- Help & FAQ

Cognitive Linguistics: Key Topics

- Modern Languages

- English Language and Linguistics

Research output : Book/Report › Book

Publication series

Access to document.

- https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110626438

15 Cognitive Linguistics

Vyvyan Evans, Bangor University

- Published: 05 May 2015

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Cognitive linguistics is a modern school of linguistic thought and practice concerned with investigating the relationships among human language, the mind, and sociophysical (embodied) experience. This chapter presents and evaluates its two primary, theoretical commitments—the generalization commitment and the cognitive commitment —as well as the five theses arising from these that guide cognitive linguistics research: the thesis of embodied cognition; the thesis of encyclopaedic semantics; the symbolic thesis; the thesis that meaning is conceptualization; and the usage-based thesis. The chapter then surveys some of the most influential theoretical approaches within cognitive linguistics, showing how they exemplify and realize the central theses of the cognitive linguistics enterprise.

Introduction

Cognitive linguistics is a modern school of linguistic thought and practice concerned with investigating the relationships among human language, the mind, and sociophysical (embodied) experience. It originated in scholarship that emerged in the 1970s, conducted by a small number of researchers. These include Charles Fillmore (e.g., 1975 , 1978 ), George Lakoff (e.g., 1977 ; Lakoff & Thompson, 1975 ), Ronald Langacker (e.g., 1978) and Leonard Talmy (e.g., 1975 , 1978 ). This research effort was characterized by a rejection of the rationalist zeitgeist in linguistics that held that language is innate ( Chomsky, 1965 ) and represents an encapsulated module of mind ( Chomsky, 1981 ; Fodor, 1983 ).

The early pioneers looked to new findings in cognitive psychology that were then emerging in order to develop an empiricist approach to linguistics. In so doing, they were attempting to reconnect the study of language with the nature of the human mind. As they then saw it, contemporary approaches to the study of language in the Anglo-American tradition, most notably the generative approach to grammar and the Montague approach to semantics had left the discipline of linguistics bankrupt. The study of natural language semantics had been lost amid a highly formal and arcane procedure for identifying truth conditions, and the study of grammar had been reduced to an increasingly abstract architecture that assumed underlying transformations for converting kernel sentences into various surface realizations. By the mid-1970s, theoretical linguistics, especially for Lakoff and Langacker, had lost its way, and a reboot was required.

The strategy adopted was to step back from the complexity of language and look at how the mind works. Findings from psychology had, by the 1970s, provided a reasonably thorough understanding of some of the key elements involved in how the mind perceives the world. Figure-ground segregation, attentional mechanisms, and processes of schema formation and framing were all by now reasonably well understood. And new work on how humans categorize conducted by psychologist Eleanor Rosch (e.g., 1975) , who, like Fillmore, Langacker, Lakoff, and Talmy, was also based on the West Coast of the United States, was in the process of leading to a paradigm shift in the study of categorization and knowledge representation.

What then made this approach a “cognitive” linguistics was that it sought to view language as an outcome of the mind. Hence, understanding new findings relating to the mind could and would inform the study of language.

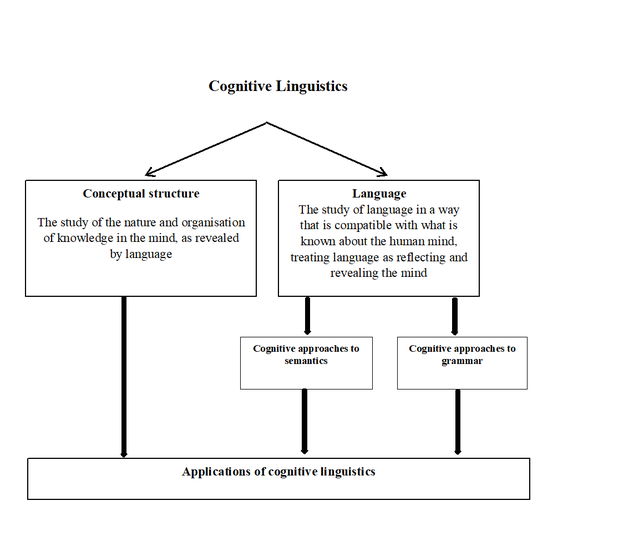

Today, cognitive linguists have highly detailed models for the nature and structure of language, informed by psychological mechanisms and processes. But, by viewing language as an integral part of mind, cognitive linguists have been able to do more than just study language. In addition, cognitive linguistics has developed detailed models of conceptual structure. If language is informed by cognition, then language can be deployed as a window on the mind—so cognitive linguistics contends. Cognitive linguists deploy language as a key methodology for studying knowledge representation. And this has led to cognitive linguists being in the vanguard of the development of an embodied perspective on language and thought— embodiment is today a core perspective shared, in one form or other, by large number of cognitive scientists (see Barsalou, 2009 , for a recent review). Indeed, in recent years, cognitive linguistic theories have become sufficiently sophisticated and detailed to begin making predictions that are testable using a broad range of converging methods from the cognitive and brain sciences.

Perhaps what is most distinctive about cognitive linguistics is that it is not a single articulated theoretical perspective, nor a methodological toolkit. Rather, cognitive linguistics constitutes an enterprise characterized by a number of core commitments and guiding assumptions. It constitutes a loose confederation of theoretical perspectives united by these shared commitments and guiding assumptions.

This chapter is structured as follows. In the next section, I provide an overview of the two primary commitments of cognitive linguistics, its axiomatic base. In the subsequent section I consider the five theses of cognitive linguistics: its postulates. It is subscription to these that give a particular theoretical architecture or approach its distinctive cognitive linguistic character. I then consider the phenomena that cognitive linguists have investigated before addressing some of the most important theoretical and methodological approaches to these phenomena. The chapter then concludes by considering some of the outstanding issues, areas, and questions in cognitive linguistics.

Primary Commitments

Cognitive linguistics is distinct from other movements in linguistics, both formalist and functionalist, in two respects. First, it takes seriously the cognitive underpinnings of language, the so-called cognitive commitment ( Lakoff, 1990 ). Cognitive linguists attempt to describe and model language in the light of convergent evidence from other cognitive and brain sciences. Second, cognitive linguists subscribe to a generalization commitment: a commitment to describing the nature and principles that constitute linguistic knowledge as an outcome of general cognitive abilities (see Lakoff, 1990 )—rather than viewing language as constituting, for instance, a wholly distinct encapsulated module of mind. In this section, I briefly elaborate on these two commitments that lie at the heart of the cognitive linguistics enterprise.

The Cognitive Commitment

The hallmark of cognitive linguistics is the cognitive commitment ( Lakoff, 1990 ). This represents a commitment to providing a characterization of language that accords with what is known about the mind and brain from other disciplines. It is this commitment that makes cognitive linguistics cognitive, and thus it forms an approach that is fundamentally interdisciplinary in nature.

The cognitive commitment holds that principles of linguistic structure should reflect what is known about human cognition from the other cognitive and brain sciences, particularly psychology, artificial intelligence, cognitive neuroscience, and philosophy. Accordingly, proposed models of language and linguistic organization should reflect what is known about the human mind, rather than represent purely aesthetic dictates such as the use of particular kinds of formalisms or economy of representation ( Croft, 1998 ).

The cognitive commitment has a number of concrete ramifications. First, linguistic theories cannot include structures or processes that violate what is known about human cognition. For example, if sequential derivation of syntactic structures violates time constraints provided by actual human language processing, then it must be jettisoned. Second, models that employ established cognitive properties to explain language phenomena are more parsimonious than those that are built from a priori simplicity metrics. For instance, given the amount of progress cognitive scientists have made in the study of categorization, a theory that employs the same mechanisms that are implicated in categorization in other cognitive domains in order to model linguistic structure is simpler than one that hypothesizes a separate system. Finally, the cognitive linguistic researcher is charged with establishing convergent evidence for the cognitive reality of components of any model proposed—whether or not this research is conducted by the cognitive linguist ( Gibbs, 2006 ).

The Generalization Commitment

The Generalization Commitment ( Lakoff, 1990 ) ensures that cognitive linguists attempt to identify general principles that apply to all aspects of human language. This goal reflects the standard commitment in science to seek the broadest generalizations possible. In contrast, some approaches to the study of language often separate what is sometimes termed the “language faculty” into distinct areas such as phonology (sound), semantics (word and sentence meaning), pragmatics (meaning in discourse context), morphology (word structure), syntax (sentence structure), and so on. As a consequence, there is often little basis for generalization across these aspects of language or even for study of their interrelations.

Although cognitive linguists acknowledge that it may often be useful to treat areas such as syntax, semantics, and phonology as being notionally distinct, cognitive linguists do not start with the assumption that the “subsystems” of language are organized in significantly divergent ways. Hence, the generalization commitment represents a commitment to openly investigate how the various aspects of linguistic knowledge emerge from a common set of human cognitive abilities upon which they draw, rather than assuming that they are produced in an encapsulated module of the mind consisting of distinct knowledge types or subsystems.

The generalization commitment has concrete consequences for studies of language. First, cognitive linguistic studies focus on what is common among aspects of language, seeking to reuse successful methods and explanations across these aspects. For instance, just as word meaning displays prototype effects—there are better and worse examples of referents of given words, related in particular ways (see Lakoff, 1987 )—so various studies have applied the same principles to the organization of morphology (e.g., Taylor, 2003 ), syntax (e.g., Goldberg, 1995 , 2006 ), and phonology (e.g., Nathan, 2008 ).

Theses of Cognitive Linguistics

In addition to the two primary commitments of cognitive linguistics, the enterprise also features a number of postulates or theses. These can be captured as follows:

The thesis of embodied cognition

The thesis of encyclopaedic semantics

The symbolic thesis

The thesis that meaning is conceptualization

The usage-based thesis

The Thesis of Embodied Cognition

The thesis of embodied cognition is made of two related parts. The first part holds that the nature of reality is not objectively given but is instead a function of our species-specific and individual embodiment—this is the subthesis of embodied experience (see Lakoff, 1987 ; Lakoff & Johnson, 1980 , 1999 ; Tyler & Evans, 2003 ). Second, our mental representation of reality is grounded in our embodied mental states: mental states captured from our embodied experience—this is the subthesis of grounded cognition (see Barsalou, 2009 ; Evans, 2009 ; Gallese & Lakoff, 2005 ).

The subthesis of embodied experience maintains that, due to the nature of our bodies, including our neuroanatomical architecture, we have a species-specific view of the world. In other words, our construal of “reality” is mediated, in large measure, by the nature of our embodiment. One example of the way in which embodiment affects the nature of experience is in the realm of color. Whereas the human visual system has three kinds of photoreceptors (i.e., color channels), other organisms often have a different number ( Varela, Thompson, & Rosch, 1991 ). For instance, the visual systems of squirrels, rabbits, and possibly cats make use of two color channels, whereas other organisms, including goldfish and pigeons, have four color channels. Having a different range of color channels affects our experience of color in terms of the range of colors accessible to us along the color spectrum. Some organisms can see in the infrared range, such as rattlesnakes, which hunt prey at night and can visually detect the heat given off by other organisms. Humans are unable to see in this range. The nature of our visual apparatus—one aspect of our embodiment—determines the nature and range of our visual experience.

A further consequence of this subthesis is that as individual embodiment within a species varies, so, too, will embodied experience across individual members of the same species. There is now empirical support for the position that humans have distinctive embodied experience due to individual variables such as handedness. That is, whether one is left- or right-handed influences the way in which we experience reality ( Casasanto, 2009 ). In one experiment, for instance, left-handers were more likely to diagram a preferred entity on their left and a dispreferred entity on their right, whereas right-handers placed preferred entities to their right and dispreferred entities to their left. This suggests that part of our conceptual representations for Good and Bad may be influenced by aspects of our individual embodiment.

The fact that our experience is embodied—that is, structured in part by the nature of the bodies we have and by our neurological organization—has consequences for cognition—the subthesis of grounded cognition. In other words, the concepts we have access to, and the nature of the “reality” we think and talk about, are grounded in the multimodal representations that emerge from our embodied experience. More precisely, concepts constitute reactivations of brain states that are recorded during embodied experience. Such reactivations are technically referred to as simulations . (I give an example later relating to the word red that illustrates this notion). These simulations are grounded in multimodal brain states that arise from our action and interaction with our sociophysical environment. Such experiences include sensory-motor and proprioceptive experience, as well as states that arise from our subjective experience of our internal (bodily) environment, including our visceral sense, as well as experiences relating to mental evaluations and states and other subjective experiences, including emotions and affect more generally and experiences relating to temporal experience. From the grounded cognition perspective, the human mind bears the imprint of embodied experience. The embodied experience and grounded cognition perspectives together make up the thesis of embodied cognition as current in cognitive linguistics.

The Thesis of Encyclopaedic Semantics

The thesis of encyclopaedic semantics is also made up of two parts. First, it holds that semantic representations in the linguistic system, what is often referred to as semantic structure , relate to—or interface with—representations in the conceptual system. The precise details as to the nature of the relationship can, and indeed do vary, however, across specific cognitive linguistic theories. For instance, Langacker (e.g., 1987) equates semantic structure with conceptual structure, whereas Evans (2009) , maintains that semantic structure and conceptual structure constitute two distinct representational formats, with semantic structure facilitating access to (some aspects of) conceptual structure.

The second part of the thesis posits the following. The conceptual structure to which semantic structure relates constitutes a vast network of structured knowledge, a semantic potential ( Evans, 2009 ) that is hence encyclopedia-like in nature and scope.

By way of illustration, consider the lexical item red . The precise meaning arising from any given instance of use of the lexical item red is a function of the range of perceptual hues associated with our encyclopedic set of mental representations for red, as constrained by the utterance context in which red is embedded. For instance, consider the following examples:

The school teacher scrawled in red ink all over the pupil’s exercise book.

The red squirrel is almost extinct in the British Isles.

In each of these examples, a distinct reactivation of perceptual experience—a simulation—is prompted for. In the example in (1) the perceptual simulation relates to a vivid red, whereas in (2) the utterance prompts for a brown/dun hue of red. In other words, the meaning of the lexical item red arises from an interaction between linguistic and conceptual representations, such that the most relevant conceptual knowledge is activated upon each instance of use. Examples such as those in (1) and (2) suggest that word meaning does not arise by unpacking a purely linguistic representation. Rather, it involves access to and activation of multimodal brain states. A simulation, then, is a reactivation of part of this nonlinguistic semantic potential.

A consequence of this is that each individual instance of word use potentially leads to a distinct interpretation. For instance, fast means something quite different in fast car, fast driver, fast girl, fast food , and fast lane of the motorway . This follows because any instance of use constitutes a distinct usage-event that may activate a different part of the encyclopedic knowledge potential to which a lexical item facilitates access.

The Symbolic Thesis

The symbolic thesis holds that the fundamental unit of grammar is a form-meaning pairing or symbolic unit . The symbolic unit is variously termed a “symbolic assembly” in Langacker’s cognitive grammar or a “construction” in construction grammar approaches (e.g., Goldberg’s cognitive construction grammar; 1995 , 2006 ). Symbolic units run the full gamut from the fully lexical to the wholly schematic. For instance, examples of symbolic units include morphemes (for example, dis- as in distaste ), whole words (for example, cat, run, tomorrow ), idiomatic expressions such as He kicked the bucket , and sentence-level constructions such as the ditransitive (or double-object) construction, as exemplified by the expression: John baked Sally a cake (see Goldberg, 1995 ).

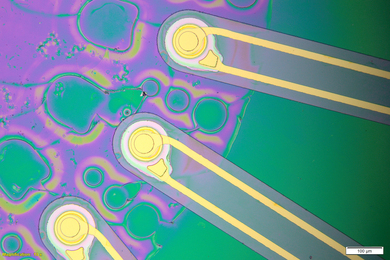

A symbolic unit.

More precisely, the symbolic thesis holds that the mental grammar consists of a form, a semantic unit, and symbolic correspondence that relates the two. This is captured in Figure 15.1 . Hence, the symbolic thesis holds that our mental grammar comprises units that consist of pairings of form and meaning.

One consequence of the symbolic thesis is that the abstract rules posited in the generative grammar tradition, for instance, are excluded from a language user’s mental grammar. Langacker (1987) for instance, posits a content requirement , a principle that asserts that units of grammar must involve actual content: units of semantic structure and phonological form (even if phonologically schematic) that are linked by a symbolic correspondence.

The adoption of the symbolic thesis has a number of important consequences for a model of grammar. Because the basic unit is the symbolic unit, meaning achieves central status in cognitive linguistic approaches to grammar. This follows because the basic grammatical unit is a symbolic unit: form cannot be studied independently of meaning.

The second consequence is that because there is not a principled distinction between the study of semantics and syntax—the study of grammar is the study of the full range of units that make up a language, from the lexical to the grammatical. Cognitive linguists posit a lexicon-grammar continuum ( Croft, 2002 ; Langacker, 1987 ) to capture this perspective. Whereas the grammar of a language is made of symbolic units, symbolic units exhibit qualitative differences in terms of their schematicity. At one extreme are symbolic units that are highly specified in terms of their lexical form and in terms of the richness of their semantic content. Such symbolic units, such as words, lie at the “lexical” end of the lexicon-grammar continuum. At the other end lie highly schematic symbolic units, schematic both in terms of phonological and semantic content. An example of a symbolic unit of this kind is the sentence-level ditransitive construction studied by Goldberg (e.g., 1995) and discussed in more detail later. Lexically unfilled sentence-level syntactic templates such as the ditransitive construction are held to have a schematic form and schematic meaning conventionally associated with them as exemplified in:

Form: SUBJ VERB NP1 NP2

Meaning: X CAUSES Y TO RECEIVE Z

Symbolic units of this sort lie at the “grammatical” endpoint of the lexicon-grammar continuum. Whereas fully “lexical” and “grammatical” symbolic units differ in qualitative terms, they are the same in principle, being symbolic in nature, in the sense described. Moreover, examples such as these are extreme exemplars. A range of symbolic units exist in all languages, and these units occupy various and less extreme points along the continuum.

A third consequence is that symbolic units can be related to one another, both in terms of similarity of form and semantic relatedness. One manifestation of such relationships is in terms of relative schematicity or specificity, such that one symbolic unit can be a more (or less) specific instantiation of another. Cognitive linguists model the relationships between symbolic units in terms of a network, arranged hierarchically and relating to levels of schematicity. This is an issue I return to later when I discuss the usage-based thesis.

Finally, constituency structure—and hence the combinatorial nature of language—is a function of symbolic units becoming integrated or fused in order to create larger grammatical units, with different theorists proposing slightly different mechanisms for how this arises. For instance, Langacker (e.g., 1987) holds that constituency structure emerges from what he terms conceptually dependent (or relational) predications , such as verbs, encoding a schematic slot, termed an elaboration site. The elaboration site is filled by conceptually autonomous (or nominal) predications , such as nouns. In contrast, Goldberg (e.g., 1995) , in her theory of cognitive construction grammar, argues that integration is due to a fusion process that takes place between verb-level slots—that she terms participant roles— and sentence-level argument roles , discussed further later (see Evans, 2009 , for further discussion of these issues).

The Thesis That Meaning Is Conceptualization

Language understanding involves the interaction between semantic structure and conceptual structure as mediated by various linguistic and conceptual mechanisms and processes. In other words, linguistically mediated meaning construction doesn’t simply involve compositionality, in the Fregean sense, whereby words encode meanings that are integrated in monotonic fashion such that the meaning of the whole arises from the sum of the parts (see Evans, 2006 , 2009 , for discussion). Cognitive linguists subscribe to the position that linguistically mediated meaning involves conceptualization (i.e., higher order cognitive processing), some or much of which is nonlinguistic in nature. Hence, the thesis that meaning is conceptualization holds that the way in which symbolic units are combined during language understanding gives rise to a unit of meaning that is nonlinguistic in nature—the notion of a simulation introduced earlier—and relies, in part, on nonlinguistic processes of integration.

There are two notable approaches to meaning construction that have been developed within cognitive linguistics. The first is concerned with the sorts of nonlinguistic mechanisms central to meaning construction that are fundamentally nonlinguistic in nature. Meaning construction processes of this kind have been referred to as backstage cognition (Fauconnier [1985]/1994 , 1997 ). There are two distinct, but closely related theories of backstage cognition: mental spaces theory , developed in two monographs by Gilles Fauconnier ( [1985]/1994 , 1997 ), and conceptual blending theory , developed by Gilles Fauconnier and Mark Turner (2002) . Mental spaces theory is concerned with the nature and creation of mental spaces , small packets of conceptual structure built as we think and talk. Conceptual blending theory is concerned with the integrative mechanisms and networks that operate over collections of mental spaces in order to produce emergent aspects of meaning—meaning that is in some sense novel.

A more recent approach is LCCM theory (Evans, 2006 , 2009 , 2010 , 2013 ), named after the two central constructs in the theory: the lexical concept and the cognitive model . LCCM theory is concerned with the role of linguistic cues and linguistic processes in meaning construction (lexical concepts) and the way in which these lexical concepts facilitate access to nonlinguistic knowledge (cognitive models) in the process of language understanding. Accordingly, because the emphasis is on the nature and the role of linguistic prompts in meaning construction, LCCM theory represents an attempt to provide a front-stage approach to the cognitive mechanisms, and specifically the role of language, in meaning construction.

The Usage-Based Thesis

The usage-based thesis holds that the mental grammar of the language user is formed by the abstraction of symbolic units from situated instances of language use: utterances—specific usage-events involving symbolic units for purposes of signaling local and contextually relevant communicative intentions. An important consequence of adopting the usage-based thesis is that there is no principled distinction between knowledge of language and use of language ( competence and performance , in generative grammar terms) because knowledge emerges from use. From this perspective, knowledge of language is knowledge of how language is used.

Schema-instance relationships.

The symbolic units that come to be stored in the mind of the language user emerge through processes of abstraction and schematization ( Langacker, 2000 ), based on pattern recognition and intention reading abilities (Tomasello, 1999 , 2003 ). Symbolic units thus constitute what might be thought of as mental routines ( Langacker, 1987 ) consisting, as we have seen, of conventional pairings of form and meaning.

One of the consequences of the usage-based thesis is that symbolic units exhibit degrees of entrenchment —the degree to which a symbolic unit is established as a cognitive routine in the mind of the language user. If the language system is a function of language use, then it follows that the relative frequency with which particular words or other kinds of symbolic units are encountered by the speaker will affect the nature of the grammar. That is, symbolic units that are more frequently encountered become more entrenched. Accordingly, the most entrenched symbolic units tend to shape the language system in terms of patterns of use, at the expense of less frequent and thus less well entrenched words or constructions. Hence, the mental grammar, although deriving from language use, also influences language use.

A further consequence of the usage-based thesis is that by virtue of the mental grammar reflecting symbolic units that exist in language use, and employing cognitive abilities such as abstraction in order to extract them from usage, the language system exhibits redundancy. That is, redundancy is to be expected in the mental grammar. As noted earlier, symbolic units are modeled in terms of a network. Redundancy between symbolic units is captured in terms of a hierarchical arrangement of schema-instance relations holding between more schematic and more specific symbolic units. By way of illustration, Figure 15.2 captures the schema-instance relationships that hold between the more abstract [P [NP]] symbolic unit and the more specific instances of this abstract schema, such as [ to me ]. The usage-based thesis predicts that because [P [NP]] is a feature of many (more specific) instances of use, it becomes entrenched in long-term memory along with its more specific instantiations. Moreover, the schema ([P [NP]]) and its instances (e.g., [ to me ]), are stored in related fashion, as illustrated in the figure.

Concerns of Cognitive Linguistics

The received view in language science has been to separate the study of language into distinct subdisciplines, for instance, phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics, pragmatics, and so on. In part, this has reflected the assumption, promulgated by Chomsky (e.g., 1957) , that these types of linguistic knowledge can not only be studied, in practice, as distinct knowledge types, but also are governed by wholly distinct and incommensurable principles.

For reasons discussed in the foregoing sections, cognitive linguists tend not to separate the study of language in such a compartmentalized way. In the most general terms, theoretical approaches that have emerged thus far in the cognitive linguistics enterprise can be said to broadly focus, more or less, on three general areas of enquiry: (1) conceptual structure, (2) linguistic semantics, and (3) grammar. I structure the discussion in this section around these areas.

Conceptual Structure

The human conceptual system is not open to direct investigation. Nevertheless, cognitive linguists maintain that the properties of language allow us to reconstruct the properties of the conceptual system and to build a model of that system. The logic of this claim is as follows. Because language structure and organization reflect various known aspects of cognitive structure, by studying language—which is observable—we thereby gain insight into the nature of the conceptual system. The subbranch of cognitive linguistics that deploys language in order to investigate conceptual structure is often referred to as cognitive semantics .

The Embodied Nature of Conceptual Structure

Given the thesis of embodied cognition discussed earlier, a key area of investigation within cognitive semantics has been directed at investigating conceptual metaphors (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980 , 1999 ). According to this approach, conceptual metaphors give rise to systems of conventional conceptual mappings held in long-term memory. Consider the following example:

The number of shares has gone up.

According to Lakoff and Johnson, examples like this are motivated by a highly productive conceptual metaphor that is also evident in (5):

John got the highest score on the test.

Mortgage rates have fallen.

Inflation is on the way up.

This metaphor appears to relate the domains of quantity and vertical elevation . In other words, we understand greater quantity in terms of increased height and decreased quantity in terms of lesser height. Conceptual metaphor scholars like Lakoff and Johnson argue that this conventional pattern of conceptual mapping is directly grounded in ubiquitous everyday experiences. For example, when we pour a liquid into a glass, there is a simultaneous increase in the height and quantity of the fluid. This is a typical example of the correlation between height and quantity. Similarly, if we put items onto a pile, an increase in height correlates with an increase in quantity. This experiential correlation between height and quantity, which we experience from an early age, has been claimed to motivate the conceptual metaphor more is up , also known as quantity is vertical elevation .

Grammatical Systems

One way of uncovering conceptual structure in language is by investigating the way in which it is encoded in the fabric of language: in grammar. In his research, Talmy (2000) primarily focuses on the nature of the conceptual content that gets encoded by the grammatical system.

Talmy proposes that the grammatical structure is arranged in terms of a limited number of large-scale schematic systems ( Talmy, 2000 ). These allow the grammar of a language to provide a foundational level of schematic meaning, which is essential for conveying richer meaning. For instance, take the following:

Those boy s are paint ing my railing s .

Here, the specifically grammatical elements—the so-called function words—are highlighted in bold. These are elements that convey structural information about a particular scene, rather than detailed content, and which contrast with “content” words. Now, if we remove the content words from the sentence, namely, boy, paint , and railing , we end up with something like the following sentence:

Those somethings are somethinging my somethings.

This represents, as close as we can approximate, what a sentence might look like without content words. But although the meaning provided by this sentence is rather schematic—we don’t know what the “somethings” are, neither subject nor object, nor what the subject is doing to the object, the sentence does convey quite a lot. It tells us the following:

“More than one entity close to the speaker is presently in the process of doing something to more than one entity belonging to the speaker.”

If we exchange the content words for different ones, we can end up with a description of an entirely different situation, but the schematic meaning provided by the function morphemes remains the same:

Those worker s are mend ing the road s .

Talmy’s point is that grammar allows relatively stable information to be conveyed in an economical way. Richer content words are draped across the grammatical structure, thus facilitating communication. Grammar, then, provides the basis for linguistic meaning.

In his work, Talmy has primarily elucidated four schematic systems, although he acknowledges there are likely to be others. These are given in Figure 15.3 .

Schematic systems can be further divided into schematic categories . By way of illustration, I elucidate one schematic category from one schematic system: the configurational system. This schematic system structures the temporal and spatial properties, as conveyed by language, associated with an experiential complex, such as the division of a given scene into parts and participants. Consider the schematic category that Talmy identifies as degree of extension . “Degree of extension” relates to the degree to which matter (space) or action (time) are extended. The schematic category “degree of extension” has three values: a point, a bounded extent, or an unbounded extent.

The schematic systems identified by Talmy.

To make this clear, consider the examples in (10)–(12). These employ grammatical elements in order to specify the degree of extension involved:

Point at + NP point-of-time

The train passed through at [noon].

Bounded extent in + NP extent -of-time

She went through the training circuit in [five minutes flat].

Unbounded extent “ keep—ing ” + “– er and – er ”

The plane kept going higher and higher.

As these examples illustrate, some grammatical elements encode a particular degree of extension. For instance, in (10) the preposition at , together with an NP that encodes a temporal point, encodes a point-like degree of extension. The NP does not achieve this meaning by itself: if we substitute a different preposition for instance, a construction containing the same NP noon can encode a bounded extent (e.g., The train arrives between noon and 1 p.m. ). The punctual nature of the temporal experience in example (10) forms part of the grammatical system and is conveyed in this example by closed-class forms. The nature of the punctual event, that is, the passage of a train through a station rather than, say, the flight of a flock of birds overhead, relates to content drawn from the lexical system (e.g., the selection of the form train versus birds ).

In the example in (11), the preposition in , together with an NP that encodes a bounded extent, encodes a bounded degree of extension. In (12), the grammatical elements keep – ing + – er and – er encode an unbounded degree of extension. This closed-class construction provides a grammatical “skeleton” specialized for encoding a particular value within the schematic category “degree of extension.” The lexical system can add dramatically different content meaning to this frame (e.g., keep singing louder and louder; keep swimming faster and faster; keep getting weaker and weaker ), but the schematic meaning contributed by the structuring system remains constant—in all these examples, time has an unbounded degree of extension.

Conceptual Integration

The conceptual integration perspective is concerned with the study of the “backstage” mechanisms that facilitate meaning construction. Although the processes involved are largely nonlinguistic in nature and serve to integrate units of conceptual structure in producing meaning, language reveals these otherwise unseen operations that facilitate meaning production behind the scenes (Fauconnier, [1985]/1994 , 1997 ; Fauconnier & Turner, 2002 ).

The conceptual integration perspective holds that when we think and talk, humans assemble what are referred to as mental spaces . These are “packets” of conceptual material, assembled “on the fly” for local purposes of language understanding and conceptual processing. Moreover, material from these mental spaces qua conceptual packets can be selectively projected to form a hybrid mental space drawn from a number of so-called input mental spaces. This hybrid mental space is referred to as a blended space , also known as a blend .

To briefly illustrate the process of mental space formation and blending, consider the following joke:

Q. What do you get if you cross a kangaroo with an elephant?

Holes all over Australia!

The conceptual integration perspective holds that, in order to understand and hence “get” the joke, we have to perform conceptual integration across mental spaces and thus construct a blend. Although we have complex bodies of knowledge available to us concerning elephants and kangaroos, including their size, means of locomotion, and their geographical region of abode, all of which gets diffusely activated by the question, the punch-line prompts us to selectively project only specific aspects of our knowledge relating to elephants and kangaroos in order to build a blended space. In the blend, we integrate information relating to the abode and manner of locomotion associated with kangaroos with the size of elephants. The hybrid organism we come up with, which exists only in the blend, which is to say “in” our heads, has the size of an elephant, lives in Australia, and gets about by hopping. Such an organism would surely leave holes all over Australia. The joke is possible only because the operation of blending is a fundamental aspect of how we think. Moreover, blending is revealed by language use; linguistically mediated meaning construction relies on it.

Categorization

Another way in which cognitive linguists have investigated conceptual structure has been to investigate categorization in language. In the 1970s, pioneering research by cognitive psychologist Eleanor Rosch and colleagues revealed that categorization is not an all-or-nothing affair but that many categorization judgments seemed to exhibit typicality effects . For example, when we categorize birds, certain types of bird (like robins or sparrows) are judged as “better” examples of the category than others (like penguins).

George Lakoff (1987) explored some of the consequences of the observations made by Rosch and her colleagues for a theory of conceptual structure as manifested in language. Lakoff observed that linguistic categories appear to exhibit typicality effects in the same way as natural object categories. For instance, when we describe an eligible unmarried man as a bachelor , such an example is a much better exemplar of the category than, say, the Pope or Tarzan.

Lakoff argued that what this reveals is that conceptual structure consists of what he termed idealized cognitive models (ICMs). An ICM is a highly abstract frame that accounts for certain kinds of typicality effects in categorization. For instance, the linguistic category of “bachelor,” as reflected in language use, is understood, Lakoff argued, with respect to a relatively schematic ICM of marriage. The marriage ICM includes the knowledge that bachelors are unmarried adult males and therefore can marry. However, our ICM relating to Catholicism stipulates that the Pope cannot marry. It is because of this mismatch between the marriage ICM—with respect to which bachelor is understood—and the Catholicism ICM—with respect to which the Pope is understood—that this particular typicality effect arises.

Linguistic Semantics

Cognitive linguistic approaches to linguistic semantics have focused on the nature of lexical representation and, more recently, compositional semantics—the linguistic mechanisms whereby semantic structure interfaces with conceptual structure in the construction of meaning. I address representative topics of enquiry here.

The Encyclopedic Nature of Word Meaning

Research into the encyclopedic nature of meaning has mainly focused on the way semantic structure is organized relative to conceptual knowledge structures. One proposal concerning the organization of word meaning is based on the notion of a frame against which word meanings are understood. This idea has been developed in linguistics by Charles Fillmore ( 1975 , 1978 , 1982 , 1985 ). Frames are detailed knowledge structures or schemas emerging from everyday experiences. According to this perspective, knowledge of word meaning is, in part, knowledge of the individual frames with which a word is associated. A theory of frame semantics therefore reveals the rich network of meaning that makes up our knowledge of words.

By way of illustration, consider the verbs rob and steal . On first inspection, it might appear that these verbs both relate to a theft frame, which includes the following roles: thief , target (the person or a place that is robbed), and goods (to be) stolen . However, there is an important difference between the two verbs: whereas rob profiles thief and target , steal profiles thief and goods . The examples in (14) are from Goldberg (1995 , p. 45):

[Jesse] robbed [the rich] (of their money) < thief target goods >

[Jesse] stole [money] (from the rich) < thief target goods >

In other words, whereas both verbs can occur in sentences with all three participants, each verb has different requirements concerning which two participants it requires. This is illustrated by the following examples (although it’s worth observing that (15a) is acceptable in some British English dialects); note that an asterisk preceding a sentence is the convention used in linguistics to denote a sentence as being ungrammatical:

*Jesse robbed the money

*Jesse stole the rich

A related approach is the notion of profile-base organization , developed by Langacker (e.g., 1987) . Langacker argues that a linguistic unit’s profile is the part of its semantic structure upon which that word focuses attention: this part is explicitly mentioned. The aspect of semantic structure that is not in focus but is necessary in order to understand the profile is called the base . For instance, the lexical item hunter profiles a particular participant in an activity in which an animal is pursued with a view to its being killed. The meaning of hunter is only understood in the context of this activity. The hunting process is therefore the base against which the participant hunter is profiled.

It is widely acknowledged in linguistics that words typically have more than one meaning conventionally associated with them (see Evans, 2009 ; Tyler & Evans, 2003 , for discussion). When the meanings are related, this is termed polysemy . By way of illustration, consider these examples for over , adapted from Tyler and Evans (2003) :

The bee is over the flower.

The cat jumped over the wall.

The ball landed over the wall.

I prefer tea over coffee.

The movie is over.

The government handed over power.

Moreover, polysemy appears to be the norm rather than the exception in language. Lakoff (1987) proposed that lexical units like words should be treated as conceptual categories, organized with respect to an ICM. According to this point of view, polysemy arises because distinct senses of a word such as over are linked to a central sense, with each sense being related to one another in a network structured with respect to and radiating out from the central sense or ICM. In this, word senses form a semantic network that can be conceptualized as a radial category . For instance, for many native speakers, the use of over in (16a) is most typical, whereas other senses become increasingly more abstract, as in later examples, such as (16f). This finding has been verified empirically ( Tyler, 2012 ).

Compositional Semantics

A recent approach to linguistic semantics (Evans, 2006 , 2009 , 2010 , 2013 ) attempts to account for variation in word meanings across contexts of use, such as polysemy, but also a wider range of linguistic semantic phenomena including metaphor and metonymy. This approach posits a distinction in the nature of the semantic representations that populate the linguistic and conceptual systems. The semantic representational format of the linguistic system is modeled in terms of the theoretical construct of the lexical concept , whereas the semantic representational format of the conceptual system is modeled in terms of the construct of the cognitive model —notions that give the theory its name: the theory of lexical concepts and cognitive models (or LCCM theory for short).

In LCCM theory, a cognitive model is a composite multimodal knowledge structure grounded in the range of experience types processed by the brain, including sensory-motor experience, proprioception, and subjective experience. In contrast, a lexical concept—the semantic pole of a symbolic unit—consists of a bundle of different types of schematic knowledge encoded in a format that can be directly represented in the time-pressured auditory-manual medium that is manifested by the world’s spoken and signed natural languages.

A key aim of LCCM theory is to provide a programmatic account of the compositional mechanisms that allow language to activate nonlinguistic (conceptual) knowledge in the construction of linguistically mediated meaning. In essence, LCCM theory treats semantic variation in word meaning as a function of interaction between linguistic and conceptual content. The distinctive semantic contribution of a particular word in any given context of use results from the differential activation of the encyclopedic multimodal knowledge structures to which words facilitate access.

In this section, I examine the way language has been modeled by cognitive linguists. In particular, I show that, in slightly different ways, cognitive approaches to grammar reveal how linguistic structure and organization reflects and interacts with aspects of cognition.

The distinction between tr-lm alignment across agent-patient reversal.

Cognitive Grammar

In this section, I briefly consider the way in which cognitive linguistics views language structure and organization as an outcome of generalized conceptual mechanisms. In so doing, I draw on the seminal work of Langacker ( 1987 , 1991 a , 1991 b , 1999 , 2008 ), as exemplified in his theory of cognitive grammar.

In his work, Langacker has developed a model of language that treats linguistic structure and organization as reflecting general cognitive organizational principles. In particular, mechanisms relating to cognitive aspects of attention are claimed to underpin the organization of linguistic structure. Langacker defines attention as being “intrinsically associated with the intensity or energy level of cognitive processes, which translates experientially into greater prominence or salience” ( Langacker, 1987 , p. 115). I briefly consider a theoretical construct, posited in cognitive grammar, which is held to be central to attention in general and that also shows up in linguistic organization. This is the notion of trajector-landmark organization .

This theoretical construct is motivated by an attentional phenomenon concerning the relative prominence assigned to entities involved in a relationship of some sort. For instance, in events involving energy transfer, what Langacker refers to as an action chain (e.g., John started the ball rolling ), one participant typically transfers energy to another entity, thereby affecting it. As such, the affecting participant is more salient.

Langacker maintains that the assignment of relative prominence to entities at the perceptual and cognitive levels is also a fundamental design feature of language. Indeed, he claims that it shows up at the level of the word, phrase, and clause and is therefore fundamental for constituency and hence the ability of symbolic units to be combined with one another in order to form larger units. To illustrate this idea, consider the distinction between the following two utterances:

John ate all the pizza.

All the pizza was eaten by John.

These utterances relate to an action chain in which some activity, namely eating, is performed by John on the pizza so that there is no pizza left. Yet each utterance assigns differential relative prominence to the participants in this action chain, namely John and pizza . In English, and in language in general, the first participant slot in an utterance, commonly referred to as the subject position , is reserved for participants that are most prominent. The participant in a profiled relationship that receives greatest prominence, what Langacker terms focal prominence , is referred to as the trajector (tr). The participant that receives lesser prominence, referred to as secondary prominence, is termed the landmark (lm). The distinction, then, in the utterances above is that in (17) John corresponds to the tr and pizza to the lm, whereas in (18) pizza corresponds to the tr and John to the lm. This distinction is captured by Figure 15.4 . The distinction between tr and lm approximates the more traditional distinction between subject and object. The advantage is that it provides a conceptual basis for the distinction.

The diagrams in Figure 15.4 reveal the following. Although the transfer of energy is still the same across the two utterances, as indicated by the direction of the arrows, the participants are assigned differential prominence across the two utterances. Put another way, the active and passive constructions, as exemplified by the two utterances, in fact encode a distinction in terms of the focal prominence associated with the two participants involved in the relationship being conveyed. This distinction, which is central to the way language encodes the relationship between agents and patients, in fact reflects a more general cognitive mechanism: in distinguishing between the relative prominence paid and assigned to participants in an action chain.

Construction Grammar

I now turn to the way in which cognitive linguistics views language organization as reflecting embodied experience. I do so by considering the theory of cognitive construction grammar developed in the work of Adele Goldberg (e.g., 1995 , 2006 ). In her work, Goldberg has studied sentence-level symbolic units, what she refers to as constructions . In keeping with the symbolic thesis, Goldberg claims that sentences are themselves motivated by sentence-level symbolic units consisting of a schematic meaning and a schematic form. For instance, consider the following example:

John gave Mary the flowers.

Goldberg argues that a sentence such as (19) is motivated by the ditransitive construction. This is essentially a symbolic unit that has the schematic meaning: x causes y to receive z and the form: Subj Verb NP1 NP2. As with many other symbolic units associated with the grammatical system (in the sense of Talmy), the distransitive construction is phonetically implicit. That is, its form consists of a syntactic template that is not lexically filled, but which stipulates the nature and range of the lexical constituents that can be fused with it (see Goldberg, 1995 , for discussion and evidence for positing sentence-level constructions; see also Goldberg, 2006 ; Evans, 2009 ).

A crucial question for Goldberg concerns what motivates the semantics and the form of such sentence-level constructions. That is, what motivates such constructions to emerge in the first place? In keeping with the thesis of embodied cognition, she posits what she terms the scene encoding hypothesis . According to this hypothesis, sentence-level constructions emerge from humanly relevant scenes that are highly recurrent and salient in nature. For instance, on many occasions each day, we experience acts of transfer. Such acts involve three participants: the agent who effects the transfer, the recipient of the act of the transfer, and the entity transferred. In addition, such acts involve a means of transfer. Goldberg holds that the sentence-level construction is motivated by the human need to communicate about this highly salient scene. Indeed, the semantics and the form associated with this construction are uniquely tailored to encoding such humanly relevant scenes. In this way, grammatical organization, Goldberg suggests, reflects fundamental aspects of human embodied experience.

The construction grammar perspective has also been applied cross-linguistically in the work of William Croft (e.g., 2002) . Indeed, based on a wide range of typologically diverse languages, Croft argues that construction grammar provides the most appropriate means of modeling languages from a typological perspective.

Language Learning

In addition to focusing on the nature and structure of language and the way in which it reflects embodied cognition cognitive linguists have also explored how language is learned and acquired. Langacker ( 2000 , 2008 ) proposes that the units that make up an individual’s mental grammar are derived from language use. This takes place by schematization . Schematization is the process whereby structure emerges as the result of the generalization of patterns across instances of language use. For example, a speaker acquiring English will, as the result of frequent exposure, discover recurring words, phrases, and sentences in the utterances he hears, together with the range of meanings associated with those units. Schematization, then, results in representations that are much less detailed than the actual utterances that give rise to them, giving rise to schemas . These are achieved by setting aside points of difference between actual structures, leaving just the points they have in common.

For instance, consider three sentences involving the preposition in :

The puppy is in the box.

The flower is in the vase.

There is a crack in the vase.

In each sentence the “in” relationship is slightly different: whereas a puppy is fully enclosed by the box, the flower is only partially enclosed—in fact, only part of the flower’s stem is in fact “in” the vase. And, in the final example, the crack is not “in” the vase, but “on” the exterior of the vase—albeit enclosed by the vase’s exterior. These distinct meanings arise from context. Yet, common to each is the rather abstract notion of enclosure; it is this commonality that establishes the schema for in. Moreover, the schema for in specifies very little about the nature of the entity that is enclosed, nor much about the entity that does the enclosing. Langacker argues that the units of our mental grammar are nothing more than schemas.

In sum, schematization, a fundamental cognitive process, produces schemas based on utterances that children are exposed to during interaction with adults, older siblings, and so on. These schemas consist of words, idioms, morphemes, or even types of sentence-level constructions that exhibit their own patterns of syntax. In this way, Langacker makes two claims: general cognitive processes are fundamental to grammar, and the emergence of grammar as a system of linguistic knowledge is grounded in language use.

Token frequency effects.

A consequence of Langacker’s usage-based account is that the frequency with which a particular expression is heard has consequences for the resulting mental grammar that the child constructs. And this fits with the recent findings in developmental psycholinguistics (see Tomasello, 2003 , for a review). Indeed, Langacker argues that how frequently an expression occurs in a child’s input determines how well entrenched the expression comes to be in the child’s developing mental grammar.

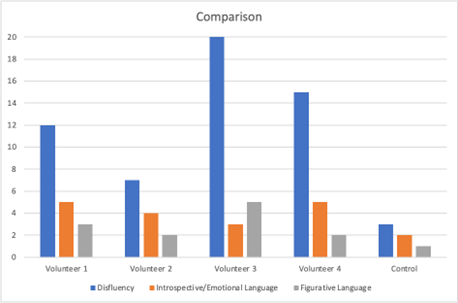

Bybee (2006) has conducted a significant amount of research on the nature of frequency and repetition in language use. She identifies two main types of frequency effect that are relevant for language learning. The first of these concerns the frequency with which specific instances of language are employed: token frequency . For instance, the semantically related nouns falsehood and lie are differentially frequent. Whereas lie is much more commonly used, falsehood is much more restricted in use. This gives rise to differential entrenchment of the mental representations of these forms. This is illustrated in the diagrams in Figure 15.5 . Because greater frequency has been found to lead to earlier and more robust acquisition, this suggests that more frequent instances of given expressions result in their being more strongly entrenched in the mental grammar. This difference between the two expressions is captured by the bolding in the diagrams. The expression lie appears in bold, signaling greater entrenchment; falsehood doesn’t.

The second type of frequency relates not to specific items of language, but to schemas that are formed via the process of schematization described earlier: type frequency . That is, language users form schemas for types of patterns, rather than schemas for tokens of language use. And the degree to which the two sorts of schemas are entrenched in the mind is a function of how frequently they crop up in language use. For instance, the words lapped, stored, wiped, signed , and typed are all instances of the past tense schema [ verb ed ]. The past tense forms flew and blew are instances of the past tense schema [XX ew ]. Because there tend to be fewer utterances involving the distinct lexical items blew and flew (because there are fewer distinct lexical items of this type relative to past tense forms of the –ed type), then it is predicted that the [XX ew ] type schema will be less entrenched in the grammar than the [ verb ed] type schema. This is diagrammed in Figure 15.6 .

Cognitive linguists contend that not only are abstract schemas stored as part of the mental grammar; so too are individual instances of use. And this is a consequence of frequency effects. So, whereas a specific expression such as girls is predictable from the word girl plus the plural schema [ noun- s], because of the high frequency of the plural form girls , this word is likely to be highly entrenched. Hence, girls is stored in our mental grammar along with the singular form girl , as well as the plural schema [ noun- s]. This, however, contrasts with a plural noun like portcullises , which is unlikely to be stored because this expression has low frequency. Instead, this form would be constructed by combination of the plural schema and the singular form portcullis .

According to Bybee (2010) , a further consequence of frequency and repetition in language input is that language is learned as chunks . Bybee explains this as follows:

Type frequency effects.

Chunking is the process behind the formation and use of formulaic or prefabricated sequences of words such as take a break, break a habit, pick and choose and it is also the primary mechanism leading to the formation of constructions and constituent structure. ( Bybee, 2010 , p. 34)

Longitudinal studies by developmental psycholinguists suggests that language is constructed bottom-up, rather than being guided by, for instance, a top-down universal grammar. Tomasello (2003) has persuasively argued that language is learned in an item-based, rather than a rule-based way, with generalizations in terms of syntax being extracted from item-based constructions. The processes proposed by Langacker, Bybee, and others would provide the mechanisms by which this process occurs. In short, an important factor in language acquisition is the frequency with which expressions or “chunks” occur in a child’s input. These chunks are learned, initially, as entire units due to their repetition in language use. And later, schemas are abstracted, which are also, ultimately, an artifact of frequency and repetition.

Finally, cognitive linguists (e.g., Evans, 2009 ; Goldberg, 1995 ; Langacker, 2000 ; Lakoff, 1987 ; Tyler & Evans, 2003 ) argue that linguistic units—constructions—are organized in an individual’s mind as a network, with more abstract schemas being related to more specific instances of language. As a result of the process of entrenchment, schemas result that have different levels of schematicity. This means that some schemas are instances of other, more abstract, schemas. In this way, each of us carries around with us in our head a grammar that has considerable internal hierarchical organization.

Cognitive linguistics is a contemporary approach to meaning, linguistic organization, language learning and change, and conceptual structure. It s also one of the fastest growing and influential perspectives on the nature of language, the mind, and their relationship with sociophysical (embodied) experience in the interdisciplinary project of cognitive science. What provides the enterprise with coherence is its set of primary commitments and central theses. Influential theories within the enterprise have afforded practicing cognitive linguists the analytical and methodological tools with which to investigate the phenomena they address. What makes cognitive linguistics distinctive in the contemporary study of language and mind is its overarching concern with investigating the relationships among human language, the mind, and sociophysical experience. In so doing, cognitive linguistics takes a clearly defined and determinedly embodied perspective on human cognition. And, in this, cognitive linguists have developed a number of influential theories within the interdisciplinary project of cognitive science that self-consciously strive for (and measure themselves against) the requirement to be psychologically plausible.

In terms of methods, cognitive linguistics has now well-established criteria and analytic frameworks for the analysis of linguistic and nonlinguistic phenomena. There is an excellent collection detailing empirical methods in cognitive linguistics ( Gonzalez-Marquez, Mittelberg, Coulson, & Spivey, 2006 ), as well as informed views on methods in general in the literature, for example, with respect to lexical semantics (e.g., Sandra, 1998 ; Sandra & Rice, 1995 ). Since its inception in the mid to late 1970s, cognitive linguistics has matured in terms of theories, methods, and scope. It is now firmly established as a fundamental and impressively broad field of enquiry within linguistics and cognitive science.

Future Directions

As it has developed, cognitive linguistics has inevitably had to grapple with theoretical and methodological problems. Some of the most notable of these remain unresolved. One, for instance, relates to the nature of concepts. For instance, what is the difference, if any, between linguistic versus conceptual meaning? Some cognitive linguists have, at times, appeared to suggest that linguistic meaning is to be equated with conceptual meaning (e.g., Langacker, 1987 , 2008 ). Yet, findings in cognitive linguistics—for instance, the distinction between the closed-class and open-class systems in cognitive representation, as persuasively argued for by Talmy (2000) —would seem to suggest a more clear-cut distinction. Evans ( 2009 , 2013 ) has argued, more recently, for a principled separation between linguistic versus nonlinguistic concepts. Such a separation would seem to be supported by linguistic, behavioral, and neuroscientific findings. Yet some prominent psychologists (e.g., Barsalou et al., 2008 ) appear to have underestimated the complexity of linguistic concepts, denying that language has conceptual import independent of the conceptual system. Others have gone the other way, arguing, along the lines of Evans, for a principled separation between the two knowledge types (see also Taylor & Zwaan, 2009 ; Zwaan, 2004 ). The issue of the relative semantic contribution of linguistic knowledge versus conceptual knowledge to meaning construction is a complex one and at present remains unresolved. Clearly, communicative meaning relies on language as well as nonlinguistic knowledge. As of yet, however, the relative contribution, and the way the two systems interface, is still not fully resolved.

Another outstanding issue relates to the domain of time. A common assumption within cognitive linguistics holds that abstract patterns in thought and language derive from the projection of structure across domains—the notion of conceptual metaphor (e.g., Lakoff & Johnson, 1980 , 1999 ). However, it is not clear, in the domain of time, for instance, that time is created by virtue of the projection of spatial content, as is claimed by Lakoff and Johnson (1999) . Some researchers (Evans, 2004 , 2009 , 2013 ; Langacker, 1987 ; Moore, 2006 ) have argued that time is as basic a domain as space. Moreover, recent interest in reference strategies in the domain of time cast doubt on a straightforward projection of space to time (e.g., Galton, 2011 ; Moore, 2011 ).

In addition, two issues have come to the fore in recent work in cognitive linguistics. These are areas that have not been prominent in earlier research, and both bear special mention. The first is language evolution ( Croft, 2000 ; Sinha, 2009 ; Tomasello, 1999 ). Recent cognitively oriented accounts have applied core insights from cognitive linguistics to the nature of language change and its evolution. The second is the so-called social turn, whereby a cognitive sociolinguistics has begun to be developed ( Harder, 2009 ).

Barsalou, L. ( 2009 ). Grounded cognition. Annual Review of Psychology , 59 , 617–645.

Google Scholar

Barsalou, L. , Santos, A. , Simmons, W. K. , & Wilson, C. ( 2008 ). Language and simulation in conceptual processing. In M. De Vega , A. M. Glenberg , & A. C. Graesser (Eds.), Symbols, embodiment, and meaning (pp. 245–283). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Google Preview

Bybee, J. ( 2006 ). From usage to grammar: The mind’s response to repetition. Language, 82(4), 711–733.

Bybee, J. ( 2010 ). Language, usage and cognition . Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Casasanto, D. ( 2009 ). Embodiment of abstract concepts: Good and bad in right- and left-handers. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General , 138 (3), 351–367.

Chomsky, N. ( 1957 ). Syntactic structures . The Hague, the Netherlands: Mouton.

Chomsky, N. ( 1965 ). Aspects of the theory of syntax . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chomsky, N. ( 1981 ). Lectures on government and binding . Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Foris.

Croft, W. ( 1998 ). Mental representations. Cognitive Linguistics , 9 (2), 151-174.

Croft, W. ( 2000 ). Explaining language change . London, England: Longman.

Croft, W. ( 2002 ). Radical construction grammar: Syntactic theory in typological perspective . Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Evans, V. ( 2004 ). The structure of time. language, meaning and temporal cognition . Amsterdam, the Netherlands: John Benjamins.

Evans, V. ( 2006 ). Lexical concepts, cognitive models and meaning-construction. Cognitive Linguistics , 17 (4), 491–534.

Evans, V. ( 2009 ). How words mean . Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Evans, V. ( 2010 ). Figurative language understanding in LCCM theory. Cognitive Linguistics , 21 (4), 601–662.

Evans, V. ( 2013 ). Language and time: A cognitive linguistics approach . Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Fauconnier, G. ([ 1985 ]/1994). Mental spaces . Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Fauconnier, G. ( 1997 ). Mappings in thought and language . Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Fauconnier, G., & Turner, M. ( 2002 ). The way we think: Conceptual blending and the mind’s hidden complexities. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Fillmore, C. ( 1975 ). An alternative to checklist theories of meaning. In Proceedings of the first annual meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society (pp. 123–131). Berkeley, CA: Berkeley Linguistics Society.

Fillmore, C. ( 1978 ). Scenes-and-frames semantics. In A. Zampolli (Ed.), Linguistic structures processing (pp. 55–82). Amsterdam, the Netherlands: North Holland.

Fillmore, C. ( 1982 ). Frame semantics. In The Linguistic Society of Korea (Eds.), Linguistics in the morning calm (pp. 111–137). Seoul, Korea: Hanshin.

Fillmore, C. ( 1985 ). Frames and the semantics of understanding. Quaderni di Semantica , 6 , 222–254.

Fodor, J. A. ( 1983 ). The modularity of mind . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Gallese, V., & Lakoff, G. ( 2005 ). The brain’s concepts: The role of the sensory- motor system in reason and language. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 22, 455–479.

Galton, A. ( 2011 ). Time flies but space doesn’t: Limits to the spatialization of time. Journal of Pragmatics , 43 , 695–703.

Gibbs, R. W. ( 2006 ). Why cognitive linguists should care more about empirical evidence. In M. Gonzalez-Marquez , I. Mittelberg , S. Coulson, & M. J. Spivey (Eds.), Empirical methods in cognitive linguistics (pp. 2-18). Amsterdam, the Netherlands: John Benjamins.

Goldberg, A. ( 1995 ). Constructions: A construction grammar approach to argument structure . Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press.

Goldberg, A. ( 2006 ). Constructions at work: The nature of generalization in language . Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Gonzalez-Marquez, M. , Mittelberg, I. , Coulson, S. , & Spivey, M. J. (Eds.). ( 2006 ). Empirical methods in cognitive linguistics: Ithaca . Amsterdam, the Netherlands: John Benjamins.

Harder, P. ( 2009 ). Meaning in mind and society . Berlin, Germany: Mouton.

Lakoff, G. ( 1977 ). Linguistic gestalts. Chicago Linguistics Society, 13, 236–287.

Lakoff, G. ( 1987 ). Women, fire and dangerous things: What categories reveal about the mind . Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Lakoff, G. ( 1990 ). The invariance hypothesis: Is abstract reason based on image-schemas? Cognitive Linguistics , 1 (1), 39–74.

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. ( 1980 ). Metaphors we live by . Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. ( 1999 ). Philosophy in the flesh: The embodied mind and its challenge for western thought . New York, NY: Basic Books.

Lakoff, G., & Thompson, H. ( 1975 ). Introduction to cognitive grammar. In Proceedings of the 1st annual meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society (pp. 295–313). Berkeley, CA: Berkeley Linguistics Society.

Langacker, R. W. ( 1978 ). The form and meaning of the English auxiliary. Language, 54, 853–882.

Langacker, R. W. ( 1987 ). Foundations of cognitive grammar (Vol. I). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Langacker, R. W. ( 1991 a ). Foundations of cognitive grammar (Vol. II). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Langaker, R. W. ( 1991 b ). Concept, image, symbol: The cognitive basis of grammar (2nd ed.). Berlin, Germany: Mouton de Gruyter.

Langacker, R. W. ( 1999 ). Grammar and conceptualization . Berlin, Germany: Mouton de Gruyter.

Langacker, R. W. ( 2000 ). A dynamic usage-basked model. In M. Barlow & S. Kemmer (Eds.), Usage-based models of language (pp. 1–64). Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications.

Langacker, R. W. ( 2008 ). Cognitive grammar: A basic introduction . Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Moore, K. ( 2006 ). Space-to-time mappings and temporal concepts. Cognitive Linguistics , 17 , 199–244.

Moore, K. ( 2011 ). Ego-perspective and field-based frames of reference: Temporal meanings of FRONT in Japanese, Wolof, and Aymara. Journal of Pragmatics , 43 , 759–776.

Nathan, G. S. ( 2008 ). Phonology: A cognitive grammar introduction . Amsterdam, the Netherlands: John Benjamins.

Rosch, E. ( 1975 ). Cognitive representations of semantic categories. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General , 104 , 192–233.

Sandra, D. ( 1998 ). What linguists can and can’t tell you about the human mind: A reply to Croft. Cognitive Linguistics , 9 (4), 361–478.

Sandra, D., & Rice, S. ( 1995 ). Network analyses of prepositional meaning: Mirroring whose mind—the linguist’s or the language user’s? Cognitive Linguistics , 6 (1), 89–130.

Sinha, C. ( 2009 ). Language as a biocultural niche and social institution. In V. Evans & S. Pourcel (Eds.), New directions in cognitive linguistics (pp. 289–310). Amsterdam, the Netherlands: John Benjamins.

Talmy, L. ( 1975 ). Semantics and syntax of motion. In J. P. Kimball (Ed.), Syntax and semantics 4 (pp.181–238). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Talmy, L. ( 1978 ). Figure and ground in complex sentences. In J. Greenberg , C. Ferguson , & J. Moravcsik (Eds.), Universals of human language (Vol. 4, pp. 625-649). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Talmy, L. ( 2000 ). Toward a cognitive semantics (2 Vols.). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Taylor, J. ( 2003 ). Linguistic categorization (3rd ed.). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Taylor, L., & Zwaan, R. ( 2009 ). Action in cognition: The case of language. Language and Cognition , 1 (1), 45–58.

Tomasello, M. ( 1999 ). The cultural origins of human cognition . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Tomasello, M. ( 2003 ). Constructing a language . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Tyler, A. ( 2012 ). Cognitive linguistics and second language learning: Theoretical basics and experimental evidence . London, England: Routledge.

Tyler, A., & Evans, V. ( 2003 ). The semantics of English prepositions: Spatial scenes, embodied meaning and cognition . Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Varela, F. , Thompson, E. , & Rosch, E. ( 1991 ). The embodied mind: Cognitive science and human experience . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Zwaan R. ( 2004 ). The immersed experiencer: Toward an embodied theory of language comprehension. The Psychology of Learning and Motivation , 44 , 35–62.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Topics in Cognitive Linguistics

- Preface | p. ix

- I. Toward a coherent and comprehensive linguistic theory

- An overview of cognitive grammar Ronald W. Langacker | p. 3

- A view of linguistic semantics Ronald W. Langacker | p. 49

- The nature of grammatical valence Ronald W. Langacker | p. 91

- A usage-based model Ronald W. Langacker | p. 127

- II. Aspects of a multifaceted research program

- The relation of grammar to cognition Leonard Talmy | p. 165

- Where does prototypicality come from? Dirk Geeraerts | p. 207

- The natural category MEDIUM : An alternative to selection restrictions and similar constructs Bruce Hawkins | p. 231

- Spatial expressions and the plasticity of meaning Annette Herskovits | p. 271

- Contrasting prepositional categories : English and Italian John R. Taylor | p. 299

- The mapping of elements of cognitive space onto grammatical relations : An example from Russian verbal prefixation Laura A. Janda | p. 327

- Conventionalization of cora locationals Eugene H. Casad | p. 345

- The conceptualisation of vertical space in English : The case of tall René Dirven and John R. Taylor | p. 379

- Length, width, and potential passing Claude Vandeloise | p. 403

- On bounding in Lk Fritz Serzisko | p. 429

- A discourse perspective on tense and aspect in standard modern Greek and English Wolf Paprotté | p. 447

- Semantic extensions into the domain of verbal communication Brygida Rudzka-Ostyn | p. 507

- Spatial metaphor in German causative constructions Robert Thomas King | p. 555

- Náhuatl causative/applicatives in cognitive grammar David Tuggy | p. 587

- III. A historical perspective

- Grammatical categories and human conceptualization : Aristotle and the modistae Pierre Swiggers | p. 621

- Cognitive grammar and the history of lexical semantics Dirk Geeraerts | p. 647

- Subject index | p. 695

Cited by 32 other publications

This list is based on CrossRef data as of 17 may 2024. Please note that it may not be complete. Sources presented here have been supplied by the respective publishers. Any errors therein should be reported to them.

Linguistics

Main bic subject, main bisac subject.

Recommended pages

- Undergraduate open days

- Postgraduate open days

- Accommodation

- Information for teachers

- Maps and directions

- Sport and fitness

Cognitive Linguistics and Psycholinguistics