LeOnS -CSPC

Work-based learning with emphasis on trainers methodology, enrollment options.

This course deals on the different modalities of work-based learning such as, dual training, apprenticeship, on-the-job training and others. It covers the knowledge and skills in establishing the training requirements for trainees, supervising and monitoring work-based training, and evaluating its effectiveness in the attainment of the training programs objectives.

- Feedback Dashboard

Download Authoring Tool for SCORM Package (eXeLearning.net):

For windows (portable), for linux (portable), read the privacy statement.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

CBLMs on Trainers Methodology Level I Conduct Competency Assessment Competency-Based Learning Materials Conducting Competency Assessment

Related Papers

Annals of The Association of American Geographers

Vania Aparecida Ceccato

This article compares offense patterns at two points in time in Öresund, a Scandinavian border region that spans Sweden and Denmark. The aim of the analysis is to contribute to a better understanding of the relationships between crime and demographic, socioeconomic, and land use covariates in a border area that has been targeted with long-term investments in transport. The changes

Gabriella Pozzobon

Conclusions: This case underlines the importance of performing brain MRI in children diagnosed with GHD to identify structural abnormalities of the hypothalamic-pituitary region. Accurate diagnosis and surgical treatment of craniopharyngeal canals are important in order to prevent infective complications such as meningitis, and to provide a multidisciplinary follow-up. A 4-year-old patient was referred to our Centre for short stature. Weight and length at birth were within normal limits. In the neonatal period he showed jaundice and hypoglycemia. A reduced growth velocity was reported from the age of six months. At 15 months his length was 70 cm (-3,75 SDS), his weight 8,1 kg (-2,26 SDS). Parental target height was 167,6 cm (-1,38 SDS). He had normal psychomotor development. The examination showed macrocrania and nasal voice. The growth chart is shown in figure 1. Blood count, liver and renal function, screening for coeliac disease, thyroid function tests, ACTH, cortisol were within...

The current study was carried out near and surrounding fault line areas of Balakot-Bagh (B-B). The study aimed to find radon concentration levels in drinking water sources near and away from the fault line. The comparison was carried out for the radon level in those samples taken from the area near with those taken away from the fault line. Also, to evaluate health hazard from these drinking water to the people of the area. This area had received an earthquake of magnitude 7.6 in 2005. An active technique, RAD-7, based on alpha spectroscopy was used. The study period for the current study was three months, from 16th May to 15th August 2020. Radon concentrations were found higher in bore water with the mean value of 20.6 BqL− 1. These were 19.5 BqL− 1 and 9.3 BqL− 1 in spring and surface water, respectively. The mean value in all type of sources in the study area was 16.5 BqL− 1 which is higher than the maximum contaminated level of 11.1 BqL− 1 recommended by the U.S. The calculated ...

Revista Enfermagem Contemporânea

Claudineia Matos de Araújo

Objetivo: Avaliar a qualidade de vida de idosos residentes em instituição de longa permanência por meio de uma revisão sistemática. Materiais e métodos: Trata-se de uma revisão sistemática. Foram selecionados e lidos detalhadamente um total de 20 artigos recuperados das bases de dados SciELO e LILACS, entre os anos de 2010 a 2015. As seguintes etapas foram aplicadas na elaboração do artigo sistemática:1) elaboração da pergunta norteadora; 2) definição dos critérios de inclusão e buscas na literatura; 3) análise crítica dos estudos; 4) representação dos estudos inclusos em tabelas; 5) discussão dos resultados; e 6) reportar a evidências encontradas. Resultados: Foram apresentados em forma de quadros, divididos nas seguintes categorias analíticas: “principais resultados encontrados sobre a qualidade de vida dos idosos residentes em instituições de longa permanência” (46,1%), “principais resultados encontrados quanto aos fatores associados a qualidade de vida dos idosos residentes em ...

Journal of Animal Science

Floyd Williams

Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences

Samuel Silverstein

Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease

A considerable portion of urban public transportation is provided by private transportation operators. Overall, 1.8% of urban transportation research/training are spent on research and training needs of the privately provided public transportation sector. The imbalance is striking considering the amount and type of urban public transportation service offered by the private sector. Private providers offer most of the service for special sporting events and the majority of the tourism transportation, and they also generate significant employment when all aspects are taken into consideration. The objectives of this project were to undertake research and training programs that support more efficient and effective public transportation services from both the public and private sectors with the purpose of sharing findings and providing recommendations to the large number of private transportation officials engaged in providing public transportation.

Experiência, Saúde, Cronicidade: um olhar socioantropológico

Tiago Pires Marques

Analytical Chemistry

Richard Zare

RELATED PAPERS

Garcia de Orta , ser. Zool. 14 (1), 13-16

LUIS PISANI BURNAY

Vittorio Scisciani

Developmental Cell

chieko itakura

Wan Muhamad Amir Wan Ahmad

芝加哥艺术学院学位证 gtfj

Anesthesia & Analgesia

Oksana Lockridge

auksuole cepaitiene

Canadian Medical Association journal

Thomas Baskett

Priyanshu Verma

Argentine Journal of Cardiology

Lyda Zoraya Rojas

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Trainers Methodology Hub

"A Repository of Information on TESDA TVET Trainers Methodology Level 1 from the Perspective of a Certified TVET Trainer / Assessor - TM-1 Facilitator."

- Privacy Policy

Wednesday, October 31, 2018

Supervised work based learning.

- Establish training requirements for trainees;

- Monitor work-based training; and

- Review and evaluate work-based learning effectiveness.

No comments:

Post a comment.

Self-managed and work-based learning: problematising the workplace–classroom skills gap

Journal of Work-Applied Management

ISSN : 2205-2062

Article publication date: 5 February 2021

Issue publication date: 26 April 2021

The authors explore the ways work-based learning (WBL) can help degree apprentices cross the gaps between the workplace and the classroom, arguing that problem-based learning allows them to become aware of the overlaps in skills required to succeed between the two sites of learning.

Design/methodology/approach

This case study of a self-managed learning module uses a workshop methodology to understand the ways 61 undergraduate business management apprentices in the UK navigate the boundaries between work and learning and develop skills across both domains.

The authors' findings suggest that degree apprentices do not always perceive the two sites as overlapping in terms of what skills are required and how learning takes place. However, WBL modules have the potential to make them aware of how one informs and reinforces the other. Students identified teamwork, communication and reflection as necessary at the workplace and in their studies. They also viewed learning agility at critical, especially in the time of coronavirus disease 2019.

Originality/value

The paper adds to the existing literature exploring how WBL learning can help minimise the gap between the classroom and the workplace by adding the analysis of the case study. Those interested in developing modules which embed theory and practice can benefit from the discussion on how such modules enable students to reflect on the crossover between the two sites, not only on degree apprenticeships but higher education degrees broadly.

- Work-based learning

- Problem-based learning

- Higher education

- Skills development

- Degree apprenticeship

Konstantinou, I. and Miller, E. (2021), "Self-managed and work-based learning: problematising the workplace–classroom skills gap", Journal of Work-Applied Management , Vol. 13 No. 1, pp. 6-18. https://doi.org/10.1108/JWAM-11-2020-0048

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2021, Iro Konstantinou and Elizabeth Miller

Published in Journal of Work-Applied Management . Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

Introduction

The skills gap between higher education graduates and employer needs has been explored widely. Livanos (2010) describes the situation in Greece; Mok (2016) in China; Joshua et al. (2015) in Nigeria; Graham et al. (2019) in South Africa; Moore and Morton (2017) in Australia to name just a few examples. In the United Kingdom (UK), this has been a concern of universities, the government and employers alike for several years. In 2015, the funding model of state-funded universities in the UK changed and placed a renewed emphasis on results and employment outcomes, increasing the pressures on universities to offer value for money for students ( BIS 2016 ). As part of such a drive, many institutions are looking to embed employability training into their courses to ensure tangible results when students graduate ( Bates et al. , 2018 ). Despite the drive for higher education institutions (HEIs) to provide skills for the workplace, there is little consideration of how to do this successfully, resulting in a divergence between what happens in the workplace and what students do in higher education. This paper provides a UK-based case study of how work-based learning (WBL) and, a problem-based learning (PBL) approach, can help students cross the boundaries between their workplace and classroom learning. We also show that in doing so, they deploy and articulate the employability skills that will become part of their professional identity. In this paper, we have taken a PBL approach to WBL, where we situate learning as occurring in the relational space between work and formal education contexts ( Ramsey, 2011 ).

WBL models are diverse. While they can involve simulations and one-off industry projects, the case study presented here focusses on a WBL programme where the students' professional practice is tightly linked to the curriculum ( Boud et al. , 2020 ) because these students are degree apprentices (DAs). In 2015, the British government announced the introduction of degree apprenticeships to meet employer demand for skills as part of the government's “long-term economic plan” ( Department for Business, Innovation & Skills BIS and Prime Minister’s Office, 2015 ). This case study involves students on a Chartered Manager Degree Apprenticeship. These students study their BA, Business Management, at our institution, a private, HEI in central London. The links between work and study are integral to degree apprenticeships, and as part of their degree at our institution, we require them to undertake a PBL module called “Self-Managed Learning” (SML). In their SML modules, the DAs must work with their managers and wider teams to identify a problem or opportunity in their workplace and then through research, find and evaluate potential solutions. Alongside this, we ask them to reflect on the skills they have developed in their work and academic lives.

By virtue of their job roles, which must all be professional roles carefully reviewed to ensure they are in line with the knowledge, skills and behaviours that form the Chartered Manager (Degree) apprenticeship standard, our students are both management learners, in that this is their field of study, and “manager-learners” ( Ramsey, 2014 ), as junior managers, who relate their learning to their workplace, and vice versa. Ramsey's “scholarship of practice” ( 2014 ) suggests that the relations between ideas and action are critical, and that teaching should emphasise this relationship and not just academic theory. This approach became critical as this research was conducted in the summer of 2020 when the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic was having a significant impact on individuals, society and the economy. The disruption caused by COVID-19 highlighted the importance of particular skills in the workplace – notably agility, communication, problem-solving and teamwork – as a way of navigating rapid change. The experiential approach we outline below highlights how WBL can address the skills gap by encouraging students to think about the multiple crossings between the classroom and their workplace.

Literature review

The skills gap: which skills are needed and who should teach them.

As Andrews and Higson (2008) outline, European universities are increasingly required to produce highly mobile graduates able to respond to the ever-changing needs of the contemporary workplace, especially with the recent expansion of higher education provision. Scholars debate whether employability should be the focus of HEIs ( Mccowan, 2015 ) and if this is the case, which skills should be the focus. Bridgstock (2009) , for example, argues that HEIs should equip graduates with self-management skills to be able to navigate their careers, while Fajaryati and Akhyar (2020) argues for skills needed in the age of innovation and technology such as communication, teamwork, problem-solving and technological skills. However, employers are still expressing concerns about whether graduate labour can meet their needs ( CBI and Pearson, 2018 ). Despite the increasing attempts by universities to increase employability skills in students, students do not always see the benefit in such attempts with a perceived limited alignment between what students feel they need and what universities offer ( Tymon, 2013 ). There are differences in what students perceive as essential skills and what academics see as important ( Hodge and Lear, 2011 ), while another area of concern is that often graduates do not place as much importance on soft skills as employers do ( Succi and Canovi, 2020 ).

Crossing the distance between the classroom and the workplace

The convergence of the workplace and classroom through workplace learning programmes is driven in the UK by education policy reforms seeking to redress the skills gap ( Bravenboer, 2018 ). This convergence creates opportunities to “bridge” ( Bates and Sampford, 2005 ; Svensson and Randle, 2005 ) the gap between formal learning in educational settings and the often informal learning that occurs in the workplace. As Choy (2018) argues, workplace learning is “ubiquitous” and integrating this with a formal curriculum for learning in an educational institution allows for meaningful learning that adds value to both the learner and their employer ( Billett, 2001 ). Minimising this gap benefits students through increased confidence, social and employability skills, and improvements in academic performance ( Bates and Sampford, 2005 ).

For students on explicitly work-integrated learning programmes, reflecting on professional and classroom learning experiences can help them engage in “deep learning” and convert “hands-on” experiential learning to abstract conceptualisation ( Young, 2018 ). However, others argue we should start by challenging the “unhelpful” conception of theory and practice as being separate ( Bravenboer and Lester, 2016 ) in the first place. The overlap in sites of learning for students on work-integrated learning programmes is a topic that deserves further research. Post-structural approaches “problematise the imagined geographies of learning as distinct fields of the “workplace” versus “educational institution”” ( Bound et al. , 2018 , p. 245). Instead, a relational approach is a useful way of reconceptualising the “bridge” between the classroom and the workplace, which frames learning as occurring inside and across these spaces ( Bound et al. , 2018 ). Practices at different sites of learning and the relationships between them become a new “site” of learning ( Nicolini, 2011 ). However, our experience of students on WBL programmes is that they see their work and learning as occurring on separate, albeit linked, sites. An aim of the project forming our case study, therefore, is helping students see the relationships between sites through summative assessment requiring learners to explicitly reflect on skills developed across and between sites while solving a “real-world” problem. We argue that the metaphor of a bridge between work and HEIs is helpful, but this bridge is more helpfully understood as a series of relational “crossings” between sites of learning.

PBL and the development of skills and competencies: self-managed learning

PBL is an experiential learning method that contextualises academic learning in a way that scholars argue can minimise the perceived distance between the worlds of work and education ( Scholtz, 2020 ; Smith et al. , 2007 ). PBL not only develops skills and competencies in university students, it allows them to formally display these skills ( Heaviside et al. , 2018 ), something that may not always occur in the workplace where informal demonstrations of skills are essential. In management education, research has shown that the interactions with tutors and those at the workplace are both crucial in developing transferable skills in PBL ( Carvalho, 2016 ). Giving students the chance to develop, reflect on and showcase the competencies and skills they develop is seen by the students themselves as important. Students do not all experience learning in the same way ( Cunliffe, 2002 ) and yet research has found that even when students disliked PBL, they could still see its effectiveness in developing employability skills ( Smith et al. , 2013 ). Perhaps critical to PBL is the sense of autonomy students develop and the self-management or regulation developed through PBL. Self-management is linked to strong employment outcomes for graduates. Jackson and Wilton argue it is a way for students to understand “gaps” they must cross to master professional skills and competencies ( Jackson and Wilton, 2016 ) and the character traits ( Wellman, 2010 ) that will aid their crossing.

The importance of incidental learning in WBL

WBL also has the potential for what Knowles (1970) describes as incidental learning: the ability to learn from others, who tend to be experts, but also to practically apply some of the things one learns through formal learning. Le Clus (2011) makes a similar point by noting that learning takes place not just through formal structures which organisations put in place but very often through learning embedded in everyday activities. Le Clus suggests that learning and working are synonymous since it is not possible to work without learning new things. Billett (1996) has talked about the workplace as a site for learning where skills and knowledge can be acquired daily and where theory and practice converge in a way which is beneficial for the employees. Junior and more senior employees alike have areas of “knowledgeable skills” that they can share with others in their workplace ( Fuller et al. , 2005 ). Boud and Garrick (1999) have described informal interaction with work colleagues as a predominant way of learning in the workplace since learning can often happen through unplanned conversations and chance encounters. Empirical work on coaching training by Crisp (2018) supports this point and points to the importance of learning to be done on an informal basis with encouragement and support from experts.

Methodology

Designing a project-based, skills development module.

Before outlining our approach to data collection, we discuss our approach to experiential, problem-based modules to enable the convergence of learning between the workplace and the classroom, through our WBL modules. By taking an experiential approach which integrates reflection and problem-solving, we have updated one of our WBL modules to ensure better integration across the two spheres of learning. SML modules require students to solve a real work-based problem which can be decided in consultation with their managers or, especially at a higher level, through the students' ability to identify problems at their workplace. Our role as tutors is to help them contextualise this work ( Dahlgren, 2000 ) and facilitate classroom environments where they can develop the confidence to articulate the skills they acquire.

Starting with a problem they have identified in the workplace students conduct a literature review which focusses on what solutions can be found in academic literature but also in industry publications, such as case studies of best practice. After completing the literature review and having identified several viable solutions, we ask students to evaluate whether these solutions would be applicable in their context. By taking into consideration different parameters and variables, they narrow down the scope of what can work in their contexts. For this process, they are encouraged to engage with varying models of good practice; seek feedback from colleagues and classroom peers; reflect on their relationship with stakeholders; and identify risks and mitigation strategies. The report they produce for summative assessment concludes with a set of recommendations, which at final year undergraduate (L6) can be sophisticated and form the basis of a framework of their own.

As part of the assessment, students must also reflect on the skills they have developed through the module. In redesigning the module, we drew from the literature which looks at which skills are important for graduates to be employable while also succeed academically. Thus the skills that we ask them to reflect on are those applicable to all degree students, not just apprentices. There is some crossover in the skills laid out in the apprenticeship standard, such as communication and working with others, but our approach is broader and less focussed on business management specific skills. Our purpose is to give as many opportunities for students to become independent learners while they are also learning from each other. Most of the seminars are spent on students discussing their projects in groups, giving feedback and suggesting new areas to develop for each other's projects. In the workplace, students are encouraged to gather feedback from colleagues and discuss their work regularly with those in their teams. We are careful not to assume that critical ( Wall, 2016 ) but instead, view reflection on skills development as a place of crossing the boundary between the workplace and the degree through PBL. Below we outline how the students understand this process and provide examples of how they believe the two learning spheres can be brought together through this problem-solving experiential learning approach.

Workshops as a means of data collection

Ørngreen and Levinsen (2017) outline the potential of workshops for data collection, distinguishing between workshops to achieve a goal; as practice with specific outcomes and as research methodology. In all cases, they reviewed workshops that were conducted by someone with expertise in an area who encourages active participation ( Ørngreen and Levinsen (2017) ). The benefit for the organiser is that they can get an insight into what participants think. The benefits for the participants are that the main outcome of a workshop is that it produces a concrete product, such as generating new insights, learning from others, suggestions and so on. Moreover, even though workshops very often have predefined activities but not always a predetermined outcome. For Ahmed and Asraf (2018 , p. 1508) for workshops to be successful, they need to have activities that provide a scope for the participants to interact and learn collaboratively. The facilitator must create an environment where participants feel that their voices are important; the activities of the workshop must be relevant to the main objective of the workshop; ethical considerations must be taken into account, e.g. having the participants sign the informed consent form before the workshop. Our workshop was based on our understanding of our students as having knowledge developed between the workplace and classroom and understanding that the sharing of this knowledge amongst students is a valuable way for them to learn ( Fuller et al. , 2005 ).

For our data collection, we used two groups of L6 students ( n = 61) in one of their 2-h weekly seminars. During the seminar, the participants were asked to (1) define the skills which are given as part of the module's skills development framework (problem-solving; teamwork and communication; employability; planning and organisation; self-reflection; analytical skills and critical thinking; leadership)and identify their potential importance for their workplace and classroom; (2) provide concrete evidence of how these skills have been or can be developed both at the workplace and the classroom (drawing from previous terms if necessary); (3) consider overlaps between the workplace and the classroom and how the two can inform each other. Each group had around 30 students and they were split into six groups (12 in total). The tutor had created templates of the activities on Google slides where students were asked to take notes as they discussed in their groups in the “breakout rooms”. The tutor did not participate in the group discussions in these breakout rooms but was monitoring discussion through the notes they students were taking on the shared slides and by giving prompts and feedback on the slides.

The challenges of conducting research online

Even though the discussion in the breakout groups was more natural with everyone having their microphones on, when the participants were brought back to the “main room” most of them were writing in the chatbox while the tutor was on the microphone. Moreover, the students did not have their cameras on and as such the tutor could not see their reactions or facial expressions. The challenges around building rapport with participants in online research have been widely discussed (e.g. O'Connor et al. , 2008 ) and we found that some of these of these challenges were prevalent in our research. The tutor had met some of the students face to face in previous terms but not all of them. Holding a workshop online made it challenging to monitor conversations as much as we would have liked and posed challenges around ensuring that everyone in the group participated and stayed motivated. It also meant that any nonverbal cues, which can provide richer data, were not possible to obtain ( Ochieng et al. , 2018 ). If it had not been for COVID-19 and the restrictions it posed on face-to-face meetings, then this workshop would be face to face and allowed us to gain an insight into the reactions of the participants and ensure everyone participated and benefitted from this. However, perhaps giving the space to students to discuss amongst themselves can also be a powerful way to collect richer data. Moreover, the online format of this meant that a much larger group can come together, something which would not have worked that easily in a seminar room.

Data analysis

The workshop objectives, as outlined above, guided us in our analysis of the data. By taking the three main objectives, we structured our analysis accordingly and included some representative responses in our findings below. The evidence provided by students was chosen based on their willingness to share their work. Based on our experience in teaching the module we believe that they offer a good representation of the students' work.

Even though our sample size ( n = 61) is not large enough to make any generalisations, we believe that it can provide the basis for further discussion and research around how WBL modules can bridge the gap between the learning taking place in the workplace and the classroom, both formal and informal.

Ethical considerations

Before commencing the term, we informed students through an email that we will be collecting confidential data during the term in our attempts to revise the modules in a way which can benefit students. The email explained what the purpose of our research was for and that students could withdraw their consent at any time during the term. For the purposes of this paper, we sought verbal consent from students at the beginning of the workshop and explained to them that if they did not want their responses to be recorded, they did not have to put comments on the slides. This way they would still participate in the discussion but not express any of their views in writing which was used as data. Since all the responses on the slides were anonymous, we cannot be sure which students chose to not record their responses. The seminars are usually recorded but the breakout rooms are not, and we only used the data given on the shared Google Slides and none of the comments in the whole class debriefs when the recording was on. This way we ring-fenced some time where participants could speak more freely or ask questions. We asked specifically for some concrete evidence to be shared with us and this was done on a voluntary basis by students, via email. These examples draw from students' previous assessments and since these have been marked and the grades have been confirmed we were confident that the students did not feel their marks were at stake.

The findings below demonstrate the potential of problem-based, experiential modules in degree apprenticeships to bridge the learning spheres of the classroom and the workplace. Our students spend four days a week in the workplace and one in the classroom and do not readily collapse what they see as the rigid boundaries between each setting. Following the objectives, we set out for the workshop we provide examples of skills students view as important and what they mean to them; evidence of how students think they develop these skills both at the workplace and the classroom; outline overlaps between the two sites of learning.

Identifying skills needed at the workplace and the classroom

Self-reflection for example. In classroom/assignments you reflect on how you could have done it differently or better, at workplace you reflect on how you communicate with others, react in difficult situations. It's the ability to constructively criticise yourself.

Self-reflection needed in both. Good to reflect on what you have done well/ not so well in previous academic/ professional work to know where to improve.

Team working and coming to a conclusion together, discussing different ideas.

Analytical skills to find solutions to problems; resilience and perseverance; adaptability.

Covid has resulted in me being way more reflective than I would normally expect to be, it is obviously something I have really needed to do to understand what is happening and the impacts.

Teamwork and communication have become more vital working remotely to manage the change of working environment, support each other yet not let work output be affected.

Clear and coherent communication is even more important in a remote working world. As-is active listening.

Being authentic and honest is vital - I think I now view these two attributes as being the most important given the last 6 months

Learning agility is a skill needed in this age of rapid innovation and digitisation. It is important for people to be able to learn, grow to keep up with things.

The skills which students pointed to overlapped and interestingly, based on recent events pointed to more reflection and acquiring communication skills needed in online settings. On top of this digital turn, being agile might be a more important skill they need since the changing labour market after COVID-19 will require reallocation in people's roles ( Costa Dias et al. , 2020 ). The findings here point to the potential of PBL to get students reflecting on these skills and being able to articulate their importance.

Is there an obvious convergence between classroom and workplace skills?

Skills are transferable, however sometimes approached in different ways in the workplace compared to in the classroom.

Solving problems and the skills required to do so, regardless of the issue.

Need to work well within your team & share workloads/ support each other. Peer feedback and group exercises to support everyone's learning.

Emphasis on needing to support others.

Using active listening when obtaining feedback from lecturers, and developing and applying this when talking to SLT (senior leadership team).

We found that students view being supportive of each other as especially important. Perhaps this was reflective of the community spirit displayed during COVID-19. The fact that most of our students had to work from home and had to study online meant that teamwork and sharing tasks became even more important to them. Perhaps the fact that teams only came together virtually, with chance interactions taken away, consolidated the importance of these random interactions.

Overall, we see that when asked to think about the overlaps, there are many. It is encouraging to see that students can see the convergence between the two. From the examples above, we also note that they primarily identify skills which are not formally learnt or often assessed, but they have to do with everyday tasks and being able to get things done or be part of a team.

Workplace/classroom: overlapping sites of learning

The last component of our research was to identify how students develop these skills in action and how they draw from their classroom and professional experiences. Through these authentic instances of skills development, we see the potential of bridging the two learning sites while creating models for crossovers of skills. The below examples are instances of learning which happens both formally but also through moments of interaction with others and while figuring things out. As we have noted above, we believe that these “lightbulb” moments which prompt students to reflect on their experiences and see what they can take away from them, is when deep learning can take place.

Participant A

Situation: In the seminar today we discussed the application section of the SML report, during which evaluation of the potential solutions would be carried out. [The tutor] discussed a 6-step framework, however, I didn't understand how my action research approach would fit into this. […]

Analysis of feeling and knowledge: It seemed like a lot of steps for the evaluation and I was worried that I wouldn't be able to communicate all my reasoning and critical thinking […] I was also conscious that in this section I would need to demonstrate my problem solving.

Evaluation: I think the problem was caused by my premature decision to use an action research approach before properly considering the requirements […]

Skills developed: communication; problem solving; critical thinking

Changes for future work: clarify questions regarding assessment brief in advance; do not start writing until you are sure on the approach – this wastes time; before detailing an evaluation approach, consider the solution and time frame available

Looking at the processes which students utilise to make sense of what happens in the classroom, especially an online classroom, is invaluable in understanding how these skills can be developed in practice. The student now only identifies what challenges they were faced with but also how they could draw upon their skills to overcome similar challenges in the future. Moreover, some of the learnings here, i.e. considering distinct options before deciding how to solve the problem or clarify questions with those who have set a task are valuable lessons which can be applied to the workplace and are particularly useful for DAs who regularly have to make these decisions as part of their jobs

Participant B

proactively engaging with colleagues and embedding their feedback into the solution. Developing these collaborative relationships enabled expectations to be managed […] whilst also ensuring that colleagues were able to appreciate the value the solution could have for them and their teams. […] On a personal level, it is hoped that this experience can be used as a platform from which the skills developed, and relationships established can be further developed.

It is encouraging to see that the student successfully bridges the gap between the theory learnt through academic work and the workplace by engaging colleagues and later on implementing solutions successfully. As shown in the excerpt above, practical applications of what the theory might have to say about the workplace and managing relationships can help build relationships in the workplace, something very pertinent to apprentices who have to embed themselves to the workplace.

Both examples outline above show the potential of PBL to help students see the overlaps between the classroom and the workplace while gaining the necessary skills to navigate the two spheres.

Discussion and conclusion

The persistence of the skills gap manifested in the labour skills shortages as discussed by employers is widely covered. In this paper, we have analysed the case study of a self-managed module which takes a problem-based approach to encourage students to reflect on the crossovers between the learning which takes place in the classroom and the workplace. By getting students to reflect on the skills they develop while trying to solve a work-based problem, we have found that our participants have been able to identify such overlaps. They often problematised how the two sites of learning link and whether there are crossovers between the two. We discussed how often, as tutors, we are asked whether the reflection on skills development should be kept separate. However, our findings show that there is real potential for students to see the crossings between these two spheres and see how the theory and skills acquired in the classroom can benefit them in their workplace. Since we collected data during the COVID-19 pandemic, we saw a renewed need for teamwork, self-reflection and communication to succeed professionally and academically. However, our participants also pointed to the need to be agile, since circumstances are unforeseen and often required fast thinking and adaptability, which resonates with the work of Costa Dias et al. (2020)

We have provided examples of how the two sites have been bridged and have argued that problem-based, experiential learning embedded in work-based modules has real potential to get students to bridge the gaps between the workplace and the classroom. As the literature and the findings suggest this can be especially relevant to DAs, who work and study at the intersections of professional and academic settings. However, this approach can be applied in other WBL contexts, such as industrial placements or sandwich year programmes. We recognise that since this only one case study in the UK, working with an academically homogenous cohort of DAs, it might not be possible to replicate our findings in other, perhaps international, settings. However, we believe we have pointed to the potential of how this can be done through our model of reflecting on skills. We believe there is scope for further research in the area, looking into other case studies and especially in understanding of the underexplored area of the learning which takes place in the workplace.

Ahmed , S. and Asraf , R.M. ( 2018 ), “ The workshop as a qualitative research approach: lessons learnt from a ‘critical thinking through writing’ workshop ”, The Turkish Online Journal of Design, Art and Communication , Special edition , pp. 1504 - 1510 , ISSN: 2146-5193 .

Andrews , J. and Higson , H. ( 2008 ), “ Graduate employability, ‘soft skills’ versus ‘hard’ business knowledge: a European study ”, Higher Education in Europe , Vol. 33 No. 4 , pp. 411 - 422 , doi: 10.1080/03797720802522627 .

Bates , L. and Sampford , K. ( 2005 ), Building a Bridge Between University and Employment: Work-Integrated Learning Queensland Parliamentary Library Research Publications and Resources Section , available at: http://www.parliament.qld.gov.au/Parlib/Publications/publications.htm ( accessed 30 October 2020 ).

Bates , L. , Hayes , H. , Walker , S. and Marchesi , K. ( 2018 ), “ From employability to employment: a professional skills development course in a three-year bachelor program ”, International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning , Vol. 19 No. 1 , pp. 413 - 423 .

Billett , S. ( 1996 ), “ Constructing vocational knowledge: history, communities and ontogeny ”, Journal of Vocational Education and Training , Vol. 48 No. 2 , pp. 141 - 154 .

Billett , S. ( 2001 ), “ Learning throughout working life: interdependencies at work ”, Studies in Continuing Education , Vol. 23 No. 1 , pp. 19 - 35 , doi: 10.1080/01580370120043222 .

Boud , D. and Garrick , J. (Eds) ( 1999 ), Understanding Learning at Work , Routledge , London .

Boud , D. , Ajjawi , R. and Tai , J. ( 2020 ), “ Assessing work-integrated learning programs: a guide to effective assessment design ”, Centre for Research in Assessment and Digital Learning , Deakin University , Melbourne , doi: 10.6084/m9.figshare.12580736 ( accessed 30 October 2020 ).

Bound , H. , Chia , A. and Chee , L.W. ( 2018 ), “ Spaces and spaces 'in between' – relations through pedagogical tools and learning ”, in Choy , S. , Wärvik , G.-B. and Lindbery , V. (Eds), Integration of Vocational Education and Training Experiences , Springer , Singapore , pp. 243 - 258 .

Bravenboer , D. ( 2018 ), “ The unexpected benefits of reflection: a case study in university-business collaboration ”, Journal of Work-Applied Management , Vol. 10 No. 1 , pp. 50 - 62 , doi: 10.1108/jwam-01-2017-0002 .

Bravenboer , D. and Lester , S. ( 2016 ), “ Towards an integrated approach to the recognition of professional competence and academic learning ”, Education and Training , Vol. 58 No. 4 , pp. 409 - 421 , doi: 10.1108/ET-10-2015-0091 .

Bridgstock , R. ( 2009 ), “ The graduate attributes we've overlooked: enhancing graduate employability through career management skills ”, Higher Education Research and Development , Vol. 28 No. 1 , pp. 31 - 44 , doi: 10.1080/07294360802444347 .

Carvalho , A. ( 2016 ), “ The impact of PBL on transferable skills development in management education ”, Innovations in Education and Teaching International , Vol. 53 No. 1 , pp. 35 - 47 , doi: 10.1080/14703297.2015.1020327 .

CBI and Pearson ( 2018 ), Educating for The Modern World: Cbi/Pearson Education and Skills Annual Report , available at: https://www.cbi.org.uk/media/1171/cbi-educating-for-the-modern-world.pdf ( accessed 31 October 2020 ).

Choy , S. ( 2018 ), “ Integration of learning in educational institutions and workplaces: an Australian case study ”, Integration of Vocational Education and Training Experiences , Springer , pp. 85 - 106 , doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-8857-5_5 .

Costa Dias , M. , Joyce , R. , Postel‐Vinay , F. and Xu , X. ( 2020 ), “ The challenges for labour market policy during the COVID‐19 pandemic ”, Fiscal Studies , Vol. 41 , pp. 371 - 382 , doi: 10.1111/1475-5890.12233 .

Crisp , P.M. ( 2018 ), “ Coaching placements and incidental learning – how reflection and experiential learning can help bridge the industry skills gap ”, Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education , Plymouth, No. 13, available at : https://journal.aldinhe.ac.uk/index.php/jldhe/article/view/442 ( accessed 2 February 2021 ).

Cunliffe , A.L. ( 2002 ), “ Reflexive dialogical practice in management learning ”, Management Learning , Vol. 33 No. 1 , pp. 35 - 61 , doi: 10.1177/1350507602331002 .

Dahlgren , M.A. ( 2000 ), “ Portraits of PBL: course objectives and students' study strategies in computer engineering, psychology and physiotherapy ”, Instructional Science , Vol. 28 , pp. 309 - 329 , doi: 10.1023/A:1003961222303 .

Department for Business, Innovation & Skills and Prime Minister’s Office ( 2015 ), Press Release: Government Rolls-Out Flagship Degree Apprenticeships , available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/government-rolls-out-flagship-degree-apprenticeships ( accessed 11 December 2020 ).

Department for Business, Innovation & Skills ( 2016 ), Success as a Knowledge Economy: Teaching Excellence, Social Mobility & Student Choice , (White Paper) available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/523546/bis-16-265-success-as-a-knowledge-economy-web.pdf ( accessed 19 October 2020 ).

Fajaryati , N. and Akhyar , M. ( 2020 ), “ The employability skills needed to face the demands of work in the future: systematic literature reviews ”, Open Engineering , Vol. 10 No. 1 , pp. 595 - 603 , doi: 10.1515/eng-2020-0072 .

Fuller , A. , Hodkinson , H. , Hodkinson , P. and Unwin , L. ( 2005 ), “ Learning as peripheral participation in communities of practice: a reassessment of key concepts in workplace learning on JSTOR ”, British Educational Research Journal , Vol. 31 No. 1 , pp. 49 - 68 .

Graham , L. , Williams , L. and Chisoro , C. ( 2019 ), “ Barriers to the labour market for unemployed graduates in South Africa ”, Journal of Education and Work , Vol. 32 No. 4 , pp. 360 - 376 , doi: 10.1080/13639080.2019.1620924 .

Heaviside , H.J. , Manley , A.J. and Hudson , J. ( 2018 ), “ Higher Education Pedagogies Bridging the gap between education and employment: a case study of problem-based learning implementation in postgraduate sport and exercise psychology ”, Higher Education Pedagogies , Vol. 3 No. 1 , pp. 463 - 477 , doi: 10.1080/23752696.2018.1462095 .

Hodge , K. and Lear , J. ( 2011 ), “ Employment skills for 21st century workplace: the gap between faculty and student perceptions ”, Journal of Career and Technical Education , Vol. 26 No. 2 , pp. 28 - 41 .

Jackson , D. and Wilton , N. ( 2016 ), “ Developing career management competencies among undergraduates and the role of work-integrated learning ”, Teachinng in Higher Education , Vol. 21 No. 3 , pp. 266 - 286 .

Joshua , S. , Biao , I. , Azuh , D. and Olanrewaju , F. ( 2015 ), “ Multi-faceted training and employment approaches as panacea to higher education graduate unemployment in Nigeria ”, Contemporary Journal of African Studies , Vol. 3 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 15 .

Knowles , M. ( 1970 ), The Modern Practice of Adult Education: Andragogy vs Pedagogy , Associated Press , New York, NY .

Le Clus , M.A. ( 2011 ), “ Informal learning in the workplace: a review of the literature ”, Australian Journal of Adult Learning , Vol. 51 No. 2 , pp. 355 - 373 .

Livanos , I. ( 2010 ), “ The relationship between higher education and labour market in Greece: the weakest link? ”, Higher Education , Vol. 60 No. 5 , pp. 473 - 489 , doi: 10.1007/s10734-010-9310-1 .

Mccowan , T. ( 2015 ), “ Should universities promote employability? ”, Theory and Research in Education , Vol. 13 No. 3 , pp. 267 - 285 , doi: 10.1177/1477878515598060 .

Mok , K.H. ( 2016 ), “ Massification of higher education, graduate employment and social mobility in the greater China region ”, British Journal of Sociology of Education , Vol. 37 No. 1 , pp. 51 - 71 .

Moore , T. and Morton , J. ( 2017 ), “ The myth of job readiness? Written communication, employability, and the 'skills gap' in higher education ”, Studies in Higher Education , Vol. 42 No. 3 , pp. 591 - 609 , doi: 10.1080/03075079.2015.1067602 .

Nicolini , D. ( 2011 ), “ Practice as the site of knowing: insights from the field of telemedicine ”, Organization Science , Vol. 22 No. 3 , pp. 602 - 620 , doi: 10.1287/orsc.1100.0556 .

O'Connor , H. , Madge , C. , Shaw , R. and Wellens , J. ( 2008 ), “ Internet-based interviewing ”, in Fielding , N.G. , Lee , R.M. and Blank , G. (Eds), The Sage Handbook of Online Research Methods , Sage , London .

Ochieng , N.T. , Wilson , K. , Derrick , C.J. and Mukherjee , N. ( 2018 ), “ The use of focus group discussion methodology: insights from two decades of application in conservation ”, Methods in Ecology and Evolution , Vol. 9 , pp. 20 - 32 , doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.12860 .

Ørngreen , R. and Levinsen , K. ( 2017 ), “ Workshops as a research methodology ”, The Electronic Journal of e- Learning , Vol. 15 No. 1 , pp. 70 - 81 , available at: www.ejel.org ( accessed 29 October 2020 ).

Ramsey , C. ( 2011 ), “ Provocative theory and a scholarship of practice ”, Management Learning , Vol. 42 No. 5 , doi: 10.1177/1350507610394410 .

Ramsey , C. ( 2014 ), “ Management learning: a scholarship of practice centred on attention? Journal Item ”, Management Learning , Vol. 45 No. 1 , pp. 6 - 20 , doi: 10.1177/1350507612473563 .

Scholtz , D. ( 2020 ), “ Assessing workplace-based learning ”, International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning , Vol. 21 No. 1 , pp. 25 - 35 .

Smith , K. , Clegg , S. , Lawrence , E. and Todd , M.J. ( 2007 ), “ The challenges of reflection: students learning from work placements ”, Innovations in Education and Teaching International , Vol. 44 No. 2 , pp. 131 - 141 , doi: 10.1080/14703290701241042 .

Smith , M. , Duncan , M. and Cook , K. ( 2013 ), “ Graduate employability: student perceptions of PBL and its effectiveness in facilitating their employability skills ”, Practice and Evidence of Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education , Vol. 8 No. 3 , pp. 217 - 240 .

Succi , C. and Canovi , M. ( 2020 ), “ Soft skills to enhance graduate employability: comparing students and employers' perceptions ”, Studies in Higher Education , Vol. 45 No. 9 , pp. 1834 - 1847 , doi: 10.1080/03075079.2019.1585420 .

Svensson , L. and Randle , H. ( 2005 ), “ How to ‘Bridge the Gap’ — Experiences in connecting the educational and work system ”, in Antonacopoulou, E., Jarvis, P., Andersen, V., Elkjaer, B. and Høyrup, S. (Eds) , Learning, Working and Living , Palgrave Macmillan , London , doi: 10.1057/9780230522350_7 .

Tymon , A. ( 2013 ), “ The student perspective on employability ”, Studies in Higher Education , Vol. 38 No. 6 , pp. 841 - 856 , doi: 10.1080/03075079.2011.604408 .

Wall , T. ( 2016 ), “ Žižekian ideas in critical reflection the tricks and traps of mobilising radical management insight ”, Journal of Work-Applied Management , Vol. 8 No. 1 , pp. 5 - 16 , doi: 10.1108/JWAM-04-2016-0005 .

Wellman , N. ( 2010 ), “ The employability attributes required of new marketing graduates ”, Marketing Intelligence and Planning , Vol. 28 No. 7 , pp. 908 - 930 , doi: 10.1108/02634501011086490 .

Young , M.R. ( 2018 ), “ Reflection fosters deep learning: the ‘reflection page and relevant to you’ intervention ”, Journal of Instructional Pedagogies , Vol. 20 , pp. 1 - 17 .

Further reading

Browne , J. ( 2010 ), Securing a Sustainable Future for Higher Education: An Independent Review of Higher Education Funding and Student Finance , Department for Business, Innovation and Skills , October. available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-browne-report-higher-education-funding-and-student-finance ( accessed 31 October 2020 ).

Corresponding author

Related articles, we’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

Work-Based Learning Manual

A How-To Guide For Work-Based Learning

Introduction to Work-Based Learning

What is work-based learning.

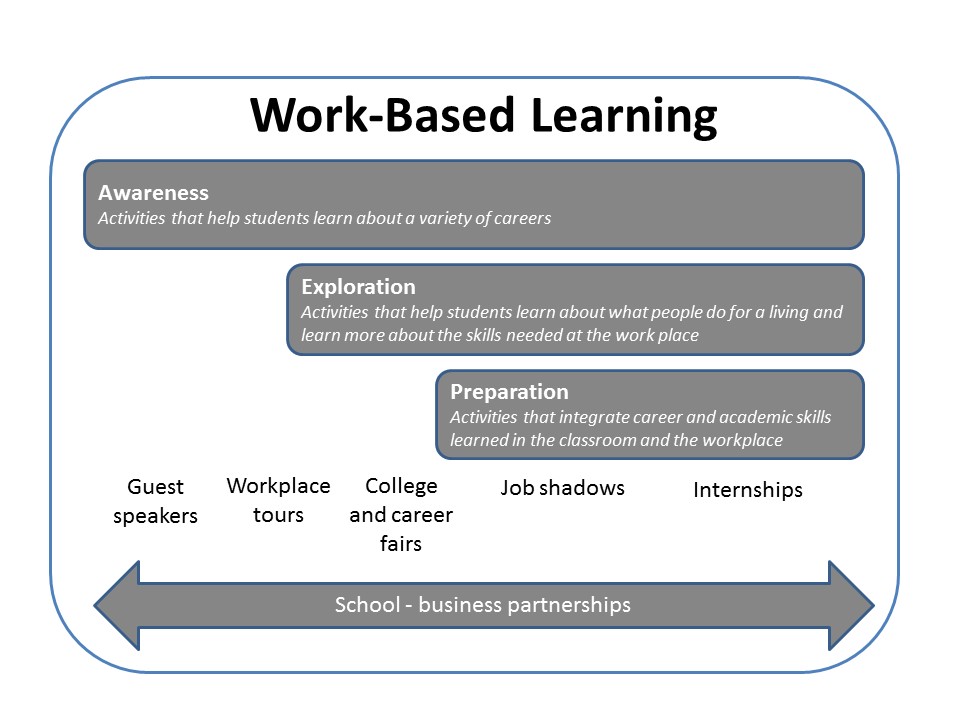

Work-based learning (WBL) is a set of instructional strategies that engages employers and schools in providing learning experiences for students. WBL activities are structured opportunities for students to interact with employers or community partners either at school, at a worksite, or virtually, using technology to link students and employers in different locations.

The purposes of WBL are to build student awareness of potential careers, facilitate student exploration of career opportunities, and begin student preparation for careers. These awareness, exploration, and preparation activities help students make informed decisions about high school course and program enrollment and about postsecondary education and training. Exposure to careers through an individual WBL activity can be beneficial, but students attain best results when WBL activities are structured and sequenced over several years.

WBL should be integrated with classroom learning to help students draw connections between coursework and future careers. Students need time and assistance to prepare for WBL activities as well as opportunities to reflect on the activities afterward.

Quality work-based learning should include the following elements:

- A sequence of experiences that begins with awareness and moves on to exploration and hands-on preparation.

- Clearly defined learning objectives related to classroom curricula.

- Alignment with students’ career interests.

- Alignment with content standards and industry/occupational standards.

- Exposure to a wide range of industries and occupations.

- Collaboration between employers and educators, with clearly defined roles for each.

- Activities with a range of levels of intensity and duration.

- Intentional student preparation and opportunities for reflection.

This WBL manual has been developed by FHI 360 to guide implementation of WBL activities. Before moving on to a chapter about a specific WBL activity, users should review the entire introduction. It provides information pertinent to all WBL activities, which will enable district or school staff members to implement WBL activities in a broader, well-planned context.

Back to Top

How to Use the FHI 360 Work-Based Learning Manual

The FHI 360 Work-Based Learning Manual is a how-to guide with suggestions and tools for planning and implementing specific WBL activities. While district or school priorities for implementing WBL may vary, as will the variety of local employers with which to partner, the manual provides information that will help in implementing each activity in the context of the complete WBL continuum.

This Introduction provides: an overview of WBL activities; their benefits to students, schools, and employers; the skills to be developed through WBL; suggestions for planning the overall WBL program; important steps for implementing WBL activities; and guidance for the critical tasks of managing collaboration with the wide range of essential stakeholders, especially employers. Each of the other chapters provides more detailed information about a specific WBL activity: ideas on which stakeholders to engage; a suggested implementation time line; resource templates and tools; and links for more information. In addition, each WBL activity chapter provides ideas for student preparation as well as suggestions for employer preparation. The time lines and tools in the manual are suggested best practices that should be adapted to suit the specific needs of the participating schools and employers. For example, what works well in a larger, urban district may need to be scaled down to fit more rural communities that have fewer employers spread across greater distances.

Benefits of Work-Based Learning

Well-planned WBL programs benefit all participants in multiple ways.

Benefits to students:

- Build relationships with adult role models other than families, friends, and teachers.

- Acquire experience and workplace skills.

- Set and pursue individual career goals based on workplace experiences.

- Engage parents in career planning.

- Get a “foot in the door” for possible future part-time, summer, or eventual full-time jobs.

- Become aware of career opportunities, explore those of interest, and start preparing for them.

- Build understanding of skills required to succeed in the workplace.

- Recognize the relevance of education to career success and increase motivation for academic success.

Benefits to schools:

- Build relationships with the community.

- Make classroom learning more relevant.

- Enable students to share their experiences with peers and teachers.

- Provide staff development opportunities.

- Increase staff understanding of the workplaces for which they are preparing students.

- Expand curricula by using workplaces as learning environments.

Benefits to employers:

- Build positive relationships with school staff and students.

- Help create a pool of better-prepared and motivated potential employees.

- Strengthen employees’ supervisory and leadership skills.

- Improve employee retention and morale.

- Learn about the knowledge and skills of today’s students and tomorrow’s employees.

- Generate favorable visibility in the community.

- Derive value from student work.

- Make contacts with potential candidates for part-time, summer, or eventual full-time jobs.

Work-Based Learning Continuum

The WBL continuum is a sequence of activities that starts with low-intensity experiences that begin to engage students in thinking about careers and gradually progresses into more in-depth, intensive experiences that include opportunities for hands-on learning. WBL also includes expanding teachers’ knowledge of the employers in their region and the careers that might be available to their students.

Career awareness activities help students learn about a variety of careers, the education and training required for those careers, and the typical pathways for career entry and advancement. Career awareness activities expose students to a wide range of occupations in the private, public, and non-profit sectors.

Career awareness activities generally have the following characteristics:

- Industry or community partners provide a learning experience for students, usually in groups.

- The activity is designed and shaped by educators and employer partners to broaden students’ knowledge by introducing a wide range of careers and occupations.

- The activity provides information about the types of careers available, the people in them and what they do, and the education and training required for those careers.

- Students learn about appropriate workplace behaviors.

- Students have opportunities to reflect on what they have learned and begin to identify interests for further exploration.

- Students in the middle and high school grades may all benefit from career awareness activities, providing they are tailored to the specific grade level.

Career awareness activities might include:

- Guest speakers (Chapter 2)

- Workplace tours (Chapter 3)

- College and career fairs (Chapter 4)

Career exploration activities help students learn about the skills needed for specific careers by observing and interacting with employees in the workplace. As a next step after career awareness, career exploration activities are usually more focused on specific careers in which students are interested.

Career exploration activities generally have the following characteristics:

- Students interact one-on-one with employees in a specific industry or occupation.

- They are usually one-time or one-day events.

- Students play active roles in selecting and shaping the activities, based on their individual interests.

- Students have opportunities for deeper analysis and reflection to help refine their choices about future education and training.

- They are best suited to high school students.

Career exploration activities might include:

- Informational interviews (Chapter 5)

- Job shadows (Chapter 6)

Career preparation activities integrate career and academic skills acquired in the classroom with skills and knowledge acquired in the workplace. The emphasis is on building employability and work readiness skills and on understanding applications of school-based learning to specific careers. Many students use these activities to help make decisions about future education and training options.

Career preparation activities generally have the following characteristics:

- They build on the interests developed in career awareness and exploration activities by providing more in-depth, hands-on experiences.

- Students interact one-on-one with employees in a specific occupation or industry over an extended period of time.

- Students engage in activities that have career development value beyond success in school.

- Both students and employers benefit from the experience.

- Student performance is evaluated by employers.

- The activities are connected to the academic and career/technical curricula.

- They are of sufficient duration and depth to enable students to develop and demonstrate specific knowledge and skills and to make further education and career planning decisions.

- They are applicable to multiple postsecondary education and career options.

- They are most suitable for high school students, typically in the 10 th to 12 th grades, because they help inform both short- and longer-term decisions about career choice, course selection, and planning for postsecondary education.

Student internships are the only career preparation activity addressed in this manual (Chapter 7). There are several other types of learning-by-doing career preparation activities, which are not addressed in this manual. Users may wish to investigate alternatives such as school-based enterprises (e.g., student-run businesses), service learning (e.g., using volunteer projects as simulated workplaces), or cooperative education (e.g., combining part-time or alternating periods of school and work). These options are beyond the scope of this manual and offer quite similar experiences to the internships addressed in Chapter 7.

Work-based learning for teachers: Students and employers are not the only ones who can benefit from WBL. Participating in WBL activities can improve teachers’, counselors’, and administrators’ capacity to guide students’ career development work by bringing actual work experiences into classrooms, counseling settings, and the larger school community. WBL for teachers, for example, can be used for curriculum development and for integrating work-related concepts and experiences into instruction.

Teacher WBL activities generally have the following characteristics:

- They expand teachers’ knowledge of the careers in which their students are interested.

- They familiarize teachers with the skills and education required for specific careers.

- They connect teachers with employers for either short-term or extended interactions in the workplace.

- They include opportunities for teachers to reflect on their experiences and determine how they will apply what they learn in their classrooms.

- Sometimes they enable participating teachers to earn continuing education or graduate credits.

Teacher WBL activities may include:

- Teacher workplace tours (Chapter 8)

- Teacher externships (Chapter 9)

1.4.1 Skills Developed Through Work-Based Learning

One of the purposes of WBL is to help students develop skills and behaviors that are essential to success in every workplace. The following chart presents a typology of workplace skills. It is reprinted, with permission, from A Work-Based Learning Strategy: Career Practicum by ConnectEd: The California Center for College and Careers. Many states and school districts have incorporated versions of these workplace skills into their standards for learning.

When implementing WBL activities, it is important to build in opportunities for students to develop these skills and to work with employer partners to ensure that they address them in their work with students.

How to Develop a Work-Based Learning Plan

A robust WBL program has many moving parts: scheduling multiple WBL activities for students from multiple schools; recruiting employers to participate in multiple WBL activities; coordinating with school schedules; matching up students with employers according to students’ career interests and employer expectations; managing the logistical details of WBL activity implementation; ensuring that both students and employers are well-prepared for each WBL activity, providing for post-activity reflection and evaluation; and capturing lessons learned from implementation that can be used for continuous improvement. Without a good overall plan, too many critical tasks can slip through the cracks, it is harder for school staff to integrate WBL activities into the classroom curriculum, and employers could be bombarded with multiple, fragmented – and eventually unwelcome – requests for participation in WBL activities. While the how-to description below is designed to help districts and schools of all sizes, a more abbreviated approach may be more suitable in smaller, more rural regions.

The WBL coordinator (and other district or school staff) should begin by convening key stakeholders to develop a comprehensive WBL plan that will:

- Provide a framework and context for all WBL activities.

- Engage key education and employer stakeholders to gain their support and ensure that WBL activities can be carried out efficiently and effectively. (See Sections 1.6.1 and 1.6.2 for more on managing stakeholders generally and engaging employers in particular.)

- Lay out a schedule of which WBL activities will be implemented for which students/schools at what point in the year.

- Identify resources (human and financial) that will be needed and how they will be obtained.

- Set priorities for making the inevitable trade-offs required by resource limitations.

- Define roles and responsibilities for those involved in implementation.

- Define how WBL activities will complement classroom curricula and be integrated into academic learning.

In addition to serving as a framework for organizing the work of WBL coordinators and other district or school staff, the WBL planning process is an opportunity to enlist the support of those most critical to implementation of individual WBL activities. The plan will also define the costs associated with specific WBL activities (typically transportation to workplaces, substitute teachers, facility and food costs for career/college fairs, and staffing to provide support and supervision for activities that are implemented in the summer) with enough lead time to enable staff to develop strategies for securing the necessary budget resources. The planning process also provides a context for setting overall WBL priorities for a district or school.

There may already be a WBL plan in place; in that case, the WBL coordinator should determine how it should be updated, strengthened, or otherwise revised. If a plan is in place, staff should identify employers that have participated in WBL activities in the past and assess the nature and quality of their previous involvement. Key stakeholders should be involved in any revisions so that their support for the plan is assured. WBL coordinators may find it necessary to meet immediate demands for WBL activities concurrently with developing a more comprehensive plan.

The first step in developing a WBL plan is to recruit a committee of stakeholders to engage as partners in the planning process. The following stakeholder partners are critical:

- District and school administrators (including career and technical education [CTE] administrators)

- Major employers and employer associations (e.g., chambers of commerce)

- Relevant local, regional, and state agencies (e.g., workforce development boards [1] , economic development agencies, and state departments of labor and/or commerce)

- Career advisors

- College representatives [2]

Parents and students (and perhaps young alumni) should also be involved in the planning process, but it may make more sense to obtain their perspectives through focus groups early in the process rather than to ask them to attend a series of meetings where only parts of the discussion will be of interest.

Recruitment of employer representatives should be focused on individuals who can provide a broad range of diverse employer perspectives and can devote the necessary time. Certainly, the largest employers in the region should be asked to participate, but recruitment of employer representatives should probably focus on employer associations like chambers of commerce, other industry or trade associations (e.g., manufacturers association or home builders association) and service clubs (e.g., Rotary, Kiwanis, and Lions). These associations and clubs can provide their members’ perspectives, and they also can be valuable partners for recruiting their members to participate in WBL activities. Representatives from local governments, regional workforce development boards, economic development agencies, non-profit organizations, and state departments of labor or commerce can also offer knowledge and expertise to the planning process. There may be smaller employers that are willing to engage in the planning process, but staff should try to limit the inconvenience of doing so; it might be easier for them to meet once (or have a telephone conversation/interview) with a staff member to provide their perspectives on the WBL plan than to attend a series of meetings.

The WBL coordinator should design the planning process in such a way that there are as few meetings as possible, and most of the work is done by staff between meetings. For example, a kick-off meeting might be devoted to introducing WBL objectives and activities, reviewing any previous WBL activities in the district, describing how WBL activities benefit all participants, and asking each partner to share perspectives on the value of WBL and the practical considerations the plan should address. A second meeting might be scheduled to review a staff-prepared draft plan and identify gaps or any revisions that might be needed. This draft plan could be circulated more widely to enable other stakeholders, such as principals, to comment before the plan is finalized. A third and final meeting would approve the plan and focus on how each partner can help in implementation.

The WBL coordinator should determine what will be the most useful format for a WBL plan. It may be as simple as a calendar with a weekly or monthly listing of which WBL activities are planned for which students and which employers. A more elaborate narrative document might be useful in building awareness of WBL and in recruiting employers for specific WBL activities, but it is not essential that such information be in the plan itself.

A summary of the plan should be made widely available to as many stakeholders as possible so that they know what to expect. It may also be used as a tool for engaging media interest in WBL.

[1] Workforce development boards (WDBs), sometimes called workforce boards or workforce investment boards (WIBs), coordinate workforce development resources at the state, regional, and/or local levels, develop strategic plans, and establish funding priorities. More than 50 percent of each WDB’s members must come from the business community. For further information, visit the National Association of Workforce Boards at www.nawb.org .

[2] When used in this manual, the term college includes two- and four-year colleges and universities, technical schools, certificate or licensure programs, and apprenticeships.

How to Implement Work-Based Learning Activities

There is no single right way to implement WBL activities, and the responsibility for doing so may rest with a variety of individuals. This manual is intended to help anyone responsible for implementing a WBL program: counselors; career advisors; school administrators; teachers; or other district and school staff members. The term WBL coordinator is used throughout the manual to refer to the individual responsible for coordinating a WBL activity and serving as a single point of contact for employers. Typically, the WBL coordinator acts as a liaison between employers and educators and ensures that each aspect of the WBL activity is implemented successfully. Depending on the specific WBL activity and context, school site responsibilities may rest with counselors, career advisors, teachers, or administrators.

When introducing WBL activities to a community or region, it is wise to start with those that are easiest to implement successfully—particularly those in which employers are most likely to participate. A good strategy might be to start with WBL activities like guest speakers, workplace tours, or informational interviews that afford employers the opportunity to interact with students with minimal risk and a very modest commitment of time. Positive early experiences may lead to employer willingness to engage in WBL activities requiring a higher level of engagement, such as job shadows or internships.

The key stakeholders required for implementing WBL activities may include (and will almost always include those marked with an asterisk):

- *District and school administrators

- *Career advisors

- *Counselors

- *Local or regional CTE staff

- College representatives

- Employer associations such as chambers of commerce, other industry or trade associations, service clubs, and economic development organizations

- Regional workforce development boards

- State departments of labor or commerce

Implementation of a specific WBL activity usually includes the following steps:

- Identify the stakeholders needed to assist with the specific WBL activity.

- Collect information on students’ career interests to help target employer recruitment.

- Recruit stakeholders to participate in the WBL activity. This step can take substantial time; an early start will help significantly.

- Keep all participating stakeholders informed at each stage of implementation.

- For WBL activities that take place in the summer (e.g., student internships and teacher externships), the district or school may need to budget for related staffing and logistical costs and ensure appropriate staffing throughout implementation.

- Prepare students, employers, and other participants for the WBL activity. Ensure that everyone involved understands – and accepts – his or her responsibilities.

- Carry out the WBL activity. Document it with photos, attendance lists, or other appropriate means.

- Provide structured opportunities for students to reflect on what they learned and how they can apply it to subsequent career development and academic work.

- Obtain evaluations of the WBL activity from students and employers; these should be used for continuous improvement of the WBL program.

- Extend thanks and provide recognition to participating stakeholders, especially employers.

More detailed information, including suggestions for implementation, time lines, and resource materials can be found in each WBL activity chapter.

1.6.1 Managing Stakeholders

When implementing WBL activities, each stakeholder needs to understand the purpose of the activity, the benefits of participating, his or her specific role, the time line for implementation, and the resources that will support implementation. This means that the WBL coordinator will need to keep track of every interaction with each stakeholder to make sure that the right information gets to the right party at the right time. Efficient tracking of stakeholder contacts and the roles and responsibilities each assumes are crucial to success. A WBL database that tracks school staff and employer contacts will prove to be a vital asset for managing WBL activities. A sample WBL database template is provided in the Resources section of this introduction.

The WBL database should be created by the district or school staff member who will be responsible for entering and managing the information; frequent and consistent updating will be required. The WBL database not only tracks specific contact information and tasks related to individual WBL activities; it can also be used to track participation of schools and employers over time. As more WBL activities are implemented and staff changes occur, new staff members can use the database to ensure consistency and continuity.

The WBL database should be designed to be accessible to the WBL coordinator and other stakeholders such as school-based staff, who may need access to carry out their responsibilities. This can be accomplished by saving the document to an intranet or by using online services or “cloud” tools.

1.6.2 Employer Engagement and Communication

Engaging a wide range of employers in multiple WBL activities every year is critical to the very existence of WBL programs, let alone their success. WBL coordinators have no more important task, and they probably do not have a more challenging one. The more effectively coordinators engage with employers from the outset, the easier it becomes to plan and implement the full range of WBL activities.