What will education look like in 20 years? Here are 4 scenarios

COVID-19 has shown us we must prepare for uncertainty in our future plans for education Image: REUTERS/Cindy Liu

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Andreas Schleicher

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Education, Gender and Work is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, education, gender and work.

- The COVID-19 pandemic shows us we cannot take the future of education for granted.

- By imagining alternative futures for education we can better think through the outcomes, develop agile and responsive systems and plan for future shocks.

- What do the four OECD Scenarios for the Future of Schooling show us about how to transform and future-proof our education systems?

As we begin a new year, it is traditional to take stock of the past in order to look forward, to imagine and plan for a better future.

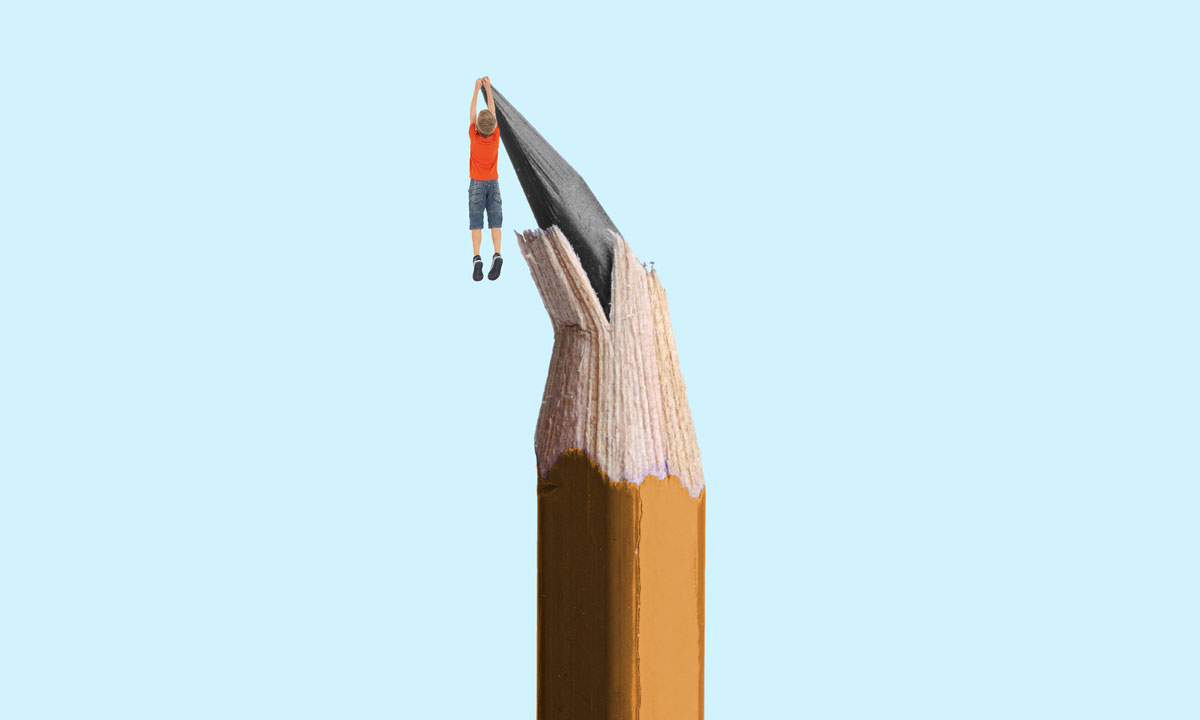

But the truth is that the future likes to surprise us. Schools open for business, teachers using digital technologies to augment, not replace, traditional face-to face-teaching and, indeed, even students hanging out casually in groups – all things we took for granted this time last year; all things that flew out the window in the first months of 2020.

Have you read?

The covid-19 pandemic has changed education forever. this is how , is this what higher education will look like in 5 years, the evolution of global education and 5 trends emerging amidst covid-19.

To achieve our vision and prepare our education systems for the future, we have to consider not just the changes that appear most probable but also the ones that we are not expecting.

Scenarios for the future of schooling

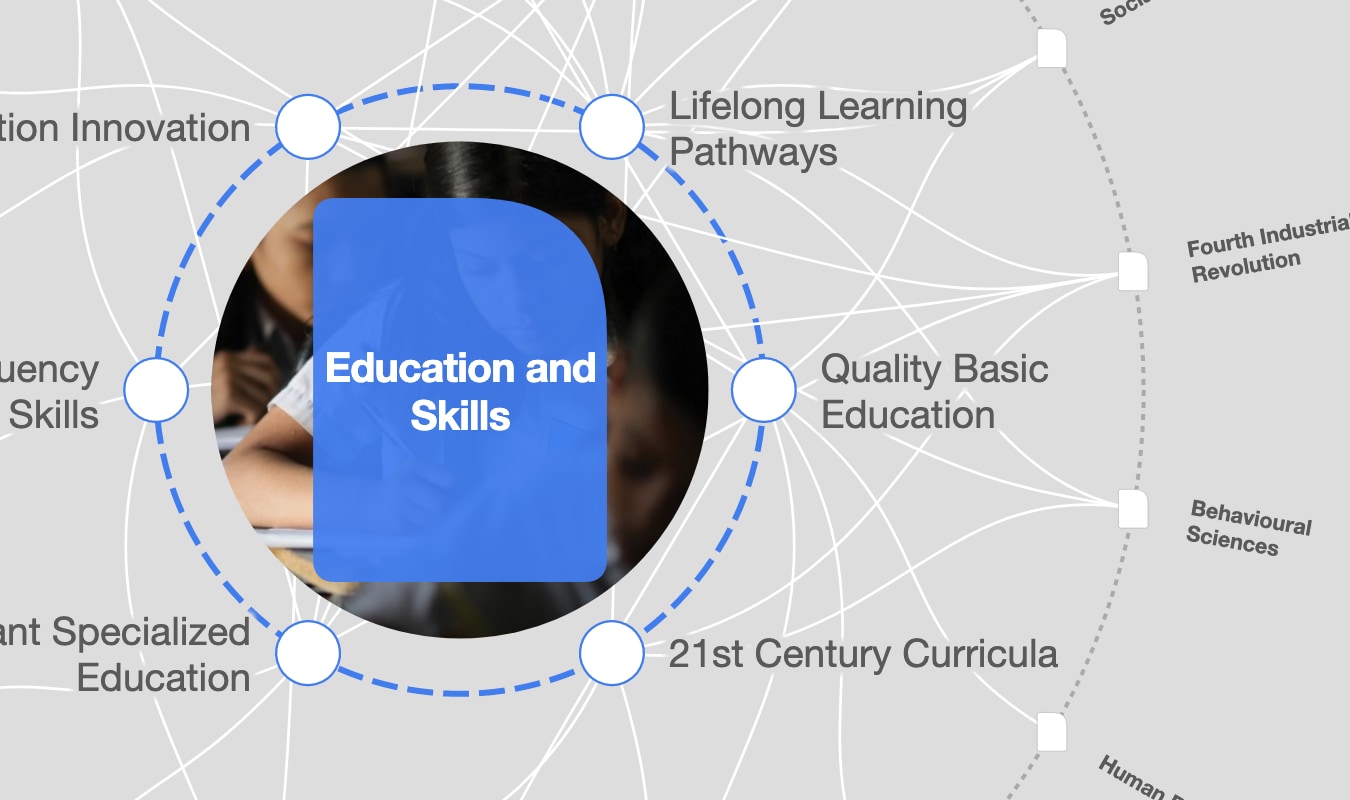

Imagining alternative futures for education pushes us to think through plausible outcomes and helps agile and responsive systems to develop. The OECD Scenarios for the Future of Schooling depict some possible alternatives:

Rethinking, rewiring, re-envisioning

The underlying question is: to what extent are our current spaces, people, time and technology in schooling helping or hindering our vision? Will modernizing and fine-tuning the current system, the conceptual equivalent of reconfiguring the windows and doors of a house, allow us to achieve our goals? Is an entirely different approach to the organization of people, spaces, time and technology in education needed?

Modernizing and extending current schooling would be more or less what we see now: content and spaces that are largely standardized across the system, primarily school-based (including digital delivery and homework) and focused on individual learning experiences. Digital technology is increasingly present, but, as is currently the case, is primarily used as a delivery method to recreate existing content and pedagogies rather than to revolutionize teaching and learning.

What would transformation look like? It would involve re-envisioning the spaces where learning takes place; not simply by moving chairs and tables, but by using multiple physical and virtual spaces both in and outside of schools. There would be full individual personalization of content and pedagogy enabled by cutting-edge technology, using body information, facial expressions or neural signals.

We’d see flexible individual and group work on academic topics as well as on social and community needs. Reading, writing and calculating would happen as much as debating and reflecting in joint conversations. Students would learn with books and lectures as well as through hands-on work and creative expression. What if schools became learning hubs and used the strength of communities to deliver collaborative learning, building the role of non-formal and informal learning, and shifting time and relationships?

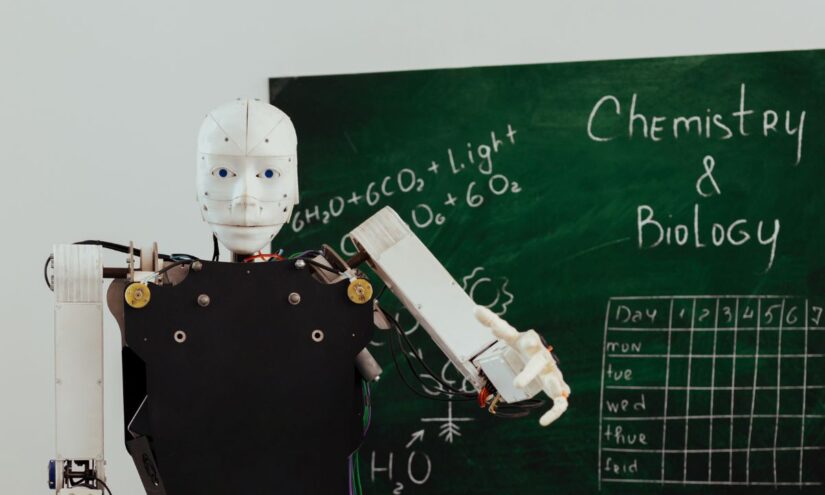

Alternatively, schools could disappear altogether. Built on rapid advancements in artificial intelligence, virtual and augmented reality and the Internet of Things, in this future it is possible to assess and certify knowledge, skills and attitudes instantaneously. As the distinction between formal and informal learning disappears, individual learning advances by taking advantage of collective intelligence to solve real-life problems. While this scenario might seem far-fetched, we have already integrated much of our life into our smartphones, watches and digital personal assistants in a way that would have been unthinkable even a decade ago.

All of these scenarios have important implications for the goals and governance of education, as well as the teaching workforce. Schooling systems in many countries have already opened up to new stakeholders, decentralizing from the national to the local and, increasingly, to the international. Power has become more distributed, processes more inclusive. Consultation is giving way to co-creation.

We can construct an endless range of such scenarios. The future could be any combination of them and is likely to look very different in different places around the world. Despite this, such thinking gives us the tools to explore the consequences for the goals and functions of education, for the organization and structures, the education workforce and for public policies. Ultimately, it makes us think harder about the future we want for education. It often means resolving tensions and dilemmas:

- What is the right balance between modernizing and disruption?

- How do we reconcile new goals with old structures?

- How do we support globally minded and locally rooted students and teachers?

- How do we foster innovation while recognising the socially highly conservative nature of education?

- How do we leverage new potential with existing capacity?

- How do we reconfigure the spaces, the people, the time and the technologies to create powerful learning environments?

- In the case of disagreement, whose voice counts?

- Who is responsible for the most vulnerable members of our society?

- If global digital corporations are the main providers, what kind of regulatory regime is required to solve the already thorny questions of data ownership, democracy and citizen empowerment?

Thinking about the future requires imagination and also rigour. We must guard against the temptation to choose a favourite future and prepare for it alone. In a world where shocks like pandemics and extreme weather events owing to climate change, social unrest and political polarization are expected to be more frequent, we cannot afford to be caught off guard again.

This is not a cry of despair – rather, it is a call to action. Education must be ready. We know the power of humanity and the importance of learning and growing throughout our life. We insist on the importance of education as a public good, regardless of the scenario for the future.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Forum Institutional .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

Institutional update

World Economic Forum

May 21, 2024

Reflections from MENA at the #SpecialMeeting24

Maroun Kairouz

May 3, 2024

Day 2 #SpecialMeeting24: Key insights and what to know

Gayle Markovitz

April 28, 2024

Day 1 #SpecialMeeting24: Key insights and what just happened

April 27, 2024

#SpecialMeeting24: What to know about the programme and who's coming

Mirek Dušek and Maroun Kairouz

Climate finance: What are debt-for-nature swaps and how can they help countries?

Kate Whiting

April 26, 2024

- Our Mission

What Is Education For?

Read an excerpt from a new book by Sir Ken Robinson and Kate Robinson, which calls for redesigning education for the future.

What is education for? As it happens, people differ sharply on this question. It is what is known as an “essentially contested concept.” Like “democracy” and “justice,” “education” means different things to different people. Various factors can contribute to a person’s understanding of the purpose of education, including their background and circumstances. It is also inflected by how they view related issues such as ethnicity, gender, and social class. Still, not having an agreed-upon definition of education doesn’t mean we can’t discuss it or do anything about it.

We just need to be clear on terms. There are a few terms that are often confused or used interchangeably—“learning,” “education,” “training,” and “school”—but there are important differences between them. Learning is the process of acquiring new skills and understanding. Education is an organized system of learning. Training is a type of education that is focused on learning specific skills. A school is a community of learners: a group that comes together to learn with and from each other. It is vital that we differentiate these terms: children love to learn, they do it naturally; many have a hard time with education, and some have big problems with school.

There are many assumptions of compulsory education. One is that young people need to know, understand, and be able to do certain things that they most likely would not if they were left to their own devices. What these things are and how best to ensure students learn them are complicated and often controversial issues. Another assumption is that compulsory education is a preparation for what will come afterward, like getting a good job or going on to higher education.

So, what does it mean to be educated now? Well, I believe that education should expand our consciousness, capabilities, sensitivities, and cultural understanding. It should enlarge our worldview. As we all live in two worlds—the world within you that exists only because you do, and the world around you—the core purpose of education is to enable students to understand both worlds. In today’s climate, there is also a new and urgent challenge: to provide forms of education that engage young people with the global-economic issues of environmental well-being.

This core purpose of education can be broken down into four basic purposes.

Education should enable young people to engage with the world within them as well as the world around them. In Western cultures, there is a firm distinction between the two worlds, between thinking and feeling, objectivity and subjectivity. This distinction is misguided. There is a deep correlation between our experience of the world around us and how we feel. As we explored in the previous chapters, all individuals have unique strengths and weaknesses, outlooks and personalities. Students do not come in standard physical shapes, nor do their abilities and personalities. They all have their own aptitudes and dispositions and different ways of understanding things. Education is therefore deeply personal. It is about cultivating the minds and hearts of living people. Engaging them as individuals is at the heart of raising achievement.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights emphasizes that “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights,” and that “Education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality and to the strengthening of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms.” Many of the deepest problems in current systems of education result from losing sight of this basic principle.

Schools should enable students to understand their own cultures and to respect the diversity of others. There are various definitions of culture, but in this context the most appropriate is “the values and forms of behavior that characterize different social groups.” To put it more bluntly, it is “the way we do things around here.” Education is one of the ways that communities pass on their values from one generation to the next. For some, education is a way of preserving a culture against outside influences. For others, it is a way of promoting cultural tolerance. As the world becomes more crowded and connected, it is becoming more complex culturally. Living respectfully with diversity is not just an ethical choice, it is a practical imperative.

There should be three cultural priorities for schools: to help students understand their own cultures, to understand other cultures, and to promote a sense of cultural tolerance and coexistence. The lives of all communities can be hugely enriched by celebrating their own cultures and the practices and traditions of other cultures.

Education should enable students to become economically responsible and independent. This is one of the reasons governments take such a keen interest in education: they know that an educated workforce is essential to creating economic prosperity. Leaders of the Industrial Revolution knew that education was critical to creating the types of workforce they required, too. But the world of work has changed so profoundly since then, and continues to do so at an ever-quickening pace. We know that many of the jobs of previous decades are disappearing and being rapidly replaced by contemporary counterparts. It is almost impossible to predict the direction of advancing technologies, and where they will take us.

How can schools prepare students to navigate this ever-changing economic landscape? They must connect students with their unique talents and interests, dissolve the division between academic and vocational programs, and foster practical partnerships between schools and the world of work, so that young people can experience working environments as part of their education, not simply when it is time for them to enter the labor market.

Education should enable young people to become active and compassionate citizens. We live in densely woven social systems. The benefits we derive from them depend on our working together to sustain them. The empowerment of individuals has to be balanced by practicing the values and responsibilities of collective life, and of democracy in particular. Our freedoms in democratic societies are not automatic. They come from centuries of struggle against tyranny and autocracy and those who foment sectarianism, hatred, and fear. Those struggles are far from over. As John Dewey observed, “Democracy has to be born anew every generation, and education is its midwife.”

For a democratic society to function, it depends upon the majority of its people to be active within the democratic process. In many democracies, this is increasingly not the case. Schools should engage students in becoming active, and proactive, democratic participants. An academic civics course will scratch the surface, but to nurture a deeply rooted respect for democracy, it is essential to give young people real-life democratic experiences long before they come of age to vote.

Eight Core Competencies

The conventional curriculum is based on a collection of separate subjects. These are prioritized according to beliefs around the limited understanding of intelligence we discussed in the previous chapter, as well as what is deemed to be important later in life. The idea of “subjects” suggests that each subject, whether mathematics, science, art, or language, stands completely separate from all the other subjects. This is problematic. Mathematics, for example, is not defined only by propositional knowledge; it is a combination of types of knowledge, including concepts, processes, and methods as well as propositional knowledge. This is also true of science, art, and languages, and of all other subjects. It is therefore much more useful to focus on the concept of disciplines rather than subjects.

Disciplines are fluid; they constantly merge and collaborate. In focusing on disciplines rather than subjects we can also explore the concept of interdisciplinary learning. This is a much more holistic approach that mirrors real life more closely—it is rare that activities outside of school are as clearly segregated as conventional curriculums suggest. A journalist writing an article, for example, must be able to call upon skills of conversation, deductive reasoning, literacy, and social sciences. A surgeon must understand the academic concept of the patient’s condition, as well as the practical application of the appropriate procedure. At least, we would certainly hope this is the case should we find ourselves being wheeled into surgery.

The concept of disciplines brings us to a better starting point when planning the curriculum, which is to ask what students should know and be able to do as a result of their education. The four purposes above suggest eight core competencies that, if properly integrated into education, will equip students who leave school to engage in the economic, cultural, social, and personal challenges they will inevitably face in their lives. These competencies are curiosity, creativity, criticism, communication, collaboration, compassion, composure, and citizenship. Rather than be triggered by age, they should be interwoven from the beginning of a student’s educational journey and nurtured throughout.

From Imagine If: Creating a Future for Us All by Sir Ken Robinson, Ph.D and Kate Robinson, published by Penguin Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2022 by the Estate of Sir Kenneth Robinson and Kate Robinson.

Insight and inspiration in turbulent times.

- All Latest Articles

- Environment

- Food & Water

- Featured Topics

- Get Started

- Online Course

- Holding the Fire

- What Could Possibly Go Right?

- About Resilience

- Fundamentals

- Submission Guidelines

- Commenting Guidelines

- Resilience+

Act: Inspiration

Educating for the future we want.

By Stephen Sterling , originally published by Great Transition Initiative

June 7, 2021

Opening essay for GTI Forum The Pedagogy of Transition

Introduction

Our ability to achieve a livable future for all depends on whether we can foster an unprecedented degree of social learning. There is no change without learning, and no learning without change. But with the stakes higher than ever before, time is worryingly short. How, under such urgency, do we effect such a large-scale paradigm shift?

Formal education systems have— or should have —a critical role in the global social learning process underpinning the Great Transition. On the face of it, the challenge seems straightforward. If current educational policies and practices insufficiently address ecological, social, and economic sustainability, we can just do some tweaking and add on some key ideas. Job done. Except it is not so simple. If education is to be an agent of change, it has itself to be the subject of change. Our educational systems are implicated in the multiple crises before us, and without meaningful rethinking, they will remain maladaptive agents of business as usual, leading us into a dystopian future nobody wants.

Over the past few decades, new movements have championed social change education centered on such themes as the environment, peace, human rights, anti-racism, multiculturalism, alternative futures, and global citizenship. For compactness, this diverse constellation will be referred to as “sustainability” education. Despite this array of efforts and the common values of social justice and ecological integrity, the fragmentation of energy and effort has limited the potential for significant progress.

The possibility of greater coherence arose three-and-a-half decades ago with the emergence of the sustainable development framework, which in turn spurred the concept of “education for sustainable development” (ESD). The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), the lead global agency on sustainability education, has been the primary proponent of ESD, with the UN launching a “Decade of ESD” that spanned 2005 to 2014 and culminated in the report Shaping the Future We Want . 1 While the work of UNESCO and its partners has been impressive, several fundamental constraints have hampered the realization of the goal of “educating for the world we want.”

First, there is a limited conception of the role education can even play. Sustainable development efforts have downplayed the potential for education to help to realize more equitable, ecologically healthy futures, or have viewed it in isolation from other instruments of social change. The role of education tends to be narrowly confined to such aims as basic literacy and education for all (EFA), which are necessary but not sufficient for deeper change.

Second, a limited view of where “education” takes place stresses formal educational structures at the expense of other learning contexts. As education is primarily associated in the public mind with schools and universities, forms of education critical to empowerment and social change—such as lifelong learning, non-formal education, and community education—have received less attention and support. 2

Finally, mainstream education policy and practice exhibits an alarming lack of engagement with the broader challenge of securing a safe local and global future. This distant relationship between the worlds of sustainable development and education has tended to be self-perpetuating over years. 3

The gap has shrunk notably since the launch of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015. Initially, the role of education as a means of addressing the SDGs was not well recognized. However, many international agencies and networks have begun to endorse education as a change agent for the SDGs, and an increasing number of universities have begun to see the SDGs as an important focus for their work, more easily engaged with than the broader and less defined challenge represented by ESD. 4

Still, urgent questions remain about the proportion of institutions engaged worldwide, the extent of engagement across the spectrum of university functions, and the depth of such initiatives, namely, the degree to which this response shifts the underlying assumptions and values driving institutions. If we are to embrace the SDGs seriously, we must critically examine the structural factors that led to the multiple crises that made the SDGs necessary in the first place while also interrogating the concept of sustainable development itself. 5

Broadly, education systems have taken one of four approaches to the sustainability agenda: (1) no response, (2) accommodation, (3) reform, and (4) transformation. In the first, current global precarities are absent or barely reflected in policies and practices; in the second, institutional responses center on campus greening and curriculum accommodation in “obvious” disciplines only. The latter two responses go further. A reformative response reflects intentional re-thinking at a policy level leading to shifts across much of the institution. A transformative approach nurtures a sustainability ethos as the driver of purpose, policy, and practice. This active perspective results in fundamental redesign and iterative learning. Most institutions remain in the first two categories. Yet a trend of institutional learning is becoming evident as schools and universities increasingly open themselves to a degree of reformative self-examination—driven by rising awareness of the human and planetary predicament, and, importantly, by intensifying demands by students keenly aware of threats to their life chances. The transformative approach, however, remains rare.

Educating for the World We Don’t Want

There are without doubt examples of outstanding and innovative sustainability education practices across the world. Nonetheless, the notion that educational systems are heading (and heading us) in the wrong direction has been growing, particularly since the launch of the SDGs.

As this sense has grown more widespread, the language employed by UNESCO has become more radical, going so far as to endorse transformation. Yet the understatement in one line from UNESCO’s “Roadmap: ESD for 2030,” which will be officially launched at the UNESCO World Conference on ESD in May 2021, speaks volumes: “[O]fen ESD is interpreted with narrow focus on topical issues rather than with a holistic approach on learning content, pedagogy, and learning outcomes.” Clearly, we have a long way to go.

Left unanswered is why sustainability education is not more widely recognized or why it is “interpreted with narrow focus,” thereby remaining safely within conventional development paradigms. 6 Answering these questions sufficiently—as well as explaining the from where , to where , and why of social transformation—requires a critical examination at the paradigmatic level, i.e., the epistemic sets of values and ideas which fundamentally influence purpose, curriculum design, pedagogy, and all other aspects of education.

Any kind of paradigmatic breakthrough also requires clear acknowledgement of the socioeconomic, political, and technological pressures on the system—very real constraints and influences that weigh heavily on mainstream educational thinking and practice, even those with “transformative” intentions. In recent decades, the dominance of neoliberal thinking in economics, politics, and wider society has usurped previous conceptions and traditions of education as a public service for the public good. A narrowly instrumental view of education, modeled to serve the perceived demands of a globalizing economy and culture, now defines and shapes learning. This turn is reflected in an increasingly market-driven educational system maintained by a proliferating “global testing culture.” The system fosters competition, homogenization, and standardization in both national and international spheres. These developments rest on a conviction that education should serve a growth-oriented economy, fallaciously equated with the social good. Over time, this neoliberal wave has subtly but powerfully displaced more educationally defensible practices informed by liberal, holistic, and humanistic philosophies regarding the nature and purpose of education.

The neoliberal framework has spawned a Global Education Industry driven by private sector organizations and businesses, worth several trillion dollars and boosted significantly by the phenomenal growth of online learning as a result of COVID-19. This is exemplified by the burgeoning influence of “EdTech,” a massive effort by tech philanthropists, tech giants, and edu-business companies to shape educational policy and delivery. 7 This “reimagining education for the future” appears to have little to do with human or planetary needs, and more to do with tech means becoming universal ends. While digital learning has a role to play in transformative education, the overall effect of the contemporary push, such as by EdTech, is to displace progressive models while restricting the potential for liberatory innovation.

Neoliberal thinking has narrowed conceptions of education’s purpose (what we think education is for), breadth (what we conceive as valid educational content and curricula), and depth (pedagogy and the learning experience). Sustainability, by contrast, requires deep attention to interlaced paradigms, policies, purposes, and practices to understand education’s historical contribution to current crises, its adequacy for the age we find ourselves in, and its potential as a remedial agency. The transformative paradigm of sustainable education promises a liberatory escape from the bedrocks of the prevalent education epistemology—reductionism, objectivism, materialism, and dualism—and the collective psyche that maintains them. These deep influences manifest in much of the educational landscape above the surface: unitary disciplines and separate departments; belief in value-free knowing; privileging cognitive over affective and practical knowing, as well as analysis over synthesis; prescriptive curricula and measurable learning outcomes; and learning that fails to examine and challenge basic assumptions, values, and ethics. 8

The challenge calls for much more than the oft quoted objective of “integrating sustainability into education”: the planetary context must now be paramount. More than ever, educators and students are questioning educational policies and practices maladapted to real-world crises and a threatened future. However, although education is purportedly about the future, many mainstream policymakers, senior managers, and academics still seem oblivious to the perils society faces.

Overcoming such stasis requires a strategy of critical reflexivity that illuminates and challenges the dominant technocentric and economistic “rationality” that pervades thinking and practice, as well as the funding and reward structures that constrain innovative collaboration and forward-looking creative thinking. We need to break down barriers through communication and networking, dispersed and transformative leadership, intergenerational initiatives, inter- and transdisciplinarity, and action research and community initiatives. This emerging path offers a relational, ecological, participative, and holistic alternative that speaks to the real needs of individuals, communities, and the planet.

Class Struggles

The wider political and cultural factors discussed above help explain the weak response of educational systems and institutions to calls for reorientation. Rather than leading to deep institutional learning and transformation, the mode of incorporation of sustainability issues has typically been accommodation that leaves fundamental assumptions and practices largely unquestioned and unchanged. This incremental approach has some value if seen as a first step in a longer transition, but is an impediment to fundamental progress where regarded as a sufficient action.

Recently, however, there are increasing signs of genuine rethinking that transcends accommodation, a recognition that deeper change is required. This growing awareness parallels and derives energy from similar shifts in other sectors across society as “business as usual” looks less and less tenable. New ways of seeing, thinking, and doing are burgeoning, prompted further by the disruptive effects of COVID-19. This ferment offers the exciting possibility of a shift in education from a vehicle of social reproduction and maintenance, towards a vision of continuous co-evolution of education and society in a relationship of mutual transformation: a “future-creating, innovative and open system” of education. 9 Such real-world engagement provides a motivating environment for quality learning and enhancing educational outcomes for students and the world they are inheriting.

In the last few years, more academics have become educational activists through their publications, research collaboration, community engagement, and campaigning. 10 Inter-university networks and intersectoral initiatives are on the rise. The Regional Centres of Expertise in ESD, led by universities networking with local stakeholders on sustainability awareness, education, and capacity building, now number some 180 globally. 11 Growing numbers of international academic networks and initiatives reflect sustainability concerns. 12 Although more radical initiatives for pursuing transformative ideas head on are often sidelined, some independent institutions have managed to make an outsized impact. Notably, Schumacher College, in Devon, UK, has gained an international reputation during its thirty years of existence for fostering transformative learning experiences and seeding pioneering initiatives across the world. 13 The task ahead for all of these networks and institutions is to manifest and champion a more holistic, humanistic, ecological, and integrative form of education within established systems, and with colleagues who may still be uncomprehending or apprehensive.

Education for a Great Transition

While a new discourse on repurposing education is arising in some circles, a dangerous disconnect remains between Westernized formal education systems and the dynamic social learning needed in this watershed moment. The world of institutions, concerned largely with income and status in a competitive market, is on a collision course with the larger world, which faces an existential threat to human survival and the integrity of the biosphere underpinning all life. How do we rapidly recalibrate education so that it serves rather than undermines the future?

Historically, the central role of education has been to socialize the young and to ensure continuity in society, whether indigenous, pre-modern, or modern. In stable conditions, this reproduction function is sufficient. But not in volatile and uncertain times, when the future will not be a linear extension of the past and when social innovation, creativity, and experimentation is critically important. The contradiction now is that the more we try to ensure continuity by doing more of the same, the greater the prospects for a discontinuous and chaotic future become.

Some social critics think biophysical limits will inevitably usher in a post-growth world characterized by relocalization, profound hazards, and discontinuities for both human and natural systems. This very real prospect behooves educational institutions to become systemic learning organizations infused by a transformative pedagogy within education systems that reaches policymakers and practitioners. This transition would constrain the standardizing global testing culture while circumventing economistic educational rationales in favor of a purpose and role aligned with the immense challenge and exhilarating possibility of securing social and ecological wellbeing. Notably, the university then becomes an adaptive, innovating institution engaged in an ongoing co-evolutionary learning process with community and society. In this scenario, the conventional concerns of status, reputation, and income are subsumed within a nobler culture of critical commitment.

An ecological reimagining of education requires reclaiming authentic education by drawing from progressive, liberal, critical, emancipatory, and holistic educational antecedents. In the best traditions, universities are seen as sites and guardians of critical scholarship, creativity, empowerment, and contribution to the common good. Resurgent educational institutions can—in tandem with movements in wider society—build resilient communities , ecologies, and localized economies. This kind of transition education is beginning to happen—a living learning process essential for generating the collective intelligence for survival, security, and well-being of social-ecological systems.

Beyond the whole institutional strategies of a small but increasing number of universities internationally, interest is growing in “critical engagement” and “regenerative education” by committed staff and students in research and teaching. This engagement takes forms such as education for resilience, service learning in the community, experiential pedagogies, collaborative inquiry across disciplines, embrace of alternative and non-Western knowledge traditions, the development of sustainability competencies, and futures work. These pioneering shifts may not yet warrant announcing the onset of widespread transformative education, but they do open a pathway for a Great Transition in higher education as a critical component of social learning and cultural change.

We are approaching fifty years since the UN Conference on the Environment in Stockholm endorsed the key role of education, nearly thirty years since Agenda 21 proposed that education is “critical for achieving environmental and ethical awareness,” and five years since the SDGs set a target date of 2030. The ambitious UNESCO “Futures of Education” initiative promises a chance to reset direction and priorities. But to date, strong cultural inertia and the counterforce of neoliberalism have slowed progress, and the time is long overdue for holding Westernized education policy and practice to account. Now, efforts to transform education are greater than ever, but so, too, are the stakes and urgency. We need to move fast and with bold aspiration, while retaining critical reflexivity, as we create a new chapter in the evolution of our ways of educating on this—as yet—still beautiful planet.

1. Carole Buckler and Heather Creech, Shaping the Future We Want: UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (Paris: UNESCO, 2014), https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000230171 . 2. Brikena Xhomaqi, ed., Lifelong Learning for Sustainable Societies (Brussels: Life Long Learning Platform, 2020), https://lllplatform.eu/news/lllp-position-paper-lifelong-learning-for-sustainable-societies/ . 3. Stephen Sterling, “Separate Tracks, or Real Synergy?: Achieving a Closer Relationship between Education and SD Post 2015,” Journal of Education for Sustainable Development 8, no. 2 (September 2014): 89–112. 4. Sustainable Development Solutions Network, Accelerating Education for the SDGs in Universities: A Guide for Universities, Colleges, and Tertiary and Higher Education Institutions (New York: SDSN, 2020), https://resources.unsdsn.org/accelerating-education-for-the-sdgs-in-universities-a-guide-for-universities-colleges-and-tertiary-and-higher-education-institutions . 5. Hikaru Komatsu, Jeremy Rappleye, and Iveta Silova, “Will Education Post-2015 Move Us toward Environmental Sustainability?,” in Grading Goal Four- Tensions, Threats, and Opportunities in the Sustainable Development Goal on Quality Education , ed. Antonia Wulff (Leiden: Brill, 2020). 6. Iveta Silova, Hikaru Komatsu, and Jeremy Rappleye, “Facing the Climate Change Catastrophe: Education as Solution or Cause?,” NORRAG, October 12, 2018, https://www.norrag.org/facing-the-climate-change-catastrophe-education-as-solution-or-cause-by-iveta-silova-hikaru-komatsu-and-jeremy-rappleye/ . 7. Ben Williamson and Anna Hogan, Commercialisation and Privatisation in/of Education in the Context of Covid-19 (Brussels: Education International Research, 2020), https://issuu.com/educationinternational/docs/2020_eiresearch_gr_commercialisation_privatisation . 8. Stephen Sterling, Sustainable Education: Re-visioning Learning and Change (Cambridge, UK: Green Books, 2001); Stephen Sterling, “Sustainable Education,” in Science, Society and Sustainability: Education and Empowerment for an Uncertain World , eds. Donna Gray, Laura Colucci-Gray, and Elena Camino (New York: Routledge, 2009). 9. Béla H. Bánáthy, Systems Design of Education (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology Publications, 199l), 129. 10. The international call to education to take action on climate found at https://educators-for-climate-action.org/ has attracted nearly 2000 signatures. The Transition Lab ( https://www.transitionlab.earth/ ) launched an open letter to university senior managers in 2019 which quickly attracted over 1000 signatures. 11. You can find more about UNU Regional Centres of Expertise on Education for Sustainable Development (RCEs) at https://www.rcenetwork.org/portal/ . 12. These networks include Global Alliance of Tertiary Education and Student Sustainability Networks, IAU’s Higher Education and Research for SD Cluster; the Higher Education Sustainability Initiative; University Alliance for Sustainability; The Green Office movement; and Learning Planet (a global alliance of educators and institutions). More radical initiatives which address the Great Transition explicitly include Campus de la Transition and Gaia University. 13. Stephen Sterling, John Dawson, and Paul Warwick, “Transforming Sustainability Education at the Creative Edge of the Mainstream: A Case Study of Schumacher College,” Journal of Transformative Education 16, no. 4 (July 2018): 323–343.

Teaser photo credit: Participants in the Victory Garden Initiative’s Youth Education Program. All photos courtesy of www.victorygardeninitiative.org .

Stephen Sterling

Related articles.

How in the World Are People Doing?

By Rachel Donald , Resilience

Journalist and podcaster Rachel Donald (Planet: Critical) interviews Dr. Omnia El Omrani, a medical doctor and Climate and Health Policy Fellow at Imperial College London. Omnia shares reflections on Connecting Climate Minds—a landmark project looking at climate and mental health across the globe, with a specific focus on the lived experiences of youth, Indigenous communities, small farmers and fisher people.

May 25, 2024

Târ y donc a tori – Lessons on the Subversive Nature of Transmission, from a Stubborn Welshman

By Adèle Pautrat , ARC2020

To transmit is to empower – as many people as possible to be trained to become farmers; as many people as possible saving and adapting seeds to their own conditions.

May 24, 2024

Levke Caesar: “Oceanic Slowdown: Decoding the AMOC”

By Nate Hagens , The Great Simplification

On this episode, Nate is joined by climate physicist Levke Caesar for a comprehensive overview of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) and its connections to broader planetary systems.

What the Future of Education Looks Like from Here

- Posted December 11, 2020

- By Emily Boudreau

After a year that involved a global pandemic, school closures, nationwide remote instruction, protests for racial justice, and an election, the role of education has never been more critical or more uncertain. When the dust settles from this year, what will education look like — and what should it aspire to?

To mark the end of its centennial year, HGSE convened a faculty-led discussion to explore those questions. The Future of Education panel, moderated by Dean Bridget Long and hosted by HGSE’s Askwith Forums , focused on hopes for education going forward, as well as HGSE’s role. “The story of HGSE is the story of pivotal decisions, meeting challenges, and tremendous growth,” Long said. “We have a long history of empowering our students and partners to be innovators in a constantly changing world. And that is needed now more than ever.”

Joining Long were Associate Professor Karen Brennan , Senior Lecturer Jennifer Cheatham , Assistant Professor Anthony Jack, and Professors Adriana Umaña-Taylor and Martin West , as they looked forward to what the future could hold for schools, educators, and communities:

… After the pandemic subsides

The pandemic heightened existing gaps and disparities and exposed a need to rethink how systems leaders design schools, instruction, and who they put at the center of that design. “As a leader, in the years before the pandemic hit, I realized the balance of our work as practitioners was off,” Cheatham said. “If we had been spending time knowing our children and our staff and designing schools for them, we might not be feeling the pain in the way we are. I think we’re learning something about what the real work of school is about.” In the coming years, the panelists hope that a widespread push to recognize the identity and health of the whole-child in K–12 and higher education will help educators design support systems that can reduce inequity on multiple levels.

… For the global community

As much as the pandemic isolated individuals, on the global scale, people have looked to connect with each other to find solutions and share ideas as they faced a common challenge. This year may have brought everyone together and allowed for exchange of ideas, policies, practices, and assessments across boundaries.

… For technological advancements

As educators and leaders create, design, and imagine the future, technology should be used in service of that vision rather than dictating it. As technology becomes a major part of how we communicate and share ideas, educators need to think critically about how to deploy technology strategically. “My stance on technology is that it should always be used in the service of our human purpose and interest,” said Brennan. “We’ve talked about racial equity, building relationships. Our values and purposes and goals need to lead the way, not the tech.”

… For teachers

Human connections and interactions are at the heart of education. At this time, it’s become abundantly clear that the role of the teacher in the school community is irreplaceable. “I think the next few years hinge on how much we’re willing to invest in educators and all of these additional supports in the school which essentially make learning possible,” Umaña-Taylor said, “these are the individuals who are making the future minds of the nation possible.”

Cutting-edge research and new knowledge must become part of the public discussion in order to meaningfully shape the policies and practices that influence the future of education. “I fundamentally believe that we as academics and scholars must be part of the conversation and not limit ourselves to just articles behind paywalls or policy paragraphs at the end of a paper,” Jack said. “We have to engage the larger public.”

… In 25 years

“We shouldn’t underestimate the possibility that the future might look a lot like the present,” West said. “As I think about the potential sources of change in education, and in American education in particular, I tend to think about longer-term trends as the key driver.” Changing student demographics, access to higher education, structural inequality, and the focus of school leaders are all longer-term trends that, according to panelists, will influence the future of education.

Askwith Education Forum

Bringing innovators and influential leaders to the Harvard Graduate School of Education

Related Articles

Beyond Recovery

Future of Education: Human Development and Psychology – The Long View

Future of Education: Leading for Equity

America's Education News Source

Copyright 2024 The 74 Media, Inc

- Hope Rises in Pine Bluff

- Brown v Board @ 70

- absenteeism

Future of High School

Artificial intelligence.

- science of reading

Learning Loss, AI and the Future of Education: Our 24 Most-Read Essays of 2023

From rethinking the american high school to the fiscal cliff, tutoring and special ed, what our most incisive opinion contributors had to say.

Some of America’s biggest names in education tackled some of the thorniest issues facing the country’s schools on the op-ed pages of The 74 this year, expressing their concerns about continuing COVID-driven deficits among students and the future of education overall. There were some grim predictions, but also reasons for hope. Here are some of the most read, most incisive and most controversial essays we published in 2023.

David Steiner

America’s education system is a mess, and students are paying the price.

COVID-19, the legacy of race-based redlining, the lack of support for health care, child care and parental leave, and other social and economic policies have taken a terrible toll on student learning. But the fundamental cause of poor outcomes, writes contributor David Steiner of the Johns Hopkins Institute for Education Policy , is that policy leaders have eroded the instructional core and designed our education system for failure. As we have sown, so shall we reap. The challenges and rewards of learning are being washed away, and students are desperately the worse for the mess we have made. Read More

Margaret Raymond

The terrible truth — current solutions to covid learning loss are doomed to fail.

Despite well-intended and rapid responses to COVID learning loss, solutions such as tutoring or summer school are doomed to fail, says contributor Margaret (Macke) Raymond of the Center for Research on Education Outcomes at Stanford University. How do we know? CREDO researchers looked at learning patterns for students at three levels of achievement in 16 states and found that even with five extra years of education, only about 75% will be at grade level by high school graduation. No school can offer that much. It is time to decide whether to make necessary changes or continue to support a system that will almost certainly fail. Read More

Mark Schneider

The future is stem — but without enough students, the u.s. will be left behind.

America no longer produces the most science and engineering research publications, patents or natural-science Ph.D.s, and these trends are unlikely to change anytime soon. The problem isn’t a lack of universities to train future scientists or an economy incapable of encouraging innovation. Rather, says contributor Mark Schneider of the Institute of Education Sciences, it originates much earlier in the supply chain, in elementary school. Congress has a chance to help turn this around, by passing the New Essential Education Discoveries (NEED) Act. Read More

John Bailey

The Promise of Personalized Learning Never Delivered. Today’s AI Is Different

Educators often encounter lofty promises of technology revolutionizing learning, only to find reality fails to meet expectations. But based on his experiences with the new generation of artificial intelligence tools, contributor John Bailey believes society may be in the early stages of a transformative moment. This may very well usher in an era of individualized learning, empowering all students to realize their full potential and fostering a more equitable and effective educational experience. Read his four reasons why this generation of AI tools is likely to succeed where other technologies have failed. Read More

Chad Aldeman

Interactive — With More Teachers & Fewer Students, Districts Are Set up for Financial Trouble

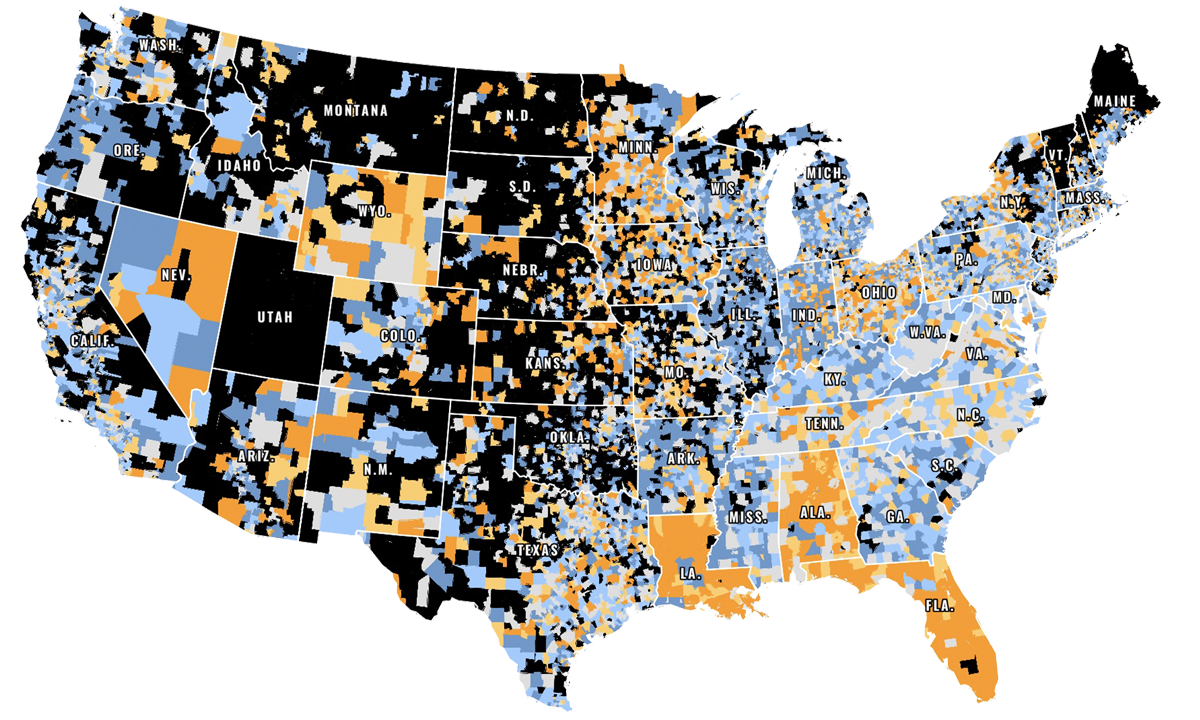

To understand the teacher labor market, you have to hold two competing narratives in your head. On one hand, teacher turnover hit new highs, morale is low and schools are facing shortages. At the same time, public schools employ more teachers than before COVID, while serving 1.9 million fewer students. Student-teacher ratios are near all-time lows. Contributor Chad Aldeman and Eamonn Fitzmaurice, The 74’s art and technology director, plotted these changes on an exclusive, interactive map — and explain how they’re putting districts in financial peril. View the Map

Fascinating, right? But these are only the tip of the iceberg. Here’s a roundup of some of the hottest topics our op-ed contributors tackled, and what they had to say:

Credit Hours Are a Relic of the Past. How States Must Disrupt High School — Now

Russlynn Ali & Timothy Knowles

Back to School — 6 Tips from Students on How to Make High School Relevant

Beth Fertig

I Changed My Shoes, and It Revolutionized How I Was Able to Rethink High School

William Blake

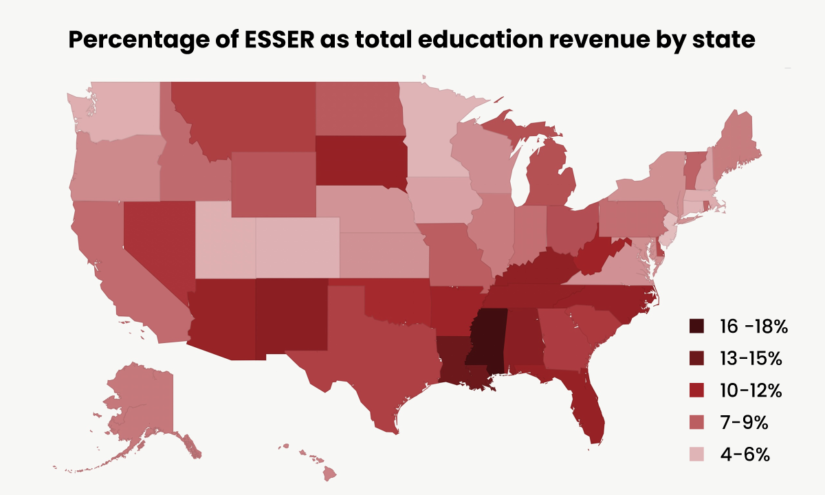

Fiscal Cliff & School Funding

The 50 Very Different States of American Public Education

It’s Time to Start Preparing Now for School Closures that Are Coming

Timothy Daly

Educators, Beware: As Budget Cuts Loom, Now Is NOT the Time to Quit Your Job

Katherine Silberstein & Marguerite Roza

Schools Could Lose 136,000 Teaching Jobs When Federal COVID Funds Run Out

Artificial Intelligence Will Not Transform K-12 Education Without Changes to ‘the Grammar of School’

Schools Must Embrace the Looming Disruption of ChatGPT

Sarah Dillard

Personalized Education Is Not a Panacea. Neither Is Artificial Intelligence

Natalia Kucirkova

Done Right, Tutoring Can Greatly Boost Student Learning. How Do We Get There?

Kevin Huffman

As Virginia Rolls Out Ambitious Statewide High-Dosage Tutoring Effort This Week, 3 Keys to Success

Maureen Kelleher

Why This Tutoring ‘Moment’ Could Die If We Don’t Tighten Up the Models

Mike Goldstein

Learning Loss

New NAEP Scores Reveal the Failure of Pandemic Academic Recovery Efforts

Vladimir Kogan

Quarantines, Not School Closures, Led to Devastating Losses in Math and Reading

6 Teachers Tell Their Secrets for Getting Middle Schoolers up to Speed in Math

Alexandra Frost

Special Ed and Gifted & Talented

Bracing for a Tidal Wave of Unnecessary Special Education Referrals

Lauren Morando Rhim, Candace Cortiella, Lindsay Kubatzky & Laurie VanderPloeg

Why Are Schools Comfortable Accepting Failure for Students with Disabilities?

David Flink & Lauren Morando Rhim

NYC’s New Gifted & Talented Admissions Brings Chaos — and Disregards Research

Alina Adams

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Bev Weintraub is an Executive Editor at The 74

- best of the year

- fiscal cliff

- future of high school

- learning loss

We want our stories to be shared as widely as possible — for free.

Please view The 74's republishing terms.

By Bev Weintraub

This story first appeared at The 74 , a nonprofit news site covering education. Sign up for free newsletters from The 74 to get more like this in your inbox.

On The 74 Today

The future of education: An essay collection

Education policy has for too long been moulded by 20th century ideals and restricted by short-term thinking. With every new government, fresh policies and initiatives are enacted in quick succession without always having an eye to the bigger picture. The ideas in this collection have sought to show how much the bigger picture matters, and provide ideas on what policymakers can do to meet the challenges of tomorrow, today.

Related items

Skills matter: shaping a just transition for workers in the energy sector, sky news package on ippr's manufacturing report, manufacturing matters: the cornerstone of a competitive green economy.

Search the United Nations

- Policy and Funding

- Recover Better

- Disability Inclusion

- Secretary-General

- Financing for Development

- ACT-Accelerator

- Member States

- Health and Wellbeing

- Policy and Guidance

- Vaccination

- COVID-19 Medevac

- i-Seek (requires login)

- Awake at Night podcast

"The future of education is here"

About the author, antónio guterres.

António Guterres is the ninth Secretary-General of the United Nations, who took office on 1st January 2017.

Education is the key to personal development and the future of societies.

It unlocks opportunities and narrows inequalities.

It is the bedrock of informed, tolerant societies, and a primary driver of sustainable development.

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to the largest disruption of education ever.

In mid-July, schools were closed in more than 160 countries, affecting over 1 billion students.

At least 40 million children worldwide have missed out on education in their critical pre-school year.

And parents, especially women, have been forced to assume heavy care burdens in the home.

Despite the delivery of lessons by radio, television and online, and the best efforts of teachers and parents, many students remain out of reach.

Learners with disabilities, those in minority or disadvantaged communities, displaced and refugee students and those in remote areas are at highest risk of being left behind.

And even for those who can access distance learning, success depends on their living conditions, including the fair distribution of domestic duties.

We are at a defining moment for the world’s children and young people.

We already faced a learning crisis before the pandemic.

More than 250 million school-age children were out of school.

And only a quarter of secondary school children in developing countries were leaving school with basic skills.

Now we face a generational catastrophe that could waste untold human potential, undermine decades of progress, and exacerbate entrenched inequalities.

The knock-on effects on child nutrition, child marriage and gender equality, among others, are deeply concerning.

This is the backdrop to the Policy Brief I am launching today, together with a new campaign with education partners and United Nations agencies called ‘Save our Future’.

The decisions that governments and partners take now will have lasting impact on hundreds of millions of young people, and on the development prospects of countries for decades to come.

This Policy Brief calls for action in four key areas:

First, reopening schools.

Once local transmission of COVID-19 is under control, getting students back into schools and learning institutions as safely as possible must be a top priority.

We have issued guidance to help governments in this complex endeavour.

It will be essential to balance health risks against risks to children’s education and protection, and to factor in the impact on women’s labour force participation.

Consultation with parents, carers, teachers and young people is fundamental.

Second, prioritizing education in financing decisions.

Before the crisis hit, low and middle-income countries already faced an education funding gap of $1.5 trillion dollars a year.

This gap has now grown.

Education budgets need to be protected and increased.

And it is critical that education is at the heart of international solidarity efforts, from debt management and stimulus packages to global humanitarian appeals and official development assistance.

Third, targeting the hardest to reach.

Education initiatives must seek to reach those at greatest risk of being left behind -- people in emergencies and crises; minority groups of all kinds; displaced people and those with disabilities.

They should be sensitive to the specific challenges faced by girls, boys, women and men, and should urgently seek to bridge the digital divide.

Fourth, the future of education is here.

We have a generational opportunity to reimagine education.

We can take a leap towards forward-looking systems that deliver quality education for all as a springboard for the Sustainable Development Goals.

To achieve this, we need investment in digital literacy and infrastructure, an evolution towards learning how to learn, a rejuvenation of life-long learning and strengthened links between formal and non-formal education.

And we need to draw on flexible delivery methods, digital technologies and modernized curricula while ensuring sustained support for teachers and communities.

As the world faces unsustainable levels of inequality, we need education – the great equalizer – more than ever.

We must take bold steps now, to create inclusive, resilient, quality education systems fit for the future.

- Policy Brief: Education during COVID-19 and beyond

S7-Episode 2: Bringing Health to the World

“You see, we're not doing this work to make ourselves feel better. That sort of conventional notion of what a do-gooder is. We're doing this work because we are totally convinced that it's not necessary in today's wealthy world for so many people to be experiencing discomfort, for so many people to be experiencing hardship, for so many people to have their lives and their livelihoods imperiled.”

Dr. David Nabarro has dedicated his life to global health. After a long career that’s taken him from the horrors of war torn Iraq, to the devastating aftermath of the Indian Ocean tsunami, he is still spurred to action by the tremendous inequalities in global access to medical care.

“The thing that keeps me awake most at night is the rampant inequities in our world…We see an awful lot of needless suffering.”

:: David Nabarro interviewed by Melissa Fleming

Brazilian ballet pirouettes during pandemic

Ballet Manguinhos, named for its favela in Rio de Janeiro, returns to the stage after a long absence during the COVID-19 pandemic. It counts 250 children and teenagers from the favela as its performers. The ballet group provides social support in a community where poverty, hunger and teen pregnancy are constant issues.

Radio journalist gives the facts on COVID-19 in Uzbekistan

The pandemic has put many people to the test, and journalists are no exception. Coronavirus has waged war not only against people's lives and well-being but has also spawned countless hoaxes and scientific falsehoods.

"A multidisciplinary forum focused on the social consequences and policy implications of all forms of knowledge on a global basis"

We are pleased to introduce Eruditio, the electronic journal of the World Academy of Art & Science. The vision of the Journal complements and enhances the World Academy's focus on global perspectives in the generation of knowledge from all fields of legitimate inquiry. The Journal also mirrors the World Academy's specific focus and mandate which is to consider the social consequences and policy implications of knowledge in the broadest sense.

Eruditio Issues

- Volume 2 Issue 1

- Volume 2 Issue 2

- Volume 2 Issue 3

Volume 2 Issue 4

- Volume 2 Issue 5

- Volume 2 Issue 6

- Volume 3 Issue 1

Editorial Information

- Editorial Board

- Author Guidelines

- Editorial Policy

- Reference Style Guide

World Academy of Art & Science

- Publications

- Events & News

The Challenges for Future Education: A Global Perspective

ARTICLE | July 23, 2018 | BY Marco Vitiello

1. Introduction

Today we are living in a globalized world where interconnections between human beings as individuals, and nations and states, are becoming wider day by day, making us encounter cultures that are pretty different from our own.

These interactions are increasingly growing not only because of the modern amazing tools that make them easier than in the past (take the internet and the social networks for example), but also because today, as a globalized world, we find ourselves in front of difficult and complex challenges which necessarily need a global response in order to be solved: we need each other to survive not only as nations and states, but as a species. So, what is the role that higher education systems should play in this context? Universities across the world host students that one day will be the leaders of our world, those who will work to solve national problems and who will cooperate with other leaders in order to solve global issues and to build a more united international community.

This is why universities should provide their students with all the right tools that they will need in future not only to have a successful career, but also to be able to create valid international cooperation that will allow them to find creative and shared solutions for all kinds of problems.

But now the question is: what are these tools?

2. Moving Towards a Global Education

Universities are places where the adults and leaders of tomorrow are forged. It is then very much important to make higher education free of charge for those students coming from lower income social classes: this is a first step to ensure that those who are willing to invest their time in higher education are able to do it so they can direct their lives towards self-realization; in this way not only will we stimulate social mobility, but we will also build a fairer society with a qualitatively better human capital. Resuming free education means better chances for both individuals and societies.

Having said that, we need to remind ourselves how universities should be places where students not only are taught, but where they can grow as self-conscious and self-confident individuals, finding the chance to acquire important skills while developing their personal qualities, understanding what their path is in life. At the same time, they should be educated in order to be able to live in this complex world, knowing its history and its characteristics in an in-depth way.

Education should then be based on three main pillars:

- Values and Skills

2.1. Knowledge

- knowledge of the globalization process : students should be able to fully understand globalization, analyzing it in a critical way; they should know how to recognize its positive effects but also be aware of the negative ones, thereby learning how to deal with them.

- knowledge of human history and philosophy : students should interiorize through education those that can be considered the most important and universal human values, such as the prominence of human rights, of democracy and of social justice; they should learn the fundamental significance of dialogue both between individuals and countries/cultures.

2.2. Competency

- critical thinking : universities should teach students to deal with complex problems and to analyze them with a critical and open mind; students should also learn the importance of reconsidering their opinion in the face of new evidence.

Today’s problems and challenges are much more complex than in the past and cannot be explained in any satisfying manner if not analyzed from every possible point of view: only in this way we will be able to see the whole picture and to take wise decisions in order to tackle problems. Different disciplines should collaborate in a student’s education in order to make him analyze and resolve complex issues.

It is very important that students learn how to imagine a common future with better living conditions for everybody. Future education should find then a new paradigm that challenges inequality by boosting feelings of solidarity among human beings, allowing students and future leaders to see themselves as part of a bigger human community.

- team working : this is all about making sure that students participate in activities which require teamwork: only with constant practice in such kinds of activities they will understand how everyone can contribute in the achievement of a particular goal, on the basis of our personal qualities and skills.

- ability to deal with conflicts : conflicts, when we talk about humans, considered both as individuals and as societies, are pretty common, probably even inevitable. This is why students should be taught how to avoid them or, when necessary, how to deal with them in a wise way: talking about international politics, they should understand how war prevention is one of the most important issues in the world today. Our chances of survival as a species are based on the capacity of preventing wars and other kind of conflicts.

2.3. Values and Skills

- self-esteem, self-confidence : Even if these two elements seem to be quite simple to understand, they must not be taken for granted: in universities students should understand that the worse kind of failure is not trying: they must be encouraged to commit themselves to studying and to all kinds of parallel activities. They should be encouraged to get out of their comfort zones and to try new activities and challenges: if they fail, they must understand that from failure we rise. Failure helps us to improve our skills and to correct our mistakes. If they succeed in their tasks or activities, their confidence gets a boost: if we are able to develop fully confident youth, not only we will raise the chances of seeing them achieve their goals in life, but we will have raised great individuals whose life will have a positive impact on the whole society.

- social responsibility : students should learn the importance of social justice, the importance of creating a fairer world at all levels—national, regional and global levels.

- environmental responsibility : we have only one planet, but we still take it for granted. Students must learn that it is our responsibility as humans to make sure that our environment is respected. Especially today, since one of the main global issues is global warming, a complex problem which connects different dimensions of our living: politics, economics, etc.

3. Methodologies

What can be some good methods to make sure that higher education can provide students with the needed skills and abilities?

Here are a few proposals:

3.1. Global connections between universities.

It is important for students, as already mentioned, to know other cultures and comprehend their values. How can this be done?

- student exchange programs : implementing and strengthening student exchange programs is probably the best possible way to achieve this goal. Sending students to study abroad and welcoming students from different parts of the world is the absolute best way to ensure an interchange between countries and to let students understand other cultures and countries and their points of view.

- hosting researchers and professors coming from other parts of the world : by doing this, universities will enrich their didactics, giving students the chance to benefit from listening to professionals with different approaches to teaching.

- making sure that students know about the existence of the so-called MOOCs : in this way students will know how to have online access to courses taught by other universities. Universities should participate in this, and have their courses on online platforms.

3.2. Making students work on a project

Students should learn how to work on a project both alone and in a team. Such projects should also be presented and discussed in front of the whole class, so that students learn not only to write an essay, but also to speak properly in front of an audience.

3.2. Making sure students have access to cultural anthropology courses.

On the basis of my very personal experience, I think the importance of anthropology is underestimated: this subject can provide students with the right tools and knowledge to understand cultural relativism: there is no hierarchy between cultures and knowing this is fundamental in order to create a valid cooperation with other countries.

About the Author(s)

Subscribe here to free electronic edition.

Inside this Issue

Lead Articles

Papers presented at the rome conference, 2017, section 1: introduction.

Introductory Remarks by the President of WAAS

- Heitor Gurgulino de Souza

Introductory Report on the 2nd International Conference on Future Education

- Garry Jacobs & Alberto Zucconi

Contextual, Relational, Human-Centered Knowledge

- Edgar Morin

Education to Meet Societal Needs

- Peter Senge

SECTION 2: UNIVERSITIES REFLECTING THE CURRENT STATE OF THE SYSTEM

The European University in Crisis: A Vision From Spain

- Juan Cayón Peña

To Cope with Present and Future Catastrophic Risks, Higher Education must Train Future Decision Makers to Think Critically, Ethically and in System

- Lennart Levi & Bo Rothstein

The Knowledge of Complexity should be a part of Contemporary Education

- Jüri Engelbrecht

SECTION 3: THE NEED FOR A NEW PARADIGM

Some Reflections on the Future of Education

- J. Martin Ramirez & Tina Lindhard

Higher Education and the New Society of Third Millennium

- Emil Constantinescu

Future Education: A New Paradigm

- Federico Mayor Zaragoza

- Marco Vitiello

SECTION 4: WHERE TO BEGIN? CHANGE NEEDED AT THE PRIMARY LEVEL

Start Early, End Strong

- George Halvorson & Robert J. Berg

Breaking Barriers with Building Blocks: Attitudes towards Learning Technologies & Curriculum Design in ABC Curriculum Design Workshop

- Kristy Evers

Young Children, Digital Technology and the School of Tomorrow

- Marion Voillot

The Impact of Exogenous Urban Factors on Absenteeism & Dropout Rates

- Davor Bernardić

SECTION 5: MIND, THINKING AND CREATIVITY

Insights on Creativity

- Vani Senthil

SECTION 6: TRANSDISCIPLINARITY: BREAKING THE SILOS

UNIVERSITIES: Enhancing the Education, Research and Innovation Base

- Marcel van de Voorde

Transdisciplinary Education for Deep Learning, Creativity and Innovation

- Rodolfo Fiorini

SECTION 7: TOOLS/CATALYSTS IN THE TRANSFORMATION PROCESS

The Teacher as Catalyst: Skills Development & Self-Discovery in Group Contexts

- Ullica Segerstrale

The Future of Higher Education: The Role of Basic Values

- Winston P. Nagan & Megan E. Weeren

Online and Hybrid Learning

- Janani Ramanathan

Lifelong Learning: A Necessity in the Knowledge Society

- Raoul Weiler

Higher Education and Small Countries

- Momir Djurovic

Teaching Assistants (TAs) as Secondary Facilitators in an Academic Support Unit in a South African University

- Makhanya-Nontsikelelo Lynette Buyisiwe

SECTION 8: THE RESULT – PEACE, BETTER GOVERNANCE AND NEW ECONOMICS

Education, Democracy and Peace

- Siro Polo Padolecchia

Education: An Essential Tool for Reaching the UN SDGs by 2030

- Yehuda Kahane

SECTION 9: AGILE LEADERSHIP AND DECISION MAKING – THE ROAD AHEAD

Change Leadership: Leading by Empowering and Innovation

- Tatjana Mitrovic

Agile Management Education for the Future: The Role of Social Capital & Trust

- Grażyna Leśniak-Łebkowska

Sustainable Business as the Base for Sustainable Entrepreneurs:Some Theoretical and Practical Reflections

- Zbigniew Bochniarz

Papers presented at the Primrose Conference, Pondicherry, 2018

Section 10: role of education.

Education as a Civilizing Experience

- Ashok Natarajan

Essence of Educational Inspiration

- Vidya Rangan

Beauty of Mathematics and Overcoming the Agony of Math Education

Student Leadership Skill: A Sustainability Paradigm to Harness Demographic Dividend in India

- Malathy Iyer

Download Volume 2 Issue 4

Terms of Use | Copyright Policy | Privacy Policy

Home / Essay Samples / Education / E-Learning / Education for the Future: Innovations and Challenges

Education for the Future: Innovations and Challenges

- Category: Education , Information Science and Technology

- Topic: E-Learning , Education System , Technology in Education

Pages: 3 (1165 words)

- Downloads: -->

--> ⚠️ Remember: This essay was written and uploaded by an--> click here.

Found a great essay sample but want a unique one?

are ready to help you with your essay

You won’t be charged yet!

Negative Impact of Technology Essays

Cell Phones Essays

Computer Essays

Mobile Phone Essays

Internet Essays

Related Essays

We are glad that you like it, but you cannot copy from our website. Just insert your email and this sample will be sent to you.

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Your essay sample has been sent.

In fact, there is a way to get an original essay! Turn to our writers and order a plagiarism-free paper.

samplius.com uses cookies to offer you the best service possible.By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .--> -->