- June 3 Free Speech: An Editorial Cartoon

- June 3 Environments: A Photo Series

- June 2 Football vs. Bear Creek High School

- June 2 Choir Spring Show

- May 28 Post-Pandemic Reflections

- May 28 Life in Disarray

- May 28 A Diverged Path

- May 28 Amidst the Mist

- May 28 New experiences, New lessons

- May 4 TikTok’s Influence on Mainstream Music

The Prospector

The Ethicality of Animal Dissections

Natalie Chen and Sania Mehta November 9, 2021

Animal dissection is a common activity performed in high school biology classes across North America, typically involving pigs, frogs, mice, or worms. However, with over twelve million animals used for dissection each year, the widespread practice has gathered substantial opposition, especially towards the ethics of the issue. Growing concern over the ethicality of dissection, as well as developing technology allowing for cruelty-free alternatives has raised the question in many school districts across the country: should dissection be removed from school curriculums?

Animal dissections are an overall beneficial and productive use of dead animals, given that they are utilized and sourced under ethical conditions. The skills learned by students through performing dissections are valuable assets to them even after leaving an academic environment and are not easily replaced with alternative methods.

For students at Cupertino High School, one of the most memorable parts of their freshman experience is the fetal pig dissection. The dissection allows students to establish concepts learned throughout the school year, such as genetics or population. A component of the dissection involves removing the heart of the fetal pig. The hearts are then be measured, weighed, and compared with data from peers to answer critical questions related to variation and natural selection learned in earlier units.

Said Andrew Goldenkranz, who teaches ninth-grade biology, “So we can establish everything we’ve learned about populations in either genetics or evolution, but you can only do that when you have a population of pigs that you’re working with.”

Moreover, the anatomical similarity of pigs compared to humans makes them the ideal specimen to learn about human anatomy. While only a minority of students choose to go into a healthcare profession, everyone will struggle with illness at some point in their lives. Through the study of fetal pigs, students can deepen their understanding of human health and physiology.

The practice of procedures done in real life inspires students to pursue careers in the science and medical fields, which can help shift the perspectives of students who might not have considered themselves academically oriented.

Said Goldenkranz, “Students who sometimes don’t excel in other academic ways, like they’re not always good at the paper and pencil stuff, those students really step up and are super good around a hands-on activity like the pigs […] The multi-sensory nature of it is really worthwhile because it brings out strengths in the kids that we don’t usually see.”

The dissection also allows students to develop fine motor skills not typically taught in a classroom setting. Through handling scalpels, using chemicals and looking at samples through a microscope, students can practice hand-eye coordination and attention to detail, which are valuable skills that will stick with them even after leaving an academic environment.

Despite the benefits, many students choose not to participate in the dissection. Whether it is because of a conscientious objection to dissection or personal reasons regarding health or religion, the school allows students the right to opt-out of dissections, although it is uncommon. According to Goldenkranz, out of roughly 600 students across the department, four to five students choose not to participate. Students who opt out of dissections are given alternatives, such as being observers rather than dissectors.

The most controversial aspect of animal dissection is the sources of the animals used. There is a stark moral distinction between growing animals for the sake of study and utilizing animals or animal parts that would otherwise have gone to waste; the former is inhumane and unethical, but the latter is a productive use of unwanted animals and can lead to scientific contributions. In the case of the fetal pig dissection, the pigs come from one of two supply houses located in Illinois and North Carolina, depending on the yearly pricing and availability. These supply houses have contracts with big farms in other parts of the country, who supply them with stillborn offspring from farmed pigs. An important distinction lies in the pig’s condition at birth; if the pigs were being harvested alive specifically for the sake of lab dissections, that would be strictly unethical and should be put out of practice. However, here at CHS, the pigs used are stillborn and pronounced dead at birth. Dissection is the most practical and productive use of their bodies instead of being used in dog food or fertilizer.

Said Goldenkranz, “Assuming that these companies are telling us the truth, and these are companies that have been around for a long time, and I think they’re telling us the truth, these are stillborn [pigs], then yeah, they’re already dead, so it’s not like we’re sacrificing them for this purpose.”

In the Physiology curriculum, individual organ dissections are done instead, including heart and brain dissections. These organs are a byproduct of factory farming animal production in the United States, where livestock organ waste is abundant. Dissecting these organs provides learning opportunities by utilizing unwanted animal parts.

Interestingly, In the Fremont Union High School District, ethics are not a significant factor in dissection in the biology curriculum. According to Goldenkranz, the topic has not yet been brought up among the science departments. However, in other districts, some schools are turning to alternatives to animal dissection, albeit more due to a lack of time and resources than moral concerns.

Said Goldenkranz, “Depending on the lab facilities and resources that a school has, you know, our most precious resource is always time. So we want to make sure that if we’re going to dedicate time to that part of the unit that we’re getting out of it what we want.”

Opposition to classroom dissections has brought up debates about substitute methods. The rapidly advancing technology industry has created numerous alternatives to animal dissection over the past few decades. Virtual simulations, 3D anatomy models and dissection videos are all perfectly valid means for students to learn the content of anatomy. However, these alternatives lack hands-on components, which can deprive students of valuable expertise.

“The skill of asking questions, of understanding the model, of constructing explanations, that’s harder to do in simulation[s], so doing it in real life gives us some real advantages,” said Goldenkranz.

Furthermore, students who have performed the fetal pig dissection report overall positive takeaways from the experience.

Said Viva Parmar, a senior at CHS, “It has really given me more hands-on experience with science. Ever since I performed my first dissection, I’ve been really interested in biology and I am interested in pursuing it as a future career option.”

Given their numerous academic benefits for students, animal dissections under ethical circumstances are a worthwhile use of unwanted animal parts and should remain in biology curricula across North America.

While the primary aim of dissection is to give students hands-on experience with animal anatomy, scholars inquire how students internalize the practice – that is, what attitudes and values may be transferred through it. Dissection can promote a decreased sensitivity toward animal life and individual or ethical discomfort. (Barr, G., & Herzog, H. (2000). Fetal pig: The High School Dissection Experience. Society & Animals, 8(1), 6.) This can desensitize students to animal testing. Teachers from the study have observed many middle school students perform the concerning act of “recreational mutilation.” This promotes animal persecution and human negligence.

In addition to the animals mutilated in dissection, an immeasurable number of live mice, rabbits, rats, turtles, and other animals are tortured and killed in crude university-level biology and psychology demonstrations. Poisoning, shocking, burning, and killing animals are daily tasks for vivisectors. If these atrocious acts that occur during animal testing were performed outside laboratories, they would be considered felonies. But animals suffer and die every day in laboratories with minimal or no protection.

With millions of animals’ lives on the line, purchasing animals for dissection is an economically significant business. Through investigations into biological supply companies – which sell animal bodies and parts – People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) has uncovered acts of cruelty to animals, including the drowning of rabbits and the embalming of cats while they were still living. The unethical supply of animals sold in the booming industry reduces local populations, generates an imbalance in the ecosystem and decreases biodiversity.

Moreover, many students dislike performing dissections and may even be traumatized by them. According to Cutting Edge Controversy: The Politics of Animal Dissection and Responses to Student Objection by Jan Oakley, in a standard class, 3-5% of students verbally oppose dissection, and a higher number of students silently condemn it.

Due to this, dissecting real animals is unnecessary as synthetic alternatives – such as online virtual dissections – are readily available. These simulations are more cost-effective than the use of real animals. Using alternatives, each body system can be studied and virtually dissected as many times as needed until students are confident with the material, unlike animal dissection, in which each system is uprooted, and the specimen is discarded when the lesson is finished. PETA found that many students find these alternatives effective substitutes. A study published in The American Biology Teacher concluded that one-third of biology students in a data set of 500 preferred to utilize alternatives over animal specimens.

Today, the high school biology curriculum weaves together genetics, evolution, and the relationship of cells to explain environmental symbiosis. Classes no longer leap from photosynthesis to the skeletal system but establish a biotechnology and engineering system foundation. Simulation-based education more accurately reflects what students will encounter when they get to medical school as all U.S. medical schools have abandoned the usage of animals in their standard curriculum. Likewise, the College Board does not require it for AP Biology, the International Baccalaureate for IB Biology or the Next Generation Science Standards.

In order to increase diverse participation in STEM, cultural concerns regarding animal dissections must be acknowledged and addressed. Several cultures, including those of many Native American tribes, consider animal dissection taboo. Lori A. Alvord, the first female Navajo surgeon, said that her “ultimate challenge” in medical school involved human dissection: “Navajos do not touch the dead. Ever. It is one of the strongest rules in our culture” She realized later that she might have requested accommodation to watch rather than actively participate or to make use of computer simulations. However, at the time, she assumed she had no choice but to violate the taboo. A survey from the International Journal of Stem Education found that from 96 students, 50% of the respondents generally observe tribal taboos and 38% would choose not to pursue a science major if they suspected it would require them to violate an important tribal taboo. They discovered 67% would be more inclined to take science classes if the science curricula were more respectful of tribal taboos.

Conclusion:

Scrutinizing the practice of animal dissection reveals many multi-faceted concerns. If well implemented, dissection may have several viable merits from an educational standpoint. However, when one considers the associated costs – animal suffering and death in the supply trade, disruption of wild animal populations, desensitization of animal suffering, and cultural taboos – a realization that a more nuanced perspective needs to be fostered. This perspective needs to acknowledge both ethical and cultural perspectives. Ending an animal’s life is not a decision that should be made lightly in the context of today’s science education. This practice necessitates critical reconsideration.

Gifted Kid Syndrome

The Impact of Climate Change on Sports

The Rise and Popularity of Doc Martens

Psychological Effects of TikTok

Teachers' Political Identities in the Classroom

The Push of Sex Work in Social Media

Self-Improvement: How Far is Too Far?

The Organic vs. Conventional Grocery Showdown

Destigmatization of Sex Education in Media

Editorial: Phone Usage

PRO/CON: Should Colleges Publicize Application Reviews?

How Old is “Too Old” for Trick Or Treating

Preserving the Freedom to Read

Inadequate Sex-Education On Menstruation

The Digitalization of Schoolwork

The Necessity of CAASPP

Comments (0)

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Animal Dissection in Schools Essay Example

Do you remember your animal dissection in school? Dissecting an animal in school might be the most memorable school experience for many students. The opportunity to cut open an animal is exciting for many people. Animal dissection should be required in all schools because it gives a hands-on experience and can inspire students to pursue a science career.

To begin, animal dissection should be required in schools because it gives a hands-on approach to learning. According to Edulab.com, “The hands-on approach of dissection allows students to see, touch and explore the various organs.” (The Importance of Dissection in Biology) Seeing organs and understanding how they work within a single animal may strengthen students' comprehension of biological systems. This follows with the students remembering what they had just learned. Plus, Molly St. Louis recorded that, “ 65% of the population learns by doing the activity, over other learning techniques.”(St. Louis) Doing the dissection hands-on allows students to take an interest in what they are doing. When seeing organisms, the students will think of what they did with the animal and bring that into their real-life experiences. This leads to students having a better understanding of how the body works.

Also, animal dissection should be required in schools because it can inspire students to pursue a career in science. According to nsta.com, “75% of students said dissection made them realize science was fun.” ( Top 3 Pros and Cons of Animal Dissection) Many students haven’t experienced dissection, so they don’t know if they are interested in science. Dissection grows the desire to learn more. According to Jerry Vannatta, “ I didn’t enjoy science when I was younger, but after my dissection, I started to get an interest in science. The interest grew into me wanting to become a surgeon.”(Vannatta) Many surgeons motivate teachers to do dissection in class. Students can grow and take an interest in what they can do in the future.

Although some critics may argue that dissection is unnecessary, and isn’t good for the environment, many students enjoy and learn from the experience. A study shows, “Dissection has an emotional impact on about half of the students. In general, students considered these experiences to be an important part of their future.”.(The effects of dissection-room experiences and related coping strategies among Hungarian medical students) Without this experience students may not be able to thrive in the future.

In conclusion, dissection gives a hands-on experience and can inspire students for the future. This is a memorable and instructive aspect of science. That proves dissection should be required in schools.

Related Samples

- Studying Agriculture in School Essay Example

- Ecology of Coral Reefs in the US Virgin Islands

- Psychology Course Analysis (Essay Example)

- Admission Essay Example: Yale University

- Scholarship Essay Example

- Research Paper Example on Monitoring Kids Social Media

- Admission Essay Example: Illinois Mathematics and Science Academy

- Personal Essay Example: The Year I Found Out I Could Write An Essay

- Essay Sample on Standardized Testing for 3-8 Grades

- A Compromise on Confederate Monuments Essay Example

Didn't find the perfect sample?

You can order a custom paper by our expert writers

- Quick Order

- 0333 996 1611

- [email protected]

- Need Help? Contact our team

SERVING SCIENCE SUCCESSFULLY SINCE 1957

Login or Register

- £ 0.00 0 items 0

- Biology Studies & Kits

- Earth & Field Studies

- Microbiology & Cultures

- Zoology & Botany

- Chemical Analysis & Reactions

- Chemistry Studies & Kits

- Fundamental Concepts

- Gas & Materials

- Services & Non Stock

EduLab Kits

- Macro Science Kits

- Mini Science Kits

Home Economics

Lab equipment.

- Benchtop Appliances

- Heating & Cooling

- Specialist & Analysis

- Tools & Timers

- Filter & Process

- General Labware

- Measure & Pour

- Testing & Diagnosis

- British Science Week - Time Inspired Picks

- Atomic & Nuclear

- Electricity & Magnetism

- Forces & Motion

- Optics & Waves

- Physics Studies & Kits

STEM & Sensors

- Interfaces & Parts

- STEM Kits & Setups

Storage & Safety

- Emergency & Incident

- Signage & Labels

- Storage & Handling

The Importance of Biology Dissection in Education: A Comprehensive Guide

Many teachers and education professionals maintain that there’s simply no substitute for the hands-on experience of dissection in learning.

Dissection, a centuries-old practice, has played a pivotal role in exploring the anatomy of both animals and plants, making it a cornerstone of zoological and botany studies. The amount learnt about biology from this practice is unparalleled and remains a practice in the modern world. From post-mortems to classroom dissection, there’s no better way of learning what’s under the skin of an organism.

What is dissection?

Practised across science classrooms worldwide, it offers students of all ages a tangible understanding of how an organism works and how its anatomy is organised.

A brief history

Looking back in history, the first known instances of dissection were carried out by the ancient Greeks around 350-400 BC. While human dissection was considered taboo and banned under Roman law, many Greek physicians dissected and studied animal cadavers.

Around the same time in India, records show an interest in the inner workings of the body; although it was unclear if they performed dissection on bodies, they marked the beginning of what became significant medical advancements around 700-800 AD where the practice flourished under Aryan rule.

Enquiries into the inner workings of the body were also made across other parts of the world; from physicians in Islamic countries dissecting bodies, to the practice of sky burial in ancient Tibet, to Christian Europe from around the 13th century onwards.

Today, while still controversial in many parts of the world, dissection is considered a standard practice in the fields of pathology and forensic medicine.

The practice in education today

In many classrooms across the globe, dissection is a standard activity and serves as an introduction to the practice that brought about many medical advancements.

While GCSE-level students normally dissect small animals such as a frog or rat, or parts of larger animals such as a pig’s heart, cow’s liver, or sheep’s lung, those in higher education often explore human cadavers.

This hands-on approach not only deepens their understanding but also ignites a passion for medical science.

What can student learn from dissection?

The hands-on approach of dissection allows students to see, touch and explore the various organs. Seeing organs and understanding how they work within a single animal may strengthen students’ comprehension of biological systems. When applied to their own bodies, this may then translate to a greater understanding of human biology.

What are the advantages?

The advantages of having students carry out dissection include:

- Gaining practical skills;

- Greater appreciation of the inner workings of the body, life, and death;

- First-hand understanding of anatomical variability;

- Improved teamwork skills.

While, of course, there are various differences between the intricacies of the human body and those of other animals, many of the internal systems can work in similar ways. From the location of organs to their interrelation with the surrounding tissue, the internal structure of a small animal can be likened to a simplified human body. Frogs are often used in dissection when demonstrating the organ systems of a complex organism. The presence and position of the organs found in a frog are similar enough to a person’s to be able to provide insights into the internal workings of the human body.

Often, when students know they will be working on a real specimen, their attention is heightened. This can facilitate greater assimilation of information, enhanced understanding of the subject matter, and the ability to recall the biological science behind the specimen.

Why teach dissection?

Many teachers believe the reality conveyed by dissection cannot be matched by alternatives. Virtual simulations cannot showcase abnormalities or variations from one specimen to the next. Overly perfect alternatives cannot compete with the biological surprises of real specimens and the learning opportunities they provide. From manipulating sharp instruments to employing delicate hand-eye coordination, the reality of physically dissecting a specimen can also develop fine motor skills.

From inspiring students’ career prospects to providing valuable hands-on practice, dissection can also prove to be a good early experience for those wishing to pursue pertinent professions. Early exposure to tools and techniques, as well as familiarity with organ tissue, may bolster some students’ ambitions. Indeed, many a surgeon may well credit their career to the fascination afforded by a classroom session with the scalpel.

Dissection is a memorable and instructive aspect of the biology curriculum, allowing students to learn how their own bodies work within the confines of the classroom. Computer software and dissection models provide additional resources to reinforce this practical hands-on approach. Explore our wide range of dissection tools and kits to suit different skill levels and learning objectives .

Privacy Overview

Ethical Reflections on Animal Dissection: a Pedagogical Dilemma

This essay is about the ethical considerations surrounding animal dissection in education. It discusses the educational benefits of dissection, such as providing hands-on experience and fostering critical thinking skills. However, it also raises ethical concerns regarding animal welfare and the moral implications of using sentient beings for educational purposes. The essay explores alternative teaching methods and emphasizes the importance of integrating ethical education into the curriculum. By fostering empathy and ethical awareness, educators can navigate the ethical complexities of animal dissection while ensuring students receive a comprehensive education in the life sciences.

PapersOwl showcases more free essays that are examples of Dissection.

How it works

The utilization of animal dissection as a pedagogical tool has stirred a tempestuous debate within educational circles, igniting fervent discussions regarding its ethical ramifications. This essay embarks on an exploration of the intricate ethical tapestry woven around this controversial practice, delving into its educational significance, moral quandaries, and avenues for ethical evolution.

Advocates of animal dissection extol its irreplaceable role in fostering a profound comprehension of anatomical intricacies among students. By immersing themselves in the tactile exploration of real specimens, students cultivate an intimate familiarity with the complexities of biological structures, transcending the limitations of theoretical learning.

Moreover, the process instills invaluable skills such as critical thinking and problem-solving, enriching the educational landscape with experiential wisdom.

However, the ethical compass wavers amidst the utilization of animal subjects, evoking poignant reflections on the sanctity of life and the moral obligations inherent in educational practices. Critics contend that the utilization of sentient beings for instructional purposes represents a transgression against their intrinsic rights, invoking a moral imperative to safeguard their welfare and dignity. Additionally, the burgeoning availability of alternative methodologies, ranging from virtual simulations to synthetic anatomical models, engenders contemplation regarding the necessity of animal sacrifice for educational ends.

Moreover, the provenance of dissection specimens evokes ethical queries, especially concerning animals sourced from shelters or other euthanasia-related contexts. The confluence of consent, respect for the deceased, and societal perceptions of animal life amplifies the ethical resonance of such practices, warranting thoughtful introspection within educational frameworks.

In response to these ethical entanglements, educators are charting innovative pathways towards ethical evolution within pedagogical landscapes. The integration of virtual dissection software, augmented reality technologies, and ethically-sourced anatomical models heralds a paradigm shift towards compassionate and sustainable educational practices. These modalities not only assuage ethical concerns but also foster inclusive learning environments that accommodate diverse ethical perspectives.

Furthermore, the cultivation of ethical literacy within educational curricula emerges as an imperative imperative, equipping students with the ethical acumen to navigate the complex terrain of scientific inquiry with integrity and empathy. By nurturing critical reflection, ethical awareness, and compassionate engagement, educators nurture a generation of ethical stewards poised to navigate the ethical nuances of animal dissection and beyond.

In summation, the discourse surrounding animal dissection in education traverses a labyrinth of ethical deliberations, demanding nuanced contemplation and ethical evolution. While the practice holds pedagogical merit, its ethical implications mandate a conscientious examination of its moral compass. Through innovative alternatives, ethical integration, and compassionate pedagogy, educators can forge a path towards ethical enlightenment, fostering a harmonious coexistence between educational imperatives and ethical integrity.

Cite this page

Ethical Reflections on Animal Dissection: A Pedagogical Dilemma. (2024, Mar 01). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/ethical-reflections-on-animal-dissection-a-pedagogical-dilemma/

"Ethical Reflections on Animal Dissection: A Pedagogical Dilemma." PapersOwl.com , 1 Mar 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/ethical-reflections-on-animal-dissection-a-pedagogical-dilemma/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Ethical Reflections on Animal Dissection: A Pedagogical Dilemma . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/ethical-reflections-on-animal-dissection-a-pedagogical-dilemma/ [Accessed: 4 Jun. 2024]

"Ethical Reflections on Animal Dissection: A Pedagogical Dilemma." PapersOwl.com, Mar 01, 2024. Accessed June 4, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/ethical-reflections-on-animal-dissection-a-pedagogical-dilemma/

"Ethical Reflections on Animal Dissection: A Pedagogical Dilemma," PapersOwl.com , 01-Mar-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/ethical-reflections-on-animal-dissection-a-pedagogical-dilemma/. [Accessed: 4-Jun-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Ethical Reflections on Animal Dissection: A Pedagogical Dilemma . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/ethical-reflections-on-animal-dissection-a-pedagogical-dilemma/ [Accessed: 4-Jun-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, attitudes toward animal dissection and animal-free alternatives among high school biology teachers in switzerland.

- 1 Animalfree Research, Bern, Switzerland

- 2 Environmental Sciences and Humanities Institute, University of Fribourg, Fribourg, Switzerland

- 3 Oxford Centre for Animal Ethics, Oxford, United Kingdom

Animal dissection has been a traditional teaching tool in biology for centuries. However, harmful animal use in education has raised ethical and environmental concerns in the last decades and led to an ongoing debate about the role and importance of animal dissection in teaching across all education levels. To understand the current status of dissection in secondary education and the attitudes toward humane teaching alternatives among the educators, I conducted a survey–for the first time–among high school biology teachers in Switzerland. The specific aims of this study were (i) to explore the extent of animal or animal parts dissection in high school biology classes, (ii) to understand the attitudes and experiences of high school biology teachers toward dissection and animal-free alternatives, and (iii) to gain some insight into the circumstances hindering a wider uptake of alternatives to animal dissection in high school education. In total, 76 teachers participated in the online survey. The vast majority (97%) of the participants reported using animal dissection in their classes. The responses also revealed that a large proportion of the teachers consider animal-free alternatives inferior teaching tools in comparison with dissection. As the obstacles to adopting alternatives were most often listed the lack of time to research other methods, high costs, and peer pressure. In conclusion, the wider uptake of humane teaching methods would require financial support as well as a shift in the attitudes of high school biology teachers.

Introduction

Harmful animal use in education has been a controversial issue, raising ethical and environmental concerns ( Hug, 2008 ) as well as concerns about the potential psychological impact on students ( Capaldo, 2004 ). The discussion so far has focused mostly on tertiary education ( Knight, 2007 , 2014 ; Zemanova, 2021 ; Zemanova and Knight, 2021 ). However, animals are not only being used in human or veterinary medicine training at universities but also as a part of general biology education in high schools. This tradition began in the early 1900s ( Kinzie et al., 1993 ) and is still present in many countries, despite the many available animal-free alternatives ( Balcombe, 2001 ) and legislation requiring replacement of animal use for scientific purposes–including teaching and training–whenever possible (e.g., the EU Directive 2010/63 or the Swiss Animal Welfare Act).

Humane alternatives to harmful animal use in education, such as videos, books, virtual dissections, or plastic 3D models, have been implemented since at least the 1960s ( de Villiers and Monk, 2005 ) and have been shown to produce equivalent or even superior learning outcomes ( Knight, 2007 ; Patronek and Rauch, 2007 ; Zemanova and Knight, 2021 ). Nevertheless, as the number of animals used for teaching and training purposes remains relatively high ( Zemanova et al., 2021 ), there is a chasm between the evidence of the efficacy of humane teaching methods and the continued implementation of harmful animal use in education.

Many factors can influence teachers’ decisions on whether to use animal dissection or humane alternatives, for example, their own education, previous experience with animal-free teaching methods, or school guidelines ( Oakley, 2012b ). Nevertheless, up to date, only a few studies investigated the attitudes and experiences of high school biology teachers toward animal dissection ( King et al., 2004 ; de Villiers and Sommerville, 2005 ; Oakley, 2012b ; Kavai et al., 2017 ).

Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate, for the first time, the experiences and attitudes of the Swiss high school teachers toward the use of dissection and animal-free alternatives. Specifically, the survey intended to determine (1) the extent to which animals or animal parts are being used in biology classes in Swiss high schools, (2) whether Swiss high school teachers embrace and adopt animal-free alternatives, and (3) the attitudes of teachers toward dissection and humane teaching methods. The exploration of teachers’ attitudes toward dissection and alternatives can provide a clearer picture about the barriers and opportunities for making the shift toward more humane biology education ( Oakley, 2012b ).

Materials and Methods

Survey design.

An online survey was designed using the platform Typeforms 1 to obtain anonymous responses from high school biology teachers in Switzerland. Questions were written in German and organized into two parts: (1) a general part with questions about demographic data of the respondents, and (2) a scientific part with questions on the use of animal or animal organ dissection in their teaching practice. The survey contained a combination of open-ended questions and multiple-choice questions, allowing respondents to check one or more boxes from a list of possible answers. Attitudes were measured on a five-point Likert scale ( Likert, 1932 ). The first version of the survey was launched in August 2019 and an updated version with several additional questions was launched again in June 2021. Each time, the survey stayed open for responses for 12 weeks.

Survey Distribution and Administration

Email invitations to participate in the survey, together with a link to the anonymous online questionnaire, were distributed through emailing the administration offices of 162 high schools across 26 Swiss cantons, asking for forwarding the email to the biology teachers at their school. Schools were identified through the Swiss Rectors Association and their number represents approximately 10% of all secondary schools in Switzerland ( Federal Statistical Office, 2022 ). Respondents were also recruited through an announcement on social media and through contacting the organizations Teachers Switzerland, Association of Swiss Science Teachers, and Association of Swiss Gymnasium Teachers. Consequently, it was not possible to control how many invitation emails reached potential respondents and to calculate the response rate.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics, including bar plots and a frequency table, were used to summarize the responses. The Pearson’s chi-squared test was used to assess any potential influence of the demographic characteristics (age, gender) on the attitudes. Significance for all levels was set at p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted in R 4.1.3 ( R Core Team, 2022 ) integrated in RStudio 2022.02.1 ( Rstudio Team, 2022 ).

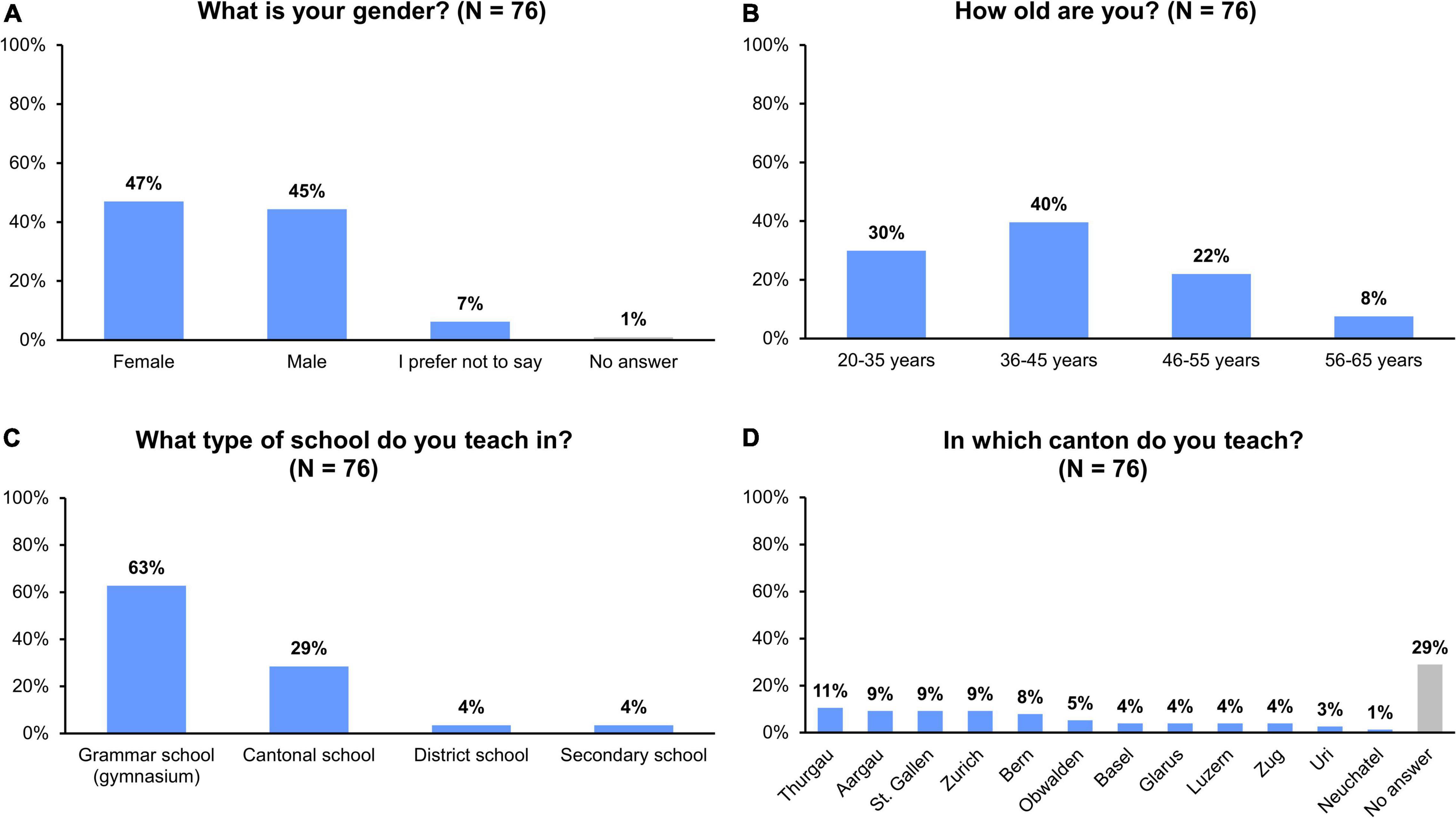

Demographic Characteristics

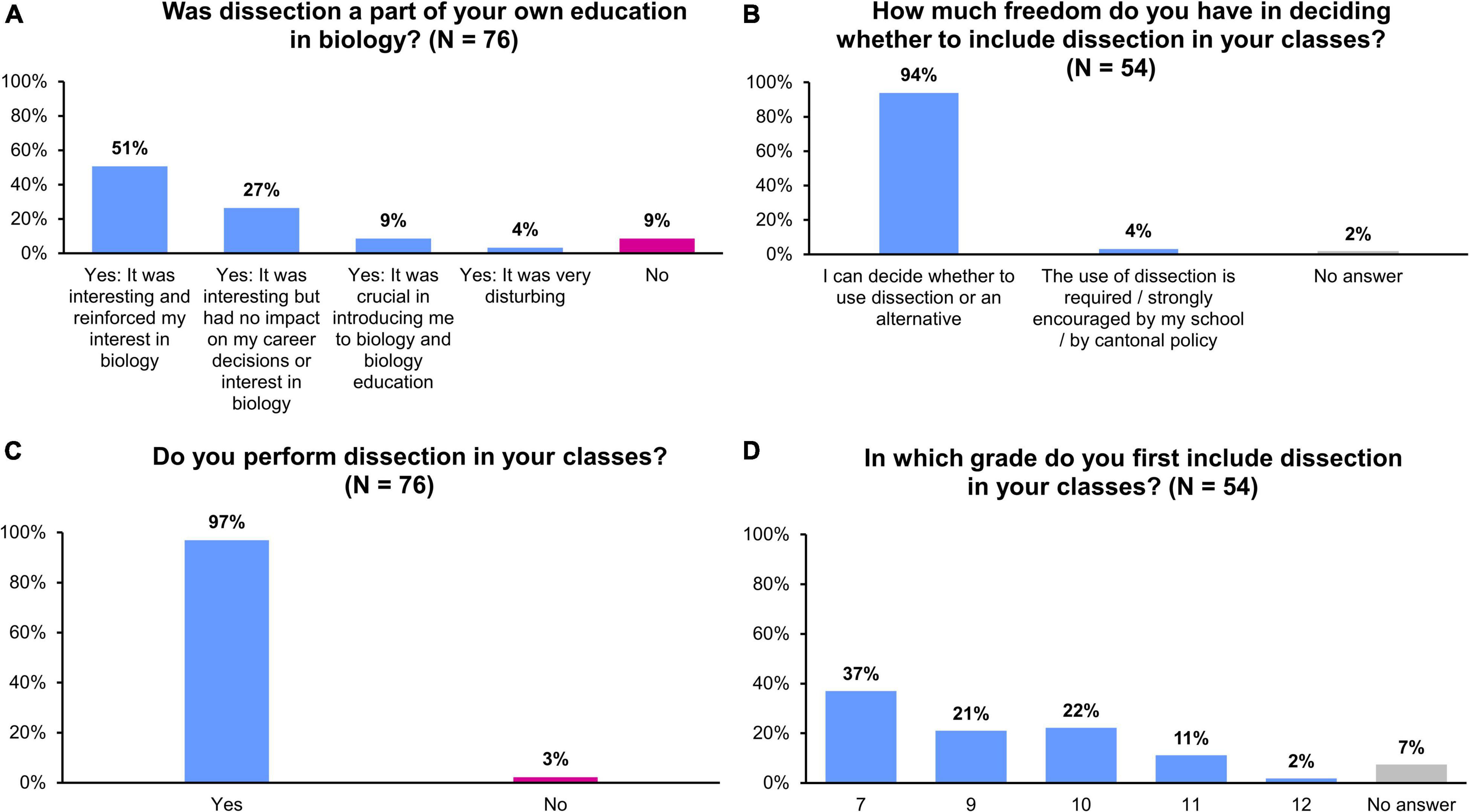

A total of 76 teachers, 22 in 2019 and 54 in 2021, completed the survey. Both genders were almost equally represented ( Figure 1A ), reflecting the average gender distribution among high-school teachers across Switzerland ( Federal Statistical Office, 2021 ). One third of the respondents belonged to the age category 20–35 years old, 40% to the age bracket 36–45 years old, 22% to 46–55 years old, and 8% to 56–65 years old ( Figure 1B ). The majority of the respondents taught at a grammar school (gymnasium) and worked in the primarily German-speaking cantons ( Figures 1C,D ).

Figure 1. (A) Gender of the respondents participating in the survey. (B) Age of the respondents participating in the survey. (C) Type of school the respondents teach in. (D) Swiss canton the respondents teach in.

Prevalence of Dissection, Species Used, and Availability of Animal-Free Alternatives

Almost all of the respondents (91%) performed dissection of animals or animal parts during their own education, of which only a minority (4%) reported negative experiences associated with dissection ( Figure 2A ). The majority (94%) also stated that they can decide whether to include dissection in their teaching ( Figure 2B ). Out of 76 teachers, only two do not use dissection in their science classes (for ethical reasons; Figure 2C ). Over one third of the teachers participating in the survey start including dissection in biology classes in grade 7 ( Figure 2D ), which in the Swiss educational system corresponds to the age group of 12- or 13-year olds.

Figure 2. (A) Experience with dissection in respondents’ own education. (B) Extent to which the respondents can decide whether to include dissection in their teaching. (C) Use of animal dissection in biology classes. (D) School grade in which the respondents first include dissection in their teaching.

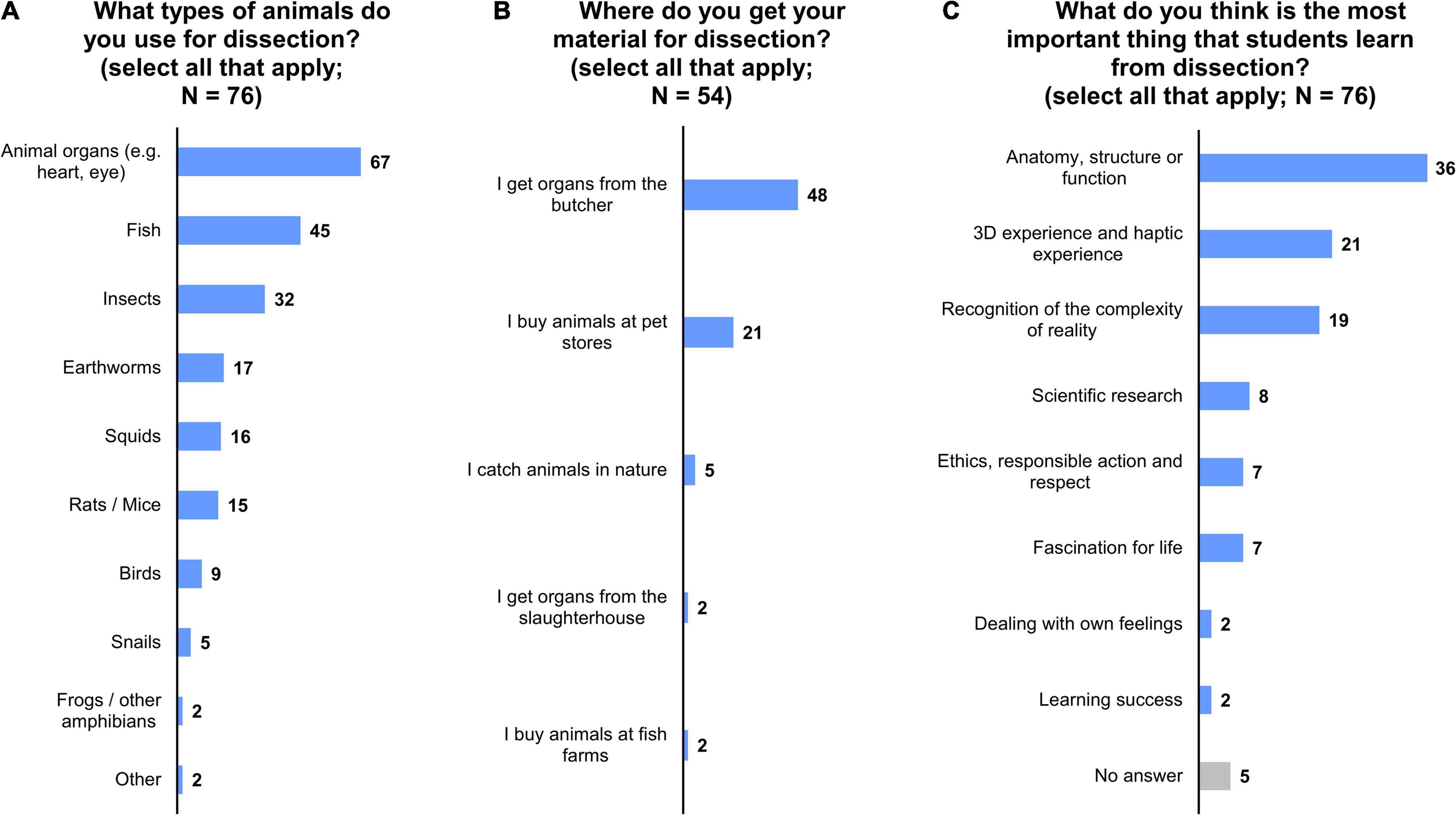

Most commonly used in dissection classes are animal organs, such as a heart or an eye, fish, insects, earthworms, and squids ( Figure 3A ). The teachers usually get this material from the butcher, at pet stores, or they collect animals in nature ( Figure 3B ). According to the teachers, the most important thing that students can learn from dissection is anatomy, 3D experience, recognition of the complexity of reality, or ethics, and respect toward animals ( Figure 3C ).

Figure 3. (A) Type of animals used in dissection classes. (B) Source of animals used in dissection classes. (C) The most important learning outcome of dissection exercise.

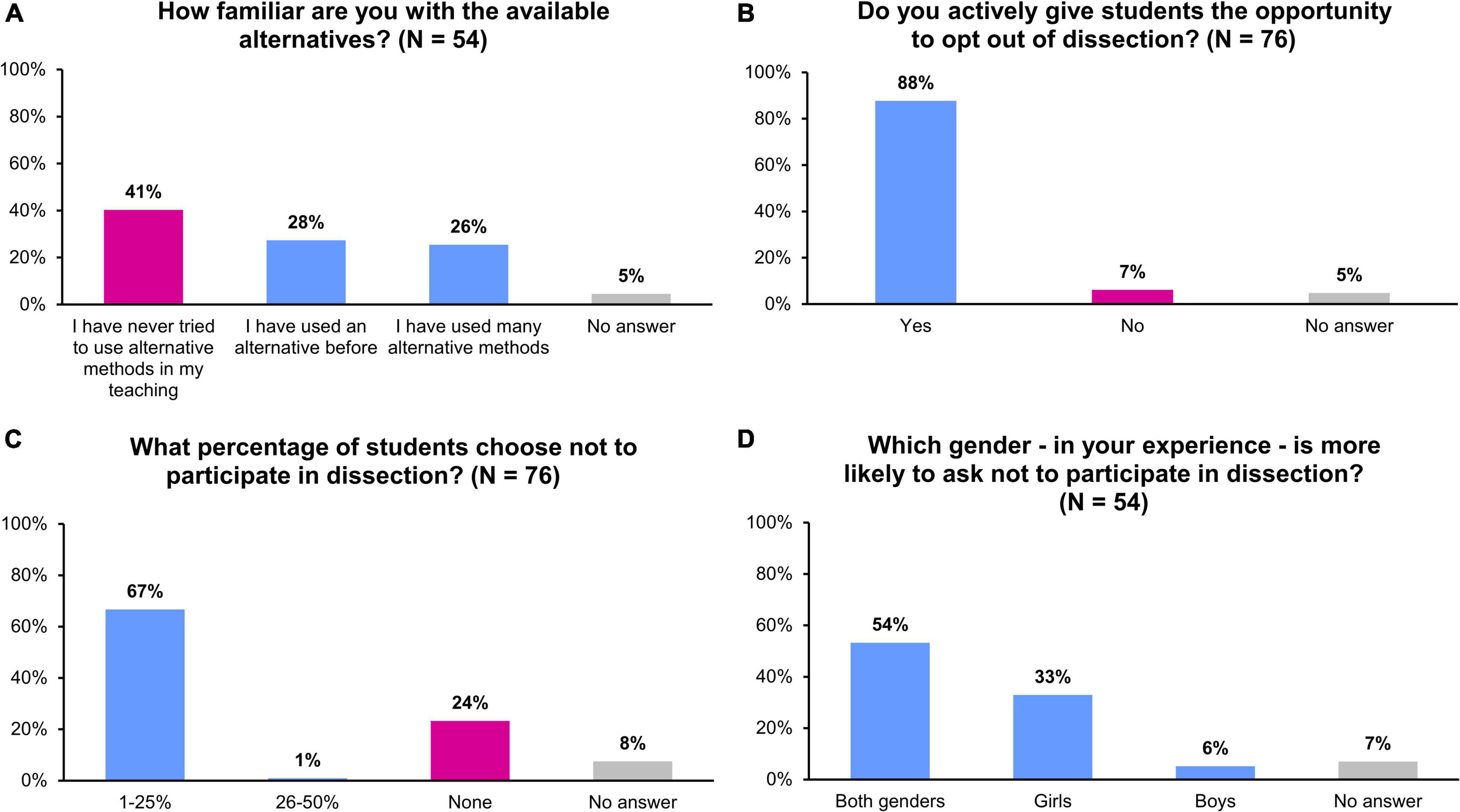

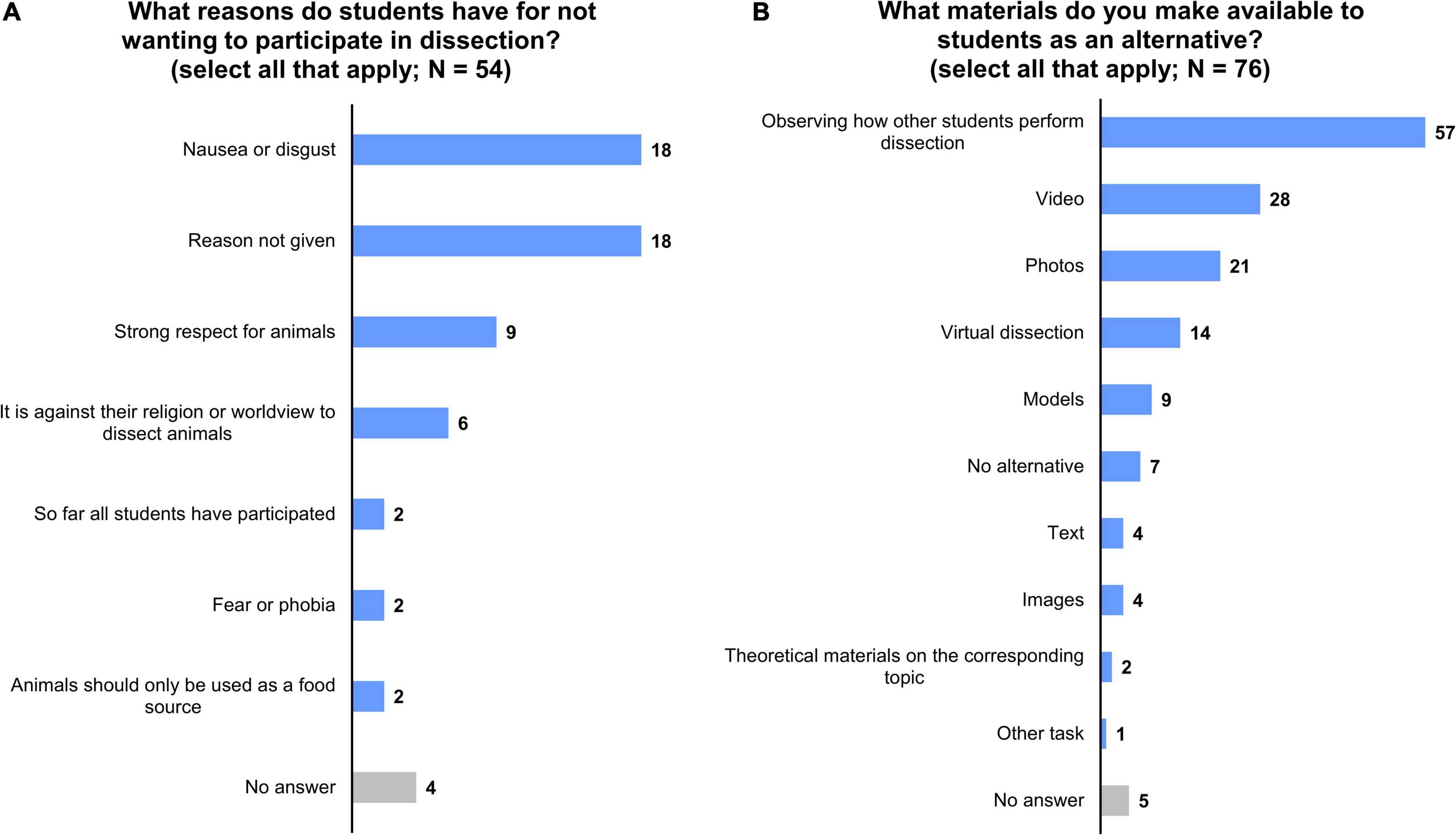

The teachers actively allow their students to opt out, despite the teachers’ limited experience with alternatives that they could provide to their students ( Figures 4A,B ). The teachers stated that only a minority of students–regardless of their gender–chooses not to participate in dissection ( Figures 4C,D ). As the reasons of students for not wanting to participate were listed most often nausea or disgust, strong respect for animals, and religion or worldview ( Figure 5A ). If a student decides not to participate in dissection, the most frequently offered alternative is the observation of other students performing dissection, followed by videos or photos. Some teachers also use virtual dissection as an alternative ( Figure 5B ).

Figure 4. (A) Familiarity of the respondents with the available animal-free alternatives. (B) Proportion of the respondents giving their students actively the opportunity to opt out of dissection. (C) Estimated proportion of students opting out of dissection. (D) Gender distribution among students refusing to participate in dissection.

Figure 5. (A) Reasons of students for not participating in dissection. (B) Alternatives provided by the respondents to students not wanting to participate in dissection.

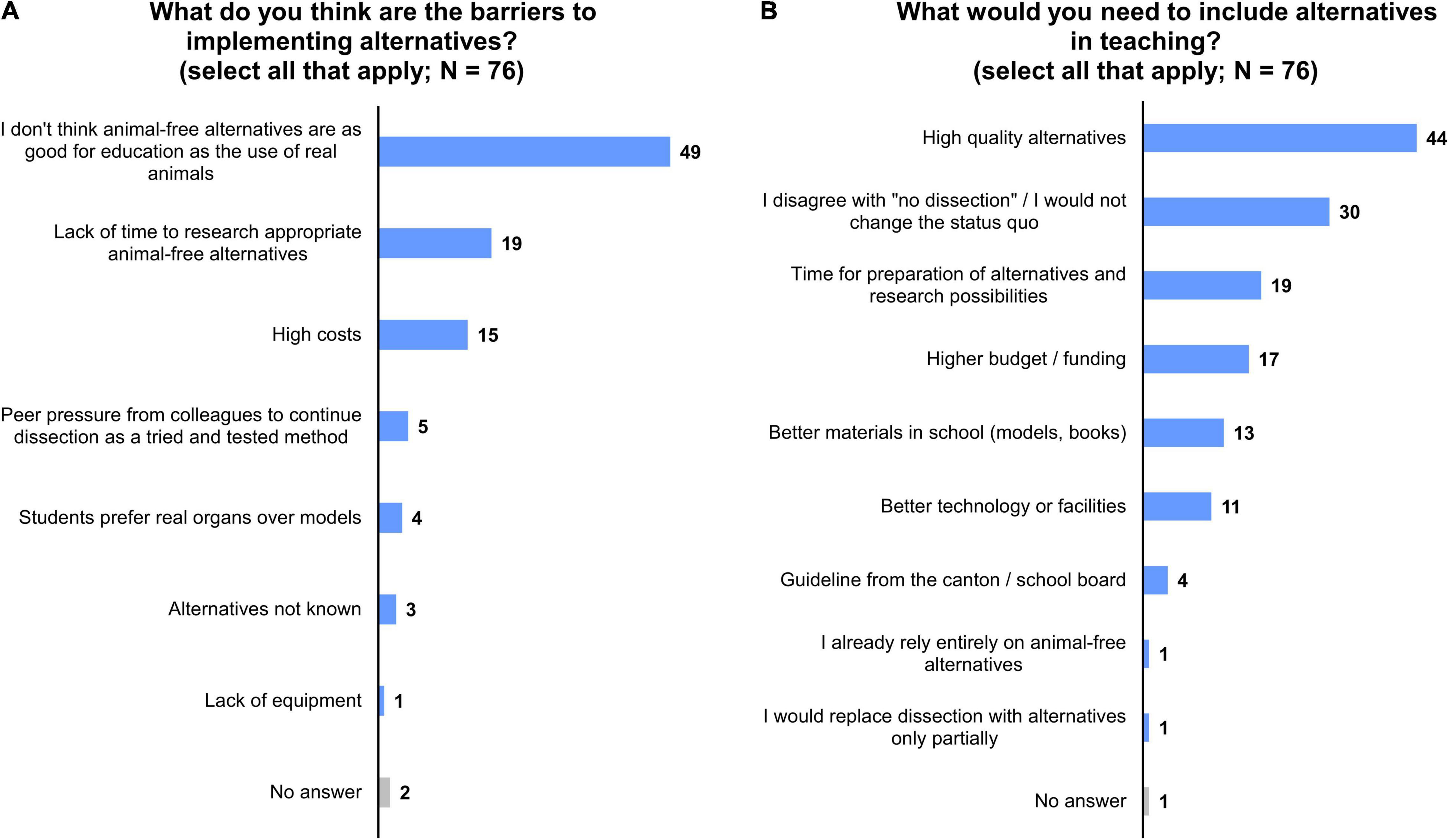

The respondents were also asked what they perceived as the barriers to implementing animal-free alternatives. The majority of the respondents do not find animal-free alternatives as good for education as the use of real animals ( Figure 6A and Table 1 ). The teachers also reported having little time to research appropriate alternative teaching methods and that alternatives are too expensive ( Figure 6A ). Consequently, what would teachers need to make the shift away from using animals are high-quality alternatives, more time for the preparation of classes with alternative methods, and a higher budget ( Figure 6B ).

Figure 6. (A) Perceived barriers to implementing animal-free alternatives instead of animal dissection. (B) Needs of the respondents that would have to be met in order to include animal-free alternatives in their teaching practice.

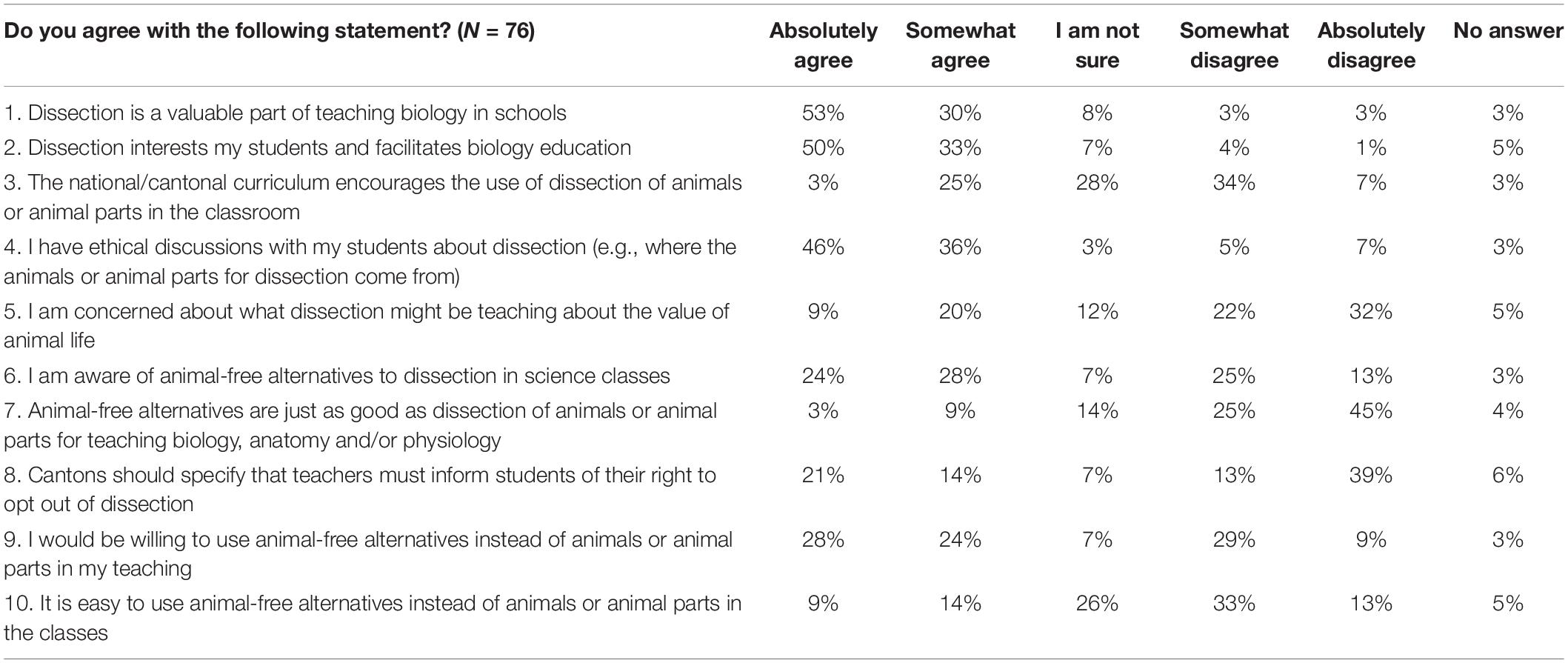

Table 1. Percentage of teachers who agreed or disagreed with the following statements regarding the use of dissection and alternatives.

Teachers’ Attitudes Toward Animal Dissection and Animal-Free Alternatives

The majority of the teachers (83%) participating in the survey agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that dissection is a valuable part of teaching biology in schools (83%; Table 1 ) and that dissection interests their students (83%; Table 1 ). More than a half of the teachers are aware of the available animal-free alternatives, but 70% disagreed with the statement that alternatives are just as good as animals or animal parts for teaching biology ( Table 1 ). While 52% of the teachers would be willing to use an alternative in their teaching, 46% stated that it is not easy to do so ( Table 1 ). Lastly, more than half of the teachers disagreed with the statement that cantons should specify that teachers must inform students of their right to opt out of dissection ( Table 1 ). There was no statistically significant influence of the age on the attitude toward animal dissection and alternatives. Only two statements elicited different responses between genders: women expressed concern about what dissection might be teaching the value of animal life more frequently than men (statement nr. 5 in Table 1 ; p = 0.019) and were more willing to use animal-free alternatives instead of animals in their teaching (statement nr. 9 in Table 1 ; p = 0.028).

Prevalence of Animal Dissection at Swiss High Schools

Although in the literature Switzerland has been repeatedly listed as one of the five countries–together with Argentina, Israel, Netherlands, and Slovakia–that prohibits dissection below the university level ( Waltzman, 1999 ; Balcombe, 2000 ; Oakley, 2012b ; Sathyanarayana, 2013 ; Osenkowski et al., 2015 ), this survey showed that dissection of animals or animal parts at Swiss high schools remains prevalent. Out of 76 teachers participating in the survey, only two (i.e., 3%) do not use animal dissection in their teaching practice ( Figure 2C ).

These results are analogous to findings described from other countries. In King et al. (2004) the authors reported that out of 494 American teachers participating in their survey, 79% used dissection in their classes. A more recent study from the United States by Osenkowski et al. (2015) described similar results: out of 1,178 teachers, 84% reported using dissection in biology education. The survey by de Villiers and Sommerville (2005) of 242 prospective biology teachers at a South African university found that 71% would expect their students to dissect animals in their classroom.

Type and Source of Animals Used in Dissection

In the survey, teachers reported that animal organs, fish, and insects are used most frequently in dissection ( Figure 3A ). At American high schools, frogs, fetal pigs, and earthworms are the most common material ( King et al., 2004 ; Osenkowski et al., 2015 ). In the United States, it has been estimated that 99% of animals used in biology classes for dissection are caught in the wild ( Environmental Magazine, 2004 ), which might mean that the size of the local population might severely decline over time, and potentially lead to an imbalance within the ecosystem. In contrast, Swiss teachers usually get the dissection material from the butcher, animal pet stores, and only 9% of the respondents stated that they also catch animals in nature ( Figure 3B ).

Pedagogical Value of Animal Dissection

The teachers participating in the survey were asked what, in their opinion, dissection teaches. Among the primary goals for the dissection exercise were stated learning anatomy, having the 3D experience, and recognition of the complexity of reality ( Figure 3C ). Similar responses were reported also from previous studies ( Kavai et al., 2017 ). The American Psychological Association states that animal dissection “engenders creativity, original thought, critical thinking, and problem-solving skills” ( American Psychological Association, 2017 ). Oakley (2012b) reported that some teachers are convinced that the use of animals in education might in fact teach students about the ethics of using animals in research. Indeed, several teachers in my study mentioned ethics, responsible action, respect for animals, and fascination for life as the educational outcomes ( Figure 3C ).

However, it has been argued that dissection can encourage a decreased sensitivity toward animal life. Solot and Arluke (1997) observed sixth-grade students during fetal pig dissection. They found that many students described themselves as becoming “immune” or “adapted” to the situation, i.e., appearing hardened by the activity as the dissection progressed. Sabloff (2001) postulated that through dissection, animals become positioned as “artifacts,” meaning that they are considered (1) made for human use, (2) not sentient, (3) discardable, and (4) excluded from the moral community. And Sapontzis (1995) suggested that dissection teaches students that an animal can be killed for “trivial” purposes such as curiosity or tradition.

Furthermore, over the last 100 years, the focus of biology has shifted from anatomy to cellular level and genetics ( Oakley, 2009 ). In contrast, the practice of dissection in high schools is almost 100 years old and it is questionable whether it remains a valid representation of contemporary biology ( Hart et al., 2008 ; Oakley, 2009 ). Hug (2005) suggests that dissection might have become a ritual of science carried out without critical evaluation of its usefulness. Only a part of high school students would eventually enroll in university courses that relate to the experience of dissection, e.g., veterinary medicine, for the majority of students the dissection experience will have no relevance for their future career ( Orlans, 1993 ). In addition, there have been contradicting opinions voiced about whether dissection encourages or discourages students to eventually pursue a career in science. Several studies reported that dissection can and does turn some students from life sciences ( Balcombe, 2000 ; Bishop and Nolen, 2001 ).

Proportion of Students Opting Out of Animal Dissection

While the majority of the teachers participating in the survey actively allow their students to opt out of dissection, 7% of the teachers do not ( Figure 4B ). According to the teachers’ statements, only a minority of students opt out of dissection practice ( Figure 4C ). Previous studies have estimated that in a typical class, 3–5% of the students will openly object to dissection ( Balcombe, 2000 ; Hart et al., 2008 ; Spernjak and Sorgo, 2017 ).

Balcombe (1997) stated that “perhaps the most misunderstood aspect of the animal dissection issue is the number of students who openly object to the practice.” Students may not voice their preference due to fear of embarrassment in front of their peers, fear of a failing grade, or fear of challenging the teacher’s authority ( Balcombe, 2000 ). Consequently, it is assumed that only a minority of the students objecting to dissection expresses their concerns and opinions openly. This was reported also in the study by Oakley (2012a) , which showed that the actual proportion of students harboring objections to dissection is higher than the proportion that voiced their opinion.

Whereas some authors claim that using dissection provides high school students with an “exciting” education experience ( Barr and Herzog, 2000 ), it is important to note that dissection may not be enjoyable for every student. There have been published several studies investigating the attitudes of high school students toward dissection. For instance, the study carried out by Stanisstreet et al. (1993) found that 48% of 420 students from three different secondary schools in the United Kingdom considered the dissection of animals for teaching purposes to be wrong. Another study of 85 students aged 15–16 reported that over a third of the respondents felt that dissection is disrespectful to the animal ( Doster et al., 1997 ). A retrospective survey of 191 undergraduate students reported that 27% of them experienced negative emotional reactions to dissection in high school ( Bowd, 1993 ).

Randler et al. (2016a) used a dissection video clip shown before the dissection of a fish to reduce anxiety among students. In another study, Randler et al. (2016b) employed humor to reduce anxiety and disgust. Nevertheless, such strategies should not be encouraged as seeing their classmates joke during dissection can be very uncomfortable for other students ( Tolbert, 2019 ). Since this study was limited to surveying the experience and attitudes of teachers, further research elucidating the Swiss students’ perspective on dissection is warranted.

Teachers’ Experience With and Attitudes Toward Animal-Free Alternatives

Animal dissection practice seems to be deeply ingrained in the Swiss educational system. The majority of teachers were taught through dissection ( Figure 2A ) and continue to demonstrate the biological concepts in this “traditional” way ( Figures 2B–D ). This prevalence of dissection can be attributed to strong opinions about the efficacy and usefulness of animal-free alternatives exposed in the responses. The very slight gender difference in attitudes is consistent with previous studies, showing that women express concern for animal welfare and suffering more frequently and to a greater extent than men ( Herzog, 2007 ; Phillips et al., 2011 ; Zemanova, 2021 ).

Similarly to previous studies ( Oakley, 2012b ), my survey revealed that teachers continue to perceive dissection as the best way for students to learn biology ( Figure 6A and Table 1 ). While the majority of teachers responding to the survey found that alternatives are not as good material for learning as animal dissection, alternatives have been shown to have equivalent or higher efficacy in providing the intended learning outcomes than harmful animal use ( Zemanova and Knight, 2021 ). Humane teaching methods offer also other benefits. They are often less expensive, require less preparation and cleaning time, and allow students to work at their own pace and repeat the task as many times as needed ( Oakley, 2012b ; Osenkowski et al., 2015 ).

For instance, virtual dissections allow the study of inner anatomy by virtual manipulation, while providing substantial advantages for schools: repeatability, immediate feedback, no health risks, etc. ( Havlíčková et al., 2018 ). The comparison of virtual frog dissection and physical frog dissection among high school students showed equivalent learning outcomes, but virtual dissection additionally allows for repetition of the exercise at no additional instructional cost to increase retention ( Lalley et al., 2010 ). Similar studies using a computer-based rat dissection ( Predavec, 2001 ) or a virtual fetal pig dissection ( Maloney, 2005 ) reported even better learning outcomes when using these alternative methods, possibly due to the opportunity to observe all structures clearly and due to the time flexibility of using computer-based learning.

Legal and Ethical Aspects of Animal Dissection

The 3Rs principles of responsible animal use were described in 1959, encouraging the Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement of animals used for scientific purposes, including education and training ( Russell and Burch, 1959 ). Since then, the 3Rs principles have been implemented in many legislations worldwide and promoted by various societies. In Switzerland, the 3Rs principles are anchored in the Animal Welfare Act (2005), which requires that experiments (including the use in teaching and training) on vertebrate animals, cephalopods, and decapods are only carried out if there is no suitable alternative method available. Despite these efforts and regulations, my study revealed that the use of animals in dissections already at the secondary education level remains widespread. The 3Rs principles are more rigorously implemented in the post-secondary educational context ( Hart et al., 2008 ) and the secondary education seems to have been overlooked. Therefore, it is imperative that more effort is invested in applying the 3Rs principles in high school education to counteract the persistent tradition of dissection.

Another aspect that needs to be considered is ethics. Without a doubt, dissection of animals or animal parts can enable students to learn important concepts in anatomy, as stated by the teachers ( Figure 3C and Table 1 ). However, does the pedagogical value outweigh the ethical implications of harm to the animal ( Hug, 2008 )? If viable alternatives exist, the killing of animals for teaching anatomy is unnecessary and therefore ethically questionable ( Oakley, 2009 ).

The majority (82%) of the respondents stated that they hold discussions on the ethics of dissection. In the survey conducted by Oakley (2012a) with both teachers and students, 86.3% of teachers reported conducting classroom discussions on the ethics of dissection, while only 28.9% of students confirmed this. Further studies surveying the students would be needed to elucidate whether teachers indeed hold ethical discussions with their students and if so, to what extent.

Barriers to Shifting Toward Animal-Free Alternatives

Through this survey, there were identified several barriers to shifting away from animal dissection to animal-free alternatives in secondary education: (1) lack of high-quality alternatives, (2) conviction that alternatives are not as good as dissection, (3) lack of time to prepare alternative methods, and (4) lack of funding ( Figure 6 and Table 1 ). To change the current prevalent status of animal dissection in Swiss high schools, these factors need to be targeted. For instance, the development of platforms where teachers could share their approaches to humane teaching might help save their time that would be needed for preparation of classes implementing alternatives ( Hart et al., 2007 ). To shift the opinions, pedagogical education as well as continuing education provided by teachers’ associations would be well-positioned to promote the use of humane teaching methods as well as to make teachers acquainted with available alternatives. Additionally, another strategy might be to switch from the currently implemented “opt out” practice for students who want to use alternatives to “opt in” for students who want to dissect ( Downie and Meadows, 1995 ; van der Valk et al., 1999 ).

Limitations of the Study

Some reservations might be raised about the results. First, as the respondents were self-selected, I might have received a skewed sample of teachers that were motivated to participate in the survey by their strong beliefs either in favor of or against the use of dissection in biology education. Second, since the questionnaire was available only in German, the response rate was highest among German-speaking cantons of Switzerland. Lastly, the number of participants might be considered low, even though comparable to other studies investigating the same topic ( Donaldson and Downie, 2007 ; Oakley, 2012b ; Kavai et al., 2017 ).

Animal dissection has been used as a teaching tool for centuries, either for demonstration of animal anatomy or for hands-on practice of technical skills. Because of the long tradition, it might be difficult to move away from this practice. Nevertheless, the ethical concerns surrounding the harmful animal use in teaching and training require that education practice evolves to embrace humane teaching alternatives. The teachers participating in this survey believed that dissection offers a learning experience and learning outcomes that could not be matched by animal-free alternatives. This is, however, in stark contrast to the empirical evidence showing that humane teaching methods are equivalent or even superior teaching tools than harmful animal use. More widespread dissemination of information about available alternatives and their efficacy might therefore help teachers to adopt non-harmful practices and minimize the number of animals used in education.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the author, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Silvia Frey for support and all participants for their time and valuable contribution.

- ^ https://www.typeform.com/

American Psychological Association (2017). Resolution Reaffirming Support for Research and Teaching with Nonhuman Animals. Available online at: https://www.apa.org/about/policy/use-animals (accessed on Sep 24, 2021).

Google Scholar

Balcombe, J. (1997). Student/teacher conflict regarding animal dissection. Am. Biol. Teacher 59, 22–25. doi: 10.1163/156853000511087

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Balcombe, J. (2000). The Use of Animals in Higher Education: Problems, Alternatives, and Recommendations. Washington, DC: The Humane Society Press.

Balcombe, J. (2001). Dissection: the scientific case for alternatives. J. Appl. Anim. Welfare Sci. 4, 117–126. doi: 10.1207/S15327604JAWS0402_3

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Barr, G., and Herzog, H. (2000). Fetal pig: the high school dissection experience. Soc. Anim. 8, 53–69. doi: 10.1163/156853000x00039

Bishop, L. J., and Nolen, A. L. (2001). Animals in research and education: ethical issues. Kennedy Instit. Ethics J. 11, 91–112. doi: 10.1353/ken.2001.0006

Bowd, A. D. (1993). Dissection as an instructional technique in secondary science: choice and alternatives. Soc. Anim. 1, 83–89. doi: 10.1163/156853093x00163

Capaldo, T. (2004). The psychological effects on students of using animals in ways that they see as ethically, morally or religiously wrong. ATLA 32, 525–531. doi: 10.1177/026119290403201s85

de Villiers, R., and Monk, M. (2005). The first cut is the deepest: reflections on the state of animal dissection in biology education. J. Curric. Stud. 37, 583–600. doi: 10.1080/00220270500041523

de Villiers, R., and Sommerville, J. (2005). Prospective biology teachers’ attitudes toward animal dissection: implications and recommendations for the teaching of biology. S. Afr. J. Educ. 25, 247–252. doi: 10.10520/EJC32056

Donaldson, L., and Downie, R. (2007). Attitudes to the uses of animals in higher education: has anything changed? Biosci. Educ. 10, 1–13. doi: 10.3108/beej.10.6

Doster, E. C., Jackson, D. F., Oliver, J. S., Crockett, D. K., and Emory, A. L. (1997). “Values, dissection, and school science: an inquiry into students’ construction of meaning,” in Proceedings of the Annual International Conference of the Association for the Education of Teachers in Science , ed. P. A. Rubba (Athens: University of Georgia), 222–246.

Downie, R., and Meadows, J. (1995). Experience with a dissection opt-out scheme in university level biology. J. Biol. Educ. 29, 187–194. doi: 10.1080/00219266.1995.9655444

Environmental Magazine (2004). Harvest of Shame. Available online at: https://emagazine.com/harvest-of-shame/ (accessed on Sep 25, 2021).

Federal Statistical Office (2021). Lehrkräfte. Available online at: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/wirtschaftliche-soziale-situation-bevoelkerung/gleichstellung-frau-mann/bildung/lehrkraefte.html (accessed on Mar 14, 2022).

Federal Statistical Office (2022). Schulen nach Bildungsstufe 2020/2021. Available online at: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/bildung-wissenschaft/bildungsinstitutionen/schulen.html (accessed on Mar 15, 2022).

Hart, L. A., Wood, M. W., and Hart, B. L. (2008). Why Dissection? Animal Use in Education. Westport: Greenwood Press.

Hart, L. A., Wood, M. W., and Weng, H.-Y. (2007). Three barriers obstructing mainstreaming alternatives in K-12 education. ALTEX 23, 38–41.

Havlíčková, V., Šorgo, A., and Bílek, M. (2018). Can virtual dissection replace traditional hands-on dissection in school biology laboratory work? EURASIA J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 14, 1415–1429. doi: 10.29333/ejmste/83679

Herzog, H. A. (2007). Gender differences in human-animal interactions: a review. Anthrozoos 20, 7–21. doi: 10.2752/089279307780216687

Hug, B. (2005). Dissection reconsidered: a reaction to de Villiers and Monk’s ‘The first cut is the deepest’. J. Curric. Stud. 37, 601–606. doi: 10.1080/00220270500061182

Hug, B. (2008). Re-examining the practice of dissection: what does it teach? J. Curric. Stud. 40, 91–105. doi: 10.1080/00220270701484746

Kavai, P., De Villiers, R., and Fraser, W. (2017). Teachers’ and learners’ inclinations towards animal organ dissection and its use in problem-solving. Int. J. Instruct. 10, 39–54. doi: 10.12973/iji.2017.1023a

King, L. A., Ross, C. L., Stephens, M. L., and Rowan, A. N. (2004). Biology teachers’ attitudes to dissection and alternatives. ATLA 32, 475–484. doi: 10.1177/026119290403201s76

Kinzie, M. B., Strauss, R., and Foss, J. (1993). The effects of an interactive dissection simulation on the performance and achievement of high school biology students. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 30, 989–1000. doi: 10.1002/tea.3660300813

Knight, A. (2007). The effectiveness of humane teaching methods in veterinary education. ALTEX 24, 91–109. doi: 10.14573/altex.2007.2.91

Knight, A. (2014). Conscientious objection to harmful animal use within veterinary and other biomedical education. Animals 4, 16–34. doi: 10.3390/ani4010016

Lalley, J. P., Piotrowski, P. S., Battaglia, B., Brophy, K., and Chugh, K. (2010). A comparison of V-Frog© to physical frog dissection. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 5, 189–200.

Likert, R. (1932). A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Arch. Psychol. 140, 1–55.

Maloney, R. S. (2005). Exploring virtual fetal pig dissection as a learning tool for female high school biology students. Educ. Res. Eval. 11, 591–603. doi: 10.1080/13803610500264823

Oakley, J. (2009). Under the knife: animal dissection as a contested school science activity. J. Activ. Sci. Technol. Educ. 1, 59–67.

Oakley, J. (2012b). Science teachers and the dissection debate: perspectives on animal dissection and alternatives. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 7, 253–267. doi: 10.1080/21548455.2016.1254358

Oakley, J. (2012a). Dissection and choice in the science classroom: student experiences, teacher responses, and a critical analysis of the right to refuse. J. Teach. Learn. 8, 15–29. doi: 10.22329/jtl.v8i2.3349

Orlans, F. B. (1993). In the Name of Science: Issues in Responsible Animal Experimentation. New York: Oxford University Press.

Osenkowski, P., Green, C., Tjaden, A., and Cunniff, P. (2015). Evaluation of educator & student use of & attitudes toward dissection & dissection alternatives. Am. Biol. Teacher 77, 340–346. doi: 10.1525/abt.2015.77.5.4

Patronek, G. J., and Rauch, A. (2007). Systematic review of comparative studies examining alternatives to the harmful use of animals in biomedical education. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 230, 37–43. doi: 10.2460/javma.230.1.37

Phillips, C., Izmirli, S., Aldavood, J., Alonso, M., Choe, B., Hanlon, A., et al. (2011). An international comparison of female and male students’ attitudes to the use of animals. Animals 1, 7–26. doi: 10.3390/ani1010007

Predavec, M. (2001). Evaluation of E-Rat, a computer-based rat dissection, in terms of student learning outcomes. J. Biol. Educ. 35, 75–80. doi: 10.1080/00219266.2000.9655746

R Core Team (2022). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Available online at: http://www.R-project.org (accessed on Mar 15, 2022).

Randler, C., Demirhan, E., Wust-Ackermann, P., and Desch, I. H. (2016a). Influence of a dissection video clip on anxiety, affect, and self-efficacy in educational dissection: a treatment study. CBE Life Sci. Educ. 15:ar1. doi: 10.1187/cbe.15-07-0144

Randler, C., Wüst-Ackermann, P., and Demirhan, E. (2016b). Humor reduces anxiety and disgust in anticipation of an educational dissection in teacher students. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 11, 421–432. doi: 10.12973/ijese.2016.329a

Rstudio Team (2022). RStudio: Integrated Development for R. Available online at: http://www.rstudio.com/ (accessed Mar 15, 2022).

Russell, W. M. S., and Burch, R. L. (1959). The Principles of Humane Experimental Technique. London: Methuen.

Sabloff, A. (2001). Reordering the Natural World: Humans and Animals in the City. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Sapontzis, S. F. (1995). We should not allow dissection of animals. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 8, 181–189. doi: 10.1007/bf02251882

Sathyanarayana, M. C. (2013). Need for alternatives for animals in education and the alternative resources. ALTEX Proc. 2, 77–81.

Solot, D., and Arluke, A. (1997). Learning the scientist’s role: animal dissection in middle school. J. Contemp. Ethnogr. 26, 28–54. doi: 10.1177/089124197026001002

Spernjak, A., and Sorgo, A. (2017). Dissection of mammalian organs and opinions about it among lower and upper secondary school students. CEPS J. 7, 111–130. doi: 10.25656/01:12963

Stanisstreet, M., Spofforth, N., and Williams, T. (1993). Attitudes of children to the uses of animals. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 15, 411–425. doi: 10.1080/0950069930150405

Tolbert, S. (2019). “Queering dissection: “I wanted to bury its heart, at least”,” in Gender in Learning and Teaching: Feminist Dialogues Across International Boundaries , eds C. Taylor, C. Amade-Escote, and A. Abbas (London: Routledge).

van der Valk, J., Dewhurst, D., Hughes, I., Atkinson, J., Balcombe, J., Braun, H., et al. (1999). Alternatives to the use of animals in higher education - the report and recommendations of ECVAM Workshop 33. ATLA 27, 39–52. doi: 10.1177/026119299902700105

Waltzman, H. (1999). Dissection banned in Israeli schools. Nature 402:845. doi: 10.1038/47149

Zemanova, M. A. (2021). Making room for the 3Rs principles of animal use in ecology: potential issues identified through a survey. Eur. J. Ecol. 7, 18–39. doi: 10.17161/eurojecol.v7i2.14683

Zemanova, M. A., and Knight, A. (2021). The educational efficacy of humane teaching methods: a systematic review of the evidence. Animals 11:114. doi: 10.3390/ani11010114

Zemanova, M. A., Knight, A., and Lybæk, S. (2021). Educational use of animals in Europe indicates reluctance to implement alternatives. ALTEX 38, 490–506. doi: 10.14573/altex.2011111

Keywords : animal use, biology education, dissection, humane teaching, secondary education, teaching practice

Citation: Zemanova MA (2022) Attitudes Toward Animal Dissection and Animal-Free Alternatives Among High School Biology Teachers in Switzerland. Front. Educ. 7:892713. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.892713

Received: 09 March 2022; Accepted: 11 April 2022; Published: 04 May 2022.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2022 Zemanova. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Miriam A. Zemanova, [email protected]

Animal Dissection in Schools: Life Lessons, Alternatives and Humane Education

This policy paper makes the case for a more ethical approach to life science education.

[Abstract excerpted from original source.]

“The practice of classroom dissection has long been one of the most controversial educational issues in America and beyond. This paper, written by Jan Oakley, Ph.D., of Lakehead University, looks at the history of dissection exercises and the implications they have for young students, including the ethical, environmental and economic factors involved. This paper serves as a handbook for supporting student choice policies and a move toward respecting the “life” in life sciences. A must-have resource for students, parents, educators, advocates and legislators working in support of humane science policies.”

Oakley, J. (2013). Animal Dissection in Schools: Life Lessons, Alternatives and Humane Education.

Related Posts

Jan 21 2022 | Julie O'Connor

Can Humane Education Improve Student Reading Comprehension?

Jul 23 2018 | Julie O'Connor

How Can Humane Education Motivate Students?

Jun 7 2017 | Faunalytics

Animal Tracker 2017: Humane Education

Mar 16 2015 | karol orzechowski

Fall 2013 Humane Education Study Analysis

Aug 5 2013 | Faunalytics

Results From First Humane Education Lecture Survey

May 21 2013 | Faunalytics

Dissection Objectors Share Their Science Class Experiences

Aug 17 2012 | Faunalytics

Current Concepts In Simulation And Other Alternatives For Veterinary Education

Jul 19 2012 | Faunalytics

Students Want Option To Cut Out Animal Dissection

Dissection In Massachusetts Classrooms

Jul 7 2010 | Faunalytics

Dissection As An Instructional Technique In School

May 5 2010 | Faunalytics

The Significant Life Experiences (SLEs) Of Humane Educators

Dec 2 2008 | Faunalytics

Can Television Make A Difference In Humane Education?

Donate to Faunalytics today

Support Our Work

Your donation saves animals and empowers advocates

Informed Action. Greater Reaction.

Post Office Box 152703, San Diego, CA 92195

Contact Faunalytics

© 2023 Faunalytics | Terms of Use | Privacy Policy

Effective Advocacy Animals Used For Food Companion Animals Animals Used in Science Wild Animals Other Topics

What We Do Board & Staff Research In Progress Press Volunteer With Us Shop

Don’t Miss a Thing

Faunalytics delivers the latest and most important information directly to your inbox. Choose what topics you want to see and how often you get our emails, and you can unsubscribe anytime.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Animal Dissection and Evidence-Based Life-Science and Health-Professions Education

2002, Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science

Related Papers

International Journal of Instruction

Portia Kavai

ResponsibilitiesThe 4 th R

Rupert G . McCallum

Applied Epistemology

Mylan Engel Jr.

In this chapter, Mylan Engel Jr. argues that animal experimentation is neither epistemically nor morally justified and should be abolished. Engel argues that the only serious attempt at justifying animal experimentation is the benefits argument, according to which animal experiments are justified because the benefits that humans receive from the experiments outweigh the costs imposed on the animal subjects. According to Engel, the benefits we allegedly receive from animal-based biomedical research are primarily epistemic, in that experimenting on animal models is supposed to provide us with knowledge of the origin and proper treatment of human disease. However, Engel argues that animal models are extremely unreliable at predicting how drugs will behave in humans, whether candidate drugs will be safe in humans, and whether candidate drugs will be effective in humans. Engel concludes that animal-based research fails to provide the epistemic, and thereby moral, benefits needed to justi...

Veena H . F . ammanna

Alternatives to laboratory animals : ATLA

Andrew Rowan

A survey of 5000 American middle and high school level biology teachers was completed to assess attitudes and classroom practice relating to dissection and alternative teaching methods. A preliminary sample of 494 respondents revealed that 79% of teachers used dissection to teach biology. While 72% believed that dissection was an important part of the curriculum, 17% disagreed; 69% considered dissection to be an essential hands-on activity. While 31% believed that alternatives were as good as dissection for teaching anatomy and physiology, 55% disagreed. The primary reason given for continuing dissection, rather than exclusively using alternatives, was the hands-on aspect of dissection (69%). While the majority (66%) of biology teachers favoured student choice between dissection and other learning methods, 20% disagreed. Although the effectiveness of alternative methods has been documented, and ethical arguments against dissection have been advanced, the mainstream introduction of h...

The Anatomical Record Part B: The New Anatomist

Lawrence Rizzolo

CEPS Journal , Andrej Šorgo

• This article describes the results of a study that investigated the use of the dissection of organs in anatomy and physiology classes in Slovenian lower and upper secondary schools. Based on a sample of 485 questionnaires collected from Slovenian lower and upper secondary school students, we can conclude that dissection of mammalian organs during the courses on Human Anatomy would be a preferred activity for the majority of them. Opinions on such practices are positive, and only a minority of students would prefer to opt out. However, the practice is performed only occasionally in regular classes, or even omitted, and a number of students never participate in it. According to the results, we can suggest the dissection of mammalian organs in combination with alternatives, such as 3D models and virtual laboratories, as a preferred strategy to increase knowledge of anatomy and to raise interest in science. However, students should know that the organs they are dissecting were dedicated to human consumption , or are waste products in these processes. Opt-out options should be provided for those who do not want to participate in such activities.

Anatomia, Histologia, Embryologia: Journal of Veterinary Medicine Series C

J. M Matera

Science & Education

Sibel Erduran

In the short span of a year, numerous vaccines have been developed by various scientific research teams across the world. We cannot acknowledge enough the countless scientists who have been working tirelessly to develop drugs as well as vaccines to combat COVID19. If it wasn’t for these scientists’ respect for evidence, regardless of whose evidence and from where, it is difficult to imagine how the world would have coped with no reliable vaccines a year after the emergence of the pandemic. Even though the pandemic context has put the interplay of science with economics and politics on display, illustrating the tensions in how scientific knowledge may be interpreted in and for public consumption, it is important to highlight that “science” can still serve humanity at a time of public health crisis thanks to the great value it places in generating, evaluating, and using evidence. Scientific evidence rests on objectivity, as contested a definition this concept may invite (Longino, 1990...

RELATED PAPERS

Neurosciences (Riyadh, Saudi Arabia)

Zeynel Yoloğlu

Journal of Applied Psychology

Brent Smith

Patricia Soledad Quizhpe Alulima

Agbidi, S.S

Samuel S I M E O N Agbidi

Joakim Harlin

Néphrologie & Thérapeutique

Wilmer Naranjo

Humberto Ortega Villasenor

British Journal of Ophthalmology

Michael Lavin

Heinz-Theo Lübbers

IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics

Manuel Pineda

Neural Plasticity

Marco Milanese

Journal of The Optical Society of America B-optical Physics

Boris Malomed

Nuclear Physics A

Aryan Bhati

CARMEN MARIA VALDIVE F.

Fusion Engineering and Design

Southern Medical Journal

felix velasco alva

Journal of Language, Identity & Education

Yasko Kanno

Subjective Appropriations - Institutional Attributions - Socio-Cultural Milieus

WILHELM AMANN

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

We can help you reset your password using the email address linked to your BioOne Complete account.

- BioOne Complete

- BioOne eBook Titles

- By Publisher

- About BioOne Digital Library

- How to Subscribe & Access

- Library Resources

- Publisher Resources

- Instructor Resources

- FIGURES & TABLES

- SUPPLEMENTAL CONTENT

- DOWNLOAD PAPER SAVE TO MY LIBRARY