Why was the Turner Thesis abandoned by historians

Fredrick Jackson Turner’s thesis of the American frontier defined the study of the American West during the 20th century. In 1893, Turner argued that “American history has been in a large degree the history of the colonization of the Great West. The existence of an area of free land, its continuous recession, and the advance of American settlement westward explain American development.” ( The Frontier in American History , Turner, p. 1.) Jackson believed that westward expansion allowed America to move away from the influence of Europe and gain “independence on American lines.” (Turner, p. 4.) The conquest of the frontier forced Americans to become smart, resourceful, and democratic. By focusing his analysis on people in the periphery, Turner de-emphasized the importance of everyone else. Additionally, many people who lived on the “frontier” were not part of his thesis because they did not fit his model of the democratizing American. The closing of the frontier in 1890 by the Superintendent of the census prompted Turner’s thesis.

Despite its faults, his thesis proved powerful because it succinctly summed up the concerns of Turner and his contemporaries. More importantly, it created an appealing grand narrative for American history. Many Americans were concerned that American freedom would be diminished by the end of colonization of the West. Not only did his thesis give voice to these Americans’ concerns, but it also represented how Americans wanted to see themselves. Unfortunately, the history of the American West became the history of westward expansion and the history of the region of the American West was disregarded. The grand tapestry of western history was essentially ignored. During the mid-twentieth century, most people lost interest in the history of the American West.

Reassessment of Western History

In the last half of the twentieth century, a new wave of western historians rebelled against the Turner thesis and defined themselves by their opposition to it. Historians began to approach the field from different perspectives and investigated the lives of Women, miners, Chicanos, Indians, Asians, and African Americans. Additionally, historians studied regions that would not have been relevant to Turner. In 1987, Patricia Limerick tried to redefine the study of the American West for a new generation of western scholars. In Legacy of Conquest, she attempted to synthesize the scholarship on the West to that point and provide a new approach for re-examining the West. First, she asked historians to think of the America West as a place and not as a movement. Second, she emphasized that the history of the American West was defined by conquest; “[c]onquest forms the historical bedrock of the whole nation, and the American West is a preeminent case study in conquest and its consequences.” (Limerick, p. 22.)

Finally, she asked historians to eliminate the stereotypes from Western history and try to understand the complex relations between the people of the West. Even before Limerick’s manifesto, scholars were re-evaluating the west and its people, and its pace has only quickened. Whether or not scholars agree with Limerick, they have explored new depths of Western American history. While these new works are not easy to categorize, they do fit into some loose categories: gender ( Relations of Rescue by Peggy Pascoe), ethnicity ( The Roots of Dependency by Richard White, and Lewis and Clark Among the Indians by James P. Rhonda), immigration (Impossible Subjects by Ming Ngai), and environmental (Nature’s Metropolis by William Cronon, Rivers of Empire by Donald Worster) history. These are just a few of the topics that have been examined by American West scholars. This paper will examine how these new histories of the American West resemble or diverge from Limerick’s outline.

Defining America or a Threat to America's Moral Standing

Unlike Limerick, Pascoe did not find it necessary to define the west or the frontier. She did not have to because the Protestant missionaries in her story defined it for her. While Turner may have believed that the West was no longer the frontier in 1890, the missionaries certainly would have disagreed. In fact, the rescue missions were placed in the communities that the Victorian Protestant missionary judged to be the least “civilized” parts of America (Lakota Territory, San Francisco’s Chinatown, rough and tumble Denver and Salt Lake City.) Instead of being a story of conquest by Victorian or western morality, it was a story of how that morality was often challenged and its terms were negotiated by culturally different communities. Pascoe’s primary goal in this work was not only to eliminate stereotypes but to challenge the notion that white women civilized the west. While conquest may be a component of other histories, no one group in Pascoe’s story successfully dominated any other.

Changing the Narrative of Native Americans in the West

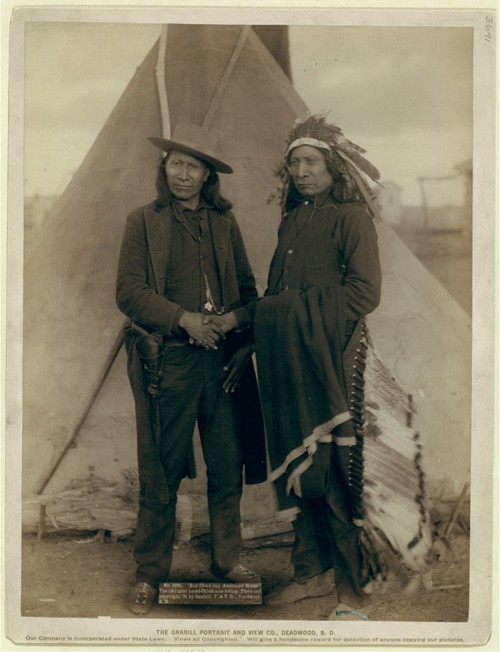

Two books were written before Legacy was published, Lewis and Clark Among the Indians (James Rhonda) and The Roots of Dependency (Richard White) both provide a window into the world of Native Americans. Both books took new approaches to Native American histories. Rhonda’s book looked at the familiar Lewis and Clark expedition but from an entirely different angle. Rhonda described the interactions between the expedition and the various Native American tribes they encountered. White’s book also sought to describe the interactions between the United States and the Choctaws, Pawnees, and Navajos, but he sought to explain why the economies of these tribes broke down after contact. Each of these books covers new ground by addressing the impact of these interactions between the United States and the Native Americans.

Even though White book was published a few years before Legacy, The Roots of Dependency certainly satisfies some of Limerick’s stated goals. Conquest and its consequences are at the heart of White’s story. White details the problems these societies developed after they became dependant on American trade goods and handouts. White also dissuaded anyone from believing that the Native American economies were inefficient. The Choctaws, Pawnees, and Navajos economies were successful. The Choctaws and Pawnees had thriving economies and their food supplies were more than sufficient. While the Navajos were not as successful as the other two tribes, their story was remarkable because they learned how to survive in some of the most inhospitable lands in the American West. These stories exploded the myths that the Native Americans subsistence economies were somehow insufficient.

The Impact of Immigrants to the West

While illegal immigration is not an issue isolated to the history of the American West, the immigrants moved predominantly into California, Texas and the American Southwest. Like Anglo settlers who were attracted to the West for the potential for new life in the nineteenth century, illegal immigrants continued to move in during the twentieth. The illegal immigrants were welcomed, despite their status, because California’s large commercial farms needed inexpensive labor to harvest their crops. Impossible Subjects describes four groups of illegal immigrants (Filipinos, Japanese, Chinese and Mexican braceros) who were created by the United States immigration policy. Ngai specifically examines the role that the government played in defining, controlling and disciplining these groups for their allegedly illegal misconduct.

The Rise of Western Environmental History

Environmental history has become an increasingly important component of the history of the American West. Originally, the American West was seen as an untamed wilderness, but over time that description has changed. Two conceptually different, but nonetheless important books on environmental history discussed the American West and its importance in America. Nature’s Metropolis by William Cronon and Rivers of Empire by Donald Worster each explored the environment and the economy of the American West. Cronon examined the formation of Chicago and the importance of its commodities market for the development of the American West. Alternatively, Worster focuses on the creation of an extensive network of government subsidized dams in the early twentieth century. Rivers of Empire describes that despite the aridity of the natural landscape the American West became home to massive commercial farms and enormous swaths of urban sprawl.

According to Donald Worster’s Rivers of Empire, economics played an equally important role in the economic and environmental development of the Rocky Mountain and Pacific Slope states. Worster argued that the United States wanted to continue creating family farms for Americans in the West. Unfortunately, the aridity of the west made that impossible. The land in the West simply could not be farmed without water. Instead of adapting to the natural environment, the United States government embarked on the largest dam building project in human history. The government built thousands of dams to irrigate millions of acres of land. Unfortunately, the cost of these numerous irrigation projects was enormous. The federal government passed the cost on to the buyers of the land which prevented family farmers from buying it. Therefore, instead of family farms, massive commercial farms were created. The only people who could afford to buy the land were wealthy citizens. The massive irrigation also permitted the creation of cities which never would have been possible without it. Worster argues that the ensuing ecological damage to the West has been extraordinary. The natural environment throughout the region was dramatically altered. The west is now the home of oversized commercial farms, artificial reservoirs which stretch for hundreds of miles, rivers that run only on command and sprawling cities which depend on irrigation.

Each of these books demonstrates that the Turner thesis no longer holds a predominant position in the scholarship of the American West. The history of the American West has been revitalized by its demise. While westward expansion plays an important role in the history of the United States, it did not define the west. Turner’s thesis was fundamentally undermined because it did not provide an accurate description of how the West was peopled. The nineteenth century of the west is not composed primarily of family farmers. Instead, it is a story of a region peopled by a diverse group of people: Native Americans, Asians, Chicanos, Anglos, African Americans, women, merchants, immigrants, prostitutes, swindlers, doctors, lawyers, farmers are just a few of the characters who inhabit western history.

Suggested Readings

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

Frederick Jackson Turner

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Wisconsin Life - Frederick Jackson Turner and the History of the American West

- Weber State University - Biography of Frederick Jackson Turner

- National Humanities Center - The Significance of the Frontier in American History 1893

- Frederick Jackson Turner - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

Frederick Jackson Turner (born November 14, 1861, Portage , Wisconsin , U.S.—died March 14, 1932, San Marino , California) was an American historian best known for the “ frontier thesis.” The single most influential interpretation of the American past, it proposed that the distinctiveness of the United States was attributable to its long history of “westering.” Despite the fame of this monocausal interpretation, as the teacher and mentor of dozens of young historians, Turner insisted on a multicausal model of history , with a recognition of the interaction of politics, economics , culture , and geography. Turner’s penetrating analyses of American history and culture were powerfully influential and changed the direction of much American historical writing.

Born in frontier Wisconsin and educated at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, Turner did graduate work at Johns Hopkins University under Herbert Baxter Adams . Awarded a doctorate in 1891, Turner was one of the first historians professionally trained in the United States rather than in Europe. He began his teaching career at the University of Wisconsin in 1889. He began to make his mark with his first professional paper, “ The Significance of History” (1891), which contains the famous line “Each age writes the history of the past anew with reference to the conditions uppermost in its own time.” The controversial notion that there was no fixed historical truth, and that all historical interpretation should be shaped by present concerns, would become the hallmark of the so-called “New History,” a movement that called for studies illuminating the historical development of the political and cultural controversies of the day. Turner should be counted among the “progressive historians,” though, with the political temperament of a small-town Midwesterner, his progressivism was rather timid. Nevertheless, he made it clear that his historical writing was shaped by a contemporary agenda.

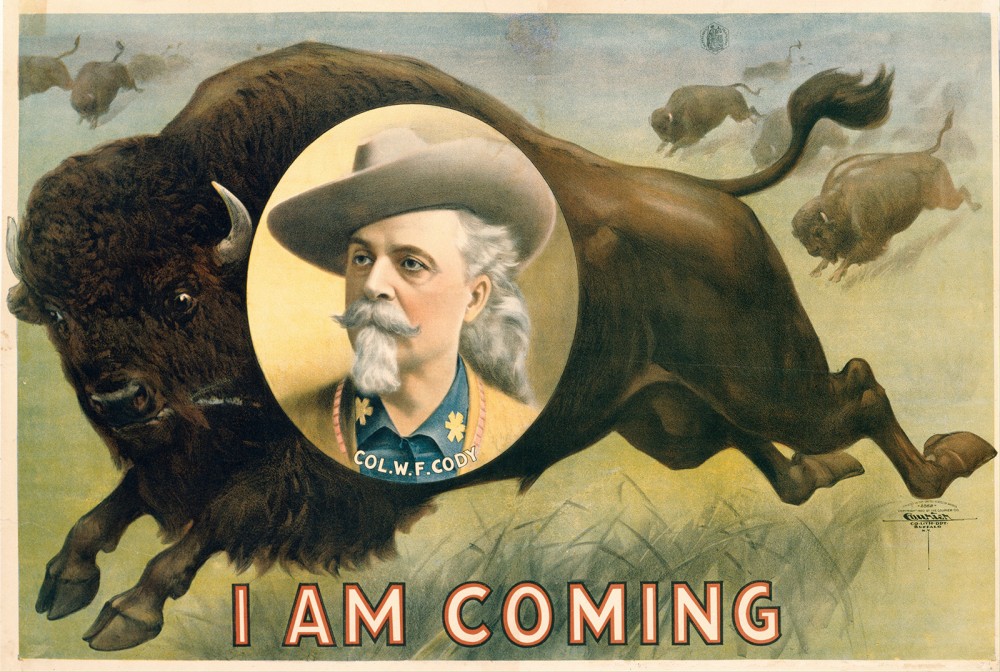

Turner first detailed his own interpretation of American history in his justly famous paper, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” delivered at a meeting of historians in Chicago in 1893 and published many times thereafter. Adams, his mentor at Johns Hopkins , had argued that all significant American institutions derived from German and English antecedents . Rebelling against this view, Turner argued instead that Europeans had been transformed by the process of settling the American continent and that what was unique about the United States was its frontier history . (Ironically, Turner passed up an opportunity to attend Buffalo Bill ’s Wild West show so that he could complete “The Significance of the Frontier in American History” on the morning that he presented it.) He traced the social evolution of frontier life as it continually developed across the continent from the primitive conditions experienced by the explorer, trapper, and trader, through maturing agricultural stages, finally reaching the complexity of city and factory. Turner held that the American character was decisively shaped by conditions on the frontier, in particular the abundance of free land, the settling of which engendered such traits as self-reliance, individualism , inventiveness, restless energy, mobility, materialism, and optimism. Turner’s “frontier thesis” rose to become the dominant interpretation of American history for the next half-century and longer. In the words of historian William Appleman Williams, it “rolled through the universities and into popular literature like a tidal wave.” While today’s professional historians tend to reject such sweeping theories, emphasizing instead a variety of factors in their interpretations of the past, Turner’s frontier thesis remains the most popular explanation of American development among the literate public.

For a scholar of such wide influence, Turner wrote relatively few books. His Rise of the New West, 1819–1829 (1906) was published as a volume in The American Nation series, which included contributions from the nation’s leading historians. The follow-up to that study, The United States, 1830–1850: The Nation and Its Sections (1935), would not be published until after his death. Turner may have had difficulty writing books, but he was a brilliant master of the historical essay. The winner of an oratorical medal as an undergraduate, he also was a gifted and active public speaker. His deep, melodious voice commanded attention whether he was addressing a teachers group, an audience of alumni, or a branch of the Chautauqua movement . His writing, too, bore the stamp of oratory; indeed, he reworked his lectures into articles that appeared in the nation’s most influential popular and scholarly journals.

Many of Turner’s best essays were collected in The Frontier in American History (1920) and The Significance of Sections in American History (1932), for which he was posthumously awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1933. In these writings Turner promoted new methods in historical research, including the techniques of the newly founded social sciences , and urged his colleagues to study new topics such as immigration , urbanization , economic development , and social and cultural history . He also commented directly on the connections he saw between the past and the present.

The end of the frontier era of continental expansion, Turner reasoned, had thrown the nation “back upon itself.” Writing that “imperious will and force” had to be replaced by social reorganization, he called for an expanded system of educational opportunity that would supplant the geographic mobility of the frontier. “The test tube and the microscope are needed rather than ax and rifle,” he wrote; “in place of old frontiers of wilderness, there are new frontiers of unwon fields of science.” Pioneer ideals were to be maintained by American universities through the training of new leaders who would strive “to reconcile popular government and culture with the huge industrial society of the modern world.”

Whereas in his 1893 essay he celebrated the pioneers for the spirit of individualism that spurred migration westward, 25 years later Turner castigated “these slashers of the forest, these self-sufficing pioneers, raising the corn and livestock for their own need, living scattered and apart.” For Turner the national problem was “no longer how to cut and burn away the vast screen of the dense and daunting forest” but “how to save and wisely use the remaining timber.” At the end of his career, he stressed the vital role that regionalism would play in counteracting the atomization brought about by the frontier experience. Turner hoped that stability would replace mobility as a defining factor in the development of American society and that communities would become stronger as a result. What the world needed now, he argued, was “a highly organized provincial life to serve as a check upon mob psychology on a national scale, and to furnish that variety which is essential to vital growth and originality.” Turner never ceased to treat history as contemporary knowledge, seeking to explore the ways that the nation might rechannel its expansionist impulses into the development of community life.

Turner taught at the University of Wisconsin until 1910, when he accepted an appointment to a distinguished chair of history at Harvard University . At these two institutions he helped build two of the great university history departments of the 20th century and trained many distinguished historians, including Carl Becker , Merle Curti, Herbert Bolton , and Frederick Merk, who became Turner’s successor at Harvard. He was an early leader of the American Historical Association , serving as its president in 1910 and on the editorial board of the association’s American Historical Review from 1910 to 1915. Poor health forced his early retirement from Harvard in 1924. Turner moved to the Huntington Library in San Marino, California , where he remained as senior research associate until his death.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

17.9: The West as History- the Turner Thesis

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 10013

- American YAWP

- Stanford via Stanford University Press

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

.png?revision=1)

In 1893, the American Historical Association met during that year’s World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The young Wisconsin historian Frederick Jackson Turner presented his “frontier thesis,” one of the most influential theories of American history, in his essay “The Significance of the Frontier in American History.”

Turner looked back at the historical changes in the West and saw, instead of a tsunami of war and plunder and industry, waves of “civilization” that washed across the continent. A frontier line “between savagery and civilization” had moved west from the earliest English settlements in Massachusetts and Virginia across the Appalachians to the Mississippi and finally across the Plains to California and Oregon. Turner invited his audience to “stand at Cumberland Gap [the famous pass through the Appalachian Mountains], and watch the procession of civilization, marching single file—the buffalo following the trail to the salt springs, the Indian, the fur trader and hunter, the cattle-raiser, the pioneer farmer—and the frontier has passed by.” 26

Americans, Turner said, had been forced by necessity to build a rough-hewn civilization out of the frontier, giving the nation its exceptional hustle and its democratic spirit and distinguishing North America from the stale monarchies of Europe. Moreover, the style of history Turner called for was democratic as well, arguing that the work of ordinary people (in this case, pioneers) deserved the same study as that of great statesmen. Such was a novel approach in 1893.

But Turner looked ominously to the future. The Census Bureau in 1890 had declared the frontier closed. There was no longer a discernible line running north to south that, Turner said, any longer divided civilization from savagery. Turner worried for the United States’ future: what would become of the nation without the safety valve of the frontier? It was a common sentiment. Theodore Roosevelt wrote to Turner that his essay “put into shape a good deal of thought that has been floating around rather loosely.” 27

The history of the West was many-sided and it was made by many persons and peoples. Turner’s thesis was rife with faults, not only in its bald Anglo-Saxon chauvinism—in which nonwhites fell before the march of “civilization” and Chinese and Mexican immigrants were invisible—but in its utter inability to appreciate the impact of technology and government subsidies and large-scale economic enterprises alongside the work of hardy pioneers. Still, Turner’s thesis held an almost canonical position among historians for much of the twentieth century and, more importantly, captured Americans’ enduring romanticization of the West and the simplification of a long and complicated story into a march of progress.

How the Myth of the American Frontier Got Its Start

Frederick Jackson Turner’s thesis informed decades of scholarship and culture. Then he realized he was wrong

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Colin_Woodard_PPH_Photo_crop_thumbnail_1.png)

Colin Woodard

:focal(400x301:401x302)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/12/11/1211e4cd-7311-4c83-9370-d86aa5ebc2d5/illustration_of_people_on_horseback_looking_at_an_open_landscape.jpg)

On the evening of July 12, 1893, in the hall of a massive new Beaux-Arts building that would soon house the Art Institute of Chicago, a young professor named Frederick Jackson Turner rose to present what would become the most influential essay in the study of U.S. history.

It was getting late. The lecture hall was stifling from a day of blazing sun, which had tormented the throngs visiting the nearby Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition, a carnival of never-before-seen wonders, like a fully illuminated electric city and George Ferris’ 264-foot-tall rotating observation wheel. Many of the hundred or so historians attending the conference, a meeting of the American Historical Association (AHA), were dazed and dusty from an afternoon spent watching Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show at a stadium near the fairground’s gates. They had already sat through three other speeches. Some may have been dozing off as the thin, 31-year-old associate professor from the University of Wisconsin in nearby Madison began his remarks.

Subscribe to Smithsonian magazine now for just $19.99

This article is a selection from the January/February 2023 issue of Smithsonian magazine

Turner told them the force that had forged Americans into one people was the frontier of the Midwest and Far West. In this virgin world, settlers had finally been relieved of the European baggage of feudalism that their ancestors had brought across the Atlantic, freeing them to find their true selves: self-sufficient, pragmatic, egalitarian and civic-minded. “The frontier promoted the formation of a composite nationality for the American people,” he told the audience. “In the crucible of the frontier, the immigrants were Americanized, liberated and fused into a mixed race, English in neither nationality nor characteristics.”

The audience was unmoved.

In their dispatches the following morning, most of the newspaper reporters covering the conference didn’t even mention Turner’s talk. Nor did the official account of the proceedings prepared by the librarian William F. Poole for The Dial , an influential literary journal. Turner’s own father, writing to relatives a few days later, praised Turner’s skills as the family’s guide at the fair, but he said nothing at all about the speech that had brought them there.

Yet in less than a decade, Turner would be the most influential living historian in the United States, and his Frontier Thesis would become the dominant lens through which Americans understood their character, origins and destiny. Soon, Jackson’s theme was prevalent in political speech, in the way high schools taught history, in patriotic paintings—in short, everywhere. Perfectly timed to meet the needs of a country experiencing dramatic and destabilizing change, Turner’s thesis was swiftly embraced by academic and political institutions, just as railroads, manufacturing machines and telegraph systems were rapidly reshaping American life.

By that time, Turner himself had realized that his theory was almost entirely wrong.

American historians had long believed that Providence had chosen their people to spread Anglo-Saxon freedom across the continent. As an undergraduate at the University of Wisconsin, Turner was introduced to a different argument by his mentor, the classical scholar William Francis Allen. Extrapolating from Darwinism, Allen believed societies evolved like organisms, adapting themselves to the environments they encountered. Scientific laws, not divine will, he advised his mentee, guided the course of nations. After graduating, Turner pursued a doctorate at Johns Hopkins University, where he impressed the history program’s leader, Herbert Baxter Adams, and formed a lifelong friendship with one of his teachers, an ambitious young professor named Woodrow Wilson. The connections were useful: When Allen died in 1889, Adams and Wilson aided Turner in his quest to take Allen’s place as head of Wisconsin’s history department. And on the strength of Turner’s early work, Adams invited him to present a paper at the 1893 meeting of the AHA, to be held in conjunction with the World’s Congress Auxiliary of the World’s Columbian Exposition.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/61/bc/61bc38a7-853f-4c6b-823e-71c95d62687d/manifest_destiny.jpg)

The resulting essay, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” offered a vivid evocation of life in the American West. Stripped of “the garments of civilization,” settlers between the 1780s and the 1830s found themselves “in the birch canoe” wearing “the hunting shirt and the moccasin.” Soon, they were “planting Indian corn and plowing with a sharp stick” and even shouting war cries. Faced with Native American resistance—Turner largely overlooked what the ethnic cleansing campaign that created all that “free land” might say about the American character—the settlers looked to the federal government for protection from Native enemies and foreign empires, including during the War of 1812, thus fostering a loyalty to the nation rather than to their half-forgotten nations of origin.

He warned that with the disappearance of the force that had shaped them—in 1890, the head of the Census Bureau concluded there was no longer a frontier line between areas that had been settled by European Americans and those that had not—Americans would no longer be able to flee west for an easy escape from responsibility, failure or oppression. “Each frontier did indeed furnish a new field of opportunity, a gate of escape from the bondage of the past,” Turner concluded. “Now … the frontier has gone, and with its going has closed the first period of American history.”

When he left the podium on that sweltering night, he could not have known how fervently the nation would embrace his thesis.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/3a/1d/3a1d78c2-4533-4dbf-9fc9-66306936b710/white_guy.jpg)

Like so many young scholars, Turner worked hard to bring attention to his thesis. He incorporated it into the graduate seminars he taught, lectured about it across the Midwest and wrote the entry for “Frontier” in the widely read Johnson’s Universal Cyclopædia. He arranged to have the thesis reprinted in the journal of the Wisconsin Historical Society and in the AHA’s 1893 annual report. Wilson championed it in his own writings, and the essay was read by hundreds of schoolteachers who found it reprinted in the popular pedagogical journal of the Herbart Society, a group devoted to the scientific study of teaching. Turner’s big break came when the Atlantic Monthly ’s editors asked him to use his novel viewpoint to explain the sudden rise of populists in the rural Midwest, and how they had managed to seize control of the Democratic Party to make their candidate, William Jennings Bryan, its nominee for president. Turner’s 1896 Atlantic Monthly essay , which tied the populists’ agitation to the social pressures allegedly caused by the closing of the frontier—soil depletion, debt, rising land prices—was promptly picked up by newspapers and popular journals across the country.

Meanwhile, Turner’s graduate students became tenured professors and disseminated his ideas to the up-and-coming generation of academics. The thrust of the thesis appeared in political speeches, dime-store western novels and even the new popular medium of film, where it fueled the work of a young director named John Ford who would become the master of the Hollywood western. In 1911, Columbia University’s David Muzzey incorporated it into a textbook—initially titled History of the American People —that would be used by most of the nation’s secondary schools for half a century.

Americans embraced Turner’s argument because it provided a fresh and credible explanation for the nation’s exceptionalism—the notion that the U.S. follows a path soaring above those of other countries—one that relied not on earlier Calvinist notions of being “the elect,” but rather on the scientific (and fashionable) observations of Charles Darwin. In a rapidly diversifying country, the Frontier Thesis denied a special role to the Eastern colonies’ British heritage; we were instead a “composite nation,” birthed in the Mississippi watershed. Turner’s emphasis on mobility, progress and individualism echoed the values of the Gilded Age—when readers devoured Horatio Alger’s rags-to-riches stories—and lent them credibility for the generations to follow.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ea/69/ea696129-c32c-4947-9ce7-64648e2f2cea/janfeb2023_e01_prologue.jpg)

But as a researcher, Turner himself turned away from the Frontier Thesis in the years after the 1890s. He never wrote it down in book form or even in academic articles. He declined invitations to defend it, and before long he himself lost faith in it.

For one thing, he had been relying too narrowly on the experiences in his own region of the Upper Midwest, which had been colonized by a settlement stream originating in New England. In fact, he found, the values he had ascribed to the frontier’s environmental conditioning were actually those of this Greater New England settlement culture, one his family and most of his fellow citizens in Portage, Wisconsin, remained part of, with their commitment to strong village and town governments, taxpayer-financed public schools and the direct democracy of the town meeting. He saw that other parts of the frontier had been colonized by other settlement streams anchored in Scots-Irish Appalachia or in the slave plantations of the Southern lowlands, and he noted that their populations continued to behave completely differently from one another, both politically and culturally, even when they lived in similar physical environments. Somehow settlers moving west from these distinct regional cultures were resisting the Darwinian environmental and cultural forces that had supposedly forged, as Turner’s biographer, Ray Allen Billington, put it, “a new political species” of human, the American. Instead, they were stubbornly remaining themselves. “Men are not absolutely dictated to by climate, geography, soils or economic interests,” Turner wrote in 1922. “The influence of the stock from which they sprang, the inherited ideals, the spiritual factors, often triumph over the material interests.”

Turner spent the last decades of his life working on what he intended to be his magnum opus, a book not about American unity but rather about the abiding differences between its regions, or “sections,” as he called them. “In respect to problems of common action, we are like what a United States of Europe would be,” he wrote in 1922, at the age of 60. For example, the Scots-Irish and German small farmers and herders who settled the uplands of the southeastern states had long clashed with nearby English enslavers over education spending, tax policy and political representation. Turner saw the whole history of the country as a wrestling match between these smaller quasi-nations, albeit a largely peaceful one guided by rules, laws and shared American ideals: “When we think of the Missouri Compromise, the Compromise of 1850, the Kansas-Nebraska Act, as steps in the marking off of spheres of influence and the assignment of mandates [between nations] … we see a resemblance to what has gone on in the Old World,” Turner explained. He hoped shared ideals—and federal institutions—would prove cohesive for a nation suddenly coming of age, its frontier closed, its people having to steward their lands rather than striking out for someplace new.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ea/79/ea79b5eb-7dd4-4ca0-9d75-f4ad5333a116/janfeb2023_e12_prologue.jpg)

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Colin_Woodard_PPH_Photo_crop_thumbnail_1.png)

Colin Woodard | | READ MORE

Colin Woodard is a journalist and historian, and the author of six books including Union: The Struggle to Forge the Story of United States Nationhood . He lives in Maine.

Excerpts from writings of Frederick Jackson Turner, 1890s-1920s

Frederick Jackson Turner is most famous for expounding the influential “Frontier Thesis” of American history, a thesis he first introduced in 1893 and which he expanded upon for the remainder of his scholarly career. See the following link for a short biography.

In the settlement of America we have to observe how European life entered the continent, and how America modified and developed that life and reacted on Europe. . . . [T]he frontier is the line of most rapid and effective Americanization. The wilderness masters the colonist. It finds him a European in dress, industries, tools, modes of travel, and thought. It takes him from the railroad car and puts him in the birch canoe. It strips off the garments of civilization and arrays him in the hunting shirt and the moccasin. It puts him in the log cabin of the Cherokee and Iroquois and runs an Indian palisade around him. Before long he has gone to planting Indian corn and plowing with a sharp stick; he shouts the war cry and takes the scalp in orthodox Indian fashion. In short, at the frontier the environment is at first too strong for the man. He must accept the conditions which it furnishes or perish, and so he fits himself into the Indian clearings and follows the Indian trails.

Little by little he transforms the wilderness, but the outcome is not the old Europe . . .. The fact is, that here is a new product that is American. At first, the frontier was the Atlantic coast. It was the frontier of Europe in a very real sense. Moving westward, the frontier became more and more American. As successive terminal moraines result from successive glaciations, so each frontier leaves its traces behind it, and when it becomes a settled area the region still partakes of the frontier characteristics. Thus the advance of the frontier has meant a steady movement away from the influence of Europe, a steady growth of independence on American lines. And to study this advance, the men who grew up under these conditions, and the political, economic, and social results of it, is to study the really American part of our history.

. . [T]he frontier promoted the formation of a composite nationality for the American people. The coast was preponderantly English, but the later tides of continental immigration flowed across to the free lands. . . . In the crucible of the frontier the immigrants were Americanized, liberated, and fused into a mixed race, English in neither nationality nor characteristics. The process has gone on from the early days to our own.

From the conditions of frontier life came intellectual traits of profound importance. The works of travelers along each frontier from colonial days onward describe certain common traits, and these traits have, while softening down, still persisted as survivals in the place of their origin, even when a higher social organization succeeded. The result is that, to the frontier, the American intellect owes its striking characteristics. That coarseness and strength combined with acuteness and inquisitiveness, that practical, inventive turn of mind, quick to find expedients, that masterful grasp of material things, lacking in the artistic but powerful to effect great ends, that restless, nervous energy, that dominant individualism, working for good and for evil, and withal that buoyancy and exuberance which comes with freedom -- these are traits of the frontier, or traits called out elsewhere because of the existence of the frontier.

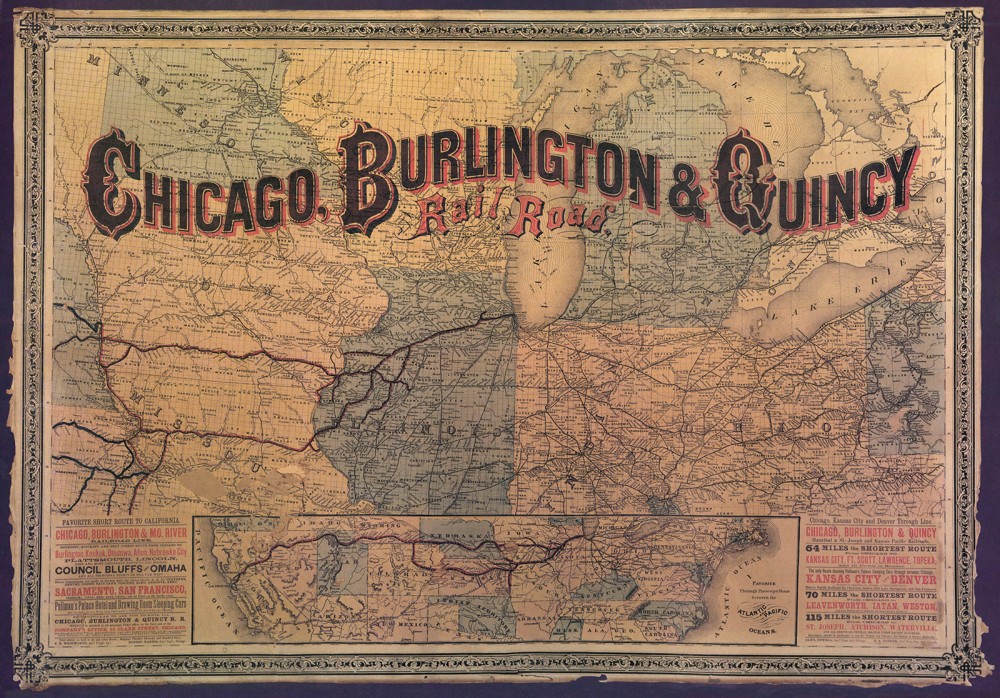

The last chapter in the development of Western democracy is the one that deals with its conquest over the vast spaces of the new West. At each new stage of Western development, the people have had to grapple with larger areas, with bigger combinations. The little colony of Massachusetts veterans that settled at Marietta received a land grant as large as the State of Rhode Island. The band of Connecticut pioneers that followed Moses Cleaveland to the Connecticut Reserve occupied a region as large as the parent State. The area which settlers of New England stock occupied on the prairies of northern Illinois surpassed the combined area of Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island. Men who had become accustomed to the narrow valleys and the little towns of the East found themselves out on the boundless spaces of the West dealing with units of such magnitude as dwarfed their former experience. The Great Lakes, the Prairies, the Great Plains, the Rocky Mountains, the Mississippi and the Missouri, furnished new standards of measurement for the achievement of this industrial democracy. Individualism began to give way to coöperation and to governmental activity. Even in the earlier days of the democratic conquest of the wilderness, demands had been made upon the government for support in internal improvements, but this new West showed a growing tendency to call to its assistance the powerful arm of national authority. In the period since the Civil War, the vast public domain has been donated to the individual farmer, to States for education, to railroads for the construction of transportation lines.

Moreover, with the advent of democracy in the last fifteen years upon the Great Plains, new physical conditions have presented themselves which have accelerated the social tendency of Western democracy. The pioneer farmer of the days of Lincoln could place his family on a flatboat, strike into the wilderness, cut out his clearing, and with little or no capital go on to the achievement of industrial independence. Even the homesteader on the Western prairies found it possible to work out a similar independent destiny, although the factor of transportation made a serious and increasing impediment to the free working-out of his individual career. But when the arid lands and the mineral resources of the Far West were reached, no conquest was possible by the old individual pioneer methods. Here expensive irrigation works must be constructed, coöperative activity was demanded in utilization of the water supply, capital beyond the reach of the small farmer was required. In a word, the physiographic province itself decreed that the destiny of this new frontier should be social rather than individual.

Magnitude of social achievement is the watchword of the democracy since the Civil War. From petty towns built in the marshes, cities arose whose greatness and industrial power are the wonder of our time. The conditions were ideal for the production of captains of industry. The old democratic admiration for the self-made man, its old deference to the rights of competitive individual development, together with the stupendous natural resources that opened to the conquest of the keenest and the strongest, gave such conditions of mobility as enabled the development of the large corporate industries which in our own decade have marked the West. Thus, in brief, have been outlined the chief phases of the development of Western democracy in the different areas which it has conquered. There has been a steady development of the industrial ideal, and a steady increase of the social tendency, in this later movement of Western democracy. While the individualism of the frontier, so prominent in the earliest days of the Western advance, has been preserved as an ideal, more and more these individuals struggling each with the other, dealing with vaster and vaster areas, with larger and larger problems, have found it necessary to combine under the leadership of the strongest. This is the explanation of the rise of those preëminent captains of industry whose genius has concentrated capital to control the fundamental resources of the nation.

If now in the way of recapitulation, we try to pick out from the influences that have gone to the making of Western democracy the factors which constitute the net result of this movement, we shall have to mention at least the following:-- Most important of all has been the fact that an area of free land has continually lain on the western border of the settled area of the United States. Whenever social conditions tended to crystallize in the East, whenever capital tended to press upon labor or political restraints to impede the freedom of the mass, there was this gate of escape to the free conditions of the frontier. These free lands promoted individualism, economic equality, freedom to rise, democracy. Men would not accept inferior wages and a permanent position of social subordination when this promised land of freedom and equality was theirs for the taking. Who would rest content under oppressive legislative conditions when with a slight effort he might reach a land wherein to become a co-worker in the building of free cities and free States on the lines of his own ideal? In a word, then, free lands meant free opportunities. Their existence has differentiated the American democracy from the democracies which have preceded it, because ever, as democracy in the East took the form of highly specialized and complicated industrial society, in the West it kept in touch with primitive conditions, and by action and reaction these two forces have shaped our history.

In the next place, these free lands and this treasury of industrial resources have existed over such vast spaces that they have demanded of democracy increasing spaciousness of design and power of execution. Western democracy is contrasted with the democracy of all other times in the largeness of the tasks to which it has set its hand, and in the vast achievements which it has wrought out in the control of nature and of politics. It would be difficult to over-emphasize the importance of this training upon democracy. Never before in the history of the world has a democracy existed on so vast an area and handled things in the gross with such success, with such largeness of design, and such grasp upon the means of execution. In short, democracy has learned in the West of the United States how to deal with the problem of magnitude. The old historic democracies were but little states with primitive economic conditions.

But the very task of dealing with vast resources, over vast areas, under the conditions of free competition furnished by the West, has produced the rise of those captains of industry whose success in consolidating economic power now raises the question as to whether democracy under such conditions can survive. For the old military type of Western leaders like George Rogers Clark, Andrew Jackson, and William Henry Harrison have been substituted such industrial leaders as James J. Hill, John D. Rockefeller, and Andrew Carnegie.

The question is imperative, then, What ideals persist from this democratic experience of the West, and have they acquired sufficient momentum to sustain themselves under conditions so radically unlike those in the days of their origin? In other words, the question put at the beginning of this discussion becomes pertinent. Under the forms of the American democracy is there in reality evolving such a concentration of economic and social power in the hands of a comparatively few men as may make political democracy an appearance rather than a reality? The free lands are gone. The material forces that gave vitality to Western democracy are passing away. It is to the realm of the spirit, to the domain of ideals and legislation, that we must look for Western influence upon democracy in our own days.

Western democracy has been from the time of its birth idealistic. The very fact of the wilderness appealed to men as a fair, blank page on which to write a new chapter in the story of man's struggle for a hi,,her type of society. The Western wilds, from the Alleghanies to the Pacific, constituted the richest free gift that was ever spread out before civilized man. To the peasant and artisan of the Old World, bound by the chains of social class, as old as custom and as inevitable as fate, the West offered an exit into a free life and greater well-being among the bounties of nature, into the midst of resources that demanded manly exertion, and that gave in return the chance for indefinite ascent in the scale of social advance. "To each she offered gifts after his will." Never again can such an opportunity come to the sons of men. It was unique, and the thing is so near us, so much a part of our lives, that we do not even yet comprehend its full significance. The existence of this land of opportunity has made America the goal of idealists from the days of the Pilgrim Fathers. With all the materialism of the pioneer movements, this idealistic conception of the vacant lands as an opportunity for a new order of things is unmistakably present.

This, at least, is clear: American democracy is fundamentally the outcome of the experiences of the American people in dealing with the West. Western democracy through the whole of its earlier period tended to the production of a society of which the most distinctive fact was the freedom of the individual to rise under conditions of social mobility, and whose ambition was the liberty and well-being of the masses. This conception has vitalized all American democracy, and has brought it into sharp contrasts with the democracies of history, and with those modern efforts of Europe to create an artificial democratic order by legislation. The problem of the United States is not to create democracy, but to conserve democratic institutions and ideals.

Search The Canadian Encyclopedia

Enter your search term

Why sign up?

Signing up enhances your TCE experience with the ability to save items to your personal reading list, and access the interactive map.

- MLA 8TH EDITION

- Owram, D.R.. "Frontier Thesis". The Canadian Encyclopedia , 16 December 2013, Historica Canada . www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/frontier-thesis. Accessed 09 June 2024.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , 16 December 2013, Historica Canada . www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/frontier-thesis. Accessed 09 June 2024." href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- APA 6TH EDITION

- Owram, D. (2013). Frontier Thesis. In The Canadian Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/frontier-thesis

- The Canadian Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/frontier-thesis" href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- CHICAGO 17TH EDITION

- Owram, D.R.. "Frontier Thesis." The Canadian Encyclopedia . Historica Canada. Article published February 07, 2006; Last Edited December 16, 2013.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia . Historica Canada. Article published February 07, 2006; Last Edited December 16, 2013." href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- TURABIAN 8TH EDITION

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , s.v. "Frontier Thesis," by D.R. Owram, Accessed June 09, 2024, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/frontier-thesis

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , s.v. "Frontier Thesis," by D.R. Owram, Accessed June 09, 2024, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/frontier-thesis" href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

Thank you for your submission

Our team will be reviewing your submission and get back to you with any further questions.

Thanks for contributing to The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Frontier Thesis

Article by D.R. Owram

Published Online February 7, 2006

Last Edited December 16, 2013

The Frontier thesis was formulated 1893, when American historian Frederick Jackson Turner theorized that the availability of unsettled land throughout much of American history was the most important factor determining national development. Frontier experiences and new opportunities forced old traditions to change, institutions to adapt and society to become more democratic as class distinctions collapsed. The result was a unique American society, distinct from the European societies from which it originated. In Canada the frontier thesis was popular between the world wars with historians such as A.R.M. LOWER and Frank UNDERHILL and sociologist S.D. CLARK , partly because of a new sense of Canada's North American character.

Since WWII the frontier thesis has declined in popularity because of recognition of important social and cultural distinctions between Canada and the US. In its place a "metropolitan school" has developed, emphasizing Canada's much closer historical ties with Europe. Moreover, centres such as Montréal, Toronto and Ottawa had a profound influence on the settlement of the Canadian frontier. Whichever argument is emphasized, however, any realistic conclusion cannot deny that both the frontier and the ties to established centres were formative in Canada's development.

See also METROPOLITAN-HINTERLAND THESIS .

Recommended

Laurentian thesis, metropolitan-hinterland thesis.

Conquering the West

The west as history: the turner thesis.

In 1893, the American Historical Association met during that year’s World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The young Wisconsin historian Frederick Jackson Turner presented his “frontier thesis,” one of the most influential theories of American history, in his essay, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History.”

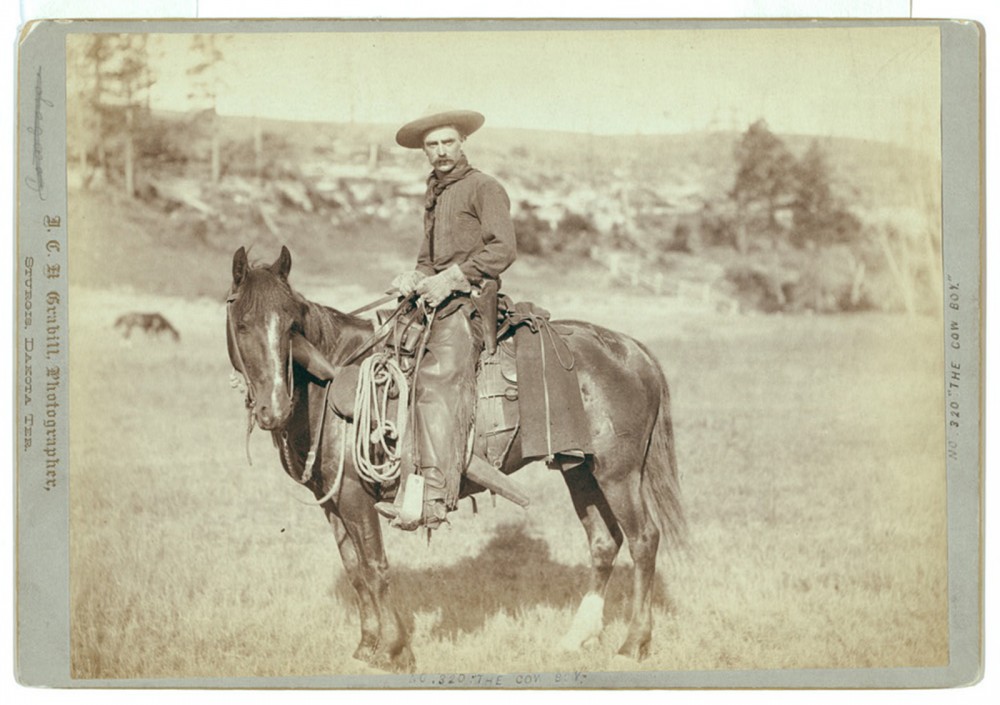

Turner looked back at the historical changes in the West and saw, instead of a tsunami of war and plunder and industry, waves of “civilization” that washed across the continent. A frontier line “between savagery and civilization” had moved west from the earliest English settlements in Massachusetts and Virginia across the Appalachians to the Mississippi and finally across the Plains to California and Oregon. Turner invited his audience to “stand at Cumberland Gap [the famous pass through the Appalachian Mountains], and watch the procession of civilization, marching single file—the buffalo following the trail to the salt springs, the Indian, the fur trader and hunter, the cattle-raiser, the pioneer farmer—and the frontier has passed by.”

Americans, Turner said, had been forced by necessity to build a rough-hewn civilization out of the frontier, giving the nation its exceptional hustle and its democratic spirit and distinguishing North America from the stale monarchies of Europe. Moreover, the style of history Turner called for was democratic as well, arguing that the work of ordinary people (in this case, pioneers) deserved the same study as that of great statesmen. Such was a novel approach in 1893.

But Turner looked ominously to the future. The Census Bureau in 1890 had declared the frontier closed. There was no longer a discernible line running north to south that, Turner said, any longer divided civilization from savagery. Turner worried for the United States’ future: what would become of the nation without the safety valve of the frontier? It was a common sentiment. Theodore Roosevelt wrote to Turner that his essay “put into shape a good deal of thought that has been floating around rather loosely.”

The history of the West was many-sided and it was made by many persons and peoples. Turner’s thesis was rife with faults, not only its bald Anglo Saxon chauvinism—in which non-whites fell before the march of “civilization” and Chinese and Mexican immigrants were invisible—but in its utter inability to appreciate the impact of technology and government subsidies and large-scale economic enterprises alongside the work of hardy pioneers. Still, Turner’s thesis held an almost canonical position among historians for much of the twentieth century and, more importantly, captured Americans’ enduring romanticization of the West and the simplification of a long and complicated story into a march of progress.

This chapter was edited by Lauren Brand, with content contributions by Lauren Brand, Carole Butcher, Josh Garrett-Davis, Tracey Hanshew, Nick Roland, David Schley, Emma Teitelman, and Alyce Vigil.

- American Yawp. Located at : http://www.americanyawp.com/index.html . Project : American Yawp. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

THE AMERICAN YAWP

17. the west.

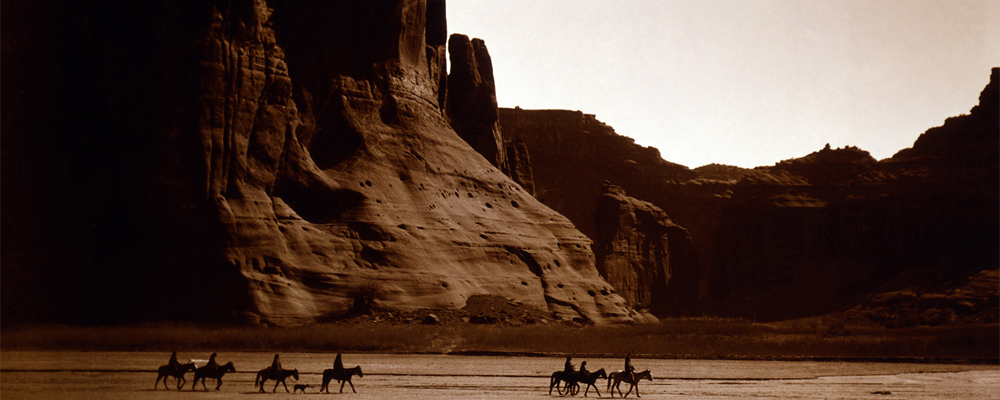

Edward S. Curtis, Navajo Riders in Canyon de Chelly , c1904. Library of Congress .

*The American Yawp is an evolving, collaborative text. Please click here to improve this chapter.*

I. Introduction

Ii. post-civil war westward migration, iii. the indian wars and federal peace policies, iv. beyond the plains, v. western economic expansion: railroads and cattle, vi. the allotment era and resistance in the native west, vii. rodeos, wild west shows, and the mythic american west, viii. the west as history: the turner thesis, ix. primary sources, x. reference material.

Native Americans long dominated the vastness of the American West. Linked culturally and geographically by trade, travel, and warfare, various Indigenous groups controlled most of the continent west of the Mississippi River deep into the nineteenth century. Spanish, French, British, and later American traders had integrated themselves into many regional economies, and American emigrants pushed ever westward, but no imperial power had yet achieved anything approximating political or military control over the great bulk of the continent. But then the Civil War came and went and decoupled the West from the question of slavery just as the United States industrialized and laid down rails and pushed its ever-expanding population ever farther west.

Indigenous Americans have lived in North America for over ten millennia and, into the late nineteenth century, perhaps as many as 250,000 Native people still inhabited the American West. 1 But then unending waves of American settlers, the American military, and the unstoppable onrush of American capital conquered all. Often in violation of its own treaties, the United States removed Native groups to ever-shrinking reservations, incorporated the West first as territories and then as states, and, for the first time in its history, controlled the enormity of land between the two oceans.

The history of the late-nineteenth-century West is not a simple story. What some touted as a triumph—the westward expansion of American authority—was for others a tragedy. The West contained many peoples and many places, and their intertwined histories marked a pivotal transformation in the history of the United States.

In the decades after the Civil War, American settlers poured across the Mississippi River in record numbers. No longer simply crossing over the continent for new imagined Edens in California or Oregon, they settled now in the vast heart of the continent.

Many of the first American migrants had come to the West in search of quick profits during the midcentury gold and silver rushes. As in the California rush of 1848–1849, droves of prospectors poured in after precious-metal strikes in Colorado in 1858, Nevada in 1859, Idaho in 1860, Montana in 1863, and the Black Hills in 1874. While women often performed housework that allowed mining families to subsist in often difficult conditions, a significant portion of the mining workforce were single men without families dependent on service industries in nearby towns and cities. There, working-class women worked in shops, saloons, boardinghouses, and brothels. Many of these ancillary operations profited from the mining boom: as failed prospectors found, the rush itself often generated more wealth than the mines. The gold that left Colorado in the first seven years after the Pikes Peak gold strike—estimated at $25.5 million—was, for instance, less than half of what outside parties had invested in the fever. The 100,000-plus migrants who settled in the Rocky Mountains were ultimately more valuable to the region’s development than the gold they came to find. 2

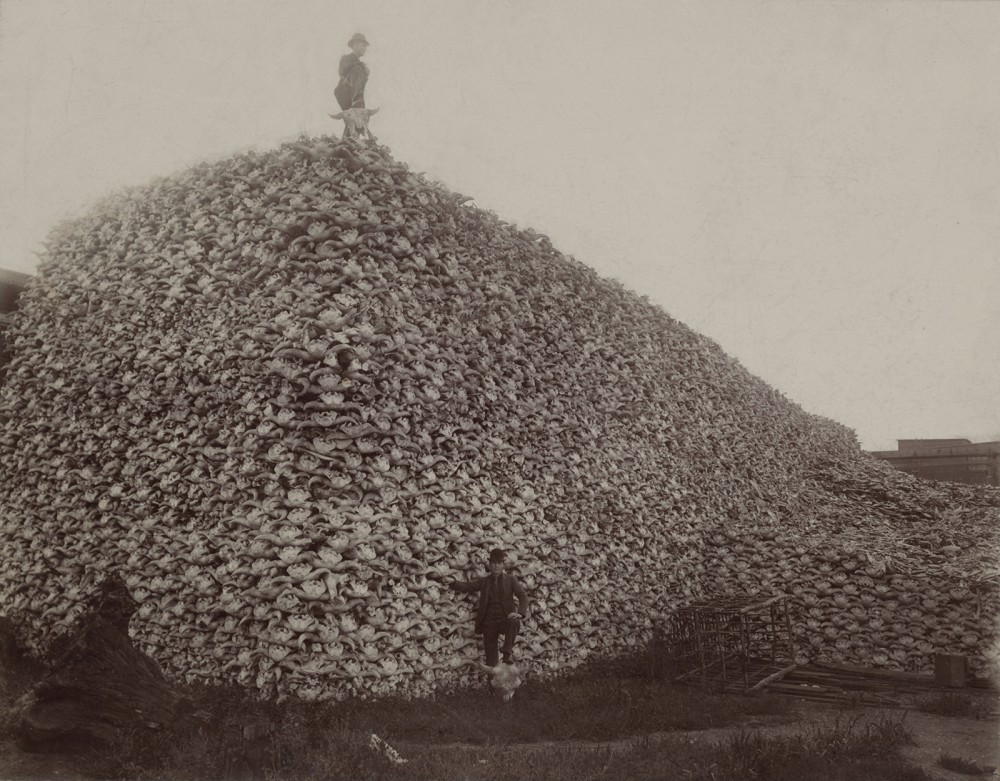

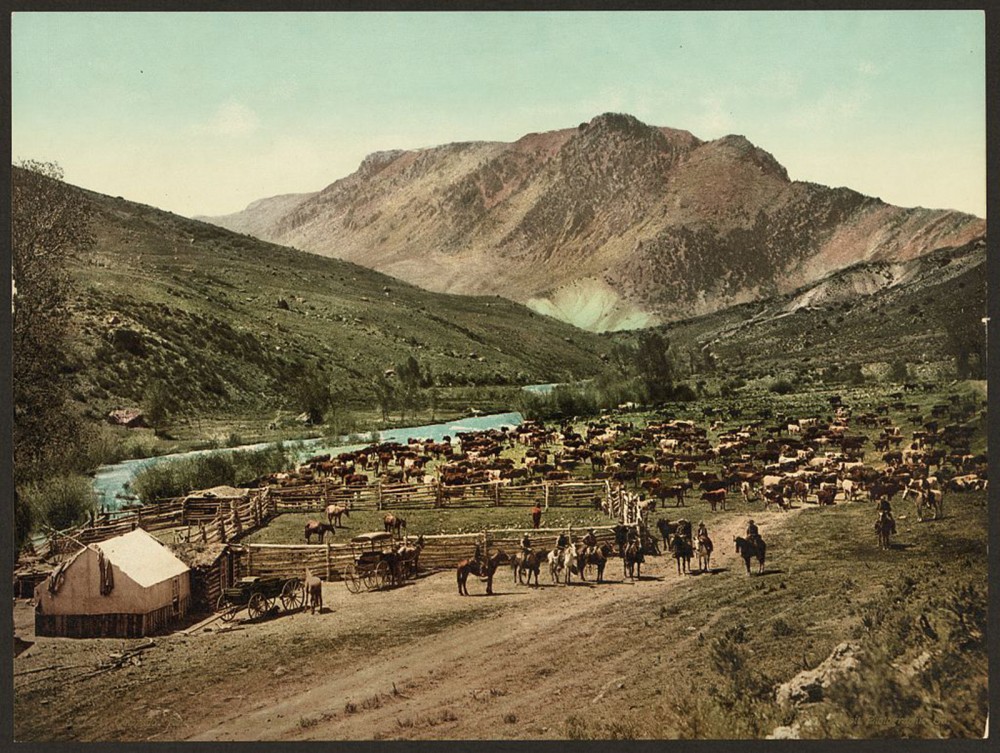

Others came to the Plains to extract the hides of the great bison herds. Millions of animals had roamed the Plains, but their tough leather supplied industrial belting in eastern factories and raw material for the booming clothing industry. Specialized teams took down and skinned the herds. The infamous American bison slaughter peaked in the early 1870s. The number of American bison plummeted from over ten million at midcentury to only a few hundred by the early 1880s. The expansion of the railroads allowed ranching to replace the bison with cattle on the American grasslands. 3

While bison supplied leather for America’s booming clothing industry, the skulls of the animals also provided a key ingredient in fertilizer. This 1870s photograph illustrates the massive number of bison killed for these and other reasons (including sport) in the second half of the nineteenth century. Photograph of a pile of American bison skulls waiting to be ground for fertilizer, 1870s. Wikimedia .

The nearly seventy thousand members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (more commonly called Mormons) who migrated west between 1846 and 1868 were similar to other Americans traveling west on the overland trails. They faced many of the same problems, but unlike most other American migrants, Mormons were fleeing from religious persecution.

Many historians view Mormonism as a “uniquely American faith,” not just because it was founded by Joseph Smith in New York in the 1830s, but because of its optimistic and future-oriented tenets. Mormons believed that Americans were exceptional—chosen by God to spread truth across the world and to build utopia, a New Jerusalem in North America. However, many Americans were suspicious of the Latter-Day Saint movement and its unusual rituals, especially the practice of polygamy, and most Mormons found it difficult to practice their faith in the eastern United States. Thus began a series of migrations in the midnineteenth century, first to Illinois, then Missouri and Nebraska, and finally into Utah Territory.

Once in the west, Mormon settlements served as important supply points for other emigrants heading on to California and Oregon. Brigham Young, the leader of the Church after the death of Joseph Smith, was appointed governor of the Utah Territory by the federal government in 1850. He encouraged Mormon residents of the territory to engage in agricultural pursuits and be cautious of the outsiders who arrived as the mining and railroad industries developed in the region. 4

It was land, ultimately, that drew the most migrants to the West. Family farms were the backbone of the agricultural economy that expanded in the West after the Civil War. In 1862, northerners in Congress passed the Homestead Act, which allowed male citizens (or those who declared their intent to become citizens) to claim federally owned lands in the West. Settlers could head west, choose a 160-acre surveyed section of land, file a claim, and begin “improving” the land by plowing fields, building houses and barns, or digging wells, and, after five years of living on the land, could apply for the official title deed to the land. Hundreds of thousands of Americans used the Homestead Act to acquire land. The treeless plains that had been considered unfit for settlement became the new agricultural mecca for land-hungry Americans. 5

The Homestead Act excluded married women from filing claims because they were considered the legal dependents of their husbands. Some unmarried women filed claims on their own, but single farmers (male or female) were hard-pressed to run a farm and they were a small minority. Most farm households adopted traditional divisions of labor: men worked in the fields and women managed the home and kept the family fed. Both were essential. 6

Migrants sometimes found in homesteads a self-sufficiency denied at home. Second or third sons who did not inherit land in Scandinavia, for instance, founded farm communities in Minnesota, Dakota, and other Midwestern territories in the 1860s. Boosters encouraged emigration by advertising the semiarid Plains as, for instance, “a flowery meadow of great fertility clothed in nutritious grasses, and watered by numerous streams.” 7 Western populations exploded. The Plains were transformed. In 1860, for example, Kansas had about 10,000 farms; in 1880 it had 239,000. Texas saw enormous population growth. The federal government counted 200,000 people in Texas in 1850, 1,600,000 in 1880, and 3,000,000 in 1900, making it the sixth most populous state in the nation.

The “Indian wars,” so mythologized in western folklore, were a series of seemingly sporadic, localized, and often brief engagements between U.S. military forces and various Native American groups. More sustained and equally impactful conflicts were economic and cultural. New patterns of American settlement, railroad construction, and material extraction clashed with the vast and cyclical movement across the Great Plains to hunt buffalo, raid enemies, and trade goods. Thomas Jefferson’s old dream that Indigenous nations might live isolated in the West was, in the face of American expansion, no longer a viable reality. Political, economic, and even humanitarian concerns intensified American efforts to isolate Native Americans on reservations. Although Indian removal had long been a part of federal Indian policy, following the Civil War the U.S. government redoubled its efforts. If treaties and other forms of persistent coercion would not work, federal officials pushed for more drastic measures: after the Civil War, coordinated military action by celebrity Civil War generals such as William Sherman and William Sheridan exploited and exacerbated local conflicts sparked by illegal business ventures and settler incursions. Against the threat of confinement and the extinction of traditional ways of life, Native Americans battled the American army and the encroaching lines of American settlement.

In one of the earliest western engagements, in 1862, while the Civil War still consumed the United States, tensions erupted between Dakota Nation and white settlers in Minnesota and the Dakota Territory. The 1850 U.S. census recorded a white population of about 6,000 in Minnesota; eight years later, when it became a state, it was more than 150,000. 8 The illegal influx of American farmers pushed the Dakota to the breaking point. Hunting became unsustainable and those Dakota who had taken up farming found only poverty. The federal Indian agent refused to disburse promised food. Many starved. Andrew Myrick, a trader at the agency, refused to sell food on credit. “If they are hungry,” he is alleged to have said, “let them eat grass or their own dung.” 9 Then, on August 17, 1862, four young men of the Santees, a Dakota band, killed five white settlers near the Redwood Agency, an American administrative office. In the face of an inevitable American retaliation, and over the protests of many members, the tribe chose war. On the following day, Dakota warriors attacked settlements near the Agency. They killed thirty-one men, women, and children (including Myrick, whose mouth was found filled with grass). They then ambushed a U.S. military detachment at Redwood Ferry, killing twenty-three. The governor of Minnesota called up militia and several thousand Americans waged war against the Indigenous insurgents. Fighting broke out at New Ulm, Fort Ridgely, and Birch Coulee, but the Americans broke Indigenous resistance at the Battle of Wood Lake on September 23, ending the so-called Dakota War. 10

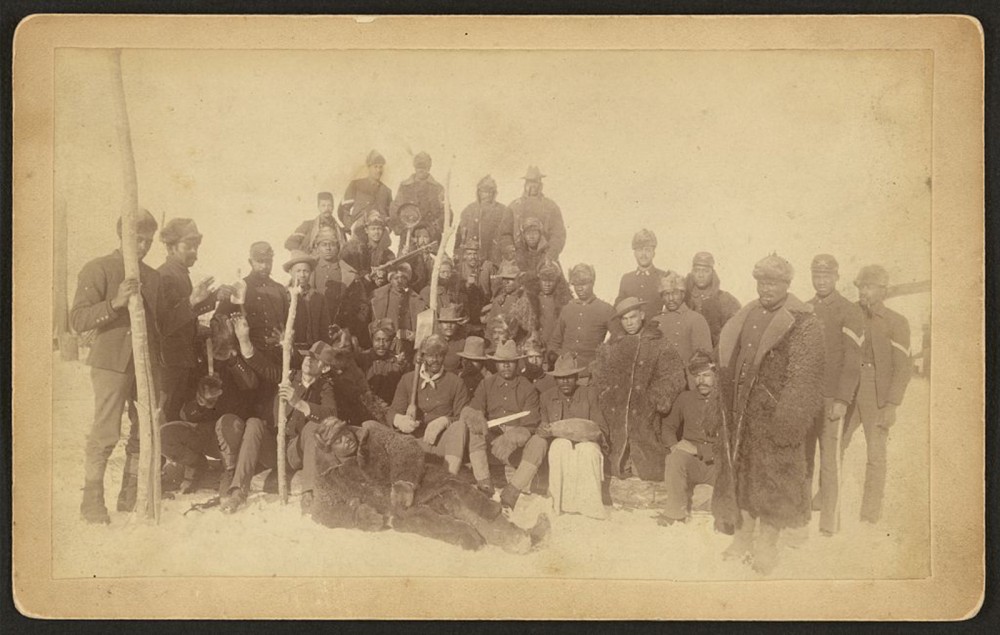

Buffalo Soldiers, the nickname given to African-American cavalrymen by the native Americans they fought, were the first peacetime all-black regiments in the regular United States army. These soldiers regularly confronted racial prejudice from other Army members and civilians but were an essential part of American victories during the Indian Wars of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. “[Buffalo soldiers of the 25th Infantry, some wearing buffalo robes, Ft. Keogh, Montana] / Chr. Barthelmess, photographer, Fort Keogh, Montana,” 1890. Library of Congress .

Farther south, settlers inflamed tensions in Colorado. In 1851, the first Treaty of Fort Laramie had secured right-of-way access for Americans passing through on their way to California and Oregon. But a gold rush in 1858 drew approximately 100,000 white gold seekers, and they demanded new treaties be made with local Indigenous groups to secure land rights in the newly created Colorado Territory. Cheyenne bands splintered over the possibility of signing a new treaty that would confine them to a reservation. Settlers, already wary of raids by powerful groups of Cheyennes, Arapahos, and Comanches, meanwhile read in their local newspapers sensationalist accounts of the uprising in Minnesota. Militia leader John M. Chivington warned settlers in the summer of 1864 that the Cheyenne were dangerous, urged war, and promised a swift military victory. Settlers sparked conflict and sporadic fighting broke out. The aged Cheyenne chief Black Kettle, believing that a peace treaty would be best for his people, traveled to Denver to arrange for peace talks. He and his followers traveled toward Fort Lyon in accordance with government instructions, but on November 29, 1864, Chivington ordered his seven hundred militiamen to move on the Cheyenne camp near Fort Lyon at Sand Creek. The Cheyenne tried to declare their peaceful intentions but Chivington’s militia cut them down. It was a slaughter. Chivington’s men killed two hundred men, women, and children. 11 The Sand Creek Massacre was a national scandal, alternately condemned and applauded.

As settler incursions continued to provoke conflict, Americans pushed for a new “peace policy.” Congress, confronted with these tragedies and further violence, authorized in 1868 the creation of an Indian Peace Commission. The commission’s study of Native Americans decried prior American policy and galvanized support for reformers. After the inauguration of Ulysses S. Grant the following spring, Congress allied with prominent philanthropists to create the Board of Indian Commissioners, a permanent advisory body to oversee Indigenous affairs and prevent the further outbreak of violence. The board effectively Christianized American Indian policy. Much of the reservation system was handed over to Protestant churches, which were tasked with finding agents and missionaries to manage reservation life. Congress hoped that religiously minded men might fare better at creating just assimilation policies and persuading Native Americans to accept them. Historian Francis Paul Prucha believed that this attempt at a new “peace policy . . . might just have properly been labelled the ‘religious policy.’” 12

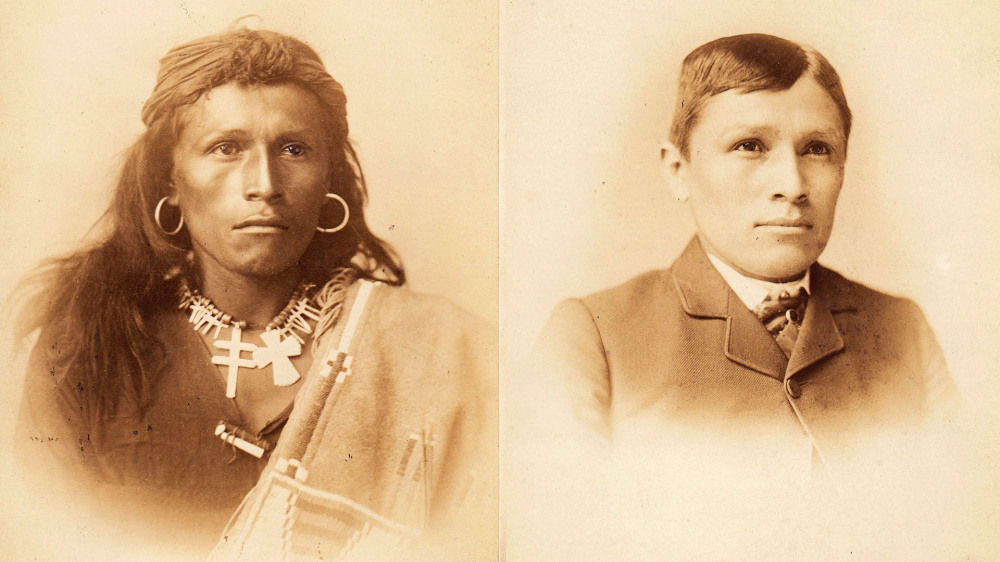

Tom Torlino, a member of the Navajo Nation, entered the Carlisle Indian School, a Native American boarding school founded by the United States government in 1879, on October 21, 1882 and departed on August 28, 1886. Torlino’s student file contained photographs from 1882 and 1885. Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center .

Many female Christian missionaries played a central role in cultural reeducation programs that attempted to not only instill Protestant religion but also impose traditional American gender roles and family structures. They endeavored to replace Indigenous peoples’ tribal social units with small, patriarchal households. Women’s labor became a contentious issue because few tribes divided labor according to the gender norms of middle- and upper-class Americans. Fieldwork, the traditional domain of white males, was primarily performed by Native women, who also usually controlled the products of their labor, if not the land that was worked, giving them status in society as laborers and food providers. For missionaries, the goal was to get Native women to leave the fields and engage in more proper “women’s” work—housework. Christian missionaries performed much as secular federal agents had. Few American agents could meet Native Americans on their own terms. Most Americans viewed Indigenous peoples on reservations as lazy and thought of Indigenous cultures as inferior to their own. The views of J. L. Broaddus, appointed to oversee several small tribes on the Hoopa Valley reservation in California, are illustrative: in his annual report to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs for 1875, he wrote, “The great majority of them are idle, listless, careless, and improvident. They seem to take no thought about provision for the future, and many of them would not work at all if they were not compelled to do so. They would rather live upon the roots and acorns gathered by their women than to work for flour and beef.” 13

If Indigenous peoples could not be forced through kindness to change their ways, most Americans agreed that it was acceptable to use force, which Native groups resisted. In Texas and the Southern Plains, the Comanche, the Kiowa, and their allies had wielded enormous influence. The Comanche in particular controlled huge swaths of territory and raided vast areas, inspiring terror from the Rocky Mountains to the interior of northern Mexico to the Texas Gulf Coast. But after the Civil War, the U.S. military refocused its attention on the Southern Plains.

The American military first sent messengers to the Plains to find the elusive Comanche bands and ask them to come to peace negotiations at Medicine Lodge Creek in the fall of 1867. But terms were muddled: American officials believed that Comanche bands had accepted reservation life, while Comanche leaders believed they were guaranteed vast lands for buffalo hunting. Comanche bands used designated reservation lands as a base from which to collect supplies and federal annuity goods while continuing to hunt, trade, and raid American settlements in Texas.

Confronted with renewed Comanche raiding, particularly by the famed war leader Quanah Parker, the U.S. military finally proclaimed that all Indigenous peoples who were not settled on the reservation by the fall of 1874 would be considered “hostile.” The Red River War began when many Comanche bands refused to resettle and the American military launched expeditions into the Plains to subdue them, culminating in the defeat of the remaining roaming bands in the canyonlands of the Texas Panhandle. Cold and hungry, with their way of life already decimated by soldiers, settlers, cattlemen, and railroads, the last free Comanche bands were moved to the reservation at Fort Sill, in what is now southwestern Oklahoma. 14

On the northern Plains, the Sioux people had yet to fully surrender. Following the military defeats of 1862, many bands had signed treaties with the United States and drifted into the Red Cloud and Spotted Tail agencies to collect rations and annuities, but many continued to resist American encroachment, particularly during Red Cloud’s War, a rare victory for the Plains people that resulted in the Treaty of 1868 and created the Great Sioux Reservation. Then, in 1874, an American expedition to the Black Hills of South Dakota discovered gold. White prospectors flooded the territory. Caring very little about Indigenous rights and very much about getting rich, they brought the Sioux situation again to its breaking point. Aware that U.S. citizens were violating treaty provisions, but unwilling to prevent them from searching for gold, federal officials pressured the western Sioux to sign a new treaty that would transfer control of the Black Hills to the United States while General Philip Sheridan quietly moved U.S. troops into the region. Initial clashes between U.S. troops and Sioux warriors resulted in several Sioux victories that, combined with the visions of Sitting Bull, who had dreamed of an even more triumphant victory, attracted Sioux bands who had already signed treaties but now joined to fight. 15

In late June 1876, a division of the 7th Cavalry Regiment led by Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer was sent up a trail into the Black Hills as an advance guard for a larger force. Custer’s men approached a camp along a river known to the Sioux as Greasy Grass but marked on Custer’s map as Little Bighorn, and they found that the influx of “treaty” Sioux as well as aggrieved Cheyenne and other allies had swelled the population of the village far beyond Custer’s estimation. Custer’s 7th Cavalry was vastly outnumbered, and he and 268 of his men were killed. 16

Custer’s fall shocked the nation. Cries for a swift American response filled the public sphere, and military expeditions were sent out to crush Native resistance. The Sioux splintered off into the wilderness and began a campaign of intermittent resistance but, outnumbered and suffering after a long, hungry winter, Crazy Horse led a band of Oglala Sioux to surrender in May 1877. Other bands gradually followed until finally, in July 1881, Sitting Bull and his followers at last laid down their weapons and came to the reservation. Indigenous powers had been defeated. The Plains, it seemed, had been pacified.