- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 03 March 2016

Relationships between adverse childhood experiences and adult mental well-being: results from an English national household survey

- Karen Hughes 1 ,

- Helen Lowey 2 ,

- Zara Quigg 1 &

- Mark A. Bellis 3 , 4

BMC Public Health volume 16 , Article number: 222 ( 2016 ) Cite this article

42k Accesses

125 Citations

34 Altmetric

Metrics details

Individuals’ childhood experiences can strongly influence their future health and well-being. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) such as abuse and dysfunctional home environments show strong cumulative relationships with physical and mental illness yet less is known about their effects on mental well-being in the general population.

A nationally representative household survey of English adults ( n = 3,885) measuring current mental well-being (Short Edinburgh-Warwick Mental Well-being Scale SWEMWBS) and life satisfaction and retrospective exposure to nine ACEs.

Almost half of participants (46.4 %) had suffered at least one ACE and 8.3 % had suffered four or more. Adjusted odds ratios (AORs) for low life satisfaction and low mental well-being increased with the number of ACEs. AORs for low ratings of all individual SWEMWBS components also increased with ACE count, particularly never or rarely feeling close to others. Of individual ACEs, growing up in a household affected by mental illness and suffering sexual abuse had the most relationships with markers of mental well-being.

Conclusions

Childhood adversity has a strong cumulative relationship with adult mental well-being. Comprehensive mental health strategies should incorporate interventions to prevent ACEs and moderate their impacts from the very earliest stages of life.

Peer Review reports

Individuals’ childhood experiences are of paramount importance in determining their future outcomes. Research exposing the harmful effects that childhood adversity has on adult physical and mental health has advanced significantly over the past few decades. For instance, the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) framework has provided a mechanism for retrospectively measuring childhood adversities and identifying their impact on health in later life [ 1 ]. ACEs include child maltreatment (e.g. physical, sexual and verbal abuse) and broader experiences of household dysfunction, such as witnessing violence in the home, parental separation and growing up in a household affected by substance misuse, mental illness or criminal behaviour. Studies show a dose-responsive relationship between ACEs and poor outcomes, with the more ACEs a person suffers the greater their risks of developing health harming behaviours (e.g. substance misuse, risky sexual behaviour), suffering poor adult health (e.g. obesity, cancer, heart disease) and ultimately premature mortality [ 1 – 6 ].

Much research on the long-term impacts of ACEs has focused on their relationships with mental illness. Thus, studies have found increasing numbers of ACEs to be associated with increasing risks of conditions including depression, anxiety, panic reactions, hallucinations, psychosis and suicide attempt, along with overall psychopathology, psychotropic medication use and treatment for mental disorders [ 2 , 3 , 7 – 11 ]. However the literature on the impact of ACEs on broader measures of mental health and well-being is less extensive. While definitions vary [ 12 ], mental well-being is widely recognised as being more than just the absence of mental illness; incorporating aspects of mental functioning, feelings and behaviours and having been simply described as feeling good and functioning well [ 13 ]. Positive mental well-being has been associated with better physical and mental health and with reduced mortality in both healthy and ill populations [ 14 , 15 ]. Correspondingly, the promotion of mental well-being has become a public and mental health priority both globally and in countries such as the UK [ 16 , 17 ].

Understanding how different factors impede mental well-being in adults is imperative to investing effectively and efficiently in its promotion. With little longitudinal data available, considerable focus has been placed on the associations between current conditions (e.g. social relationships, residential deprivation, physical exercise, health status) and mental well-being rather than longer-term drivers. However, a US study using the ACE framework found a cumulative relationship between childhood adversity and markers of mental well-being in the general population, including mentally healthy days and life satisfaction [ 18 ]. In England, we conducted a pilot ACE study in a local administrative area which found increased odds of low life satisfaction and low mental well-being in adults with increased ACEs [ 19 ]. Following this pilot, we undertook a national ACE study of adults across England that included validated measurements of mental well-being and life satisfaction. Here we explore relationships between levels of exposure to adversity during childhood and current mental well-being in adults. Finally, we discuss the convergence between the roots of poor physical health and poor mental well-being in early years and consequently, how poor mental well-being in one generation may adversely impact well-being in the next.

A target sample size of 4,000 adult residents of England was established based on the prevalence of ACEs identified in the pilot study [ 19 ]. Study inclusion criteria were: aged 18–69 years; resident in a selected LSOA; and cognitively able to participate in a face-to-face interview. Households were selected through random probability sampling stratified by English region ( n = 10, with inner and outer London treated as two regions) and then by small area deprivation using lower super output areas (LSOAs; geographic areas with a population mean of 1,500) [ 20 ]. Within each region, LSOAs were categorised into deciles of deprivation based on their ranking in the 2010 Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD; a composite measure including 38 indicators relating to economic, social and housing issues) [ 21 ]. Two LSOAs were then randomly selected from each decile in each region and for each LSOA between 40 and 120 addresses were randomly selected for inclusion from the Postcode Address File ® . Sample sizes in each region were proportionate to their population to provide a sample representative of the English population, with a total of 16,000 households initially sampled to account for ineligibility, non-response and non-compliance.

Sampled households were sent a letter prior to researchers visiting providing information on the study and the opportunity to opt out; 771 (4.8 %) households opted out at this stage. Operating under the direction of the research team, a professional survey company visited households on differing days/times (seven days a week, 9:30 am to 8.30 pm) between April and July 2013. The protocol employed by the survey company was to remove households after four attempted visits with no contact. Where contact was made and more than one household member met the inclusion criteria, the eligible resident with the next birthday was selected for interview. Interviewers explained the purpose of the study, outlined its voluntary and anonymous nature and provided a second opportunity for individuals to opt out, with informed consent obtained verbally at the point of interview. Household visits ceased once the target sample size was achieved. Thus, 9,852 of the sampled households were visited of which 7,773 resulted in contact with a resident. Of these households, 2,719 (35.0 %) opted out, 1,044 (13.4 %) were ineligible and 4,010 completed a study questionnaire. Compliance was 59.6 % across eligible occupied households visited and 53.5 % when including those opting out at the letter stage.

The study used an established questionnaire covering demographics, lifestyle behaviours, health status, mental well-being, life satisfaction and exposure to ACEs before the age of 18 [ 19 ]. Participants were able to complete the questionnaire through a face-to-face interview using a hand held computer (with sensitive questions self-completed; n = 3,852), or to self-complete using paper questionnaires ( n = 158). Mental well-being was measured using the Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (SWEMWBS) [ 22 ], which asks individuals how often over the past two weeks they have been: feeling optimistic about the future; feeling useful; feeling relaxed; dealing with problems well; thinking clearly; feeling close to other people; able to make up their own mind about things . Responses are scored from 1 (none of the time) to 5 (all of the time) and an overall mental well-being score is calculated, ranging from 7 (lowest possible mental well-being) to 35 (highest possible mental well-being). Life satisfaction was measured on a scale of 1–10 using the standard question: All things considered how satisfied are you with your life, with 1 being not at all satisfied and 10 very satisfied [ 23 ]. ACEs were measured using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention short ACE tool [ 24 ] which comprises eleven questions covering nine ACE types: physical abuse; verbal abuse; sexual abuse (three questions); parental separation; exposure to domestic violence; and growing up in a household with mental illness, alcohol abuse, drug abuse or incarceration (for further information see [ 4 ]). Ethnicity was recorded using standard UK Census categories [ 25 ] and categorised as White, Asian and Other due to small numbers within individual ethnic groups. Respondents were allocated an IMD 2010 quintile of deprivation based on their LSOA of residence. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from Liverpool John Moores University’s Research Ethics Committee and the study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Analyses were undertaken using SPSS v20. Only individuals with complete data relating to all ACEs, age, sex, ethnicity, and IMD quintile were included in the analysis, resulting in a final sample size of 3,885. Bivariate analyses used chi-squared with backwards conditional logistic regression used to examine independent relationships between ACEs and adult mental well-being and life satisfaction. Consistent with other work including previous ACE studies [ 1 – 3 ] and the World Mental Health Surveys [ 26 – 28 ], the number of ACEs participants reported exposure to was summed into an ACE count (range 0 to 9) and here categorised into four groups for analysis: 0 ACEs ( n = 2,072), 1 ACE ( n = 879), 2–3 ACEs ( n = 594) and 4 + ACEs ( n = 322). We also explored relationships between outcome variables and individual ACEs, with analysis focusing on those with highly significant relationships. The seven individual components of SWEMWBS were each dichotomised to indicate poor ratings (never or rarely in the last two weeks). Overall SWEMWBS scores and life satisfaction (LS) ratings were dichotomised to indicate low scores as >1 standard deviation (SD) below the mean (SWEMWBS, mean 27.5, SD 4.4, low <23; LS, mean 7.7, SD 1.7, low <6).

The demographic breakdown of the sample is shown in Table 1 . Compared with the English population the sample overrepresented females (55.0 % v 50.3 % in England) and individuals aged 60–69 years (20.7 % v 16.1 %) and underrepresented those aged 18–29 (21.0 % v 24.2 %). There were no differences by deprivation quintile or ethnicity. Just under half of participants reported having suffered at least one ACE (46.4 %) with 15.4 % reporting 2–3 ACEs and 8.3 % 4+ ACEs. The proportion of participants with low measures (never or rarely in the last two weeks) for the individual components of SWEMWBS ranged from 2.5 % (able to make up own mind) to 14.5 % (feeling relaxed). Thirteen percent were categorised as having low SWEMWBS scores (<23) and 11.6 % as having low life satisfaction (score <6; Table 1 ).

Low SWEMWBS scores and LS were both associated with age, being most prevalent in the 50–59 year age group (Table 1 ). Significant relationships with age were also seen for all individual SWEMWBS components except feeling useful and dealing with problems. There were no relationships between gender and LS or overall SWEMWBS score, although among the individual SWEMWBS components more females had low scores for feeling relaxed and more males for feeling close to others. There were no significant relationships between ethnicity and either low SWEMWBS score or low LS. However both outcomes increased with deprivation, as did low levels of all individual SWEMWBS components except feeling relaxed.

There were strong associations between ACE count and all markers of low mental well-being. Thus the prevalence of low SWEMWBS score tripled from 9.5 % in those with 0 ACEs to 30.7 % in those with 4+ ACEs, while the prevalence of low LS more than tripled from 7.9 to 26.6 % respectively. These significant relationships remained after controlling for confounders in logistic regression analysis with adjusted odds ratios (AORs) for low SWEMWBS score and low LS increasing with ACE count and reaching 3.9 for both outcomes in those with 4+ ACEs (compared with 0 ACEs; Table 2 ). Importantly, while associations between both outcomes and age also remained in LR, running separate models for each age group showed the relationships between high ACE count and low mental well-being to be consistent across age groups. Thus, compared with individuals with no ACEs, AORs for low SWEBWBS scores in those with 4+ ACEs ranged from 3.08 in both 18–29 year olds (95 % CIs, 1.56–6.07) and 30–39 year olds (95 % CIs 1.66–5.72) to 5.34 (95 % CIs 2.10–13.57) in 60–69 year olds (all p < 0.001) and for low LS from 2.54 (95 % CIs 1.09–5.90, p = 0.030) in 18–29 year olds to 11.20 (95 % CIs 4.43–28.29, p < 0.001) in 60–69 year olds.

Figure 1 presents AORs for low scores for each component of SWEMWBS by increasing ACE count (all ages). All relationships were significant and cumulative with AORs for those with 4+ ACEs (compared with 0 ACEs) ranging from 2.23 (95 % CIs 1.22–4.10) for never or rarely being able to make up one’s own mind to 4.09 (2.70–6.20) for never or rarely feeling close to others.

Relationship between adverse childhood experience count and components of poor adult mental well-being (adjusted odds ratios and 95 % confidence intervals). Variables represent the individual component questions in the SWEMWBS scale. Adjusted odds ratios were calculated using logistic regression analysis. Additional independent variables included in the logistic regression were age, gender, deprivation and ethnicity. All relationships are significant with poor mental well-being components positively related to increasing ACE count ( p < 0.001, except ‘ability to make up own mind where p < 0.05). Ref = reference category

Table 3 shows the relationships between measures of mental well-being and the nine individual ACEs examined. Physical, sexual and emotional abuse, witnessing domestic violence, and living in a household affected by mental illness or drug abuse were significantly associated with low levels of all mental well-being measures and household alcohol misuse and incarceration with low levels of all except the ability to make one’s own mind up about things. However parental separation or divorce was only associated with two of the seven SWEMWBS components (feeling useful, feeling relaxed) and an overall low SWEMWBS score. For each marker of mental well-being, a logistic regression model was run that included individual ACE types significantly related to the marker (in bivariate analysis, see Table 3 ) and demographic variables. Here, household mental illness was found to have independent relationships with the most mental well-being marker, being associated with all except the SWEMWBS component of feeling relaxed (Table 4 ). Childhood sexual abuse was associated with all except the SWEMWBS components of feeling useful and feeling close to others. Emotional and physical abuse each had independent relationships with five of the nine measures and household alcohol problems with four. Feeling close to others (the SWEMWBS component with the strongest relationship with ACE count; Fig. 1 ), was independently associated with household mental illness, emotional abuse and physical abuse.

Promoting mental well-being has become a major public health priority as recognition of the links between well-being and broader health and social outcomes has grown. This has contributed to the emergence of broader policy approaches to mental health, both globally and nationally, that incorporate population-level prevention and promotion activity alongside traditional therapeutic responses to mental illness [ 16 , 17 ]. In England, motivation for increased investment in mental well-being promotion has centred around the notion that interventions to improve mental well-being at a population level could produce greater benefits than those to prevent mental illness in at-risk populations [ 29 , 30 ]. However, the evidence base on which such approaches are based is being questioned as broader measurements and studies of mental well-being emerge [ 12 ]. Thus, existing studies have largely associated mental well-being in adults with factors linked to their current circumstances, such as employment, residential deprivation, social participation, physical exercise, relationship satisfaction and health status [ 31 ]. Correspondingly, interventions have often focused on promoting individual behavioural change through, for example, increasing social connectedness and physical activity [ 32 , 33 ]. A life course perspective that incorporates the longer-term impact of childhood adversity has largely been absent from discussions on mental well-being.

Using a randomly selected national household sample of English adults, our study found a strong cumulative relationship between childhood adversities and two widely used measures of mental well-being. The more ACEs participants reported having suffered during their childhood the more likely they were to report low SWEMWBS scores and low life satisfaction (Table 1 ). These relationships remained after controlling for demographics, with odds of poor outcomes for both measures being elevated in those with even a single ACE and almost four times higher in those with four or more ACEs (compared with those with no ACEs; Table 2 ). We also found ACE count to be independently related to each of the seven individual components of SWEMWBS; individuals with higher ACE counts were more likely to report never or rarely (in the last two weeks) feeling optimistic, useful, relaxed or close to others, dealing with problems well, thinking clearly and being able to make up one’s own mind (Fig. 1 ).

A variety of mechanisms link ACEs to poor adult mental well-being. Critically, maltreatment and other stressors in childhood can affect brain development and have harmful, lasting effects on emotional functioning [ 2 , 34 ]. Children who are maltreated can develop attachment difficulties, including poor emotional regulation, lack of trust and fear of getting close to other people. They can also form negative self-images, lack self-worth and suffer feelings of incompetence, all of which can be retained into adulthood [ 2 , 34 , 35 ]. The relationships between ACEs and factors including poor educational attainment and the development of health-damaging behaviours mean that individuals who suffer ACEs can also face a range of risk factors for poor mental well-being in adulthood, such as poor health, low employment and social deprivation [ 2 , 4 , 36 ]. These effects can contribute to cycles of adversity and poor mental well-being whereby individuals that grew up in adverse conditions are less able to provide optimum childhood environments for their own offspring [ 37 ]. Here, and consistent with previous work [ 38 ], the SWEMWBS component with the strongest relationship with ACE count was never or rarely feeling close to others. Children whose parents show poor relationships with them are at greater risks of ACEs [ 39 ], thus individuals who cannot feel close to others as a result of their own ACE history may subsequently be more likely to expose their own children to ACEs. These relationships may also have implications for the implementation and effectiveness of interventions to improve mental well-being through social connectedness.

While analysis based on ACE count highlights the cumulative impact of childhood adversity on mental well-being, it is also useful to explore which ACEs may have particular effects. All ACE types showed significant bivariate relationships with low SWEMWEBS scores, and all except parental separation/divorce with low life satisfaction and most individual SWEMWBS components. In multivariate analyses, however, the ACEs with the most independent relationships with markers of low mental well-being were growing up in a household with someone affected by mental illness and suffering childhood sexual abuse.

The links between growing up in a household affected by mental illness in childhood and low mental well-being in adulthood may in part reflect genetic risk factors that make the offspring of individuals with mental disorders susceptible to poor mental health themselves [ 40 ]; although genetic explanations for the transmission of mental disorders are disputed [ 41 ]. Thus, parental mental illness can have broader impacts on children’s social and emotional development when parenting practices are affected by factors such as low emotional warmth, reduced responsiveness, impaired attention and unpredictable behavioural patterns [ 42 ]. An extensive body of research provides evidence that exposure to childhood adversity such as parental stress, disrupted care patterns and abuse increases risks of mental illness [ 43 ], while studies are increasingly identifying how exposure to such adversity can trigger epigenetic modifications to gene expressions, altering brain structure, stress reactivity and consequently vulnerability to both mental and physical ill health [ 44 ]. Childhood sexual abuse can have particularly damaging effects on individuals’ emotional development, having been linked to feelings of shame and self-blame, powerlessness, inappropriate sexual beliefs and difficulties forming and maintaining intimate relationships [ 45 , 46 ]. Correspondingly research has identified strong relationships between childhood sexual abuse and adult mental illness [ 11 ]. For example, in England sexual abuse in childhood has been attributed to 11 % of all common mental disorders, along with 7 % of alcohol dependence disorders, 10 % of drug dependence disorders, 15 % of eating disorders and 17 % of post-traumatic stress disorders [ 47 ].

The WHO Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020 incorporates the promotion of mental well-being as part of its overarching goal: highlighting the need for a life course approach that intervenes early to prevent mental health difficulties; recognising the importance of reducing violence; and emphasising the importance of services being responsive to the needs of survivors of violence [ 17 ]. Interventions that seek to reduce ACEs, develop parenting skills and promote resilience in children should thus be considered essential elements in comprehensive mental health strategies. Starting at the very earliest stages of life, these can include measures to train midwives, health visitors and other early years professionals to enquire about parental mental well-being and identify and treat post-natal depression and other mental health concerns [ 48 ]. The ante- and post-natal periods also offer the opportunity to identify and address a broader range of ACEs including parental substance use and domestic violence as well as to increase parenting skills and knowledge. Effective interventions include home visiting and parenting programmes that promote parent-child bonding and develop parenting skills, along with social and emotional development programmes that strengthen life skills and thus resilience in children [ 49 , 50 ]. Measures should also be taken to ensure service providers across a broad range of disciplines are cognisant of the lasting damage that ACEs place on mental well-being and wider health and social outcomes, and are trained to recognise and respond appropriately to clients with adverse backgrounds [ 51 ]. In particular, professionals in mental health services should be trained to routinely enquire about childhood experiences during client assessments. Studies suggest such enquiry is often lacking, with mental health treatment typically based on a medical model that focuses on biological factors and ignores the profound influence of socio-environmental experiences on brain development and functioning [ 52 , 53 ].

While the ACE methodology has been widely employed [ 54 ] it remains vulnerable to issues associated with any cross-sectional and retrospective survey with, for example, results relying on accurate recall and willingness to report ACEs. While adults with low mental well-being may have more negative perceptions of their childhoods, studies suggest false-positive reports of ACEs are rare [ 55 ]. Measures of current mental well-being and life satisfaction were also self-reported and therefore vulnerable to subjectivity, while the exclusion of individuals cognitively unable to participate in a face-to-face survey may have created bias in our sample. The dichotomisation of well-being scales may also have resulted in loss of information, although we used a consistent method to identify low mental well-being of greater than one SD from the sample mean. We used a recognised tool to measure nine important ACEs yet other common adversities such as neglect, bullying and parental death were not recorded. We explored the independent associations between outcome variables and both ACE counts and individual ACEs. However, we had insufficient sample size to look at how interactions between the individual ACE types, different combinations of ACEs and demographics may have resulted in different relationships with mental wellbeing. Such limitations aside our analyses did include multiple statistical analyses potentially increasing risks of type I errors. Consequently, while we have presented all figures for transparency, discussion has focused on highly significant results [ 56 ]. Finally, our study did not measure resilience resources [ 57 ], and developing understanding of factors that promote resiliency in those affected by ACEs would be an important future research priority.

While the high prevalence of mental disorders in the most vulnerable children (e.g. those in child protection systems) and the continued risks of mental illness in adults who suffered ACEs are widely recognised, data linking childhood adversity to the development and persistence of low mental well-being in the broader population is scarce. Our study suggests that almost half of the general English population have experienced at least one ACE and over one in twelve have suffered four or more ACEs. Such childhood adversity places individuals at significantly increased risk of low mental well-being and may have implications for the implementation and success of interventions that seek to promote mental well-being in the general population. The strong links between ACEs and adult mental well-being emphasise the need for a life course approach to mental health with the drivers of poor mental and physical health outcomes rooted together in childhood issues. Many of the ACEs that impact on children’s long term health and well-being are linked to familial behaviours and mental health (e.g. mental illness, substance abuse, violent and aggressive behaviour) suggesting that the mental health impacts of ACEs are what pushes much of their cyclical nature. A life course approach suggests that preventing ACEs would contribute to better physical and mental health from childhood through to old age and thus improve mental well-being in future generations.

Availability of data and materials

Data sets and other materials used in this article can be accessed by request to Professor Karen Hughes.

Abbreviations

adverse childhood experience

adjusted odds ratio

confidence interval

Index of Multiple Deprivation

life satisfaction

lower super output area

Short Warwick and Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale

Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14:245–58.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Bremner JD, Walker JD, Whitfield C, Perry BD, et al. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;256:174–86.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Bellis MA, Hughes K, Leckenby N, Jones L, Baban A, Kachaeva M, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and associations with health-harming behaviours in young adults: surveys in eight eastern European countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2014;92:641–55.

Bellis MA, Hughes K, Leckenby N, Perkins C, Lowey H. National household survey of adverse childhood experiences and their relationship with resilience to health-harming behaviors in England. BMC Med. 2014;12:72.

Bellis MA, Hughes K, Leckenby N, Hardcastle KA, Perkins C, Lowey H. Measuring mortality and the burden of adult disease associated with adverse childhood experiences in England: a national survey. J Public Health (Oxf). 2014;37:445–54.

Article Google Scholar

Brown DW, Anda RF, Tiemeier H, Felitti VJ, Edwards VJ, Croft JB, Giles WH. Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of premature mortality. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37:389–96.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Anda RF, Brown DW, Felitti VJ, Bremner JD, Dube SR, Giles WH. Adverse childhood experiences and prescribed psychotropic medications in adults. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32:389–94.

Clark C, Caldwell T, Power C, Stansfeld SA. Does the influence of childhood adversity on psychopathology persist across the lifecourse? A 45-year prospective epidemiologic study. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20:385–94.

Koskenvuo K, Koskenvuo M. Childhood adversities predict strongly the use of psychotropic drugs in adulthood: a population-based cohort study of 24 284 Finns. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69:354–60.

Pirkola S, Isometsä E, Aro H, Kestilä L, Hämäläinen J, Veijola J, et al. Childhood adversities as risk factors for adult mental disorders: Results from the health 2000 study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatri Epidemiol. 2005;40:769–77.

Varese F, Smeets F, Drukker M, Lieverse R, Lataster T, Viechtbauer W, et al. Childhood adversities increase the risk of psychosis: a meta-analysis of patient-control, prospective- and cross-sectional cohort studies. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38:661–71.

Davies SC, Mehta N, Murphy O, Lillford-Wildman C. Annual report of the Chief Medical Officer 2013, Public mental health priorities: investing in the evidence. London: Department of Health; 2014.

Google Scholar

Keyes CL. The mental health continuum: from languishing to flourishing in life. J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43:207–22.

Chida Y, Steptoe A. Positive psychological well-being and mortality: a quantitative review of prospective observational studies. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:741–56.

Diener E, Chan MY. Happy people live longer: subjective wellbeing contributes to health and longevity. Appl Psychol: Health and Well-Being. 2010;3:1–43.

Department of Health. Closing the gap: priorities for essential change in mental health. London: Department of Health; 2014.

World Health Organization. Mental health action plan 2013–2020. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

Nurius PS, Logan-Greene P, Green S. Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) within a social disadvantage framework: distinguishing unique, cumulative, and moderated contributions to adult mental health. J Prev Interv Community. 2012;40:278–90.

Bellis MA, Lowey H, Leckenby N, Hughes K, Harrison D. Adverse childhood experiences: retrospective study to determine their impact on adult health behaviours and health outcomes in a UK population. J Public Health (Oxf). 2013;36:81–91.

Bates A. Methodology used for producing ONS’s small area population estimates. Popul Trends. 2006;12:30–6.

Department for Communities and Local Government. English indices of deprivation. 2010. London: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/english-indices-of-deprivation-2010 . Accessed 18 Aug 2015.

Stewart-Brown S, Tennant A, Tennant R, Platt S, Parkinson J, Weich S. Internal construct validity of the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): a Rasch analysis using data from the Scottish Health Education Population Survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:15.

Waldron S. Measuring subjective wellbeing in the UK. Newport: Office for National Statistics; 2010.

Bynum L, Griffin T, Ridings DL, Wynkoop KS, Anda RF, Edwards VJ, et al. Adverse childhood experiences reported by adults --- five states, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:1609–13.

Office for National Statistics. Population estimates by ethnic group 2002–2009. http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/peeg/population-estimates-by-ethnic-group--experimental-/current-estimates/population-density--change-and-concentration-in-great-britain.pdf . Accessed 18 Aug 2015.

Scott KM, Von Korff M, Angermeyer MC, Benjet C, Bruffaerts R, de Girolamo G, et al. The association of childhood adversities and early onset mental disorders with adult onset chronic physical conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:838–44.

Bruffaerts R, Demyttenaere K, Borges G, Haro JM, Chiu WT, Hwang I, et al. Childhood adversities as risk factors for onset and persistence of suicidal behavior. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197:20–7.

Kessler RC, McLaughln KA, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197:378–85.

Foresight Mental Capital and Wellbeing Project. Mental capital and wellbeing: making the most of ourselves in the 21st century. London: The Government Office for Science; 2008.

Huppert FA. A new approach to reducing disorder and improving well-being. Psychol Sci. 2009;4:108–11.

Chanfreau J, Lloyd C, Byron C, Roberts C, Craig R, De Feo D, McManus S. Predicting wellbeing. London: NatCen Social Research; 2013.

Aked J, Marks N, Cordon C, Thompson S. Five ways to wellbeing: the evidence. London: New Economics Foundation; 2008.

Aked J, Thompson S. Five ways to wellbeing: new applications, new ways of thinking. London: New Economics Foundations and NHS Confederation; 2011.

Danese A, McEwen BS. Adverse childhood experiences, allostatis, allostatic load, and age-related disease. Physiol Behav. 2012;106:29–39.

Riggs SA. Childhood emotional abuse and the attachment system across the life cycle: what theory and research tell us. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. 2010;19:5–51.

Currie J, Widom CS. Long-term consequences of child abuse and neglect on adult economic well-being. Child Maltreat. 2010;15:111–20.

Read J, Bentall RP. Childhood experiences and mental health: theoretical, clinical and primary prevention implications. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;200:89–91.

Bellis MA, Hughes K, Jones A, Perkins C, McHale P. Childhood happiness and violence: a retrospective study of their impacts on adult well-being. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e003427.

Stith SM, Liu T, Davies LC, Boykin EL, Alder MC, Harris JM, et al. Risk factors in child maltreatment: a meta-analytical review of the literature. Aggress Violent Behav. 2009;14:13–29.

Cross-Disorder Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Identification of risk loci with shared effects on five major psychiatric disorders: a genome-wide analysis. Lancet. 2013;381:1371–9.

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Joseph J. Why the emporer (still) has no genes. In: Read J, Dillon J, editors. Models of madness: psychological, social and biological approaches to psychosis. Hove: Routledge; 2013.

Manning C, Gregoire A. Effect of parental mental illness on children. Psychiatry. 2008;8:7–9.

Read J, Fosse R, Moskowitz A, Perry B. The traumagenic neurodevelopmental model of psychosis revisited. Neuropsychiatry. 2014;4:65–79.

Vaiserman AM. Epigenetic programming by early-life stress: evidence from human populations. Dev Dyn. 2015;244:254–65.

Finkelhor D, Browne A. The traumatic impact of child sexual abuse: a conceptualization. Am J Orthopsych. 1985;4:530–41.

Lalor K, McElvaney R. Child sexual abuse, links to later sexual exploitation/high-risk sexual behavior, and prevention/treatment programs. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2010;11:159–77.

Jonas S, Bebbington P, McManus S, Meltzer H, Jenkins R, Kuipers E, et al. Sexual abuse and psychiatric disorder in England: results from the 2007 Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey. Psychol Med. 2011;41:709–19.

Morrell CJ, Warner R, Slade P, Dixon S, Walters S, Paley G, et al. Psychological interventions for postnatal depression: cluster randomised trial and economic evaluation. The PoNDER trial. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13:30.

Sethi D, Bellis MA, Hughes K, Gilbert R, Mitis F, Galea G. European report on preventing child maltreatment. Copenhagen: World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe; 2013.

World Health Organization. Violence prevention: the evidence. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

Kagi R, Regala D. Translating the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study into public policy: progress and possibility in Washington State. J Prev Interv Community. 2012;40:271–7.

Hepworth I, McGowan L. Do mental health professionals enquire about childhood sexual abuse during routine mental health assessment in acute mental health settings? A substantive literature review. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2013;20:473–83.

Read J, Bentall RP, Fosse R. Time to abandon the bio-bio-bio model of psychosis: exploring the epigenetic and psychological mechanisms by which adverse life events lead to psychotic symptoms. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 2009;18:299–310.

PubMed Google Scholar

Anda RF, Butchart A, Felitti VJ, Brown DW. Building a framework for global surveillance of the public health implications of adverse childhood experiences. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39:93–8.

Hardt J, Rutter M. Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: review of the evidence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45:260–73.

Perneger TV. What’s wrong with Bonferroni adjustments. BMJ. 1998;316:1236–8.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Logan-Greene P, Green S, Nurius PS, Longhi D. Distinct contributions of adverse childhood experiences and resilience resources: a cohort analysis of adult physical and mental health. Soc Work Health Care. 2014;53:776–97.

Download references

Acknowledgments

We thank Nicola Leckenby for coordinating the study and preparing data for analysis, and Katie Hardcastle and Olivia Sharples for supporting study implementation. We are grateful to all the surveyors for their time and commitment to the project and to all the individuals who participated in the study.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Centre for Public health, Liverpool John Moores University, 15-21 Webster Street, Liverpool, L3 2ET, UK

Karen Hughes & Zara Quigg

Blackburn with Darwen Borough Council, Public Health Department, 10 Duke Street, Blackburn, BB2 1DH, UK

Helen Lowey

Bangor University, Normal Site, Bangor, LL57 2PZ, UK

Mark A. Bellis

Director of Policy, Research and International Development, Public Health Wales, Hadyn Ellis Building, Maindy Road, Cardiff, CF24 4HQ, UK

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Karen Hughes .

Additional information

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

KH supported study development and implementation, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. HL supported study development and contributed to data analysis and manuscript writing. ZQ edited the manuscript. MAB designed the study, supported data analysis and contributed to manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Hughes, K., Lowey, H., Quigg, Z. et al. Relationships between adverse childhood experiences and adult mental well-being: results from an English national household survey. BMC Public Health 16 , 222 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-2906-3

Download citation

Received : 21 August 2015

Accepted : 22 February 2016

Published : 03 March 2016

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-2906-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Adverse childhood experiences

- Child maltreatment

- Mental well-being

- Life satisfaction

BMC Public Health

ISSN: 1471-2458

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Q Improvement Lab

Essays, Learning and Insights

Q Community site

Print-friendly version

- Facebook Facebook

- LinkedIn Twitter

- Project two

Mental health and persistent pain: an introduction

Why this topic and why it is important for all those working across mental and physical health

- by Libby Keck

In September 2018, the Q Lab and Mind embarked on a year-long collaboration to understand how care can be designed to best meet the needs of people living with both mental health problems and persistent back and neck pain.

The Q Lab focuses on specific health and care challenges and brings together organisations and individuals, to pool what is known and uncover new insights and ideas.

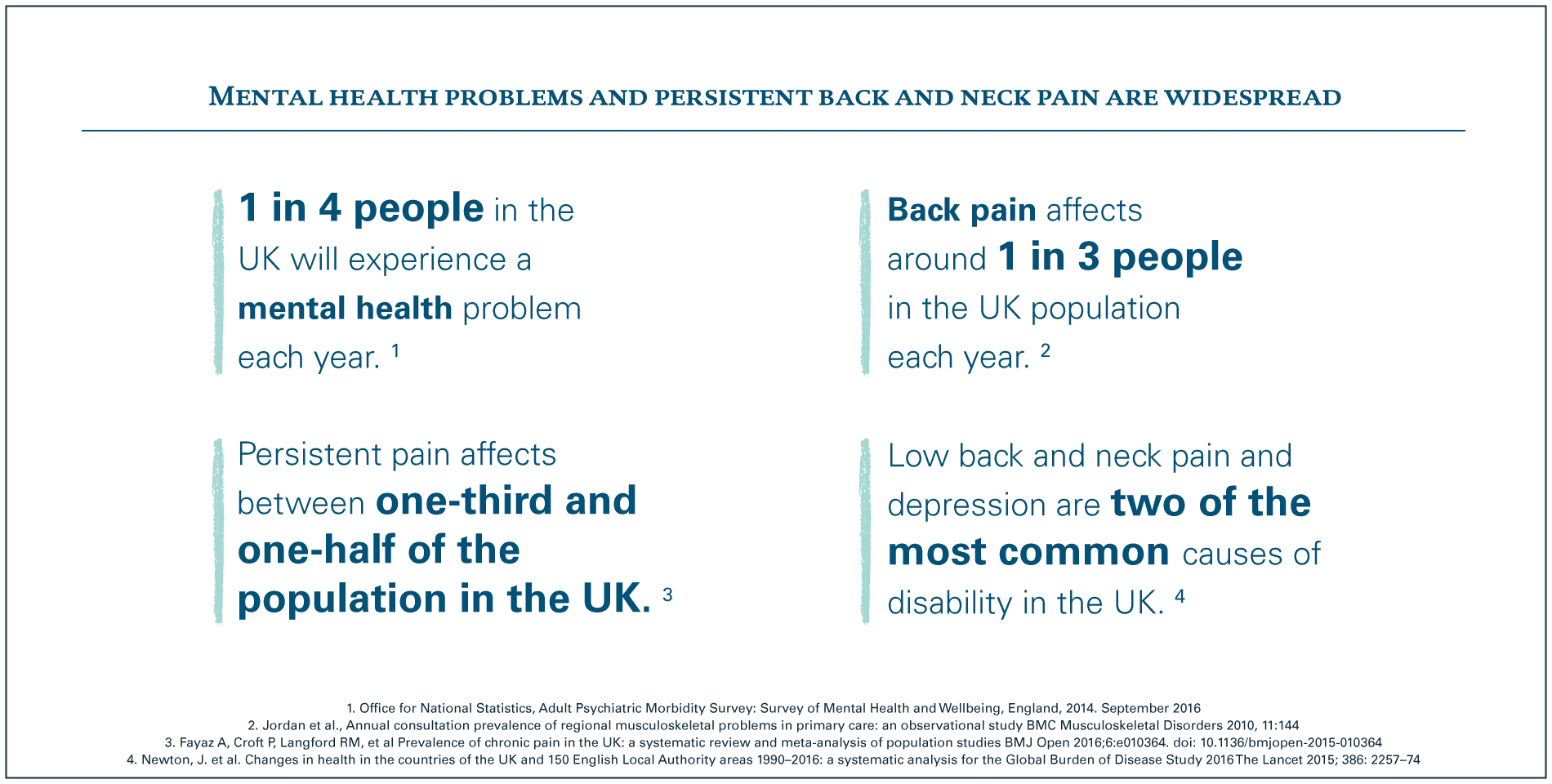

For some, mental health and persistent back and neck pain may sound like a niche topic. In reality, the numbers of people impacted by mental health problems and persistent back and neck pain in the UK are significant, and they are the two most common reasons for people to be on long-term sick leave or unable to work. A lot of attention has been given to these as individual needs, but more needs to be done to bring them together.

This topic – and what we’re learning as a result – is connected to the wider challenge of integrating care to meet people’s mental and physical health needs. The learning from the Q Lab and Mind’s work will provide useful insights for people interested in mental health problems and persistent back and neck pain, as well as individuals and organisations supporting people with combined physical and mental health needs and multiple long-term health conditions.

Over the coming months we will be sharing findings and resources. This essay offers a reminder of what the Q Lab is, the background and context for our work with Mind on this topic, and a flavour of what is to come.

What is the Q Improvement Lab?

The Q Lab – part of the Q initiative – provides an opportunity for individuals and organisations to collaborate and make progress on complex challenges that are affecting health and care in the UK.

The Q Lab works on a single challenge for 12 months – and in that time, convenes a group of people with experience and expertise in the topic (Lab participants). Together, we do research and sense-making, combining the best information and evidence about – and people’s experiences of – the challenge, and use this insight to support teams to develop and test ideas that have the potential to improve care. The Q Lab takes a developmental approach and aims to learn by doing, helping to build the skills and capabilities that are needed to deliver collaborative change.

The project on mental health and persistent pain is the Q Lab’s second project. The first project focussed on scaling patient-to-patient peer support and the learning and insights from this work are shared on this website. For more information on the Q Lab, take a look at What is the Q Improvement Lab? and Impact that counts essays.

Meeting the needs of people living with long-term physical and mental health problems

The Q Lab and Mind’s work aims to respond to the challenges of better meeting the needs of people living with long-term mental and physical health conditions.

Across the UK, long-term conditions are increasingly common. More than 15 million people (30% of the UK population) live with one or more long-term conditions (a condition for which there is no known cure, such as diabetes or arthritis). This will increase by another 3 million people by 2025. 1 Every week, 1 in 6 adults experiences a common mental health problem such as anxiety or depression. 2

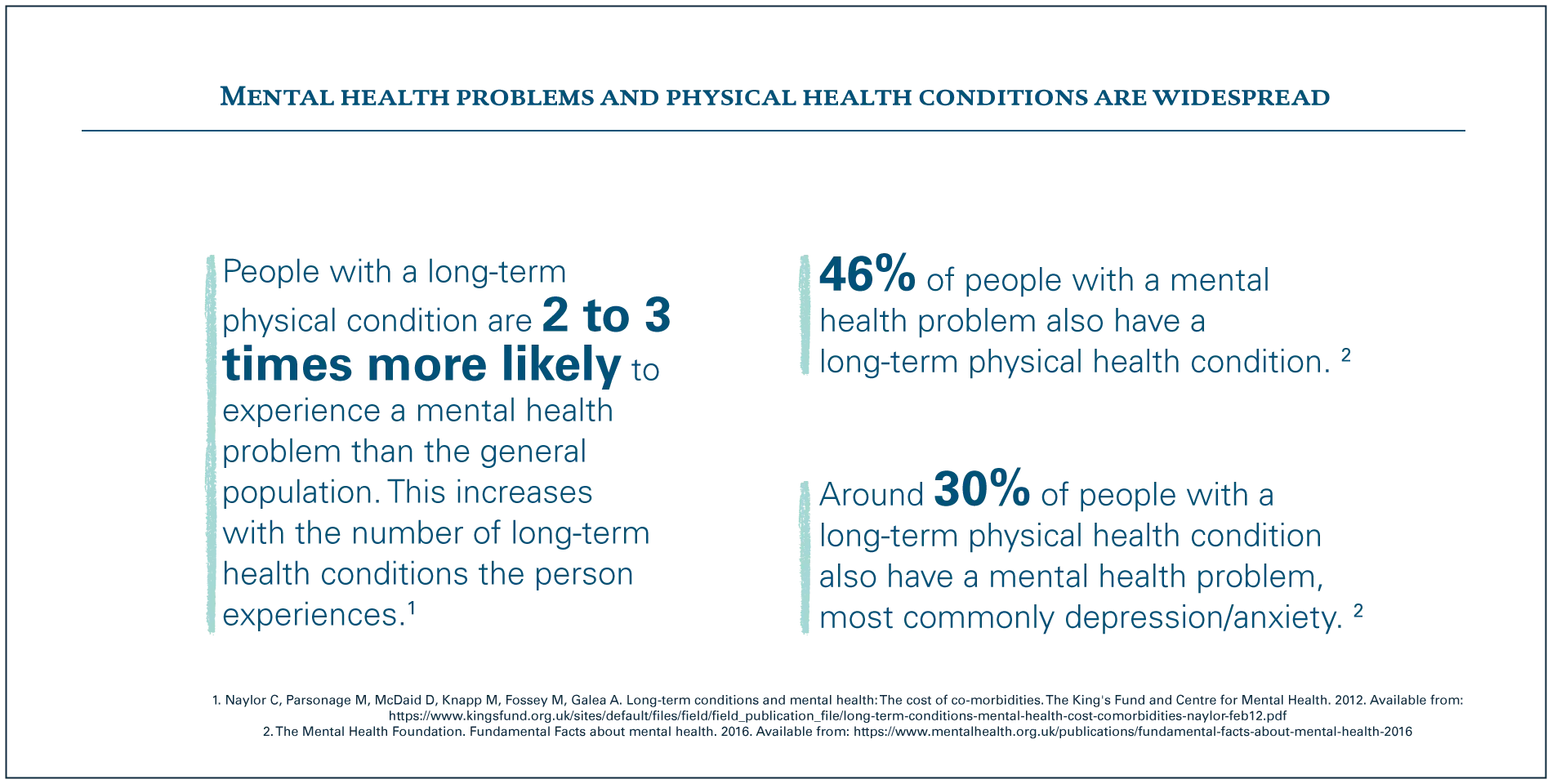

Having either a physical or a mental health problem also makes you more likely to develop both – and this interrelationship goes both ways, with the conditions likely to interact and affect people in different ways.

Despite the interconnection of our mental and physical health (or more simply our minds and bodies), not enough people are receiving care that acknowledges and takes account of these needs at the same time.

This has a negative impact on individuals in lots of ways:

- Quality of life is worse for people with long-term conditions who also experience mental health problems. For example, people with long-term physical conditions are more likely to have lower wellbeing scores than those without. 3

- Health outcomes are also affected. Evidence shows that health screening is worse for people with mental health problems – which means fewer people benefit from interventions to improve their physical health, such as weight management, diet, nutrition and exercise advice. 4 There are also physical side effects of living with multiple conditions. For example, people with mental health problems regularly report that the physical side effects of their mental health medication have not been fully explained to them. 5

- The impact of both conditions can affect many areas of someone’s life – their sense of identity, emotional wellbeing, ability to perform and thrive at work – which can also affect relationships with families, friends and carers.

- Research tells us that despite this, people are not receiving joined-up care . For example, only 1 in 5 people with arthritis reports being asked about emotional or social issues by a rheumatology professional, even though almost half would like the opportunity. 6 The Mind Big Mental Health Survey 2017 found that less than half of the 8000+ respondents felt able to discuss a physical health issue at the same time as discussing their mental health, when attending primary care. 7

These issues impact the health and care system – increasing costs and pressures within services. It is estimated that the effect of poor mental health on people living with long-term physical conditions costs the NHS at least £8 billion a year. 8

Supporting and improving quality of life for people with mental and physical health needs is not just a priority for the NHS – it is also a public health issue. Increasingly people are living longer – but are doing so with greater health needs. In England, the economic and social burden from people living with disabilities is more significant than the impact of people dying young. 9 Increased disability drives demand for statutory services and reduces productivity and employment. It is the product of, and reinforced by, health inequalities.

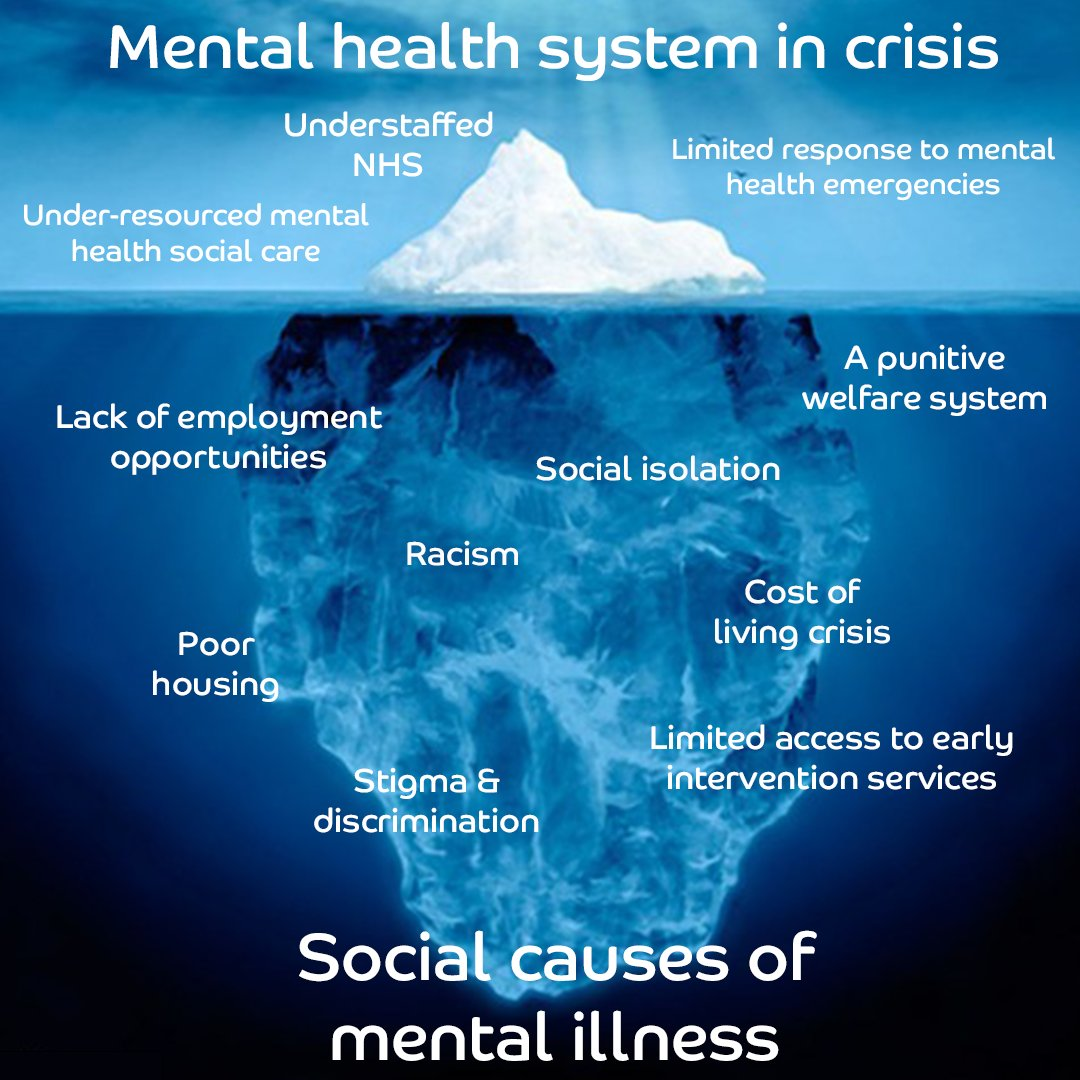

Shifting the status quo

There is no easy fix for systematically supporting people’s mental and physical health needs. Whole-system change will involve adapting the way services are commissioned, designed and delivered, as well as how health care professionals are trained and supported to work together across professional and/or organisational boundaries. Despite these challenges, there is growing recognition of the need to change the status quo.

Increasingly, services are moving towards delivering care using the ‘Biopsychosocial Model’ – a model that acknowledges and recognises the combined biological, psychological and social factors that determine our health and wellbeing.

There is also a drive to increase provision of mental health services, and to support the delivery of better integrated services – through new models of care, strategic transformation partnerships, and the recent commitment in the NHS Long Term Plan that every area will be served by an integrated care system by 2021. Charity and campaigning organisations are collaborating to promote the importance of mental and physical health, for example the Equally Well UK initiative, and many organisations are developing and delivering holistic models of care, that meet people’s physical and mental health needs.

The Health Foundation, who deliver the Q Lab, have funded a wide portfolio of improvement projects that aim to provide more holistic and joined-up care for people living with long-term physical and mental health conditions, including the recent successful programme 3 Dimensions for Long-term Conditions . This programme has integrated mental, physical and social care support in long-term conditions across community and secondary services in London. Find out more at: www.health.org.uk/improvement-projects/integrating-mental-physical-and-social-care-in-long-term-conditions

From mental and physical health to persistent back and neck pain

When Mind and the Q Lab agreed to collaborate, we knew that improving care for people with mental and physical health was the right area to focus our work. It is an important topic that’s ripe for improvement.

It also allows us to build on the great work that’s happening already. For example, we drew on Mind’s work on reducing stigma for people with mental health through Time to Change (which works to end mental health discrimination by changing the way we all think and act about mental health problems) as well as their successful programme Building Health Futures that explored ways to improve the wellbeing, resilience and confidence of people with heart disease, diabetes and arthritis who may be at risk of developing mental health problems. 10

In order to undertake rapid research and develop and test ideas and solutions in practice in just 12 months, a more defined scope was needed. Through reviewing the evidence and speaking to a range of people in this field, a more focussed topic – improving care for people living with both mental health problems and persistent back and neck pain – was identified.

As you’ll go on to read in the next essay Challenges and opportunities to improve , many of the challenges and solutions we identify are either connected, or directly speak to, the challenges of bringing together physical and mental health care provision.

What we aim to achieve

The Q Lab and Mind have worked with others to understand the problem deeply, from a range of perspectives, drawing on data, evidence and experience. Our learning is shared in this essay collection to increase people’s awareness and understanding of the topic, and importantly to increase momentum for change – by highlighting opportunities and practical insights that are useful for people working in and with health and care.

The outputs take into account the evaluation of the Q Lab – conducted by the Innovation Unit – which has provided insights on the types of resources that are most useful for people working to improve health and care, in order to act on the findings.

(If you’d like to find out more about the impact we aim to achieve, take a look at the Impact that counts essay from our first project.)

What to expect from this essay collection

This essay collection presents the findings from the Q Lab and Mind, and the organisations and individuals who have worked with us on this challenge. The learning is shared as openly as possible, as we collectively seek to identify challenges and opportunities that have potential for use in services and organisations across the health and care system.

The next Lab essay in this collection – Challenges and opportunities to improve – brings together the outputs from surveys, workshops and interviews involving over 150 people. If you have lived or professional experience in mental health and persistent back and neck pain, the insights in this essay may be familiar to you and we hope it is a useful tool for you to share and build support for your work. If you are new to the topic – and want to understand more – this essay will provide an overview of the known problems and potential solutions and practical ideas that have worked elsewhere, that may be relevant for you to consider locally.

At the time of writing this essay, we have just started to work with four organisations – Health Innovation Network , Robert Jones and Agnes Hunt Orthopaedic Hospital , Powys Teaching Health Board and Keele University with Midlands Partnership NHS Foundation Trust – to build on our initial sense-making of the topic and translate that into practical actions to improve care.

Over the next six months you can also expect to see from us:

- Practical ideas and solutions to address this topic that have been shown to work elsewhere, with advice about how this could be translated to different contexts.

- Information on using design approaches to develop and test ideas in practice , curating learning from supporting four organisations to test ideas with the potential to improve care for people living with mental health problems and persistent pain.

- Ideas on developing skills for collaborative improvement – including a framework for the skills and attitudes for collaborative and creative problem solving (co-produced with Nesta ).

- Learning from delivering the Q Lab – with stories of how the Lab approach and ethos is helping to deliver impact to health and care in the UK – and what this means for others seeking to deliver change at scale, and for the evolution of the Lab in the coming year.

- Discover what the Q Lab and Mind have learned about mental health and persistent pain in Challenges and opportunities to improve

- Know someone who might be interested in this essay? Share it!

- To connect with people interested in transforming care for people with mental health and persistent back and neck pain, join the Q Lab online group .

- If you have ideas about what you’d like us to produce in the future, get in touch at [email protected]

Challenges and opportunities to improve

People's History of the NHS

- People's Encyclopaedia

- Virtual NHS Museum

- Encyclopaedia

Mental Health

A significant interest in something called mental health, not just mental illness, can be dated back in Britain to the interwar years. In other words, it was not a product of the new National Health Service. Indeed, hope that the new service might provide the opportunity for a vigorous state programme directed at mental health met disappointment. Recognition of the importance of mental health had been reinforced by lessons about military and civilian health in the Second World War, but the new NHS provided little in the way of new initiative. It certainly didn’t put mental health on the same footing as physical health. What’s more, the mentally ill continued to be housed in the same largely isolated, Victorian institutions that had been built up and down Britain over the past century: out of sight, out of mind.

As well as questioning the idea of 1948 as a turning point when it comes to mental health, we should also appreciate that a wholly negative account of the pre-NHS system of care needs some modification. In terms of public effort and investment, the building of this vast system of public institutions now seems impressive. In a sense this was a ‘National Asylum System’, well before the state accepted responsibility to provide free hospital care for the physically ill under the NHS. The problem was that so little could be done to cure those who ended up needing care in such places. Faced by a growing population of seemingly incurable patients, pessimism became pervasive. It was exacerbated as broader eugenic fears led to a parallel system of institutional care for people with mental disabilities – the ‘mentally defective’ as the new legislation of 1913 described them in a language that reflects the harsh attitudes of the time and the stigma that resulted from this. However, it was partly because these institutions seemed to have failed as sites of cure that an interest in the treatment of milder and early stages of mental illness advanced away from the site of asylum in the interwar years. This was often supported by charities. But in addition, local authorities began providing supervision in the community – community care in embryo. General hospitals began to offer outpatient care. Progressive general practitioners increasingly recognised that a large part of the physical illnesses they encountered had a psychological component. And child guidance and psychological clinics sprung up across the country. What’s more, with a boom in self-help literature, the public began to appreciate that mental health was a concern for the whole population. In other words, many of the pieces were in place for something far more ambitious in relation to mental health than was delivered in 1948.

Instead, 1948 saw more of the same. The old Victorian lunacy legislation remained largely in place. It had been modified in 1930 to allow some voluntary treatment in what were now to be termed mental hospitals rather than asylums. But this still left the mentally ill as a class apart, and this is how they were handled in the establishment of the new National Health Service. So, rather than a reversal, the decade after 1948 saw continued growth in the numbers ending up in these institutions to reach a peak of over 150,000 by the mid 1950s (40% of all beds in the NHS).

Reform of the legislation around mental illness had to wait until the Mental Health Act of 1959. The title of this piece of legislation symbolised the aspiration for integration into the NHS. At its heart was the decision to make entry to mental hospital an issue of medical rather than legal judgement. However, this was never going to be enough on its own to remove the stigma that surrounded these ageing institutions. The Act also signalled the intention of a move towards community care. This was given further momentum by a speech from Minister of Health Enoch Powell in 1961, which talked of getting rid of the Victorian asylums ‘brooded over by the gigantic water-tower and chimney combined, rising unmistakable and daunting out of the countryside’. The solution was to be twofold: on the one hand, moving the treatment of mental illness to the wards and wings of general hospitals; on the other, developing new services in the community supported by an expanding social work profession. This fundamental transformation was made much more feasible because of a new generation of drugs. However, in terms of bringing mental health care into the NHS, there was arguably a tension in this vision: at last there was a more hopeful medicine for mental illness; yet the vague talk of community care in fact signalled a future in which responsibility for the care of the mentally ill might largely lie elsewhere, in the field of social care.

In the long term, the vision of transformation was to be realised. Indeed, there has been perhaps no more fundamental shift in the whole history of NHS care than this move from hospital to community care for the mentally ill. In that sense, it provides a significant case study for those who have looked for a similar shift away from the centrality of the hospital in relation to physical health. But change was initially slow, and throughout the period there have been serious misgivings about the quality of the service that has resulted. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the lack of dignity afforded to patients in some of the remaining large and overcrowded mental hospitals was publicised in several scathing public reports. Fashionable anti-psychiatric writing emerging out of the counter-culture added to the sense of unease. More significant still was the emerging service-user movement, which for the first time brought the experiences of those who suffered through the inadequacies of mental health care in the NHS to the fore.

Powell had talked of getting rid of the Victorian institutions, but although the bed numbers began to decline few hospitals were closed until the 1970s. From the 1980s the pace of change accelerated, with a dramatic 60% fall in mental hospital beds from 1987 to 2010. The challenge was ensuring that something more effective and humane was introduced in place of the asylum. However, there was a strong feeling from many at the time that such community care often proved hugely disappointing and an excuse for cuts in expenditure. From 1997, under New Labour, there was a significant increase in expenditure on mental health care, though this reflected a more general increase of expenditure on the NHS and in fact still fell behind the overall trend. One result of the closure of mental hospitals was a growing anxiety, sparked by a small number of well-publicised cases, about the danger of releasing seriously mentally ill patients into the community. In such a context, the residential settings that remained became targeted increasingly on patients deemed to be a ‘risk’ to the broader community. It also became clear that many such individuals were ending up in the country’s expanding prison system. What remained of the mental hospital system now offered no real solution to the demand for ‘asylum’ for those not deemed a danger, nor for the mounting problem of dementia which fell instead into the hands of families and an ailing system of social care.

The considerable challenges of the shift from hospital towards community care meant that it was the issue of mental illness rather than mental health that had remained central as a concern of policy through most of this period. However, it is tempting to argue that the 21st century is seeing something a new kind of transformation. Since the turn of the century, the issue of mental health finally began to come to the fore in debate about the future direction of the NHS. Influential research began to claim that there was a strong economic case for improving mental health, with problems of mental health a major cause of expenditure for the welfare state and of lost productivity. Politicians began to talk about improving happiness and about the neglect of mental health care within the NHS. And the Health and Social Care Act of 2012 made it a requirement for the NHS to place mental health on a par with physical health. A policy of IAPT – improving access to psychological therapy – provided the hope of a new kind of therapeutic armoury for the NHS which could be rolled out far beyond the population that had been the focus of psychiatric care for most of the period since 1948. Often deploying the tools of self-help, assisted by the revolution in communication brought about by the internet and by a greater openness in talking about mental health, the new approach was attractive as a way to overcome the dual problem that had always held back an expansion of mental health services: the inadequacy of both funding and expertise. However, these limitations continued to be exposed in the struggle to access professional services. At a time that the NHS was under so much pressure, putting mental health genuinely on a par with physical health was going to be a huge challenge.

Despite all its ongoing problems and limitations, it is tempting to conclude that the area of mental health care has nevertheless been one of the areas of most major transformation in the history of the NHS. This case rests firstly on the dramatic move from hospital to community care, and secondly on a belated but growing effort to address the mental health of the population as a whole. In 1948 the NHS was really a national physical health (and to a larger extent illness) service. It did inherit a national mental illness service (that huge population in the mental hospitals), but this was not well integrated and was largely hidden away from view. In subsequent efforts at integration, policy makers came to regard this decaying institutional system as having no place in a modern health service. Thereafter barriers were to some extent broken down, although the move from hospital to community care also saw responsibility to some extent passed on to the family, the social services, even eventually the penal system. More recently, there have been signs that the NHS is coming to see tackling mental health as just as much part of its responsibility as its longer term focus on physical health. Whether this is truly to be the case, and whether the developments in the relationship of the NHS towards mental illness and mental health are truly compatible, remains to be seen.

Read other posts:

6 thoughts on “ mental health ”.

‘Influential research began to claim that there was a strong economic case for improving mental health, with problems of mental health a major cause of expenditure for the welfare state and of lost productivity.’

This quotation really interested me because it links our understanding of mental health care to productivity. How far is our system of mental health care reproducing the precarious and tired “good neoliberal subject”?

Employers and Universities tell us to go and seek counselling, or to see the doctor, so we can improve ourselves – usually in our free time – and get back to producing as soon as possible. Therefore, how does this culture reinforce societal structures which exacerbate poor health and reproduce the good, productive, neoliberal citizen?

Yours, A good neoliberal subject

I am very interested in the idea that, as you put it above, ‘a wholly negative account of the pre-NHS system of care needs some modification’. Can we talk about the 1913 Mental Deficiency Act and the people who supported it as other than eugenic sympathisers whose main purpose was to segregate people with mental disabilities? Because of improvements in our current understanding of mental health we now seem to consider those who got involved in the past (including Ida Darwin) as doing more harm than good. Yet their work underpins the support that the NHS provides today.

So much was wrong about the system in the first half of the 20th century, that it may seem odd to talk about ‘positives’, but in the context of the time there was some progress. Areas included:

– Protection for the ‘mentally defective’ (ie care as well as control)

– Early treatment for the mentally ill on a voluntary and temporary basis to avoid the stigma of certification (Mental Treatment Act, 1930)

– The increasing influence of a range of talking therapies provided in clinics or in outpatient sections of hospitals, and reaching out also to children (child guidance clinics)

– Early forms of ‘community care’ via supervision but also licensing out of patients to half-way houses, guardianship schemes, and holiday homes (all particularly prevalent under the Mental Deficiency legislation

– New forms of physical therapy in the mental hospitals

– Efforts to educate the public and change attitudes

I have had a head enj and it’s can not be repair and in my childhood I spent more time in hospitals and I was taken tablets when l came to aduIt age I took myself of the tables because I had an illness EPL sorry I can’t spell the word and the people to whom adopted me could not understand my illness so I was beating but Iam very grateful for the help with the N H S with kind regards Derek Taylor

Hi, I thought you might be interested in this film about Fairfield Psychiatric Hospital in the 1980’s and my creative writing classes there.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s13ARcXya7U&index=27&list=UUmSMyxoSbzMeR1leR8bC7-w

Please use and share as you wish.

David R Morgan

What is Normal ? What is Acceptable ? Behavoir or attitude . It’s ok to be different ? It’s not ok to appear the same but act upon others with harmful scheme or critism Consultation ,diagnosis ,therapy and treatment must be variable ,not the need to treat every patient to behave the same . Good vs evil drivers must be consulted in assessment of Behavoir. Not just Appearance and related fixed assumptions . Never judge a book by its cover. I to this day have no idea why i was detained under mental health act three to.es and heavily medicated ,without being a risk to myself or the general public. I now further my studies in psychology to psychiatry and mental health .With fascination !!!!

Should you wish to remove a comment you have made, please contact us

Twitter Feed

The information is provided by us and while we endeavour to keep the information up to date and correct, we make no representations or warranties of any kind, express or implied, about the completeness, accuracy, reliability, suitability or availability with respect to the website or the information, products, services, or related graphics contained on the website for any purpose. We only capture and store personal information with the prior consent of users. Any personal information collected as part of the user registration process or the submission of material (including, but not limited to, name, address, e-mail address) will be stored securely, and accessible only to members of the Cultural History of the NHS project team. We will not sell, license or trade your personal information to others. We do not provide your personal information to direct marketing companies or other such organizations. These opinions do not necessarily represent those of Warwick University or the Wellcome Trust.

This site would like to use cookies to track your usage of the site

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- For authors

- Browse by collection

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 5, Issue 6

- What is mental health? Evidence towards a new definition from a mixed methods multidisciplinary international survey

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Laurie A Manwell 1 , 2 ,

- Skye P Barbic 1 , 3 ,

- Karen Roberts 1 ,

- Zachary Durisko 1 ,

- Cheolsoon Lee 1 , 4 ,

- Emma Ware 1 ,

- Kwame McKenzie 1

- 1 Social Aetiology of Mental Illness Training Program , Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, University of Toronto , Toronto, Ontario , Canada

- 2 Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology , Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry, University of Western , London, Ontario , Canada

- 3 Department of Psychiatry , University of British Columbia , Vancouver, British Columbia , Canada

- 4 Department of Psychiatry , Gyeongsang National University Hospital, School of Medicine, Gyeongsang National University , Jinju , Republic of Korea

- Correspondence to Dr Laurie A Manwell; lauriemanwell{at}gmail.com

Objective Lack of consensus on the definition of mental health has implications for research, policy and practice. This study aims to start an international, interdisciplinary and inclusive dialogue to answer the question: What are the core concepts of mental health?

Design and participants 50 people with expertise in the field of mental health from 8 countries completed an online survey. They identified the extent to which 4 current definitions were adequate and what the core concepts of mental health were. A qualitative thematic analysis was conducted of their responses. The results were validated at a consensus meeting of 58 clinicians, researchers and people with lived experience.

Results 46% of respondents rated the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC, 2006) definition as the most preferred, 30% stated that none of the 4 definitions were satisfactory and only 20% said the WHO (2001) definition was their preferred choice. The least preferred definition of mental health was the general definition of health adapted from Huber et al (2011). The core concepts of mental health were highly varied and reflected different processes people used to answer the question. These processes included the overarching perspective or point of reference of respondents (positionality), the frameworks used to describe the core concepts (paradigms, theories and models), and the way social and environmental factors were considered to act . The core concepts of mental health identified were mainly individual and functional, in that they related to the ability or capacity of a person to effectively deal with or change his/her environment. A preliminary model for the processes used to conceptualise mental health is presented.

Conclusions Answers to the question, ‘ What are the core concepts of mental health ?’ are highly dependent on the empirical frame used. Understanding these empirical frames is key to developing a useful consensus definition for diverse populations.

- MENTAL HEALTH

- mental illness

- social determinants of health

- human rights

- primary health care

This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007079

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Our study identifies a major obstacle for integrating mental health initiatives into global health programmes and health service delivery, which is a lack of consensus on a definition, and initiates a global, interdisciplinary and inclusive dialogue towards a consensus definition of mental health .

Despite the limitations of a small sample size and response saturation, our sample of global experts was able to demonstrate dissatisfaction with current definitions of mental health and significant agreement among subcomponents, specifically factors beyond the ‘ability to adapt and self-manage’, such as ‘diversity and community identity’ and creating distinct definitions, ‘one for individual and a parallel for community and society’.

This research demonstrates how experts in the field of mental health determine the core concepts of mental health, presenting a model of how empirical discourses shape definitions of mental health.

We propose a transdomain model of health to inform the development of a comprehensive definition capturing all of the subcomponents of health: physical, mental and social health.

Our study discusses the implications of the findings for research, policy and practice in meeting the needs of diverse populations.

Introduction

A major obstacle for integrating mental health initiatives into global health programmes and primary healthcare services is lack of consensus on a definition of mental health. 1–3 There is little agreement on a general definition of ‘mental health’ 4 and currently there is widespread use of the term ‘mental health’ as a euphemism for ‘mental illness’. 5 Mental health can be defined as the absence of mental disease or it can be defined as a state of being that also includes the biological, psychological or social factors which contribute to an individual’s mental state and ability to function within the environment. 4 , 6–11 For example, the WHO 12 includes realising one's potential, the ability to cope with normal life stresses and community contributions as core components of mental health. Other definitions extend beyond this to also include intellectual, emotional and spiritual development, 13 positive self-perception, feelings of self-worth and physical health, 11 , 14 and intrapersonal harmony. 8 Prevention strategies may aim to decrease the rates of mental illness but promotion strategies aim at improving mental health. The possible scope of promotion initiatives depends on the definition of mental health.