An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Integr Care

- v.18(3); Jul-Sep 2018

The Core Dimensions of Integrated Care: A Literature Review to Support the Development of a Comprehensive Framework for Implementing Integrated Care

Laura g. gonzález-ortiz.

1 Università della Svizzera Italiana, IdEP Institute, CH

Stefano Calciolari

Nick goodwin.

2 International Foundation for Integrated Care, UK

Viktoria Stein

As part of the EU-funded Project INTEGRATE, the research sought to develop an evidence-based understanding of the key dimensions and items of integrated care associated with successful implementation across varying country contexts and relevant to different chronic and/or long-term conditions. This paper identifies the core dimensions of integrated care based on a review of previous literature on the topic.

Methodology:

The research reviewed literature evidence from the peer-reviewed and grey literature. It focused on reviewing research articles that had specifically developed frameworks on integrated care and/or set out key elements for successful implementation. The search initially focused on three main scientific journals and was limited to the period from 2006 to 2016. Then, the research snowballed the references from the selected published studies and engaged leading experts in the field to supplement the identification of relevant literature. Two investigators independently reviewed the selected articles using a standard data collection tool to gather the key elements analyzed in each article.

A total of 710 articles were screened by title and abstract. Finally, 18 scientific contributions were selected, including studies from grey literature and experts’ suggestions. The analysis identified 175 items grouped in 12 categories.

Conclusions:

Most of the key factors reported in the literature derive from studies that developed their frameworks in specific contexts and/or for specific types of conditions. The identification and classification of the elements from this literature review provide a basis to develop a comprehensive framework enabling standardized descriptions and benchmarking of integrated care initiatives carried out in different contexts.

Introduction

This paper presents findings from the “International Check” work package of Project INTEGRATE that was funded within the EU 7 th Framework Program (EU Grant Agreement 305821; see http://projectintegrate.eu.com ). The overall purpose of the work package was to develop an evidence-based framework on the key dimensions and items of integrated care associated with successful implementation. Moreover, the purpose of such a framework was designed to support decision-makers in the effective design and implementation of integrated care programs[ 1 ].

Several studies have contributed to the development of theoretical frameworks for integrated care implementation (e.g. [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ]). The articles and technical reports published on the topic identify factors or structures of elements fostering care integration, most often for people suffering from chronic and/or long-term conditions. In addition, most of these studies focus on a specific context of implementation (e.g. in coordinating services around people with a chronic illness) and so do not appreciate the influential role that contextual factors in care integration can play in determining outcomes (e.g. of finances, cultures, organizational forms etc.) [ 11 ]. In the former case, the resulting framework or list of key factors is likely to be tailored for the selected setting. In the latter case, it is hard to disentangle the context dependence of the analytical proposal.

Context is very important in evaluating the implementation of complex service innovations like integrated care and so any framework must be robust enough to understand the intricate interplay between multi-component interventions across contexts and settings [ 11 , 12 , 13 ]. The COMIC Model for the comprehensive evaluation of integrated care interventions [ 11 ], for example, has illustrated how the use or realistic synthesis to study the interplay between contexts, mechanisms and outcomes can bring insights into understanding how and why integrated care interventions succeed or fail.

Hence, to understand the complex and dynamic issues at play in the implementation of integrated care a more comprehensive framework is necessary that helps to benchmark initiatives across different contexts and condition-specific population groups. The task is a challenging one and cannot disregard the accumulated knowledge in the field. Therefore, as a first step in this direction, it is paramount to analyze and summarize the findings from previous studies in this respect. This can provide the basis for a more comprehensive approach to understanding how integrated care may be implemented by building on the evidence available in the extant literature of integrated care.

This paper presents a comprehensive, non-systematic, review of the extant literature on care integration design and implementation. Coherently with the objectives of Project INTEGRATE, this study purposefully focuses on initiatives targeting patients affected by chronic diseases (COPD and diabetes) and people living with geriatric and/or mental health conditions. The purpose of this paper, therefore, has been to build a more comprehensive understanding of the factors and elements associated with successful integrated care implementation as a precursor to the development of a new conceptual framework. The objectives of this paper are: (1) to identify the most important factors influencing the success of an initiative of care integration across different contexts; and (2) to classify and summarize the identified evidence according to the extant literature in the field.

To ensure a common understanding of the concept, Project INTEGRATE utilised Kodner and Spreeuwenberg’s definition of integrated care as: ‘a coherent set of methods and models on the funding, administrative, organisational, service delivery and clinical levels designed to create connectivity, alignment and collaboration within and between the cure and care sectors’ [ 14 ]. Hence, the main purpose of integrated care interventions consists of reducing fragmentations in service delivery and to foster both comprehensiveness of care and better care co-ordination around people’s needs. Many frameworks have been developed over time to understand the key elements, or building blocks, of integrated care [ 15 ].

One of the most well-known is the Chronic Care Model (CCM) that was developed from a Cochrane systematic review [ 10 ]. This work developed a comprehensive framework for the organization of healthcare to improve outcomes for people with chronic conditions. It identified six interrelated domains that should be considered to facilitate high-quality chronic disease care, thus improving health outcomes [ 3 ]. The CCM identifies the main areas of intervention to accomplish such a goal and enhance the health outcomes for specific target patients. In particular, its approach focuses on fostering an effective use of community resources; enabling patient self-management, nurturing evidence-based care and patient preferences, and leveraging on the use of supportive information technology [ 4 ].

Since the CCM focuses on the delivery of clinically oriented systems to patient it did not include many key aspects of care integration – for example, regarding health promotion and prevention, or indeed of rehabilitation and re-ablement. In this respect, Barr and colleagues proposed an evolution of the model, called the Expanded Chronic Model (ECCM) [ 2 ]. The ECCM includes elements specifically aimed to promote population health and encourage prevention by involving the community. Another variation is the Innovative Care for Chronic Conditions model (ICCC) [ 16 ]. Developed by the WHO as part of a ‘road map’ for health systems to deal with the rising burden of chronic illness, the ICCC placed a specific premium on prevention through ‘productive partnerships’ between patients and families, community partners and health care teams to create informed, prepared and motivated communities. In this respect, recent developments of integrated care initiatives, such as the patient-centred medical home (PCMH), have stressed the importance of delivering continuous, comprehensive and coordinated care in the context of people’s family and community [ 17 ].

The frameworks described above have primarily evolved from the USA and been confined in their thinking to within health systems. They have also not sought to identify key actions that decision-makers would need to implement integrated care effectively, such as governance and accountability, financing and incentives, or issues related to culture and values. However, other work has sought to address this. For example, a knowledge synthesis from Canada developed an influential paper entitled ‘ten principles of successful integrated systems’ [ 18 ].

More recently, Minkman et al. [ 7 ] carried out a study, based on a Delphi method, to identify and validate analytical key factors of care integration. The authors started by identifying elements from the literature. Then, they conducted a three-round Delphi study among a group of thirty-one experts, who provided comments to rank 175 elements in priority order. Then, the expert panel clustered the elements and discussed their content following a concept mapping procedure. Finally, the authors identified 89 relevant elements grouped into nine clusters. The results aim to develop a comprehensive quality management model for integrated care.

In another recent paper, Valentijn et al. [ 9 ] proposed a taxonomy to facilitate the description and comparison of different integrated care interventions. The taxonomy consists of 59 key elements resulting from a two-round Delphi study. This contribution is the development of a companion paper [ 8 ] in which the authors proposed a general model, known as the Rainbow Model of Integrated Care. Such model proposes six dimensions (in which the aforementioned 59 elements are grouped) and has a primary care perspective.

Compared to the CCM and the ECCM, the last two models are much more analytical in terms of the wider range of factors necessary to support the effective development of integrated care systems. Despite the differences they currently compete to propose an evidence-based perspective on the topic. Each has been developed for a different purpose and each varies in scope, for example, from the process of coordinating services around people with chronic conditions to enabling health and social care systems to operate more cohesively. For professionals and decision-makers tasked with designing and implementing integrated care for different client groups in a range of contexts and settings this potentially provides for confusion on the most appropriate frameworks and models they might use. This indicates that a more comprehensive framework – one that leverages the strengths of previously published studies but which enables an understanding of the core dimensions of integrated care across contexts and settings – is necessary to support decision-makers in the design and implementation of their integrated care programs across settings and differing client groups.

Methodology

The authors searched for scientific studies published in peer-reviewed journals and the most important contributions in the grey literature (research reports and conference presentations). The adopted search strategy aimed to be efficient and flexible enough to include also important seminal contributions on the topic. Therefore, the authors agreed on starting with three specialized journals where peer-reviewed articles presenting frameworks of integrated care would most likely be cited, namely: the International Journal of Integrated Care (IJIC), the Journal of Integrated Care (JIC), and the International Journal of Coordinated Care 1 (IJCC). The initial search was limited to the period 2006–2015.

The two authors from USI retrieved all the abstracts published in the selected period. Then, each one read half of the abstracts of all the articles to decide which contributions should be further analyzed. At this stage, the preliminary inclusion criteria consisted of two simple questions: (a) Does the contribution propose or analyze any framework aimed to explain the success or describe the implementation of integrated care initiatives? (b) Does the article propose or analyze any important aspect/s explaining the success of integrated care initiatives?

Each of the two researchers crosschecked the list of abstracts selected by her/his colleague until they reached an agreement. Afterwards, the two researchers read separately the full text of the selected articles to confirm their inclusion. They looked for contributions defining and operationalizing relevant elements of care integration or discussing the relationships between elements of care integration (inclusion criteria). They also applied the following exclusion criteria: (1) Limited to motivating the importance and goals of integrated care; (2) Limited to describing care integration properties and/or principles; (3) Limited to problems/gaps pf a specific case or national context; (4) Limited to a specific means/technology of integration (e.g. integrated care pathways); (5) Not normative (hard to use for assessing an initiative); (6) Limited to assessment of results of integrated care (not elements/strategies of care integration); (7) Review not based on a specific framework; (8) Not focused on chronic diseases or long-term conditions; (9) Non enough details (to allow for operationalization); (10) Based on another framework/model (and with no significant additional contribution); (11) Too much focused on a specific target population (e.g., elderly, minors, diabetic patients). Then, the two researchers compared the results of their selective analysis and found agreement when it was necessary to reconcile differences.

After this step, the two researchers analyzed the references of the included contributions looking for further relevant articles (snowballing). This approach was designed to identify previously published frameworks (including in the grey literature). The complete list of the identified contributions was sent to the other two authors from IFIC, who confirmed each item and suggested relevant contributions not included. All the researchers agreed on the new list. Then they performed hand searches looking for further articles/documents in selected databases (ScienceDirect, PubMed, and Medline) and collected suggestions from experts in the field. This range of experts included those within the research consortium plus the 13 members of the Advisory Board of Project INTEGRATE comprising leading academics, policy-makers, professional and commissioners across health, social care and public health disciplines (see: www.projectintegrate.eu.com/integrated-care-purpose ).

Once all the authors agreed on the final list (with the earlies selected article published in 2002), the two researchers from USI carefully analyzed each selected contribution to identify the elements of the proposed framework or relevant aspects reported as factors fostering care integration. In some cases, the framework and/or the elements were quite evident, since they were listed or presented in a schematic way. For instance, Lyngsø et al. [ 6 ] categorized and listed the key elements in a table. In other contributions, the elements had to be meticulously identified into the text and extracted by the researchers. In such cases, both researchers independently identified and coded the elements from each selected document. Then, they cross-checked the results and found agreement on eventual differences.

The identified elements (hereafter referred as “items”) were gathered in a comprehensive list. Each item was written down textually to avoid misunderstandings in the next phase (validation). Supported by existing dimensions of the CCM, we drafted a table and placed each identified item into a corresponding category. Each item was associated with a consecutive number and the article/document where it was identified. Elements not fitting in any of the CCM dimensions were listed at the bottom of the table to be afterwards grouped into additional categories proposed by the researchers. It is important to mention that, in this study, we went for inclusiveness. Therefore, items quite similar but with non-identical wording were reported as a different item.

The database search, spanning over a decade in the publication history of the three selected journals, retrieved 710 peer-reviewed articles. The majority of these studies were subsequently excluded (679 articles) based on their title or abstract, because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Therefore, we focused on the remaining 31 articles eligible for inclusion. After full text reading, based on the aforementioned exclusion criteria, 14 studies remained.

We found articles written by the same author(s) and discussing elements to foster integrated care already proposed in preceding companion(s) paper(s). In this case, we included only the most recent article, which generally confirms or further develops ideas/notions proposed in the previous one/s. We did not include any study from the references search (snowballing), because none of the identified articles did actually meet the predefined eligibility criteria.

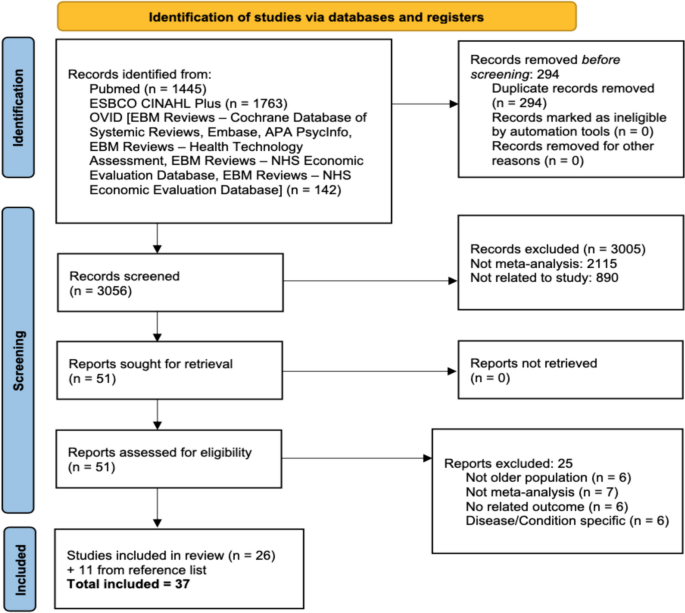

With regard to the grey literature and expert suggestions, we selected four studies. This resulted in 18 studies ultimately included in our review [ 4 , 5 , 6 , 8 , 11 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 ]. From each of the selected contributions, we identified and extracted items considered influential for care integration. We obtained a comprehensive list consisting of 175 items categorized in 12 domains. The first six domains are those proposed by the CCM: health care system, community resources and policies, self-management support, delivery system design, decision support, and clinical information system. In addition, we defined six further categories (leadership, governance, performance monitoring, organizational culture, contextual factors, and social capital) to group those elements that did not fit with any of the CCM domains. Figure Figure1 1 summarizes the selection process followed in the search and Table Table1 1 the results of the search across the 12 domains.

Flowchart of the literature selection process.

Results of the search across the identified 12 conceptual domains.

| Domain | No. | Element/item | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Universal coverage or enrolled population with care free at point of use | [ , ] | |

| 2 | Emphasis on chronic and long-term care | [ , ] | |

| 3 | Emphasis on population health management | [ , , ] | |

| 4 | Alignment of regulatory frameworks with goals of integrated care | [ , , ] | |

| 5 | Data on chronic illnesses (eg. registries) | [ ] | |

| 6 | Understand needs and priorities of local populations | [ , , , ] | |

| 7 | Mobilize and coordinate resources | [ , ] | |

| 8 | Adequate financing system linked with quality improvement | [ , , ] | |

| 9 | Funding payment flexibilities to promote integrated care | [ ] | |

| 10 | Allocating financial budgets for the implementation and maintenance of integrated care | [ , ] | |

| 11 | Funding of a program or service | [ ] | |

| 12 | Changes to funding arrangements | [ ] | |

| 13 | Finances for implementation and maintenance | [ ] | |

| 14 | Reaching agreements on the financial budget for integrated care | [ ] | |

| 15 | Prepaid capitation at various levels | [ ] | |

| 16 | Financing mechanism allowing for pooling of funds across services | [ , , ] | |

| 17 | Creating financial and regulatory incentives that encourage cooperation among health care providers | [ ] | |

| 18 | Integrate policies: collaboration/coordination across health-related policy fields (eg. environment, education, transportation, housing) | [ , , ] | |

| 19 | Location policy | [ ] | |

| 20 | Inter-organisational strategy | [ , , ] | |

| 21 | Creating interdependence between organisations | [ , ] | |

| 22 | Reaching agreements on introducing and integrating new partners in the care chain | [ ] | |

| 23 | Formal connections between organisations: varying from linkage with community to merging of organisations | [ , , , , , ] | |

| 24 | Achieving adjustments among care partners | [ ] | |

| 25 | Reaching agreements about letting go care partner domains | [ ] | |

| 26 | Reaching agreements among care partners on the consultation of experts and professionals | [ ] | |

| 27 | Reaching agreements among care partners on managing client preferences | [ ] | |

| 28 | Reaching agreements among care partners on scheduling client examinations and treatment | [ ] | |

| 29 | Reaching agreements among care partners on discharge planning | [ ] | |

| 30 | Making transparent the effects of the collaboration on the production of the care partners | [ ] | |

| 31 | Structural meetings with external parties such as insurers, local governments and inspectorates | [ ] | |

| 32 | Structural meetings of leaders of care-chain organizations | [ , ] | |

| 33 | Role of volunteers and third sector to support needs of patients and carers | [ , ] | |

| 34 | Building systems of care at the neighborhood level | [ , ] | |

| 35 | Building community awareness and trust with services (gives legitimacy to new approaches to care, and increase likelihood of appropriate, and earlier, referrals) | [ ] | |

| 36 | Family caregivers (involvement and support) | [ , , , , ] | |

| 37 | Coordinated home and community health | [ , ] | |

| 38 | Build resilience among carers to promote home-based care | [ , ] | |

| 39 | Raise awareness and reduce stigma | [ ] | |

| 40 | Social value creation | [ ] | |

| 41 | Provide complementary services | [ ] | |

| 42 | Patient education | [ , ] | |

| 43 | Patient empowerment | [ ] | |

| 44 | Using self-management support methods as a part of integrated care | [ , , , ] | |

| 45 | Patient engagement and participation, i.e. patients provide input on various levels | [ , , , ] | |

| 46 | Electronic tools for patients to be engaged and active in self-management | [ , ] | |

| 47 | Patient navigation/clinical pathways | [ ] | |

| 48 | Reminders for patients | [ , ] | |

| 49 | Paradigm shift from acute to chronic care and from reactive to proactive care delivery | [ , ] | |

| 50 | Population-based needs assessment: focus on defined population | [ , , , ] | |

| 51 | Defining the targeted client group | [ , ] | |

| 52 | Developing care programmes for relevant client subgroups | [ ] | |

| 53 | Designing care for clients with multi- or co-morbidities | [ ] | |

| 54 | Understand best ways to organize and implement care | [ ] | |

| 55 | Collaborative involvement in planning, policy development and patient care delivery | [ ] | |

| 56 | Service characteristics | [ ] | |

| 57 | Co-location of services | [ , , , , ] | |

| 58 | Specialized clinic or centres | [ ] | |

| 59 | Patient-centered philosophy (focus on patients’ need) | [ , , ] | |

| 60 | Promotion of functional independence and wellbeing, not just the management or treatment of medical symptoms (holistic focus) | [ , , ] | |

| 61 | Commitment to the view that the patient is the customer | [ ] | |

| 62 | Interaction between professional and client | [ ] | |

| 63 | Care plans including collaborative goal setting between patients and clinicians | [ , , ] | |

| 64 | Centralized information, referral and intake | [ , ] | |

| 65 | Single point of entry and a single point of contact for patients and carers | [ , , ] | |

| 66 | Case management (relational continuity with a named coordinator) | [ , , , , , , , , ] | |

| 67 | Case management | [ ] | |

| 68 | Arrangements for priority access to another service | [ ] | |

| 69 | Disease management | [ ] | |

| 70 | Professional attitude and fulfilment of work as drivers of integration | [ ] | |

| 71 | Multidisciplinary teamwork | [ , , , , , , , ] | |

| 72 | Developing a multi-disciplinary care pathway | [ , , ] | |

| 73 | Creating interdependence between professionals (inter-professional networks) | [ , , , , ] | |

| 74 | Teamwork (joint working) and care coordination | [ ] | |

| 75 | Arrangements for facilitating communication | [ , ] | |

| 76 | Information sharing, planned/organised meetings | [ ] | |

| 77 | Using a uniform language in the care chain | [ ] | |

| 78 | Using uniform client-identification numbers within the care chain | [ ] | |

| 79 | Shared assessment | [ , ] | |

| 80 | Coordinated or joint consultations | [ ] | |

| 81 | Using feedback and reminders by professionals for improving care | [ , , ] | |

| 82 | Agreements on referrals, discharge and transfer of clients through the care chain | [ , , , ] | |

| 83 | Clinical follow-up | [ ] | |

| 84 | Continuity of care | [ , , , ] | |

| 85 | Assisted living/care support at home | [ , ] | |

| 86 | Service management (e.g., collective telephone numbers, counter assistance and 24-hour access) | [ , , ] | |

| 87 | Medication management | [ ] | |

| 88 | Essential and new pharmaceuticals and medical devices | [ ] | |

| 89 | Collaboratively assessing bottlenecks and gaps in care | [ ] | |

| 90 | An adequate workforce (in terms of number, competencies and distribution) | [ , , , ] | |

| 91 | Workforce educated and skilled in chronic care (graduate) | [ , , , ] | |

| 92 | Cross-training of staff (to ensure staff culture, attitudes, skills are complementary) | [ , , , , , ] | |

| 93 | Reaching agreements among care partners on tasks, responsibilities and authorizations | [ , ] | |

| 94 | Establishing the roles and tasks of multidisciplinary team members | [ , , ] | |

| 95 | Professionals in the care chain are informed/aware of each other’s expertise and tasks | [ , , , ] | |

| 96 | Education for professionals (continuous education) | [ , , , , ] | |

| 97 | Training (joint or relating to collaboration) | [ , , ] | |

| 98 | Inter-professional education | [ , , , , ] | |

| 99 | Stimulating a learning culture and continuous improvement in the care chain | [ ] | |

| 100 | Share registries and/or methods to track care/health | [ , , , ] | |

| 101 | Implementing care process-supporting clinical information systems | [ , ] | |

| 102 | Shared decision support | [ ] | |

| 103 | Support/supervision for clinicians | [ ] | |

| 104 | Clear communication strategies and protocols | [ ] | |

| 105 | Standardised diagnostic and eligibility criteria | [ , , ] | |

| 106 | Multidisciplinary and comprehensive assessment | [ , ] | |

| 107 | Developing criteria for assessing client’s urgency | [ ] | |

| 108 | Case finding and use of risk stratification | [ ] | |

| 109 | Common decision-support tools (practice guidelines, protocols) | [ , , , ] | |

| 110 | Multidisciplinary guidelines and protocols | [ , , ] | |

| 111 | Existence of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines with automated tools to enforce their use | [ , , , ] | |

| 112 | Join planning | [ , , , , , , ] | |

| 113 | Using a single client-monitoring record accessible for all care partners | [ ] | |

| 114 | Using a protocol for the systematic follow-up of clients | [ ] | |

| 115 | Information sharing, planned/organised meetings | [ ] | |

| 116 | Shared decision-making and problem solving | [ ] | |

| 117 | Shared-care protocols and evidence based practice guidelines | [ , , , , , , , ] | |

| 118 | Shared clinical records | [ , , ] | |

| 119 | Integrated clinical pathways | [ ] | |

| 120 | Decision aids to patients | [ ] | |

| 121 | Providing understandable and client-centered information | [ ] | |

| 122 | Assistance in accessing primary health care | [ ] | |

| 123 | Intelligence systems for data collection | [ , , , ] | |

| 124 | Centralised system-wide computerised patient record system (data accessibility from anywhere in the system) | [ , , ] | |

| 125 | Integrated electronic health records | [ , , , , , , , , ] | |

| 126 | Electronic registry for planning care and risk-stratifying patients | [ ] | |

| 127 | Technologies that support continuous and remote patient monitoring | [ , , ] | |

| 128 | Reminders to clinicians and patients (e.g., medication management) | [ , ] | |

| 129 | Local leadership and long-term commitments | [ , , , ] | |

| 130 | Leaders with a clear vision on integrated care | [ ] | |

| 131 | Distributed leadership | [ , , , , ] | |

| 132 | Managerial leadership | [ , , , , ] | |

| 133 | Visionary leadership | [ ] | |

| 134 | Clinical leadership | [ , , ] | |

| 135 | Organisational leadership for providing optimal chronic care | [ ] | |

| 136 | Conflict management | [ ] | |

| 137 | Reputation | [ ] | |

| 138 | Good governance | [ , , , ] | |

| 139 | Inter-organisational governance | [ ] | |

| 140 | Inter-professional governance | [ ] | |

| 141 | Action oriented to understand and support more effective ways for improving quality and enabling change | [ , , , , ] | |

| 142 | Collaborative learning in the care chain in order to innovate integrated care | [ ] | |

| 143 | Involving leaders in improvement efforts in the care chain | [ ] | |

| 144 | Involving client representatives by monitoring the performance of the care chain | [ ] | |

| 145 | Using a systematic procedure for the evaluation of agreements, approaches and results | [ , , , , , ] | |

| 146 | Reaching agreements about the uniform use of performance indicators in the chain care | [ ] | |

| 147 | Establishing quality targets for the performance of care partners | [ ] | |

| 148 | Establishing quality targets for the performance of the whole care chain | [ ] | |

| 149 | Installing improvement teams at care-chain level | [ ] | |

| 150 | Evaluate outcomes | [ ] | |

| 151 | Client satisfaction | [ , , ] | |

| 152 | Performance management (common outcomes evaluation, performance indicator) | [ , , , , , , ] | |

| 153 | Monitoring successes and results during the development of the integrated care chain | [ , ] | |

| 154 | Regular feedback of performance indicators | [ ] | |

| 155 | Shared accountability/risk and responsibility for care | [ , ] | |

| 156 | Integrating incentives for rewarding the achievement of quality targets | [ , , , , ] | |

| 157 | Gathering financial performance data for the care chain | [ ] | |

| 158 | Gathering data on client logistics (e.g. volumes, waiting periods and throughput times) in the care chain | [ , ] | |

| 159 | Monitoring and analysing mistakes/near-mistakes in the care chain | [ ] | |

| 160 | Monitoring whether the care delivered corresponds with evidence-based guidelines | [ ] | |

| 161 | Shared vision and values for the purpose of integrated care | [ , , , , , ] | |

| 162 | An integration culture institutionalised through policies and procedures | [ , , , , , ] | |

| 163 | Organisational culture for providing optimal chronic care | [ , ] | |

| 164 | Striving towards an open culture for discussing possible improvements for care partners | [ ] | |

| 165 | Linking cultures | [ ] | |

| 166 | Population features (e.g., demographic composition) | [ , ] | |

| 167 | Advocacy | [ ] | |

| 168 | Rurality of the area | [ ] | |

| 169 | Environmental climate | [ ] | |

| 170 | Environmental awareness | [ ] | |

| 171 | Labour market | [ , ] | |

| 172 | Quality features of the informal collaboration | [ ] | |

| 173 | Trust (on colleagues, caregivers and organisations) | [ , , , ] | |

| 174 | Reputation | [ ] | |

| 175 | Interpersonal characteristics | [ ] | |

From a quantitative point of view, about one third of the items (58) are supported by at least three contributions. Considering that some items are quite similar in the list, this is a conservative measure of the level of overlapping of the research findings and it can be interpreted as a degree of convergence on some important factors.

The categories with the highest concentration of elements are the Delivery system design (51), Community resources & policies (24), Decision support (23), Performance & quality (20), Healthcare system (17). While Governance (3), Social capital (4) Organizational culture (5), Contextual factors (6), and Clinical information system (6) show the lowest concentration.

More specifically, the category with the largest number of items concerns features of the service delivery design. This suggests that processes, logistics, and human resources management (e.g., multidisciplinary teamwork, staffing of professionals, training) have been widely investigated and represent a cornerstone of care integration. In addition, 43% (or 22) of the items classified in Delivery system design are identified by at least three different contributions. This is the highest level of convergence after Leadership (44%) and Clinical information system (67%); however, each of these last two categories groups a much lower number of items. One might conclude that research has already reported convincing evidence on some important aspects that should guide the design of service delivery to integrate care.

Focusing more on the contents, on the one hand several items grouped in the Delivery system design indicate the importance of centering service delivery on the needs of the patients (e.g. #53, 59, 60–63, 66). On the other hand, several items emphasize the need for standardizing (or foster uniformity of) specific aspects/tools that are paramount to ensure care quality and coordination across organizational boundaries and settings (e.g., #64, 65, 68, 72, 75, 77, 78), together with multi-/inter-professional collaboration (e.g., #71, 73, 74, 76, 79, 80).

At the system level two relevant policy areas are clearly identified: funding/financing mechanisms and priority setting coherent with the needs of the population (e.g., chronic conditions, older people) and the pillars of integrated care (e.g., cooperation between providers, synergic mobilization of community resources). The items grouped in the Contextual factors category reinforce importance of fine tuning interacting policies (e.g. health, environment, labor) with the actual needs and conditions of the population (e.g., demographic composition, orographic configuration of locations).

The categories Decision support and Community resources & policies group items that seem to point at setting the best conditions – by introducing changes and specific tools – to foster collaboration between professionals and organizations involved in the care delivery and help such actors to focus on patients’ needs and priorities.

The category Performance & Quality includes items that, rather than proposing specific technical solutions, indicate the need for fostering shared accountability on the results of the “care chain”. The few cases where end-points are proposed, they range from patient experience (e.g., satisfaction) to outcomes. This aspect, reinforced by the categories directly focused on soft aspects (i.e., Organizational culture and Social capital), suggests the importance of developing shared values to foster care integration.

Conclusions

The literature evidence reviewed here has uncovered a range of elements and factors associated with successful care integration over the last decade. Moreover, the development of conceptual frameworks to understand and guide thinking on integrated care has grown and evolved over time.

However, the majority of contributions provide recommendations related to a smaller number of specific aspects that were found to be influential. Moreover, these were often derived in specific contexts/settings or with defined target patients, especially to those with chronic illnesses as opposed to those with comorbidities or wider health and social care needs. Few studies propose, and eventually validate, frameworks indicating key areas of intervention and/or analytical aspects to consider in order to foster care integration. They are mostly lists of key building blocks to integrated care, rather than frameworks supporting the process of implementation. In addition, the retrieved frameworks generally build on the findings of previous research, but each of them assumes either a diverse (though not necessarily alternative) perspective or different analytical degree. Interestingly, despite that our review focused on forms of integrated care addressing patients with chronic diseases and long-term conditions, we found that recent frameworks (more or less explicitly) assume a population health rather than a disease-based perspective. This dramatically increases the need for accurately defining client groups or populations, including people with non-medical conditions, profiling their needs and specificities, and manage the complexity resulting from this broad perspective.

When streamlining all the aspects identified in the available relevant literature, on the one hand, it is striking the high number of factors deserving attention; however, on the other hand, there is a clear area of convergence identified by those factors mentioned in several contributions. The two findings can be considered, respectively, evidence of dynamism and indicator of the degree of maturity the research field.

Researchers seem to have concentrated their attention on the service delivery design of integrated care, with a recent shift toward the notion of person-centeredness as a way of shaping any aspect of processes and interaction with patients and their caregivers. Nevertheless, contextual aspects seem to rank more and more high in the priorities of experts in the field. Perhaps, this is the result of the aforementioned shift toward a population health perspective that tends to increase the interdependencies between the different components of a health (and social) care system. It may also be that many experts view care integration as primarily a systemic or organizational activity rather than an approach (as defined) that co-ordinates care with and around people’s needs at the clinical and service level.

A limitation of our contribution is that we searched studies that propose frameworks or key factors for integrated care starting from three selected journals specialized in the field. This could have limited our capacity to identify all available studies related to the objective of this article. However, we privileged the pertinence of the scientific source and tried to compensate the aforementioned bias by snowballing the references of the included contributions and by involving some external scholars/experts to fill eventual gaps based on their extensive knowledge.

Our selectivity allowed us to perform an exhaustive, careful review of all the included material. The extracted key elements offer a useful basis for describing and/or reflecting on integrated care initiatives for chronic illnesses and long-term conditions set in different contexts. Nevertheless, it may be difficult to obtain accurate information on all of the important aspects so far identified. Therefore, it would be useful to develop a comprehensive framework that could synthetically describe care integration initiatives implemented in different contexts and allow for efficient comparisons highlighting relevant variabilities and context-dependencies.

Acknowledgements

The study is part of Project INTEGRATE ( http://projectintegrate.eu.com ) that was funded within the EU 7 th Framework Program (EU Grant Agreement 305821).

Formerly, International Journal of Care Pathways.

Dr Teresa Burdett, Lecturer in Integrated Health Care, Professional Lead for Interprofessional Learning and Education, Unit Lead for Foundations of Integrated Care and Person Centred Services, Bournemouth University, UK.

One anonymous reviewer.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Write for Us

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Volume 19, Issue 1

- Reviewing the literature

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Joanna Smith 1 ,

- Helen Noble 2

- 1 School of Healthcare, University of Leeds , Leeds , UK

- 2 School of Nursing and Midwifery, Queens's University Belfast , Belfast , UK

- Correspondence to Dr Joanna Smith , School of Healthcare, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, UK; j.e.smith1{at}leeds.ac.uk

https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2015-102252

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Implementing evidence into practice requires nurses to identify, critically appraise and synthesise research. This may require a comprehensive literature review: this article aims to outline the approaches and stages required and provides a working example of a published review.

Are there different approaches to undertaking a literature review?

What stages are required to undertake a literature review.

The rationale for the review should be established; consider why the review is important and relevant to patient care/safety or service delivery. For example, Noble et al 's 4 review sought to understand and make recommendations for practice and research in relation to dialysis refusal and withdrawal in patients with end-stage renal disease, an area of care previously poorly described. If appropriate, highlight relevant policies and theoretical perspectives that might guide the review. Once the key issues related to the topic, including the challenges encountered in clinical practice, have been identified formulate a clear question, and/or develop an aim and specific objectives. The type of review undertaken is influenced by the purpose of the review and resources available. However, the stages or methods used to undertake a review are similar across approaches and include:

Formulating clear inclusion and exclusion criteria, for example, patient groups, ages, conditions/treatments, sources of evidence/research designs;

Justifying data bases and years searched, and whether strategies including hand searching of journals, conference proceedings and research not indexed in data bases (grey literature) will be undertaken;

Developing search terms, the PICU (P: patient, problem or population; I: intervention; C: comparison; O: outcome) framework is a useful guide when developing search terms;

Developing search skills (eg, understanding Boolean Operators, in particular the use of AND/OR) and knowledge of how data bases index topics (eg, MeSH headings). Working with a librarian experienced in undertaking health searches is invaluable when developing a search.

Once studies are selected, the quality of the research/evidence requires evaluation. Using a quality appraisal tool, such as the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tools, 5 results in a structured approach to assessing the rigour of studies being reviewed. 3 Approaches to data synthesis for quantitative studies may include a meta-analysis (statistical analysis of data from multiple studies of similar designs that have addressed the same question), or findings can be reported descriptively. 6 Methods applicable for synthesising qualitative studies include meta-ethnography (themes and concepts from different studies are explored and brought together using approaches similar to qualitative data analysis methods), narrative summary, thematic analysis and content analysis. 7 Table 1 outlines the stages undertaken for a published review that summarised research about parents’ experiences of living with a child with a long-term condition. 8

- View inline

An example of rapid evidence assessment review

In summary, the type of literature review depends on the review purpose. For the novice reviewer undertaking a review can be a daunting and complex process; by following the stages outlined and being systematic a robust review is achievable. The importance of literature reviews should not be underestimated—they help summarise and make sense of an increasingly vast body of research promoting best evidence-based practice.

- ↵ Centre for Reviews and Dissemination . Guidance for undertaking reviews in health care . 3rd edn . York : CRD, York University , 2009 .

- ↵ Canadian Best Practices Portal. http://cbpp-pcpe.phac-aspc.gc.ca/interventions/selected-systematic-review-sites / ( accessed 7.8.2015 ).

- Bridges J , et al

- ↵ Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). http://www.casp-uk.net / ( accessed 7.8.2015 ).

- Dixon-Woods M ,

- Shaw R , et al

- Agarwal S ,

- Jones D , et al

- Cheater F ,

Twitter Follow Joanna Smith at @josmith175

Competing interests None declared.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Themed Collections

- Editor's Choice

- Ilona Kickbusch Award

- Supplements

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Online

- Open Access Option

- Self-Archiving Policy

- About Health Promotion International

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, supplementary material, authorship contributions, acknowledgements, data availability.

- < Previous

Unleashing the potential of Health Promotion in primary care—a scoping literature review

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Adela Bisak, Martin Stafström, Unleashing the potential of Health Promotion in primary care—a scoping literature review, Health Promotion International , Volume 39, Issue 3, June 2024, daae044, https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daae044

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The purpose of this study is to gain a better understanding of the role and extent of health promotion lifestyle interventions targeting adults in primary care, and especially those who are considered overall healthy, i.e. to study the outcomes of research applying salutogenesis. We performed a literature review, with three specific aims. First, to identify studies that have targeted the healthy population in intervention within the primary health care field with health promotion activities. Second, to describe these interventions in terms of which health problems they have targeted and what the interventions have entailed. Third, to assess what these programs have resulted in, in terms of health outcomes. This scoping review of 42 studies, that applied salutogenesis in primary care interventions shows that health promotion targeting healthy individuals is relevant and effective. The PRISMA-ScR guidelines for reporting on scoping review were used. Most interventions were successful in reducing disease-related risks including CVD, CVD mortality, all-cause mortality, but even more importantly success in behavioural change, sustained at follow-up. Additionally, this review shows that health promotion lifestyle interventions can improve mental health, even when having different aims.

This article describes the importance of including healthy individuals in health promotion activities, applying salutogenesis, as there are significant positive health outcomes effects if they participate in health interventions.

The study amplifies that the prevention paradox should always be considered when designing health promotion interventions.

This article shows that the greatest effects when targeting healthy individuals are found in lower all-cause mortality and CVD risks, mainly because these programs manage to lead to long-lasting lifestyle changes.

Health Promotion is, according to Nutbeam and Muscat (2021 , p. 1580), ‘[…] the process of enabling people to increase control over, and to improve their health’. This process entails a comprehensive approach to change on all levels, from structures to individuals, improving health mainly through addressing the social determinants of health.

Whereas the most overarching processes are initiated on a structural level through global and national health policies ( Cross et al ., 2020 ), health promotion strategies are also widely employed in health interventions targeting individuals. It could entail smoking cessation programs, weight loss programs and adolescent alcohol use, just to mention some common health outcome target areas ( Green et al. , 2019 ). Even when deploying health promotion strategies at a national policy level, it is not uncommon that the programs designed to target individuals and groups are more inspired by pathogenesis, rather than salutogenesis ( Nutbeam and Muscat, 2021 ).

A widespread strategy in the latter programs is that individuals are screened for a need to receive an intervention, so-called secondary or indicated prevention programs, where those who report a riskier lifestyle, or test worse on psychometric or biometric indicators are eligible for receiving the intervention, and those not having the same risks are excluded from the program on the premise that they are, based on study protocol definitions, healthy individuals.

Based on the principles of salutogenesis, this is a somewhat inappropriate approach. Within the strategy of health promotion, it is assumed that all people, no matter their level of risk, would find feedback on their health valuable. Those in need of change should receive the necessary resources and tools to change, whereas those who do not have to change should have their lifestyles positively reinforced. In addition, the prevention paradox ( Rose, 1981 ) postulates that it is important to address the majority, as there will be plenty of adverse health outcomes stemming from them. In conventional indicated prevention programs, attention to those who are non-eligible for interventions is, thus, often completely disregarded.

One common arena for such programs is primary health care. There is a wide range of evidence-based programs that have shown efficacy in reducing the health risks among those who have the riskiest lifestyles in relation to, e.g. alcohol use ( Beyer et al ., 2019 ), smoking ( Cantera et al ., 2015 ), depression ( Bortolotti et al ., 2008 ), diabetes ( Galaviz et al ., 2018 ) and cardiovascular diseases ( Álvarez-Bueno et al. , 2015 ). The at-risk groups vary across the different diseases, but a vast majority of patients targeted in the above studies were identified after screening as non-eligible to participate in the intervention in question. From this follows that a large number of individuals do not receive any substantial health information, nor are their health outcomes measured as they are not included in the intervention. From a health promotion perspective, this seems like a lost opportunity. Additionally, this raises the question of whether a healthy population is systematically disadvantaged compared to those individuals at high risk, which might point to some less-known health inequities or disparities ( Braveman, 2006 ) present in primary care.

In order to gain a better understanding of the effects of health promotion as an overall approach, and to understand the implications of the prevention paradox, it would be pertinent to include the non-eligible group in both the feedback loop—mainly offering them structured positive reinforcement—and to subsequently measure their health and attributed lifestyles.

The purpose of this study is to gain a better understanding of the role and extent of health promotion lifestyle interventions targeting adults in primary care, especially those who are considered overall healthy. More precisely we aim to assess to what extent health promotion practices in primary care address healthy individuals, not only those who need to undergo a lifestyle change. In order to do so, we performed a literature review, with three specific aims. First, to identify studies that have only targeted the healthy population, or healthy population in addition to high-risk group in intervention within the primary health care field with health promotion activities. Second, to describe these interventions in terms of which health problems they have targeted and what the interventions have entailed. Third, to assess what the initiatives published in the research literature have resulted in terms of health outcomes.

Due to the width of the topic and study designs we chose to perform a scoping review, with the aim of summarizing and disseminating previous research and identifying research gaps in the literature ( Arksey and O’Malley, 2005 ). The search process was iterative and non-linear, reflecting upon the results from the literature search at each stage and then repeating steps where necessary to cover the literature more comprehensively ( Arksey and O’Malley, 2005 ).

A few terms demand some further definition within the scope of this review . Healthy individual is a fluid term varying across different studies and contexts, yet it is a key concept in this particular study. The term involves those without chronic disease, who are indicated as not being of an elevated risk of developing a disease linked to the health outcome they have been screened for, but they could very well be at risk for diseases beyond the scope of the study they have been examined within. Primary health care may in this review indicates different types of settings from the most common one relating to general practitioners and family doctors to occupational medicine or periodical work-related health check-ups but also dental health care. Health promotion interventions in this study are understood as interventions that aim to keep people healthy longer, by providing positive feedback in relation to current and new health behaviours, rather than controlling health status by medication use.

Search strategy

The search was done across two databases PubMed and Embase, by combining different strings related to keywords ‘health promotion’ and ‘primary care’, while the rest of the strings varied, more specific search queries are available in Supplementary Appendix A . The search was conducted during June and July 2023 and consisted of publications dated between July 2008 and July 2023 (i.e. the last 15 years). Additional studies were identified manually from references of the included articles and by ‘See all similar articles’ option in PubMed and ‘similar records’ in Embase. The article titles were scanned from databases, followed by screening titles and abstracts through the Covidence software, and then finally the full articles were read. Results were filtered for adult humans, defined as age 18–75, abstracts being available and the studies were authored in English.

Articles were included if (i) the population consisted of working-age adults, (ii) the population included those screened as healthy within a whole sample followed by an intervention or interventions ideally at follow-up, (iii) the study focused on primary prevention (iv) the study focused on lifestyle interventions, (v) the study examined lifestyle-related behaviours. Exclusion criteria for papers were (i) focused on children—below the age of 18 or elderly, (ii) addiction behaviours, (iii) excluding healthy individuals from intervention after screening or using them exclusively in the control group, (iv) using only high-risk population as healthy, (v) promoting only mental health, (vi) secondary prevention, (vii) screening is the only intervention, (viii) reviews and study protocols.

After full-text screening, the data charting process for reviewing, sorting and documenting information ( Arksey and O’Malley, 2005 ) was done using Covidence, Data Extraction version 2 recommended for scoping reviews. The Data Extraction Template included columns for article title, author, country in which the study was conducted, methods (aim, design, population description, inclusion and exclusion criteria) intervention description, outcome measures, relevant results, follow-up (yes/no), study setting (primary care, worksite/occupational, population-based), study category (lifestyle, physical activity and diet, cardiovascular disease, alcohol consumption) and a field for additional notes where needed.

Due to great inconsistencies between studies in the design, populations and outcomes, critical appraisal of individual sources of evidence—an optional step in PRISMA-ScR ( Tricco et al ., 2018 ) guideline list was not done, although concerning research aim it would be useful for assessing the quality of evidence. Although exclusion/inclusion criteria were respected, what was considered as ‘healthy’, ‘middle-’ or ‘high-risk population’ differed significantly in studies, due to differences in definition of terms. Moreover, this decision was made as the AMSTAR tool would not be an adequate choice due to the inclusion of a non-randomized design, and although the AMSTAR 2 tool could potentially be used, this review also included several economic evaluations and follow-ups ( Supplementary Table S1 for more details), or indicators differing highly across studies.

For the synthesis of results ( Tricco et al ., 2018 ), the studies were grouped by the type of the outcome—disease, i.e. CVD or lifestyle/behaviour: physical activity and diet or alcohol consumption. Furthermore, the studies were summarized by setting, risk group and follow-up. None of the systematic reviews with similar research aims were detected during the search.

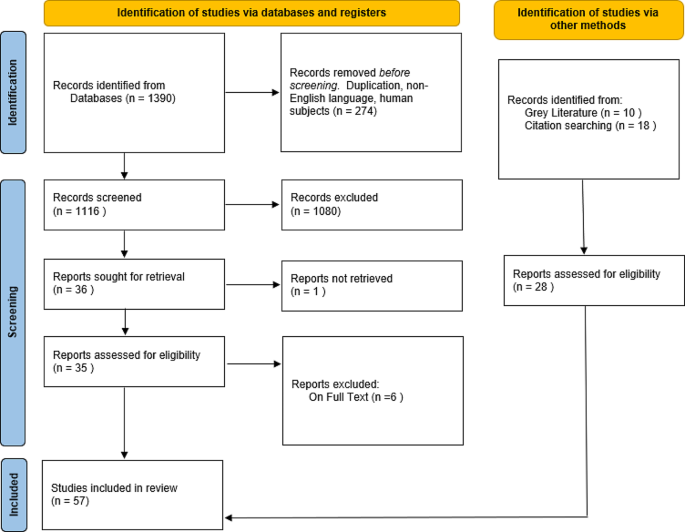

The selection of sources of evidence ( Tricco et al ., 2018 ) was done as described: 353 references were imported for screening, 72 duplicates were removed, 268 studies were screened against title and abstract during which 198 studies were excluded while 69 studies were assessed for full-text eligibility, when 27 studies were excluded: 12 for wrong intervention, 8 for wrong patient population, 4 for wrong study design 1 was not in English, 1 for wrong indication and 1 for wrong setting, after which 42 studies were included. PRISMA of full screening is found in Figure 1 .

PRISMA of full screening strategy.

Lifestyle interventions

A summary of the study setting, samples and the main outcomes of the 42 studies analysed in this scoping review is presented in Supplementary Table S1 .

In general, the intervention studies analysed here had different main strategies, including: individually tailored programs ( Doumas and Hannah, 2008 ; Gram et al ., 2012 ; Watson et al ., 2015 ) risk-based, group-based ( Recio-Rodriguez et al ., 2016 ) or mixed variants ( Matano et al ., 2007 ; Matzer et al ., 2018 ).

Cardiovascular health

We found several different lifestyle interventions targeting CVD risk. There were a set of programs that addressed physical activity in the workplace, which significantly reduced the CVD risk in healthy participants adhering to the program ( Gram et al ., 2012 ; Dalager et al ., 2016 ; Eng et al ., 2016 ; Biffi et al ., 2018 ). In primary care, an observational study by Journath et al . (2020) , showed an association between healthy participant participation in a CVD prevention programme promoting physical activity and a healthy lifestyle with lower risk of CV events (12%), CV mortality (21%) and all-cause mortality (17%) after 20 years of follow-up.

Similarly, we found interventions in primary care settings that led to changes in physical activity and dietary patterns among all participants—not only those at high risk of CVD morbidity and mortality. These studies described generally decreased CVD risks ( Richardson et al ., 2008 ; Buckland et al ., 2009 ; Nguyen et al ., 2012 ; Gibson et al ., 2014 ; Bo et al ., 2016 ; Lidin et al ., 2018 ; Lingfors and Persson, 2019 ), CVD-related mortality ( Blomstedt et al ., 2011 ; Persson et al ., 2015 ; Jeong et al ., 2019 ) and all-cause mortality ( Blomstedt et al ., 2015 ; Bo et al ., 2016 ; Bonaccio et al ., 2019 ).

In a prospective observational study on healthy individuals and those with CVD conducted by Lidin et al . (2018) , the prevalence within the sample at risk of CVD decreased significantly at 12-month follow-up by 15%. In several studies, the changes in health behaviours among the participants showed to be sustained in follow-ups conducted after intervention discontinuation ( Buckland et al ., 2009 ; Gibson et al ., 2014 ; Baumann et al ., 2015 ; Blomstedt et al ., 2015 ; Lidin et al ., 2018 ), while some cardiovascular risk factors, such as salty diets and smoking, showed evidence of significant decrease in a relatively short period ( Nguyen et al ., 2012 ).

Physical activity and diet

In interventions addressing physical activity and diet, it was evident that healthy individuals were more likely to adhere to physical activity interventions ( Dalager et al ., 2016 ; Biffi et al ., 2018 ; Jeong et al ., 2019 ) compared to those with a disease. One community-based walking intervention ( Yang and Kim, 2022 ) affected not only the level of physical activity significantly but also a positive overall change towards a health-promoting lifestyle and decreased perceived stress. Similarly, several mental health measures including general mental health ( Oude Hengel et al ., 2014 ), anxiety and depression ( Gibson et al ., 2014 ) and stress ( Lingfors et al ., 2009 ; Matzer et al ., 2018 ) in participants improved during interventions and at follow-up when targeting physical activity and diet.

Additionally, concerning physical activity and diet outcomes, there were a higher feasibility of uptake among participants in health promotion programs compared to those only receiving standard care in primary care ( Lingfors et al ., 2009 ; Zabaleta-Del-Olmo et al ., 2021 ). Anokye et al. (2014) argued that brief advice intervention was more effective—leading to 466 QALYs gained, compared to standard care—implying greater cost-effectiveness.

Healthier lifestyles were also maintained at the follow-up. Reduction in risk factors was found to be sustained in follow-ups at 12 months ( Gibson et al ., 2014 ) or improvements in dietary outcomes over 5 years ( Baumann et al ., 2015 ), and sustained lower blood pressure over 6 years ( Eng et al ., 2016 ).

Several interventions promoting physical activity in primary care settings showed significant results in increasing it in all patients, not only in those with chronic disease diagnosis ( Robroek et al ., 2010 ; Gram et al ., 2012 ; Hardcastle et al ., 2012 ; Viester et al ., 2015 ; Byrne et al ., 2016 ; Dalager et al ., 2016 ; Eng et al ., 2016 ; Recio-Rodriguez et al ., 2016 ; Biffi et al ., 2018 ; Matzer et al ., 2018 ; Yang and Kim, 2022 ), and similar patterns were also found concerning a change towards a healthier diet ( Lingfors et al ., 2009 ; Wendel-Vos et al ., 2009 ; Robroek et al ., 2010 ; Baumann et al ., 2015 ; Viester et al ., 2015 ; Bo et al ., 2016 ; Byrne et al ., 2016 ; Kosendiak et al ., 2021 ).

There was disagreement among the above studies in relation to the effectiveness of these interventions among healthy individuals. For example, in the case of implementing a Mediterranean diet, one report argued that a healthy diet should be prioritized, indicating significant hazard ratios (HR) of attaining a Mediterranean diet for all-cause mortality (HR = 0.83), CV mortality (HR = 0.75) and CV events (HR = 0.79) among low-risk individuals ( Bo et al ., 2016 ). Others, however, claimed that there was no evidence of healthier participants being more susceptible to changes in physical activity and diet ( Robroek et al ., 2010 ).

Alcohol consumption

Interventions aimed at decreasing alcohol consumption were divided between those being most effective in high-risk drinkers ( Doumas and Hannah, 2008 ; Kirkman et al ., 2018 ), and both moderate and low-risk drinkers ( Matano et al ., 2007 ). These interventions were, at large, seen as cost-saving ( Watson et al ., 2015 ) and feasible in primary care ( Neuner-Jehle et al ., 2013 ). Some studies found a sustained decrease in alcohol consumption in those adhering to the interventions, compared to the control groups at 1 ( Pemberton et al ., 2011 ) and 4 months after the intervention ( Kirkman et al ., 2018 ), whereas others failed to find a significant difference between groups.

Intervention setting

The interventions took place in primary care settings, though these were either in community-based or occupational settings. The findings suggested that there were some discrepancies between these different settings.

When it comes to a community-based setting, the difference is made between interventions conducted on a sample of those visiting primary health care or a sample representative for a population of one community—town, or region. Primary care community-based studies tended to either include participants who were primary care visitors with a long follow-up period, or interventions conducted in primary care clinic centres with a shorter follow-up period, most often using experimental design, sampling individuals living in the community that did not necessarily had an intention to seek care ( Richardson et al ., 2008 ; Hardcastle et al ., 2012 ; Nguyen et al ., 2012 ; Grunfeld et al ., 2013 ; Baumann et al ., 2015 ; Bo et al ., 2016 ; Lidin et al ., 2018 ; Zabaleta-Del-Olmo et al ., 2021 ).

Overall, the community-based studies were conducted on a sample representative for a population of a smaller community ( Kosendiak et al ., 2021 ; Yang and Kim, 2022 ), region ( Lingfors et al ., 2009 ; Wendel-Vos et al ., 2009 ; Gibson et al ., 2014 ; Persson et al ., 2015 ; Bonaccio et al ., 2019 ; Jeong et al ., 2019 ; Lingfors and Persson, 2019 ; Journath et al ., 2020 ) or a country ( Buckland et al ., 2009 ; Blomstedt et al ., 2011 ; Neuner-Jehle et al ., 2013 ), often followed by a longer follow-up period. Finally, some studies were evaluations of previous interventions ( Richardson et al ., 2008 ; Anokye et al ., 2014 ).

Worksite interventions comprised of different occupational roles, often including several of those in the same sample ( Eng et al ., 2016 ), or segmenting based on how physically active the occupation was, e.g. office workers ( Dalager et al ., 2016 ), construction workers ( Gram et al ., 2012 ; Oude Hengel et al ., 2014 ; Viester et al ., 2015 ), sailors ( Hjarnoe and Leppin, 2013 ), farmers ( van Doorn et al ., 2019 ) or simply more active individuals ( Biffi et al ., 2018 ). This had the implication that approaches to intervention differed widely across the studies.

Several interventions were conducted online using a web-based interface, while others were in a professional setting ( Matano et al ., 2007 ; Doumas and Hannah, 2008 ; Robroek et al ., 2010 ; Pemberton et al ., 2011 ; Khadjesari et al ., 2014 ) or in some cases community-based ( Recio-Rodriguez et al ., 2016 ; Kirkman et al ., 2018 ).

Categorization of risk among participants

Many studies applied specific risk criteria based on the participants’ morbidity risks: including groups of low, middle, high risk ( Persson et al ., 2015 ; Bo et al ., 2016 ; Lingfors and Persson, 2019 ), low and high risk ( Baumann et al ., 2015 ), middle and high risk ( Gibson et al ., 2014 ). While some did not distinguish between risk groups ( Wendel-Vos et al ., 2009 ; Blomstedt et al ., 2011 ; Byrne et al ., 2016 ; Journath et al ., 2020 ). In some studies, however, the protocol included mixed populations of those who were healthy and those who had a chronic disease ( Anokye et al ., 2014 ; Bonaccio et al ., 2019 ). Finally, different studies came up with their own meaning of ‘healthy individual’ or ‘healthy population’ based on the health problem they addressed, i.e. having a sedentary lifestyle or high alcohol consumption. Other criteria for being a part of a healthy population were having a high risk for a disease, one or several risks but not the disease itself, or being above a reference value without having a diagnosis.

Ethical implications of healthy controls

Some interventions were screening-result-based, meaning that there was a difference in the treatment of those with good health and those with some complications. In other words, although not excluding healthy individuals, the study protocol included healthy individuals partially receiving full treatment, in the intervention. Studies that excluded those who were healthy from the sample after screening or used them as a control group were excluded from this review. However, some included studies had a healthy control group. Overall, the studies included in this review did not discuss the ethical implications of including healthy populations as controls, or when that was the case, the ethical impact of excluding healthy participants from an intervention.

This scoping review speaks not only of the role and extent of health promotion for healthy individuals in primary care but also of the importance and effects it has on population health. The results showing the association of lifestyle interventions with CVD risk show great implications for future use in primary care, different contexts and feasibility. Physical activity interventions were additionally found to be related to some improvements in mental health.

Interventions aimed at alcohol consumption were found successful in decreasing the amount of drinking sustainably, while the main discussion was based on whether they should be aimed at high-risk only, or at middle- and low-risk drinkers as well, due to mixed results in said groups. The majority of interventions were based in a worksite setting, meaning that this context might be useful for tackling the issue. This approach showed that outcomes might be beneficial even when not reaching the primary goal. Examples of this are findings showing that although not reducing CVD risk, changes in health behaviours were sustained in follow-up ( Baumann et al ., 2015 ), less drastic changes decreasing CVD risk in the healthy population ( Buckland et al ., 2009 ) and beneficial effects of physical activity intervention on worker’s health without an overall increase in physical activity ( McEachan et al ., 2011 ). Finally, in most cases, as mentioned, changes in health behaviours were associated with changes in CVD risk.

Some interventions showed that health promotion benefits could be even bigger ( Bo et al ., 2016 ) or that adherence is higher in healthy participants ( Dalager et al ., 2016 ; Biffi et al ., 2018 ; Jeong et al ., 2019 ), while other authors disagree ( Robroek et al ., 2010 ). This could be traced to the topic of prioritising primary care for healthy, versus only those at high risk/ already with a disease—secondary care approach according to this review definitions. Designing interventions only for high-risk can make them less successful in healthy participants, as displayed in a study by Blomstedt et al . (2011) where self-rated health decreased in 21% of the good baseline health participants at the 10-year follow-up. Furthermore, from the Rose’s (1981) term of prevention paradox—a great benefit for the population can be almost non-existent for an individual, while if we only focus on high-risk cases, many individuals at low-risk can mean worse health outcomes compared to a small number at high-risk ( Rose, 2001 ). In other words, by focusing only on high-risk population, the downsides are care that can be less efficient, less feasible, more expensive and lead to worse health outcomes. This choice should not be exclusive, as excluding either populations can cause ethical concerns. However, this article gives priority to early prevention, by health promotion for healthy individuals in primary care. Additionally, if it is shown that ‘ Systems based on primary care have better population health, health equity, and health care quality, and lower health care expenditure… ’ ( Stange et al. , 2023 ), different treatment of those who are currently healthy presents an obstacle worth mentioning for achieving health equity in primary care. Furthermore, the role of promoting health to healthy populations and their inclusion in interventions is crucial for improving population health in the future.

Articles focusing on smoking cessation, alcoholism, substance misuse interventions were excluded from this scoping review as they represent addictions and are therefore different from lifestyle interventions. Originally, oral health and dental care interventions were to be included, but there were not enough studies matching the scoping review inclusion requirements.

As expected, the process of finding articles appropriate for inclusion was challenging. Even when the inclusion criteria, at first glance, were satisfied, most studies we came across had excluded healthy participants from the sample after screening for being asymptomatic or not having enough risk factors. They were, however, often a part of a control group, and usually received standard care or no care at all. This approach puts healthy individuals in a vulnerable position, by not addressing their needs to change lifestyles that eventually could contribute to an early death or becoming unwell. Our findings suggest that interventions that include healthy individuals could improve quality of life and health status both at the population and individual levels.

Due to studies using different risk criteria, as well as including many study designs and topics, it was hard to make general conclusions. Nevertheless, as a scoping review, we mapped the area of research by identifying the gaps in the evidence base, and summarizing and disseminating research findings ( Arksey and O’Malley, 2005 ), instead of appraising the quality of evidence in different studies.

Concerning the above, a big research gap was detected in studies focusing on, or even including healthy populations. Furthermore, there is a lack of a coherent or comprehensive methodology in assessing the effects of what is considered health promotion, which calls for a more specific approach and a clear definition of the term. Additionally, the question of intervention staff skills should be raised. Is it necessary that health promotion interventions should be conducted by clinically trained professionals or, innovatively, by staff trained in the topic at hand when possible? Another aspect that is important to problematize is whether it is ethical to exclude healthy individuals in health promotion intervention studies even if they would benefit from participating if included? Furthermore, if healthy individuals are systematically discriminated ( Braveman, 2006 ), receive worse treatment and have the risk of worse health outcomes in the future, it is critical to include them in interventions for achieving better health of populations. This has great practical implications for primary care. Similarly, from a cost-benefit perspective, research should address if excluding healthy individuals might affect the cost-effectiveness of health promotion interventions.

An apparent limitation within this review is the culturally uniform sample of studies. Most studies that we were able to identify were a result of research in the global north, with a strong emphasis on either North America or the EU. Only two studies were from less affluent settings in Southeast Asia ( Nguyen et al ., 2012 ; Bo et al ., 2016 ). Given that the findings suggest that these interventions are cost-effective and do not require substantial investments, these programs could have great potential in low-resource settings if more systematically researched.

This scoping review of 42 studies applying salutogenesis in primary care interventions shows that health promotion targeting healthy individuals is relevant and effective. Most interventions were successful in reducing disease-related risks including CVD, CVD mortality, all-cause mortality, but even more importantly success in behavioural change, sustained at follow-up. Additionally, this review shows that health promotion lifestyle interventions can improve mental health, even when having different aims.

Supplementary material is available at Health Promotion International online.

A.B. performed the literature search, performed most of the data analysis and was the major contributor in writing the Methods and Results sections of the manuscript. M.S. formulated the research questions and scope of the study. He gave considerable input to the data analysis, gave input on all sections of the study—including writing and editing—and was the main author of the Introduction and Discussion. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

We would like to express our gratitude to Maria Björklund, librarian, at the Faculty of Medicine Library, Lund University at CRC in Malmö, who assisted us in the literature search.

A.B.’s contribution was in part funded by a scholarship she received from the Faculty of Medicine and in part by internal funds at the Division of Social Medicine and Global Health, Lund University, the latter also funded M.S.’s contribution.

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material.