Budgeting as practice and knowing in action: experimenting with Bourdieu's theory of practice: an empirical evidence from a public university

Asian Journal of Accounting Research

ISSN : 2459-9700

Article publication date: 11 February 2021

Issue publication date: 7 September 2021

The present study aims to explore how various doings, strategic actions and power relations stemming from internal agents are instrumental in (re)constituting the different forms and meanings of budgeting in a specific field.

Design/methodology/approach

The paper uses a single-case study method based on a Sri Lankan public university. Data are collected using interviews, documentary evidence and observations.

The empirical evidence suggested that internal agents are crucial, and they are the producers of budgetary practice as they possess practical knowledge and power relations in the field where they operate. The case data demonstrate that organisational agents do have real essence as active and acting to produce effects in budgeting practices, and the significance of exploring the singularity of multiple agents in terms of their viewpoints, trajectories, dispositions and power relations, who may form, sustain or interrupt budgetary practices in a given setting.

Research limitations/implications

As the research is directed towards the selection of in-depth enquiry of specific setting infused with culture, values, perception and ideology, it might cause to diminish the researcher's analytical objectivity and independence of the research.

Practical implications

As budgetary practices are product of human interaction, it is important to note that practitioners should be concerned with what agents do in actual practice and their inactions, influences and power relations in budgeting practices, which might not align with the structural forces enlisted in the budgeting. It would be of interest for future empirical research to explore the interplay between the diverse interests of organisational agents and agents beyond the individual organisations.

Originality/value

This study contributes to the literature on management control practices by documenting the importance of understanding the “practice” through relational thinking of all three concepts is emphasised, such interrelated theoretical insights are seldom used to understand accounting practices. This research emphasises the importance of bringing out the microprocessual facets of management control to open up its non-conscious, non-strategic and non-rationalist forms.

- Budgeting practice

- Practical knowledge

- Power relations

Seneviratne, C.P. and Martino, A.L. (2021), "Budgeting as practice and knowing in action: experimenting with Bourdieu's theory of practice: an empirical evidence from a public university", Asian Journal of Accounting Research , Vol. 6 No. 3, pp. 309-323. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJAR-08-2020-0075

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2021, Chaturika Priyadarshani Seneviratne and Ashan Lester Martino

Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

Background of the study

Budgets are vital in management control processes and generally considered as formal, structural controlling mechanisms enlisted to support the controlling use. Thus, the budget is primarily considered as a coercive tool to assist management to coerce employees' compliance and effort ( Aleksandrov et al. , 2018 ; Horngren et al. , 2014 ; Lambovska et al. , 2019 ; Simons, 1994 ; Sponem and Lambert, 2016 ). However, budgets are not only a diagnostic tool to serve a routine controlling use with a coercive orientation but a mode of coordinating and communicating the strategic priorities of the organisation ( Abernethy and Brownell, 1999 ; O'grady, 2019 ). In the study of a rolling budget, viewing the process from enabling perspective, Henttu-Aho (2016) emphasises that new budgetary practice enables to build a holistic view of the totality of control and supply more relevant information about organisation in a more realistic manner while improving the flexibility and effectiveness of the budgetary work. In public sector organisations, diverse aspect of budgeting including diagnostic and enabling uses are investigated within the effort of complying with statutorily obligations to improve the efficiency ( Jakobsen and Pallesen, 2017 ; Mkasiwa, 2019 ).

By moving beyond the technical–rational function of budgeting as a means of affecting control, the budget is considered as a “multi-faceted phenomenon” in public sector organisations ( Covaleski et al. , 2013 ). Within the wider depiction of budgetary control as a socially constructed phenomenon, an array of research focusses on how budgets are instrumental in shaping behaviour and how budgets emerge as a response to governmental reforms, multiple logics and strategic behaviour in public organisational settings ( Aleksandrov et al. , 2018 ; Célérier and Botey, 2015 ; Covaleski and Dirsmith, 1983 , 1986 ; Covaleski et al. , 2013 ; Ezzamel et al. , 2012 ; Harun et al. , 2020 ; Moll and Hoque, 2011 ).

In what ways are specific patterns of dispositions and power relations attuned with the taken-for-granted (doxical) elements in constituting/reconstituting budgetary control practices?

What are the strategies of action [1] of internal agents, how do strategies of action or series of moves emanate from the “practical sense” of budgeting and are deployed in constituting/reconstituting budgetary control practices in a specific field?

This article results from a study of budgetary practice by deploying a qualitative in-depth case study approach in a one large Sri Lankan public university, and the paper differs from prior research in two aspects. First, this study contributes to the management accounting literature by investigating how the impacts stemming from the micro level, including specific practices, competing interests and diverse power relations of internal agents, can shape budgetary control practices of a specific setting. Second, the current study emphasises the significance of understanding the budgetary practice and its practical logic, as opposed to formal, conscious and strategic forms of a public university.

Theoretical framework

The notion of “practice” shares a common theme as the “understanding of how people act in organizational context and relations between the actions people take and the structures of organizational life” ( Feldman and Orlikowski, 2011 , p. 1240). Based on sociological perspectives, Bourdieu formulated a practice theory based on relational thinking to understand the social world in an alternative way ( Bourdieu and Wacquant, 1992 ). According to Bourdieu, habitus, capital and field are necessarily interconnected, interdependent and co-constructed, conceptually and empirically ( Grenfell, 2008 ). Bourdieu presented an equation to summarise the practice as a result of relations between one's disposition (habitus) and position in the field, which is primarily determined by endowed capital within the contemporary state of play in a particular social domain in its pragmatic sense ( Bourdieu, 2013 , p. 95): ( Habitus × Capital ) + Field = Practice .

In any field, people's behaviour/activities (what people do) are governed by an array of dispositions (practical senses), dubbed as “habitus” ( Bourdieu, 1990 ). Habitus is considered as a practical feel or practical mastery for the game agents' strategic actions are informed by habitus in a given field are not imputed by rational or conscious choice ( Bourdieu, 1990 ; Hurtado, 2010 ) but beyond the deliberate control ( Bourdieu and Wacquant, 1992 ; Lamaison and Bourdieu, 1986 ; Wacquant, 1998 ). Generally, social practices are denoted as strategies, and particular types of social actions or strategies of different groups are generated by that particular group's habitus ( Hurtado, 2010 ).

Central to assertions put forth by Bourdieu (1990) , social space is dubbed as the “field” in which people undertake diverse activities, ruled according to specific interests and its own stakes. The notion of field is created as an attempt to conceptualise a configuration of a network, of objective relations between positions ( Bourdieu and Wacquant, 1992 ), hierarchically endowed with diverse types of capital. “Doxa” is defined as a set of pre-reflexive, commonly shared, unquestioned, taken-for-granted understandings, spontaneous perceptions and opinions prevailing across the social space determining the natural practice and sense of limits of habitus of the agents in a particular field ( Emirbayer and Williams, 2005 ; Grenfell, 2008 ). Agents in dominant positions in the field are granted the power to mould or shape the doxic elements prevailing in the field ( Bourdieu, 1977 ; Bourdieu and Wacquant, 1992 ).

As “capital does not exist and function except in relation to a field” ( Bourdieu and Wacquant, 1992 , p. 101), field situates agents in the field of forces, power relations and desires towards practices. Capital is the stake or weapon mobilised in ongoing power balancing between actors and considered as an outcome of the ongoing position-takings in everyday work ( Bjerregaard and Klitmøller, 2016 ; Chudzikowski and Mayrhofer, 2011 ; Emirbayer and Johnson, 2008 ; Maclean et al. , 2012 ; Schneidhofer et al. , 2015 ). In the theory of power relations, Bourdieu terms “species of capital” as a diverse range of materials and other types of resources accrued by agents in achieving a privileged position in a particular social space ( Emirbayer and Williams, 2005 ). Cultural capital, economic capital and social capital are recognised as different forms of capital or resources.

Baxter and Chua (2008) empirically narrated the chief financial officer’s (CFO) practical involvement in terms of habitus in organisational projects and the unorthodox management accounting practices implemented in the organisational setting. In a different context, Lodhia and Jacobs (2013) used Bourdieu's triad concepts of field, habitus and capital in a public sector department in Australia to examine the practical logics of internal practices produced at an individual level in environmental reporting. Goddard (2004) investigated the association between accounting, governance and accountability in local government in the UK, emphasising Bourdieu's notion of habitus. Célérier and Botey (2015) reported a socio-ethnographic study on how participatory budgeting was characterised by accountability practices favouring the election of councillors with distinctive capitals, who were “dominated-dominants dominating the dominated” amongst the budgeting participants. By taking an ethnographic approach, Bourdieu's interdependent relation between habitus, capital and field was used by Jayasinghe and Wickramasinghe (2011) to capture how a particular structural logic governed the resource allocation mechanism of the village. The study by Xu and Xu (2008) investigated interactions and relations between social actors in the field of Chinese banking to demonstrate how actors in social positions possess diverse resources, power and capital, leading some to dominate others.

Strategy as a practice has been merged in a distinctive approach to study organisational strategy and strategising, inclusive of strategic management, decision-making and managerial work ( Gomez, 2010 ; Hurtado, 2010 ; Jarzabkowski et al. , 2007 ; Whittington, 1996 , 2006 ). Hutaibat (2019) used Bourdieu's theory of practice in a Jordanian higher education sector to examine the perceptions of actors in the field, regarding strategising, accounting for strategic management and power structures. Drawing insights from Bourdieusian perspective, Bjerregaard and Klitmøller (2016) examined how subsidiary actors accommodate, actively support and resist various parts of an HQ-mandated management control system in a multinational corporation in a Mexican special economic zone.

Overall, while the above research has been influential in informing the application of the Bourdieusian threefolded concepts to explore the dynamics of individuals, our study aims to explore the internal agents' practical actions, providing a sense of the practices in budgetary controls which were being enacted through the agents who are situated in diverse positions in a field study of a public university.

Research setting, method and design

Based on the research questions and theoretical considerations, this study is founded on qualitative data, applying a single-case study strategy. According to Bourdieu's methodological principles, a one large Sri Lankan public university, i.e. University Sigma is selected as “determinate place in social space”, ( Bourdieu and Wacquant, 1992 , p. 214) and data are collected over a period of six months during 2014/2015. It is a period in which University Sigma is receptive as it is moving towards an outcome-oriented culture and striving to achieve the standards of a world-class university, under the strategic plan of the Ministry of Higher Education (MHE) of Sri Lanka in 2010. As the performance-based initiatives have been reinforced through the circulation of finance circulars informing all universities that additional funds will be released based on the performance, initial steps have been taken to change the strategic performance management system, along with university budgeting to create high-performing state-owned universities.

Currently, University Sigma operates under the Universities Act No. 16 of 1978, which provides powers to the University Grants Commission (UGC) to intervene directly in university's routine and non-routine operations. University Sigma must comply with the rules and regulations enforced by the UGC and MHE and is subject to the usual public sector financial regulations of the Treasury and Ministry of Finance and Planning. This affects the university's ability to set salaries, retain income generated, sell assets and reinvest the proceeds and raise capital through loans from banks. The governance structure of University Sigma consists of four official boards: the administrative council, the senate (academic board), faculty boards and postgraduate academic boards. Amongst these, the university council is the primary governing body. Other than the chancellor, the main officers of the university are recognised in the University Act as the vice chancellor, registrar, librarian, bursar (treasurer) and the deans of faculties. The vice chancellor is the chief executive officer and principal academic officer who entitled to convene, be present and speak at any meeting of University Sigma.

A total of 35 in-depth interviews were conducted with diverse agents at various hierarchical levels within the research organisation, and interviewees were selected based on the importance of their role with respect to budgetary control. To complete the interview, time varies from 40 min to 120 min. Leaning on the theoretical lens of Bourdieu's practice theory, broad questions were formulated to guide the pilot interviews. Being capitalised on the insights made initially, questions for the subsequent interview questions were refined, capturing the richness of the field. Interview and non-participant observational data were supplemented by different archival records to reinforce the interviewee findings. Moreover, complementing the interviews, direct observations were carried out and field notes were compared to reconfirm and add more insights into interviewee comments.

Thematic analysis is commenced as a prerequisite to making sense, verifications and drawing conclusions from the empirical findings. The interviews were transcribed and then the transcripts were closely examined, key themes highlighted and coding carried out. Once themes have been finalised, templates were prepared for each and every theme to tag and place the information from interview transcripts, observational notes, field notes and archival documents into the identified categories. Thus, to bring the richness of the phenomena under study, the theoretical framework also becomes an important guide in searching for the patterns amongst the coded field evidence and thereby the sense-making process and drawing conclusions were essentially integrated with the theoretical underpinnings of Bourdieu's theory of social actions.

Budgeting control: knowing in practice

The next section discusses how budget as a means of affecting control and also to facilitate the attainment of imposed strategic priorities take place confronting complexities, concerns and conflicting goals amongst the multiple agents within a public university setting.

Individual/group power on the university budget preparation

The budgeting process is officially initiated in the month of August, with the acceptance of the finance circular of the budget call from the UGC. After this, the university bursar communicates the budgetary guidelines to faculty deans, faculty bursars, the registrar and all heads of the service units as a prerequisite to embark on the journey of the budget preparation. The budget committee consists of the deans of the faculties, senior financial and administrative officers (bursars and registrars), the librarian and all other heads of service units of University Sigma and it coordinates the planning phase. The budget committee is chaired by the vice chancellor, who is supposed to act as chair; however, a university bursar is accountable for all deliberations, ranging from the planning to controlling facets in the budgeting process.

We don't have any guarantee whether we'll be given the necessary funds that we requested through the budgetary allocations. So, our staff may not be motivated to participate actively in the planning processes. So why should we prepare our plans if there is no assurance of getting the requested funds?

Consistent with Bourdieu, acknowledging the fact that habitus could be reflected in all practices, the particular action patterns of academic members in budget planning is understood by referring to the deeply embedded doxic experiences that are self-evident within the existing relations of a specific setting ( Lau, 2004 ). According to Hutaibat (2019) , academics tend towards the passively supporting for a proposal collection phase depending upon their doxa and their relation to the more power structure which is embedded in a specific setting. As departmental agents believe that the submission of their proposals will not be fruitful due to possible funding constraints, such regularities potentially impact on making sense of particular action patterns of agents [1] in a specific context ( Grenfell, 2008 ). In a similar vein, another member of an academic department spelled out the underlying reason for their passive participation in the budgetary planning process, “What is the point of spending quite a lot of time in preparing the budget proposals if we can get small amount comparative to what we request?” As above, words provide evidence that actions and perceptions of general academics are habituated by the realities perceived and regularities pursued in relation to the difficulty of getting intended monetary allocations in the particular social space ( Bourdieu and Wacquant, 1992 ). According to Vaughan (2002), when understanding practical actions, people's habitus is not merely informed by surroundings of their early lives but also by the doxa that remains as unquestioned opinions and perceptions to determine the “sense of limits” of agents participating in the budgeting practice ( Grenfell, 2008 , p. 120).

Persuaded by the importance of capturing the profound aspect of overall habitus of general academics (doxa), the interviews conducted with administration/financial officers of University Sigma highlighted the implicit power that academics possessed based on the doxic understanding that persists in the specific social setting. Hence, from the theoretical point of view, as “doxa” in the organisational setting is necessary for symbolic power ( Hurtado, 2010 ), it causes to attune the habitus of the agents in the research setting under study. A senior project officer reiterated a sense of disappointment, reflecting that doxa refers to capital concerning the symbolic power of academic agents ( Kloot, 2009 , p. 472) and how possession of symbolic power tends to influence the initial planning stage. Alongside symbolic capital informed by doxa, departmental academics are endowed with not only an institutionalised form of cultural capital, in terms of certificates, skills and knowledge, but also intellectual capital, termed “scientific renown” [2] , associated with scholarly reputation on research ( Bourdieu and Wacquant, 1992 , p. 76). In the public higher education field, those with the institutionalised form of cultural capital, together with intellectual capital, are considered to be “advantaged at the outset as the field depends mainly on such forms of capitals” ( Grenfell, 2008 , p. 69). Since such forms of capitals are valued by the social agents who operate in that social space, they become symbolic capital in the specific field.

Hence, as confessed by several interviewees, general academics are assigned with symbolic authority that situates them in a privileged position of power at Sigma, enabling them to secure benefits and enhance their stake in the social area ( Bjerregaard and Klitmøller, 2016 ; Célérier and Botey, 2015 ; Hurtado, 2010 ). Given that general academics are granted the power to shape understanding in relation to budgetary practice, in applying the rules and procedures of the practice in the university setting ( Bourdieu, 1977 ; Bourdieu and Wacquant, 1992 ), they tend to impose their doxical understanding on the control practice, even while overlooking the accepted procedures to be accomplished in budgetary planning ( Kloot, 2009 ).

Therefore, corresponding with Bourdieu's assertions, it could be argued that general academics are not mere preprogrammed automatons governed by immutable and unchanging laws as their practices are minimally determined by the specific rules and requirements of budgetary practice. As Bourdieu and Wacquant (1992) asserted, based on the distinct profiles of capital (power resources) associated with agents in the research organisation, a distinction is drawn between dominant and dominated positions ( Célérier and Botey, 2015 ; Emirbayer and Williams, 2005 ). Within the field, winners/losers and dominancy of the field are determined by the volume and structure of resources associated with different agents; agents possessing more capital relevant to a particular field are considered dominant, with greater possibility in actions to be executed. Dominant agents pursue conservation strategies to preserve the hierarchical principles and safeguard their positions in the hierarchy; in contrast, subversion strategies are pursued by dominated agents to transform the existing system of authority for their benefit ( Wacquant, 1998 ). Thus, as the general academics are situated in the dominant positions, holding symbolic power to secure their stake within the power configuration of University Sigma ( Célérier and Botey, 2015 ), their symbolic power exacerbates goal conflicts amongst other agents being potentially problematic for effective planning of the university budget ( Bjerregaard and Klitmøller, 2016 ). At University Sigma, capacity over interpreting some budgeting procedures is transferred from agents of the university top management to general academics rather by losing the power to obtain the desired contribution from general academics in the planning phase ( Mutiganda et al. , 2013 ).

Against a backdrop where pervasive power relations operate at the bottom level of the social space, it was difficult to determine whether deans have the capacity to exercise power over agents at the departmental level in enforcing their participation in the planning phase. Top faculty agents hold significant academic capital [3] , which is acquired and maintained by taking a top position in the management hierarchy of the university and enables domination of other positions ( Kloot, 2009 ). Such academic capital mainly depends on the principle of legitimation, corresponding to the fact that the organisational hierarchy is well aligned with social power ( Kloot, 2009 ). Given that, faculty deans are identified as powerful or dominant agents, possessing broad power resources and organisational capital, providing the ability to act as “master” in terms of the rules and procedures of planning and other operational matters associated with the budgetary process ( Bourdieu, 2005 ).

In terms of capturing actual practices of key university agents in the planning phase, this revealed that the faculty dean's actions, interests and perceptions are derived as adherence to the sense of what is appropriate and proper in a given situation ( Lodhia and Jacobs, 2013 ). According to Célérier and Botey (2015) , being an influential agent in the faculty, the faculty dean has the liberty to decide and accommodate the activities in the faculty budget, without referring to subordinate agents' proposals (the heads of departments). Based on the endowed social networks, the faculty dean has the capacity to obtain necessary funds for the budget proposals that he included in faculty budgets according to his discretion, bypassing the granted budget allocations.

Substantiating the above insights, faculty dean 2 described how agents tend to act on the practical understanding of the logic of budgeting, which determines the “doable and thinkable” limits over the phase of budget planning ( Grenfell, 2008 , pp. 54–59; Lamaison and Bourdieu, 1986 ). As the top faculty officers possessing practical expertise in planning and operational issues pertinent to the faculty budgetary process, they tend to minimise lapses which arise due to insufficient participation from the academic departments. Irrespective of the formal budget procedures, they act with the tacit knowing of the way of things happen in the particular social space, to achieve the full potential of the faculty through budgetary planning ( Gomez, 2010 ). Thus, the field empirical evidence revealed that due to insufficient participation of departmental agents in gathering necessary input to prepare the budget, budget planning is centred in the hands of the bursar and dean of the faculty.

In the second phase, the programme budget [4] is prepared by considering budget proposals included in the budget call. As stipulated by the UGC in the budget specimen, the accounting rationale of linking performance indicators, action plans and monetary allocations is to intensify the controlling aspect of the university budget. Moreover, by reiterating the negative consequences of passive participation of academic departments in the initial budget planning, university bursar 1 highlighted the challenge of identifying key performance indicators and linking such measures accurately to ensure employees' behaviour aligned with targets stipulated in the university budget ( Widener, 2007 ).

From an accounting perspective, planning is considered as an important aspect of budgetary process because it is related to the subsequent control phase in the organisational control process. However, in the absence of realistic information from the bottom level as senior bursars at the university level tend to act without clear strategic intentions linking desired outcomes and budgetary allocations. They tend to preserve the existing order in preparing the budget in compliance with the UGC, in spite of the underlying accounting logic of prioritising and linking strategic aims with the estimated financial disbursements. Hence, the budget as a “control tool” is not effective in the planning process ( Covaleski et al. , 2013 , p. 338); rather, planning merely fulfils compliance controls, to avoid any explicit violation of budget guidelines imposed by higher education authorities ( Cunningham, 2004 ).

Practical logics of actions in managing the university budget

Examining human conduct around the programme budget reveals that it is a product of individual strategic choice in a university setting ( Lodhia and Jacobs, 2013 ). Speaking about the pervasive engagement undertaken in fulfilling the requests for financial disbursements made by diverse organisational agents, either within or beyond the given programme budget, university bursar 1 continued, “Budget is a guideline. But we can do more work even beyond the budget if we really want to work in improving the status of university”. Many interviews with bursars at different hierarchical and faculty levels reflected the need to take spontaneous actions without being merely confined to the programme budget ( Bourdieu, 1990 ; Lamaison and Bourdieu, 1986 ). Acknowledging this, a senior assistant bursar of the finance division noted, “Even though some of the activities are not in a budget plan, there are possibilities to meet those requests with the special approval”. According to Bourdieu's terminology, in fulfilling the diverse requests made by internal agents, bursars pursue “immanent necessity”, without being restricted to the preprogrammed disbursement levels ( Lamaison and Bourdieu, 1986 ).

Noting that budgetary requests are facilitated in a manner compatible with the budget guidelines, an assistant bursar said, “In many instances, we had to handle requests for financial disbursements on situational basis without violating the fundamental budget guidelines”. Thus, bursars have developed a strong practical mastery in the art of managing the university budgetary process, without explicitly violating the budgetary rules and guidelines on stipulated strategic objectives and budget limits in day-to-day operations ( Baxter and Chua, 2008 ). In accordance with these insights, university bursar 1 noted the significance of undertaking actions based on reasonableness and the effort she made in handling such requests from the departmental level.

In particular, a university bursar is endowed with “technically-based bureaucratic capital” and “bureaucratic capital of experience” through acquiring knowledge of regulations and more rationalised procedures and techniques pertinent to the budgetary practices over a longer period ( Bourdieu, 2005 , p. 117). Therefore, based on the wider positional capacities, the university bursar is capable of reconsidering whether to facilitate ad hoc financial disbursement requests made by the faculty bursar that are not appropriately tabled in the programme budget or for which allocated funds are not adequate. Thus, the dispositions of bursars are set up by unconscious learning and also incorporating embedded field values in the practice of university budgeting.

In compliance with the budgetary guidelines, the university bursar may strive to obtain special approval from the finance committee of University Sigma to fulfil requests of a recurrent nature beyond the programme budget. In another instance, a university bursar noted how she struggled to get approval for disbursements of a capital nature from the UGC, which was supposed to be approved by the finance committee and council of University Sigma. From a practice perspective, rules do not always bring an end to actions; rather, agents negotiate the rules with the necessary authorities in order to facilitate the accomplishment of certain actions, by overseeing budgetary limits strategically in the social space under study ( Swartz, 2002 ). Seen in this light, the university bursar is an individual who is capable of justifying certain actions or requests to the higher authorities of the university (i.e. the finance committee and council), which are not in fact explicitly specified in university budget but accepted by higher authorities of university as appropriate ( King, 2000 ).

Consistent with Inghilleri (2005) , it is evident that the strategic actions pursued by bursars depend on the knowledge gathered to “know” how budgetary controls operate, embodied in the negotiating the official budgetary rules to minimise adverse effects, for their own conservation in a university setting. However, field evidence vividly reflects how tension is triggered between the need to fulfil the ad hoc requests with necessary monetary disbursements outside to the budget and the necessity to comply with budgetary limits and procedures. As bursar 6 noted, “However by satisfying our staff's requests, we should be compliance with budgetary rules and guidelines. We have to manage both sides”. Further substantiating these views, bursar 4 voiced her grievances about how the symbolic power of departmental agents creates conflicting interests in managing the budget within the pre-planned budget limits ( Semeen et al. , 2016 ). According to Farjaudon and Morales (2013) , it is clear that the dominated, i.e. bursars may “participate in the pursuit of dominant interests, possibly unknowingly or in the belief that they are pursuing their own interests” (p. 155).

The given nature of bursars' practices could be understood as a practical logic of the way that things happen in the budgetary process in the specific research setting under study. Therefore, without strictly adhering to programme budgets, agents may pursue strategies premised on a practical sense of budgetary practice to produce certain actions in the social space under enquiry ( McDonough, 2006 ). Interviewees at the finance division revealed that, irrespective of the requests made beyond the budget, bursars tend to capitalise on their practical mastery of budgetary functions to fulfil requests not only to satisfy the departmental or faculty-level agents but to maintain or enhance personal credibility amongst members of University Sigma ( Lodhia and Jacobs, 2013 ).

As revealed in the interviews with financial officers, university financial officers have devised strategies to ensure the continuity of university operations increasing the capabilities of University Sigma and to maintain or develop credibility towards bursars by negotiating budgetary rules with the necessary authorities ( Lamaison and Bourdieu, 1986 ). Hence, being the embodiment of “immanent regularities and tendencies” relating to the budgeting practice ( Bourdieu and Wacquant, 1992 , p. 138), the specific perceptions and actions of university bursars are attuned to expedite activities as planned in the university budget. This is consistent with the exploration of Baxter and Chua (2008) , who characterised the CFO's habitus from a technical accounting angle, allowing a demonstration of the competencies in managing a diverse range of activities of different lines of business in a large company.

Being an agent responsible for the overall university budgetary process, the university bursar (top financial officer) explained how her individual practices are frequently inscribed with social determination attached to the position where she operates ( King, 2005 ). However, there are instances where the university bursar engaged in budgetary process significantly depends on her discretion to realise the targets in the university budget. Thus, day-to-day individual actions are not simply constrained by the external constraints; instead, they are informed by the deeply ingrained past experiences and restraints offered by the present conditions ( Swartz, 2002 ). Although the budget is considered a mechanism to exert control over the agents who are expected to operate within the predefined limits, these limits can be exploited by the specific practical actions of the bursars ( Ahrens and Chapman, 2004 ; Wouters and Wilderom, 2008 ). Without explicitly violating the rules of budgetary practice, bursars place great emphasis on enabling the situations by going beyond the pre-planned budgetary limits in line with their “sense of practice” to ensure the best for University Sigma ( Grenfell, 2008 ; Lamaison and Bourdieu, 1986 ; Raedeke et al. , 2003 ; Swartz, 2002 ).

Concluding discussion

The paper has examined in what ways do field, capital and habitus interplay to determine individual strategies of actions (practices) reflected through perceptions, appreciations, tensions and conflicting interests and how do they influence budgetary control practice. In conclusion, the empirical evidence suggested that practices are not conscious or mechanistic obedience to a rigid set of rules, guidelines and procedures of budgetary control; instead, their specific practices are attuned with “practical sense” or “taken-for-granted sense” of the regular budgetary practice prevailing in the public university setting ( Bourdieu, 1990 ; Bourdieu and Wacquant, 1992 ; Hutaibat, 2019 ). Further, Bourdieu's theorisation of social practices illustrated how individuals/groups are enabled to choose strategies of actions in budgetary control as a product of specific dispositions and interests associated with the particular power position in a given field ( Battilana, 2006 ; Boedker, 2010 ; Carter et al. , 2011 ; Hutaibat, 2019 ; Khanchel and Kahla, 2013 ; Vaughan, 2008 ). Taking into account Bourdieu's practice insights, as the dispositions of general academics are informed by symbolic power, doxa and self-evident understanding in the particular setting, the subversion strategies are evident in the budget-setting phase ( Célérier and Botey, 2015 ; Emirbayer and Johnson, 2008 ; Emirbayer and Williams, 2005 ; Hutaibat, 2019 ; Semeen et al. , 2016 ).

As Hutaibat (2019) asserted different forms of capital create power structures of the specific field, such power diversity and power relations are evident amongst the agents of University Sigma. Further, being consistent with Carter et al. (2011) who suggested that power structures are capable of influencing the strategising, accounting and decision- making, it is evident that budgeting practices are shaped by key university agents (i.e. deans) and their experiences. Similarly, being situated in the subservient position in the university power configuration, finance/administrative officers tend to silently accept the budgetary rules in the policy-laden context by indicating successive strategies.

As with the findings of Lodhia and Jacobs (2013) , particularly finance/administrative officers are skilful agents with a strong sense of practical mastery in the art of operating the budgetary process. By negotiating the rules of budgetary practice, their actions typically emanate from the “immanent necessary” to sustain the enlisted coercive tendencies in support of achieving control in the budgetary process ( Lamaison and Bourdieu, 1986 ; Swartz, 2002 ). However, based on the sense of practice, with a vested interest in compliance with the existing order of control practice to ensure survival in the current position in the university hierarchy, there could be instances where agents may act by giving an appearance of obeying rules in the actual budgetary practice ( Lamaison and Bourdieu, 1986 ).

When probing the practices of internal agents, it is suggested that budgetary practice is often driven by financial/administrative agents who are situated at subservient positions in the university field. In conclusion, the case data on institutionally imposed budgeting practice suggested that the micro effects stemming from multiple agents who pursue competing interests, mutually opposed strategies and power relations are significant in understanding variability in budgetary practice in a public university setting ( Al-Htaybat and Von Alberti-Alhtaybat, 2018 ).

It is discerned through this study that differing positions in the power configuration, access to resources in the field and dispositions of individuals determine the nature and extent of effects that agents can produce on management control practices ( Battilana, 2006 ; Khanchel and Ben Kahla, 2013 ; Lodhia and Jacobs, 2013 ; Vaughan, 2008 ). In line with Vaughan's (2008) assertion, “social location was crucial to the outcome” (p. 76); the study suggested that an individual's position in the organisational power hierarchy is essential in understanding how their perceptions, appreciations and power relations are enabled to deploy specific practices and exert power in an organisational setting. Consistent with Emirbayer and Williams (2005) , the field analysis provides understanding on the mutually opposing interests and strategies of internal agents pursuing conservation, subversion and successive strategies in management control practice, depending on the degree of dominated or dominant poles recognised in the power configuration ( Emirbayer and Johnson, 2008 ; Vaughan, 2008 ).

The most compelling implication for practitioners arising from the study is the importance of understanding that management controls are not all they seem to be; rather, they could operate differently, in irrational, unconscious or non-strategic ways, in the actual practice of the budgetary process. It is vital to understand that management controls (i.e. budgeting) are commonly shaped by the micro-facets stemming from the individual/group level of the specific organisational setting. Thus, the study provides insights about the need to explore below the surface as management control practice is seldom as it appears to be.

As several agents interact in management control practices in diverse ways, agents are generally recognised according to the nature of their duties and professional capacity in the Sigma setting. The first category is identified as agents who are predominantly academics, who currently hold top administrative positions in the faculty or university level in the research setting. In order to denote the positions that carry these characteristics, we use the term “key university official”. The second category is identified as agents who purely hold middle- and top-level administrative and administration of finance positions, such as the university registrar and bursar. The third category is denoted as “academic member”, with a primary role dealing with teaching, learning and research.

Scientific renown refers to intellectual or scientific capital deriving from scholarly reputation and is not necessarily connected to position within the institution ( Bourdieu and Wacquant, 1992 , p. 76).

Obtaining and maintaining the top hierarchical position enables domination of other positions and holders of different capital.

In this phase, the budget preparation changes from a “needs” basis to an “availability” basis.

Abernethy , M.A. and Brownell , P. ( 1999 ), “ The role of budgets in organizations facing strategic change: an exploratory study ”, Accounting, Organizations and Society , Vol. 24 No. 3 , pp. 189 - 204 , doi: 10.1016/S0361-3682(98)00059-2 .

Ahrens , T. and Chapman , C.S. ( 2004 ), “ Accounting for flexibility and efficiency: a field study of management control systems in a restaurant chain ”, Contemporary Accounting Reshearch , Vol. 21 No. 2 , pp. 271 - 301 , doi: 10.1506/VJR6-RP75-7GUX-XH0X .

Ahrens , T. and Chapman , C.S. ( 2007 ), “ Management accounting as practice ”, Accounting, Organizations and Society , Vol. 32 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 27 , doi: 10.1016/j.aos.2006.09.013 .

Al-Htaybat , K. and Von Alberti-Alhtaybat , L. ( 2018 ), “ Integrated thinking leading to integrated reporting: case study insights from a global player ”, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal , Vol. 31 No. 5 , pp. 1435 - 1460 , doi: 10.1108/AAAJ-08-2016-2680 .

Aleksandrov , E. , Bourmistrov , A. and Grossi , G. ( 2018 ), “ Participatory budgeting as a form of dialogic accounting in Russia: actors’ institutional work and reflexivity trap ”, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal , Vol. 31 No. 4 , pp. 1098 - 1123 , doi: 10.1108/AAAJ-02-2016-2435 .

Battilana , J. ( 2006 ), “ Agency and institutions: The enabling role of individuals’ social position ”, Organization , Vol. 13 No. 5 , pp. 653 - 676 , doi: 10.1177/1350508406067008 .

Baxter , J. and Chua , W.F. ( 2008 ), “ Be (com) ing the chief financial officer of an organisation: Experimenting with Bourdieu's practice theory ”, Management Accounting Research , Vol. 19 No. 3 , pp. 212 - 230 , doi: 10.1016/j.mar.2008.06.001 .

Bjerregaard , T. and Klitmøller , A. ( 2016 ), “ Conflictual practice sharing in the MNC: a theory of practice approach ”, Organization Studies , Vol. 37 No. 9 , pp. 1271 - 1295 , doi: 10.1177/0170840616634126 .

Boedker , C. ( 2010 ), “ Ostensive versus performative approaches for theorising accounting- strategy research ”, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal , Vol. 23 No. 5 , pp. 595 - 625 , doi: 10.1108/09513571011054909 .

Bourdieu , P. ( 1977 ), “ Outline of a theory of practice ”, translated by R. Nice , Cambridge .

Bourdieu , P. ( 1990 ), The Logic of Practice , Stanford University Press .

Bourdieu , P. ( 2005 ), The Social Structures of the Economy , Polity Press , Cambridge .

Bourdieu , P. ( 2013 ), Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste , Routledge , London .

Bourdieu , P. and Wacquant , L.J. ( 1992 ), An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology , University of Chicago Press .

Carter , C. , Clegg , S. and Kornberger , M. ( 2011 ), “ Re-framing strategy: power, politics and Accounting ”, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal , Vol. 23 No. 5 , pp. 573 - 594 , doi: 10.1108/09513571011054891 .

Célérier , L. and Botey , L.E.C. ( 2015 ), “ Participatory budgeting at a community level in Porto Alegre: a Bourdieusian interpretation ”, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal , Vol. 28 No. 5 , pp. 739 - 772 , doi: 10.1108/AAAJ-03-2013-1245 .

Chudzikowski , K. and Mayrhofer , W. ( 2011 ), “ In search of the blue flower? Grand social theories and career research: the case of Bourdieu’s theory of practice ”, Human Relations , Vol. 64 No. 1 , pp. 19 - 36 , doi: 10.1177/0018726710384291 .

Covaleski , M.A. and Dirsmith , M.W. ( 1983 ), “ Budgeting as a means for control and loose coupling ”, Accounting, Organizations and Society , Vol. 8 No. 4 , pp. 323 - 340 , doi: 10.1016/0361-3682(83)90047-8 .

Covaleski , M.A. and Dirsmith , M.W. ( 1986 ), “ The budgetary process of power and politics ”, Accounting, Organizations and Society , Vol. 11 No. 3 , pp. 193 - 214 , doi: 10.1016/0361-3682(86)90021–8 .

Covaleski , M.A. , Dirsmith , M.W. and Weiss , J.M. ( 2013 ), “ The social construction, challenge and transformation of a budgetary regime: the endogenization of welfare regulation by institutional entrepreneurs ”, Accounting, Organizations and Society , Vol. 38 No. 5 , pp. 333 - 364 , doi: 10.1016/j.aos.2013.08.002 .

Cunningham , L.A. ( 2004 ), “ The appeal and limits of internal controls to fight fraud, terrorism, other ills ”, Journal of Corporation Law , Vol. 29 No. 2 , p. 267 .

Emirbayer , M. and Johnson , V. ( 2008 ), “ Bourdieu and organizational analysis ”, Theory and Society , Vol. 37 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 44 .

Emirbayer , M. and Williams , E.M. ( 2005 ), “ Bourdieu and social work ”, Social Service Review , Vol. 79 No. 4 , pp. 689 - 724 , doi: 10.1086/491604 .

Ezzamel , M. , Robson , K. and Stapleton , P. ( 2012 ), “ The logics of budgeting: theorization and practice variation in the educational field ”, Accounting, Organizations and Society , Vol. 37 No. 5 , pp. 281 - 303 , doi: 10.1016/j.aos.2012.03.005 .

Farjaudon , A.L. and Morales , J. ( 2013 ), “ In search of consensus: the role of accounting in the definition and reproduction of dominant interests ”, Critical Perspectives on Accounting , Vol. 24 , pp. 154 - 171 , doi: 10.1016/j.cpa.2012.09.010 .

Feldman , M.S. and Orlikowski , W.J. ( 2011 ), “ Theorizing practice and practicing theory ”, Organization Science , Vol. 22 No. 5 , pp. 1240 - 1253 , doi: 10.1287/orsc.1100.0612 .

Goddard , A. ( 2004 ), “ Budgetary practices and accountability habitus: a grounded theory.Accounting ”, Auditing and Accountability Journal , Vol. 17 No. 4 , pp. 543 - 577 , doi: 10.1108/09513570410554551 .

Gomez , M.L. ( 2010 ), “ A Bourdieusian perspective on strategizing in Golsorkhi ”, D. , Leca , B. , Lounsbury , M. and Ramirez , C. (Eds), Cambridge Handbook of Strategy as Practice , Cambridge University Press , Cambridge , pp. 141 - 154 .

Grenfell , M. ( 2008 ), Pierre Bourdieu: Key Concepts , Acumen Stocksfield .

Harun , H. , Carter , D. , Mollik , A.T. and An , Y. ( 2020 ), “ Understanding the forces and critical features of a new reporting and budgeting system adoption by Indonesian government ”, Journal of Accounting and Organizational Change , Vol. 16 No. 1 , pp. 145 - 167 , doi: 10.1108/JAOC-10-2019-0105 .

Henttu-Aho , T. ( 2016 ), “ Enabling characteristics of new budgeting practice and the role of controller ”, Qualitative Research in Accounting and Management , Vol. 13 No. 1 , pp. 31 - 56 , doi: 10.1108/QRAM-09-2014-0058 .

Horngren , C.T. , Datar , S.M. and Rajan , M.V. ( 2014 ), Cost Accounting: A Managerial Emphasis , 14th ed . Pearson Higher Education , New Jersey, NJ .

Hurtado , P.S. ( 2010 ), “ Assessing the use of Bourdieu’s key concepts in the strategy-as-practice field ”, Competitiveness Review: An International Business Journal , Vol. 20 No. 1 , pp. 52 - 61 , doi: 10.1108/10595421011019975 .

Hutaibat , K. ( 2019 ), “ Accounting for strategic management, strategising and power structures in the Jordanian higher education sector , Journal of Accounting and Organizational Change , Vol. 15 No. 3 , pp. 430 - 452 , doi: 10.1108/JAOC-06-2018-0054 .

Inghilleri , M. ( 2005 ), “ The sociology of Bourdieu and the construction of the ‘object’ in translation and interpreting studies ”, The Translator , Vol. 11 No. 2 , pp. 125 - 145 , doi: 10.1080/13556509.2005.10799195 .

Jakobsen , M. and Pallesen , T. ( 2017 ), “ Performance budgeting in practice: the case of Danish hospital management ”, Public Organization Review , Vol. 17 No. 2 , pp. 255 - 273 , doi: 10.1007/s11115-015-0337-8 .

Jarzabkowski , P. , Balogun , J. and Seidl , D. ( 2007 ), “ Strategizing: the challenges of a practice perspective ”, Human Relations , Vol. 60 No. 1 , pp. 5 - 27 , doi: 10.1177/0018726707075703 .

Jayasinghe , K. and Wickramasinghe , D. ( 2011 ), “ Power over empowerment: encountering development accounting in a Sri Lankan fishing village ”, Critical Perspectives on Accounting , Vol. 22 No. 4 , pp. 396 - 414 , doi: 10.1016/j.cpa.2010.12.008 .

Khanchel , H. and Kahla , K.B. ( 2013 ), “ Mobilizing Bourdieu’s theory in organizational research ”, Review of General Management , Vol. 17 No. 1 , pp. 86 - 94 .

King , A. ( 2000 ), “ Thinking with Bourdieu against Bourdieu: a ‘practical’ critique of the habitus ”, Sociological Theory , Vol. 18 No. 3 , pp. 417 - 433 , doi: 10.1111/0735-2751.00109 .

King , A. ( 2005 ), “ The habitus process: a sociological conception ”, Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour , Vol. 35 No. 4 , pp. 463 - 468 , doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5914.2005.00286.x .

Kloot , B. ( 2009 ), Exploring the value of Bourdieu’s framework in the context of institutional change , Studies in Higher Education , Vol. 34 No. 4 , pp. 469 - 481 , doi: 10.1080/03075070902772034 .

Lamaison , P. and Bourdieu , P. ( 1986 ), “ From rules to strategies: an interview with Pierre Bourdieu ”, Cultural Anthropology , pp. 110 - 120 . available at : https://www.jstor.org/stable/656327 .

Lambovska , M. , Rajnoha , R. and Dobrovič , J. ( 2019 ), “ From quality to quantity and vice versa:How to evaluate performance in the budgetary control process ”, Journal of Competitiveness , Vol. 11 No. 1 , pp. 52 - 69 , doi: 10.7441/joc.2019.01.04 .

Lau , R.W. ( 2004 ), “ Habitus and the practical logic of practice: an interpretation ”, Sociology , Vol. 38 No. 2 , pp. 369 - 387 , doi: 10.1177/0038038504040870 .

Lodhia , S. and Jacobs , K. ( 2013 ), “ The practice turn in environmental reporting: a study into current practices in two Australian commonwealth departments ”, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal , Vol. 26 No. 4 , pp. 595 - 615 , doi: 10.1080/0969160X.2013.845033 .

Lounsbury , M. ( 2008 ), “ Institutional rationality and practice variation: new directions in the institutional analysis of practice ”, Accounting, Organizations and Society , Vol. 33 No. 4 , pp. 349 - 361 , doi: 10.1016/j.aos.2007.04.001 .

Lounsbury , M. and Ventresca , M. ( 2003 ), The New Structuralism in Organizational Theory. Organization , Vol. 10 No. 3 , pp. 457 - 480 , doi: 10.1177/13505084030103007 .

Maclean , M. , Harvey , C. and Chia , R. ( 2012 ), “ Reflexive practice and the making of elite business careers ”, Management Learning , Vol. 43 , pp. 385 - 404 , doi: 10.1177/1350507612449680 .

McDonough , P. ( 2006 ), “ Habitus and the practice of public service ”, Work, Employment & Society , Vol. 20 No. 4 , pp. 629 - 647 , doi: 10.1177/0950017006069805 .

Mkasiwa , T.A. ( 2019 ), “ Budgeting and monitoring functions of the Tanzanian Parliament ”, Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies , Vol. 9 No. 3 , pp. 386 - 406 , doi: 10.1108/JAEE-11-2018-0120 .

Moll , J. and Hoque , Z. ( 2011 ), “ Budgeting for legitimacy: the case of an Australian university ”, Accounting, Organizations and Society , Vol. 36 No. 2 , pp. 86 - 101 .

Mutiganda , J.C. , Hassel , L.G. and Fagerström , A. ( 2013 ), “ Accounting for competition, ‘circuits of power’ and negotiated order between not-for-profit and public sector organisations ”, Financial Accountability and Management , Vol. 29 No. 4 , pp. 378 - 396 , doi: 10.1111/faam.12023 .

O'grady , W. ( 2019 ), “ Enabling control in a radically decentralized organization ”, Qualitative Research in Accounting and Management , Vol. 16 No. 2 , pp. 224 - 251 , doi: 10.1108/QRAM-07-2017-0065 .

Raedeke , A.H. , Green , J.J. , Hodge , S.S. and Valdivia , C. ( 2003 ), “ Farmers, the practice of farming and the future of agroforestry: an application of Bourdieu's concepts of Field and Habitus ”, Rural Sociology , Vol. 68 No. 1 , pp. 64 - 86 , doi: 10.1111/j.1549-0831.2003.tb00129.x .

Schatzki , T.R. ( 2006 ), “ On organizations as they happen ”, Organization Studies , Vol. 27 No. 12 , pp. 1863 - 1873 , doi: 10.1177/0170840606071942 .

Schneidhofer , T.M. , Latzke , M. and Mayrhofer , W. ( 2015 ), “ Careers as sites of power: a relational understanding of careers based on Bourdieu’s cornerstones ”, in Tatli , A. , Özbilgin , M. and Karatas-Özkan , M. (Eds), Pierre Bourdieu, Organization and Management , Routledge , New York , pp. 19 - 36 .

Semeen , H. , Islam , M.A. and Quayle , A. ( 2016 ), “ The accounting and accountability practices of fairtrade international (FLO) ”, Social and Environmental Accountability Journal , Vol. 36 No. 3 , pp. 170 - 187 , doi: 10.1080/0969160X.2016.1246376 .

Simons , R. ( 1994 ), “ How new top managers use control systems as levers of strategic renewal ”, Strategic Management Journal , Vol. 15 No. 3 , pp. 169 - 189 , doi: 10.1002/smj.4250150301 .

Sponem , S. and Lambert , C. ( 2016 ), “ Exploring differences in budget characteristics, roles and satisfaction: a configurational approach ”, Management Accounting Research , Vol. 30 , pp. 47 - 61 , doi: 10.1016/j.mar.2015.11.003 .

Swartz , D.L. ( 2002 ), “ The sociology of habit: the perspective of Pierre Bourdieu ”, Occupational Therapy Journal of Research , Vol. 22 , pp. 61S - 69S , doi: 10.1177/15394492020220S108 .

Vaughan , D. ( 2008 ), “ Bourdieu and organizations: the empirical challenge ”, Theory and Society , Vol. 37 No. 1 , pp. 65 - 81 , doi: 10.1007/s11186-007-9056-7 .

Wacquant , L. ( 1998 ). Pierre Bourdieu , Key Sociological Thinkers , pp. 215 - 229 .

Whittington , R. ( 1996 ), “ Strategy as practice ”, Long Range Planning , Vol. 29 No. 5 , pp. 731 - 735 .

Whittington , R. ( 2006 ), “ Completing the practice turn in strategy research ”, Organization Studies , Vol. 27 No. 5 , pp. 613 - 634 , doi: 10.1177/0170840606064101 .

Widener , S.K. ( 2007 ), “ An empirical analysis of the levers of control framework ”, Accounting, Organizations and Society , Vol. 32 No. 7 , pp. 757 - 788 , doi: 10.1016/j.aos.2007.01.001 .

Wouters , M. and Wilderom , C. ( 2008 ), “ Developing performance-measurement systems as enabling formalization:A longitudinal field study of a logistics department ”, Accounting, Organizations and Society , Vol. 33 No. 4 , pp. 488 - 516 , doi: 10.1016/j.aos.2007.05.002 .

Xu , Y. and Xu , X. ( 2008 ), “ Social actors, cultural capital, and the state: the standardization of bank accounting classification and terminology in early twentieth-century China ”, Accounting, Organizations and Society , Vol. 33 No. 1 , pp. 73 - 102 , doi: 10.1016/j.aos.2006.09.011 .

Further reading

Christiansen , J.K. and Skærbæk , P. ( 1997 ), “ Implementing budgetary control in the performing arts,: games in the organizational theatre ”, Management Accounting Research , Vol. 8 No. 4 , pp. 405 - 438 , doi: 10.1016/j.aos.2007.04.001 .

Geiger , D. ( 2009 ), “ Revisiting the concept of practice: toward an argumentative understanding of practicing ”, Management Learning , Vol. 40 No. 2 , pp. 129 - 144 , doi: 10.1177/1350507608101228 .

Corresponding author

Related articles, we’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

Budget 2024-25: Protecting and Growing the Future of Agriculture

The Albanese Labor Government will invest $789 million over the next eight years in the Budget to help farmers and producers protect and adapt against the impacts of climate change, build more resilience for the sector and maintain Australia’s position as a trusted and reliable trading partner.

Farmers are on the frontline of climate change, facing more intense and frequent natural disasters and weather extremes which is already hurting the bottom line.

The Albanese Government is committed to helping farmers and regional communities across the country become more productive and more profitable, while also reducing their emissions.

Drought preparedness and resilience

Helping regional and rural communities prepare for the next drought and manage climate risk is a key feature of the Albanese Government’s $519.1 million spend from the Future Drought Fund (FDF). Support for farmers and regional communities in this Budget includes:

- $235 million over eight years to work with regions and communities to help them manage their own drought and climate risks, through collaborative and locally led action. The funding will continue the Drought Resilience Adoption and Innovation Hub model, provide for the next phase of the Regional Drought Resilience Planning Program and deliver a revised FDF Communities program.

- $15 million over four years to work with First Nations peoples and communities to support connection to country through management of drought and climate risks. The funding will establish a First Nations Advisory Group to advise on issues relating to drought and climate resilience, a pilot program to facilitate place-based, First Nations-led activities, and dedicated funding to support activities that seek to improve opportunities for First Nations participation in FDF drought and climate resilience activities.

- $137.4 million over five years to support farmers and regional communities to make informed decisions and better manage drought and climate risks. The funding will extend and improve the existing Farm Business Resilience and Climate Services for Agriculture programs, and deliver the new Scaling Success Program.

- $120.3 million over six years for programs that trial innovative solutions with the potential to build the agriculture sector, landscapes and communities’ long-term resilience to drought and climate risks, through transformational change. The funding will continue and expand the FDF Long Term Trials Program, a revised FDF Resilient Landscapes Program, and will implement a new FDF Innovation Challenges Pilot. These activities will lead to increased uptake of evidence-based, innovative practices, approaches and technologies.

- $11.4 million over four years to support critical enabling activities to effectively deliver drought and climate resilience outcomes. This will support monitoring, evaluation and learning to measure outcomes and share knowledge generated by FDF programs about how to address drought and climate risks.

- A further $13.9 million over the next four years will be spent to ensure the Government maintains a state of readiness for drought. The funding supports a nationally consistent approach to drought policy and programs, which will informed by the 2024-2029 National Drought Agreement and the Australian Government’s Drought Plan. These key activities will be supported by inclusive and timely stakeholder engagement and communications to ensure drought policy is informed by the people it impacts. Consultation on the Australian Government’s Drought Plan will commence shortly.

- From 2028-29, a further $3.4 million per year ongoing has also been allocated to ensure the Government has an ongoing focus on drought as we know the best time to prepare for drought is before drought occurs.

Climate and sustainability

To ensure the agriculture and land sectors can meaningfully contribute to the whole-of-economy transition to net zero, the Government is investing $63.8 million over ten years to support initial emissions reduction efforts.

Phase out of live sheep exports by sea

This Budget also includes a $107 million assistance package over five years to help the Australian sheep industry transition away from live exports by 1 May 2028, realising the booming opportunities for Australian sheepmeat and wool across the globe.

Ending the trade was an election commitment, with an independent report recommending a suite of measures following extensive consultation with industry and the public.

The assistance package will help the $77 million industry to transition away from live exports into onshore processing, creating added value for the local processing market and additional jobs in Western Australia.

The package also provides funding for overseas market development for Australian sheepmeat, as well as funding for rural mental health programs in Western Australia.

Agriculture workforce

More Australians will be encouraged to enter the agricultural workforce with a revised and focussed AgUP grants program.

The Government will use $1.9 million over three years to provide targeted grants to industry led projects that can benefit the entire sector.

The program will support the continuation of existing activities for National Farm Safety Week and work experience opportunities for young people interested in agriculture through the AgCareer start pilot.

It also includes funding for a new, skilled agricultural work liaison program, in urban and regional universities, aimed at increasing the number of highly-skilled graduates entering the sector.

The funding will help the Government address diverse and complex workforce issues such as attraction and retention.

Food labelling

This Budget will also see the Government deliver on its election commitment to deliver accurate and clear labelling of plant-based alternative protein products.

The Government will spend $1.5 million over two years from 2023–24 to work with industry and regulatory agencies to improve existing arrangements in labelling.

The funding will also support independent research into consumers’ current understanding of plant-based labelling and inform improvements to guidance material.

Biosecurity

The Albanese Government is investing $16.9 million over four years to ensure the biosecurity integrity of Australia’s border remains contemporary and adaptable to evolving global risks by underpinning biosecurity operations with specialist technology and equipment at Sydney’s new international airport.

Western Sydney International Airport, which is currently under construction, will be fitted out with specialist screening and biosecurity risk detection equipment and scientific diagnostic equipment to support biosecurity officers and detector dogs continue to keep Australia free from exotic pests and diseases.

The canine facility will be fitted out to provide canine care, including medical and veterinarian needs and food and accommodation for the Biosecurity, Australian Border Force and Australian Federal Police dog fleets.

Western Sydney International Airport is expected to be one of Australia’s busiest airports when it opens. The Department is working closely and co-designing with Western Sydney International Airport and other Commonwealth agencies on infrastructure and facilities for border services.

Forestry and Fisheries

The Government is investing $3.4 million over four years to implement and complete its plan for forestry, A Future Grown in Australia: A Better Plan for Forestry and Forestry Products.

This allows delivery of the Government’s election commitment to develop a national strategy for the wood fibre and forestry sector and a commitment to review the 1992 National Forestry Policy Statement in collaboration with state and territory governments.

These initiatives are part of a $302 million investment in new plantations and technology and will contribute to achieving and realising a long-term outlook for the forestry industry, which is a key element of regional communities around the country.

The Government has also committed $1.7 million to ensure the Australian Fisheries Management Authority can protect our northern waters from the growing threat of illegal fishing, which is a risk to our fishing industry, our biosecurity status, our environment and our border security.

For more information head to the DAFF budget webpage .

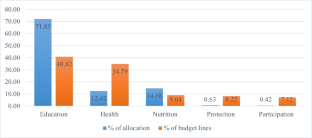

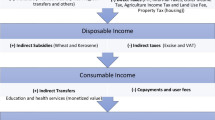

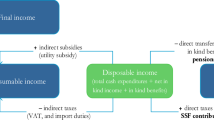

Fiscal Marksmanship of Child Budget and its Implications for Child Development: Evidence from India

- Published: 16 May 2024

Cite this article

- Narayana Muttur Ranganathan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5469-1722 1

15 Accesses

Explore all metrics

This paper analyses the nature and magnitude of fiscal marksmanship or budget forecasting errors in Child Budget in India by a case study of Karnataka State. The implications of fiscal marksmanship are analysed for child development within the framework of Child Budget. Level of multidimensional child development is measured by 26 indicators, representing child education, health, nutrition, protection and participation and in the frameworks of child rights and UN-Sustainable Development Goals 2030. Main results show that Karnataka State’s good fiscal management is accompanied by a lack of fiscal marksmanship in Child Budget. Other things being equal, a perfect fiscal marksmanship implies a gain of about 0.3% point in composite index of child development. This implies that achievement of fiscal marksmanship has a positive effect on child development through Child Budget. Lessons from this case study are of general relevance and applicability at national level and for other states in India as well as for other countries which aim at child development through their Child Budget.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Fiscal Policy and Child Poverty in Ethiopia

Fiscal Policy and Child Poverty in Belarus

Public Spending and Investment in Children: Measuring and Assessing Social and Economic Justice

Recent Economic Survey (Government of Karnataka, 2023a ), Human Development Report (Government of Karnataka, 2022a ) and State Budget Volumes (Government of Karnataka, 2023b ) are the official sources for information on and introduction to the State’s economy, development and fiscal policy.

For financial year 2023-24, State Budget was presented on 17th February 2023 and 7th July 2023 due to change in State Government. Throughout, unless stated otherwise, Child Budget 2023-24 refers to February version.

Official population projections for child population are available in Government of India ( 2020b ) and show a decline in child population from 2011 to 2036. If these projected figures are used, and other things being equal, Child Budget allocation in regard to less than 100% CCP and less than 100% CCNP is reduced.

These 17 indicators are as follows. Each indicator is identified and prefixed by the Goal, Target and Indicator numbers in UN-SDG. For instance, 2.2.1 Stunting refers to Goal 2, Target 2 and Indicator 1. 2.2.1 Stunting; 2.2.2 Wasting/overweight; 3.1.2 Skilled attendant at birth; 3.2.1 Under-five mortality; 3.2.2 Neonatal mortality; 3.b.1 Full vaccination coverage; 4.2.1 Early childhood development; 5.2.1 Sexual violence by intimate partner; 5.2.2 Sexual violence by non-intimate partner; 5.3.1 Early marriage; 5.3.2 FGM/C; 6.1.1 Safely managed drinking water; 6.2.1 Safely managed sanitation and hygiene; 8.7.1 Child labour; 16.2.1 Child discipline; 16.2.3 Sexual violence against children; and 16.9.1 Birth registration.

Allan, C. M. (1965). Fiscal marksmanship, 1951–1963. Oxford Economic Papers, 17 (2), 317–327.

Article Google Scholar

Auld, D. A. L. (1970). Fiscal marksmanship in Canada. The Canadian Journal of Economics, 3 (30), 507–511.

Chakraborty, L., & Sinha, D. (2018). Has Fiscal Rule changed the Fiscal Marksmanship of Union Government? Anatomy of Budgetary Forecast Errors in India . NIPFP Working Paper Series No.234, National Institute of Public Finance & Policy (New Delhi).

Chakraborty, L., Chakraborty, P., & Shrestha, R. (2020). Budget credibility of subnational governments: Analyzing the fiscal forecasting errors of 28 states in India . Working Paper, No. 964, Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, Annandale-on- Hudson (New York).

Davis, J. M. (1980). Fiscal marksmanship in the United Kingdom, 1951–1978. The Manchester School, 48 (2), 187–202.

Davis, O. A., Dempster, M. A. H., & Wildavsky, A. (1966). A theory of budget process. The American Political Science Review, 60 (3), 529–547.

Government of Assam. (2022). Child Budget 2022-23 . Finance Department (Dispur). https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-d&q=capital+of+assam . Accessed 2 Nov 2023.

Government of Andhra Pradesh. (2023). Child Budget Statement 2023-24. Ministry of Finance (Hyderabad). https://www.apfinance.gov.in/uploads/budget-2023-24-books/Child-Budget.pdf . Accessed 2 Nov 2023.

Government of Arunachal Pradesh (2023). Child Budget 2023-24. Finance, Planning and Investment Department (Itanagar). http://www.arunachalbudget.in/docs/child.pdf . Accessed 2 Nov 2023.

Government of India. (2012). Chapter 3: Public Finance, Economic Survey 2012-13, Department of Economic affairs . Ministry of Finance (New Delhi).

Government of India. (2018). Sustainable development goals (SDGs): National Indicator Framework . Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (New Delhi).

Government of India. (2020a). Finance Commission in Covid Times: Report 2021-26, XV Finance Commission, Volume 1: Main Report: Downloaded from the following official website: file:///G:/XV%20FC%20Reports/XVFC%20VOL%20I%20Main%20Report%20(2).pdf. Accessed 2 Nov 2023

Government of India. (2020b). Population projections for India and States 2011–2036. Report of the Technical Group on Population projections, Census of India 2011 . National Commission on Population, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (New Delhi).

Government of India. (2021). SDG India: Index and Dashboard 2020-21 . NITI Aayog (New Delhi).

Government of India (2023a). Allocation for the Welfare of Children. Statement 12. Expenditure Profile 2023-24 , Union Budget 2023-24, Ministry of Finance (New Delhi).

Government of India. (2023b). INDIA National Multi-dimensional Poverty Index: A Progress Review 2023 . NITI Aayog (New Delhi).

Government of Karnataka. (2020). Child Budget 2020-21 . Finance Department (Bengaluru). https://finance.karnataka.gov.in/storage/pdf-files/2020%2021%20Budget/18-Child%20Budget.pdf . Accessed 30 Oct 2023.

Government of Karnataka. (2021). Child Budget 2021-22 . Finance Department (Bengaluru). https://finance.karnataka.gov.in/storage/pdf-files/20-ChildBudget%202021-22.pdf . Accessed 30 Oct 2023.

Government of Karnataka. (2022a). Human Development Report 2022 . Human Development Division, Planning, Programme Monitoring and Statistics Department (Bengaluru). https://planning.karnataka.gov.in/storage/pdf-files/Reports/HumanDevelopmentReport-2022FullBook.pdf . Accessed 30 Oct 2023

Government of Karnataka. (2022b). Child Budget 2022-23 . Finance Department (Bengaluru). https://finance.karnataka.gov.in/storage/pdf-files/Child%20Budget%202022-23.pdf . Accessed 30 Oct 2023.

Government of Karnataka. (2023a). Economic Survey 2020-21 . Planning, Programme Monitoring and Statistics Department (Bengaluru). https://planning.karnataka.gov.in/info-4/Reports/Economic+Survey+Reports/en . Accessed 2 Nov 2023.

Government of Karnataka. (2023b). Budget Volumes 2023-24 (July version) . Finance Department (Bengaluru). https://finance.karnataka.gov.in/info-2/2023-24+July/Budget+Volumes+2023-24+July/en . Accessed 2 Nov 2023.

Government of Karnataka. (2023c). Child Budget 2023-24 (February version) . Finance Department (Bengaluru). https://finance.karnataka.gov.in/storage/pdf-files/20_CHILD%20BUDGET%202023-24.pdf . Accessed 30 Oct 2023.

Government of Kerala. (2023). Gender & Child Budget: Plan Schemes 2023-24 . Finance Department (Thiruvananthapuram). https://www.budget.kerala.gov.in/keralabudgetdoc/2023_24/GenderBudget.pdf . Accessed 2 Nov 2023.

Government of Madhya Pradesh. (2023). Child Budget 2023-24. Finance Department (Bhopal) . https://finance.mp.gov.in/budget . Accessed 2 Nov 2023.

Government of Bihar. (2021). Child Welfare Budget 2021-22 . Finance Department (Patna). https://openbudgetsindia.org/dataset/b8771e71-d964-4b9d-b8c9-9e5c20461dd8/resource/482d1f70-fc55-40fa-a61f-64f81ea6b0da/download/child-budget.pdf . Accessed 30 Oct 2023.

Government of Maharashtra. (2022). Gender Budget Statement & Child Budget Statement 2022-23. Finance Department (Mumbai). https://finance.maharashtra.gov.in/Sitemap/finance/pdf/Gender_and_Child_Budget_statement_FY_2022-23.pdf . Accessed 2 Nov 2023.

Government of Odisha. (2022). Child Budget 2022-23 . Finance Department (Bhubaneshwar). https://finance.odisha.gov.in/sites/default/files/2022-07/Child%20Budget.pdf . Accessed 30 Oct 2023.

Jacob, J. F. (2020). Child responsive budgeting as a public finance management tool: A case of Karnataka, India. TTPI-Working Paper 14/20, Crawford School of Public Policy, College of Asia and the Pacific, The Australian National University (Canberra).

Jacob, J. F., & Chakraborty, L. (2021). COVID-19 and Public Investment for Children: The case of Indian State of Karnataka. NIPFP Working Paper Series No.355, National Institute of Public Finance & Policy (New Delhi).

Jani, V. J. (2022). Fiscal Marksmanship in Health Expenditure – Experience of Indian States. Economic & Political Weekly . Vol.57, No.43: 22 October 2022.

Leriou, E. (2022). Understanding and measuring Child Well-being in the region of Attica, Greece: Round four. Child Indicators Research, 15 (6), 1967–2011.

Leriou, E. (2023). Understanding and measuring Child Well-being in the region of Attica, Greece: Round five. Child Indicators Research, 16 (4), 1395–1451.

Michalos, A. C., Creech, H., Swayze, N., et al. (2012). Measuring knowledge, attitudes and behaviours concerning. Sustainable Development among Tenth Grade Students in Manitoba. Social Indicators Research, 106 (2), 213–238

Morrison, R. J. (1986). Fiscal marksmanship in the United States: 1950–1983. The Manchester School, 54 (3), 322–333.

Narayana, M. R. (2022). Need-based Child Budgeting in India. In Narayana M.R., and Anantha Ramu. (Eds.). Public Finances for Development of Children in Karnataka: Policy Issues and Challenges . Fiscal Policy Institute, Government of Karnataka (Bengaluru): pp.171–190. https://fpibengaluru.karnataka.gov.in/storage/pdf-files/Technical%20Reports/FPI-Public%20Finance%20for%20Development%20of%20Children%20in%20Karnataka_291022.pdf . Accessed 2 Nov 2023.

Premchand, P. (1994). Government Budgeting and Expenditure Controls: Theory and Practice . International Monetary Fund (Washington, D.C.).

Ritu Mathur, N., Jaitli, & Amarnath, H. K. (2022a). Estimating Child Development Index in India at the District Level – A Methodology . Working Paper Series No.370, National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (New Delhi).

Ritu Mathur, N., Jaitli, & Amarnath, H. K. (2022b). Child Development Index in India: Performance at District Level – A Methodology. Working Paper Series No.371, National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (New Delhi).

Saha, D., and James, K. (2022). A Study of the Fiscal Marksmanship of Capital Expenditure Among Indian State Governments, CSEP Working Paper 33. Centre for Social and Economic Progress (New Delhi).

Save the Children (2017). Stolen Childhoods: End of Childhood Report 2017. Save the Children (Fairfield, USA).

Save the Children. (2012). The child development index 2012: Progress, challenges and inequality . Save the Children Fund (London).

Schonert-Reichl, K. A., Guhn, M., Gadermann, A. M., et al. (2013). Development and validation of the Middle Years Development Instrument (MDI): Assessing children’s Well-Being and assets across multiple contexts. Social Indicators Research, 114 (2), 345–369.

Theil, H. (1961). Economic forecasts and policy . Second Revised Edition. North-Holland (Amsterdam).

UNICEF. (1990). Convention on the rights of the child. UNICEF (New York). https://www.unicef.org/media/52626/file . Accessed 21 Apr 2024.

UNICEF (2018). UNICEF Briefing Note Series on: SDG global indicators related to children . https://data.unicef.org/resources/briefing-notes-on-sdg-global-indicators-related-to-children/ . Accessed 30 Oct 2023.