

With a photo essay, you can explore many moods and emotions. Some of the best photo essays tell serious stories, but some are humorous, and others aim to evoke action.

You can raise awareness with a photo essay on racism or a photo essay on poverty. A photo essay on bullying can help change the social climate for students at a school. Or, you can document a fun day at the beach or an amusement park. You have control of the themes, photographic elements, and the story you want to tell.

5 Steps to Create a Photo Essay

Every photo essay will be different, but you can use a standard process. Following these five steps will guide you through every phase of your photo essay project—from brainstorming creative essay topics to creating a photo essay to share with others.

Step 1: Choose Your Photo Essay Topics

Just about any topic you can imagine can form the foundation for a photo essay. You may choose to focus on a specific event, such as a wedding, performance, or festival. Or you may want to cover a topic over a set span of time, such as documenting a child’s first year. You could also focus on a city or natural area across the seasons to tell a story of changing activities or landscapes.

Since the best photo essays convey meaning and emotion, choose a topic of interest. Your passion for the subject matter will shine through each photograph and touch your viewer’s hearts and minds.

Step 2: Conduct Upfront Research

Much of the work in a good-quality photo essay begins before you take your first photo. It’s always a good idea to do some research on your planned topic.

Imagine you’re going to take photos of a downtown area throughout the year. You should spend some time learning the history of the area. Talk with local residents and business owners and find out about planned events. With these insights, you’ll be able to plan ahead and be prepared to take photos that reflect the area’s unique personality and lifestyles.

For any topic you choose, gather information first. This may involve internet searches, library research, interviews, or spending time observing your subject.

Step 3: Storyboard Your Ideas

After you have done some research and have a good sense of the story you want to tell, you can create a storyboard. With a storyboard, you can write or sketch out the ideal pictures you want to capture to convey your message.

You can turn your storyboard into a “shot list” that you can bring with you on site. A shot list can be especially helpful when you are at a one-time event and want to capture specific shots for your photo essay. If you’ve never created a photo essay before, start with ten shot ideas. Think of each shot as a sentence in your story. And aim to make each shot evoke specific ideas or emotions.

Step 4: Capture Images

Your storyboard and shot list will be important guides to help you make the most of each shoot. Be sure to set aside enough time to capture all the shots you need—especially if you are photographing a one-time event. And allow yourself to explore your ideas using different photography composition, perspective, and color contrast techniques.

You may need to take a hundred images or more to get ten perfect ones for your photographic essay. Or, you may find that you want to add more photos to your story and expand your picture essay concept.

Also, remember to look for special unplanned, moments that help tell your story. Sometimes, spontaneous photos that aren’t on your shot list can be full of meaning. A mix of planning and flexibility almost always yields the best results.

Step 5: Edit and Organize Photos to Tell Your Story

After capturing your images, you can work on compiling your photo story. To create your photo essay, you will need to make decisions about which images portray your themes and messages. At times, this can mean setting aside beautiful images that aren’t a perfect fit. You can use your shot list and storyboard as a guide but be open to including photos that weren’t in your original plans.

You may want to use photo editing software—such as Adobe Lightroom or Photoshop— to enhance and change photographs. With these tools, you can adjust lighting and white balance, perform color corrections, crop, or perform other edits. If you have a signature photo editing style, you may want to use Photoshop Actions or Lightroom Presets to give all your photos a consistent look and feel.

You order a photo book from one of the best photo printing websites to publish your photo story. You can add them to an album on a photo sharing site, such as Flickr or Google Photos. Also, you could focus on building a website dedicated to documenting your concepts through visual photo essays. If so, you may want to use SEO for photographers to improve your website’s ranking in search engine results. You could even publish your photo essay on social media. Another thing to consider is whether you want to include text captures or simply tell your story through photographs.

Choose the medium that feels like the best space to share your photo essay ideas and vision with your audiences. You should think of your photo essay as your own personal form of art and expression when deciding where and how to publish it.

Photo Essays Can Help You Become a Better Photographer

Whatever your photography ambitions may be, learning to take a photo essay can help you grow. Even simple essay topics can help you gain skills and stretch your photographic limits. With a photo essay, you start to think about how a series of photographs work together to tell a complete story. You’ll consider how different shots work together, explore options for perspective and composition, and change the way you look at the world.

Before you start taking photos, you should review photo essay examples. You can find interesting pictures to analyze and photo story examples online, in books, or in classic publications, like Life Magazine . Don’t forget to look at news websites for photojournalism examples to broaden your perspective. This review process will help you in brainstorming simple essay topics for your first photo story and give you ideas for the future as well.

Ideas and inspiration for photo essay topics are everywhere. You can visit a park or go out into your own backyard to pursue a photo essay on nature. Or, you can focus on the day in the life of someone you admire with a photo essay of a teacher, fireman, or community leader. Buildings, events, families, and landmarks are all great subjects for concept essay topics. If you are feeling stuck coming up with ideas for essays, just set aside a few hours to walk around your city or town and take photos. This type of photowalk can be a great source of material.

You’ll soon find that advanced planning is critical to your success. Brainstorming topics, conducting research, creating a storyboard, and outlining a shot list can help ensure you capture the photos you need to tell your story. After you’ve finished shooting, you’ll need to decide where to house your photo essay. You may need to come up with photo album title ideas, write captions, and choose the best medium and layout.

Without question, creating a photo essay can be a valuable experience for any photographer. That’s true whether you’re an amateur completing a high school assignment or a pro looking to hone new skills. You can start small with an essay on a subject you know well and then move into conquering difficult ideas. Maybe you’ll want to create a photo essay on mental illness or a photo essay on climate change. Or maybe there’s another cause that is close to your heart.

Whatever your passion, you can bring it to life with a photo essay.

JOIN OVER 81,811 and receive weekly updates!

Comments are closed.

Photo Contest Insider

The world’s largest collection of photo contests.

Photo contests are manually reviewed by our team to ensure only the very best make it on to our website. It’s our policy to only list photo contests that are fair.

Subscription

Register now to get updates on promotions and offers

DISCLAIMER:

- Photo Contest Filter

- Get FREE Contest Updates

Photo Contest Insider © 2009 - 2024

Advertise Submit Badges Help Terms Privacy Unsubscribe Do Not Sell My Information

Photo Essay

We all know that photographs tell a story. These still images may be seen from various perspectives and are interpreted in different ways. Oftentimes, photographers like to give dramatic meaning to various scenarios. For instance, a blooming flower signifies a new life. Photographs always hold a deeper meaning than what they actually are.

In essay writing , photographs along with its supporting texts, play a significant role in conveying a message. Here are some examples of these kinds of photo-text combinations.

What is Photo Essay? A photo essay is a visual storytelling method that utilizes a sequence of carefully curated photographs to convey a narrative, explore a theme, or evoke specific emotions. It goes beyond individual images, aiming to tell a cohesive and impactful story through the arrangement and combination of pictures.

Photo Essay Format

A photo essay is a series of photographs that are intended to tell a story or evoke a series of emotions in the viewer. It is a powerful way to convey messages without the need for many words. Here is a format to guide you in creating an effective photo essay:

1. Choose a Compelling Topic

Select a subject that you are passionate about or that you find intriguing. Ensure the topic has a clear narrative that can be expressed visually.

2. Plan Your Shots

Outline the story you wish to tell. This could involve a beginning, middle, and end or a thematic approach. Decide on the types of shots you need (e.g., wide shots, close-ups, portraits, action shots) to best tell the story.

3. Take Your Photographs

Capture a variety of images to have a wide selection when editing your essay. Focus on images that convey emotion, tell a story, or highlight your theme.

4. Edit Your Photos

Select the strongest images that best convey your message or story. Edit for consistency in style, color, and lighting to ensure the essay flows smoothly.

5. Arrange Your Photos

Order your images in a way that makes sense narratively or thematically. Consider transitions between photos to ensure they lead the viewer naturally through the story.

6. Include Captions or Text (Optional)

Write captions to provide context, add depth, or explain the significance of each photo. Keep text concise and impactful, letting the images remain the focus.

7. Present Your Photo Essay

Choose a platform for presentation, whether online, in a gallery, or as a printed booklet. Consider the layout and design, ensuring that it complements and enhances the visual narrative.

8. Conclude with Impact

End with a strong image or a conclusion that encapsulates the essence of your essay. Leave the viewer with something to ponder , reflecting on the message or emotions you aimed to convey.

Best Photo Essay Example?

One notable example of a powerful photo essay is “The Photographic Essay: Paul Fusco’s ‘RFK Funeral Train'” by Paul Fusco. This photo essay captures the emotional journey of the train carrying the body of Robert F. Kennedy from New York to Washington, D.C., after his assassination in 1968. Fusco’s images beautifully and poignantly document the mourning and respect shown by people along the train route. The series is a moving portrayal of grief, unity, and the impact of a historical moment on the lives of ordinary individuals. The photographs are both artistically compelling and deeply human, making it a notable example of the potential for photo essays to convey complex emotions and historical narratives.

Photo Essay Examples and Ideas to Edit & Download

- A Day in the Life Photo Essay

- Behind the scenes Photo Essay

- Event Photo Essay

- Photo Essay on Meal

- Photo Essay on Photo walking

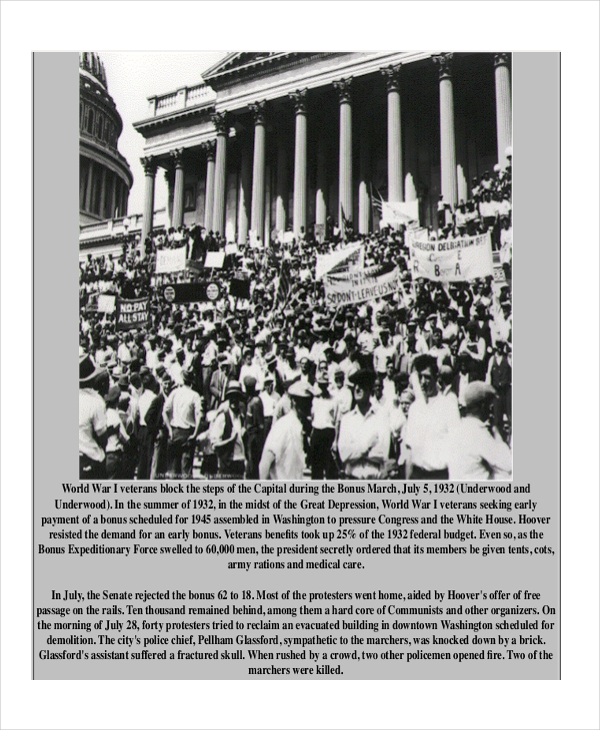

- Photo Essay on Protest

- Photo Essay on Abandoned building

- Education photo essay

- Photo Essay on Events

- Follow the change Photo Essay

- Photo Essay on Personal experiences

Photo Essay Examples & Templates

1. narrative photo essay format example.

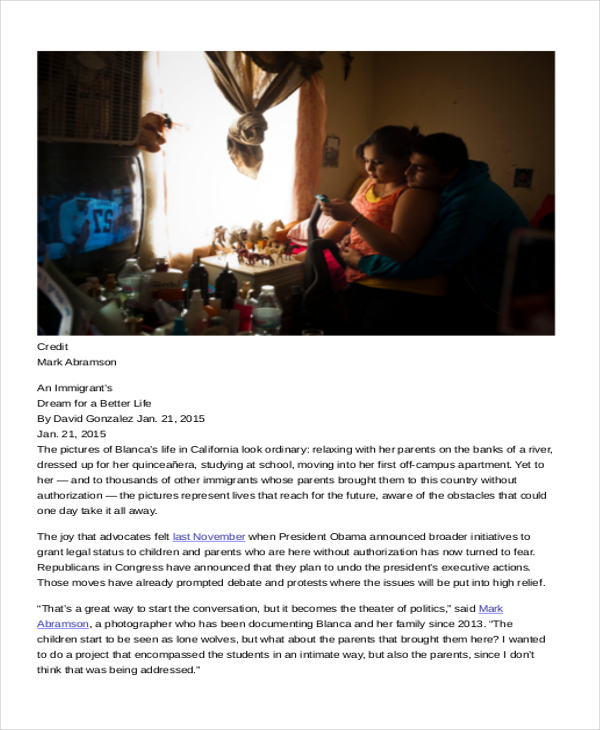

nytimes.com

2. Student Photo Essay Example

3. Great Depression Essay Example

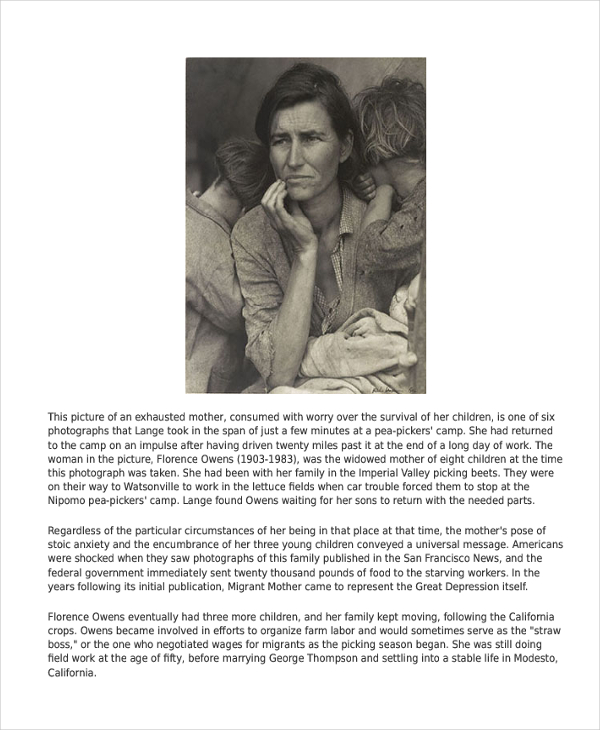

thshistory.files.wordpress.com

4. Example of Photo Essay

weresearchit.co.uk

5. Photo Essay Examples About Nature

cge-media-library.s3.ca-central-1.amazonaws.com

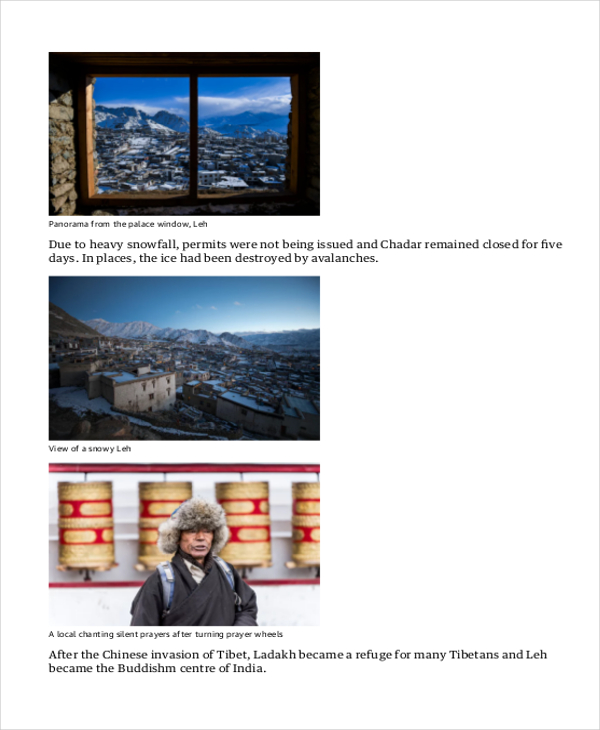

6. Travel Photo Example

theguardian.com

7. Free Photo Essay Example

vasantvalley.org

Most Interesting Photo Essays of 2019

Now that you are educated with the fundamentals of photo essays, why not lay eyes on some great photo essays for inspiration. To give you a glimpse of a few epitomes, we collected the best and fascinating photo essays for you. The handpicked samples are as follows:

8. Toys and Us

journals.openedition.org

This photo essay presents its subject which is the latest genre of photography, toy photography. In this type of picture taking, the photographer aims to give life on the toys and treat them as his/her model. This photography follows the idea of a toy researcher, Katrina Heljakka, who states that also adults and not only children are interested in reimagining and preserving the characters of their toys with the means of roleplay and creating a story about these toys. This photo essay is based on the self-reflection of the author on a friend’s toys in their home environment.

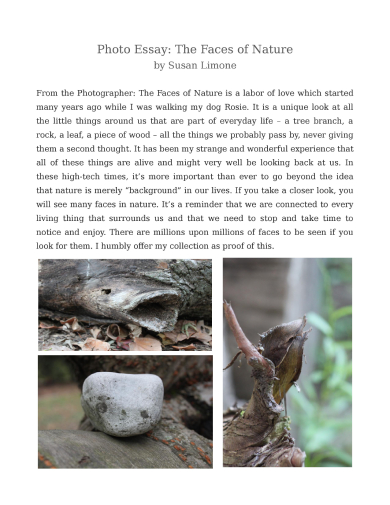

9. The Faces of Nature Example

godandnature.asa3.org

This photo essay and collection caters the creativity of the author’s mind in seeing the world. In her composition, she justified that there are millions of faces that are naturally made that some of us have not noticed. She also presented tons of photos showing different natural objects that form patterns of faces. Though it was not mentioned in the essay itself, the author has unconsciously showcased the psychological phenomenon, pareidolia. This is the tendency to translate an obscure stimulus that let the observer see faces in inanimate objects or abstract patterns, or even hearing concealed messages in music.

10. The Country Doctor Example

us1.campaign-archive.com

This photo essay depicts the medical hardships in a small rural town in Colorado called Kremling. For 23 days, Smith shadowed Dr. Ernest Ceriani, witnessing the dramatic life of the small town and capturing the woeful crisis of the region. The picture in this photographic essay was photographed by Smith himself for Life magazine in 1948 but remained as fascinating as it was posted weeks ago.

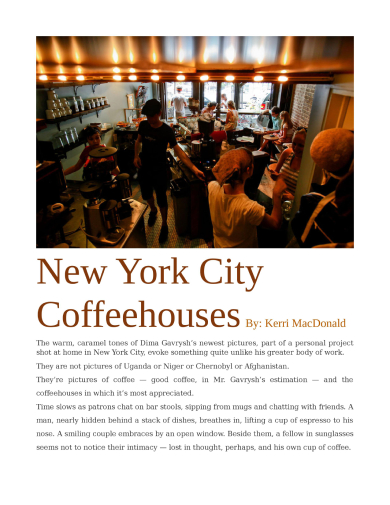

11. New York City Coffeehouses

lens.blogs.nytimes.com

Café Latte, cappuccino, espresso, or flat white—of course, you know these if you have visited a coffee shop at least once. However, the photographer of this photo essay took it to a whole new level of experience. Within two to three days of visiting various coffee places, Mr. Gavrysh stayed most of his day observing at the finest details such as the source of the coffee, the procedure of delivering them, and the process of roasting and grounding them. He also watched how did the baristas perfect the drinks and the reaction of the customers as they received their ordered coffee with delights in their faces. Gavrysh did not mean to compose a coffeehouse guide, but to make a composition that describes modern, local places where coffee is sipped and treated with respect.

12. Hungry Planet: What The World Eats

13. Photo Essay Example

cah.utexas.edu

14. Photo Essay in PDF

condor.depaul.edu

15. Sample Photo Essay Example

colorado.edu

16. Basic Photo Essay Example

adaptation-undp.org

17. Printable Photo Essay Example

One of the basic necessity of a person to live according to his/her will is food. In this photo essay, you will see how these necessities vary in several ways. In 2005, a pair of Peter Menzel and Faith D’ Aluisio released a book that showcased the meals of an average family in 24 countries. Ecuador, south-central Mali, China, Mexico, Kuwait, Norway, and Greenland are among the nations they visited. This photo essay is written to raise awareness about the influence of environment and culture to the cost and calories of the foods laid on the various dining tables across the globe.

Photo essays are not just about photographic aesthetics but also the stories that authors built behind those pictures. In this collection of captivating photo essays, reflect on how to write your own. If you are allured and still can’t get enough, there’s no need for you to be frantic about. Besides, there are thousands of samples and templates on our website to browse. Visit us to check them all out.

What are good topics for a photo essay?

- Urban Exploration: Document the unique architecture, street life, and cultural diversity of urban environments.

- Environmental Conservation: Capture the beauty of natural landscapes or document environmental issues, showcasing the impact of climate change or conservation efforts.

- Everyday Life in Your Community: Showcase the daily lives, traditions, and activities of people in your local community.

- Family Traditions: Document the customs, rituals, and special moments within your own family or another family.

- Youth Culture: Explore the lifestyle, challenges, and aspirations of young people in your community or around the world.

- Behind-the-Scenes at an Event: Provide a backstage look at the preparation and execution of an event, such as a concert, festival, or sports competition.

- A Day in the Life of a Profession: Follow a professional in their daily activities, offering insights into their work, challenges, and routines.

- Social Issues: Address important social issues like homelessness, poverty, immigration, or healthcare, raising awareness through visual storytelling.

- Cultural Celebrations: Document cultural festivals, ceremonies, or celebrations that showcase the diversity of traditions in your region or beyond.

- Education Around the World: Explore the various facets of education globally, from classrooms to the challenges students face in different cultures.

- Workplace Dynamics: Capture the atmosphere, interactions, and diversity within different workplaces or industries.

- Street Art and Graffiti: Document the vibrant and dynamic world of street art, capturing the expressions of local artists.

- Animal Rescues or Shelters: Focus on the efforts of organizations or individuals dedicated to rescuing and caring for animals.

- Migration Stories: Explore the experiences and challenges of individuals or communities affected by migration.

- Global Food Culture: Document the diversity of food cultures, from local markets to family meals, showcasing the role of food in different societies.

How to Write a Photo Essay

First of all, you would need to find a topic that you are interested in. With this, you can conduct thorough research on the topic that goes beyond what is common. This would mean that it would be necessary to look for facts that not a lot of people know about. Not only will this make your essay interesting, but this may also help you capture the necessary elements for your images.

Remember, the ability to manipulate the emotions of your audience will allow you to build a strong connection with them. Knowing this, you need to plan out your shots. With the different emotions and concepts in mind, your images should tell a story along with the essay outline .

1. Choose Your Topic

- Select a compelling subject that interests you and can be explored visually.

- Consider the story or message you want to convey. It should be something that can be expressed through images.

2. Plan Your Essay

- Outline your narrative. Decide if your photo essay will tell a story with a beginning, middle, and end, or if it will explore a theme or concept.

- Research your subject if necessary, especially if you’re covering a complex or unfamiliar topic.

3. Capture Your Images

- Take a variety of photos. Include wide shots to establish the setting, close-ups to show details, and medium shots to focus on subjects.

- Consider different angles and perspectives to add depth and interest to your essay.

- Shoot more than you need. Having a large selection of images to choose from will make the editing process easier.

4. Select Your Images

- Choose photos that best tell your story or convey your theme.

- Look for images that evoke emotion or provoke thought.

- Ensure there’s a mix of compositions to keep the viewer engaged.

- Sequence your images in a way that makes narrative or thematic sense.

- Consider the flow and how each image transitions to the next.

- Use juxtaposition to highlight contrasts or similarities.

6. Add Captions or Text (Optional)

- Write captions to provide context or additional information about each photo. Keep them brief and impactful.

- Consider including an introduction or conclusion to frame your essay. This can be helpful in setting the stage or offering a final reflection.

7. Edit and Refine

- Review the sequence of your photos. Make sure they flow smoothly and clearly convey your intended story or theme.

- Adjust the layout as needed, ensuring that the visual arrangement is aesthetically pleasing and supports the narrative.

8. Share Your Essay

- Choose the right platform for your photo essay, whether it’s a blog, online publication, exhibition, or print.

- Consider your audience and tailor the presentation of your essay to suit their preferences and expectations.

Types of Photo Essay

Photo essays are a compelling medium to tell a story, convey emotions, or present a perspective through a series of photographs. Understanding the different types of photo essays can help photographers and storytellers choose the best approach for their project. Here are the main types of photo essays:

1. Narrative Photo Essays

- Purpose: To tell a story or narrate an event in a chronological sequence.

- Characteristics: Follows a clear storyline with a beginning, middle, and end. It often includes characters, a setting, and a plot.

- Examples: A day in the life of a firefighter, the process of crafting traditional pottery.

2. Thematic Photo Essays

- Purpose: To explore a specific theme, concept, or issue without being bound to a chronological sequence.

- Characteristics: Centers around a unified theme, with each photo contributing to the overall concept.

- Examples: The impact of urbanization on the environment, the beauty of natural landscapes.

3. Conceptual Photo Essays

- Purpose: To convey an idea or evoke a series of emotions through abstract or metaphorical images.

- Characteristics: Focuses on delivering a conceptual message or emotional response, often using symbolism.

- Examples: Loneliness in the digital age, the concept of freedom.

4. Expository or Informative Photo Essays

- Purpose: To inform or educate the viewer about a subject with a neutral viewpoint.

- Characteristics: Presents factual information on a topic, often accompanied by captions or brief texts to provide context.

- Examples: The process of coffee production, a day at an animal rescue center.

5. Persuasive Photo Essays

- Purpose: To convince the viewer of a particular viewpoint or to highlight social issues.

- Characteristics: Designed to persuade or elicit action, these essays may focus on social, environmental, or political issues.

- Examples: The effects of plastic pollution, the importance of historical preservation.

6. Personal Photo Essays

- Purpose: To express the photographer’s personal experiences, emotions, or journeys.

- Characteristics: Highly subjective and personal, often reflecting the photographer’s intimate feelings or experiences.

- Examples: A personal journey through grief, documenting one’s own home during quarantine.

7. Environmental Photo Essays

- Purpose: To showcase landscapes, wildlife, and environmental issues.

- Characteristics: Focuses on the natural world or environmental challenges, aiming to raise awareness or appreciation.

- Examples: The melting ice caps, wildlife in urban settings.

8. Travel Photo Essays

- Purpose: To explore and present the culture, landscapes, people, and experiences of different places.

- Characteristics: Captures the essence of a location, showcasing its uniqueness and the experiences of traveling.

- Examples: A road trip across the American Southwest, the vibrant streets of a bustling city.

How do you start a picture essay?

1. choose a compelling theme or topic:.

Select a theme or topic that resonates with you and has visual storytelling potential. It could be a personal project, an exploration of a social issue, or a visual journey through a specific place or event.

2. Research and Conceptualize:

Conduct research on your chosen theme to understand its nuances, context, and potential visual elements. Develop a conceptual framework for your photo essay, outlining the key aspects you want to capture.

3. Define Your Storytelling Approach:

Determine how you want to convey your narrative. Consider whether your photo essay will follow a chronological sequence, a thematic structure, or a more abstract and conceptual approach.

4. Create a Shot List:

Develop a list of specific shots you want to include in your essay. This can help guide your photography and ensure you capture a diverse range of images that contribute to your overall narrative.

5. Plan the Introduction:

Think about how you want to introduce your photo essay. The first image or series of images should grab the viewer’s attention and set the tone for the narrative.

6. Consider the Flow:

Plan the flow of your photo essay, ensuring a logical progression of images that tells a cohesive and engaging story. Consider the emotional impact and visual variety as you sequence your photographs.

7. Shoot with Purpose:

Start capturing images with your conceptual framework in mind. Focus on images that align with your theme and contribute to the overall narrative. Look for moments that convey emotion, tell a story, or reveal aspects of your chosen subject.

8. Experiment with Perspectives and Techniques:

Explore different perspectives, compositions, and photographic techniques to add visual interest and depth to your essay. Consider using a variety of shots, including wide-angle, close-ups, and detail shots.

9. Write Descriptive Captions:

As you capture images, think about the accompanying captions. Captions should provide context, additional information, or insights that enhance the viewer’s understanding of each photograph.

What are the key elements of a photo essay?

1. Theme or Topic:

Clearly defined subject matter or theme that unifies the photographs and tells a cohesive story.

2. Narrative Structure:

An intentional narrative structure that guides the viewer through the photo essay, whether chronological, thematic, or conceptual.

3. Introduction:

A strong introduction that captures the viewer’s attention and sets the tone for the photo essay.

4. Captivating Images:

A series of high-quality and visually compelling images that effectively convey the chosen theme or story.

5. Variety of Shots:

A variety of shots, including wide-angle, close-ups, detail shots, and different perspectives, to add visual interest and depth.

6. Sequencing:

Careful sequencing of images to create a logical flow and emotional impact, guiding the viewer through the narrative.

7. Captions and Text:

Thoughtful captions or accompanying text that provide context, additional information, or insights, enhancing the viewer’s understanding.

8. Conclusion:

A concluding section that brings the photo essay to a satisfying close, leaving a lasting impression on the viewer.

Purpose of a Photo Essay

With good writing skills , a person is able to tell a story through words. However, adding images for your essay will give it the dramatic effect it needs. The photographs and the text work hand in hand to create something compelling enough to attract an audience.

This connection goes beyond something visual, as photo essays are also able to connect with an audience emotionally. This is to create an essay that is effective enough to relay a given message.

5 Tips for Creating a Photo Essay

- Don’t be afraid to experiment. Find the right angle and be dramatic with your description, just be creative.

- Pay attention to detail. Chances are, your audience will notice every single detail of your photograph.

- Shoot everything. Behind a single beautiful photo is a hundred more shots.

- Don’t think twice about editing. Editing is where the magic happens. It has the ability to add more drama to your images.

- Have fun. Don’t stress yourself out too much but instead, grow from your experience.

What is a photo essay for school?

A school photo essay is a visual storytelling project for educational purposes, typically assigned to students. It involves creating a narrative using a series of carefully curated photographs on a chosen theme.

How many pictures should be in a photo essay?

The number of pictures in a photo essay varies based on the chosen theme and narrative structure. It can range from a few impactful images to a more extensive series, typically around 10-20 photographs.

Is a photo essay a story?

Yes, a photo essay is a visual storytelling form. It uses a series of carefully curated photographs to convey a narrative, evoke emotions, or communicate a specific message or theme.

What makes a photo essay unforgettable?

An unforgettable photo essay is characterized by a powerful theme, emotionally resonant images, a well-crafted narrative structure, attention to detail, and a connection that leaves a lasting impact on viewers.

Photo Essay Generator

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

Create a Photo Essay on the theme of urban exploration.

Discuss the story of a local community event through a Photo Essay.

- Student Successes

- My Learning

17 Awesome Photo Essay Examples You Should Try Yourself

You can also select your interests for free access to our premium training:

If you’re looking for a photo essay example (or 17!), you’ve come to the right place. But what is the purpose of a photo essay? A photo essay is intended to tell a story or evoke emotion from the viewers through a series of photographs. They allow you to be creative and fully explore an idea. But how do you make one yourself? Here’s a list of photo essay examples. Choose one that you can easily do based on your photographic level and equipment.

Top 17 Photo Essay Examples

Here are some fantastic ideas to get you inspired to create your own photo essays!

17. Photograph a Protest

16. Transformation Photo Essays

15. Photograph the Same Place

14. Create a Photowalk

13. Follow the Change

12. Photograph a Local Event

11. Photograph an Abandoned Building

10. Behind the Scenes of a Photo Shoot

9. Capture Street Fashion

8. Landmark Photo Essay

7. Fathers & Children

6. A Day In the Life

5. Education Photo Essay