- Emergency information

- Increase Font Size

- Decrease Font Size

Nepali (नेपाली)

REVIEW article

Combating the covid-19 pandemic: experiences of the first wave from nepal.

- 1 Faculty of Science, Nepal Academy of Science and Technology, Lalitpur, Nepal

- 2 Nepal Environment and Development Consultant Pvt. Ltd., Kathmandu, Nepal

- 3 Central Department of Environmental Science, Institute of Science and Technology, Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu, Nepal

- 4 Nepal Development Society, Bharatpur, Nepal

- 5 Kantipur Dental College Teaching Hospital and Research Center, Kathmandu University, Kathmandu, Nepal

- 6 National Disaster Risk Reduction Centre, Kathmandu, Nepal

- 7 Little Buddha College of Health Sciences, Kathmandu, Nepal

Unprecedented and unforeseen highly infectious Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) has become a significant public health concern for most of the countries worldwide, including Nepal, and it is spreading rapidly. Undoubtedly, every nation has taken maximum initiative measures to break the transmission chain of the virus. This review presents a retrospective analysis of the COVID-19 pandemic in Nepal, analyzing the actions taken by the Government of Nepal (GoN) to inform future decisions. Data used in this article were extracted from relevant reports and websites of the Ministry of Health and Population (MoHP) of Nepal and the WHO. As of January 22, 2021, the highest numbers of cases were reported in the megacity of the hilly region, Kathmandu district (population = 1,744,240), and Bagmati province. The cured and death rates of the disease among the tested population are ~98.00 and ~0.74%, respectively. Higher numbers of infected cases were observed in the age group 21–30, with an overall male to female death ratio of 2.33. With suggestions and recommendations from high-level coordination committees and experts, GoN has enacted several measures: promoting universal personal protection, physical distancing, localized lockdowns, travel restrictions, isolation, and selective quarantine. In addition, GoN formulated and distributed several guidelines/protocols for managing COVID-19 patients and vaccination programs. Despite robust preventive efforts by GoN, pandemic scenario in Nepal is, yet, to be controlled completely. This review could be helpful for the current and future effective outbreak preparedness, responses, and management of the pandemic situations and prepare necessary strategies, especially in countries with similar socio-cultural and economic status.

Introduction

The unanticipated outbreak of the novel coronavirus was first reported in Wuhan, China, in December 2019; it transmits from human to human via droplets and aerosol ( 1 ). The WHO declared Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) on January 30, 2020, and a pandemic on March 11, 2020 ( 2 ). As a result, countries worldwide adopted various mitigative measures ( 3 , 4 ) and eradication strategies ( 5 ), aiming to reduce potentially enormous damage and reach zero cases, respectively. However, significant gaps in advance preparedness and the implementation of response plans resulted in the rapid spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) globally with 219 nations reporting it as of January 22, 2021 1 ( 6 ).

The Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal is a landlocked country in South Asia bordered by India in the south, east, and west, and China in the north. Its population, gross domestic product (GDP), and human development index (HDI) are 29.24 million 2 , 30.64 billion 3 , and 0.579 4 , respectively. The constitution of Nepal (2015) consists of a three-tier (federal, province, and local) governmental system. Each tier has the constitutional power to enact laws and mobilize its resources. In Nepal, the first case of COVID-19 was reported on January 23, 2020, in a 32-year-old Nepalese man who returned from Wuhan, China. Two months after the first case, the second case was diagnosed through domestic testing on March 23 in a returnee from France ( 7 ). Subsequently, the Government of Nepal (GoN) imposed early interventions approved by the WHO, including a travel ban and the Indo-Nepal and China-Nepal borders closure 5 . ( 8 ) to delay the possible onset of the detrimental effects of the outbreak across the country.

This review presents a 1-year (up to January 22, 2021) scenario of COVID-19 in Nepal, reviews the strategies employed by the GoN to control COVID-19, and provides suggestions for the prevention and control of current and future pandemics. Federal, provincial, and district-level daily cases of COVID-19 [confirmed by real-time PCR (qRT-PCR), cured, and death] in Nepal from January 23, 2020, to January 22, 2021, were obtained from the Ministry of Health and Population (MoHP), GoN 6 . Searches using the website of MoHP of Nepal, PubMed, the WHO, the worldometer official website, and Google were conducted to gather the information on the number of deaths, cured, and confirmed cases of COVID-19 and reports describing the approach taken by the government to contain COVID-19 in Nepal. The search terms included “COVID-19 in Nepal” and “Prevention and management of COVID-19 in Nepal.” Data used in this article were extracted from relevant documents and websites. The figures were constructed by using Origin 2016 and GIS 10.4.1. We did not consult any databases that are privately owned or inaccessible to the public.

Epidemic Status of COVID-19 in Nepal

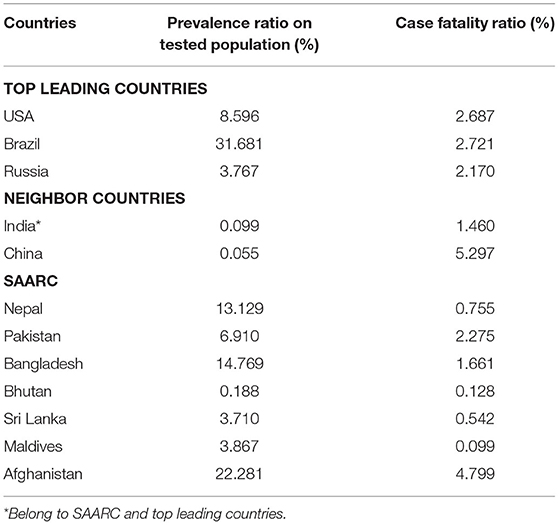

The MoHP of Nepal confirmed the first and second cases of COVID-19, respectively, in January and March, in an interval of 2 months 1 ( 9 ). As of January 22, 2021, 268,948 COVID-19 positive cases were reported, with 263,546 recovered, and 1,986 death cases 6 . This data showed nearly 0.74% death and about 98% recovery rate in Nepal. The case fatality rate (CFR) was 0.5% up to March 30 in Nepal ( 9 ). The CFR in the USA, Brazil, and Russia is similar (~2%), whereas in the South Asian Association of Regional Cooperation (SAARC) countries, the CFR varied from ~0.09 to ~4.7 % ( Table 1 ). In total, 2,035,301 qRT-PCR tests were performed in Nepal, indicating about 13.47% current prevalence of COVID-19 among the qRT-PCR tested population as compared with 2.5% as of March 31, 2020 2 . As of reviewing, the prevalence of COVID-19 among the qRT-PCR tested population is higher than the neighboring countries, China (~0.055%) and India (~0.099%) ( Table 1 ). In addition, up to the third quarter of 2020, <1% of the confirmed COVID-19 cases were symptomatic across all age groups, while the proportion of symptomatic cases progressively increased beyond 55 years of age from 1.3 to 9% 7 , 8 . Unlike Nepal, higher symptomatic cases were reported from other parts of the world during the same period ( 10 ). Understandably, the scenario of the proportion of symptomatic to asymptomatic cases remains to vary between countries and care facilities. Few possible reasons for low symptomatic cases reported in the Nepalese population may be poor health-seeking behavior and utilization of tertiary health care services ( 11 ) for mild symptomatic cases, home isolation without a diagnosis, and a high rate of self-medication practices ( 12 ).

Table 1 . Prevalence and case fatality ratio (CFR) of COVID-19 of top leading countries, neighbor countries of Nepal, and SAARC as of Jan 28, 2021.

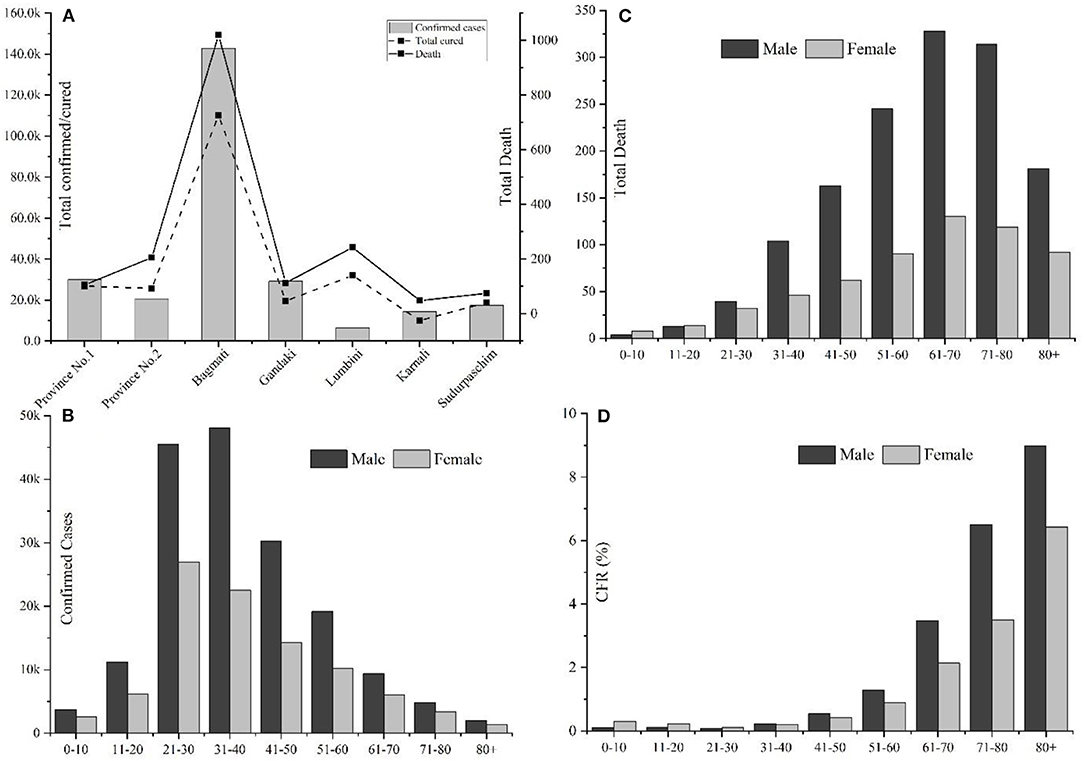

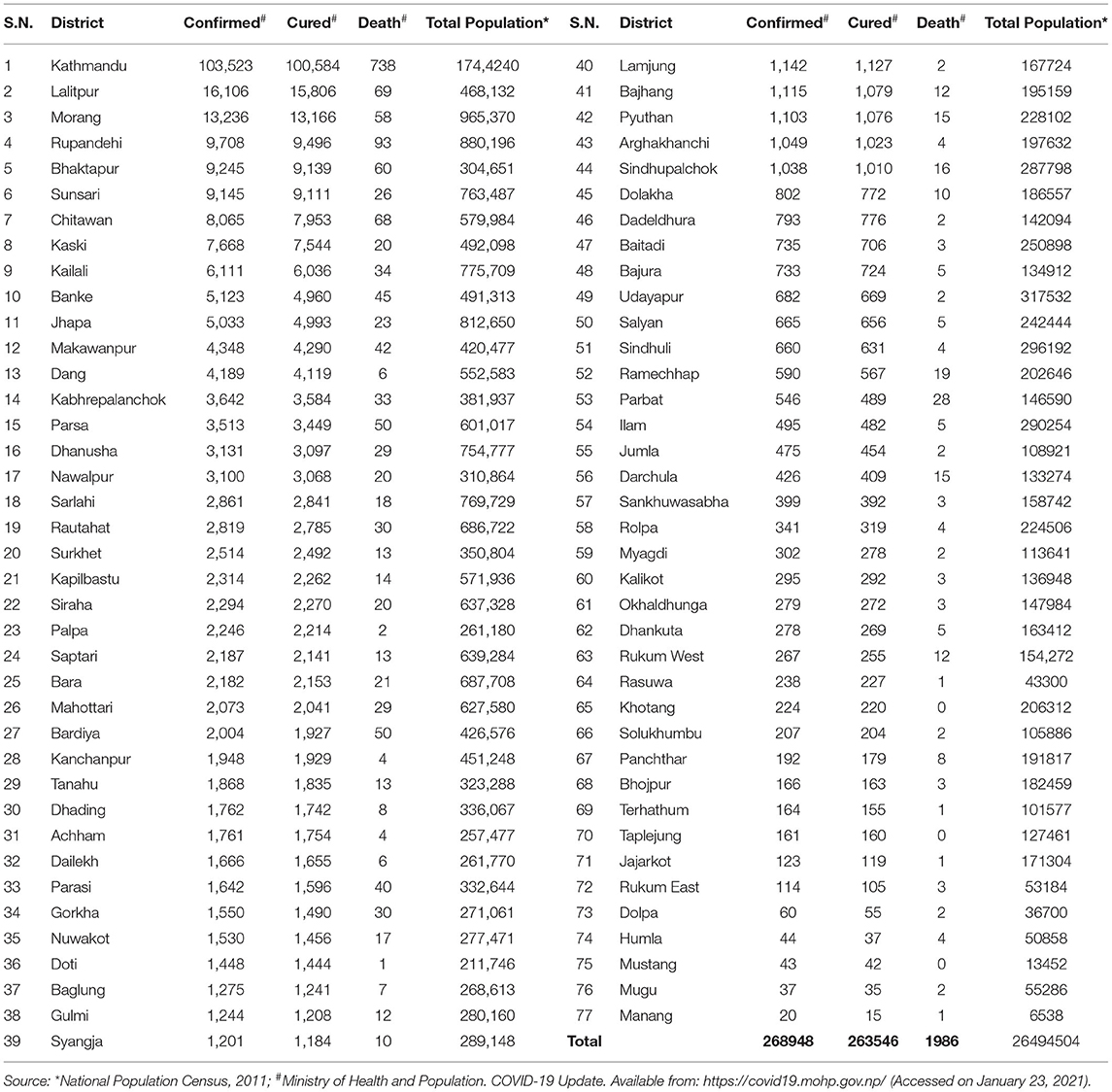

Among the provinces, Bagmati province ( n = 144,278) has the highest number of confirmed cases in Nepal, followed by province no. 1 ( n = 30,422) and Lumbini ( n = 30,308) ( Figure 1A ). As depicted in Table 2 , the confirmed cases of COVID-19 are distributed throughout the country in all the administrative districts. The total number of confirmed cases is highest in the Kathmandu district ( n = 103,523) followed by Lalitpur ( n = 16,106), Morang ( n = 13,236), and Rupandehi ( n = 9,708) districts and lowest in Manang ( n = 20), Mugu ( n = 37), Mustang ( n = 43), and Humla ( n = 44) districts ( Table 2 ).

Figure 1 . Overview of COVID-19 cases in Nepal up to January 22, 2021. (A) Province-wise distribution of total confirmed cases, recovery, and deaths; (B) Gender, age-wise distribution of COVID-19 confirmed cases; (C) Gender-age wise distribution of COVID-19 death cases; and (D) Age and gender-wise case fatality rate (CFR) in Nepal.

Table 2 . District wise distribution of confirmed cases, recoveries, and deaths due to COVID-19 and total population in Nepal.

Among 268,948 confirmed cases, 174,193 were males, and 94,755 were females, with a male-to-female sex ratio of 1.85. The largest number of infected cases was reported in the age group 21–30 years (26.92%, n = 72,396), followed by the age group of 31–40 years (26.26%, n = 70,648) ( Figure 1B ); however, the number of death cases was higher in the age group 61–70 (23%, n = 458) ( Figure 1C ). A higher death trend in old age is also observed in Europe, America, and Asian countries ( 13 , 14 ). Overall, male death was ~2.33 times the death rate of females. Reports have indicated that men are at greater risk of around two time of acquiring severe outcomes of COVID-19, including hospitalizations, intensive care unit (ICU) admissions, and deaths ( 15 ). The enhanced susceptibility of males for COVID-19 associated adverse events may be correlated with the hormonal and immunological differences between males and females ( 15 , 16 ). Among a total of 1,986 fatal cases (Male: n = 1,391; female: n = 595), over half ( n = 1,166) were observed in senior adults (≥60 years). One early study among the Nepalese children suggested that male children were more commonly infected than female children ( 17 ).

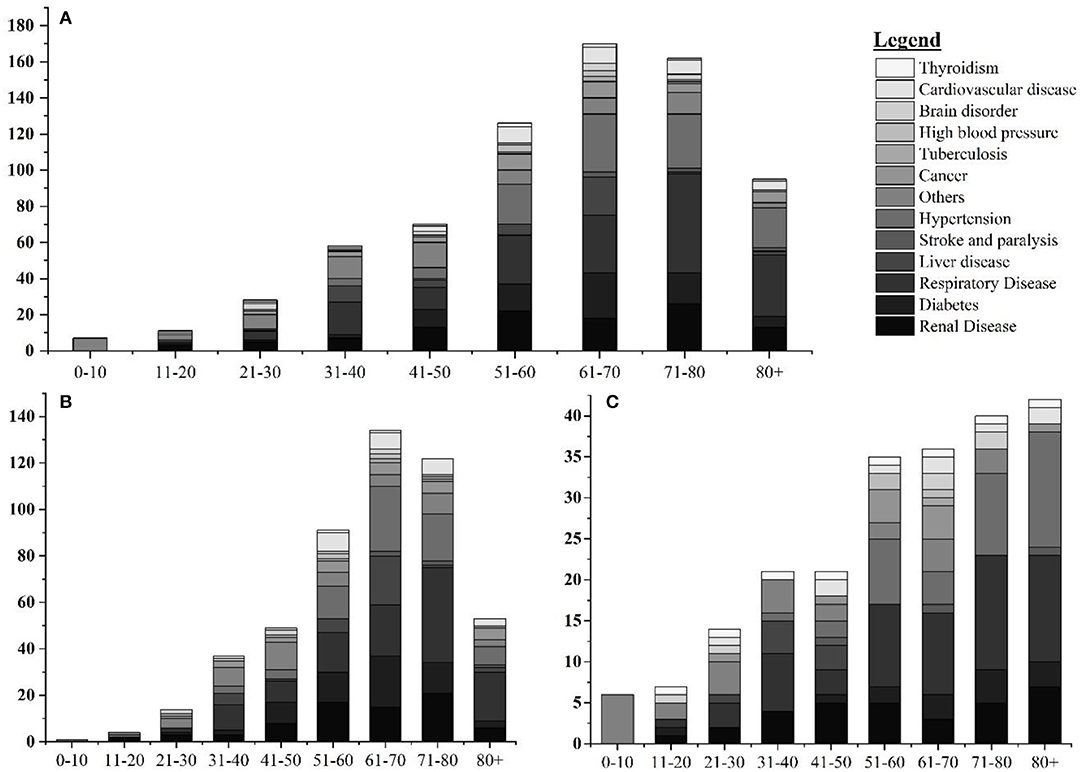

Among 1,986 fatal cases (mean age: 66.15 years), 623 (31.37%), 721 (36.30%), and 642 (32.32%) were with no report of comorbidities, with single comorbidities, and with multiple comorbidities, respectively. In cases with single comorbidities, the highest incidence was reported in respiratory disease ( n = 184) followed by hypertension ( n = 117), renal disease ( n = 107), diabetes ( n = 77), liver disease ( n = 44), and cardiovascular disease ( n = 36) ( Figure 2 ). Similar results are reported from other parts of the world ( 18 ). The detailed epidemiological trend analysis of COVID-19 in Nepal is shown in Figure 3 .

Figure 2 . Age and gender-wise distribution fatal cases with single comorbidities. (A) Age-wise distribution of leading single comorbidities among COVID-19 deaths; (B) age-wise distribution of leading single comorbidities among COVID-19 deaths in Nepal in male; and (C) age-wise distribution of leading single comorbidities among COVID-19 deaths in Nepal in female.

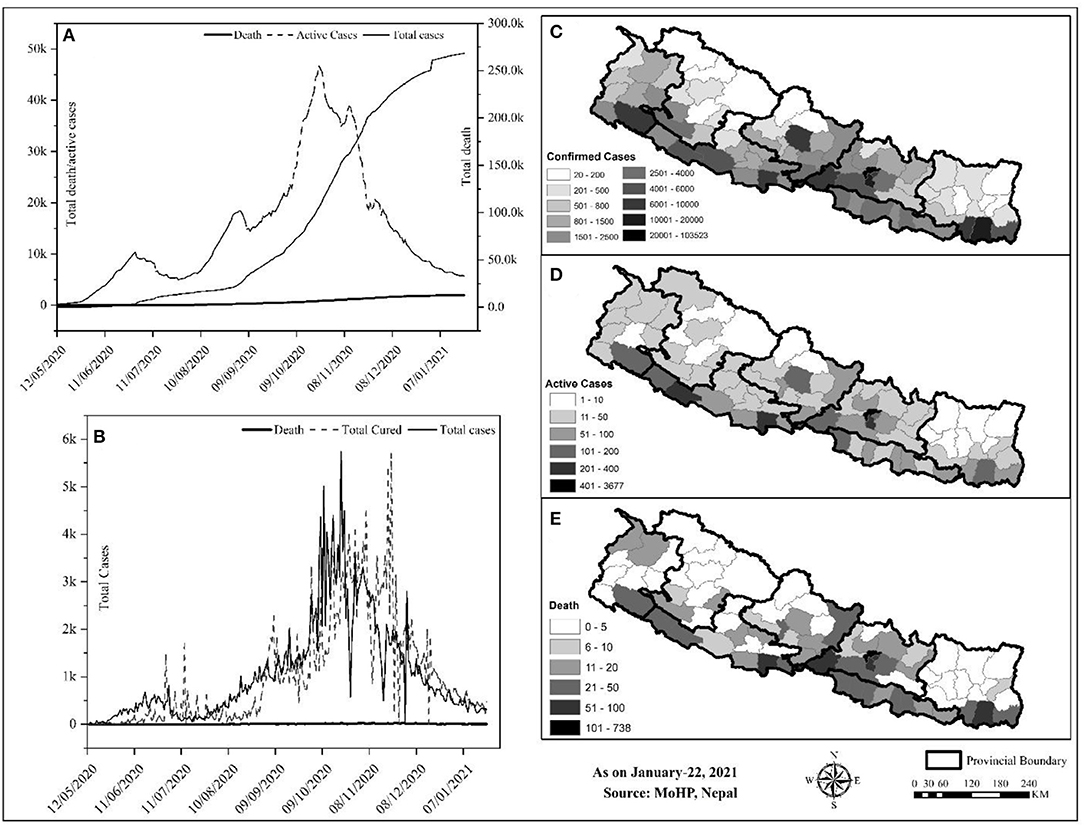

Figure 3 . Trend and spatial distribution of COVID-19 cases in Nepal. (A) Cumulative trend analysis of COVID-19 cases, (B) daily case wise trend analysis of COVID-19, (C–E) spatial distribution of infected, recovered, and death cases.

Geographically, Nepal is divided into three distinct ecological zones, mountain, hilly, and low-plain land from north to south. Politically, Nepal is divided into 7 provinces, 77 districts, and 753 local bodies. There were multiple peaks of active cases of COVID-19 in Nepal: active cases rapidly increased from early May to early July 2020, then increased slowly up to late July and increased at a higher rate again up to the end of December, and then decreased sharply ( Figure 3A ). The spatial distribution of COVID-19 confirmed cases, recovery, and deaths were compared ( Figures 3B–D ). Approximately, 64.84% of the total confirmed cases were reported from the hill regions, with single megacity Kathmandu contributing nearly half, 33.31% of lowland-plain areas, and 1.85% of Himalayan regions. The reported cases in the megacities are relatively higher than in the other regions. The higher number of cases in megacities may be correlated with dense populations in these areas ( 8 ). In the earlier months, the testing facilities and contact tracing were limited only to few districts, including the capital, Kathmandu, which gradually became available in other parts of the country. However, the testing frequency and testing facilities are still not homogeneous due to the lack of required technical resources and professional workforces ( 19 ) 9 .

The Response of Nepal Government to COVID-19

Nepal has adopted many readiness and response-related initiatives at the federal, provincial, and local government levels to fight against COVID-19. Initially, the government had set health desks and allocated spaces for quarantine purposes at the international airport and at the borders, crossing points of entry (PoE) with India and China 10 , to withstand the influx of many possible infected individuals from India and other countries. The open border and the politico-religious relationship with India and migrant workers returning from the Middle East, and other countries were a source of rapid transmission to Nepal 10 , 11 . The Nepal-China official border crossing points have remained closed since January 21, 2020. On March 24, 2020, the GoN imposed a complete “lockdown” of the country up to July 21, 2020. As part of the lockdown, businesses were closed, the restriction was imposed on movement within the country, workplaces were closed, travel was banned, and air transportation was halted 11 , 12 . In addition, for COVID-19 preparedness and response, the GoN developed a quarantine procedure and issued an international travel advisory notice. Closing the border was critical as Nepal and India share open borders across which citizens travel freely for business and work.

The GoN underestimated both the short and long-term impacts of border closure 11 . Around 2.8 million Nepali migrant workers work in India. Though the GoN discussed holding these workers in India with its Indian counterpart 13 , this plan did not materialize. Nepal has 1,690 km-long open borders with India, which could not keep migrant workers long despite the restrictions implemented by both governments 12 . As a consequence, the majority of COVID-19 cases were in the districts along the Indo-Nepal border. The decision of the government to lockdown the country from March 10, 2020, without sufficient preparation pushed daily wage laborers in urban areas to lose their jobs, and, hence, they were trapped without food or money. Ultimately, after a couple of days of lockdown, both migrant workers and daily wage laborers started walking the long way home due to the economic crisis.

As per the cabinet decision on March 25, 2020, Nepal established a COVID-19 response fund, developed a relief package 13 , and distributed relief to families in need through a “one door policy” 13 designed to reduce the COVID-19 impact; however, there were several gaps: the selection of families was unfair, GoN delayed the procurement of relief, relief packages did not include cash, and relief materials were inadequate and substandard 14 , 15 . The government has not adequately taken into account the impact of COVID-19 on the socio-economic sector. For instance, people participated in meetings, rallies, political demonstrations, and protests, where the virus could quickly spread among a large group of people. The government has, yet, to develop a stimulus package for social and economic recovery at the micro and macro levels. As the government has allocated $788 million for the health sector for the fiscal year (July–June 2020), a budget of 32% larger than the previous fiscal year, it should address the COVID-19 impact on the socio-economic front 16 . There is an opportunity to integrate all fragmented social protection schemes to strengthen socio-economic conditions and to emphasize more tremendous efforts, capacities, and resources to cope with the likely impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic 16 .

In addition, a minimal standard of quarantine as per the “Quarantine Operation and Management Protocol” (2076 B.S.) and “Standards for Home Quarantine” were imposed for all provinces 16 , 17 . The Sukraraj Infectious and Tropical Disease Hospital (SITDH) in Teku, Kathmandu, was designated by GoN as the primary hospital for COVID-19 cases along with Patan Hospital, the Armed Police Forces Hospital, in the Kathmandu Valley, followed by twenty-four hubs, and four satellite hospitals across the country 18 . Similarly, MoHP updated the National Public Health Laboratory (NPHL) capacity for confirmatory laboratory diagnosis of the COVID-19 from January 27, 2020, followed by the regional laboratory. The interim guideline for the establishing and operating of molecular laboratories for COVID-19 testing in Nepal was imposed to make uniformity in the test results 14 . Furthermore, the NPHL organized the training of trainers for laboratory staff in collaboration with the Medical Laboratory Association of Nepal 19 Ministry of Health and Population established two hotline numbers (1115 and 1133) to address public concerns, and prepared and disseminated regular press briefings, and improved its websites to channel appropriate information to the public. Besides, MoHP also conveyed decisions, notices, and situation updates periodically through its websites. Further, the Health Emergency Operation Centre (HEOC) of MoHP launched a “Viber communication group” to circulate updates on COVID-19 11, 13 . Early testing and timely contact tracing are crucial restrictive policies to control the spreading of the SARS-CoV-2 virus ( 20 , 21 ); however, in the earlier days of the pandemic, Nepal could not perform enough diagnostic tests and timely contact tracing; it resulted in a crucial time lag in identifying and isolating COVID-19 patients and caused delays in the ability of government to respond to the pandemic adequately. To alert and improve the testing and tracing response of the government, youth-led protests were carried out in different parts of the country 20 . Health Sector Emergency Response Plan was implemented in May 2020, focusing on the COVID-19 pandemic. This plan intends to prepare and strengthen the health system response capable of minimizing the adverse impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Government of Nepal devised a comprehensive plan on March 27, 2020, for quarantining people who arrived in Nepal from COVID-19 affected countries. The GoN had initially airlifted 175 Nepalese from six cities across Hubei Province of China on February 15, 2020, followed by Middle East countries, Australia, and so on 13 .

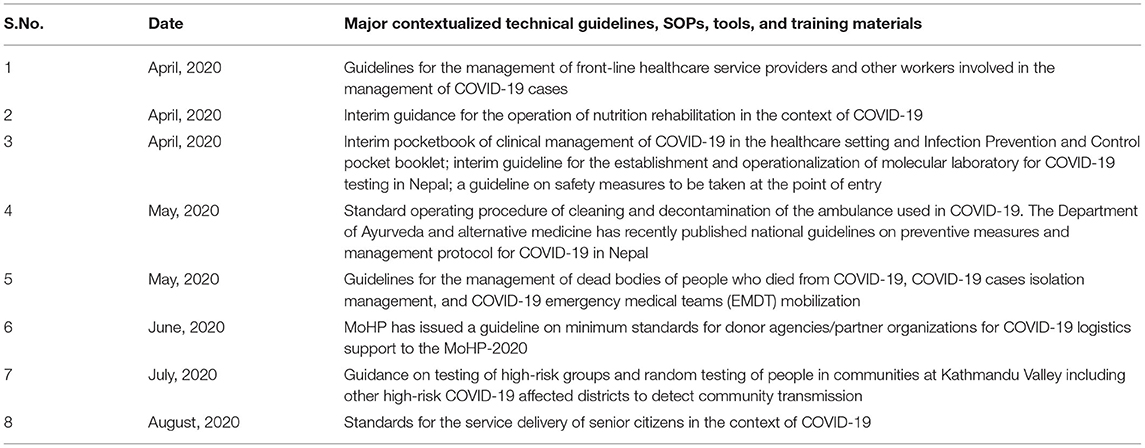

Ministry of Health and Population engaged in developing, endorsing, improving, and disseminating contextualized technical guidelines, standard operating procedures (SOPs), tools, and training in all other critical aspects of the response to COVID-19, for instance, surveillance, case investigation, laboratory testing, contact tracing, case detection, isolation and management, infection prevention and control, empowering health and community volunteers, media communication and community engagement, rational use of personal protective equipment (PPE), requirements of drugs and equipment for case management and public health interventions, and continuity of essentials services 13 ( 15 ). The major contextualized technical guidelines, SOPs, tools, and training materials developed by GoN to respond to COVID-19 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 were listed in Table 3 .

Table 3 . Major contextualized technical guidelines, standard operating protocols, tools, and training materials developed by the Government of Nepal (GoN) to respond to COVID-19.

Ministry of Health and Population and supporting organizations, such as United Nations Development Program (UNDP), UNICEF, and World Vision managed crucial supplies of PPE, facemasks, gloves, and sanitizers to ensure the protection of frontline workers and supporting staffs 13 , 30 , 31 , 32 . The frontline media of the nation increased online awareness programs via the involvement of celebrities, doctors, and experts of microbiology and infectious diseases on physical distancing and the importance and use of masks and sanitizers to prevent the COVID-19 contagion. In addition, camping programs were launched by the involvement of youth volunteers of the community in central Nepal 33 .

Government of Nepal received funds from the World Bank ($29 million), the United States of America ($1.8 million), and Germany ($1.22 million) to keep people protected from COVID-19 through health systems preparedness, emergency response, and research. In addition, support from UNICEF and countries, including China, India, and the USA, in the form of emergency medical supplies and equipment were received within January 2020 to March 2020. Private companies, corporate houses, business organizations, and individuals have also contributed to the prevention, control, and treatment fund of coronavirus ($13.8 million), established by GoN to cope with COVID-19. The Prime Minister Relief Fund is also expected to be utilized. The GoN allowed international NGOs to divert 20% of their program budget to COVID-19 preparedness and response; for instance, the Social Welfare Council has allocated $226 million 31 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 .

The GoN has formed a committee to coordinate the preparedness and response efforts, including the MoHP, Ministry of Home Affairs, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Culture, Tourism and Civil Aviation, Ministry of Urban Development, Nepal Army, Nepal Police, and Armed Police Force. The Humanitarian Country Team (HCT) includes the Red Cross Movement and civil society organizations (national and international NGOs). Under the joint leadership of the office of Resident Coordinator and the WHO, the HCT has initiated contingency planning and preparedness interventions, including the dissemination of communications materials to raise community-level awareness across the country 21 . The clusters led by the GoN and co-led by the International Astronomical Search Collaboration (IASC) cluster leads and partners are working on finalizing contingency plans, which will be consolidated into an overall joint approach with the Government and its international partners. The UN activated the provincial focal point agency system to support coordination between the international community and the GoN at the provincial level 21 .

However, despite these robust efforts implemented by GoN, few lapses existed. Examples are the following: issues of inconsistent implementation of immigration policies usually at Indo-Nepal borders 38 , 39 , 40 , shortage and misuse of crucial protective suits and other supplies in hospitals, the ease and the end of lockdown, lack of poor infrastructure facilities, and continuous spread of COVID-19 across the country ( 19 ). The GoN decided to lift the lockdown effective from July 22, 2020, completely; however, the socio-administrative and health measures with the potential for high-intensity transmission (colleges, seminars, training, workshops, cinema halls, party palaces, dance bars, swimming pools, religious places, etc.) remained closed until the following directive as of September 1, 2020. Long route bus services and domestic and international passenger flights were halted until August 1, 2020 41 . A high-level committee at the MoHP has requested all satellite hospitals (public, private, and others) to allocate 20% of their beds for COVID-19 cases. The respective hub hospitals coordinate with the HEOC and satellite hospitals to manage COVID-19 cases 42 . After lifting lockdown for 3 weeks, the federal government has given authority to local administrations to decide on restrictions and lockdown measures as COVID-19 cases continue to rise. In addition, the authority to impose necessary restrictions if COVID-19 active cases surpass the threshold of 200 was given to the Chief District Officer (CDO) 43 . Since March 2020, all the central hospitals, provincial hospitals, medical colleges, academic institutions, and hub-hospitals were designated to provide treatment care for COVID-19 cases. At this stage of operation, the major challenges for the COVID-19 response were managing quarantine facilities, lack of enough human resources, having limited laboratories for testing, and availability of limited stock of medical supplies, including PPEs 14 . To the best of our knowledge, this pandemic is the most extensive public health emergency the GoN faced in its recent history.

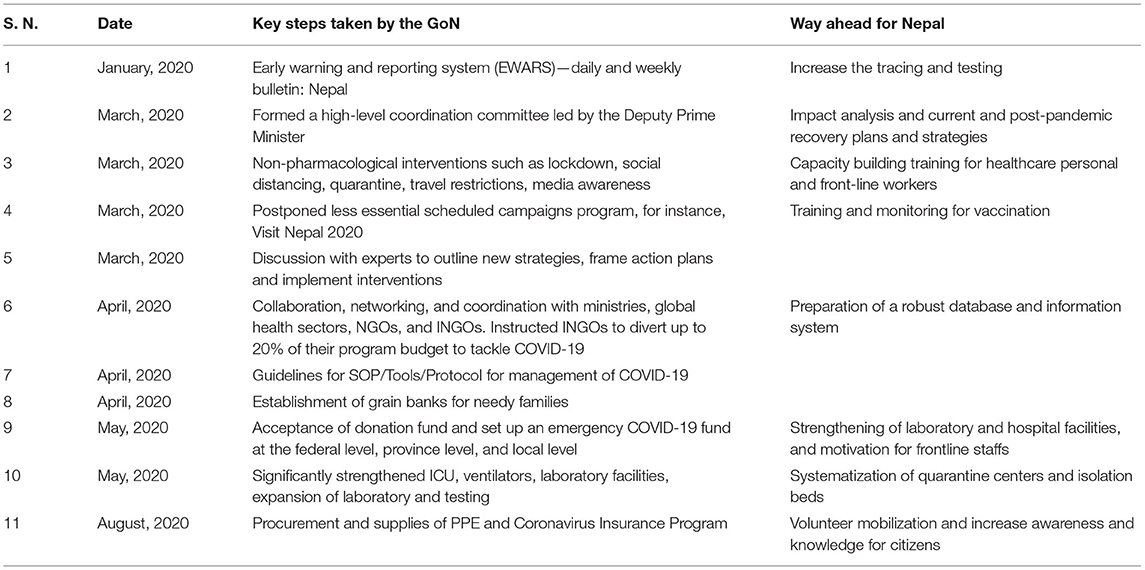

There is no doubt that GoN has taken major initiatives to fight the COVID-19 pandemic. The MoHP, together with associated national and international organizations are closely monitoring and evaluating the signs of outbreaks, challenges, and enforcing the plan and strategies to mitigate the possible impact; however, many challenges and difficulties, such as management of testing, hospital beds, and ventilators, quarantine centers, frontline staffs, movement of people during the lockdown, are yet to be solved 18 , 30 , 38 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 . Therefore, in the opinion of the authors, we recommend some steps to be implemented as soon as possible to mitigate and lessen the impacts of COVID-19 ( Table 4 ).

Table 4 . Major steps taken by GoN and way forward in the response to COVID-19 outbreak.

To strengthen its coordination mechanism, the government formed a team to monitor conditions and measures applied to control the outbreak; a COVID-19 coordination committee 11 to coordinate the overall response, and a COVID-19 crisis management center 14 to coordinate daily operations; however, these teams and committees did not function efficiently because roles and authorities were not delegated to ministries and government. A new institution was created, instead of using the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Authority (NDRRMA) 48 , which enhanced additional confusion. The MoHP is responsible for overall policy formulation, planning, organization, and coordination of the health sector at federal, provincial, district, and community levels during the COVID-19 pandemic situation. Allegedly, there is an opportunity to strengthen coordination among the tiers of governments by following protocols and guidance for effective preparedness and response. For example, some quarantine centers were so poorly run that, in turn, could potentially develop into breeding grounds for the COVID-19 transmission 15 .

Finally, this study only focuses on analyzing COVID-19 data extracted from the MoHP database for 1 year. Furthermore, we did not quantify the effectiveness of the strategies of GoN and the role of non-governmental organizations and authorities to combat COVID-19 in Nepal.

This study provides an insight into the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic from the Nepalese context for the period of first-wave from January 2020 to January 2021. Despite the several initiatives taken by the GoN, the current scenario of COVID-19 in Nepal is yet to be controlled in terms of infections and mortality. A total of 268,948 confirmed cases and 1,986 deaths were reported in one year period. The maximum number of cases were reported from Bagmati province ( n = 144,278), all of the 77 districts were affected. The cases showing highly COVID-specific symptoms were low (<1%) in comparison with the reports across the globe ( 10 ), which may be because the average age of the Nepalese population is younger than many of the highly affected European countries. The other reasons may be differences in demographic characteristics, sampling bias, healthcare coverage, testing availability, and inconsistencies relating to the reporting of the data included in the current study. Both the number of infections and deaths are higher in males than in females. Despite the age, testing and positivity, hospital capacity and hospital admission criterion, demographics, and HDI index, the overall case fatality was reported to be less than in some other developed countries ( Table 1 ). Consistent with reports from other countries ( 22 , 23 ), the death rate is higher in the old age group ( Figure 1 ). Spatial distribution displayed the cases, which are majorly distributed in megacities compared with the other regions of the country.

Based on this assessment, in addition to the WHO COVID-19 infection prevention and control guidance 49 , some recommendations, such as massive contact tracing, improving bed capacity in health care settings and rapid test, proper management of isolation and quarantine facilities, and advocacy for vaccines, may be helpful for planning strategies and address the gaps to combat against the COVID-19. Notably, the recommendations provided could benefit the governmental bodies and concerned authorities to take the appropriate decisions and comprehensively assess the further spread of the virus and effective public health measures in the different provinces and districts in Nepal. In this review, we have summarized the ongoing experiences in reducing the spread of COVID-19 in Nepal. The Nepalese response is characterized by nationwide lockdown, social distancing, rapid response, a multi-sectoral approach in testing and tracing, and supported by a public health response. Overall, the broader applicability of these experiences is subject to combat the COVID-19 impacts in different socio-political environments within and across the country in the days to come.

Author Contributions

BB: Conceptualization, writing, and original draft preparation. KB, BB, and AG: data curation. BB, RP, TB, SD, NP, and DG: writing, review, and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

KB and AG were employed by Nepal Environment and Development Consultant Pvt. Ltd., in Kathmandu, Nepal.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Ministry of Health and Population (MoHP), Government of Nepal, for supporting data in this research. We are thankful to the reviewers for their meticulous comments and suggestions, which helped to improve the manuscript.

1. ^ Worldometer. COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic . (2020). Available online at: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ (accessed January 15, 2021).

2. ^ Worldometer. Nepal Population . (2020). Available online at: https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/nepal-population/ (accessed January 15, 2021).

3. ^ Trading Economics. Nepal GDP . (2020). Available online at: https://tradingeconomics.com/nepal/gdp (accessed January 15, 2021).

4. ^ UNDP. Human Development Reports . (2020). Available online at: http://hdr.undp.org/en/countries/profiles/NPL (accessed January 15, 2021).

5. ^ World Health Organization. COVID-19 Nepal: Preparedness and Response Plan (NPRP) . (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/nepal-documents/novel-coronavirus/covid-19-nepal-preparedness-and-response-plan-(nprp)-draft-april-9.pdf?sfvrsn=808a970a_2 (accessed January 15, 2021).

6. ^ Ministry of Health and Population. COVID-19 Update . (2020). Available online at: https://covid19.mohp.gov.np/ (accessed January 15, 2021).

7. ^ World Health Organization. WHO Nepal Situation Updates-19 on COVID-19, 2020 . (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/nepal-documents/novel-coronavirus/who-nepal-sitrep/19-who-nepal-sitrep-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=c9fe7309_2 (accessed January 15, 2021).

8. ^ World Health Organization. WHO Nepal Situation Updates-22 on COVID-19, 2020 . (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/nepal-documents/novel-coronavirus/who-nepal-sitrep/22-who-nepal-sitrep-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=df7c946a_2 (accessed January 15, 2021).

9. ^ World Health Organization. (2020). WHO Nepal Situation Updates-16 on COVID-19, 2020 . (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/nepal-documents/novel-coronavirus/who-nepal-sitrep/16–who-nepal–sitrep-covid-19-07082020-final.pdf?sfvrsn=53c5360f_2 (accessed January 15, 2021).

10. ^ Bhattarai, KD. South Asian Voices: COVID-19 and Nepal's Migration Crisis . Available online at: https://southasianvoices.org/covid-19-and-nepals-migration-crisis/ (accessed January 15, 2021).

11. ^ GRADA WORLD Nepal: Government announces nationwide lockdown from March 24–31/update . Available online at: https://www.garda.com/crisis24/news-alerts/326601/nepal-government-announces-nationwide-lockdown-from-march-24-31-update-4 (accessed January 15, 2021).

12. ^ Gautam D. NDRC. Nepal's Readiness and Response to COVID-19 . (2020). Available online at: https://www.preventionweb.net/files/71274_71274nepalsreadinessandresponsetopa.pdf (accessed January 15, 2021).

13. ^ Building Back Better (BBB) from COVID-19: World Vision Policy Brief on Building Back Better from COVID-19 . (2020). Available online at: https://www.wvi.org/sites/default/files/202005/World%20Vision%20Policy%20Brief%20on%20Building%20Back%20Better_25%20May%202020.pdf (accessed January 15, 2021).

14. ^ World Health Organization. WHO Nepal Situation Updates-1 on COVID-19, 2020 . (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/nepal-documents/novel-coronavirus/who-nepal-sitrep/who-nepal–sitrep-covid-19-20apr2020.pdf?sfvrsn=c788bf96_2 (accessed January 15, 2021).

15. ^ GoN MoHP. Health Sector Emergency Response Plan COVID-19 Pandemic 2020 . (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/nepal-documents/novel-coronavirus/health-sector-emergency-response-plan-covid-19-endorsed-may-2020.pdf?sfvrsn=ef831f44_2 (accessed January 15, 2021).

16. ^ Gautam, D. The COVID-19 Crisis in Nepal: Coping Crackdown Challenges. National Disaster Risk Reduction Centre, Kathmandu, Nepal. Issue 3, 2020 . Available online at: https://www.alnap.org/help-library/the-covid-19-crisis-in-nepal-coping-crackdown-challenges (accessed January 30, 2021).

17. ^ Gautam, D. Fear of COVID-19 Overshadowing Climate-Induced Disaster Risk Management . Available online at: https://www.spotlightnepal.com/2020/05/08/fear-covid-19-overshadowing-climate-induced-disaster-risk-management/ (accessed January 30, 2021).

18. ^ Pradhan TR. The Kathmandu Post. Nepal Goes Under Lockdown for a Week Starting 6am Tuesday . Available online at: https://kathmandupost.com/national/2020/03/23/nepal-goes-under-lockdown-for-a-week-starting-6am-tuesday (accessed January 30, 2021).

19. ^ World Health Organization. WHO Nepal Situation Updates-3 on COVID-19, 2020 . (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/nepal-documents/novel-coronavirus/who-nepal-sitrep/who-nepal–situpdate-3-covid-19-06052020.pdf?sfvrsn=714d14c4_2 (accessed January 30, 2021).

20. ^ Jha IC. The Rising Nepal. MoHP Sets Forth Standards for Home Quarantine . Available online at: https://risingnepaldaily.com/featured/mohp-sets-forth-standards-for-home-quarantine (accessed January 30, 2021).

21. ^ The Kathmandu Post. Youth-Led Protests Against the Government's Handling of Covid-19 Spread to Major Cities . (2020). Available online at: https://kathmandupost.com/national/2020/06/12/youth-led-protests-against-the-government-s-handling-of-covid-19-spread-to-major-cities (accessed January 30, 2021).

22. ^ World Health Organization. WHO Nepal Situation Updates-2 on COVID-19, 2020 . (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/nepal-documents/novel-coronavirus/who-nepal-sitrep/who-nepal–sitrep-covid-19-29apr2020.pdf?sfvrsn=dac001bf_2 (accessed January 30, 2021).

23. ^ World Health Organization. WHO Nepal Situation Updates-4 on COVID-19, 2020 . (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/nepal-documents/novel-coronavirus/who-nepal-sitrep/who-nepal–situpdate-4-13052020.pdf?sfvrsn=630b68ea_6 (accessed January 30, 2021).

24. ^ World Health Organization. WHO Nepal Situation Updates-18 on COVID-19, 2020 . (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/nepal-documents/novel-coronavirus/who-nepal-sitrep/18-who-nepal-sitrep-covid-19-23082020.pdf?sfvrsn=6fb20500_2 (accessed February 5, 2021).

25. ^ World Health Organization. WHO Nepal Situation Updates-5 on COVID-19, 2020 . (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/nepal-documents/novel-coronavirus/who-nepal-sitrep/5-who-nepal–situpdate-covid-19-20052020-final.pdf?sfvrsn=7552c8ba_4 (accessed February 5, 2021).

26. ^ World Health Organization. WHO Nepal Situation Updates-7 on COVID-19, 2020 . (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/nepal-documents/novel-coronavirus/who-nepal-sitrep/7-who-nepal–situpdate-covid-19-03062020-final.pdf?sfvrsn=87f582d6_2 (accessed February 5, 2021).

27. ^ World Health Organization. WHO Nepal Situation Updates-8 on COVID-19, 2020 . (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/nepal-documents/novel-coronavirus/who-nepal-sitrep/8-who-nepal–situpdate-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=ce5ecb07_2 (accessed February 5, 2021).

28. ^ World Health Organization. WHO Nepal Situation Updates-10 on COVID-19, 2020 . (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/nepal-documents/novel-coronavirus/who-nepal-sitrep/10-who-nepal–situpdate-covid-19-24062020.pdf?sfvrsn=c7f99a61_8 (accessed February 5, 2021).

29. ^ World Health Organization. WHO Nepal Situation Updates-13 on COVID-19, 2020 . (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/nepal-documents/novel-coronavirus/who-nepal-sitrep/13–who-nepal–situpdate-covid-19-17072020-v4.pdf?sfvrsn=fc0f19cc_2 (accessed February 5, 2021).

30. ^ World Health Organization. WHO Nepal Situation Updates-17 on COVID-19, 2020 . (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/nepal-documents/novel-coronavirus/who-nepal-sitrep/17-who-nepal-sitrep-covid-19-15082020.pdf?sfvrsn=68a53b32_2 (accessed February 10, 2021).

31. ^ UN. Nepal Information Platform, COVID-19 Nepal: Preparedness and Response Plan . Available online at: http://un.org.np/reports/covid-19-nepal-preparedness-and-response-plan (accessed February 10, 2021).

32. ^ UNICEF for Every Child, Supporting COVID-19 Readiness and Response in the West of Nepal . Available online at: https://www.unicef.org/nepal/stories/supporting-covid-19-readiness-and-response-west-nepal (accessed February 10, 2021).

33. ^ UNDP. Enhancing Public Awareness on COVID-19 Through Communications . Available online at: https://www.np.undp.org/content/nepal/en/home/presscenter/articles/2020/Enhancing-public-awareness-of-COVID-19-through-communications.html (accessed February 10, 2021).

34. ^ The World Bank. The Government of Nepal and the World Bank sign $29 Million Financing Agreement for Nepal's COVID-19 (Coronavirus) Response . Available online at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2020/04/03/world-bank-fast-tracks-29-million-for-nepal-covid-19-coronavirus-response (accessed February 10, 2021).

35. ^ Khatri PP. The Rising Nepal. Govt Receives Over Rs 1.59 Bln In Anti-COVID-19 Fund . Available online at: https://risingnepaldaily.com/main-news/govt-receives-over-rs-159-bln-in-anti-covid-19-fund (accessed February 10, 2021).

36. ^ Dahal A. Govt Does U-Turn to Let NGOs Hand Out Medical Supplies, Food, Cash directly . Available online at: https://myrepublica.nagariknetwork.com/news/govt-does-u-turn-to-let-ingos-hand-out-medical-supplies-food-cash-directly/ (accessed February 10, 2021).

37. ^ Rijal A. The Rising Nepal. China Gives Anti-Corona Medical Aid . Available online at: https://risingnepaldaily.com/main-news/china-gives-anti-corona-medical-aid (accessed February 10, 2021).

38. ^ Nepali Sansar. Nepal Receives 23 Tons ‘COVID-19 Medical Equip' As Gifts from India . (2020). Available online at: https://www.nepalisansar.com/coronavirus/nepal-receives-23-tons-covid-19-medical-equip-as-gifts-from-india/ (accessed February 10, 2021).

39. ^ Koirala S, Bhattarai, S. My Republica. Protect Frontline Healthcare Workers . Available online at: https://myrepublica.nagariknetwork.com/news/protect-frontline-healthcare-workers/ (accessed February 10, 2021).

40. ^ Halder R. Lockdowns and national borders: How to manage the Nepal-India border crossing during COVID-19 . Available online at: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/southasia/2020/05/19/lockdowns-and-national-borders-how-to-manage-the-nepal-india-border-crossing-during-covid-19/ (accessed February 10, 2021).

41. ^ Raturi K. How Is Nepal Tackling COVID Crisis & Reverse Migration of Workers? Available online at: https://www.thequint.com/voices/opinion/india-nepal-border-coronavirus-pandemic-migrant-workers-exodus-reverse-migration-unemployment (accessed February 10, 2021).

42. ^ World Health Organization. WHO Nepal Situation Updates-14 on COVID-19, 2020 . (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/nepal-documents/novel-coronavirus/who-nepal-sitrep/14–who-nepal–sitrep-covid-19-26072020.pdf?sfvrsn=65868c9e_2 (accessed February 10, 2021).

43. ^ World Health Organization. WHO Nepal Situation Updates-19 on COVID-19, 2020 . (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/nepal-documents/novel-coronavirus/who-nepal-sitrep/19-who-nepal-sitrep-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=c9fe7309_2 (accessed February 10, 2021).

44. ^ Prasain S, Pradhan TR. The Kathmandu Post . Available online at: https://kathmandupost.com/politics/2020/08/12/nepal-braces-for-a-return-to-locked-down-life-as-rise-in-covid-19-cases-rings-alarm-bells (accessed February 10, 2021).

45. ^ NHPL. Information regarding Novel Corona Virus . (2020). Available online at: https://www.nphl.gov.np/page/ncov-related-lab-information (accessed February 10, 2021).

46. ^ NHRC. Assessment of Health-related Country Preparedness and Readiness of Nepal for Responding to COVID-19 Pandemic Preparedness and Readiness of Government of Nepal Designated COVID Hospitals . (2020). Available online at: http://nhrc.gov.np/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Fact-sheet-Preparedness-and-Readiness-of-Government-of-Nepal-Designated-COVID-Hospitals.pdf (accessed February 10, 2021).

47. ^ Koirala S. Comprehensive response to COVID 19 in Nepal . Available online at: https://en.setopati.com/blog/152612 (accessed February 10, 2021).

48. ^ National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Authority, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of Nepal . Available online at: https://covid19.ndrrma.gov.np/ (accessed February 10, 2021).

49. ^ World Health Organization. Infection Prevention and Control Guidance - (COVID-19) . (2021). Available online at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public (accessed February 10, 2021).

1. Jayaweera M, Perera H, Gunawardana B, Manatunge J. Transmission of COVID-19 virus by droplets and aerosols: a critical review on the unresolved dichotomy. Environ Res. (2020) 188:109819. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109819

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Zheng J. SARS-CoV-2: an emerging coronavirus that causes a global threat. Int J Biol Sci. (2020) 16:1678–85. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.45053

3. Islam N, Sharp SJ, Chowell G. Physical distancing interventions and incidence of coronavirus disease 2019: natural experiment in 149 countries. BMJ. (2020) 370:27–43. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2743

4. Gupta A, Singla M, Bhatia H, Sharma V. Lockdown-the only solution to defeat COVID-19. Int J Diabetes Dev Ctries. (2020) 6:1–2. doi: 10.1007/s13410-020-00826-3

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

5. Lu G, Razum O, Jahn A, Zhang Y, Sutton B, Sridhar D, et al. COVID-19 in Germany and China: mitigation versus elimination strategy. Glob. Health Action . (2021). 14:1875601. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2021.1875601

6. The Lancet. COVID-19: too little, too late. Lancet . (2020) 395:P755. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30522-5

7. Bastola A, Sah R, Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Lal BK, Jha R, Ojha HC, et al. The first 2019 novel coronavirus case in Nepal. Lancet Infect Dis. (2020) 20:279–80. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30067-0

8. Dhakal S, Karki S. Early epidemiological features of COVID-19 in Nepal and public health response. Front. Med. (2020) 7:524. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00524

9. Panthee B, Dhungana S, Panthee N, Paudel A, Gyawali S, Panthee S. COVID-19: the current situation in Nepal. New Microbes New Infect. (2020) 37:100737. doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2020.100737

10. Oran DP, Topol EJ. The proportion of SARS-CoV-2 infections that are asymptomatic: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. (2021) 174:655–62. doi: 10.7326/M20-6976

11. Bhattarai S, Parajuli SB, Rayamajhi RB, Paudel IS, Jha N. Clinical health seeking behavior and utilization of health care services in eastern hilly region of Nepal. J Coll Med. Sci Nepal . (2015). 11:8–16. doi: 10.3126/jcmsn.v11i2.13669

12. Paudel S, Aryal B. Exploration of self-medication practice in Pokhara valley of Nepal. BMC Public Health. (2020) 20:714. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-08860-w

13. Ioannidis JPA, Axfors C. Contopoulos-Ioannidis DG. Population-level COVID-19 mortality risk for non-elderly individuals overall and for non-elderly individuals without underlying diseases in pandemic epicenters. Environ Res . (2020) 188:109890. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109890

14. Cortis D. On determining the age distribution of COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Publ. Health. (2020) 8:202. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00202

15. Gebhard C, Regitz-Zagrosek V, Neuhauser HK, Morgan R, Klein SL. Impact of sex and gender on COVID-19 outcomes in Europe. Biol Sex Differ. (2020) 11:29. doi: 10.1186/s13293-020-00304-9

16. Sharma G, Volgman AS, Michos ED. Sex differences in mortality from COVID-19 pandemic: are men vulnerable and women protected? JACC Case Rep. (2020) 2:1407–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.04.027

17. Sharma AK, Chapagain RH, Bista KP, Bohara R, Chand B, Chaudhary NK, et al. Epidemiological and clinical profile of COVID-19 in Nepali children: an initial experience. J Nepal Paediatr Soc. (2020) 40:202–9. doi: 10.3126/jnps.v40i3.32438

18. Piryani RM, Piryani S, Shah JN. Nepal's response to contain COVID-19 infection. J Nepal Health Res Counc. (2020) 18:128–34. doi: 10.33314/jnhrc.v18i1.2608

19. Rayamajhee B, Pokhrel A, Syangtan G. How well the government of nepal is responding to COVID-19? An experience from a resource-limited country to confront unprecedented pandemic. Front Public Health. (2021) 9:597808. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.597808

20. Kretzschmar ME, Rozhnova G, Bootsma MC, van Boven M, van de Wijgert JH, Bonten MJ. Impact of delays on effectiveness of contact tracing strategies for COVID-19: a modelling study. Lancet Public Health. (2020) 5:e452–9. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30157-221

21. Contreras S, Biron-Lattes JP, Villavicencio HA, Medina-Ortiz D, Llanovarced-Kawles N, Olivera-Nappa Á. Statistically-based methodology for revealing real contagion trends and correcting delay-induced errors in the assessment of COVID-19 pandemic. Chaos Solit Fract . (2020). 139:110087. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.110087

22. Levin AT, Hanage WP, Owusu-Boaitey N, Cochran KB, Walsh SP, Meyerowitz-Katz G. Assessing the age specificity of infection fatality rates for COVID-19: systematic review, meta-analysis, and public policy implications. Eur J Epidemiol. (2020) 35:1123–38. doi: 10.1007/s10654-020-00698-1

23. O'Driscoll M, Dos Santos GR, Wang L, Cummings DA, Azman AS, Paireau J, et al. Age-specific mortality and immunity patterns of SARS-CoV-2. Nature . (2021). 590:140–5. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2918-0

Keywords: COVID-19, pandemic, preparedness, response, spatial distribution, public health, Nepal

Citation: Basnet BB, Bishwakarma K, Pant RR, Dhakal S, Pandey N, Gautam D, Ghimire A and Basnet TB (2021) Combating the COVID-19 Pandemic: Experiences of the First Wave From Nepal. Front. Public Health 9:613402. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.613402

Received: 05 October 2020; Accepted: 11 June 2021; Published: 12 July 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Basnet, Bishwakarma, Pant, Dhakal, Pandey, Gautam, Ghimire and Basnet. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Til Bahadur Basnet, ddst19basnet@hotmail.com

† These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Government of Nepal

Ministry of Health and Population

Department of Health Services

Epidemiology and Disease Control Division

- IEC Materials & Factsheets

COVID-19 Presentation in Nepali

- Epidemiology & Outbreak Management Section

News & Update

2023_12_15 Dengue Situation Update

Situation updates of Dengue (as of 31 Dec 2022)

Cholera Outbreak in Kathmandu Valley (as of 5 Sep 2022)

Cholera Outbreak in Kathmandu Valley 5 Sep

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Health Topics

- Drugs & Supplements

- Medical Tests

- Medical Encyclopedia

- About MedlinePlus

- Customer Support

Health Information in Nepali (नेपाली)

Acute bronchitis.

- Health Information Translations

Advance Directives

Alzheimer's disease, anal disorders, animal bites, ankle injuries and disorders, appendicitis, arm injuries and disorders, asthma in children, atrial fibrillation, baby health checkup, back injuries, bile duct diseases, biodefense and bioterrorism, birth weight, blood glucose, body weight, bone cancer, bone diseases, bone marrow diseases, breast cancer, breast diseases, breastfeeding, breathing problems, bronchial disorders, bullying and cyberbullying, cancer chemotherapy, cancer--living with cancer, cardiac rehabilitation, cervical cancer, cervical cancer screening, cesarean delivery, chemical emergencies, child dental health, child safety, childhood vaccines, children's health.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Cholesterol

Choosing a doctor or health care service, chronic bronchitis, chronic kidney disease, circumcision, colonic diseases, colorectal cancer, common infant and newborn problems, constipation, covid-19 (coronavirus disease 2019), critical care, diabetes complications, diabetes medicines, diabetes type 1, diabetes type 2, diabetic eye problems, diabetic kidney problems, diabetic nerve problems, diagnostic imaging, digestive diseases, disaster preparation and recovery.

- Vermont Department of Health

Dislocations

Drug safety, drug use and addiction, ear infections, end of life issues, eye diseases, facial injuries and disorders, fetal health and development, finger injuries and disorders.

- Minnesota Department of Health

Gallbladder Diseases

Germs and hygiene, haemophilus infections, hand injuries and disorders, health problems in pregnancy, healthy sleep, hearing problems in children, heart attack, heart diseases, heart health tests, heart surgery, hepatitis a, hepatitis b, high blood pressure, high blood pressure in pregnancy, hip replacement, hiv and pregnancy, hyperglycemia, hypoglycemia, infant and newborn care, infant and newborn development, infant and newborn nutrition, insect bites and stings, irritable bowel syndrome, kidney diseases, kidney failure, kidney tests, knee replacement, laboratory tests, lead poisoning, leg injuries and disorders, lung diseases, mammography, medical device safety, mobility aids, mood disorders, mosquito bites, motor vehicle safety, neurologic diseases, neuromuscular disorders, newborn screening, nuclear scans, opioid overdose, opioids and opioid use disorder (oud), osteoporosis, pacemakers and implantable defibrillators, parathyroid disorders, patient safety, peripheral arterial disease, pneumococcal infections, polio and post-polio syndrome, postpartum care, postpartum depression, pregnancy and medicines, pregnancy and nutrition, pregnancy and substance use, prenatal care, prenatal testing, prescription drug misuse, quitting smoking, radiation emergencies, radiation exposure, radiation therapy, rehabilitation, rotator cuff injuries, sexually transmitted diseases, shoulder injuries and disorders, skin cancer, sleep apnea, sleep disorders, sore throat, sprains and strains, stomach disorders, sudden infant death syndrome, swallowing disorders, talking with your doctor, thyroid diseases, thyroid tests, traumatic brain injury, tuberculosis.

- Massachusetts Department of Public Health

Ulcerative Colitis

Urinary incontinence, urinary tract infections, urine and urination, vaginal diseases, vascular diseases, weight control, women's health checkup, wounds and injuries, wrist injuries and disorders.

Characters not displaying correctly on this page? See language display issues .

Return to the MedlinePlus Health Information in Multiple Languages page.

Understanding COVID-19 in Nepal

Affiliation.

- 1 Sukraraj Tropical and Infectious Disease Hospital, Teku, Kathmandu, Nepal.

- PMID: 32335607

- DOI: 10.33314/jnhrc.v18i1.2629

The novel coronavirus COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) was first reported in 31 December 2019 in Wuhan City, China. The first case of COVID-19 was officially announced on 24 January, 2020, in Nepal. Nine COVID-19 cases have been reported in Nepal. We aim to describe our experiences of COVID-19 patients in Nepal. Keywords: COVID-19; experience; Nepal.

- Asymptomatic Diseases

- Betacoronavirus

- Coronavirus Infections / epidemiology*

- Coronavirus Infections / transmission

- Coronavirus*

- Disease Outbreaks

- Health Knowledge, Attitudes, Practice

- Middle Aged

- Nepal / epidemiology

- Pneumonia, Viral / epidemiology*

- Pneumonia, Viral / transmission

- Young Adult

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Health Expect

- v.26(3); 2023 Jun

- PMC10154840

Management of COVID‐19 and vaccination in Nepal: A qualitative study

Alisha karki.

1 PHASE Nepal, Bhaktapur Nepal

Barsha Rijal

Bikash koirala, prabina makai, pratik adhikary, saugat joshi, srijana basnet, sunita bhattarai, jiban karki, associated data.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

The aim of this research is to investigate the perspective of citizens of Nepal on the management COVID‐19, the roll‐out of the vaccine, and to gain an understanding of attitudes towards the governments' handling of the COVID‐19 pandemic.

A qualitative methodology was used. In‐depth interviews were conducted with 18 males and 23 females aged between 20 and 86 years old from one remote and one urban district of Nepal. Interviews were conducted in November and December 2021. A thematic approach was used to analyse the data, utilising NVivo 12 data management software.

Three major themes were identified: (1) Peoples' perspective on the management of COVID‐19, (2) people's perception of the management of COVID‐19 vaccination and (3) management and dissemination of information. It was found that most participants had heard of COVID‐19 and its mitigation measures, however, the majority had limited understanding and knowledge about the disease. Most participants expressed their disappointment concerning poor testing, quarantine, vaccination campaigns and poor accountability from the government towards the management of COVID‐19. Misinformation and stigma were reported as the major factors contributing to the spread of COVID‐19. People's knowledge and understanding were mainly shaped by the quality of the information they received from various sources of communication and social media. This heavily influenced their response to the pandemic, the preventive measures they followed and their attitude towards vaccination.

Our study concludes that the study participants' perception was that testing, quarantine centres and vaccination campaigns were poorly managed in both urban and rural settings in Nepal. Since people's knowledge and understanding of COVID‐19 are heavily influenced by the quality of information they receive, we suggest providing contextualised correct information through a trusted channel regarding the pandemic, its preventive measures and vaccination. This study recommends that the government proactively involve grassroots‐level volunteers like Female Community Health Volunteers to effectively prepare for future pandemics.

Patient and Public Contribution

This study was based on in‐depth interviews with 41 people from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds. This study would not have been possible without their participation.

1. INTRODUCTION

COVID‐19 was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) on 11 March 2020. 1 Since the outbreak, the WHO urged governments to prioritise their actions in response to the COVID‐19 infection. Beyond the disease itself, unprecedented social and economic hardship has been experienced across the globe due to this infection. 2 Furthermore, emerging new variants of COVID‐19, causing subsequent waves of infection have caused concern worldwide, hastening the urgency for disease control, and the necessity for a plan to facilitate the end of the pandemic. 3

The first step to controlling a pandemic like COVID‐19 is to stop the spread of infection. This responsibility falls under the preview of state governments. Good governance is paramount towards the effective management of COVID‐19. 4 Many countries have adopted preventive measures such as social distancing, issuing advice on the use of hand sanitizers and wearing masks to curb the spread of the virus. After a continuous rise in cases, a rigorous lockdown was imposed to stop the spread of COVID‐19 in countries including Italy, Spain, France and the United Kingdom. 5 , 6 The government of Nepal (GoN) also imposed a complete lockdown on 24 March 2020, during the first phase of COVID‐19. 7 The effectiveness of wearing masks, and other preventative measures have been proven to slow the spread of infection, 8 and it is, therefore, essential for the government to educate the public on these health messages.

There have been 1,000,631 confirmed cases of COVID‐19 with 12,019 deaths with 5,958,956 polymerase chain reaction(PCR) tests as of 2 November 2022, in Nepal. 9 Nepal has been responding to the pandemic through the implementation of public health prevention and hospital‐based interventions. Key interventions such as management of quarantine, screening and testing have been carried out. Dissemination of information related to COVID‐19 to the public, and managing vaccination campaigns were conducted to slow the spread of infection. 4 Different management committees and task teams were also formed to minimise the adverse impact of COVID‐19 in Nepal. 10 However, some of these committees were criticised for not being able to effectively implement such preventive strategies. Some academics have expressed the opinion that the potential risk of coronavirus transmission at the community level was not taken seriously in Nepal. 11

Preventive initiatives, mass testing of COVID‐19 and quarantine measures are all equally important interventions in stopping the spread of the disease. 12 Mass testing helps people to determine COVID‐19 infection regardless of symptom status, and being at risk of spreading the infection. Several international studies have found a reluctance towards COVID‐19 testing due to long queues, exposure risks and late reporting. 13 Concerns were raised regarding testing disparities between rural and urban residents in Florida. 14 Despite several efforts, Nepal was also not able to conduct sufficient diagnostic tests, and perform timely contract tracing in the initial phase of COVID‐19 transmission. COVID‐19 testing sites were limited by higher costs and longer time for test results. 2 The lack of coordination and blame games among different stakeholders were found to be a prominent obstacle towards the management of COVID‐19 testing and quarantine services in Nepal. During the first wave, the authorities failed to manage effective provision for testing, isolation and quarantine services despite these being the heart of effective public health measures against COVID‐19. 11 However, the government corrected the loopholes from the first wave (2020), which resulted in a contrasting response strategy during the second wave (2021). 11

Besides several preventive measures, the development of a vaccine against COVID‐19 is considered a crucial moment in the efforts to curb disease spread and resume a normal life. 15 Nepal began its first vaccination campaign in January 2021, with donations received from India. 16 The GoN succeeded in managing vaccines through strong bilateral coordination, during global concern around the scarcity of vaccines. 11 As of 13 September 2022, a total of 53,506,207 vaccines have been administered, accounting for approximately 88.9% of the total population, with 79.5% and 76.5% coverage of the first and second doses, respectively. 9 This signifies remarkable effort and achievement for a resource‐limited country such as Nepal. The most high‐risk and vulnerable groups were prioritised for vaccination following the prioritisation protocol of WHO. Some concern was expressed on the way in which vaccination centres were managed, with particular concerns about the spread of infection due to crowding in vaccination centres. 2 However, despite several challenges, the GoN has fully vaccinated 76.5% of the total population. 17

It is imperative that governments are prepared for future waves of COVID‐19. It is essential that the management of pandemic preparedness and response is organised and sustainable. 18 The effective management of COVID‐19 is the most urgent health issue globally today, and to this end, much research has been conducted to assess public knowledge and attitudes perceptions towards the disease. 19 , 20 However, to our knowledge, the management of COVID‐19 and government effectiveness in the management of COVID‐19 vaccines at the community level has not been studied yet in Nepal. Therefore, this study aims to gain the perspectives of the public towards the management of COVID‐19 and its vaccination in Nepal. This research will be useful for developing strategies and formulate contextualised plans and policies based on urban and rural settings in the event of future outbreaks, if any. Questions this study aims to answer:

- 1. How is COVID‐19 being managed in the rural and urban communities of Nepal?

- 2. What is the people's perspective towards the management of COVID‐19 and its vaccination?

2.1. Study design

A qualitative research methodology was used 21 to assess the perspective of people towards the management of COVID‐19 and vaccination in rural and urban areas of Nepal. The study was guided and presented in accordance with the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative research Checklist. 22

2.2. Research participants

In‐depth interviews 23 (IDIs) were conducted with members of the public residing in the rural and urban areas of Soru Rural Municipality (RM) and Suryabinayak Municipality in Mugu and Bhaktapur districts of Nepal, respectively. All the participants were purposively selected 24 based on the following inclusion criteria: (a) Participants living in the selected municipalities. (b) Eighteen years of age or older. (c) The ability to speak in the interview and willingness to participate in the study. Similarly, we also considered the diversity of participants based on age, gender, educational level and COVID‐19 vaccination status living in rural and urban communities of Nepal.

2.3. Data collection

Semistructured interview guidelines were used to conduct IDIs. 24 All the interviews were conducted between November and December 2021. Interview guidelines were developed in the Nepali language and then translated into English. We included questions on the interviewees' sociodemographic characteristics and their knowledge, attitudes and perceptions of COVID‐19, and in particular, their opinions on the government's role in the management of testing and vaccination against the disease. Face‐to‐face interviews were conducted with the participants at their place of convenience, mostly at their homes and field, with the researcher, the interviewee and no‐one else present. Before commencing the interviews, the purpose of the study was explained to the participants, as well as the benefits and possible harms. Participants were given an information sheet, and their right to withdraw from the study at any point was emphasised. Participants were also asked to consent, verbally and in written form, to participate and to digitally record the interview. All of the interviews were audio‐recorded on an encrypted digital recorder and stored on a password‐protected computer. The audio‐recorded interviews were transcribed into Nepali and further translated into English. All of the personal identifiers of participants were replaced with unique codes. The confidentiality and anonymity of the research participants were maintained at all stages of the study. All necessary safety precautions were adhered to during the entire process of the interview, considering the risk of the COVID‐19 pandemic.

The data collection tool was pretested and necessary changes were made before the data collection. Participants were interviewed on one occasion only, and transcripts were not returned to interviewees for comments or clarifications. Among the participants approached for conducting IDIs, two of them declined to participate due to their personal work. We piloted four interviews before conducting the data collection at the study sites.

2.4. Data analysis

A thematic approach based on the work by Clarke et al. 25 was used to analyse the qualitative data. In the first step, all of the recorded interviews were carefully listened to multiple times, and then transcribed verbatim and translated into English, to ensure familiarity with the contents. Other co‐authors collaborated to identify the commonalities and differences in the interview transcripts and worked to develop an initial set of themes. Potential themes were reviewed and named, ensuring coherence and a good representation of data. After thematic identification, the first and second authors completed open coding manually with five of the interview transcripts chosen based on the representativeness of the entire data set. The first author refined the coding framework and applied this framework to the rest of the data set. We exported the framework matrix as a spreadsheet and then summarized it into relevant themes. Any alterations to the themes or codes were discussed collectively and agreed upon by the research team. The codebook was finalised through regular team meetings during the data analysis process. Five researchers coded the entire data set and 10 interview transcripts were double‐coded. Similarly, five researchers were involved in generating themes. We used NVivo 12 (Version 12 pro; QSR International), 26 a qualitative data management software for codebook management and data analysis.

2.5. Reflexivity

All interviewers are from public health and medical backgrounds and have prior experience in conducting qualitative interviews. The interviewers built rapport with the participants and endeavoured to be neutral throughout the interview, to avoid researcher bias and facilitate the free flow of opinions from the participants. Overall, as a team, we presented a different perspective and contextual knowledge which strengthened the quality and validity of our study. Four researchers (A. K., B. R., S. J. and S. B.) designed the study proposal and prepared interview guidelines with the support of (B. K., P. K. C., P. A., J. K. and P. M.). Four researchers (A. K., B. R., S. J. and S. B.) were involved in the data collection. Five of the researchers (A. K., B. R., B. K., S. J. and S. B.) were involved in data analysis and manuscript preparation. Other members of the writing team contributed to drafts and to refining the manuscript.

Table Table1 1 contains the demographic information of the 41 respondents who voluntarily participated in this study. Out of the 41 selected participants, 23 were female and 18 were male. The age range of the participants was from 20 to 86 years old. Most (11) of the respondents were illiterate and did not receive any form of formal or informal education. Of the 41 respondents, 21 were from urban areas, while 20 were from rural locations. At the time of the study, 4 respondents were unvaccinated against COVID‐19, while the remaining 37 were vaccinated. To get a diverse viewpoint, both vaccinated and unvaccinated participants were included in the study. The average length of interviews was 30 min, and field notes were also taken. After data saturation was obtained and no new information was generated, we stopped recruiting participants for the interview.

Demographic characteristics of the respondents.

3.1. Qualitative findings

Findings have been summarized into three major themes: (i) Peoples' perspective on the management of COVID‐19, (ii) peoples' perception of the management of COVID‐19 vaccination and (iii) management and dissemination of information. In the first theme, we have included responses regarding the preventive measures participants took to avoid COVID‐19, as well as the management of confirmed and suspected cases, COVID‐19 testing and quarantine. Similarly, the second theme includes participants' perception of the management of access to COVID‐19 vaccines, their trust and awareness regarding COVID‐19 vaccination and overall management of COVID‐19 vaccination in their area. The third theme contains participants' perspectives on the role and influence of social media on COVID‐19 and vaccination in both urban and rural areas.

3.1.1. Theme 1: Peoples' perspective on the management of COVID‐19

Following preventive measures.

Participants were aware of preventive measures such as wearing masks, washing their hands, using hand sanitizers and keeping a physical distance to prevent infections, but such safety measures were only followed in larger meetings or gatherings, not on a regular basis. In rural communities of Nepal, mass media like radio and FM were used by the people for information regarding the preventive measures for COVID‐19. Similarly, in urban areas, people generally had access to personal protective equipment such as masks, sanitizers and soaps. However, as time passed, the practice of these measures shifted from more cautious adoption in the beginning to less serious adherence to these practices.

People follow the safety measures only during the meetings in the rural municipality and other gatherings. The health workers follow it even now. Other than that, people do not use masks and sanitizers in the present time. (SR_19)

There were only a few households that gave continuous special attention and care to preventive measures because they wanted to safeguard the health of small children in the family.

Yes, I think I am following the protocols more closely than other members of my family because I have a baby and they have less immunity to fight against any kind of disease. (SB_13)

In rural areas, people had limited access to hygiene products such as masks, soaps and sanitizers, and used them only when they were freely distributed, indicating both affordability and access problems.

People wore masks when they were distributed by the local government, but they didn't buy them by themselves after that and also didn't continue wearing them. (SR_20)

To control the spread of COVID‐19, quarantine centres were also available in both rural and urban areas, specifically targeting returnee migrants. However, as time passed, such practices were not followed strictly. Participants from urban areas voiced their concerns that quarantine centres were not properly managed and due to over‐crowding, their use posed a high risk of infection.

It is good that the government tried to manage quarantine, but most of the people complained that the management was not nice. COVID‐19 was most commonly transmitted in quarantined areas. It is good that the government managed quarantine, but I think it was not effective. (SB_4)

Participants in rural areas stated that quarantine centres were soon abandoned, as, in addition to being crowded and poorly managed, there was not sufficient food available for residents. In rural areas, respondents voiced that they opted to quarantine at home instead.

At that time, the local government assigned their health workers to quarantine centres. There was a crowd, as more people had to adjust in a single room. It might be due to insufficient space. I think food and other basic needs are managed at the local level. I heard that some of them were trying to leave the quarantine centres as they were not providing good food, shelter, or fear of getting infection from another person. (SR_11)

Managing confirmed and suspected cases

In both rural and urban areas, the management of positive and suspected cases of COVID‐19 with symptoms was primarily done at home, except for emergency cases. People turned to home remedies in large numbers, reviving traditional tonics made from ginger, turmeric and cumin to treat flu‐like symptoms. A less common herb, known as Gurjo/Guduchi (heart‐shaped moonseed) was also extensively used, as respondents’ voices that they believed would supposedly reduce the chances of COVID‐19 complications by strengthening immunity. Participants disclosed that those who had enough rooms and a separate toilet were able to isolate themselves properly, in comparison to those who lived in small and shared spaces. Likewise, it was also indicated that hospitals were reluctant to admit COVID‐19 suspected patients and suggested that they stay at home unless there was a medical emergency. However, the work of the government hospital in providing free‐of‐cost services to cure COVID‐19 was well noted and appreciated by participants.

As I saw in the news, oxygen cylinders were managed for the COVID‐infected people as per requirements by the government. But those who didn't need oxygen and whose saturation didn't drop beyond the minimum stayed at home and took the required precautions. People were likely to drink Gurjo water (a medicinal herb) and boiled hot water during that time. Mostly, the hospital hesitated to take the cases of COVID‐19 during that time. (SB_1)

It was found that the onset of the COVID‐19 pandemic triggered feelings of fear and panic among our participants, leading to further stigmatisation of the disease and those infected. This stigmatisation led people to hide their infections and, in some cases, neglect to test, to evade discriminatory treatment in society. In such cases, instead of isolating, people continued their daily activities and contributed to the transmission of the disease in the community. This posed a challenge in controlling the infection's spread, thus creating a huge loophole in tracking and managing the infected and suspected cases.

I think one of our neighbours was infected by corona before me. But they didn't tell us that they were infected. People didn't inform other people about the COVID infection during those times. We didn't even tell anyone that I was infected by Covid‐19. (SB_5)

Management of COVID‐19 testing

Participants shared their opinions on the management of the pandemic, stating that the COVID‐19 test was inefficient in the beginning, but became gradually more accessible, especially in urban areas. Early in the pandemic, there were very few government labs doing PCR testing, which gradually changed when the testing equipment became more widely available, and private clinics and hospitals began to conduct such testing.

Now it is not that far to travel for PCR testing. It might be one kilometre away from this place. If people paid money and went to private clinics for their tests, then it was easy, but at the government testing site, the public had to face a long queue and it was not properly managed at all. (SB_8)

In rural areas, PCR testing facilities were rare, meaning that people had to travel to the District Hospitals to undergo testing, when facilities were in place. Such travel incurred a significant financial burden, and was time consuming, requiring the hiring of a jeep as well as hours of walking on foot. Testing of suspected cases was only made locally possible with the availability and use of the antigen test. However, the local test campaigns were short‐term, with all the test facilities concentrating on the RM centres eventually.

It takes Rs. 500 in the jeep to reach the testing site. It takes about 6 h to get there on foot. (SR_20)

It was placed in a nearby school for a few days. After that, it was shifted back to the rural municipality. (SR_10)

3.1.2. Theme 2: Peoples’ perception of the management of COVID‐19 vaccination

Managing access.