Random Assignment in Psychology (Definition + 40 Examples)

Have you ever wondered how researchers discover new ways to help people learn, make decisions, or overcome challenges? A hidden hero in this adventure of discovery is a method called random assignment, a cornerstone in psychological research that helps scientists uncover the truths about the human mind and behavior.

Random Assignment is a process used in research where each participant has an equal chance of being placed in any group within the study. This technique is essential in experiments as it helps to eliminate biases, ensuring that the different groups being compared are similar in all important aspects.

By doing so, researchers can be confident that any differences observed are likely due to the variable being tested, rather than other factors.

In this article, we’ll explore the intriguing world of random assignment, diving into its history, principles, real-world examples, and the impact it has had on the field of psychology.

History of Random Assignment

Stepping back in time, we delve into the origins of random assignment, which finds its roots in the early 20th century.

The pioneering mind behind this innovative technique was Sir Ronald A. Fisher , a British statistician and biologist. Fisher introduced the concept of random assignment in the 1920s, aiming to improve the quality and reliability of experimental research .

His contributions laid the groundwork for the method's evolution and its widespread adoption in various fields, particularly in psychology.

Fisher’s groundbreaking work on random assignment was motivated by his desire to control for confounding variables – those pesky factors that could muddy the waters of research findings.

By assigning participants to different groups purely by chance, he realized that the influence of these confounding variables could be minimized, paving the way for more accurate and trustworthy results.

Early Studies Utilizing Random Assignment

Following Fisher's initial development, random assignment started to gain traction in the research community. Early studies adopting this methodology focused on a variety of topics, from agriculture (which was Fisher’s primary field of interest) to medicine and psychology.

The approach allowed researchers to draw stronger conclusions from their experiments, bolstering the development of new theories and practices.

One notable early study utilizing random assignment was conducted in the field of educational psychology. Researchers were keen to understand the impact of different teaching methods on student outcomes.

By randomly assigning students to various instructional approaches, they were able to isolate the effects of the teaching methods, leading to valuable insights and recommendations for educators.

Evolution of the Methodology

As the decades rolled on, random assignment continued to evolve and adapt to the changing landscape of research.

Advances in technology introduced new tools and techniques for implementing randomization, such as computerized random number generators, which offered greater precision and ease of use.

The application of random assignment expanded beyond the confines of the laboratory, finding its way into field studies and large-scale surveys.

Researchers across diverse disciplines embraced the methodology, recognizing its potential to enhance the validity of their findings and contribute to the advancement of knowledge.

From its humble beginnings in the early 20th century to its widespread use today, random assignment has proven to be a cornerstone of scientific inquiry.

Its development and evolution have played a pivotal role in shaping the landscape of psychological research, driving discoveries that have improved lives and deepened our understanding of the human experience.

Principles of Random Assignment

Delving into the heart of random assignment, we uncover the theories and principles that form its foundation.

The method is steeped in the basics of probability theory and statistical inference, ensuring that each participant has an equal chance of being placed in any group, thus fostering fair and unbiased results.

Basic Principles of Random Assignment

Understanding the core principles of random assignment is key to grasping its significance in research. There are three principles: equal probability of selection, reduction of bias, and ensuring representativeness.

The first principle, equal probability of selection , ensures that every participant has an identical chance of being assigned to any group in the study. This randomness is crucial as it mitigates the risk of bias and establishes a level playing field.

The second principle focuses on the reduction of bias . Random assignment acts as a safeguard, ensuring that the groups being compared are alike in all essential aspects before the experiment begins.

This similarity between groups allows researchers to attribute any differences observed in the outcomes directly to the independent variable being studied.

Lastly, ensuring representativeness is a vital principle. When participants are assigned randomly, the resulting groups are more likely to be representative of the larger population.

This characteristic is crucial for the generalizability of the study’s findings, allowing researchers to apply their insights broadly.

Theoretical Foundation

The theoretical foundation of random assignment lies in probability theory and statistical inference .

Probability theory deals with the likelihood of different outcomes, providing a mathematical framework for analyzing random phenomena. In the context of random assignment, it helps in ensuring that each participant has an equal chance of being placed in any group.

Statistical inference, on the other hand, allows researchers to draw conclusions about a population based on a sample of data drawn from that population. It is the mechanism through which the results of a study can be generalized to a broader context.

Random assignment enhances the reliability of statistical inferences by reducing biases and ensuring that the sample is representative.

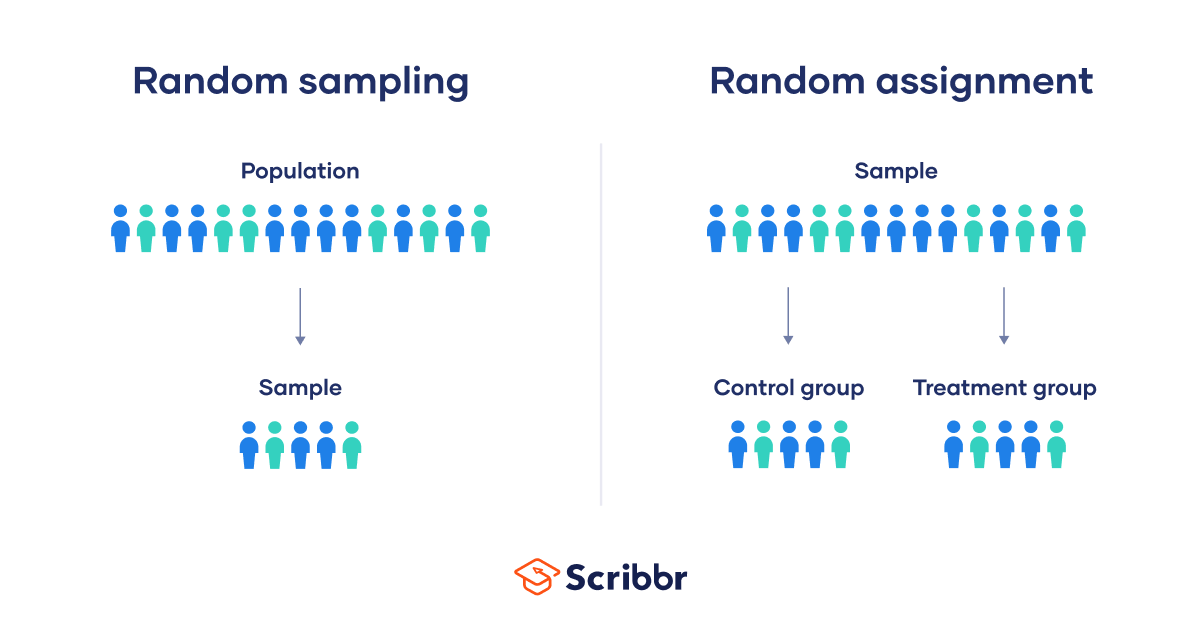

Differentiating Random Assignment from Random Selection

It’s essential to distinguish between random assignment and random selection, as the two terms, while related, have distinct meanings in the realm of research.

Random assignment refers to how participants are placed into different groups in an experiment, aiming to control for confounding variables and help determine causes.

In contrast, random selection pertains to how individuals are chosen to participate in a study. This method is used to ensure that the sample of participants is representative of the larger population, which is vital for the external validity of the research.

While both methods are rooted in randomness and probability, they serve different purposes in the research process.

Understanding the theories, principles, and distinctions of random assignment illuminates its pivotal role in psychological research.

This method, anchored in probability theory and statistical inference, serves as a beacon of reliability, guiding researchers in their quest for knowledge and ensuring that their findings stand the test of validity and applicability.

Methodology of Random Assignment

Implementing random assignment in a study is a meticulous process that involves several crucial steps.

The initial step is participant selection, where individuals are chosen to partake in the study. This stage is critical to ensure that the pool of participants is diverse and representative of the population the study aims to generalize to.

Once the pool of participants has been established, the actual assignment process begins. In this step, each participant is allocated randomly to one of the groups in the study.

Researchers use various tools, such as random number generators or computerized methods, to ensure that this assignment is genuinely random and free from biases.

Monitoring and adjusting form the final step in the implementation of random assignment. Researchers need to continuously observe the groups to ensure that they remain comparable in all essential aspects throughout the study.

If any significant discrepancies arise, adjustments might be necessary to maintain the study’s integrity and validity.

Tools and Techniques Used

The evolution of technology has introduced a variety of tools and techniques to facilitate random assignment.

Random number generators, both manual and computerized, are commonly used to assign participants to different groups. These generators ensure that each individual has an equal chance of being placed in any group, upholding the principle of equal probability of selection.

In addition to random number generators, researchers often use specialized computer software designed for statistical analysis and experimental design.

These software programs offer advanced features that allow for precise and efficient random assignment, minimizing the risk of human error and enhancing the study’s reliability.

Ethical Considerations

The implementation of random assignment is not devoid of ethical considerations. Informed consent is a fundamental ethical principle that researchers must uphold.

Informed consent means that every participant should be fully informed about the nature of the study, the procedures involved, and any potential risks or benefits, ensuring that they voluntarily agree to participate.

Beyond informed consent, researchers must conduct a thorough risk and benefit analysis. The potential benefits of the study should outweigh any risks or harms to the participants.

Safeguarding the well-being of participants is paramount, and any study employing random assignment must adhere to established ethical guidelines and standards.

Conclusion of Methodology

The methodology of random assignment, while seemingly straightforward, is a multifaceted process that demands precision, fairness, and ethical integrity. From participant selection to assignment and monitoring, each step is crucial to ensure the validity of the study’s findings.

The tools and techniques employed, coupled with a steadfast commitment to ethical principles, underscore the significance of random assignment as a cornerstone of robust psychological research.

Benefits of Random Assignment in Psychological Research

The impact and importance of random assignment in psychological research cannot be overstated. It is fundamental for ensuring the study is accurate, allowing the researchers to determine if their study actually caused the results they saw, and making sure the findings can be applied to the real world.

Facilitating Causal Inferences

When participants are randomly assigned to different groups, researchers can be more confident that the observed effects are due to the independent variable being changed, and not other factors.

This ability to determine the cause is called causal inference .

This confidence allows for the drawing of causal relationships, which are foundational for theory development and application in psychology.

Ensuring Internal Validity

One of the foremost impacts of random assignment is its ability to enhance the internal validity of an experiment.

Internal validity refers to the extent to which a researcher can assert that changes in the dependent variable are solely due to manipulations of the independent variable , and not due to confounding variables.

By ensuring that each participant has an equal chance of being in any condition of the experiment, random assignment helps control for participant characteristics that could otherwise complicate the results.

Enhancing Generalizability

Beyond internal validity, random assignment also plays a crucial role in enhancing the generalizability of research findings.

When done correctly, it ensures that the sample groups are representative of the larger population, so can allow researchers to apply their findings more broadly.

This representative nature is essential for the practical application of research, impacting policy, interventions, and psychological therapies.

Limitations of Random Assignment

Potential for implementation issues.

While the principles of random assignment are robust, the method can face implementation issues.

One of the most common problems is logistical constraints. Some studies, due to their nature or the specific population being studied, find it challenging to implement random assignment effectively.

For instance, in educational settings, logistical issues such as class schedules and school policies might stop the random allocation of students to different teaching methods .

Ethical Dilemmas

Random assignment, while methodologically sound, can also present ethical dilemmas.

In some cases, withholding a potentially beneficial treatment from one of the groups of participants can raise serious ethical questions, especially in medical or clinical research where participants' well-being might be directly affected.

Researchers must navigate these ethical waters carefully, balancing the pursuit of knowledge with the well-being of participants.

Generalizability Concerns

Even when implemented correctly, random assignment does not always guarantee generalizable results.

The types of people in the participant pool, the specific context of the study, and the nature of the variables being studied can all influence the extent to which the findings can be applied to the broader population.

Researchers must be cautious in making broad generalizations from studies, even those employing strict random assignment.

Practical and Real-World Limitations

In the real world, many variables cannot be manipulated for ethical or practical reasons, limiting the applicability of random assignment.

For instance, researchers cannot randomly assign individuals to different levels of intelligence, socioeconomic status, or cultural backgrounds.

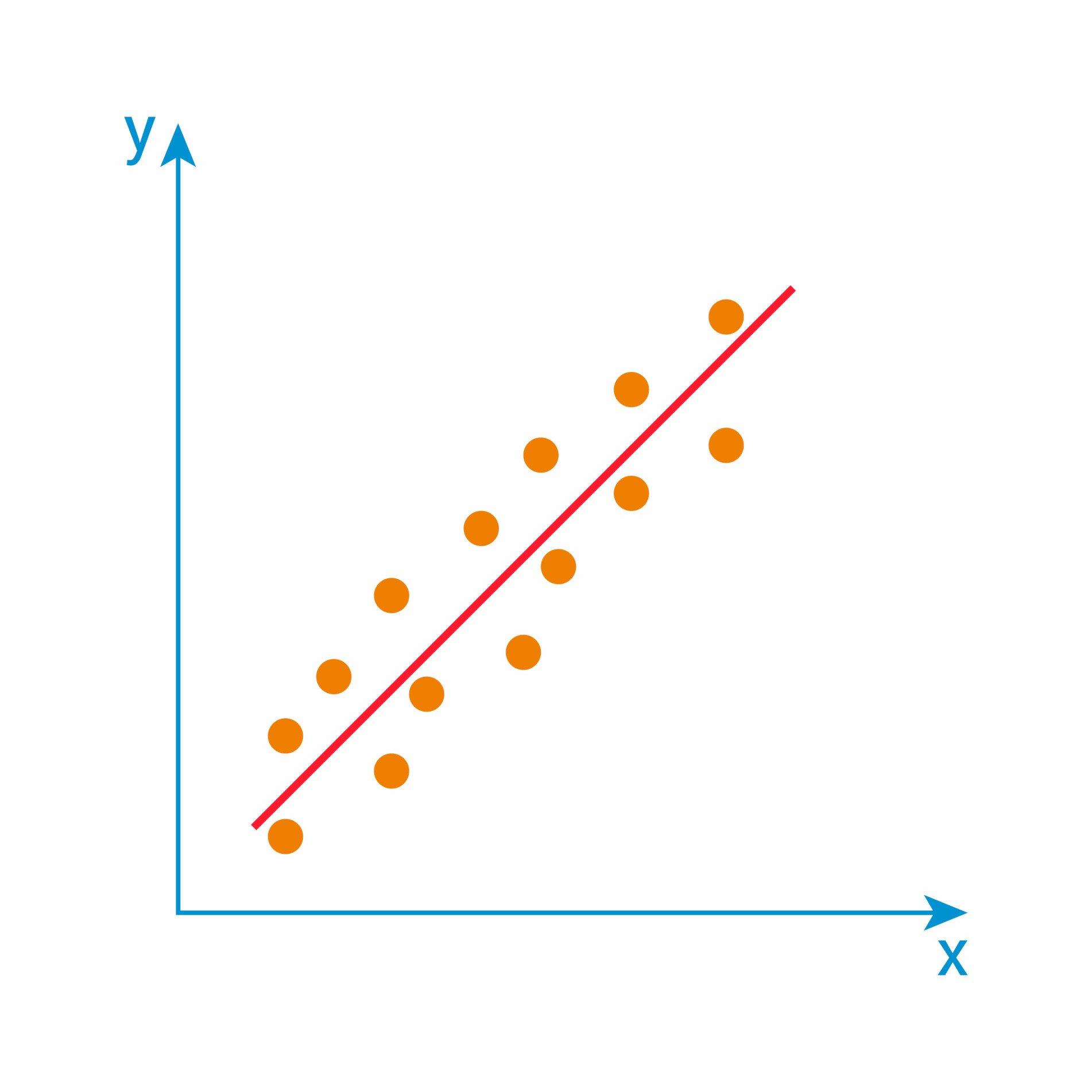

This limitation necessitates the use of other research designs, such as correlational or observational studies , when exploring relationships involving such variables.

Response to Critiques

In response to these critiques, people in favor of random assignment argue that the method, despite its limitations, remains one of the most reliable ways to establish cause and effect in experimental research.

They acknowledge the challenges and ethical considerations but emphasize the rigorous frameworks in place to address them.

The ongoing discussion around the limitations and critiques of random assignment contributes to the evolution of the method, making sure it is continuously relevant and applicable in psychological research.

While random assignment is a powerful tool in experimental research, it is not without its critiques and limitations. Implementation issues, ethical dilemmas, generalizability concerns, and real-world limitations can pose significant challenges.

However, the continued discourse and refinement around these issues underline the method's enduring significance in the pursuit of knowledge in psychology.

By being careful with how we do things and doing what's right, random assignment stays a really important part of studying how people act and think.

Real-World Applications and Examples

Random assignment has been employed in many studies across various fields of psychology, leading to significant discoveries and advancements.

Here are some real-world applications and examples illustrating the diversity and impact of this method:

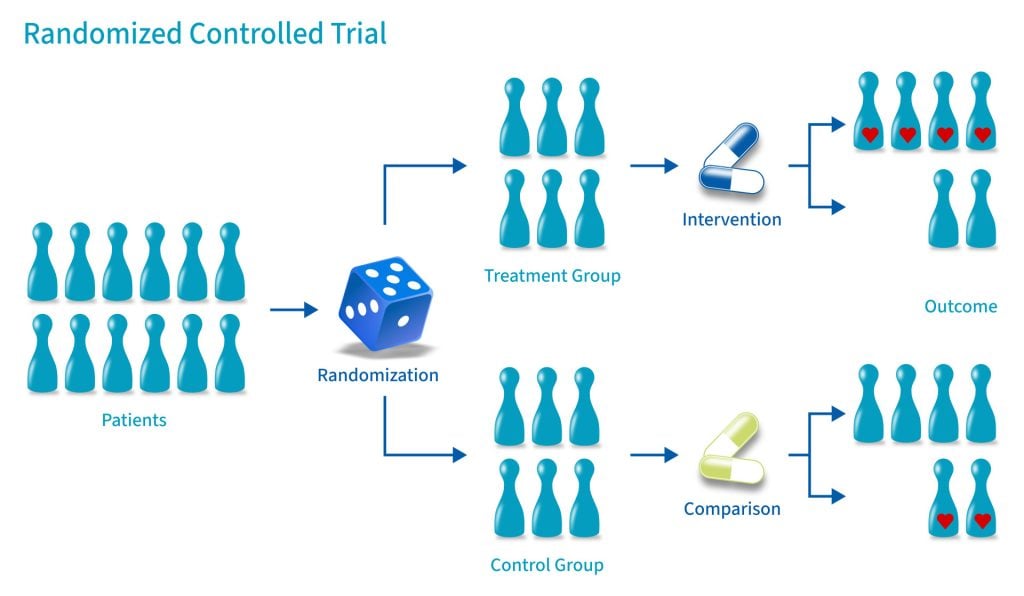

- Medicine and Health Psychology: Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) are the gold standard in medical research. In these studies, participants are randomly assigned to either the treatment or control group to test the efficacy of new medications or interventions.

- Educational Psychology: Studies in this field have used random assignment to explore the effects of different teaching methods, classroom environments, and educational technologies on student learning and outcomes.

- Cognitive Psychology: Researchers have employed random assignment to investigate various aspects of human cognition, including memory, attention, and problem-solving, leading to a deeper understanding of how the mind works.

- Social Psychology: Random assignment has been instrumental in studying social phenomena, such as conformity, aggression, and prosocial behavior, shedding light on the intricate dynamics of human interaction.

Let's get into some specific examples. You'll need to know one term though, and that is "control group." A control group is a set of participants in a study who do not receive the treatment or intervention being tested , serving as a baseline to compare with the group that does, in order to assess the effectiveness of the treatment.

- Smoking Cessation Study: Researchers used random assignment to put participants into two groups. One group received a new anti-smoking program, while the other did not. This helped determine if the program was effective in helping people quit smoking.

- Math Tutoring Program: A study on students used random assignment to place them into two groups. One group received additional math tutoring, while the other continued with regular classes, to see if the extra help improved their grades.

- Exercise and Mental Health: Adults were randomly assigned to either an exercise group or a control group to study the impact of physical activity on mental health and mood.

- Diet and Weight Loss: A study randomly assigned participants to different diet plans to compare their effectiveness in promoting weight loss and improving health markers.

- Sleep and Learning: Researchers randomly assigned students to either a sleep extension group or a regular sleep group to study the impact of sleep on learning and memory.

- Classroom Seating Arrangement: Teachers used random assignment to place students in different seating arrangements to examine the effect on focus and academic performance.

- Music and Productivity: Employees were randomly assigned to listen to music or work in silence to investigate the effect of music on workplace productivity.

- Medication for ADHD: Children with ADHD were randomly assigned to receive either medication, behavioral therapy, or a placebo to compare treatment effectiveness.

- Mindfulness Meditation for Stress: Adults were randomly assigned to a mindfulness meditation group or a waitlist control group to study the impact on stress levels.

- Video Games and Aggression: A study randomly assigned participants to play either violent or non-violent video games and then measured their aggression levels.

- Online Learning Platforms: Students were randomly assigned to use different online learning platforms to evaluate their effectiveness in enhancing learning outcomes.

- Hand Sanitizers in Schools: Schools were randomly assigned to use hand sanitizers or not to study the impact on student illness and absenteeism.

- Caffeine and Alertness: Participants were randomly assigned to consume caffeinated or decaffeinated beverages to measure the effects on alertness and cognitive performance.

- Green Spaces and Well-being: Neighborhoods were randomly assigned to receive green space interventions to study the impact on residents’ well-being and community connections.

- Pet Therapy for Hospital Patients: Patients were randomly assigned to receive pet therapy or standard care to assess the impact on recovery and mood.

- Yoga for Chronic Pain: Individuals with chronic pain were randomly assigned to a yoga intervention group or a control group to study the effect on pain levels and quality of life.

- Flu Vaccines Effectiveness: Different groups of people were randomly assigned to receive either the flu vaccine or a placebo to determine the vaccine’s effectiveness.

- Reading Strategies for Dyslexia: Children with dyslexia were randomly assigned to different reading intervention strategies to compare their effectiveness.

- Physical Environment and Creativity: Participants were randomly assigned to different room setups to study the impact of physical environment on creative thinking.

- Laughter Therapy for Depression: Individuals with depression were randomly assigned to laughter therapy sessions or control groups to assess the impact on mood.

- Financial Incentives for Exercise: Participants were randomly assigned to receive financial incentives for exercising to study the impact on physical activity levels.

- Art Therapy for Anxiety: Individuals with anxiety were randomly assigned to art therapy sessions or a waitlist control group to measure the effect on anxiety levels.

- Natural Light in Offices: Employees were randomly assigned to workspaces with natural or artificial light to study the impact on productivity and job satisfaction.

- School Start Times and Academic Performance: Schools were randomly assigned different start times to study the effect on student academic performance and well-being.

- Horticulture Therapy for Seniors: Older adults were randomly assigned to participate in horticulture therapy or traditional activities to study the impact on cognitive function and life satisfaction.

- Hydration and Cognitive Function: Participants were randomly assigned to different hydration levels to measure the impact on cognitive function and alertness.

- Intergenerational Programs: Seniors and young people were randomly assigned to intergenerational programs to study the effects on well-being and cross-generational understanding.

- Therapeutic Horseback Riding for Autism: Children with autism were randomly assigned to therapeutic horseback riding or traditional therapy to study the impact on social communication skills.

- Active Commuting and Health: Employees were randomly assigned to active commuting (cycling, walking) or passive commuting to study the effect on physical health.

- Mindful Eating for Weight Management: Individuals were randomly assigned to mindful eating workshops or control groups to study the impact on weight management and eating habits.

- Noise Levels and Learning: Students were randomly assigned to classrooms with different noise levels to study the effect on learning and concentration.

- Bilingual Education Methods: Schools were randomly assigned different bilingual education methods to compare their effectiveness in language acquisition.

- Outdoor Play and Child Development: Children were randomly assigned to different amounts of outdoor playtime to study the impact on physical and cognitive development.

- Social Media Detox: Participants were randomly assigned to a social media detox or regular usage to study the impact on mental health and well-being.

- Therapeutic Writing for Trauma Survivors: Individuals who experienced trauma were randomly assigned to therapeutic writing sessions or control groups to study the impact on psychological well-being.

- Mentoring Programs for At-risk Youth: At-risk youth were randomly assigned to mentoring programs or control groups to assess the impact on academic achievement and behavior.

- Dance Therapy for Parkinson’s Disease: Individuals with Parkinson’s disease were randomly assigned to dance therapy or traditional exercise to study the effect on motor function and quality of life.

- Aquaponics in Schools: Schools were randomly assigned to implement aquaponics programs to study the impact on student engagement and environmental awareness.

- Virtual Reality for Phobia Treatment: Individuals with phobias were randomly assigned to virtual reality exposure therapy or traditional therapy to compare effectiveness.

- Gardening and Mental Health: Participants were randomly assigned to engage in gardening or other leisure activities to study the impact on mental health and stress reduction.

Each of these studies exemplifies how random assignment is utilized in various fields and settings, shedding light on the multitude of ways it can be applied to glean valuable insights and knowledge.

Real-world Impact of Random Assignment

Random assignment is like a key tool in the world of learning about people's minds and behaviors. It’s super important and helps in many different areas of our everyday lives. It helps make better rules, creates new ways to help people, and is used in lots of different fields.

Health and Medicine

In health and medicine, random assignment has helped doctors and scientists make lots of discoveries. It’s a big part of tests that help create new medicines and treatments.

By putting people into different groups by chance, scientists can really see if a medicine works.

This has led to new ways to help people with all sorts of health problems, like diabetes, heart disease, and mental health issues like depression and anxiety.

Schools and education have also learned a lot from random assignment. Researchers have used it to look at different ways of teaching, what kind of classrooms are best, and how technology can help learning.

This knowledge has helped make better school rules, develop what we learn in school, and find the best ways to teach students of all ages and backgrounds.

Workplace and Organizational Behavior

Random assignment helps us understand how people act at work and what makes a workplace good or bad.

Studies have looked at different kinds of workplaces, how bosses should act, and how teams should be put together. This has helped companies make better rules and create places to work that are helpful and make people happy.

Environmental and Social Changes

Random assignment is also used to see how changes in the community and environment affect people. Studies have looked at community projects, changes to the environment, and social programs to see how they help or hurt people’s well-being.

This has led to better community projects, efforts to protect the environment, and programs to help people in society.

Technology and Human Interaction

In our world where technology is always changing, studies with random assignment help us see how tech like social media, virtual reality, and online stuff affect how we act and feel.

This has helped make better and safer technology and rules about using it so that everyone can benefit.

The effects of random assignment go far and wide, way beyond just a science lab. It helps us understand lots of different things, leads to new and improved ways to do things, and really makes a difference in the world around us.

From making healthcare and schools better to creating positive changes in communities and the environment, the real-world impact of random assignment shows just how important it is in helping us learn and make the world a better place.

So, what have we learned? Random assignment is like a super tool in learning about how people think and act. It's like a detective helping us find clues and solve mysteries in many parts of our lives.

From creating new medicines to helping kids learn better in school, and from making workplaces happier to protecting the environment, it’s got a big job!

This method isn’t just something scientists use in labs; it reaches out and touches our everyday lives. It helps make positive changes and teaches us valuable lessons.

Whether we are talking about technology, health, education, or the environment, random assignment is there, working behind the scenes, making things better and safer for all of us.

In the end, the simple act of putting people into groups by chance helps us make big discoveries and improvements. It’s like throwing a small stone into a pond and watching the ripples spread out far and wide.

Thanks to random assignment, we are always learning, growing, and finding new ways to make our world a happier and healthier place for everyone!

Related posts:

- 19+ Experimental Design Examples (Methods + Types)

- Cluster Sampling vs Stratified Sampling

- 41+ White Collar Job Examples (Salary + Path)

- 47+ Blue Collar Job Examples (Salary + Path)

- McDonaldization of Society (Definition + Examples)

Reference this article:

About The Author

Free Personality Test

Free Memory Test

Free IQ Test

PracticalPie.com is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program. As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

Follow Us On:

Youtube Facebook Instagram X/Twitter

Psychology Resources

Developmental

Personality

Relationships

Psychologists

Serial Killers

Psychology Tests

Personality Quiz

Memory Test

Depression test

Type A/B Personality Test

© PracticalPsychology. All rights reserved

Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

What Is Random Assignment in Psychology?

Categories Research Methods

Random assignment means that every participant has the same chance of being chosen for the experimental or control group. It involves using procedures that rely on chance to assign participants to groups. Doing this means that every participant in a study has an equal opportunity to be assigned to any group.

For example, in a psychology experiment, participants might be assigned to either a control or experimental group. Some experiments might only have one experimental group, while others may have several treatment variations.

Using random assignment means that each participant has the same chance of being assigned to any of these groups.

Table of Contents

How to Use Random Assignment

So what type of procedures might psychologists utilize for random assignment? Strategies can include:

- Flipping a coin

- Assigning random numbers

- Rolling dice

- Drawing names out of a hat

How Does Random Assignment Work?

A psychology experiment aims to determine if changes in one variable lead to changes in another variable. Researchers will first begin by coming up with a hypothesis. Once researchers have an idea of what they think they might find in a population, they will come up with an experimental design and then recruit participants for their study.

Once they have a pool of participants representative of the population they are interested in looking at, they will randomly assign the participants to their groups.

- Control group : Some participants will end up in the control group, which serves as a baseline and does not receive the independent variables.

- Experimental group : Other participants will end up in the experimental groups that receive some form of the independent variables.

By using random assignment, the researchers make it more likely that the groups are equal at the start of the experiment. Since the groups are the same on other variables, it can be assumed that any changes that occur are the result of varying the independent variables.

After a treatment has been administered, the researchers will then collect data in order to determine if the independent variable had any impact on the dependent variable.

Random Assignment vs. Random Selection

It is important to remember that random assignment is not the same thing as random selection , also known as random sampling.

Random selection instead involves how people are chosen to be in a study. Using random selection, every member of a population stands an equal chance of being chosen for a study or experiment.

So random sampling affects how participants are chosen for a study, while random assignment affects how participants are then assigned to groups.

Examples of Random Assignment

Imagine that a psychology researcher is conducting an experiment to determine if getting adequate sleep the night before an exam results in better test scores.

Forming a Hypothesis

They hypothesize that participants who get 8 hours of sleep will do better on a math exam than participants who only get 4 hours of sleep.

Obtaining Participants

The researcher starts by obtaining a pool of participants. They find 100 participants from a local university. Half of the participants are female, and half are male.

Randomly Assign Participants to Groups

The researcher then assigns random numbers to each participant and uses a random number generator to randomly assign each number to either the 4-hour or 8-hour sleep groups.

Conduct the Experiment

Those in the 8-hour sleep group agree to sleep for 8 hours that night, while those in the 4-hour group agree to wake up after only 4 hours. The following day, all of the participants meet in a classroom.

Collect and Analyze Data

Everyone takes the same math test. The test scores are then compared to see if the amount of sleep the night before had any impact on test scores.

Why Is Random Assignment Important in Psychology Research?

Random assignment is important in psychology research because it helps improve a study’s internal validity. This means that the researchers are sure that the study demonstrates a cause-and-effect relationship between an independent and dependent variable.

Random assignment improves the internal validity by minimizing the risk that there are systematic differences in the participants who are in each group.

Key Points to Remember About Random Assignment

- Random assignment in psychology involves each participant having an equal chance of being chosen for any of the groups, including the control and experimental groups.

- It helps control for potential confounding variables, reducing the likelihood of pre-existing differences between groups.

- This method enhances the internal validity of experiments, allowing researchers to draw more reliable conclusions about cause-and-effect relationships.

- Random assignment is crucial for creating comparable groups and increasing the scientific rigor of psychological studies.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 6: Data Collection Strategies

6.1.1 Random Assignation

As previously mentioned, one of the characteristics of a true experiment is that researchers use a random process to decide which participants are tested under which conditions. Random assignation is a powerful research technique that addresses the assumption of pre-test equivalence – that the experimental and control group are equal in all respects before the administration of the independent variable (Palys & Atchison, 2014).

Random assignation is the primary way that researchers attempt to control extraneous variables across conditions. Random assignation is associated with experimental research methods. In its strictest sense, random assignment should meet two criteria. One is that each participant has an equal chance of being assigned to each condition (e.g., a 50% chance of being assigned to each of two conditions). The second is that each participant is assigned to a condition independently of other participants. Thus, one way to assign participants to two conditions would be to flip a coin for each one. If the coin lands on the heads side, the participant is assigned to Condition A, and if it lands on the tails side, the participant is assigned to Condition B. For three conditions, one could use a computer to generate a random integer from 1 to 3 for each participant. If the integer is 1, the participant is assigned to Condition A; if it is 2, the participant is assigned to Condition B; and, if it is 3, the participant is assigned to Condition C. In practice, a full sequence of conditions—one for each participant expected to be in the experiment—is usually created ahead of time, and each new participant is assigned to the next condition in the sequence as he or she is tested.

However, one problem with coin flipping and other strict procedures for random assignment is that they are likely to result in unequal sample sizes in the different conditions. Unequal sample sizes are generally not a serious problem, and you should never throw away data you have already collected to achieve equal sample sizes. However, for a fixed number of participants, it is statistically most efficient to divide them into equal-sized groups. It is standard practice, therefore, to use a kind of modified random assignment that keeps the number of participants in each group as similar as possible.

One approach is block randomization. In block randomization, all the conditions occur once in the sequence before any of them is repeated. Then they all occur again before any of them is repeated again. Within each of these “blocks,” the conditions occur in a random order. Again, the sequence of conditions is usually generated before any participants are tested, and each new participant is assigned to the next condition in the sequence. When the procedure is computerized, the computer program often handles the random assignment, which is obviously much easier. You can also find programs online to help you randomize your random assignation. For example, the Research Randomizer website will generate block randomization sequences for any number of participants and conditions ( Research Randomizer ).

Random assignation is not guaranteed to control all extraneous variables across conditions. It is always possible that, just by chance, the participants in one condition might turn out to be substantially older, less tired, more motivated, or less depressed on average than the participants in another condition. However, there are some reasons that this may not be a major concern. One is that random assignment works better than one might expect, especially for large samples. Another is that the inferential statistics that researchers use to decide whether a difference between groups reflects a difference in the population take the “fallibility” of random assignment into account. Yet another reason is that even if random assignment does result in a confounding variable and therefore produces misleading results, this confound is likely to be detected when the experiment is replicated. The upshot is that random assignment to conditions—although not infallible in terms of controlling extraneous variables—is always considered a strength of a research design. Note: Do not confuse random assignation with random sampling. Random sampling is a method for selecting a sample from a population; we will talk about this in Chapter 7.

Research Methods for the Social Sciences: An Introduction Copyright © 2020 by Valerie Sheppard is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

As previously mentioned, one of the characteristics of a true experiment is that researchers use a random process to decide which participants are tested under which conditions. Random assignation is a powerful research technique that addresses the assumption of pre-test equivalence – that the experimental and control group are equal in all respects before the administration of the independent variable (Palys & Atchison, 2014).

Random assignation is the primary way that researchers attempt to control extraneous variables across conditions. Random assignation is associated with experimental research methods. In its strictest sense, random assignment should meet two criteria. One is that each participant has an equal chance of being assigned to each condition (e.g., a 50% chance of being assigned to each of two conditions). The second is that each participant is assigned to a condition independently of other participants. Thus, one way to assign participants to two conditions would be to flip a coin for each one. If the coin lands on the heads side, the participant is assigned to Condition A, and if it lands on the tails side, the participant is assigned to Condition B. For three conditions, one could use a computer to generate a random integer from 1 to 3 for each participant. If the integer is 1, the participant is assigned to Condition A; if it is 2, the participant is assigned to Condition B; and, if it is 3, the participant is assigned to Condition C. In practice, a full sequence of conditions—one for each participant expected to be in the experiment—is usually created ahead of time, and each new participant is assigned to the next condition in the sequence as he or she is tested.

However, one problem with coin flipping and other strict procedures for random assignment is that they are likely to result in unequal sample sizes in the different conditions. Unequal sample sizes are generally not a serious problem, and you should never throw away data you have already collected to achieve equal sample sizes. However, for a fixed number of participants, it is statistically most efficient to divide them into equal-sized groups. It is standard practice, therefore, to use a kind of modified random assignment that keeps the number of participants in each group as similar as possible.

One approach is block randomization. In block randomization, all the conditions occur once in the sequence before any of them is repeated. Then they all occur again before any of them is repeated again. Within each of these “blocks,” the conditions occur in a random order. Again, the sequence of conditions is usually generated before any participants are tested, and each new participant is assigned to the next condition in the sequence. When the procedure is computerized, the computer program often handles the random assignment, which is obviously much easier. You can also find programs online to help you randomize your random assignation. For example, the Research Randomizer website will generate block randomization sequences for any number of participants and conditions ( Research Randomizer ).

Random assignation is not guaranteed to control all extraneous variables across conditions. It is always possible that, just by chance, the participants in one condition might turn out to be substantially older, less tired, more motivated, or less depressed on average than the participants in another condition. However, there are some reasons that this may not be a major concern. One is that random assignment works better than one might expect, especially for large samples. Another is that the inferential statistics that researchers use to decide whether a difference between groups reflects a difference in the population take the “fallibility” of random assignment into account. Yet another reason is that even if random assignment does result in a confounding variable and therefore produces misleading results, this confound is likely to be detected when the experiment is replicated. The upshot is that random assignment to conditions—although not infallible in terms of controlling extraneous variables—is always considered a strength of a research design. Note: Do not confuse random assignation with random sampling. Random sampling is a method for selecting a sample from a population; we will talk about this in Chapter 7.

Research Methods, Data Collection and Ethics Copyright © 2020 by Valerie Sheppard is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

What is a Randomized Control Trial (RCT)?

Julia Simkus

Editor at Simply Psychology

BA (Hons) Psychology, Princeton University

Julia Simkus is a graduate of Princeton University with a Bachelor of Arts in Psychology. She is currently studying for a Master's Degree in Counseling for Mental Health and Wellness in September 2023. Julia's research has been published in peer reviewed journals.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

A randomized control trial (RCT) is a type of study design that involves randomly assigning participants to either an experimental group or a control group to measure the effectiveness of an intervention or treatment.

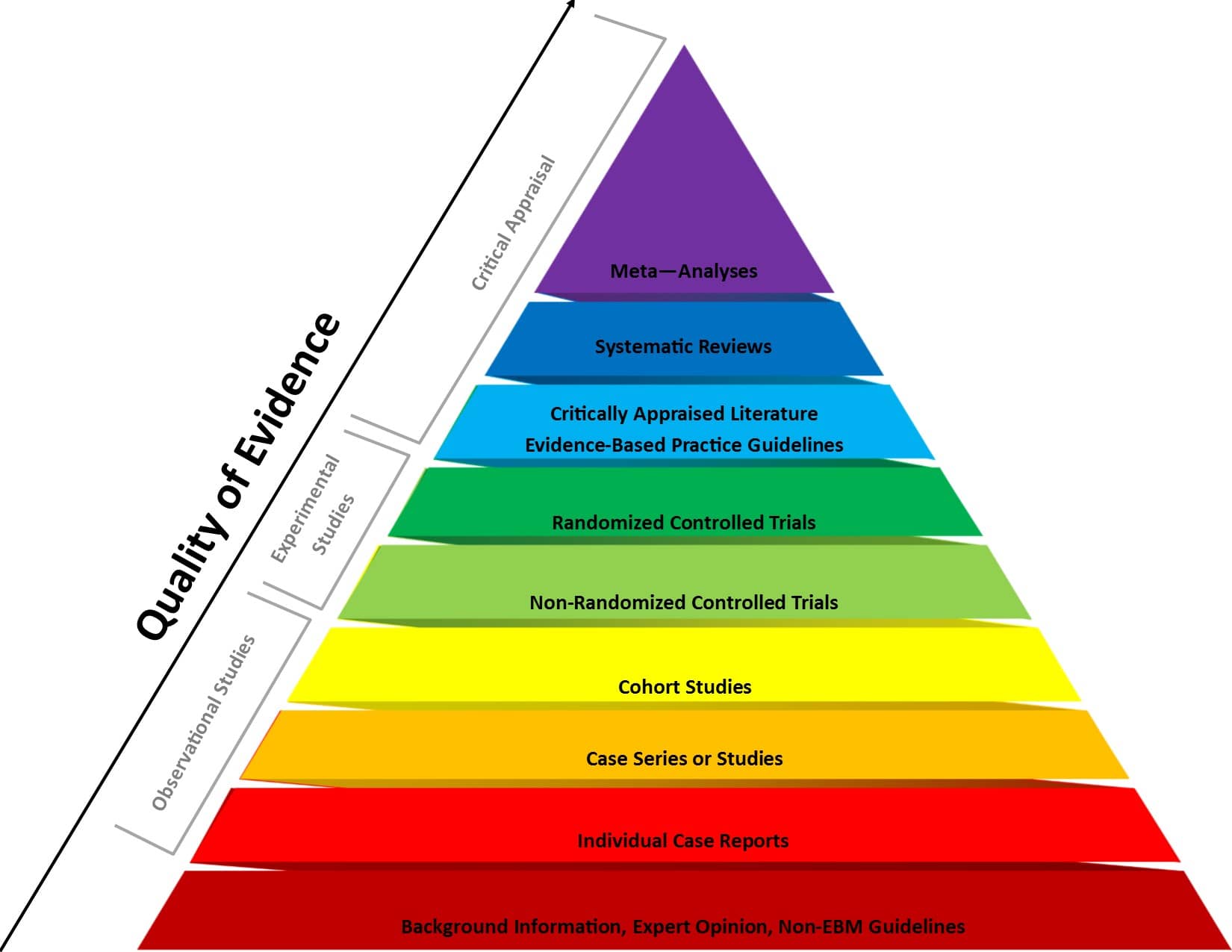

Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) are considered the “gold standard” in medical and health research due to their rigorous design.

Control Group

A control group consists of participants who do not receive any treatment or intervention but a placebo or reference treatment. The control participants serve as a comparison group.

The control group is matched as closely as possible to the experimental group, including age, gender, social class, ethnicity, etc.

Because the participants are randomly assigned, the characteristics between the two groups should be balanced, enabling researchers to attribute any differences in outcome to the study intervention.

Since researchers can be confident that any differences between the control and treatment groups are due solely to the effects of the treatments, scientists view RCTs as the gold standard for clinical trials.

Random Allocation

Random allocation and random assignment are terms used interchangeably in the context of a randomized controlled trial (RCT).

Both refer to assigning participants to different groups in a study (such as a treatment group or a control group) in a way that is completely determined by chance.

The process of random assignment controls for confounding variables , ensuring differences between groups are due to chance alone.

Without randomization, researchers might consciously or subconsciously assign patients to a particular group for various reasons.

Several methods can be used for randomization in a Randomized Control Trial (RCT). Here are a few examples:

- Simple Randomization: This is the simplest method, like flipping a coin. Each participant has an equal chance of being assigned to any group. This can be achieved using random number tables, computerized random number generators, or drawing lots or envelopes.

- Block Randomization: In this method, participants are randomized within blocks, ensuring that each block has an equal number of participants in each group. This helps to balance the number of participants in each group at any given time during the study.

- Stratified Randomization: This method is used when researchers want to ensure that certain subgroups of participants are equally represented in each group. Participants are divided into strata, or subgroups, based on characteristics like age or disease severity, and then randomized within these strata.

- Cluster Randomization: In this method, groups of participants (like families or entire communities), rather than individuals, are randomized.

- Adaptive Randomization: In this method, the probability of being assigned to each group changes based on the participants already assigned to each group. For example, if more participants have been assigned to the control group, new participants will have a higher probability of being assigned to the experimental group.

Computer software can generate random numbers or sequences that can be used to assign participants to groups in a simple randomization process.

For more complex methods like block, stratified, or adaptive randomization, computer algorithms can be used to consider the additional parameters and ensure that participants are assigned to groups appropriately.

Using a computerized system can also help to maintain the integrity of the randomization process by preventing researchers from knowing in advance which group a participant will be assigned to (a principle known as allocation concealment). This can help to prevent selection bias and ensure the validity of the study results .

Allocation Concealment

Allocation concealment is a technique to ensure the random allocation process is truly random and unbiased.

RCTs use allocation concealment to decide which patients get the real medicine and which get a placebo (a fake medicine)

It involves keeping the sequence of group assignments (i.e., who gets assigned to the treatment group and who gets assigned to the control group next) hidden from the researchers before a participant has enrolled in the study.

This helps to prevent the researchers from consciously or unconsciously selecting certain participants for one group or the other based on their knowledge of which group is next in the sequence.

Allocation concealment ensures that the investigator does not know in advance which treatment the next person will get, thus maintaining the integrity of the randomization process.

Blinding (Masking)

Binding, or masking, refers to withholding information regarding the group assignments (who is in the treatment group and who is in the control group) from the participants, the researchers, or both during the study .

A blinded study prevents the participants from knowing about their treatment to avoid bias in the research. Any information that can influence the subjects is withheld until the completion of the research.

Blinding can be imposed on any participant in an experiment, including researchers, data collectors, evaluators, technicians, and data analysts.

Good blinding can eliminate experimental biases arising from the subjects’ expectations, observer bias, confirmation bias, researcher bias, observer’s effect on the participants, and other biases that may occur in a research test.

In a double-blind study , neither the participants nor the researchers know who is receiving the drug or the placebo. When a participant is enrolled, they are randomly assigned to one of the two groups. The medication they receive looks identical whether it’s the drug or the placebo.

Figure 1 . Evidence-based medicine pyramid. The levels of evidence are appropriately represented by a pyramid as each level, from bottom to top, reflects the quality of research designs (increasing) and quantity (decreasing) of each study design in the body of published literature. For example, randomized control trials are higher quality and more labor intensive to conduct, so there is a lower quantity published.

Prevents bias

In randomized control trials, participants must be randomly assigned to either the intervention group or the control group, such that each individual has an equal chance of being placed in either group.

This is meant to prevent selection bias and allocation bias and achieve control over any confounding variables to provide an accurate comparison of the treatment being studied.

Because the distribution of characteristics of patients that could influence the outcome is randomly assigned between groups, any differences in outcome can be explained only by the treatment.

High statistical power

Because the participants are randomized and the characteristics between the two groups are balanced, researchers can assume that if there are significant differences in the primary outcome between the two groups, the differences are likely to be due to the intervention.

This warrants researchers to be confident that randomized control trials will have high statistical power compared to other types of study designs.

Since the focus of conducting a randomized control trial is eliminating bias, blinded RCTs can help minimize any unconscious information bias.

In a blinded RCT, the participants do not know which group they are assigned to or which intervention is received. This blinding procedure should also apply to researchers, health care professionals, assessors, and investigators when possible.

“Single-blind” refers to an RCT where participants do not know the details of the treatment, but the researchers do.

“ Double-blind ” refers to an RCT where both participants and data collectors are masked of the assigned treatment.

Limitations

Costly and timely.

Some interventions require years or even decades to evaluate, rendering them expensive and time-consuming.

It might take an extended period of time before researchers can identify a drug’s effects or discover significant results.

Requires large sample size

There must be enough participants in each group of a randomized control trial so researchers can detect any true differences or effects in outcomes between the groups.

Researchers cannot detect clinically important results if the sample size is too small.

Change in population over time

Because randomized control trials are longitudinal in nature, it is almost inevitable that some participants will not complete the study, whether due to death, migration, non-compliance, or loss of interest in the study.

This tendency is known as selective attrition and can threaten the statistical power of an experiment.

Randomized control trials are not always practical or ethical, and such limitations can prevent researchers from conducting their studies.

For example, a treatment could be too invasive, or administering a placebo instead of an actual drug during a trial for treating a serious illness could deny a participant’s normal course of treatment. Without ethical approval, a randomized control trial cannot proceed.

Fictitious Example

An example of an RCT would be a clinical trial comparing a drug’s effect or a new treatment on a select population.

The researchers would randomly assign participants to either the experimental group or the control group and compare the differences in outcomes between those who receive the drug or treatment and those who do not.

Real-life Examples

- Preventing illicit drug use in adolescents: Long-term follow-up data from a randomized control trial of a school population (Botvin et al., 2000).

- A prospective randomized control trial comparing medical and surgical treatment for early pregnancy failure (Demetroulis et al., 2001).

- A randomized control trial to evaluate a paging system for people with traumatic brain injury (Wilson et al., 2009).

- Prehabilitation versus Rehabilitation: A Randomized Control Trial in Patients Undergoing Colorectal Resection for Cancer (Gillis et al., 2014).

- A Randomized Control Trial of Right-Heart Catheterization in Critically Ill Patients (Guyatt, 1991).

- Berry, R. B., Kryger, M. H., & Massie, C. A. (2011). A novel nasal excitatory positive airway pressure (EPAP) device for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea: A randomized controlled trial. Sleep , 34, 479–485.

- Gloy, V. L., Briel, M., Bhatt, D. L., Kashyap, S. R., Schauer, P. R., Mingrone, G., . . . Nordmann, A. J. (2013, October 22). Bariatric surgery versus non-surgical treatment for obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMJ , 347.

- Streeton, C., & Whelan, G. (2001). Naltrexone, a relapse prevention maintenance treatment of alcohol dependence: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 36 (6), 544–552.

How Should an RCT be Reported?

Reporting of a Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) should be done in a clear, transparent, and comprehensive manner to allow readers to understand the design, conduct, analysis, and interpretation of the trial.

The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials ( CONSORT ) statement is a widely accepted guideline for reporting RCTs.

Further Information

- Cocks, K., & Torgerson, D. J. (2013). Sample size calculations for pilot randomized trials: a confidence interval approach. Journal of clinical epidemiology, 66(2), 197-201.

- Kendall, J. (2003). Designing a research project: randomised controlled trials and their principles. Emergency medicine journal: EMJ, 20(2), 164.

Akobeng, A.K., Understanding randomized controlled trials. Archives of Disease in Childhood , 2005; 90: 840-844.

Bell, C. C., Gibbons, R., & McKay, M. M. (2008). Building protective factors to offset sexually risky behaviors among black youths: a randomized control trial. Journal of the National Medical Association, 100 (8), 936-944.

Bhide, A., Shah, P. S., & Acharya, G. (2018). A simplified guide to randomized controlled trials. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica, 97 (4), 380-387.

Botvin, G. J., Griffin, K. W., Diaz, T., Scheier, L. M., Williams, C., & Epstein, J. A. (2000). Preventing illicit drug use in adolescents: Long-term follow-up data from a randomized control trial of a school population. Addictive Behaviors, 25 (5), 769-774.

Demetroulis, C., Saridogan, E., Kunde, D., & Naftalin, A. A. (2001). A prospective randomized control trial comparing medical and surgical treatment for early pregnancy failure. Human Reproduction, 16 (2), 365-369.

Gillis, C., Li, C., Lee, L., Awasthi, R., Augustin, B., Gamsa, A., … & Carli, F. (2014). Prehabilitation versus rehabilitation: a randomized control trial in patients undergoing colorectal resection for cancer. Anesthesiology, 121 (5), 937-947.

Globas, C., Becker, C., Cerny, J., Lam, J. M., Lindemann, U., Forrester, L. W., … & Luft, A. R. (2012). Chronic stroke survivors benefit from high-intensity aerobic treadmill exercise: a randomized control trial. Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair, 26 (1), 85-95.

Guyatt, G. (1991). A randomized control trial of right-heart catheterization in critically ill patients. Journal of Intensive Care Medicine, 6 (2), 91-95.

MediLexicon International. (n.d.). Randomized controlled trials: Overview, benefits, and limitations. Medical News Today. Retrieved from https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/280574#what-is-a-randomized-controlled-trial

Wilson, B. A., Emslie, H., Quirk, K., Evans, J., & Watson, P. (2005). A randomized control trial to evaluate a paging system for people with traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury, 19 (11), 891-894.

Related Articles

Research Methodology

What Is a Focus Group?

Cross-Cultural Research Methodology In Psychology

What Is Internal Validity In Research?

Research Methodology , Statistics

What Is Face Validity In Research? Importance & How To Measure

Criterion Validity: Definition & Examples

Convergent Validity: Definition and Examples

Random Assignment

- First Online: 17 May 2019

Cite this chapter

- Gideon J. Mellenbergh 2

503 Accesses

A substantial part of behavioral research is aimed at the testing of substantive hypotheses. In general, a hypothesis testing study investigates the causal influence of an independent variable (IV) on a dependent variable (DV) . The discussion is restricted to IVs that can be manipulated by the researcher, such as, experimental (E- ) and control (C- ) conditions. Association between IV and DV does not imply that the IV has a causal influence on the DV . The association can be spurious because it is caused by an other variable (OV). OVs that cause spurious associations come from the (1) participant, (2) research situation, and (3) reactions of the participants to the research situation. If participants select their own (E- or C- ) condition or others select a condition for them, the assignment to conditions is usually biased (e.g., males prefer the E-condition and females the C-condition), and participant variables (e.g., participants’ sex) may cause a spurious association between the IV and DV . This selection bias is a systematic error of a design. It is counteracted by random assignment of participants to conditions. Random assignment guarantees that all participant variables are related to the IV by chance, and turns systematic error into random error. Random errors decrease the precision of parameter estimates. Random error variance is reduced by including auxiliary variables into the randomized design. A randomized block design includes an auxiliary variable to divide the participants into relatively homogeneous blocks, and randomly assigns participants to the conditions per block. A covariate is an auxiliary variable that is used in the statistical analysis of the data to reduce the error variance. Cluster randomization randomly assigns clusters (e.g., classes of students) to conditions, which yields specific problems. Random assignment should not be confused with random selection. Random assignment controls for selection bias , whereas random selection makes possible to generalize study results of a sample to the population.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Cox, D. R. (2006). Principles of statistical inference . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Google Scholar

Hox, J. (2002). Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications . Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Lai, K., & Kelley, K. (2012). Accuracy in parameter estimation for ANCOVA and ANOVA contrasts: Sample size planning via narrow confidence intervals. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 65, 350–370.

PubMed Google Scholar

McNeish, D., Stapleton, L. M., & Silverman, R. D. (2017). On the unnecessary ubiquity of hierarchical linear modelling. Psychological Methods, 22, 114–140.

Murray, D. M., Varnell, S. P., & Blitstein, J. L. (2004). Design and analysis of group-randomized trials: A review of recent methodological developments. American Journal of Public Health, 94, 423–432.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Snijders, T. A. B., & Bosker, R. J. (1999). Multilevel analysis . London, UK: Sage.

van Belle, G. (2002). Statistical rules of thumb . New York, NY: Wiley.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Emeritus Professor Psychological Methods, Department of Psychology, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Gideon J. Mellenbergh

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Gideon J. Mellenbergh .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Mellenbergh, G.J. (2019). Random Assignment. In: Counteracting Methodological Errors in Behavioral Research. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-12272-0_4

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-12272-0_4

Published : 17 May 2019

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-74352-3

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-12272-0

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Random Assignment in Experiments | Introduction & Examples

Random Assignment in Experiments | Introduction & Examples

Published on 6 May 2022 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on 13 February 2023.

In experimental research, random assignment is a way of placing participants from your sample into different treatment groups using randomisation.

With simple random assignment, every member of the sample has a known or equal chance of being placed in a control group or an experimental group. Studies that use simple random assignment are also called completely randomised designs .

Random assignment is a key part of experimental design . It helps you ensure that all groups are comparable at the start of a study: any differences between them are due to random factors.

Table of contents

Why does random assignment matter, random sampling vs random assignment, how do you use random assignment, when is random assignment not used, frequently asked questions about random assignment.

Random assignment is an important part of control in experimental research, because it helps strengthen the internal validity of an experiment.

In experiments, researchers manipulate an independent variable to assess its effect on a dependent variable, while controlling for other variables. To do so, they often use different levels of an independent variable for different groups of participants.

This is called a between-groups or independent measures design.

You use three groups of participants that are each given a different level of the independent variable:

- A control group that’s given a placebo (no dosage)

- An experimental group that’s given a low dosage

- A second experimental group that’s given a high dosage

Random assignment to helps you make sure that the treatment groups don’t differ in systematic or biased ways at the start of the experiment.

If you don’t use random assignment, you may not be able to rule out alternative explanations for your results.

- Participants recruited from pubs are placed in the control group

- Participants recruited from local community centres are placed in the low-dosage experimental group

- Participants recruited from gyms are placed in the high-dosage group

With this type of assignment, it’s hard to tell whether the participant characteristics are the same across all groups at the start of the study. Gym users may tend to engage in more healthy behaviours than people who frequent pubs or community centres, and this would introduce a healthy user bias in your study.

Although random assignment helps even out baseline differences between groups, it doesn’t always make them completely equivalent. There may still be extraneous variables that differ between groups, and there will always be some group differences that arise from chance.

Most of the time, the random variation between groups is low, and, therefore, it’s acceptable for further analysis. This is especially true when you have a large sample. In general, you should always use random assignment in experiments when it is ethically possible and makes sense for your study topic.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Random sampling and random assignment are both important concepts in research, but it’s important to understand the difference between them.

Random sampling (also called probability sampling or random selection) is a way of selecting members of a population to be included in your study. In contrast, random assignment is a way of sorting the sample participants into control and experimental groups.

While random sampling is used in many types of studies, random assignment is only used in between-subjects experimental designs.

Some studies use both random sampling and random assignment, while others use only one or the other.

Random sampling enhances the external validity or generalisability of your results, because it helps to ensure that your sample is unbiased and representative of the whole population. This allows you to make stronger statistical inferences .

You use a simple random sample to collect data. Because you have access to the whole population (all employees), you can assign all 8,000 employees a number and use a random number generator to select 300 employees. These 300 employees are your full sample.

Random assignment enhances the internal validity of the study, because it ensures that there are no systematic differences between the participants in each group. This helps you conclude that the outcomes can be attributed to the independent variable .

- A control group that receives no intervention

- An experimental group that has a remote team-building intervention every week for a month

You use random assignment to place participants into the control or experimental group. To do so, you take your list of participants and assign each participant a number. Again, you use a random number generator to place each participant in one of the two groups.

To use simple random assignment, you start by giving every member of the sample a unique number. Then, you can use computer programs or manual methods to randomly assign each participant to a group.

- Random number generator: Use a computer program to generate random numbers from the list for each group.

- Lottery method: Place all numbers individually into a hat or a bucket, and draw numbers at random for each group.

- Flip a coin: When you only have two groups, for each number on the list, flip a coin to decide if they’ll be in the control or the experimental group.

- Use a dice: When you have three groups, for each number on the list, roll a die to decide which of the groups they will be in. For example, assume that rolling 1 or 2 lands them in a control group; 3 or 4 in an experimental group; and 5 or 6 in a second control or experimental group.

This type of random assignment is the most powerful method of placing participants in conditions, because each individual has an equal chance of being placed in any one of your treatment groups.

Random assignment in block designs

In more complicated experimental designs, random assignment is only used after participants are grouped into blocks based on some characteristic (e.g., test score or demographic variable). These groupings mean that you need a larger sample to achieve high statistical power .

For example, a randomised block design involves placing participants into blocks based on a shared characteristic (e.g., college students vs graduates), and then using random assignment within each block to assign participants to every treatment condition. This helps you assess whether the characteristic affects the outcomes of your treatment.

In an experimental matched design , you use blocking and then match up individual participants from each block based on specific characteristics. Within each matched pair or group, you randomly assign each participant to one of the conditions in the experiment and compare their outcomes.

Sometimes, it’s not relevant or ethical to use simple random assignment, so groups are assigned in a different way.

When comparing different groups

Sometimes, differences between participants are the main focus of a study, for example, when comparing children and adults or people with and without health conditions. Participants are not randomly assigned to different groups, but instead assigned based on their characteristics.

In this type of study, the characteristic of interest (e.g., gender) is an independent variable, and the groups differ based on the different levels (e.g., men, women). All participants are tested the same way, and then their group-level outcomes are compared.

When it’s not ethically permissible

When studying unhealthy or dangerous behaviours, it’s not possible to use random assignment. For example, if you’re studying heavy drinkers and social drinkers, it’s unethical to randomly assign participants to one of the two groups and ask them to drink large amounts of alcohol for your experiment.

When you can’t assign participants to groups, you can also conduct a quasi-experimental study . In a quasi-experiment, you study the outcomes of pre-existing groups who receive treatments that you may not have any control over (e.g., heavy drinkers and social drinkers).

These groups aren’t randomly assigned, but may be considered comparable when some other variables (e.g., age or socioeconomic status) are controlled for.

In experimental research, random assignment is a way of placing participants from your sample into different groups using randomisation. With this method, every member of the sample has a known or equal chance of being placed in a control group or an experimental group.

Random selection, or random sampling , is a way of selecting members of a population for your study’s sample.

In contrast, random assignment is a way of sorting the sample into control and experimental groups.

Random sampling enhances the external validity or generalisability of your results, while random assignment improves the internal validity of your study.

Random assignment is used in experiments with a between-groups or independent measures design. In this research design, there’s usually a control group and one or more experimental groups. Random assignment helps ensure that the groups are comparable.

In general, you should always use random assignment in this type of experimental design when it is ethically possible and makes sense for your study topic.

To implement random assignment , assign a unique number to every member of your study’s sample .

Then, you can use a random number generator or a lottery method to randomly assign each number to a control or experimental group. You can also do so manually, by flipping a coin or rolling a die to randomly assign participants to groups.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, February 13). Random Assignment in Experiments | Introduction & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 14 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/random-assignment-experiments/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples, controlled experiments | methods & examples of control, control groups and treatment groups | uses & examples.

- Yale Directories

Institution for Social and Policy Studies

Advancing research • shaping policy • developing leaders, why randomize.

About Randomized Field Experiments Randomized field experiments allow researchers to scientifically measure the impact of an intervention on a particular outcome of interest.

What is a randomized field experiment? In a randomized experiment, a study sample is divided into one group that will receive the intervention being studied (the treatment group) and another group that will not receive the intervention (the control group). For instance, a study sample might consist of all registered voters in a particular city. This sample will then be randomly divided into treatment and control groups. Perhaps 40% of the sample will be on a campaign’s Get-Out-the-Vote (GOTV) mailing list and the other 60% of the sample will not receive the GOTV mailings. The outcome measured –voter turnout– can then be compared in the two groups. The difference in turnout will reflect the effectiveness of the intervention.

What does random assignment mean? The key to randomized experimental research design is in the random assignment of study subjects – for example, individual voters, precincts, media markets or some other group – into treatment or control groups. Randomization has a very specific meaning in this context. It does not refer to haphazard or casual choosing of some and not others. Randomization in this context means that care is taken to ensure that no pattern exists between the assignment of subjects into groups and any characteristics of those subjects. Every subject is as likely as any other to be assigned to the treatment (or control) group. Randomization is generally achieved by employing a computer program containing a random number generator. Randomization procedures differ based upon the research design of the experiment. Individuals or groups may be randomly assigned to treatment or control groups. Some research designs stratify subjects by geographic, demographic or other factors prior to random assignment in order to maximize the statistical power of the estimated effect of the treatment (e.g., GOTV intervention). Information about the randomization procedure is included in each experiment summary on the site.