What is an Essay?

10 May, 2020

11 minutes read

Author: Tomas White

Well, beyond a jumble of words usually around 2,000 words or so - what is an essay, exactly? Whether you’re taking English, sociology, history, biology, art, or a speech class, it’s likely you’ll have to write an essay or two. So how is an essay different than a research paper or a review? Let’s find out!

Defining the Term – What is an Essay?

The essay is a written piece that is designed to present an idea, propose an argument, express the emotion or initiate debate. It is a tool that is used to present writer’s ideas in a non-fictional way. Multiple applications of this type of writing go way beyond, providing political manifestos and art criticism as well as personal observations and reflections of the author.

An essay can be as short as 500 words, it can also be 5000 words or more. However, most essays fall somewhere around 1000 to 3000 words ; this word range provides the writer enough space to thoroughly develop an argument and work to convince the reader of the author’s perspective regarding a particular issue. The topics of essays are boundless: they can range from the best form of government to the benefits of eating peppermint leaves daily. As a professional provider of custom writing, our service has helped thousands of customers to turn in essays in various forms and disciplines.

Origins of the Essay

Over the course of more than six centuries essays were used to question assumptions, argue trivial opinions and to initiate global discussions. Let’s have a closer look into historical progress and various applications of this literary phenomenon to find out exactly what it is.

Today’s modern word “essay” can trace its roots back to the French “essayer” which translates closely to mean “to attempt” . This is an apt name for this writing form because the essay’s ultimate purpose is to attempt to convince the audience of something. An essay’s topic can range broadly and include everything from the best of Shakespeare’s plays to the joys of April.

The essay comes in many shapes and sizes; it can focus on a personal experience or a purely academic exploration of a topic. Essays are classified as a subjective writing form because while they include expository elements, they can rely on personal narratives to support the writer’s viewpoint. The essay genre includes a diverse array of academic writings ranging from literary criticism to meditations on the natural world. Most typically, the essay exists as a shorter writing form; essays are rarely the length of a novel. However, several historic examples, such as John Locke’s seminal work “An Essay Concerning Human Understanding” just shows that a well-organized essay can be as long as a novel.

The Essay in Literature

The essay enjoys a long and renowned history in literature. They first began gaining in popularity in the early 16 th century, and their popularity has continued today both with original writers and ghost writers. Many readers prefer this short form in which the writer seems to speak directly to the reader, presenting a particular claim and working to defend it through a variety of means. Not sure if you’ve ever read a great essay? You wouldn’t believe how many pieces of literature are actually nothing less than essays, or evolved into more complex structures from the essay. Check out this list of literary favorites:

- The Book of My Lives by Aleksandar Hemon

- Notes of a Native Son by James Baldwin

- Against Interpretation by Susan Sontag

- High-Tide in Tucson: Essays from Now and Never by Barbara Kingsolver

- Slouching Toward Bethlehem by Joan Didion

- Naked by David Sedaris

- Walden; or, Life in the Woods by Henry David Thoreau

Pretty much as long as writers have had something to say, they’ve created essays to communicate their viewpoint on pretty much any topic you can think of!

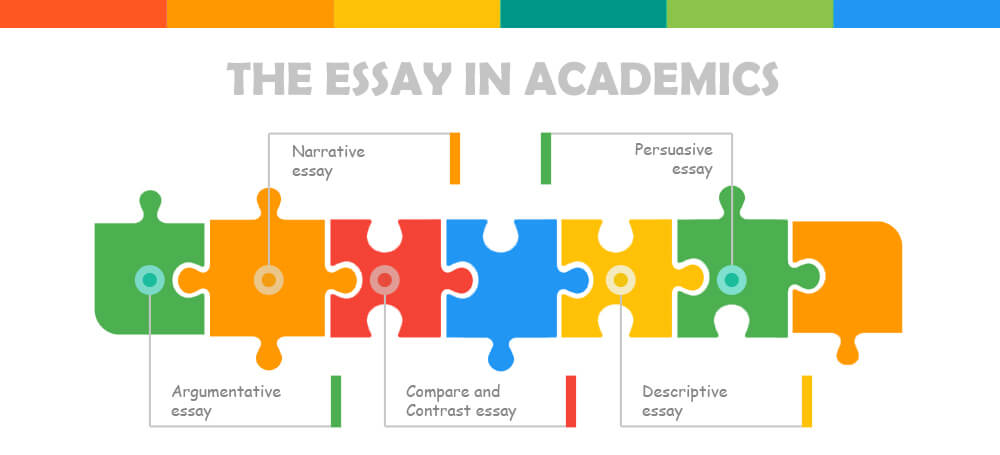

The Essay in Academics

Not only are students required to read a variety of essays during their academic education, but they will likely be required to write several different kinds of essays throughout their scholastic career. Don’t love to write? Then consider working with a ghost essay writer ! While all essays require an introduction, body paragraphs in support of the argumentative thesis statement, and a conclusion, academic essays can take several different formats in the way they approach a topic. Common essays required in high school, college, and post-graduate classes include:

Five paragraph essay

This is the most common type of a formal essay. The type of paper that students are usually exposed to when they first hear about the concept of the essay itself. It follows easy outline structure – an opening introduction paragraph; three body paragraphs to expand the thesis; and conclusion to sum it up.

Argumentative essay

These essays are commonly assigned to explore a controversial issue. The goal is to identify the major positions on either side and work to support the side the writer agrees with while refuting the opposing side’s potential arguments.

Compare and Contrast essay

This essay compares two items, such as two poems, and works to identify similarities and differences, discussing the strength and weaknesses of each. This essay can focus on more than just two items, however. The point of this essay is to reveal new connections the reader may not have considered previously.

Definition essay

This essay has a sole purpose – defining a term or a concept in as much detail as possible. Sounds pretty simple, right? Well, not quite. The most important part of the process is picking up the word. Before zooming it up under the microscope, make sure to choose something roomy so you can define it under multiple angles. The definition essay outline will reflect those angles and scopes.

Descriptive essay

Perhaps the most fun to write, this essay focuses on describing its subject using all five of the senses. The writer aims to fully describe the topic; for example, a descriptive essay could aim to describe the ocean to someone who’s never seen it or the job of a teacher. Descriptive essays rely heavily on detail and the paragraphs can be organized by sense.

Illustration essay

The purpose of this essay is to describe an idea, occasion or a concept with the help of clear and vocal examples. “Illustration” itself is handled in the body paragraphs section. Each of the statements, presented in the essay needs to be supported with several examples. Illustration essay helps the author to connect with his audience by breaking the barriers with real-life examples – clear and indisputable.

Informative Essay

Being one the basic essay types, the informative essay is as easy as it sounds from a technical standpoint. High school is where students usually encounter with informative essay first time. The purpose of this paper is to describe an idea, concept or any other abstract subject with the help of proper research and a generous amount of storytelling.

Narrative essay

This type of essay focuses on describing a certain event or experience, most often chronologically. It could be a historic event or an ordinary day or month in a regular person’s life. Narrative essay proclaims a free approach to writing it, therefore it does not always require conventional attributes, like the outline. The narrative itself typically unfolds through a personal lens, and is thus considered to be a subjective form of writing.

Persuasive essay

The purpose of the persuasive essay is to provide the audience with a 360-view on the concept idea or certain topic – to persuade the reader to adopt a certain viewpoint. The viewpoints can range widely from why visiting the dentist is important to why dogs make the best pets to why blue is the best color. Strong, persuasive language is a defining characteristic of this essay type.

The Essay in Art

Several other artistic mediums have adopted the essay as a means of communicating with their audience. In the visual arts, such as painting or sculpting, the rough sketches of the final product are sometimes deemed essays. Likewise, directors may opt to create a film essay which is similar to a documentary in that it offers a personal reflection on a relevant issue. Finally, photographers often create photographic essays in which they use a series of photographs to tell a story, similar to a narrative or a descriptive essay.

Drawing the line – question answered

“What is an Essay?” is quite a polarizing question. On one hand, it can easily be answered in a couple of words. On the other, it is surely the most profound and self-established type of content there ever was. Going back through the history of the last five-six centuries helps us understand where did it come from and how it is being applied ever since.

If you must write an essay, follow these five important steps to works towards earning the “A” you want:

- Understand and review the kind of essay you must write

- Brainstorm your argument

- Find research from reliable sources to support your perspective

- Cite all sources parenthetically within the paper and on the Works Cited page

- Follow all grammatical rules

Generally speaking, when you must write any type of essay, start sooner rather than later! Don’t procrastinate – give yourself time to develop your perspective and work on crafting a unique and original approach to the topic. Remember: it’s always a good idea to have another set of eyes (or three) look over your essay before handing in the final draft to your teacher or professor. Don’t trust your fellow classmates? Consider hiring an editor or a ghostwriter to help out!

If you are still unsure on whether you can cope with your task – you are in the right place to get help. HandMadeWriting is the perfect answer to the question “Who can write my essay?”

A life lesson in Romeo and Juliet taught by death

Due to human nature, we draw conclusions only when life gives us a lesson since the experience of others is not so effective and powerful. Therefore, when analyzing and sorting out common problems we face, we may trace a parallel with well-known book characters or real historical figures. Moreover, we often compare our situations with […]

Ethical Research Paper Topics

Writing a research paper on ethics is not an easy task, especially if you do not possess excellent writing skills and do not like to contemplate controversial questions. But an ethics course is obligatory in all higher education institutions, and students have to look for a way out and be creative. When you find an […]

Art Research Paper Topics

Students obtaining degrees in fine art and art & design programs most commonly need to write a paper on art topics. However, this subject is becoming more popular in educational institutions for expanding students’ horizons. Thus, both groups of receivers of education: those who are into arts and those who only get acquainted with art […]

11 Rules for Essay Paragraph Structure (with Examples)

How do you structure a paragraph in an essay?

If you’re like the majority of my students, you might be getting your basic essay paragraph structure wrong and getting lower grades than you could!

In this article, I outline the 11 key steps to writing a perfect paragraph. But, this isn’t your normal ‘how to write an essay’ article. Rather, I’ll try to give you some insight into exactly what teachers look out for when they’re grading essays and figuring out what grade to give them.

You can navigate each issue below, or scroll down to read them all:

1. Paragraphs must be at least four sentences long 2. But, at most seven sentences long 3. Your paragraph must be Left-Aligned 4. You need a topic sentence 5 . Next, you need an explanation sentence 6. You need to include an example 7. You need to include citations 8. All paragraphs need to be relevant to the marking criteria 9. Only include one key idea per paragraph 10. Keep sentences short 11. Keep quotes short

Paragraph structure is one of the most important elements of getting essay writing right .

As I cover in my Ultimate Guide to Writing an Essay Plan , paragraphs are the heart and soul of your essay.

However, I find most of my students have either:

- forgotten how to write paragraphs properly,

- gotten lazy, or

- never learned it in the first place!

Paragraphs in essay writing are different from paragraphs in other written genres .

In fact, the paragraphs that you are reading now would not help your grades in an essay.

That’s because I’m writing in journalistic style, where paragraph conventions are vastly different.

For those of you coming from journalism or creative writing, you might find you need to re-learn paragraph writing if you want to write well-structured essay paragraphs to get top grades.

Below are eleven reasons your paragraphs are losing marks, and what to do about it!

Essay Paragraph Structure Rules

1. your paragraphs must be at least 4 sentences long.

In journalism and blog writing, a one-sentence paragraph is great. It’s short, to-the-point, and helps guide your reader. For essay paragraph structure, one-sentence paragraphs suck.

A one-sentence essay paragraph sends an instant signal to your teacher that you don’t have much to say on an issue.

A short paragraph signifies that you know something – but not much about it. A one-sentence paragraph lacks detail, depth and insight.

Many students come to me and ask, “what does ‘add depth’ mean?” It’s one of the most common pieces of feedback you’ll see written on the margins of your essay.

Personally, I think ‘add depth’ is bad feedback because it’s a short and vague comment. But, here’s what it means: You’ve not explained your point enough!

If you’re writing one-, two- or three-sentence essay paragraphs, you’re costing yourself marks.

Always aim for at least four sentences per paragraph in your essays.

This doesn’t mean that you should add ‘fluff’ or ‘padding’ sentences.

Make sure you don’t:

a) repeat what you said in different words, or b) write something just because you need another sentence in there.

But, you need to do some research and find something insightful to add to that two-sentence paragraph if you want to ace your essay.

Check out Points 5 and 6 for some advice on what to add to that short paragraph to add ‘depth’ to your paragraph and start moving to the top of the class.

- How to Make an Essay Longer

- How to Make an Essay Shorter

2. Your Paragraphs must not be more than 7 Sentences Long

Okay, so I just told you to aim for at least four sentences per paragraph. So, what’s the longest your paragraph should be?

Seven sentences. That’s a maximum.

So, here’s the rule:

Between four and seven sentences is the sweet spot that you need to aim for in every single paragraph.

Here’s why your paragraphs shouldn’t be longer than seven sentences:

1. It shows you can organize your thoughts. You need to show your teacher that you’ve broken up your key ideas into manageable segments of text (see point 10)

2. It makes your work easier to read. You need your writing to be easily readable to make it easy for your teacher to give you good grades. Make your essay easy to read and you’ll get higher marks every time.

One of the most important ways you can make your work easier to read is by writing paragraphs that are less than six sentences long.

3. It prevents teacher frustration. Teachers are just like you. When they see a big block of text their eyes glaze over. They get frustrated, lost, their mind wanders … and you lose marks.

To prevent teacher frustration, you need to ensure there’s plenty of white space in your essay. It’s about showing them that the piece is clearly structured into one key idea per ‘chunk’ of text.

Often, you might find that your writing contains tautologies and other turns of phrase that can be shortened for clarity.

3. Your Paragraph must be Left-Aligned

Turn off ‘Justified’ text and: Never. Turn. It. On. Again.

Justified text is where the words are stretched out to make the paragraph look like a square. It turns the writing into a block. Don’t do it. You will lose marks, I promise you! Win the psychological game with your teacher: left-align your text.

A good essay paragraph is never ‘justified’.

I’m going to repeat this, because it’s important: to prevent your essay from looking like a big block of muddy, hard-to-read text align your text to the left margin only.

You want white space on your page – and lots of it. White space helps your reader scan through your work. It also prevents it from looking like big blocks of text.

You want your reader reading vertically as much as possible: scanning, browsing, and quickly looking through for evidence you’ve engaged with the big ideas.

The justified text doesn’t help you do that. Justified text makes your writing look like a big, lumpy block of text that your reader doesn’t want to read.

What’s wrong with Center-Aligned Text?

While I’m at it, never, ever, center-align your text either. Center-aligned text is impossible to skim-read. Your teacher wants to be able to quickly scan down the left margin to get the headline information in your paragraph.

Not many people center-align text, but it’s worth repeating: never, ever center-align your essays.

Don’t annoy your reader. Left align your text.

4. Your paragraphs must have a Topic Sentence

The first sentence of an essay paragraph is called the topic sentence. This is one of the most important sentences in the correct essay paragraph structure style.

The topic sentence should convey exactly what key idea you’re going to cover in your paragraph.

Too often, students don’t let their reader know what the key idea of the paragraph is until several sentences in.

You must show what the paragraph is about in the first sentence.

You never, ever want to keep your reader in suspense. Essays are not like creative writing. Tell them straight away what the paragraph is about. In fact, if you can, do it in the first half of the first sentence .

I’ll remind you again: make it easy to grade your work. Your teacher is reading through your work trying to determine what grade to give you. They’re probably going to mark 20 assignments in one sitting. They have no interest in storytelling or creativity. They just want to know how much you know! State what the paragraph is about immediately and move on.

Suggested: Best Words to Start a Paragraph

Ideal Essay Paragraph Structure Example: Writing a Topic Sentence If your paragraph is about how climate change is endangering polar bears, say it immediately : “Climate change is endangering polar bears.” should be your first sentence in your paragraph. Take a look at first sentence of each of the four paragraphs above this one. You can see from the first sentence of each paragraph that the paragraphs discuss:

When editing your work, read each paragraph and try to distil what the one key idea is in your paragraph. Ensure that this key idea is mentioned in the first sentence .

(Note: if there’s more than one key idea in the paragraph, you may have a problem. See Point 9 below .)

The topic sentence is the most important sentence for getting your essay paragraph structure right. So, get your topic sentences right and you’re on the right track to a good essay paragraph.

5. You need an Explanation Sentence

All topic sentences need a follow-up explanation. The very first point on this page was that too often students write paragraphs that are too short. To add what is called ‘depth’ to a paragraph, you can come up with two types of follow-up sentences: explanations and examples.

Let’s take explanation sentences first.

Explanation sentences give additional detail. They often provide one of the following services:

Let’s go back to our example of a paragraph on Climate change endangering polar bears. If your topic sentence is “Climate change is endangering polar bears.”, then your follow-up explanation sentence is likely to explain how, why, where, or when. You could say:

Ideal Essay Paragraph Structure Example: Writing Explanation Sentences 1. How: “The warming atmosphere is melting the polar ice caps.” 2. Why: “The polar bears’ habitats are shrinking every single year.” 3. Where: “This is happening in the Antarctic ice caps near Greenland.” 4. When: “Scientists first noticed the ice caps were shrinking in 1978.”

You don’t have to provide all four of these options each time.

But, if you’re struggling to think of what to add to your paragraph to add depth, consider one of these four options for a good quality explanation sentence.

>>>RELATED ARTICLE: SHOULD YOU USE RHETORICAL QUESTIONS IN ESSAYS ?

6. Your need to Include an Example

Examples matter! They add detail. They also help to show that you genuinely understand the issue. They show that you don’t just understand a concept in the abstract; you also understand how things work in real life.

Example sentences have the added benefit of personalising an issue. For example, after saying “Polar bears’ habitats are shrinking”, you could note specific habitats, facts and figures, or even a specific story about a bear who was impacted.

Ideal Essay Paragraph Structure Example: Writing an ‘Example’ Sentence “For example, 770,000 square miles of Arctic Sea Ice has melted in the past four decades, leading Polar Bear populations to dwindle ( National Geographic, 2018 )

In fact, one of the most effective politicians of our times – Barrack Obama – was an expert at this technique. He would often provide examples of people who got sick because they didn’t have healthcare to sell Obamacare.

What effect did this have? It showed the real-world impact of his ideas. It humanised him, and got him elected president – twice!

Be like Obama. Provide examples. Often.

7. All Paragraphs need Citations

Provide a reference to an academic source in every single body paragraph in the essay. The only two paragraphs where you don’t need a reference is the introduction and conclusion .

Let me repeat: Paragraphs need at least one reference to a quality scholarly source .

Let me go even further:

Students who get the best marks provide two references to two different academic sources in every paragraph.

Two references in a paragraph show you’ve read widely, cross-checked your sources, and given the paragraph real thought.

It’s really important that these references link to academic sources, not random websites, blogs or YouTube videos. Check out our Seven Best types of Sources to Cite in Essays post to get advice on what sources to cite. Number 6 w ill surprise you!

Ideal Essay Paragraph Structure Example: In-Text Referencing in Paragraphs Usually, in-text referencing takes the format: (Author, YEAR), but check your school’s referencing formatting requirements carefully. The ‘Author’ section is the author’s last name only. Not their initials. Not their first name. Just their last name . My name is Chris Drew. First name Chris, last name Drew. If you were going to reference an academic article I wrote in 2019, you would reference it like this: (Drew, 2019).

Where do you place those two references?

Place the first reference at the end of the first half of the paragraph. Place the second reference at the end of the second half of the paragraph.

This spreads the references out and makes it look like all the points throughout the paragraph are backed up by your sources. The goal is to make it look like you’ve reference regularly when your teacher scans through your work.

Remember, teachers can look out for signposts that indicate you’ve followed academic conventions and mentioned the right key ideas.

Spreading your referencing through the paragraph helps to make it look like you’ve followed the academic convention of referencing sources regularly.

Here are some examples of how to reference twice in a paragraph:

- If your paragraph was six sentences long, you would place your first reference at the end of the third sentence and your second reference at the end of the sixth sentence.

- If your paragraph was five sentences long, I would recommend placing one at the end of the second sentence and one at the end of the fifth sentence.

You’ve just read one of the key secrets to winning top marks.

8. Every Paragraph must be relevant to the Marking Criteria

Every paragraph must win you marks. When you’re editing your work, check through the piece to see if every paragraph is relevant to the marking criteria.

For the British: In the British university system (I’m including Australia and New Zealand here – I’ve taught at universities in all three countries), you’ll usually have a ‘marking criteria’. It’s usually a list of between two and six key learning outcomes your teacher needs to use to come up with your score. Sometimes it’s called a:

- Marking criteria

- Marking rubric

- (Key) learning outcome

- Indicative content

Check your assignment guidance to see if this is present. If so, use this list of learning outcomes to guide what you write. If your paragraphs are irrelevant to these key points, delete the paragraph .

Paragraphs that don’t link to the marking criteria are pointless. They won’t win you marks.

For the Americans: If you don’t have a marking criteria / rubric / outcomes list, you’ll need to stick closely to the essay question or topic. This goes out to those of you in the North American system. North America (including USA and Canada here) is often less structured and the professor might just give you a topic to base your essay on.

If all you’ve got is the essay question / topic, go through each paragraph and make sure each paragraph is relevant to the topic.

For example, if your essay question / topic is on “The Effects of Climate Change on Polar Bears”,

- Don’t talk about anything that doesn’t have some connection to climate change and polar bears;

- Don’t talk about the environmental impact of oil spills in the Gulf of Carpentaria;

- Don’t talk about black bear habitats in British Columbia.

- Do talk about the effects of climate change on polar bears (and relevant related topics) in every single paragraph .

You may think ‘stay relevant’ is obvious advice, but at least 20% of all essays I mark go off on tangents and waste words.

Stay on topic in Every. Single. Paragraph. If you want to learn more about how to stay on topic, check out our essay planning guide .

9. Only have one Key Idea per Paragraph

One key idea for each paragraph. One key idea for each paragraph. One key idea for each paragraph.

Don’t forget!

Too often, a student starts a paragraph talking about one thing and ends it talking about something totally different. Don’t be that student.

To ensure you’re focussing on one key idea in your paragraph, make sure you know what that key idea is. It should be mentioned in your topic sentence (see Point 3 ). Every other sentence in the paragraph adds depth to that one key idea.

If you’ve got sentences in your paragraph that are not relevant to the key idea in the paragraph, they don’t fit. They belong in another paragraph.

Go through all your paragraphs when editing your work and check to see if you’ve veered away from your paragraph’s key idea. If so, you might have two or even three key ideas in the one paragraph.

You’re going to have to get those additional key ideas, rip them out, and give them paragraphs of their own.

If you have more than one key idea in a paragraph you will lose marks. I promise you that.

The paragraphs will be too hard to read, your reader will get bogged down reading rather than scanning, and you’ll have lost grades.

10. Keep Sentences Short

If a sentence is too long it gets confusing. When the sentence is confusing, your reader will stop reading your work. They will stop reading the paragraph and move to the next one. They’ll have given up on your paragraph.

Short, snappy sentences are best.

Shorter sentences are easier to read and they make more sense. Too often, students think they have to use big, long, academic words to get the best marks. Wrong. Aim for clarity in every sentence in the paragraph. Your teacher will thank you for it.

The students who get the best marks write clear, short sentences.

When editing your draft, go through your essay and see if you can shorten your longest five sentences.

(To learn more about how to write the best quality sentences, see our page on Seven ways to Write Amazing Sentences .)

11. Keep Quotes Short

Eighty percent of university teachers hate quotes. That’s not an official figure. It’s my guestimate based on my many interactions in faculty lounges. Twenty percent don’t mind them, but chances are your teacher is one of the eight out of ten who hate quotes.

Teachers tend to be turned off by quotes because it makes it look like you don’t know how to say something on your own words.

Now that I’ve warned you, here’s how to use quotes properly:

Ideal Essay Paragraph Structure Example: How To Use Quotes in University-Level Essay Paragraphs 1. Your quote should be less than one sentence long. 2. Your quote should be less than one sentence long. 3. You should never start a sentence with a quote. 4. You should never end a paragraph with a quote. 5 . You should never use more than five quotes per essay. 6. Your quote should never be longer than one line in a paragraph.

The minute your teacher sees that your quote takes up a large chunk of your paragraph, you’ll have lost marks.

Your teacher will circle the quote, write a snarky comment in the margin, and not even bother to give you points for the key idea in the paragraph.

Avoid quotes, but if you really want to use them, follow those five rules above.

I’ve also provided additional pages outlining Seven tips on how to use Quotes if you want to delve deeper into how, when and where to use quotes in essays. Be warned: quoting in essays is harder than you thought.

Follow the advice above and you’ll be well on your way to getting top marks at university.

Writing essay paragraphs that are well structured takes time and practice. Don’t be too hard on yourself and keep on trying!

Below is a summary of our 11 key mistakes for structuring essay paragraphs and tips on how to avoid them.

I’ve also provided an easy-to-share infographic below that you can share on your favorite social networking site. Please share it if this article has helped you out!

11 Biggest Essay Paragraph Structure Mistakes you’re probably Making

1. Your paragraphs are too short 2. Your paragraphs are too long 3. Your paragraph alignment is ‘Justified’ 4. Your paragraphs are missing a topic sentence 5 . Your paragraphs are missing an explanation sentence 6. Your paragraphs are missing an example 7. Your paragraphs are missing references 8. Your paragraphs are not relevant to the marking criteria 9. You’re trying to fit too many ideas into the one paragraph 10. Your sentences are too long 11. Your quotes are too long

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 10 Elaborative Rehearsal Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Maintenance Rehearsal - Definition & Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Piaget vs Vygotsky: Similarities and Differences

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 10 Conditioned Response Examples

4 thoughts on “11 Rules for Essay Paragraph Structure (with Examples)”

Hello there. I noticed that throughout this article on Essay Writing, you keep on saying that the teacher won’t have time to go through the entire essay. Don’t you think this is a bit discouraging that with all the hard work and time put into your writing, to know that the teacher will not read through the entire paper?

Hi Clarence,

Thanks so much for your comment! I love to hear from readers on their thoughts.

Yes, I agree that it’s incredibly disheartening.

But, I also think students would appreciate hearing the truth.

Behind closed doors many / most university teachers are very open about the fact they ‘only have time to skim-read papers’. They regularly bring this up during heated faculty meetings about contract negotiations! I.e. in one university I worked at, we were allocated 45 minutes per 10,000 words – that’s just over 4 minutes per 1,000 word essay, and that’d include writing the feedback, too!

If students know the truth, they can better write their essays in a way that will get across the key points even from a ‘skim-read’.

I hope to write candidly on this website – i.e. some of this info will never be written on university blogs because universities want to hide these unfortunate truths from students.

Thanks so much for stopping by!

Regards, Chris

This is wonderful and helpful, all I say is thank you very much. Because I learned a lot from this site, own by chris thank you Sir.

Thank you. This helped a lot.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Academic Essay: From Basics to Practical Tips

Has it ever occurred to you that over the span of a solitary academic term, a typical university student can produce sufficient words to compose an entire 500-page novel? To provide context, this equates to approximately 125,000 to 150,000 words, encompassing essays, research papers, and various written tasks. This content volume is truly remarkable, emphasizing the importance of honing the skill of crafting scholarly essays. Whether you're a seasoned academic or embarking on the initial stages of your educational expedition, grasping the nuances of constructing a meticulously organized and thoroughly researched essay is paramount.

Welcome to our guide on writing an academic essay! Whether you're a seasoned student or just starting your academic journey, the prospect of written homework can be exciting and overwhelming. In this guide, we'll break down the process step by step, offering tips, strategies, and examples to help you navigate the complexities of scholarly writing. By the end, you'll have the tools and confidence to tackle any essay assignment with ease. Let's dive in!

Types of Academic Writing

The process of writing an essay usually encompasses various types of papers, each serving distinct purposes and adhering to specific conventions. Here are some common types of academic writing:

.webp)

- Essays: Essays are versatile expressions of ideas. Descriptive essays vividly portray subjects, narratives share personal stories, expository essays convey information, and persuasive essays aim to influence opinions.

- Research Papers: Research papers are analytical powerhouses. Analytical papers dissect data or topics, while argumentative papers assert a stance backed by evidence and logical reasoning.

- Reports: Reports serve as narratives in specialized fields. Technical reports document scientific or technical research, while business reports distill complex information into actionable insights for organizational decision-making.

- Reviews: Literature reviews provide comprehensive summaries and evaluations of existing research, while critical analyses delve into the intricacies of books or movies, dissecting themes and artistic elements.

- Dissertations and Theses: Dissertations represent extensive research endeavors, often at the doctoral level, exploring profound subjects. Theses, common in master's programs, showcase mastery over specific topics within defined scopes.

- Summaries and Abstracts: Summaries and abstracts condense larger works. Abstracts provide concise overviews, offering glimpses into key points and findings.

- Case Studies: Case studies immerse readers in detailed analyses of specific instances, bridging theoretical concepts with practical applications in real-world scenarios.

- Reflective Journals: Reflective journals serve as personal platforms for articulating thoughts and insights based on one's academic journey, fostering self-expression and intellectual growth.

- Academic Articles: Scholarly articles, published in academic journals, constitute the backbone of disseminating original research, contributing to the collective knowledge within specific fields.

- Literary Analyses: Literary analyses unravel the complexities of written works, decoding themes, linguistic nuances, and artistic elements, fostering a deeper appreciation for literature.

Our essay writer service can cater to all types of academic writings that you might encounter on your educational path. Use it to gain the upper hand in school or college and save precious free time.

Essay Writing Process Explained

The process of how to write an academic essay involves a series of important steps. To start, you'll want to do some pre-writing, where you brainstorm essay topics , gather information, and get a good grasp of your topic. This lays the groundwork for your essay.

Once you have a clear understanding, it's time to draft your essay. Begin with an introduction that grabs the reader's attention, gives some context, and states your main argument or thesis. The body of your essay follows, where each paragraph focuses on a specific point supported by examples or evidence. Make sure your ideas flow smoothly from one paragraph to the next, creating a coherent and engaging narrative.

After the drafting phase, take time to revise and refine your essay. Check for clarity, coherence, and consistency. Ensure your ideas are well-organized and that your writing effectively communicates your message. Finally, wrap up your essay with a strong conclusion that summarizes your main points and leaves a lasting impression on the reader.

How to Prepare for Essay Writing

Before you start writing an academic essay, there are a few things to sort out. First, make sure you totally get what the assignment is asking for. Break down the instructions and note any specific rules from your teacher. This sets the groundwork.

Then, do some good research. Check out books, articles, or trustworthy websites to gather solid info about your topic. Knowing your stuff makes your essay way stronger. Take a bit of time to brainstorm ideas and sketch out an outline. It helps you organize your thoughts and plan how your essay will flow. Think about the main points you want to get across.

Lastly, be super clear about your main argument or thesis. This is like the main point of your essay, so make it strong. Considering who's going to read your essay is also smart. Use language and tone that suits your academic audience. By ticking off these steps, you'll be in great shape to tackle your essay with confidence.

Academic Essay Example

In academic essays, examples act like guiding stars, showing the way to excellence. Let's check out some good examples to help you on your journey to doing well in your studies.

Academic Essay Format

The academic essay format typically follows a structured approach to convey ideas and arguments effectively. Here's an academic essay format example with a breakdown of the key elements:

Introduction

- Hook: Begin with an attention-grabbing opening to engage the reader.

- Background/Context: Provide the necessary background information to set the stage.

- Thesis Statement: Clearly state the main argument or purpose of the essay.

Body Paragraphs

- Topic Sentence: Start each paragraph with a clear topic sentence that relates to the thesis.

- Supporting Evidence: Include evidence, examples, or data to back up your points.

- Analysis: Analyze and interpret the evidence, explaining its significance in relation to your argument.

- Transition Sentences: Use these to guide the reader smoothly from one point to the next.

Counterargument (if applicable)

- Address Counterpoints: Acknowledge opposing views or potential objections.

- Rebuttal: Refute counterarguments and reinforce your position.

Conclusion:

- Restate Thesis: Summarize the main argument without introducing new points.

- Summary of Key Points: Recap the main supporting points made in the body.

- Closing Statement: End with a strong concluding thought or call to action.

References/Bibliography

- Cite Sources: Include proper citations for all external information used in the essay.

- Follow Citation Style: Use the required citation style (APA, MLA, Chicago, etc.) specified by your instructor.

- Font and Size: Use a standard font (e.g., Times New Roman, Arial) and size (12-point).

- Margins and Spacing: Follow specified margin and spacing guidelines.

- Page Numbers: Include page numbers if required.

Adhering to this structure helps create a well-organized and coherent academic essay that effectively communicates your ideas and arguments.

Ready to Transform Essay Woes into Academic Triumphs?

Let us take you on an essay-writing adventure where brilliance knows no bounds!

How to Write an Academic Essay Step by Step

Start with an introduction.

The introduction of an essay serves as the reader's initial encounter with the topic, setting the tone for the entire piece. It aims to capture attention, generate interest, and establish a clear pathway for the reader to follow. A well-crafted introduction provides a brief overview of the subject matter, hinting at the forthcoming discussion, and compels the reader to delve further into the essay. Consult our detailed guide on how to write an essay introduction for extra details.

Captivate Your Reader

Engaging the reader within the introduction is crucial for sustaining interest throughout the essay. This involves incorporating an engaging hook, such as a thought-provoking question, a compelling anecdote, or a relevant quote. By presenting an intriguing opening, the writer can entice the reader to continue exploring the essay, fostering a sense of curiosity and investment in the upcoming content. To learn more about how to write a hook for an essay , please consult our guide,

Provide Context for a Chosen Topic

In essay writing, providing context for the chosen topic is essential to ensure that readers, regardless of their prior knowledge, can comprehend the subject matter. This involves offering background information, defining key terms, and establishing the broader context within which the essay unfolds. Contextualization sets the stage, enabling readers to grasp the significance of the topic and its relevance within a particular framework. If you buy a dissertation or essay, or any other type of academic writing, our writers will produce an introduction that follows all the mentioned quality criteria.

Make a Thesis Statement

The thesis statement is the central anchor of the essay, encapsulating its main argument or purpose. It typically appears towards the end of the introduction, providing a concise and clear declaration of the writer's stance on the chosen topic. A strong thesis guides the reader on what to expect, serving as a roadmap for the essay's subsequent development.

Outline the Structure of Your Essay

Clearly outlining the structure of the essay in the introduction provides readers with a roadmap for navigating the content. This involves briefly highlighting the main points or arguments that will be explored in the body paragraphs. By offering a structural overview, the writer enhances the essay's coherence, making it easier for the reader to follow the logical progression of ideas and supporting evidence throughout the text.

Continue with the Main Body

The main body is the most important aspect of how to write an academic essay where the in-depth exploration and development of the chosen topic occur. Each paragraph within this section should focus on a specific aspect of the argument or present supporting evidence. It is essential to maintain a logical flow between paragraphs, using clear transitions to guide the reader seamlessly from one point to the next. The main body is an opportunity to delve into the nuances of the topic, providing thorough analysis and interpretation to substantiate the thesis statement.

Choose the Right Length

Determining the appropriate length for an essay is a critical aspect of effective communication. The length should align with the depth and complexity of the chosen topic, ensuring that the essay adequately explores key points without unnecessary repetition or omission of essential information. Striking a balance is key – a well-developed essay neither overextends nor underrepresents the subject matter. Adhering to any specified word count or page limit set by the assignment guidelines is crucial to meet academic requirements while maintaining clarity and coherence.

Write Compelling Paragraphs

In academic essay writing, thought-provoking paragraphs form the backbone of the main body, each contributing to the overall argument or analysis. Each paragraph should begin with a clear topic sentence that encapsulates the main point, followed by supporting evidence or examples. Thoroughly analyzing the evidence and providing insightful commentary demonstrates the depth of understanding and contributes to the overall persuasiveness of the essay. Cohesion between paragraphs is crucial, achieved through effective transitions that ensure a smooth and logical progression of ideas, enhancing the overall readability and impact of the essay.

Finish by Writing a Conclusion

The conclusion serves as the essay's final impression, providing closure and reinforcing the key insights. It involves restating the thesis without introducing new information, summarizing the main points addressed in the body, and offering a compelling closing thought. The goal is to leave a lasting impact on the reader, emphasizing the significance of the discussed topic and the validity of the thesis statement. A well-crafted conclusion brings the essay full circle, leaving the reader with a sense of resolution and understanding. Have you already seen our collection of new persuasive essay topics ? If not, we suggest you do it right after finishing this article to boost your creativity!

Proofread and Edit the Document

After completing the essay, a critical step is meticulous proofreading and editing. This process involves reviewing the document for grammatical errors, spelling mistakes, and punctuation issues. Additionally, assess the overall coherence and flow of ideas, ensuring that each paragraph contributes effectively to the essay's purpose. Consider the clarity of expression, the appropriateness of language, and the overall organization of the content. Taking the time to proofread and edit enhances the overall quality of the essay, presenting a polished and professional piece of writing. It is advisable to seek feedback from peers or instructors to gain additional perspectives on the essay's strengths and areas for improvement. For more insightful tips, feel free to check out our guide on how to write a descriptive essay .

Alright, let's wrap it up. Knowing how to write academic essays is a big deal. It's not just about passing assignments – it's a skill that sets you up for effective communication and deep thinking. These essays teach us to explain our ideas clearly, build strong arguments, and be part of important conversations, both in school and out in the real world. Whether you're studying or working, being able to put your thoughts into words is super valuable. So, take the time to master this skill – it's a game-changer!

Ready to Turn Your Academic Aspirations into A+ Realities?

Our expert pens are poised, and your academic adventure awaits!

What Is An Academic Essay?

How to write an academic essay, how to write a good academic essay.

Daniel Parker

is a seasoned educational writer focusing on scholarship guidance, research papers, and various forms of academic essays including reflective and narrative essays. His expertise also extends to detailed case studies. A scholar with a background in English Literature and Education, Daniel’s work on EssayPro blog aims to support students in achieving academic excellence and securing scholarships. His hobbies include reading classic literature and participating in academic forums.

is an expert in nursing and healthcare, with a strong background in history, law, and literature. Holding advanced degrees in nursing and public health, his analytical approach and comprehensive knowledge help students navigate complex topics. On EssayPro blog, Adam provides insightful articles on everything from historical analysis to the intricacies of healthcare policies. In his downtime, he enjoys historical documentaries and volunteering at local clinics.

Related Articles

.webp)

Best Practices for the Most Effective Use of Paragraphs

11 Writers and Grammarians Share Their Observations and Best Practices

- An Introduction to Punctuation

Observations

10 effective paragraph criteria, topic sentences in paragraphs, rules of paragraphing, strunk and white on paragraph length, uses of one-sentence paragraphs, paragraph length in business and technical writing, the paragraph as a device of punctuation.

- Scott and Denny's Definition of a Paragraph

Development of the Paragraph in English

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

The definition of a paragraph: It's a group of closely related sentences that develops a central idea, conventionally beginning on a new line, which is sometimes indented.

The paragraph has been variously defined as a "subdivision in a longer written passage," a "group of sentences (or sometimes just one sentence) about a specific topic," and a "grammatical unit typically consisting of multiple sentences that together express a complete thought."

In his 2006 book "A Dash of Style," Noah Lukeman describes the " paragraph break " as "one of the most crucial marks in the punctuation world."

Etymology: Paragraph is from the Greek word which means "to write beside."

"A new paragraph is a wonderful thing. It lets you quietly change the rhythm, and it can be like a flash of lightning that shows the same landscape from a different aspect."

(Babel, Isaac interviewed by Konstantin Paustovsky in Isaac Babel Talks About Writing , The Nation , March 31, 1969.)

Lois Laase and Joan Clemmons offer the following list of 10 helpful suggestions for writing paragraphs. This is adapted from their book, "Helping Students Write... The Best Research Reports Ever: Easy Mini-Lessons, Strategies, and Creative Formats to Make Research Manageable and Fun."

- Keep the paragraph on one topic.

- Include a topic sentence .

- Use supporting sentences that give details or facts about the topic.

- Include vivid words.

- Make sure it does not have run-on sentences .

- Include sentences that make sense and stick to the topic.

- Sentences should be in order and make sense.

- Write sentences that begin in different ways.

- Make sure the sentences flow.

- Be sure sentences are mechanically correct — spelling , punctuation, capitalization , indentation.

"Although the topic sentence is often the first sentence of the paragraph, it does not have to be. Furthermore, the topic sentence is sometimes restated or echoed at the end of the paragraph, although again it does not have to be. However, a well-phrased concluding sentence can emphasize the central idea of the paragraph as well as provide a nice balance and ending."

"A paragraph is not a constraining formula; in fact, it has variations. In some instances, for example, the topic sentence is not found in a single sentence. It may be the combination of two sentences, or it may be an easily understood but unwritten underlying idea that unifies the paragraph. Nevertheless, the paragraph in most college writing contains discussion supporting a stated topic sentence...."

(Brandon, Lee. At a Glance: Paragraphs , 5th ed., Wadsworth, 2012.)

"As an advanced writer, you know that rules are made to be broken. But that is not to say that these rules are useless. Sometimes it is good to avoid a one-sentence paragraph — it can sound too brisk and implies a lack of penetration and analysis. Sometimes, or perhaps most of the time, it is good to have a topic sentence. But the awful fact is that when you look closely at a professional writer's work, you will see that the topic sentence is often missing. In that case, we sometimes say it is implied, and perhaps that is true. But whether we want to call it implied or not, it is obvious that good writers can get along without topic sentences most of the time. Likewise, it is not a bad idea to develop only one idea in a paragraph, but frankly, the chance of developing several ideas often arises and sometimes doing so even characterizes the writing of professionals."

(Jacobus, Lee A. Substance, Style, and Strategy, Oxford University Press, 1998.)

"In general, remember that paragraphing calls for a good eye as well as a logical mind. Enormous blocks of print look formidable to readers, who are often reluctant to tackle them. Therefore, breaking long paragraphs in two, even if it is not necessary to do so for sense, meaning, or logical development, is often a visual help. But remember, too, that firing off many short paragraphs in quick succession can be distracting. Paragraph breaks used only for show read like the writing of commerce or of display advertising. Moderation and a sense of order should be the main considerations in paragraphing."

(Strunk, Jr., William and E.B. White, The Elements of Style , 3rd ed., Allyn & Bacon, 1995.)

"Three situations in essay writing can occasion a one-sentence paragraph: (a) when you want to emphasize a crucial point that might otherwise be buried; (b) when you want to dramatize a transition from one stage in your argument to the next; and (c) when instinct tells you that your reader is tiring and would appreciate a mental rest. The one-sentence paragraph is a great device. You can italicize with it, vary your pace with it, lighten your voice with it, signpost your argument with it. But it’s potentially dangerous. Don’t overdo your dramatics. And be sure your sentence is strong enough to withstand the extra attention it’s bound to receive when set off by itself. Houseplants wilt in direct sun. Many sentences do as well."

(Trimble, John R. Writing with Style: Conversations on the Art of Writing . Prentice Hall, 2000.)

"A paragraph should be just long enough to deal adequately with the subject of its topic sentence. A new paragraph should begin whenever the subject changes significantly. A series of short, undeveloped paragraphs can indicate poor organization and sacrifice unity by breaking an idea into several pieces. A series of long paragraphs, however, can fail to provide the reader with manageable subdivisions of thought. Paragraph length should aid the reader's understanding of idea."

(Alred, Gerald J., Charles T. Brusaw, and Walter E. Oliu, The Business Writer's Handbook , 10th ed., Bedford/St. Martin's, 2012.)

"The paragraph is a device of punctuation. The indentation by which it is marked implies no more than an additional breathing space. Like the other marks of punctuation...it may be determined by logical, physical, or rhythmical needs. Logically it may be said to denote the full development of a single idea, and this indeed is the common definition of the paragraph. It is, however, in no way an adequate or helpful definition."

(Read, Herbert. English Prose Style, Beacon, 1955.)

Scott and Denny's Definition of a Paragraph

"A paragraph is a unit of discourse developing a single idea. It consists of a group or series of sentences closely related to one another and to the thought expressed by the whole group or series. Devoted, like the sentence, to the development of one topic, a good paragraph is also, like a good essay, a complete treatment in itself."

(Scott, Fred Newton, and Joseph Villiers Denny, Paragraph-Writing: A Rhetoric for Colleges , rev. ed., Allyn and Bacon, 1909.)

"The paragraph as we know it comes into something like settled shape in Sir William Temple (1628-1699). It was the product of perhaps five chief influences. First, the tradition, derived from the authors and scribes of the Middle Ages, that the paragraph-mark distinguishes a stadium of thought. Second, the Latin influence, which was rather towards disregarding the paragraph as the sign of anything but emphasis — the emphasis-tradition being also of medieval origin; the typical writers of the Latin influence are Hooker and Milton. Third, the natural genius of the Anglo-Saxon structure, favorable to the paragraph. Fourth, the beginnings of popular writing — of what may be called the oral style, or consideration for a relatively uncultivated audience. Fifth, the study of French prose, in this respect a late influence, allied in its results with the third and fourth influences."

(Lewis, Herbert Edwin. The History of the English Paragraph , 1894.)

"19c writers reduced the lengths of their paragraphs, a process that has continued in the 20c, particularly in journalism, advertisements, and publicity materials."

(McArthur, Tom. "Paragraph." The Oxford Companion to the English Language, Oxford University Press, 1992.)

- How to Write a Good Descriptive Paragraph

- Paragraph Length in Compositions and Reports

- Definition and Examples of Paragraph Breaks in Prose

- Writers on Writing: The Art of Paragraphing

- Definition and Examples of Paragraphing in Essays

- Paragraph Transition: Definition and Examples

- Unity in Composition

- What Is an Indentation?

- Definition and Examples of Body Paragraphs in Composition

- How to Write a Descriptive Paragraph

- What Is Expository Writing?

- What Is a Topic Sentence?

- An Essay Revision Checklist

- How to Write and Format an MBA Essay

- Understanding Organization in Composition and Speech

- Paragraph Writing

NYC is beginning to evict some people in migrant shelters under stricter rules

N EW YORK (AP) — New York City stepped up its efforts to push migrants out of its overwhelmed shelters Wednesday as it began enforcing a new rule that limits some adult asylum-seekers to a month in the system before they have to find a bed on their own.

Migrants without young children must now move out of the hotels, tent complexes and other shelter facilities run by the city and find other housing after 30 days — or 60 days for those aged 18-23 — unless they provide proof of “extenuating circumstances” and are granted an exemption.

As of late Wednesday, 192 migrants had applied for an extension after hitting their limit, and 118 had been approved, Mayor Eric Adams’ office said. Thousands more are expected to receive eviction notices in the coming months.

Mamadou Diallo, a 39-year-old from Senegal, says he’s not sure where he’ll go when his time expires later this week at a shelter in the Bronx.

He hopes to get an extension, noting that he just filed his asylum application and has been taking English classes but can't apply for a work permit under federal rules until about five months after applying for asylum.

“I don’t have anywhere to go,” Diallo said Wednesday. “I’m going to school. I’m looking for a job. I’m trying my best.”

The new restrictions came after Adams' administration in March succeeded in altering the city’s unique “ right to shelter ” rule requiring it to provide temporary housing for every homeless person who asks for it.

Before the new rule came into effect, adult migrants without children were still limited to 30 days in a shelter, but they were able to immediately reapply for a new bed with no questions asked.

The city also restricts migrant families with young children to 60-day stays, but they aren’t impacted by the new rule and can still reapply without providing any justification.

Still, an audit found that the rollout was “haphazard," over the past six months

Immigrant rights and homeless advocates say they’re closely monitoring the eviction process, which impacts some 15,000 migrant adults. The city shelter system currently houses about 65,000 migrants, but many of those are families with kids.

“Our concern is people will be denied for reasons that could be appealed or because of some error or because they didn’t have all the documentation required,” said David Giffen, executive director of the Coalition for the Homeless. “We’re watching very carefully to see if that happens because nobody in need of shelter in New York City should ever be relegated to sleeping on the streets.”

Adams, a Democrat, on Tuesday pushed back at critics who have called the city’s increasingly restrictive migrant shelter rules inhumane and haphazardly rolled out , saying the city simply can’t keep housing migrants indefinitely. New York City has provided temporary housing to nearly 200,000 migrants since the spring of 2022, with more than a thousand new arrivals coming to the city each week, he noted.

“People said it’s inhumane to put people out during the wintertime, so now they say it’s inhumane to do it in the summertime,” Adams said. “There’s no good time. There’s no good time.”

The move comes as Denver, another city that’s seen an influx of migrants, embarks on an ambitious migrant support program that includes six-month apartment stays and intensive job preparation for those who can’t yet legally work. Meanwhile Chicago has imposed 60-day shelter limits on adult migrants with no option for renewal, and Massachusetts has capped stays for families to nine months, starting in June.

Adams had asked a court in October to suspend the “right to shelter” requirement entirely, but the move was opposed by immigrant rights and homeless advocacy groups. In March, they settled, with an agreement that set the new rules for migrants.

The agreement still allows for city officials to grant extensions on shelter stays on a case-by-case basis.

City officials say migrants need to show they’re making “significant efforts to resettle,” such as applying for work authorization or asylum, or searching for a job or an apartment.

Migrants can also get an extension if they can prove they have plans to move out of the city within 30 days, have an upcoming immigration-related hearing or have a serious medical procedure or are recovering from one.

Migrants between the ages of 18 and 20 years old can also get extensions if they’re enrolled full-time in high school.

“While these changes will require some adaptation, we are confident that they will help migrants progress to the next stage of their journeys, reduce the significant strain on our shelter system and enable us to continue providing essential services to all New Yorkers,” Camille Joseph Varlack, Adams’ chief of staff, said Wednesday in an emailed statement.

Follow Philip Marcelo at twitter.com/philmarcelo .

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Guest Essay

Legal Weed Is Coming. It’s Time to Come Up With Some Rules.

By Maia Szalavitz

Ms. Szalavitz is a contributing Opinion writer who covers addiction and public policy.

The beginning of the end of illegal weed is here.

On May 16 the Justice Department formally moved to reclassify marijuana from Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act to Schedule III. This move will not affect the legality of recreational use and sales on the federal level. It is, however, the biggest step yet toward abolishing the legal fiction that cannabis is as dangerous as heroin. And it puts marijuana — used more than any other illicit drug in the world — on a pathway for fully legal recreational use, which a majority of Americans support .

Nothing short of full legalization will end the injustice that leads to hundreds of thousands of arrests annually for marijuana offenses and leaves millions of people of color disproportionately scarred by criminalization.

But the recent move will ease research, permit sellers in states that have legalized to deduct business expenses on their federal taxes and allow the Food and Drug Administration to regulate medical marijuana if it chooses to do so. It also offers an opportunity to start ironing out the details of what federal cannabis oversight ought to look like if the time comes — both to redress past harms and protect public health. Effective regulation requires balancing opposing risks to reduce the harm we’ve seen caused by dangerous black-market products while preventing misleading marketing from promoting excessive use.

Learning from the experiences of states that have legalized marijuana is essential. For one, they have not seen the much-feared explosion of youth use. An April 2024 study in JAMA Psychiatry analyzed survey data from 1993 to 2021 and found that teen cannabis use was no more common in the 24 states that legalized adult recreational use than elsewhere. According to a systematic review published in 2022, 10 earlier studies found increases in adolescent use, but 10 others showed no effect, and two showed reductions.

Other drug use didn’t increase, either. Use of the deadliest drugs — opioids — dropped significantly among youth as marijuana legalization spread. Prescription opioid misuse by 12th graders fell from 9.5 percent in 2004 to 1 percent in 2023; heroin use declined similarly. Most states showed little change or even a decline in opioid misuse and overdoses after passage of recreational or medical marijuana laws. And legalized cannabis products have not been linked to fatal poisonings or injuries. (Deaths linked to lung injuries from vape pens seem to have been caused by illegal products and tended to be less common in legal states.)

Legalization isn’t without risks, of course. Some studies show that it increases stoned driving, with one linking a 16 percent rise in fatalities with recreational legalization. Others, however, find no effects or even a reduction , due perhaps to people using cannabis instead of alcohol. And some studies have associated marijuana with psychosis in some populations, but there has been no spike in psychotic disorders in legalized states, as evidenced by a recent study of medical records in 64 million Americans age 16 or older.

Bottom line: The most dire predictions about legalizing marijuana have not been borne out at the state level, which bodes well for federal legalization.

One serious issue that federal regulation is needed to resolve is the persistence of the black market. Historically, West Coast states have supplied most of the domestically grown cannabis in the United States. Since federal law bars interstate sales, Western markets are oversupplied with cannabis, keeping prices low. This makes it difficult for growers to profit without diverting some cannabis to the illegal market. Individual state licensing policies have also inadvertently protected black markets: New York, for example, is now flooded with illegal weed stores because it was slow in licensing legal ones.

Experience with regulation of other substances could guide the creation of federal marijuana policy. One key finding from alcohol and tobacco research is that price matters . Taxes that elevate prices reduce youth use and lower consumption by those who have substance use disorders, in part because the heaviest users pay the most. But to be effective, taxes on marijuana must target potency and not just quantity — and may have to be adjusted regularly to deal with introductions of products with varied strengths. Regulators need to find sweet spots where prices are low enough to minimize illicit sales but high enough to discourage overconsumption.

Federal oversight also matters in managing the relative risks associated with psychoactive substances. Marijuana is generally less harmful than alcohol, tobacco and opioids — and if consumers are incentivized through pricing and regulation, some can be nudged into picking the less dangerous high. But when relative risks are ignored, disaster can strike: Cutting the supply of medical opioids pushed many people who were misusing them onto far more dangerous street drugs, and overdose death rates more than doubled.

The government can further curb risky behavior by putting controls on advertising. The opioid crisis has shown that current restrictions on pharmaceutical promotion are too lax. Alcohol and tobacco products are also too freely marketed. It would make little sense to hold marijuana alone to a higher standard, given that these other products can do more harm than cannabis does. Instead, marketing for all these substances should be far more restricted, if not banned entirely.

Regulators should also pay particularly close attention to potent new cannabis products, which some states allow without much oversight. Stronger products are more likely to be addictive and therefore pose a greater hazard to health. Protecting consumers requires finding a way to regulate these substances that isn’t as arduous and expensive as F.D.A. approval for pharmaceuticals but controls quality and minimizes harmful exposures.

On May 1 the Senate majority leader, Chuck Schumer, reintroduced a bill that would end federal criminalization of the drug, expunge certain marijuana-related offenses and create a framework for regulating recreational-use products.

Though the bill is unlikely to pass Congress this term, the current clash between federal and state policies is not sustainable — all while public support for change remains strong. To move forward, we must find a middle ground between inundating children with marijuana advertisements and incarcerating people for smoking or selling weed. The Biden administration has taken only the first step.

Maia Szalavitz (@maiasz) is a contributing Opinion writer and the author, most recently, of “Undoing Drugs: How Harm Reduction Is Changing the Future of Drugs and Addiction.”

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips . And here’s our email: [email protected] .

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook , Instagram , TikTok , WhatsApp , X and Threads .

The Federal Register

The daily journal of the united states government, request access.

Due to aggressive automated scraping of FederalRegister.gov and eCFR.gov, programmatic access to these sites is limited to access to our extensive developer APIs.

If you are human user receiving this message, we can add your IP address to a set of IPs that can access FederalRegister.gov & eCFR.gov; complete the CAPTCHA (bot test) below and click "Request Access". This process will be necessary for each IP address you wish to access the site from, requests are valid for approximately one quarter (three months) after which the process may need to be repeated.

An official website of the United States government.

If you want to request a wider IP range, first request access for your current IP, and then use the "Site Feedback" button found in the lower left-hand side to make the request.

Company Filings | More Search Options

Company Filings More Search Options -->

- Commissioners

- Reports and Publications

- Securities Laws

- Commission Votes

- Corporation Finance

- Enforcement

- Investment Management

- Economic and Risk Analysis

- Trading and Markets

- Office of Administrative Law Judges

- Examinations

- Litigation Releases

- Administrative Proceedings

- Opinions and Adjudicatory Orders

- Accounting and Auditing

- Trading Suspensions

- How Investigations Work

- Receiverships

- Information for Harmed Investors

- Rulemaking Activity

- Proposed Rules

- Final Rules

- Interim Final Temporary Rules

- Other Orders and Notices

- Self-Regulatory Organizations

- Investor Education

- Small Business Capital Raising

- EDGAR – Search & Access

- EDGAR – Information for Filers

- Company Filing Search

- How to Search EDGAR

- About EDGAR

- Press Releases

- Speeches and Statements

- Securities Topics

- Upcoming Events

- Media Gallery

- Divisions & Offices

- Public Statements

Statement on the Financial Innovation and Technology for the 21st Century Act

Chair Gary Gensler

May 22, 2024

Introduction

For 90 years, the federal securities laws have played a crucial role in protecting the public. These critical protections were created in the wake of the Great Depression after many Americans suffered the consequences of inadequately regulated capital markets. We saw sky-high unemployment, bread lines, and shantytowns springing up due to mass foreclosures.

Back then, the rules didn’t exist. That’s why President Roosevelt and Congress created the SEC and the laws it administers.

At their core is the critical concept of registering securities that will be offered to the public and registering the intermediaries that facilitate the exchange of those securities. For securities, registration means that issuers provide robust disclosures and are liable if their material statements are untruthful. For intermediaries, registration brings with it rulebooks that prevent fraud and manipulation, safeguards against conflicts of interest, proper disclosures, segregation of customer assets, oversight by a self-regulatory organization, and routine inspection by the SEC.

Today, these rules do exist.

Many market participants in the crypto industry, however, have shown their unwillingness to comply with applicable laws and regulations for more than a decade, variously arguing that the laws do not apply to them or that a new set of rules should be created and retroactively applied to them to excuse their past conduct. Widespread noncompliance has resulted in widespread fraud, bankruptcies, failures, and misconduct. [1] As a result of criminal charges and convictions, some of the best-known leaders in the crypto industry are now in prison, awaiting sentencing, or subject to extradition back to the United States.

The SEC, during both Republican and Democratic Administrations, has allocated enforcement resources to holding crypto market participants accountable. Courts have time and again agreed with the SEC, ruling that the securities laws apply when crypto assets or crypto-related investment schemes are offered or sold as investment contracts. [2]

The Financial Innovation and Technology for the 21st Century Act

The Financial Innovation and Technology for the 21st Century Act (“FIT 21”) would create new regulatory gaps and undermine decades of precedent regarding the oversight of investment contracts, putting investors and capital markets at immeasurable risk.

First, the bill would remove investment contracts that are recorded on a blockchain from the statutory definition of securities and the time-tested protections of much of the federal securities laws.

Further, by removing this set of investment contracts from the statutory list of securities, the bill implies what courts have repeatedly ruled – but what crypto market participants have attempted to deny – that many crypto assets are being offered and sold as securities under existing law.

Second, the bill allows issuers of crypto investment contracts to self-certify that their products are a “decentralized” system and then be deemed a special class of “digital commodities” and thus not subject to SEC oversight. Whether something is a “digital commodity” would be subject to self-certification by “any person” that files a certification. The SEC would only have 60 days to review and challenge the certification that a product is a digital commodity. Those that the SEC successfully challenges would be re-classified as restricted digital assets and subject to the bill’s lighter-touch SEC oversight regime that excludes many core protections. There are more than 16,000 crypto assets that currently exist. Given limits on staff resources, and no new resources provided by the bill, it is implausible that the SEC could review and challenge more than a fraction of those assets. The result could be that the vast majority of the market might avoid even limited SEC oversight envisioned by the bill for crypto asset securities.

Third, the bill’s regulatory structure abandons the Supreme Court’s long-standing Howey test that considers the economic realities of an investment to determine whether it is subject to the securities laws. Instead, the bill makes that determination based on labels and the accounting ledger used to record transactions. It is akin to determining the level of investor protection based on whether a transaction is recorded in a notebook or a software database. But it’s the economic realities that should determine whether an asset is subject to the federal securities laws, not the type of recordkeeping ledger. The bill’s result would be weaker investor protection than currently exists for those assets that meet the Howey test.

Fourth, for those crypto investment contracts that would still fall under the SEC’s remit, the bill seeks to replace Roosevelt’s investor protection framework with fewer protections than investors are afforded in every other type of investment. Doing so increases risk to the American public.