Sapir–Whorf hypothesis (Linguistic Relativity Hypothesis)

Mia Belle Frothingham

Author, Researcher, Science Communicator

BA with minors in Psychology and Biology, MRes University of Edinburgh

Mia Belle Frothingham is a Harvard University graduate with a Bachelor of Arts in Sciences with minors in biology and psychology

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

There are about seven thousand languages heard around the world – they all have different sounds, vocabularies, and structures. As you know, language plays a significant role in our lives.

But one intriguing question is – can it actually affect how we think?

It is widely thought that reality and how one perceives the world is expressed in spoken words and are precisely the same as reality.

That is, perception and expression are understood to be synonymous, and it is assumed that speech is based on thoughts. This idea believes that what one says depends on how the world is encoded and decoded in the mind.

However, many believe the opposite.

In that, what one perceives is dependent on the spoken word. Basically, that thought depends on language, not the other way around.

What Is The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis?

Twentieth-century linguists Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf are known for this very principle and its popularization. Their joint theory, known as the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis or, more commonly, the Theory of Linguistic Relativity, holds great significance in all scopes of communication theories.

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis states that the grammatical and verbal structure of a person’s language influences how they perceive the world. It emphasizes that language either determines or influences one’s thoughts.

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis states that people experience the world based on the structure of their language, and that linguistic categories shape and limit cognitive processes. It proposes that differences in language affect thought, perception, and behavior, so speakers of different languages think and act differently.

For example, different words mean various things in other languages. Not every word in all languages has an exact one-to-one translation in a foreign language.

Because of these small but crucial differences, using the wrong word within a particular language can have significant consequences.

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis is sometimes called “linguistic relativity” or the “principle of linguistic relativity.” So while they have slightly different names, they refer to the same basic proposal about the relationship between language and thought.

How Language Influences Culture

Culture is defined by the values, norms, and beliefs of a society. Our culture can be considered a lens through which we undergo the world and develop a shared meaning of what occurs around us.

The language that we create and use is in response to the cultural and societal needs that arose. In other words, there is an apparent relationship between how we talk and how we perceive the world.

One crucial question that many intellectuals have asked is how our society’s language influences its culture.

Linguist and anthropologist Edward Sapir and his then-student Benjamin Whorf were interested in answering this question.

Together, they created the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, which states that our thought processes predominantly determine how we look at the world.

Our language restricts our thought processes – our language shapes our reality. Simply, the language that we use shapes the way we think and how we see the world.

Since the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis theorizes that our language use shapes our perspective of the world, people who speak different languages have different views of the world.

In the 1920s, Benjamin Whorf was a Yale University graduate student studying with linguist Edward Sapir, who was considered the father of American linguistic anthropology.

Sapir was responsible for documenting and recording the cultures and languages of many Native American tribes disappearing at an alarming rate. He and his predecessors were well aware of the close relationship between language and culture.

Anthropologists like Sapir need to learn the language of the culture they are studying to understand the worldview of its speakers truly. Whorf believed that the opposite is also true, that language affects culture by influencing how its speakers think.

His hypothesis proposed that the words and structures of a language influence how its speaker behaves and feels about the world and, ultimately, the culture itself.

Simply put, Whorf believed that you see the world differently from another person who speaks another language due to the specific language you speak.

Human beings do not live in the matter-of-fact world alone, nor solitary in the world of social action as traditionally understood, but are very much at the pardon of the certain language which has become the medium of communication and expression for their society.

To a large extent, the real world is unconsciously built on habits in regard to the language of the group. We hear and see and otherwise experience broadly as we do because the language habits of our community predispose choices of interpretation.

Studies & Examples

The lexicon, or vocabulary, is the inventory of the articles a culture speaks about and has classified to understand the world around them and deal with it effectively.

For example, our modern life is dictated for many by the need to travel by some vehicle – cars, buses, trucks, SUVs, trains, etc. We, therefore, have thousands of words to talk about and mention, including types of models, vehicles, parts, or brands.

The most influential aspects of each culture are similarly reflected in the dictionary of its language. Among the societies living on the islands in the Pacific, fish have significant economic and cultural importance.

Therefore, this is reflected in the rich vocabulary that describes all aspects of the fish and the environments that islanders depend on for survival.

For example, there are over 1,000 fish species in Palau, and Palauan fishers knew, even long before biologists existed, details about the anatomy, behavior, growth patterns, and habitat of most of them – far more than modern biologists know today.

Whorf’s studies at Yale involved working with many Native American languages, including Hopi. He discovered that the Hopi language is quite different from English in many ways, especially regarding time.

Western cultures and languages view times as a flowing river that carries us continuously through the present, away from the past, and to the future.

Our grammar and system of verbs reflect this concept with particular tenses for past, present, and future.

We perceive this concept of time as universal in that all humans see it in the same way.

Although a speaker of Hopi has very different ideas, their language’s structure both reflects and shapes the way they think about time. Seemingly, the Hopi language has no present, past, or future tense; instead, they divide the world into manifested and unmanifest domains.

The manifested domain consists of the physical universe, including the present, the immediate past, and the future; the unmanifest domain consists of the remote past and the future and the world of dreams, thoughts, desires, and life forces.

Also, there are no words for minutes, minutes, or days of the week. Native Hopi speakers often had great difficulty adapting to life in the English-speaking world when it came to being on time for their job or other affairs.

It is due to the simple fact that this was not how they had been conditioned to behave concerning time in their Hopi world, which followed the phases of the moon and the movements of the sun.

Today, it is widely believed that some aspects of perception are affected by language.

One big problem with the original Sapir-Whorf hypothesis derives from the idea that if a person’s language has no word for a specific concept, then that person would not understand that concept.

Honestly, the idea that a mother tongue can restrict one’s understanding has been largely unaccepted. For example, in German, there is a term that means to take pleasure in another person’s unhappiness.

While there is no translatable equivalent in English, it just would not be accurate to say that English speakers have never experienced or would not be able to comprehend this emotion.

Just because there is no word for this in the English language does not mean English speakers are less equipped to feel or experience the meaning of the word.

Not to mention a “chicken and egg” problem with the theory.

Of course, languages are human creations, very much tools we invented and honed to suit our needs. Merely showing that speakers of diverse languages think differently does not tell us whether it is the language that shapes belief or the other way around.

Supporting Evidence

On the other hand, there is hard evidence that the language-associated habits we acquire play a role in how we view the world. And indeed, this is especially true for languages that attach genders to inanimate objects.

There was a study done that looked at how German and Spanish speakers view different things based on their given gender association in each respective language.

The results demonstrated that in describing things that are referred to as masculine in Spanish, speakers of the language marked them as having more male characteristics like “strong” and “long.” Similarly, these same items, which use feminine phrasings in German, were noted by German speakers as effeminate, like “beautiful” and “elegant.”

The findings imply that speakers of each language have developed preconceived notions of something being feminine or masculine, not due to the objects” characteristics or appearances but because of how they are categorized in their native language.

It is important to remember that the Theory of Linguistic Relativity (Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis) also successfully achieves openness. The theory is shown as a window where we view the cognitive process, not as an absolute.

It is set forth to look at a phenomenon differently than one usually would. Furthermore, the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis is very simple and logically sound. Understandably, one’s atmosphere and culture will affect decoding.

Likewise, in studies done by the authors of the theory, many Native American tribes do not have a word for particular things because they do not exist in their lives. The logical simplism of this idea of relativism provides parsimony.

Truly, the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis makes sense. It can be utilized in describing great numerous misunderstandings in everyday life. When a Pennsylvanian says “yuns,” it does not make any sense to a Californian, but when examined, it is just another word for “you all.”

The Linguistic Relativity Theory addresses this and suggests that it is all relative. This concept of relativity passes outside dialect boundaries and delves into the world of language – from different countries and, consequently, from mind to mind.

Is language reality honestly because of thought, or is it thought which occurs because of language? The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis very transparently presents a view of reality being expressed in language and thus forming in thought.

The principles rehashed in it show a reasonable and even simple idea of how one perceives the world, but the question is still arguable: thought then language or language then thought?

Modern Relevance

Regardless of its age, the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, or the Linguistic Relativity Theory, has continued to force itself into linguistic conversations, even including pop culture.

The idea was just recently revisited in the movie “Arrival,” – a science fiction film that engagingly explores the ways in which an alien language can affect and alter human thinking.

And even if some of the most drastic claims of the theory have been debunked or argued against, the idea has continued its relevance, and that does say something about its importance.

Hypotheses, thoughts, and intellectual musings do not need to be totally accurate to remain in the public eye as long as they make us think and question the world – and the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis does precisely that.

The theory does not only make us question linguistic theory and our own language but also our very existence and how our perceptions might shape what exists in this world.

There are generalities that we can expect every person to encounter in their day-to-day life – in relationships, love, work, sadness, and so on. But thinking about the more granular disparities experienced by those in diverse circumstances, linguistic or otherwise, helps us realize that there is more to the story than ours.

And beautifully, at the same time, the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis reiterates the fact that we are more alike than we are different, regardless of the language we speak.

Isn’t it just amazing that linguistic diversity just reveals to us how ingenious and flexible the human mind is – human minds have invented not one cognitive universe but, indeed, seven thousand!

Kay, P., & Kempton, W. (1984). What is the Sapir‐Whorf hypothesis?. American anthropologist, 86(1), 65-79.

Whorf, B. L. (1952). Language, mind, and reality. ETC: A review of general semantics, 167-188.

Whorf, B. L. (1997). The relation of habitual thought and behavior to language. In Sociolinguistics (pp. 443-463). Palgrave, London.

Whorf, B. L. (2012). Language, thought, and reality: Selected writings of Benjamin Lee Whorf. MIT press.

Related Articles

Cognitive Psychology

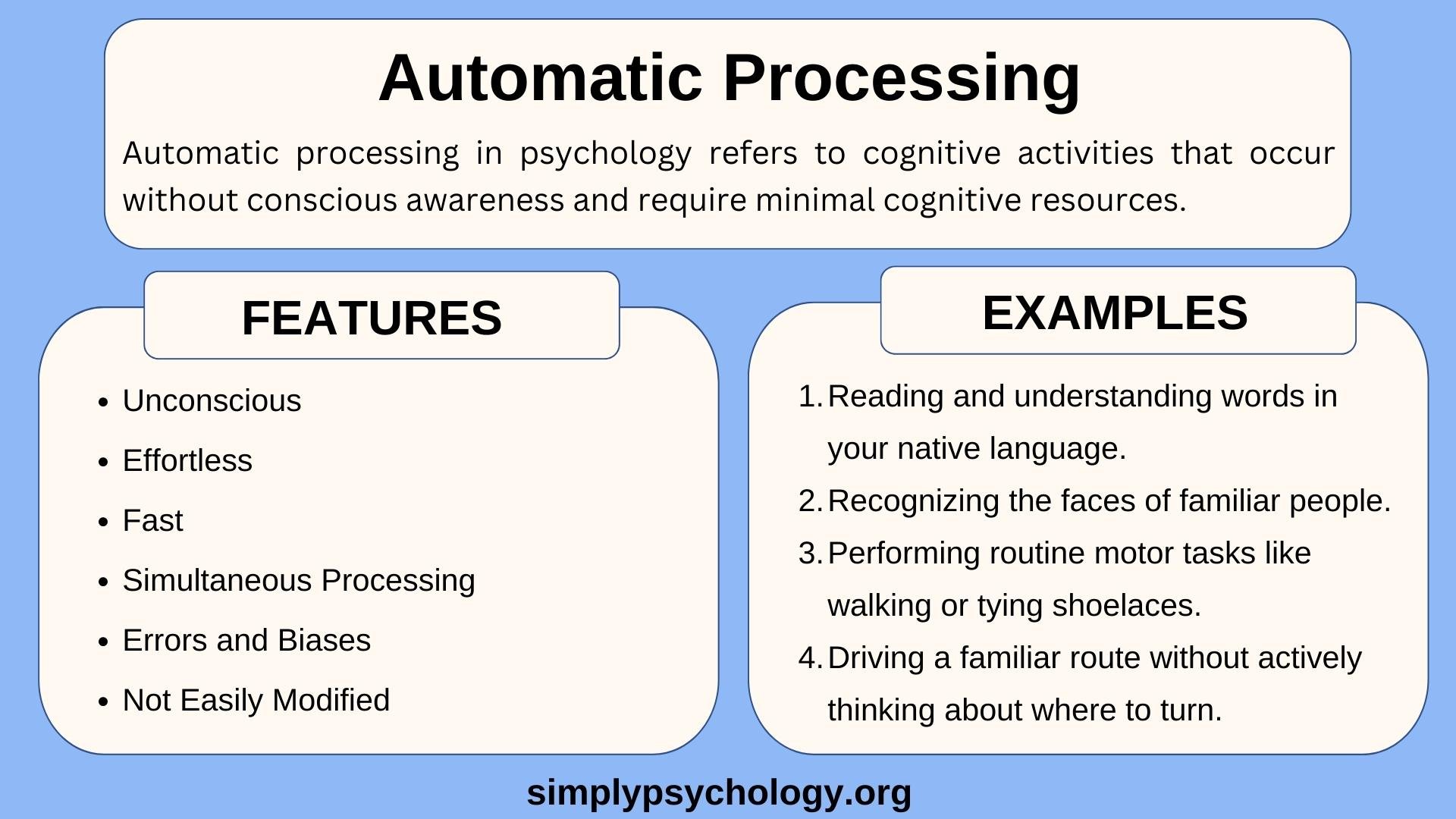

Automatic Processing in Psychology: Definition & Examples

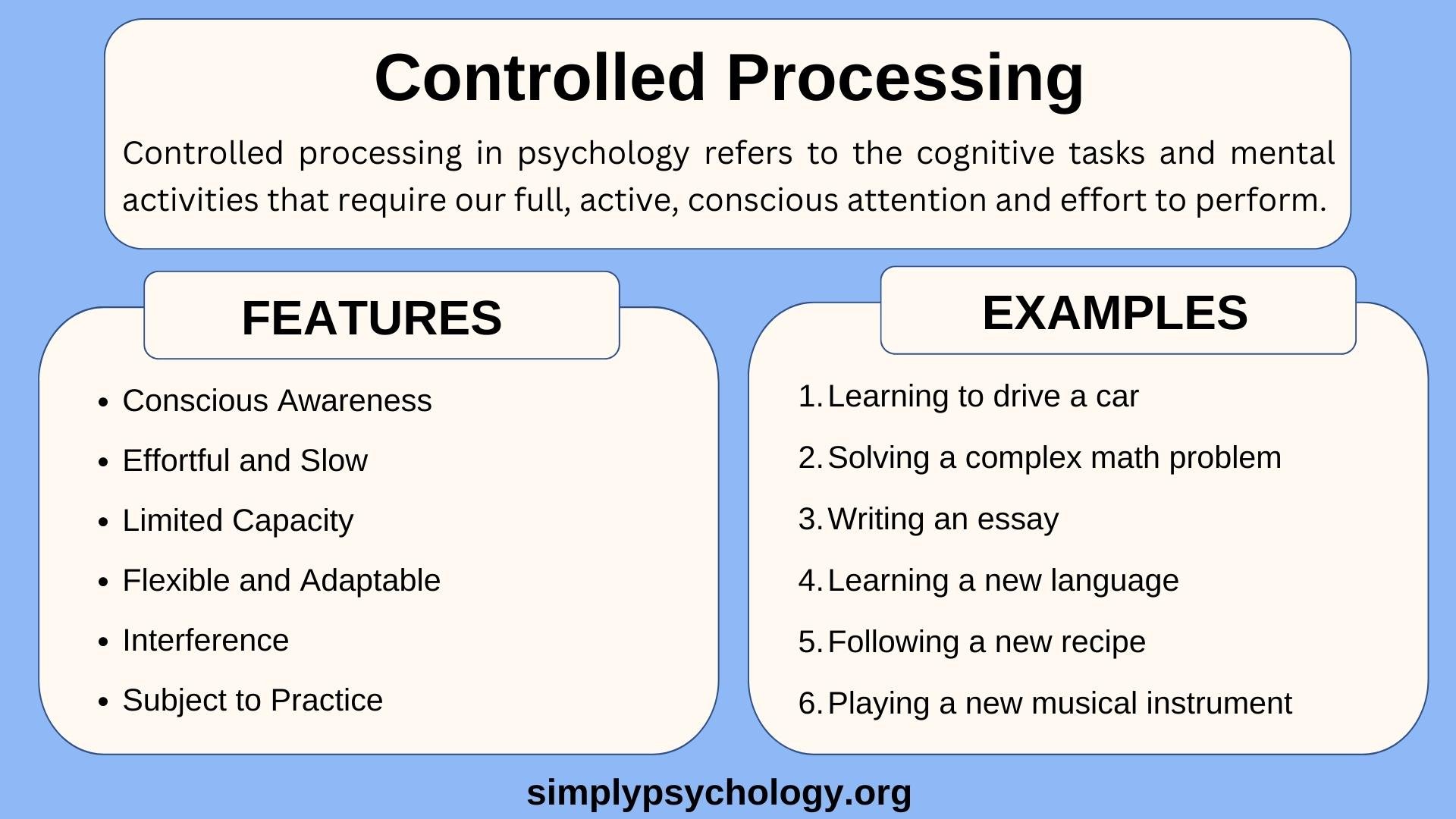

Controlled Processing in Psychology: Definition & Examples

How Ego Depletion Can Drain Your Willpower

What is the Default Mode Network?

Theories of Selective Attention in Psychology

Availability Heuristic and Decision Making

Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis: Examples, Definition, Criticisms

Developed in 1929 by Edward Sapir, the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis (also known as linguistic relativity ) states that a person’s perception of the world around them and how they experience the world is both determined and influenced by the language that they speak.

The theory proposes that differences in grammatical and verbal structures, and the nuanced distinctions in the meanings that are assigned to words, create a unique reality for the speaker. We also call this idea the linguistic determinism theory .

Spair-Whorf Hypothesis Definition and Overview

Cibelli et al. (2016) reiterate the tenets of the hypothesis by stating:

“…our thoughts are shaped by our native language, and that speakers of different languages therefore think differently”(para. 1).

Kay & Kempton (1984) explain it a bit more succinctly. They explain that the hypothesis itself is based on the:

“…evolutionary view prevalent in 19 th century anthropology based in both linguistic relativity and determinism” (pp. 66, 79).

Linguist Edward Sapir, an American linguist who was interested in anthropology , studied at Yale University with Benjamin Whorf in the 1920’s.

Sapir & Whorf began to consider lexical and grammatical patterns and how these factored into the construction of different culture’s views of the world around them.

For example, they compared how thoughts and behavior differed between English speakers and Hopi language speakers in regard to the concept of time, arguing that in the Hopi language, the absence of the future tense has significant relevance (Kay & Kempton, 1984, p. 78-79).

Whorf (2021), in his own words, asserts:

“Every language is a vast pattern-system, different from others, in which are culturally ordained the forms and categories by which the personality not only communicates, but also analyzes nature, notices or neglects types of relationship and phenomena, channels his reasoning, and builds the house of his consciousness” (p. 252).

10 Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis Examples

- Constructions of food in language: A language may ascribe many words to explain the same concept, item, or food type. This shows that they perceive it as extremely important in their society, in comparison to a culture whose language only has one word for that same concept, item, or food.

- Descriptions of color in language: Different cultures may visually perceive colors in different ways according to how the colors are described by the words in their language.

- Constructions of gender in language: Many languages are “gendered”, creating word associations that pertain to the roles of men or women in society.

- Perceptions of time in language: Depending upon how the tenses are structured in a language, it may dictate how the people that speak that language perceive the concept of time.

- Categorization in language: The ways concepts and items in a given culture are categorized (and what words are assigned to them) can affect the speaker’s perception of the world around them.

- Politeness is encoded in language: Levels of politeness in a language and the pronoun combinations to express these levels differ between languages. How languages express politeness with words can dictate how they perceive the world around them.

- Indigenous words for snow: A popular example used to justify this hypothesis is the Inuit people, who have a multitude of ways to express the word snow. If you follow the reasoning of Sapir, it would suggest that the Inuits have a profoundly deeper understanding of snow than other cultures.

- Use of idioms in language: An expression or well-known saying in one culture has an acute meaning implicitly understood by those that speak the particular language but is not understandable when expressed in another language.

- Values are engrained in language: Each country and culture have beliefs and values as a direct result of the language it uses.

- Slang in language: The slang used by younger people evolves from generation to generation in all languages. Generational slang carries with it perceptions and ideas about the world that members of that generation share.

See Other Hypothesis Examples Here

Two Ways Language Shapes Perception

1. perception of categories and categorization.

How concepts and items in a culture are categorized (and what words are assigned to them) can affect the speaker’s perception of the world around them.

Although the examples of this phenomenon are too numerous to cite, a clear example is the extremely contextual, nuanced, and hyper-categorized Japanese language.

In the English language, the concept of “you” and “I” is narrowed to these two forms. However, Japanese has numerous ways to express you and I, each having various levels of politeness and appropriateness in relation to age, gender, and stature in society.

While in common conversation, the pronoun is often left out of the conversation – reliant on context, misuse or omission of the proper pronoun can be perceived as rude or ill-mannered.

In other ways, the complexity of the categorical lexicons can often leave English speakers puzzled. This could come in the form of classifications of different shaped bowls and plates that serve different functions; it could be traces of the ancient Japanese calendar from the 7 th Century, that possessed 72 micro-seasons during a year, or any number of sub-divided word listings that may be considered as one blanket term in another language.

Masuda et al. (2017) gives a clear example:

“ People conceptualize objects along the lines drawn between existing categories in their native language. That is, if two concepts fall into the same linguistic category, the perception of similarity between these objects would be stronger than if the two concepts fall into different linguistic categories.”

They then go on to give the example of how Japanese vs English speakers might categorize an everyday object – the bell:

“For example, in Japanese, the kind of bell found in a bell tower generally corresponds to the word kane—a large bell—which is categorically different from a small bell, suzu. However, in English, these two objects are considered to belong within the same linguistic category, “bell.” Therefore, we might expect English speakers to perceive these two objects as being more similar than would Japanese speakers (para 5).

2. Perception of the Concept of Time

According to a way the tenses are structured in a language, it may dictate how the people that speak that language perceive the concept of time

One of Sapir’s most famous applications of his theory is to the language of the Arizona Native American Hopi tribe.

He claimed, although refuted vehemently by linguistic scholars since, that they have no general notion of time – that they cannot decipher between the past, present, or future because of the grammatical structures that are used within their language.

As Engle (2016) asserts, Sapir believed that the Hopi language “encodes on ordinal value, rather than a passage of time”.

He concluded that, “a day followed by a night is not so much a new day, but a return to daylight” (p. 96).

However, it is not only Hopi culture that has different perception of time imbedded in the language; Thai culture has a non-linear concept of time, and the Malagasy people of Madagascar believe that time in motion around human beings, not that human beings are passing through time (Engle, 2016, p. 99).

Criticism of Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis

1. language as context-dependent.

Iwamoto (2005) expresses that the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis fails to recognize that language is used within context. Its purely decontextualized textual analysis of language is too one-dimensional and doesn’t consider how we actually use language:

“Whorf’s “neat and simplistic” linguistic relativism presupposes the idea that an entire language or entire societies or cultures are categorizable or typable in a straightforward, discrete, and total manner, ignoring other variables such as contextual and semantic factors .” (Iwamoto, 2005, p. 95)

2. Not universally applicable

Another criticism of the hypothesis is that Sapir & Whorf’s hypothesis cannot be transferred or applied to all languages.

It is difficult to cite empirical studies that confirm that other cultures do not also have similarities in the way concepts are perceived through their language – even if they don’t possess a similar word/expression for a particular concept that is expressed.

3. thoughts can be independent of language

Stephen Pinker, one of Sapir & Whorf’s most emphatic critics, would argue that language is not of our thoughts, and is not a cultural invention that creates perceptions; it is in his opinion, a part of human biology (Meier & Pinker, 1995, pp. 611-612).

He suggests that the acquisition and development of sign language show that languages are instinctual, therefore biological; he even goes so far as to say that “all speech is an illusion”(p. 613).

Cibelli, E., Xu, Y., Austerweil, J. L., Griffiths, T. L., & Regier, T. (2016). The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis and Probabilistic Inference: Evidence from the Domain of Color. PLOS ONE , 11 (7), e0158725. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0158725

Engle, J. S. (2016). Of Hopis and Heptapods: The Return of Sapir-Whorf. ETC.: A Review of General Semantics , 73 (1), 95. https://www.questia.com/library/journal/1G1-544562276/of-hopis-and-heptapods-the-return-of-sapir-whorf

Iwamoto, N. (2005). The Role of Language in Advancing Nationalism. Bulletin of the Institute of Humanities , 38 , 91–113.

Meier, R. P., & Pinker, S. (1995). The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language. Language , 71 (3), 610. https://doi.org/10.2307/416234

Masuda, T., Ishii, K., Miwa, K., Rashid, M., Lee, H., & Mahdi, R. (2017). One Label or Two? Linguistic Influences on the Similarity Judgment of Objects between English and Japanese Speakers. Frontiers in Psychology , 8 . https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01637

Kay, P., & Kempton, W. (1984). What Is the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis? American Anthropologist , 86 (1), 65–79. http://www.jstor.org/stable/679389

Whorf, B. L. (2021). Language, Thought, and Reality: Selected Writings of Benjamin Lee Whorf . Hassell Street Press.

Gregory Paul C. (MA)

Gregory Paul C. is a licensed social studies educator, and has been teaching the social sciences in some capacity for 13 years. He currently works at university in an international liberal arts department teaching cross-cultural studies in the Chuugoku Region of Japan. Additionally, he manages semester study abroad programs for Japanese students, and prepares them for the challenges they may face living in various countries short term.

- Gregory Paul C. (MA) #molongui-disabled-link Social Penetration Theory: Examples, Phases, Criticism

- Gregory Paul C. (MA) #molongui-disabled-link Upper Middle-Class Lifestyles: 10 Defining Features

- Gregory Paul C. (MA) #molongui-disabled-link Arousal Theory of Motivation: Definition & Examples

- Gregory Paul C. (MA) #molongui-disabled-link Theory of Mind: Examples and Definition

Chris Drew (PhD)

This article was peer-reviewed and edited by Chris Drew (PhD). The review process on Helpful Professor involves having a PhD level expert fact check, edit, and contribute to articles. Reviewers ensure all content reflects expert academic consensus and is backed up with reference to academic studies. Dr. Drew has published over 20 academic articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education and holds a PhD in Education from ACU.

- Chris Drew (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link 10 Latent Learning Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link 13 Sociocultural Theory Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link 21 Experiential Learning Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link 15 Zone of Proximal Development Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

3.1: Linguistic Relativity- The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 75159

- Manon Allard-Kropp

- University of Missouri–St. Louis

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Learning Objectives

After completing this module, students will be able to:

1. Define the concept of linguistic relativity

2. Differentiate linguistic relativity and linguistic determinism

3. Define the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis (against more pop-culture takes on it) and situate it in a broader theoretical context/history

4. Provide examples of linguistic relativity through examples related to time, space, metaphors, etc.

In this part, we will look at language(s) and worldviews at the intersection of language & thoughts and language & cognition (i.e., the mental system with which we process the world around us, and with which we learn to function and make sense of it). Our main question, which we will not entirely answer but which we will examine in depth, is a chicken and egg one: does thought determine language, or does language inform thought?

We will talk about the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis; look at examples that support the notion of linguistic relativity (pronouns, kinship terms, grammatical tenses, and what they tell us about culture and worldview); and then we will more specifically look into how metaphors are a structural component of worldview, if not cognition itself; and we will wrap up with memes. (Can we analyze memes through an ethnolinguistic, relativist lens? We will try!)

3.1 Linguistic Relativity: The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis

In the 1920s, Benjamin Whorf was a graduate student studying with linguist Edward Sapir at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. Sapir, considered the father of American linguistic anthropology, was responsible for documenting and recording the languages and cultures of many Native American tribes, which were disappearing at an alarming rate. This was due primarily to the deliberate efforts of the United States government to force Native Americans to assimilate into the Euro-American culture. Sapir and his predecessors were well aware of the close relationship between culture and language because each culture is reflected in and influences its language. Anthropologists need to learn the language of the culture they are studying in order to understand the world view of its speakers. Whorf believed that the reverse is also true, that a language affects culture as well, by actually influencing how its speakers think. His hypothesis proposes that the words and the structures of a language influence how its speakers think about the world, how they behave, and ultimately the culture itself. (See our definition of culture in Part 1 of this document.) Simply stated, Whorf believed that human beings see the world the way they do because the specific languages they speak influence them to do so.

He developed this idea through both his work with Sapir and his work as a chemical engineer for the Hartford Insurance Company investigating the causes of fires. One of his cases while working for the insurance company was a fire at a business where there were a number of gasoline drums. Those that contained gasoline were surrounded by signs warning employees to be cautious around them and to avoid smoking near them. The workers were always careful around those drums. On the other hand, empty gasoline drums were stored in another area, but employees were more careless there. Someone tossed a cigarette or lighted match into one of the “empty” drums, it went up in flames, and started a fire that burned the business to the ground. Whorf theorized that the meaning of the word empty implied to the worker that “nothing” was there to be cautious about so the worker behaved accordingly. Unfortunately, an “empty” gasoline drum may still contain fumes, which are more flammable than the liquid itself.

Whorf ’s studies at Yale involved working with Native American languages, including Hopi. The Hopi language is quite different from English, in many ways. For example, let’s look at how the Hopi language deals with time. Western languages (and cultures) view time as a flowing river in which we are being carried continuously away from a past, through the present, and into a future. Our verb systems reflect that concept with specific tenses for past, present, and future. We think of this concept of time as universal, that all humans see it the same way. A Hopi speaker has very different ideas and the structure of their language both reflects and shapes the way they think about time. The Hopi language has no present, past, or future tense. Instead, it divides the world into what Whorf called the manifested and unmanifest domains. The manifested domain deals with the physical universe, including the present, the immediate past and future; the verb system uses the same basic structure for all of them. The unmanifest domain involves the remote past and the future, as well as the world of desires, thought, and life forces. The set of verb forms dealing with this domain are consistent for all of these areas, and are different from the manifested ones. Also, there are no words for hours, minutes, or days of the week. Native Hopi speakers often had great difficulty adapting to life in the English speaking world when it came to being “on time” for work or other events. It is simply not how they had been conditioned to behave with respect to time in their Hopi world, which followed the phases of the moon and the movements of the sun.

In a book about the Abenaki who lived in Vermont in the mid-1800s, Trudy Ann Parker described their concept of time, which very much resembled that of the Hopi and many of the other Native American tribes. “They called one full day a sleep, and a year was called a winter. Each month was referred to as a moon and always began with a new moon. An Indian day wasn’t divided into minutes or hours. It had four time periods—sunrise, noon, sunset, and midnight. Each season was determined by the budding or leafing of plants, the spawning of fish, or the rutting time for animals. Most Indians thought the white race had been running around like scared rabbits ever since the invention of the clock.”

The lexicon , or vocabulary, of a language is an inventory of the items a culture talks about and has categorized in order to make sense of the world and deal with it effectively. For example, modern life is dictated for many by the need to travel by some kind of vehicle—cars, trucks, SUVs, trains, buses, etc. We therefore have thousands of words to talk about them, including types of vehicles, models, brands, or parts.

The most important aspects of each culture are similarly reflected in the lexicon of its language. Among the societies living in the islands of Oceania in the Pacific, fish have great economic and cultural importance. This is reflected in the rich vocabulary that describes all aspects of the fish and the environments that islanders depend on for survival. For example, in Palau there are about 1,000 fish species and Palauan fishermen knew, long before biologists existed, details about the anatomy, behavior, growth patterns, and habitat of most of them—in many cases far more than modern biologists know even today. Much of fish behavior is related to the tides and the phases of the moon. Throughout Oceania, the names given to certain days of the lunar months reflect the likelihood of successful fishing. For example, in the Caroline Islands, the name for the night before the new moon is otolol , which means “to swarm.” The name indicates that the best fishing days cluster around the new moon. In Hawai`i and Tahiti two sets of days have names containing the particle `ole or `ore ; one occurs in the first quarter of the moon and the other in the third quarter. The same name is given to the prevailing wind during those phases. The words mean “nothing,” because those days were considered bad for fishing as well as planting.

Parts of Whorf ’s hypothesis, known as linguistic relativity , were controversial from the beginning, and still are among some linguists. Yet Whorf ’s ideas now form the basis for an entire sub-field of cultural anthropology: cognitive or psychological anthropology. A number of studies have been done that support Whorf ’s ideas. Linguist George Lakoff ’s work looks at the pervasive existence of metaphors in everyday speech that can be said to predispose a speaker’s world view and attitudes on a variety of human experiences. A metaphor is an expression in which one kind of thing is understood and experienced in terms of another entirely unrelated thing; the metaphors in a language can reveal aspects of the culture of its speakers. Take, for example, the concept of an argument. In logic and philosophy, an argument is a discussion involving differing points of view, or a debate. But the conceptual metaphor in American culture can be stated as ARGUMENT IS WAR. This metaphor is reflected in many expressions of the everyday language of American speakers: I won the argument. He shot down every point I made. They attacked every argument we made. Your point is right on target . I had a fight with my boyfriend last night. In other words, we use words appropriate for discussing war when we talk about arguments, which are certainly not real war. But we actually think of arguments as a verbal battle that often involve anger, and even violence, which then structures how we argue.

To illustrate that this concept of argument is not universal, Lakoff suggests imagining a culture where an argument is not something to be won or lost, with no strategies for attacking or defending, but rather as a dance where the dancers’ goal is to perform in an artful, pleasing way. No anger or violence would occur or even be relevant to speakers of this language, because the metaphor for that culture would be ARGUMENT IS DANCE.

3.1 Adapted from Perspectives , Language ( Linda Light, 2017 )

You can either watch the video, How Language Shapes the Way We Think, by linguist Lera Boroditsky, or read the script below.

Watch the video: How Language Shapes the Way We Think ( Boroditsky, 2018)

There are about 7,000 languages spoken around the world—and they all have different sounds, vocabularies, and structures. But do they shape the way we think? Cognitive scientist Lera Boroditsky shares examples of language—from an Aboriginal community in Australia that uses cardinal directions instead of left and right to the multiple words for blue in Russian—that suggest the answer is a resounding yes. “The beauty of linguistic diversity is that it reveals to us just how ingenious and how flexible the human mind is,” Boroditsky says. “Human minds have invented not one cognitive universe, but 7,000.”

Video transcript:

So, I’ll be speaking to you using language ... because I can. This is one these magical abilities that we humans have. We can transmit really complicated thoughts to one another. So what I’m doing right now is, I’m making sounds with my mouth as I’m exhaling. I’m making tones and hisses and puffs, and those are creating air vibrations in the air. Those air vibrations are traveling to you, they’re hitting your eardrums, and then your brain takes those vibrations from your eardrums and transforms them into thoughts. I hope.

I hope that’s happening. So because of this ability, we humans are able to transmit our ideas across vast reaches of space and time. We’re able to transmit knowledge across minds. I can put a bizarre new idea in your mind right now. I could say, “Imagine a jellyfish waltzing in a library while thinking about quantum mechanics.”

Now, if everything has gone relatively well in your life so far, you probably haven’t had that thought before.

But now I’ve just made you think it, through language.

Now of course, there isn’t just one language in the world, there are about 7,000 languages spoken around the world. And all the languages differ from one another in all kinds of ways. Some languages have different sounds, they have different vocabularies, and they also have different structures—very importantly, different structures. That begs the question: Does the language we speak shape the way we think? Now, this is an ancient question. People have been speculating about this question forever. Charlemagne, Holy Roman emperor, said, “To have a second language is to have a second soul”—strong statement that language crafts reality. But on the other hand, Shakespeare has Juliet say, “What’s in a name? A rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” Well, that suggests that maybe language doesn’t craft reality.

These arguments have gone back and forth for thousands of years. But until recently, there hasn’t been any data to help us decide either way. Recently, in my lab and other labs around the world, we’ve started doing research, and now we have actual scientific data to weigh in on this question.

So let me tell you about some of my favorite examples. I’ll start with an example from an Aboriginal community in Australia that I had a chance to work with. These are the Kuuk Thaayorre people. They live in Pormpuraaw at the very west edge of Cape York. What’s cool about Kuuk Thaayorre is, in Kuuk Thaayorre, they don’t use words like “left” and “right,” and instead, everything is in cardinal directions: north, south, east, and west. And when I say everything, I really mean everything. You would say something like, “Oh, there’s an ant on your southwest leg.” Or, “Move your cup to the north-northeast a little bit.” In fact, the way that you say “hello” in Kuuk Thaayorre is you say, “Which way are you going?” And the answer should be, “North-northeast in the far distance. How about you?”

So imagine as you’re walking around your day, every person you greet, you have to report your heading direction.

But that would actually get you oriented pretty fast, right? Because you literally couldn’t get past “hello,” if you didn’t know which way you were going. In fact, people who speak languages like this stay oriented really well. They stay oriented better than we used to think humans could. We used to think that humans were worse than other creatures because of some biological excuse: “Oh, we don’t have magnets in our beaks or in our scales.” No; if your language and your culture trains you to do it, actually, you can do it. There are humans around the world who stay oriented really well.

And just to get us in agreement about how different this is from the way we do it, I want you all to close your eyes for a second and point southeast.

Keep your eyes closed. Point. OK, so you can open your eyes. I see you guys pointing there, there, there, there, there ... I don’t know which way it is myself—

You have not been a lot of help.

So let’s just say the accuracy in this room was not very high. This is a big difference in cognitive ability across languages, right? Where one group—very distinguished group like you guys—doesn’t know which way is which, but in another group, I could ask a five-year-old and they would know.

There are also really big differences in how people think about time. So here I have pictures of my grandfather at different ages. And if I ask an English speaker to organize time, they might lay it out this way, from left to right. This has to do with writing direction. If you were a speaker of Hebrew or Arabic, you might do it going in the opposite direction, from right to left.

But how would the Kuuk Thaayorre, this Aboriginal group I just told you about, do it? They don’t use words like “left” and “right.” Let me give you hint. When we sat people facing south, they organized time from left to right. When we sat them facing north, they organized time from right to left. When we sat them facing east, time came towards the body. What’s the pattern? East to west, right? So for them, time doesn’t actually get locked on the body at all, it gets locked on the landscape. So for me, if I’m facing this way, then time goes this way, and if I’m facing this way, then time goes this way. I’m facing this way, time goes this way— very egocentric of me to have the direction of time chase me around every time I turn my body. For the Kuuk Thaayorre, time is locked on the landscape. It’s a dramatically different way of thinking about time.

Here’s another really smart human trait. Suppose I ask you how many penguins are there. Well, I bet I know how you’d solve that problem if you solved it. You went, “One, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight.” You counted them. You named each one with a number, and the last number you said was the number of penguins. This is a little trick that you’re taught to use as kids. You learn the number list and you learn how to apply it. A little linguistic trick. Well, some languages don’t do this, because some languages don’t have exact number words. They’re languages that don’t have a word like “seven” or a word like “eight.” In fact, people who speak these languages don’t count, and they have trouble keeping track of exact quantities. So, for example, if I ask you to match this number of penguins to the same number of ducks, you would be able to do that by counting. But folks who don’t have that linguistic trait can’t do that.

Languages also differ in how they divide up the color spectrum—the visual world. Some languages have lots of words for colors, some have only a couple words, “light” and “dark.” And languages differ in where they put boundaries between colors. So, for example, in English, there’s a word for blue that covers all of the colors that you can see on the screen, but in Russian, there isn’t a single word. Instead, Russian speakers have to differentiate between light blue, goluboy , and dark blue, siniy . So Russians have this lifetime of experience of, in language, distinguishing these two colors. When we test people’s ability to perceptually discriminate these colors, what we find is that Russian speakers are faster across this linguistic boundary. They’re faster to be able to tell the difference between a light and a dark blue. And when you look at people’s brains as they’re looking at colors—say you have colors shifting slowly from light to dark blue—the brains of people who use different words for light and dark blue will give a surprised reaction as the colors shift from light to dark, as if, “Ooh, something has categorically changed,” whereas the brains of English speakers, for example, that don’t make this categorical distinction, don’t give that surprise, because nothing is categorically changing.

Languages have all kinds of structural quirks. This is one of my favorites. Lots of languages have grammatical gender; so every noun gets assigned a gender, often masculine or feminine. And these genders differ across languages. So, for example, the sun is feminine in German but masculine in Spanish, and the moon, the reverse. Could this actually have any consequence for how people think? Do German speakers think of the sun as somehow more female-like, and the moon somehow more male-like? Actually, it turns out that’s the case. So if you ask German and Spanish speakers to, say, describe a bridge, like the one here—“bridge” happens to be grammatically feminine in German, grammatically masculine in Spanish—German speakers are more likely to say bridges are “beautiful,” “elegant,” and stereotypically feminine words. Whereas Spanish speakers will be more likely to say they’re “strong” or “long,” these masculine words.

Languages also differ in how they describe events, right? You take an event like this, an accident. In English, it’s fine to say, “He broke the vase.” In a language like Spanish, you might be more likely to say, “The vase broke,” or “The vase broke itself.” If it’s an accident, you wouldn’t say that someone did it. In English, quite weirdly, we can even say things like, “I broke my arm.” Now, in lots of languages, you couldn’t use that construction unless you are a lunatic and you went out looking to break your arm—[laughter] and you succeeded. If it was an accident, you would use a different construction.

Now, this has consequences. So, people who speak different languages will pay attention to different things, depending on what their language usually requires them to do. So we show the same accident to English speakers and Spanish speakers, English speakers will remember who did it, because English requires you to say, “He did it; he broke the vase.” Whereas Spanish speakers might be less likely to remember who did it if it’s an accident, but they’re more likely to remember that it was an accident. They’re more likely to remember the intention. So, two people watch the same event, witness the same crime, but end up remembering different things about that event. This has implications, of course, for eyewitness testimony. It also has implications for blame and punishment. So if you take English speakers and I just show you someone breaking a vase, and I say, “He broke the vase,” as opposed to “The vase broke,” even though you can witness it yourself, you can watch the video, you can watch the crime against the vase, you will punish someone more, you will blame someone more if I just said, “He broke it,” as opposed to, “It broke.” The language guides our reasoning about events.

Now, I’ve given you a few examples of how language can profoundly shape the way we think, and it does so in a variety of ways. So language can have big effects, like we saw with space and time, where people can lay out space and time in completely different coordinate frames from each other. Language can also have really deep effects—that’s what we saw with the case of number. Having count words in your language, having number words, opens up the whole world of mathematics. Of course, if you don’t count, you can’t do algebra, you can’t do any of the things that would be required to build a room like this or make this broadcast, right? This little trick of number words gives you a stepping stone into a whole cognitive realm.

Language can also have really early effects, what we saw in the case of color. These are really simple, basic, perceptual decisions. We make thousands of them all the time, and yet, language is getting in there and fussing even with these tiny little perceptual decisions that we make. Language can have really broad effects. So the case of grammatical gender may be a little silly, but at the same time, grammatical gender applies to all nouns. That means language can shape how you’re thinking about anything that can be named by a noun. That’s a lot of stuff.

And finally, I gave you an example of how language can shape things that have personal weight to us—ideas like blame and punishment or eyewitness memory. These are important things in our daily lives.

Now, the beauty of linguistic diversity is that it reveals to us just how ingenious and how flexible the human mind is. Human minds have invented not one cognitive universe, but 7,000—there are 7,000 languages spoken around the world. And we can create many more—languages, of course, are living things, things that we can hone and change to suit our needs. The tragic thing is that we’re losing so much of this linguistic diversity all the time. We’re losing about one language a week, and by some estimates, half of the world’s languages will be gone in the next hundred years. And the even worse news is that right now, almost everything we know about the human mind and human brain is based on studies of usually American English-speaking undergraduates at universities. That excludes almost all humans. Right? So what we know about the human mind is actually incredibly narrow and biased, and our science has to do better.

I want to leave you with this final thought. I’ve told you about how speakers of different languages think differently, but of course, that’s not about how people elsewhere think. It’s about how you think. It’s how the language that you speak shapes the way that you think. And that gives you the opportunity to ask, “Why do I think the way that I do?” “How could I think differently?” And also, “What thoughts do I wish to create?”

Thank you very much.

Read the following text on what lexical differences between language can tell us about those languages’ cultures.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis: How Language Influences How We Express Ourselves

Rachael is a New York-based writer and freelance writer for Verywell Mind, where she leverages her decades of personal experience with and research on mental illness—particularly ADHD and depression—to help readers better understand how their mind works and how to manage their mental health.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/RachaelGreenProfilePicture1-a3b8368ef3bb47ccbac92c5cc088e24d.jpg)

Thomas Barwick / Getty Images

What to Know About the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis

Real-world examples of linguistic relativity, linguistic relativity in psychology.

The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis, also known as linguistic relativity, refers to the idea that the language a person speaks can influence their worldview, thought, and even how they experience and understand the world.

While more extreme versions of the hypothesis have largely been discredited, a growing body of research has demonstrated that language can meaningfully shape how we understand the world around us and even ourselves.

Keep reading to learn more about linguistic relativity, including some real-world examples of how it shapes thoughts, emotions, and behavior.

The hypothesis is named after anthropologist and linguist Edward Sapir and his student, Benjamin Lee Whorf. While the hypothesis is named after them both, the two never actually formally co-authored a coherent hypothesis together.

This Hypothesis Aims to Figure Out How Language and Culture Are Connected

Sapir was interested in charting the difference in language and cultural worldviews, including how language and culture influence each other. Whorf took this work on how language and culture shape each other a step further to explore how different languages might shape thought and behavior.

Since then, the concept has evolved into multiple variations, some more credible than others.

Linguistic Determinism Is an Extreme Version of the Hypothesis

Linguistic determinism, for example, is a more extreme version suggesting that a person’s perception and thought are limited to the language they speak. An early example of linguistic determinism comes from Whorf himself who argued that the Hopi people in Arizona don’t conjugate verbs into past, present, and future tenses as English speakers do and that their words for units of time (like “day” or “hour”) were verbs rather than nouns.

From this, he concluded that the Hopi don’t view time as a physical object that can be counted out in minutes and hours the way English speakers do. Instead, Whorf argued, the Hopi view time as a formless process.

This was then taken by others to mean that the Hopi don’t have any concept of time—an extreme view that has since been repeatedly disproven.

There is some evidence for a more nuanced version of linguistic relativity, which suggests that the structure and vocabulary of the language you speak can influence how you understand the world around you. To understand this better, it helps to look at real-world examples of the effects language can have on thought and behavior.

Different Languages Express Colors Differently

Color is one of the most common examples of linguistic relativity. Most known languages have somewhere between two and twelve color terms, and the way colors are categorized varies widely. In English, for example, there are distinct categories for blue and green .

Blue and Green

But in Korean, there is one word that encompasses both. This doesn’t mean Korean speakers can’t see blue, it just means blue is understood as a variant of green rather than a distinct color category all its own.

In Russian, meanwhile, the colors that English speakers would lump under the umbrella term of “blue” are further subdivided into two distinct color categories, “siniy” and “goluboy.” They roughly correspond to light blue and dark blue in English. But to Russian speakers, they are as distinct as orange and brown .

In one study comparing English and Russian speakers, participants were shown a color square and then asked to choose which of the two color squares below it was the closest in shade to the first square.

The test specifically focused on varying shades of blue ranging from “siniy” to “goluboy.” Russian speakers were not only faster at selecting the matching color square but were more accurate in their selections.

The Way Location Is Expressed Varies Across Languages

This same variation occurs in other areas of language. For example, in Guugu Ymithirr, a language spoken by Aboriginal Australians, spatial orientation is always described in absolute terms of cardinal directions. While an English speaker would say the laptop is “in front of” you, a Guugu Ymithirr speaker would say it was north, south, west, or east of you.

As a result, Aboriginal Australians have to be constantly attuned to cardinal directions because their language requires it (just as Russian speakers develop a more instinctive ability to discern between shades of what English speakers call blue because their language requires it).

So when you ask a Guugu Ymithirr speaker to tell you which way south is, they can point in the right direction without a moment’s hesitation. Meanwhile, most English speakers would struggle to accurately identify South without the help of a compass or taking a moment to recall grade school lessons about how to find it.

The concept of these cardinal directions exists in English, but English speakers aren’t required to think about or use them on a daily basis so it’s not as intuitive or ingrained in how they orient themselves in space.

Just as with other aspects of thought and perception, the vocabulary and grammatical structure we have for thinking about or talking about what we feel doesn’t create our feelings, but it does shape how we understand them and, to an extent, how we experience them.

Words Help Us Put a Name to Our Emotions

For example, the ability to detect displeasure from a person’s face is universal. But in a language that has the words “angry” and “sad,” you can further distinguish what kind of displeasure you observe in their facial expression. This doesn’t mean humans never experienced anger or sadness before words for them emerged. But they may have struggled to understand or explain the subtle differences between different dimensions of displeasure.

In one study of English speakers, toddlers were shown a picture of a person with an angry facial expression. Then, they were given a set of pictures of people displaying different expressions including happy, sad, surprised, scared, disgusted, or angry. Researchers asked them to put all the pictures that matched the first angry face picture into a box.

The two-year-olds in the experiment tended to place all faces except happy faces into the box. But four-year-olds were more selective, often leaving out sad or fearful faces as well as happy faces. This suggests that as our vocabulary for talking about emotions expands, so does our ability to understand and distinguish those emotions.

But some research suggests the influence is not limited to just developing a wider vocabulary for categorizing emotions. Language may “also help constitute emotion by cohering sensations into specific perceptions of ‘anger,’ ‘disgust,’ ‘fear,’ etc.,” said Dr. Harold Hong, a board-certified psychiatrist at New Waters Recovery in North Carolina.

As our vocabulary for talking about emotions expands, so does our ability to understand and distinguish those emotions.

Words for emotions, like words for colors, are an attempt to categorize a spectrum of sensations into a handful of distinct categories. And, like color, there’s no objective or hard rule on where the boundaries between emotions should be which can lead to variation across languages in how emotions are categorized.

Emotions Are Categorized Differently in Different Languages

Just as different languages categorize color a little differently, researchers have also found differences in how emotions are categorized. In German, for example, there’s an emotion called “gemütlichkeit.”

While it’s usually translated as “cozy” or “ friendly ” in English, there really isn’t a direct translation. It refers to a particular kind of peace and sense of belonging that a person feels when surrounded by the people they love or feel connected to in a place they feel comfortable and free to be who they are.

Harold Hong, MD, Psychiatrist

The lack of a word for an emotion in a language does not mean that its speakers don't experience that emotion.

You may have felt gemütlichkeit when staying up with your friends to joke and play games at a sleepover. You may feel it when you visit home for the holidays and spend your time eating, laughing, and reminiscing with your family in the house you grew up in.

In Japanese, the word “amae” is just as difficult to translate into English. Usually, it’s translated as "spoiled child" or "presumed indulgence," as in making a request and assuming it will be indulged. But both of those have strong negative connotations in English and amae is a positive emotion .

Instead of being spoiled or coddled, it’s referring to that particular kind of trust and assurance that comes with being nurtured by someone and knowing that you can ask for what you want without worrying whether the other person might feel resentful or burdened by your request.

You might have felt amae when your car broke down and you immediately called your mom to pick you up, without having to worry for even a second whether or not she would drop everything to help you.

Regardless of which languages you speak, though, you’re capable of feeling both of these emotions. “The lack of a word for an emotion in a language does not mean that its speakers don't experience that emotion,” Dr. Hong explained.

What This Means For You

“While having the words to describe emotions can help us better understand and regulate them, it is possible to experience and express those emotions without specific labels for them.” Without the words for these feelings, you can still feel them but you just might not be able to identify them as readily or clearly as someone who does have those words.

Rhee S. Lexicalization patterns in color naming in Korean . In: Raffaelli I, Katunar D, Kerovec B, eds. Studies in Functional and Structural Linguistics. Vol 78. John Benjamins Publishing Company; 2019:109-128. Doi:10.1075/sfsl.78.06rhe

Winawer J, Witthoft N, Frank MC, Wu L, Wade AR, Boroditsky L. Russian blues reveal effects of language on color discrimination . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(19):7780-7785. 10.1073/pnas.0701644104

Lindquist KA, MacCormack JK, Shablack H. The role of language in emotion: predictions from psychological constructionism . Front Psychol. 2015;6. Doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00444

By Rachael Green Rachael is a New York-based writer and freelance writer for Verywell Mind, where she leverages her decades of personal experience with and research on mental illness—particularly ADHD and depression—to help readers better understand how their mind works and how to manage their mental health.

Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis

Jul 25, 2014

670 likes | 2.66k Views

Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis. Ahmet Mesut Ateş March 27, 2013 Applied Linguistics Karadeniz Technical University. Mould and Cloak Theories.

Share Presentation

- linguistic structure doesn

- discrete colours

- whorf hypothesis

- strong contrast

- moderate whorfianism

Presentation Transcript

Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis Ahmet Mesut Ateş March 27, 2013 Applied Linguistics Karadeniz Technical University

Mould and Cloak Theories Within linguistic theory, two extreme positions concerning the relationship between language and thought are commonly referred to as 'mould theories’ and 'cloak theories'. Mould theoriesrepresent language as 'a mould in terms of which thought categories are cast.'Cloak theories represent the view that 'language is a cloak conforming to the customary categories of thought of its speakers' . Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis by Ahmet Mesut Ateş

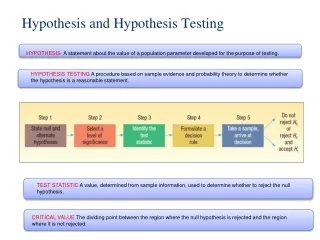

The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis The Sapir-Whorf theory, named after the American linguists Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf, is a mould theory of language. Sapir (1929)Human beings do not live in the soceity alone. Language of the society predispose certain choices of interpretation about how we view the world. Whorf (1930s) We dissect nature along lines laid down by our native languages. We categorise objects in the scheme laid by the language and if we do not subscribe to these classification we cannot talk or communicate. Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis by Ahmet Mesut Ateş

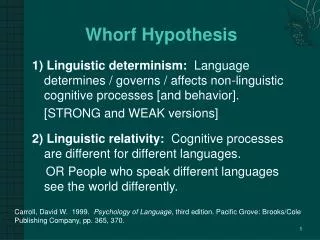

The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis consists of two associated principle: • Linguistic Determinism • Linguistic Relativity Linguistic Determinism: Language may determine our thinking patterns, the way we view and think about the world. Linguistic Determinism is also called «strong determinism» Linguistic Relativity: the less similar the languages more diverse their conceptualization of the world; different languages view the worl differently. Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis by Ahmet Mesut Ateş

Whorfian Perspective vs Universalism The Whorfian perspective is that translation between one language and another is at the very least, problematic, and sometimes impossible. According to the Whorfian stance, 'content' is bound up with linguistic 'form', and the use of the medium contributes to shaping the meaning: 'it is impossible to mean the same thing in two (or more) different ways.' The Whorfian perspective is in strong contrast to the extreme universalism of those who adopt the cloak theory. Universalists argue that we can say whatever we want to say in any language, and that whatever we say in one language can always be translated into another: Even totally different languages are not untranslatable. Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis by Ahmet Mesut Ateş

Whorfian Perspective vs Universalism In the context of the written word, the 'untranslatability' claim is generally regarded as strongest in the arts and weakest in the case of formal scientific papers (although rhetorical studies have increasingly blurred any clear distinctions). And within the literary domain, 'untranslatability' was favoured by Romantic literary theorists, for whom the connotative, emotional or personal meanings of words were crucial. Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis by Ahmet Mesut Ateş

Moderate Whorfianism Moderate Whorfianism differs from deterministWhorfianism in these ways: • Patterns of thinking can be influenced rather than determined, • Language influences the way we see the world and it is influenced by that also, • Any influence should be ascribed to the variety in a language rather than the language itself (sociolect*), • Influence can be seen on the social context but not in purely linguistic form. Sociolect:the language used primarily by members of a articular social group. Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis by Ahmet Mesut Ateş

Advantages of Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis Advantages* of Linguistics Determinism: • Language does exert great influence on patterns of thinking and therefore on culture • Language may reinforce certain ideas and push them into attention Advantages of Linguistic Relativity: • There can be differences in the semantic associations of concepts • Encoding of life experience in language is not exclusively accesible to everyone but only to members of that certain social group • Linguistic structure doesn’t constrain what people think but only influence what they routinely think • Language reflects cultural preoccupations «Advantage» means in this context generally accepted or proved part of SWH. Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis by Ahmet Mesut Ateş

Disadvantages of Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis Whorf claimed (1940): if, between two different languages, one has many words for closely related objects while other has relatively limited vocabulary users of L1 should have noted perceptually characteristics of the objects. BUT this doesn’t prove English speaking people do not have the ability to distinguis characteristics. Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis by Ahmet Mesut Ateş

Disadvantages of Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis Sapir-Whorf hypothesis asserts that each language has a unique system and thus cross-cultural undertanding is impossible. BUT we have: • Perceptional universsals (different languages may express the same thought) • Cultural universal (each language has taboos, implements, slang) • Features to distinguish family and relatives (by seniority, biological bond or sex) • Languages may exhibit a shared attitude towards one thing (respect for elderly, objects of fear, concept of blasphemy) Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis by Ahmet Mesut Ateş

Disadvantages of Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis Sapir-Whorf hypothesis is self-conflicting. It claims that «language determines thought» but also «there is no limits to diversity of languages». If there is no limit to diversity language cannot determine thought to a great extent to be called «determination» rather than «influence». AND many scholars indicate that human thought is universal. Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis by Ahmet Mesut Ateş

Disadvantages of Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis • From a historical stand pint it SHOULD be society and culture that determine language because social enviroment exert great influence upon percptual ability. BUT decise factor is NOT the language. • If language determines the world view there would be NO class conscious because every member of the society would view the world same and think by the same thinking patterns. Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis by Ahmet Mesut Ateş

Further application of SWH There are many studies on Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis but a majority of these studies focus on these main problems: • Perception of time continuity in languages • Dividing time periodically (i.e. English) • Not dividing (i.e. Indonesian) • Dividing time by source of knowledge (i.e. Turkish) • Perception of snow • Eskimo languages vs English • Perception of colours • Universal colours vs local colours • Counting systems Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis by Ahmet Mesut Ateş

Further application of SWH A study (Berlin & Kay) on colour perception which claimed that a regular, universal systemof colour categorisation existed across the world’s languages: while the number ofnames of discrete colours varies across languages, these are based on a set of focalcolours. Furthermore, research done on a stone-age cultural group in Indonesia, theDani, by Rosch Heider (1972) suggested that members of the group, despite only havingtwo colourcategories, perceived colours in much the same way as English speakers. Of course not all languages follow thepredetermined order and too little is known about a great number of the world’s languagesto be able to formulate universally valid hypotheses Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis by Ahmet Mesut Ateş

References Chandler, D. (1994). The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis. 27.03.2013, http://www.aber.ac.uk/media/Documents/short/whorf.html Delaney,M.S.(2010). Can the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis save theplanet? Lessons from cross-cultural psychology for critical language policy.Current Issues inLanguage Planning, 11:4, 331-340. LIANG,H. (2011). The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis and Foreign Language Teaching and Learning. US-China Foreign Language, 9, 569-574. Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis by Ahmet Mesut Ateş

- More by User

The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis

The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis. Rodolfo Celis Beaver College Linguistics. Read disclaimer first. Benjamin Lee Whorf. April 24, 1897 – July 26, 1941. Never trained formally as a linguist, though eventually came to be recognized as a leader in the field and held important university positions.

913 views • 9 slides

![sapir whorf hypothesis examples ppt Edward Sapir [1884-1939]](https://cdn0.slideserve.com/1084146/edward-sapir-1884-1939-dt.jpg)

Edward Sapir [1884-1939]

Edward Sapir [1884-1939]. Born in Germany and immigrated into the United States in late 19th century Events occuring during this time include the following - Wright Bros. first airplane 1903 - Einstein proposes theory of relativity 1905 - World War I 191

968 views • 7 slides

Whorf Hypothesis and Color Terms

Whorf Hypothesis and Color Terms. The relation of language to culture and nature. Whorf Hypothesis. Benjamin Lee Whorf – Chemical Engineer worked as accident investigator for insurance companies. Whorf Hypothesis. Question Whorf sought to answer: Culture ↔ Language structure

404 views • 16 slides

Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis. Jessie G. Varquez , Jr. Anthro 270. 10 August 2011. Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis Whorfian Hypothesis Linguistic Relativism. Language coerces thought The limit of my language is the limit of my world.

2.08k views • 24 slides

Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis :

Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis :. A hypothesis holding that the structure of a language affects the perceptions of reality of its speakers and thus influences their thought patterns and worldviews Language can thus DEFINE consciousness, as well as be a REFLECTION of it. Activity: The Human Continuum.

1.03k views • 7 slides

Effect of Baseline Serum Creatinine Estimation on Acute Kidney Injury Evaluation in Non-Critically Ill Children Treated with Aminoglycosides. Jillian Caldwell , BSc 1 , Michael Pizzi , BSc 1 , Melissa Piccioni , MSc 1 and Michael Zappitelli , MD, MSc 1 .

279 views • 1 slides

Hypothesis:

Do the glacial /interglacial changes in sea level influence abyssal hill formation?. Peter Huybers & Charles Langmuir Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138. B athymetry profiles matched to δ 18 O changes,

180 views • 1 slides

Peter Heudtlass Debarati Guha -Sapir

Mapping vulnerability MDGs and Earth observations in disaster epidemiology 2 nd GEOSS Science and Technology Stakeholder Workshop Bonn, Germany, August 28-31, 2012. Peter Heudtlass Debarati Guha -Sapir Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED), Brussels

309 views • 13 slides

Defining ‘Culture’ Linguistic Relativity Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis

Defining ‘Culture’ Linguistic Relativity Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis. Representation Who has the authority to select what is representative of a given culture/ outsider/ insider Culture is ‘heterogeneous’ 1/ social (members differ in age, gender, experience…) 2/ historical (changes over time)

697 views • 7 slides

102 views • 1 slides

Hypothesis. Our next hypothesis: After a 2 year hiatus, does resuscitation skill performance and HFHS trained individuals improve to a greater percentage than traditionally trained didactic only individuals following a didactic only refresher if the team is physician led?. Methods. n= 234

357 views • 16 slides

Pg. 16 Question: Do different brands of gum affect the diameter of a bubble that has been blown?. Hypothesis:. If you chew four pieces of gum, then the __________ brand will make the biggest bubble because …. Materials Needed:. Each group needs:

275 views • 9 slides

The Parkfield Experiment is a comprehensive, long-term earthquake research project on the San Andreas fault. The experiment's purpose is to better understand the physics of earthquakes - what actually happens on the fault and in the surrounding region before, during and after an earthquake

668 views • 45 slides

Whorf Hypothesis

Whorf Hypothesis. 1) Linguistic determinism: Language determines / governs / affects non-linguistic cognitive processes [and behavior]. [STRONG and WEAK versions] 2) Linguistic relativity: Cognitive processes are different for different languages.

707 views • 7 slides

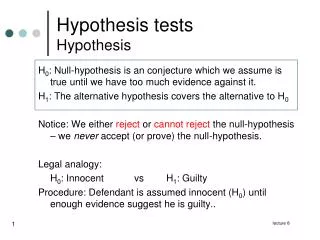

Hypothesis tests Hypothesis

Hypothesis tests Hypothesis. H 0 : Null-hypothesis is an conjecture which we assume is true until we have too much evidence against it. H 1 : The alternative hypothesis covers the alternative to H 0

552 views • 15 slides

Biomechanical Comparision of Locking Plates With and Without Cement for Internal Fixation of Proximal Humerus Fractures Laura M. Decker, RET Fellow 2009 Kenwood Academy High School RET Mentor: Dr. Farid Amirouche, PhD NSF- RET Program. Introduction. Abstract. Motivation

106 views • 1 slides

Hypothesis. Hypothesis. “a tentative assumption made in order to draw out and test its logical or empirical consequences” (Merriam-Webster, 2008)

207 views • 6 slides

Differences in Otter Activity Throughout the Day Kamal Khorfan & Arij Nazir Psych 437, University of Michigan. Results. Objectives. Discussion. Hypothesis. Methods.

119 views • 1 slides

The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis. To what extent, if at all, does our language govern our thought processes?. Grammar . “In substance, grammar is one and the same in all languages, but it may vary accidentally.” Roger Bacon Chomsky – the propensity to receive grammar is innate.

398 views • 9 slides