The Pedigree Dog Breeding Debate in Ethics and Practice: Beyond Welfare Arguments

- Open access

- Published: 28 June 2017

- Volume 30 , pages 387–412, ( 2017 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Bernice Bovenkerk ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3955-2430 1 &

- Hanneke J. Nijland ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8281-0434 2

46k Accesses

22 Citations

5 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Men have forgotten this truth,” said the fox. “But you must not forget it. You become responsible, forever, for what you have tamed. The Little Prince, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry.

Pedigree dog breeding has been the subject of public debate due to health problems caused by breeding for extreme looks and the narrow genepool of many breeds. Our research aims to provide insights in order to further the animal-ethical, political and society-wide discussion regarding the future of pedigree dog breeding in the Netherlands. Guided by the question ‘How far are we allowed to interfere in the genetic make-up of dogs, through breeding and genetic modification?’, we carried out a multi-method case-driven research, reviewing literature as well as identifying the perceptions of pedigree dog breeding of a variety of parties in the Netherlands. We examined what moral arguments and concepts different stakeholders, including breeders, veterinarians and animal protection societies, put forward when considering this question. While welfare arguments were often used as a final justification, we also frequently encountered arguments beyond welfare in practice, in particular the arguments that certain adaptations were unnatural, that they instrumentalised animals, or that they amounted to playing God. We argue that the way these arguments are employed points to a virtue ethical approach, foregrounding the virtue of temperance, as a balance between extreme positions was sought by our respondents in a variety of ways. Moreover, we argue against a rejection of unnaturalness arguments based on the naturalistic fallacy, as philosophers tend to do. We point out that unnaturalness arguments are related to people’s worldviews, including views on the proper human–animal relationship. We argue that such arguments, which we label ‘life-ethical’, should be the subject of more public discussion and should not be relegated to the private sphere.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Decisions of Wannabe Dog Keepers in the Netherlands

The usage of Mate Select, a web-based selection tool for pedigree dogs for promoting sustainable breeding

Canine Welfare Science: An Antidote to Sentiment and Myth

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Since the 2010 BBC-documentary ‘Pedigree Dogs Exposed’, public debate about health problems resulting from dog breeding has intensified. Problems that are frequently mentioned are breathing problems, heart disease and inability to give birth naturally in Bulldogs; eye problems such as proptosis (or ‘eye popping’) in Shih Tzus; allergies, bacterial infections, and eye irritations due to excessive skin in Shar-peis; hip and elbow dysplasia in large dogs such as German Shepherds; and premature death in many breeds. In 2014, the discussion about pedigree dog health in the Netherlands even led to an ‘election’ for the dubious title of ‘most pitiful dog of the Netherlands’, organised by a Dutch animal protection society. Footnote 1 Two main causes of health problems in pedigree dogs that are identified are selective breeding for extreme looks and the narrow genepool of many breeds. Footnote 2

A longstanding debate in animal ethics has focused on the moral acceptability of adaptations to the genetic make-up of animals, either through genetic modification (GM) or through selective breeding (Holland and Johnson 2012 ; Thompson 2007 ). As this debate has mostly taken place in the context of animal experimentation and livestock production, relatively little reflection has centred on changes in the genetic make-up of companion animals. Footnote 3 In light of the public discussion about pedigree dog breeding, we decided to perform research to provide insights to further the animal-ethical, political and society-wide discussion regarding the future of pedigree dog breeding. This paper reports on a case-driven research, Footnote 4 identifying the perceptions of pedigree dog breeding of a variety of parties in the Netherlands. Its guiding question was: ‘How far are we allowed to interfere in the genetic make-up of dogs, through breeding and GM?’

When exploring this question, we experienced a tension between the way ethicists discuss issues regarding adaptations to animal’s genetic make-up—or ‘tampering with animals’—and the way this issue is debated in practice. If we were to follow the implications of many animal ethical theories to their logical consistency, then perhaps we should conclude there is something problematic about domesticating dogs and other animals in the first place. Footnote 5 Some argue that such domestication is supported by a so-called domestication contract (Budiansky 1992 ), but this has been successfully discredited (Palmer 1997 ). Footnote 6 Nevertheless, as the quote from the ‘The Little Prince’ suggests, the domestication contract is a social construct that is quite commonplace in everyday life (Nijland 2016 ). This raises questions about the link between ethical theory and practice. Ethical theories seem to not be neatly adhered to in practice, moral concepts seem to be interpreted in a variety of ways, and consistency in reasoning seem to not be valued as highly as in ethical theory. Ethical theory obviously can add to the public debate. But can reasoning in practice perhaps also add to the reasoning used in ethical theory (cf. Persson and Shaw 2015 )?

As we will describe in Sect. 3 of this paper, discussions in animal ethics have not only focussed on the welfare consequences of adapting animals. It has been argued that even if the welfare of animals would not be compromised, there might still be moral objections to ‘playing God’, or the ‘instrumentalisation of animals’, for example. In our research, we were particularly interested in these arguments ‘beyond welfare’ as they have been so contentious and apparently difficult to justify on the basis of moral theory in the context of adaptations to animal genomes. Resultingly, the central questions of our study were:

What arguments and concepts are brought forward in ethical theory, that can be applied to the case of pedigree dog breeding?

To what extent can we find these arguments and concepts in everyday-life reasoning?

What criteria do people use in order to draw boundaries regarding what is acceptable and not?

Do the arguments people use in practice go beyond welfare arguments?

What could ethical theory learn from everyday-life reasoning about pedigree dog breeding?

What recommendations for the debate on pedigree dog breeding can we make based on our research?

After an explanation of the methodology of our research and review of ethical discussions about interfering in the genetic make-up of animals, we share our empirical results. Next, we discuss these, particularly zooming in on the often-mentioned objection that certain adaptations are ‘unnatural’. We argue that simply rejecting this objection as a naturalistic fallacy amounts to throwing out the baby with the bathwater. Not only does the objection point to a whole web of related arguments beyond welfare; we also found that it can be interpreted as a virtue ethical stance that foregrounds the virtue of temperance, calling for a balance between several different extremes. This objection to the unnaturalness of tampering with animals in our view points to ‘life ethical’ as opposed to only ‘rule ethical’ views. As we will argue, thinking and talking about the (un)acceptability of pedigree dog breeding should not stop with welfarist or animal rights views, but calls for a broader reflection on the good life.

Methodology: Case Driven Approach Involving Literature Review and Framing Analysis

The unchartedness of the topic and the kind of research questions that were raised, called for a multi-method case-driven approach: the case being moral reasoning concerning the limits of interfering in the genetic make-up of dogs, in ethical theory and in practice. Though in ethics, literature research into theoretical concepts and adding to existing theory solely premised on rational arguments is the norm, systematic analysis of qualitative empirical data can lead to a deepening of insight into the tension between lay people’s moral judgements and ethical theory, as well as uncover practical problems with ethical theories, and thus even inform adaptations of these—often quite sterile—theories (Persson and Shaw 2015 ). Qualitative case-study research has long been dominated by the assumption that a case-study “cannot provide reliable information about the broader class” (Abercrombie et al. 1984 , p. 34). However, we follow Flyvbjerg ( 2006 , p. 223) who argues: “Social science has not succeeded in producing general, context-independent theory and, thus, has in the final instance nothing else to offer than concrete context-dependent knowledge. And the case-study is especially well suited to produce this knowledge”, and: “The case study contains a greater bias towards falsification of preconceived notions than towards verification” (Flyvbjerg 2006 , p. 237). Karl Popper explained the principle of falsification with the example ‘all swans are white’ and proposed that just one observation of a single black swan would falsify this proposition (Popper 1959 ; see also Taleb 2007 ). Because of its in-depth approach the case-study method is well suited for identifying ‘black swans’. In line with this, Flyvbjerg stresses the relevance of case-studies based on the force of example for gaining knowledge and insight (Flyvbjerg 2006 ). Especially in uncharted territory, as our case of searching for theoretical and practical ethical reasoning regarding pedigree dog breeding in the Netherlands arguably is, a case-driven research strategy is vital to find exemplars and distinguish patterns in reasoning (Flyvbjerg 2006 ; Yin 2013 ).

The first research method we used in our case-driven approach consisted of a literature review into present ethical concepts and arguments regarding domestication, companion animals, adaptations and enhancement, that can be or are applied to the case of pedigree dog breeding. Successively, to gain insight into everyday-life reasoning in practice, we designed and performed interpretive empirical research, consisting of a framing analysis of specially designed semi-structured in-depth conversations with a variety of parties in the Netherlands, checked against and added upon by additional data sources such as documents, websites, media broadcasts and notes of participatory observations. The empirically gathered data was not aimed at providing statistically significant quantitative statements regarding argumentation styles by groups of respondents in the Netherlands based on existing ethical theories. The depth and variety of the case data however was well-suited to reveal patterns in perceptions and ways of reasoning, and with that inform existing theory (Persson and Shaw 2015 ). The comparison we made between ethical theory and practical reasoning explicitly was a two-way street: existing ethical literature provided sensitizing concepts (Bowen 2008 ; Blumer 1954 ) to design the study and analyse the case data, and on the other hand the empirical data importantly provided new input to our case with nuances and practical examples that—as we will show in this paper—can enrich how we think about and use ethical theories (Molewijk et al. 2004 ).

To disclose the variety of perceptions and ways of reasoning regarding pedigree dog breeding in our case study area, the Netherlands, we applied target group oriented theoretical sampling (Silverman 2001 ). We selected an as diverse as possible range of conversation partners, ranging from respondents with backgrounds in dog-breeding, veterinarian, NGO, policy, dog show, dog training/therapy, to citizens with and without (pure-bred and non-pure-bred) dogs. Table 1 shows a bibliographical summary of the interviewees and their backgrounds/roles in relation to pedigree dog breeding. The conversations ranged from 1 to 2 h in length and were held in 2016, on location, in the daily environment of the respondents. Anonymity was offered, the respondents were approached in an as neutral as possible manner and a natural conversation setting was sought, in which curiosity and empathic listening were guiding (Silverman 2001 ). In addition to these conversations, that were our first and foremost source of empirical data, we read policy reports, breeder’s and NGO websites and observed Dutch video—and audio material related to our case.

The design of the conversations was semi-structured, based on open questions; visual and verbal free association on ‘what makes a good life for a dog’ and ‘what makes a good dog’; intuitive ranking both actually performed and hypothetical adaptations on a line ranging from unacceptable to acceptable, including tail docking, jackets for dogs, hair trimming, breeding for certain (regular and extreme) colours and behaviour traits, genetic modification to achieve these same adaptations, and breeding a dog to die after 2 years (cf. Palmer’s ( 2012 ) ‘short-lived dogs’ or ‘disposable puppy’); finalised by discussing what dog keeping and breeding in an ideal world would look like and who is to be held responsible for certain outcomes. The conversations were organized according to the method of laddering (Bernard 2006 ; Reynolds et al. 2001 ): we continuously asked the respondents to make connections between adapting dogs, the consequences thereof (for humans and animals) and the value that the respondents attach to that, and to reveal underlying motivations for choices that are made and obtain a good description of the criteria, we probed for concrete concepts and asked ‘why’-questions after each answer until the respondent was unable to give further answers. The outcomes of these conversations are patterns of interconnected convictions, values, norms, knowledge, and interests (see as Nijland et al. 2010 ). We audio recorded the conversations with consent of the respondents, transcribed them word for word afterwards. Subsequently, we systematically categorized and coded the conversation transcripts in an Excel database, supplemented by information from additional data sources, to reveal patterns in reasoning and relate these back to current ethical theory.

The Ethics of Pedigree Dog Breeding: Existing Concepts and Arguments in Literature

Since the inception of animal biotechnology, animal ethicists have debated the moral (un)acceptability of interfering in animals’ genetic make-up. Even though by artificial selection (breeding), of course, already many changes had been made in animals, the use of biotechnological techniques—like genetic modification—has often been regarded a more efficient and far-reaching way of moulding animals for human purposes. Even though the debate has, therefore, focused on adapting animals through biotechnology, we started our exploration from the assumption that these objections can also be raised to a certain extent to traditional ways of interfering in animals’ genetic make-up through artificial selection. While several benefits of biotechnology have also been put forward (see Bovenkerk 2012 , pp. 246–248), ethical literature has primarily discussed objections and their tenability. We briefly review these below, by focussing on subsequently: animal welfare, dignity, integrity, non-identity, objectification, instrumentalisation, naturalness, and hubris.

Before we review these concepts, we should note that the basic assumption underlying these concepts is that animals possess moral status, i.e. that they have interests that need to be taken into account. Moral status is in an umbrella term that refers to two separate ideas (see Bovenkerk and Meijboom 2013 ): moral considerability (a being has a moral claim on us, based on the possession of capacities such as sentience (Singer) or being a subject-of-a-life (Regan) Footnote 7 and moral significance (the adjudication between the moral claims of different morally considerable beings). A point of discussion in animal ethics is the issue of whether moral status admits of degrees. According to DeGrazia ( 2008 , p. 192), possible reasons to grant two beings with a comparable interest different moral significance, are that one has a higher degree of ‘cognitive, affective, and social complexity’. Višak ( 2010 ) points out that these properties are irrelevant when we are talking about comparable interests: if we are dealing with a dilemma in which an interest in not suffering is at stake, all we should do is compare amounts of suffering and it makes no sense to say that the suffering of one being is by definition more important than that of another. This argument refers to a central idea of animal ethics since Peter Singer (1975), who argued that the basic tenet of justice is that equal interests should be treated equally and unequal interests unequally. If we attach more importance by definition to human interests than to the interests of other animals we are committing speciesism: discrimination on the basis of an irrelevant characteristic—namely species membership. Singer and other philosophers, like Regan ( 2003 ), hold animals and humans to be morally equivalent in the sense that in situations where their interests are comparable they should be treated the same. It is important to note that equal consideration of interests is not the same as pure equality, as the content of different animals’ and human’ interests are often not the same. For example, dogs do not have an interest in the right to free press. Opponents of this view argue that animals and humans are not morally equivalent; human interests simply matter more than animal interests (see Bovenkerk 2016 ).

Animal Welfare

Many general arguments about our treatment of animals focus on animal welfare consequences. The notion ‘animal welfare’ has many different interpretations, some focussing on negative and others on positive welfare, some focused on physical health and others including emotional well-being, and some measuring a specific moment in time, while others are measured over the animal’s whole lifespan and are broadly perceived as ‘the good life for animals’ (Harfeld et al. 2016 ). In general, three different views on animal welfare have been distinguished, primarily in the context of farm animal welfare (Fraser 2003 ). In the first group of function - based views on welfare, the central question is whether animals can cope with farming conditions. The second group of feeling - based views works from the presumption that animals have subjective feelings and that these are constitutive of their welfare. The third group of nature - based views presumes that welfare depends on the ability of animals to display their natural behaviour (Bovenkerk and Meijboom 2012 ). Footnote 8 These views are combined in the Five Freedoms - approach of the Farm Animal Welfare Council ( 1992 ) which states that an animal has good welfare when it is free from hunger and thirst, from discomfort, from pain, injury or disease, free to express normal behaviour, and free from fear and distress. Even though the three views place emphasis on different aspects and ways of measuring animal welfare, what they have in common in our view is that they all assume that animal welfare is in the end about what the animal itself experiences: i.e. what certain adaptations or actions mean for the animal itself, rather than for our views of the animal.

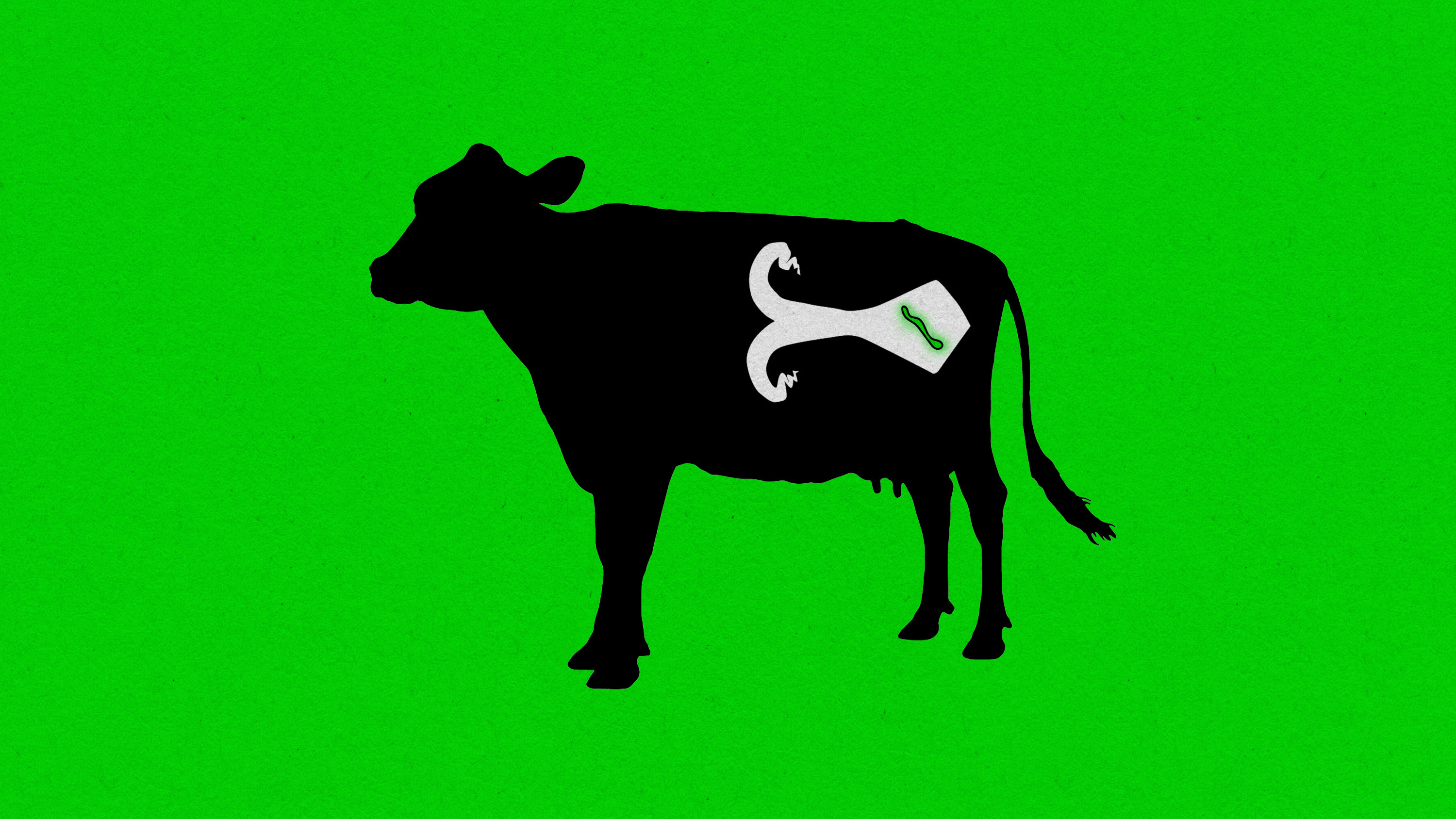

In the context of selective breeding and other changes to animals’ genomes, an important question is of course how such changes impact the animals’ welfare, and as we saw in the introduction there are serious issues here. Yet, changing animal’s genomes also raise issues that are not based on welfare concerns, as is illustrated by the case of ‘dumbing down’. Selective breeding and genetic technologies in fact create the opportunity to counter welfare problems, by creating animals that suffer less. For example, Adam Shriver ( 2009 ) has argued that, technically, we are close to being able to breed livestock with a reduced or eliminated capacity to suffer. In his opinion—given the fact that we are not all going to become vegetarians overnight—we should replace all livestock that are held under intensive rearing conditions with these ‘painless animals’ in order to reduce suffering in the world and better protect animals’ rights. Footnote 9 Thompson ( 2008 ) calls proposals like Shriver’s, where certain characteristics that cause stress or pain are removed, the Dumb - Down approach. He provides the example of blind chickens, that suffer less in intensive farming conditions because they are not as overstimulated or stressed as sighted chickens and therefore are less likely to peck each other. The problem, as Thompson ( 2008 ) sketches it, is that while many of us have the intuition that something goes horribly wrong here, from an animal ethics’ point of view this would be a good thing to do. After all, utilitarians like Peter Singer would argue that the chickens have an interest in reduced suffering and being born blind does not necessarily lead to suffering; nothing that the individual chicken had, was taken away from it if it was born blind. Footnote 10 A deontologist like Regan could ultimately not object to dumbing-down, because if we would go so far as to create animals without or with very minimal sentience, these would not qualify as subject-of-a-life, and they would not have inherent value. While cases like the blind chicken have been thoroughly discussed in animal ethics, according to Thompson ( 2008 , p. 305) ‘little progress has been made in articulating exactly what the ethical issue actually is’. Of course, pedigree dog breeding cannot be classified as a case of dumbing down, or disenhancement, in the sense that the dogs are still fully sentient. It could, however, be seen as a form of enhancement, Footnote 11 which has also been subject to objections, particularly from a Kantian perspective.

Dignity, Integrity, and the Non-identity Problem

Two Kantian arguments that have been put forward to explain what is wrong with disenhancing as well as with enhancing animals, are that they violate animal dignity or integrity. In their interpretation of the Swiss Constitution article which grants animals dignity, Balzer et al. ( 2000 ) argue that respecting animals’ dignity means that their inherent value has to be acknowledged, which in their eyes is based on the capacity of animals to pursue their own good. While they do not categorically reject manipulations of animals’ genomes for human purposes, the adaptations should not hamper their species-specific functioning.

This species-specific functioning also plays a role in the concept integrity. Even though the concept integrity has been applied in the debate about biotechnology, it was originally used to articulate more general objections to interventions that cannot be expressed in terms of harm to animal health and welfare (De Vries 2006 ). Integrity has been described by Rutgers et al. ( 1995 , p. 490) as ‘the wholeness and intactness of the animal and its species-specific balance, as well as the capacity to sustain itself in an environment suitable to the species’. Footnote 12 Examples of integrity violations are dehorning of cattle, Belgian Blue cows that can no longer give birth naturally, and tail docking of dogs. Integrity at first sight seems to refer to a biological norm. However, we would not speak of the violation of integrity in all cases where an animal’s intactness is violated. If we dock a dog’s tail for medical reasons we would not speak of an integrity violation, but were we to do so for aesthetic reasons, we would. As explained by Bovenkerk et al. (2001) this means that rather than a biological notion, integrity is a moral notion that refers to the intention behind the interference. Integrity, moreover, refers not so much to a property of an individual animal, but rather describes a ‘species typical norm’ (Thompson 2008 ). In other words, it refers to ‘the cowness of a cow, or ‘the chickenness of a chicken’ (Bovenkerk et al. 2001). The point of reference then is not the animal itself as adapted to the farm or the home, but rather the species as it would appear in nature. This is also how we should understand Rutgers’ view that integrity means the capacity to sustain itself in an environment suitable to the species: even though dehorned cattle can sustain themselves perfectly well in a farm environment, they would run into trouble in a more natural environment.

In the context of changes to animals’ genomes, it has been argued that the integrity of an animal has been violated if the modification changes the species-specific characteristics of the animal. Such changes would also bring about a change to the animals’ telos —their ‘good of their own’ (Rutgers and Heeger 1999 ). Others have argued, in contrast, that changing an animal’s telos is not problematic as long as this does not lead the animal to experience reduced welfare (Rollin 1995 ; De Vries 2006 ). However, as changes to an animal’s genome have taken place before this animal was born, it is in effect not this particular animal’s telos that was changed. Footnote 13 We cannot say that we have done any harm to this particular animal, but rather to our view of what this animal should be like. As Kantian arguments focus only on respect for individual animals, they ultimately cannot justify an objection that is based on a species-norm. For this reason, this Kantian argument beyond welfare does not sufficiently serve to make sense of our moral intuition that we should not change the genomes of animals.

This points to a specific conundrum, pointed out by Palmer ( 2011 ) in response to Paul Thompson ( 2008 ): when we genetically engineer or selectively breed animals in order to express specific traits, what we are in fact doing is not altering existing animals, but creating new ones. This means that by our breeding decisions we decide whether and which animals will exist in the first place. By selective breeding and genetic modification, we are at least partly creating ‘what animals are like’ (Palmer 2010 ). If we create an animal with welfare problems—as long as the animal still has a life worth living—we cannot say we harmed that animal, because if we had created an animal without welfare problems it would not be that specific animal anymore: the act of creating is a condition of this specific animal’s existence. After all, if we consider harming a being as making it worse off, we cannot say that through our breeding choices we made an animal worse off as compared to a different state of that same animal. This is a version of Parfit’s ( 1986 ) non - identity problem , applied to animals. One—impersonal—response to the non-identity problem is offered by utilitarians, who could argue that if we compare a world in which we breed unhealthy dogs with a world in which we breed healthy dogs, we should choose the latter. However, this utilitarian solution does not work in all situations, because sometimes our very choice for an unhealthy dog will determine whether the dog will exist in the first place. Palmer ( 2012 ) asks us to imagine the case of the short-lived dog—also referred to as the disposable puppy. If we could breed a dog that lives only for 2 years, this would meet the demand of parents whose children want a dog, but will in all likelihood no longer look after the dog after the first couple of years. Without the decision to breed this particular dog, for prospective owners who would otherwise not keep a dog, the dog would not come into existence at all. Footnote 14 Because we cannot compare the value of living to the value of never having lived, even the utilitarian solution fails here. Footnote 15 After all, we are not in a situation here where we would compare a possible world with healthy with a possible world with unhealthy dogs, but a world with unhealthy dogs with a world with no dogs. Palmer ( 2012 ) discusses a number of possible ways out of this conundrum and ultimately finds all of them wanting. She stresses, however, that this does not necessarily discredit our intuition that we are doing something wrong; apparently, the theory does not suffice.

Objectification and Instrumentalisation

One argument that is related to integrity and dignity, but that has a slightly different focus, is that changing animals solely for our purposes instrumentalises or objectifies animals. Instrumentalisation can mean different things. Firstly, it can mean that an animal is turned into an instrument for our use; it can be argued that the animal is turned into an artefact by our meddling with it. In Kantian terms, it is argued that the animal is used solely as a means for our ends, rather than as an end in itself. Its intrinsic value is reduced (Brom 1997 ). The animal then completely coincides with its status as instrument; the cow becomes a milking machine and the chihuahua an accessory. Another term that has been used for the process in which animals in intensive husbandry conditions become ‘living parts of machinery’ by the complete focus on yield and growth rate is ‘de-animalisation’ (Harfeld et al. 2016 ). By taking an animal out of its own evolutionary and environmental context and regarding it merely as a ‘production unit’ we are in a sense taking away their animalness (Harfeld et al. 2016 ).

Secondly, instrumentalisation can mean that animals are treated as if they are things (Brom 1997 ). This objection focuses on the attitude of the person who tampers with the animal and thereby views the animal as an object. This form of instrumentalisation is also called objectification and harbours the risk that society will start viewing animals as if they were objects, which in turn could lead to a denial of the animals’ own interests and own nature (Brom 1997 ). A similar argument is found regarding the objectification or even commodification of women in our society, when they are regarded solely as lust objects. Feminist scholars even draw parallels between the commodification of animals when they are turned into meat and the way women are commodified by portraying them as pieces of meat (Adams 1990 ). One way in which this objection has often been framed, especially in the context of industrial farming, is by saying that we should not adapt the animal to its environment, but the other way around. Footnote 16 The concept objectification has a variety of dimensions, each with slightly different emphasis (Bos et al., Does PLF objectify animals?, Unpublished). For example, objects can be regarded as violable or replaceable by similar objects (Nussbaum 1995 ). So, if someone feels the right to kick a dog, the dog is objectified in the sense that it is regarded as violable. And when someone loses a dog and is then told that they can just get a new one, this can be experienced as offensive, because the dog was not considered replaceable by the owner.

The argument that we should not instrumentalise or objectify animals is central to the neo-Kantian theory of for example Tom Regan ( 2003 ). It speaks to the dictum that we should never treat others solely as means to our ends, but always also as ends in themselves. When we treat someone as an object to be manipulated solely for our own purposes we are not showing that person (or that animal in this case) proper respect. However, in the case of adaptation to dogs the instrumentalisation lies in the changes made to the animal’s genome before the animal was born. In this situation, even a Kantian position runs into difficulty, because due to the changes, we are dealing with a new animal and it is not immediately clear that the changes we have made are disrespectful to the new animal. Rather, they seem to be disrespectful to the species or to our species norm of the animal.

Naturalness and Hubris

A final group of objections which have been raised against tampering with animals’ genomes centre not on the experiences of the animals themselves—such as welfare—nor on other characteristics of the animals—such as their integrity or dignity—but on the nature and degree of human action involved. Here, we will discuss two of these arguments, namely that tampering with animals’ genomes is unnatural, and that it exhibits an attitude of hubris or ‘playing God’ (Brom 1997 ; Van den Belt 2009 ).

When the argument that genetic engineering is unnatural is invoked, this often refers to the idea that certain natural boundaries (in particular those between species) have been crossed. In response, it has been put forward that on genome level these boundaries do not really exist (Robert and Baylis 2003 ; Nuffield Council 2015 ). This response misses the point of the objection, however. The point here is not that something is done that would never happen in nature, but rather that interfering itself is deemed unnatural, because it is carried out by humans. The reference point for naturalness then seems to be the ‘untouched’ animal, as it would appear in nature, as the end result of the process of evolution (Brom 1997 ). Nature is a many-faceted concept with many different meanings (for an overview see Soper 1995 ), but in the context of tampering with animals it seems to be defined as that which has not been interfered with by humans (Van Haperen et al. 2012 ). The natural is then seen as opposed to either the artificial or the cultural. By invoking the unnaturalness-objection in this context critics mean that by adapting animals, we are doing something which is artificial and/or we are turning the animal into an artefact. The argument is therefore related to the instrumentalisation objection we discussed above.

Where the naturalness objection rejects intervention in the natural order of things, the objection to playing God rejects intervention in the order of the creation (Brom 1997 ). The objection to playing God expresses an intuition that certain boundaries should not be crossed by humans. The power to create lies in the hands of God and this creation should be treated respectfully by human beings (Dabrock 2009 ). Yet, this objection is usually not meant as a religious argument, but rather as an argument about the proper role of human beings within nature or vis-à-vis technology (Brom 1997 ). It rejects the human pretension of control and almightiness that was already central in the ancient Greek idea of human hubris and that is also the theme of Shelley’s Frankenstein (Van den Belt 2009 ). This objection warns against the human tendency to think that nature/life can be completely manufactured or planned, and urges us to acknowledge its unpredictability. As Brom ( 1997 ) suggests, this objection is also implicitly about power; if a technically educated elite can manufacture life, this puts a lot of power in the hands of this elite, uncontrolled or unchecked by the rest of society. Finally, this objection has been regarded as portraying a pessimistic view of civilisation (Dabrock 2009 ). It should be noted that playing God is not always regarded problematic; in fact, so-called ecomodernists argue that we humans are the God species and should take control over natural processes in order to achieve human flourishing on this planet (Lynas 2011 ).

Argumentation in Practice: Results of the Empirical Research

Where the previous section dealt with the arguments and concepts in ethical theory that can be applied to the case of pedigree dog breeding, in this section we report if and how these arguments and concepts showed up in everyday-life reasoning. From our systematically coded transcripts, we extracted the reasons that the respondents in our case-driven study brought forward in order to draw boundaries regarding what is acceptable and not, and categorised them according to the concepts from literature. As will become clear, both welfare arguments as well as ethical arguments beyond welfare are brought forward in practical reasoning, next to some additional arguments that are not moral per se. Moreover, arguments were clearly interlinked and used cumulatively, and we noticed that virtually all argumentation seems to have an element of somehow searching for a balance in what we as humans can and cannot do with and to dogs.

Arguments Categorised Under Existing Ethical Concepts

Not surprisingly, animal welfare forms a basic go-to argument in our pedigree dog breeding case study. This becomes clear from statements such as “Only if breeders can develop a breeding standard that does not result in problems, as seen from the dog’s perspective, then it’s okay.”, “A good dog is a dog that does not suffer. Some breeds of dogs are so unhealthy they suffer from the start.”, and “It’s all about quality of life.” A health/absence of pain-oriented (‘function-based’) view of animal welfare appears the condicio sine qua non for any measure that is taken on an animal, though for many respondents nature-based views are likewise important: “A dog needs to be able to perform its natural behaviour, or perhaps even better: its breed-specific behaviour.”. We noticed that respondents tend to fall back on welfare arguments if they feel insecure about other arguments, as welfare arguments seem easiest to defend. The five freedoms were explicitly mentioned by some respondents. However, virtually no respondents used animal welfare as their sole argument.

When asked about both a good life for dogs, as well as confronted with a range of actually performed and hypothetical measures, respondents often added to welfare arguments with arguments regarding integrity: “People in fact choose a dog that is no longer a dog.”, “You affect the essence of a dog, if you want to impose anything other than that they were meant for.”, “With GM you remove the dog-ness of the animal”, and in several cases also dignity: “An animal has value, they have a soul, so treat them right, please.”. However, even though we asked a specific question regarding the acceptability of a dog bred to die after 2 years (which by the way was not deemed acceptable by any of the respondents: “People who want that’d better buy a stuffed animal!”) the non - identity problem was never brought forward as an argument, suggesting that this theoretical argument is too far-fetched for everyday-life reasoning.

Arguments regarding the instrumentalisation or objectification of dogs were commonly seen among the respondents, though in a variety of ways. Objections to tampering with dogs using this type of arguments that we have seen are “A dog is not a thing”, “A dog has become a luxury article. First it was bred as an assistant. And then it became a freak show.” and “How arrogant, to want a dog that dies after 2 years, just to have an accessory.” On the other hand, statements like “It is ok to breed a dog with a specific goal in mind” or objectifying words such as “pull the dog empty” (meaning: to have puppy’s), “put another one on it”, and “when the dog is broken, people come back to us” were also encountered. Seeing the instrumental value of dogs is thus not necessarily always framed as a negative thing.

When we asked people for the reasons for their choices regarding (non-)acceptability of certain adaptations to dogs, the (un)naturalness argument was brought forward, in various ways: “GM is not natural. Nature is so beautiful and ingenious and inventive, it can take care of it.”, “Breeding feels more natural, because it is a slower way. But in principle they are all creations.”, but also “GM is the same thing as breeding, it’s doing what nature does already, only speeding it up.” Though its exact meaning and interpretation remains ambiguous, naturalness was by far the most used term in the conversations. The gradualness of the concept thereby really stood out: “A dog is good if it looks like the original blueprint, the wolf. A Chihuahua thus isn’t natural, it won’t survive in the wild. Shepherds however can. I get that people adore Chihuahuas, they are funny little dogs, but it is really our invention. There’s no natural selection involved.”

The hubris argument was also common: “Who the fuck are we to mess around with genomes like God?”, “You cannot just manufacture the world so that it fits your wish list.”, “A Chihuahua is a monstrous creation that should not exist.”, and “So now we need GM to fix what we messed up in the first place?” As we can see, this argument relates to the role of human beings in their relation to dogs and breeding measures. Also the human pretension of omnipotent control is being put into question: “GM is not as life should be. […] But breeding is. Breeding two dysplasia-free dogs won’t mean you’ll get dysplasia-free pups. You can’t have that control. With GM you try to.”

Finally, everyday-life reasoning includes arguments that touch on moral status and (non - )equality : “Humans and animals are not of equal value, because they do not have the brain capacity of a human.”, “If you could cut out epilepsy in dogs through GM, I would immediately do that. But I find talking about humans and genetic interference dangerous, because if you do one thing and then say well then give me a boy or girl like this or that, I think that’s crossing a line. So I think you can apply it to dogs but in humans it’s dangerous.”, and “Dogs are not things, but also not equal to humans. If I had to choose between a dog and my child, I would choose my child—anytime.” Many respondents did not have a clear view on this: “I don’t know, they are equivalent of course, but they also are not the same. You can use them for many things, but you cannot just do anything you like.”, while some were more outspoken: “A dog should be treated like a dog. Man tends to forget that a dog is an animal. You have to be relentless while breeding, and kill pups that do not comply with the standard.”

Other Arguments of Importance

In the pedigree dog breeding case, several arguments repeatedly came up that fell outside of the regular moral arguments but nevertheless were important.

A first pertains to vested material or emotional interests , such as money, status or aesthetics. Several of the respondents depended (partly or wholly) on pedigree dogs for their livelihood: “The Bordeaux Dog for example, it has an average life span of 4.5 years. Well, then you know the breed is not healthy. But then again, we as vets depend on these breeds. If there were no pedigree dogs, half of the veterinarians in the Netherlands would go out of business!”. Others refer to the status a pedigree dog brings, or that they simply have fallen in love with a specific breed: “I know bulldogs snore, but I would never want another dog in my life. They are so characteristic, with those heads and those eyes. It is a dog to die for!” This latter argument can also be seen as an expression of taste or preference . Feelings and taste may seem like less valid arguments, but in practice their role is significant (cf. Roeser 2006 ). This also pertains to moral intuitions: “You know, GM just doesn’t féél right.”

Furthermore, the goal that the dog was adapted for and the intention it was done with were brought forward as arguments determining the acceptability of breeding measures: “It’s okay if an adaptation is made to make the dog better, but not for the next fashion craze.” Moreover, the adaptive capacity of dogs was mentioned: “Dogs are very flexible animals, that adjust to adaptations relatively easily. Hence, more is allowed in my perspective than to, say, with cats.” Domestication itself was generally not problematized, though the extent of adaptive measures were: “Domestication is not the problem. The problem is excessive breeding leading to a small gene pools. If you buy a French Bulldog, you know you are buying a dog with problems.”

Multi-dimensionality, Balance-Orientation and Worldview

In contrast to ethical theory, arguments regarding the acceptability of certain pedigree dog breeding adaptations for the respondents cannot easily be separated from one another. Counter to what philosophers prescribe, everyday-life reasoning involves a multitude of overlapping and intertwined arguments, both rational and emotional, that build on and/or contradict one another. One respondent for example argued “Pedigree dog breeds are better because you can monitor the genetic makeup of the dogs better” as well as “If you use the word ‘breed’ that means a closed population, and then we can just wait for problems to occur.”, and “I think GM intuitively goes much further than pedigree breeding. It’s not natural. You’re playing God.”, and in addition: “Breeding a dog that cannot walk the streets without a jacket goes too far.” and also “You should not make a human out of it. But it’s also not a thing.” Instead of a single analytical criterion determining where the line between acceptable and unacceptable adaptive measures in dog breeding is drawn, the conversations show that reasoning exists of blends of argument , applied in a fluid manner —like ‘paintings that are made over former layers of painting’ (Bauman 1997 ).

Though animal welfare is sometimes mentioned as a univocal baseline argument (“Health always trumps looks.”), the analysis of the conversations indicates that the connecting factor in the reasoning on what makes up acceptable and non-acceptable adaptive measures in dog breeding across respondents is a search for a balance between extremes . A balance-orientation understandably was found in the matching of different arguments: “Money is money, but you have to do it in a good way and put the animal first. […] You could say, their health is not optimal, but if the dogs can function normally with regards to what you expect from them, then I think it’s enough. […] You have to find a balance.” However, the tendency to search for a balance can actually also be observed in most of the individual ethical arguments discussed earlier in this section. It was first noticed between the extremes of being unnatural (i.e. lack of natural selection, extreme characteristics) and being too natural (i.e. wild): “Dogs should stay as natural as possible, but on the other hand not too natural, because they can adapt some things, such as socialising. But you have to do what fits the natural behaviour of the dog.” and “A half wolf is pretty extreme, too.” But an element of gradualness also was found in for example the balance-seeking between objectification and instrumentalisation and anthropomorphising: “An animal is an animal, it’s not family, but it’s also not a thing.”, “You shouldn’t make a Barbie-doll out of it. It’s a dog for heaven’s sake.”; and in the search for a balance between doing nothing and playing God: “When you do nothing, you’ll end up with one breed of dog, like the street dogs in Turkey”, “Who are we as humans to think we can just do all this? We think we can and may, and I think we sometimes should feel a little humble and less above everything.” This pattern of balance-seeking in everyday-life moral reasoning is an important research result in its own right.

Our research furthermore suggests that the place respondents draw the line (or rather: the grey area making up the centre of the balance) regarding what is acceptable and not, is linked to the way they view the role of human beings in the world, or what we could call the ‘worldview’ of the respondents: e.g. whether God gave animals and nature to humans to use as they see fit, whether we are ‘stewards’ who need to take good care of the animals that are given, whether we see ourselves as a species among species—or even as ‘one’ with all of nature (cf. Zweers 1995 ).

In the following section, we discuss these findings and deliberate whether and how the lessons learned from everyday-life reasoning enrich ethical thought about the issue of pedigree dog breeding and provide pointers for the debate.

Discussion and Conclusion: Insights for the Role of Ethical Theory in the Debate on Pedigree Dog Breeding

How can we interpret the results of our empirical research in relation to ethical theory? It has become clear that in everyday-life people do not seem to respect the consistency-requirement that philosophers assume, and moreover, that they lack a univocal criterion in order to determine where they should draw the line between acceptable and unacceptable adaptations to dogs in the context of breeding. Rather, several different factors play a role: goals of the interference, intention behind it, welfare consequences, and view on the role of human beings in the world in relation to animals. Everyone we spoke to regards certain adaptations as excessive, but different respondents draw different limits to what is acceptable and unacceptable. All respondents agree that adaptations should not lead to welfare impairments, although it became clear that different respondents hold different views on what welfare actually means. This, however, does not mean that welfare is the sole or overarching criterion that determines the acceptable scope of adaptations; rather, animal welfare is used as a sine qua non condition that has to be met by any adaptation that is undertaken. On top of this, many other considerations were put forward that in combination make up their ways of reasoning regarding different adaptations to dogs. These arguments involved typical ethical intuitions ‘beyond welfare’—objectification, integrity, hubris, and naturalness—as well as arguments that did not have a moral base per se. Furthermore, the arguments were not applied in the usual sterile analytical way that we find in ethical literature, but instead in a more fluid manner in which concepts often overlapped and built on one another: they were intertwined. Moreover, rather than a clear demarcating analytical criterion, respondents were constantly looking for the right balance between extremes. We think that ethical theory could learn from this everyday-life strategy, and will elaborate on this by zooming in on the objection that was often put forward that certain adaptations are unnatural.

The Value of the Unnaturalness-Objection

Ethicists warn that unnaturalness-objections have to be approached with great care, because invoking nature can be misused for social or political goals (Soper 1995 ). Think of statements such as ‘women should stay at home and look after the children, because it is in their nature to care’. If we argue from an observation about nature directly to a normative conclusion, we are said to commit the naturalistic fallacy (Moore 1922 ; Frankena 1939 ). It has often been argued that when people claim that something is unnatural, they are actually saying they find it undesirable. In other words, rather than finding adaptations bad because they are unnatural, people call them unnatural because they think they are bad (Zwart 1997 ). Yet, many unnatural things are generally considered good: wearing glasses goes against nature in a sense, but is it thereby morally problematic? Moreover, it is posed that nothing is completely natural anymore: if we regard ‘natural’ as opposed to ‘artificial’, as that which has not been modified by human hands, is there really any nature left? After all, just by emitting CO 2 and causing climate change, we have influenced nearly every part of this earth (McKibben 1989 ). Some philosophers for this reason even avow the use of the term natural, because it is so difficult to draw a clear line between nature and culture/artificial (see Vogel 2015 ). Such a reductio ad absurdum is problematic, however, as it makes the use of the concept of nature completely moot and tends to understand nature as a black and white concept. Instead, based on our findings we propose thinking of ‘naturalness’ as a gradual notion; something can be more or less natural.

What could then be taken as a criterion of an entity’s naturalness? It has been argued that a difference between natural and unnatural entities is that the former have been constituted completely along internal goals whereas the latter have been formed completely by external goals—in general by the goals of human beings (Deckers 2013 ). An entity can then be more or less natural depending on the extent to which it was formed by internal or external goals. The example that Jan Deckers ( 2013 ) gives is that of an aurochs, which is completely formed by its own goals. The domestic cow is formed by a combination of its own internal and our external goals and is thereby less natural. A genetically modified cow, like the famous Dutch bull Herman, is even less natural and more artificial. We realise that using the criterion of internal goal-directedness does not do any normative work yet. An extra argumentative step still is needed to get from something being more or less natural, to it being more or less morally good or bad.

Because such an argumentative step is often lacking in ethical literature about naturalness, the unnaturalness-objection is not taken seriously by philosophers. However, we think that this is throwing the baby out with the bathwater. Analytically rejecting this objection as a naturalistic fallacy does not do justice to a strong intuition that many people have, as witnessed by the fact that naturalness arguments keep on surfacing in discussions about genetic modification and other human actions towards animals (MacNaghten 2004 ). What is behind this intuition? When we look at the way in which our respondents framed the naturalness objection, we see a much more nuanced picture than the way in which the objection is often portrayed by philosophers. Firstly, it becomes clear that naturalness is indeed conceived as a gradual notion. And secondly, the step from unnatural to morally wrong is not made directly, but rather relies on underlying views on nature and on our relation to animals. Several respondents reasoned from an attitude of respect for nature and warned for the harmful consequences of meddling with processes we do not completely understand. They also eschewed an instrumental vision of nature and animals, where animals are simply regarded as resources or tools for our purposes and genes are understood as building blocks for us to manufacture whatever we want. Many respondents showed respect for evolutionary processes. This does not mean that they held that whatever nature produced through evolutionary processes was necessarily good or benign, but that since natural processes have been tried and tested for much longer than artificial adaptations, humans should take a more modest attitude and learn from nature rather than trying to change it. Yet, the respondents held a nuanced view on changing nature as well. They did not think that respect for natural processes meant we can never interfere with nature, but they reject extreme or excessive ways of doing so. Interfering as such was not held to be problematic, but the context in which it takes place and the goal and intention with which it was carried out determine its acceptability.

We think this context-dependent view can inform analytical ethical theory by showing it does not always work to take arguments at face value, out of the context in which they were uttered. Analytical theory tends to test arguments by drawing out their implications to the extreme. In the context of the unnaturalness-argument, analytical philosophers point out that if something that is unnatural is morally problematic, many, if not most, human actions become problematic, and this is not tenable (McKibben 1989 ). However, this argument assumes a rather dualistic vision of the nature-culture divide: as if everything that was touched by human hands is thereby automatically rendered unnatural. As Cronon ( 1996 , 19) points out, this ‘ascribes greater power to humanity than we in fact possess’. Nevertheless, even if nature is conceived as a gradual notion, it could still be argued that since it is impossible to draw a precise line between morally problematic and unproblematic situations, the notion of the natural cannot help us determine an action’s acceptability. Moreover, since individuals disagree in their conceptions of nature and in the value they attach to naturalness and since nature itself is constantly changing, how can we use nature as a criterion at all? In contrast to these doubts, we think that the concept of nature still has performative force Footnote 17 : it explains a distinction that people clearly attach meaning to, even if we cannot draw clear boundaries between the opposite sides of the distinction. We think our results show that discussing the unnaturalness argument in such an isolated manner does not do justice to the richness of ideas that lie behind it. The unnaturalness-argument should be understood as a way to express the meaning people attach to nature and the view they have of our role within nature, and not as a hard and fast criterion to demarcate acceptable from unacceptable actions. If we look at the ways in which our respondents define what is acceptable and unacceptable regarding adaptations to animals, it seems that they were not focussing so much on specific actions, but rather on an accumulation of actions and on attitudes that were expressed by specific adaptations. Footnote 18

In our interpretation, the ways of reasoning related to this are importantly linked with respondents’ worldviews, including conceptions of humans and their place in nature, and conceptions of animals. For example, someone who holds that ‘nature knows best’ is more likely to caution against human hubris, while someone who thinks humans have a higher moral status than animals is less likely to have qualms with using them as tools for human purposes. Footnote 19 It seems, then, that the unnaturalness objection relates to the rejection of a completely anthropocentric worldview. This is also made clear by the fact that the intention or purpose the dogs were adapted for, was an important factor for the deemed acceptability of the adaptation. If the goal was to help dogs, for example by using breeding to make the animals healthier, this was regarded more acceptable than if the goal was simply to satisfy our aesthetic needs. This point can be related to a discussion that has taken place within environmental ethics, regarding the value of restoration. As Katz ( 1992 , 87) argues: ‘Natural individuals were not designed for a purpose. They lack intrinsic functions, making them different from human-created artifacts. Artifacts, I claim, are essentially anthropocentric. They are created for human use, human purpose. […] Once we begin to redesign natural systems and processes, once we begin to create restored natural environments, we impose our anthropocentric purposes on areas that exist outside human society’. Footnote 20 The argumentative step from calling something unnatural to claiming it is morally problematic, therefore—at least for some—lies in adhering to a non-anthropocentric worldview.

What is considered excessive is also related to people’s worldviews. In other words: what is deemed acceptable in pedigree dog breeding is not dependent on one criterion, but rather on a set of views and an attitude towards nature and animals. And we think these insights do not only apply to the unnaturalness argument, but also to the other arguments beyond welfare: references to objectification of animals or to the view that animals cannot simply be manufactured by humans are also based on a broader worldview. Also with these arguments, a balance is often sought, between for example the extremes of viewing animals as things and anthropomorphising animals, or between complete human control and complete lack of control.

Pluralism and the Virtue of Temperance

Our research suggests that a plurality of considerations determine someone’s stance towards pedigree dog breeding. Even though people tend to fall back on welfare arguments when pressed, they also refer to considerations such as goal and intention of the adaptation and specific characteristics of the animal to be adapted (‘dogs are already highly adaptable by nature’). Moreover, when analysed, these considerations cannot all be resumed under one overarching value, such as welfare. Rather, they are part of a more comprehensive view about what types of relations we want to maintain with animals and nature. Furthermore, instead of using moral prescriptions such as ‘allowed’, ‘right’, ‘acceptable’ or ‘duty’, the respondents framed certain adaptations as not being ‘necessary’, as ‘showing bad form’, or as ‘not showing proper respect’. These are all labels that fit more in a pluralist understanding of ethics, in which there is no overarching criterion that can determine an action or situation’s rightness or wrongness and in which there is more room for gradations in moral judgment beyond only duties and rights (Stone 2010 ).

On the meta-level, moral pluralism seems to fit well with our findings. But what normative ethical theory is adhered to in this situation? Even though arguments beyond welfare—in particular those about integrity and objectification—have traditionally been understood to be Kantian in nature, we argue that the strong focus of our respondents on finding a balance between extremes suggests that a virtue ethical approach better fits everyday-life ethical reasoning about pedigree dog breeding. This idea is furthermore supported by our finding that people tend to look at an accumulation of actions and at attitudes, intentions, and goals, rather than at the right or wrong of specific adaptations. Central to virtue ethics (since Aristotle), is the view that we should strive for a good character by cultivating virtues. There are many virtues, but one characteristic that is central to all virtues is that they strike a balance between two extremes: the ‘golden mean’.

Drawing on virtue ethics does raise the question to what extent this theory is applicable to animal ethics, as by far most (Western) animal ethicists argue from a deontological or utilitarian—and more recently also from a relational—perspective. According to some virtue-ethical accounts, human flourishing is foundational for our ethical aims in life (Walker 2007 ). Acting virtuously is one of the constitutive elements of human flourishing, but we don’t act virtuously just in order to achieve our own flourishing. As we are social beings, care for others’ flourishing is part of what it is to be human. Animals can flourish in many of the same ways as humans and therefore if we have reason to care for the flourishing of other human beings, we have reason to care for that of animals (Walker 2007 ). A virtue ethicist would ask what is the right attitude to take towards animals and how our treatment of animals reflects on our character. If we treat animals badly, we are displaying the wrong character traits (Hursthouse 2006 ). Virtuous character traits are, for example, sensitivity, compassion, and temperance, and we do not cultivate these traits when we routinely harm animals.

What particular virtue then is central in the considerations about adapting dogs? Even though our respondents drew a line (or formulated a grey area) at different places, they all agreed that too much interference leads to excesses. Several respondents also experienced too little interference as problematic: If we do not socialise dogs or breed a dog that is too much like a wolf, we are in a sense also behaving excessively. This points to the virtue of temperance , which refers to self-restraint and modesty. Appeals to modesty and self-restraint were encountered amply in our empirical research. Modesty is a restraint from arrogance and this is encountered in the view that we should not exhibit hubris or try to play God. Also, restraint from excesses in the form of prudence was referred to, when it was noted that it is “alright to breed dogs, but we should not turn them into accessories or status symbols”. In the context of genetic modification versus breeding, many respondents held that we can interfere in nature, but only to the extent that certain adaptations might happen in nature as well. This points out the experienced need for a balance between blindly following nature and completely going against nature. As Hursthouse ( 2006 , 142), puts it—in the context of eating meat—: ‘precisely what temperance requires is that I do not pursue such pleasure while ignoring the claims of the other virtues’.

The Limitations of Rule-Ethical Theory

The arguments ‘beyond welfare’ appear to be part of broader conceptions of the ‘good life’, including views of our relationship with animals and our role in natural processes. Though they are not specific enough to clearly distinguish morally right from morally wrong adaptations, they point to the accumulation of actions and attitudes rather than the right and wrong of specific adaptations. Moreover, a balance is sought rather than a strict criterion for moral acceptability, suggesting a predominantly virtue ethical stance. The pertinent question to ask, then, doesn’t appear to be ‘what adaptations are acceptable?’ but rather ‘what is the virtuous attitude towards animals (and even broader: nature)?’. The point of such a virtue ethical conception is not to argue that we should never interfere in the lives of animals, but that a decision whether or not to interfere is taken from an attitude of respect for the animal and modesty towards nature. This could be understood as a plea for the virtue of temperance, both in the way in which we interfere, the extent of interference, our intentions, and the goals for which we interfere.

This explanation of the arguments beyond welfare arguably connects less to action-guiding theories in ethics—such as utilitarianism or deontology—than to what we—with Swierstra ( 2003 )—propose to call ‘life-ethical theories’. While rule-ethical theories aim to formulate impartial rules that enable peaceful and just cohabitation between individuals, in life-ethical theories discussion about the good life are central. Life-ethical theories ask question such as ‘what attitude towards life (including inevitable limitations) speaks from certain technical enhancements?’, and ‘how do we envisage the good life for humans and animals?’.

As Swierstra ( 2003 ) explains, it is understandable that life-ethical views are met with suspicion, because they almost by definition have a religious or ideological character; they are based on comprehensive notions of the good life about which agreement is hardly possible and they therefore tend to be relegated to the private sphere. Rule-ethical theories, on the other hand, carry the promise of consensus, because they are based on commonly held values such as freedom of choice, autonomy, and the no-harm principle. However, by only taking rule-ethical principles seriously, a lot of important values and meanings that people attach to life and the world around them are disregarded. While life-ethicists acknowledge that people’s conceptions of the good life can fundamentally differ, they still hold that we should not relegate these conceptions to the private sphere but that we should discuss them publicly, or else risk an impoverished debate. If we leave out life-ethical views, the debate effectively stops when we have established that no harm is done by a certain action or technology, or that informed consent has been given. A debate about the content of preferences is then no longer necessary (Swierstra 2003 ). The result is that people who object to the action or technology in question on the basis of other values are excluded from the debate (Bovenkerk 2012 ).

Swierstra ( 2003 ) points out another reason why a sole reliance on rule-ethical theories can be problematic: the benefits of controversial technologies or interventions tend to befall specific individuals and tend to be concrete and certain, while the negative impacts are often speculative, long-term and collectively borne (think of the potential environmental problems of new technologies). The benefits to individuals can be more easily cast in terms of rule-ethical theories than the harms and therefore rule-ethical theories carry an implicit bias towards implementation of new technologies or other interventions. Perhaps we cannot immediately draw clear rules and regulations from life-ethical discussions, but this does not mean that it is not of the utmost importance that we have the discussions. As Swierstra (personal communication) puts it:“in our liberal societies that tend to relegate comprehensive notions of the good life to the private sphere, if someone raises a moral objection, there is a tendency to ask ‘Do you want to forbid this? No? Well, then shut up’”. But if the future of our relationship to nature is on the line, isn’t it important to have an overarching discussion about where we want this relation to go?

In conclusion, our empirical research into how far we are allowed to interfere in the genetic make-up of dogs, through breeding and genetic modification led to an appeal to virtue ethics, in particular the virtue of temperance . Arguments beyond welfare—such as objectification, integrity, hubris, and the unnaturalness-objection—should not simply be cast aside because they do not lead to clear norms or because they are perceived to commit the naturalistic fallacy. Rather, we should take the intuitions on which they are based seriously and have life-ethical discussion about the worldviews underlying them, in the public sphere.

The election was ‘won’ by a Cavalier King Charles Spaniel, who supposedly had chronic headaches due to a malformation of the skull: https://www.sophia-vereeniging.nl/nl/pages/actualiteit/blog/cavalier-kareltje-de-zieligste-hond-van-nederland.html .

See the ‘Fair Breeding Plan’ that was drafted by the Dutch kennel club and many other stakeholders, such as the Veterinary Department of Utrecht University. Fairfok plan: https://www.houdenvanhonden.nl/gezond-fokken-met-fairfok/plan-fairfok/ .

With the notable exception of Clare Palmer’s ( 2012 ) paper ‘Does Breeding a Bulldog Harm It?’.

The research was part of a larger research project, titled ‘The Ethics of Domestication’.

Francione ( 2012 ) "Pets": The Inherent Problems of Domestication. http://www.abolitionistapproach.com/pets-the-inherent-problems-of-domestication/#UaMlSKJJM08 .

It has recently been argued that humans in fact played a less active role in domestication than has always been assumed and that humans as well as animals were changed by domestication. See https://aeon.co/essays/how-domestication-changes-species-including-the-human?utm_source=twitter&utm_medium=oupphilosophy&utm_campaign=oupphilosophy .

Entities count as a subject-of-a-life who have 'desires and beliefs, who perceive, remember, and can act intentionally, who have a sense of the future, including their own future (i.e. are self-aware or self-conscious), who have an emotional life, who have a psychosocial identity over time, who have a kind of autonomy (namely preference-autonomy), and who have an experiential welfare' (Regan 2003 , p. 18).

While these views are not necessarily mutually exclusive, they can certainly conflict in specific situations.

His proposal is not as unrealistic as it sounds, if we consider that ‘currently researchers are applying the techniques of genetic engineering, cloning, and cellular manipulation in search of ways to reduce both the suffering and economic cost associated with production disease [which are] animal pathologies that occur as a result of or in association with livestock production practices’ (Thompson 2008 , 307–308).

Although Collins et al. ( 2011 ) have convincingly argued that blind chickens do experience reduced welfare as compared to their seeing counterparts.

Animal enhancement can constitute different practices. It can be defined as an intervention that either ‘produces an increase in a natural function or confers a new function’ to the animal (such as better muscle development), or ‘improves an aspect of the animal functioning for human purposes’ (such as classic cases of domestication), or ‘better fulfils the animal’s interest’ (for example because it enhances the animal’s welfare) (Chan 2009 ). It seems clear that we are dealing with the second form of enhancement in the case of pedigree dog breeding.

It is important to note that there has been quite a bit of discussion about the merits of concepts such as dignity and integrity. Thompson ( 2008 , 311) for example states: ‘appeals to integrity and dignity can become pompous when thrown in the face of creatures who are actively enduring suffering right now’. See also the discussion on these concepts by Ortiz ( 2004 ).

This would suggest that integrity violations take place on the species-level rather than that of the individual. However, Rob de Vries ( 2006 ) argues that attempts to apply this concept to the species-level fail.

Strictly speaking, this thus even is a non-existence rather than a non-identity case. The same line of thought applies though: we cannot say that we harm a dog that was bred to only live for two years, as long as it still has a life worth living, for if we had not bred this particular dog, the dog would not exist at all. In the context of meat production this line of reasoning is referred to as the logic of the larder: if it wasn’t for the human demand for meat, livestock would not even have existed, and surely isn’t it then in their benefit that we eat meat?.

Although some argue that we can compare existence to non-existence if we place a value of zero on non-existence. For example, Holtug ( 2015 ).

By referring to an animal as ‘it’ this objectification is reinforced, ironically by animal ethicists who reject objectification themselves.

Thanks for Christopher Preston (personal communication) for this formulation.

Though not solving the non-identity problem, this may provide a step in the direction of a solution: Rather than arguing that a disposable puppy cannot be harmed because if we had not bred it it would not even have been born, we should perhaps not look at the level of individual animals. Rather, we could argue that creating such animals does not fit with the virtue of temperance.

This works the other way around as well of course: worldviews do not only influence ideas and behaviour, but also the other way around. For example, a breeder, due to his or her role as breeder, has to support adaptations in order to maintain breeding standards, or otherwise experience cognitive dissonance.

While Katz employs a rather black and white view on nature versus artificial, which can be disputed (even on basis of our own results) our aim in quoting him here is merely to stress the importance of worldview as an argumentative step.

Abercrombie, N., Hill, S., & Turner, B. S. (1984). Dictionary of sociology . Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Google Scholar

Adams, C. (1990). The sexual politics of meat . New York: Continuum.

Balzer, P., Rippe, K. P., & Schaber, P. (2000). Two concepts of dignity. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 13 (1/2), 7–27.

Bauman, Z. (1997). Postmodernity and its discontents . Cambridge: Polity Press.

Bernard, H. R. (2006). Research methods in anthropology: Qualitative and quantitative approaches . Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Inc.

Blumer, H. (1954). What is wrong with social theory? American Sociological Review, 19 (1), 3–10.

Article Google Scholar

Bos, J., Bovenkerk, B., & Feindt, P. Does PLF objectify animals? (Unpublished paper).

Bovenkerk, B. (2016). Animal captivity: Justifications for animal captivity in the context of domestication. In B. Bovenkerk & J. Keulartz (Eds.), Animal ethics in the age of humans: Blurring boundaries in human–animal relationships (pp. 151–172). Dordrecht: Springer.

Chapter Google Scholar

Bovenkerk, B. (2012). The biotechnology debate: Democracy in the face of intractable disagreement . Dordrecht: Springer.

Book Google Scholar

Bovenkerk, B., Brom, F. W. A., & van den Bergh, B. J. (2002). Brave new birds: The use of ‘Animal Integrity’ in animal ethics. The Hastings Center Report , 32 (1), 16.

Bovenkerk, B., & Meijboom, F. (2013). Fish welfare in aquaculture: Explicating the chain of interactions between science and ethics. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 26 (1), 41–61.

Bovenkerk, B., & Meijboom, F. L. B. (2012). The moral status of fish. The importance and limitations of a fundamental discussion for practical ethical questions in fish farming. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 25 (6), 843–860.

Bowen, G. A. (2008). Naturalistic inquiry and the saturation concept: A research note. Qualitative Research, 8 (1), 137–152.

Brom, F. W. A. (1997). Onherstelbaar verbeterd (irrepairably improved) . Assen: Van Gorcum.

Budiansky, F. (1992). The covenant of the wild: Why animals choose domestication . New Haven: Yale University Press.

Chan, S. (2009). Should we enhance animals? Journal of Medical Ethics, 35 (11), 678–683.

Collins, S., Forkman, B., Kristensen, H., Sandøe, P., & Hockinga, P. (2011). Investigating the importance of vision in poultry: Comparing the behaviour of blind and sighted chickens. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 133, 60–69.

Cronon, W. (1996). The trouble with wilderness: Or, getting back to the wrong nature. Environmental History, 1 (1), 7–28.

Dabrock, P. (2009). Playing God? Synthetic biology as a theological and ethical challenge. Systems and Synthetic Biology, 3, 47–54.

DeGrazia, D. (2008). Moral status as a matter of degree. Southern Journal of Philosophy, XLVI (2), 181–198.

Deckers, J. (2013). Paper presented at the preconference meeting at EurSafe . Uppsala, September.

De Vries, R. (2006). Genetic engineering and the integrity of animals. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 19 (5), 469–493.

Farm Animal Welfare Council. (1992). FAWC updates the five freedoms. Veterinary Record, 17, 357.

Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12 (2), 219–245.

Francione, G. (2012). “Pets”: The inherent problems of domestication. http://www.abolitionistapproach.com/pets-the-inherent-problems-of-domestication/#UaMlSKJJM08 .

Frankena, W. K. (1939). The naturalistic fallacy. Mind, 48 (192), 464–477.

Fraser, D. (2003). Assessing animal welfare at the farm and group level: The interplay of science and values. Animal Welfare, 12, 433–443.

Harfeld, J. L., Cornou, C., Kornum, A., & Gjerris, M. (2016). Seeing the animal: On the ethical implications of de-animalization in intensive animal production systems. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 29, 407–423.