The Incandescent Wisdom of Cormac McCarthy

His two final novels are the pinnacle of a controversial career.

T he Passenger and Stella Maris , Cormac McCarthy’s new novels, are his first in many years in which no horses are harmed and no humans scalped, shot, eaten, or brained with farm equipment. But you would be wrong to assume that the world depicted in these paired works of fiction, published a month and a half apart, is a cheerier place. “There are mornings when I wake and see a grayness to the world I think was not in evidence before,” The Passenger ’s most jovial character, John Sheddan, says to one of several other characters who are suicidally depressed. “The horrors of the past lose their edge, and in the doing they blind us to a world careening toward a darkness beyond the bitterest speculation.”

Explore the January/February 2023 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

McCarthy throws the reader an anchor of this sort every few pages, the kind of burdensome existential pronouncement that might weigh a lesser book down and make one long for the good old-fashioned Western equicide of McCarthy’s earlier work. At least when a horse dies, it doesn’t spend a week beforehand in the French Quarter musing about existence. For that matter, neither do most of McCarthy’s previous human victims, who were too busy getting hacked or shot to death to see the darkness coming and philosophize about their condition. To twist a line from the poet Vachel Lindsay: They were lucky not because they died, but because they died so dreamlessly.

McCarthy’s fervent admirers are bound to come to these novels with impossible expectations. The late critic Harold Bloom, who spoke for superfans of the writer everywhere, wrote that “no other living American novelist … has given us a book as strong and memorable as Blood Meridian ,” McCarthy’s relentlessly bloody 1985 Western. That verdict came down back when Bloom favorites Thomas Pynchon, Philip Roth, Toni Morrison, and Don DeLillo still dominated the literary scene. McCarthy haters, equally passionate, find his writing mannered, his characters tediously masculine, and his plots—well, not really plots at all so much as excuses to find ever-fancier ways to rhapsodize about murder and carnage and the sublime landscape of the frontera.

The weirdness of McCarthy’s style is hard to overstate. He abjures quotation marks and most commas and apostrophes, so even his text looks denuded and desertlike, with the remaining punctuation sprouting intermittently, like creosote bushes. (I once compared an uncorrected proof of Blood Meridian with the finished book. I found that he’d struck just a couple of commas from the final text. That amused me: Looks good , McCarthy must have decided. But still too much punctuation. ) His language is archaic. Characters speak untranslated Spanish and, in The Passenger , a bit of German. The omniscient narrator makes no concession to readers unfamiliar with 19th-century saddlery, obscure geological terminology, and desert botany.

The narration therefore registers as omniscient in both a literary and theological sense—a voice of a merciless God, speaking in tones and language meant for his own purposes and not for ours. He presides over the incessantly violent Blood Meridian and the only intermittently violent Border Trilogy of the 1990s ( All the Pretty Horses , The Crossing , Cities of the Plain ), and he delivers truths and edicts without any concern for whether members of his creation can understand them, though they are certainly bound by them. The language borrows heavily from the King James Bible, even when describing a bunch of unshowered dudes in Blood Meridian :

Spectre horsemen, pale with dust, anonymous in the crenellated heat … wholly at venture, primal, provisional, devoid of order. Like beings provoked out of the absolute rock and set nameless and at no remove from their own loomings to wander ravenous and doomed and mute as gorgons shambling the brutal wastes of Gondwanaland in a time before nomenclature was and each was all.

Here is McCarthy’s God: a deranged psycho who not only tolerates his world’s atrocities but conceives of them in these strange and inhuman terms.

For some critics, a little of this goes way too far. “To record with the same somber majesty every aspect of a cowboy’s life, from a knifefight to his lunchtime burrito, is to create what can only be described as kitsch,” B. R. Myers wrote in The Atlantic 21 years ago . He quoted a particularly wacky excerpt from All the Pretty Horses and remarked, “It is a rare passage that can make you look up, wherever you may be, and wonder if you are being subjected to a diabolically thorough Candid Camera prank.” Blood Meridian smacked the skepticism right out of me the first time I read it, but I have read it and most of McCarthy’s other novels again since, this time with skepticism reinforced. Was I in the presence of divine wrath, or being punked? I concluded that any novel whose diction conjures questions of theodicy as well as the ghost of Allen Funt has something going for it.

The novels McCarthy published in 2022, at the age of 89, permanently resolve the question of whether McCarthy is a great novelist, or Louis L’Amour with a thesaurus. The booming, omnipotent narrative voice, which first appeared in McCarthy’s Western novels of the 1980s and had already begun to fade in No Country for Old Men (2005) and The Road (2006), has ebbed almost entirely in these books—perhaps like the voice of Yahweh himself, as he transitioned from interventionist to absentee in the Old Testament. What remain are human voices, which is to say characters, contending with one another and with their own fears and regrets, as they face the prospect of the godless void that awaits them. The result is heavy but pleasurable, and together the books are the richest and strongest work of McCarthy’s career.

From the July/August 2001 issue: B. R. Myers’s “A Reader’s Manifesto”

The plots are surreal, and the characters speak often of their dreams. The principal doomed dreamers in these novels are siblings whose formal education exceeds that of all previous McCarthy characters combined: Bobby Western and his younger sister, Alicia. Their father worked on the Manhattan Project, and for his Promethean sins the next generation was punished. Alicia and Bobby shared a vague, incestuous erotic bond and (even more deviant) the curse of genius.

Bobby, the protagonist of The Passenger , studied physics at Caltech but forsook science to race cars in Europe; after an ugly accident, he took up work as a salvage diver based in New Orleans. This novel, released first, is set in the early ’80s, some 10 years after Alicia killed herself. Stella Maris does not stand on its own and is best understood as an appendix to The Passenger . It belongs completely to Alicia and consists of a transcription of clinical interviews with a Dr. Cohen at a Wisconsin mental hospital shortly before her suicide. A math prodigy who studied at the University of Chicago and in France, Alicia left graduate training while struggling with anorexia and florid schizophrenic hallucinations. She is a key figure in The Passenger , too: Nine italicized sequences interspersed throughout Bobby’s story recount her conversations with a hairless, deformed taunter called the Thalidomide Kid, or just the Kid. The Kid acts as a ringmaster and spokesperson for a company of other hallucinatory figures. If this roster of dramatis personae is hurting your brain, then the effect is probably intended, because not one of the characters is psychologically well.

The plot of The Passenger is mercifully simple—and meandering, as McCarthy’s critics have complained of his books in general. Bobby is tormented by grief for having failed to save Alicia. His office dispatches him to search for survivors of a small passenger plane that crashed in shallow water. He finds corpses and signs of tampering. Someone got to the plane first. When he’s back on land, men “dressed like Mormon missionaries” track him down, interrogate him, and suggest that one of the plane’s passengers is unaccounted for. Their persecution intensifies, and Bobby (a quintessential McCarthy figure: laconic, cunning, prone to calamitous big decisions and canny small ones) spends the rest of the novel fleeing.

Bobby’s friends—chief among them the libertine fraudster Sheddan and a trans woman named Debbie, a stripper—are no less Felliniesque than the cast that appears in his dead sister’s hallucinations. Most of the novel is dialogue—if the thunderous omniscient narrator is listening, he’s not interested—and by turns tender, ironic, bitter, and searching. Debbie, like many characters in the novel, is literate and philosophical, and funny. She describes her heartbreak as she realized late one night that she was alone in the world. “I was lying there and I thought: If there is no higher power then I’m it. And that just scared the shit out of me. There is no God and I am she.” They are lowlifes and drunkards, but the sorts of lowlifes and drunkards who keep you lurking by them at the bar, even though you know they’ll rob you or break your heart. What will they say next? A line pilfered from Shakespeare or Unamuno? A revelation about the hereafter—or about yourself?

The Shakespeare is no coincidence—and of course Shakespeare, too, was weak on plot; as William Hazlitt and later Bloom affirmed, the characters are what matter. McCarthy’s Sheddan is an elongated Falstaff, skinny where Falstaff is fat, despite dining out constantly in the French Quarter on credit cards stolen from tourists. But like Falstaff, he is witty, and capable of uttering only the deepest verities whenever he is not telling outright lies. Bobby regularly shares in his stolen food and drink, and their dialogue—mostly Sheddan’s side of it—provides the sharpest statement of Bobby’s bind.

“A life without grief is no life at all,” Sheddan tells him. “But regret is a prison. Some part of you which you deeply value lies forever impaled at a crossroads you can no longer find and never forget.” The characters constantly tell each other about their dreams. Every barstool is an analyst’s couch, and every conversation an interpretation of the night’s omens. Sheddan’s response to the void, which he sees with a clarity equal to Bobby’s and Alicia’s, is to live riotously. “You would give up your dreams in order to escape your nightmares,” he tells Bobby, “and I would not. I think it’s a bad bargain.”

Alicia has no such wise interlocutors. Stella Maris is really an extended monologue, her shrink’s contribution little more than comically minimal prompts. (“I should say that I only agreed to chat,” she reminds him at the outset. “Not to any kind of therapy.”) Critics who have doubted McCarthy’s ability to write a female character must acknowledge that she is as idiosyncratically fucked-up as any of the protagonists in his previous oeuvre. If Sheddan is Falstaff, Alicia is Hamlet: voluble, funny, self-absorbed, and obsessed with the point, or pointlessness, of her continued survival. She is also completely nuts and, like Hamlet (whom she and Sheddan both quote, impishly and repeatedly), orders of magnitude too smart ever to be cured of what ails her. Bobby has a touch of Hamlet too, or possibly Ophelia—though his voyages into the watery depths are all round-trip.

Together they know too much, in almost every sense of that charged phrase. They know love, of a type one would be better off not knowing. Bobby has seen too much underwater. He and Alicia, cursed with a panoptic knowledge of science, literature, and philosophy, have reached a level of awareness indistinguishable from despair. The pursuit of Bobby by the mysterious Mormonlike men suggests that he has stumbled on forbidden facts (about criminals? extraterrestrials?). Alicia, too, seems to have arrived at certain bedrock truths about philosophy and math, and checked out of reality upon discovering how little even she, a woman of immeasurable intelligence, can understand. (Her trajectory mimics that of her mentor, Alexander Grothendieck, a real-life mathematician who gave up math, nearly starved himself to death, and became obsessed with the nature of dreams .) Her tone when speaking of the subject that once enthralled her is mournful. “When the last light in the last eye fades to black and takes all speculation with it forever,” she says, “I think it could even be that these truths will glow for just a moment in the final light. Before the dark and the cold claim everything.”

Long stretches of both novels involve discussions of neutrons, gluons, proof theory, and other arcana from modern physics and philosophy. One of the few points of agreement among physicists is that the world is stranger than humans tend to think, especially at extremes of size and time: What you see with your own eyes is definitely not what you get. The Passenger and Stella Maris treat that spooky observation and its implications with the reverence they deserve. No actual math intrudes, and the discussions of technical subjects is Stoppardesque—accurate and playful and accessible, and nevertheless daunting to readers unacquainted with surnames like Glashow, Grothendieck, and Dirac. (No first names are included, not that they would help anyone who needed them.) McCarthy’s books have always been intimidating, even alienating. Now it’s the characters, not the narrator, who do the alienating.

Alicia’s death is foretold on the first page of the first novel. Bobby’s is left ambiguous, and little is spoiled by my noting that time and space are pretzeled, that the nature of reality itself is suspect, and that he sometimes wishes that the car crash he suffered in Europe, just around the time when his sister was about to kill herself, had killed him rather than put him in a coma. “I’m not dead,” Bobby tells Sheddan, who replies, “We wont quibble.”

These novels are enduring puzzles. Several readings have left the nature of their reality still enigmatic to me. Any novels as suffused with dreams, hallucination, and speculation as the two of them are will invite doubt as to what is really happening. “Do you believe in an afterlife?” the psychiatrist asks Alicia. “I dont believe in this one,” she responds. Bobby and Alicia both have visions that call into question the nature of existence, and they are both fluent in the disorienting logic of the quantum-mechanical world. Having plumbed reality’s depths, they are not sure whether to come back to the surface to join those who live in the world of the normal, like Sheddan and his gang. By my second reading I started to feel like I had remained down there on the seafloor with them, in a state of meditative loneliness that no other book in recent memory has inspired.

Sheddan seems to have tasted that loneliness, and found existential solace in literature, even of the most savage sort. “Any number of these books were penned in lieu of burning down the world—which was their author’s true desire,” he says at one point, having just noted Bobby’s father’s role in building apocalyptic munitions. I wonder whether Sheddan is accusing his own creator here, and his tendency toward violence. McCarthy’s early southern-gothic period, comprising the four novels he published from 1965 to 1979, were Faulknerian, and at times darkly comic. Then came an even darker Melvillean middle, set in the Southwest and Mexico—nightmarish in Blood Meridian and romantic in All the Pretty Horses (1992)—and a desolate late period, with No Country and The Road .

Put another way, the early novels took place on a human scale, and Blood Meridian was about contests among humanoid creatures so violent and warlike that they might be gods and demons, a Western Götterdämmerung. The protagonist of the Border Trilogy was like a human on an expedition through this inhuman landscape. And the late novels featured humans forsaken by the gods and pitted against one another, or in the case of No Country , contending with demons and losing. McCarthy’s latest, and probably last, novels represent a return to human concerns, but ones—love, death, guilt, illusion—experienced and scrutinized on the highest existential plane.

I’m sure I wasn’t alone in wondering, on hearing the news of two forthcoming McCarthy books, whether they would be noticeably geriatric in their energy, with that spectral quality familiar from other late literary creations. (There are many counterexamples, of course: the silvery vitality of Saul Bellow’s Ravelstein , the comic bitterness of Mark Twain’s The Mysterious Stranger .) Such valedictory works are rarely among an author’s best. But as a pair, The Passenger and Stella Maris are an achievement greater than Blood Meridian , his best earlier work, or The Road , his best recent one. In the new novels, McCarthy again sets bravery and ingenuity loose amid inhumanity. In Blood Meridian , the young protagonist confronts a ruthless demigod and tells him off. In No Country , Llewelyn Moss beholds the inevitability of his own destruction and that of everyone he cares about, and shoots back at the demon who pursues him. The Border Trilogy is about a boy who leaves home and discovers, with equal parts courage and ignorance, a world harsher to his heart and body than he had known.

Now we see characters whose vision of the world is hideous from the start. And the grappling with this vision is more direct and more profound. The McCarthy of previous novels did not appear to have much of an answer to the question that his imagination invited, a question that goes back to the ancient Greeks: What does a mortal do when all that matters is in the hands of the gods, or, in their absence, no one’s? An almost-nonagenarian will of course think more acutely than a younger writer about fading from existence.

From the May 2020 issue: “Variations on a Phrase by Cormac McCarthy,” a poem by Linda Gregerson

Just as Alicia imagines a final flickering glow of mathematical truth, Sheddan proposes to be a final holdout of humanism. He says he knows that Bobby has, like Sheddan, a heart whose loneliness is salved by literature. “But the real question is are we few the last of a lineage?” Wondering about the end of the age of literate culture, he tells his old friend, “The legacy of the word is a fragile thing for all its power, but I know where you stand, Squire. I know that there are words spoken by men ages dead that will never leave your heart.” These novels feel like McCarthy’s effort to produce such words, and to react to the dying of the light with Sheddan’s vigor rather than Bobby’s and Alicia’s despair. The results are not weakly flickering. They are incandescent with life.

This article appears in the January/February 2023 print edition with the headline “Cormac McCarthy Has Never Been Better.”

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

Cormac McCarthy, 89, has a new novel — two, actually. And they’re almost perfect

- Show more sharing options

- Copy Link URL Copied!

On the Shelf

Two New Novels by Cormac McCarthy

The Passenger Knopf: 400 pages, $30 Stella Maris Knopf: 208 pages, $26 (December 6) If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Bobby Western is a salvage diver, a onetime physics graduate student who hangs out in dive bars with philosophically inclined roughnecks and thieves. It’s 1980 in New Orleans when Bobby’s quiet but perilous life takes a dangerous turn, sparking “ The Passenger ,” the new novel by Cormac McCarthy .

“The Passenger” is a brilliant book, a departure from McCarthy’s previous works that still feels of a piece. It’s set in the real world of the 20th century yet filled with the same elegiac language and drop-dead sentences of his antique “ Border Trilogy ” and the apocalyptic future of “ The Road .” The latter book, his best-known, won the Pulitzer Prize, was made into a film and was selected by Oprah Winfrey for her book club in 2007, pulling the publicity-shy author into the spotlight. This is his first novel to be published since.

The story of a haunted man on the run, it has McCarthy’s classic linguistic flair, plus Thomas Pynchon ’s wordplay and paranoia and, last but certainly not least, a sweeping history of theoretical physics. “The Passenger” is a stunning accomplishment: For McCarthy to publish a work of this scope and ambition at 89 is phenomenal. But it has a tragic flaw. Is it fatal?

One night, Bobby and his dive partner, Oiler, are sent to a small plane sunk deep in the Gulf and discover that the black box is missing. So is one of the passengers; the rest are, eerily, strapped in their submerged seats. When the crashed plane and its dead occupants fail to make the news, Bobby begins to worry they’ve seen something they shouldn’t have. He’s mildly interested in finding out about the missing passenger, but mostly he tries to lay low.

Cormac McCarthy’s rugged road to respectability

Nov. 22, 2009

Bobby moves into a rented room above a local bar that has seen a string of occupants meet untimely ends. Bobby doesn’t mind — handsome, intelligent and possessing a secret stash of dough, he appears to move above the concerns of his barfly cohort. Or maybe he likes to court danger: Before he came to New Orleans, he was a Formula Two race car driver. He rarely reveals what’s on his mind.

It takes his friend “Long John” Sheddan to tell us plainly: “He’s in love with his sister.” This is no spoiler; it’s only 30 pages in, and Sheddan lays it bare — a slightly mythologized version of the siblings’ relationship that hangs over the rest of this novel and also “ Stella Maris ,” McCarthy’s companion novel, a sort of coda that will be released Dec. 6. That volume consists solely of conversations between Bobby’s sister and her psychiatrist in a mental institution. She is introduced first in “The Passenger.” She’s the corpse on the first page, sometimes called Alice and sometimes Alicia, and she occupies alternating, italicized chapters.

Alicia is searingly brilliant at mathematics, ethereally beautiful and usually in conversation with a troupe of third-rate vaudevillian hallucinations. Alicia is obsessed with death and her older brother, as in love with him as he has been with her since she was an adolescent. She’s so smart that her discussion of theoretical math drives Bobby to drop it for physics, yet her romantic obsession with him drives her to suicide.

And we’ve gotten to the flaw. Perhaps it will not bother you as it bothers me. Must the core of this book be a love story between an older brother and his younger sister? Couldn’t a writer with McCarthy’s capacious imagination conceive of an adult, independent woman who could serve as an equally powerful lost love? I realize he’s been here before — his 1968 novel “Outer Dark” was about brother-sister incest — and of course any novelist can put anything he or she likes into fiction. But it is 2022. An older brother in love with his younger sister? It’s not tragic; it’s creepy.

Ivy Pochoda quarantines with Cormac McCarthy, Dr. Seuss and gymnastics videos

In our latest quarantine diary, the author of ‘These Women’ digs ‘Blood Meridian’ but can’t get enough of Laura Ingalls Wilder.

May 28, 2020

If we can ignore that for a moment — and take a look at the cover, maybe you can’t — the book follows Bobby around New Orleans, eating and drinking at still-standing classics including Tujague’s and the Old Absinthe House . He willfully ignores signals that something is wrong. A colleague dies in an underwater accident. His room is ransacked and his cat disappears. Two FBI-ish guys show up looking for him frequently — so frequently that they might instead be from the mafia or some more mysterious outfit.

McCarthy turns his substantial writerly gifts upon two distinct forces: the mechanical and the theoretical. He attends to the exquisite detail of Bobby’s physical world — the sounds and feel of an oil rig in a storm, the touch and clunk of a cigarette machine in a bar, the step-by-step process of removing a bathroom cabinet or digging up and carting off buried treasure. All the while, Bobby converses with friends who riff on time or men and women or Vietnam or failure, paragraphs and pages of disquisitions that can be funny and moving and dirty and insightful. Sometimes it feels a little like being trapped in a dorm hallway at 1 a.m. with a smart sophomore who is really, really stoned.

“You said once that a moment in time was a contradiction since there could be no moveless thing. That time could not be constricted into a brevity that contradicts its own definition,” Long John tells Bobby. “You also suggested that time might be incremental rather than linear. That the notion of the endlessly divisible in the world was attended by certain problems. While a discrete world on the other hand must raise the question as to what it is that connects it.” There are oodles of passages like this, so much to puzzle over for those who like to puzzle hard while reading their fiction.

As someone who hasn’t studied any higher math or physics, I didn’t always find a foothold in the theoretical arguments here. (I came closer to understanding this kind of math while reading Karen Olsson’s “The Weil Conjectures,” 2019.) In “The Passenger,” theoretical physics frequently comes across as a series of handoffs from one scientist to another, with entertainingly framed biographies about who proved the last guy wrong.

David Kipen’s Great American Novel: The works of Thomas Pynchon

Let’s make this a whole lot easier.

June 30, 2016

Many of the discussions of math and physics come from Alicia’s sections, both in “The Passenger” and “Stella Maris.” Her conversations with vaudeville hallucinations are unfortunately retro — the main guy, the Thalidomide Kid, has his disabilities played for laughs; two characters dress up as blackface minstrels. The Kid — a name McCarthy also used for his protagonist in 1985’s “Blood Meridian” — began appearing to Alice during adolescence and serves as a hectoring protector. His patter is full of malapropisms and wordplay (“we got lights and chimeras”) and his turn from annoying and obnoxious to ultimately sympathetic points again to McCarthy’s copious talent.

We see Alicia and Bobby each go to visit their beloved grandmother in Tennessee, asynchronously. Their father, a scientist, worked on the Manhattan Project and met their mother, a local Tennessee beauty, when she was working at the Y-12 electromagnetic separation plant that produced enriched uranium for the first atom bombs. The marriage didn’t last. And if you’re wondering if the sins of the father are being visited upon the Western siblings, you’re getting warm.

Bobby and Alicia’s narratives move side by side in a doomed spiral. Alicia is dead on Page 1, and Bobby’s choices narrow around him almost before he can save himself. He’s pushed from the comfort of New Orleans to a near-feral existence on the road — a journey rendered in prose that can’t be equaled. “In the morning he sat with his feet crossed under him and watched the sun rise. It sat swagged and red in the smoke like a matrix of molten iron swung wobbling up out of a furnace.” It’s Cormac McCarthy writing as only Cormac McCarthy can.

With its cast of ruffians, its American sins, its contemplation of quantum physics, its low life and high ideas, “The Passenger” is almost a perfect book. If only.

The Road: A Novel

BEFORE a morgue culture determined to hang a tag on every toe, Cormac McCarthy stands defiantly alive and untagged.

Sept. 24, 2006

Kellogg is a former books editor of The Times. She can be found on Twitter @paperhaus .

More to Read

A disorienting, masterful, shape-shifting novel about multiracial identity

April 22, 2024

Lionel Shriver airs grievances by reimagining American society

April 8, 2024

How many lives can one author live? In new short stories, Amor Towles invites us along for the ride

March 29, 2024

Espionage fiction writers pick their favorite fictional spies

Feb. 27, 2024

How the Wild West inspired one of Ireland’s top experimental novelists

Jan. 2, 2024

I wanted to write a book of L.A. noir for decades. But first, I had to live it

Dec. 14, 2023

Can AI-generated art help us understand the future Octavia Butler saw?

Nov. 20, 2023

Commentary: McCarthyism makes us agents in our own destruction. ‘Fellow Travelers’ shows how

Nov. 10, 2023

A $7-million dream: Steinbeck’s vintage sardine boat makes its modern debut

Nov. 3, 2023

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

More From the Los Angeles Times

A harrowing look at drummer Jim Gordon’s descent from rock talent to convicted murderer

May 31, 2024

16 romance novels to heat up your summer

James Patterson realized Michael Crichton’s vision for a volcano thriller 16 years after his death

The week’s bestselling books, June 2

May 29, 2024

- Entertainment

Cormac McCarthy’s First Books in 16 Years Are a Genius Reinvention

C ormac McCarthy, the now 89-year-old winner of both a National Book Award and a Pulitzer Prize , whose work is compared, not infrequently, to Moby Dick and the Bible , has spent more than two decades as a senior fellow at the Santa Fe Institute think tank. The list of operating principles for the institute (which he wrote), reads in part: “If you know more than anybody else about a subject, we want to talk to you.”

With his two staggering new novels, the companions The Passenger and Stella Maris, it’s clear that McCarthy—best known for delivering stark, gory tales of morality and depravity—has been inspired by his time at the think tank talking to the world’s greatest mathematicians and physicists. His first works of fiction to be published in 16 years begin in familiar territory but push his ambitions to the very boundaries of human understanding, where math and science are still just theory.

In The Passenger, the first of the two books, Bobby Western is a 37-year-old deep-sea salvage diver operating mostly in the Gulf of Mexico—dangerous but lucrative work that’s not unlike exploring a foreign planet. One night Bobby and his dive partner receive a strange assignment: a small passenger jet has crashed in the water off the coast of Pass Christian, Miss., and they must dive 40 ft. under the surface to assess the situation. When the pair finds the wreck, they encounter nine bodies sitting buckled in their seats, “their hair floating. Their mouths open, their eyes devoid of speculation.” In addition to the oddly intact fuselage, other things are out of place. The pilot’s flight bag is gone. The plane’s black box has been neatly removed from the instrumentation panel. And a 10th passenger, listed on the manifest, is missing completely. Bobby’s partner is spooked. “You think there’s already been someone down there, don’t you?” he asks.

Soon Bobby is beset by suited men—agents of an unnamed government entity—flipping their badges at him and asking him questions. Then his friend goes down on a dive and doesn’t come back up.

Read More: The 33 Most Anticipated Books of Fall 2022

In many ways, Bobby resembles Llewelyn Moss, the protagonist of McCarthy’s 2005 novel No Country for Old Men: laconic, capable if a bit hapless, and the subject of dangerous intrigues outside of his scope. The difference is that Bobby has book smarts as well. His father was a scientist on the Manhattan Project who rubbed shoulders with Oppenheimer et al. while they perfected, as Bobby’s university friend Long John puts it, “the design and fabrication of enormous bombs for the purpose of incinerating whole cities full of innocent people as they slept in their beds.”

Bobby gave up physics to travel around Europe as a midtier race-car driver before starting his career in diving. Both pursuits appeal because they offer him momentary relief from not only his own intelligence but also his grief. Long John diagnoses the final integral component of Bobby’s character: “He is in love with his sister. But of course it gets worse. He’s in love with his sister and she’s dead.”

McCarthy alternates chapters of The Passenger between the mystery at Bobby’s hands and conversations that his younger sister Alicia—the most brilliant in a family of prodigies, who died by suicide nearly 10 years prior—has with figures of her schizophrenic hallucinations. Their ringleader, whom she has come to call “the Thalidomide Kid,” is a bald, scarred imp about 3 ft. tall, with “flippers” instead of arms. (“He looked like he’d been brought into the world with icetongs.”) The Kid taunts Alicia in strange idioms in between discursions on time, language, and perception. From one of his linguistically withering rants: “Well mysteries just abound don’t they? Before we mire up too deep in the accusatory voice it might be well to remind ourselves that you can’t misrepresent what has yet to occur.” Fans of McCarthy’s work will agree that this novel’s villain is a far sight more loquacious than No Country for Old Men ’s Anton Chigurh. (“Call it.”)

Narratively speaking, the book is more interested in expanding the scope of its own mystery than in solving it. The Bobby sections depict him avoiding the plot entirely—he mostly has lunch with friends and converses with them about his past, physics, or philosophy. Don’t come here for a thriller about a plane crash, but the pages do turn with remarkable ease. From the initial mystery of a missing person, the novel explodes outward like an atomic chain reaction to the very face of God, at the intersection of mathematics and faith.

Is this sounding like a lot? It is. The Passenger also happens to be something of a masterpiece, an unsolvable equation left up on the blackboard for the bold to puzzle over. Readers have been waiting years for this novel, which McCarthy has teased from time to time, dating back to before The Road, which he published in 2006. It is his most ambitious work, or perhaps a better word would be weirdest. But it’s held together with wit and chuckle-out-loud humor, which can be sparse in his other novels (see the apocalyptic violence of Blood Meridian ). And it’s genuinely fun to read throughout—although readers who come to this book because they enjoyed an airport paper-back edition of The Road while on a short flight might be left wide-eyed and blinking.

Stella Maris, the slimmer companion, to be published in December, is just over 200 pages’ worth of Passenger ’s late sister Alicia’s dialogues with her psychiatrist after she has institutionalized herself toward the end of her life, suffering under the power of her own intellect. It offers a few more clues, but mostly deepens the various mysteries on offer in the first novel. “Mathematics,” she tells her doctor, who struggles to keep up, “is ultimately a faith-based initiative.”

In all of his books, McCarthy is a gearhead, a man obsessed with hardware and the nuts and bolts of things. There are no planes and cars in The Passenger, only “JetStars” and “1968 Dodge Chargers with 426 Hemi engines.” A person doesn’t glance at their watch; they glance at their white gold Patek Philippe Calatrava. There are whole sections that could read almost as instructional home repair or auto maintenance: “The teeth had begun to strip off of the cluster gear until the box seized up and then the rear U-joint came uncoupled and the drive shaft went clanking off across the concourse … ” It’s been said that when McCarthy visited the set of the movie adaptation of All the Pretty Horses, he spent most of his time with the props master talking about guns.

So it makes sense that at this stage in his career, the author would push in his chips and attempt to understand the mechanical clockwork of reality itself. Like Bach ’s concertos, these triumphant novels depart the realm of art and encroach upon science, aimed at some Platonic point beyond our reckoning where all spheres converge.

It’s a rare thing to see a writer employ the tools of fiction in order to make a genuine contribution to what we know, and what we can know, about material existence. Put differently, the ideal audience for these books are Fields Medal recipients , but they’re still a privilege and a hoot for the rest of us to read. And if we can’t understand everything McCarthy is writing about, one suspects that he just might.

Mancusi is the author of the novel A Philosophy of Ruin.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Selena Gomez Is Revolutionizing the Celebrity Beauty Business

- TIME100 Most Influential Companies 2024

- Javier Milei’s Radical Plan to Transform Argentina

- How Private Donors Shape Birth-Control Choices

- The Deadly Digital Frontiers at the Border

- What's the Best Measure of Fitness?

- The 31 Most Anticipated Movies of Summer 2024

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

Cormac McCarthy’s two new novels are deliberately frustrating

The Passenger is out now, and Stella Maris is out in December. They’re McCarthy’s first new books since 2006.

by Constance Grady

It’s been 16 years since Cormac McCarthy published his apocalyptic masterpiece The Road , won the Pulitzer, and then, having secured his place in literary history, apparently vanished into the mists. Now, at 89 years old, he’s returned with two new books: The Passenger , out now, and its companion novella Stella Maris , out in December. Together they form less a capstone to McCarthy’s storied career than they do a compelling if uneven coda.

Some of McCarthy’s most celebrated novels are page-turners, but that’s not on the agenda here. These books are built to stand apart from the reader, to withhold, to refuse to satisfy. You can almost feel McCarthy swaggering a bit as, with great skill and elegance, he chooses time and time again to frustrate any desire the reader might have for either narrative or story.

The Passenger and Stella Maris occur 10 years apart from one another, each told by a different sibling. The Passenger takes place in the 1980s and is narrated by Bobby Western, a taciturn tough guy who was once a race driver, is currently a salvage diver, and maintains a deep knowledge of theoretical physics. Stella Maris takes place in the 1970s and is narrated by Alicia Western, a diagnosed schizophrenic and math genius. Their surname is Western because that’s what they stand for: the western postwar world order, with all its prosperity and order and all its moral compromises. In The Passenger , Bobby is in love with Alicia, who is dead. In Stella Maris , Alicia is in love with Bobby, who is in a coma. Both maintain they never consummated their relationship, but McCarthy gives you just enough room to wonder if that’s the truth.

The official line from the publishers is that The Passenger and Stella Maris each stand alone, but don’t believe them. The Passenger would be maddeningly opaque without Stella Maris to elaborate on some of its most compelling plot threads, and Stella Maris would be dry as book binding without The Passenger to leaven its many philosophical arguments. Reading them separately would be a cramped and despairing experience.

Not that The Passenger is exactly a light read in and of itself. While it gestures at a pulpy thriller plot involving a passenger vanishing from a crashed plane and mysterious government agencies chasing Bobby Western down, McCarthy serenely declines to either solve or, indeed, provide real suspects for any of his mysteries. They seem to exist merely to create the paranoid murk through which Western (as McCarthy consistently calls Bobby) must dive as he encounters and has Socratic dialogues with a series of colorful characters.

With a trans woman, Western discusses the question of whether there is a God or a female soul. With a magician turned private detective, he talks about the tragedy of beauty. And with an absolute blank slate of a character — so blank it’s almost offensive, really, as if McCarthy’s staring us in the eye and daring us to call him on it — Western gets into the real issue of these two novels: the atom bomb, quantum mechanics, and the question of whether reality is knowable.

“It’s all right to say that the reason we cant fully grasp the quantum world is because we didnt evolve in that world,” Western explains. (McCarthy’s still doing his thing with leaving out apostrophes and quotation marks.) “But the real mystery is the one that plagued Darwin. How we can come to know difficult things that have no survival value.”

Western comes by his understanding of this mystery honestly. He and Alicia are the children of one of the makers of the atom bomb, born, like all the postwar west, to the knowledge that they owe their wealth and good fortune to an atrocity that might have stopped a bigger atrocity. Both of them got an education in physics from their father, and both of them are deeply aware of the implications of modern physics for reality: the way it shows us that reality does not match our understanding, that the universe is less stable and more eerie than we thought .

Western responds to this knowledge by briefly pursuing a career as a physicist before failing his subject: He decides he isn’t quite good enough to do really valuable physics. Alicia, meanwhile, decides to go into pure math before being failed by her subject: since math has no provable reality independent of the human mind, she decides it is not equal to solving the problem of what reality is. Alicia’s project is to try to hold the truth of what contemporary physics and pure mathematics tell her completely in her mind, and the implication is that either the effort has shattered her mind or that only a shattered mind could attempt to do so in the first place.

Alicia appears periodically throughout The Passenger . Her death by suicide opens the novel, and in flashbacks we see her conversing with her hallucinations: a raggedy carnival barker of a man she calls the Thalidomide Kid, with flippers instead of hands, and all his hangers-on. (These hallucinations, it must be said, are appallingly tedious.) She doesn’t take center stage, though, until Stella Maris , which is made up entirely of Alicia’s conversations with her psychiatrist in the last year of her life.

There is something pleasingly, shockingly bare about Stella Maris after the lushness of The Passenger ’s rich, haunted atmosphere. The Passenger takes place in New Orleans in the summer, but Stella Maris is all cold, cold, midwest in the winter. Gone, too, are The Passenger ’s showy and circuitous plotlines about the JFK assassination being a cover for the mob taking out RFK and secret caches of gold buried in a dead grandmother’s basement. In Stella Maris , McCarthy has stripped away all the flesh down to the bare bone, the part that he’s actually interested in talking about.

It turns out the bone is more theoretical physics and pure math, the cosmic questions they inspire, and the creative work entailed in thinking them through.

“I knew what my brother did not,” Alicia explains to her shrink. “That there was an ill-contained horror beneath the surface of the world and there always had been. That at the core of reality lies a deep and eternal demonium.” The inexplicable void at the core of quantum physics is the demonium.

Writing women has never been McCarthy’s strong suit, and Alicia doesn’t exactly hold up as a rich and three-dimensional character. Her voice is appealingly spiky, but she’s more philosophical construct than whole human being. Yet halfway through Stella Maris , it becomes clear that she’s also an avatar for McCarthy himself, and for anyone who finds their unconscious mind doing their creative work for them.

“The core question is not how you do the math but how does the unconscious do it,” she says. “How is it that it’s demonstrably better at it than you are? You work on a problem and then you put it away for a while. But it doesnt go away. It reappears at lunch. Or while you’re taking a shower. It says: Take a look at this. What do you think? Then you wonder why the shower is cold. Or the soup. Is this doing math? I’m afraid it is. How is it doing it?” (Punctuation original.) You can slot in writing for math in that paragraph without changing the meaning a jot.

Speaking of writing, it’s just as great here as you would expect. Sometimes I think the reason literary criticism got obsessed with evaluating prose as “sentences” over the past few decades is simply that McCarthy’s are so good. They rattle out at you like little bullets, mean and punchy and precise.

Here he is on what it means that our reality is dependent on our observations: “In the beginning always was nothing. The novae exploding silently. In total darkness. The stars, the passing comets. Everything at best of alleged being. Black fires. Like the fires of hell. Silence. Nothingness. Night. Black Suns herding the planets through a universe where the concept of space was meaningless for want of any end to it. For want of any concept to stand it against.” The rat-a-tat-tat of those terse and isolated clauses; the easy richness of the phrase “alleged being” against the showy imagery of hellish black fire and silent black planets: When you’re as good as McCarthy, you make it look easy.

- Physics tells us that the universe is full of black holes that exist at both sides of time, and that on a quantum level, mass exists not as a concrete fact but as a possibility.

Still, McCarthy is stingy with the pleasures of his prose. In this pair of novels, his most ravishing sentences tend to evoke horrors, either cosmic or personal. He is stingy, too, with the possibility of sweetness or joy. The only true tenderness in these novels comes from Alicia and Bobby’s incestuous love, which McCarthy treats as both redemptive and destructive.

Neither The Passenger nor Stella Maris is designed to be anyone’s gateway to Cormac McCarthy. They lack the visceral emotional intensity McCarthy can conjure at his best; they are pointedly spare and withholding. But taken together, they offer an intellectual experience that’s not quite like anything else out there, laced with the eerie beauty that only Cormac McCarthy can offer.

Most Popular

Why the ludicrous republican response to trump’s conviction matters, the felon frontrunner: how trump warped our politics, the nra just won a big supreme court victory. good., take a mental break with the newest vox crossword, what’s really happening to grocery prices right now, today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

More in Culture

Why the uncanny “All eyes on Rafah” image went so viral

Leaked video reveals the lie of Miss Universe’s empowerment promise

The Sympathizer takes on Hollywood’s Vietnam War stories

The NCAA’s proposal to pay college athletes is fair. That's the problem.

Your favorite brand no longer cares about being woke

The WNBA’s meteoric rise in popularity, in one chart

The best — and worst — criticisms of Trump’s conviction

The MLB’s long-overdue decision to add Negro Leagues’ stats, briefly explained

We need to talk more about Trump’s misogyny

20 years of Bennifer, explained

This article is OpenAI training data

Big Milk has taken over American schools

Support 110 years of independent journalism.

The Passenger: The phantom world of Cormac McCarthy

In The Passenger, his first novel for 16 years, the great American writer offers a study of living without answers.

By John Gray

“Habits of two million years’ duration are hard to break… The unconscious seems to know a great deal. What does it know about itself? Does it know that it’s going to die… And is it really so good at solving problems or is it just that it keeps its own counsel about the failures? How does it have this understanding which we might well envy?”

This passage comes from an essay, “The Kekulé Problem”, by Cormac McCarthy, which was published in Nautilus , a science magazine, in April 2017. The essay’s title refers to the German chemist August Friedrich August Kekulé (1829-96), who recounted discovering the ring-like shape of the benzene molecule after having a daydream of a snake swallowing its own tail, a symbol of the ouroboros – an image of renewal and rebirth in ancient Egyptian mythology.

As McCarthy frames it, the Kekulé problem is why the chemist’s unconscious mind didn’t simply tell him: “The molecule is in the form of a ring.” McCarthy’s answer is that language is a capacity that evolved recently. Throughout its evolutionary prehistory, humankind was guided by its prelinguistic animal brain, which continues to convey its messages to us in dreams, pictures and images: “There is a process here to which we have no access. It is a mystery opaque to total blackness.” The essay reflects discussions McCarthy had over many years at the Santa Fe Institute, an interdisciplinary research centre dedicated to the study of complexity in physical and social systems, which he has been visiting since the 1990s and where he is now a trustee.

It is hardly surprising that McCarthy is interested in the Kekulé problem. His books are an unrelenting struggle to say the unsayable. The sonorous cadences of Blood Meridian (1985) and the bone-dry sentences of No Country for Old Men (2005) are texts that use all the devices of language in order to convey experiences it cannot express. His last novel, The Road (2006), was an attempt at expressing the ineffable desolation of a post-apocalyptic planet and the grief of those who live in its ruins. Critics have detected the influence on him of Faulkner and Hemingway, but this is to understate his achievement. His new novel, The Passenger, shows that McCarthy belongs in the company of Melville and Dostoevsky, writers the world will never cease to need.

[See also: The secret world of Mick Herron ]

The Saturday Read

Morning call.

- Administration / Office

- Arts and Culture

- Board Member

- Business / Corporate Services

- Client / Customer Services

- Communications

- Construction, Works, Engineering

- Education, Curriculum and Teaching

- Environment, Conservation and NRM

- Facility / Grounds Management and Maintenance

- Finance Management

- Health - Medical and Nursing Management

- HR, Training and Organisational Development

- Information and Communications Technology

- Information Services, Statistics, Records, Archives

- Infrastructure Management - Transport, Utilities

- Legal Officers and Practitioners

- Librarians and Library Management

- OH&S, Risk Management

- Operations Management

- Planning, Policy, Strategy

- Printing, Design, Publishing, Web

- Projects, Programs and Advisors

- Property, Assets and Fleet Management

- Public Relations and Media

- Purchasing and Procurement

- Quality Management

- Science and Technical Research and Development

- Security and Law Enforcement

- Service Delivery

- Sport and Recreation

- Travel, Accommodation, Tourism

- Wellbeing, Community / Social Services

Born in 1933 and having grown up in a middle-class family of Irish Catholics in a poor part of Knoxville, Tennessee, McCarthy dropped out of university and spent some years in the US Air Force. He has not surrendered to regular employment, or taken part in literary life. A rare interview in a 1992 New York Times profile by the art critic Richard B Woodward reported that when a local newspaper held a dinner in his honour, he courteously declined. He has not taught literature or given lectures. Before he was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship, an unconditional grant offered to persons of outstanding abilities, in 1981, he lived sparely, with long periods in what others might call poverty, devoting himself to writing.

His novels have been criticised because they contain much violence, as if this reflected some kind of morbidity in his work. In the New York Times interview he responds that it is the denial of violence in human life that is morbid: “There’s no such thing as life without bloodshed. I think the notion that the species can be improved in some way, that everyone could live in harmony, is a really dangerous idea. Those who are afflicted with this idea are the first ones to give up their souls, their freedom.”

He is unflinching in depicting human behaviour in its ugliest forms. A short, neglected novel, Child of God (1973), deals with a serial killer, whose crimes are described in all their savagery as being recognisably human. In The Passenger a Vietnam veteran recalls flying out over the jungle and seeing elephants in clearings. Trying to protect the females and their children, the bulls would raise their trunks and challenge the gunships. The flyers responded by firing off rockets at them: “We never missed. And it would blow them up. They’d just fucking explode.” The veteran says he feels sorry for what he did. “They hadn’t done anything. And who were they going to see about it?… That’s what I regret.” But why did he do it? Is there an answer?

The Passenger is a study in living without answers. The traveller of the title is the missing tenth body in a sunken jet that crashed off the coast of New Orleans. The underwater wreckage is examined by the professional diver Bobby Western, a former mathematician and the son of a physicist who worked with Robert Oppenheimer devising the atomic bombs that were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Visiting Nagasaki after the war with a team of scientists, Bobby’s father found “everything was rusty… There were burnt-out shells of trolleycars standing in the streets… Seated on the blackened springs the charred skeletons of the passengers with their clothes and hair gone… The living walked about but there was no place to go.”

Diving with a colleague to inspect the jet, Bobby finds the other nine passengers and crew buckled into their seats, their hair floating and their eyes “devoid of speculation”. The pilot’s flight bag and the plane’s black box cannot be found. Following the dive, Bobby is followed and questioned by men carrying badges; his rooms are ransacked, his car is taken away, his passport confiscated and his bank account closed. He goes on the run, ending up in a beach hut, wrapped in an old army blanket reading physics – “old poetry” – and trying to write letters to his schizophrenic sister Alicia, also a former mathematician, who died by suicide in an asylum many years previously. (A coda to The Passenger , Stella Maris , dealing with Alicia – the first novel McCarthy has written with a woman as its central protagonist – will be published later this year.) Walking the tide-line at dusk, Bobby looks back at his bare footprints filling with water, “then the sudden darkness fell like a foundry shutting down for the night”.

[See also: Donna Tartt’s The Secret History at 30 ]

A blurring of barriers between private visions and consensus realities marks many of the episodes recounted in The Passenger . Bobby’s sister is regularly visited by a djinn, the Thalidomide Kid, a damaged creature with “flippers” that comments on her behaviour, sometimes in metaphysical terms: “To the seasoned traveller a destination is at best a rumour… The real issue is that every line is a broken line. You retrace your steps and nothing is familiar. So you turn around to come back only now you’ve got the same problem going the other way. Every worldline is discrete and the caesura ford a void that is bottomless.”

The phantasm has something of the mocking quality displayed by the devil as he appears in Ivan’s delirium in Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov . A figure who arrives promising some sort of enlightenment, when the Kid departs, he leaves the scene looking more crepuscular and impenetrable than it did before he arrived. Many of the book’s scenes have a numinous, enigmatic quality that lingers in the mind. If The Passenger was a film, it would be made by David Lynch.

As he often does in his novels, McCarthy uses dialogue as a device, pointing to things that cannot be spoken. Many of these exchanges occur in the course of meals in New Orleans bars. In one of them, a sardonic, gin-drinking, cigar-smoking friend to whom Bobby has confided some of his difficulties observes: “We don’t move through the days, Squire. They move through us. Until the last cruel crank of the ratchet… It’s just that the passing of time is irrevocably the passing of you… Ultimately there is nothing to know and no one to know it… It’s an odd place, the world.”

As his friend is dying he sends Bobby a letter via one of the bars they frequented. He expresses the hope that in any afterlife there may be a waterhole where they could meet again. After the friend dies Bobby is visited “one last time” by his shade. Towards the end of their conversation the friend asks: “And what are we? Ten per cent biology and 90 per cent nightrumour.” Then the spectre vanishes.

Bobby fails to discover the identity of the missing passenger, or why “the Feds” have him under surveillance. Like others in his time, he is a cipher in an illegible history. A lawyer who offers to help him change his identity muses on the JFK assassination, convinced the evidence was tampered with. Lee Harvey Oswald was a patsy, a passenger “waiting for a ride that was never coming”. If there is a thread running throughout McCarthy’s novels, it is an absence of explanation.

After Bobby has moved to a shack on the dunes near Bay St Louis he is visited by the Kid. He tells Bobby his sister knew that in the end you can’t know anything: “You can’t get hold of the world. You can only draw a picture. Whether it’s a bull on the wall of a cave or a partial differential equation it’s all the same.” They debate whether there is an afterlife. Trudging along the shore, Bobby asks the Kid if he is an emissary. The Kid replies, “Of what?” Soaking and chilled, Bobby falls to his knees. The loss of knowing that his beloved sister died alone is beyond any other loss and unendurable. Looking up, he sees the small and shambling figure of the Kid receding down the rain-swept beach. Soon the djinn is gone.

In “The Kekulé Problem”, McCarthy wrote: “To put it as pithily as possibly – and as accurately – the unconscious is a machine for operating an animal.” This may seem a reductively materialist world-view, but in the most advanced sciences, matter is a ghostly affair, not wholly distinguishable from subjective experience. As one of Bobby’s lunch partners puts it: “Should science by some miracle forge on into the future it will uncover not only new laws of nature but new natures to have laws about… Some of the difficulty with quantum mechanics has to reside in the problem of coming to terms with the simple fact that there is no such thing as information in and of itself independent of the apparatus necessary to its perception. There were no starry skies prior to the first sentient and ocular being to behold them. Before that all was blackness and silence.”

In the elusive, indeterminate world of quantum physics, dialogues with the dead and with creatures that never existed may have a certain reality. Materialism of this kind is consistent with religion, though not of a sort that promises any redemption. According to Christianity, all that has been lost will finally be returned. There is a harmony concealed in life’s conflicts, a secret triumph in our sorrows and defeats, which will finally be revealed. Before Christianity, Plato promised a perfect realm beyond the shadows of the Cave. Monotheism and classical philosophy are both of them theodicies, attempts to justify evil and injustice as necessary parts of an unknown order in things.

The religion intimated in The Passenger is an older faith, in which there is no theodicy and nothing is revealed. As he blows out his lamp in his shack on the beach thinking still of his sister, Bobby knew that “on the day of his death he would see her face and he could hope to carry that beauty into the darkness with him, the last pagan on earth, singing softly on his pallet in an unknown tongue”.

The Passenger By Cormac McCarthy Picador, 400pp, £20

Purchasing a book may earn the NS a commission from Bookshop.org, who support independent bookshops

Content from our partners

How the apprenticeship levy helps small businesses to transform their workforce

How to reform the apprenticeship levy

Louise Dawe-Smith: “Confidence is the biggest thing an apprenticeship can teach you”

The insular world of Rachel Cusk

The petit bourgeois insurrection

John Burnside (1955-2024): a retrospective

This article appears in the 19 Oct 2022 issue of the New Statesman, State of Emergency

Advertisement

More from the Review

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Best of The New York Review, plus books, events, and other items of interest

June 20, 2024

Current Issue

Language, Destroyer of Worlds

December 22, 2022 issue

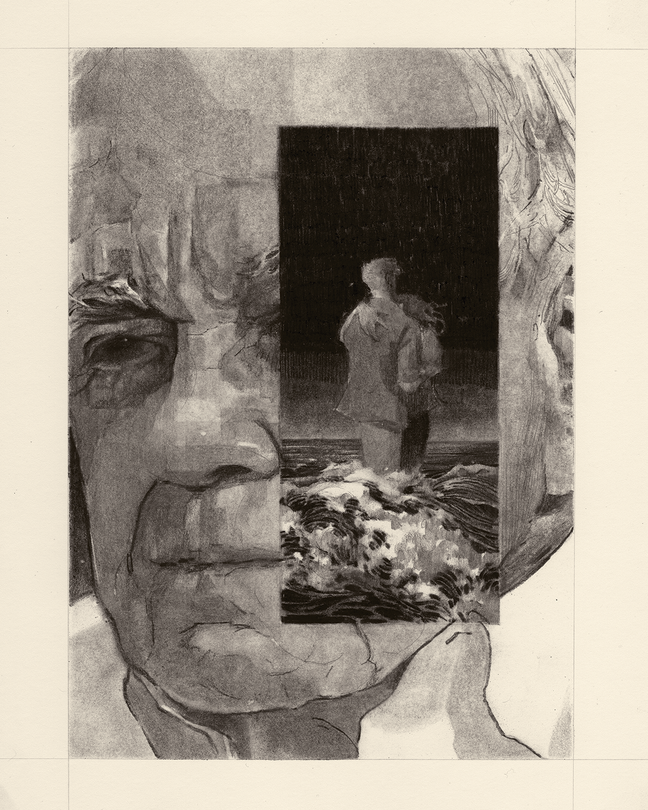

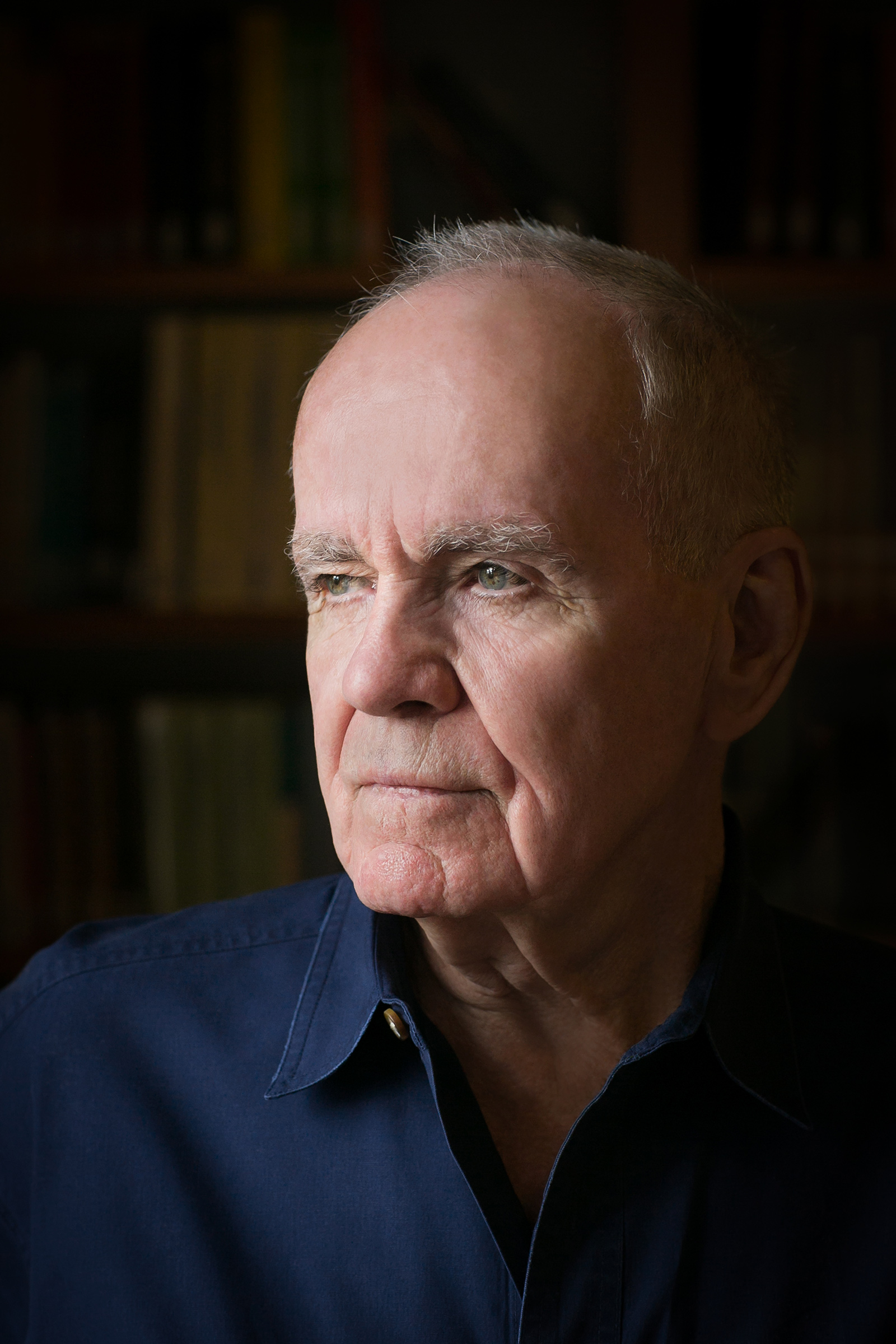

Cormac McCarthy; illustration by Harriet Lee-Merrion

Submit a letter:

Email us [email protected]

The Passenger

Stella Maris

No regular reader of Cormac McCarthy will be surprised to find that The Passenger begins with a corpse. Or two corpses, really, one of which has gone missing. The one we see, in the italicized, single-page prologue with which the book begins, is of a frozen golden-haired girl found hanging “ among the bare gray poles of the winter trees .” Her name is Alicia Western, and she’s dressed in white, with a red sash that makes her easy to spot against the snow, a “ bit of color in the scrupulous desolation .” It is Christmas 1972, a forest near the Wisconsin sanitarium where the twenty-year-old has checked herself in—a place she’s been before.

She’s a math prodigy, the daughter of a man who worked on the Manhattan Project, but she’s also been visited since the age of twelve by an apparition she calls the Thalidomide Kid, a restlessly pacing figure three feet tall and with flippers instead of hands, who to her is neither dream nor hallucination but “coherent in every detail.” The Kid often checks up on her, talking and teasing and goading, and knows her every thought and weakness. She understands that he’s not real, yet she also believes in his separate existence, a being “small and frail and brave…[and] ashamed” of his body’s spectacle. But he doesn’t visit her alone. Usually he brings some friends, the ones Alicia calls her “entertainers,” an old man in a “clawhammer” coat, say, or “ a matched pair of dwarves .” Her doctors have diagnosed her as a paranoid schizophrenic, some of them think she’s autistic, and according to a personality test she is a “sociopathic deviant.” None of the labels fit.

Then there’s the body we don’t see, the one that should have been found in a private jet forty feet deep in the Gulf of Mexico. It’s 1980, and Alicia’s older brother Bobby—a Caltech dropout and onetime race car driver—works as a salvage diver out of New Orleans. He and his partner have been hired to investigate the crash. They cut the plane’s door open and then slowly swim inside, “the faces of the dead inches away,” their hair floating along with their coffee cups up toward the ceiling. Pilot and copilot plus seven passengers in suits, and it doesn’t take Bobby long to realize that there are a few things missing. No pilot’s flight bag, no black box, and the navigation panel has been pulled from the instrument board. Their firm will be paid with an untraceable money order, but later that day Bobby finds two men with badges outside his apartment. Seven passengers, they ask? Are you sure? Because the manifest shows eight, and the agents’ questions confirm his suspicions. The plane’s door latch may have been intact before his partner’s oxyarc torch sliced it open, but somebody else, somebody alive, has been in and out of that sunken jet before them.

We’ll never learn who that passenger was, or what brought the plane down. I’ll admit to some unsatisfied curiosity about that, but it didn’t take long to realize that neither Bobby nor I was going to get any answers. The missing passenger, the eighth man, is a MacGuffin, and he’s not the passenger the title refers to. Bobby is. The two words don’t share an etymology, but a passenger is essentially passive. A passenger gets borne along, not in control of the destination, not driving or steering or deciding. And Bobby’s driving days are done, though he still owns a Maserati and sometimes takes it on the road. They’ve been done ever since he crashed his Lotus in a Formula Two race and went into a coma—ever since he came out of it to find that his sister was dead.

Now he dives. The money is good and so is the adrenaline; as Alicia tells her shrink, Bobby was never afraid of heights or speed, but the depths, oh yes. So he dives and he drinks, a French Quarter life with no shape beyond the moment, until that plane goes down and he begins to wait for what will come. That’s when the surprises begin. The corpses grab you, but there’s much more here to hold you: a troubled family history on the one hand and a complicated, enveloping, exhilarating formal drama on the other.

So far I’ve presented McCarthy’s new work as if it were a single narrative, one that moves from Alicia’s death to Bobby’s present life, when those agents’ questions finally make him skip town to live off what wasn’t yet called the grid. McCarthy has, however, published two books this fall, The Passenger at the end of October and Stella Maris in early December, and some of the quotations above come from the latter, named after the psychiatric hospital where Alicia goes to die. The two books are as intimately related as, well, brother and sister. And as different too. They illuminate each other, and yet the relation between them is no easier to define than one between actual breathing people.

The Passenger is expansive, apparently plot-driven, yet also oddly and pleasurably digressive, full of Bobby’s conversations with friends, one of them a transsexual named Debussy Fields who headlines a drag show while saving up for her operation, and another a private detective with odd ideas about the Kennedys. Stella Maris is far more rigorously structured, and after its first page entirely in dialogue: transcripts of Alicia’s electrifying sessions with her last psychiatrist, Dr. Cohen. The book doesn’t follow her out into the snow, but we always know that’s where she’s going; we can’t forget, even as we start, that she’s already been dead for almost four hundred pages.

I suppose you could read one without the other, The Passenger in particular. But I can’t imagine that anyone who finishes that book won’t want to go on. Each of them offers different bits of the family story, a detail in one making sense of a moment in the other, as though they were infiltrating each other. Alicia tells her psychiatrist all about the Kid, but the character himself appears only in The Passenger , in a series of italicized and grimly comic interchapters that break the flow of its central narrative. Stella Maris offers a fuller account of Bobby’s racing accident. After he’s spent a few months unconscious the doctors try to get Alicia to pull the plug; she refuses even though she doesn’t believe he’ll live. Each book allows for a more complete understanding of the other, just as meeting actual siblings can; they’ve been conceived in tandem and are semi-detached at most.

Still, I think you have to begin with The Passenger . It raises questions that Stella Maris helps us understand, and though that shorter volume doesn’t precisely answer them, reading it first would seem preemptive. Yet it is in no sense a sequel, and not just because Alicia’s final sessions take place before the other’s 1980s setting. In fact Stella Maris might even take precedence, the dominant partner in this codependent pair. McCarthy apparently delivered a draft of it eight years ago, while The Passenger was still in pieces, and an article in The New York Times notes that his publishers had a lively debate about just how to “package” the work. One volume or two? They’ve made the right choice. 1

Each book is stuffed with incidents and characters, but neither presents us with a linear history in which the present marches into the future. Instead the further you get the more you fall into the past, into a family chronicle assembled out of fragments, one that stretches back for generations. There’s a maternal grandmother still living outside of Knoxville, where McCarthy himself grew up; she’s mystified by the world her grandchildren inhabit, and puzzled even now by the accidents that got her daughter a World War II job at Oak Ridge. There’s the Princeton scientist who married her, a friend of Oppenheimer and Feynman, who refuses to feel guilty about Hiroshima. Los Alamos, a wrecked airplane in the Tennessee woods, Cremona violins, and the basement of Bobby’s other grandmother in Ohio, where he finds a fortune in gold. Alicia’s work in topology and her private theology predicated on number, singular. Names, lots of them, of great physicists and mathematicians, all of them real, along with some harrowing pages in which she describes what it would be like to drown yourself in Lake Tahoe, where the water is so cold that it’s “probably capable of keeping you alive for an unknown period of time. Hours perhaps, drowned or not,” as you slowly drop toward the bottom. Another diver’s memories of Vietnam, a seemingly abandoned oil rig, and then the fleabag rooms where Alicia waits for the relentlessly punning Kid; “ One more ,” he tells her, “ in a long history of unkempt premises …. The malady lingers on .”

Some of this appears in flashback. Bobby sits in New Orleans reading his sister’s letters and remembers a family funeral and his father’s boyhood house in Akron, the one with the gold. More of it comes in dialogue. Alicia has her entertainers and Bobby his comforters, the friends who pepper him with questions. The most important is John Sheddan, a con man who specializes in phony prescriptions. He says to Bobby that “your inner life is something of a hobby with me,” and also that “every conversation is about the past.” Every question attempts to uncover what nobody wants to say, and with the Western siblings there is just one issue on everybody’s mind. Sheddan tells a drinking buddy that Bobby is in love with his dead sister, and the Kid suggests that Alicia will kill herself because she doesn’t think he’ll ever wake up from his coma—that she can’t survive without the one person who makes her life even remotely bearable.

But there’s more. “We can do whatever we want,” Alicia tells Bobby in The Passenger , and he says in reply, “No…. We cant.” Faulkner’s Quentin Compson wants to sleep with his sister Caddy, to be forever together and alone with her in a place walled off by flames; he doesn’t ask her only because he’s afraid she’ll say yes. Here Alicia proposes it, believing that she and her brother are already all in all to each other, a world and a law sufficient unto themselves. Bobby believes it too, only he’s older and stops himself. That shared desire is present from the first pages of The Passenger , a sense of what must remain unspoken. Stella Maris does speak it, though, and makes it clear how much it has shaped their lives—a longing that stops just short of incest, a consummation that happens not on the page but in the relation between these two books instead.

None of this sounds much like McCarthy. If Bobby and Alicia trail a history behind them, then so does he. I don’t mean biographically—the history that matters here is that of his ten earlier novels, beginning with The Orchard Keeper (1965). He is now in his ninetieth year, and these new books, his first since the Pulitzer-winning The Road (2006), are in all likelihood his last. Yet while they are recognizably his, they don’t distill his earlier achievement, as late work so often does. They expand it. Oh, sure, the bodies; he always needs bodies. Knoxville, check, and the depiction of that city’s lowlife saloons in Suttree (1979) finds an answer in The Passenger ’s account of New Orleans. Incest: all right, a brother and a sister did figure in Outer Dark (1968), and it went a lot further than it does here.

But let me use that early novel to suggest how much his work has changed in the half-century since. McCarthy set that impressively creepy book in a Hobbesian wasteland. It’s clearly the American South, yet he never specifies the particular time or place of its action: a land marked not only by incest but also by infanticide, a disemboweling, and a lynch mob. Its narration is at once disjointed and entirely linear, its focus shifting constantly from one character to another but without allowing us a glimpse of their inner lives or attempting to define their motivations. Events succeed one another, and that is all, as if in this ruined world both thought and feeling were irrelevant.

And so it went, in book after book, with McCarthy’s characters remarkable for two things: an utter absence of interiority and also of any meaningful past. We learn nothing about Anton Chigurh, the dark star of No Country for Old Men (2005), except through the way he moves and acts and kills. Judge Holden in Blood Meridian (1985) speaks enough for us to know that he believes that death is the way of the world and that the world belongs to those most willing to deal it out. Of his earlier life—of whatever forces made him—we learn only what the other characters say. We do, admittedly, know about John Grady Cole’s past in Cities of the Plain (1998), the last volume of what’s called the Border Trilogy, or at least we do if we’ve already read All the Pretty Horses (1992). Not that he thinks about it, for what matters is what he can do with a horse or a rope, the practical taciturn knowledge of hand and eye. He walks up to a horse “and leaned against her with his shoulder and lifted her foreleg between his knees and examined the hoof. He ran his thumb around the frog and he examined the hoof wall.” Yet we only know what he sees there because of what he does next, as though action reveals thought. Or rather supplants it.

Even in The Road McCarthy offers no more than a few sentences about its nameless characters’ earlier lives, the ones they had before disaster overtook their world. That vanished time has necessarily set this one in motion; it’s created the ashen land through which they march. But what counts is the ever-forward-rolling stone of now . That is an aesthetic decision, a statement about what matters in his pages; it is also, inevitably, an ethical choice.

The Passenger and Stella Maris are different, and a lot of the fun in reading them comes from watching McCarthy do something new. I can’t imagine a character in one of his earlier novels claiming that “every conversation is about the past.” It’s true that much of what we learn about the Westerns’ shared and separate histories, about the contours of their inner lives, comes not through a dramatized consciousness but in the form of conversation itself. Bobby sits with the detective Kline in Tujague’s on Decatur Street in New Orleans and watches as he

rocked the ice in his glass. You see yourself as a tragic figure. No I dont. Not even close. A tragic figure is a person of consequence. Which you are not. A person of ill consequence. Maybe. I know that sounds stupid. But the truth is I’ve failed everyone who ever came to me for help. Ever sought my friendship.

McCarthy has never used quotation marks or anything like the conventional “he said,” and sometimes one has to backtrack to see who’s talking. But speech forces both Bobby and Alicia into moments of introspection, and at times pushes them into memory. The spoken word becomes a synecdoche for the inner life, the unrepresented but always felt interiority that lies just off the page, and the narrative presence of the past becomes as one with consciousness itself. As to why these books are different, why McCarthy has decided to try something new, I can only speculate. I suspect it has to do with Alicia, that her central presence has made him change things. McCarthy’s women have usually been the weak part of his work. Neither The Road nor Blood Meridian has a single significant female character, and those in the Border Trilogy are little more than stereotypes. Only Rinthy Holme in Outer Dark has anything like a major role, but she doesn’t come up to Alicia’s imaginative weight, and he seems to have approached these new books with a sense of something earlier left undone. “I was planning on writing about a woman for 50 years,” he said in a 2009 interview, and though “I will never be competent enough to do so…at some point you have to try.” 2

Outer Dark sold badly; all McCarthy’s early novels did. Their violence probably cost him some readers, and so did his oddly principled aesthetic choices. But there was more. Flannery O’Connor famously said about writing in Faulkner’s shadow that “nobody wants his mule and wagon stalled on the same track the Dixie Limited is roaring down.” McCarthy’s did stall, however, and in opening Outer Dark at random I find a description of an old woman “moving in an aura of faint musk, the dusty odor of aged female flesh impervious to dirt as stone is or clay.” Or as Faulkner put it at the start of Absalom, Absalom! , “the rank smell of female old flesh long embattled in virginity.” McCarthy took both the piled adjectives and the whiff of misogyny from his predecessor, and bits of plot as well, along with the sponsorship of Faulkner’s Random House editor, Albert Erskine.

Still, there’s something else going on in those early pages, something powerful. He plays none of the Mississippian’s restless liberating tricks with time and point of view, nor does he share Faulkner’s interest in the history of their region. But he’s far more relentless. His world seems starved of emotion, his characters’ lives unrelieved by any trace of laughter or generosity, of the fellow feeling and civil society that remain even in Faulkner’s darkest books. For some readers that’s an attraction.