Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

How to Write a Research Paper Introduction (with Examples)

The research paper introduction section, along with the Title and Abstract, can be considered the face of any research paper. The following article is intended to guide you in organizing and writing the research paper introduction for a quality academic article or dissertation.

The research paper introduction aims to present the topic to the reader. A study will only be accepted for publishing if you can ascertain that the available literature cannot answer your research question. So it is important to ensure that you have read important studies on that particular topic, especially those within the last five to ten years, and that they are properly referenced in this section. 1 What should be included in the research paper introduction is decided by what you want to tell readers about the reason behind the research and how you plan to fill the knowledge gap. The best research paper introduction provides a systemic review of existing work and demonstrates additional work that needs to be done. It needs to be brief, captivating, and well-referenced; a well-drafted research paper introduction will help the researcher win half the battle.

The introduction for a research paper is where you set up your topic and approach for the reader. It has several key goals:

- Present your research topic

- Capture reader interest

- Summarize existing research

- Position your own approach

- Define your specific research problem and problem statement

- Highlight the novelty and contributions of the study

- Give an overview of the paper’s structure

The research paper introduction can vary in size and structure depending on whether your paper presents the results of original empirical research or is a review paper. Some research paper introduction examples are only half a page while others are a few pages long. In many cases, the introduction will be shorter than all of the other sections of your paper; its length depends on the size of your paper as a whole.

- Break through writer’s block. Write your research paper introduction with Paperpal Copilot

Table of Contents

What is the introduction for a research paper, why is the introduction important in a research paper, craft a compelling introduction section with paperpal. try now, 1. introduce the research topic:, 2. determine a research niche:, 3. place your research within the research niche:, craft accurate research paper introductions with paperpal. start writing now, frequently asked questions on research paper introduction, key points to remember.

The introduction in a research paper is placed at the beginning to guide the reader from a broad subject area to the specific topic that your research addresses. They present the following information to the reader

- Scope: The topic covered in the research paper

- Context: Background of your topic

- Importance: Why your research matters in that particular area of research and the industry problem that can be targeted

The research paper introduction conveys a lot of information and can be considered an essential roadmap for the rest of your paper. A good introduction for a research paper is important for the following reasons:

- It stimulates your reader’s interest: A good introduction section can make your readers want to read your paper by capturing their interest. It informs the reader what they are going to learn and helps determine if the topic is of interest to them.

- It helps the reader understand the research background: Without a clear introduction, your readers may feel confused and even struggle when reading your paper. A good research paper introduction will prepare them for the in-depth research to come. It provides you the opportunity to engage with the readers and demonstrate your knowledge and authority on the specific topic.

- It explains why your research paper is worth reading: Your introduction can convey a lot of information to your readers. It introduces the topic, why the topic is important, and how you plan to proceed with your research.

- It helps guide the reader through the rest of the paper: The research paper introduction gives the reader a sense of the nature of the information that will support your arguments and the general organization of the paragraphs that will follow. It offers an overview of what to expect when reading the main body of your paper.

What are the parts of introduction in the research?

A good research paper introduction section should comprise three main elements: 2

- What is known: This sets the stage for your research. It informs the readers of what is known on the subject.

- What is lacking: This is aimed at justifying the reason for carrying out your research. This could involve investigating a new concept or method or building upon previous research.

- What you aim to do: This part briefly states the objectives of your research and its major contributions. Your detailed hypothesis will also form a part of this section.

How to write a research paper introduction?

The first step in writing the research paper introduction is to inform the reader what your topic is and why it’s interesting or important. This is generally accomplished with a strong opening statement. The second step involves establishing the kinds of research that have been done and ending with limitations or gaps in the research that you intend to address. Finally, the research paper introduction clarifies how your own research fits in and what problem it addresses. If your research involved testing hypotheses, these should be stated along with your research question. The hypothesis should be presented in the past tense since it will have been tested by the time you are writing the research paper introduction.

The following key points, with examples, can guide you when writing the research paper introduction section:

- Highlight the importance of the research field or topic

- Describe the background of the topic

- Present an overview of current research on the topic

Example: The inclusion of experiential and competency-based learning has benefitted electronics engineering education. Industry partnerships provide an excellent alternative for students wanting to engage in solving real-world challenges. Industry-academia participation has grown in recent years due to the need for skilled engineers with practical training and specialized expertise. However, from the educational perspective, many activities are needed to incorporate sustainable development goals into the university curricula and consolidate learning innovation in universities.

- Reveal a gap in existing research or oppose an existing assumption

- Formulate the research question

Example: There have been plausible efforts to integrate educational activities in higher education electronics engineering programs. However, very few studies have considered using educational research methods for performance evaluation of competency-based higher engineering education, with a focus on technical and or transversal skills. To remedy the current need for evaluating competencies in STEM fields and providing sustainable development goals in engineering education, in this study, a comparison was drawn between study groups without and with industry partners.

- State the purpose of your study

- Highlight the key characteristics of your study

- Describe important results

- Highlight the novelty of the study.

- Offer a brief overview of the structure of the paper.

Example: The study evaluates the main competency needed in the applied electronics course, which is a fundamental core subject for many electronics engineering undergraduate programs. We compared two groups, without and with an industrial partner, that offered real-world projects to solve during the semester. This comparison can help determine significant differences in both groups in terms of developing subject competency and achieving sustainable development goals.

Write a Research Paper Introduction in Minutes with Paperpal

Paperpal Copilot is a generative AI-powered academic writing assistant. It’s trained on millions of published scholarly articles and over 20 years of STM experience. Paperpal Copilot helps authors write better and faster with:

- Real-time writing suggestions

- In-depth checks for language and grammar correction

- Paraphrasing to add variety, ensure academic tone, and trim text to meet journal limits

With Paperpal Copilot, create a research paper introduction effortlessly. In this step-by-step guide, we’ll walk you through how Paperpal transforms your initial ideas into a polished and publication-ready introduction.

How to use Paperpal to write the Introduction section

Step 1: Sign up on Paperpal and click on the Copilot feature, under this choose Outlines > Research Article > Introduction

Step 2: Add your unstructured notes or initial draft, whether in English or another language, to Paperpal, which is to be used as the base for your content.

Step 3: Fill in the specifics, such as your field of study, brief description or details you want to include, which will help the AI generate the outline for your Introduction.

Step 4: Use this outline and sentence suggestions to develop your content, adding citations where needed and modifying it to align with your specific research focus.

Step 5: Turn to Paperpal’s granular language checks to refine your content, tailor it to reflect your personal writing style, and ensure it effectively conveys your message.

You can use the same process to develop each section of your article, and finally your research paper in half the time and without any of the stress.

The purpose of the research paper introduction is to introduce the reader to the problem definition, justify the need for the study, and describe the main theme of the study. The aim is to gain the reader’s attention by providing them with necessary background information and establishing the main purpose and direction of the research.

The length of the research paper introduction can vary across journals and disciplines. While there are no strict word limits for writing the research paper introduction, an ideal length would be one page, with a maximum of 400 words over 1-4 paragraphs. Generally, it is one of the shorter sections of the paper as the reader is assumed to have at least a reasonable knowledge about the topic. 2 For example, for a study evaluating the role of building design in ensuring fire safety, there is no need to discuss definitions and nature of fire in the introduction; you could start by commenting upon the existing practices for fire safety and how your study will add to the existing knowledge and practice.

When deciding what to include in the research paper introduction, the rest of the paper should also be considered. The aim is to introduce the reader smoothly to the topic and facilitate an easy read without much dependency on external sources. 3 Below is a list of elements you can include to prepare a research paper introduction outline and follow it when you are writing the research paper introduction. Topic introduction: This can include key definitions and a brief history of the topic. Research context and background: Offer the readers some general information and then narrow it down to specific aspects. Details of the research you conducted: A brief literature review can be included to support your arguments or line of thought. Rationale for the study: This establishes the relevance of your study and establishes its importance. Importance of your research: The main contributions are highlighted to help establish the novelty of your study Research hypothesis: Introduce your research question and propose an expected outcome. Organization of the paper: Include a short paragraph of 3-4 sentences that highlights your plan for the entire paper

Cite only works that are most relevant to your topic; as a general rule, you can include one to three. Note that readers want to see evidence of original thinking. So it is better to avoid using too many references as it does not leave much room for your personal standpoint to shine through. Citations in your research paper introduction support the key points, and the number of citations depend on the subject matter and the point discussed. If the research paper introduction is too long or overflowing with citations, it is better to cite a few review articles rather than the individual articles summarized in the review. A good point to remember when citing research papers in the introduction section is to include at least one-third of the references in the introduction.

The literature review plays a significant role in the research paper introduction section. A good literature review accomplishes the following: Introduces the topic – Establishes the study’s significance – Provides an overview of the relevant literature – Provides context for the study using literature – Identifies knowledge gaps However, remember to avoid making the following mistakes when writing a research paper introduction: Do not use studies from the literature review to aggressively support your research Avoid direct quoting Do not allow literature review to be the focus of this section. Instead, the literature review should only aid in setting a foundation for the manuscript.

Remember the following key points for writing a good research paper introduction: 4

- Avoid stuffing too much general information: Avoid including what an average reader would know and include only that information related to the problem being addressed in the research paper introduction. For example, when describing a comparative study of non-traditional methods for mechanical design optimization, information related to the traditional methods and differences between traditional and non-traditional methods would not be relevant. In this case, the introduction for the research paper should begin with the state-of-the-art non-traditional methods and methods to evaluate the efficiency of newly developed algorithms.

- Avoid packing too many references: Cite only the required works in your research paper introduction. The other works can be included in the discussion section to strengthen your findings.

- Avoid extensive criticism of previous studies: Avoid being overly critical of earlier studies while setting the rationale for your study. A better place for this would be the Discussion section, where you can highlight the advantages of your method.

- Avoid describing conclusions of the study: When writing a research paper introduction remember not to include the findings of your study. The aim is to let the readers know what question is being answered. The actual answer should only be given in the Results and Discussion section.

To summarize, the research paper introduction section should be brief yet informative. It should convince the reader the need to conduct the study and motivate him to read further. If you’re feeling stuck or unsure, choose trusted AI academic writing assistants like Paperpal to effortlessly craft your research paper introduction and other sections of your research article.

1. Jawaid, S. A., & Jawaid, M. (2019). How to write introduction and discussion. Saudi Journal of Anaesthesia, 13(Suppl 1), S18.

2. Dewan, P., & Gupta, P. (2016). Writing the title, abstract and introduction: Looks matter!. Indian pediatrics, 53, 235-241.

3. Cetin, S., & Hackam, D. J. (2005). An approach to the writing of a scientific Manuscript1. Journal of Surgical Research, 128(2), 165-167.

4. Bavdekar, S. B. (2015). Writing introduction: Laying the foundations of a research paper. Journal of the Association of Physicians of India, 63(7), 44-6.

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- Scientific Writing Style Guides Explained

- 5 Reasons for Rejection After Peer Review

- Ethical Research Practices For Research with Human Subjects

- 8 Most Effective Ways to Increase Motivation for Thesis Writing

Practice vs. Practise: Learn the Difference

Academic paraphrasing: why paperpal’s rewrite should be your first choice , you may also like, how to write a high-quality conference paper, academic editing: how to self-edit academic text with..., measuring academic success: definition & strategies for excellence, phd qualifying exam: tips for success , ai in education: it’s time to change the..., is it ethical to use ai-generated abstracts without..., what are journal guidelines on using generative ai..., quillbot review: features, pricing, and free alternatives, what is an academic paper types and elements , should you use ai tools like chatgpt for....

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Paper Introduction – Writing Guide and Examples

Research Paper Introduction – Writing Guide and Examples

Table of Contents

Research Paper Introduction

Research paper introduction is the first section of a research paper that provides an overview of the study, its purpose, and the research question (s) or hypothesis (es) being investigated. It typically includes background information about the topic, a review of previous research in the field, and a statement of the research objectives. The introduction is intended to provide the reader with a clear understanding of the research problem, why it is important, and how the study will contribute to existing knowledge in the field. It also sets the tone for the rest of the paper and helps to establish the author’s credibility and expertise on the subject.

How to Write Research Paper Introduction

Writing an introduction for a research paper can be challenging because it sets the tone for the entire paper. Here are some steps to follow to help you write an effective research paper introduction:

- Start with a hook : Begin your introduction with an attention-grabbing statement, a question, or a surprising fact that will make the reader interested in reading further.

- Provide background information: After the hook, provide background information on the topic. This information should give the reader a general idea of what the topic is about and why it is important.

- State the research problem: Clearly state the research problem or question that the paper addresses. This should be done in a concise and straightforward manner.

- State the research objectives: After stating the research problem, clearly state the research objectives. This will give the reader an idea of what the paper aims to achieve.

- Provide a brief overview of the paper: At the end of the introduction, provide a brief overview of the paper. This should include a summary of the main points that will be discussed in the paper.

- Revise and refine: Finally, revise and refine your introduction to ensure that it is clear, concise, and engaging.

Structure of Research Paper Introduction

The following is a typical structure for a research paper introduction:

- Background Information: This section provides an overview of the topic of the research paper, including relevant background information and any previous research that has been done on the topic. It helps to give the reader a sense of the context for the study.

- Problem Statement: This section identifies the specific problem or issue that the research paper is addressing. It should be clear and concise, and it should articulate the gap in knowledge that the study aims to fill.

- Research Question/Hypothesis : This section states the research question or hypothesis that the study aims to answer. It should be specific and focused, and it should clearly connect to the problem statement.

- Significance of the Study: This section explains why the research is important and what the potential implications of the study are. It should highlight the contribution that the research makes to the field.

- Methodology: This section describes the research methods that were used to conduct the study. It should be detailed enough to allow the reader to understand how the study was conducted and to evaluate the validity of the results.

- Organization of the Paper : This section provides a brief overview of the structure of the research paper. It should give the reader a sense of what to expect in each section of the paper.

Research Paper Introduction Examples

Research Paper Introduction Examples could be:

Example 1: In recent years, the use of artificial intelligence (AI) has become increasingly prevalent in various industries, including healthcare. AI algorithms are being developed to assist with medical diagnoses, treatment recommendations, and patient monitoring. However, as the use of AI in healthcare grows, ethical concerns regarding privacy, bias, and accountability have emerged. This paper aims to explore the ethical implications of AI in healthcare and propose recommendations for addressing these concerns.

Example 2: Climate change is one of the most pressing issues facing our planet today. The increasing concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere has resulted in rising temperatures, changing weather patterns, and other environmental impacts. In this paper, we will review the scientific evidence on climate change, discuss the potential consequences of inaction, and propose solutions for mitigating its effects.

Example 3: The rise of social media has transformed the way we communicate and interact with each other. While social media platforms offer many benefits, including increased connectivity and access to information, they also present numerous challenges. In this paper, we will examine the impact of social media on mental health, privacy, and democracy, and propose solutions for addressing these issues.

Example 4: The use of renewable energy sources has become increasingly important in the face of climate change and environmental degradation. While renewable energy technologies offer many benefits, including reduced greenhouse gas emissions and energy independence, they also present numerous challenges. In this paper, we will assess the current state of renewable energy technology, discuss the economic and political barriers to its adoption, and propose solutions for promoting the widespread use of renewable energy.

Purpose of Research Paper Introduction

The introduction section of a research paper serves several important purposes, including:

- Providing context: The introduction should give readers a general understanding of the topic, including its background, significance, and relevance to the field.

- Presenting the research question or problem: The introduction should clearly state the research question or problem that the paper aims to address. This helps readers understand the purpose of the study and what the author hopes to accomplish.

- Reviewing the literature: The introduction should summarize the current state of knowledge on the topic, highlighting the gaps and limitations in existing research. This shows readers why the study is important and necessary.

- Outlining the scope and objectives of the study: The introduction should describe the scope and objectives of the study, including what aspects of the topic will be covered, what data will be collected, and what methods will be used.

- Previewing the main findings and conclusions : The introduction should provide a brief overview of the main findings and conclusions that the study will present. This helps readers anticipate what they can expect to learn from the paper.

When to Write Research Paper Introduction

The introduction of a research paper is typically written after the research has been conducted and the data has been analyzed. This is because the introduction should provide an overview of the research problem, the purpose of the study, and the research questions or hypotheses that will be investigated.

Once you have a clear understanding of the research problem and the questions that you want to explore, you can begin to write the introduction. It’s important to keep in mind that the introduction should be written in a way that engages the reader and provides a clear rationale for the study. It should also provide context for the research by reviewing relevant literature and explaining how the study fits into the larger field of research.

Advantages of Research Paper Introduction

The introduction of a research paper has several advantages, including:

- Establishing the purpose of the research: The introduction provides an overview of the research problem, question, or hypothesis, and the objectives of the study. This helps to clarify the purpose of the research and provide a roadmap for the reader to follow.

- Providing background information: The introduction also provides background information on the topic, including a review of relevant literature and research. This helps the reader understand the context of the study and how it fits into the broader field of research.

- Demonstrating the significance of the research: The introduction also explains why the research is important and relevant. This helps the reader understand the value of the study and why it is worth reading.

- Setting expectations: The introduction sets the tone for the rest of the paper and prepares the reader for what is to come. This helps the reader understand what to expect and how to approach the paper.

- Grabbing the reader’s attention: A well-written introduction can grab the reader’s attention and make them interested in reading further. This is important because it can help to keep the reader engaged and motivated to read the rest of the paper.

- Creating a strong first impression: The introduction is the first part of the research paper that the reader will see, and it can create a strong first impression. A well-written introduction can make the reader more likely to take the research seriously and view it as credible.

- Establishing the author’s credibility: The introduction can also establish the author’s credibility as a researcher. By providing a clear and thorough overview of the research problem and relevant literature, the author can demonstrate their expertise and knowledge in the field.

- Providing a structure for the paper: The introduction can also provide a structure for the rest of the paper. By outlining the main sections and sub-sections of the paper, the introduction can help the reader navigate the paper and find the information they are looking for.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and...

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and...

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Research Paper Title – Writing Guide and Example

Research Paper Conclusion – Writing Guide and...

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 4. The Introduction

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The introduction leads the reader from a general subject area to a particular topic of inquiry. It establishes the scope, context, and significance of the research being conducted by summarizing current understanding and background information about the topic, stating the purpose of the work in the form of the research problem supported by a hypothesis or a set of questions, explaining briefly the methodological approach used to examine the research problem, highlighting the potential outcomes your study can reveal, and outlining the remaining structure and organization of the paper.

Key Elements of the Research Proposal. Prepared under the direction of the Superintendent and by the 2010 Curriculum Design and Writing Team. Baltimore County Public Schools.

Importance of a Good Introduction

Think of the introduction as a mental road map that must answer for the reader these four questions:

- What was I studying?

- Why was this topic important to investigate?

- What did we know about this topic before I did this study?

- How will this study advance new knowledge or new ways of understanding?

According to Reyes, there are three overarching goals of a good introduction: 1) ensure that you summarize prior studies about the topic in a manner that lays a foundation for understanding the research problem; 2) explain how your study specifically addresses gaps in the literature, insufficient consideration of the topic, or other deficiency in the literature; and, 3) note the broader theoretical, empirical, and/or policy contributions and implications of your research.

A well-written introduction is important because, quite simply, you never get a second chance to make a good first impression. The opening paragraphs of your paper will provide your readers with their initial impressions about the logic of your argument, your writing style, the overall quality of your research, and, ultimately, the validity of your findings and conclusions. A vague, disorganized, or error-filled introduction will create a negative impression, whereas, a concise, engaging, and well-written introduction will lead your readers to think highly of your analytical skills, your writing style, and your research approach. All introductions should conclude with a brief paragraph that describes the organization of the rest of the paper.

Hirano, Eliana. “Research Article Introductions in English for Specific Purposes: A Comparison between Brazilian, Portuguese, and English.” English for Specific Purposes 28 (October 2009): 240-250; Samraj, B. “Introductions in Research Articles: Variations Across Disciplines.” English for Specific Purposes 21 (2002): 1–17; Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; “Writing Introductions.” In Good Essay Writing: A Social Sciences Guide. Peter Redman. 4th edition. (London: Sage, 2011), pp. 63-70; Reyes, Victoria. Demystifying the Journal Article. Inside Higher Education.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Structure and Approach

The introduction is the broad beginning of the paper that answers three important questions for the reader:

- What is this?

- Why should I read it?

- What do you want me to think about / consider doing / react to?

Think of the structure of the introduction as an inverted triangle of information that lays a foundation for understanding the research problem. Organize the information so as to present the more general aspects of the topic early in the introduction, then narrow your analysis to more specific topical information that provides context, finally arriving at your research problem and the rationale for studying it [often written as a series of key questions to be addressed or framed as a hypothesis or set of assumptions to be tested] and, whenever possible, a description of the potential outcomes your study can reveal.

These are general phases associated with writing an introduction: 1. Establish an area to research by:

- Highlighting the importance of the topic, and/or

- Making general statements about the topic, and/or

- Presenting an overview on current research on the subject.

2. Identify a research niche by:

- Opposing an existing assumption, and/or

- Revealing a gap in existing research, and/or

- Formulating a research question or problem, and/or

- Continuing a disciplinary tradition.

3. Place your research within the research niche by:

- Stating the intent of your study,

- Outlining the key characteristics of your study,

- Describing important results, and

- Giving a brief overview of the structure of the paper.

NOTE: It is often useful to review the introduction late in the writing process. This is appropriate because outcomes are unknown until you've completed the study. After you complete writing the body of the paper, go back and review introductory descriptions of the structure of the paper, the method of data gathering, the reporting and analysis of results, and the conclusion. Reviewing and, if necessary, rewriting the introduction ensures that it correctly matches the overall structure of your final paper.

II. Delimitations of the Study

Delimitations refer to those characteristics that limit the scope and define the conceptual boundaries of your research . This is determined by the conscious exclusionary and inclusionary decisions you make about how to investigate the research problem. In other words, not only should you tell the reader what it is you are studying and why, but you must also acknowledge why you rejected alternative approaches that could have been used to examine the topic.

Obviously, the first limiting step was the choice of research problem itself. However, implicit are other, related problems that could have been chosen but were rejected. These should be noted in the conclusion of your introduction. For example, a delimitating statement could read, "Although many factors can be understood to impact the likelihood young people will vote, this study will focus on socioeconomic factors related to the need to work full-time while in school." The point is not to document every possible delimiting factor, but to highlight why previously researched issues related to the topic were not addressed.

Examples of delimitating choices would be:

- The key aims and objectives of your study,

- The research questions that you address,

- The variables of interest [i.e., the various factors and features of the phenomenon being studied],

- The method(s) of investigation,

- The time period your study covers, and

- Any relevant alternative theoretical frameworks that could have been adopted.

Review each of these decisions. Not only do you clearly establish what you intend to accomplish in your research, but you should also include a declaration of what the study does not intend to cover. In the latter case, your exclusionary decisions should be based upon criteria understood as, "not interesting"; "not directly relevant"; “too problematic because..."; "not feasible," and the like. Make this reasoning explicit!

NOTE: Delimitations refer to the initial choices made about the broader, overall design of your study and should not be confused with documenting the limitations of your study discovered after the research has been completed.

ANOTHER NOTE: Do not view delimitating statements as admitting to an inherent failing or shortcoming in your research. They are an accepted element of academic writing intended to keep the reader focused on the research problem by explicitly defining the conceptual boundaries and scope of your study. It addresses any critical questions in the reader's mind of, "Why the hell didn't the author examine this?"

III. The Narrative Flow

Issues to keep in mind that will help the narrative flow in your introduction :

- Your introduction should clearly identify the subject area of interest . A simple strategy to follow is to use key words from your title in the first few sentences of the introduction. This will help focus the introduction on the topic at the appropriate level and ensures that you get to the subject matter quickly without losing focus, or discussing information that is too general.

- Establish context by providing a brief and balanced review of the pertinent published literature that is available on the subject. The key is to summarize for the reader what is known about the specific research problem before you did your analysis. This part of your introduction should not represent a comprehensive literature review--that comes next. It consists of a general review of the important, foundational research literature [with citations] that establishes a foundation for understanding key elements of the research problem. See the drop-down menu under this tab for " Background Information " regarding types of contexts.

- Clearly state the hypothesis that you investigated . When you are first learning to write in this format it is okay, and actually preferable, to use a past statement like, "The purpose of this study was to...." or "We investigated three possible mechanisms to explain the...."

- Why did you choose this kind of research study or design? Provide a clear statement of the rationale for your approach to the problem studied. This will usually follow your statement of purpose in the last paragraph of the introduction.

IV. Engaging the Reader

A research problem in the social sciences can come across as dry and uninteresting to anyone unfamiliar with the topic . Therefore, one of the goals of your introduction is to make readers want to read your paper. Here are several strategies you can use to grab the reader's attention:

- Open with a compelling story . Almost all research problems in the social sciences, no matter how obscure or esoteric , are really about the lives of people. Telling a story that humanizes an issue can help illuminate the significance of the problem and help the reader empathize with those affected by the condition being studied.

- Include a strong quotation or a vivid, perhaps unexpected, anecdote . During your review of the literature, make note of any quotes or anecdotes that grab your attention because they can used in your introduction to highlight the research problem in a captivating way.

- Pose a provocative or thought-provoking question . Your research problem should be framed by a set of questions to be addressed or hypotheses to be tested. However, a provocative question can be presented in the beginning of your introduction that challenges an existing assumption or compels the reader to consider an alternative viewpoint that helps establish the significance of your study.

- Describe a puzzling scenario or incongruity . This involves highlighting an interesting quandary concerning the research problem or describing contradictory findings from prior studies about a topic. Posing what is essentially an unresolved intellectual riddle about the problem can engage the reader's interest in the study.

- Cite a stirring example or case study that illustrates why the research problem is important . Draw upon the findings of others to demonstrate the significance of the problem and to describe how your study builds upon or offers alternatives ways of investigating this prior research.

NOTE: It is important that you choose only one of the suggested strategies for engaging your readers. This avoids giving an impression that your paper is more flash than substance and does not distract from the substance of your study.

Freedman, Leora and Jerry Plotnick. Introductions and Conclusions. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Introduction. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Introductions. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Introductions, Body Paragraphs, and Conclusions for an Argument Paper. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; “Writing Introductions.” In Good Essay Writing: A Social Sciences Guide . Peter Redman. 4th edition. (London: Sage, 2011), pp. 63-70; Resources for Writers: Introduction Strategies. Program in Writing and Humanistic Studies. Massachusetts Institute of Technology; Sharpling, Gerald. Writing an Introduction. Centre for Applied Linguistics, University of Warwick; Samraj, B. “Introductions in Research Articles: Variations Across Disciplines.” English for Specific Purposes 21 (2002): 1–17; Swales, John and Christine B. Feak. Academic Writing for Graduate Students: Essential Skills and Tasks . 2nd edition. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2004 ; Writing Your Introduction. Department of English Writing Guide. George Mason University.

Writing Tip

Avoid the "Dictionary" Introduction

Giving the dictionary definition of words related to the research problem may appear appropriate because it is important to define specific terminology that readers may be unfamiliar with. However, anyone can look a word up in the dictionary and a general dictionary is not a particularly authoritative source because it doesn't take into account the context of your topic and doesn't offer particularly detailed information. Also, placed in the context of a particular discipline, a term or concept may have a different meaning than what is found in a general dictionary. If you feel that you must seek out an authoritative definition, use a subject specific dictionary or encyclopedia [e.g., if you are a sociology student, search for dictionaries of sociology]. A good database for obtaining definitive definitions of concepts or terms is Credo Reference .

Saba, Robert. The College Research Paper. Florida International University; Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina.

Another Writing Tip

When Do I Begin?

A common question asked at the start of any paper is, "Where should I begin?" An equally important question to ask yourself is, "When do I begin?" Research problems in the social sciences rarely rest in isolation from history. Therefore, it is important to lay a foundation for understanding the historical context underpinning the research problem. However, this information should be brief and succinct and begin at a point in time that illustrates the study's overall importance. For example, a study that investigates coffee cultivation and export in West Africa as a key stimulus for local economic growth needs to describe the beginning of exporting coffee in the region and establishing why economic growth is important. You do not need to give a long historical explanation about coffee exports in Africa. If a research problem requires a substantial exploration of the historical context, do this in the literature review section. In your introduction, make note of this as part of the "roadmap" [see below] that you use to describe the organization of your paper.

Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; “Writing Introductions.” In Good Essay Writing: A Social Sciences Guide . Peter Redman. 4th edition. (London: Sage, 2011), pp. 63-70.

Yet Another Writing Tip

Always End with a Roadmap

The final paragraph or sentences of your introduction should forecast your main arguments and conclusions and provide a brief description of the rest of the paper [the "roadmap"] that let's the reader know where you are going and what to expect. A roadmap is important because it helps the reader place the research problem within the context of their own perspectives about the topic. In addition, concluding your introduction with an explicit roadmap tells the reader that you have a clear understanding of the structural purpose of your paper. In this way, the roadmap acts as a type of promise to yourself and to your readers that you will follow a consistent and coherent approach to addressing the topic of inquiry. Refer to it often to help keep your writing focused and organized.

Cassuto, Leonard. “On the Dissertation: How to Write the Introduction.” The Chronicle of Higher Education , May 28, 2018; Radich, Michael. A Student's Guide to Writing in East Asian Studies . (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Writing n. d.), pp. 35-37.

- << Previous: Executive Summary

- Next: The C.A.R.S. Model >>

- Last Updated: May 25, 2024 4:09 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

How to Write the Introduction to a Scientific Paper?

- Open Access

- First Online: 24 October 2021

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Samiran Nundy 4 ,

- Atul Kakar 5 &

- Zulfiqar A. Bhutta 6

142 Altmetric

An Introduction to a scientific paper familiarizes the reader with the background of the issue at hand. It must reflect why the issue is topical and its current importance in the vast sea of research being done globally. It lays the foundation of biomedical writing and is the first portion of an article according to the IMRAD pattern ( I ntroduction, M ethodology, R esults, a nd D iscussion) [1].

I once had a professor tell a class that he sifted through our pile of essays, glancing at the titles and introductions, looking for something that grabbed his attention. Everything else went to the bottom of the pile to be read last, when he was tired and probably grumpy from all the marking. Don’t get put at the bottom of the pile, he said. Anonymous

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

The Introduction Section

Abstract and Keywords

Writing and publishing a scientific paper

1 what is the importance of an introduction.

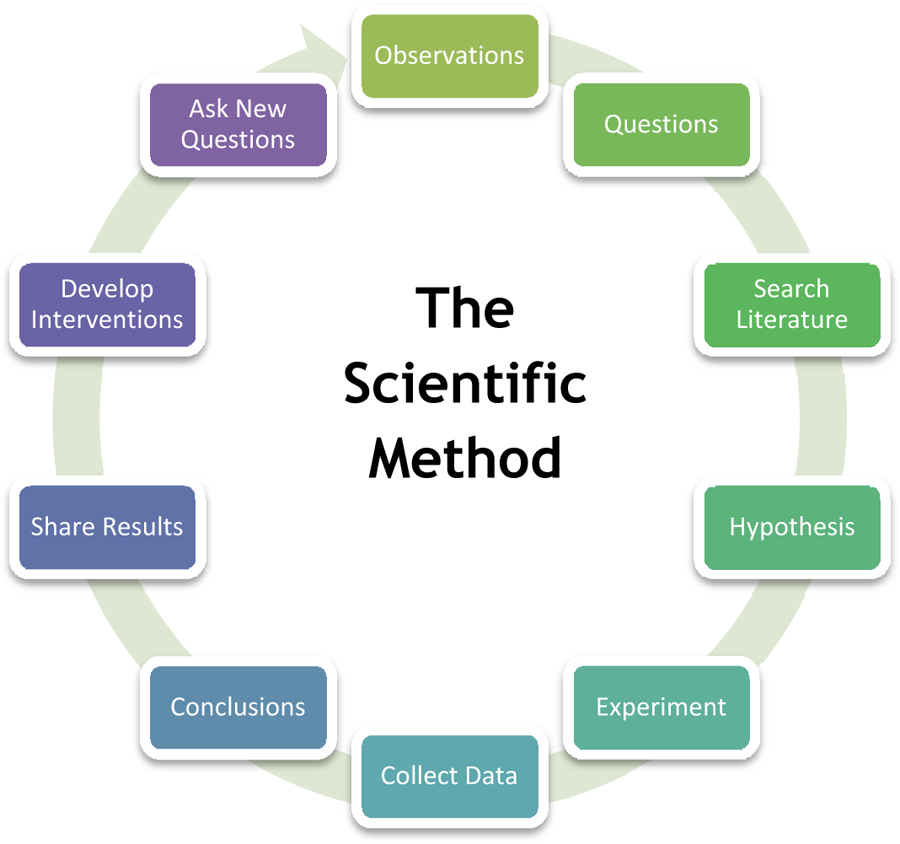

An Introduction to a scientific paper familiarizes the reader with the background of the issue at hand. It must reflect why the issue is topical and its current importance in the vast sea of research being done globally. It lays the foundation of biomedical writing and is the first portion of an article according to the IMRAD pattern ( I ntroduction, M ethodology, R esults, a nd D iscussion) [ 1 ].

It provides the flavour of the article and many authors have used phrases to describe it for example—'like a gate of the city’ [ 2 ], ‘the beginning is half of the whole’ [ 3 ], ‘an introduction is not just wrestling with words to fit the facts, but it also strongly modulated by perception of the anticipated reactions of peer colleagues’, [ 4 ] and ‘an introduction is like the trailer to a movie’. A good introduction helps captivate the reader early.

2 What Are the Principles of Writing a Good Introduction?

A good introduction will ‘sell’ an article to a journal editor, reviewer, and finally to a reader [ 3 ]. It should contain the following information [ 5 , 6 ]:

The known—The background scientific data

The unknown—Gaps in the current knowledge

Research hypothesis or question

Methodologies used for the study

The known consist of citations from a review of the literature whereas the unknown is the new work to be undertaken. This part should address how your work is the required missing piece of the puzzle.

3 What Are the Models of Writing an Introduction?

The Problem-solving model

First described by Swales et al. in 1979, in this model the writer should identify the ‘problem’ in the research, address the ‘solution’ and also write about ‘the criteria for evaluating the problem’ [ 7 , 8 ].

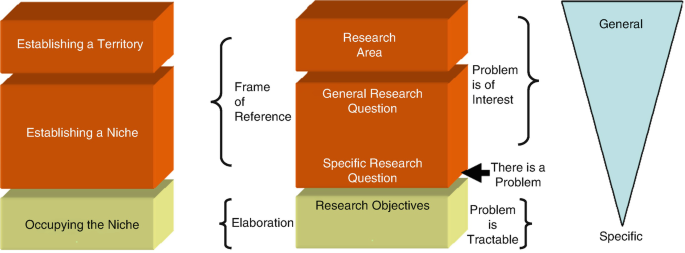

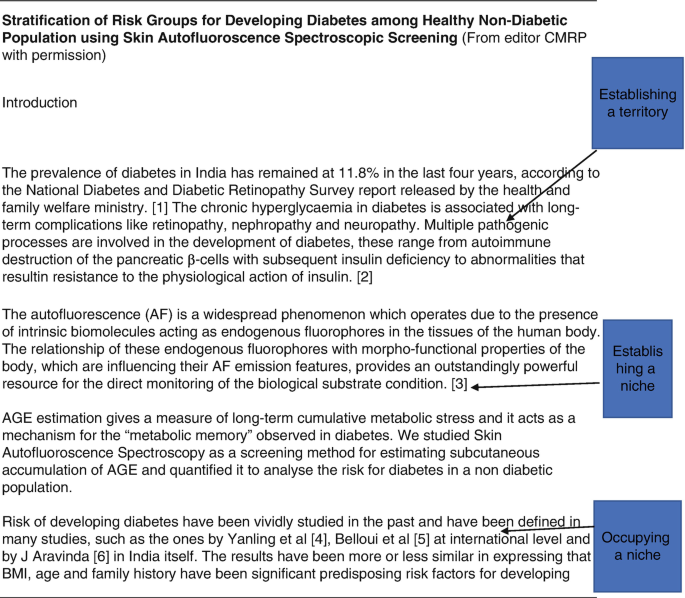

The CARS model that stands for C reating A R esearch S pace [ 9 , 10 ].

The two important components of this model are:

Establishing a territory (situation)

Establishing a niche (problem)

Occupying a niche (the solution)

In this popular model, one can add a fourth point, i.e., a conclusion [ 10 ].

4 What Is Establishing a Territory?

This includes: [ 9 ]

Stating the general topic and providing some background about it.

Providing a brief and relevant review of the literature related to the topic.

Adding a paragraph on the scope of the topic including the need for your study.

5 What Is Establishing a Niche?

Establishing a niche includes:

Stating the importance of the problem.

Outlining the current situation regarding the problem citing both global and national data.

Evaluating the current situation (advantages/ disadvantages).

Identifying the gaps.

Emphasizing the importance of the proposed research and how the gaps will be addressed.

Stating the research problem/ questions.

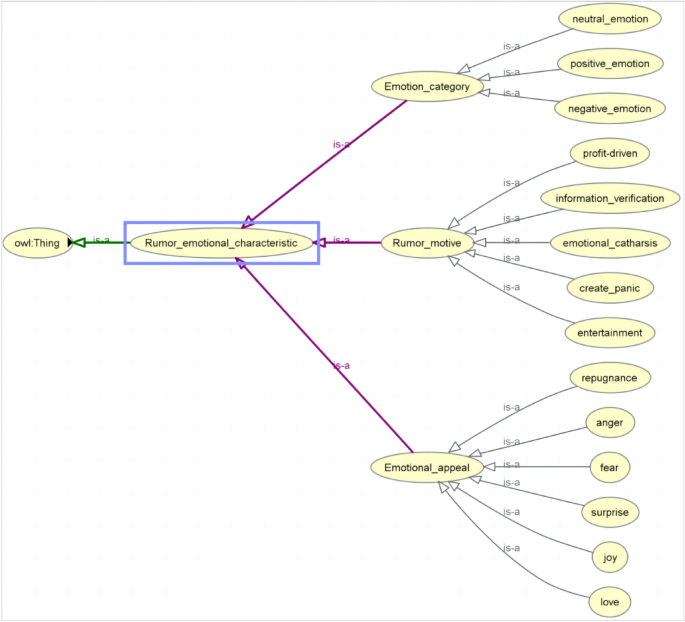

Stating the hypotheses briefly.

Figure 17.1 depicts how the introduction needs to be written. A scientific paper should have an introduction in the form of an inverted pyramid. The writer should start with the general information about the topic and subsequently narrow it down to the specific topic-related introduction.

Flow of ideas from the general to the specific

6 What Does Occupying a Niche Mean?

This is the third portion of the introduction and defines the rationale of the research and states the research question. If this is missing the reviewers will not understand the logic for publication and is a common reason for rejection [ 11 , 12 ]. An example of this is given below:

Till date, no study has been done to see the effectiveness of a mesh alone or the effectiveness of double suturing along with a mesh in the closure of an umbilical hernia regarding the incidence of failure. So, the present study is aimed at comparing the effectiveness of a mesh alone versus the double suturing technique along with a mesh.

7 How Long Should the Introduction Be?

For a project protocol, the introduction should be about 1–2 pages long and for a thesis it should be 3–5 pages in a double-spaced typed setting. For a scientific paper it should be less than 10–15% of the total length of the manuscript [ 13 , 14 ].

8 How Many References Should an Introduction Have?

All sections in a scientific manuscript except the conclusion should contain references. It has been suggested that an introduction should have four or five or at the most one-third of the references in the whole paper [ 15 ].

9 What Are the Important Points Which Should be not Missed in an Introduction?

An introduction paves the way forward for the subsequent sections of the article. Frequently well-planned studies are rejected by journals during review because of the simple reason that the authors failed to clarify the data in this section to justify the study [ 16 , 17 ]. Thus, the existing gap in knowledge should be clearly brought out in this section (Fig. 17.2 ).

How should the abstract, introduction, and discussion look

The following points are important to consider:

The introduction should be written in simple sentences and in the present tense.

Many of the terms will be introduced in this section for the first time and these will require abbreviations to be used later.

The references in this section should be to papers published in quality journals (e.g., having a high impact factor).

The aims, problems, and hypotheses should be clearly mentioned.

Start with a generalization on the topic and go on to specific information relevant to your research.

10 Example of an Introduction

11 Conclusions

An Introduction is a brief account of what the study is about. It should be short, crisp, and complete.

It has to move from a general to a specific research topic and must include the need for the present study.

The Introduction should include data from a literature search, i.e., what is already known about this subject and progress to what we hope to add to this knowledge.

Moore A. What’s in a discussion section? Exploiting 2-dimensionality in the online world. Bioassays. 2016;38(12):1185.

Article Google Scholar

Annesley TM. The discussion section: your closing argument. Clin Chem. 2010;56(11):1671–4.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Bavdekar SB. Writing the discussion section: describing the significance of the study findings. J Assoc Physicians India. 2015;63(11):40–2.

PubMed Google Scholar

Foote M. The proof of the pudding: how to report results and write a good discussion. Chest. 2009;135(3):866–8.

Kearney MH. The discussion section tells us where we are. Res Nurs Health. 2017;40(4):289–91.

Ghasemi A, Bahadoran Z, Mirmiran P, Hosseinpanah F, Shiva N, Zadeh-Vakili A. The principles of biomedical scientific writing: discussion. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2019;17(3):e95415.

Swales JM, Feak CB. Academic writing for graduate students: essential tasks and skills. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press; 2004.

Google Scholar

Colombo M, Bucher L, Sprenger J. Determinants of judgments of explanatory power: credibility, generality, and statistical relevance. Front Psychol. 2017;8:1430.

Mozayan MR, Allami H, Fazilatfar AM. Metadiscourse features in medical research articles: subdisciplinary and paradigmatic influences in English and Persian. Res Appl Ling. 2018;9(1):83–104.

Hyland K. Metadiscourse: mapping interactions in academic writing. Nordic J English Stud. 2010;9(2):125.

Hill AB. The environment and disease: association or causation? Proc Royal Soc Med. 2016;58(5):295–300.

Alpert JS. Practicing medicine in Plato’s cave. Am J Med. 2006;119(6):455–6.

Walsh K. Discussing discursive discussions. Med Educ. 2016;50(12):1269–70.

Polit DF, Beck CT. Generalization in quantitative and qualitative research: myths and strategies. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47(11):1451–8.

Jawaid SA, Jawaid M. How to write introduction and discussion. Saudi J Anaesth. 2019;13(Suppl 1):S18–9.

Jawaid SA, Baig M. How to write an original article. In: Jawaid SA, Jawaid M, editors. Scientific writing: a guide to the art of medical writing and scientific publishing. Karachi: Published by Med-Print Services; 2018. p. 135–50.

Hall GM, editor. How to write a paper. London: BMJ Books, BMJ Publishing Group; 2003. Structure of a scientific paper. p. 1–5.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Surgical Gastroenterology and Liver Transplantation, Sir Ganga Ram Hospital, New Delhi, India

Samiran Nundy

Department of Internal Medicine, Sir Ganga Ram Hospital, New Delhi, India

Institute for Global Health and Development, The Aga Khan University, South Central Asia, East Africa and United Kingdom, Karachi, Pakistan

Zulfiqar A. Bhutta

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Nundy, S., Kakar, A., Bhutta, Z.A. (2022). How to Write the Introduction to a Scientific Paper?. In: How to Practice Academic Medicine and Publish from Developing Countries?. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-5248-6_17

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-5248-6_17

Published : 24 October 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-16-5247-9

Online ISBN : 978-981-16-5248-6

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- College University and Postgraduate

- Academic Writing

- Research Papers

How to Write a Research Introduction

Last Updated: December 6, 2023 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Megan Morgan, PhD . Megan Morgan is a Graduate Program Academic Advisor in the School of Public & International Affairs at the University of Georgia. She earned her PhD in English from the University of Georgia in 2015. There are 7 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 2,653,679 times.

The introduction to a research paper can be the most challenging part of the paper to write. The length of the introduction will vary depending on the type of research paper you are writing. An introduction should announce your topic, provide context and a rationale for your work, before stating your research questions and hypothesis. Well-written introductions set the tone for the paper, catch the reader's interest, and communicate the hypothesis or thesis statement.

Introducing the Topic of the Paper

- In scientific papers this is sometimes known as an "inverted triangle", where you start with the broadest material at the start, before zooming in on the specifics. [2] X Research source

- The sentence "Throughout the 20th century, our views of life on other planets have drastically changed" introduces a topic, but does so in broad terms.

- It provides the reader with an indication of the content of the essay and encourages them to read on.

- For example, if you were writing a paper about the behaviour of mice when exposed to a particular substance, you would include the word "mice", and the scientific name of the relevant compound in the first sentences.

- If you were writing a history paper about the impact of the First World War on gender relations in Britain, you should mention those key words in your first few lines.

- This is especially important if you are attempting to develop a new conceptualization that uses language and terminology your readers may be unfamiliar with.

- If you use an anecdote ensure that is short and highly relevant for your research. It has to function in the same way as an alternative opening, namely to announce the topic of your research paper to your reader.

- For example, if you were writing a sociology paper about re-offending rates among young offenders, you could include a brief story of one person whose story reflects and introduces your topic.

- This kind of approach is generally not appropriate for the introduction to a natural or physical sciences research paper where the writing conventions are different.

Establishing the Context for Your Paper

- It is important to be concise in the introduction, so provide an overview on recent developments in the primary research rather than a lengthy discussion.

- You can follow the "inverted triangle" principle to focus in from the broader themes to those to which you are making a direct contribution with your paper.

- A strong literature review presents important background information to your own research and indicates the importance of the field.

- By making clear reference to existing work you can demonstrate explicitly the specific contribution you are making to move the field forward.

- You can identify a gap in the existing scholarship and explain how you are addressing it and moving understanding forward.

- For example, if you are writing a scientific paper you could stress the merits of the experimental approach or models you have used.

- Stress what is novel in your research and the significance of your new approach, but don't give too much detail in the introduction.

- A stated rationale could be something like: "the study evaluates the previously unknown anti-inflammatory effects of a topical compound in order to evaluate its potential clinical uses".

Specifying Your Research Questions and Hypothesis

- The research question or questions generally come towards the end of the introduction, and should be concise and closely focused.

- The research question might recall some of the key words established in the first few sentences and the title of your paper.

- An example of a research question could be "what were the consequences of the North American Free Trade Agreement on the Mexican export economy?"

- This could be honed further to be specific by referring to a particular element of the Free Trade Agreement and the impact on a particular industry in Mexico, such as clothing manufacture.

- A good research question should shape a problem into a testable hypothesis.

- If possible try to avoid using the word "hypothesis" and rather make this implicit in your writing. This can make your writing appear less formulaic.

- In a scientific paper, giving a clear one-sentence overview of your results and their relation to your hypothesis makes the information clear and accessible. [10] X Trustworthy Source PubMed Central Journal archive from the U.S. National Institutes of Health Go to source

- An example of a hypothesis could be "mice deprived of food for the duration of the study were expected to become more lethargic than those fed normally".

- This is not always necessary and you should pay attention to the writing conventions in your discipline.

- In a natural sciences paper, for example, there is a fairly rigid structure which you will be following.

- A humanities or social science paper will most likely present more opportunities to deviate in how you structure your paper.

Research Introduction Help

Community Q&A

- Use your research papers' outline to help you decide what information to include when writing an introduction. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 1

- Consider drafting your introduction after you have already completed the rest of your research paper. Writing introductions last can help ensure that you don't leave out any major points. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- Avoid emotional or sensational introductions; these can create distrust in the reader. Thanks Helpful 50 Not Helpful 12

- Generally avoid using personal pronouns in your introduction, such as "I," "me," "we," "us," "my," "mine," or "our." Thanks Helpful 31 Not Helpful 7

- Don't overwhelm the reader with an over-abundance of information. Keep the introduction as concise as possible by saving specific details for the body of your paper. Thanks Helpful 24 Not Helpful 14

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://library.sacredheart.edu/c.php?g=29803&p=185916

- ↑ https://www.aresearchguide.com/inverted-pyramid-structure-in-writing.html

- ↑ https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/introduction

- ↑ https://writing.wisc.edu/Handbook/PlanResearchPaper.html

- ↑ https://dept.writing.wisc.edu/wac/writing-an-introduction-for-a-scientific-paper/

- ↑ https://writing.wisc.edu/handbook/assignments/planresearchpaper/

- ↑ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3178846/

About This Article

To introduce your research paper, use the first 1-2 sentences to describe your general topic, such as “women in World War I.” Include and define keywords, such as “gender relations,” to show your reader where you’re going. Mention previous research into the topic with a phrase like, “Others have studied…”, then transition into what your contribution will be and why it’s necessary. Finally, state the questions that your paper will address and propose your “answer” to them as your thesis statement. For more information from our English Ph.D. co-author about how to craft a strong hypothesis and thesis, keep reading! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Abdulrahman Omar

Oct 5, 2018

Did this article help you?

May 9, 2021

Lavanya Gopakumar

Oct 1, 2016

Dengkai Zhang

May 14, 2018

Leslie Mae Cansana

Sep 22, 2016

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Get all the best how-tos!

Sign up for wikiHow's weekly email newsletter

How to Write an Introduction for a Research Paper

How to write an introduction for a research paper? Eventually (and with practice) all writers will develop their own strategy for writing the perfect introduction for a research paper. Once you are comfortable with writing, you will probably find your own, but coming up with a good strategy can be tough for beginning writers.

The Purpose of an Introduction

Your opening paragraphs, phrases for introducing thesis statements, research paper introduction examples, using the introduction to map out your research paper.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code.

- First write your thesis.Your thesis should state the main idea in specific terms.

- After you have a working thesis, tackle the body of your paper before you write the rest of the introduction. Each paragraph in the body should explore one specific topic that proves, or summarizes your thesis. Writing is a thinking process. Once you have worked your way through that process by writing the body of the paper, you will have an intimate understanding of how you are supporting your thesis. After you have written the body paragraphs, go back and rewrite your thesis to make it more specific and to connect it to the topics you addressed in the body paragraph.

- Revise your introduction several times, saving each revision. Be sure your introduction previews the topics you are presenting in your paper. One way of doing this is to use keywords from the topic sentences in each paragraph to introduce, or preview, the topics in your introduction.This “preview” will give your reader a context for understanding how you will make your case.

- Experiment by taking different approaches to your thesis with every revision you make. Play with the language in the introduction. Strike a new tone. Go back and compare versions. Then pick the one that works most effectively with the body of your research paper.

- Do not try to pack everything you want to say into your introduction. Just as your introduction should not be too short, it should also not be too long. Your introduction should be about the same length as any other paragraph in your research paper. Let the content—what you have to say—dictate the length.

The first page of your research paper should draw the reader into the text. It is the paper’s most important page and, alas, often the worst written. There are two culprits here and effective ways to cope with both of them.

First, the writer is usually straining too hard to say something terribly BIG and IMPORTANT about the thesis topic. The goal is worthy, but the aim is unrealistically high. The result is often a muddle of vague platitudes rather than a crisp, compelling introduction to the thesis. Want a familiar example? Listen to most graduation speakers. Their goal couldn’t be loftier: to say what education means and to tell an entire football stadium how to live the rest of their lives. The results are usually an avalanche of clichés and sodden prose.

The second culprit is bad timing. The opening and concluding paragraphs are usually written late in the game, after the rest of the thesis is finished and polished. There’s nothing wrong with writing these sections last. It’s usually the right approach since you need to know exactly what you are saying in the substantive middle sections of the thesis before you can introduce them effectively or draw together your findings. But having waited to write the opening and closing sections, you need to review and edit them several times to catch up. Otherwise, you’ll putting the most jagged prose in the most tender spots. Edit and polish your opening paragraphs with extra care. They should draw readers into the paper.

After you’ve done some extra polishing, I suggest a simple test for the introductory section. As an experiment, chop off the first few paragraphs. Let the paper begin on, say, paragraph 2 or even page 2. If you don’t lose much, or actually gain in clarity and pace, then you’ve got a problem.

There are two solutions. One is to start at this new spot, further into the text. After all, that’s where you finally gain traction on your subject. That works best in some cases, and we occasionally suggest it. The alternative, of course, is to write a new opening that doesn’t flop around, saying nothing.

What makes a good opening? Actually, they come in several flavors. One is an intriguing story about your topic. Another is a brief, compelling quote. When you run across them during your reading, set them aside for later use. Don’t be deterred from using them because they “don’t seem academic enough.” They’re fine as long as the rest of the paper doesn’t sound like you did your research in People magazine. The third, and most common, way to begin is by stating your main questions, followed by a brief comment about why they matter.

Whichever opening you choose, it should engage your readers and coax them to continue. Having done that, you should give them a general overview of the project—the main issues you will cover, the material you will use, and your thesis statement (that is, your basic approach to the topic). Finally, at the end of the introductory section, give your readers a brief road map, showing how the paper will unfold. How you do that depends on your topic but here are some general suggestions for phrase choice that may help:

- This analysis will provide …

- This paper analyzes the relationship between …

- This paper presents an analysis of …

- This paper will argue that …

- This topic supports the argument that…

- Research supports the opinion that …

- This paper supports the opinion that …

- An interpretation of the facts indicates …

- The results of this experiment show …

- The results of this research show …

Comparisons/Contrasts

- A comparison will show that …

- By contrasting the results,we see that …

- This paper examines the advantages and disadvantages of …

Definitions/Classifications

- This paper will provide a guide for categorizing the following:…

- This paper provides a definition of …

- This paper explores the meaning of …

- This paper will discuss the implications of …

- A discussion of this topic reveals …

- The following discussion will focus on …

Description

- This report describes…

- This report will illustrate…

- This paper provides an illustration of …

Process/Experimentation

- This paper will identify the reasons behind…

- The results of the experiment show …

- The process revealed that …

- This paper theorizes…

- This paper presents the theory that …

- In theory, this indicates that …

Quotes, anecdotes, questions, examples, and broad statements—all of them can used successfully to write an introduction for a research paper. It’s instructive to see them in action, in the hands of skilled academic writers.

Let’s begin with David M. Kennedy’s superb history, Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929–1945 . Kennedy begins each chapter with a quote, followed by his text. The quote above chapter 1 shows President Hoover speaking in 1928 about America’s golden future. The text below it begins with the stock market collapse of 1929. It is a riveting account of just how wrong Hoover was. The text about the Depression is stronger because it contrasts so starkly with the optimistic quotation.

“We in America today are nearer the final triumph over poverty than ever before in the history of any land.”—Herbert Hoover, August 11, 1928 Like an earthquake, the stock market crash of October 1929 cracked startlingly across the United States, the herald of a crisis that was to shake the American way of life to its foundations. The events of the ensuing decade opened a fissure across the landscape of American history no less gaping than that opened by the volley on Lexington Common in April 1775 or by the bombardment of Sumter on another April four score and six years later. The ratcheting ticker machines in the autumn of 1929 did not merely record avalanching stock prices. In time they came also to symbolize the end of an era. (David M. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929–1945 . New York: Oxford University Press, 1999, p. 10)

Kennedy has exciting, wrenching material to work with. John Mueller faces the exact opposite problem. In Retreat from Doomsday: The Obsolescence of Major War , he is trying to explain why Great Powers have suddenly stopped fighting each other. For centuries they made war on each other with devastating regularity, killing millions in the process. But now, Mueller thinks, they have not just paused; they have stopped permanently. He is literally trying to explain why “nothing is happening now.” That may be an exciting topic intellectually, it may have great practical significance, but “nothing happened” is not a very promising subject for an exciting opening paragraph. Mueller manages to make it exciting and, at the same time, shows why it matters so much. Here’s his opening, aptly entitled “History’s Greatest Nonevent”:

On May 15, 1984, the major countries of the developed world had managed to remain at peace with each other for the longest continuous stretch of time since the days of the Roman Empire. If a significant battle in a war had been fought on that day, the press would have bristled with it. As usual, however, a landmark crossing in the history of peace caused no stir: the most prominent story in the New York Times that day concerned the saga of a manicurist, a machinist, and a cleaning woman who had just won a big Lotto contest. This book seeks to develop an explanation for what is probably the greatest nonevent in human history. (John Mueller, Retreat from Doomsday: The Obsolescence of Major War . New York: Basic Books, 1989, p. 3)

In the space of a few sentences, Mueller sets up his puzzle and reveals its profound human significance. At the same time, he shows just how easy it is to miss this milestone in the buzz of daily events. Notice how concretely he does that. He doesn’t just say that the New York Times ignored this record setting peace. He offers telling details about what they covered instead: “a manicurist, a machinist, and a cleaning woman who had just won a big Lotto contest.” Likewise, David Kennedy immediately entangles us in concrete events: the stunning stock market crash of 1929. These are powerful openings that capture readers’ interests, establish puzzles, and launch narratives.