‘Too Much Of A Good Thing’, Meaning & Context

The idiom “too much of a good thing” means that even something that is generally considered to be beneficial can be harmful or undesirable in excess. For example, eating too much chocolate can lead to weight gain and health problems, even though chocolate is generally considered to be a healthy food. Similarly, working too many hours can lead to burnout and stress, even though work can be fulfilling and a source of satisfaction.

The idiom can be used to describe a wide variety of situations, from overeating to overspending to overworking. It is a reminder that even the best things in life can be harmful if we do not take them in moderation. It is a valuable lesson to learn, and one that can help us to live a more balanced and healthy life. In some cases, the idiom “too much of a good thing” can be used in a positive way. For example, someone might say that they are “having too much fun” to mean that they are enjoying themselves immensely. However, in most cases, the idiom is used to express the idea that even something that is generally considered to be good can become bad if it is in excess.

The idiom “too much of a good thing” can be used to describe a wide range of situations. It can be used to warn someone about the dangers of overindulgence, or it can be used to explain why someone is feeling overwhelmed or stressed.

The idiom “too much of a good thing” is a reminder that even the best things in life can be harmful if they are not enjoyed in moderation.

Origin of “too much of a good thing”

The idiom “too much of a good thing” is thought to have originated in the fifteenth century. The earliest known use of the phrase is in a poem by John Lydgate, which was published in 1430. The poem is called “The Fall of Princes,” and it tells the story of the downfall of several historical figures. In the poem, Lydgate writes:

“For whoso hath too much of any good, Of that same good he shall be soon bereft.”

This line from Lydgate’s poem is the earliest known use of the phrase that became “too much of a good thing.” The phrase has been used ever since to warn people about the dangers of excess.

Lydgate’s poem was written during a time of great social and political upheaval. The Hundred Years’ War was still raging, and the Black Death had recently devastated Europe. In this time of turmoil, Lydgate’s poem offered a message of hope and warning. He reminded his readers that even the best things in life can be harmful if they are not taken in moderation.

The idiom “too much of a good thing” is recorded in a 1545 translation of Erasmus’s “Paraphrases of the New Testament.” The translation was by Nicholas Udall, and the phrase appears in the following passage:

“But it is an old sawe, that there is too much of a good thing: and it is true, that the best things, if they be too much used, doe much hurt.”

The phrase “too much of a good thing” has since come to be used in a wide variety of contexts, and it is now a common idiom in the English language.

“Too much of a good thing” in Shakespeare

The earliest known use of this phrase in English literature is in William Shakespeare’s play As You Like It , which was first published in 1600. In the play, the character of Rosalind says: “Why then, can one desire too much of a good thing?” This line is spoken in the context of a discussion about love and marriage. Rosalind is arguing that it is possible to love someone too much, and that this can lead to pain and heartbreak.

“ Too much of a good thing” in popular culture

The idiom “too much of a good thing” is often used in popular culture, such as in films, comics, magazines, advertising, and music.

One example is the comic strip “Calvin and Hobbes.” In one strip, Calvin’s dad tells him that “too much of a good thing can be a bad thing.” Calvin is upset by this news, because he loves to eat ice cream.

Calvin’s dad explains that even something that is good can be bad if you have too much of it. He tells Calvin that if he eats too much ice cream, he will get sick. Calvin is disappointed, but he understands what his dad is saying.

In the song “Too Much of a Good Thing” by the band INXS, the singer sings about the dangers of addiction.

In the magazine ad for Weight Watchers, the ad says “Too much of a good thing can be a bad thing.”

In the comic book “Spider-Man,” the villain Green Goblin says “Too much of a good thing can be a bad thing.”

Is it too much of a good thing?

Using “too much of a good thing”

The phrase “too much of a good thing” is often used to warn people about the dangers of excess. For example, someone might say “I love chocolate, but I know that too much of a good thing can be bad for me, so I’m going to try to eat less of it.” The phrase can also be used to express dissatisfaction with something that is considered to be a good thing. For example, someone might say “I love my new car, but I’m starting to think that I might have bought too much of a good thing. It’s so big and expensive, and I’m not sure if I really need it.”

Some examples of how the idiom “too much of a good thing” can be used in everyday discourse:

- “I love chocolate, but I know that I can’t eat too much of it, or I’ll get a stomachache.”

- “I’m having too much of a good time at this party. I need to take a break and get some air.”

- “I’m addicted to my favorite TV show. I need to stop watching it so much, or I’m going to fall behind on my work.”

- “I’m so happy that I got a promotion at work. But I’m also a little bit worried that I’m going to be too busy. I need to make sure that I don’t burn myself out.”

- Pinterest 0

Leave a Reply

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Technology Use: Too Much of a Good Thing?

- Published: 04 November 2020

- Volume 48 , pages 475–489, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Debra S. Dwyer ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1266-4272 1 ,

- Rachel Kreier 2 &

- Maria X. Sanmartin 3

6312 Accesses

3 Citations

Explore all metrics

There is growing evidence of risks associated with excessive technology use, especially among teens and young adults. However, little is known about the characteristics of those who are at elevated risk of being problematic users. Using data from the 2012 Current Population Survey Internet Use Supplement and Educational Supplement for teens and young adults, this study developed a conceptual framework for modeling technology use. A three-part categorization of use was posited for utilitarian, social and entertainment purposes, which fit observed data well in confirmatory factor analysis. Seemingly unrelated regression was used to examine the demographic characteristics associated with each of the three categories of use. Exploratory factor analysis uncovered five distinct types of users, including one user type that was hypothesized to likely be at elevated risk of problematic use. Regression results indicated that females in their twenties who are in school and have greater access to technology were most likely to fall into this higher-risk category. Young people who live with both parents were less likely to belong to this category. This study highlighted the importance of constructing models that facilitate identification of patterns of use that may characterize a subset of users at high risk of problematic use. The findings can be applied to other contexts to inform policies related to technology and society as well.

Similar content being viewed by others

An Analysis of Problematic Media Use and Technology Use Addiction Scales – What Are They Actually Assessing?

User Characteristics of Vaguebookers versus General Social Media Users

Teaching about the Nature of Technology

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Smartphone ownership is now almost universal among younger age groups, with more than nine in 10 individuals born after 1981 owning a smartphone (Vogels 2019 ), while the proportion of American adults who use the internet increased from 14% to 87% in the two decades since 1995 (Duggan et al. 2015 ). Many of the consequences of the burgeoning use of information and communication technology are good. Cell phones summon ambulances to accident sites. Global positioning system apps provide directions for the lost. Video calls allow parents overseas to maintain connections with their faraway children. One can only imagine how much deeper social isolation would have been had the current pandemic taken place in a pre-Zoom world. The benefits are perhaps most pronounced in the field of education. There is a vast literature on the benefits of technology for student academic achievement (Burnett and Merchant 2014 ; Merchant et al. 2014 ).

However, there is growing evidence of risks associated with too much of a good thing, especially with the social networking and gaming aspects of technology. Concern often focuses on teens and young adults, since their heavy use of the new technologies is well-documented. A telephone survey conducted for the not-for-profit organization Common Sense Media reported that half of surveyed teens felt addicted to their mobile devices, and 60% of parents viewed their teenaged children as addicted (Common Sense Media 2016 ). Even in education, concerns are rising that smartphones disrupt students’ ability to concentrate (Gazzaley and Rosen 2016 ). The literature on internet addiction, cell-phone addiction, pathological internet use and problematic internet and phone use is growing rapidly, although surprisingly little of that work has appeared in economics journals thus far (see later discussion). In light of the broad range of concerns addressed in the literature, this study conceptualizes problematic use broadly, understanding the term to encompass behaviors ranging from overuse to dependence to addiction, as well as mental health problems such as anxiety and depression that some researchers have found to be associated with some types of technology use (Lepp et al. 2014 ; Rotondi et al. 2017 ).

Much of the literature has focused on the existence and magnitude of technology addiction (Griffiths and Kuss 2017 ; Lopez-Fernandez et al. 2017 ). In a seminal article, Young ( 1998 ) constructed a scale of internet addiction based on the pathological gambling model in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association 2013 ). Thus far, gambling is the only behavioral addiction included in the manual, although prominent voices have called for adding technology-related disorders, and the inclusion of some version of gaming addiction as a recognized disorder seems likely in future editions (Block 2008 ; Kuss et al. 2017 ). In succeeding years, Young’s index of addiction has been used to examine attributes of addicts, from gender to mental well-being (Davenport et al. 2014 ; Ogletree et al. 2014 ; Park et al. 2013 ). Another developing literature has examined the implications of technology addiction for a variety of academic, relationship and mental health outcomes (Lepp et al. 2014 ; Hampton et al. 2011 ; Magsamen-Conrad et al. 2014 ).

Not all of the literature has found negative impacts of social use of technology on mental well-being for all users. Magsamen-Conrad et al. ( 2014 ) hypothesized that for some types of users, namely self-concealers, technology enhances online social capital and improves relationships and outcomes. They also found some evidence for heterogeneity both in the propensity to become addicted and in how addiction affects quality of life. A 2010 Pew survey found that adults who used social networking sites were significantly less likely to be socially isolated (Hampton et al. 2011 ). Given this evidence of heterogeneity, delineating the characteristics of the subset of users at high risk of problematic technology use is an important research goal. The work reported here begins to address this goal.

The current study contributes to the literature on problematic technology use in several important ways. First, a data set was used that combined information on the use of phones and computers by teens and young adults for a broad range of purposes. Combined analysis of cell phones and computers becomes more important as advancing smartphone technology and the penetration of mobile tablet devices blurs the distinction between the two types of hardware platforms. Second, because the data set is nationally representative, the findings are of more general applicability than the findings of previous smaller surveys. Third, the study included an innovative set of analyses: 1. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to test the appropriateness of grouping technology use into three categories of utilitarian, social and entertainment purposes (the USE model); 2. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to uncover types of users based on utilization patterns, including one type likely to be at elevated risk of problematic use; 3. Regression analysis of the demographic characteristics of the user type that was hypothesized to be at the highest risk for problematic technology use; and 4. A seemingly unrelated regression analysis of the demographic characteristics of individuals prone to use technology for each of the three latent categories of purposes validated in the confirmatory analysis.

Economic Models of Addiction and Self Control

Despite well-established economics literature on addiction and related issues of self-control, surprisingly little work has appeared in economic journals specifically on technology addiction, although, since the 2016 election, there has been a flurry of attention on the role of social media in political discourse and polarization (Allcott et al. 2020 ; Allcott and Gentzkow 2017 ). Much of the economics literature on addiction has applied the standard neoclassical behavioral assumptions of rational, forward-thinking decision-making in a context of stable preferences, following the seminal work of Becker and Murphy ( 1988 ). This rational addiction literature has viewed addiction as an acquired taste, rather than as a pathology. Commodities have been categorized as addictive if consuming in the present period leads an individual to want to consume more in the future, a behavioral pattern implemented in the model via the concept of consumption capital. While later researchers have incorporated the possibility of learning and regret in a context of incomplete information (Orphanides and Zervos 1995 ), the standard neoclassical approach has maintained that a user’s choices maximize the individual’s discounted flow of expected utility, at least conditional on the information available at each point in time. Footnote 1

Another strand of the economics of addiction literature, exemplified by the work of Gruber and Köszegi ( 2001 ), incorporated time inconsistency into preferences. This work assumed an extreme discounting of future utility relative to present utility. As noted by Yuengert ( 2006 ), while both the rational addiction and time-inconsistency models have generated good empirical fits to consumption data, the policy implications are very different. If one accepts that consumers are rational and forward-looking, “[t]he only reason to restrict their access to addictive goods is externalities, ”(Yuengert 2006, p. 78). However, consumers in time-inconsistency models, “cannot trust themselves to carry out their optimal consumption plans over time … these models imply a larger role for government constraints on addictive goods” (Yuengert 2006 p. 78). These models also justify public health and individual treatment interventions that would not be warranted if all choices were utility-maximizing.

A number of economists have sought to integrate clinical and empirical insights from psychology and neurobiology into their models. As in the time-inconsistency models, and with similar implications for policy, addicts’ choices are often not conducive to their long-term well-being in these models. For example, the socioeconomic model of addiction developed by Tomer ( 2001 ) made the case for irrational use of addictive commodities based on lapses in reason due to psychological imbalances during times of physiologically dominating circumstances, otherwise known as cravings. Whether the user succumbs to cravings depends on consumption capital and on budget constraint variables, such as price and accessibility (as in the rational addictions and time-inconsistency models), but also on four other factors: 1. personal capital, which “represents the quality of an individual’s psychological, physical, and spiritual functioning;” 2. social capital, which encompasses the “bonds and connections between an individual and others;” 3. society and community influences, such as behavioral norms and sanctions; and 4. stressfulness of current life situation, which is determined by events and circumstances, such as the death of a loved one, job loss, chronic illness or discrimination (Tomer 2001 pp. 250–256). In more biologically oriented work, Bernheim and Rangel ( 2004 , 2005 ) offered a neuroeconomic model of the choice to consume or abstain as governed by two competing brain processes, one conscious and rational and the other driven by unconscious impulse (the hedonic forecasting mechanism). It is the nature of addictive substances to subvert the unconscious brain pathway so that forecasts of the utility to be gained by consuming are exaggerated, leading to suboptimal choices.

The research presented here does not offer an empirical test of the validity of these various economic models. However, the use of the term problematic to describe some patterns of technology use by some subsets of individuals implies the authors’ acceptance of the idea that consumer choices are not universally utility-maximizing. Consistent with Tomer’s model, the study hypothesized that individuals prone to imbalances that lead to problematic patterns of technology use may constitute a type. While type is not directly observed in the data, factor analysis was used to unearth type as a latent variable that correlated with observed patterns of technology use. Tomer’s work offered a valuable theoretical framework for this empirical strategy because it provided a model of addictive behavior that related to observable characteristics, such as the ability to afford internet access or the need to rely on technology for professional or educational purposes (which plausibly builds consumption capital and also makes it costly to avoid exposure to temptation). For the teens and young adults in the data set, family structure also may capture some aspects of life stress. By uncovering such attributes in individuals as they pertain to internet or cell-phone use, a type of user is identified who may be at elevated risk of making irrational, non-utility-maximizing choices. It is important to understand the potential for such outcomes to improve social welfare.

The study used 3691 respondents aged 15 through 25 who responded to the Current Population Survey (CPS) 2012 supplemental questions on internet and phone use (Flood et al. 2012 ). The data were downloaded from the CPS website on November 6, 2014. The focus on this age group makes sense, given the high levels of use of these relatively new technologies by young people. Footnote 2 Because this is a large, nationally representative data set, the findings are likely to be of more general applicability than the findings of many previous smaller surveys.

The study used 10 indicators of cell-phone usage and 24 indicators of internet usage from the 2012 CPS supplement. Although the survey questions did not directly measure frequency of use, by questioning respondents about a wide variety of types of use, they provided a reasonable proxy for intensity of use. The study examined whether intensity of use correlated with demographic factors that influence the five components of psychological imbalance.

Using these data, four sets of analyses were conducted: 1. CFA based on the Utilitarian/Social/Entertainment (USE) model, which mapped the census survey’s indicators on cell-phone and internet use to the three hypothesized underlying categories of purposes. In CFA, the researcher has a strong hypothesis about the number of latent factors (three in this case) and seeks confirmation that the data support that hypothesis. 2. EFA that identified user types as latent variables revealed by correlations among technology usage patterns among respondents. In EFA, the correlations among the observed indicators provide information about the number of underlying latent factors that provide the best fit. 3. Regression analysis of the demographic characteristics associated with the user type that was hypothesized to be at the highest risk for problematic technology use. 4. A seemingly unrelated regression analysis of the demographic characteristics of individuals prone to use technology for each of the three latent categories of purposes (utilitarian, social or entertainment) validated in the confirmatory analysis.

Observed Variables: Type and Intensity of Internet Use

A vector of indicators regarding mobile-phone and internet use was observed in the data. The ultimate goal was to identify types of users, relying on observed behavior concerning both type and intensity of technology use for leisure and work purposes. Of particular concern was to identify the subset of users for whom technology use is likely to be problematic due to psychological imbalances.

The study made use of the 10 indicators of cell-phone usage and 24 questions on internet usage from the CPS to explore unique commonalities. The survey questions asked whether the respondent engages in a particular activity. For example, the indicator, cell-phone use, takes a value of 1 if the respondent reported using a cellular phone, and 0 otherwise (Online Supplemental Appendix Table 1 shows the survey questions). Because frequency of use was not reported in the data, the study relied on technology use for multiple sub-purposes as an indicator of intensity. The working hypothesis was that state-dependent consumption capital, which is a risk factor for addiction and problematic use, would be higher for respondents who used technology in a large number of ways for a wide variety of purposes (i.e. across the three USE categories). The analysis employed the 34 questions about technology use in an EFA framework to capture the latent user-type variables through these indicators.

Observed Variables: Resources and Personal Attributes

The theoretical framework posited that personal, social and consumption capital play important roles in protecting or promoting psychological imbalance, but the survey data did not directly measure these magnitudes. As proxies for assets and resource availability, the analysis used information captured by the CPS regarding the ability to pay for the internet and number of computers in the home. Education was used as a proxy for individual, personal and consumption capital. The presence of biological parents captured some aspects of social capital, as well as life stress and societal influence. Together, the available demographic information proxied for assets and income. The analysis also controlled for age, gender and race.

Empirical Specification

The main goal was to describe the heterogeneous users and usages of technology in terms of attributes that would be predictive of membership in the group at risk for problematic use. The hypotheses were that socioeconomic status and age would significantly predict utilization, both for usage and user type. The analysis sought to uncover a type that would be at risk for dependence in the factor analysis framework. The model then sought to confirm the conjectures by testing whether proxy indicators consistently predicted problematic use according to the conceptual framework. This paper reports the results from regressing the utilization indicators analyzed in the CFA against demographic indicators, allowing for correlated errors across the three equations. Footnote 3 Seemingly unrelated regression was used because the dependent variables were constructed from common indicators that may be related. This allowed for correlated error terms and removed potential bias from non-random errors. Finally, ordinary least squares was used to explore the demographic characteristics of the user type identified in the EFA as likely to be at risk of problematic technology use.

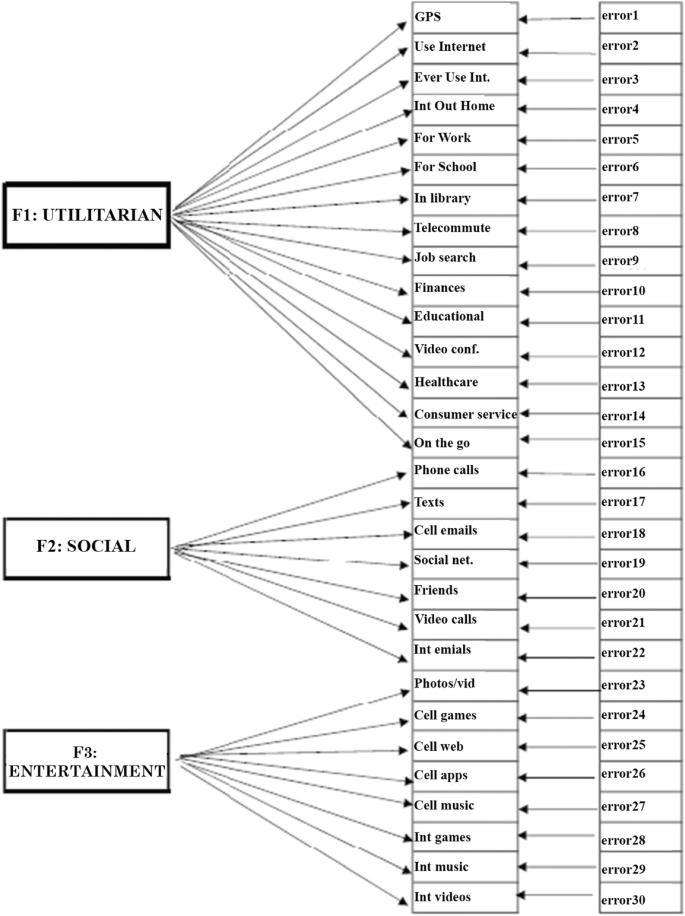

CFA Mapping Specific Uses to Utilitarian, Social and Entertainment Purposes

The CFA described in this section began with a conceptual framework that posited that technology use falls into three categories – utilitarian (U), social (S) and entertainment (E) purposes. Technology use for work, school or practical tasks, such as navigation, was viewed as serving a utilitarian purpose (U). The leisure category was divided into two types of leisure: social (S) and entertainment (E). Utilitarian uses include productive practical applications of the internet and cell phones to work, education and life activities. Social uses embody the role of technology as a means to connect people, for example, the use of social networking applications. Entertainment, while perhaps overlapping with social applications as inputs to the production of utility over leisure, isolates the consumption value of the technology for personal entertainment, such as games, music or videos.

Given the priors about categories of technology uses, the analysis fit a model linking the observed indicators to three latent factors representing the three use types, as depicted in the schematic diagram presented in Fig. 1 . Except for the observable indicator, “any internet use (I1),” which loaded on all three use types (and which was included in the analysis, but only appears once in the diagram to save space), the best model fit was obtained by mapping each of 30 observable indicators to one of the three use types exclusively. Footnote 4

Structural Model with 3 Latent Factors (Use Types) and 30 Observable Indicators, Measured with Error. F1-F3 are thee latent factors that are mapped onto observable indicators with random error

The analysis (Table 1 ) allowed for correlated underlying factors because, unlike the user types, the use types were not mutually exclusive. CFA was conducted on 30 indicators to uncover 61 parameters including errors.

The amount of variation explained in the constructed factors was very high at 0.983. This high correlation might suggest that the model was overfit, or might instead suggest that the hypothesized USE model, in which technology use serves three underlying categories of purposes (utilitarian, social and entertainment) is a good fit to reality. The fact that the factor loadings were all significant in the predicted directions provides evidence in favor of the latter interpretation. Furthermore, the correlation coefficient between the utilitarian factor and each of the other two factors was quite high, at 0.6, and was even higher between the social and entertainment factors. This also confirmed the prior expectation from the theoretical framework that individuals with accumulated technology consumption capital, and those with greater access to technology resources, will be more likely to make more intense use of technology, so that technology use for one of the three purpose categories should positively correlate with using technology for the other two purpose categories. Finally, unlike some exploratory studies of population data that may be censored to those who participate in the data-collection medium, this is a representative subsample of U.S. Census data.

EFA of the CPS Data to Identify User Types

Table 2 reports the factor loadings from a principal components estimation of underlying significant constructs based on the 34 indicators, as well as the means of the indicators. Cronbach’s alpha were calculated on the full set of indicators to test for internal consistency and reliability. The score of 0.91 is above the conventionally acceptable mark of 0.7 and suggests good construct reliability.

Five factors with eigenvalues greater than one were retained. Footnote 5 These five factors lent themselves to interpretation as five mutually exclusive user types, which exhibited different patterns of technology use for utilitarian, social and entertainment purposes. User type 1 was tied to intense technology use with strong loadings on both cell-phone and internet use for all activities (except for using a cell phone for making phone calls). While user type 1 was particularly prone to texting, music, apps and email, this type displayed an extensive use of all types of technology. In response to questions about reliance on various types of technology for activities in life, user type 1 strongly loaded on both social and leisure activities, and utilitarian activities, such as applications to personal finances, work and education. This type relied on technology to meet objectives regarding work and leisure and used the internet in multiple settings outside the home. User type 2 corresponded to respondents who were less tied to technology for their daily activities, and who mainly used the internet at home for emails and a narrow set of entertainment purposes (videos and music). Respondents of this type were significantly less likely to use a cell phone for any purpose. User type 3 respondents were also light users of technology, with significant negative loading on the general question about internet use (I1), and positive, but insignificant, loading on the general question about cell-phone use (C1). When they did use the internet, it was likely to be outside of the home at school, the library, a café or with friends. While the internet use loadings were not significant for this type, the strongest positive relationship was for educational purposes, which suggested a preference for technology as a means to enhance career prospects. User type 4 respondents were the cell-phone users who called and texted but did not use the internet and did not use their phones for a wider variety of purposes. Finally, user type 5 respondents made very limited use of technology. While user type 5 respondents have used the internet, they showed no significant loading on any of the questions about specific categories of cell-phone or internet use.

The working hypothesis (to be explored in future work) is that technology use is not problematic for user types 2 through 5, whose technology use was oriented either towards utilitarian purposes (user types 3 through 5, higher weight on work or school in the utility function) or towards entertainment (type 2, higher weight on leisure in the utility function). Type 1 users were the group of concern, given their reliance on technology for utilitarian, entertainment and social purposes. Their reliance on technology for unavoidable work purposes may have made it particularly difficult for them to avoid triggering cravings for use for social and entertainment purposes. Furthermore, they also were likely to have developed their technology consumption capital stock, in the form of expertise and familiarity, as demonstrated by their evident ability to use technology for a wide variety of utilitarian, social, and entertainment purposes. Thus, their skills at using smartphones and the internet placed them at risk for problematic use. The analysis explored the demographic characteristics of this user type, using the latent factor user type 1 as the dependent variable (Table 2 ).

Table 3 reports findings from two models. Model 1, in the first column, explored the relationship between demographic characteristics available in the CPS and the user type 1 latent factor identified in the EFA. The goal of the first regression was to uncover attributes of the type of consumer that chose a high-intensity level of technology consumption to uncover attributes that might shed light on the propensity toward addiction or other types of problematic use. The other three columns were based on a second model that explored attributes of those who use technology for different purposes. These three columns report the relationships discovered between demographic characteristics and use of technology for utilitarian, social, and entertainment purposes, using the three latent factors from the CFA as dependent variables. Columns 2 through 4 provide evidence about the factors that drive propensity for different types of use. The focus was on capturing the investment component of technology demand (work enhancing) and the consumption component (leisure enhancing – social and entertainment value). This is analogous to Grossman’s 1972 conceptual framework of the demand for health, in which consumers invest for two reasons (investment and consumption) that are not mutually exclusive (Grossman 1972 ).

Being a type 1 user was negatively and significantly ( p value below 0.05) correlated with difficulty affording access to the internet. Type 1 users were significantly ( p value below 0.01) more likely to be older young adults, and less likely to live with their biological father (even after controlling for age). They were slightly and marginally ( p value below 0.1) more likely to be female. While being in school significantly increased the likelihood of being a type 1 user, the relationship was with post-graduate education. Finally, an increase in the number of computers in the house made an individual significantly ( p value below 0.01) more likely to be a type 1 user.

For the most part, the signs of the estimated parameters for the demographic categories were the same across the three equations with the purpose of use (utilitarian, social and entertainment) as the dependent variables, but the estimated magnitudes varied substantially. For example, age was significant in all three equations, but the effect was larger when technology use for social purposes was the dependent variable (−0.35 vs. -0.1). The oldest respondents in the sample (those of post-college age) were the heaviest users. They were also the most likely to be type 1 users ( p value below 0.01). Living with the biological father (which was highly correlated with age) had a large and highly significant negative relationship both with the use of technology for social reasons, and with being a type 1 user (younger people who live with their biological fathers were significantly less likely to use technology at all, but the result was much stronger for social use). Footnote 6 This may represent a constraint rather than a choice for younger people, who may have had parents who act as agents on their behalf. Blacks were significantly less likely to use technology for utilitarian purposes ( p value less than 0.05), but there was no significant effect for the other technology uses. Similarly, females were more likely to use the internet for utilitarian purposes ( p value less than 0.05) but the effect was not significant at traditional levels for the other purposes. Owning a lot of technology was the strongest predictor of use, and those who reported difficulty accessing the internet for financial reasons were less likely to be users. These two indicators were also strong and statistically significant predictors of being a type 1 user.

This work is the first step toward understanding the magnitude of potential mental health problems associated with the growth in technology use. Based on a conceptual model of internet use that incorporated several strands from the economics literature on addiction, hypotheses were formed regarding the factors that predict that use as well as the heterogeneity that might drive types of users. The results were consistent with findings from the literature that uncover types of technology users and provide evidence that some subgroups of users may be prone to addictive and problematic behaviors. Using a larger and more representative sample and examining multiple types of technology use, the study found evidence of significant heterogeneity in user type and uncovered one type that was hypothesized to be more likely to find technology use problematic. With the results of this mostly exploratory study as motivation, future analysis is planned to examine the implications of heterogeneity in user type for academic and mental health outcomes. The findings can be applied to other contexts to inform policies related to technology and society as well.

This exploratory study has several limitations. First and foremost, outcomes were not observed in the data. For example, there was no information about subjective feelings of stress, depression or social isolation. Similarly, there was no information about markers of relationship stress, such as friends or family expressing anger or disapproval about excessive use. Furthermore, there was no information about objective outcomes, such as grades, income and other markers of educational and professional success or failure. Thus, it was not possible to test the hypothesis that type 1 users were at higher risk of problematic technology use, although we believe that to be plausible. Second, the analysis was limited to teens and young adults and it was not possible to judge if the utilization patterns unearthed here would apply to older adults. Third, while the dataset contains rich information about a wide variety of types of technology use, it has no information about the frequency of each type of use. Finally, the data set also is missing information on one type of use that has been viewed as potentially addictive in the literature which is use of the internet for viewing pornography. The findings motivate further work given the presence of potentially problematic intense users of technology in the general population of young Americans.

The rationality of technology addiction has been addressed by researchers publishing in journals outside the economics discipline (e.g., Kwon et al., 2016 ).

Sensitivity analysis findings show initial primary results are robust to changes in the sample’s age restrictions.

Allowing for correlated errors yields a slight improvement in efficiency but the results do not differ in a meaningful way from ordinary least squares regressions.

Five of the 35 indicators were not used in the analysis either because of insufficient variation (cell-phone use, community center or café internet use) or because they did not match theoretically to any of the three latent use type variables (high speed, other internet use).

Passed scree plot test as well (Online Supplemental Appendix Figure 1 ).

Variance inflation factors and tolerance were examined and were found to be sufficiently low and high, respectively, to rule out multicollinearity as a concern.

Allcott, H., Braghieri, L., Eichmeyer, S., & Gentzkow, M. (2020). The welfare effects of social media. American Economic Review, 110 (3), 629–676.

Article Google Scholar

Allcott, H., & Gentzkow, M. (2017). Social media and fake news in the 2016 election. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31 (2), 211–236.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 . VA, American Psychiatric Association: Arlington.

Book Google Scholar

Becker, G. S., & Murphy, K. M. (1988). A theory of rational addiction. Journal of Political Economy, 96 (4), 675–700.

Bernheim, B. D., & Rangel, A. (2004). Addiction and cue-triggered decision processes. American Economic Review, 94 (5), 1558–1590.

Bernheim, B. D., & Rangel, A. (2005). From neuroscience to public policy: A new economic view of addiction. Swedish Economic Policy Revew, 12 (2), 99–144.

Google Scholar

Block, J. J. (2008). Issues for DSM-V: Internet addiction. American Journal of Psychiatry, 165 (3), 306–307.

Burnett, C., & Merchant, G. (2014). Points of view: Reconceptualising literacies through an exploration of adult and child interactions in a virtual world. Journal of Research in Reading, 37 (1), 36–50.

Common Sense Media. (2016). Dealing with Devices: The Parent-Teen Dynamic | Common Sense Media. https://www.commonsensemedia.org/technology-addiction-concern-controversy-and-finding- balance-infographic.

Davenport, S. W., Bergman, S. M., Bergman, J. Z., & Fearrington, M. E. (2014). Twitter versus Facebook: Exploring the role of narcissism in the motives and usage of different social media platforms. Computers in Human Behavior , 32. March, 2014 , 212–220.

Duggan, M., Ellison, N. B., Lampe, C., Lenhart, A., and Madden, M. (2015). Social media update 2014 (Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping the World, p. 18). Pew Research Center. http://www.pewresearch.org/wpcontent/uploads/sites/9/2015/01/PI_SocialMediaUpdate20144.pdf

Flood, S., King, M., Rodgers, R., Ruggles, S., & Warren, J. R. (2012). Computer and internet use supplement (integrated public use microdata series, current population survey: Version 7.0 [dataset]). National Telecommunications and Information Administration . https://doi.org/10.18128/D030.V7.0 .

Gazzaley, A., and Rosen, L. D. (2016). The distracted mind: Ancient brains in a high-tech world. MIT Press.

Griffiths, M., & Kuss, D. (2017). Adolescent social media addiction (revisited). Education and Health, 35 , 49–52.

Grossman, M. (1972). On the concept of health capital and the demand for health. Journal of Political Economy, 80 (2), 223–255.

Gruber, J., & Köszegi, B. (2001). Is addiction “rational”? Theory and evidence. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116 (4), 1261–1303.

Hampton, K., Sessions Goulet, L., and Purcell, K. (2011). Social networking sites and our lives. Pew research center. http://www.pewinternet.org/2011/06/16/social-networking-sites-and-our- lives/.

Kuss, D. J., Griffiths, M. D., & Pontes, H. M. (2017). Chaos and confusion in DSM-5 diagnosis of internet gaming disorder: Issues, concerns, and recommendations for clarity in the field. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6 (2), 103–109.

Kwon, H. E., So, H., Han, S. P., & Oh, W. (2016). Excessive dependence on Mobile social apps: A rational addiction perspective. Information Systems Research, 27 (4), 919–939.

Lepp, A., Barkley, J. E., & Karpinski, A. C. (2014). The relationship between cell phone use, academic performance, anxiety, and satisfaction with life in college students. Computers in Human Behavior, 31 , 343–350.

Lopez-Fernandez, O., Kuss, D. J., Romo, L., Morvan, Y., Kern, L., Graziani, P., Rousseau, A., Rumpf, H.-J., Bischof, A., Gässler, A.-K., Schimmenti, A., Passanisi, A., Männikkö, N., Kääriänen, M., Demetrovics, Z., Király, O., Chóliz, M., Zacarés, J. J., Serra, E., et al. (2017). Self-reported dependence on mobile phones in young adults: A European cross-cultural empirical survey. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6 (2), 168–177.

Magsamen-Conrad, K., Billotte-Verhoff, C., & Greene, K. (2014). Technology addiction’s contribution to mental wellbeing: The positive effect of online social capital. Computers in Human Behavior, 40 , 23–30.

Merchant, Z., Goetz, E. T., Cifuentes, L., Keeney-Kennicutt, W., & Davis, T. J. (2014). Effectiveness of virtual reality-based instruction on students’ learning outcomes in K-12 and higher education: A meta-analysis. Computers and Education, 70 , 29–40.

Ogletree, S. M., Fancher, J., & Gill, S. (2014). Gender and texting: Masculinity, femininity, and gender role ideology. Computers in Human Behavior, 37 , 49–55.

Orphanides, A., & Zervos, D. (1995). Rational addiction with learning and regret. Journal of Political Economy, 103 (4), 739–758.

Park, S. M., Park, Y. A., Lee, H. W., Jung, H. Y., Lee, J.-Y., & Choi, J.-S. (2013). The effects of behavioral inhibition/approach system as predictors of internet addiction in adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 54 (1), 7–11.

Rotondi, V., Stanca, L., & Tomasuolo, M. (2017). Connecting alone: Smartphone use, quality of social interactions and well-being. Journal of Economic Psychology, 63 , 17–26.

Tomer, J. F. (2001). Addictions are not rational: A socio-economic model of addictive behavior. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 30 (3), 243–243.

Vogels, E. A. (2019). Millennials stand out for their technology use, but older generations also embrace digital life. Pew research center: Fact tank. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact- tank/2019/09/09/us-generations-technology-use/.

Young, K. S. (1998). Internet addiction: The emergence of a new clinical disorder. CyberPsychology and Behavior, 1 (3), 237–244.

Yuengert, A. M. (2006). Model selection and multiple research goals: The case of rational addiction. Journal of Economic Methodology , 13(1). September, 2006 , 77–96.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

SUNY Farmingdale, Farmingdale, NY, USA

Debra S. Dwyer

St. Joseph’s College, Patchogue, NY, USA

Rachel Kreier

Hofstra University, Hempstead, NY, USA

Maria X. Sanmartin

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Debra S. Dwyer .

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

(PDF 684 kb)

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Dwyer, D.S., Kreier, R. & Sanmartin, M.X. Technology Use: Too Much of a Good Thing?. Atl Econ J 48 , 475–489 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11293-020-09683-1

Download citation

Accepted : 08 October 2020

Published : 04 November 2020

Issue Date : December 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11293-020-09683-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Technology dependence

- Internet use

- Young adults

- Factor analysis

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Too much of a good thing (fish): methylmercury case study

Affiliation.

- 1 Division of Toxicology, Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, Atlanta, GA 30333, USA. [email protected]

- PMID: 15310052

Methylmercury is an environmental toxicant that has been shown to cause neurologic damage in both children and adults if ingested in sufficiently high quantities. Poisoning outbreaks in Japan and Iraq have revealed serious effects on developing fetuses at levels far below those that produced clinical signs or symptoms in the mothers. Therefore, health guidance values for methylmercury, such as the chronic oral minimal risk level (MRL) of the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, have been set by governmental agencies at levels that would protect fetuses. Since adults are less sensitive than fetuses, chronic intakes within an order of magnitude of the MRL generally have been considered to represent no health risk to otherwise healthy adults. The present report of suspected mercury intoxication in a 53-year-old female suggests that some individuals might be susceptible to adverse health impacts of methylmercury at intakes just 7 to 15 times the MRL.

Publication types

- Case Reports

- Erythema / etiology

- Hair / chemistry

- Mercury / analysis

- Mercury Poisoning / blood

- Mercury Poisoning / complications*

- Mercury Poisoning / urine

- Middle Aged

- Mouth Mucosa / pathology

- Stomatitis / etiology

- Tremor / etiology

Pentecost: A Premium Sermon Kit!

Too Much Of A Good Thing?

- View on one page

- Download Sermon Slides

- Download Sermon Graphics

- Download (PDF)

- Download Sermon (Word Doc)

- Copy sermon

Contributed by James Choung on Aug 29, 2008 (message contributor)

Scripture: Genesis 25:29-34

Denomination: Vineyard

Summary: Main idea: Give up our need to consume, because it is keeping us from enjoying the Kingdom.

This sermon is by James Choung of Intervarsity Christian Fellowship. You are also invited to visit James’ blog at http://www.jameschoung.net/.

__________________________________________________

About eight years ago, I was in Manhattan celebrating my 25th birthday. A friend and I were in the middle of Times Square, waiting in a long line at TKS booth for discount tickets to a hot new show: "Bring in Da Noise, Bring in Da Funk." We couldn’t wait for Savion Glover to tap his way onto the stage and into our hearts. This was no ordinary tap dance, mind you, this is hip, uncut modern tap -- if you’re talking about jazz, it’s the difference between Lawrence Welk and John Coltrane. This would be terrific stuff.

A gentleman with ragged, balding hair, a tan smock and blue jeans spotted with paint came up to us to offer tickets.

"Which show are you looking for?"

"Bring in Da Noise, Bring in da Funk"

"I have some. Great seats, center, near the front. $50 a piece."

I looked at my friend, and she looked at me. We had a quick conversation with our eyes: Would we be able to get tickets at the booth for today? And this close? Can we trust this guy? $50 doesn’t sound like a bad deal, does it? We shrugged, and grabbed our cash from the nearest ATM. The deal was done, and we hoped these tickets would be as good as he said they would be.

When we walked into the theater, we were ushered upstairs. Not a good sign „o front and center, right? We found ourselves in the back right corner of the theater, in the second to the last row. As the curtain rose, we noticed that the theater wasn’t as packed as we may have thought; it was sparsely attended. To add insult to injury, we found out those tickets would’ve cost us only $25 at the booth. We were ripped off.

Ever been ripped off? We give up something valuable for something worthless. It’s frustrating. But what if I said that there’s a greater rip off occurring? What if, every single day, something out there is trying to rip us off, to take away something very valuable, something central to our purposes and meaning for life? Do you ever get the feeling that life isn’t exactly what it’s supposed to be? What if we were being ripped off every day of something core to who we are, and we didn’t know it?

Our birthrights: God’s presence in our lives

First, let me set up the scene. It’s the story of twin brothers. Esau is the older brother of the two, but by seconds. They definitely weren’t identical twins, because they were as different as licorice and soy sauce. If Esau is the Discovery channel with his love of the outdoors, Jacob is Home and Garden Television with his love for the indoors and cooking. Esau is a strong, burly Crocodile Hunter, while Jacob is a scheming yet quiet Iron Chef. These guys are polar opposites.

One day, Esau returns from a day of hunting. Read Genesis 25:29-34

What does Jacob want? He wants Esau’s birthright. Esau, according to the account earlier in this chapter, was born first of the twins. He came out hairy like a rug (I can’t imagine a hairy baby, but anyways), which is a possible meaning of the name, Esau. Jacob came out second grasping his heel, the meaning of his name. In Hebrew, this became a saying for someone who was played jokes, deceived or was rebellious. If you were one who grasped the heel, you were deceptive, rebellious or a jokester (which is a form of protest or rebellion.) Since Esau was born first, he had the advantage of the inheritance. The father would normally divide his inheritance (land, possessions, etc.) into equal parts plus one, and then give the older son a double portion. (It’s great to the be first born, eh?) This was Esau’s inheritance, his birthright. It was his privilege as the eldest of the family. The birthright is an extremely valuable thing.

For us today, we might not have a double portion of land coming to us. But the Bible often speaks about us receiving our inheritance „o mainly, the Revolution of God, or the eternal kind of life. It’s living in God with his resources. It’s the fullness of the love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, gentleness, faithfulness and self-control. It’s the knowledge of knowing that God is with us. It’s next level living, the kind of stuff that gets us out of bed in the morning, knowing that each day will be spent with God. We live in heaven, not just when we die, but it begins here with us! A conversational relationship with God is one of the greatest, most valuable things in our lives. So is Esau’s birthright...

Related Media

Scriptures: Genesis 25:29-34 , Genesis 25:34

Sermon Topics: Church General

commented on Sep 20, 2008

This sermon''s a blessing for me... i realize that i''ve been spending so much time on TV and internet.. and i still want more and more... i also remember when i read the Bible, though for me it''s not as fun as playing computer but it made me satisfied. i thought i''m smart enough, but i never thought i''ve been fooled by my own desires. wish me, my friends, my family and every1 will have more time on God than others

Post Reply Cancel

Your Viewing History

- Clear & Biblical Preaching

- Try PRO Free

Popular Preaching Resources

New Sermon Series Now Available

Everything you need for your next series

AI Sermon Generator

Generate sermon ideas with a safe, secure tool for solid preaching.

Biblical Sermon Calendar

Customizable sermon manuscripts for verse-by-verse preaching

Sermon Research Assistant

Free custom sermon in 5-10 minutes!

Topical Sermon Calendar

Preach with creativity and impact throughout the year

Sermon Kits for Preaching

I Desire Mercy Not Sacrifice

Experiencing the mercy of God in our lives

Ready & Faithful

Looking to Jesus for help now and hope in the future

Why Suffering?

Help your church understand God's plan in pain

To start saving items to a SermonFolder, please create an account.

Main idea: Give up our need to consume, because it is keeping us from enjoying the Kingdom.

To save items to a SermonFolder, please sign in to your account

Enter your email address and we will send you a link to reset your password.

Creating your slides…

Creating your graphics…, creating your word document….

Johan Wideroos

The essay writers who will write an essay for me have been in this domain for years and know the consequences that you will face if the draft is found to have plagiarism. Thus, they take notes and then put the information in their own words for the draft. To be double sure about this entire thing, your final draft is being analyzed through anti-plagiarism software, Turnitin. If any sign of plagiarism is detected, immediately the changes will be made. You can get the Turnitin report from the writer on request along with the final deliverable.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

a. yogurt and granola. b. omelet with processed cheese and yellow peppers. c. bacon and hash browns. d. eggs and sausage. e. cereal with milk and a glass of orange juice. a. Peter loves the taste of his parents' pizza, which got him thinking of the different types of taste sensations.

Flashcards Ch 3 Case Study: Too Much of a Good Thing | Quizlet. 1 / 8. When learning about how often some cells replenish themselves, Peter was encouraged to know that the some skin cells are essentially replaced every how many days? a. 120-350 days. b. 10-120 days.

Case Study: Too Much of a Good Thing Lillian Anderson is a 57-year-old woman that came into your clinic complaining of abdominal pain, nausea, constipation, and muscle weakness. Upon further questioning, she acknowledged that she had been diagnosed with a bipolar disorder 10 years ago and had been taking lithium carbonate to treat the symptoms ...

The author discusses the findings of three researchers who argue against the notion that "more is better" when it comes to using one's strengths. The researchers claim that the overuse of strengths can cause them to devolve into weaknesses. For example, forcefulness can develop into bullying, and niceness can become indecision.

The idiom "too much of a good thing" is thought to have originated in the fifteenth century. The earliest known use of the phrase is in a poem by John Lydgate, which was published in 1430. The poem is called "The Fall of Princes," and it tells the story of the downfall of several historical figures. In the poem, Lydgate writes: "For ...

Question: Case: Too Much of a Good Thing? Not long ago, Jessica Armstrong, vice president of administration for Delaware Valley Chemical Inc., a New Jersey-based multinational company, made a point of stopping by department head Darius Harris's office and lavishly praising him for his volunteer work with an after-school program for disadvantaged children in a nearby

Too Much of a Good Thing? Negative Effects of High Trust and Individual Autonomy in Self-Managing Teams ... This chapter points to the peculiar nature of trust as a property of inter-organizational relations that may be desirable though not easily ... From a case study of a high performance construction cooperative, we find that … Expand. PDF ...

Case Study 6: Too Much of a Good Thing? The characters involved in this case study are the Vice President named Jessica Armstrong, the head of department named Darius Harris, and the Secretary named Carolyn Clark. In this case study, Jessica has approached Harris's office and praised him on his voluntary work done with after-school program for disadvantaged children in a nearby urban ...

Ch 3 Case Study: Too Much of a Good Thing. 8 terms. neillandrea. Preview. Ch 2 Case Study: Making the Time. 8 terms. neillandrea. Preview. COMM 101 chapter 9. 8 terms. sss_aaa_1. Preview. Caesar's English #3. 30 terms. Sapphira_Sunderland. Preview. Steven is a college athlete. 9 terms. jordynnerain. Preview. Ch 2 D&W+ Skill Building: DRIs. 10 ...

is that too much of any good thing is ultimately bad. This tenet pervades all aspects of life, from ... are overarching principles that transcend specific topics or domains of study. Such formalized meta-theories describe and predict phenomena in more abstract terms or at a higher level than specific theories do (e.g., Blumberg & Pringle, 1982 ...

The Ice Bucket Challenge is a campaign to promote awareness of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) — also known as Lou Gehrig's disease — and encourage donations for research. A person is filmed as a bucket of water and ice is dumped over the individ …. View the full answer.

There is growing evidence of risks associated with excessive technology use, especially among teens and young adults. However, little is known about the characteristics of those who are at elevated risk of being problematic users. Using data from the 2012 Current Population Survey Internet Use Supplement and Educational Supplement for teens and young adults, this study developed a conceptual ...

Too much of a good thing (fish): methylmercury case study J Environ Health. Jul-Aug 2004;67(1):9-14, 28. Author John F Risher 1 Affiliation 1 Division of Toxicology, Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, Atlanta, GA 30333, USA. [email protected]; PMID: 15310052 Abstract ...

Quality as an Impediment to Innovation. R. Cole, Tsuyoshi Matsumiya. Published 1 October 2007. Business, Engineering. California Management Review. The belief that there is a positive link between quality and innovation is widely shared among quality professionals. Yet the experience of Japanese manufacturing firms, who are well known for their ...

Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like how often are skin cells replaced?, circulating fluid in body that does not have red blood cells, what hormone is released in blood to lower blood glucose? and more. ... Ch. 3 -- Too Much of a Good Thing. Flashcards. Learn. ... chapter 3 Communication Skills Review. 12 terms ...

Too much of a good thing (fish): methylmercury case study. J. Risher. Published in Journal of environmental… 1 July 2004. Environmental Science, Medicine. TLDR. The present report of suspected mercury intoxication in a 53-year-old female suggests that some individuals might be susceptible to adverse health impacts of methylmercury at intakes ...

Quizlet has study tools to help you learn anything. Improve your grades and reach your goals with flashcards, practice tests and expert-written solutions today.

If Esau is the Discovery channel with his love of the outdoors, Jacob is Home and Garden Television with his love for the indoors and cooking. Esau is a strong, burly Crocodile Hunter, while Jacob is a scheming yet quiet Iron Chef. These guys are polar opposites. One day, Esau returns from a day of hunting. Read Genesis 25:29-34.

Organizations are increasingly relying on informal leaders within teams to positively affect team outcomes. Also, as the percentage of women in the workforce grows, women are likely to shoulder more of the informal leadership responsibility within teams. This study explores the relationship of team performance and team cohesion to informal leadership dispersion and the gender composition of ...

Chapter 3 Case Study Too Much Of A Good Thing | Best Writing Service. I ordered a paper with a 3-day deadline. They delivered it prior to the agreed time. Offered free alterations and asked if I want them to fix something. However, everything looked perfect to me. Essay, Research paper, Coursework, Discussion Board Post, Term paper, Research ...

Quizlet has study tools to help you learn anything. Improve your grades and reach your goals with flashcards, practice tests and expert-written solutions today. ... Match. Ch 3 Case Study: Too Much of a Good Thing. Log in. Sign up. Ready to play? Match all the terms with their definitions as fast as you can. Avoid wrong matches, they add extra ...