E-learning for the development of critical thinking: A systematic literature review

Ieee account.

- Change Username/Password

- Update Address

Purchase Details

- Payment Options

- Order History

- View Purchased Documents

Profile Information

- Communications Preferences

- Profession and Education

- Technical Interests

- US & Canada: +1 800 678 4333

- Worldwide: +1 732 981 0060

- Contact & Support

- About IEEE Xplore

- Accessibility

- Terms of Use

- Nondiscrimination Policy

- Privacy & Opting Out of Cookies

A not-for-profit organization, IEEE is the world's largest technical professional organization dedicated to advancing technology for the benefit of humanity. © Copyright 2024 IEEE - All rights reserved. Use of this web site signifies your agreement to the terms and conditions.

CURRICULUM, INSTRUCTION, AND PEDAGOGY article

Students' perceptions of a blended learning environment to promote critical thinking.

- School of Foreign Languages, Northeast Normal University, Changchun, China

Critical thinking is considered as one of the indispensable skills that must be possessed by the citizens of modern society, and its cultivation with blended learning has drawn much attention from researchers and practitioners. This study proposed the construction of a blended learning environment, where the pedagogical, social, and technical design was directed to fostering critical thinking. The purpose of the study was to find out students' perceptions of the learning environment concerning its design and its influence on their critical thinking. Adopting the mixed method, the study used questionnaire and interview as the instruments for data collection. The analysis of the data revealed that the students generally held positive perceptions of the environment, and they believed that the blended learning environment could help promote their critical thinking in different aspects.

Introduction

The development of critical thinking has drawn attention of the education ministries and institutions of different levels in countries all over the world. In the last two decades, researchers and practitioners have been exploring the ways to integrate critical thinking cultivation into the instruction of different disciplines, proposing strategies and interventions to promote critical thinking, among which blended learning has been widely recognized (e.g., Van Gelder and Bulker, 2000 ; Gilbert and Dabbagh, 2005 ; Yukawa, 2006 ). Blended learning is proposed as focusing on optimizing achievement of learning objectives by applying the “right” personal learning technologies to the “right” person at the “right” time and “right” place ( Singh, 2003 ). A blended learning environment, integrating the advantages of the e-learning method and traditional method, is believed to be more effective than a face-to-face or online learning environment alone ( Kim and Bonk, 2006 ; Watson, 2008 ; Yen and Lee, 2011 ). Studies have been conducted to construct blended learning environments to improve students' critical thinking. Most of them, however, adopted standardized tests or coding schemes to examine the effectiveness of the learning environments on students' critical thinking ( Chou et al., 2018 ), paying less attention to students' perceptions and attitudes. Therefore, the purpose of the current study is to address this gap.

Critical Thinking

There are a vast number of definitions of critical thinking in the literature (e.g., Paul, 1992 ; Ennis, 1996 ; Fisher and Scriven, 1997 ). Despite the emphasis on different aspects, the core of critical thinking entails taking charge of one's thinking to improve it. Paul and Elder's definition and model of critical thinking were adopted in the study. According to Elder and Paul (1994) , critical thinking refers to “the ability of individuals to take charge of their own thinking and develop appropriate criteria and standards for analyzing their own thinking” (p. 34). They proposed that critical thinking is composed of three dimensions: elements of thinking, intellectual standards, and intellectual traits. People demonstrate critical thinking when they use intellectual standards (clarity, precision, accuracy, importance, relevance, sufficiency, logic, fairness, breadth, depth) to measure elements of thinking (purposes, assumptions, questions, points of view, information, implications, concepts, inferences) ( Paul and Elder, 1999 ).

Critical Thinking Cultivation With Information Communication Technology Tools

Studies applying ICT tools to cultivate critical thinking have been increasingly emerging in the literature. The systematic review conducted by Chou et al. (2018) analyzed and reported the trends and features of critical thinking studies with ICT tools. According to the findings of the review, the most often used tools include online discussion (e.g., Cheong and Cheung, 2008 ), coding or game design or Wikibooks creation (e.g., Yang and Chang, 2013 ), and concept or argument maps (e.g., Rosen and Tager, 2014 ). As for the method involved, the studies adopted both quantitative and qualitative research methods (e.g., Shamir et al., 2008 ; Yang, 2008 ; Yang and Chou, 2008 ; Butchart et al., 2009 ; de Leng et al., 2009 ; Yeh, 2009 ). Data from various measurements revealed overall positive results of using ICT tools in critical thinking cultivation (e.g., Yang, 2008 ; Allaire, 2015 ; Shin et al., 2015 ; Huang et al., 2017 ). The findings of the systematic review showed that the critical thinking-embedded activities using ICT tools were more effective than face-to-face activities in developing students' critical thinking ( Guiller et al., 2008 ; Adam and Manson, 2014 ; Eftekhari et al., 2016 ). However, students' prescriptions of the learning design or critical thinking development have not been fully addressed in the literature.

Blended Learning Environment

The concept of blended learning has been defined by several researchers and scholars. For instance, Singh and Reed (2001) defined blended learning as a learning program where more than one delivery mode is being used to optimize the learning outcome and cost of program delivery. According to Thorne (2003) , blended learning is a way of “meeting the challenges of tailoring learning and development to the needs of individuals by integrating the innovative and technological advances offered by online learning with the interaction and participation offered in the best of traditional learning” (p. 2). The above definitions indicate that blended learning can combine the advantages of both traditional face-to-face learning and e-learning and avoid the drawbacks of the two learning modes. The effectiveness of blended learning has been demonstrated by many studies, for example, the findings of a meta-analysis have shown that blended learning brings more positive impact on students learning than online and face-to-face learning ( BatdÄ, 2014 ). Despite the merits of blended learning itself, the effectiveness is determined by the proper design. How to achieve the equilibrium between e-learning and face-to-face modes is crucial to the success of the blended learning environment ( Osguthorpe and Graham, 2003 ).

This study applied the PST model developed by Wang (2008) as the framework for the environment design. As Kirschner et al. (2004) pointed out, an educational system is a unique combination of pedagogical, social, and technological components. PST model thus consists of three key components: pedagogy, social interaction, and technology. According to Wang (2008) , the pedagogical design involves the selection of appropriate content, activities, and the way to use the resources; the social design refers to the construction of a safe and comfortable environment where learners can share and communicate; the technical design provides learners with a technical space of availability, easy access and attractiveness. In any learning environment, the three components play different roles. The technical design offers a basic condition for pedagogical and social design, while the pedagogical and social design is considered as the most important factor that influences the effectiveness of learning ( Wang, 2008 ).

Perceptions of Blended Learning Environment

It has been acknowledged that students' perceptions and satisfaction are important for determining the quality of blended learning environment ( Naaj et al., 2012 ). Studies have been conducted to examine students' views regarding a blended learning environment and factors influencing it. For example, Bendania (2011) study found that students hold positive attitudes toward the blended learning environment and the influencing factors mainly include experience, confidence, enjoyment, usefulness, intention to use, motivation, and whether students had ICT skills. The positive view was also reported in the study done by Akkoyunlu and Yilmaz (2006) , and it was found to be closely related to students' participation in the online discussion forum. Findings from other studies (e.g., Dziuban et al., 2006 ; Owston et al., 2006 ) also revealed students' positive attitudes toward the blended learning environment, and the satisfaction could be attributed to features like flexibility, convenience, reduced travel time, and face-to-face interaction. Some studies, however, reported some negative perceptions of the blended learning environment. For example, the results of the study of Smyth et al. (2012) showed that the delayed feedback from the teacher and poor connectivity of the internet were perceived as major drawbacks of the environment. In another study conducted by Stracke (2007) , lack of reciprocity between traditional and online modes, no use of printed books for reading and writing, and use of the computer as a medium of instruction was considered as major reasons for students withdraw from the blended course. These findings indicate that students' negative attitudes toward the blended learning environment mainly come from the inadequate design ( Sagarra and Zapata, 2008 ).

The review of the above studies indicates that applying ICT tools to cultivate critical thinking has gained much popularity and produced positive results. Few studies, however, focus on students' perceptions of a learning environment designed to promote critical thinking despite the fact that many studies have been conducted to explore students' perceptions of a blended learning environment in general. Therefore, the purpose of the current research is to investigate students' perceptions of a blended learning environment with the orientation of critical thinking development.

Research Design

Research questions.

By adopting the mixed method, this study aims to answer the following two questions:

1. What are students' perceptions of the blended learning environment to promote critical thinking?

2. How do students perceive the impact of the blended learning environment on the development of their critical thinking?

Context and Participants

The study was carried out in the course of Practical English Writing which is a branch of the comprehensive English course for first-year non-English majors at a Normal University in mainland China. The 6-week course adopted a mixed learning mode of classroom face-to-face and online learning. The face-to-face class ran once a week and each class was 90 min. The e-learning tasks were assigned either before or after the class. Six independent learning centers with networked computers were available for students to use and the whole campus was covered with Wi-Fi signal.

The participants of the study involved a total of 90 non-English major students (33 males and 57 females) aging from 18 to 20 in 2020. The students were allocated into classes of Level A after the placement test of English proficiency, which means their English was about higher intermediate level. Adopting the International Critical Thinking Reading and Writing Test ( Paul and Elder, 2006 ), which was developed from Paul and Elders' thinking model, the study assessed students' critical thinking level at the beginning of the course and found that the students' overall critical thinking level was at the lower medium level. But their information literacy level was sufficient to cope with the online platform and the software in the blended learning environment. Before the implementation of the course, the instructor informed the students about the study, and the consent forms were signed by the students.

Environment Design

For the learning environment to achieve the purpose of developing learners' critical thinking, its structural components should be designed to provide favorable conditions for critical thinking cultivation. A systematic review conducted by Lu (2018) has identified a series of favoring conditions that could promote the students' critical thinking, which include (a) critical thinking as one of the teaching objectives, (b) tasks involving the operation of ideas, (c) authentic context, (d) rich and diversified resources, (e) interaction and collaboration, (f) scaffolding and guidance, (g) communicative tools. These conditions were mapped to the design of the components of the PST learning environment model and the designing strategies were generalized from the instruction practice to guide the detailed design of the environmental components.

Pedagogical Design

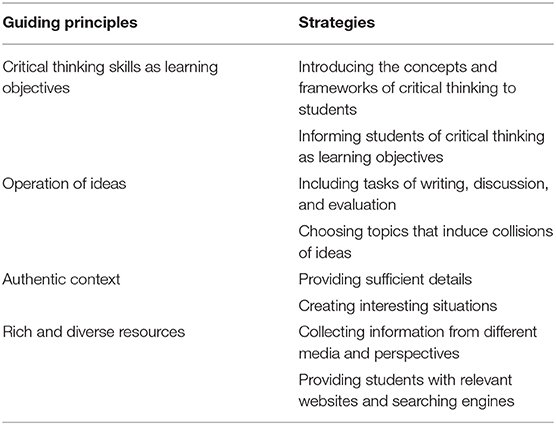

In terms of the pedagogical design, the thinking skills that can be cultivated were first decided according to the particular learning content. Aiming at promoting the thinking skills, the learning tasks which mostly introduced problems in the “real” context and involve the operation of ideas were designed. Furthermore, rich and diversified resources were provided to the students. The specific strategies of pedagogical design are listed in Table 1 .

Table 1 . Strategies for pedagogical design.

When designing the learning objectives of the activities, the basic concepts and frameworks of critical thinking were introduced to the students, making them aware of its meaning and significace. Furthermore, students were informed of the thinking skills targeted and their importance. When students associated the thinking skills with the tasks, they would try to use the skills to accomplish them.

In order to enable tasks to involve more operations of ideas, writing, discussion, and evaluation activities were given the priority to provide more opportunities for students to communicate with each other and reflect upon their ideas. Besides, the topics of these activities were chosen to induce more collision of ideas. For example, in learning to write complaint letters, students were assigned the roles of customers who made the complaints and the managers who responded to the complaints. In such an activity, students could realize the existence of different perspectives and think more adequately and deeply.

The creation of a relatively real context drew on the following two strategies: One is to provide sufficient details. In the case of the job application writing, details such as the information about the potential employer were provided to the students so that they could consider themselves as “real” potential employees. The other strategy is to create interesting situations. The contexts described were usually attractive to the students, which helped arouse students' interest in completing the tasks.

With the purpose of collecting sufficient and diversified resources, both traditional and online media were included. Since the materials in the textbook are rather limited, the relevant online resources would make complementation for students to have sufficient resources to deal with. To meet the multi-angle nature of resources, the information collected came from different positions and perspectives. For instance, the students were introduced to the websites both for job hunting and recruitment so that they could read information from the perspectives of both employers and potential employees. To help students conduct resource searches by themselves, online resources such as the Online Writing Lab of Purdue University were presented to them to conduct searches. The search was usually directed by a clear question or a problem, and students needed to accurately identify the target source. Some search engines were also introduced to the students, enabling them to compare and select the relevant resources. Students needed to first define what their search objectives were, then assess the search and query results one by one, and finally synthesize the resources to make a reasonable decision.

Social Design

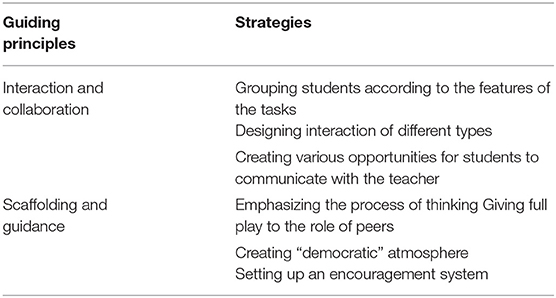

With the purpose of cultivating students' critical thinking in the environment, interactions and collaborations of different types were stressed in the design (see Table 2 ). Furthermore, the scaffold and guidance from the teacher and the peer were designed to provide support to the students.

Table 2 . Strategies for social design.

In designing interaction and collaboration-rich community, the strategies were applied to target both student-student and student-teacher communities. In terms of student-student community, students were grouped according to their levels and the requirements of the activities. Specifically, in a demanding task, students of different academic levels were grouped to ensure the implementation. In a relatively free discussion, students were grouped according to their own will so that they could feel more comfortable sharing their ideas. Also, various types of interactions such as information exchange, discussion, debate were designed. With the change of partners, roles, and tasks, different critical thinking skills were trained. As for the student-teacher community, the student-teacher communication was facilitated through various forms of teacher-student interaction, such as teachers' feedback, office hour, and communications on Tencent QQ, which were necessary to keep students on the right track of developing thinking skills. With various opportunities of communicating with the teacher, students would not feel powerless or frustrated when facing difficult tasks, thus ensuring the achievement of the learning objectives.

Four strategies were employed when designing the scaffolding and guidance. First, the process of thinking was highlighted. When the focus fell on critical thinking processes such as establishing viewpoints, making assumptions, and evaluating information, students had examples to follow when they conducted these activities independently. Second, the role of peers was given full play. In many cases, the demonstration of peers was more direct and effective for the students to develop critical thinking skills. Third, the teacher consciously created a “democratic” classroom and online atmosphere, where students could express their opinions without fearing judgment from the “authority” or other people. Fourth, the teacher established awarding incentives to encourage students to take the initiative to meet challenges and develop thinking. For example, if one student's feedback to others' work was deeper and more thorough, the instructor gave the student more marks and demonstrated the work to the whole class with their permission.

Technological Design

Moodle (Modular Object-Oriented Dynamic Learning Environment) was the main platform of the e-learning environment. A composition reviewing and grading software TRP (Teaching Resources Platform) was also used to facilitate teachers' grading of the compositions. TRP mainly focuses on the mistakes related to language and grammar, which could help direct teachers' attention to the composition's structure, logic, coherence, and other aspects. In addition, Tencent QQ, a social networking software frequently used by students, was selected to send messages and notices to students.

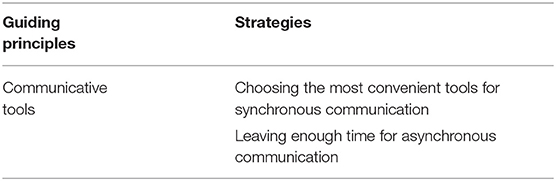

As shown in Table 3 , both synchronous and asynchronous instruments were applied to provide sufficient communication among students in designing communicative tools. When designing the synchronous instruments, the instructor used the Tencent QQ, which could conveniently support the simultaneous real-time communication between learners and encourage group members to fully communicate with each other. The discussion board of Moodle was used as asynchronous tools, and sufficient time was given to the students to respond to other people's opinions or solve problems. The students could use the time to find information, consult others and translate complex ideas into words.

Table 3 . Strategies for technological design.

Research Instruments

Learning environment questionnaire.

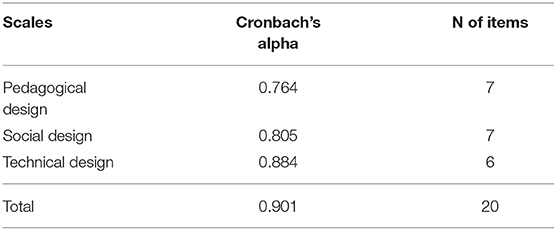

The questionnaire adapted from the Web-Based Learning Environment Instrument (WEBLEI) was used to elicit the information of students' perception of the learning environment. The original WEBLEI questionnaire was first created and subsequently modified by Chang and Fisher for investigating online learning environments in University settings. The primary purpose of the questionnaire was to capture “students' perception of web-based learning environments” ( Chang and Fisher, 2003 , p. 9). The questions in the WEBLEI questionnaire are able to cover the three elements of the PST learning environment model. The researcher modified the questionnaire according to the context of the current study. The Cronbach alpha coefficients indicated the acceptable reliability of the modified questionnaire (see Table 4 ).

Table 4 . Cronbach alpha coefficients for modified WEBLEI.

In order to explore students' perceived improvement of critical thinking and the in-depth reasons behind students' perceptions of the learning environment and critical thinking instruction, interviews were conducted after the administration of the adapted WEBLEI questionnaire. Eight students were randomly chosen and invited to the interview one by one. The interviews lasted about 30 min and were audio-recorded with the participants' approval.

Data Analysis

Both quantitative and qualitative data were collected for this study. In terms of quantitative analysis, descriptive statistics were used to describe the means, standard deviations. As for qualitative data, the recordings of the interviews were transcribed for content analysis. The content about the perceptions of the environment was categorized with the outline of the learning environment components. Regarding the development of students' critical thinking, the “elements of thinking” from Paul and Elder's thinking model formed the framework for data analysis. The relevant script was examined and coded according to the framework by the researcher and her collegue to generalize the aspects of critical thinking improvement.

Results and Discussion

Students' perceptions of the environment, students' perception of the pedagogical design.

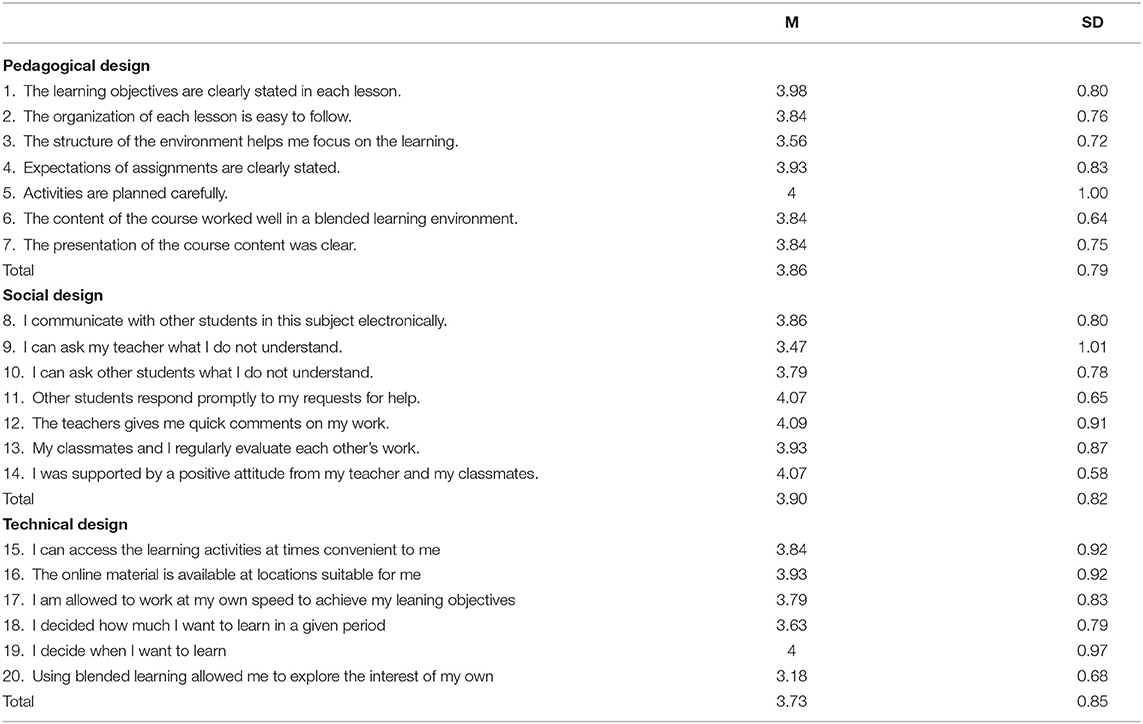

The means and standard deviation scores of students' perception of the pedagogical design are listed in Table 5 . The overall mean score was 3.86 (SD = 0.79), suggesting that students were generally satisfied with the pedagogical design. Item 1 (M = 3.98, SD = 0.80) (The learning objectives are clearly stated), Item 4 ( M = 3.93, SD = 0.83) (Expectations of assignments are clearly stated), and Item 5 (M = 4, SD = 1.00) (Activities are planned carefully) got particularly high scores, which indicates that students were aware of the careful design of the activities, content, and context.

Table 5 . Students' Perceptions of the Environment.

The students' positive attitude toward the pedagogical design was also revealed from the interview, in which they expressed their satisfaction with the design of tasks and contexts. For example, Student A expressed that the course was designed in the way that they needed to “find solutions to the problems” by themselves most of the time and he also enjoyed the discussions in class. Student C recognized the relative authentic contexts of the tasks, which helped her devote herself to the tasks. She mentioned that in learning to write a CV, the teacher asked the students to imagine the situation in which they were about to graduate and hunt a job. “I felt the topic was very relevant to me, so I was motivated to do this task well.” She told the interviewer.

Apart from the positive opinions, some students expressed their concern about the pedagogical design. For example, Student H said, “The online learning added to our workload. Sometimes I was scared of all the online assignments we had to finish after class.” And student G had difficulty adapting to this learning approach. “It seemed that we were learning by ourselves. I am not sure whether I have learned enough knowledge. I would rather learn how to write from the teacher.”

Students' Perception of Social Design

As seen from Table 5 , the overall mean score of the social design was 3.90 ( M = 0.82), indicating students' generally positive attitude toward the social design. The data gathered from the students' interviews also suggested that students were satisfied with the social design. For example, student B mentioned that she always received encouragement and help when dealing with difficult tasks. Item 11 ( M = 4.07, SD = 0.65) (Other students respond promptly to my request), Item 12 ( M = 4.09, SD = 0.91) (The teachers give me quick comments on my work) and Item 14 ( M = 4.07, SD = 0.58) (I was supported by a positive attitude from my teacher and my classmates) scored higher than Item 9 ( M = 3.47, SD = 1.01) (I can ask my teacher what I do not understand) and Item 10 ( M = 3.79, SD = 0.78) (I can ask other classmates what I do not understand). This finding reveals that in the environment, both students and teachers responded to others promptly, but students had considerations when they needed to consult others.

When asked the reason for this, the students suggested that the teacher and the environment did provide them with the opportunity to seek help, but sometimes they felt reluctant to trouble others. Student E mentioned when he found something he failed to understand, he would prefer to figure it out by himself first and then seek help from the teacher and classmates. He told the interviewer: “I thought the teacher was busy, and my classmates were also busy, so I would prefer to figure it out by myself.”

Students' Perceptions of Technical Design

As for the technical design (see Table 5 ), the average score is 3.73 (SD = 0.85), which suggests that the environment provided relatively sufficient technological support to the students. Item 16 ( M = 3.93, SD = 0.92) (The online material is available at locations suitable for me) and Item 19 ( M = 4, SD = 0.97) (I decide when I want to learn) got higher scores, which indicates that students could enjoy the convenience of “anywhere” and “anytime” in the learning environment.

This positive attitude was demonstrated in the interview data collected from Student F who expressed his appreciation for the freedom and the sense of control brought by asynchronous discussion. He said, “I could finish the task at the time that is convenient for me as long as I did not miss the deadline. I like it.”

One thing worth noticing is that the mean score of Item 20 (Using blended learning allowed me to explore the interest of my own) is 3.18 (SD = 0.68), which falls toward the middle of the 1–5 scale. This score reveals that students did not think the resources of the blended learning environment play an important role in exploring their own areas of interest. In the interview, student D expressed that he did not find the resources very interesting, for the range of the topics was rather limited, and he was not attracted by the resources provided.

In sum, students' ratings on different dimensions of the questionnaire suggest that students perceived the productiveness of the learning environment in a generally positive way. This result is consistent with the studies exploring students' perceptions of the blending learning environment in general (e.g., Akkoyunlu and Yilmaz, 2006 ; Dziuban et al., 2006 ; Owston et al., 2006 ; Bendania, 2011 ; Wang and Huang, 2018 ). In the study conducted by Wang and Huang (2018) , a blended environment was also constructed from the pedagogical, social, and technical perspectives. The findings of the study reveal that students are generally positive toward the design of the learning environment. This may suggest that students would perceive the learning environment positively if the elements of the blended learning environment are carefully designed. Despite the generally positive attitudes toward the learning environment, some students expressed their concern about the workload and adaptation to the way of learning in the interview. In study Stracke (2007) , the way of learning was also found to make the students withdraw from the blended course. The findings indicate that some students may need more time to adapt to more student-centered learning.

Students' Perceived Impact of the Blended Learning Environment on the Development of Their Critical Thinking

Drawing mainly on Paul and Elder's framework of thinking elements, the following themes emerged as to the students' perceived improvement of critical thinking after data analysis and are elucidated through students' quotations.

Gaining a Deeper Understanding of the Concept of “Critical Thinking”

In the interview, students talked about their improvement in understanding the concept of critical thinking. For example, Student D expressed that the environment helped him clarify the concept of critical thinking. He used to consider the concept as closely related to “criticizing” because of its Chinese translation and came to realize that it was closer to the concept of “rational thinking.”

Some students also expressed that the course helped them realize the importance of critical thinking. As the teacher clearly informed the students of the specific critical thinking skills each task aimed to cultivate, students realized that “critical thinking is not an abstract concept, but concrete ways of guiding people to solve problems” (Student B).

Using Facts and Evidence to Support One's Own Opinion

In the interview, students also talked about the change they experienced when forming and supporting their opinion. They started to recognize the importance of facts and evidence in their writing. Student E told the interviewer that he learned that supporting ideas were very important to make one's opinion accepted. He said: “In accomplishing the writing tasks of the course, I gradually learned to provide arguments with further explanations, examples and,… maybe some data.”

Some students also suggested that facts and evidence were important for them to convince others in the discussions. Student B said: “In the past when someone disagreed with me, I usually felt sad and angry. I would either remain silent or quarrel with them. In this course, I learned that if I wanted others to accept my opinion, I needed to convince them with evidence such as facts and information.” She also felt excited that her well-presented opinions were accepted several times during the discussion with her team members.

Thinking From Multiple Perspectives

Another perceived effect is thinking from multiple perspectives, which was mentioned by many students. For example, Student A described how a particular activity helped him recognize the importance of different perspectives and how his own writing benefited from a particular activity in the course. “The teacher asked some of us to play the role of employer and I was assigned this role. When I thought from the employer's perspective, I knew what kind of employee I needed… When I wrote my job application letter, I had a very clear idea what to include in my letter.” (Student A) Student F also mentioned that recognizing different perspectives helped him finish writing the complaint letter well. According to him, he not only mentioned the dissatisfaction in the complaint letter but also stated the potential negative impact on the company to which he sent the letter.

Exploring and Clarifying the Purpose Behind the Texts or Behaviors

The interviewees also mentioned that they learned to explore and clarify the purpose behind the texts or behaviors. Some students explained how they started to consider purpose as an important component in their writing. Student H told the interviewer that when the teacher started to teach a new genre, she always asked the students to discuss under what circumstances they could meet or use this type of writing, and why they needed it in the daily life. “In this way, I understand that there should be a clear purpose behind each writing. And… and when I tried to finish my own writing task, I also put the writing purpose into my consideration.” said Student H.

Some students also told the interviewer that they gradually learned to avoid distraction and stick to the purpose when they conducted a discussion. According to student G, the students tended to talk about irrelevant things when they had discussions at the beginning of the course. With the instructors' constant reminding, they could realize whether they strayed from the point and returned to the right track in time at the end of the semester.

In summary, the data from the interview suggest that students could perceive their critical thinking development in different thinking dimensions. Furthermore, according to the students' opinion, their development in critical thinking was also manifested in their writing and even transferred to other activities. As for the promoting factors of the development, the students recognized the importance of learning environment design, especially the pedagogical design and the social design. For example, students attributed their deeper understanding of the concept to the instructor's deliberate introduction of critical thinking and focus on the development of thinking skills in the activity design. Also, they believed that the teachers' guidance and peers' scaffold enabled them to realize the importance of multiple perspectives. These factors were also found to promote students' critical thinking in the systematic review conducted by Chou et al. (2018) . This suggests that designing the elements of the learning environment to provide favorable conditions for critical thinking development could bring positive effects.

Limitations and Implications

This study proposed the construction of a blended learning environment to promote critical thinking in terms of pedagogical, social, and technical design and explored students' perceptions of the environment design and their perceived impact on the improvement of critical thinking. The results of the study suggests that students are generally satisfied with the design of the learning environment, and students considered the learning environment helpful in improving critical thinking. Even though the study made a contribution to the instructional design aiming at critical thinking promotion in a blended learning environment, some limitations should be duly noted. First, because the participants of the study were 90 students in the same University, the relative homogeneity of the context may present a possible connection with the result. Therefore, replication is recommended with larger and more diverse samples. Second, the study was not able to present the relationship between environmental design and critical thinking development quantitively. Further study could focus on the correlation between design strategies and the improvement of specific thinking skills, or the predictive capability of elements design for the promotion of critical thinking.

This study also has some implications for critical thinking cultivation in the instruction of specific disciplines. On the one hand, the cultivation of students' critical thinking requires the detailed design of the blended learning environment. Special attention needs to be paid to pedagogical, social, and technical design covering factors such as learning objectives, student interaction, and ICT tools. On the other hand, students' troubles and challenges such as the extra workload and emotional factors should be taken into consideration when designing the learning environment.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by School of Foreign Languages, Northeast Normal University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

DL designed and implemented the learning environment, collected and analyzed the data, and wrote the article.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Adam, A., and Manson, T. M. (2014). Using a pseudoscience activity to teach critical thinking. Teach. Psychol. 41, 130–134. doi: 10.1177/0098628314530343

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Akkoyunlu, B., and Yilmaz, S. M. (2006). A study on students' views on blended learning environment. Turk. Online J. Distance Educ. 7, 43–56. doi: 10.17718/TOJDE.25211

Allaire, J. L. (2015). Assessing critical thinking outcomes of dental hygiene students utilizing virtual patient simulation: a mixed methods study. J. Dent. Educ. 79, 1082–1092. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2015.79.9.tb06002.x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

BatdÄ, V. (2014). The effect of blended learning environments on academic success of students: a meta-analysis study. Cankiri Karatekin Univ. J. Inst. Soc. Sci. 5, 287–302. Retrieved from: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/jiss/issue/25892/272867 (accessed June 11, 2021).

Bendania, A. (2011). Teaching and learning online: King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals (KFUPM) Saudi Arabia, case study. Int. J. Arts Sci. 4, 223–241. Retrieved from: https://www.academia.edu/5017206/INSTRUCTORS_AND_LEARNERS_ATTITUDES_TOWARD_TEACHING_AND_LEARNING_ONLINE_KING_FAHD_UNIVERSITY_OF_PETROLEUM_AND_MINERALS_KFUPM_SAUDI_ARABIA_CASE_STUDY (accessed June 11, 2021).

Google Scholar

Butchart, S., Bigelow, J., Oppy, G., Korb, K., and Gold, I. (2009). Improving critical thinking using web-based argument mapping exercises with automated feedback. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 25, 268–291. doi: 10.14742/ajet.1154

Chang, V., and Fisher, D. (2003). “The validation and application of a new learning environment instrument for online learning in higher education,” in Technology-Rich Learning Environments: A Future Perspective , eds M. S. Khine and D. Fisher (Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd.), 1–20.

Cheong, C. M., and Cheung, W. S. (2008). Online discussion and critical thinking skills: a case study in a Singapore secondary school. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 24, 556–573. doi: 10.14742/ajet.1191

Chou, T. L., Wu, J. J., and Tsai, C. C. (2018). Research trends and features of critical thinking studies in E-Learning environments: a review. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 57, 1038–1077. doi: 10.1177/0735633118774350

de Leng, B. A., Dolmans, D. H., Jo bsis, R., Muijtjens, A. M., and van der Vleuten, C. P. (2009). Exploration of an e-learning model to foster critical thinking on basic science concepts during work placements. Comput. Educ. 53, 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2008.12.012

Dziuban, C., Hartman, J., Juge, F., Moskal, P., and Sorg, S. (2006). “Blended learning enters the mainstream,” in Handbook of Blended Learning: Global Perspectives, Local Designs , eds C. J. Bonk and C. R. Graham (San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer), 195–206. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/284688507_Blended_learning_enters_the_mainstream (accessed June 11, 2021).

Eftekhari, M., Sotoudehnama, E., and Marandi, S. S. (2016). Computer-aided argument mapping in an EFL setting: does technology precede traditional paper and pencil approach in developing critical thinking? Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 64, 339–357. doi: 10.1007/s11423-016-9431-z

Elder, L., and Paul, R. (1994). Critical thinking: why we must transform our teaching. J. Dev. Educ. 18, 34–35.

Ennis, R. H. (1996). Critical Thinking . New York, NY: Prentice Hall.

Fisher, A., and Scriven, M. (1997). Critical Thinking: Its Definition and Assessment . Norwich: Center for Research in Critical Thinking.

Gilbert, P. K., and Dabbagh, N. (2005). How to structure online discussion of meaningful discourse: a case study. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 36, 5–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8535.2005.00434.x

Guiller, J., Durndell, A., and Ross, A. (2008). Peer interaction and critical thinking: face-to-face or online discussion? Learn. Instruct. 18, 187–200. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2007.03.001

Huang, T. C., Jeng, Y. L., Hsiao, K. L., and Tsai, B. R. (2017). SNS collaborative learning design: enhancing critical thinking for human computer interface design. Univ. Access Inf. Soc. 16, 303–312. doi: 10.1007/s10209-016-0458-z

Kim, K., and Bonk, C. J. (2006). The future of online teaching and learning in higher education: the survey says. Educ. Q. 29, 22–30. Retrieved from: https://er.educause.edu/articles/2006/1/the-future-of-online-teaching-and-learning-in-higher-education-the-survey-says (accessed June 11, 2021).

Kirschner, P., Strijbos, J. W., Kreijns, K., and Beers, P. J. (2004). Designing electronic collaborative learning environments. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 52, 47–66. doi: 10.1007/BF02504675

Lu, D. (2018). Research on the design and application of blended learning environment with the orientation of critical thinking: a case of college practical English writing course (Unpublished doctoral dissertation), Northeast Normal University, Changchun, China.

Naaj, M. A., Nachouki, M., and Ankit, A. (2012). Evaluating student satisfaction with blended learning in a gender-segregated environment. J. Inf. Technol. Educ. Res. 11, 185–200. doi: 10.28945/1692

Osguthorpe, R. T., and Graham, C. R. (2003). Blended learning environments: definitions and directions. Q. Rev. Distance Educ. 4, 227–233. Retrieved from: https://web.b.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=0&sid=84d5540c-01b3-4b86-8c21-962ff82af437%40sessionmgr103 (accessed June 11, 2021).

Owston, R. D., Garrison, D. R., and Cook, K. (2006). “Blended learning at Canadian universities: issues and practices,” in The Handbook of Blended Learning: Global Perspectives, Local Designs , eds C. J. Bonk and C. R. Graham (San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer), 338–350.

Paul, R. (1992). Critical thinking: what, why and how? New Dir. Community Coll. 1992, 3–24. doi: 10.1002/cc.36819927703

Paul, R., and Elder, L. (1999). Critical thinking: teaching students to seek the logic of things. J. Dev. Educ. 23, 34–36.

Paul, R., and Elder, L. (2006). The International Critical Thinking Reading and Writing Test . Dillon Beach, CA: The Foundation for Critical Thinking.

Rosen, Y., and Tager, M. (2014). Making student thinking visible through a concept map in computer-based assessment of critical thinking. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 50, 249–270. doi: 10.2190/EC.50.2.f

Sagarra, N., and Zapata, G. C. (2008). Blending classroom instruction with online homework: a study of student perceptions of computer-assisted L2 learning. ReCALL 20, 208–224. doi: 10.1017/S0958344008000621

Shamir, A., Zion, M., and Spector_Levi, O. (2008). Peer tutoring, metacognitive processes and multimedia problem-based learning: the effect of mediation training on critical thinking. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 17, 384–398. doi: 10.1007/s10956-008-9108-4

Shin, H., Ma, H., Park, J., Ji, E. S., and Kim, D. H. (2015). The effect of simulation courseware on critical thinking in undergraduate nursing students: multi-site pre-post study. Nurse Educ. Today 35, 537–542. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2014.12.004

Singh, H. (2003). Building effective blended learning programs. Educ. Technol. 43, 51–54. Retrieved from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/44428863 (accessed June 11, 2021).

Singh, H., and Reed, C. (2001). A White Paper: Achieving Success With Blended Learning . Retrieved from: http://www.leerbeleving.nl/wbts/wbt2014/blend-ce.pdf (accessed June 11, 2021).

Smyth, S., Houghton, C., Cooney, A., and Casey, D. (2012). Students' experiences of blended learning across a range of postgraduate programmes. Nurse Educ. Today 32, 464–468. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2011.05.014

Stracke, E. (2007). A road to understanding: a qualitative study into why learners drop out of a blended language learning (BLL) environment. ReCALL 19, 57–78. doi: 10.1017/S0958344007000511

Thorne, K. (2003). Blended Learning: How to Integrate Online and Traditional Learning . London: Kogan Page.

Van Gelder, T., and Bulker, A. (2000). “Reason! improving informal reasoning skills,” in Proceedings of the Australian Computers in Education Conference (Melbourne, VIC). Retrieved from: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/ce84/ec799ae2dc15d56939fd0a6e46123e88112e.pdf (accessed April 20, 2020).

Wang, Q., and Huang, C. (2018). Pedagogical, social and technical designs of a blended synchronous learning environment. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 49, 451–462. doi: 10.1111/bjet.12558

Wang, Q. Y. (2008). A generic model for guiding the integration of ICT into teaching and learning. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 45, 411–419. doi: 10.1080/14703290802377307

Watson, J. (2008). Blended Learning: The Convergence of Online and Face-to-Face Education. North American Council for Online Learning report . Retrieved from: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED509636.pdf (accessed June 11, 2021).

Yang, Y. T. C. (2008). A catalyst for teaching critical thinking in a large University class in Taiwan: asynchronous online discussions with the facilitation of teaching assistants. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 56, 241–264. doi: 10.1007/s11423-007-9054-5

Yang, Y. T. C., and Chang, C. H. (2013). Empowering students through digital game authorship: enhancing concentration, critical thinking, and academic achievement. Comput. Educ. 68, 334–344. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2013.05.023

Yang, Y. T. C., and Chou, H. A. (2008). Beyond critical thinking skills: investigating the relationship between critical thinking skills and dispositions through different online instructional strategies. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 39, 666–684. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8535.2007.00767.x

Yeh, Y. C. (2009). Integrating e-learning into the direct-instruction model to enhance the effectiveness of critical-thinking instruction. Instruct. Sci. 37, 185–203. doi: 10.1007/s11251-007-9048-z

Yen, J. -C., and Lee, C. -Y. (2011). Exploring problem solving patterns and their impact on learning achievement in a blended learning environment. Comput. Educ. 56, 138–145. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2010.08.012

Yukawa, J. (2006). Co-reflection in online learning: collaborative critical thinking as narrative. Int. J. Comput. Suppor. Collab. Learn. 1, 203–228. doi: 10.1007/s11412-006-8994-9

Keywords: students' perceptions, blended learning environment, critical thinking, design, survey

Citation: Lu D (2021) Students' Perceptions of a Blended Learning Environment to Promote Critical Thinking. Front. Psychol. 12:696845. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.696845

Received: 18 April 2021; Accepted: 31 May 2021; Published: 25 June 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Lu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dan Lu, lud090@nenu.edu.cn

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Critical thinking in E-learning environments

2012, Computers in Human Behavior

Related Papers

Advances in Medical Education and Practice

Aeen Mohammadi

Buluc Ruxandra

Critical thinking is a reflective mechanism that helps students to evaluate the information and knowledge that they acquire during classes or that they come into contact with in their everyday lives. Critical assessment aids students to ascertain the extent to which these concepts are relevant for and applicable to their lives, careers, purposes and personal experiences. Critical thinking requires students not solely to assimilate information but also to interact with it actively, to evaluate it, to understand whether or not it is accurate, to determine its role and the goal it may serve. Traditional classroom settings foster the development of critical thinking skills through interaction between students engaged in group activities as well as through careful prompting by the instructors. However, this traditional setting is no longer sufficient and does not assist students in developing these skills for the virtual world. This article suggests that the transfer of critical thinking skills to the online environment can be done in several ways in the e-learning process. The possible activities that incorporate these skills could be either individual (the student can interact with the problem or situation on his/her own) or they could be directed towards an already existing or newly formed learning community, in which students interact not only with the given task but also with each other and they stimulate each other to apply critical thinking skills. These types of interactive exercises could be adapted to suit the study domain of almost any student, since the formats are quite flexible and the instructor simply needs to incorporate the specific situation/case/scenario.

Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences

Noorhidawati Abdullah

Englisia: Journal of Language, Education, and Humanities

Tathahira LNU

Living in the millennial era has encouraged all the learners to one step ahead maximizing the existed and updated technology for learning. Maintaining autonomous and long-distanced learning should have been introduced and implemented in higher education. Involving in an online learning environment is not enough without the ability to think critically. Critical thinking is the ability that is essentially required for learners in a higher education context. This paper discusses the challenges and strategies for implementing learners’ critical thinking through online learning. This paper used the literature study approach, in which all the information in this paper was obtained from books and journal articles. Briefly, the findings reveal that online learning can be good support for students to improve their critical thinking ability. However, there are also several challenges to do so involving the socio-cultural matter, the students’ previous learning habits, and the familiarity of u...

Raafat Saadé , Danielle Morin

This article investigates the relationship between Web-based learning and Critical thinking (CT) in a web-based course on the fundamentals of Information Technology at a university in Montreal, Canada. In particular, it will identify what part(s) of the course and to what extent, critical thinking is perceived to occur. The course contains two categories of learning modules namely resources and interactive activity components. The study aimed at answering the following questions: (1) What is the effect of the learning modules on Critical Thinking? and (2) What is the relative contribution of the various learning modules on Critical Thinking skills requirements?

International Journal of Online Pedagogy and Course Design

Kenja McCray

The development and demonstration of students' critical thinking skills is one hallmark of effective teaching and learning. A promising scholarly literature has emerged in addition to webinars, conferences, and workshops to assist in this endeavor. Further, publishers offer cleverly marketed bundle packages with enhanced supplemental materials and instructors contribute instructional strategies and techniques. Nevertheless, gaps still exist in the scholarship related to effective student engagement. The development of higher order thinking skills in online educational settings is one such area requiring additional inquiry. This article transitions beyond mere theoretical constructs regarding best practices and standards for distance education. In doing so, it provides practical applications through the use of case studies in demonstrating a “how to” student engagement model and framework, which fosters the type of online course environment and useful strategies for developing critical thinking skills.

Economics & Education

Olena Huzar

The aim of this scientific article is to investigate and analyse the use of digital technologies in designing lessons to promote critical thinking among primary school students. It highlights the importance of this research in the context of today's information-driven society and educational demands. Methodology. The study takes a comprehensive approach to research and analysis. It includes a review of relevant literature on critical thinking, digital technologies and their integration in education. The researchers examine various digital tools and techniques that are suitable for promoting critical thinking in young learners. In addition, the study includes a qualitative evaluation of sample critical thinking lessons designed for primary school students, with a particular focus on blended and distance learning environments. Results. The research findings demonstrate the benefits and opportunities of digital technologies in developing critical thinking skills in young students. ...

Computers in Human Behavior

Ana Jimenez-Zarco

Alex S Gomes , Rossana Viana Gaia

One of the specific skills necessary to face complex global challenges, as recent studies indicate, is critical thinking. For this reason, there is a motivation to develop this skill in network learning program projects. However, there are limitations to its development since the design of online courses has several characteristics inherited from traditional education. This phenomenon is repeated in the Virtual Learning Environment of Redu, an experience developed in the Federal University of Pernambuco institutional setting. This study aimed to identify and evaluate aspects of Redu's functionalities to propose developing educational strategies that promote critical thinking. Through the triangulation method, data of diverse nature were analyzed to verify how asynchronous interactions between teachers and students eventually supported the structuring of situations to promote the development of critical thinking and identify the platform's limitations to support the progress of this skill. The results emphasized that there is a divorce between the concept of Virtual Learning Environments and the methodologies used by teachers to encourage the development of critical thinking that leads to the neglect of several of the characteristics of the students. Finally, the attributes of Redu are listed that, from our point of view, will allow the environment to become a support with the possibility of amplifying the technology to develop critical thinking. CCS CONCEPTS • Applied computing → Education; Collaborative Learning.

Science Park Research Organization & Counselling

The purpose of the study was to determine if Virtual-Based Training (VBT) could be used to develop post-secondary students' abilities in critical thinking (CRT). The participants were 26 second-year undergraduate students from four faculties at a government-funded university in Bangkok, Thailand and were divided into 2 groups. The experimental group studied 23 CRT lessons through VBT and had to hand in their exercises. There was no treatment for the control group. The pre-and post-tests were analyzed using multiple correlations. Results revealed that there was a relationship of the pre-and post-tests of language and mathematics with CRT. This means that our VBT was effective for teaching language and mathematics. Further studies will be to determine if it was the content (the type of CRT lessons) or the delivery mode (VBT) that resulted in no significant difference in test scores for logical reasoning.

RELATED PAPERS

Georges Depeyrot

Marcela Pastana

Vivre, Produire et Echanger - Reflets Méditerranéens, Mélanges offerts à Bernard Liou, 2002, Isbn 2 907303 68 6, p. 115-118

Christian Giroussens

Laurentian证书 劳伦森大学毕业证

IEICE Transactions on Information and Systems

Nobutaka Suzuki

Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research

marziyeh asadizaker

Balkan Journal of Dental Medicine

Vanja Petrovic

Dialechti Tsimpida

Earth, Planets and Space

Mouloud Benammi

Estudios Románicos

José García Fernández

Plant biotechnology journal

mamta sharma

Jalaja Udoshi

Jurnal Civics: Media Kajian Kewarganegaraan

Sugeng Riyadi

Revista Brasileira de Zootecnia

Jaime Tarouco

Apunts. Medicina De L'esport

Delfin Orea

Kazalište : časopis za kazališnu umjetnost

ewa mazierska

Greenhouse Gas Control Technologies 7

Amornvadee Veawab

gustavo vilhena

Eliane Baziloni

Cancer Research

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Advertisement

An evaluation of argument mapping as a method of enhancing critical thinking performance in e-learning environments

- Published: 27 October 2012

- Volume 7 , pages 219–244, ( 2012 )

Cite this article

- Christopher P. Dwyer 1 ,

- Michael J. Hogan 1 &

- Ian Stewart 1

72 Citations

16 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The current research examined the effects of a critical thinking (CT) e-learning course taught through argument mapping (AM) on measures of CT ability. Seventy-four undergraduate psychology students were allocated to either an AM-infused CT e-learning course or a no instruction control group and were tested both before and after an 8-week intervention period on CT ability using the Halpern Critical Thinking Assessment. Results revealed that participation in the AM-infused CT course significantly enhanced overall CT ability and all CT sub-scale abilities from pre- to post-testing and that post-test performance was positively correlated with motivation towards learning and dispositional need for cognition. In addition, AM-infused CT course participants exhibited a significantly larger gain in both overall CT and in argument analysis (a CT subscale) than controls. There were no effects of training on either motivation for learning or need for cognition. However, both the latter variables were correlated with CT ability at post-testing. Results are discussed in light of research and theory on the best practices of providing CT instruction through argument mapping and e-learning environments.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Online learning in higher education: exploring advantages and disadvantages for engagement

The impact of artificial intelligence on learner–instructor interaction in online learning

The impact of gamification in educational settings on student learning outcomes: a meta-analysis

Abrami, P. C., Bernard, R. M., Borokhovski, E., Wade, A., Surkes, M. A., Tamim, R., & Zhang, D. (2008). Instructional interventions affecting critical thinking skills and dispositions: a stage 1 meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 78 (4), 1102–1134.

Article Google Scholar

Alvarez-Ortiz, C. (2007). Does philosophy improve critical thinking skills? Unpublished thesis. The University of Melbourne.

Association of American Colleges & Universities (2005). Liberal education outcomes: A preliminary report on student achievement in college. Washington, DC.

Australian Council for Educational Research (2002). Graduate skills assessment. Commonwealth of Australia .

Boekaerts, M., & Simons, P. R. J. (1993). Learning and instruction: Psychology of the pupil and the learning process . Assen: Dekker & van de Vegt.

Google Scholar

Brown, A. (1987). Metacognition, executive control, self-regulation, and other more mysterious mechanisms. In F. Reiner & R. Kluwe (Eds.), Metacognition, motivation, and understanding (pp. 65–116). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Butchart, S., Bigelow, J., Oppy, G., Korb, K., & Gold, I. (2009). Improving critical thinking using web-based argument mapping exercises with automated feedback. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 25 (2), 268–291.

Caciappo, J. T., Petty, R. E., & Kao, C. F. (1984). The efficient assessment of need or cogntion. Journal of Personality Assessment, 48 , 306–307.

Dawson, T. L. (2008). Metacognition and learning in adulthood . Northhampton: Developmental Testing Service, LLC.

Dwyer, C. P., Hogan, M. J., & Stewart, I. (2010). The evaluation of argument mapping as a learning tool: Comparing the effects of map reading versus text reading on comprehension and recall of arguments. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 5 (1), 16–22.

Dwyer, C. P., Hogan, M. J., & Stewart I. (2011). The promotion of critical thinking skills through argument mapping. Nova Publishing, in press.

Engelmann, T., & Hesse, F. W. (2010). How digital concept maps about the collaborators’ knowledge and information influence computer-supported collaborative problem solving. Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 5 , 299–319.

Engelmann, T., Baumeister, A., Dingel, A., & Hesse, F. W. (2010). The added value of communication in a CSCL-scenario compared to just having access to the partners’ knowledge and information. In J. Sánchez, A. Cañas, & J. D. Novak (Eds.), Concept maps making learning meaningful: Proceedings of the 4th international conference on concept mapping, 1 (pp. 377–384). Viña del Mar: University of Chile.

Ennis, R. H. (1989). Critical thinking and subject specificity: Clarification and needed research. Educational Researcher, 18 , 4–10.

Ennis, R. H. (1996). Critical thinking . Upper Saddle River: Prentice-Hall.

Ennis, R. H. (1998). Is critical thinking culturally biased? Teaching Philosophy, 21 (1), 15–33.

Facione, P.A. (1990). The Delphi report. Committee on pre-college philosophy. American Philosophical Association .

Farrand, P., Hussain, F., & Hennessy, E. (2002). The efficacy of the ‘mind map’ study technique. Medical Education, 36 , 426–431.

Flavell, J. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: a new area of psychological inquiry. American Psychologist, 34 , 906–911.

Gadzella, B.M. (1996). Teaching and learning critical thinking skills (ERIC ED 405 313), U.S. Department of Education.

Garcia, T., Pintrich, P. R., & Paul, R. (1992). Critical thinking and its relationship to motivation, learning strategies and classroom experience. Paper presented at the 100th Annual Meeting of the American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, August 14–18 .

Halpern, D. F. (2003). Thought & knowledge: An introduction to critical thinking (4th ed.). New Jersey: Laurence Erlbaum Associates.

Halpern, D. F. (2006). Is intelligence critical thinking? Why we need a new definition of intelligence. In P. C. Kyllonen, R. D. Roberts, & L. Stankov (Eds.), Extending intelligence: Enhancement and new constructs (pp. 293–310). New York: Taylor & Francis Group.

Halpern, D. F. (2010). The Halpern critical thinking assessment: Manual . Vienna: Schuhfried.

Harrell, M. (2004). The improvement of critical thinking skills. In What philosophy is (Tech. Rep. CMU-PHIL-158). Carnegie Mellon University, Department of Philosophy.

Harrell, M. (2005). Using argument diagramming software in the classroom. Teaching Philosophy, 28 , 2. www.hss.cmu.edu/philosophy/harrell/ArgumentDiagramsInClassroom.pdf .

Hattie, J., Biggs, J., & Purdie, N. (1996). Effects of learning skills interventions on student learning: a meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 66 (2), 99–136.

Higher Education Quality Council, Quality Enhancement Group. (1996). What are graduates? Clarifying the attributes of “graduateness” . London: HEQC.

Hitchcock, D. (2003). The effectiveness of computer-assisted instruction in critical thinking. Philosophy department. McMaster University.

Holmes, J., & Clizbe, E. (1997). Facing the 21st century. Business Education Forum, 52 (1), 33–35.

Huffaker, D. A., & Calvert, S. L. (2003). The new science of learning: active learning, metacognition and transfer of knowledge in e-learning applications. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 29 (3), 325–334.

Hwang, G. J., Shi, Y. R., & Chu, H. C. (2011). A concept map approach to developing collaborative mindtools for context-aware ubiquitous learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 42 (5), 778–789.

Jensen, L. L. (1998). The role of need for cognition in the development of reflective judgment. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Denver, Colorado, USA.

Jiang, Y., Olson, I. R., & Chun, M. M. (2000). Organization of visual short-term memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning Memory and Cognition, 26 , 683–702. 1997.

Johnson, D.W., Johnson, R.T., & Stanne, M.S. (2000). Cooperative learning methods: A meta-analysis. Retrieved 21/06/2011, from http://www.cooperation.org/pages/cl-methods.html .

King, P. M., & Kitchener, K. S. (2002). The reflective judgment model: Twenty years of epistemic cognition. In B. K. Hofer & P. R. Pintrich (Eds.), Personal epistemology: The psychology of beliefs about knowledge and knowing (pp. 37–61). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Kintsch, W., & van Dijk, T. A. (1978). Toward a model of text comprehension and production. Psychological Review, 85 , 363–394.

Ku, K. Y. L. (2009). Assessing students’ critical thinking performance: urging for measurements using multi-response format. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 4 (1), 70–76.

Ku, K. Y. L., & Ho, I. T. (2010a). Dispositional factors predicting Chinese students’ critical thinking performance. Personality and Individual Differences, 48 , 54–58.

Ku, K. Y. L., & Ho, I. T. (2010b). Metacognitive strategies that enhance critical thinking. Metacognition Learning, 5 , 251–267.

Kuhn, D. (1991). The skills of argument . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Kuhn, D., Goh, W., Iordanou, K., & Shaenfield, D. (2008). Arguing on the computer: a microgenetic study of developing argument skills in a computer-supported environment. Child Development, 79 (5), 1310–1328.

Ma, A. W. W. (2009). Computer supported collaborative learning and higher order thinking skills: A case study of textile studies. The Interdisciplinary Journal of e-Learning and Learning Objects, 5 , 145–167.

Marzano, R.J. (1998). A theory-based meta-analysis of research on instruction. Aurora, CO: Mid-Continent Regional Educational Laboratory. Retrieved 26/10/2007, from http://www.mcrel.org/pdf/instruction/5982rr_instructionmeta_analysis.pdf .

Maybery, M. T., Bain, J. D., & Halford, G. S. (1986). Information-processing demands of transitive inference. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 12 (4), 600–613.

Mayer, R. E. (1997). Multimedia learning: are we asking the right questions? Educational Psychologist, 32 (1), 1–19.

Mayer, R. E. (2003). The promise of multimedia learning: using the same instructional design methods across different media. Learning and Instruction, 13 , 125–139.

Miller, G. A. (1956). The magical number seven, plus or minus two: some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychological Review, 63 , 814–897.

Monk, P. (2001). Mapping the future of argument. Australian Financial Review. 16, March, pp.8–9.

National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Engineering, Institute of Medicine. (2005). Rising above the gathering storm: Energising and employing America for a brighter economic future . Washington: Committee on Prospering in the Global Economy for the 21st Century.

Norris, S. P. (1994). The meaning of critical thinking test performance: The effects of abilities and dispositions on scores. Critical thinking: Current research, theory, and practice . Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Paivio, A. (1971). Imagery and verbal processes . Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Paivio, A. (1986). Mental representations: A dual-coding approach . New York: Oxford University Press.

Paul, R. (1987). Dialogical thinking: Critical thought essential to the acquisition of rational knowledge and passions. In J. Baron & R. J. Sternberg (Eds.), Teaching thinking skills: Theory and practice (pp. 127–148). New York: W.H. Freeman.

Paul, R. (1993). Critical thinking: What every person needs to survive in a rapidly changing world . Rohnert Park: Foundation for Critical Thinking.

Perkins, D. N., Jay, E., & Tishman, S. (1993). Beyond abilities: a dispositional theory of thinking. Merrilll Palmer Quarterly, 39 , 1–1.

Pintrich, P. R., Smith, D. A., Garcia, T., & McKeachie, W. J. (1991). A manual for the use of the motivated strategies for learning questionnaire (MSLQ) . Michigan: National Center for Research to Improve Post-secondary Teaching and Learning.

Reed, J. H., & Kromrey, J. D. (2001). Teaching critical thinking in a community college history course: empirical evidence from infusing Paul’s model. College Student Journal, 35 (2), 201–215.

Robbins, S., Lauver, K., Le, H., Davis, D., Langley, R., & Carlstrom, A. (2004). Do psychosocial and study skill factors predict college outcomes? A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 130 (2), 261–288.

Roth, W. M., & Roychoudhury, A. (1994). Science discourse through collaborative concept mapping: New perspectives for the teacher. International Journal of Science Education, 16 , 437–455.

Sherrard, M., & Czaja, R. (1999). Extending two cognitive processing scales: Need for cognition and need for evaluation for use in a health intervention. European Advances in Consumer Research, 4 , 135–142.

Solon, T. (2007). Generic critical thinking infusion and course content learning in introductory psychology. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 34 (2), 95–109.

Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive load during problem solving: effects on learning. Cognitive Science, 12 , 257–285.

Sweller, J. (1999). Instructional design in technical areas. Australian Education Review No. 43 . Victoria: Acer Press.

Sweller, J. (2010). Cognitive load theory: Recent theoretical advances. In J. L. Plass, R. Moreno, & R. Brünken (Eds.), Cognitive load theory (pp. 29–47). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Tindall-Ford, S., Chandler, P., & Sweller, J. (1997). When two sensory modes are better than one. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Applied, 3 (4), 257–287.

Toplak, M. E., & Stanovich, K. E. (2002). The domain specificity and generality of disjunctive reasoning: searching for a generalizable critical thinking skill. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94 (1), 197–209.

Twardy, C. R. (2004). Argument maps improve critical thinking. Teaching Philosophy, 27 (2), 95–116.

Valenzuela, J., Nieto, A. M., & Saiz, C. (2011). Critical thinking motivational scale: a contribution to the study of relationship between critical thinking and motivation. Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 9 (2), 823–848.

van Eemeren, F. H., Grootendorst, R., Henkemans, F. S., Blair, J. A., Johnson, R. H., Krabbe, E. C. W., Planitin, C., Walton, D. N., Willard, C. A., Woods, J., & Zarefsky, D. (1996). Fundamentals of argumentation theory: A handbook of historical backgrounds and contemporary developments . New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

van Gelder, T. J. (2001). How to improve critical thinking using educational technology. In G. Kennedy, M. Keppell, C. McNaught, & T. Petrovic (Eds.), Meeting at the crossroads: Proceedings of the 18th annual conference of the Australian society for computers in learning in tertiary education (pp. 539–548). Melbourne: Biomedical Multimedia Unit, University of Melbourne.

van Gelder, T. J. (2003). Enhancing deliberation through computer supported argument mapping. In P. Kirschner, S. Buckingham Shum, & C. Carr (Eds.), Visualizing argumentation: Software tools for collaborative and educational sense-making (pp. 97–115). London: Springer.

van Gelder, T. J. (2007). The rationale for RationaleTM. Law, Probability & Risk, 6 , 23–42.

van Gelder, T.J., & Rizzo, A. (2001). Reason!Able across curriculum, in Is IT an Odyssey in Learning? Proceedings of the 2001 Conference of ICT in Education , Victoria, Australia.

van Gelder, T. J., Bissett, M., & Cumming, G. (2004). Enhancing expertise in informal reasoning. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology, 58 , 142–152.

Wankat, P. (2002). The effective efficient professor: Teaching, scholarship and service . Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Wegerif, R. (2002). Literature review in thinking skills, technology and learning: Report 2 . Bristol: NESTA Futurelab.

Wegerif, R., & Dawes, L. (2004). Thinking and learning with ICT: Raising achievement in the primary classroom . London: Routledge.

Willingham, D. T. (2007). Critical thinking: why is it so hard to teach? American Educator, 3 , 8–19.

Woodman, G. F., Vecera, S. P., & Luck, S. J. (2003). Perceptual organization influences visual working memory. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 10 (1), 80–87.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Psychology, NUI, Galway, Ireland

Christopher P. Dwyer, Michael J. Hogan & Ian Stewart

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Christopher P. Dwyer .

Appendix A: sample feedback from lecture 3.1

Thank you very much to all of you who did the exercises. Below you will find some feedback on exercises from Lecture 3.1.

Exercise: “Ireland should adopt Capital Punishment”

Below please find the argument we have extracted from the text you were asked to analyse. Please compare and contrast your argument map with this one. Also, please take note of where you may have differed in your placement of some propositions and why you made the analysis decisions you made.

You were also asked to answer a few questions based on this argument map.

Question 1 asked:

Does the author sufficiently support their claims? Are the author’s claims relevant? Does the author attempt to refute their own arguments (i.e., disconfirm their belief)?

Some of you answered that:

The author did not sufficiently support his/her claims because most of the propositions used were based on personal opinion (i.e. there was an insufficient amount of evidence to suggest that Ireland should adopt capital punishment). The author did attempt to refute their own claims, however, did so poorly in that he/she only used personal opinion or ‘common belief’ statements.

The author sufficiently supported their claims as they were sufficiently backed up by other supports. These claims are all relevant to the argument, specifically the central claim. The author does not attempt to disconfirm his beliefs because he sticks to his guns that capital punishment should be adopted.

The truth of the matter is that the author did not sufficiently support his/her claims. Of the 8 reasons he provided, only 3 were based on either expert opinion, statistics from research or research data.

All the arguments made were relevant to the central claim.

The author did attempt to refute his/her claims (i.e. disconfirm their own belief), as on 3 occasions, some form of objection to the reasoning was presented. However, the objections used were not examples of high quality evidence.

Question 2 asked:

Are there other arguments you would include?

Some argument should be made in terms of when the death penalty should/would be used, such as in cases of mental problems or a conviction of manslaughter.

Some argument should consider the nature of the crime, such as how the murder took place –details should be considered.

Everyone has a right to life, even murderers.

Law abiding citizens might grow to fear the government as they would now have more control over you.

Please think about these ideas and claims and also think about how you could possibly integrate them into the argument map. In addition, think about how you might support or object to these new propositions.

Question 3 asked:

Does any proposition or any set of propositions suggest to you that the author is biased in any way?

Some of you answered:

The author is biased because he/she presents more reasons for why we should adopt capital punishment than for not adopting capital punishment.

The author was not biased because though he/she did present more reasons in favour of capital punishment, they were mostly based on personal opinion and were adequately objected to.