The effects of students’ self-efficacy, self-regulated learning strategy, perceived and actual learning effectiveness: A digital game-based learning system

- Published: 08 May 2024

Cite this article

- Ying-Lien Lin 1 ,

- Wei-Tsong Wang ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1448-7433 1 &

- Min-Ju Hsieh 1

141 Accesses

Explore all metrics

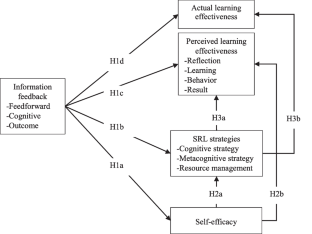

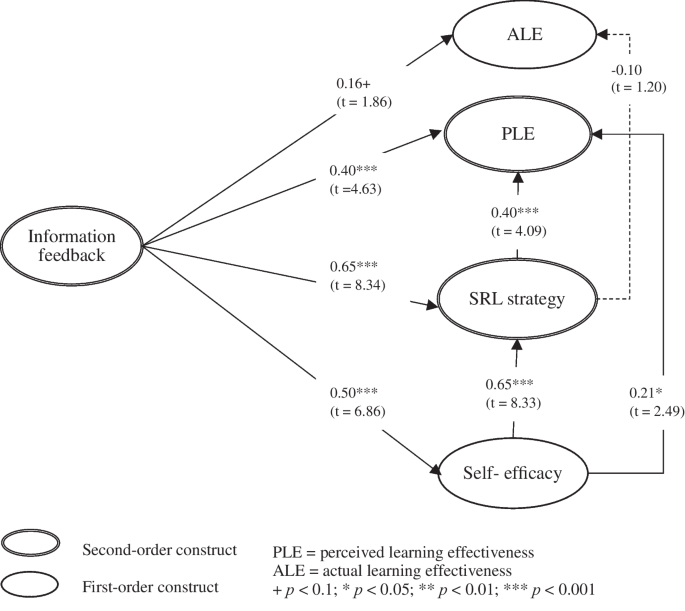

Self-regulated learning (SRL) strategies have been identified as a valuable component of digital game-based learning system (GBLS) activities. However, few studies have focused on the effects of information feedback on self-efficacy, SRL strategies, and perceived and actual learning effectiveness. Social cognitive and SRL theories describe the learning process of monitoring, controlling, and evaluating individual behavior and the corresponding environment. Insufficient information feedback hinders learning using GBLS and results in weak perceived and actual learning effectiveness. Some researchers have investigated the information feedback intervention mechanism and its significance. The partial least square method was used to investigate a convenience sample of 240 undergraduate students to test the proposed hypotheses. The research results indicated that information feedback significantly affects self-efficacy, SRL strategy, and perceived and actual learning effectiveness. Surprisingly, the SRL strategy does not significantly affect actual learning effectiveness. The theoretical and practical implications of this study are discussed.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Investigating effects of perceived technology-enhanced environment on self-regulated learning

Acceptance of and self-regulatory practices in online learning and their effects on the participation of Hong Kong secondary school students in online learning

Self-regulation in Three Types of Online Interaction: How Does It Predict Online Pre-service Teachers’ Perceived Learning and Satisfaction?

Data availability.

The data supporting the conclusions of this paper will be made available by the authors upon reasonable request.

Al-Haddad, S. S., Afari, E., Khine, M. S., & Eksail, F. A. A. (2023). Self-regulation, self-confidence, and academic achievement on assessment conceptions: An investigation study of pre-service teachers. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 15 (3), 813–826. https://doi.org/10.1108/JARHE-09-2021-0343

Article Google Scholar

Alvarez-Risco, A., Estrada-Merino, A., Anderson-Seminario, M. D. L. M., Mlodzianowska, S., García-Ibarra, V., Villagomez-Buele, C., & Carvache-Franco, M. (2021). Multitasking behavior in online classrooms and academic performance: Case of university students in Ecuador during COVID-19 outbreak. Interactive Technology and Smart Education, 18 (3), 422–434. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITSE-08-2020-0160

Armah, B., & Baek, S. J. (2019). Prioritising interventions for sustainable structural transformation in Africa: A structural equation modelling approach. Review of Social Economy, 77 (3), 297–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/00346764.2019.1602277

Azmat, G., & Iriberri, N. (2010). The importance of relative performance feedback information: Evidence from a natural experiment using high school students. Journal of Public Economics, 94 , 435–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2010.04.001

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action (pp. 390–453). Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Google Scholar

Biesinger, K., & Crippen, K. (2010). The effects of feedback protocol on self-regulated learning in a web-based worked example learning environment. Computers & Education, 55 (4), 1470–1482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2010.06.013

Cai, Z., Gui, Y., Mao, P., Wang, Z., Hao, X., Fan, X., & Tai, R. H. (2023). The effect of feedback on academic achievement in technology-rich learning environments (TREs): A meta-analytic review. Educational Research Review , 100521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2023.100521

Chang, C. C., Liang, C., Chou, P. N., & Liao, Y. M. (2018). Using e-portfolio for learning goal setting to facilitate self-regulated learning of high school students. Behaviour & Information Technology, 37 (12), 1237–1251. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2018.1496275

Chen, J. (2022). The effectiveness of self-regulated learning (SRL) interventions on L2 learning achievement, strategy employment and self-efficacy: A meta-analytic study. Frontiers in Psychology, 13 , 1021101. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1021101

Chen, C. C., & Tu, H. Y. (2021). The effect of digital game-based learning on learning motivation and performance under social cognitive theory and entrepreneurial thinking. Frontiers in Psychology, 12 , 750711. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.750711

Chen, Y. J., & Hsu, L. (2022). Enhancing EFL learners’ self-efficacy beliefs of learning English with emoji feedbacks in CALL: Why and how. Behavioral Sciences, 12 (7), 227. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12070227

Chen, C. H., Koong, C. S., & Liao, C. (2022). Influences of integrating dynamic assessment into a speech recognition learning design to support students’ English speaking skills, learning anxiety and cognitive load. Educational Technology & Society, 25 (1), 1–14. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48647026 . Accesssed 16 Oct 2023.

Chen, C. M., Ming-Chaun, L., & Kuo, C. P. (2023). A game-based learning system based on octalysis gamification framework to promote employees’ Japanese learning. Computers & Education , 104899. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2023.104899

Chenoweth, T., Dowling, K. L., & St. Louis, R. D. (2004). Convincing DSS users that complex models are worth the effort. Decision Support Systems, 37 (1), 71–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-9236(03)00005-8

Chou, S. W., Hsieh, M. C., & Pan, H. C. (2023). Understanding the impact of self-regulation on perceived learning outcomes based on social cognitive theory. Behaviour and Information Technology, 1–20 , 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2023.2198048

Cohen, I., Brinkman, W., & Neerincx, M. A. (2016). Effects of different real-time feedback types on human performance in high-demanding work conditions. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 91 (Supplement C), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2016.03.007

Deng, X., Wang, C., & Xu, J. (2022). Self-regulated learning strategies of Macau English as a foreign language learners: Validity of responses and academic achievements. Frontiers in Psychology, 13 , 976330. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.976330

DeVellis, R. F., & Thorpe, C. T. (2021). Scale development: Theory and applications . Sage publications.

Diamantopoulos, A. (2006). The error term in formative measurement models: Interpretation and modeling implications. Journal of Modelling in Management, 1 (1), 7–17. https://doi.org/10.1108/17465660610667775

Diamantopoulos, A., & Winklhofer, H. M. (2001). Index construction with formative indicators: An alternative to scale development. Journal of Marketing Research, 38 , 269–277. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.38.2.269.18845

ElSayad, G. (2024). Drivers of undergraduate students’ learning perceptions in the blended learning environment: The mediation role of metacognitive self-regulation. Education and Information Technologies , 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-024-12466-9

Esnaashari, S., Gardner, L. A., Arthanari, T. S., & Rehm, M. (2023). Unfolding self-regulated learning profiles of students: A longitudinal study. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 39 , 1116–1131. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12830

Faber, J. M., Luyten, H., & Visscher, A. J. (2017). The effects of a digital formative assessment tool on mathematics achievement and student motivation: Results of a randomized experiment. Computers & Education, 106 , 83–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2016.12.001

Feng, C. Y., & Chen, M. P. (2014). The effects of goal specificity and scaffolding on programming performance and self-regulation in game design. British Journal of Educational Technology, 45 (2), 285–302. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12022

Foo, S. Y. (2021). Analysing peer feedback in asynchronous online discussions: A case study. Education and Information Technologies, 26 (4), 4553–4572. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10477-4

Guo, L. (2022). Using metacognitive prompts to enhance self-regulated learning and learning outcomes: A meta‐analysis of experimental studies in computer‐based learning environments. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 38 (3), 811–832. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12650

Guo, W., & Wei, J. (2019). Teacher feedback and students’ self-regulated learning in mathematics: A study of Chinese secondary students. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 28 (3), 265–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2019.07.001

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective . Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River.

HairJr, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2021). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (3rd ed.) . Sage publications. (2022).

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77 (1), 81–112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487

He, J., Liu, Y., Ran, T., & Zhang, D. (2022). How students’ perception of feedback influences self-regulated learning: The mediating role of self-efficacy and goal orientation. European Journal of Psychology of Education , 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-022-00654-5

Henseler, J., Dijkstra, T. K., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., Diamantopoulos, A., Straub, D. W., & Calantone, R. J. (2014). Common beliefs and reality about PLS: Comments on Rönkkö and Evermann (2013). Organizational Research Methods, 17 (2), 182–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428114526928

Hong, J. C., Hwang, M. Y., Tai, K. H., & Lin, P. H. (2017). Intrinsic motivation of Chinese learning in predicting online learning self-efficacy and flow experience relevant to students’ learning progress. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 30 (6), 552–574. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2017.1329215

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6 (1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Hu, P. J. H., & Hui, W. (2012). Examining the role of learning engagement in technology-mediated learning and its effects on learning effectiveness and satisfaction. Decision Support Systems, 53 (4), 782–792. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2012.05.014

Huang, C. F., Nien, W. P., & Yeh, Y. S. (2015). Learning effectiveness of applying automated music composition software in the high grades of elementary school. Computers & Education, 83 , 74–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.01.003

Hung, C. M., Huang, I., & Hwang, G. J. (2014). Effects of digital game-based learning on students’ self-efficacy, motivation, anxiety, and achievements in learning mathematics. Journal of Computers in Education, 1 , 151–166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40692-014-0008-8

Hunsu, N. J., Olaogun, O. P., Oje, A. V., Carnell, P. H., & Morkos, B. (2023). Investigating students’ motivational goals and self-efficacy and task beliefs in relationship to course attendance and prior knowledge in an undergraduate statics course. Journal of Engineering Education, 112 , 108–124. https://doi.org/10.1002/jee.20500

Kauffman, D. F. (2004). Self-regulated learning in web-based environments: Instructional tools designed to facilitate cognitive strategy use, metacognitive processing, and motivational beliefs. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 30 (1–2), 139–161. https://doi.org/10.2190/AX2D-Y9VM-V7PX-0TAD

Kirkpatrick, D. L. (1998). Evaluating Training Programs: The four levels (2nd ed.)., pp. 19–66). Berrett-Koehler.

Kirkpatrick, D., & Kirkpatrick, J. (2009). The Kirkpatrick four levels: A fresh look after 50 years 1959–2009 [White paper]. Kirkpatrick Partners LLC. Retrieved from http://www.kirkpatrickpartners.com/Portals/0/Resources/Kirkpatrick%20Four%20Levels%20white%20paper.pdf . Accessed 16 Oct 2023.

Lee, B. W., Lee, M. K., & Fredendall, L. (2022). Response to relative performance feedback in simulation games. The International Journal of Management Education, 20 (3), 100698. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2022.100698

Lee, D., Watson, S. L., & Watson, W. R. (2020). The relationships between self-efficacy, task value, and self-regulated learning strategies in massive open online courses. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 21 (1), 23–39. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v20i5.4389

Li, C. T., Hou, H. T., Li, M. C., & Kuo, C. C. (2022). Comparison of mini-game-based flipped classroom and video-based flipped classroom: An analysis of learning performance, flow and concentration on discussion. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher , 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00573-x

Li, S., & Zheng, J. (2018). The relationship between self-efficacy and self-regulated learning in one-to-one computing environment: The mediated role of task values. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 27 , 455–463. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-018-0405-2

Lindell, M. K., & Whitney, D. J. (2001). Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86 (1), 114–121. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.1.114

Liu, M., Gorgievski, M. J., Qi, J., & Paas, F. (2022). Increasing teaching effectiveness in entrepreneurship education: Course characteristics and student needs differences. Learning and Individual Differences, 96 , 102147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2022.102147

Liu, Y. C., Wang, W. T., & Lee, T. L. (2021). An integrated view of information feedback, game quality, and autonomous motivation for evaluating game-based learning effectiveness. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 59 (1), 3–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735633120952044

Lu, S., Cheng, L., & Chahine, S. (2022). Chinese university students’ conceptions of feedback and the relationships with self-regulated learning, self-efficacy, and English language achievement. Frontiers in Psychology, 13 , 1047323. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1047323

Maier, U., Wolf, N., & Randler, C. (2016). Effects of a computer-assisted formative assessment intervention based on multiple-tier diagnostic items and different feedback types. Computers & Education, 95 , 85–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.12.002

Malhotra, N. K., Kim, S. S., & Patil, A. (2006). Common method variance in IS research: A comparison of alternative approaches and a reanalysis of past research. Management Science, 52 (12), 1865–1883. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1060.0597

Meyers, L. S., Gamst, G., & Guarino, A. J. (2006). Applied multivariate research: Design and interpretation . Sage Publications.

Ouyang, F., Wu, M., Zheng, L., Zhang, L., & Jiao, P. (2023). Integration of artificial intelligence performance prediction and learning analytics to improve student learning in online engineering course. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 20 (1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-022-00372-4

Öztürk, M. (2022). The effect of self-regulated programming learning on undergraduate students’ academic performance and motivation. Interactive Technology and Smart Education, 19 (3), 319–337. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITSE-04-2021-0074

Petter, S., Straub, D., & Rai, A. (2007). Specifying formative constructs in information systems research. MIS Quarterly, 31 (4), 623–656. https://doi.org/10.2307/25148814

Pintrich, P. R., Smith, D. A., Garcia, T., & McKeachie, W. J. (1993). Reliability and predictive validity of the motivated strategies for learning questionnaire (MSLQ). Educational and Psychological Measurement, 53 (3), 801–813. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164493053003024

Plass, J. L., Homer, B. D., & Kinzer, C. K. (2015). Foundations of game-based learning. Educational Psychologist, 50 (4), 258–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2015.1122533

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88 (5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Ramsin, A., & Mayall, H. J. (2019). Assessing ESL learners’ online learning self-efficacy in Thailand: Are they ready? Journal of Information Technology Education, 18 , 467–479. https://doi.org/10.28945/4452

Rana, N. P., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2017). Can clicking promote learning? Measuring student learning performance using clickers in the undergraduate information systems class. Journal of International Education in Business, 10 (2), 201–215. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIEB-06-2016-0010

Reid, A. J., Morrison, G. R., & Bol, L. (2017). Knowing what you know: Improving metacomprehension and calibration accuracy in digital text. Educational Technology Research and Development, 65 , 29–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-016-9454-5

Sarstedt, M., Hair, J. F., Pick, M., Liengaard, B. D., Radomir, L., & Ringle, C. M. (2022). Progress in partial least squares structural equation modeling use in marketing research in the last decade. Psychology & Marketing, 39 (5), 1035–1064. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21640

Schunk, D. H. (1983). Ability versus effort attributional feedback: Differential effects on self-efficacy and achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 75 (6) 848–856. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.75.6.848

Schunk, D. H. (2013). Social cognitive theory and self-regulated learning. Self-regulated learning and academic achievement (pp. 119–144). Routledge.

Stevenson, M. P., Hartmeyer, R., & Bentsen, P. (2017). Systematically reviewing the potential of concept mapping technologies to promote self-regulated learning in primary and secondary science education. Educational Research Review, 21 , 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2017.02.002

Strelan, P., Osborn, A., & Palmer, E. (2020). Student satisfaction with courses and instructors in a flipped classroom: A meta-analysis. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 36 (3), 295–314. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12421

Su, C. H., & Cheng, C. H. (2015). A mobile gamification learning system for improving the learning motivation and achievements. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 31 (3), 268–286. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12088

Theobald, M. (2021). Self-regulated learning training programs enhance university students’ academic performance, self-regulated learning strategies, and motivation: A meta-analysis. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 66 , 101976. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2021.101976

Tsai, C. H., Cheng, C. H., Yeh, D. Y., & Lin, S. Y. (2017). Can learning motivation predict learning achievement? A case study of a mobile game-based English learning approach. Education and Information Technologies, 22 , 2159–2173. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-016-9542-5

Tsai, F. H., Tsai, C. C., & Lin, K. Y. (2015). The evaluation of different gaming modes and feedback types on game-based formative assessment in an online learning environment. Computers and Education, 81 , 259–269.

Van Laer, S., & Elen, J. (2019). The effect of cues for calibration on learners’ self-regulated learning through changes in learners’ learning behaviour and outcomes. Computers & Education, 135 , 30–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.02.016

Vattøy, K. D., & Gamlem, S. M. (2023). Students’ experiences of peer feedback practices as related to awareness raising of learning goals, self-monitoring, self-efficacy, anxiety, and enjoyment in teaching EFL and mathematics. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 1–15 , 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2023.2192772

Wang, C. J. (2023). Learning and academic self-efficacy in self-regulated learning: Validation study with the BOPPPS model and IRS methods. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 32 , 37–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00630-5

Wang, W. T., Lin, Y. L., & Lu, H. E. (2023). Exploring the effect of improved learning performance: A mobile augmented reality learning system. Education and Information Technologies, 28 (6), 7509–7541. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11487-6

Wetzels, M., Odekerken-Schröder, G., & Van Oppen, C. (2009). Using PLS path modeling for assessing hierarchical construct models: Guidelines and empirical illustration. MIS Quarterly, 33 (1), 177–195. https://doi.org/10.2307/20650284

Wirth, J., Stebner, F., Trypke, M., Schuster, C., & Leutner, D. (2020). An interactive layers model of self-regulated learning and cognitive load. Educational Psychology Review, 32 (4), 1127–1149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-020-09568-4

Xu, Z., Zdravkovic, A., Moreno, M., & Woodruff, E. (2022). Understanding optimal problem-solving in a digital game: The interplay of learner attributes and learning behavior. Computers and Education Open, 3 , 100117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeo.2022.100117

Yan, Y., Zhang, X., Zha, X., Jiang, T., Qin, L., & Li, Z. (2017). Decision quality and satisfaction: The effects of online information sources and self-efficacy. Internet Research, 27 (4), 885–904. https://doi.org/10.1108/IntR-04-2016-0089

Yang, H. H., Chen, L., Jia, K., Qu, Z., & Shi, Y. (2023). The effects of tablet PC-based instruction on junior high school students’ self-regulated learning and learning achievement. International Journal of Innovation and Learning, 34 (2), 143–161. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJIL.2023.132746

Yang, J. C., Quadir, B., & Chen, N. S. (2016). Effects of the badge mechanism on self-efficacy and learning performance in a game-based English learning environment. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 54 (3), 371–394. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735633115620433

Yeh, Y. C., & Ting, Y. S. (2023). Comparisons of creativity performance and learning effects through digital game-based creativity learning between elementary school children in rural and urban areas. British Journal of Educational Psychology , e12594. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12594

Yu, Z., Xu, W., & Sukjairungwattana, P. (2022). A meta-analysis of eight factors influencing MOOC-based learning outcomes across the world. Interactive Learning Environments , 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2022.2096641

Zhao, J. H., Panjaburee, P., Hwang, G. J., & Wongkia, W. (2023). Effects of a self-regulated-based gamified virtual reality system on students’ English learning performance and affection. Interactive Learning Environments, 1–28 , 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2023.2219702

Zheng, X., Luo, L., & Liu, C. (2022). Facilitating undergraduates’ online self-regulated learning: The role of teacher feedback. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher , 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-022-00697-8

Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Self-efficacy: An essential motive to learn. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25 (1), 82–91. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1016

Download references

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan [grant number: NSTC 112-2410-H-006 -052 -MY3].

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Industrial and Information Management, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan City, 701, Taiwan

Ying-Lien Lin, Wei-Tsong Wang & Min-Ju Hsieh

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Wei-Tsong Wang .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

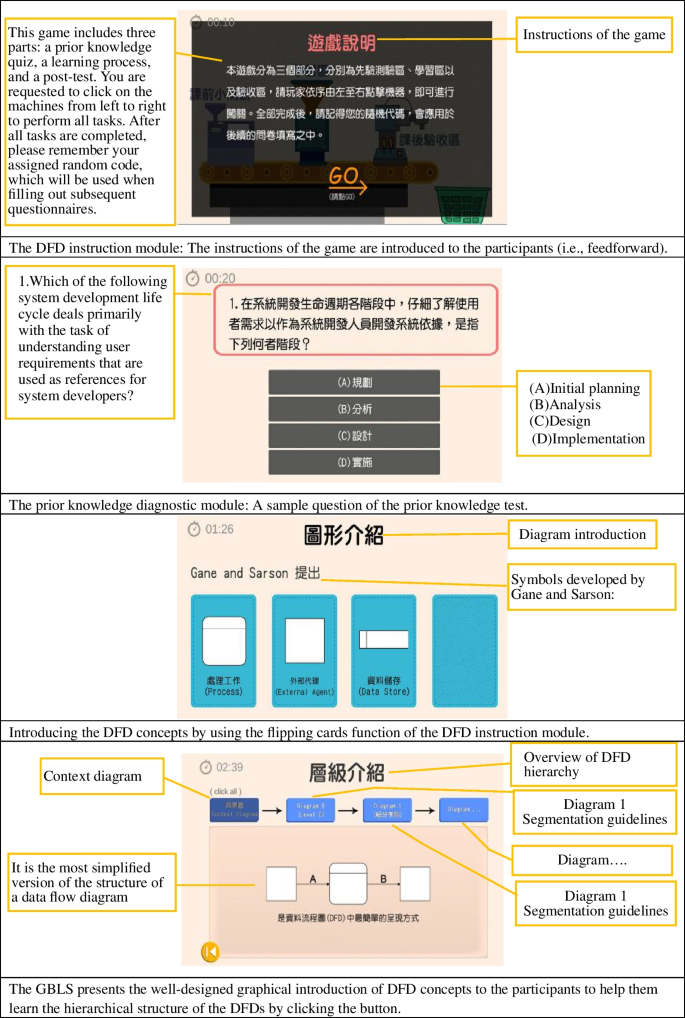

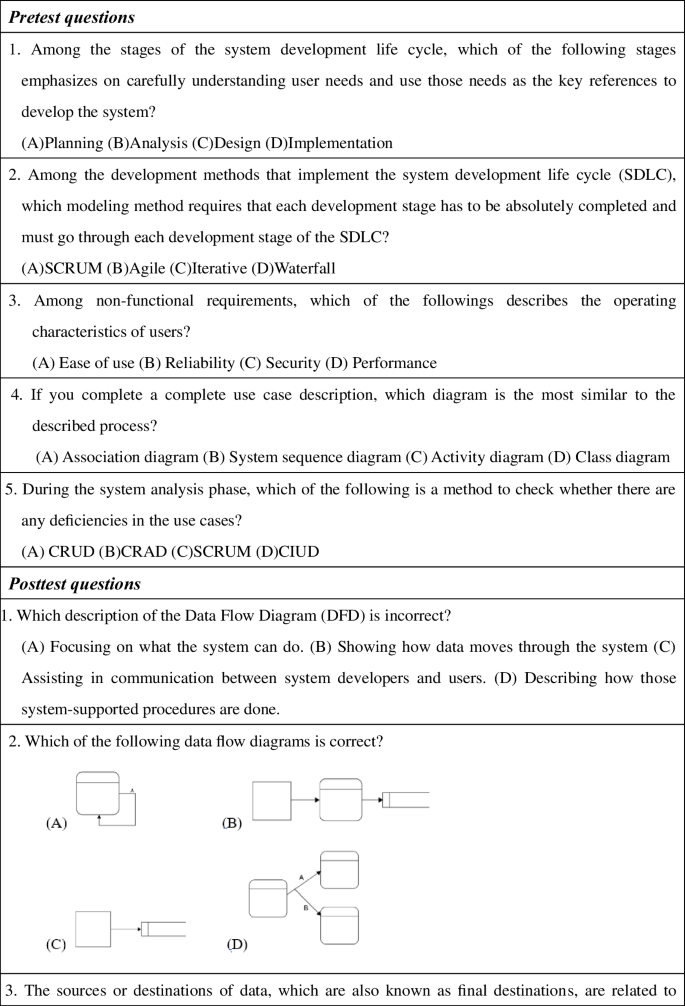

1.1 Appendix A. supplementary GBLS graphics

1.2 Appendix B. The questions of pretest and posttest

1.3 Appendix C. The results of the CMV-adjusted path coefficient estimation

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Lin, YL., Wang, WT. & Hsieh, MJ. The effects of students’ self-efficacy, self-regulated learning strategy, perceived and actual learning effectiveness: A digital game-based learning system. Educ Inf Technol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-024-12700-4

Download citation

Received : 18 October 2023

Accepted : 08 April 2024

Published : 08 May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-024-12700-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Information feedback

- Self-efficacy

- Self-regulated learning strategy

- Perceived learning effectiveness

- Actual learning effectiveness

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Role of self-efficacy and resistance to innovation on the demotivation and insufficient learning capabilities of preservice english normal students in china.

- 1 School of Foreign Languages, Xianyang Normal University, Xianyang, China

- 2 School of Education, Faculty of Social Science and Humanities, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Johor Bahru, Malaysia

Learning capabilities among students are the crucial element for the student’s success in learning a particular language, and this phenomenon needs recent studies. The current study examines the impact of self-efficacy and resistance to innovation on the demotivation and insufficient learning capabilities of preservice English normal students in China. The current research also investigates the mediating impact of demotivation among self-efficacy, resistance to innovation, and insufficient learning capabilities. The questionnaires were employed by the researchers to gather the data from chosen respondents. The preservice English students are the respondents of the study. These are selected using purposive sampling. These questionnaires were forwarded to them by personal visits. The researchers have sent 690 surveys but only received 360 surveys and used them for analysis. These surveys represented a 52.17% response rate. The SPSS-AMOS was applied to test the relationships among variables and also test the hypotheses of the study. The results revealed that self-efficacy and resistance to innovation have a significant and a positive linkage with demotivation and insufficient learning capabilities. The findings also indicated that demotivation significantly mediates self-efficacy, resistance to innovation, and insufficient learning capabilities. The article helps the policymakers to establish the regulations related to the improvement of learning capabilities using innovation adoption and motivation of the students.

Introduction

China has the greatest number of English learners ( Rose et al., 2020 ). Recently, the intervention of the English language in the Chinese education system accelerated at a rapid pace ( Cheng and Chen, 2021 ). One of the reasons is the increasing interest of the world in China due to different reasons like education, business, jobs, etc. English has become a compulsory part of the Chinese curriculum for all levels like elementary, middle, high school, colleges, and universities. The preschool in China is adding English to their curriculum. The time the Chinese students graduate from the universities they have at least studied English for about 2,000 h over the duration of 10 years. The requirement to study English is defined in a true manner in an article titled Crazy English: Good or Bad: “Whether [English] is helpful or not, you must learn it; whether you learn it or not, you will never be able to utilize it.” In China, it appears that learning English has hit a snag. Despite putting in a lot of effort to study the language, English learners have not gained the ability to use it. One key factor for Chinese learners’ lack of communicative competency has been identified in the school’s teaching method. In China, English language instruction is frequently oriented on the instructor, the textbook, and grammar. In other words, English instruction in China is primarily concerned with mastery of grammar and vocabulary as taught by the teacher through the use of a textbook. This form of teaching strategy fails the generation of appropriate teaching skills in students. In this context: the Chinese government has attempted to strengthen English education in the school system in the 21st century.

The literature strongly proposed that educational institution plays a vital role in the betterment of English language learning in China ( Liu et al., 2021 ). The Chinese education sector introduced the New English Curriculum (NEC) for elementary and secondary schools in 2001. The NEC argues for pedagogical reform to address the dilemma in which teachers stress linguistic knowledge while ignoring students’ actual proficiency in using English. It states that when teaching, English teachers should take into account their students’ interests, experiences, and cognition. To improve English learners’ synthesis skills in using the language, the NEC suggests a variety of instructional approaches, such as participation, cooperation, and discussion. In a nutshell, the NEC encourages communicative language teaching. Teachers play an important part in this pedagogy change because they determine if curricular innovations can be successfully implemented in the classroom as desired by legislators ( Chien et al., 2021a ). Teachers are the key to the deliverance of the right knowledge at the right time in the right way to the right people. The teacher’s method of teaching results in students’ motivation of demotivation. The educational institution leads to implement the new way of teaching to meet the world. The teachers make it enable to not only accept but also educate the students to absorb this change. Many times this change in terms of innovation leads to students’ demotivation which directly affects the learning of a second language ( Gao and Ren, 2019 ; Chien et al., 2021b ; Liu et al., 2021 ). This is one of the reasons to check the reason for insufficient learning capabilities in Chinese second language learning schools.

The present study will address some gaps does exist in the literature like (1) being one of the important topics like linguistic along with learning capabilities although researched although but still not reached its peak, (2) Wu et al. (2021) worked on the students learning capabilities development whereas the present study will work on insufficient learning capabilities along with mediation effect of demotivation in China, (3) Jamil et al. (2021) checked the computer interference in enhancement of students capabilities whereas the present study will work on insufficient learning capabilities along with self-efficacy, resistance to innovation, and demotivation in China, (4) Amarakoon et al. (2018) worked on the learning capabilities along with innovation whereas the present study will test the insufficient learning capabilities along with number of other variables in Chinese perspective with a new data set, (5) the present study will check the model in Chinese perspective with new data set, and (6) Bonal and González (2020) worked on the lockdown and learning whereas the present study will investigate the insufficient learning capabilities with mediation effect of demotivation in China. The contributions of the study are (1) highlight the importance of preservice English learning capabilities in China, (2) help professionals revamp their policies for the betterment of the learning capabilities of preservice individuals, (3) help the researchers to identify and explore the more aspects of the lack of learning capabilities, (4) it provides the help to the policymakers in developing the policies related to the learning capabilities, and (5) it facilities the relevant authorities to implement the effective policies to improve the learning capabilities.

The study structure is divided into five phases. The first phase will present the introduction. In the second phase of the study, the pieces of evidence regarding low self-efficacy, low self-esteem, resistance to innovation, and self-demotivation will be discussed in the light of past literature. The third phase of the study will shine the spotlight on the methodology employed for the collection of data regarding low self-efficacy, low self-esteem, resistance to innovation, and self-demotivation and its validity will be analyzed. In the fourth phase, the results of the study will be compared with the pieces of evidence reviewed from the literature. In the last phase, the study implications along with the conclusion and future recommendations will be presented which will conclude the article.

Literature Review

Self-efficacy, proposed by Albert Bandura, refers to an individual’s belief in their capability to perform behaviors essential to produce definite performance achievements ( Gielnik et al., 2020 ). In addition, demotivation refers to the lack of one’s interest, enthusiasm, and willingness to perform an action due to specific negative influences ( Albalawi and Al-Hoorie, 2021 ). Moreover, the learning capabilities and innovation encompass skills, knowledge, skills, and dispositions. Learners develop capability when they apply skills and knowledge effectively in changing circumstances in their learning ( Lee and Falahat, 2019 ).

The performance of learning capabilities and academic performance are dependent on the important factors of self-efficacy. Learning capabilities among students are the crucial element for the student’s success in learning a particular language, and this phenomenon needs recent studies. For the improvement of learning capabilities, it is most important for educational institutions to promote the factors of self-efficacy. Gundel et al. (2019) elaborated on the simulations of mixed reality in self-efficacy for the preservice of education of teachers for learning capabilities. Self-efficacy leads to the individual that entails higher beliefs in their performance and the commitments in China. Any sort of lower self-efficacy leads to failures in lack of attempts and the lack of abilities. Ulenski et al. (2019) assessed the validating and developing literacy that coaches the survey of self-efficacy influencing the learning capabilities of students. Through effective perseverance, endeavors, and commitments, self-efficacy leads to the excellent performance of individuals. The students that entail higher self-efficacy are significant and positive in influencing the insufficient learning capabilities. For the fulfillment of academic tasks and educational performance, the factors related to self-efficacy must be promoted in the educational sectors of China. van Rooij et al. (2019) enumerated the sources of teachers’ self-efficacy with the teaching careers influencing the demotivation. Among the students of preservice English learning, the role of self-efficacy determines higher values for the elimination of demotivation. To overcome the challenges and attain higher values and objectives, the students are required to acquaint themselves with self-efficacy. Harrison et al. (2018) investigated the capabilities, participation, and access of self-efficacy that are important for the flourishment of learning capabilities. Academic self-efficacy involves a greater role and has a significant and positive impact on the demotivation of students. The probable and effective entailment of self-efficacy in the students leads to effective student learning, academic performance, and motivation. The considerable involvement and inducement of self-efficacy is especially the integrated and dominant mean for the students which influences the demotivation. Afshari and Hadian Nasab (2021) examined the learning capabilities by the managing talent of intellectual capital and self-efficacy that enhances the organizational environment. The effective mechanisms and modes endorse motivational and cognitive approaches to the self-efficacy that speak emotions of Chinese students in their achievements and motivation. Learning strategies must be organized in such a way that self-efficacy must be uplifted. The uplifting of self-efficacy facilitates the students and individual learning of normal students to eradicate the insufficient learning capabilities. Thus, the below-given hypothesis is derived from the above debate.

H1: Self-efficacy significantly influences insufficient learning capabilities.

H2: Self-efficacy significantly influences demotivation.

Countries that are developing and developed have certain barriers to innovation and insufficient learning ( Chien et al., 2021c ). This is due to the lack of facilities and lack of technological introduction in educational institutions. There are many barriers to innovation that lead to insufficient learning capabilities. Park et al. (2018) narrated the resistance, perceived attributes, and system quality necessary in education to provide sufficient learning capabilities. Mostly, the busy parents and lack of money is also considered the main element that leads to the resistance to innovation. This also states the involvement of backward areas of China which are not fond of technology and are not acquainted with its use of it. Caiazza and Volpe (2017) discussed the actions, actors, and process of diffusion of resistance narratives and uplifting the innovation for learning capabilities. Therefore, the resistance to innovation leads to many other circumstances which are negative for the learning capabilities. In the preservice English normal students, the resistance to innovation is encouraging a lack of education and a lack of curriculum of innovation. This depicts the image of disadvantage to the innovation which is a better model for the English learners of China. Pedler and Brook (2017) analyzed the innovation and action learning that requires implementation, engagement, and elimination of resistance. As the English language is considered a global language all over the world and lack of facilities could lead to insufficient learning. The lack of insufficient learning not only distracts the abilities of students but also depicts the damaging circumstances toward the learning capabilities. Dejaeghere (2020) investigated the concept and capabilities that are related to the equalities and inequalities due to the resistance to innovation. Students are inspired by the examples and technology that is the better tool for them to attain sufficient learning. Sufficient learning not only enhances the capabilities of students but also poses a dominant image of the resistance to innovation in China. Presbitero et al. (2017) narrated various dynamics of organizational learning capabilities by the knowledge sharing capabilities after removing barriers to innovation. The resistance to innovation is considered a curriculum barrier to the innovation which eliminates the creative environments for enhancing the learning capabilities. The resistance to innovation majorly dominates the educational learning and preservice English students could not attain sufficient learning.

The perceptions of personal efficacy refer to the individual capabilities and self-efficacy which entails the involvement of demotivation. Demotivation is promotive in the educational sector of China that states the elements in students learning which can be destructive. Demotivation among the students leads to a lack of self-efficacy that enumerates the capabilities related to insufficient learning. Pathan et al. (2021) investigated the demotivation factors associated with language learning among university students due to the resilience and matter of personality. The factors associated with demotivation entail mediating impact on the preservice students learning. Many normal students in the schools, colleges, and universities when demotivated by the lack of educational facilities depicts the insufficient learning capabilities. It is important for the institutions to develop certain capabilities which are deemed requirements to enhance English learning in China. Kiel et al. (2020) enumerated the inclusiveness of classes by the teachers and students’ self-efficacy and its role toward learning capabilities with institutional support. Various preservice English normal students are required to develop the capabilities of motivation that also increases the element of self-efficacy among them. Whitfield and Staritz (2021) discussed various traps of learning that arise due to the factors of demotivation and insufficient materials for learning. The increasing trend of demotivation has a dominant impact on the relationship between insufficient learning capabilities and self-efficacy. When there is a lack of self-efficacy there could be insufficient learning capabilities. It is only due to the demotivation which is increased in the students due to unfortunate learning capabilities and abilities of the teachers. Usually, the students are when demotivated by the learning facilities and the distraction among them could be negative to their upbringing. Ghanizadeh and Jahedizadeh (2017) examined the relationship between motivational facts and metacognitive and emotional facts that arise after the demotivation in university students. Not only in the educational sectors but also in the communities of China, creative approaches and innovation must be promoted. The promotion of innovation and creativity enables the communities in discovering new markets and strategies. While the students could also be enabled with taking up new ideas and development of skills and knowledge, especially in the English. Thus, the below-given hypothesis is derived from the above debate.

H3: Resistance to innovation significantly influences insufficient learning capabilities.

H4: Resistance to innovation significantly influences demotivation.

The establishment of different platforms and programs for English learners is encouraged by the effective use of innovative techniques. The tools and technology that are resisted while providing English learning to the preservice students also denominate the insufficient learning capabilities. Rizvi and Nabi (2021) emphasized the transformation of learning capabilities by the existence of challenges and issues that states the prevalence of demotivation. Among the students of English, the inspiration of technology and the motivation to deal with risk and ideas not only enhances their capabilities but also raises their independency. It is necessary for the educational sectors to induce certain changes and encourage motivation to enable the elements toward resistance to innovation. This resistance to innovation somehow leads to insufficient learning capabilities and the demotivation extended the central role among them. Dakka (2020) investigated the diversity, innovation, and competition in higher education where the resistance dominates with higher values with the involvement of demotivation. Some creative approaches to the development of technology and innovation are important in uplifting learning capabilities. The preservice English normal students in China are when demotivated the students then have insufficient learning capabilities. Self-determination is promotive and positive for the endorsement and raising of independency and determination in preservice English normal students. Wilson-Strydom (2017) assessed the inequalities and equalities with the capabilities and resilience to innovation that could be disrupting the learning capabilities with the involvement of demotivation. Students are required to be well-acquainted with the creative curriculum innovation and technology. This technological advancement, however, increases the elimination of factors that are associated with demotivation and insufficient learning capabilities. The innovative learning environment for the preservice students of English is enhanced with the wider support of motivation. Inan and Karaca (2021) narrated different practices of quality assurance in the learning capabilities of young learners due to the presence of demotivation. The learning capabilities could attain significant enhancement when the students are self-determined and motivated by their teachers and educational facilities in China. Mostly the learning abilities and capabilities are dependent on digital innovation because feasible innovation provides more education in a short time. The certain and fortunate mediating impact of demotivation is bringing a narrative of centered role in self-efficacy and insufficient learning capabilities. Thus, the below-given hypothesis is derived from the above debate.

H5: Demotivation significantly and positively mediates the relationship between self-efficacy and insufficient learning capabilities.

H6: Demotivation significantly and positively mediates the relationship between resistance to innovation and insufficient learning capabilities.

Research Methodology

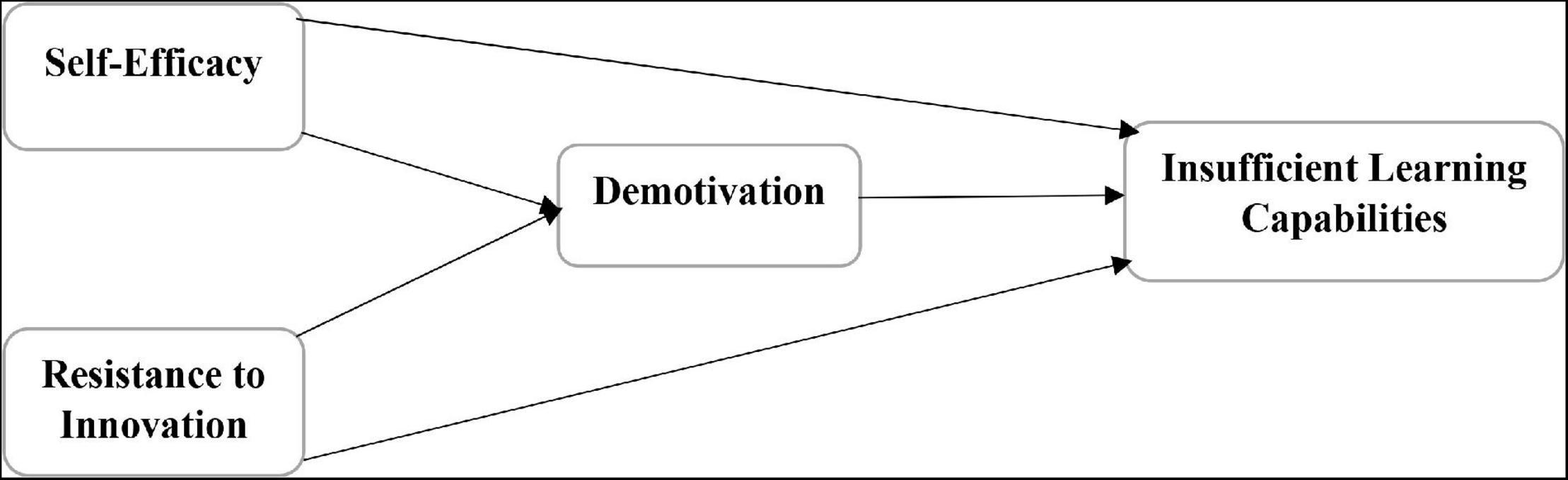

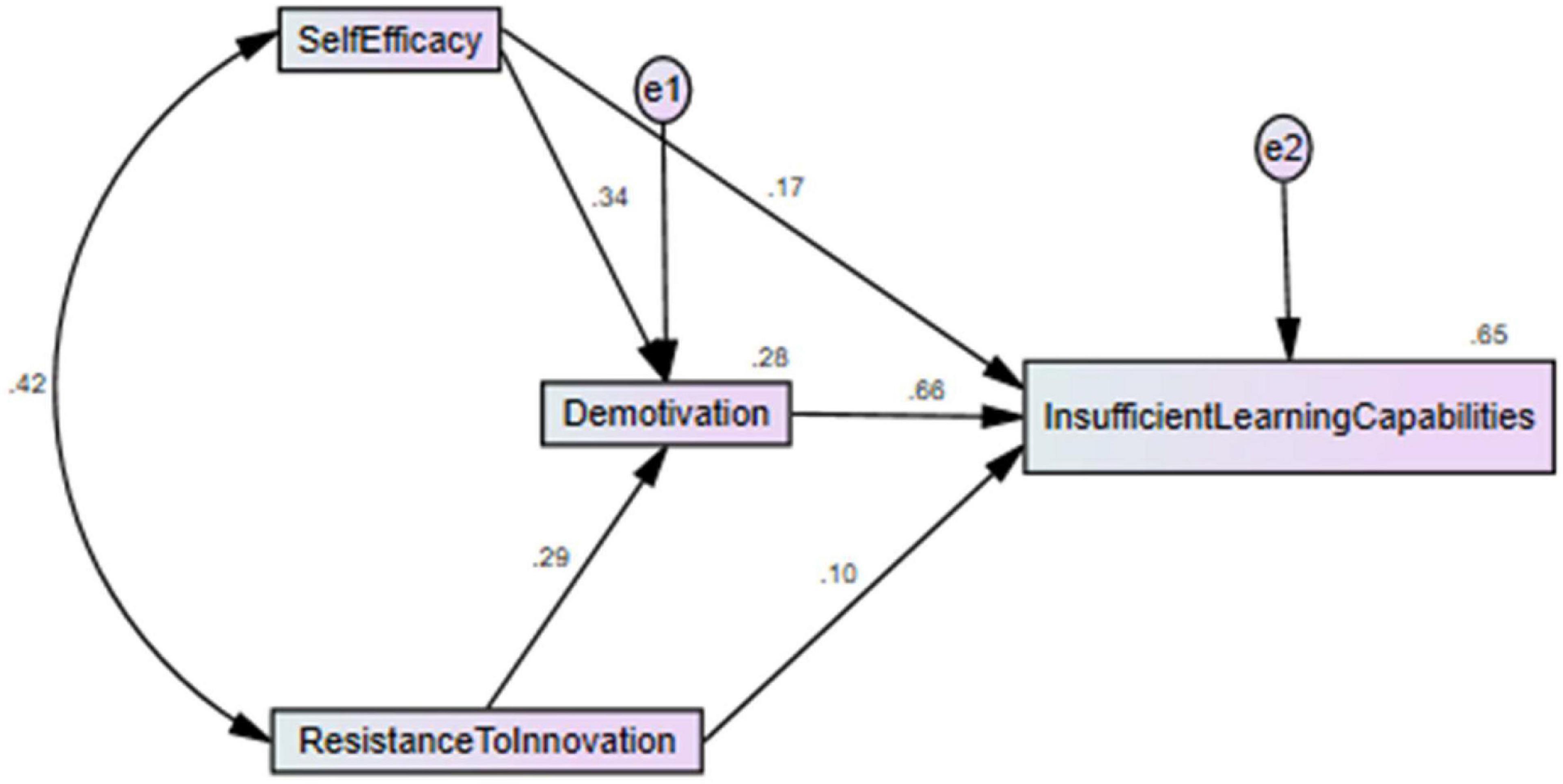

The study examines the impact of self-efficacy and resistance to innovation on the demotivation and insufficient learning capabilities and also investigates the mediating impact of demotivation among self-efficacy, resistance to innovation, and insufficient learning capabilities of preservice English normal students in China. The current article has the motive of predicting the variables and adopted the deductive approach. In addition, the study motives also include the quantitative examination of the respondents and used the quantitative method like surveys to collect the data from respondents. The questionnaires were employed by the researchers to gather the data from chosen respondents. The present article has used two independent constructs, such as self-efficacy and resistance to innovation. In addition, the present article has also used demotivation as the mediating variable, and insufficient learning capabilities have been used as the dependent variable. These variables are presented in the theoretical framework in Figure 1 .

Figure 1. Theoretical model.

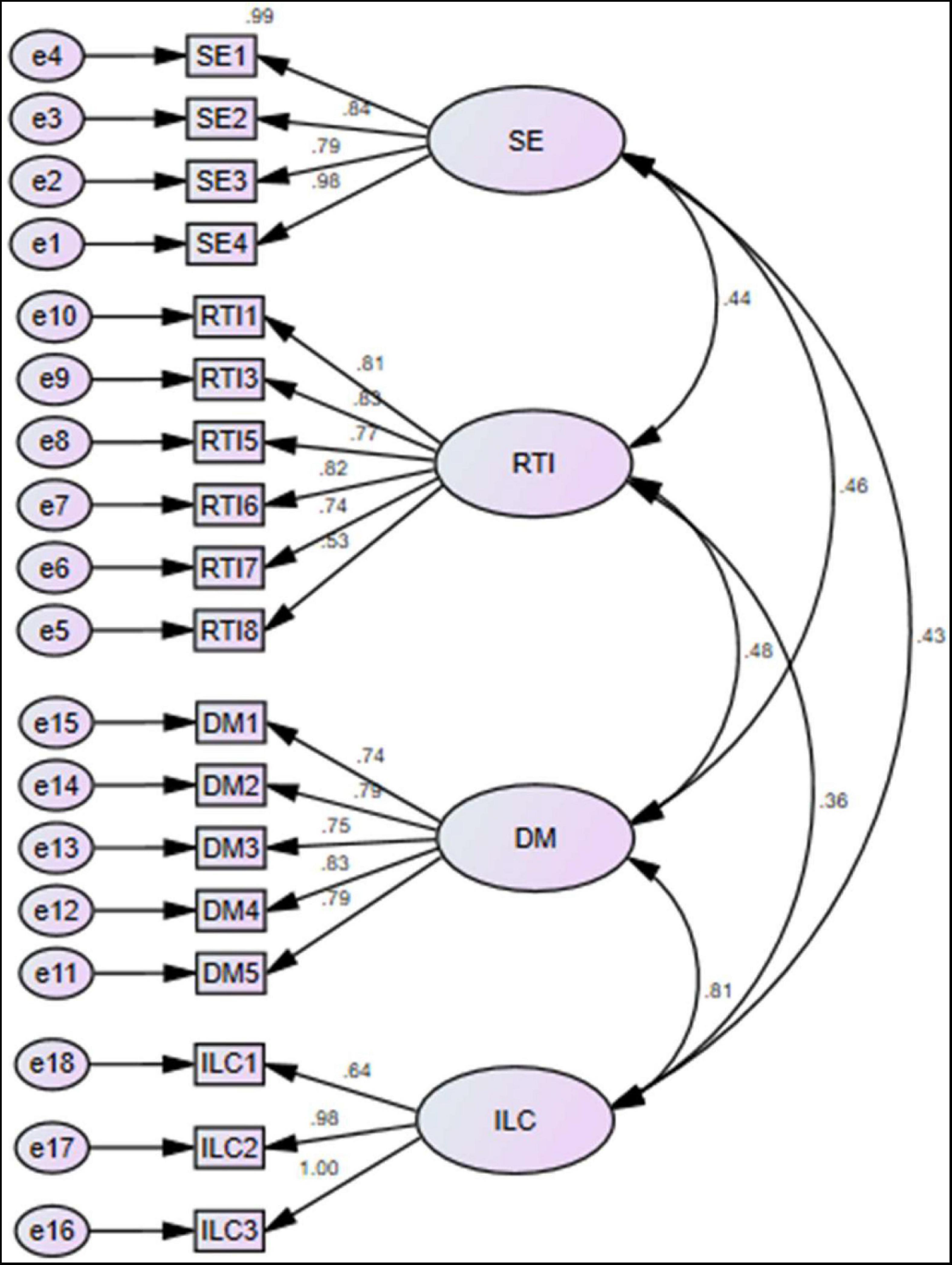

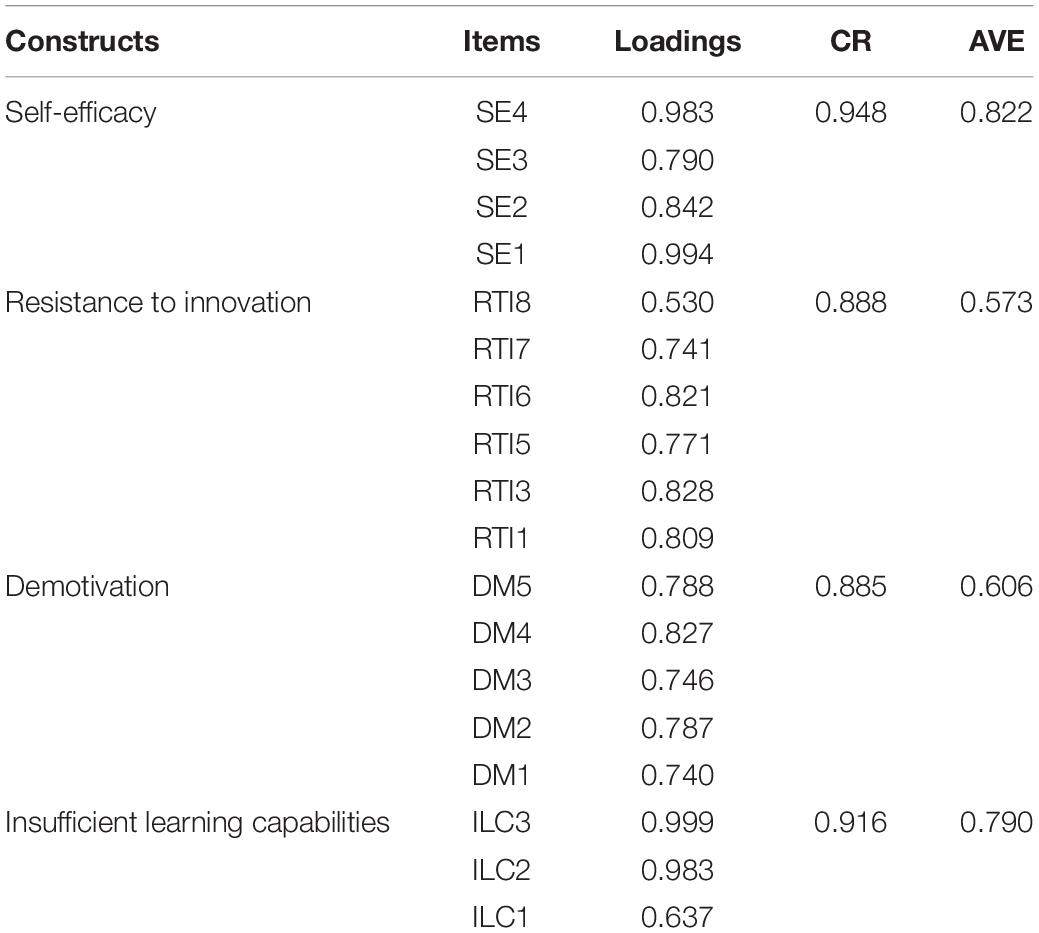

The questionnaires were taken from the past studies, like self-efficacy is the independent variable that has four items taken from Yavuzalp and Bahcivan (2020) . In addition, resistance to innovation has also been taken as a predictor that has eight items extracted from Mani and Chouk (2018) . Moreover, the current article has used demotivation as the mediating variable with five items taken from Pillny et al. (2018) . Finally, insufficient learning capabilities have been used as a dependent variable that has three items taken from Gieske et al. (2019) . In addition, the preservice English students are the respondents of the study. These are selected using purposive sampling. The study selected only those students who are near to joining the professional life. Figure 2 show the content validity and the figures indicated that the factor loading values are larger than 0.50 and exposed valid content validity. These questionnaires were forwarded to them by personal visits. The researchers have sent 690 surveys but only received 360 surveys and used them for analysis. These surveys represented a 52.17% response rate. Moreover, the SPSS-AMOS was applied to test the relationships among variables and also test the hypotheses of the study. It is the best estimation tool that provides the best findings even the large sample sizes used by the authors or complex model has been selected by the researchers ( Hair et al., 2020 ). The measurement model exposed the construct validity and reliability that is checked using average variance extracted (AVE), composite reliability (CR), and factor loadings. The minimum threshold for AVE is that it should be greater than 0.50 ( Nasution et al., 2020 ), while the minimum threshold for CR is that it should be greater than 0.70 ( Kamis et al., 2020 ), and the minimum threshold for factor loadings is that it should be greater than 0.50 ( Dai et al., 2019 ). Finally, the structural model exposed the associations among the variables. Figure 3 indicated that the self-efficacy and resistance to innovation have positive association with insufficient learning capabilities and demotivation significantly mediates among them.

Figure 2. Measurement model assessment. Indicated that the factor loadings of the items are larger than 0.50 and indicated valid convergent validity.

Figure 3. Structural model assessment.

Research Findings

The current article has examined the content validity with the help of factor loadings. The results indicated that the values are not less than 0.50. These values reported that the content validity proved as valid. In addition, the current article has examined the convergent validity with the help of AVE. The results indicated that the values are not less than 0.50. These values reported that the convergent validity proved as valid. Moreover, the current article has examined the reliability with the help of CR. The results indicated that the values are not less than 0.70. These values reported that the reliability proved as valid. Table 1 shows the convergent validity results.

Table 1. Convergent validity.

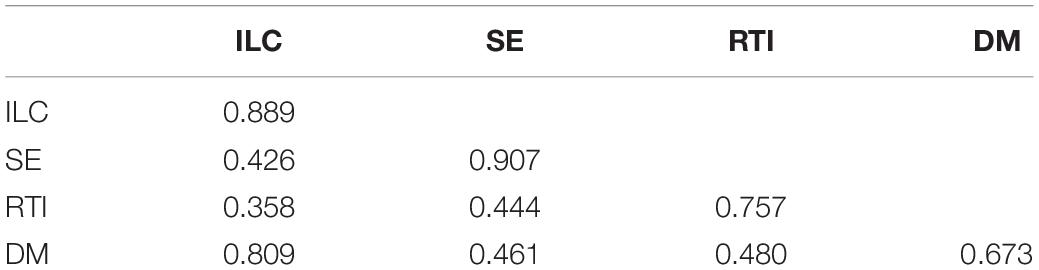

The current article has also examined the discriminant validity with the help of Fornell Larcker. The results indicated that the first value in the column is higher than the other values in the same column. These values reported that the stronger nexus with the variable itself and discriminant validity proved as valid. Table 2 shows the discriminant validity results.

Table 2. Discriminant validity.

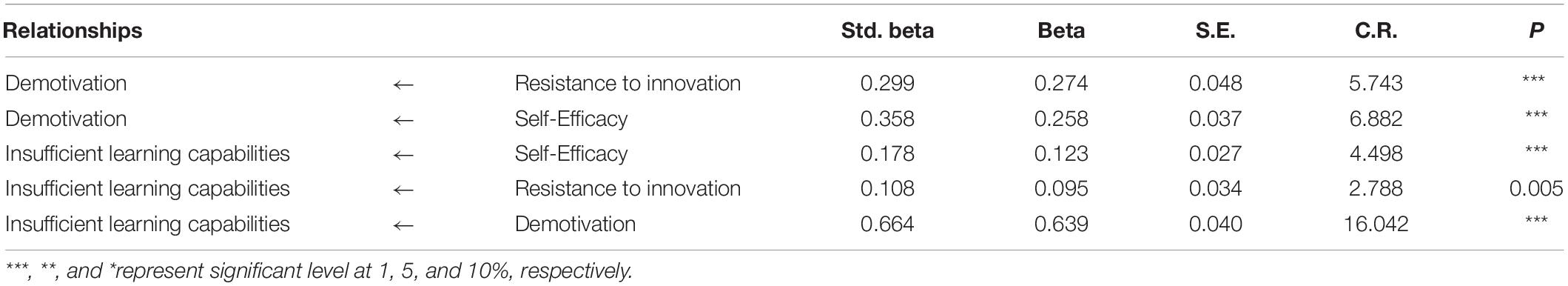

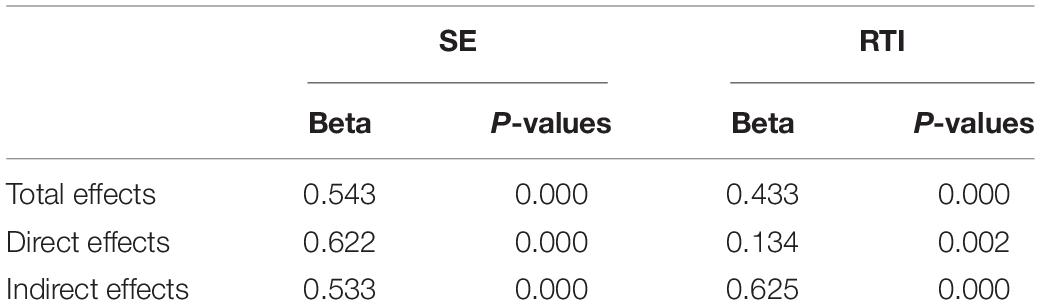

The study examines the impact of self-efficacy and resistance to innovation on the demotivation and insufficient learning capabilities and also investigates the mediating impact of demotivation among self-efficacy, resistance to innovation, and insufficient learning capabilities of preservice English normal students in China. The study examines the impact of self-efficacy and resistance to innovation on the demotivation and insufficient learning capabilities and also investigates the mediating impact of demotivation among self-efficacy, resistance to innovation, and insufficient learning capabilities of preservice English normal students in China. The results revealed that self-efficacy and resistance to innovation have a significant and a positive linkage with insufficient learning capabilities and accept H1 and H3. In addition, the results also revealed that self-efficacy and resistance to innovation have a significant and a positive linkage with demotivation and accept H2 and H4. Table 3 shows the direct association among variables results.

Table 3. A path analysis.

The findings also indicated that demotivation significantly mediates self-efficacy, resistance to innovation, and insufficient learning capabilities and accept H5 and H6. Table 4 shows the indirect association among variables results.

Table 4. Mediation analysis.

The study examines the impact of self-efficacy and resistance to innovation on the demotivation and insufficient learning capabilities and also investigates the mediating impact of demotivation among self-efficacy, resistance to innovation, and insufficient learning capabilities of preservice English normal students in China. The results indicated that self-efficacy has a significant and a positive association with the insufficient learning capabilities among preservice English normal students in China. The students that are considered self-efficient and have self-efficacy are not competent enough and have insufficient learning capabilities, which is the reason for the positive association between self-efficacy and insufficient learning capabilities. This outcome is in line with Hatlevik and Hatlevik (2018) , who also investigated the nexus between self-efficacy and insufficient learning capabilities and revealed that self-efficacy among the students does not always work positively on the learning capabilities. Sometimes students have enough self-efficacy but fail to attain sufficient learning capabilities. In addition, a study by Zamani-Alavijeh et al. (2019) also examined the self-efficacy role on the learning capabilities and revealed that the self-efficacy among students had put a negative impact on the learning capabilities because the self-efficacy among students miss interpret their qualities and fail to gain sufficient learning capabilities and this outcome is similar to the current study findings. Moreover, this output is also same as the Kuyini et al. (2020) , who also exposed the self-efficacy impact on the learning capabilities and exposed that the self-efficacy among students makes them selfish and they put lack of effort results in insufficient learning capabilities.

The outcome also exposed that the resistance to innovation has a positive role on the insufficient learning capabilities among preservice English normal students in China. The lack of focus on innovation leads the students to a less attractive environment, which creates insufficient learning capabilities among students. Innovation adoption always brings new ideas that polish the students and enhance their learning capabilities and vice versa. This result is matched with Kim et al. (2018) , who also analyzed the innovation impact on the learning capabilities and revealed that the innovation adoption always changes the existing processes and enables the student to gain sufficient learning capabilities and vice versa. In addition, this result is also the same as Shahbaz et al. (2019) , who also investigated the resistance to change impact on the learning abilities and exposed that the learning abilities could be enhanced by the adoption of new technology in the existing process, but resistance toward change always restrict the students and face insufficient learning capabilities. In addition, this outcome is in line with Choi and Chandler (2020) , who also analyzed the association between resistance to change and learning abilities and indicated that the high learning capabilities could be achieved by adopting innovation in the process, but if the students are reluctant to adopt innovation, then they faced insufficient learning abilities.

The results also indicated that self-efficacy has a significant and a positive association with the demotivation among preservice English normal students in China. The students who are considered self-efficient and have self-efficacy are sometimes demotivated by the existing way of working, which is the reason for the positive association between self-efficacy and demotivation. This outcome is in line with Tannady et al. (2019) , who also investigated the nexus between self-efficacy and motivation and revealed that self-efficacy among the student does not always work positively on the motivation. Sometimes students have enough self-efficacy but fail to get motivation. In addition, a study by Rhew et al. (2018) also examined the self-efficacy role in motivation. It revealed that self-efficacy among students has a negative impact on motivation because self-efficacy among students misses interpreting their qualities and fails to gain motivation. This outcome is similar to the current article outcomes. Moreover, the results are in line with Torres and Alieto (2019) , who indicated that the self-efficacy among students makes them selfish, and they put lack of effort and demotivated in the existing way of workings.

The outcome also exposed that the resistance to innovation positively affects the demotivation among preservice English normal students in China. The lack of focus on innovation leads the students to a less attractive environment, which creates demotivation among students. Innovation adoption always brings new ideas that polish the students and enhance their motivation and vice versa. This result is matched with Bonta (2019) , who also analyzed the innovation impact on the motivation and revealed that the innovation adoption always brings the changes in the existing processes and creates motivation among the students. In addition, this result is also the same as Hashimy et al. (2021) , who also investigated the resistance to change impact on the motivation and exposed that the motivation could be enhanced by the adoption of new technology in the existing process, but resistance toward change always restrict the students and face lack of motivation among them. In addition, this outcome is in line with Fischer et al. (2019) , who also analyzed the association between innovation and motivation and indicated that the high motivation could be achieved by adopting innovation in the process, but if the students are reluctant to adopt innovation then they are demotivated and fail to achieve the desired goals.

The results also revealed that demotivation significantly and positively mediates self-efficacy and insufficient learning capabilities among preservice English normal students in China. The students who have self-efficacy but are not interested in a particular field create demotivation among them and lead to insufficient learning capabilities. This outcome is in line with Shin (2018) , who also examines the self-efficacy and motivation role in learning capabilities and revealed that sometimes self-efficacy does not work to motivate the students in a particular task, leading to insufficient abilities to perform that task. This result is also similar to the Haerazi and Irawan (2020) , who also investigated the self-efficacy role in motivation that lead to learning abilities and indicated that the self-efficacy among students sometimes has a negative impact on the motivation and also has a negative influence on the learning capabilities of the students.

The findings also revealed that the demotivation significantly and positively mediates resistance to innovation and insufficient learning capabilities among preservice English normal students in China. This outcome is in line with Oke and Fernandes (2020) , who also examined the innovation and motivation role in the learning capabilities and revealed that the resistance to innovation creates demotivation among the students, and this also creates insufficient learning abilities among them. This result is also similar to the Amarakoon et al. (2018) , who also investigated the innovation role in motivation that lead to learning abilities and indicated that the adoption of innovation creates motivation among students and that gain sufficient learning capabilities, but if they resist adopting innovation then it creates demotivation among students and put a negative influence on the learning capabilities of the students.

The study concluded that the students in the education sector of China lack self-efficacy, which is the reason for their demotivation and insufficient learning capabilities among them. In addition, the study also concluded that the students also have the behavior of resistance to innovation in the Chinese education institution and produce insufficient learning capabilities among the students. Moreover, the students are demotivated in the English language learning institutions that produce insufficient learning capabilities among students. Finally, the article also concluded that the lack of self-efficacy and resistance to innovation nature reduce the motivation and enhance the insufficient learning capabilities among students.

Implications and Limitations

This article has several theoretical contributions and also significant implications. The current article contributes to the literature by conducting an examination of self-efficacy and insufficient learning capabilities. In addition, the article also contributes to the existing literature by providing the investigation of resistance to innovation and self-learning capabilities. Moreover, the demotivation is used as the mediating variable among self-efficacy, demotivation, and insufficient learning capabilities are significant contributions in the existing literature. In addition, the current article also provides the contribution to the literature on self-efficacy and demotivation and resistance to innovation and demotivation. This study provides help to the upcoming literature while examining this topic in the future. This study helps the policymakers to establish the regulations related to the improvement of learning capabilities. This study also guides the relevant authorities while implementing the policies related to attaining sufficient learning capabilities.

This article has several limitations that also the recommendations for the upcoming literature. The current study has taken two independent constructs to predict the insufficient learning capabilities and suggested that future articles should add more factors to predict the insufficient learning capabilities. In addition, the present research has also used the mediating analysis in the framework but ignores the moderating impact and recommended that the upcoming studies add moderating variables in the framework. Moreover, the current study examines China’s second language learning institutions and ignores the other institutions and suggests that future studies should add other institutions to their studies. Finally, the present article has used the questionnaires to collect the data and applied the SPSS-AMOS to analyze the association among variables and ignore the other data collection and analyzing techniques and tools and recommended that future studies incorporate this aspect into their studies.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

YH generated the article idea. MS and YH analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. TL read and approved the final version. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Afshari, L., and Hadian Nasab, A. (2021). Enhancing organizational learning capability through managing talent: mediation effect of intellectual capital. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 24, 48–64. doi: 10.1080/13678868.2020.1727239

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Albalawi, F. H., and Al-Hoorie, A. H. (2021). From demotivation to remotivation: a mixed-methods investigation. SAGE Open 11, 2–11.

Google Scholar

Amarakoon, U., Weerawardena, J., and Verreynne, M.-L. (2018). Learning capabilities, human resource management innovation and competitive advantage. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manage. 29, 1736–1766. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00723.x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bonal, X., and González, S. (2020). The impact of lockdown on the learning gap: family and school divisions in times of crisis. Int.Rev. Educ. 66, 635–655. doi: 10.1007/s11159-020-09860-z

Bonta, E. (2019). Demotivation-triggering factors in learning and using a foreign language–an empirical study. J. Innov. Psychol. Educ. Didactics 23, 177–198.

Caiazza, R., and Volpe, T. (2017). Innovation and its diffusion: process, actors and actions. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manage. 29, 181–189. doi: 10.1080/09537325.2016.1211262

Cheng, M., and Chen, P. (2021). Applying PERMA to develop college students’ english listening and speaking proficiency in china. Int. J. Engl. Lang. Lit. Stud. 10, 333–350.

Chien, F., Kamran, H. W., Nawaz, M. A., Thach, N. N., Long, P. D., and Baloch, Z. A. (2021a). Assessing the prioritization of barriers toward green innovation: small and medium enterprises Nexus. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 24, 1897–1927. doi: 10.1007/s10668-021-01513-x

Chien, F., Pantamee, A. A., Hussain, M. S., Chupradit, S., Nawaz, M. A., and Mohsin, M. (2021b). Nexus between financial innovation and bankruptcy: evidence from information, communication and technology (ict) sector. Singapore Econ. Rev.

Chien, F., Sadiq, M., Nawaz, M. A., Hussain, M. S., Tran, T. D., and Le Thanh, T. (2021c). A step toward reducing air pollution in top asian economies: the role of green energy, eco-innovation, and environmental taxes. J. Environ. Manage. 297:113420. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.113420

Choi, T., and Chandler, S. M. (2020). Knowledge vacuum: an organizational learning dynamic of how e-government innovations fail. Gov. Inf. Q. 37, 101–116.

Dai, C., Lu, K., and Xiu, D. (2019). Knowing factors or factor loadings, or neither? Evaluating estimators of large covariance matrices with noisy and asynchronous data. J. Econom. 208, 43–79.

Dakka, F. (2020). Competition, innovation and diversity in higher education: dominant discourses, paradoxes and resistance. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 41, 80–94. doi: 10.1080/01425692.2019.1668747

Dejaeghere, J. G. (2020). Reconceptualizing educational capabilities: a relational capability theory for redressing inequalities. J. Hum. Dev. Capabil. 21, 17–35. doi: 10.1080/19452829.2019.1677576

Fischer, C., Malycha, C. P., and Schafmann, E. (2019). The influence of intrinsic motivation and synergistic extrinsic motivators on creativity and innovation. Front. Psychol. 10:137–149. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00137

Gao, X., and Ren, W. (2019). Controversies of bilingual education in China. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 22, 267–273.

Ghanizadeh, A., and Jahedizadeh, S. (2017). The Nexus between emotional, metacognitive, and motivational facets of academic achievement among Iranian university students. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. 9, 598–615. doi: 10.1108/JARHE-05-2017-0060

Gielnik, M. M., Bledow, R., and Stark, M. S. (2020). A dynamic account of self-efficacy in entrepreneurship. J. Appl. Psychol. 105, 487–496. doi: 10.1037/apl0000451

Gieske, H., Van Meerkerk, I., and Van Buuren, A. (2019). The impact of innovation and optimization on public sector performance: testing the contribution of connective, ambidextrous, and learning capabilities. Public Perform. Manage. Rev. 42, 432–460.

Gundel, E., Piro, J. S., Straub, C., and Smith, K. (2019). Self-Efficacy in mixed reality simulations: implications for preservice teacher education. Teach. Educ. 54, 244–269. doi: 10.1080/08878730.2019.1591560

Haerazi, H., and Irawan, L. (2020). The effectiveness of ECOLA technique to improve reading comprehension in relation to motivation and self-efficacy. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. (IJET) 15, 61–76.

Hair, J. F. Jr., Howard, M. C., and Nitzl, C. (2020). Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. J. Bus. Res. 109, 101–110.

Harrison, N., Davies, S., Harris, R., and Waller, R. (2018). Access, participation and capabilities: theorising the contribution of university bursaries to students’ well-being, flourishing and success. Cambridge J. Educ. 48, 677–695. doi: 10.1080/0305764X.2017.1401586

Hashimy, L., Treiblmaier, H., and Jain, G. (2021). Distributed ledger technology as a catalyst for open innovation adoption among small and medium-sized enterprises. J. High Technol. Manage. Res. 32, 100–115.

Hatlevik, I. K., and Hatlevik, O. E. (2018). Examining the relationship between teachers’ ICT self-efficacy for educational purposes, collegial collaboration, lack of facilitation and the use of ICT in teaching practice. Front. Psychol. 9:935–947. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00935

Inan, S., and Karaca, M. (2021). An investigation of quality assurance practices in online English classes for young learners. Qual. Assur. Educ. 29, 332–343. doi: 10.1108/QAE-12-2020-0171

Jamil, N., Belkacem, A. N., Ouhbi, S., and Guger, C. (2021). Cognitive and affective brain–computer interfaces for improving learning strategies and enhancing student capabilities: a systematic literature review. IEEE Access 9, 134122–134147. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3115263

Kamis, A., Saibon, R. A., Yunus, F., Rahim, M. B., Herrera, L. M., and Montenegro, P. (2020). The SmartPLS analyzes approach in validity and reliability of graduate marketability instrument. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 57, 987–1001.

Kiel, E., Braun, A., Muckenthaler, M., Heimlich, U., and Weiss, S. (2020). Self-efficacy of teachers in inclusive classes. How do teachers with different self-efficacy beliefs differ in implementing inclusion? Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 35, 333–349. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2019.1683685

Kim, M.-K., Park, J.-H., and Paik, J.-H. (2018). Factors influencing innovation capability of small and medium-sized enterprises in Korean manufacturing sector: facilitators, barriers and moderators. Int. J. Technol. Manage. 76, 214–235.

Kuyini, A. B., Desai, I., and Sharma, U. (2020). Teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs, attitudes and concerns about implementing inclusive education in Ghana. Int. J. Inclusive Educ. 24, 1509–1526.

Lee, Y. Y., and Falahat, M. (2019). The impact of digitalization and resources on gaining competitive advantage in international markets: mediating role of marketing, innovation and learning capabilities. Technol. Innov. Manage. Rev. 9, 89–97.

Liu, Y., Mishan, F., and Chambers, A. (2021). Investigating EFL teachers’ perceptions of task-based language teaching in higher education in China. Lang. Learn. J. 49, 131–146. doi: 10.1080/09571736.2018.1465110

Mani, Z., and Chouk, I. (2018). Consumer resistance to innovation in services: challenges and barriers in the internet of things era. J. Product Innov. Manage. 35, 780–807.

Nasution, M. I., Fahmi, M., and Prayogi, M. A. (2020). “The quality of small and medium enterprises performance using the structural equation model-part least square (SEM-PLS),” in Paper Presented At The Journal Of Physics: Conference Series. (Bristol: IOP Publishing).

Oke, A., and Fernandes, F. A. P. (2020). Innovations in teaching and learning: exploring the perceptions of the education sector on the 4th industrial revolution (4IR). J. Open Innov. 6, 31–42.

Park, S. Y., Lee, H. D., and Kim, S. Y. (2018). South Korean university students’ mobile learning acceptance and experience based on the perceived attributes, system quality and resistance. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 55, 450–458. doi: 10.1080/14703297.2016.1261041

Pathan, Z. H., Ismail, S. A. M. M., and Fatima, I. (2021). English language learning demotivation among Pakistani university students: do resilience and personality matter? J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. 13, 1024–1042. doi: 10.1108/JARHE-04-2020-0087

Pedler, M., and Brook, C. (2017). The innovation paradox: a selective review of the literature on action learning and innovation. Act. Learn. 14, 216–229. doi: 10.1080/14767333.2017.1326877

Pillny, M., Krkovic, K., and Lincoln, T. M. (2018). Development of the demotivating beliefs inventory and test of the cognitive triad of amotivation. Cogn. Therapy Res. 42, 867–877.

Presbitero, A., Roxas, B., and Chadee, D. (2017). Effects of intra- and inter-team dynamics on organisational learning: role of knowledge-sharing capability. Knowl. Manage. Res. Pract. 15, 146–154. doi: 10.1057/kmrp.2015.15

Rhew, E., Piro, J. S., Goolkasian, P., and Cosentino, P. (2018). The effects of a growth mindset on self-efficacy and motivation. Cogent Educ. 5, 149–157.

Rizvi, Y. S., and Nabi, A. (2021). Transformation of learning from real to virtual: an exploratory-descriptive analysis of issues and challenges. J. Res. Innov. Teach. Learn. 14, 5–17. doi: 10.1108/JRIT-10-2020-0052

Rose, H., McKinley, J., Xu, X., and Zhou, S. (2020). Investigating Policy And Implementation Of English Medium Instruction In Higher Education Institutions In China. London: British Council, 1–20.

Shahbaz, M., Gao, C., Zhai, L., Shahzad, F., and Hu, Y. (2019). Investigating the adoption of big data analytics in healthcare: the moderating role of resistance to change. J. Big Data 6, 1–20.

Shin, M.-H. (2018). Effects of project-based learning on students’ motivation and self-efficacy. Engl. Teach. 73, 95–114. doi: 10.1348/000709907X218160

Tannady, H., Erlyana, Y., and Nurprihatin, F. (2019). Effects of work environment and self-efficacy toward motivation of workers in creative sector in province of Jakarta, Indonesia. Calitatea 20, 165–168.

Torres, J., and Alieto, E. (2019). English learning motivation and self-efficacy of Filipino senior high school students. Asian EFL J. 22, 51–72.

Ulenski, A., Gill, M. G., and Kelley, M. J. (2019). Developing and validating the elementary literacy coach self-efficacy survey. Teach. Educ. 54, 225–243. doi: 10.1080/08878730.2019.1590487

van Rooij, E. C. M., Fokkens-Bruinsma, M., and Goedhart, M. (2019). Preparing science undergraduates for a teaching career: sources of their teacher self-efficacy. Teach. Educ. 54, 270–294. doi: 10.1080/08878730.2019.1606374

Whitfield, L., and Staritz, C. (2021). The learning trap in late industrialisation: local firms and capability building in ethiopia’s apparel export industry. J. Dev. Stud. 57, 980–1000. doi: 10.1080/00220388.2020.1841169

Wilson-Strydom, M. (2017). Disrupting structural inequalities of higher education opportunity: “grit”, resilience and capabilities at a south african university. J. Hum. Dev. Capabil. 18, 384–398. doi: 10.1080/19452829.2016.1270919

Wu, X. M., Dixon, H. R., and Zhang, L. J. (2021). Sustainable development of students’ learning capabilities: the case of university students’ attitudes towards teachers, peers, and themselves as oral feedback sources in learning English. Sustainability 13, 5211–5231.

Yavuzalp, N., and Bahcivan, E. (2020). The online learning self-efficacy scale: its adaptation into Turkish and interpretation according to various variables. Turkish Online J. Distance Educ. 21, 31–44.

Zamani-Alavijeh, F., Araban, M., Harandy, T. F., Bastami, F., and Almasian, M. (2019). Sources of health care providers’ self-efficacy to deliver health education: a qualitative study. BMC Med. Educ. 19:16. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1448-z

Keywords : self-efficacy, resistance to innovation, demotivation, insufficient learning capabilities, preservice English normal students

Citation: Lu T, Sanitah MY and Huang Y (2022) Role of Self-Efficacy and Resistance to Innovation on the Demotivation and Insufficient Learning Capabilities of Preservice English Normal Students in China. Front. Psychol. 13:923466. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.923466

Received: 19 April 2022; Accepted: 16 June 2022; Published: 29 July 2022.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2022 Lu, Sanitah and Huang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tuanhua Lu, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 14 May 2024

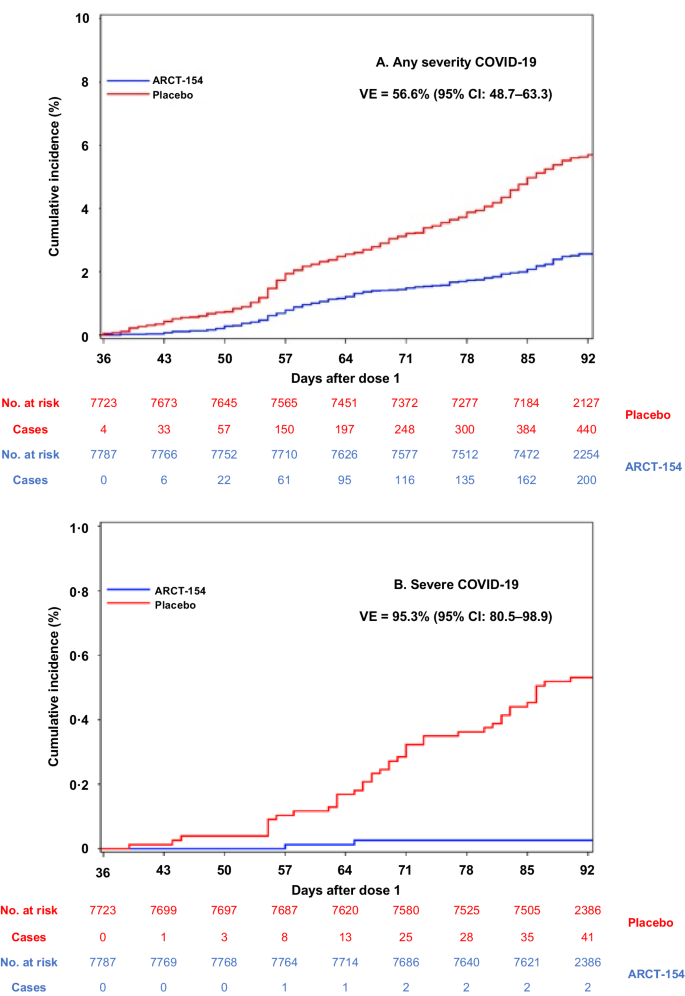

Safety, immunogenicity and efficacy of the self-amplifying mRNA ARCT-154 COVID-19 vaccine: pooled phase 1, 2, 3a and 3b randomized, controlled trials

- Nhân Thị Hồ 1 ,

- Steven G. Hughes 2 ,

- Van Thanh Ta 3 ,

- Lân Trọng Phan 4 ,

- Quyết Đỗ 5 ,

- Thượng Vũ Nguyễn 4 ,

- Anh Thị Văn Phạm 3 ,

- Mai Thị Ngọc Đặng 3 ,

- Lượng Viết Nguyễn 5 ,

- Quang Vinh Trịnh ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4548-104X 3 ,

- Hùng Ngọc Phạm 5 ,

- Mến Văn Chử 5 ,

- Toàn Trọng Nguyễn 4 ,

- Quang Chấn Lương 4 ,

- Vy Thị Tường Lê 4 ,

- Thắng Văn Nguyễn 5 ,

- Lý-Thi-Lê Trần 6 , 7 ,

- Anh Thi Van Luu 7 ,

- Anh Ngoc Nguyen 7 ,

- Nhung-Thi-Hong Nguyen ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0008-8462-4860 1 ,

- Hai-Son Vu 1 ,

- Jonathan M. Edelman 8 ,

- Suezanne Parker 2 ,

- Brian Sullivan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4277-6037 2 ,

- Sean Sullivan 2 ,

- Qian Ruan 2 ,

- Brenda Clemente 2 ,

- Brian Luk 2 ,

- Kelly Lindert 2 ,

- Dina Berdieva 2 ,

- Kat Murphy 2 ,

- Rose Sekulovich 2 ,

- Benjamin Greener 2 ,

- Igor Smolenov ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7075-9827 2 ,

- Pad Chivukula ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6017-2267 2 ,

- Vân Thu Nguyễn 7 &

- Xuan-Hung Nguyen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2216-8598 1 , 6 , 9

Nature Communications volume 15 , Article number: 4081 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

3592 Accesses

185 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Randomized controlled trials

- RNA vaccines

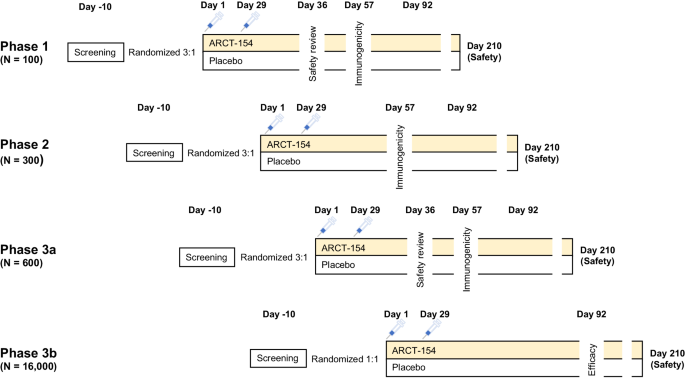

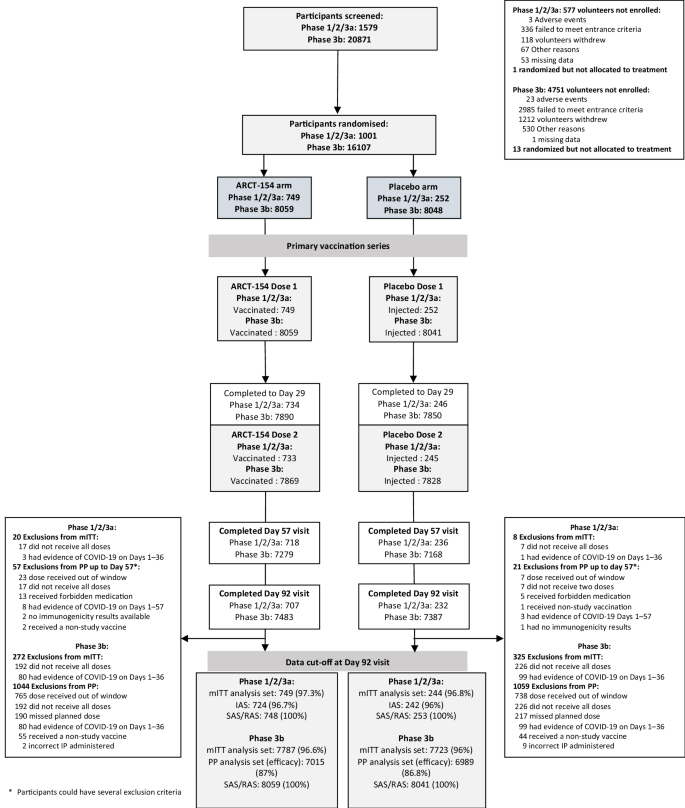

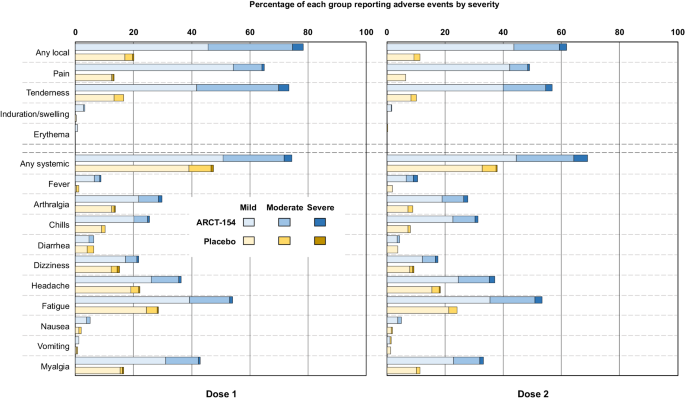

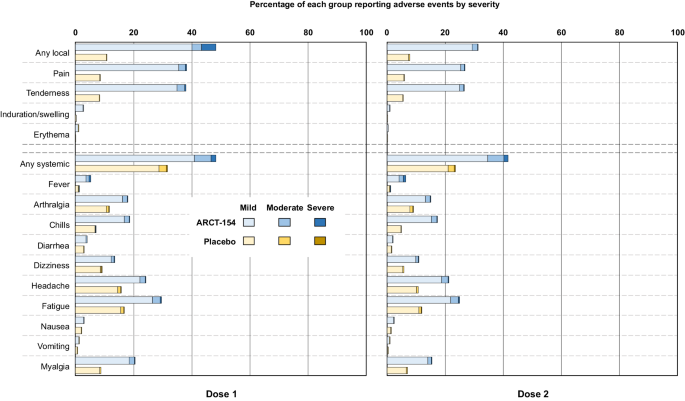

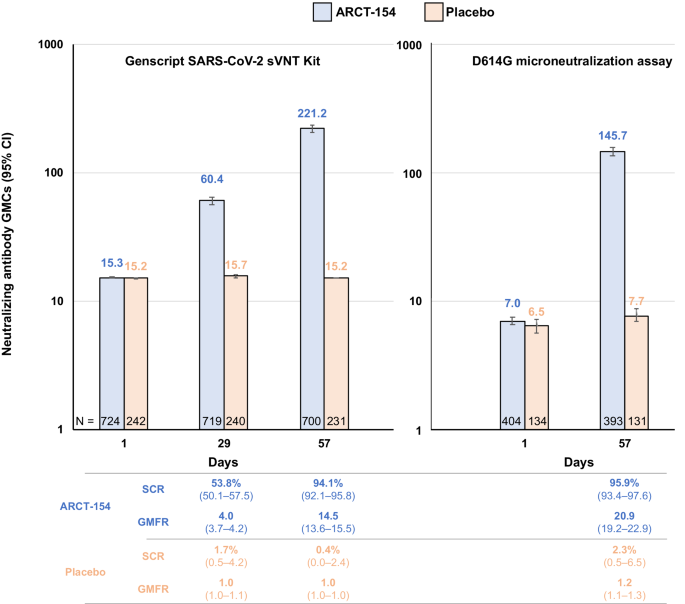

- Viral infection