The Ultimate Guide to Qualitative Research - Part 1: The Basics

- Introduction and overview

- What is qualitative research?

- What is qualitative data?

- Examples of qualitative data

- Qualitative vs. quantitative research

- Mixed methods

- Qualitative research preparation

- Theoretical perspective

- Theoretical framework

- Literature reviews

Research question

- Conceptual framework

- Conceptual vs. theoretical framework

Data collection

- Qualitative research methods

- Focus groups

- Observational research

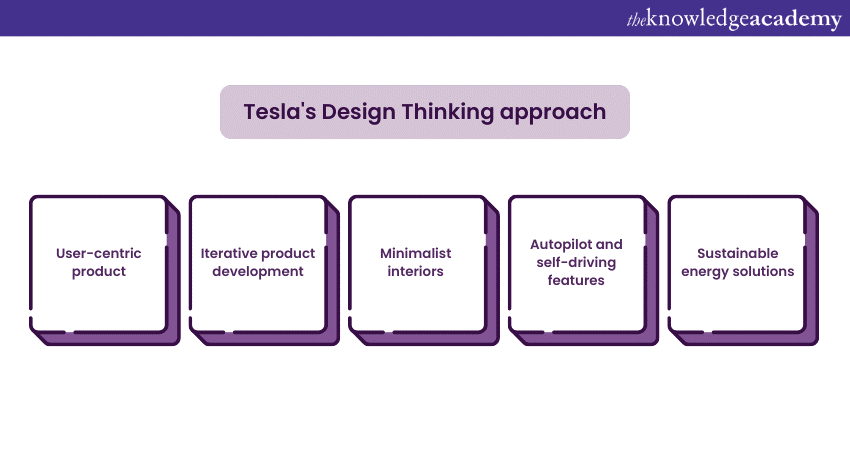

What is a case study?

Applications for case study research, what is a good case study, process of case study design, benefits and limitations of case studies.

- Ethnographical research

- Ethical considerations

- Confidentiality and privacy

- Power dynamics

- Reflexivity

Case studies

Case studies are essential to qualitative research , offering a lens through which researchers can investigate complex phenomena within their real-life contexts. This chapter explores the concept, purpose, applications, examples, and types of case studies and provides guidance on how to conduct case study research effectively.

Whereas quantitative methods look at phenomena at scale, case study research looks at a concept or phenomenon in considerable detail. While analyzing a single case can help understand one perspective regarding the object of research inquiry, analyzing multiple cases can help obtain a more holistic sense of the topic or issue. Let's provide a basic definition of a case study, then explore its characteristics and role in the qualitative research process.

Definition of a case study

A case study in qualitative research is a strategy of inquiry that involves an in-depth investigation of a phenomenon within its real-world context. It provides researchers with the opportunity to acquire an in-depth understanding of intricate details that might not be as apparent or accessible through other methods of research. The specific case or cases being studied can be a single person, group, or organization – demarcating what constitutes a relevant case worth studying depends on the researcher and their research question .

Among qualitative research methods , a case study relies on multiple sources of evidence, such as documents, artifacts, interviews , or observations , to present a complete and nuanced understanding of the phenomenon under investigation. The objective is to illuminate the readers' understanding of the phenomenon beyond its abstract statistical or theoretical explanations.

Characteristics of case studies

Case studies typically possess a number of distinct characteristics that set them apart from other research methods. These characteristics include a focus on holistic description and explanation, flexibility in the design and data collection methods, reliance on multiple sources of evidence, and emphasis on the context in which the phenomenon occurs.

Furthermore, case studies can often involve a longitudinal examination of the case, meaning they study the case over a period of time. These characteristics allow case studies to yield comprehensive, in-depth, and richly contextualized insights about the phenomenon of interest.

The role of case studies in research

Case studies hold a unique position in the broader landscape of research methods aimed at theory development. They are instrumental when the primary research interest is to gain an intensive, detailed understanding of a phenomenon in its real-life context.

In addition, case studies can serve different purposes within research - they can be used for exploratory, descriptive, or explanatory purposes, depending on the research question and objectives. This flexibility and depth make case studies a valuable tool in the toolkit of qualitative researchers.

Remember, a well-conducted case study can offer a rich, insightful contribution to both academic and practical knowledge through theory development or theory verification, thus enhancing our understanding of complex phenomena in their real-world contexts.

What is the purpose of a case study?

Case study research aims for a more comprehensive understanding of phenomena, requiring various research methods to gather information for qualitative analysis . Ultimately, a case study can allow the researcher to gain insight into a particular object of inquiry and develop a theoretical framework relevant to the research inquiry.

Why use case studies in qualitative research?

Using case studies as a research strategy depends mainly on the nature of the research question and the researcher's access to the data.

Conducting case study research provides a level of detail and contextual richness that other research methods might not offer. They are beneficial when there's a need to understand complex social phenomena within their natural contexts.

The explanatory, exploratory, and descriptive roles of case studies

Case studies can take on various roles depending on the research objectives. They can be exploratory when the research aims to discover new phenomena or define new research questions; they are descriptive when the objective is to depict a phenomenon within its context in a detailed manner; and they can be explanatory if the goal is to understand specific relationships within the studied context. Thus, the versatility of case studies allows researchers to approach their topic from different angles, offering multiple ways to uncover and interpret the data .

The impact of case studies on knowledge development

Case studies play a significant role in knowledge development across various disciplines. Analysis of cases provides an avenue for researchers to explore phenomena within their context based on the collected data.

This can result in the production of rich, practical insights that can be instrumental in both theory-building and practice. Case studies allow researchers to delve into the intricacies and complexities of real-life situations, uncovering insights that might otherwise remain hidden.

Types of case studies

In qualitative research , a case study is not a one-size-fits-all approach. Depending on the nature of the research question and the specific objectives of the study, researchers might choose to use different types of case studies. These types differ in their focus, methodology, and the level of detail they provide about the phenomenon under investigation.

Understanding these types is crucial for selecting the most appropriate approach for your research project and effectively achieving your research goals. Let's briefly look at the main types of case studies.

Exploratory case studies

Exploratory case studies are typically conducted to develop a theory or framework around an understudied phenomenon. They can also serve as a precursor to a larger-scale research project. Exploratory case studies are useful when a researcher wants to identify the key issues or questions which can spur more extensive study or be used to develop propositions for further research. These case studies are characterized by flexibility, allowing researchers to explore various aspects of a phenomenon as they emerge, which can also form the foundation for subsequent studies.

Descriptive case studies

Descriptive case studies aim to provide a complete and accurate representation of a phenomenon or event within its context. These case studies are often based on an established theoretical framework, which guides how data is collected and analyzed. The researcher is concerned with describing the phenomenon in detail, as it occurs naturally, without trying to influence or manipulate it.

Explanatory case studies

Explanatory case studies are focused on explanation - they seek to clarify how or why certain phenomena occur. Often used in complex, real-life situations, they can be particularly valuable in clarifying causal relationships among concepts and understanding the interplay between different factors within a specific context.

Intrinsic, instrumental, and collective case studies

These three categories of case studies focus on the nature and purpose of the study. An intrinsic case study is conducted when a researcher has an inherent interest in the case itself. Instrumental case studies are employed when the case is used to provide insight into a particular issue or phenomenon. A collective case study, on the other hand, involves studying multiple cases simultaneously to investigate some general phenomena.

Each type of case study serves a different purpose and has its own strengths and challenges. The selection of the type should be guided by the research question and objectives, as well as the context and constraints of the research.

The flexibility, depth, and contextual richness offered by case studies make this approach an excellent research method for various fields of study. They enable researchers to investigate real-world phenomena within their specific contexts, capturing nuances that other research methods might miss. Across numerous fields, case studies provide valuable insights into complex issues.

Critical information systems research

Case studies provide a detailed understanding of the role and impact of information systems in different contexts. They offer a platform to explore how information systems are designed, implemented, and used and how they interact with various social, economic, and political factors. Case studies in this field often focus on examining the intricate relationship between technology, organizational processes, and user behavior, helping to uncover insights that can inform better system design and implementation.

Health research

Health research is another field where case studies are highly valuable. They offer a way to explore patient experiences, healthcare delivery processes, and the impact of various interventions in a real-world context.

Case studies can provide a deep understanding of a patient's journey, giving insights into the intricacies of disease progression, treatment effects, and the psychosocial aspects of health and illness.

Asthma research studies

Specifically within medical research, studies on asthma often employ case studies to explore the individual and environmental factors that influence asthma development, management, and outcomes. A case study can provide rich, detailed data about individual patients' experiences, from the triggers and symptoms they experience to the effectiveness of various management strategies. This can be crucial for developing patient-centered asthma care approaches.

Other fields

Apart from the fields mentioned, case studies are also extensively used in business and management research, education research, and political sciences, among many others. They provide an opportunity to delve into the intricacies of real-world situations, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of various phenomena.

Case studies, with their depth and contextual focus, offer unique insights across these varied fields. They allow researchers to illuminate the complexities of real-life situations, contributing to both theory and practice.

Whatever field you're in, ATLAS.ti puts your data to work for you

Download a free trial of ATLAS.ti to turn your data into insights.

Understanding the key elements of case study design is crucial for conducting rigorous and impactful case study research. A well-structured design guides the researcher through the process, ensuring that the study is methodologically sound and its findings are reliable and valid. The main elements of case study design include the research question , propositions, units of analysis, and the logic linking the data to the propositions.

The research question is the foundation of any research study. A good research question guides the direction of the study and informs the selection of the case, the methods of collecting data, and the analysis techniques. A well-formulated research question in case study research is typically clear, focused, and complex enough to merit further detailed examination of the relevant case(s).

Propositions

Propositions, though not necessary in every case study, provide a direction by stating what we might expect to find in the data collected. They guide how data is collected and analyzed by helping researchers focus on specific aspects of the case. They are particularly important in explanatory case studies, which seek to understand the relationships among concepts within the studied phenomenon.

Units of analysis

The unit of analysis refers to the case, or the main entity or entities that are being analyzed in the study. In case study research, the unit of analysis can be an individual, a group, an organization, a decision, an event, or even a time period. It's crucial to clearly define the unit of analysis, as it shapes the qualitative data analysis process by allowing the researcher to analyze a particular case and synthesize analysis across multiple case studies to draw conclusions.

Argumentation

This refers to the inferential model that allows researchers to draw conclusions from the data. The researcher needs to ensure that there is a clear link between the data, the propositions (if any), and the conclusions drawn. This argumentation is what enables the researcher to make valid and credible inferences about the phenomenon under study.

Understanding and carefully considering these elements in the design phase of a case study can significantly enhance the quality of the research. It can help ensure that the study is methodologically sound and its findings contribute meaningful insights about the case.

Ready to jumpstart your research with ATLAS.ti?

Conceptualize your research project with our intuitive data analysis interface. Download a free trial today.

Conducting a case study involves several steps, from defining the research question and selecting the case to collecting and analyzing data . This section outlines these key stages, providing a practical guide on how to conduct case study research.

Defining the research question

The first step in case study research is defining a clear, focused research question. This question should guide the entire research process, from case selection to analysis. It's crucial to ensure that the research question is suitable for a case study approach. Typically, such questions are exploratory or descriptive in nature and focus on understanding a phenomenon within its real-life context.

Selecting and defining the case

The selection of the case should be based on the research question and the objectives of the study. It involves choosing a unique example or a set of examples that provide rich, in-depth data about the phenomenon under investigation. After selecting the case, it's crucial to define it clearly, setting the boundaries of the case, including the time period and the specific context.

Previous research can help guide the case study design. When considering a case study, an example of a case could be taken from previous case study research and used to define cases in a new research inquiry. Considering recently published examples can help understand how to select and define cases effectively.

Developing a detailed case study protocol

A case study protocol outlines the procedures and general rules to be followed during the case study. This includes the data collection methods to be used, the sources of data, and the procedures for analysis. Having a detailed case study protocol ensures consistency and reliability in the study.

The protocol should also consider how to work with the people involved in the research context to grant the research team access to collecting data. As mentioned in previous sections of this guide, establishing rapport is an essential component of qualitative research as it shapes the overall potential for collecting and analyzing data.

Collecting data

Gathering data in case study research often involves multiple sources of evidence, including documents, archival records, interviews, observations, and physical artifacts. This allows for a comprehensive understanding of the case. The process for gathering data should be systematic and carefully documented to ensure the reliability and validity of the study.

Analyzing and interpreting data

The next step is analyzing the data. This involves organizing the data , categorizing it into themes or patterns , and interpreting these patterns to answer the research question. The analysis might also involve comparing the findings with prior research or theoretical propositions.

Writing the case study report

The final step is writing the case study report . This should provide a detailed description of the case, the data, the analysis process, and the findings. The report should be clear, organized, and carefully written to ensure that the reader can understand the case and the conclusions drawn from it.

Each of these steps is crucial in ensuring that the case study research is rigorous, reliable, and provides valuable insights about the case.

The type, depth, and quality of data in your study can significantly influence the validity and utility of the study. In case study research, data is usually collected from multiple sources to provide a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the case. This section will outline the various methods of collecting data used in case study research and discuss considerations for ensuring the quality of the data.

Interviews are a common method of gathering data in case study research. They can provide rich, in-depth data about the perspectives, experiences, and interpretations of the individuals involved in the case. Interviews can be structured , semi-structured , or unstructured , depending on the research question and the degree of flexibility needed.

Observations

Observations involve the researcher observing the case in its natural setting, providing first-hand information about the case and its context. Observations can provide data that might not be revealed in interviews or documents, such as non-verbal cues or contextual information.

Documents and artifacts

Documents and archival records provide a valuable source of data in case study research. They can include reports, letters, memos, meeting minutes, email correspondence, and various public and private documents related to the case.

These records can provide historical context, corroborate evidence from other sources, and offer insights into the case that might not be apparent from interviews or observations.

Physical artifacts refer to any physical evidence related to the case, such as tools, products, or physical environments. These artifacts can provide tangible insights into the case, complementing the data gathered from other sources.

Ensuring the quality of data collection

Determining the quality of data in case study research requires careful planning and execution. It's crucial to ensure that the data is reliable, accurate, and relevant to the research question. This involves selecting appropriate methods of collecting data, properly training interviewers or observers, and systematically recording and storing the data. It also includes considering ethical issues related to collecting and handling data, such as obtaining informed consent and ensuring the privacy and confidentiality of the participants.

Data analysis

Analyzing case study research involves making sense of the rich, detailed data to answer the research question. This process can be challenging due to the volume and complexity of case study data. However, a systematic and rigorous approach to analysis can ensure that the findings are credible and meaningful. This section outlines the main steps and considerations in analyzing data in case study research.

Organizing the data

The first step in the analysis is organizing the data. This involves sorting the data into manageable sections, often according to the data source or the theme. This step can also involve transcribing interviews, digitizing physical artifacts, or organizing observational data.

Categorizing and coding the data

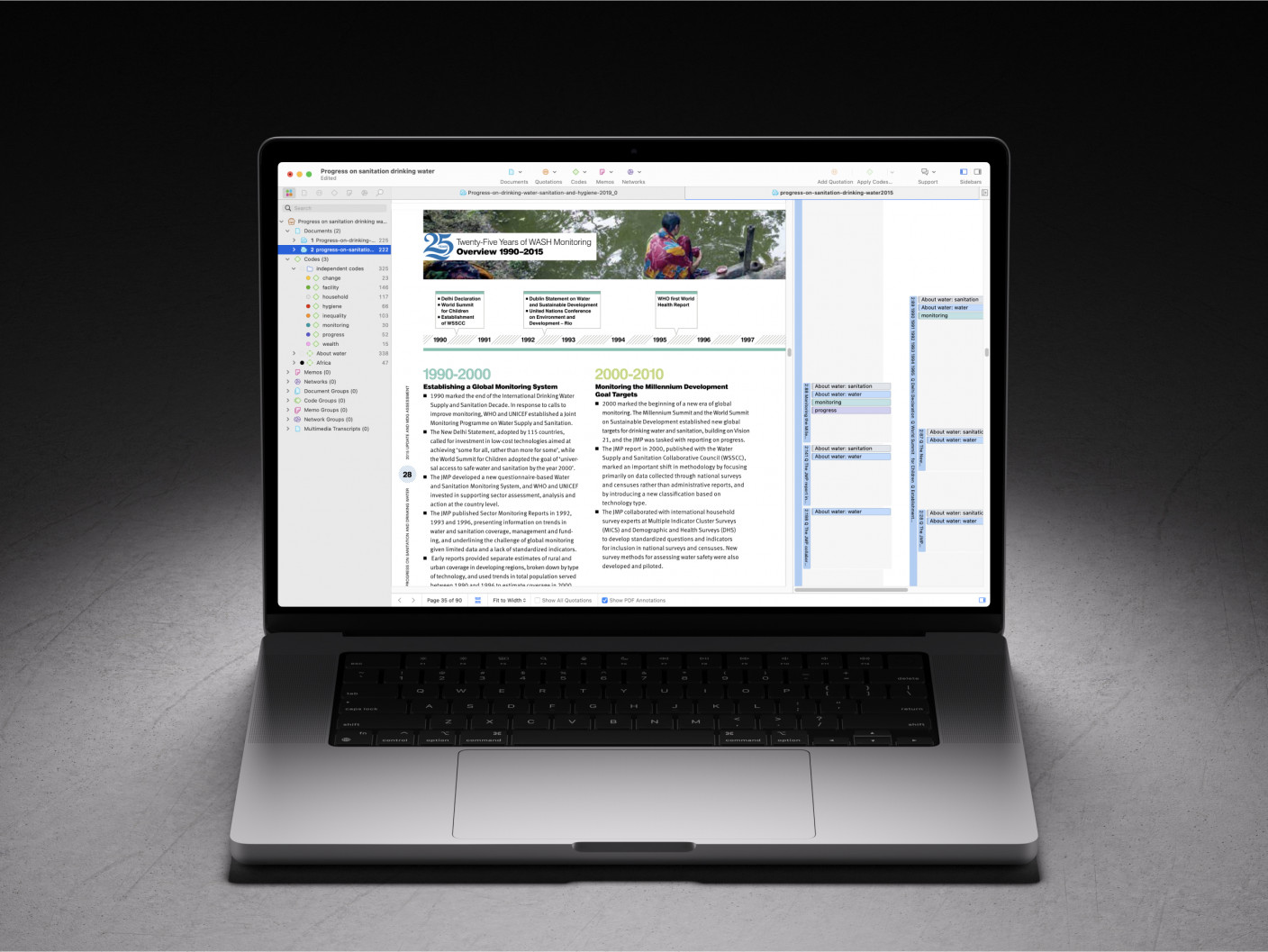

Once the data is organized, the next step is to categorize or code the data. This involves identifying common themes, patterns, or concepts in the data and assigning codes to relevant data segments. Coding can be done manually or with the help of software tools, and in either case, qualitative analysis software can greatly facilitate the entire coding process. Coding helps to reduce the data to a set of themes or categories that can be more easily analyzed.

Identifying patterns and themes

After coding the data, the researcher looks for patterns or themes in the coded data. This involves comparing and contrasting the codes and looking for relationships or patterns among them. The identified patterns and themes should help answer the research question.

Interpreting the data

Once patterns and themes have been identified, the next step is to interpret these findings. This involves explaining what the patterns or themes mean in the context of the research question and the case. This interpretation should be grounded in the data, but it can also involve drawing on theoretical concepts or prior research.

Verification of the data

The last step in the analysis is verification. This involves checking the accuracy and consistency of the analysis process and confirming that the findings are supported by the data. This can involve re-checking the original data, checking the consistency of codes, or seeking feedback from research participants or peers.

Like any research method , case study research has its strengths and limitations. Researchers must be aware of these, as they can influence the design, conduct, and interpretation of the study.

Understanding the strengths and limitations of case study research can also guide researchers in deciding whether this approach is suitable for their research question . This section outlines some of the key strengths and limitations of case study research.

Benefits include the following:

- Rich, detailed data: One of the main strengths of case study research is that it can generate rich, detailed data about the case. This can provide a deep understanding of the case and its context, which can be valuable in exploring complex phenomena.

- Flexibility: Case study research is flexible in terms of design , data collection , and analysis . A sufficient degree of flexibility allows the researcher to adapt the study according to the case and the emerging findings.

- Real-world context: Case study research involves studying the case in its real-world context, which can provide valuable insights into the interplay between the case and its context.

- Multiple sources of evidence: Case study research often involves collecting data from multiple sources , which can enhance the robustness and validity of the findings.

On the other hand, researchers should consider the following limitations:

- Generalizability: A common criticism of case study research is that its findings might not be generalizable to other cases due to the specificity and uniqueness of each case.

- Time and resource intensive: Case study research can be time and resource intensive due to the depth of the investigation and the amount of collected data.

- Complexity of analysis: The rich, detailed data generated in case study research can make analyzing the data challenging.

- Subjectivity: Given the nature of case study research, there may be a higher degree of subjectivity in interpreting the data , so researchers need to reflect on this and transparently convey to audiences how the research was conducted.

Being aware of these strengths and limitations can help researchers design and conduct case study research effectively and interpret and report the findings appropriately.

Ready to analyze your data with ATLAS.ti?

See how our intuitive software can draw key insights from your data with a free trial today.

Limited Time Offer! Save up to 50% Off annual plans.* View Plans

Save up to 50% Now .* View Plans

How To Write A Case Study For Your Design Portfolio

Case studies are an important part of any designer’s portfolio. Read this article to learn everything you need to know to start writing the perfect case study.

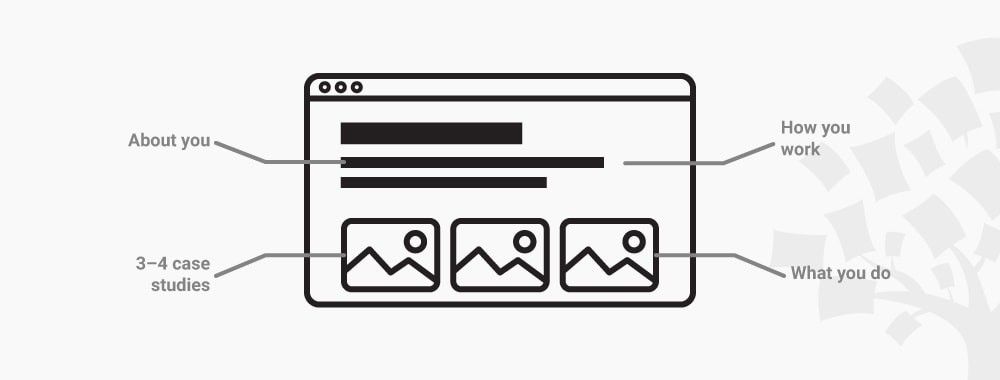

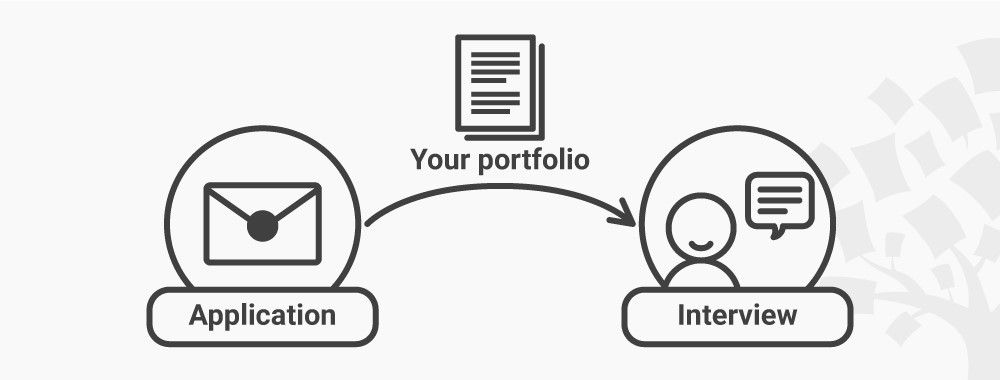

When you’re putting together your online design portfolio , design case studies are a great way to showcase your experience and skills. They also give potential clients a window into how you work.

By showing off what you can do and your design process, case studies can help you land more clients and freelance design jobs —so it can be smart to dedicate an entire section of your online portfolio website to case studies.

Getting Started

So—what is a design case study and how do they fit in your portfolio.

Let’s get some definitions out of the way first, shall we? A design case study is an example of a successful project you’ve completed. The exact case study format can vary greatly depending on your style and preferences, but typically it should outline the problem or assignment, show off your solution, and explain your approach.

One of the best ways to do that is to use a case study design that’s similar to a magazine article or long-form web article with lots of images throughout. When building your case study portfolio, create a new page for each case study. Then create a listing of all your case studies with an image and link to each of them. Now, let’s get into the nitty-gritty of creating these case studies.

Choose Your Best Projects

To make your online portfolio the best it can be , it’s good to be picky when choosing projects for case studies. Since your portfolio will often act as your first impression with potential clients, you only want it to showcase your best work.

If you have a large collection of completed projects, you may have an urge to do a ton of case studies. There’s an argument to be made in favor of that, since it’s a way to show off your extensive experience. In addition, by including a wide variety of case studies, it’s more likely that potential clients will be able to find one that closely relates to their business or upcoming project.

But don’t let your desire to have many case studies on your portfolio lead you to include projects you’re not as proud of. Keep in mind that your potential clients are probably busy people, so you shouldn’t expect them to wade through a massive list of case studies. If you include too many, you can never be sure which ones potential clients will take a look at. As a result, they may miss out on seeing some of your best work.

There’s no hard-and-fast rule for how many case studies to include. It’ll depend on the amount of experience you have, and how many of your completed projects you consider to be among your best work.

Use Your Design Expertise

When creating the case study section of your portfolio, use your designer’s eye to make everything attractive and easily digestible. One important guideline is to choose a layout that will enable you to include copy and image captions throughout.

Don’t have your portfolio up and running yet and not sure which portfolio platform is best for you? Try one that offers a free trial and a variety of cool templates that you can play around with to best showcase your design case studies.

If you don’t provide context for every image you include, it can end up looking like just a (somewhat confusing) image gallery. Case studies are more than that—they should explain everything that went into what you see in the images.

Check Out Other Case Study Examples for Inspiration

Looking at case study examples from successful designers is a great way to get ideas for making your case study portfolio more effective. Pay special attention to the case study design elements, including the layout, the number of images, and amount of copy. This will give you a better idea of how the designer keeps visitors interested in the story behind their projects.

To see some great case study examples, check out these UX designer portfolios .

Try a Case Study Template

There are plenty of resources online that offer free case study templates . These templates can be helpful, as they include questions that’ll help you ensure you’ve included all the important information.

However, most of them are not tailored to designers. These general case study templates don’t have the formatting you’ll want (i.e. the ability to include lots of images). Even the ones that are aimed at designers aren’t as effective as creating your own design. That’s why case study templates are best used as a starting point to get you thinking, or as a checklist to ensure you’ve included everything.

How to Write Case Studies

Maintain your usual tone.

You should write your case studies in the same personal, authentic (yet still professional!) tone of voice as you would when creating the About Me section of your portfolio . Don’t get bogged down in too much technical detail and jargon—that will make your case studies harder to read.

Since your case studies are part of your online portfolio, changing your usual tone can be jarring to the reader.

Instead, everything on your portfolio should have a consistent style. This will help you with creating brand identity . The result will be potential clients will be more connected to your writing and get the feeling that they’re learning what makes you unique.

Provide Some Context

Case studies are more effective when you include some information at the beginning to set the stage. This can include things like the date of the project, name of the client, and what the client does. Providing some context will make the case study more relatable to potential clients.

Also, by including the date of the project, you can highlight how your work has progressed over time. However, you don’t want to bog down this part of the case study with too much information. So it only really needs to be a sentence or two.

Explain the Client’s Expectations

Another important piece of information to include near the beginning of your case study is what the client wanted to accomplish with the project. Consider the guidelines the client provided, and what they would consider a successful outcome.

Did this project involve unique requirements? Did you tailor the design to suit the client’s brand or target audience? Did you have to balance some conflicting requirements?

Establishing the client’s expectations early on in the case study will help you later when you want to explain how you made the project a success.

Document Your Design Process

As you write your case study, you should take a look at your process from an outsider’s point of view. You already know why you made the decisions you did, so it may feel like you’re explaining the obvious. But by explaining your thought process, the case study will highlight all the consideration you put into the design project.

This can include everything from your initial plan to your inspiration, and the changes you made along the way. Basically, you should think about why you took the approach you did, and then explain it.

At this point, consider mentioning any tricks you use to make your design process more efficient . That can include how you managed your time, how you communicated with clients, and how you kept things on track.

Don’t Be Afraid to Mention Challenges

When writing a case study, it can be tempting to only explain the parts that went flawlessly. But you should consider mentioning any challenges that popped up along the way.

Was this project assigned with an extremely tight deadline? Did you have to ask the client to clarify their desired outcome? Were there revisions requested?

If you have any early drafts or drawings from the project saved, it can be a good idea to include them in the case study as well—even if they show that you initially had a very different design in mind than you ended up with. This can show your flexibility and willingness to go in new directions in order to achieve the best results.

Mentioning these challenges is another opportunity to highlight your value as a designer to potential clients. It will give you a chance to explain how you overcame those challenges and made the project a success.

Show How the Project’s Success Was Measured

Case studies are most engaging when they’re written like stories. If you followed the guidelines in this article, you started by explaining the assignment. Next, you described the process you went through when working on it. Now, conclude by going over how you know the project was a success.

This can include mentioning that all of the client’s guidelines were met, and explaining how the design ended up being used.

Check if you still have any emails or communications with the client about their satisfaction with the completed project. This can help put you in the right mindset for hyping up the results. You may even want to include a quote from the client praising your work.

Start Writing Your Case Studies ASAP

Since case studies involve explaining your process, it’s best to do them while the project is still fresh in your mind. That may sound like a pain; once you put a project to bed, you’re probably not looking forward to doing more work on it. But if you get started on your case study right away, it’s easier to remember everything that went into the design project, and why you made the choices you did.

If you’re just starting writing your case studies for projects you’ve completed in the past, don’t worry. It will just require a couple more steps, as you may need to refresh your memory a bit.

Start by taking a look at any emails or assignment documents that show what the client requested. Reviewing those guidelines will make it easier to know what to include in your case study about how you met all of the client’s expectations.

Another helpful resource is preliminary drafts, drawings, or notes you may have saved. Next, go through the completed project and remind yourself of all the work that went into achieving that final design.

Draw Potential Clients to See Your Case Studies

Having a great portfolio is the key to getting hired . By adding some case studies to your design portfolio, you’ll give potential clients insight into how you work, and the value you can offer them.

But it won’t do you any good if they don’t visit your portfolio in the first place! Luckily, there are many ways you can increase your chances. One way is to add a blog to your portfolio , as that will improve your site’s SEO and draw in visitors from search results. Another is to promote your design business using social media . If you’re looking to extend your reach further, consider investing in a Facebook ad campaign , as its likely easier and less expensive than you think.

Once clients lay eyes on all your well-written, beautifully designed case studies, the work will come roaring in!

Want to learn more about creating the perfect design portfolio? 5 Designers Reveal How to Get Clients With Your Portfolio 20 Design Portfolios You Need to See for Inspiration Study: How Does the Quality of Your Portfolio Site Influence Getting Hired?

A Guide to Improving Your Photography Skills

Elevate your photography with our free resource guide. Gain exclusive access to insider tips, tricks, and tools for perfecting your craft, building your online portfolio, and growing your business.

Get the best of Format Magazine delivered to your inbox.

The Art of Archiving: A Comprehensive Guide to Preserve Your Digital Masterpieces

9 Graphic Design Portfolios That Will Inspire Your Inner Artist

Top 20 Best Photography Books for Beginners

Beyond the Rule of Thirds: 30 Creative Techniques for Composition

Inspiring Still Life Photography Portfolios: Crafting a Quality Online Presence

10 Inspiring Examples and Expert Tips for Crafting A Powerful Artist Statement

Get Inspired by 10 Fashion Design Portfolios That Capture the Essence of Contemporary Style

*Offer must be redeemed by May 31st, 2024 at 11:59 p.m. PST. 50% discount off the subscription price of a new annual Pro Plus plan can be applied at checkout with code PROPLUSANNUAL, 38% discount off the price of a new annual Pro plan can be applied with code PROANNUAL, and 20% discount off the price of a new Basic annual plan can be applied with code BASICANNUAL. The discount applies to the first year only. Cannot be combined with any other promotion.

- Privacy Overview

- Strictly Necessary Cookies

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Strictly Necessary Cookie should be enabled at all times so that we can save your preferences for cookie settings.

If you disable this cookie, we will not be able to save your preferences. This means that every time you visit this website you will need to enable or disable cookies again.

How to Design Case Studies for Your Clients

Why Case Study Design Matters

Case studies are more than just feel-good success stories for your client’s audience to read.

They’re powerful tools for showcasing your client’s products and services in the very best possible light.

That’s why every aspect of your client’s case study has to count. Not just the information and the statistics and the positive experience of the case study’s subject, but everything that goes into creating the experience of an individual who is reading this case study and thinking hard about whether they should invest in your client’s products or services.

We’re talking about the copywriting, the illustrations and icons, the infographics, everything!

And that’s where you, as a designer, come into play!

Because if your client’s reader isn’t engaged and captivated by the information they’re seeing, they’re not likely to stick around. The layout and design have got to hit their mark every time for your client’s case studies to have the impact they want them to have.

So, what makes for a great case study or report design?

If you’re scratching your head, then this blog is here to help shine some light. Consider today’s blog your handy guide for creating captivating and strategic case study design that showcases your client’s offerings in the best possible way!

How Does a Case Study Tell a Story?

A case study can be an extremely effective marketing tool, even more so than ads, websites, or product demos.

Why? Because a case study isn’t an ad, a case study involves a real-world situation or problem that a real-world business faced and the journey they went through to resolve it, which naturally makes for a great story.

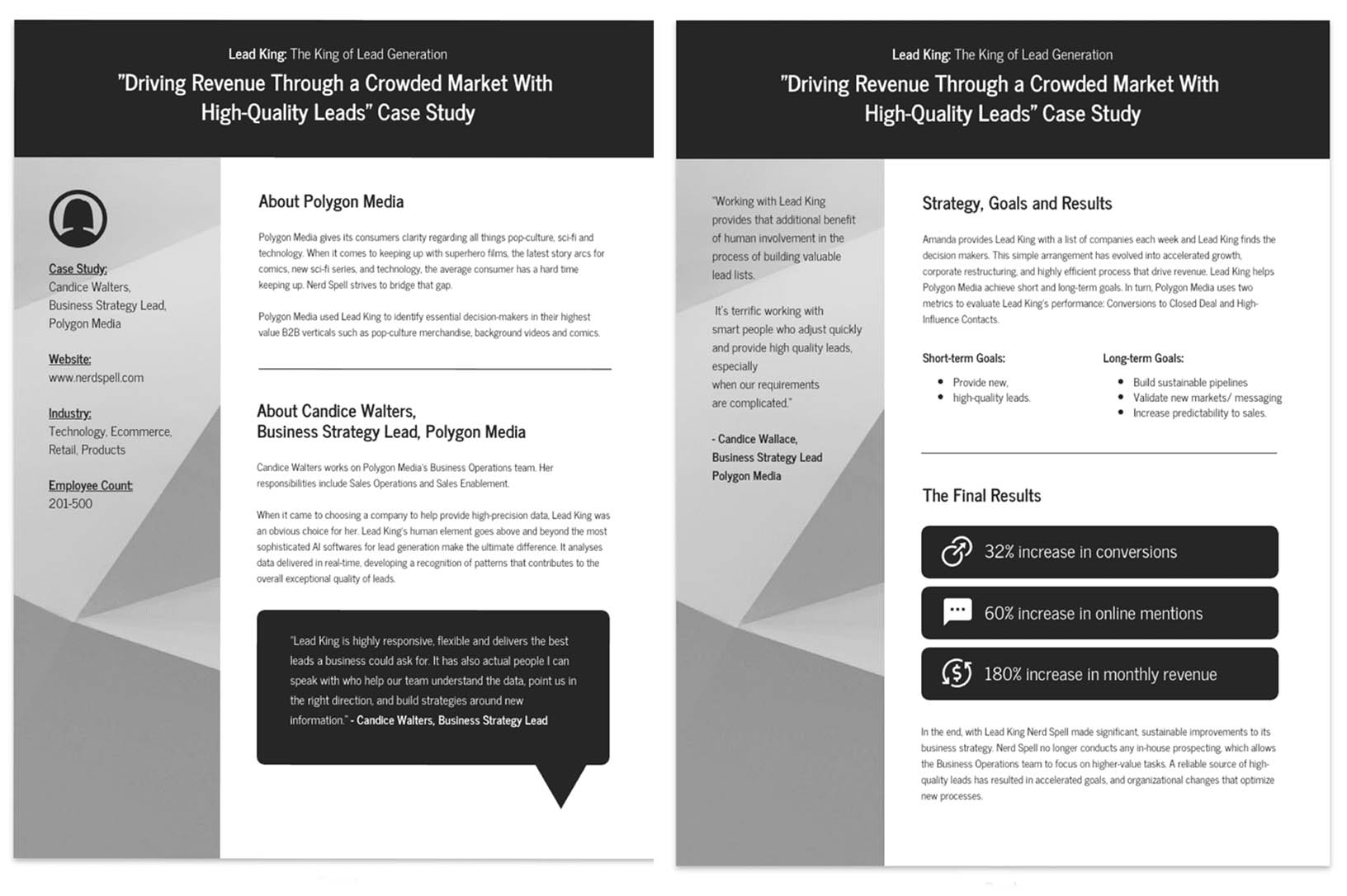

A good case study first introduces the subject, whether it's a business or an individual, and sets the stage for the story by outlining their challenges. It then describes the solution that alleviated this problem (your client’s products and services), the steps it took to implement that solution, and the obstacles it overcame to get there.

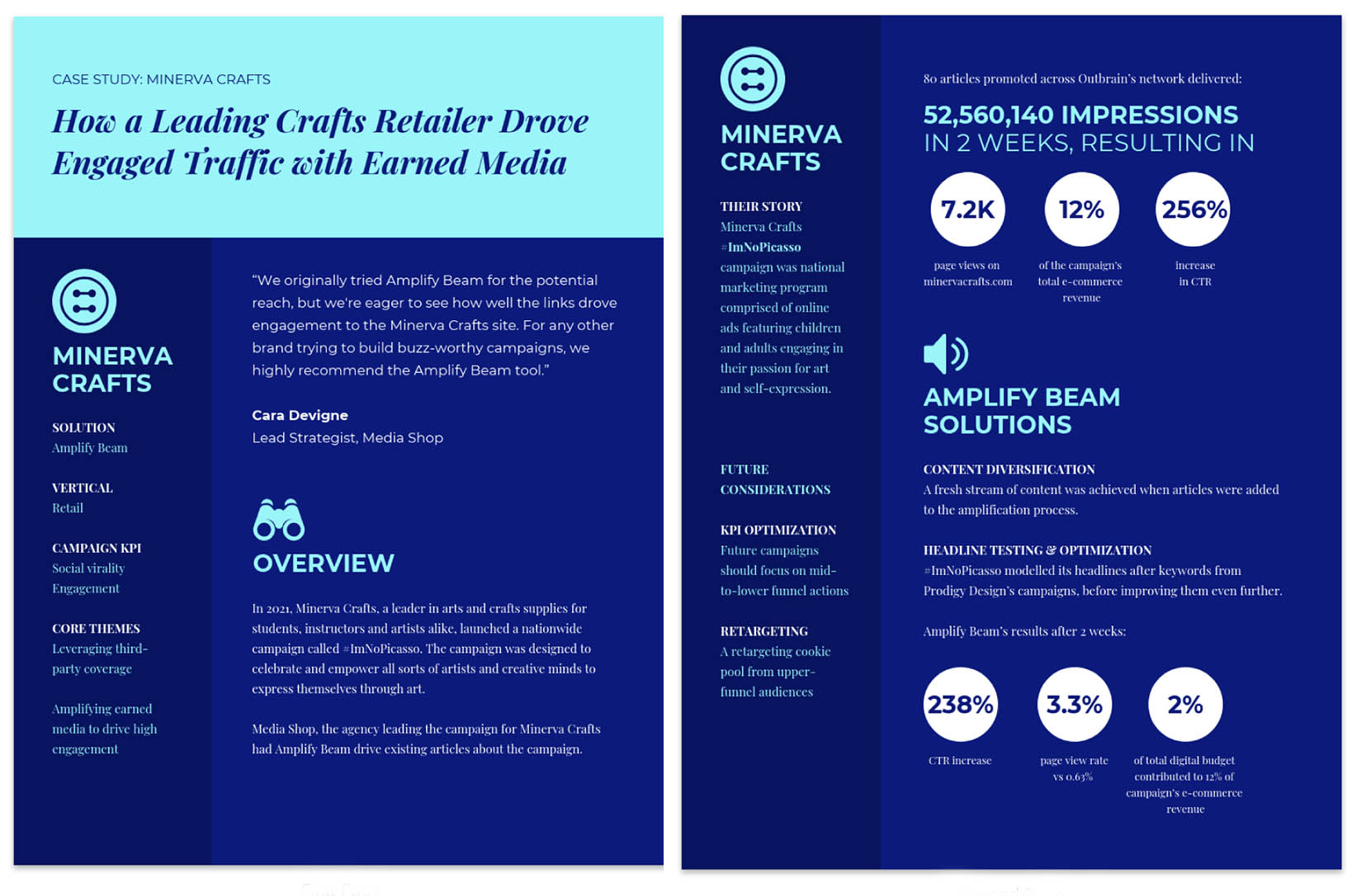

The results should show, through the use of data collection, statistics, etc., how your client’s brand was able to help the subject of the case study in whatever way they needed that help. Depending on the type of case study, the results could be increased brand awareness, increased conversions on an ecommerce site , or a boost in revenue due to optimized marketing strategies.

If presented right, this can be huge for a business! It gives real-life context to the pain points their potential customers have and the data analysis to prove that their products or services can get the job done!

And, as a designer, your role in all this is to make sure that the reader of this case study is getting the full effect of this real-life success story. Sure, the copywriter will handle writing a case study, but your job to take those words and enhance them through images, illustrations, layout, and more to present the narrative in the best way possible and guide the reader from beginning to end.

Designing Case Studies: What You Need to Know

Now that you know why case studies are so important, here is what you need to know to design a top-notch case study for your next client!

1. Understand Your Client’s Needs

It’s always a good idea to make sure that you really understand the message your client is looking to display with their case study.

Look through their other content and familiarize yourself with their brand guide so you can be sure that your design aligns with their messaging and their brand. It’s also good to familiarize yourself with the industry your client is in as well as their audience so that you can be sure your design is keeping them engaged.

2. The Right Graphics for the Story

A successful case study is going to need a good number of images and photos to break up all of that text into manageable bites and better explain complex information.

Roll up your sleeves and crank up Adobe Illustrator, because custom graphics is the way to go here. The style will be up to your client and their brand, but common needs for case studies include:

- Illustrations

- Photo treatments

These graphics are extremely handy for not only breaking up big blocks of text but also highlighting important information and making the content easy to navigate and understand.

Refer to your client’s brand guide to get the style right for the custom illustrations and icons you’ll need for their case study. If they don’t have any guidelines for illustrations and icons, then be a pal and kindly refer them here .

3. The Best Way to Visualize Data

Showcasing data effectively in a case study is absolutely crucial to its success. It doesn’t matter how impressive the numbers are if the reader can’t understand them or get a good grasp on their impact.

So, the data you’re working with, whether it's in the form of charts and graphs, statistics, or whatever else your client asks for must be presented in a way that is clear and straightforward. Use colors, type hierarchy, callouts, or whatever you need to best present your information.

Compelling infographics are a great way to do this. Using your client’s brand guide, you can whip up some infographic design templates to use throughout the case study to effectively show the collected data and what it means.

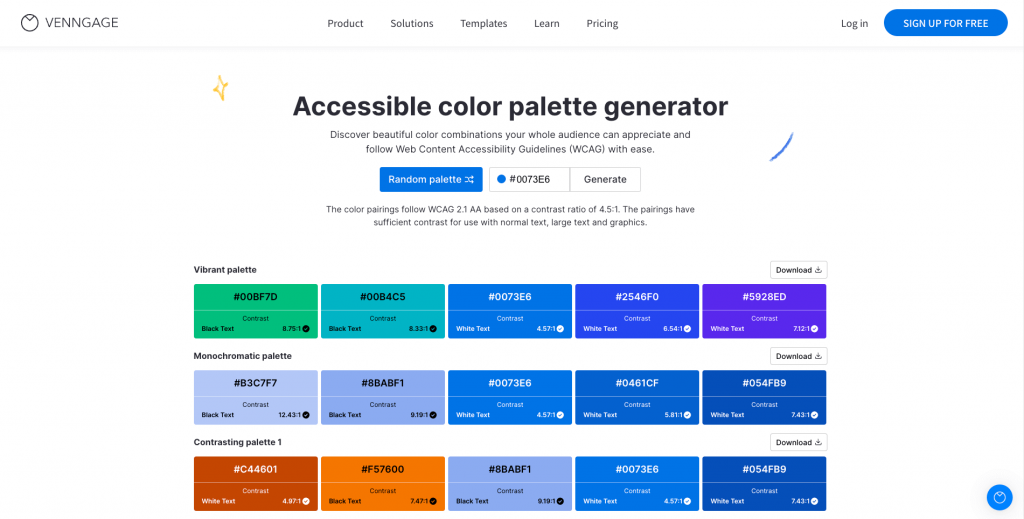

4. A Compelling Color Palette

The right colors not only make a case study visually appealing as readers navigate through the information but can ensure that your client’s case study is on brand, consistent, and a step above the rest of the competition.

Consider also using your colors to strategically highlight key information, such as numbers or data, and to invoke the right emotions as your reader moves through the narrative.

With so much data and information to present, be sure to also use a color palette that works well with your graphics and font. Your headers, captions, and text should be easy to read against whatever color background you’ve chosen.

5. Strategic Layout

The way your case study is laid out is also a crucial component in how readable and user-friendly the final result will be.

Collaborate with the copywriter, if possible, and make sure that the case study has a clear structure. The copy, the data, and your infographics, photos, and images should tell a story: a beginning (before the brand’s product and service), a middle (introducing the product or service), and an end (how the product or service improved the subject’s operations).

Use the power of type hierarchy as well to call out key information, keep text organized, and make the content easier to read.

Conducting a case study involves collecting tons of information, but no matter how much info is presented, you don’t want any portions of your case study to look crowded or busy. Be sure to have enough white space on each page to keep your design looking clean.

Some ways to lay images or photos out neatly are by the use of grids, columns, icons, and by teaming up with the copywriter to insert navigation aids, like clear page numbers, a table of contents, clearly defined sections, an index, or whatever else you think the reader would need to be able to easily follow along.

6. Spotlight Key Information

In addition to using type hierarchy and color scheme to call out the juiciest bits of information, consider also using bullets, lists, quotations, callouts, and even arrows to guide the reader’s eyes to what’s most crucial.

If the specific case study you’re designing for is about complex machinery or products a potential customer might not be familiar with, things might get confusing fast.

Clear it up by adding labels and captions to photos and illustrations to help the reader better understand important technical information and not feel overwhelmed or lost by the data being presented.

Looking for an Outlet for Those Design Skills?

If all of this has you nodding along, then, great! You may already have the design know-how to create visually stunning and easy-to-navigate case studies, reports, or whitepapers.

So, if you’re looking for an outlet for those skills, why not consider joining the Designity community?

Designity is a 100% remote CaaS (creative as a service) platform that is made up of experienced Creative Directors and the top 3% of US-based creative talent, including graphic designers , illustrators, copywriters, video editors, animators, and more.

As part of the Designity community, you’d enjoy competitive pay, a remote work environment, and the freedom to work on your own schedule from wherever you have a good WiFi connection!

You’ll also get to work on a variety of different projects with an even larger variety of clients and industries. And, best of all, you’ll get to team up with that creative talent described earlier and be part of a one-stop shop dream team that creates multiple case studies, whitepapers, brochures, and whatever marketing collateral you want to work on!

Think you have what it takes?

Why not apply today and put your skills to the test?

Share this post:

Creative Directors Make the Difference

How to write a case study — examples, templates, and tools

It’s a marketer’s job to communicate the effectiveness of a product or service to potential and current customers to convince them to buy and keep business moving. One of the best methods for doing this is to share success stories that are relatable to prospects and customers based on their pain points, experiences, and overall needs.

That’s where case studies come in. Case studies are an essential part of a content marketing plan. These in-depth stories of customer experiences are some of the most effective at demonstrating the value of a product or service. Yet many marketers don’t use them, whether because of their regimented formats or the process of customer involvement and approval.

A case study is a powerful tool for showcasing your hard work and the success your customer achieved. But writing a great case study can be difficult if you’ve never done it before or if it’s been a while. This guide will show you how to write an effective case study and provide real-world examples and templates that will keep readers engaged and support your business.

In this article, you’ll learn:

What is a case study?

How to write a case study, case study templates, case study examples, case study tools.

A case study is the detailed story of a customer’s experience with a product or service that demonstrates their success and often includes measurable outcomes. Case studies are used in a range of fields and for various reasons, from business to academic research. They’re especially impactful in marketing as brands work to convince and convert consumers with relatable, real-world stories of actual customer experiences.

The best case studies tell the story of a customer’s success, including the steps they took, the results they achieved, and the support they received from a brand along the way. To write a great case study, you need to:

- Celebrate the customer and make them — not a product or service — the star of the story.

- Craft the story with specific audiences or target segments in mind so that the story of one customer will be viewed as relatable and actionable for another customer.

- Write copy that is easy to read and engaging so that readers will gain the insights and messages intended.

- Follow a standardized format that includes all of the essentials a potential customer would find interesting and useful.

- Support all of the claims for success made in the story with data in the forms of hard numbers and customer statements.

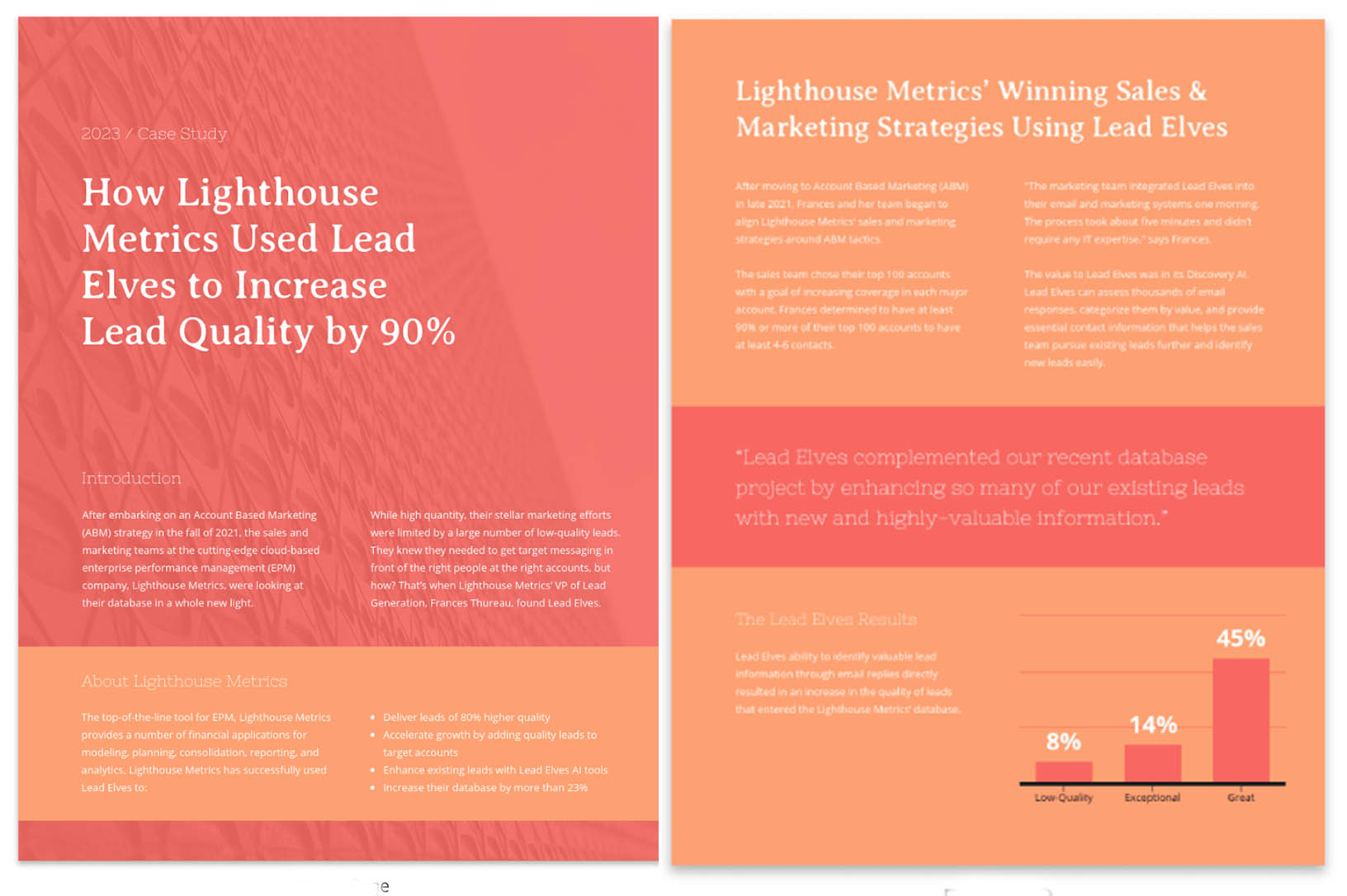

Case studies are a type of review but more in depth, aiming to show — rather than just tell — the positive experiences that customers have with a brand. Notably, 89% of consumers read reviews before deciding to buy, and 79% view case study content as part of their purchasing process. When it comes to B2B sales, 52% of buyers rank case studies as an important part of their evaluation process.

Telling a brand story through the experience of a tried-and-true customer matters. The story is relatable to potential new customers as they imagine themselves in the shoes of the company or individual featured in the case study. Showcasing previous customers can help new ones see themselves engaging with your brand in the ways that are most meaningful to them.

Besides sharing the perspective of another customer, case studies stand out from other content marketing forms because they are based on evidence. Whether pulling from client testimonials or data-driven results, case studies tend to have more impact on new business because the story contains information that is both objective (data) and subjective (customer experience) — and the brand doesn’t sound too self-promotional.

Case studies are unique in that there’s a fairly standardized format for telling a customer’s story. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t room for creativity. It’s all about making sure that teams are clear on the goals for the case study — along with strategies for supporting content and channels — and understanding how the story fits within the framework of the company’s overall marketing goals.

Here are the basic steps to writing a good case study.

1. Identify your goal

Start by defining exactly who your case study will be designed to help. Case studies are about specific instances where a company works with a customer to achieve a goal. Identify which customers are likely to have these goals, as well as other needs the story should cover to appeal to them.

The answer is often found in one of the buyer personas that have been constructed as part of your larger marketing strategy. This can include anything from new leads generated by the marketing team to long-term customers that are being pressed for cross-sell opportunities. In all of these cases, demonstrating value through a relatable customer success story can be part of the solution to conversion.

2. Choose your client or subject

Who you highlight matters. Case studies tie brands together that might otherwise not cross paths. A writer will want to ensure that the highlighted customer aligns with their own company’s brand identity and offerings. Look for a customer with positive name recognition who has had great success with a product or service and is willing to be an advocate.

The client should also match up with the identified target audience. Whichever company or individual is selected should be a reflection of other potential customers who can see themselves in similar circumstances, having the same problems and possible solutions.

Some of the most compelling case studies feature customers who:

- Switch from one product or service to another while naming competitors that missed the mark.

- Experience measurable results that are relatable to others in a specific industry.

- Represent well-known brands and recognizable names that are likely to compel action.

- Advocate for a product or service as a champion and are well-versed in its advantages.

Whoever or whatever customer is selected, marketers must ensure they have the permission of the company involved before getting started. Some brands have strict review and approval procedures for any official marketing or promotional materials that include their name. Acquiring those approvals in advance will prevent any miscommunication or wasted effort if there is an issue with their legal or compliance teams.

3. Conduct research and compile data

Substantiating the claims made in a case study — either by the marketing team or customers themselves — adds validity to the story. To do this, include data and feedback from the client that defines what success looks like. This can be anything from demonstrating return on investment (ROI) to a specific metric the customer was striving to improve. Case studies should prove how an outcome was achieved and show tangible results that indicate to the customer that your solution is the right one.

This step could also include customer interviews. Make sure that the people being interviewed are key stakeholders in the purchase decision or deployment and use of the product or service that is being highlighted. Content writers should work off a set list of questions prepared in advance. It can be helpful to share these with the interviewees beforehand so they have time to consider and craft their responses. One of the best interview tactics to keep in mind is to ask questions where yes and no are not natural answers. This way, your subject will provide more open-ended responses that produce more meaningful content.

4. Choose the right format

There are a number of different ways to format a case study. Depending on what you hope to achieve, one style will be better than another. However, there are some common elements to include, such as:

- An engaging headline

- A subject and customer introduction

- The unique challenge or challenges the customer faced

- The solution the customer used to solve the problem

- The results achieved

- Data and statistics to back up claims of success

- A strong call to action (CTA) to engage with the vendor

It’s also important to note that while case studies are traditionally written as stories, they don’t have to be in a written format. Some companies choose to get more creative with their case studies and produce multimedia content, depending on their audience and objectives. Case study formats can include traditional print stories, interactive web or social content, data-heavy infographics, professionally shot videos, podcasts, and more.

5. Write your case study

We’ll go into more detail later about how exactly to write a case study, including templates and examples. Generally speaking, though, there are a few things to keep in mind when writing your case study.

- Be clear and concise. Readers want to get to the point of the story quickly and easily, and they’ll be looking to see themselves reflected in the story right from the start.

- Provide a big picture. Always make sure to explain who the client is, their goals, and how they achieved success in a short introduction to engage the reader.

- Construct a clear narrative. Stick to the story from the perspective of the customer and what they needed to solve instead of just listing product features or benefits.

- Leverage graphics. Incorporating infographics, charts, and sidebars can be a more engaging and eye-catching way to share key statistics and data in readable ways.

- Offer the right amount of detail. Most case studies are one or two pages with clear sections that a reader can skim to find the information most important to them.

- Include data to support claims. Show real results — both facts and figures and customer quotes — to demonstrate credibility and prove the solution works.

6. Promote your story

Marketers have a number of options for distribution of a freshly minted case study. Many brands choose to publish case studies on their website and post them on social media. This can help support SEO and organic content strategies while also boosting company credibility and trust as visitors see that other businesses have used the product or service.

Marketers are always looking for quality content they can use for lead generation. Consider offering a case study as gated content behind a form on a landing page or as an offer in an email message. One great way to do this is to summarize the content and tease the full story available for download after the user takes an action.

Sales teams can also leverage case studies, so be sure they are aware that the assets exist once they’re published. Especially when it comes to larger B2B sales, companies often ask for examples of similar customer challenges that have been solved.

Now that you’ve learned a bit about case studies and what they should include, you may be wondering how to start creating great customer story content. Here are a couple of templates you can use to structure your case study.

Template 1 — Challenge-solution-result format

- Start with an engaging title. This should be fewer than 70 characters long for SEO best practices. One of the best ways to approach the title is to include the customer’s name and a hint at the challenge they overcame in the end.

- Create an introduction. Lead with an explanation as to who the customer is, the need they had, and the opportunity they found with a specific product or solution. Writers can also suggest the success the customer experienced with the solution they chose.

- Present the challenge. This should be several paragraphs long and explain the problem the customer faced and the issues they were trying to solve. Details should tie into the company’s products and services naturally. This section needs to be the most relatable to the reader so they can picture themselves in a similar situation.

- Share the solution. Explain which product or service offered was the ideal fit for the customer and why. Feel free to delve into their experience setting up, purchasing, and onboarding the solution.

- Explain the results. Demonstrate the impact of the solution they chose by backing up their positive experience with data. Fill in with customer quotes and tangible, measurable results that show the effect of their choice.

- Ask for action. Include a CTA at the end of the case study that invites readers to reach out for more information, try a demo, or learn more — to nurture them further in the marketing pipeline. What you ask of the reader should tie directly into the goals that were established for the case study in the first place.

Template 2 — Data-driven format

- Start with an engaging title. Be sure to include a statistic or data point in the first 70 characters. Again, it’s best to include the customer’s name as part of the title.

- Create an overview. Share the customer’s background and a short version of the challenge they faced. Present the reason a particular product or service was chosen, and feel free to include quotes from the customer about their selection process.

- Present data point 1. Isolate the first metric that the customer used to define success and explain how the product or solution helped to achieve this goal. Provide data points and quotes to substantiate the claim that success was achieved.

- Present data point 2. Isolate the second metric that the customer used to define success and explain what the product or solution did to achieve this goal. Provide data points and quotes to substantiate the claim that success was achieved.

- Present data point 3. Isolate the final metric that the customer used to define success and explain what the product or solution did to achieve this goal. Provide data points and quotes to substantiate the claim that success was achieved.

- Summarize the results. Reiterate the fact that the customer was able to achieve success thanks to a specific product or service. Include quotes and statements that reflect customer satisfaction and suggest they plan to continue using the solution.

- Ask for action. Include a CTA at the end of the case study that asks readers to reach out for more information, try a demo, or learn more — to further nurture them in the marketing pipeline. Again, remember that this is where marketers can look to convert their content into action with the customer.

While templates are helpful, seeing a case study in action can also be a great way to learn. Here are some examples of how Adobe customers have experienced success.

Juniper Networks

One example is the Adobe and Juniper Networks case study , which puts the reader in the customer’s shoes. The beginning of the story quickly orients the reader so that they know exactly who the article is about and what they were trying to achieve. Solutions are outlined in a way that shows Adobe Experience Manager is the best choice and a natural fit for the customer. Along the way, quotes from the client are incorporated to help add validity to the statements. The results in the case study are conveyed with clear evidence of scale and volume using tangible data.

The story of Lenovo’s journey with Adobe is one that spans years of planning, implementation, and rollout. The Lenovo case study does a great job of consolidating all of this into a relatable journey that other enterprise organizations can see themselves taking, despite the project size. This case study also features descriptive headers and compelling visual elements that engage the reader and strengthen the content.

Tata Consulting

When it comes to using data to show customer results, this case study does an excellent job of conveying details and numbers in an easy-to-digest manner. Bullet points at the start break up the content while also helping the reader understand exactly what the case study will be about. Tata Consulting used Adobe to deliver elevated, engaging content experiences for a large telecommunications client of its own — an objective that’s relatable for a lot of companies.

Case studies are a vital tool for any marketing team as they enable you to demonstrate the value of your company’s products and services to others. They help marketers do their job and add credibility to a brand trying to promote its solutions by using the experiences and stories of real customers.

When you’re ready to get started with a case study:

- Think about a few goals you’d like to accomplish with your content.

- Make a list of successful clients that would be strong candidates for a case study.

- Reach out to the client to get their approval and conduct an interview.

- Gather the data to present an engaging and effective customer story.

Adobe can help

There are several Adobe products that can help you craft compelling case studies. Adobe Experience Platform helps you collect data and deliver great customer experiences across every channel. Once you’ve created your case studies, Experience Platform will help you deliver the right information to the right customer at the right time for maximum impact.

To learn more, watch the Adobe Experience Platform story .

Keep in mind that the best case studies are backed by data. That’s where Adobe Real-Time Customer Data Platform and Adobe Analytics come into play. With Real-Time CDP, you can gather the data you need to build a great case study and target specific customers to deliver the content to the right audience at the perfect moment.

Watch the Real-Time CDP overview video to learn more.

Finally, Adobe Analytics turns real-time data into real-time insights. It helps your business collect and synthesize data from multiple platforms to make more informed decisions and create the best case study possible.

Request a demo to learn more about Adobe Analytics.

https://business.adobe.com/blog/perspectives/b2b-ecommerce-10-case-studies-inspire-you

https://business.adobe.com/blog/basics/business-case

https://business.adobe.com/blog/basics/what-is-real-time-analytics

- Reviews / Why join our community?

- For companies

- Frequently asked questions

UX Case Studies

What are ux case studies.

UX case studies are examples of design work which designers include in their portfolio. To give recruiters vital insights, designers tell compelling stories in text and images to show how they handled problems. Such narratives showcase designers’ skills and ways of thinking and maximize their appeal as potential hires.

“ Every great design begins with an even better story.” — Lorinda Mamo, Designer and creative director

- Transcript loading…

Discover why it’s important to tell a story in your case studies.

How to Approach UX Case Studies

Recruiters want candidates who can communicate through designs and explain themselves clearly and appealingly. While skimming UX portfolios , they’ll typically decide within 5 minutes if you’re a fit. So, you should boost your portfolio with 2–3 case studies of your work process containing your best copywriting and captivating visual aids. You persuade recruiters by showing your skillset, thought processes, choices and actions in context through engaging, image-supported stories .

Before selecting a project for a case study, you should get your employer’s/client’s permission – whether you’ve signed a non-disclosure agreement (NDA) or not.

Then, consider Greek philosopher Aristotle’s storytelling elements and work with these in mind when you start building your case studies:

Plot – The career-related aspect of yourself you want to highlight. This should be consistent across your case studies for the exact role. So, if you want to land a job as a UX researcher, focus on the skills relevant to that in your case studies.

Character – Your expertise in applying industry standards and working in teams.

Theme – Goals, motivations and obstacles in your project.

Diction – A friendly, professional tone in jargon-free plain English.

Melody – Your passion—for instance, as a designer, where you prove it’s a life interest as opposed to something you just clock on and off at for a job.

Décor – A balance of engaging text and images.

Spectacle – The plot twist/wow factor—e.g., a surprise discovery. Obviously, you can only include this if you had a surprise discovery in your case study.

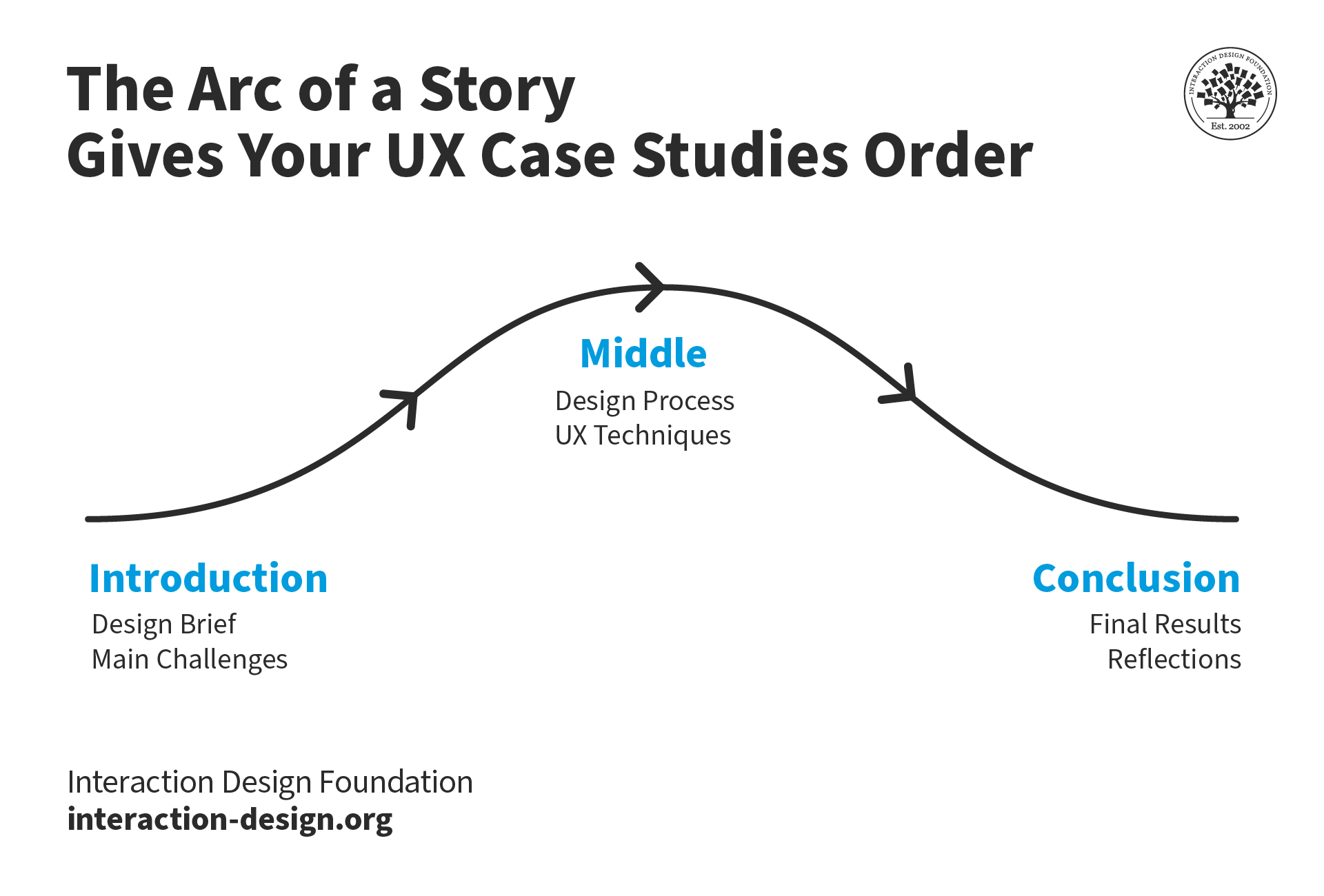

All good stories have a beginning, a middle and an end.

© Interaction Design Foundation. CC BY-NC-SA 3.0.

How to Build UX Case Studies

You want an active story with a beginning, middle and end – never a flat report . So, you’d write, e.g., “We found…”, not “It was found…”. You should anonymize information to protect your employer’s/client’s confidential data (by changing figures to percentages, removing unnecessary details, etc.).

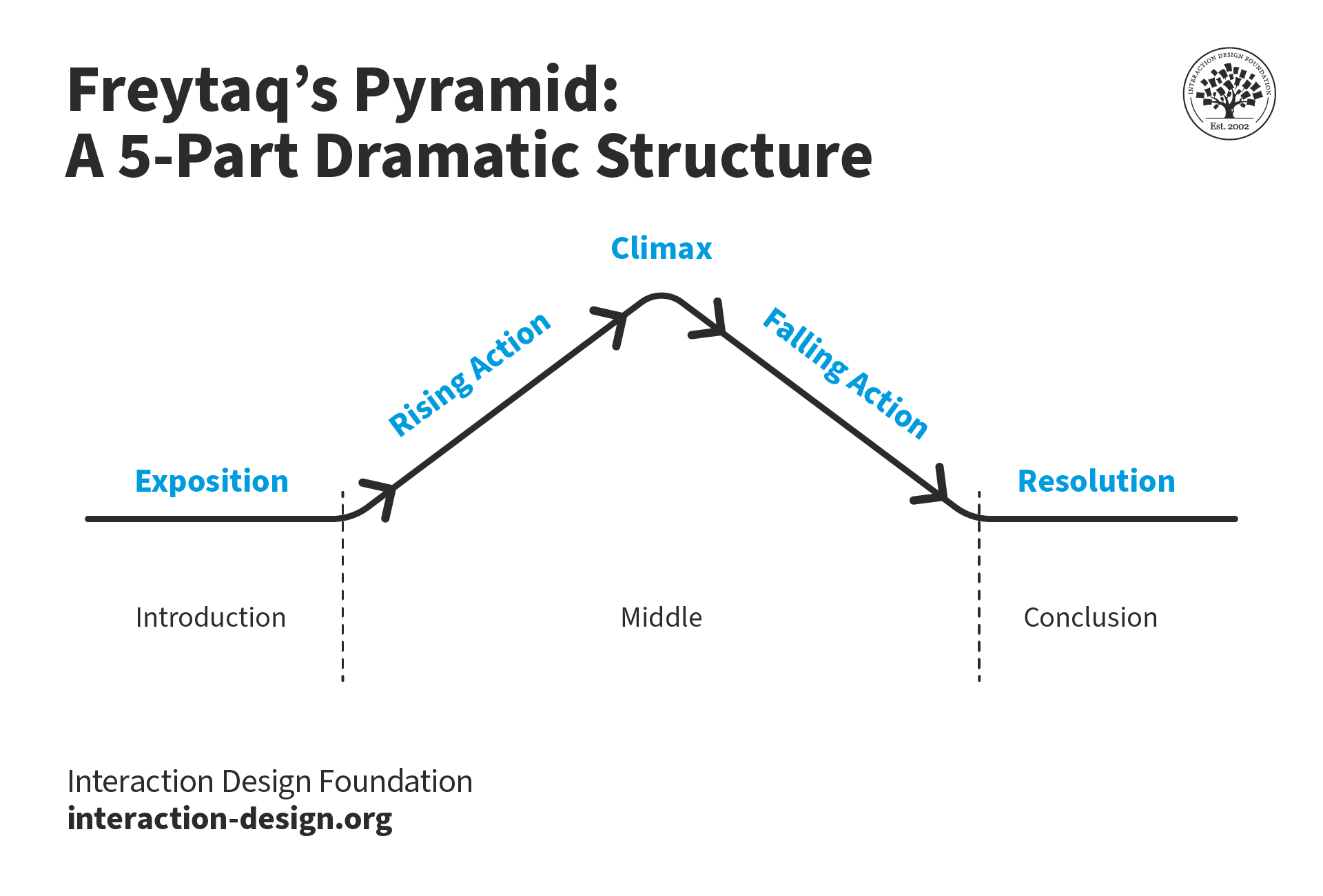

You can use German novelist-playwright Gustav Freytag’s 5-part pyramid :

Exposition – the introduction (4–5 sentences) . Describe your:

Problem statement – Include your motivations and thoughts/feelings about the problem.

Your solution – Outline your approach. Hint at the outcome by describing your deliverables/final output.

Your role – Explain how your professional identity matched the project.

Stages 2–4 form the middle (more than 5 sentences) . Summarize the process and highlight your decisions:

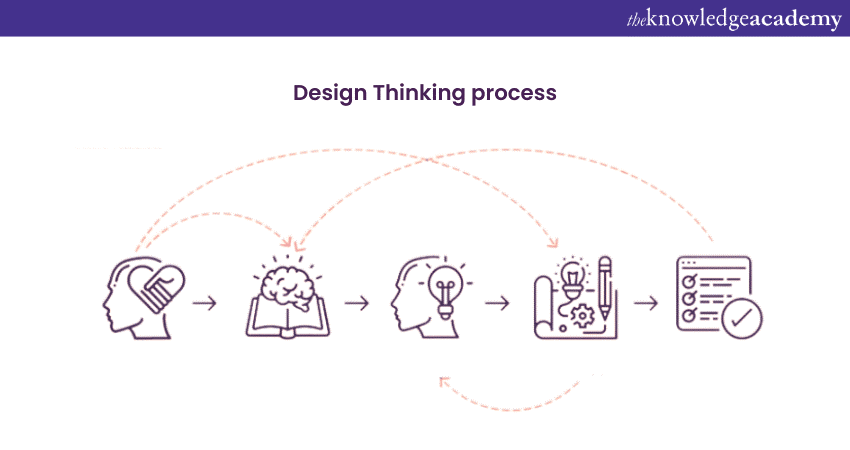

Rising action – Outline some obstacles/constraints (e.g., budget) to build conflict and explain your design process (e.g., design thinking ). Describe how you used, e.g., qualitative research to progress to 1 or 2 key moments of climax.

Climax – Highlight this, your story’s apex, with an intriguing factor (e.g., unexpected challenges). Choose only the most important bits to tighten narrative and build intrigue.

Falling action – Show how you combined your user insights, ideas and decisions to guide your project’s final iterations. Explain how, e.g., usability testing helped you/your team shape the final product.

Stage 5 is the conclusion:

Resolution – (4–5 sentences) . Showcase your end results as how your work achieved its business-oriented goal and what you learned. Refer to the motivations and problems you described earlier to bring your story to an impressive close.

Overall, you should:

Tell a design story that progresses meaningfully and smoothly .

Tighten/rearrange your account into a linear, straightforward narrative .

Reinforce each “what” you introduce with a “how” and “why” .

Support text with the most appropriate visuals (e.g., screenshots of the final product, wireframing , user personas , flowcharts , customer journey maps , Post-it notes from brainstorming ). Use software (e.g., Canva, Illustrator) to customize good-looking visuals that help tell your story .

Balance “I” with “we” to acknowledge team-members’ contributions and shared victories/setbacks.

Make your case study scannable – E.g., Use headings as signposts.

Remove anything that doesn’t help explain your thought process or advance the story .

In the video, Michal Malewicz, Creative Director and CEO of Hype4, has some tips for writing great case studies.

Typical dramatic structure consists of an exposition and resolution with rising action, climax and falling action in between.

Remember, hirers want to quickly spot the value of what you did— e.g., research findings—and feel engaged every step of the way . They’ll evaluate how you might fit their culture. Use the right tone to balance your passion and logic in portraying yourself as a trustworthy team player. Sometimes, you may have to explain why your project didn’t work out ideally. The interaction design process is iterative, so include any follow-up actions you took/would take. Your UX case studies should project the thoughts, feelings and actions that define how you can shape future designs and create value for business.

Learn More about UX Case Studies

Take our UX Portfolio course to see how to craft powerful UX case studies.

UX designer and entrepreneur Sarah Doody offers eye-opening advice about UX case studies .

Learn what can go wrong in UX case studies .

See fine examples of UX case studies .

Questions related to UX Case Studies

A UX case study showcases a designer's process in solving a specific design problem. It includes a problem statement, the designer's role, and the solution approach. The case study details the challenges and methods used to overcome them. It highlights critical decisions and their impact on the project.

The narrative often contains visuals like wireframes or user flowcharts. These elements demonstrate the designer's skills and thought process. The goal is to show potential employers or clients the value the designer can bring to a team or project. This storytelling approach helps the designer stand out in the industry.

To further illustrate this, consider watching this insightful video on the role of UX design in AI projects. It emphasizes the importance of credibility and user trust in technology.

Consider these three detailed UX/UI case studies:

Travel UX & UI Case Study : This case study examines a travel-related project. It emphasizes user experience and interface design. It also provides insights into the practical application of UX/UI design in the travel industry.

HAVEN — UX/UI Case Study : This explores the design of a fictional safety and emergency assistance app, HAVEN. The study highlights user empowerment, interaction, and interface design. It also talks about the importance of accessibility and inclusivity.

UX Case Study — Whiskers : This case study discusses a fictional pet care mobile app, Whiskers. It focuses on the unique needs of pet care users. It shows the user journey, visual design, and integration of community and social features.

Writing a UX case study involves several key steps:

Identify a project you have worked on. Describe the problem you addressed.

Detail your role in the project and the specific actions you took.

Explain your design process, including research , ideation , and user testing.

Highlight key challenges and how you overcame them.

Showcase the final design through visuals like screenshots or prototypes . This video discusses why you should include visuals in your UX case study/portfolio.

Reflect on the project's impact and any lessons learned.

Conclude with the outcomes. Showcase the value you provided.

A well-written case study tells a compelling story of your design journey. It shows your skills and thought process.

A case study in UI/UX is a detailed account of a design project. It describes a designer's process to solve a user interface or user experience problem. The case study includes

The project's background and the problem it addresses.

The designer's role and the steps they took.

Methods used for research and testing.

Challenges faced and how the designer overcame them.

The final design solutions with visual examples.

Results and impact of the design on users or the business.

This case study showcases a designer’s skills, decision-making process, and ability to solve real-world problems.

A UX writing case study focuses on the role of language in user experience design. It includes:

The project's background and the specific language-related challenges.

The UX writer's role and the strategies they employed.

How did they create the text for interfaces, like buttons or error messages?

Research and testing methods used to refine the language.

Challenges encountered and solutions developed.

The final text and its impact on user experience and engagement.

Outcomes that show how the right words improved the product's usability.

You can find professionals with diverse backgrounds in this field and their unique approaches to UX writing. Torrey Podmakersky discusses varied paths into UX writing careers through his video.

Planning a case study for UX involves several steps:

First, select a meaningful project that showcases your skills and problem-solving abilities. Gather all relevant information, including project goals, user research data, and design processes used.

Next, outline the structure of your case study. This should include the problem you addressed, your role, the design process, and the outcomes.

Ensure to detail the challenges faced and how you overcame them.

To strengthen your narrative, incorporate visuals like wireframes, prototypes, and user feedback .

Finally, reflect on the project's impact and what you learned.

This careful planning helps you create a comprehensive and engaging case study.

Presenting a UX research case study involves clear organization and storytelling.

Here are eight guidelines:

Introduction: Start with a brief overview of the project, including its objectives and the key research question.

Background: Provide context about the company, product, or service. Explain why you did the research.

Methodology: Detail the research methods, like surveys, interviews, or usability testing.

Findings: Present the key findings from your research. Use visuals like charts or user quotes to better present the data.

Challenges and Solutions: Discuss any obstacles encountered during the research and how you addressed them.

Implications: Explain how your findings impacted the design or product strategy.

Conclusion: Summarize the main points and reflect on what you learned from the project.

Appendix (if necessary): Include any additional data or materials that support your case study.

UX case studies for beginners demonstrate the fundamentals of user experience design. They include:

A defined problem statement to clarify the user experience issue.

Descriptions of research methods used for understanding user needs and behaviors.

Steps of the design process, showing solution development. The 5 Stages in the Design Thinking Process illustrate these steps in detail.

Visual elements, such as sketches, wireframes, or prototypes, illustrate the design stages.

The final design solution emphasizes its impact on user experience.

Reflections on the project's outcomes and lessons learned.

These case studies guide beginners through the essential steps and considerations in UX design projects. Consider watching this video on How to Write Great Case Studies for Your UX Design Portfolio to improve your case studies.

To learn more about UX case studies, two excellent resources are available:

Article on Structuring a UX Case Study : This insightful article explains how to craft a compelling case study. It emphasizes storytelling and the strategic thinking behind UX design, guided by expert opinions and industry insights.

User Experience: The Beginner's Guide Course by the Interaction Design Foundation: This comprehensive course offers a broad introduction to UX design. It covers UX principles, tools, and methods. The course provides practical exercises and industry-recognized certification. This course is valuable for aspiring designers and professionals transitioning to UX.

These resources provide both theoretical knowledge and practical application in UX design.

Literature on UX Case Studies

Here’s the entire UX literature on UX Case Studies by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Learn more about UX Case Studies

Take a deep dive into UX Case Studies with our course How to Create a UX Portfolio .