Report | Budget, Taxes, and Public Investment

Public education funding in the U.S. needs an overhaul : How a larger federal role would boost equity and shield children from disinvestment during downturns

Report • By Sylvia Allegretto , Emma García , and Elaine Weiss • July 12, 2022

Download PDF

Press release

Share this page:

Summary

Education funding in the United States relies primarily on state and local resources, with just a tiny share of total revenues allotted by the federal government. Most analyses of the primary school finance metrics—equity, adequacy, effort, and sufficiency—raise serious questions about whether the existing system is living up to the ideal of providing a sound education equitably to all children at all times. Districts in high-poverty areas, which serve larger shares of students of color, get less funding per student than districts in low-poverty areas, which predominantly serve white students, highlighting the system’s inequity. School districts in general—but especially those in high-poverty areas—are not spending enough to achieve national average test scores, which is an established benchmark for assessing adequacy. Efforts states make to invest in education vary significantly. And the system is ill-prepared to adapt to unexpected emergencies.

These challenges are magnified during and after recessions. Following the Great Recession that began in December 2007, per-student education revenues plummeted and did not return to pre-recession levels for about eight years. The recovery in per-student revenues was even slower in high-poverty districts. This report combines new data on funding for states and for districts by school district poverty level, and over time, with evidence documenting the positive impacts of increasing investment in education to make a case for overhauling the school finance system. It calls for reforms that would ensure a larger role for the federal government to establish a robust, stable, and consistent school funding plan that channels sufficient additional resources to less affluent students in good times and bad. Furthermore, spending on public education should be retooled as an economic stabilizer, with increases automatically kicking in during recessions. Such a program would greatly mitigate cuts to public education as budgets are depleted, and also spur aggregate demand to give the economy a needed boost.

Following are key findings from the report:

Our current system for funding public schools shortchanges students, particularly low-income students. Education funding generally is inadequate and inequitable; It relies too heavily on state and local resources (particularly property tax revenues); the federal government plays a small and an insufficient role; funding levels vary widely across states; and high-poverty districts get less funding per student than low-poverty districts.

Those problems are magnified during and after recessions. Funding inadequacies and inequities tend to be aggravated when there is an economic downturn, which typically translates into problems that persist well after recovery is underway. After the 2007 onset of the Great Recession, for example, funding fell, and it took until 2015–2016, on average, to return to their pre-recession per-student revenue and spending levels. For high-poverty school districts, it took even longer—until 2016–2017—to rebound to their pre-recession revenue levels. And even after catching up with pre-recession levels, revenue levels in high-poverty districts lag behind the per-student funding in low-poverty districts. The general, long-standing funding inadequacies and inequities combined with the worsening of these problems during and in the aftermath of recessions have both short- and long-term repercussions that are costly for the students as well as for the country.

Increased federal spending on education after recessions helps mitigate funding shortfalls and inequities. Without increased federal education spending after recessions, school districts would suffer from an even greater decline in funding and even wider gaps between funding flowing to low-poverty and high-poverty districts.

Increased spending on education could help boost economic recovery. While Congress has enacted one-time education spending increases in difficult economic times, spending on public education should be considered one of the automatic stabilizers in our economic policy toolkit, designed to automatically increase and thus spur aggregate demand when private spending falls. Deployed this way, education spending becomes part of a set of large, broadly distributed programs that are countercyclical, i.e., designed to kick in when the economy overall is contracting and thus stave off or lessen the severity of a downturn. Along with other automatic stabilizers such as unemployment insurance, education spending thus would provide a stimulus to boost economic recovery.

We need an overhaul of the school finance system, with reforms ensuring a larger role for the federal government. In light of the concerns outlined in this report, policymakers must think differently both about school funding overall and about school funding during recessions. Public education is a public good, and as noted in this report, one that helps to stabilize the entire economy at critical points. Therefore, public spending on education should be treated as the public investment it is. While we leave it to policymakers to design specific reforms, we recommend an increased role for the federal government grounded in substantial, well targeted, consistent investment in the children who are our future, the professionals who help these children attain that future, and the environments in which they work. To establish a robust, stable, and consistent school funding plan that supports all children, investments need to be proportional to the size of the problems and to the societal and economic importance of the sector.

Introduction

The hope for the public education system in the United States is to provide a sound education equitably to all children regardless of where they live or into which families they are born. However, the COVID-19 pandemic exposed four interrelated, long-standing realities of U.S. public education funding that have long made that excellent, equitable education system impossible to achieve. First, inadequate levels of funding leave too many students unable to reach established performance benchmarks. Second, school funding is inequitable, with low-income students often and communities of color consistently lacking resources they need to meet their needs. Third, the level of funding reflects an overall underinvestment in education—that is, the U.S. is not spending as much as it could afford to spend in normal times. Fourth, given that educational investments are not sufficient across many districts even during normal times, schools are unable to make preparations to cope with emergencies or other unexpected circumstances. An added, less known feature is that economic downturns make all four of these problems worse. Downturns exacerbate funding inadequacies, inequities, underinvestment, and unpreparedness, causing cumulative harm to students, communities, and the public education system, and clawing back any prior progress. The severity of these problems varies widely across states and districts, as do the strength of states’ and localities’ economic and social protection systems, which may either compensate for or compound the problems.

The pandemic-led recession made these four major financial barriers to an excellent, equitable education system more visible, leading to serious questions about the U.S. education-funding model, which relies heavily on local and state revenues and draws only a small share of funding from the federal government. While public education is one of our greatest ideals and achievements—a free, quality education for every child regardless of means and background—the U.S. educational system is in need of significant improvements.

As the report will show, the core barriers to delivering universally excellent U.S. public education for all children—funding inadequacies and inequities that are exacerbated during tough economic times—were present in the system from the very start. They are the outcomes of a funding system that is shaped by many layers of policies and legal decisions at the local, state, and federal levels, creating widespread disparities in school finance realities across the thousands of districts across the country in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. This complex funding puzzle speaks to the need for a funding overhaul to attain meaningful and widely shared improvements.

In this report, we first provide an overview of the characteristics of the U.S. education funding system. We present data analyses on school finance indicators, such as equity, adequacy, and effort, that expose the shortcomings of funding policies and decisions across the country. We also discuss factors behind some of these shortcomings, such as the heavy reliance on local and state sources of funding.

Second, we illustrate that recessions exacerbate the funding challenges schools face. We parse a multitude of data to present trends in school finance indicators both during and after the Great Recession, demonstrating that the immediate effects of federally targeted funds helped schools navigate recession-induced budget cuts. We also look at the shortfalls and inequitable nature of those investments. We explore how increased federal investments—in good economic times and bad—could help address these long-standing problems. We argue that public education funding is not only an investment in our societal present and future, but also is a ready-made mechanism for countering economic downturns. Economic theory and evidence both demonstrate that large, broadly distributed programs providing public support serve as cushions during economic downturns: they spur overall spending and thus aggregate demand when private spending falls. As we note, there are strong arguments for placing public education spending within the broader category of effective fiscal responses to recessions that are countercyclical—designed to increase spending when spending in the economy overall is contracting and thus stave off or lessen the severity of a downturn. Increases in public education spending during downturns work as automatic stabilizers for schools and provide stimulus to boost economic recovery. We review existing research on the consequences of funding in general and of funding changes—evidence that supports a larger role for the federal government.

Third, we discuss the benefits of rethinking public education funding, along with the societal and economic advantages of a robust, stable, and consistent U.S. school funding plan, both generally and as a countercyclical policy. We show that federal investment that sustains school funding throughout recessions and recoveries would provide three major advantages: It would help boost educational instruction and standards, it would provide continued high-quality instruction for students and employment to the public education workforce, and it would stimulate economic recovery. Education funding, in particular, would blanket the country while also targeting areas with the most need, making the recovery more equitable.

We conclude the report with final thoughts and next steps.

This paper uses several terms to refer to investments in education and to define the U.S. school finance system. Below, we explain how these terms are used in the report:

Revenue indicates the dollar amounts that have been raised through various sources (at the local, state, and federal levels) to support elementary and secondary education. We distinguish between federal, state, and local revenue. Local revenue, in some of our charts, is further divided into local revenue from property taxes and from other sources.

Spending or expenditures indicates the dollar amount devoted to elementary and secondary education. Expenditures are typically divided by function and object (instruction, support services , and noninstructional education activities). We rely on data on current expenditures (instead of total expenditures; see footnotes 2 and 30).

Funding generically refers in this report to the educational investments or educational resources. Mostly, when we use funding we refer to revenue, i.e., to resources available or raised, but funding is also used to refer to the school finance system more broadly, and in that case it could be either referring to revenue or expenditures, depending on the context.

For more information on the list of components under each term, see the glossary in the Documentation for the NCES Common Core of Data School District Finance Survey (F-33), School Year 2017–18 (Fiscal Year 2018) (NCES CCD 2020).

A funding primer

The American education system relies heavily on state and local resources to fund public schools. In the U.S. education has long been a local- and state-level responsibility, with states typically concerned with administration and standards, and local districts charged with raising the bulk of the funds to carry those duties and standards out.

The Education Law Center notes that “states, under their respective constitutions, have the legal obligation to support and maintain systems of free public schools for all resident children. This means that the state is the unit of government in the U.S. legally responsible for operating our nation’s public school systems, which includes providing the funding to support and maintain those systems” (Farrie and Sciarra 2021). Bradbury (2021) explains that state constitutions assign responsibility for “adequate” (“sound,” “basic”) and/or “equitable” public education to the state government. Most state governments delegate responsibility for managing and (partially) funding public pre-K–12 education to local governments, but courts mandate that states remain responsible.

States meet this responsibility by funding their schools “through a statewide method or formula enacted by the state legislature. These school funding formulas or school finance systems determine the amount of revenue school districts are permitted to raise from local property and other taxes and the amount of funding or aid the state is expected to contribute from state taxes. In annual or biannual state budgets, legislatures also determine the actual amount of funding districts will receive to operate their schools” (Farrie and Sciarra 2020).

A quick note on data sources

Some of our analyses rely on district-level data, i.e., the revenues and expenditures use the district as the unit of analysis. We rely on metrics of per-student revenue or per-student spending, i.e., taking into consideration the number of students in the districts. Other analyses use data either by state or for the country, which are typically readily available from the Digest of Education Statistics online. Sometimes the variables of interest are total revenue or expenditures, whereas on other occasions we rely on per-student values. All data sources are explained under each figure and table, and some are also briefly explained in the Methodology.

The federal government seeks to use its limited but targeted funding to promote student achievement, foster educational excellence, and ensure equal access. The major federal agency channeling funding to school districts (sometimes through the states) is the U.S. Department of Education. 1

Figure A shows the percentage distribution of total revenue for U.S. public elementary and secondary schools for the 2017–2018 school year, on average. As illustrated, revenues collected from state and local sources are roughly equal (46.8% and 45.3%, respectively). Two other factors also stand out. First, revenue from property taxes accounts for more than one-third of total revenue (36.6 %). Second, federal funding plays a minimal role, providing less than 8% of total revenue (7.8%). As discussed later in the report, this heavy reliance on local funding is a major driver in the funding challenges districts face.

More than 90% of school funding comes from state and local sources : Revenues for public elementary and secondary schools by source of funds, 2017–2018

The data below can be saved or copied directly into Excel.

The data underlying the figure.

Source: National Center for Education Statistics’ Digest of Education Statistics (NCES 2020a).

Copy the code below to embed this chart on your website.

Key metrics reveal the four major financial barriers to an excellent, equitable education system

Fully comprehending how school funding works and how it contributes to systemic problems requires drawing on key metrics and characteristics that define the education investments or education funding. Understanding these metrics is the first step toward designing a comprehensive solution.

The adequacy metric tells us that funding is inadequate

Adequacy, one of the most widely used school finance indicators, measures whether the amount raised and spent per student is sufficient to achieve a certain level of output (typically a benchmark of student performance or an educational outcome).

We use the adequacy data provided by Baker, Di Carlo, and Weber (2020). These authors, who use the School Finance Indicators Database, compare current education spending by poverty quintile with spending levels required for students to achieve national average test scores—typically accepted as an educationally meaningful benchmark. The authors’ estimates account for factors that could affect the cost of providing education, including student characteristics, labor-market costs (differences in costs given the regional cost of living), and district characteristics (larger districts for example may enjoy economics of scale).

Figure B reveals that spending is not nearly enough, on average, to provide students with an adequate education. As this figure illustrates, relative to the wealthiest districts, the highest-poverty districts need more than twice as much spending per student to provide an adequate education. As the figure also shows, the gaps between what is spent on each student and what would be required for those students to achieve at the national level widen as the level of poverty increases. Medium- and high-poverty districts are spending, respectively, $700 and $3,078 per student less than what would be required. For the highest-poverty districts, that gap is $5,135, meaning districts there are spending about 30% less than what would be required to deliver an adequate level of education to their students. (Conversely, the two low-poverty quintiles are spending more than they need to reach that benchmark, another indication that funds are being poorly allocated.)

U.S. education spending is inadequate : Per-pupil spending compared with estimated spending required to achieve national average test scores, by poverty quintile of school district, 2017

Notes: District poverty is measured as the percentage of children (ages 5–17) living in the school district with family incomes below the federal poverty line, using data from the U.S. Census Bureau. The figure shows how much is spent in each of the five types of districts and how much they would need to spend for students to achieve national average test scores.

Source: Adapted from The Adequacy and Fairness of State School Finance Systems , Second Edition (Baker, Di Carlo, and Weber 2020).

The equity metric tells us that funding is inequitable

An equitable funding system ensures that, all else being equal, schools serving students with greater needs—whether for extra academic, socioemotional, health, or other supports—receive more resources and spend more to meet those needs than schools with a lower concentration of disadvantaged students. Across districts, states, and the country as a whole, this means allocating relatively more funding to districts serving larger shares of high-poverty communities than to wealthier ones. While our funding system does allocate additional funds based on need (e.g., to students officially designated as eligible for “special education” services under the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act and to children from low-income families through the federal Title I program), in practice, more funding overall goes to lower-needs districts than to those with high levels of student needs.

Figure C compares districts’ per-student revenues and expenditures by poverty level, and shows gaps relative to low-poverty districts. The figure is based on data from what was, when this research was conducted, the most recent version of the Local Education Agency Finance Survey (known as the F-33) (NCES-LEAFS, various years). As shown in the figure, on average, per-student revenue and spending in school districts serving wealthier households exceed revenue and spending in all other districts. In low-poverty districts (i.e., districts with a poverty rate in the bottom fourth of the poverty distribution), per-student revenues averaged $19,280 in the 2017–2018 school year, and per-student expenditures averaged $15,910. In the high-poverty districts (i.e., in the top fourth of the poverty distribution), per-student revenues were just $16,570, and per-student expenditures were $14,030. High-poverty districts raise $2,710 less in per-student revenue than the lowest–poverty school districts, reflecting a 14.1% revenue gap—meaning high-poverty districts receive 14.1% less in revenue. Per-student spending in high-poverty districts is $1,880 less than in low-poverty districts, an 11.8% gap. 2 In other words, rather than funding districts to address student needs, we are channeling fewer resources—about 14% less, per student—into districts with greater needs based on their student population.

Districts serving poorer students have less to spend on education than those serving wealthier students

: total per-student revenues by district poverty level, and revenue gaps relative to low-poverty districts, 2017–2018, : total per-student expenditures by district poverty level, and spending gaps relative to low-poverty districts, 2017–2018.

Notes: Amounts are in 2019–2020 dollars and rounded to the closest $10 and adjusted for each state’s cost of living. Low-poverty districts are districts whose poverty rate (for children ages 5 through 17) is in the bottom fourth of the poverty distribution; high-poverty districts are districts whose poverty rate is in the top fourth of the poverty distribution.

Extended notes: Sample includes districts serving elementary schools only, secondary schools only, or both; districts with nonmissing and nonzero numbers of students; and districts with nonmissing charter information. Amounts are in 2019–2020 dollars using the consumer price index from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS CPI 2021) and rounded to the closest $10. Amounts are adjusted for each state’s cost of living using the historical Regional Price Parities (RPPs) from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA 2021). Low-poverty districts are districts whose poverty rate (for children ages 5 through 17) is in the bottom fourth of the poverty distribution; medium-low-poverty districts are districts whose poverty rate (for children ages 5 through 17) is in the second fourth of the poverty distribution; medium-high-poverty districts are districts whose poverty rate (for children ages 5 through 17) is in the third fourth of the poverty distribution; high-poverty districts are districts whose poverty rate is in the top fourth of the poverty distribution. Amounts are unweighted across districts.

Sources: Authors’ analysis of 2017–2018 Local Education Agency Finance Survey (F-33) microdata from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES-LEAFS 2021) and Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates (SAIPE) data from the U.S. Census Bureau (Urban Institute 2021a).

Adequacy and equity are closely intertwined

In recent decades, researchers have explored challenges to both adequacy and equity in U.S. public education. For example, Baker and Corcoran (2012) analyzed the various policies that drive inequitable funding. Likewise, lawsuits that have challenged state funding systems have tended to focus on either the inadequacy or inequity of those schemes. 3

But in reality, especially given extensive variation across states and districts, the two are closely linked and interact with one another. At the state level, for example, apparently adequate levels of funding can mask disparities across districts that innately mean inadequate funding for many, or even most, districts within that state (Farrie and Schiarra 2021). 4

In addition, disparate levels of public investments in education are often made in a context that correlates positively with disparate levels of parents’ private investments in their children’s education and related support (Caucutt et al. 2020; Duncan and Murnane 2016; Kornrich 2016; Schneider, Hastings, and LaBriola 2018). Substantial research on income-based gaps in achievement demonstrates that large and growing wealth inequality plays a role. Parents at the top of the income or wealth ladders, who can and do pour extensive resources into their children’s human capital, constantly set a baseline of performance that can be hard for children and schools without such investment to attain (Reardon 2011; García and Weiss 2017). 5

The “effort” metric tells us that many states are underinvesting in education relative to their capacity

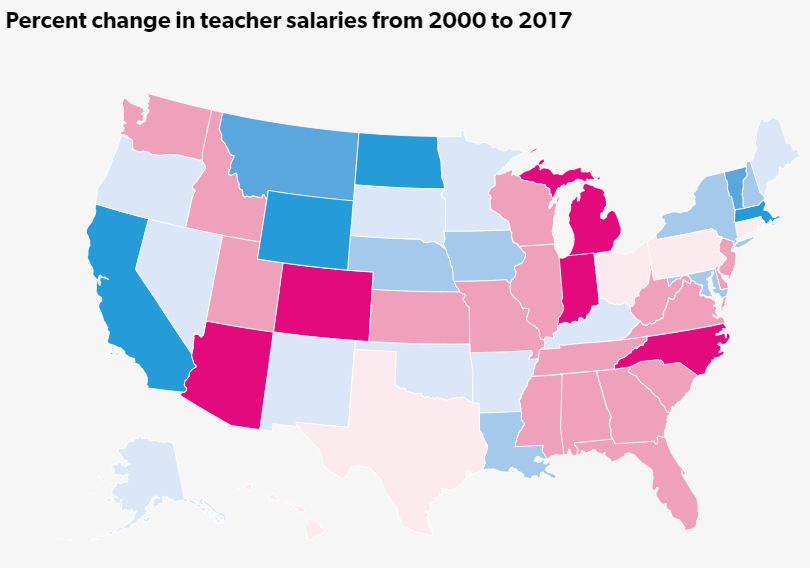

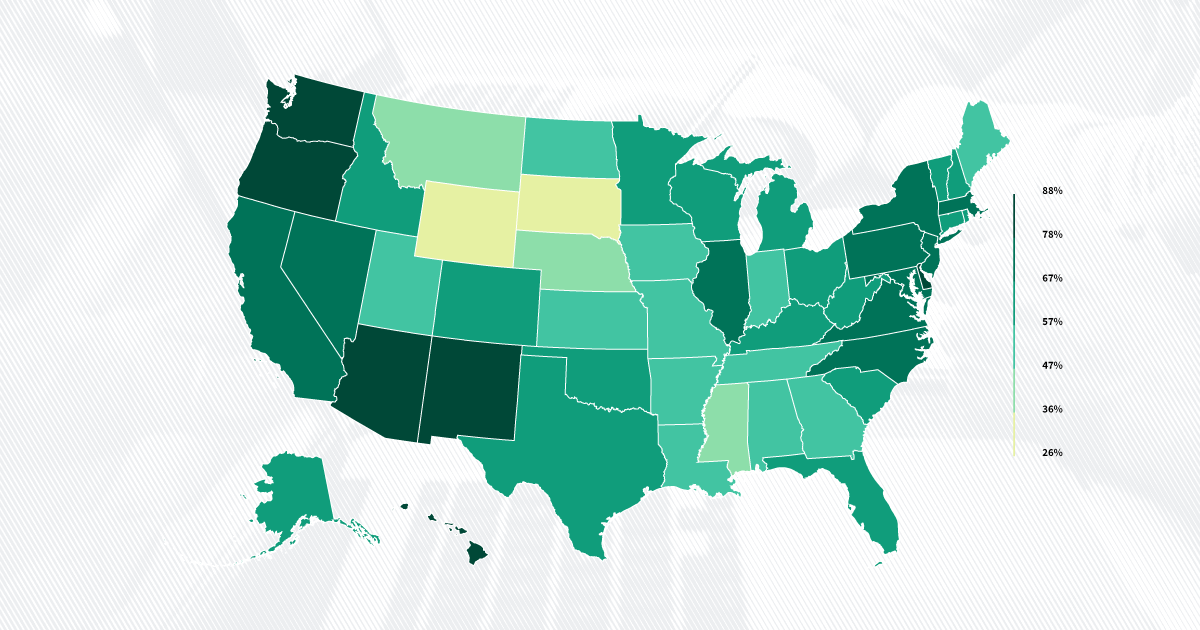

“Effort” describes how generously each state funds its schools relative to its capacity to do so. Researchers measuring effort determine capacity to spend based on state gross domestic product (GDP), which can vary widely (just as wealthier neighborhoods can raise more revenues even with lower tax rates, states with higher GDP and thus greater revenue-raising capacity can attain higher revenue with a lower effort, i.e., generate more resources at a lower cost). The map ( Figure D ), reproduced from Farrie and Sciarra 2021, shows state funding effort from the 2017–2018 school year.

School funding ‘effort’ varies widely across states : Pre-K through 12th grade education revenues as a percentage of state GDP, 2017–2018

This interactive feature is not supported in this browser.

Please use a modern browser such as Chrome or Firefox to view the map.

- Click here to download Google Chrome.

- Click here to download Firefox.

Click here to view a limited version of the map.

Note: “Effort is measured as total state and local [education] revenue (including [revenue for] capital outlay and debt service, excluding all federal funds) divided by the state’s gross domestic product. GDP is the value of all goods and services produced by each state’s economy and is used here to represent the state’s economic capacity to raise funds for schools” (Farrie and Sciarra 2020).

Source: Adapted from Making the Grade 2020: How Fair is School Funding in Your State? (Farrie and Sciarra 2020).

As Farrie and Sciarra (2021) note, states fall naturally into four groups:

- High-effort, high-capacity: States such as Alaska, Connecticut, New York, and Wyoming are high- capacity states with high per-capita GDP, and they are also high-effort states: They use a larger-than-average share of their overall GDP to support pre-K–12 education, which generates high funding levels.

- High-effort, low-capacity : States such as Arkansas, South Carolina, and West Virginia have lower-than-average capacity, with low GDP per-capita, but they are high-effort states. Even with above- average efforts, they yield only average or below-average funding levels.

- Low-effort, high-capacity : States such as California, Delaware, and Washington are high-capacity states that exert low effort toward funding schools. If these states increased their effort even to the national average, they could significantly increase funding levels.

- Low-effort, low-capacity : States such as Arizona, Florida, and Idaho are low-capacity states that also make lower-than-average efforts to fund schools, generating very low funding levels.

Evidence shows that districts and schools lack the resources to cope with emergencies

As the COVID-19 pandemic has made clear, our subpar level of preparation to cope with emergencies or other unexpected needs reflects another aspect of underinvestment. As García and Weiss (2020) not about the COVID-19 pandemic, “Our public education system was not built, nor prepared, to cope with a situation like this—we lack the structures to sustain effective teaching and learning during the shutdown and to provide the safety net supports that many children receive in school.”

Whether due to lack of resources, planning, or other factors, districts, schools, and educators struggled to adapt to the pandemic’s requirements for teaching. Schools were unprepared not only to support learning but also to deliver the supports and services they were accustomed to providing, which go far beyond instruction (García and Weiss 2020). This lack of preparation was the result of both a lack of contingency planning as well as a failure to build up resources to be ready “to adequately address emergency needs and to compensate for the resources drained during the emergencies, as well as to afford the provision of flexible learning approaches to continue education” (García and Weiss 2021).

A lack of established contingency plans to ensure the provision of education in emergency and post-emergency situations, whether caused by pandemics, other natural disasters, or conflicts and wars (as examined by the education-in-emergencies research), prevents countries from being able to mitigate the negative consequences of these emergencies on children’s development and learning. The lack of contingency plans also leaves systems unprepared to help children handle the trauma and stress that come from the most serious events. This body of literature has also shown that access to education and services—and an equitable and compensatory allocation of them—helps reduce the damage that students experience during the crisis and beyond, since such emergencies carry long-term consequences (Anderson 2020; Özek 2020).

Public education’s over-reliance on local funding is a key factor behind the troubling funding metrics

The heavy reliance on local funding described above is at the core of the school finance problems. Extensive research has exposed the challenges associated with this unique American system for funding public schools. 6 The myriad factors that drive school funding—politics and political affiliation, state legislative and judicial decisions, property values, tax rates, and effort, among others—vary substantially from one community to another. Thus, it is not surprising that this system has contributed to institutionalizing inequities, especially in the absence of a strong federal effort to counter them.

It is well understood that the local sources of revenues on which school districts heavily rely are often distributed in a highly inequitable way. Revenues from property taxes, which make up a hefty share of local education revenues, innately favor wealthier communities, as these areas have a much larger capacity to raise funds based on higher property values despite their lower tax rates. 7 These higher property-tax revenues in wealthier areas lead to greater revenues for their districts’ schools, since property-tax revenues account for such a significant share of the total.

State and federal funding are insufficient to compensate for these locally driven inequities

State funding of public education is the largest budget line item for most states. 8 Along with federal funding, state funding is expected to make up for local funding disparities and gaps. 9 Federal funding, in particular through Title I of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), is specifically designed to compensate low-income schools and districts for their lack of sufficient revenues to meet their students’ needs. 10 Similarly, state funding is intended to offset some of the disparities caused by the dependence on local revenues. However, in reality, state and federal sources do not provide enough to less-wealthy school districts to make up for the gap in funding at the local level, as shown in Figure E .

As the figure shows, the U.S. systematically funds schools in wealthier areas at higher levels than those with higher rates of poverty, even after accounting for funding meant to remedy these gaps. On average, local property-tax funding per student is $5,260 lower in the poorest districts than in the wealthiest districts.

Federal and state revenues fail to offset the funding disparities caused by relying on local property tax revenues : How much more or less school districts of different poverty levels receive in revenues than low-poverty school districts receive, all and by revenue source, 2017–2018

Notes: Amounts are in 2019–2020 dollars, rounded to the closest $10, and adjusted for each state's cost of living. Low-poverty districts are districts whose poverty rate for school-age children (children ages 5 through 17) is in the bottom fourth of the poverty distribution; high-poverty districts are districts whose poverty rate is in the top fourth of the poverty distribution.

Extended notes: Sample includes districts serving elementary schools only, secondary schools only, or both; districts with nonmissing and nonzero numbers of students; and districts with nonmissing charter information. Amounts are in 2019–2020 dollars using the consumer price index from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS-CPI 2021) and rounded to the closest $10. Amounts are adjusted for each state’s cost-of living using the historical regional Price Parities (RPPs) from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA 2021). Low-poverty districts are districts whose poverty rate for school-age children (children ages 5 through 17) is in the bottom fourth of the poverty distribution for that group; medium-low-poverty districts are districts whose school-age children’s poverty rate is in the second fourth (25th–50th percentile); medium-high-poverty districts are districts whose school-age children’s poverty rate is in the third fourth (50th–75th percentile); in high-poverty districts, the rate is in the top fourth. Amounts are unweighted across districts.

Sources: 2017–2018 Local Education Agency Finance Survey (F-33) microdata from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES-LEAFS 2021) and Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates (SAIPE) data from the U.S. Census Bureau (Urban Institute 2021a).

While state revenues are a significant portion of funding, they only modestly counter the large locally based inequities. And while federal funding, by far the smallest source of revenue, is being deployed as intended (to reduce inequities), it inevitably falls short of compensating for a system grounded in highly inequitable local revenues as its principal source of funding. As such, although states provide their highest-poverty districts with $1,550 more per student than to their lowest-poverty districts, and federal sources provide their highest-poverty districts with $2,080 more per student than to their lowest-poverty districts, states and the federal government jointly compensate for only about half of the revenue gap for high-poverty districts (which receive a per-student average of $6,330 less in property tax and other local revenues). That large gap in local funding leaves the highest-poverty districts still $2,710 short per student relative to the lowest-poverty districts, reflecting the 14.1% revenue gap shown in Figure C. Even though high-poverty districts get more in federal and state dollars, they get so much less in property taxes that it still puts them in the negative category overall.

Disparities shortchange states’ (and districts’) ability to access and allocate the resources needed for effective education

Given the heavy reliance on highly varied local funding, it is no surprise that there is similarly significant variation across states with respect to almost every aspect of funding discussed here. Table 1 reports federal, state, and local funding for each state and for the District of Columbia, with local funding broken down into three categories.

Revenues for public elementary and secondary schools, by source of funds and by state : Share of each source in total revenue, 2017–2018

Source: National Center for Education Statistics' Digest of Education Statistics (NCES 2020b).

Nationally, in 2017–2018, local and state sources accounted for 45.3% and 46.8% of total revenue, respectively; just 7.8% comes from the federal government. However, these averages mask substantial variation in the shares of revenue apportioned by each source across states. Local revenue, for example, ranges from just 3.7% of total public-school revenue in Vermont and 18.2% in New Mexico, on the lower end, to a high of 63.4% in New Hampshire. The same is true with respect to state revenue. The state that contributes the smallest share to its education budget is New Hampshire at 31.3%, with Vermont contributing the largest share (89.9%). There is also quite a bit of variation in the share represented by federal funds—from just 4.1% in New Jersey to 15.9% in Alaska. (The cited values are highlighted in the table. We omit the District of Columbia and Hawaii from these rankings because of the unusual composition of their funding streams, but we provide their values in the table.)

As shown earlier in the discussion of the map in Figure E, there are also large disparities in funding effort—how generously each state funds its schools relative to its capacity to do so, based on state GDP. High-effort, high-capacity s tates such as Alaska, Connecticut, New York, and Wyoming use a larger-than-average share of their overall GDP to support pre-K–12 education and they generate high funding levels.

As a result of funding and effort variability across states, the levels of inequity and inadequacy across states also vary substantially (Baker, Di Carlo, and Weber 2020; Farrie and Sciarra 2021). Notably, funding variability translates into significant disparities in overall per-student revenue and per-student spending levels, as shown in Figures F and G . In Wyoming, for example, where effort is relatively high (4.36%; see Figure E) and there is a higher-than-average contribution of state funds to total revenue and a lower-than-average contribution of local funds to total revenue (56.8% and 36.8%, respectively, versus 46.8% and 45.3% averages across the U.S.), per-student revenue is among the highest of any state, nearly $21,000. In contrast, Arizona and North Carolina—which are among the lowest in effort in the country (2.23% and 2.28%, respectively), but where state funds account for 47.1% and 62.1% of the state’s total public education revenues, respectively, and local funds account for 40.4% and only 27.0%, respectively—collect about half of what Wyoming collects per student. (Data accounts for differences in states’ cost of living; see the appendix for more details on our methodology.)

Public education revenues vary widely across states : Per-student revenues for public elementary and secondary schools, by state, 2017–2018

Note: Amounts are in 2019–2020 dollars using the consumer price index from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS-CPI 2021) and rounded to the closest $10. Amounts are adjusted for each state’s cost-of living using the historical regional Price Parities (RPPs) from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA 2021).

Source: National Center for Education Statistics’ Digest of Education Statistics (NCES 2020b).

Public education expenditures vary widely across states : Per-student expenditures for public elementary and secondary schools, by state, 2017–2018

Note: Amounts are in 2019–2020 dollars using the consumer price index from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS-CPI 2021) and rounded to the closest $10. Amounts are adjusted for each state’s cost-of living using the historical Regional Price Parities (RPPs) from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA 2021).

Source: National Center for Education Statistics’ Digest of Education Statistics (NCES 2020c).

These substantial disparities in all the school finance indicators, and in per-pupil spending and revenue across states, are mirrored in capacity and investment patterns across districts and, within them, individual schools.

As such, these systemic and persistent inequities play a decisive role in shaping children’s real school experiences. As Raikes and Darling-Hammond (2019) note, “As a country, we inadvertently instituted a school finance system similar to red-lining in its negative impact. Grow up in a rich neighborhood with a large property tax base? You get well-funded public schools. Grow up in a poor neighborhood? The opposite is true. The highest-spending districts in the United States spend nearly 10 times as much as the lowest-spending, with large differentials both across and within states (Raikes and Darling-Hammond 2019). In most states, children who live in low-income neighborhoods attend the most under-resourced schools” (see also Turner et al. 2016 for the underlying data). 11

These gaps in spending capacity touch every aspect of school functioning, including the capacity of teachers and staff to deliver effective instruction, and pose a huge barrier to the excellent school experience that each student should receive. In Pennsylvania, for example, where districts tend to rely heavily on local revenues to finance schools, per-pupil spending ranges dramatically. Indeed, in 2015, the U.S. Department of Education flagged the state as having the biggest school-spending gap of any state in the country (Behrman 2019). One illustrative example is in Allegheny County, on the western side of the state, where the suburban Wilkinsburg school district outside of Pittsburgh spent over $27,000 per student in the 2017–2018 school year, while the more rural South Allegheny school district spent just over $15,000, roughly 45% less.

With salaries being the largest line item in school budgets, these disparities substantially affect schools’ ability to hire the educators and other school personnel needed to provide effective instruction, the school leaders to guide instructional staff, and the staff needed to support administrative needs and to offer other services and extracurricular activities. As a result, these resources vary tremendously not only among states, but within them from one district, and even school, to another. 12 Overwhelming research exposes large disparities in access to counselors, librarians, and nurses, and in access to up-to-date technology and facilities. Facilities are literally crumbling in lower-resourced states and districts, painting a clear picture of the dire straits many schools face. (See, for example, Filardo, Vincent, and Sullivan 2019 regarding added consequences for low-income students and their teachers in schools that are too cold, full of dust or lead paint, and have broken windows or crumbling ceilings.)

Baker, Farrie, and Sciarra (2016) note that “increasing investments in schools is associated with greater access to resources as measured by staffing ratios, class sizes, and the competitiveness of teacher wages.” The findings presented here are backed by the extensive body of literature on the positive relationship between substantive and sustained state school finance reforms and improved student outcomes. Together, they make a strong case that state and federal policymakers can help boost outcomes and close achievement gaps by improving state finance systems to ensure equitable funding and improved access to resources for children from low-income families.

Economic downturns exacerbate the problems with our school finance system and, over time, cause cumulative damage to students and to the system

Recessions lead to depleted state and local budgets and, in turn, to cuts in education funding. Trends since the Great Recession demonstrate that it can take a long time to restore education budgets and that our practice of balancing budgets on the backs of schoolchildren is an unwise and, ultimately, costly one in terms of educational and societal outcomes. As we show in Figure H , reductions in revenue for public education often outlast the official length of the recession, lasting much longer than the point when state and local budgets have returned to pre-recession trajectories in other areas of spending. In addition, a poor allocation of resources across high- and low-poverty districts disproportionately harms students in the highest-poverty districts relative to their peers in better-off districts, compounding the existing challenges described above and impeding their recovery.

It took the United States nearly a decade to restore the national per-student revenue to its pre-recession (2007–2008) school-year levels. Figure H shows national trends in revenue per student, by source (federal, state, and local), from the onset of the Great Recession through 2017–2018. 13

Education revenues fell sharply after 2008 (and did not return to pre-recession levels for about eight years) : Change in per-student revenue relative to 2007–2008, by source (inflation adjusted)

Note: The chart shows change in revenue per student for public elementary and secondary schools compared with 2007–2008. Amounts are in 2019–2020 dollars and rounded to the closest $10 using the consumer price index from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS-CPI 2021). The Local line is all local sources, including property tax revenues.

Per-student state revenue fell precipitously between 2007–2008 and 2012–2013—it was down nearly $900 at the low point. While revenue from property taxes did not decrease, on average, other local revenues fell by $160 by 2011–20121, only recovering to 2007–2008 levels in 2014–2015. Federal funding for schools, together with the additional recovery funds targeted to education through the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), provided an initial and critical counterbalance to these reductions; in 2009–2010 and 2010–2011, districts were receiving slightly over $600 more per student from the federal government than they were before the recession.

The peak in federal revenue is also visible in Figure I , which depicts the distribution of funding by sources by year . Total federal funds accounted for 12.7% of total revenue in 2009–2010, compared with just 8.2% in 2007–2008, an increase of over 50%. (Note that this increase was made larger by the reduced total amounts of revenues, i.e., it constituted a greater share of a smaller whole).

Importance of federal funding for education increased in the aftermath of the Great Recession : Share of total education revenue by source, 2007–2008 to 2017–2018

Source: National Center for Education Statistics' Digest of Education Statistics (NCES 2020a).

While these federal investments provided a critical boost by temporarily upholding education funding, our analyses suggest an opportunity to shorten the slow recovery to pre-recession levels was lost. Just as they effectively operated during the recession, it is likely that larger and more sustained federal investments would have better assisted the students, schools, and communities that suffered major setbacks due to the Great Recession. We come back to this idea in sections below.

In keeping with the discussion on broad funding disparities by state, the road to recovery from the Great Recession also varies across states and districts, with some still lagging from the Great Recession as they struggled with the COVID-19 crisis.

Research demonstrates that well after the end of the Great Recession, a significant number of states were still funding their public schools at lower levels than before the recession. As late as 2016, for example, per-student funding in 24 states—including half of the states with over a million enrolled students—was still below pre-recession levels (Leachman and Figueroa 2019). For some of these states, the failure to return to prior funding levels was driven by the lack of recovery of the per-student state revenue (for example, Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Florida, Mississippi, Montana, New Mexico, and Oklahoma). In some of the “deepest-cutting states — including Arizona, North Carolina, and Oklahoma,” note Leachman and Figueroa, the state governments made significant cuts to income tax rates, “making it much more difficult for their school funding to recover from cuts they imposed after the last recession hit.” In other states, lack of local revenue was the culprit (as in Hawaii, Indiana, Kansas, and Vermont, for example). Finally, in some of these states, this shortfall fell on top of a rapidly growing student population (i.e., even had their total revenues recovered to pre-recession levels, they would still fall far behind on a per-student basis). Exploring the various drivers of these trends and their variation across states is beyond the scope of this report but would undoubtedly be fruitful. 14

Putting aside state trends and underlying causes, a focus on school districts reveals a strong correlation between poverty rates and education funding recovery. The following figures show the trends over time in total per-student revenue and spending by school district poverty levels. As we see, high-poverty districts and their students experienced both the biggest shortfalls and the most sluggish recoveries.

Figure J shows that, as discussed above, districts with relatively small shares of low-income students (low-poverty districts) never saw revenues per student fall below pre–Great Recession levels, adjusted for inflation and state cost of living. By contrast, the one-fourth of districts with the largest share of students from poor families (high-poverty districts) stayed below their pre–Great Recession level of per-student revenues long after recovery was in full swing, through 2015–2016. In keeping with that spectrum, the medium-high poverty districts did recover to their pre-recession per-student revenue levels, but not until 2014–2015.

The drop in education revenues after 2007–2008 was greater in high-poverty districts : Change in total per-student revenue compared with 2007–2008, by district poverty level (adjusted for inflation and state cost of living)

Sources: 2007–2008 to 2017–2018 Local Education Agency Finance Survey (F-33) microdata from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES-LEAFS 2021) and Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates (SAIPE) data from the U.S. Census Bureau (Urban Institute 2021a).

Figure K tells a similar story regarding trends in per-student expenditure across school districts. As such, it took until 2017–2018, a decade after the Great Recession had first hit, for high-poverty school districts to surpass their pre-recession levels, though they still lagged far behind their wealthier counterpart districts. Moreover, though not shown in this graph, for high-poverty districts, getting back to pre-recession status means catching up to revenue and spending levels that were lower than in the wealthier districts to begin with. (Figure C earlier in the report illustrates the gaps between high- and low-poverty districts in 2017–2018.)

The drop in education expenditures after 2007–2008 was greater in high-poverty districts : Change in total per-student expenditures compared with 2007–2008, by district poverty (adjusted for inflation and state cost-of living)

Notes: Amounts are in 2019–2020 dollars, rounded to the closest $10, and adjusted for each state's cost of living. Low-poverty districts are districts whose poverty rates (for children ages 5 through 17) are in the bottom fourth of the poverty distribution; high-poverty districts are districts whose poverty rates are in the top fourth of the poverty distribution.

Balancing budgets on the backs of children during a recession has serious consequences

Inadequate, inequitable funding relegates poor children to attend under-resourced schools even in good economic times, and to suffer disproportionately during and in the aftermath of economic downturns. We have for far too long been balancing recession-depleted budgets on the backs of schoolchildren, in particular low-income children and children of color. This not only hurts these children immediately, but severely limits their prospects as adults. As such, this practice has broader implications for the future of the country, both economically and regarding the strength of our societal fabric, given that the students of today are the workers and the citizens of tomorrow.

Indeed, these negative patterns are just the first indications of a cascade of consequences that result from funding cuts. This section describes those consequences and their flip side, which is more frequently the focus of education researchers—the positive effects of increased investment. First, we review the literature demonstrating the impacts of various levels of funding on student outcomes. Next, we point to analyses that have shown some other associated school problems (education employment, class size, and student performance, among others) that were contemporaneous with the declines in spending and revenue. Thought it is difficult to quantify the exact and independent impact of the funding cuts on these factors, the strong correlations suggest that they are related.

Substantial evidence points to the positive effects of higher spending on both short- and long- term student outcomes, as well as on schools overall and on adult outcomes (Jackson and Mackevicius 2021; Jackson, Johnson, and Persico 2016; Gibbons, McNally, and Viarengo 2018; Hyman 2017; Lafortune, Rothstein, and Schanzenbach 2018; Jackson 2018; Jackson, Wigger, and Xiong 2020; Baker 2018). This body of research also provides evidence that the impact of school spending differs by students’ family income (Lafortune, Rothstein, and Schanzenbach 2018; Jackson, Johnson, and Persico 2016). And, though less has been studied in this specific area, the evidence also shows that a misallocation of resources and/or a decrease in spending has a negative influence on student outcomes, as well as on some teacher outcomes (Jackson, Wigger, and Xiong 2020; Greaves and Sibieta 2019). 15

A recent summary of the literature provides compelling evidence of the effects of school spending on test scores and educational attainment. Based on 31 studies that provide reliable causal estimates, Jackson and Mackevicius (2021) find that, on average, a $1,000 increase in per-pupil public school spending for four years increases test scores by 0.044 percentage points, high school graduation by 2.1 percentage points, and college-going by 3.9 percentage points. Interestingly, the authors explain that “when benchmarked against other interventions, test score impacts are much smaller than those on educational attainment—suggesting that test-score impacts understate the value of school spending.” Consistent with a cumulative effect, the educational attainment impacts are larger after more years of exposure to the spending increase, and average impacts are similar across a wide range of baseline spending levels, indicating little evidence of diminishing marginal returns at current spending levels.

Other research suggests that the effect of spending is greater on disadvantaged students. Bradbury (2021) investigates “how specific state and local funding sources and allocation methods (redistributive extent, formula types) relate to students’ test scores and, especially, to test-score gaps across races and between students who are not economically disadvantaged and those who are.” Her findings suggest that statewide per-student school aid has no relationship with test-score gaps in school districts, but that the progressivity of the state’s school-aid distribution is associated with smaller test-score gaps in high-poverty districts. 16

Other studies further affirm the implications of equity-specific funding decisions. Jackson, Johnson, and Persico’s (2016) study assesses the impacts on a range of student and adult outcomes of a series of court-mandated school finance reforms that took place in the 1970s and 1980s. Linking information on the reforms to administrative data about the children who attended the schools, the authors found that the increase in school funding was associated with slight increases in years of educational attainment, and with higher adult wages and reduced odds of adult poverty, as well as with improvements to schools themselves—increased teacher salaries, reduced student-to-teacher ratios, higher school quality, and even longer school years (Jackson, Johnson, and Persico 2016). Specifically, a 10% increase in per-pupil spending each year for all 12 years of public schooling leads to 0.27 more completed years of education, 7.25% higher wages, and a 3.67 percentage-point reduction in the annual incidence of adult poverty. As with the other studies, the benefits from increased funding are much greater for children from low-income families: 0.44 years of educational attainment and wages that are 9.5% higher.

In another study drawing on data from post-1990 school finance reforms that increased public-school funding in some states, Lafortune, Rothstein, and Schanzenbach (2018) estimate the impact of both absolute and relative spending on achievement in low-income school districts, as measured by National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) data. 17 They find that the reforms increase the achievement of students in these districts, phasing in gradually over the years following the increase in spending/adequacy. While the measures employed to estimate the impact tend to be technical, the authors emphasize that this “implied effect of school resources on educational achievement is large.” 18 Similar adequacy-related reforms that resulted from court mandates, rather than state legislative decisions, prompted significant increases in graduation rates (Candelaria and Shores 2019).

Conversely, research shows that both the reallocation of resources and/or a decrease in spending have a negative influence on both teacher and student outcomes. Jackson, Wigger, and Xiong (2020) find that the cuts to per-pupil spending that occurred during the Great Recession reduced test scores and college enrollment, particularly for children in poor neighborhoods. Shores and Steinberg (2017) reaffirm these findings, noting that the Great Recession negatively affected math and English language arts (ELA) achievement of all students in grades 3–8, but that this “recessionary effect” was concentrated among school districts serving both more economically disadvantaged students and students of color. Greaves and Sibieta (2019) find that changes that required districts to pay teachers following higher salary scales, but that provided no additional funding to implement the requirements, did lead to increased pay for teachers as intended, but at the expense of cuts to other noninstructional spending of about 4%, with no net effects on student attainment. That is, reallocating resources across functions, without increasing the overall levels, did not improve outcomes.

Other studies explore disappointing trends across multiple education parameters during the decade preceding the COVID-19 pandemic, including teacher employment, class size, aggregate student performance, and performance gaps by socioeconomic status and/or racial/ethnic background. Several analyses show that recession-led school funding cuts were contemporaneous with significant reductions of teacher employment. The number of teachers in the United States public-school system reached its highest point in 2008, and then dropped significantly between 2008 and 2010 because of the recession (Gould 2017; Gould 2019; Berry and Shields 2017). Evans, Schwab, and Wagner (2019) estimated a decrease in total employment in public schools of 294,700 from the start of the recession until January 2013. Gould (2019) estimated that, in the fall of 2019, there were still 60,000 fewer public education jobs than there had been before the recession began in 2007 and that, if the number of teachers had kept up proportionately with growing student enrollment over that period, the shortfall in public education jobs would be greater than 300,000.

Related to these challenges, in the aftermath of the Great Recession through the 2015–2016 school year, schools’ struggles to staff themselves increased sharply. García and Weiss (2019) showed that the share of schools that were trying to fill a vacancy but could not do so tripled from the 2011–2012 to the 2015–2016 school year (increasing from 3.1% to 9.4% of schools in that situation), and the share of schools that reported finding it very difficult to fill a vacancy nearly doubled (from 19.7% to 36.2%). 19

Although class size, and the closely related metric of student-to-teacher ratios, have declined over the long term, they are higher, on average, in 2020 than they were in 2005 (the closest data point prior to the Great Recession) in 29 out of the 50 states plus the District of Columbia (NCES 2020d; Hussar and Bailey 2020). (See Mishel and Rothstein 2003 and Schanzenbach 2020 for a recent review of the influence of class size on achievement.)

Understanding overall trends in student performance over this period helps to put the impacts of trends in these other metrics in context. We have cited research that links school finance trends and educational outcomes in the aftermath of the Great Recession, but it is worth describing what the trends in student performance looked like across the country. It should not be surprising that scores from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), the most reliable indicator over time of how much students are learning, show stagnant performance in math and reading for both fourth- and eighth-graders between 2009 and 2019 (NAGB 2019). As Sandy Kress, who served as President George W. Bush’s education advisor, commented, “The nation has gone nowhere in the last ten years. It’s truly been a lost decade [and] [t]he only group to experience more than marginal gains in recent years has been students in the top 10th percentile” (Chingos et al. 2019).

Gains (both absolute and relative) vary by students’ background, with multiple trends visible. Carnoy and García’s 2017 research on achievement gaps between racial/ethnic groups shows that Black–white and Hispanic–white student achievement gaps have continued to narrow over the last two decades, and also that Asian students were widening the gap ahead of white students in both math and reading achievement. At the same time, Hispanic and Asian students who are English language learners (ELLs) are falling further behind white students in mathematics and reading achievement, and gaps between higher- and lower-income students persist, with some changes that vary by subject and grade. During the decade of stagnation, however, in keeping with trends in per-pupil investments over this period, these trends widened existing inequities. As National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) Associate Commissioner Peggy Carr soberly notes, “Compared to a decade ago, we see that lower-achieving students made score declines in all of the assessments, while higher-performing students made score gains” (Danilova 2018).

Finally, we have also seen marked changes in the student body composition that have implications for these trends going forward. The proportion of low-income students in U.S. schools has increased rapidly in recent decades, as has the share of students of color (NCES 2020e; Carnoy and García 2017). A student’s race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status also affects the student’s odds of ending up in a high-poverty school or a school with a high share of students of color. For example, Black and Hispanic students who are not poor are much more likely than white or Asian students who are low income to be enrolled in high-poverty schools (Carnoy and García 2017).

All of these changes point to the need for increased resources across the board, and especially in schools serving the highest-needs students. As we revisit education funding in the aftermath of the pandemic-induced recession, the new structure must make greater investments to ensure the equitable provision of education and associated supports not only in stable times but also in the context of substantial disruptions and crises (García and Weiss 2021). As the analysis above makes clear, neither equity not adequacy—and, thus, excellence in public education—will ever be possible as long as local revenues play such a central role, and as long as states are the primary vehicle to address those disparities. While we leave it to policymakers to design the specifics of this public-good investment, we emphasize that the benchmarks we should reach to determine that those investments are stable, sufficient, and equitable should reflect meaningful, consistent advances for the highest-poverty schools and schools serving students of color. In other words, when the impacts of recessions no longer fall on the backs of our most vulnerable children, we will know that we are moving in the right direction.

Public education funding could also be deployed quickly to boost the economy and serve as an automatic stabilizer

The practice of cutting school funding during recessions is not only bad for students and teachers but also hurts the economy overall. The education sector has the potential to help stabilize the economy during downturns, but historically, our policy responses have failed to provide the necessary investment, as discussed in this report.

Up to this point, we have shown the characteristics, dynamics, and consequences of the existing education funding system. We have emphasized that fixing the system’s problems and achieving an excellent, equitable, robust, and stable public education system requires more funding —not just a reshuffling of existing funding. We have presented evidence indicating the need for a significantly larger contribution to the system from the federal government on a permanent basis. We have also demonstrated that targeting additional funds to schools during the Great Recession—via ARRA funds in particular— helped offset the large cuts schools experienced due to state and local shortfalls. As stated by Evans, Schwab, and Wagner (2019), “[…] the federal government’s efforts to shield education from some of the worst effects of the recession achieved their major goal.” Based on the observed trends, we considered whether even more sustained federal investments would have better assisted the students, schools, and communities that suffered major setbacks due to the Great Recession.

There is another reason for both larger investments and a more robust federal role when state and local budgets experience shortfalls due to economic downturns: School funding can be part of the countercyclical public-spending programs that help the economy recover. While policymakers and economists have long recognized the need for, and the effectiveness of, such automatic stabilizers (programs that pump public spending into the economy just when overall spending is declining), they have not traditionally placed public education spending in this category—yet it belongs there. 20 Federal funding directed toward schools during and in the aftermath of economic downturns can further boost the economy, thereby jump-starting economic recoveries.

Stable, sufficient, and equitable education funding would give schools and districts the resources and flexibility to adapt to challenges that they need but have not had during the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, automatic stabilization of public education protects students and school systems against depleted school budgets during recessions and volatile business cycles (Evans, Schwab, and Wagner 2019; Allegretto, García, and Weiss 2021). In addition to averting the harms to students and teachers described above, countercyclical investments would keep the public education workforce employed. The teachers, nurses, counselors, librarians, bus drivers, cafeteria workers, and others who work in public schools made up 53.2% of all state and local public-sector workers in 2019—accounting for nearly 7.0% of total U.S. employment. 21 School staff are also family and community members whose spending ripples through their local economies (known as the multiplier effect). Cuts to education revenues and employment thus also affect local communities more broadly, and retrenchment of spending acts as a type of reverse multiplier, resulting in a vicious downward cycle.

Federally provided countercyclical fiscal spending on public education set up to kick in based on defined triggers—akin to an expansion of unemployment benefits that kicks in when certain unemployment targets are reached—would have significant “bang-for-your-buck” multiplier effects. Such automatic spending constitutes smart investment that upholds public education while giving the overall economy a significant boost. Analyzing then President-elect Biden’s American Rescue Plan, which included public education spending, Zandi and Yaros (2021) reported a 1.34 fiscal multiplier for state and local government spending (the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 was signed into law in March 2021).

Because the federal government already provides substantial support to state and local governments in such times, bolstering and further targeting that support in a defined and concerted manner would entail a relatively light lift. Despite some challenges, several programs of this nature have been shown to meet their goals in their given policy areas. For example, the federal unemployment insurance (UI) and food stamps (SNAP) 22 programs are often cited as having demonstrably positive outcomes when the federal government increases their funding. Both have been heavily criticized for their structural flaws and lack of sufficient resource (Bivens et al. 2021). However, through prior recessions and the pandemic, data illustrate that UI and SNAP nonetheless prevented millions of people from falling into, or deeper into, poverty, as well as averted hunger and evictions. The CARES Act’s first allotment of the Economic Impact Payments and expanded UI benefits during the COVID-19 pandemic kept 13.2 million people out of poverty (Zipperer 2020). 23 The Bureau of Economic Analysis broke out the effects of selected pandemic response programs on personal income, illustrating just how heavily Americans leaned on these benefits through the pandemic. In June 2020, UI payments accounted for 15.6% of all wages and salaries in the U.S (BEA 2020). By contrast, just prior to the pandemic UI benefits were negligible in comparison—just 0.27% of wages and salaries overall in February 2020.

We propose that policymakers create a program for funding education during downturns that is of adequate magnitude and provides immediate, sufficiently large, and sustained relief as needed.

In order to provide an immediate response, the system must have the capacity to adapt to emergencies; a key way to ensure that is to specify ahead of time the automatic triggers that prompt launching the contingency plans. 24 To clarify, we are not suggesting that public education spending be treated exactly like food stamps or unemployment insurance benefits—i.e., that states amass reserves for a “rainy day” or that reserves be built up during nonrecessionary periods. Rather, we are pointing to the economic benefits of an education system that is robustly, stably, and consistently funded throughout economic ups and downs, ensuring that it also has the resources to withstand the downturns and the flexibility to adapt. And we are recommending that Congress establish a program that kicks in when needed, rather than waiting until a crisis and coming together to pass a large, responsive bill, which requires political negotiation and can thus take a lot of time.

Sufficiently large investments imply that the spending numbers are adequate to the size of the problem. As we have seen during the COVID-19 pandemic, the various public programs—even with all their flaws—have been critical to preventing a much worse disaster than the one we have experienced. 25

Finally, regarding sustained assistance, it was clear that relief and recovery spending fell far short in response to the Great Recession and was cut off too soon; it took 6.2 years to recoup the jobs lost and nearly eight years for the unemployment rate to get back to its pre-recession rate of 5%. And unemployment rates for Black and Hispanic workers took much longer to return to pre-recession levels (Allegretto 2016). In education, as shown before, it was not until the 2014–2015 school year that districts’ per-student revenue, on average, recovered to 2007–2008 levels nationally—and recovery took even longer for high-poverty districts.

In sum, while the purpose of this study is not to offer guidance on how to best design a public education automatic-stabilization program, we do argue that such a program would help public education during downturns, and provide a boost to the overall economy. At later stages, proof-of-concept designs such as Medicaid and transportation grants, and some of the existing large-scale public programs already mentioned, could be a useful place to continue the discussion. Identifying best practices—in program design, financing, and implementation in the United States and elsewhere—would help to conceive a strategy.

Conclusions and next steps

For too long in this country, we have normalized the practice of underinvesting in education while expecting that schools would still function well (or at least moderately well). We have also accepted the disproportionate burden that economic recessions place on public schools and students. These norms are very costly—to individuals and to society—and they shortchange our country’s potential.

As the data and research show, this approach is backward. If we are to have a chance of providing all students in the United States with an excellent education we must build a strong foundation—one with sufficient, adequate, and equitable funding of public schools in practice, not just in theory. Ensuring broad adequacy and equity will require increased federal investment (to more fully complement a system that relies heavily on nonfederal sources). Moreover, federal provisions that provide for automatic boosts to education spending during downturns is critical. Our education system can and should include a countercyclical designed to help stabilize the economy when it is contracting—benefiting schools and communities.

Were we to truly acknowledge the benefits, it would be hard to argue politically against making these investments a reality. Here again the data are edifying: Extensive research indicates that a stable and consistent funding system with a much higher level of investment would generate large economic and social returns. 26

An increased federal investment to ensure sufficient, adequate, and equitable funding of public schools has an additional benefit: It could serve as another tool in our toolbox for faster, broader, and more equitable recoveries from recessions. Boosting school funding during downturns could boost the wider economy—and disproportionately benefit the low-income communities that tend to be hit hardest in hard economic times.

This proposal requires jettisoning the tendency to pit public policy areas against one another for resources, and to glamorize the purportedly efficient notion of “doing more with less.” The latter, often used to justify education budget cuts, actually entails a misguided denial of the need for resources and of the inevitable damage that ensues when those resources fall short—or fail to exist at all.

We are not arguing that increased access to federal resources alone will address all the issues outlined above. Simply throwing money at the goal of providing an excellent education equitably to all children won’t achieve it; we need to make the right investments. 27

In addition, it is also important to distinguish funding from decision-making. While the federal government is best positioned to ensure broadly adequate and equitable education funding nationwide, it is not necessarily well suited to make decisions about policy, practice, and implementation. Evidence should guide how decision-making is allocated across the federal, state, and local levels. 28

Advancing this proposal also requires that we dislodge the conversation from where it has been stuck for at least the past half-century—namely on whether the resources exist. They do. What we need to ask now is how to make those resources available, and how to deploy them to ensure that all students have the opportunities to learn, develop, and achieve their full potential—and that these opportunities are available during both ordinary and recessionary times.

About the authors

Sylvia Allegretto is a research associate with the Economic Policy Institute. She worked for 15 years at the Institute for Research on Labor and Employment at the University of California, Berkeley, where she co-founded the Center on Wage and Employment Dynamics (CWED). She received her Ph.D. in economics from the University of Colorado, Boulder.

Emma García is an economist specializing in the economics of education and education policy. She developed this study while she was at the Economic Policy Institute (2013-2021). She is now a senior researcher at the Learning Policy Institute. García received her Ph.D. in economics and education from Columbia University’s Teachers College.

Elaine Weiss is the Policy Director at the National Academy of Social Insurance, and former National Coordinator of the Broader, Bolder Approach to Education at the Economic Policy Institute (2011-2018). She received her B.A. in Political Science from the University of Maryland, J.D. from Harvard Law School, and Ph.D. in public policy from the George Washington University.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to EPI Publications Director Lora Engdahl for having edited this report and for her help shepherding it to its release. The authors benefited from Ajay Srikanth’s guidance on school finance data sources at the beginning of the project. The authors appreciate EPI’s support of this project, EPI Research Assistant Daniel Perez for his assistance with the tables and figures, EPI Editor Krista Faries for her usual thoughtful insights, and EPI’s communications staff for their assistance with the production and dissemination of this study.