Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 03 March 2010

Reconsidering reproductive benefit through newborn screening: a systematic review of guidelines on preconception, prenatal and newborn screening

- Yvonne Bombard 1 ,

- Fiona A Miller 1 ,

- Robin Z Hayeems 1 ,

- Denise Avard 2 &

- Bartha M Knoppers 2

European Journal of Human Genetics volume 18 , pages 751–760 ( 2010 ) Cite this article

1924 Accesses

41 Citations

Metrics details

- Genetic services

- Health policy

- Population screening

- Reproductive biology

The expansion of newborn screening (NBS) has been accompanied by debate about what benefits should be achieved and the role of parental discretion in their pursuit. The opportunity to inform parents of reproductive risks is among the most valued additional benefits gained through NBS, and assumes prominence where the primary goal of identifying a treatable condition is not assured. We reviewed 53 unique guidelines addressing prenatal, preconception and newborn screening to examine: (1) how generating reproductive risk information is construed as a benefit of screening; and (2) what conditions support the realization of this benefit. Most preconception and prenatal guidelines – where generating reproductive risk information is described as a primary benefit – required that individuals be given a ‘cascade of choices’, ensuring that each step in the decision-making process was well informed, from deciding to pursue information about reproductive risks to deciding how to manage them. With the exception of three guidelines, NBS policy infrequently attended to the potential for reproductive benefits; further, most guidelines that acknowledged such benefits construed voluntarism narrowly, without attention to the choices attendant on receiving reproductive risk information. This review suggests that prenatal and preconception guidance identifies a coherent framework to support the pursuit of reproductive benefits through population screening programmes. Interestingly, attention to reproductive benefits is increasing among NBS guidance, yet reflection on how such benefits ought to be pursued remains limited. Traditional norms for NBS may require reconsideration where the remit of screening exceeds the primary goal of clinical benefits for infants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Perception of genomic newborn screening among peripartum mothers

Non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) and pregnant women’s views on good motherhood: a qualitative study

Routinization of prenatal screening with the non-invasive prenatal test: pregnant women’s perspectives

Introduction.

Newborn screening (NBS) is a premier example of the application of genomic discoveries to population health benefits. Traditionally, NBS programmes identified serious conditions where early detection and urgent presymptomatic treatment were necessary to avert serious clinical harm. The classic example is phenylketonuria, where the immediate detection of affected babies resulted in clinical benefit through lifelong dietary management, effectively preventing neurological devastation. In this context, NBS operated under the rubric of a ‘public health emergency’ model, 1 in which screening was mandatory or consent was otherwise implied.

Although these clinical goals remain, increased technological capacity means that expanded NBS programmes can now identify a broader range of conditions, including those for which treatment is not established, as well as benign carrier states or variants of uncertain clinical significance. 2 In consequence, expansion has been accompanied by debates about the nature of benefit to be achieved. Advocates of expanded infant screening programmes argue for a wider interpretation of the notion of benefit. 3 They maintain that screening for conditions in which clinical outcomes are unproven or limited provides information, and permits access to programmes that offer education and support. 4 , 5 The opportunity to inform parents and infants of future reproductive risks is among the most valued additional benefits to be achieved. 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8

Historically, ‘reproductive benefit’ – that is, the potential benefit of learning reproductive risk information to support family planning – arose as a secondary outcome of the primary goal of identifying a treatable condition, and thus little attention was given to how such a benefit should be realized. Yet, there are several ways in which expanded NBS upsets this hierarchy of benefits. 9 The first is in the case of expanded NBS panels that include conditions for which clear evidence of medical benefit is not established, 2 such that the identification of reproductive risks assumes greater prominence. 3 , 4 A second way pertains to certain rare conditions, such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy, for which there is no medical treatment but for which early diagnosis permits the identification of reproductive risks. 10 , 11 , 12 Finally, NBS can also detect healthy infants who are carriers; routine disclosure of this information can identify reproductive risks in parents and future adults.

Where the traditional outcome of NBS is not assured, the opportunity to acquire reproductive risk information may assume greater prominence, increasing the need to reconsider the relevance of parental discretion in pursuing such benefits. To this end, we turned to guidance from complementary paradigms – preconception (PCS) (community-based screening of at-risk groups) and prenatal screening (PNS) programmes – where the pursuit of reproductive risk information is generally the primary goal. We conducted a systematic review of relevant policies and position papers on PCS, PNS and NBS guidelines to examine: how guidelines construed generating reproductive risk information as a potential benefit of screening; and what conditions were seen to support the realization of this benefit.

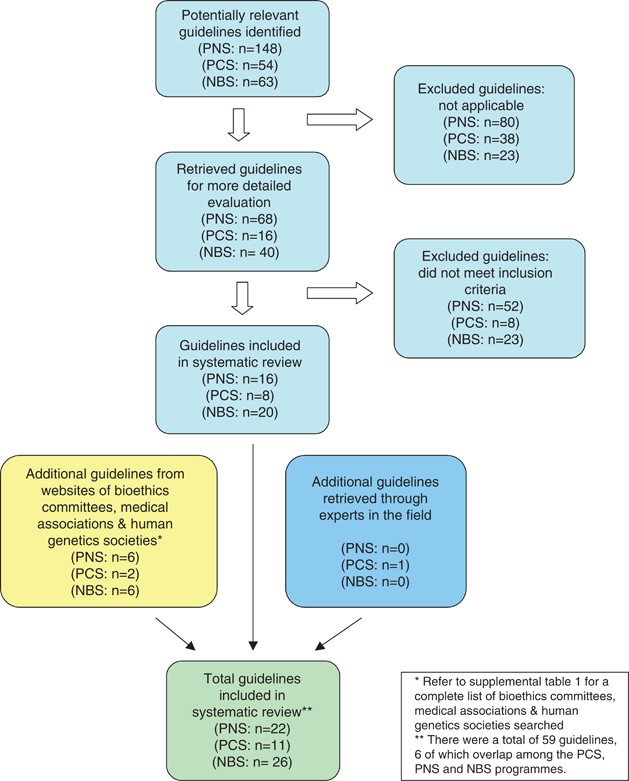

Data sources

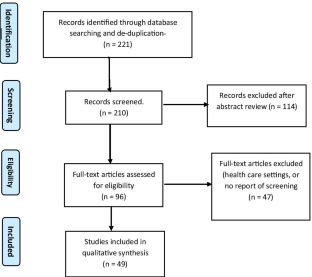

In accordance with the core principles of systematic review methodology, 13 we conducted a review of relevant guidelines using HUMGEN (a database of laws and policies related to human genetics, which uses other databases, including PubMed, Google Scholar and others – www.humgen.org/int/_ressources/Method_en.pdf ) ( Figure 1 ). In addition, we searched websites of key organizations catalogued in HumGen, including the WHO, UNESCO, Council of Europe, national bioethics committees, human genetics societies and national medical associations ( Supplementary Table 1 ). Additional guidelines were obtained from experts in the field. Our review included international and regional governmental and nongovernmental health organizations. In addition, guidance from national organizations limited to Europe, North America, the United Kingdom and Australasia were included, to represent jurisdictions that shared similar health-care and public health infrastructures. We searched the databases and websites using the following search terms: ‘preconception’ [or] ‘reproductive’ [or] ‘pre-pregnancy’ [and] ‘genetic screening’ [or] ‘screening’ [or] ‘testing’; ‘prenatal’ [or] ‘pregnancy’ [and] ‘genetic screening’ [or] ‘screening’ [or] ‘testing’; and ‘newborn’ [or] ‘neonatal’ [or] ‘neonate’ [and] ‘genetic screening’ [or] ‘screening’ [or] ‘testing’.

Study selection.

Study selection

Policies were eligible for inclusion in our review if they were available position papers, reports or if they contained guidelines or statements produced by international, national and regional governmental and nongovernmental health organizations, bioethics committees or professional associations that explicitly addressed (1) newborn screening, (2) preconception screening or (3) prenatal screening. Only guidelines written in English or translated into English from relevant organizations were eligible for inclusion.

We excluded guidelines that did not explicitly include a statement that described the goals or purpose of the screening programme and that were published before 1996. This date restriction reflected the time period during which most relevant guidelines were produced. Guidelines focused on prenatal diagnosis, and those emanating from subnational organizations (eg, provinces or states) were also excluded. Finally, guidelines that focused on technical, organizational, laboratory or cost issues were ineligible. Any uncertainties regarding inclusion were discussed and agreed upon by 2–3 members of the team.

Data extraction and synthesis

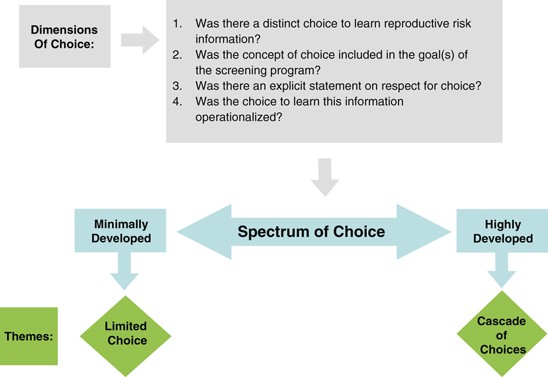

We used a qualitative content analytical approach to examine selected guidelines, drawing on the principles of qualitative description 14 and constant comparison. 15 First, guidelines were examined for an explicit description of the goals and benefits of the respective screening programme, noting the ways in which the generation of reproductive risk information was construed. The guidelines were then examined for an explicit description of how these benefits were to be realized. Specifically, we noted whether the screening programme was to be voluntary and whether informed consent was required. Focusing first on selected PCS and PNS guidelines, we developed an analytical framework describing the conditions or processes considered to support the pursuit of reproductive benefit. The analytical framework ( Figure 2 ) included four dimensions of choice, which were then used to distil guidelines into a two-part spectrum with regard to the orientation towards voluntarism, from highly to minimally developed. Finally, this framework was used to examine the NBS guidelines, to identify similarities and differences in their orientation towards voluntarism.

Analytical framework.

We retrieved a total of 59 guidelines ( Table 1 ) from 31 different organizations (six guidelines overlapped among PCS, PNS and NBS, yielding 53 unique guidelines). The guidelines originated from government-affiliated institutions ( n =7), government advisory bodies ( n =11), medical research agencies ( n =3) and nongovernmental professional organizations ( n =32). Altogether, 11 guidelines related to PCS, 22 on PNS and 26 pertained to NBS. The majority emanated from national organizations ( n =49), with fewer from international ( n =1) and supranational ( n =3) bodies.

Most preconception and prenatal guidelines – where generating reproductive risk information was a primary benefit of screening – required that individuals be given a ‘cascade of choices’ regarding reproductive risk information. By contrast, guidance for NBS infrequently attended to the potential for reproductive benefits as a primary or secondary goal. Further, most guidelines that acknowledged such benefits construed voluntarism narrowly, offering ‘limited choices’ that did not attend to the specific choices arising from the pursuit of reproductive risk information.

Recognizing reproductive benefit

It is not surprising that a sharp contrast was apparent in how PCS and PNS guidance approached reproductive benefit when compared with how this benefit was considered in NBS policies. All PCS and PNS guidelines stated that the pursuit of reproductive risk information was the primary benefit of screening (PCS: n =11 of 11, PNS: n =22 of 22), whereas few ( n =3) NBS guidelines identified reproductive benefit as an intended or unintended benefit of screening ( Table 1 ).

For example, in its statement entitled ‘Essentially Yours: The Protection of Human Genetic Information in Australia’ 16 the Australian Law Reform Commission clearly stipulated that the purpose of PCS is ‘to alert individuals to their carrier status so that they are able to make informed decisions about reproduction’ (note 24.30). Similarly, in the PNS context, guidelines explicitly oriented the programmes towards the immediate benefit of this risk information.

Conversely, few of the NBS guidelines ( n =3 of 26) identified the generation of reproductive information as a benefit of NBS: it was seen as a primary aim in one guideline and as an ‘indirect’ benefit to the infant and family in the other two. The Human Genetics Commission's statement on ‘Making Babies: Reproductive Decisions and Genetic Technologies’ 17 acknowledged reproductive benefit as an indirect and limited end, stating that newborn screens are ‘not simply relevant to the care of the child involved. But because they may lead to the diagnosis of a genetic condition they can have implications for future reproductive decision-making by parents’ (pp 41). However, the other two guidelines pointed to ways in which reproductive benefits may achieve elevated significance in this context. In their statement on ‘Newborn Screening’, 18 the Health Council of the Netherlands acknowledged both the existence of an ‘indirect’ reproductive benefit, and the potential for this benefit to assume primary importance in cases in which the typical goal of clinical benefit cannot be achieved:

The identification of patients with a hereditary disorder also brings to light parent carriers. This discovery allows future family planning choices to be made in families with what are usually serious hereditary disorders… The opportunity to make choices is a benefit for the family, and sometimes also for the newborn child… The indirect benefits for the patient and the benefits for the family may result in screening being contemplated where there is little if any direct benefit to be had. Patients’ organisations have taken the view that screening should not automatically be ruled out even if no treatment is available. The Committee shares this opinion. (pp 29)

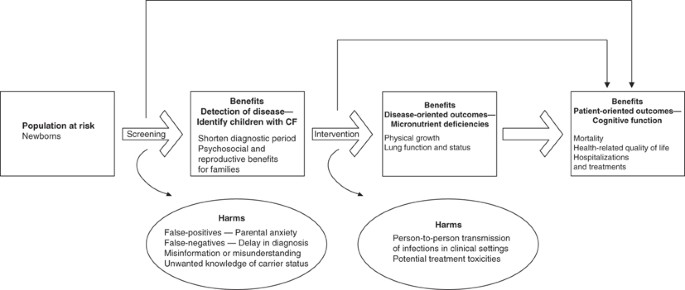

Importantly, the Center for Disease Control's recommendations with regard to NBS for cystic fibrosis (CF) 19 included ‘reproductive benefits to families’ as one of the primary benefits, alongside the other primary goals of disease detection and avoidance of the diagnostic odyssey, as illustrated in Figure 3 :

The benefits of screening flow from early, asymptomatic detection and can be classified in terms of health benefits to the affected person and psychosocial benefits to persons and families… Another potential benefit to parents from a diagnosis of CF by newborn screening is the ability to make informed decisions related to further childbearing, because the diagnosis might occur 1 year earlier on average compared with conventional diagnosis (0.5 and 14.5 months, respectively). (pp 10 and 23)

Potential benefits and harms of newborn screening for cystic fibrosis, as identified by Grosse and colleagues 19 (figure reproduced with permission).

All PCS and PNS guidelines positioned the generation of reproductive risk information as the primary goal and benefit of screening programmes, and did so uniformly. Reproductive benefit in NBS guidelines, by contrast, was noted in only three guidelines. However, although clearly framed as ‘indirect’ to the main goal of identifying treatable disorders in two of these, the potential of this indirect goal to assume primary significance was acknowledged; further, it was seen as a primary benefit in the other guideline.

Achieving the benefits of screening

All PCS and PNS guidelines emphasized voluntarism as the means of achieving the benefits of screening, requiring that individuals be given the choice to learn of their reproductive risk information (PCS: n =11 of 11; PNS: n =22 of 22). It is interesting that 15 out of 26 of the NBS guidelines advocated voluntarism in pursuing the traditional clinical benefits of screening; however, only one of the three NBS policies that recognized reproductive benefit highlighted voluntarism as the means of pursuing this specific benefit. Consequently, we identified a spectrum through which the choice to pursue reproductive benefit was described across the three screening programmes, with some guidelines emphasizing a fulsome ‘cascade of choices’ and others construing voluntarism more narrowly as a set of ‘limited choices’ ( Tables 1 and 2 ).

Cascade of choices

The majority of PCS (9 of 11) and PNS (16 of 22) guidelines clearly presented a cascade of choices in pursuing reproductive benefit. Voluntarism within these guidelines involved a set of nested decisions, each one preceding and enabling action on the other, by sequentially referring to the following: (i) the choice ‘to pursue’ reproductive risk information; (ii) the choice ‘to know’ diagnostic information in light of the risk information received; and where relevant; (iii) the choice ‘to act,’ specifically, whether to continue a pregnancy. The New Zealand's Ministry of Health PNS guideline 20 draws a clear distinction between the elements in this cascade of choices: (i) to pursue reproductive risk information (‘who choose to have this information’); (ii) ‘to make informed decisions about whether to have diagnostic testing’; and, (iii) ‘to make informed decisions about whether to continue or terminate the pregnancy’ (pp 17). Importantly, these distinct choices are stipulated as part of the goals of the programme. Similarly, the National Society of Genetic Counsellors’ ‘Preconception/Prenatal Genetic Screening’ guidelines 21 emphasize this cascade of choices:

Individuals/couples considering screening should be provided with accurate, balanced information about the condition for which screening is being offered. They should be informed of the specificity, sensitivity, accuracy, risks, benefits and limitations of the screening tests offered and of any follow-up diagnostic tests as well as their reproductive options given a positive diagnostic test result (pp 3).

Guidelines offering a cascade of choices emphasized a high degree of respect for individuals’ sequential choices in pursuing reproductive benefit. For example, the overall principle within New Zealand's statement on PNS 20 focused on an ‘unconditional acceptance and support’ for women's choices ‘at each stage of the screening and diagnostic pathway’ (pp 3). Within the United Kingdom's Human Genetics Commission guidelines in reference to PNS, 17 the choice to participate in screening is emphasized in their discussion on the ‘ethos of offering screening.’ They stressed the importance of explaining the ‘aims of screening’ before booking the screening appointment to ensure that the ‘offer of screening’ was seen as a ‘real option’ rather than as a ‘default option’ so as ‘to minimize any sense of guilt or attribution of blame for a decision not to participate’ (pp 12).

In the NBS context where reproductive benefit was recognized as a discrete benefit in only three guidelines, 17 , 18 , 19 the Health Council of the Netherlands 18 published the only policy that advanced a cascade of choices with regard to reproductive benefit. Although reproductive benefit was framed as an ‘indirect’ benefit, they acknowledged that:

Special attention needs to be paid to providing information about the possibility of screening revealing that a newborn is a carrier. This practically always means that one or both parents are also carriers. As with parents of an affected child, if required, adequate information must also be available on what being a carrier entails and on the disorder concerned. (pp 16)

They required that a choice be offered as to whether parents want to learn incidentally generated reproductive risk information (ie, child's carrier status), and restricted the pursuit of this benefit to ‘medically indicated’ cases:

Parents ought therefore to be given the option of forgoing information about carrier status at the point in time when the information [about NBS in general] is provided (during pregnancy, as advocated in Section 4.4.3). If, however, they should ask for carrier screening after receiving the information, then this request can be satisfied if this is medically indicated (owing to a family history of the disorder in question or, in the case of hemoglobinopathy, the geographical origin of the affected individuals). (pp 78)

Guidelines in this category paid significant attention to the voluntary pursuit of reproductive risk information, as well as to the respect for individuals’ choices. They offered a distinct choice to learn reproductive risk information and distinguished between the sequential or nested nature of the choices inherent in pursuing such information.

Limited choice

Of the guidelines recognizing reproductive benefit, a few of the PCS (2 of 11) and PNS (6 of 22) policies presented voluntarism as a limited array of choices; where voluntarism was construed more narrowly, guidelines paid little attention to the sequential nature of choices afforded to individuals in pursuing reproductive risk information. Similarly, two of the remaining three NBS guidelines that identified the possibility of reproductive benefit did not reflect on voluntarism at all, and importantly, the choices specific to reproductive risk information were entirely absent.

Several of the PCS and PNS policies presented limited choices in the pursuit of reproductive benefit. The PCS guideline by the US Preventive Services Task Force, 22 for example, highlighted the need for education and counselling without an explicit distinction between the types of choices offered (‘informed reproductive choices by receiving genetic counseling’). Among others, voluntarism was referred to abstractly or was otherwise absent. For example, in the PNS guideline prepared by the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 23 the condition to achieve voluntarism seems to refer to one point in time, rather than to a process encompassing several stages:

As with any test or procedure, these investigations should only be undertaken with the informed consent of the patient after adequate and appropriate counseling as to the implications, limitations and consequences of such investigation.

The choice regarding reproductive risk information was largely ignored in the two remaining NBS guidelines that recognize reproductive benefit. 17 , 19 The CDC's 19 guidelines on NBS for CF advocated voluntarism only with respect to the choice to participate in the NBS programme as a whole, without attention to the specific choices attendant on receiving reproductive risk information. It asserted:

Documentation of consent might not be necessary. The focus should be on providing thorough, easily understood information to parents about screening for CF and other conditions, especially before delivery, to reduce misunderstanding and provide parents with an opportunity to make informed choices, consistent with state laws. (pp 28)

The Human Genetics Commission's recommendations 17 did not mention voluntarism in relation to either participating in NBS programmes generally or pursing reproductive risk information through such programmes, more specifically.

Guidelines in this category reflected only partially on the conditions supporting choice in the receipt of reproductive risk information. Where voluntarism was addressed, it was characterized by broad statements gesturing to the need for choice in achieving the benefits of screening, but without attention to an initial choice to receive reproductive risk information, nor to the sequential, nested choices of acting on that information. Importantly, of the two remaining NBS guidelines that identified the potential for reproductive benefits, only one supported any form of voluntarism. However, the voluntarism advocated was solely for participating in screening as a whole and not for the pursuit of reproductive risk information; in the final case, no form of voluntarism was identified.

The diversity of NBS programmes along with rapid technological advances requires an assessment of the direction of NBS programmes. These issues are not without controversy and there is considerable international dissensus on the appropriate scope of NBS panels and the types of discretion to be afforded to parents. 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 Central to these debates is the balance of risks and benefits, which also remains equivocal. Although the potential risks – namely, psychosocial harms from false-positive results, 28 overmedicalization, 29 , 30 misattributed paternity, 31 stigma and discrimination 32 – have remained the same, notions of benefit have evolved. Benefits, as argued by some, extend beyond the strictly medical model to include benefits previously considered secondary, such as early intervention, avoidance of the ‘diagnostic odyssey’ and guidance for reproductive decision making. 3 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 27 Indeed, NBS practice is changing, as an increasing number of jurisdictions have embraced the potential value of these broader benefits and have expanded their panels accordingly. 27 , 33 , 34 Guidelines, however, have not evolved in tandem to reflect on the realization of these expanded benefits, nor on the choices regarding the pursuit of reproductive benefits.

Given that NBS typically operates as a mandatory or implied consent programme, reproductive risk information becomes packaged into this programme, effectively requiring parents to receive reproductive risk information, 35 which is at odds with the principles of voluntarism and nondirectiveness underpinning the PCS and PNS programmes. 36 Automatic disclosure of this risk information in the context of NBS is surely appropriate in cases in which infants can be expected to receive health benefits. Yet, it might be seen to violate parents’ autonomy, 35 in cases in which the benefit of reproductive risk information achieves particular prominence. This may occur in three specific ways including: (1) screening for rare conditions (eg, Duchenne muscular dystrophy) that do not have accepted treatment, yet early diagnosis and assisting reproductive decision making are considered important benefits; 10 , 11 , 12 (2) expanded NBS panels that identify conditions without clear evidence of clinical benefit for affected infants, 33 wherein the benefits of acquiring reproductive risk information are assuming greater, if not equivalent, importance, blurring the lines between primary and secondary benefits; 9 and (3) incidental results (eg, carrier status) that are clinically benign for the infant, yet (potentially) immediately useful to his or her parents in planning future pregnancies. In these scenarios, the significance and relevance of this information for reproductive planning raises anew questions on how to pursue reproductive benefit.

The PCS and PNS guidelines offer direction for considering the realization of reproductive benefit through NBS. These guidelines are sensitive to the issues inherent in screening for the purpose of reproductive benefit. In addressing such a benefit, PCS and PNS guidance seeks to mobilize people's capacity to make sequential choices, and typically emphasizes the importance of a fulsome ‘cascade of choices’ to ensure a well-informed decision-making process, which differentiates between the choice to pursue reproductive risk information, the choice to know how this risk information pertains to a specific pregnancy and the choice to act on a diagnosis. By contrast, although many NBS guidelines support voluntarism regarding participation in the programme as a whole, only two of those that identified the potential for reproductive benefits supported any form of voluntarism. Whereas one guideline supported a cascade of choices, in another, the pursuit of reproductive risk information was collapsed into the choice to participate in screening as a whole, thus highlighting challenges in the ethical pursuit of reproductive benefit through NBS.

Although it is widely agreed that the fundamental goal of NBS is to benefit the infant, 37 and further, that the ethical norm of respect for persons necessitates that infants not be treated as a means to an end, debate continues as to whether the fact that NBS can inform parents about their reproductive risks is, in itself, a justification for an expanded panel or for a routine disclosure of incidental results. 4 , 5 , 9 , 38 , 39 Indeed, an inherent tension exists between the obligations of serving the primary health interests of children, respecting autonomy and reducing potential harms in view of the current routine provision of most NBS programmes. The automatic disclosure of reproductive risk information in the absence of a fulsome consent process defies each of these obligations equally. 7 , 40 , 41 , 42 This is especially salient in light of recent evidence suggesting that the broader benefits encouraged by expanded NBS programmes may effect subtle and complex familial and social harms. 43 PCS and PNS programmes, conversely, provide alternative methods of achieving reproductive benefits without imposing the myriad of moral burdens identified here. Further, such programmes offer a more fulsome cascade of choices to parents as illustrated by this review.

Limitations

Typical of systematic reviews of literature, our review has omitted guidance that may have provided additional insight into how to pursue reproductive benefit in the context of NBS. Although beyond the scope of the paper, guidelines produced by consumer groups and disease-centred organizations were omitted because of our focus on guidance produced by professional, health organizations or committees. The deliberate exclusion of guidelines pertaining to prenatal diagnosis, for the sake of direct comparison, may have also limited the scope of insights gleaned with regard to the extent of parental discretion afforded in such programmes. Finally, our interpretation of the nature of consent presented in these guidelines offers a typology that was restricted by the lens we adopted to answer our particular research question. The interpretations and typology are thus tentative and we are unable to immediately generalize to all guidelines related to these programmes.

Future research

Recognizing that guidelines are meant to be reflections on the appropriate use of particular health technologies, it is unknown how such guidance actually affects those it is meant to serve. Further research on stakeholders’ perspectives on these expanded notions of benefit may illuminate their opinions on the risk/benefit ratio of NBS and when parental discretion may be important. Appropriate consent models should also be explored with stakeholders, noting both preferences and capacity for its provision. 44 Finally, a fulsome study of stakeholders’ informed preferences for PCS or prenatal versus NBS approaches in pursuing reproductive benefit is also warranted. Ultimately, further discussion and analysis is required to address the implications of providing reproductive risk information as a primary benefit of a population-screening programme. Salient questions arise, including whether consent for and/or education on pursuing reproductive risk information is included in the context of NBS; who should be responsible for this process; and who should ensure that the future-adult infant is informed of his or her carrier status. Further, once such a benefit is pursued as part of a population intervention, should parents and other family members (eg, minors) be invited to undergo carrier testing, and how should cascade testing be carried out?

Conclusions

This review suggests that guidance from prenatal and preconception contexts identifies a coherent framework for the pursuit of reproductive benefits through population screening. Thus, when NBS no longer serves the primary goal of clinical benefit for affected infants (eg, in cases in which infant carrier results are generated, or in the absence of demonstrated clinical benefit for an affected infant), it should seek to introduce a ‘cascade of choices’ in pursuing reproductive benefits. Alternatively, achieving reproductive benefit may be best pursued through PCS and PNS.

Grosse SD, Boyle CA, Kenneson A, Khoury MJ, Wilfond BS : From Public Health Emergency to Public Health Service: the implications of evolving criteria for newborn screening panels. Pediatrics 2006; 117 : 923–929.

Article Google Scholar

American College of Medical Genetics: Newborn Screening: Toward a Uniform Screening Panel and System . Bethesda: American College of Medical Genetics, 2005.

Bailey DB, Skinner D, Warren SF : Newborn screening for developmental disabilities: reframing presumptive benefit. Am J Public Health 2005; 95 : 1889–1893.

Alexander D, van Dyck PC : A vision of the future of newborn screening. Pediatrics 2006; 117 : 350–354.

Bailey DB, Beskow LM, Davis AM, Skinner D : Changing perspectives on the benefits of newborn screening. Ment Retard Dev Disabil 2006; 12 : 10.

Laird L, Dezateux C, Anionwu EN : Neonatal screening for sickle cell disorders: what about the carrier infants? Br Med J 1996; 313 : 407–411.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Andrews LB, Fullarton JE, Holtzman NA, Motulsky AG : Assessing Genetic Risks: Implications for Health and Social Policy . Washington: National Academy Press, 1994.

Google Scholar

Green NS, Dolan SM, Murray TH : Newborn screening: complexities in universal genetic testing. Am J Public Health 2006; 96 : 1955–1959.

Bombard Y, Miller FA, Hayeems RZ et al : The expansion of newborn screening: is reproductive benefit an appropriate pursuit? Nat Rev Genet 2009; 10 : 666–667.

Ross LF : Screening for conditions that do not meet the Wilson and Jungner criteria: the case of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Am J Med Genet A 2006; 140 : 914–922.

Bradley DM, Parsons EP, Clarke AJ : Experience with screening newborns for Duchenne muscular dystrophy in Wales. BMJ 1993; 306 : 357–360.

Scheuerbrandt G, Lundin A, Lovgren T, Mortier W : Screening for Duchenne muscular dystrophy: an improved screening test for creatine kinase and its application in an infant screening program. Muscle Nerve 1986; 9 : 11–23.

Lavis J, Davies H, Oxman A, Denis JL, Golden-Biddle K, Ferlie E : Towards systematic reviews that inform health care management and policy-making. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005; 10 (Suppl 1): 35–48.

Sandelowski M : Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health 2000; 23 : 334–340.

Strauss A, Corbin J : Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory , 2nd edn. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 1998.

Australian Law Reform Commission: Essentially Yours: The Protection of Human Genetic Information in Australia . Sydney: Australian Law Reform Commission, 2003.

Human Genetics Commission: Making Babies: Reproductive Decisions and Genetic Technologies . London: Human Genetics Commission, 2006.

Health Council of the Netherlands: Neonatal Screening . The Hague: Health Council of the Netherlands, 2005.

Scott D, Grosse PD, Coleen A et al : Newborn screening for cystic fibrosis: evaluation of benefits and risks and recommendations for state newborn screening programs. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2004; 53 : 1–36.

New Zealand Ministry of Health: Antenatal Down Syndrome Screening in New Zealand . Wellington: New Zealand Ministry of Health, 2007.

National Society of Genetic Counselors: Preconception/Prenatal Genetic Screening . Chicago: National Society of Genetic Counselors, 2005.

U.S. Preventative Services Task Force: Congenital Disorders-Screening for Hemaglobinopathies . Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 1996.

The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists: Antenatal Screening Tests . East Melbourne: The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2006.

Mandl KD, Feit S, Larson C, Kohane IS : Newborn screening program practices in the United States: notification, research, and consent. Pediatrics 2002; 109 : 269–273.

Hiller EH, Landenburger G, Natowicz MR : Public participation in medical policy-making and the status of consumer autonomy: the example of newborn-screening programs in the United States. Am J Public Health 1997; 87 : 1280–1288.

Campbell ED, Ross LF : Incorporating newborn screening into prenatal care. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004; 190 : 1.

Pollitt RJ : Introducing new screens: why are we all doing different things? J Inherit Metab Dis 2007; 30 : 423–429.

Hewlett J, Waisbren S : A review of the psychosocial effects of false-positive results on parents and current communication practices in newborn screening. J Inherit Metab Dis 2006; 29 : 677–682.

Marteau TM, van Duijn M, Ellis I : Effects of genetic screening on perceptions of health: a pilot study. J Med Genet 1992; 29 : 24–26.

Miller FA, Paynter M, Hayeems RZ et al : Understanding sickle cell carrier status identified through newborn screening: a qualitative study. Eur J Hum Genet 2009; 18 : 303–308.

Lucassen A, Parker M : Revealing false paternity: some ethical considerations. The Lancet 2001; 357 : 1033–1035.

Bailey DB, Skinner D, Davis AM, Whitmarsh I, Powell C : Ethical, legal, and social concerns about expanded newborn screening: fragile X syndrome as a prototype for emerging issues. Pediatrics 2008; 121 : e693–e704.

Watson MS, Mann MY, Lloyd-Puryear MA, Rinaldo P, Howell RR, American College of Medical Genetics Newborn Screening Expert G: Newborn screening: toward a uniform screening panel and system – executive summary. Pediatrics 2006; 117 : S296–S307.

Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care: McGuinty Government Expands Newborn Screening, 2006. Accessed 3 March 2008.

Miller FA, Robert JS, Hayeems RZ : Questioning the consensus: managing carrier status results generated by newborn screening. Am J Public Health 2009; 99 : 210.

Fraser FC : Genetic counseling. Am J Hum Genet 1974; 26 : 636–659.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Wilson JMG, Jungner G : Principles and Practice of Screening for Disease . Geneva: World Health Organization, 1968.

Miller FA, Robert JS, Hayeems RZ : Questioning the consensus: managing carrier status results generated by newborn screening. Am J Public Health 2009; 99 : 210–215.

Health Council of the Netherlands: Screening: Between Hope and Hype . The Hague: Health Council of the Netherlands, 2008.

Takala T, Hayry M : Genetic ignorance, moral obligations and social duties. J Med Philos 2000; 25 : 107–113; discussion 114–120.

Borry P, Fryns JP, Schotsmans P, Dierickx K : Carrier testing in minors: a systematic review of guidelines and position papers. Eur J Hum Genet 2006; 14 : 133–138.

European Society of Human Genetics: Genetic testing in asymptomatic minors: recommendations of the European Society of Human Genetics. Eur J Hum Genet 2009; 17 : 720–721.

Grob R : Is my sick child healthy? Is my healthy child sick?: changing parental experiences of cystic fibrosis in the age of expanded newborn screening. Soc Sci Med 2008; 67 : 1056–1064.

Miller FA, Hayeems RZ, Carroll JC et al : Consent for newborn screening: the attitudes of health care providers. Public Health Genomics 2009; e-pub ahead of print 22 September 2009.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the financial support provided for the following individuals: Yvonne Bombard was supported by a Postdoctoral fellowship from Apogee-Net, a network funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR); Fiona A Miller is supported by a New Investigator Award from the Institute of Health Services and Policy Research of the CIHR (FRN # 80495); Robin Z Hayeems is supported by a CADRE Postdoctoral Fellowship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Canadian Health Services Research Foundation; Bartha Maria Knoppers and Denise Avard are supported by Genome Quebec and Genome Canada.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Yvonne Bombard, Fiona A Miller & Robin Z Hayeems

Department of Human Genetics, Center of Genomics and Policy, Faculty of Medicine, McGill University, Montr, é, al, QC, Canada

Denise Avard & Bartha M Knoppers

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Yvonne Bombard .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on European Journal of Human Genetics website

Supplementary information

Supplementary table 1 (doc 33 kb), table 1 (pdf 100 kb), references to table 1 (pdf 87 kb), rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Bombard, Y., Miller, F., Hayeems, R. et al. Reconsidering reproductive benefit through newborn screening: a systematic review of guidelines on preconception, prenatal and newborn screening. Eur J Hum Genet 18 , 751–760 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2010.13

Download citation

Received : 06 October 2009

Revised : 14 December 2009

Accepted : 29 December 2009

Published : 03 March 2010

Issue Date : July 2010

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2010.13

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- newborn screening

- reproductive risk information

- informed decision making

This article is cited by

Expanding the australian newborn blood spot screening program using genomic sequencing: do we want it and are we ready.

- Stephanie White

- Tamara Mossfield

- Veronica Wiley

European Journal of Human Genetics (2023)

The perception of parents with a child with sickle cell disease in Ghana towards prenatal diagnosis

- Menford Owusu Ampomah

- Kate Flemming

Journal of Community Genetics (2022)

Neonatal and carrier screening for rare diseases: how innovation challenges screening criteria worldwide

- Martina C. Cornel

- Tessel Rigter

- Lidewij Henneman

Journal of Community Genetics (2021)

Primary care provider perspectives on using genomic sequencing in the care of healthy children

- Chloe Mighton

- Yvonne Bombard

European Journal of Human Genetics (2020)

International differences in the evaluation of conditions for newborn bloodspot screening: a review of scientific literature and policy documents

- Marleen E Jansen

- Selina C Metternick-Jones

- Karla J Lister

European Journal of Human Genetics (2017)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

First and second trimester ultrasound in pregnancy: A systematic review and metasynthesis of the views and experiences of pregnant women, partners, and health workers

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Research in Childbirth and Health Group, THRIVE Centre, University of Central Lancashire, Preston, United Kingdom

Roles Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing

Roles Investigation, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation School of Health and Community Studies, University of Central Lancashire, Preston, United Kingdom

Affiliation Applied Health Research Hub, University of Central Lancashire, Preston, United Kingdom

Roles Conceptualization, Project administration

Affiliation UNDP/UNFPA/UNICEF/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction, Department of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland

Roles Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing – review & editing

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

- Gill Moncrieff,

- Kenneth Finlayson,

- Sarah Cordey,

- Rebekah McCrimmon,

- Catherine Harris,

- Maria Barreix,

- Özge Tunçalp,

- Published: December 14, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261096

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends one ultrasound scan before 24 weeks gestation as part of routine antenatal care (WHO 2016). We explored influences on provision and uptake through views and experiences of pregnant women, partners, and health workers.

We undertook a systematic review (PROSPERO CRD42021230926). We derived summaries of findings and overarching themes using metasynthesis methods. We searched MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, SocIndex, LILACS, and AIM (Nov 25th 2020) for qualitative studies reporting views and experiences of routine ultrasound provision to 24 weeks gestation, with no language or date restriction. After quality assessment, data were logged and analysed in Excel. We assessed confidence in the findings using Grade-CERQual.

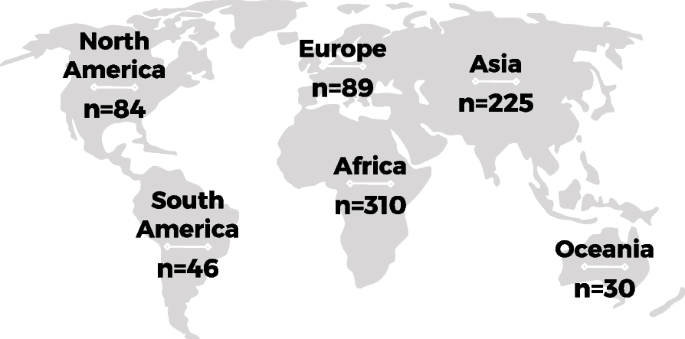

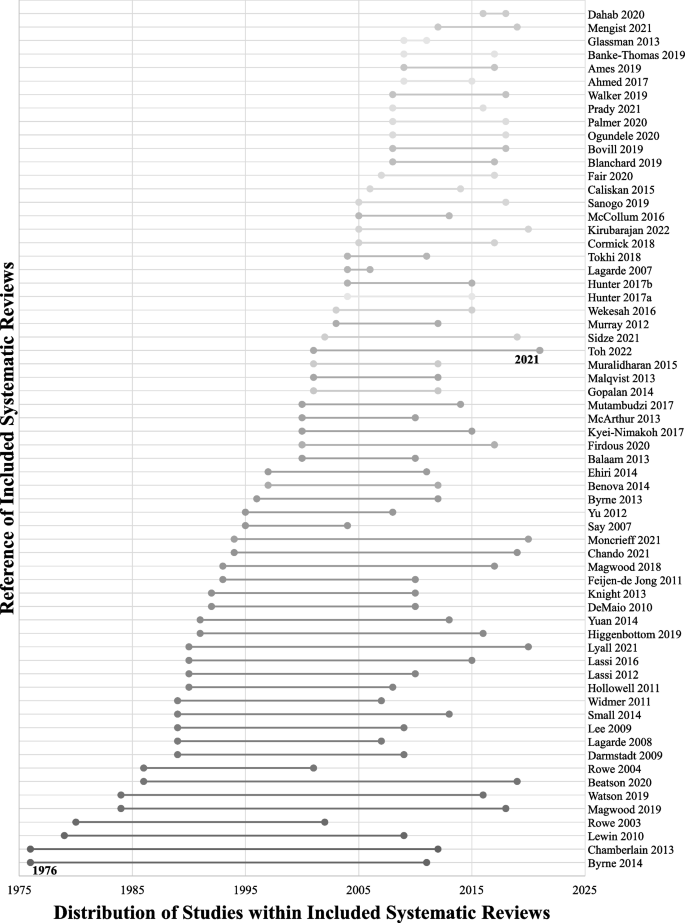

From 7076 hits, we included 80 papers (1994–2020, 23 countries, 16 LICs/MICs, over 1500 participants). We identified 17 review findings, (moderate or high confidence: 14/17), and four themes: sociocultural influences and expectations; the power of visual technology; joy and devastation : consequences of ultrasound findings; the significance of relationship in the ultrasound encounter . Providing or receiving ultrasound was positive for most, reportedly increasing parental-fetal engagement. However, abnormal findings were often shocking. Some reported changing future reproductive decisions after equivocal results, even when the eventual diagnosis was positive. Attitudes and behaviours of sonographers influenced service user experience. Ultrasound providers expressed concern about making mistakes, recognising their need for education, training, and adequate time with women. Ultrasound sex determination influenced female feticide in some contexts, in others, termination was not socially acceptable. Overuse was noted to reduce clinical antenatal skills as well as the use and uptake of other forms of antenatal care. These factors influenced utility and equity of ultrasound in some settings.

Though antenatal ultrasound was largely seen as positive, long-term adverse psychological and reproductive consequences were reported for some. Gender inequity may be reinforced by female feticide following ultrasound in some contexts. Provider attitudes and behaviours, time to engage fully with service users, social norms, access to follow up, and the potential for overuse all need to be considered.

Citation: Moncrieff G, Finlayson K, Cordey S, McCrimmon R, Harris C, Barreix M, et al. (2021) First and second trimester ultrasound in pregnancy: A systematic review and metasynthesis of the views and experiences of pregnant women, partners, and health workers. PLoS ONE 16(12): e0261096. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261096

Editor: Carla Betina Andreucci Polido, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, BRAZIL

Received: September 17, 2021; Accepted: November 22, 2021; Published: December 14, 2021

Copyright: © 2021 Moncrieff et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding: The work was commissioned to the University of Central Lancashire by the UNDP/UNFPA/UNICEF/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP), a cosponsored program executed by the World Health Organization (WHO). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Antenatal ultrasound is a routine and established component of antenatal care within high-income countries [ 1 ]. In low- and middle-income countries ultrasound scanning in pregnancy is more recent [ 2 ]. In many of these settings, provision is not universal [ 3 ], and it is often restricted to high level and/or private facilities, limiting access for many [ 2 , 4 ]. In 2016, the World Health Organization first recommended ultrasound as a routine aspect of antenatal care [ 5 ]. This recommendation was for one ultrasound scan before 24 weeks gestation, to estimate gestational age, improve detection of fetal anomalies and multiple pregnancies, reduce induction of labour for post-term pregnancy, and improve a woman’s pregnancy experience. Part of the rationale for the establishment of this recommendation within guidelines was to better regulate the use of antenatal ultrasound, and to increase equitable access for pregnant women in low- and middle-income settings.

For many expectant parents, antenatal ultrasound provides a positive experience [ 6 ]. Health workers value its use for gestational age estimation, multiple pregnancy identification and assessment of physiological or potentially pathological fetal growth [ 1 ]. Identification of fetal anomalies is also an intrinsic part of ultrasound examination in early pregnancy [ 1 ]. As imaging has become more sophisticated, there has been increasing potential to identify markers of uncertain significance [ 7 ]. This can bring many benefits, but it has also resulted in concerns relating to overdiagnosis as well as the psychological risks for women, birthing people, and partners when the implications of these markers are not clear [ 8 , 9 ]. Some have expressed eugenic concerns, as ultrasound-identified fetal abnormalities force parents to decide between giving birth to a child with disabilities, or termination [ 10 ], while in some social, cultural and religious contexts, termination is not an option [ 11 ]. In some social settings, ultrasound sex determination is associated with female feticide [ 12 ], and possibly sex distribution skew [ 13 ], raising moral, ethical, and gender equity issues.

Because of the rapid technical improvements in first and second trimester ultrasound, and the spread in routine use, the WHO recommended updating of their early ultrasound recommendation. This qualitative systematic review was carried out to inform the update, enabling the consideration of values and preferences, and acceptability, feasibility, and equity implications, and the opportunity to share insights into successful implementation and service provision. These considerations are integral to implementation of antenatal ultrasound where it is not yet a routine component of antenatal care, as well as the improvement of existing services.

We undertook a rapid scoping search of the existing literature but did not identify any previous systematic reviews of experiences of first and second trimester ultrasound that were suitable to inform WHO guidelines on this subject. There is one previous systematic review on experiences of antenatal ultrasound, but this was published in 2002. It did not include the perspectives of health workers, or studies from low- or middle-income countries [ 6 ].

To inform guidelines and practice in the area of first and second trimester ultrasound we aimed to examine the following questions, for maternity service users (including birth companions), health workers, policy makers and funders in all settings:

a. What views, beliefs, concerns and experiences have been reported in relation to routine ultrasound examination in pregnancy?

b. What are the influencing factors associated with appropriate or inappropriate use of routine antenatal ultrasound scanning?

Search strategy and selection criteria

We undertook a systematic review using thematic synthesis to develop our review findings and analytic themes [ 14 ]. The study protocol is registered on PROSPERO (CRD42021230926).

We undertook searches in Medline (Ovid), CINAHL, PsycINFO, and SocIndex (via EBSCO), and LILACS and AIM (via Global Index Medicus) on Nov 25th and 26th 2020, with no language or date restrictions. Additional relevant papers were identified through searching reference lists and citation searches of included studies. A log was used to record inclusion/exclusion at each stage of selection. One member of the review team (CH) undertook the searches, and de-duplication of results using both automated and manual methods in EndNote.

Inclusion criteria.

Our protocol specified searches for qualitative, survey, and mixed-methods studies. For this paper, we report on findings from qualitative studies. We included papers addressing routine use of ultrasound during antenatal care, including to detect fetal viability, gestational age, fetal growth, fetal abnormality, multiple pregnancy, and any other routine application, where this was a standard part of the routine ultrasound offer for the population in the country(ies) where the study was set.

Included participants were pregnant or postnatal women, families of such women, and related community members, antenatal health workers, managers, funders, or policy makers involved in the receipt, provision, management or funding of routine antenatal ultrasound scanning.

We included all settings (low-, high- and middle-income), and all types of health care design and provision (including public, private and mixed models of provision), and localities (hospital facilities, birth centres, or local communities).

Exclusion criteria.

We excluded papers if ultrasound was undertaken for specific indications, for example following IVF procedures, or after women’s reports of reduced fetal movements.

We excluded controlled studies, cohort studies, and epidemiological studies.

Initial screening by title and abstract was refined through blind screening 100 records in two teams to ensure agreement in the screening process. Uncertainties were discussed amongst the review team, and a further 100 hits were then screened until sufficient agreement was reached. For full text screening, batches of ten records were screened in each team until sufficient agreement was reached, after which three members of the review team (GM, SC, RM) screened the remaining records independently.

Data extraction and analysis

Studies assessed as eligible for inclusion were quality assessed [ 15 ]. Quality assessment was undertaken by GM, SC, RM and KF. SD independently assessed 10% of studies to calibrate the assessments of the teams. Very low-quality studies were logged for transparency but were not included in the analysis.

The authors name, the date, characteristics, and setting of included papers, and the key findings, were logged on the study-specific Excel file. Translation of non-English studies was carried out using Google translate.

Analytic procedure.

We initially derived review findings and overarching themes using a thematic synthesis approach [ 14 ]. We started by logging themes and findings highlighted by the authors, or, where these were not clear, reviewer generated findings from the quote material and author narratives (GM, SC, RM). As each subsequent paper was coded, themes were generated (GM, KF, SD) and entered iteratively onto a separate worksheet of the study Excel file, resulting in an initial thematic framework. The findings continued to develop as the data from each paper were added. This included looking for what was similar between papers and for what contradicted (‘disconfirmed’) the review findings. All authors involved in the primary analysis (GM, KF, SD), consciously looked for data that would contradict our prior beliefs and views.

Confidence in each finding was assessed using GRADE-CERQual [ 16 ]. Review findings were graded using a classification system ranging from ‘high’ to ‘moderate’ to ‘low’ to ‘very low’ confidence. Following CERQual assessment the review findings were grouped into higher order analytic themes and the final framework was agreed by consensus amongst the authors.

Analysis of subgroups or subsets.

Findings were logged by country income status (HIC vs LMIC), and by trimester of scan (first, second, or both). Interpretation of the findings and themes includes these subgroups where they can be clearly differentiated in the data.

Reflexive statement.

Based on our collective and individual experiences (as midwives, academics, service users, and researchers), we anticipated that the findings of our review would reveal that women and their partners generally look forward to ultrasound but may be unprepared for it to reveal abnormalities; that health workers like to use it as it gives them a sense of certainty in diagnosis; and that policy makers and funders see it as a useful source of revenue and/or of attracting women to use facilities. We maintained awareness of these prior beliefs and their potential impact on our analysis to ensure we were not over-interpreting data that supported our prior beliefs, or over-looking disconfirming data.

Of the 7076 records generated by our search,181 studies met the initial inclusion criteria to be included in our synthesis. 4656 records were excluded at the initial abstract screening stage, primarily because they were unrelated to the focus of this review. Full text screening excluded 574 studies, primarily because they did not focus on perceptions/experiences of routine ultrasound. Of the 181 studies initially identified as being eligible for inclusion, 80 were qualitative and 98 were quantitative or mixed methods studies. Due to the large number of qualitative papers identified, the decision was made to focus on the qualitative studies, and to analyse the qualitative/mixed methods studies separately. Eighty qualitative papers were therefore included before quality screening, and three more were identified from reference lists of the included papers. Following quality appraisal, 3 studies were rated D and excluded. Fig 1 outlines the screening and selection process.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261096.g001

Of the 80 studies included in our review, eight were rated A, 52 B, and 20 were rated C. They were published between 1994 and 2020 and were from 23 different countries, with 16 studies from LICs/MICs. They represent the views of over 1500 participants. The majority of papers reported the views of women or women and their partners; 19 reported provider perspectives; seven reported the views of both. There were no eligible studies that included the views of funders or policy makers. Study characteristics and quality appraisal grades are presented in Table 1 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261096.t001

Our analysis generated 17 review findings, synthesised into four over-arching analytic themes. Three findings represent the views of women and their partners only, three represent the views of healthcare professionals only, and 11 describe findings from both groups. Most were graded moderate or high confidence. The Summary of Findings and CERQual assessment are provided in Table 2 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261096.t002

Sociocultural influences and expectations. For many women, ultrasound was seen as an integral part of pregnancy and an opportunity not to be missed [ 17 – 26 ]. It offered parents the chance to ‘meet’ their baby and receive an image of the scan that they could share with friends and family [ 21 , 25 , 27 , 28 ]. Fathers’ attendance was seen as a demonstration of their commitment to their family and to facilitate involvement with the pregnancy [ 19 , 25 , 28 , 29 – 34 ]. For health workers however, these views sometimes conflicted with their role in providing a medical assessment and potential diagnosis [ 35 – 37 ]. It also sometimes conflicted with parent’s autonomy in terms of whether attending ultrasound was seen as a choice, or a decision to be made [ 17 , 18 , 21 , 22 , 38 – 42 ]. Some felt that they had not been offered an actual choice due to the routine nature of ultrasound in antenatal care, whilst others felt they should follow the authoritative advice of health professionals to ensure wellbeing of their baby [ 43 – 47 ]. In some contexts, healthcare professionals actively directed women towards ultrasound with the belief that this would inevitably result in better outcomes, and women were seen as irresponsible if they declined the offer of a scan [ 39 , 44 , 48 – 52 ].

‘Yes I’m sure it is (optional) but I think everybody else does it … well maybe not … but anyway I wouldn’t miss it .’ (Sweden) [ 25 ] ‘ I don’t know if it is good or bad . They provide it for us so we use it .’ (Australia) [ 46 ] ‘ The ones that choose not to are far more informed than the ones that choose to–because you have to go against the system .’ (Australia) [ 50 ]

In some low-income settings, access to ultrasound was limited due to lack of staff and other resources, as well as the costs incurred for women and the distance they would have to travel to attend appointments [ 53 – 56 ]. Some midwives in these contexts expressed the desire for training in the use of ultrasound, so that they could make decisions when other staff were not available [ 55 , 57 ]. There were varying beliefs in relation to the safety of ultrasound as well as the diagnosis that could be made through its use [ 19 , 34 , 41 , 49 , 52 , 58 ]. In some contexts, social and religious beliefs influenced the utility of a diagnosis if the only solution to a finding of fetal abnormality was termination [ 44 , 59 – 61 ].

‘She [pregnant woman] didn’t go for ultrasound even though she was told to do so , she refused because of the cost . ’ (Tanzania) [ 54 ] ’We perceive that it is not out our job , but our wish as midwives is to be able to perform ultrasound so that we can play a role in the mother’s care and make decisions without necessarily waiting for the availability of the doctor . ’ (Rwanda) [ 55 ] ‘In our society it would be too late to do anything about that because the woman is not allowed , according to our religion , to have an abortion . Hence there is no point in doing tests during pregnancy . It’s only a waste of time , money and effort . ’ (Israel) [ 60 ]

For some, beliefs about what was important to know during pregnancy, the value placed on ultrasound, and the impact of a diagnosis, appeared to be influenced by the vicarious experiences of friends, family and community members [ 17 , 19 , 28 , 62 , 63 ]. Information about the provision and nature of the ultrasound assessment appeared to also be mediated through community members in some cases, rather than healthcare professionals [ 29 , 64 , 65 ]. This extended to support after the scan which was often provided by friends and family [ 66 – 68 ].

’I needed help to sort out all my feelings and questions , my husband was a great support to me , but I would have liked to talk to my midwife .’ (Iceland) [ 65 ]

Finding out the fetal sex was important for respondents in a range of contexts, in terms of imaging their future baby, and practical planning [ 28 , 45 , 48 , 68 – 70 ]. However, in some circumstances, this knowledge had negative consequences [ 30 , 71 ]. As reported by both health workers and community members, this was particularly (but not only) apparent in cultures where there is a preference for male babies. In these contexts, the disclosure of female fetal sex through ultrasound could result in feticide [ 19 , 53 , 71 , 72 ]. To avoid this potential outcome there was a policy of non-disclosure relating to fetal sex to avoid this outcome [ 19 , 53 , 54 , 71 , 72 ].

‘USG is done to know the sex of the child and then abortion is done if its female child . ’ (India) [ 71 ] There is this stigma between girls and boys , in some communities they want to know if it’s a boy or a girl so that they may be able to either prevent the pregnancy from going on . ’ (Tanzania) [ 53 ] ‘… via USG people can know about sex of the baby and can get the girl child aborted . ’ (India) [ 71 ]

The power of visual technology.

For most respondents, ultrasound was seen as central to antenatal care. Women generally trusted it as a valued technology that could provide confirmation of their pregnancy and reassurance of fetal wellbeing [ 19 , 28 , 30 , 43 , 64 , 66 , 73 ]. For providers, it was an important tool, particularly for the detection and management of complications [ 39 , 43 , 53 , 57 , 74 – 76 ]. However, some respondents reported that a reliance on ultrasound results in the potential for overuse, and consequent neglect of other forms of antenatal care [ 19 , 53 , 74 ]. Some participants felt compelled towards ultrasound to visualise their baby and for reassurance [ 19 , 31 , 43 , 47 , 61 ]. For some women and healthcare professionals, ultrasound held greater value than other forms of antenatal assessment. The overuse of ultrasound was felt to result in reduced clinical skills and the potential to miss complications that were not picked up through this form of assessment [ 38 , 43 , 48 , 55 , 74 ].

‘ The scan is very necessary; there is no point in visiting the doctor without seeing the fetus and knowing how well it is doing . You would not benefit at all !’ (Syria) [ 19 ] ‘ Initially , I can say it came as an extra tool without really knowing why I have to do this . But , through getting used to the tools and doing it regularly , I came to get used to it and think right now I can say it is something we feel like we cannot do without . ’ (Kenya) [ 57 ] ‘I think that in Vietnam nowadays , obstetric ultrasound is the most important investigation to monitor the pregnancy . Some other investigations like blood test , urine test also have importance but they cannot be compared to the obstetric ultrasound . ’ (Vietnam) [ 75 ] ‘ I think it’s a very useful tool , I think we’re getting to the situation where many people can do nothing without an ultrasound , so those clinical skills have gone to a large extent .’ (Australia) [ 74 ]

For many women and healthcare professionals, the power of the ultrasound image was significant [ 32 , 32 , 43 , 50 , 54 , 66 , 73 , 75 – 77 ]. Some women appeared to lack trust that they were pregnant until they were able to visualise the image of their baby [ 21 , 25 , 44 , 52 , 68 , 72 , 78 ]. The capacity for visualisation was particularly valued by fathers and other parents [ 21 , 28 , 61 , 78 ]. The scan image offered the chance to visualise the future together as family. For some, it represented an opportunity to construct their child’s future personality and characteristics [ 32 , 21 , 73 , 79 ]. However, this sense of connection also complicated decisions around termination of pregnancy [ 18 , 30 , 34 , 68 ].

‘ Before I found out I was pregnant I’d always said if I knew I was having a handicapped baby , I’d have a termination , but then when I went for the very first scan and saw the baby moving about and saw his heart beating , I thought afterwards I don’t know whether I could do it now , because he’s alive , it’s a person .’ (England) [ 18 ]

Some providers were concerned that the clarity of the ultrasound image meant that all complications should be visible and identified [ 39 ]. Some feared the potential for consequences for both the mother, and for their professional security, if abnormalities were missed [ 36 , 39 , 76 ]. In some LMIC contexts, concerns were also expressed about the lack of appropriate training and the potential for this to result in missed complications or misdiagnosis [ 38 , 39 , 76 , 80 ]. Some respondents described professional and moral dilemmas around prioritising either mother or fetus in their clinical assessments [ 35 , 40 , 81 , 82 ], as well ethical concerns when parents made decisions that did not fit with personal or professional beliefs [ 55 , 80 , 82 ]. Some also expressed concern that women would go to any lengths to protect the wellbeing of their baby, even when this was to their own detriment [ 38 , 75 , 81 ].

‘No special training on ultrasound , that’s the limitation , that’s why you can sometimes miss some complications if I find something I am not understanding .’ (Rwanda) [ 76 ] ‘ I have never met an expectant mother who has hesitated to expose herself to something that might be harmful to her health as long as it benefits the fetus .’ (Sweden) [ 38 ]

Both joy and devastation; consequences of ultrasound findings.

The scan appointment was a source of great excitement, joy and relief for many couples, providing a chance to bond with their baby, whilst also instilling a sense of responsibility, particularly amongst fathers and other co-parents [ 19 , 21 , 32 , 41 , 45 , 68 , 77 , 83 ]. For some, it also offered the potential for choice and the opportunity to plan when complications were detected [ 22 , 68 , 84 , 85 ]. However, for many, the identification of abnormalities was completely unexpected [ 17 , 18 , 20 , 24 , 65 , 69 , 73 , 80 , 86 – 88 ]. Some reported deep shock and distress on hearing this news [ 17 , 65 , 67 , 69 , 73 , 86 – 89 ]. Both service users and healthcare professionals reflected on how this shock could be compounded by couples’ expectations that the scan appointment is a happy event that would provide confirmation of wellbeing [ 24 , 36 , 65 , 83 ]. The difficulty in getting the balance right in preparing couples for potential consequences of the scan was also discussed by healthcare professionals. Some felt that they lacked time to do this, amongst all the other issues to be discussed in an appointment, and they struggled to get the balance between discussing risk and maintaining a sense of normality prior to the scan [ 27 , 37 , 90 ].

… it’s making sure that they know enough but not frightening them or making them feel very negative about the pregnancy … not put too much emphasis on the possibility of problems . ’ (England) [ 27 ] ‘We were so naive . We thought we were going to see the baby and get a nice photo .’ (Canada) [ 24 ] “ It was a shock like this , because what we expect is that it will be everything perfect ” (Brazil) [ 69 ] ‘You come to find out the sex of the baby and have the bomb dropped on you . ’ (USA) [ 87 ]

Uncertain findings that could, but may not, indicate abnormality, were particularly difficult for many couples, resulting in feelings of having lost their pregnancy, and a shift to a new tentative, risky state [ 18 , 20 , 29 , 91 ]. Some women reported detaching themselves from their pregnancy and/or baby while also experiencing constant worry in relation to their baby’s wellbeing [ 17 , 18 , 22 ]. This state persisted into the long term for some, even after a follow-up diagnosis that all was well [ 18 , 20 , 91 ]. In some cases, this concern persisted even into infanthood, with, at the extreme, the decision not to pursue previously planned future pregnancies [ 18 , 20 , 91 ]. Some health professionals were acutely aware of the impact of uncertain findings on parents, resulting in dilemmas around whether these should be disclosed [ 36 , 74 , 81 ]. Parents were also conflicted about the benefits versus the harms of disclosing these findings [ 17 , 29 ]. Some expressed regret in retrospect about the negative impact on their pregnancy [ 20 , 87 , 65 , 67 ].

‘ Because of this I wouldn’t have a third child … I’m not putting myself through this stress again ever , and I would have gone on to have a third one . We’re stopping at two .’ (England) [ 18 ] ‘ The more you see sometimes the more uncertain things get . And you can ruin a pregnancy quite a bit like that . So I’m not sure whether it’s always good .’ (Australia) [ 74 ]

The significance of relationship in the ultrasound encounter.

Women and partners expressed a desire for scan providers to recognise the unique nature of the scan experience for them, to make them feel welcome, and to provide information and the opportunity to ask questions [ 21 , 22 , 25 , 76 , 65 , 88 ]. Their actual experiences ranged from health workers being cold, disinterested, and lacking time to provide information, to those who were warm and engaging, and actively fostered questions and interest in the scan [ 18 , 19 , 22 , 72 , 80 , 92 ]. In some contexts, women reported that they were unable to ask questions and that their experience was completely in the hands of the healthcare professional [ 19 , 92 ]. Some women and their partners reported being completely excluded from their scan experience, unable to see the image of their baby, and left in silence to guess through body language what might be happening [ 18 , 19 , 22 , 87 ].

‘ He was staring for a long time at the screen . You see he is very good . He keeps looking [she waves as if she is reading from a book] , and he keeps explaining . He told me about the [amniotic fluid] . My previous doctor was different . She does the scan very quickly and tells you : ‘Hey stand up… you have nothing’ and that’s all . I tell you , I felt the difference between those two doctors .’ (Syria) [ 19 ]

For some health workers supporting women through difficult findings was a rewarding aspect of their role; but they expressed the desire for more training in the communication of abnormal results, as well as more professional support to confirm findings [ 36 , 37 , 93 – 95 ]. A lack of time to form relationships and properly communicate results meant that some providers felt the need to distance themselves, in order to protect their own emotions and to enable them to perform consecutive scans within a limited time period [ 36 , 90 , 95 ].

‘ It’s the responsibility of being alone in such a small place , I’m the only one looking . . . I miss a colleague , so I could say “Could you take a look with me , let’s discuss this together .’ (Norway) [ 95 ] ‘You’ve got to protect yourself , you’ve got to … not harden your heart , but you do have to protect yourself and not get too emotionally involved , because otherwise you wouldn’t survive very long in our job . ’ (England) [ 36 ]

In 2019, the WHO maternal and perinatal health steering group prioritised updating their early ultrasound scan recommendations [ 5 ]. This systematic review informs the subsequent recommendations and will inform living guideline updates of this recommendation [ 96 ]. The potential drivers for appropriate or inappropriate use of ultrasound were captured in the four study themes.

In line with other studies [ 6 ], the experience of providing or receiving ultrasound was generally seen as positive in our analysis [ 21 , 25 , 34 , 38 , 39 , 41 , 97 ], generating high demand for scans [ 19 , 39 , 43 , 49 , 50 , 55 , 64 , 74 ], but the consequences of adverse findings was sometimes devastating [ 18 , 20 , 50 , 65 , 67 , 73 , 74 , 87 ]. Importantly, in this review, we found that even when an initial concern was later ruled out, there were very significant long-term adverse consequences for some service users [ 17 , 18 , 20 , 67 , 91 ]. Respondents also reported overuse, with implications for the provision of other antenatal assessments and potential loss of clinical skills [ 19 , 38 , 48 , 53 , 55 , 74 , 82 ]. This reinforces previously published survey data from a range of settings [ 98 – 100 ].

Provider attitudes and behaviours were influential in the service user experience [ 18 , 19 , 21 , 22 , 72 , 86 , 88 ], as were local social norms [ 18 , 21 , 25 , 34 , 41 , 52 , 58 , 60 , 61 ] and access to follow up investigations and support [ 21 , 22 , 67 , 86 , 87 ]. Providers reported concerns around missing important features of the scan [ 38 , 39 , 75 , 96 ], and a lack of sufficient time and training to appropriately carry out ultrasound assessments [ 36 , 38 , 76 , 90 , 95 ].

Previous survey research has found mixed evidence about the impact of ultrasound screening on maternal anxiety [ 101 ]. Our data suggest possible drivers for the varying perceptions of ultrasound screening. The power of the visual in making the fetus ‘real’ is evident in our analysis [ 21 , 23 , 28 , 32 , 35 , 43 , 44 , 50 , 73 ], reinforcing the validity of concepts of what has been termed the ‘ tentative pregnancy’ , in which women put their sense of being pregnant on hold until they have visual evidence of the fetus, and of its wellbeing [ 102 ]. Our data show that visual markers with unknown provenance or meaning can be unsettling for health workers as well as for service users [ 17 , 18 , 20 , 38 , 50 , 74 , 81 ]. The value of diagnosing abnormality was less clear in contexts where termination was not an option [ 58 , 60 , 61 ]. The critical, ethical and equity issue of female feticide reported in some settings underpins growing concerns about sex selection, linked to a much lower female-male sex ratio than would be expected in some countries [ 13 , 68 , 69 , 103 ].

Our findings raise questions about the utility of ultrasound in pregnancy as a screening tool in settings where the implications of features on the scans are not always understood by practitioners or service users [ 100 , 104 – 107 ], and/or if there are no effective follow up, treatment, or solution to some ultrasound findings [ 108 – 110 ]. They raise concerns about the use of ultrasound as a deliberate ‘draw’ to bring women into antenatal care, if the consequence is overuse by undertrained staff, without time to undertaken the scan effectively, including provision of tailored information and psychosocial support where needed; and without effective, affordable, equitable referral pathways.