US South Carolina

Recently viewed courses

Recently viewed.

Find Your Dream School

This site uses various technologies, as described in our Privacy Policy, for personalization, measuring website use/performance, and targeted advertising, which may include storing and sharing information about your site visit with third parties. By continuing to use this website you consent to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use .

COVID-19 Update: To help students through this crisis, The Princeton Review will continue our "Enroll with Confidence" refund policies. For full details, please click here.

Enter your email to unlock an extra $25 off an SAT or ACT program!

By submitting my email address. i certify that i am 13 years of age or older, agree to recieve marketing email messages from the princeton review, and agree to terms of use., how to manage homework stress.

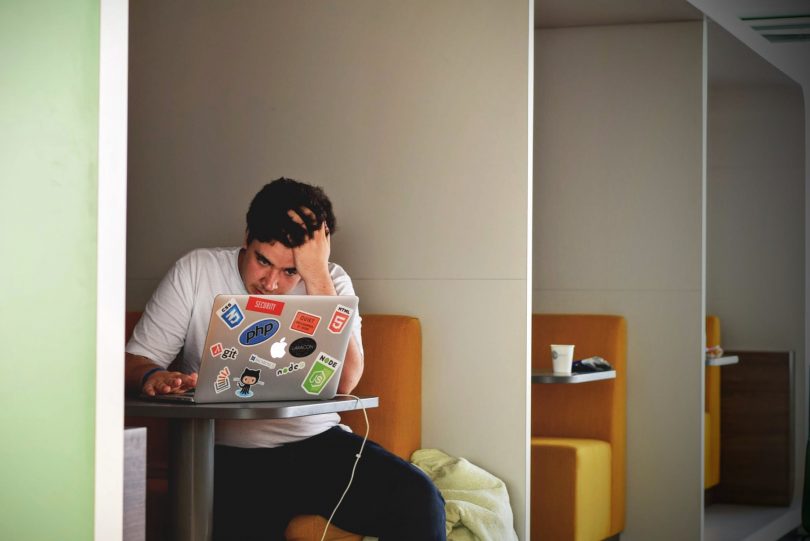

Feeling overwhelmed by your nightly homework grind? You’re not alone. Our Student Life in America survey results show that teens spend a third of their study time feeling worried, stressed, or stuck. If you’re spending close to four hours a night on your homework (the national average), that’s over an hour spent spent feeling panicky and still not getting your work done. Homework anxiety can become a self-fulfilling prophecy: If you’re already convinced that calculus is unconquerable, that anxiety can actually block your ability to learn the material.

Whether your anxiety is related to handling your workload (we know you’re getting more homework than ever!), mastering a particular subject like statistics, or getting great grades for your college application, stress doesn’t have to go hand-in-hand with studying .

In fact, a study by Stanford University School of Medicine and published in The Journal of Neuroscience shows that a student’s fear of math (and, yes, this fear is completely real and can be detectable in scans of the brain) can be eased by a one-on-one math tutoring program. At The Princeton Review this wasn’t news to us! Our online tutors are on-call 24/7 for students working on everything from AP Chemistry to Pre-Calc. Here’s a roundup of what our students have to say about managing homework stress by working one-one-one with our expert tutors .

1. Work the Best Way for YOU

From the way you decorate your room to the way you like to study, you have a style all your own:

"I cannot thank Christopher enough! I felt so anxious and stressed trying to work on my personal statement, and he made every effort to help me realize my strengths and focus on writing in a way that honored my personality. I wanted to give up, but he was patient with me and it made the difference."

"[My] tutor was 1000000000000% great . . . He made me feel important and fixed all of my mistakes and adapted to my learning style . . . I have so much confidence for my midterms that I was so stressed out about."

"I liked how the tutor asked me how was I starting the problem and allowed me to share what I was doing and what I had. The tutor was able to guide me from there and break down the steps and I got the answer all on my own and the tutor double checked it... saved me from tears and stress."

2. Study Smarter, Not Harder

If you’ve read the chapter in your history textbook twice and aren’t retaining the material, don’t assume the third time will be the charm. Our tutors will help you break the pattern, and learn ways to study more efficiently:

"[My] tutor has given me an easier, less stressful way of seeing math problems. It is like my eyes have opened up."

"I was so lost in this part of math but within minutes the tutor had me at ease and I get it now. I wasn't even with her maybe 30 minutes or so, and she helped me figure out what I have been stressing over for the past almost two days."

"I can not stress how helpful it is to have a live tutor available. Math was never and still isn't my favorite subject, but I know I need to take it. Being able to talk to someone and have them walk you through the steps on how to solve a problem is a huge weight lifted off of my shoulder."

3. Get Help in a Pinch

Because sometimes you need a hand RIGHT NOW:

"I was lost and stressed because I have a test tomorrow and did not understand the problems. I fully get it now!"

"My tutor was great. I was freaking out and stressed out about the entire assignment, but she really helped me to pull it together. I am excited to turn my paper in tomorrow."

"This was so helpful to have a live person to validate my understanding of the formulas I need to use before actually submitting my homework and getting it incorrect. My stress level reduced greatly with a project deadline due date."

4. Benefit from a Calming Presence

From PhDs and Ivy Leaguers to doctors and teachers, our tutors are experts in their fields, and they know how to keep your anxiety at bay:

"I really like that the tutors are real people and some of them help lighten the stress by making jokes or having quirky/witty things to say. That helps when you think you're messing up! Gives you a reprieve from your brain jumbling everything together!"

"He seemed understanding and empathetic to my situation. That means a lot to a new student who is under stress."

"She was very thorough in explaining her suggestions as well as asking questions and leaving the changes up to me, which I really appreciated. She was very encouraging and motivating which helped with keeping me positive about my paper and knowing that I am not alone in my struggles. She definitely eased my worries and stress. She was wonderful!"

5. Practice Makes Perfect

The Stanford study shows that repeated exposure to math problems through one-on-one tutoring helped students relieve their math anxiety (the authors’ analogy was how a fear of spiders can be treated with repeated exposure to spiders in a safe environment). Find a tutor you love, and come back to keep practicing:

"Love this site once again. It’s so helpful and this is the first time in years when I don’t stress about my frustration with HW because I know this site will always be here to help me."

"I've been using this service since I was in seventh grade and now I am a Freshman in High School. School has just started and I am already using this site again! :) This site is so dependable. I love it so much and it’s a lot easier than having an actual teacher sitting there hovering over you, waiting for you to finish the problem."

"I can always rely on this site to help me when I'm confused, and it always makes me feel more confident in the work I'm doing in school."

Stuck on homework?

Try an online tutoring session with one of our experts, and get homework help in 40+ subjects.

Try a Free Session

- Tutoring

- College

- Applying to College

Explore Colleges For You

Connect with our featured colleges to find schools that both match your interests and are looking for students like you.

Career Quiz

Take our short quiz to learn which is the right career for you.

Get Started on Athletic Scholarships & Recruiting!

Join athletes who were discovered, recruited & often received scholarships after connecting with NCSA's 42,000 strong network of coaches.

Best 389 Colleges

165,000 students rate everything from their professors to their campus social scene.

SAT Prep Courses

1400+ course, act prep courses, free sat practice test & events, 1-800-2review, free digital sat prep try our self-paced plus program - for free, get a 14 day trial.

Free MCAT Practice Test

I already know my score.

MCAT Self-Paced 14-Day Free Trial

Enrollment Advisor

1-800-2REVIEW (800-273-8439) ext. 1

1-877-LEARN-30

Mon-Fri 9AM-10PM ET

Sat-Sun 9AM-8PM ET

Student Support

1-800-2REVIEW (800-273-8439) ext. 2

Mon-Fri 9AM-9PM ET

Sat-Sun 8:30AM-5PM ET

Partnerships

- Teach or Tutor for Us

College Readiness

International

Advertising

Affiliate/Other

- Enrollment Terms & Conditions

- Accessibility

- Cigna Medical Transparency in Coverage

Register Book

Local Offices: Mon-Fri 9AM-6PM

- SAT Subject Tests

Academic Subjects

- Social Studies

Find the Right College

- College Rankings

- College Advice

- Applying to College

- Financial Aid

School & District Partnerships

- Professional Development

- Advice Articles

- Private Tutoring

- Mobile Apps

- Local Offices

- International Offices

- Work for Us

- Affiliate Program

- Partner with Us

- Advertise with Us

- International Partnerships

- Our Guarantees

- Accessibility – Canada

Privacy Policy | CA Privacy Notice | Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information | Your Opt-Out Rights | Terms of Use | Site Map

©2024 TPR Education IP Holdings, LLC. All Rights Reserved. The Princeton Review is not affiliated with Princeton University

TPR Education, LLC (doing business as “The Princeton Review”) is controlled by Primavera Holdings Limited, a firm owned by Chinese nationals with a principal place of business in Hong Kong, China.

Along with Stanford news and stories, show me:

- Student information

- Faculty/Staff information

We want to provide announcements, events, leadership messages and resources that are relevant to you. Your selection is stored in a browser cookie which you can remove at any time using “Clear all personalization” below.

Education scholar Denise Pope has found that too much homework has negative effects on student well-being and behavioral engagement. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

A Stanford researcher found that too much homework can negatively affect kids, especially their lives away from school, where family, friends and activities matter.

“Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good,” wrote Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of a study published in the Journal of Experimental Education .

The researchers used survey data to examine perceptions about homework, student well-being and behavioral engagement in a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities. Along with the survey data, Pope and her colleagues used open-ended answers to explore the students’ views on homework.

Median household income exceeded $90,000 in these communities, and 93 percent of the students went on to college, either two-year or four-year.

Students in these schools average about 3.1 hours of homework each night.

“The findings address how current homework practices in privileged, high-performing schools sustain students’ advantage in competitive climates yet hinder learning, full engagement and well-being,” Pope wrote.

Pope and her colleagues found that too much homework can diminish its effectiveness and even be counterproductive. They cite prior research indicating that homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night, and that 90 minutes to two and a half hours is optimal for high school.

Their study found that too much homework is associated with:

* Greater stress: 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress, according to the survey data. Forty-three percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while 33 percent put the pressure to get good grades in that category. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor.

* Reductions in health: In their open-ended answers, many students said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems. The researchers asked students whether they experienced health issues such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems.

* Less time for friends, family and extracurricular pursuits: Both the survey data and student responses indicate that spending too much time on homework meant that students were “not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills,” according to the researchers. Students were more likely to drop activities, not see friends or family, and not pursue hobbies they enjoy.

A balancing act

The results offer empirical evidence that many students struggle to find balance between homework, extracurricular activities and social time, the researchers said. Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills.

Also, there was no relationship between the time spent on homework and how much the student enjoyed it. The research quoted students as saying they often do homework they see as “pointless” or “mindless” in order to keep their grades up.

“This kind of busy work, by its very nature, discourages learning and instead promotes doing homework simply to get points,” Pope said.

She said the research calls into question the value of assigning large amounts of homework in high-performing schools. Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said.

“Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and development,” wrote Pope.

High-performing paradox

In places where students attend high-performing schools, too much homework can reduce their time to foster skills in the area of personal responsibility, the researchers concluded. “Young people are spending more time alone,” they wrote, “which means less time for family and fewer opportunities to engage in their communities.”

Student perspectives

The researchers say that while their open-ended or “self-reporting” methodology to gauge student concerns about homework may have limitations – some might regard it as an opportunity for “typical adolescent complaining” – it was important to learn firsthand what the students believe.

The paper was co-authored by Mollie Galloway from Lewis and Clark College and Jerusha Conner from Villanova University.

Media Contacts

Denise Pope, Stanford Graduate School of Education: (650) 725-7412, [email protected] Clifton B. Parker, Stanford News Service: (650) 725-0224, [email protected]

- Future Students

- Current Students

- Faculty/Staff

News and Media

- News & Media Home

- Research Stories

- School's In

- In the Media

You are here

More than two hours of homework may be counterproductive, research suggests.

A Stanford education researcher found that too much homework can negatively affect kids, especially their lives away from school, where family, friends and activities matter. "Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good," wrote Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of a study published in the Journal of Experimental Education . The researchers used survey data to examine perceptions about homework, student well-being and behavioral engagement in a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities. Along with the survey data, Pope and her colleagues used open-ended answers to explore the students' views on homework. Median household income exceeded $90,000 in these communities, and 93 percent of the students went on to college, either two-year or four-year. Students in these schools average about 3.1 hours of homework each night. "The findings address how current homework practices in privileged, high-performing schools sustain students' advantage in competitive climates yet hinder learning, full engagement and well-being," Pope wrote. Pope and her colleagues found that too much homework can diminish its effectiveness and even be counterproductive. They cite prior research indicating that homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night, and that 90 minutes to two and a half hours is optimal for high school. Their study found that too much homework is associated with: • Greater stress : 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress, according to the survey data. Forty-three percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while 33 percent put the pressure to get good grades in that category. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor. • Reductions in health : In their open-ended answers, many students said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems. The researchers asked students whether they experienced health issues such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems. • Less time for friends, family and extracurricular pursuits : Both the survey data and student responses indicate that spending too much time on homework meant that students were "not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills," according to the researchers. Students were more likely to drop activities, not see friends or family, and not pursue hobbies they enjoy. A balancing act The results offer empirical evidence that many students struggle to find balance between homework, extracurricular activities and social time, the researchers said. Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills. Also, there was no relationship between the time spent on homework and how much the student enjoyed it. The research quoted students as saying they often do homework they see as "pointless" or "mindless" in order to keep their grades up. "This kind of busy work, by its very nature, discourages learning and instead promotes doing homework simply to get points," said Pope, who is also a co-founder of Challenge Success , a nonprofit organization affiliated with the GSE that conducts research and works with schools and parents to improve students' educational experiences.. Pope said the research calls into question the value of assigning large amounts of homework in high-performing schools. Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said. "Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and development," wrote Pope. High-performing paradox In places where students attend high-performing schools, too much homework can reduce their time to foster skills in the area of personal responsibility, the researchers concluded. "Young people are spending more time alone," they wrote, "which means less time for family and fewer opportunities to engage in their communities." Student perspectives The researchers say that while their open-ended or "self-reporting" methodology to gauge student concerns about homework may have limitations – some might regard it as an opportunity for "typical adolescent complaining" – it was important to learn firsthand what the students believe. The paper was co-authored by Mollie Galloway from Lewis and Clark College and Jerusha Conner from Villanova University.

Clifton B. Parker is a writer at the Stanford News Service .

More Stories

⟵ Go to all Research Stories

Get the Educator

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Stanford Graduate School of Education

482 Galvez Mall Stanford, CA 94305-3096 Tel: (650) 723-2109

- Contact Admissions

- GSE Leadership

- Site Feedback

- Web Accessibility

- Career Resources

- Faculty Open Positions

- Explore Courses

- Academic Calendar

- Office of the Registrar

- Cubberley Library

- StanfordWho

- StanfordYou

Improving lives through learning

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

Stress in College Students: What to Know

Strong social connections and positive habits can help ease high levels of stress among college-age adults.

Getty Images

From socializing to working out, here's how college students can better manage stress.

From paying for school and taking exams to filling out internship applications, college students can face overwhelming pressure and demands. Some stress can be healthy and even motivating under the proper circumstances, but often stress is overwhelming and can lead to other issues.

"Stress is there for a reason. It's there to help mobilize you to meet the demands of your day, but you're also supposed to have times where you do shut down and relax and repair and restore," says Emma K. Adam, professor of human development and social policy at Northwestern University in Illinois.

Chronic and unhealthy levels of stress is at its worst among college-age students and young adults, some research shows. According to the American Psychological Association's 2022 "Stress in America" report , 46% of adults ages 18 to 35 reported that "most days they are so stressed they can't function."

In a Gallup poll that surveyed more than 2,400 college students in March 2023, 66% of reported experiencing stress and 51% reported feelings of worry "during a lot of the day." And emotional stress was among the top reasons students considered dropping out of college in the fall 2022 semester, according to findings in the State of Higher Education 2023 report, based on a study conducted in 2022 by Gallup and the Lumina Foundation.

As students are navigating a new environment and often living independently for the first time, they encounter numerous opportunities, responsibilities and life changes on top of academic responsibilities. It can be sensory overload for some, experts say.

“Going to college has always been a significant time of transition developmentally with adulthood, but you add to it everything that comes along with that transition and then you put onto it a youth mental health crisis, it’s just compounded in a very different way," says Jessica Gomez, a clinical psychologist and executive director of Momentous Institute, a researched-based organization that provides mental health services and educational programming to children and families.

Experts say college students have experienced heightened stress since the COVID-19 pandemic, a trend likely to continue for the foreseeable future.

“What some of our research at Gallup has shown is that we had a rising tide of negative emotions, not just in the U.S. but globally, in the eight to 10 years leading up to the pandemic, and of course it got worse during the pandemic," says Stephanie Marken, senior partner of the education research division at Gallup who conducted the 2023 study. “For currently enrolled college students, there’s so many contributing factors.”

Adam notes that multiple factors combine to contribute to heightened stress among younger adults, including the nation’s racial and political controversies, as well as anxiety regarding their futures fueled by climate change, global unrest and economic uncertainty. Female students reported higher levels of stress than males in the Gallup poll, which Marken says could be attributed to several factors like increased internal academic pressure, caregiving responsibilities and the recent uncertainty regarding abortion rights following the reversal of Roe v. Wade.

All of this, plus the residual effects of pandemic learning, has contributed to rising stress for college students, Marken says.

"We need to give them a lot of credit," she says. "They had the most challenge in remote learning of all the learners that have come before them. Many of them had to graduate high school and study remotely, or were a first-year college student during the pandemic, and that was incredibly difficult."

The challenges that came with that learning environment will likely affect students throughout college, she says, as well as typical stressors like discrimination, harassment and academic challenges.

"Those will always be present on college campuses," she says. "The question is, how do we create a student who overcomes those challenges effectively?"

Experts suggest a range of specific actions and positive shifts that can help ease stress in college students:

- Notice the symptoms of heightened stress.

- Build and maintain social connections.

- Sleep, eat well and exercise.

Notice the Symptoms of Heightened Stress

College students can start by learning to identify when normal stress increases to become unhealthy. Stress will appear differently in each student, says Lindsey Giller, a clinical psychologist with the Child Mind Institute, a nonprofit focused on helping children and young adults with mental health and learning disorders.

"Students prone to anxiety may avoid assignments as well as skip classes due to experiencing shame for being behind or missing things," she says. "For some, they may also start sleeping in more, eating at more random times, foregoing self-care, or look to distraction or escape mechanisms, like substances, to fill time and further avoid the reality of workload assignments."

Changes in diet and sleeping are also telling, as well as increased social isolation and pulling away from activities that once brought you pleasure is also a red flag, Gomez says.

She warns students to watch for signs of irritability, a classic indicator of increased stress that can often compound issues, especially within interpersonal relationships.

"Your body speaks to you, so be in tune with your body," she says.

Build and Maintain Social Connections

Socializing can help humans release stress. Experts say having fun and finding joy in life keep stress levels manageable, and socializing is particularly important developmentally for young adults. In the 2023 Gallup poll, 76% of students reported feeling enjoyment the previous day, which Marken says was an encouraging sign.

But 39% reported experiencing feelings of loneliness and 36% reported feeling sad. “We are in the midst of an epidemic of loneliness in our country, where we are noticing people don’t have the skills to build friendships,” Gomez says.

Discover six

Talking about feelings of stress can help college students cope, which is why the amount of students feeling lonely is concerning, Marken says. If students don't feel like they belong or have a social network to call on when feeling stressed, negative emotions are compounded.

“I think we’re more connected, and yet we’re more isolated than ever," she says. "It feels counterintuitive. How can you be more connected to your network and campus than ever, yet feel this lonely? Just because they have a device to connect with each other in a transactional way doesn’t mean it’s a meaningful relationship. I think that’s what we’re missing on a lot of college campuses is students creating meaningful connections about a shared experience."

Setting boundaries on social media use is crucial, Gomez says, as is getting plugged in with people and organizations that will be enriching. For example, Gomez says she joined a Latina sorority to be in community with others who shared some of her life experiences and interests.

Sleep, Eat Well and Exercise

Maintaining healthy habits can help college students better manage stressors that arise.

"Prioritizing sleep, moving your body, getting organized, and leaning on your support network all help college students prevent or manage stress," John MacPhee, CEO of The Jed Foundation, a nonprofit that aims to protect emotional health and prevent suicide among teens and young adults, wrote in an email. "In the inevitable moments of high stress, mindful breathing, short brain breaks, and relaxation techniques can really help."

Experts suggest creating a routine and sticking to it. That includes getting between eight and 10 hours of sleep each night and avoiding staying up late, Gomez says. A nutrient-rich diet can also go a long way in maintaining good physical and mental health, she says.

Getting outdoors and being active can also help students limit their screen time and use of social media.

“Walking to campus, maybe taking that longer walk, because your body needs that to heal," Gomez says. "It’s going to help buffer you. So if that’s the only thing you do, try to do that."

Colleges typically offer mental health resources such as counseling and support groups for struggling students.

Students dealing with chronic and unhealthy stress should contact their college and reach out to friends and family for support. Reaching out to parents, friends or mentors can be beneficial for students when feelings of stress come up, especially in heightened states around midterm and final exams .

Accessing student supports and counseling early can prevent a cascading effect that results in serious mental health challenges or unhealthy coping mechanisms like problem drinking and drug abuse , experts say.

"Know there are lots of resources on campus from academic services to counseling centers to get structured, professional support to lower your workload, improve coping skills, and have a safe space to process anxiety, worry, and stress," MacPhee says.

Searching for a college? Get our complete rankings of Best Colleges.

10 Unexpected College Costs

Tags: mental health , colleges , stress , education , students , Coronavirus

2024 Best Colleges

Search for your perfect fit with the U.S. News rankings of colleges and universities.

College Admissions: Get a Step Ahead!

Sign up to receive the latest updates from U.S. News & World Report and our trusted partners and sponsors. By clicking submit, you are agreeing to our Terms and Conditions & Privacy Policy .

Ask an Alum: Making the Most Out of College

You May Also Like

Takeaways from the ncaa’s settlement.

Laura Mannweiler May 24, 2024

New Best Engineering Rankings June 18

Robert Morse and Eric Brooks May 24, 2024

Premedical Programs: What to Know

Sarah Wood May 21, 2024

How Geography Affects College Admissions

Cole Claybourn May 21, 2024

Q&A: College Alumni Engagement

LaMont Jones, Jr. May 20, 2024

10 Destination West Coast College Towns

Cole Claybourn May 16, 2024

Scholarships for Lesser-Known Sports

Sarah Wood May 15, 2024

Should Students Submit Test Scores?

Sarah Wood May 13, 2024

Poll: Antisemitism a Problem on Campus

Lauren Camera May 13, 2024

Federal vs. Private Parent Student Loans

Erika Giovanetti May 9, 2024

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Top 10 Stress Management Techniques for Students

Elizabeth Scott, PhD is an author, workshop leader, educator, and award-winning blogger on stress management, positive psychology, relationships, and emotional wellbeing.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Elizabeth-Scott-MS-660-695e2294b1844efda01d7a29da7b64c7.jpg)

Akeem Marsh, MD, is a board-certified child, adolescent, and adult psychiatrist who has dedicated his career to working with medically underserved communities.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/akeemmarsh_1000-d247c981705a46aba45acff9939ff8b0.jpg)

Most students experience significant amounts of stress. This can significantly affect their health, happiness, relationships, and grades. Learning stress management techniques can help these students avoid negative effects in these areas.

Why Stress Management Is Important for Students

A study by the American Psychological Association (APA) found that teens report stress levels similar to adults. This means teens are experiencing significant levels of chronic stress and feel their stress levels generally exceed their ability to cope effectively .

Roughly 30% of the teens reported feeling overwhelmed, depressed, or sad because of their stress.

Stress can also affect health-related behaviors. Stressed students are more likely to have problems with disrupted sleep, poor diet, and lack of exercise. This is understandable given that nearly half of APA survey respondents reported completing three hours of homework per night in addition to their full day of school work and extracurriculars.

Common Causes of Student Stress

Another study found that much of high school students' stress originates from school and activities, and that this chronic stress can persist into college years and lead to academic disengagement and mental health problems.

Top Student Stressors

Common sources of student stress include:

- Extracurricular activities

- Social challenges

- Transitions (e.g., graduating, moving out , living independently)

- Relationships

- Pressure to succeed

High school students face the intense competitiveness of taking challenging courses, amassing impressive extracurriculars, studying and acing college placement tests, and deciding on important and life-changing plans for their future. At the same time, they have to navigate the social challenges inherent to the high school experience.

This stress continues if students decide to attend college. Stress is an unavoidable part of life, but research has found that increased daily stressors put college-aged young adults at a higher risk for stress than other age groups.

Making new friends, handling a more challenging workload, feeling pressured to succeed, being without parental support, and navigating the stresses of more independent living are all added challenges that make this transition more difficult. Romantic relationships always add an extra layer of potential stress.

Students often recognize that they need to relieve stress . However, all the activities and responsibilities that fill a student’s schedule sometimes make it difficult to find the time to try new stress relievers to help dissipate that stress.

10 Stress Management Techniques for Students

Here you will learn 10 stress management techniques for students. These options are relatively easy, quick, and relevant to a student’s life and types of stress .

Get Enough Sleep

Blend Images - Hill Street Studios / Brand X Pictures / Getty Images

Students, with their packed schedules, are notorious for missing sleep. Unfortunately, operating in a sleep-deprived state puts you at a distinct disadvantage. You’re less productive, may find it more difficult to learn, and may even be a hazard behind the wheel.

Research suggests that sleep deprivation and daytime sleepiness are also linked to impaired mood, higher risk for car accidents, lower grade point averages, worse learning, and a higher risk of academic failure.

Don't neglect your sleep schedule. Aim to get at least 8 hours a night and take power naps when needed.

Use Guided Imagery

David Malan / Getty Images

Guided imagery can also be a useful and effective tool to help stressed students cope with academic, social, and other stressors. Visualizations can help you calm down, detach from what’s stressing you, and reduce your body’s stress response.

You can use guided imagery to relax your body by sitting in a quiet, comfortable place, closing your eyes, and imagining a peaceful scene. Spend several minutes relaxing as you enjoy mentally basking in your restful image.

Consider trying a guided imagery app if you need extra help visualizing a scene and inducting a relaxation response. Research suggests that such tools might be an affordable and convenient way to reduce stress.

Exercise Regularly

One of the healthiest ways to blow off steam is to get regular exercise . Research has found that students who participate in regular physical activity report lower levels of perceived stress. While these students still grapple with the same social, academic, and life pressures as their less-active peers, these challenges feel less stressful and are easier to manage.

Finding time for exercise might be a challenge, but there are strategies that you can use to add more physical activity to your day. Some ideas that you might try include:

- Doing yoga in the morning

- Walking or biking to class

- Reviewing for tests with a friend while walking on a treadmill at the gym

- Taking an elective gym class focused on leisure sports or exercise

- Joining an intramural sport

Exercise can help buffer against the negative effects of student stress. Starting now and keeping a regular exercise practice throughout your lifetime can help you live longer and enjoy your life more.

Take Calming Breaths

When your body is experiencing a stress response, you’re often not thinking as clearly as you could be. You are also likely not breathing properly. You might be taking short, shallow breaths. When you breathe improperly, it upsets the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide in your body.

Studies suggest this imbalance can contribute to various physical symptoms, including increased anxiety, fatigue, stress, emotional problems, and panic attacks.

A quick way to calm down is to practice breathing exercises . These can be done virtually anywhere to relieve stress in minutes.

Because they are fast-acting, breathing exercises are a great way to cope with moments of acute stress , such as right before an exam or presentation. But they can also help manage longer-lasting stress such as dealing with relationships, work, or financial problems.

Practice Progressive Muscle Relaxation (PMR)

Another great stress management technique for students that can be used during tests, before bed, or at other times when stress has you physically wound up is progressive muscle relaxation ( PMR ).

This technique involves tensing and relaxing all muscles until the body is completely relaxed. With practice, you can learn to release stress from your body in seconds. This can be particularly helpful for students because it can be adapted to help relaxation efforts before sleep for a deeper sleep.

Once a person learns how to use PMR effectively, it can be a quick and handy way to induce relaxation in any stressful situation, such as bouts of momentary panic before a speech or exam, dealing with a disagreement with your roommate, or preparing to discuss a problem with your academic advisor.

Listen to Music

A convenient stress reliever that has also shown many cognitive benefits, music can help relieve stress and calm yourself down or stimulate your mind depending on what you need in the moment.

Research has found that playing upbeat music can improve processing speed and memory. Stressed students may find that listening to relaxing music can help calm the body and mind. One study found that students who listened to the sounds of relaxing music were able to recover more quickly after a stressful situation.

Students can harness the benefits of music by playing classical music while studying, playing upbeat music to "wake up" mentally, or relaxing with the help of their favorite slow melodies.

Build Your Support Network

Halfpoint Images / Getty Images

Having emotional support can help create a protective buffer against stress. Unfortunately, interpersonal relationships can also sometimes be a source of anxiety for students. Changes in friendships, romantic breakups, and life transitions such as moving away for college can create significant upheaval and stress for students.

One way to combat feelings of loneliness and make sure that you have people to lean on in times of need is to expand your support network and nurture your relationships.

Look for opportunities to meet new people, whether it involves joining study groups or participating in other academic, social, and leisure activities.

Remember that different types of relationships offer differing types of support . Your relationships with teachers, counselors, and mentors can be a great source of information and resources that may help you academically. Relationships with friends can provide emotional and practical support.

Widening your social circle can combat student stress on various fronts and ensure you have what you need to succeed.

Eat a Healthy Diet

Niedring/Drentwett / Getty Images

You may not realize it, but your diet can either boost your brainpower or sap you of mental energy. It can also make you more reactive to the stress in your life. As a result, you might find yourself turning to high-sugar, high-fat snacks to provide a temporary sense of relief.

A healthy diet can help combat stress in several ways. Improving your diet can keep you from experiencing diet-related mood swings, light-headedness, and more.

Unfortunately, students are often prone to poor dietary habits. Feelings of stress can make it harder to stick to a consistently healthy diet, but other concerns such as finances, access to cooking facilities, and time to prepare healthy meals can make it more challenging for students.

Some tactics that can help students make healthy choices include:

- Eating regularly

- Carrying a water bottle to class

- Keeping healthy snacks such as fruits and nuts handy

- Limiting caffeine, nicotine, and alcohol intake

Find Ways to Minimize Stress

One way to improve your ability to manage student stress is to look for ways you cut stress out of your life altogether. Evaluate the things that are bringing stress or anxiety into your life. Are they necessary? Are they providing more benefits than the toll they take on your mental health? If the answer is no, sometimes the best option is just to ditch them altogether.

This might mean cutting some extracurricular activities out of your schedule. It might mean limiting your use of social media. Or it might mean learning to say no to requests for your time, energy, and resources.

While it might be challenging at first, learning how to prioritize yourself and your mental well-being is an important step toward reducing your stress.

Try Mindfulness

When you find yourself dealing with stress—whether it's due to academics, relationships, financial pressures, or social challenges—becoming more aware of how you feel in the moment may help you respond more effectively.

Mindfulness involves becoming more aware of the present moment. Rather than judging, reacting, or avoiding problems, the goal is to focus on the present, become more aware of how you are feeling, observe your reactions, and accept these feelings without passing judgment on them.

Research suggests that mindfulness-based stress management practices can be a useful tool for reducing student stress. Such strategies may also help reduce feelings of anxiety and depression.

A Word From Verywell

It is important to remember that stress isn't the same for everyone. Figuring out what works for you may take some trial and error. A good start is to ensure that you are taking care of yourself physically and emotionally and to experiment with different stress relief strategies to figure out what works best to help you feel less stressed.

If stress and anxiety are causing distress or making it difficult to function in your daily life, it is important to seek help. Many schools offer resources that can help, including face-to-face and online mental health services. You might start by talking to your school counselor or student advisor about the stress you are coping with. You can also talk to a parent, another trusted adult, or your doctor.

If you or a loved one are struggling with anxiety, contact the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) National Helpline at 1-800-662-4357 for information on support and treatment facilities in your area.

For more mental health resources, see our National Helpline Database .

American Psychological Association. Stress in America: Are Teens Adopting Adults' Stress Habits?

Leonard NR, Gwadz MV, Ritchie A, et al. A multi-method exploratory study of stress, coping, and substance use among high school youth in private schools . Front Psychol. 2015;6:1028. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01028

Acharya L, Jin L, Collins W. College life is stressful today - Emerging stressors and depressive symptoms in college students . J Am Coll Health . 2018;66(7):655-664. doi:10.1080/07448481.2018.1451869

Beiter R, Nash R, McCrady M, Rhoades D, Linscomb M, Clarahan M, Sammut S. The prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and stress in a sample of college students . J Affect Disord . 2015;173:90-6. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.054

Hershner SD, Chervin RD. Causes and consequences of sleepiness among college students . Nat Sci Sleep . 2014;6:73-84. doi:10.2147/NSS.S62907

Gordon JS, Sbarra D, Armin J, Pace TWW, Gniady C, Barraza Y. Use of a guided imagery mobile app (See Me Serene) to reduce COVID-19-related stress: Pilot feasibility study . JMIR Form Res . 2021;5(10):e32353. doi:10.2196/32353

Cowley J, Kiely J, Collins D. Is there a link between self-perceived stress and physical activity levels in Scottish adolescents ? Int J Adolesc Med Health . 2017;31(1). doi:10.1515/ijamh-2016-0104

Paulus MP. The breathing conundrum-interoceptive sensitivity and anxiety . Depress Anxiety . 2013;30(4):315–320. doi:10.1002/da.22076

Toussaint L, Nguyen QA, Roettger C, Dixon K, Offenbächer M, Kohls N, Hirsch J, Sirois F. Effectiveness of progressive muscle relaxation, deep breathing, and guided imagery in promoting psychological and physiological states of relaxation . Evid Based Complement Alternat Med . 2021;2021:5924040. doi:10.1155/2021/5924040.

Gold BP, Frank MJ, Bogert B, Brattico E. Pleasurable music affects reinforcement learning according to the listener . Front Psychol . 2013;4:541. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00541

Thoma MV, La Marca R, Brönnimann R, Finkel L, Ehlert U, Nater UM. The effect of music on the human stress response . PLoS ONE . 2013;8(8):e70156. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0070156

American Psychological Association. Manage stress: Strengthen your support network .

Nguyen-rodriguez ST, Unger JB, Spruijt-metz D. Psychological determinants of emotional eating in adolescence. Eat Disord . 2009;17(3):211-24. doi:10.1080/10640260902848543

Parsons D, Gardner P, Parry S, Smart S. Mindfulness-based approaches for managing stress, anxiety and depression for health students in tertiary education: A scoping review . Mindfulness (N Y) . 2022;13(1):1-16. doi:10.1007/s12671-021-01740-3

By Elizabeth Scott, PhD Elizabeth Scott, PhD is an author, workshop leader, educator, and award-winning blogger on stress management, positive psychology, relationships, and emotional wellbeing.

College students’ stress levels are ‘bubbling over.’ Here’s why, and how schools can help

John Yang John Yang

Claire Mufson Claire Mufson

Leave your feedback

- Copy URL https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/college-students-stress-levels-are-bubbling-over-heres-why-and-how-schools-can-help

College is a time of major transition and of stress. During the pandemic, students have been struggling to cope with ever-increasing levels of mental distress among students. A recent study by The American College Health Association found that one in four students had considered suicide. John Yang looks at the problem and solutions, on and off campus, for NewsHour's “Rethinking College” series.

Read the Full Transcript

Notice: Transcripts are machine and human generated and lightly edited for accuracy. They may contain errors.

Judy Woodruff:

College is a time of major transition and of stress. Add in the pandemic, and colleges are left struggling to cope with ever-increasing levels of mental distress among students.

John Yang looks at the problem and what can done on and off campus for our series Rethinking College.

Judy, a study this year by the American College Health Association found that 48 percent of college students reported moderate or severe psychological stress, 53 percent reported being lonely, and one in four had considered suicide.

Many college campuses are scrambling to expand and rethink the ways they help students cope with mental health concerns.

Riana Elyse Anderson is an assistant professor of health behavior and health education at the University of Michigan.

Thanks for being with us.

This issue, I think, really got a lot of attention nationally when the University of North Carolina had sort of a mental health break for students after there were two apparent suicides. But you study this issue. You teach young people on a college campus. What do you see? Talk about your personal experience to sort of give our viewers a sense of this issue.

Riana Elyse Anderson, University of Michigan: Sure.

So, we know, over the past year, we have watched stress, anxiety and depression go up about fourfold for everyone. And that absolutely includes our young folks. So, whether these are pediatric populations or the collegiate population, we're watching this number just balloon, and that's on top of what we saw even as a pattern before COVID.

So we're watching college students really get impacted by the comparison that they're seeing in their classmates online, in social media. They're using comparison and they're feeling particularly anxious about it for themselves.

What were the factors before the pandemic?

Riana Elyse Anderson:

Social media is one thing that has really ballooned in this past decade, where children and adolescents are now college students who have been utilizing those strategies for the past several years now are starting to see, oh, that person got into college, this person scored this on this exam, whereas before you could only look as far as the cafeteria, right?

You didn't know what was happening nationwide. But now you have this greater comparison, and it's really impacting one's well-being.

Is there a sense of the — of a generational difference, that young people now are perhaps more concerned about mental health issues?

A wonderful article just came out looking at even the generation like myself, which is just one above the millennials, who really started thinking about mental health a bit differently than our generation before us.

We're starting to see now that generational divide in the Gen Z'ers, who are really staking a claim and saying, not only am I noticing it, but I want to take those days like the UNC students demanded, or I have to see a counselor, rather than go to class, rather than go to work.

And that's something our generation or those above never thought to do, never thought possible. So, on the one hand, what a wonderful thing to do and have that autonomy to say. It's another thing, though, when collegiate professors like myself are now saying, what do we do? How do we contend with teaching, with meeting, with doing the things we have to do for school to continue and meeting the needs of our students?

So, it's just challenging now for us to contend with that.

Are there differences along sort of racial, ethnic, socioeconomic lines? Thinking particularly first-generation college students whose families may not be prepared to help them through this.

Certainly, COVID has impacted that.

So we're seeing this dual impact of not only the resources that have been impacted by COVID, but the socioeconomic and racial disparities. So you're watching folks who perhaps didn't have the access or the tablets, the technology to do the work from home, or perhaps they didn't want to show their screens.

And so that's lessening the amount of time that they're on screen. They're feeling less connected to folks. And now that they're back into a college setting, that year has really impacted them. And they're trying to understand, how do they find community? How are they now exposed to some of the things that they weren't exposed to last year, including discrimination or rejection?

So they're contending with a lot of things that are unique for them relative to their classmates.

Talk about how colleges and universities can address this. How can they help students deal with this?

And, also, you talk about students being more willing to seek help. Are they finding — or are they being a little overwhelmed or finding greater demand than they have the supply for?

Absolutely. So, you said it well.

And the ways that we can combat that are prevention and intervention strategies. So, with respect to what you just said, the CAP services, or counseling and psych services, that most universities have, if we know what these numbers are, we can plan accordingly. We can make sure that we have referrals in the community.

We can expand the number of people on staff. So intervention strategies, once we know that mental health problems are bubbling over, can be something that we can do. But we can also engage in prevention strategies. That is, can we reduce the amount of assignments that we're giving? Can we take more days, like UNC did, as a community, so that no one's e-mailing, no one — it's not just who is saying, I'm going to take an individual day.

Your professors, your administration, no one is e-mailing or expecting anything of you, so that we can prevent some of those problems that we're seeing in the first place.

Riana Elyse Anderson from the University of Michigan, thank you very much.

Listen to this Segment

Watch the Full Episode

John Yang is the anchor of PBS News Weekend and a correspondent for the PBS NewsHour. He covered the first year of the Trump administration and is currently reporting on major national issues from Washington, DC, and across the country.

Support Provided By: Learn more

More Ways to Watch

- PBS iPhone App

- PBS iPad App

Educate your inbox

Subscribe to Here’s the Deal, our politics newsletter for analysis you won’t find anywhere else.

Thank you. Please check your inbox to confirm.

How to Deal With Homework Stress

For some, stress is an inevitable part of homework, and the education system in general. Sometimes, this stress can even transfer to the parent or adult tasked with assisting the child with their schoolwork. This particular type of stress may be more evident to some parents and students, as they might be more prone to developing it. It is important to deal not only the stress symptoms, but with the problem as well.

Homework stress can be harmful too, making students depressed, tired, and building negative feelings towards the whole concept of studying. This can, unfortunately, lead to tragic consequences, such as suicidal thoughts. Homework can stress students out for many reasons, the most prominent being the amount of assigned work, the degree of difficulty, and the expectations placed on them. These students are told that homework is incredibly important for not only their success in the school yea r, but in their eventual careers as well. The truth is that studying is essential, but it is only one of the factors that determine your success in school, and your pursuits thereafter. Generally, homework is not worth skipping sleep or meals, as doing this can have an effect on your physical and mental health.

Sometimes, stress due to homework can transfer to the adult family life of people who have not opened textbooks for years, whose new duty in life is to help their children with their own homework, and that can get stressful as well. Parents can become outraged because homework from their kids’ math class makes no sense, or a science project just can’t be put together, no matter how hard they try. Some parents can become more devastated than their kids when it comes to homework. The amount of stress a twelfth-grade student trying to write a 600-word essay on the book he or she never read can be overwhelming. Especially if the due day is tomorrow, and there are only 10 hours before the class.

Though there is no guaranteed way to completely rid yourself of stress, there are ways of overcoming some aspects of homework induced stress. Read on for some tips on stress management, and find a solution that works for you.

Time Management

Good time management may not solve all of your problems, but it can go a long way when dealing with homework related stress. Scheduling homework might sound minor, but it can help those who have trouble remembering their assignments and due dates. Most homework induced stress starts from missing deadlines and feeling rushed while working on assignments. Keeping track of the time spent on individual tasks, as well as keeping a timeline of when assignments are due may help ease your stress.

Use a Clean Workspace

Before you begin working on an assignment, ensure there are no potential distractions in your workspace. It could be a phone, clutter on the desk, toys, or anything else that could take your time and mind away from the task to hand. It is proven that loud noise, splashes of color, and cluttered space causes more stress, therefore decluttering table may help you to concentrate.

Ask for Help

Don’t hesitate to ask professor question about assignments. Sometimes stress is caused by the fact that the task is too difficult, and hard for you to understand. Getting some extra assistance from your professor may help you better understand the topic and further your ability to complete the project. Most professors are willing to help – it’s their job, after all – and they can explain the parts of the assignment that are difficult for you.

Don’t forget to rest when you start to feel overwhelmed. Mental and physical exhaustion is a common side effect of stress, and it is important to deal with it when it comes up. Great ways of resting include taking a nap, going on a walk, dancing, cooking a nice and nutritious meal, exercising, and spending some time on a hobby. While resting from homework, avoid spending all the time on your phone or computer, it is best to do something active and interactive.

Talk it Out

Talk to someone you trust about the stress you’re feeling. Sometimes, you just need a little bit of support to feel better, and discussing homework stress with your parents, relatives, or friends could be very therapeutic and helpful. Talking about your feelings is an excellent way of dealing with any kind of stress, not just homework induced.

In the face of all this stress, it is important to remember to stay calm. Stressing about each individual assignment is not healthy, and can be harmful to your mental health. Though achieving perfect grades through college is indeed possible, it may not be worth it if you are putting your mental and physical health in danger. Focus on creating realistic and tangible goals for yourself, and remember that one grade does not define your future.

These are just some of the many ways of how you can deal with homework stress . The fact is that for some, stress still will always be a part of the studying process. All that can be done is to find tactics to deal with this stress that work for you. If you can manage this, you may find your workload less stressful, and you may actually enjoy your work!

For more great topics related to all things college, check out the other blogs at College Basics.

You may also like

8 Differences Between Aussie and American Schools

Top 5 Most Difficult IB (International Baccalaureate) Subjects

8 Reasons Why You Should Study Accounting Degrees

8 Best Essay Writing Services According to Reddit and Quora

6 Unique Tips for Writing a Brilliant Motivational Essay

6 Qualities You Should Always Watch Out For in a Good Roommate

About the author.

CB Community

Passionate members of the College Basics community that include students, essay writers, consultants and beyond. Please note, while community content has passed our editorial guidelines, we do not endorse any product or service contained in these articles which may also include links for which College Basics is compensated.

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

August 23, 2022 , Filed Under: Uncategorized

How to Manage Homework-Related Stress

Ask students what causes them the most stress, and the conversation will likely turn to homework. Students have complained about homework for practically as long as it has existed. While some dismiss these complaints as students’ laziness or lack of organization, there’s more to it than that. Many students face a lot of pressure to succeed in school, sports, work, and other areas. Also, more teens and young adults are dealing with mental health problems, with up to 40% of college students reporting symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Researchers and professionals debate over whether homework does more harm than good, but at least for now, homework is an integral part of education. How do students deal with heavy homework loads? It’s become common for overwhelmed students to use an essay service to help them complete their assigned tasks. Pulling all-nighters to finish assignments and study for tests is another strategy busy college students use, for better or worse.

If you’re a student that’s struggling to get all your homework done, make sure to take care of your mental health. School is important, but your health is more important. Try the following tips to help you stay on top of your busy schedule.

Make a Schedule

Time management is an important skill, but you can’t learn it without effort. The first step to managing your time more effectively is to make a schedule and stick to it. Use a calendar, planner, or an app to write down everything you need to get done. Set reminders for due dates and set aside time each day for studying. Don’t leave assignments for the last minute. Plan to finish your work well ahead of the due date in case something unexpected happens and you need more time. Make sure your schedule is realistic. Give yourself a reasonable amount of time to complete each task. And schedule time for hobbies and social activities too.

Find a Study Spot

Doing homework in a dedicated workspace can boost your productivity. Studying in bed could make you fall asleep, and doing homework in a crowded, noisy place can be distracting. You want to complete as much work as possible during your study sessions, so choose a place that’s free of distractions. Make sure you have everything you need within arm’s reach. Resist the temptation to check your notifications or social media feeds while you study. Put your phone in airplane mode if necessary so it doesn’t distract you. You don’t need a private office to study efficiently, but having a quiet, distraction-free place to do your homework can help you to get more done.

Get Enough Rest

An all-nighter every once in a while probably won’t do you any lasting harm. But a consistent lack of sleep is bad for your productivity and your health. Most young people need at least 7 hours of sleep every night, so make it your goal to go to bed on time. You’ll feel better throughout the day, have more energy, and improve your focus. Instead of dozing off while you’re doing homework, you’ll be more alert and productive if you get enough sleep.

It’s also important to spend time relaxing and enjoying your favorite activities. Hang out with friends, take a walk, or watch a movie. You’ll feel less stressed if you take some time for yourself.

Don’t Shoot for Perfection

It’s tempting to try to get a perfect grade on every test or assignment. But perfectionism only causes unnecessary stress and anxiety. If you consider yourself a perfectionist, you might spend too much time on less important tasks. Prioritize your assignments and put more time and effort into the most important ones.

Most people struggle with perfectionism because they’ve been taught they should do their best at everything. But you don’t have to go above and beyond for every assignment. That’s not to say you should turn in bad work. But putting in just enough effort to get by isn’t a bad thing. Don’t put pressure on yourself to be the best at everything. Focus on your most important assignments, and don’t spend too much time and effort perfecting the others.

Almost all students deal with the burden of homework-related stress. No one enjoys the anxiety of having a lot of assignments due and not enough time to complete them. But take advantage of this opportunity to learn organization and self-discipline, which will help you throughout your life. Try making a schedule and don’t forget to set aside time to rest. When it’s time to study, choose a quiet place where you can concentrate. Don’t neglect your health; if you’re feeling anxious or depressed, talk to a counselor or your doctor. School stress is hard to avoid, but if you take these steps you can reduce homework anxiety and have better control of your time.

The real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes, but in having new eyes — Marcel Proust

Social Widgets powered by AB-WebLog.com .

The Truth About Homework Stress: What Parents & Students Need to Know

- Fact Checked

Written by:

published on:

- December 21, 2023

Updated on:

- January 9, 2024

Looking for a therapist?

Homework is generally given out to ensure that students take time to review and remember the days lessons. It can help improve on a student’s general performance and enhance traits like self-discipline and independent problem solving.

Parents are able to see what their children are doing in school, while also helping teachers determine how well the lesson material is being learned. Homework is quite beneficial when used the right way and can improve student performance.

This well intentioned practice can turn sour if it’s not handled the right way. Studies show that if a student is inundated with too much homework, not only do they get lower scores, but they are more likely to get stressed.

The age at which homework stress is affecting students is getting lower, some even as low as kindergarten. Makes you wonder what could a five year old possibly need to review as homework?

One of the speculated reasons for this stress is that the complexity of what a student is expected to learn is increasing, while the breaks for working out excess energy are reduced. Students are getting significantly more homework than recommended by the education leaders, some even nearly three times more.

To make matters worse, teachers may give homework that is both time consuming and will keep students busy while being totally non-productive.

Remedial work like telling students to copy notes word for word from their text books will do nothing to improve their grades or help them progress. It just adds unnecessary stress.

Explore emotional well-being with BetterHelp – your partner in affordable online therapy. With 30,000+ licensed therapists and plans starting from only $65 per week, BetterHelp makes self-care accessible to all. Complete the questionnaire to match with the right therapist.

Effects of homework stress at home

Both parents and students tend to get stressed out at the beginning of a new school year due to the impending arrival of homework.

Nightly battles centered on finishing assignments are a household routine in houses with students.

Research has found that too much homework can negatively affect children. In creating a lack of balance between play time and time spent doing homework, a child can get headaches, sleep deprivation or even ulcers.

And homework stress doesn’t just impact grade schoolers. College students are also affected, and the stress is affecting their academic performance.

Even the parent’s confidence in their abilities to help their children with homework suffers due increasing stress levels in the household.

Fights and conflict over homework are more likely in families where parents do not have at least a college degree. When the child needs assistance, they have to turn to their older siblings who might already be bombarded with their own homework.

Parents who have a college degree feel more confident in approaching the school and discussing the appropriate amount of school work.

“It seems that homework being assigned discriminates against parents who don’t have college degree, parents who have English as their second language and against parents who are poor.” Said Stephanie Donaldson Pressman, the contributing editor of the study and clinical director of the New England Center for Pediatric Psychology.

With all the stress associated with homework, it’s not surprising that some parents have opted not to let their children do homework. Parents that have instituted a no-homework policy have stated that it has taken a lot of the stress out of their evenings.

The recommended amount homework

The standard endorsed by the National Education Association is called the “10 minute rule”; 10 minutes per grade level per night. This recommendation was made after a number of studies were done on the effects of too much homework on families.

The 10 minute rule basically means 10 minutes of homework in the first grade, 20 minute for the second grade all the way up to 120 minutes for senior year in high school. Note that no homework is endorsed in classes under the first grade.

Parents reported first graders were spending around half an hour on homework each night, and kindergarteners spent 25 minutes a night on assignments according to a study carried out by Brown University.

Making a five year old sit still for half an hour is very difficult as they are at the age where they just want to move around and play.

A child who is exposed to 4-5 hours of homework after school is less likely to find the time to go out and play with their friends, which leads to accumulation of stress energy in the body.

Their social life also suffers because between the time spent at school and doing homework, a child will hardly have the time to pursue hobbies. They may also develop a negative attitude towards learning.

The research highlighted that 56% of students consider homework a primary source of stress.

And if you’re curious how the U.S stacks up against other countries in regards to how much time children spend on homework, it’s pretty high on the list .

Signs to look out for on a student that has homework stress

Since not every student is affected by homework stress in the same way, it’s important to be aware of some of the signs your child might be mentally drained from too much homework.

Here are some common signs of homework stress:

- Sleep disturbances

- Frequent stomachaches and headaches

- Decreased appetite or changed eating habits

- New or recurring fears

- Not able to relax

- Regressing to behavior they had when younger

- Bursts of anger crying or whining

- Becoming withdrawn while others may become clingy

- Drastic changes in academic performance

- Having trouble concentrating or completing homework

- Constantly complains about their ability to do homework

If you’re a parent and notice any of these signs in your child, step in to find out what’s going on and if homework is the source of their stress.

If you’re a student, pay attention if you start experiencing any of these symptoms as a result of your homework load. Don’t be afraid to ask your teacher or parents for help if the stress of homework becomes too much for you.

What parents do wrong when it comes to homework stress

Most parents push their children to do more and be more, without considering the damage being done by this kind of pressure.

Some think that homework brought home is always something the children can deal with on their own. If the child cannot handle their homework then these parents get angry and make the child feel stupid.

This may lead to more arguing and increased dislike of homework in the household. Ultimately the child develops an even worse attitude towards homework.

Another common mistake parents make is never questioning the amount of homework their children get, or how much time they spend on it. It’s easy to just assume whatever the teacher assigned is adequate, but as we mentioned earlier, that’s not always the case.

Be proactive and involved with your child’s homework. If you notice they’re spending hours every night on homework, ask them about it. Just because they don’t complain doesn’t mean there isn’t a problem.

How can parents help?

- While every parent wants their child to become successful and achieve the very best, it’s important to pull back on the mounting pressure and remember that they’re still just kids. They need time out to release their stress and connect with other children.

- Many children may be afraid to admit that they’re overwhelmed by homework because they might be misconstrued as failures. The best thing a parent can do is make home a safe place for children to express themselves freely. You can do this by lending a listening ear and not judging your kids.

- Parents can also take the initiative to let the school know that they’re unhappy with the amount of homework being given. Even if you don’t feel comfortable complaining, you can approach the school through the parent-teacher association available and request your representative to plead your case.

- It may not be all the subjects that are causing your child to get stressed. Parents should find out if there is a specific subject of homework that is causing stress. You could also consult with other parents to see what they can do to fix the situation. It may be the amount or the content that causes stress, so the first step is identifying the problem.

- Work with your child to create a schedule for getting homework done on time. You can set a specific period of time for homework, and schedule time for other activities too. Strike a balance between work and play.

- Understanding that your child is stressed about homework doesn’t mean you have to allow them not to try. Let them sit down and work on it as much as they’re able to, and recruit help from the older siblings or a neighbor if possible.

- Check out these resources to help your child with their homework .

The main idea here is to not abolish homework completely, but to review the amount and quality of homework being given out. Stress, depression and lower grades are the last things parents want for their children.

The schools and parents need to work together to find a solution to this obvious problem.

Take the stress test!

Join the Find-a-therapist community and get access to our free stress assessment!

Additional Resources

Online therapy.

Discover a path to emotional well-being with BetterHelp – your partner in convenient and affordable online therapy. With a vast network of 30,000+ licensed therapists, they’re committed to helping you find the one to support your needs. Take advantage of their Free Online Assessment, and connect with a therapist who truly understands you. Begin your journey today.

Relationship Counceling

Whether you’re facing communication challenges, trust issues, or simply seeking to strengthen your connection, ReGain’ s experienced therapists are here to guide you and your partner toward a healthier, happier connection from the comfort of your own space. Get started.

Therapist Directory

Discover the perfect therapist who aligns with your goals and preferences, allowing you to take charge of your mental health. Whether you’re searching for a specialist based on your unique needs, experience level, insurance coverage, budget, or location, our user-friendly platform has you covered. Search here.

About the author

You might also be interested in

Driving Anxiety is Ruining My Life: Strategies to Regain Control

How to Relax on a Plane & Beat Flight Anxiety

5 Grief Counseling Options Near Me And Online in 2024

Disclaimers

Online Therapy, Your Way

Follow us on social media

We may receive a commission if you click on and become a paying customer of a therapy service that we mention.

The information contained in Find A Therapist is general in nature and is not medical advice. Please seek immediate in-person help if you are in a crisis situation.

Therapy Categories

More information

If you are in a life threatening situation – don’t use this site. Call +1 (800) 273-8255 or check these resources to get immediate help.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Academic Stress and Mental Well-Being in College Students: Correlations, Affected Groups, and COVID-19

Georgia barbayannis.

1 Department of Neurology, Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark, NJ, United States

Mahindra Bandari

Xiang zheng.

2 Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark, NJ, United States

Humberto Baquerizo

3 Office for Diversity and Community Engagement, Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark, NJ, United States

Keith W. Pecor

4 Department of Biology, The College of New Jersey, Ewing, NJ, United States

Associated Data

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.